-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaGenome-Wide Association Studies Reveal a Simple Genetic Basis of Resistance to Naturally Coevolving Viruses in

Variation in susceptibility to infectious disease often has a substantial genetic component in animal and plant populations. We have used genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in Drosophila melanogaster to identify the genetic basis of variation in susceptibility to viral infection. We found that there is substantially more genetic variation in susceptibility to two viruses that naturally infect D. melanogaster (DCV and DMelSV) than to two viruses isolated from other insects (FHV and DAffSV). Furthermore, this increased variation is caused by a small number of common polymorphisms that have a major effect on resistance and can individually explain up to 47% of the heritability in disease susceptibility. For two of these polymorphisms, it has previously been shown that they have been driven to a high frequency by natural selection. An advantage of GWAS in Drosophila is that the results can be confirmed experimentally. We verified that a gene called pastrel—which was previously not known to have an antiviral function—is associated with DCV-resistance by knocking down its expression by RNAi. Our data suggest that selection for resistance to infectious disease can increase genetic variation by increasing the frequency of major-effect alleles, and this has resulted in a simple genetic basis to variation in virus resistance.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003057

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003057Summary

Variation in susceptibility to infectious disease often has a substantial genetic component in animal and plant populations. We have used genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in Drosophila melanogaster to identify the genetic basis of variation in susceptibility to viral infection. We found that there is substantially more genetic variation in susceptibility to two viruses that naturally infect D. melanogaster (DCV and DMelSV) than to two viruses isolated from other insects (FHV and DAffSV). Furthermore, this increased variation is caused by a small number of common polymorphisms that have a major effect on resistance and can individually explain up to 47% of the heritability in disease susceptibility. For two of these polymorphisms, it has previously been shown that they have been driven to a high frequency by natural selection. An advantage of GWAS in Drosophila is that the results can be confirmed experimentally. We verified that a gene called pastrel—which was previously not known to have an antiviral function—is associated with DCV-resistance by knocking down its expression by RNAi. Our data suggest that selection for resistance to infectious disease can increase genetic variation by increasing the frequency of major-effect alleles, and this has resulted in a simple genetic basis to variation in virus resistance.

Introduction

Variation in susceptibility to infectious disease often has a substantial genetic component in animal and plant populations [1]–[4]. As pathogens are a powerful selective force in the wild, natural selection is expected to play an important role in determining the nature of this genetic variation. Selection for resistance to infectious disease can change rapidly, as new pathogens appear in the population [5], or existing pathogens evolve, for example to evade or sabotage host defences [6]. This selection can result both in positive selection increasing the frequency of mutations that generate new resistance alleles [7], [8], and balancing selection stably maintaining resistant and susceptible alleles of a gene [9].

Over the last decade, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have provided a more complete picture of the genetic architecture of disease susceptibility [10]. The majority of these studies have investigated non-communicable diseases in humans, and while many polymorphisms associated with susceptibility have been identified, these often have small effects and together can explain only a small proportion of the heritability [11] (but see [12]). It has been suggested that the reason for this is that new mutations that increase susceptibility to non-communicable disease may tend to be deleterious, so alleles that have large effects are either removed from the population or kept at a low frequency by purifying selection [11]. However, both GWAS and classical linkage mapping studies suggest that the genetic architecture of infectious disease susceptibility may be qualitatively different [13], as major effect polymorphisms that protect hosts against infection have been identified in many organisms, including plants [11], humans [3], [13] and insects [7], [14]. Furthermore, these polymorphisms are often under strong positive or balancing selection [7]–[9]. It has therefore been argued that natural selection may cause the variation in infectious disease susceptibility to have a simpler genetic architecture than non-communicable diseases as major-effect alleles can reach a higher frequency in populations [13].

In arthropods, several studies suggest that susceptibility to infectious disease may often be affected by major-effect polymorphisms (e.g.[7], [14], [15]). In Drosophila melanogaster, linkage mapping has been used to identify major effect resistance polymorphisms that affect susceptibility to both the sigma virus (DMelSV) [16], [17] and parasitoid wasps [18]. In the case of DMelSV, two of these loci have been identified at the molecular level (ref(2)P and CHKov1), and they have been found to be common in natural populations [7], [14], [19]. In addition, polymorphisms in known immunity genes have been found to affect susceptibility to bacterial infection, and some of these have substantial effects [2], [20], [21].

To understand how natural selection affects the genetics of disease susceptibility, we have used GWAS to examine the effects of selection for resistance to pathogens on patterns of genetic variation. To do this we infected D. melanogaster both with viruses that naturally occur in this species and viruses isolated from other species. The two of the viruses that naturally infect D. melanogaster are Drosophila C Virus (DCV), which is a positive sense RNA virus in the Dicistroviridae that infects a range of Drosophila species [22], [23], and the sigma virus DMelSV, which is a rhabdovirus that is a specialist on D. melanogaster [16]. The other two viruses naturally infect other insect species are DAffSV, which is another sigma virus that naturally infects Drosophila affinis [24], [25] and Flock House Virus (FHV), which is a nodavirus that was isolated from beetles but can infect an extremely broad range of organisms [26]. We found that the heritability of susceptibility to the two natural D. melanogaster viruses is high due to a small number of common major-effect polymorphisms. In contrast there is less genetic variation in susceptibility to viruses isolated from other species, and here there is no evidence of major effect polymorphisms.

Results

Genetic variation in virus resistance

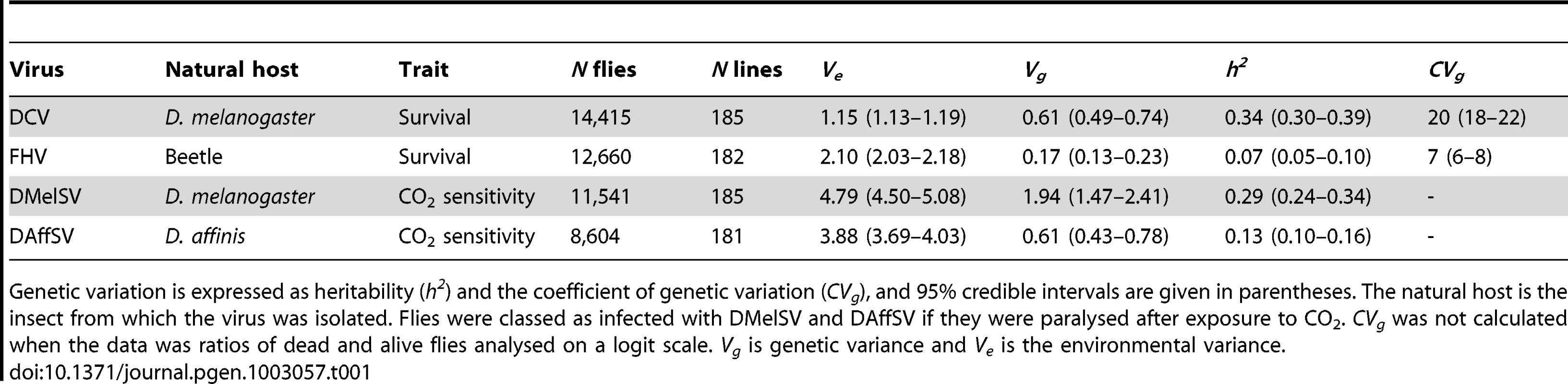

To investigate genetic variation in resistance to viruses, we injected 47,220 flies from 185 different inbred lines from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP) with four different viruses (Table 1; note that the DMelSV data, but not this analysis, has been published before [7]). The extent of genetic variation in susceptibility varied considerably between the different viruses, with the greatest genetic variation being present when flies are exposed to viruses that infect D. melanogaster in nature. Comparing the two viruses where resistance was measured in terms of survival time—DCV and FHV—we found DCV resistance has significantly greater heritability (Table 1). When the two sigma viruses, DMelSV and DAffSV, are compared, again the heritability is significantly greater in resistance to the naturally occurring virus DMelSV (Table 1). While differences in heritability can be caused by differences in genetic or environmental variation, it is clear that there is genetic variation in resistance to the natural pathogens of D. melanogaster. In the case of DCV and FHV, DCV has the greater coefficient of genetic variation (Table 1; CVg) [27]. It is not possible to calculate the coefficient on variation for the sigma virus data as it is analysed on a logit scale. However, by inspecting Ve and Vg in Table 1, it is clear that the differences in the heritability of resistance to DMelSV and DAffSV are primarily driven by differences in Vg.

Tab. 1. Genetic variation in susceptibility to four different viruses.

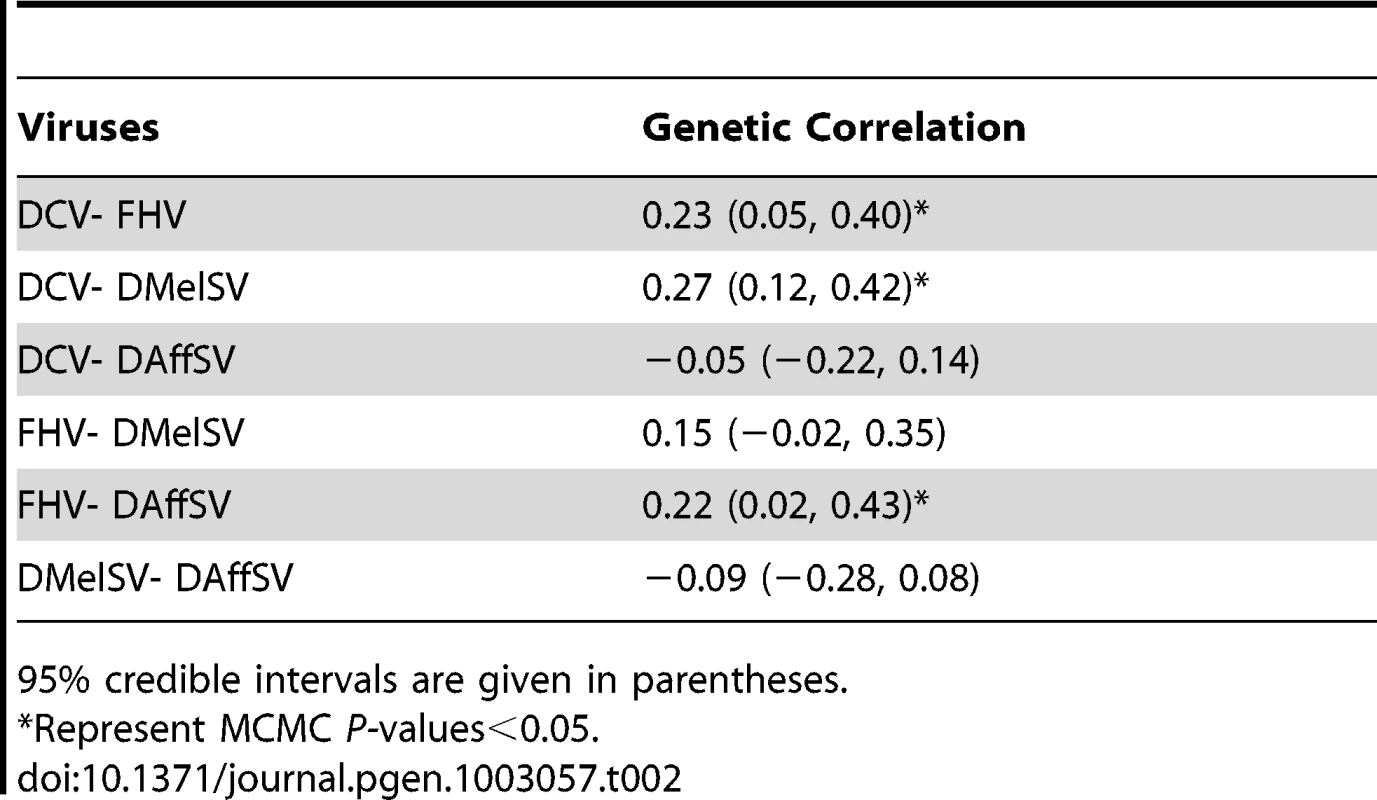

Genetic variation is expressed as heritability (h2) and the coefficient of genetic variation (CVg), and 95% credible intervals are given in parentheses. The natural host is the insect from which the virus was isolated. Flies were classed as infected with DMelSV and DAffSV if they were paralysed after exposure to CO2. CVg was not calculated when the data was ratios of dead and alive flies analysed on a logit scale. Vg is genetic variance and Ve is the environmental variance. In all cases the genetic correlation in the level of resistance to different viruses is low, indicating that different genes are controlling resistance to different viruses (Table 2). In particular, the sigma viruses (DMelSV and DAffSV) showed no evidence of any genetic correlation, despite being relatively closely related [24], [25]. Despite being small, there is a significant positive genetic correlation in susceptibility between three pairs of viruses, indicating that there may be some variation in the ability to survive viral infection in general. The low genetic correlations also confirm that we are measuring susceptibility to the different viruses and not an artefact of the injection procedure.

Tab. 2. Genetic correlations in susceptibility to four different viruses.

95% credible intervals are given in parentheses. Resistance to viruses that infect D. melanogaster in the wild has a simple genetic basis

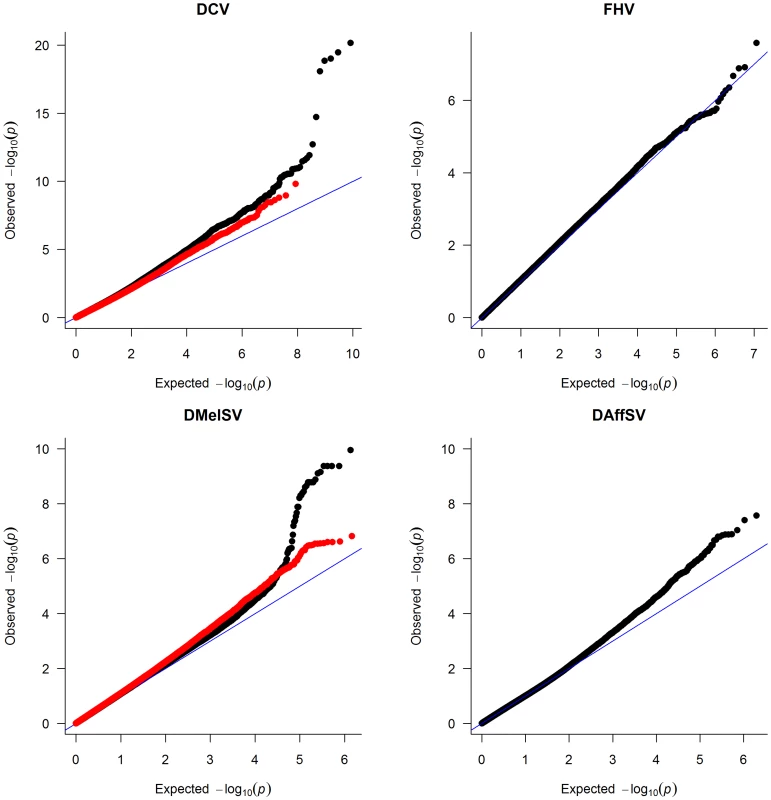

To identify polymorphisms that are associated with resistance to the four viruses, we performed genome-wide association studies using the published genome sequences of the DGRP lines [28]. To correct for multiple tests and obtain a genome-wide significance threshold, we permuted the trait data across the lines and repeated the GWAS 400 times, each time recording the lowest P-value across the entire genome. Quantile-quantile (qq) plots of the P-values show that there are highly significant associations in the experiments using DCV and DMelSV — the two viruses that infect D. melanogaster in the wild — but not in the experiments using FHV and DAffSV (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Quantile–quantile plots of P-values.

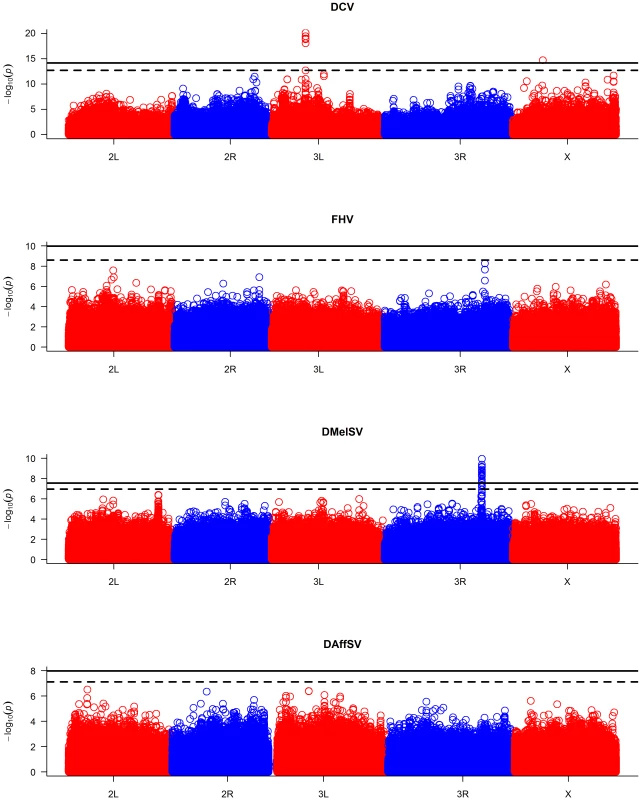

The black dots represent the observed P-values against the P-values that are expected under the null hypothesis (that there are no true associations with resistance to four viruses), and the straight line is the distribution expected if the observed values equal the expected values. The red points show the P-values after the effect of the polymorphisms in pastrel (DCV), ref(2)P (DMelSV) and CHKov1 (DMelSV) have been accounted for. The null distribution of expected P-values was obtained by permutation. When the P-values are plotted along the chromosomes, it is clear that the most significant P-values cluster together (Figure 2, Figure S1). In the case of DMelSV there is a cluster of significant SNPs around CHKov1 on chromosome arm 3R, which is a gene where we have previously shown that a transposable element insertion is associated with resistance to this virus [7] (Figure 2, Figure S1). The second most significant cluster of SNPs in this experiment falls just below the genome-wide significance threshold, and is on chromosome arm 2L (Figure 2, Figure S1). The SNPs in this cluster are all in strong linkage disequilibrium with a polymorphism in ref(2)P that is known to cause resistance (the causal polymorphism was genotyped by PCR and included in this analysis),[8], [14]. In the case of DCV there is a cluster of significant SNPs in and around a gene on chromosome arm 3L called pastrel, which has not previously been implicated in antiviral defence. There were no significant associations with susceptibility to FHV or DAffSV using a genome-wide significance threshold of P<0.05 (Figure 2, Figure S1).

Fig. 2. Manhattan plots of the P-values for the association between SNPs and virus resistance.

The horizontal lines are genome-wide significance thresholds of P = 0.05 (solid line) and P = 0.2 (dashed line) that were obtained by permutation. The five chromosome arms are different colours. We repeated the GWAS accounting for the effects of the polymorphisms in ref(2)P, CHKov1 and pastrel. The quantile-quantile plots of the resulting P-values (Figure 1, red points) show that these genes can account for all of the large excess of highly significant associations with DCV and DMelSV resistance. The resulting distribution of P-values resembles that seen for the other two viruses that do not naturally infect D. melanogaster.

To investigate how much of the genetic variation in susceptibility is explained by our GWAS, we calculated the proportion of the heritability that is explained by these genes. Assuming the polymorphisms have additive effects, then their contribution to additive genetic variation is 2pqa2, where p and q are the frequencies of the alleles, and a and −a are the genotypic values of the resistant and susceptible homozygotes. In the case of DCV, pastrel (3L:7350895) can explain 47% of the heritability. In the case of DMelSV, ref(2)P explains 8% of the heritability, the doc element insertion in CHKov1 explains 29% of the heritability, and in combination these polymorphisms explain 37% of the heritability.

The proportion of the heritability explained by these polymorphisms may be biased by two factors. First, we are injecting the virus, which is an unnatural route of infection, and in the case of the sigma viruses we are assaying a symptom of infection rather than viral titres or effects on host survival. Second, we can only estimate the amount of genetic variation explained in inbred lines, and this can only be directly extrapolated to outcrossed populations if all the genes affecting resistance are additive. Unfortunately, we cannot estimate the importance or direction of this bias as we only used inbred lines (the only one of the three genes for which levels of dominance has been investigated is ref(2)P, where heterozygotes have intermediate levels of resistance when injected with the virus [29]). However, the bias could be substantial if we make the extreme assumptions about dominance. If the susceptible pastrel allele is recessive and only half the remaining genetic variance is additive, this polymorphism will explain 84% of Va in an outcrossed population. Conversely, if the resistant pastrel allele is fully dominant and all the remaining genetic variance is additive, this polymorphism will explain just 7% of Va in an outcrossed population.

In addition to these major-effect polymorphisms, there were also other suggestive results. The most significant association for DAffSV was a synonymous SNP in scavenger receptor C1 (2L:4123156 A/T; individual P = 6.41×10−8; genome-wide permutation P = 0.18). This gene functions both as a pattern recognition receptor of bacteria [30] and allows the uptake of dsRNA into cells [31]. A polymorphism in the gene Anaphase promoting complex 7 was associated with a 3.7 day increase in survival after injection with DCV (X:6491634 G/T; individual P = 1.95×10−15; genome-wide permutation P<0.05). This was at a low frequency, with the resistant variant present in 4 of 145 lines. Furthermore, it is a synonymous polymorphism, suggesting that it may not be a causal variant. The QQ plots also show that there is an excess of small P-values in three of the analyses (Figure 1), suggesting that there may be many more polymorphisms to be discovered, or that there is some unidentified population stratification.

As the polymorphisms in pastrel, CHKov1 and ref(2)P have a large effect on resistance, we repeated the GWAS taking account of these polymorphisms by including them as fixed effects in the model. However, this did not lead to the identification of additional SNPs associated with resistance (Figure S2). The most significant association with DCV resistance remained Anaphase promoting complex 7 (X:6491634 G/T). For DMelSV it was a SNP in the intron of off-track (2R:7899322 A/T, genome-wide P = 0.29), which is a transmembrane receptor that controls a variety of developmental and physiological processes [32].

Resistance genes are specific to different viruses

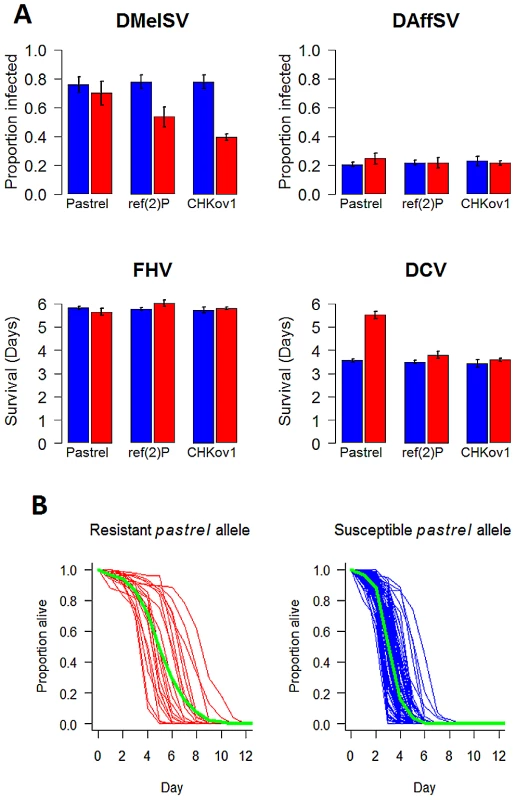

The polymorphisms in pastrel, CHKov1 and ref(2)P have highly specific effects, altering susceptibility to just one of the four viruses (Figure 3). Against these target viruses, the effect on the susceptibility of individual flies is considerable (Figure 3). Comparing flies that are homozygous for the resistant and susceptible alleles, the most significant SNP in pastrel increases survival times by 55%. The doc element insertion in CHKov1 reduces the proportion of infected flies by 39%, while the ref(2)P polymorphism is associated with a 24% reduction in infection rates (see also [7]). When large numbers of statistical tests are performed and the statistical power is low, as is the case in many genetic association studies, there is a tendency to overestimate effect sizes [33]. However, the extremely low P-values associated with our resistance genes suggest our statistical power was high and therefore these effect size estimates are reliable.

Fig. 3. The effect of the three polymorphisms affecting susceptibility on four different viruses.

In Panel A, blue bars are the susceptible allele and red bars the resistant allele. The estimates and standard errors were obtained using a general linear mixed model with the mean survival or proportion infected in each vial as the response. Significant associations are controlled for when estimating the effects of other genes, and the estimates assume that the flies have the susceptible allele of other genes. Panel B, shows the survival curves of lines with the two alleles of pastrel (3L:7350895 Ala/Thr). The green lines show the combined survival of all the flies with each allele (combined across the different lines). pastrel confers resistance to DCV

In pastrel there are six SNPs that are associated with resistance to DCV at P<10−12. These include two adjacent SNPs in the 3′UTR (genome positions: 3L:7350452 T/G, 3L:7350453 A/G), two non-synonymous SNPs (3L:7350895 Ala/Thr, 3L:7352880 Glu/Gly) and two SNPs in introns (3L:7351494 C/T, 3L:7352966 T/G). All of these are in linkage disequilibrium, with the two SNPs in the 3′ UTR being perfectly associated (these are therefore considered as a single variant in subsequent analyses). To try and disentangle which of the polymorphisms might be a causal variant, we fitted a general linear mixed-effects model in which all five variants were included as fixed effects. This allows us to calculate the marginal significance of each polymorphism (i.e. the P-value after controlling for the effects of all the other SNPs). In this analysis only a non-synonymous SNP in the last coding exon of the pastrel remained highly significant (3L:7350895: F1,116 = 18.2, P<0.0001; all other P-values>0.01). This SNP occurred in 21 of 142 lines that were sequenced at this site. We then tested the significance of each of the other four variants individually while controlling for the effects of 3L:7350895, by fitting general linear mixed-effects models and calculating sequential P-values from an ANOVA table. When we did this, all the other SNPs are significant (P<0.0001 in all cases). If we assume that we have included all the polymorphisms in this region in our analysis, this suggests that the non-synonymous polymorphism 3L:7350895 and at least one of the other sites are causal variants — but strong linkage disequilibrium prevents us from identifying which one(s). However, many polymorphisms, including indels, are missing from this dataset, so another polymorphism in this region that is not included in our analysis may be causing flies to be resistant to DCV.

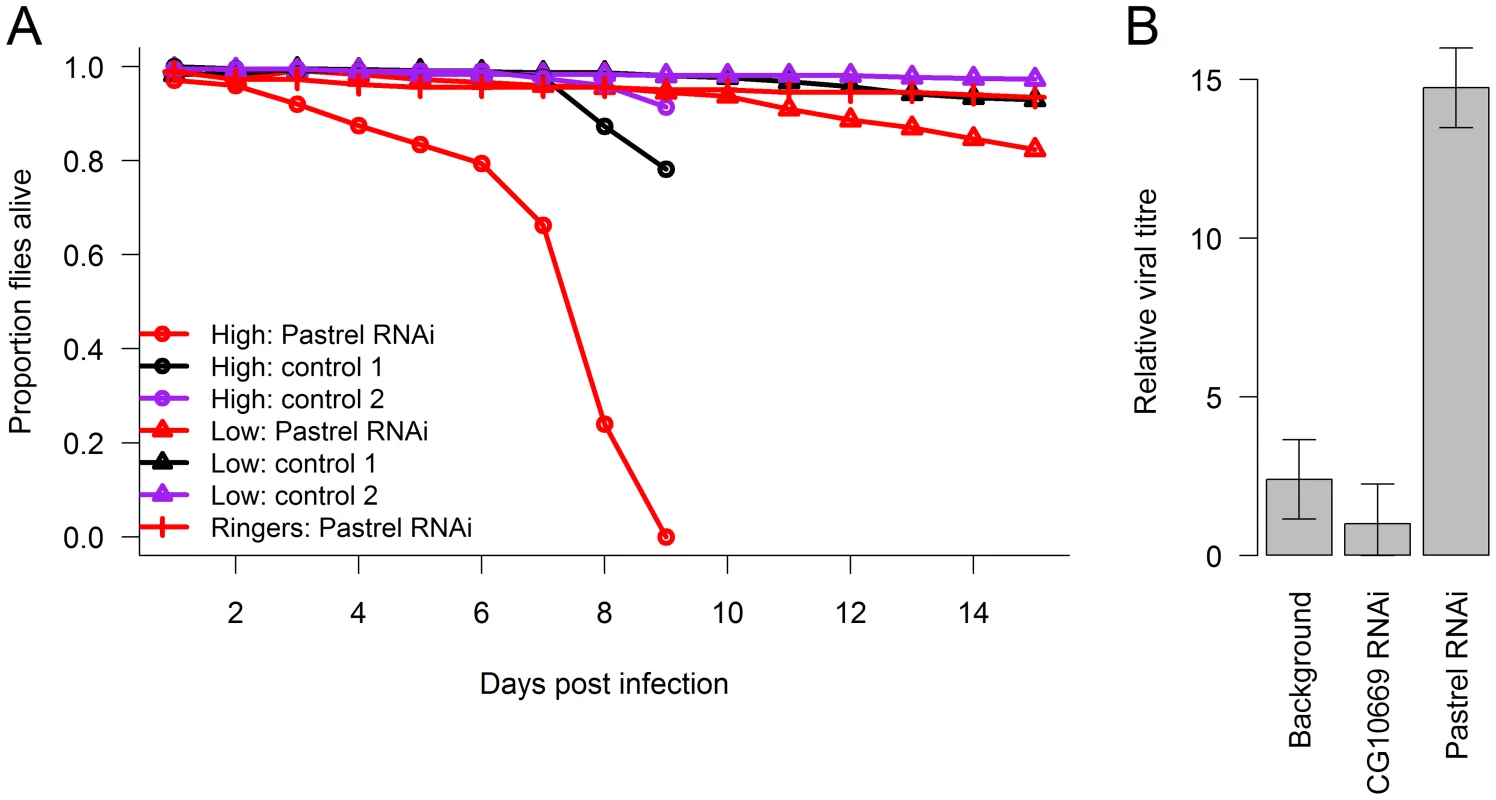

To confirm the antiviral role of pastrel, we used RNAi to knock down the gene in flies that were homozygous for the susceptible allele. To do this, we expressed hairpin RNAs that target the pastrel gene under the control of a constitutively and ubiquitously expressed Gal4 driver. When the flies were infected with a high dose of DCV, this resulted in a large reduction in survival rates relative to both a control with a similar genetic background (Figure 4A; Cox proportional hazard mixed model: z = 3.62, P = 0.0003) and a control where we knocked down a gene unrelated to viral resistance (Figure 4A; Cox proportional hazard mixed model: z = 3.19 P = 0.001). To allow us to investigate viral titres, we also infected flies with a lower dose of DCV, which caused less mortality (Figure 4A). The viral titre in the flies where pastrel had been knocked down was ∼6 times greater than the background control and ∼15 times greater than the control gene (Figure 4B; F2,18 = 23.3, P = 10−5).

Fig. 4. The effect of knocking down pastrel expression.

The effect of knocking down pastrel expression on (A) the survival of infected flies with a high or low dose of DCV (see methods) and (B) viral titres 14 days post infection with the low dose. Control 1 were flies in which a gene unrelated to viral infection was knocked down (CG10669), and Control 2 were flies with the same genetic background as the pastrel-RNAi flies. Error bars are standard errors. Observations on the high dose treatment stopped on day 9. Discussion

We have found that a small number of major-effect polymorphisms can explain a substantial proportion of the genetic variation in the susceptibility of D. melanogaster to viral infection. These genes have either been previously identified by linkage mapping, or, in the case of pastrel, were verified by RNAi in this study. These polymorphisms are only seen when flies were infected with the two viruses that occur naturally in D. melanogaster populations — we were unable to detect any significant associations when using viruses that naturally infect other insects. The consequence of this is that the genetic variation in susceptibility to the naturally occurring viruses is substantially greater than to viruses from other species. Combined with previous data showing that two of these resistance alleles have been driven to a high frequency by positive selection [7], [8], [34], these results suggest that selection by viruses in natural populations may be increasing genetic variation in disease susceptibility. As the resistance alleles that we detected have highly specific effects against a single virus, genetic variation in susceptibility to infection by viruses isolated from other species of insects has remained low.

Our results support the suggestion that the genetic architecture of infectious disease susceptibility may be different from non-communicable diseases due to selection by parasites [13], [35]. GWAS in humans have mostly focused on non-communicable disease, and have tended to find polymorphisms of modest effect. In contrast, work on infectious disease in humans has described numerous loci with a major-effect on susceptibility [3], [13], [35], and similar patterns have been reported by QTL studies in other animals [36]. This has led to the suggestion that variation in pathogen resistance may often be controlled by a mixture of major-effect polymorphisms and other loci that are difficult to detect because they are rare or have small effects [13]. Our results corroborate this pattern, as while we find a few major-effect genes, over half of the total genetic variation remains unexplained. Furthermore, our results provide support for the role of natural selection by parasites in increasing the frequency and effect size of disease susceptibility loci. If this pattern proves to apply to other species, then GWAS on susceptibility to infectious disease promises to be a productive direction for future research.

Parasites can result both in balancing selection maintaining polymorphisms in host resistance, and directional selection, which will ultimately fix the resistant allele [6]. Previous work has shown that the resistant alleles of CHKov1 and ref(2)P both arose recently by mutation and natural selection has caused them to increase in frequency [7], [8], [34], [37]. Therefore, it appears as though directional selection is driving new resistance genes through the population, and this is increasing genetic variation in disease susceptibility.

Directional selection on a trait can result in higher genetic variance when selection is acting on alleles that are initially at a low frequency [38]–[40]. If this is the case, selection will increase the frequency of rare alleles that previously contributed little to genetic variation in the population, and will therefore increase genetic variation in the trait [38]–[40]. For example, this process is thought to explain why selection by mate choice increases genetic variation in the cuticular hydrocarbons produced by Drosophila serrata [41]. In the case of the polymorphisms in ref(2)P and CHKov1, previous work has suggested that they have undergone a ‘hard’ selective sweep, where selection has been acting on new or rare polymorphisms [7], [8], [34], [37]. Therefore, they will have contributed little to genetic variation before selection, but now explain much of the heritability in this population. Certain traits, such as insecticide resistance, normally evolve in this way with selection acting on rare alleles [42]. This is thought to be because there are relatively few genetic changes that can cause insecticide resistance, and therefore there are too few mutations to generate much standing genetic variation [42]. If resistance to viruses also normally evolves due to selection on rare alleles, it may be common for directional selection to increase genetic variation. Fluctuating selection by parasites through time and space, or negatively frequency-dependent selection may also play an important role in increasing genetic variation.

In addition to the genes that we have identified, the bacterial symbiont Wolbachia also makes D. melanogaster more resistant to viral infection [43], [44]. Wolbachia occurs in natural populations, and protects flies against two of the viruses we studied — DCV and FHV [43], [44] (but not sigma viruses, Teixeira, Magwire and Wilfert, Pers. Comm.). As Wolbachia is transmitted vertically from mother to offspring, in many ways it can be regarded as another major-effect resistance polymorphism. We cured Wolbachia in our experiments with DCV and FHV and therefore have no data on its effects, but in natural populations of D. melanogaster it varies in prevalence from below 1% to near fixation [45]. This may affect how selection acts on the polymorphisms that we have identified, as our resistance genes may confer less of a benefit in populations where Wolbachia is common.

Will the genetic architecture of resistance to other classes of pathogens be similar to the pattern we have seen for viruses? In Drosophila, parasitoid wasps are one of the main causes of mortality in natural populations [46], and both linkage mapping and artificial selection experiments suggest that resistance against these parasites is controlled by a few major-effect loci [18], [47], [48]. There is also extensive variation in bacterial resistance, and polymorphisms in immune system genes explain a substantial proportion of this variation [49], [50]. It is difficult to compare these results directly to our own as comparatively few markers were genotyped and only known immune genes were investigated. Nonetheless, it would appear possible that bacterial resistance may have a more complex genetic architecture than virus resistance, involving more genes and epistatic interactions. Furthermore, there was not the clear difference between bacteria isolated from D. melanogaster and other organisms that we observed among our viruses [49], [50]. This may be because there is a broad-spectrum induced immune response against bacteria [51] but not viruses [52], or because the viruses may have a narrower host range, resulting in more rapid coevolution.

In the long term, the spread of the resistance genes through populations could either result in the virus evolving to overcome host resistance, or a permanent increase in the levels of resistance seen in the host population. Due to their high mutation rates, short generation times and large population sizes, RNA viruses can evolve rapidly [53]. Therefore, it is perhaps unsurprising that during the 1980s and 1990s sigma virus genotypes that were not affected by ref(2)P resistance spread through European populations of D. melanogaster [54]. This suggests that we may be observing one side of a coevolutionary arms race between hosts and parasites.

While the antimicrobial immune response of Drosophila is well-understood, we have only begun to understand in detail how Drosophila defends itself against viruses in the last six years [55]. Resistance to viruses could potentially evolve by altering the immune system (antiviral genes), or host factors that are usually exploited by viruses during the viral replication cycle (proviral genes). The only highly significant gene that we identified with a well-characterised function encodes ref(2)P, which is a homolog of the mammalian protein p62 [56]. This is a scaffold protein that has several functions, including in targeting cargoes such as protein aggregates and pathogens for destruction by autophagy — a process by which the cargo is wrapped in a double membrane vesicle called an autophagosome, which then fuses with the lysosome and is degraded [57], [58]. Autophagy was recently found to be an important component of antiviral immunity in D. melanogaster infected with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), which is another rhabdovirus that is related to DMelSV [24], [59]. Therefore, it is possible that this polymorphism is affecting the antiviral immune response. We also found suggestive evidence that a polymorphism in scavenger receptor C1 may be important in defence against DAffSV. This gene functions both as a pattern recognition receptor of bacteria [30] and allows the uptake of dsRNA into cells, resulting in an RNAi response [31]. The function of this gene therefore suggests it is a strong candidate as a component of antiviral immunity.

The functions of the two genes that have the largest effects on susceptibility, CHKov1 and pastrel, in antiviral defence remain unclear, although pastrel is thought to play a role in protein secretion [60]. Interestingly, knocking down the susceptible allele of this gene further increased susceptibility, suggesting that even the susceptible allele of the gene has some antiviral effect. Therefore, this gene may be part of the flies antiviral immune system. Characterising the role of CHKov1 and pastrel in the immune system or the viral life cycle promises to yield new insights into both how animals evolve resistance to infection, and how viruses interact with their hosts.

Methods

Resistance assays

Many of the DGRP lines are infected with Wolbachia bacteria [28], which affects susceptibility to DCV and FHV [44]. To clear the stocks of Wolbachia infection, flies were reared for two generations on food prepared by adding 6 ml of 0.05% w/v tetracycline to a vial containing 5 g instant Drosophila medium (Carolina Biological, Burlington, North Carolina, U.S.A.) and yeast. We checked the flies were uninfected by PCR as described in reference [61]. Lab fly stocks can also be naturally infected by DCV, so the lines were also cleared of natural virus infections by aging adult flies for 20 days and then dechorionating embryos with a ∼5% sodium hypochlorite solution [16]. A small number of the lines assayed for DAffSV were not treated in this way, but excluding these lines did not alter the results. Note that the DMelSV data was collected previously, before the lines were treated [7] (Wolbachia does not affect sigma viruses, Teixeira, Magwire and Wilfert, Pers. Comm.).

The generation prior to injecting the viruses, vials were set up containing two male and two female flies on cornmeal-agar food. For each fly line/virus combination, we set up 4 vials whenever possible. To maximise the level of cross-factoring, we always used different combinations of fly lines on each day of injecting. The flies were injected with 69 nl of the virus suspension intra-abdominally as described in detail in references [62], [63]. The infection of D. melanogaster by DAffSV has not been characterised before, so we first injected flies with the virus and monitored viral titres and the characteristic symptom of sigma virus infection — sensitivity to CO2. These pilot experiments confirmed previous results that the virus can replicate in D. melanogaster [62], and also showed that infected flies are paralysed following exposure to CO2 (Figure S3).

Therefore, to assay for infection by DAffSV, flies were exposed to pure carbon dioxide for 15 min at 12°C at 15 days post-injection. By 30 min post-exposure, flies are awake from this anaesthesia were classed as uninfected, but flies that were dead or paralysed were classed as infected [24]. To assay for susceptibility to DCV and FHV we recorded survival every 24 hours until all the flies had died. Due to a historical accident, the DCV and FHV experiments used male flies and the DAffSV and DMelSV experiments used females. Therefore, care should be taken in comparing these datasets (note that these pairs of experiments also differ in the trait being measured). The DMelSV data has been published previously [7], [8]. We have genotyped the DGRP lines for the polymorphisms in CHKov1 and ref(2)P by PCR as described in reference [7], [8].

We knocked down the pastrel gene by RNAi. Males from line UAS-pst (P{KK105159}VIE-260B) were crossed to Actin-GAL4 (w*;; P{GAL4-da.G32}UH1) virgins. As controls, males from a line with the same genetic background as UAS-pst (y,w1118;P{attP,y+,w3′}) and UAS-CG10669 (P{KK105150}VIE-260B) were also crossed to Actin-GAL4 virgins. F1 females were injected with DCV. We used two doses of DCV (high: TCID50 = 1000 and low: TCID50 = 690). We note that these were from different viral preparations, which may explain why this small difference in TCID50 caused a large difference in mortality.

We measured DCV titres by quantitative PCR using the SensiFAST™ SYBR & Fluorescein Kit (Bioline, UK). DCV was amplified using the primers DCV 6060F (5′-CTTGCGGACCCTTTGTACGAC-3′) and DCV 7320R (5′-GCCATTCGAACTTGACCACGCAG-3′). As an endogenous control we amplified Actin5c using the primers qActin5c_for2 (5′GAGCGCGGTTACTCTTTCAC 3′) and qActin5c_rev2 (5′ AAGCCTCCATTCCCAAGAAC 3′).We performed three technical replicates of each PCR and used the mean of these in subsequent analyses. We calculated the titre of DCV relative to Actin5c as 2ΔCt, where ΔCt is the critical threshold cycle of DCV minus the critical threshold cycle of Actin5c. This approach assumes near 100% primer efficiency, which was confirmed using a dilution series of the template cDNA.

Analysis of genetic variation

We fitted a series of linear models to estimate genetic variances and covariances. For FHV and DCV, our data consisted of the lifespan of individual flies, which we treat as a Gaussian response in a general linear model. We fitted separate models for each virus, which were formulated as follows. Let yijk be survival time (days after injection) of fly k from line i and vial j.

where β is the mean survival time across all lines, bi is a random variable representing the deviation from the overall mean of the ith line, cj is a random variable representing the deviation jth vial from the line mean, and εi,j,k is the residual error.For DMelSV and DAffSV our data consist of numbers of infected and uninfected flies in each vial, which we treat as a binomial response in a generalized linear model. Let vi,k be the probability of flies in vial k from line i being infected.

where β is the overall mean, bi is a random variable representing the deviation from the overall mean of the ith line, and εik is a residual which captures over-dispersion within each vial due to unaccounted for heterogeneity between vials in the probability of infection.To estimate the genetic correlations between the viruses, we analysed data from all four viruses using a single model. To allow us to treat data from all four viruses as a binomial response in a generalized linear model, for FHV and DCV we used the numbers of dead and alive flies on a single day. Let vi,j,k be the probability of flies, in vial k from line i and infected with virus j being dead.

where β is a vector of the mean survival times of the four virus types, and xi is a row vector relating this fixed effect to vial i. bi,j is the random effect of virus k on line j, and was assumed to be multivariate normally distributed, allowing us to estimate separate line variances for each virus type and covariances between all pairwise combinations of viruses. εi,j,k is the residual which captures over-dispersion within each vial. The residuals were assumed to be normally distributed with a separate variance estimated for each virus type.The parameters of the models were estimated using the R library MCMCglmm [64], which uses Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques. Each model was run for 1.3 million iterations with a burn-in of 300,000, a thinning interval of 100 and improper priors. We confirmed these results were not influenced by the choice of prior in the Bayesian analysis by also fitting models 1 and 2 using maximum likelihood (data not shown). Credible intervals on variances, correlations, and heritability were calculated from highest posterior density intervals.

As these fly lines are homozygous across most genes in the genome, the genetic variance, Vg, is half the between-line variance (assuming additive genetic variation). This allows us to calculate the heritability of DCV and FHV as:

Where Vv is the between vial variance and Vr is the residual variance. As the DMelSV and DAffSV parameters are on a logit scale, we calculated heritability as: where is the variance of a logistic distribution (the cumulative distribution function of the logistic distribution is the inverse logit function, the link function used in the model; [65], [66]). Note that the between-vial variance is included in Vr in this model. In Table 1, we calculate Ve as Vr+. When calculating the proportion of the heritability explained by the polymorphisms we identified, we recalculated Vg after accounting for these polymorphisms, and then adjusted the numerators of equations (4) and (5) accordingly.We also calculated the coefficient of genetic variation, CVg, for DCV and FHV as , where β is the mean survival time [27]. To estimate the proportion of the heritability that is explained by these genes we assumed the polymorphisms have additive effects, so their contribution to additive genetic variation is 2pqa2, where p and q are the frequencies of the alleles in the population used to calculate h2, and a is half the difference in the survival or infection probability of flies that are homozygous for the resistant and susceptible alleles (i.e. a and −a are the genotypic values of the resistant and susceptible homozygotes). The maximum likelihood estimate of a, , was obtained by regressing genotype against the line means during the GWAS (see below). An unbiased estimate of a2 was obtained as 2 minus the square of the standard error of . In this calculation, the heritability of resistance to DMelSV was recalculated from the line means which were treated as Gaussian data.

We used robust statistics to analyse data on viral titres due to the presence of an outlier in the data. We fitted a linear model by robust regression using an M estimator and used a robust F test to assess significance [67].

Genome-wide association study

To identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were associated to susceptibility, we performed a GWAS using the published DGRP genome sequences [28]. We only included biallelic SNPs where the minor allele occurred in at least 4 lines, and treated segregating sites within lines as missing data. In the case of DCV and FHV, the susceptibility of the line was measured as the mean survival time of flies in each line (with the vials of flies weighted by the number of flies in each vial). In the case of DMelSV and DAffSV, the susceptibility of the line was measured as the proportion of flies that were infected, as determined by the CO2 assay. The DAffSV data was arcsine square root transformed to remove the dependence of the variance on the mean. To each SNP we fitted the linear model ri,j = β+mi+εi, where ri,j is the susceptibility of flies with SNP genotype i from line j, β is the overall mean, mi is the SNP i genotype, and εik the residual. As major-effect polymorphisms affect the susceptibility of flies to DCV and DMelSV, the analysis was then repeated including the genotype of these genes as an additional explanatory variable.

Because we are performing multiple correlated tests, we determined a genome-wide significance threshold for the association between a SNP and phenotype by permutation. The phenotype data were permuted over the different recombinant lines, the genome-wide association study was repeated as described above, and the minimum P-value across the entire genome was recorded. This was carried out 400 times to generate a null distribution.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. TinsleyMC, BlanfordS, JigginsFM (2006) Genetic variation in Drosophila melanogaster pathogen susceptibility. Parasitology 132 : 767–773.

2. LazzaroB, SceurmanB, ClarkA (2004) Genetic basis of natural variation in D-melanogaster antibacterial immunity. Science 303 : 1873–1876.

3. CookeGS, HillAVS (2001) Genetics of susceptibility to human infectious disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 2 : 967–977.

4. ThompsonJ, BurdonJ (1992) Gene-for-gene coevolution between plants and parasites. Nature 360 : 121–125.

5. WoolhouseMEJ, HaydonDT, AntiaR (2005) Emerging pathogens: the epidemiology and evolution of species jumps. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20 : 238–244.

6. WoolhouseMEJ, WebsterJP, DomingoE, CharlesworthB, LevinBR (2002) Biological and biomedical implications of the co-evolution of pathogens and their hosts. Nature Genetics 32 : 569–577.

7. MagwireMM, BayerF, WebsterCL, CaoC, JigginsFM (2011) Successive Increases in the Resistance of Drosophila to Viral Infection through a Transposon Insertion Followed by a Duplication. PLoS Genet 7: e1002337 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002337.

8. BanghamJ, ObbardDJ, KimKW, HaddrillPR, JigginsFM (2007) The age and evolution of an antiviral resistance mutation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 274 : 2027–2034.

9. StahlEA, DwyerG, MauricioR, KreitmanM, BergelsonJ (1999) Dynamics of disease resistance polymorphism at the Rpm1 locus of Arabidopsis. Nature 400 : 667–671.

10. VisscherPM, BrownMA, McCarthyMI, YangJ (2012) Five Years of GWAS Discovery. American Journal of Human Genetics 90 : 7–24.

11. PritchardJK (2001) Are rare variants responsible for susceptibility to complex diseases? American Journal of Human Genetics 69 : 124–137.

12. YangJA, BenyaminB, McEvoyBP, GordonS, HendersAK, et al. (2010) Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nature Genetics 42 : 565–U131.

13. HillA (2012) Evolution, revolution and heresy in the genetics of infectious disease susceptibility. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 367 : 840–849.

14. ContamineD, PetitjeanAM, AshburnerM (1989) Genetic resistance to viral infection - the molecular-cloning of a Drosophila gene that restricts infection by the rhabdovirus sigma. Genetics 123 : 525–533.

15. LuijckxP, FienbergH, DuneauD, EbertD (2012) Resistance to a bacterial parasite in the crustacean Daphnia magna shows Mendelian segregation with dominance. Heredity 108 : 547–551.

16. Brun G, Plus N (1998) The viruses of Drosophila. In: Ashburner M, Wright T, editors. The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. London: Academic Press. pp. 625–700.

17. BanghamJ, KnottSA, KimKW, YoungRS, JigginsFM (2008) Genetic variation affecting host-parasite interactions: major-effect quantitative trait loci affect the transmission of sigma virus in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Ecology 17 : 3800–3807.

18. PoirieM, FreyF, HitaM, HuguetE, LemeunierF, et al. (2000) Drosophila resistance genes to parasitoids: chromosomal location and linkage analysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 267 : 1417–1421.

19. WilfertL, JigginsFM (2010) Disease association mapping in Drosophila can be replicated in the wild. Biology Letters 6 : 666–668.

20. LazzaroBP, SacktonTB, ClarkAG (2006) Genetic variation in Drosophila melanogaster resistance to infection: A comparison across bacteria. Genetics 174 : 1539–1554.

21. SacktonTB, LazzaroBP, ClarkAG (2010) Genotype and Gene Expression Associations with Immune Function in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 6: e1000797 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000797.

22. KapunM, NolteV, FlattT, SchlottererC (2010) Host Range and Specificity of the Drosophila C Virus. PLoS ONE 5: e12421 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012421.

23. Christian PD (1987) Studies on Drosophila C and A viruses in Australian populations of Drosophila melanogaster: Australian National University.

24. LongdonB, ObbardDJ, JigginsFM (2010) Sigma viruses from three species of Drosophila form a major new clade in the rhabdovirus phylogeny. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 277 : 35–44.

25. LongdonB, WilfertL, Osei-PokuJ, CagneyH, ObbardDJ, et al. (2011) Host-switching by a vertically transmitted rhabdovirus in Drosophila. Biology Letters 7 : 747–750.

26. PriceB, RueckertR, AhlquistP (1996) Complete replication of an animal virus and maintenance of expression vectors derived from it in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 : 9465–9470.

27. HouleD (1992) Comparing evolvability and variability of quantitative traits. Genetics 130 : 195–204.

28. MackayTFC, RichardsS, StoneEA, BarbadillaA, AyrolesJF, et al. (2012) The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature 482 : 173–178.

29. NakamuraN (1978) Dosage effects of non-permissive allele of Drosophila ref(2)P gene on sensitive strains of sigma virus. Molecular & General Genetics 159 : 285–292.

30. RametM, PearsonA, ManfruelliP, LiXH, KozielH, et al. (2001) Drosophila scavenger receptor Cl is a pattern recognition receptor for bacteria. Immunity 15 : 1027–1038.

31. UlvilaJ, ParikkaM, KleinoA, SormunenR, EzekowitzRA, et al. (2006) Double-stranded RNA is internalized by scavenger receptor-mediated endocytosis in Drosophila S2 cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 281 : 14370–14375.

32. PeradziryiH, KaplanN, PodleschnyM, LiuX, WehnerP, et al. (2011) PTK7/Otk interacts with Wnts and inhibits canonical Wnt signalling. Embo Journal 30 : 3729–3740.

33. Beavis WD (1998) QTL analyses: power, precision, and accuracy. In: Paterson AH, editor. Molecular Dissection of Complex Traits. New York: CRC Press. pp. 145–162.

34. AminetzachYT, MacphersonJM, PetrovDA (2005) Pesticide resistance via transposition-mediated adaptive gene truncation in Drosophila. Science 309 : 764–767.

35. ChapmanS, HillA (2012) Human genetic susceptibility to infectious disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 13 : 175–188.

36. WilfertL, Schmid-HempelP (2008) The genetic architecture of susceptibility to parasites. Bmc Evolutionary Biology 8.

37. WayneML, ContamineD, KreitmanM (1996) Molecular population genetics of ref(2)P, a locus which confers viral resistance in Drosophila. Molecular Biology and Evolution 13 : 191–199.

38. BartonN, TurelliM (1987) Adaptive landscapes, genetic-distance and the evolution of quantitative characters. Genetical Research 49 : 157–173.

39. BlowsM, HoffmannA (2005) A reassessment of genetic limits to evolutionary change. Ecology 86 : 1371–1384.

40. ReeveJ (2000) Predicting long-term response to selection. Genetical Research 75 : 83–94.

41. BlowsM, HiggieM (2003) Genetic constraints on the evolution of mate recognition under natural selection. American Naturalist 161 : 240–253.

42. McKenzieJ, BatterhamP (1998) Predicting insecticide resistance: mutagenesis, selection and response. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 353 : 1729–1734.

43. HedgesL, BrownlieJ, O'NeillS, JohnsonK (2008) Wolbachia and Virus Protection in Insects. Science 322 : 702–702.

44. TeixeiraL, FerreiraA, AshburnerM (2008) The Bacterial Symbiont Wolbachia Induces Resistance to RNA Viral Infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol 6: e1000002 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002.

45. VerspoorR, HaddrillP (2011) Genetic Diversity, Population Structure and Wolbachia Infection Status in a Worldwide Sample of Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans Populations. PLoS ONE 6: e26318 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026318.

46. FleuryF, RisN, AllemandR, FouilletP, CartonY, et al. (2004) Ecological and genetic interactions in Drosophila-parasitoids communities: a case study with D-melanogaster, D-simulans and their common Leptopilina parasitoids in south-eastern France. Genetica 120 : 181–194.

47. KraaijeveldA, GodfrayH (1997) Trade-off between parasitoid resistance and larval competitive ability in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 389 : 278–280.

48. HitaM, EspagneE, LemeunierF, PascualL, CartonY, et al. (2006) Mapping candidate genes for Drosophila melanogaster resistance to the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina boulardi. Genetical Research 88 : 81–91.

49. LazzaroBP, SceurmanBK, ClarkAG (2004) Genetic basis of natural variation in D-melanogaster antibacterial immunity. Science 303 : 1873–1876.

50. LazzaroB, SacktonT, ClarkA (2006) Genetic variation in Drosophila melanogaster resistance to infection: A comparison across bacteria. Genetics 174 : 1539–1554.

51. LemaitreB, HoffmannJ (2007) The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annual Review of Immunology 25 : 697–743.

52. CarpenterJ, HutterS, BainesJF, RollerJ, Saminadin-PeterSS, et al. (2009) The Transcriptional Response of Drosophila melanogaster to Infection with the Sigma Virus (Rhabdoviridae). PLoS ONE 4: e6838 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006838.

53. Holmes EC (2009) The Evolution and Emergence of RNA Viruses [electronic resource]. Oxford: OUP Oxford. 1 online resource (267 p.) p.

54. FleurietA, SperlichD (1992) Evolution of the Drosophila-melanogaster-sigma virus system in a natural population from Tubingen. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 85 : 186–189.

55. KempC, ImlerJL (2009) Antiviral immunity in drosophila. Current Opinion in Immunology 21 : 3–9.

56. NezisIP, SimonsenA, SagonaAP, FinleyK, GaumerS, et al. (2008) Ref(2) P, the Drosophila melanogaster homologue of mammalian p62, is required for the formation of protein aggregates in adult brain. Journal of Cell Biology 180 : 1065–1071.

57. KorolchukVI, MansillaA, MenziesFM, RubinszteinDC (2009) Autophagy Inhibition Compromises Degradation of Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway Substrates. Molecular Cell 33 : 517–527.

58. LamarkT, KirkinV, DikicI, JohansenT (2009) NBR1 and p62 as cargo receptors for selective autophagy of ubiquitinated targets. Cell Cycle 8 : 1986–1990.

59. ShellyS, LukinovaN, BambinaS, BermanA, CherryS (2009) Autophagy Is an Essential Component of Drosophila Immunity against Vesicular Stomatitis Virus. Immunity 30 : 588–598.

60. BardF, CasanoL, MallabiabarrenaA, WallaceE, SaitoK, et al. (2006) Functional genomics reveals genes involved in protein secretion and Golgi organization. Nature 439 : 604–607.

61. JigginsF, HurstG, MajerusM (2000) Sex-ratio-distorting Wolbachia causes sex-role reversal in its butterfly host. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 267 : 69–73.

62. LongdonB, HadfieldJD, WebsterCL, ObbardDJ, JigginsFM (2011) Host phylogeny determines viral persistence and replication in novel hosts. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002260 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002260.

63. LongdonB, FabianD, HurstG, JigginsF (2012) Male-killing Wolbachia do not protect Drosophila bifasciata against viral infection. BMC Microbiology 12: S8.

64. HadfieldJD (2010) MCMC Methods for Multi-Response Generalized Linear Mixed Models: The MCMCglmm R Package. Journal of Statistical Software 33 : 1–22.

65. LeeY, NelderJA (2001) Hierarchical generalised linear models: A synthesis of generalised linear models, random-effect models and structured dispersions. Biometrika 88 : 987–1006.

66. NakagawaS, SchielzethH (2010) Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: a practical guide for biologists. Biological Reviews 85 : 935–956.

67. Huber PJ (1981) Robust statistics. New York ; Chichester: Wiley. ix,308p. p.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The Covariate's DilemmaČlánek Plant Vascular Cell Division Is Maintained by an Interaction between PXY and Ethylene SignallingČlánek Lessons from Model Organisms: Phenotypic Robustness and Missing Heritability in Complex Disease

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 11

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Inference of Population Splits and Mixtures from Genome-Wide Allele Frequency Data

- The Covariate's Dilemma

- Plant Vascular Cell Division Is Maintained by an Interaction between PXY and Ethylene Signalling

- Plan B for Stimulating Stem Cell Division

- Discovering Thiamine Transporters as Targets of Chloroquine Using a Novel Functional Genomics Strategy

- Is a Modifier of Mutations in Retinitis Pigmentosa with Incomplete Penetrance

- Evolutionarily Ancient Association of the FoxJ1 Transcription Factor with the Motile Ciliogenic Program

- Genome Instability Caused by a Germline Mutation in the Human DNA Repair Gene

- Transcription Factor Oct1 Is a Somatic and Cancer Stem Cell Determinant

- Controls of Nucleosome Positioning in the Human Genome

- Disruption of Causes Defective Meiotic Recombination in Male Mice

- A Novel Human-Infection-Derived Bacterium Provides Insights into the Evolutionary Origins of Mutualistic Insect–Bacterial Symbioses

- Trps1 and Its Target Gene Regulate Epithelial Proliferation in the Developing Hair Follicle and Are Associated with Hypertrichosis

- Zcchc11 Uridylates Mature miRNAs to Enhance Neonatal IGF-1 Expression, Growth, and Survival

- Population-Based Resequencing of in 10,330 Individuals: Spectrum of Genetic Variation, Phenotype, and Comparison with Extreme Phenotype Approach

- HP1a Recruitment to Promoters Is Independent of H3K9 Methylation in

- Transcription Elongation and Tissue-Specific Somatic CAG Instability

- A Germline Polymorphism of DNA Polymerase Beta Induces Genomic Instability and Cellular Transformation

- Interallelic and Intergenic Incompatibilities of the () Gene in Mouse Hybrid Sterility

- Comparison of Mitochondrial Mutation Spectra in Ageing Human Colonic Epithelium and Disease: Absence of Evidence for Purifying Selection in Somatic Mitochondrial DNA Point Mutations

- Mutations in the Transcription Elongation Factor SPT5 Disrupt a Reporter for Dosage Compensation in Drosophila

- Evolution of Minimal Specificity and Promiscuity in Steroid Hormone Receptors

- Blockade of Pachytene piRNA Biogenesis Reveals a Novel Requirement for Maintaining Post-Meiotic Germline Genome Integrity

- RHOA Is a Modulator of the Cholesterol-Lowering Effects of Statin

- MIG-10 Functions with ABI-1 to Mediate the UNC-6 and SLT-1 Axon Guidance Signaling Pathways

- Loss of the DNA Methyltransferase MET1 Induces H3K9 Hypermethylation at PcG Target Genes and Redistribution of H3K27 Trimethylation to Transposons in

- Genome-Wide Association Studies Reveal a Simple Genetic Basis of Resistance to Naturally Coevolving Viruses in

- The Principal Genetic Determinants for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in China Involve the Class I Antigen Recognition Groove

- Molecular, Physiological, and Motor Performance Defects in DMSXL Mice Carrying >1,000 CTG Repeats from the Human DM1 Locus

- Genomic Study of RNA Polymerase II and III SNAP-Bound Promoters Reveals a Gene Transcribed by Both Enzymes and a Broad Use of Common Activators

- Long Telomeres Produced by Telomerase-Resistant Recombination Are Established from a Single Source and Are Subject to Extreme Sequence Scrambling

- The Yeast SR-Like Protein Npl3 Links Chromatin Modification to mRNA Processing

- Deubiquitylation Machinery Is Required for Embryonic Polarity in

- dJun and Vri/dNFIL3 Are Major Regulators of Cardiac Aging in Drosophila

- CtIP Is Required to Initiate Replication-Dependent Interstrand Crosslink Repair

- Notch-Mediated Suppression of TSC2 Expression Regulates Cell Differentiation in the Intestinal Stem Cell Lineage

- A Combination of H2A.Z and H4 Acetylation Recruits Brd2 to Chromatin during Transcriptional Activation

- Network Analysis of a -Mouse Model of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Identifies HNF4α as a Disease Modifier

- Mitosis in Neurons: Roughex and APC/C Maintain Cell Cycle Exit to Prevent Cytokinetic and Axonal Defects in Photoreceptor Neurons

- CELF4 Regulates Translation and Local Abundance of a Vast Set of mRNAs, Including Genes Associated with Regulation of Synaptic Function

- Mechanisms Employed by to Prevent Ribonucleotide Incorporation into Genomic DNA by Pol V

- The Genomes of the Fungal Plant Pathogens and Reveal Adaptation to Different Hosts and Lifestyles But Also Signatures of Common Ancestry

- A Genome-Scale RNA–Interference Screen Identifies RRAS Signaling as a Pathologic Feature of Huntington's Disease

- Lessons from Model Organisms: Phenotypic Robustness and Missing Heritability in Complex Disease

- Population Genomic Scan for Candidate Signatures of Balancing Selection to Guide Antigen Characterization in Malaria Parasites

- Tissue-Specific Regulation of Chromatin Insulator Function

- Disruption of Mouse Cenpj, a Regulator of Centriole Biogenesis, Phenocopies Seckel Syndrome

- Genome, Functional Gene Annotation, and Nuclear Transformation of the Heterokont Oleaginous Alga CCMP1779

- Antagonistic Gene Activities Determine the Formation of Pattern Elements along the Mediolateral Axis of the Fruit

- Lung eQTLs to Help Reveal the Molecular Underpinnings of Asthma

- Identification of the First ATRIP–Deficient Patient and Novel Mutations in ATR Define a Clinical Spectrum for ATR–ATRIP Seckel Syndrome

- Cooperativity of , , and in Malignant Breast Cancer Evolution

- Loss of Prohibitin Membrane Scaffolds Impairs Mitochondrial Architecture and Leads to Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Neurodegeneration

- Microhomology Directs Diverse DNA Break Repair Pathways and Chromosomal Translocations

- MicroRNA–Mediated Repression of the Seed Maturation Program during Vegetative Development in

- Selective Pressure Causes an RNA Virus to Trade Reproductive Fitness for Increased Structural and Thermal Stability of a Viral Enzyme

- The Tumor Suppressor Gene Retinoblastoma-1 Is Required for Retinotectal Development and Visual Function in Zebrafish

- Regions of Homozygosity in the Porcine Genome: Consequence of Demography and the Recombination Landscape

- Histone Methyltransferases MES-4 and MET-1 Promote Meiotic Checkpoint Activation in

- Polyadenylation-Dependent Control of Long Noncoding RNA Expression by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein Nuclear 1

- A Unified Method for Detecting Secondary Trait Associations with Rare Variants: Application to Sequence Data

- Genetic and Biochemical Dissection of a HisKA Domain Identifies Residues Required Exclusively for Kinase and Phosphatase Activities

- Informed Conditioning on Clinical Covariates Increases Power in Case-Control Association Studies

- Biochemical Diversification through Foreign Gene Expression in Bdelloid Rotifers

- Genomic Variation and Its Impact on Gene Expression in

- Spastic Paraplegia Mutation N256S in the Neuronal Microtubule Motor KIF5A Disrupts Axonal Transport in a HSP Model

- Lamin B1 Polymorphism Influences Morphology of the Nuclear Envelope, Cell Cycle Progression, and Risk of Neural Tube Defects in Mice

- A Targeted Glycan-Related Gene Screen Reveals Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan Sulfation Regulates WNT and BMP Trans-Synaptic Signaling

- Dopaminergic D2-Like Receptors Delimit Recurrent Cholinergic-Mediated Motor Programs during a Goal-Oriented Behavior

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Mechanisms Employed by to Prevent Ribonucleotide Incorporation into Genomic DNA by Pol V

- Inference of Population Splits and Mixtures from Genome-Wide Allele Frequency Data

- Zcchc11 Uridylates Mature miRNAs to Enhance Neonatal IGF-1 Expression, Growth, and Survival

- Histone Methyltransferases MES-4 and MET-1 Promote Meiotic Checkpoint Activation in

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání