-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Small RNA Rli27 Regulates a Cell Wall Protein inside Eukaryotic Cells by Targeting a Long 5′-UTR Variant

Listeria monocytogenes has evolved to adapt to numerous environments, including the intracellular niche of eukaryotic cells. Small RNAs (sRNA) play important regulatory roles in changing environments, and are thus predicted to modulate L. monocytogenes adaption to the intracellular lifestyle. This study shows how the regulatory activity of an sRNA on a defined target is restricted to bacteria in the intracellular infection phase. This regulation relies on a long (234-nucleotide) 5′-UTR that bears the sRNA-binding site present in a transcript variant that is upregulated by intracellular L. monocytogenes. The concomitant increase in both the target transcript containing the long 5′-UTR and the sRNA, which is postulated to facilitate opening of the Shine-Dalgarno site, culminates in markedly higher protein levels in intracellular bacteria. The limited amounts of both the target and the regulator in extracellular bacteria ensure that production of this bacterial protein is confined mainly to the host rather than the non-host environment.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004765

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004765Summary

Listeria monocytogenes has evolved to adapt to numerous environments, including the intracellular niche of eukaryotic cells. Small RNAs (sRNA) play important regulatory roles in changing environments, and are thus predicted to modulate L. monocytogenes adaption to the intracellular lifestyle. This study shows how the regulatory activity of an sRNA on a defined target is restricted to bacteria in the intracellular infection phase. This regulation relies on a long (234-nucleotide) 5′-UTR that bears the sRNA-binding site present in a transcript variant that is upregulated by intracellular L. monocytogenes. The concomitant increase in both the target transcript containing the long 5′-UTR and the sRNA, which is postulated to facilitate opening of the Shine-Dalgarno site, culminates in markedly higher protein levels in intracellular bacteria. The limited amounts of both the target and the regulator in extracellular bacteria ensure that production of this bacterial protein is confined mainly to the host rather than the non-host environment.

Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes is a facultative intracellular food-borne bacterium responsible for serious clinical manifestations including febrile gastroenteritis, meningitis, encephalitis and maternofetal infections in humans and livestock, with an estimated fatality rate of 20–30% of infected individuals [1]–[3]. Following ingestion, L. monocytogenes is able to cross the intestinal, blood-brain and placental barriers. The bacterium expresses a number of virulence factors that promote entry into phagocytic and non-phagocytic eukaryotic cells, intracellular survival and proliferation, and spreading to adjacent cells [4].

Genome studies show that all Listeria species sequenced to date have more than 40 genes that encode predicted surface proteins bearing an LPXTG sorting motif [5]. This motif is recognized by sortase enzymes, which anchor these proteins covalently to the cell wall. In pathogenic Listeria, some of these LPXTG proteins direct essential steps throughout the infection process, including bacterial adhesion and uptake by the host cell [6]–[9]. Proteomic analyses indicated that levels of many of these LPXTG surface proteins change on adaptation to different environments. The Listeria cell wall subproteome thus changes substantially in actively growing and resting bacteria. Mutants that lack sortase SrtA and SrtB activity show impaired LPXTG protein anchoring to the peptidoglycan [10] as well as differences in the relative levels of certain LPXTG proteins [11]. Recent studies also showed major changes in the cell wall proteome when L. monocytogenes proliferate inside epithelial cells [12]. Upregulation of defined LPXTG proteins has been observed in intracellular bacteria, including Internalin-A and Lmo0514 [12]. The mechanisms that regulate the coordinated production of such a large number of LPXTG proteins nonetheless remain largely unknown.

Bacterial small RNAs (sRNA) are a class of bacterial gene expression regulators important in many physiological processes, including virulence and cell envelope homeostasis [13], [14]. sRNA coordinate target gene expression in response to environmental changes and have regulatory functions that affect protein activity and mRNA stability/translation in many microorganisms, including bacterial pathogens [15], [16]. More than 100 sRNA have been identified for L. monocytogenes by the use of tiling arrays, global RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and bioinformatics methods [14], [17], [18]; more than 30 of these have been validated by northern blot, but their biological function and mechanisms of action are so far unknown [19]. There is little information on the regulation of sRNA expression in L. monocytogenes. Some reports implicate the alternative sigma factor SigB in regulating expression of the sRNA SbrA (Rli11) and SbrE (Rli47) [17], [20], [21]. In addition, 22 sRNA genes are preceded by putative sigma A boxes in the L. monocytogenes genome [14]. Recent studies also show that the sRNAs Rli31, Rli33-1, Rli38 and Rli50 modulate virulence in L. monocytogenes [14], [17]. Despite these studies, there is no model that describes how sRNA expression in L. monocytogenes responds to infection of eukaryotic cells. With the exception of LhrA, which controls expression of the chitinase ChiA post-transcriptionally [22], and of the multicopy sRNA LhrC, which modulates LapB adhesin expression [23], the identity of the functions targeted by L. monocytogenes sRNA inside or outside eukaryotic cells, remains unknown.

Here we studied the regulatory mechanism responsible for the increase in the LPXTG protein Lmo0514 in the cell wall of intracellular bacteria [12]. Our data demonstrate an sRNA that is a key regulatory element in modulating levels of this cell wall surface protein during intracellular infection. This response to the eukaryotic niche is directed by the activity of two promoters in the target gene that generate transcripts with 5′-untranslated regions (5′-UTR) of distinct length. The relative abundance of these two transcripts differs in extra - and intracellular bacteria. Only the ‘long’ version, enriched in intracellular bacteria, bears the sRNA binding site. This mechanism confines the regulation of lmo0514 by this sRNA to the intracellular eukaryotic niche.

Results

The L. monocytogenes gene that encodes the LPXTG surface protein Lmo0514 is expressed as two variants with distinct 5′-UTR

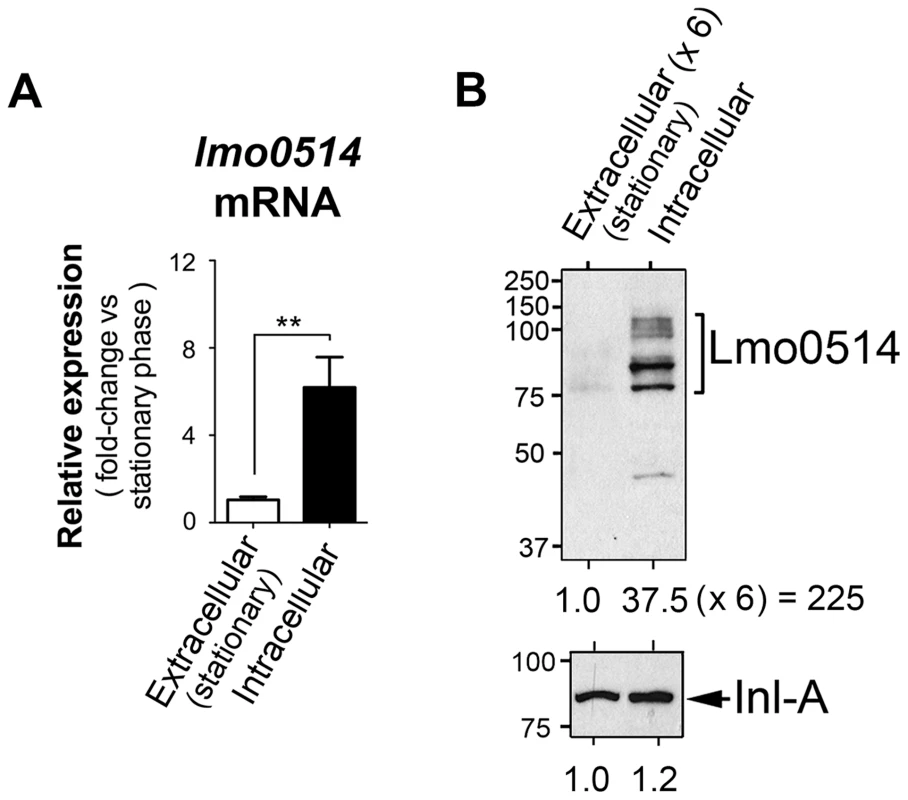

Lmo0514, a L. monocytogenes LPXTG surface protein of unknown function, is encoded by a gene upregulated by bacteria located within macrophages [24]. Lmo0514 is also more abundant in the cell wall of bacteria that proliferate inside epithelial cells than in bacteria growing in laboratory media [12]. To study the basis of this regulation, we compared lmo0514 expression in extra - and intracellular bacteria. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays showed enhanced lmo0514 mRNA expression (∼6-fold) in intracellular bacteria after infection of JEG-3 human epithelial cells (Fig. 1A). Consistent with our previous work [12], the Lmo0514 protein was detected mainly in the cell wall of intracellular bacteria, with very low levels in extracellular bacteria (Fig. 1B). Changes in relative levels of Lmo0514 protein were estimated to be>200-fold (Fig. 1B), much higher than those for lmo0514 mRNA (∼6-fold). This lack of correlation between induction of lmo0514 transcript and protein levels in intracellular bacteria led us to hypothesize that post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms act on this gene.

Fig. 1. Regulation of the L. monocytogenes gene that encodes the LPXTG surface protein Lmo0514 in intracellular bacteria located inside eukaryotic cells.

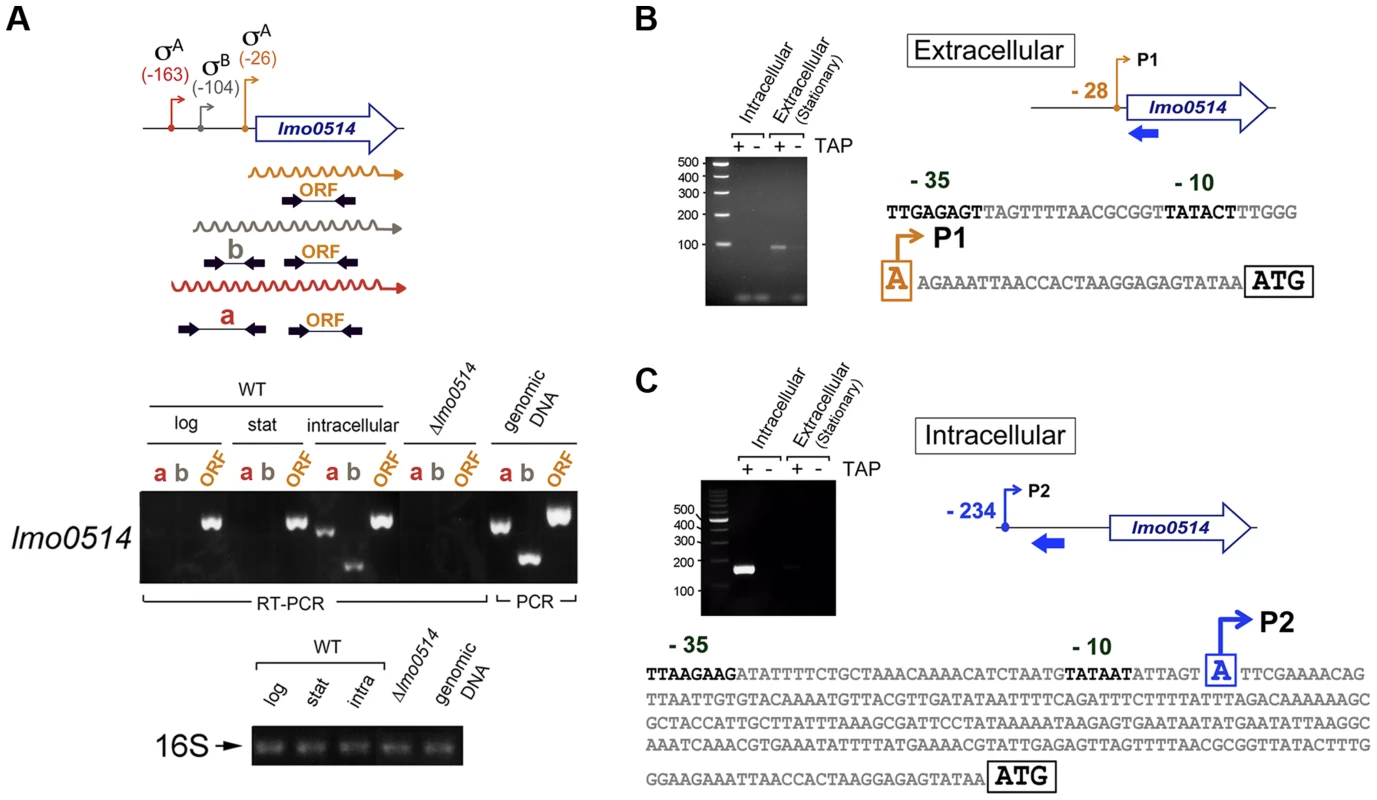

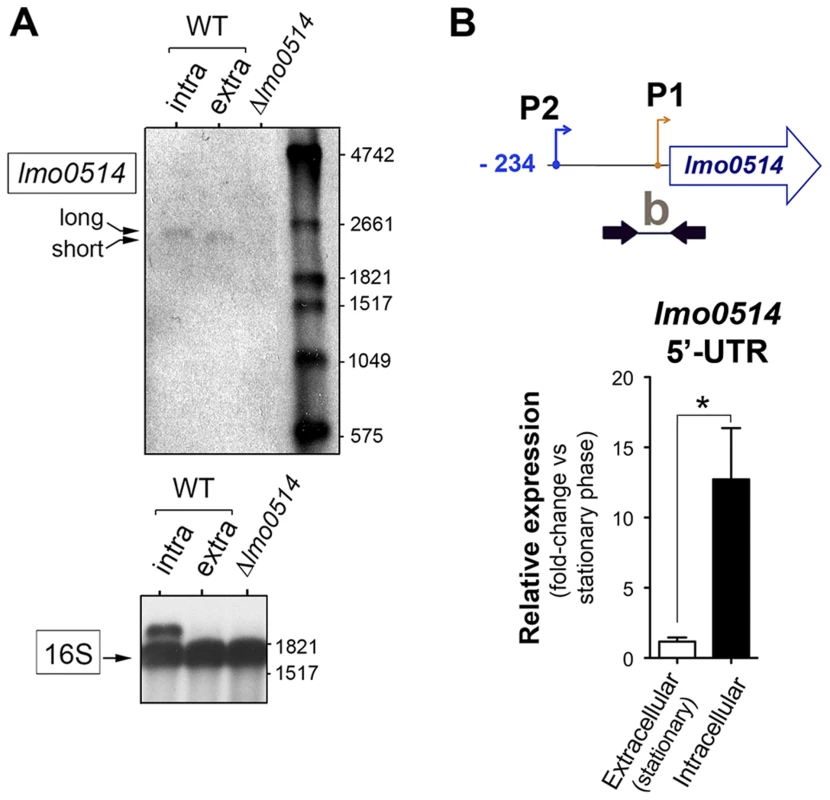

Total RNA and cell wall protein extracts were prepared from L. monocytogenes wild-type strain EGD-e grown in BHI medium to stationary phase (extracellular) and from bacteria collected in JEG-3 epithelial cells at 6 h post-infection (intracellular). (A) lmo0514 transcript levels monitored by real-time qPCR using primers Lmo0514-F and Lmo0514-R, which map within the lmo0514 coding region (Table S2). (B) Lmo0514 protein levels detected by Western blot. Levels of another LPXTG surface protein, Internalin-A (Inl-A), are shown for comparison. Densitometry analysis of bands is shown as numbers relative to the band detected in wild-type bacteria. Cell wall extracts of extracellular bacteria are concentrated 6-fold relative to those of intracellular bacteria. In intracellular bacteria, note the marked increase in relative levels of Lmo0514 protein (37.5×6 = 225), which contrasts with the ∼6-fold increase in lmo0514 mRNA. To evaluate this possibility, we sought lmo0514 gene expression control mechanisms that operate specifically in intracellular bacteria. Previous in silico predictions by Loh et al. [25] indicated that lmo0514 could be expressed from three promoters at positions −26, −104 and −163. Two of these, −26 and −163, were assigned as tentatively regulated by sigma A (σA) and the third, at position −104, as controlled by sigma B (σB) [25] (Fig. 2A). The activity of these putative promoters and the presence of the different transcripts were analyzed by RT-PCR on RNA isolated from L. monocytogenes grown extracellularly and from intracellular bacteria that colonized JEG-3 epithelial cells. lmo0514 transcripts with a long 5′-UTR were detected specifically in intracellular bacteria (Fig. 2A). To confirm these findings, rapid amplification of 5′-cDNA ends (5′-RACE) assays were used to map transcriptional start sites (TSS) of lmo0514 in bacteria grown extracellularly and in bacteria isolated from eukaryotic cells. These 5′-RACE assays revealed two distinct TSS at positions −28 and −234 (Fig. 2B, C), and also confirmed expression of the long lmo0514 transcript by intracellular bacteria (Fig. 2C). Putative promoters for these TSS, which we termed P1 and P2, both bear bona fide −10 TATA boxes (Fig. 2B, C). The existence of two lmo0514 transcripts of different length was verified by northern blot (Fig. 3A), with sizes compatible with cotranscription of lmo0514 with the downstream gene lmo0515, which encodes a universal stress protein [26]. lmo0514-lm0515 cotranscription was verified by RT-PCR (Fig. S1). qRT-PCR assays confirmed that expression of the lmo0514 transcript variant with the long 234-nucleotide (nt) 5′-UTR was upregulated by ∼12-fold in intracellular bacteria (Fig. 3B). These findings suggested that the specific induction of this mRNA variant with a longer 5′-UTR in intracellular bacteria accounts for or contributes to the 6-fold increase in total lmo0514 mRNA (Fig. 1A). These data supported a model in which intracellular bacteria specifically upregulate expression from the P2 promoter, resulting in an lmo0514 transcript with a long 5′-UTR. This assumption takes into account the different ratios between the two lmo0514 transcripts when L. monocytogenes colonizes the eukaryotic cell.

Fig. 2. lmo0514 is expressed differentially from two distinct transcriptional start sites in extra- and intracellular L. monocytogenes.

(A) Position of the three transcriptional start sites (TSS) predicted in silico for lmo0514 by Loh et al. [25]. Primers used to amplify the lmo0514 coding sequence are indicated (ORF, primers Lmo0514-F, Lmo0514-R, see Table S2), as well as two fragments of the 5′-UTR of different lengths, amplicon “a” (254 nt), obtained with primers UTR-B and UTR-1R (Table S2) and amplicon “b” (134 nt), obtained with primers UTR-A and UTR-1R (Table S2). Reverse transcriptase-PCR assays showing upregulation in intracellular bacteria of an lmo0514 transcript isoform with a long 5′-UTR. 16S rRNA was monitored as loading control. RNA was obtained from extracellular bacteria grown in BHI medium to exponential logarithmic phase (log), stationary phase (stat), and from intracellular bacteria. (B) 5′-RACE assay showing a TSS at position −28 relative to the ATG site in extracellular bacteria. Colored bar indicates the position of the primer lmo0514-PE-1rv (Table S2) used for this reaction. (C) 5′-RACE assay showing the production by intracellular bacteria of an lmo0514 transcript with a long 5′-UTR derived from a TSS at position −234 relative to the ATG site. Colored bar indicates the position of the primer lmo0514-PE-6rv (Table S2) used for this reaction. TAP, tobacco acid pyrophosphatase. Fig. 3. Northern blot and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays confirm the predominance of lmo0514 transcripts of different lengths in extra- and intracellular L. monocytogenes.

(A) Northern blot assays showing the short and long lmo0514 transcript isoforms in RNA isolated from extra- and intracellular bacteria, respectively. Transcript size is compatible with cotranscription of lmo0514 with downstream gene lmo0515 (Fig. S1). Relative 16S rRNA levels are shown for comparison. (B) Relative lmo0514 transcript levels detected by qPCR in extra- and intracellular bacteria, with Utr0514_qPCR_F and Utr0514_qPCR_R primers (Table S2) specific for the 5′-UTR. Data derived from a minimum of three independent experiments. *, P≤0.05, Student's t-test. The lmo0514 long 5′-UTR variant has a binding site for Rli27, an sRNA induced in intracellular bacteria

The increased length of the lmo0514 transcript variant that is upregulated in intracellular bacteria prompted us to test whether the distinctive 234-nt 5′-UTR is a target region for sRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation. We used in silico analysis to search for putative non-coding RNAs in the L. monocytogenes reference strain EGDe [27] that could bind to this lmo0514 long 5′-UTR. The targetRNA program (http://cs.wellesley.edu/~btjaden/TargetRNA2/) [28] gave a high score to a pairing between defined stretches of the lmo0514 234-nt 5′-UTR and a sequence in the lmo0411-lmo0412 intergenic region. A gene in this region encodes an sRNA termed Rli27 that is upregulated by L. monocytogenes in the intestine of infected mice and in human blood, as shown by transcriptomics [17]; RNA-seq corroborated the expression of this sRNA [18]. Although Rli27 was identified as an sRNA induced in infection conditions [17], no further characterization of its function or targets was reported.

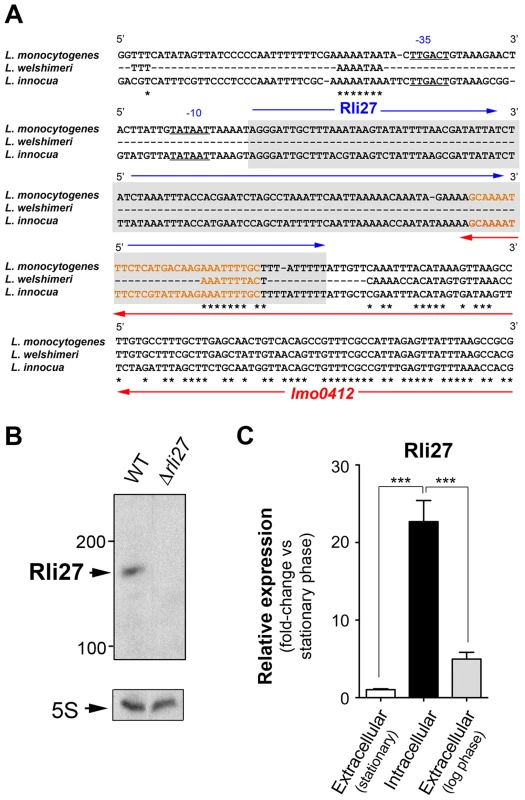

Genomic comparisons of pathogenic and non-pathogenic species are usually carried out to identify virulence genes, including sRNAs [18], [29]. We analyzed the genomic region of L. monocytogenes containing rli27 and those of the non-pathogenic species L. innocua and L. welshimeri. In L. monocytogenes, rli27 is flanked by lmo0411 and lmo0412, two genes that map in the opposite DNA strand (Fig. S2), whereas in the L. welshimeri genome, the same intergenic region has a small ORF (lwe0373) that codes for a predicted protein of unknown function (Fig. S2). We nonetheless found that Rli27 is highly conserved in L. innocua (82% identity, Fig. 4A), in contrast with a previous report [17]. The extremely variable rli27 genomic region might thus have been shaped by gain and/or loss of genes during Listeria speciation. Apart from Listeria species, BLAST searches did not identify rli27 orthologs in other bacterial species. Rli27, identified as a 131-nt sRNA [14], [18], is not predicted to encode any protein using the Small Open Reading Frame (ORF) tool in the ORF finder program (http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/orf_find.html).

Fig. 4. Rli27 is a bona fide L. monocytogenes sRNA induced by intracellular bacteria.

(A) Sequence alignment of the rli27 genomic region from L. monocytogenes, L. welshimeri and L. innocua. The −35 and −10 predicted sites for the rli27 promoter and the rli27 itself (grey background) are highlighted. Nucleotide sequence in orange corresponds to the predicted terminator shared by rli27 and lmo0412. Note that rli27 is absent in L. welshimeri. (B) Northern blot assay performed with total RNAs isolated from bacteria grown in BHI medium to stationary phase. L. monocytogenes strains used included EGDe (WT) and the Δrli27 mutant. 5S rRNA was used as loading control. (C) Real-time qPCR showing upregulation of Rli27 expression in intracellular bacteria. Bacteria were grown in BHI medium to exponential (log) or stationary phase, or collected from epithelial cells. Data derive from a minimum of three independent experiments. ***, P≤0.001, Student's t-test. Although the existence of Rli27 sRNA was inferred based on its detection by genomic and transcriptomic approaches, it has not yet been formally demonstrated. The presence of rli27 and its flanking genes in different strands ruled out the possibility that its detection by tiling arrays and RNA-seq analyses was due to untranslated regions of neighbor genes. rli27 has its own predicted transcription start site and Rho-independent terminator sequence (Fig. 4A), and the respective promoter regions in L. monocytogenes and L. innocua showed no significant divergence (Fig. 4A). Northern blot assays using total RNA isolated from L. monocytogenes wild-type EGD-e and an isogenic Δrli27 mutant strain demonstrated a small transcript consistent with the ascertained size of Rli27 (∼130 nt) (Fig. 4B). Real-time qPCR showed that Rli27 expression is induced (∼20-fold) in intracellular bacteria when compared with extracellular bacteria grown in rich medium to logarithmic or stationary phases (Fig. 4C). These findings indicate that Rli27 is a bona fide sRNA that is upregulated by L. monocytogenes inside eukaryotic cells.

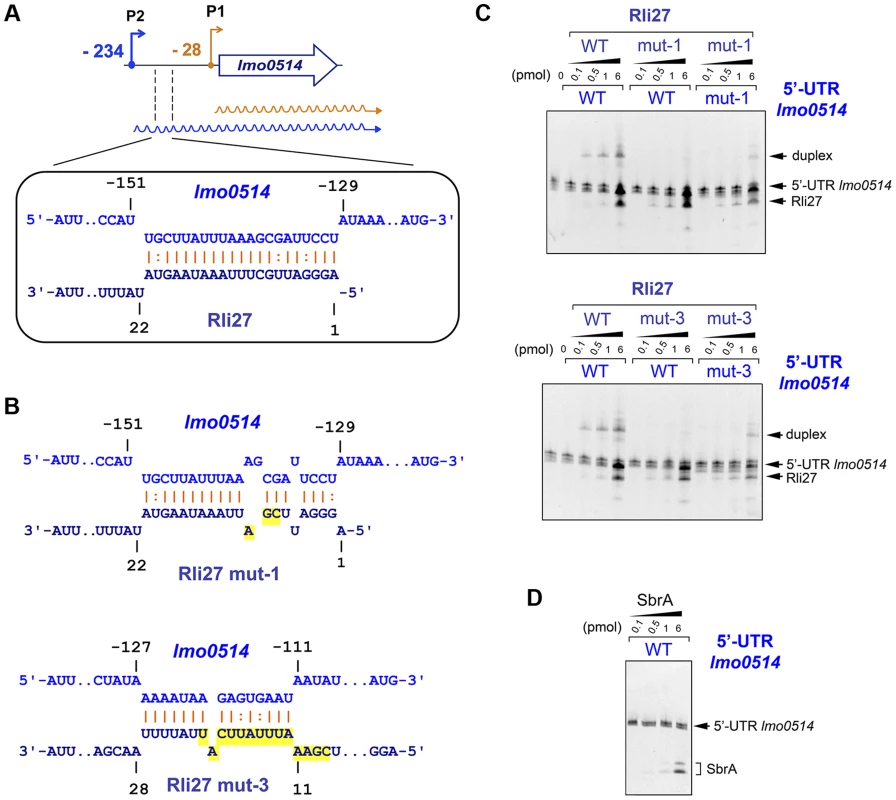

Rli27 interacts physically with the 5′-UTR specific to the lmo0514 long transcript

Rli27 interaction with the lmo0514 5′-UTR extends to several regions, although it shows a major predicted pairing region involving Rli27 nucleotides 1 to 21 (Fig. 5A, Fig. S3). We used electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) to assess the validity of this prediction. We generated in vitro wild-type versions of Rli27 and 5′-UTR-lmo0514, together with variants of both RNA molecules bearing mutations in 3 nt (mut-1) or 14 nt (mut-3) important for pairing (Fig. 5B). Incubation of Rli27 and 5′-UTR-lmo0514 wild-type molecules resulted in a duplex with low electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 5C). Conversely, combination of wild-type 5′-UTR-lmo0514 with mutated Rli27 (either mut-1 or mut-3 variants), reduced duplex formation (Fig. 5C). Duplex formation was partially restored by combining mutations in Rli27 with compensatory mutations in 5′-UTR-lmo0514 (Fig. 5C). Specificity of the Rli27-5′-UTR-lmo0514 interaction was confirmed by lack of duplex formation after incubation of the 5′-UTR-lmo0514 wild-type molecule with SbrA, an unrelated sRNA (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5. Rli27 interacts in vitro with the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR.

(A) Scheme of the major interaction region between Rli27 and the lmo0514 5′-UTR predicted with the targetRNA program (http://cs.wellesley.edu/~btjaden/TargetRNA2/). The complete set of putative interaction sites is shown in Fig. S3. (B) Effect of Rli27-mut1 and Rli27-mut3 mutations on the predicted Rli27-5′-UTR-lmo0514 interaction. Changes are highlighted in yellow. Compensatory mutations designed in 5′-UTR molecules synthesized in vitro are also shown in Fig. S3. (C) EMSA assays showing formation of a 5′-UTR-lmo0514/Rli27 duplex with slow migration in the gel. This duplex is not formed after co-incubation of the 5′-UTR molecule with the Rli27-mut1 or Rli27-mut3 variants, and is partially restored by compensatory mutations in the lmo0514 5′-UTR. (D) Control EMSA showing no duplex formation after incubation of the lmo0514 5′-UTR with an unrelated sRNA, SbrA. Rli27 interaction with the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR is necessary to increase Lmo0514 protein levels in intracellular bacteria

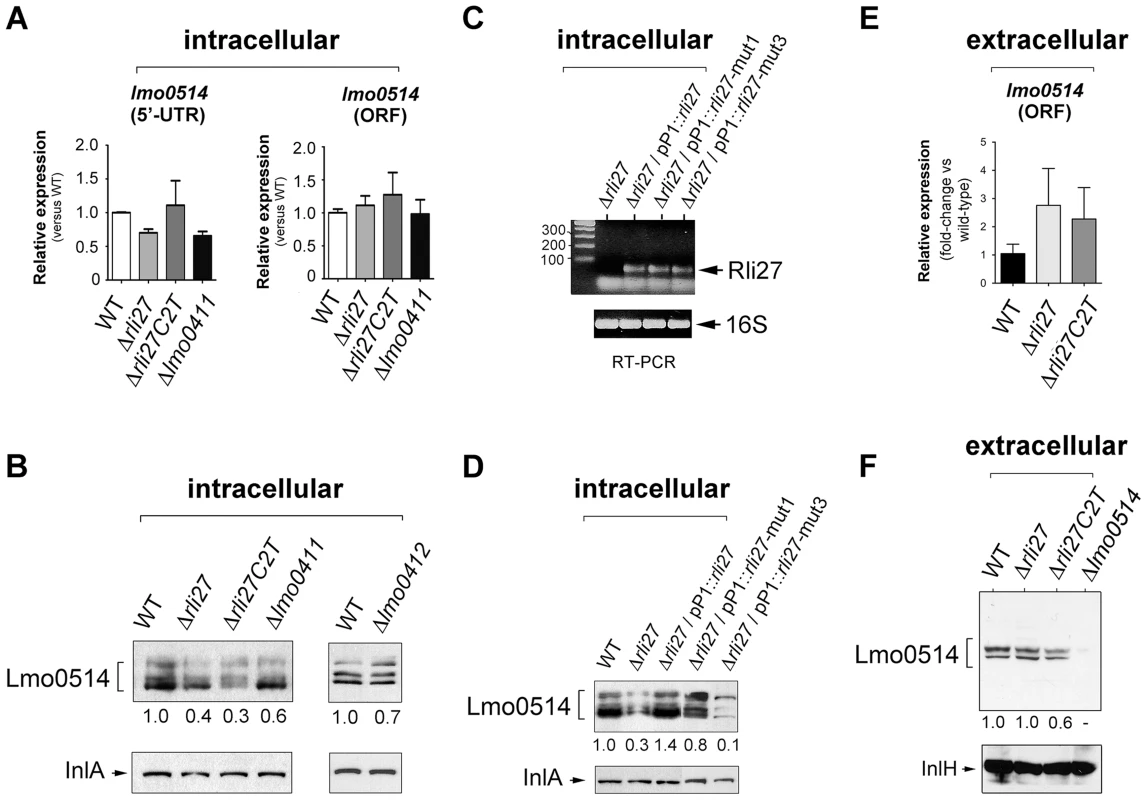

To determine the biological relevance of the 5′-UTR-lmo0514-Rli27 interaction in vivo, we analyzed the specific contribution of Rli27 binding to Lmo0514 protein upregulation in bacteria that infect eukaryotic cells. We generated a Δrli27 strain and a second isogenic mutant, Δrli27C2T, which bears an artificial strong terminator between the remaining rli27 sequences. This mutant was intended to avoid polar effects on the flanking genes lmo0411 and lmo0412 (Fig. S4); we also included mutants in these flanking genes, Δlmo0411 and Δlmo0412 [30]. In addition, we designed a qPCR assay specific for the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR for comparison to the lmo0514 coding region. There were no notable differences among strains in the relative levels of the long 5′-UTR region or the lmo0514 ORF (Fig. 6A). In contrast, Lmo0514 protein levels were ∼2.5 - to 3-fold lower in the cell wall of the two Rli27-lacking mutant strains isolated from the eukaryotic cell (Fig. 6B). This phenotype was complemented by overproduction of wild-type or mut1 versions of Rli27 from a plasmid (Fig. 6C, D). In contrast, when we tested mut3, the Rli27 mutant bearing 14 nt changes in the major region predicted to interact with the lmo0514 5′-UTR (Fig. 5A), it did not restore Lmo0514 protein levels in intracellular bacteria (Fig. 6D). Wild-type, mut1 and mut3 Rli27 versions were all produced by the plasmid at similar levels (Fig. 6C). These data showed that Rli27 interaction with the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR was essential for induction of the protein in intracellular bacteria, and that elimination of the Rli27-lmo0514 5′-UTR interaction interfered with the Lmo0514 protein increase while levels for the long transcript isoform remained unchanged. Our findings thus supported the need for Rli27 binding for efficient Lmo0514 translation. Control qPCR experiments in extracellular bacteria showed similar lmo0514 transcript levels in this mutant series (Fig. 6E), whereas there were no marked changes in Lmo0514 protein levels (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6. Rli27 is necessary for upregulation of Lmo0514 protein levels in intracellular bacteria by a mechanism that involves interaction with the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR isoform.

(A) Real-time qPCR assays showing no changes in relative levels of the lmo0514 ORF (fragment amplified with Lmo0514-F and Lmo0514-R primers) or the isoform bearing the long 5′-UTR (fragment amplified with UTR-B and UTR-1R primers) in intracellular bacteria that lack Rli27 or are defective for the rli27-flanking lmo0411 gene. (B) Decrease in levels of Lmo0514 protein produced by intracellular bacteria, caused by absence of Rli27. No such effect was seen in lmo0411- or lmo0412-defective strains. Levels of InlA, another cell wall-bound LPXTG protein, were monitored as loading control. (C) RT-PCR assays showing expression of Rli27 and mutated versions Rli27-mut1 and Rli27-mut3 produced in trans from the pP1 plasmid. (D) Western blot assays showing the effect of the mut3 mutation in Rli27, which impedes upregulation of the Lmo0514 protein in intracellular bacteria. InlA levels were monitored as loading control. (E) Real-time qPCR showing that lack of Rli27 does not affect lmo0514 transcript stability in extracellular bacteria grown in BHI medium to stationary phase. Primers correspond to those that map in the coding region (Lmo0514-F and Lmo0514-R). Data are derived from a minimum of three independent experiments. (F) Western blot showing that Rli27 is not necessary for Lmo0514 protein production by extracellular bacteria. Due to the small amount of Lmo0514 protein produced by extracellular bacteria (see Fig. 1B), the anti-Lmo0514 antibody-treated membrane was overexposed. Levels of InlH, another cell wall-bound LPXTG protein, were monitored as loading control. Densitometry values are indicated in Western blots beneath panels B, D, and F. These in vivo experiments based on complementation assays with Rli27 variants supported a mechanism that involves Rli27 binding to the 5′-UTR of the long lmo0514 transcript variant that is upregulated by L. monocytogenes inside eukaryotic cells. Such an interaction could promote translation, which would lead to increased Lmo0514 protein levels (Fig. 7).

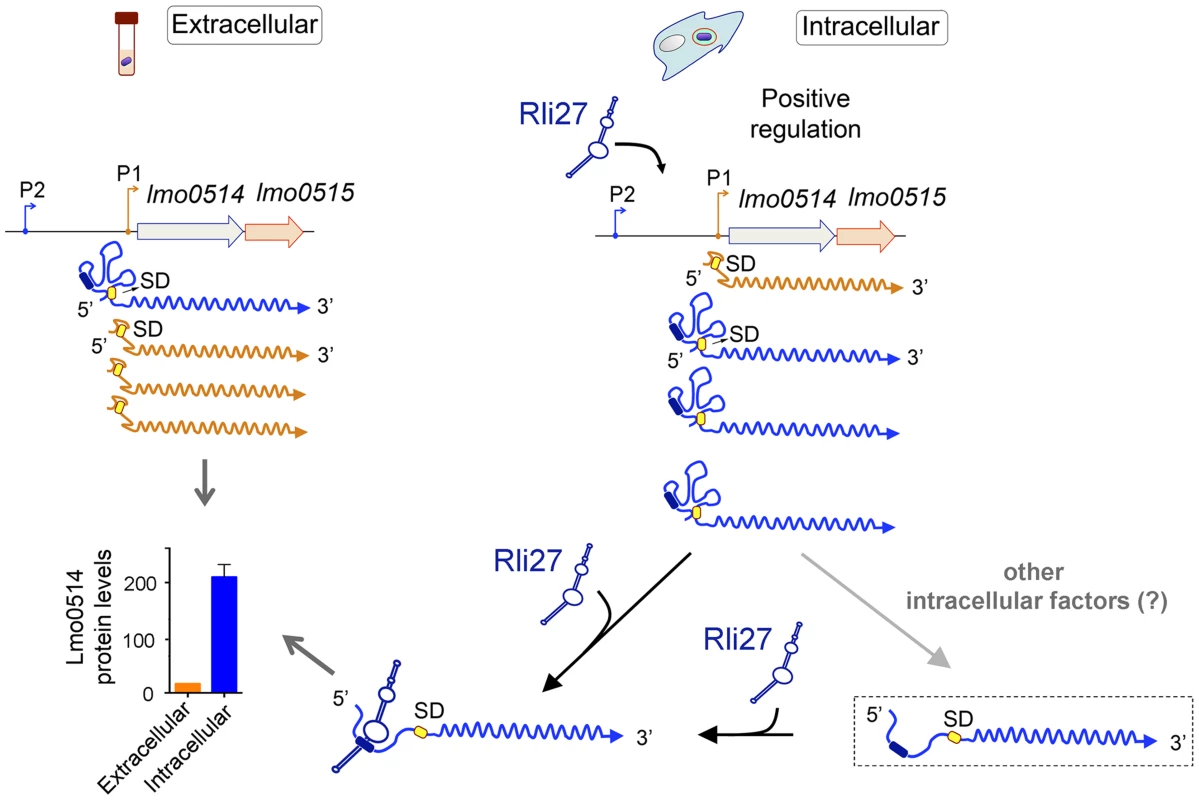

Fig. 7. Model of the mechanism by which the L. monocytogenes sRNA Rli27 could positively regulate production of the cell wall protein Lmo0514 inside eukaryotic cells.

Rli27 production is markedly stimulated in intracellular L. monocytogenes. A similar effect is observed for the lmo0514 long transcript isoform expressed from promoter P2 (blue). Rli27 interaction with the 5′-UTR region located between promoters P1 and P2 could render the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) site (yellow oval) accessible and facilitate Lmo0514 protein translation. The Rli27-binding site is present only in the transcript with the long 5′-UTR (dark blue oval). The model also considers a hypothetical transient state between the occluded and open states of the long 5′-UTR (dashed rectangle). This transient state could be generated by the intervention of other intracellular factors that might help to open or to stabilize the long 5′-UTR for productive ribosome binding and/or Rli27interaction. These putative factors could also promote Lmo0514 translation in the absence of Rli27, as this protein was detected, although at lower levels, in mutant intracellular bacteria that lack this sRNA. Discussion

Given the unique architecture of the cell envelope in Gram-positive bacterial pathogens, cell wall-associated proteins have essential functions in the interplay of these microorganisms with the host [31]. Despite the recognized importance of these proteins in infection, relatively few studies address the spatio-temporal regulation of the production of these proteins following host colonization. Obtaining this information is particularly challenging for Gram-positive pathogens such as L. monocytogenes or Staphylococcus aureus, which produce a large arsenal of surface proteins with distinct modes of association to the cell wall [31]–[33].

In this study of the Gram-positive bacterium L. monocytogenes, we identify sRNA-mediated regulation that acts on a cell wall-associated protein, Lmo0514, during the infection process. During the review process of this work, another report showed regulation of L. monocytogenes adhesin LapB by the multicopy sRNA LhrC, although this regulation was not studied in the context of infection [23]. Our data for lmo0514 also distinguish two transcript isoforms with 5′-UTR of distinct length that are expressed differentially when the pathogen transits between non-host and host environments. These findings are consistent with a regulatory role for the sRNA Rli27, based on its exclusive binding to the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR variant. This long 5′-UTR is generated from a promoter, here termed P2, which must respond to environmental cues of the eukaryotic intracellular niche. The regulator itself, Rli27, is also upregulated by L. monocytogenes following entry into host cells. Transcriptional regulators of L. monocytogenes that operate in intracellular bacteria include the alternative sigma factor SigB and the Listeria-specific virulence regulator PrfA. Transcriptomic analyses in sigB and prfA mutants grown in laboratory media did not indicate lmo0514 as a gene regulated by these factors [34]; our results in intracellular bacteria were also negative (Fig. S5A). A yet undetermined regulator might thus be involved in enhancing transcription from the lmo0514 P2 promoter. Neither SigB nor PrfA appear to upregulate Rli27 in intracellular bacteria, as determined by real-time qPCR in sigB and prfA mutants isolated from infected epithelial cells (Fig. S5B).

Comparative transcriptomic studies of L. monocytogenes and L. innocua show that ∼87% of the genes are transcribed with 5′-UTR shorter than 100 nt, whereas there is a subgroup of approximately 100 genes with long 5′-UTR (>100 nt) [18]; this subgroup includes virulence-related genes and genes with riboswitches [17]. Similar distribution of 5′-UTR length was also described in the related model organism Bacillus subtilis [35]. About 80 genes shared by L. monocytogenes and L. innocua are produced with different-length 5′-UTR [18], which might indicate differences in post-transcriptional regulation of these transcripts. Our data imply a third group of genes based on distinct transcript isoforms that differ in 5′-UTR length. lmo0514 is a representative example, as it is expressed as two isoforms with 28 - and 234-nt 5′-UTR in extra - and intracellular bacteria, respectively. A close parallel is found in a recent work that analyzed sRNA RydC regulation of the Salmonella enterica cfa gene, which encodes a cyclopropane fatty acid synthase [36]. RydC selectively stabilizes the longer of two cfa transcript isoforms, which is associated to the activity of a distal promoter controlled by σA and a proximal promoter modulated by σB [36]. Unlike lmo0514, both cfa isoforms are expressed by S. enterica growing extracellularly in laboratory media. These observations indicate that transcript isoforms with distinct 5′-UTR target platforms for sRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation could profoundly influence protein production. It is noteworthy that long 5′-UTRs are frequently associated with genes involved in pathogenesis [18], [37].

An interesting feature predicted by the Mfold program is that Rli27 binding to the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR could expose the Shine-Dalgarno site, in contrast to the occluded configuration predicted when this 5′-UTR folds as single molecule (Fig. S6, S7). This led us to propose that Rli27 positively regulates Lmo0514 protein levels by altering the long 5′-UTR conformation. This mechanism resembles that of the translational regulation of the rpoS transcript in Escherichia coli [38]. The Shine-Dalgarno site is blocked by a stem-loop in the rpoS 5′-UTR, which is released by base pairing of three distinct Hfq-binding sRNA to the same region. Other paradigmatic cases in L. monocytogenes include the virulence regulator prfA, actA, and the hemolysin (hly) genes [25], [39]–[41]. Our hypothesis for lmo0514 implies that its 234-nt 5′-UTR has considerable secondary structural complexity in the absence of Rli27. This assumption is consistent with the study by Wurtzel et al. [18], in which RNA-seq did not define the lmo0514 transcriptional start site, although 2018 such sites were mapped in the L. monocytogenes genome, which account for 88% of all annotated transcriptional units. Our tentative model (Fig. 7) also considers the lmo0514 transcript as ‘low-efficiency’ in terms of translation; there are marked differences in Lmo0514 protein levels in bacteria isolated from epithelial cells (>200-fold increase) that are not reflected at the transcript level. The secondary structure prediction for the short (28-nt) 5′-UTR of the extracellular lmo0514 isoform also suggests probable occlusion of the Shine-Dalgarno site (Fig. S8). Further work is needed to clarify the extent to which such potential structural changes in the 5′-UTR might explain Rli27-mediated regulation.

Our EMSA data infer direct Rli27-5′-UTR-lmo0514 interaction, which was also relevant in vivo, based on data obtained with the Rli27-mut3 variant. This variant did not restore the Lmo0514 protein levels produced by intracellular bacteria (Fig. 6D). We did not obtain perfect complementation with compensatory mutations in the predicted interacting regions, which allows other interpretations. For example, the targetRNA program might have predicted an incorrect pairing site, pairing between the two molecules might require additional factors with a precise stoichiometry, or the lmo0514 transcript could undergo alternative post-transcriptional regulation; future work will address these possibilities.

We designed in vivo experiments to assess the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR requirement in Lmo0514 protein production in the cell wall of bacteria located inside eukaryotic cells. We tested strains that bear chromosomal mutations in the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR predicted interaction site or that lack most of the 5′-UTR upstream of the P1 promoter −10 and −35 sites (Fig. S9A, S9B). Lmo0514 protein levels dropped markedly inside the eukaryotic cells for some these mutants, especially in that lacking the lmo0514 5′-UTR (Fig. S9C, S9D). Nonetheless, lmo0514 transcript levels were affected in these mutants in both extra - and intracellular conditions (Fig. S9C, S9D). Due to the clear side effect of the mutations on transcription, these findings remained inconclusive.

In summary, our results demonstrate that Rli27 is a regulatory sRNA in L. monocytogenes, with an essential role as a positive regulator of the Lmo0514 surface protein during the intracellular infection cycle. We also provide evidence that the Rli27 regulatory role is directed to a transcript isoform that bears the binding site for this sRNA; in addition, we show that this isoform is specifically upregulated by intracellular bacteria. Further research will be necessary to determine how Rli27 might modify the secondary structure of the 5′-UTR after binding, and whether such a role requires additional factors also probably upregulated in intracellular bacteria. Another challenge will be to identify the host-derived signal that triggers transcription from the P2 promoter in intracellular L. monocytogenes and the bacterial transcriptional factor responsible.

Materials and Methods

Comparative genomics

To compare the genome region bearing rli27 in L. monocytogenes EGD-e, L. innocua Clip11262 and L. welshimeri serovar 6b str. SLCC5334, we used the WEBACT program (http://www.webact.org/WebACT/home). Genome sequences were obtained from the Genbank repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) with entry numbers NC_003210.1, NC_003212.1 and NC_008555.1 for L. monocytogenes EGD-e, L. innocua Clip11262 and L. welshimeri serovar 6b str. SLCC5334, respectively.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The L. monocytogenes strains of serotype 1/2a used here are isogenic to wild-type strain EGD-e [27] (listed in Table S1). For sRNA overexpression analyses, the rli27 wild-type allele was cloned in the pP1 plasmid [42] using Lmorli27-pP1-F and Lmorli27-pP1-R primers (Table S2). Relative expression of cloned sRNA was monitored by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using Lmorli27-F and Lmorli27-R primers (Table S2). L. monocytogenes strains were grown at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth. For cloning, E. coli strains were grown in Luria Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C. When appropriate, media were supplemented with erythromycin (1.5 µg/ml) or ampicillin (100 µg/ml).

Generation of Rli27 variants for overexpression in in vivo assays

Two Rli27 variants, Rli27-mut1 and Rli27-mut3, were constructed by amplification of the rli27 gene with degenerate primers Lmorli27-pP1-F-mut1 and Lmorli27-pP1-F-mut3 (Table S2) and subsequent cloning in pP1 plasmid [42]. The mut1 mutation introduces 3 nt changes and mut3, 14 nt changes in the major predicted interaction site (see Fig. 5B).

Construction of Rli27-defective L. monocytogenes mutants

To generate the Δrli27 mutant strain, fragments of ∼500-bp DNA flanking rli27 were amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA of L. monocytogenes strain EGD-e and cloned into the thermo-sensitive suicide integrative vector pMAD [43] with primers Lmorli27-A, Lmorli27B, Lmorli27-C and Lmorli27-D (Table S2). Genes were deleted by double recombination as described [43], and deletion was verified by PCR. To generate the Δrli27 mutant, we left 9 nt in the 5′ end and 50 nt in the 3′ end of the rli27 gene, to avoid interference with the lmo0412 terminator (shared with rli27) and the lmo0411 predicted promoter sequence (Fig. S4). This Δrli27 mutation affected lmo0411 transcript levels slightly. A new deletion mutant was generated (Δrli27C2T), which retains a 5′ extended region of the predicted lmo0411 promoter, thus maintaining 21 nt in the 5′ end and 50 nt in the 3′ end of rli27 (Fig. S4). In addition, a strong artificial terminator sequence between the remaining rli27 sequences was introduced in the Δrli27C2T mutant (Fig. S4). All deletions were confirmed by PCR and sequencing, using primers listed in Table S2.

Construction of L. monocytogenes mutants with chromosomal mutations in the lmo0514 5′-UTR

Three types of mutants were constructed with the following chromosomal mutations: i) changes in 3 nt of the long 5′-UTR-lmo0514 to compensate the mutation in Rli27-mut1 (see Fig. S3, S9), ii) changes in 14 nt of the long 5′-UTR-lmo0514 to compensate the mutation in Rli27-mut3 (see Fig. S3, S9), and iii) a 174-nt deletion upstream of the −10 and −35 sites of the P1 lmo0514 promoter (Fig. S9). These changes were generated by double recombination as described [43] and when required, using overlapping SOEing PCR. The oligonucleotide primers for these procedures included Δ0514_P2_A, Δ0514_P2_B, Δ0514_P2_C, Δ0514_P2_D, Mut0514pXG_1-overlap, Mut0514pXG_2-overlap, Mut0514pXG_5-overlap and Mut0514pXG_6-overlap (Table S2).

Isolation of intracellular bacteria for RNA expression and proteomic analyses

Intracellular bacteria were collected from the human epithelial cell line JEG-3 at 6 h post-infection, as described [12]. For total RNA isolation, epithelial cells cultured in BioDish-XL plates (351040, BD Biosciences) at ∼80% confluence (∼5.6×107 cells) were infected (30 min) with L. monocytogenes grown in BHI medium (37°C, overnight) in static non-shaking conditions. RNA was purified using the TRIzol reagent method [17]. For cell wall protein analysis, intracellular bacteria were obtained from JEG-3 cells cultured on four BioDish-XL plates and infected for 6 h [12]. Subcellular fractions containing protoplasts and peptidoglycan-associated proteins were obtained by mutanolysin treatment of intact bacteria as described [10], [12], except that bacterial pellets were incubated for 5 h in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris HCl pH 6.9, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 M sucrose, 60 µg/ml mutanolysin, 250 µg/ml RNAse-A, 1× protease inhibitor).

Bacterial fractionation and western blot analysis

Subcellular fractions containing protoplasts and cell wall-associated proteins of L. monocytogenes grown at 37°C in BHI media were obtained as described [10]. A volume of protoplasts and the cell wall fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot using B. subtilis RecA-specific rabbit polyclonal antibody (a gift of Dr. JC Alonso, Centro Nacional de Biotecnología-CSIC) and rabbit poyclonal sera to the L. monocytogenes LPXTG surface proteins Lmo0263 (InlH), Lmo0433 (InlA) and Lmo0514 [12]. RecA (for the protoplast fraction) and LPXTG proteins InlA and InlH (for the cell wall fraction) were used as loading controls. Goat anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad) were used as secondary antibodies. Proteins were visualized by chemoluminescence using luciferin-luminol reagents.

RNA preparation and reverse transcriptase PCR assays

Total RNA from extracellular bacteria grown to exponential (OD600 ∼0.2) and non-shaking stationary phase (OD600 ∼1.0) was prepared as described [11]. Oligonucleotides for RT-PCR assays were designed using Primer Express v3.0 (Applied Biosystems)(listed in Table S2). RNA was treated with DNase I (Turbo DNA-free kit, Ambion/Applied Biosystems) at 37°C for 30 min. RNA integrity was assessed by agarose-TAE electrophoresis. RT-PCR was performed using the one-step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). Briefly, RT-PCR were carried out with 10 to 70 ng RNA (depending on the gene analyzed) in the following conditions: 50°C for 35 min, 95°C for 15 min, followed by 30 cycles (16 cycles for the 16S rRNA gene) of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and then an additional elongation step at 72°C for 10 min. The gene that encodes 16S rRNA was used as a housekeeping gene for all strains in all experimental conditions [44].

cDNA libraries and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

For cDNA library construction, we used 1 µg of total DNA-free RNA and the High-Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems) including a random hexamer mix. Reverse transcription was performed at a one-step run of 25°C for 10 min, 37°C for 2 h and 85°C for 5 min. Primers for qPCR were designed using Primer3 [45](listed in Table S2). qPCR was performed in a 10 µl final volume with 1 ng of the cDNA library as template, 500 nM of gene-specific primers and the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Reactions and data analysis were carried out as described [46].

5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE)

5′-RACE was performed as described [47], with minor modifications. To convert 5′triphosphates to monophosphates, 15 µg DNA-free RNA, isolated from L. monocytogenes growing extracellularly at 37°C to stationary phase or from intracellular bacteria collected at 6 h post-infection of epithelial cells, was treated with 25 U tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) (Epicentre Technologies) at 37°C for 60 min in a total reaction volume of 50 µl containing 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 6.0), 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100 and 80 U RNAsin (Promega). TAP-negative (TAP−) control RNA was processed in the same conditions in the absence of TAP. Following TAP treatment, RNA was phenol/chloroform-extracted and precipitated with sodium acetate and ethanol. Pellets were rinsed with 70% ethanol in DEPC-dH2O, then resuspended in 65 µl DEPC-dH2O; 29 µl of these TAP+ or TAP-treated RNA were combined with 5.5 µl 10× buffer, 120 U RNasin, 10% (v/v) dimethylsulfoxide, 70 U RNA ligase, 150 µM ATP and 150 ng RNA oligonucleotide adapter, in a total reaction volume of 55 µl. Samples were denatured (95°C, 5 min) and then chilled on ice. RNA adapter ligation was performed (17°C, 12 h). Following ligation, RNA was phenol/chloroform-extracted and converted to cDNA with a lmo0514-specific primer (Lmo0514-Pe-3rv) and the Thermoscript RT System (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was performed in three cycles (55°C, 60°C and 65°C; 20 min each), followed by RNAseH treatment (37°C, 20 min). lmo0514 cDNA (2 µl) was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides RaceIN and lmo0514-PE-1rv (30 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min), or with oligonucleotides RaceIN and lmo0514-PE-6rv in the same cycling conditions. PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels and bands of interest were excised and subcloned into pCR 2.1 TOPO-vector (Invitrogen). Plasmids containing inserts were purified using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (QIAgen) and sequenced.

Northern blot assays

To detect the sRNA Rli27 and the 5S rRNA, 15 µg total RNA were electrophoresed in a 6% polyacrylamide 8 M urea gel (1 h, 200 V in 1× TBE). RNA was transferred to a Hybond membrane (Amersham) for 2.5 h at 40 V in 0.5× TBE at 4°C and RNA was UV-crosslinked to the membrane. Membranes were pre-hybridized with UltraHyb buffer (Ambion; 65°C, 2 h) and hybridized with 106 cpm 32P-labeled specific riboprobes (65°C, overnight). Membranes were washed with 2× SSC, 0.5% SDS and 1× SSC, 0.1% SDS and exposed to X-ray film. 5S rRNA was used as control [22]. A nonradioactive digoxigenin (DIG)-based RNA detection protocol was used for Northern blot analysis of lmo0514 and the 16S rRNA. Total RNA (1 µg for lmo0514 or 200 ng for 16S rRNA) was separated on a 1.5% agarose denaturing gel (2% formaldehyde, 1× MOPS), overnight capillary transferred to a Hybond membrane in 20× SSC, and UV-crosslinked. The membrane was prehybridized (68°C, 1 h) and then hybridized with DIG-labeled lmo0514 and 16S rRNA probes (68°C, overnight). Immunological detection of RNA was performed (DIG Northern starter kit; Roche) and exposed to X-ray film.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

Gel mobility shift assays were performed with 1.48 pmol in vitro-transcribed RNA corresponding to the lmo0514 5′-UTR (nucleotides −234 to −14 from the lmo0514 ATG codon) and increasing concentrations of in vitro-transcribed RNAs for Rli27 wild-type, Rli27-mut1 and Rli27-mut3. These in vitro-transcribed molecules included Rli27 nucleotides 1 to 131 plus an additional 60 nt at the 3′ end, as designed for optimal amplification. We produced lmo0514 5′-UTR variants with compensatory mutations in 3 nt (mut-1) or 14 nt (mut-3) for those generated in Rli27. Oligonucleotide primers used are listed in Table S2. We also generated an amplified molecule corresponding to RNA SbrA (Rli11) encompassed nucleotides 1 to 69 of the total of 71 nucleotides. The reaction was carried out in 10 µl of 1× binding buffer (20 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.6, 100 mM sodium acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 20 mM EDTA) (37°C, 1 h). The binding reactions were mixed with 2 µl loading dye (48% glycerol, 0.01% orange G) and loaded on native 4% polyacrylamide gels, followed by electrophoresis in 0.5× TBE buffer (200 V, 4°C). Gels were stained with Gel Red nucleic acid stain (Biotium) and photographed under UV transillumination with the GelDoc 2000 system (Bio-Rad).

Computational prediction of potential interactors with the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR region

The bioinformatic program TargetRNA (http://cs.wellesley.edu/~btjaden/TargetRNA2/) [28] was used to predict non-coding RNAs that could bind to the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR (234 nt from the ATG codon). Predictive folding of the lmo0514 long 5′-UTR alone or with sRNA Rli27 was done using Mfold (http://mfold.rna.albany.edu/?q=mfold).

Statistical and densitometry analyses

Statistical significance was analyzed with GraphPad Prism v5.0b software (GraphPad Inc.) using Student's t-test. A P value≤0.05 was considered significant. For densitometry of bands obtained in western blots, we used ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health of USA [http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/]).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. CossartP, Toledo-AranaA (2008) Listeria monocytogenes, a unique model in infection biology: an overview. Microbes Infect 10 : 1041–1050.

2. HamonM, BierneH, CossartP (2006) Listeria monocytogenes: a multifaceted model. Nat Rev Microbiol 4 : 423–434.

3. Vazquez-BolandJA, KuhnM, BercheP, ChakrabortyT, Dominguez-BernalG, et al. (2001) Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin Microbiol Rev 14 : 584–640.

4. CossartP (2011) Illuminating the landscape of host-pathogen interactions with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 19484–19491.

5. DoumithM, CazaletC, SimoesN, FrangeulL, JacquetC, et al. (2004) New aspects regarding evolution and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes revealed by comparative genomics and DNA arrays. Infect Immun 72 : 1072–1083.

6. GaillardJL, BercheP, FrehelC, GouinE, CossartP (1991) Entry of L. monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminiscent of surface antigens from gram-positive cocci. Cell 65 : 1127–1141.

7. BuchrieserC (2007) Biodiversity of the species Listeria monocytogenes and the genus Listeria. Microbes Infect 9 : 1147–1155.

8. ReisO, SousaS, CamejoA, VilliersV, GouinE, et al. (2010) LapB, a novel Listeria monocytogenes LPXTG surface adhesin, required for entry into eukaryotic cells and virulence. J Infect Dis 202 : 551–562.

9. MariscottiJF, QueredaJJ, Garcia-Del PortilloF, PucciarelliMG (2014) The Listeria monocytogenes LPXTG surface protein Lmo1413 is an invasin with capacity to bind mucin. Int J Med Microbiol 304 : 393–404.

10. PucciarelliMG, CalvoE, SabetC, BierneH, CossartP, et al. (2005) Identification of substrates of the Listeria monocytogenes sortases A and B by a non-gel proteomic analysis. Proteomics 5 : 4808–4817.

11. MariscottiJF, QueredaJJ, PucciarelliMG (2012) Contribution of sortase A to the regulation of Listeria monocytogenes LPXTG surface proteins. International Microbiology 15 : 43–51.

12. Garcia-del PortilloF, CalvoE, D'OrazioV, PucciarelliMG (2011) Association of ActA to peptidoglycan revealed by cell wall proteomics of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes. J Biol Chem 286 : 34675–34689.

13. Valentin-HansenP, JohansenJ, RasmussenAA (2007) Small RNAs controlling outer membrane porins. Curr Opin Microbiol 10 : 152–155.

14. MraheilMA, BillionA, MohamedW, MukherjeeK, KuenneC, et al. (2011) The intracellular sRNA transcriptome of Listeria monocytogenes during growth in macrophages. Nucleic Acids Res 39 : 4235–4248.

15. Toledo-AranaA, RepoilaF, CossartP (2007) Small noncoding RNAs controlling pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 10 : 182–188.

16. PapenfortK, VogelJ (2010) Regulatory RNA in bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 8 : 116–127.

17. Toledo-AranaA, DussurgetO, NikitasG, SestoN, Guet-RevilletH, et al. (2009) The Listeria transcriptional landscape from saprophytism to virulence. Nature 459 : 950–956.

18. WurtzelO, SestoN, MellinJR, KarunkerI, EdelheitS, et al. (2012) Comparative transcriptomics of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Listeria species. Mol Syst Biol 8 : 583.

19. MellinJR, CossartP (2012) The non-coding RNA world of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. RNA Biol 9 : 372–378.

20. MujahidS, BergholzTM, OliverHF, BoorKJ, WiedmannM (2012) Exploration of the role of the non-coding RNA SbrE in L. monocytogenes stress response. Int J Mol Sci 14 : 378–393.

21. NielsenJS, OlsenAS, BondeM, Valentin-HansenP, KallipolitisBH (2008) Identification of a sigma B-dependent small noncoding RNA in Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 190 : 6264–6270.

22. NielsenJS, LarsenMH, LillebaekEM, BergholzTM, ChristiansenMH, et al. (2011) A small RNA controls expression of the chitinase ChiA in Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS One 6: e19019.

23. SieversS, LillebaekEM, JacobsenK, LundA, MollerupMS, et al. (2014) A multicopy sRNA of Listeria monocytogenes regulates expression of the virulence adhesin LapB. Nucleic Acids Res doi:10.1093/nar/gku630

24. ChatterjeeSS, HossainH, OttenS, KuenneC, KuchminaK, et al. (2006) Intracellular gene expression profile of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun 74 : 1323–1338.

25. LohE, GripenlandJ, JohanssonJ (2006) Control of Listeria monocytogenes virulence by 5′-untranslated RNA. Trends Microbiol 14 : 294–298.

26. Seifart GomesC, IzarB, PazanF, MohamedW, MraheilMA, et al. (2011) Universal Stress Proteins Are Important for Oxidative and Acid Stress Resistance and Growth of Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e In Vitro and In Vivo. PLoS One 6: e24965.

27. GlaserP, FrangeulL, BuchrieserC, RusniokC, AmendA, et al. (2001) Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294 : 849–852.

28. TjadenB (2008) TargetRNA: a tool for predicting targets of small RNA action in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 36: W109–113.

29. Padalon-BrauchG, HershbergR, Elgrably-WeissM, BaruchK, RosenshineI, et al. (2008) Small RNAs encoded within genetic islands of Salmonella typhimurium show host-induced expression and role in virulence. Nucleic Acids Res 36 : 1913–1927.

30. QueredaJJ, PucciarelliMG (2014) Deletion of the membrane protein Lmo0412 increases the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Microbes Infect doi 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.07.002

31. MarraffiniLA, DedentAC, SchneewindO (2006) Sortases and the art of anchoring proteins to the envelopes of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70 : 192–221.

32. BierneH, CossartP (2007) Listeria monocytogenes surface proteins: from genome predictions to function. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71 : 377–397.

33. DreisbachA, HempelK, BuistG, HeckerM, BecherD, et al. (2010) Profiling the surfacome of Staphylococcus aureus. Proteomics 10 : 3082–3096.

34. MilohanicE, GlaserP, CoppeeJY, FrangeulL, VegaY, et al. (2003) Transcriptome analysis of Listeria monocytogenes identifies three groups of genes differently regulated by PrfA. Mol Microbiol 47 : 1613–1625.

35. IrnovI, SharmaCM, VogelJ, WinklerWC (2010) Identification of regulatory RNAs in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res 38 : 6637–6651.

36. FrohlichKS, PapenfortK, FeketeA, VogelJ (2013) A small RNA activates CFA synthase by isoform-specific mRNA stabilization. EMBO J 32 : 2963–2979.

37. SharmaCM, HoffmannS, DarfeuilleF, ReignierJ, FindeissS, et al. (2010) The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 464 : 250–255.

38. SoperT, MandinP, MajdalaniN, GottesmanS, WoodsonSA (2010) Positive regulation by small RNAs and the role of Hfq. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 9602–9607.

39. WongKK, BouwerHG, FreitagNE (2004) Evidence implicating the 5′ untranslated region of Listeria monocytogenes actA in the regulation of bacterial actin-based motility. Cell Microbiol 6 : 155–166.

40. JohanssonJ, MandinP, RenzoniA, ChiaruttiniC, SpringerM, et al. (2002) An RNA thermosensor controls expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell 110 : 551–561.

41. ShenA, HigginsDE (2005) The 5′ untranslated region-mediated enhancement of intracellular listeriolysin O production is required for Listeria monocytogenes pathogenicity. Mol Microbiol 57 : 1460–1473.

42. DramsiS, BiswasI, MaguinE, BraunL, MastroeniP, et al. (1995) Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of inIB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol Microbiol 16 : 251–261.

43. ArnaudM, ChastanetA, DebarbouilleM (2004) New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70 : 6887–6891.

44. TasaraT, StephanR (2007) Evaluation of housekeeping genes in Listeria monocytogenes as potential internal control references for normalizing mRNA expression levels in stress adaptation models using real-time PCR. FEMS Microbiol Lett 269 : 265–272.

45. UntergasserA, CutcutacheI, KoressaarT, YeJ, FairclothBC, et al. (2012) Primer3–new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 40: e115.

46. OrtegaAD, Gonzalo-AsensioJ, Garcia-del PortilloF (2012) Dynamics of Salmonella small RNA expression in non-growing bacteria located inside eukaryotic cells. RNA Biol 9 : 469–488.

47. ArgamanL, HershbergR, VogelJ, BejeranoG, WagnerEG, et al. (2001) Novel small RNA-encoding genes in the intergenic regions of Escherichia coli. Curr Biol 11 : 941–950.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice Deficient for miR-34b/c and miR-449 LociČlánek The Kinesin AtPSS1 Promotes Synapsis and is Required for Proper Crossover Distribution in MeiosisČlánek Payoffs, Not Tradeoffs, in the Adaptation of a Virus to Ostensibly Conflicting Selective PressuresČlánek Examination of Prokaryotic Multipartite Genome Evolution through Experimental Genome ReductionČlánek BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian SkinČlánek Role of STN1 and DNA Polymerase α in Telomere Stability and Genome-Wide Replication in ArabidopsisČlánek RNA-Processing Protein TDP-43 Regulates FOXO-Dependent Protein Quality Control in Stress ResponseČlánek Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping StudiesČlánek Salt-Induced Stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 Confers Salinity Tolerance by Deterring ROS Accumulation inČlánek Ethylene-Induced Inhibition of Root Growth Requires Abscisic Acid Function in Rice ( L.) SeedlingsČlánek Metabolic Respiration Induces AMPK- and Ire1p-Dependent Activation of the p38-Type HOG MAPK PathwayČlánek Signature Gene Expression Reveals Novel Clues to the Molecular Mechanisms of Dimorphic Transition inČlánek A Mouse Model Uncovers LKB1 as an UVB-Induced DNA Damage Sensor Mediating CDKN1A (p21) DegradationČlánek Dominant Sequences of Human Major Histocompatibility Complex Conserved Extended Haplotypes from to

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 10

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- An Deletion Is Highly Associated with a Juvenile-Onset Inherited Polyneuropathy in Leonberger and Saint Bernard Dogs

- Licensing of Yeast Centrosome Duplication Requires Phosphoregulation of Sfi1

- Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice Deficient for miR-34b/c and miR-449 Loci

- Basement Membrane and Cell Integrity of Self-Tissues in Maintaining Immunological Tolerance

- The Kinesin AtPSS1 Promotes Synapsis and is Required for Proper Crossover Distribution in Meiosis

- Germline Mutations in Are Associated with Familial Gastric Cancer

- POT1a and Components of CST Engage Telomerase and Regulate Its Activity in

- Controlling Meiotic Recombinational Repair – Specifying the Roles of ZMMs, Sgs1 and Mus81/Mms4 in Crossover Formation

- Payoffs, Not Tradeoffs, in the Adaptation of a Virus to Ostensibly Conflicting Selective Pressures

- FHIT Suppresses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Metastasis in Lung Cancer through Modulation of MicroRNAs

- Genome-Wide Mapping of Yeast RNA Polymerase II Termination

- Examination of Prokaryotic Multipartite Genome Evolution through Experimental Genome Reduction

- White Cells Facilitate Opposite- and Same-Sex Mating of Opaque Cells in

- BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian Skin

- Genome-Wide Association Study of CSF Levels of 59 Alzheimer's Disease Candidate Proteins: Significant Associations with Proteins Involved in Amyloid Processing and Inflammation

- COE Loss-of-Function Analysis Reveals a Genetic Program Underlying Maintenance and Regeneration of the Nervous System in Planarians

- Fat-Dachsous Signaling Coordinates Cartilage Differentiation and Polarity during Craniofacial Development

- Identification of Genes Important for Cutaneous Function Revealed by a Large Scale Reverse Genetic Screen in the Mouse

- Sensors at Centrosomes Reveal Determinants of Local Separase Activity

- Genes Integrate and Hedgehog Pathways in the Second Heart Field for Cardiac Septation

- Systematic Dissection of Coding Exons at Single Nucleotide Resolution Supports an Additional Role in Cell-Specific Transcriptional Regulation

- Recovery from an Acute Infection in Requires the GATA Transcription Factor ELT-2

- HIPPO Pathway Members Restrict SOX2 to the Inner Cell Mass Where It Promotes ICM Fates in the Mouse Blastocyst

- Role of and in Development of Abdominal Epithelia Breaks Posterior Prevalence Rule

- The Formation of Endoderm-Derived Taste Sensory Organs Requires a -Dependent Expansion of Embryonic Taste Bud Progenitor Cells

- Role of STN1 and DNA Polymerase α in Telomere Stability and Genome-Wide Replication in Arabidopsis

- Keratin 76 Is Required for Tight Junction Function and Maintenance of the Skin Barrier

- Encodes the Catalytic Subunit of N Alpha-Acetyltransferase that Regulates Development, Metabolism and Adult Lifespan

- Disruption of SUMO-Specific Protease 2 Induces Mitochondria Mediated Neurodegeneration

- Caudal Regulates the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Pair-Rule Waves in

- It's All in Your Mind: Determining Germ Cell Fate by Neuronal IRE-1 in

- A Conserved Role for Homologs in Protecting Dopaminergic Neurons from Oxidative Stress

- The Master Activator of IncA/C Conjugative Plasmids Stimulates Genomic Islands and Multidrug Resistance Dissemination

- An AGEF-1/Arf GTPase/AP-1 Ensemble Antagonizes LET-23 EGFR Basolateral Localization and Signaling during Vulva Induction

- The Proteomic Landscape of the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus Clock Reveals Large-Scale Coordination of Key Biological Processes

- RNA-Processing Protein TDP-43 Regulates FOXO-Dependent Protein Quality Control in Stress Response

- A Complex Genetic Switch Involving Overlapping Divergent Promoters and DNA Looping Regulates Expression of Conjugation Genes of a Gram-positive Plasmid

- ZTF-8 Interacts with the 9-1-1 Complex and Is Required for DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in the Germline

- Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping Studies

- Tpz1-Ccq1 and Tpz1-Poz1 Interactions within Fission Yeast Shelterin Modulate Ccq1 Thr93 Phosphorylation and Telomerase Recruitment

- Salt-Induced Stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 Confers Salinity Tolerance by Deterring ROS Accumulation in

- Telomeric (s) in spp. Encode Mediator Subunits That Regulate Distinct Virulence Traits

- Ethylene-Induced Inhibition of Root Growth Requires Abscisic Acid Function in Rice ( L.) Seedlings

- Ancient Expansion of the Hox Cluster in Lepidoptera Generated Four Homeobox Genes Implicated in Extra-Embryonic Tissue Formation

- Mechanism of Suppression of Chromosomal Instability by DNA Polymerase POLQ

- A Mutation in the Mouse Gene Leads to Impaired Hedgehog Signaling

- Keeping mtDNA in Shape between Generations

- Targeted Exon Capture and Sequencing in Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- TIF-IA-Dependent Regulation of Ribosome Synthesis in Muscle Is Required to Maintain Systemic Insulin Signaling and Larval Growth

- At Short Telomeres Tel1 Directs Early Replication and Phosphorylates Rif1

- Evidence of a Bacterial Receptor for Lysozyme: Binding of Lysozyme to the Anti-σ Factor RsiV Controls Activation of the ECF σ Factor σ

- Hsp40s Specify Functions of Hsp104 and Hsp90 Protein Chaperone Machines

- Feeding State, Insulin and NPR-1 Modulate Chemoreceptor Gene Expression via Integration of Sensory and Circuit Inputs

- Functional Interaction between Ribosomal Protein L6 and RbgA during Ribosome Assembly

- Multiple Regulatory Systems Coordinate DNA Replication with Cell Growth in

- Fast Evolution from Precast Bricks: Genomics of Young Freshwater Populations of Threespine Stickleback

- Mmp1 Processing of the PDF Neuropeptide Regulates Circadian Structural Plasticity of Pacemaker Neurons

- The Nuclear Immune Receptor Is Required for -Dependent Constitutive Defense Activation in

- Genetic Modifiers of Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Café-au-Lait Macule Count Identified Using Multi-platform Analysis

- Juvenile Hormone-Receptor Complex Acts on and to Promote Polyploidy and Vitellogenesis in the Migratory Locust

- Uncovering Enhancer Functions Using the α-Globin Locus

- The Analysis of Mutant Alleles of Different Strength Reveals Multiple Functions of Topoisomerase 2 in Regulation of Chromosome Structure

- Metabolic Respiration Induces AMPK- and Ire1p-Dependent Activation of the p38-Type HOG MAPK Pathway

- The Specification and Global Reprogramming of Histone Epigenetic Marks during Gamete Formation and Early Embryo Development in

- The DAF-16 FOXO Transcription Factor Regulates to Modulate Stress Resistance in , Linking Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling to Protein N-Terminal Acetylation

- Genetic Influences on Translation in Yeast

- Analysis of Mutants Defective in the Cdk8 Module of Mediator Reveal Links between Metabolism and Biofilm Formation

- Ribosomal Readthrough at a Short UGA Stop Codon Context Triggers Dual Localization of Metabolic Enzymes in Fungi and Animals

- Gene Duplication Restores the Viability of Δ and Δ Mutants

- Selection on a Variant Associated with Improved Viral Clearance Drives Local, Adaptive Pseudogenization of Interferon Lambda 4 ()

- Break-Induced Replication Requires DNA Damage-Induced Phosphorylation of Pif1 and Leads to Telomere Lengthening

- Dynamic Partnership between TFIIH, PGC-1α and SIRT1 Is Impaired in Trichothiodystrophy

- Signature Gene Expression Reveals Novel Clues to the Molecular Mechanisms of Dimorphic Transition in

- Mutations in Moderate or Severe Intellectual Disability

- Multifaceted Genome Control by Set1 Dependent and Independent of H3K4 Methylation and the Set1C/COMPASS Complex

- A Role for Taiman in Insect Metamorphosis

- The Small RNA Rli27 Regulates a Cell Wall Protein inside Eukaryotic Cells by Targeting a Long 5′-UTR Variant

- MMS Exposure Promotes Increased MtDNA Mutagenesis in the Presence of Replication-Defective Disease-Associated DNA Polymerase γ Variants

- Coexistence and Within-Host Evolution of Diversified Lineages of Hypermutable in Long-term Cystic Fibrosis Infections

- Comprehensive Mapping of the Flagellar Regulatory Network

- Topoisomerase II Is Required for the Proper Separation of Heterochromatic Regions during Female Meiosis

- A Splice Mutation in the Gene Causes High Glycogen Content and Low Meat Quality in Pig Skeletal Muscle

- KDM5 Interacts with Foxo to Modulate Cellular Levels of Oxidative Stress

- H2B Mono-ubiquitylation Facilitates Fork Stalling and Recovery during Replication Stress by Coordinating Rad53 Activation and Chromatin Assembly

- Copy Number Variation in the Horse Genome

- Unifying Genetic Canalization, Genetic Constraint, and Genotype-by-Environment Interaction: QTL by Genomic Background by Environment Interaction of Flowering Time in

- Spinster Homolog 2 () Deficiency Causes Early Onset Progressive Hearing Loss

- Genome-Wide Discovery of Drug-Dependent Human Liver Regulatory Elements

- Developmentally-Regulated Excision of the SPβ Prophage Reconstitutes a Gene Required for Spore Envelope Maturation in

- Protein Phosphatase 4 Promotes Chromosome Pairing and Synapsis, and Contributes to Maintaining Crossover Competence with Increasing Age

- The bHLH-PAS Transcription Factor Dysfusion Regulates Tarsal Joint Formation in Response to Notch Activity during Leg Development

- A Mouse Model Uncovers LKB1 as an UVB-Induced DNA Damage Sensor Mediating CDKN1A (p21) Degradation

- Notch3 Interactome Analysis Identified WWP2 as a Negative Regulator of Notch3 Signaling in Ovarian Cancer

- An Integrated Cell Purification and Genomics Strategy Reveals Multiple Regulators of Pancreas Development

- Dominant Sequences of Human Major Histocompatibility Complex Conserved Extended Haplotypes from to

- The Vesicle Protein SAM-4 Regulates the Processivity of Synaptic Vesicle Transport

- A Gain-of-Function Mutation in Impeded Bone Development through Increasing Expression in DA2B Mice

- Nephronophthisis-Associated Regulates Cell Cycle Progression, Apoptosis and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition

- Beclin 1 Is Required for Neuron Viability and Regulates Endosome Pathways via the UVRAG-VPS34 Complex

- The Not5 Subunit of the Ccr4-Not Complex Connects Transcription and Translation

- Abnormal Dosage of Ultraconserved Elements Is Highly Disfavored in Healthy Cells but Not Cancer Cells

- Genome-Wide Distribution of RNA-DNA Hybrids Identifies RNase H Targets in tRNA Genes, Retrotransposons and Mitochondria

- The Chromosomal Association of the Smc5/6 Complex Depends on Cohesion and Predicts the Level of Sister Chromatid Entanglement

- Cell-Autonomous Progeroid Changes in Conditional Mouse Models for Repair Endonuclease XPG Deficiency

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The Master Activator of IncA/C Conjugative Plasmids Stimulates Genomic Islands and Multidrug Resistance Dissemination

- A Splice Mutation in the Gene Causes High Glycogen Content and Low Meat Quality in Pig Skeletal Muscle

- Keratin 76 Is Required for Tight Junction Function and Maintenance of the Skin Barrier

- A Role for Taiman in Insect Metamorphosis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání