-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaPcG-Mediated Higher-Order Chromatin Structures Modulate Replication Programs at the BX-C

Polycomb group proteins (PcG) exert conserved epigenetic functions that convey maintenance of repressed transcriptional states, via post-translational histone modifications and high order structure formation. During S-phase, in order to preserve cell identity, in addition to DNA information, PcG-chromatin-mediated epigenetic signatures need to be duplicated requiring a tight coordination between PcG proteins and replication programs. However, the interconnection between replication timing control and PcG functions remains unknown. Using Drosophila embryonic cell lines, we find that, while presence of specific PcG complexes and underlying transcription state are not the sole determinants of cellular replication timing, PcG-mediated higher-order structures appear to dictate the timing of replication and maintenance of the silenced state. Using published datasets we show that PRC1, PRC2, and PhoRC complexes differently correlate with replication timing of their targets. In the fully repressed BX-C, loss of function experiments revealed a synergistic role for PcG proteins in the maintenance of replication programs through the mediation of higher-order structures. Accordingly, replication timing analysis performed on two Drosophila cell lines differing for BX-C gene expression states, PcG distribution, and chromatin domain conformation revealed a cell-type-specific replication program that mirrors lineage-specific BX-C higher-order structures. Our work suggests that PcG complexes, by regulating higher-order chromatin structure at their target sites, contribute to the definition and the maintenance of genomic structural domains where genes showing the same epigenetic state replicate at the same time.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003283

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003283Summary

Polycomb group proteins (PcG) exert conserved epigenetic functions that convey maintenance of repressed transcriptional states, via post-translational histone modifications and high order structure formation. During S-phase, in order to preserve cell identity, in addition to DNA information, PcG-chromatin-mediated epigenetic signatures need to be duplicated requiring a tight coordination between PcG proteins and replication programs. However, the interconnection between replication timing control and PcG functions remains unknown. Using Drosophila embryonic cell lines, we find that, while presence of specific PcG complexes and underlying transcription state are not the sole determinants of cellular replication timing, PcG-mediated higher-order structures appear to dictate the timing of replication and maintenance of the silenced state. Using published datasets we show that PRC1, PRC2, and PhoRC complexes differently correlate with replication timing of their targets. In the fully repressed BX-C, loss of function experiments revealed a synergistic role for PcG proteins in the maintenance of replication programs through the mediation of higher-order structures. Accordingly, replication timing analysis performed on two Drosophila cell lines differing for BX-C gene expression states, PcG distribution, and chromatin domain conformation revealed a cell-type-specific replication program that mirrors lineage-specific BX-C higher-order structures. Our work suggests that PcG complexes, by regulating higher-order chromatin structure at their target sites, contribute to the definition and the maintenance of genomic structural domains where genes showing the same epigenetic state replicate at the same time.

Introduction

One of the key open questions in biology is how epigenetic traits are faithfully duplicated during the cell cycle and how this safeguards the correct maintenance of transcriptional programs and cell identity. During S-phase, replication of chromatin domains containing differentially expressed genes appears to be regulated in a spatial and temporal manner. In general it is widely accepted that active transcriptional units are preferentially replicated early whereas silenced genes and heterochromatin are replicated in late S-phase [1]. However, the contribution of epigenetic regulators to this dynamics remains to be elucidated.

Polycomb group (PcG) multiprotein complexes are evolutionary conserved epigenetic regulators required for the maintenance of repressed transcriptional states during development and in adult tissues [2]. In Drosophila melanogaster five PcG complexes have been identified, controlling gene silencing at different levels by regulating RNA Pol II function, histone modifications and higher-order chromatin structures; Polycomb repressive complexes 1 (PRC1) and 2 (PRC2), Pho-repressive complex (PhoRC), dRing-associated factors (dRAF) complex and Polycomb repressive deubiquitinase (PR-DUB) complex [2]. PcG complexes exert their function by interacting with specialized cis-regulatory regions termed PcG Response Elements (PREs) [3], [4] and with transcription start sites (TSSs) [5]. The zinc finger protein Pleiohometic (PHO) of PhoRC is thought to play an important role in PRC1 and PRC2 recruitment [6]. Once recruited, the PRC2 complex, via its catalytic subunit E(z), deposits the characteristic repressive chromatin mark, histone H3 trimethylated at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) [7]–[9], which in turn serves as docking site for PRC1 [10]. Previous works have revealed that PcG-bound regulatory regions can interact with promoters and modulate their activity via mechanisms involving looping between regulatory elements and long-distance interactions in cis or in trans (between different chromosomes) [11]–[13]. The genome is topologically organized into chromatin loops also during the process of DNA replication, when hundreds of replication factories are formed, each containing clusters of replication origins that fire almost simultaneously [14]. It has been proposed that, in these replication foci, neighbouring origins are located in physical proximity to each other while inter-origin DNA regions are looped out, forming rosette-like structures [15], [16]. In each factory large segments of the chromosome are replicated in a coordinated manner at characteristic times during S-phase. In higher eukaryotes the choice of replication origins and the time of firing are cell-type specific [17]–[19] and change dynamically during differentiation and development [20]–[22]. It has been proposed that epigenetic mechanisms regulating chromatin structure and chromosome organization could play a role in regulating the selection of DNA replication origins and the time of firing [23]–[26]. Conversely, timing and selection of replication origins can contribute to the establishment of chromatin domains thus modulating transcription [27].

In Drosophila it was shown that at the 340 kb, PcG-repressed homeotic Bithorax Complex (BX-C), distally spaced PREs, promoters and 3′ ends of repressed genes interact with each other to form multi-looped structures that are dynamically regulated during replication [13], [28]. In order to investigate the functional role of PcG-mediated silencing and higher-order chromatin structures in the modulation of replication programs in Drosophila, we used cell lines derived from embryonic tissue as model system. By means of genome-wide bioinformatic and statistical analyses we investigated whether PRC1, PRC2 or PhoRC bound regions would show any preferential replication timing in Drosophila embryonic Schneider 2 cell line (S2). We found that PRC2-targeted promoters replicate later than non-target ones, in agreement with the generally accepted concept that inactive genes are, on average, late replicating [28]–[33]. However, no significant difference in replication timing distributions emerged between PRC1 or Pho-RC bound and non-bound promoters. To gain deeper insight on the interplay between PcG-mediated silencing, higher-order structures and replication timing we focused on the repressed and late replicating BX-C in S2 cells. We found that, simple derepression of BX-C genes does not result in changes in replication timing or higher-order structures, while a combined PcG dependent (PHO, PC and E(z)) impairment of BX-C higher-order structures is accompanied by an anticipation in replication timing. Further, we found that epigenetically distinct cell lines, differing in BX-C gene transcription and topological three-dimensional conformations show PRE specific replication timing profiles. Our work reveals that PcG mediated BX-C higher-order structures coincide with replication domains and that PcG complexes act synergistically for the epigenetic maintenance of replication timing programs.

Results

PRC1-, PRC2-, and PhoRC-bound promoters show different replication timing distributions in Drosophila S2 cells

A positive correlation between PcG-mediated H3K27me3 mark and late replication has been previously reported [34]. Using public available data sets we analyzed the genome-wide replication timing distribution of PRC2, PhoRC and PRC1 bound promoters, defined as all regions within 500 bp of a unique RefSeq Transcription Start site (TSS). The replication timing of each promoter was estimated as described in Material and Methods. As representatives of PRC2 complex and its enzymatic activity we used, respectively, E(z) and H3K27me3 whereas PHO was used as representative of the PhoRC complex. All three datasets are available from modENCODE as ChIP-chip genome-wide profiles (see Material and Methods for details). Feature enrichments at promoters and their statistical significance have been computed using a conservative approach as described in Material and Methods.

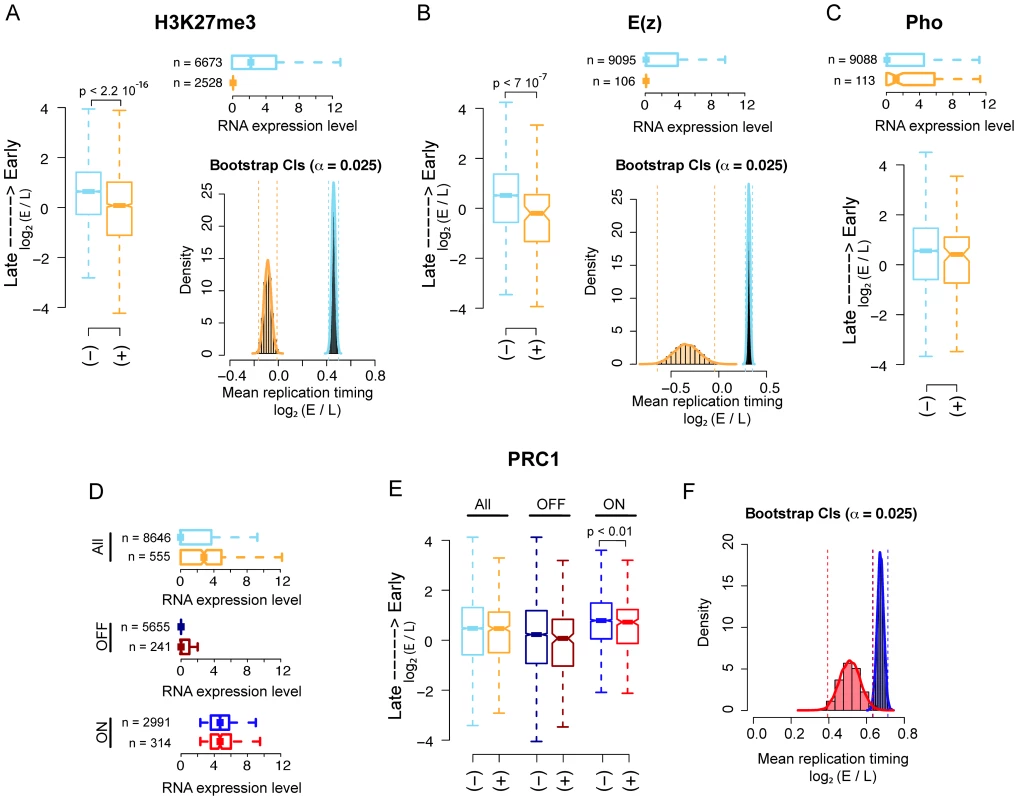

First, we found that both H3K27me3 and E(z) enriched regions replicate significantly later than their non-enriched counterparts as shown by both boxplot and percentile bootstrap confidence intervals, left and right panel, respectively in Figure 1A and 1B. Of note, 94% of E(z) bound promoters are also significantly enriched for H3K27me3 in our analysis. To test whether the observed difference in replication timing could be entirely explained by the significantly lower transcriptional activity of PRC2 bound promoters (Figure 1A, 1B, upper panels), we used weighted bootstrap to compute confidence intervals for the mean replication timing of H3K27me3 enriched and non-enriched promoters using probability weights that account for the different transcriptional activity distributions between the two groups (see Materials and Methods for details).

Fig. 1. PRC2, PhoRC, and PRC1 show different replication timing distributions in Drosophila S2 cells.

(A) Boxplot (left panel) of genome-wide Drosophila embryonic S2 cell line replication timing for significantly H3K27me3 enriched promoters (orange) and non-enriched promoters (light blue). Horizontal boxplot (top right panel) of RNA expression levels in the two previous groups, where group sizes are indicated to the left. Bootstrap distributions (bottom right panel) of mean replication timing for H3K27me3 significantly enriched promoters (orange) and non-enriched promoters (light blue). Percentile confidence intervals (α = 0.025) are indicated with dashed vertical lines. (B) Same as (A), with promoters classified as E(z) bound (orange) and non-bound (light blue). (C) Same as the first two panels of (B), with promoters classified as PHO bound (orange) and non-bound (light blue). (D) Horizontal boxplot of RNA expression levels for genome-wide PRC1 bound (orange) and non-bound (light blue) promoters, PRC1 bound (dark red) and non-bound (dark blue) OFF promoters only and PRC1 bound (red) and non-bound (blue) ON promoters only (see Material and Methods). Group sizes are indicated to the left. (E) Boxplot of replication timing for the three previous groups. (F) Bootstrap distributions of mean replication timing for PRC1 bound (red) and non-bound (blue) ON promoters. Percentile confidence intervals (α = 0.025) are indicated with dashed vertical lines. All p-values have been computed using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Interestingly, the distributions of the mean replication timing within the two groups remained largely separated after resampling (Figure S1A and Materials and Methods), suggesting that transcription might not be the sole determinant of late replication timing for H3K27me3 enriched promoters.

Second, we analyzed the correlation between PHO binding and replication timing and we did not find any significant difference in the mean replication timing of PHO bound promoters compared to non-bound promoters as shown in Figure 1C, lower panel. The upper panel shows the transcriptional activity of the promoters in the two groups.

Third, we investigated whether PRC1 binding at promoters significantly correlates with their replication timing. We defined PRC1 bound those promoter regions showing joint enrichment for all three PRC1 core components: PC, Ph and Psc. All three proteins were profiled genome-wide in [5] using ChIP-Seq. Differently from what we observed for H3K27me3 and E(z) bound promoters, PRC1 bound promoters are globally more transcribed than their non-bound counterparts (Figure 1D, upper panel). When all promoters were considered, we did not find any significant difference between the mean replication timing of PRC1 bound and non-bound promoters (Figure 1E, left boxplot). The differential replication timing distribution between PRC1, PhoRC and PRC2 may reflect a specific regulatory difference between these complexes, which has already been reported in previous works [5], [35]–[37]. Moreover, these data support emerging evidence that PRC bound promoters are not universally silent [5], [37]–[40]. PRC1 components have been shown to colocalize with TrxG complexes on stalled promoters, where RNA Pol II is “poised” for subsequent activation in response to developmental cues [5]. These promoters could be functionally considered as the fly's analogs of the ‘bivalent domains’ found in mammals, representing poised states for lineage-specific activation of key regulatory and developmental genes [36], [39]. To quantify the contribution of bivalent PRC1 bound regions to replication timing, we compared all promoters bound by PRC1 with promoters co-bound by PRC1 and Trx (Figure S1B), finding no difference between the two classes. To dissect the link between transcription and replication timing of PRC1 bound promoters, we divided them into two subgroups: OFF promoters, represented by promoters with none or little transcriptional output, and ON promoters containing actively transcribed promoters (Figure 1D, mid and lower panel, respectively, see Material and Methods). Of note, approximately half of the stalled promoters were considered ON in our analysis according to this definition. We then analyzed the mean replication timing within each subgroup. Interestingly, although OFF promoters are late replicating, no significant difference in replication timing distribution was found between PRC1 bound and non-bound (Figure 1E, mid boxplot). This result might be explained by the considerable amount of late replicating constitutive heterochromatic promoters that are not occupied by PRC1, thus masking a possible contribution of PRC1 to replication program regulation. On the other hand, PRC1 bound ON promoters are significantly later replicating than PRC1 non-bound ON promoters (Figure 1E, right boxplot) despite the two sets exhibit no significantly different transcriptional activity (Figure 1D, lower boxplot). This result is in agreement with recent observations showing active transcription of PRC1 bound promoters [5] and reinforces the idea that transcription is not the unique discriminator of replication timing of a given locus. Figure 1F shows percentile bootstrap confidence intervals for the mean replication timing within the two groups of active promoters.

Taken together, these results corroborate the view of a functional difference between PRC2, PhoRC and PRC1 complexes and suggest that PRC2 complex, but not PRC1 or PhoRC, can be considered a genome-wide predictor of replication timing in Drosophila.

Forced transcriptional reactivation by depletion of single PcG complex subunits changes neither replication timing nor the overall BX-C higher-order interactions

To further investigate the possible contribution of PRC1 and other PcG complexes to replication timing at repressed targets (OFF TSSs), we focused our attention on the fully silenced and late replicating locus BX-C (Figure 2A). We performed loss of function experiments by treating Drosophila S2 cells with dsRNA against mRNA encoding either PHO, E(z) or PC proteins, members of the PhoRC, PRC2 and PRC1 complexes respectively, in order to evaluate and dissect the contribution of PcG complexes on BX-C transcriptional silencing, higher-order structures maintenance and replication program control. Extending previous reports [13], after single PcG-knockdown we observed a transcriptional reactivation of all three BX-C homeotic genes accompanied by a mild derepression of the intervening non-coding transcripts encompassing PREs (Figure S2A). Notably, depletion of specific PcG proteins differentially affects BX-C transcription. In particular PC depletion results in a stronger derepression, causing an increase of transcription up to ten thousand fold for the Ubx transcript. In contrast, E(z) or PHO depletions, despite their suggested role in PRC1 recruitment [6] cause a weaker transcriptional increase. Massive transcription in the region corresponding to bx PRE (Figure S2A, right panel) in PC depleted cells reflects the strong activation of Ubx homeotic gene transcript encompassing bx region (Figure S2A, left panel). The different transcriptional effects observed upon depletion of each specific PcG subunit did not depend on interference efficiency, as all targeted proteins were not detected by western blot after three rounds of dsRNA treatment (Figure S2B).

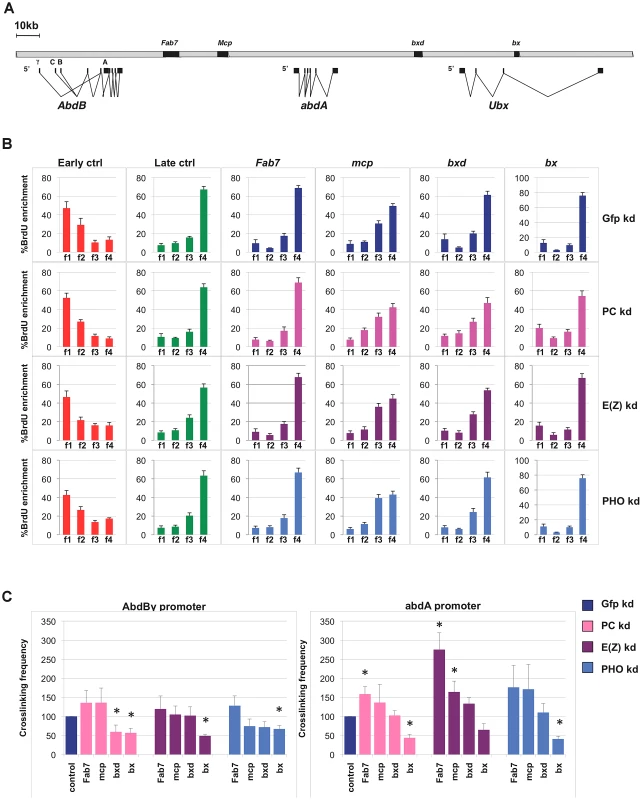

Fig. 2. Single PcG subunit depletion does not affect BX-C replication timing or higher-order structures.

(A) Schematic representation of the Bithorax Complex (BX-C) including homeotic genes and characterized PREs. (B) Enrichment of BrdU labelled DNA in the four FACS sorted S-phase fractions as quantified by real time PCR with indicated primers in control cells (blue) and in cells treated with PC-dsRNA, E(z)-dsRNA or PHO-dsRNA (pink, purple and light blue, respectively). The relative abundance of locus-specific DNA in each cell-cycle fraction is calculated from the average values of threshold cycle (Ct), normalized to the Ct of a mitochondrial sequence as internal control (Ctmit), using the following equation: , where i is one of the four fractions. All data points were generated from an average of six independent experiments. Standard error of the mean is indicated. (C) Crosslinking frequencies, normalized to the internal control, between the fixed fragments spanning two homeotic promoters (AbdBγ and abdA) and BX-C PREs. Crosslinking frequencies observed in GFP–dsRNA-treated cells are shown in blue while data obtained in cells treated with PC-dsRNA E(z)-dsRNA or PHO-dsRNA are in pink, purple and light blue, respectively. Standard error of the mean is indicated. All data points were generated from an average of four independent biological replicates. Two-tailed t-test was applied for statistical analysis. Asterisks indicate statistically relevant differences: (α = 0.05). P values: PC-dsRNA treated cells: AbdBγp/bxd: P = 0,04 AbdBγp/bx: P = 0,03×10−1; abdA/Fab7: P = 0,01; abdA/bx: P = 0,01×10−2; E(z)-dsRNA treated cells: AbdBγp/bx: P = 0,06×10−6; abdA/Fab7 P = 0,07×10−2; abdA/mcp: P = 0,04; PHO-dsRNA treated cells AbdBγp/bx: P = 0,02×10−1; abdA/bx: P = 0,09×10−4. To determine BX-C replication timing, we pulse-labelled asynchronous S2 cells with BrdU and FACS sorted four S-phase fractions, from the earliest (f1) to the latest (f4), according to DNA content (Figure S2C). DNA was prepared from an equal number of cells representing the four fractions. BrdU-labelled DNA was immunoprecipitated from these fractions to enrich for those genomic sequences that replicate during the labelling period. We then performed quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), using primers specific for control sequence regions previously shown in S2 cells to be early and late replicating [34], for Fab-7, Mcp, bxd and bx PREs and for homeotic gene promoters (Figure 2B, Figure S2D). As an internal control we used a unique region of the mitochondrial genome, expected to replicate throughout the cell cycle (see Materials and Methods for details). Our analysis showed that repressed BX-C PREs replicate during late S phase in control cells, being enriched in the latest S-phase fraction (Figure 2B). In PcG-depleted cells where PREs and homeotic genes were no longer repressed, late replication was maintained (Figure 2B, Figure S2D), suggesting that single PcG proteins do not have a strong influence on BX-C replication programs. This result was confirmed by statistical analysis, in which we calculated the ratio between the amounts of amplified products in the earliest (f1) and the latest (f4) S-phase fraction (Figure S2E). Interestingly, abdA and Ubx promoters were late replicating in control cells, while the 5′ region of the AbdB gene, being situated in a transition region of replication timing (Figure S3), shows an intermediate timing of replication, presenting the highest BrdU incorporation in f2 and f3 S-phase fractions (Figure S2D). We have previously shown that reduced levels of the single PRC1 subunit Polycomb (PC) determines minor changes in higher-order structures [13]. Similar results were obtained in mammals [41], [42]. In order to investigate to what extent BX-C higher-order structures are affected by depletion of different PcG proteins, we used Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) analysis to monitor DNA/DNA interactions between PcG targets. Comparison of crosslinking frequencies in depleted versus control cells reveals that PRE/promoter interactions were affected more in PC depleted than in E(z) and PHO depleted cells, but the overall BX-C structure was maintained upon single PcG knock-down (Figure 2C), reinforcing and extending previous reports [13]. Notably, E(z) depletion caused an increased frequency of some interactions between abdA promoter and PREs (Figure 2C, right panel). Taken together, these data indicate that transcriptional reactivation of homeotic genes after depletion of single PcG subunits, only partially impairs BX-C three-dimensional structure and it is not sufficient per se to change the replication timing.

Simultaneous depletion of multiple subunits of PcG protein complexes determines changes of BX-C transcription, replication timing, and high-order structures

We went on and performed simultaneous depletions of the PHO, E(z) and PC subunits. As shown in Figure S4A and S4B, mRNA and protein levels of targeted PcG subunits were consistently reduced. As expected, in triple PcG depleted cells we observed a transcriptional reactivation of homeotic genes one order of magnitude higher than in a single PcG knock-down (Figure S4C). In addition, we found that transcription through PREs quantitatively correlates with homeotic gene reactivation (Figure S4D) being nearly ten fold for Fab-7, Mcp and bxd in respect to the GFP control. Strikingly, when we performed replication timing analyses in triple depleted cells, a clear anticipation of Fab7, Mcp and bxd replication timing was observed, being enriched in f3 S-phase fraction after PcG depletion (Figure 3A). Analysis done on two S phase fractions (Figure S4E) confirmed the above changes and identified the indicated PREs as mid replicating sequences, becoming statistically different from both early and late replicating sequences. Interestingly, each PRE was differently affected, with bx not susceptible to the triple PcG protein depletion (Figure 3A, Figure S4E). Notably, this trend does not correlate with a higher degree of transcriptional reactivation (Figure S4D), suggesting again that transcription per se does not influence replication timing. We then measured replication timing of homeotic gene promoters and we found that only Ubx gene promoter showed anticipation in replication timing after triple PcG depletion (Figure 3B, Figure S4E).

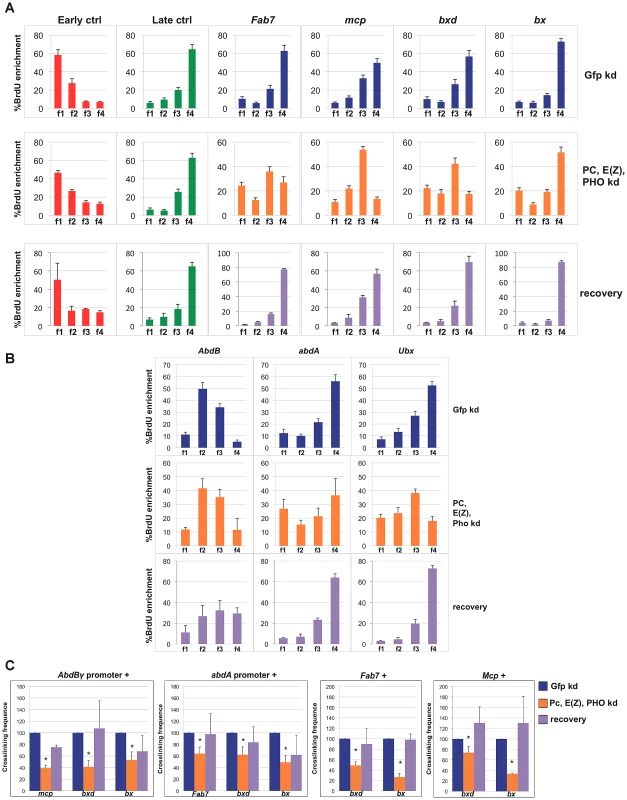

Fig. 3. Simultaneous depletion of three PcG proteins determines reversible changes of BX-C higher-order interactions and replication timing.

Data obtained in control cells are shown in blue, data obtained in cells treated with dsRNA against PC, E(z) and PHO and in recovered cells are in orange and violet, respectively. (A, B) Enrichment of BrdU labelled DNA in the four FACS sorted S-phase fractions as quantified by real time PCR with indicated primers of controls and PREs (A) or homeotic genes promoters (B) as measured by quantitative RT-PCR. All data points were generated from an average of at least four independent experiments. Standard error of the mean is indicated. (C) Left panels: crosslinking frequencies, normalized to the control, between the fixed fragments spanning two homeotic promoters (AbdBγ and abdA) and BX-C PREs in triple PcG depleted cells and recovered cells; right panels: crosslinking frequencies, normalized to the control, between the indicated PREs. Asterisks indicate statistically relevant differences. Standard error of the mean is indicated. Two-tailed t-test was applied for statistical analysis. α = 0.05. P values: AbdBγp/mcp P 0,05×10−7; AbdBp/bxd P = 0,01×10−1; AbdBγp/bx P = 0,02; abdAp/fab7 P = 0,01×10−2. abdAp/bxd P = 0,02; abdAp/bx P = 0,04×10−7; Fab-7/bxd P = 0,07×10−2; Fab-7/bx P = 0,02×10−5. mcp/bxd P = 0,02; mcp/bx P = 0,07×10−9. We further analysed functional DNA/DNA interactions in triple PcG depleted cells. Interestingly, 3C analysis revealed that, although homeotic gene promoters (AbdBγ promoter and abdA promoter) maintained the association with their functional PRE (Fab-7 and Mcp, respectively, Figure S4F), other promoter/PRE and PRE/PRE interactions were impaired (Figure 3C). Of note, the overall BX-C conformation was not completely lost (Figure S4F), suggesting the presence of other regulators of BX-C structure that are not affected by PcG depletion.

In order to follow the stability of the loss of function phenotype, PcG depleted, BX-C reactivated cells were grown for additional 30 days (almost 20 cell divisions) in the absence of dsRNA to restore normal PcG levels. In all the independent samples we found a complete recovery of PcG transcripts and a partial recovery of protein levels (Figure S4A and S4B). In recovered cells, we found a general tendency to restore BX-C repression, here partially re-established for Ubx and abdA and fully for AbdB (Figure S4C), in agreement with previous findings in imaginal discs [43]. Similarly, PRE transcripts were re-repressed with the exception of bx that reflects the higher level of derepression of Ubx (Figure S4D). To exclude that the recovery effect could be due to poorly depleted cells that could have repopulated the culture, we compared the proliferation of control cells with triple depleted cells after each round of transfection (see Material and Methods). The results showed no difference between the proliferative potential of both type of cells (Figure S4G). We then measured PRE replication timing and crosslinking frequency between PREs and promoters in recovered cells. After 30 days BX-C late replication timing was restored in recovered cells, showing values indistinguishable from control cells (Figure 3A, 3B; Figure S4E, S4H). Concomitantly, we observed a complete recovery of PRE/promoter and PRE/PRE interactions (Figure 3C). These data indicate that differences in replication timing and higher-order structures were influenced by a temporary loss of multiple PcG proteins. This effect can be reversed when wild type conditions are re-established, thus indicating that PcG complexes act synergistically to maintain programmed silencing, topological order and replication timing at BX-C.

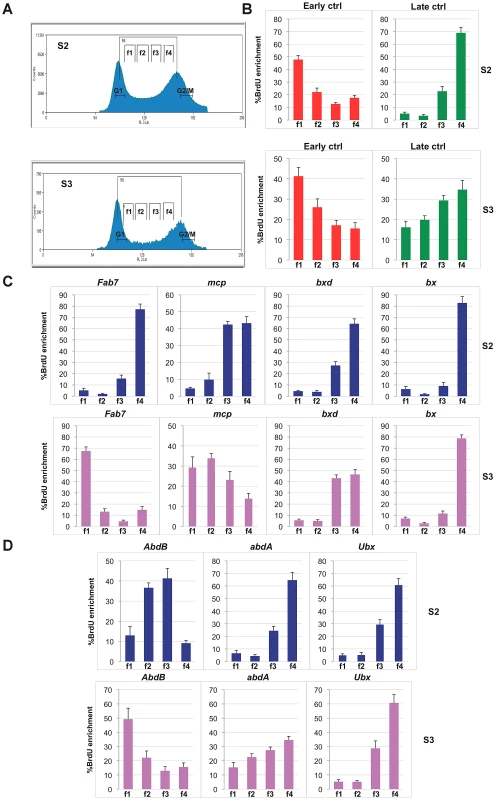

A different topological order at the BX-C correlates with distinct replication timing programs

To understand whether early established PcG-mediated chromatin structures are associated with specific replication programs, we analysed two Drosophila embryonic cell lines, S2 and S3, showing distinct BX-C gene expression and structural conformation [13]. We have previously shown that in S2 as in S3 cells, Ubx and abdA are repressed or transcribed at low levels, while all three AbdB and the downstream intervening non-coding transcripts are strongly expressed only in S3 cells [13], [44] (Figure S5A). In these cells the AbdB domain features several epigenome structural differences in respect to S2 cells, such as reduced PcG protein binding [38], different histone mark enrichment [44] and different higher-order chromatin interactions [13]. While in S2 cells all PcG binding sites are clustered and mediate the formation of a multi-loop higher-order structure, in S3 cells the genomic section containing the AbdB gene as well as the Fab-7 and Mcp PREs loses contact with other repressed PcG bound elements of the BX-C cluster, creating a distinct domain [13] (Figure S5B). We performed replication timing analysis in S3 in comparison to S2 cells (Figure 4A). In S3 cell line, we observed a different replication timing profile for specific BX-C PREs (Figure 4B and 4C). In particular, while in S2 cells all PREs are enriched in the f4 fraction, representing the latest S phase (Figure 4C and S5C), in S3 cells, repressed bx and bxd PREs are enriched in the late S-phase fraction, while expressed Fab-7 and Mcp PREs show their highest abundance in the earlier fractions (f1 and f2, respectively). In line with these findings, promoters of repressed genes are late replicating in both cell lines, while the region at the 5′end of AbdB gene, differentially expressed in the two cell lines, shows different replication timing, being mid replicating in S2 cells and early replicating in S3 (Figure 4D and Figure S5C). These data suggest that while in S2 cells the entire BX-C forms a single late replicating structural unit, in S3 cells the BX-C is divided into two structural domains showing distinct replication timing.

Fig. 4. Different replication timing profiles at BX-C PREs in S2 and S3 cell lines.

(A) Cell-cycle profiles of D. melanogaster S2 cells (top) and S3 cells (bottom) after BrdU pulse labelling and propidium iodide staining. Cells between the G1 and G2 peaks are in S phase. Gates indicate the sorted fractions: f1 represents the earliest and f4 the latest S-phase fraction. (B, C, D) Enrichment of BrdU labelled DNA in the four FACS sorted fractions as quantified by real time PCR with primers specific for early and late replication timing controls (B), PREs (C) and homeotic gene promoters (D) in S2 and S3 cell lines. All data points were generated from an average of at least four independent experiments. Standard error of the mean is indicated. Discussion

The epigenome in its overall complexity, including covalent modifications of DNA and histones, higher-order chromatin structures and nuclear positioning, influences transcription and replication programs of the cell. It is well known that timing of DNA replication is correlated with relative transcription state, in particular transcriptionally active genes tend to replicate early and inactive genes tend to replicate late (for a review, see [1], [45], [46]). However, in recent years, genome-wide analyses revealed several exceptions to this rule [18], [47], [48]. These and other evidence suggested that the transcriptional potential of chromatin, expressed as histone modifications and transcription factors binding (rather than the process of transcription per se) is most closely related to replication timing [18], [49], [50]. A recent work in Drosophila has shown that the selection and the timing of firing of replication origins are associated with distinct sets of chromatin marks and DNA binding proteins [34]. This reinforces previous works showing that mutation, overexpression, depletion or tethering of chromatin modifying proteins to specific loci in yeast, Drosophila and vertebrates determines changes in replication timing locally or/and at a global level [25], [51]–[56]. In mammals, it has been suggested that higher-order chromatin structures more than basal epigenome modifications better correlate with replication timing profiles [57], [58]. Although several proteins have been reported to control higher-order chromatin structure formation, their role in replicon structure and replication timing regulation remains to be elucidated. Among these, cohesins have been shown to co-localize with ORC binding sites [59], [60] and to influence replication origin choice and density through the regulation of specific chromatin loops [59]. Previously, we and others reported that PcG proteins are key regulators of higher-order chromatin structures and that condensins complex components and Topoisomerase II take part in PRE and BX-C silencing function [11]–[13], [41], [61]. Moreover, depletion of the mammalian PC homologue M33 determines a switch of the INK4a/ARF locus replication timing [62], suggesting a role for PcG proteins in the regulation of replication programs at their targets.

However, the interplay between PcG-mediated silencing, higher-order structures and control of replication timing in Drosophila has not been elucidated. We first addressed this issue on a genome-wide level finding that H3K27me3 enriched and PRC2 bound sequences replicate later than their unbound counterparts (Figure 1A, 1B). Surprisingly, the same is not true for PRC1 or PhoRC target sites, where the binding of PcG proteins does not significantly correlate with genome-wide replication timing distributions (Figure 1C–1E), highlighting a difference between PRC1, PhoRC and PRC2 complexes at a genome-wide scale. Notably, replication timing is more correlated to PRC1 binding at transcribed TSSs than at silenced TSSs (Figure 1D–1F).

To investigate the possible contribution of PRC1 and other PcG complexes at repressed genes, we decided to analyse in detail the functional interplay between PcG-dependent epigenetic signatures and maintenance of replication programs at one of the major PcG targets: the Drosophila BX-C. After depletion of single PcG proteins in S2 cells, we found reactivation of BX-C genes and their related PREs (Figure S2A). Interestingly, depletion of PHO protein causes only a mild effect on homeotic genes transcription, although this protein has been reported to be required for recruitment of PRC1 and 2 [6]. This suggests that multiple additional mechanisms of recruitment, such as ncRNAs or other protein partners, may act simultaneously at PcG target loci, as described particularly in mammalian cells (for a review, see [4]). Interestingly, also 3C analysis in single PcG depleted cells reveals a different response to E(z) depletion with respect to PC and PHO depletions. In particular, in PC and PHO depleted cells we could see no change or the small reduction of some PRE-PRE and PRE-promoter BX-C interactions, while in E(z) depleted cells even an increase in specific crosslinking frequencies for some interactions was observed (Figure 2). Moreover, both 3C and replication timing analysis in single PcG depleted cells (Figure 2) show that transcription per se cannot dramatically perturb the BX-C higher-order structures neither change the timing of replication. This result is in agreement with recent findings in mammalian cells showing that spatial chromatin organization and replication timing are not a direct consequence of transcription [50].

Conversely, simultaneous depletion of components of the three major PcG complexes (PhoRC, PRC2 and PRC1) determines major changes in BX-C transcription as well as in higher-order structure and an anticipation in replication timing (Figure 3; Figure S4C–S4E), suggesting that PcG proteins act synergistically on three-dimensional structures and on replication program maintenance. In line with these findings, in recovered cells, BX-C topological structure and PRE replication timing are indistinguishable from controls (Figure 3, Figure S4), suggesting that the observed variations are not sufficient to determine a stable epigenetic switch. In this context the more stable contacts might hamper an irreversible disruption of the three-dimensional BX-C structure (Figure S4F).

Our findings were further confirmed by the comparison of two different cell lines: S2 and S3 that differ for their embryonic origin. We have previously shown that in S3 cells, active transcription of AbdB is associated with different topological conformation of the locus, where AbdB gene and its regulative PREs are topologically separated from the other repressed and clustered epigenetic elements of the locus [13]. We found that distinct chromatin structures in S2 and S3 are associated with different replication timings (Figure 4, Figure S5), thus confirming that these epigenetic parameters vary in parallel.

Our analysis, in line with recent observations [50], [63], [64] indicate that the genome may be organized into distinct structural and functional domains in which DNA regions that stay together replicate together as a stable unit for many cell generations irrespective of single gene transcription state. It was shown that major adjustments of chromatin higher-order structure and replication program are necessary for a correct differentiation and are required for reprogramming of cell identity [65], [66]. The high stability of higher-order chromatin structures and replication programs can explain one of the underlying molecular basis counteracting cellular reprogramming and representing an epigenetic barrier [20] and PcG complexes may play an important role in the maintenance of this barrier. Our data show that correct levels of PcG components can fully restore silencing, higher-order structures and late replication timing at derepressed BX-C gene loci. Of course, we do not exclude that additional functions may be involved in the maintenance of these epigenetic parameters either at the BX-C and in the rest of the genome. For example, other factors involved in the regulation of higher-order chromatin structure, including the insulator CTCF protein, condensin complex subunits and Topoisomerase II, were shown to have a role in PcG-mediated gene silencing function [61], [67]. Interestingly, Topoisomerase II has been shown to be required for a global resetting of replicon organization in the context of somatic cell reprogramming [65]. Hence, a deeper understanding of the functional interplay between epigenetic mechanisms modulating the stability of higher-order chromatin structure and replication program will be crucial to unravel the molecular basis of maintenance of cell identity and its metastability in developmental and pathogenic processes.

Materials and Methods

The following public available data sets in S2 cells were used for bioinformatic analyses (accession numbers are indicated in parenthesis). The genome-wide replication timing profile (GSM336376) was generated in [25] using Affymetrix tiling arrays. Pre-processed and normalized data were used for the analysis; E(z) (modENCODE_284), H3K27me3 (modENCODE_298) and PHO (modENCODE_3894). ChIP-chip profiles were downloaded from the modENCODE data warehouse as wiggle files containing smoothed M-values. PRC1 core components (PC, Psc and Ph) and Trx ChIP-Seq profiles as well as RNA-Seq gene expression profile were generated in [6] (GSE24521) and processed starting from fastq files.

Definition of unique TSSs

Bioinformatic and statistical analyses have been performed using R (R Development Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, 2011, Vienna, Austria), Bioconductor and custom scripts. Ensembl gene annotations were pre-processed to obtain a set of unique Transcription Start Sites (TSSs, n = 9268). A TSS was defined as unique if no other TSS within a 2 kb window centered on it was annotated. The 1 kb window centered on a given unique TSS was used to define its promoter region. The replication timing of each promoter was computed as the median replication timing of the probes in the tiling array entirely mapping within the promoter region. Promoters with less than 10 mapping probesets were discarded (n = 67) in order to increase the robustness of replication timing estimates, rendering a set of 9201 unique promoters (simply referred to as promoters in the following) further considered for the analysis. Promoters were classified in transcriptional activity classes (0–4) according to the expression level of the corresponding genes. Non-transcribed promoters were assigned to class 0, whereas transcribed promoters were classified according to expression level quartiles (classes 1–4). Transcriptional classes 0 and 1 were considered as inactive promoters (OFF) whereas classes 2–4 defined active promoters (ON).

Computing enrichments at promoters

PRC1 core components and Trx enrichments as well as RNA expression values at promoters were computed as described in [6]. H3K27me3, E(z) and PHO enrichments at promoters were estimated as the median smoothed M-value of probes entirely mapping within the promoters. Promoters significantly enriched for a given feature were defined using the following conservative approach based on the estimation of the genome-wide distribution of probe levels. First, a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) was fit to genome-wide smoothed M-values X. This is equivalent to say that the distribution of X was modelled as a mixture of two univariate Gaussian components

where is the distribution of probe values in non-enriched regions and N2 is the distribution of probe values in enriched regions. Second, the parameters vector was estimated using a Maximum Likelihood approach via Expectation Maximization. Then, Bayesian inference was used to compute posterior probabilities for each individual probe. These can be viewed as the responsibility that component k takes in explaining the probe value. Each probe was then classified according to a Maximum a Posteriori (MAP) criterion, namely it was assigned to the class that maximizes the posterior probability. Finally, a promoter was called significantly enriched for a given feature if at least 80% of the probes mapping within the promoter region were assigned to class k = 2 meaning that overall probe levels are consistently more likely to originate from an enriched region. Notice that this choice leads to a rather conservative estimate of the number of significantly enriched promoters.Bootstrap and weighted bootstrap

Given a set of promoters, the percentile confidence interval for their mean replication timing was computed using nonparametric bootstrap [68]. A resampling depth of 104 and a significance level were used for all the analyses. The same parameters were applied for the weighted bootstrap with importance weights assigned to each promoter depending on its transcriptional activity class (ON/OFF) as inversely proportional to the cardinality of the class (i.e. the number of promoters belonging to the class).

Cell cultures

Drosophila embryonic S2 cells were grown at 25°C in serum-free insect culture medium (HyQ SFX; Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin. Drosophila embryonic S3 cells were grown at 25°C in Schneider's medium (Gibco#11720-034) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin.

RNAi

Exonic fragments of 600 bp, 1400 bp, 658 bp or 810 bp, respectively, from Gfp, Pc, Pho or E(z) genes, were amplified by PCR, creating T7 polymerase binding sites for the transcription of both strands. RNAi was performed as described previously [69]. Briefly, cells were diluted at 1*106/ml and transfected with 2 micrograms of dsRNA. Three rounds of transfection were performed. Primer sequences used for PcG knock down: Gfp 5′ACGTAAACGGCCACAAGTTC3′-5′TGCTCAGGTAGTGGTTGTCG3′; Pc 5′ATTGGCAAGTTAAGCACGGGCA3′-5′ACATCCTGGATCGCCGCCTCA3′; Pho 5′ACAGTACGATGAAGATATAGGC3′-5′TGATCTGAACTGAGCTTATAGG3′; E(z) 5′TCGAAGGCATTATGAATAGCAC3′-5′ATCCGCATCTTCAGTCTCC3′.

Replication timing analysis

Exponentially growing cells (1×106 cells/ml) were cultured in presence of 50 µM Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) for 60 min. For sorting, cells were divided into aliquots containing 5×106 cells per tube, washed with cold PBS, resuspended in 0.5 ml of cold PBS, fixed with drop-by-drop addition of 5 ml of 70% cold ethanol and incubated for 1 h on ice. Cells were then washed with PBS, resuspended in PBS/RNase A (1 mg/ml) 30 min at 37°C followed by addition of Propidium Iodide (20 µg/ml) and incubated 30 min in the dark at 4°C. On the basis of DNA content, cells were sorted into different S phase fractions using four selective gates. Equal numbers of cells from each cell cycle fraction (100,000) were sorted (using a Moflo, Coulter) into microcentrifuge tubes containing lysis buffer (50 mM TrisHCl pH 8; 10 mM EDTA; 0,8% SDS; supplemented with 0.2 mg of proteinase K per ml). The samples collected by FACS were processed for replication timing analysis as previously described [70]. The preparations were analyzed by real-time PCR. The relative abundance of locus-specific DNA in each cell-cycle fraction was calculated from the average values of threshold cycle (Ct), normalized to the Ct of a unique mitochondrial sequence as internal control, using the following equation: , where i is one of the four fractions. All data points were generated from an average of six independent experiments. Primer sequences: EarlyCtrl-up 5′GGCGTGGCCTCATCGGATGG3′, EarlyCtrl-low 5′ACGAGTCCTGCCGCAAAGCC3′; LateCtrl-up 5′AAAGGCCTGGTTCGGCTGGC3′, LateCtrl-low 5′TTGCTACTTGCCGTGCGCGA3′;′ mitochondria up 5′AGCAACAGGATTCCACGGAATTC3′, mitochondria low 5′ATCATGCAGCTGCTTCAAAACCA3′; fab7-up 5′GAAAATGCCCAACAAAATGC3′, fab7-low 5′CGCTGTCTCGCCTCTTCTTC3′; mcp-up 5′TGCGGACGCCATTTGACAC3′, mcp-low 5′GAGCCACGCAGCGAGTTC3′: bxd-up 5′AGTTATCGGCACTTTGGTTCTG3′, bxd-low 5′GTAATTATCCAAACAAGCGACGG3′; bx-up 5′TTATTGTTGCTACACCGCTG3′, bx-low 5′AGTAGGTGCCGCGTATGTG3′; Ubxp-up 5′TCAGCCCTCCTCCATGATG3′, Ubxp-low 5′CCAAATCGCAGTTGCCAGTG3′; abdAp-up 5′TTGAGTCAGGGAGTGAGCC3′, abdAp-low 5′CGCTTTGAGTCGTTGGAGAC3′; AbdBpγ-up 5′TCGGAAGATTGTATTTGTGCGG3′, AbdBpγ-low 5′CAGTACGACAGTTCAGATGC3′; 5′UTRAbdBA-up 5′AGACAGCGGAGAACTCGCAC3′, 5′UTRAbdBA-low 5′TTG CCAATAGTCTG CAATTACAC3′.

Chromosome conformation capture (3C)

The 3C assay was performed as previously described [13]. The 3C preparations were analyzed by real-time PCR. Primer sequences: int2-up 5′TTATCCACGGACGGCAGTC3′, int2-low 5′TCTGTGGGATTTGTGGGATC3′; AbdBpγ-up 5′ATAGATGGGCTGAGTGAGAG3′; Fab7-up 5′CTCACTTCTCCATGGCCTG3′; mcp22b-up 5′ATAGAAGTCAACATCCAGGC3′; mcp23-up 5′GGCCTGTCGAAGGAACGC3′; abdAp-up 5′ATGGCGCCAATGTGCTCTG3′; bxd-up 5′CCTTAGCACGTTGTCAAGTG3′; bx-up 5′AGTGATAATTGGTCCGGGAG3′.

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). 1 µg of RNA from each sample was subjected to cDNA synthesis using a QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). DNA from BrdU immunoprecipitation, 3C or cDNA preparation was amplified in 20 µl reaction mixtures in the presence of 10 µl 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green master mix (Qiagen) and 0.5 µM of corresponding primers. Real-time PCR was performed using DNA Engine Opticon 2 (MJ) apparatus. Copy number was determined using the cross-point (Cp) value, which is automatically calculated using the Opticon Monitor 2 software (MJ). Primer sequences used for transcriptional analyses: RTgapdh-f 5′AAGGGAATCCTGGGCTACAC3′, RTgapdh-r 5′ACCGAACTCGTTGTCGTACC3′; RTpho-f 5′TCAGTTGGTTCACACCGGTG3′, RTpho-r 5′GAGGTATCTTCACTCTGGCTG3′; RTpc-f 5′TTCAAGACTCAAGTGCTGCC3′, RTpc-r 5′CCATGGGAAATAAGCAGGAG3′; RTez-f 5′CTGTGGCTGAGATCAACTCC3′, RTez-r 5′GACAGGTCTTGGTCAGCATG3′; RTUbx-f 5′AGTGTCAGCGGCGGCAAC3′, RTUbx-r 5′AGTCTGGTAGAAGTGAGCCCG3′; RTabdA-f 5′CAAATACAACGCAACCCGAGAC3′, RTabdA-r 5′AGCGATCGTGTTGCTGCTG3′; RTAbdBA-f 5′AATCTCCAGCAGCAGCAGC3′, RTAbdBA-r 5′ TGCCGTGTGCCGCTTGACCG3′.

Recovery

In the recovery experiment, depleted cells were diluted once a week in fresh medium without the addition of new dsRNA, for 30 days (approximately 20 cell divisions).

Protein extraction and Western blot analyses

Total proteins were prepared by resuspending 2×106 S2 cells in extraction buffer (50 mM TrisHCl pH 7.6; 0.15 M NaCl; 5 mM EDTA; 16 Protease Inhibitors; 1% Triton X-100). Three pulses of 10 sec sonication at 30% amplitude were performed to allow dissociation of protein from chromatin and solubilization. Extracts were analysed by SDS-PAGE using an 8% gel (37.5∶1 Acryl/Bis Acrylamide).

Antibodies

Antibodies against PHO and E(z) were kindly provided by J. Muller. Actin (Santa Cruz I-19 sc-1616).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HirataniI, GilbertDM (2009) Replication timing as an epigenetic mark. Epigenetics 4 : 93–97.

2. LanzuoloC, OrlandoV (2012) Memories from the Polycomb Group Proteins. Annu Rev Genet

3. MihalyJ, MishraRK, KarchF (1998) A conserved sequence motif in Polycomb-response elements. Mol Cell 1 : 1065–1066.

4. BeiselC, ParoR (2011) Silencing chromatin: comparing modes and mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet 12 : 123–135.

5. EnderleD, BeiselC, StadlerMB, GerstungM, AthriP, et al. (2011) Polycomb preferentially targets stalled promoters of coding and noncoding transcripts. Genome Res 21 : 216–226.

6. WangL, BrownJL, CaoR, ZhangY, KassisJA, et al. (2004) Hierarchical recruitment of polycomb group silencing complexes. Mol Cell 14 : 637–646.

7. CzerminB, MelfiR, McCabeD, SeitzV, ImhofA, et al. (2002) Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell 111 : 185–196.

8. KuzmichevA, NishiokaK, Erdjument-BromageH, TempstP, ReinbergD (2002) Histone methyltransferase activity associated with a human multiprotein complex containing the Enhancer of Zeste protein. Genes Dev 16 : 2893–2905.

9. MullerJ, HartCM, FrancisNJ, VargasML, SenguptaA, et al. (2002) Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111 : 197–208.

10. CaoR, WangL, WangH, XiaL, Erdjument-BromageH, et al. (2002) Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298 : 1039–1043.

11. BantigniesF, RoureV, CometI, LeblancB, SchuettengruberB, et al. (2011) Polycomb-dependent regulatory contacts between distant Hox loci in Drosophila. Cell 144 : 214–226.

12. CometI, SchuettengruberB, SextonT, CavalliG (2011) A chromatin insulator driving three-dimensional Polycomb response element (PRE) contacts and Polycomb association with the chromatin fiber. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 2294–2299.

13. LanzuoloC, RoureV, DekkerJ, BantigniesF, OrlandoV (2007) Polycomb response elements mediate the formation of chromosome higher-order structures in the bithorax complex. Nat Cell Biol 9 : 1167–1174.

14. BerezneyR, DubeyDD, HubermanJA (2000) Heterogeneity of eukaryotic replicons, replicon clusters, and replication foci. Chromosoma 108 : 471–484.

15. EaswaranHP, LeonhardtH, CardosoMC (2007) Distribution of DNA replication proteins in Drosophila cells. BMC Cell Biol 8 : 42.

16. KitamuraE, BlowJJ, TanakaTU (2006) Live-cell imaging reveals replication of individual replicons in eukaryotic replication factories. Cell 125 : 1297–1308.

17. HansenRS, ThomasS, SandstromR, CanfieldTK, ThurmanRE, et al. (2010) Sequencing newly replicated DNA reveals widespread plasticity in human replication timing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 139–144.

18. SchwaigerM, StadlerMB, BellO, KohlerH, OakeleyEJ, et al. (2009) Chromatin state marks cell-type - and gender-specific replication of the Drosophila genome. Genes Dev 23 : 589–601.

19. ZhouJ, ErmakovaOV, RibletR, BirshteinBK, SchildkrautCL (2002) Replication and subnuclear location dynamics of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus in B-lineage cells. Mol Cell Biol 22 : 4876–4889.

20. HirataniI, RybaT, ItohM, RathjenJ, KulikM, et al. (2010) Genome-wide dynamics of replication timing revealed by in vitro models of mouse embryogenesis. Genome Res 20 : 155–169.

21. PerryP, SauerS, BillonN, RichardsonWD, SpivakovM, et al. (2004) A dynamic switch in the replication timing of key regulator genes in embryonic stem cells upon neural induction. Cell Cycle 3 : 1645–1650.

22. SimonI, TenzenT, MostoslavskyR, FibachE, LandeL, et al. (2001) Developmental regulation of DNA replication timing at the human beta globin locus. EMBO J 20 : 6150–6157.

23. BellO, SchwaigerM, OakeleyEJ, LienertF, BeiselC, et al. (2010) Accessibility of the Drosophila genome discriminates PcG repression, H4K16 acetylation and replication timing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17 : 894–900.

24. Casas-DelucchiCS, van BemmelJG, HaaseS, HerceHD, NowakD, et al. (2011) Histone hypoacetylation is required to maintain late replication timing of constitutive heterochromatin. Nucleic Acids Res

25. JorgensenHF, AzuaraV, AmoilsS, SpivakovM, TerryA, et al. (2007) The impact of chromatin modifiers on the timing of locus replication in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genome Biol 8: R169.

26. YinS, DengW, HuL, KongX (2009) The impact of nucleosome positioning on the organization of replication origins in eukaryotes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 385 : 363–368.

27. Lande-DinerL, ZhangJM, CedarH (2009) Shifts in Replication Timing Actively Affect Histone Acetylation during Nucleosome Reassembly. Molecular Cell 34 : 767–774.

28. LanzuoloC, Lo SardoF, DiamantiniA, OrlandoV (2011) PcG complexes set the stage for epigenetic inheritance of gene silencing in early S phase before replication. PLoS Genet 7: e1002370 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002370

29. KarnaniN, TaylorC, MalhotraA, DuttaA (2007) Pan-S replication patterns and chromosomal domains defined by genome-tiling arrays of ENCODE genomic areas. Genome Res 17 : 865–876.

30. KlochkovDB, GavrilovAA, VassetzkyYS, RazinSV (2009) Early replication timing of the chicken alpha-globin gene domain correlates with its open chromatin state in cells of different lineages. Genomics 93 : 481–486.

31. LanzuoloC, Lo SardoF, OrlandoV (2012) Concerted epigenetic signatures inheritance at PcG targets through replication. Cell Cycle 11.

32. MacAlpineDM, RodriguezHK, BellSP (2004) Coordination of replication and transcription along a Drosophila chromosome. Genes Dev 18 : 3094–3105.

33. SchubelerD, ScalzoD, KooperbergC, van SteenselB, DelrowJ, et al. (2002) Genome-wide DNA replication profile for Drosophila melanogaster: a link between transcription and replication timing. Nat Genet 32 : 438–442.

34. EatonML, PrinzJA, MacAlpineHK, TretyakovG, KharchenkoPV, et al. (2011) Chromatin signatures of the Drosophila replication program. Genome Res 21 : 164–174.

35. AspP, BlumR, VethanthamV, ParisiF, MicsinaiM, et al. (2011) Genome-wide remodeling of the epigenetic landscape during myogenic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: E149–158.

36. KuM, KocheRP, RheinbayE, MendenhallEM, EndohM, et al. (2008) Genomewide analysis of PRC1 and PRC2 occupancy identifies two classes of bivalent domains. PLoS Genet 4: e1000242 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000242

37. SchwartzYB, KahnTG, NixDA, LiXY, BourgonR, et al. (2006) Genome-wide analysis of Polycomb targets in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet 38 : 700–705.

38. BeiselC, BunessA, Roustan-EspinosaIM, KochB, SchmittS, et al. (2007) Comparing active and repressed expression states of genes controlled by the Polycomb/Trithorax group proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 16615–16620.

39. BrookesE, de SantiagoI, HebenstreitD, MorrisKJ, CarrollT, et al. (2012) Polycomb Associates Genome-wide with a Specific RNA Polymerase II Variant, and Regulates Metabolic Genes in ESCs. Cell Stem Cell 10 : 157–170.

40. PappB, MullerJ (2006) Histone trimethylation and the maintenance of transcriptional ON and OFF states by trxG and PcG proteins. Genes Dev 20 : 2041–2054.

41. Kheradmand KiaS, Solaimani KartalaeiP, FarahbakhshianE, PourfarzadF, von LindernM, et al. (2009) EZH2-dependent chromatin looping controls INK4a and INK4b, but not ARF, during human progenitor cell differentiation and cellular senescence. Epigenetics & Chromatin 2.

42. TiwariVK, McGarveyKM, LicchesiJD, OhmJE, HermanJG, et al. (2008) PcG proteins, DNA methylation, and gene repression by chromatin looping. PLoS Biol 6: e306 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060306

43. BeuchleD, StruhlG, MullerJ (2001) Polycomb group proteins and heritable silencing of Drosophila Hox genes. Development 128 : 993–1004.

44. BreilingA, O'NeillLP, D'EliseoD, TurnerBM, OrlandoV (2004) Epigenome changes in active and inactive polycomb-group-controlled regions. EMBO Rep 5 : 976–982.

45. HirataniI, TakebayashiS, LuJ, GilbertDM (2009) Replication timing and transcriptional control: beyond cause and effect–part II. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19 : 142–149.

46. SchwaigerM, SchubelerD (2006) A question of timing: emerging links between transcription and replication. Curr Opin Genet Dev 16 : 177–183.

47. HirataniI, RybaT, ItohM, YokochiT, SchwaigerM, et al. (2008) Global reorganization of replication domains during embryonic stem cell differentiation. PLoS Biol 6: e245 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060245

48. KimSM, DubeyDD, HubermanJA (2003) Early-replicating heterochromatin. Genes Dev 17 : 330–335.

49. SantosJ, PereiraCF, Di-GregorioA, SpruceT, AlderO, et al. (2010) Differences in the epigenetic and reprogramming properties of pluripotent and extra-embryonic stem cells implicate chromatin remodelling as an important early event in the developing mouse embryo. Epigenetics Chromatin 3 : 1.

50. TakebayashiS, DileepV, RybaT, DennisJH, GilbertDM (2012) Chromatin-interaction compartment switch at developmentally regulated chromosomal domains reveals an unusual principle of chromatin folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 12574–12579.

51. CornacchiaD, DileepV, QuivyJP, FotiR, TiliF, et al. (2012) Mouse Rif1 is a key regulator of the replication-timing programme in mammalian cells. EMBO J 31 : 3678–3690.

52. Hassan-ZadehV, ChilakaS, CadoretJC, MaMK, BoggettoN, et al. (2012) USF binding sequences from the HS4 insulator element impose early replication timing on a vertebrate replicator. PLoS Biol 10: e1001277 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001277

53. LiJ, SantoroR, KobernaK, GrummtI (2005) The chromatin remodeling complex NoRC controls replication timing of rRNA genes. EMBO J 24 : 120–127.

54. SchwaigerM, KohlerH, OakeleyEJ, StadlerMB, SchubelerD (2010) Heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) modulates replication timing of the Drosophila genome. Genome Res 20 : 771–780.

55. TazumiA, FukuuraM, NakatoR, KishimotoA, TakenakaT, et al. (2012) Telomere-binding protein Taz1 controls global replication timing through its localization near late replication origins in fission yeast. Genes Dev 26 : 2050–2062.

56. YamazakiS, IshiiA, KanohY, OdaM, NishitoY, et al. (2012) Rif1 regulates the replication timing domains on the human genome. EMBO J 31 : 3667–3677.

57. RybaT, HirataniI, LuJ, ItohM, KulikM, et al. (2010) Evolutionarily conserved replication timing profiles predict long-range chromatin interactions and distinguish closely related cell types. Genome Res 20 : 761–770.

58. YaffeE, Farkash-AmarS, PoltenA, YakhiniZ, TanayA, et al. (2010) Comparative analysis of DNA replication timing reveals conserved large-scale chromosomal architecture. PLoS Genet 6: e1001011 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001011

59. GuillouE, IbarraA, CoulonV, Casado-VelaJ, RicoD, et al. (2010) Cohesin organizes chromatin loops at DNA replication factories. Genes Dev 24 : 2812–2822.

60. MacAlpineHK, GordanR, PowellSK, HarteminkAJ, MacAlpineDM (2010) Drosophila ORC localizes to open chromatin and marks sites of cohesin complex loading. Genome Res 20 : 201–211.

61. LupoR, BreilingA, BianchiME, OrlandoV (2001) Drosophila chromosome condensation proteins Topoisomerase II and Barren colocalize with Polycomb and maintain Fab-7 PRE silencing. Mol Cell 7 : 127–136.

62. AgherbiH, Gaussmann-WengerA, VerthuyC, ChassonL, SerranoM, et al. (2009) Polycomb mediated epigenetic silencing and replication timing at the INK4a/ARF locus during senescence. PLoS ONE 4: e5622 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005622

63. SextonT, YaffeE, KenigsbergE, BantigniesF, LeblancB, et al. (2012) Three-dimensional folding and functional organization principles of the Drosophila genome. Cell 148 : 458–472.

64. SextonT, YaffeE, KenigsbergE, BantigniesF, LeblancB, et al. (2012) Three-Dimensional Folding and Functional Organization Principles of the Drosophila Genome. Cell

65. LemaitreJM, DanisE, PaseroP, VassetzkyY, MechaliM (2005) Mitotic remodeling of the replicon and chromosome structure. Cell 123 : 787–801.

66. ShufaroY, Lacham-KaplanO, TzuberiBZ, McLaughlinJ, TrounsonA, et al. (2010) Reprogramming of DNA Replication Timing. Stem Cells 28 : 443–449.

67. HolohanEE, KwongC, AdryanB, BartkuhnM, HeroldM, et al. (2007) CTCF genomic binding sites in Drosophila and the organisation of the bithorax complex. PLoS Genet 3: e112 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030112

68. EfronBTR (1986) Bootsrtrap Methods for Standard Errors, Confdence Intervals, and Other Measures of Statistical Accuracy. Statistical Science 1 : 54–75.

69. BreilingA, TurnerBM, BianchiME, OrlandoV (2001) General transcription factors bind promoters repressed by Polycomb group proteins. Nature 412 : 651–655.

70. AzuaraV (2006) Profiling of DNA replication timing in unsynchronized cell populations. Nat Protoc 1 : 2171–2177.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek MSH3 Polymorphisms and Protein Levels Affect CAG Repeat Instability in Huntington's Disease MiceČlánek Yemanuclein and HIRA Cooperate for Assembly of H3.3-Containing Nucleosomes in the Male Pronucleus

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 2

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Complex Inheritance of Melanoma and Pigmentation of Coat and Skin in Grey Horses

- A Meta-Analysis of Thyroid-Related Traits Reveals Novel Loci and Gender-Specific Differences in the Regulation of Thyroid Function

- Genetic Landscape of Open Chromatin in Yeast

- Deleterious Alleles in the Human Genome Are on Average Younger Than Neutral Alleles of the Same Frequency

- Age-Dependent Transition from Cell-Level to Population-Level Control in Murine Intestinal Homeostasis Revealed by Coalescence Analysis

- Next-Generation Sequencing Identifies the Danforth's Short Tail Mouse Mutation as a Retrotransposon Insertion Affecting Expression

- ImmunoChip Study Implicates Antigen Presentation to T Cells in Narcolepsy

- Massive Mitochondrial Gene Transfer in a Parasitic Flowering Plant Clade

- Comment on “Genomic Hypomethylation in the Human Germline Associates with Selective Structural Mutability in the Human Genome”

- The Prefoldin Bud27 Mediates the Assembly of the Eukaryotic RNA Polymerases in an Rpb5-Dependent Manner

- Genetic Determinants of Trabecular and Cortical Volumetric Bone Mineral Densities and Bone Microstructure

- Encodes a Novel and -Genus-Specific Regulator of Photoperiodic Flowering in Rice

- Only One Isoform of CTP Synthase Forms the Cytoophidium

- Mechanisms Involved in the Functional Divergence of Duplicated GroEL Chaperonins in DK1622

- A Genome-Wide RNAi Screen in Identifies the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit ACR-7 as an Antipsychotic Drug Target

- Autophagy Induction Is a Tor- and Tp53-Independent Cell Survival Response in a Zebrafish Model of Disrupted Ribosome Biogenesis

- Ancient DNA Reveals Prehistoric Gene-Flow from Siberia in the Complex Human Population History of North East Europe

- Inflammation-Mediated Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations Drive Cancer Development in the Neighboring Epithelium upon Stromal Abrogation of TGF-β Signaling

- MicroRNA-3148 Modulates Allelic Expression of Toll-Like Receptor 7 Variant Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- RNAi–Based Functional Profiling of Loci from Blood Lipid Genome-Wide Association Studies Identifies Genes with Cholesterol-Regulatory Function

- CELF Family RNA–Binding Protein UNC-75 Regulates Two Sets of Mutually Exclusive Exons of the Gene in Neuron-Specific Manners in

- Coordination of Chromatid Separation and Spindle Elongation by Antagonistic Activities of Mitotic and S-Phase CDKs

- The Ubiquitin Ligase Subunit Acts in Target Tissue to Restrict Tracheal Terminal Cell Branching and Hypoxic-Induced Gene Expression

- Mitotic Evolution of Shows a Stable Core Genome but Recombination in Antigen Families

- Tysnd1 Deficiency in Mice Interferes with the Peroxisomal Localization of PTS2 Enzymes, Causing Lipid Metabolic Abnormalities and Male Infertility

- A Regulatory Pathway, Ecdysone-Transcription Factor Relish-Cathepsin L, Is Involved in Insect Fat Body Dissociation

- PcG-Mediated Higher-Order Chromatin Structures Modulate Replication Programs at the BX-C

- MSH3 Polymorphisms and Protein Levels Affect CAG Repeat Instability in Huntington's Disease Mice

- JNK-Interacting Protein 3 Mediates the Retrograde Transport of Activated c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase and Lysosomes

- Discovery of a Splicing Regulator Required for Cell Cycle Progression

- Rearrangements of 2.5 Kilobases of Noncoding DNA from the Locus Define Predictive Rules of Genomic -Regulatory Logic

- Admixture Mapping in Lupus Identifies Multiple Functional Variants within IFIH1 Associated with Apoptosis, Inflammation, and Autoantibody Production

- Roles of the Developmental Regulator Homothorax in Limiting Longevity in

- miR-199a-5p Is Upregulated during Fibrogenic Response to Tissue Injury and Mediates TGFbeta-Induced Lung Fibroblast Activation by Targeting Caveolin-1

- A Kinome-Wide RNAi Screen in Glia Reveals That the RIO Kinases Mediate Cell Proliferation and Survival through TORC2-Akt Signaling in Glioblastoma

- Assembly of the Auditory Circuitry by a Genetic Network in the Mouse Brainstem

- SOX2 Co-Occupies Distal Enhancer Elements with Distinct POU Factors in ESCs and NPCs to Specify Cell State

- Retrotransposon Activates Ectopic Expression: A Short Tail

- Confounding by Repetitive Elements and CpG Islands Does Not Explain the Association between Hypomethylation and Genomic Instability

- Cell Reprogramming Requires Silencing of a Core Subset of Polycomb Targets

- Properties and Modeling of GWAS when Complex Disease Risk Is Due to Non-Complementing, Deleterious Mutations in Genes of Large Effect

- Essential Developmental, Genomic Stability, and Tumour Suppressor Functions of the Mouse Orthologue of

- Conditional Inactivation of the DNA Damage Response Gene in Mouse Testis Reveals Separable Roles for Components of the RAD9-RAD1-HUS1 Complex in Meiotic Chromosome Maintenance

- Genome-Wide Analysis Points to Roles for Extracellular Matrix Remodeling, the Visual Cycle, and Neuronal Development in Myopia

- Patterning of Leaf Vein Networks by Convergent Auxin Transport Pathways

- An Evolutionary Perspective on Epistasis and the Missing Heritability

- A Retrotransposon Insertion in the 5′ Regulatory Domain of Ptf1a Results in Ectopic Gene Expression and Multiple Congenital Defects in Danforth's Short Tail Mouse

- The Mub1/Ubr2 Ubiquitin Ligase Complex Regulates the Conserved Dsn1 Kinetochore Protein

- Mutations Can Cause Enamel-Renal Syndrome (ERS)

- Yemanuclein and HIRA Cooperate for Assembly of H3.3-Containing Nucleosomes in the Male Pronucleus

- Hepatocyte Growth Factor, a Determinant of Airspace Homeostasis in the Murine Lung

- ISWI and CHD Chromatin Remodelers Bind Promoters but Act in Gene Bodies

- COM-1 Promotes Homologous Recombination during Meiosis by Antagonizing Ku-Mediated Non-Homologous End Joining

- Control of Multicellular Development by the Physically Interacting Deneddylases DEN1/DenA and COP9 Signalosome

- Antagonism Versus Cooperativity with TALE Cofactors at the Base of the Functional Diversification of Hox Protein Function

- Dynamic Association of NUP98 with the Human Genome

- Ectopic Expression of Induces Spinal Defects, Urogenital Defects, and Anorectal Malformations in Mice

- Regulation of Contributes to the Lineage Potential of Neurogenin3+ Endocrine Precursor Cells in the Pancreas

- Gene-Based Testing of Interactions in Association Studies of Quantitative Traits

- The Amidation Step of Diphthamide Biosynthesis in Yeast Requires , a Gene Identified through Mining the - Interaction Network

- Plant-Symbiotic Fungi as Chemical Engineers: Multi-Genome Analysis of the Clavicipitaceae Reveals Dynamics of Alkaloid Loci

- Genome-Wide Diversity in the Levant Reveals Recent Structuring by Culture

- DNA Methylation Mediated Control of Gene Expression Is Critical for Development of Crown Gall Tumors

- Identification of the SlmA Active Site Responsible for Blocking Bacterial Cytokinetic Ring Assembly over the Chromosome

- Expression of a Novel P22 ORFan Gene Reveals the Phage Carrier State in Typhimurium

- Altered Cohesin Gene Dosage Affects Mammalian Meiotic Chromosome Structure and Behavior

- Quantitative Analysis of Histone Modifications: Formaldehyde Is a Source of Pathological N-Formyllysine That Is Refractory to Histone Deacetylases

- Duplicate Abalone Egg Coat Proteins Bind Sperm Lysin Similarly, but Evolve Oppositely, Consistent with Molecular Mimicry at Fertilization

- Lessons from on the Strengths and Weaknesses of Structured Association Mapping

- DNA–Methylome Analysis of Mouse Intestinal Adenoma Identifies a Tumour-Specific Signature That Is Partly Conserved in Human Colon Cancer

- Transposon Variants and Their Effects on Gene Expression in

- Polygenic Modeling with Bayesian Sparse Linear Mixed Models

- Single Transmembrane Peptide DinQ Modulates Membrane-Dependent Activities

- The JNK Signaling Pathway Activates Expression of Stress Response Genes by Derepressing the Fos/HDAC Repressor Complex

- The Interaction of CtIP and Nbs1 Connects CDK and ATM to Regulate HR–Mediated Double-Strand Break Repair

- Regulation of Metamorphosis by Xenobiotic Response Regulators

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Complex Inheritance of Melanoma and Pigmentation of Coat and Skin in Grey Horses

- Coordination of Chromatid Separation and Spindle Elongation by Antagonistic Activities of Mitotic and S-Phase CDKs

- Autophagy Induction Is a Tor- and Tp53-Independent Cell Survival Response in a Zebrafish Model of Disrupted Ribosome Biogenesis

- Assembly of the Auditory Circuitry by a Genetic Network in the Mouse Brainstem

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání