-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaBurning Down the House: Cellular Actions during Pyroptosis

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 9(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003793

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003793Summary

article has not abstract

Introduction

Under threat of pathogen invasion, timely initiation of inflammation is a critical first step in generating a protective immune response. One major obstacle for the immune system is discriminating pathogenic microbes from non-pathogenic microbiota. Some members of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) family of pattern recognition receptors accomplish this distinction based on localization—typically, only pathogens deliver NLR ligands into the cytosol, where these receptors are localized. Ultimately, these NLRs initiate assembly of an inflammasome complex that activates the proteases caspase-1 and caspase-11. These caspases were originally identified for their role in IL-1β processing and release but are now known to direct additional important cellular processes during infection, inflammatory disorders, and response to injury. In this brief review, we enumerate these emerging pathways (Figure 1) and highlight their roles in disease.

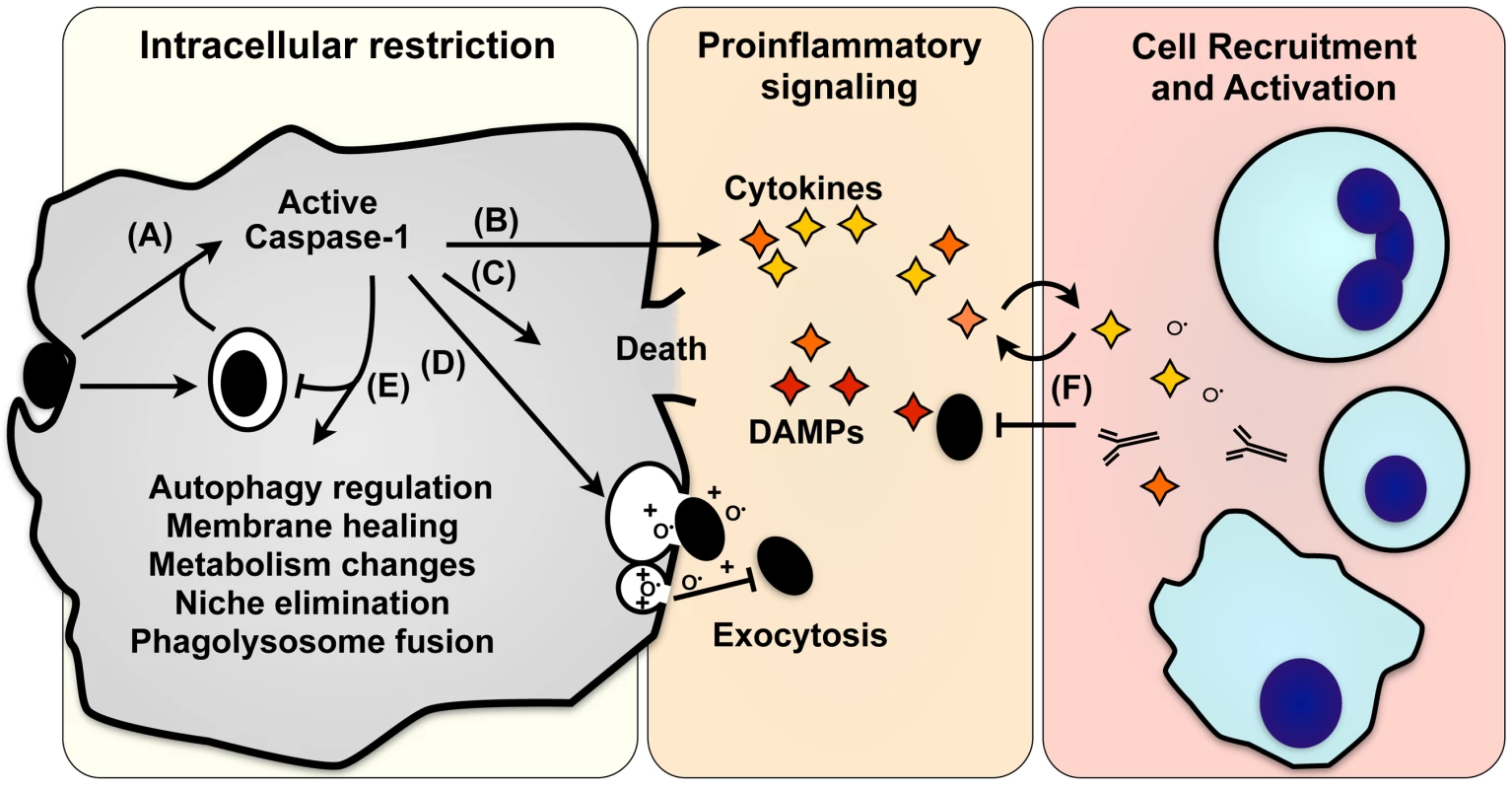

Fig. 1. Effector mechanisms of pyroptosis.

(A) Caspase-1 activation in response to microbial infection (black ovals) initiates numerous pathways that promote death or recovery of the cell, directly combat pathogen infection, or signal to other cells. (B) The proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 are cleaved and secreted, and HMGB1, IL-1α, FGF2, and numerous damage-associated molecular patterns are also released. (C) Caspase-1 can also initiate programmed cell death, eliminating a niche for intracellular pathogens while releasing both pathogen and proinflammatory signals. (D) Intracellular pathogens and antimicrobial factors that kill extracellular bacteria can be released by lysosomal exocytosis, also promoting adaptive immune responses through cross-priming. (E) Caspase-1 promotes cellular integrity by removing microbes or damaged organelles by stimulating autophagy, enhanced lysosome activity, induction of lipid metabolism, and exocytosis of damaged or infected organelles. (F) Proinflammatory signals released by lysis, exocytosis, and other secretory pathways recruit and activate immune cells (blue; clockwise from top: neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages/dendritic cells). The specific responses of a cell vary depending on the kinetics and magnitude of caspase-1 stimulation, the activating stimulus, and cell type. IL-1β and IL-18

The proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 were the earliest studied caspase-1 substrates. IL-1β directs diverse processes, including extravasation, cell proliferation and differentiation, cytokine secretion, angiogenesis, wound healing, and pyrexia [1]. IL-18 is best known for stimulating NK and T cells to secrete IFN-γ, another broad-activity cytokine. Production of these potent cytokines is tightly regulated: expression requires NF-κB signaling, biological activity requires cleavage of a pro-domain by caspase-1, and secretion is also directed by caspase-1 [1]. Mice unable to signal via IL-1β and IL-18 are more susceptible to several diverse pathogens, including Shigella, Salmonella, Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, and influenza virus [1]. However, caspase-1−/− mice are more susceptible to some infections than IL-1β−/−IL-18−/− mice [2], underscoring the importance of additional caspase-1 substrates that alter the immune response.

Pyroptosis

Proinflammatory programmed cell death by pyroptosis is often the terminal fate of a cell with active caspase-1 or caspase-11 [3]. The specific pathways contributing to this complex cellular response are only now becoming defined. Caspase proteolytic activity is required, indicating one or more proteins key to cell survival are cleaved and inactivated. Numerous caspase-1 targets have been identified [4]–[7], but the identity of this/these critical substrate(s) is not yet known. An early step in pyroptosis is formation of small cation-permeable pores in the plasma membrane [8]. This dissipates the cellular ionic gradient and leads to osmotic swelling and lysis [8]. Ca++ flux through these pores is responsible for many of the caspase-1–dependent signaling events that will be discussed in this review. Nuclear condensation, DNA fragmentation that is independent of ICAD (inhibitor of caspase(3)-activated DNase), and IL-1β secretion all precede lysis [8]. These features, along with the unique biochemical requirement for caspase-1, distinguish pyroptosis from other cell death programs such as apoptosis, autophagy, necrosis, NETosis, oncosis, pyronecrosis, and necroptosis [9].

Some pathogens take steps to avoid pyroptosis. Yersinia sp. avoid inflammation by directly inhibiting pyroptosis [10] and inducing death by non-inflammatory apoptosis [11]. Poxviruses, similarly, inhibit pyroptosis and also suppress IL-18 and IL-1β signaling with receptor antagonists [12]. In contrast, Salmonella typhimurium-infected macrophages rapidly activate caspase-1 and undergo pyroptosis. Lysis of infected macrophages releases intracellular Salmonella for subsequent phagocytosis and killing by neutrophils [2]. Thus, depriving a replicative niche to intracellular pathogens through pyroptosis is one critical contribution of caspase-1 during some infections.

Additional Proinflammatory Signals

Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as ATP, DNA, RNA, and heat-shock proteins are strongly proinflammatory when extracellular, and are released during pyroptosis [13]. DAMPs recruit cells to the inflammatory focus, initiate cytokine secretion, and serve as adjuvants for T-cell priming [12]. One DAMP in particular, HMGB1, has a well-understood role in pyroptosis. HMGB1 is a nuclear transcriptional regulator released during pyroptosis that can subsequently be detected by TLR4 and RAGE receptors to stimulate cytokine release and cell migration [14]. In a murine model of endotoxic shock, caspase-1–dependent release of HMGB1 drives inflammation independent of IL-1β, IL-18, or other DAMPs [14].

Members of the eicosanoid family of signaling lipids, such as leukotrienes and prostaglandins, induce vascular leakage and recruitment of cells to the inflammatory focus. Recently, it was shown that the Ca++ influx after caspase-1 activation can induce eicosanoid synthesis [15]. Glycine, an inhibitor of cell lysis but not caspase-1–directed secretion pathways [8], did not block eicosanoid release, suggesting release is a secretion event and not due to cell leakage [15]. Caspase-1 activation of this pathway has not yet been characterized in many models of inflammation, but eicosanoid signaling represents a very rapid and severe proinflammatory response initiated by caspase-1.

Multi-functional Secretory Mechanisms

Unlike typical cytokines that contain signal sequences for canonical ER/Golgi-mediated export, IL-1β and IL-18 reside in the cytosol until caspase-1-dependent secretion mechanisms are activated [1]. IL-1β and IL-18 can be found in secreted plasma membrane, lysosomal, and autophagic vesicles, but appear to often be secreted by other mechanisms that yield soluble, non-vesicle–associated cytokines [16]–[18]. Several other proteins lacking typical secretion signals are released, including a membrane-bound analog of IL-1β, IL-1α, and the growth factor FGF2 [18], induced by the Ca++ influx accompanying caspase-1 activation [19]. Ca++ influx, either upon cell wounding [20] or pyroptosis [17], also induces exocytosis of lysosomes to help repair membrane lesions [20] and release antimicrobial compounds that can kill extracellular bacteria [17]. Phagocytosed particles and intracellular pathogens are also exocytosed, allowing their removal from the cell prior to lysis [17]. Concurrent release of pathogens, antimicrobial compounds, and DAMPs likely cooperate to amplify the immune response through cross-priming and other mechanisms.

Remodeling of Cellular Pathways

Several reports have identified links between caspase-1 and autophagy, a program for removal of cellular debris and microbes. These pathways typically have reciprocal activities; active caspase-1 can limit autophagy [21], while autophagy antagonizes caspase-1 activation [22] and depletes both cytosolic IL-1β [23] and inflammasomes [24]. Factors critical for autophagy are involved in numerous cell processes and also function in proinflammatory capacities [25]. Even after caspase-1 activation, autophagy may aid a cell's recovery by limiting further caspase-1 activity and antagonizing lysis [26]. Also promoting cell survival is SREBP, a transcription factor that regulates lipid metabolic pathways involved in membrane repair [27]. SREBP is membrane-bound and inert until proteolytically released; during pyroptosis, caspase-1 cleaves and activates SREBP-regulating proteases [27]. Like autophagy and lysosomal exocytosis, induction of SREBP may help cells recover from low-level caspase-1 activation. These pathways could allow bifurcated responses in which modestly damaged cells survive, while sustained caspase-1 activity in terminally wounded or persistently infected cells can overcome pro-survival pathways.

Proteome-scale analysis of caspase-1 substrates has hinted at additional pathways affected by caspase-1. Substrates of caspase-1 may gain function or have altered localization, but are most likely to lose function from cleavage. Many proteins identified by proteomics, such as cytoskeletal [4], [5], [7], translational [5], [7], and trafficking [5], [7] proteins, may yet prove to be false positives due to their relative abundance and the promiscuity of caspase-1 [6]. One substrate set that has been experimentally verified includes proteins of the glycolysis metabolic pathway: aldolase, triose-phosphate isomerase, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase, enolase, and pyruvate kinase [5]. Cleavage of these enzymes disrupts glycolysis, which may contribute to death of the cell, and may also restrict intracellular pathogens by limiting nutrients [5]. Also processed by caspase-1 are other caspases: caspases-4, -5, and -7 [4], [7]. Caspase-4 and -5 are the human homologs of murine caspase-11, which overlaps with caspase-1 function and can be activated in a parallel mechanism [28], [29]. Cleavage and activation of caspase-7 likely accounts for the number of substrates cleaved at caspase-7–like sites during pyroptosis [4], [7]. Caspase-7 is an executioner caspase of apoptosis but is dispensable for pyroptosis [4], indicating death by pyroptosis occurs independently of the apoptosis program.

Concluding Remarks

Significant work remains to clarify the relationship between PAMP, signaling pathway(s), cell type, and the outputs during pyroptosis. For example, pyroptosis can occur without IL-1β secretion [2], TLR stimulation alone induces monocytes to secrete IL-1β [30], neutrophils secrete comparatively little IL-1β [31], and caspase-1-dependent secretion of eicosanoids is only seen with resident peritoneal macrophages [15]. Additionally, earlier caspase-1−/− mice also lacked caspase-11, and the role of this regulator in pyroptosis merits further investigation [28]. Despite our incomplete understanding of all of these processes, it is clear that integration of inflammatory programs, with caspase-1 as their central regulator, allows a cell to comprehensively react to injury or infection, preventing deleterious delays in initiating immune responses. The robustness of this pathway is normally well-controlled by NLR stringency; however, “hair-trigger” activation of caspase-1 drives inflammation during atherosclerosis, diabetes, Alzheimer's, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and several auto-inflammatory genetic disorders. Thus, implications for treatment of the diseases of both industrial and developing countries can come from further study of caspase-1 regulation and signaling.

Zdroje

1. NeteaMG, SimonA, van de VeerdonkFLV, KullbergBJ, Van der MeerJ, et al. (2010) IL-1beta Processing in Host Defense: Beyond the Inflammasomes. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000661 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000661

2. MiaoEA, LeafIA, TreutingPM, MaoDP, DorsM, et al. (2010) Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat Immunol 11 : 1136–1142.

3. CooksonBT, BrennanMA (2001) Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol 9 : 113–114.

4. LamkanfiM, KannegantiT-D, Van DammeP, BergheTV, VanoverbergheI, et al. (2008) Targeted peptidecentric proteomics reveals caspase-7 as a substrate of the caspase-1 inflammasomes. Mol Cell Proteomics 7 : 2350–2363.

5. ShaoW, YeretssianG, DoironK, HussainSN, SalehM (2007) The caspase-1 digestome identifies the glycolysis pathway as a target during Infection and Septic Shock. J Biol Chem 282 : 36321–36329.

6. WalshJG, LogueSE, LüthiAU, MartinSJ (2011) Caspase-1 Promiscuity Is Counterbalanced by Rapid Inactivation of Processed Enzyme. J Biol Chem 286 : 32513–32524.

7. AgardNJ, MaltbyD, WellsJA (2010) Inflammatory stimuli regulate caspase substrate profiles. Mol Cell Proteomics 9 : 880–893.

8. FinkSL, CooksonBT (2006) Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell Microbiol 8 : 1812–1825.

9. GalluzziL, VitaleI, AbramsJM, AlnemriES, BaehreckeEH, et al. (2012) Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ 19 : 107–120.

10. LaRockCN, CooksonBT (2012) The Yersinia Virulence Effector YopM Binds Caspase-1 to Arrest Inflammasome Assembly and Processing. Cell Host Microbe 12 : 799–805.

11. BergsbakenT, CooksonBT (2007) Macrophage Activation Redirects Yersinia-Infected Host Cell Death from Apoptosis to Caspase-1-Dependent Pyroptosis. PLoS Pathog 3: e161 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030161

12. BergsbakenT, FinkSL, CooksonB (2009) Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol 7 : 99–109.

13. ChenGY, NuñezG (2010) Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol 10 : 826–837.

14. LamkanfiM, SarkarA, Vande WalleL, VitariAC, AmerAO, et al. (2010) Inflammasome-dependent release of the alarmin HMGB1 in endotoxemia. J Immunol 185 : 4385–4392.

15. von MoltkeJ, TrinidadNJ, MoayeriM, KintzerAF, WangSB, et al. (2012) Rapid induction of inflammatory lipid mediators by the inflammasome in vivo. Nature 490 : 107–111.

16. MacKenzieA, WilsonHL, Kiss-TothE, DowerSK, NorthRA, et al. (2001) Rapid secretion of interleukin-1B by microvesicle shedding. Immunity 8 : 825–835.

17. BergsbakenT, FinkSL, den HartighAB, LoomisWP, CooksonBT (2011) Coordinated Host Responses during Pyroptosis: Caspase-1-Dependent Lysosome Exocytosis and Inflammatory Cytokine Maturation. J Immunol 187 : 2748–2754.

18. KellerM, RueggA, WernerS, BeerH (2008) Active caspase-1 is a regulator of unconventional protein secretion. Cell 132 : 818–831.

19. GroßO, YazdiAS, ThomasCJ, MasinM, HeinzLX, et al. (2012) Inflammasome activators induce interleukin-1α secretion via distinct pathways with differential requirement for the protease function of caspase-1. Immunity 36 : 388–400.

20. ReddyA, CalerEV, AndrewsNW (2001) Plasma Membrane Repair Is Mediated by Ca2+-Regulated Exocytosis of Lysosomes. Cell 106 : 157–169.

21. SuzukiT, FranchiL, TomaC, AshidaH, OgawaM, et al. (2007) Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog 3: e111 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111

22. NakahiraK, HaspelJA, RathinamVAK, LeeS-J, DolinayT, et al. (2011) Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 8 : 222–230.

23. HarrisJ, HartmanM, RocheC, ZengSG, O'SheaA, et al. (2011) Autophagy controls IL-1β secretion by targeting pro-IL-1β for degradation. J Biol Chem 286 : 9587–9597.

24. ShiC-S, ShenderovK, HuangN-N, KabatJ, Abu-AsabM, et al. (2012) Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1 [beta] production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat Immunol 13 : 255–263.

25. DupontN, JiangS, PilliM, OrnatowskiW, BhattacharyaD, et al. (2011) Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. EMBO J 30 : 4701–4711.

26. ByrneBG, DubuissonJ-F, JoshiAD, PerssonJJ, SwansonMS (2013) Inflammasome Components Coordinate Autophagy and Pyroptosis as Macrophage Responses to Infection. MBio 4: e00620–00612.

27. GurcelL, AbramiL, GirardinS, TschoppJ, van der GootFG (2006) Caspase-1 activation of lipid metabolic pathways in response to bacterial pore-forming toxins promotes cell survival. Cell 126 : 1135–1145.

28. KayagakiN, WarmingS, LamkanfiM, WalleLV, LouieS, et al. (2011) Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479 : 117–121.

29. AachouiY, LeafIA, HagarJA, FontanaMF, CamposCG, et al. (2013) Caspase-11 Protects Against Bacteria That Escape the Vacuole. Science 339 : 975–978.

30. NeteaMG, NoldMF, JoostenLA, OpitzB, van de VeerdonkFLV, et al. (2009) Differential requirement for the activation of the inflammasome for processing and release of IL-1B in monocytes and macrophages. Blood 113 : 2324–2335.

31. HolzingerD, GieldonL, MysoreV, NippeN, TaxmanDJ, et al. (2012) Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin induces an inflammatory response in human phagocytes via the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Leukoc Biol 92 : 1069–1081.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Parental Transfer of the Antimicrobial Protein LBP/BPI Protects Eggs against Oomycete InfectionsČlánek Immune Therapeutic Strategies in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Virus or Inflammation Control?Článek Coronaviruses as DNA Wannabes: A New Model for the Regulation of RNA Virus Replication FidelityČlánek CRISPR-Cas Immunity against Phages: Its Effects on the Evolution and Survival of Bacterial PathogensČlánek The Cyst Wall Protein CST1 Is Critical for Cyst Wall Integrity and Promotes Bradyzoite PersistenceČlánek The Malarial Serine Protease SUB1 Plays an Essential Role in Parasite Liver Stage Development

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 12- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Host Susceptibility Factors to Bacterial Infections in Type 2 Diabetes

- LysM Effectors: Secreted Proteins Supporting Fungal Life

- Influence of Mast Cells on Dengue Protective Immunity and Immune Pathology

- Innate Lymphoid Cells: New Players in IL-17-Mediated Antifungal Immunity

- Cytoplasmic Viruses: Rage against the (Cellular RNA Decay) Machine

- Balancing Stability and Flexibility within the Genome of the Pathogen

- The Evolution of Transmissible Prions: The Role of Deformed Templating

- Parental Transfer of the Antimicrobial Protein LBP/BPI Protects Eggs against Oomycete Infections

- Host Defense via Symbiosis in

- Regulatory Circuits That Enable Proliferation of the Fungus in a Mammalian Host

- Immune Therapeutic Strategies in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Virus or Inflammation Control?

- Burning Down the House: Cellular Actions during Pyroptosis

- Coronaviruses as DNA Wannabes: A New Model for the Regulation of RNA Virus Replication Fidelity

- CRISPR-Cas Immunity against Phages: Its Effects on the Evolution and Survival of Bacterial Pathogens

- Combining Regulatory T Cell Depletion and Inhibitory Receptor Blockade Improves Reactivation of Exhausted Virus-Specific CD8 T Cells and Efficiently Reduces Chronic Retroviral Loads

- Shaping Up for Battle: Morphological Control Mechanisms in Human Fungal Pathogens

- Identification of the Virulence Landscape Essential for Invasion of the Human Colon

- Nodular Inflammatory Foci Are Sites of T Cell Priming and Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection in the Neonatal Lung

- Hepatitis B Virus Disrupts Mitochondrial Dynamics: Induces Fission and Mitophagy to Attenuate Apoptosis

- Mycobacterial MazG Safeguards Genetic Stability Housecleaning of 5-OH-dCTP

- Systematic MicroRNA Analysis Identifies ATP6V0C as an Essential Host Factor for Human Cytomegalovirus Replication

- Placental Syncytium Forms a Biophysical Barrier against Pathogen Invasion

- The CD8-Derived Chemokine XCL1/Lymphotactin Is a Conformation-Dependent, Broad-Spectrum Inhibitor of HIV-1

- Cyclin A Degradation by Primate Cytomegalovirus Protein pUL21a Counters Its Innate Restriction of Virus Replication

- Genome-Wide RNAi Screen Identifies Novel Host Proteins Required for Alphavirus Entry

- Zinc Sequestration: Arming Phagocyte Defense against Fungal Attack

- The Cyst Wall Protein CST1 Is Critical for Cyst Wall Integrity and Promotes Bradyzoite Persistence

- Biphasic Euchromatin-to-Heterochromatin Transition on the KSHV Genome Following Infection

- The Malarial Serine Protease SUB1 Plays an Essential Role in Parasite Liver Stage Development

- HIV-1 Vpr Accelerates Viral Replication during Acute Infection by Exploitation of Proliferating CD4 T Cells

- A Human Torque Teno Virus Encodes a MicroRNA That Inhibits Interferon Signaling

- The ArlRS Two-Component System Is a Novel Regulator of Agglutination and Pathogenesis

- An In-Depth Comparison of Latent HIV-1 Reactivation in Multiple Cell Model Systems and Resting CD4+ T Cells from Aviremic Patients

- Enterohemorrhagic Hemolysin Employs Outer Membrane Vesicles to Target Mitochondria and Cause Endothelial and Epithelial Apoptosis

- Overcoming Antigenic Diversity by Enhancing the Immunogenicity of Conserved Epitopes on the Malaria Vaccine Candidate Apical Membrane Antigen-1

- The Type-Specific Neutralizing Antibody Response Elicited by a Dengue Vaccine Candidate Is Focused on Two Amino Acids of the Envelope Protein

- Tmprss2 Is Essential for Influenza H1N1 Virus Pathogenesis in Mice

- Signatures of Pleiotropy, Economy and Convergent Evolution in a Domain-Resolved Map of Human–Virus Protein–Protein Interaction Networks

- Interference with the Host Haemostatic System by Schistosomes

- RocA Truncation Underpins Hyper-Encapsulation, Carriage Longevity and Transmissibility of Serotype M18 Group A Streptococci

- Gene Fitness Landscapes of at Important Stages of Its Life Cycle

- Phagocytosis Escape by a Protein That Connects Complement and Coagulation Proteins at the Bacterial Surface

- t Is a Structurally Novel Crohn's Disease-Associated Superantigen

- An Increasing Danger of Zoonotic Orthopoxvirus Infections

- Myeloid Dendritic Cells Induce HIV-1 Latency in Non-proliferating CD4 T Cells

- Transcriptional Analysis of Murine Macrophages Infected with Different Strains Identifies Novel Regulation of Host Signaling Pathways

- Serotonergic Chemosensory Neurons Modify the Immune Response by Regulating G-Protein Signaling in Epithelial Cells

- Genome-Wide Detection of Fitness Genes in Uropathogenic during Systemic Infection

- Induces an Unfolded Protein Response via TcpB That Supports Intracellular Replication in Macrophages

- Intestinal CD103+ Dendritic Cells Are Key Players in the Innate Immune Control of Infection in Neonatal Mice

- Emerging Functions for the RNome

- KSHV MicroRNAs Mediate Cellular Transformation and Tumorigenesis by Redundantly Targeting Cell Growth and Survival Pathways

- HrpA, an RNA Helicase Involved in RNA Processing, Is Required for Mouse Infectivity and Tick Transmission of the Lyme Disease Spirochete

- A Toxin-Antitoxin Module of Promotes Virulence in Mice

- Real-Time Imaging of the Intracellular Glutathione Redox Potential in the Malaria Parasite

- Hypoxia Inducible Factor Signaling Modulates Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Infection via a Nitric Oxide Dependent Mechanism

- Novel Strategies to Enhance Vaccine Immunity against Coccidioidomycosis

- Dual Expression Profile of Type VI Secretion System Immunity Genes Protects Pandemic

- —What Makes the Species a Ubiquitous Human Fungal Pathogen?

- αvβ6- and αvβ8-Integrins Serve As Interchangeable Receptors for HSV gH/gL to Promote Endocytosis and Activation of Membrane Fusion

- -Induced Activation of EGFR Prevents Autophagy Protein-Mediated Killing of the Parasite

- Semen CD4 T Cells and Macrophages Are Productively Infected at All Stages of SIV infection in Macaques

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Influence of Mast Cells on Dengue Protective Immunity and Immune Pathology

- Host Defense via Symbiosis in

- Coronaviruses as DNA Wannabes: A New Model for the Regulation of RNA Virus Replication Fidelity

- Myeloid Dendritic Cells Induce HIV-1 Latency in Non-proliferating CD4 T Cells

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání