-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Nonsense Mutation in Encoding a Nondescript Transmembrane Protein Causes Idiopathic Male Subfertility in Cattle

Genetic variants underlying reduced male reproductive performance have been identified in humans and model organisms, most of them compromising semen quality. Occasionally, male fertility is severely compromised although semen analysis remains without any apparent pathological findings (i.e., idiopathic subfertility). Artificial insemination (AI) in most cattle populations requires close examination of all ejaculates before insemination. Although anomalous ejaculates are rejected, insemination success varies considerably among AI bulls. In an attempt to identify genetic causes of such variation, we undertook a genome-wide association study (GWAS). Imputed genotypes of 652,856 SNPs were available for 7962 AI bulls of the Fleckvieh (FV) population. Male reproductive ability (MRA) was assessed based on 15.3 million artificial inseminations. The GWAS uncovered a strong association signal on bovine chromosome 19 (P = 4.08×10−59). Subsequent autozygosity mapping revealed a common 1386 kb segment of extended homozygosity in 40 bulls with exceptionally poor reproductive performance. Only 1.7% of 35,671 inseminations with semen samples of those bulls were successful. None of the bulls with normal reproductive performance was homozygous, indicating recessive inheritance. Exploiting whole-genome re-sequencing data of 43 animals revealed a candidate causal nonsense mutation (rs378652941, c.483C>A, p.Cys161X) in the transmembrane protein 95 encoding gene TMEM95 which was subsequently validated in 1990 AI bulls. Immunohistochemical investigations evidenced that TMEM95 is located at the surface of spermatozoa of fertile animals whereas it is absent in spermatozoa of subfertile animals. These findings imply that integrity of TMEM95 is required for an undisturbed fertilisation. Our results demonstrate that deficiency of TMEM95 severely compromises male reproductive performance in cattle and reveal for the first time a phenotypic effect associated with genomic variation in TMEM95.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004044

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004044Summary

Genetic variants underlying reduced male reproductive performance have been identified in humans and model organisms, most of them compromising semen quality. Occasionally, male fertility is severely compromised although semen analysis remains without any apparent pathological findings (i.e., idiopathic subfertility). Artificial insemination (AI) in most cattle populations requires close examination of all ejaculates before insemination. Although anomalous ejaculates are rejected, insemination success varies considerably among AI bulls. In an attempt to identify genetic causes of such variation, we undertook a genome-wide association study (GWAS). Imputed genotypes of 652,856 SNPs were available for 7962 AI bulls of the Fleckvieh (FV) population. Male reproductive ability (MRA) was assessed based on 15.3 million artificial inseminations. The GWAS uncovered a strong association signal on bovine chromosome 19 (P = 4.08×10−59). Subsequent autozygosity mapping revealed a common 1386 kb segment of extended homozygosity in 40 bulls with exceptionally poor reproductive performance. Only 1.7% of 35,671 inseminations with semen samples of those bulls were successful. None of the bulls with normal reproductive performance was homozygous, indicating recessive inheritance. Exploiting whole-genome re-sequencing data of 43 animals revealed a candidate causal nonsense mutation (rs378652941, c.483C>A, p.Cys161X) in the transmembrane protein 95 encoding gene TMEM95 which was subsequently validated in 1990 AI bulls. Immunohistochemical investigations evidenced that TMEM95 is located at the surface of spermatozoa of fertile animals whereas it is absent in spermatozoa of subfertile animals. These findings imply that integrity of TMEM95 is required for an undisturbed fertilisation. Our results demonstrate that deficiency of TMEM95 severely compromises male reproductive performance in cattle and reveal for the first time a phenotypic effect associated with genomic variation in TMEM95.

Introduction

Impaired reproductive performance is a prevalent condition in both sexes of many species and up to 15% of couples are affected in humans [1], [2]. The disability to reproduce is defined as infertility (i.e., sterility), whereas subfertility refers to any form of reduced fertility [3].

Low sperm concentration (i.e., oligospermia) and the absence of spermatozoa (i.e., azoospermia), respectively, are frequently diagnosed in males with impaired fertility [4]. Further aberrant semen quality traits (e.g., abnormal sperm morphology [5], reduced motility [6], [7]) account for another substantial fraction of reduced male fertility. However, semen analysis of a considerable number of males with impaired reproductive performance remains without any apparent pathological findings (i.e., unexplained/idiopathic infertility) [8], [9].

Semen quality traits have low to medium heritability in cattle populations [10]. Numerous genetic variants underlying routinely assessed semen quality traits have been identified so far in humans [11], [12], model species [13] and livestock populations [14]. However, the number of known genetic mechanisms causing idiopathic male subfertility is very small [15], [16] and identified polymorphisms explain only a small fraction of its genetic variation [17].

Artificial insemination (AI) is predominant over natural service in most cattle populations and all ejaculates are closely examined immediately after semen collection. Only semen samples without any apparent abnormalities, such as low sperm count, reduced progressive motility, low viability, abnormal morphology of spermatozoa, are used for insemination. However, the reproductive performance indicated by the proportion of successful inseminations varies considerably among AI sires [18], [19]. So far, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for male reproductive traits were of limited success in cattle populations [20], [21] and only one putatively causative mutation has been identified [22].

Here we report a new recessively inherited variant of idiopathic male subfertility in the Fleckvieh (FV) cattle population. The mapping of the underlying genomic region was facilitated by using high-density genotypes in a large sample of artificial insemination bulls with phenotypes for reproductive performance assessed based on 15 million artificial inseminations. Exploiting whole-genome re-sequencing data revealed a causative loss-of-function mutation in the transmembrane protein 95 encoding gene TMEM95.

Results

Male subfertility in the Fleckvieh cattle population

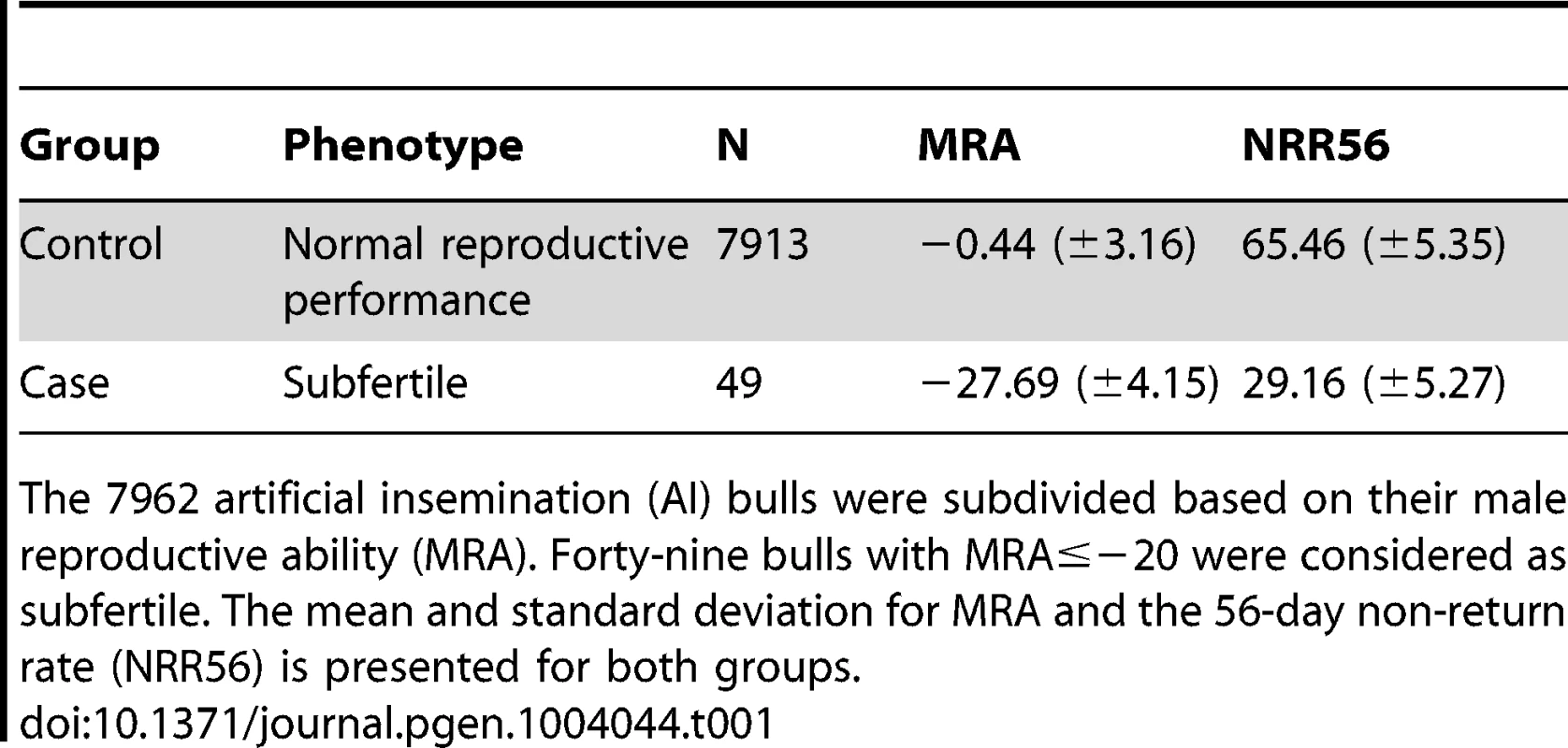

Phenotypes for male reproductive ability (MRA) were obtained for 7962 bulls of the FV population based on 15.3 Mio artificial inseminations (AI). The values for MRA range from −40 to +13 and reflect the bulls' reproductive performance as percentage deviation from the population mean. Male reproductive ability is highly correlated (r = 0.59) with the 56-day non-return rate (NRR56) in cows. The NRR56 is the proportion of cows that are not re-inseminated within a 56-day interval after the first insemination. After visual inspection of the distribution of MRA, forty-nine bulls with exceptionally poor reproductive performance (MRA<−20) were considered as subfertile (Figure S1 and Table 1). Animals with values for MRA below −20 ( = five standard deviations below the population mean) were used as case group in a case-control design.

Tab. 1. Characteristics of the case/control design.

The 7962 artificial insemination (AI) bulls were subdivided based on their male reproductive ability (MRA). Forty-nine bulls with MRA≤−20 were considered as subfertile. The mean and standard deviation for MRA and the 56-day non-return rate (NRR56) is presented for both groups. Bovine male subfertility maps to chromosome 19

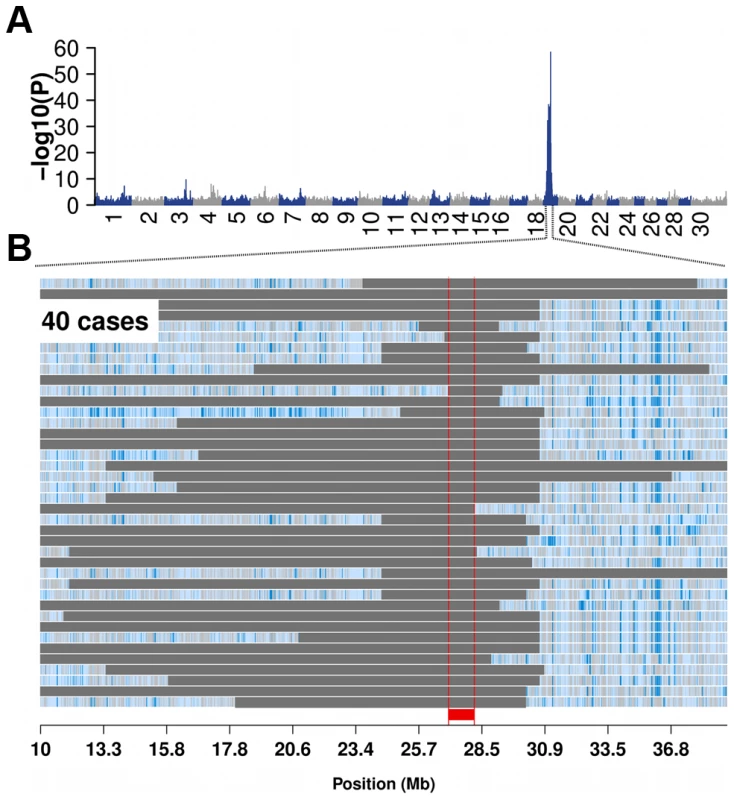

Using MRA as quantitative trait in a genome-wide association study (GWAS) yielded a strong association signal on bovine chromosome (BTA) 19 (P = 4.38×10−20, Figure S2). However, the association signal was more pronounced using 49 subfertile animals (MRA<−20) as case group and the remaining 7913 animals as controls (Table 1 and Figure 1A). The most significantly associated SNP is located at 30,220,186 bp (ARS-BFGL-NGS-11488; P = 4.08×10−59).

Fig. 1. Bovine male subfertility maps to chromosome 19 in the Fleckvieh cattle population.

Association of 652,856 SNPs with male reproductive ability (MRA) in 7962 FV bulls (A). P-values were obtained by fitting a linear mixed model. Autozygosity mapping in 40 subfertile bulls (B). Blue and pale blue represent homozygous genotypes (AA and BB), heterozygous genotypes (AB) are displayed in light grey. The solid grey bars represent segments of extended homozygosity in 40 subfertile bulls. The red bar indicates the common segment of homozygosity. The shared segment of homozygosity encompasses 80 transcripts, among them TMEM95. The full list of genes within the 1386 kb segment is presented in Table S1. Autozygosity mapping revealed a common 1386 kb segment (26,580,096 bp–27,956,634 bp) of extended homozygosity in 40 subfertile bulls containing 80 genes (Figure 1B and Table S1). None of 7913 bulls with normal reproductive performance was homozygous for the 1386 kb segment, indicating recessive inheritance. Semen samples of 40 homozygous bulls had been used for 35,671 artificial inseminations with an average of 892 inseminations per bull. This is a typical number for test inseminations performed with semen samples of young bulls in progeny testing based breeding programmes. However, only 619 (1.74%) of those inseminations were successful (Table S2).

There was no evidence for the presence of large structural variants (i.e., copy number variations) within the segment of extended homozygosity (Figure S3). The proportion of missing genotypes did not significantly differ between cases and controls (P>0.09) for all SNPs located within the associated region.

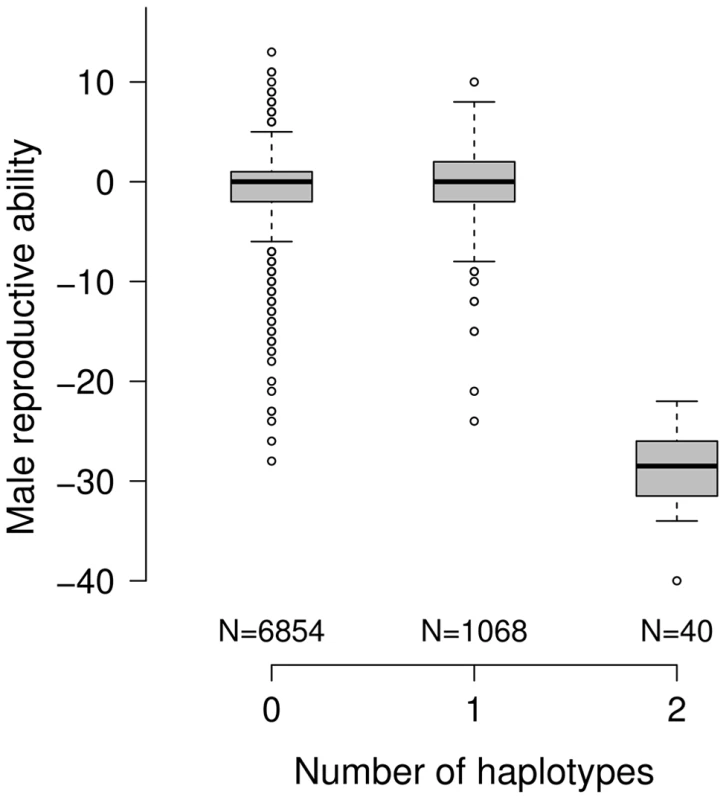

The frequency of the subfertility-associated haplotype amounts to 7.2%. Of 7962 genotyped bulls with phenotypes for MRA, 1068 (13.41%) carry the deleterious haplotype in heterozygous state. The carrier frequency increased considerably within the last years (P = 0.0002, Figure S4). The reproductive performance of heterozygous bulls is normal, indicating recessive inheritance (Figure 2). Of 1952 primiparous cows, 291 are heterozygous and 17 are homozygous for the subfertility-associated haplotype. The haplotype neither affects reproductive performance nor milk production traits in females (Table S3). The haplotype distribution does not deviate from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, neither in females (P = 0.303) nor in males (P = 0.817).

Fig. 2. Effect of the subfertility-associated haplotype on male reproductive ability.

The boxplots display the male reproductive ability (MRA) of 7962 artificial insemination bulls as a function of copies of the subfertility-associated haplotype. The reproductive performance of heterozygous bulls (N = 1068) is normal, whereas MRA is <−20 for homozygous bulls (N = 40). Both, haplotype and pedigree analysis allowed to trace the mutation back to the bull HAXL (*1966) (Figure S5). HAXL appears in the pedigrees of 7779 out of 7962 bulls (97.70%) and can be considered as the most important ancestor of the current FV population [23].

Exploiting whole-genome re-sequencing data for mutation detection

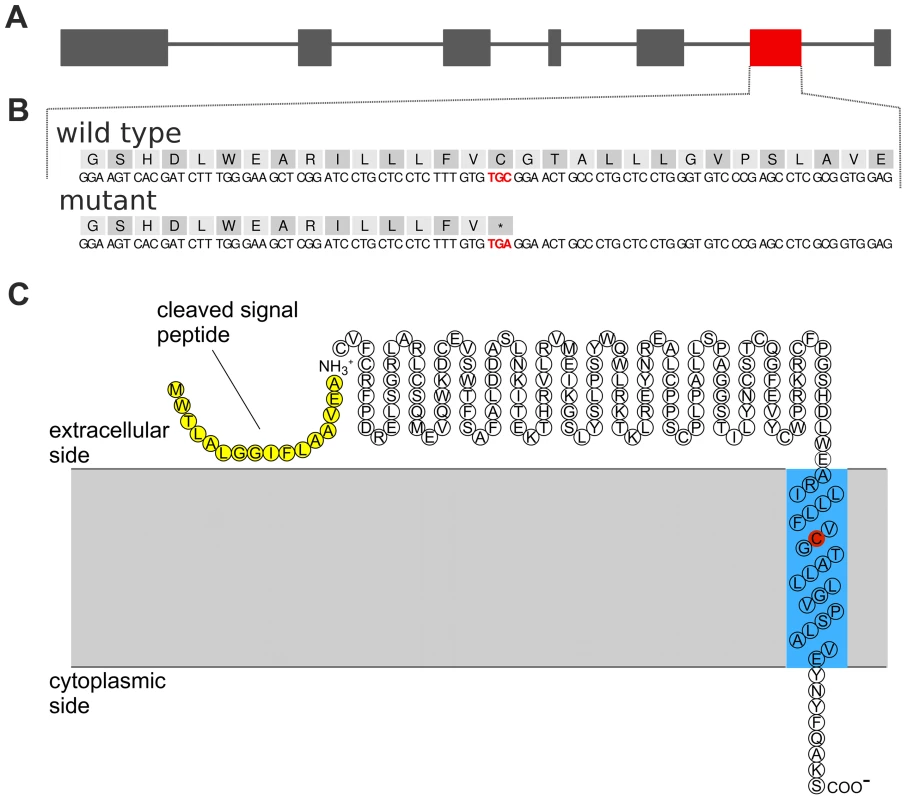

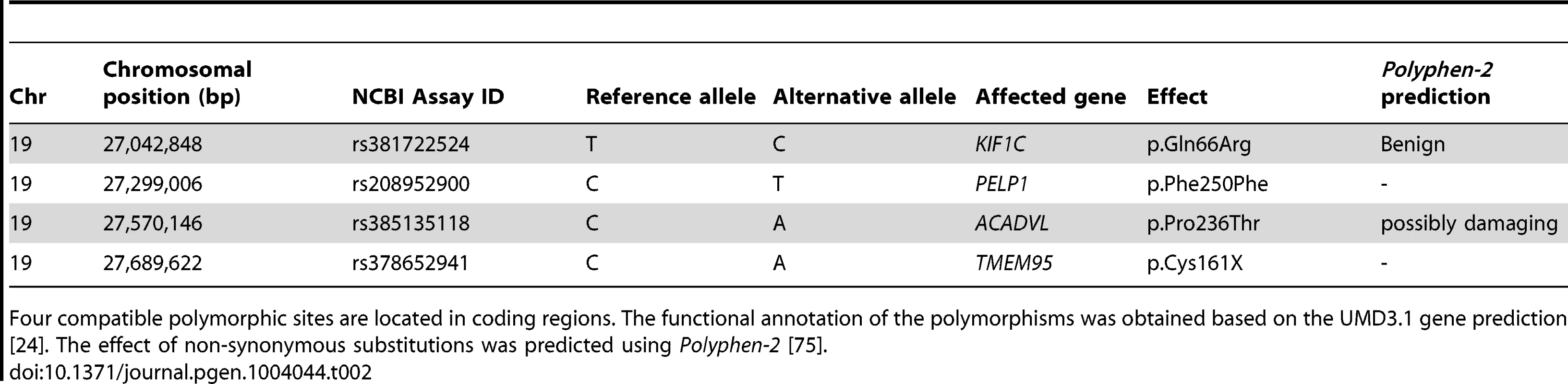

Whole genome re-sequencing of 43 animals and subsequent multi-sample variant calling yielded genotypes at 17.17 million sites [23]. Among them, 5965 (5287 SNPs and 678 INDELs) are located within the subfertility-associated region on BTA19 (26,580,096 bp to 27,956,634 bp). Six of the 43 re-sequenced animals were identified as carriers of the associated haplotype via high-density genotypes. The sequence data were filtered for variants compatible with the supposed recessive inheritance, i.e., heterozygous in carriers and homozygous for the reference allele in non-carriers (see Material & Methods, Figure S6). After filtering, 26 SNPs and six INDELs were retained as candidate causal mutations (Table S4 and S5). The functional effects of those variants were predicted based on the gene annotation of the UMD3.1 assembly of the bovine genome [24]. Four of the 32 compatible variants were located in coding regions (Table 2). Among them, we considered a nonsense mutation in TMEM95 (rs378652941, c.483C>A, p.Cys161X, Chr19 : 27,689,622 bp) as the prime candidate causal mutation (Figure 3A and 3B). The nonsense mutation was subsequently confirmed in the re-sequenced animals by classical Sanger sequencing (Figure S7 and S8).

Fig. 3. A nonsense mutation in TMEM95 resides within the predicted transmembrane domain of the encoded transmembrane protein 95.

Genomic structure of the transmembrane protein 95 encoding gene TMEM95 (A). Grey and red boxes represent exons. The red box represents exon 6 including rs378652941, introducing a premature stop codon. Genomic and protein sequence of exon 6 of TMEM95 (B). The affected codon (p.Cys161X, TGC→TGA) is highlighted with red colour. Predicted protein topology of TMEM95 (C). TMEM95 is a single-pass type I transmembrane protein with a predicted N-terminal signal peptide sequence (yellow) and a 23-amino acid transmembrane domain (blue). The affected codon (p.Cys161X) resides within the predicted transmembrane domain (red). Tab. 2. Coding variants compatible with recessive inheritance.

Four compatible polymorphic sites are located in coding regions. The functional annotation of the polymorphisms was obtained based on the UMD3.1 gene prediction [24]. The effect of non-synonymous substitutions was predicted using Polyphen-2 [75]. A loss-of-function mutation in TMEM95 causes male subfertility in cattle

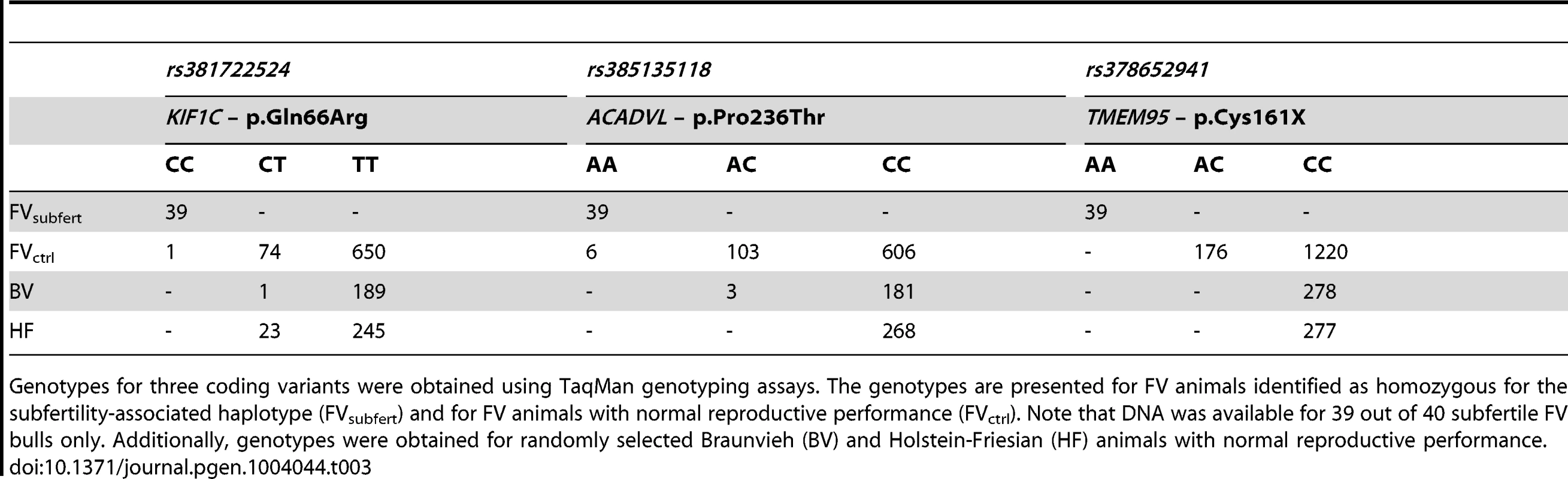

Genotypes for two non-synonymous substitutions in ACDVL and KIF1C and for the nonsense mutation in TMEM95 were obtained for cases and controls using TaqMan genotyping assays (Table 3). Only c.483C>A, introducing the premature stop-codon in TMEM95 (p.Cys161X), was perfectly associated. All animals, which are homozygous for the subfertility-associated haplotype, are homozygous for the non-reference allele, whereas none of 1396 FV bulls with normal reproductive performance are homozygous. The polymorphism is present in the FV breed only; 277 Holstein-Friesian and 278 Braunvieh animals are homozygous for the reference allele. The c.483C>A-mutation is not segregating among 15 Jersey, 47 Angus and 129 Holstein-Friesian animals which were sequenced in the context of the 1000 bull genomes project [25].

Tab. 3. Validation of three coding variants.

Genotypes for three coding variants were obtained using TaqMan genotyping assays. The genotypes are presented for FV animals identified as homozygous for the subfertility-associated haplotype (FVsubfert) and for FV animals with normal reproductive performance (FVctrl). Note that DNA was available for 39 out of 40 subfertile FV bulls only. Additionally, genotypes were obtained for randomly selected Braunvieh (BV) and Holstein-Friesian (HF) animals with normal reproductive performance. TMEM95 encodes a highly conserved single-pass type I transmembrane protein consisting of 183 amino acids with a predicted extracellular N-terminal signal peptide, a 23-amino acid transmembrane domain (amino acid position 153 to 175) and a 8-amino acid intracellular C-terminal domain (Figure 3C and Figure S9 and S10). The premature stop codon introduced by the c.483C>A-mutation is located within the predicted transmembrane domain and truncates the protein by 22 amino acids.

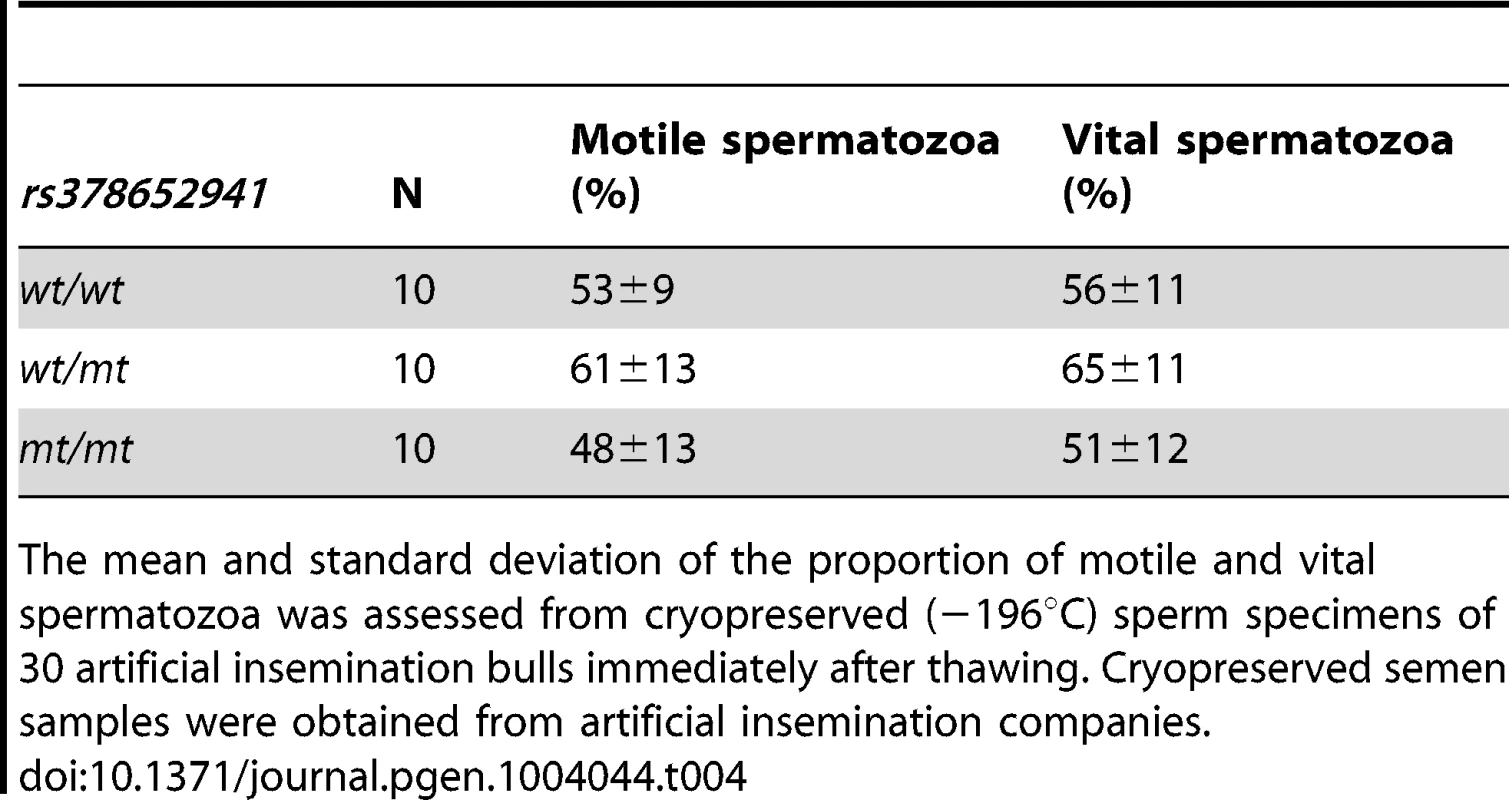

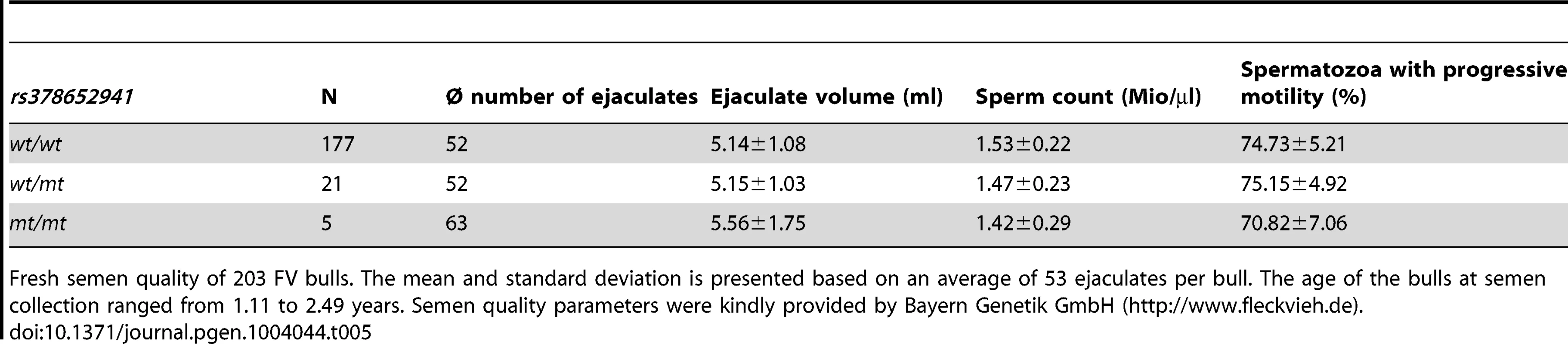

The c.483C>A-mutation does not affect semen quality

Semen quality (morphology, vitality, total motility) was analysed using cryopreserved semen samples of 30 bulls (10 wt/wt, 10 wt/mt, 10 mt/mt). In all ejaculates, spermatozoa showed less than 20% morphological alterations and less than 5% morphological alterations of the head. Total motility after thawing ranged from 50 to 65%. Statistical analysis showed no significant differences in the proportion of motile spermatozoa from wt/wt, wt/mt and mt/mt bulls (Table 4). As shown by eosin staining, 40 to 70% of the spermatozoa were viable after thawing. There were no significant differences in the percentages of viable spermatozoa between wt/wt, wt/mt and mt/mt bulls. Additionally, ejaculate volume, sperm concentration and progressive motility were assessed in fresh semen samples of 203 AI bulls (177 wt/wt, 21wt/mt, 5 mt/mt). Ejaculate volume was above 5 ml, sperm count was above 1.42 Mio/µl and the proportion of spermatozoa with progressive motility was above 70% for all animals (Table 5).

Tab. 4. Assessment of cryopreserved semen quality after thawing.

The mean and standard deviation of the proportion of motile and vital spermatozoa was assessed from cryopreserved (−196°C) sperm specimens of 30 artificial insemination bulls immediately after thawing. Cryopreserved semen samples were obtained from artificial insemination companies. Tab. 5. Assessment of fresh semen quality.

Fresh semen quality of 203 FV bulls. The mean and standard deviation is presented based on an average of 53 ejaculates per bull. The age of the bulls at semen collection ranged from 1.11 to 2.49 years. Semen quality parameters were kindly provided by Bayern Genetik GmbH (http://www.fleckvieh.de). Localization of TMEM95 in spermatozoa

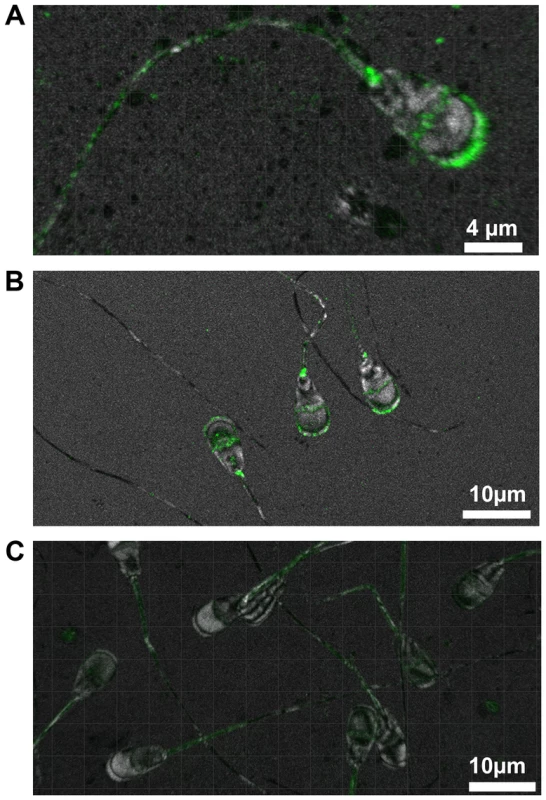

A mouse-derived polyclonal antibody generated against human transmembrane protein 95 was used to locate its position in spermatozoa of 33 bulls (10 wt/wt, 10 wt/mt and 13 mt/mt). In spermatozoa of wt/wt bulls, TMEM95 was distinctly located on the plasma membrane of the acrosome (Figure 4A). Staining was also visible on the equatorial segment of the head. The sperm neck was regularly labelled. Spermatozoa of wt/mt and wt/wt bulls showed an identical staining pattern (Figure 4B), whereas spermatozoa of mt/mt bulls did not show any staining on the head (Figure 4C). Weak fluorescence was detected in the midpiece of the tail in spermatozoa of all animals due to the autofluorescence of the mitochondria. In the negative controls, there was no signal detectable on the sperm head whereas the midpiece of the tail showed weak autofluorescence (Figure S11).

Fig. 4. Immunohistochemical localisation of TMEM95.

In spermatozoa of wt/wt animals, TMEM95 is located at the plasma membrane of the acrosome, on the equatorial segment and at the neck (A). Spermatozoa of wt/mt animals show the same fluorescence pattern as spermatozoa of wt/wt animals (B). Transmembrane protein 95 is absent in spermatozoa of mt/mt animals (C). Note that all spermatozoa exhibit weak fluorescence at the midpiece of the tail due to the autofluorescence of the mitochondria. Discussion

The genome-wide association study (GWAS) with imputed genotypes for 7962 artificial insemination bulls identified a genomic region on BTA19 for male reproductive ability (MRA) in the FV population. Autozygosity mapping revealed a common 1386 kb segment of extended homozygosity in 40 bulls with unexplained exceptionally poor reproductive performance. None of the bulls with normal reproductive performance was homozygous indicating recessive inheritance. Only 1.74% of inseminations performed with semen samples of affected bulls were successful, although semen quality parameters were within a normal range, reflecting idiopathic subfertility [26]. The newly identified congenital defect is denominated as “Bovine Male Subfertility” and accounts for 82% of FV bulls with exceptionally poor reproductive performance. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that homozygous males are infertile and that the very low proportion of successful inseminations reflects errors in parentage recording which might be as high as 10% in dairy cattle breeding programmes [27]. In progeny testing based breeding programmes, semen doses of young bulls are used for approximately 1000 test inseminations [28]. These artificial inseminations are performed within very short time, precluding the early identification of subfertile/infertile bulls. Identifying and culling bulls with poor fertility prognosis (i.e., homozygous bulls) before they are used for artificial insemination is now possible. There was no evidence for any additional genomic region underlying idiopathic male subfertility in the FV population, although the reproductive ability of nine bulls which are not homozygous for the c.483C>A-mutation, is very low. However, the number (n = 9) of subfertile bulls not attributable to the BTA19 locus might not be sufficient for detecting additional loci (Figure S12 and Table S6).

The potential of targeted or whole genome re-sequencing for the identification of causal trait variants has been demonstrated in several species (e.g., [29]–[31]) including cattle [32]–[34]. Causal trait variants for monogenic disorders are traditionally identified by sequencing case/control-panels and by subsequently comparing allele counts in affected and unaffected individuals. However, the concept of the present study is different: the identification of the underlying mutation was based on whole genome re-sequencing data of 43 unaffected FV animals explaining a vast majority of the population's genomic variation [23]. As the frequency of the mutation was reasonably high (7.2%), the affected haplotype was present in heterozygous state in six of the re-sequenced animals. Filtering the re-sequencing data for variants compatible with the supposed recessive inheritance pattern revealed a plausible candidate causative loss-of-function mutation in TMEM95 encoding the transmembrane protein 95.

The nonsense mutation was perfectly associated in 1990 animals representing three different breeds. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a phenotypic effect associated with variation in TMEM95 in any organism. So far, there are no clues about the precise function of TMEM95. However, it seems likely that TMEM95 is involved in sperm-egg interactions, which has been shown to be the main function of sperm-specific transmembrane proteins (e.g., [35], [36]). The phenotype in the present study resembles phenotypic patterns of Caenorhabditis elegans resulting from an impaired function of sperm-specific transmembrane proteins [37], [38]. Taken together, our findings evidence genomic variation within TMEM95 to severely compromise the reproductive performance in cattle.

The causative polymorphism (c.483C>A, rs378652941) introduces a premature stop codon in TMEM95 (p.Cys161X). The affected codon resides within the predicted transmembrane domain of TMEM95 most likely resulting in a disturbed anchorage of the truncated protein in the sperm plasma membrane bilayer. It is also likely that the resulting truncated protein is absent due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay [39]. Our data show no evidence that the mutation affects any of the routinely assessed semen quality parameters in vitro. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the mutation affects semen quality parameters, e.g., vitality and motility, in vivo [40], [41].

Transmembrane protein 95 is primarily located on the acrosomal membrane of the sperm head indicating that it may be involved in the acrosome reaction. Spermatozoa of mt/mt animals showed no fluorescence at the acrosomal membrane implying deficiency of TMEM95. Thus, successful fertilization by spermatozoa of mt/mt animals might be compromised. This is supported by the fact that the equatorial segment of the acrosome, which provides the first contact of the spermatozoon with the cell membrane of the oocyte [42], is also labelled in spermatozoa of fertile animals. The sperm neck contains the centriole and is essential for cell division and development of the early embryo [43]. Labelling of the neck indicates an additional potential role of TMEM95 after fertilization during the first cell divisions of the early embryo.

Although spermatozoa of mt/mt animals showed fluorescence, neither on the acrosomal membrane and the equatorial segment nor at the centriole, weak unspecific fluorescence was observed at the midpiece of the tail. This fluorescence pattern is also present in spermatozoa of wt/wt and wt/mt animals. The midpiece is the only region of spermatozoa that contains mitochondria [44]. The weak fluorescence of the midpiece is due to unspecific autofluorescence of the mitochondria, which has been described in several organs and species [45]–[47].

Male subfertility is also present in other species besides cattle [9], [48]–[50], and compromised sperm surface proteins account for a substantial number of males with distinctly reduced reproductive ability in humans [15], [40]. Our results demonstrate that TMEM95 is another sperm surface protein, which is likely to be involved in sperm-egg plasma membrane interactions. Its protein sequence is highly conserved among species (Figure S10) and genetic variants disrupting TMEM95 are likely to induce male subfertility also in other species than cattle. Numerous polymorphic sites have been identified in human TMEM95, among them several potential loss-of-function variants (Figure S13). Based on our findings it is highly recommended to systematically survey variants in TMEM95 as potentially causal for idiopathic male in - or subfertility in any species.

Frequencies of variants that disrupt protein-coding genes are usually low in human populations [51], [52]. However, in livestock populations, the frequency of deleterious alleles might increase rapidly because individual sires can generate tens of thousands of progeny by artificial insemination (e.g., [53], [54], [32]). The loss-of-function mutation in TMEM95 can be traced back to HAXL (*1966), the most important ancestor of the current FV population. Within eight generations, the frequency of the deleterious allele increased to 8.9% and 1443 (13.92%) animals of the present study are heterozygous. This increase of the allele frequency had been possible because phenotypic effects become apparent in homozygous males only. There are no phenotypic effects detectable neither in heterozygous nor in homozygous females (Table S3).

In agreement with previous findings in livestock [55] and humans [15], our results evidence that standard assessment of spermatozoa (i.e., morphology, motility and vitality) is not sufficient to reliably anticipate male reproductive performance. All routinely assessed semen parameters of bulls homozygous for the nonsense mutation in TMEM95 comply with current requirements for artificial insemination in cattle [56]. It might be advisable to develop functional assays, e.g., for the integrity of sperm surface proteins, for an efficient prospective monitoring of male fertility.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Semen samples were collected by approved commercial artificial insemination stations as part of their regular breeding and reproduction measures in cattle industry. No ethical approval was required for this study.

Animals and phenotypes

Male reproductive ability (MRA) was evaluated in 7962 AI bulls of the German FV population. Semen samples of those bulls were used for 15,321,171 artificial inseminations with an average of 1924 artificial inseminations per bull. The phenotypes for MRA were obtained from routine breeding value estimation for reproductive traits, which are jointly estimated for males and females [57]. The resulting phenotypes for MRA represent the bulls' reproductive performance adjusted for environmental and genetic effects (i.e., year, season, flock, female mating partner). The lower the value for MRA, the worse is the bull's reproductive performance (i.e., the smaller the proportion of successful inseminations).

Genotypes, quality control and genotype imputation

A total of 3545 animals (1475 AI bulls, 2070 primiparous cows) of the FV population were genotyped with the Illumina BovineHD Bead chip comprising 777,962 SNPs. Another 7073 AI bulls were genotyped with the BovineSNP50 Bead chip comprising ∼54,000 SNPs. The chromosomal position of the SNPs was determined according to the UMD3.1 assembly of the bovine genome [58]. Mitochondrial, Y-chromosomal and those SNPs with unknown chromosomal position were not considered for further analyses. Stringent quality control was carried out for each dataset separately using PLINK v1.07 [59]. Animals and SNPs with call-rate <0.95 were excluded, as well as SNPs with minor allele frequency <0.5% and those SNPs deviating significantly from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P<10−6). The pairwise genomic relationship [60] was compared with the pedigree relationship tracing pedigree records back to 1920 [61]. Animals showing major discrepancies of the pedigree and the genomic relationship were removed from the dataset, as such patterns indicate sample swaps. After quality control, the high-density dataset contained 3332 animals and 652,856 SNPs with an average per-individual call-rate of 99.17%. The medium-density dataset contained 7031 animals and 42,907 SNPs with an average per-individual call-rate of 99.75%. Genotype imputation was performed to extrapolate medium-density genotypes to higher density using a pre-phasing based approach. Haplotypes were inferred for the two datasets separately using Beagle [62] and subsequent haplotype-based imputation was performed with Minimac [63]. This approach yields high imputation accuracy in cattle [64]. The imputed dataset comprised 10,363 animals (8411 AI bulls/1952 primiparous cows) and genotypes for 652,856 SNPs. Phenotypic records for MRA were available for 7962 bulls.

Genome-wide association study

Genome-wide association studies were performed applying a variance component based approach to account for population stratification. We used EMMAX [65] to fit the mixed model , where Y is a vector of phenotypes, b is the SNP effect, X is a design matrix of imputed SNP genotypes, u is a vector of additive genetic effects assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and (co)variance , with being the additive genetic variance and G being the realized genomic relationship matrix (GRM) of the 7962 bulls with phenotype information built based on 635,224 autosomal SNPs (see above) and where e is a vector of random normal deviates .

Exploiting whole genome re-sequencing data for mutation screening

The genomes of 42 key and contemporary animals of the FV population were sequenced at low - to medium coverage (ø 7.4-fold) and one animal was sequenced at high coverage (25-fold) using Illumina GA IIx and HiSeq 2000 instruments [66], [23]. Paired-end reads were obtained and mapped to the bovine reference sequence (UMD3.1 [58]) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) [67]. PICARD (http://picard.sourceforge.net) was used to mark PCR-duplicates. Subsequent multi-sample variant calling with mpileup [68] yielded genotypes at 17.17 million sites. The re-sequencing data were contributed to the 1000 bull genomes project [25] and all variants were submitted to dbSNP [23]. Beagle phasing and imputation within the 43 sequenced animals improved the primary genotype calls (a detailed overview of the entire variant calling pipeline and all obtained variants is presented in Jansen et al. [23]). Of 17.17 million sites, 5287 SNPs and 678 INDELs were located within the 1386 kb segment (26,580,096 bp to 27,956,634 bp) of extended homozygosity on BTA19. Of the 43 sequenced animals, six were identified as carriers of the subfertility-associated haplotype via high-density genotypes, among them the animal sequenced at high coverage. Assuming perfect correlation between the subfertility-associated haplotype and the causal mutation, the allele frequency of the causal mutation should be 7% (6 of 86 affected alleles) in the sequence-derived genotypes. To account for inaccurately genotyped variants due to the low-coverage sequence data (e.g., mis-calling of heterozygous genotypes for rare variants [69]) [70] and for possible phasing errors, a conservative mutation scan was performed to identify variants compatible with recessive inheritance (Figure S6). The 5965 polymorphic sites were filtered for variants that met three conditions: (i) the frequency of the non-reference allele is below 10%, (ii) the variant is heterozygous in the animal sequenced at high coverage and (iii) the variant is present in heterozygous state in at least three of five carrier sequenced at low coverage.

Validation of three identified polymorphisms

PCR primers (5′-CACCCTGCCTTGTCTTTCAT-3′ and 5′-AGGCTCTGTCCTCGTTTTCA-3′) were designed for exon 6 of TMEM95 to scrutinize the rs378652941-polymorphism by classical Sanger sequencing in the re-sequenced animals as recommended by Jansen et al. [23]. Genomic PCR products were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies) on the ABI 3130x1 Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies). Genotypes for rs378652941 (TMEM95:c.483C>A, p.Cys161X, Chr19 : 27689622), rs381722524 (KIF1C:c.197A>G, p.Gln66Arg, Chr19 : 27042848) and rs385135118 (ACADVL:c.706C>A, p.Pro236Thr, Chr19 : 27570146) were obtained by TaqMan genotyping assays (Life Technologies) in 1990, 1222 and 1206 animals, respectively, representing three different breeds (BV, FV, HF). The primer and probe sequences are listed in Table S7.

Topology prediction for TMEM95

The topology of bovine transmembrane protein 95 (NCBI reference sequence: XP_002695846.1) was predicted with SPOCTOPUS [71] and PHOBIUS [72]. Both methods predict the transmembrane protein topology while accounting for the existence of a N-terminal signal peptide sequence. The protein topology was visualized with SOSUI [73]. ClustalW [74] was used for multi-species alignment of the protein sequence and for the prediction of conserved regions.

Assessment of sperm morphology, motility and viability

Cryopreserved (−196°C) sperm specimens of 30 bulls (10 wt/wt, 10 wt/mt, 10 mt/mt) were obtained from artificial insemination companies. Two different ejaculates of each bull were evaluated with two straws pooled per ejaculate. After thawing (37°C, 30 s), sperm morphology was assessed by staining with Diff-Quik (Siemens Healthcare, Germany). Sperm total motility was investigated immediately after thawing by phase-contrast microscopy using the Leica DM 1000 microscope (Leica, Germany). Viability of spermatozoa was investigated after thawing by mixing 5 µl of the thawed ejaculate with aqueous Eosin Y solution (Sigma Aldrich, Germany) in a volume ratio of 1∶1. Intact and viable spermatozoa stay colourless whereas spermatozoa with disturbed membrane integrity stain red. Counting of viable sperm was done within 10 seconds after mixing. Two hundred spermatozoa in at least two different fields of view were investigated at a magnification of 400× to analyse morphology, viability and motility.

Assessment of ejaculate volume, sperm count and progressive motility

Fresh semen traits (ejaculate volume, sperm count and progressive motility) of 203 AI bulls (177 wt/wt, 21wt/mt, 5 mt/mt) were provided by an artificial insemination company. Semen quality was analysed based on 10,682 ejaculates with an average of 52.6 ejaculates per bull. At semen collection, the age of the bulls ranged from 1.1 to 2.5 years.

Immunohistochemical localization of TMEM95

Immunohistochemistry on cryopreserved sperm specimens of 33 bulls (10 wt/wt, 10 wt/mt,13 mt/mt) was repeated for 3 times. After thawing (37°C, 30 s), spermatozoa were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice and were diluted in PBS to a concentration of 500,000 spermatozoa/ml. Thereafter, drops of 7 µl were placed on 3-aminopropyl-ethoxysilane-coated slides and dried on a heating-plate at a temperature of 38°C. Subsequently, the slides were fixed in Bouin's solution for 7 min and washed in PBS twice. Non-specific binding was blocked by incubation in blocking buffer (0.1% bovine serum Albumin in PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) for 5 minutes and in normal goat serum (dilution 1∶5 in PBS, Invitrogen, Germany). Next, the spermatozoa were incubated with the first antibody Yomics Ab989 (mouse-derived against human TMEM95, Primm, USA) in a dilution of 1∶200 in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. The secondary antibody was the Fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated AffiniPure Goat anti Mouse IgG (H+L) (Dianova, Germany, dilution 1∶200). Negative controls were done by a) replacing the first antibody with PBS and b) using a non-relevant anti-mouse antibody directed against Villin (1∶75, Beckman Coulter). Specimens were evaluated by using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica DM IRBE) in magnifications from 400 to 800.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. IrvineDS (1998) Epidemiology and aetiology of male infertility. Hum Reprod 13 Suppl 1 : 33–44.

2. De KretserD (1997) Male infertility. The Lancet 349 : 787–790.

3. GurunathS, PandianZ, AndersonRA, BhattacharyaS (2011) Defining infertility–a systematic review of prevalence studies. Hum Reprod Update 17 : 575–588.

4. BhasinS, de KretserDM, BakerHW (1994) Clinical review 64: Pathophysiology and natural history of male infertility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 79 : 1525–1529.

5. GuzickDS, OverstreetJW, Factor-LitvakP, BrazilCK, NakajimaST, CoutifarisC, CarsonSA, CisnerosP, SteinkampfMP, HillJA, XuD, VogelDL (2001) Sperm morphology, motility, and concentration in fertile and infertile men. N Engl J Med 345 : 1388–1393.

6. MundyAJ, RyderTA, EdmondsDK (1995) Asthenozoospermia and the human sperm mid-piece. Hum Reprod 10 : 116–119.

7. TomarR, MishraAK, MohantyNK, JainAK (2012) Altered Expression of Succinic Dehydrogenase in Asthenozoospermia Infertile Male. Am J Reprod Immunol

8. Effectiveness and treatment for unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril 86: S111–114.

9. QuaasA, DokrasA (2008) Diagnosis and Treatment of Unexplained Infertility. Rev Obstet Gynecol 1 : 69–76.

10. DruetT, FritzS, SellemE, BassoB, GérardO, Salas-CortesL, HumblotP, DruartX, EggenA (2009) Estimation of genetic parameters and genome scan for 15 semen characteristics traits of Holstein bulls. J Anim Breed Genet 126 : 269–277.

11. FerlinA, RaicuF, GattaV, ZuccarelloD, PalkaG, ForestaC (2007) Male infertility: role of genetic background. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 14 : 734–745.

12. O'Flynn O'BrienKL, VargheseAC, AgarwalA (2010) The genetic causes of male factor infertility: a review. Fertil Steril 93 : 1–12.

13. HarrisT, MarquezB, SuarezS, SchimentiJ (2007) Sperm Motility Defects and Infertility in Male Mice with a Mutation in Nsun7, a Member of the Sun Domain-Containing Family of Putative RNA Methyltransferases. Biol Reprod 77 : 376–382.

14. SironenA, UimariP, VenhorantaH, AnderssonM, VilkkiJ (2011) An exonic insertion within Tex14 gene causes spermatogenic arrest in pigs. BMC Genomics 12 : 591.

15. TollnerTL, VennersSA, HolloxEJ, YudinAI, LiuX, TangG, XingH, KaysRJ, LauT, OverstreetJW, XuX, BevinsCL, CherrGN (2011) A common mutation in the defensin DEFB126 causes impaired sperm function and subfertility. Sci Transl Med 3 : 92ra65.

16. WuW, ShenO, QinY, NiuX, LuC, XiaY, SongL, WangS, WangX (2010) Idiopathic Male Infertility Is Strongly Associated with Aberrant Promoter Methylation of Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase (MTHFR). PLoS ONE 5: e13884.

17. CarrellDT, AstonKI (2011) The search for SNPs, CNVs, and epigenetic variants associated with the complex disease of male infertility. Syst Biol Reprod Med 57 : 17–26.

18. KastelicJP, ThundathilJC (2008) Breeding soundness evaluation and semen analysis for predicting bull fertility. Reprod Domest Anim 43 Suppl 2 : 368–373.

19. BlaschekM, KayaA, ZwaldN, MemiliE, KirkpatrickBW (2011) A whole-genome association analysis of noncompensatory fertility in Holstein bulls. J Dairy Sci 94 : 4695–4699.

20. HuangW, KirkpatrickBW, RosaGJM, KhatibH (2010) A genome-wide association study using selective DNA pooling identifies candidate markers for fertility in Holstein cattle. Anim Genet 41 : 570–578.

21. PeñagaricanoF, WeigelKA, KhatibH (2012) Genome-wide association study identifies candidate markers for bull fertility in Holstein dairy cattle. Anim Genet 43 Suppl 1 : 65–71.

22. LanXY, PeñagaricanoF, DejungL, WeigelKA, KhatibH (2013) Short communication: A missense mutation in the PROP1 (prophet of Pit 1) gene affects male fertility and milk production traits in the US Holstein population. J Dairy Sci 96 : 1255–1257.

23. JansenS, AignerB, PauschH, WysockiM, EckS, Benet-PagèsA, GrafE, WielandT, StromTM, MeitingerT, FriesR (2013) Assessment of the genomic variation in a cattle population by re-sequencing of key animals at low to medium coverage. BMC Genomics 14 : 446.

24. FloreaL, SouvorovA, KalbfleischTS, SalzbergSL (2011) Genome Assembly Has a Major Impact on Gene Content: A Comparison of Annotation in Two Bos Taurus Assemblies. PLoS ONE 6: e21400.

25. Daetwyler HD, Capitan A, Pausch H, Stothard P, van Binsbergen R, Brøndrum RF, Liao X, Djari A, Rodriguez SC, Grohs C, Jung S, Esquerré D, Bouchez O, Gollnick NS, Rossignol M-N, Klopp C, Rocha D, Fritz S, Eggen A, Bowman PJ, Coote D, Chamberlain AJ, VanTassel CP, Hulsegge I, Goddard ME, Guldbrandtsen B, Lund MS, Veerkam RF, Boichard DA, Fries R, Hayes BJ (2013) The 1000 bull genomes project. submitted.

26. DaviesMJ, deLaceySL, NormanRJ (2005) Towards less confusing terminology in reproductive medicine Clarifying medical ambiguities to the benefit of all. Hum Reprod 20 : 2669–2671.

27. VisscherPM, WoolliamsJA, SmithD, WilliamsJL (2002) Estimation of Pedigree Errors in the UK Dairy Population using Microsatellite Markers and the Impact on Selection. J Dairy Sci 85 : 2368–2375.

28. RobertsonA, RendelJM (1950) The use of progeny testing with artificial insemination in dairy cattle. Journ. of Genetics 50 : 21–31.

29. Gonzaga-JaureguiC, LupskiJR, GibbsRA (2012) Human Genome Sequencing in Health and Disease. Annual Review of Medicine 63 : 35–61.

30. ArnoldCN, XiaY, LinP, RossC, SchwanderM, SmartNG, MullerU, BeutlerB (2011) Rapid Identification of a Disease Allele in Mouse Through Whole Genome Sequencing and Bulk Segregation Analysis. Genetics 187 : 633–641.

31. FormanOP, PenderisJ, HartleyC, HaywardLJ, RickettsSL, MellershCS (2012) Parallel Mapping and Simultaneous Sequencing Reveals Deletions in BCAN and FAM83H Associated with Discrete Inherited Disorders in a Domestic Dog Breed. PLoS Genet 8: e1002462.

32. CharlierC, AgerholmJS, CoppietersW, Karlskov-MortensenP, LiW, de JongG, FasquelleC, KarimL, CireraS, CambisanoN, AharizN, MullaartE, GeorgesM, FredholmM (2012) A Deletion in the Bovine FANCI Gene Compromises Fertility by Causing Fetal Death and Brachyspina. PLoS ONE 7: e43085.

33. SonstegardTS, ColeJB, VanradenPM, Van TassellCP, NullDJ, SchroederSG, BickhartD, McClureMC (2013) Identification of a Nonsense Mutation in CWC15 Associated with Decreased Reproductive Efficiency in Jersey Cattle. PLoS ONE 8: e54872.

34. FritzS, CapitanA, DjariA, RodriguezSC, BarbatA, BaurA, GrohsC, WeissB, BoussahaM, EsquerréD, KloppC, RochaD, BoichardD (2013) Detection of Haplotypes Associated with Prenatal Death in Dairy Cattle and Identification of Deleterious Mutations in GART, SHBG and SLC37A2. PLoS ONE 8: e65550.

35. SuriA (2004) Sperm specific proteins-potential candidate molecules for fertility control. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2 : 10.

36. WangH, LiuJ, ChoK-H, RenD (2009) A Novel, Single, Transmembrane Protein CATSPERG Is Associated with CATSPER1 Channel Protein. Biol Reprod 81 : 539–544.

37. SingsonA, MercerKB, L'HernaultSW (1998) The C. elegans spe-9 Gene Encodes a Sperm Transmembrane Protein that Contains EGF-like Repeats and Is Required for Fertilization. Cell 93 : 71–79.

38. ChatterjeeI, RichmondA, PutiriE, ShakesDC, SingsonA (2005) The Caenorhabditis elegans spe-38 gene encodes a novel four-pass integral membrane protein required for sperm function at fertilization. Development 132 : 2795–2808.

39. ChangY-F, ImamJS, WilkinsonMF (2007) The nonsense-mediated decay RNA surveillance pathway. Annu Rev Biochem 76 : 51–74.

40. QiH, MoranMM, NavarroB, ChongJA, KrapivinskyG, KrapivinskyL, KirichokY, RamseyIS, QuillTA, ClaphamDE (2007) All four CatSper ion channel proteins are required for male fertility and sperm cell hyperactivated motility. PNAS 104 : 1219–1223.

41. Rodriguez-MartinezH, BarthAD (2007) In vitro evaluation of sperm quality related to in vivo function and fertility. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl 64 : 39–54.

42. BedfordJM, MooreHDM, FranklinLE (1979) Significance of the equatorial segment of the acrosome of the spermatozoon in eutherian mammals. Experimental Cell Research 119 : 119–126.

43. PalermoGD, ColomberoLT, RosenwaksZ (1997) The human sperm centrosome is responsible for normal syngamy and early embryonic development. Rev Reprod 2 : 19–27.

44. Ruiz-PesiniE, DiezC, LapeñaAC, Pérez-MartosA, MontoyaJ, AlvarezE, ArenasJ, López-PérezMJ (1998) Correlation of sperm motility with mitochondrial enzymatic activities. Clin Chem 44 : 1616–1620.

45. RameyNA, ParkCY, GehlbachPL, ChuckRS (2007) Imaging mitochondria in living corneal endothelial cells using autofluorescence microscopy. Photochem Photobiol 83 : 1325–1329.

46. EckersE, DeponteM (2012) No Need for Labels: The Autofluorescence of Leishmania tarentolae Mitochondria and the Necessity of Negative Controls. PLoS ONE 7: e47641.

47. AnwerAG, GosnellME, PerincherySM, InglisDW, GoldysEM (2012) Visible 532 nm laser irradiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells: Effect on proliferation rates, mitochondria membrane potential and autofluorescence. Lasers Surg Med 44 : 769–778.

48. HerreraJ, FierroR, ZayasH, ConejoJ, JiménezI, GarcíaA, BetancourtM (2002) Acrosome reaction in fertile and subfertile boar sperm. Arch Androl 48 : 133–139.

49. BrinskoSP, LoveCC, BauerJE, MacphersonML, VarnerDD (2007) Cholesterol-to-phospholipid ratio in whole sperm and seminal plasma from fertile stallions and stallions with unexplained subfertility. Anim Reprod Sci 99 : 65–71.

50. Lopes-SantiagoB, MonteiroG, BittencourtR, ArduinoF, OvidioP, Jordão-JuniorA, AraújoJ, LopesM (2012) Evaluation of Sperm DNA Peroxidation in Fertile and Subfertile Dogs. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 47 : 208–209.

51. MacArthurDG, BalasubramanianS, FrankishA, HuangN, MorrisJ, WalterK, JostinsL, HabeggerL, PickrellJK, MontgomerySB, AlbersCA, ZhangZD, ConradDF, LunterG, ZhengH, AyubQ, DePristoMA, BanksE, HuM, HandsakerRE, RosenfeldJA, FromerM, JinM, MuXJ, KhuranaE, YeK, KayM, SaundersGI, SunerM-M, HuntT, BarnesIHA, AmidC, Carvalho-SilvaDR, BignellAH, SnowC, YngvadottirB, BumpsteadS, CooperDN, XueY, RomeroIG, WangJ, LiY, GibbsRA, McCarrollSA, DermitzakisET, PritchardJK, BarrettJC, HarrowJ, HurlesME, GersteinMB, Tyler-SmithC (2012) A Systematic Survey of Loss-of-Function Variants in Human Protein-Coding Genes. Science 335 : 823–828.

52. Consortium T 1000 GP (2012) An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491 : 56–65.

53. DrögemüllerC, ReichartU, SeuberlichT, OevermannA, BaumgartnerM, Kühni BoghenborK, StoffelMH, SyringC, MeylanM, MüllerS, MüllerM, GredlerB, SölknerJ, LeebT (2011) An Unusual Splice Defect in the Mitofusin 2 Gene (MFN2) Is Associated with Degenerative Axonopathy in Tyrolean Grey Cattle. PLoS ONE 6: e18931.

54. SarteletA, DruetT, MichauxC, FasquelleC, GéronS, TammaN, ZhangZ, CoppietersW, GeorgesM, CharlierC (2012) A Splice Site Variant in the Bovine RNF11 Gene Compromises Growth and Regulation of the Inflammatory Response. PLoS Genet 8: e1002581.

55. GredlerB, FuerstC, Fuerst-WaltlB, SchwarzenbacherH, SölknerJ (2007) Genetic Parameters for Semen Production Traits in Austrian Dual-Purpose Simmental Bulls. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 42 : 326–328.

56. MathevonM, BuhrMM, DekkersJCM (1998) Environmental, Management, and Genetic Factors Affecting Semen Production in Holstein Bulls. Journal of Dairy Science 81 : 3321–3330.

57. FürstC, GredlerB (2009) Genetic Evaluation for Fertility Traits in Austria and Germany. Interbull Bulletin 40 : 3–9.

58. ZiminAV, DelcherAL, FloreaL, KelleyDR, SchatzMC, PuiuD, HanrahanF, PerteaG, Van TassellCP, SonstegardTS, MarçaisG, RobertsM, SubramanianP, YorkeJA, SalzbergSL (2009) A whole-genome assembly of the domestic cow, Bos taurus. Genome Biol 10: R42–R42.

59. PurcellS, NealeB, Todd-BrownK, ThomasL, FerreiraMAR, BenderD, MallerJ, SklarP, de BakkerPIW, DalyMJ, ShamPC (2007) PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81 : 559–575.

60. HayesB, BowmanP, ChamberlainA, VerbylaK, GoddardM (2009) Accuracy of genomic breeding values in multi-breed dairy cattle populations. Genetics Selection Evolution 41 : 51.

61. ColeJ (2007) PyPedal: A computer program for pedigree analysis. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 57 : 107–113.

62. BrowningBL, BrowningSR (2009) A Unified Approach to Genotype Imputation and Haplotype-Phase Inference for Large Data Sets of Trios and Unrelated Individuals. The American Journal of Human Genetics 84 : 210–223.

63. HowieB, FuchsbergerC, StephensM, MarchiniJ, AbecasisGR (2012) Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nature Genetics 44 : 955–959.

64. PauschH, AignerB, EmmerlingR, EdelC, GötzK-U, FriesR (2013) Imputation of high-density genotypes in the Fleckvieh cattle population. Genet Sel Evol 45 : 3.

65. KangHM, SulJH, ServiceSK, ZaitlenNA, KongS, FreimerNB, SabattiC, EskinE (2010) Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 42 : 348–354.

66. EckS, Benet-PagesA, FlisikowskiK, MeitingerT, FriesR, StromT (2009) Whole genome sequencing of a single Bos taurus animal for SNP discovery. Genome Biology 10: R82.

67. LiH, DurbinR (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25 : 1754–1760.

68. LiH, HandsakerB, WysokerA, FennellT, RuanJ, HomerN, MarthG, AbecasisG, DurbinR (2009) The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25 : 2078–2079.

69. LiY, SidoreC, KangHM, BoehnkeM, AbecasisGR (2011) Low-coverage sequencing: Implications for design of complex trait association studies. Genome Res 21 : 940–951.

70. DePristoMA, BanksE, PoplinR, GarimellaKV, MaguireJR, HartlC, PhilippakisAA, del AngelG, RivasMA, HannaM, McKennaA, FennellTJ, KernytskyAM, SivachenkoAY, CibulskisK, GabrielSB, AltshulerD, DalyMJ (2011) A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 43 : 491–498.

71. ViklundH, BernselA, SkwarkM, ElofssonA (2008) SPOCTOPUS: a combined predictor of signal peptides and membrane protein topology. Bioinformatics 24 : 2928–2929.

72. KällL, KroghA, SonnhammerELL (2004) A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol 338 : 1027–1036.

73. HirokawaT, Boon-ChiengS, MitakuS (1998) SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics 14 : 378–379.

74. ThompsonJD, HigginsDG, GibsonTJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22 : 4673–4680.

75. AdzhubeiIA, SchmidtS, PeshkinL, RamenskyVE, GerasimovaA, BorkP, KondrashovAS, SunyaevSR (2010) A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 7 : 248–249.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Unwrapping BacteriaČlánek A Chaperone-Assisted Degradation Pathway Targets Kinetochore Proteins to Ensure Genome StabilityČlánek The Candidate Splicing Factor Sfswap Regulates Growth and Patterning of Inner Ear Sensory OrgansČlánek The SPF27 Homologue Num1 Connects Splicing and Kinesin 1-Dependent Cytoplasmic Trafficking inČlánek Down-Regulation of eIF4GII by miR-520c-3p Represses Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma DevelopmentČlánek Meta-Analysis Identifies Gene-by-Environment Interactions as Demonstrated in a Study of 4,965 MiceČlánek High Risk Population Isolate Reveals Low Frequency Variants Predisposing to Intracranial Aneurysms

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- How Much Is That in Dog Years? The Advent of Canine Population Genomics

- The Sense and Sensibility of Strand Exchange in Recombination Homeostasis

- Unwrapping Bacteria

- DNA Methylation Changes Separate Allergic Patients from Healthy Controls and May Reflect Altered CD4 T-Cell Population Structure

- Evidence for Mito-Nuclear and Sex-Linked Reproductive Barriers between the Hybrid Italian Sparrow and Its Parent Species

- Translation Enhancing ACA Motifs and Their Silencing by a Bacterial Small Regulatory RNA

- Relationship Estimation from Whole-Genome Sequence Data

- Genetic Models of Apoptosis-Induced Proliferation Decipher Activation of JNK and Identify a Requirement of EGFR Signaling for Tissue Regenerative Responses in

- ComEA Is Essential for the Transfer of External DNA into the Periplasm in Naturally Transformable Cells

- Loss and Recovery of Genetic Diversity in Adapting Populations of HIV

- Bioelectric Signaling Regulates Size in Zebrafish Fins

- Defining NELF-E RNA Binding in HIV-1 and Promoter-Proximal Pause Regions

- Loss of Histone H3 Methylation at Lysine 4 Triggers Apoptosis in

- Cell-Cycle Dependent Expression of a Translocation-Mediated Fusion Oncogene Mediates Checkpoint Adaptation in Rhabdomyosarcoma

- How a Retrotransposon Exploits the Plant's Heat Stress Response for Its Activation

- A Nonsense Mutation in Encoding a Nondescript Transmembrane Protein Causes Idiopathic Male Subfertility in Cattle

- Deletion of a Conserved -Element in the Locus Highlights the Role of Acute Histone Acetylation in Modulating Inducible Gene Transcription

- Developmental Link between Sex and Nutrition; Regulates Sex-Specific Mandible Growth via Juvenile Hormone Signaling in Stag Beetles

- PP2A/B55 and Fcp1 Regulate Greatwall and Ensa Dephosphorylation during Mitotic Exit

- Differential Effects of Collagen Prolyl 3-Hydroxylation on Skeletal Tissues

- Comprehensive Functional Annotation of 77 Prostate Cancer Risk Loci

- Evolution of Chloroplast Transcript Processing in and Its Chromerid Algal Relatives

- A Chaperone-Assisted Degradation Pathway Targets Kinetochore Proteins to Ensure Genome Stability

- New MicroRNAs in —Birth, Death and Cycles of Adaptive Evolution

- A Genome-Wide Screen for Bacterial Envelope Biogenesis Mutants Identifies a Novel Factor Involved in Cell Wall Precursor Metabolism

- FGFR1-Frs2/3 Signalling Maintains Sensory Progenitors during Inner Ear Hair Cell Formation

- Regulation of Synaptic /Neuroligin Abundance by the /Nrf Stress Response Pathway Protects against Oxidative Stress

- Intrasubtype Reassortments Cause Adaptive Amino Acid Replacements in H3N2 Influenza Genes

- Molecular Specificity, Convergence and Constraint Shape Adaptive Evolution in Nutrient-Poor Environments

- WNT7B Promotes Bone Formation in part through mTORC1

- Natural Selection Reduced Diversity on Human Y Chromosomes

- In-Vivo Quantitative Proteomics Reveals a Key Contribution of Post-Transcriptional Mechanisms to the Circadian Regulation of Liver Metabolism

- The Candidate Splicing Factor Sfswap Regulates Growth and Patterning of Inner Ear Sensory Organs

- The Acid Phosphatase-Encoding Gene Contributes to Soybean Tolerance to Low-Phosphorus Stress

- p53 and TAp63 Promote Keratinocyte Proliferation and Differentiation in Breeding Tubercles of the Zebrafish

- Affects Plant Architecture by Regulating Local Auxin Biosynthesis

- The SET Domain Proteins SUVH2 and SUVH9 Are Required for Pol V Occupancy at RNA-Directed DNA Methylation Loci

- Down-Regulation of Rad51 Activity during Meiosis in Yeast Prevents Competition with Dmc1 for Repair of Double-Strand Breaks

- Multi-tissue Analysis of Co-expression Networks by Higher-Order Generalized Singular Value Decomposition Identifies Functionally Coherent Transcriptional Modules

- A Neurotoxic Glycerophosphocholine Impacts PtdIns-4, 5-Bisphosphate and TORC2 Signaling by Altering Ceramide Biosynthesis in Yeast

- Subtle Changes in Motif Positioning Cause Tissue-Specific Effects on Robustness of an Enhancer's Activity

- C/EBPα Is Required for Long-Term Self-Renewal and Lineage Priming of Hematopoietic Stem Cells and for the Maintenance of Epigenetic Configurations in Multipotent Progenitors

- The SPF27 Homologue Num1 Connects Splicing and Kinesin 1-Dependent Cytoplasmic Trafficking in

- Down-Regulation of eIF4GII by miR-520c-3p Represses Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma Development

- Genome Sequencing Highlights the Dynamic Early History of Dogs

- Re-sequencing Expands Our Understanding of the Phenotypic Impact of Variants at GWAS Loci

- Meta-Analysis Identifies Gene-by-Environment Interactions as Demonstrated in a Study of 4,965 Mice

- , a -Antisense Gene of , Encodes a Evolved Protein That Inhibits GSK3β Resulting in the Stabilization of MYCN in Human Neuroblastomas

- A Transcription Factor Is Wound-Induced at the Planarian Midline and Required for Anterior Pole Regeneration

- A Comprehensive tRNA Deletion Library Unravels the Genetic Architecture of the tRNA Pool

- A PNPase Dependent CRISPR System in

- Genomic Confirmation of Hybridisation and Recent Inbreeding in a Vector-Isolated Population

- Zinc Finger Transcription Factors Displaced SREBP Proteins as the Major Sterol Regulators during Saccharomycotina Evolution

- GATA6 Is a Crucial Regulator of Shh in the Limb Bud

- Tissue Specific Roles for the Ribosome Biogenesis Factor Wdr43 in Zebrafish Development

- A Cell Cycle and Nutritional Checkpoint Controlling Bacterial Surface Adhesion

- High Risk Population Isolate Reveals Low Frequency Variants Predisposing to Intracranial Aneurysms

- E3 Ubiquitin Ligase CHIP and NBR1-Mediated Selective Autophagy Protect Additively against Proteotoxicity in Plant Stress Responses

- Evolutionary Rate Covariation Identifies New Members of a Protein Network Required for Female Post-Mating Responses

- 3′ Untranslated Regions Mediate Transcriptional Interference between Convergent Genes Both Locally and Ectopically in

- Single Nucleus Genome Sequencing Reveals High Similarity among Nuclei of an Endomycorrhizal Fungus

- Metabolic QTL Analysis Links Chloroquine Resistance in to Impaired Hemoglobin Catabolism

- Notch Controls Cell Adhesion in the Drosophila Eye

- AL PHD-PRC1 Complexes Promote Seed Germination through H3K4me3-to-H3K27me3 Chromatin State Switch in Repression of Seed Developmental Genes

- Genomes Reveal Evolution of Microalgal Oleaginous Traits

- Large Inverted Duplications in the Human Genome Form via a Fold-Back Mechanism

- Variation in Genome-Wide Levels of Meiotic Recombination Is Established at the Onset of Prophase in Mammalian Males

- Age, Gender, and Cancer but Not Neurodegenerative and Cardiovascular Diseases Strongly Modulate Systemic Effect of the Apolipoprotein E4 Allele on Lifespan

- Lifespan Extension Conferred by Endoplasmic Reticulum Secretory Pathway Deficiency Requires Induction of the Unfolded Protein Response

- Is Non-Homologous End-Joining Really an Inherently Error-Prone Process?

- Vestigialization of an Allosteric Switch: Genetic and Structural Mechanisms for the Evolution of Constitutive Activity in a Steroid Hormone Receptor

- Functional Divergence and Evolutionary Turnover in Mammalian Phosphoproteomes

- A 660-Kb Deletion with Antagonistic Effects on Fertility and Milk Production Segregates at High Frequency in Nordic Red Cattle: Additional Evidence for the Common Occurrence of Balancing Selection in Livestock

- Comparative Evolutionary and Developmental Dynamics of the Cotton () Fiber Transcriptome

- The Transcription Factor BcLTF1 Regulates Virulence and Light Responses in the Necrotrophic Plant Pathogen

- Crossover Patterning by the Beam-Film Model: Analysis and Implications

- Single Cell Genomics: Advances and Future Perspectives

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- GATA6 Is a Crucial Regulator of Shh in the Limb Bud

- Large Inverted Duplications in the Human Genome Form via a Fold-Back Mechanism

- Differential Effects of Collagen Prolyl 3-Hydroxylation on Skeletal Tissues

- Affects Plant Architecture by Regulating Local Auxin Biosynthesis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání