-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaMolecular Mechanisms Generating and Stabilizing Terminal 22q13 Deletions in 44 Subjects with Phelan/McDermid Syndrome

In this study, we used deletions at 22q13, which represent a substantial source of human pathology (Phelan/McDermid syndrome), as a model for investigating the molecular mechanisms of terminal deletions that are currently poorly understood. We characterized at the molecular level the genomic rearrangement in 44 unrelated patients with 22q13 monosomy resulting from simple terminal deletions (72%), ring chromosomes (14%), and unbalanced translocations (7%). We also discovered interstitial deletions between 17–74 kb in 9% of the patients. Haploinsufficiency of the SHANK3 gene, confirmed in all rearrangements, is very likely the cause of the major neurological features associated with PMS. SHANK3 mutations can also result in language and/or social interaction disabilities. We determined the breakpoint junctions in 29 cases, providing a realistic snapshot of the variety of mechanisms driving non-recurrent deletion and repair at chromosome ends. De novo telomere synthesis and telomere capture are used to repair terminal deletions; non-homologous end-joining or microhomology-mediated break-induced replication is probably involved in ring 22 formation and translocations; non-homologous end-joining and fork stalling and template switching prevail in cases with interstitial 22q13.3. For the first time, we also demonstrated that distinct stabilizing events of the same terminal deletion can occur in different early embryonic cells, proving that terminal deletions can be repaired by multistep healing events and supporting the recent hypothesis that rare pathogenic germline rearrangements may have mitotic origin. Finally, the progressive clinical deterioration observed throughout the longitudinal medical history of three subjects over forty years supports the hypothesis of a role for SHANK3 haploinsufficiency in neurological deterioration, in addition to its involvement in the neurobehavioral phenotype of PMS.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002173

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002173Summary

In this study, we used deletions at 22q13, which represent a substantial source of human pathology (Phelan/McDermid syndrome), as a model for investigating the molecular mechanisms of terminal deletions that are currently poorly understood. We characterized at the molecular level the genomic rearrangement in 44 unrelated patients with 22q13 monosomy resulting from simple terminal deletions (72%), ring chromosomes (14%), and unbalanced translocations (7%). We also discovered interstitial deletions between 17–74 kb in 9% of the patients. Haploinsufficiency of the SHANK3 gene, confirmed in all rearrangements, is very likely the cause of the major neurological features associated with PMS. SHANK3 mutations can also result in language and/or social interaction disabilities. We determined the breakpoint junctions in 29 cases, providing a realistic snapshot of the variety of mechanisms driving non-recurrent deletion and repair at chromosome ends. De novo telomere synthesis and telomere capture are used to repair terminal deletions; non-homologous end-joining or microhomology-mediated break-induced replication is probably involved in ring 22 formation and translocations; non-homologous end-joining and fork stalling and template switching prevail in cases with interstitial 22q13.3. For the first time, we also demonstrated that distinct stabilizing events of the same terminal deletion can occur in different early embryonic cells, proving that terminal deletions can be repaired by multistep healing events and supporting the recent hypothesis that rare pathogenic germline rearrangements may have mitotic origin. Finally, the progressive clinical deterioration observed throughout the longitudinal medical history of three subjects over forty years supports the hypothesis of a role for SHANK3 haploinsufficiency in neurological deterioration, in addition to its involvement in the neurobehavioral phenotype of PMS.

Introduction

Deletions involving the distal portion of chromosomes are among the most commonly observed rearrangements detected by cytogenetics [1] and result in several well-known genetic syndromes such as 1p36 monosomy (MIM: 607872), Cri-du-chat (5p-, MIM: 123450), Miller-Dieker (17p-, MIM: 247200), monosomy 18q (18q-, MIM: 6011808) monosomy 9p (MIM: 158171), Wolf-Hirschhorn (4p-, MIM: #194190), 9q34.3 microdeletion (MIM: 610253), monosomy 2q37 (MIM: 600430) and Phelan-McDermid (PMS, MIM: 606232) syndromes. Over the past 15 years, technological advances in the molecular cytogenetic diagnosis of mental retardation, such as subtelomere screening and high-resolution genome analysis, have strongly enhanced the detection rate of an increasing number of chromosome rearrangements involving subtelomeric regions associated with mental retardation.

Telomere loss caused by double-strand breaks (DSBs) can generate, if not properly repaired, chromosome instability, cell senescence, and/or apoptotic cell death. Terminal deletions can be repaired and stabilized through the synthesis of a new telomere (telomere healing), demonstrated through sequence analysis of terminal deletions that showed de novo telomeric repeats attached to the remaining chromosomal sequences [2]–[4]; by telomerase-independent recombination-based mechanisms [5], [6]; by obtaining a telomeric sequence from another chromosome (telomere capture) resulting in derivative chromosomes [7], [8]; finally, by chromosomal circularization, leading to the formation of a ring chromosome [9], [10]. However, in spite of their relatively frequent occurrence, the molecular bases for generating and stabilizing terminal chromosome deletions in humans are still poorly understood, since the breakpoints have been analyzed at the base-pair level in only few studies [11], [12]. Questions remain about the timing of breakpoint repair, the relative importance of the above-mentioned mechanisms in terminal deletions affecting specific chromosomes, the role of repetitive elements, long terminal repeats and other DNA elements in chromosome breakage and stabilization.

In this study, we used deletions of 22q13, which represent a substantial source of human pathology [13], [14], as a model for investigating the molecular mechanisms of terminal deletions.

We characterized at the molecular level 40 new and 4 previously published subjects with 22q13 chromosome rearrangements [15], [16] aiming to identify the molecular mechanisms involved in stabilizing the deletions in patients with monosomy 22q13 and, more generally, to obtain new insight in the mechanisms underlying terminal deletions. Genotype-phenotype relationship, including the detailed clinical history of three adult patients that may help to define the lifelong outcome of PMS, is also discussed.

Results

Clinical profile of patients with 22q13 microdeletion syndrome

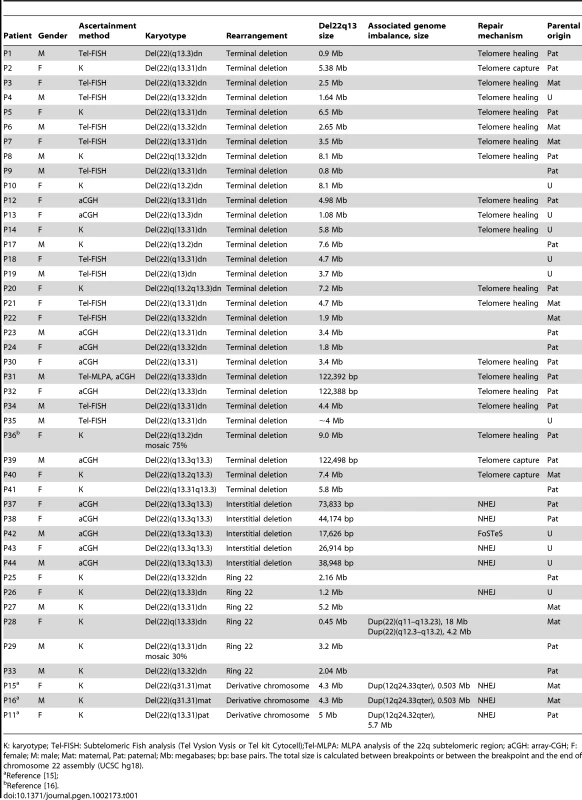

Patients included 26 females and 18 males, with ages ranging from birth to 47 years. Six patients (P25–29, P33) had a ring chromosome 22, five (P37–38, P42–44) had interstitial 22q13.3 deletions, three (P11, P15, P16) carried derivative chromosomes, while the remaining patients had terminal deletions (Table 1).

Tab. 1. Description of the rearrangements in 44 subjects with 22q13 deletions.

K: karyotype; Tel-FISH: Subtelomeric Fish analysis (Tel Vysion Vysis or Tel kit Cytocell);Tel-MLPA: MLPA analysis of the 22q subtelomeric region; aCGH: array-CGH; F: female; M: male; Mat: maternal, Pat: paternal; Mb: megabases; bp: base pairs. The total size is calculated between breakpoints or between the breakpoint and the end of chromosome 22 assembly (UCSC hg18). We excluded from the clinical analysis patients with a derivative chromosome 22 (P11, P15, P16) and subject P28 with a complex ring 22 rearrangement, since the additional duplicated regions could complicate the assessment.

The features observed in the 40 cases in our series were compared to the characteristic features of the 22q13 deletion syndrome [17] (Table S1).

Clinical medical history of adult patients

Since to date old patients with 22q13.3 deletion syndrome have not been described and no longitudinal data are available to determine their life expectancy, we report the medical and clinical history of three adult patients over forty years (P10, P30 and P33) (Text S1 for additional medical details).

Subject P10:

The patient is a woman referred to a geneticist at the age of 40 years in the context of a diagnostic evaluation of people living in an institution for mentally disabled people. She presented absence of language and severe mental retardation. Facial dysmorphisms were also evident (Figure S1F–S1J). Neurological evaluation showed spastic paraparesis. At age 39, she suffered from frequent epileptic seizures, in spite of antiepileptic drugs. At age 43, she experienced very fast motor and cognitive decline; as a consequence, she was not able to stand, walk or even make eye contact anymore; her spastic tetraparesis markedly increased. Right renal agenesis was diagnosed during a control abdominal ultrasonography. She died at 47 years for renal failure while in a vegetative state.

Subject P30:

The patient is a woman referred for clinical genetics evaluation at the age of 40 years because of severe cognitive impairment and mild craniofacial dysmorphisms. She suffered from epilepsy, cortical tremor (starting at the age of 39 years) and poor speech. Minor facial dysmorphic features were observed (Figure S1A–S1E).

Subject P33:

The patient is a male first referred to a geneticist at the age of 41 years in the context of familial genetic counseling. The dysmorphological examination revealed evident aspecific dysmorphisms (Figure S1K–S1N). He presented with total absence of language, severe mental retardation, delayed motor development and microcephaly. At the age of 34 years, he developed type 2 diabetes, well compensated by oral hypoglycemic therapy, and had three spontaneous pneumothorax episodes at the upper lobe of his left lung.

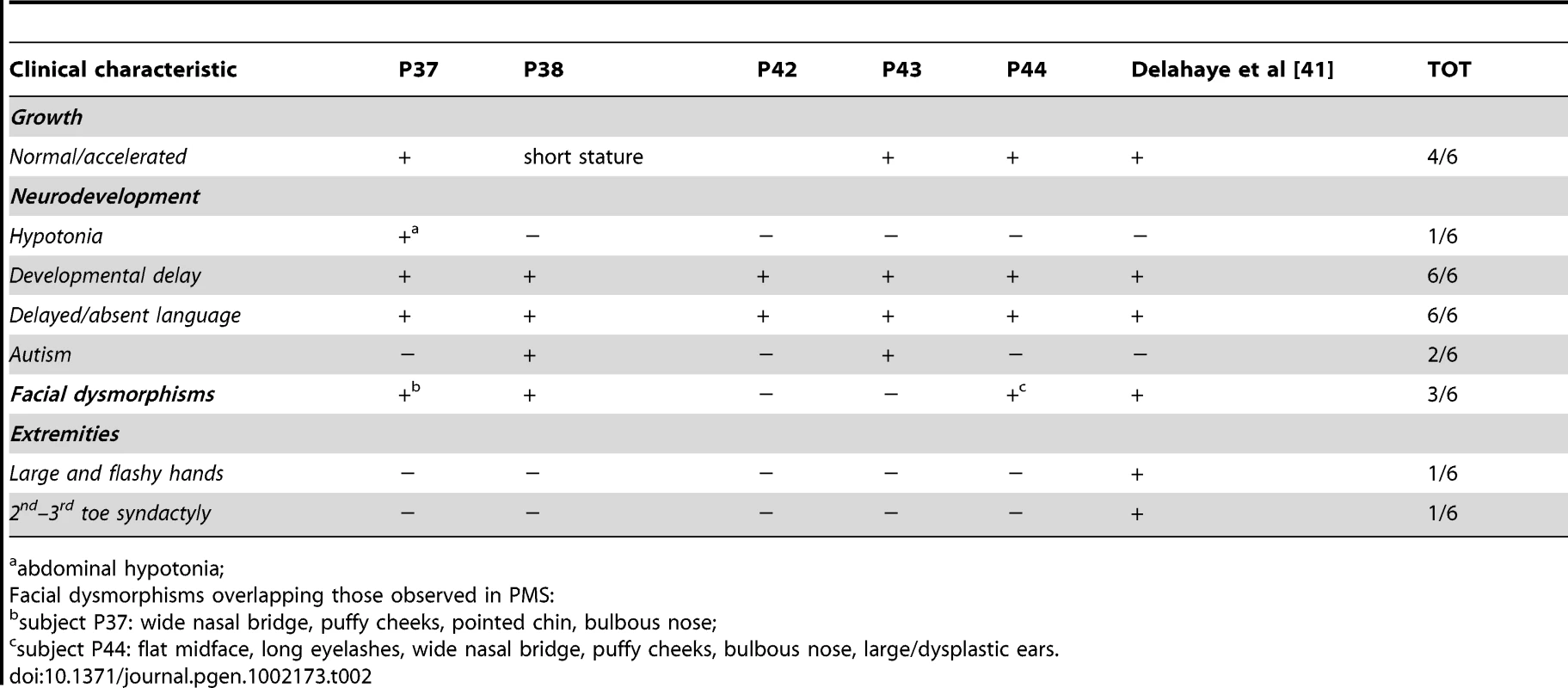

Patients with cryptic interstitial 22q13.3 deletion disrupting the SHANK3 gene

The clinical features of five cases with microdeletions involving only SHANK3 (P37, P44) or SHANK3 and ACR (P38, P42–43) are summarized in Table 2; their detailed medical history is described in Text S1.

Tab. 2. Clinical characteristic of PMS in subjects with interstitial 22q13 microdeletions.

abdominal hypotonia; Parental origin of the deletions

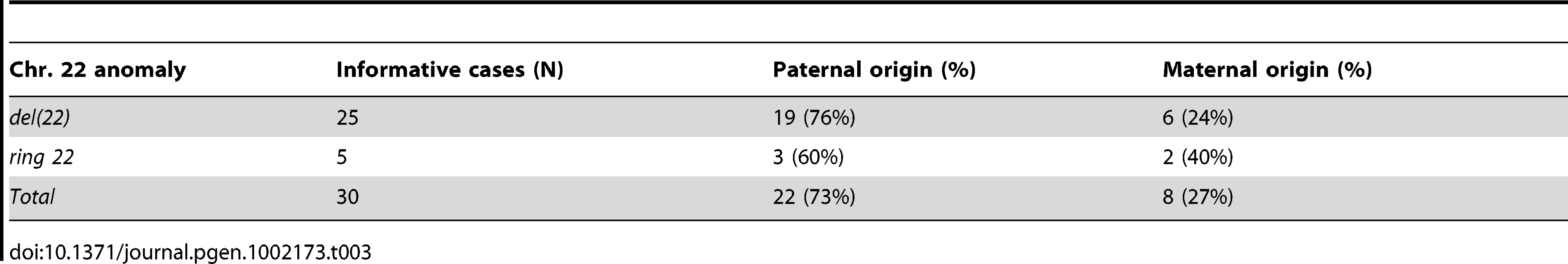

The parental origin of the de novo 22q13 rearrangements was elucidated in 30 families (Table 3).

Tab. 3. Parental origin of the <i>de novo</i> 22q13 deletions.

The majority of terminal (17/23) and interstitial (2/2) deletions for which parental origin was available had paternal origin. Three of five ring 22 cases (60%) were also of paternal origin, while two were maternal.

Molecular characterization of 22q13 deletions

We collected 40 new unrelated patients with 22q13 deletions and re-analyzed four previously published cases (Table 1).

Nine subjects (P2, P8, P10, P14, P17, P20, P36, P40, P41) showed a 22q13 deletion on high - resolution G - banding karyotype (550 bands); in three of them, previous low resolution banding karyotype had missed the rearrangement. Six cases showed a ring 22 at karyotype analysis. One of them (P29) was a mosaic. In one subject (P31), the presence of a terminal 22q13.3 microdeletion was first suspected in a routine subtelomere screening by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA, kit P036, MRC Holland) that showed a possible deletion at the RABL2B locus, and subsequently diagnosed by aCGH analysis (244k, Agilent). Subtelomeric FISH screening with cosmid clones covering the distal 22q-140 kb [18] (data not shown) further confirmed the terminal 22q13.3 microdeletion with breakpoint between exons 8–9 of the SHANK3 gene. The remaining twenty-four patients had normal karyotype results and were ascertained either through subtelomere-FISH or array-CGH analysis.

Whole-genome array-CGH using several available platforms (44k, 105k, 244k) was performed on all patients diagnosed through classical cytogenetic methods, except for subject P35, in order to determine the genomic size of the deletion and exclude any concurrent microdeletion/microduplication elsewhere in the genome.

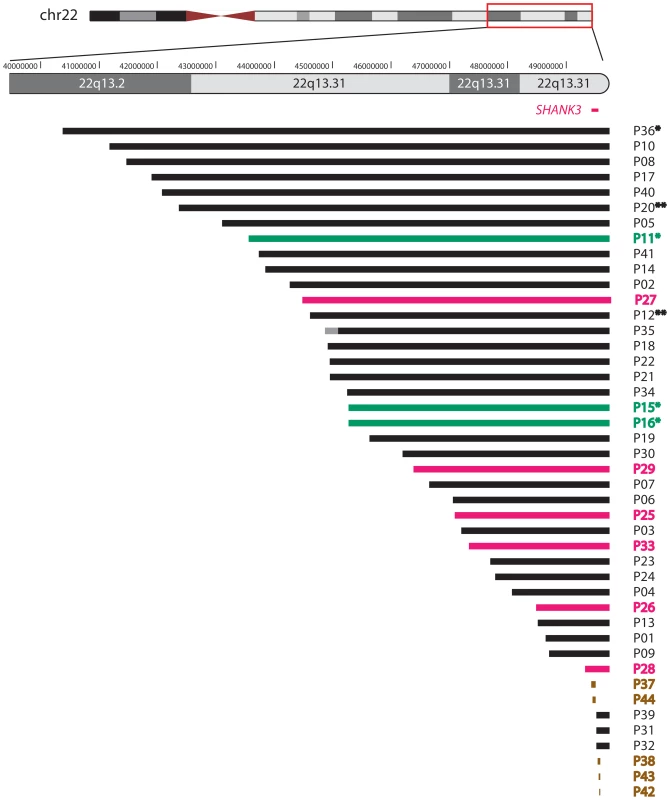

This approach allowed the identification of 22q13 deletions, varying in size between 0.14 and 9.0 Mb, in 39 subjects (Figure 1). The breakpoints were scattered along the 22q13 region and no breakpoint grouping was observed. We precisely delineated the boundaries of each deletion by commercial high-resolution (244k, Agilent) or customized aCGH analysis. Further improvements in resolution, obtained with subject-specific qPCR amplification experiments, allowed the design of oligonucleotide primers to specifically amplify the junction fragments.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the 22q13 rearrangements.

An ideogram of chromosome 22 is shown at the top with genomic coordinates of the boxed terminal region of interest shown at 1 Mb intervals. The location of the SHANK3 gene is marked in red. Each patient is represented by a horizontal line corresponding to the size of his deletion as determined by aCGH analysis. Each patient's code number is shown on the right side of the lines; asterisks (*) indicate previously published cases. Double asterisks (**) indicate mosaic deletions. The lines' colors correspond to 22q13 rearrangement categories: simple deletions are depicted in black, derivative chromosomes 22 in green, rings 22 in pink, and interstitial deletions in brown. Forty-four patients are represented; the breakpoint interval (represented in grey) in subject P35 was narrowed down to ∼400 kb by FISH analysis with BAC clones RP11-194L8 (chr22:44,951,438–45,122,714, still present) and RP11-266G21 (chr22:45,543,178–45,711,912, deleted). Terminal deletions

We attempted to clone the deletion breakpoints of all 33 patients with apparently terminal 22q13 deletions by postulating healing of the truncated 22q sequences through the addition of a new telomere sequence at the breakpoint. Forward primers were designed proximally to each breakpoint and used for nested PCR, together with telomere-specific primers. Using this strategy, we isolated twenty-two breakpoints from 20 cases with terminal deletions (P1, P3–P8, P12–P14, P20, P21, P30–P32, P34, P36) (Figure S2). Nineteen breakpoints from 17 subjects contain 3–48 copies of the GGTTAG hexamer. Alignment of the chromosome-specific sequences flanking the telomeric repeats with the human genome reference sequence revealed the immediate proximity of the repeats to the chromosome-specific sequences in 16 breakpoints. Three breakpoints (P20 BP3, P8, P7) contain 2, 14, and 20 additional bases not present in the reference sequence, respectively. Two subjects (P31, P32) carry recurrent 22q terminal deletions [18]. The junction fragment in subject P8 contains a perfect 7-bp inverted palindrome. Thirteen of the 19 breakpoints fall inside repetitive sequences (SINE, LINE, DNA-type, simple repeats) (Figure S2). One breakpoint junction (P2) contains a (GGTGAG)n repeat, fortuitously amplified because of its homology with the Tel-ACP primer, instead of the expected (GGTTAG)n. In a second junction (P39), the telomere sequence is preceded by (GGTCAG)6. A third breakpoint (P40) is joined to the terminal 450 bp of a Xp/Yp chromosome arm.

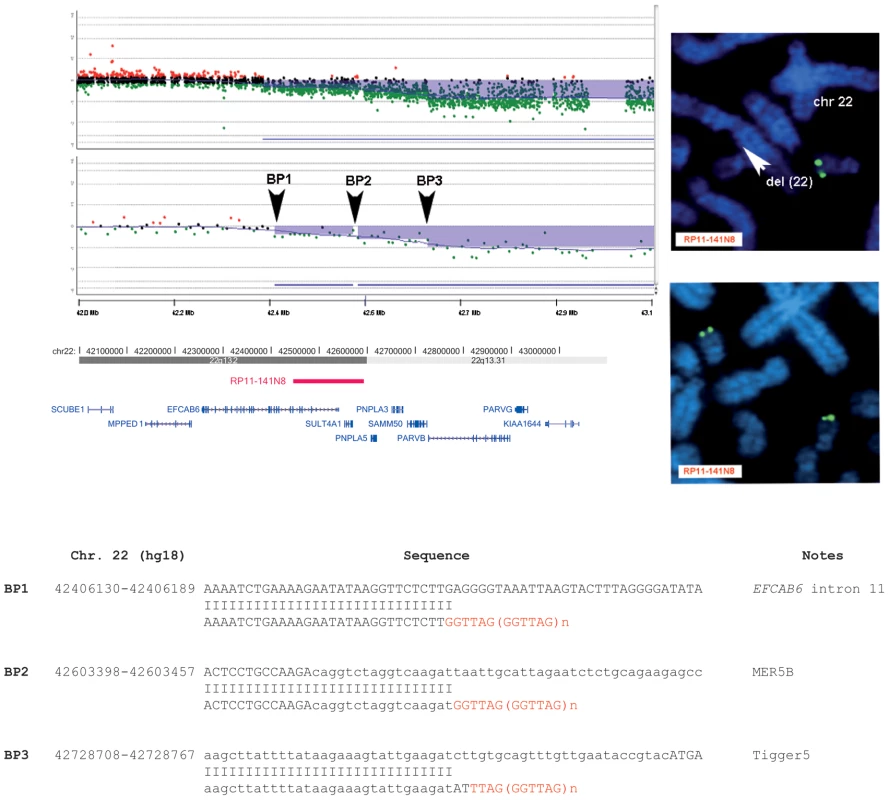

Interestingly, high-resolution aCGH analysis allowed the identification of a patient (P20) carrying a mosaic of at least three lines with 22q13.2 terminal deletions, each with a different breakpoint (Figure 2A). All breakpoints were located in a ∼400 kb interval. FISH analysis with clone RP11-141N8 (AQ388763 at 22q13.2), positioned between BP1 and BP2 (Figure 2A, 2B) confirmed the presence of a mosaic deletion in 30% of the metaphases analyzed (Figure 2B). We cloned all three identified breakpoints: the more proximal is located in intron 11 of the EFCAB6 gene; the intermediate falls in a MER5B repeat; the more distal in a Tigger5 repeat (Figure 2C). High-resolution aCGH profiling suggested the presence of at least two mosaic breakpoints in a second patient (P12) (Figure S3A, S3B), but we were only able to clone one of them (Figure S3C).

Fig. 2. Molecular characterization of the 22q13.2 terminal deletion in subject P20.

A, Magnified view of the aligned breakpoint boundaries detected by array-CGH analysis using an oligonucleotide-based custom 22q13 microarray (top) and a 180k Agilent kit (bottom); the deleted regions are shaded in blue. Arrowheads delimit two mosaic-deleted regions: the BP1–BP2 deletion region (from 42406240 to 42603381 bp) has an average log ratio of −0.3; the BP2–BP3 deletion region (from 42603381 to 42726895 bp) has an average log ratio of −0.5; the deleted region between BP3 and the telomere (from 42726895 to the end of chromosome 22) has an average log ratio of −0.8. The aligned UCSC map (hg18) is depicted at the bottom. The red bar indicates the map position of the RP11-141N8 BAC clone we used to confirm by FISH the mosaicism of the BP1–BP2 region. All genes (blue bars) mapping within the BP1–BP3 regions are shown. B, FISH analysis using the RP11-141N8 clone confirms a mosaic deletion of the BP1–BP2 region revealing: (top) the presence of hybridization signals (green signal) on only one chromosome 22 (arrowhead) in 30% of the metaphases analyzed; (bottom) the presence of hybridization signals (green signals) on both chromosome 22 homologues in the remaining 70% of the metaphases analyzed (bottom). C, Tel-ACP amplification and direct sequencing of the amplified fragments revealed the breakpoint junctions at BP1, BP2 and BP3. A telomere repeat is present at all three breakpoints. Interstitial deletions

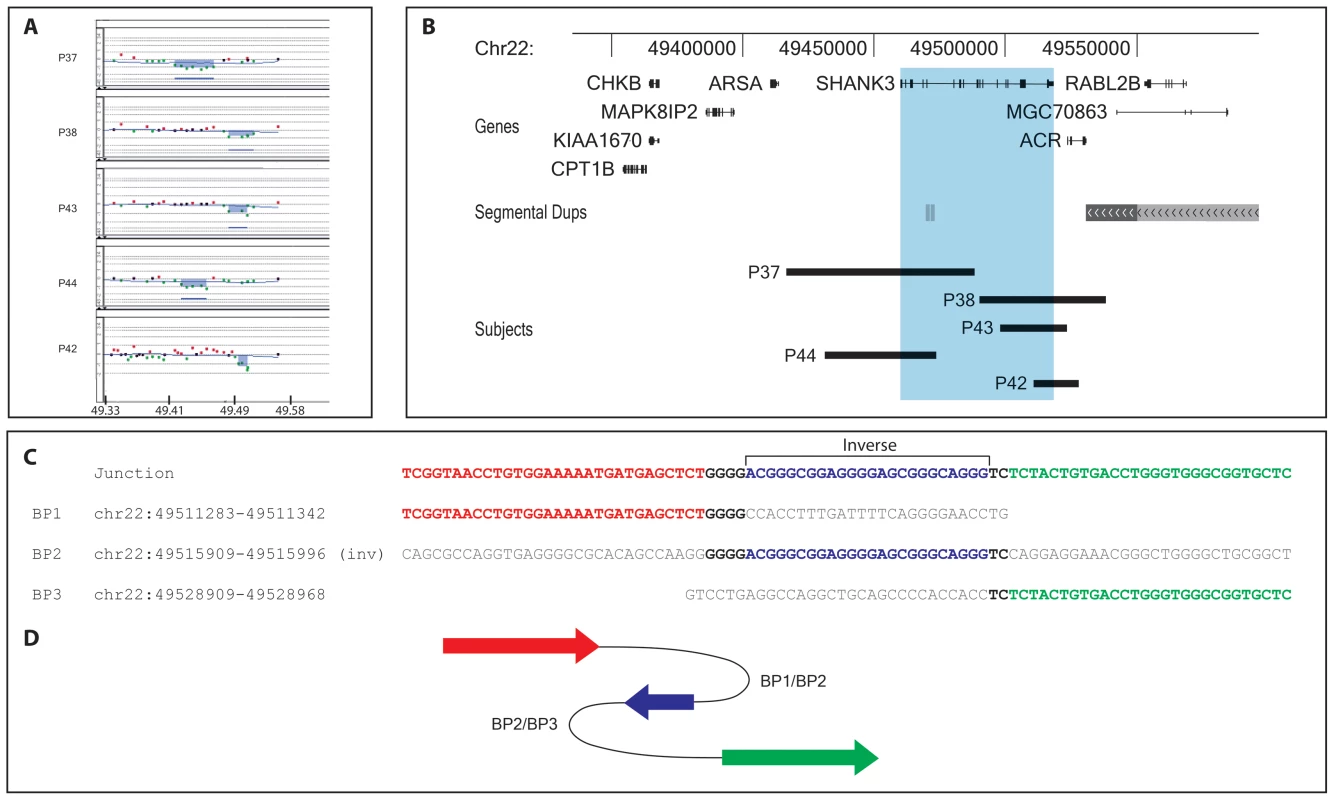

Our series also includes five patients with interstitial 22q13.3 deletions disrupting the SHANK3 gene (P37, P38, P42–44) (Table 2, Figure 3A, 3B). The region distal to the deletions in P38 and P42 lies in a paralogous sequence containing the RABL2B gene, with almost complete identity with the chromosome 2 region containing RABL2A, and only one 180k/244k (Agilent) aCGH probe covers it. Subtelomere FISH screening with cosmid probes spanning the terminal 100 kb of distal 22q (data not shown) and qPCR experiments confirmed the findings. Specific amplification of the junctions by long-range PCR followed by sequencing analysis precisely defined each rearrangement's structure (Figure 3C, Figure S2).

Fig. 3. 22q13.3 interstitial microdeletion detected by array-CGH analysis.

A, aligned aCGH profile (P37–38, P43–44: 180k Agilent kit; P42: 244k Agilent kit) details of all interstitial deletions; the deleted regions are shaded. B, map of the distal 22q13.3 region; the deletions are represented by black bars; the region overlapping the SHANK3 gene is shaded in light blue. All genes mapping in the region are shown. C, sequence alignment of the breakpoint junctions of subject P42 showing the homology with three genomic regions. The proximal breakpoint sequence is shown in red, the middle 24 bases in inverted orientation are blue, the distal breakpoint sequence in green; microhomologies between sequences at the breakpoints are depicted in bold. D, cartoon showing the respective position and orientation of the breakpoint sequences in P42 as arrows, colored as in C. The 74 kb interstitial deletion in P37 encompasses exons 1–17 of SHANK3; the 44 kb deletion in P38 covers exons 19–23 of SHANK3 and the whole ACR gene; the 18 kb deletion in P42 includes exon 23 of SHANK3 and exons 1–3 of ACR; the 27 kb deletion in P43 includes exons 20–23 of SHANK3 and exons 1–3 of ACR; the 34 kb deletion in P44 overlaps exons 1–9 of SHANK3 (Figure 3B). We found no homology between any proximal and distal breakpoint region. Repeated sequences (LTR and LINE) are present in three breakpoints; ten additional nucleotides were inserted at the junction of P37 (Figure S2). In P42, the breakpoint junction contains 23–29 bps identical to the reverse complement of a sequence in the middle of the deleted region; this sequence shows 4 and 2 bp microhomologies with the proximal and distal breakpoints, respectively (Figure 3C).

Ring 22 chromosomes

Six subjects (P25–P29, P33) carry a 22q13 terminal deletion associated to ring 22 chromosome; one of them (P29) shows a mosaic deletion in 30% of the cells (not shown). We also identified a complex ring 22 rearrangement consisting of a 240 kb terminal 22q deletion, concurrent with two additional, non-contiguous, ∼18 Mb and ∼4.2 Mb 22q duplications at 22q11–q12.3 and 22q12.3–q13.2, respectively, in subject P28 (Figure S4).

The only breakpoint we were able to identify in a patient with ring 22 (P26) (Figure S5A) was cloned using inverse PCR and shows a junction between an Alu sequence on 22q and a repeated sequence with homology to pericentromeric and subtelomeric regions on several chromosomes (Figure S5B). There is no homology between the two breakpoints. In this case, as well as in cases P27 and P29, we verified the absence of interstitial pan-telomeric sequences with a PNA probe (Figure S5C). Unfortunately, FISH analysis could not be performed on the remaining three cases (P25, P28, P33) due to the lack of archival material.

Unbalanced translocations

Three patients (P11 and brother/sister pair P15–16) (Cases 1, 2, and 3, respectively, in [15]) carry a derivative chromosome 22 inherited from a parent carrier of a balanced translocation.

In case P11, aCGH analysis identified the loss of a 5 Mb segment of distal 22q13.31–q13.3 and the gain of a 5.7 Mb region of chromosome 12q24.32–q24.33 (Figure S6A); the proband's father carries a balanced 12q;22q translocation. We amplified the junction between 12q24.32 and 22q13.31 by long-range PCR using a forward primer (22F) from the der(22) undeleted flanking region and a reverse primer (12R) corresponding to the 12q duplicated region. The same fragment was amplified from the carrier father but not from the mother or other control DNAs (not shown). Sequencing of the junction fragments revealed that the two breakpoints share only a 4 bp microhomology (Figure S6B). Similarly, sibs P15 and P16 both inherited the der(22) chromosome from their mother who carries a balanced 12q;22q translocation. The two sibs carry a 4.3 Mb 22q13 deletion and a 0.5 Mb 12q24.33–q24.33 duplication (Figure S6C). In these patients, the rearrangement is between an Alu repeat on chromosome 22q and a (TGAG)n simple repeat on chromosome 12q. The two breakpoints share only a 5-bp microhomology (Figure S6D).

Discussion

The constitutional 22q13 deletion is a fairly recently described genomic disorder that results in global developmental delay, delayed/absent speech, hypotonia and minor dysmorphic features. In spite of the fact that to date more than 100 cases (excluding ring 22s) have been detected by different molecular methods, when and how terminal deletions arise is still poorly understood. We have characterized from the clinical and molecular points of view 44 subjects with PMS resulting from simple 22q13 deletions (30 subjects, 72%), ring chromosomes (six subjects, 14%), unbalanced translocations (three subjects, 7%) and interstitial deletions (five subjects, 9%); all rearrangements result in haploinsufficiency of the SHANK3 gene (Table 1). We have also determined the breakpoint junction sequences of twenty subjects with terminal deletions, five with interstitial deletions, one with ring 22 and three with unbalanced translocations.

Clinical profile and genotype/phenotype comparison

Although in our cases age at diagnosis ranged from birth to 41 years, no specific clinical phenotype diagnostic for 22q13 deletion could be identified at any age (Table S1), as already noted by Phelan et al. [13]. Thus, successful diagnosis of this syndrome depends almost exclusively on the use of molecular diagnostic tools, mainly subtelomeric FISH and high-resolution genome-wide array-CGH. The latter is also suitable to identify cryptic interstitial deletions involving only the SHANK3 gene, that are associated with an even less specific phenotype, as observed in our five patients (P37, P38, P42–P44). Their phenotype consisted mainly of developmental and language delay. PMS-suggestive facial dysmorphisms and hypotonia (limited to abdominal muscles) were observed only in one patient (P37), while no other physical abnormalities were noted in any of the patients. (Table 2). In patient P43, a defect in the abdominal wall with gut protrusion was detected by ultrasound during pregnancy and surgically corrected immediately after birth.

Owing to its emerging role in neuropsychiatric disorders and to the phenotypic overlap between autism and PMS, SHANK3 has become a target for mutation screening in patients with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) and several studies [19]–[21] have discovered de novo mutations in such patients. Mutations in SHANK3 have also been found in schizophrenia [22] and non-syndromic intellectual disability [23]. The contribution of additional genes to the 22q13 deletion phenotype has also been debated. Very recently it has been proposed that deletion of the IB2 gene (also named MAPK8IP2 or JP2), mapping 70 kb proximal to SHANK3, may play a relevant role in PMS-associated ASD [24].

Two of our patients with interstitial microdeletions disrupting SHANK3 and ACR only (P38, P43) (Figure 3B) fulfill the clinical criteria for a diagnosis of autism, while the others (P37, P42, P44), do not (Table 2). Our findings emphasize the incomplete penetrance of the ASD phenotype in PMS, while confirming a role for SHANK3 in ASD. Additional deleted genes may contribute more strongly to accessory features, such as dysmorphisms and hypotonia, than to developmental and language delay.

Longitudinal clinical data on adult patients were collected in three subjects aged 40, 41 and 47 years. The severe progressive neurological deterioration reported in adult patients P10 (starting when she was 39 years old) and P30 (aged 40 years) was also described by Anderlid in a 30-year-old patient [25]. The minimal overlapping 22q13 region deleted in these three cases contains only SHANK3, RABL2B and ACR. In addition, subject P37 carrying an interstitial deletion involving only SHANK3 experienced tremors and tics starting at age 23 (Text S1). Shank proteins, that organize glutamate receptors at excitatory synapses, are dramatically altered in Alzheimer disease [26]. In turn, disruption of glutamate receptors at the postsynaptic platform had been reported to contribute to the destruction of the postsynaptic density underlying mental deterioration in Alzheimer disease [27]. According to our results, SHANK3 defects might indeed be responsible for progressive neurodegeneration, in addition to causing the neurobehavioral phenotype of the 22q13 syndrome.

Previous studies on a large cohort of patients with ring 22 demonstrated that there is considerable molecular and phenotypic overlap between individuals with ring 22 and those with del 22q13 [28]–[29]. All six subjects reported here showed features commonly found in 22q13.3 deletion syndrome, including accelerated growth in two of them (P26, P27), whereas one (P25) had slightly delayed growth.

Parental origin

Parental origin was determined in 30/44 cases. We observed a larger proportion of 22q13 deletions of paternal (22/30, 73%), compared to maternal (8/30, 27%) origin, in agreement with a previous large study in which 69% of the deletions were of paternal origin [14]. There was no deletion size bias. Interestingly, we observed that both recurrent deletions (P31, P32), as all previously reported cases [18], [19], [30], were of paternal origin. Furthermore, the two interstitial deletions (P37, P38) we characterized were also paternal. In other terminal deletion cohorts, the majority of patients carry small 1p36 deletions on the maternal chromosome, while larger deletions are predominantly paternal [31]. In contrast, de novo simple small terminal 9q34.3 deletions are predominantly paternal, whereas larger terminal deletions, interstitial deletions, complex rearrangements and unbalanced translocations are frequently maternal in origin [12].

Telomere healing and capture in terminal deletions

Broken chromosome ends can be stabilized through at least three mechanisms: de novo telomere addition mediated by telomerase; telomere capture resulting in a derivative chromosome; stabilization by break-fusion-break (BFB) cycles, generating terminal deletions and proximal inverted duplications. The first two mechanisms have been identified in this study. Almost 60% of our patients carried apparently simple terminal deletions. Nineteen of the twenty-two breakpoints we cloned, including all three breakpoints in mosaic subject P20, show evidence of telomere healing. Fourteen breakpoints contain 1–5 base microhomologies with the canonical GGTTAG sequence at the fusion point of genomic and telomeric sequences (Figure S2), possibly reflecting the template-driven mechanism that telomerase uses to replicate chromosome ends [32], [33]. The same mechanism applies to terminal 4p deletions [34] where microhomology with telomere repeats was found in all analyzed subjects. Human telomeres contain large blocks of 100–300 kb TAR sequences, located just proximally to the (TTAGGG)n tandem repeats, providing significant sequence homology between non-homologous chromosome ends [35]. Two terminal deletions in our cohort (P2, P39) were healed by telomere capture of TAR sequences (Figure S2). One deletion (P40) was repaired by the capture of the distal portion of Xp/Yp (Figure S2).

Failure to identify the nine remaining breakpoints may be due to the presence of regions containing large repetitive sequences or other complex sequences that would hinder amplification. Alternatively, some of the deletions may lack a telomere repeat at the breakpoint because the deletion may have been repaired by alternative mechanisms.

The presence of short repetitive elements may play a role in generating or stabilizing terminal deletions. In this study, we have determined 42 breakpoint junctions within the 22q13 region. Repetitive sequences, such as Alu, LINE, SINE, LTR and simple repeats were often, but not always, present at or near the breakpoints (Table S2). These repetitive elements are susceptible to DSBs due to replication errors or to the formation of unusual secondary structures, including cruciforms, hairpins, and tetraplexes [36]. On the other hand, there is no hard proof that the breakpoints of terminal deletions are the actual site of the original DSB, rather than the site where telomerase was able to synthesize a new telomere sequence.

Analysis of case P20 revealed a mosaic of at least three cell lines carrying different terminal 22q13 deletions. Their breakpoints were located approximately 100 Kb from each other. This mosaicism may be due to distinct stabilizing events, occurring in different cells of the early embryo, of the same unstable terminal deletion. Our results demonstrate that primary terminal deletion breakpoints and repair sites are not necessarily coincident and can actually be far apart. We had already shown, in an exceptional case of mosaicism for maternal 22q13.2-qter deletion (45% of cells) and 22q13.2-qter paternal segmental isodisomy (55% of cells) that complex mosaicism can also arise from a postzygotic or early embryonic recombination event [16]. These data suggest that terminal deletions can be repaired by multistep healing events. Cryptic mosaics may also render genotype-phenotype relationship in deletions more complex than expected.

Deletion sizes in patients with monosomy 1p36 [31] and 9p21–p24 [37] vary widely, up to 20 Mb, while 9q34.3 deletions [12] do not exceed 3.5–4 Mb. The size of 22q13 deletions is highly variable, ranging from 100 kb to 9 Mb [14]. No single common breakpoint has been discovered in deletions of 1p36 [31] and 9q34.3 [12], both studied in great detail. In contrast, 9 cases with terminal 140 kb deletion and a breakpoint occurring in a short GC-rich simple repeat in intron 8 of the SHANK3 gene have been reported [18], [19], [25], [30], [38], [39]. In this study, we detected two new unrelated cases (P31, P32) with the same recurrent terminal deletion healed by de novo telomere addition. Computational analysis [40] predicts that this repeat would be able to form a secondary structure that may predispose to DNA double strand breaks, stabilize the broken chromosome end, or recruit telomerase more efficiently [36]. Subject P39 has a slightly larger deletion repaired by the capture of a TAR sequence.

Interstitial deletions

Interstitial deletions affecting the 22q13 region have previously been described in three cases, one disrupting the SHANK3 gene [41] and two more proximal [42]; none of them has been finely characterized at the molecular level. We characterized five additional de novo interstitial deletions between 17 and 74 Kb in size and sequenced their breakpoints: three of the deletions (P37, P44) disrupt exclusively SHANK3, the others (P38, P42, P43) both SHANK3 and ACR (Figure 3B).

The interstitial deletions in four patients (P37,38, P42, P44) are compatible with NHEJ repair. P42 carries a more complex rearrangement where 40–47 bp from the deleted region are inserted in opposite orientation in the middle of the breakpoint junction (Figure 3C). A DNA replication model named FoSTeS [43], later generalized to the microhomology-mediated break-replication (MMBIR) model [44], has been proposed to explain complex rearrangements associated with several diseases. The rearrangement in P42 can indeed be explained by the FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism (Figure 3D).

Apart from the cases described in this report, we have no information on the percentage of defects in SHANK3 caused by deletions/duplications involving only one or a few exons. The small size of these rearrangements poses substantial problems for their identification, at least with current commercial aCGH platforms having necessarily limited coverage of the SHANK3 gene. Arrays designed for the detection of clinically relevant exonic CNVs [45] may offer a solution.

Ring 22 chromosomes and unbalanced translocations

NHEJ is the most likely repair mechanism leading to ring 22 formation in case P26. As this is the only ring 22 breakpoint we were able to clone, we cannot be sure that the same mechanism will apply to all cases with ring 22. Our inability to capture more breakpoints of ring 22 deletions may stem from the occurrence of the 22p breakpoints within highly repetitive sequences. Generation of breakpoints at both arms of the same chromosome, followed by circularization, has been usually assumed to be the basis of ring chromosome formation. Alternatively, telomere healing through circularization after the occurrence of a simple distal deletion, as it seems the be the case for ring chromosomes with concurrent deletion and duplication at one end [10], cannot be excluded. Thus, distal deletions and ring chromosomes might share the same initial event.

We also demonstrated that the complex phenotype in one ring 22 patient (P28) can be explained by the presence of further chromosome duplications at 22q11–12.3 and 22q12.3–13.2, undetectable with conventional cytogenetic analysis, in addition to the 22q13.3 deletion. The identification of the complex ring 22 rearrangement in this patient directly stems from the whole-genome aCGH analysis required by our protocol in order to exclude additional genomic aberrations.

All unbalanced translocations we analyzed (P11, P15, P16) were inherited from a parent carrying a balanced translocation. The microhomology found at all breakpoints points to NHEJ or MMBIR as the most likely mechanisms for these rearrangements; therefore they should be considered mechanistically different from all previously discussed chromosome 22 rearrangements.

Conclusions

All adult patients with 22q13 deletion showed progressive clinical deterioration, supporting the hypothesis of a role for SHANK3 haploinsufficiency in neurological deterioration. All patients with interstitial deletions involving only SHANK3 showed a neurological and behavioral phenotype, demonstrating once again the specific role of the gene in this syndrome.

The study of breakpoints in subjects with 22q13 deletion provides a realistic snapshot of the variety of mechanisms driving non-recurrent deletion and repair at chromosome ends, including de novo telomere synthesis, telomere capture and circularization. Distinct stabilizing events of the same terminal deletion can also occur in different early embryonic cells. These data are in agreement with those demonstrating that mosaic structural chromosome abnormalities are common in early IVF embryos [46] and that chromosomally unbalanced zygotes are submitted, during first mitotic divisions, to intense genomic reshuffling eventually leading to different situations, all compatible with survival [47]. As recently suggested, the burst of DNA replication that accompanies the rapid cell division required to go from a single post-zygotic cell to an embryo and then a fetus is a time in the human life cycle when more new mutations may occur than was previously appreciated. Depending on the timing, many such events may be difficult, if not impossible, to identify at the DNA level [48].

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee at the “Eugenio Medea” Scientific Institute.

Human subjects

Blood samples were obtained from probands and their parents after informed consent. All patients were referred for genetic evaluation to different medical centers because of developmental delay, delayed/absent language and dysmorphic features. Physical examination and review of medical and family history records were performed on each patient. The diagnosis of terminal 22q13 deletion syndrome had not been proposed in any of the patients before identification of the deletion by cytogenetic or molecular diagnostic analysis. Cytogenetic and molecular diagnosis had been obtained by conventional karyotyping, subtelomere FISH, 22q13 MLPA analysis, or oligonucleotide-based aCGH (44k, 105k, 180k or 244k Agilent platforms)(Table 1).

Array-CGH studies

A very high-resolution 22q13 custom array was designed using the eArray software (http://earray.chem.agilent.com/); probes were selected among those available in the Agilent database (UCSC hg18, http://genome.ucsc.edu). A total of 24624 probes were selected within the distal 9.4 Mb region of 22q13 (chr22 : 40269203–49565875), and 8660 probes within the distal ∼3.2 Mb of chromosome 12q (chr12 : 129000012–132289374); the latter set was used to identify the breakpoint interval in cases with a derivative chromosome 22 associated with a 12q genomic segment (P11, P15, P16), and for quality control/normalization. The probes provided an average resolution of 400 bp. Genomic DNA was isolated from blood samples using the GenElute-Blood kit (Sigma). Gender-matched genomic DNAs were obtained from individuals NA10851 (male) and NA15510 (female) (Coriell). The quality of each DNA was evaluated by conventional absorbance measurements (NanoDrop 1000, Thermo Scientific) and electrophoretic gel mobility assays. Quality of experiments was assessed using Feature Extraction QC Metric v10.1.1 (Agilent). The derivative log ratio spread (DLR) value was calculated using the Agilent Genomics Workbench software. Only experiments having a DLR spread value <0.30 were taken into consideration.

Cytogenetic and FISH analysis

Metaphase chromosomes and interphase nuclei were obtained from all patients and their parents from PHA-stimulated blood lymphocyte cultures. G-banding karyotypes at 400–550 bands resolution were performed using standard high-resolution techniques. FISH experiments with 22q13.3 subtelomeric cosmids n66c4 (AC000050), n85a3 (AC000036), n94h12 (AC0020556) and n1g3 (AC002055) [18] were performed to confirm the aCGH results in cases where the 22q13.3 deletion disrupted the SHANK3 gene (P31–32 P37–38, P42–43). FISH analysis with BAC clones, labeled with biotin-dUTP (Vector laboratories, Burligame, CA) using a nick translation kit (Roche), or probes for all subtelomeric regions (TelVysion kit, VYSIS) were performed on selected cases. The pan-telomeric peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe (PNA FISH kit/Cy3, Dako Denmark A/S) which recognizes the consensus sequence (TTAGGG)n of human pan-telomeres was hybridized according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Hybridizations were analyzed with an Olympus BX61 epifluorescence microscope and images were captured with the Power Gene FISH System (PSI, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK).

Parental origin determination

Genotyping of polymorphic sequence-tagged sites (STS) was performed by amplification with primers labeled with fluorescent probes followed by analysis on an ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). In cases where STS analysis was not informative, SNP genotyping was performed by PCR amplification followed by sequencing. All amplifications were performed with AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems) using standard protocols.

Real-time PCR and MLPA analysis

Chromosome-specific target sequences for quantitative PCR analysis were selected within non - repeated sequences using Primer Express 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems) as described in Bonaglia et al. [18]. The annotated genomic sequence of chromosome 22 (March 2006 assembly, hg18) is available through the UCSC Human Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification analysis (MLPA) of the 22q13 region was performed with the SALSA MLPA kit P188 22q13 (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam).

Breakpoint cloning

Amplification of 22q13 deletions repaired by chromosome healing was performed as in Bonaglia et al [18]. PCR products were both directly sequenced and cloned with a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen), followed by sequencing of individual clones. Inverse PCR was performed on Sau3A-cut, ligated (in 1 ml volume to facilitate self-ligation of individual fragments) genomic DNA, using nested sets of primers. Long-range PCRs were performed with JumpStart Red ACCUTaq LA DNA polymerase (Sigma) and the following protocol: 30 sec at 96°C, 35 cycles of 15 sec at 94°C/20 sec at 58°C/15 min at 68°C, 15 min final elongation time. Sequencing reactions were performed with a Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and run on an ABI Prism 3130xl Genetic Analyzer. Primer sequences are available in Table S2.

Web resources

The accession number and URLs for data presented herein are as follow: UCSC Human Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BorgaonkarDS 1984 Chromosomal variation in man New York Liss

2. WilkieAOLambJHarrisPCFinneyRDHiggsDR 1990 A truncated human chromosome 16 associated with alpha thalassaemia is stabilized by addition of telomeric repeat (TTAGGG)n. Nature 346 868 871

3. LambJHarrisPCWilkieAOWoodWGDauwerseJG 1993 De novo truncation of chromosome 16p and healing with (TTAGGG)n in the alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome (ATR-16). Am J Hum Genet 52 668 676

4. FlintJCraddockCFVillegasABentleyDPWilliamsHJ 1994 Healing of broken human chromosomes by the addition of telomeric repeats. Am J Hum Genet 3 505 512

5. NeumannAAReddelRR 2002 Telomere maintenance and cancer – look, no telomerase. Nat Rev Cancer 2 879 884

6. VarleyHPickettHAFoxonJLReddelRRRoyleNJ 2002 Molecular characterization of inter-telomere and intra-telomere mutations in human ALT cells. Nat Genet 30 301 305

7. MeltzerPSGuanXYTrentJM 1993 Telomere capture stabilizes chromosome breakage. Nat Genet 4 252 255

8. NingYLiangJCNagarajanLSchrockERiedT 1998 Characterization of 5q deletions by subtelomeric probes and spectral karyotyping. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 103 170 172

9. KnijnenburgJvan HaeringenAHanssonKBLankesterASmitMJ 2007 Ring chromosome formation as a novel escape mechanism in patients with inverted duplication and terminal deletion. Eur J Hum Genet 5 548 555

10. RossiERiegelMMessaJGimelliSMaraschioP 2008 Duplications in addition to terminal deletions are present in a proportion of ring chromosomes: Clues to the mechanisms of formation. J Med Genet 4 147 154

11. BallifBCWakuiKGajeckaMShafferLG 2004 Translocation breakpoint mapping and sequence analysis in three monosomy 1p36 subjects with der(1)t(1;1)(p36;q44) suggest mechanisms for telomere capture in stabilizing de novo terminal rearrangements. Hum Genet 114 198 206

12. YatsenkoSABrundageEKRoneyEKCheungSWChinaultAC 2009 Molecular mechanisms for subtelomeric rearrangements associated with the 9q34.3 microdeletion syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 18 1924 1936

13. PhelanMCRogersRCSaulRAStapletonGASweetK 2001 22q13 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet 101 91 99

14. WilsonHLWongACShawSRTseWYStapletonGA 2003 Molecular characterisation of the 22q13 deletion syndrome supports the role of haploinsufficiency of SHANK3/PROSAP2 in the major neurological symptoms. J Med Genet 40 575 584

15. RodriguezLMartinez GuardiaNHerensCJamarMVerloesA 2003 Subtle trisomy 12q24.3 and subtle monosomy 22q13.3: Three new cases and review. Am J Med Genet A 122A 119 124

16. BonagliaMCGiordaRBeriSBigoniSSensiA 2009 Mosaic 22q13 deletions: Evidence for concurrent mosaic segmental isodisomy and gene conversion. Eur J Hum Genet 17 426 433

17. PhelanK 2007 22q13.3 deletion syndrome. GENEReviews, University of Washington, Seattle (www.genetests.org)

18. BonagliaMCGiordaRManiEAcetiGAnderlidBM 2006 Identification of a recurrent breakpoint within the SHANK3 gene in the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome. J Med Genet 43 822 828

19. DurandCMBetancurCBoeckersTMBockmannJChasteP 2007 Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet 39 25 27

20. MoessnerRMarshallCRSutcliffeJSSkaugJPintoD 2007 Contribution of SHANK3 mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet 81 1289 1297

21. GauthierJSpiegelmanDPitonALafrenièreRGLaurentS 2009 Novel de novo SHANK3 mutation in autistic patients. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 150B 421 424

22. GauthierJChampagneNLafrenièreRGXiongLSpiegelmanD 2010 De novo mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 in patients ascertained for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 7863 7868

23. HamdanFFGauthierJArakiYLinDTYoshizawaY 2011 Excess of de novo deleterious mutations in genes associated with glutamatergic systems in nonsyndromic intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet 88 306 316

24. GizaJUrbanskiMJPrestoriFBandyopadhyayBYamA 2010 Behavioral and cerebellar transmission deficits in mice lacking the autism-linked gene islet brain-2. J Neurosci 30 14805 14816

25. AnderlidBMSchoumansJAnnerenGTapia-PaezIDumanskiJ 2002 FISH-mapping of a 100-kb terminal 22q13 deletion. Hum Genet 5 439 443

26. PhamECrewsLUbhiKHansenLAdameA 2010 Progressive accumulation of amyloid-beta oligomers in Alzheimer's disease and in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice is accompanied by selective alterations in synaptic scaffold proteins. FEBS J 277 3051 3067

27. GongYLippaCFZhuJLinQRossoAL 2009 Disruption of glutamate receptors at shank-postsynaptic platform in alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 1292 191 198

28. LucianiJJde MasPDepetrisDMignon-RavixCBottaniA 2003 Telomeric 22q13 deletions resulting from rings, simple deletions, and translocations: Cytogenetic, molecular, and clinical analyses of 32 new observations. J Med Genet 40 690 696

29. JeffriesARCurranSElmslieFSharmaAWengerS 2005 Molecular and phenotypic characterization of ring chromosome 22. Am J Med Genet A 137 139 147

30. WongACNingYFlintJClarkKDumanskiJP 1997 Molecular characterization of a 130-kb terminal microdeletion at 22q in a child with mild mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 60 113 120

31. HeilstedtHABallifBCHowardLALewisRAStalS 2003 Physical map of 1p36, placement of breakpoints in monosomy 1p36, and clinical characterization of the syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 72 1200 1212

32. MullerFWickyCSpicherAToblerH 1991 New telomere formation after developmentally regulated chromosomal breakage during the process of chromatin diminution in Ascaris lumbricoides. Cell 67 815 822

33. BottiusEBakhsisNScherfA 1998 Plasmodium falciparum telomerase: de novo telomere addition to telomeric and nontelomeric sequences and role in chromosome healing. Mol Cell Biol 18 919 925

34. HannesFVan HoudtJQuarrellOWPootMHochstenbachR 2010 Telomere healing following DNA polymerase arrest-induced breakages is likely the main mechanism generating chromosome 4p terminal deletions. Hum Mutat 31 1343 1351

35. KnightSJFlintJ 2000 Perfect endings: A review of subtelomeric probes and their use in clinical diagnosis. J Med Genet 37 401 409

36. ZhaoJBacollaAWangGVasquezKM 2010 Non-B DNA structure-induced genetic instability and evolution. Cell Mol Life Sci 67 43 62

37. ChristLACroweCAMicaleMAConroyJMSchwartzS 1999 Chromosome breakage hotspots and delineation of the critical region for the 9p-deletion syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 5 1387 1395

38. PhilippeABoddaertNVaivre-DouretLRobelLDanon-BoileauL 2008 Neurobehavioral profile and brain imaging study of the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics 122 e376 82

39. DharSUdel GaudioDGermanJRPetersSUOuZ 2010 22q13.3 deletion syndrome: Clinical and molecular analysis using array CGH. Am J Med Genet A 152A 573 581

40. D'AntonioLBaggaP 2004 Computational methods for predicting intramolecular G-quadruplexes in nucleotide sequences. Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE Computational Systems Bioinformatics Conference (CSB 2004)

41. DelahayeAToutainAAbouraADupontCTabetAC 2009 Chromosome 22q13.3 deletion syndrome with a de novo interstitial 22q13.3 cryptic deletion disrupting SHANK3. Eur J Med Genet 52 328 332

42. WilsonHLCrollaJAWalkerDArtifoniLDallapiccolaB 2008 Interstitial 22q13 deletions: genes other than SHANK3 have major effects on cognitive and language development. Eur J Hum Genet 16 1301 1310

43. SlackAThorntonPCMagnerDBRosenbergSMHastingsPJ 2006 On the mechanism of gene amplification induced under stress in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet 2 e48 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020048

44. HastingsPJIraGLupskiJR 2009 A microhomology-mediated break-induced replication model for the origin of human copy number variation. PLoS Genet 5 e1000327 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000327

45. BoonePMBacinoCAShawCAEngPAHixsonPM 2010 Detection of clinically relevant exonic copy-number changes by array CGH. Hum Mutat 31 1326 1342

46. VannesteEVoetTLe CaignecCAmpeMKoningsP 2009 Chromosome instability is common in human cleavage-stage embryos. Nat Med 15 577 583

47. ConlinLKThielBDBonnemannCGMedneLErnstLM 2010 Mechanisms of mosaicism, chimerism and uniparental disomy identified by single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Hum Mol Genet 19 1263 1275

48. LupskiJR 2010 New mutations and intellectual function. Nat Genet 42 1036 1038

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Pervasive Sign Epistasis between Conjugative Plasmids and Drug-Resistance Chromosomal MutationsČlánek Stress-Induced PARP Activation Mediates Recruitment of Mi-2 to Promote Heat Shock Gene ExpressionČlánek Histone Crosstalk Directed by H2B Ubiquitination Is Required for Chromatin Boundary IntegrityČlánek A Functional Variant at a Prostate Cancer Predisposition Locus at 8q24 Is Associated with ExpressionČlánek Replication and Explorations of High-Order Epistasis Using a Large Advanced Intercross Line PedigreeČlánek Expression of Tumor Suppressor in Spermatogonia Facilitates Meiotic Progression in Male Germ Cells

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 7

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Gene-Based Tests of Association

- The Demoiselle of X-Inactivation: 50 Years Old and As Trendy and Mesmerising As Ever

- Variants in and Underlie Natural Variation in Translation Termination Efficiency in

- SHH1, a Homeodomain Protein Required for DNA Methylation, As Well As RDR2, RDM4, and Chromatin Remodeling Factors, Associate with RNA Polymerase IV

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies as a Susceptibility Gene for Pediatric Asthma in Asian Populations

- Pervasive Sign Epistasis between Conjugative Plasmids and Drug-Resistance Chromosomal Mutations

- Genetic Anticipation Is Associated with Telomere Shortening in Hereditary Breast Cancer

- Identification of a Mutation Associated with Fatal Foal Immunodeficiency Syndrome in the Fell and Dales Pony

- Stress-Induced PARP Activation Mediates Recruitment of Mi-2 to Promote Heat Shock Gene Expression

- An Epigenetic Switch Involving Overlapping Fur and DNA Methylation Optimizes Expression of a Type VI Secretion Gene Cluster

- Recombination and Population Structure in

- A Rice Plastidial Nucleotide Sugar Epimerase Is Involved in Galactolipid Biosynthesis and Improves Photosynthetic Efficiency

- A Role for Phosphatidic Acid in the Formation of “Supersized” Lipid Droplets

- Colon Stem Cell and Crypt Dynamics Exposed by Cell Lineage Reconstruction

- Loss of the BMP Antagonist, SMOC-1, Causes Ophthalmo-Acromelic (Waardenburg Anophthalmia) Syndrome in Humans and Mice

- Interactions between Glucocorticoid Treatment and Cis-Regulatory Polymorphisms Contribute to Cellular Response Phenotypes

- Translation Reinitiation Relies on the Interaction between eIF3a/TIF32 and Progressively Folded -Acting mRNA Elements Preceding Short uORFs

- DAF-12 Regulates a Connected Network of Genes to Ensure Robust Developmental Decisions

- Adult Circadian Behavior in Requires Developmental Expression of , But Not

- Histone Crosstalk Directed by H2B Ubiquitination Is Required for Chromatin Boundary Integrity

- Proteins in the Nutrient-Sensing and DNA Damage Checkpoint Pathways Cooperate to Restrain Mitotic Progression following DNA Damage

- Complex Evolutionary Events at a Tandem Cluster of Genes Resulting in a Single-Locus Genetic Incompatibility

- () and Its Regulated Homeodomain Gene Mediate Abscisic Acid Response in

- A Functional Variant at a Prostate Cancer Predisposition Locus at 8q24 Is Associated with Expression

- LGI2 Truncation Causes a Remitting Focal Epilepsy in Dogs

- Adaptations to Endosymbiosis in a Cnidarian-Dinoflagellate Association: Differential Gene Expression and Specific Gene Duplications

- The Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E Regulates the Sex-Specific Expression of the Master Switch Gene in

- Somatic Genetics Empowers the Mouse for Modeling and Interrogating Developmental and Disease Processes

- Molecular Mechanisms Generating and Stabilizing Terminal 22q13 Deletions in 44 Subjects with Phelan/McDermid Syndrome

- Replication and Explorations of High-Order Epistasis Using a Large Advanced Intercross Line Pedigree

- Mechanisms of Chromosome Number Evolution in Yeast

- Regulatory Cross-Talk Links Chromosome II Replication and Segregation

- Ancestral Genes Can Control the Ability of Horizontally Acquired Loci to Confer New Traits

- Expression of Tumor Suppressor in Spermatogonia Facilitates Meiotic Progression in Male Germ Cells

- Rare and Common Regulatory Variation in Population-Scale Sequenced Human Genomes

- The Epistatic Relationship between BRCA2 and the Other RAD51 Mediators in Homologous Recombination

- Identification of Novel Genetic Markers Associated with Clinical Phenotypes of Systemic Sclerosis through a Genome-Wide Association Strategy

- NatF Contributes to an Evolutionary Shift in Protein N-Terminal Acetylation and Is Important for Normal Chromosome Segregation

- Araucan and Caupolican Integrate Intrinsic and Signalling Inputs for the Acquisition by Muscle Progenitors of the Lateral Transverse Fate

- Pathologic and Phenotypic Alterations in a Mouse Expressing a Connexin47 Missense Mutation That Causes Pelizaeus-Merzbacher–Like Disease in Humans

- Recombinant Inbred Line Genotypes Reveal Inter-Strain Incompatibility and the Evolution of Recombination

- Epistatic Relationships in the BRCA1-BRCA2 Pathway

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Novel Restless Legs Syndrome Susceptibility Loci on 2p14 and 16q12.1

- Genetic Loci Associated with Plasma Phospholipid n-3 Fatty Acids: A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies from the CHARGE Consortium

- Fine Mapping of Five Loci Associated with Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Detects Variants That Double the Explained Heritability

- CHD1 Remodels Chromatin and Influences Transient DNA Methylation at the Clock Gene

- Nonlinear Fitness Landscape of a Molecular Pathway

- Genome-Wide Scan Identifies , , and as Novel Risk Loci for Systemic Sclerosis

- Quantitative and Qualitative Stem Rust Resistance Factors in Barley Are Associated with Transcriptional Suppression of Defense Regulons

- A Systematic Screen for Tube Morphogenesis and Branching Genes in the Tracheal System

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Novel Restless Legs Syndrome Susceptibility Loci on 2p14 and 16q12.1

- Loss of the BMP Antagonist, SMOC-1, Causes Ophthalmo-Acromelic (Waardenburg Anophthalmia) Syndrome in Humans and Mice

- Gene-Based Tests of Association

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies as a Susceptibility Gene for Pediatric Asthma in Asian Populations

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání