-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaBasement Membrane and Cell Integrity of Self-Tissues in Maintaining Immunological Tolerance

Autoimmune diseases may be caused by failures in the immune system or by altered selfness in target tissues; however, which of these is more critical is controversial. To better understand such diseases, it is necessary to first define the molecular mechanisms that provide self-tolerance to healthy tissues. As a model system, we used Drosophila melanotic mass formation, in which blood cells encapsulate degenerating self-tissues. By manipulating basement-membrane components specifically in target tissues, not in blood cells, we could elicit autoimmune responses against the altered self-tissues. Moreover, we found that at least two different checkpoints for self-tolerance operate discretely in Drosophila tissues. This parallels mammalian immunity and provides etiological insight into certain autoimmune diseases in which structural abnormalities precede immune system pathology, such as Sjögren's syndrome and type I diabetes mellitus.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004683

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004683Summary

Autoimmune diseases may be caused by failures in the immune system or by altered selfness in target tissues; however, which of these is more critical is controversial. To better understand such diseases, it is necessary to first define the molecular mechanisms that provide self-tolerance to healthy tissues. As a model system, we used Drosophila melanotic mass formation, in which blood cells encapsulate degenerating self-tissues. By manipulating basement-membrane components specifically in target tissues, not in blood cells, we could elicit autoimmune responses against the altered self-tissues. Moreover, we found that at least two different checkpoints for self-tolerance operate discretely in Drosophila tissues. This parallels mammalian immunity and provides etiological insight into certain autoimmune diseases in which structural abnormalities precede immune system pathology, such as Sjögren's syndrome and type I diabetes mellitus.

Introduction

The discovery of Toll-like receptors and other categories of pattern recognition receptors has greatly enhanced our understanding of how the immune system recognizes different types of pathogens [1], [2]; however, it is less clear why the immune system often turns its arsenal toward self-tissues. In fact, the same receptors that were originally found to bind specific types of pathogens are often involved in autoimmune diseases, making this issue more puzzling [3]. To understand this process, it is imperative to molecularly define the notion of the “immunological self”.

Autoimmune-like responses are also observed in invertebrates. In Drosophila, degenerating internal tissues are subjected to hemocyte (insect blood cell) encapsulation, in which large, flat lamellocytes wrap up the target tissues in layers and melanize them via the phenoloxidase cascade. This process is called melanotic mass formation [4]–[6]. The same process occurs as part of the immunological defense against oversized pathogenic invaders, such as parasitoid wasp eggs, which are too large to be engulfed by the most abundant phagocytic hemocytes, the plasmatocytes [7], [8]. Currently, about 100 genes have been found to display melanotic masses upon mutation or overexpression (see FlyBase.org). These genes are seemingly unrelated, and the specific triggers of this autoimmune-like reaction are largely obscure.

More than 30 years ago, Rizki and Rizki reported that the basement membrane (BM) appeared to serve as a barrier against hemocyte attack of self-tissues in Drosophila [9]–[11]. Whereas a same-species implant with the intact BM remained in the host, implants that had been mechanically damaged or pre-treated with collagenase to disrupt the BM triggered lamellocyte encapsulation [11]. Moreover, undamaged implants from sibling species did not induce lamellocyte encapsulation, whereas undamaged implants from distantly related species did, suggesting that hemocytes may recognize the molecular architecture of the BM of its own species. This interesting study raises several important questions as to which molecular component of the BM is crucial for blocking melanotic mass formation of self-tissues, and whether the BM is the sole surface feature for self-tolerance. Furthermore, their experiments were carried out in a sensitized genetic background, tu(1)Szts, in which the hemocytes were marginally hyperactive at a permissive temperature, which made it unclear whether the mass formation is caused primarily by defects in immune cells or target tissues. These questions have never been probed with genetic tools, largely due to the essential nature of the genes encoding the BM components collagen IV and laminin [12]–[16]. More recently, BM disruption was shown to act as a signal to recruit hemocytes to wound regions or to metastasizing tumors, providing further evidence for the BM-hemocyte relationship [17]–[19].

The BM is located on the basal side of epithelial tissues and serves multiple functions as a cell-supporting matrix, a tissue barrier, and ligands for cell surface receptors [20], [21]. The composition of the BM varies between tissue types, but in general, the BM contains the following four major components: collagen IV and laminin, which together form a meshwork, and the proteoglycan Perlecan and Nidogen, which function in the scaffold. The BM is maintained by evolutionarily conserved cell surface receptors, such as integrin and dystroglycan [22]. Drosophila melanogaster has two collagen IV genes, Cg25C (for α1 chain) and vkg (α2), and four laminin genes, wb (for laminin α1,2), LanA (α3,5), LanB1 (β), and LanB2 (γ) [16], [23]–[25]. Collagen IV is thought to exist mostly as Cg25C/Vkg heterotrimers, and LanB1 and LanB2 form the common core of the two laminin trimers, laminin W and laminin A. Thus, the mutant phenotypes of these genes are very similar in their own categories, and absence of one subunit is known to prevent BM incorporation of the other(s) [14], [15], [26]. The major BM components are expressed and secreted predominantly by the fat body and hemocytes [12], [26], [27], although laminins are also expressed in various other tissues [16], [27].

Here, we genetically removed each of the major BM components using RNA interference (RNAi) followed by careful immunohistochemical analysis and examined their roles in melanotic mass formation. We discovered that lamellocyte encapsulation may be blocked by two separate and discrete self-tolerance checkpoints that operate in healthy target tissues. The first checkpoint involves laminin of the BM, and the second involves cell integrity as determined by cell-cell adhesion and apicobasal cell polarity.

Results

BM disruption induces melanotic mass formation

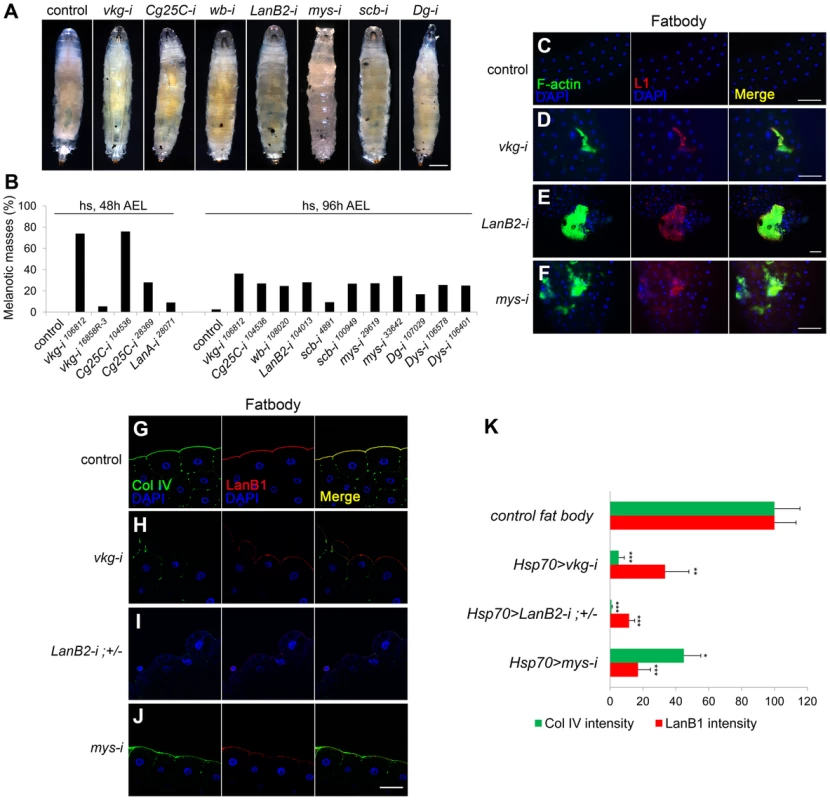

To systematically investigate the relationship between the BM and the melanotic mass phenotype, we disrupted the BM using genetic approaches. We knocked down genes for the two collagen IV subunits and the four laminin subunits individually via UAS-RNAi using ubiquitous (Act5C-GAL4), inducible (Hsp70-GAL4), and tissue-specific GAL4 drivers (HmlΔ-GAL4, FB-GAL4, and Cg-GAL4) (summarized in Table S1). Knockdown of any one of the six genes consistently induced black masses in the larvae with either Hsp70-GAL4 or Cg-GAL4 drivers (Figure 1A and 1B; Table S1). Knockdown of the genes for the BM receptor integrins (scb for αPS3 and mys for βPS), Dystroglycan (Dg), or its cytosolic adaptor Dystrophin (Dys) similarly induced black masses (Figure 1A and 1B; Table S1). Melanotic masses formed mainly in fat bodies and salivary glands. We analyzed the fat bodies of these larvae by immunostaining with the lamellocyte-specific L1 antibody. Pale brown-colored fat bodies (dissected in early stages of melanin deposition) from larvae in which collagen IV, laminin, or integrin had been knocked down by RNAi were encapsulated by a few lamellocytes (Figure 1C–F). Black nodules (dissected in late stages of melanin deposition) recovered from these larvae were also L1-positive (Figure S1A). Using confocal microscopy, we confirmed the complete disappearance or severe disruption of the BM in the fat bodies of these larvae (Figure 1G–K). This immune response did not appear to be caused by pathogen infection, as the larvae did not induce the antimicrobial peptide gene Attacin-A (Figure S1B; Text S1). Thus, these data indicate that BM loss induced melanotic mass formation.

Fig. 1. BM disruption induces melanotic mass formation.

(A, B) Pictures (A) and percentages (B) of the third instar larvae of the different genotypes containing melanotic nodules. Hsp70-GAL4 was used. The control represents GAL4 only. n>150 for each genotype. Heat shock was carried out as described in Methods. (C–F) The larval fat bodies were analyzed for lamellocyte encapsulation. Hsp70>GAL4 was used. The control was GAL4 only. Anti-L1 (red) and phalloidin-FITC (green) marked F-actin-rich lamellocytes. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (G–J) Confocal images of the fat body BM. Hsp70-GAL4 was used. The control was GAL4-only. LanB2-i;+/− indicates Hsp70>LanB2-i;LanB2+/LanB2−. Collagen IV (Col IV), laminin, and nuclei were visualized after staining with anti-Col IV (green), anti-LanB1 (red), and DAPI (blue), respectively. (K) Quantitation of the fluorescence intensities for collagen IV in the BM after staining with anti-Col IV antibody (green) and for BM laminin after staining with anti-LanB1 (red). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEM). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 by Student's t test. For each genotype, n≥5. Scale bar: 500 µm (A), 100 µm (C–F), and 50 µm (G–J). Analysis of the BM in extant melanotic mass mutants

To determine whether loss of the BM is a general feature of the melanotic mass phenotype, we examined various genes that had been previously associated with the melanotic mass using mutant or RNAi-treated larvae. Because we were primarily interested in the target tissues as opposed to hemocytes, we first excluded mutants that might be classifiable as “true blood cell tumors”, in which melanotic mass formation was due to hemocyte hyperactivation [4]. The following four genes were analyzed for the BM: spag [6], krz [6], mRpS30 [28], and hyx [28]. We found that mutant or RNAi-treated larvae for these genes commonly had disrupted BMs in the fat bodies and that the fat bodies were positive for L1 (Figure S1C and S1D). We also examined 30 other melanotic mass-associated genes; however, the RNAi-treated larvae did not reproduce black nodules with the available UAS transgenes and tissue-specific GAL4 drivers or exhibited early lethality with either ubiquitous or stronger GAL4 drivers, thus precluding further analysis (Table S2). We also analyzed hopTum larvae, in which the JAK kinase Hopscotch is constitutively active and melanotic mass phenotype is dominant at restrictive temperatures (>25°C) [29]. Although the melanotic phenotype of this mutant may fit the classification for the blood cell tumors [30] in that hemocyte numbers increase dramatically (see Figure 2A and 2B), we sought to determine its target tissues. At 25°C, only the collagen IV level decreased severely, while at the restrictive temperature (29°C), both collagen IV and laminin were absent, and numerous lamellocytes attached to the fat body and the salivary gland (Figure S1C and S1D). Altogether, these observations corroborated the evidence that BM-deficient tissues induce melanotic masses.

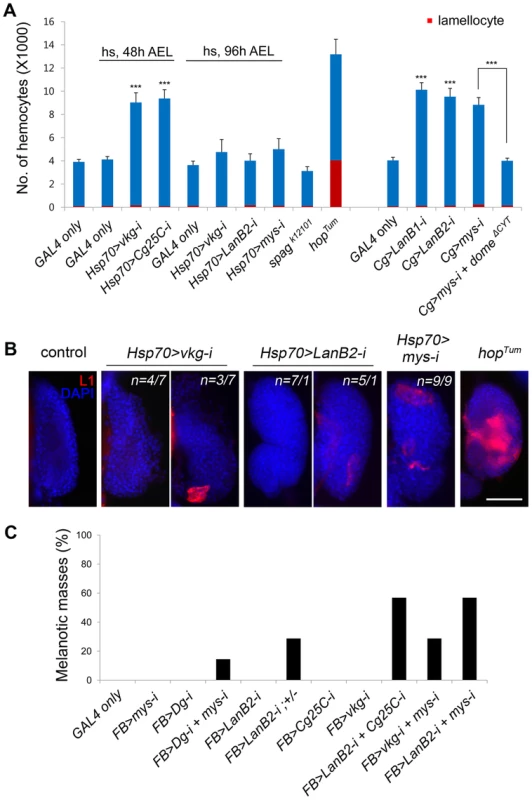

Fig. 2. Melanotic mass formation in the BM-deficient larvae is a normal immune response against altered self.

(A) Numbers of circulating hemocytes (blue+red) and lamellocytes (red) in each larva were counted in the various genotypes. Cg-GAL4 drives gene expression in hemocytes and the fat body. hopTum was raised at 29°C. Error bars represent SEM. ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test. Percentages of larvae containing melanotic masses: Cg>mys-i, 27.38% (n = 141/515); Cg>mys-i domeΔCYT, 32.00% (n = 72/225). (B) Lamellocyte differentiation in the lymph gland was analyzed by staining with anti-L1 antibodies (red) in the larvae of the indicated genotypes. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). For the vkg and LanB2 knockdowns, two classes were observed, the frequency of which plus an example is shown. The control panel represents Oregon R. hopTum was raised at 25°C. Scale bar: 50 µm. (C) Melanotic mass formation after knockdown of genes for collagen IV, laminin, and integrin in various combinations using the fat body-specific FB-GAL4. For each genotype, n>150. Melanotic mass formation in BM-deficient larvae is an autoimmune response against altered self

To see whether lamellocyte encapsulation of BM-deficient tissues was a normal hemocyte reaction to abnormal self-tissue or rather due to an abnormality in the hemocyte itself [4], we assessed the activation state of hemocytes first by counting the cells. The numbers of circulating hemocytes of some of the BM-deficient larvae were 2–2.5-fold higher than those of controls (Figure 2A); however, the numbers of lamellocytes and crystal cells, a third type of hemocytes that contain phenol oxidation enzymes as a crystal form in their cytosol [31], did not increase significantly in any of the cases (Figure 2A, S2A, and S2B; Text S1). This result was in stark contrast to the results for hopTum (Figure 2A), TollD, or cactus mutants, which harbor hyperactive hemocytes [5], [30]. To inhibit hemocyte hyperproliferation displayed by some of the BM-deficient larvae, we expressed a dominant-negative allele for the JAK/STAT pathway receptor Domeless (domeΔCYT) in mys RNAi larvae [18], [32]. Hemocyte numbers were restored to a normal level in these larvae; however, melanotic mass formation was not abrogated or reduced, indicating that the mass phenotype was not due to hemocyte hyperproliferation (Figure 2A).

We then examined the larval hematopoietic lymph gland, as robust lamellocyte differentiation in the lymph gland is a common feature of blood cell tumors [28], [33]–[36]. The lymph glands of wild-type larvae rarely contained the L1-positive lamellocytes [37] (Figure 2B). The lymph glands of collagen IV - or laminin-knockdown larvae occasionally contained 1–5 L1-positive cells, while lymph glands of integrin-knockdown larvae had 5–20 of these cells. The observed levels of activation may be expected for melanotic mass-forming larvae, but the levels were significantly different from that of hopTum in which the cortical zone of the lymph gland was filled with L1-positive cells [38] (Figure 2B). We then examined sessile hemocytes, another source of lamellocytes upon wasp egg infection [39]. Collagen IV knockdown did not change the sessile hemocyte population, as analyzed by plasmatocyte-specific Eater-GFP (Figure S2C). Finally, we knocked down the BM genes using the fat body-specific FB-GAL4 [28] to determine whether gene manipulation at the target site only, and not in the hemocyte or in the hematopoietic organs, still induced melanotic masses. Knockdown using any of the available UAS-RNAi transgenes singly did not induce melanotic masses, presumably due low knockdown efficiencies with FB-GAL4 driver (Figure 2C); however, knockdown of various combinations of the transgenes induced melanotic masses specifically in the fat body in the absence of a sensitized genetic background [11]. We obtained similar results following fat body-specific RNAi knockdown for integrins or Dystroglycan, which should act strictly in a cell-autonomous manner (Figure 2C). Circulating hemocytes produced collagen IV and laminin, as reported previously [12], [26], [27], but were not enclosed by a sheet of collagen IV or laminin outside of the cell (Figure S2D; Text S1), excluding the possibility that knockdown of these components in the fat body may have produced the mass phenotype by affecting the surface of the hemocyte rather than the target. Based on these results, we conclude that melanotic mass formation in BM-deficient larvae results from a normal immune response (operationally defined by FB-GAL4) against altered self and is not ascribed to a failure in the immune system.

Laminin deficiency in the BM induces melanotic masses

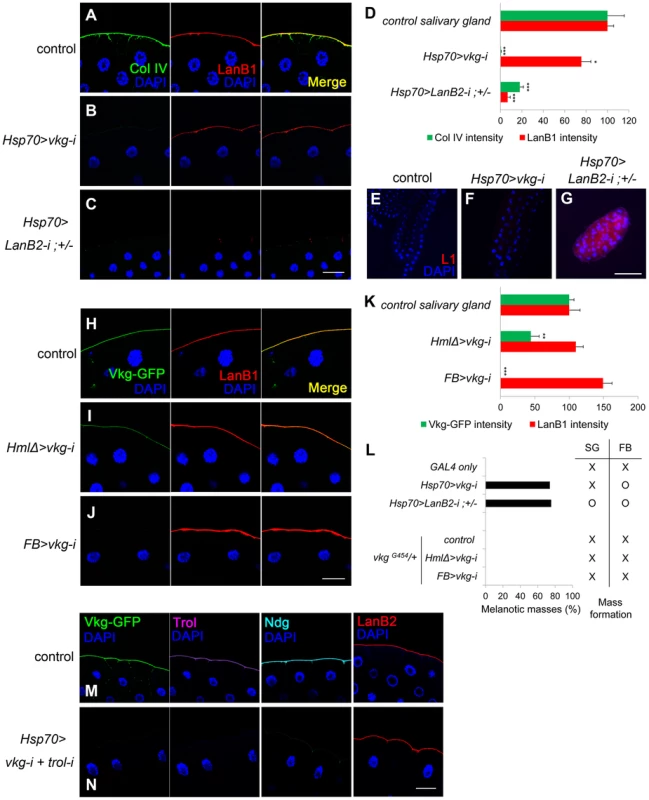

To investigate which component of the BM is crucial in self-tolerance, we individually knocked down each of the BM genes using various GAL4 drivers and analyzed BM integrity and the melanotic mass phenotype. Since melanotic masses in the BM-deficient larvae formed mainly in fat bodies and salivary glands, we focused on these two organs. In fat bodies, collagen IV knockdown with Hsp70-GAL4 reduced not only collagen IV (the fluorescence intensity was 5.23% of the control level) but also laminin in the BM (hereafter, BM laminin) effectively (33.46%; Figure 1H and 1K). Similarly, laminin knockdown (11.56%) nearly completely eliminated the BM collagen IV (0.91%; Figure 1I and 1K), indicating that these factors are structurally inter-dependent in this organ. In salivary glands, however, collagen IV knockdown with the same Hsp70-GAL4 eliminated only collagen IV (0.47%), while leaving 75.61% of laminin in the BM (Figure 3B and 3D), allowing for separation of the two components in this organ. Laminin knockdown (6.71%) effectively removed the BM collagen IV (18.02%) in the salivary gland (Figure 3C and 3D), as in the fat bodies. These results were consistent with the fact that laminin is the key component of BM assembly [14], [20], [21]. More importantly, collagen IV knockdown induced melanotic masses only in the fat body and not in the salivary gland, whereas laminin knockdown induced melanotic masses in both organs (Figure 3E–G and L, the first four experiments; melanotic encapsulation often occurred regionally but not in the entire organs, which might be due to incomplete removal of the BM laminin). These results strongly suggest that BM laminin and possibly other factors that are tightly associated with laminin block melanotic mass formation, whereas collagen IV is not necessary for blocking this process as the collagen IV-deficient larvae did not form melanotic masses in the salivary gland (Figure 3F and 3L).

Fig. 3. Laminin alone sufficiently blocks melanotic mass formation.

(A–C) Confocal images of salivary-gland BMs after staining for collagen IV (anti-Col IV in green), laminin (anti-LanB1 in red), and nuclei (DAPI in blue). The control is GAL4-only. (D) Quantitation of the fluorescence intensities in (A–C). Error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test. (E–G) Salivary glands from (A–C) after staining lamellocytes using anti-L1 antibodies (red) and the nuclei with DAPI (blue). (H–J) Confocal images of salivary-gland BMs after visualizing collagen IV using Vkg-GFP (green), laminin using anti-LanB1 antibodies (red), and nuclei using DAPI (blue). HmlΔ-GAL4 and FB-GAL4 drive gene expression in hemocytes the fat body, respectively. The control represents vkgG454/+. (K) Quantitation of the fluorescence intensities in (H–J). Error bars represent SEM. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test. (L) Percentages of larvae containing melanotic masses in (A–C) and (H–J) and their mass-forming positions. SG and FB indicate salivary gland and fat body, respectively. (M, N) Confocal images of the salivary-gland BMs of vkgG454/+ (M) and vkgG454 UAS-vkg-i/+ +; Hsp70-GAL4/UAS-trol-i (N) larvae after visualization of collagen IV using Vkg-GFP (green), Perlecan (Trol) using anti-Trol antibodies (purple), Nidogen using anti-Ndg antibodies (cyan), laminin using anti-LanB2 antibodies (red), and nuclei using DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 µm (A–C, H–J, M, N) and 200 µm (E–G). Laminin is the key element in the self-tolerance checkpoint

To further explore the self-tolerance checkpoint function of the BM components, we knocked down the collagen IV and laminin genes using HmlΔ-GAL4 and FB-GAL4, which are active in hemocytes and fat bodies, respectively [28], [40]. Laminin knockdown using these GAL4 drivers was inefficient. As for collagen IV knockdown, the changes in BM integrity induced by these two GAL4 drivers were generally the same as those with Hsp70-GAL4 (Figure 3H–K), except that collagen IV knockdown specifically eliminated the BM collagen IV but left considerable laminin at the BM even in the fat bodies (Figure S3A–D). These larvae did not form black masses, further demonstrating that collagen IV is dispensable in the BM for blocking melanotic masses (Figure 3L, the last four experiments).

We next examined Perlecan and Nidogen, the other two major components of the BM. Knockdown of the Perlecan-coding gene trol with Act5C-GAL4 did not induce black masses, indicating that Perlecan is not required in this process (Figure S3E; Table S1). Knockdown of Nidogen using available RNAi transgenes were unsuccessful; however, we found that Nidogen was completely absent in collagen IV-deficient, melanotic mass-free larvae, indicating that Nidogen is not required for blocking melanotic mass formation (Figure S3F; Table S1). Finally, we knocked down both trol and vkg, leaving laminin as the only major BM component, and found that melanotic masses were not formed (Figure 3M and 3N). Thus, these results indicate that the BM laminin was sufficient to block melanotic mass formation against self-tissue.

Loss of cell integrity correlates with melanotic mass formation

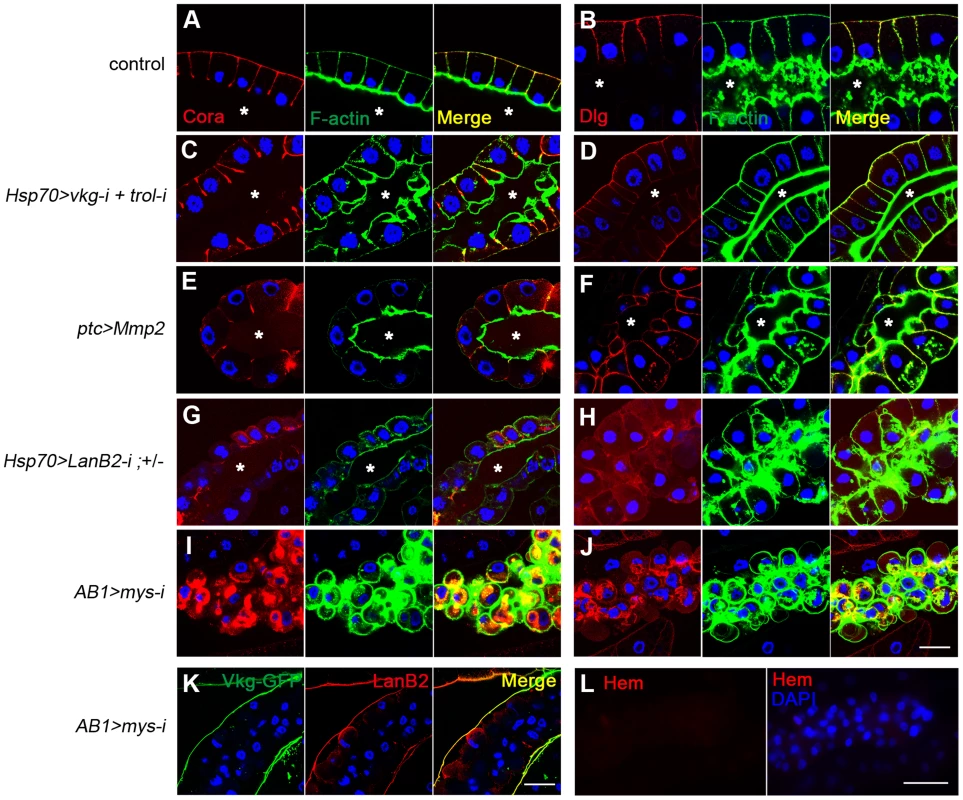

As an independent approach to determine BM function, we removed the BM by overexpressing Matrix metalloproteinase 2 (Mmp2). Mmp2 expression in the salivary gland severely disrupted BM integrity, as reported previously [18] (Figure S4A and S4B), but contrary to our expectations, the larvae did not form melanotic masses. Hemocytes attached to the salivary gland, indicating that hemocyte access to the target cells was not blocked (Figure S4C and S4D). We noticed that the salivary gland cells of these larvae looked similar to those of wild-type larvae (Figure 4A and 4B vs. 4E and 4F), whereas the cells of laminin-knockdown larvae were dissociative and round (Figure 4G and 4H), indicative of the loss of cell-cell adhesion. We further examined whether these melanotic mass-containing larvae had defects in cell polarity using apicobasal cell polarity markers [41]. In wild-type larvae, Cora and Dlg localized to the lateral and basal sides of cells (Figure 4A and 4B). A similar pattern was observed in vkg trol RNAi larvae (Figure 4C and 4D). In ptc>Mmp2 larvae in which Mmp2 is expressed in the salivary gland [18], the lumen often twisted as it expanded, and cell arrangement occasionally became abnormal (Figure 4F). Dlg diffused throughout the membrane, albeit weakly (Figure 4F). Nevertheless, Cora was still excluded from the apical side (Figure 4E), indicating that apicobasal polarity was partially maintained, perhaps due to the remains of the disrupted BM on the cell surface (Figure S4B). In contrast, the salivary gland cells of laminin-knockdown larvae displayed complete loss of apicobasal polarity. Cora and Dlg were localized throughout the cell membrane and were more often lost from the membrane in these larvae (Figure 4G and 4H). Cell-cell contacts were also severely disrupted. These results strongly suggest that loss of cell integrity, in addition to the loss of the BM, may be required for melanotic mass formation. In this report, we will subsequently use the term “cell integrity” to refer to the cellular aspects involving cell-cell adhesion and cell polarity.

Fig. 4. Cell integrity is severely disrupted specifically in BM-deficient, melanotic mass-containing larvae.

(A–J) Confocal images of larval salivary glands from the indicated genotypes illustrate defects in apicobasal cell polarity and cell-cell adhesion. Cora and Dlg were stained with anti-Cora (red; A, C, E, G, I) and anti-Dlg (red; B, D, F, H, J), respectively. F-actin and the nuclei were stained with phalloidin-FITC (green) and DAPI (blue), respectively. ptc-GAL4 is active in the salivary gland and various other tissues. AB1-GAL4 is active in the salivary gland. The control was Oregon R. Asterisks mark the lumen. (K) Confocal images of the salivary-gland BMs of AB1>mys-i larvae showing BM collagen IV (Vkg-GFP in green) and BM laminin (anti-LanB2 in red). (L) Confocal images of the salivary gland revealed that the organ surface is negative for the pan-hemocyte marker Hemese (Hem, red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 µm (A–J, K) and 100 µm (L). Cell integrity and the BM are two discrete checkpoints for self-tolerance

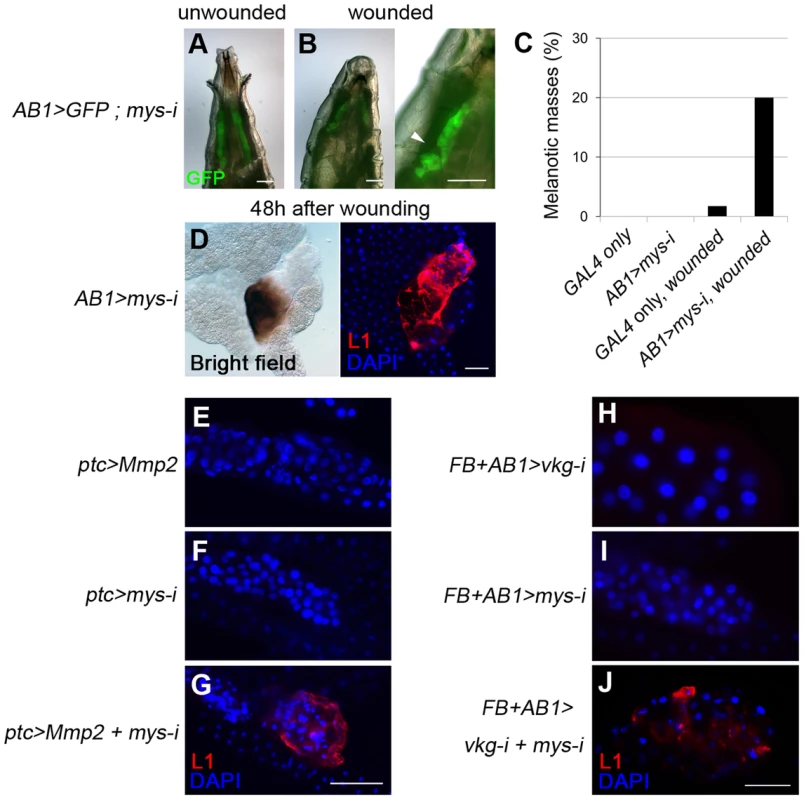

To examine the possible role of cell integrity as another checkpoint, we used melanotic mass-free AB1>mys-i larvae. Integrin knockdown with the salivary gland driver AB1-GAL4 [42] did not disrupt the BM but resulted in detachment of the BM from the salivary gland tissue (Figure 4K). The cells lost both cell polarity and adhesion properties, and as a result, the BM appeared as a sack containing sticky balls (Figure 4I–K). As expected, hemocytes were not detected on the surface of the salivary gland in these larvae (Figure 4L). To explore this phenotype in more depth, we first mechanically sheared the salivary gland BM by pinching the AB1>mys-i, GFP larva at its anterior side with forceps (Figure 5A and 5B). After two days, these larvae developed black masses in the salivary gland at a rate that was 12-fold higher than that of the pinched control larvae (Figure 5C). Melanized salivary glands dissected from the wounded larvae were positive for L1 (Figure 5D). Second, we enzymatically disrupted the salivary gland BM of ptc>mys-i larvae by overexpressing Mmp2, as a means to more specifically manipulate the larvae. These larvae developed black masses, and the salivary glands dissected from the larvae were positive for L1 (Figure 5E–G). In these experiments, ptc-GAL4 and mys-i27735 were used instead of the previously used AB1-GAL4 and mys-i33642 because the latter combination with UAS-Mmp2 caused severe growth retardation of salivary glands. The reproducibility of the knockdown phenotypes was confirmed using mys-i27735 (Figure S5). Third, we tried to wear out the BM by reducing levels of collagen IV in mys-i larvae. Black masses formed only in the fat bodies of FB>vkg-i, mys-i larvae (Figure 2C): but due to the additional AB1-GAL4 driver, a few of FB+AB1>vkg-i, mys-i larvae developed black masses also in the salivary glands, and again, the salivary glands of those larvae were positive for L1 (Figure 5J). Neither mys-i nor vkg-i alone formed black masses in the salivary gland with the same FB+AB1 GAL4 drivers (Figure 5H and 5I). Taken together, our data demonstrate that cell integrity is an additional and discrete checkpoint for tolerance to self-tissues. We sought to define cell integrity in this system by knocking down genes known to be involved in cell-cell adhesion and cell polarity. Knockdown of either scrib, dlg, cora, FasIII, shg, or arm together with Mmp2 overexpression, however, did not induce melanotic mass formation, indicating that loss of any of these components at least singly did not affect cells sufficiently for disrupting the cell-integrity checkpoint function.

Fig. 5. Loss of cell integrity is required in addition to BM disruption for melanotic mass formation.

(A, B) Mechanical disruption (arrowhead) of the salivary-gland BM of AB1>mys-i, GFP larvae with GFP expression (green) in the salivary gland. (C) Melanotic mass formation in pinch-wounded larvae of AB1>GFP control (n = 1/57) and AB1>mys-i, GFP (n = 17/84) larvae. (D) Melanized salivary glands of wounded AB1>mys-i larvae were positive for L1 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (E–J) Confocal images of the larval salivary glands of the indicated genotypes after staining lamellocytes with anti-L1 antibodies (red) and nuclei with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 200 µm (A, B, E–G) and 100 µm (D, H–J). Discussion

Based on the results of these studies, we propose that BM laminin on target tissues functions as a crucial component not only in BM assembly but as a tolerance checkpoint to self-tissues (Figure 6). As a self-tolerance checkpoint, the BM may either serve as a physical barrier or provide an inhibitory ligand for hemocyte receptors. We speculate that the latter is the case for several reasons. First, the heterospecific implantation experiments described above suggest that the hemocyte recognizes the BM structure of its own species [11]. Second, insect hemocytes are known to encapsulate a wide range of foreign materials, from parasitoid wasp eggs to synthetic beads, when injected into the hemocoel [37], [43], [44]. Encapsulation of parasites is faster than encapsulation of non-parasitic, heterospecific implants [discussed in 11]. Thus, hemocytes must be equipped with various cell surface receptors, including some as activating receptors with different binding spectra for pathogen-associated molecular patterns, and others as inhibitory receptors with narrow binding specificities to self-tissues. More specifically, laminin-coating of Sephadex beads inhibit melanotic encapsulation of the beads in mosquito hemocoel [43]. The outer surface of the Plasmodium oocyst appears to bind to mosquito-derived laminin upon passage through the midgut epithelium of the mosquito [45], suggesting that the insect laminin may indeed serve as an inhibitory ligand to hemocytes of its own species.

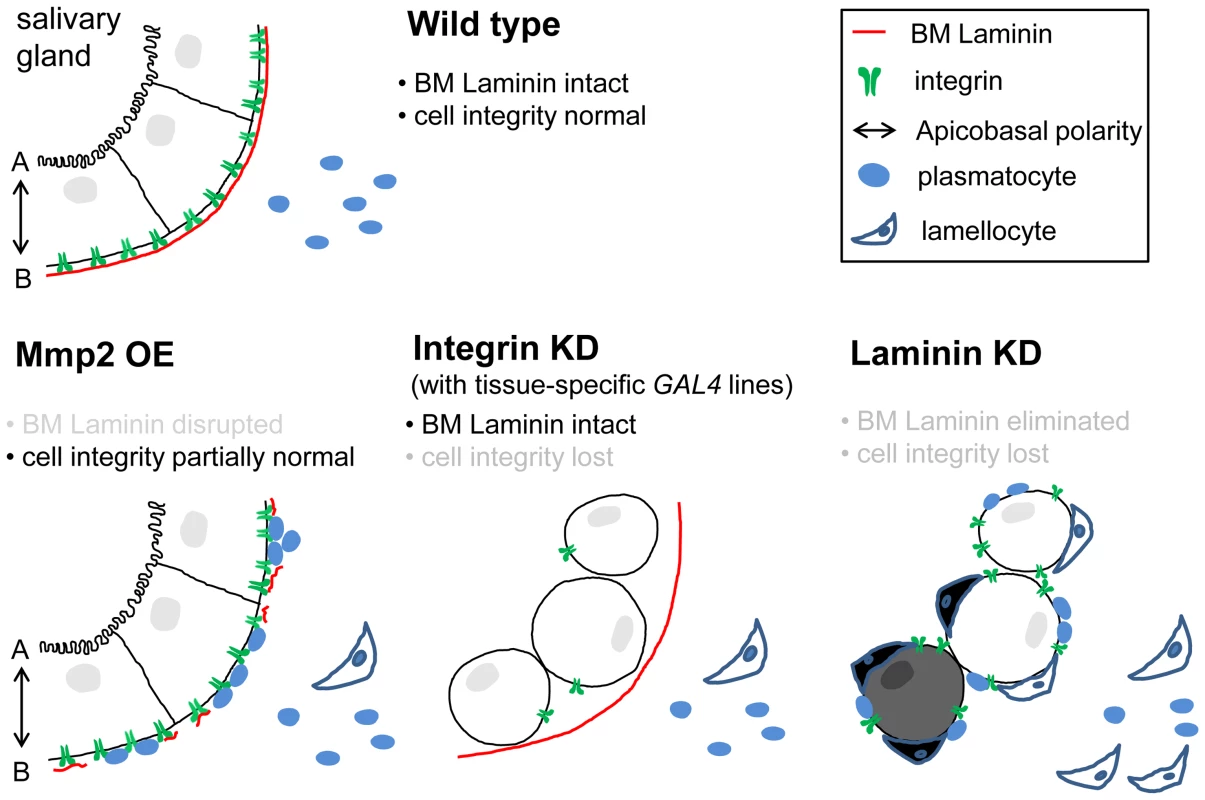

Fig. 6. Proposed model for the self-tolerance checkpoint function in the Drosophila immune system.

Epithelial tissues are equipped with at least two self-tolerance checkpoints: BM laminin and cell integrity. The latter is currently less well-defined but appears to include apicobasal cell polarity and cell-cell adhesion. With either one of the checkpoints, self-tissue may become tolerant to the immune system of its own. Upon Mmp2 overexpression (OE), the salivary gland loses BM integrity to an extent that allows plasmatocyte access; however, cell integrity remains largely intact (intact 2nd checkpoint). Upon integrin knockdown (KD) in the salivary gland (AB1>mys-i), cells lose cell integrity, while the organ maintains the BM (intact 1st checkpoint). In the presence of laminin knockdown, both of the self-tolerance checkpoints are non-functional, and the tissues are subjected to lamellocyte encapsulation. Avirulent parasitoid eggs or wing disc implants from distantly related species [11] do not have either of the checkpoints that are compatible with the host immune system, and thus, these foreign bodies are also sequestered by lamellocyte encapsulation. Furthermore, we have identified cell integrity as another checkpoint for self-tolerance. Self-tissues must lose both the BM and cell integrity in order to be subjected to lamellocyte encapsulation (Figure 6). The two checkpoints are indeed discrete and experimentally separable. In our experimental system, BM integrity or cell integrity could be disrupted in the salivary gland selectively via ptc>Mmp2 or AB1>mys-i, respectively. The salivary glands of these larvae are subjected to melanotic encapsulation if the tissues fail to acquire the state of self-tolerance from the other, remaining checkpoint. Therefore, multiple failures on sequential self-tolerance checkpoints elicit autoimmune responses, which is analogous to the mechanism of self-tolerance in the mammalian adaptive immune system [46]. In this respect, BM laminin is unique in that knockdown of laminin disrupted both BM integrity and cell integrity simultaneously. During pharyngeal tube formation of the C. elegans embryo, laminin is required for establishment of cell polarity of a group of precursor cells called the double plate [47]. Since this process occurs before the tissue BM is formed and the mutant phenotype is not shared by collagen IV or perlecan mutants, the authors concluded that this function of laminin is distinguished from its role in the BM. Our results indicate that the Drosophila laminin functions similarly and thus is unique among the BM components.

Since cell integrity was identified as a discrete self-tolerance checkpoint, it is interesting that target tissue is not subjected to encapsulation during wound healing or developmental processes in which BM integrity is disrupted temporarily. Upon tissue damage, circulating plasmatocytes attach to the wound region as early as 5 min [17], presumably to help remodel the tissue, including the disrupted BM, as hemocytes also produce BM components [12], [27] (Figure 3I). According to our model, as long as cell integrity remains intact, this checkpoint would warrant self-tolerance and block lamellocyte encapsulation in these cases, and thus, wound repair would proceed safely (as in Figure 5C). Cancer metastasis is a more complex problem, as the hallmarks of cancer include BM degradation and loss of epithelial polarity [48], [49]. Additional work will be required to probe this situation, but it is plausible that cell integrity may exert its checkpoint function normally through inhibitory cytokines, and prior to successful metastasis, cancer cells may have to obtain the ability to secret such cytokines independently of the state of cell integrity.

While our results were obtained in the invertebrate Drosophila system, we think these findings have relevance to mammalian autoimmunity. In type I diabetes in humans and in a mouse model, leukocyte infiltration and subsequent β cell destruction have been shown to correlate with disruption of the peri-islet BM, suggesting that the BM may protect islets from autoimmune attack [50], [51]. In Sjögren's syndrome, which mainly affects the exocrine tissues such as tear and salivary glands, increased degradation of the basal lamina is observed in labial salivary glands, and changes in laminin composition of the salivary acini correlates well with disease progression [52], [53]. A clear causal relationship is still lacking, but it is tempting to speculate that at least some of the autoimmune diseases may be caused by alterations in BM integrity and/or cell polarity and loss of these features may be recognized by the immune system as “missing self”, similar to the way natural killer cells distinguish between self and nonself [54], [55].

Methods

Fly strains

The following strains were obtained from public stock centers: UAS-vkg-i (106812†), UAS-Cg25C-i (104536, 28369), UAS-LanA-i (18873), UAS-wb-i (108020), UAS-LanB1-i (23119, 23121), UAS-LanB2-i (42559, 42560, 104013†), UAS-trol-i (22642), UAS-Ndg-i (13208), UAS-mew - i (44890), UAS-if-i (100770, 44885), UAS-scb-i (4891, 100949), UAS-ItgαPS4-i (37172) UAS - ItgαPS5-i (6646, 100120), UAS-mys-i (29619†), UAS-Itgβν-i (893), UAS-Dg-i (107029), UAS-Dys-i (106401, 106578), and UAS-krz-i (103756†) from Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center; UAS-vkg-i (16858R-3), UAS-trol-i (12497R-1), UAS-Ndg-i (12908R-3), UAS-mew - i (1771R-1), UAS - ItgαPS4-i (16827R-2), UAS - Itgβν-i (1762R-1), UAS-mys-i (1560R-1), UAS-mRpS30-i (8470R-4†), UAS-hyx-i (11990R-2†), UAS-dlg1-i (1725R-1), and UAS-FasIII-i (5803R-1) from National Institute of Genetics, Japan; and Hsp70-GAL4 (1799), Cg-GAL4 (7011) [56], HmlΔ-GAL4 (30141), ptc-GAL4 (2017), AB1-GAL4 (1824), Act5C-GAL4 (3954), UAS-Dcr2 (24650), UAS-Ser.mg5603 (5815), UAS-GFP (4775), LanB2MI03747 (37366), hopTum (8492), spagK12101 (12200), UAS-LanA-i (28071), UAS-trol-i (29440†), UAS-mys-i (33642, 27735), UAS-cora-i (28993), UAS-dlg1-i (33620), UAS-scrib-i (29552), UAS-shg-i (32904), and UAS-arm-i (35004) from the Bloomington Stock Center. The following stocks were obtained from private collections: Eater-GFP(X) from R. A. Schulz [57]; FB-GAL4 from R. P. Kühnlein [58]; and UAS-domeΔCYT, vkgG454, and UAS-Mmp2 from T. Xu [18]. The RNAi constructs marked with † proved stronger in knockdown experiments than others and were used for further analysis including imaging.

Culture conditions and heat shock induction

All flies were maintained at 25°C unless otherwise indicated on standard cornmeal and agar media. For RNAi knockdown using Hsp70-GAL4, a single heat pulse of 30 min at 37°C was applied at 24, 48, 72, or 96 h after egg laying (AEL). After counting larval black nodules, 48 h and 96 h time points were chosen as the two optimal conditions for later experiments as 24 h yielded a lower rate of melanotic mass induction and 72 h resulted in a higher rate of lethality. For imaging the BM, a single heat-shock pulse was applied at 48 h AEL for Hsp70>vkg-i, and double pulses were applied at 48 h and 96 h AEL for Hsp70>LanB2-i104013;+/LanB2MI03747 for stronger knockdown.

Counting melanotic masses

Larval density and stage were tightly controlled during culture due to the fact that melanotic mass formation was affected by overcrowding growth conditions. Ten virgin females of GAL4 strains were crossed to 5–7 males carrying different UAS-RNA-i strains. After 2 days, eggs were collected for 6 h (approximately 40–60 eggs). Melanotic masses were counted at the wandering third instar stage by rotating the larvae under the dissection microscope. The percentages of larvae containing at least one melanotic mass in their bodies were determined after counting 3 or more vials (n≥150) for each genotype or developmental time point.

Immunostaining, antibodies, and imaging

Wandering third instar larvae were dissected on a silicone pad in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using a pair of forceps. Larval organs were transferred immediately to 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and fixed for 15–30 min at room temperature. Samples were washed four times in PBS plus 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) and incubated in a blocking solution of PBST plus 5% normal goat serum for 1 h (PBST-NGS). Samples were then incubated with primary antibodies in PBST-NGS overnight at 4°C and then washed four times with PBST-NGS. Samples were then incubated with secondary antibodies alone or together with phalloidin-FITC in PBST-NGS for 2 h at room temperature. After four washes, samples were mounted in Vectorshield plus DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) and were subjected to fluorescent microscopy (Olympus BX40) or confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510 META). For junction staining of the salivary gland, PBS plus 0.3% Triton X-100 was used as the buffer. The following antibodies and reagents were used: mouse anti-collagen IV [59] (Col IV) (6G7, 1∶100), rabbit anti-LanB1 (1∶500; Abcam), rabbit anti-LanB2 (1∶500; Abcam), rabbit anti-Trol [60] (1∶2000), rabbit anti-Ndg [61] (1∶2000), mouse anti-Hemes [62] (H2) (1∶500), mouse anti-L1 [63] (1∶500), mouse anti-Mys (1∶200; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB]), mouse anti-Dlg 4F3 (1∶100; DSHB), mouse anti-Coracle C615.16 (1∶100; DSHB), anti-mouse IgG-Cy3 (1∶200; Jackson ImmunoResearch), phalloidin-FITC (1∶50 dilution of 400 µM stock; Sigma–Aldrich), and anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 or Alexa 546 (1∶200; Molecular Probes). For quantification of the BM fluorescence intensity, 400× magnified confocal images for the middle-marginal part of the salivary gland or region ‘6’ of the fat body were collected [11]. The fluorescence intensity was measured in 5–7 samples per genotype using the Image J software as described previously [26].

Counting hemocytes

Wandering third instar larvae were washed in PBS and dried. A single larva was bled on a silicone pad in a 12-µl drop of PBS by ripping the epidermis with two fine forceps. The PBS/hemocyte drop was swirled gently using a micropipette tip and mounted on the Neubauer hemocytometer for counting. The total hemocytes were counted, and the lamellocytes were counted based on their characteristic morphology. For each genotype, at least 15 larvae were analyzed.

Wounding

In situ wounding was performed as described previously [18] with minor modifications. Third instar larvae were immersed in water on a silicone pad. Under the GFP/dissection microscope, larvae were gently pinched at the salivary glands (with help of AB1>GFP) using a pair of forceps (Fine Science Tools, Cat. No. 11295-00). Larvae were transferred to fresh cornmeal-agar media and incubated at 25°C. Dead or melanized larvae that were identified within the first 3 h were removed. After 48 h of wounding, non-pupariated larvae were dissected and analyzed for melanotic mass formation on the salivary gland.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. TakeuchiO, AkiraS (2010) Pattern Recognition Receptors and Inflammation. Cell 140 : 805–820.

2. MedzhitovR, Preston-HurlburtP, JanewayCAJr (1997) A human homologue of the Drosophila toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature 388 : 394–397.

3. Marshak-RothsteinA, RifkinIR (2007) Immunologically active autoantigens: the role of toll-like receptors in the development of chronic inflammatory disease. Annu Rev Immunol 25 : 419–441.

4. WatsonKL, JohnsonTK, DenellRE (1991) Lethal(1) aberrant immune response mutations leading to melanotic tumor formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Developmental Genetics 12 : 173–187.

5. QiuP, PanPC, GovindS (1998) A role for the Drosophila Toll/Cactus pathway in larval hematopoiesis. Development 125 : 1909–1920.

6. MinakhinaS, StewardR (2006) Melanotic mutants in Drosophila: Pathways and phenotypes. Genetics 174 : 253–263.

7. RizkiRM, RizkiTM (1984) Selective destruction of a host blood cell type by a parasitoid wasp. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 81 : 6154–6158.

8. MeisterM (2004) Blood cells of Drosophila: Cell lineages and role in host defence. Current Opinion in Immunology 16 : 10–15.

9. RizkiRM, RizkiTM (1974) Basement membrane abnormalities in melanotic tumor formation of Drosophila. Experientia 30 : 543–546.

10. RizkiTM, RizkiRM (1980) Developmental analysis of a temperature-sensitive melanotic tumor mutant in Drosophila melanogaster. Wilhelm Roux's Archives of Developmental Biology 189 : 197–206.

11. RizkiRM, RizkiTM (1980) Hemocyte responses to implanted tissues in Drosophila melanogaster larvae. Wilhelm Roux's Archives of Developmental Biology 189 : 207–213.

12. RodriguezA, ZhouZ, TangML, MellerS, ChenJ, et al. (1996) Identification of immune system and responses genes, and novel mutations causing melanotic tumor formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 143 : 929–940.

13. HenchcliffeC, Garcia-AlonsoL, TangJ, GoodmanCS (1993) Genetic analysis of laminin A reveals diverse functions during morphogenesis in Drosophila. Development 118 : 325–337.

14. UrbanoJM, TorglerCN, MolnarC, TepassU, López-VareaA, et al. (2009) Drosophila laminins act as key regulators of basement membrane assembly and morphogenesis. Development 136 : 4165–4176.

15. WolfstetterG, HolzA (2012) The role of LamininB2 (LanB2) during mesoderm differentiation in Drosophila. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 69 : 267–282.

16. MartinD, ZusmanS, LiX, WilliamsEL, KhareN, et al. (1999) wing blister, a new Drosophila laminin alpha chain required for cell adhesion and migration during embryonic and imaginal development. Journal of Cell Biology 145 : 191–201.

17. BabcockDT, BrockAR, FishGS, WangY, PerrinL, et al. (2008) Circulating blood cells function as a surveillance system for damaged tissue in Drosophila larvae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 : 10017–10022.

18. Pastor-ParejaJC, MingW, TianX (2008) An innate immune response of blood cells to tumors and tissue damage in Drosophila. DMM Disease Models and Mechanisms 1 : 144–154.

19. PaddibhatlaI, LeeMJ, KalamarzME, FerrareseR, GovindS (2010) Role for sumoylation in systemic inflammation and immune homeostasis in Drosophila larvae. PLoS Pathogens 6: e1001234.

20. SasakiT, FässlerR, HohenesterE (2004) Laminin: The crux of basement membrane assembly. Journal of Cell Biology 164 : 959–963.

21. YurchencoPD (2011) Basement membranes: Cell scaffoldings and signaling platforms. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 3 : 1–27.

22. ColognatoH, YurchencoPD (2000) Form and function: The laminin family of heterotrimers. Developmental Dynamics 218 : 213–234.

23. NatzleJE, MonsonJM, McCarthyBJ (1982) Cytogenetic location and expression of collagen-like genes in Drosophila. Nature 296 : 368–371.

24. YasothornsrikulS, DavisWJ, CramerG, KimbrellDA, DearolfCR (1997) viking: identification and characterization of a second type IV collagen in Drosophila. Gene 198 : 17–25.

25. MontellDJ, GoodmanCS (1988) Drosophila substrate adhesion molecule: sequence of laminin B1 chain reveals domains of homology with mouse. Cell 53 : 463–473.

26. Pastor-ParejaJ, XuT (2011) Shaping Cells and Organs in Drosophila by Opposing Roles of Fat Body-Secreted Collagen IV and Perlecan. Developmental Cell 21 : 245–256.

27. Kusche-GullbergM, GarrisonK, MacKrellAJ, FesslerLI, FesslerJH (1992) Laminin A chain: expression during Drosophila development and genomic sequence. The EMBO Journal 11 : 4519–4527.

28. Avet-RochexA, BoyerK, PoleselloC, GobertV, OsmanD, et al. (2010) An in vivo RNA interference screen identifies gene networks controlling Drosophila melanogaster blood cell homeostasis. BMC Developmental Biology 10 : 65.

29. HarrisonDA, BinariR, NahreiniTS, GilmanM, PerrimonN (1995) Activation of a Drosophila Janus kinase (JAK) causes hematopoietic neoplasia and developmental defects. The EMBO Journal 14 : 2857–2865.

30. LuoH, RoseP, BarberD, HanrattyWP, LeeS, et al. (1997) Mutation in the Jak kinase JH2 domain hyperactivates Drosophila and mammalian Jak-Stat pathways. Molecular and Cellular Biology 17 : 1562–1571.

31. EvansCJ, HartensteinV, BanerjeeU (2003) Thicker than blood: Conserved mechanisms in Drosophila and vertebrate hematopoiesis. Developmental Cell 5 : 673–690.

32. BrownS, HuN, Castelli-Gair HombriaJ (2001) Identification of the first invertebrate interleukin JAK/STAT receptor, the Drosophila gene domeless. Current Biology 11 : 1700–1705.

33. LuoH, RoseP, RobertsT, DearolfC (2002) The Hopscotch Jak kinase requires the Raf pathway to promote blood cell activation and differentiation in Drosophila. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 267 : 57–63.

34. HuangL, OhsakoS, TandaS (2005) The lesswright mutation activates Rel-related proteins, leading to overproduction of larval hemocytes in Drosophila melanogaster. Developmental Biology 280 : 407–420.

35. SorrentinoRP, TokusumiT, SchulzRA (2007) The Friend of GATA protein U-shaped functions as a hematopoietic tumor suppressor in Drosophila. Developmental Biology 311 : 311–323.

36. MarkovicMP, KylstenP, DushayMS (2009) Drosophila lamin mutations cause melanotic mass formation and lamellocyte differentiation. Molecular Immunology 46 : 3245–3250.

37. RizkiTM, RizkiRM (1992) Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Developmental and Comparative Immunology 16 : 103–110.

38. TokusumiT, SorrentinoRP, RussellM, FerrareseR, GovindS, et al. (2009) Characterization of a lamellocyte transcriptional enhancer located within the misshapen gene of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 4: e6429.

39. MárkusR, LaurinyeczB, KuruczÉ, HontiV, BajuszI, et al. (2009) Sessile hemocytes as a hematopoietic compartment in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 : 4805–4809.

40. SinenkoSA, Mathey-PrevotB (2004) Increased expression of Drosophila tetraspanin, Tsp68C, suppresses the abnormal proliferation of ytr-deficient and Ras/Raf-activated hemocytes. Oncogene 23 : 9120–9128.

41. WoodsDF, WuJOW, BryantPJ (1997) Localization of proteins to the apico-lateral junctions of Drosophila epithelia. Developmental Genetics 20 : 111–118.

42. MunroS, FreemanM (2000) The Notch signalling regulator Fringe acts in the Golgi apparatus and requires the glycosyltransferase signature motif DXD. Current Biology 10 : 813–820.

43. WarburgA, ShternA, CohenN, DahanN (2007) Laminin and a Plasmodium ookinete surface protein inhibit melanotic encapsulation of Sephadex beads in the hemocoel of mosquitoes. Microbes and Infection 9 : 192–199.

44. Salt G (1970) The cellular defence reactions of insects: Cambridge University Press.

45. NacerA, WalkerK, HurdH (2008) Localisation of laminin within Plasmodium berghei oocysts and the midgut epithelial cells of Anopheles stephensi. Parasites & Vectors 1 : 33.

46. GoodnowCC (2007) Multistep Pathogenesis of Autoimmune Disease. Cell 130 : 25–35.

47. RasmussenJP, ReddySS, PriessJR (2012) Laminin is required to orient epithelial polarity in the C. elegans pharynx. Development 139 : 2050–2060.

48. PagliariniRA, XuT (2003) A Genetic Screen in Drosophila for Metastatic Behavior. Science 302 : 1227–1231.

49. BilderD (2004) Epithelial polarity and proliferation control: Links from the Drosophila neoplastictumor suppressors. Genes and Development 18 : 1909–1925.

50. Irving-RodgersHF, ZiolkowskiAF, ParishCR, SadoY, NinomiyaY, et al. (2008) Molecular composition of the peri-islet basement membrane in NOD mice: A barrier against destructive insulitis. Diabetologia 51 : 1680–1688.

51. KorposE, KadriN, KappelhoffR, WegnerJ, OverallCM, et al. (2013) The peri-islet basement membrane, a barrier to infiltrating leukocytes in type 1 diabetes in mouse and human. Diabetes 62 : 531–542.

52. LaineM, VirtanenI, SaloT, KonttinenYT (2004) Segment-specific but pathologic laminin isoform profiles in human labial salivary glands of patients with Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis and Rheumatism 50 : 3968–3973.

53. LaineM, VirtanenI, PorolaP, RotarZ, RozmanB, et al. (2008) Acinar epithelial cell laminin-receptors in labial salivary glands in Sjögren's syndrome. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 26 : 807–813.

54. KarreK, LjunggrenHG, PiontekG, KiesslingR (1986) Selective rejection of H-2-deficient lymphoma variants suggests alternative immune defence strategy. Nature 319 : 675–678.

55. VivierE, RauletDH, MorettaA, CaligiuriMA, ZitvogelL, et al. (2011) Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science 331 : 44–49.

56. AshaH, NagyI, KovacsG, StetsonD, AndoI, et al. (2003) Analysis of ras-induced overproliferation in Drosophila hemocytes. Genetics 163 : 203–215.

57. TokusumiT, ShoueDA, TokusumiY, StollerJR, SchulzRA (2009) New hemocyte-specific enhancer-reporter transgenes for the analysis of hematopoiesis in Drosophila. Genesis 47 : 771–774.

58. GronkeS, BellerM, FellertS, RamakrishnanH, JackleH, et al. (2003) Control of fat storage by a Drosophila PAT domain protein. Current Biology 13 : 603–606.

59. MurrayM, FesslerL, PalkaJ (1995) Changing Distributions of Extracellular Matrix Components during Early Wing Morphogenesis in Drosophila. Developmental biology 168 : 150–165.

60. FriedrichMVK, SchneiderM, TimplR, BaumgartnerS (2000) Perlecan domain V of Drosophila melanogaster. Sequence, recombinant analysis and tissue expression. European Journal of Biochemistry 267 : 3149–3159.

61. WolfstetterG, ShirinianM, StuteC, GrabbeC, HummelT, et al. (2009) Fusion of circular and longitudinal muscles in Drosophila is independent of the endoderm but further visceral muscle differentiation requires a close contact between mesoderm and endoderm. Mechanisms of Development 126 : 721–736.

62. KuruczE, ZettervallCJ, SinkaR, VilmosP, PivarcsiA, et al. (2003) Hemese, a hemocyte-specific transmembrane protein, affects the cellular immune response in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 : 2622–2627.

63. KuruczE, VácziB, MárkusR, LaurinyeczB, VilmosP, et al. (2007) Definition of Drosophila hemocyte subsets by cell-type specific antigens. Acta Biologica Hungarica 58 : 95–111.

64. DuvicB, HoffmannJA, MeisterM, RoyetJ (2002) Notch signaling controls lineage specification during Drosophila larval hematopoiesis. Current Biology 12 : 1923–1927.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice Deficient for miR-34b/c and miR-449 LociČlánek The Kinesin AtPSS1 Promotes Synapsis and is Required for Proper Crossover Distribution in MeiosisČlánek Payoffs, Not Tradeoffs, in the Adaptation of a Virus to Ostensibly Conflicting Selective PressuresČlánek Examination of Prokaryotic Multipartite Genome Evolution through Experimental Genome ReductionČlánek BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian SkinČlánek Role of STN1 and DNA Polymerase α in Telomere Stability and Genome-Wide Replication in ArabidopsisČlánek RNA-Processing Protein TDP-43 Regulates FOXO-Dependent Protein Quality Control in Stress ResponseČlánek Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping StudiesČlánek Salt-Induced Stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 Confers Salinity Tolerance by Deterring ROS Accumulation inČlánek Ethylene-Induced Inhibition of Root Growth Requires Abscisic Acid Function in Rice ( L.) SeedlingsČlánek Metabolic Respiration Induces AMPK- and Ire1p-Dependent Activation of the p38-Type HOG MAPK PathwayČlánek Signature Gene Expression Reveals Novel Clues to the Molecular Mechanisms of Dimorphic Transition inČlánek A Mouse Model Uncovers LKB1 as an UVB-Induced DNA Damage Sensor Mediating CDKN1A (p21) DegradationČlánek Dominant Sequences of Human Major Histocompatibility Complex Conserved Extended Haplotypes from to

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 10

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- An Deletion Is Highly Associated with a Juvenile-Onset Inherited Polyneuropathy in Leonberger and Saint Bernard Dogs

- Licensing of Yeast Centrosome Duplication Requires Phosphoregulation of Sfi1

- Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice Deficient for miR-34b/c and miR-449 Loci

- Basement Membrane and Cell Integrity of Self-Tissues in Maintaining Immunological Tolerance

- The Kinesin AtPSS1 Promotes Synapsis and is Required for Proper Crossover Distribution in Meiosis

- Germline Mutations in Are Associated with Familial Gastric Cancer

- POT1a and Components of CST Engage Telomerase and Regulate Its Activity in

- Controlling Meiotic Recombinational Repair – Specifying the Roles of ZMMs, Sgs1 and Mus81/Mms4 in Crossover Formation

- Payoffs, Not Tradeoffs, in the Adaptation of a Virus to Ostensibly Conflicting Selective Pressures

- FHIT Suppresses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Metastasis in Lung Cancer through Modulation of MicroRNAs

- Genome-Wide Mapping of Yeast RNA Polymerase II Termination

- Examination of Prokaryotic Multipartite Genome Evolution through Experimental Genome Reduction

- White Cells Facilitate Opposite- and Same-Sex Mating of Opaque Cells in

- BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian Skin

- Genome-Wide Association Study of CSF Levels of 59 Alzheimer's Disease Candidate Proteins: Significant Associations with Proteins Involved in Amyloid Processing and Inflammation

- COE Loss-of-Function Analysis Reveals a Genetic Program Underlying Maintenance and Regeneration of the Nervous System in Planarians

- Fat-Dachsous Signaling Coordinates Cartilage Differentiation and Polarity during Craniofacial Development

- Identification of Genes Important for Cutaneous Function Revealed by a Large Scale Reverse Genetic Screen in the Mouse

- Sensors at Centrosomes Reveal Determinants of Local Separase Activity

- Genes Integrate and Hedgehog Pathways in the Second Heart Field for Cardiac Septation

- Systematic Dissection of Coding Exons at Single Nucleotide Resolution Supports an Additional Role in Cell-Specific Transcriptional Regulation

- Recovery from an Acute Infection in Requires the GATA Transcription Factor ELT-2

- HIPPO Pathway Members Restrict SOX2 to the Inner Cell Mass Where It Promotes ICM Fates in the Mouse Blastocyst

- Role of and in Development of Abdominal Epithelia Breaks Posterior Prevalence Rule

- The Formation of Endoderm-Derived Taste Sensory Organs Requires a -Dependent Expansion of Embryonic Taste Bud Progenitor Cells

- Role of STN1 and DNA Polymerase α in Telomere Stability and Genome-Wide Replication in Arabidopsis

- Keratin 76 Is Required for Tight Junction Function and Maintenance of the Skin Barrier

- Encodes the Catalytic Subunit of N Alpha-Acetyltransferase that Regulates Development, Metabolism and Adult Lifespan

- Disruption of SUMO-Specific Protease 2 Induces Mitochondria Mediated Neurodegeneration

- Caudal Regulates the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Pair-Rule Waves in

- It's All in Your Mind: Determining Germ Cell Fate by Neuronal IRE-1 in

- A Conserved Role for Homologs in Protecting Dopaminergic Neurons from Oxidative Stress

- The Master Activator of IncA/C Conjugative Plasmids Stimulates Genomic Islands and Multidrug Resistance Dissemination

- An AGEF-1/Arf GTPase/AP-1 Ensemble Antagonizes LET-23 EGFR Basolateral Localization and Signaling during Vulva Induction

- The Proteomic Landscape of the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus Clock Reveals Large-Scale Coordination of Key Biological Processes

- RNA-Processing Protein TDP-43 Regulates FOXO-Dependent Protein Quality Control in Stress Response

- A Complex Genetic Switch Involving Overlapping Divergent Promoters and DNA Looping Regulates Expression of Conjugation Genes of a Gram-positive Plasmid

- ZTF-8 Interacts with the 9-1-1 Complex and Is Required for DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in the Germline

- Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping Studies

- Tpz1-Ccq1 and Tpz1-Poz1 Interactions within Fission Yeast Shelterin Modulate Ccq1 Thr93 Phosphorylation and Telomerase Recruitment

- Salt-Induced Stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 Confers Salinity Tolerance by Deterring ROS Accumulation in

- Telomeric (s) in spp. Encode Mediator Subunits That Regulate Distinct Virulence Traits

- Ethylene-Induced Inhibition of Root Growth Requires Abscisic Acid Function in Rice ( L.) Seedlings

- Ancient Expansion of the Hox Cluster in Lepidoptera Generated Four Homeobox Genes Implicated in Extra-Embryonic Tissue Formation

- Mechanism of Suppression of Chromosomal Instability by DNA Polymerase POLQ

- A Mutation in the Mouse Gene Leads to Impaired Hedgehog Signaling

- Keeping mtDNA in Shape between Generations

- Targeted Exon Capture and Sequencing in Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- TIF-IA-Dependent Regulation of Ribosome Synthesis in Muscle Is Required to Maintain Systemic Insulin Signaling and Larval Growth

- At Short Telomeres Tel1 Directs Early Replication and Phosphorylates Rif1

- Evidence of a Bacterial Receptor for Lysozyme: Binding of Lysozyme to the Anti-σ Factor RsiV Controls Activation of the ECF σ Factor σ

- Hsp40s Specify Functions of Hsp104 and Hsp90 Protein Chaperone Machines

- Feeding State, Insulin and NPR-1 Modulate Chemoreceptor Gene Expression via Integration of Sensory and Circuit Inputs

- Functional Interaction between Ribosomal Protein L6 and RbgA during Ribosome Assembly

- Multiple Regulatory Systems Coordinate DNA Replication with Cell Growth in

- Fast Evolution from Precast Bricks: Genomics of Young Freshwater Populations of Threespine Stickleback

- Mmp1 Processing of the PDF Neuropeptide Regulates Circadian Structural Plasticity of Pacemaker Neurons

- The Nuclear Immune Receptor Is Required for -Dependent Constitutive Defense Activation in

- Genetic Modifiers of Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Café-au-Lait Macule Count Identified Using Multi-platform Analysis

- Juvenile Hormone-Receptor Complex Acts on and to Promote Polyploidy and Vitellogenesis in the Migratory Locust

- Uncovering Enhancer Functions Using the α-Globin Locus

- The Analysis of Mutant Alleles of Different Strength Reveals Multiple Functions of Topoisomerase 2 in Regulation of Chromosome Structure

- Metabolic Respiration Induces AMPK- and Ire1p-Dependent Activation of the p38-Type HOG MAPK Pathway

- The Specification and Global Reprogramming of Histone Epigenetic Marks during Gamete Formation and Early Embryo Development in

- The DAF-16 FOXO Transcription Factor Regulates to Modulate Stress Resistance in , Linking Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling to Protein N-Terminal Acetylation

- Genetic Influences on Translation in Yeast

- Analysis of Mutants Defective in the Cdk8 Module of Mediator Reveal Links between Metabolism and Biofilm Formation

- Ribosomal Readthrough at a Short UGA Stop Codon Context Triggers Dual Localization of Metabolic Enzymes in Fungi and Animals

- Gene Duplication Restores the Viability of Δ and Δ Mutants

- Selection on a Variant Associated with Improved Viral Clearance Drives Local, Adaptive Pseudogenization of Interferon Lambda 4 ()

- Break-Induced Replication Requires DNA Damage-Induced Phosphorylation of Pif1 and Leads to Telomere Lengthening

- Dynamic Partnership between TFIIH, PGC-1α and SIRT1 Is Impaired in Trichothiodystrophy

- Signature Gene Expression Reveals Novel Clues to the Molecular Mechanisms of Dimorphic Transition in

- Mutations in Moderate or Severe Intellectual Disability

- Multifaceted Genome Control by Set1 Dependent and Independent of H3K4 Methylation and the Set1C/COMPASS Complex

- A Role for Taiman in Insect Metamorphosis

- The Small RNA Rli27 Regulates a Cell Wall Protein inside Eukaryotic Cells by Targeting a Long 5′-UTR Variant

- MMS Exposure Promotes Increased MtDNA Mutagenesis in the Presence of Replication-Defective Disease-Associated DNA Polymerase γ Variants

- Coexistence and Within-Host Evolution of Diversified Lineages of Hypermutable in Long-term Cystic Fibrosis Infections

- Comprehensive Mapping of the Flagellar Regulatory Network

- Topoisomerase II Is Required for the Proper Separation of Heterochromatic Regions during Female Meiosis

- A Splice Mutation in the Gene Causes High Glycogen Content and Low Meat Quality in Pig Skeletal Muscle

- KDM5 Interacts with Foxo to Modulate Cellular Levels of Oxidative Stress

- H2B Mono-ubiquitylation Facilitates Fork Stalling and Recovery during Replication Stress by Coordinating Rad53 Activation and Chromatin Assembly

- Copy Number Variation in the Horse Genome

- Unifying Genetic Canalization, Genetic Constraint, and Genotype-by-Environment Interaction: QTL by Genomic Background by Environment Interaction of Flowering Time in

- Spinster Homolog 2 () Deficiency Causes Early Onset Progressive Hearing Loss

- Genome-Wide Discovery of Drug-Dependent Human Liver Regulatory Elements

- Developmentally-Regulated Excision of the SPβ Prophage Reconstitutes a Gene Required for Spore Envelope Maturation in

- Protein Phosphatase 4 Promotes Chromosome Pairing and Synapsis, and Contributes to Maintaining Crossover Competence with Increasing Age

- The bHLH-PAS Transcription Factor Dysfusion Regulates Tarsal Joint Formation in Response to Notch Activity during Leg Development

- A Mouse Model Uncovers LKB1 as an UVB-Induced DNA Damage Sensor Mediating CDKN1A (p21) Degradation

- Notch3 Interactome Analysis Identified WWP2 as a Negative Regulator of Notch3 Signaling in Ovarian Cancer

- An Integrated Cell Purification and Genomics Strategy Reveals Multiple Regulators of Pancreas Development

- Dominant Sequences of Human Major Histocompatibility Complex Conserved Extended Haplotypes from to

- The Vesicle Protein SAM-4 Regulates the Processivity of Synaptic Vesicle Transport

- A Gain-of-Function Mutation in Impeded Bone Development through Increasing Expression in DA2B Mice

- Nephronophthisis-Associated Regulates Cell Cycle Progression, Apoptosis and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition

- Beclin 1 Is Required for Neuron Viability and Regulates Endosome Pathways via the UVRAG-VPS34 Complex

- The Not5 Subunit of the Ccr4-Not Complex Connects Transcription and Translation

- Abnormal Dosage of Ultraconserved Elements Is Highly Disfavored in Healthy Cells but Not Cancer Cells

- Genome-Wide Distribution of RNA-DNA Hybrids Identifies RNase H Targets in tRNA Genes, Retrotransposons and Mitochondria

- The Chromosomal Association of the Smc5/6 Complex Depends on Cohesion and Predicts the Level of Sister Chromatid Entanglement

- Cell-Autonomous Progeroid Changes in Conditional Mouse Models for Repair Endonuclease XPG Deficiency

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The Master Activator of IncA/C Conjugative Plasmids Stimulates Genomic Islands and Multidrug Resistance Dissemination

- A Splice Mutation in the Gene Causes High Glycogen Content and Low Meat Quality in Pig Skeletal Muscle

- Keratin 76 Is Required for Tight Junction Function and Maintenance of the Skin Barrier

- A Role for Taiman in Insect Metamorphosis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání