-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaSmall Regulatory RNA-Induced Growth Rate Heterogeneity of

Bacterial cells that share the same genetic information can display very different phenotypes, even if they grow under identical conditions. Despite the relevance of this population heterogeneity for processes like drug resistance and development, the molecular players that induce heterogenic phenotypes are often not known. Here we report that in the Gram-positive model bacterium Bacillus subtilis a small regulatory RNA (sRNA) can induce heterogeneity in growth rates by increasing cell-to-cell variation in the levels of the transcriptional regulator AbrB, which is important for rapid growth. Remarkably, the observed variation in AbrB levels is induced post-transcriptionally because of AbrB’s negative autoregulation, and is not observed at the abrB promoter level. We show that our observations are consistent with mathematical models of sRNA action, thus suggesting that induction of protein expression noise could be a new general aspect of sRNA regulation. Since a low growth rate can be beneficial for cellular survival, we propose that the observed subpopulations of fast - and slow-growing B. subtilis cells reflect a bet-hedging strategy for enhanced survival of unfavorable conditions.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005046

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005046Summary

Bacterial cells that share the same genetic information can display very different phenotypes, even if they grow under identical conditions. Despite the relevance of this population heterogeneity for processes like drug resistance and development, the molecular players that induce heterogenic phenotypes are often not known. Here we report that in the Gram-positive model bacterium Bacillus subtilis a small regulatory RNA (sRNA) can induce heterogeneity in growth rates by increasing cell-to-cell variation in the levels of the transcriptional regulator AbrB, which is important for rapid growth. Remarkably, the observed variation in AbrB levels is induced post-transcriptionally because of AbrB’s negative autoregulation, and is not observed at the abrB promoter level. We show that our observations are consistent with mathematical models of sRNA action, thus suggesting that induction of protein expression noise could be a new general aspect of sRNA regulation. Since a low growth rate can be beneficial for cellular survival, we propose that the observed subpopulations of fast - and slow-growing B. subtilis cells reflect a bet-hedging strategy for enhanced survival of unfavorable conditions.

Introduction

In their natural habitats, bacteria constantly adapt to changing environmental conditions while simultaneously anticipating further disturbances. To efficiently cope with these changes, intricate interlinked metabolic and genetic regulation has evolved [1]. This complex regulatory network includes the action of small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) [2]. sRNAs are a widespread means for bacterial cells to coordinate (stress) responses by fine-tuning levels of mRNAs or proteins, and they have been studied in great detail in Gram-negative bacteria [3]. Regulation by some sRNAs takes place by short complementary base pairing to their target mRNA molecules, for instance in the region of the ribosome-binding site (RBS) to inhibit translation or trigger mRNA degradation. In Gram-negative bacteria many of these sRNA-mRNA interactions are mediated by the RNA chaperone Hfq [4]. However, the Hfq homologue in the Gram-positive model bacterium Bacillus subtilis has no effect on the regulation of the eight sRNA targets reported in this species so far [5–7]. Owing to the complexity of sRNA regulation, only a relatively small number of studies have focused specifically on the physiological necessity of sRNA-target interactions. This is again particularly true for Gram-positive bacteria, such as B. subtilis, despite the fact that many potential sRNAs have been identified [8, 9].

Within a bacterial population, genes and proteins can be expressed with a large variability, with high expression levels in some cells and low expression levels in others [10]. Examples of expression heterogeneity in B. subtilis are the extensively studied development of natural competence for DNA binding and uptake and the differentiation into spores [11–13]. In both cases, expression heterogeneity is generated by positive feedback loops, and results in bistable or ON-OFF expression of crucial regulators [14]. Distinctly from bistability, proteins can also be expressed with large cell-to-cell variability. This variation in expression levels, or noise, can originate from intrinsic or extrinsic sources [15, 16]. Extrinsic noise is related to cell-to-cell fluctuations in numbers of RNA polymerase, numbers of genome copies, or numbers of free ribosomes. Conversely, intrinsic noise is caused by factors directly involved in the transcription or translation of the respective gene or protein. Interestingly, particularly noisy genes are often found to be regulators of development and bacterial persistence [12, 17, 18]. Because of the importance of noise in protein expression, cells have evolved mechanisms to regulate the noise levels of at least some proteins [10]. Reducing noise levels has been suggested as an important explanation why many transcriptional regulators in bacteria (40% in E. coli [19]) autorepress the transcription of their own promoter (i.e. negative autoregulation (NAR)).

AbrB is a global transcriptional regulator in Gram-positive bacteria, including the important human pathogens Bacillus anthracis and Listeria monocytogenes [20, 21]. B. subtilis AbrB positively regulates some genes when carbon catabolite repression (CCR) is relieved [22], and negatively regulates the expression of over two hundred genes in the exponential growth phase [23]. Transcription of abrB is negatively autoregulated by binding of AbrB tetramers to the abrB promoter [24, 25]. Upon entry into stationary phase, abrB transcription is repressed via increasing levels of Spo0A-P and AbrB is inactivated by AbbA [26, 27]. The resulting AbrB depletion is consequently followed by activation of AbrB repressed genes, which are often important for stationary phase processes. Notably, because of its role in the elaborate sporulation and competence decision making network [26, 27], AbrB has mainly been studied in the context of entry into stationary phase while much less is known about its exact role in the exponential growth phase.

We selected putative sRNAs from a rich tiling array dataset of 1583 potentially regulatory RNAs [9]. This selection was made for evolutionary conserved putative sRNAs with a high expression level on defined minimal medium. Deletion strains of these putative B. subtilis sRNAs were subsequently tested for growth phenotypes. One sRNA—RnaC/S1022—stood out since the mutant strain displayed a strongly increased final optical density on minimal medium with sucrose as the sole carbon source. The present study was therefore aimed at determining how RnaC/S1022 influences the growth of B. subtilis. Inspection of consistently observed predicted RnaC/S1022 targets indicated that the aberrant growth phenotype could relate to elevated AbrB levels. Here we show that, under certain conditions, B. subtilis employs RnaC/S1022 to post-transcriptionally modulate AbrB protein expression noise. The observed noise in AbrB protein levels is remarkable, because the abrB gene displays low transcriptional noise consistent with its NAR. Importantly, the sRNA-induced noise in the AbrB protein levels generates growth rate heterogeneity in the exponential phase.

Results

RnaC/S1022 deletion enhances growth on minimal medium

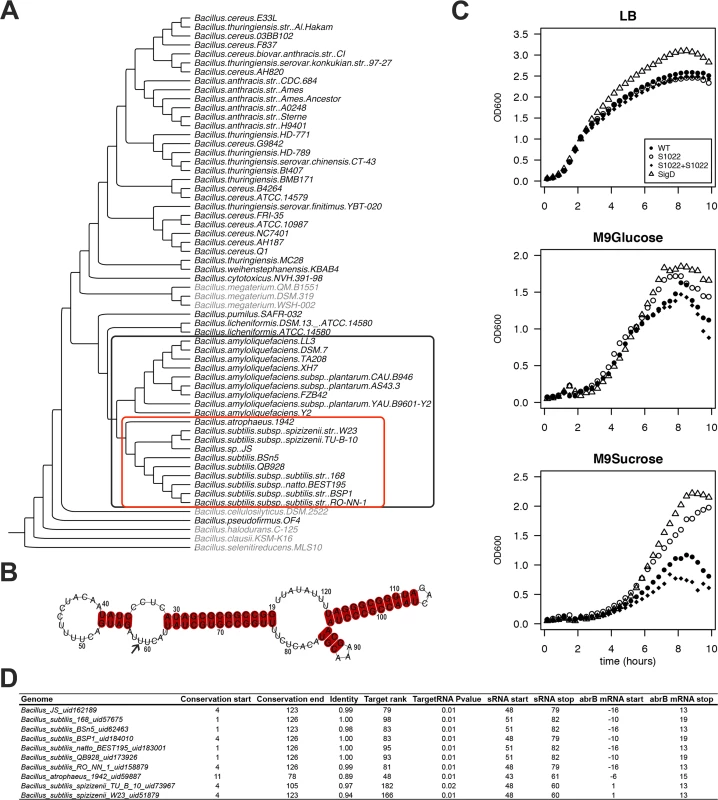

RnaC/S1022 was first identified in a systematic screening of B. subtilis intergenic regions with an oligonucleotide microarray [28]. RnaC/S1022 is located in between yrhK, a gene of unknown function, and cypB, encoding cytochrome P450 NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (also known as yrhJ). We tested the conservation of the B. subtilis RnaC/S1022 sequence with BLAST analysis against a set of 62 Bacillus genomes, and found evolutionary conservation in a clade of the phylogenetic tree including 19 B. subtilis, Bacillus atrophaeus, and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens genomes (Fig. 1A and S1 Fig. for extensive alignments). Within these 19 genomes, the 5’ and 3’ ends of the RnaC/S1022 sequence are conserved, but the core sequence is disrupted in all 9 B. amyloliquefaciens genomes (S1 Fig.). Notably, the RnaC/S1022 from B. atropheus 1942 seems to represent an in-between form of RnaC/S1022 that mostly resembles the RnaC/S1022 sequences from the B. amyloliquefaciens sp. genomes. Therefore, an alignment of only the RnaC/S1022 sequences from the 9 remaining B. subtilis genomes was used to predict the RnaC/S1022 secondary structure using the LocARNA tool [29] (Fig. 1B, S1 Fig.). These analyses predict RnaC/S1022 to fold into a stable structure with a Gibbs free energy for the sequence shown in Fig. 1B of −38.5 kcal/mol, as calculated with RNAfold [30].

Fig. 1. The RnaC/S1022 growth phenotype is linked to the evolutionary target prediction of abrB.

A) Phylogenetic tree of Bacillus genomes. The tree was constructed based on an alignment of rpoB (present in 60 of the 62 genomes; except for two Bacillus coagulans genomes for which no significant rpoB nBLAST hits were found). The outer (black) box indicates 19 genomes in which RnaC/S1022 is present. The inner (red) box indicates 10 genomes in which the predicted RnaC/S1022-abrB interaction is consistently observed. A significant nBLAST hit for AbrB was not obtained for the species shaded in grey. B) LocARNA structural conservation alignment of RnaC/S1022 based on the sequence published by Schmalisch et al. [28]. The alignment includes RnaC/S1022 sequences from genomes in which the RnaC/S1022-abrB interaction is consistently observed (marked in the red box in panel A), except the RnaC/S1022 from B. atrophaeus (see also S1 Fig.). Numbers indicate the coordinates of S1022 defined by Nicolas et al. [9]. The arrow highlights the uracil base that is required for the interaction with abrB. C) Growth curves of parental strain 168trp+, ΔRnaC/S1022, ΔsigD, and the ΔRnaC/S1022 amyE::RnaC/S1022 complemented strain grown on LB, M9G or M9S. Each experiment was repeated at least three times in 96-well plates and shake flasks. Averages from triplicates from a representative 96-well plate experiment are shown. The OD600 was monitored every 10 min. One in two time-points were plotted. D) Overview of the predicted RnaC/S1022-abrB interaction. “Genome”, name of the bacterium in which the interaction was predicted. “Conservation start”, the base of the RnaC/S1022 sequence as defined by Nicolas et al. [9] where the significant nBLAST hit starts. “Conservation end”, end coordinate of the significant nBLAST hit. “Identity”, fraction of identity of the conserved RnaC/S1022 sequence compared to RnaC/S1022 of B. subtilis 168. “Target Rank” the ranking of the abrB target in the predicted RnaC/S1022 targets for the respective genome. “TargetRNA P value” TargetRNA_v1 prediction P-value. “sRNA_start”, start coordinate of RnaC/S1022 homologue in the predicted target interaction. “sRNA_stop”, end coordinate of RnaC/S1022 homologue in the predicted target interaction. “abrB mRNA_start”, start coordinate of abrB in the predicted target interaction relative to its start codon. “abrB mRNA_stop”, end coordinate of abrB in the predicted target interaction relative to its start codon. RnaC/S1022 was recently included in a screen for possible functions of conserved putative sRNAs identified by Nicolas et al. [9] that are highly expressed on M9 minimal medium supplemented with different carbon sources. Here, the RnaC/S1022 mutant stood out, because it consistently grew to a higher optical density (OD) in M9 minimal medium supplemented with sucrose (M9S) than the parental strain (Fig. 1C). To distinguish effects on the growth rate and growth yield, lin-log plots of these growth profiles are presented in S2 Fig., which show that the growth rate was only slightly influenced by the RnaC/S1022 deletion while the growth yield was strongly increased. Compared to M9S, the growth phenotype was less pronounced in M9 with glucose (M9G). Since transcription of RnaC/S1022 is exclusively regulated by SigD [28], we also tested a sigD mutant for growth under these conditions. Interestingly, the ΔsigD mutant displayed similar growth characteristics as the ΔRnaC/S1022 mutant (Fig. 1C). Differential growth and increased competitiveness were previously reported for a sigD mutant [31], and our observations suggest that in some conditions the increased final OD of the ΔsigD strain is partly due to deregulation of RnaC/S1022.

AbrB is a consistently predicted target of RnaC/S1022

We wondered whether deregulation of an sRNA target was responsible for the remarkable growth phenotype observed for the ΔRnaC/S1022 mutant and decided to perform exploratory target predictions using TargetRNA [32]. Predicting sRNA targets can be successful, but target verification is complicated by the large number of false-positively predicted targets. We argued that additional information about the likelihood of a true target could be obtained by determining whether the predicted interaction is conserved over evolutionary time. To identify predicted RnaC/S1022-target interactions that are conserved, a bioinformatics pipeline was established that predicts sRNA targets in genomes in which the RnaC/S1022 sequence is conserved. Since we were interested in finding true B. subtilis sRNA targets, we only considered targets also predicted in B. subtilis, and these are listed in S1 Table. This analysis reduced the number of considered RnaC/S1022 targets to 47 (from 147 predicted targets for TargetRNA_v1 predictions with P value ≤ 0.01 on the B. subtilis 168 genome). These 47 predicted targets included seven sporulation-related genes (phrA, spoVAD, spoIIM, spoIIIAG, cotO, sspG, spsI). The sigma factor sigM was also consistently predicted but, since a sigM mutant strain only displays a growth phenotype under conditions of high salinity [33], this seemed unrelated to the observed growth phenotype of the ΔRnaC/S1022 mutant on M9 medium. In addition, two consistently predicted targets are involved in cell division (racA and ftsW), but we observed no specific cell-division abnormalities of the ΔRnaC/S1022 strain by live-imaging microscopy. Furthermore, the TCA cycle genes citB and citZ were predicted targets and tested by Western blot analysis, but no deregulation was observed. The last consistently predicted target of initial interest was the gene for the transition state regulator AbrB (Fig. 1D). Reviewing the literature on abrB pointed us to an interesting observation where a spo0A mutant was reported to display increased growth rates on media similar to our M9 medium [22]. Furthermore, it had been reported that AbrB has an additional role in modulating the expression of some genes during slow growth in suboptimal environments [34], which we argued could also be relevant to the M9S growth condition. Since abrB is a consistently predicted target of RnaC/S1022 (Fig. 1D), we checked whether the presence of this sRNA coincides with the presence of the abrB gene. Indeed, abrB is conserved in 53 out of 62 available Bacillus genomes, and RnaC/S1022 is present in 19 of these 53 genomes (Fig. 1A). In addition, we identified no genomes that contain RnaC/1022 but lack the abrB gene (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, we hypothesized that RnaC/S1022 might be a regulator of AbrB.

AbrB levels are elevated in an RnaC/S1022 mutant

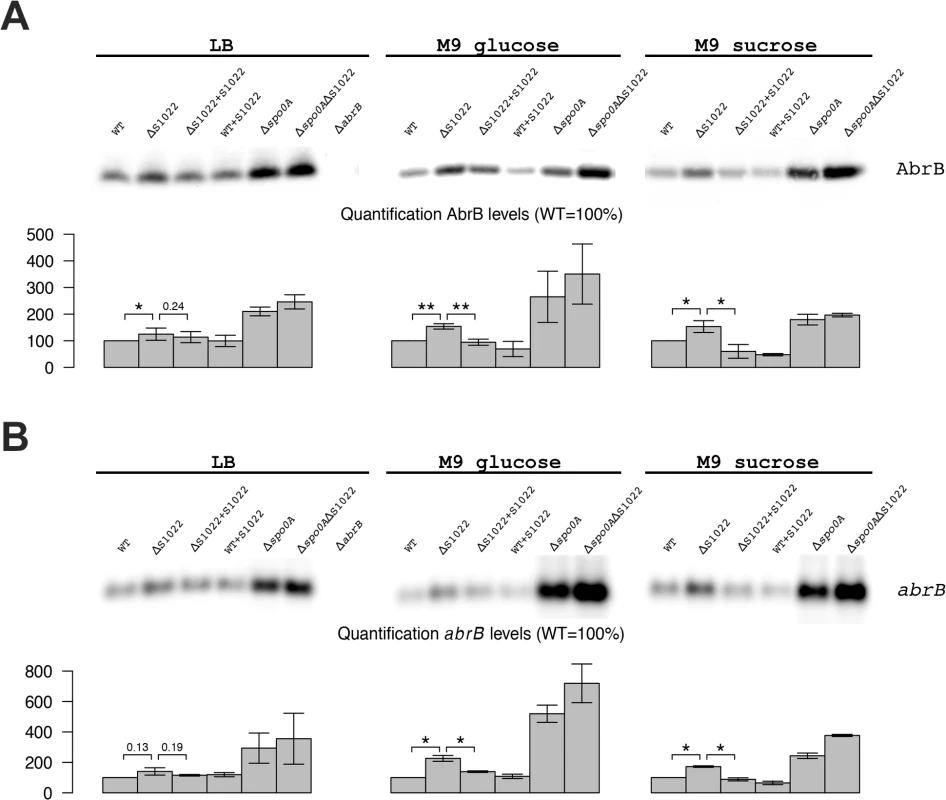

The combined clues from bioinformatics analyses and literature suggested that the growth phenotype of the ΔRnaC/S1022 mutant could relate to elevated AbrB levels. To test whether AbrB levels are indeed altered in this mutant, we performed Western blot and Northern blot analyses. This indeed revealed a strong trend towards higher AbrB protein and mRNA levels in the RnaC/S1022 mutant and for cells grown in M9G or M9S this effect was statistically significant (Fig. 2). Importantly, the growth phenotype as well as AbrB protein and mRNA levels returned to wild-type (wt) by ectopic expression of RnaC/S1022 under control of its native promoter from the amyE locus (Fig. 1C and 2). We also tested the effects of a Δspo0A mutation by Western and Northern blot analyses. Interestingly, the combined deletion of RnaC/S1022 and spoOA seemed to lead to a further increase in the AbrB protein and mRNA levels compared to the already elevated levels in the spo0A mutant background. Lastly, we observed a three-fold reduced natural competence of the ΔRnaC/S1022 mutant, which is expected when the AbrB levels are elevated [35] (S3 Fig.).

Fig. 2. AbrB levels are dependent on the presence of RnaC/S1022.

A) AbrB Western blot analysis. The position of AbrB is indicated. The bar diagrams show the relative AbrB levels, with the level in the parental strain (wt) set at 100%. All AbrB levels were corrected for the internal control protein BdbD. Error bars represent the standard deviation between triplicate experiments. The effect of RnaC/S1022 absence is most pronounced in cells grown on M9G and M9S, which corresponds to higher expression levels under these growth conditions. Statistical data analyis was performed with a one-sided Welch two-sample t-test (H1: AbrB/abrB levels in ΔRnaC/S1022 > than in the parental strain and the RnaC/S1022 complementation strain). The respective p-values are either indicated, or marked with asterisks (* p-value <0.05; ** p-value <0.01). B) abrB Northern blot analysis. Equal amounts of RNA were loaded in each lane. The bar diagrams show the relative abrB mRNA levels, with the level in the parental strain (wt) set at 100%. Quantifications are based on minimally two independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation between experiments. Data was analyzed for significance as in A. To test whether the AbrB levels were directly dependent on RnaC/S1022 levels, we placed the RnaC/S1022 complementation cassette in the amyE locus of the parental strain and used Western and Northern blotting to measure AbrB protein and mRNA levels. These analyses showed a trend towards reduction of both the AbrB protein and mRNA levels in cells grown on M9G and M9S, which would be consistent with elevated RnaC/S1022 expression and increased abrB regulation (Fig. 2). Since the amount of AbrB was apparently correlated to the amount of RnaC/S1022, this suggested a stoichiometric relationship between these two molecules.

Before testing whether there could be a direct interaction between RnaC/S1022 and the abrB mRNA, we decided to investigate the fate of the abrB mRNA in the presence or absence of RnaC/S1022. For this purpose, we assayed the levels of the abrB mRNA at different time points after blocking transcription initiation with rifampicin in the RnaC/S1022 mutant strain and in the strain with two chromosomal copies of RnaC/S1022. This analysis showed that the abrB mRNA level decreased significantly faster in the presence of RnaC/S1022 than in its absence (S4 Fig.). In case of a direct interaction between RnaC/S1022 and the abrB mRNA, the observed difference could relate to an RnaC/S1022-triggered degradation of the abrB mRNA. Alternatively, this difference could be due to an RnaC/S1022-precluded protection of the abrB mRNA by elongating ribosomes [36].

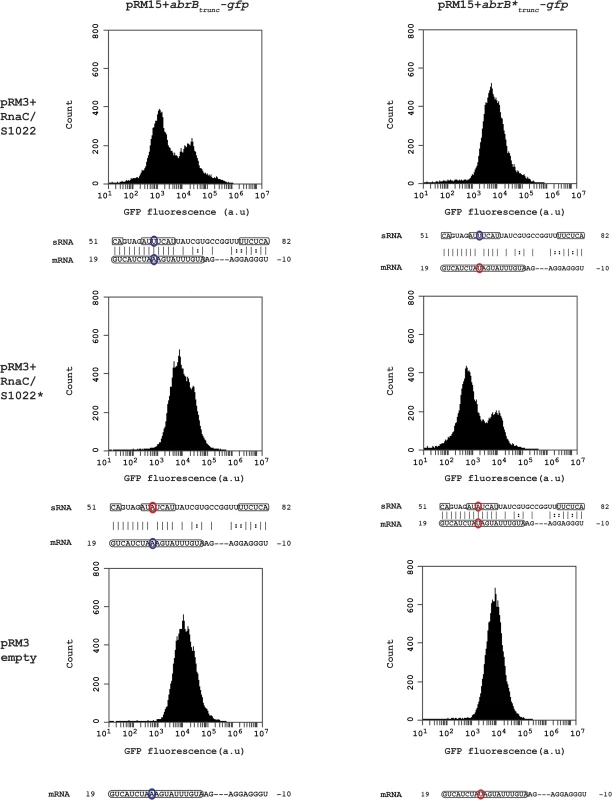

The RnaC/S1022 sRNA regulates AbrB by a direct sRNA-mRNA interaction

The apparently stoichiometric relationship between AbrB and the sRNA RnaC/S1022 is suggestive of a direct sRNA—target interaction. The predicted interaction region in B. subtilis 168 spans a region from the RBS of abrB (-10) until 19 bp after the start of the abrB ORF of which the strongest consecutive stretch of predicted base-pair interactions are present from +7 bp till +19 bp (left top panel in Fig. 3). In addition, only this region within the abrB-encoding sequence is part of the conserved predicted interaction region in B. atrophaeus and B. subtilis spizinenzii (Fig. 1D). It has been reported that loop-exposed bases of sRNAs are more often responsible for regulation than bases in stems [37]. Two predicted loop regions of RnaC/S1022 are complementary with the predicted abrB interaction region (one of two basepairs and one of seven basepairs; bases 51–52 and 57–63 in Fig. 1B and 3). We therefore decided to introduce a point-mutation by a U to A substitution in the predicted 7-bp loop of RnaC/S1022 encoded by plasmid pRM3 and a compensatory mutation in a plasmid pRM15-borne truncated abrB-gfp reporter construct (abrBtrunc-gfp). Strains containing different combinations of the respective plasmids were grown on M9G and assayed by Flow Cytometry (FC) in the exponential growth phase. Cells containing one of the abrBtrunc-gfp constructs in combination with the empty pRM3 plasmid displayed a unimodal distribution in GFP levels (Fig. 3, lower panels). However, when the wt abrBtrunc-gfp was assayed in combination with the wt RnaC/S1022, a bimodal distribution in AbrBtrunc-GFP levels was observed, including a new peak of lowered fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3, top left). Interestingly, a unimodal fluorescence distribution was found when the wt abrBtrunc-gfp construct was combined with point-mutated RnaC/S1022* (Fig. 3, middle left) or the mutated abrB*trunc-gfp with the wt RnaC/S1022 (Fig. 3, top right). In the case of the point-mutated abrB*-gfp construct, however, a bimodal fluorescence distribution was only observed when this construct was combined with the mutated RnaC/S1022* (Fig. 3, middle right). This implies that a direct mRNA-sRNA interaction takes place between abrB and RnaC/S1022.

Fig. 3. RnaC/S1022 regulates abrB by a direct mRNA-sRNA interaction.

Wild-type and base pair-substituted (marked with asterix *) abrBtrunc-gfp constructs were expressed from plasmid pRM15 and combined with one of three variants of the pRM3 plasmid (pRM3+RnaC/S1022, pRM3+RnaC/S1022*, pRM3 empty). All combinations of these constructs were assayed by FC and one representative histogram per combination is shown. Base-pairs high-lighted in identical color indicate the possibility for regulation due to base-pairing, while bases highlighted in two different colors indicate an inability for regulating due to the absence of base-pairing. Boxed regions in the abrB mRNA indicate the coding sequence, and boxed regions in the sRNA (RnaC/S1022) indicate predicted exposed bases in the structure shown in Fig. 1B. The base pair found to be essential for sRNA regulation corresponds to U59 in a predicted RnaC/S1022 loop region (RnaC/S1022* U59A) and the 11th base in the abrB-encoding region (abrB*A11U). RnaC/S1022 sRNA is condition-dependently expressed

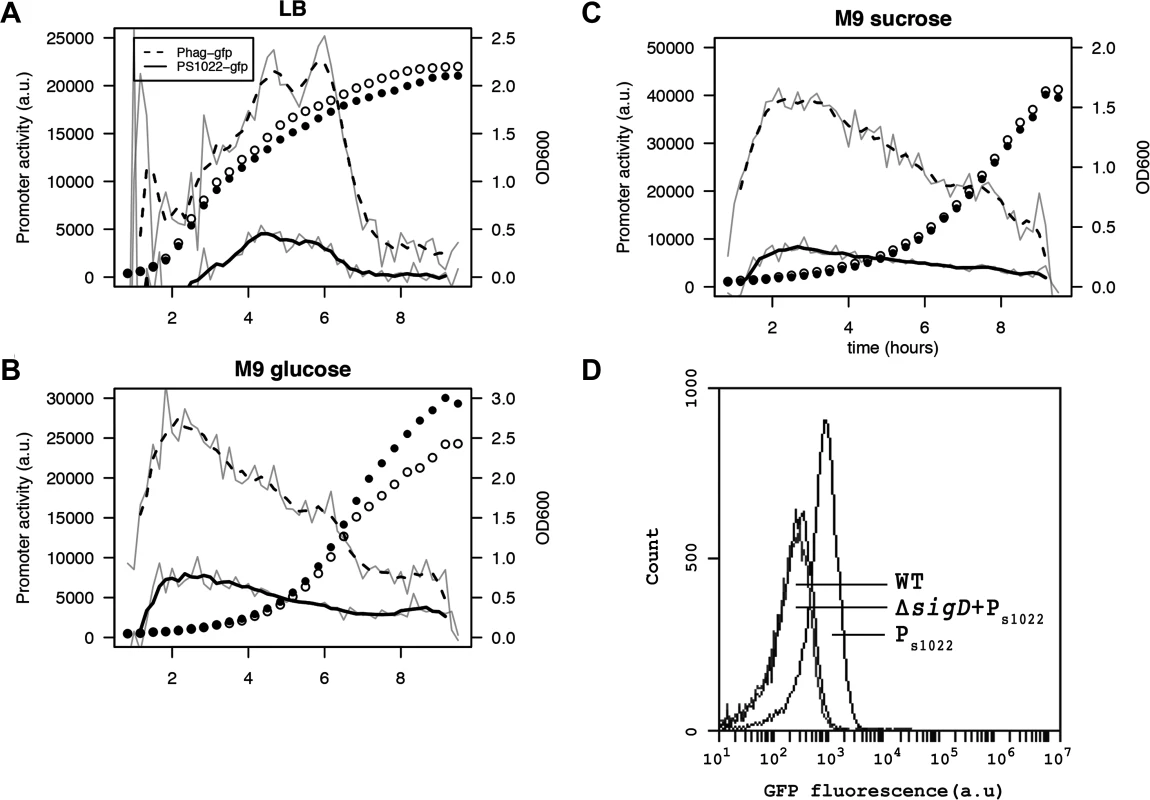

Studying the condition-dependency of sRNA expression can give clues to its function and targets. To obtain high-resolution expression profiles, we constructed an integrative RnaC/S1022 promoter-gfp fusion [38]. As expected, the presence of this PRnaC/S1022-gfp fusion caused GFP fluorescence in wild-type cells, but not in cells with a sigD mutation (Fig. 4D). Next, a live cell array approach was used to compare the PRnaC/S1022-gfp activity with that of another SigD-dependent promoter, Phag, which drives flagellin expression. These promoter fusion strains revealed that the expression of hag was consistently ∼4 fold higher than that of RnaC/S1022 (Fig. 4), which is in agreement with previously published expression data [9]. On LB medium, the expression of both RnaC/S1022 and hag peaked in the late exponential and transition phase, while on both tested minimal media the peak in expression occurred in early exponential phase (Fig. 4). This higher RnaC/S1022 expression level in the exponential phase on M9 relative to that in LB is in concordance with the stronger effect of ΔRnaC/S1022 on AbrB levels, as indicated by the Northern and Western blot analyses.

Fig. 4. RnaC/S1022 is condition-dependently expressed.

Promoter activity of the PRnaC/S1022-gfp and Phag-gfp fusions in cells grown on LB (A), M9G (B), and M9S (C). Promoter activities were computed by subtraction of GFP level from the previous time-point as described by Botella et al. [38]. The experiment was performed three times in triplicate. Average data from triplicate measurements of one representative experiment are shown. The grey line indicates mean data and the black line a smoothed version of this mean. One in two time-points were plotted for the growth curve as open circles for the Phag-gfp strain and closed circles for the PRnaC/S1022-gfp strain. D) Representative FC results for PRnaC/S1022-gfp expression in mid-exponentially growing cells with or without a sigD deletion. The cells were grown in M9G. Wt, B. subtilis 168 not expressing GFP. The RnaC/S1022 sRNA modulates protein expression noise of AbrB-GFP

Experimental methods that measure average protein levels in a population obscure possible cell-to-cell variation. To further study the cell-to-cell variation of AbrB-GFP in the exponential growth phase (as observed in Fig. 3), we therefore employed a full-length translational abrB-gfpmut3 fusion that was integrated into the chromosome via single cross-over (Campbell-type) recombination. Specifically, this integration resulted in a duplication of abrB where one full-length copy of abrB was expressed from its own promoter and fused in-frame to gfp, while the downstream abrB copy was truncated lacking the start codon required for translation [39]. In this AbrB-GFP strain all AbrB monomers have a C-terminally attached GFP molecule. While AbrB-GFP still localized to the nucleoid (S5 Fig.), this AbrB-GFP strain displayed a somewhat reduced growth rate on media where AbrB is required for rapid growth. Since the translational abrB-gfp fusion is chromosomally integrated at the abrB locus, this system is insensitive to fluctuations in noise levels by plasmid copy number variation and its chromosomal location in the division cycle.

We first used the AbrB-GFP fusion to test whether B. subtilis Hfq might have an effect of the RnaC/1022-abrB interaction. Consistent with previous studies on other sRNA targets of B. subtilis [5–7], the direct RnaC/S1022-abrB regulation was found to be independent of Hfq since comparable FC profiles for AbrB-GFP expression were obtained for the parental strain and the hfq deletion mutant (S6 Fig.).

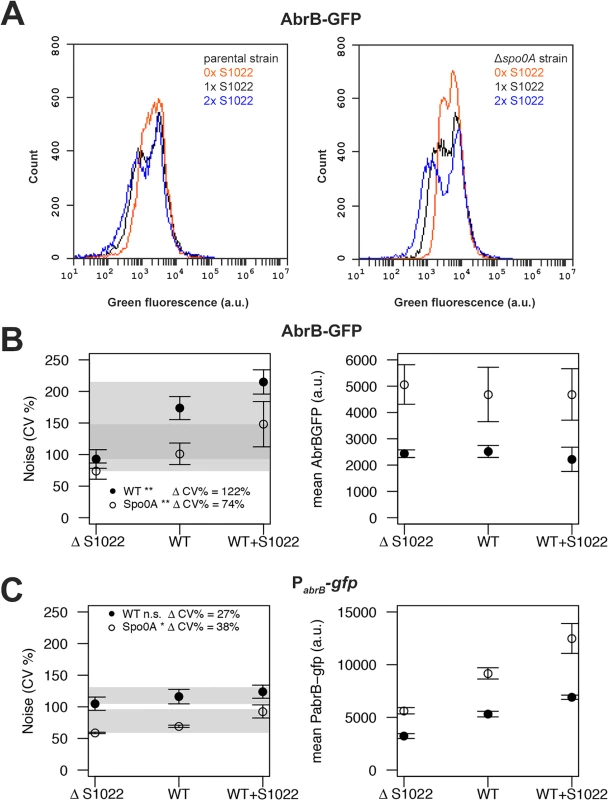

Next, we analyzed all AbrB-GFP strains by FC in the exponential phase on both LB and M9G. Noise measurements were not performed on M9S because of the strong growth difference between the parental and ΔRnaC/S1022 strains on this medium (Fig. 1C). We observed that the difference between cells expressing AbrB-GFP at the highest level and those at the lowest level was large (Fig. 5A). This means that AbrB-GFP is expressed with high noise (quantified as the coefficient of variation; CV%). Interestingly, we observed lower AbrB-GFP noise in strains lacking RnaC/S1022 and, crucially, the presence of an additional genomic RnaC/S1022 copy further increased AbrB-GFP noise. Remarkably, increased RnaC/S1022 levels only reduced the minimal expression level of the distribution while not affecting the maximum AbrB-GFP expression level (Fig. 5A), which is consistent with the data presented in Fig. 3. There was a statistically significant positive linear correlation between RnaC/S1022 levels (0, 1 or 2 genomic copies) and AbrB-GFP noise (on LB for pooled data points from Δspo0A and parental backgrounds R2 0.48, P-value <0.001, and M9G R2 0.43, P-value <0.001) (Fig. 5B). Direct statistical comparisons between AbrB-GFP noise levels at different sRNA levels also revealed significant changes (Fig. 5). The noise increase therefore seems correlated to the level of RnaC/S1022. Notably, this relation was also observed for noise measurements in a spo0A deletion background, even though the mean AbrB-GFP expression was between 1.37 and 2.32 fold (for LB and M9G respectively, μ = 1.79) higher in Δspo0A strains. This suggests that RnaC/S1022 has a specific role in noise modulation of AbrB-GFP.

Fig. 5. RnaC/S1022 induces protein expression noise of AbrB-GFP.

A) Representative FC data for the translational AbrB-GFP fusion expressed from a single copy of the respective gene fusion integrated into the B. subtilis chromosome. All strains were grown on M9G. The left panel shows histograms for, from left to right, the AbrB-GFP-producing strain with two chromosomal RnaC/S1022 copies, the AbrB-GFP-producing parental strain with one chromosomal RnaC/S1022 copy, and the AbrB-GFP-producing strain with the ΔRnaC/S1022 mutation. The right panel shows data for the same strains with an additional Δspo0A mutation. Please note the increase in the width of the distribution with increasing RnaC/S1022 gene dosage. B) Quantification of AbrB-GFP noise (left panel) and mean expression data (right panel) from three independent experiments with cells grown on M9G. Shaded areas indicate the noise increase (ΔCV%) from 0 to 2 sRNA copies in the spo0A-proficient background (wt) and the Δspo0A mutant background. Statistical significance of the comparisons of data obtained for spo0A-proficient or -deficient strains containing 0 to 2 sRNA copies are indicated with asterisks in the legend (* p-value <0.05; ** p-value <0.01; ANOVA with Tukey HSD test). Error bars represent the standard deviation. C) Quantification of PabrB-gfp noise (left panel) and mean PabrB-gfp activity data (right panel) from three independent experiments with cells grown on M9G. Statistical significance of the comparisons of data obtained for spo0A-proficient or -deficient strains containing 0 to 2 sRNA copies are indicated with asterisks in the legend (* p-value <0.05; n.s. means not significant; ANOVA with Tukey HSD test). Error bars represent the standard deviation. RnaC/S1022 has no indirect effect on the abrB promoter and is expressed homogeneously

After observing that RnaC/S1022 specifically increases AbrB-GFP expression noise, we aimed to elucidate the origin of this AbrB-GFP noise. Three possibilities for noise generation by an sRNA are conceivable. Firstly RnaC/S1022 could have an additional indirect effect on abrB expression, leading to noisy expression from the abrB promoter and subsequent propagation of this noise to the AbrB protein level. Secondly, RnaC/S1022 may itself be expressed either in bimodal fashion or with high noise. The third possibility would be an AbrB-dependent repression of the RnaC/S1022 promoter and subsequent repression of AbrB protein levels by RnaC/S1022. This double negative repression would correspond to positive feedback on the AbrB protein level, and positive feedback is a known source of expression heterogeneity [40].

To study the distribution of the abrB promoter, we integrated the pBaSysBioII plasmid [38] directly behind the Spo0A binding site in the promoter region of abrB [41], resulting in a single-copy promoter fusion at the native genomic locus (PabrB; -41bp of the abrB start codon). This location was selected to include the effect of AbrB autorepression and Spo0A(-P) repression, while excluding RnaC/S1022 regulation. We observed no bimodal or particularly noisy expression of this abrB promoter fusion, showing that transcription from the abrB promoter is homogeneous in the exponential phase (Fig. 5C). Of note, bimodal or noisy expression of PabrB would have been surprising since transcription of abrB is autorepressed and it is generally found that this NAR reduces the noise of promoter expression [42, 43]. Interestingly, the expression from the abrB promoter rises with increasing levels of RnaC/S1022. This observation can be explained by AbrB autorepression and noise. There are more cells with low AbrB levels when the levels of RnaC/S1022 are increased. On average, this will lead to lowered repression of the abrB promoter, leading to a higher level of expression (but not more noise) from the abrB promoter (Fig. 5C). This higher expression from the abrB promoter is apparently compensated for at the protein level by the elevated regulation of RnaC/S1022 (Fig. 2 and 5B). Since we observed only a slight increase in abrB promoter noise specific to RnaC/S1022 (Fig. 5C), the hypothesis that AbrB-GFP noise promotion originates from an additional effect of RnaC/S1022 on the abrB promoter can be rejected.

A second possibility of noise promotion by RnaC/S1022 is that it is itself expressed with large noise similar to the SigD-dependent hag gene [44]. In this case, large cell-to-cell variation in sRNA levels would only lead to regulation in cells that have above-threshold sRNA levels, and this could generate the variation in AbrB-GFP levels. We tested this at the promoter level by FC analysis of the integrative RnaC/S1022 promoter-gfp fusion (PRnaC/S1022; Fig. 4) and found this promoter fusion to be homogenously expressed with a tight distribution of GFP levels (CV% of 64% for the M9G condition; Fig. 4D). Furthermore, we argued that the relatively low expression of PRnaC/S1022 could result in threshold-level regulation where the sRNA is only involved in regulating abrB in cells with above-threshold levels of RnaC/S1022. However, this is not consistent with the observation of further increased noise levels in cells with two genomic copies of RnaC/S1022 (Fig. 5B). We therefore consider the possibility of AbrB noise promotion via heterogeneous expression of RnaC/S1022 unlikely. It cannot be excluded, however, that variation in the levels of RnaC/S1022 might be introduced further downstream, for instance via mRNA degradation, or via regulation by a dedicated RNA chaperone.

The third option would be a double-negative feedback loop consisting of sRNA repression of AbrB levels and AbrB repression of sRNA levels, which would ultimately lead to an increase in AbrB protein expression noise. This would thus depend on repression of the RnaC/S1022 promoter by AbrB, in addition to the confirmed negative regulation of abrB by RnaC/S1022. Together this would lead to a decrease in AbrB protein levels in cells that start with below-threshold AbrB levels. First of all, we found no indication for AbrB binding sites in the region upstream of RnaC/S1022 in the dataset of Chumsakul et al., where the binding sites of AbrB were mapped genome-wide [24]. To test whether the RnaC/S1022 promoter is indeed not directly controlled by AbrB, or possibly under indirect control of AbrB, we deleted the abrB gene from the above-mentioned PRnaC/S1022 promoter fusion strain. As expected, the RnaC/S1022 promoter activity levels were not detectably affected by the abrB deletion (S7 Fig.), showing that it is unlikely that there is a negative feedback loop consisting of AbrB-dependent RnaC/S1022 repression and RnaC/S1022-dependent abrB repression.

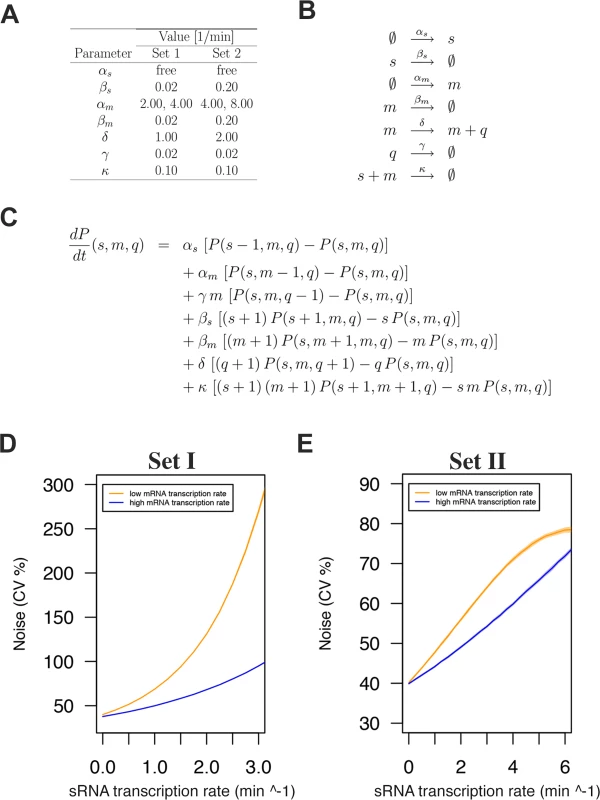

sRNA-induced protein expression noise is consistent with mathematical models of sRNA regulation

Since the experimental data presented above pointed to a direct role of the RnaC/S1022 sRNA in AbrB protein noise promotion, we wondered whether this possibility is consistent with mathematical models of sRNA regulation. To verify this, we considered a simple model of RNA regulation with two independently transcribed RNA species (sRNA and mRNA) [45–47]. In this model, these molecules are synthesized with constant transcription rates αs and αm, respectively. Translation of mRNA into protein Q, and the degradation of sRNA, mRNA, and protein molecules were modeled as linear processes that occur with rates δ. βs, βm, and γ, respectively. The sRNA-mRNA duplex formation was assumed to be an irreversible second-order process that occurs with a rate κ. In the model, molecules in the sRNA-mRNA duplex were removed from the dynamical system. A summary of all reactions and the master equation used in the model can be found in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. sRNA regulation increases protein expression noise in a stochastic simulation model.

A) Noise-generating dynamics of sRNA regulation were simulated in a stochastic simulation model for two sets of parameters with two mRNA transcription rates and the sRNA transcription rate as a free parameter. B) Reactions considered in the model. C) Master equation used for the model. D) Modeling outcome for parameter Set I. E) Modeling outcome for parameter Set II. Note that modeling with both parameter sets predicts increased protein expression noise with increased sRNA transcription rates. In both cases this effect is buffered by a higher mRNA transcription rate as was observed for the Δspo0A mutant background (see Fig. 5B). We first implemented model parameters used in an earlier sRNA modeling study by Jia et al. [47] (Set I; Fig. 6A and D). Of note, these parameters were essentially the same as those of Levine et al. [45]. In all cases the sRNA transcription rate (αs) was a free variable to capture the effect of 0, 1, or 2 genomic copies of RnaC/S1022. In addition, for each set of parameters we included two possible αm values to model the effect in the Spo0A deletion strain where the abrB transcription rate (αm) is approximately two-fold higher than in the parental strain (as determined with PabrB-gfp). Varying extrinsic noise in the abrB transcription rate had no effect on the general modeling outcome (S8 Fig.) and the intermediate αm CV% level of 40% was selected for plots in the main text. After running the model with parameters from Set I, we observed that model-predicted protein noise strongly increased with increasing αs. This trend of increasing protein noise with increasing sRNA transcription rates was similar to what we observed for the genomic AbrB-GFP fusion (Fig. 5A and B). Importantly, doubling αm (two-fold higher mRNA transcription rate) resulted in a more gradual noise increase with increasing αs, just as was observed in the Δspo0A mutant with the AbrB-GFP fusion (Fig. 5).

We next sought to determine the effect of changing modeling parameters on the modeling outcome, because the selected mRNA half-life of ∼35 min (βm 0.02) in parameter Set I would only be relevant for a subset of mRNA molecules as shown experimentally by Hambraeus et al. [48] (with a relation between these of mean lifetime from Fig. 6A * ln 2 = half-life). We therefore constructed a second set of modeling parameters (Set II), which gave the mRNA and sRNA species a half-life of ∼3.5 min (βm and βs 0.20) while keeping protein half-life at ∼35 min. In addition, αm was increased from 2 transcripts per minute to 4 per minute, and δ was doubled to 2 synthesized proteins per minute. Although the maximum noise level from these Set II simulations was markedly different, it again clearly showed the trend of increasing protein noise with increasing sRNA transcription rates. We can therefore conclude that the modeling results robustly support the idea that sRNA regulation can generate noise at the protein level. This noise would be induced locally at the level of mRNA degradation or translation initiation, and the corresponding fluctuations would subsequently be propagated to the protein level. Recently, the theoretical background of this concept was also reported by Jost et al., who stated that such behavior is especially expected when the levels of the srRNA and the mRNA are approximately equal [49]. Altogether, our experimental data and the modeling approach are consistent with the view that RnaC/S1022 is an intrinsic noise generator for AbrB-GFP at the post-transcriptional level.

RnaC/S1022-induced AbrB expression noise generates diversity in growth speeds in the exponential phase

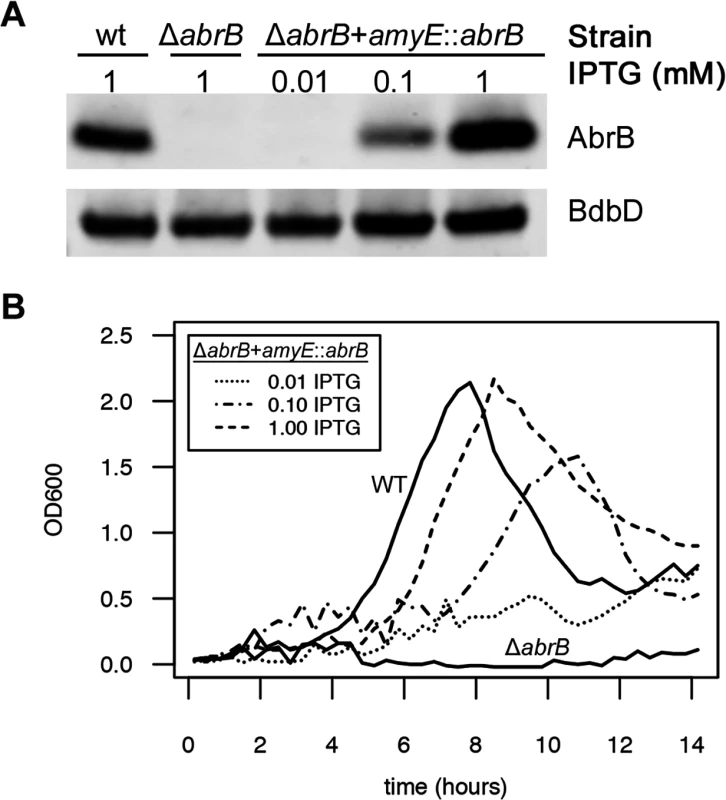

After defining the experimental and theoretical framework for noise promotion by the RnaC/S1022 sRNA, we wondered what the physiological relevance of this regulation might be. Since we and others (Fig. 1A; [22]) have reported an effect of AbrB levels on the growth of B. subtilis, a growth-related function seemed obvious. We therefore tested whether AbrB levels are a direct determinant of growth rate and yield under the relevant conditions. To do this, we placed the abrB gene under control of an isopropyl ß-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter in the amyE locus using plasmid pDR111 [50], and subsequently deleted the abrB gene from its native locus in this strain. We first verified the IPTG-dependent expression of AbrB from this construct by growing the parental strain, the ΔabrB strain, and the ΔabrB amyE::abrB strain on LB medium and, in the case of the ΔabrB amyE::abrB strain, the medium was supplemented with increasing IPTG concentrations. Subsequently, AbrB production was assessed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 7A), which showed that AbrB production in the ΔabrB amyE::abrB strain was indeed IPTG-dependent. Notably, the abrB mutant strain displays a growth phenotype on LB medium, but this is only apparent in the late exponential growth phase [51]. To analyze the effect of differing AbrB levels on growth under conditions that are more relevant for the RnaC/S1022—abrB interaction, we grew the same strains on M9G, which was supplemented with differing amounts of IPTG for the ΔabrB amyE::abrB strain. As shown in Fig. 7B, the abrB deletion mutant did not grow in this medium. Importantly however, IPTG-induced expression of abrB in this mutant repaired the growth phenotype in a dose-dependent manner. This shows that the AbrB levels determine the growth rate and yield when cells are cultured on M9G.

Fig. 7. AbrB levels determine the growth rate and growth yield on M9 minimal medium.

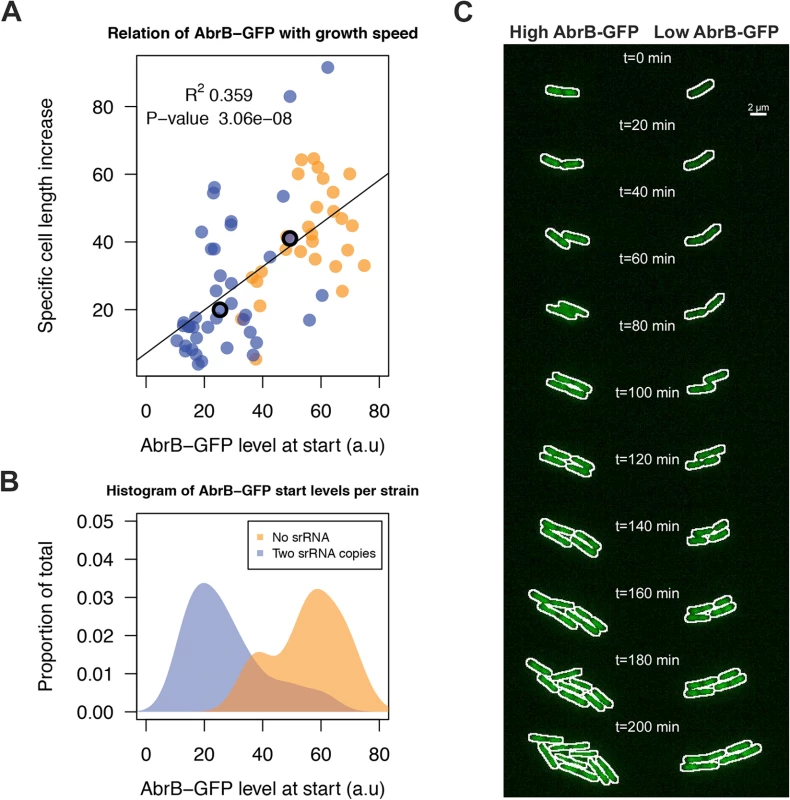

A) Representative Western blot data for AbrB production by the indicated strains grown on LB medium as a test for IPTG-dependent AbrB production from the amyE::abrB construct. At the lowest level of IPTG induction (0.01 mM), the AbrB production remained below the detection level. BdbD was used as a loading control. AbrB and BdbD were visualized with specific antibodies. B) Growth profiles on M9G determined for the strains from panel A. The abrB mutant is unable to grow on this medium, but its growth defect is rescued by IPTG-induced AbrB expression from the amyE::abrB construct. Averages of triplicate measurements from one representative 96-well plate experiment are shown. We next aimed to unravel the effect of sRNA-induced AbrB heterogeneity on growth. This requires the tracking of cells with low and high AbrB-GFP levels over time. To do this, we performed a live imaging experiment with the Δspo0A AbrB-GFP strain either containing zero sRNA copies due to the ΔRnaC/S1022 mutation, or two genomic copies due to the insertion of an additional RnaC/S1022 copy in amyE. The Δspo0A background was used to elevate AbrB-GFP levels and thereby to facilitate fluorescence measurements. Cells were pre-cultured in M9G as was done for the FC measurements and applied to agarose pads (at OD600 ∼0.15) essentially as was described by Piersma et al. [52]. From these experiments, and consistent with FC data in Fig. 5, it was apparent that there was a larger variation in AbrB-GFP levels in the strain with two genomic RnaC/S1022 copies, compared to the strain lacking RnaC/S1022 (Fig. 8B; S1 Movie). In addition, this variation in AbrB-GFP levels was correlated to the variation in growth rates (quantified as the specific cell length increase) observed during the first 20 min of each live imaging run (Fig. 8A). We excluded the possibility that this growth rate difference was dependent on the position on, or quality of the slide. Instead, it was solely linked to the cellular level of AbrB-GFP (Fig. 8C; S1 Movie).

Fig. 8. RnaC/S1022-induced variation in AbrB-GFP levels leads to heterogeneity in growth rates.

A) Tracing of growth and AbrB-GFP levels of 71 individual micro-colonies from Δspo0A AbrB-GFP strains with either zero or two chromosomal copies of RnaC/S1022. Data originates from three independent experiments. Cell growth is expressed as the cell length (Feret’s diameter) increase per hour as determined in the first 20 min after spotting of the cells onto agarose slides. The plotted AbrB-GFP level is the average of fluorescence in the first and second picture. B) Distribution of AbrB-GFP start levels for both strains. Note that two genomic RnaC/S1022 copies lead to a wider distribution of AbrB-GFP levels. C) Montage of the two adjacent dividing cells from the S1 Movie. The white outline marks the contours of the cell. The positions of these cells in panel A are marked with an O. Individual cells were cropped for illustration purposes only. Notably, in the two example cells from Fig. 8C (S1 Movie) AbrB-GFP levels gradually increase in the cell with a low start level (i.e. high level of sRNA repression), which would be consistent with a gradual reduction in RnaC/S1022 expression on this solid agarose medium (S9 Fig.). However, our experimental setting determines the effect of AbrB-GFP on growth before this reduction in RnaC/S1022 becomes relevant (e.g. the first 5 pictures, or 20 min) (Fig. 8A). Beyond this, the increase in AbrB-GFP levels observed later (>150 min) in the live imaging experiment seems coupled to a concomitant increase in growth rate (S9 Fig.). This is again consistent with the positive correlation of AbrB-GFP levels with growth rate. Interestingly, while we observed a few cells switching their AbrB-GFP expression state from high to low, the AbrB-GFP levels were generally stable throughout a cell’s lineage. Combined, these analyses show that the RnaC/S1022-induced heterogeneity in the AbrB-GFP expression levels generates diversity in growth rates within the exponential phase of growth.

Discussion

In this study we show that B. subtilis employs the RnaC/S1022 sRNA to post-transcriptionally regulate AbrB and that this regulation results in increased heterogeneity in growth rates during the exponential phase of growth. RnaC/S1022 is the third sRNA in B. subtilis for which a direct target has been reported and this study reveals the value of evolutionary target predictions to identify true sRNA targets for this species.

The observed growth rate heterogeneity induced by RnaC/S1022 is conceivably of physiological relevance since slowly growing bacterial cells are generally less susceptible to antibiotics and other environmental insults than fast growing cells [53–55]. Specifically, it was noted for hip strains of E. coli that slowly growing cells within a population will develop into persister cells when challenged with ampicillin [17]. Notably, in this system, the initial heterogeneity in growth rates was reported to be dependent on the HipAB toxin-antitoxin module [56]. Analogously, it is conceivable that a B. subtilis toxin-antitoxin module under negative AbrB control could be responsible for the heterogeneity observed in the present study. Another perhaps more likely possibility is that low AbrB levels cause the premature activation of transition - or stationary phase genes, thereby slowing down growth and causing premature stationary phase entry. AbrB has also been implicated in the activation of some genes when CCR is relieved [22, 23], and this could be related to the stronger growth phenotype observed on M9S compared to M9G. However, the AbrB level also determines growth rates on M9G (this study; [22]), when CCR is active and AbrB is not known to have an activating role [22].

The initially observed growth phenotype of the ΔRnaC/S1022 mutant can be explained by the present observation that AbrB is an important determinant for growth on M9 medium, and that RnaC/S1022 regulation of AbrB is specifically linked to increasing AbrB noise. Specifically, the absence of RnaC/S1022 will reduce the number of cells expressing AbrB at a low level. Growth of the ΔRnaC/S1022 population will therefore be more homogeneous and, when inspected as an average, the population will enter stationary phase later than the parental strain. Beyond the mechanism of AbrB-mediated growth regulation, we show that noisy regulation of a growth regulator can also cause heterogeneity in growth rates. This suggests that the AbrB noise level has been fine-tuned in evolution, possibly as a bet-hedging strategy to deal with environmental insults.

Two other questions addressed by this study are the origin of AbrB expression noise, and the likely reason why this noise is generated at the post-transcriptional level. The origin of AbrB expression noise via triggering of abrB mRNA degradation and/or inhibition of abrB translation fits the definition of an intrinsic noise source where the absence of RnaC/S1022 reduces the number of sources for intrinsic noise by one, and therefore results in lower protein expression noise. This specific noise-generating capacity of sRNA regulation might be due to the specific kinetics of the RnaC/S1022 - abrB mRNA interaction. It is currently unclear whether this feature of sRNA-mediated regulation can be extended to other sRNA-mRNA pairs. Specifically, subtle consequences of sRNA regulation, such as noise generation, may have been overlooked in previous studies due to the use of plasmid-encoded translational fusions with fluorescent proteins expressed from strong non-native promoters as reporters. We therefore expressed all RnaC/S1022 and AbrB-GFP constructs from their native genomic location, from their native promoters, and assayed the effects in the relevant growth phase.

NAR of AbrB seems to be the answer to the second question why noise is generated post-transcriptionally and not at the promoter level. AbrB’s NAR is important for its functioning in the stationary phase sporulation network [26, 27] and is therefore likely a constraint for evolutionary optimization of AbrB expression in the exponential phase, which is the growth phase addressed in this study. In turn, NAR is a clear constraint on noise generation since it is generally believed to dampen noise [42, 43]. Consistent with this view, we observed only a slight increase in PabrB promoter noise upon increasing AbrB protein noise, suggesting that AbrB NAR is responsible for minimizing promoter noise. Besides reducing noise, NAR has been implicated in decreasing the response time of a genetic circuit, linearizing the dose response of an inducer, and increasing the input dynamic range of a transcriptional circuit [19]. Individually, and in combination, these mechanistic aspects of NAR could explain why NAR is such a widespread phenomenon in transcriptional regulation. Besides this, the idea that AbrB and AbrB NAR are more widely conserved than RnaC/S1022 would be in line with the idea that AbrB expression in B. subtilis 168 has become fine-tuned by an additional regulator, which has evolved later in time. Lastly, on a more general note, the inconsistency between the abrB promoter and AbrB protein noise measurements make it clear that it is premature to draw conclusions about homogeneity or heterogeneity of protein expression when only data is gathered at the promoter level, especially for genes under a NAR regime.

In conclusion, we have identified a novel direct sRNA target in the important B. subtilis transcriptional regulator abrB. Specifically, we provide functionally and physiologically relevant explanations for the evolution of the noise-generation aspects of this regulation in generating heterogeneity in growth rates. This noise is induced at the post-transcriptional level due to AbrB NAR. Based on our present observations, we hypothesize that the resulting subpopulations of fast - and slow-growing B. subtilis cells reflect a bet-hedging strategy for enhanced survival of unfavorable conditions.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strain construction

E. coli and B. subtilis strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in S2 Table and oligonucleotides in S3 Table. E. coli TG1 was used for all cloning procedures. All B. subtilis strains were based on the trpC2-proficient parental strain 168 [1]. B. subtilis transformations were performed as described previously [57]. The isogenic RnaC/S1022 mutant was constructed according to the method described by Tanaka et al. [58]. pRMC was derived from pXTC [59] by Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) [60] with primers ORM0054 and ORM0055 using pXTC as PCR template and ORM0056 to circularize this PCR fragment in the final CPEC reaction. In this manner, the xylose-inducible promoter of pXTC was replaced with the AscI Ligation Independent Cloning (LIC; [61]) site from pMUTIN-GFP [39]. As a consequence, pRMC carries a cassette that can be integrated into the amyE locus via double cross-over recombination, allowing ectopic expression of genes in single copy from their native promoter. RnaC/S1022 was cloned in pRMC under control of its native promoter as identified by Schmalisch et al. [28], and the subsequent integration of RnaC/S1022 into the amyE locus via double cross-over recombination was confirmed by verifying the absence of α-amylase activity on starch plates. The LIC plasmid pRM3+Pwt RnaC/S1022, which is a derivative of plasmid pHB201 [51], was used to express RnaC/S1022 under control of its native promoter. For IPTG-inducible expression of abrB, the abrB gene was cloned into pDR111 [50], and subsequently placed in the amyE locus via homologous recombination. Deletion alleles were introduced into this and other strains by transformation with chromosomal DNA containing the respective mutations. The RnaC/S1022, hag and abrB promoter gfp fusions were constructed at the native chromosomal locus by single cross-over integration of the pBaSysBioII plasmid [38]. A minimum of three clones were checked to exclude possible multi-copy integration of the plasmid.

Media and growth conditions

Lysogeny Broth (LB) consisted of 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract and 1% NaCl, pH 7.4. M9 medium supplemented with either 0.3% glucose (M9G) or 0.3% sucrose (M9S) was freshly prepared from separate stock solutions on the day of the experiment as previously described [9]. For live cell imaging experiments, the M9 medium was filtered through a 0.2 μm Whatman filter (GE Healthcare). Strains were grown with vigorous agitation at 37°C in either Luria LB or M9 medium using an orbital shaker or a Biotek Synergy 2 plate reader at maximal shaking. Growth was recorded by optical density readings at 600 nm (OD600). For all growth experiments, overnight B. subtilis cultures in LB with antibiotics were diluted >1 : 50 in fresh prewarmed LB medium and grown for approximately 2.5 hours. This served as the pre-culture for all experiments with cells grown on LB medium. For experiments with cells grown on M9 medium, the LB pre-culture was subsequently diluted 1 : 20 in pre-warmed M9 medium and incubated for approximately 2.5 hours, which corresponds to mid - or early exponential growth. This culture then served as the pre-culture for experiments with cells grown on M9 medium. When required, media for E. coli were supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) or chloramphenicol (10 μg ml−1); media for B. subtilis were supplemented with phleomycin (4 μg ml−1), kanamycin (20 μg ml−1), tetracyclin (5 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (10 μg ml−1), erythromycin (2 μg ml−1), and spectinomycin (100 μg ml−1) or combinations thereof.

Evolutionary conservation analysis of RnaC/S1022 targets

In order to find predicted targets co-conserved with RnaC/S1022, we used the 62 Bacillus genomes available in Genbank (as of January 31, 2013). On each of these genomes a BLAST search (Blastn v2.2.26 with default parameters) was conducted with the B. subtilis 168 RnaC/S1022 sequence as identified in Nicolas et al. [9]. Genomes where a homologue of RnaC/S1022 (E-value < 0.001) was found were then subjected to TargetRNA_v1 search with extended settings around the 5’UTR (−75 bp; +50 bp around the start codon and additional command line arguments “-z 250 -y 2 -l 6”) using as query the sequence of the first high-scoring-pair of the first BLAST hit in that particular genome. A bidirectional best hit criterion (based on Blastp v2.2.26 with default parameters and E-value cut-off 0.001) was used to compare the predicted targets in each genome with the predicted targets in the reference B. subtilis 168 genome (Genbank: AL009126-3). The data was tabulated and subsetted for B. subtilis 168 genes predicted for RnaC/S1022 in 8 or more genomes.

The Bacillaceae phylogenetic tree was computed based on an alignment of the rpoB gene BLAST result from the same set of genomes mentioned above. RpoB was reported to be a better determinant of evolutionary relatedness for Bacillus species than 16S rRNA [62].

Western blot, RNA isolation and northern blot

Cultures grown on LB, M9G, or M9S were sampled in mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 0.4–0.6) and were directly harvested in killing buffer and processed as previously described [9]. Northern blot analysis was carried out as described previously [63]. The digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe was synthesized by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase and an abrB specific PCR product as template. 5 μg of total RNA per lane was separated on 1.2% agarose gels. Chemiluminescence signals were detected using a ChemoCam Imager (Intas Science Image Instruments GmbH, Göttingen, Germany).

Western blot analysis was performed as described [64] using crude whole cell lysates. To prepare lysates, cell pellets were resuspended in LDS-sample buffer with reducing agent (Life technologies), and disrupted with glass beads in a bead beater (3 x 30 sec at 6500 rpm with 30 sec intermittences). Before loading on Novex nuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris gels (Life technologies), samples were boiled for 10 min and centrifuged to pellet the glass beads and cell debris. Equal OD units were loaded on gel and the intensity of the AbrB band was corrected with the intensity for the unrelated BdbD control.

Data from Northern blots and Western blots were quantified ImageJ software (available via http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Analysis of mRNA decay

Rifampicin (Sigma Aldrich) was added to 100 ml of exponentially growing M9G culture to a final concentration of 150 μg/ml from a 100x stock solution in methanol stored at −20°C. Just before the rifampicin addition and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 min after rifampicin addition, 10 ml of cells were harvested in killing buffer as described previously [9]. Cell pellets were washed once with 1 ml killing buffer and frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted according to the hot phenol method as described previously [63]. Quantitative PCR was performed as described by Reilman et al. [51]. The Ct value corresponds to the PCR cycle at which the signal came above background.

We analyzed the four mRNA decay time-series (two strains and two replicates) with a non-linear model of mRNA concentration described in [65] that aims at capturing initial exponential decay followed by a plateau. The rate of the initial decay is supposed to correspond to the physiological degradation of the mRNA. In contrast, the final plateau can be contributed by several factors, such as background noise in measurement, a stable subpopulation of molecules, or a higher stability of the mRNAs at the end of the dynamic. In our context, we assumed that the mRNA concentration is proportional to 2-Ct and thus we fitted (with the nls function of the R package stats) the model-Ct(ti) = log2(A*(α1exp(-γ1ti)+α2)) + εi, for i = 1…7 (ti = 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 min) with A>0, α1>0, α2>0, γ1>0,α1+α2 = 0 and εi a Gaussian white noise. The estimates of the γ1 parameters of the first model were compared between the two genetic backgrounds (0 genomic copies vs. 2 copies of RnaC/S1022) with a student t-test after a log-transformation to stabilize the variance. For the 2-copy background, we also examined a second model that involves two exponential decay terms as would for instance arise when two sub-populations of mRNAs with distinct degradation rates coexist. It writes-Ct(ti) = log2(A*(α1exp(-γ1ti)+α2exp(-γ2ti)+α3)) + εi with A>0, α1>0, α2>0, α3>0, γ1>γ2>0, and α1+α2+α3 = 0. For each pair of background and model, we plotted a “consensus” line whose parameters were obtained from the geometric mean between the two replicate experiments.

Computation of promoter activity

Promoter activity was monitored every 10 min from cells grown in 96-well plates in a Biotek® Synergy 2 plate reader. Promoter activity was computed by subtracting the fluorescence of the previous time-point from that of the measured time-point (as in Botella et al. [38]). Moving average filtering (filter function in R with filter = rep(1/5, 5) was applied for smoothing of the promoter activity plots.

Flow cytometry and noise measurements

Cultures grown on LB, M9G, or M9S were sampled in mid-exponential growth phase OD600 0.4–0.5 and were directly analyzed in an Accuri C6 flow cytometer. The number of recorded events within a gate set with growth medium was 15,000. The coefficient of variation (i.e. relative standard deviation) (CV%; standard deviation / mean * 100%) was used as a measure of the width of the distribution, or protein/promoter expression noise.

Microscopy and live imaging

To inspect co-localization of AbrB-GFP with the nucleoid, cells were cultured until the exponential growth phase, pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 400μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1μl 500 ng/μl 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and incubated for 10 min on ice. After this, the cells were washed once with PBS and slides were prepared for microscopy.

Live imaging analysis was conducted on aerated agarose cover slips as described previously [52]. Segmentation, calculation of Feret diameter, and auto-fluorescence correction for every microcolony were performed with ImageJ also as described by Piersma et al. [52]. Subsequent computations and plotting was done with R. The specific cell length (Feret diameter) increase per hour was computed as follows: ((cumulative Feret diameter at t20 min / number of cells at t0 min) – (cumulative Feret diameter at t0 min / number of cells at t0 min)) / ((t20 min—t0 min) / 60 min).

Modeling noise

Noise promoting dynamics by sRNA regulation was modeled in a stochastic simulation model [45–47]. The considered reactions, employed parameters, and the master equation are listed in Fig. 6. The master equation was numerically integrated by employing an in-house developed implementation of the Gillespie algorithm [66] for each combination of model parameters. The stochastic simulations were started without any molecules and were run until a quasi-stationary state was reached. To capture the inherent stochasticity of the model we performed, for each set of model parameters, 50 x 10,000 simulation replicates (i.e. 500,000 in total). This can be interpreted as 50 experiments involving 10,000 cells each. Mean, standard deviation, and the median was computed for every molecular species in the population of 10,000 cells.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Buescher JM, Liebermeister W, Jules M, Uhr M, Muntel J, et al. (2012) Global network reorganization during dynamic adaptations of Bacillus subtilis metabolism. Science 335(6072): 1099–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.1206871 22383848

2. Beisel CL, Storz G. (2010) Base pairing small RNAs and their roles in global regulatory networks. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34(5): 866–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00241.x 20662934

3. Storz G, Vogel J, Wassarman KM. (2011) Regulation by small RNAs in bacteria: Expanding frontiers. Mol Cell 43(6): 880–891. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.022 21925377

4. Aiba H. (2007) Mechanism of RNA silencing by Hfq-binding small RNAs. Curr Opin Microbiol 10(2): 134–139. 17383928

5. Gaballa A, Antelmann H, Aguilar C, Khakh SK, Song KB, et al. (2008) The Bacillus subtilis iron-sparing response is mediated by a Fur-regulated small RNA and three small, basic proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(33): 11927–11932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711752105 18697947

6. Heidrich N, Chinali A, Gerth U, Brantl S. (2006) The small untranslated RNA SR1 from the Bacillus subtilis genome is involved in the regulation of arginine catabolism. Mol Microbiol 62(2): 520–536. 17020585

7. Smaldone GT, Revelles O, Gaballa A, Sauer U, Antelmann H, et al. (2012) A global investigation of the Bacillus subtilis iron-sparing response identifies major changes in metabolism. J Bacteriol 194(10): 2594–2605. doi: 10.1128/JB.05990-11 22389480

8. Irnov I, Sharma CM, Vogel J, Winkler WC. (2010) Identification of regulatory RNAs in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res 38(19): 6637–6651. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq454 20525796

9. Nicolas P, Mader U, Dervyn E, Rochat T, Leduc A, et al. (2012) Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science 335(6072): 1103–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.1206848 22383849

10. Raj A, van Oudenaarden A. (2008) Nature, nurture, or chance: Stochastic gene expression and its consequences. Cell 135(2): 216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.050 18957198

11. Losick R, Desplan C. (2008) Stochasticity and cell fate. Science 320(5872): 65–68. doi: 10.1126/science.1147888 18388284

12. Maamar H, Raj A, Dubnau D. (2007) Noise in gene expression determines cell fate in Bacillus subtilis. Science 317(5837): 526–529. 17569828

13. Chastanet A, Vitkup D, Yuan GC, Norman TM, Liu JS, et al. (2010) Broadly heterogeneous activation of the master regulator for sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(18): 8486–8491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002499107 20404177

14. Veening JW, Smits WK, Kuipers OP. (2008) Bistability, epigenetics, and bet-hedging in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 62 : 193–210. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163002 18537474

15. Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. (2002) Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science 297(5584): 1183–1186. 12183631

16. Paulsson J. (2004) Summing up the noise in gene networks. Nature 427(6973): 415–418. 14749823

17. Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S. (2004) Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science 305(5690): 1622–1625. 15308767

18. Eldar A, Elowitz MB. (2010) Functional roles for noise in genetic circuits. Nature 467(7312): 167–173. doi: 10.1038/nature09326 20829787

19. Madar D, Dekel E, Bren A, Alon U. (2011) Negative auto-regulation increases the input dynamic-range of the arabinose system of Escherichia coli. BMC Syst Biol 5 : 111–0509–5–111. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-111.Negative 21749723

20. Saile E, Koehler TM. (2002) Control of anthrax toxin gene expression by the transition state regulator abrB. J Bacteriol 184(2): 370–380. 11751813

21. Glaser P, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Rusniok C, Amend A, et al. (2001) Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294(5543): 849–852. 11679669

22. Fisher SH, Strauch MA, Atkinson MR, Wray LV Jr. (1994) Modulation of Bacillus subtilis catabolite repression by transition state regulatory protein AbrB. J Bacteriol 176(7): 1903–1912. 8144456

23. Mader U, Schmeisky AG, Florez LA, Stulke J. (2012) SubtiWiki—a comprehensive community resource for the model organism Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res 40(Database issue): D1278–87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr923 22096228

24. Chumsakul O, Takahashi H, Oshima T, Hishimoto T, Kanaya S, et al. (2011) Genome-wide binding profiles of the Bacillus subtilis transition state regulator AbrB and its homolog Abh reveals their interactive role in transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 39(2): 414–428. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq780 20817675

25. Bobay BG, Benson L, Naylor S, Feeney B, Clark AC, et al. (2004) Evaluation of the DNA binding tendencies of the transition state regulator AbrB. Biochemistry 43(51): 16106–16118. 15610005

26. Banse AV, Chastanet A, Rahn-Lee L, Hobbs EC, Losick R. (2008) Parallel pathways of repression and antirepression governing the transition to stationary phase in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(40): 15547–15552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805203105 18840696

27. Schultz D, Wolynes PG, Ben Jacob E, Onuchic JN. (2009) Deciding fate in adverse times: Sporulation and competence in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(50): 21027–21034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912185106 19995980

28. Schmalisch M, Maiques E, Nikolov L, Camp AH, Chevreux B, et al. (2010) Small genes under sporulation control in the Bacillus subtilis genome. J Bacteriol 192(20): 5402–5412. doi: 10.1128/JB.00534-10 20709900

29. Will S, Joshi T, Hofacker IL, Stadler PF, Backofen R. (2012) LocARNA-P: Accurate boundary prediction and improved detection of structural RNAs. RNA 18(5): 900–914. doi: 10.1261/rna.029041.111 22450757

30. Hofacker IL, Stadler PF. (2006) Memory efficient folding algorithms for circular RNA secondary structures. Bioinformatics 22(10): 1172–1176. 16452114

31. Nicholson WL. (2012) Increased competitive fitness of Bacillus subtilis under nonsporulating conditions via inactivation of pleiotropic regulators AlsR, SigD, and SigW. Appl Environ Microbiol 78(9): 3500–3503. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07742-11 22344650

32. Tjaden B. (2008) TargetRNA: A tool for predicting targets of small RNA action in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 36(Web Server issue): W109–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn264 18477632

33. Horsburgh MJ, Moir A. (1999) Sigma M, an ECF RNA polymerase sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis 168, is essential for growth and survival in high concentrations of salt. Mol Microbiol 32(1): 41–50. 10216858

34. Xu K, Clark D, Strauch MA. (1996) Analysis of abrB mutations, mutant proteins, and why abrB does not utilize a perfect consensus in the-35 region of its sigma A promoter. J Biol Chem 271(5): 2621–2626. 8576231

35. Hahn J, Roggiani M, Dubnau D. (1995) The major role of Spo0A in genetic competence is to downregulate abrB, an essential competence gene. J Bacteriol 177(12): 3601–3605. 7768874

36. Deana A, Belasco JG. (2005) Lost in translation: The influence of ribosomes on bacterial mRNA decay. Genes Dev 19(21): 2526–2533. 16264189

37. Peer A, Margalit H. (2011) Accessibility and evolutionary conservation mark bacterial small-RNA target-binding regions. J Bacteriol 193(7): 1690–1701. doi: 10.1128/JB.01419-10 21278294

38. Botella E, Fogg M, Jules M, Piersma S, Doherty G, et al. (2010) pBaSysBioII: An integrative plasmid generating gfp transcriptional fusions for high-throughput analysis of gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 156(Pt 6): 1600–1608. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.035758-0 20150235

39. Doherty GP, Fogg MJ, Wilkinson AJ, Lewis PJ. (2010) Small subunits of RNA polymerase: Localization, levels and implications for core enzyme composition. Microbiology 156(Pt 12): 3532–3543. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.041566-0 20724389

40. Smits WK, Kuipers OP, Veening JW. (2006) Phenotypic variation in bacteria: The role of feedback regulation. Nat Rev Microbiol 4(4): 259–271. 16541134

41. Greene EA, Spiegelman GB. (1996) The Spo0A protein of Bacillus subtilis inhibits transcription of the abrB gene without preventing binding of the polymerase to the promoter. J Biol Chem 271(19): 11455–11461. 8626703

42. Becskei A, Serrano L. (2000) Engineering stability in gene networks by autoregulation. Nature 405(6786): 590–593. 10850721

43. Dublanche Y, Michalodimitrakis K, Kummerer N, Foglierini M, Serrano L. (2006) Noise in transcription negative feedback loops: Simulation and experimental analysis. Mol Syst Biol 2 : 41. 16883354

44. Kearns DB, Losick R. (2005) Cell population heterogeneity during growth of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev 19(24): 3083–3094. 16357223

45. Levine E, Zhang Z, Kuhlman T, Hwa T. (2007) Quantitative characteristics of gene regulation by small RNA. PLoS Biol 5(9): e229. 17713988

46. Arbel-Goren R, Tal A, Friedlander T, Meshner S, Costantino N, et al. (2013) Effects of post-transcriptional regulation on phenotypic noise in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 41(9): 4825–4834. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt184 23519613

47. Jia Y, Liu W, Li A, Yang L, Zhan X. (2009) Intrinsic noise in post-transcriptional gene regulation by small non-coding RNA. Biophys Chem 143(1–2): 60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2009.05.003 19487068

48. Hambraeus G, von Wachenfeldt C, Hederstedt L. (2003) Genome-wide survey of mRNA half-lives in Bacillus subtilis identifies extremely stable mRNAs. Mol Genet Genomics 269(5): 706–714. 12884008

49. Jost D, Nowojewski A, Levine E. (2013) Regulating the many to benefit the few: Role of weak small RNA targets. Biophys J 104(8): 1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.02.020 23601324

50. Britton RA, Eichenberger P, Gonzalez-Pastor JE, Fawcett P, Monson R, et al. (2002) Genome-wide analysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor (sigma-H) regulon of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 184(17): 4881–4890. 12169614

51. Reilman E, Mars RA, van Dijl JM, Denham EL. (2015) The multidrug ABC transporter BmrC/BmrD of Bacillus subtilis is regulated via a ribosome-mediated transcriptional attenuation mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res 42(18): 11393–11407.

52. Piersma S, Denham EL, Drulhe S, Tonk RH, Schwikowski B, et al. (2013) TLM-quant: An open-source pipeline for visualization and quantification of gene expression heterogeneity in growing microbial cells. PLoS One 8(7): e68696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068696 23874729

53. Gefen O, Balaban NQ. (2009) The importance of being persistent: Heterogeneity of bacterial populations under antibiotic stress. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33(4): 704–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00156.x 19207742

54. Tuomanen E, Cozens R, Tosch W, Zak O, Tomasz A. (1986) The rate of killing of Escherichia coli by ß-lactam antibiotics is strictly proportional to the rate of bacterial growth. Journal of General Microbiology 132(5): 1297–1304. 3534137

55. Hecker M, Pane-Farre J, Volker U. (2007) SigB-dependent general stress response in Bacillus subtilis and related Gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 61 : 215–236. 18035607

56. Rotem E, Loinger A, Ronin I, Levin-Reisman I, Gabay C, et al. (2010) Regulation of phenotypic variability by a threshold-based mechanism underlies bacterial persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(28): 12541–12546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004333107 20616060

57. Kunst F, Rapoport G. (1995) Salt stress is an environmental signal affecting degradative enzyme synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 177(9): 2403–2407. 7730271

58. Tanaka K, Henry CS, Zinner JF, Jolivet E, Cohoon MP, et al. (2013) Building the repertoire of dispensable chromosome regions in Bacillus subtilis entails major refinement of cognate large-scale metabolic model. Nucleic Acids Res 41(1): 687–699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks963 23109554

59. Darmon E, Dorenbos R, Meens J, Freudl R, Antelmann H, et al. (2006) A disulfide bond-containing alkaline phosphatase triggers a BdbC-dependent secretion stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol 72(11): 6876–6885. 17088376

60. Quan J, Tian J. (2009) Circular polymerase extension cloning of complex gene libraries and pathways. PLoS One 4(7): e6441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006441 19649325

61. Haun RS, Serventi IM, Moss J. (1992) Rapid, reliable ligation-independent cloning of PCR products using modified plasmid vectors. BioTechniques 13(4): 515–518. 1362067

62. Ki JS, Zhang W, Qian PY. (2009) Discovery of marine bacillus species by 16S rRNA and rpoB comparisons and their usefulness for species identification. J Microbiol Methods 77(1): 48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.01.003 19166882

63. Homuth G, Masuda S, Mogk A, Kobayashi Y, Schumann W. (1997) The dnaK operon of Bacillus subtilis is heptacistronic. J Bacteriol 179(4): 1153–1164. 9023197

64. Zweers JC, Wiegert T, van Dijl JM. (2009) Stress-responsive systems set specific limits to the overproduction of membrane proteins in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol 75(23): 7356–7364. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01560-09 19820159

65. Shock JL, Fischer KF, DeRisi JL. (2007) Whole-genome analysis of mRNA decay in Plasmodium falciparum reveals a global lengthening of mRNA half-life during the intra-erythrocytic development cycle. Genome Biol 8(7): R134. 17612404

66. Gillespie DT. (1977) Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. J Phys Chem 81(25): 2340–2361.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek NLRC5 Exclusively Transactivates MHC Class I and Related Genes through a Distinctive SXY ModuleČlánek Inhibition of Telomere Recombination by Inactivation of KEOPS Subunit Cgi121 Promotes Cell LongevityČlánek HOMER2, a Stereociliary Scaffolding Protein, Is Essential for Normal Hearing in Humans and MiceČlánek LRGUK-1 Is Required for Basal Body and Manchette Function during Spermatogenesis and Male FertilityČlánek The GATA Factor Regulates . Developmental Timing by Promoting Expression of the Family MicroRNAsČlánek Systems Biology of Tissue-Specific Response to Reveals Differentiated Apoptosis in the Tick VectorČlánek Phenotype Specific Analyses Reveal Distinct Regulatory Mechanism for Chronically Activated p53Článek The Nuclear Receptor DAF-12 Regulates Nutrient Metabolism and Reproductive Growth in NematodesČlánek The ATM Signaling Cascade Promotes Recombination-Dependent Pachytene Arrest in Mouse SpermatocytesČlánek The Small Protein MntS and Exporter MntP Optimize the Intracellular Concentration of Manganese

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 3

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- NLRC5 Exclusively Transactivates MHC Class I and Related Genes through a Distinctive SXY Module

- Licensing of Primordial Germ Cells for Gametogenesis Depends on Genital Ridge Signaling

- A Genomic Duplication is Associated with Ectopic Eomesodermin Expression in the Embryonic Chicken Comb and Two Duplex-comb Phenotypes

- Genome-wide Association Study and Meta-Analysis Identify as Genome-wide Significant Susceptibility Gene for Bladder Exstrophy

- Mutations of Human , Encoding the Mitochondrial Asparaginyl-tRNA Synthetase, Cause Nonsyndromic Deafness and Leigh Syndrome

- Exome Sequencing in an Admixed Isolated Population Indicates Variants Confer a Risk for Specific Language Impairment

- Genome-Wide Association Studies in Dogs and Humans Identify as a Risk Variant for Cleft Lip and Palate

- Rapid Evolution of Recombinant for Xylose Fermentation through Formation of Extra-chromosomal Circular DNA

- The Ribosome Biogenesis Factor Nol11 Is Required for Optimal rDNA Transcription and Craniofacial Development in

- Methyl Farnesoate Plays a Dual Role in Regulating Metamorphosis

- Maternal Co-ordinate Gene Regulation and Axis Polarity in the Scuttle Fly

- Maternal Filaggrin Mutations Increase the Risk of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: An Effect Independent of Mutation Inheritance

- Inhibition of Telomere Recombination by Inactivation of KEOPS Subunit Cgi121 Promotes Cell Longevity

- Clonality and Evolutionary History of Rhabdomyosarcoma