-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaPlant-Symbiotic Fungi as Chemical Engineers: Multi-Genome Analysis of the Clavicipitaceae Reveals Dynamics of Alkaloid Loci

The fungal family Clavicipitaceae includes plant symbionts and parasites that produce several psychoactive and bioprotective alkaloids. The family includes grass symbionts in the epichloae clade (Epichloë and Neotyphodium species), which are extraordinarily diverse both in their host interactions and in their alkaloid profiles. Epichloae produce alkaloids of four distinct classes, all of which deter insects, and some—including the infamous ergot alkaloids—have potent effects on mammals. The exceptional chemotypic diversity of the epichloae may relate to their broad range of host interactions, whereby some are pathogenic and contagious, others are mutualistic and vertically transmitted (seed-borne), and still others vary in pathogenic or mutualistic behavior. We profiled the alkaloids and sequenced the genomes of 10 epichloae, three ergot fungi (Claviceps species), a morning-glory symbiont (Periglandula ipomoeae), and a bamboo pathogen (Aciculosporium take), and compared the gene clusters for four classes of alkaloids. Results indicated a strong tendency for alkaloid loci to have conserved cores that specify the skeleton structures and peripheral genes that determine chemical variations that are known to affect their pharmacological specificities. Generally, gene locations in cluster peripheries positioned them near to transposon-derived, AT-rich repeat blocks, which were probably involved in gene losses, duplications, and neofunctionalizations. The alkaloid loci in the epichloae had unusual structures riddled with large, complex, and dynamic repeat blocks. This feature was not reflective of overall differences in repeat contents in the genomes, nor was it characteristic of most other specialized metabolism loci. The organization and dynamics of alkaloid loci and abundant repeat blocks in the epichloae suggested that these fungi are under selection for alkaloid diversification. We suggest that such selection is related to the variable life histories of the epichloae, their protective roles as symbionts, and their associations with the highly speciose and ecologically diverse cool-season grasses.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003323

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003323Summary

The fungal family Clavicipitaceae includes plant symbionts and parasites that produce several psychoactive and bioprotective alkaloids. The family includes grass symbionts in the epichloae clade (Epichloë and Neotyphodium species), which are extraordinarily diverse both in their host interactions and in their alkaloid profiles. Epichloae produce alkaloids of four distinct classes, all of which deter insects, and some—including the infamous ergot alkaloids—have potent effects on mammals. The exceptional chemotypic diversity of the epichloae may relate to their broad range of host interactions, whereby some are pathogenic and contagious, others are mutualistic and vertically transmitted (seed-borne), and still others vary in pathogenic or mutualistic behavior. We profiled the alkaloids and sequenced the genomes of 10 epichloae, three ergot fungi (Claviceps species), a morning-glory symbiont (Periglandula ipomoeae), and a bamboo pathogen (Aciculosporium take), and compared the gene clusters for four classes of alkaloids. Results indicated a strong tendency for alkaloid loci to have conserved cores that specify the skeleton structures and peripheral genes that determine chemical variations that are known to affect their pharmacological specificities. Generally, gene locations in cluster peripheries positioned them near to transposon-derived, AT-rich repeat blocks, which were probably involved in gene losses, duplications, and neofunctionalizations. The alkaloid loci in the epichloae had unusual structures riddled with large, complex, and dynamic repeat blocks. This feature was not reflective of overall differences in repeat contents in the genomes, nor was it characteristic of most other specialized metabolism loci. The organization and dynamics of alkaloid loci and abundant repeat blocks in the epichloae suggested that these fungi are under selection for alkaloid diversification. We suggest that such selection is related to the variable life histories of the epichloae, their protective roles as symbionts, and their associations with the highly speciose and ecologically diverse cool-season grasses.

Introduction

Alkaloids play key roles in plant ecology by targeting the central and peripheral nervous systems of invertebrate and vertebrate animals, affecting their behavior, eliciting toxicoses, and reducing herbivory [1]. Alkaloids are very common in plants as well as certain plant-associated fungi, particularly those in the family Clavicipitaceae. Plant parasites such as Claviceps species often produce high levels of ergot alkaloids or indole-diterpenes, probably to defend their resting and overwintering structures (commonly called ergots) [2], [3]. A closely related group of fungi, the epichloae (Epichloë and Neotyphodium species) live as systemic symbionts of grasses, and produce a wide array of alkaloids that combat various herbivorous animals, a key determinant of mutualism in many grass-endophyte symbioses [4], [5].

Fungi of family Clavicipitaceae are generally biotrophs that grow in invertebrates, fungi, or plants. The major clade of plant-associated Clavicipitaceae [6] includes mutualistic symbionts as well as plant pathogens, many of which produce alkaloids with diverse neurotropic effects on vertebrate and invertebrate animals with important implications for human health, agriculture and food security [7], [8]. Most species of plant-associated Clavicipitaceae grow in or on grasses, but the group also includes systemic parasites of sedges or other plants, and heritable symbionts of morning glories [9]. The plant-associated Clavicipitaceae have very high chemotypic diversity, ecological significance [10], and agricultural impact [11]. Many produce abundant alkaloids such as ergot alkaloids and indole-diterpenes, which have potent neurotropic activities in mammals. The ergot alkaloids are named for the ergot fungi (Claviceps species), which are infamous for causing mass poisonings throughout much of human history, although ergot alkaloids also have numerous pharmaceutical uses [7], [12]–[14]. In contrast to the Claviceps species, the epichloae (Epichloë or Neotyphodium species) are systemic and often heritable, mutualistic symbionts of cool-season grasses (Poaceae, subfamily Poöideae)(Figure 1) [4]. Epichloae have diverse alkaloid profiles, and in addition to ergot alkaloids or indole-diterpenes, many produce lolines or peramine, which help to protect their grass hosts from insects [15], [16] and possibly other invertebrates [17].

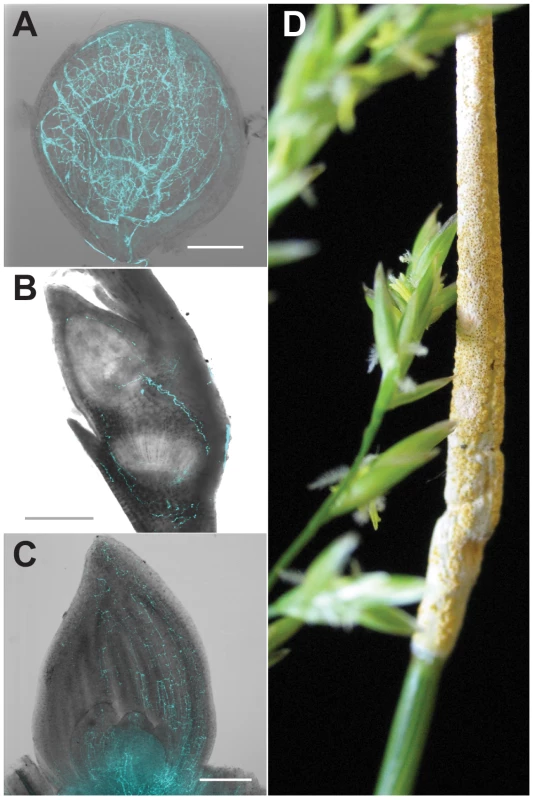

Fig. 1. Symbiosis of meadow fescue with Epichloë festucae, a heritable symbiont.

Single optical slice confocal micrographs of E. festucae expressing enhanced cyan-fluorescent protein were overlain with DIC bright field images of (A) ovules (bar = 100 µm), (B) embryos (bar = 200 µm), and (C) shoot apical meristem and surrounding new leaves (bar = 200 µm). (D) Asymptomatic (left) and “choked” (right) inflorescences simultaneously produced on a single grass plant infected with a single E. festucae genotype. Vertical (seed) transmission of the symbiont occurs via the asymptomatic inflorescence, whereas the choked inflorescence bears the E. festucae fruiting structure (stroma), which produces sexually derived spores (ascospores) that mediate horizontal transmission. The activities of alkaloids in animal nervous systems relates to their chemical similarities to biogenic amines [1]. Although poisoning of humans by alkaloids of clavicipitaceous fungi is now rare, toxicity to livestock is frequently observed [18]–[20]. Morning glories such as Ipomoeae asarifolia cause toxicity to livestock on ranges in Brazil, probably due to alkaloids produced by symbiotic Periglandula ipomoeae [9], [21]. Indole-diterpene or ergot alkaloids produced by epichloae in wild and cultivated grasses also can cause livestock toxicosis [7], [22]. For example, in 1993, losses to pastured U.S. beef production were estimated at $600 million due to widespread plantings of tall fescue symbiotic with ergot-alkaloid-producing strains of Neotyphodium coenophialum [23]. In addition to chemotypic variation [24], the epichloae also exhibit an extraordinary variety of host-interactions, whereby some are pathogenic and contagious, others are mutualistic and vertically transmitted (heritable), and others have both mutualistic and pathogenic characteristics [4], [25]. Relative benefits of epichloae and their alkaloids to host grasses are related to variations in life history [26], [27] and ecological contexts [28], [29], which may well explain why they have evolved such chemotypic diversity.

Even within an alkaloid class, structural variations can profoundly affect pharmacological spectra, as reflected for example in the diverse uses of ergot alkaloids in medicine [14], [30](Figure 2). Ergonovine ( = ergometrine) was long used to aid in childbirth, ergotamine is used for migraines, and, in recent years, 2-bromonated ergocryptine (bromocriptine) has been adopted for treatment of numerous disorders of the central nervous system, such as Parkinsonism and pituitary gland adenomas. In contrast, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), a semisynthetic ergot alkaloid originally developed as an antidepressant, is the most potent hallucinogen known [31], and was a major factor in the drug culture of the 1960's and 1970's. Historic episodes of mass poisoning in humans have resulted from contamination of grains with ergots (the resting structures of Claviceps species) [32], and the effects vary depending on which alkaloids are present. Symptoms range from the disfiguring dry gangrene of St. Anthony's fire to convulsions and hallucinations such as those associated with the Salem witch trials [33]. For example, outbreaks of convulsive ergotism in India in the late 1970's were due to Claviceps fusiformis producing mainly elymoclavine [34], while Ethiopia experienced a gangrenous ergotism outbreak in 1978 caused by C. purpurea producing ergopeptines [35].

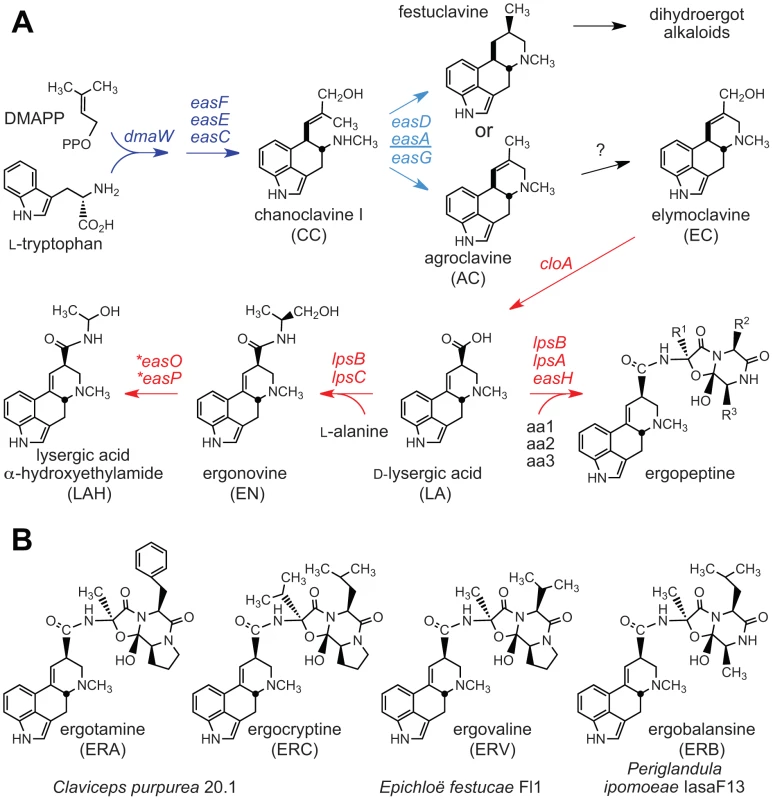

Fig. 2. Ergot alkaloids and summary of biosynthesis pathway.

(A) Ergoline alkaloid biosynthesis pathways in the Clavicipitaceae. Arrows indicate one or more steps catalyzed by products of genes indicated. Arrows and genes in blue indicate steps in synthesis of the first fully cyclized intermediate (skeleton). Variation in the easA gene (underlined) determines whether the ergoline skeleton is festuclavine or agroclavine. Arrows and genes in red indicate steps in decoration of the skeleton to give the variety of ergolines in the Clavicipitaceae. Asterisks indicate genes newly discovered in the genome sequences of C. paspali, N. gansuense var. inebrians and P. ipomoeae. (B) Ergopeptines produced by strains in this study. Other alkaloids produced by Clavicipitaceae variously present hazards or benefits to agriculture. The indole-diterpenes (Figure 3) represent a broad diversity of bioactive compounds that exhibit mammalian and insect toxicity through activation of various ion channels [36], [37]. Livestock afflicted with indole-diterpene toxicity display symptoms of ataxia and sustained tremors [20]. For example, Paspalum staggers is caused by paspalitrems produced by Claviceps paspali and Claviceps cynodontis on seed-heads of dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum) and Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon), respectively [3], and common strains of Neotyphodium lolii symbiotic with perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) produce lolitrems, which cause ryegrass staggers [20]. In contrast, lolines (Figure 4) and peramine produced by many endophytic epichloae in forage grasses have not been linked to any toxic symptoms in grazing mammals, but instead provide potent protection from herbivorous insects [15], [16].

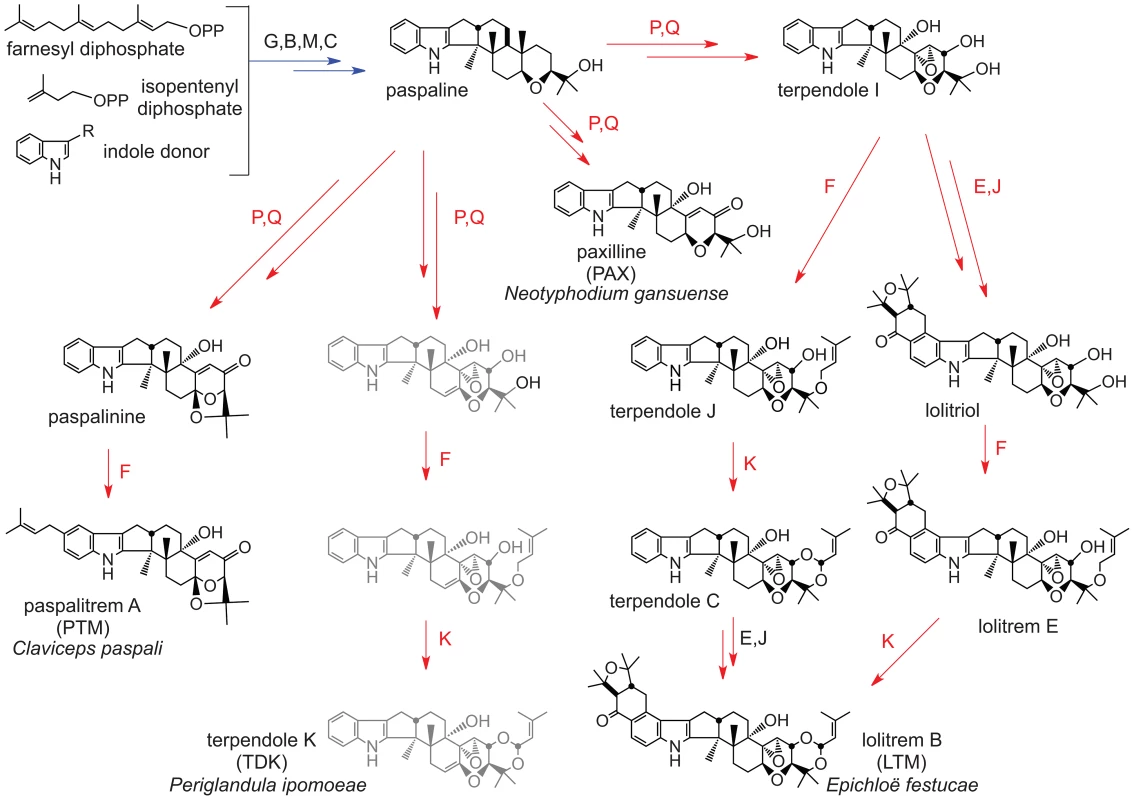

Fig. 3. Summary of indole-diterpene biosynthesis pathway.

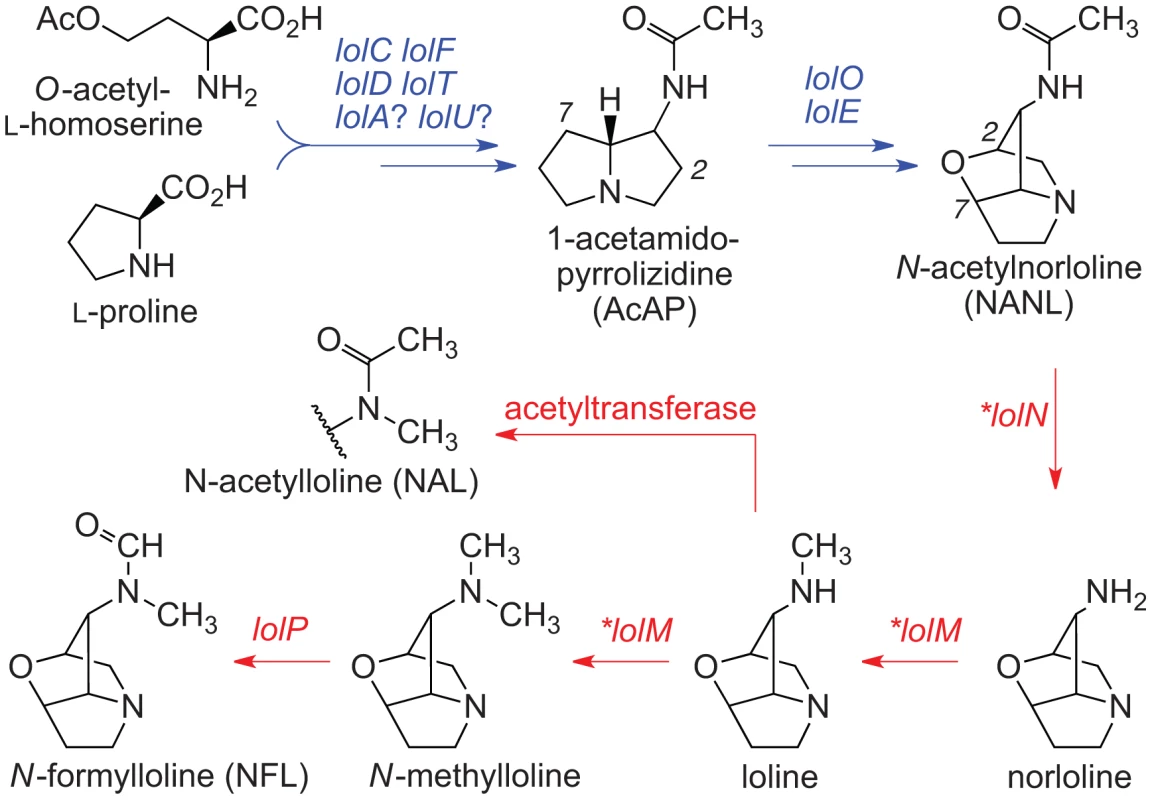

Arrows indicate one or more steps catalyzed by products of the genes indicated, where each idt/ltm gene is designated by its final letter (G = idtG/ltmG, etc.). Arrows and genes in blue indicate steps in synthesis of the first fully cyclized intermediate (paspaline). Arrows and genes in red indicate steps in decoration of paspaline to give the variety of indole-diterpenes in the Clavicipitaceae. Structures shown in gray are not yet verified. Fig. 4. Summary of loline alkaloid-biosynthesis pathway.

Arrows indicate one or more steps catalyzed by products of the genes indicated. Arrows and genes in blue indicate steps in synthesis of the first fully cyclized intermediate (NANL). Arrows and genes in red indicate steps in modification of NANL to give the variety of lolines found in the epichloae. Asterisks indicate LOL genes that were newly discovered in the genome sequence of E. festucae E2368. The discoveries of individual genes involved in biosynthetic pathways for each of the four alkaloid classes [16], [38]–[40] has led to elucidation of clusters of biosynthesis genes for ergot alkaloids (EAS) in C. purpurea [41], lolines (LOL) in Neotyphodium uncinatum [42], and lolitrems (a group of indole-diterpenes, IDT/LTM) in Neotyphodium lolii [43], as well as characterization of the perA gene of Epichloë festucae [16]. The identification of these genetic loci, elucidation of structural diversity within each alkaloid class, and new technologies for high-throughput DNA sequencing together provide an outstanding opportunity to investigate the genome dynamics governing chemotypic variation in fungi with diverse life histories and ecological functions. To that end, we sequenced genomes and compared alkaloid locus structures of 15 plant-associated Clavicipitaceae, including 10 epichloae, three Claviceps species, the nonculturable morning glory symbiont Periglandula ipomoeae, and the bamboo witch's broom pathogen Aciculosporium take (Table S1). We report that the alkaloid loci tend to be arranged with genes for conserved early pathway steps in their cores, and peripheral genes that vary in presence or absence, or in sequence, to diversify structures within each alkaloid class. Transposon-derived repeats, miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs), and telomeres were often associated with unstable loci or the variable peripheral genes, and were especially common in alkaloid clusters of the epichloae. We suggest that structures of the alkaloid loci, including distributions of repeat blocks, reflect selection on these fungi for niche adaptation.

Results

Genome sequences

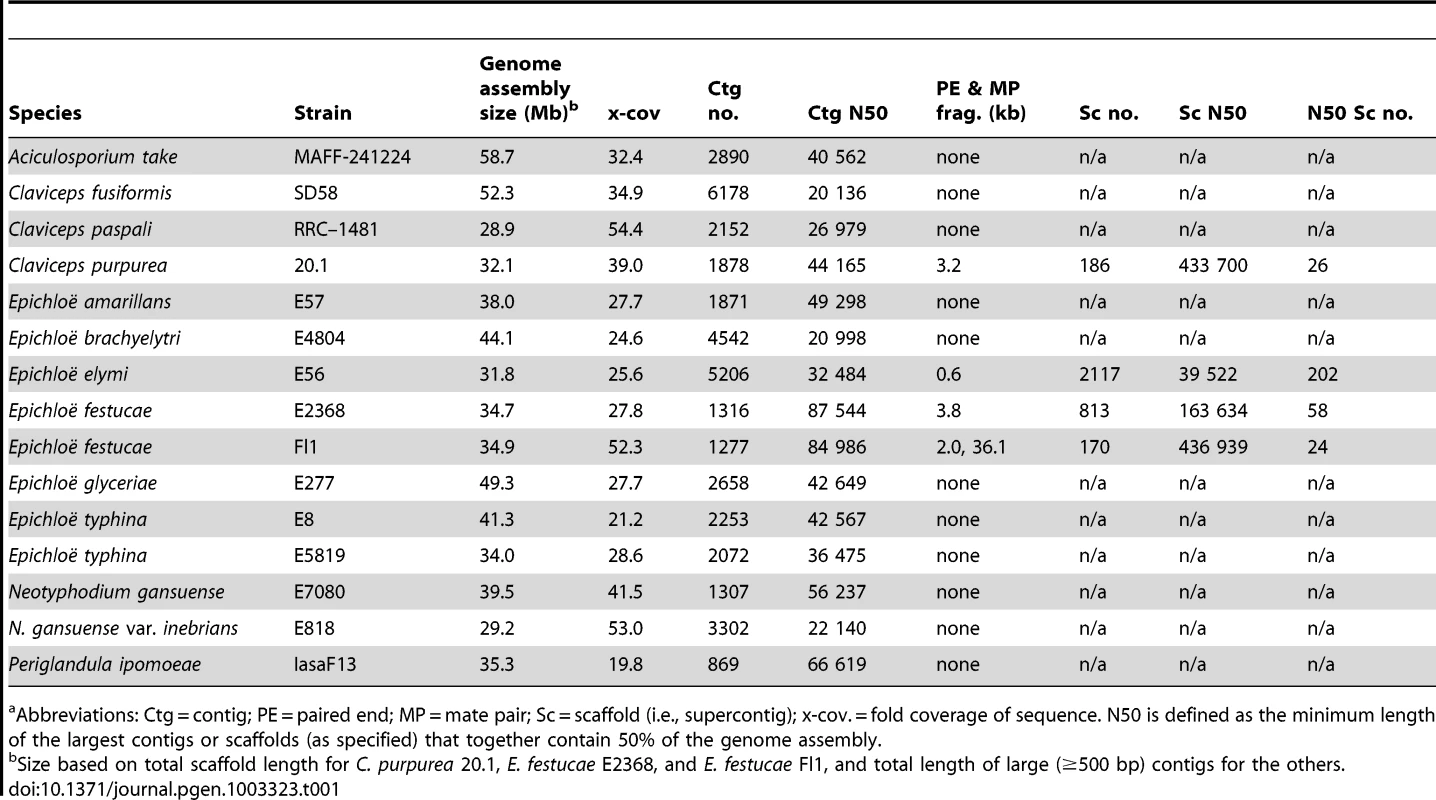

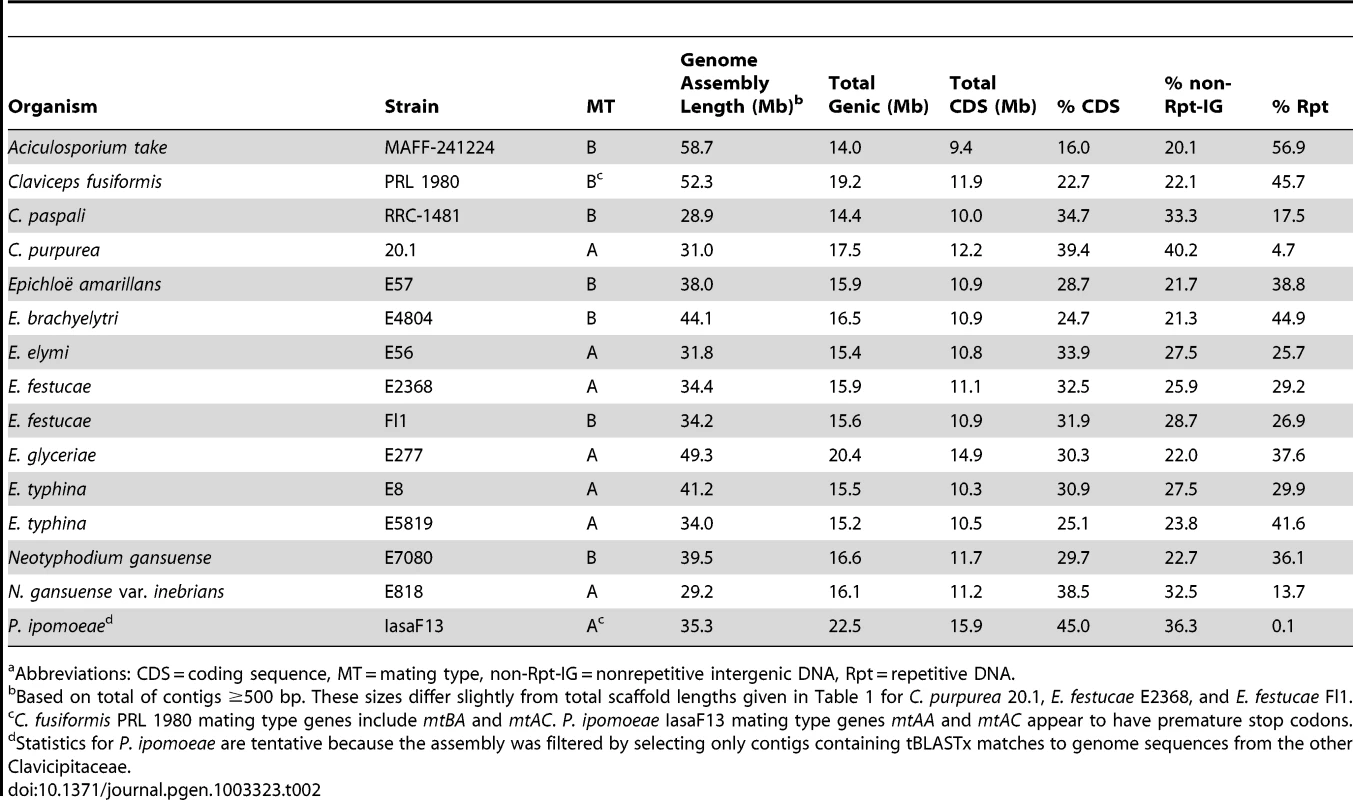

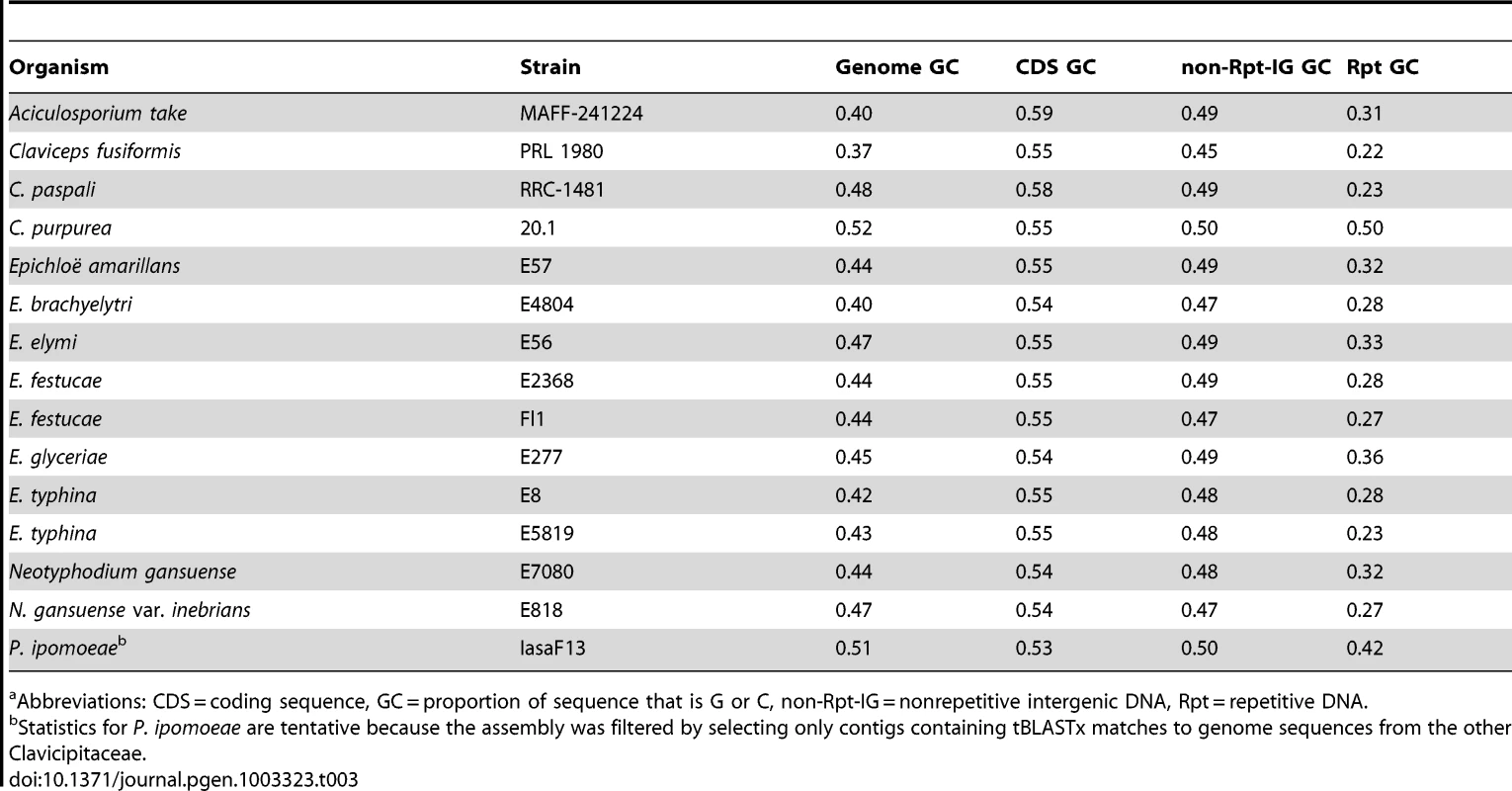

Clusters of genes have been identified for the four alkaloid biosynthesis classes [16], [41]–[43], but in the absence of complete genome sequences it was unknown if the clusters had been fully characterized for any known producers in the Clavicipitaceae. Therefore, we sequenced 15 genomes of diverse species in the family with various alkaloid profiles (Figure 5, Table 1). The genomes were primarily sequenced by shotgun pyrosequencing, but paired-end and mate-pair reads were used to scaffold several assemblies. Notably, adding mate-pair pyrosequencing of C. purpurea DNA resulted in a 186-supercontig (scaffold) assembly of 32.1 Mb, and adding end-sequencing of fosmid clones E. festucae Fl1 DNA resulted in a 170-supercontig assembly of 34.9 Mb. Annotated genome sequences have been posted at www.endophyte.uky.edu, and (for C. purpurea 20.1) at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/Project:76493, and GenBank and EMBL project numbers are listed in Table S2. Assembled genome sizes among the sequenced strains varied 2-fold from 29.2 to 58.7 Mb, with wide ranges even within the genera Claviceps (31–52.3 Mb) and Epichloë (29.2–49.3 Mb) (Table 1). The majority of genome size variation was due to repeat sequences, which ranged from 4.7–56.9% overall (excluding P. ipomoeae from consideration because contigs that lacked coding sequences may have been filtered from that assembly), and from 13.7–44.9% repeat DNA among the epichloae (Table 2). Also, the average GC contents of repeat sequences varied widely, from 22% in C. fusiformis PRL 1980 to 50% in C. purpurea 20.1 (Table 3). The sums of coding sequence lengths were estimated from ab initio gene predictions with FGENESH, and ranged from 9.4 Mb in A. take MAFF-241224 to 15.9 Mb in P. ipomoeae IasaF13 (Table 2). Most of the epichloae had approximately 11 Mb of coding sequence, with the exception of E. glyceriae E277, which had 14.9 Mb of coding sequence. Gene contents were not correlated with genome size, and although A. take had the largest genome at 58.7 Mb, it had the least coding sequence at 9.4 Mb.

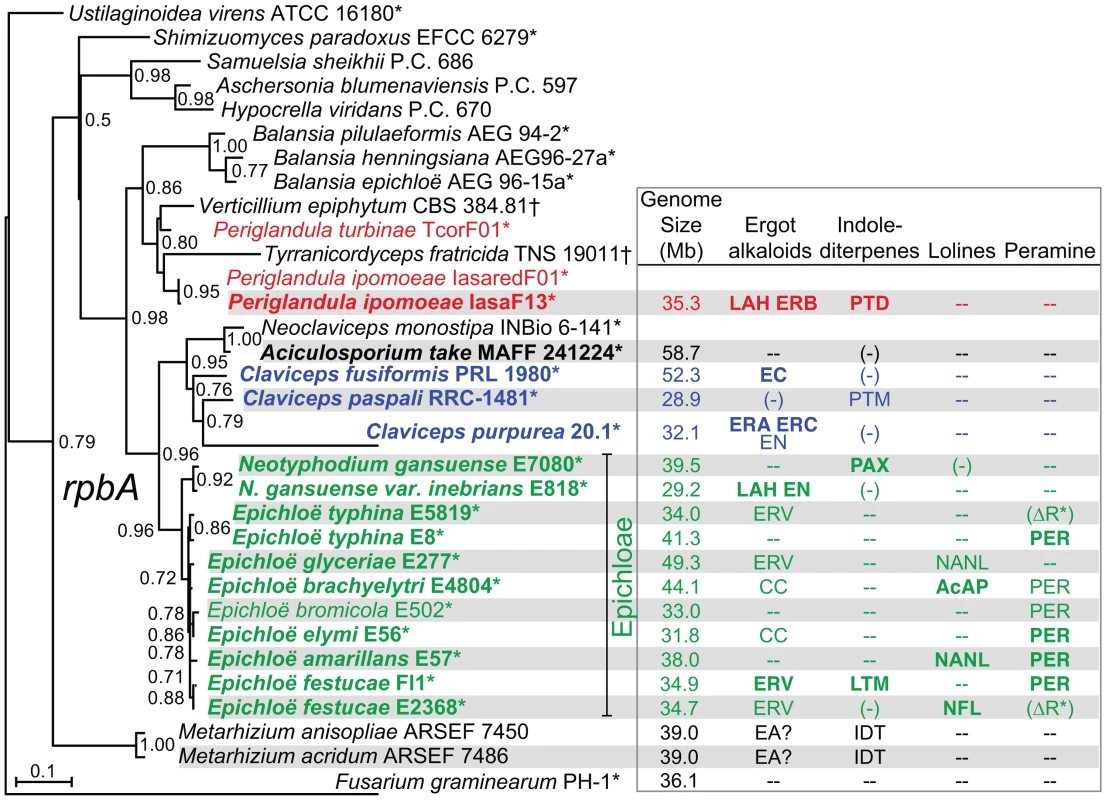

Fig. 5. Phylogenies of rpbA from sequenced isolates and other Clavicipitaceae.

The phylogenetic tree is based on nucleotide alignment for a portion of the RNA polymerase II largest subunit gene, rpbA. This tree is rooted with Fusarium graminearum as the outgroup. Epichloae are indicated in green, Claviceps species are indicated in blue, Periglandula species are indicated in red, and Aciculosporium take is in black. Species for which genomes were sequenced in this study are shown in bold type, and asterisks indicate plant-associated fungi. Alkaloids listed are the major pathway end-products predicted from the genome sequences, abbreviated as shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4. Other abbreviations: (−) = some genes or remnants present, but not predicted to make alkaloids of this class, – = no genes present for this alkaloid class, EA = ergot alkaloids may be produced; IDT = indole-diterpenes may be produced, (ΔR*) = deletion of terminal reductase domain of perA. Tab. 1. Genome sequencing statistics for plant-associated Clavicipitaceae.a

Abbreviations: Ctg = contig; PE = paired end; MP = mate pair; Sc = scaffold (i.e., supercontig); x-cov. = fold coverage of sequence. N50 is defined as the minimum length of the largest contigs or scaffolds (as specified) that together contain 50% of the genome assembly. Tab. 2. Genic and repeat DNA contents of sequenced genomes.a

Abbreviations: CDS = coding sequence, MT = mating type, non-Rpt-IG = nonrepetitive intergenic DNA, Rpt = repetitive DNA. Tab. 3. GC proportions in genic and repeat DNA of sequenced genomes.a

Abbreviations: CDS = coding sequence, GC = proportion of sequence that is G or C, non-Rpt-IG = nonrepetitive intergenic DNA, Rpt = repetitive DNA. Phylogenetic relationships

Phylogenetic analysis of aligned partial coding sequences for the RNA polymerase II largest subunit (rpbA) for all of the sequenced isolates, together with related fungi for which the sequence data are available (Figure 5), supported the relationships previously indicated for subsets of these fungi [44], [45]. The sequenced strains were contained in a clade that mainly included Clavicipitaceae associated with the plant families, Poaceae (grasses), and Convolvulaceae (morning glories). These had more distant relationships to the Clavicipitaceae associated with insects. The Epichloë and Neotyphodium species grouped in a single clade (epichloae), and until recently the sexual species were classified in genus Epichloë, and those with no known sexual state were classified in form genus Neotyphodium [25]. (This was in accord with the dual naming system for fungi, formerly specified in the botanical code of nomenclature.) The sister clade to the epichloae included the Claviceps, Aciculosporium and Neoclaviceps species. Outside of this clade grouped other plant associates and insect associates, including two Metarhizium species for which there are recently published genome sequences [46]. Metarhizium species are well-known insect pathogens, although some strains of Metarhizium anisopliae have recently been shown to be associated with plant rhizospheres [47].

Phylogenies of partial coding sequences for rpbA and two other housekeeping genes, rpbB (encoding RNA polymerase II second-largest subunit) and tefA (encoding translation elongation factor 1-α) (Figure S1) were compared by the Shimodaira-Hasegawa test (Table S3). The rpbA phylogeny was congruent with the rpbB phylogeny, but the tefA phylogeny was significantly incongruent with those of rpbA and rpbB. The tefA tree had a very different placement of M. anisopliae than did the other two phylogenies. Nevertheless, all three gene trees were in agreement with respect to the grouping of the epichloae in a single clade, with a sister clade that included Claviceps species and A. take. All trees also supported a relationship of P. ipomoeae (and, for rbpA, P. turbinae) with the fungal parasite, Verticillium epiphytum. Inclusion of another fungal parasite, Tyranicordyceps fratricidam, with Periglandula spp. and V. epiphytum was supported by the rpbA and rpbB trees, and not significantly contradicted by the tefA tree.

Alkaloid profiles

Plant-associated Clavicipitaceae generally produce alkaloids most consistently in association with host plants [16], [42], [43], [48], [49], so samples of plant material symbiotic with several epichloae were profiled for combinations of ergot alkaloids, indole-diterpenes, lolines and peramine, depending on which gene clusters were identified in the sequenced genomes. Symbiotic material was available for E. amarillans E57, E. elymi E56, E. festucae E2368 and Fl1, E. glyceriae E2772, E. typhina E8, N. gansuense E7080, N. gansuense var. inebrians E818, and N. uncinatum E167, and in limited amounts (sufficient for a loline alkaloid analysis) from E. brachyelytri E4804. Leaves and seeds of morning glory symbiotic with P. ipomoeae IasaF13 were assayed for ergot alkaloids and indole-diterpenes. Ergot alkaloids also were analyzed from ergots of C. purpurea 20.1, and the ergot alkaloid profile of C. fusiformis PRL 1980 is well established [50]. No infected plant material was available to assay the alkaloid profile of E. typhina E5819, and no ergots of C. paspali RRC-1481 were available. Alkaloid profiles listed in Table 4 indicated both interspecific and intraspecific variation.

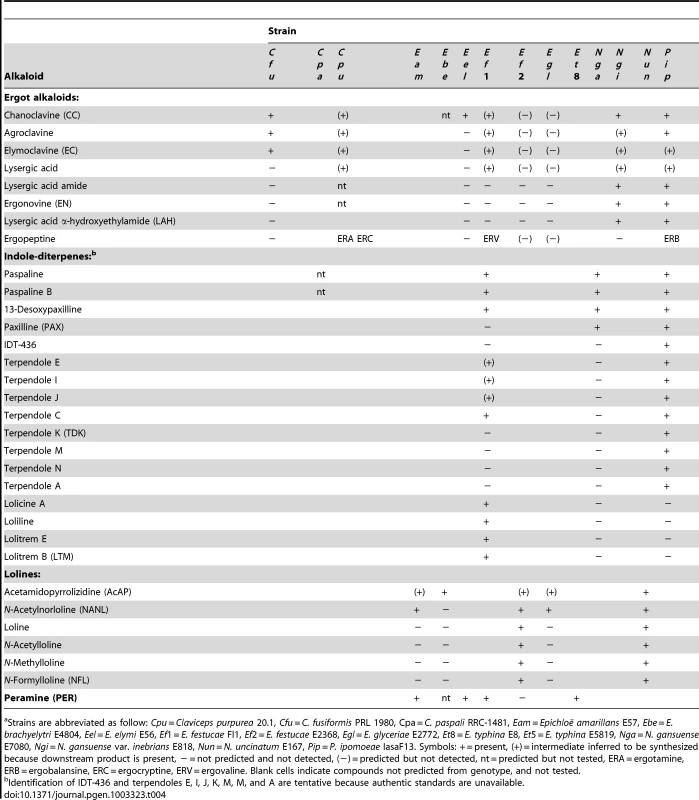

Tab. 4. Alkaloid profiles of sequenced isolates.a

Strains are abbreviated as follow: Cpu = Claviceps purpurea 20.1, Cfu = C. fusiformis PRL 1980, Cpa = C. paspali RRC-1481, Eam = Epichloë amarillans E57, Ebe = E. brachyelytri E4804, Eel = E. elymi E56, Ef1 = E. festucae Fl1, Ef2 = E. festucae E2368, Egl = E. glyceriae E2772, Et8 = E. typhina E8, Et5 = E. typhina E5819, Nga = N. gansuense E7080, Ngi = N. gansuense var. inebrians E818, Nun = N. uncinatum E167, Pip = P. ipomoeae IasaF13. Symbols: + = present, (+) = intermediate inferred to be synthesized because downstream product is present, − = not predicted and not detected, (−) = predicted but not detected, nt = predicted but not tested, ERA = ergotamine, ERB = ergobalansine, ERC = ergocryptine, ERV = ergovaline. Blank cells indicate compounds not predicted from genotype, and not tested. Comparisons of ergot alkaloid profiles (Table 4) indicated likely presence, absence, or sequence variation in EAS genes among strains (Figure 2). For example, variations in lpsA were evident by the production of different ergopeptines, as previously demonstrated for C. purpurea [51]. More specifically, grass plants symbiotic with E. festucae Fl1 had ergovaline, morning glories symbiotic with P. ipomoeae IasaF13 had ergobalansine, and ergots of C. purpurea 20.1 had ergotamine and ergocryptine. Other strains lacked ergopeptines. The principal alkaloids in grass plants with N. gansuense var. inebrians E818 were simpler lysergyl amides, including high levels of ergonovine (EN), low levels of lysergic acid α-hydroxyethylamide (LAH), and intermediate levels of lysergic acid amide ( = ergine), which can result from breakdown of EN, LAH, or both. Morning glories with IasaF13 also had these simple lysergyl amides, which have been reported from C. paspali ergots as well [52]. Other strains produced compounds that were intermediates of the lysergic acid pathway; namely, elymoclavine (EC) produced by C. fusiformis PRL 1980, and chanoclavine I (CC) produced by E. elymi E56.

Each strain that produced indole-diterpenes had a different major pathway end product, although pathway intermediates were typically detected as well (Table 4). Different profiles were likely to be due to different specificities of idtP and idtQ, and the presence or absence of combinations of idtF, idtK, ltmE, and ltmJ (Figure 3) [53]. As apparent pathway end products, grass plants with E. festucae Fl1 had lolitrem B, plants with N. gansuense E7080 had paxilline, and morning glories with P. ipomoeae IasaF13 had terpendoles. Furthermore, C. paspali is reported to produce paspalitrem A [54].

Three different profiles of loline alkaloids (Figure 4) were evident among grass plants symbiotic with epichloae (Table 4). Grasses with E. festucae E2368 had primarily N-formylloline (NFL), but also the N-acetylloline (NAL), N-methylloline (NML), N-acetylnorloline (NANL), and loline. These alkaloids were also produced in planta by N. uncinatum E167. Plants with E. amarillans E57 and E. glyceriae E2772 accumulated NANL, and the plant material with E. brachyelytri E4804 accumulated 1-acetamidopyrrolizidine (AcAP).

Peramine, production of which is dependent upon the perA gene [16], was detected in grass plants symbiotic with E. festucae Fl1, but not with E. festucae E2368 (Table 4). This alkaloid was also detected in plants with symbiotic E. amarillans E57, E. elymi E56 and E. typhina E8.

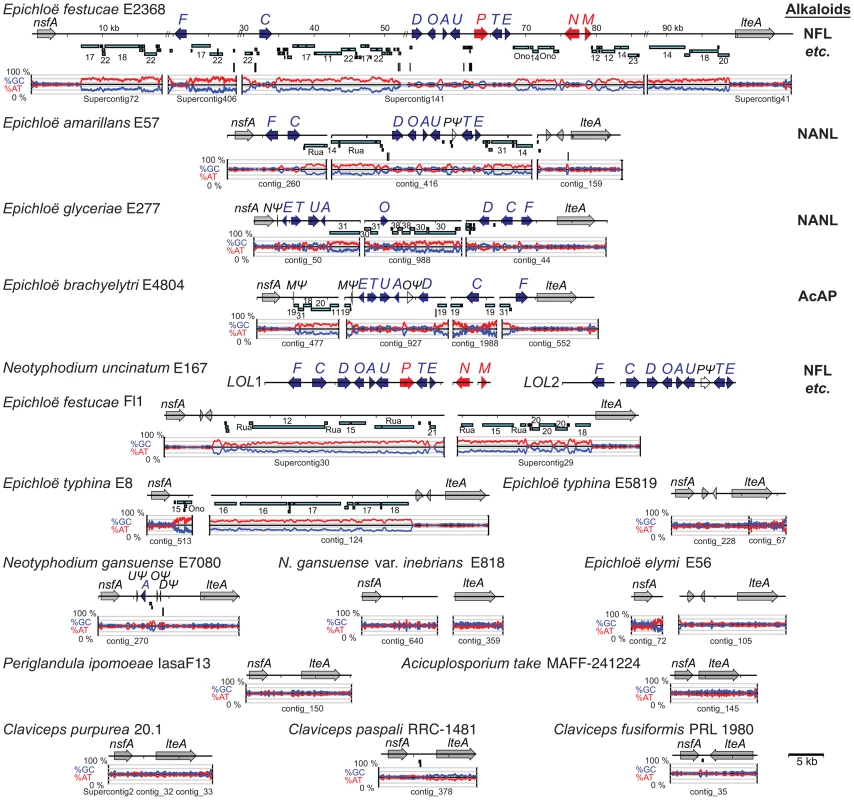

Ergot alkaloid (EAS) loci

In the scaffolded assemblies of the C. purpurea and E. festucae Fl1 genomes, and the scaffolded E2368 assembly of 2010-06, the EAS genes were clustered within individual supercontigs (Figure 6). Also in the assemblies of C. fusiformis, C. paspali and P. ipomoeae genomes functional EAS genes were contained in single contigs. Other non-scaffolded assemblies had EAS genes in two or three contigs, but only in the case of E818 were the EAS genes unequivocally separated in two separate clusters. Long-range physical mapping of the EAS genes of E2368 confirmed that they were clustered (Figure S2).

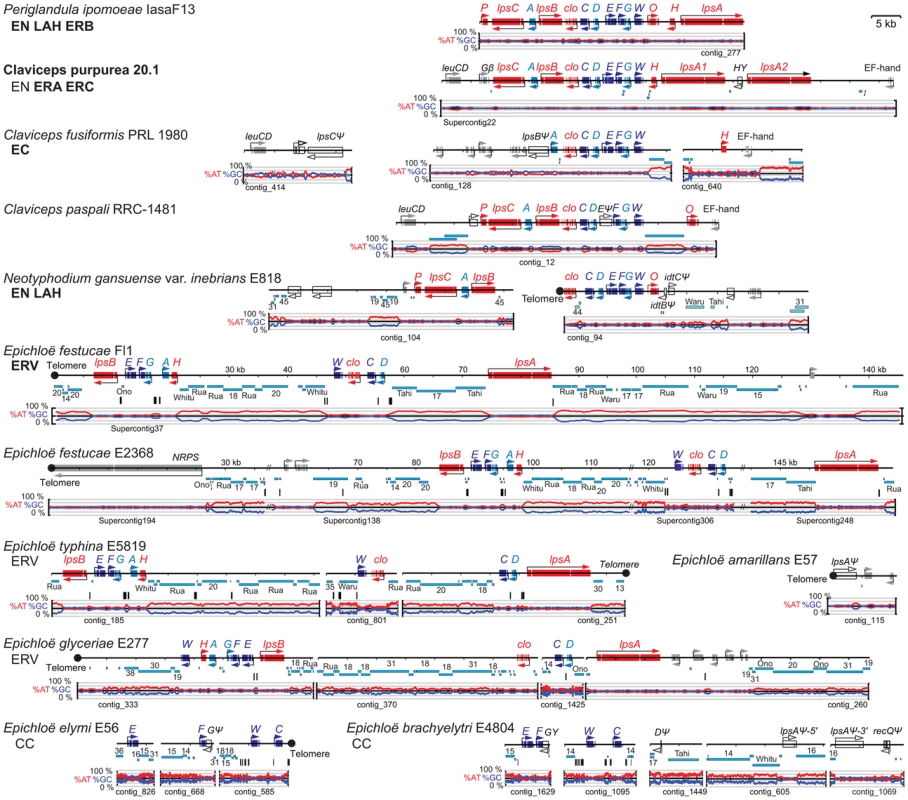

Fig. 6. Structures of the ergot alkaloid biosynthesis loci (EAS) in sequenced genomes.

Tracks from top to bottom of each map represent the following: genes, repeats, MITEs, and graphs of AT (red) and GC (blue) contents. Each gene is represented by one or more boxes representing the coding sequences in exons, and an arrow indicating the direction of transcription. Double-slash marks (//) indicate sequence gaps within scaffolds of the assembled E. festucae genome sequences. Closed circles indicate telomeres, and distances from the telomere on the E. festucae map are indicated in kilobasepairs (kb). Cyan bars beneath each map represent repeat sequences, and are labeled with names or numbers to indicate relationships between repeats in the different species. Vertical bars beneath the repeat maps indicate MITEs. Gene names are abbreviated A through P for easA through easP, W for dmaW, and clo for cloA. Genes for synthesis of the ergoline ring system (skeleton) are shown in dark blue for the steps to chanoclavine-I (W, F, E, and C), and in light blue (D, A, and G) for steps to agroclavine. Genes for subsequent chemical decorations are shown in red (clo, H, O, P, lpsA, lpsB, and lpsC). Identifiable genes flanking the clusters are indicated in gray, and unfilled arrows indicate pseudogenes. The major pathway end-products for each strain are listed below each species name, abbreviated as indicated in Figure 2, and in bold for those confirmed in this study. Note that LAH is a reported product of C. paspali, but the sequenced strain is predicted not to synthesize it due to a defective easE gene. Functions determined to date for enzymes in the ergot alkaloid biosynthetic pathway (Figure 2) [7], [55] were consistent with the presence or absence of specific EAS genes (Figure 6) in strains with particular ergot-alkaloid profiles (Table 4 and Table 5). Furthermore, genes without experimentally determined roles in the pathway could be linked with hypothesized steps on the basis of the functions predicted from their sequences, their presence in clusters among strains that produce specific ergot-alkaloid forms, and their absence from fungi lacking those forms. For example, easH was predicted to encode a nonheme-iron dioxygenase, and was present in all ergopeptine-producing strains and absent from most ergopeptine nonproducers, suggesting that EasH may catalyze oxidative cyclization of ergopeptams to ergopeptines. Likewise, easO and easP, were discovered within the EAS loci upon sequencing the genomes of the two LAH producers, P. ipomoeae and N. gansuense var. inebrians, and were absent from strains of species not known to produce LAH. These genes were also present in C. paspali, but the sequenced strain had a defective easE, and for this reason was not predicted to produce ergot alkaloids. Nevertheless, the fact that other C. paspali strains are reported to produce LAH [52] strengthens the association of easO and easP with LAH production.

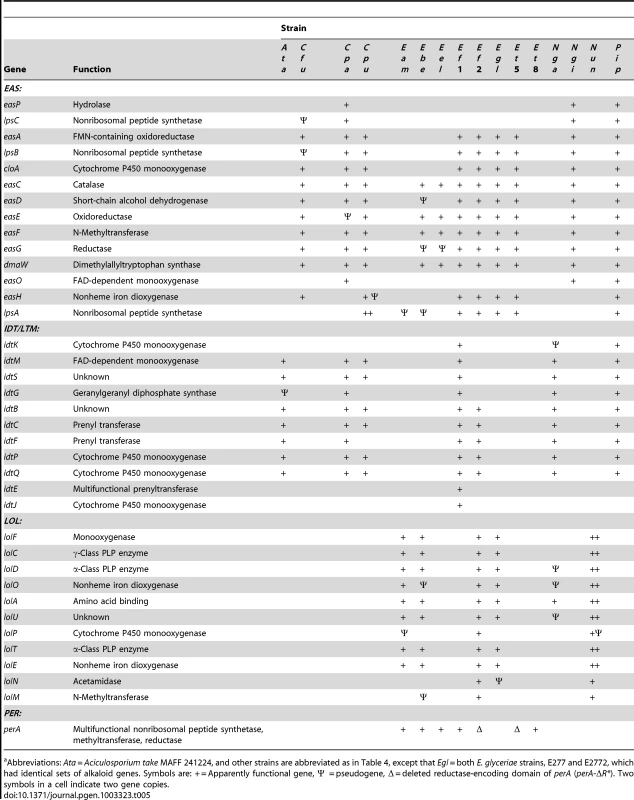

Tab. 5. Alkaloid biosynthesis genes in sequenced isolates.a

Abbreviations: Ata = Aciculosporium take MAFF 241224, and other strains are abbreviated as in Table 4, except that Egl = both E. glyceriae strains, E277 and E2772, which had identical sets of alkaloid genes. Symbols are: + = Apparently functional gene, Ψ = pseudogene, Δ = deleted reductase-encoding domain of perA (perA-ΔR*). Two symbols in a cell indicate two gene copies. The genome of P. ipomoeae was the only one sequenced that contained functional orthologs of all 14 EAS genes (Figure 6), and this was the only strain that produced EN, LAH, and an ergopeptine (ergobalansine). (The Metarhizium genomes described in [46] contained all of these genes, but some either had defects or sequencing errors.) Orthologs of twelve of these genes were clustered in the C. purpurea 20.1 genome, which had two lpsA genes consistent with production of two different ergopeptines (Figure 6). Also, based on gene content, C. purpurea 20.1 was predicted to produce EN, though this was not tested. The absence of a functional lpsB gene in C. fusiformis PRL 1980 accounts for termination of its ergot alkaloid pathway at an earlier position. This strain produces EC, although there was no obvious EAS cluster gene for a (mono)oxygenase to catalyze the final step from agroclavine to elymoclavine. The required enzyme seems likely to be encoded either by a non-cluster gene or the C. fusiformis isoform of cloA. The genome of N. gansuense var. inebrians E818 lacked only lpsA and easH in keeping with its chemotype as a producer of EN and LAH, but not of ergopeptines. In contrast, E. glyceriae E277, E. typhina E5819, and the two E. festucae isolates lacked lpsC, consistent with the observation that E. festucae Fl1 produced an ergopeptine (ergovaline) but not EN or LAH. The fact that no ergot alkaloids were detected in plants with E. festucae E2368 reflected the observation that most of the EAS genes in E2368 were not expressed (data not shown). Finally, E. brachyelytri E4804 and E. elymi E56 had functional copies of only the first four pathway genes, which accounted for the observed accumulation of CC in plants symbiotic with E56.

Indole-diterpene (IDT) loci

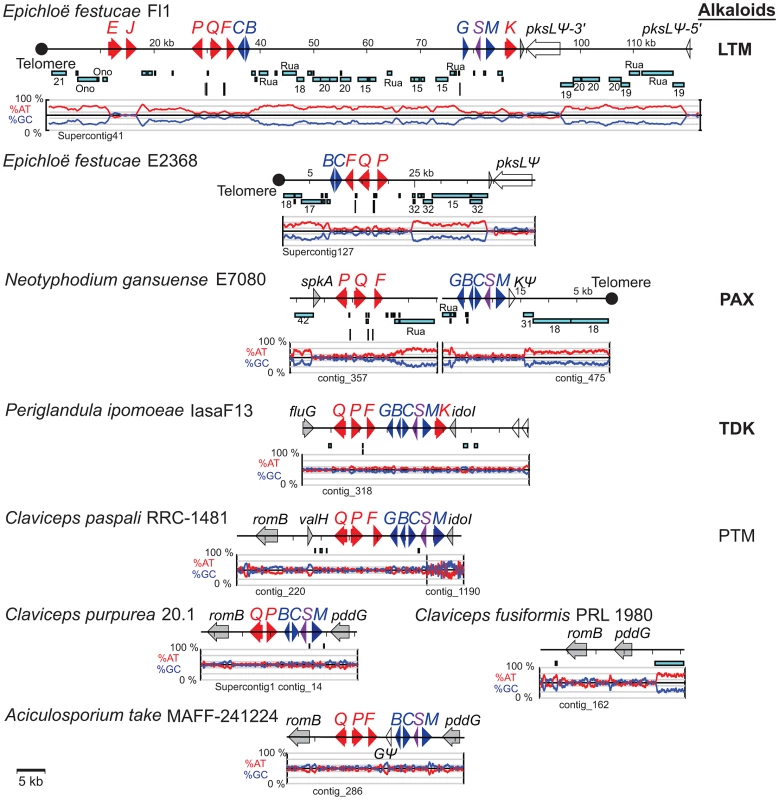

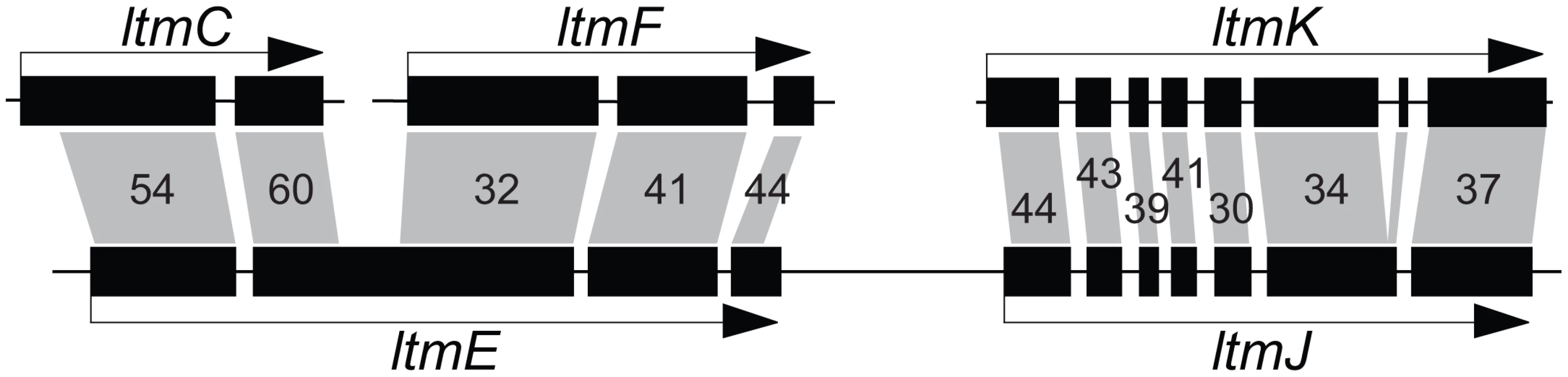

The IDT gene clusters in C. paspali , P. ipomoeae, N. gansuense var. inebrians and E. festucae Fl1 had conserved cores that contained the four genes for synthesis of paspaline (idt/ltmG, M, B, and C) (Figure 7). The gene cores also included the newly discovered gene idt/ltmS (discussed below) that was conserved in all indole-diterpene producers. Genes idt/ltmP, Q, K, and F, which by virtue of their presence, absence or sequence variation determine the particular forms of indole-diterpenes produced [56], were identified in the periphery of each cluster. Two more peripheral genes, ltmE and ltmJ, were present in the lolitrem producer, E. festucae Fl1, but not in the other sequenced genomes (Figure 7, Figure S3). Reciprocal blast analysis of inferred protein products, as well as identification of conserved intron locations, indicated that LtmJ was most closely related to LtmK with 36% overall identity (Figure 8). Furthermore, LtmE was most closely related to LtmC in its N-terminal region and to LtmF in its carboxy-terminal region. These relationships indicated duplications and neofunctionalizations of indole-diterpene modification genes, whereby ltmJ was probably derived from a duplication of ltmK, and ltmE was probably derived from a fusion of duplicated ltmC and ltmF genes.

Fig. 7. Structures of the indole-diterpene biosynthesis loci (IDT/LTM) in sequenced genomes.

IDT/LTM genes are indicated by single letters, whereby Q = idtQ or ltmQ (in E. festucae), and so forth. Tracks from top to bottom of each map represent the following: genes, repeats, MITEs, and graphs of AT (red) and GC (blue) contents. Each gene is represented by a filled arrow indicating its direction of transcription. Closed circles indicate telomeres, and distances from the telomere on the E. festucae map are indicated in kilobasepairs (kb). Cyan bars representing repeat sequences are labeled with names or numbers to indicate relationships between repeats in the different species. Vertical bars beneath the repeat maps indicate MITEs. Genes for the first fully cyclized intermediate, paspaline, are indicated in blue, those for subsequent chemical decorations are shown in red, and idt/ltmS, with undetermined function, is in purple. Identifiable genes flanking the clusters are indicated in gray, and unfilled arrows indicate pseudogenes. The major pathway end-product for each strain is listed at the right of its map, abbreviated as indicated in Figure 3, and in bold for those confirmed in this study. Fig. 8. Relationships of ltmE and ltmJ with other LTM genes.

Filled boxes indicate coding sequences of exons. Gray polygons indicate closest BLASTp matches to inferred polypeptide sequences for each exon, and are labeled with percent amino-acid identities. The gene arrangements in the IDT/LTM loci were conserved in Claviceps species, P. ipomoeae, and A. take MAFF-241224, and varied slightly in E. festucae Fl1 and N. gansuense E7080 (Figure 7, Figure S3). The gene order in N. gansuense E7080 differed by an inversion of the block containing peripheral genes itdP and idtQ. In turn, the gene order in E. festucae Fl1 differed from that of E7080 by an additional inversion of the segment containing three core genes, idt/ltmC, B, and G. Some strains had alterations that eliminated their potential to produce these alkaloids. Specifically, in C. purpurea 20.1 and A. take the idtG gene encoding the first pathway step was either absent or defective. This and several other IDT genes were absent from E. festucae E2368, and the remaining epichloae (E8, E56, E57, E167, E277, E2772, E818, E4804, and E5819) completely lacked IDT genes (Table 5), although E818 had two remnant IDT pseudogenes linked to its telomeric EAS locus (Figure 6).

The newly discovered ltmS gene was identified within the LTM cluster of E. festucae Fl1 using RNA-seq data of Fl1 and its ΔsakA mutant [57] mapped back to the Fl1 genome. The ltmS gene followed the same expression pattern as the other LTM genes, being significantly down-regulated in the ΔsakA mutant. An ortholog of ltmS was identified in each IDT/LTM gene cluster from C. pupurea, C. paspali, A. take, P. ipomoeae and N. gansuense E7080 (Figure 7). However, homology search (BLASTp) against the nonredundant protein database identified no orthologs in non-clavicipitaceous fungi, and no protein domains were evident in InterPro analysis. Topology prediction tools HMMTOP [58], TMHMM [59] and TopPred [60] indicated that LtmS contains at least four transmembrane domains. The inferred LtmS peptide sequence was compared to the inferred product of the paxA gene, which is located in the P. paxilli indole-diterpene cluster gene in a similar orientation between the orthologs of ltmM (paxM) and ltmG (paxG) [61]. Although sequence similarity was not significant, hydrophobicity plots (data not shown) suggested a shared transmembrane domain structure. Currently, roles for paxA and ltmS remain to be elucidated, but their shared characteristics, common placement within orthologous IDT/LTM and PAX clusters, and co-regulation with other LTM genes suggested that they may be required for indole-diterpene production.

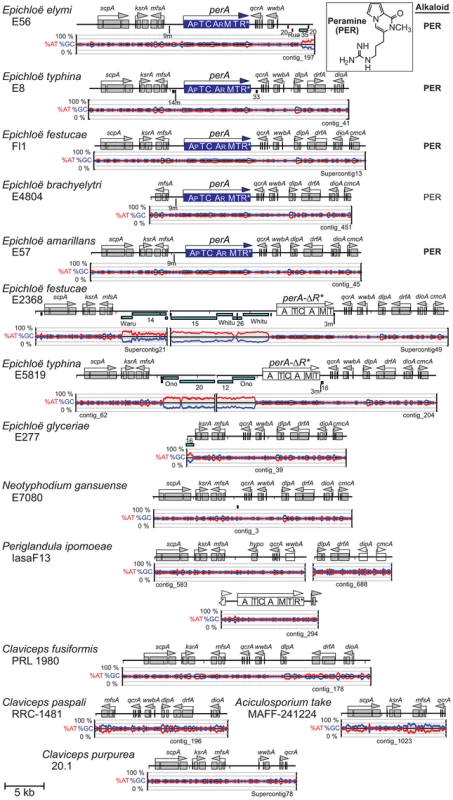

Loline alkaloid (LOL) loci

The loline alkaloid biosynthesis (LOL) genes were found only in the sequenced genomes of epichloae that produce lolines, and a remnant LOL cluster was identified in an additional epichloid strain. Figure 9 compares the LOL clusters with the two clusters previously characterized in the hybrid endophyte Neotyphodium uncinatum E167 [42]. In the periphery of the LOL locus of E. festucae E2368 were two divergently transcribed, newly discovered genes designated lolN and lolM. Orthologous lolN and lolM genes were also identified in survey sequencing of E167, which has a similar loline alkaloid profile to that of E2368, adding support to the hypothesis that these genes specify certain loline-decorating steps. Scaffolding and long-range physical mapping confirmed and extended previous analysis of large-insert clones [62], indicating that the LOL gene order in E2368 was similar to that in E167. In E2368, 10 of the 11 LOL genes were in pairs of divergently transcribed genes. In the other strains the precise LOL-gene orders were not completely elucidated, but no rearrangements within the cluster were evident. However, orientation of the LOL clusters relative to flanking housekeeping genes, nsfA and lteA, were not conserved. Also, several loline-alkaloid producers had missing or inactive decoration genes (lolN, lolM, and lolP). The LOL cluster of E. brachyelytri E4804, which accumulates AcAP without an ether bridge, had an inactive lolO gene due to an internal deletion, and also lacked functional lolN, lolM, and lolP genes.

Fig. 9. Loline alkaloid biosynthesis loci (LOL) in epichloae and the homologous loci in other Clavicipitaceae.

LOL genes are indicated by single letters, whereby F = lolF, C = lolC, and so forth. Features are indicated as in Figure 7. Double-slash marks (//) indicate sequence gaps within scaffolds of the assembled E. festucae E2368 genome sequence. Genes for the first fully cyclized intermediate, NANL, are indicated in blue, and those for subsequent chemical decorations are shown in red. The major pathway end-product for each strain is listed at the right of its map, abbreviated as indicated in Figure 4, and in bold for those confirmed in this study. No LOL genes were identified in E. typhina isolate E8 or E5819, E. festucae Fl1, N. gansuense var. inebrians E818, or E. elymi E56. Orthologs of the genes that flank LOL—namely, nsfA and lteA—were linked in the E5819 genome, with two additional hypothetical genes between them (Figure 9). The hypothetical genes were also associated with lteA in E8, E56, and E. amarillans E57, and nsfA in Fl1, although the orientation of the genes differed in E57 and Fl1. In genome assemblies of E8, Fl1, E56, and E818 linkage of nsfA and lteA was not established, and large repeat blocks were identified downstream of nsfA and upstream of lteA in E8 and Fl1. There was no indication of any LOL genes in the genomes of Claviceps species, A. take, or P. ipomoeae, and the nsfA and lteA orthologs were closely linked in all, although lteA was reoriented in C. fusiformis PRL 1980 (Figure 9).

Peramine (PER) loci

As was the case for the other alkaloid loci, the peramine (PER) locus was variable, containing the entire multifunctional perA gene in the peramine producers, no perA gene, or a partially deleted perA gene designated perA-ΔR* (Figure 10). The complete gene encodes a multifunctional protein with peptide synthetase, methyltransferase and reductase domains that together may be sufficient for synthesis of peramine [16]. The PER locus in E. festucae E2368 and E. typhina E5819 shared identical deletions of the C-terminal reductase domain. Nevertheless, perA-ΔR* was expressed in E2368, raising the possibility that this form also encodes a multifunctional protein, which may participate in the biosynthesis of a metabolite related to peramine if an appropriate thioesterase, condensation, cyclization or reduction domain is provided in trans.

Fig. 10. Peramine biosynthesis loci (PER) in epichloae and the homologous loci in other Clavicipitaceae.

On each map perA is color-coded blue for a complete gene and as an open box for perA-ΔR*. Domains of perA are indicated as A (adenylation), T (thiolation), C (condensation), M (N-methylation) and R* (reduction). Subscripts indicate postulated specificity of adenylation domains for 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate (AP) and arginine (AR) [16]. Other features are indicated as in Figure 7. Long, syntenous regions flanked both the 5′ and 3′ sides of the functional perA genes of E. typhina E8, E. festucae Fl1 and E. elymi E56 as well as the complete and probably functional perA genes in E. brachyelytri E4804 and E. amarillans E57 (Figure 10). The 5′ region included the divergently transcribed gene mfsA. The two genomes with perA-ΔR* shared synteny of the 3′ flanking region, but repeat blocks in the 5′ flanks apparently disrupted sequence assembly.

A possible perA ortholog was identified in P. ipomoeae, but it was a pseudogene, and was located in a different locus from the PER locus of the epichloae (Figure 10). The predicted gene product included all of the domains of PerA in the same order, with 47.6% amino acid sequence identity over 98.8% of the length of PerA.

Telomere positions relative to alkaloid loci

In the epichloae, EAS and IDT/LTM loci were almost always linked to telomeres but LOL and PER loci were not. In contrast, no telomere linkage of alkaloid loci was evident in Claviceps species, A. take or P. ipomoeae.

Out of the eight epichloae with EAS genes, seven had EAS clusters linked to terminal telomeres (Figure 6, Figure S2). Long-range mapping of EAS genes, telomeres, and other specialized (secondary) metabolism (SM) genes of E. festucae E2368 indicated that its EAS cluster was linked to a 6-module nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) gene located near a telomere (Figure S2). Other epichloae had terminal telomere repeat arrays on a contig or supercontig containing some or all of their EAS genes. The sole exception was E. brachyelytri E4804, which had a RecQ helicase pseudogene near an lpsA gene fragment, suggesting possible telomere linkage [63]. Interestingly, although the EAS cluster of N. gansuense var. inebrians E818 was arranged similarly to that of P. ipomoeae and the Claviceps species, it was broken into two clusters, one of which ended in a telomere located one bp from the cloA stop codon. In contrast, the C. purpurea EAS cluster clearly was not near a telomere, since it spanned positions 235,054 to 290,780 of the 464,384-bp Supercontig22, and that supercontig had no telomeric repeats at either end.

Among the IDT/LTM loci the functional clusters in N. gansuense E7080 and E. festucae Fl1, as well as the partial cluster in E. festucae E2368, were all telomere-linked (Figure 7). (The terminal telomere sequence adjacent to E2368 LTM was evident in the 2010-06 assembly, which is also posted at www.endophyte.uky.edu.) Like the EAS loci, these IDT/LTM loci had the telomeres at different relative positions. (Interestingly, although N. gansuense var. inebrians E818 lacked functional IDT genes, it had two remnant IDT pseudogenes adjacent to the telomere-linked EAS cluster, as indicated in Figure 6.) In contrast to the epichloid IDT/LTM clusters, the orthologous cluster in C. purpurea 20.1 was not telomere-linked. This cluster (which was predicted to be nonfunctional because it lacked idtG) extended from positions 574,647 to 587,656 on the 978,494-bp Supercontig1 of the C. purpurea assembly, and no telomere was present on this scaffold. Also, no telomeres were present on the contigs containing IDT genes in the genomes of A. take, C. paspali, or P. ipomoeae.

The LOL clusters were not near telomeres. Instead, in all loline-alkaloid producers the clusters were flanked on both sides by groups of housekeeping genes. Published analysis of E. festucae large-insert clones [62] indicated that lolF is linked to nsfA, and lolT and lolE are linked to lteA. The nsfA gene was near the end of the 148,125-bp Supercontig71, and the lteA gene was near the end of 217,442-bp Supercontig41, and neither of these scaffolds had a telomere end. Likewise, the PER loci with complete perA genes were not subtelomeric, and no terminal telomere repeats were present on contigs with perA-ΔR*.

Synteny with the Fusarium graminearum PH-1 genome

The genome of F. graminearum PH-I is almost completely assembled into its known linkage groups [64], and because this species is within the same order (Hypocreales), but a different family from the Clavicipitaceae, we considered it appropriate to compare regions of the alkaloid loci for synteny with the F. graminearum genome. None of the four alkaloid loci in the Clavicipitaceae was present in the F. graminearum genome. In cases where the alkaloid loci were subtelomeric, flanking genes on their centromeric sides were not orthologous to F. graminearum genes. Alkaloid loci that were not subtelomeric and had flanking genes orthologous to F. graminearum genes were the EAS loci of Claviceps species, IDT loci of Claviceps species and A. take, and LOL and PER loci of the epichloae. The genes flanking the EAS clusters of Claviceps species were linked and similarly oriented in a syntenous region of the F. graminearum genome (Figure S4A). In contrast to the EAS loci, the genes flanking Claviceps and A. take IDT clusters were not syntenous in the F. graminearum genome (Figure S4B). The F. graminearum orthologs of the LOL-flanking genes were contained in a syntenous block (Figure S4C). Likewise, as reported previously [16], perA of E. festucae Fl1 had apparently been inserted into a block of genes syntenous with their F. graminearum orthologs (Figure S4D). These observations raise the possibility that the non-terminal EAS, LOL and PER loci had inserted into their respective genome locations, but where they originally assembled cannot be discerned because no intermediate stages in the evolution of the alkaloid gene clusters have yet been identified.

Repeat blocks in alkaloid loci

The alkaloid loci of most Clavicipitaceae were associated with repeat DNA derived from transposable elements, which were often stacked and nested extensively into long blocks. The distribution of repeat blocks in alkaloid loci constituted a major and consistent structural difference distinguishing the epichloae from the other Clavicipitaceae. The epichloae typically had long and dynamic repeat blocks predominantly of transposon relics, interspersed throughout their alkaloid loci. This characteristic was not a reflection of overall repeat content of the genomes, considering that epichloae had proportionately less repeat content than C. fusiformis and A. take (Table 2).

Repeat blocks at alkaloid gene loci were usually very AT-rich. RIP-index analysis (Figure S5) indicated that this was most likely due to the repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) process of selective C to T transitions that is common in fungi [65]. The possibility of RIP was further substantiated by the identification of homologs of the Neurospora crassa rid-1 gene [66] in all of the sequenced genomes except that of C. purpurea 20.1, which paradoxically had one of the lowest repeat contents (Table 2). In most Clavicipitaceae the overall GC content of repeat sequences was very low (Table 3). An exception was C. purpurea 20.1, consistent with its lack of rid-1 homolog and therefore presumed inability to perform RIP. Among the epichloae, the GC contents of E. glyceriae repeats tended to be relatively higher, suggesting less history of RIP since the repeat blocks emerged in that lineage.

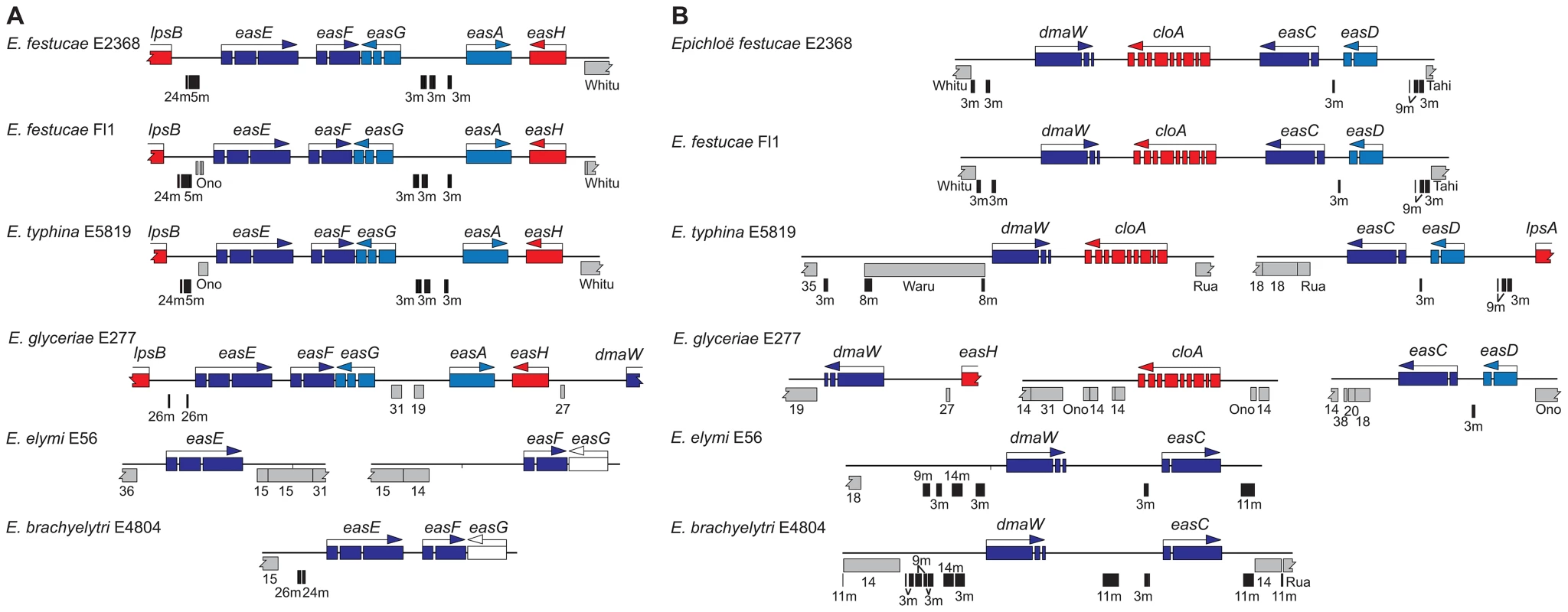

The EAS and IDT clusters of Claviceps species, P. ipomoeae and A. take had very little repeat DNA within them, although repeat blocks flanked the EAS clusters of C. fusiformis PRL 1980 and C. paspali RRC-1481 (Figure 6, Figure 7). These Claviceps strains had lost or inactivated one (C. paspali) or all (C. fusiformis) lysergyl peptide synthetase (lps) genes at the cluster periphery, but the conserved-gene cores of their EAS and IDT clusters remained nearly free of repeat sequences. In contrast, the epichloae all had long blocks of repeat sequences associated with their alkaloid gene loci, and (except for the EAS loci of E818, which were divided by a telomere) all EAS and IDT loci of epichloae were broken up further into subclusters by such long repeat blocks. Even within subclusters a large number of MITE insertions were evident in intergenic regions (Figure 11).

Fig. 11. Fine-mapping of repeats in two regions of the EAS clusters of epichloae.

(A) The easE-easF-easG regions. (B) The dmaW-cloA-easC-easD regions. Genes are colored as in Figure 6. AT-rich repeats are in gray, and named or numbered to indicate relationships between repeats in the different species. MITEs are indicated by labeled vertical black bars. In some cases, the gene cluster orientation is different from those shown in Figure 6 to facilitate gene alignment. The Waru element is an autonomous parent element of MITE 8m. The positions and lengths of repeat blocks and arrangements of MITEs within EAS and IDT clusters, as well as the gene orders and orientations, widely varied among the sequenced epichloae (Figure 6, Figure 7). Expansions and losses of repeat blocks resulted in variation with respect to the grouping of genes within subclusters. The repeat blocks often extended well beyond the alkaloid gene loci. For example, they dominated the entire Fl1 267-kb scaffold, Supercontig41, extending from the telomere, separating the LTM genes into three clusters, and disrupting a polyketide synthase gene in an adjacent SM gene cluster (Figure 7).

In some cases, the order of repeat insertions could be identified within the gene clusters. For example, in E. festucae Fl1 the easD-lpsA intergenic region apparently had been invaded by Tahi, which in turn was invaded by repeat number 17 (Figure 6). However, many of the multiple repeat insertions were much more complex than this example and varied among the different species. Several differences in MITE positions relative to the genes also appeared to be related to insertions of one or more repeat elements. By example the Waru DNA-transposon relic adjacent to dmaW in E. typhina E5819 had displaced the proximity of the 3m MITE (Figure 11A), and MITEs adjacent to easE in E. elymi may have also been displaced by the insertion of a repeat (Figure 11B). Compared to the other epichloae, E. glyceriae E277 had fewer MITEs in its EAS cluster and throughout its genome.

The perA and LOL genes were only found in epichloae (Figure 9, Figure 10). Nevertheless, LOL loci resembled the other epichloid alkaloid gene clusters in that they contained multiple blocks of nested repeats. Furthermore, positions of the repeat blocks in LOL varied greatly between strains, even though the gene orders and orientations appeared to be stable. Repeats in the PER loci were associated with perA-ΔR* rather than perA (Figure 10). In those strains with the deleted R*domain, repeat blocks extended upstream of mfsA to the contig ends, leaving it unresolved whether mfsA and perA-ΔR* were linked. Also, MITE 3m was immediately downstream of the perA-ΔR* coding sequence, thus associated with the R*-domain deletion, as previously noted [67].

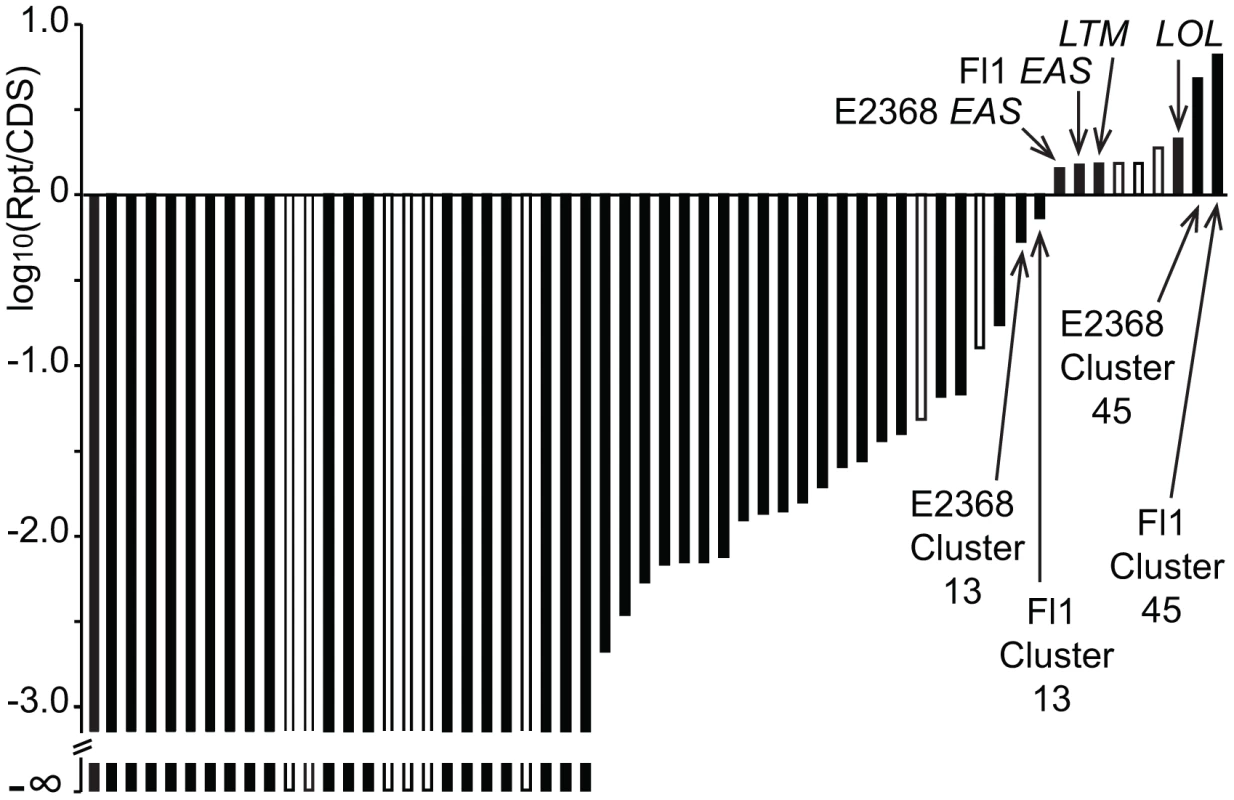

In order to assess whether large repeat blocks were mainly a feature of epichloid alkaloid clusters or, alternatively, a general feature of their SM clusters, the SM loci of both sequenced E. festucae strains as well as C. purpurea were manually identified and delineated (Table S4), and the proportions of repeat and coding sequences were determined. Each of these genome assemblies had been scaffolded by paired-end or mate-pair reads. In C. purpurea 20.1, repeat sequences within SM clusters were rare and small, though large repeat blocks flanked three SM clusters. For the SM clusters of the E. festucae strains, a logarithmic plot of total repeat sequence versus coding sequence lengths (Figure 12) demonstrated that only two active SM loci had comparable proportions of repeat sequence as the EAS, LTM, and LOL loci.

Fig. 12. Relative repeat contents in specialized metabolite clusters of Epichloë festucae.

Log-ratios of repeat sequences (Rpt) to coding sequences (CDS) are shown in order of increasing proportions of repeats. Open boxes represent clusters that are apparently nonfunctional due to inactivation of signature genes. Discussion

Alkaloids play a major role in the ecology of many Clavicipitaceae, protecting seeds and foliage of host grasses and morning glories from herbivores, or protecting fungal structures (such as ergots) from fungivores. Typically the effects of alkaloids on animals (insects, mammals, etc.) are much more immediate than is the case for many other specialized metabolites because alkaloids target the nervous systems and directly affect behavior [1]. Systemic symbionts such as epichloae and Periglandula species supplement the diversity of protective metabolites in grasses and morning glories, respectively, and such diversification should serve an important role in bet-hedging [68], [69] to enhance overall fitness in populations of plant-fungus symbiota on an ecologically variable landscape. Alkaloid diversification occurs at two levels, one being the presence or complete absence of each of several different classes, and the other being variations within each class. Here we compared alkaloid profiles and total alkaloid gene contents among 15 Clavicipitaceae, and also compared the arrangements of those genes and their associations with telomeres and blocks of repeat sequences. Two noteworthy patterns emerged. First, in most alkaloid loci in most species, the periphery of each cluster was enriched in genes that by virtue of their presence, absence, or sequence variations determined the diversity of alkaloids within the respective chemical class. Second, alkaloid gene loci of the epichloae had extraordinarily large and pervasive blocks of AT-rich repeats derived from retroelements, DNA transposons, and MITEs. In the epichloae these gene clusters were clearly unstable, probably because of the repeat blocks and, in the cases of EAS and IDT/LTM clusters, nearby telomeres. This instability was manifested in strains that had lost complete clusters, strains that had lost large portions of clusters, and strains with variant alkaloids attributable to gene duplications and neofunctionalizations. Partial or complete losses of alkaloid gene clusters generated diversity both between and within species of epichloae, as was apparent in comparisons of two isolates from each of three species, N. gansuense, E. festucae, and E. typhina. Also, gene duplications and neofunctionalizations resulted in the two novel IDT genes, ltmE and ltmJ, required for lolitrem B biosynthesis in E. festucae. Here we discuss how the alkaloid locus architectures relate to chemical diversity for each class of alkaloids, and how different ecological contexts of these fungi might select for those architectural differences.

Comprehensive genome sequencing was necessary to identify, with high confidence, all biosynthesis genes for each class of alkaloids in each fungal strain. Every indication has been that, like many fungi, the Clavicipitaceae tend to cluster these genes [7], [42], [70]. However, traditional methods have proven slow and unreliable for complete characterization of each cluster. Cloning and genome walking through these regions is especially difficult when, as is typical of the epichloae, they contain very large blocks of repeat DNA sequence, most of which is highly AT-rich, and cloned fragments containing these sequences are unstable and underrepresented in most gene libraries [42], [43], [71]. Therefore, current genome sequencing technologies facilitated not only a more comprehensive analysis of the gene clusters (including flanking repeats), but also the identification of previously unknown genes in or near these loci. In this way, two genes were newly discovered in the peripheries of some EAS loci (easO and easP), and two new LOL genes were also discovered (lolN and lolM). Furthermore, transcriptome analysis revealed the ltmS gene, which eluded de novo gene prediction, but was present in all IDT/LTM loci of the clavicipitaceous fungi.

Although the role of ltmS is not yet apparent, reasonable hypotheses for roles of the newly discovered EAS and LOL genes could be formulated based on gene presence or absence, along with comparisons of alkaloid profiles. For example, easO and easP were associated with LAH production. The sequence of easO indicates that it encodes a flavin-binding monooxygenase that, in the context of LAH biosynthesis, may oxidize the α-carbon of the alanine-derived residue in ergonovine or the ergonovine precursor attached to the LpsB/LpsC peptide synthetase complex. Furthermore, the sequence of easP indicates that it encodes an α/β hydrolase-fold protein, which could be involved in subsequent hydrolysis to release LAH. Similarly, the presence of lolN and lolM, predicted to encode an acetamidase and an N-methyltransferase, respectively, fits well with late enzymatic steps needed for NFL biosynthesis. Evidence from the genomes and chemotypes of strains with different loline alkaloid profiles suggest that the first fully cyclized loline alkaloid is NANL, which has an acetylated 1-amine. In order to produce NFL from NANL, it would be necessary first to deacetylate, then di-methylate that amine to generate NML. These are the likely roles for LolN and LolM, respectively, and the previously characterized lolP gene encodes a cytochrome P450 involved in the final process of oxygenating NML to NFL [72].

The Clavicipitaceae are best known for their ergot alkaloids, and among species and strains there are dramatic differences in ergot-alkaloid profiles [2], [73]. This variation is due to the particular mid-pathway or late-pathway genes that they possess, as well as differences in substrate or product specificity due to gene sequence variations [51], [70], [74]. In this study we associated chemotypes of Claviceps species with presence or absence of the genes lpsA, lpsB, lpsC, easH, easO and easP. In the Claviceps and Periglandula species, these genes are all in the cluster periphery, in contrast to the early-pathway and most mid-pathway genes in the core. (The mid-pathway gene easA is an exception, but with a unique role in alkaloid diversification as discussed below.) Even in the extensively rearranged EAS clusters of the epichloae the lps genes are often in the periphery. This placement is interesting considering the key role of lps genes in much of ergot-alkaloid diversity [51], and the propensity we observed for transposon-derived repeats to flank the EAS clusters in most Clavicipitaceae. Indeed, long repeat blocks were generally evident whenever lps genes were partially or wholly deleted or inactivated by extensive mutation.

In addition to gene presence or absence, sequence variation of certain genes resulted in further diversification of ergot alkaloids. This was dramatically evident for the multi-module lysergyl peptide synthase subunit I encoded by lpsA. Variations in lpsA among genera, and even between the two copies found in C. purpurea 20.1 [51], dictate which three amino acids are added to lysergic acid, hence which of 19 known ergopeptines are produced [7]. In addition, easA, which encodes a mid-pathway step in synthesis of the first fully cyclized ergoline, is also one for which sequence variation results in diversification of ergot alkaloids. Different easA forms determine if ergolines or dihydroergolines are produced [74]. (None of the strains sequenced in this study produce dihydroergolines.) Conceivably, variation in cloA also plays a role in ergot-alkaloid diversity. The C. purpurea CloA cytochrome-P450 catalyzes oxygenation of elymoclavine to paspalic acid [75], which spontaneously rearranges to lysergic acid. The cloA gene from C. fusiformis PRL 1980, though expressed and without any apparent defect, fails to complement this role in a cloA-deleted strain of C. purpurea [70]. However, it is unknown whether the variant form of CloA in C. purpurea has another role, for example in the oxygenation of agroclavine to elymoclavine.

Clearly the EAS loci in the epichloae are unstable and subject to rearrangements and partial or complete elimination. We characterized genomes of several epichloae that have the 11 genes required to synthesize the complex ergopeptines, others that had only the four functional genes required for chanoclavine I biosynthesis, and still others that lacked any functional EAS genes. Extensive rearrangements of the epichloid EAS clusters contrasted with the gene arrangements conserved among Claviceps species, P. ipomoeae, and the published Metarhizium genomes [46]. Interestingly, although N. gansuense var. inebrians E818 had an EAS locus structure and chemotype more similar to that of P. ipomoeae IasaF13 than to other epichloae, the E818 EAS locus had been broken up with a telomere and had lost lpsA and easH. Therefore, a tendency for rearrangements and telomere associations was consistently evident in, and contributed to, the chemotypic diversity of the epichloae.

The organization of IDT/LTM genes showed an even more distinct and consistent positioning of early and late pathway genes compared to the EAS loci. Furthermore, sequence variations in essentially all of the peripheral IDT/LTM genes account for differences in specificities of the cytochromes P450 and prenyltransferases that they encode, resulting in broad diversity of alkaloids within this class [53]. Rearrangements of IDT/LTM genes in the epichloae associated with large repeat blocks and telomeres were probably also responsible for gene duplications and neofunctionalizations that generated two new peripheral genes (ltmE and ltmJ) in the LTM cluster, allowing E. festucae to produce an especially complex group of indole-diterpenes, the lolitrems. This is a dramatic illustration of chemical diversification by cluster rearrangements almost certainly facilitated by the blocks of transposon-derived repeats.

The LOL loci, which were found only in epichloae, had features similar to EAS and IDT/LTM. Two of the three decoration genes identified in E. festucae E2368 were at the locus periphery, and all functional LOL loci were riddled with large and dynamic blocks of transposon-derived repeats. One notable difference was that, unlike the EAS and IDT/LTM clusters, the LOL clusters were not subtelomeric. Nevertheless, like EAS and IDT/LTM, the LOL loci were subject to partial or complete loss, resulting in different loline alkaloid profiles. Even the PER locus of some strains contained repeat blocks, and the perA gene also exhibited instability.

It is noteworthy that ergot alkaloids and indole-diterpenes are known among diverse ascomycetes, for which they undoubtedly have a variety of ecological roles. For example, the presence of EAS and IDT genes in Metarhizium species could indicate that these neurotropic alkaloids contribute to their abilities to affect behavior of parasitized insects. In contrast, peramine and loline alkaloids are characteristic of the epichloae, but unknown among other fungi. Consequently, compared to other Clavicipitaceae the epichloae have an even more diverse pallet of alkaloids to draw on to protect host plants. As systemic, and often vertically transmitted symbionts, epichloae depend on host plants throughout their life cycles, so it is to be expected that such an arsenal of plant protectants greatly benefits the epichloae.

The dynamics of alkaloid loci in the Clavicipitaceae, and especially the epichloae, promote chemotypic diversification even within species, and with respect both to the classes of alkaloids as well as the particular structures within each class that are produced. Transposon-derived repeats such as typify these loci can promote both recombination and mutation, and their insertions or deletions can radically alter gene regulation [76], [77]. We suggest that selection for chemotypic diversification within epichloid species may be imposed by their exceptional variety of life histories and host interactions. Whereas most other Clavicipitaceae are either contagious parasites (A. take and Claviceps species) or vertically transmitted mutualists (P. ipomoeae), epichloae vary widely in relative mutualistic or parasitic effects on their hosts based largely on transmission mode, and many (e.g., E. amarillans, E. brachyelytri, E. elymi, E. festucae and, in some hosts, E. typhina) have the remarkable capability to exhibit both transmission modes simultaneously on different tillers of the same plant [25]. Variation in relative vertical or horizontal transmission is expected to impose variation in selection on the symbiont, whereby vertical transmission selects for enhancements of host fitness [78]. Alkaloids, which typically deter herbivores [1], can be major contributors to host fitness, but also expensive to produce [79]. We suggest that variation in life history traits among the epichloae, as well as variation in ecological settings of their hosts, selects for exceptionally dynamic alkaloid loci that ensure high interspecific and intraspecific chemotypic variability.

Materials and Methods

Biological materials

Fungal strains and their sources are listed in Table S1. The Epichloë and Neotyphodium species, Claviceps fusiformis, Claviceps paspali, and Aciculosporium take were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) on a cellophane layer, or in potato dextrose broth (PDB) with shaking at 23°C. Mycelia were collected by centrifugation for 20 min at 5525× g, frozen and lyophilized prior to DNA isolation. Culture conditions for C. purpurea were as in Mey et al. [80].

Because Periglandula ipomoeae is so far nonculturable, the adaxial sides of the leaves of an infected host plant (Ipomoea asarifolia) were wetted with deionized water, and mycelia were picked off with a scalpel, placed into a vial with 70% ethanol, and stored at −20°C. The mycelium was harvested by centrifugation, frozen and lyophilized.

DNA was isolated by the method of Al-Samarrai et al. [81] or, for C. purpurea, by the method of Cenis [82].

Microscopic examination of Epichloë festucae in symbio

In order to document the stages of the life cycle of Epichloë festucae Fl1, the fungus was transformed with the plasmid, pCA49, which includes an enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (eCFP) coding sequence controlled by the Pyrenophora tritici-repentis TOXA gene promoter [83]. Fungal transformation was performed as previously described [72] and transformants were selected for resistance to hygromycin B. The transformants were introduced into seedlings of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) [84], and the symbiotic fungus was detected by tissue-print immunoblot with antiserum raised against a protein extract from Neotyphodium coenophialum [85]. Plants were grown in the greenhouse, and vernalized to induce flowering and seed development [86]. Plant tissues were dissected manually with the aid of a dissecting scope, placed on a glass slide in a drop of 50% glycerol, and covered with a coverslip. Confocal micrographs were generated with an Olympus FV1000 point-scanning/point-detection laser scanning confocal microscope, equipped with a 440 nm laser. Emission fluorescence was captured and collected at 467±15 nm through the eCFP filter. Image acquisition was performed at a resolution of 512×512 pixels and a scan rate of 20 µs pixel−1. The objective, Olympus water immersion PLAN APO 20×-Water (NA 0.75), was used for observing and generating micrographs. FLUOVIEW 1.5 software (Olympus) was used to control the microscope and export images as TIFF files.

Alkaloid analyses

Methods of analyses were as described previously for ergot alkaloids [75], [87], lolines [88], peramine [89], and indole-diterpenes [90].

Clone libraries

For Sanger sequencing of the E. festucae E2368 genome, a clone library of randomly sheared genomic DNA was constructed as follows. Nuclear DNA was enriched by bisbenzimide-CsCl isopycnic ultracentrifugation, randomly sheared with a GeneMachines Hydroshear (DigiLab Genomic Solutions, Inc.), twice gel-fractionated to select DNA fragments of 3.5–4.5 kb, and cloned into pBCKS+ (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, CA, USA). The library consisted of approx. 5 million clones, of which 2.5 million cfu were stored at −80°C as aliquots of transformed T1-phage resistant Escherichia coli cells (Electromax DH10B; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the remainder as ligation mixture. The E. coli transformants were grown on LB agar with chloramphenicol (25 mg/L). Colonies were picked by a QPix robot (Genetix, Hampshire, UK) into 96-deep-well plates with 2× YT medium (1.5 ml per well), and grown overnight in a HiGro (GeneMachines, San Carlos, CA, USA) oxygenated shaking incubator for microtiter plates. The plasmids were purified robotically (Biomek FX, Beckman Coulter Inc, Fullerton, CA, USA) with the Perfect-Prep Plasmid 96 kit (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg Germany). Sequence reactions and capillary electrophoresis were conducted using vector primers and BigDye3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at 1/16th reaction strength. The reactions were cleaned by ethanol precipitation and capillary electrophoresis was performed in a model 3730 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Both ends of each plasmid were sequenced. Sequencing results indicated that 99.8 of the clones contained genomic DNA inserts.

For the E. festucae Fl1 genome, a library was prepared in the fosmid vector pCC1FOS (Epicentre). DNA was fragmented with a Hydroshear equipped with the LARGE assembly, at speed setting 36, for 15 cycles. The fragments were end-repaired with the End-It kit (Epicentre), size-selected by electrophoresis in 0.4% agarose gel with Gelgreen stain (Biotium), imaged with blue light, purified from the agarose with Gelase (Epicentre), and blunt-end ligated to the fosmid arms using Fast-link (Epicentre). Escherichia coli Epi-300 T1R cells were transformed and selected for chloramphenicol resistance.

Genome sequencing

All DNA sequencing was conducted at the University of Kentucky Advanced Genetic Technologies Center. Most sequencing was conducted on a Roche/454 Titanium pyrosequencer. DNA was nebulized and size-selected to approximately 600 bp with AMPure beads (Agencourt), and subjected to shotgun pyrosequencing using the GS FLX Titanium General Library Preparation Kit, GS FLX Titanium LV emPCR Kit (Lib-L), and GS FLX Titanium Sequencing Kit XLR70 (Roche). Paired-end pyrosequencing was also conducted for E. festucae Fl1 (2-kb fragments 960,278 true paired end reads), E. festucae E2368 (3.0-kb fragments, 113,208 true paired end reads), and Claviceps purpurea (3.0-kb fragments, 1,128,137 true paired end reads). For paired ends, DNA was sheared with a Hydroshear with standard assembly, 20 cycles at speed setting of 12, then size selected with AMPure beads (Agencourt). The GS FLX Titanium Paired End adaptor set from Roche was used with Cre Recombinase, Exonuclease 1, and Bst polymerase from NEB according to the Roche GS FLX Titanium 3 kb Paired End Library Preparation Method Manual. Survey sequencing was conducted on and Ion Torrent PGM (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer's instructions. Sanger sequencing of the E. festucae E2368 genome was conducted on paired-ends of a library of cloned 3.8-kb (ave.) DNA fragments as described above (119,114 reads incorporated). In addition, the E2368 sequence assembly incorporated 235 reads of ca. 11-kb clones of genomic DNA in the pJAZZ system (Lucigen), as well as directly cloned telomere-containing fragments [91]. Sanger sequencing of the E. festucae Fl1 genome was conducted on paired-ends of the fosmid library of cloned 36-kb (ave.) DNA fragments (7259 read-pairs incorporated).

Data sets consisted of 2.3 M to 6.0 M reads per genome. Assemblies of E. festucae Fl1 and E2368 genomes incorporated paired-end data from Sanger sequencing in addition to 454 paired-end and single-end pyrosequencing data from a Roche/454 Titanium sequencer. The C. purpurea assembly used both single-end and paired-end pyrosequencing reads. All other genome assemblies used single-end pyrosequencing reads, some supplemented with sequences obtained on an Ion Torrent PGM (Life Technologies). Pyrosequencing reads that were duplicates, very short (<80 nt), or very long (>650 nt), or that had more than 1% of uncalled bases, were purged using utility program prinseq-lite-1.5 (http://prinseq.sourceforge.net) as suggested in Huse et al. [92]. Ion Torrent reads were trimmed of all base-calls after the first 230 bases. All genomes were assembled using Newbler Assembler ver. 2.5.3 (Roche/4540) with default parameters and the -sio option to ensure proper order of input data, with single-end reads preceding any paired-end data, and paired-end read libraries (Sanger and pyrosequencing) ordered by increasing insert size. Assemblies were uploaded to GenBank (Table S2), and are provided with annotations on GBrowse web sites (www.endophyte.uky.edu). The annotated assembly of the C. purpurea genome sequence can be viewed at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/Project:76493.

Annotation of repetitive DNA elements

Repetitive DNA families in the genome sequences were defined by processing a self-BLASTN report from each genome using a custom PERL script (Amyotte S.G. et.al Manuscript in preparation) that identified sequences with multiple genome copies and classified these repeats into non-redundant families. The repeat families were then manually curated to correct or remove families misidentified in the automated process above. The genome distribution of repeated sequences was characterized using RepeatMasker version 3.2.9 [93], with Cross_Match [94] version 0.990329, with the final set of repetitive families serving as a custom library. Results have been included in the GBrowse web sites (www.endophyte.uky.edu). All unique repeats identified from the genome custom libraries were compared by reciprocal BLASTn to identify conserved sequences within and between each species. Repeat sequences with BLAST scores greater than 100 were used to develop a matrix table of corresponding repeat numbers. A common number was given to each repeat association to rapidly identify repeat families conserved across species. The matrix table was used to label repeats within each gene cluster with the universal repeat numbers (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11). Repeats were assigned to putative superfamilies, and families where possible, based on BLASTx analysis and the presence and orientation of terminal repeats (Table S5).

Miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs) previously characterized in E. festucae [67] were identified in other genomes by BLASTn using a personal database. To determine whether short repeats found in non-epichloid clusters were MITEs they were analyzed for terminal inverted repeats using einverted (EMBOSS; http://emboss.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/emboss/einverted). Individual repeat-containing loci were aligned using MUSCLE and manually analyzed for evidence of recombination.

RIP-index analysis

RIP indices were calculated using a sliding window analysis with a 200 bp window and a step size of 20-bp (in the centromere-to-telomere direction). RIP indices (ApT/TpA) [95] were calculated for each window. The process was repeated until the window met the end of the sequence (i.e partial windows were not counted). These operations were performed automatically using a perl script (Protocol S1).

Gene identification and orthology and phylogenetic analyses

Gene predictions were conducted by various methods available in MAKER version 2.0.3 [96]. In the MAKER runs, assembled contigs were filtered against RepBase [97] model organism “fungi,” using RepeatMasker [93] version open-3.2.8. Our MAKER runs used the predictors AUGUSTUS 2.3.1 (Fusarium model) [98], FGENESH 3.1.1 (Fusarium model) [99], GeneMark-ES 2.3a (self-trained), and SNAP 2006-07-28 (trained with C. purpurea gene predictions for genus Claviceps, and with E. festucae E2368 gene predictions for other genera). These ab initio predictions were supplemented with evidence from Clavicipitaceae proteins in the NCBI non-redundant protein database and from assembled E. festucae ESTs (unigenes). Relationships of predicted proteins to known protein families were assessed by running InterProScan [100] on the inferred protein sequences inferred from the predicted genes. Results, including MAKER and FGENESH predictions and subsequent analyses, have been included in a collection of web sites based on GBrowse 1.70 [101], [102], posted at www.endophyte.uky.edu.

Gene modeling for C. purpurea was done similarly, by applying three different gene prediction programs: 1) FGENESH [99] with different matrices (trained with Aspergillus nidulans, Neurospora crassa and a mixed matrix based on different species); 2) GeneMark-ES [103] and 3) AUGUSTUS [98] with available ESTs as hints. The different gene structures were displayed in GBrowse [101], [102], allowing manual validation of all coding sequences (CDSs). Annotation was aided by BLASTx hits between the C. purpurea genome and those from Blumeria graminis, Neurospora crassa, Fusarium graminearum and Ustilago maydis, respectively. For the cluster regions and selected genes of interest the best fitting model per locus was selected manually and gene structures were adjusted by manually splitting them or redefining exon-intron boundaries based on EST data where necessary.

Orthology analysis was conducted on FGENESH-predicted proteins with length 10 amino acids or greater. Each inferred protein sequence was assigned a unique label with a prefix indicating its source genome. The predicted genes were first compared to the curated ortholog groups in OrthoMCL-DB [104] version 4 using the OrthoMCL web service (http://orthomcl.org/cgi-bin/OrthoMclWeb.cgi?rm=proteomeUploadForm), to which each predicted proteome was submitted independently. Next, the combined set of inferred proteins from all of the sequenced Clavicipitaceae was analyzed as described in the OrthoMCL algorithm document (http://docs.google.com/Doc?id=dd996jxg_1gsqsp6). The software versions used for this procedure were: OrthoMCL version 2.0.2 [105], MCL-bio [100], MCL version 10–201 (http://micans.org/mcl/) [106], and NCBI BLAST version 2.2.25 [107].