-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Novel Human-Infection-Derived Bacterium Provides Insights into the Evolutionary Origins of Mutualistic Insect–Bacterial Symbioses

Despite extensive study, little is known about the origins of the mutualistic bacterial endosymbionts that inhabit approximately 10% of the world's insects. In this study, we characterized a novel opportunistic human pathogen, designated “strain HS,” and found that it is a close relative of the insect endosymbiont Sodalis glossinidius. Our results indicate that ancestral relatives of strain HS have served as progenitors for the independent descent of Sodalis-allied endosymbionts found in several insect hosts. Comparative analyses indicate that the gene inventories of the insect endosymbionts were independently derived from a common ancestral template through a combination of irreversible degenerative changes. Our results provide compelling support for the notion that mutualists evolve from pathogenic progenitors. They also elucidate the role of degenerative evolutionary processes in shaping the gene inventories of symbiotic bacteria at a very early stage in these mutualistic associations.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002990

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002990Summary

Despite extensive study, little is known about the origins of the mutualistic bacterial endosymbionts that inhabit approximately 10% of the world's insects. In this study, we characterized a novel opportunistic human pathogen, designated “strain HS,” and found that it is a close relative of the insect endosymbiont Sodalis glossinidius. Our results indicate that ancestral relatives of strain HS have served as progenitors for the independent descent of Sodalis-allied endosymbionts found in several insect hosts. Comparative analyses indicate that the gene inventories of the insect endosymbionts were independently derived from a common ancestral template through a combination of irreversible degenerative changes. Our results provide compelling support for the notion that mutualists evolve from pathogenic progenitors. They also elucidate the role of degenerative evolutionary processes in shaping the gene inventories of symbiotic bacteria at a very early stage in these mutualistic associations.

Introduction

Obligate host-associated bacteria often have reduced genome sizes in comparison to related bacteria that are known to engage in free-living or opportunistic lifestyles [1]. This is exemplified by inspection of the genome sequences of mutualistic, maternally transmitted, bacterial endosymbionts of insects, many of which have been maintained in their insect hosts for long periods of evolutionary time [2]. Often these obligate endosymbionts maintain only a small fraction of the gene inventory that is found in related free-living counterparts [3]–[5], indicating that the obligate host-associated lifestyle facilitates genome degeneration and size reduction. At a simple level, the process of genome degeneration in obligate endosymbionts can be viewed as a streamlining of the gene inventory to yield a minimal gene set that is compatible with the symbiotic lifestyle. Genes that have no adaptive benefit are inactivated and deleted as a consequence of mutations that accumulate under relaxed selection at an increased rate in the asexual symbiotic lifestyle as a result of frequent population bottlenecks occurring during symbiont transmission [6].

Although we now have a detailed understanding of the mechanisms and evolutionary trajectory of genome degeneration in ancient obligate insect symbionts, the fundamental question of how these mutualistic associations arise remains to be answered. Studies focusing on insect-bacterial symbioses of recent origin show that closely related bacterial endosymbionts are often found in distantly related insect hosts [7], [8]. This could be explained by the interspecific transmission of symbionts, mediated by parasitic wasps and mites that facilitate the transfer of symbionts between distantly related hosts [9], [10]. Horizontal symbiont transmission could also be mediated by intraspecific mating, as demonstrated in the pea aphid [11]. Another possibility is that symbionts could be acquired de novo from an environmental source.

Symbiont acquisition, at least initially, requires the symbiont to overcome or evade the insect immune response. Given that many insects are known to possess a potent immune system that repels invading microorganisms [12], it has been assumed that mutualistic symbionts arise from pathogenic progenitors that have evolved specialized molecular mechanisms to facilitate evasion of the immune response and invasion of insect tissues [2]. In support of this notion, it has been shown that the genomes of recently acquired mutualistic insect endosymbionts maintain genes similar to virulence factors and toxins that are found in related plant and animal pathogens [13]–[18].

In the current study we describe the discovery of a novel human-infective bacterium, designated “strain HS”, isolated from a patient who sustained a hand wound following impalement with a tree branch. Phylogenetic analyses show that strain HS is a member of the Sodalis-allied clade of insect endosymbionts. Comparative analyses of the genome sequences of strain HS and related insect symbionts suggest that close relatives of strain HS gave rise to mutualistic associates in a wide range of insect hosts.

Results

Isolation and Culture of Strain HS

A 71-year-old male presented to his primary care physician for a routine physical examination three days after sustaining a puncture wound to the right hand. The patient fell and was impaled between the thumb and forefinger by a ∼1 cm diameter branch while removing branches from a dead crab apple tree. Upon presentation the patient denied fever or other constitutional symptoms and had a mild peripheral blood monocytosis (11.8%; reference range = 1.7–9.3%). A palpable cyst was noted in the right hand at the sight of impalement. Warm compresses were applied and cephalexin was prescribed at a dose of 500 mg four times daily for 10 days. The patient was evaluated again three days later due to continuing wound pain. The cyst was drained by aspiration and serosanguineous fluid was submitted for Gram stain and bacterial culture. The Gram stain showed scattered white blood cells, but no bacteria were visualized. A follow-up visit seven days later revealed the presence of an abscess, although the patient was afebrile and without local lymphadenopathy. The abscess was again drained by aspiration and the patient was advised to consult an orthopedic surgeon for evaluation. Subsequent surgery, approximately six weeks later, removed several foreign bodies from the wound and the patient recovered on a second course of cephalexin without incident. Two days after the original cyst aspiration, small numbers of gram negative rods resembling enteric bacteria were isolated on MacConkey agar at 35°C and 5% CO2. Colonies were wet, mucoid, variable in size, and slowly fermented lactose. The isolate could not be definitively identified by a manual phenotypic method (RapID ONE, Remel, Lenexa KS) and was misidentified as Escherichia coli at 98% confidence by an automated system (Phoenix, BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD).

Phylogenetic Analysis of Strain HS

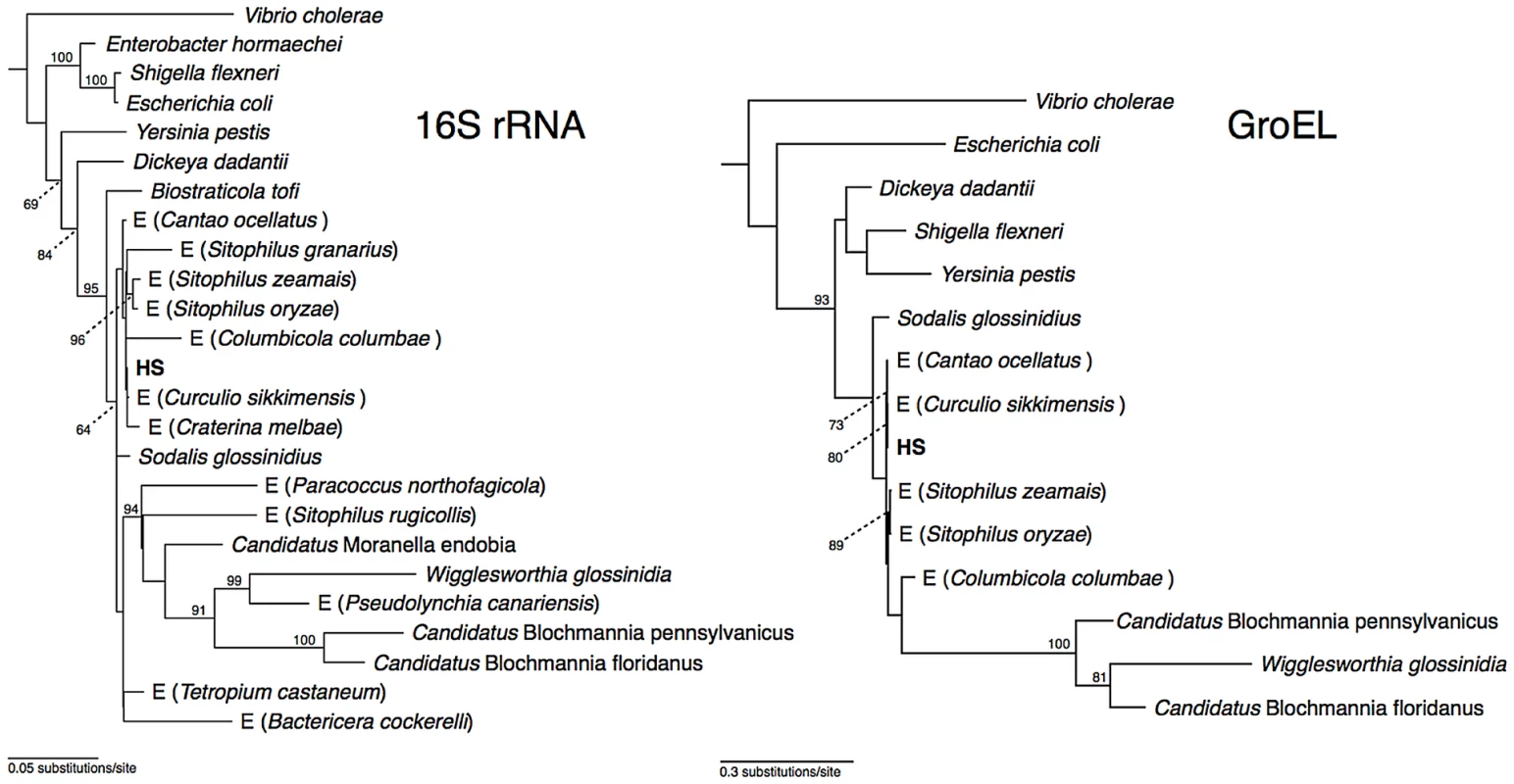

Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA placed strain HS in a well-supported clade comprising Sodalis-allied insect endosymbionts sharing >97% sequence identity in their 16S rRNA sequences (Figure 1), which is a commonly used threshold for species-level conservation among bacteria [19]. Aside from strain HS, the closest non-insect associated relative of this clade is Biostraticola tofi, which was isolated from a biofilm on a tufa deposit in a hard water rivulet [20]. However, B. tofi shares only 96.5% sequence identity in 16S rRNA with its closest insect associated relative (S. glossinidius), while strain HS shares >99% sequence identity with the primary endosymbionts of the grain weevils Sitophilus oryzae and S. zeamais and with recently discovered endosymbionts from the chestnut weevil, Curculio sikkimensis and the stinkbug, Cantao occelatus [21]–[23]. Analysis of a protein-coding gene, groEL, corroborated these findings, confirming that strain HS is a close relative of the grain weevils, chestnut weevil and stinkbug endosymbionts (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Phylogeny of strain HS and related Sodalis-allied endosymbionts and free-living bacteria based on maximum likelihood analyses of a 1.46 kb fragment of 16S rRNA and a 1.68 kb fragment of groEL.

Insect endosymbionts that do not have proper nomenclature are designed by the prefix “E”, followed by the name of their insect host. The numbers adjacent to nodes indicate maximum likelihood bootstrap values shown for nodes with bootstrap support >70%. Genome Sequences of Strain HS and Related Insect Symbionts

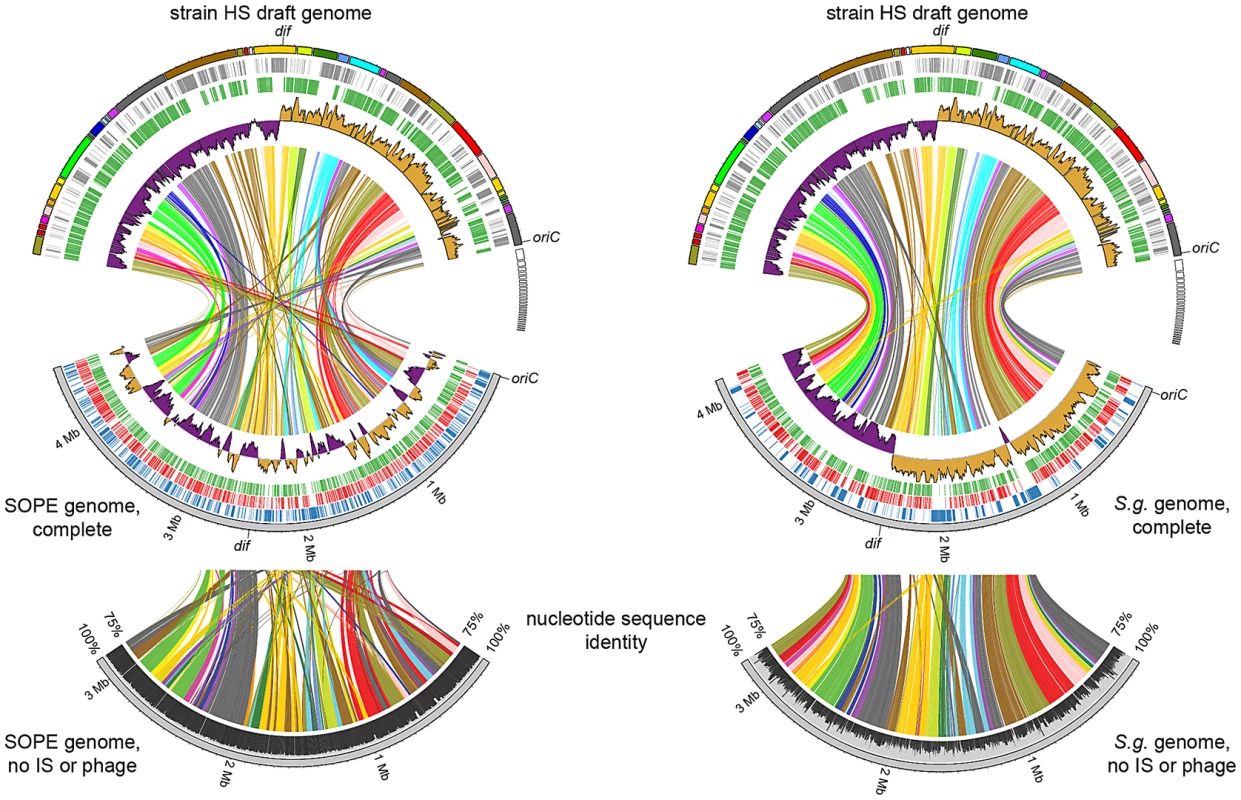

To compare the genome sequences of strain HS and related Sodalis-allied endosymbionts, we aligned a draft sequence assembly of strain HS, comprising a total of 5.15 Mb of DNA in 271 contigs, with the complete genome sequences of the tsetse fly secondary endosymbiont, S. glossinidius (4.3 Mb) [24], [25], and the recently completed sequence of Sitophilus oryzae primary endosymbiont (SOPE; 4.5 Mb). The resulting alignments (Figure 2) reveal a remarkable level of conservation in gene content and organization between strain HS, S. glossinidius and SOPE. To determine if this high level of conservation is simply a consequence of the close evolutionary relationship between these bacteria, we also constructed a whole genome sequence alignment between strain HS and Dickeya dadantii, which represents the next most closely related free-living bacterium whose whole genome sequence is available (Figure S1). This alignment shows that strain HS and D. dadantii are substantially more divergent in terms of their gene inventories, consistent with the notion that they occupy distinct ecological niches. Considering the alignments between strain HS, S. glossinidius and SOPE, it is notable that while the genome sequences of strain HS and S. glossinidius display an increased level of co-linearity, the relationship between strain HS and SOPE is predicted to be closer based on the fact that they share a higher level of genome-wide sequence identity (Figure 2). The genome sequences of strain HS and S. glossinidius demonstrate a typical pattern of polarized nucleotide composition in each replichore (G+C skew, Figure 2), whereas the SOPE genome has numerous perturbations in G+C skew that must result from recent chromosome rearrangements. These rearrangements likely arose as a consequence of intragenomic recombination events between repetitive insertion sequence (IS)-elements, which are highly abundant in the SOPE genome (Figure S2), and have been documented as a causative agent of deletogenic rearrangements in other bacteria [26]–[28].

Fig. 2. Alignment between strain HS contigs (top) and chromosomes of SOPE (left) and S. glossinidius (right).

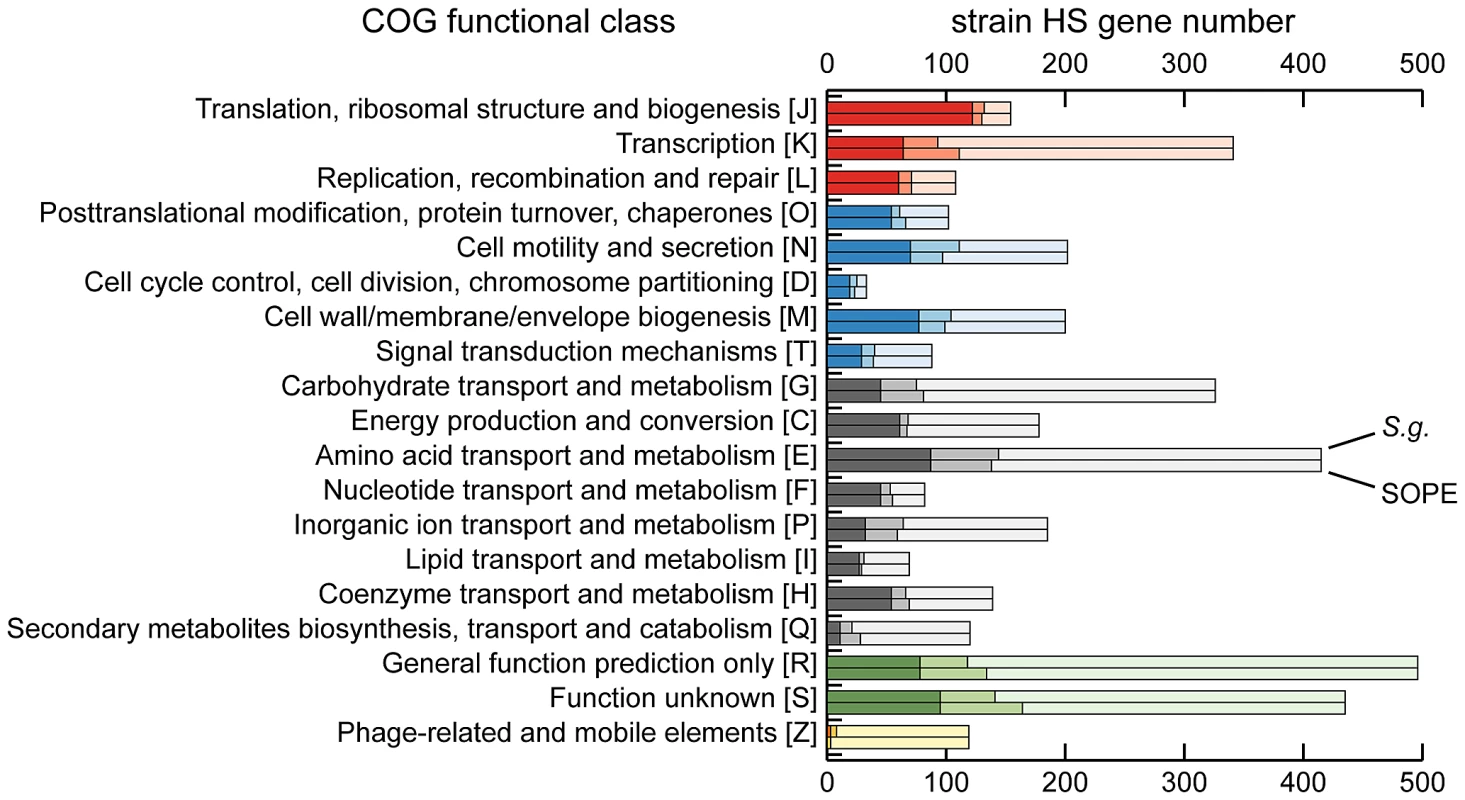

The draft strain HS contigs are depicted in an arbitrary color scheme (outer top ring). Contigs sharing <5 kb synteny with either the SOPE or S. glossinidius genome are uncolored. The uppermost plot (colored in purple and orange) depicts G+C skew, based on a 40 kb sliding window. For upper tracks, grey bars depict genes unique to strain HS whereas green bars depict strain HS genes that share orthologs with the aligned symbiont chromosome. For lower tracks, green and red bars represent (respectively) intact and disrupted orthologs of strain HS genes in the insect symbiont genomes, whereas blue bars highlight prophage and IS-element sequences in the insect symbiont chromosomes. Plots of pairwise nucleotide sequence identity are shown in the lower alignment following in silico removal of prophage and IS-elements from the SOPE and S. glossinidius sequences. Consensus oriC and dif sequences are labeled to indicate putative origins and termini of chromosome replication. Although the gene inventories of strain HS, S. glossinidius and SOPE share many genes in common, as expected given their close evolutionary relationship, each bacterium also maintains a fraction of unique genes. In strain HS we identified a total of 1.9 Mb of DNA encoding genes not found in either S. glossinidius or SOPE that are classified in a wide range of functional categories (Figure 3). This indicates that strain HS has many unique genetic and biochemical properties, and is consistent with the observation that strain HS, unlike the fastidious and microaerophilic S. glossinidius [14], grows under atmospheric conditions on minimal media. In addition, strain HS maintains a number of unique genes sharing high levels of sequence identity with virulence factors found in both animal and plant pathogens, including an Hrp-type effector protein that is characteristically utilized by plant pathogenic bacteria [29] (Table S1). This may be indicative of the ability of strain HS to sustain infection in plant tissues. In comparison with strain HS, the unique fractions of the S. glossinidius and SOPE chromosomes are composed almost exclusively of components of mobile genetic elements, including integrated prophage islands and IS-elements. Following excision of these mobile genetic elements in silico prior to alignment, the resulting genome sequences of S. glossinidius (3.21 Mb) and SOPE (3.15 Mb) represent near-perfect subsets of the strain HS genome (Figure 2), indicating that S. glossinidius and SOPE are abridged derivatives of a strain HS-like ancestor.

Fig. 3. Retention of strain HS orthologs in S. glossinidius and SOPE according to COG functional category.

The dark shaded component of each bar refers to intact genes retained in both S. glossinidius and SOPE. The intermediate shaded component refers to intact genes retained in only S. glossinidius (upper bar) or SOPE (lower bar) and the lighter shaded component refers to genes that are either absent or disrupted in both S. glossinidius and SOPE. The COG categories are organized in five larger groups with red representing genes involved in information storage and processing, blue representing genes involved in cellular processes and signaling, black representing genes involved in metabolism, green representing genes with poorly characterized functions, and yellow representing components of phages and IS-elements. Independent Gene Inactivation and Deletion in S. glossinidius and SOPE

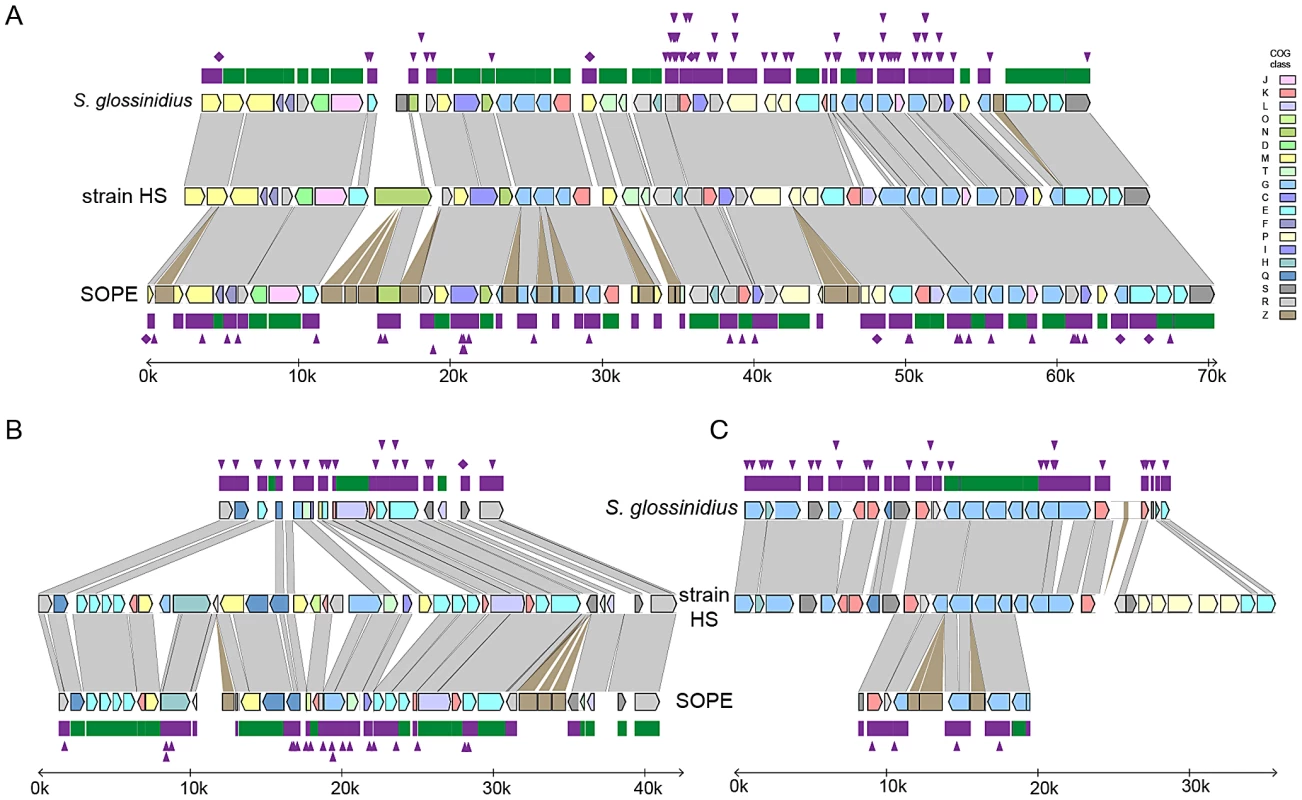

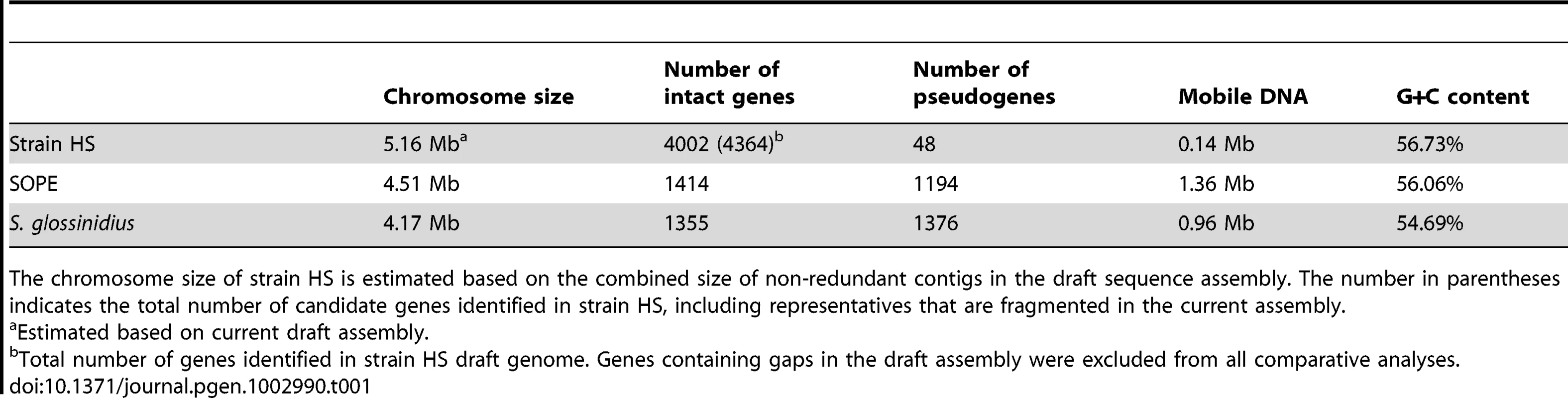

To further understand genetic differences between strain HS, S. glossinidius and SOPE, we analyzed three genomic regions containing relatively high densities of pseudogenes in both S. glossinidius and SOPE (Figure 4). The most notable finding to arise from this comparison is the absence of pseudogenes in the three genomic regions of strain HS. Furthermore, our comparative analysis shows that S. glossinidius and SOPE each have a unique complement of pseudogenes. Indeed, even for orthologous genes that have been inactivated in both S. glossinidius and SOPE, mutations leading to gene inactivation in each insect symbiont genome are distinct, indicating that gene inactivation and loss took place independently in S. glossinidius and SOPE, mostly as a consequence of small frameshifting indels. However, it should also be noted that the reductions observed in the gene inventories of S. glossinidius and SOPE are very similar at the level of functional categories, indicating that the insect-associated lifestyle imposes similar constraints on the retention of genes encoding core functions such as replication, transcription, translation and energy generation (Figure 3). In order to determine the number of pseudogenes throughout the genome of strain HS, we performed a manual annotation and careful inspection of the complete draft strain HS sequence assembly. Out of a total of 4,002 intact candidate ORFs identified in the draft annotation (Table S1), only 48 (including phage and IS elements) were found to be translationally frameshifted or truncated by more than 10% of the size of their most closely related orthologs in the GenBank database (Table 1). This finding stands in stark contrast to the gene inventories of both S. glossinidius and SOPE, in which pseudogenes represent a substantial fraction of their total genomic coding capacity (Figure 2) [24], [25]. Thus, for both S. glossinidius and SOPE, the predominant evolutionary trajectory following obligate insect association involved the inactivation and/or loss of a substantial component of the ancestral (strain HS-like) gene inventory.

Fig. 4. Alignments of three regions of the S. glossinidius, strain HS, and SOPE chromosomes.

Alignments of three regions of the S. glossinidius, strain HS, and SOPE chromosomes, corresponding to SG0948–SG0977 (A), ps_SGL0466–SG0918 (B) and ps_SGL0318–ps_SGL0330 (C) in the most recent S. glossinidius annotation [25]. Putative ORFs and intergenic regions are drawn according to scale, oriented according to their inferred direction of transcription and color-coded according to COG functional categories. While all of the depicted strain HS genes have intact reading frames, the status of their orthologs in S. glossinidius and SOPE are shown in the outer bars (green = intact, purple = inactivated). Nonsense mutations (premature stop codons) are depicted by purple diamonds, and frameshifting indels are depicted by purple triangles. Light grey connecting bars are syntenic nucleotide alignments, while brown bars illustrate IS-element acquisitions that occur more frequently in SOPE. Tab. 1. General features of the strain HS, SOPE, and S. glossinidius genome sequences.

The chromosome size of strain HS is estimated based on the combined size of non-redundant contigs in the draft sequence assembly. The number in parentheses indicates the total number of candidate genes identified in strain HS, including representatives that are fragmented in the current assembly. Evolution of Pseudogenes in S. glossinidius and SOPE

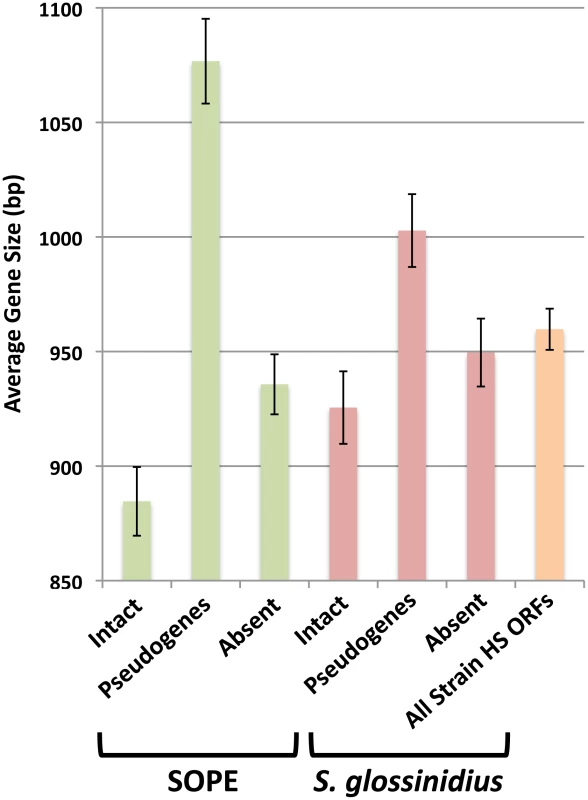

The close evolutionary relationships between strain HS, S. glossinidius and SOPE indicate that the respective insect symbioses are recent in origin. This raises the possibility that a subset of selectively neutral genes in the S. glossinidius and SOPE genomes have not yet accumulated mutations that lead to disruption of their open reading frames. Such “cryptic” pseudogenes are assumed to have no adaptive benefit in the symbiosis and are expected to accumulate nonsense and/or frameshifting mutations in the future [30]. To determine if the genomes of S. glossinidius and SOPE maintain cryptic pseudogenes, we compared the average size of all strain HS genes with the average sizes of strain HS orthologs that are classified either as intact, absent (lost via large deletion) or pseudogenes (visibly disrupted) in the S. glossinidius and SOPE genomes (Figure 5). First, it is important to note that the average size of the absent strain HS orthologs in S. glossinidius and SOPE is not significantly different from the average size of all strain HS ORFs, indicating that large deletion events are not significantly biased with respect to size. However, in both S. glossinidius and SOPE, genes in the pseudogene class were found to have a larger average size in comparison to all strain HS orthologs. Similarly, genes in the intact class were found to have a smaller size in comparison to all strain HS orthologs. This can be explained by the fact that larger genes have an increased likelihood of accumulating at least one disrupting mutation in a given time frame. Based on the same logic, we can infer that the intact gene class contains a subset of smaller, cryptic pseudogenes that have not yet had sufficient time to accumulate any nonsense or frameshifting mutations. Furthermore, since the difference between the average size of intact and disrupted genes is significantly larger in SOPE (192 bases) in comparison to S. glossinidius (77 bases), it follows that SOPE likely maintain a larger number of cryptic pseudogenes than S. glossinidius.

Fig. 5. Average size of strain HS orthologs classified as intact, pseudogenized, and absent in SOPE (green) and S. glossinidius (red).

The average size of all strain HS ORFs is also shown in orange. Error bars depict the standard errors of the mean. Estimating Numbers of Cryptic Pseudogenes in S. glossinidius and SOPE

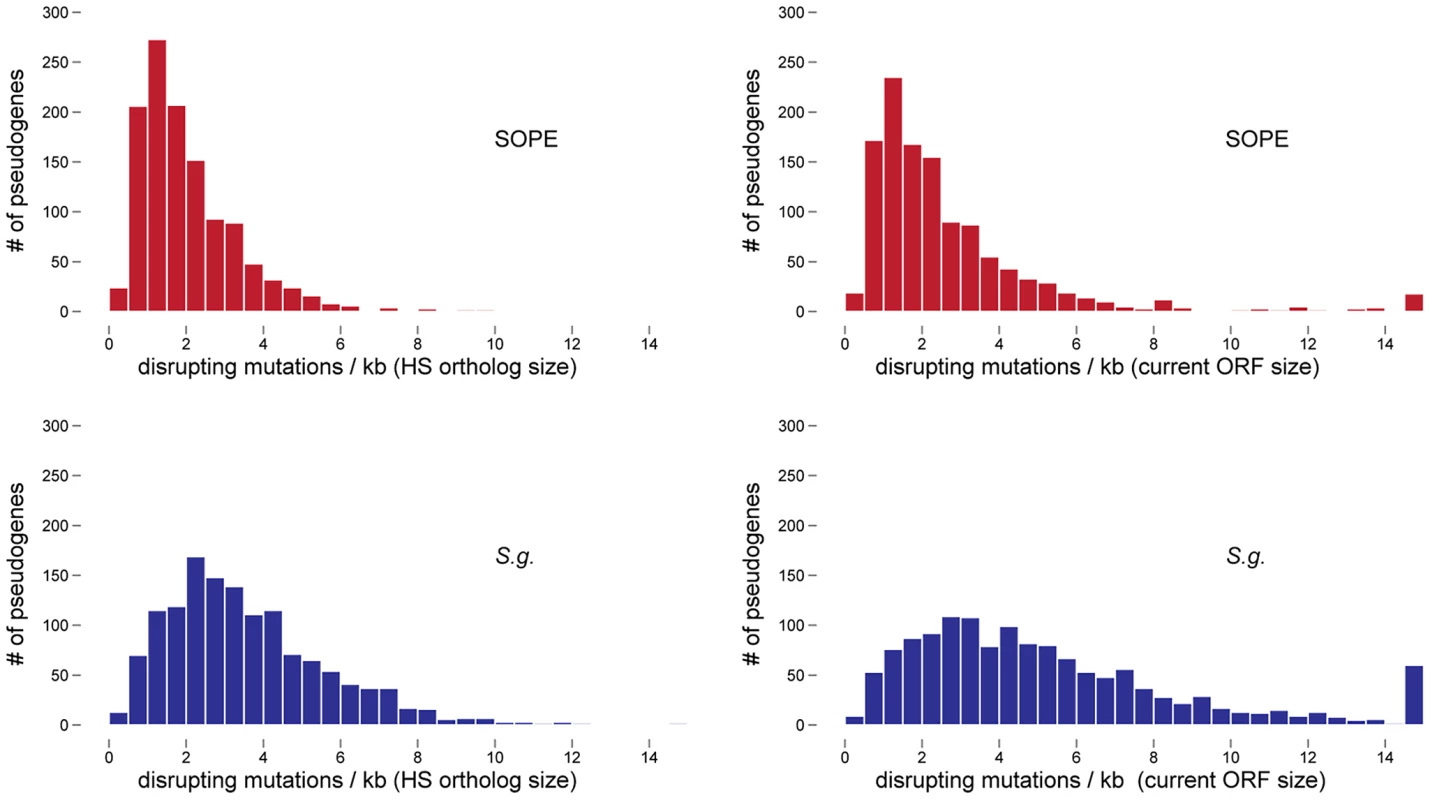

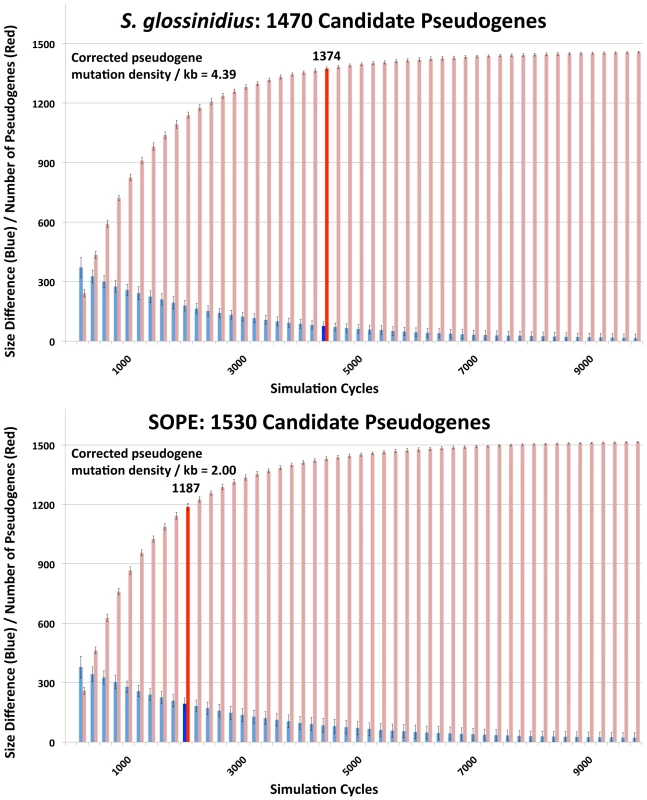

In a previous study, the numbers of cryptic pseudogenes in the recently derived aphid symbiont, Serratia symbiotica, were estimated by extrapolation from a Poisson distribution of disrupting mutations found in existing pseudogenes [30]. The expectation of a Poisson distribution is based on the assumption that the switch to an insect-associated lifestyle leads to the synchronous relaxation of selection on genes no longer required for persistence in an insect host [30]. In the case of both SOPE and S. glossinidius, plots of the densities of disrupting mutations in pseudogenes indicate that the data is overdispersed relative to a Poisson distribution (Figure 6). This effect is exacerbated when current ORF sizes are used for the calculation of mutation densities. This results from the fact that large deletions erase any evidence of previous disrupting mutations. In order to estimate the numbers of cryptic pseudogenes in SOPE and S. glossinidius, we used a Monte Carlo simulation in which a randomly selected class of candidate pseudogenes, selected from all strain HS genes, was permitted to accumulate random disrupting mutations over time, in accordance with ORF size. In this simulation, both pseudogene counts and size differences between the strain HS orthologs of intact and disrupted S. glossinidius and SOPE genes were recorded at regular intervals. The simulation was repeated with an increasing number of neutral genes until the size difference and pseudogene count matched the empirically determined values shown in Figure 5 and Table 1. For S. glossinidius and SOPE, matches were obtained when the predicted numbers of genes evolving under relaxed selection reached 1,470 and 1,530, respectively (Figure 7). Thus, although S. glossinidius and SOPE are predicted to have almost the same numbers of genes evolving under relaxed selection, the degeneration of pseudogenes is at a more advanced stage in S. glossinidius, and SOPE has a larger proportion of neutral genes that have not yet acquired any obvious disrupting changes. Assuming that the relaxation of selection was imposed synchronously at the onset of obligate insect-association, these results suggest that the SOPE-weevil symbiosis originated more recently than the S. glossinidius-tsetse fly symbiosis. This is further supported by a comparison of the estimates of corrected mutation density derived from the simulation (Figure 7). While SOPE is estimated to maintain only 2 disrupting mutations/kb of pseudogenes, S. glossinidius is estimated to maintain more than twice that density of disrupting substitutions (4.39 disrupting mutations/kb). On a related note, we were unable to utilize dN/dS ratios to identify cryptic pseudogenes in SOPE or S. glossinidius. This is likely due to the fact that stochastic variation resulting from differences in expression level, codon bias and other factors greatly exceeds any signal resulting from a recent relaxation of selection.

Fig. 6. Densities of disrupting mutations in SOPE and S. glossinidius pseudogenes.

The numbers of frameshifting and truncating indels and nonsense mutations were computed from alignments of strain HS, SOPE and S. glossinidius orthologs. Mutation densities were computed according to the original strain HS ORF sizes (left) or the current SOPE or S. glossinidius pseudogene sizes (right). Fig. 7. Numbers of cryptic pseudogenes in S. glossinidius and SOPE estimated using a Monte Carlo simulation.

The simulation was repeated with an increasing number of candidate pseudogenes until estimates of pseudogene number (red) and the size difference between pseudogenes and intact genes (blue) matched empirical values shown in Figure 5 and Table 1, as highlighted by bold bars. The densities of disrupting mutations in S. glossinidius and SOPE pseudogenes (which include cryptic pseudogenes) are shown in the upper left inset, corresponding to the data points highlighted in bold. Accelerated Sequence Evolution and Base Composition Bias in SOPE and S. glossinidius

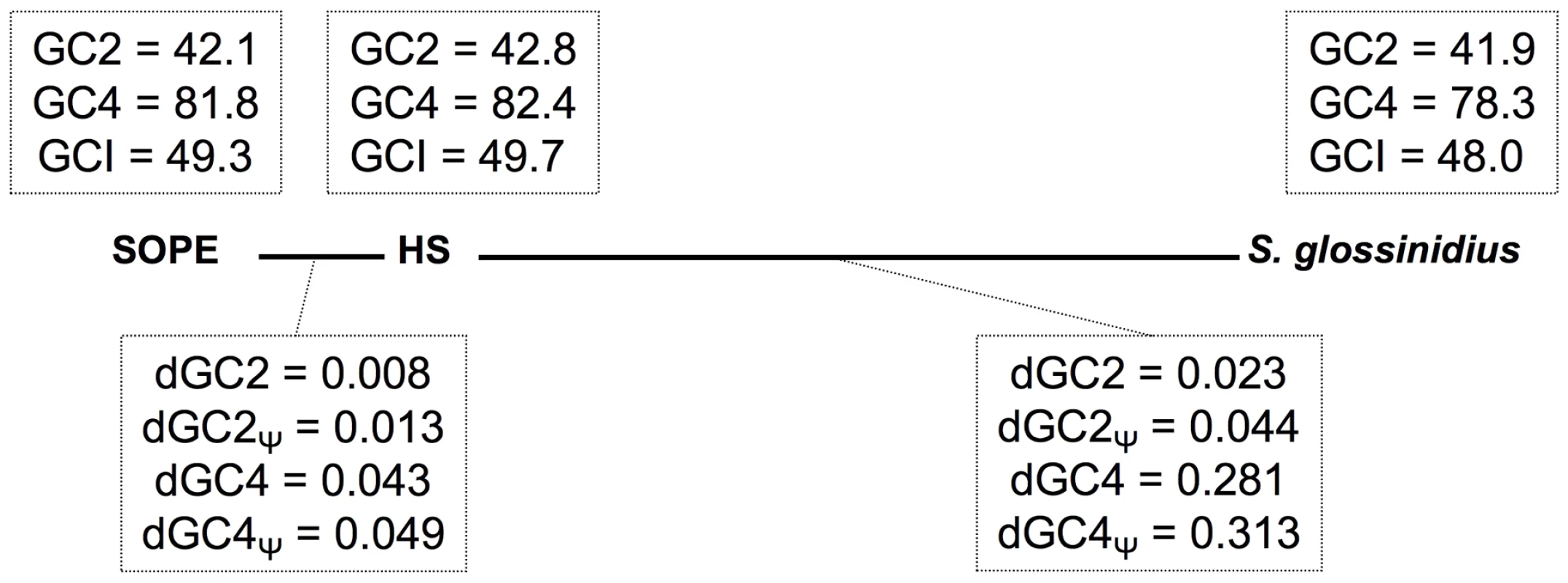

The transition to obligate insect-association is also known to catalyze base composition bias and accelerated polypeptide sequence evolution on the part of the symbiont [31]. The results outlined in Table 1 show that the genomic GC-contents of S. glossinidius and SOPE are lower than that of strain HS. However, to avoid any bias arising from the differential gene content of these organisms, we also performed comparative analyses focusing solely on orthologous sequences. This facilitated the comparison of 1,355 intact genes and 1,376 pseudogenes shared between strain HS and S. glossinidius, and 1,414 intact genes and 1,194 pseudogenes shared between strain HS and SOPE. Although the symbioses in the current study are anticipated to be relatively recent in origin, comparisons focusing on these shared sequences also show that both S. glossinidius and SOPE have reduced GC-contents relative to strain HS (Figure 8). This effect is most notable at 4-fold degenerate (GC4) sites in S. glossinidius, which demonstrate the highest levels of sequence divergence and AT-bias in comparison to orthologs from strain HS. Assuming that the onset of AT-bias is coincident with the origin of symbiosis, this further supports the notion that the symbiosis involving S. glossinidius is more ancient in origin. It is also notable that the number of substitutions at the 2nd codon position sites of pseudogenes (dGC2, Figure 8) is elevated by approximately the same extent (relative to intact genes) in S. glossinidius and SOPE. This implies that pseudogenes have been evolving under relaxed selection for approximately the same proportion of time since each symbiont diverged from strain HS. However, given that sequence divergence at silent sites (GC4) is greater between strain HS and S. glossinidius, this again invokes the interpretation that pseudogenes arose earlier in the S. glossinidius line of descent. It is also interesting to note that the level of divergence at GC2 sites (dGC2, Figure 8) relative to GC4 sites (dGC4, Figure 8) is greater in SOPE than in S. glossinidius. This can be explained by the fact that the pairwise comparison between strain HS and SOPE is expected to capture an increased proportion of mutations that are fixed in the insect-associated phase of life in which selection on polypeptide evolution is anticipated to be more relaxed.

Fig. 8. Base composition bias and mutation rates observed in pairwise comparisons between strain HS, S. glossinidius and SOPE.

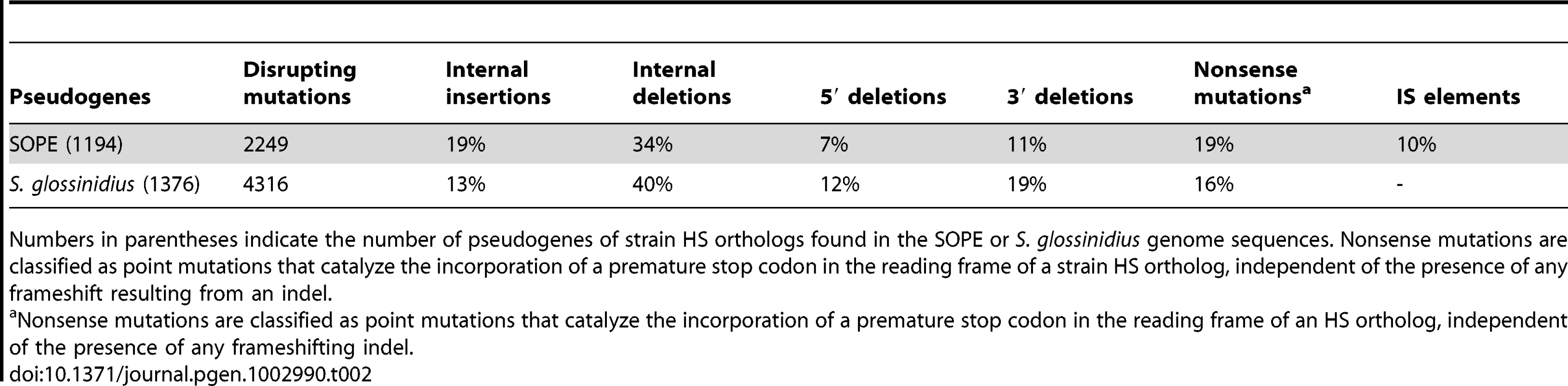

The evolutionary relationships between SOPE, strain HS and S. glossinidius are depicted by bold lines drawn to scale in accordance with levels of genome-wide divergence at 4-fold degenerate (GC4) sites. Upper boxes show genome-wide GC-percentages at 2nd codon position (GC2), GC4 and intergenic (GCI) sites. Lower boxes depict the number of substitutions per site for intact genes (dGC2 and dGC4) and pseudogenes (dGC2Ψ and dGC4Ψ). The data were obtained from pairwise analysis of point mutations in 1,355 intact genes and 1,376 pseudogenes shared between strain HS and S. glossinidius, and 1,414 intact genes and 1,194 pseudogenes shared between strain HS and SOPE. Mutational Dynamics of Gene Inactivation in SOPE and S. glossinidius

Considering only those mutations that have led to gene inactivation, we found that the relative ratios of truncating (large) indels, frameshifting (small) indels and nonsense mutations are similar in SOPE and S. glossinidius (Table 2). Inspection of the data reveals that small frameshifting deletions constitute the most abundant class of mutations leading to gene inactivation. However, it should be noted that the effects of large deletions are, for obvious reasons, not captured in our analyses. Another important point is that IS-element insertions appear to have contributed relatively little to the overall spectrum of mutations leading to gene inactivation in SOPE, representing only 10% of the total count. Indeed, the majority of IS-elements in SOPE are located either in intergenic regions or, more commonly, clustered inside other IS-elements. One potential explanation is that IS-element insertions in genic sequences might be more deleterious towards processes of transcription and/or translation in the cell, such that pseudogenes with IS-element insertions are preferentially deleted relative to pseudogenes with nonsense point mutations or small indels. However, it is conspicuous that clustering of IS-elements has also been reported for mobile DNA elements found in eukaryotes, including the MITE elements found in plants [32] and mosquitoes [33], and the Alu and L1 elements found in the human genome [34]. The relative paucity of IS-elements in genic DNA is surprising given the fact that the SOPE genome has such a large number of pseudogenes that provide neutral space for IS-element colonization. However, the inability of IS-elements to occupy this territory can be rationalized as a consequence of an inherited adaptive bias that facilitates the avoidance of genic insertion. This makes sense when considering the perspective of an IS-element residing in a free-living bacterium that has relatively few dispensable genes. It also explains the propensity for IS-elements to insert themselves into the sequences of other IS-elements, because the safety of this approach has already been validated by natural selection. Clearly, in the case of SOPE, when the opportunity arose for expansion into novel territory (i.e. neutralized genic sequences), IS-elements were largely unable to overcome these basic evolutionary directives.

Tab. 2. Allelic spectrum of pseudogene mutations in strain HS orthologs found in SOPE and S. glossinidius.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of pseudogenes of strain HS orthologs found in the SOPE or S. glossinidius genome sequences. Nonsense mutations are classified as point mutations that catalyze the incorporation of a premature stop codon in the reading frame of a strain HS ortholog, independent of the presence of any frameshift resulting from an indel. Discussion

Phylogenetic analysis of strain HS indicates that it shares a close relationship with the Sodalis-allied endosymbionts that are found in a wide range of insect hosts, including tsetse flies, weevils, lice and stinkbugs. In terms of 16S rRNA sequence identity, strain HS is most closely related to endosymbionts found in the chestnut weevil, Curculio sikkimensis and the stinkbug, Cantao occelatus. Interestingly, only limited numbers of these insects maintain Sodalis-allied endosymbionts in their natural environment [21]–[23], suggesting that they do not maintain persistent (maternally-transmitted) infections. Furthermore, it is notable that the sequences from strain HS, C. sikkimensis and C. occelatus are localized on very short branches in our phylogenetic trees, indicating that these particular lineages are evolving slowly in comparison to other Sodalis-allied endosymbionts. This low rate of molecular sequence evolution, along with the observation that the strain HS genome shows no sign of the characteristic degenerative changes that are known to accompany the transition to the obligate host-associated lifestyle, leads us to propose that strain HS represents an environmental progenitor of the Sodalis-allied clade of insect endosymbionts.

Closely related members of the Sodalis-allied clade of insect endosymbionts have now been identified in a wide range of distantly related insect taxa, including some that are known to feed exclusively on plants and others that are known to feed exclusively on animals [8]. Although strain HS was isolated from the wound of a human host, it is difficult to assess the extent of its pathogenic capabilities, due to the fact that antibiotic treatment commenced three days prior to microscopic examination and culturing. In addition, the available evidence indicates that the original source of the infection was a branch from a dead crab apple tree. This implies that strain HS was present either on the bark or in the woody tissue of this tree, possibly acting as a pathogen or saprophyte. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that C. sikkimensis and C. occelatus, whose symbionts are most closely related to strain HS, are both known to feed on trees [35], [36]. In addition, some wood and bark-inhabiting longhorn beetles, including Tetropium castaneum (Figure 1) have recently been found to maintain Sodalis-allied endosymbionts [37]. Moreover, the ability of strain HS to persist in both plant and animal tissues is compatible with the observation that diverse representatives of both herbivorous and carnivorous insects have acquired Sodalis-allied symbionts.

In a comparative sense, relationships involving the Sodalis-allied endosymbionts are considered to be relatively recent in origin. Indeed, evidence of host-symbiont co-speciation only exists in the case of grain weevils, Sitophilus spp., which were estimated to have co-evolved with their Sodalis-allied endosymbionts for a period of around 20 MY, following the replacement of a more ancient lineage of endosymbionts in these insects [38], [39]. The notion of a recent origin of the Sodalis-allied endosymbionts is further supported by the fact that the whole genome sequence of S. glossinidius is substantially larger than that of long-established mutualistic insect endosymbionts, and is close to the size of related free-living bacteria [24]. However, the S. glossinidius genome does have an unusually low coding capacity resulting from the presence of a large number of pseudogenes [24], [25]. This suggests that S. glossinidius is at an intermediate stage in the process of genome degeneration, in which many protein coding genes have been inactivated by indels and nonsense mutations but have not yet been deleted from the genome. In the current study we show that the genome of the grain weevil symbiont, SOPE, is at a similar stage of degeneration as evidenced by the presence of a comparable number of pseudogenes and a large number of repetitive insertion sequence elements.

In a comparative sense, it is interesting to note that SOPE and strain HS share a substantially higher level of sequence similarity, genome-wide, in comparison to S. glossinidius and strain HS (Figure 2). In the context of the progenitor hypothesis, the disparity in the relationship between strain HS, SOPE and S. glossinidius can be explained by the idea that there may be a substantial level of diversity among free-living relatives of the Sodalis-allied symbionts in the environment, and that we simply happened to characterize a representative that is more closely related to the ancestral progenitor of SOPE. While this is likely to be true to some extent, the close relationship between strain HS and SOPE can also be explained by the notion that the SOPE-grain weevil symbiosis has a more recent origin than the S. glossinidius-tsetse symbiosis. Our results provide several compelling lines of evidence in support of this idea. Most significantly, we found that the pseudogenes of S. glossinidius contain a higher average density of disrupting mutations relative to their counterparts in SOPE. This suggests that the pseudogenes of S. glossinidius have been evolving under relaxed selection for a longer period of time, consistent with the hypothesis of a more ancient origin of host association catalyzing the neutralization of these genes. In addition, the genome of SOPE is predicted to have a larger proportion of “cryptic” pseudogenes; genes evolving neutrally that have not yet had sufficient time to accumulate nonsense or frameshifting mutations that disrupt their translation. Finally, it is notable that the GC4 sites of S. glossinidius have a higher AT-content than those of strain HS and SOPE (Figure 8). Assuming that the AT-bias at GC4 sites accumulates in a clock-like manner following the onset of the symbiosis, this again supports a more ancient origin for the symbiosis involving S. glossinidius.

In the current study, a comparative analysis of the genome sequences of strain HS, SOPE and S. glossinidius has provided an unprecedentedly detailed view of the nascent stages of genome degeneration in symbiosis. Taken together, our results indicate that irreversible degenerative changes, including gene inactivation and loss, in addition to base composition bias, commence rapidly following the onset of an obligate relationship. Indeed, the close relationship observed between strain HS and SOPE illustrates the potency of the degenerative evolutionary process at an early stage in the evolution of a symbiotic interaction. This is exemplified by the fact that SOPE is predicted to have lost 55% of its ancestral gene inventory (34% via gene loss and 21% via gene inactivation) in a period of time sufficient to incur a substitution frequency of only 4.3% at the highly variable GC4 sites of intact protein coding genes (Figure 8). Although estimates of genome wide synonymous clock rates vary by several orders of magnitude in bacteria [40], an estimate of μs = 2.2×10−7, derived recently for another insect endosymbiont, Buchnera aphidicola [41], places the divergence of strain HS and SOPE at only c. 28,000 years, which is much more recent than previous estimates obtained for the origin of the SOPE symbiosis [38], [39].

While the broad distribution of recently derived endosymbionts in phylogenetically distant insect hosts has previously been attributed to interspecific symbiont transfer events [10], [11], the results outlined in the current study indicate that diverse insect species can also acquire novel symbionts through the domestication of bacteria that reside in their local environment. In the case of S. glossinidius and SOPE, our comparative analyses support the notion that these symbionts were acquired independently, as evidenced by the presence of distinct mutations in shared pseudogenes. This also implies that symbionts rapidly become specialized towards a given host, likely restricting their abilities to switch hosts. Although the current study highlights the first description of a close free-living relative of the Sodalis-allied symbionts, it should be noted that environmental microbial diversity is vastly undersampled [42]. Thus, it is conceivable that close relatives of extant insect endosymbionts, such as strain HS, are widespread in nature and provide ongoing opportunities for a wide range of insect hosts to domesticate new symbiotic associates. Furthermore, since many insects serve as vectors for plant and animal pathogens [43], it is conceivable that mutualistic associations arise as a consequence of the domestication of vectored pathogens. This hypothesis is compelling because such pathogens are not expected to negatively impact the fitness of their insect vectors [44] and under those circumstances the transition to a mutualistic lifestyle could be achieved without any need to attenuate virulence towards the insect host.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Phylogenetic Analysis of Strain HS

Strain HS was isolated on MacConkey agar at 35°C and 5% CO2. 16S rRNA and groEL sequences were amplified from strain HS using universal primers. Following cloning of PCR products, eight clones were sequenced from each gene and consensus sequences were used in phylogenetic analyses. Sequence alignments were generated for 16S rRNA and groEL using MUSCLE [45]. PhyML [46] was then used to construct phylogenetic trees using the HKY85 [47] model of sequence evolution with 25 random starting trees and 100 bootstrap replicates.

Weevil Cultures and DNA Isolation

Synchronous cultures of Sitophilus oryzae and Sitophilus zeamais were reared on organic soft white wheat grains and corn kernels respectively, and maintained at 25°C with 70% relative humidity. Bacteriomes (containing the bacterial endosymbionts SOPE and SZPE) were isolated from 5th instar S. oryzae and S. zeamais larvae by dissection and homogenized at a sub-cellular level to release bacteria from host bacteriocyte cells; bacterial cells were then separated from host cells via centrifugation (2,000×g, 5 min). Total genomic DNA was then isolated from bacteria using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

SOPE and SZPE Shotgun Library Construction

Six mg of genomic DNA was hydrodynamically sheared in 5 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl (pH 8) buffer to a mean fragment size of 10 kb. The sample was washed and concentrated by ultrafiltration in a Centricon-100 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and eluted in 250 µl of 2 mM Tris (pH 8). The fragments were end-repaired by treatment with T4 DNA polymerase (New England Biolab, Beverly, MA) to generate blunt ends. The DNA was then extracted with phenol/chloroform, ethanol precipitated, and 5′ phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB). Ten mM of double-stranded, biotinylated oligonucleotide adaptors were blunt-end ligated onto the sheared genomic fragments at room temperature for 25 h using 10,000 cohesive end units of high concentration T4 DNA ligase (NEB). Unligated adaptors were removed by ultrafiltration in a Centricon-100. The adaptored fragments were bound to streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Invitrogen), and after binding and washing, the adaptored genomic fragments were eluted in 10 mM TE (pH 8). Fragments in the 9.5–11.5 kb size range were gel purified after separation on a 0.7% 1× TAE agarose gel, and the purified DNA was electroeluted from the agarose and desalted by ultrafiltration in a Centricon-100.

SOPE and SZPE Shotgun Sequencing

pWD42 vector (GenBank: AF129072.1) was linearized by digestion with BamHI (NEB) at 37°C for 4 h, extracted with phenol/chloroform, ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 100 ml of 2 mM Tris (pH 8.0). Ten picomoles of double-stranded, biotinylated oligo adaptors were ligated onto the BamHI-digested vector at 25°C for 16 hrs using 4,000 units of T4 DNA ligase (NEB). Unligated adaptors were removed by ultrafiltration in a Centricon-100. The adaptored vector was bound to streptavidin-coated magnetic beads and the non-biotinylated adaptored vector was eluted in 10 mM TE (pH 8). One hundred ng each of adaptored vector and genomic DNA were annealed without ligase in 10 ml of T4 DNA ligase buffer (NEB) at 25°C for one hour. Two ml aliquots of the annealed vector/insert were transformed into 100 ml of XL-10 chemically competent E. coli cells (Agilent Technologies, Santa Lara, CA) and plated on LB agar plates containing 20 µg/ml ampicillin. A total of 23,808 bacterial colonies were picked into 96-well microtiter dishes containing 600 ml of terrific broth (TB)+20 µg/ml ampicillin and grown at 30°C for 16 h. Fifty ml aliquots were removed from the library cultures, mixed with 50 ml of 14% DMSO, and archived at −80°C. The 200 ml cultures were diluted 1∶4 in TB amp and runaway plasmid replication was induced at 42°C for 2.25 h. Plasmid DNA was purified by alkaline lysis, and cycle sequencing reactions were performed with forward and reverse sequencing primers using ABI BigDye v3.1 Terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The reactions were ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 15 ul of dH2O, and sequence ladders were resolved on an ABI 3730 capillary instrument prepared with POP-5 capillary gel matrix.

SOPE Genome Sequence Assembly and Finishing

Following elimination of any sequences encoding contaminating plasmid vector or host insect sequences, 38,755 shotgun reads were assembled using the Phusion assembler [48] using the paired-end sequences as mate-pair assembly constraints. Contig assemblies were viewed and edited in Consed [49], and reads with high quality (Phred>20) discrepancies were disassembled. After inspection and manual assembly to extend contigs, gaps were closed by iterative primer walking (895 primer walk sequence reads) and gamma-delta transposon-mediated full-insert sequencing of plasmid clones (6,165 sequence reads across 103 transposed plasmid clones) using an established protocol [50]. The average insert size of the plasmid library in the finished SOPE assembly was found to be 8.2 kb.

SOPE Fosmid Library Construction and Genome Sequence Validation

The SOPE fosmid library was constructed using the Epicenter EpiFOS Fosmid Library Production Kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI), using SOPE total genomic DNA. 1,404 paired-end reads were generated from 702 fosmid inserts and mapped onto the assembly derived from the plasmid shotgun sequencing for validation (Figure S2).

Strain HS Sequencing

Strain HS genomic DNA was isolated from liquid culture using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Five micrograms of total genomic DNA was used to construct a paired-end sequencing library using the Illumina paired-end sample preparation kit (Illumina, Inc. San Diego, CA) with a mean fragment size of 378 base pairs. This library was then sequenced on the Illumina GAIIx platform generating 26,891,485 paired-end reads of 55 bases in length.

Strain HS Sequence Assembly

Paired-end reads were quality filtered using Galaxy [51], [52] and low quality paired-end reads (Phred<20) were discarded. The remaining 17,054,405 reads were then assembled using Velvet [53] with a k-mer value of 37, with expected coverage of 119 and a coverage cutoff value of 0.296. The resulting assembly consisted of 271 contigs with an N50 size of 231,573 and a total of 5,135,297 bases. No sequences were found to share significant sequence identity with genes encoding plasmid replication functions, suggesting that strain HS does not maintain any extrachromosomal elements.

Strain HS Annotation

The assembled draft genome sequence of strain HS was annotated by automated ORF prediction using GeneMark.hmm [54]. The annotation was then adjusted manually in Artemis [55] using the published Sodalis glossinidius genome sequence [25] as a guide. ORFs were annotated as putatively functional only if (i) their size was ≥90% of the most closely related ORF derived from a free-living bacterium in the GenBank database, and (ii) they did not contain any frameshifting indel(s).

Genome Alignment, COG Classification, and Computational Analyses

Curation of the strain HS genome sequence was performed in Artemis [55]. ORFs were classified into COG categories using the Cognitor software [56]. Syntenic links shown in Figure 2 were determined by pairwise nucleotide alignments between strain HS contigs and S. glossinidius (GenBank: NC_007712.1) or the finished SOPE genome using the Smith-Waterman algorithm as implemented in the cross_match algorithm [49]. Figure 2 was prepared from data obtained from these alignments using CIRCOS [57]. The metrics depicted in Table 1, Table 2, and Figure 8 were computed from pairwise nucleotide sequence alignments of strain HS, S. glossinidius and SOPE ORFs using custom scripts. Candidate genes were classified as intact orthologs when their alignment spanned >99% of the HS ORF length (or 90% for ORFs <300 nucleotides in size) and did not contain frameshifting indels or premature stop codons.

Monte Carlo Pseudogene Simulation

A simple Monte Carlo approach was implemented to simulate the evolution of pseudogenes in S. glossinidius and SOPE. The simulation facilitated the progressive accumulation of random mutations in all strain HS orthologs of both intact genes and pseudogenes identified in the current S. glossinidius or SOPE gene inventories. Mutations accumulated in proportion to ORF size in a randomly selected class of neutral genes of user-defined size over a defined number of mutational cycles. At preset cycle intervals, the simulation recorded (i) the difference in size between intact and disrupted sequences, (ii) the number of neutral genes that have accumulated one or more disrupting mutations, and (iii) the density of disrupting mutations, which was calculated based on the cumulative size of all neutral genes.

Accession Numbers

The GenBank accession numbers for sequences used in Figure 1 are as follows: Endosymbiont of Circulio sikkimensis 16S rRNA, (AB559929.1), groEL, (AB507719); Vibrio cholerae 16S rRNA, (NC_002506.1), groEL, (NC_002506.1); Dickeya dadantii 16S rRNA (CP002038.1), groEL, (CP002038.1); Escherichia coli 16S rRNA, (NC_000913.2), groEL, (NC_000913.2); Candidatus Moranella endobia 16S rRNA, (NC_015735), groEL, (NC_015735); Sodalis glossinidius 16S rRNA, (NC_007712.1), groEL, (NC_007712.1); Yersinia pestis 16S rRNA, (NC_008150.1), groEL, (NC_008150.1); Wigglesworthia glossinidia 16S rRNA, (NC_004344.2), groEL, (NC_004344.2); Candidatus Blochmannia pennsylvanicus 16S rRNA, (NC_007292), groEL, (NC_007292); Endosymbiont of Cantao ocellatus 16S rRNA, (AB541010), groEL, (BAJ08314); Endosymbiont of Columbicola columbae 16S rRNA, (AB303387), groEL, (JQ063388); Sitophilus zeamais primary endosymbiont 16S rRNA, (AF548142), groEL (JX444567); Sitophilus oryzae primary endosymbiont 16S rRNA, (AF548137), groEL (AF005236); Strain HS 16S rRNA, (JX444565), groEL (JX444566). The GenBank accession numbers for sequences used in Figure 4 are as follows: Strain HS Figure 4A (JX444569), Figure 4B (JX444571), Figure 4C (JX444572); Sitophilus oryzae primary endosymbiont Figure 4A (JX444568), Figure 4B (JX444570), Figure 4C (JX444573).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. AnderssonSG, KurlandCG (1998) Reductive evolution of resident genomes. Trends Microbiol 6 : 263–268.

2. DaleC, MoranNA (2006) Molecular interactions between bacterial symbionts and their hosts. Cell 126 : 453–465.

3. Pérez-BrocalV, GilR, RamosS, LamelasA, PostigoM, et al. (2006) A small microbial genome: the end of a long symbiotic relationship? Science 314 : 312–313.

4. McCutcheonJP, MoranNA (2007) Parallel genomic evolution and metabolic interdependence in an ancient symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 19392–19397.

5. NakabachiA, YamashitaA, TohH, IshikawaH, DunbarHE, et al. (2006) The 160-kilobase genome of the bacterial endosymbiont Carsonella. Science 314 : 267.

6. MoranNA, McCutcheonJP, NakabachiA (2008) Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu Rev Genet 42 : 165–190.

7. NovákováE, HypsaV, MoranNA (2009) Arsenophonus, an emerging clade of intracellular symbionts with a broad host distribution. BMC Microbiol 9 : 143.

8. SnyderAK, McMillenCM, WallenhorstP, RioRV (2011) The phylogeny of Sodalis-like symbionts as reconstructed using surface-encoding loci. FEMS Microbiol Lett 317 : 143–151.

9. HuigensME, de AlmeidaRP, BoonsPA, LuckRF, Stouthamer (2004) Natural interspecific and intraspecific horizontal transfer of parthenogenesis-inducing Wolbachia in Trichogramma wasps. Proc Biol Sci 271 : 509–515.

10. JaenikeJ, PolakM, FiskinA, HelouM, MinhasM (2007) Interspecific transmission of endosymbiotic Spiroplasma by mites. Biol Lett 3 : 23–25.

11. MoranNA, DunbarHE (2006) Sexual acquisition of beneficial symbionts in aphids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 : 12803–12806.

12. HoffmannJA (1995) Innate immunity of insects. Curr Opin Immunol 7 : 4–10.

13. PontesMH, SmithKL, De VooghtL, Van Den AbbeeleJ, DaleC (2011) Attenuation of the sensing capabilities of PhoQ in transition to obligate insect-bacterial association. PLoS Genet 7: e1002349 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002349.

14. DaleC, YoungS, HaydonDT, WelburnSC (2001) The insect endosymbiont Sodalis glossinidius utilizes a type-III secretion system for cell invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 : 1883–1888.

15. DaleC, PlagueGR, WangB, OchmanH, MoranNA (2002) Type III secretion systems and the evolution of mutualistic endosymbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 : 12397–12402.

16. DegnanPH, YuY, SisnerosN, WingRA, MoranNA (2009) Hamiltonella defensa, genome evolution of protective bacterial endosymbiont from pathogenic ancestors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 9063–9068.

17. NovákováE, HypsaV (2007) A new Sodalis lineage from bloodsucking fly Craterina melbae (Diptera, Hippoboscoidea) originated independently of the tsetse flies symbiont Sodalis glossinidius. FEMS Microbiol Lett 269 : 131–135.

18. DarbyAC, ChoiJ-H, WilkesT, HughesMA, WerrenJH, et al. (2009) Characteristics of the genome of Arsenophonus nasoniae, son-killer bacterium of the wasp Nasonia. Insect Mol Biol Suppl 1 : 75–89.

19. StackebrandE, GoebelBM (1994) Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Bacteriol 44 : 846–849.

20. VerbargS, FrühlingA, CousinS, BrambillaE, GronowS, et al. (2008) Biostraticola tofi gen. nov., spec. nov., a novel member of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Curr Microbiol 56 : 603–608.

21. KaiwaN, HosokawaT, KikuchiY, NikohN, MengXY, et al. (2010) Primary gut symbiont and secondary, Sodalis-allied symbiont of the Scutellerid stinkbug Cantao ocellatus. Appl Environ Microbiol 76 : 3486–3494.

22. TojuH, HosokawaT, KogaR, NikohN, MengXY, et al. (2009) “Candidatus Curculioniphilus buchneri,” a novel clade of bacterial endocellular symbionts from weevils of the genus Curculio. Appl Environ Microbiol 76 : 275–282.

23. TojuH, FukatsuT (2011) Diversity and infection prevalence of endosymbionts in natural populations of the chestnut weevil: relevance of local climate and host plants. Mol Ecol 20 : 853–868.

24. TohH, WeissBL, PerkinSA, YamashitaA, OshimaK, et al. (2006) Massive genome erosion and functional adaptations provide insights into the symbiotic lifestyle of Sodalis glossinidius in the tsetse host. Genome Res 16 : 149–156.

25. BeldaE, MoyaA, BentleyS, SilvaFJ (2010) Mobile genetic element proliferation and gene inactivation impact over the genome structure and metabolic capabilities of Sodalis glossinidius, the secondary endosymbiont of tsetse flies. BMC Genomics 11 : 449.

26. NeversP, SaedlerH (1977) Transposable genetic elements as agents of gene instability and chromosomal rearrangements. Nature 268 : 109–115.

27. BickhartDM, GogartenJP, LapierreP, TisaLS, NormandP, et al. (2009) Insertion sequence content reflects genome plasticity in strains of the root nodule actinobacterium Frankia. BMC Genomics 10 : 468.

28. ParkhillJ, BerryC (2003) Genomics: Relative pathogenic values. Nature 423 : 23–25.

29. TampakakiAP, SkandalisN, GaziAD, BastakiMN, SarrisPF, et al. (2010) Playing the “Harp”: evolution of our understanding of hrp/hrc genes. Annu Rev Phytopathol 48 : 347–370.

30. BurkeGR, MoranNA (2011) Massive genomic decay in Serratia symbiotica, a recently evolved symbiont of aphids. Genome Biol Evol 3 : 195–208.

31. McCutcheonJP, MoranNA (2011) Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 10 : 13–26.

32. TarchiniR, BiddleP, WinelandR, TingeyS, RafalskiA (2000) The complete sequence of 340 kb of DNA around the rice Adh1–adh2 region reveals interrupted colinearity with maize chromosome 4. Plant Cell 12 : 381–391.

33. FeschotteC, MouchèsC (2000) Recent amplification of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements in the vector mosquito Culex pipiens: characterization of the Mimo family. Gene 250 : 109–116.

34. JurkaJ, KohanyO, PavlicekA, KapitonovVV, JurkaMV (2004) Duplication, coclustering, and selection of human Alu retrotransposons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 1268–1272.

35. TojuH, FukatsuT (2011) Diversity and infection prevalence of endosymbionts in natural populations of the chestnut weevil: relevance of local climate and host plants. Mol Ecol 20 : 853–868.

36. KaiwaN, HosokawaT, KikuchiY, NikohN, MengXY, et al. (2010) Primary gut symbiont and secondary, Sodalis-allied symbiont of the Scutellerid stinkbug Cantao ocellatus. Appl Environ Microbiol 76 : 3486–3494.

37. GrünwaldS, PilhoferM, HöllW (2010) Microbial associations in gut systems of wood - and bark-inhabiting longhorned beetles [Coleoptera: Cerambycidae]. Syst Appl Microbiol 33 : 25–34.

38. LefèvreC, CharlesH, VallierA, DelobelB, FarrellB, et al. (2004) Endosymbiont phylogenesis in the dryophthoridae weevils: evidence for bacterial replacement. Mol Biol Evol 21 : 965–973.

39. ConordC, DespresL, VallierA, BalmandS, MiquelC, et al. (2008) Long-term evolutionary stability of bacterial endosymbiosis in curculionoidea: additional evidence of symbiont replacement in the dryophthoridae family. Mol Biol Evol 25 : 859–868.

40. MorelliG, DidelotX, KusecekB, SchwarzS, BahlawaneC, et al. (2010) Microevolution of Helicobacter pylori during prolonged infection of single hosts and within families. PLoS Genet 6: e1001036 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001036.

41. MoranNA, McLaughlinH, SorekR (2009) The Dynamics and Time Scale of Ongoing Genomic Erosion in Symbiotic Bacteria. Science 323 : 379–382.

42. GreenJ, BohannanBJ (2006) Spatial scaling of microbial diversity. Trends Ecol Evol 21 : 501–507.

43. NadarasahG, StavrinidesJ (2011) Insects as alternative hosts for phytopathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 35 : 555–575.

44. StavrinidesJ, NoA, OchmanH (2010) A single genetic locus in the phytopathogen Pantoea stewartii enables gut colonization and pathogenicity in an insect host. Environ Microbiol 12 : 147–155.

45. EdgarRC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32 : 1792–1797.

46. GuindonS, GascuelO (2001) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52 : 696–704.

47. HasegawaM, KishinoH, YamoT (1985) Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol 22 : 160–174.

48. MullikinJC, NingZ (2003) The phusion assembler. Genome Res 13 : 81–90.

49. GordonD, AbajianC, GreenP (1998) Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res 8 : 195–202.

50. RobbFT, MaederDL, BrownJR, DiRuggieroJ, StumpMD, et al. (2001) Genomic sequence of hyperthermophile, Pyrococcus furiosus: implications for physiology and enzymology. Methods Enzymol 330 : 134–157.

51. BlankenbergD, Von KusterG, CoraorN, AnandaG, LazarusR, et al. (2010) Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 19: Unit 19.10.1–21.

52. GoecksJ, NekrutenkoA, TaylorJ (2010) Galaxy Team (2010) Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol 11: R86.

53. ZerbinoDR, BirneyE (2008) Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 18 : 821–829.

54. LukashinAV, BorodovskyM (1998) GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res 26 : 1107–1115.

55. RutherfordK, ParkhillJ, CrookJ, HorsnellT, RiceP, et al. (2000) Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16 : 944–945.

56. TatusovRL, FedorovaND, JacksonJD, JacobsAR, KiryutinB, et al. (2003) The COG database: and updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 4 : 41.

57. KrzywinskiM, ScheinJ, BirolI, ConnorsJ, GascoyneR, et al. (2009) Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res 19 : 1639–1645.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The Covariate's DilemmaČlánek Plant Vascular Cell Division Is Maintained by an Interaction between PXY and Ethylene SignallingČlánek Lessons from Model Organisms: Phenotypic Robustness and Missing Heritability in Complex Disease

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 11

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Inference of Population Splits and Mixtures from Genome-Wide Allele Frequency Data

- The Covariate's Dilemma

- Plant Vascular Cell Division Is Maintained by an Interaction between PXY and Ethylene Signalling

- Plan B for Stimulating Stem Cell Division

- Discovering Thiamine Transporters as Targets of Chloroquine Using a Novel Functional Genomics Strategy

- Is a Modifier of Mutations in Retinitis Pigmentosa with Incomplete Penetrance

- Evolutionarily Ancient Association of the FoxJ1 Transcription Factor with the Motile Ciliogenic Program

- Genome Instability Caused by a Germline Mutation in the Human DNA Repair Gene

- Transcription Factor Oct1 Is a Somatic and Cancer Stem Cell Determinant

- Controls of Nucleosome Positioning in the Human Genome

- Disruption of Causes Defective Meiotic Recombination in Male Mice

- A Novel Human-Infection-Derived Bacterium Provides Insights into the Evolutionary Origins of Mutualistic Insect–Bacterial Symbioses

- Trps1 and Its Target Gene Regulate Epithelial Proliferation in the Developing Hair Follicle and Are Associated with Hypertrichosis

- Zcchc11 Uridylates Mature miRNAs to Enhance Neonatal IGF-1 Expression, Growth, and Survival

- Population-Based Resequencing of in 10,330 Individuals: Spectrum of Genetic Variation, Phenotype, and Comparison with Extreme Phenotype Approach

- HP1a Recruitment to Promoters Is Independent of H3K9 Methylation in

- Transcription Elongation and Tissue-Specific Somatic CAG Instability

- A Germline Polymorphism of DNA Polymerase Beta Induces Genomic Instability and Cellular Transformation

- Interallelic and Intergenic Incompatibilities of the () Gene in Mouse Hybrid Sterility

- Comparison of Mitochondrial Mutation Spectra in Ageing Human Colonic Epithelium and Disease: Absence of Evidence for Purifying Selection in Somatic Mitochondrial DNA Point Mutations

- Mutations in the Transcription Elongation Factor SPT5 Disrupt a Reporter for Dosage Compensation in Drosophila

- Evolution of Minimal Specificity and Promiscuity in Steroid Hormone Receptors

- Blockade of Pachytene piRNA Biogenesis Reveals a Novel Requirement for Maintaining Post-Meiotic Germline Genome Integrity

- RHOA Is a Modulator of the Cholesterol-Lowering Effects of Statin

- MIG-10 Functions with ABI-1 to Mediate the UNC-6 and SLT-1 Axon Guidance Signaling Pathways

- Loss of the DNA Methyltransferase MET1 Induces H3K9 Hypermethylation at PcG Target Genes and Redistribution of H3K27 Trimethylation to Transposons in

- Genome-Wide Association Studies Reveal a Simple Genetic Basis of Resistance to Naturally Coevolving Viruses in

- The Principal Genetic Determinants for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in China Involve the Class I Antigen Recognition Groove

- Molecular, Physiological, and Motor Performance Defects in DMSXL Mice Carrying >1,000 CTG Repeats from the Human DM1 Locus

- Genomic Study of RNA Polymerase II and III SNAP-Bound Promoters Reveals a Gene Transcribed by Both Enzymes and a Broad Use of Common Activators

- Long Telomeres Produced by Telomerase-Resistant Recombination Are Established from a Single Source and Are Subject to Extreme Sequence Scrambling

- The Yeast SR-Like Protein Npl3 Links Chromatin Modification to mRNA Processing

- Deubiquitylation Machinery Is Required for Embryonic Polarity in

- dJun and Vri/dNFIL3 Are Major Regulators of Cardiac Aging in Drosophila

- CtIP Is Required to Initiate Replication-Dependent Interstrand Crosslink Repair

- Notch-Mediated Suppression of TSC2 Expression Regulates Cell Differentiation in the Intestinal Stem Cell Lineage

- A Combination of H2A.Z and H4 Acetylation Recruits Brd2 to Chromatin during Transcriptional Activation

- Network Analysis of a -Mouse Model of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Identifies HNF4α as a Disease Modifier

- Mitosis in Neurons: Roughex and APC/C Maintain Cell Cycle Exit to Prevent Cytokinetic and Axonal Defects in Photoreceptor Neurons

- CELF4 Regulates Translation and Local Abundance of a Vast Set of mRNAs, Including Genes Associated with Regulation of Synaptic Function

- Mechanisms Employed by to Prevent Ribonucleotide Incorporation into Genomic DNA by Pol V

- The Genomes of the Fungal Plant Pathogens and Reveal Adaptation to Different Hosts and Lifestyles But Also Signatures of Common Ancestry

- A Genome-Scale RNA–Interference Screen Identifies RRAS Signaling as a Pathologic Feature of Huntington's Disease

- Lessons from Model Organisms: Phenotypic Robustness and Missing Heritability in Complex Disease

- Population Genomic Scan for Candidate Signatures of Balancing Selection to Guide Antigen Characterization in Malaria Parasites

- Tissue-Specific Regulation of Chromatin Insulator Function

- Disruption of Mouse Cenpj, a Regulator of Centriole Biogenesis, Phenocopies Seckel Syndrome

- Genome, Functional Gene Annotation, and Nuclear Transformation of the Heterokont Oleaginous Alga CCMP1779

- Antagonistic Gene Activities Determine the Formation of Pattern Elements along the Mediolateral Axis of the Fruit

- Lung eQTLs to Help Reveal the Molecular Underpinnings of Asthma

- Identification of the First ATRIP–Deficient Patient and Novel Mutations in ATR Define a Clinical Spectrum for ATR–ATRIP Seckel Syndrome

- Cooperativity of , , and in Malignant Breast Cancer Evolution

- Loss of Prohibitin Membrane Scaffolds Impairs Mitochondrial Architecture and Leads to Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Neurodegeneration

- Microhomology Directs Diverse DNA Break Repair Pathways and Chromosomal Translocations

- MicroRNA–Mediated Repression of the Seed Maturation Program during Vegetative Development in

- Selective Pressure Causes an RNA Virus to Trade Reproductive Fitness for Increased Structural and Thermal Stability of a Viral Enzyme

- The Tumor Suppressor Gene Retinoblastoma-1 Is Required for Retinotectal Development and Visual Function in Zebrafish

- Regions of Homozygosity in the Porcine Genome: Consequence of Demography and the Recombination Landscape

- Histone Methyltransferases MES-4 and MET-1 Promote Meiotic Checkpoint Activation in

- Polyadenylation-Dependent Control of Long Noncoding RNA Expression by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein Nuclear 1

- A Unified Method for Detecting Secondary Trait Associations with Rare Variants: Application to Sequence Data

- Genetic and Biochemical Dissection of a HisKA Domain Identifies Residues Required Exclusively for Kinase and Phosphatase Activities

- Informed Conditioning on Clinical Covariates Increases Power in Case-Control Association Studies

- Biochemical Diversification through Foreign Gene Expression in Bdelloid Rotifers

- Genomic Variation and Its Impact on Gene Expression in

- Spastic Paraplegia Mutation N256S in the Neuronal Microtubule Motor KIF5A Disrupts Axonal Transport in a HSP Model

- Lamin B1 Polymorphism Influences Morphology of the Nuclear Envelope, Cell Cycle Progression, and Risk of Neural Tube Defects in Mice

- A Targeted Glycan-Related Gene Screen Reveals Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan Sulfation Regulates WNT and BMP Trans-Synaptic Signaling

- Dopaminergic D2-Like Receptors Delimit Recurrent Cholinergic-Mediated Motor Programs during a Goal-Oriented Behavior

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Mechanisms Employed by to Prevent Ribonucleotide Incorporation into Genomic DNA by Pol V

- Inference of Population Splits and Mixtures from Genome-Wide Allele Frequency Data

- Zcchc11 Uridylates Mature miRNAs to Enhance Neonatal IGF-1 Expression, Growth, and Survival

- Histone Methyltransferases MES-4 and MET-1 Promote Meiotic Checkpoint Activation in

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání