-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaRetroactive Maintains Cuticle Integrity by Promoting the Trafficking of Knickkopf into the Procuticle of

Molting, or the replacement of the old exoskeleton with a new cuticle, is a complex developmental process that all insects must undergo to allow unhindered growth and development. Prior to each molt, the developing new cuticle must resist the actions of potent chitinolytic enzymes that degrade the overlying old cuticle. We recently disproved the classical dogma that a physical barrier prevents chitinases from accessing the new cuticle and showed that the chitin-binding protein Knickkopf (Knk) protects the new cuticle from degradation. Here we demonstrate that, in Tribolium castaneum, the protein Retroactive (TcRtv) is an essential mediator of this protective effect of Knk. TcRtv localizes within epidermal cells and specifically confers protection to the new cuticle against chitinases by facilitating the trafficking of TcKnk into the procuticle. Down-regulation of TcRtv resulted in entrapment of TcKnk within the epidermal cells and caused molting defects and lethality in all stages of insect growth, consistent with the loss of TcKnk function. Given the ubiquity of Rtv and Knk orthologs in arthropods, we propose that this mechanism of new cuticle protection is conserved throughout the phylum.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003268

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003268Summary

Molting, or the replacement of the old exoskeleton with a new cuticle, is a complex developmental process that all insects must undergo to allow unhindered growth and development. Prior to each molt, the developing new cuticle must resist the actions of potent chitinolytic enzymes that degrade the overlying old cuticle. We recently disproved the classical dogma that a physical barrier prevents chitinases from accessing the new cuticle and showed that the chitin-binding protein Knickkopf (Knk) protects the new cuticle from degradation. Here we demonstrate that, in Tribolium castaneum, the protein Retroactive (TcRtv) is an essential mediator of this protective effect of Knk. TcRtv localizes within epidermal cells and specifically confers protection to the new cuticle against chitinases by facilitating the trafficking of TcKnk into the procuticle. Down-regulation of TcRtv resulted in entrapment of TcKnk within the epidermal cells and caused molting defects and lethality in all stages of insect growth, consistent with the loss of TcKnk function. Given the ubiquity of Rtv and Knk orthologs in arthropods, we propose that this mechanism of new cuticle protection is conserved throughout the phylum.

Introduction

A critical feature of the insect molting process is the simultaneous synthesis and degradation of chitin at different sites associated with the cuticle [1], [2]. Chitinolytic enzymes (molting fluid chitinases and N-acetylglucosaminidases) dissolve parts of the old chitinous exoskeleton into oligomeric and monomeric N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) units, which are subsequently recycled into the collective pool of biosynthetically derived activated precursors of GlcNAc monomers (UDP-GlcNAc) used for the synthesis of new cuticular chitin [3], [4]. The enzyme that catalyzes the addition of these monomers onto the growing chitin oligosaccharide is the membrane-bound chitin synthase [3], [5], [6]. Upon synthesis and secretion into the extracellular (subcuticular) space by epidermal cells, nascent chitin aggregates into microfibrils and accumulates within the assembly zone (the layer immediately above the apical surface of the epidermal cells) to eventually organize into new cuticular laminae [7], [8].

At the ultrastructural level, the new cuticle extends from its inner boundary on the apical side of the epidermal cell membrane to its outer “envelope” layer that appears to partition it from the overlying old procuticle [9]. However the envelope layer functions only as a structural boundary at the early stages of molting, and does not function as a barrier against molting fluid chitinases [10]. Indeed, the molting fluid chitinase of T. castaneum (TcCht-5) was observed throughout the new procuticle co-localized with chitin. The mysterious stability of the new cuticle in intimate contact with enzymatically active chitinases was shown to be due to its physical association with the cuticle assembly protein, Knickkopf (TcKnk; homologue of D. melanogaster knickkopf, DmKnk) [10].

Like DmKnk, the protein Retroactive from Drosophila melanogaster (DmRtv) was also previously demonstrated to affect cuticle differentiation and tracheal tube morphogenesis [11], [12], [13]. DmRtv was predicted to form a membrane-anchored, three-finger loop structure that interacts with chitin via two aromatic residues situated in each loop [11]. Although a direct role for this protein in cuticular chitin filament organization in embryonic tracheal tubules of D. melanogaster was envisaged, the mechanism of this ordering process is unclear. In the current study we show that a direct effect of the T. castaneum Rtv homologue (TcRtv) on cuticular chitin organization is unlikely, given its predominant intracellular distribution within epidermal cells. Instead, its activity is shown to be crucial for the proper trafficking of TcKnk to the procuticle where the latter protein associates with and protects chitin. Hence, TcRtv promotes cuticle synthesis and organization by facilitating TcKnk's localization in the integument.

Results

TcRtv is an evolutionarily conserved protein required for insect molting

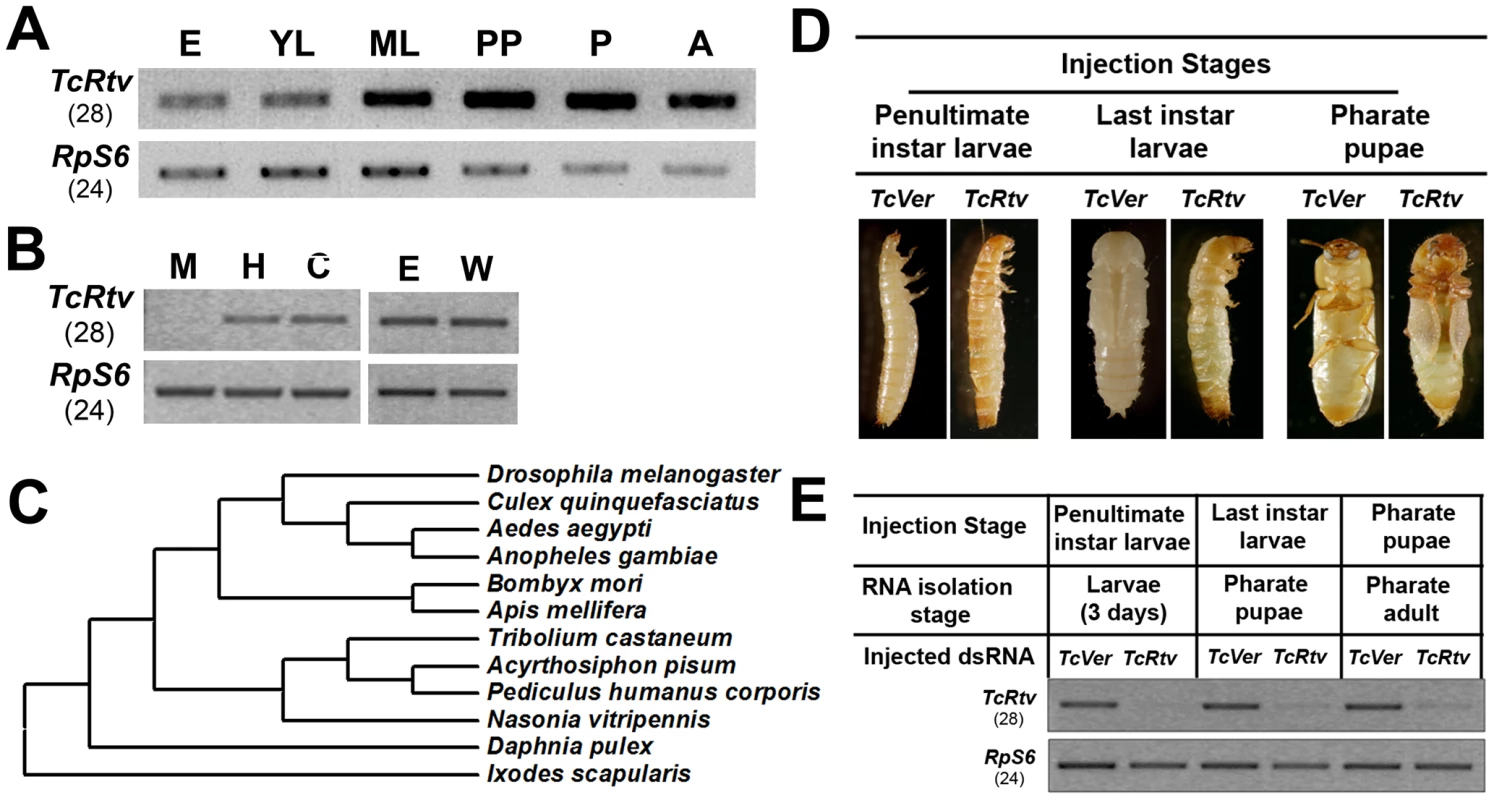

TBLASTN and BLASTP searches of the T. castaneum genome using the DmRtv protein sequence as query identified only a single gene coding for an orthologous protein. T. castaneum retroactive (TcRtv) (JX470185) maps on LG4, position 24.3 cM. TcRtv is composed of three exons and encodes a 150 - amino acid residue long protein with a predicted C-terminal GPI anchor and an ω-asparagine at position 124 (Figure S1A and S1B) (GPIPred). A predicted cleavable signal peptide at its N-terminus suggests that this protein enters the ER secretory pathway prior to GPI-anchoring and is transported to the cell surface via intracellular secretory vesicles. Expression analysis revealed the presence of TcRtv transcripts throughout development including embryonic, larval, pupal and adult stages (Figure 1A). Lower levels of TcRtv expression were detected at the embryonic and young larval stages relative to later stages of development. Tissue-specific expression of TcRtv revealed that TcRtv transcripts could only be detected in the hindgut and carcass but not in midgut tissues indicating that this gene is expressed in tissues of ectodermal origin (Figure 1B). TcRtv transcripts were also detected in pharate adult elytra and hindwings (Figure 1B).

Fig. 1. TcRtv is a conserved protein required for insect molting.

(A) Expression of TcRtv during T. castaneum development. Total RNA was extracted at different stages of development: E, eggs; YL, young larvae; ML, mature larvae (last instar larvae); PP, pharate pupae; P, pupae and A, adult. RT-PCR (28 cycles) was performed using cDNA prepared from total RNA and gene-specific primers. TcRpS6 (T. castaneum ribosomal protein-S6) was used as an internal loading control (24 cycles). (B) Tissue-specific expression pattern of TcRtv in T. castaneum late last instar larval midgut (M), hindgut (H) and carcass (C) (whole body minus gut) and pharate pupal elytra (E) and hindwing (W) was detected by RT-PCR using gene specific primers (28 cycles). TcRpS6 was used as an internal loading control (24 cycles). (C) Phylogenetic analysis of Rtv orthologs from several orders of insect species was done using MEGA 4.0 neighbor joining method, with Ixodes scapularis included as outlier. (D) Effect of TcRtv dsRNA treatment on development of T. castaneum (n = 20). dsRNA for the Vermilion gene (TcVer) was used as a control (n = 20 each). (E) Effect of TcRtv dsRNA treatment on the transcript levels. RT-PCR was performed (28 cycles) to check the level of TcRtv transcripts using gene-specific primers. TcRpS6 was used as a loading control (24 cycles). When other fully sequenced arthropod genomes were queried with DmRtv or TcRtv sequences, only a single homolog was identified in all the insect species. The presence of an ortholog of TcRtv gene in all sequenced insect genomes suggests an essential function for this protein in insect survival and development (Figure 1C). Interestingly, a single Rtv ortholog is also present even in non-insect arthropod species including the water flea, Daphnia pulex, and the deer tick, Ixodes scapularis, suggesting that Rtv may have a conserved biological function in all species that produce a chitinous exoskeleton. On the other hand, we could not identify Rtv homologs in the genome of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, which does synthesize chitin in its eggshells and the pharyngeal lumenal walls. Thus Rtv may have appeared early during arthropod evolution.

Given the ubiquitous presence of TcRtv transcripts during insect growth, we hypothesized a critical role for this protein in post-embryonic development. To test this hypothesis, we depleted TcRtv transcripts via RNA interference (RNAi) by administration of TcRtv-specific dsRNA (dsRtv) during multiple developmental stages of T. castaneum. RNAi of TcRtv led to molting arrest at larval-larval, larval-pupal or pupal-adult stages, depending upon the developmental stage at the time of injection, with significant reductions in transcript levels at each stage tested (Figure 1D and 1E). Apolysis and partial slippage of the old larval cuticle proceeded at the subsequent molt after injection of TcRtv dsRNA into penultimate-instar larvae, but the larvae failed to complete the larval-larval molt and remained entrapped within their old larval cuticle. Similarly, insects injected with TcRtv dsRNA at later stages were arrested at the larval-pupal or pupal-adult molts and failed to shed their old cuticle. These phenotypes were reminiscent of those that we have reported previously following RNAi for TcChs-A [5]. Control insects injected with the same dose of dsRNA for the eye pigmentation gene, TcVer (T. castaneum Vermilion), developed normally except for the loss of eye color. These results demonstrate that Rtv is essential for molting in T. castaneum.

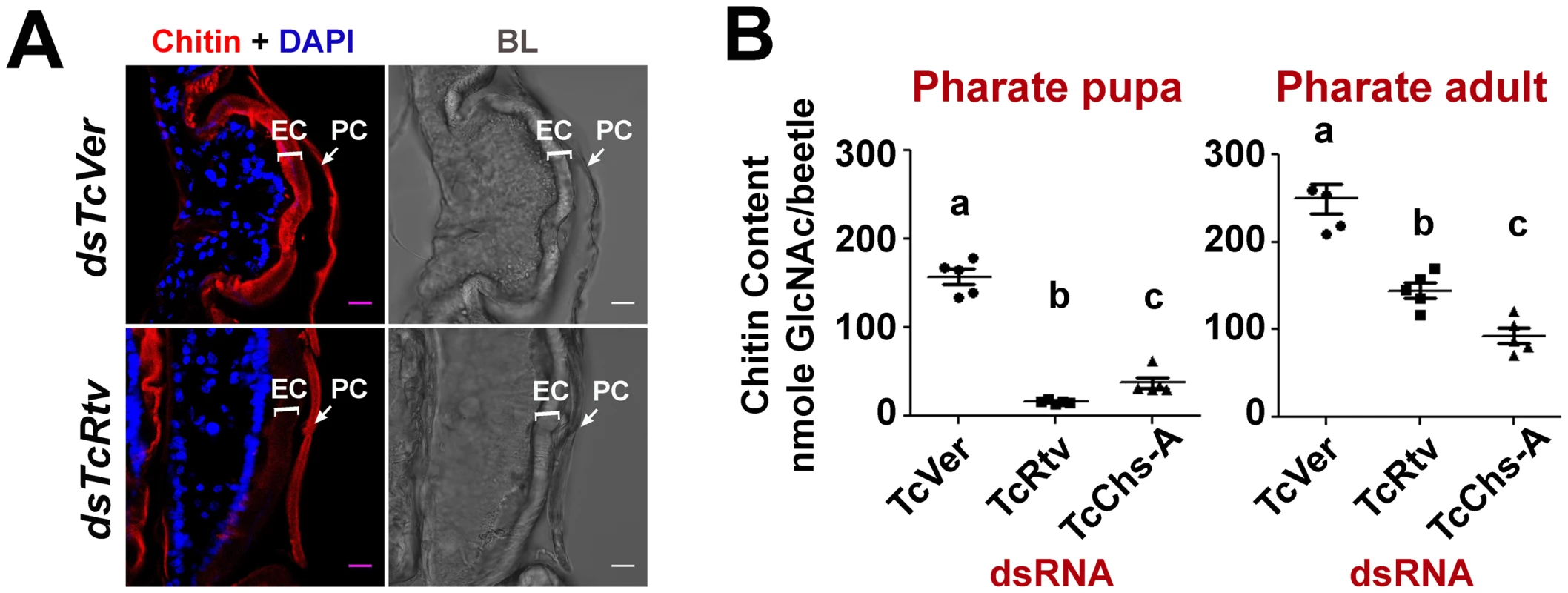

TcRtv is important for the maintenance of procuticular chitin

Because of the terminal phenotypic resemblance of insects treated with dsRNAs against TcRtv or TcChs-A [5], we suspected a reduction of procuticular chitin content resulting in loss of mechanical strength of the new cuticle may account for the failure to complete ecdysis. To test this hypothesis, insects at the pharate pupal stage were treated with TcRtv-specific dsRNA and their chitin contents were probed qualitatively and quantitatively just prior to the adult molt (pharate adult). Confocal microscopic analysis of the pharate adult elytra stained with a chitin-binding domain (CBD) probe (rhodamine-conjugated CBD) showed a near complete loss of chitin in the new cuticle of TcRtv-depleted insects when compared to control insects (Figure 2A). A similar reduction in new cuticular chitin was also detected in the pharate adult insect body wall after RNAi for TcRtv compared to TcVer-depleted insects (Figure 3B, column 1 - row 2). Independently, quantitative analysis of total body chitin content by a modified Morgan-Elson assay confirmed chitin depletion in these insects during both larval-pupal and pupal-adult molts (Figure 2B). The reduction of chitin content following RNAi of TcRtv was comparable to that observed in TcChs-A-depleted insects, and varied depending on the stage of insect development from ∼2 - to 10-fold relative to control insects (Figure 2B). Collectively, these data reveal that TcRtv affects molting by modulating the level of chitin, predominantly in the newly forming cuticle.

Fig. 2. TcRtv is important for the sustenance of procuticular chitin.

(A) Chitin staining (red) of cryosections of pharate adult insects containing both the old pupal cuticle (PC) and the newly synthesized elytral cuticle (EC). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) Quantitative analysis of chitin content from whole animals at pharate pupal and pharate adult stages was carried out using a modified Morgan-Elson assay (n = 5). TcVer and TcChs-A dsRNA-treated insects were used as controls. TcRtv RNAi resulted in a significant loss of chitin in comparison with the TcChs-A knockout. Data are reported as mean ± SE (n = 5 each). Statistical significance was computed with Student's t test. Means identified by different letters (a, b and c) are significantly different at P<0.05. Fig. 3. TcRtv prevents chitinase-mediated degradation of procuticular chitin.

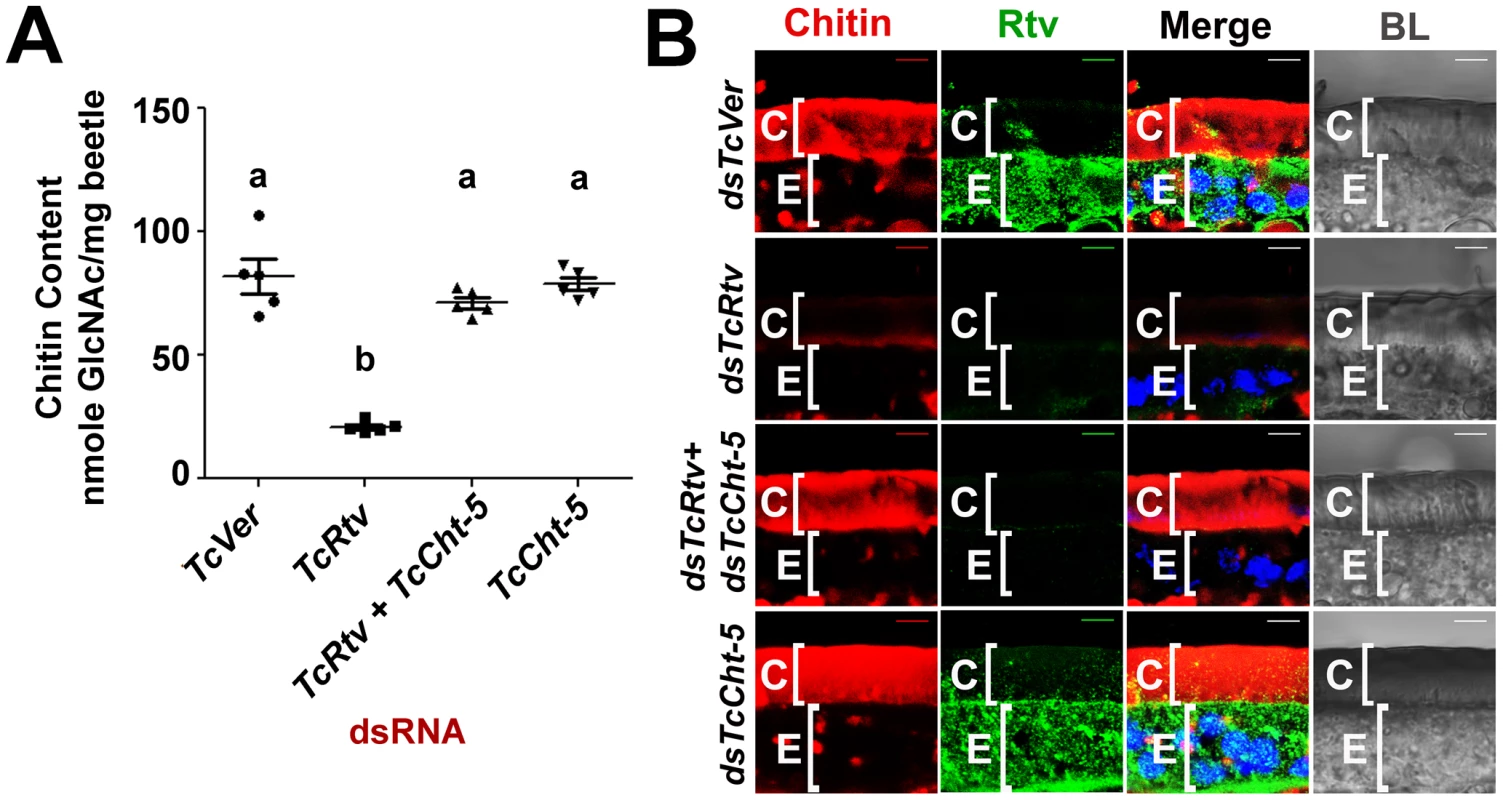

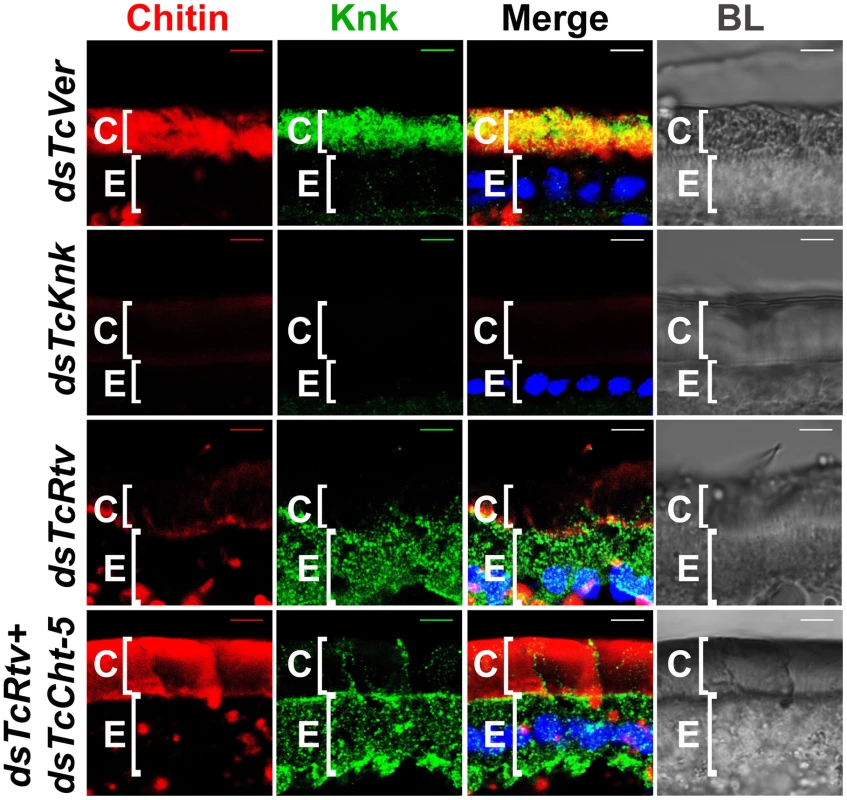

(A) Quantitative analysis of total chitin content of pharate adult insects after dsRNA treatment for TcVer, TcRtv, TcRtv+TcCht-5 and TcCht-5 was performed using a modified Morgan-Elson assay (n = 5). Chitin depletion resulting from TcRtv RNAi was rescued following double RNAi for both TcRtv and TcCht-5. Data are reported as mean ± SE (n = 5 each). Statistical significance was computed with Student's t-test. Means identified by different letters (a and b) are significantly different at P<0.05. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of TcVer, TcRtv, TcRtv+TcCht-5 and TcCht-5 dsRNA-treated insects revealed rescue of the chitin level upon co-knockdown of TcRtv and TcCht5 (dsTcRtv+dsTcCht-5). Chitin (red), TcRtv (green), DAPI (blue), C, cuticle; E, epithelial cell. Scale bar = 5 µm. TcRtv prevents chitinase-mediated degradation of procuticular chitin

The total amount of chitin in an insect is likely to change dynamically during periods of growth as a result of repeated cycles of cuticle deposition and turnover. The dynamics are more complex during molting when there is an overlap of the period of chitin synthesis in the new cuticle with that of chitin degradation in the old cuticle. As a result, several possible mechanisms by which TcRtv may regulate chitin levels in the procuticle can be envisioned. The loss of chitin following RNAi for TcRtv suggests that this protein might be an activator of chitin synthesis or an inhibitor of chitin degradation. In the first scenario, TcRtv might affect chitin synthesis via its effect on TcChs-A at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational or post-translational levels. However, our observation that steady-state levels and cellular distribution of TcChs-A protein were similar in control and TcRtv-depleted insects (Figure S2) argues against a direct effect of TcRtv on TcChs-A expression and localization. An alternative hypothesis that would explain the observed reduction in chitin in the newly forming procuticle following TcRtv RNAi is that TcRtv protects newly synthesized chitin from molting fluid chitinases. Indeed, we have shown recently that chitin is co-localized with chitinases, which are not excluded from the newly forming procuticle as had been assumed in the past. We have further shown that the chitin-binding protein, TcKnk, is needed to protect the nascent chitin in the procuticle from chitinase-mediated degradation [10]. To test the hypothesis that TcRtv also protects chitin, we down-regulated the expression of the major molting fluid chitinase (TcCht-5) at the pharate adult stage either alone or in combination with TcRtv and subjected these samples to quantitative chitin content analysis. Remarkably, the analysis revealed that insects subjected to RNAi for TcRtv alone exhibited significant chitin reduction, but co-depletion of both TcRtv and TcCht-5 transcripts resulted in nearly a complete rescue of cuticular chitin content relative to control levels (Figure 3A). These results also rule out a requirement for TcRtv for the synthesis and transport of chitin to the procuticle by Chs-A and suggest that Rtv-mediated stabilization of chitin involves a step after the synthesis of chitin.

This conclusion was further supported by confocal microscopy, which showed a near complete loss of chitin in the procuticle following depletion of TcRtv transcripts compared to the dsRNA TcVer-treated insects. But RNAi for both TcCht-5 and TcRtv, rhodamine-CBD staining indicated that the level of chitin within the new cuticle of body wall was restored to the same level as dsTcVer controls (Figure 3B, compare row 3 with row 1).

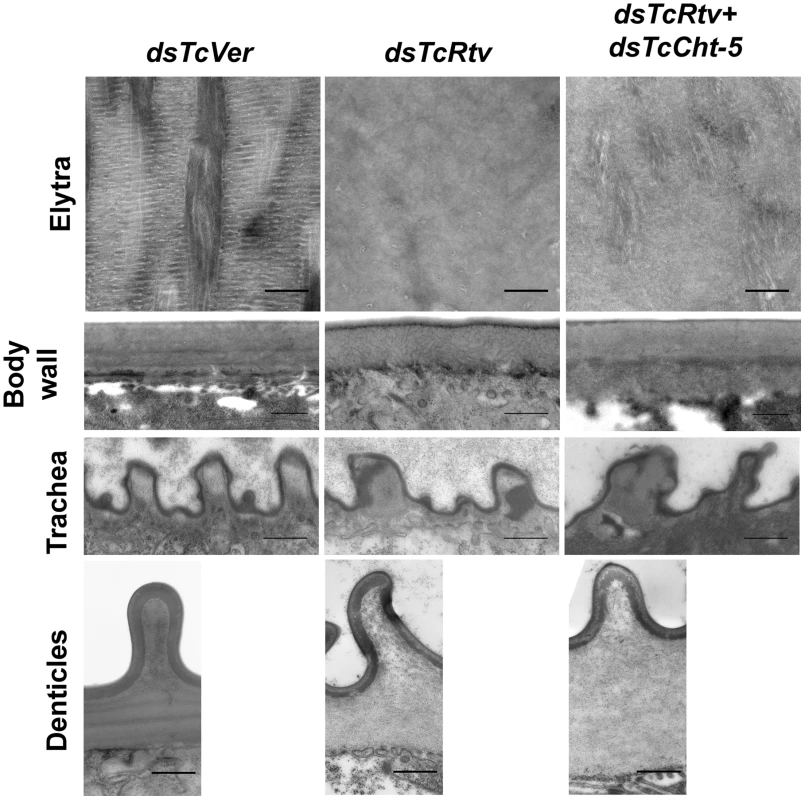

TcRtv affects the ultrastructure of the procuticle

To gain a better understanding of the nature of the restored chitin in the procuticle following depletion of transcripts for both TcCht-5 and TcRtv, we performed Transmission Electron Microscopic (TEM) analysis of the elytra, body wall, tracheae and denticles of insects treated with the indicated combination of dsRNAs. Ultrathin sections of elytral and body wall cuticle from control insects were characterized by a well-organized laminar architecture. Along with the drastic reduction in procuticular chitin, the laminar architecture was completely disrupted following RNAi for TcRtv. Although simultaneous down-regulation of TcRtv and TcCht-5 transcripts resulted in the restoration of chitin within the procuticle, the laminar organization was not reestablished (Figure 4). Interestingly, this phenotype was indistinguishable from the phenotype that we have recently observed in elytra of pharate adults depleted of transcripts for both TcKnk and TcCht-5.

Fig. 4. TcRtv is essential for maintenance of normal cuticle architecture.

Transmission electron microscopic analyses of pharate adult elytral and dorsal body wall cuticles show loss of laminar organization upon TcRtv dsRNA (dsTcRtv) treatment (upper two panels). Although simultaneous down-regulation of TcRtv and TcCht-5 transcripts resulted in the restoration of chitin within the procuticle, the laminar organization of chitin was not restored (panels marked dsTcRtv+dsTcCht5). dsRNA for Vermilion (dsTcVer) was used as a control. Compared to control, after RNAi for TcRtv, the tracheae were misshapen and had electron dense material. This phenotype was not restored to normal after simultaneous down-regulation of Rtv and Cht5 genes (panels marked dsTcRtv+dsTcCht5). The panels in the bottom row show that the horizontal laminae were missing under the misshapen denticles after TcRtv dsRNA treatment. Co-injection of dsRNAs for Rtv and Cht5 did not restore the normal phenotype. Scale bar = 500 nm. Additional analyses also revealed structural deformities of denticles protruding at the lateral body wall that is consistent with loss of laminar architecture in denticular procuticle following down-regulation of TcRtv in these insects (Figure 4). Similarly the taenidial cuticle that lines the tracheal lumen and stabilizes the tracheal tube in these insects also appeared to exhibit structural defects possibly due to the disorganized procuticle (Figure 4) and electron-dense inclusions they harbored. Simultaneous down-regulation of TcRtv and TcCht-5 transcripts, which restores chitin back to normal levels, did not rescue these phenotypes in either the denticles or taenidia, indicating the importance of TcRtv in maintaining the morphology of both taenidia and denticles (Figure 4).

TcRtv is essential for the procuticular localization of TcKnk

Since the phenotypes of RNAi for TcRtv and TcKnk are indistinguishable, we considered the possibility that these two proteins may be involved in the same linear pathway. Immunohistochemistry carried out on sections of control insects (dsTcVer-treated) and those treated with dsRNAs specific for TcRtv, using a polyclonal antibody against Knk indicated that depletion of TcRtv transcripts alone resulted in the mislocalization of TcKnk from its normal distribution predominantly in the procuticle to an exclusive presence within the epidermal cells, perhaps with some TcKnk in the plasma membrane (Figure 5, compare row 3 with row 1).

Fig. 5. TcRtv influences the localization of TcKnk to the procuticle.

Cryosections of T. castaneum pharate adult lateral body wall (20 µm thick) of control TcVer (dsTcVer), TcKnk (dsTcKnk), TcRtv (dsTcRtv) or TcRtv+TcCht-5 (dsTcRtv+dsTcCht-5) dsRNA-treated insects were immunostained with D. melanogaster Knk (DmKnk) antiserum (green). Confocal microscopy reveals that Knk is localized predominantly in the procuticle (row 1). Mislocalization of TcKnk in pharate adults injected with TcRtv dsRNA (row 3) and co-injected with dsRNAs for TcRtv and TcCht-5 is evident (row 4). Although chitin levels were restored to near normal levels in the procuticle after co-injecting dsRNA for TcRtv and TcCht-5, TcKnk was mislocalized, remaining entirely inside the cell rather than being secreted into the procuticle (row 4). Chitin (red), TcKnk (green), DAPI (blue), C, cuticle; E, epithelial cell. Scale bar = 5 µm. However it is likely that the altered localization of TcKnk may have been brought about indirectly by a reduction of chitin which acts as a signal for TcKnk's release into the procuticle and not by a direct effect of TcRtv on TcKnk trafficking. To distinguish between these two possibilities, TcKnk localization was examined in insects depleted of both TcRtv and TcCht-5 transcripts by co-injection of both dsRNAs. This enabled us to disable TcRtv function without concomitant depletion of procuticular chitin, and thus observe the direct effect of TcRtv on localization of TcKnk independently of any possible contributing effects of procuticular chitin itself. Although chitin levels remained at near normal levels in the procuticle after such treatment, TcKnk was mislocalized, remaining entirely inside the cell rather than being secreted into the procuticle (Figure 5, compare row 4 with row 1). The distribution of TcKnk in these double-knockout insects was indistinguishable from that observed in those treated with dsRNA for TcRtv alone. These observations support the hypothesis that TcRtv facilitates the trafficking of TcKnk into the procuticle.

Discussion

The assembly of chitin into the laminated procuticle of insects is a complex process that involves the coordinated action of multiple proteins involved in the synthesis and modification of chitin as well as other chitin-binding and chitin-organizing proteins. While the functions of chitin synthases, deacetylases and chitinases have been studied in some detail [5], [14], [15], [16], the role of non-enzymatic chitin-binding and organizing proteins are less well understood [10], [17]. Mutational analysis in D. melanogaster has implicated two genes, Knk and Rtv, in the organization of tracheal tube chitin and of the embryonic cuticular matrix [11], [12]. More recently, we have shown that the TcKnk protein is localized primarily in the procuticle, possibly bound to chitin [10]. Furthermore, we have shown that procuticular TcKnk is crucial to the protection of chitin from the action of chitinases, which are not excluded from chitin in the newly forming procuticle as previously believed. In addition, TcKnk is needed for the organization of procuticular chitin into an ordered laminar array. However, the role of the protein TcRtv has not been studied extensively even though the phenotypes of Rtv and Knk mutants of D. melanogaster are virtually indistinguishable [11], [12].

Both TcKnk and TcRtv are predicted to encode proteins with GPI anchors by bioinformatic prediction tools (big-PI Predictor, PredGPI and GPI-SOM). However, experimental evidence for the GPI anchor is available only in the case of Knk. TcKnk and DmKnk are released from the plasma membrane of cells expressing this protein by treatment with phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC), an enzyme known to cleave the GPI anchor of membrane-bound proteins [10], [12]. TcRtv expressed in insect cell lines infected with a recombinant virus containing the Rtv coding sequences is not released by PI-PLC treatment (Figure S3). We suspect that TcRtv does not have a true GPI anchor and may merely have a membrane-spanning segment at the C-terminus, suggesting that this protein remains embedded in the ER or attached within vesicles and plasma membranes. Therefore, we propose that TcRtv may not have a direct role in protecting chitin from chitinases and that the loss of procuticular chitin observed after RNAi of TcRtv expression must be via an indirect effect. The finding that there are no significant differences in the amount or localization of TcChs-A in control and dsRNA TcRtv-treated insects also suggests that TcRtv does not have a direct effect on TcChs-A expression or localization. Finally, the full recovery of chitin levels in the procuticle in the absence of TcRtv upon down-regulation of chitinases rules out any role for TcRtv in the synthesis and transport of chitin to the procuticle.

Then how does TcRtv affect cuticle integrity? We have demonstrated that the absence of chitin in the procuticle alone does not account for the mislocalization of the TcKnk protein after RNAi-mediated transcript depletion of TcRtv, because simultaneous RNAi of TcRtv and chitinase genes, while restoring procuticular chitin, fails to rescue the intracellular mislocalization of TcKnk. Rather, it appears that the targeting of TcKnk protein to the procuticle requires the presence of TcRtv. Whether this is due to a direct protein-protein interaction between TcRtv and TcKnk or through a more complex targeting pathway remains to be established.

A search of the SCOP database revealed that the insect Retroactive proteins share broad structural similarity with the snake toxin-like superfamily of proteins with the three-finger domain (TFD) or Ly-6/uPAR domain implicated in protein-protein interactions (Figure S4) [11], [18]. The Ly-6 protein family is composed of several membrane-bound receptors, GPI-anchored proteins, and soluble ligands. These proteins are characterized by the presence of an approximately 100-residue long extracellular motif called the three-finger domain (TFD) [18]. In the prototypical structure described for proteins of this family, the sea snake venom neurotoxin or erabutoxin b, 10 cysteines form a series of disulfide bridges that stabilize the protein core and allow three finger-like loops to protrude [18], [19]. These finger-like extensions with variable sequences are believed to enable interaction of these proteins with a broad range of substrates or ligands, each with a high degree of specificity. Insect Rtv proteins contain 10 cysteines that are predicted to adopt the TFD fold (Figure S4) [11], suggesting that they may be members of the snake toxin-like superfamily of proteins.

Our work has uncovered a novel mechanism involved in cuticular chitin maintenance, wherein presence of TcRtv inside the cells triggers the accretion of TcKnk to the growing chitinous matrix of the procuticle whereupon the latter protein facilitates chitin organization and confers protection from chitinolytic enzymes during the process of molting [10]. The mechanism described herein is probably conserved in all chitinous invertebrates.

Materials and Methods

Insect cultures

The GA-1 strain of T. castaneum was used for all experiments. Insects were reared at 30°C in wheat flour containing 5% brewer's yeast under standard conditions as described previously [20].

Identification of the TcRtv gene in the T. castaneum genome database

An extensive, genome-wide search for homologs of DmRtv in the T. castaneum genome database was performed using NCBI programs TBLASTN and BLASTP and using the amino acid sequence of DmRTV as query.

Cloning and sequencing of a TcRtv cDNA

A DNA fragment containing the complete coding sequence of TcRtv (453 bp) was amplified by reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) using the gene-specific primers (forward primer 5′ - ATGGGTCTGTTTAGATCAATTT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′ - TTACAAAAATCGTAAAATCAGTCT-3′) using cDNA prepared from the RNA extracted from different stages of beetle development as template. Additional 5′ and 3′ UTR sequences were obtained by 5′ - and 3′ - RACE. The amplified fragment was cloned into the pGEMT vector. Sequencing of the cDNA clone was carried out at the DNA sequencing facility at Kansas State University.

Phylogenetic analysis of TcRtv

Rtv-like proteins were identified by TBLASTN searches of the fully sequenced genomes of T. castaneum, Anopheles gambiae, Aedes aegypti, Culex quinquefasciatus, Bombyx mori, Acyrthosiphon pisum, Nasonia vitripennis and Ixodes scapularis using the amino acid sequence of DmRtv as query. Multiple sequence alignments of TcRtv and the related Rtv-like proteins from other insects and arthropods were carried out using the ClustalW software prior to phylogenetic analysis. A consensus phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 4.0 neighbor joining method [21].

Determination of expression profiles of TcRtv

The isolation of RNA and preparation of cDNA from different stages of T. castaneum development were carried out as described previously [10]. These cDNA templates and the pair of TcRtv-specific primers, forward primer 5′-ATGGGTCTGTTTAGATCAATTT-3′ and reverse primer 5′ - TTACAAAAATCGTAAAATCAGTCT -3′, were used for RT-PCR to determine the TcRtv expression profile. The T. castaneum ribosomal protein-6 (TcRpS6) gene was used as an internal control for equal loading of cDNA templates [22].

RNA interference studies

Two different regions of the TcRtv gene were selected for making dsRNAs. Pairs of forward and reverse primers for the chosen regions (Table S1) were used to amplify the dsRNA sequences by using the cloned TcRtv cDNA as template. The Ampliscribe T7-Flash Transcription Kit (Epicentre Technologies) was used to synthesize dsRNA as described previously [5]. dsRNA for the tryptophan oxygenase, dsVermilion (dsVer) gene, which is required for eye pigmentation, was used as a control. dsRNAs for TcRtv or TcVer were injected into animals in the young larval, last instar larval, or pharate pupal stages of T. castaneum development (200 ng per insect, n = 30). Five insects were collected at the young larval, pharate pupal and pharate adult stages of development 3–5 d after dsRNA treatment. Total RNA was extracted from the collected insects for measuring transcript levels by RT-PCR using gene-specific primer-pairs.

Expression of recombinant TcRtv

The full-length TcRtv cDNA clone was used as template to amplify the complete coding region of the TcRtv gene. A primer pair containing appropriate restriction enzyme sites [forward primer 5′-TATCCCGGGATGGGTCTGTTTAGATC-3′ (Sma I) and a reverse primer 5′-CAGACTGATTTTACGATTTTTGTAATCTAGATAT-3′ (Xba I)] was used to facilitate directional cloning of the TcRtv open reading frame (ORF) DNA in the pVL1393 baculovirus expression vector (BD Pharmingen). PCR-amplified, full length TcRtv DNA and the pVL1393 vector DNA were digested with the same pair of restriction enzymes and ligated as described previously [15]. Hi-5 cells (Trichoplusia ni cell line) were used to express the TcRtv protein as described earlier [15].

Immunohistochemistry

TcRtv dsRNA-treated pharate adult insects were collected and fixed as described previously [10]. Cryosections of 20 µm thickness were made and stained for specific proteins using chicken antiserum to T. castaneum Rtv (1∶100), rabbit antiserum (1∶100) to D. melanogaster Knk and rabbit antiserum to T. castaneum Chs-A (1∶50) as primary antibodies. Alexa 488 goat-anti-chicken IgG (1∶1000) or Alexa 488 goat-anti-rabbit IgG (1∶1000) were used as secondary antibodies for the fluorescence detection of TcRtv, TcKnk and TcChs-A proteins. Rhodamine conjugated chitin-binding probe (1∶100) and DAPI (1∶15) were used for staining of chitin and nuclei, respectively. Confocal microscopy was performed with an LSM META 510 laser scanning confocal microscope using laser lines of 405 nm, 488 nm and 543 nm for excitation. Images were taken using an oil objective (40×/1.3 NA) with 8× zoom and processed in Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

PI-Phospholipase-C (PI-PLC) treatment

Hi-5 cells were infected with a recombinant baculovirus containing the TcRtv and TcKnk open reading frame and incubated at 30°C for 3 d for expression of proteins. Three days post-infection, Hi-5 cells expressing respective proteins were treated with PI-PLC as described previously [10].

Chitin content analysis

Following dsRNA treatment, pharate pupae and pharate adults of T. castaneum were collected for chitin content analysis by a modified Morgan-Elson method as described previously [5]. TcVer dsRNA and TcChs-A dsRNA-treated insects were used as negative and positive controls for the experiment, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) analysis

Pharate pupae were injected with dsRNA and pharate adult samples were collected on pupal day 5, fixed and embedded in EMBED 812/Araldite resin as described previously [10]. Resin embedded samples were then thin-sectioned (silver to gold section) and imaged on a CM-100 TEM.

Accession numbers

cDNA sequence for T. castaneum Retroactive (TcRtv) is deposited at NCBI with accession number JX470185.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LockeM (2001) The Wigglesworth Lecture: Insects for studying fundamental problems in biology. J Insect Physiology 47 : 495–507.

2. Reynolds SE, Samuels RI (1996) Physiology and biochemistry of insect moulting fluid. Advances in Insect Physiology. London: Academic Press Ltd. pp. 157–232.

3. MerzendorferH (2006) Insect chitin synthases: a review. J Comp Physiol B 176 : 1–15.

4. Noble-NesbittJ (1963) Cuticle and associated structures of Podura aquatica at moult. Q J Microsc Sci 104 : 369–391.

5. ArakaneY, MuthukrishnanS, KramerKJ, SpechtCA, TomoyasuY, et al. (2005) The Tribolium chitin synthase genes TcCHS1 and TcCHS2 are specialized for synthesis of epidermal cuticle and midgut peritrophic matrix. Insect Mol Biol 14 : 453–463.

6. MerzendorferH, ZimochL (2003) Chitin metabolism in insects: structure, function and regulation of chitin synthases and chitinases. J Exp Biol 206 : 4393–4412.

7. MoussianB (2010) Recent advances in understanding mechanisms of insect cuticle differentiation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 40 : 363–375.

8. MoussianB, SeifarthC, MullerU, BergerJ, SchwarzH (2006) Cuticle differentiation during Drosophila embryogenesis. Arthropod Struct Dev 35 : 137–152.

9. Reynolds SE, Samuels RI (1996) Physiology and biochemistry of insect moulting fluid. Advances in Insect Physiology, Vol 26. pp. 157–232.

10. ChaudhariSS, ArakaneY, SpechtCA, MoussianB, BoyleDL, et al. (2011) Knickkopf protein protects and organizes chitin in the newly synthesized insect exoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 17028–17033.

11. MoussianB, SodingJ, SchwarzH, Nusslein-VolhardC (2005) Retroactive, a membrane-anchored extracellular protein related to vertebrate snake neurotoxin-like proteins, is required for cuticle organization in the larva of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Dyn 233 : 1056–1063.

12. MoussianB, TangE, TonningA, HelmsS, SchwarzH, et al. (2006) Drosophila Knickkopf and Retroactive are needed for epithelial tube growth and cuticle differentiation through their specific requirement for chitin filament organization. Development 133 : 163–171.

13. OstrowskiS, DierickHA, BejsovecA (2002) Genetic control of cuticle formation during embryonic development of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 161 : 171–182.

14. ArakaneY, DixitR, BegumK, ParkY, SpechtCA, et al. (2009) Analysis of functions of the chitin deacetylase gene family in Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 39 : 355–365.

15. ZhuQ, ArakaneY, BeemanRW, KramerKJ, MuthukrishnanS (2008) Characterization of recombinant chitinase-like proteins of Drosophila melanogaster and Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 38 : 467–477.

16. ZhuQS, ArakaneY, BeemanRW, KramerKJ, MuthukrishnanS (2008) Functional specialization among insect chitinase family genes revealed by RNA interference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 6650–6655.

17. JasrapuriaS, ArakaneY, OsmanG, KramerKJ, BeemanRW, et al. (2010) Genes encoding proteins with peritrophin A-type chitin-binding domains in Tribolium castaneum are grouped into three distinct families based on phylogeny, expression and function. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 40 : 214–227.

18. HijaziA, MassonW, AugeB, WaltzerL, HaenlinM, et al. (2009) boudin is required for septate junction organisation in Drosophila and codes for a diffusible protein of the Ly6 superfamily. Development 136 : 2199–2209.

19. BamezaiA (2004) Mouse Ly-6 proteins and their extended family: markers of cell differentiation and regulators of cell signaling. Arch Immunol Ther EX 52 : 255–266.

20. BeemanRW, StuartJJ (1990) A gene for lindane+cyclodiene resistance in the red flour beetle (Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae). J Econ Entomol 83 : 1745–1751.

21. TamuraK, DudleyJ, NeiM, KumarS (2007) MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24 : 1596–1599.

22. ArakaneY, BaguinonMC, JasrapuriaS, ChaudhariS, DoyunganA, et al. (2011) Both UDP N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylases of Tribolium castaneum are critical for molting, survival and fecundity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 41 : 42–50.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Comparative Genome Structure, Secondary Metabolite, and Effector Coding Capacity across PathogensČlánek TATES: Efficient Multivariate Genotype-Phenotype Analysis for Genome-Wide Association StudiesČlánek Secondary Metabolism and Development Is Mediated by LlmF Control of VeA Subcellular Localization inČlánek Human Disease-Associated Genetic Variation Impacts Large Intergenic Non-Coding RNA ExpressionČlánek The Roles of Whole-Genome and Small-Scale Duplications in the Functional Specialization of GenesČlánek The Role of Autophagy in Genome Stability through Suppression of Abnormal Mitosis under Starvation

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Model of High Sugar Diet-Induced Cardiomyopathy

- Comparative Genome Structure, Secondary Metabolite, and Effector Coding Capacity across Pathogens

- Emerging Function of Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Protein (Fto)

- Positional Cloning Reveals Strain-Dependent Expression of to Alter Susceptibility to Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice

- Genetics of Ribosomal Proteins: “Curiouser and Curiouser”

- Transposable Elements Re-Wire and Fine-Tune the Transcriptome

- Function and Regulation of , a Gene Implicated in Autism and Human Evolution

- MAML1 Enhances the Transcriptional Activity of Runx2 and Plays a Role in Bone Development

- Predicting Mendelian Disease-Causing Non-Synonymous Single Nucleotide Variants in Exome Sequencing Studies

- A Systematic Mapping Approach of 16q12.2/ and BMI in More Than 20,000 African Americans Narrows in on the Underlying Functional Variation: Results from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study

- Transcription of the Major microRNA–Like Small RNAs Relies on RNA Polymerase III

- Histone H3K56 Acetylation, Rad52, and Non-DNA Repair Factors Control Double-Strand Break Repair Choice with the Sister Chromatid

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Susceptibility Locus at 12q23.1 for Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Han Chinese

- Genetic Disruption of the Copulatory Plug in Mice Leads to Severely Reduced Fertility

- The [] Prion Exists as a Dynamic Cloud of Variants

- Adult Onset Global Loss of the Gene Alters Body Composition and Metabolism in the Mouse

- Fis Protein Insulates the Gene from Uncontrolled Transcription

- The Meiotic Nuclear Lamina Regulates Chromosome Dynamics and Promotes Efficient Homologous Recombination in the Mouse

- Genome-Wide Haplotype Analysis of Expression Quantitative Trait Loci in Monocytes

- TATES: Efficient Multivariate Genotype-Phenotype Analysis for Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Structural Basis of a Histone H3 Lysine 4 Demethylase Required for Stem Elongation in Rice

- The Ecm11-Gmc2 Complex Promotes Synaptonemal Complex Formation through Assembly of Transverse Filaments in Budding Yeast

- MCM8 Is Required for a Pathway of Meiotic Double-Strand Break Repair Independent of DMC1 in

- Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Endosymbionts of Herbivorous Insects Reveals Eco-Environmental Adaptations: Biotechnology Applications

- Integration of Nodal and BMP Signals in the Heart Requires FoxH1 to Create Left–Right Differences in Cell Migration Rates That Direct Cardiac Asymmetry

- Pharmacodynamics, Population Dynamics, and the Evolution of Persistence in

- A Hybrid Likelihood Model for Sequence-Based Disease Association Studies

- Aberration in DNA Methylation in B-Cell Lymphomas Has a Complex Origin and Increases with Disease Severity

- Multiple Opposing Constraints Govern Chromosome Interactions during Meiosis

- Transcriptional Dynamics Elicited by a Short Pulse of Notch Activation Involves Feed-Forward Regulation by Genes

- Dynamic Large-Scale Chromosomal Rearrangements Fuel Rapid Adaptation in Yeast Populations

- Heterologous Gln/Asn-Rich Proteins Impede the Propagation of Yeast Prions by Altering Chaperone Availability

- Gene Copy-Number Polymorphism Caused by Retrotransposition in Humans

- An Incompatibility between a Mitochondrial tRNA and Its Nuclear-Encoded tRNA Synthetase Compromises Development and Fitness in

- Secondary Metabolism and Development Is Mediated by LlmF Control of VeA Subcellular Localization in

- Single-Stranded Annealing Induced by Re-Initiation of Replication Origins Provides a Novel and Efficient Mechanism for Generating Copy Number Expansion via Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination

- Tbx2 Controls Lung Growth by Direct Repression of the Cell Cycle Inhibitor Genes and

- Suv4-20h Histone Methyltransferases Promote Neuroectodermal Differentiation by Silencing the Pluripotency-Associated Oct-25 Gene

- A Conserved Helicase Processivity Factor Is Needed for Conjugation and Replication of an Integrative and Conjugative Element

- Telomerase-Null Survivor Screening Identifies Novel Telomere Recombination Regulators

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Selection for Important Traits in Domestic Horse Breeds

- Coordinated Degradation of Replisome Components Ensures Genome Stability upon Replication Stress in the Absence of the Replication Fork Protection Complex

- Nkx6.1 Controls a Gene Regulatory Network Required for Establishing and Maintaining Pancreatic Beta Cell Identity

- HIF- and Non-HIF-Regulated Hypoxic Responses Require the Estrogen-Related Receptor in

- Delineating a Conserved Genetic Cassette Promoting Outgrowth of Body Appendages

- The Telomere Capping Complex CST Has an Unusual Stoichiometry, Makes Multipartite Interaction with G-Tails, and Unfolds Higher-Order G-Tail Structures

- Comprehensive Methylome Characterization of and at Single-Base Resolution

- Loci Associated with -Glycosylation of Human Immunoglobulin G Show Pleiotropy with Autoimmune Diseases and Haematological Cancers

- Switchgrass Genomic Diversity, Ploidy, and Evolution: Novel Insights from a Network-Based SNP Discovery Protocol

- Centromere-Like Regions in the Budding Yeast Genome

- Sequencing of Loci from the Elephant Shark Reveals a Family of Genes in Vertebrate Genomes, Forged by Ancient Duplications and Divergences

- Mendelian and Non-Mendelian Regulation of Gene Expression in Maize

- Mutational Spectrum Drives the Rise of Mutator Bacteria

- Human Disease-Associated Genetic Variation Impacts Large Intergenic Non-Coding RNA Expression

- The Roles of Whole-Genome and Small-Scale Duplications in the Functional Specialization of Genes

- Sex-Specific Signaling in the Blood–Brain Barrier Is Required for Male Courtship in

- A Newly Uncovered Group of Distantly Related Lysine Methyltransferases Preferentially Interact with Molecular Chaperones to Regulate Their Activity

- Is Required for Leptin-Mediated Depolarization of POMC Neurons in the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus in Mice

- Unlocking the Bottleneck in Forward Genetics Using Whole-Genome Sequencing and Identity by Descent to Isolate Causative Mutations

- The Role of Autophagy in Genome Stability through Suppression of Abnormal Mitosis under Starvation

- MTERF3 Regulates Mitochondrial Ribosome Biogenesis in Invertebrates and Mammals

- Downregulation and Altered Splicing by in a Mouse Model of Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy (FSHD)

- NBR1-Mediated Selective Autophagy Targets Insoluble Ubiquitinated Protein Aggregates in Plant Stress Responses

- Retroactive Maintains Cuticle Integrity by Promoting the Trafficking of Knickkopf into the Procuticle of

- Phenome-Wide Association Study (PheWAS) for Detection of Pleiotropy within the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Network

- Genetic and Functional Modularity of Activities in the Specification of Limb-Innervating Motor Neurons

- A Population Genetic Model for the Maintenance of R2 Retrotransposons in rRNA Gene Loci

- A Quartet of PIF bHLH Factors Provides a Transcriptionally Centered Signaling Hub That Regulates Seedling Morphogenesis through Differential Expression-Patterning of Shared Target Genes in

- A Genome-Wide Integrative Genomic Study Localizes Genetic Factors Influencing Antibodies against Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA-1)

- Mutation of the Diamond-Blackfan Anemia Gene in Mouse Results in Morphological and Neuroanatomical Phenotypes

- Life, the Universe, and Everything: An Interview with David Haussler

- Alternative Oxidase Expression in the Mouse Enables Bypassing Cytochrome Oxidase Blockade and Limits Mitochondrial ROS Overproduction

- An Evolutionarily Conserved Synthetic Lethal Interaction Network Identifies FEN1 as a Broad-Spectrum Target for Anticancer Therapeutic Development

- The Flowering Repressor Underlies a Novel QTL Interacting with the Genetic Background

- Telomerase Is Required for Zebrafish Lifespan

- and Diversified Expression of the Gene Family Bolster the Floral Stem Cell Network

- Susceptibility Loci Associated with Specific and Shared Subtypes of Lymphoid Malignancies

- An Insertion in 5′ Flanking Region of Causes Blue Eggshell in the Chicken

- Increased Maternal Genome Dosage Bypasses the Requirement of the FIS Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 in Arabidopsis Seed Development

- WNK1/HSN2 Mutation in Human Peripheral Neuropathy Deregulates Expression and Posterior Lateral Line Development in Zebrafish ()

- Synergistic Interaction of Rnf8 and p53 in the Protection against Genomic Instability and Tumorigenesis

- Dot1-Dependent Histone H3K79 Methylation Promotes Activation of the Mek1 Meiotic Checkpoint Effector Kinase by Regulating the Hop1 Adaptor

- A Heterogeneous Mixture of F-Series Prostaglandins Promotes Sperm Guidance in the Reproductive Tract

- Starvation, Together with the SOS Response, Mediates High Biofilm-Specific Tolerance to the Fluoroquinolone Ofloxacin

- Directed Evolution of a Model Primordial Enzyme Provides Insights into the Development of the Genetic Code

- Genome-Wide Screens for Tinman Binding Sites Identify Cardiac Enhancers with Diverse Functional Architectures

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Function and Regulation of , a Gene Implicated in Autism and Human Evolution

- An Insertion in 5′ Flanking Region of Causes Blue Eggshell in the Chicken

- Comprehensive Methylome Characterization of and at Single-Base Resolution

- Susceptibility Loci Associated with Specific and Shared Subtypes of Lymphoid Malignancies

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání