-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaGenome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Susceptibility Locus at 12q23.1 for Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Han Chinese

Adenocarcinoma (AC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) are two major histological subtypes of lung cancer. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have made considerable advances in the understanding of lung cancer susceptibility. Obvious heterogeneity has been observed between different histological subtypes of lung cancer, but genetic determinants in specific to lung SqCC have not been systematically investigated. Here, we performed the GWAS analysis specifically for lung SqCC in 833 SqCC cases and 3,094 controls followed by a two-stage replication in additional 2,223 lung SqCC cases and 6,409 controls from Chinese populations. We found that rs12296850 in SLC17A8-NR1H4 gene region at12q23.1 was significantly associated with risk of lung SqCC at genome-wide significance level [additive model: odds ratio (OR) = 0.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.72–0.84, P = 1.19×10−10]. Subjects carrying AG or GG genotype had a 26% (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.67–0.81) or 32% (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.56–0.83) decreased risk of lung SqCC, respectively, as compared with AA genotype. However, we did not observe significant association between rs12296850 and risk of lung AC in a total of 4,368 cases with lung AC and 9,486 controls (OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.90–1.02, P = 0.173). These results indicate that genetic variations on chromosome 12q23.1 may specifically contribute to lung SqCC susceptibility in Chinese population.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003190

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003190Summary

Adenocarcinoma (AC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) are two major histological subtypes of lung cancer. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have made considerable advances in the understanding of lung cancer susceptibility. Obvious heterogeneity has been observed between different histological subtypes of lung cancer, but genetic determinants in specific to lung SqCC have not been systematically investigated. Here, we performed the GWAS analysis specifically for lung SqCC in 833 SqCC cases and 3,094 controls followed by a two-stage replication in additional 2,223 lung SqCC cases and 6,409 controls from Chinese populations. We found that rs12296850 in SLC17A8-NR1H4 gene region at12q23.1 was significantly associated with risk of lung SqCC at genome-wide significance level [additive model: odds ratio (OR) = 0.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.72–0.84, P = 1.19×10−10]. Subjects carrying AG or GG genotype had a 26% (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.67–0.81) or 32% (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.56–0.83) decreased risk of lung SqCC, respectively, as compared with AA genotype. However, we did not observe significant association between rs12296850 and risk of lung AC in a total of 4,368 cases with lung AC and 9,486 controls (OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.90–1.02, P = 0.173). These results indicate that genetic variations on chromosome 12q23.1 may specifically contribute to lung SqCC susceptibility in Chinese population.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death around the world [1]. Adenocarcinoma (AC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) are two major histological subtypes of lung cancer [2]. Although tobacco smoking increases the risk of all major histological subtypes of lung cancer, it appears to be stronger for SqCC than AC [3]. Different spectra and frequencies of “driver” mutations have been described between lung AC and SqCC and result in a histology-specific therapy [4]. These evidences support a histology-specific pathogenesis process and biological characteristics of lung cancer, and studies specifically focused on individual histological subtype are required for understanding lung carcinogenesis.

Several large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of lung cancer have been conducted to uncover genetic factors associated with lung cancer risk [5]–[15] (Table S1). Three loci at 5p15, 6p21 and 15q25 were initially identified to contribute to the susceptibility to lung cancer in populations of European ancestry [5], [6], [16]–[18]. These findings have provided new clues for the mechanism of lung cancer development. Interestingly, some of these loci reflected different associations across lung cancer histology. For example, the 5p15 locus defined by rs2736100 showed stronger association with AC in populations of both European [7] and Asian [19] ancestries. However, most of lung cancer GWAS combined lung cancer cases with multiple subtypes of histology together when compared with controls in the discovery stage, making it difficult to identify histology-specific susceptibility loci due to dilution of effect.

With efforts to determine genetic variants associated with a specific type of lung cancer, two GWAS of lung AC have been conducted in populations of eastern Asian. Hsiung et al. performed a GWAS of AC and subsequent replications in never-smoking females and further confirmed that rs2736100 at 5p15 is associated with risk of lung AC [20]. Recently, Miki et al. carried out a GWAS of lung AC in Japanese and Korean populations and identified a new susceptibility locus at TP63 on 3q28 [13], which have also been confirmed by following studies [11], [21]. Interestingly, Landi et al. conducted a lung cancer histology-specific association study in 917 selected genes with 19,802 SNPs in the HuGE-defined “inflammation” pathway using available GWAS data from populations of European descent, and identified a locus at 12p13.33 associated with SqCC risk [15]. These evidences suggest the importance of exploring susceptibility loci by subtypes in lung cancer.

Recently, we conducted a three-stage GWAS for overall lung cancer in the Han Chinese populations and identified two new loci at 13q12.12 and 22q12.2 that were consistently associated with multiple subtypes of lung cancer [11]. Here, in order to identify genetic variants across whole genome specifically related to lung SqCC risk, we carried out the GWAS analysis in 833 cases with lung SqCC and 3,094 controls (Nanjing study: 428 cases and 1,977 controls; and Beijing study: 405 cases and 1,117 controls), and further evaluated suggestive associations involving lung SqCC risk by a two-stage replication with a total of 2,223 cases with lung SqCC and 6,409 controls in the Han Chinese populations.

Results

After filtering by standard quality-control procedures, a total of 3,927 subjects (833 lung SqCC cases and 3,094 controls) with 570,009 SNPs were qualified for further GWAS analysis (Table S2). A quantile-quantile plot using P values from additive model showed a relatively low inflation factor (λ = 1.04), suggesting a low possibility of false-positive associations due to population substructure (Figure S1). After excluding the SNPs at reported loci of our previous study [11], P-value on a -log scale for each SNP was plotted by location on chromosome (i.e., Manhattan plot; Figure S2).

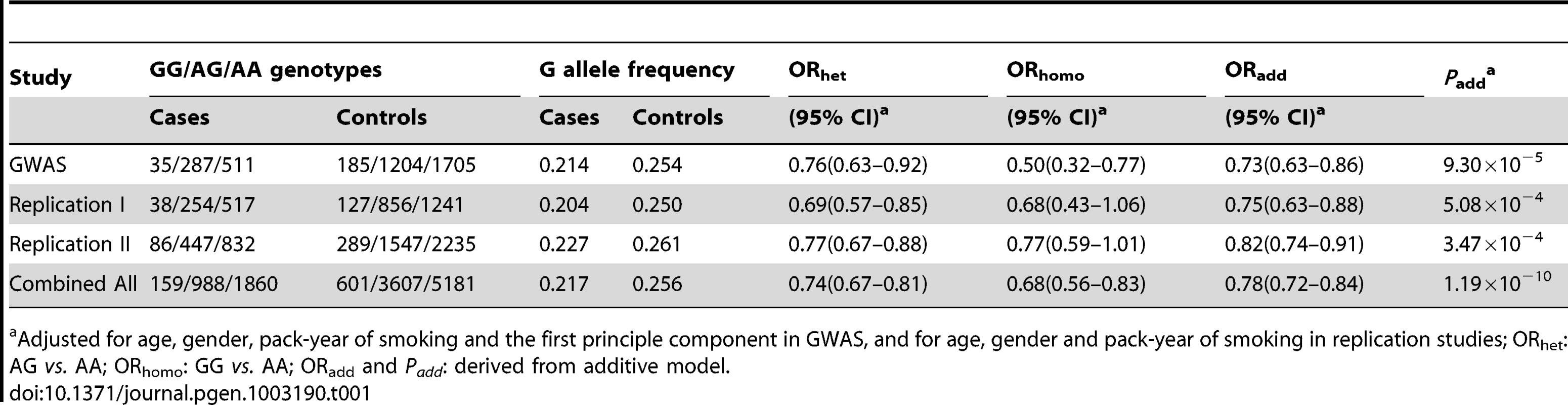

We determined promising SNPs associated with risk of lung SqCC based on P value of ≤1×10−4 in additive model and consistent associations between Nanjing and Beijing studies (P<0.01 with the same direction of associations). After linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis (excluding 9 SNPs at r2 of 0.8; Table S4), 14 autosome SNPs were selected to be further evaluated in the first replication stage (Replication I) including 822 cases with lung SqCC and 2,243 controls (Table S3). Three SNPs at 6p22.2 (rs16889835), 11p15.1 (rs7112278) and 12q23.1 (rs12296850) that were confirmed in the Replication I were further assessed in the second replication stage (Replication II) using additional 1,401 cases and 4,166 controls (Tables S5). In the Replication II, rs12296850 at 12q23.1 remained to be significantly associated with risk of lung SqCC (OR = 0.82, 95%CI = 0.74–0.91, P = 3.47×10−4), consistent with those observed in the GWAS stage (OR = 0.73, 95%CI = 0.63–0.86, P = 9.30×10−5) and the fist replication stage (OR = 0.75, 95%CI = 0.63–0.88, P = 5.08×10−4) (Table S5; Table 1). After combining results from the GWAS and two-stage replications, rs12296850 was associated with the risk of lung SqCC at genome-wide significance level (P<5.0×10−8), and the OR for additive model is 0.78 (95%CI = 0.72–0.84, Pcombined = 1.19×10−10). The combined ORs for the heterozygote (AG) and minor homozygote (GG) are 0.74 (95% CI = 0.67–0.81) and 0.68 (95%CI = 0.56–0.83), respectively, as compared with major homozygote (AA) (Table 1).

Tab. 1. Summary of GWAS scan and replication studies for association between rs12296850 at 12q23.1 and risk of lung squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC).

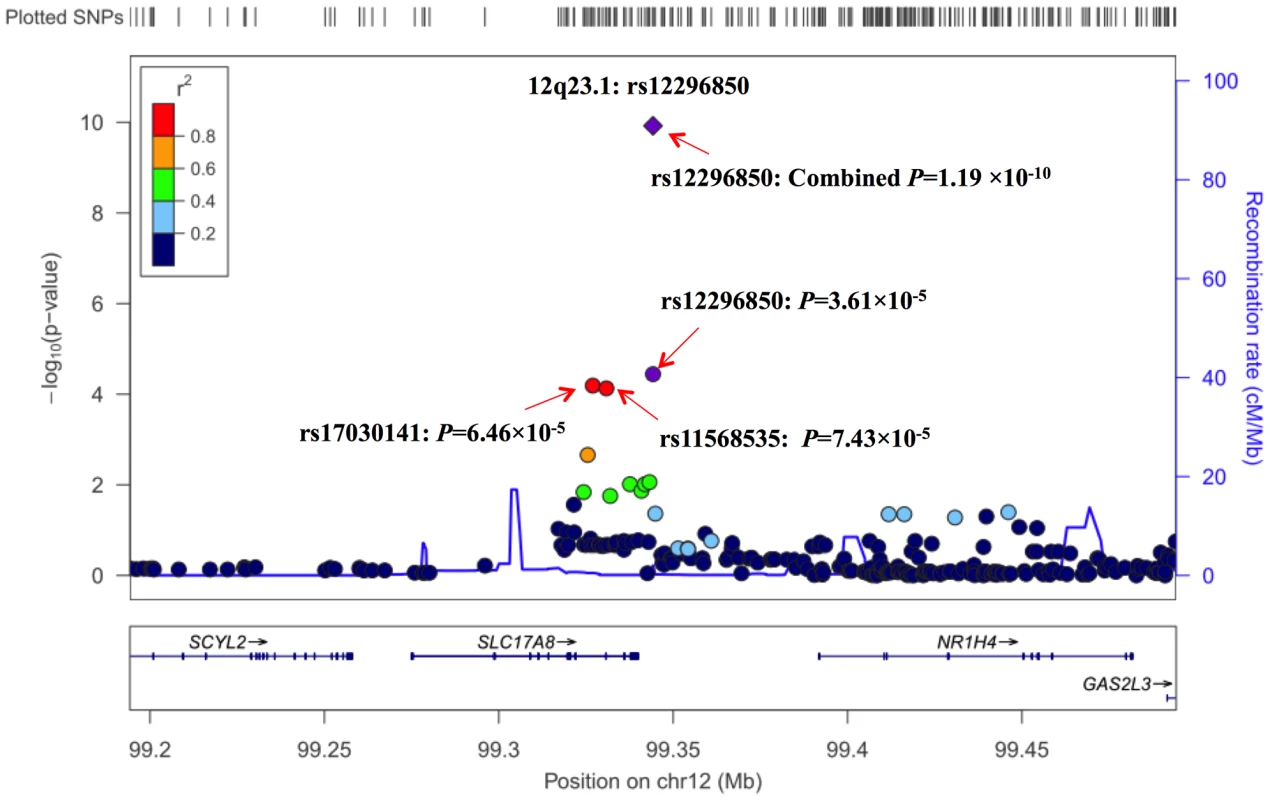

Adjusted for age, gender, pack-year of smoking and the first principle component in GWAS, and for age, gender and pack-year of smoking in replication studies; ORhet: AG vs. AA; ORhomo: GG vs. AA; ORadd and Padd: derived from additive model. To further characterize the association of genetic variants at 12q23.1 with lung SqCC risk, we performed imputation analyses based on CHB+JPT data of 1000 Genomes Project (released at June 2010). In a 300-kb region around rs12296850, 243 imputed SNPs at imputed r2>0.5 and MAF>0.05 were evaluated with association of lung SqCC risk. As shown in Figure 1 and Table S6, two SNPs, rs17030141 and rs11568535 having strong LD (r2>0.9) with rs12296850, showed similar associations with risk of lung SqCC at a P value of 6.46×10−5 and 7.43×10−5, respectively.

Fig. 1. Regional plot of the identified marker rs12296850 at 12q23.1.

Results (−log10 P) are shown for SNPs in the region flanking 150 kb on either side of rs12296850. The marker SNP are shown in purple and the r 2 values of the rest of the SNPs are indicated by different colors. The genes within the region of interest are annotated, with arrows indicating transcription direction. We further conducted stratification analysis on the association between rs12296850 at 12q23.1 and lung SqCC risk by age, gender and smoking dose. As shown in Table S7, none of different associations were significantly observed between subgroups. In addition, we did not detect significant interaction between rs12296850 and smoking on lung SqCC risk. Similar associations were observed among populations of Nanjing and Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenyang, and no significant heterogeneity between populations was detected for the association, though a non-significant association was shown in Guangzhou population (Figure S3).

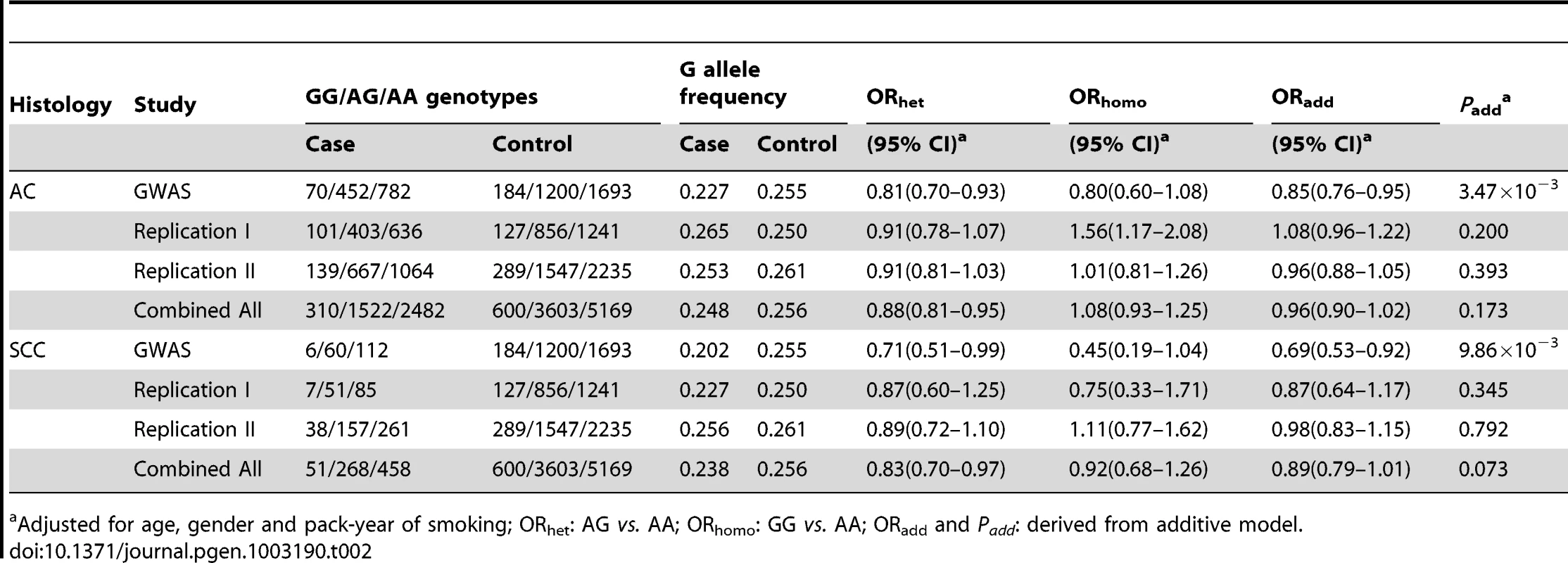

To investigate whether the variant rs12296850 was SqCC-specific, we further evaluated the association between rs12296850 and the risk of lung AC and small cell carcinoma (SCC) using the shared controls as SqCC study for each stage. We found that rs12296850 was not consistently associated with risk of lung AC in the three stages (GWAS: OR = 0.85, 95%CI = 0.76–0.95; Replication I: OR = 1.08, 95%CI = 0.96–1.22; Replication II: OR = 0.96, 95%CI = 0.88–1.05) (Table 2). After combining three stages, rs12296850 was not significantly associated with lung AC risk (OR = 0.96, 95%CI = 0.90–1.02, P = 0.173). Similarly, rs12296850 was not consistently associated with lung SCC risk with a combined OR of 0.89 (95%CI = 0.79–1.01; P = 0.073) (Table 2). These results indicate that rs12296850 at 12q23.1 may be a specific susceptibility locus to lung SqCC in Chinese population.

Tab. 2. Association between rs12296850 at 12q23.1 and risk of lung adenocarcinoma (AC) and small cell carcinoma (SCC).

Adjusted for age, gender and pack-year of smoking; ORhet: AG vs. AA; ORhomo: GG vs. AA; ORadd and Padd: derived from additive model. To characterize the functional relevance of the rs12296850, we further evaluated the relationship of this variant with the expression levels of two surrounding genes (NRIH4 and SLC17A8). We examined NRIH4 mRNA levels in 46 paired lung cancer tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues using quantitative RT-PCR, and observed that the relative expression of NRIH4 in adjacent non-tumor tissues was significantly higher in subjects with G allele of rs12296850 (n = 18) as compared with those carrying AA genotype (n = 28) (AG/GG: 0.54±0.25 versus AA: 0.36±0.19, P = 0.008)(Figure S4). Similar but non-significant results were also observed in tumor tissues (AG/GG: 0.50±0.22 versus AA: 0.39±0.26, P = 0.143). However, the mRNA expression level of SLC17A8 could not be detectable (Ct>40) in all of the adjacent non-tumor tissues (n = 46) and most of tumor tissues (n = 43) whereas only 3 subjects were measured with low expression levels in tumor tissues (Ct = 33.7, 36.1 and 39.0).

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a GWAS analysis in specific to lung SqCC in Chinese populations and identified a novel locus at 12q23.1 (lead SNP: rs12296850) that was specifically associated with lung SqCC. In our prior GWAS on overall lung cancer, we also showed genome-wide significant associations of loci at 3q28, 5p15.33, 13q12.12, and 22q12.2 with lung SqCC in stratification analysis [11]. Unlike previous study designed for overall lung cancer followed by a ‘post-hoc’ analysis on lung SqCC, the current study directly evaluated genetic variants across genome that might be specifically associated with lung SqCC risk. The identified locus was further assessed whether it was also associated with lung AC or SCC risk. This study represents an improved approach on exploring subtype-specific susceptibility loci for diseases with heterogeneous phenotypes, such as lung cancer.

We also evaluated the association of the SNP rs12296850 with SqCC risk in lung cancer GWAS data of European descent from MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) [16]. After imputation based on HapMap 2 CEU population, rs12296850 was not significantly associated with SqCC risk (OR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.52–1.24; P = 0.325) in 306 SqCC cases and 1,135 controls from the MDACC GWAS. The inconsistent results may be due to small sample size of MDACC study and different genetic backgrounds between Chinese and European descents. The minor allele (G) frequency of rs12296850 in Chinese population (>0.20 for all three stages) is more common than that in MDACC (0.053). The relative small sample size and low frequency may result in a negative result due to limited statistical power. In addition, the subjects of MDACC GWAS were all smokers, which may not represent the similar target population used in our study. However, at this stage, we have no substantial evidence to extend our findings to other populations, and further studies in other populations are required to further confirm our findings.

Genomic alterations on chromsome12q23 have been frequently linked to a spectrum of cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), prostate cancer, adenoid cystic carcinoma and oligodendrogliomas and colorectal carcinoma [22]–[26]. For NSCLC, cigarette smoking dose has been associated with copy number alterations in12q23 [26]. In addition, chromosomal gains at 12q23–24.3 facilitated tumour progression and metastasis of lung SqCC and may serve as potential predictors for this disease [27]. These evidences as well as our findings collectively suggested the importance of chromosome 12q23 in the development of lung cancer, especially for SqCC.

At 12q23.1, the lead SNP rs12296850 is located in 4.2 kb downstream of SLC17A8 (encoding vesicular glutamate transporter 3) and 47.6 kb upstream of NR1H4 (encoding a ligand-activated transcription factor). Correlation analysis results indicate that this SNP may be associated with the expression of NR1H4, a gene known as nuclear farnesoid X receptor (FXR). FXR is a member of the nuclear receptor family of transcription factors and highly expressed in the entero-hepatic system where it transcriptionally regulates bile acid and lipid metabolism [28]. Bile acids are natural ligands for the FXR, and the bile acid-FXR interaction has been suggested to be involved in the pathophysiology of a number of inflammatory-associated cancers [29], [30]. Loss of FXR increased tumor progression via promoting Wnt signaling by infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages, and elevated the tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) production in vivo [30]. Furthermore, FXR was involved in CYP regulation through mutual repression with NF-kappaB which indirectly regulates the transcription of CYP genes [31]. Further studies are required to elucidate the potential role of NR1H4 on SqCC development.

SLC17A8 (also known as Vesicular Glutamate Transporter Type 3, VGLUT3) is a member of the solute carrier (SLC) superfamily encoding multiple transmembrane transporters that may involve in the development and progression of a number of diseases, including cancers [32]. Genetic variants in the urea transporter (UT) gene SLC14A were reported to be significantly associated with susceptibility to urinary bladder cancer in a GWAS of European population, whereas SLC5A8 may function as a tumor suppressor gene whose silencing by epigenetic changes may contribute to carcinogenesis and progression of pancreatic cancer [33], [34]. However, the expression levels of SLC17A8 were very low in lung cancer tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues. Whether this gene involves in SqCC development is still unclear to date.

In addition, SCYL2 and GAS2L3 were another two genes around the SNP rs12296850 in a relatively long distance. SCYL2 (also known as CVAK104) is located at 86.2 kb upstream of rs12296850, encoding a coated vesicle-associated kinase of 104 kDa. SCYL2 can regulate the levels of frizzled 5 (Fzd5) via inducing lysosomal degradation, which probably inhibit the Wnt signaling pathway [35]. GAS2L3, encoding proteins with putative actins and microtubule binding domains, is located at 147.4 kb downstream of rs12296850. GAS2L3 was reported to localize to the spindle midzone and the midbody during anaphase and cytokinesis, respectively, and to act as a novel target of DREAM and play an important role in accurate cell division [36]. However, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis did not reveal any significant correlation between rs12296850 and the expressions of these two genes.

In this GWAS of lung SqCC in Chinese, we reported evidence that common genetic variants at 12q23.1 are implicated in the development of lung SqCC. Our findings highlight the importance of studying subtype of lung cancer and may provide new insight into the mechanism of SqCC. Further studies, such as resequencing this region followed by fine-mapping study and eQTL analysis in lung tissues as well as biochemical assays, may affiliate to determine causal variants at 12q23.1 that directly regulate the development of lung SqCC. In addition, the moderate sample size in GWAS scan stage may have decreased statistical power in the current study, and further studies with larger sample size or pooling multiple studies may promise to identify more SqCC-specific loci.

Materials and Methods

Study populations

A three-stage case-control study was designed to evaluate the associations between genetic variants across human genome and the risk of lung SqCC. Study subjects for GWAS scan of lung cancer and two-stage replication have been described elsewhere [11]. Briefly, the cases newly diagnosed with lung cancer were recruited from hospitals. The histology for each case was histopathologically or cytologically confirmed by at least two local pathologists. Cancer-free control subjects were recruited in local hospitals for individuals receiving routine physical examinations or in the communities for those participating screening of noncommunicable diseases. The controls were frequency-matched to lung cancer cases for age, gender and geographic regions. Demographic information was collected using standard questionnaire through interviews. Individuals were defined as smokers if they had smoked at an average of one cigarette or more per day and for at least one year in their lifetime; otherwise, subjects were considered as non-smokers. Smokers were considered as former smokers who quit for at least one year before recruitment. Both current and former smokers were divided into light and heavy smokers according to the threshold of 25 pack-year (median value among the controls).

The patients with lung SqCC and all of the controls that were included in previous GWAS of overall lung cancer [11] were considered as the cases and controls in the current study. As a result, 833 SqCC cases and 3,094 controls were included in the GWAS scan stage, including 428 cases and 1977 controls from Nanjing and Shanghai (Nanjing Study), and 405 cases and 1,117 controls from Beijing (Beijing Study). The first replication stage (Replication I) included 822 SqCC cases and 2,243 controls that were from Nanjing and Shanghai (235 cases and 754 controls) and Beijing (587 cases and 1,489 controls). The second replication stage (Replication II) included 1,401 SqCC cases and 4,166 controls that were from Nanjing and Shanghai (238 cases and 1,069 controls), Beijing (362 cases and 936 controls), Shenyang (306 cases and 1,027 controls) and Guangzhou (495 cases and 1,134 controls).

Ethics statement

All study subjects provided informed consent and each study was approved by its respective institution's IRB.

Quality control (QC) in GWAS

A total of 906,703 SNPs were genotyped in the GWAS scan in 844 lung SqCC cases and 3,160 controls by using Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 chips as described previously [11]. A systematic quality control (QC) procedure was applied to both SNPs and samples before association analysis. SNPs were excluded if they (i) did not map on autosomal chromosomes; (ii) had a call rate <95%; (iii) had a minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.05; or (iv) deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P<1×10−5 in all GWAS samples or P<1×10−4 in either of the Nanjing Study or the Beijing Study samples). We removed samples with low genotype call rates <0.95 (3 subjects) and ambiguous gender (4 subjects). Unexpected duplicates or probable relatives (52 subjects) identified by pairwise identity-by-state comparisons were also excluded according to their PI_HAT value in PLINK (all PI_HAT>0.25). Heterozygosity rates were calculated, and samples were excluded if they were more than 6 s.d. away from the mean (12 subjects were excluded). We detected population outliers using a method based on principle component analysis and 6 subjects were removed. As a result, 833 lung SqCC cases and 3,094 controls with 570,009 SNPs remained after QC.

SNP selection and genotyping in the replication study

After genome-wide association analyses, we selected SNPs for the first stage replication based on the following criteria: (i) SNPs had P≤1.0×10−4 for all GWAS samples; (ii) they showed consistent associations between the Nanjing study and the Beijing study at P≤1.0×10−2; (iii) they are not located in the same chromosome regions or genes of SNPs reported in previous GWAS; (iv) they had clear genotyping clusters; (v) only the SNP with the lowest P value was selected when multiple SNPs were observed in a strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2≥0.8). As s results, a total of 23 SNPs satisfied the criteria (i), (ii), (iii) and (iv), and 14 SNPs survived according to criterion (v). Therefore, we genotyped these 14 SNPs in the first replication stage (Table S3) and the other 9 SNPs that were in strong LD with 14 selected SNPs were excluded from further analysis (Table S4). The SNPs showed significant associations with lung SqCC risk with P<0.05 in the first stage replication were selected for the second replication stage.

Genotyping were performed by using the TaqMan OpenArray Genotyping Platform (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) and the iPLEX Sequenom MassARRAY platform (Sequenom, Inc) for SNPs selected in the first replication stage, and TaqMan allelic discrimination Assay (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) for SNPs selected in the second replication stage. A series of methods was used to control the quality of genotyping: (i) case and control samples were mixed on each plate and genotyped without knowing the case or control status; (ii) two water controls in each plate were used as blank controls; (iii) five percent of the samples were randomly selected to repeat the genotyping, as blind duplicates, and the reproducibility was 100%; (iv) 1,347 samples were randomly selected and detected using both TaqMan Openarray platform and TaqMan assay for rs12296850, yielding a concordance rate of 99.97%.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis methodology of our lung cancer GWAS was described previously [11]. In brief, genome-wide association analysis was performed using logistic regression analysis in additive model as implemented in PLINK 1.07 (see URLs). EIGENSTRAT 3.0 was used for the principal component analysis of population structure. Minimac software (see URLs) was used to impute untyped SNPs using the CHB+JPT data from the hg18/1000 Genomes database (released at June 2010) as reference set. Regional plot was generated using the LocusZoom 1.1(see URLs). R software (version 2.11.1; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was also used for statistical analysis and generating plots, including Q-Q plot and Manhattan plot.

Tissue samples

To determine the expression levels of NRIH4 and SLC17A8, we collected 46 paired lung cancer tissues from the patients who had undergone resection between June 2009 and April 2010 from the Nantong Cancer Hospital. All cases were histopathologically diagnosed lung cancer without radiotherapy or chemotherapy before surgical operation.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed to determine the mRNA expressions of NRIH4 and SLC17A8. RNAs from lung cancer tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues were isolated with the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). We used TaqMan gene expression probes (Applied Biosystems Inc.) to perform qRT-PCR assay. All real-time PCR reactions, including no-template controls and real-time minus controls, were run by using the ABI7900 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems Inc.) and performed in triplicate. β-actin gene was used to normalize the expression levels. A relative expression was calculated using the equation 2−ΔCt (Ct, Cycle Threshold), in which ΔCt = Ct gene−Ct β-actin.

Cis-eQTL analysis

We applied the publicly available data from GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) eQTL Browser, eQTL.Chicago.edu and Gene Expression Analysis Based on Imputed Genotypes (see URLs) to perform cis-eQTL analysis and evaluated the cis association between rs12296850 and the expression of nearby genes in a variety of cells/tissues, including lymphoblastoid cell lines [37]–[42], monocytes [43], fibroblasts [42], liver [44] and brain tissues [45].

URLs

PLINK1.07, http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/; R 2.11.1 statistical environment, http://www.cran.r-project.org/; Minimac, http://genome.sph.umich.edu/wiki/Minimac ;LocusZoom 1.1, http://csg.sph.umich.edu/locuszoom/; GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) eQTL Browser, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtex/test/GTEX2/gtex.cgi ; eQTL.Chicago.edu, http://eqtl.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/gbrowse/eqtl/; Gene Expression Analysis Based on Imputed Genotypes, http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/liang/imputation/.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. JemalA, BrayF, CenterMM, FerlayJ, WardE, et al. (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61 : 69–90.

2. TravisWD (2002) Pathology of lung cancer. Clin Chest Med 23 : 65–81, viii.

3. KenfieldSA, WeiEK, StampferMJ, RosnerBA, ColditzGA (2008) Comparison of aspects of smoking among the four histological types of lung cancer. Tob Control 17 : 198–204.

4. HeistRS, EngelmanJA (2012) SnapShot: non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 21 : 448 e442.

5. HungRJ, McKayJD, GaborieauV, BoffettaP, HashibeM, et al. (2008) A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature 452 : 633–637.

6. McKayJD, HungRJ, GaborieauV, BoffettaP, ChabrierA, et al. (2008) Lung cancer susceptibility locus at 5p15.33. Nat Genet 40 : 1404–1406.

7. LandiMT, ChatterjeeN, YuK, GoldinLR, GoldsteinAM, et al. (2009) A genome-wide association study of lung cancer identifies a region of chromosome 5p15 associated with risk for adenocarcinoma. Am J Hum Genet 85 : 679–691.

8. GalvanA, FalvellaFS, SpinolaM, FrullantiE, LeoniVP, et al. (2008) A polygenic model with common variants may predict lung adenocarcinoma risk in humans. Int J Cancer 123 : 2327–2330.

9. YoonKA, ParkJH, HanJ, ParkS, LeeGK, et al. (2010) A genome-wide association study reveals susceptibility variants for non-small cell lung cancer in the Korean population. Hum Mol Genet 19 : 4948–4954.

10. LiY, SheuCC, YeY, de AndradeM, WangL, et al. (2010) Genetic variants and risk of lung cancer in never smokers: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Oncol 11 : 321–330.

11. HuZ, WuC, ShiY, GuoH, ZhaoX, et al. (2011) A genome-wide association study identifies two new lung cancer susceptibility loci at 13q12.12 and 22q12.2 in Han Chinese. Nat Genet 43 : 792–796.

12. AhnMJ, WonHH, LeeJ, LeeST, SunJM, et al. (2012) The 18p11.22 locus is associated with never smoker non-small cell lung cancer susceptibility in Korean populations. Hum Genet 131 : 365–372.

13. MikiD, KuboM, TakahashiA, YoonKA, KimJ, et al. (2010) Variation in TP63 is associated with lung adenocarcinoma susceptibility in Japanese and Korean populations. Nat Genet 42 : 893–896.

14. ShiraishiK, KunitohH, DaigoY, TakahashiA, GotoK, et al. (2012) A genome-wide association study identifies two new susceptibility loci for lung adenocarcinoma in the Japanese population. Nat Genet 44 : 900–903.

15. ShiJ, ChatterjeeN, RotunnoM, WangY, PesatoriAC, et al. (2012) Inherited variation at chromosome 12p13.33, including RAD52, influences the risk of squamous cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Discov 2 : 131–139.

16. AmosCI, WuX, BroderickP, GorlovIP, GuJ, et al. (2008) Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet 40 : 616–622.

17. ThorgeirssonTE, GellerF, SulemP, RafnarT, WisteA, et al. (2008) A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature 452 : 638–642.

18. WangY, BroderickP, WebbE, WuX, VijayakrishnanJ, et al. (2008) Common 5p15.33 and 6p21.33 variants influence lung cancer risk. Nat Genet 40 : 1407–1409.

19. JinG, XuL, ShuY, TianT, LiangJ, et al. (2009) Common genetic variants on 5p15.33 contribute to risk of lung adenocarcinoma in a Chinese population. Carcinogenesis 30 : 987–990.

20. HsiungCA, LanQ, HongYC, ChenCJ, HosgoodHD, et al. (2010) The 5p15.33 locus is associated with risk of lung adenocarcinoma in never-smoking females in Asia. PLoS Genet 6: e1001051 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001051.

21. HosgoodHD3rd, WangWC, HongYC, WangJC, ChenK, et al. (2012) Genetic variant in TP63 on locus 3q28 is associated with risk of lung adenocarcinoma among never-smoking females in Asia. Hum Genet 131 : 1197–1203.

22. BestCJ, GillespieJW, YiY, ChandramouliGV, PerlmutterMA, et al. (2005) Molecular alterations in primary prostate cancer after androgen ablation therapy. Clin Cancer Res 11 : 6823–6834.

23. RutherfordS, HamptonGM, FriersonHF, MoskalukCA (2005) Mapping of candidate tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 12 in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Lab Invest 85 : 1076–1085.

24. HongC, MaunakeaA, JunP, BollenAW, HodgsonJG, et al. (2005) Shared epigenetic mechanisms in human and mouse gliomas inactivate expression of the growth suppressor SLC5A8. Cancer Res 65 : 3617–3623.

25. UmetaniN, FujimotoA, TakeuchiH, ShinozakiM, BilchikAJ, et al. (2004) Allelic imbalance of APAF-1 locus at 12q23 is related to progression of colorectal carcinoma. Oncogene 23 : 8292–8300.

26. HuangYT, LinX, LiuY, ChirieacLR, McGovernR, et al. (2011) Cigarette smoking increases copy number alterations in nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 16345–16350.

27. MaJ, GaoM, LuY, FengX, ZhangJ, et al. (2006) Gain of 1q25–32, 12q23–24.3, and 17q12–22 facilitates tumorigenesis and progression of human squamous cell lung cancer. J Pathol 210 : 205–213.

28. GardmoC, TamburroA, ModicaS, MoschettaA (2011) Proteomics for the discovery of nuclear bile acid receptor FXR targets. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812 : 836–841.

29. MaranRR, ThomasA, RothM, ShengZ, EsterlyN, et al. (2009) Farnesoid X receptor deficiency in mice leads to increased intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and tumor development. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 328 : 469–477.

30. ModicaS, MurzilliS, SalvatoreL, SchmidtDR, MoschettaA (2008) Nuclear bile acid receptor FXR protects against intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 68 : 9589–9594.

31. ZordokyBN, El-KadiAO (2009) Role of NF-kappaB in the regulation of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Curr Drug Metab 10 : 164–178.

32. HeL, VasiliouK, NebertDW (2009) Analysis and update of the human solute carrier (SLC) gene superfamily. Hum Genomics 3 : 195–206.

33. ParkJY, HelmJF, ZhengW, LyQP, HodulPJ, et al. (2008) Silencing of the candidate tumor suppressor gene solute carrier family 5 member 8 (SLC5A8) in human pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 36: e32–39.

34. RafnarT, VermeulenSH, SulemP, ThorleifssonG, AbenKK, et al. (2011) European genome-wide association study identifies SLC14A1 as a new urinary bladder cancer susceptibility gene. Hum Mol Genet 20 : 4268–4281.

35. TerabayashiT, FunatoY, FukudaM, MikiH (2009) A coated vesicle-associated kinase of 104 kDa (CVAK104) induces lysosomal degradation of frizzled 5 (Fzd5). J Biol Chem 284 : 26716–26724.

36. WolterP, SchmittK, FacklerM, KremlingH, ProbstL, et al. (2012) GAS2L3, a target gene of the DREAM complex, is required for proper cytokinesis and genomic stability. J Cell Sci 125 : 2393–2406.

37. DixonAL, LiangL, MoffattMF, ChenW, HeathS, et al. (2007) A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat Genet 39 : 1202–1207.

38. StrangerBE, NicaAC, ForrestMS, DimasA, BirdCP, et al. (2007) Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat Genet 39 : 1217–1224.

39. VeyrierasJB, KudaravalliS, KimSY, DermitzakisET, GiladY, et al. (2008) High-resolution mapping of expression-QTLs yields insight into human gene regulation. PLoS Genet 4: e1000214 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000214.

40. PickrellJK, MarioniJC, PaiAA, DegnerJF, EngelhardtBE, et al. (2010) Understanding mechanisms underlying human gene expression variation with RNA sequencing. Nature 464 : 768–772.

41. MontgomerySB, SammethM, Gutierrez-ArcelusM, LachRP, IngleC, et al. (2010) Transcriptome genetics using second generation sequencing in a Caucasian population. Nature 464 : 773–777.

42. DimasAS, DeutschS, StrangerBE, MontgomerySB, BorelC, et al. (2009) Common regulatory variation impacts gene expression in a cell type-dependent manner. Science 325 : 1246–1250.

43. ZellerT, WildP, SzymczakS, RotivalM, SchillertA, et al. (2010) Genetics and beyond—the transcriptome of human monocytes and disease susceptibility. PLoS ONE 5: e10693 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010693.

44. SchadtEE, MolonyC, ChudinE, HaoK, YangX, et al. (2008) Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol 6: e107 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107.

45. MyersAJ, GibbsJR, WebsterJA, RohrerK, ZhaoA, et al. (2007) A survey of genetic human cortical gene expression. Nat Genet 39 : 1494–1499.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Comparative Genome Structure, Secondary Metabolite, and Effector Coding Capacity across PathogensČlánek TATES: Efficient Multivariate Genotype-Phenotype Analysis for Genome-Wide Association StudiesČlánek Secondary Metabolism and Development Is Mediated by LlmF Control of VeA Subcellular Localization inČlánek Human Disease-Associated Genetic Variation Impacts Large Intergenic Non-Coding RNA ExpressionČlánek The Roles of Whole-Genome and Small-Scale Duplications in the Functional Specialization of GenesČlánek The Role of Autophagy in Genome Stability through Suppression of Abnormal Mitosis under Starvation

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Model of High Sugar Diet-Induced Cardiomyopathy

- Comparative Genome Structure, Secondary Metabolite, and Effector Coding Capacity across Pathogens

- Emerging Function of Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Protein (Fto)

- Positional Cloning Reveals Strain-Dependent Expression of to Alter Susceptibility to Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice

- Genetics of Ribosomal Proteins: “Curiouser and Curiouser”

- Transposable Elements Re-Wire and Fine-Tune the Transcriptome

- Function and Regulation of , a Gene Implicated in Autism and Human Evolution

- MAML1 Enhances the Transcriptional Activity of Runx2 and Plays a Role in Bone Development

- Predicting Mendelian Disease-Causing Non-Synonymous Single Nucleotide Variants in Exome Sequencing Studies

- A Systematic Mapping Approach of 16q12.2/ and BMI in More Than 20,000 African Americans Narrows in on the Underlying Functional Variation: Results from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study

- Transcription of the Major microRNA–Like Small RNAs Relies on RNA Polymerase III

- Histone H3K56 Acetylation, Rad52, and Non-DNA Repair Factors Control Double-Strand Break Repair Choice with the Sister Chromatid

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Susceptibility Locus at 12q23.1 for Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Han Chinese

- Genetic Disruption of the Copulatory Plug in Mice Leads to Severely Reduced Fertility

- The [] Prion Exists as a Dynamic Cloud of Variants

- Adult Onset Global Loss of the Gene Alters Body Composition and Metabolism in the Mouse

- Fis Protein Insulates the Gene from Uncontrolled Transcription

- The Meiotic Nuclear Lamina Regulates Chromosome Dynamics and Promotes Efficient Homologous Recombination in the Mouse

- Genome-Wide Haplotype Analysis of Expression Quantitative Trait Loci in Monocytes

- TATES: Efficient Multivariate Genotype-Phenotype Analysis for Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Structural Basis of a Histone H3 Lysine 4 Demethylase Required for Stem Elongation in Rice

- The Ecm11-Gmc2 Complex Promotes Synaptonemal Complex Formation through Assembly of Transverse Filaments in Budding Yeast

- MCM8 Is Required for a Pathway of Meiotic Double-Strand Break Repair Independent of DMC1 in

- Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Endosymbionts of Herbivorous Insects Reveals Eco-Environmental Adaptations: Biotechnology Applications

- Integration of Nodal and BMP Signals in the Heart Requires FoxH1 to Create Left–Right Differences in Cell Migration Rates That Direct Cardiac Asymmetry

- Pharmacodynamics, Population Dynamics, and the Evolution of Persistence in

- A Hybrid Likelihood Model for Sequence-Based Disease Association Studies

- Aberration in DNA Methylation in B-Cell Lymphomas Has a Complex Origin and Increases with Disease Severity

- Multiple Opposing Constraints Govern Chromosome Interactions during Meiosis

- Transcriptional Dynamics Elicited by a Short Pulse of Notch Activation Involves Feed-Forward Regulation by Genes

- Dynamic Large-Scale Chromosomal Rearrangements Fuel Rapid Adaptation in Yeast Populations

- Heterologous Gln/Asn-Rich Proteins Impede the Propagation of Yeast Prions by Altering Chaperone Availability

- Gene Copy-Number Polymorphism Caused by Retrotransposition in Humans

- An Incompatibility between a Mitochondrial tRNA and Its Nuclear-Encoded tRNA Synthetase Compromises Development and Fitness in

- Secondary Metabolism and Development Is Mediated by LlmF Control of VeA Subcellular Localization in

- Single-Stranded Annealing Induced by Re-Initiation of Replication Origins Provides a Novel and Efficient Mechanism for Generating Copy Number Expansion via Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination

- Tbx2 Controls Lung Growth by Direct Repression of the Cell Cycle Inhibitor Genes and

- Suv4-20h Histone Methyltransferases Promote Neuroectodermal Differentiation by Silencing the Pluripotency-Associated Oct-25 Gene

- A Conserved Helicase Processivity Factor Is Needed for Conjugation and Replication of an Integrative and Conjugative Element

- Telomerase-Null Survivor Screening Identifies Novel Telomere Recombination Regulators

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Selection for Important Traits in Domestic Horse Breeds

- Coordinated Degradation of Replisome Components Ensures Genome Stability upon Replication Stress in the Absence of the Replication Fork Protection Complex

- Nkx6.1 Controls a Gene Regulatory Network Required for Establishing and Maintaining Pancreatic Beta Cell Identity

- HIF- and Non-HIF-Regulated Hypoxic Responses Require the Estrogen-Related Receptor in

- Delineating a Conserved Genetic Cassette Promoting Outgrowth of Body Appendages

- The Telomere Capping Complex CST Has an Unusual Stoichiometry, Makes Multipartite Interaction with G-Tails, and Unfolds Higher-Order G-Tail Structures

- Comprehensive Methylome Characterization of and at Single-Base Resolution

- Loci Associated with -Glycosylation of Human Immunoglobulin G Show Pleiotropy with Autoimmune Diseases and Haematological Cancers

- Switchgrass Genomic Diversity, Ploidy, and Evolution: Novel Insights from a Network-Based SNP Discovery Protocol

- Centromere-Like Regions in the Budding Yeast Genome

- Sequencing of Loci from the Elephant Shark Reveals a Family of Genes in Vertebrate Genomes, Forged by Ancient Duplications and Divergences

- Mendelian and Non-Mendelian Regulation of Gene Expression in Maize

- Mutational Spectrum Drives the Rise of Mutator Bacteria

- Human Disease-Associated Genetic Variation Impacts Large Intergenic Non-Coding RNA Expression

- The Roles of Whole-Genome and Small-Scale Duplications in the Functional Specialization of Genes

- Sex-Specific Signaling in the Blood–Brain Barrier Is Required for Male Courtship in

- A Newly Uncovered Group of Distantly Related Lysine Methyltransferases Preferentially Interact with Molecular Chaperones to Regulate Their Activity

- Is Required for Leptin-Mediated Depolarization of POMC Neurons in the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus in Mice

- Unlocking the Bottleneck in Forward Genetics Using Whole-Genome Sequencing and Identity by Descent to Isolate Causative Mutations

- The Role of Autophagy in Genome Stability through Suppression of Abnormal Mitosis under Starvation

- MTERF3 Regulates Mitochondrial Ribosome Biogenesis in Invertebrates and Mammals

- Downregulation and Altered Splicing by in a Mouse Model of Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy (FSHD)

- NBR1-Mediated Selective Autophagy Targets Insoluble Ubiquitinated Protein Aggregates in Plant Stress Responses

- Retroactive Maintains Cuticle Integrity by Promoting the Trafficking of Knickkopf into the Procuticle of

- Phenome-Wide Association Study (PheWAS) for Detection of Pleiotropy within the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Network

- Genetic and Functional Modularity of Activities in the Specification of Limb-Innervating Motor Neurons

- A Population Genetic Model for the Maintenance of R2 Retrotransposons in rRNA Gene Loci

- A Quartet of PIF bHLH Factors Provides a Transcriptionally Centered Signaling Hub That Regulates Seedling Morphogenesis through Differential Expression-Patterning of Shared Target Genes in

- A Genome-Wide Integrative Genomic Study Localizes Genetic Factors Influencing Antibodies against Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA-1)

- Mutation of the Diamond-Blackfan Anemia Gene in Mouse Results in Morphological and Neuroanatomical Phenotypes

- Life, the Universe, and Everything: An Interview with David Haussler

- Alternative Oxidase Expression in the Mouse Enables Bypassing Cytochrome Oxidase Blockade and Limits Mitochondrial ROS Overproduction

- An Evolutionarily Conserved Synthetic Lethal Interaction Network Identifies FEN1 as a Broad-Spectrum Target for Anticancer Therapeutic Development

- The Flowering Repressor Underlies a Novel QTL Interacting with the Genetic Background

- Telomerase Is Required for Zebrafish Lifespan

- and Diversified Expression of the Gene Family Bolster the Floral Stem Cell Network

- Susceptibility Loci Associated with Specific and Shared Subtypes of Lymphoid Malignancies

- An Insertion in 5′ Flanking Region of Causes Blue Eggshell in the Chicken

- Increased Maternal Genome Dosage Bypasses the Requirement of the FIS Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 in Arabidopsis Seed Development

- WNK1/HSN2 Mutation in Human Peripheral Neuropathy Deregulates Expression and Posterior Lateral Line Development in Zebrafish ()

- Synergistic Interaction of Rnf8 and p53 in the Protection against Genomic Instability and Tumorigenesis

- Dot1-Dependent Histone H3K79 Methylation Promotes Activation of the Mek1 Meiotic Checkpoint Effector Kinase by Regulating the Hop1 Adaptor

- A Heterogeneous Mixture of F-Series Prostaglandins Promotes Sperm Guidance in the Reproductive Tract

- Starvation, Together with the SOS Response, Mediates High Biofilm-Specific Tolerance to the Fluoroquinolone Ofloxacin

- Directed Evolution of a Model Primordial Enzyme Provides Insights into the Development of the Genetic Code

- Genome-Wide Screens for Tinman Binding Sites Identify Cardiac Enhancers with Diverse Functional Architectures

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Function and Regulation of , a Gene Implicated in Autism and Human Evolution

- An Insertion in 5′ Flanking Region of Causes Blue Eggshell in the Chicken

- Comprehensive Methylome Characterization of and at Single-Base Resolution

- Susceptibility Loci Associated with Specific and Shared Subtypes of Lymphoid Malignancies

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání