-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Gain-of-Function Mutation in Impeded Bone Development through Increasing Expression in DA2B Mice

Distal arthrogryposis type 2B (DA2B) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder. The typical clinical features of DA2B include hand and/or foot contracture and shortness of stature in patients. To date, mutations in TNNI2 can explain approximately 20% of familial incidences of DA2B. TNNI2 encodes a subunit of the Tn complex, which is required for calcium-dependent fast twitch muscle fiber contraction. In the absence of Ca2+ ions, TNNI2 impedes sarcomere contraction. Here, we reported a knock-in mouse carrying a DA2B mutation TNNI2 (K175del) had typical limb abnormality and small body size that observed in human DA2B. However, the small body did not seem to be convincingly explained using the present knowledge of TNNI2 associated skeletal muscle contraction. Our findings showed that the Tnni2K175del mutation impaired bone development of Tnni2K175del mice. Our data further showed that the mutant tnni2 protein had a higher capacity to transactivate Hif3a than the wild-type protein and led to a reduction in Vegf expression in bone of DA2B mice. Taken together, our findings demonstrated that the disease-associated Tnni2K175del mutation caused bone defects, which accounted for, at least in part, the small body size of Tnni2K175del mice. Our data also suggested, for the first time, a novel role of tnni2 in the regulation of bone development of mice by affecting Hif-vegf signaling.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004589

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004589Summary

Distal arthrogryposis type 2B (DA2B) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder. The typical clinical features of DA2B include hand and/or foot contracture and shortness of stature in patients. To date, mutations in TNNI2 can explain approximately 20% of familial incidences of DA2B. TNNI2 encodes a subunit of the Tn complex, which is required for calcium-dependent fast twitch muscle fiber contraction. In the absence of Ca2+ ions, TNNI2 impedes sarcomere contraction. Here, we reported a knock-in mouse carrying a DA2B mutation TNNI2 (K175del) had typical limb abnormality and small body size that observed in human DA2B. However, the small body did not seem to be convincingly explained using the present knowledge of TNNI2 associated skeletal muscle contraction. Our findings showed that the Tnni2K175del mutation impaired bone development of Tnni2K175del mice. Our data further showed that the mutant tnni2 protein had a higher capacity to transactivate Hif3a than the wild-type protein and led to a reduction in Vegf expression in bone of DA2B mice. Taken together, our findings demonstrated that the disease-associated Tnni2K175del mutation caused bone defects, which accounted for, at least in part, the small body size of Tnni2K175del mice. Our data also suggested, for the first time, a novel role of tnni2 in the regulation of bone development of mice by affecting Hif-vegf signaling.

Introduction

Distal arthrogryposis type 2B (DA2B) (also called Sheldon-Hall syndrome, or SHS) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder with marked genetic heterogeneity. The typical clinical phenotypes of DA2B patients include hand and/or foot contracture malformation and shortness of stature [1]–[3]. Approximately 20% of familial incidences of DA2B can be explained by mutations in TNNI2 that encodes a subunit of the troponin complex consisting of troponin C, troponin I and troponin T. Troponin complex is set of muscle proteins that are part of the contractile apparatuses for contraction of fast skeletal muscle.

The previous knowledge shows that the two functional domains of TNNI2 are located at the N terminus (residues 96 to 115 and residues 140 to 148). In absence of Ca2+, TNNI2 prevents muscle contraction through binding to actin and tropomyosin using the two domains [4], [5]. However, to date, all of the etiological mutations reported in DA2B families [6]–[10] are mapped at the TNNI2 C terminus that appears to regulate, in part, its sensitivity to Ca2+ ions [11], [12]. These TNNI2 mutations include p.R156X, p.E167del, p.R174Q, p.K175del and p.K176del [6]–[10]. They are highly conserved in eukaryotes from zebrafish to humans. Evidence from in vitro cell assays has suggested that the p.R156X and p.R174Q mutations facilitate muscle contractility through increasing the sensitivity of TNNI2 to Ca2+ [13].

To investigate pathogenesis of DA2B, we generated genetically modified mice with an endogenous Tnni2K175del mutation, which had been mapped by our previous study, using targeted gene editing [10]. Besides limb deformity, we observed that both the homozygous and heterozygous mutant mice consistently showed a small body size that was similar to the reduced size phenotype in human DA2B. However, this phenotype did not seem to be convincingly explained using the present knowledge of TNNI2 associated skeletal muscle contraction. Thus, we hypothesized that an additional function of TNNI2 might be responsible for this abnormal body development. To test this possibility, we focused on investigating the potential mechanism that leads to the small body size phenotype in DA2B mice.

Results

DA2B mice showed a small body size phenotype

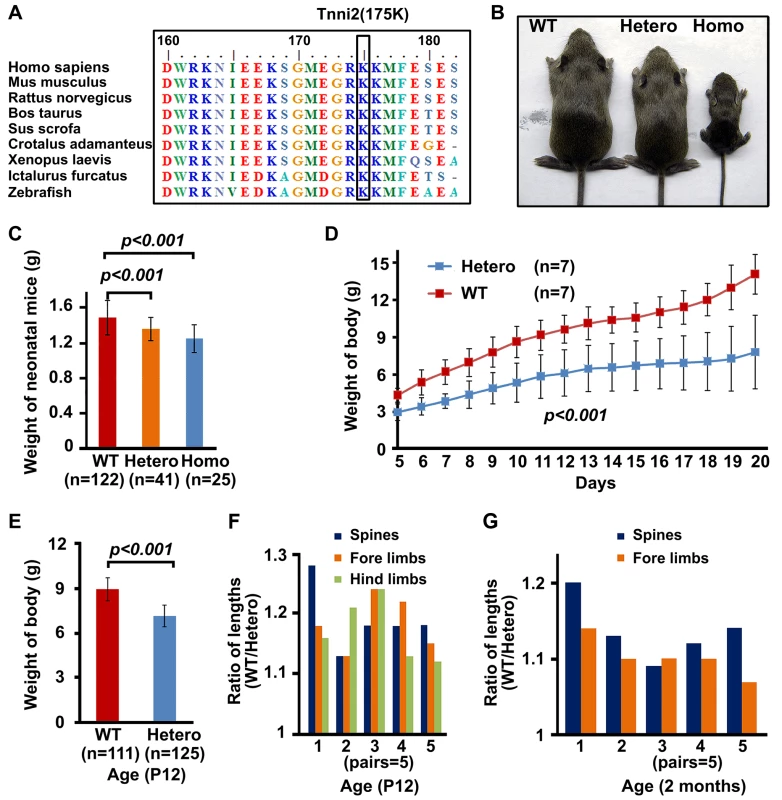

Using site-directed mutagenesis and targeted gene editing, we generated genetically modified mice with an endogenous Tnni2K175del mutation (DA2B mice) (Figure S1), which has been mapped to a large Chinese DA2B family in our previous study [10]. The 175K amino acid is highly conserved from zebrafish to humans (Figure 1A). Like DA2B patients, homozygous and heterozygous mutant mice exhibited an obviously smaller body size than their wild-type counterparts (Figure 1B and Figure S2B), as well as forelimb contracture (Figure S2A and C), supporting the idea that the mutation has a dominant effect on body development and limb formation. Newborn heterozygous (n = 41) and homozygous mice (n = 25) had lower birth weights (by approximately 10% and 15%, respectively) than wild-type littermates (n = 122) (P<0.001) (Figure 1C). The growth rates of heterozygous (Tnni2+/K175del) mice from post-neonatal day (P) 5 to P20 were significantly slower than wild-type controls (P<0.001, n = 7) (Figure 1D), and further analysis indicated that P12 Tnni2+/K175del mice (n = 125) were smaller and lighter than wild-type controls (n = 111) (P<0.001) (Figure 1E). The lengths of the spines, forelimbs and hindlimbs of P12 heterozygous mice were consistently shorter than those of their wild-type littermates (by 13–28% in the spines; by 13–24% in the forelimbs; and by 12–24% in the hindlimbs) (n = 5, Figure 1F). The length of the spine, fore limbs and hind limbs (Figure 1F) seemed to vary between the different pairs, and we considered that the difference between the different pairs of mutant mice could be due to individual variability in breastfeeding. However, the differences were not significant (for spines P = 0.21; for forelimbs P = 0.34; for hindlimbs P = 0.53). In addition, the respective lengths of the spines and forelimbs of Tnni2+/K175del mice were 9–14% and 7–14% shorter than wild-type littermates at 2 months (n = 5, Figure 1G). Except for the small body size and contracture in the forelimbs, we did not observe any limitations in movement of heterozygous or homozygous DA2B mice. Neither heterozygous nor homozygous embryos displayed differences in body size and weight relative to their wild-type littermates before embryonic day (E) 18.5 (Figure S3), indicating that mutant mice apparently experienced growth retardation during late embryonic development. Because the majority of homozygous Tnni2K175del/K175del mice always died within a few hours after birth and less than 2% of Tnni2K175del/K175del mice survived until weaning (Figure S4), subsequent studies were performed mainly using heterozygous mutants. Together, our data indicated that the phenotypes of Tnni2K175del mutant mice were similar to those in human.

Fig. 1. Tnni2K175del mutant mice showed small body size.

(A) The conservation of the 175K amino acid in TNNI2 from humans to zebrafish. (B) P18 mutants exhibited smaller body sizes than wild-type littermates. (C) The comparison of weights of newborn wild-type and mutant mice. (D) The weight changes of heterozygous (n = 7) and wild-type mice littermates (n = 7) from P5 to P20. (E) Weights of heterozygous mutant mice (n = 125) and wild-type littermates (n = 111) at P12. (F) P12 heterozygous mice and wild-type littermates were sacrificed for measurement of the length of spines and limbs. Length ratio of the spines (blue), fore limbs (orange) and hind limbs (green) of wild-type mice (n = 5) to Tnni2K175del littermates (n = 5) at P12. (G) 2-month-old heterozygous mice and wild-type littermates were narcotized for measurement of the length of spines and limbs. Lengths ratio of the spines (blue) and fore limbs (orange) of heterozygous littermates (n = 5) to those of wild-type littermates (n = 5) at 2 months of age. Student t-test, mean±s.d. Postnatal day, P. Tnni2 was expressed in the osteoblasts and chondrocytes of the growth plate

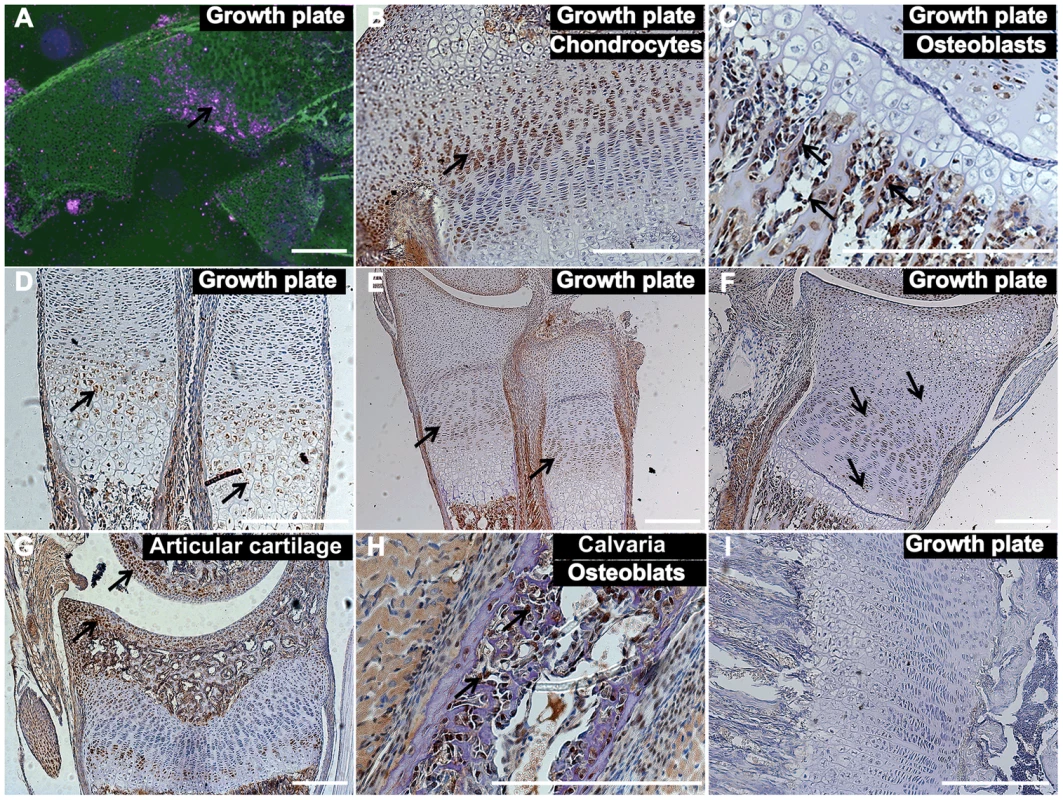

Given that the known function of TNNI2 in regulating muscle contraction does not seem to reasonably explain the characteristic small body size that was observed in the DA2B mice and DA2B patients [14]–[15], we speculated that TNNI2 might have unknown roles in body development. Therefore, we initially performed in situ hybridization analyses to characterize the Tnni2 expression in different organs from E15.5 wild-type embryos (Figure 2A, Figure S5). Tnni2 mRNA was detected in the growth plates of long bones of radii and ulnae (Figure 2A), oesophagus (Figure S5B) and skeletal muscle as well (Figure S5G). Subsequent immunostaining analyses showed that tnni2 was present in the chondrocytes (Figure 2B) of growth plates and in the osteoblasts (Figure 2C) surrounding the border of the growth plates. Moreover, the expression of Tnni2 in the growth plates exhibited a particular spatial and temporal change in wild-type mice (Figure 2D–F). In E15.5 wild-type embryos, tnni2 protein was observed in pre-hypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes (Figure 2D), whereas at E17.5, tnni2 was mainly observed in proliferating cells zones (Figure 2E). After birth, tnni2 was expressed by resting, immature-proliferating, pre-hypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes, but no discernible tnni2 was observed in mature proliferative chondrocytes (Figure 2F). In addition, we observed the expression of Tnni2 in articular chondrocytes (Figure 2G) and calvarial osteoblasts (Figure 2H) of wild-type mice. The similar expression pattern was also observed in Tnni2K175del mice (Figure S6). Thus, the expression in the mouse growth plate and cranium suggested that the tnni2 protein might be involved in bone development.

Fig. 2. Tnni2 was expressed in chondrocytes and osteoblasts.

(A) In situ hybridization analyses with antisense Tnni2 riboprobe on histological sections of wild-type radii of E15.5 embryos showed that Tnni2 mRNA was expressed at the growth plates. Pink indicated Tnni2 mRNA signal (arrow). (B–G) Immunostaining analyses of tnni2 expression in growth plate. (B–C) tnni2 was expressed at chondrocytes (B, arrow) and osteoblasts (C, arrows) of the tibia growth plates from P8 wild-type mice. (D–F) The expression of tnni2 in the growth plates of radii and ulnae exhibited a spatial and temporal change. (D) In E15.5 wild-type embryos, tnni2 was expressed in pre-hypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes (arrows). (E) At E17.5 wild-type embryos, tnni2 was mainly observed in proliferating chondrocytes (arrows). (F) At P6 wild-type radii, expression of tnni2 was in pre-hypertrophic, hypertrophic, immature proliferating and rest chondrocytes (arrows), whereas no discernible tnni2 was observed in mature proliferative chondrocytes. (G) Expression of tnni2 was in articular chondrocytes of tibiae of P12 wild-type mice (arrows). (H) tnni2 was observed in calvarial osteoblasts of P6 wild-type mice (arrows). (I) Negative staining for tnni2 protein. Scale bar, 100 µm (A–I). Embryonic day, E. The bone development of DA2B mice was impeded

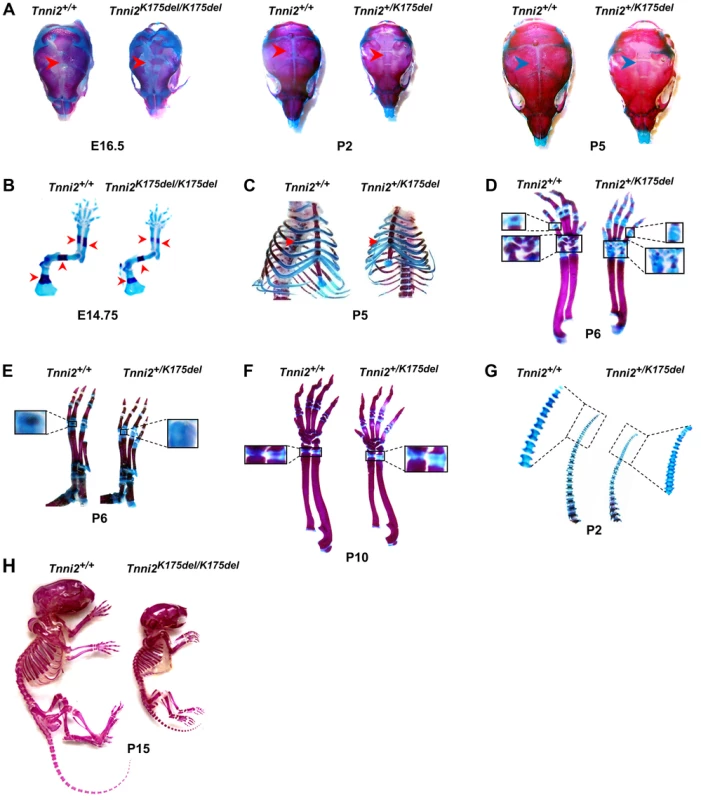

We then investigated the bone morphology in DA2B mice by performing skeletal analyses. All skeletal elements of DA2B mice had a markedly smaller size and lower mineral content than those observed in wild-type mice. The degree of mineralization in the cranium was significantly reduced at E16.5 homozygous mutant embryos, P2 and P5 heterozygous mutant mice (Figure 3A and Figure S7), indicating that intramembranous ossification was delayed in Tnni2K175del mutants. At E14.75, the long bones of the forelimbs of Tnni2K175del/K175del embryos were smaller, and the primary centers of ossification in radii, ulnae, humeri and scapulae were evidently shorter than those in their wild-type littermates (Figure 3B and Figure S8). The heterozygous mutants had delayed cartilage ossifications in the ribs (Figure 3C), carpus and metacarpus (Figure 3D), phalanx (Figure 3E), growth plates of radii and ulnae (Figure 3F) and tail cartilage (Figure 3G) at P2, P5, P6, and P10. The primary and secondary ossification centers in the long bones of DA2B mice were impeded (Figure 3B–G), and their skeletal structures were smaller (Figure 3H), indicating that endochondral ossification was also impaired in Tnni2K175del mutants. Taken together, our data indicated that the Tnni2K175del mutation impeded the intramembranous (Figure 3A and Figure S7) and endochondral (Figure 3B–G) ossification of DA2B mice.

Fig. 3. The Tnni2K175del mutation disturbed bone development of mice.

Skeletons staining using Alcian blue for cartilage (blue) and Alizarin Red S for calcified bone (red). (A) Decreased mineralization (arrows) in the calvarias from Tnni2K175del/K175del mice at E16.5 and from Tnni2+K175del mice at P2 and P5 compared to their wild-type littermates, respectively. (B) The primary ossification centers (arrows) in forelimb bones from Tnni2K175del/K 175del mice at E14.75 were shorter than those of their wild-type controls. (C) Reduced ossification (arrows) in P5 mutant ribs. (D and E) At P6, the secondary ossification in phalanxes and carpals (D, the boxed regions) and metatarsal bones (E, the boxed regions) of Tnni2+/K175del mice were fewer than those of wild-type littermates. (F) Growth plates (the boxed regions) in radii and ulnae of heterozygous mutant mice at P10 were longer and less ossified than those of wild-type littermates. (G) Decrease in cartilage ossification in the P2 tails of mutants (the rectangle regions). (H) Skeletal preparation of homozygous mice and wild-type littermates at P15. All experiments were repeated using at least two pairs of samples. The Tnni2K175del mutation disturbed the expression of molecules involved in Hif-signaling in the mutant bones

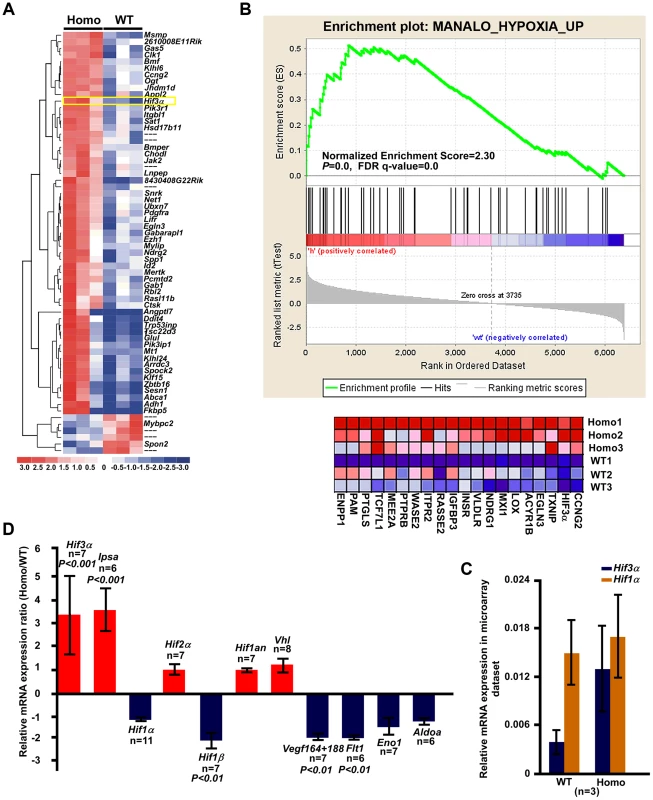

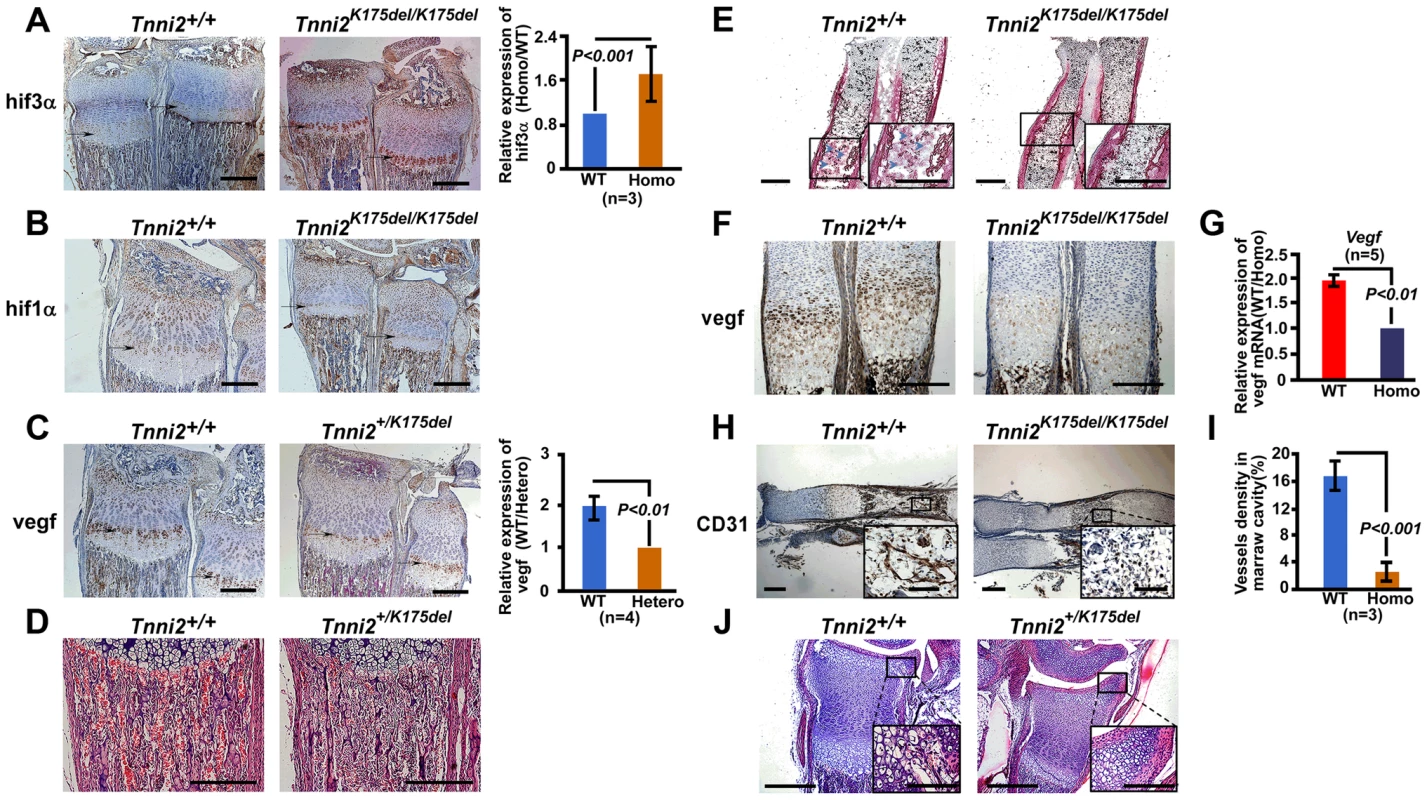

To characterize the molecules involved in the impeded bone development in Tnni2K175del mutant mice, we performed a microarray analysis using three pairs of intact radii and ulnas from 1-day-old Tnni2K175del/K175del and wild-type littermate mice. We tested differential gene expression using the SAM package. The Tnni2K175del mutation was associated with upregulation of 58 and downregulation of 6 probe sets (Score ≥3 and fold ≥2) (Figure 4A and Table S1). Furthermore, gene set enrichment analysis (GESA) of these mutant and wild-type samples showed significant enrichment of a set of hypoxia induced genes [16] (Normalized Enrichment Score = 2.30, P = 0.0, FDR q-value = 0.0) (Figure 4B). Hypoxia signaling, which is mainly mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1A) and its downstream target genes, including VEGF and its receptor FLT1, is important for bone development [17]–[20]. Notably, in our microarray dataset (SAM analysis, Table S1), Hif3a ranked in the top fifth of the significant differential expression genes. Of the genes that were observed to be dramatically upregulated in our microarray dataset, Hif3a had higher expression levels (more than 3-fold) in homozygous mutants than in the wild-type littermates (Figure 4C). HIF3A negatively regulates HIF1A signaling by binding to HIF1A or HIF1B and antagonizing HIF1-induced gene expression [21]–[22]. Therefore, we further examined the expression patterns of Hif3a and Hif1a in mRNA levels by qPCR in 1-day-old wild-type and mutant radii and ulnas (Figure 4D). Consistently, Hif3a and a main splicing variant of the Hif3a (Ipas) [23] were significantly increased by approximately 3.6-fold on average in homozygous mutant bones (Figure 4D). Hif1a expression was no significant difference between mutant bones and wild-type controls (Figure 4D). Furthermore, immunostaining showed that hif3a protein was significantly increased in the hypertrophic cell zones of mutant radii and ulnae compared to wild-type controls (Figure 5A). However, hif1a did not seem to differ in the growth plate of radii at P12 mutant and wild-type controls (Figure 5B). Thus, the marked increase in Hif3a expression in Tnni2K175del mutant bones suggested that Hif-signaling could be compromised in the mutant bones of DA2B mice.

Fig. 4. The Hif3a expression was significantly upregulated in the Tnni2K175del mutant long bones.

(A) Heat map diagram of the 64 top ranking differentially expressed genes (Table S1) in 1-day-old homozygous mutant radii and ulnae (n = 3) compared to wild-type littermate controls (n = 3). Genes are shown in rows; samples are showed in columns. Red bar indicated higher expression and blue bar indicated lower expression. (B) GSEA plot (top) showed that differential expression of genes between the entire radii and ulnae from 1-day-old homozygous mice (n = 3) and wild-type littermates (n = 3) were significantly enriched in hypoxia induced gene set. Heat-map diagram (bottom) showed the 20 core-enriching genes in the leading edge. The number of permutation was 1000 times. (C) Relative mRNA expression of Hif1a and Hif3a (normalized to Gapdh) in our microarray dataset. (D) The relative mRNA expression of Hif-associated signaling molecules (normalized to Gapdh) in 1-day-old homozygous mutant radii and ulnae over those of wild-type littermates (Homo/WT), using qPCR analyses. Fig. 5. The disturbed Hif associated signaling in Tnni2K175del mice resulted in reduced angiogenesis and impeded formation of ossification centers of long bones.

(A–B) Immunostaining analyses of the hif3a (A) and hif1a (B) expression in the hypertrophic cell zones (arrows) of radii and ulnae from Tnni2K175del/K175del mice and wild-type littermates at P12. Right panel of A: Quantification of hif3a expression (n = 3). (C) Immunostaining analyses revealed a decreased vegf in the hypertrophic cell zones of growth plates of radii and ulnae (arrows) from P12 heterozygous mutant mice compared to that of wild-type littermates. Right panel of C: Quantification of vegf expression (n = 3). (D) HE staining showed that the number of blood vessels surrounding trabecular bones were markedly decreased in radii from P12 mutants. Red blood cells were stained as red color. (E) Alkaline phosphatase staining exhibited a retarded formation of the primary ossification centers in radii of E15.5 homozygous mutants. Osteoblasts (blue arrows) have entered the marrow cavity and replaced the apoptotic chondrocytes in wild-type embryos but not in homozygous embryos. (F) Immunostaining revealed a decreased vegf in the hypertrophic cell zones of growth plates of radii and ulnae (arrows) from E15.5 homozygous mutant mice compared to those of wild-type littermates. (G) The relative mRNA expression of Vegf (normalized to Gapdh) in E15.5 homozygous mutant radii and ulnae over those of wild-type littermates (WT/Homo) using qPCR analyses. (H) CD31 stained the vessel endothelial cells in bone marrow of E15.5 homozygous mutant radii and wild-type controls. Insets showed magnified views of the box regions. (I) Quantification of blood vessel density in (H). (J) HE staining showed the growth plate of radii at P6. All experiments were repeated using at least three pairs of samples. Quantification analyses in A, C, G and I: Student's t-test, mean±s.d.; Scale bar, 100 µm (A–F, H, and J). We next tested the expression of molecules involved in Hif-signaling using qPCR analyses in 1-day-old homozygous mutant radii and ulnae and wild-type controls. The results showed that many hypoxia-associated genes, including Hif1b, Vegf164/188, and Flt1, were downregulated (approximately 1.85–2.2-fold) in homozygous mice compared to the wild-type controls (Figure 4D). Similarly, Aldoa and Eno1, two Hif1a target genes, were slightly decreased in Tnni2K175del mutants compared to controls (Figure 4D). In addition, the expression patterns of Hif3a/Hif1a/Vegf/Flt1 in calvaria were consistent with those of the radii and ulnae (Figure S9). Taken together, our data suggested that the Tnni2K175del mutation disturbed the expression of molecules involved in Hif-signaling in the mutant bones.

Tnni2K175del mutation impeded the formation of primary and secondary ossification, and impaired chondrocyte differentiation and osteoblast proliferation in bones.

Vegf is important for bone development [18]–[20] and was significantly decreased in the bones of Tnni2K175del mice (Figure 4D and Figure S9). In accordance with diminished transcription, the vegf protein level was dramatically lower (96%, P<0.001, n = 4) at the hypertrophic cell zones of growth plates of radii and ulnae from heterozygous mutant mice than at those regions of wild-type mice (Figure 5C). As a consequence, fewer blood vessels were observed in the trabecular bones of heterozygous mutant mice at P12 than wild-type littermates (Figure 5D).

Vegf plays important roles in the formation of ossification centers [18], [24]. It is produced by hypertrophic chondrocytes, and then induces blood vessel invasion into the matrix of hypertrophic zones. In this study, we observed a delay in the formation of primary and secondary ossification centers in mutant mice (Figure 5E–J). At E15.5, apoptotic chondrocytes were replaced by osteoblasts in the cartilage of wild-type mice, but not in their Tnni2K175del/175K counterparts (Figure 5E). The vegf expression was reduced in growth plates of radii and ulnae from E15.5 homozygous mutant mice compared to that of wild-type littermates (Figure 5F and G). As a consequence, the recruitment of blood vessels into the cartilage plates was evidently fewer in E15.5 homozygous embryos than wild-type embryos (Figure 5H and I). At P6, early stage of the secondary ossification, the hypertrophy of growth plate chondrocytes and the invasion of vascular canals were normal in wild-type mice. However, these characteristics were not observed in heterozygous mutant mice (Figure 5J).

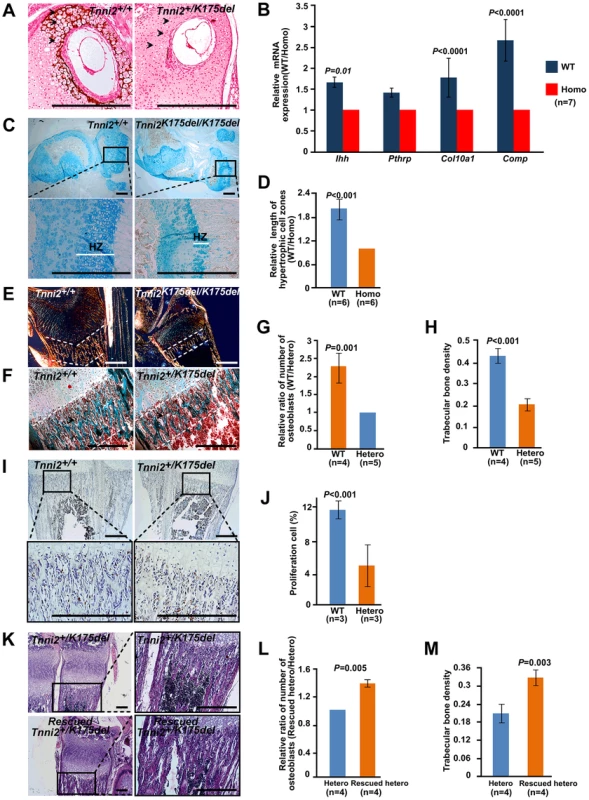

Vegf also promotes chondrocyte differentiation and stimulates osteoblast proliferation [24]–[26]. We next tested the effect of the decreased vegf on chondrocyte and osteoblast. We observed that the mineralization of the matrix and hypertrophic chondrocytes was absent at P6 nasal cartilage from Tnni2+/K175del mice compared to those of their wild-type littermates (Figure 6A). At 1-day-old homozygous mutant radii, the mineralization of the matrix at hypertrophic cells was fewer than that of wild-type littermate bones (Figure S10). Notably, the lengths of the hypertrophic cartilage zones in homozygous mice were significantly shorter than those of wild-type controls (Figure 6C and D). Furthermore, we tested the expression of differential chondrocyte markers using qPCR. The results showed that Ihh, Pthrp, Col10a1 and Comp were decreased in radii and ulnae from 1-day-old homozygous mutant mice (Figure 6B). Together, these observations indicated a delay in chondrocyte differentiation in DA2B mice.

Fig. 6. Chondrocytes differentiation and osteoblasts proliferation were impaired in mutant long bones.

(A) Von Kossa stained at P6 nasal cartilage from Tnni2+/K175del mice and their wild-type littermates. Mineralization of the matrix and hypertrophic chondrocytes (arrows) were observed in the wild-type nasal cartilage, but few in mutant. (B) The relative mRNA expression of Ihh, Pthrp, Col10a1 and Comp (normalized to Gapdh) in 1-day-old wild-type radii and ulnae over those of homozygous mutant littermates (WT/Homo), using qPCR analyses. (C) Alcian blue stained growth plate of tibiae. Hypertrophic zones (HZ) were markedly shorter in the growth plate of tibiae of Tnni2K175del/K175del mice at P12 than those of their wild-type littermates. (D) Quantification of the length of hypertrophic cell zones in (C) in growth plates of tibiae at p12 wild-type (n = 6) and Tnni2K175del/K175del mice (n = 6). (E) Polarization irradiation staining showed that type I collagen (orange) at trabecular bone domains (the regions between white dotted lines) in tibia of P12 homozygous mice was sparse relative to those of control littermates. (F) Masson's trichrome staining showed that the amount of osteoid and osteoblasts. At P6, the amount of osteoid was sparse (the regions between white dotted lines), and the number of osteoblasts (arrows) surrounding trabecular bone was decreased in radii of heterozygous mice compared to wild-type littermates. (G, H) Quantification of the number of osteoblasts surrounding trabecular bones (G) and the number of trabecular bones per unit area (H) at the radii and ulnae of Tnni2+/K175del mice (n = 5) and wild-type controls (n = 4) at P12. The trabecular bone and the number of osteoblasts were decreased on average by 53% and 57% in heterozygous DA2B mice, respectively. (I) BrdU incorporation to detect proliferating osteoblasts surrounding trabecular bones at P12. The number of osteoblasts in Tnni2+/K175del mice at P12 was significantly decreased relative to their wild-type littermates. (J) Quantification analysis of BrdU-positive cells in (I). The percentage of positive cells relative to total cell count was determined (n = 3). (K) HE staining showed that vegf treatment was able to partially rescue the number and thickness of trabecular bones and the number of osteoblasts in heterozygous mutants. (L, M) Quantification of the number of osteoblasts surrounding trabecular bones (L) and the number of trabecular bones per unit area (M) in (K) (n = 4). All experiments were repeated using at least three pairs of samples. B, D, G, H, J, L and M: Student's t-test, mean±s.d., Scale bar, 100 µm (A, C, E, F, I and K). Osteoblasts produce osteoid, which is mainly composed of type I collagen and is mineralized to form trabecular bone and compact bone [27]–[28]. We found that the type I collagen, trabecular bones and the number of osteoblasts surrounding the trabecular bones were significantly decreased in Tnni2+/K175del mutant radii and ulnae compared to those of wild-type littermates (Figure 6E–H). The in vitro cultures of primary osteoblasts showed that the differentiation of osteoblasts of the mutants had no appreciable effect on alkaline phosphatase expression compared to that of control cells (Figure S11). However, BrdU incorporation experiments showed that the proliferation rate of the osteoblasts in heterozygous mutant mice was markedly lower (by 2.4-fold) than that of wild-type controls (Figure 6I and J). These results suggested that a deficiency in proliferative osteoblasts in DA2B mice might, at least in part, contribute to a reduction in trabecular bone.

Taken together, our data showed that Tnni2K175del mutant mice exhibited an impairment of angiogenesis, delay in endochondral ossification, and decrease in chondrocyte differentiation and osteoblast proliferation, which were similar to those bone defects observed in Vegf-deficient mice [18], [29]. Subsequently, we administered recombinant vegf to heterozygous mutants from P4 to P12. Notably, after supplementation with recombinant mouse vegf, the number of osteoblasts surrounding the trabecular bone was increased by approximately 30% on average (Figure 6K and L), and the number and density of trabecular bones in the treated mice were increased by approximately 36% (Figure 6K and M). These observations further suggested that the reduced vegf could contribute to defective bone development of the Tnni2K175del mice.

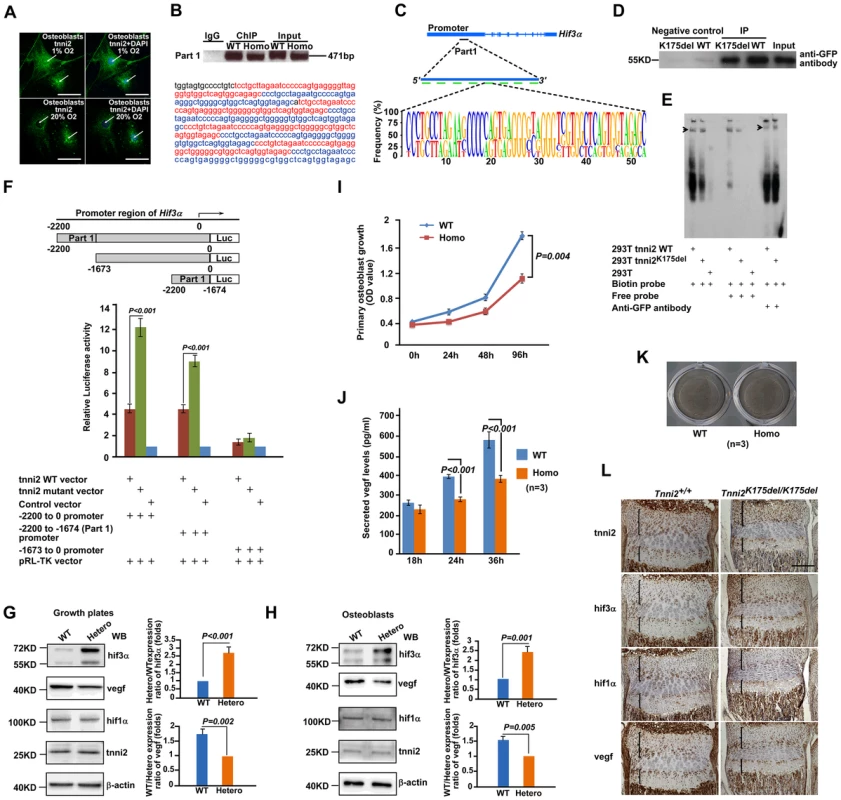

The gain-of-function Tnni2K175del mutation resulted in the enhanced ability to transactivate Hif3a and the reduced vegf expression

We next determined how the Tnni2K175del mutation resulted in an increase in Hif3a expression. A proteomic analysis was employed to identify novel TNNI2 interaction partners (Table S2). Immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry analysis was performed using the nuclear extract from 293T cells ectopically expressing tnni2-GFP fusion protein. Interestingly, a group set of nucleocytoplasmic transporters including KPNB1, IPO5, IPO8, IPO9, TNPO1 and TNPO2, was identified as potential TNNI2 binding partner (Table S2), which suggested that tnni2 might be a nucleocytosolic shuttling protein and that its nuclear localization might be implicated in the regulation of Hif3a expression. To test this possibility, we examined the subcellular distribution of tnni2 in primary mouse osteoblasts. As shown in Figure 7A and Figure S12, tnni2 was observed in the cytoplasm and the nucleus of osteoblasts, and tnni2 nuclear distribution was independent of environmental oxygen tension.

Fig. 7. Mutant tnni2 protein increased hif3a and reduced vegf expression.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining of tnni2 (arrows) in the cytoplasm and nucleus of the primary osteoblasts under both hypoxic (1% O2) and normoxic (20% O2) conditions. tnni2 was stained as green. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Upper panel: Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR assay was performed using primary osteoblasts from 1-day-old Tnni2K175del/K175del mice and control littermates. Both wild-type tnni2 and tnni2K175del mutant protein bond to the mouse Hif3a promoter by a 471 bp fragment (referred to as Part 1) in vivo; Lower panel: Nucleotide sequence of DNA of the Part 1. The eight highly conserved fragments were highlighted with Red or Blue color. (C) Schematic diagram of the Part 1. Upper panel: The position of Part 1 at Hif3a promoter. Middle panel: The Part 1 is consists of eight highly conserved fragments shown with green bars; Lower panel: The sequence feature of these repeat fragments. (D) DNA pull-down assays (DPDAs) performed with avidin-labeled dynabeads using the nuclear extracts (NE) from wild-type tnni2-GFP 293T stable cell line (WT) and NE from tnni2K175del-GFP 293 stable cell line (K175del). Biotin-labeled single repeat fragment of the Part 1 was used as DNA probe. Negative controls: wild-type or mutant NE incubated with non-labeled beads for nonspecific binding. Input: NE from wild-type TNNI2-GFP. Immunoblotting was performed using an anti-GFP antibody. (E) EMSA and Super-EMSA were performed using NE from wild-type tnni2-GFP 293T stable cell line and tnni2K175del-GFP 293T stable cell line. The DNA probe in (D) used here. (F) Luciferase assays of the truncated fragment (−1673 to 0 Hif3a promoter), the whole length fragment (−2200 to 0 Hif3a promoter) and the Part 1 fragment (−2200 to −1674 Hif3a promoter) were performed using 293T cell line under 20% O2 condition. Firefly Luciferase expression was measured and normalized by activity of Renilla Luciferase (pRP-TK). Ratio of the normalized Firefly Luciferase expression to that of control vector was used to represent relative luciferase activity. Data represents the mean±s.d. of five experiments carried out in quadruplicate. (G) Western blot analyses of tnni2, hif3a, vegf and hif1a in growth plates from P12 heterzyous mutant and wild-type littermate mice under normoxia condition. (H) Western blot analyses of tnni2, hif3a, vegf and hif1a in primary osteoblasts from newborn homozygous mutant and wild-type littermate mice. (I) MTT assay for testing proliferation of primary homozygous mutant osteoblasts and wild-type control (n = 3). (J) ELISA assay for testing secreted vegf in cell culture supernatant from primary homozygous mutant osteoblasts and wild-type control (n = 3). The secreted vegf levels of wild-type and mutant osteoblasts were normalized by cell number of the respective genotype at corresponding time point. (K) Von Kossa staining to test deposits of calcium of primary homozygous mutant osteoblasts and wild-type control. (L) Immunostaining for tnni2, hif3a, hif1a and vegf on consecutive sections of radii and ulnae of P12 homozygous mutant mice and wild-type littermate mice. Similar results were also observed in the primary Tnni2K175del mutant osteoblasts (Figure S13), and other cell types, such as 293T and HepG2 cells (Figure S14). To determine whether nuclear-localized tnni2 was involved in the transcriptional regulation of Hif3a, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using primary osteoblasts from the craniums of homozygous mutants and their wild-type littermates (Figure 7B and C, and Table S3). In Figure 7B, we identified a potential tnni2-binding fragment (471 bp, referred to as Part 1) residing in the Hif3a promoter region. The Part 1 consists of eight highly conserved sequences (Figure 7C). Our data suggested that wild-type and mutated tnni2 protein associate with the endogenous Hif3a promoter at similar strengths (Figure 7B). The binding of wild-type and mutated tnni2 to the Hif3a promoter was further verified by two in vitro experiments, DNA pull-down assays (DPDA) (Figure 7D) and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) (Figure 7E). DPDA showed that the Part 1 was capable of pulling down both wild-type and mutant tnni2 from nuclear extracts of wild-type tnni2-GFP 293T stable line and tnni2K175del-GFP stable line. In addition, EMSA and Super-EMSA verified the physical interaction between tnni2 and the Part 1 fragment. Consistent with the ChIP results, the in vitro binding assays confirmed that wild-type and mutated tnni2 exhibited a comparable abilities to bind the Hif3a promoter. Furthermore, to test whether tnni2 was capable of activating the transcription of Hif3a through the Part 1, we constructed the whole length fragment (−2200 to 0 Hif3a promoter), the truncated fragment (−1673 to 0 Hif3a promoter) and Part 1 fragment (−2200 to −1674 Hif3a promoter) luciferase reporter vectors, and performed luciferase reporter assays. Our data showed that the whole length fragment and the Part 1 fragment both had significantly stronger luciferase activity compared with the truncated fragment (Figure 7F), and Tnni2K175del mutant exhibited a much stronger transactivation capacity (more than 2 folds) than its wild-type counterparts under normoxia (Figure 7F) and hypoxia (Figure S15). This finding indicated that the Tnni2K175del mutation enhanced the transactivation of tnni2 for Hif3a expression.

To further validate the effect of Tnni2k175del mutant protein on expression of Hif3a, Hif1a and Vegf in mutant bone, we performed western blot analyses using growth plates of radii and ulnae from P12 Tnni2+/K175del mutant mice and their wild-type littermates, primary osteoblasts from calvariae of newborn Tnni2K175del/K175del mutants and wild-type littermates, and primary chondrocytes from radii and ulnae of newborn Tnni2K175del/K175del mutants and wild-type littermate mice, respectively. The results consistently showed that the expression of hif3a was significantly increased, vegf was reduced and hif1a was not evidently altered in Tnni2K175del mutant growth plate and cells (Figure 7 G, H and Figure S16). Next, to show in vivo the potential interaction between tnni2, hif3a, hif1a and vegf, we performed a set of immunostaining on consecutive sections of radii and ulnae from P12 heterozygous mutant mice and wild-type controls. The staining displayed that the four proteins all were localized in resting, immature-proliferating, pre-hypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes of the growth plates (Figure 7L). Moreover, to assess skeletal cell-specific role of the mutant tnni2, we conducted MTT and ELISA assays using primary osteoblasts harboring the Tnni2K175del/K175del mutant protein. Our data showed that the Tnni2K175del/K175del protein led to a reduction in proliferation and in secreted vegf levels of mutant osteoblasts (Figure 7I and J). Von Kossa staining displayed that no appreciable effect on mineral deposition in mutant cells compared to that of control cells (Figure 7K). Furthermore, we tested the expression of differential osteoblast markers using qPCR. The data showed that Ocn, Spp1 and Ibsp were no significant difference between mutant and wild-type osteoblasts (Figure S17). These data suggested that the mutant tnni2 did not seem to affect differentiation of mutant osteoblasts. Taken together, our data indicated that the mutant tnni2 protein had a higher capacity to transactivate Hif3a than the wild-type protein, resulting in a reduction in vegf expression in mutant bone.

Discussion

In this study, we presented genetic evidence that the Tnni2K175del mutation impaired bone development and disturbed hif-vegf signaling in DA2B mice. Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) belong to a group of heterodimeric transcription factors consisting of HIF1A, HIF2 A, HIF3A and HIF1B HIF1A or HIF2A binds to HIF1B and induces the transcription of targeted genes, such as VEGF, under hypoxic conditions. Unlike HIF1A and HIF2A, HIF3A can negatively regulate HIF1-mediated gene expression by combination with HIF1A or HIF1B [21], [23]. In the human renal cell carcinoma cells and osteosarcoma cells, overexpressed HIF3A evidently inhibited HIF1-induced VEGF expression [30]–[31]. In mouse, ipas, a main isoform of hif3a, is induced under hypoxic condition [23]. Makino et al. reported that ectopic expression of Ipas in hepatoma cells reduced vegf production under condition of hypoxia and significantly decreased tumor vascular density. Moreover, obvious angiogenesis was observed in mouse corneas treated with IPAS antisense oligonucleotide [23]. The results strongly suggested that HIF3A suppressed angiogenesis through negative regulation of VEGF expression. In this study, we found that the growth plates of mice expressed Hif3a. And the hif3a was significantly elevated in Tnni2K175del mutant growth plates, primary osteoblasts and chondrocytes. However, the hif1a expression was not different between mutant groups and their wild-type littermate groups. Together, our results suggested that hif3a might inhibit hif1a-induced Vegf expression in the mutant growth plates and cells. The suggestion was further supported by the data that tnni2, hif3a, hif1a and vegf being localized in the same chondrocytes zones of the growth plates (Fig. 7L).

Our data indicated that tnni2 regulates Hif3a expression at transcriptional level. The Tnni2K175del mutant protein had a higher capacity to transactivate Hif3a expression than wild-type protein. Our results showed that both wild-type and Tnni2K175del mutant protein had a comparable capacity of attaching the Part 1 fragment (Figure 7C) locating at the promoter of mouse Hif3a gene.

HIF1A-VEGF signaling mediates angiogenesis in osteogenesis and regulates the differentiation of chondrocytes and the proliferation of osteoblasts [17], [18], [24]–[27], [32]. In HIF1A or VEGF deficient mice, abundant researches have reported the impairment of bone development including diminished angiogenesis, delayed primary ossification centers, decreased mineralized extracellular matrix in chondrocytes, reduced osteoblasts proliferation and reduced trabecular bone formation [17], [18], [24]–[27], [32]. In the current study, Tnni2K175del mice showed bone development deficiencies that were similar to mice lacking Hif1a or Vegf. These data strongly suggested that the impairment of bone development in the Tnni2K175del mutant mice was mediated by the reduced Vegf expression. This suggestion was supported by the partial recovery of trabecular bone density and the number of osteoblasts when the Tnni2K175del mutant mice were treated with recombinant mouse vegf (Figure 6 K, L and M). Taken together, our data suggested that the abnormal bone development associated with the Tnni2K175del mutation could be partly attributed to the disturbed Hif-Vegf signaling.

In addition, Vegf and its receptor Flt1 are crucial for osteoclast activity [19], [26]. However, we did not observe an evident difference in the number or size of osteoclasts between E16.5 homozygous mutant radii and wild-type controls using the tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity test (Figure S18A). We also tested expression of Trap and Mmp9, two marker genes of activated osteoclasts, in the radii and ulnae of homozygous mutant mice and their wild-type littermates. However, their expression had not obvious change between mutant bones and wild-type controls (Figure S18B and C). Besides HIF1A, CBFA1, also known as RUNX2, is important for regulating VEGF expression in bone development [33]. However, our microarray and immunostaining analyses did not show significant difference in the Runx2 expression in the radii and ulnae from 1-day-old and E16.5 homozygous mutants compared to their wild-type controls (Figure S19).

In the study, we described that tnni2 expressed in the chondrocytes and osteoblasts of long bone growth plate of mouse. Furthermore, we observed a decreased angiogenesis in the cartilage plate of Tnni2K175del bones. The observation was in the agreement with the report from Marsha, et al [34]. Their findings showed that TNNI2 was present in human cartilage and angiogenesis in corneas was inhibited through administration of TNNI2. Notably the extent of suppression of angiogenesis in corneas which was administrated with TNNI2 was similar to that of ipas in corneas [23], suggesting that TNNI2 inhibited angiogenesis in corneas might be mediated by HIF3A Interestingly, three independent reports have shown that TNNI2 acted as an inhibitor of angiogenesis to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis [35]–[37]. However, the molecular mechanism by which TNNI2 suppresses angiogenesis in tumors remains unclear to date. Our findings may provide a clue for the pathological process.

In this study, we focused on the mechanism causing the small body size phenotype of DA2B mice. Our findings showed that the Tnni2K175del mutation led to small body size in DA2B mice by impairing bone development. However, it needs to further investigate whether the small body size phenotype is also resulted from other abnormal tissue function. Besides TNNI2, the patients with mutations of MYH3 also show the short stature phenotype [38]. Yet, the molecular mechanism is unknown. Recently a study reported that myosin directly interacted with runx2 in rat osteoblasts and that the expression of myosin was associated with osteoblast differentiation in vitro [39]. These data suggests that MYH3 was possibly involved in bone development as well.

In summary, our data indicated that the disease-associated Tnni2K175del mutation resulted in an abnormal increase in hif3a and a reduction in Vegf expression in bone. Furthermore, the decreased vegf impeded bone development and contributed to the small body size phenotype of DA2B mice. Our findings demonstrated, for the first time, a novel role of Tnni2 in the regulation of bone development in mice. These findings might provide an insight into the short stature in human DA2B disorder.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Institute of Biological Sciences (NIBS) (Beijing, China).

Generation of Tnni2K175del knock-in mice

Mouse R1 genomic DNA was used as a DNA template to amplify the Tnni2 gene. The mutation of c.523–525del-aag (K175del) in Tnni2 was produced by overlapping-PCR. The 5′ homology arm (long arm) consists of a 2-kb promoter region and the entire Tnni2 genomic DNA sequence. The 3′ homology arm (short arm) begins 400 bp downstream of the Tnni2. 3′ UTR and extends to 2-kb-downstream sequence. The ploxp vector was used as the targeting vector. An EcoR V site was added to the reverse primer for the short arm of recombination to facilitate Southern blot analysis. The targeting construct was introduced into 129Sv embryonic stem cells by electroporation. Positive ESC lines were selected following G418 screening and were confirmed by PCR-sequencing. Correctly targeted clones were injected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice and transferred into uteri of pseudopregnant females. Chimeric males were mated with ICR mice, and PCR-sequencing and Southern blot were used to determine germ line transmission of the targeted allele. cDNA from the muscle tissue of Tnni2K175del/K175del mice was sequenced to validate the Tnni2 transcript with the del-aag mutation.

In situ hybridization

Expression of Tnni2 in the brains, hearts, lungs, stomachs, spleens, skeletal muscles, kidneys, radii, and ulnae at E15.5 was detected using in situ hybridization as previously described [40]. A Tnni2 cDNA fragment of 546 bp was subcloned into pBluescript. Sense and antisense 35S-labeled RNA probes were generated by T7 and SP6 polymerases, respectively. The activity of the probes was approximately 2×109 disintegrations/minute/µg. Frozen sections (10 µm) of organs of wild-type mice at E15.5 were mounted onto poly-L-lysine-coated slides and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde diluted in PBS at 4°C for 15 minutes. After hybridization and washing, the slides were incubated with RNase A (20 µg/mL) at 37°C for 15 minutes. The hybrids with RNase A resistance were detected after 1 week of autoradiography using Kodak NTB-2 liquid emulsion. The slides were post-stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Skeletal preparation

To observe the development of the whole skeleton, we consecutively stained skeletons of wild-type and mutant mice from E14.5 to E18.5 and from P0 to P20 for 24 hours with Alcian blue (pH 5). The skeletons were fixed for 6 hours in 95% ethanol followed by staining with Alizarin Red S. The clarification of soft tissue was performed using 1% potassium hydroxide. Each bone staining experiment was performed at least using two pair of samples.

Histological and immunohistochemical examinations

For histological examination, the tibiae, radii, ulnae, and skulls from mutant mice and wild-type littermates were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Paraffin sections and ice sections (4 µm thickness) were stained with HE for histological structures. Von Kossa method was used to stain mineralized trabecular bones and cartilage matrix. Masson's trichrome and Picrosirius-polarization staining was performed to test type-I collagen at osteoid at P6, P7, and P12 mice. Alkaline phosphatase staining showed osteoblasts in E15.5 mice (Alkaline Phosphatase kit, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Alcian blue was used to stain chondrocytes at P12, P13, and P19 mice. Immunohistochemical analyses were conducted using anti-runx2 (1/50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), anti-CD31 (1/100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), anti-hif3a (1/50, Abcam Biotech, Cambridge, UK), anti-hif1a (1/50, Abcam Biotech, Cambridge, UK), anti-vegf (1/50, Abcam Biotech, Cambridge, UK), anti-tnni2 (1/40, Merck Chemicals, Nottingham, UK) at E15.5 to E18.5, P0, P6 to P8, and P12 mutant mice and wild-type littermates. Whole radii and ulnae from E16.5 homozygous mutant and wild-type littermates were stained for TRAP activity using Sigma-Acid Phosphatase and Tartrate Resistant Acid Phosphatase Kit. TRAP-positive cells on bone surfaces that contained more than two nuclei were counted as osteoclasts. These histological and immunohistochemical analyses were performed using at least three biological repeats.

Primary osteoblast culture

Osteoblasts were obtained from calvariae of newborn Tnni2K175del/K175del mutants and wild-type littermates. The experiment was performed as previously described [41]. Briefly, calvariae from newborn homozygous mutants and their wild-type littermates were carefully removed. They were digested for 2 hours at 37°C in DMEM containing 0.2% collagenase type I. Cells were isolated and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS. The primary osteoblasts from neonatal mice were inoculated at a density of 105 cells per dish in 6-cm dishes. The primary osteoblastic cells were placed at a density of 5×104 cells per well in a 24-well plate and cultured for 48 hours and ALP activity were assessed using the Sigma-Aldrich Alkaline Phosphatase kit. The primary wild-type and homozygous mutant osteoblasts were cultured in the presence of 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid to 14 days, and then were stained using Von Kossa method to test minerization and differential osteoblast markers.

Immunofluorescent staining

Primary osteoblasts were grown on cover glasses under 1% O2 or 20% O2 conditions for 30 hours. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours. After incubation with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 2.5% BSA for 4 hours, the osteoblasts were stained with an antibody against tnni2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with a fluorescent antibody for 1 hour. DNA was stained using 1 µg/mL DAPI.

BrdU incorporation assay

P12 and P13 heterozygous mutants and wild-type littermates were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU at 200 µg/g of body weight for 2 hours and were then sacrificed for BrdU staining (n = 4). BrdU labeled osteoblasts were assessed (BrdU positive osteoblast counts/area) using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

Vegf recovery experiment

A subcutaneous injection of recombinant mouse vegf165 (50 ng/g, PeproTech, USA) was performed on Tnni2+/K175del mice (n = 4) from day 4 to day 12. Heterozygous littermate controls were treated with NaCl (50 ng/g). Treated heterozygous mice and their heterozygous littermate controls were sacrificed at 13 days of age, and the radii and ulnae were collected for H&E staining. The trabecular bone density and number of osteoblasts was assessed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software. The trabecular bones/area was defined as the density of trabecular bones and the number of osteoblasts/density of trabecular bone was used to assess relative osteoblast number.

Gene expression microarray analysis

Total RNA from the entire radii and ulnae of newborn Tnni2K175del/K175del mice (n = 3) and wild-type littermates (n = 3) was extracted using TRIZOL reagent. The mRNA was labeled, hybridized and scanned by CaptialBio (Beijing, China). Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Array was used to generate mRNA expression profile data. Differentially expressed genes associated with the Tnni2K175del mutation were analyzed using the SAM software 3.02. The GEO ID of the expression profile data is GSE32163. Gene enrichment analyses were performed on our Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0 ST microarray expression dataset of wild-type and mutant bones using GSEA 2.0 software [42]. An enrichment score and nominal P value were obtained for the genes that are be induced in human arterial endothelial cells following exposure to hypoxia condition [16].

qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from the radii and ulnae of newborn Tnni2K175del/175K mice and wild-type littermates using TRIZOL reagent. Reverse transcription was performed using the M-MLV reverse system (Promega, USA). mRNA expression of Hif-associated signaling molecules, Ihh, Pthrp, Col10a1, Comp, Ocn, SPP1 and Ibsp were quantified using qPCR. Data were analyzed using the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR

Primary osteoblasts from newborn Tnni2K175del/K175del mice (n = 3) and wild-type littermates (n = 3) were cultured as described above for ChIP-PCR. ChIP was performed as previously described [43]. Approximately 1×107 osteoblasts from homozygous mice and wild-type littermates were prepared. Osteoblasts were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde solution at 37°C for 10 min followed by 1/20 volume of 2.5 M glycine to stop the crosslinking. The cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS, transferred to 15 mL conical centrifuge tubes, and spun for 4 min at 3000 rpm. Cell pellets were re-suspended in 10 mL of LB1 (50 mM Hepes–KOH, pH 7.5; 140 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 10% glycerol; 0.5% NP-40; 0.25% Triton X-100). The samples were rocked at 4°C for 10 min followed by a spin at 2000 rpm at 4°C for 4 min. The pellets were re-suspended in 10 mL of LB2 (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0; 200 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 0.5 mM EGTA). The samples were gently rocked at 4°C for 5 min. The nuclei were pelleted and collected by spinning at 2000 rpm at 4°C for 5 min. The pellets were resuspended in 3 mL LB3 (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8; 100 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 0.5 mM EGTA; 0.1% Na–deoxycholate; 0.5% N-lauroylsarcosine). The samples were sonicated using the following settings: 30 cycles of 15 s ON and 59 s OFF, power-output 31 watts. 10% Triton X-100 was added to sonicated lysate, followed by a 10 min spin at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatants were combined and eluted with 3-fold volume LB3. A subsample of 100 µL of cell lysate from sonication was saved as an input control and stored at −20°C. A total of 100 µL magnetic beads (Invitrogen, California, USA) was added to 30 µg of TNNI2 goat polyclonal IgG antibody (Santa Cruz,Biotechnology, USA) and 1 mg of goat serum, and incubated overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed twice in 1 mL block solution (0.5% BSA (w/v) in PBS). The beads were then collected using a magnetic stand and re-suspended in 100 µL block solution. A total of 100 µL of antibody/magnetic bead mix was added into cell lysates and gently mixed overnight at 4°C. The beads were collected with a magnetic stand and washed with 1 mL RIPA buffer (50 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5; 500 mM LiCl; 1 mM EDTA; 1% NP-40; 0.7% Na-deoxycholate) four times, followed by one wash with 1 mL TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 150 mM NaCl). The beads were then spun at 1500 rpm for 3 min at 4°C to remove any residual TBS buffer using the magnetic stand. A total of 200 µL of elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 10 mM EDTA; 1% SDS) was added into each IP beads and 50 µL input control to reverse crosslink at 65°C for 16 hours. A total of 200 µL TE was added with 8 µL of 1 mg/mL RNaseA to each IP bead and input control DNA at 37°C for 30 min. A total of 4 µL 20 mg/mL proteinase K was added and incubated at 55°C for 2 hours. DNA was extracted with 400 µL phenol-chloroform isoamyl alcohol and precipitated DNA with cold ethanol. PCR was performed to test potent tnni2 binding sequences. PCR reactions contained 0.15 ng IP DNA and input control DNA. The primers for PCR reactions were shown in Table S3. The PCR products were tested using electrophoresis and Sanger sequencing.

Establishing 293T stable cell lines that constitutively express wild-type tnni2-GFP and mutated tnni2-GFP

cDNA fragments of wild-type and Tnni2K175del mutation were subcloned into an EGFP-N1 vector to produce wild-type tnni2-GFP and mutated tnni2-GFP proteins, respectively. 293T cells were transfected with 20 µg mutated vector and the same amount of Tnni2 wild-type vector. 1 mg/mL of G418 was used to screen anti-G418 cells for 2 weeks. GFP-positive cells were sorted by Flow Cytometry.

Luciferase reporter assays

Wild-type and mutated Tnni2 cDNA fragments were subcloned into pcDNA 3.1 vector. The truncated fragment (−1673 to 0 Hif3a promoter), the whole length fragment (−2200 to 0 Hif3a promoter) and the Part 1 fragment (−2200 to −1674 Hif3a promoter) were obtained by PCR amplification from mouse genomic DNA and subcloned into pGL3 luciferase reporter vector. 293T cells were respectively transfected with 100 ng mutated tnni2K175del vector, wild-type tnni2 vector, hif3a (−1673 to 0) pGL3 vector, hif3a (−2200 to 0) pGL3 vector, hif3a (−2200 to −1674) pGL3 vector and pEGFP vector (as negative control), combined with 5 ng pRL-TK reporter vector and incubated under 1% or 20% O2 conditions for 30 hours. Dual reporter experiments were performed using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, Wisconsin, USA). The luminescence signals were detected using a GloMax-96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega, Wisconsin, USA). Firefly Luciferase was measured 30 hours later and normalized by Renilla Luciferase (pRP-TK) for transfection efficiency.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) and mass spectrometry

Total cytoplasm extracts (CE) and nuclear extracts (NE) from 293T tnni2 wild-type-GFP stable cells were prepared according to the following method: Buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1 M HEPES, 10 mM KCL, 2 M KCL, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 M EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA) was added with 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM DTT into the cell pellet and then suspension was vortexed at 4°C for 10 min. After a spin at 3000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, supernatant (CE) was collected and 5-fold volume buffer C (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1% NP40, 10% glycerol) was added with 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM DTT to isolate the nuclear extract. The lysate was rotated for 20 min at 4°C and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant (NE) was transferred to a new tube. 20 mg of CE or NE was incubated with 200 µL agarose beads (Invitrogen, California, USA) that were coupled with an antibody against GFP protein at 4°C for 4 hours, followed by a spin at 1000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the agarose beads were resuspended with 1 mL Buffer C three times. The agarose beads were boiled in 1× protein loading buffer at 95°C for 30 min to separate the protein from the beads. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at room temperature, the supernatant was collected. The IP products were used for mass spectrometry analyses.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts of wild-type tnni2-GFP 293T stable cell lines and tnni2K175del-GFP stable cell lines were prepared as described above. The protein-DNA binding reactions were performed using the Thermo Scientific LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit. 20 mg of nuclear extract and 10 fmol of biotin-labeled probe were used for each binding reaction. For the competition assay, 5 pmol of cold probe was incubated with the samples at room temperature for 10 min prior to the addition of biotin-labeled probes. For the super-shift assay, 2 µg anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (Sigma) was used for each reaction. Incubated samples were separated by 6% non-denaturing PAGE at 100 V on ice for 80 min and transferred to a nitrocellulose filter membrane at 350 mA on ice for 40 min. The sequences of the 5′ biotin-labeled probe used for EMSA and Super-EMSA was: forward, 5′-ccctgtctagaatcccccagtgaggggctgggggcgtggctcagtggtagagc-3′, reverse, 5′-gctctaccactgagccacgcccccagcccctcactgggggattctagacaggg - 3′.

DNA pull-down assay

10 mg of the 5′ biotin-labeled probe (the same as the probe used in EMSA assay) and 100 µL avidin magnetic beads (Invitrogen, Dynabeads) were added into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube with 0.5 mL buffer C (refer to IP assays above) and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The beads were collected using a magnetic stand. 20 mg of NE from wild-type tnni2-GFP and tnni2K175del-GFP 293T stable lines were added into the centrifuge tubes with a magnetic bead-probe and they were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The supernatant was removed, and the magnetic beads were collected with a magnetic bead stand. The beads were carefully washed with buffer C three times. The magnetic beads were boiled using 80 µL 1×protein loading buffer at 95°C for 30 min to separate the protein from the beads. Following centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at room temperature, the supernatant was collected. 40 mL of IP products from wild-type and mutated NE were examined by western blotting using an anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (Sigma). The products isolated from beads that were incubated only with wild-type and mutant NE were used as negative controls. The NE from wild-type TNNI2-GFP were used as Input. The experiment was performed using four independent biological repeats.

ELISA

Protein concentrations of soluble vegf were determined using the Valukine ELISA kit for mouse VEGF (R&D Systems). Cell culture supernatants (Tnni2K175del/K175del and wild type primary osteoblast cells) from triplicates of three different experiments were harvested after 18 hours, 24 hours and 36 hours respectively, centrifuged with 12,000 rpm for 5 min and stored at −20°C. Each corresponding well was subsequently trypsinized and the numbers of live cells were counted to permit the appropriate correction of secreted vegf. ELISA assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell proliferation assays

Cell proliferation assays were performed with a CellTiter 96 AQueous Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions, and the plates were measured with a Molecular Devices plate reader.

Western blotting

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk and incubated with rabbit anti-HIF3A (1/500, Abcam Biotech, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-HIF1A (1/500, Abcam Biotech, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-VEGF (1/1000, Abcam Biotech, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-TNNI2 (1/500, Merck Chemicals, Nottingham, UK), Rabbit ant-histone H3 (1/800, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, USA) or mouse anti-β-actin (1/10000, Sigma, St Louis, USA) antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed using SPSS 17.0 and denoted as the mean±s.d. A comparison between the quantitative data of the two groups was performed using Student's t-test (two-tailed distribution). Statistical significance was indicated by P<0.05.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KrakowiakPA, O'QuinnJR, BohnsackJF, WatkinsWS, CareyJC, et al. (1997) A variant of Freeman-Sheldon.syndrome maps to 11p15.5-pter. Am J Hum Genet 60 : 426–432.

2. TajsharghiH, KimberE, HolmgrenD, TuliniusM, OldforsA (2007) Distal arthrogryposis and muscle weakness associated with a beta-tropomyosin mutation. Neurology 68 : 772–5.

3. ToydemirRM, BamshadMJ (2009) Sheldon-Hall syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 23 : 4–11.

4. SyskaH, WilkinsonJM, GrandRJ, PerrySV (1976) The relationship between biological activity and primary structure of troponin I from white skeletal muscle of the rabbit. Biochem J 153 : 375–387.

5. FarahCS, MiyamotoCA, RamosCH, da SilvaAC, QuaggioRB, et al. (1994) Structural and regulatory functions of the NH2 - and COOH-terminal regions of skeletal muscle troponin I. J Biol Chem 269 : 5230–5240.

6. SungSS, BrassingtonAM, GrannattK, RutherfordA, WhitbyFG, et al. (2003) Mutations in genes encoding fast-twitch contractile proteins cause distal arthrogryposis syndromes. Am J Hum Genet 72 : 681–690.

7. KimberE, TajsharghiH, KroksmarkAK, OldforsA, TuliniusM (2006) A mutation in the fast skeletal muscle troponin I gene causes myopathy and distal arthrogryposis. Neurology 67 : 597–601.

8. ShrimptonAE, HooJJ (2006) A TNNI2 mutation in a family with distal arthrogryposis type 2B. Eur J Med Genet 49 : 201–206.

9. DreraB, ZoppiN, BarlatiS, ColombiM (2006) Recurrence of the p.R156X TNNI2 mutation in distal arthrogryposis type 2B. Clin Genet 70 : 532–534.

10. JiangM, ZhaoX, HanW, BianC, LiX, et al. (2006) A novel deletion in TNNI2 causes distal arthrogryposis in a large Chinese family with marked variability of expression. Hum Genet 120 : 238–242.

11. DigelJ, AbugoO, KobayashiT, GryczynskiZ, LakowiczJR, et al. (2001) Calcium - and magnesium-dependent interactions between the C-terminus of troponin I and the N-terminal, regulatory domain of troponin C. Arch Biochem Biophys 387 : 243–9.

12. BurtonD, AbdulrazzakH, KnottA, ElliottK, RedwoodC, et al. (2002) Two mutations in troponin I that cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have contrasting effects on cardiac muscle contractility. Biochem J 362 : 443–51.

13. RobinsonP, LipscombS, PrestonLC, AltinE, WatkinsH, et al. (2007) Mutations in fast skeletal troponin I, troponin T, and beta-tropomyosin that cause distal arthrogryposis all increase contractile function. FASEB J 21 : 896–905.

14. HallJG, ReedSD, GreeneG (1982) The distal arthrogryposes: delineation of new entities–review and nosologic discussion. Am J Med Genet 11 : 185–239.

15. ReissJA, SheffieldLJ (1986) Distal arthrogryposis type II: a family with varying congenital abnormalities. Am J Med Genet 24 : 255–267.

16. ManaloDJ, RowanA, LavoieT, NatarajanL, KellyBD, et al. (2005) Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial cell responses to hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood 105 : 659–669.

17. SchipaniE, RyanHE, DidricksonS, KobayashiT, KnightM, et al. (2001) Hypoxia in cartilage: HIF-1alpha is essential for chondrocyte growth arrest and survival. Genes Dev 15 : 2865–2876.

18. ZelzerE, McLeanW, NgYS, FukaiN, ReginatoAM, et al. (2002) Skeletal defects in VEGF(120/120) mice reveal multiple roles for VEGF in skeletogenesis. Development 129 : 1893–1904.

19. OtomoH, SakaiA, UchidaS, TanakaS, WatanukiM, et al. (2007) Flt-1 tyrosine kinase-deficient homozygous mice result in decreased trabecular bone volume with reduced osteogenic potential. Bone 40 : 1494–501.

20. NiidaS, KondoT, HiratsukaS, HayashiS, AmizukaN, et al. (2005) VEGF receptor 1 signaling is essential for osteoclast development and bone marrow formation in colony-stimulating factor 1-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 14016–14021.

21. AugsteinA, PoitzDM, Braun-DullaeusRC, StrasserRH, SchmeisserA (2010) Cell-specific and hypoxia-dependent regulation of human HIF-3alpha: inhibition of the expression of HIF target genes in vascular cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 68 : 2627–2642.

22. HeikkiläM, PasanenA, KivirikkoKI, MyllyharjuJ (2011) Roles of the human hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-3a variants in the hypoxia response. Cell Mol Life Sci 68 : 3885–901.

23. MakinoY, CaoR, SvenssonK, BertilssonG, AsmanM, et al. (2001) Berkenstam A, Poellinger L. Inhibitory PAS domain protein is a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible gene expression. Nature 414 : 550–554.

24. MaesC, StockmansI, MoermansK, Van LooverenR, SmetsN, et al. (2004) Soluble VEGF isoforms are essential for establishing epiphyseal vascularization and regulating chondrocyte development and survival. J Clin Invest 113 : 188–199.

25. GerberHP, VuTH, RyanAM, KowalskiJ, WerbZ, et al. (1999) VEGF couples hypertrophic cartilage remodeling, ossification and angiogenesis during endochondral bone formation. Nat Med 5 : 623–628.

26. MaesC, GoossensS, BartunkovaS, DrogatB, CoenegrachtsL, et al. (2009) Increased skeletal VEGF enhances beta-catenin activity and results in excessively ossified bones. EMBO J 29 : 424–441.

27. BaudCA (1968) Submicroscopic structure and functional aspects of the osteocyte. Clin Orthop Relat Res 56 : 227–236.

28. EkanayakeS, HallBK (1988) Ultrastructure of the osteogenesis of acellular vertebral bone in the Japanese medaka, Oryzias latipes (Teleostei, Cyprinidontidae). Am J Anat 182 : 241–249.

29. MaesC, CarmelietP, MoermansK, StockmansI, SmetsN, et al. (2002) Impaired angiogenesis and endochondral bone formation in mice lacking the vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms VEGF164 and VEGF188. Mech Dev 111 : 61–73.

30. HaraS, HamadaJ, KobayashiC, KondoY, ImuraN (2001) Expression and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-3alpha in human kidney: suppression of HIF-mediated gene expression by HIF-3alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 287 : 808–813.

31. MaynardMA, EvansAJ, HosomiT, HaraS, JewettMA, et al. (2005) Human HIF-3alpha4 is a dominant-negative regulator of HIF-1 and is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. FASEB J 19 : 1396–1406.

32. WangY, WanC, DengL, LiuX, CaoX, et al. (2007) The hypoxia-inducible factor alpha pathway couples angiogenesis to osteogenesis during skeletal development. J Clin Invest 117 : 1616–1626.

33. ZelzerE, GlotzerDJ, HartmannC, ThomasD, FukaiN, et al. (2001) Tissue specific regulation of VEGF expression during bone development requires Cbfa1/Runx2. Mech Dev 106 : 97–106.

34. MosesMA, WiederschainD, WuI, FernandezCA, GhazizadehV, et al. (1999) Troponin I is present in human cartilage and inhibits angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 : 2645–50.

35. KernBE, BalcomJH, AntoniuBA, WarshawAL, Fernandez-del CastilloC (2003) Troponin I peptide (Glu94-Leu123), a cartilage-derived angiogenesis inhibitor: in vitro and in vivo effects on human endothelial cells and on pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 7 : 961–968.

36. FeldmanL, RouleauC (2002) Troponin I inhibits capillary endothelial cell proliferation by interaction with the cell's bFGF receptor. Microvasc Res 63 : 41–9.

37. SchmidtK, HoffendJ, AltmannA, KiesslingF, StraussL, et al. (2006) Troponin I overexpression inhibits tumor growth, perfusion, and vascularization of morris hepatoma. J Nucl Med 47 : 1506–14.

38. TajsharghiH, KimberE, KroksmarkAK, JerreR, TuliniusM, et al. (2008) Embryonic myosin heavy-chain mutations cause distal arthrogryposis and developmental myosin myopathy that persists postnatally. Arch Neurol 65 : 1083–90.

39. ZhangJ, LazarenkoOP, BlackburnML, ShankarK, BadgerTM, et al. (2011) Feeding blueberry diets in early life prevent senescence of osteoblasts and bone loss in ovariectomized adult female rats. PLoS One 6: e24486.

40. DasSK, WangXN, PariaBC, DammD, AbrahamJA, et al. (1994) Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor gene is induced in the mouse uterus temporally by the blastocyst solely at the site of its apposition: a possible ligand for interaction with blastocyst EGF-receptor in implantation. Development 120 : 1071–1083.

41. Ecarot-CharrierB, GlorieuxFH, van der RestM, PereiraG (1983) Osteoblasts isolated from mouse calvaria initiate matrix mineralization in culture. J Cell Biol 96 : 639–643.

42. SubramanianA, TamayoP, MoothaVK, MukherjeeS, EbertBL, et al. (2005) Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 15545–50.

43. SchmidtD, WilsonMD, SpyrouC, BrownGD, HadfieldJ, et al. (2009) ChIP-seq: using high-throughput sequencing to discover protein-DNA interactions. Methods 48 : 240–248.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice Deficient for miR-34b/c and miR-449 LociČlánek The Kinesin AtPSS1 Promotes Synapsis and is Required for Proper Crossover Distribution in MeiosisČlánek Payoffs, Not Tradeoffs, in the Adaptation of a Virus to Ostensibly Conflicting Selective PressuresČlánek Examination of Prokaryotic Multipartite Genome Evolution through Experimental Genome ReductionČlánek BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian SkinČlánek Role of STN1 and DNA Polymerase α in Telomere Stability and Genome-Wide Replication in ArabidopsisČlánek RNA-Processing Protein TDP-43 Regulates FOXO-Dependent Protein Quality Control in Stress ResponseČlánek Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping StudiesČlánek Salt-Induced Stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 Confers Salinity Tolerance by Deterring ROS Accumulation inČlánek Ethylene-Induced Inhibition of Root Growth Requires Abscisic Acid Function in Rice ( L.) SeedlingsČlánek Metabolic Respiration Induces AMPK- and Ire1p-Dependent Activation of the p38-Type HOG MAPK PathwayČlánek Signature Gene Expression Reveals Novel Clues to the Molecular Mechanisms of Dimorphic Transition inČlánek A Mouse Model Uncovers LKB1 as an UVB-Induced DNA Damage Sensor Mediating CDKN1A (p21) Degradation

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 10

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- An Deletion Is Highly Associated with a Juvenile-Onset Inherited Polyneuropathy in Leonberger and Saint Bernard Dogs

- Licensing of Yeast Centrosome Duplication Requires Phosphoregulation of Sfi1

- Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice Deficient for miR-34b/c and miR-449 Loci

- Basement Membrane and Cell Integrity of Self-Tissues in Maintaining Immunological Tolerance

- The Kinesin AtPSS1 Promotes Synapsis and is Required for Proper Crossover Distribution in Meiosis

- Germline Mutations in Are Associated with Familial Gastric Cancer

- POT1a and Components of CST Engage Telomerase and Regulate Its Activity in

- Controlling Meiotic Recombinational Repair – Specifying the Roles of ZMMs, Sgs1 and Mus81/Mms4 in Crossover Formation

- Payoffs, Not Tradeoffs, in the Adaptation of a Virus to Ostensibly Conflicting Selective Pressures

- FHIT Suppresses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Metastasis in Lung Cancer through Modulation of MicroRNAs

- Genome-Wide Mapping of Yeast RNA Polymerase II Termination

- Examination of Prokaryotic Multipartite Genome Evolution through Experimental Genome Reduction

- White Cells Facilitate Opposite- and Same-Sex Mating of Opaque Cells in

- BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian Skin

- Genome-Wide Association Study of CSF Levels of 59 Alzheimer's Disease Candidate Proteins: Significant Associations with Proteins Involved in Amyloid Processing and Inflammation

- COE Loss-of-Function Analysis Reveals a Genetic Program Underlying Maintenance and Regeneration of the Nervous System in Planarians

- Fat-Dachsous Signaling Coordinates Cartilage Differentiation and Polarity during Craniofacial Development

- Identification of Genes Important for Cutaneous Function Revealed by a Large Scale Reverse Genetic Screen in the Mouse

- Sensors at Centrosomes Reveal Determinants of Local Separase Activity

- Genes Integrate and Hedgehog Pathways in the Second Heart Field for Cardiac Septation

- Systematic Dissection of Coding Exons at Single Nucleotide Resolution Supports an Additional Role in Cell-Specific Transcriptional Regulation

- Recovery from an Acute Infection in Requires the GATA Transcription Factor ELT-2

- HIPPO Pathway Members Restrict SOX2 to the Inner Cell Mass Where It Promotes ICM Fates in the Mouse Blastocyst

- Role of and in Development of Abdominal Epithelia Breaks Posterior Prevalence Rule

- The Formation of Endoderm-Derived Taste Sensory Organs Requires a -Dependent Expansion of Embryonic Taste Bud Progenitor Cells

- Role of STN1 and DNA Polymerase α in Telomere Stability and Genome-Wide Replication in Arabidopsis

- Keratin 76 Is Required for Tight Junction Function and Maintenance of the Skin Barrier

- Encodes the Catalytic Subunit of N Alpha-Acetyltransferase that Regulates Development, Metabolism and Adult Lifespan

- Disruption of SUMO-Specific Protease 2 Induces Mitochondria Mediated Neurodegeneration

- Caudal Regulates the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Pair-Rule Waves in

- It's All in Your Mind: Determining Germ Cell Fate by Neuronal IRE-1 in

- A Conserved Role for Homologs in Protecting Dopaminergic Neurons from Oxidative Stress

- The Master Activator of IncA/C Conjugative Plasmids Stimulates Genomic Islands and Multidrug Resistance Dissemination

- An AGEF-1/Arf GTPase/AP-1 Ensemble Antagonizes LET-23 EGFR Basolateral Localization and Signaling during Vulva Induction

- The Proteomic Landscape of the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus Clock Reveals Large-Scale Coordination of Key Biological Processes

- RNA-Processing Protein TDP-43 Regulates FOXO-Dependent Protein Quality Control in Stress Response

- A Complex Genetic Switch Involving Overlapping Divergent Promoters and DNA Looping Regulates Expression of Conjugation Genes of a Gram-positive Plasmid

- ZTF-8 Interacts with the 9-1-1 Complex and Is Required for DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in the Germline

- Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping Studies

- Tpz1-Ccq1 and Tpz1-Poz1 Interactions within Fission Yeast Shelterin Modulate Ccq1 Thr93 Phosphorylation and Telomerase Recruitment

- Salt-Induced Stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 Confers Salinity Tolerance by Deterring ROS Accumulation in

- Telomeric (s) in spp. Encode Mediator Subunits That Regulate Distinct Virulence Traits

- Ethylene-Induced Inhibition of Root Growth Requires Abscisic Acid Function in Rice ( L.) Seedlings

- Ancient Expansion of the Hox Cluster in Lepidoptera Generated Four Homeobox Genes Implicated in Extra-Embryonic Tissue Formation

- Mechanism of Suppression of Chromosomal Instability by DNA Polymerase POLQ

- A Mutation in the Mouse Gene Leads to Impaired Hedgehog Signaling

- Keeping mtDNA in Shape between Generations

- Targeted Exon Capture and Sequencing in Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- TIF-IA-Dependent Regulation of Ribosome Synthesis in Muscle Is Required to Maintain Systemic Insulin Signaling and Larval Growth

- At Short Telomeres Tel1 Directs Early Replication and Phosphorylates Rif1

- Evidence of a Bacterial Receptor for Lysozyme: Binding of Lysozyme to the Anti-σ Factor RsiV Controls Activation of the ECF σ Factor σ

- Hsp40s Specify Functions of Hsp104 and Hsp90 Protein Chaperone Machines

- Feeding State, Insulin and NPR-1 Modulate Chemoreceptor Gene Expression via Integration of Sensory and Circuit Inputs

- Functional Interaction between Ribosomal Protein L6 and RbgA during Ribosome Assembly

- Multiple Regulatory Systems Coordinate DNA Replication with Cell Growth in

- Fast Evolution from Precast Bricks: Genomics of Young Freshwater Populations of Threespine Stickleback

- Mmp1 Processing of the PDF Neuropeptide Regulates Circadian Structural Plasticity of Pacemaker Neurons

- The Nuclear Immune Receptor Is Required for -Dependent Constitutive Defense Activation in

- Genetic Modifiers of Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Café-au-Lait Macule Count Identified Using Multi-platform Analysis

- Juvenile Hormone-Receptor Complex Acts on and to Promote Polyploidy and Vitellogenesis in the Migratory Locust

- Uncovering Enhancer Functions Using the α-Globin Locus

- The Analysis of Mutant Alleles of Different Strength Reveals Multiple Functions of Topoisomerase 2 in Regulation of Chromosome Structure

- Metabolic Respiration Induces AMPK- and Ire1p-Dependent Activation of the p38-Type HOG MAPK Pathway

- The Specification and Global Reprogramming of Histone Epigenetic Marks during Gamete Formation and Early Embryo Development in

- The DAF-16 FOXO Transcription Factor Regulates to Modulate Stress Resistance in , Linking Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling to Protein N-Terminal Acetylation

- Genetic Influences on Translation in Yeast

- Analysis of Mutants Defective in the Cdk8 Module of Mediator Reveal Links between Metabolism and Biofilm Formation

- Ribosomal Readthrough at a Short UGA Stop Codon Context Triggers Dual Localization of Metabolic Enzymes in Fungi and Animals