-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaTelomerase Is Required for Zebrafish Lifespan

Telomerase activity is restricted in humans. Consequentially, telomeres shorten in most cells throughout our lives. Telomere dysfunction in vertebrates has been primarily studied in inbred mice strains with very long telomeres that fail to deplete telomeric repeats during their lifetime. It is, therefore, unclear how telomere shortening regulates tissue homeostasis in vertebrates with naturally short telomeres. Zebrafish have restricted telomerase expression and human-like telomere length. Here we show that first-generation tert−/− zebrafish die prematurely with shorter telomeres. tert−/− fish develop degenerative phenotypes, including premature infertility, gastrointestinal atrophy, and sarcopaenia. tert−/− mutants have impaired cell proliferation, accumulation of DNA damage markers, and a p53 response leading to early apoptosis, followed by accumulation of senescent cells. Apoptosis is primarily observed in the proliferative niche and germ cells. Cell proliferation, but not apoptosis, is rescued in tp53−/−tert−/− mutants, underscoring p53 as mediator of telomerase deficiency and consequent telomere instability. Thus, telomerase is limiting for zebrafish lifespan, enabling the study of telomere shortening in naturally ageing individuals.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003214

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003214Summary

Telomerase activity is restricted in humans. Consequentially, telomeres shorten in most cells throughout our lives. Telomere dysfunction in vertebrates has been primarily studied in inbred mice strains with very long telomeres that fail to deplete telomeric repeats during their lifetime. It is, therefore, unclear how telomere shortening regulates tissue homeostasis in vertebrates with naturally short telomeres. Zebrafish have restricted telomerase expression and human-like telomere length. Here we show that first-generation tert−/− zebrafish die prematurely with shorter telomeres. tert−/− fish develop degenerative phenotypes, including premature infertility, gastrointestinal atrophy, and sarcopaenia. tert−/− mutants have impaired cell proliferation, accumulation of DNA damage markers, and a p53 response leading to early apoptosis, followed by accumulation of senescent cells. Apoptosis is primarily observed in the proliferative niche and germ cells. Cell proliferation, but not apoptosis, is rescued in tp53−/−tert−/− mutants, underscoring p53 as mediator of telomerase deficiency and consequent telomere instability. Thus, telomerase is limiting for zebrafish lifespan, enabling the study of telomere shortening in naturally ageing individuals.

Introduction

Telomeres constitute the ends of linear chromosomes, comprising DNA (TTAGGG)n repeats and its associated proteins, known as the shelterin complex [1]. Telomeres provide protection against erosion of chromosome-ends that occurs with each cell division as a result of the “end-replication problem” [2]. Additionally, they prevent the recognition of chromosome termini as deleterious DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). If this function fails, chromosome-ends induce DNA damage responses (DDRs) that comprise the activation of p53 [3]. Telomerase, a reverse transcriptase, counteracts chromosome-end depletion by elongating telomeres through the action of its catalytic unit (Tert) and RNA template (Terc) [4], [5]. Because telomerase expression is restricted in human somatic cells, telomeres shorten during our lifespan [6]. Human somatic cells lose around 100 base pairs of telomeres per population doubling [7], leading to a limit of about 50–80 cell divisions in culture, known as the Hayflick limit [8].

Impaired tissue homeostasis is at the core of several human diseases, including ageing-associated degeneration [9]. Premature ageing syndromes such as Werner, Hutchinson-Gilford and Dyskeratosis Congenita (DC) share the common trait of shorter telomeres, accelerated ageing and reduced lifespan [10]. DC, in particular, can be caused by mutations in the telomerase tert or terc genes, and there is a direct correlation between telomere length and disease severity [11].

Telomeres become dysfunctional due to critical shortening, oxidative damage or uncapping [12]. Dysfunctional telomeres induce DDRs characteristic of damage-induced DSBs [13]. Depending on the cell type, level of DNA damage and p53/p63/p73 status, dysfunctional telomeres initiate an apoptotic response or a G1 cell cycle arrest, leading to senescence [14]. While high levels of DNA damage are thought to trigger apoptosis via puma (p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis) activation, low levels are most likely to cause cell cycle arrest via p21 activation [14]. Telomere maintenance, therefore, dictates survival and replicative potential of cells, directing tissue homeostasis.

Most of our knowledge of vertebrate telomeres comes from inbred mice strains with long telomeres [15]. Several generations of intercrossing between telomerase deficient mice are needed before telomere shortening has a noticeable impact at the organism level [16]–[18]. Data from late generation telomerase knockout mice suggest that cell senescence [19] and/or apoptosis [20] play a critical role in the observed degenerative phenotypes. Either puma [21] or p21 [19] deletion separately ameliorate degenerative phenotypes observed in late generation telomerase knock-out (KO) mice. Stem cell exhaustion via puma-mediated apoptosis is crucial in limiting the life span of late generation terc knockout mice [21]. Whether artificially shortening telomeres in the long telomere mouse strains or the use of other genetic backgrounds with shorter telomeres reproduces the way in which human tissues respond to telomere lifetime erosion remains an open question.

Recently, a wild-derived inbred mouse strain (Cast/EiJ) has been proposed as a better model for understanding telomere dysfunction in humans, given its shorter telomeres [22]. Telomerase deficiency in this strain gives rise to first generation defects similar to the ones observed in human DC syndromes [22]. Thus, telomere length may be limiting for Cast/EiJ longevity, making it a promising alternative to the current mouse models. However, molecular responses to dysfunctional telomeres in this model remain to be elucidated.

It is critical to investigate complementary vertebrate models to understand what is the most likely impact of telomere exhaustion in a biological system that, like humans, has evolved to have telomere length as an internal cell division “clock”. Zebrafish, a teleost fish that exhibits gradual senescence, is a promising vertebrate model for telomere biology. Contrary to the inbred laboratory mouse, zebrafish have heterogeneous telomeres of human-like length [23]. Despite detection of telomerase activity in various tissues, zebrafish telomeres shorten with age [24]. Like humans [6], telomerase expression in zebrafish somatic cells is not sufficient to prevent telomere shortening [24]. Telomere shortening was associated with impaired regenerative responses in the aged fish, denoting a role for telomere in homeostasis of adult tissues. Accordingly, a zebrafish mutant for the telomere repeat binding factor 2 (Terf2) accumulates senescence markers and this is accompanied by central nervous system necrosis and decreased survival [25].

Here we show that first generation telomerase deficient zebrafish have shorter telomeres than wild-type siblings and die prematurely. tert−/− fish are born and develop normally until adulthood, but progressively develop accelerated degenerative phenotypes characteristic of disrupted tissue homeostasis. These include premature infertility, gastrointestinal atrophy, loss of body mass, increased inflammation and sarcopaenia at terminal stages. Underlying these phenomena is a sustained decrease in cell proliferation, an acute apoptotic response and accumulation of DDR foci. Removal of p53 function rescues cell proliferation, but not apoptosis, in high turnover tissues, such as testes and gut. This implicates p53 as a critical mediator of telomerase-dependent proliferative defects observed in tert−/−. Thus telomerase and consequent telomere shortening play a key and limiting role in tissue maintenance during a zebrafish lifespan.

Results

Telomerase mutant zebrafish have shorter telomeres

In order to examine the consequences of telomerase depletion in zebrafish, we used the currently available but yet uncharacterized, terthu3430 line produced by ENU-tilling screen at Utrecht University, Netherlands [26]. This telomerase mutant line carries a T→A transition in the second exon of the tert gene giving rise to an early stop codon. For simplicity, we will refer to the terthu3430 homozygous mutant strain as tert−/−.

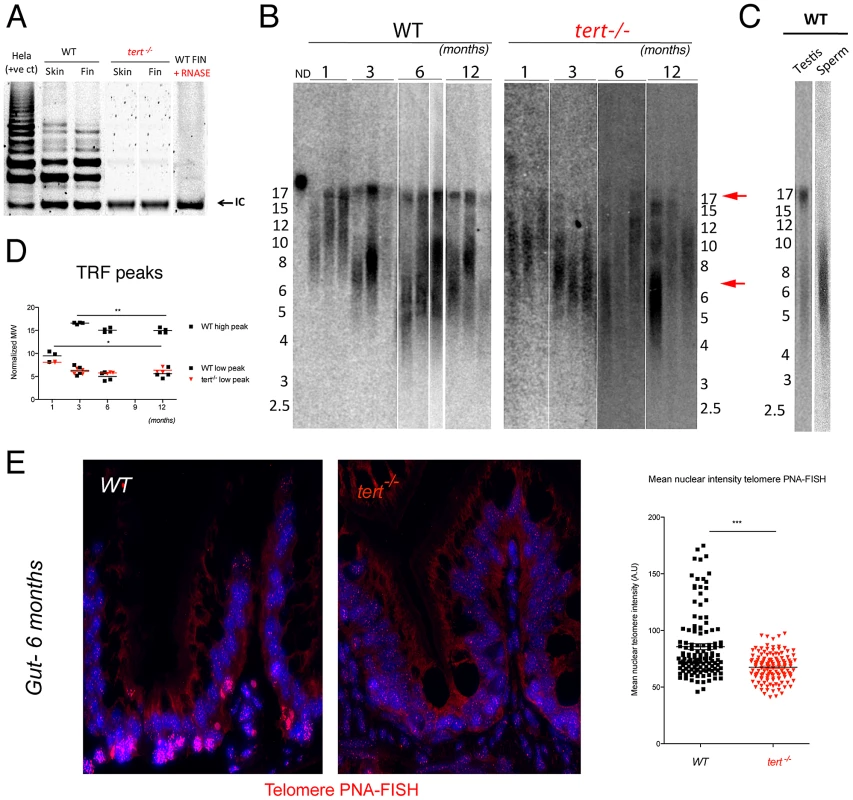

To test whether tert−/− mutants had a functional telomerase, we performed the commonly used Telomere Repeat Amplification (TRAP) assay [27]. We observed no amplification bands corresponding to telomere elongation in the TRAP assay as compared to tert+/+ controls (Figure 1A), indicating that tert−/− mutants lack active telomerase. The consequence of absence of telomerase is continuous telomere shortening. Accordingly, Telomere Restriction Fragment (TRF) analysis by Southern blot revealed a significant reduction in average telomere size (Figure 1B and 1D). This attrition was highlighted by the significant reduction in intensity of the higher molecular weight TRFs (∼16 Kbp), as compared to tert+/+ siblings (Figure 1B), in all tissues tested (Figure S1). Additionally, a lower molecular weight TRF population of approximately 6 Kbp is present in both tert+/+ and tert−/− (arrows in Figure 1B and 1D and Figure S1). Zebrafish telomere sequences are exclusively terminal, as all TRF signal disappears after BAL-31 (5′ - and 3′-exonuclease) digestion (Figure S1C).

Fig. 1. Telomerase mutant zebrafish have shorter telomeres than WT siblings.

A) Representative image of TRAP assay showing that telomerase is not active in the tert−/− zebrafish, as compared to tert+/+ siblings. Here shown are caudal fin and skin protein extracts. Hela cell extract is shown as positive control. N = 4. B) Representative image of restriction fragment analysis of caudal fin genomic DNA of 3 different individuals at different ages, by southern blot (random primer-labelled telomeric probe (CCCTAA)12 32P-dCTP). tert+/+ Zebrafish have heterogeneous telomeres, with two distinct peaks of different lengths. In tert+/+ the highest peak (∼16 Kb, top red arrow) becomes more distinct after 1 months of age and decreases in length over-time (B and D). The lowest peak of telomere intensity also decreases in length (bottom red arrow, B and D). tert−/− zebrafish have shorter telomeres than tert+/+ siblings in different tissues (see also Figure S1A and S1B), observed by the decrease in length of the higher TRF peak. The shortest TRF peaks accompany those of tert+/+ siblings, and decrease over-time at similar rates. C) Testes fractionation in tert+/+ reveals the two-telomere length populations in whole testes, whereas mature sperm only shows the shorter TRF smear of about 6 Kb, suggesting different telomere lengths in different cells within a tissue. D) TRF mean sizes were calculated as described in [50]. E) Telomere PNA-FISH in 6-month-old gut tissue shows cells with different telomere intensities in the wild type, mainly localizing to the proliferative niche. In contrast tert−/− mutants display cells with less bright and more homogeneous telomere intensity. The presence of two telomere populations in tert+/+ zebrafish is suggestive of restricted telomerase activity. Accordingly, the lower population of TRFs shortens over-time both in tert+/+ and tert−/− (Figure 1B, 1D, 1E). We also observe discrete but significant shortening of the higher TRF population in tert+/+, suggesting that telomerase activity is not sufficient to prevent telomere loss. This bimodal TRF pattern was observed in all tert+/+ tissues except for blood, where we detect a single TRF of higher molecular weight (∼16 kbp; Figure S1A, S1B) and in sperm, where we observed a single TRF signal of approximately 6 Kbp (Figure 1C).

Consistent with our TRF analysis, we observe the presence of cell populations with different telomere intensities by telomere-PNA FISH (Figure 1E). This technique clearly shows that tert+/+ tissues, such as the gut, are composed of cells with different telomere intensities. Cells with high intensity in telomere signal localize primarily to the base of the villus, suggestive of being early precursor cells. In contrast, tert−/− tissue shows more homogeneous, low intensity, telomere-PNA FISH. Such pattern mirrors our TRF results of high and low telomere lengths and suggests that telomerase expression is restricted to certain cells types as observed in humans [6].

Telomerase zebrafish mutants die prematurely of body wasting

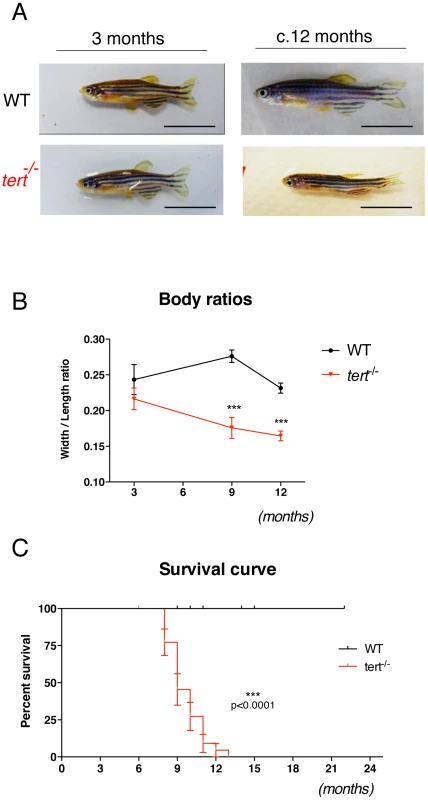

First generation tert−/− mutants, resulting from a heterozygous incross, are born healthy and develop past sexual maturity without any obvious defects (Figure 2A). From 4–6 months onwards, we observed a consistent gradual decrease in body mass reflected in declining width/length body ratios (Figure 2B). This wasting phenotype was observed in all tert−/− individuals at their time of death (n = 24). In contrast, we were unable to detect wasting in any of the tert+/+ siblings (n = 45) until the end of the experiment (22 months). Wasting (also known as cachexia) is a common phenotypic alteration in aged organisms, including humans, and is usually associated with muscle sarcopaenia and frailty syndromes [28].

Fig. 2. First-generation telomerase mutant zebrafish show progressive body wasting and die prematurely.

A) Representative images of tert+/+ and tert−/− zebrafish show that tert−/− fish are born and develop normally until reproductive maturity at ∼3 months of age, but progressively lose body mass since then, B) represented as an overall reduction in width/length ratios as compared to wild-type siblings N≥6 p<0.001. This progressive wasting phenotype is accompanied by increase in mortality. C) Kaplan-Meier curve showing that tert−/− zebrafish have significantly reduced survival when compared to tert+/+ siblings (AVG lifespan 9 versus >22 months (p<0.005)). N = 24 tert−/−; N = 45 tert+/+. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. Scale bar = 1 cm. Progressive wasting in tert−/− fish was accompanied by an increase in mortality (Figure 2C). tert−/− mutants die significantly earlier than their tert+/+ siblings (average lifespan of 9 versus >22 months, p<0.005). Due to a male sex bias in our crosses that affected all tert+/+, tert+/− and tert−/− progeny, we were unable to obtain significant numbers for female analysis and so the data hereafter presented reflects the study of males alone. Sex determination in zebrafish is still largely unknown, but it is thought to be highly influenced by environmental factors [29].

Telomerase depletion produces a time - and tissue-specific degeneration

Histopathological analysis of different tissues revealed important phenotypic alterations in tert−/− mutants. Telomere shortening has been shown to affect primarily high turnover tissues in both humans [10] and late generation terc KO mice [30]. Accordingly, we noticed an order of events during tissue atrophy of tert−/− zebrafish. tert−/− zebrafish testes were the first to depict histopathological abnormalities; second were the liver, intestine, gills and pancreas; the third to be affected was the kidney and remaining organs, including the muscle (Figure 3, Figure 4 and summarized in Table S2).

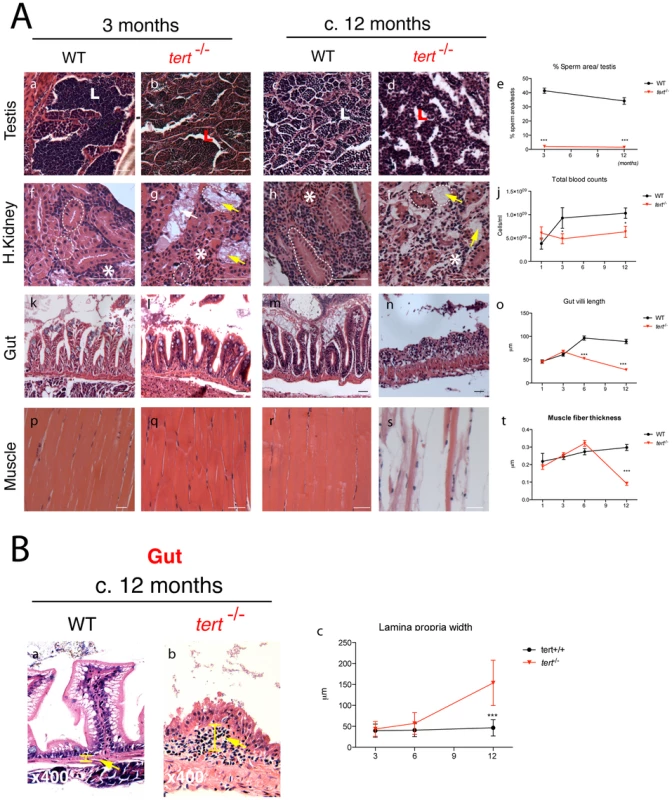

Fig. 3. Telomerase depletion leads to a time- and tissue-dependent degeneration.

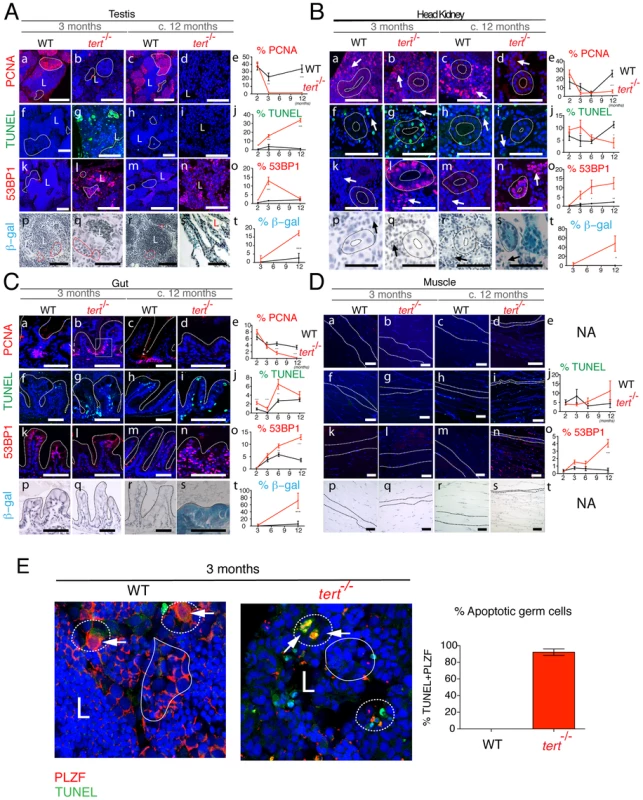

A) Representative images of tissue sections of tert−/− Zebrafish and tert+/+ siblings, stained with hematoxilin-eosin. tert−/− zebrafish show progressive tissue deterioration. Severe histological abnormalities are first evident in proliferative tissues (testes, gut and head kidney marrow) and later in non-proliferative (muscle). tert−/− Zebrafish show reduced sperm in testes lumen (L) (Ab and d; p<0.001). The head kidney shows progressive defects in the marrow area (white asterisks) (Ag and i, which correlates with a decrease in total blood (p = 0.0228) cells when compared to tert+/+ siblings from an early age (3 months, N≥5) (Aj). Mesonephric tubules in the head kidney also degenerate in tert−/− (Ag and i dashed outlines). Gut atrophy in tert−/−, reflected as decreased villi length (Al, n, o), becomes significant from the age of 6 months (p<0.001). Muscle fibres are significantly thinner (p<0.001) at terminal time-points (c.12 months) (Aq, s, t, dashed outline); N≥5. B) tert−/− display progressive thickening of gut lamina propria, indicative of inflammation (Bb, c, yellow bar and arrow, N≥4). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. Scale bar = 50 µm. Fig. 4. Proliferative tissue degeneration is accompanied by a sustained decrease in proliferation, acute apoptotic responses, and progressive accumulation of DDR foci.

Representative immunofluorescence images of tissue sections in F1 tert−/− and tert+/+ zebrafish show levels of proliferation (PCNA), apoptosis (TUNEL), DNA damage (53BP1) and senescence-associated β–galactosidase at the ages of 3 to c.12 months. Proliferative tissues such as A) testes, B) head kidney and C) gut sections show sustained significant decrease in proliferation in tert−/− as compared to tert+/+ siblings (panels b, d and e) (p<0.001) and an acute apoptotic response at 3 months of age (p<0.001), which clears by c. 12 months (panels g, i and j). This is accompanied by a progressive increase in 53BP1 foci, reaching maximum significance at c. 12 months (panels l, n and o; p<0.001). This coincides with the presence of senescence-associated β –galactosidase at c.12 months (panels s and t). Note in the testes that most of apoptosis (TUNEL) seems to localize to the spermatogenic zone (Ag, dashed outline) and panel E, where we see an increase in TUNEL-labelled germ cells, labelled with the specific marker PLZF. Most of DNA damage (53BP1) locates to the proliferative zone of maturing spermatocytes (Al, uniform outline). Note in the head kidney B), both the proliferative haematopoietic tissue (Ba–d, arrows) and the non-proliferative mesonephric tubule epithelium (Ba–d, dashed outline) are affected by increased apoptosis (Bg, I, j), DNA damage (Bl, n and o) and senescence (Bs and t) in the tert−/−. D) Muscle, a largely non-proliferative tissue (Da–d) shows significant accumulation of DNA damage foci at in tert−/− by the age of c.12 months (Dn and o; p<0.001), when the muscle fibres are already atrophic (Dn, dashed outline). Quantifications were performed in at least 3 different fields of view of at least 3 different individuals of each genotype at the different time-points indicated in the graphs. Gut IF quantifications were calculated as number of positive cells per “crypt” zone (C) uniform square outline exemplified). Other tissues' IF was quantified as overall % positive cells. β-galactosidase was quantified as % area stained blue, per field of view. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. Scale bar = 50 µm. Testes of tert−/− zebrafish show a severe imbalance, as early as 3 months of age, in size and ratio of the main spermatogenic classes: spermatogonia, spermatocytes and spermatids [31]. There was an atrophy of the differentiating and maturing spermatogenic stages (Figure 3Ab and 3Ad). This atrophy is consistent with what was observed in spermatogonia in the late generation terc KO mice [30] and tert KO mice [18], [32]. A consequence of these alterations is the significant decrease in mature sperm volume observed in the lumen of seminiferous tubules of tert−/− male fish (L in Figure 3Ab and 3Ad). Consistently, we observed that tert−/− zebrafish males are prematurely infertile (Figure S2). The scarce progeny originating from a tert−/− incross was not viable and displayed embryonic deficiencies consistent with lack of cell proliferation, such as failure to close the neural tube and body truncations (Figure S2). Female tert−/− mutants were initially fertile (Figure S2) but became infertile later in life, when body wasting became apparent (data not shown).

Similar to telomerase deficiencies in humans and mice with critically short telomeres, tert−/− zebrafish display blood defects, translated into a mild but significant decrease in total blood cells (Figure 3Aj). Accordingly, histopathological analysis of the head kidney marrow (the major hematopoietic organ in fish) revealed a trend towards depletion of the hematopoietic compartment, particularly at late time points (asterisks in Figure 3Ai). Other proliferative tissues, such as the gut, show a progressive decrease in microvilli length (Figure 3Al,n,o) and increased inflammation of the lamina propria, significant after the age of 6 months (Figure 3Bc). These changes progress into severe gut degeneration (necrotizing enteritis), most visible at terminal stages (Figure 3An). During this period, we observed a pervasive mucosal thickening (sloughing; bar in Figure 3Bb), denuded villous tips, and inflammatory cell infiltration (arrows in Figure 3Bb). Atypical intestinal epithelium compatible with severe dysplasia was also observed (data not shown).

Low-proliferative tissues such as the muscle (Figure 3Ap–t and Figure 4Dp–t) and liver (data not shown) only exhibit obvious degeneration at the latest time points of the tert−/− zebrafish lifespan. We observed acute and significant muscle degeneration (sarcopaenia) at terminal stages (Figure 3As) consistent with the wasting phenotype (Figure 2A and 2B). These observations suggest that low-proliferative tissues are also targets of telomere dysfunction, as has been suggested before in mice models [33]–[35]. Whether this happens in a cell autonomous or non-autonomous manner remains to be clarified.

Severe gut degeneration (necrotizing enteritis) is a prime candidate for cause of death of tert−/− zebrafish. This could account for mal-nutrition, consequent loss of muscle and wasting. Consistently, exocrine pancreas of 12 month-old tert−/− zebrafish lacked large numbers of bright secretory granules, characteristic of actively feeding fish (Table S2). Lastly, we did not observe neoplastic changes in any of the tissues studied.

Tissue atrophy is preceded by lack of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and senescence

Telomere depletion was shown to affect primarily proliferative tissues with a high cell turnover. Quantification of cell division in tert−/− zebrafish using the S-phase marker PCNA revealed an overall decrease in cell division in proliferative tissues (Figure 4A–4C, panels a–e). This was particularly clear in the spermatogenic zone of the testes (filled-line outline in Figure 4Ab,d). Spermatogenesis is initiated by the proliferation of stem cells (Spermatogonia A and progenitor stem cells - Spermatogonia B). These are responsible for the continuous renewing of this highly proliferative tissue. Decrease in cell proliferation in the testis was accompanied by an initial burst in apoptosis, as detected by TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL; dashed line outline in Figure 4Ag). This burst of apoptosis in tert−/− is restricted to the germinal centres, as shown by co-localization with the specific germ cell marker PLZF [36] (Figure 4E), explaining why tissue homeostasis is compromised in these animals, as shown in mice [37]. Initial increase of apoptosis was followed by a progressive decline, losing statistical significance at later time points (Figure 4Ag,i,j).

A second player in disrupting tissue integrity is the accumulation of senescent cells [9], [20], [38]. We observed a progressive increase in cells presenting strong 53BP1 foci in tert−/− testes, indicative of persistent or irreparable DNA damage (Figure 4Al,n,o and Figure S3d). Persistent 53BP1 has been described as a hallmark of cell senescence, accumulating preferentially at telomeres [39], [40]. Consistently, we observed an increase in senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining at later time points (Figure 4As,t).

Similar to testes, both kidney marrow and gut show an initial up-regulation of apoptosis, statistically significant at 3 months old (Figure 4Bg,j and 4Cg,j). The head kidney in zebrafish has a dual function of excretion and haematopoiesis [41]. Apoptosis is up regulated both in the kidney mesonephric tubules and haematopoietic tissue (dashed outline and arrow, respectively, in Figure 4Bg), consistent with the decreased blood cell levels observed (Figure 3Aj). In the gut, this increase in apoptosis is accompanied by decreased proliferation at the base of the villi, statistically significant from 6 months onwards (Figure 4Ca–e). Decreased cell proliferation in the gut is accompanied by progressive increase in DNA damage foci, as detected by 53BP1 staining (Figure 4Ck–o and Figure S3b). In all proliferative tissues, 53BP1 staining reached its peak at terminal stages, where no apoptosis is detected (Figure 4A–4C, panels n,o). Senescent cells have been described to be resistant to apoptosis [42]. Consistently, in proliferative tissues, we noticed that 53BP1 foci containing cells corresponded to regions where SA-β-gal staining was evident (panels n and s in Figure 4A–4C).

Low-proliferative tissues, such as the muscle, only show significant defects at later time points. Muscle sarcopaenia is accompanied by an acute increase in cells stained with 53BP1 (Figure 4Dn,o). Contrary to proliferative tissues, 53BP1 staining in the muscle (Figure 4Dn) did not correlate with an increase in cell senescence, as we were unable to detect significant SA-β-gal staining (Figure 4Ds,t).

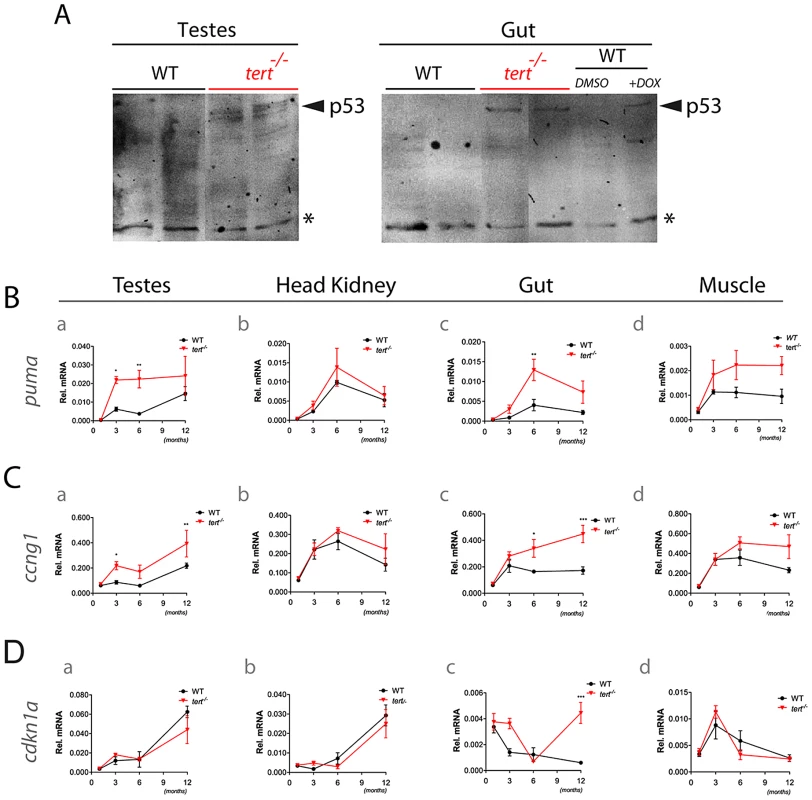

p53 expression leads to puma-apoptosis and ccng1-senescence

In late generation telomerase KO mice, telomere shortening activates a p53 dependent DDR that culminates in apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest [21]. Similarly, we observed a p53 response in proliferative tissues of tert−/− zebrafish, such as the testes and gut (Figure 5A). This response is accompanied by an acute up-regulation of puma (Figure 5B a, c). Consistent with our apoptosis data, puma expression is reduced at later stages (c.12 months of age; Figure 5B a, c). In the gut, puma expression is replaced by sustained up-regulation of the cell cycle arrest targets cdkn1a and cyclin G1 (Figure 5Cc and 5Dc). Recently, cyclin G1 has been depicted as a p53-dependent target in zebrafish [43]. Consistently, up-regulation of cell cycle inhibitors through p53 activation led to G1 arrest and cell senescence. This has been described as recurrent phenomena in telomerase knockout murine tissues with dysfunctional telomeres [19]. Finally, we do not detect a significant p53 response in either the head kidney (an heterogeneous tissue), or in the muscle, a low-proliferative tissue.

Fig. 5. Tissue degeneration is accompanied by p53 induction with a puma acute response and sustained increase of cyclin G1 and cdkn1a expression.

A) Immunoblot analysis of p53 in 10-month old WT and tert−/− testes and gut lysates. 6 month-old WT zebrafish were injected with the DNA damaging agent doxorubicin to serve as positive control for p53 activation. Asterisk depicts a non-specific cross-reactive band that serves as loading control. RT-qPCR analysis showing expression of B) pro-apoptotic (puma) and cell cycle arrest targets (C) cyclin G1 and D) cdkn1a) in testes, head kidney, gut and muscle of 1, 3, 6 and c.12 months old WT and tert−/− zebrafish (N = 3 to 8 fish per genotype). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. Rel. mRNA refers to relative mRNA levels of each gene normalized to beta-actin. Elimination of tp53 function partially rescues tert−/− phenotypes

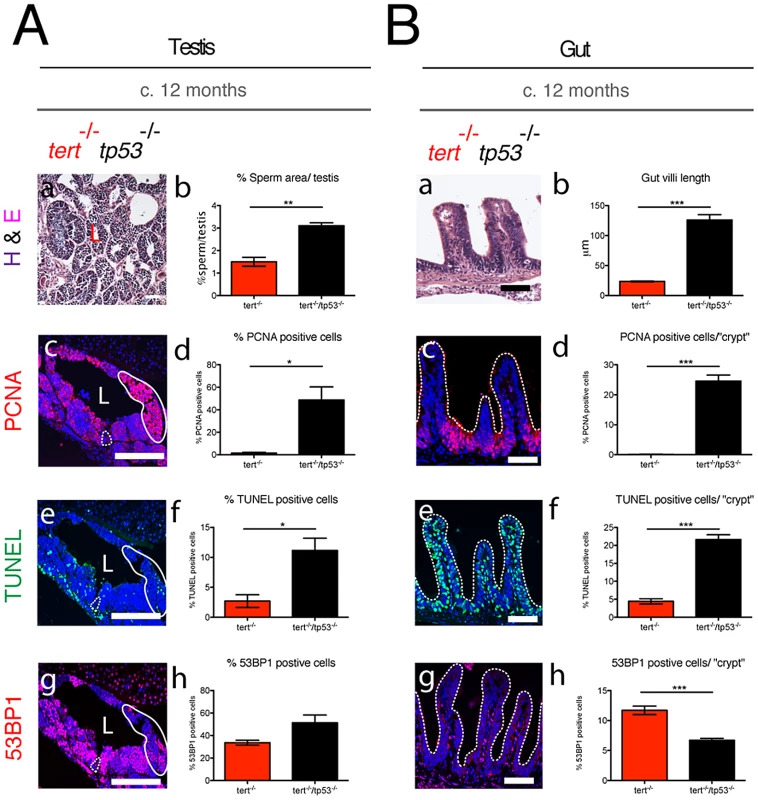

Our data show that telomerase deficiency in zebrafish gives rise to a p53 response, which ultimately culminates in cell cycle arrest (Figure 5), as observed in mice models [19]. Accordingly, tp53 deletion in mice was shown to ameliorate late generation tert KO phenotypes such as infertility [44]. To test whether p53 could be mediating the phenotypes observed in the tert−/− zebrafish, we crossed tert+/− with tp53−/− mutants (tp53 zdf1/zdf1 [45]) to produce double mutant tert−/−tp53−/− zebrafish. Mortality was significantly rescued, since at c.12 months, approximately 87% of tert−/− tp53−/− (N = 31) were alive, compared to 0% of tert−/− (N = 24). Immunofluorescence analysis in tert−/− tp53−/− proliferative tissues, revealed a dramatic rescue of cell proliferation in tissues that were most affected in tert−/− (testes and gut at c.12 months; Figure 6Ac, d and 6Bc, d).

Fig. 6. Elimination of tp53 function partially rescues tert−/− degeneration in proliferative tissues.

tert−/−tp53−/− show increased proliferation and apoptosis in both testes (Ac, d and e, f) and gut (Bc, d and e, f), as compared to tert−/− alone. In the testis, dashed outline represents spermatogenic zone, uniform outline proliferative zone of maturing spermatocytes and L the lumen where mature sperm is located. Elimination of tp53 function partially rescues mature sperm numbers (Aa, b) but completely rescues gut villi length (Ba, b). DNA damage as assessed by 53BP1 is maintained in tert−/−tp53−/− testes (Ag and h) and decreased in the gut (Bg and h), as compared to tert−/−. N≥3. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. Scale bar = 50 µm. This rescue in cell proliferation, however, was not sufficient to prevent testis atrophy and decreased number of mature sperm in tert−/− tp53−/− (Figure 6Aa,b). In contrast, rescue of the proliferative capacity in the gut of the double mutant clearly suppressed tert−/− gut villi length defects (Figure 6Ba,b). Despite an increased cell proliferation, this partial phenotypic rescue was accompanied by a significant increase in TUNEL-labelled cells in the tert−/− tp53−/− testis (Figure 6Ae, f) and gut (Figure 6Be, f) and maintenance or slight decrease in 53BP1 staining (Figure 6Ag, h and 6Bg, h). Thus, similar to the mouse model [44], p53 appears to mediate tert−/− phenotypes, as tp53 function depletion partially rescues or delays proliferative tissue degeneration observed in tert−/− zebrafish.

Discussion

Most of our knowledge on how vertebrates respond to short telomeres derives from laboratory mice, which are particularly different from humans not only in what respects telomere length, but also in cell immortalization and entry into senescence [46]. Zebrafish has recently emerged as an attractive complementary vertebrate model for studying telomere biology. Zebrafish possess short telomeres that decline with age and correlate with impaired tissue repair [24]. These observations motivated us to investigate the impact of telomere shortening in a biological system that, like humans, may have evolved to use telomere length as an internal cell division “clock”.

In our current work, we show that zebrafish telomerase mutants have premature degenerative phenotypes and decreased lifespan in the F1 generation. This contrasts with results obtained from telomerase KO mice, where degenerative phenotypes are only observed upon several generations of null crosses [16]–[18], [32]. The phenotypes we observe correlate well with the accumulation of short telomeres in tert−/− zebrafish, along with the disappearance of long telomeres. The two telomere populations may reflect different phenomena: 1) Presence of undigested genomic DNA; 2) Distinct populations of sub-telomeric sequences in the same cells or 3) Telomeres of different lengths present in distinct cells. We excluded the first two possibilities. Regarding the first point, undigested genomic DNA samples used as controls run at different sizes to the long TRF population (ND in Figure 1B). As for the second, different DNA methylation patterns in tert+/+ and mutants could account for the presence of unequal TRF populations due to restriction enzyme sensitivity. To exclude this possibility, we used a restriction enzyme insensitive to DNA methylation, Tru9I, and observed an equivalent TRF pattern (data not shown).

We favour the third hypothesis in which high molecular weight TRFs are derived from cells with longer telomeres present in the same tissue. This is probably the case for testes. Mature sperm from the same individual exhibited only the shorter TRF population, whereas whole testes tissue possesses both. Thus, cells that comprise the testes, other than sperm, must have longer telomeres and are maintained through time by telomerase. In contrast to mature sperm, blood cells isolated from WT individuals exhibited exclusively long telomeres. Consistent with other tissues, tert−/− zebrafish also have shorter telomeres in blood.

The hypothesis that tissues harbour cells with telomeres of different lengths is corroborated by our telomere PNA-FISH data. tert+/+ tissues, such as the gut, have cells with very different telomere intensities suggestive of shorter and longer telomeres. In contrast, tert−/− tissues show more homogeneous, low intensity, telomere-FISH. Notably, the majority of high-telomere-intensity cells in tert+/+ are located to the villus proliferative zone. These cells are generally absent in the tert−/− tissues, suggesting that cells with longer telomeres are strictly telomerase dependent. This suggests that telomerase is activated during embryogenesis and elongates telomeres in stem and early precursor cells. In tert−/− mutants this cannot happen and, even though cells proliferate initially, their telomeres shorten with each cell division giving rise to populations with shorter telomeres.

Together, our data support the idea that telomerase is limiting for zebrafish telomere maintenance, since we observe long and short telomeres in WT. Accordingly, shorter telomeres in tert+/+ are equivalent in size to the ones present in tert−/− zebrafish mutants. Shorter telomeres decline rapidly in the first three months of life both in tert+/+ and mutant fish, steadily decreasing for the next three to six months. This period of fast telomere shortening correlates with intense body growth preceding sexual maturity, was also observed in humans [47].

Our work describes a choreography of defects caused by telomere shortening in different tissues over-time. Consistent with the late generation telomerase KO mice, tert−/− zebrafish die prematurely due to an acute depletion of proliferating cells [30]. The choice between senescence and apoptosis in different cells may dictate the homeostatic threshold of individual tissues. This regulation will determine how the whole organism responds to telomere dysfunction. Proliferative tissues, such as testes, gut and kidney marrow are affected first. Progressive gut degeneration, with severe necrotizing enteritis, is the most likely cause for body wasting and premature death. We observed different apoptotic and senescent responses in different tissues. Immunofluorescence data identified an acute apoptotic response in proliferative tissues, namely the testes and gut and, to a lesser extent, in head kidney. This correlated with increased p53 levels and puma expression measured by RT-qPCR, particularly evident in proliferative tissues, such as the gut and testes. This increase in apoptosis is largely cleared at later time points, where DNA damage and senescence became the dominant phenomena in degenerated tert−/− tissues.

Interfering with tp53 function in tert−/−tp53−/− double mutants significantly increased proliferation in testes and gut, partially rescuing degenerative phenotypes. This indicates that p53 is a crucial mediator of the tert−/− degenerative phenotypes in proliferative tissues. Rescue of cell proliferation is not without consequence, since cells continue to accumulate 53BP1 DDR markers and enter apoptosis. However, the apoptotic response in tert−/−tp53−/− zebrafish differs from the tert/tp53 KO mice [44], [48], since apoptosis increases in comparison to tert−/− single mutants, whereas it decreases in mice. Increase in apoptosis in tert−/−tp53−/− zebrafish is mediated via p53-independent mechanisms, such as those under the control of p63 or p73 [14]. This suggests different mechanistic responses in zebrafish to telomere dysfunction to those in present in the mouse. It also reinforces the idea of separate homeostatic thresholds in different tissues, since p53 removal can only partially rescue testes integrity whereas gut villi length is completely restored in tert−/−tp53−/−.

In conclusion, zebrafish is a suitable model system to understand the effects of telomere shortening during lifespan of an organism. Telomerase is also required for low-proliferative tissue homeostasis. Whether this occurs in an autonomous or non cell-autonomous manner remains to be clarified. Nevertheless, tert−/− also have shorter telomeres in low-proliferative tissues, suggesting that both scenarios are possible. Reduced or absent telomerase may trigger whole body degeneration by blocking cell proliferation causing an unbalanced tissue homeostasis, and this is largely p53-mediated in high proliferating tissues.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All Zebrafish work was conducted according to National Guidelines and approved by the Ethical Committee of the DGV (Portuguese Veterinary Authority) and the European Union Regulatory Agency.

Zebrafish lines and maintenance

Zebrafish were maintained in accordance with Institutional and National animal care protocols. The telomerase mutant line tert AB/hu3430 possesses a T→A point-mutation in the tert gene. Zebrafish mutant lines were generated by N-Ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis (Utrecht University, Netherlands) [49]. Briefly, adult male zebrafish were randomly mutagenized with ENU and outcrossed against wild-type females. A library of F1 animals was then constructed. Genomic DNA of these F1 animals was isolated and arrayed in PCR plates. The DNA was screened for mutations in target genes by re-sequencing or TILLING. Animals with interesting mutations were recovered from the library (either re-identified from a pool of living F1 fish or recovered by in vitro fertilization with frozen sperm) and outcrossed against wild-type fish.

tert AB/hu3430 line is available at the ZFIN repository (ZFIN ID: ZDB-GENO-100412-50) from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC) and was generously provided to us by Dr. L. Bally-Cuif at the Zebrafish Neurogenetics Department, German Research Center for Environmental Health. The tertAB/hu3430 used in this paper was subsequently outcrossed 5 times with WT AB for clearing of potential background mutations derived from the random ENU mutagenesis from which this line was originated. The terthu3430/hu3430 homozygous mutant is referred in the paper as tert−/− and was obtained by incrossing our tertAB/hu3430 strain. Genotyping was performed by PCR of the tert gene (Table S1) followed by sequencing.

Overall characterization of tert−/− zebrafish was performed in F1 and F2 animals produced by tert+/− incross. All 1, 3 and 6 months analysis refers to F1 animals and 12 months analysis refers to F2. The premature death phenotype depicted in Figure 2C refers to F1 animals only

Telomerase activity assay (TRAP)

Telomerase activity was measured using the TRAPEZE Telomerase Detection Kit (S7700, Millipore, MA, USA) as described by manufacturers. Briefly, fish were sacrificed in 200 mg/L of MS-222 (Sigma, MO, USA) and a small portion of skin and fin were extracted from at least three different individuals of the different genotypes. Protein extracts were prepared by mashing tissue sections on ice with a micro-pestle in a 1.5 ml eppendorf tube, in 100 µl of CHAPS buffer with proteinase inhibitors cocktail (Sigma, MO, USA) and RNase inhibitor (200 U/ml, Invitrogen, UK). Cell extracts were incubated on ice for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 12,000×g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was quantified using Bradford protein quantification reagent (Pierce, IL, USA) and the TRAP assay was performed using 2 µg of protein/sample. The positive control was provided by the TRAP kit and used as described (S7700, Millipore, MA, USA).

Telomere restriction fragment (TRF) analysis by Southern blot

TRF analysis was performed as previously described [50]. Briefly, genomic DNA extraction from freshly isolated tissue was performed using extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8; 50 mM EDTA; 10 mM NaCl; 1% SDS) supplemented with 1 mg/ml Proteinase K (Sigma, MO, USA) and RNase A (1∶100 dilution, Sigma, MO, USA) prior to use. Samples were incubated at 50°C for 18 h in a thermomixer and genomic DNA was extracted by equilibrated phenol-chloroform (Sigma, MO, USA) and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction (Sigma, MO, USA). Blood genomic DNA was extracted with TNES buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.4; 100 mM NaCl; 10 mM EDTA; 0.5% SDS), supplemented with RNase A (1∶100 dilution, Sigma, MO, USA) prior to use. Samples were incubated 10 minutes at RT and extracted as for other tissues. Genomic DNA was quantified and normalized so the same amount of DNA was digested with RSAI and HINFI enzymes (NEB, MA, USA) as described previously [50] for 12 h at 37°C. BAL31 (NEB, MA, USA) digestion was performed at 30°C for different time points. Samples were ran on a 20 cm 0.6% agarose gel, in 0.5% TBE buffer, at 4°C for 17 h at 110 constant voltage. Southern blotting was performed as previously described [51].

Histological preparation and phenotypic analysis

Fish were sacrificed as described above, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and decalcified in 0.5 M EDTA for 24–48 h at 4°c. Whole fish were then paraffin-embedded and 5 micrometer sections were stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin for histopathological analysis. Embryos were fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C as above and then placed in 100% methanol at 4°C before processing. After several washes in PBS (phosphate buffer saline) the embryos were cryoprotected on a sucrose 15%/PBS solution and then embedded in 7,5% pork skin gelatine (Sigma)/15% sucrose/PBS for one hour at 37°C. The 1 cm2 blocks were frozen in isopenthane/liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until sectioning. The embedded samples were cut in 12 um sections with a cryostat (Leica CM 3050S). Hematoxilin-Eosin staining was performed in serial cuts.

Immunofluorescence (IF) and confocal analysis

Whole fish slides were sub-boiled for 10 minutes at 800 W in a microwave in citrate buffer (10 mM Sodium Citrate, pH 6) for antigen retrieval. Slides were washed 3 times in dH20 for 5 minutes each, followed by TBST (Tween 0.1%) for 5 minutes. After washes, slides were blocked for 1 hour at RT in 0.25% BSA in PBST (Triton 0.3%). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit monoclonal antibodies against Proliferation Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 1∶50 dilution), 53BP1 (Life-span Biosciences, WA, USA, 1∶100) and anti-PLZF (Life-span Biosciences, WA, USA, 1∶100). Incubation with primary antibodies was performed overnight in the dark, at 4°C, followed by 5 minutes, 1 hour and two 10 minutes PBS washes. Secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, UK, 1∶500 dilution) was then applied overnight at 4°C, followed by final washes in PBS, as described for the primary antibody washes. Apoptosis was detected using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, SW) according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after de-parafinization, slides were incubated with 40 µg/ml Proteinase K in 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 30 minutes at 37°C. Slides were washed in 2×5 minutes in PBS and then incubated with TUNEL labelling mix (protocol indicated by the supplier). Washes were performed as previously described. Slides were incubated with TO-PRO3 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, UK, 1∶5000 dilution) and DAPI (Sigma, MO, USA, 1∶2000 dilution) nuclear staining for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark, followed by two 5 minutes' washes with PBS. Coverslips were then mounted with DAKO Fluorescence Mounting Medium (Sigma, MO, USA). Confocal images were acquired on Leica TCS SP5 II (Leica Microsystems, GER) equipped with Leica Las AF Lite software and with appropriate configurations for multiple colour acquisition. For quantitative and comparative imaging, equivalent image acquisition parameters were used.

Telomere PNA-FISH

Immuno-FISH was performed as in [39]. Briefly, zebrafish paraffin sections, processed as for IF were hydrated by incubation in 100% Histoclear, 100, 95 and 70% methanol for 5 min and in distilled water for 5 min. Whole fish slides were sub-boiled for 10 minutes at 800 W in a microwave in citrate buffer (10 mM Sodium Citrate, pH 6) for antigen retrieval. After cooling the slides were washed with distilled water for 5 min (2×). Slides were washed three times in PBS and dehydrated with 70, 90 and 100% ethanol for 3 min each. Sections were denatured for 5 min at 80°C in hybridization buffer (70% formamide (Sigma), 25 mM MgCl2, 1 M Tris pH 7.2, 5% blocking reagent (Roche)) containing 2.5 µg/ml Cy-3-labelled telomere specific (CCCTAA) peptide nuclei acid probe (Panagene), followed by hybridization for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. The slides were washed twice with 70% formamide in 2×SSC for 15 minutes, followed by 10 minutes wash with 2×SSC and PBS. Sections were incubated with DAPI (SIGMA), mounted and imaged. Z stacking was performed (a minimum of 40 optical slices with ×100 objective) followed by Image-J deconvolution.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay

β-galactosidase assay was performed as previously described [25]. Briefly, sacrificed zebrafish adults were fixed as before and then washed 3 times for 1 h in PBS-pH 7.4 and for a further 1 h in PBS-pH 6.0 at 4°C. β-galactosidase staining was performed for 24 h at 37°C in 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 2 mM MgCl2 and 1 mg/ml X-gal, in PBS adjusted to pH 6.0. After staining, fish were washed 3× for 5 minutes in PBS pH 7 and processed for de-calcification and paraffin embedding as before. Sections were stained with hematoxilin for nuclear detection and images were acquired in a bright field microscope (Leica DMLB2, GER).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Age - and sex-matched fish were sacrificed in 200 mg/L of MS-222 (Sigma, MO, USA) and portions of each tissue (gonads, gut, liver, head kidney and muscle) were retrieved and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA extraction was performed in TRIzol (Invitrogen, UK) by mashing each individual tissue with a pestle in a 1.5 ml eppendorff tube. After incubation at RT for 10 minutes in TRIzol, chlorophorm extractions were performed. Quality of RNA samples was assessed through BioAnalyzer (Agilent 2100, CA, USA). Transcription into cDNA was performed using random primers (20 µg) (Promega C1181, WI, USA). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix, ROX (Quanta, MD, USA) and an ABI 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). qPCRs were carried out in triplicate for each cDNA sample. Relative mRNA expression was normalized to beta-actin and rpl13 α (data not shown) mRNA expression using the ΔCT method (derived from the Livak & Schmittgen method, 2001). Primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

Immunoblot analysis

Each tissue was dissected and homogenized in HEPES buffer (HEPES 10 mM, KCl 300 mM, MgCl2 3 mM, CaCl2 100 mM, Triton X-100 0.45%, Tween-20 0.05%, pH 7.6) including complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). Cell extracts were incubated on ice and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and quantified using Bradford protein quantification reagent (Pierce). Loading mix was added to protein extracts, heated at 95°C for 5 minutes and loaded onto a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel (80 µg of protein/sample).

After electroblotting the gel onto a PVDF membrane, incubation was performed overnight at 4°C with anti-Tp53 (AnaSpec, 55342) specific for zebrafish, in TBS-T with 5% milk powder (using a 1∶300 dilution). Chemiluminescence detection was performed with an ECL KIT (Amersham).

Western blots were performed on WT and tert−/ − 10 month-old tissue samples (N = 3–4).

Doxorubicin assay

To induce a DNA-damage p53-dependent response, adult fish were anesthetized in MS-222 (Sigma) and doxorubicin (Sigma) was injected intraperitoneally. A dosage of 15 mg/kg body weight was used. Fish were allowed to recover for 24 h, after which they were sacrificed in 200 mg/L of MS-222 (Sigma) and the organs collected for analysis of p53 protein levels by western blot.

Statistical analysis

Immunofluorescence

Image edition was performed in Adobe Photoshop CS5.1. All statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism5, using Mann Whitney's unpaired t-test when only two points were compared. More than one point comparison over-time was performed by two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni post-correction. A critical value for significance of p<0.05 was used throughout the study.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism5, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-correction. A critical value for significance of p<0.05 was used throughout the study.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. de LangeT (2005) Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev 19 : 2100–2110.

2. LevyMZ, AllsoppRC, FutcherAB, GreiderCW, HarleyCB (1992) Telomere end-replication problem and cell aging. J Mol Biol 225 : 951–960.

3. d'Adda di FagagnaF, ReaperPM, Clay-FarraceL, FieglerH, CarrP, et al. (2003) A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature 426 : 194–198.

4. GreiderCW, BlackburnEH (1985) Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell 43 : 405–413.

5. GreiderCW, BlackburnEH (1989) A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature 337 : 331–337.

6. ForsythNR, WrightWE, ShayJW (2002) Telomerase and differentiation in multicellular organisms: turn it off, turn it on, and turn it off again. Differentiation 69 : 188–197.

7. KarlsederJ, SmogorzewskaA, de LangeT (2002) Senescence induced by altered telomere state, not telomere loss. Science 295 : 2446–2449.

8. HayflickL (1965) The Limited in Vitro Lifetime of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res 37 : 614–636.

9. CampisiJ, SedivyJ (2009) How does proliferative homeostasis change with age? What causes it and how does it contribute to aging? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64 : 164–166.

10. HoferAC, TranRT, AzizOZ, WrightW, NovelliG, et al. (2005) Shared phenotypes among segmental progeroid syndromes suggest underlying pathways of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60 : 10–20.

11. AlterBP, RosenbergPS, GiriN, BaerlocherGM, LansdorpPM, et al. (2012) Telomere length is associated with disease severity and declines with age in dyskeratosis congenita. Haematologica 97 : 353–359.

12. FerreiraMG, MillerKM, CooperJP (2004) Indecent exposure: when telomeres become uncapped. Mol Cell 13 : 7–18.

13. SahinE, DepinhoRA (2010) Linking functional decline of telomeres, mitochondria and stem cells during ageing. Nature 464 : 520–528.

14. RoosWP, KainaB (2006) DNA damage-induced cell death by apoptosis. Trends Mol Med 12 : 440–450.

15. ManningEL, CrosslandJ, DeweyMJ, Van ZantG (2002) Influences of inbreeding and genetics on telomere length in mice. Mamm Genome 13 : 234–238.

16. BlascoMA, LeeHW, HandeMP, SamperE, LansdorpPM, et al. (1997) Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell 91 : 25–34.

17. RudolphKL, ChangS, LeeHW, BlascoM, GottliebGJ, et al. (1999) Longevity, stress response, and cancer in aging telomerase-deficient mice. Cell 96 : 701–712.

18. ErdmannN, LiuY, HarringtonL (2004) Distinct dosage requirements for the maintenance of long and short telomeres in mTert heterozygous mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 6080–6085.

19. ChoudhuryAR, JuZ, DjojosubrotoMW, SchienkeA, LechelA, et al. (2007) Cdkn1a deletion improves stem cell function and lifespan of mice with dysfunctional telomeres without accelerating cancer formation. Nat Genet 39 : 99–105.

20. ArtandiSE, AttardiLD (2005) Pathways connecting telomeres and p53 in senescence, apoptosis, and cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 331 : 881–890.

21. SperkaT, SongZ, MoritaY, NalapareddyK, GuachallaLM, et al. (2012) Puma and p21 represent cooperating checkpoints limiting self-renewal and chromosomal instability of somatic stem cells in response to telomere dysfunction. Nat Cell Biol 14 : 73–79.

22. ArmaniosM, AlderJK, ParryEM, KarimB, StrongMA, et al. (2009) Short telomeres are sufficient to cause the degenerative defects associated with aging. Am J Hum Genet 85 : 823–832.

23. ElmoreLW, NorrisMW, SircarS, BrightAT, McChesneyPA, et al. (2008) Upregulation of telomerase function during tissue regeneration. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233 : 958–967.

24. AnchelinM, MurciaL, Alcaraz-PerezF, Garcia-NavarroEM, CayuelaML (2011) Behaviour of telomere and telomerase during aging and regeneration in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 6: e16955 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016955.

25. KishiS, BaylissPE, UchiyamaJ, KoshimizuE, QiJ, et al. (2008) The identification of zebrafish mutants showing alterations in senescence-associated biomarkers. PLoS Genet 4: e1000152 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000152.

26. WienholdsE, van EedenF, KostersM, MuddeJ, PlasterkRH, et al. (2003) Efficient target-selected mutagenesis in zebrafish. Genome Res 13 : 2700–2707.

27. KimNW, PiatyszekMA, ProwseKR, HarleyCB, WestMD, et al. (1994) Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 266 : 2011–2015.

28. ThomasDR (2007) Loss of skeletal muscle mass in aging: examining the relationship of starvation, sarcopenia and cachexia. Clin Nutr 26 : 389–399.

29. LiewWC, BartfaiR, LimZ, SreenivasanR, SiegfriedKR, et al. (2012) Polygenic sex determination system in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 7: e34397 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034397.

30. LeeHW, BlascoMA, GottliebGJ, HornerJW2nd, GreiderCW, et al. (1998) Essential role of mouse telomerase in proliferative organs. Nature 392 : 569–574.

31. GrierHJ, LintonJR, LeatherlandJF, De VlamingVL (1980) Structural evidence for two different testicular types in teleost fishes. Am J Anat 159 : 331–345.

32. MeznikovaM, ErdmannN, AllsoppR, HarringtonLA (2009) Telomerase reverse transcriptase-dependent telomere equilibration mitigates tissue dysfunction in mTert heterozygotes. Dis Model Mech 2 : 620–626.

33. Tomas-LobaA, FloresI, Fernandez-MarcosPJ, CayuelaML, MaraverA, et al. (2008) Telomerase reverse transcriptase delays aging in cancer-resistant mice. Cell 135 : 609–622.

34. JaskelioffM, MullerFL, PaikJH, ThomasE, JiangS, et al. (2011) Telomerase reactivation reverses tissue degeneration in aged telomerase-deficient mice. Nature 469 : 102–106.

35. Bernardes de JesusB, VeraE, SchneebergerK, TejeraAM, AyusoE, et al. (2012) Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer. EMBO Mol Med

36. OzakiY, SaitoK, ShinyaM, KawasakiT, SakaiN (2011) Evaluation of Sycp3, Plzf and Cyclin B3 expression and suitability as spermatogonia and spermatocyte markers in zebrafish. Gene Expr Patterns 11 : 309–315.

37. HemannMT, RudolphKL, StrongMA, DePinhoRA, ChinL, et al. (2001) Telomere dysfunction triggers developmentally regulated germ cell apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell 12 : 2023–2030.

38. SharplessNE, DePinhoRA (2007) How stem cells age and why this makes us grow old. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 : 703–713.

39. HewittG, JurkD, MarquesFD, Correia-MeloC, HardyT, et al. (2012) Telomeres are favoured targets of a persistent DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence. Nat Commun 3 : 708.

40. FumagalliM, RossielloF, ClericiM, BarozziS, CittaroD, et al. (2012) Telomeric DNA damage is irreparable and causes persistent DNA-damage-response activation. Nat Cell Biol 14 : 355–365.

41. DavidsonAJ, ZonLI (2004) The ‘definitive’ (and ‘primitive’) guide to zebrafish hematopoiesis. Oncogene 23 : 7233–7246.

42. SalminenA, OjalaJ, KaarnirantaK (2011) Apoptosis and aging: increased resistance to apoptosis enhances the aging process. Cell Mol Life Sci 68 : 1021–1031.

43. DanilovaN, KumagaiA, LinJ (2010) p53 upregulation is a frequent response to deficiency of cell-essential genes. PLoS ONE 5: e15938 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015938.

44. ChinL, ArtandiSE, ShenQ, TamA, LeeSL, et al. (1999) p53 deficiency rescues the adverse effects of telomere loss and cooperates with telomere dysfunction to accelerate carcinogenesis. Cell 97 : 527–538.

45. BerghmansS, MurpheyRD, WienholdsE, NeubergD, KutokJL, et al. (2005) tp53 mutant zebrafish develop malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 407–412.

46. WrightWE, ShayJW (2000) Telomere dynamics in cancer progression and prevention: fundamental differences in human and mouse telomere biology. Nat Med 6 : 849–851.

47. AubertG, LansdorpPM (2008) Telomeres and aging. Physiol Rev 88 : 557–579.

48. FloresI, BlascoMA (2009) A p53-dependent response limits epidermal stem cell functionality and organismal size in mice with short telomeres. PLoS ONE 4: e4934 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004934.

49. WienholdsE, PlasterkRH (2004) Target-selected gene inactivation in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol 77 : 69–90.

50. KimuraM, StoneRC, HuntSC, SkurnickJ, LuX, et al. (2010) Measurement of telomere length by the Southern blot analysis of terminal restriction fragment lengths. Nat Protoc 5 : 1596–1607.

51. RogO, MillerKM, FerreiraMG, CooperJP (2009) Sumoylation of RecQ helicase controls the fate of dysfunctional telomeres. Mol Cell 33 : 559–569.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Comparative Genome Structure, Secondary Metabolite, and Effector Coding Capacity across PathogensČlánek TATES: Efficient Multivariate Genotype-Phenotype Analysis for Genome-Wide Association StudiesČlánek Secondary Metabolism and Development Is Mediated by LlmF Control of VeA Subcellular Localization inČlánek Human Disease-Associated Genetic Variation Impacts Large Intergenic Non-Coding RNA ExpressionČlánek The Roles of Whole-Genome and Small-Scale Duplications in the Functional Specialization of GenesČlánek The Role of Autophagy in Genome Stability through Suppression of Abnormal Mitosis under Starvation

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Model of High Sugar Diet-Induced Cardiomyopathy

- Comparative Genome Structure, Secondary Metabolite, and Effector Coding Capacity across Pathogens

- Emerging Function of Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Protein (Fto)

- Positional Cloning Reveals Strain-Dependent Expression of to Alter Susceptibility to Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice

- Genetics of Ribosomal Proteins: “Curiouser and Curiouser”

- Transposable Elements Re-Wire and Fine-Tune the Transcriptome

- Function and Regulation of , a Gene Implicated in Autism and Human Evolution

- MAML1 Enhances the Transcriptional Activity of Runx2 and Plays a Role in Bone Development

- Predicting Mendelian Disease-Causing Non-Synonymous Single Nucleotide Variants in Exome Sequencing Studies

- A Systematic Mapping Approach of 16q12.2/ and BMI in More Than 20,000 African Americans Narrows in on the Underlying Functional Variation: Results from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study

- Transcription of the Major microRNA–Like Small RNAs Relies on RNA Polymerase III

- Histone H3K56 Acetylation, Rad52, and Non-DNA Repair Factors Control Double-Strand Break Repair Choice with the Sister Chromatid

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Susceptibility Locus at 12q23.1 for Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Han Chinese

- Genetic Disruption of the Copulatory Plug in Mice Leads to Severely Reduced Fertility

- The [] Prion Exists as a Dynamic Cloud of Variants

- Adult Onset Global Loss of the Gene Alters Body Composition and Metabolism in the Mouse

- Fis Protein Insulates the Gene from Uncontrolled Transcription

- The Meiotic Nuclear Lamina Regulates Chromosome Dynamics and Promotes Efficient Homologous Recombination in the Mouse

- Genome-Wide Haplotype Analysis of Expression Quantitative Trait Loci in Monocytes

- TATES: Efficient Multivariate Genotype-Phenotype Analysis for Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Structural Basis of a Histone H3 Lysine 4 Demethylase Required for Stem Elongation in Rice

- The Ecm11-Gmc2 Complex Promotes Synaptonemal Complex Formation through Assembly of Transverse Filaments in Budding Yeast

- MCM8 Is Required for a Pathway of Meiotic Double-Strand Break Repair Independent of DMC1 in

- Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Endosymbionts of Herbivorous Insects Reveals Eco-Environmental Adaptations: Biotechnology Applications

- Integration of Nodal and BMP Signals in the Heart Requires FoxH1 to Create Left–Right Differences in Cell Migration Rates That Direct Cardiac Asymmetry

- Pharmacodynamics, Population Dynamics, and the Evolution of Persistence in

- A Hybrid Likelihood Model for Sequence-Based Disease Association Studies

- Aberration in DNA Methylation in B-Cell Lymphomas Has a Complex Origin and Increases with Disease Severity

- Multiple Opposing Constraints Govern Chromosome Interactions during Meiosis

- Transcriptional Dynamics Elicited by a Short Pulse of Notch Activation Involves Feed-Forward Regulation by Genes

- Dynamic Large-Scale Chromosomal Rearrangements Fuel Rapid Adaptation in Yeast Populations

- Heterologous Gln/Asn-Rich Proteins Impede the Propagation of Yeast Prions by Altering Chaperone Availability

- Gene Copy-Number Polymorphism Caused by Retrotransposition in Humans

- An Incompatibility between a Mitochondrial tRNA and Its Nuclear-Encoded tRNA Synthetase Compromises Development and Fitness in

- Secondary Metabolism and Development Is Mediated by LlmF Control of VeA Subcellular Localization in

- Single-Stranded Annealing Induced by Re-Initiation of Replication Origins Provides a Novel and Efficient Mechanism for Generating Copy Number Expansion via Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination

- Tbx2 Controls Lung Growth by Direct Repression of the Cell Cycle Inhibitor Genes and

- Suv4-20h Histone Methyltransferases Promote Neuroectodermal Differentiation by Silencing the Pluripotency-Associated Oct-25 Gene

- A Conserved Helicase Processivity Factor Is Needed for Conjugation and Replication of an Integrative and Conjugative Element

- Telomerase-Null Survivor Screening Identifies Novel Telomere Recombination Regulators

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Selection for Important Traits in Domestic Horse Breeds

- Coordinated Degradation of Replisome Components Ensures Genome Stability upon Replication Stress in the Absence of the Replication Fork Protection Complex

- Nkx6.1 Controls a Gene Regulatory Network Required for Establishing and Maintaining Pancreatic Beta Cell Identity

- HIF- and Non-HIF-Regulated Hypoxic Responses Require the Estrogen-Related Receptor in

- Delineating a Conserved Genetic Cassette Promoting Outgrowth of Body Appendages

- The Telomere Capping Complex CST Has an Unusual Stoichiometry, Makes Multipartite Interaction with G-Tails, and Unfolds Higher-Order G-Tail Structures

- Comprehensive Methylome Characterization of and at Single-Base Resolution

- Loci Associated with -Glycosylation of Human Immunoglobulin G Show Pleiotropy with Autoimmune Diseases and Haematological Cancers

- Switchgrass Genomic Diversity, Ploidy, and Evolution: Novel Insights from a Network-Based SNP Discovery Protocol

- Centromere-Like Regions in the Budding Yeast Genome

- Sequencing of Loci from the Elephant Shark Reveals a Family of Genes in Vertebrate Genomes, Forged by Ancient Duplications and Divergences

- Mendelian and Non-Mendelian Regulation of Gene Expression in Maize

- Mutational Spectrum Drives the Rise of Mutator Bacteria

- Human Disease-Associated Genetic Variation Impacts Large Intergenic Non-Coding RNA Expression

- The Roles of Whole-Genome and Small-Scale Duplications in the Functional Specialization of Genes

- Sex-Specific Signaling in the Blood–Brain Barrier Is Required for Male Courtship in

- A Newly Uncovered Group of Distantly Related Lysine Methyltransferases Preferentially Interact with Molecular Chaperones to Regulate Their Activity

- Is Required for Leptin-Mediated Depolarization of POMC Neurons in the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus in Mice

- Unlocking the Bottleneck in Forward Genetics Using Whole-Genome Sequencing and Identity by Descent to Isolate Causative Mutations

- The Role of Autophagy in Genome Stability through Suppression of Abnormal Mitosis under Starvation

- MTERF3 Regulates Mitochondrial Ribosome Biogenesis in Invertebrates and Mammals

- Downregulation and Altered Splicing by in a Mouse Model of Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy (FSHD)

- NBR1-Mediated Selective Autophagy Targets Insoluble Ubiquitinated Protein Aggregates in Plant Stress Responses

- Retroactive Maintains Cuticle Integrity by Promoting the Trafficking of Knickkopf into the Procuticle of

- Phenome-Wide Association Study (PheWAS) for Detection of Pleiotropy within the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Network

- Genetic and Functional Modularity of Activities in the Specification of Limb-Innervating Motor Neurons

- A Population Genetic Model for the Maintenance of R2 Retrotransposons in rRNA Gene Loci

- A Quartet of PIF bHLH Factors Provides a Transcriptionally Centered Signaling Hub That Regulates Seedling Morphogenesis through Differential Expression-Patterning of Shared Target Genes in

- A Genome-Wide Integrative Genomic Study Localizes Genetic Factors Influencing Antibodies against Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA-1)

- Mutation of the Diamond-Blackfan Anemia Gene in Mouse Results in Morphological and Neuroanatomical Phenotypes

- Life, the Universe, and Everything: An Interview with David Haussler

- Alternative Oxidase Expression in the Mouse Enables Bypassing Cytochrome Oxidase Blockade and Limits Mitochondrial ROS Overproduction

- An Evolutionarily Conserved Synthetic Lethal Interaction Network Identifies FEN1 as a Broad-Spectrum Target for Anticancer Therapeutic Development

- The Flowering Repressor Underlies a Novel QTL Interacting with the Genetic Background

- Telomerase Is Required for Zebrafish Lifespan

- and Diversified Expression of the Gene Family Bolster the Floral Stem Cell Network

- Susceptibility Loci Associated with Specific and Shared Subtypes of Lymphoid Malignancies

- An Insertion in 5′ Flanking Region of Causes Blue Eggshell in the Chicken

- Increased Maternal Genome Dosage Bypasses the Requirement of the FIS Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 in Arabidopsis Seed Development

- WNK1/HSN2 Mutation in Human Peripheral Neuropathy Deregulates Expression and Posterior Lateral Line Development in Zebrafish ()

- Synergistic Interaction of Rnf8 and p53 in the Protection against Genomic Instability and Tumorigenesis

- Dot1-Dependent Histone H3K79 Methylation Promotes Activation of the Mek1 Meiotic Checkpoint Effector Kinase by Regulating the Hop1 Adaptor

- A Heterogeneous Mixture of F-Series Prostaglandins Promotes Sperm Guidance in the Reproductive Tract

- Starvation, Together with the SOS Response, Mediates High Biofilm-Specific Tolerance to the Fluoroquinolone Ofloxacin

- Directed Evolution of a Model Primordial Enzyme Provides Insights into the Development of the Genetic Code

- Genome-Wide Screens for Tinman Binding Sites Identify Cardiac Enhancers with Diverse Functional Architectures

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Function and Regulation of , a Gene Implicated in Autism and Human Evolution

- An Insertion in 5′ Flanking Region of Causes Blue Eggshell in the Chicken

- Comprehensive Methylome Characterization of and at Single-Base Resolution

- Susceptibility Loci Associated with Specific and Shared Subtypes of Lymphoid Malignancies

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání