-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Genome-Wide Scan of Ashkenazi Jewish Crohn's Disease Suggests Novel Susceptibility Loci

Crohn's disease (CD) is a complex disorder resulting from the interaction of intestinal microbiota with the host immune system in genetically susceptible individuals. The largest meta-analysis of genome-wide association to date identified 71 CD–susceptibility loci in individuals of European ancestry. An important epidemiological feature of CD is that it is 2–4 times more prevalent among individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) descent compared to non-Jewish Europeans (NJ). To explore genetic variation associated with CD in AJs, we conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) by combining raw genotype data across 10 AJ cohorts consisting of 907 cases and 2,345 controls in the discovery stage, followed up by a replication study in 971 cases and 2,124 controls. We confirmed genome-wide significant associations of 9 known CD loci in AJs and replicated 3 additional loci with strong signal (p<5×10−6). Novel signals detected among AJs were mapped to chromosomes 5q21.1 (rs7705924, combined p = 2×10−8; combined odds ratio OR = 1.48), 2p15 (rs6545946, p = 7×10−9; OR = 1.16), 8q21.11 (rs12677663, p = 2×10−8; OR = 1.15), 10q26.3 (rs10734105, p = 3×10−8; OR = 1.27), and 11q12.1 (rs11229030, p = 8×10−9; OR = 1.15), implicating biologically plausible candidate genes, including RPL7, CPAMD8, PRG2, and PRG3. In all, the 16 replicated and newly discovered loci, in addition to the three coding NOD2 variants, accounted for 11.2% of the total genetic variance for CD risk in the AJ population. This study demonstrates the complementary value of genetic studies in the Ashkenazim.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002559

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002559Summary

Crohn's disease (CD) is a complex disorder resulting from the interaction of intestinal microbiota with the host immune system in genetically susceptible individuals. The largest meta-analysis of genome-wide association to date identified 71 CD–susceptibility loci in individuals of European ancestry. An important epidemiological feature of CD is that it is 2–4 times more prevalent among individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) descent compared to non-Jewish Europeans (NJ). To explore genetic variation associated with CD in AJs, we conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) by combining raw genotype data across 10 AJ cohorts consisting of 907 cases and 2,345 controls in the discovery stage, followed up by a replication study in 971 cases and 2,124 controls. We confirmed genome-wide significant associations of 9 known CD loci in AJs and replicated 3 additional loci with strong signal (p<5×10−6). Novel signals detected among AJs were mapped to chromosomes 5q21.1 (rs7705924, combined p = 2×10−8; combined odds ratio OR = 1.48), 2p15 (rs6545946, p = 7×10−9; OR = 1.16), 8q21.11 (rs12677663, p = 2×10−8; OR = 1.15), 10q26.3 (rs10734105, p = 3×10−8; OR = 1.27), and 11q12.1 (rs11229030, p = 8×10−9; OR = 1.15), implicating biologically plausible candidate genes, including RPL7, CPAMD8, PRG2, and PRG3. In all, the 16 replicated and newly discovered loci, in addition to the three coding NOD2 variants, accounted for 11.2% of the total genetic variance for CD risk in the AJ population. This study demonstrates the complementary value of genetic studies in the Ashkenazim.

Introduction

Ashkenazi Jews (AJs) comprise a single genetic community of individuals of Eastern and Central European descent. Several lines of evidence suggest genetic differences between the Jewish and non-Jewish peoples of Europe (NJ). It has been demonstrated that the genomes of individuals with one to four grandparents of Jewish descent carry an unambiguous signature of their heritage allowing a perfect inference of their Jewish ancestry [1]. When studied separately, Jewish populations represent a series of geographical clusters with each group demonstrating Middle Eastern ancestry and variable admixture with European populations [2], [3]. Moreover, Price et al. [4] have shown that AJ ancestry is one of the major determinants of population structure amongst disease groups of European Americans and can be easily discerned by a small panel of genetic markers.

Genetic differences between Jewish and non-Jewish populations have been detected in the context of multiple monogenic conditions that are more prevalent in AJ populations. More than 25 recessive disease founder alleles have been found to afflict Ashkenazi populations at much elevated frequencies [5], [6] compared to NJ populations, resulting in a higher incidence of rare disorders including Tay Sachs disease, Canavan, Niemann-Pick, Gaucher, and others. Considerably higher frequencies of particular mutations strongly associated with common diseases, such as breast cancer (BRCA1 185delAG) [7] and Parkinson's disease (LRRK2 G2019S) [8] have also been detected in AJ compared to NJ. Moreover, a three-phase genome-wide association study (GWAS) conducted in an AJ population has identified a novel region on 6q22.33 associated with familial breast cancer risk [9].

Crohn's disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease resulting from dysregulated mucosal immune responses to enteric microbiota which arise in genetically susceptible individuals (reviewed in [10]). CD is 2–4 times more prevalent among AJs compared to NJ populations [11], [12]. Association scans in predominantly NJ CD studies have identified 71 susceptibility loci associated with the disease risk including coding polymorphisms at NOD2, IL23R, ATG16L1 and an intergenic region on chromosome 5p13 [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. In our recent work, we showed that genetic risks associated with CD in the AJ population for the 22 most frequently replicated variants were similar to those reported in NJ populations [19] and, therefore, are unlikely to explain the excess disease prevalence in individuals of AJ descent. Although underlying mechanisms responsible for ethnicity-specific differences may include epigenetic and environmental factors, it has been hypothesized that substantially increased risk of CD in AJ versus NJ can be explained through the involvement of yet unknown genetic variants predominantly in this population. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to conduct a comprehensive GWAS to identify AJ-specific loci that predispose to CD, by testing for association in participants of self-identified and genetically verified AJ ancestry across multiple collections of cases and controls.

Results

Confirming Ashkenazi ancestry of study participants

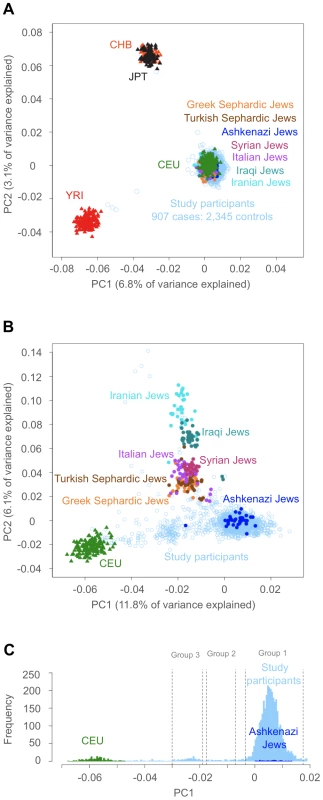

The population under examination in this study is a genetically distinct group in terms of ancestry, thus it was especially important to verify the genetic AJ ancestry of the study participants in the discovery stage. We performed PCA to determine the main axis of variation explaining the study cohort data. Results of the principal component analysis (PCA), plotting the samples with the three continental HapMap reference panels (European; CEU, African; YRI and Asian; CHB and JPT) and seven panels from the Jewish HapMap consortium consisting of one Ashkenazi Jewish, one European Jewish, three Middle Eastern and two Sephardic Jewish panels, are shown on Figure 1A. As expected, the first principal component (PC 1) distinguishes Africans from non-Africans and PC 2 distinguishes East Asians from Africans and individuals of European and Jewish ancestry (Figure 1A). Close examination of within-continent variation was performed by repeating this analysis excluding the CHB, JPT and YRI samples. Here we show that PC 1 distinguished European from Jewish ancestry (Figure 1B) and PC 2 shows a Middle Eastern to European cline of Jewish populations, with the majority of AJ individuals (∼80%) clustering distinctly from other European Jewish populations. Most of the remaining AJ samples (n = ∼500) are intermediate on a PC 1 cline between the AJ cluster and the European (CEU) cluster (Figure 1B). Upon examining the distribution of PC1 values in these samples, three distinct modes were defined; Group 1 (PC1<−0.005), Group 2 (PC1 −0.039 - −0.046) and Group 3 (PC1 −0.036 - −0.019) (Figure 1C). We postulated, based on previous PCA analysis of AJ individuals that groups 2 and 3 might represent individuals with 75% (one non-AJ grandparent) and 50% (one non-AJ parent or two non-AJ grandparents) AJ ancestry, respectively (Table S1). To avoid exclusion of individuals with partial AJ ancestry, we performed association mapping within each group independently to control for admixture effects, and combined the p-values from each group under a meta-analysis design to construct a single test statistic.

Fig. 1. PCA analysis of the study participants.

(A) PCA showing the first (X-axis) and second (Y-axis) eigenvectors plotting all 3,252 study participants (907 CD cases and 2,345 controls) across ∼22 K unlinked SNPs indicated by light blue open circles. Also included and color-coded in the graph are the four HapMap (www.hapmap.org) reference samples as solid triangles; CEPH-Utah (CEU; green), Yoruban-Nigeria (YRI; red), Han Chinese (CHB; orange) and Japanese (JPT; dark grey); and seven Jewish samples from the Jewish Hapmap project [2] as solid circles, consisting of Ashkenazi Jews (AJ; blue), one European (Italian; purple), three Middle Eastern (Syrian; fuchsia, Iraqi; teal and Iranian; turquoise) and two Sephardic Jewish cohorts (Turkey; brown and Greek; orange). (B) The same analysis excluding the YRI and CHB+JPT reference panels. (C) A histogram of PC1 values for study participants (light blue) near the AJ cluster and intermediate between the AJ and CEU clusters. The histogram of PC1 values for the included samples show three distinct modes (Groups 1–3), with AJ reference (blue) and CEU (green) indicated. Genome-wide association mapping of CD in AJ population

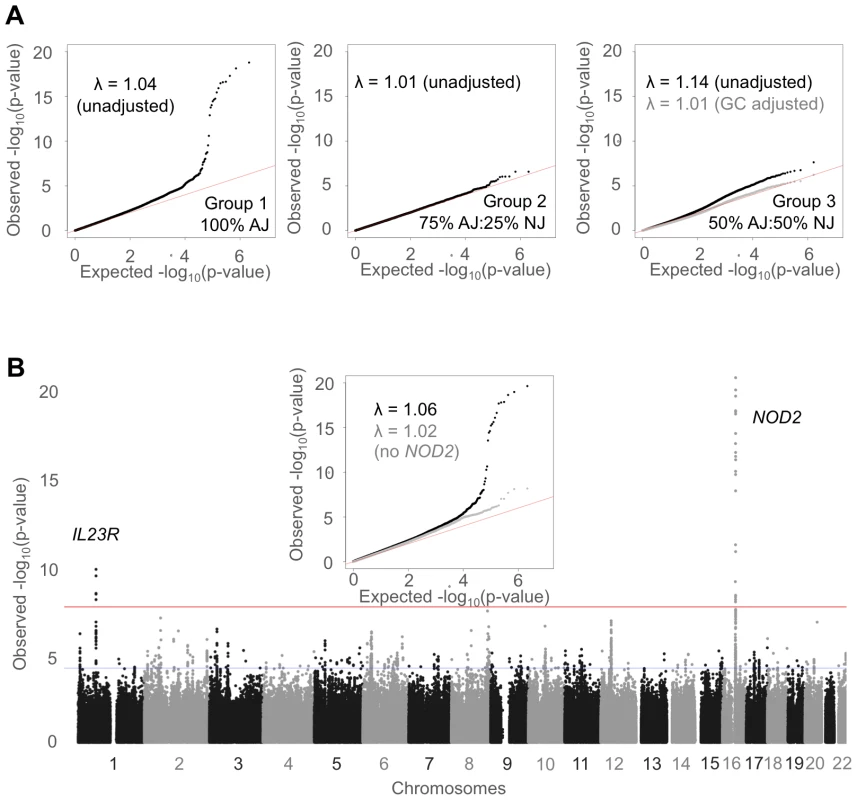

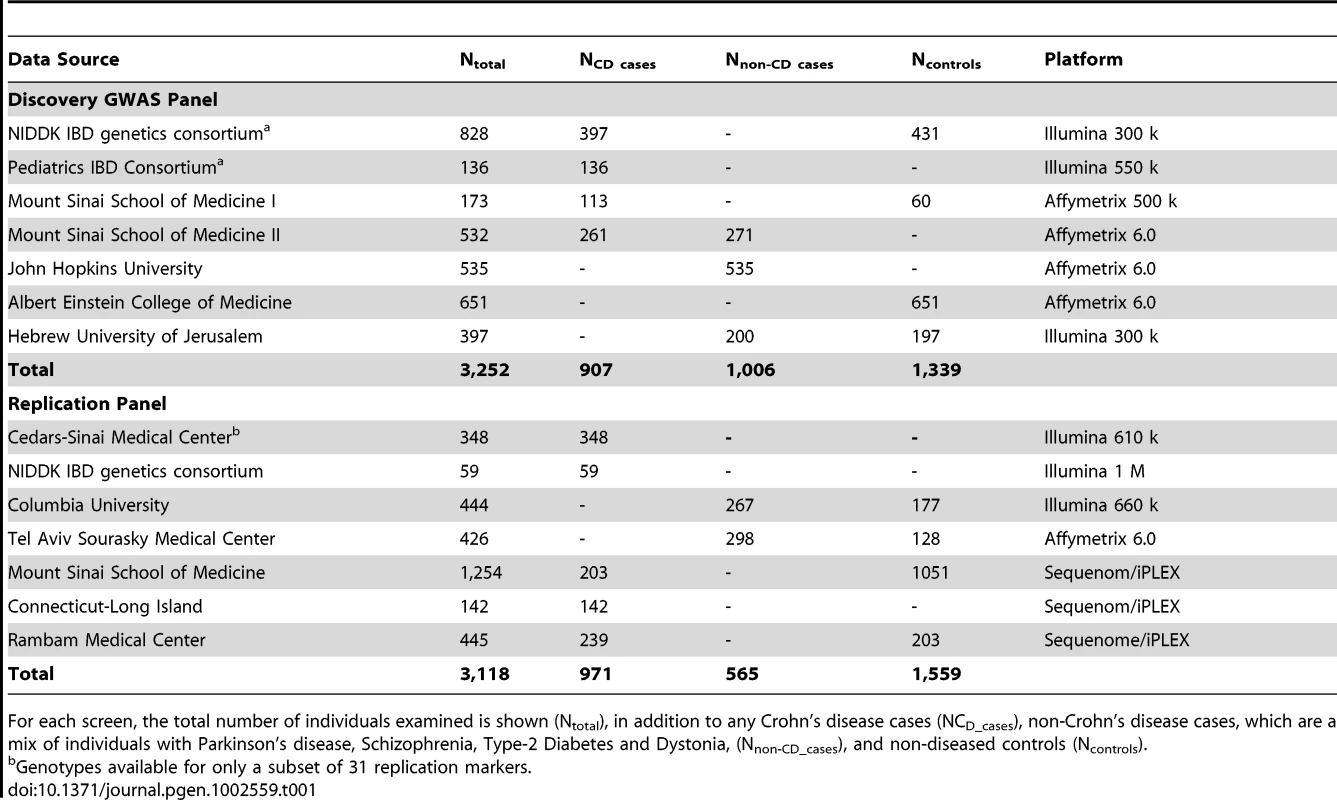

Details of the initial discovery GWAS panels and an independent AJ replication panel as well as the genotyping platforms used are given in Table 1. The final filtered dataset used for association mapping comprised 1,060,934 genotyped and imputed markers across 3,016 individuals (Figure S1). The dataset was divided into three groups according to AJ ancestry (Figure 1C). Figure 2A shows the QQ-plots for 100%, 75% and 50% AJ ancestry groups (groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively). In the case of group 3, the p-values were overinflated (λ = 1.14) and were corrected by genomic control to approximate normality uniform distribution [20]. Figure 2B shows the combined score from all three groups. Two known CD loci exceed the genome-wide significance threshold: NOD2 (16q12; rs2076756; p<2.32×10−20) and IL23R (1p31; rs11209026; p<9.42×10−9) [14], [15], [16], [21]. In addition, 11 other previously reported CD signals at p<10−4 were PUS10/REL (2p16.1; rs13003464; p<1.98×10−7), ATG16L1 (2q37; rs2241880; p<2.88×10−6), intergenic region >300 kb upstream of PTGER4 (5p13.1; rs9292777; 6.92×10−5), IL3 (5q31; rs3091338; p<4.86×10−5), HLA region (6p22.1; rs9258260), an intergenic region on 8q24.13 (p<9.25×10−5), JAK2 (9p24.1;rs2230724; p<8.11×10−5), ZNF365 (10q21; rs1076165; p<1.86×10−5), NKX2-3 (10q24.2; rs11190141; 9.8×10−5), PSMB10 (16q22.1; rs11574514; p<8.05×10−5) and CCL7/CCL2 (17q12; rs3091316; 1.93×10−5) [13], [17]. The full set of SNPs showing association signal at a level of p<10−4 includes 616 SNPs across 137 distinct regions. Finally, since strong signals are prone to skew p-value distribution and can cause over-dispersion, especially at the tail, we assessed the p-value distribution with and without NOD2 SNPs. The signal at these loci persists even after controlling for the strong signal at NOD2 (Figure 2B inset).

Fig. 2. Association mapping of Crohn's disease in Ashkenazi Jews.

(A) QQ-plots of the 100%, 75% and 50% AJ ancestry groups (Groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively). The inflation factors for the p-value distributions are given. For group 3, the p-values were genomic control-adjusted for over-inflation. (B) A Manhattan plot and QQ-plot (inset – in black) of the combined association scores from all three groups. The genome-wide threshold is shown in red and the replication threshold is shown in blue. The QQ-plot also shows association scores from all three groups but with 298 markers around the region of the NOD2 signal on chromosome 16 removed before association mapping (in grey). Tab. 1. Study cohort description.

For each screen, the total number of individuals examined is shown (Ntotal), in addition to any Crohn's disease cases (NCD_cases), non-Crohn's disease cases, which are a mix of individuals with Parkinson's disease, Schizophrenia, Type-2 Diabetes and Dystonia, (Nnon-CD_cases), and non-diseased controls (Ncontrols). Replication studies in independent AJ samples identify five novel regions associated to CD

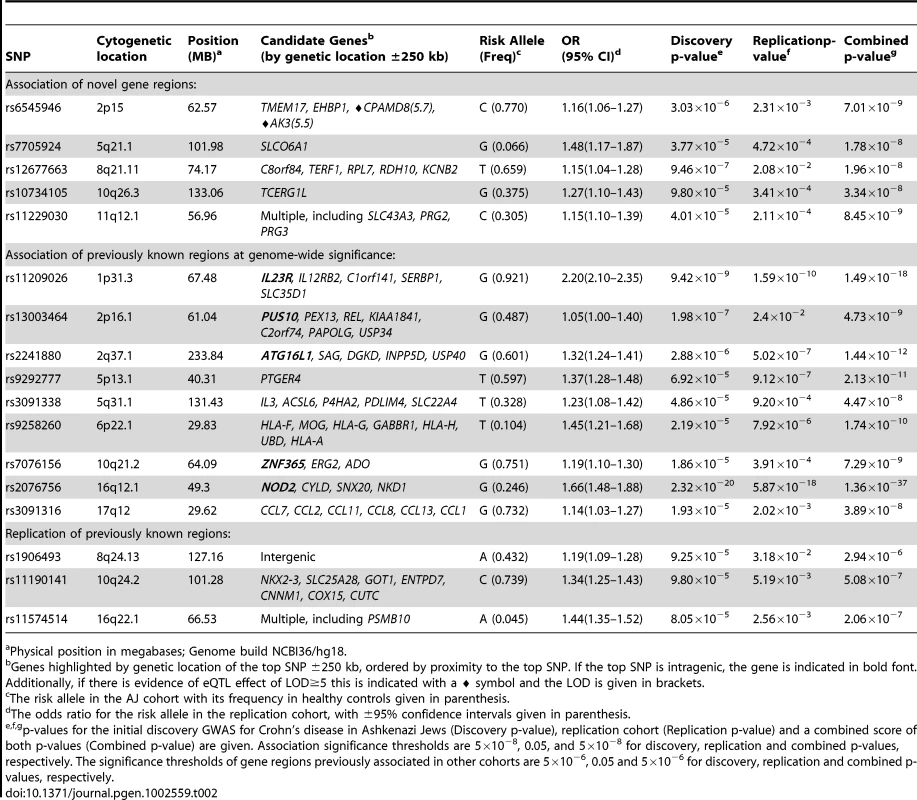

We followed a region-centric strategy for replication. If a single marker exceeded p<1×10−4 in a “signal region” (defined by the furthest up - and down-stream SNP in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the marker, r2>0.2), it was included in the replication dataset. In the cases where a region contained multiple markers with p<1×10−4, 1–7 tag SNPs were selected from the region. The final set of replication markers comprised 175 SNPs across 137 regions, 139 of which were successfully genotyped in the replication dataset (see Table S2). Applying a standard genome-wide significance threshold of 5×10−8 for the combined discovery and replication signals, we observed 21 SNPs that surpassed this threshold in 14 distinct genetic regions (Table 2).

Tab. 2. Regions identified in the Ashkenazi Jewish CD GWAS, replication, and combined association analyses.

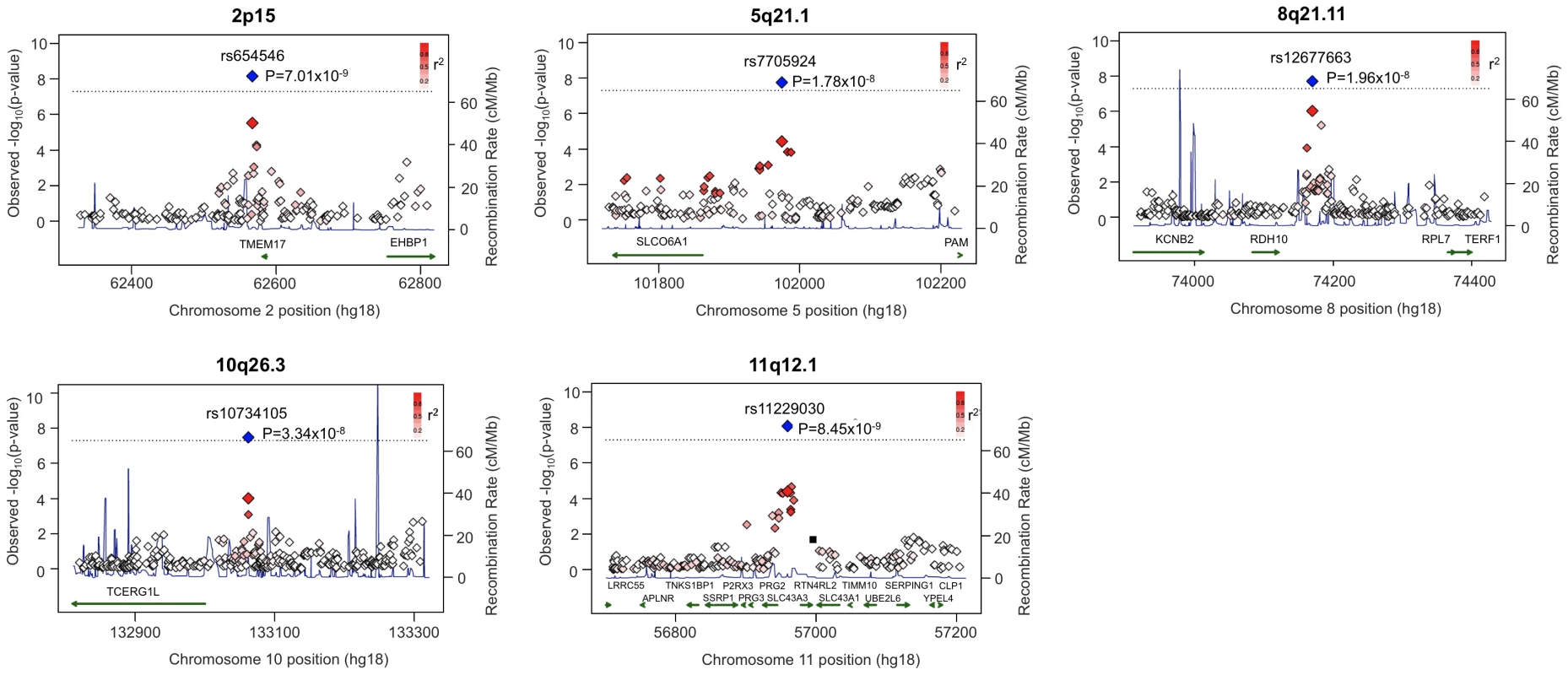

Physical position in megabases; Genome build NCBI36/hg18. As positive controls, we report 9 of the 13 known loci listed in the previous section exceeding our threshold of association in the AJ population, with a further three surpassing our replication threshold for known regions of association to CD, 5×10−6 (Table 2 and Figure S2). Furthermore, novel signals of association in the AJ sample were observed for five regions not previously reported. Regional association plots of all five novel regions are shown in Figure 3 and their risk allele frequencies and odd ratios (ORs) are shown in Table 2. Two of these regions (5q21.1; rs7705924; 1.78×10−8 and 10q26.3; rs10734105; 3.34×10−8) contained just a single gene, SLCO6A1 and TCERG1L, respectively, with moderate effects (OR>1.25). The other three regions, rs6545946 (2p15; 7.01×10−9), rs12677663 (8q21.11; 1.96×10−8) and rs11229030 (11q12.1; 8.45×10−9), each contained multiple candidate genes. Additionally, interrogation of publically available eQTL databases revealed that rs6545946 correlated with both CPAMD8 and AK3 expression [22]. Further investigation of a gap next to the 11q12.1 peak of association detected a previously reported 625 bp copy number variant (CNV) found in 1 Yoruban (YRI) HapMap sample [23], which is ∼50 kb downstream of our top SNP rs11229030. Also, in this region, 17 SNPs were filtered out due to poor imputation quality.

Fig. 3. Regional plots of five novel associations to Crohn's disease in Ashkenazi Jews.

Regional plots of the SNP p-values obtained in the discovery GWAS for a ±250 kb window around each of the 5 novel SNPs. The X-axis shows the chromosome and physical distance (kb), the left Y-axis shows the negative base ten logarithm of the p-value and the right y-axis shows recombination activity (cM/Mb) as a blue line. The chromosomal band is given above each plot. The replication SNP is indicated as a large red diamond, and linkage disequilibrium of surrounding SNPs with the replication SNP is indicated by a scale of intensity of red color filling as shown in the legend at the upper right hand corner of each plot. The combined discovery and replication p-value for the replication SNP is shown in blue, and is annotated with the SNP identifier and combined p-values. The position and location of any copy number variation in the mapping intervals are shown as a black rectangle. Positions, recombination rates and gene annotations are according the NCBI's build 36 (hg 18). Comparison of CD signals found in AJ to NJ European ancestry-derived loci

We examined LD architecture at the five novel regions in AJ and NJ CD cases from the Wellcome Trust GWAS [18] (Figure S3). We found 85 pairs of variants >150 kb apart around the top SNPs having r2>0.2 in AJs compared to one pair in NJs across all 5 loci. Sixty two out of the 85 linked pairs in AJs were detected at 5q21.1 versus 0 pairs in non-AJs.

To examine the established CD risks in AJ populations, we compared the signals in 71 unique susceptibility loci for CD identified in the largest meta-analysis of CD in NJ populations to date [24] to those in our sample (Table S3). We note that 57 susceptibility loci passed quality control in our analysis, of which, 31 surpassed nominal significance and 30/31 showed effects in the same direction in AJ as observed previously (p<6.98×10−4). We selected a subset of these 30 loci for a direct comparison of genetic variance explained at susceptibility loci in NJ and AJ. Assuming similar effect sizes in both populations, we had >80% power to detect variants conferring OR≥1.22 at the nominal significance of 0.05, assuming a minor allele frequency of >20% in healthy controls. At these thresholds, we were powered to examine signals at 12 of the known loci in the AJ sample. Of the 12 loci, 11 passed QC in our discovery panel. Greater than the nominal signal (p<0.05) was observed for 9 of the 11 loci (Table S3), which agreed with our expectation by chance (based on the power for detection, the number of signals that had been expected to attain p<0.05 is 10.15±0.86). Specifically, all 9 loci with >0.85 power to be detected were observed and altogether they explained 4.3% and 3.7% of genetic variance in AJs compared to NJs, respectively (Table S4). In all, with the three coding NOD2 mutations, 11 confirmed SNPs (excluding the NOD2 tagSNP rs2076756), and 5 newly-discovered variants, we can account for 11.2% of genetic contribution for CD in AJs (Table S4).

Discussion

CD has been a forerunner for common-disease genetics, demonstrating dozens of markers associated with disease prevalence in NJ populations. Here, we report the first GWAS for CD in a sizeable increased-risk AJ population. As expected, a significant number of markers previously associated with CD in predominantly non-Jewish European cohorts were also associated with CD risk in the AJ population. That is, of the 57 loci reported in Franke et al. [24] and successfully assayed in our study, we observed nominal signal in same direction for 30 variants. Importantly, five novel loci were identified that attained genome-wide significance.

We observed genome-wide significant association with subsequent replication in a novel region on chromosome 2p15. Evidence of sizable, trans-acting eQTL effects of rs6545946 were detected, which influence CPAMD8 (chromosome 19p13) and AK3 (chromosome 9p24). CPAMD8 belongs to the complement component-3/alpha-2-macroglobulin (A2M) family of proteins involved in innate immunity and damage control. Complement components recognize and eliminate pathogens by leading to direct pathogen injury or by mediating phagocytosis and intracellular killing. CPAMD8 is expressed in a number of human tissues, including the small intestine. In response to immune stimulants, CPAMD8 expression has been shown to be markedly up-regulated in cell culture [25]. AK3, or adenylate kinase, encodes a GTP:ATP phosphotransferase that is found in the mitochondrial matrix [26]. Of interest, a GWAS examining hematologic parameters identified associations to the AK3 region with platelet count and volume [27].

The GWAS and replication samples also showed combined genome-wide significant evidence for association at 8q21.11 that spans a number of genes, including RPL7 and KCNB2. RPL7, ribosomal protein L7, has been established as an autoantigen representing a frequent target for autoantibodies from patients with systemic autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis [28]. The humoral autoimmune response to RPL7 apparently is driven by antigen and is T cell dependent [29]. KCNB2 is a potassium voltage-gated channel expressed in a number of tissues, including gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells [30], [31]. Cardiac left ventricular systolic dimensions [32] and the common migraine is associated to a region that includes KCNB2 [33].

The chromosome 11q12.1 association signal mapped to a broad region that spans multiple genes, including SLC43A3, PGR2 and PRG3. Solute carrier family 43, member 3 (SLC43A3) is a putative transporter identified in a survey of microarray expression databases as having endothelial cell specific expression across multiple organs whose mRNA expression is enriched in macrophages and vascular endothelial cells [34]. Also in the region, PGR2 and PRG3, proteoglycan 2 and 3, are eosinophil granule major basic proteins known as natural killer cell activators [35]. PGR2 is believed to be involved in antiparasitic defense mechanisms as a cytotoxin and helminthotoxin, and in immune hypersensitivity reactions, including allergies and asthma [36], [37]. High levels of the proform of this protein are also present in placenta and pregnancy serum [38]. PGR3 possesses similar cytotoxic and cytostimulatory activities to PRG2. In vitro, PRG3 has been shown to stimulate superoxide production and IL8 release from neutrophils, and histamine and leukotriene C4 release from basophils [39]. Furthermore, a rare copy number variant has been reported in 1 YRI HapMap sample 34 kb downstream of the top SNP [23].

In addition, we observed genome-wide significant evidence for association on chromosome 10q26.3 that was subsequently replicated at rs10734105. This region is devoid of established coding genes and detailed functions of a single nearby gene encoding for transcription elongation regulator 1-like protein (TCERG1L) have not yet been reported. The most significant chromosome 5q21.1 association signal was flanked by SLCO6A1 (solute carrier organic anion transporter family gene).

Notably, none of these novel variants have been identified by the largest CD meta-analysis of individuals of European descent [24], which was sufficiently powered to detect effect sizes reported by the present study. However, we observed substantial differences in LD architecture around the top hits across the 5 novel signals. These regions were enriched in variants >150 kb apart with moderate and high LD (r2>0.2) compared to individuals of European ancestry, which can, at least in part, explain the lack of signal in non-AJs. Also, existence of rare variants in these regions specific to this population cannot be ruled out.

Our data also suggest that refinement of causal alleles may increase present estimates of heritability accounted for by presently identified genetic loci. That is, the top GWAS SNP at the NOD2 locus in AJs appears to explain 1.5% of genetic variance, whereas the three NOD2 coding mutations themselves account for 6.1% (Table S4), which is slightly higher than in NJs (0.8% and 5%, respectively [24]). Due to the historical population bottleneck and subsequent isolation of AJs [40], it is possible that there are population-specific rare variants in the newly discovered regions contributing to CD susceptibility, reflecting allelic heterogeneity. Therefore, resequencing analysis aimed at detecting the population-specific rare variants in these regions may prove to be a more successful approach to identify functional variants associated with the disease. In all, with 19 variants, we can account for 11.2% of genetic contribution for CD in AJs.

This study brings forth some lessons from using a specific, isolated population in a large GWAS. First, as observed in other contexts, self-declared ethnicity is an imperfect indicator of genetic ancestry. Caution must be applied when considering samples purported as part of a genetically distinct population. In this study, we applied a mixed model of association, EMMAX [46], in each group separately (100%, 75%, 50% AJ, Figure 1C), thereby excluding 236 samples from analysis; of note is that among the nine previously established loci which we were powered to identify, we observed more significant evidence for association in seven of these nine loci with this grouped approach, as opposed to using a mixed model of association on the full cohort (data not shown). An additional limitation of a study in an isolated population is the availability of samples. In this case, we collected samples across multiple diseases, and rely on CD being rare enough for most of the individuals to be good controls for this disease. While the reliance on multiple cohorts from various studies exposes our study to concerns of platform-specific and center-specific artifacts, these concerns are shared by many multi-center GWAS published during the last few years. As such studies often exchanged summary statistics for meta-analysis, our study had the advantage of analyzing individual-level data at the same site and controlling their quality uniformly.

The focus on the AJ population highlights the pros and cons of conducting GWAS in a specific, isolated population versus more outbred populations. On the one hand, we observe increased detectability of some known common variants previously discovered in NJ populations in this study. That is, we observed sizable differences in the risk allele frequencies between AJ and NJ controls for some SNPs, including IRGM rs7714584 (16.2% vs. 8.8%) and LRRK2 rs11564258 (5.6% versus 2.5%). While the latter can be associated with the ascertainment bias related to the inclusion of patients with Parkinson's disease as non-disease controls, the former trend was observed previously [19]. On the other, some common variants that confer CD risk in NJ populations, such as PTPN2 and TNFSF18, did not replicate in the AJ panel despite sufficient power. While we assembled the largest sample of CD patients of Ashkenazi descent to date, potential explanations can include limited size, and therefore lack of power. There have been no reported sub-phenotypic differences in Crohn's disease comparing Jewish and non-Jewish cohorts. Yet, it is quite possible that different gene-environment interactions could account for the distinct genetic loci identified. In addition, our study design might have overlooked joint disease loci as many of our controls were ascertained for several complex disorders. Yet, our results follow observations in other isolated populations [41], [42] and delineate the distinct vs. shared repertoires of CD causal variants in AJs vs. NJs, in addition to population differences in patterns of LD between the causal variant and the detected marker. Resolution of the source of these differences may become available through high throughput sequencing in such samples.

Finally, looking ahead, the diversification of the population studied in SNP-based association studies is likely to become even more important with the current transition to sequencing. Population genetics theory suggests that repertoires of rare, recently-arising alleles would differ more between distinct and isolated groups. This promises increased value for isolated populations for sequencing studies that aim at dissecting the genetics of complex diseases.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all participating institutions, including the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York University, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Yale University, University of Pittsburgh, Johns Hopkins University, University of Toronto, Columbia University, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Rambam Medical Center, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and North Shore University Hospital-Long Island Jewish Medical Center. All patients provided written informed consent (in English or Hebrew) for the collection of samples and subsequent analysis.

Sample collection

Participants in this study were ascertained from 11 different centers in the United States or Canada (New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, New Haven, Baltimore and Toronto) and Israel (Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem). In total, 6,370 individuals who self-identified as AJ participated in the study. Blood samples were taken with informed consent for DNA extraction. Standard criteria that were used for the diagnosis of Crohn's disease (CD) at each center included the characteristic symptoms of chronic duration and objective validation, including endoscopic, radiologic and/or pathologic confirmation [43].

The initial discovery GWAS analysis combined raw genotype data obtained from genome-wide screening arrays across five studies. The combined discovery AJ GWAS sample consisted of 907 CD cases and 2,345 “controls”, where the control population was made up of individuals ascertained as non-Crohn's disease (non-CD) cases (AJ individuals with Parkinson's disease, Schizophrenia, Type-2 Diabetes and Dystonia) or AJ individuals ascertained as non-diseased controls (1,006 and 1,339, respectively) (Table 1).

An independent AJ replication sample was used to validate findings from the discovery GWAS. These included samples that had been genotyped both on large-scale platforms and on custom arrays. The final replication cohort consisted of 623 CD cases and 2,124 controls of AJ descent (565 and 1,559 non-CD cases and non-disease controls, respectively). For a subset of 31 replication markers, we included an extra 348 AJ cases genotyped using the Illumina 610 k array. Details of all cases and controls genotyped and the genotyping platforms used are given in Table 1.

Quality control (QC) measures for combining multiple genome-scale datasets

We devised a strategy to combine the raw genotypes from nine separate genome-scale datasets of variable size (59–1,067 individuals) and case:control composition, that were genotyped across several different platforms (Illumina 300 k, 500 k, 660 k and 1 M and Affymetrix 500 k and 6.0) (see Text S1 for details). All of the analyses were performed in PLINK [44]. The combined analysis QC pipeline is shown in Figure S1.

AJ ancestry verification

PCA was conducted with smartpca software [45] using the intersection of markers typed on all Illumina and Affymetrix platforms in the combined dataset. We trained a coordinate system across the ∼22 K unlinked SNPs in the sample, including the three continental Hapmap populations (Yoruban (YRI, n = 167), combined Han Chinese and Japanese (CHB, n = 84 and JPT, n = 86) and European (CEU, n = 164)) and populations from the Jewish Hapmap [2] of Middle Eastern Jews (Iraqi (n = 40), Iranian (n = 32) and Syrian Jews (n = 25)), and European origin Jews (Italian (n = 39), Ashkenazi (n = 35) and Sephardic Jews from Greece (n = 44) and Turkey (n = 34)) (Figure 1A). The analysis was repeated excluding the YRI, CHB and JPT samples. Ancestry for all participants in the study was assessed by PCA projection of their genotypes onto coordinates derived from training on the reference panels. Individuals that clustered distinctly with the Ashkenazi reference panel were deemed to have 100% AJ ancestry (group 1) (Figure 1B). In addition, two other groups of individuals that were intermediate between the Ashkenazi and CEU reference panel clusters were included in the subsequent analysis; individuals with 75% AJ:25% European ancestry and 50% AJ:50% NJ, groups 2 and 3, respectively (Figure 1C). Samples that fell outside group 1–3 modes as determined by PCA analysis, were excluded from the study (n = 236) (Table S1 and Text S1).

Constructing an AJ reference panel

Due to concerns over poor quality for imputed genotypes in AJ samples using any of the standard HapMap reference panels, we constructed a population-specific AJ reference panel comprised of 100 AJ individuals who had been typed on both the Affymetrix 6.0 and Illumina Omni1 platforms (see Figure S4 and Text S1).

Discovery GWAS

After cleaning and pruning for ancestry, the discovery GWAS comprised a total of 2,994 participants, 737 CD cases and 2,257 controls. The discovery GWAS population was divided according to AJ ancestry groups (Figure 1C). The final counts of CD cases/controls in each group were: group 1 (100% AJ) 632/2,107, group 2 (75% AJ) 36/38 and group 3 (50% AJ) 69/212.

AJ populations are known to exhibit a high degree of cryptic relatedness relative to outbred populations [5], therefore we selected a mixed-model method for association, EMMAX, that could account for any residual substructure of the AJ population [46]. We tested for association to CD in each group separately. To test for over-dispersion in the presence of strong effects, we repeated the analysis excluding the top 7 NOD2 SNPs. Any over-inflation of the p-value distributions was adjusted by genomic control to approximate normality uniform p-value distribution [20]. P-values were combined across the three groups using METAL [47] (Text S1).

Replication

A total of 175 markers were selected for replication (Table S2). The replication dataset consisted of participants with (a) confirmed AJ ancestry genotyped on genome-scale Affymetrix and Illumina platforms from QC-filtered cohorts which had not been included in the discovery GWAS (n = 929) and (b) self-reported AJ ancestry genotyped on custom Sequenom iPlex arrays (n = 1,841) (Table 1). For a subset of replication markers (n = 31), we included additional set (c) of CD cases with AJ ancestry identified by PCA and genotyped on the Illumina 610 k platform (n = 348) (Table 1).

The direction of effect of markers surpassing nominal significance in the replication dataset was compared between both the discovery and replication datasets and markers that had opposite effects were excluded. The one-tailed p-value of replicating markers was then combined with the discovery p-value using Fisher's combined p-value method to produce the per-SNP combined score.

Comparison to known European ancestry hits

Risk alleles and direction of effect were compared in both NJ and AJ samples for concordance. Power calculations were performed using the Genetic Power Calculator [48]. We also compared LD architecture 250 kb upstream and downstream of the novel hits between AJs and NJs using 1,748 CD cases of European ancestry from the Wellcome Trust GWAS [18] by assessing the number of SNP pairs located far apart with various levels of linkage disequilibrium. Fraction of genetic variance explained by the top risk alleles was assessed using the liability threshold model of Risch [49] considering contributions to be additive. The calculations were based on a prevalence of Crohn's disease in AJs of 1 per 100. For the coding NOD2 variants, we used previously reported frequencies and effect sizes [19].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. NeedACKasperaviciuteDCirulliETGoldsteinDB 2009 A genome-wide genetic signature of Jewish ancestry perfectly separates individuals with and without full Jewish ancestry in a large random sample of European Americans. Genome Biol 10 R7

2. AtzmonGHaoLPe'erIVelezCPearlmanA 2010 Abraham's Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora Populations Comprise Distinct Genetic Clusters with Shared Middle Eastern Ancestry. Am J Hum Genet

3. BeharDMYunusbayevBMetspaluMMetspaluERossetS 2010 The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people. Nature 466 238 242

4. PriceALButlerJPattersonNCapelliCPascaliVL 2008 Discerning the ancestry of European Americans in genetic association studies. PLoS Genet 4 e236 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030236

5. OstrerH 2001 A genetic profile of contemporary Jewish populations. Nat Rev Genet 2 891 898

6. RischNTangHKatzensteinHEksteinJ 2003 Geographic distribution of disease mutations in the Ashkenazi Jewish population supports genetic drift over selection. Am J Hum Genet 72 812 822

7. JohnEMMironAGongGPhippsAIFelbergA 2007 Prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1 mutation carriers in 5 US racial/ethnic groups. JAMA 298 2869 2876

8. ThalerAAshEGan-OrZOrr-UrtregerAGiladiN 2009 The LRRK2 G2019S mutation as the cause of Parkinson's disease in Ashkenazi Jews. J Neural Transm 116 1473 1482

9. GoldBKirchhoffTStefanovSLautenbergerJVialeA 2008 Genome-wide association study provides evidence for a breast cancer risk locus at 6q22.33. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 4340 4345

10. AbrahamCChoJH 2009 Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 361 2066 2078

11. YangHMcElreeCRothMPShanahanFTarganSR 1993 Familial empirical risks for inflammatory bowel disease: differences between Jews and non-Jews. Gut 34 517 524

12. RotterJIYangHShohatT 1992 Genetic complexities of inflammatory bowel disease and its distribution among the Jewish people. Bonne-TamirBAdamA Genetic diversity among Jews: disease and markers at the DNA level Oxford Oxford University Press 395 411

13. BarrettJCHansoulSNicolaeDLChoJHDuerrRH 2008 Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease. Nat Genet 40 955 962

14. DuerrRHTaylorKDBrantSRRiouxJDSilverbergMS 2006 A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science 314 1461 1463

15. RiouxJDXavierRJTaylorKDSilverbergMSGoyetteP 2007 Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet 39 596 604

16. LibioulleCLouisEHansoulSSandorCFarnirF 2007 Novel Crohn disease locus identified by genome-wide association maps to a gene desert on 5p13.1 and modulates expression of PTGER4. PLoS Genet 3 e58 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030058

17. ParkesMBarrettJCPrescottNJTremellingMAndersonCA 2007 Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet 39 830 832

18. ConsortiumWTCC 2007 Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature 447 661 678

19. PeterIMitchellAAOzeliusLErazoMHuJ 2011 Evaluation of 22 genetic variants with Crohn's Disease risk in the Ashkenazi Jewish population: a case-control study. BMC Med Genet 12 63

20. DevlinBRoederK 1999 Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics 55 997 1004

21. FrankeAHampeJRosenstielPBeckerCWagnerF 2007 Systematic association mapping identifies NELL1 as a novel IBD disease gene. PLoS ONE 2 e691 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000691

22. DixonALLiangLMoffattMFChenWHeathS 2007 A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat Genet 39 1202 1207

23. ConradDFPintoDRedonRFeukLGokcumenO 2010 Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature 464 704 712

24. FrankeAMcGovernDPBarrettJCWangKRadford-SmithGL 2010 Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet 42 1118 1125

25. LiZFWuXHEngvallE 2004 Identification and characterization of CPAMD8, a novel member of the complement 3/alpha2-macroglobulin family with a C-terminal Kazal domain. Genomics 83 1083 1093

26. NomaTFujisawaKYamashiroYShinoharaMNakazawaA 2001 Structure and expression of human mitochondrial adenylate kinase targeted to the mitochondrial matrix. Biochem J 358 225 232

27. SoranzoNSpectorTDManginoMKuhnelBRendonA 2009 A genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 22 loci associated with eight hematological parameters in the HaemGen consortium. Nat Genet 41 1182 1190

28. von MikeczAHemmerichPPeterHHKrawinkelU 1994 Characterization of eukaryotic protein L7 as a novel autoantigen which frequently elicits an immune response in patients suffering from systemic autoimmune disease. Immunobiology 192 137 154

29. DonauerJWochnerMWitteEPeterHHSchlesierM 1999 Autoreactive human T cell lines recognizing ribosomal protein L7. Int Immunol 11 125 132

30. WeiACovarrubiasMButlerABakerKPakM 1990 K+ current diversity is produced by an extended gene family conserved in Drosophila and mouse. Science 248 599 603

31. SchmalzFKinsellaJKohSDVogalisFSchneiderA 1998 Molecular identification of a component of delayed rectifier current in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. Am J Physiol 274 G901 911

32. VasanRSLarsonMGAragamJWangTJMitchellGF 2007 Genome-wide association of echocardiographic dimensions, brachial artery endothelial function and treadmill exercise responses in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet 8 Suppl 1 S2

33. NyholtDRLaForgeKSKallelaMAlakurttiKAnttilaV 2008 A high-density association screen of 155 ion transport genes for involvement with common migraine. Hum Mol Genet 17 3318 3331

34. WallgardELarssonEHeLHellstromMArmulikA 2008 Identification of a core set of 58 gene transcripts with broad and specific expression in the microvasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28 1469 1476

35. YoshimatsuKOhyaYShikataYSetoTHasegawaY 1992 Purification and cDNA cloning of a novel factor produced by a human T-cell hybridoma: sequence homology with animal lectins. Mol Immunol 29 537 546

36. FujisawaTKephartGMGrayBHGleichGJ 1990 The neutrophil and chronic allergic inflammation. Immunochemical localization of neutrophil elastase. Am Rev Respir Dis 141 689 697

37. FrigasEMotojimaSGleichGJ 1991 The eosinophilic injury to the mucosa of the airways in the pathogenesis of bronchial asthma. Eur Respir J Suppl 13 123s 135s

38. OvergaardMTHaaningJBoldtHBOlsenIMLaursenLS 2000 Expression of recombinant human pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A and identification of the proform of eosinophil major basic protein as its physiological inhibitor. J Biol Chem 275 31128 31133

39. MaciasMPWelchKCDenzlerKLLarsonKALeeNA 2000 Identification of a new murine eosinophil major basic protein (mMBP) gene: cloning and characterization of mMBP-2. J Leukoc Biol 67 567 576

40. BeharDMGarriganDKaplanMEMobasherZRosengartenD 2004 Contrasting patterns of Y chromosome variation in Ashkenazi Jewish and host non-Jewish European populations. Hum Genet 114 354 365

41. BonnenPELoweJKAltshulerDMBreslowJLStoffelM 2010 European admixture on the Micronesian island of Kosrae: lessons from complete genetic information. Eur J Hum Genet 18 309 316

42. Van HoutCVLevinAMRampersaudEShenHO'ConnellJR 2010 Extent and distribution of linkage disequilibrium in the Old Order Amish. Genet Epidemiol 34 146 150

43. NikolausSSchreiberS 2007 Diagnostics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 133 1670 1689

44. PurcellSNealeBTodd-BrownKThomasLFerreiraMA 2007 PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81 559 575

45. PriceALPattersonNJPlengeRMWeinblattMEShadickNA 2006 Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 38 904 909

46. KangHMSulJHServiceSKZaitlenNAKongSY 2010 Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 42 348 354

47. WillerCJLiYAbecasisGR 2010 METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26 2190 2191

48. PurcellSChernySSShamPC 2003 Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics 19 149 150

49. RischNJ 2000 Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature 405 847 856

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Physiological Notch Signaling Maintains Bone Homeostasis via RBPjk and Hey Upstream of NFATc1Článek Intronic -Regulatory Modules Mediate Tissue-Specific and Microbial Control of / TranscriptionČlánek Probing the Informational and Regulatory Plasticity of a Transcription Factor DNA–Binding DomainČlánek Repression of Germline RNAi Pathways in Somatic Cells by Retinoblastoma Pathway Chromatin ComplexesČlánek An Alu Element–Associated Hypermethylation Variant of the Gene Is Associated with Childhood ObesityČlánek Three Essential Ribonucleases—RNase Y, J1, and III—Control the Abundance of a Majority of mRNAsČlánek Genomic Tools for Evolution and Conservation in the Chimpanzee: Is a Genetically Distinct Population

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 3

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Comprehensive Research Synopsis and Systematic Meta-Analyses in Parkinson's Disease Genetics: The PDGene Database

- Genomic Analysis of the Hydrocarbon-Producing, Cellulolytic, Endophytic Fungus

- Networks of Neuronal Genes Affected by Common and Rare Variants in Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Akirin Links Twist-Regulated Transcription with the Brahma Chromatin Remodeling Complex during Embryogenesis

- Too Much Cleavage of Cyclin E Promotes Breast Tumorigenesis

- Imprinted Genes … and the Number Is?

- Genetic Architecture of Highly Complex Chemical Resistance Traits across Four Yeast Strains

- Exploring the Complexity of the HIV-1 Fitness Landscape

- MNS1 Is Essential for Spermiogenesis and Motile Ciliary Functions in Mice

- A Fundamental Regulatory Mechanism Operating through OmpR and DNA Topology Controls Expression of Pathogenicity Islands SPI-1 and SPI-2

- Evidence for Positive Selection on a Number of MicroRNA Regulatory Interactions during Recent Human Evolution

- Variation in Modifies Risk of Neonatal Intestinal Obstruction in Cystic Fibrosis

- PIF4–Mediated Activation of Expression Integrates Temperature into the Auxin Pathway in Regulating Hypocotyl Growth

- Critical Evaluation of Imprinted Gene Expression by RNA–Seq: A New Perspective

- A Meta-Analysis and Genome-Wide Association Study of Platelet Count and Mean Platelet Volume in African Americans

- Mouse Genetics Suggests Cell-Context Dependency for Myc-Regulated Metabolic Enzymes during Tumorigenesis

- Transcriptional Control in Cardiac Progenitors: Tbx1 Interacts with the BAF Chromatin Remodeling Complex and Regulates

- Synthetic Lethality of Cohesins with PARPs and Replication Fork Mediators

- APOBEC3G-Induced Hypermutation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Is Typically a Discrete “All or Nothing” Phenomenon

- Interpreting Meta-Analyses of Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Error-Prone ZW Pairing and No Evidence for Meiotic Sex Chromosome Inactivation in the Chicken Germ Line

- -Dependent Chemosensory Functions Contribute to Courtship Behavior in

- Diverse Forms of Splicing Are Part of an Evolving Autoregulatory Circuit

- Phenotypic Plasticity of the Drosophila Transcriptome

- Physiological Notch Signaling Maintains Bone Homeostasis via RBPjk and Hey Upstream of NFATc1

- Precocious Metamorphosis in the Juvenile Hormone–Deficient Mutant of the Silkworm,

- Igf1r Signaling Is Indispensable for Preimplantation Development and Is Activated via a Novel Function of E-cadherin

- Accurate Prediction of Inducible Transcription Factor Binding Intensities In Vivo

- Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Alters a Pathway in Strongly Resembling That of Bile Acid Biosynthesis and Secretion in Vertebrates

- Mammalian Neurogenesis Requires Treacle-Plk1 for Precise Control of Spindle Orientation, Mitotic Progression, and Maintenance of Neural Progenitor Cells

- Tcf7 Is an Important Regulator of the Switch of Self-Renewal and Differentiation in a Multipotential Hematopoietic Cell Line

- REST–Mediated Recruitment of Polycomb Repressor Complexes in Mammalian Cells

- Intronic -Regulatory Modules Mediate Tissue-Specific and Microbial Control of / Transcription

- Age-Dependent Brain Gene Expression and Copy Number Anomalies in Autism Suggest Distinct Pathological Processes at Young Versus Mature Ages

- A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Variants Underlying the Shade Avoidance Response

- -by- Regulatory Divergence Causes the Asymmetric Lethal Effects of an Ancestral Hybrid Incompatibility Gene

- Genome-Wide Association and Functional Follow-Up Reveals New Loci for Kidney Function

- A Natural System of Chromosome Transfer in

- Cell Size and the Initiation of DNA Replication in Bacteria

- Probing the Informational and Regulatory Plasticity of a Transcription Factor DNA–Binding Domain

- Repression of Germline RNAi Pathways in Somatic Cells by Retinoblastoma Pathway Chromatin Complexes

- Temporal Transcriptional Profiling of Somatic and Germ Cells Reveals Biased Lineage Priming of Sexual Fate in the Fetal Mouse Gonad

- Rapid Analysis of Genome Rearrangements by Multiplex Ligation–Dependent Probe Amplification

- Metabolic Profiling of a Mapping Population Exposes New Insights in the Regulation of Seed Metabolism and Seed, Fruit, and Plant Relations

- The Atypical Calpains: Evolutionary Analyses and Roles in Cellular Degeneration

- The Silkworm Coming of Age—Early

- Development of a Panel of Genome-Wide Ancestry Informative Markers to Study Admixture Throughout the Americas

- Balanced Codon Usage Optimizes Eukaryotic Translational Efficiency

- The Min System and Nucleoid Occlusion Are Not Required for Identifying the Division Site in but Ensure Its Efficient Utilization

- Neurobeachin, a Regulator of Synaptic Protein Targeting, Is Associated with Body Fat Mass and Feeding Behavior in Mice and Body-Mass Index in Humans

- Statistical Analysis of Readthrough Levels for Nonsense Mutations in Mammalian Cells Reveals a Major Determinant of Response to Gentamicin

- Gene Reactivation by 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine–Induced Demethylation Requires SRCAP–Mediated H2A.Z Insertion to Establish Nucleosome Depleted Regions

- The miR-35-41 Family of MicroRNAs Regulates RNAi Sensitivity in

- Genetic Basis of Hidden Phenotypic Variation Revealed by Increased Translational Readthrough in Yeast

- An Alu Element–Associated Hypermethylation Variant of the Gene Is Associated with Childhood Obesity

- Modelling Human Regulatory Variation in Mouse: Finding the Function in Genome-Wide Association Studies and Whole-Genome Sequencing

- Novel Loci for Adiponectin Levels and Their Influence on Type 2 Diabetes and Metabolic Traits: A Multi-Ethnic Meta-Analysis of 45,891 Individuals

- Polycomb-Like 3 Promotes Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Binding to CpG Islands and Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal

- Insulin/IGF-1 and Hypoxia Signaling Act in Concert to Regulate Iron Homeostasis in

- EMF1 and PRC2 Cooperate to Repress Key Regulators of Arabidopsis Development

- Three Essential Ribonucleases—RNase Y, J1, and III—Control the Abundance of a Majority of mRNAs

- Contrasted Patterns of Molecular Evolution in Dominant and Recessive Self-Incompatibility Haplotypes in

- A Machine Learning Approach for Identifying Novel Cell Type–Specific Transcriptional Regulators of Myogenesis

- Genomic Tools for Evolution and Conservation in the Chimpanzee: Is a Genetically Distinct Population

- Nos2 Inactivation Promotes the Development of Medulloblastoma in Mice by Deregulation of Gap43–Dependent Granule Cell Precursor Migration

- Intracranial Aneurysm Risk Locus 5q23.2 Is Associated with Elevated Systolic Blood Pressure

- Heritability and Genetic Correlations Explained by Common SNPs for Metabolic Syndrome Traits

- A Genome-Wide Association Study of Nephrolithiasis in the Japanese Population Identifies Novel Susceptible Loci at 5q35.3, 7p14.3, and 13q14.1

- DNA Damage in Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome Cells Leads to PARP Hyperactivation and Increased Oxidative Stress

- DNA Resection at Chromosome Breaks Promotes Genome Stability by Constraining Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination

- Genetic Analysis of Floral Symmetry in Van Gogh's Sunflowers Reveals Independent Recruitment of Genes in the Asteraceae

- A Splice Site Variant in the Bovine Gene Compromises Growth and Regulation of the Inflammatory Response

- Promoter Nucleosome Organization Shapes the Evolution of Gene Expression

- The Nucleoside Diphosphate Kinase Gene Acts as Quantitative Trait Locus Promoting Non-Mendelian Inheritance

- The Ciliogenic Transcription Factor RFX3 Regulates Early Midline Distribution of Guidepost Neurons Required for Corpus Callosum Development

- Phosphorylation of the RNA–Binding Protein HOW by MAPK/ERK Enhances Its Dimerization and Activity

- A Genome-Wide Scan of Ashkenazi Jewish Crohn's Disease Suggests Novel Susceptibility Loci

- Parkinson's Disease–Associated Kinase PINK1 Regulates Miro Protein Level and Axonal Transport of Mitochondria

- LMW-E/CDK2 Deregulates Acinar Morphogenesis, Induces Tumorigenesis, and Associates with the Activated b-Raf-ERK1/2-mTOR Pathway in Breast Cancer Patients

- Mapping the Hsp90 Genetic Interaction Network in Reveals Environmental Contingency and Rewired Circuitry

- Autoregulation of the Noncoding RNA Gene

- The Human Pancreatic Islet Transcriptome: Expression of Candidate Genes for Type 1 Diabetes and the Impact of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

- Spo0A∼P Imposes a Temporal Gate for the Bimodal Expression of Competence in

- Antagonistic Regulation of Apoptosis and Differentiation by the Cut Transcription Factor Represents a Tumor-Suppressing Mechanism in

- A Downstream CpG Island Controls Transcript Initiation and Elongation and the Methylation State of the Imprinted Macro ncRNA Promoter

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- PIF4–Mediated Activation of Expression Integrates Temperature into the Auxin Pathway in Regulating Hypocotyl Growth

- Metabolic Profiling of a Mapping Population Exposes New Insights in the Regulation of Seed Metabolism and Seed, Fruit, and Plant Relations

- A Splice Site Variant in the Bovine Gene Compromises Growth and Regulation of the Inflammatory Response

- Comprehensive Research Synopsis and Systematic Meta-Analyses in Parkinson's Disease Genetics: The PDGene Database

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání