-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaMicroRNA-133 Inhibits Behavioral Aggregation by Controlling Dopamine Synthesis in Locusts

Phenotypic plasticity is ubiquitous and primarily controlled by interactions between environmental and genetic factors. The migratory locust, a worldwide pest, exhibits pronounced phenotypic plasticity, which is a population density-dependent transition that occurs between the gregarious and solitary phases. Genes involved in dopamine synthesis have been shown to regulate the phase transition of locusts. However, the function of microRNAs in this process remains unknown. In this study, we report the participation of miR-133 in dopamine production and the behavioral transition by negatively regulating two critical genes, henna and pale, in the dopamine pathway. miR-133 participated in the post-transcriptional regulation of henna and pale by binding to their coding region and 3′ untranslated region, respectively. miR-133 displayed cellular co-localization with henna/pale in the protocerebrum, and its expression in the protocerebrum was negatively correlated with henna and pale expression. Moreover, miR-133 agomir delivery suppressed henna and pale expression, which consequently decreased dopamine production, thus resulting in the behavioral shift of the locusts from the gregarious phase to the solitary phase. Increasing the dopamine content could rescue the solitary phenotype, which was induced by miR-133 agomir delivery. Conversely, miR-133 inhibition increased the expression of henna and pale, resulting in the gregarious-like behavior of solitary locusts; this gregarious phenotype could be rescued by RNA interference of henna and pale. This study shows the novel function and modulation pattern of a miRNA in phenotypic plasticity and provides insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms of the phase transition of locusts.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004206

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004206Summary

Phenotypic plasticity is ubiquitous and primarily controlled by interactions between environmental and genetic factors. The migratory locust, a worldwide pest, exhibits pronounced phenotypic plasticity, which is a population density-dependent transition that occurs between the gregarious and solitary phases. Genes involved in dopamine synthesis have been shown to regulate the phase transition of locusts. However, the function of microRNAs in this process remains unknown. In this study, we report the participation of miR-133 in dopamine production and the behavioral transition by negatively regulating two critical genes, henna and pale, in the dopamine pathway. miR-133 participated in the post-transcriptional regulation of henna and pale by binding to their coding region and 3′ untranslated region, respectively. miR-133 displayed cellular co-localization with henna/pale in the protocerebrum, and its expression in the protocerebrum was negatively correlated with henna and pale expression. Moreover, miR-133 agomir delivery suppressed henna and pale expression, which consequently decreased dopamine production, thus resulting in the behavioral shift of the locusts from the gregarious phase to the solitary phase. Increasing the dopamine content could rescue the solitary phenotype, which was induced by miR-133 agomir delivery. Conversely, miR-133 inhibition increased the expression of henna and pale, resulting in the gregarious-like behavior of solitary locusts; this gregarious phenotype could be rescued by RNA interference of henna and pale. This study shows the novel function and modulation pattern of a miRNA in phenotypic plasticity and provides insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms of the phase transition of locusts.

Introduction

The phenotypes of an organism are directly controlled by the underlying interactions between genetic and environmental factors [1]. Environmental factors significantly contribute to the formation and development of phenotypic plasticity in living organisms [2]. The migratory locust Locusta migratoria, a worldwide insect pest, shows remarkable phenotypic plasticity, called phase transition, which is dependent on population density changes [3], [4]. Locust plague outbreaks are triggered by phase transition, during which locusts transform from the solitary to the gregarious phase, thus forming large, fast-flying swarms [4], [5]. Previous studies on the expression and regulation of protein-coding genes have revealed the molecular regulatory mechanisms of phase changes in the migratory locust. A subset of primary phase-determining genes, including henna, pale, and vat1 in the dopamine pathway, CSP and takeout involved in olfactory sensitivity, and carnitine acetyltransferase and palmitoyl transferase from the carnitine system, have been shown to mediate the behavioral phase change in locusts [6]–[9]. However, non-coding RNAs that can mediate the molecular mechanisms of phenotypic plasticity associated with locust phase polyphenism have not been studied.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), small non-coding regulatory RNAs (∼22 nucleotides), are a class of identified genetic factors that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression. In plants, miRNAs can trigger the endonucleolytic cleavage of mRNA by targeting perfect or nearly perfect complementary sites located in the 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs), coding regions, or 3′UTRs of the target genes [10], [11]. In animals, the majority of miRNA activity leads to translational repression or mRNA degradation by a low complementary base-pairing with the 3′UTRs of the target genes [12], [13]. However, a few experimental studies have shown miRNA target sites in the coding regions of genes in animals [14]. A single miRNA may target multiple mRNAs, and a single mRNA may have binding sites for multiple miRNAs [15]. This feature creates a complex regulatory system for biological processes, such as cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, development, apoptosis, stress responses, and disease pathogenesis [15]–[18]. Interactions between miRNAs and environmental factors can critically affect phenotypes, thus resulting in phenotypic plasticity. For example, miR-7 in Drosophila buffers gene expression against fluctuating temperature conditions during development [19]. Several studies have investigated the responses of vertebrates and insects to environmental stresses such as population density and stress, freeze tolerance, anoxia tolerance, and hibernation [20]–[23]. However, the involvement of miRNAs in animal adaptation or phenotypic plasticity in response to environmental stress has not yet been fully elucidated. Given the increasing importance of studies investigating the relationship between environmental factors and miRNA, the elucidation of the functional roles of individual miRNAs in response to environmental stresses is necessary. Significant differences in miRNA profiles between gregarious and solitary locusts were identified in our previous study [24], in which we indicated that miRNAs are potentially involved in the phase transition. However, the mechanism by which miRNA regulates the phase transition remains unexplored in the migratory locust.

In the present study, we used the migratory locust as a model to study the relationship between environmental factors mediating phenotypic plasticity and miRNA function. Using bioinformatic prediction algorithms and experimental confirmation, we found that the brain-expressed miR-133 directly targets key genes (henna and pale) in the dopamine biosynthetic pathway. miR-133 regulates dopamine production during locust phase transition by targeting these genes in response to population density stresses. In vivo gain - and loss-of-function studies indicate that miR-133 is necessary to maintain the solitary behavioral features of the migratory locust. These data demonstrate that miR-133 is critical in the phase transitions of the migratory locust.

Results

miR-133 potentially targets the dopamine pathway

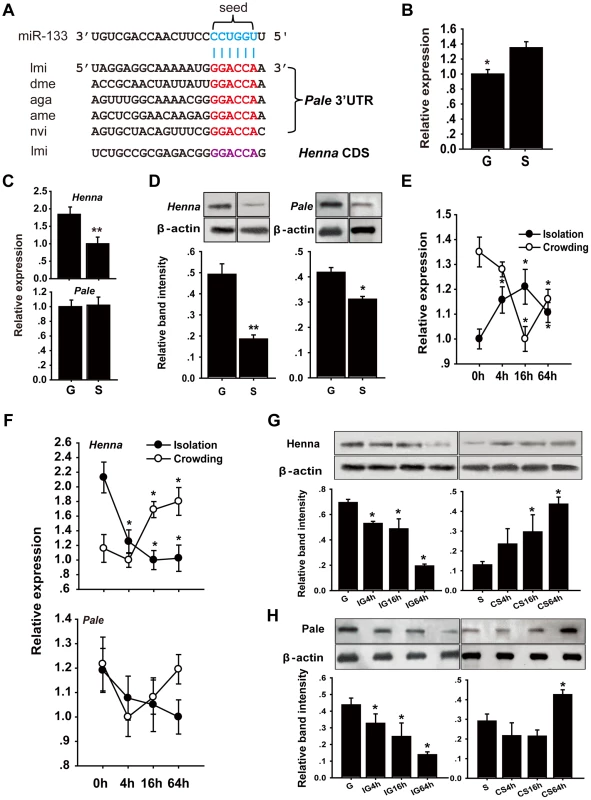

Conservation of orthologous miRNA genes is an important criterion for the identification of potential miRNA functional targets [25]. Thus, we hypothesized that the miRNA-dependent regulatory mechanism of the dopamine pathway was conserved between locusts and other insects. Using the TargetScan database, we analyzed Drosophila for miRNAs that could potentially bind to the 3′UTR of pale, which is a critical gene in the dopamine biosynthesis pathway [6]. Eight miRNAs exhibited highly conserved target sites, and 16 miRNAs possessed poorly conserved target sites located in the 3′UTR of pale in Drosophila (Table S1 and Figure S1). miR-133 and miR-994 target sites, which belong to conserved and poorly conserved groups, respectively, were also located in the 3′UTR of pale in locusts and other insects (Table S2), including Anopheles gambiae, Apis mellifera, and Nasonia vitripennis (Figure 1A). No miR-133 or miR-994 target sites were predicted in the 3′UTR or coding region of henna, which is another critical gene involved in the dopamine pathway in Drosophila. In contrast, a miR-133 target site was predicted in the coding region of henna in locusts (Figure 1A and Figure S1).

Fig. 1. The dopamine pathway may be targeted by miR-133.

(A) miR-133 target sites were predicted in the pale and henna genes of Locusta migratoria (lmi), Drosophila species (dme), Anopheles gambiae (aga), Apis mellifera (ame), and Nasonia vitripennis (nvi). (B) The expression levels of miR-133 were determined in the brains of fourth instar gregarious (G) and solitary (S) locust nymphs using qPCR. (C, D) The expression levels of henna and pale were determined in the brains of fourth instar gregarious and solitary locust nymphs using qPCR and western blot analyses. (E) The expression levels of miR-133 were determined in the brains of fourth instar gregarious nymphs after isolation (IG) and in solitary nymphs after crowding (CS) using qPCR. (F–H) The expression levels of henna and pale were determined in the brains of fourth instar nymphs over the course of IG and CS using qPCR and western blot analyses. The qPCR data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). The western blot bands were quantified using densitometry and are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 4). *p<0.05; **p<0.01. We performed stem-loop quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to quantify the miR-133 and miR-994 expression levels in the brains of gregarious and solitary locusts. The miR-133 expression level in gregarious locusts was significantly lower than that in solitary locusts (Figure 1B), whereas no significant change was found in the miR-994 expression levels between the gregarious and solitary locusts (Figure S2). We also determined the mRNA and protein expression levels of henna and pale in the locust brain. The mRNA expression level of henna was higher in the gregarious locusts than in the solitary locusts, whereas no difference was found in the mRNA expression of pale (Figure 1C). However, both henna and pale exhibited significantly higher protein expression in the gregarious locusts than in the solitary locusts (Figure 1D). Moreover, isolating the gregarious locusts (IG) resulted in a significant increase in the miR-133 expression levels, with the highest level observed at 16 h; in contrast, crowding the solitary locusts (CS) resulted in a significant decrease in miR-133 expression (Figure 1E). The protein and mRNA expression levels of henna were down-regulated by the IG and up-regulated by the CS (Figures 1F and 1G). Similarly, the protein expression of pale was suppressed by the IG and promoted by the CS (Figure 1H). However, no obvious change in pale mRNA expression was observed at the mRNA level during the IG and the CS, respectively (Figure 1F). These results indicate that miR-133 expression is negatively correlated with henna and pale protein expression during the phase transition of locusts.

Henna and pale are direct targets of miR-133

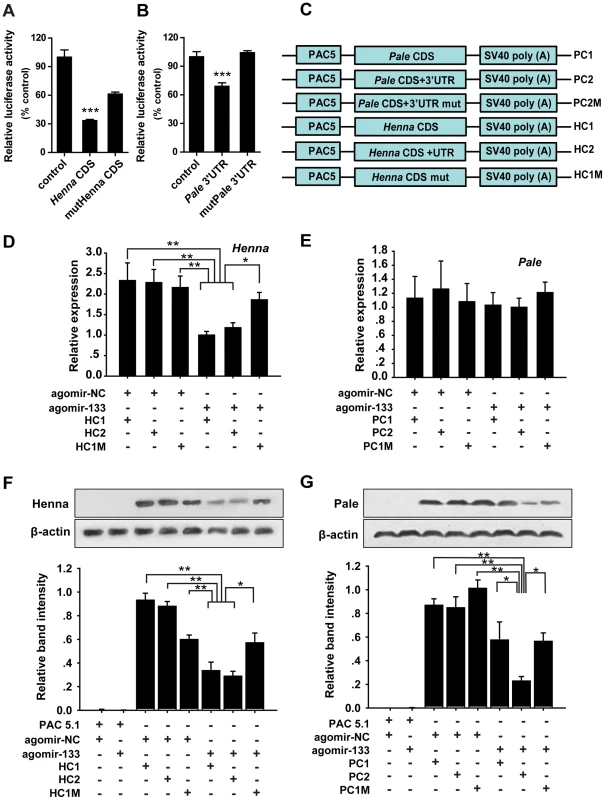

To confirm the interaction between miR-133 and henna/pale in vitro, we performed reporter assays using luciferase constructs fused to the coding region of henna and the 3′UTR of pale. Compared to the reporter constructs without miR-133 binding sites (controls), the constructs with either the henna or pale binding sites produced lower luciferase activity when co-transfected with the miR-133 overexpression vectors in S2 cells (Figures 2A and 2B). When the regions homologous to the “seed” sequence of miR-133 were mutated in the pale 3′UTR reporter constructs, the luciferase activity returned to the original levels produced by mock transfection with the empty reporter plasmid (Figure 2B). Mutations in the henna binding sites resulted in a twofold increase in luciferase activity, although this activity was still lower than that produced by the empty reporter plasmid (Figure 2A). Thus, the predicted target sites in henna and pale can be targeted by miR-133 in S2 cells.

Fig. 2. miR-133 targets the coding region of henna, but it targets the 3′ UTR of pale.

(A, B) The interactions between miR-133 and the target binding sites of henna (A) and pale (B) in migratory locusts were determined using luciferase assays. (C) The strategy used to generate the plasmid expression vectors HC1, HC2, HC1M, PC1, PC2, and PC2M. (D) The mRNA expression levels of henna were determined in S2 cells co-transfected with the plasmid expression vectors HC1, HC2, HC1M, and agomir-133 using qPCR. (E) The mRNA expression levels of pale were determined in S2 cells co-transfected with the plasmid expression vectors PC1, PC2, PC2M, and agomir-133 using qPCR. (F) The protein expression levels of henna were determined in S2 cells co-transfected with the plasmid expression vectors HC1, HC2, HC1M, and agomir-133 by western blot analysis. (G) The protein expression levels of pale were determined in S2 cells co-transfected with the plasmid expression vectors PC1, PC2, PC2M, and agomir-133 by western blot analysis. The results were normalized to the expression of β-actin. Co-transfection with the empty PAC-5.1/V5 His A vector or the agomir-control (agomir-NC) was used as a negative control. HC1: CDS of henna; HC2: both the CDS and 3′UTR of henna; HC1M: HC1 containing four seed element mutations in the coding region of henna. PC1: CDS of pale; PC2: both the CDS and 3′ UTR of pale; PC2M: PC2 containing four seed element mutations in the 3′ UTR of pale. The data for the luciferase activities and qPCR analyses are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). The western blot bands were quantified using densitometry and are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 4). *p<0.05; **p<0.01. miRNAs can affect mRNA stability and translation. Therefore, to determine the mechanism of interaction between miR-133 and henna/pale in vitro, we studied the mRNA and protein expression levels of henna and pale using three henna and three pale expression constructs based on the binding pattern of miR-133 (Figure 2C). In the presence of miR-133 sense oligonucleotides (agomir-133), the introduction of either the coding sequence (CDS) of henna alone (HC1) or the CDS and 3′UTR of henna (HC2) dramatically suppressed its mRNA and protein expression levels compared to the agomir-control (agomir-NC, Figures 2D and 2F). These suppressions were recovered by mutating the miR-133 binding site in the coding region (HC1M, Figures 2D and 2F), which indicates that the miR-133 binding sites are located in the coding region of henna. In contrast, in the presence of agomir-133, the introduction of the 3′UTR of pale (PC2) reduced its protein expression but not its mRNA expression. The reduced protein expression was rescued by the mutation of the miR-133 binding sites in its 3′UTR (PC2M, Figures 2E and 2G). However, the coding region alone (PC1) did not affect pale expression when co-transfected with agomir-133, compared to agomir-NC (Figures 2E and 2G). Thus, miR-133 participates in the post-transcriptional regulation of henna and pale by binding to the corresponding coding region and 3′UTR, respectively.

miR-133 and henna/pale interact in the locust protocerebrum

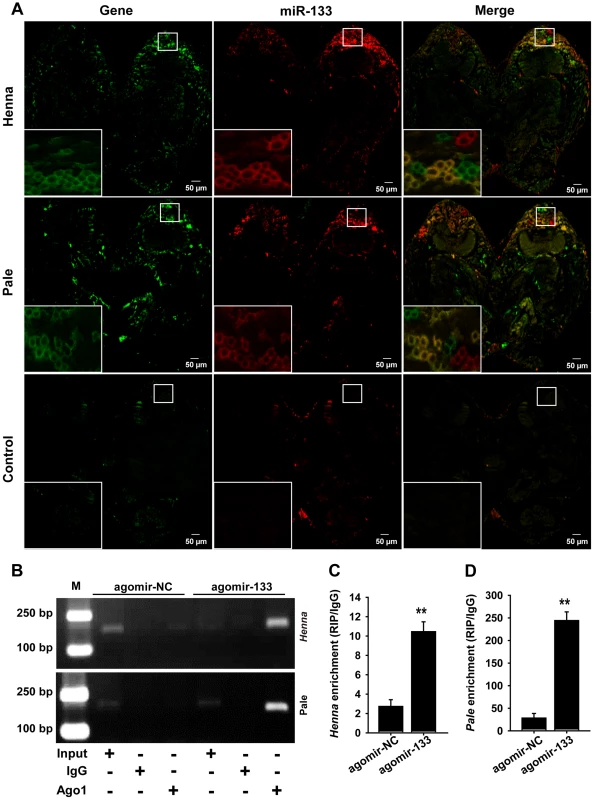

To determine whether miR-133 co-localized with henna/pale in the locust brain, we performed combined in situ analyses of miRNA-133 and henna/pale by the co-labeling of miRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry miRNA target. We found that miR-133 and henna were only detected in the neuronal cell body of the locust protocerebrum (Figures 3A and Figure S3), which is an important region in determining the behavioral responses by output neurons from the mushroom body [26]. Pale was also widely expressed in the protocerebrum, including the mushroom body and the neuronal cell body. The results showed that miR-133 is cellular co-localized with henna/pale in the protocerebrum. Thus, miR-133 and henna/pale co-localization in the protocerebrum supports the direct interactions between them in the locust brain.

Fig. 3. miR-133 can interact with henna/pale in the locust protocerebrum.

(A) The combined in situ analyses of miRNA-133 and henna/pale by the co-labeling of miRNA FISH and immunohistochemistry for miRNA target were conducted to determine the co-localization between these molecules in the locust brain. The squares specifically indicate the areas where miR-133, henna, and pale were localized in the locust protocerebrum. Where green (henna and pale) and red signals (miR-133) overlap, a yellow signal is seen, indicating the co-localization of miR-133 and its targets. The images were visualized using an LSM 710 confocal fluorescence microscope (Zeiss) at a magnification of 10× (the small squares) and 63× (the large squares), respectively. (B–D) RIP was performed with an anti-Ago-1 antibody; normal mouse IgG was used as a negative control. RT-PCR (B) or qPCR (C, D) analysis was performed to amplify the henna and pale mRNA from the Ago-1 immunoprecipitates from extracts of protocerebrum tissue treated with the miR-133 agomir (agomir-133) compared to the agomir-controls (agomir-NC). M, DNA marker. The data for the RIP assay are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). **p<0.01. We then performed an RNA immunoprecipitation assay using a monoclonal antibody against the Ago1 protein in the protocerebrum to examine the interaction of miR-133 with henna/pale (Figures 3B–3D). The results showed that henna and pale were significantly enriched in the Ago1-immunoprecipitated RNAs from the protocerebrum treated with agomir-133 compared with those from the protocerebrum treated with agomir-NC (Figures 3B–3D). Moreover, we found a significant decrease in miR-133 expression and up-regulation in pale and henna expression in the protocerebrum of gregarious locusts compared to the levels observed in solitary locusts (Figure S4). These results suggest that the direct regulation of pale and henna by miR-133 potentially occurs in the locust protocerebrum.

miR-133 controls dopamine production by targeting henna and pale

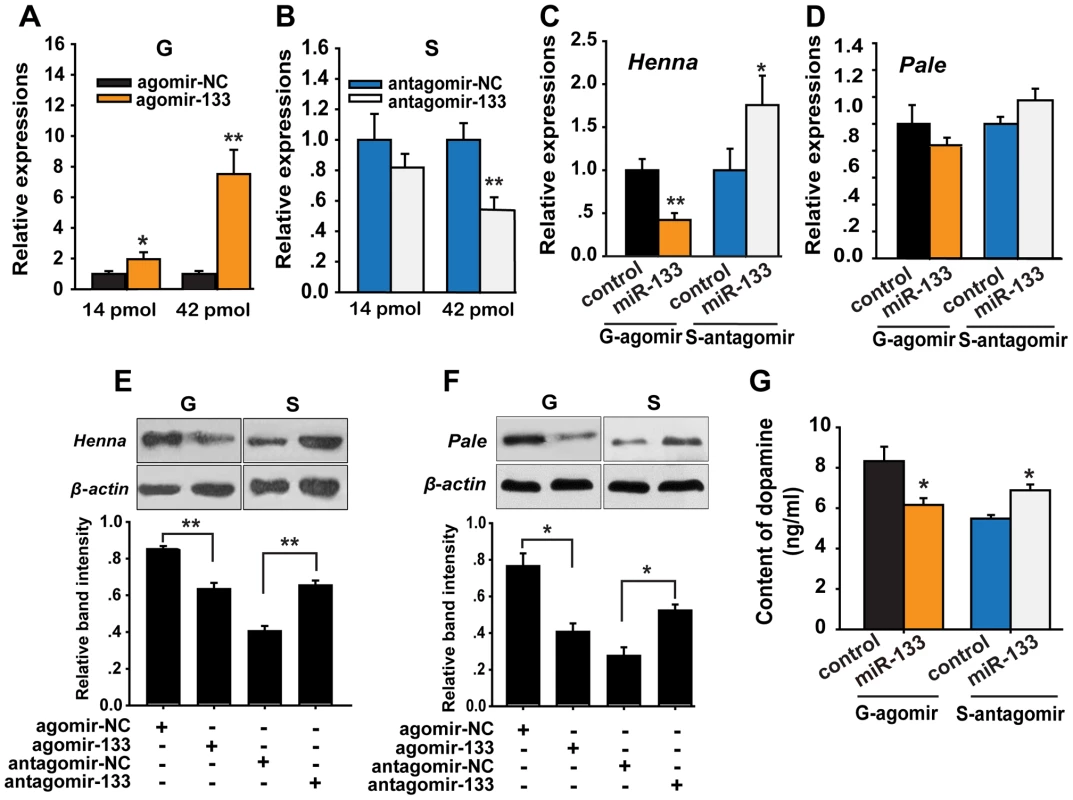

Given that henna and pale are essential genes in dopamine synthesis, we determined the effect of miR-133 on the dopamine pathway using miR-133 overexpression and knockdown experiments in vivo. No obvious change in the miR-133 expression was observed during the fourth instar stage (Figure S5). Thus, nymphs on the second day of the fourth instar stage were randomly assigned to treatment groups, and brain microinjection was performed. We injected agomir-133 or anti-sense oligonucleotides (antagomir-133) to determine the effects of the miR-133 agomir and antagomir treatments. Forty-eight hours after the local microinjection of 14 or 42 pmol of agomir-133, the miR-133 levels dramatically increased in a dose-dependent manner in the gregarious locusts (Figure 4A). Accordingly, antagomir-133 injection elicited the opposite effects on miR-133 levels in solitary locusts, even though 14 pmol of antagomir-133 did not effectively reduce miR-133 expression (Figure 4B). Significant induction or inhibition of miR-133 was also observed 24 h after injection with agomir-133 or antagomir-133, respectively (Figure S6). No significant effects were found on the expression of other miRNAs (Figure S7), including miR-7 and miR-252, which are two miRNAs with high expression in the locust brain (unpublished data), suggesting that the agomir/antagomir injection specifically acted on miR-133. These results reflect the efficiency and specificity of miR-133 manipulation.

Fig. 4. miR-133 controls dopamine production by regulating henna and pale expression in the locust brain.

(A, B) The expression levels of miR-133 were determined 48 h after injection in gregarious locusts (G) and in solitary locusts (S) after treatment with agomir or antagomir, respectively (14 or 42 pmol) using qPCR. (C, D) The effects of 42 pmol of agomir- and antagomir-133 treatment 48 h after injection on the mRNA expression levels of henna and pale in gregarious and solitary locust brains were studied using qPCR. (E, F) The effects of 42 pmol of agomir- and antagomir-133 48 h after injection on the protein expression levels of henna and pale in gregarious and solitary locust brains were studied using western blot analysis. (G) Dopamine production after treatment with 42 pmol agomir or antagomir-133 treatment in gregarious and solitary locusts brains was evaluated using HPLC-MS. The qPCR and HPLC-MS data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). The western blot bands were quantified using densitometry and are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 4). *p<0.05; **p<0.01. To determine the effects of miR-133 on the target genes, we detected the mRNA and protein levels of henna and pale after agomir-133 or antagomir-133 administration in the locust brain. At 48 h after agomir-133 injection, the mRNA levels of henna decreased by approximately 60% in the gregarious locusts when treated with both 42 and 14 pmol compared to those in the control locusts (Figures 4C and S8). Inhibition of henna expression was also observed 24 h after agomir-133 injection (Figure S8). At 48 h, injection of 42 pmol of antagomir-133 resulted in miR-133 knockdown, which increased the mRNA expression level of henna in the solitary locusts; however, this phenomenon was not observed after injection of 14 pmol antagomir-133 (Figures 4C and S8). In contrast, the mRNA level of pale in the locust brain was unaffected by either agomir-133 or antagomir-133 (Figure 4D). Moreover, western blot analysis showed that the protein expression levels of henna and pale were inhibited by miR-133 agomir administration in the gregarious locusts. Their corresponding protein levels in solitary locusts were up-regulated by miR-133 knockdown (Figures 4E and 4F).

To confirm the effects of henna and pale expression on dopamine synthesis, we measured dopamine production in the brains of gregarious and solitary locusts using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection (ECD) after miR-133 administration. Administration of the miR-133 agomir significantly reduced (approximately 30%, p<0.05) dopamine production in the gregarious locusts (Figure 4G). In contrast, miR-133 knockdown significantly increased the dopamine content (approximately 25%, p<0.05) of the solitary locusts. These results demonstrate that miR-133 controls dopamine production by regulating the expression of henna and pale in the locusts.

miR-133 regulates the phase transition of locusts by fostering solitary behavior

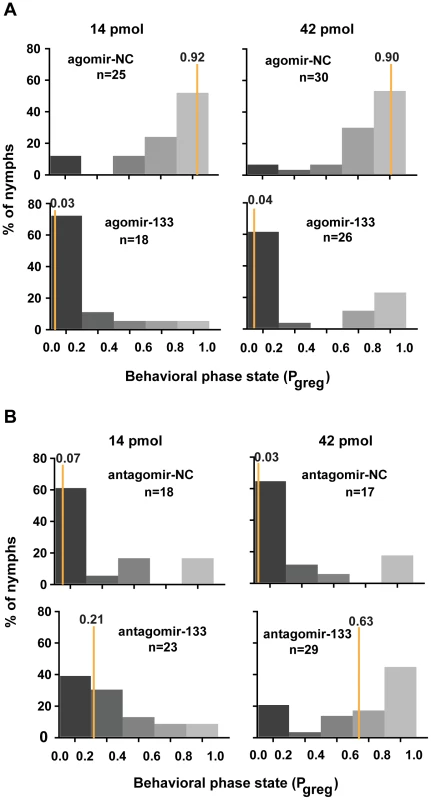

We reasoned that miR-133 controlled dopamine production by targeting henna and pale and might modulate the behavioral phase change of locusts. To determine the function of miR-133 during the phase transition, we monitored the behavioral phase changes of gregarious and solitary locusts after agomir-133 and antagomir-133 injection, respectively. The behavior of the gregarious locusts injected with agomir-133 (42 pmol) shifted to the solitary state with a Pgreg (probabilistic metric of gregariousness) interval of 0 to 0.2; 55% of the gregarious locusts became solitary after 24 h, and 62% became solitary after 48 h, as compared to 15% and 6.7% of the locusts in the agomir-NC group at 24 and 48 h, respectively (Figures 5A and S9). Moreover, the increased miR-133 expression caused by injection with 14 pmol of agomir-133 resulted in a solitary shift at 48-h intervals, with 72% of the injected locusts falling into the Pgreg interval of 0 to 0.2 (Figure 5A). In parallel, solitary locusts injected with antagomir-133 (42 pmol) exhibited a significant but incomplete shift to gregarious behavior, with 44.8% shifting into the Pgreg interval of 0.8 to 1.0 (Figure 5B). In contrast, no obvious behavioral change was observed in most of the solitary locusts injected with antagomir-133 (14 pmol) at 48 h intervals (8.7% shifting into the Pgreg interval of 0.8 to 1.0; Figure 5B). The silencing effects observed after injection of 42 pmol, but not 14 pmol, indicate that the induction of gregarious-like behavior in solitary locusts is dose-dependent, suggesting the feasibility of dose-dependent inhibition of miRNA for effective behavior modulation. These results demonstrate that miR-133 controls the phase transitions in locusts by fostering solitary behavior.

Fig. 5. miR-133 fosters the phase transition phenotype of the migratory locust.

(A) The effects of 14 or 42 pmol agomir-133 treatment on the behavior of gregarious locusts were studied 48 h after injection. (B) The effects of 14 or 42 pmol antagomir-133 treatment on the behavior of solitary locusts were studied 48 h after injection. Pgreg, probabilistic metric of gregariousness. The vertical lines indicate the median Pgreg values. Pgreg = 1 indicates fully gregarious behavior, and Pgreg = 0 indicates fully solitary behavior. The dopamine pathway is the direct effector for mediating miR-133-regulated behavioral transition

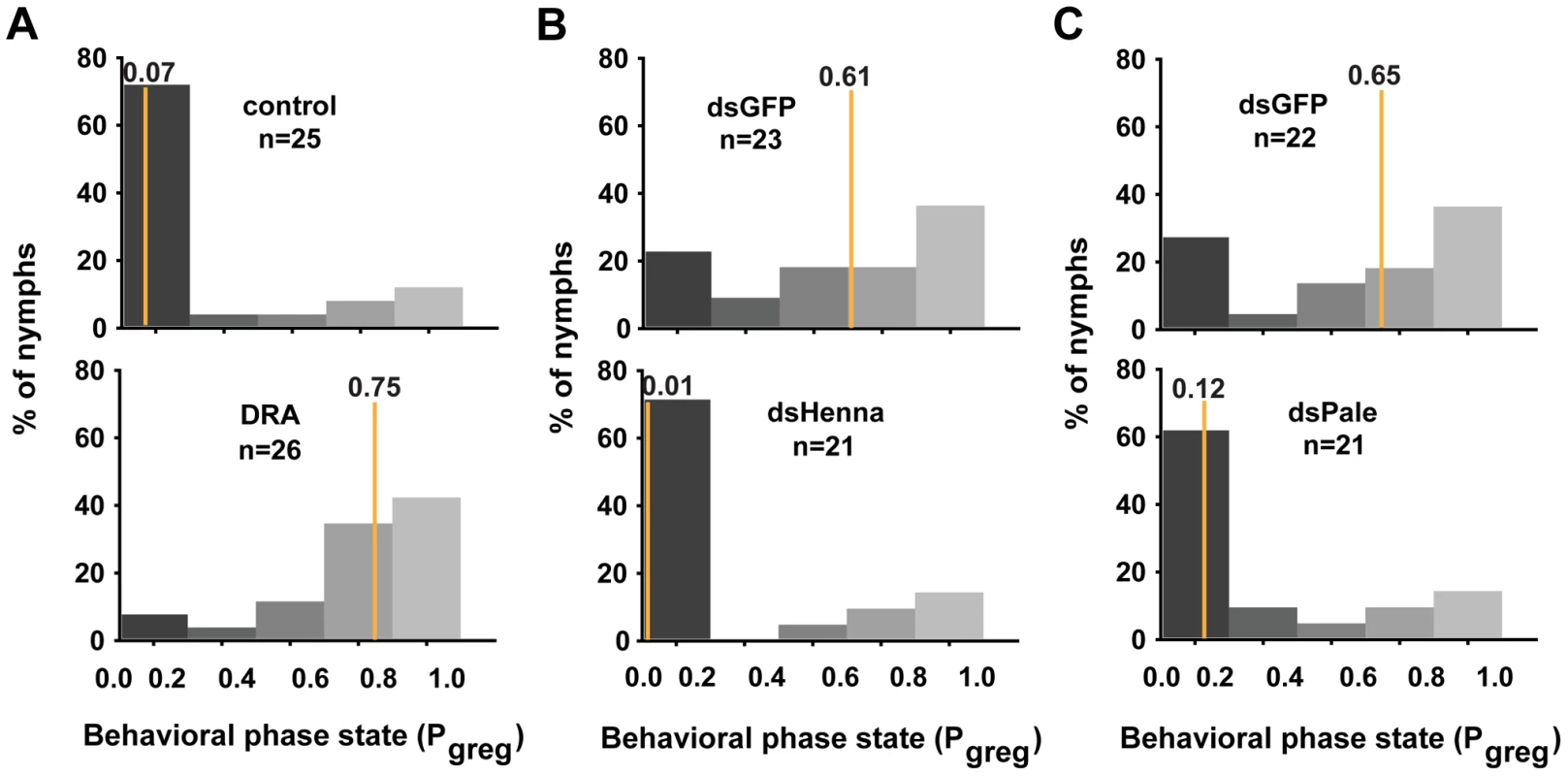

In gregarious locusts, treatment with agomir-133 decreased the dopamine content, thus promoting a significant shift toward the solitary phase. To determine whether the miR-133 delivery-induced decrease in dopamine content was responsible for the behavioral transition, we performed rescue experiments by increasing the dopamine content by injection with R-(-)-apomorphine in locusts that were treated with agomir-133. R-(-)-apomorphine is a dopamine receptor agonist that can significantly promote gregarious behavioral traits through the dopamine-dependent pathway [27]. The results showed that R-(-)-apomorphine injection robustly restored the gregarious behavior in locusts after agomir-133 pre-treatment (Pgreg = 0.75), compared to the saline-injected controls after 24 h (Pgreg = 0.07; Figure 6A). Therefore, the change in dopamine content regulated by miR-133 is a key mediator of the behavioral transition between the gregarious and solitary phases.

Fig. 6. The dopamine pathway is the direct effector for mediating the miR-133-regulated behavioral transition.

(A) The behavioral rescue experiment in gregarious locusts was performed by increasing the dopamine content through injection with the dopamine receptor agonist (DRA), R-(-)-apomorphine, or a saline control in locusts pre-treated with agomir-133. (B, C) The behavioral rescue experiment in solitary locusts was performed by injecting dsRNA against henna/pale into the locusts pre-treated with antagomir-133. Pgreg, probabilistic metric of gregariousness. The vertical lines indicate the median Pgreg values. Pgreg = 1 indicates fully gregarious behavior, and Pgreg = 0 indicates fully solitary behavior. Treatment of solitary locusts with antagomir-133 resulted in the up-regulation of henna/pale expression, thereby stimulating gregarious behavioral traits. To determine whether the henna/pale up-regulation induced by miR-133 knockdown was responsible for the behavioral transition of the locusts, we rescued the behavior phenotypes by injecting double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) against henna/pale into the locusts subjected to antagomir-133 pre-treatment. As expected, the miRNA-133 knockdown-induced behavior phenotype was fully rescued by treatment with dsHenna (Pgreg = 0.01) or dsPale (Pgreg = 0.12), compared to the dsGFP-injected controls after 24 h (Pgreg = 0.61 and Pgreg = 0.65, respectively; Figures 6B and 6C). Thus, henna and pale are the key target genes involved the post-transcriptional regulation of miR-133 during the phase transition in locusts.

Discussion

Our previous studies showed that the pale, henna, and vat1 genes, which are involved dopamine synthesis and release, are related to the behavioral phase transitions of the migratory locust [6]. However, the genetic factors that regulate locust phase transition by controlling the expression of these genes remain unknown. In this study, we show that miR-133 controls dopamine production by targeting henna and pale, resulting in the modulation of the behavioral phase changes of locusts through post-transcriptional regulation (Figures S10). This miRNA-mediated mechanism of phenotypic plasticity induced by environmental fluctuations provides insight into the molecular basis of the phase changes in locusts.

The regulatory function of miR-133 in dopamine synthesis is shared among insects and vertebrates, but the corresponding mechanisms by which this regulation is achieved are different. In locusts, miR-133 regulates dopamine synthesis by directly targeting the 3′UTR of pale, and this regulation may be conserved in insects as the miR-133 target site is conserved. In contrast, miR-133 in vertebrates targets Pitx3, a transcription factor for tyrosine hydroxylase (encoded by pale), which regulates dopamine production [28]. However, no evidence of an association between miR-133 binding sites and insect Ptx1 (a homolog to Pitx3) or the Ptx1 regulation of pale (data not shown) has been reported. In addition to the dopamine pathway, other pathways are regulated by miR-133 in vertebrates, including heart regeneration and atrial remodeling [29], [30]. Given that miR-133 is conserved across a broad range of species, the function of this miRNA may also be conserved between insects and vertebrates. Therefore, miR-133 may also regulate multiple pathways in insects in addition to dopamine synthesis. Further studies are needed to verify this interpretation.

Fine-tuning the regulation of gene expression through acquired miRNA target sites in crucial genes contributes to species evolution [31]. Canonical miRNA target sites could be divided into two classes, namely the conserved and non-conserved target sites. In our study, the miR-133 target site in henna is not conserved across insect species, which implies that the miR-133 target site in henna may have been acquired after the divergence of the locust lineage from other insects. This miRNA target is correlated with the evolutionary emergence of the phase transition traits of locusts.

We found that miR-133 targets two genes, henna and pale, in the dopamine synthesis pathway of locusts. However, only the target site located in pale is conserved among insects, whereas the miR-133 target site in henna is unique to locusts. This observation suggests that the interactions between miR-133 and henna may have co-evolved with the phase transitions in locusts. miRNAs have been shown to exert their function through the coordinated inhibition of multiple targets within the same pathway [32]. The miRNA effect on any given target is usually modest, but its cumulative effect on multiple targets becomes phenotypically significant [33], [34]. Therefore, targeting multiple genes guarantees the miR-133-controlled phase transition, which may be necessary to regulate dopamine synthesis for a complete behavioral shift between the gregarious and solitary phases. Therefore, the simultaneous effects of a single miRNA on multiple targets in the same canonical pathway are advantageous.

In locusts, miR-133 targets henna in the coding region and pale in its 3′UTR. Additionally, miR-133 can only affect the protein, but not the mRNA expression level, of pale. The targeting of the henna coding region by miR-133 leads to mRNA degradation and reduces protein expression. Previous studies have indicated that miRNAs regulate gene expression by binding to the 3′UTR of target mRNAs, thereby resulting in mRNA degradation or translational repression [35]–[38]. In some cases, miRNAs can target sites in the 5′UTR and the CDS of mRNAs [39], [40]. Additional studies have attempted to elucidate the relative degree of contribution and the timing of translation inhibition and mRNA destabilization involved in miRNA-mediated silencing [41]–[43]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the determinant effects of translation inhibition and mRNA destabilization are far from being completely clarified.

In the present study, miR-133 was down-regulated as a result of increased population density, which indicates that this miRNA can be used as a sensor of population density. However, the mechanism of miR-133 regulation by population density remains unclear. A previous study [44] reported that p38 signaling is necessary for miR-133 transcription during early muscle regeneration. Moreover, the homolog of p38 has been identified from the locust transcriptome database [45], and qRT-PCR analysis showed that p38 expression is down-regulated in the brains of gregarious locusts (data not shown). Therefore, p38 may be a regulatory factor for miR-133 expression in response to changes in population density in locusts.

In summary, we report that miR-133 is a novel regulator promoting the migratory locust phase transitions by negatively regulating two predominant genes (henna and pale) in the dopamine pathway. miR-133 target sites are conserved among several insects and locusts, strongly suggesting that miR-133-mediated pale suppression is a component of a novel, biologically relevant, and evolutionarily conserved regulatory mechanism. This miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation mechanism is particularly significant for understanding the behavioral aggregation of locusts and potentially provides new targets for controlling locust plagues worldwide.

Materials and Methods

Insects

Gregarious and solitary locusts were obtained from the same locust colonies, which were maintained at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China. Gregarious nymphs were reared in large, well-ventilated cages (40 cm×40 cm×40 cm) at a density of 500–1,000 insects per container for eight generations. Solitary nymphs were cultured alone in white metal boxes (10 cm×10 cm×25 cm) supplied with charcoal-filtered compressed air for more than eight generations before the experiment. Both colonies were reared under a 14∶10 light/dark photo regime at 30±2°C and were fed fresh wheat seedlings and bran [4].

In vitro luciferase validation

The ∼400-bp sequences of the 3′ UTR and the CDS surrounding the predicted miR-133 target sites in henna and pale, respectively, were separately cloned into the psiCHECK-2 vector (Promega) using the XhoI and NotI sites. Mutagenesis PCR was performed at the miR-133 target sites. The miRNA expression plasmid contained the region encompassing the pre-miR-133 stem-loop inserted into pAc5.1/V5-HisA (Invitrogen). S2 cells in a 24-well plate were co-transfected with 800 ng of the luciferase reporter vector or the empty vector and 500 ng of the miR-133 expression plasmid using Lipofect (Tiangen). The activities of the firefly and Renilla luciferases were measured 48 h after transfection with the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) using a luminometer (Promega).

miRNA agomir and antagomir treatment in vivo

The miRNA agomir was a chemically modified, cholesterylated, stable miRNA mimic, and its in vivo delivery resulted in target silencing similar to the effects induced by the overexpression of endogenous miRNA [46]. Thus, ‘miRNA-133 overexpression’ in this study represents the expression activation of agomir-133. The miRNA antagomir was a chemically modified, cholesterol-conjugated, single-stranded RNA analog that complemented the miRNAs and could efficiently and specifically silence the endogenous miRNAs [47]. The brains of 2-day-old gregarious or solitary fourth instar nymphs were microinjected with agomir-133 or antagomir-133. A scrambled miRNA agomir/antagomir was used as a negative control. Briefly, fourth instar nymphs were placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame specially adapted for locust surgery. A midline incision of approximately 2 mm was cut at the mid-point between the two antennae using Nevis scissors, and the underlying brain was exposed. Subsequently, 42 or 14 pmol of agomir-133 or antagomir-133 (200 µM; RiboBio) was injected into the brain. The agomir - or antagomir-negative controls (200 µM) were also injected into the gregarious or solitary locust brains (RiboBio). All injections were administered using a nanoliter injector (World Precision Instruments) with a glass micropipette tip under an anatomical lens. Treated nymphs were subjected to behavioral analysis 24 or 48 h later. Their brains were harvested, snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C.

Protocerebrum isolation

Anatomical dissection was performed using a vibratome (Leica, VT1200S) to isolate the tissues from the protocerebrum, as indicated by an anatomic diagram of the locust brain. Briefly, the brain was dissected under an anatomical lens. The protocerebrum was placed on the slide at the boundary of the deutocerebrum and tritocerebrum and was cut using the vibratome. The levels of miR-133, henna, and pale in the isolated protocerebrums were analyzed using quantitative PCR (qPCR) or western blot analyses, and the interaction between miR-133 and henna/pale was analyzed using RNA immunoprecipitation analysis.

Assays of quantitative PCR for mRNA and miRNA

Total RNA enriched for small RNAs was isolated using the mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion). Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Promega) and a miRNA first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Ambion) were used to prepare the Oligo(dT)-primed cDNA and stem-loop cDNA, respectively. The miRNAs and mRNAs were subjected to qPCR using the SYBR Green miRNA expression and gene expression assays, respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Tiangen), on a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche). Analysis of the PCR data was carried out using the 2−ΔΔCt method of relative quantification. As endogenous controls, U6 snRNA and ribosomal protein RP49 were used to quantify the miRNA and mRNA expression levels, respectively. Dissociation curves were determined for each miRNA and mRNA to confirm unique amplification. Table S3 shows the primers used for qPCR analysis.

Western blot analysis

For protein analyses, affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies against henna and pale and a monoclonal antibody against Ago-1 were developed (Abmart), and the specificities of these antibodies were evaluated (Figures S11 and S12). The locust tissues were collected on a frozen cryostat and homogenized in lysis buffer (CoWin). The total protein content of the lysates was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). The protein samples were separated by gel electrophoresis and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). Non-specific binding sites on the membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The blots were incubated with the primary antibodies (rabbit anti-henna serum, 1∶500; rabbit anti-pale serum, 1∶700; mouse anti-Ago-1, 1∶1000) in PBS-T overnight at 4°C, washed, incubated with anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1∶1000) (CoWin) for 1 h at room temperature, and then washed again. Immunological detection was subsequently carried out using a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium substrate (Tiangen). The antibodies were stripped from the blots, which were then re-blocked and probed with an anti-β-actin antibody (CoWin). The intensities of the western blot signals were quantified using densitometry.

Co-localization of miRNA and its targets by fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical detection

A combined in situ analyses of miRNA-133 and henna/pale were detected in the brains of fourth instar nymphs by the colabeling of miRNA FISH and immunohistochemistry for miRNA target, according to the method described by Nuovo et al. [48]. An antisense locked nucleic acid (LNA) detection probe for miR-133 or a scrambled control (Exiqon) was labeled with double digoxigenin. The brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. The paraffin-embedded brain tissue slides (5 µm thick) were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated with an ethanol gradient, digested with 20 µg/mL proteinase K (Roche) at 37°C for 10 min, and incubated with the LNA miR-133 probes or the scrambled control probe (2 pmol/µL) at 60°C for 5 min. The slides were then hybridized for 7–15 h at 37°C and were washed in 0.2× SSC and 2% BSA at 4°C for 5 min. The slides were incubated in anti-digoxigenin–alkaline phosphatase conjugate (1∶150 dilution) for 30 min at 37°C, followed by incubation with the HNPP substrate and TSA plus amplification (PerkinElmer) reagent working solution. After in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry was performed to detect the miRNA targets. The slides were blocked with 5% BSA for 30 min and were incubated with anti-henna (1∶200) and anti-pale primary antibodies (1∶300) for 2 h. The slides were then washed, incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor-488 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Life technologies), dehydrated, and cover slipped. miR-133 and its target signals were detected using a LSM 710 confocal fluorescence microscope (Zeiss).

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays

The RIP assay was performed using a Magna RIP Quad kit (Millipore) with slight modifications. Briefly, the monoclonal antibody against Ago-1 protein was developed in mice (Abmart). Approximately 25 protocerebrums were collected and homogenized in ice-cold RIP lysis buffer. The homogenates were stored at −80°C overnight. Magnetic beads were pre-incubated with 5 µg of Ago-1 antibody (Abmart) or with 5 µg of normal mouse IgG (Millipore), which was used as a negative control. The frozen homogenates in the RIP lysate were thawed and centrifuged, and the supernatant was incubated with the magnetic bead–antibody complex at 4°C overnight. The immunoprecipitates were digested with protease K to remove the proteins and to release the RNAs. The RNAs were then purified and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using random hexamers. Using these cDNAs as templates, RT-PCR or qPCR was performed to quantify the henna and pale RNA. The supernatants of the RIP lysate (input) and the IgG controls were assayed to normalize the relative expression levels and ensure the specificity of the RNA–protein interactions.

Behavioral assays

Behavioral assays were conducted in a rectangular arena (40 cm×30 cm×10 cm) with opaque walls, as described in a previous study [7]. The EthoVision system (Noldus) was used for video recording and behavioral data extraction [49]. The behavioral parameters were recorded and expressed as a mixture of behavioral or categorical markers [7]. To measure and quantify the behavioral phenotypes of the injected nymphs, a binary logistic regression model of the phase state was constructed using the SPSS 17.0 software for the gregarious and solitary fourth-instar locust nymphs [50]. A forward stepwise approach was performed to construct a binary logistic regression model: Pgreg = en/(1+en), where n = β0+β1·X1+β2·X2+…+βk·Xk, where Pgreg indicates the probability of a locust being considered gregarious. Pgreg = 1 indicates fully gregarious behavior, whereas Pgreg = 0 indicates fully solitary behavior. This model shared similar features with a previous logistic model [50], [51]. The regression model of the migratory locust was used to discriminate the behavioral states of the locusts treated with the miRNA agomir or antagomir.

Quantification of dopamine in the brain tissue extracts

The dopamine content of the locust brains was quantified using reverse-phase HPLC and ECD. The brain tissues of the locust nymphs were immediately dissected and stored in liquid nitrogen. Ten brains were homogenized and lysed in 400 µL of ice-cold 0.1 M perchloric acid for 10 min, after which the homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were filtered through 0.45-µm filters. Approximately 40 µL of the supernatant was automatically loaded into the HPLC system, which contained a quaternary low-pressure pump system (Waters, e2695) with a C18 reversed-phase column (Atlantis dC18, 2.1 mm×150 mm, 3 µm). The electrochemical detector electrode potential was 800 mV. The mobile phase (pH, 3.00; temperature, 35°C; flow rate, 0.25 mL/min) was composed of 7% acetonitrile, 90 mM monobasic phosphate sodium, 50 mM citric acid, 2 mM octanesulfonic acid, 2 mM NaCl, and 50 µM EDTA. Data analysis was conducted using the Empower software (Waters Corporation). Dopamine was quantified by referring to an external standard.

DNA constructs, cell transfections, and expression assays

Synthetic constructs were individually generated by cloning the sequence of HC1, HC2, PC1, or PC2 into the PAC-5.1/V5 His A vector (Invitrogen) at the EcoRI/Xbal sites. To generate HC1M and PC2M carrying the seed element mutations, four nucleotides in the seed region of the miRNA binding sites were mutated using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). S2 cells were co-transfected with the plasmid expression vectors (HC1, HC2, HC1M, PC1, PC2, PC2M, or empty vector) and agomir-133 or agomir-NC at a 1∶4 ratio using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The mRNA levels of henna and pale in the co-transfected S2 cells were investigated after 48 h of transfection. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was reverse-transcribed from 2 µg of total RNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). β-Actin was used as an internal control. qPCR was performed using a SYBR Green amplification kit (Tiangen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

To determine the protein levels of henna and pale in the co-transfected S2 cells, the cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer (Tiangen). Approximately 20 µg of total protein was subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to PVDF membranes, as previously described.

Behavioral rescue experiments in vivo

The rescue experiments were performed according to the method of miRNA agomir and antagomir treatment in vivo. In gregarious locusts, the brains of 2-day-old fourth instar nymphs were microinjected with 42 pmol of miR-133 agomir (200 µM, RiboBio). Twenty-four hours later, the gregarious nymphs were co-injected with 20 µg of R-(-)-apomorphine or a saline control. Then, 24 h after R-(-)-apomorphine injection, the nymphs were subjected to behavioral analysis. The brains of the solitary locusts were microinjected with 42 pmol of miR-133 antagomir (200 µM; RiboBio). Twenty-four hours later, the solitary nymphs were co-injected with 5 µg of dsHenna/dsPale or a dsGFP control. Then, 24 h after dsRNA injection, the nymphs were subjected to behavioral analysis.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc.) was used for statistical analysis. The differences between the treatments were compared using either Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's test for multiple comparisons. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze the behavioral data due to its non-normal distribution characteristics. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. CaspiA, MoffittTE (2006) Gene-environment interactions in psychiatry: joining forces with neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 7 : 583–590.

2. GretherGF (2005) Environmental change, phenotypic plasticity, and genetic compensation. Am Nat 166: E115–123.

3. NusseyDH, PostmaE, GienappP, VisserME (2005) Selection on heritable phenotypic plasticity in a wild bird population. Science 310 : 304–306.

4. KangL, ChenXY, ZhouY, LiuBW, ZhengW, et al. (2004) The analysis of large-scale gene expression correlated to the phase changes of the migratory locust. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 : 17611–17615.

5. MaZY, YuJ, KangL (2006) LocustDB: a relational database for the transcriptome and biology of the migratory locust (Locusta migratoria). Bmc Genomics 7 : 11.

6. MaZY, GuoW, GuoXJ, WangXH, KangL (2011) Modulation of behavioral phase changes of the migratory locust by the catecholamine metabolic pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 : 3882–3887.

7. GuoW, WangXH, MaZY, XueLA, HanJY, et al. (2011) CSP and Takeout Genes Modulate the Switch between Attraction and Repulsion during Behavioral Phase Change in the Migratory Locust. Plos Genetics 7 (2) e1001291.

8. WuR, WuZ, WangX, YangP, YuD, et al. (2012) Metabolomic analysis reveals that carnitines are key regulatory metabolites in phase transition of the locusts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 3259–3263.

9. JiangF, YangM, GuoW, WangX, KangL (2012) Large-scale transcriptome analysis of retroelements in the migratory locust, Locusta migratoria. PLoS One 7: e40532.

10. RhoadesMW, ReinhartBJ, LimLP, BurgeCB, BartelB, et al. (2002) Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell 110 : 513–520.

11. AxtellMJ, WestholmJO, LaiEC (2011) Vive la difference: biogenesis and evolution of microRNAs in plants and animals. Genome Biology 12 (4) 221.

12. LaiEC (2003) microRNAs: Runts of the genome assert themselves. Current Biology 13: R925–R936.

13. FlyntAS, LaiEC (2008) Biological principles of microRNA-mediated regulation: shared themes amid diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics 9 : 831–842.

14. DuursmaAM, KeddeM, SchrierM, le SageC, AgamiR (2008) miR-148 targets human DNMT3b protein coding region. RNA 14 : 872–877.

15. BartelDP (2004) MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116 : 281–297.

16. AmbrosV (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431 : 350–355.

17. PillaiRS (2005) MicroRNA function: Multiple mechanisms for a tiny RNA? Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society 11 : 1753–1761.

18. VasudevanS, TongY, SteitzJA (2007) Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science 318 : 1931–1934.

19. LiX, CassidyJJ, ReinkeCA, FischboeckS, CarthewRW (2009) A microRNA imparts robustness against environmental fluctuation during development. Cell 137 : 273–282.

20. BiggarKK, DubucA, StoreyK (2009) MicroRNA regulation below zero: differential expression of miRNA-21 and miRNA-16 during freezing in wood frogs. Cryobiology 59 : 317–321.

21. BiggarKK, StoreyKB (2011) The emerging roles of microRNAs in the molecular responses of metabolic rate depression. J Mol Cell Biol 3 : 167–175.

22. BiggarKK, StoreyKB (2012) Evidence for cell cycle suppression and microRNA regulation of cyclin D1 during anoxia exposure in turtles. Cell Cycle 11 : 1705–1713.

23. MorinPJr, DubucA, StoreyKB (2008) Differential expression of microRNA species in organs of hibernating ground squirrels: a role in translational suppression during torpor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1779 : 628–633.

24. WeiYY, ChenS, YangPC, MaZY, KangL (2009) Characterization and comparative profiling of the small RNA transcriptomes in two phases of locust. Genome Biology 10 (1) R6.

25. RajewskyN (2006) microRNA target predictions in animals. Nat Genet 38 Suppl: S8–13.

26. Phillips-PortilloJ, StrausfeldNJ (2012) Representation of the brain's superior protocerebrum of the flesh fly, Neobellieria bullata, in the central body. J Comp Neurol 520 : 3070–3087.

27. MaZ, GuoW, GuoX, WangX, KangL (2011) Modulation of behavioral phase changes of the migratory locust by the catecholamine metabolic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 3882–3887.

28. KimJ, InoueK, IshiiJ, VantiWB, VoronovSV, et al. (2007) A MicroRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science 317 : 1220–1224.

29. YinVP, LepilinaA, SmithA, PossKD (2012) Regulation of zebrafish heart regeneration by miR-133. Dev Biol 365 : 319–327.

30. ShanH, ZhangY, LuY, ZhangY, PanZ, et al. (2009) Downregulation of miR-133 and miR-590 contributes to nicotine-induced atrial remodelling in canines. Cardiovasc Res 83 : 465–472.

31. PlasterkRH (2006) Micro RNAs in animal development. Cell 124 : 877–881.

32. KowarschA, MarrC, SchmidlD, RueppA, TheisFJ (2010) Tissue-specific target analysis of disease-associated microRNAs in human signaling pathways. PLoS One 5: e11154.

33. BaekD, VillenJ, ShinC, CamargoFD, GygiSP, et al. (2008) The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455 : 64–71.

34. InuiM, MartelloG, PiccoloS (2010) MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 11 : 252–263.

35. HumphreysDT, WestmanBJ, MartinDI, PreissT (2005) MicroRNAs control translation initiation by inhibiting eukaryotic initiation factor 4E/cap and poly(A) tail function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 16961–16966.

36. PillaiRS, BhattacharyyaSN, ArtusCG, ZollerT, CougotN, et al. (2005) Inhibition of translational initiation by Let-7 microRNA in human cells. Science 309 : 1573–1576.

37. PetersenCP, BordeleauME, PelletierJ, SharpPA (2006) Short RNAs repress translation after initiation in mammalian cells. Mol Cell 21 : 533–542.

38. ChendrimadaTP, FinnKJ, JiX, BaillatD, GregoryRI, et al. (2007) MicroRNA silencing through RISC recruitment of eIF6. Nature 447 : 823–828.

39. OromUA, NielsenFC, LundAH (2008) MicroRNA-10a binds the 5′UTR of ribosomal protein mRNAs and enhances their translation. Mol Cell 30 : 460–471.

40. TayY, ZhangJ, ThomsonAM, LimB, RigoutsosI (2008) MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature 455 : 1124–1128.

41. GuoHL, IngoliaNT, WeissmanJS, BartelDP (2010) Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 466 : 835–U866.

42. BazziniAA, LeeMT, GiraldezAJ (2012) Ribosome Profiling Shows That miR-430 Reduces Translation Before Causing mRNA Decay in Zebrafish. Science 336 : 233–237.

43. DjuranovicS, NahviA, GreenR (2012) miRNA-mediated gene silencing by translational repression followed by mRNA deadenylation and decay. Science 336 : 237–240.

44. ZhangD, LiX, ChenC, LiY, ZhaoL, et al. (2012) Attenuation of p38-mediated miR-1/133 expression facilitates myoblast proliferation during the early stage of muscle regeneration. PLoS One 7: e41478.

45. ChenSA, YangPC, JiangF, WeiYY, MaZY, et al. (2010) De Novo Analysis of Transcriptome Dynamics in the Migratory Locust during the Development of Phase Traits. Plos One 5 (12) e15633.

46. WangXG, GuoBS, LiQ, PengJ, YangZJ, et al. (2013) miR-214 targets ATF4 to inhibit bone formation. Nature Medicine 19 : 93–100.

47. KrutzfeldtJ, RajewskyN, BraichR, RajeevKG, TuschlT, et al. (2005) Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature 438 : 685–689.

48. NuovoGJ, EltonTS, Nana-SinkamP, VoliniaS, CroceCM, et al. (2009) A methodology for the combined in situ analyses of the precursor and mature forms of microRNAs and correlation with their putative targets. Nat Protoc 4 : 107–115.

49. NoldusLPJJ, SpinkAJ, TegelenboschRAJ (2001) EthoVision: a versatile video tracking system for automation of behavioral experiments. Behavior Research Methods 33 : 398–414.

50. RoessinghP, SimpsonSJ, JamesS (1993) Analysis of Phase-Related Changes in Behavior of Desert Locust Nymphs. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 252 : 43–49.

51. AnsteyML, RogersSM, OttSR, BurrowsM, SimpsonSJ (2009) Serotonin mediates behavioral gregarization underlying swarm formation in desert locusts. Science 323 : 627–630.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Natural Polymorphisms in Influence Negative Selection and CD4∶CD8 Lineage Commitment in the RatČlánek MicroRNAs Located in the Hox Gene Clusters Are Implicated in Huntington's Disease PathogenesisČlánek Comparative RNAi Screens in and Reveal the Impact of Developmental System Drift on Gene FunctionČlánek Mutation of SLC35D3 Causes Metabolic Syndrome by Impairing Dopamine Signaling in Striatal D1 Neurons

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 2

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Fifteen Years Later: Hard and Soft Selection Sweeps Confirm a Large Population Number for HIV In Vivo

- The Same but Different: Worms Reveal the Pervasiveness of Developmental System Drift

- Serine Carboxypeptidase SCPEP1 and Cathepsin A Play Complementary Roles in Regulation of Vasoconstriction via Inactivation of Endothelin-1

- Coherent Functional Modules Improve Transcription Factor Target Identification, Cooperativity Prediction, and Disease Association

- A Long-Chain Flavodoxin Protects from Oxidative Stress and Host Bacterial Clearance

- Mammalian E-type Cyclins Control Chromosome Pairing, Telomere Stability and CDK2 Localization in Male Meiosis

- Influenza Virus Drug Resistance: A Time-Sampled Population Genetics Perspective

- Transcriptome-Wide Analyses of 5′-Ends in RNase J Mutants of a Gram-Positive Pathogen Reveal a Role in RNA Maturation, Regulation and Degradation

- Selective Disruption of Aurora C Kinase Reveals Distinct Functions from Aurora B Kinase during Meiosis in Mouse Oocytes

- X Chromosome Control of Meiotic Chromosome Synapsis in Mouse Inter-Subspecific Hybrids

- A Cohesin-Independent Role for NIPBL at Promoters Provides Insights in CdLS

- Extreme Population Differences in the Human Zinc Transporter ZIP4 (SLC39A4) Are Explained by Positive Selection in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Classic Selective Sweeps Revealed by Massive Sequencing in Cattle

- Genomic Networks of Hybrid Sterility

- Natural Polymorphisms in Influence Negative Selection and CD4∶CD8 Lineage Commitment in the Rat

- Oxidative Stress Is Not a Major Contributor to Somatic Mitochondrial DNA Mutations

- Molecular Identification of Collagen 17a1 as a Major Genetic Modifier of Laminin Gamma 2 Mutation-Induced Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa in Mice

- Uncoupling of Molecular Maturation from Peripheral Target Innervation in Nociceptors Expressing a Chimeric TrkA/TrkC Receptor

- MicroRNAs Located in the Hox Gene Clusters Are Implicated in Huntington's Disease Pathogenesis

- Loss of Trabid, a New Negative Regulator of the Immune-Deficiency Pathway at the Level of TAK1, Reduces Life Span

- Targeted Ablation of Nesprin 1 and Nesprin 2 from Murine Myocardium Results in Cardiomyopathy, Altered Nuclear Morphology and Inhibition of the Biomechanical Gene Response

- Identification of Novel Genetic Loci Associated with Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies and Clinical Thyroid Disease

- CEP-1, the p53 Homolog, Mediates Opposing Longevity Outcomes in Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Mutants

- Transcriptomics and Functional Genomics of ROS-Induced Cell Death Regulation by

- Quantitative Genome-Wide Genetic Interaction Screens Reveal Global Epistatic Relationships of Protein Complexes in

- Cascades of Genetic Instability Resulting from Compromised Break-Induced Replication

- Serine- and Threonine/Valine-Dependent Activation of PDK and Tor Orthologs Converge on Sch9 to Promote Aging

- Zfp322a Regulates Mouse ES Cell Pluripotency and Enhances Reprogramming Efficiency

- Insertional Mutagenesis and Deep Profiling Reveals Gene Hierarchies and a -Dependent Bottleneck in Lymphomagenesis

- DAAM Is Required for Thin Filament Formation and Sarcomerogenesis during Muscle Development in Drosophila

- Plasma Cholesterol–Induced Lesion Networks Activated before Regression of Early, Mature, and Advanced Atherosclerosis

- High-Resolution Profiling of Stationary-Phase Survival Reveals Yeast Longevity Factors and Their Genetic Interactions

- Comparative RNAi Screens in and Reveal the Impact of Developmental System Drift on Gene Function

- Accurate and Robust Genomic Prediction of Celiac Disease Using Statistical Learning

- Sex-Specific Embryonic Gene Expression in Species with Newly Evolved Sex Chromosomes

- Chromosome X-Wide Association Study Identifies Loci for Fasting Insulin and Height and Evidence for Incomplete Dosage Compensation

- Negative Feedback and Transcriptional Overshooting in a Regulatory Network for Horizontal Gene Transfer

- DNA Sequence Explains Seemingly Disordered Methylation Levels in Partially Methylated Domains of Mammalian Genomes

- Insights into the Genomic Landscape: Comparative Genomics Reveals Variations in Ploidy and Nutrient Utilisation Potential amongst Wine Isolates

- Molecular Evidence for the Inverse Comorbidity between Central Nervous System Disorders and Cancers Detected by Transcriptomic Meta-analyses

- The Centriolar Satellite Protein AZI1 Interacts with BBS4 and Regulates Ciliary Trafficking of the BBSome

- Fine-Mapping the Region Detects Common Variants Tagging a Rare Coding Allele: Evidence for Synthetic Association in Prostate Cancer

- Transmission Distortion Affecting Human Noncrossover but Not Crossover Recombination: A Hidden Source of Meiotic Drive

- A Variant in the Neuropeptide Receptor is a Major Determinant of Growth and Physiology

- Mutation of SLC35D3 Causes Metabolic Syndrome by Impairing Dopamine Signaling in Striatal D1 Neurons

- NSUN4 Is a Dual Function Mitochondrial Protein Required for Both Methylation of 12S rRNA and Coordination of Mitoribosomal Assembly

- MicroRNA-133 Inhibits Behavioral Aggregation by Controlling Dopamine Synthesis in Locusts

- Convergence of Light and ABA Signaling on the Promoter

- Arf4 Is Required for Mammalian Development but Dispensable for Ciliary Assembly

- Distinct Requirements for Cranial Ectoderm and Mesenchyme-Derived Wnts in Specification and Differentiation of Osteoblast and Dermal Progenitors

- Chk2 and P53 Regulate the Transmission of Healed Chromosomes in the Male Germline

- Ddc2 Mediates Mec1 Activation through a Ddc1- or Dpb11-Independent Mechanism

- Mapping the Fitness Landscape of Gene Expression Uncovers the Cause of Antagonism and Sign Epistasis between Adaptive Mutations

- Euchromatic Transposon Insertions Trigger Production of Novel Pi- and Endo-siRNAs at the Target Sites in the Germline

- miR-100 Induces Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition but Suppresses Tumorigenesis, Migration and Invasion

- Canine Hereditary Ataxia in Old English Sheepdogs and Gordon Setters Is Associated with a Defect in the Autophagy Gene Encoding

- Within-Host Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Plant Virus Infection at the Cellular Level

- Analysis of Meiosis in SUN1 Deficient Mice Reveals a Distinct Role of SUN2 in Mammalian Meiotic LINC Complex Formation and Function

- Genome-Wide Association Study of Metabolic Traits Reveals Novel Gene-Metabolite-Disease Links

- Mechanistically Distinct Mouse Models for -Associated Retinopathy

- DAF-16/FoxO Directly Regulates an Atypical AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Gamma Isoform to Mediate the Effects of Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling on Aging in

- Chromosome I Controls Chromosome II Replication in

- Integrated Genomic Characterization Reveals Novel, Therapeutically Relevant Drug Targets in FGFR and EGFR Pathways in Sporadic Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

- The Iodotyrosine Deiodinase Ortholog SUP-18 Functions through a Conserved Channel SC-Box to Regulate the Muscle Two-Pore Domain Potassium Channel SUP-9

- The Genome of Highlights a Fish Pathogen Adapted to Fluctuating Environments

- Distinct DNA Binding Sites Contribute to the TCF Transcriptional Switch in and

- The Streamlined Genome of spp. Relative to Human Pathogenic Kinetoplastids Reveals a Parasite Tailored for Plants

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Association Study of Metabolic Traits Reveals Novel Gene-Metabolite-Disease Links

- A Cohesin-Independent Role for NIPBL at Promoters Provides Insights in CdLS

- Classic Selective Sweeps Revealed by Massive Sequencing in Cattle

- Arf4 Is Required for Mammalian Development but Dispensable for Ciliary Assembly

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání