-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaTracking Proliferative History in Lymphocyte Development with Cre-Mediated Sister Chromatid Recombination

Tracking and isolating live cells based on their proliferative history in live animals remains a technical challenge in animal studies. We have designed a genetic marking system for tracking the proliferative frequency and history of lymphocytes during their development and homeostatic maintenance. This system is based on activation of a fluorescent marker after Cre-dependent recombination between sister chromatids at a specially designed tandem loxP site, named Tlox. We have demonstrated the utility of the Tlox system in tracking proliferative windows of B and T lymphocyte development. We have further applied the Tlox system in the analysis of the proliferative behavior and homeostatic maintenance of Vγ1.1 positive γδ T cells. Our data show that Vγ1.1 T cells generated in neonatal but not adult life are able to expand in the thymus. The expanded Vγ1.1 T cells are preferentially maintained in the liver but not in lymphoid organs. It has been shown that numbers of Vγ1.1 T cells were dramatically increased in the lymphoid organs of Id3 deficient mice. By combining BrdU and Tlox assays we show that this phenotype is primarily due to enhanced neonatal expansion and subsequent retention of Vγ1.1 T cells. Thus, the Tlox system provides a new genetic tool to track clonal expansion within a defined cell population or tissue type in live animals.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003887

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003887Summary

Tracking and isolating live cells based on their proliferative history in live animals remains a technical challenge in animal studies. We have designed a genetic marking system for tracking the proliferative frequency and history of lymphocytes during their development and homeostatic maintenance. This system is based on activation of a fluorescent marker after Cre-dependent recombination between sister chromatids at a specially designed tandem loxP site, named Tlox. We have demonstrated the utility of the Tlox system in tracking proliferative windows of B and T lymphocyte development. We have further applied the Tlox system in the analysis of the proliferative behavior and homeostatic maintenance of Vγ1.1 positive γδ T cells. Our data show that Vγ1.1 T cells generated in neonatal but not adult life are able to expand in the thymus. The expanded Vγ1.1 T cells are preferentially maintained in the liver but not in lymphoid organs. It has been shown that numbers of Vγ1.1 T cells were dramatically increased in the lymphoid organs of Id3 deficient mice. By combining BrdU and Tlox assays we show that this phenotype is primarily due to enhanced neonatal expansion and subsequent retention of Vγ1.1 T cells. Thus, the Tlox system provides a new genetic tool to track clonal expansion within a defined cell population or tissue type in live animals.

Introduction

Cell proliferation is a tightly regulated process in tissue development and maintenance of tissue functions. Knowing the frequency and history of cell division is not only important in the study of normal tissue development but also in the investigation of tissue regeneration and tumorogenesis. The most commonly used lineage tracking methods are based on Cre mediated activation of reporters in progenitor cells [1]–[3]. By restricting Cre activity to the progenitor cells, this method is highly effective in tracking clonal expansion of the labeled progenitors [3]. However, reporter activation is not linked to cell cycle and thus alone cannot be used to report the proliferative status of the progenitor population. Thus far, methods available for tracking cell proliferation in live animals are still limited and incompatible with recovery of live cells for subsequent analysis. The most commonly used methods for tracking cell proliferation are based on either incorporation of a nucleotide analog such as bromodeoxyurodine (BrdU) or tritiated thymidine during DNA replication [4] or natural dilution of a genetically activated protein marker such as GFP [5]. For example, BrdU pulse labeling method has been successfully used to define the proliferative windows in thymic T cell development [6]. The BrdU method is simple and generally applicable to all tissues, but the detection of chemical labels is incompatible with retrieval of live cells for further studies. In contrast, detection of GFP expression can be carried out with live cells and therefore has the potential to be combined with additional functional assays. For example, GFP intensity has been used to trace the age of naïve T cells based on the dilution of temporarily activated GFP signals associated with homeostatic proliferation of peripheral T cells [7]. However, for cells that have undergone extensive rounds of proliferation, like lymphocytes during antigen responses or cancer stem cells coming out of a dormant phase, they will lose all GFP signals and become indistinguishable from unlabeled cells in the background.

Cre-mediated mitotic recombination provides another way to permit genetic marking of proliferation events in live mice [8]. In this case, activation of a reporter is strictly dependent on mitotic recombination between homologous chromosomes. This system has been successfully used in labeling and tracking progenitor cells that give rise to tumors [9]. However, the overall recombination efficiency of Cre-mediated mitotic recombination is below 1% of the proliferating population when tested in a broad range of cell types [8] including lymphocytes [10]. While the method is powerful in mosaic analysis, the low frequency of mitotic recombination makes the system less effective as a generic method to evaluate proliferative status of progenitor populations for most tissue types.

To overcome these limitations and to enable tracking cell cycle in live cells, we have designed a sister chromatid recombination system to directly link cell cycle with permanent activation of a fluorescent protein marker. This system is based on the fact that Cre/lox mediated recombination can occur between sister chromatids during cell cycle [11], [12]. Cre-mediated sister chromatid exchange occurs at a much higher frequency than Cre-mediated mitotic recombination between homologous chromosomes [12], [13]. In our design, a non-equal exchange between the marked sister chromatids produces a fraction of progeny that acquire the fluorescent marker. We have tested the system in both cultured fibroblasts and developing lymphocytes in live mice. The mouse lymphoid system represents one of the best experimental models for understanding normal and abnormal cell proliferation in a living organism. Using mice expressing lymphoid specific Cre, we have shown that permanent activation of the fluorescent marker after Cre-mediated recombination is correlated with the well-defined windows of cell cycle. As a proof of principle, we further applied this newly established cell tracking system in the study of the expansion of γδ T cells induced by deletion of the Id3 gene.

Results

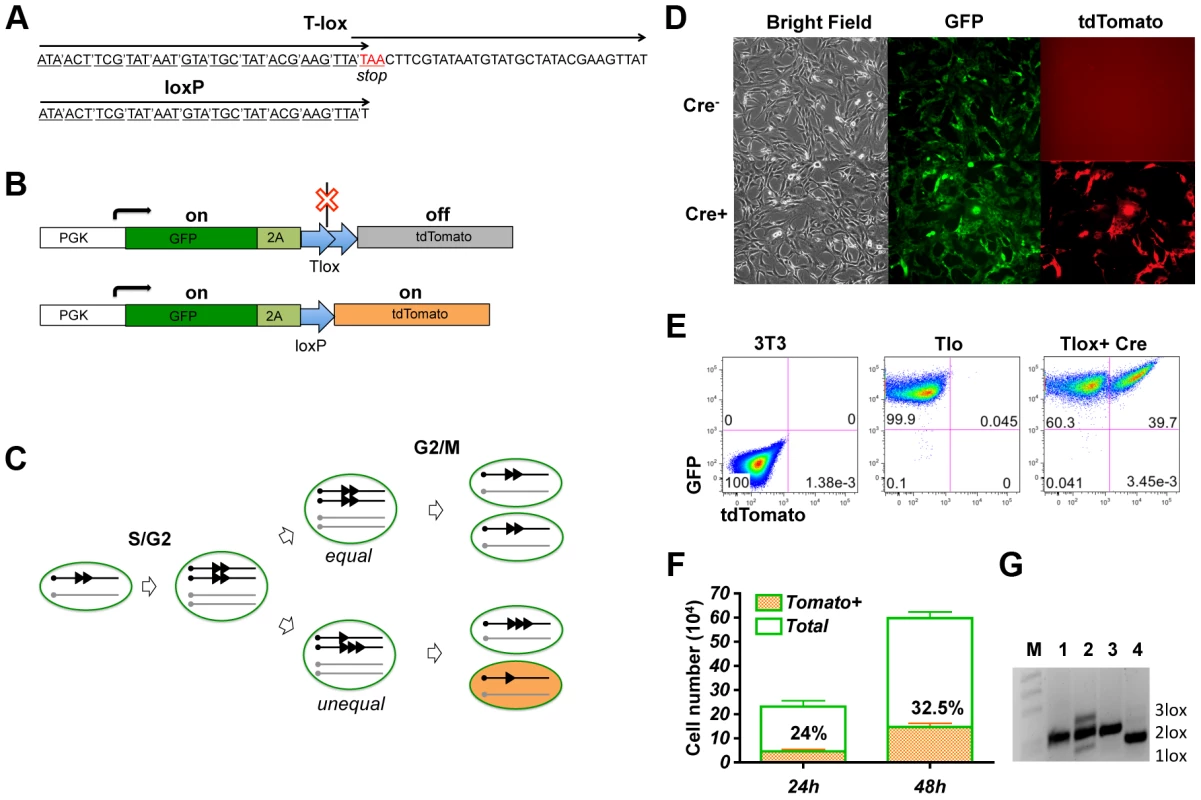

Cre recombinase has been shown to be capable of driving recombination between sister chromatids via duplicated loxP sites [11], [12]. This recombination system provides an opportunity for Cre mediated activation of a genetic marker during cell cycle. To ensure that Cre/lox mediated recombination occurs exclusively during cell cycle, we have designed a tandem overlapping loxP cassette named Tlox, which contains a stop codon at the beginning of the second loxP unit (Fig. 1A). This Tlox cassette provides a translational stop between the GFP and tdTomato markers (Fig. 1B). The stop codon is eliminated only after the Tlox has been reduced to a single loxP unit. Because recombination requires a Cre tetramer complex [14], intra Tlox recombination cannot occur due to structural constrain. However, Cre-mediated Tlox recombination can occur between two Tlox units present on neighboring sister chromatids during the S/G2/M phase of cell cycle. The recombination will result in either equal or unequal exchange between the sister chromatids (Fig. 1C). While tdTomato remains silent following equal exchange, unequal exchange between sister chromatids should lead to daughter cells inheriting either a single loxP or triple loxP sequences. Whereas cells inheriting a triple loxP remain tdTomato negative, cells inheriting a single loxP should permanently turn on the tdTomato marker. It is anticipated that triple loxP sequences will have additional chances to be converted to a single loxP in subsequent cell cycles through unequal exchange. In principle, this method will label up to one quarter of the progeny from each proliferating cycle if Cre is fully active during S/G2/M phases of each cell cycle. Because the expression of tdTomato is strictly dependent on cell cycle and is permanent, this method offers a new way to identify and isolate cells that have undergone proliferation in the developmental window defined by Cre expression.

Fig. 1. Genetic labeling of proliferating cells in vitro with the Tlox design.

(A) A comparison between the Tlox and a single loxP sequences. Codons of the reading frame are marked in the Tlox sequence. The stop codon (in red) is in the overlapping region between the first and the second loxP sequences in Tlox. (B) Schematic of Tlox on MSCV retroviral backbone. In the presence of Tlox, both GFP and tdTomato are transcribed, but only GFP (indicated by the green color) is translated. When Tlox is replaced with a single loxP, both GFP and tdTomato (indicated by the orange color) are expressed. 2A is included as a target sequence for auto cleavage [34] to separate GFP and tdTomato. (C) Diagram illustrates Cre-mediated sister chromatid recombination via the Tlox site during mitosis. Results of both equal and unequal exchanges after the G2/M phase are shown. Unequal exchange (bottom part) produces daughter chromosomes carrying either single or triple loxP site. (D–E) 3T3 cells harboring the reporter construct were transduced with control empty virus or Cre virus and analyzed by fluorescent imaging (D) or FACS (E) 48 hours post viral transduction. (F) Cell counts of total and tdTomato positive cells at 24 or 48 hours post viral transduction. Non-transduced cells were excluded based on lack of hCD2 expression. Percentages of tdTomato positive cells are indicated in the plot. (G) PCR assay of genomic DNA with primers flanking the Tlox site. M, 1 kb-DNA size ladder; 1, reporter plasmid control; 2, total cells at 48 hours after Cre transduction; 3, parental cells before Cre transduction; and 4, FACS sorted double positive cells at 48 hours after transduction. Bands representing 1loxP, 2loxP, and 3loxP were verified by sequencing analysis after subcloning the PCR products into Topo vectors. We first performed a proof-of-principle test for this genetic design by introducing the Tlox expressing cassette via a retroviral vector into 3T3 cells. As expected, only the GFP signal is detectable in Tlox infected cells in the absence of Cre (Fig. 1D,E). To test the efficiency of sister chromatid recombination, we isolated cells stably expressing GFP and transduced these cells again with a Cre-expressing retroviral vector. Efficiency of transduction was monitored with a hCD2 marker co-expressed with Cre on the retroviral vector [12]. Without cell cycle synchronization, the doubling time for NIH3T3 cells has been reported to be approximately 17 hours [15]. We found 32.5+/−0.5% of Cre transfected cells expressed tdTomato 48 hours post viral transduction, which was up from 24+/−0.7% scored at 24 hours post transduction (Fig. 1F). This number is below the predicted maximal possible frequency (25% for the first cycle and 44% for the second cycle) of tdTomato activation per cell cycle (Fig. 1C). Thus, the labeling frequency observed in real experiments is an underestimation of true proliferation frequency. PCR analysis of the Tlox cassette showed that Cre expression indeed induced generation of both single and triple loxP sequences (Fig. 1G, lane 2). FACS sorted tdTomato positive cells showed exclusively single loxP in the same PCR assay (Fig. 1G, lane 4), supporting the idea that all tdTomato positive cells were the result of Tlox conversion to single loxP.

To introduce a single Tlox cassette into the mouse genome, we used the piggyBac transposon vector [16] to deliver the expression cassette through microinjection of fertilized eggs. FACS analysis of blood samples from founder transgenic mice identified two positive founders (Fig. S1A). We mapped four independent insertion sites through inverse PCR cloning and chose a chromosome 19 insertion (Fig. S1B and C) for subsequent tests.

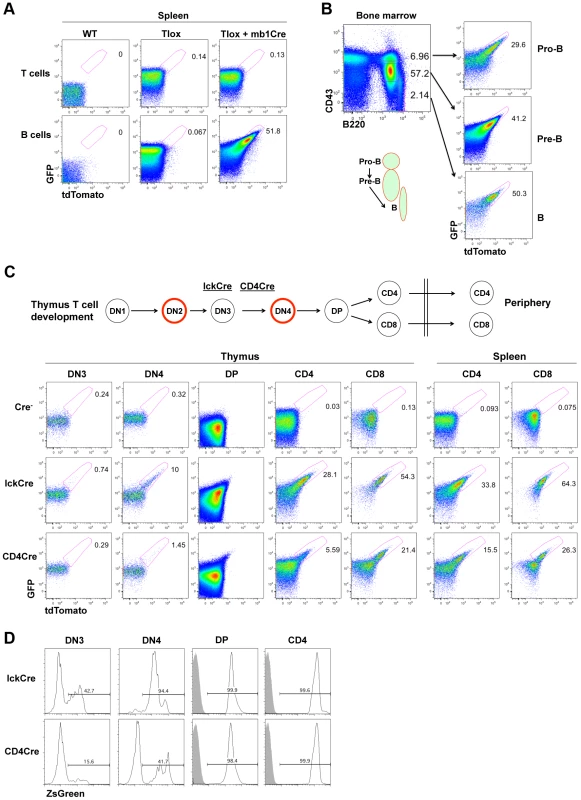

The timing and frequency of cell proliferation during lymphocyte development are dynamically regulated during the generation and maintenance of polyclonal lymphocytes. Because the proliferative windows in lymphocyte development have been mapped previously with BrdU labeling methods, we chose lymphocyte development as a test model to validate our Tlox system. We used mb1Cre [17] and LckCre [18] to drive B cell and T cell specific recombination, respectively. mb1Cre initiates Cre expression at the pro-B cell stage and keeps Cre on throughout B cell development. tdTomato expression was not detected in splenic B and T lymphocytes in the absence of mb1Cre, confirming that spontaneous exchanges between sister chromatids are negligible (Fig. 2A, middle column). tdTomato positive cells were exclusively found among B but not T cells in mice carrying both the Tlox transgene and mb1Cre. Activation of tdTomato was coupled with a further upregulation of GFP signals (Fig. S2), which could be a result of increased stability of mRNA after removal of the stop codon in the Tlox cassette and thus eliminating nonsense mediated RNA decay [19]. To further evaluate whether tdTomato expression is linked to cell proliferation, we examined B cell development in the bone marrow. B cell development proceeds in a sequential order from pro-B to pre-B, and then to mature B cells, which are marked as CD43hiB220low, CD43medB220low, and CD43lowB220hi fractions, respectively [20] (Fig. 2B). We found that tdTomato was expressed in all three fractions with the ratio gradually increasing from 30+/−1.9% in pro-B, to 38+/−9.0% in pre-B, and to 43+/−5.3% in mature B cells (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3). The increased frequency of tdTomato expression is correlated with the well-defined pro-B and pre-B windows of cell proliferation [20]. tdTomato expression frequency in mature B was maintained at around 46+/−7.3% in the spleen. The lack of further increase of tdTomato expression in mature B cells from bone marrow to periphery is consistent with their non-cycling state in the absence of antigen stimulation. This result further confirms that Cre cannot drive Tlox recombination in non-cycling cells.

Fig. 2. Tlox tracking lymphocyte proliferation in vivo.

(A) One-month old wild type, Tlox transgenic, Tlox and mb1Cre double transgenic mice were analyzed by gating on live T cells (TCRβ+) or B cells (B220+) from the spleen. tdTomato positive cells were highlighted by a region gate in the plots. (B) Bone marrow from Tlox and mb1Cre double transgenic mice was analyzed with CD43 and B220 markers. Pro-B, Pre-B and mature B cells were defined as CD43hiB220low, CD43medB220low and CD43lowB220hi, respectively, and are indicated in the FACS plot and the diagram below. Each fraction was analyzed for GFP and tdTomato expression with the tdTomato positive fraction marked in the plot. (C) Diagram and representative FACS plots of major stages of T cell development in the thymus and periphery. Red circle indicates cells undergoing proliferative expansion. The starting time for lckCre and CD4Cre expression around the DN3 stage are indicated by their relative position in the diagram. FACS analyses of tdTomato expression are displayed in sequential order according to stages of T cell development for the Tlox mice (upper panel), the Tlox and lckCre double transgenic mice (middle panel), and the Tlox and CD4Cre double transgenic mice (lower panel). Results are representative of at least three mice for each genotype. DN3 cells are defined as CD4−CD8−CD44−CD25+, DN4 cells as CD4−CD8−CD44−CD25−, DP cells as CD4+CD8+, CD4 cells as CD4+CD8−, and CD8 cells as CD4−CD8+. DN cells also exclude any CD3, NK1.1, B220 and CD11b positive cells. (D) lckCre (upper panel) and CD4Cre (lower panel) mediated activation of the R26ZsGreen reporter during T cell development. Relative percentage of ZsGreen positive cells at each developmental stage is indicated in each plot. Shaded areas are relevant control populations from ZsGreen mice without a Cre transgene. T cell development in the thymus proceeds through several developmental stages with clearly defined windows of proliferation [21]. T lineage commitment and initial expansion of the committed T cell progenitors occur at the DN1 and DN2 stages, respectively. Separation between αβ and γδ T lineage fate is completed at the end of the DN3 stage. Cells choosing the αβ fate expand further at the DN4 stage before entering the non-proliferating DP stage. Clonal selection at the DP stage leads to the formation of either CD4 helper T cells or CD8 cytolytic T cells with each cell expressing a unique TCR. The LckCre transgene has been shown to initiate Cre expression during the DN3 stage of T cell development in the thymus and to support continuing Cre expression thereafter [18], [22] (Fig. 2C). BrdU based analysis has demonstrated that proliferation occurs almost exclusively in the DN2 and DN4 stage of T cell development, although the mature CD8+ single positive (SP) T cells have also exhibited a detectable level of proliferation [6], [23]. Mice double positive for the LckCre and the Tlox transgenes were analyzed for tdTomato expression among different cell fractions representing progressive maturation status (Fig. 2C). We found that the earliest stage to detect tdTomato expression was DN4 but not DN3, which is consistent with the idea that LckCre cannot act on the non-proliferating DN3 cells. CD4CD8 double positive (DP) cells are the progeny of rapidly proliferating DN4 cells and have greatly reduced cell size comparing with other immature T cell fractions. Because the overall signal of GFP and tdTomato was dramatically reduced, it was difficult to separate tdTomato positive cells from the negative fractions even though tdTomato expression was clearly visible among DP cells. After progressing to the CD4 or CD8 single positive (SP) stage, cells showed a significantly higher frequency of tdTomato expression than DN4 cells. During the DP to SP transition, immature T cells remain in a non-proliferating state. Therefore, this elevated frequency of tdTomato+ SP cells reflected the proliferative transition between DN4 and DP cells. Within the SP populations, the percentage of tdTomato expression in CD8+ SP cells is approximately two times higher than that of CD4+ SP cells, suggesting additional rounds of cell proliferation have occurred in CD8 lineage cells. This result is consistent with BrdU pulse labeling studies, which also showed higher proliferation rate associated with CD8 SP cells [23]. The frequency of tdTomato expression in both CD4+ and CD8+ cells showed a moderate increase as they move from the thymus to the spleen. This finding is consistent with the knowledge that naïve T cells rarely proliferate under homeostatic conditions. Overall, the timing and capacity of immature T cell proliferation measured by tdTomato expression from the Tlox cassette are in agreement with the previously defined characteristics of various thymocyte populations during their development.

To gain additional evidence that tdTomato activation is dependent on cell cycle, we compared LckCre-induced with CD4Cre-induced Tlox recombination. CD4Cre is known to support Cre expression starting between the DN3 and DN4 stage [24], which is slightly later than that of LckCre. Correspondingly, the efficiency of tdTomato activation was found lower than that of LckCre at the DN4 stage (Fig. 2C bottom panel). The difference between these two Cre drivers persists even after cells have reached to the CD4 or CD8 stage. This persistent difference cannot be explained by inefficient Cre expression in these later stages since both LckCre and CD4Cre are equally capable of deleting the flox-stop cassette embedded in the R26ZsGreen reporter [25](Fig. 2D), a process independent of cell cycle. Thus, activation of the Tlox reporter requires Cre to be expressed during the proliferative phase of T cell development.

To obtain direct evidence that tdTomato activation is dependent on cell cycle, we performed in vitro cell proliferation assay with sorted tdTomato positive or negative CD4 T cells from the Tlox;CD4Cre mice (Fig. S4). TCR-induced cell proliferation was tracked by dilution of the CellTrace Violet dye. tdTomato positive cells retained tdTomato expression during cell cycle (Fig. S4A). tdTomato negative cells showed increased frequency of tdTomato expression after each round of cell cycle (Fig. S4A and B). In fact, tdTomato expression can be detected as early as when cells entering the blasting phase (Fig. S4C). During the same time frame, tdTomato expression was not observed among tdTomato negative cells when they were kept alive without proliferation (Fig. S4B). This study further demonstrates that activation of the Tlox reporter is strictly associated with cycling cells.

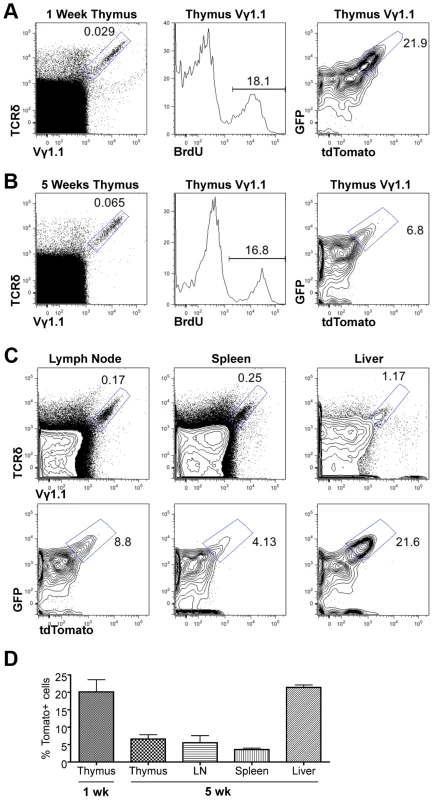

We next used the Tlox reporter system to monitor the generation and maintenance of γδ T cells in neonatal and young adult mice. Although majority of γδ T cells found in adult tissues are descendants of fetal derived γδ T cells, γδ T cells are continuously generated in parallel to αβ T cells in postnatal thymus and exported to secondary lymphoid organs [26]. Little is known about the homeostatic maintenance of these post-natal derived γδ T cells. A fraction of γδ T cells enriched for the Vγ1.1 usage (thus referred as Vγ1.1 cells) has been classified as innate-like or NK-like γδ T cells due to their ability to express mixed cytokines including IL4 and γ interferon [27]. These cells are produced in late fetal and neonatal life and detected in the thymus, secondary lymphoid organs, and liver. However, it is not clear whether these cells are continuously generated in postnatal life or maintained exclusively through self-renewal of the fetal-derived population. We first used BrdU pulse labeling method to assess the cell cycle status of γδ T cells in one-week old neonates and five-week old young adult mice (Fig. 3A&B). A similar frequency of BrdU labeling was observed in Vγ1.1 T cells of both age groups. To further evaluate the lineage relationship between the two age groups we used the Tlox assay to evaluate proliferative history of the γδ T cells. The frequency of tdTomato positive Vγ1.1 cells was found significantly higher in one-week old than in 5-week old thymus. While this result is consistent with the earlier studies that Vγ1.1 cells undergo expansion in late fetal and neonatal life [27], the decreased frequency also suggests that Vγ1.1 cells present in young adult thymus are not related to neonatal derived Vγ1.1 T cells. Further analysis of 5-week old mice revealed that Vγ1.1 T cells from other lymphoid organs including lymph nodes and the spleen exhibited a similar low frequency of dtTomato as in the thymus (Fig. 3C&D). In contrast, the frequency of dtTomato positive Vγ1.1 T cells present in the liver is as high as in neonatal thymus. Thus, circulating Vγ1.1 T cells and liver resident Vγ1.1 T cells can be separated into two distinct populations based on their proliferative history.

Fig. 3. Assessing proliferation frequency and history of Vγ1.1 T cells.

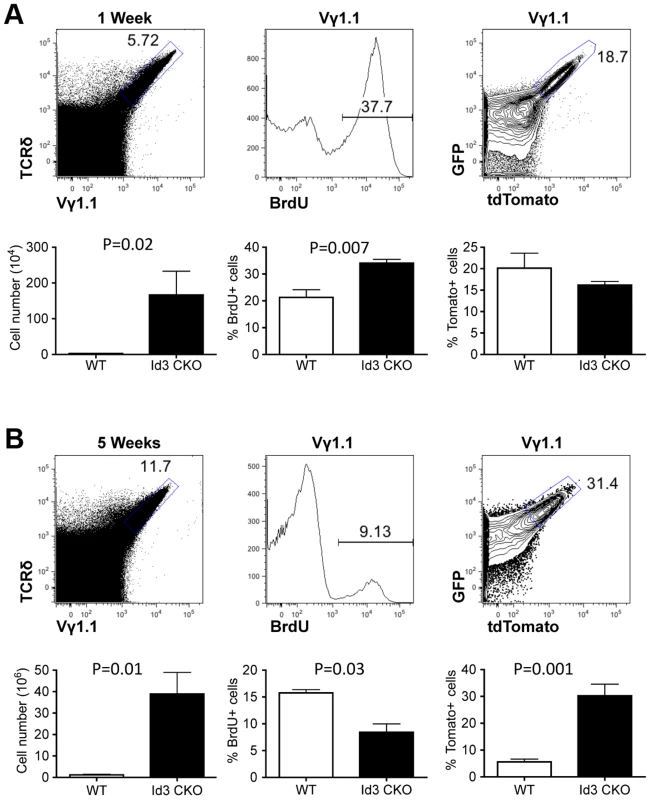

(A) Representative FACS plots of thymic Vγ1.1 γδ T cells from one-week old lckCre;Tlox neonates. Vγ1.1 cells were identified in the gated area of TCRδ and Vγ1.1 doubly stained total thymocytes (left) and used in subsequent display of BrdU incorporation (middle) and GFP/dtTomato expression (right). (B) Analyses of 5-week old mice as described in (A). (C) Analysis of Vγ1.1 T cells present in lymph node (left), spleen (middle), and liver (right) of 5-week old mice as described in (B). Frequency of tdTomato expression was shown in the contour plot below each dot plot. (D) Summary of tdTomato expression frequency in Vγ1.1 T cells obtained from (A–C). Sample sizes are three for one-week old and three for 5-week old mice. Recently, several studies have shown that deletion of the Id3 gene led to a significant expansion of Vγ1.1 T cells in adult animals [28], [29]. The Id3 gene encodes a nuclear protein, which regulates lymphocyte development through direct inhibition of E-protein transcription factors [30]. How Id3 knockout promotes development and/or expansion of Vγ1.1 T cells is still not clear. We thought to further investigate this issue by combining the traditional BrdU method with the newly established Tlox system. LckCre was used to induce T lineage specific deletion of Id3 and activation of the Tlox marker. We first analyzed cell cycle status with BrdU pulse labeling. A significant increase in BrdU positive cells was observed in Id3 deficient one-week old neonates in comparison with the wild type controls (Fig. 4A, middle column). However, analysis of young adult mice showed a moderate decrease in BrdU incorporation in Id3 deficient mice (Fig. 4B, middle column). We then used the Tlox system to track the proliferative history of Vγ1.1 cells. Analysis of Vγ1.1 T cells from one-week old neonates revealed a similar frequency of tdTomato expression between Id3 deficient and wild type controls (Fig. 4A, right column), suggesting that Vγ1.1 T cells on both backgrounds have gone through similar numbers of cell cycles at the neonatal stage. This result is in contrast to the BrdU data, which detects a higher percentage of proliferating cells in Id3 deficient Vγ1.1 T cells than in wild type controls within the 4 hour window of pulse labeling. Thus, the proliferation rate revealed by BrdU pulse labeling may not reflect the proliferative history of the cell population. The differential outcomes from these two assays become even more dramatic in the analysis of 5-week old mice. In contrast to the neonates, the frequency of tdTomato positive Vγ1.1 T cells in 5-week old mice was significantly increased in Id3 deficient mice even though BrdU labeling frequency has decreased (Fig. 4B, middle and right panels). This result supports the idea that Id3 deficiency promotes development and expansion of Vγ1.1 T cells during neonatal life and their subsequent maintenance in postnatal life.

Fig. 4. Assessing proliferation frequency and history of Vγ1.1 T cells on Id3 deficient background.

(A) Analysis of Vγ1.1 T cells in one week old LckCre;Tolx;Id3f/f thymus. Vγ1.1 T cells were first gated from analysis of total thymocytes (left) and then displayed for BrdU incorporation (middle) and tdTomato expression (right). Below each FACS plot is statistic analysis against Id3 wild type samples described in Fig. 3. Four wild type and seven Id3 mutant samples were used in the unpaired student t-test. (B) Analysis of Vγ1.1 T cells in five week old LckCre;Tolx;Id3f/f thymus. Sample display is as in (A). Student t tests were based on three wild type and three Id3 mutant samples for the left and center plot and five wild type and six Id3 mutant samples for the right plot. Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the Tlox design is an effective genetic tool to track proliferative history of Cre expressing cells in both tissue culture and live animals. This method predicts that the maximal labeling efficiency of dividing cells is 25% per cell cycle (Fig. 1C). While our tracking data clearly shows that Tlox activation is correlated with increased numbers of cell cycle, the overall labeling efficiency is below the expected rate, particularly in animal models. We speculate that multiple factors may contribute to the efficiency of Cre mediated Tlox recombination between sister chromatids. These factors, such as the accessibility of Tlox during S/G2 phase, the expression level of Cre recombinase, and the duration of the S/G2 phase, may vary during development and between tissue types. Thus, the quantitative readout from Tlox assay represents an empirical value associated with the specified developmental system. Once the relative frequency is determined for relevant tissue types in the wild type mice, this reporter assay is particularly useful in assessment of proliferative behavior associated with novel mutations.

When combined with other methods such as BrdU incorporation assays, this system can effectively reveal cell cycle behaviors, some of which would have been otherwise missed or misinterpreted by using the BrdU method alone. Our analysis of developing B cells and αβ T cells confirmed that the frequency of tdTomato expression from the Tlox marker is correlated with Cre expression and windows of cell cycles defined previously by the BrdU method [20], [23], [31]. Using this newly established Tlox assay, we further revealed a change in proliferative behavior of γδ T cells between neonatal and young adult mice. In particular, it has been shown that generation of Vγ1.1 T cells from donor hematopoietic stem cells requires neonatal thymic environment [27]. This observation led to the general hypothesis that Vγ1.1 T cells are produced in late fetal and neonatal life and maintained through self-renewal in postnatal life. Our analysis with the Tlox marker provided strong evidence indicating that most thymic resident Vγ1.1 T cells are not maintained through expansion of preexisting population. They are most likely continuously derived from thymic precursors and quickly turned over in circulation. In contrast to circulating Vγ1.1 T cells, liver resident Vγ1.1 T cells are maintained as a distinct population, which share similar features with Vγ1.1 T cells found in neonatal thymus. Our finding is consistent with the report that liver resident Vγ1.1 T cells lack N addition in their TCR, a feature associated with fetal derived T cells [27]. It remains to be determined whether circulating Vγ1.1 T cells in adult animals can be converted to tissue resident γδ T cells under certain circumstances such as in response to infection or tissue damage. Tlox mediate tracking of expanded populations may assist future investigation of function and homeostatic maintenance of Vγ1.1 T and other lymphoid populations.

Id3 deficient mice have been characterized to exhibit excess amount of Vγ1.1 T cells in the thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs [28], [29] and develop high incidence of γδ T cell lymphoma at older age [32]. Our study using both BrdU labeling and Tlox tracking methods revealed that Id3 deletion promotes the development and proliferative expansion of Vγ1.1 T cells in neonatal life. At adult age, this population is apparently maintained by accumulation of cells with a reduced frequency of cell cycle. This result provides a strong evidence to support the finding that Vγ1.1 T cells detected in Id3 deficient mice exhibit highly restricted TCR usage and often lack N nucleotide addition [29]. Our data support the idea that Id3 deficiency promotes clonal expansion of Vγ1.1 T cells in the neonatal thymus and, more importantly, their slow expansion and long-term maintenance in adult life. Such a proliferative behavior could contribute to the generation of γδ T cell lymphoma observed in aged Id3 knockout mice [32]. Our study of Id3 deficient mice established the Tlox system as a new tool for tracking clonal expansion and possibly for monitoring malignant transformation in live animals.

A major advantage of our Tlox system is the identification and isolation of live cells that have undergone proliferation in a defined window of development. However, additional efforts are still needed for broad applications of this reporter system. Preliminary studies suggest that the Tlox system is inefficiently activated by tamoxifen inducible CreER systems, although the reasons for this and possible steps to optimize efficiency are still under investigation. In addition, the Tlox design can be further adapted to drive expression of other markers or enzymes for easy detection of proliferating cells in tissues other than lymphocytes. It would be particularly attractive to use this method to label and then isolate slowly proliferating somatic stem cells or tumor initiating clones when combined with appropriate Cre drivers. Finally, this recombination system could be combined with live imaging techniques in tracking cell proliferation in situ in mice and other model organisms.

Materials and Methods

Mice and reagents

The mb1Cre knockin was generated in Dr. Reth's group [17]. The LckCre transgenic [18] and Id3 conditional knockout [33] alleles were produced in Zhuang lab as previously described. R26ZsGreen strain [25] was purchased from the Jackson Labs. Tlox transgenic lines were produced by microinjection of circular PB donor construct mixed with a helper plasmid (PCX-PBase) at a ratio of 3∶1 [16]. The transgenic procedure was performed by the Duke Transgenic Mouse Facility. Animals were bred and maintained in the SPF facility managed by Duke University Division of Laboratory Animal Research. All animal procedures were approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The antibodies used were as follows: PE/Cy7 anti-human CD2 (TS1/8), APC/Cy7 anti-mouse TCRβ (H57-597), APC/Cy7 anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5), PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD8a (53–6.7), APC anti-mouse B220 (RA2-6B2), PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD43 Activation-associated Glycoform (1B11), PE/Cy7 anti-mouse/human CD44 (IM7), APC anti-mouse CD25 (3C7), PE/Cy5 anti-mouse NK-1.1(PK136), PE/Cy5 anti-mouse Ly-6G/Ly-6C(Gr-1) (RB6-8C5), PE/Cy5 anti-mouse CD11b(M1/70), APC anti-mouse TCRδ (GL3), PE/Cy5 anti-mouse TCRδ (GL3), APC anti-mouse TCRVγ1.1/Cr4(2.11), PE anti-mouse TCRVγ1.1/Cr4(2.11), APC anti-mouse TCRβ (H57-597) were purchased from Biolegend. The APC BrdU Flow Kit was from BD Biosciences.

Construction of Tlox retroviral and piggyBac vectors

The PGK promoter was cloned into an MSCV retrovirus backbone. The GFP coding sequence together with a 2A-Tandom loxP was amplified containing multiple cloning sites (Cla I-target cassette-BamH I-Nsi I-Cla I). The fragment of GFP-2A-Tandem loxP was cloned downstream of a PGK promoter using Cla I. The coding sequence of tdTomato was amplified and cloned downstream of the Tlox site using the BamH I-Nsi I linker. For transgenic experiment, the entire GFP-2A-Tlox-tdTomato cassette was subcloned downstream of the Actin promoter present in the piggyBac vector [16].

Retrovirus and infection

Bosc cells were cultured in complete DMEM medium (containing 10% fetal bovine serum) at 60–70% confluence on 10 cm plates. 10 µg targeting plasmid and 2 µg helper plasmid (pCL-Eco) were transfected into Bosc cells using CaCl2. 48 hours later, the supernatant was harvested and filtered with a 0.45 µm-sterile syringe filter. 3T3 cells were infected with virus containing 8 µg/ml polybrene. The medium was changed back to complete DMEM medium 24 hours after infection. GFP+ cells were sorted after 2 weeks of subculture. Stable GFP+ cells were further infected with either a control virus or Cre-ires-hCD2 virus. FACS analysis and fluorescence imaging were performed at the indicated times.

FACS analysis and BrdU incorporation assay

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from thymus, spleen, peripheral lymph nodes and bone marrow, and suspended in cold FACS buffer (1×PBS supplemented with 5% bovine calf serum). 1×106 cells were stained with Abs in the dark at 4°C for 30 min. After washing with cold FACS buffer, cell suspensions were analyzed on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Flowjo software (Tree Star) was used for data analysis. Mice used for BrdU assays were injected i.p. with 1 mg BrdU 4 hours prior to sample collection. BrdU staining was performed according to the manufacture's instruction (BD Biosciences).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SorianoP (1999) Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nature genetics 21 : 70–71.

2. LivetJ, WeissmanTA, KangH, DraftRW, LuJ, et al. (2007) Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature 450 : 56–62.

3. SnippertHJ, CleversH (2011) Tracking adult stem cells. EMBO reports 12 : 113–122.

4. CavanaghBL, WalkerT, NorazitA, MeedeniyaAC (2011) Thymidine analogues for tracking DNA synthesis. Molecules 16 : 7980–7993.

5. TumbarT, GuaschG, GrecoV, BlanpainC, LowryWE, et al. (2004) Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science 303 : 359–363.

6. VasseurF, Le CampionA, PenitC (2001) Scheduled kinetics of cell proliferation and phenotypic changes during immature thymocyte generation. European journal of immunology 31 : 3038–3047.

7. HaleJS, BoursalianTE, TurkGL, FinkPJ (2006) Thymic output in aged mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 : 8447–8452.

8. ZongH, EspinosaJS, SuHH, MuzumdarMD, LuoL (2005) Mosaic analysis with double markers in mice. Cell 121 : 479–492.

9. LiuC, SageJC, MillerMR, VerhaakRG, HippenmeyerS, et al. (2011) Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals tumor cell of origin in glioma. Cell 146 : 209–221.

10. SunL, WuX, HanM, XuT, ZhuangY (2008) A mitotic recombination system for mouse chromosome 17. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 : 4237–4241.

11. LewandoskiM, MartinGR (1997) Cre-mediated chromosome loss in mice. Nature genetics 17 : 223–225.

12. ZhuY, KimYM, LiS, ZhuangY (2010) Generation and analysis of partially haploid cells with Cre-mediated chromosome deletion in the lymphoid system. The Journal of biological chemistry 285 : 26005–26012.

13. ZhuY, LiuS, YinQ, XuT, WuX, et al. (2012) Generation of Dhx9-deficient clones in T-cell development with a mitotic recombination technique. Genesis 50 : 543–551.

14. Van DuyneGD (2001) A structural view of cre-loxp site-specific recombination. Annual review of biophysics and biomolecular structure 30 : 87–104.

15. HitomiM, StaceyDW (1999) Cellular ras and cyclin D1 are required during different cell cycle periods in cycling NIH 3T3 cells. Molecular and cellular biology 19 : 4623–4632.

16. DingS, WuX, LiG, HanM, ZhuangY, et al. (2005) Efficient transposition of the piggyBac (PB) transposon in mammalian cells and mice. Cell 122 : 473–483.

17. HobeikaE, ThiemannS, StorchB, JumaaH, NielsenPJ, et al. (2006) Testing gene function early in the B cell lineage in mb1-cre mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 : 13789–13794.

18. PanL, HanrahanJ, LiJ, HaleLP, ZhuangY (2002) An analysis of T cell intrinsic roles of E2A by conditional gene disruption in the thymus. J Immunol 168 : 3923–3932.

19. ChangYF, ImamJS, WilkinsonMF (2007) The nonsense-mediated decay RNA surveillance pathway. Annual review of biochemistry 76 : 51–74.

20. HardyRR, CarmackCE, ShintonSA, KempJD, HayakawaK (1991) Resolution and characterization of pro-B and pre-pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. The Journal of experimental medicine 173 : 1213–1225.

21. BhandoolaA, von BoehmerH, PetrieHT, Zuniga-PfluckerJC (2007) Commitment and developmental potential of extrathymic and intrathymic T cell precursors: plenty to choose from. Immunity 26 : 678–689.

22. ShimizuC, KawamotoH, YamashitaM, KimuraM, KondouE, et al. (2001) Progression of T cell lineage restriction in the earliest subpopulation of murine adult thymus visualized by the expression of lck proximal promoter activity. International immunology 13 : 105–117.

23. McCaughtryTM, WilkenMS, HogquistKA (2007) Thymic emigration revisited. The Journal of experimental medicine 204 : 2513–2520.

24. WolferA, BakkerT, WilsonA, NicolasM, IoannidisV, et al. (2001) Inactivation of Notch 1 in immature thymocytes does not perturb CD4 or CD8T cell development. Nature immunology 2 : 235–241.

25. MadisenL, ZwingmanTA, SunkinSM, OhSW, ZariwalaHA, et al. (2010) A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nature neuroscience 13 : 133–140.

26. HaydayAC (2000) [gamma][delta] cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annual review of immunology 18 : 975–1026.

27. GrigoriadouK, BoucontetL, PereiraP (2003) Most IL-4-producing gamma delta thymocytes of adult mice originate from fetal precursors. Journal of immunology 171 : 2413–2420.

28. Ueda-HayakawaI, MahliosJ, ZhuangY (2009) Id3 restricts the developmental potential of gamma delta lineage during thymopoiesis. Journal of immunology 182 : 5306–5316.

29. VerykokakisM, BoosMD, BendelacA, AdamsEJ, PereiraP, et al. (2010) Inhibitor of DNA binding 3 limits development of murine slam-associated adaptor protein-dependent “innate” gammadelta T cells. PloS one 5: e9303.

30. KeeBL (2009) E and ID proteins branch out. Nature reviews Immunology 9 : 175–184.

31. GodfreyDI, KennedyJ, SudaT, ZlotnikA (1993) A developmental pathway involving four phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets of CD3-CD4-CD8 - triple-negative adult mouse thymocytes defined by CD44 and CD25 expression. Journal of immunology 150 : 4244–4252.

32. LiJ, MaruyamaT, ZhangP, KonkelJE, HoffmanV, et al. (2010) Mutation of inhibitory helix-loop-helix protein Id3 causes gammadelta T-cell lymphoma in mice. Blood 116 : 5615–5621.

33. GuoZ, LiH, HanM, XuT, WuX, et al. (2011) Modeling Sjogren's syndrome with Id3 conditional knockout mice. Immunology letters 135 : 34–42.

34. DonnellyML, HughesLE, LukeG, MendozaH, ten DamE, et al. (2001) The ‘cleavage’ activities of foot-and-mouth disease virus 2A site-directed mutants and naturally occurring ‘2A-like’ sequences. The Journal of general virology 82 : 1027–1041.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Defending Sperm FunctionČlánek How to Choose the Right MateČlánek Conserved Translatome Remodeling in Nematode Species Executing a Shared Developmental TransitionČlánek Genome-Wide and Cell-Specific Epigenetic Analysis Challenges the Role of Polycomb in SpermatogenesisČlánek The Integrator Complex Subunit 6 (Ints6) Confines the Dorsal Organizer in Vertebrate EmbryogenesisČlánek Multiple bHLH Proteins form Heterodimers to Mediate CRY2-Dependent Regulation of Flowering-Time inČlánek Playing the Field: Sox10 Recruits Different Partners to Drive Central and Peripheral MyelinationČlánek A Minimal Nitrogen Fixation Gene Cluster from sp. WLY78 Enables Expression of Active Nitrogenase inČlánek Evolutionary Tuning of Protein Expression Levels of a Positively Autoregulated Two-Component System

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 10

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Defending Sperm Function

- How to Choose the Right Mate

- A Mutation in the Gene in Labrador Retrievers with Hereditary Nasal Parakeratosis (HNPK) Provides Insights into the Epigenetics of Keratinocyte Differentiation

- Conserved Translatome Remodeling in Nematode Species Executing a Shared Developmental Transition

- A Novel Actin mRNA Splice Variant Regulates ACTG1 Expression

- Tracking Proliferative History in Lymphocyte Development with Cre-Mediated Sister Chromatid Recombination

- Correlated Occurrence and Bypass of Frame-Shifting Insertion-Deletions (InDels) to Give Functional Proteins

- Chimeric Protein Complexes in Hybrid Species Generate Novel Phenotypes

- Loss of miR-10a Activates and Collaborates with Activated Wnt Signaling in Inducing Intestinal Neoplasia in Female Mice

- Both Rare and Copy Number Variants Are Prevalent in Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum but Not in Cerebellar Hypoplasia or Polymicrogyria

- Reverse PCA, a Systematic Approach for Identifying Genes Important for the Physical Interaction between Protein Pairs

- Partial Deletion of Chromosome 8 β-defensin Cluster Confers Sperm Dysfunction and Infertility in Male Mice

- Genome-Wide and Cell-Specific Epigenetic Analysis Challenges the Role of Polycomb in Spermatogenesis

- Coordinate Regulation of Mature Dopaminergic Axon Morphology by Macroautophagy and the PTEN Signaling Pathway

- Cooperation between RUNX1-ETO9a and Novel Transcriptional Partner KLF6 in Upregulation of in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- Mobility of the Native Conjugative Plasmid pLS20 Is Regulated by Intercellular Signaling

- FliZ Is a Global Regulatory Protein Affecting the Expression of Flagellar and Virulence Genes in Individual Bacterial Cells

- Specific Tandem Repeats Are Sufficient for Paramutation-Induced Trans-Generational Silencing

- Condensin II Subunit dCAP-D3 Restricts Retrotransposon Mobilization in Somatic Cells

- Dominant Mutations in Identify the Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease Active Site and an Exonuclease 1-Independent Mismatch Repair Pathway

- The Insulator Homie Promotes Expression and Protects the Adjacent Gene from Repression by Polycomb Spreading

- Human Intellectual Disability Genes Form Conserved Functional Modules in

- Coordination of Cell Proliferation and Cell Fate Determination by CES-1 Snail

- ORFs in Drosophila Are Important to Organismal Fitness and Evolved Rapidly from Previously Non-coding Sequences

- Different Roles of Eukaryotic MutS and MutL Complexes in Repair of Small Insertion and Deletion Loops in Yeast

- The Spore Differentiation Pathway in the Enteric Pathogen

- Acceleration of the Glycolytic Flux by Steroid Receptor Coactivator-2 Is Essential for Endometrial Decidualization

- The Human Nuclear Poly(A)-Binding Protein Promotes RNA Hyperadenylation and Decay

- Genome Wide Analysis Reveals Zic3 Interaction with Distal Regulatory Elements of Stage Specific Developmental Genes in Zebrafish

- Xbp1 Directs Global Repression of Budding Yeast Transcription during the Transition to Quiescence and Is Important for the Longevity and Reversibility of the Quiescent State

- The Integrator Complex Subunit 6 (Ints6) Confines the Dorsal Organizer in Vertebrate Embryogenesis

- Incorporating Motif Analysis into Gene Co-expression Networks Reveals Novel Modular Expression Pattern and New Signaling Pathways

- The Bacterial Response Regulator ArcA Uses a Diverse Binding Site Architecture to Regulate Carbon Oxidation Globally

- Direct Monitoring of the Strand Passage Reaction of DNA Topoisomerase II Triggers Checkpoint Activation

- Multiple bHLH Proteins form Heterodimers to Mediate CRY2-Dependent Regulation of Flowering-Time in

- A Reversible Histone H3 Acetylation Cooperates with Mismatch Repair and Replicative Polymerases in Maintaining Genome Stability

- ALS-Associated Mutations Result in Compromised Alternative Splicing and Autoregulation

- Robust Demographic Inference from Genomic and SNP Data

- Preferential Binding to Elk-1 by SLE-Associated Risk Allele Upregulates Expression

- Rad52 Sumoylation Prevents the Toxicity of Unproductive Rad51 Filaments Independently of the Anti-Recombinase Srs2

- The Serum Resistome of a Globally Disseminated Multidrug Resistant Uropathogenic Clone

- Identification of 526 Conserved Metazoan Genetic Innovations Exposes a New Role for Cofactor E-like in Neuronal Microtubule Homeostasis

- SUMO Localizes to the Central Element of Synaptonemal Complex and Is Required for the Full Synapsis of Meiotic Chromosomes in Budding Yeast

- Integrated Enrichment Analysis of Variants and Pathways in Genome-Wide Association Studies Indicates Central Role for IL-2 Signaling Genes in Type 1 Diabetes, and Cytokine Signaling Genes in Crohn's Disease

- Genome-Wide High-Resolution Mapping of UV-Induced Mitotic Recombination Events in

- Genome-Wide Analysis of Cell Type-Specific Gene Transcription during Spore Formation in

- Playing the Field: Sox10 Recruits Different Partners to Drive Central and Peripheral Myelination

- Two Portable Recombination Enhancers Direct Donor Choice in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin

- Mining the Human Phenome Using Allelic Scores That Index Biological Intermediates

- Yeast Tdh3 (Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase) Is a Sir2-Interacting Factor That Regulates Transcriptional Silencing and rDNA Recombination

- A Minimal Nitrogen Fixation Gene Cluster from sp. WLY78 Enables Expression of Active Nitrogenase in

- A Review of Bacteria-Animal Lateral Gene Transfer May Inform Our Understanding of Diseases like Cancer

- High Throughput Sequencing Reveals Alterations in the Recombination Signatures with Diminishing Spo11 Activity

- Partitioning the Heritability of Tourette Syndrome and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Reveals Differences in Genetic Architecture

- Eleven Candidate Susceptibility Genes for Common Familial Colorectal Cancer

- A GDF5 Point Mutation Strikes Twice - Causing BDA1 and SYNS2

- Systematic Unraveling of the Unsolved Pathway of Nicotine Degradation in

- Natural Genetic Variation of Integrin Alpha L () Modulates Ischemic Brain Injury in Stroke

- Evolutionary Tuning of Protein Expression Levels of a Positively Autoregulated Two-Component System

- Evolutionary Change within a Bipotential Switch Shaped the Sperm/Oocyte Decision in Hermaphroditic Nematodes

- Limiting of the Innate Immune Response by SF3A-Dependent Control of MyD88 Alternative mRNA Splicing

- Multiple Signaling Pathways Coordinate to Induce a Threshold Response in a Chordate Embryo

- Distinct Regulatory Mechanisms Act to Establish and Maintain Pax3 Expression in the Developing Neural Tube

- Genome Wide Analysis of Narcolepsy in China Implicates Novel Immune Loci and Reveals Changes in Association Prior to Versus After the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic

- Mismatch Repair Genes and Modify CAG Instability in Huntington's Disease Mice: Genome-Wide and Candidate Approaches

- The Histone H3 K27 Methyltransferase KMT6 Regulates Development and Expression of Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters

- Hsp70-Hsp40 Chaperone Complex Functions in Controlling Polarized Growth by Repressing Hsf1-Driven Heat Stress-Associated Transcription

- Function and Evolution of DNA Methylation in

- Stimulation of mTORC1 with L-leucine Rescues Defects Associated with Roberts Syndrome

- Transcription Termination and Chimeric RNA Formation Controlled by FPA

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Dominant Mutations in Identify the Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease Active Site and an Exonuclease 1-Independent Mismatch Repair Pathway

- Eleven Candidate Susceptibility Genes for Common Familial Colorectal Cancer

- The Histone H3 K27 Methyltransferase KMT6 Regulates Development and Expression of Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters

- A Mutation in the Gene in Labrador Retrievers with Hereditary Nasal Parakeratosis (HNPK) Provides Insights into the Epigenetics of Keratinocyte Differentiation

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání