-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Complex Contributions of Genetics and Nutrition to Immunity in

Previous studies have indicated that dietary nutrition influences immune defense in a variety of animals, but the mechanistic and genetic basis for that influence is largely unknown. We use the model insect Drosophila melanogaster to conduct an unbiased genome-wide mapping study to identify genes responsible for variation in resistance to bacterial infection after rearing on either high-glucose or low-glucose diets. We find the flies are universally more susceptible to infection when they are reared on the high-glucose diet than when they are reared on the low-glucose diet, and that metabolite levels genetically correlate with quality of immune defense after rearing on the high-glucose diet. We identify several genes that contribute to variation in defense quality on both diets, most of which are not traditionally thought of as part of the immune system. The genetic variation we observe can be important for evolved responses to pathogen pressure, although the effectiveness of natural selection will be partially determined by the host nutritional state.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005030

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005030Summary

Previous studies have indicated that dietary nutrition influences immune defense in a variety of animals, but the mechanistic and genetic basis for that influence is largely unknown. We use the model insect Drosophila melanogaster to conduct an unbiased genome-wide mapping study to identify genes responsible for variation in resistance to bacterial infection after rearing on either high-glucose or low-glucose diets. We find the flies are universally more susceptible to infection when they are reared on the high-glucose diet than when they are reared on the low-glucose diet, and that metabolite levels genetically correlate with quality of immune defense after rearing on the high-glucose diet. We identify several genes that contribute to variation in defense quality on both diets, most of which are not traditionally thought of as part of the immune system. The genetic variation we observe can be important for evolved responses to pathogen pressure, although the effectiveness of natural selection will be partially determined by the host nutritional state.

Introduction

There is strong intuition that dietary nutrition affects the quality of immune defense, and this intuition is well supported scientifically. Starvation increases susceptibility to infection in insects as well as humans [1,2], and specific dietary components such as vitamins, carbohydrates, and proteins have been implicated in shaping immunity to bacterial infection [3–7]. Elevated dietary protein relative to sugar increases standing levels of immune activity in Drosophila melanogaster [8], and diets deficient in protein increase susceptibility to infection by Salmonella typhimurium in mice [6]. Nutrition alters development in ways that may have immunological import [9–11], and insects and other animals alter their feeding behavior in response to infection [12,13]. There is growing evidence that the ratio of protein to carbohydrates (P:C) in the diet may specifically influence several life history traits[11,14–18], including some that may predict resistance to infection. For example, the African army worm Spodoptera exempta becomes more susceptible to infection by the bacterium Bacillus subtilis when supplied with diets high in sugar relative to protein, and infected caterpillars will actively choose to eat diets higher in protein without increasing sugar intake [13]. These and other such observations have led to the suggestion that “nutritional immunology” should be employed to identify ideal dietary compositions for the combat of infection [4]. However, despite the increasingly clear impact of diet on resistance to infection, we have remarkably little insight into how nutrition alters infection outcomes, and whether or why individuals in natural populations differ genetically in their immunological response to diet.

Natural populations are rife with genetic variation for traits that determine health and evolutionary fitness, and both human and Drosophila populations are genetically variable for the ability to fight bacterial infection [19,20]. Such variation may occur in intuitively evident genes, such as those that make up the immune system [21,22], but phenotypically important variation may also map to less obvious genes that shape host physiological context. Even traits that have strong genetic determination can be influenced by the environment, including the availability of nutrition [23,24]. Importantly, different genotypes can vary in their susceptibility to environmental influence, resulting in traits that are determined by the interaction between genotype and environment (GxE) [25]. In very few cases, however, have the genes underlying sensitivity to environment been determined, and it is indeed difficult to predict a priori what the genes for environmental sensitivity might be. The genetic variation that controls both direct trait determination as well as that that controls environmentally influenced phenotypic variation are critically important to the health and evolutionary potential of populations.

We have previously used candidate-gene based approaches to map the genetic basis for variation in Drosophila melanogaster resistance to bacterial infection [26–28]. These studies were successful in identifying naturally occurring alleles that shape defense quality, but they focused exclusively on genes in the immune system. While we may expect diet to shape resistance to infection, we have no particular expectation that the effects of diet act through the canonical immune system (i.e. Toll and IMD pathways [29,30]). Dietary composition has widespread metabolic and developmental consequences, and these consequences vary quantitatively and qualitatively among genetically diverse Drosophila [31]. There is evidence for crosstalk between metabolic signaling pathways such as insulin-like signaling and canonical immune pathways in Drosophila, both during development and in the initiation of an immune response [32–36]. Thus, it is plausible to imagine that the immunological effect of diet, and especially genetic variation in immunological response to diet (genotype-by-diet interaction), could be controlled by genes outside of what is typically conceived to be the “immune system.”

In the present study, we conduct an unbiased genome-wide association study to identify genes that shape variation in resistance to bacterial infection among D. melanogaster reared on either a high glucose or low glucose diet. Specifically, we deliver experimental infections with the bacterium Providencia rettgeri and measure systemic pathogen load 24-hours post infection. This time point both provides a robust estimate of infection intensity [37] and correlates strongly with risk of mortality [38]. Throughout the manuscript we will refer to pathogen load as “resistance” or “immune defense”. We find that flies reared on a high glucose diet harbor significantly higher pathogen loads and substantially altered metabolite levels, including elevated free glucose, glycogen and triglycerides. Although there is considerable natural genetic variation for resistance to infection on both diets, resistance is generally well correlated across the two diets. Nonetheless, we find evidence of genotype-by-environment interactions determining immune defense, as well as metabolic alterations that correlate genetically with resistance in flies reared on the high glucose diet. We are able to map and validate several genes that contribute to variation in resistance in both diet-independent and diet-dependent manners. Importantly, most of these are not typically considered part of the canonical immune system.

Results

Resistance to infection varies genetically and across diets

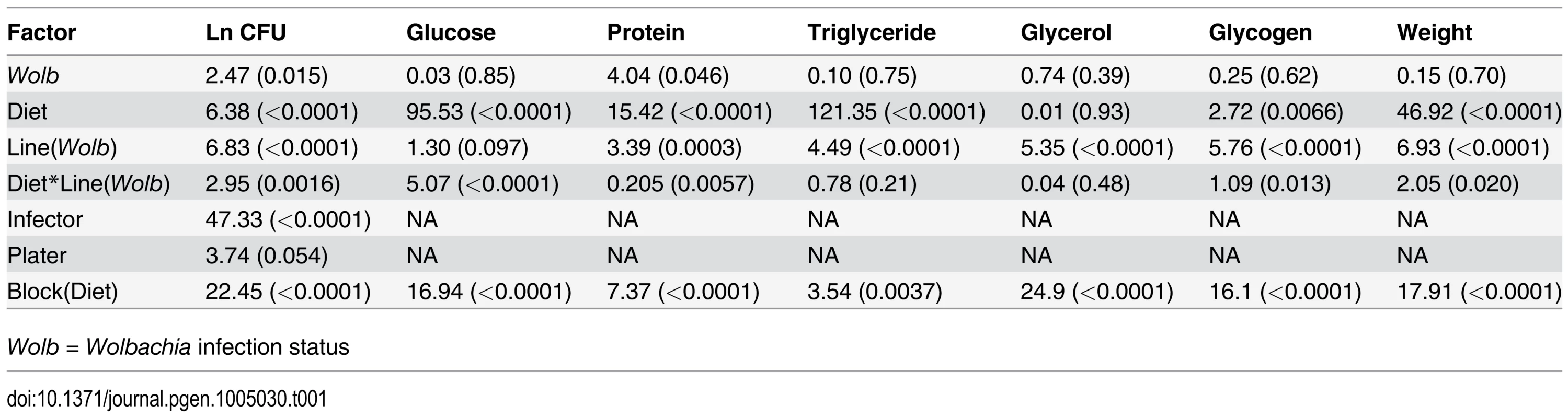

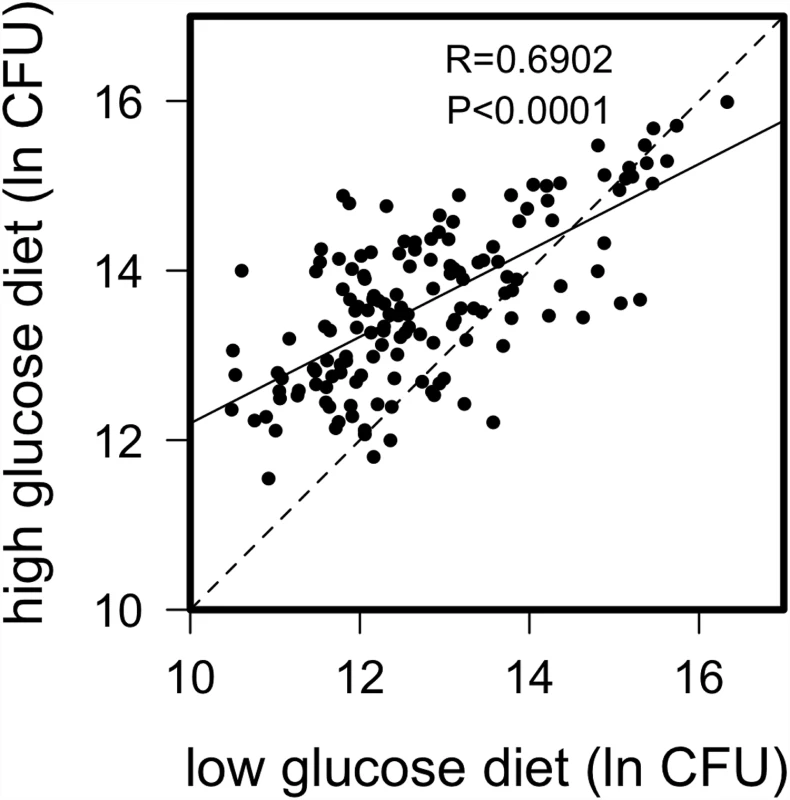

We found considerable natural genetic variation for immune defense segregating within the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP), where the quality of defense is defined as the ability to limit pathogen proliferation. We infected male flies from 172 of the complete genome-sequenced lines [39] with the Gram-negative bacterium Providencia rettgeri after rearing on either a high glucose or low glucose diet in a replicated block design (see Methods), then measured systemic pathogen load 24 hours later. Pathogen load was significantly predicted by line genotype and diet (Table 1; S1 Fig, p < 10-4 for both) as well as by a genotype-by-diet interaction (p = 0.0016), indicating that genotypes differ in their immunological sensitivity to dietary glucose. Nonetheless, pathogen load was highly correlated across the two diets (Pearson r = 0.69, p < 10-4; Fig. 1), indicating a strong main effect of genotype on immune performance. On average, flies reared on the high-glucose diet sustained systemic pathogen loads approximately 2.4 times higher than those of flies reared on the low-glucose diet.

Tab. 1. ANOVA results for phenotypes measured F value/Z value (p-value) showing significant line, diet and line by diet interaction effects for most phenotypes.

Wolb = Wolbachia infection status Fig. 1. Correlation of natural log bacterial load (CFU) 24-hours post infection for DGRP lines raised on high glucose and low glucose diets.

Dashed line represents 1 to 1 relationship; solid line from regression analysis. There is strong correlation across diets, but several lines appear to perform disproportionately poorly (i.e. carry high bacterial load) on the high glucose diet. A natural log value of 10 corresponds to about 2.2x104 bacteria, 12 corresponds to about 1.6x105 bacteria, 14 corresponds to 1.2x106 bacteria and 16 corresponds to 8.9 x106 bacteria. Diet and genotype influence nutritional status

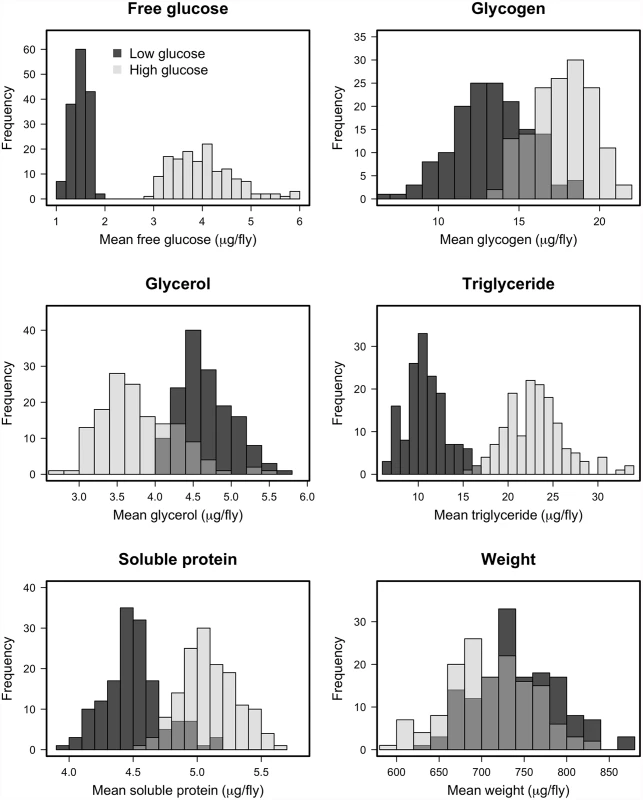

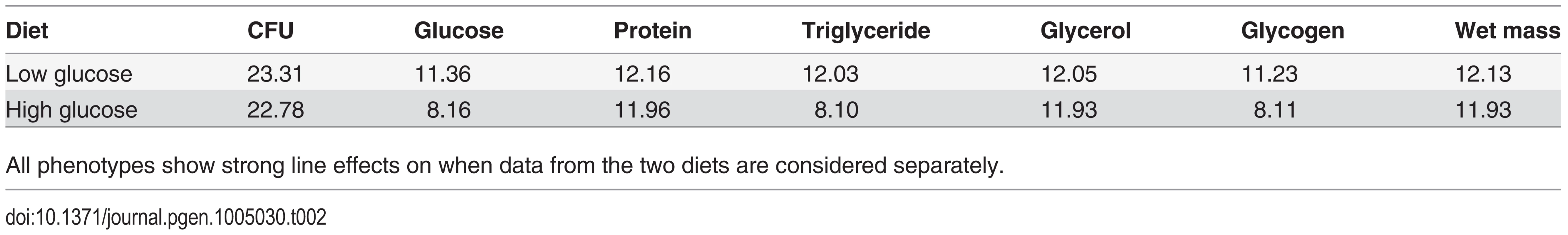

We measured several indices of nutritional status in each Drosophila line after rearing on the high-glucose and low-glucose diets because we predicted that specific metabolite profiles might be associated with changes in immunity. We measured free glucose, glycogen stores, total triglycerides, free glycerol, soluble protein, and wet mass, as these provide an overall picture of an individual’s nutritional status. The Nutritional Indices (NIs) showed predictable responses to diet. For example, levels of glucose, glycogen, and triglycerides were substantially elevated by rearing on the high-glucose diet (Fig. 2; p < 10-4 in all cases), although wet weight and free glycerol were significantly reduced by rearing on high glucose (Fig. 2; p < 10-4 in both cases). The lines exhibited highly significant genetic variation for all NIs after rearing on either diet (p < 10-4 in all cases; Table 2). Each NI was significantly genetically correlated across diets (Fig. 3), indicating strong genetic determination of NIs regardless of diet. Surprisingly, only wet mass, glycogen and free glucose showed strong genotype-by-diet interactions (Table 1).

Fig. 2. Histograms of estimated line means for nutritional indices for DGRP lines reared on high glucose and low glucose diets.

The differences in distributions on the high glucose and low glucose diets were highly significant (p < 10-4) in all cases, supporting the assertion that diet significantly alters the metabolic state of the fly. Tab. 2. Effect of genetic line in determining traits on each diet (Z-values—all P-values are less than 0.0001).

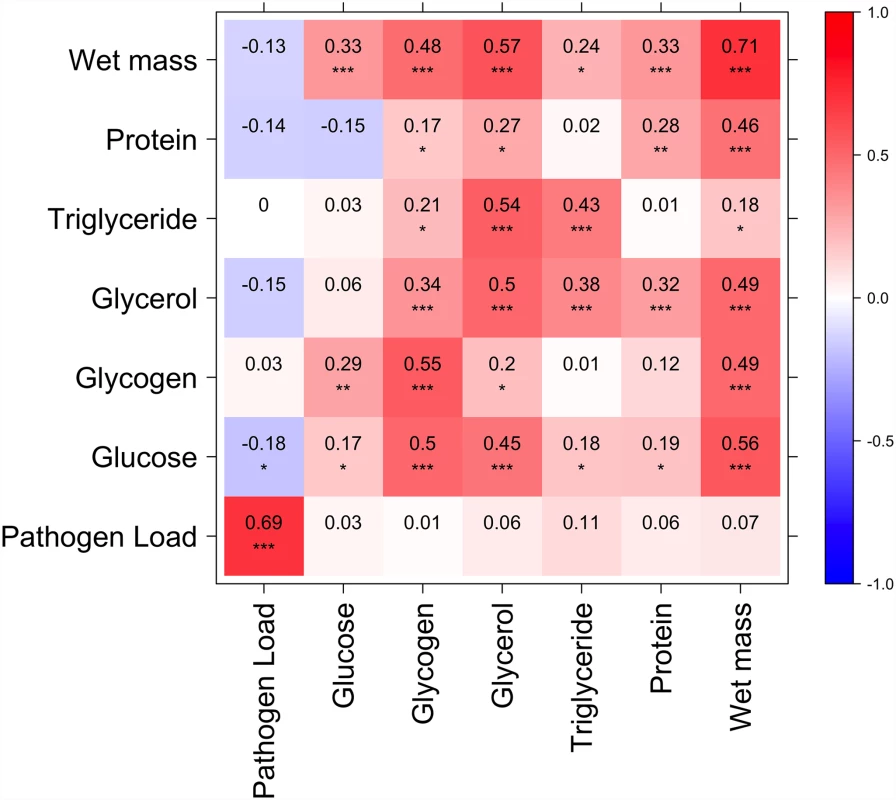

All phenotypes show strong line effects on when data from the two diets are considered separately. Fig. 3. Correlation between nutritional indices and immune defense (Ln CFU per fly).

Diagonal represents correlation for each index between high and low glucose diets; above diagonal is correlation among indices on the high glucose diet; below diagonal is correlation among indices on the low glucose diet. p<0.0001***, p<0.001**, p<0.05*. Several nutritional indices are correlated with each other but only glucose on the high glucose diet is significantly (negatively) correlated with immune defense. Resistance to infection is correlated with nutritional status and other phenotypes

Since we found that increasing dietary glucose resulted in increased pathogen load as well as alteration of metabolic profile, we asked whether metabolic profile correlated with pathogen load across genotypes. The only NI that correlated with pathogen load was free glucose, which was slightly negatively correlated with P. rettgeri load on the high-glucose diet (Pearson’s r = -0.18, p = 0.033). This is somewhat surprising given that the general effect of increased dietary glucose is both elevated blood glucose and an increase in pathogen load, and may indicate that variation in pathogen load is associated with rates of conversion between molecules.

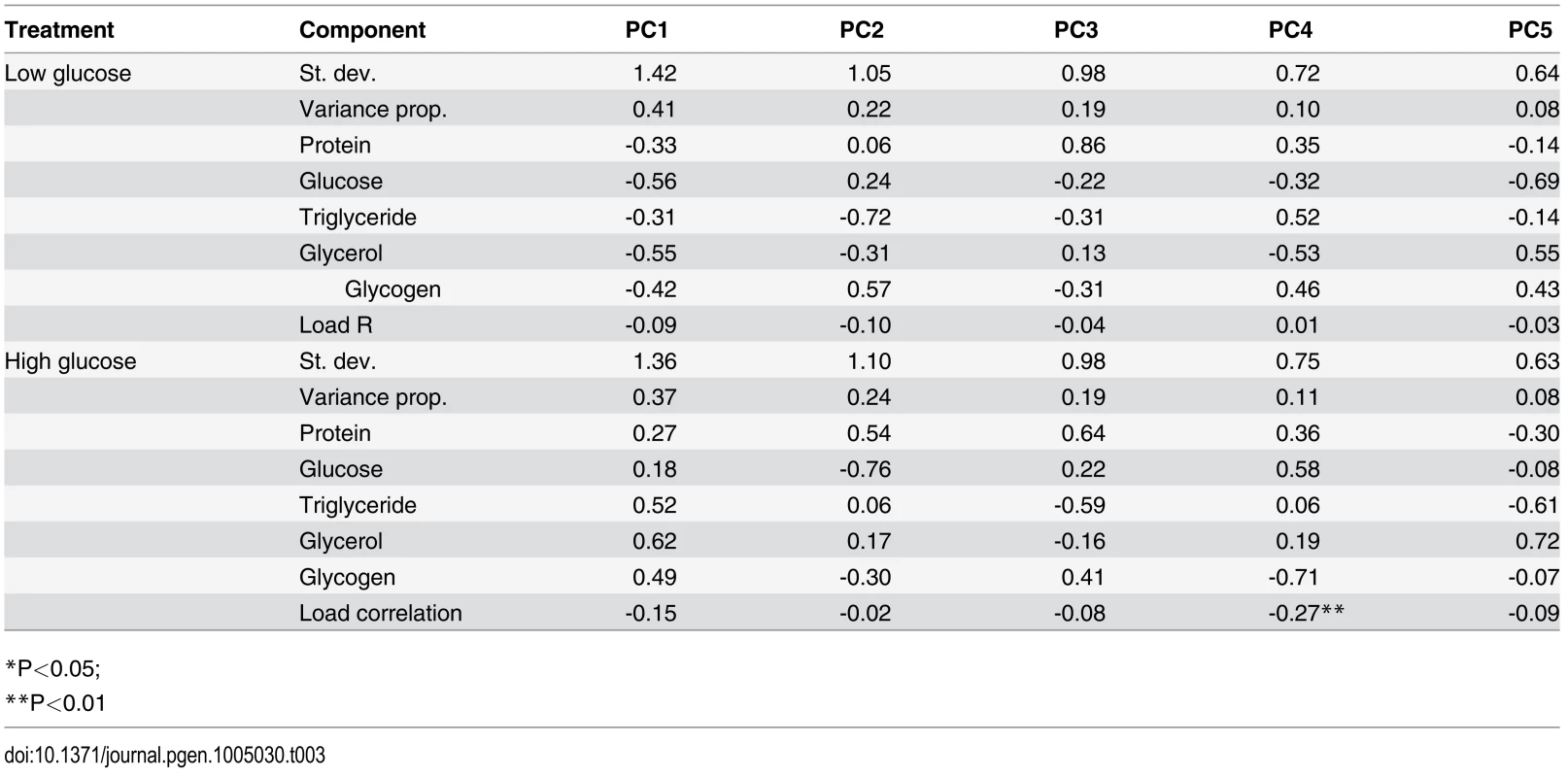

We hypothesized that genetic variation might shape the relationship between overall metabolic state and immune defense and that our nutritional indices might give more information about the overall metabolic status of the fly when considered in aggregate. We therefore performed a principal component analysis and tested whether the primary principal components (PCs) for each diet correlated with immune defense quality. The top five PCs summarizing the NIs on each diet each explain 8–41% of the total variance in nutritional state, with loadings of each NI given in Table 3. None of the metabolic PCs correlated with pathogen load on the low-glucose diet. The fourth PC on the high-glucose diet was significantly correlated with pathogen load (Pearson’s r = -0.27, p = 0.001; Table 3). This PC, which explains 11% of the total variance, is heavily positively loaded with free glucose (0.58) and soluble protein (0.36) and is negatively loaded with glycogen stores (-0.71), consistent with the observation that free glucose alone is negatively correlated with pathogen load. This is the only PC where free glucose and glycogen stores load in opposite directions, possibly indicating the rate of conversion between dietary glucose to glycogen. PC1 trends toward negative correlation with pathogen load on the high-glucose diet (Pearson’s r = -0.15; p = 0.06). This PC explains 37% of the variance and is positively loaded with all NIs, and presumably reflects overall fly mass although mass itself does not correlate with pathogen load (Fig. 3).

Tab. 3. Principal component analysis of nutritional phenotypes with data from each diet considered separately.

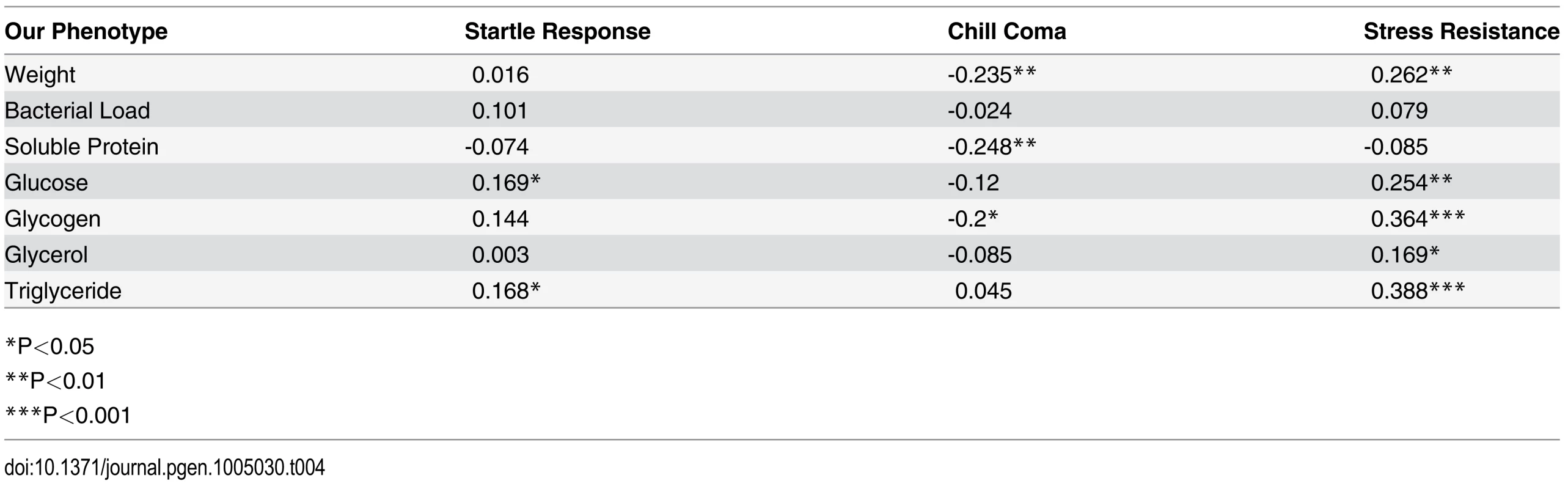

*P<0.05; When we compared our data to previously published DGRP phenotype data [39], we found correlations between our NIs and three metabolism-related traits: starvation resistance, chill coma recovery, and startle response. Starvation resistance, as determined by Mackay et al. [20], is positively correlated with all of our NIs except soluble protein with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.169 (Table 4, p = 0.044) to 0.388 (p < 10-4). Overall, genotypes with greater energy reserves were better able to withstand the stress of starvation: measures of wet mass, soluble protein, and glycogen stores were significantly negatively correlated with time to recovery from chill coma as measured by Mackay et al. (chill coma recovery correlated with wet mass: r = -0.235, p = 0.005; soluble protein: r = -0.248, p = 0.003; glycogen: r = -0.20, p = 0.016). Our measures of free glucose levels and total triglycerides were weakly correlated with Mackay et al.’s measure of startle response (Pearson’s r < 0.20 and p < 0.05 for each). This consistency in related phenotypic measures and relationships across lab groups indicates the genetic robustness of the phenotypes.

Tab. 4. Correlation coefficients (r) of phenotypes measured in this study to those of Mackay et al. (2012) show several significant correlations.

*P<0.05 The bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis has been shown to confer protection against RNA viruses in Drosophila [40,41], but previous experiments have not uncovered any protective benefit of Wolbachia against secondary bacterial infection [42,43]. Richardson et al. [44] determined that 52% of the lines in the DGRP are infected with Wolbachia, and we find Wolbachia status to be a weakly significant predictor of P. rettgeri load on both diets (S2 Fig, low glucose: p = 0.0361; high glucose: p = 0.0327; data from both diets combined: p = 0.014), with lower average bacterial loads in the Wolbachia-infected lines than in the Wolbachia-uninfected lines.

Genome-wide association mapping of resistance to infection

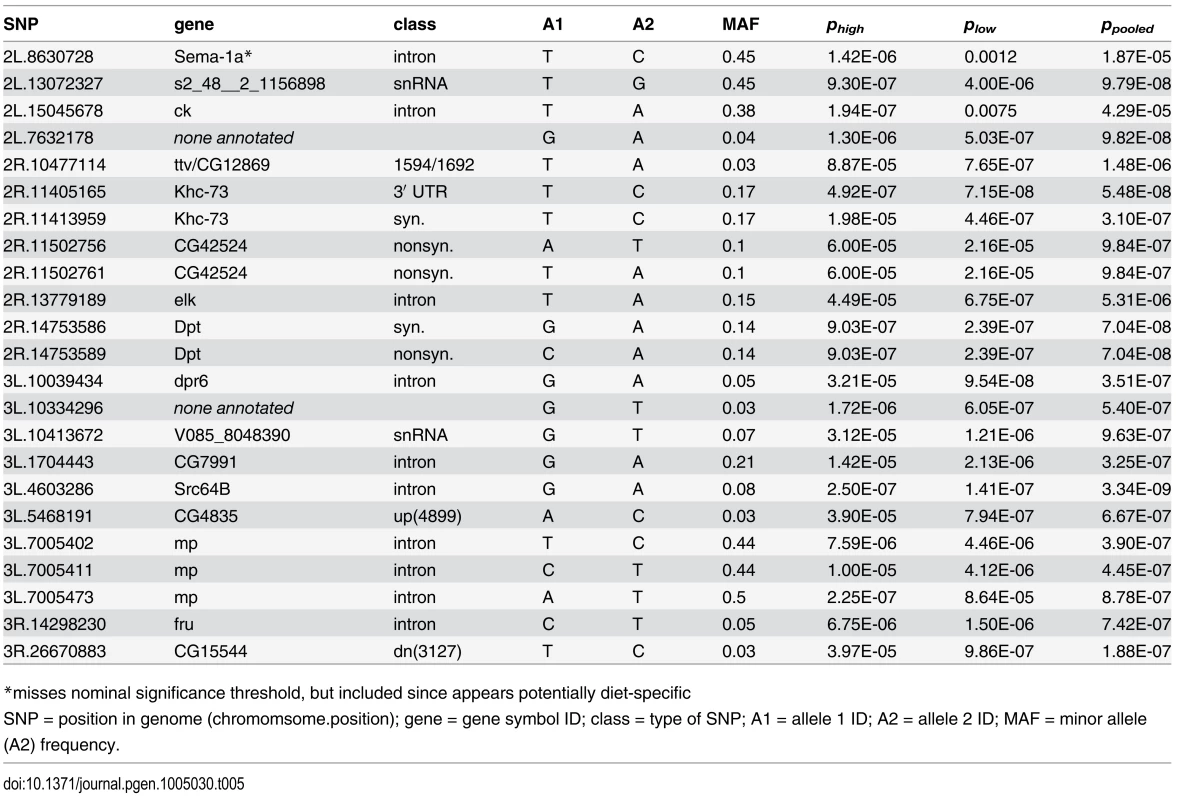

Because the complete genomes have been sequenced for every line in the DGRP, we were able to conduct unbiased genome-wide association mapping for each of our measured phenotypes. We used mixed effect linear models to identify genetic polymorphisms that predict systemic pathogen load. Using a significance criterion of 10-6 we identified seven single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in six genes that associate with variation in pathogen load on the high-glucose diet, 11 SNPs in 9 genes that associate with load on the low-glucose diet, and 19 SNPs in 12 genes that associate with pathogen load when the data from both diets is pooled (Table 5; S3 and S4 Figs). This significance threshold corresponds to a false discovery rate of 5–10% (depending on the phenotypic distribution of the particular trait being evaluated and the details of the analytical model) and provided a reasonable number of SNPs for further characterization. Several of the mapped SNPs were common to multiple analyses. Overall, we mapped SNPs in the genes crinkled, defective proboscis extension response 6, diptericin, elk, fruitless, kinesin heavy chain 73, multiplexin, Scr64B, sema-1a, tout velu/CG12869, CG42524, CG7991, CG4835 and CG15544. We additionally mapped SNPs to 2 distinct regions annotated to encode small, nontranslated RNAs, potentially revealing variation for more complex regulation of the immune system [45].

Tab. 5. Significant SNPs (P<10-6) from genome-wide association study for immune defense against Providencia rettgeri infection with data from the high glucose diet (phigh), low glucose diet (plos) and when data from both diets are combined (ppooled).

*misses nominal significance threshold, but included since appears potentially diet-specific Our mapped SNPs are highly enriched for lying within or adjacent to genes, with 21 of the total 23 (91.3%) lying within 5 kb of an annotated gene (Table 5). In contrast, only 55% of SNPs genome-wide lie within 5 kb of a known gene. Of our 5 mapped SNPs within gene coding regions, 2 are synonymous and 3 are nonsynonymous, again in stark contrast to the genome average, for which there are approximately 2.7 synonymous polymorphisms for every nonsynonymous polymorphism [46]. One of the two synonymous variants we mapped is in perfect linkage disequilibrium with an amino-acid-altering SNP in Diptericin. The other is in perfect disequilibrium with a 3′ UTR variant of kinesin heavy chain 73. Thus, both of our mapped synonymous SNPs can be considered to be redundant with more plausibly functional SNPs. We used RNAi to knock down 13 of the mapped genes, 9 of which resulted in significantly altered pathogen load either on a standard diet or in a diet-specific manner (S5 Fig, S1 Table). In contrast, only one of five control genes chosen by virtue of physical proximity to mapped genes yielded an altered bacterial load phenotype after RNAi knockdown.

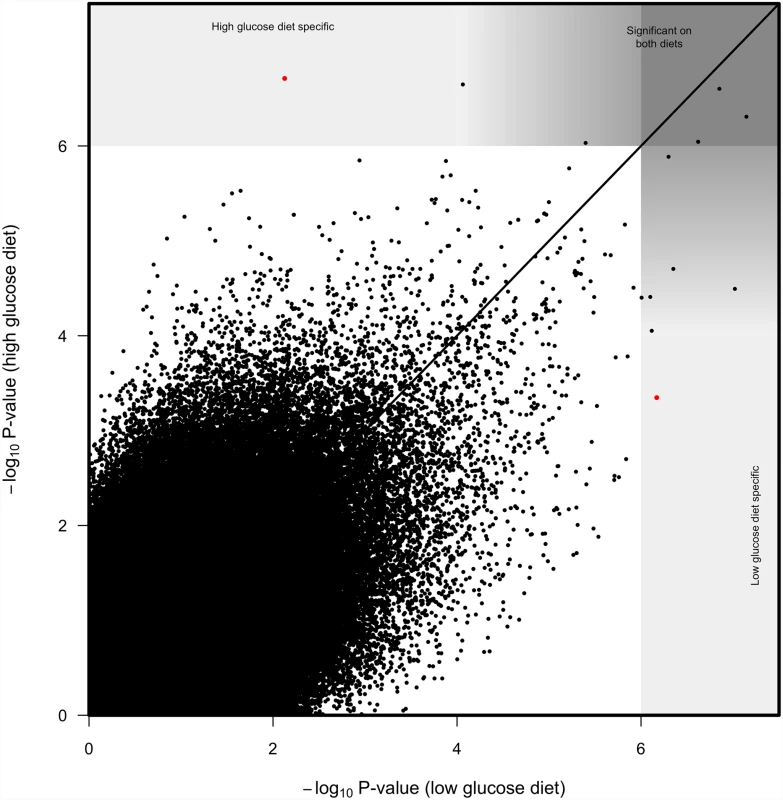

To identify SNPs that have strongly diet-dependent effects on immunity, we first considered SNPs that had significant effects (p < 10-6) on one diet but not on the other (p > 10-4; Fig. 4). Only a few SNPs meet this criterion. One SNP in crinkled (2L.15045678) was significantly associated with variation in immunity on the high glucose diet (p = 1.94 x 10-7) but not on the low glucose diet (p = 0.0074). A SNP in Sema-1a (2L.8630728) was very on the brink of significance on the high glucose diet (p = 1.42 x 10-6) and nowhere near our significance threshold on the low glucose diet (p = 0.001). Reciprocally, one SNP in elk (2R.13779189) was significant on the low glucose diet (p = 6.75 x 10-7) but not on the high glucose diet (p = 4.49 x 10-4). All SNPs with p <10-4 on either diet were significant at p < 10-6 when the data from both diets were pooled.

Fig. 4. Correlation between SNP log10 p-values from genome wide associations on high glucose diet and low glucose diet.

Solid line represents 1 to 1 value. While most significant SNPs were significant on both diets, we considered SNPs with p<10-6 on one diet and p>10-4 on the other diet to be diet specific. Our second approach to finding genes with significant diet-dependent effects was to pool the data from both diets and evaluate the SNP-by-diet interaction in a second GWAS analysis. While this approach resulted in a somewhat liberal inflation in P-values (S4b Fig), it revealed SNPs in several genes has having diet-dependent effects at a nominal threshold of p < 10-6. Of the genes mapped with this second approach, we chose TepII, gprk2, and similar to test by RNAi, and confirmed the importance of these genes on suppression of P. rettgeri proliferation (see below).

To determine whether any gene function categories were enriched in our set of significantly mapped SNPs, we performed a GO enrichment analysis using GOWINDA [47], which corrects for gene size, on the reduced GO category list defined by GO Slim [48]. Because so few SNPs mapped significantly at our cutoff of p<10-6, we performed the GO analysis at a significance threshold of p<10-5. Categories related to immunity and metabolism were among the most enriched, but no functional categories were significantly enriched after multiple correction (S2 Table). GO analysis of GWAS results implicitly assumes a quantitative genetic model where many genes in every relevant functional process each contribute small but significant effects on the overall phenotype. We have no evidence that this is an appropriate conceptual model for our defense phenotype, so we did not pursue the GO analysis further.

We performed genome-wide association mapping of each of the nutritional indices, yielding several hits in or near genes with reasonable links to metabolic status [49]. We found no overlap between SNPs significantly associated with variation in the NIs and those significantly associated with variation in immune defense. The genetic basis for altered nutritional status in response to diet will be the subject of an independent paper [49].

Characterization and RNAi knockdown of genes mapped for resistance to infection

Diptericin. Diptericin is a antimicrobial peptide that is produced in response to DAP-type peptidoglycan that makes up the cell walls of Gram-negative bacteria such as P. rettgeri [50,51]. Two SNPs in perfect linkage disequilibrium (2R.14753586—synonymous, 2R.14753589—nonsynonymous) are significantly associated with variable suppression of P. rettgeri infection in flies reared on both diets (p = 9.03 x 10-7 for each SNP on high glucose and p = 2.93 x 10-7 on low glucose) as well as when data from the two diets are pooled (p = 7.04 x 10-08 for each SNP). While it might seem intuitive that an antibacterial peptide gene would map in an immunity screen, this result was surprising as we have not identified any marked effect of Diptericin in previous association studies using other Gram-negative bacterial infections [19,27]. Indeed, it is generally believed that there is enough redundancy in AMPs that mutations in a single peptide would have little effect on organism-level immunity [e.g. 52]. The nonsynonymous SNP (2R.14753589) results in a serine versus arginine polymorphism segregating in the population. In the DGRP, the more resistant serine allele is carried by 82% of lines and the more permissive arginine by 14% of lines (4% of lines are heterozygous at the SNP). Two of the DGRP lines are homozygous for a premature stop codon in Diptericin at position 2R.14753502. While this stop codon did reach not our minor allele frequency threshold for consideration in the study, we thought it was notable that two lines carrying the premature termination exhibited the absolute highest bacterial loads across the entire DGRP mapping panel. Both of these lines carried the higher-resistance serine variant at 2R.14753589, thereby slightly decreasing the statistical significance of the independent contrast between the serine and arginine variants. If these two lines are excluded from the analysis, the P-value for 2R.14753589 is 4.43x10-9. Interestingly, we found that serine and arginine are also segregating in Drosophila simulans through an independent mutation at the same codon, suggesting the possibility of convergent balancing selection (Unckless et al. in prep.; see Discussion).

Multiplexin. Multiplexin (mp) encodes a collagen protein. Multiplexin is a huge gene (55 kb) with 15 annotated transcripts. Annotated molecular functions include carbohydrate binding and motor neuron axon guidance [53]. Loss-of-function mutants have smaller larval fat bodies than wild-type flies [54], which may be relevant since the fat body is the primary tissue that drives systemic immunity to bacterial infection. Three intronic SNPs in mp are significantly associated with variation in P. rettgeri load in flies reared on either the high glucose (p = 2.25 x 10-7) or low glucose (p = 4.12 x 10-6) diet, as well as when data from both diets are pooled (p = 3.9 x 10-7). Ubiquitous RNAi knockdown of mp resulted in significantly decreased P. rettgeri load after infection relative to controls with wild-type mp expression (p = 0.017). The relationship between resistance and the larval fat body phenotype in multiplexin mutants may suggest a role for the humoral immune response in this phenotype. Mutant flies may have altered antimicrobial peptide expression.

Defective proboscis extension response 6. An intronic SNP (3L.10039434) in Defective proboscis extension response 6 (Dpr6) was associated with variation in P. rettgeri load in flies reared on the low glucose diet (p = 9.54 x 10-8) and when data from flies reared on both diets were pooled (p = 3.51 x 10-7). Dpr6 belongs to a family of genes thought to be involved in sensory perception of chemical stimulus, including gustatory perception of food, and contains an immunoglobulin domain that may be involved in cell-cell recognition [55]. Ubiquitous RNAi knockdown of dpr6 resulted in a significant decrease in P. rettgeri load after infection (p = 0.0097).

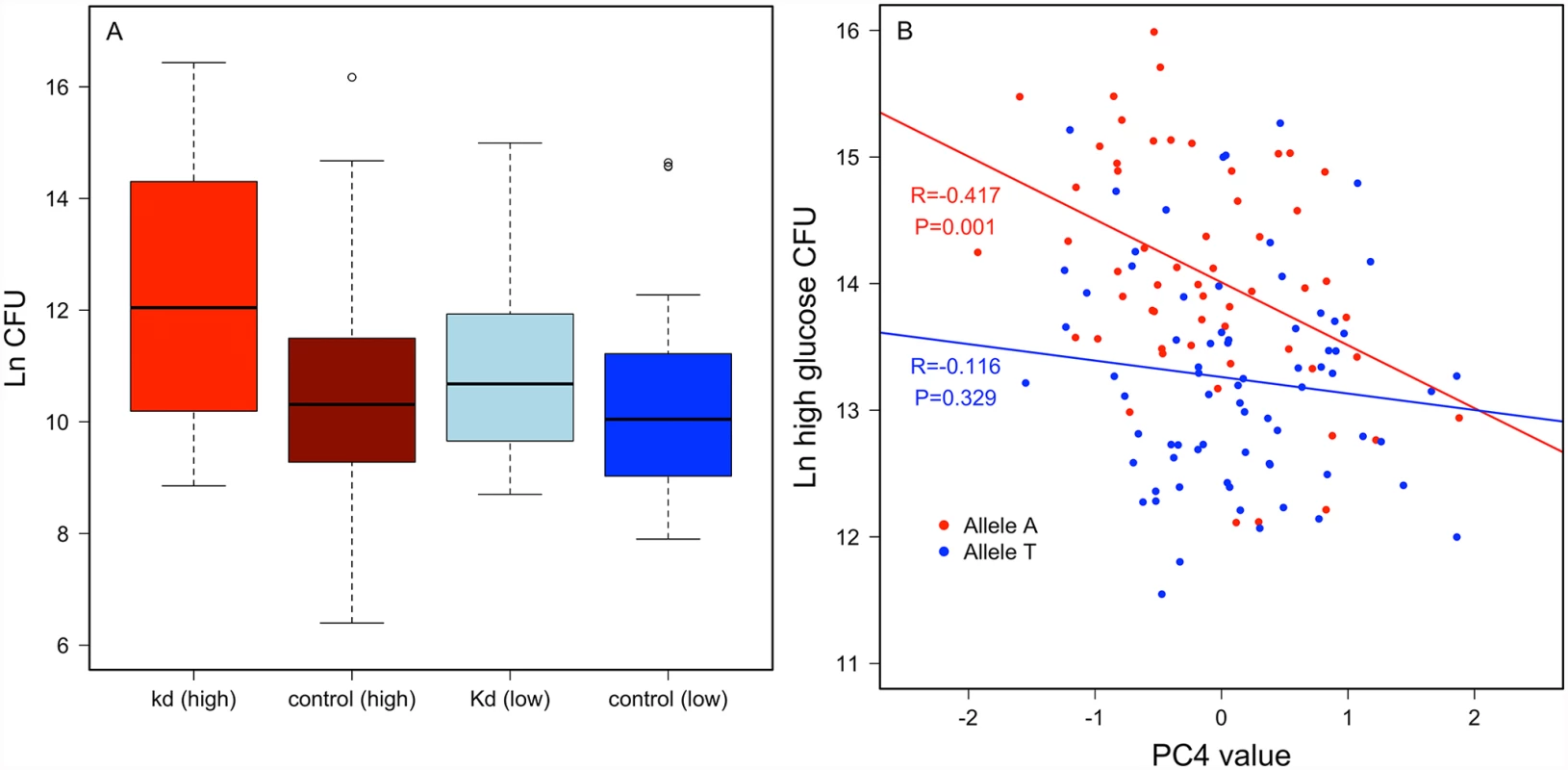

Crinkled. An intronic SNP (2L.15045678) in crinkled mapped for variable resistance specifically on the high glucose diet (p = 1.94 x 10-7), and less significantly when data from both diets were pooled (p = 4.29 x 10-5), but was not significantly associated with variation in P. rettgeri load when flies were reared on the low glucose diet (p = 0.0075). Crinkled encodes myosin VIIa, an actin-dependent ATPase. RNAi knockdown experiments for crinkled suggest that it does influence immunity in a diet-dependent manner. We used ubiquitous RNAi to knock down ck in flies reared on either the high glucose or low glucose diet. The knockdown had no significant effect on P. rettgeri load of flies reared on the low glucose diet (p = 0.45) but was marginally significant when flies were reared on the high glucose diet (p = 0.07; Fig. 5a). Further exploring the diet dependence, we found that Principle Component 4 of our nutritional indices measured on the high glucose diet correlated with P. rettgeri load in a ck allele-dependent manner. PC4 is strongly negatively correlated with bacterial load in flies homozygous for the A allele (r = -0.417, P = 0.0014) but is uncorrelated with load in flies bearing the T allele (r = – 0.115, P = 0.329; Fig. 5b). Since PC4 is loaded primarily with glucose, protein and glycogen, we also examined correlations between these NIs and P. rettgeri load within each ck allele in flies reared on the high glucose diet (S6 Fig). Mirroring the overall phenotypic data, free glucose levels trended toward negative correlation with P. rettgeri load in flies bearing the A allele (r = -0.23, p = 0.088) but not in flies bearing the T allele (r = -0.12, p = 0.32). Glycogen levels trended toward positive correlation with P. rettgeri load within the A allele (r = 0.20, p = 0.132) but not within the T allele (r = -0.07, p = 0.58).

Fig. 5. Crinkled has a diet-specific effect on immune defense.

A.) validation experiment with RNAi knockdown (kd) shows natural log CFU 24 hours post infection with P. rettgeri compared to control (see S1 Table). B.) correlation between principal component 4 of nutritional indices on the high glucose diet and bacterial load on the high glucose diet polarized by allele in crinkled showing that this correlation between nutritional status and immune defense is driven by one allele. Sema-1a. An intronic SNP (2L.8630728) in Sema-1a, which encodes a semaphorin protein, fell just below our significance threshold on the high glucose diet (p = 1.42 x 10-6) and was much less significant on the low glucose diet (p = 0.0011). The dramatic difference in effect on the different diets suggested to us that Sema-1a might have diet-dependent effects on immunity. Semaphorins tend to be highly pleiotropic and play major roles in developmental processes [56]. RNAi knockdown of Sema-1a resulted in flies with marginally significantly higher P. rettgeri loads than controls on the low glucose diet (p = 0.081), on the high glucose diet (p = 0.088), and when the data from both diets were combined (p = 0.025).

CG12869. A SNP (2R.10477114) 1594 bp upstream of functionally unannotated gene CG12869 was significantly associated with P. rettgeri load in flies reared on the low glucose diet (p = 7.65 x 10-7) and approached significance in flies reared on the high glucose diet (p = 8.87 x 10-5) and when the data from both diets were combined (p = 1.49 x 10-6). While little is known about CG12869, the encoded protein is predicted to have carboxylesterase activity. RNAi knockdown of CG12869 in flies reared on either the high-glucose or low-glucose diet resulted in modestly increased P. rettgeri loads when the data from both diets were combined (ppooled = 0.047), although not when either diet is considered independently (low glucose: p = 0.133, high glucose: p = 0.164).

G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Gprk2 was previously associated with defense response to bacteria through interaction with cactus and is required for normal AMP production [57]. It is also involved with several biological processes that might be influenced by nutritional environment including hedgehog signaling and regulation of appetite {Cheng:2012kd, Chatterjee:2010df}. An intronic SNP in Gprk2 (3R.27273757) yielded a significant SNP-by-diet interaction predicting P. rettgeri load (p = 7.75 x 10-8). RNAi knockdown of Gprk2 resulted in increased P. rettgeri load relative to control flies (p = 0.016), consistent with the results of Valanne et al. [57], who found that Gprk2 disruption reduced resistance to infection by Enterococcus faecalis. We found no distinction between knockdown on high-glucose versus low-glucose diets (pknockdown = 0.08, pdiet = 0.04, pinteraction = 0.94).

Thioester-containing protein 2. Thioester-containing proteins (TEPs) are opsonins that promote phagocytosis and parasite killing in invertebrates, including phagocytosis of Gram-negative bacteria [58]. TEPs are homologous to vertebrate complement C3 and macroglobulins, and Drosophila TepII has previously been shown to evolve under adaptive positive selection in the presumptive pathogen-binding domain [59]. P. rettgeri load was determined by a significant diet*SNP interaction for four nonsynonymous SNPs in TepII (p = 5.97 x 10-7) and an additional synonymous SNP in tight disequilibrium (p = 7.00 x 10-7). RNAi knockdown of TepII resulted in reduced immune defense (p = 0.0017), independent of diet (p = 0.94), which is consistent with the known role of TepII in insect immunity.

Similar. An intronic SNP in similar (3R.25909307) showed a significant Diet*SNP interaction (p = 9.17 x 10-7). Sima is involved in protein dimerization and signal transduction and has been associated with response to stress. RNAi knockdown of similar resulted in increased P. rettgeri load after infection of flies reared on the low glucose diet (p = 0.005) but not on the high glucose diet (p = 0.28). Variants of similar may influence how an individual responds to a nutrient-poor diet which in turn may influence their ability to resist infection.

Kinesin heavy chain 73 and Src64B. A synonymous SNP and a SNP in the 3′ UTR of Khc-73 were associated with variation in bacterial load when data from both diets are pooled (3.1 x 10-7 and 5.48 x 10-8, respectively), and an intronic SNP (3L.4603286) in Src64b mapped highly significantly on each diet (low glucose: p = 1.41 x 10-7; high glucose: p = 2.50 x 10-7) and when the data from both diets were pooled (p = 3.34 x 10-9). Khc-73 is a microtubule motor protein [53] and Src64b is a tyrosine kinase with a wide range of reported phenotypes including cellular immune response [60]. RNAi knockdown of either gene did not result in any significant change in systemic P. rettgeri load after infection (Khc-73: p = 0.67, Src64b: p = 0.97). Thus, neither of these mapped genes validated by our RNAi knockdown criteria. This could be because the two genes are false positive map results or because the RNAi failed to adequately block protein synthesis in the knockdown experiment.

Other candidate genes. We mapped SNPs associated with variation in post-infection P. rettgeri load in the genes elk, fruitless, tout velu, CG42524, CG7991, CG4835 and CG15544 (Table 5), but we were unable to establish RNAi knockdowns for these and were thus unable to test whether disruption of these genes influences resistance to infection.

Nearest-neighbor negative controls. It is unknown what proportion of genes in the genome could conceivably yield immune defense phenotypes when ubiquitous RNAi disrupts their expression. To estimate the false-positive rate on our RNAi knockdowns, we additionally knocked down several arbitrary genes that are physically adjacent to our mapped genes but are not known to have any immune function. Whereas 9 out of 13 of our mapped candidate genes yielded defense phenotypes upon RNAi knockdown, only one out of the five arbitrary neighboring genes yielded an immunity phenotype. Little is known about the function of that arbitrary gene whose knockdown resulted in a modest decrease in P. rettgeri load (p = 0.029) (CG34356), but it has been shown to be involved in protein phosphorylation [61]. Our rate of 9 in 11 positive knockdown experiments among the mapped candidates is a significant excess over the 1 in 5 negative control genes that gave immune phenotypes (Fisher’s Exact Test: p = 0.018), giving us confidence that the majority of our mapped genes are true positive results.

Genome-wide association mapping and NI correlations with Diptericin genotype as a covariate

Diptericin is a classical immunity gene with a large effect in our study. We reasoned that genotype at Diptericin might mask genes with smaller effects, and that we could increase power to detect diet-dependent variants by controlling for Diptericin genotype. Furthermore, there was significant linkage disequilibrium between SNPs in Diptericin and other mapped SNPs (S7 Fig). We therefore re-conducted the genome-wide association analysis with the addition of Diptericin genotype as a covariate that could take on three possible states: the arginine versus serine variants at position 2R.14753589 and the premature stop codon (although the two DGRP lines carrying the premature stop codon also carried the serine variant, we classified them separately because they were phenotypically so extreme). Lines carrying residual heterozygosity at Dpt were treated as having missing data for the Dpt genotype. All GWAS results and knockdown experiments reported to this point were mapped without Dpt genotype as a covariate. Unexpectedly, instead of revealing new genes that predict immune phenotype, inclusion of Dpt genotype in the mapping model caused the number of significant SNPs (p < 10-6) to drop from 19 to only 4 when the data from both diets were pooled, from 11 to 2 on the low glucose diet only, and from 7 to 1 on the high glucose diet only. Inclusion of Dpt as a covariate greatly improved the observed fit of our q-q plots to the null expectation, eliminating experiment-wide p-value inflation (S4 Fig). We observed an increase in the number of SNP-by-diet interactions from 77 to 88 when Dpt genotype is included as a covariate (S4 Fig, S3 Table). Only one SNP (2L.13072327; located in a small RNA) was significant in both the original models and when Dpt genotype was used as a covariate. For the SNPs significant for the interaction effect, 66 were significant in both methods, 14 were specific to mapping without Dpt as a covariate, and 25 were specific to mapping with Dpt as a covariate. As shown in S4 Fig, there is generally good agreement between the two methods for interaction, although both are quite inflated.

To assess whether mapping with Diptericin genotype as a covariate provided reliable results, we performed the same RNAi knockdown experiments as described above with two new candidates genes. Both resulted in increased pathogen load when knocked down (S5 Fig, S1a Table). Briefly, these genes were CG33090, a beta-glucosidase, and CG6495, a gene of unknown function that was significantly induced upon infection in a previous study [62]. We additionally chose to validate CG12004, which mapped with a P-value that missed our significance threshold (p = 4.72 x 10-6), but that has been previously shown to be involved in defense response to fungus [63]. Knockdown of CG12004 resulted in a marginally significant increase in pathogen load (P = 0.0514).

We reexamined the correlations between nutritional indices and bacterial load when Dpt variant was included as a covariate in the regression. In all cases, the model with Dpt variant was a better fit than the model that did not include Dpt genotype (S4 Table). On the high glucose diet, the correlation between free glucose level and bacterial load becomes slightly less significant (p = 0.078 vs. p = 0.033 previously), while the correlation between soluble protein and bacterial load became more significant (p = 0.036 vs. p = 0.061 previously). No principal components on the low glucose diet became significant with Dpt as a covariate. However, on the high glucose diet, PC3 became marginally significant (p = 0.052 vs. 0.194 without considering Dpt genotype) and PC4 remained significant (p = 0.007 vs. 0.001 without considering Dpt genotype).

Discussion

We found the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel to be highly variable for resistance to P. rettgeri infection. We also determined that the severity of bacterial infection increased dramatically when flies were reared on a high-glucose diet, and the flies became hyperglycemic and hyperlipidemic. Relative quality of immune defense was highly correlated across the two diets, indicating strong genetic determination of the defense phenotype. However, we also observed a significant genotype-by-diet interaction shaping defense. Specifically, there were several lines that suffered disproportionately severe infections after rearing on the high-glucose diet, although these lines fell closer to the center of the resistance distribution when they were reared on the low-glucose diet. We did not find any lines that showed markedly higher resistance on the high-glucose diet. We were able to identify several genes that contributed to variation in resistance on both diets.

Not only did severity of infection increase with elevated dietary glucose, the flies became hyperglycemic, hyperlipidemic, and had elevated glycogen stores after rearing on the high-glucose diet. Because both glucose levels and infection severity increased with rearing on the high glucose diet, we predicted that those two traits would also be genetically correlated. Unexpectedly, however, free glucose levels were negatively correlated with severity of infection across genotypes when flies were reared on the high glucose diet (the two traits were uncorrelated on the low glucose diet). We observed an even stronger correlation between resistance and a principal component that was positively loaded with free glucose and negatively loaded with glycogen stores. Because metabolic measurements were taken from uninfected flies, they indicate genetic capacity to assimilate or manage the excess dietary glucose in the absence of the pathogen. The genetic correlation with infection severity indicates that resistance to P. rettgeri infection is linked in some way to glucose metabolism, uptake, and/or conversion to and from glycogen. Our map results suggest that this effect is partially mediated by the crinkled gene, which encodes a myosin VIIa cytoskeletal ATPase. We identified a polymorphism in crinkled that highly significantly predicted bacterial load when flies were reared on the high glucose diet, although not on the low glucose diet. Flies bearing the rarer allele show strongly negatively correlated glucose levels and pathogen loads. Furthermore, independently determined expression of the crinkled gene [64] correlates with resistance to P. rettgeri and our observed glucose level. Full characterization of the mechanism by which crinkled shapes immunity and glucose metabolism will require future study.

We were more generally able to map several genes that contribute to phenotypic variation in immune performance, both in diet-specific and diet-independent manners. The mapped polymorphisms were highly significantly enriched for being nonsynonymous and for lying within or very near genes. RNAi knockdown confirmed roles for the mapped genes in resistance to P. rettgeri, with 82% of the knockdowns of mapped genes resulting in altered pathogen loads. In contrast, we found defense phenotypes after knockdown of only 17% of negative control genes that are chromosomally linked to mapped genes but were otherwise arbitrary.

Only a small handful of the mapped genes had annotated immune function. Instead, we identified genes encoding proteins annotated in processes such as feeding behavior and cytoskeletal trafficking. This is a fully expected outcome of the experiment, and such genes are precisely what GWAS studies are designed to detect. Functional variation in dedicated immune genes is probably subject to strong natural selection in the wild, and most variation is probably quickly purged from the population. In contrast, however, populations may retain genetic variation that results in smaller effects on resistance, especially when the primary selection on the gene is for a function other than immune defense. Such genetic variants can then cause a large proportion of the observed phenotypic variance in natural populations, and in mapping panels derived from natural populations, such as the DGRP. The effect on immune defense of knocking down the mapped genes by RNAi was small relative to what might be expected from disruption of core components of the immune system. For this reason, it is unsurprising that these genes have not been discovered in previous mutation screens for susceptibility to bacterial infection. That we are able to map and confirm many of these non-conventional genes opens the possibility of whole new avenues of research and illustrates the value of unbiased genome-wide mapping relative to candidate gene based studies. This result also suggests that resistance to infection, especially in the context of dietary variation, is best viewed as a synthetic trait of the whole organism phenotype and is not determined solely by the canonical immune system. Genes that influence any number of developmental or metabolic processes may carry variation that directly or indirectly influences the ability of the organism to resist infection.

At the outset of this experiment, we might have hypothesized that the genetic basis for immunological sensitivity to diet would map to stereotypical metabolic processes, either because of crosstalk between metabolic and immune signaling, varied ability to incorporate metabolites during development, or variation in the capacity to sequester nutrients from pathogens. However, our mapping did not uncover the most obvious potential metabolic processes, such as insulin-like signaling, carbohydrate metabolism, or energetic storage. Instead, we identified genes with highly diverse function, which indicates a much more nuanced and complex interaction between dietary intake and immune defense. Importantly, because the flies in our study were reared from egg-to-adult on the experimental diet of interest, we do not distinguish between defense-impacting effects that arise during development versus those that manifest during the response to infection. It is important to bear in mind that the effects of allelic variation in the mapped genes could manifest at any stage of development or in any aspect of host physiology that may ultimately influence antibacterial defense. Determining the mechanisms by which the mapped genes influence resistance will require considerable additional study. In most cases, the RNAi knockdowns of mapped genes confirmed an effect of immune phenotype, but did not necessarily recapitulate diet-specific effects on resistance. While RNAi knockdown is a useful tool for confirming the role of mapped genes in immune defense, it is expected that the effect of RNAi knockdown will be much larger than the difference in phenotype between two alleles of the gene. Thus, where the SNP variants may cause modest modification of defense phenotype—perhaps revealed only under certain dietary environments—the RNAi knockdowns are more of a sledgehammer whose effects will be seen under all dietary conditions.

One of the variants that most significantly predicted pathogen load irrespective of diet was an amino acid polymorphism in the canonical antibacterial peptide Diptericin. This was surprising to us, as previous candidate gene studies had failed to detect major effect of allelic variation in Diptericin or any other antimicrobial peptide gene on resistance to Serratia marcescens, Enterococcus faecalis, Lactococcus lactis, or Providencia burhodogranariea [26–28]. Our interpretation had been that AMPs are plentiful and functionally redundant [52], such that minor variation in any one peptide would not have major effect on organism-level resistance. However, in followup experiments we have confirmed that the Serine/Arginine variant mapped in the present study is a strong predictor of resistance to some but not all Gram-negative bacterial pathogens (Unckless et al in prep). Thus, it would appear that the relative importance of Diptericin, and by extension presumably other antibacterial peptides, depends on the agent of infection. Moreover, we have found an independent mutation in natural populations of Drosophila simulans that converges on a Serine/Arginine polymorphism at the same Diptericin codon, with the same consequence for relative resistance to this suite of bacteria. Surprisingly, natural populations of both D. melanogaster and D. simulans are additionally polymorphic for apparent loss-of-function mutations at Diptericin, and flies carrying these variants are highly susceptible to infection by P. rettgeri and other bacteria [38](Unckless et al in prep). The collective data indicate a complex evolutionary history of Diptericin that includes convergent evolution of selectively balanced polymorphisms in two species, with variation in relative resistance to a subset of pathogens.

We found that infection by the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis is associated with modest but significant resistance to infection by P. rettgeri. Previous studies have not found differences in Wolbachia-infected vs. uninfected flies in immune system activity or resistance to infection by secondary bacteria, including P. rettgeri [42,43,65]. Our present study is substantially larger than these others, and therefore may have greater power to detect small protective effects of Wolbachia infection. Unlike previous studies which have compared Wolbachia-infected flies to genetically matched lines which were cured of Wolbachia using antibiotics, our present study cannot fully distinguish between the effects of Wolbachia and host genotype. For example, Wolbachia infection status could be associated with general health of the lines and therefore resistance to P. rettgeri infection, or Wolbachia infection could be significantly associated with a genetic polymorphism that also predicts resistance to P. rettgeri. Presence of Wolbachia was weakly associated with a decrease in soluble protein in the present study (p = 0.046), and has been previously shown to alter fly physiology by buffering the effects of excess or deficit in dietary iron [66] and by modulating other metabolic processes including insulin signaling [67]. These physiological impacts may suggest indirect mechanisms by which Wolbachia infection could confer weak protection against infection by pathogens like P. rettgeri.

In summary, we have shown that natural genetic variation for immune defense can be attributed to variation in several genes, with both diet-dependent and diet-independent effects. We also find that metabolic indices are correlated with immune defense when flies are reared on a high glucose diet. Importantly, several of the mapped genes would not be considered conventional “immune” genes, yet we confirm with RNAi knockdown that they pleiotropically contribute to immune defense. The genes mapped in this study harbor allelic variation that shapes the quality of immune defense, and thus may be instrumental in the evolution of resistance to bacterial infection in natural populations experiencing varied dietary environments.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila and bacterial strains used

The Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP; [39]) is a collection of 192 lines that have been inbred to homozygosity and whose complete genomes have been sequenced. Each line is derived from an independent wild female captured in a fruit market in Raleigh, NC, USA in 2003. We used 172 of the most robust lines for this study, though the exact number and composition of lines varied slightly among replicate blocks of the experiment.

Bacterial infections were performed using Providencia rettgeri strain Dmel, which was isolated as an infection of a wild-caught D. melanogaster [68]. P. rettgeri are Gram-negative bacteria in the family Enterobacteriaceae, and are commonly found in association with insects and other animals. Injection of the Dmel strain of P. rettgeri into D. melanogaster under the conditions used here results in a highly reproducible initial dose of bacteria that proliferates 100–1000 fold over the first 24 hours post-infection, depending on the host fly genotype, with low to moderate host mortality [51]. Bacterial load at 24 hours post-infection correlates strongly with risk of host mortality [38], but pathogen load as a phenotype does not confound resistance and tolerance mechanisms in the way that survivorship does.

Drosophila diets

We used two experimental diets that varied in glucose content but otherwise had the same composition. The base diet was composed of 5% weight per volume Brewer’s yeast (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) and 1% Drosophila agar (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA). The high-glucose diet contained 10% glucose (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) while the low-glucose diet contained 2.5% glucose. All diets were supplemented with 800 mg/L methyl paraben (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) and 6 mg/L carbendazim (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) to inhibit microbial growth in the food. RNAi knockdown experiments for SNPs significant when data from both diets were pooled were performed on the “standard diet” which contained 8.2% glucose and 8.2% Brewer’s yeast. Each DGRP line was split and raised in parallel on both diets for at least three generations prior to the start of the experiment to control parental and grandparental effects within dietary treatments, and experimental flies were reared egg-to-adult in the dietary condition being assayed. We recognize that our diets differ in total caloric content as well as protein to carbohydrate ratios [4,13,14]. It is possible that Drosophila change their feeding behavior on the two diets, and that there may even be genetic variation for feeding behavioral response to diet. Our goal in this study is to determine the consequences of excess dietary glucose while remaining agnostic as to the precise cause of any altered nutritional assimilation.

Method of bacterial infection

Providencia rettgeri strain Dmel was grown overnight to stationary phase in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C prior to each infection day. On the morning of infections, stationary cultures were diluted in sterile LB broth to A600 = 1.0. Male flies from each DGRP line were infected in the lateral scutum of the thorax by pricking with needles (0.10mm, Austerlitz Insect Pins, Prague, CR) that had been dipped in the diluted bacterial suspension, delivering approximately 1000 bacteria to each infected fly. Infections were performed in three blocks for each diet with each block containing all or nearly all DGRP lines under study. Each block for each diet was performed on a different day, with replicate blocks for the two diets interspersed on alternating weeks. Three researchers performed the infections on each experimental day, with lines assigned randomly to infectors within each block. Males aged 3–6 days post-eclosion were infected from each line. All flies were maintained in an incubator at 24°C on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Infections were delivered approximately 2–4 hours after “dawn” from the perspective of the flies.

Approximately 24 hours after infection, males were homogenized in groups of 3 in 500 ul sterile LB broth. The homogenate was plated on standard LB agar plates using a robotic spiral plater (Don Whitley Scientific). Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and the resultant colonies were counted using the ProtoCOL system associated with the plater. P. rettgeri grows readily on Luria agar at 37°C, but the endogenous microbiota of D. melanogaster does not. Thus, we were able to capture colonies derived from viable infecting P. rettgeri without interference from the Drosophila gut microbiota. Counted colonies were visually inspected for morphology consistent with P. rettgeri, and homogenates from sham-infected flies always failed to yield bacterial colonies within the assay period. We used systemic pathogen load at 24 hours post-infection as our measure of immune defense.

In total, 6–9 data points representing 18–27 flies were collected from each line on each diet (high and low glucose). The total experiment consists of 1429 data points representing 4287 flies on the low glucose diet, and 1396 data points representing 4188 flies on the high glucose diet.

Nutritional indices in the DGRP

We queried a series of nutritional indices in flies reared on each diet. Each metabolite was assayed in three replicates on flies reared on each diet. Males were aged 3–6 days post-eclosion, then 10 live males were weighed using a MX5 microbalance (Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OG) and homogenized in 200 μL buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 with 0.1% v/v Triton-X-100) using lysing matrix D (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) on a FastPrep-24 homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA). An aliquot of 50 microliters were frozen immediately while 150 microliters were incubated at 72 degrees C for 20 minutes to denature host proteins. Nutrient assays were performed with minor modifications of the procedures described in [69] using the following assay kits from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO): glucose with the oxidase kit (GAGO-20); glycogen using the glucose kit and amyloglucosidase from Aspergillus niger (A7420) in 10 mM acetate buffer at pH 4.6; free glycerol and triglycerides using reagent kits F6428 and T2449, respectively. Soluble protein was assayed with the DC Protein Assay (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA). Each metabolite was assayed on each pool of weighed and homogenized flies.

Data analysis

Mixed effect linear models were used to test for genetic and other contributions to phenotypic variation in systemic pathogen load and nutritional indices. Overall genetic main effects on systemic pathogen load were tested with the model

where Y is the natural log-transformed measure of pathogen load for each data point, Wolbi (i = 1,2) has a fixed effect and indicates whether the line is infected with the endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia pipientis, Dietj (j = 1,2) has a fixed effect and indicates which of the two diets the flies were reared on, Infectorl (l = 1,3) has a fixed effect and is used to test whether the experimentor performing the infections influenced ultimate pathogen load, and Platerm (m = 1,2) has a fixed effect and indicates which of two spiral platers were used to plate the sample. Blockn(Dieto) (n = 1,3) has a fixed effect nested within the effect of Diet, and is used to test for differentiation among the three replicate blocks for each dietary treatment. Linek(Wolbi) (k = 1,172) is assumed to have a random effect, and is used to test the influence of genetic line on pathogen load within Wolbachia-infected and Wolbachia-uninfected classes. The interaction Dieto*Linek(Wolbi) is considered to have a fixed effect and tests whether genetic lines differ in their responsiveness to the two diets. This model was run in SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC) using the “mixed” procedure.We determined line means for each nutritional index using abundance of metabolite per fly. The model used was analogous to that used for bacterial load:

Again, all factors were considered to be fixed except Line(Wolb) and Diet*Line(Wolb) and best linear unbiased predictors (BLUPs) were extracted for further analysis. For comparisons between diets, the model used was Nutrient/fly~Wolb+Line(Wolb)+Block.

To determine whether there was a genetic signature of a “metabolic syndrome” that may influence immune defense, we performed principal component analysis using the BLUPs extracted for each nutritional index. This analysis was implemented in R with the prcomp function with tol = 0.1 and unit variance scaling on. The principal component values for were then tested for correlation with bacterial load. This analysis was done for each diet individually.

Genome-wide association mapping

The set of SNPs for mapping was described in Huang et al. (in revision) and consists of only SNPs with minor alleles present in at least four of the lines (MAF >2%; 2415518 total SNPs). For bacterial load (Ln CFU), we used SAS to run the following model:

LnCFU = m+SNPi+Dietj+SNPi*Dietj+Blockk(Dietj)+Wolbl+Infectorm+Platern+Lineo(SNPi)+eijklmno, where all factors were fixed except Line(SNP). P-values for the main effect of SNP and the SNP*Diet interaction were obtained for each SNP. We also ran the model separately on data obtained from flies reared on each of the two diets to obtain significance values for each SNP on each diet independently. These models were LnCFU = m+SNPi+Blockj+Wolbk+Infectorl+Platerm+Linen(SNPi)+eijklmn. We considered SNPs that mapped with significance level of p < 10-6 to be nominal positive hits and candidates for RNAi knockdown experiments. This p-value corresponds to a false discovery rate of 5–10% depending on the precise analysis being performed.

GO term analysis

To correct for gene size, we used GOWINDA [47] to test for the enrichment of particular functional groups. Here we relax our significance threshold to include all SNPs with p<10-5. This allows for more power through the inclusion of additional SNPs. Relaxing the P-value threshold even further had little effect on GO enrichment results. Significantly associated SNPs for each treatment (low glucose, high glucose, main effect) were used with a background SNP set consisting of all SNPs used in the GWAS. GO slim [48] terms were used to reduce redundancy in GO categories. GOWINDA was run using gene mode, including all SNPs within 1000bp of a gene, a minimum gene number of 5, and with 100,000 simulations. We report all GO terms with a nominal P-value less than 0.1.

RNAi knockdown experiments for genes containing SNPs significantly associated for bacterial load

For all SNPs with P-values meeting our significance threshold and falling within 1000 bp of an annotated gene, we performed the infection assay described above on RNAi knockdown lines from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (Vienna, Austria), if available.

To test the effect of the gene on resistance to infection, we crossed each RNAi line to a line carrying the ubiquitous driver (Act5C-Gal4/Cyo or da-Gal4) and infected F1 offspring of the knockdown genotype. We compared the immune defense in these F1 offspring to that of F1 progeny from the driver line crossed to the background genetic line of the RNAi transformant. Unless otherwise indicated, we performed RNAi knockdown experiments using a standard diet (1 : 1 glucose to yeast ratio, but more calorie dense than our high and low glucose diets—see methods). For those SNPs that showed a diet-specific effects, we performed RNAi knockdown experiments on the experimental high and low glucose diets.

It is completely unknown what proportion of genes throughout the genome might yield an immune phenotype when expression is repressed. To test whether genes containing our significantly associated SNPs were more likely to have an immune phenotype than a set of arbitrary genes from the genome, we also performed RNAi knockdown experiments on the genes that were physically close to those of interest but not known to be involved in immunity and not essential for viability. We refer to these as “nearest neighbor controls”.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL, Gordon JI (2011) Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature 474 : 327–336. doi: 10.1038/nature10213 21677749

2. Moret Y, Schmid-Hempel P (2000) Survival for immunity: the price of immune system activation for bumblebee workers. Science 290 : 1166–1168. 11073456

3. Gleeson M, Bishop NC (2000) Elite athlete immunology: importance of nutrition. Int J Sports Med 21 Suppl 1: S44–S50. 10893024

4. Ponton F, Wilson K, Cotter SC, Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ (2011) Nutritional immunology: a multi-dimensional approach. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002223. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002223 22144886

5. Cotter SC, Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D, Wilson K (2010) Macronutrient balance mediates trade-offs between immune function and life history traits. Funct Ecol 25 : 186–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01766.x

6. Peck MD, Babcock GF, Alexander JW (1992) The role of protein and calorie restriction in outcome from Salmonella infection in mice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 16 : 561–565. 1494214

7. Maggini S, Wenzlaff S, Hornig D (2010) Essential role of vitamin C and zinc in child immunity and health. J Int Med Res 38 : 386–414. 20515554

8. Fellous S, Lazzaro BP (2010) Larval food quality affects adult (but not larval) immune gene expression independent of effects on general condition. Mol Ecol 19 : 1462–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04567.x 20196811

9. Shingleton AW, Frankino WA, Flatt T, Nijhout HF, Emlen DJ (2007) Size and shape: the developmental regulation of static allometry in insects. Bioessays 29 : 536–548. doi: 10.1002/bies.20584 17508394

10. Awmack CS, Leather SR (2002) Host plant quality and fecundity in herbivorous insects. Annu Rev Entomol 47 : 817–844. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145300 11729092

11. Sentinella AT, Crean AJ, Bonduriansky R (2013) Dietary protein mediates a trade-off between larval survival and the development of male secondary sexual traits. Funct Ecol. 27 : 1134–144.

12. Ayres JS, Schneider DS (2009) The role of anorexia in resistance and tolerance to infections in Drosophila. PLoS Biol 7: e1000150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000150 19597539

13. Povey S, Cotter SC, Simpson SJ, Lee KP, Wilson K (2009) Can the protein costs of bacterial resistance be offset by altered feeding behaviour? J Anim Ecol 78 : 437–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01499.x 19021780

14. Lee KP, Simpson SJ, Clissold FJ, Brooks R, Ballard JWO, et al. (2008) Lifespan and reproduction in Drosophila: New insights from nutritional geometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 : 2498–2503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710787105 18268352

15. Bruce KD, Hoxha S, Carvalho GB, Yamada R, Wang H-D, et al. (2013) High carbohydrate-low protein consumption maximizes Drosophila lifespan. Exp Gerontol 48 : 1129–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.003 23403040

16. Ja WW, Carvalho GB, Zid BM, Mak EM, Brummel T, et al. (2009) Water - and nutrient-dependent effects of dietary restriction on Drosophila lifespan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 : 18633–18637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908016106 19841272

17. Adler MI, Bonduriansky R (2014) Why do the well-fed appear to die young?: a new evolutionary hypothesis for the effect of dietary restriction on lifespan. Bioessays 36 : 439–450. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300165 24609969

18. Fanson BG, Taylor PW (2012) Protein:carbohydrate ratios explain life span patterns found in Queensland fruit fly on diets varying in yeast:sugar ratios. Age (Dordr) 34 : 1361–1368. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9308-3 21904823

19. Lazzaro BP, Sceurman BK, Clark AG (2004) Genetic basis of natural variation in D. melanogaster antibacterial immunity. Science 303 : 1873–1876. doi: 10.1126/science.1092447 15031506

20. Miller SI, Ernst RK, Bader MW (2005) LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol 3 : 36–46. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1068 15608698

21. Ogus AC, Yoldas B, Ozdemir T, Uguz A, Olcen S, et al. (2004) The Arg753GLn polymorphism of the human toll-like receptor 2 gene in tuberculosis disease. Eur Respir J 23 : 219–223. 14979495

22. Dalgic N, Tekin D, Kayaalti Z, Soylemezoglu T, Cakir E, et al. (2011) Arg753Gln polymorphism of the human Toll-like receptor 2 gene from infection to disease in pediatric tuberculosis. Hum Immunol 72 : 440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.02.001 21320563

23. Silventoinen K (2003) Determinants of variation in adult body height. J Biosoc Sci 35 : 263–285. 12664962

24. Akachi Y, Canning D (2007) The height of women in Sub-Saharan Africa: the role of health, nutrition, and income in childhood. Ann Hum Biol 34 : 397–410. doi: 10.1080/03014460701452868 17620149

25. Lazzaro BP, Flores HA, Lorigan JG, Yourth CP (2008) Genotype-by-environment interactions and adaptation to local temperature affect immunity and fecundity in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000025. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000025 18369474

26. Lazzaro BP, Sceurman BK, Clark AG (2004) Genetic basis of natural variation in D. melanogaster antibacterial immunity. Science. 303 : 1873–1876. 15031506

27. Lazzaro BP, Sackton TB, Clark AG (2006) Genetic variation in Drosophila melanogaster resistance to infection: a comparison across bacteria. Genetics 174 : 1539–1554. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054593 16888344

28. Sackton TB, Lazzaro BP, Clark AG (2010) Genotype and gene expression associations with immune function in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 6: e1000797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000797 20066029

29. Kleino A, Silverman N (2014) The Drosophila IMD pathway in the activation of the humoral immune response. Dev Comp Immunol 42 : 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2013.05.014 23721820

30. Lindsay SA, Wasserman SA (2014) Conventional and non-conventional Drosophila Toll signaling. Dev Comp Immunol 42 : 16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2013.04.011 23632253

31. Reed LK, Williams S, Springston M, Brown J, Freeman K, et al. (2010) Genotype-by-diet interactions drive metabolic phenotype variation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 185 : 1009–1019. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.113571 20385784

32. Dionne MS, Pham LN, Shirasu-Hiza M, Schneider DS (2006) Akt and FOXO dysregulation contribute to infection-induced wasting in Drosophila. Curr Biol 16 : 1977–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.052 17055976

33. Libert S, Chao Y, Zwiener J, Pletcher SD (2008) Realized immune response is enhanced in long-lived puc and chico mutants but is unaffected by dietary restriction. Mol Immunol 45 : 810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.353 17681604

34. DiAngelo JR, Bland ML, Bambina S, Cherry S, Birnbaum MJ (2009) The immune response attenuates growth and nutrient storage in Drosophila by reducing insulin signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 : 20853–20858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906749106 19861550

35. Brown AE, Baumbach J, Cook PE, Ligoxygakis P (2009) Short-term starvation of immune deficient Drosophila improves survival to gram-negative bacterial infections. PLoS ONE 4: e4490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004490 19221590

36. Becker T, Loch G, Beyer M, Zinke I, Aschenbrenner AC, et al. (2010) FOXO-dependent regulation of innate immune homeostasis. Nature 463 : 369–373. doi: 10.1038/nature08698 20090753

37. Chambers MC, Jacobson E, Khalil S, Lazzaro BP (2014) Thorax injury lowers resistance to infection in Drosophila melanogaster. Infect Immun. 82 : 4380–4389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02415-14 25092914

38. Howick VM, Lazzaro BP (2014) Genotype and diet shape resistance and tolerance across distinct phases of bacterial infection. BMC Evol Biol 14 : 56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-56 24655914

39. Mackay TFC, Richards S, Stone EA, Barbadilla A, Ayroles JF, et al. (2012) The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature 482 : 173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10811 22318601

40. Teixeira L, Ferreira Á, Ashburner M (2008) The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 6:e1000002.

41. Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL, Johnson KN (2008) Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science. 322 : 702. doi: 10.1126/science.1162418 18974344

42. Wong ZS, Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, Johnson KN (2011) Wolbachia-mediated antibacterial protection and immune gene regulation in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 6: e25430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025430 21980455

43. Rottschaefer SM, Lazzaro BP (2012) No effect of Wolbachia on resistance to intracellular infection by pathogenic bacteria in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 7: e40500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040500 22808174

44. Richardson MF, Weinert LA, Welch JJ, Linheiro RS, Magwire MM, et al. (2012) Population genomics of the Wolbachia endosymbiont in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet 8: e1003129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003129 23284297

45. Celniker SE, Dillon LAL, Gerstein MB, Gunsalus KC, Henikoff S, et al. (2009) Unlocking the secrets of the genome. Nature 459 : 927–930. Available: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/459927a. doi: 10.1038/459927a 19536255

46. Huang W, Massouras A, Inoue Y, Peiffer J, Ràmia M, et al. (2014) Natural variation in genome architecture among 205 Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel lines. Genome Research 24 : 1193–1208. doi: 10.1101/gr.171546.113 24714809

47. Kofler R, Schlötterer C (2012) Gowinda: unbiased analysis of gene set enrichment for genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 28 : 2084–2085. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts315 22635606

48. Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, et al. (2000) The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287 : 2185–2195. 10731132

49. Unckless RL, Rottschaefer SM, Lazzaro BP (2015) A Genome-Wide Association Study for Nutritional Indices in Drosophila. G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.016477

50. Wicker C, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann D, Hultmark D, Samakovlis C, et al. (1990) Insect immunity. Characterization of a Drosophila cDNA encoding a novel member of the diptericin family of immune peptides. J Biol Chem 265 : 22493–22498. 2125051

51. Galac MR, Lazzaro BP (2011) Comparative pathology of bacteria in the genus Providencia to a natural host, Drosophila melanogaster. Microbes and Infection: 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.02.005 21907304

52. Tzou P, Ohresser S, Ferrandon D, Capovilla M, Reichhart JM, et al. (2000) Tissue-specific inducible expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in Drosophila surface epithelia. Immunity 13 : 737–748. 11114385

53. Marygold SJ, Leyland PC, Seal RL, Goodman JL, Thurmond J, et al. (2013) FlyBase: improvements to the bibliography. Nucleic Acids Research 41: D751–D757. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1024 23125371

54. Momota R, Naito I, Ninomiya Y, Ohtsuka A (2011) Drosophila type XV/XVIII collagen, Mp, is involved in Wingless distribution. Matrix Biol 30 : 258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.03.008 21477650

55. Nakamura M, Baldwin D, Hannaford S, Palka J, Montell C (2002) Defective proboscis extension response (DPR), a member of the Ig superfamily required for the gustatory response to salt. J Neurosci 22 : 3463–3472. 11978823

56. Zhou Y, Gunput R-AF, Pasterkamp RJ (2008) Semaphorin signaling: progress made and promises ahead. Trends Biochem Sci 33 : 161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.01.006 18374575

57. Valanne S, Myllymäki H, Kallio J, Schmid MR, Kleino A, et al. (2010) Genome-wide RNA interference in Drosophila cells identifies G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 as a conserved regulator of NF-kappaB signaling. J Immunol 184 : 6188–6198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000261 20421637

58. Blandin S, Levashina EA (2004) Thioester-containing proteins and insect immunity. Mol Immunol 40 : 903–908. 14698229

59. Jiggins FM, Kim K-W (2006) Contrasting evolutionary patterns in Drosophila immune receptors. J Mol Evol 63 : 769–780. doi: 10.1007/s00239-006-0005-2 17103056

60. Williams MJ (2009) The c-src homologue Src64B is sufficient to activate the Drosophila cellular immune response. J Innate Immun 1 : 335–339. doi: 10.1159/000191216 20375590

61. Krauchunas AR, Horner VL, Wolfner MF (2012) Protein phosphorylation changes reveal new candidates in the regulation of egg activation and early embryogenesis in D. melanogaster. Dev Biol 370 : 125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.024 22884528

62. Short SM, Lazzaro BP (2013) Reproductive status alters transcriptomic response to infection in female Drosophila melanogaster. G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics 3 : 827–840. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.005306

63. Jin LH, Shim J, Yoon JS, Kim B, Kim J, et al. (2008) Identification and functional analysis of antifungal immune response genes in Drosophila. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000168. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000168 18833296

64. Ayroles JF, Carbone MA, Stone EA, Jordan KW, Lyman RF, et al. (2009) Systems genetics of complex traits in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet 41 : 299–307. doi: 10.1038/ng.332 19234471

65. Bourtzis K, Pettigrew MM, O’Neill SL (2000) Wolbachia neither induces nor suppresses transcripts encoding antimicrobial peptides. Insect Mol Biol. 9 : 635–639. 11122472

66. Brownlie JC, Cass BN, Riegler M, Witsenburg JJ, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, et al. (2009) Evidence for metabolic provisioning by a common invertebrate endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis, during periods of nutritional stress. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000368. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000368 19343208

67. Ikeya T, Broughton S, Alic N, Grandison R, Partridge L (2009) The endosymbiont Wolbachia increases insulin/IGF-like signalling in Drosophila. Proc Biol Sci 276 : 3799–3807. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0778 19692410

68. Juneja P, Lazzaro BP (2009) Providencia sneebia sp. nov. and Providencia burhodogranariea sp. nov., isolated from wild Drosophila melanogaster. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 59 : 1108–1111. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000117-0 19406801

69. Ridley EV, Wong AC-N, Westmiller S, Douglas AE (2012) Impact of the Resident Microbiota on the Nutritional Phenotype of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 7: e36765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036765 22586494

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek NLRC5 Exclusively Transactivates MHC Class I and Related Genes through a Distinctive SXY ModuleČlánek Inhibition of Telomere Recombination by Inactivation of KEOPS Subunit Cgi121 Promotes Cell LongevityČlánek HOMER2, a Stereociliary Scaffolding Protein, Is Essential for Normal Hearing in Humans and MiceČlánek LRGUK-1 Is Required for Basal Body and Manchette Function during Spermatogenesis and Male FertilityČlánek The GATA Factor Regulates . Developmental Timing by Promoting Expression of the Family MicroRNAsČlánek Systems Biology of Tissue-Specific Response to Reveals Differentiated Apoptosis in the Tick VectorČlánek Phenotype Specific Analyses Reveal Distinct Regulatory Mechanism for Chronically Activated p53Článek The Nuclear Receptor DAF-12 Regulates Nutrient Metabolism and Reproductive Growth in NematodesČlánek The ATM Signaling Cascade Promotes Recombination-Dependent Pachytene Arrest in Mouse SpermatocytesČlánek The Small Protein MntS and Exporter MntP Optimize the Intracellular Concentration of Manganese

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 3

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- NLRC5 Exclusively Transactivates MHC Class I and Related Genes through a Distinctive SXY Module

- Licensing of Primordial Germ Cells for Gametogenesis Depends on Genital Ridge Signaling

- A Genomic Duplication is Associated with Ectopic Eomesodermin Expression in the Embryonic Chicken Comb and Two Duplex-comb Phenotypes

- Genome-wide Association Study and Meta-Analysis Identify as Genome-wide Significant Susceptibility Gene for Bladder Exstrophy

- Mutations of Human , Encoding the Mitochondrial Asparaginyl-tRNA Synthetase, Cause Nonsyndromic Deafness and Leigh Syndrome

- Exome Sequencing in an Admixed Isolated Population Indicates Variants Confer a Risk for Specific Language Impairment

- Genome-Wide Association Studies in Dogs and Humans Identify as a Risk Variant for Cleft Lip and Palate

- Rapid Evolution of Recombinant for Xylose Fermentation through Formation of Extra-chromosomal Circular DNA

- The Ribosome Biogenesis Factor Nol11 Is Required for Optimal rDNA Transcription and Craniofacial Development in

- Methyl Farnesoate Plays a Dual Role in Regulating Metamorphosis

- Maternal Co-ordinate Gene Regulation and Axis Polarity in the Scuttle Fly

- Maternal Filaggrin Mutations Increase the Risk of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: An Effect Independent of Mutation Inheritance

- Inhibition of Telomere Recombination by Inactivation of KEOPS Subunit Cgi121 Promotes Cell Longevity

- Clonality and Evolutionary History of Rhabdomyosarcoma