-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Coordinated Interdependent Protein Circuitry Stabilizes the Kinetochore Ensemble to Protect CENP-A in the Human Pathogenic Yeast

Unlike most eukaryotes, a kinetochore is fully assembled early in the cell cycle in budding yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. These kinetochores are clustered together throughout the cell cycle. Kinetochore assembly on point centromeres of S. cerevisiae is considered to be a step-wise process that initiates with binding of inner kinetochore proteins on specific centromere DNA sequence motifs. In contrast, kinetochore formation in C. albicans, that carries regional centromeres of 3–5 kb long, has been shown to be a sequence independent but an epigenetically regulated event. In this study, we investigated the process of kinetochore assembly/disassembly in C. albicans. Localization dependence of various kinetochore proteins studied by confocal microscopy and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays revealed that assembly of a kinetochore is a highly coordinated and interdependent event. Partial depletion of an essential kinetochore protein affects integrity of the kinetochore cluster. Further protein depletion results in complete collapse of the kinetochore architecture. In addition, GFP-tagged kinetochore proteins confirmed similar time-dependent disintegration upon gradual depletion of an outer kinetochore protein (Dam1). The loss of integrity of a kinetochore formed on centromeric chromatin was demonstrated by reduced binding of CENP-A and CENP-C at the centromeres. Most strikingly, Western blot analysis revealed that gradual depletion of any of these essential kinetochore proteins results in concomitant reduction in cellular protein levels of CENP-A. We further demonstrated that centromere bound CENP-A is protected from the proteosomal mediated degradation. Based on these results, we propose that a coordinated interdependent circuitry of several evolutionarily conserved essential kinetochore proteins ensures integrity of a kinetochore formed on the foundation of CENP-A containing centromeric chromatin.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002661

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002661Summary

Unlike most eukaryotes, a kinetochore is fully assembled early in the cell cycle in budding yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. These kinetochores are clustered together throughout the cell cycle. Kinetochore assembly on point centromeres of S. cerevisiae is considered to be a step-wise process that initiates with binding of inner kinetochore proteins on specific centromere DNA sequence motifs. In contrast, kinetochore formation in C. albicans, that carries regional centromeres of 3–5 kb long, has been shown to be a sequence independent but an epigenetically regulated event. In this study, we investigated the process of kinetochore assembly/disassembly in C. albicans. Localization dependence of various kinetochore proteins studied by confocal microscopy and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays revealed that assembly of a kinetochore is a highly coordinated and interdependent event. Partial depletion of an essential kinetochore protein affects integrity of the kinetochore cluster. Further protein depletion results in complete collapse of the kinetochore architecture. In addition, GFP-tagged kinetochore proteins confirmed similar time-dependent disintegration upon gradual depletion of an outer kinetochore protein (Dam1). The loss of integrity of a kinetochore formed on centromeric chromatin was demonstrated by reduced binding of CENP-A and CENP-C at the centromeres. Most strikingly, Western blot analysis revealed that gradual depletion of any of these essential kinetochore proteins results in concomitant reduction in cellular protein levels of CENP-A. We further demonstrated that centromere bound CENP-A is protected from the proteosomal mediated degradation. Based on these results, we propose that a coordinated interdependent circuitry of several evolutionarily conserved essential kinetochore proteins ensures integrity of a kinetochore formed on the foundation of CENP-A containing centromeric chromatin.

Introduction

The centromeric histone CENP-A acts as the epigenetic mark of a functional centromere from yeast to humans [1]. As a histone H3 variant, CENP-A replaces canonical histone H3 to mark specialized centromeric chromatin by a mechanism that remains largely unknown. While CENP-A deposition occurs in a sequence-dependent manner in point centromeres of certain budding yeasts including S. cerevisiae [2], [3], its recruitment to regional centromeres of most other eukaryotes is not strictly sequence dependent [1], [3]–[5]. Several lines of evidence suggest that the composition of nucleosomes that form centromeric chromatin may vary from species to species [6]–[10]. Even the hierarchy of events that assembles and stabilizes a complex macromolecular kinetochore (KT) structure on unusual centromeric chromatin, whether universal or species-specific, remains unclear. CENP-A is believed to be the initiator of the process of KT formation [1], [11]. Localization of most KT proteins is regulated by CENP-A [12]–[15]. However, a few proteins such as Ndc10 and Scm3 in S. cerevisiae [6], [16], Mis12/Mtw1 in C. albicans [17], Mis6, Mis16-Mis18 complex and Ams2 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe [18], [19], and CENP-H-I complex in humans [20] have been shown to regulate CENP-A localization.

Although the structure of metazoan KTs can be visualized under microscope, the exact nature of the KT architecture is difficult to ascertain in yeasts due to small size of these cells [21]. However, based on presence of functional homologs of several KT proteins, and their genetic as well as biochemical interaction in various eukaryotes, it is presumed that the three-layered KT structure is evolutionarily conserved from yeasts to humans. A KT helps in bridging the mitotic spindle to centromere (CEN) DNA to ensure faithful chromosome segregation during mitosis and meiosis. KT proteins exist as sub-complexes that assemble on CEN DNA [22]–[24]. In humans, inner (CENP-A, -B, -C, -H and –I) and middle (the Spc105 complex and the Mis12 complex) KT proteins are associated constitutively with CEN DNA [25] but outer KT proteins (such as the Ndc80 complex and the Ska1 complex) which help in KT-microtubule (MT) interaction are generally localized to KTs only during mitosis [26], [27]. In contrast, KTs are fully assembled in S. cerevisiae early in the cell cycle. The fungal specific Dam1 complex, an outer KT protein complex in budding yeast S. cerevisiae, remains associated with KTs throughout the cell cycle [28]–[30].

One of the less understood features of budding yeast KTs is that they are clustered together throughout the cell cycle [31]. A recent study, using chromosome conformation capture-on-chip (4C), clearly demonstrates that all chromosomes cluster via centromeres at one pole of the nucleus in S. cerevisiae suggesting interchromosomal cross-talks through inter-KT interaction [32]. KT clustering has been shown to be important for centromere function in S. cerevisiae as KTs are found to be declustered in ndc10, ame2 and nuf2 KT mutants [31], [33]. Interestingly, KTs are clustered only during interphase but not in mitosis in fission yeast S. pombe [34]. In metazoans KTs are never clustered [35].

With the notable exception of holocentric chromosomes of nematodes and aphids where KTs are formed across the entire length of a chromosome [36], only one KT is formed on each chromosome in all other organisms studied till date. A functional KT can even assemble on non-centromeric DNA to form a neocentromere in certain organisms when a native centromere is deleted or inactivated [37]–[40]. Thus there must be an underlying active mechanism to prevent formation of centromeric chromatin on neocentromeric loci when the native centromere is functional. CENP-A at non-centromeric locations is targeted for proteasomal degradation in Drosophila melanogaster and S. cerevisiae [41]–[43]. Thus ectopic CENP-A is destabilized to prevent multiple kinetochore formation although the exact cellular signal that distinguishes CENP-A molecules present at the native centromere from those ectopically localized could not be determined.

Candida albicans, a pathogenic budding yeast, that causes candidiasis in humans, carries 3–5 kb long unique centromeric chromatin on each of its eight chromosomes. There are 4 CENP-A molecules but only one MT binds to a KT in C. albicans [44]. Centromeric regions have been shown to have unusual chromatin structure [45] and histone H3 molecules are replaced by CENP-A at CENs (K. Sanyal, unpublished) in this organism. Moreover, CENP-A deposition on CENs has been shown to be epigenetically regulated [45]–[47]. We have previously cloned and characterized several evolutionarily conserved KT proteins including CENP-A/Cse4 [48], CENP-C/Mif2 [46], Mis12/Mtw1 [17] and the Dam1 complex subunits [49] in C. albicans and shown that each of these proteins is essential in a KT-MT-mediated process of chromosome segregation.

In the present work, we studied localization interdependence of KT proteins that govern KT integrity including stability of CENP-A. Our results reveal that the KT architecture is stabilized in a coordinated interdependent manner by individual components of the KT in C. albicans. Most strikingly, we provide evidence that stability of CENP-A molecules is determined by integrity of the KTs. This is the first demonstration, to our knowledge, of how an interdependent circuitry of several KT proteins helps stabilizing CENP-A at a functional KT.

Results

Centromeric localization of CENP-A is dependent upon various kinetochore proteins in C. albicans

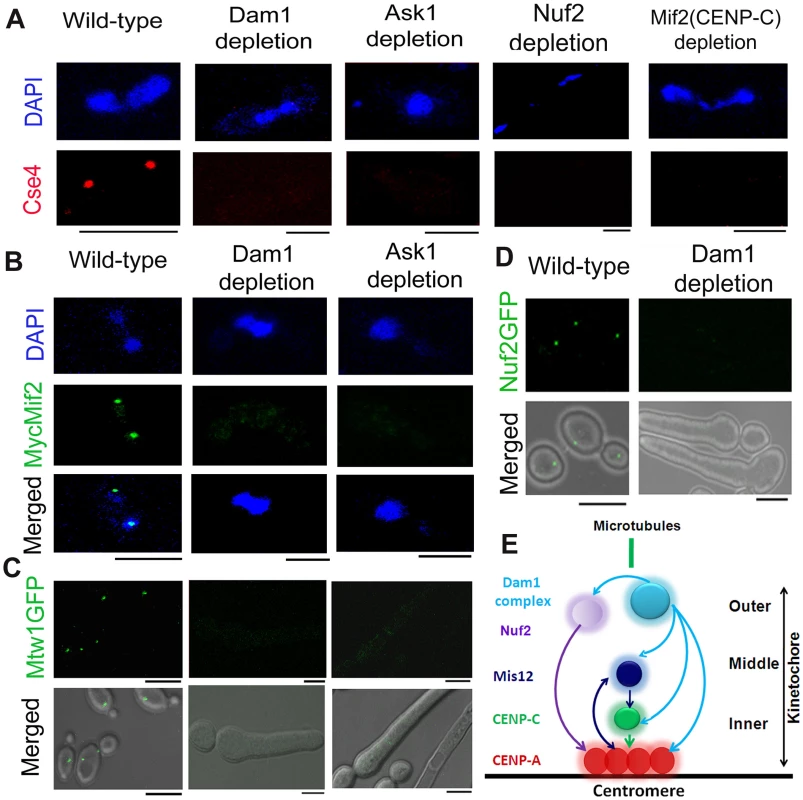

In order to understand the process of KT assembly in C. albicans, we studied localization dependence of various essential KT proteins that are evolutionarily conserved. To achieve this, we utilised conditional mutant strains carrying KT proteins under control of the MET3 or PCK1 promoter. The MET3 promoter is repressed in presence of cysteine (Cys) and methionine (Met) [50] while the PCK1 promoter is repressed when glucose (Glu) is used as the carbon source [51]. We depleted each of Dam1, Ask1, Spc19 or Dad2 - subunits of an essential outer KT protein complex, the Dam1 complex, in J102 (MET3prDAM1/dam1), J104 (MET3prASK/ask1), J106 (MET3prSPC19/spc19) or J108 (PCK1prDAD2/dad2) [49] respectively to study localization dependence of CENP-A. Immunostaining with anti-Cse4 (CENP-A) antibodies in depleted levels of each of these subunits of the Dam1 complex revealed that CENP-A localization at the KTs was dramatically reduced as compared to conditions when these proteins were present at wild-type levels (Figure 1A, Figure S1). In order to examine whether CENP-A delocalization is a specific phenomenon associated with depletion of the Dam1 complex, present only in fungal kingdom, we sought to study CENP-A localization upon depletion of the homolog of Nuf2, another evolutionarily conserved outer KT protein, in C. albicans. Depletion of Nuf2 in YJB12326 (MET3prNUF2/nuf2) showed significantly reduced CENP-A localization as well (Figure 1A). Next, we examined localization of CENP-A in absence of CENP-C/Mif2 in C. albicans. CENP-C/Mif2 proteins are evolutionarily conserved inner KT proteins. CENP-A/Cse4 staining in CAMB2 (PCK1prMIF2/mif2) grown in repressive media (Glu) for 8 h revealed a significant loss of CENP-A/Cse4 from KTs (Figure 1A). Thus various proteins that are evolutionarily conserved and present at inner, middle and outer KT in many organisms influence CENP-A localization in C. albicans.

Fig. 1. The process of kinetochore assembly is interdependent and coordinated in C. albicans.

(A) Mutant strain J102 (MET3prDAM1/dam1), J104 (MET3prASK1/ask1), YJB12326 (MET3prNUF2/nuf2) or CAMB2 (PCK1prMycMIF2/mif2) was grown for 8 h under non-permissive conditions to deplete Dam1, Ask1, Nuf2 or Mif2 respectively along with wild-type BWP17. Cells from each culture were fixed and stained with DAPI and anti-Cse4 antibodies. CENP-A/Cse4 signals, visible in wild-type cells, were undetected in Dam1, Ask1, Nuf2 or Mif2 depleted cells. (B) Wild-type J125 (PCK1prMycMIF2/MIF2), dam1 mutant J123 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 PCK1prMycMIF2/MIF2) or ask1 mutant J124 (MET3prASK1/ask1 MIF2/PCK1prMycMIF2) was grown for 8 h under non-permissive conditions (+Cys +Met +Suc) of the MET3 promoter, fixed and stained with DAPI, and anti-Myc antibodies. MycMif2 signals, clearly visible in wild-type, were undetected in Dam1- or Ask1-depleted cells. (C) Wild-type YJB10695 (MTW1GFP/MTW1), dam1 mutant J122 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 MTW1GFP/MTW1), or ask1 mutant J120 (MET3prASK1/ask1 MTW1GFP/MTW1) cells were grown under non-permissive conditions of the MET3 promoter (+Cys +Met) for 8 h and examined for GFP signals by confocal microscopy. Bright Mtw1-GFP dot-like signals were observed in wild-type cells but no Mtw1-GFP signals were detected in Dam1- or Ask-depleted cells. (D) YJB12289 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 NUF2-GFP/NUF2) cells grown in conditions where Dam1 is either expressed (−Cys −Met; wild-type) or repressed (+Cys +Met; Dam1 depleted) for 8 h were examined for GFP signals by confocal microscopy. Bright Nuf2-GFP dot-like signals were observed in wild-type cells but not in Dam1-depleted cells. (E) Schematic showing localization dependence of evolutionarily conserved KT proteins in C. albicans. Arrows show localization dependence observed in this study or reported previously [17]. Bars, 5 µm. The kinetochore super-complex is stabilized by an interdependent coordinated process

Next, to study localization patterns of CENP-C/Mif2 in absence of outer KT proteins, we performed immunostaining using anti-Myc antibodies in J123 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 MIF2/PCK1pr12XMYCMIF2) and J124 (MET3prASK1/ask1 MIF2/2PCK1pr12XMYCMIF2) expressing Myc-tagged CENP-C/Mif2 from the PCK1 promoter. Similar to CENP-A (discussed above), CENP-C/MycMif2 localization was dramatically reduced when levels of Dam1 or Ask1 were depleted due to growth of J123 or J124 for 8 h under non-permissive conditions (+Cys +Met +Suc) of the MET3 promoter (Figure 1B). Recently, we demonstrated that in C. albicans KT occupancy of these two proteins is dependent on the cellular levels Mis12/Mtw1, an evoutinarily conserved middle KT protein [17]. Thus, assembly of the inner KT is dependent on proteins from middle and outer KT in C. albicans.

These results prompted us to further investigate the role of the Dam1 complex on the occupancy of a middle KT protein. KT localized Mtw1-GFP signals that were visible in wild-type conditions were absent when Ask1 or Dam1 was repressed for 8 h in J122 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 MTW1GFP/MTW1) or J120 (MET3prASK1/ask1 MTW1GFP/MTW1) (Figure 1C). Together we conclude that integrity of the middle KT is also determined by outer KT proteins. Having established localization dependence of various domains of a KT on each other, we further examined how localization of one protein depends on another at the outer KT. As compared to wild-type, Nuf2-GFP localization at the KT was reduced dramatically when Dam1 was depleted in YJB12289 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 NUF2GFP/NUF2) (Figure 1D). These results suggest that integrity of different domains of a KT is interdependent and assembly of various components of a KT is highly coordinated (Figure 1E).

Integrity of a kinetochore remains unaffected upon disruption of the mitotic spindle

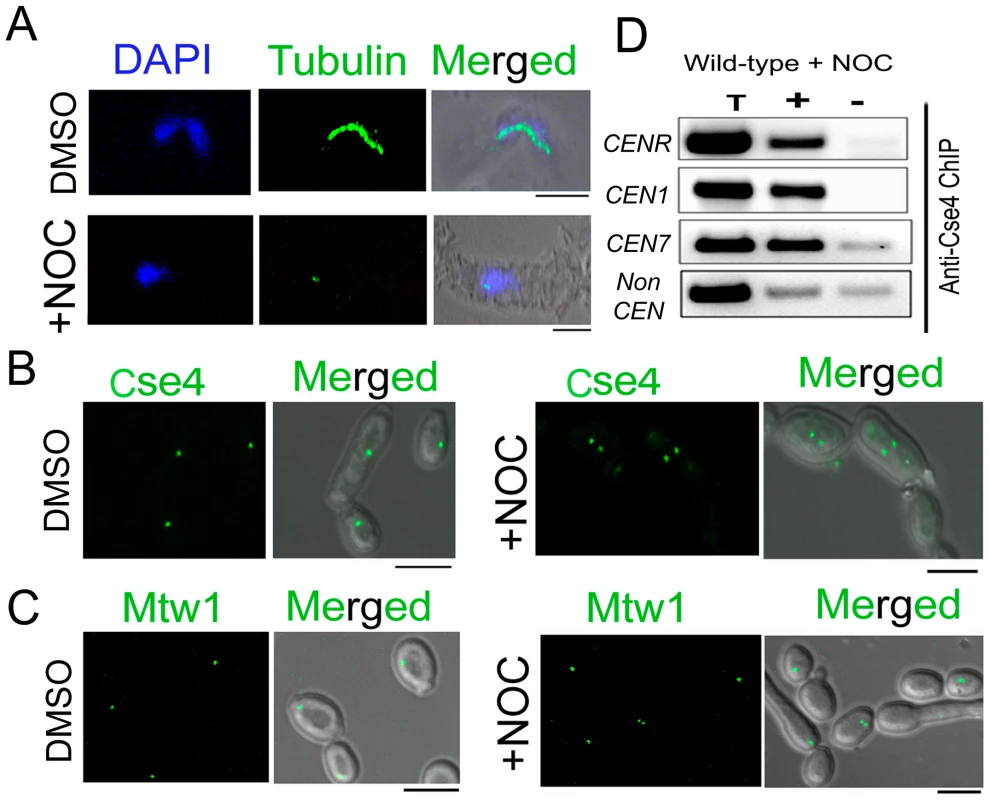

Unlike most organisms including fission yeast and humans, KTs are attached to spindle MTs throughout the cell cycle in S. cerevisiae except for a brief period of 2–3 minutes during centromere replication [52], [53]. A similar KT-MT interaction at all stages of the cell cycle is evidenced in C. albicans as well [17]. Various proteins from C. albicans discussed above have been shown to be essential in KT-MT mediated process of chromosome segregation as severe spindle defects were observed upon depletion of each of these proteins [17], [46], [48], [49]. In this study, we examined whether or not reduced KT localization of various KT proteins was due to impairment of the mitotic spindle caused by depletion of each of these proteins. To test this possibility, we disrupted the mitotic spindle in 10118 (CSE4:GFP:CSE4/cse4) expressing GFP-tagged Cse4 by treating cells with a spindle depolymerizing drug nocodazole (NOC). Tubulin staining of these NOC treated cells exhibited disruption of the mitotic spindle structure as expected (Figure 2A). However, no significant change in the intensity of Cse4-GFP signals was observed between NOC treated (mean intensity value = 225±28 a.u.) and untreated (mean intensity value = 227±32 a.u.) cells of 10118 (Figure 2B, Figure S2). A similar experiment to compare Mtw1-GFP levels in NOC treated and untreated cells of YJB10695 (MTW1GFP/MTW1) exhibited no significant difference (Figure 2C) as well. Localization of Dad2, a subunit of the Dam1 complex, is unaltered in presence or absence of NOC [49]. Together, these results showed that localization of various components of a KT is independent of integrity of the mitotic spindle. CENP-A/Cse4 ChIP analysis further indicated that spindle integrity does not have significant effect on the stability of centromeric chromatin (Figure 2D).

Fig. 2. Stability of the kinetochore structure is independent of structural integrity of the mitotic spindle.

A) Wild-type BWP17 cells, untreated (DMSO) or treated with nocodazole (+NOC), were fixed and stained with DAPI, and anti-tubulin antibodies. As compared to untreated cells (upper panels), NOC treated cells (lower panels) exhibited a significant loss of tubulin staining indicating a compromised structure of the mitotic spindle as expected by NOC treatment. (B) CENP-A/Cse4-GFP signals were analyzed in absence (DMSO) or presence of NOC (+NOC) in 10118 (CSE4:GFP:CSE4/cse4) cells. (C) Similarly, Mtw1-GFP signals were examined in absence (DMSO) or presence of NOC in YJB10695 (MTW1GFP/MTW1) cells. No significant change in intensity of either Cse4-GFP or Mtw1-GFP signals in NOC treated cells. (D) PCR analysis on Cse4 ChIP-DNA obtained from NOC treated BWP17 cells. Primers from CENR (CaChrR: 1747812–1748023), CEN1 (CaChr1: 1565723–1565967), CEN7 (CaChr7: 427369–427560) or 17 kb away from CEN7 (CaChr7: 444584–444875) (non-CEN) were used for PCR analysis. T, total DNA; +, IP DNA with anti-Cse4 antibodies and −, beads only control without antibodies. Bars, 5 µm. Partial depletion of several kinetochore proteins leads to disintegration of the clustered kinetochores

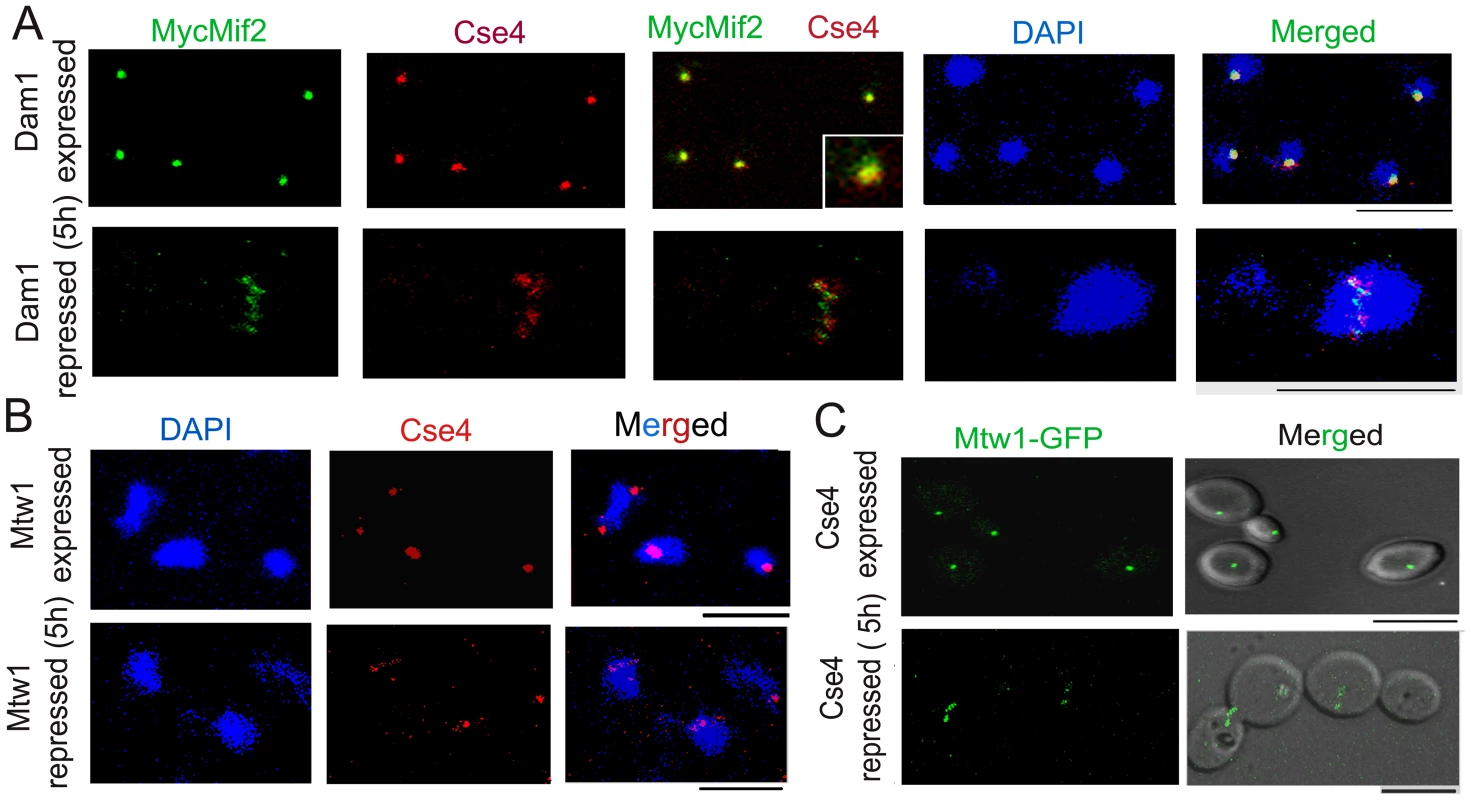

In order to understand how absence of a KT protein leads to collapse of an entire KT, we examined the KT structure at reduced (partially depleted) levels of various KT proteins. We observed both CENP-A (Cse4) and CENP-C (MycMif2) signals in wild-type or partially depleted levels of Dam1 or Ask1 in J123 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 MIF2/PCK1pr12XMYCMIF2) or J124 (MET3prASK1)/ask1 MIF2/2PCK1pr12XMYCMIF2). Interestingly, after 4–5 h of Dam1 depletion we observed multiple weak signals of CENP-A (Cse4) and CENP-C (MycMif2) associated with a single nucleus as opposed to a single bright dot-like clustered KTs observed in each wild-type cell (Figure 3A). Ask1-depleted cells showed similar declustered KTs (data not shown). We also observed multiple CENP-A (Cse4) signals in partially depleted Dad2 cells of J108 (PCK1prDAD2/dad2) after 4–5 h of growth under non-permissive conditions (Figure S3A). Subsequently, we examined Mtw1-GFP signals by partially depleting Ask1 in J120 (MET3prASK1/ask1 MTW1GFP/MTW1). We observed multiple Mtw1-GFP signals per nucleus in these cells as well (Figure S3B). Nuf2-GFP showed localization patterns in Dam1 depleted conditions (data not shown).

Fig. 3. The kinetochore ensemble maintains integrity of clustered kinetochores in C. albicans.

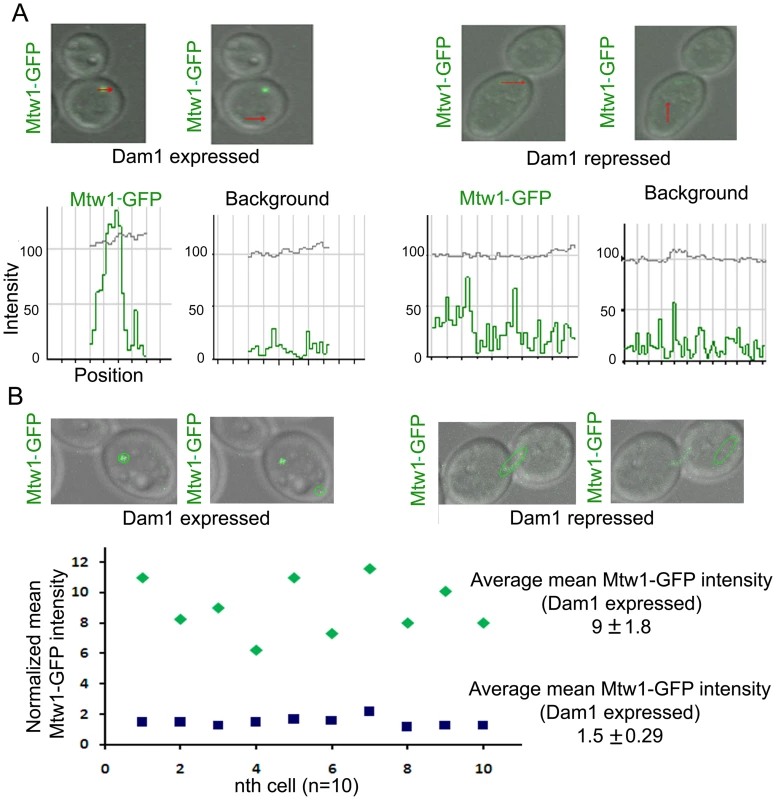

(A) J123 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 PCK1prMycMIF2/MIF2) cells were grown under conditions that expressed (−Cys −Met +Suc) or repressed (+Cys +Met +Suc for 5 h) Dam1. Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI, anti-Cse4 or anti-Myc (Mif2) antibodies. A single cluster of KTs was detected by colocalized CENP-A/Cse4 and CENP-C/Mif2 signals in each cell expressing Dam1. In contrast, declustered KTs, as evidenced by multiple weak Cse4 or MycMif2 signals, were detected in cells with reduced levels of Dam1. (B) CAKS12 (PCK1prMTW1/mtw1) cells, grown under conditions that expressed (Suc) or repressed (Glu for 5 h) Mis12/Mtw1, were fixed and stained with DAPI and anti-Cse4 antibodies. Similar KT declustering was visible in Mis12/Mtw1-depleted cells in contrast to clustered KTs in cells expressing this protein. (C) Mis12/Mtw1-GFP signals were observed in YJB11483 (PCK1prCSE4/cse4 MTW1GFP/MTW1) cells grown under conditions that expressed (Suc) or repressed (Glu for 5 h) CENP-A/Cse4. Multiple weak Mis12/Mtw1-GFP signals in each cell were observed when CENP-A/Cse4 was repressed. Bars, 5 µm. To test whether KT disintegration occurs due to depletion of middle (Mis12/Mtw1) or inner (CENP-A/Cse4) KT proteins as well, we first depleted Mis12/Mtw1 in CAKS12 (PCK1prMTW1/mtw1), and examined the integrity of the clustered KTs using anti-Cse4 antibodies. KT disinegration was clearly evident with multiple weak CENP-A signals co-localized with a single nucleus (Figure 3B). Next we monitored the process of Mis12/Mtw1 delocalization upon depletion of CENP-A. YJB11483 (PCK1prCSE4/cse4 MTW1GFP/MTW1) expressing CENP-A/Cse4 under the PCK1 promoter was grown either in permissive (+Suc) or non-permissive (+Glu for 5 h) conditions to examine Mtw1-GFP signals (Figure 3C). We observed multiple Mtw1-GFP signals per cell confirming disintegration of the KT cluster in these cells as well (as opposed to wild-type cells where properly integrated KTs remained clustered). Using the LSM examiner analysis tool (Carl Zeiss, Germany), we determined the mean intensity of GFP signals in wild-type clustered KTs and Dam1 depleted declustered KTs (Figure 4). The normalized (against background) average values of mean GFP intensity/KT in wild-type and Dam1 depleted cells were 9±1.8 and 1.5±0.29 respectively. Thus the Mtw1 levels at the disingrated KTs are significantly reduced due to Dam1 depletion.

Fig. 4. Dam1 depletion results in reduced localization of Mtw1 at the kinetochores.

(A) Intensity profiles of Mtw1-GFP or background signals in J122 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 MTW1GFP/MTW1) cells having either wild-type or reduced levels of Dam1. (B) Mean intensity values of Mtw1-GFP/KT in wild-type or Dam1 depleted cells were measured using LSM examiner (Carl Zeiss, Germany), normalized with background signals and plotted. Concerted loss of various kinetochore proteins occurs during the process of kinetochore disassembly

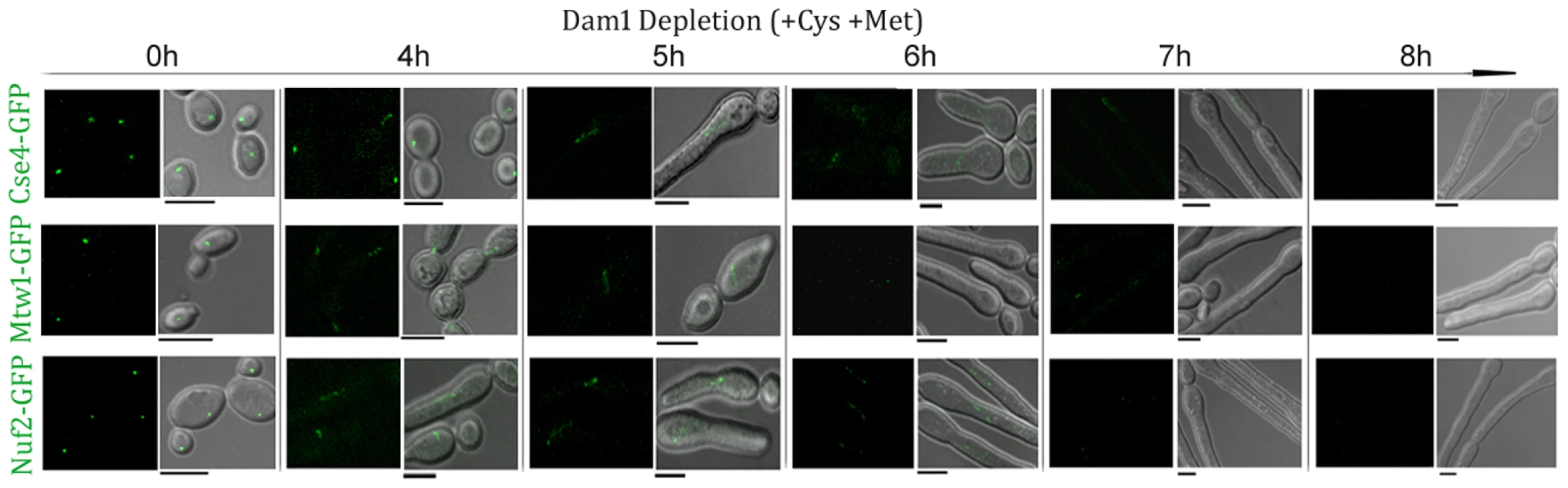

Finally, we examined the dynamics of KT disassembly by monitoring the time-dependent localization patterns of several proteins present at various domains of a KT while Dam1 is being gradually depleted. Cse4-GFP, Mtw1-GFP and Nuf2-GFP signals were monitored in J127 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 CSE4:GFP:CSE/cse4), J122 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 MTW1/MTW1GFP) and YJB12289 (MET3prDAM1/dam1, NUF2GFP/NUF2) respectively at various time intervals upon Dam1 depletion (Figure 5). In each case, disintegration of GFP signals from one bright cluster to multiple weakly fluorescent dot-like signals in each cell was observed between 4–5 h of growth in Dam1 repressing media. GFP signals were undetectable after 8 h of Dam1 depletion indicating complete collapse of KT integrity. Similar disintegration dynamics of Mtw1-GFP signals were found between 4–5 h of depletion of other proteins, CENP-A or Ask1, as well (Figure S4). These results indicated a strong correlation between a concerted loss of various domains of a KT and a concomitant reduction in the levels of an essential KT protein.

Fig. 5. Disintegration of the kinetochore cluster precedes kinetochore collapse.

Levels of GFP-tagged inner (Cse4), middle (Mtw1) or outer (Nuf2) KT proteins under gradual repression of Dam1 were monitored at indicated time after shift of strains J127 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 CSE4:GFP:CSE4/cse4), J122 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 MTW1GFP/MTW1) and YJB12289 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 NUF2GFP/NUF2) to non-permissive medium for the MET3 promoter. In each case GFP (left) and GFP+DIC (right) images were shown. Bars, 5 µm. Nuclear peripheral localization is maintained even when kinetochores are being disintegrated

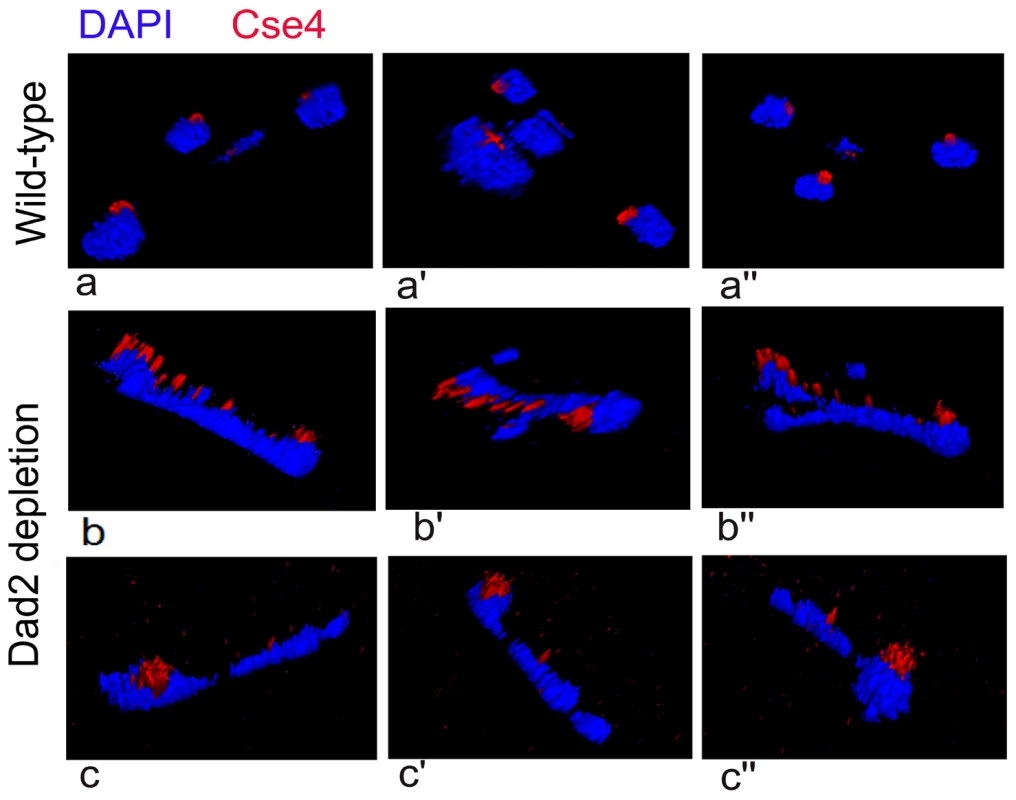

All KTs are clustered and such clustered KTs are always localized towards the nuclear periphery (Figure 6, a-a″) suggesting KTs occupy a fixed nuclear territory in wild-type C. albicans cells. Interestingly, reconstruction of three dimensional (3D) images revealed declustered KT signals resulting due to Dad2 depletion in J108 (PCK1prDAD2/dad2) retained nuclear peripheral localization. Since peripheral nuclear localization of declustered KTs is maintained (Figure 6, b-b″, c-c″), we speculate that KTs, whether clustered or not, remain largely attached to nuclear periphery through some components that are not affected due to depletion of an individual KT protein.

Fig. 6. Nuclear peripheral localization is maintained in disintegrated declustered kinetochores.

J108 (PCK1prDAD2/dad2) cells grown for 5 h under non-permissive conditions of the PCK1 promoter were fixed and stained with DAPI and anti-Cse4 antibodies. Images representing views from different rotational angles (a-a″, b-b′, c-c″) are shown in each case. Each wild-type cell exhibited a single bright dot-like signal of CENP-A/Cse4 at the periphery of the DAPI-stained nucleus (a-a″). Each Dad2-depleted cell, on the other hand, exhibited multiple weak CENP-A/Cse4 signals colocalized with a DAPI stained nucleus (b-b″ and c-c″). Similar to a single intact clustered KTs in the nucleus of each wild-type cell, multiple disintegrated declustered KT signals in the nucleus of each mutant cell were also localized at the nuclear periphery. An intact kinetochore stabilizes centromeric chromatin

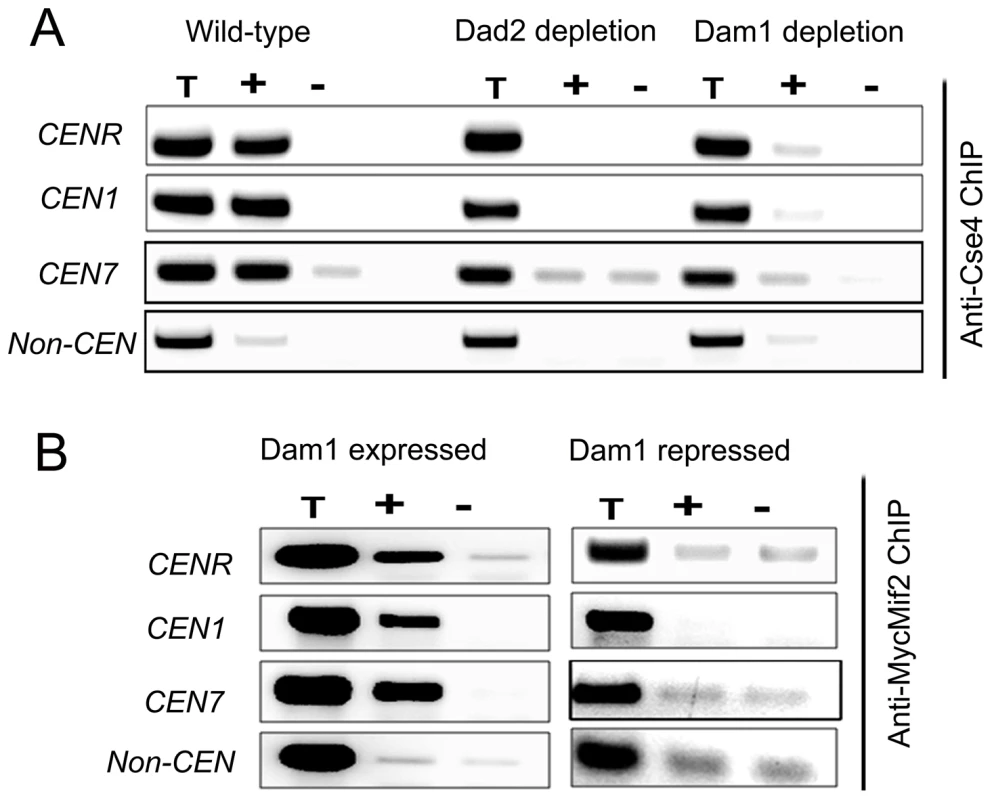

To examine the status of centromeric chromatin when KT integrity is lost, ChIP assays with anti-Cse4 antibodies were performed in BWP17 (wild-type), J102 (MET3prDAM1/dam1) and J108 (PCK1prDAD2/dad2) strains grown in non-permissive media for 8 h. These experiments revealed a drastic decrease in CENP-A binding to CENs in Dam1 or Dad2 depleted cells as compared to wild-type cells confirming that integrity of CENP-A-bound centromeric chromatin is highly affected in these mutants (Figure 7A). Since the localization of CENP-C/Mif2 was also affected when Dam1 was depleted we tested centromere occupancy of CENP-C/Mif2 in J125 (MIF2/PCK1pr12XMYCMIF2) or depleted levels of Dam1 in J123 (MET3prDAM1)/dam1 MIF2/PCK1pr12XMYCMIF2) by ChIP assays with anti-MycMif2 antibodies (Figure 7B). The ChIP-PCR analysis confirmed that CENP-C/Mif2 occupancy at centromeres was also dramatically reduced in Dam1 depleted cells as compared to wild-type cells. We have recently shown that, Mtw1/Mis12 is required for inner kinetochore assembly including localization of CENP-A and CENP-C [17]. Together these results confirmed that Dam1 is required for integrity of centromeric chromatin in C. albicans.

Fig. 7. The Dam1 complex maintains inner kinetochore assembly including integrity of centromeric chromatin.

(A) PCR analysis on Cse4 ChIP DNA obtained from wild-type BWP17, Dam1-depleted J102 (MET3prDAM1/dam1) or Dad2-depleted J108 (PCK1prDAD2/dad2) cells grown for 8 h in non-permissive conditions. Primers from CENR (CaChrR: 1747812–1748023), CEN1 (CaChr1: 1565723–1565967), CEN7 (CaChr7: 427369–427560) or 17 kb away from CEN7 (CaChr7: 444584–444875) (non-CEN) were used for PCR analysis. T, total DNA; +, IP DNA with anti-Cse4 antibodies and −, beads only control without antibodies. CENP-A/Cse4 recruitment was found to be highly reduced at centromeres in Dam1- or Dad2-depleted cells as compared to wild-type. (B) MycMif2 ChIP-PCR analysis with DNA obtained from J123 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 PCK1prMycMIF2/MIF2) either expressing Dam1 (WT) or depleted of it. Same primer pairs from CENR, CEN1, CEN7 or non-centromeric region LEU2 (non CEN) were used for PCR analysis. T, total DNA; +, IP DNA with anti-Myc antibodies and −, beads only control without antibodies. CENP-A is unstable in absence of an essential KT protein

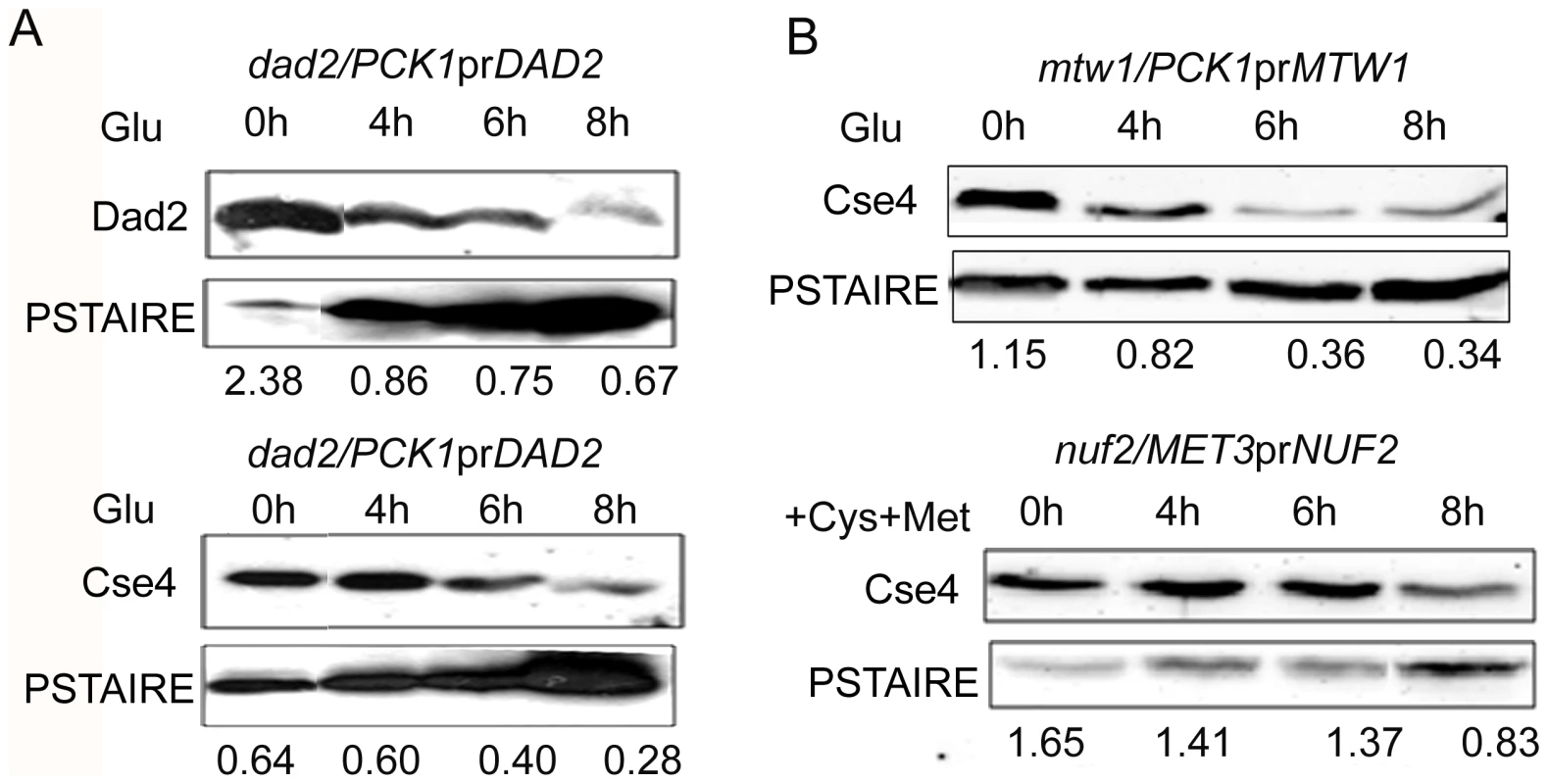

Since centromeric chromatin is disintegrated when various KT proteins are depleted, we examined protein levels of CENP-A in these conditions to find out the fate of CENP-A molecules that are no longer associated with centromeres. We prepared lysates from J108 (PCK1prDAD2/dad2) grown overnight in Suc (expressed condition) or various time intervals after transferring in Glu (repressed condition), and performed western blot analysis to measure the levels of both Dad2 and CENP-A. A decrease in Dad2 protein levels in cells grown at increasing time in Glu confirmed time-dependent repression of Dad2 expression by the PCK1 promoter (Figure 8A, top panel). Strikingly, a concomitant reduction in CENP-A levels, as determined by western blot analysis using anti-Cse4 antibodies, with decreasing levels of Dad2 was also observed (Figure 8A, bottom panel). To examine the fate of CENP-A in reduced levels of other subunits of the Dam1 complex, total cell lysates were prepared from strains where Dam1 (J102), Ask1 (J104), or Spc19 (J106) was either expressed or repressed for 8 h. As observed in Dad2-depleted cells, CENP-A levels in the total cell lysate were found to be highly reduced in absence of each of these proteins (Figure S5). Next we examined CENP-A stability in depleted conditions of CENP-C/Mif2, Mis12/Mtw1, and Nuf2 - evolutionarily conserved inner, middle and outer KT proteins respectively. Total cell lysate was prepared from each sample collected at different time points during Mif2/CENP-C, Mis12/Mtw1 or Nuf2 reprefssion in CAMB2 (PCK1prMIF/mif2), CAKS12 (PCK1prCSE4/cse4) or YJB12326 (MET3prNUF2/nuf2). Western blot analysis of these cell lysates with anti-Cse4 antibodies confirmed a decrease in CENP-A levels when either CENP-C (Figure S5), Mis12 or Nuf2 (Figure 8B) was depleted. Thus, CENP-A protein stability is dependent on wild-type levels of several KT proteins.

Fig. 8. CENP-A is protected by the kinetochore ensemble.

(A) J108 (PCK1prDAD2/dad2) was grown overnight in media expressing Dad2 (+Suc), transferred to media that repressed Dad2 (+Glu), and cells were harvested at specific time intervals as shown. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-Dad2, anti-Cse4 or anti-PSTAIRE antibodies with cell lysates prepared from these cells. Both Dad2 (left panels) and CENP-A/Cse4 (right panels) protein levels showed a gradual decrease as time of repression of Dad2 prolonged. PSTAIRE was used as the loading control. Increasing amount of protein was loaded to visualize the reduced Dad2 or CENP-A/Cse4 protein signals in these western blots. (B) Western blot analysis using anti-Cse4 and anti-PSTAIRE antibodies with cell lysates prepared from conditional mutant strains CAKS12 (PCK1prMTW1/mtw1) and YJB12326 (MET3prNUF2/nuf2) before (0 h) and at indicated time of incubation in non-permissive media after shift. Relative levels of Cse4 or Dad2 normalized by corresponding levels of PSTAIRE are shown. The proteasomal mediated pathway is involved in CENP-A degradation in absence of Dam1

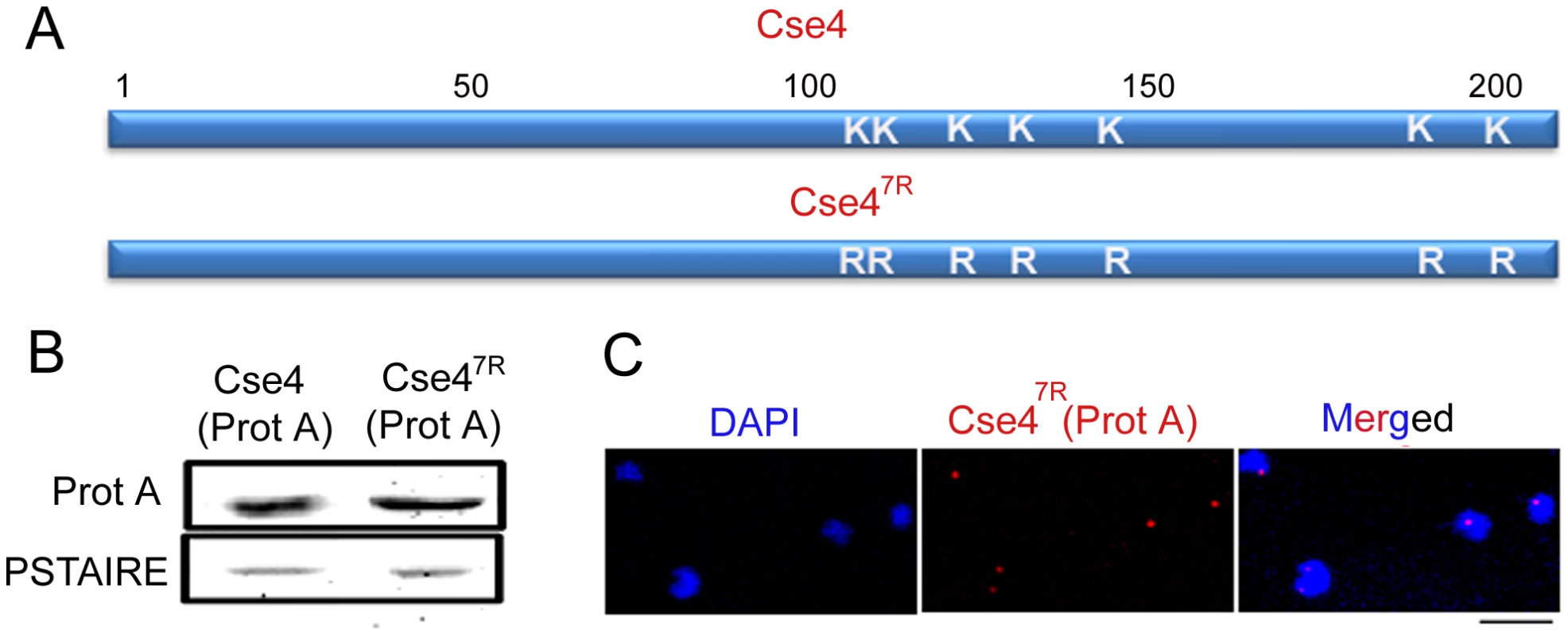

To investigate whether increased levels of CENP-A could rescue KT integrity in depleted levels of a KT protein we sought to express a mutant stable form of CENP-A in C. albicans. In budding yeast S. cerevisiae Cse4/CENP-A at non-centromeric regions is degraded by the proteasomal mediated degradation pathway which is partially prevented by replacement of all lysine residues with arginine residues in ScCse4 ORF. Using site-directed mutagenesis, all seven lysine residues in Cse4 ORF in C. albicans strain (CAKS2b) were replaced by arginine residues to construct the strain J129 (CSE47R-Prot A/cse4) where Protein A (Prot A) tagged mutated Cse47R is the only source of CENP-A (Figure 9A). All the changes were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Figure S6). Western blot analysis (Figure 9B) and immunolocalization (Figure 9C) using anti-Prot A antibodies revealed that Cse47R -Prot A is functionally expressed in C. albicans.

Fig. 9. Cse47R -Prot A is functional in C. albicans.

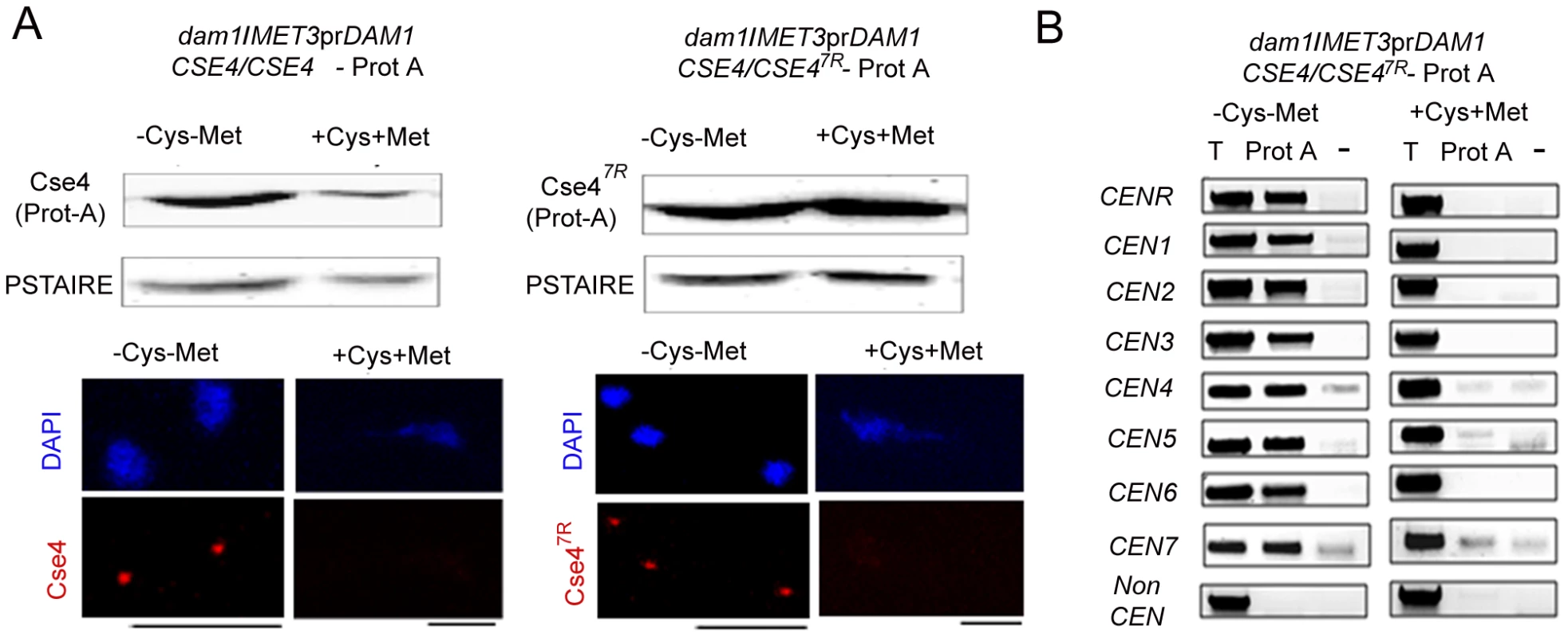

(A) Each of the 7 lysine (K) residues of Cse4 ORF shown in schematic has been mutated to arginine (R) residues by site-directed mutagenesis. (B) Lysates from strains expressing wild-type J128 (CSE4-Prot A/cse4) and J129 (CSE47R-Prot A/cse4) Cse4-Prot-A or Cse47R–Prot-A were subjected to western blot analysis with anti-Prot-A or anti-PSTAIRE antibodies. (C) Indirect immunolocalization by anti-Prot A (Cse4) antibodies in J129 (CSE47R-Prot A/cse4) exhibited normal KT localization patterns of Cse47R. Bar, 5 µm. To examine the effect of Dam1 depletion on the stability of Cse47R, we expressed Cse4-Prot A and Cse47R-Prot A in the Dam1 conditional mutant. Western blot analysis in J130 (MET3prDAM1)/dam1 CSE4-Prot A/CSE4) or J131 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 CSE47R-Prot A/CSE4) revealed that while wild-type Cse4-Prot A was degraded, Cse47R -Prot A remained stable upon Dam1 depletion (Figure 10A). This suggests that the proteasomal mediated pathway is involved in degradation of unbound CENP-A in C. albicans.

Fig. 10. Depletion of Dam1 leads to degradation of CENP-A/Cse4 through the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation pathway.

(A) Lysates were prepared from strains J130 (MET3prDAM1)/dam1 CSE4-Prot A/CSE4) and J131 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 CSE47R-Prot A/CSE4) expressing wild-type Cse4 -Prot A (left) or mutant Cse47R -Prot A (right) grown under conditions where Dam1 is either expressed (−Cys −Met) or repressed (+Cys +Met). Western blot analysis was performed with these lysates using anti-Prot A or anti-PSTAIRE antibodies. Indirect immunolocalization with anti-Cse4 antibodies revealed that recruitment of either wild-type Cse4 or mutant Cse47R at the kinetochore is compromised in absence of Dam1. (B) Prot A (Cse4) ChIP assays in strain J131 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 CSE47R-Prot A/CSE4) confirmed that stable mutated Cse47R is unable to maintain centromeric chromatin in absence of Dam1. CEN, centromeres; T, Total input DNA, Prot-A, immunoprecipitated DNA with anti-Prot A antibodies, −, beads only control. Bars, 5 µm. Cse47R fails to rescue kinetochore disassembly triggered by depleted levels of Dam1

To test whether increased levels of CENP-A (Cse47R ) could rescue KT disintegration caused by depletion of Dam1, we analysed Cse47R localization at the KTs in Dam1 mutant. Immunolocalization using anti-Cse4 antibodies in J130 (MET3prDAM1)/dam1 CSE4-Prot A/CSE4) or J131 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 CSE47R-Prot A/CSE4) cells revealed that similar to wild-type Cse4, Cse47R failed to localize at the KTs in absence of Dam1 (Figure 10A). Prot A ChIP analysis from J131 (MET3prDAM1/dam1 CSE47R-ProtA/CSE4) cells showed a significant drop in Cse47R binding to centromeres of all chromosomes under Dam1 depleted conditions. Thus Dam1 depletion leads to disintegration of centromeric chromatin containing wild-type CENP-A (Cse4) and stable form of CENP-A (Cse47R ) in the same manner (Figure 10B).

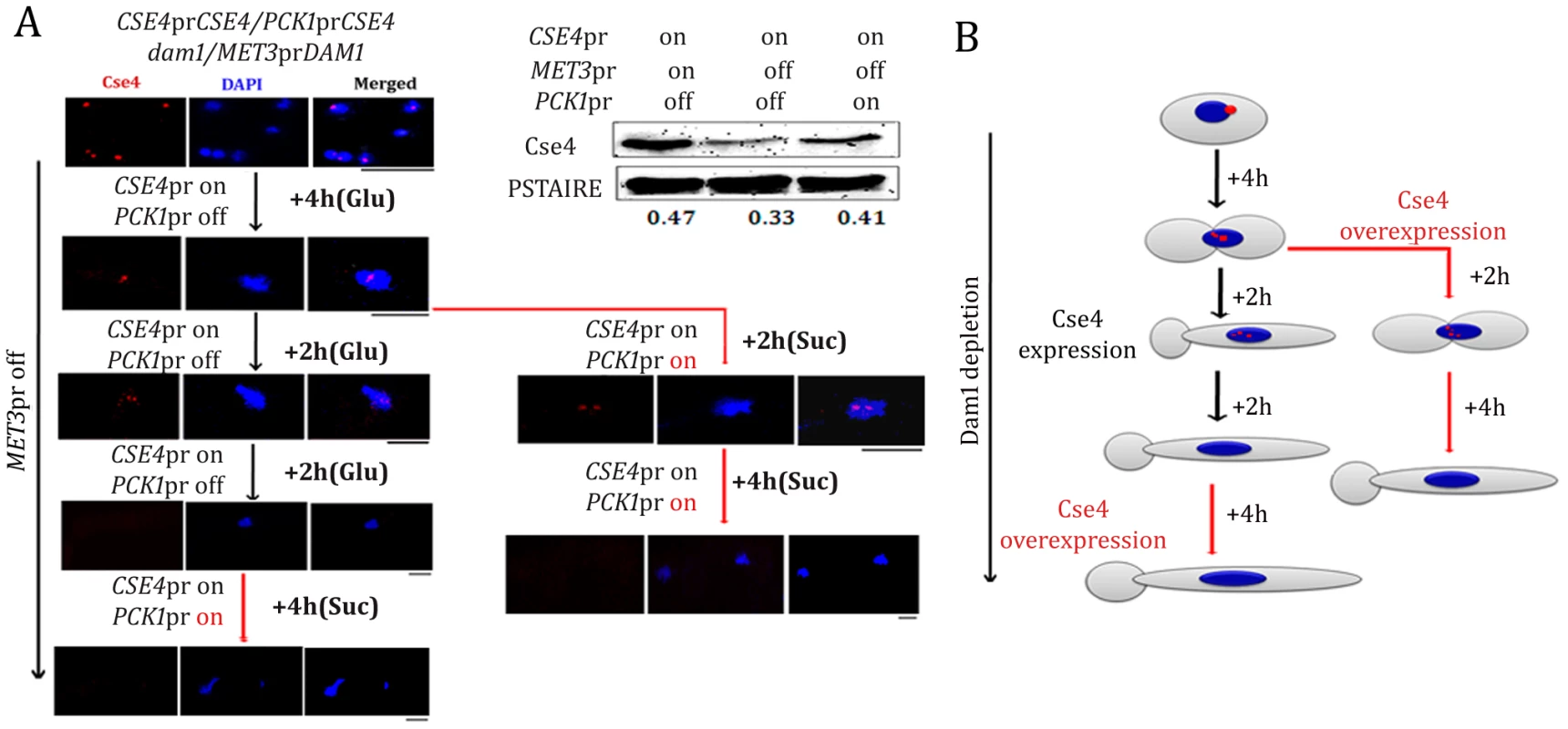

Newly synthesized CENP-A fails to localize at the kinetochores in absence of Dam1

We next examined whether newly synthesized CENP-A molecules can be recruited to the KT once the process of KT disassembly is initiated under Dam1 depleted conditions. We utilized YJB11990 (PCK1prCSE4/CSE4 MET3prDAM1/dam1) in which CSE4 and DAM1 are placed under control of the PCK1 and MET3 promoters respectively. We studied the fate of newly synthesized CENP-A molecules by inducing expression of CENP-A/Cse4 (+Suc) while Dam1 is kept in repressed state (+Cys +Met). To achieve this, YJB11990 was grown in Dam1 repressible conditions till the point where (a) KTs starts to decluster (4 h) or (b) KTs are disintegrated (8 h) (Figure 11A). These cells were then transferred to media that represses the MET3 promoter (+Cys +Met to keep Dam1 depleted) but induces the PCK1 promoter (+Suc to overexpress Cse4) and grown for an additional 4 h. Expression of new CENP-A/Cse4 molecules in such conditions was confirmed by western blot analysis (Figure 11A). Indirect immunolocalization using anti-Cse4 antibodies revealed that newly synthesized CENP-A/Cse4 molecules expressed from the induced PCK1 promoter (Figure 11A) could not be recruited at KTs under Dam1 repressible conditions (Figure 11B).

Fig. 11. Kinetochore localization of newly synthesized CENP-A/Cse4 is compromised in absence of wild-type levels of Dam1.

(A) Strain YJB11990 (PCK1prCSE4/CSE4, MET3prDAM1/dam1) was grown in conditions where CENP-A/Cse4 is expressed from its native promoter and Dam1 is expressed from the MET3 promoter (−Cys −Met +Glu). Overnight grown cells were then transferred to a media (+Cys +Met +Glu) that represses Dam1 expression but allows Cse4 expression only from its native promoter. After 4 h of growth in such conditions, one fraction (Fraction-I) of the culture was grown in the same media (+Cys +Met +Glu) for an additional 4 h. The second fraction (Fraction II) of the culture was transferred to a condition that overexpressed Cse4 but kept Dam1 repressed (+Cys +Met +Suc) for additional 6 h. Subsequently, Fraction-I grown for 8 h in +Cys +Met +Glu containing media was transferred to +Cys +Met +Suc and grown for an additional 4 h. Samples were collected from various time points indicated, fixed and stained with DAPI and anti-Cse4 antibodies. (B) Schematic showing the fate of newly synthesized CENP-A/Cse4 in Dam1 depleted conditions. Bars, 5 µm. Discussion

The kinetochore is a complex DNA-protein structure where more than 80–100 proteins assemble [23], [54], [55]. Although genetic, biochemical and microscopy studies on localization dependence of several key evolutionarily conserved KT proteins suggest a possible hierarchical assembly of a three-layered KT structure, it has also been proposed that the KT may not be assembled in a single linear order. Bloom and colleagues indicated CEN DNA bending caused by the CBF3 complex in S. cerevisiae or by CENP-B binding to alpha-satellite CEN DNA in mammalian centromeres may provide proper geometry for KT formation, a process that may be evolutionarily conserved [33]. In this work, we chose to delineate the process of KT assembly in another budding yeast C. albicans. De novo centromere formation does not take place in C. albicans suggesting that centromere formation is epigenetically determined [45]. It has also been shown that centromeres can form very efficiently on non-centromeric locations in C. albicans when a native centromere is deleted from a chromosome [37]. All these observations point toward sequence independent assembly of a KT. C. albicans lacks homologs of sequence-specific DNA binding centromeric proteins such as subunits of the point centromere-specific CBF3 complex or regional centromere-specific CENP-B. Neocentromere formation does not take place in S. cerevisiae as centromere identity is strictly maintained in sequence-dependent manner by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. CENP-B is absent from the KT assembled on human neocentromeres unlike most of other KT proteins [38] suggesting that the mechanism of KT assembly on neocentromere might be different from that of an endogenous centromere in humans. In absence of any known KT protein that binds to a specific sequence motif as well as absence of any conserved DNA sequence common to all CENs, C. albicans provides a unique system to study KT assembly that relies on an epigenetic sequence-independent process.

CENP-A localization depends on various kinetochore proteins in C. albicans

CENP-A is required for localization of many KT proteins [12], [14], [15]. In S. cerevisiae, inner and middle KT proteins (Ndc10, Mif2, Mtw1, and Okp1) showed 50% decrease in occupancy at the active conditional centromere (cCEN) in absence of CENP-A/Cse4, whereas the middle (Ctf19) and many outer (Ndc80, Dam1, Ask1, and Stu2) KT proteins completely failed to localize [43]. This suggests that CENP-A/Cse4 is the initiator of KT assembly. However, several kinetochore proteins do not require CENP-A for localization, suggesting that CENP-A independent species-specific KT assembly pathways also exist in certain organisms [15], [18], [56]. CENP-A localization has been shown to influence Mis12 localization in S. cerevisiae, D. melanogaster and humans but not in S. pombe [55], [57]–[59]. On the other hand, Mis12 does not influence localization of CENP-A in most organisms except in C. albicans where CENP-A and Mis12 localization is interdependent [15], [55], [58], [59]. Depletion of CENP-A affects CENP-C localization in S. cerevisiae, C. elegans and humans but CENP-C has no effect on CENP-A localization in these organisms [13], [14].

In this study, we examined how CENP-A localization is influenced by other KT proteins in C. albicans. Intriguingly, centromere localization of CENP-A was dramatically reduced due to depletion of inner (Mif2/CENP-C) or outer (Dam1 complex and Nuf2) KT proteins. Recently, we showed that a middle KT protein Mis12/Mtw1 homolog C. albicans influences assembly of two inner KT proteins CENP-A and CENP-C [17]. Thus localization dependence of CENP-A on various KT proteins varies from species to species.

An interdependent coordinated protein circuitry stabilizes the kinetochore structure

Since it is unusual and striking that outer KT proteins influence localization of CENP-A, we further investigated localization dependence of various other proteins to determine the sequence of events that lead to KT formation on unique short regional centromeres of C. albicans. An unprecedented observation of collapse of the KT architecture in absence of an essential protein from a KT in C. albicans raises an important question. How do KTs assemble in C. albicans? KT disassembly due to depletion of various proteins suggests that KT assembly is probably not a step-wise process in C. albicans. We propose that KT proteins of various sub-complexes assemble in a unique interdependent concerted manner to form and stabilize the macromolecular KT architecture in C. albicans Our results thus indicate that the KT in C. albicans may not even have a layered structure, unlike the one observed in humans.

Stability of the kinetochore structure is independent of structural integrity of the mitotic spindle

Since all proteins we analyzed in this study have been previously shown to be essential for the proper dynamics of a mitotic spindle in C. albicans [17], [48], [49] we investigated whether or not an intact mitotic spindle is required for maintaining integrity of KTs. Localization of CENP-A or Mis12 was found to be unaffected in presence of a MT-depolymerizing drug nocodazole. In NOC treated cells tubulin staining showed two weak dot-like signals probably representing SPBs after duplication. Cse4 and Mtw1 GFP signals in NOC treated cells are also seen as two dots situated close to each other. Thus we conclude that stabilization of the KT structure is independent of structural integrity of the mitotic spindle.

The kinetochore ensemble maintains integrity of the kinetochore cluster in C. albicans

Like S. cerevisiae, KT-MT interaction is established early during S phase in C. albicans. Live cell imaging by time-lapse microscopy in our previous study revealed that all centromeres are clustered together throughout the cell cycle in C. albicans [17]. Moreover, similar localization patterns of these clustered centromeres at the nuclear periphery were observed both in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans. In absence of a metaphase plate in budding yeasts [60], clustered centromeres may provide a platform for MT attachment and synchronous separation of sister chromatids during anaphase. Conditional KT mutants provided us an opportunity to follow the process of KT disassembly in a time dependent manner during gradual depletion of various KT proteins in C. albicans. Our results clearly indicate that disintegration of the KT cluster is a common intermediate step before KT collapse and each component is required to keep all the KTs clustered in C. albicans. Chromosome confirmation capture (3C) assay to study interaction among centromeres of different chromosomes in S. cerevisiae revealed that crosslinking frequencies between different centromeres is significantly higher than other chromosomal sites except telomeric regions [61]. A recent study, where chromosome confirmation capture on chip (4C) and massively parallel sequencing were used to globally capture inter and intrachromosomal interactions in S. cerevisiae, demonstrates centromeres as the chromosome landmarks that mediate interchromosomal interaction [32]. The clustering of centromeres that marked the primary point of engagement between different chromosomes was the most striking feature of the inter-chromosomal contacts. In the light of these observations in S. cerevisiae and our results in this study, we speculate that interchromosomal interaction at the centromeres may facilitate stabilization of the kinetochore ensemble as depletion of various KT proteins leads to disintegration of clustered centromeres in both species.

An intact kinetochore protects CENP-A from degradation

ChIP analysis and immunolocalization studies confirmed that CENP-A occupancy is severely impaired when an essential KT protein is depleted from C. albicans cells. We predicted that disintegration of centromeric chromatin in absence of KT proteins may expose free CENP-A molecules for cellular degradation. Indeed, western blot analysis confirmed that cellular CENP-A protein levels were drastically reduced in KT mutants tested. Since integrity of centromeric chromatin is also dependent upon individual KT proteins which in turn help in maintaining overall KT integrity, it is tempting to speculate that establishment of centromeric chromatin and assembly of KTs start together in a coordinated way in C. albicans.

The proteasomal mediated pathway of CENP-A degradation is evolutionarily conserved

The ubiquitin mediated degradation pathway is one of the major pathways that degrade CENP-A/Cse4 in S. cerevisiae and CENP-A/CID in Drosophila. In Dam1 depleted strain where wild-type Cse4 is unstable, the mutant Cse47R showed higher stability suggesting a similar CENP-A degradation pathway is active in C. albicans. Thus, although the process of CENP-A recruitment on point and regional centromeres may differ but the mechanism that regulates CENP-A stability to prevent ectopic KT formation (especially in C. albicans where efficiency of neocentromere formation is remarkably high) seem to be conserved among organisms carrying point and regional centromeres.

Dam1 is required for CENP-A recruitment at the kinetochores

Wild-type CENP-A is unstable when the KT ensemble is disintegrated and centromeric chromatin is disrupted in absence of an essential KT protein. It is possible that reduction in CENP-A levels is the cause not the consequence of KT disassembly under such conditions. We wondered whether expression of a stable form of CENP-A (Cse47R) can prevent disintegration of the KT structure in absence of Dam1. We examined stable mutant CENP-A, Cse47R localization at the KT in Dam1 depleted cells and found that increasing the stability of CENP-A (confirmed by western blot analysis) does not prevent CENP-A delocalization at the KT in absence of Dam1. The Cse47R failed to maintain integrity of centromeric chromatin as well. Next we sought to provide new CENP-A molecules using an inducible promoter (PCK1) to examine if newly synthesized CENP-A can be recruited to the KTs in absence of Dam1. However, these newly synthesized CENP-A molecules (detected by western blot analysis) failed to rescue KT integrity further confirming that an individual KT protein is absolutely essential for protecting the centromeric bound CENP-A by maintaining the integrity of the KT ensemble that is laid on the foundation of CENP-A associated centromeric chromatin.

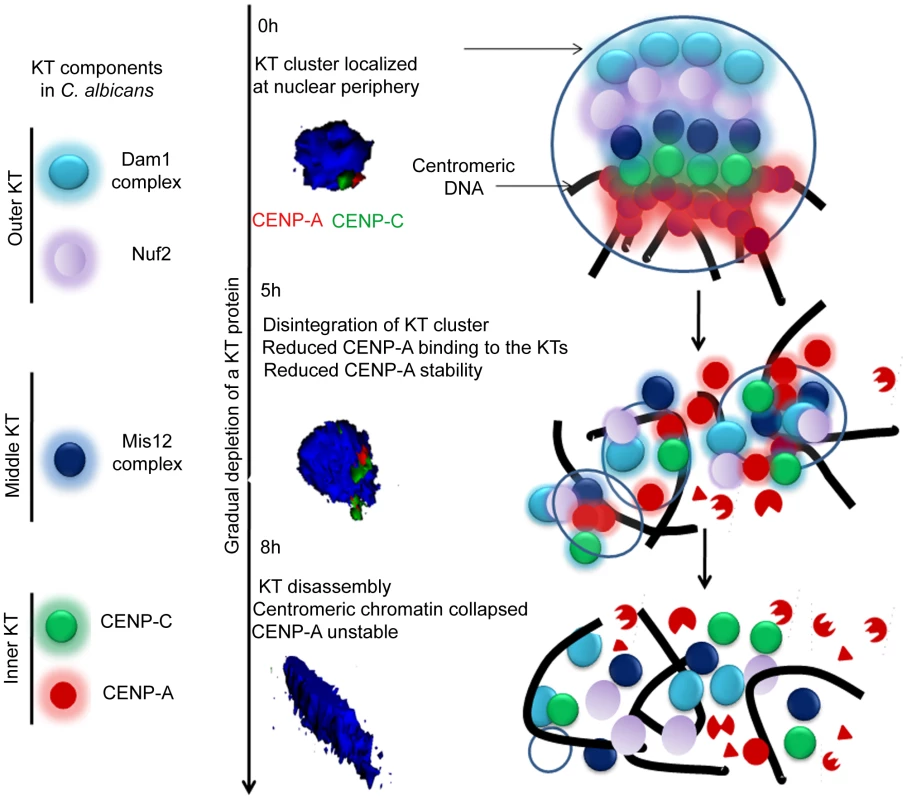

Figure 12 shows a possible pathway of KT destabilization due to depletion of an essential KT protein in C. albicans.

Fig. 12. The dynamics of kinetochore assembly/disassembly in C. albicans.

Cellular levels of an essential KT protein maintain centromere clustering and integrity of a KT formed on the foundation of CENP-A containing centromeric chromatin. The clustered KTs maintain integrity of centromeric chromatin to protect CENP-A from degradation. A gradual depletion (5 h) of any of the proteins from the inner, middle or outer KT results in declustering of KTs followed by disassembly (8 h) of the KT ensemble. Disassembled KTs fail to protect centromeric chromatin. CENP-A molecules that are no longer assembled into centromeric chromatin eventually get degraded by the proteasomal mediated pathway. The 3D images represented were constructed from original images in Figure 3. Materials and Methods

Strain construction

Strains and primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 and Table S2 respectively.

Construction of conditional mutants expressing epitope tagged kinetochore proteins

To visualize Mtw1 under Ask1 and Dam1 depleted conditions, we constructed Dam1 and Ask1 conditional mutant strains in YJB10695 (MTW1/MTW1GFP). The first copy of each of DAM1 or ASK1 was replaced by HIS1 in YJB10695. We used long primers (100–120 bp) (Table S2) whose 5′ end were homologous to sequences upstream and downstream of each gene, and 3′ ends were homologous to HIS1 gene. Using these primers deletion cassettes for ASK1 and DAM1 were amplified from the plasmid HIS1GFP [62]. Each deletion construct which carries sequences upstream and downstream of ASK1 or HIS1 flanked by HIS1 gene was used to transform YJB10695. Transformants were then selected on complete media lacking histidine (CM-His). In resulting strains J119 or J121 the remaining wild-type allele of DAM1 or ASK1 was placed under control of the MET3 promoter [50]. We replaced CaURA3 with C. dubliniensis ARG4 in the plasmids pAsk1MET3 or pDam1MET3 [49] that contained part of the corresponding ORF including the start codon of ASK1 or DAM1 respectively next to the MET3 promoter. Each of these resulting plasmids was linearized with ClaI to transform J119 or J121 and transformants were selected on media lacking arginine (CM-Arg). Resulting conditional Ask1 and Dam1 mutant strains were named J120 and J122 respectively.

To visualize Mif2 signals in Ask1 or Dam1 depleted conditions, we constructed strains expressing Myc-tagged Mif2 in Dam1 or Ask1 conditional mutant strains. A cassette containing PCK1prMycMIF2 was amplified from strain CAMB2 [46] using primers Mif2PckMycPst1-F and Mif2pck1SacII-R and subsequently cloned into PstI and SacII sites of pSF2A vector [63] that contained the nourseothricin (NAT) marker. The resulting plasmid was linearized using HpaI and introduced into J102 (Dam1 conditional mutant) or J104 (Ask1 conditional mutant) strains to get J123 (dam1/MET3DAM1, MIF2/PCK1prMycMIF2) or J124 (ask1/MET3ASK1, MIF2/PCK1prMycMIF2).

Construction of strains expressing Cse4-Prot A and Cse47R-Prot A

The CSE4 ORF was cloned into SacII and SpeI sites of pBluescript to construct pBSCSE4. All seven lysine residues were changed into arginine residues in the plasmid pBSCSE4 using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Cat # 200522) to construct pBSCSE47R. The TAP cassette (containing URA3 and TAP that contains Prot A) and CSE4 downstream sequences were cloned as NcoI/KpnI and KpnI/SacI fragments respectively into the corresponding sites of pUC19 to construct pCSE4DSTAP. The CSE47R fragment was amplified from pBSCSE47R, digested with SalI and NcoI and cloned into corresponding sites of pCSE4DSTAP to yield pCSE47RTAP. Similarly the CSE4 fragment was cloned into SalI and NcoI sites of pCSE4DSTAP to construct pCSE4TAP. Both pCSE4TAP and pCSE47RTAP were linearized using XhoI and these linearized fragments were used to transform CAKS2b (CSE4/ cse4::hisG ) to give rise to J128 (CSE4-TAP(URA3)/cse4::hisG ) and J129 (CSE47R-TAP(URA3)/cse4::hisG) respectively. Subsequently, J126 (dam1::HIS1 MET3prDAM1(ARG4)/dam1::HIS1) was transformed with XhoI-digested pCSE4TAP and pCSE47RTAP separately to give rise to J130 (dam1::HIS1 MET3prDAM1(ARG4)/dam1::HIS1 CSE4-TAP(URA3)/CSE4) and J131 (dam1::HIS1 MET3prDAM1(ARG4)/dam1::HIS1 CSE47R-TAP(URA3)/CSE4) respectively.

Media and growth conditions

Conditional mutant strains of Dam1 (J102, J121, J122, J127, J130, J131, YJB11990 and YJB12289), Ask1 (J104, J120, and J124), Spc19 (J106) and Nuf2 (YJB12326) that carry DAM1, ASK1 SPC19 and NUF2 respectively under control of the MET3 promoter were grown in YPDU (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 3% glucose and 0.01% uridine) as permissive media and YPDU+5 mM cysteine (+Cys)+5 mM methionine (+Met) as non-permissive media. Conditional mutant strains of Mif2 (CAMB2, J123, J124 and J125), Dad2 (J108), Cse4 (CAKS3b and YJB11483) and Mtw1 (CAKS12) that carry MIF2, DAD2, CSE4 and MTW1 respectively under control of the PCK1 promoter were grown in YPSU (1% Yeast Extract, 2% Peptone, 2% Succinate and 0.01% Uridine) as permissive media and YPDU as non-permissive media. All C. albicans strains were grown at 30°C.

GFP imaging

C. albicans conditional mutants with GFP tagged KT proteins grown overnight in inducing media were transferred to repressible media at initial OD600 - 0.150. Cells were harvested at various time intervals after growth in repressible media. Harvested cells were resuspeneded in 50% glycerol and subsequently imaged using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 META). Images were further processed by Adobe Photoshop.

Nocodazole treatment

For nocodazole treatment, cells were grown overnight in YPDU, reinoculated in YPDU with an initial OD600 = 0.2. Nocodazole (Sigma, Cat # M1404) was added at a concentration of 20 µg/ml when OD600 = 0.4 (1 generation) was achieved. Cells were grown for an additional 4 h before harvesting for immunolocalization and ChIP assays.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were performed using a protocol described previously [49]. An exponentially growing culture of C. albicans strain was fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min. The reaction was quenched for 5 min at room temperature using glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM. Cells were washed and suspended in resuspension buffer (0.2 mM Tris-HCl pH, 9.4, 10 mM DTT). Resuspended cells were incubated at 30°C for 15 min on a shaker at 180 rpm. Cells were washed and resuspended in spheroplasting buffer (1.2 M Sorbitol, 20 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5). Spheroplasting (95%) was performed using lyticase (Sigma, Cat # L2524) at 30°C at low speed. Spheroplasting was stopped by adding ice-cold postspheroplasting buffer (1.2 M Sorbitol, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Na-PIPES, pH 6.8). Spheroplasts were subsequently washed with ice-cold 1× PBS, Buffer I (0.25% TritonX-100, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Na-HEPES, pH 6.5), Buffer II (200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Na-HEPES) and finally resuspended in extraction buffer (140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM K-HEPES, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.5) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) at a concentration of 100 µl/100 ml starting culture. Next, sonication was performed to get sheared chromatin fragments of an average size of 300–700 bp by SONICS Vibra cell sonicator. The soluble fraction of sheared chromatin was obtained by centrifuging the sonicated solution at 13000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C.

Total DNA (T)

About 1/10th of total soluble chromatin was processed separately as total DNA (whole cell lysate). Equal volume of elution buffer I (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8/10 mM EDTA/1% SDS) was added to the chromatin solution separated for Total DNA, and incubated at 65°C overnight to reverse crosslinking. TE (1×, 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA,) was added to the starting material to make final SDS concentration 0.5%. Sample was treated with RNase A (Sigma # R4875) and Proteinase K (NEB Cat # P8102). The DNA was extracted with an equal volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25∶24∶1) in the presence of 0.4 M LiCl and precipitated with ethanol for 15 min at room temperature. It was spun at 16,000× g for 20 min at room temperature. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in TE.

Immunoprecipitated material (IP)

Rest of the soluble chromatin solution was diluted 5.7-fold with IP dilution buffer (167 mM NaCl, 1.1 mM EDTA, 1.1% Triton X-100, 167 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0) and divided equally in two tubes. Rabbit anti-CaCse4p antibody was added to a final concentration of 4 µg/ml in one tube (+Ab) and no antibody (−Ab) was added to the other. The tubes were slowly rotated overnight at 4°C. A slurry of Protein A-Sepharose beads (50 µl per ml of 50% slurry in TE) (Sigma) was added and the tube was again rotated overnight at 4°C. Next beads were sequentially washed twice in 12 ml of extraction buffer, and once each in 12 ml of extraction buffer+500 mM NaCl, LiCl wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 250 mM LiCl, 1 mM Igepal CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate/1 mM EDTA) and TE. Beads were subjected to elution of IP complexes in elution buffer I (1/10 volume of IP dilution buffer) at 65°C for 15 min, and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. Supernatant was collected and beads were washed a second time with elution buffer II (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8/1 mM EDTA/0.67% SDS) for 5 min at 65°C and the supernatant was collected as above. Pooled eluates were incubated overnight at 65°C to reverse crosslinking. To purify DNA, the SDS concentration was diluted to 0.5% with TE, and the reaction was treated with RNase A, followed by Proteinase K. The 4 M LiCl was added to a final concentration of 0.4 M and the DNA was extracted with an equal volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25∶24∶1). Aqueous layer was precipitated in 100% ethanol overnight at −20°C. DNA was recovered by centrifugation at 16,000× g for 45 min at 4°C, washed with 70% ethanol, spun for 15 min, and the DNA pellet was dried for 30 min. The recovered DNA was resuspended in TE.

ChIP assays with anti-Myc antibodies in J123 (MycMIF2) or anti-Prot-A antibodies were performed using the same protocol except for the following modification. J123 cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 45 min. The protein enrichment on a specific DNA sequence was determined by specific PCR primers (Table S2).

Subcellular immunolocalization

Indirect immunofluoroscence was performed using protocol described previously [49]. Asynchronous and exponentially growing culture was fixed using 1 ml 37% formaldehyde per 10 ml culture for 1 h. Fixed cells were washed and resuspended in 0.1 M Phosphate buffer (pH 6.4). Next, 70–80% spheroplasting was achieved using lyticase (Sigma) and β-mercaptoethanol. Spheroplasts were pelleted down gently at low speed and resuspended in PBS. Teflon coated slide was incubated with polylysine (1 mg/ml) for 5 min, washed with water and dried. Next 15 µl of fixed cells were placed onto each well and incubated for 5 min. Cells attached to the slides were fixed in ice cold methanol (−20°C) for 6 min and ice-cold acetone (−20°C) for 30 seconds. Blocking was performed with 2% skim milk in PBS for 30 min. Subsequently cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h and washed with PBS four times. Subsequently, secondary antibodies were added onto each well and incubated 1 h in a dark humid chamber. Finally the slide was washed four times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). DAPI solution (50 ng/ml in 70% glycerol) was added on to each well and coverslip and slide were sealed together. Co-immunolocalization experiments were performed using the same protocol.

Image analysis

Images were captured using Carl Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510 META) using LSM 5 Image Examiner. Three dimentional (3D) images were generated using LSM 3D rendering software (Figure 6 and Figure 12) (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Images were rotated in 3D and snapshots were taken from three different rotational angles (a-a″, b-b′, c-c″) in Figure 6. Images were susequently processed in Adobe Photoshop.

Western blot analysis

Wild-type or conditional mutant strains were grown under inducing and repressed conditions for 8 h. Protein extracts were made by disrupting the cells in RIPA buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.5% Triton-X) using glass beads (Sigma cat # G8772). The lysate were subjected to electrophoresis using 12% SDS PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for 1 h at 20 V by semi-dry method. Proper transfer was checked by Ponceau S staining. Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h followed by incubation with primary antibodies in 5% skim milk overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed five times with PBS+0.05% Tween and incubated with secondary antibodies in 5% skim milk for 2 h. Membranes were washed five times with 1× PBS+0.05% Tween and developed by VersaDoc (Bio-Rad) or exposed to X-ray films. Quantification of the western blots was performed using the Quantity one software (Bio-Rad).

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used for immunolocalization studies were as follows - affinity purified rabbit anti-Dad2 antibodies-1∶50 dilution, affinity purified rabbit anti-CENP-A antibodies - 1∶500 dilution [48], mouse anti-Myc -1∶50 dilution (Calbiochem, Cat # OP10L), rabbit anti-Prot A - 1∶1500 (Sigma Cat # P2921), rat anti-tubulin (Invitrogen, Cat # YOL1/34) - 1∶100 dilution. The fluorescent secondary antibodies for immunolocalization were obtained from Invitrogen and used at dilution 1∶500 for Alexa Fluor goat anti-rabbit IgG 568 (Cat #A11011) , 1∶100 for Alexa Fluor goat anti-rat IgG 488 (Cat # A11006) and 1∶500 for Alexa Fluor anti -mouse 488 (Cat # A11001).

Primary antibodies used for western blot analysis were rabbit anti-CENP-A (1∶500), mouse anti-PSTAIRE (1∶2000, Sigma Cat # P7962), rabbit anti-Prot A (1∶ 5000, Sigma Cat # P2921) and rabbit anti-Dad2 (1∶500, unpurified sera) antibodies. Secondary antibodies used were anti-rabbit HRP conjugated (1∶2000, Bangalore Genei Cat # 105499), anti-mouse HRP conjugated (1∶2000, Bangalore Genei, Cat # HP06).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. AllshireRCKarpenGH 2008 Epigenetic regulation of centromeric chromatin: old dogs, new tricks? Nat Rev Genet 9 923 937

2. ClarkeLCarbonJ 1980 ISOLATION OF A YEAST CENTROMERE AND CONSTRUCTION OF FUNCTIONAL SMALL CIRCULAR CHROMOSOMES. Nature 287 504 509

3. ClarkeL 1990 Centromeres of budding and fission yeasts. Trends Genet 6 150 154

4. FishelBAmstutzHBaumMCarbonJClarkeL 1988 Structural organization and functional analysis of centromeric DNA in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol 8 754 763

5. SunXWahlstromJKarpenG 1997 Molecular structure of a functional Drosophila centromere. Cell 91 1007 1019

6. CamahortRLiBFlorensLSwansonSKWashburnMP 2007 Scm3 is essential to recruit the histone h3 variant cse4 to centromeres and to maintain a functional kinetochore. Mol Cell 26 853 865

7. CamahortRShivarajuMMattinglyMLiBNakanishiS 2009 Cse4 is part of an octameric nucleosome in budding yeast. Mol Cell 35 794 805

8. DimitriadisEKWeberCGillRKDiekmannSDalalY 2010 Tetrameric organization of vertebrate centromeric nucleosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 20317 20322

9. MizuguchiGXiaoHWisniewskiJSmithMMWuC 2007 Nonhistone Scm3 and histones CenH3-H4 assemble the core of centromere-specific nucleosomes. Cell 129 1153 1164

10. FoltzDRJansenLEBaileyAOYatesJRBassettEA 2009 Centromere-specific assembly of CENP-a nucleosomes is mediated by HJURP. Cell 137 472 484

11. EkwallK 2007 Epigenetic control of centromere behavior. Annu Rev Genet 41 63 81

12. BlowerMDKarpenGH 2001 The role of Drosophila CID in kinetochore formation, cell-cycle progression and heterochromatin interactions. Nat Cell Biol 3 730 739

13. DesaiARybinaSMüller-ReichertTShevchenkoAHymanA 2003 KNL-1 directs assembly of the microtubule-binding interface of the kinetochore in C. elegans. Genes Dev 17 2421 2435

14. OegemaKDesaiARybinaSKirkhamMHymanAA 2001 Functional analysis of kinetochore assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol 153 1209 1226

15. GoshimaGKiyomitsuTYodaKYanagidaM 2003 Human centromere chromatin protein hMis12, essential for equal segregation, is independent of CENP-A loading pathway. J Cell Biol 160 25 39

16. HajraSGhoshSKJayaramM 2006 The centromere-specific histone variant Cse4p (CENP-A) is essential for functional chromatin architecture at the yeast 2-microm circle partitioning locus and promotes equal plasmid segregation. J Cell Biol 174 779 790

17. RoyBBurrackLSLoneMABermanJSanyalK 2011 CaMtw1, a member of the evolutionarily conserved Mis12 kinetochore protein family, is required for efficient inner kinetochore assembly in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol

18. HayashiTFujitaYIwasakiOAdachiYTakahashiK 2004 Mis16 and Mis18 are required for CENP-A loading and histone deacetylation at centromeres. Cell 118 715 729

19. TakahashiKTakayamaYMasudaFKobayashiYSaitohS 2005 Two distinct pathways responsible for the loading of CENP-A to centromeres in the fission yeast cell cycle. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360 595 606; discussion 606–597

20. OkadaMCheesemanIMHoriTOkawaKMcLeodIX 2006 The CENP-H-I complex is required for the efficient incorporation of newly synthesized CENP-A into centromeres. Nat Cell Biol 8 446 457

21. ClevelandDWMaoYSullivanKF 2003 Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell 112 407 421

22. LechnerJCarbonJ 1991 A 240 kd multisubunit protein complex, CBF3, is a major component of the budding yeast centromere. Cell 64 717 725

23. De WulfPMcAinshADSorgerPK 2003 Hierarchical assembly of the budding yeast kinetochore from multiple subcomplexes. Genes Dev 17 2902 2921

24. CheesemanIMDesaiA 2008 Molecular architecture of the kinetochore-microtubule interface. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9 33 46

25. McAinshADTytellJDSorgerPK 2003 Structure, function, and regulation of budding yeast kinetochores. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19 519 539

26. WelburnJPGrishchukELBackerCBWilson-KubalekEMYatesJR 2009 The human kinetochore Ska1 complex facilitates microtubule depolymerization-coupled motility. Dev Cell 16 374 385

27. BharadwajRQiWYuH 2004 Identification of two novel components of the human NDC80 kinetochore complex. J Biol Chem 279 13076 13085

28. CheesemanIMBrewCWolyniakMDesaiAAndersonS 2001 Implication of a novel multiprotein Dam1p complex in outer kinetochore function. J Cell Biol 155 1137 1145

29. Enquist-NewmanMCheesemanIMVan GoorDDrubinDGMeluhPB 2001 Dad1p, third component of the Duo1p/Dam1p complex involved in kinetochore function and mitotic spindle integrity. Mol Biol Cell 12 2601 2613

30. JankeCOrtizJTanakaTULechnerJSchiebelE 2002 Four new subunits of the Dam1-Duo1 complex reveal novel functions in sister kinetochore biorientation. Embo Journal 21 181 193

31. JinQWFuchsJLoidlJ 2000 Centromere clustering is a major determinant of yeast interphase nuclear organization. J Cell Sci 113 Pt 11 1903 1912

32. DuanZAndronescuMSchutzKMcIlwainSKimYJ 2010 A three-dimensional model of the yeast genome. Nature 465 363 367

33. AndersonMHaaseJYehEBloomK 2009 Function and assembly of DNA looping, clustering, and microtubule attachment complexes within a eukaryotic kinetochore. Mol Biol Cell 20 4131 4139

34. FunabikiHHaganIUzawaSYanagidaM 1993 Cell cycle-dependent specific positioning and clustering of centromeres and telomeres in fission yeast. J Cell Biol 121 961 976

35. BrennerSPepperDBernsMWTanEBrinkleyBR 1981 Kinetochore structure, duplication, and distribution in mammalian cells: analysis by human autoantibodies from scleroderma patients. J Cell Biol 91 95 102

36. MonenJMaddoxPSHyndmanFOegemaKDesaiA 2005 Differential role of CENP-A in the segregation of holocentric C. elegans chromosomes during meiosis and mitosis. Nat Cell Biol 7 1248 1255

37. KetelCWangHSMcClellanMBouchonvilleKSelmeckiA 2009 Neocentromeres form efficiently at multiple possible loci in Candida albicans. PLoS Genet 5 e1000400 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000400

38. MarshallOJChuehACWongLHChooKH 2008 Neocentromeres: new insights into centromere structure, disease development, and karyotype evolution. Am J Hum Genet 82 261 282

39. IshiiKOgiyamaYChikashigeYSoejimaSMasudaF 2008 Heterochromatin integrity affects chromosome reorganization after centromere dysfunction. Science 321 1088 1091

40. WilliamsBCMurphyTDGoldbergMLKarpenGH 1998 Neocentromere activity of structurally acentric mini-chromosomes in Drosophila. Nat Genet 18 30 37

41. Moreno-MorenoOTorras-LlortMAzorínF 2006 Proteolysis restricts localization of CID, the centromere-specific histone H3 variant of Drosophila, to centromeres. Nucleic Acids Res 34 6247 6255

42. CollinsKAFuruyamaSBigginsS 2004 Proteolysis contributes to the exclusive centromere localization of the yeast Cse4/CENP-A histone H3 variant. Curr Biol 14 1968 1972

43. CollinsKACastilloARTatsutaniSYBigginsS 2005 De novo kinetochore assembly requires the centromeric histone H3 variant. Mol Biol Cell 16 5649 5660

44. JoglekarAPBouckDFinleyKLiuXWanY 2008 Molecular architecture of the kinetochore-microtubule attachment site is conserved between point and regional centromeres. J Cell Biol 181 587 594

45. BaumMSanyalKMishraPKThalerNCarbonJ 2006 Formation of functional centromeric chromatin is specified epigenetically in Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 14877 14882

46. SanyalKBaumMCarbonJ 2004 Centromeric DNA sequences in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans are all different and unique. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 11374 11379

47. PadmanabhanSThakurJSiddharthanRSanyalK 2008 Rapid evolution of Cse4p-rich centromeric DNA sequences in closely related pathogenic yeasts, Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 19797 19802

48. SanyalKCarbonJ 2002 The CENP-A homolog CaCse4p in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans is a centromere protein essential for chromosome transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 12969 12974

49. ThakurJSanyalK 2011 The essentiality of the fungus-specific Dam1 complex is correlated with a one-kinetochore-one-microtubule interaction present throughout the cell cycle, independent of the nature of a centromere. Eukaryot Cell 10 1295 1305

50. CareRSTrevethickJBinleyKMSudberyPE 1999 The MET3 promoter: a new tool for Candida albicans molecular genetics. Mol Microbiol 34 792 798

51. LeukerCESonnebornADelbrückSErnstJF 1997 Sequence and promoter regulation of the PCK1 gene encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Gene 192 235 240

52. TanakaTU 2010 Kinetochore-microtubule interactions: steps towards bi-orientation. EMBO J 29 4070 4082

53. TanakaKKitamuraETanakaTU 2010 Live-cell analysis of kinetochore-microtubule interaction in budding yeast. Methods 51 206 213

54. LiuXMcLeodIAndersonSYatesJRHeX 2005 Molecular analysis of kinetochore architecture in fission yeast. EMBO J 24 2919 2930

55. LiuSTRattnerJBJablonskiSAYenTJ 2006 Mapping the assembly pathways that specify formation of the trilaminar kinetochore plates in human cells. J Cell Biol 175 41 53

56. RégnierVVagnarelliPFukagawaTZerjalTBurnsE 2005 CENP-A is required for accurate chromosome segregation and sustained kinetochore association of BubR1. Mol Cell Biol 25 3967 3981

57. WestermannSCheesemanIMAndersonSYatesJRDrubinDG 2003 Architecture of the budding yeast kinetochore reveals a conserved molecular core. J Cell Biol 163 215 222

58. PrzewlokaMRZhangWCostaPArchambaultVD'AvinoPP 2007 Molecular analysis of core kinetochore composition and assembly in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 2 e478 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000478

59. TakahashiKChenESYanagidaM 2000 Requirement of Mis6 centromere connector for localizing a CENP-A-like protein in fission yeast. Science 288 2215 2219

60. StraightAFMarshallWFSedatJWMurrayAW 1997 Mitosis in living budding yeast: anaphase A but no metaphase plate. Science 277 574 578

61. DekkerJRippeKDekkerMKlecknerN 2002 Capturing chromosome conformation. Science 295 1306 1311

62. Gerami-NejadMBermanJGaleCA 2001 Cassettes for PCR-mediated construction of green, yellow, and cyan fluorescent protein fusions in Candida albicans. Yeast 18 859 864

63. ReussOVikAKolterRMorschhäuserJ 2004 The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 341 119 127

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek A Genome-Wide Screen for Genetic Variants That Modify the Recruitment of REST to Its Target GenesČlánek Population Structure of Hispanics in the United States: The Multi-Ethnic Study of AtherosclerosisČlánek Differing Requirements for RAD51 and DMC1 in Meiotic Pairing of Centromeres and Chromosome Arms inČlánek Transcriptional Regulation of Rod Photoreceptor Homeostasis Revealed by NRL Targetome AnalysisČlánek Cell Contact–Dependent Outer Membrane Exchange in Myxobacteria: Genetic Determinants and MechanismČlánek Formation of Rigid, Non-Flight Forewings (Elytra) of a Beetle Requires Two Major Cuticular Proteins

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 4

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Runs of Homozygosity Implicate Autozygosity as a Schizophrenia Risk Factor

- Modifier Genes and the Plasticity of Genetic Networks in Mice

- The DSIF Subunits Spt4 and Spt5 Have Distinct Roles at Various Phases of Immunoglobulin Class Switch Recombination

- A Genome-Wide Screen for Genetic Variants That Modify the Recruitment of REST to Its Target Genes

- Population Structure of Hispanics in the United States: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- Deep Sequencing of Plant and Animal DNA Contained within Traditional Chinese Medicines Reveals Legality Issues and Health Safety Concerns

- Differing Requirements for RAD51 and DMC1 in Meiotic Pairing of Centromeres and Chromosome Arms in

- Insulin Signaling Mediates Sexual Attractiveness in

- Progressive Telomere Dysfunction Causes Cytokinesis Failure and Leads to the Accumulation of Polyploid Cells

- Long-Range Chromosome Organization in : A Site-Specific System Isolates the Ter Macrodomain

- Regulation of Budding Yeast Mating-Type Switching Donor Preference by the FHA Domain of Fkh1

- Polyglutamine Toxicity Is Controlled by Prion Composition and Gene Dosage in Yeast

- Patterns of Regulatory Variation in Diverse Human Populations

- Sequence-Specific Targeting of Dosage Compensation in Favors an Active Chromatin Context

- Whole-Exome Sequencing and Homozygosity Analysis Implicate Depolarization-Regulated Neuronal Genes in Autism

- Replication Fork Reversal after Replication–Transcription Collision

- Common Variants at 9p21 and 8q22 Are Associated with Increased Susceptibility to Optic Nerve Degeneration in Glaucoma

- Coordinate Regulation of Lipid Metabolism by Novel Nuclear Receptor Partnerships

- Epigenome-Wide Scans Identify Differentially Methylated Regions for Age and Age-Related Phenotypes in a Healthy Ageing Population

- A Coordinated Interdependent Protein Circuitry Stabilizes the Kinetochore Ensemble to Protect CENP-A in the Human Pathogenic Yeast

- Budding Yeast Dma Proteins Control Septin Dynamics and the Spindle Position Checkpoint by Promoting the Recruitment of the Elm1 Kinase to the Bud Neck

- , a Homolog of a Deaf-Blindness Gene, Regulates Circadian Output and Slowpoke Channels

- Transcriptional Regulation of Rod Photoreceptor Homeostasis Revealed by NRL Targetome Analysis

- Cell Contact–Dependent Outer Membrane Exchange in Myxobacteria: Genetic Determinants and Mechanism

- Defective Membrane Remodeling in Neuromuscular Diseases: Insights from Animal Models

- Formation of Rigid, Non-Flight Forewings (Elytra) of a Beetle Requires Two Major Cuticular Proteins

- SPE-44 Implements Sperm Cell Fate

- A Shared Role for RBF1 and dCAP-D3 in the Regulation of Transcription with Consequences for Innate Immunity

- A Companion Cell–Dominant and Developmentally Regulated H3K4 Demethylase Controls Flowering Time in via the Repression of Expression

- The HEN1 Ortholog, HENN-1, Methylates and Stabilizes Select Subclasses of Germline Small RNAs

- Improved Statistics for Genome-Wide Interaction Analysis

- The Probability of a Gene Tree Topology within a Phylogenetic Network with Applications to Hybridization Detection

- Context-Dependent Dual Role of SKI8 Homologs in mRNA Synthesis and Turnover

- Mu Insertions Are Repaired by the Double-Strand Break Repair Pathway of

- Competition between Replicative and Translesion Polymerases during Homologous Recombination Repair in Drosophila

- An Unbiased Assessment of the Role of Imprinted Genes in an Intergenerational Model of Developmental Programming

- Type 2 Diabetes Risk Alleles Demonstrate Extreme Directional Differentiation among Human Populations, Compared to Other Diseases

- Mutations in and Cause “Splashed White” and Other White Spotting Phenotypes in Horses

- Fine-Scale Mapping of Natural Variation in Fly Fecundity Identifies Neuronal Domain of Expression and Function of an Aquaporin

- Dynamics of Brassinosteroid Response Modulated by Negative Regulator LIC in Rice

- Genetic Inhibition of Solute-Linked Carrier 39 Family Transporter 1 Ameliorates Aβ Pathology in a Model of Alzheimer's Disease

- The Functions of Mediator in Support a Role in Shaping Species-Specific Gene Expression

- Patterns of Ancestry, Signatures of Natural Selection, and Genetic Association with Stature in Western African Pygmies

- Dissection of Pol II Trigger Loop Function and Pol II Activity–Dependent Control of Start Site Selection

- PIWI Associated siRNAs and piRNAs Specifically Require the HEN1 Ortholog

- Genome-Wide Patterns of Gene Expression in Nature

- Hypoxia Disruption of Vertebrate CNS Pathfinding through EphrinB2 Is Rescued by Magnesium

- A New Role for Translation Initiation Factor 2 in Maintaining Genome Integrity

- Sex Reversal in C57BL/6J XY Mice Caused by Increased Expression of Ovarian Genes and Insufficient Activation of the Testis Determining Pathway

- The Rac GTP Exchange Factor TIAM-1 Acts with CDC-42 and the Guidance Receptor UNC-40/DCC in Neuronal Protrusion and Axon Guidance

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- A Coordinated Interdependent Protein Circuitry Stabilizes the Kinetochore Ensemble to Protect CENP-A in the Human Pathogenic Yeast

- Coordinate Regulation of Lipid Metabolism by Novel Nuclear Receptor Partnerships