-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaEvolutionary Change within a Bipotential Switch Shaped the Sperm/Oocyte Decision in Hermaphroditic Nematodes

A subset of transcription factors like Gli2 and Oct1 are bipotential — they can activate or repress the same target, in response to changing signals from upstream genes. Some previous studies implied that the sex-determination protein TRA-1 might also be bipotential; here we confirm this hypothesis by identifying a co-factor, and use it to explore how the structure of a bipotential switch changes during evolution. First, null mutants reveal that C. briggsae TRR-1 is required for spermatogenesis, RNA interference implies that it works as part of the Tip60 Histone Acetyl Transferase complex, and RT-PCR data show that it promotes the expression of Cbr-fog-3, a gene needed for spermatogenesis. Second, epistasis tests reveal that TRR-1 works through TRA-1, both to activate Cbr-fog-3 and to control the sperm/oocyte decision. Since previous studies showed that TRA-1 can repress fog-3 as well, these observations demonstrate that it is bipotential. Third, TRR-1 also regulates the development of the male tail. Since Cbr-tra-2 Cbr-trr-1 double mutants resemble Cbr-tra-1 null mutants, these two regulatory branches control all tra-1 activity. Fourth, striking differences in the relationship between these two branches of the switch have arisen during recent evolution. C. briggsae trr-1 null mutants prevent hermaphrodite spermatogenesis, but not Cbr-fem null mutants, which disrupt the other half of the switch. On the other hand, C. elegans fem null mutants prevent spermatogenesis, but not Cel-trr-1 mutants. However, synthetic interactions confirm that both halves of the switch exist in each species. Thus, the relationship between the two halves of a bipotential switch can shift rapidly during evolution, so that the same phenotype is produce by alternative, complementary mechanisms.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003850

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003850Summary

A subset of transcription factors like Gli2 and Oct1 are bipotential — they can activate or repress the same target, in response to changing signals from upstream genes. Some previous studies implied that the sex-determination protein TRA-1 might also be bipotential; here we confirm this hypothesis by identifying a co-factor, and use it to explore how the structure of a bipotential switch changes during evolution. First, null mutants reveal that C. briggsae TRR-1 is required for spermatogenesis, RNA interference implies that it works as part of the Tip60 Histone Acetyl Transferase complex, and RT-PCR data show that it promotes the expression of Cbr-fog-3, a gene needed for spermatogenesis. Second, epistasis tests reveal that TRR-1 works through TRA-1, both to activate Cbr-fog-3 and to control the sperm/oocyte decision. Since previous studies showed that TRA-1 can repress fog-3 as well, these observations demonstrate that it is bipotential. Third, TRR-1 also regulates the development of the male tail. Since Cbr-tra-2 Cbr-trr-1 double mutants resemble Cbr-tra-1 null mutants, these two regulatory branches control all tra-1 activity. Fourth, striking differences in the relationship between these two branches of the switch have arisen during recent evolution. C. briggsae trr-1 null mutants prevent hermaphrodite spermatogenesis, but not Cbr-fem null mutants, which disrupt the other half of the switch. On the other hand, C. elegans fem null mutants prevent spermatogenesis, but not Cel-trr-1 mutants. However, synthetic interactions confirm that both halves of the switch exist in each species. Thus, the relationship between the two halves of a bipotential switch can shift rapidly during evolution, so that the same phenotype is produce by alternative, complementary mechanisms.

Introduction

Most animals carry the genetic information needed to produce two alternate sexes, and must choose which program to employ. In the nematode C. elegans, for example, a signal transduction pathway controls the activity of the master transcription factor TRA-1 to determine sex [reviewed by 1], [2], [3]. The leading model is that hermaphrodites are produced when TRA-1 prevents the expression of male genes like fog-3 in germ cells [4], egl-1 in the HSN neurons [5], and mab-3 in the intestine and tail [6]. TRA-1 activity is itself controlled by interactions between the TRA-2 receptor and a complex of FEM proteins, which target TRA-1 for degradation [7]. As a result, XX animals have abundant TRA-1, which causes hermaphrodite development, and XO animals lack TRA-1, which allows male development.

In this model, the switch that controls sex-determination is part of a linear pathway. However, the fact that TRA-1 is a Gli protein [8] implies that its regulation might be more complex. Mammalian Gli proteins and their Drosophila homolog Ci are not only cleaved to form repressors or ubiquitinylated and degraded [9], but also function as activators [10]–[12]. As a consequence, these proteins constitute a key class of bipotential transcription factors [13].

Some of these regulatory interactions are also found in nematodes. For example, TRA-1 can also be cleaved to form a repressor [14], or eliminated by ubiquitinylation and degradation [7]. Although it is not known if TRA-1 is a direct activator of any male genes, older tra-1 mutants cannot maintain spermatogenesis [15], [16]. This phenotype and several other traits make the germ line an ideal tissue for elucidating how TRA-1 functions. First, both C. elegans and the related nematode C. briggsae make XX hermaphrodites, which resemble females but produce sperm before beginning oogenesis. Thus, both sexual fates can be studied in a single animal. Second, self-fertilization simplifies genetic screens, a fact that has been used for decades in C. elegans, and is now being exploited in C. briggsae [17]. Third, information about germ cell development in C. elegans provides the background needed for dissecting TRA-1 regulation [reviewed by 2]. Fourth, although some TRA-1 mutations promote spermatogenesis and others promote oogenesis, TRA-1 is not absolutely required for either fate, since null mutants make both sperm and oocytes [15], [16]. Thus, we can isolate mutations that affect all aspects of tra-1 activity by observing how they alter the sperm/oocyte decision.

This system is also a leading model for studying evolution. Hermaphroditic reproduction originated on several independent occasions in the genus Caenorhabditis [18]–[20]. It appears to have required regulatory changes that affect both sex-determination and sperm activation [21]. Hence, comparative analyses of C. briggsae and C. elegans could elucidate not only how TRA-1 functions, but also how the sex-determination pathway changed during recent evolution.

Here, we show that TRR-1, the homolog of mammalian TRRAP (TRansformation/tRanscription domain-Associated Protein), acts as part of the Tip60 Histone Acetyl Transferase (HAT) complex to control germ cell fates in C. briggsae. Genetic and molecular experiments imply that it works with TRA-1 as a co-activator to promote the expression of genes like fog-3. This activity occurs in parallel to the regulation of TRA-1 by the receptor TRA-2 and the FEM proteins, which control the levels of a cleaved TRA-1 repressor. Although these two functions have been conserved throughout Caenorhabditis, their relative importance has changed dramatically during recent evolution. Moreover, this shift shows that a novel trait can evolve by distinct but compensatory changes within the structure of a binary switch, and explains the puzzling differences between the functions of the C. elegans and C. briggsae fem genes [22].

Results

Identification of a new fog gene in C. briggsae

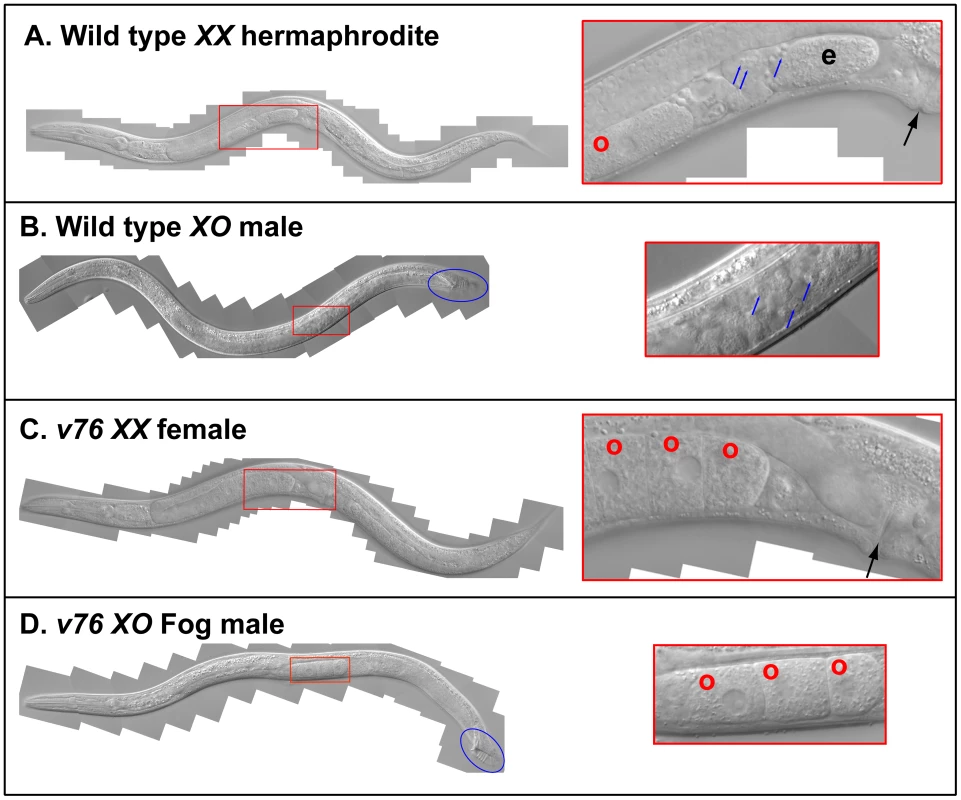

In C. elegans, three fog genes were identified by screening for mutations that cause feminization of the germ line (the Fog phenotype) [23]–[25]. Because only two of these genes have homologs in C. briggsae, the regulation of germ cell fates must have changed during recent evolution [26]. When we screened for C. briggsae Fog mutants, we identified the new gene Cbr-she-1 [17], and also recovered the mutations v76 and v104. These alleles are recessive, fail to complement each other, and affect germ cell fates in both sexes — the XX animals only make oocytes and develop as females, and the XO males make oocytes instead of sperm, but are otherwise normal (Fig. 1). Thus, this gene controls the sperm/oocyte decision. Surprisingly, it maps to the left arm of chromosome II (Methods, Fig. 2A), which contains no homologs of C. elegans fog genes.

Fig. 1. A new C. briggsae Fog gene.

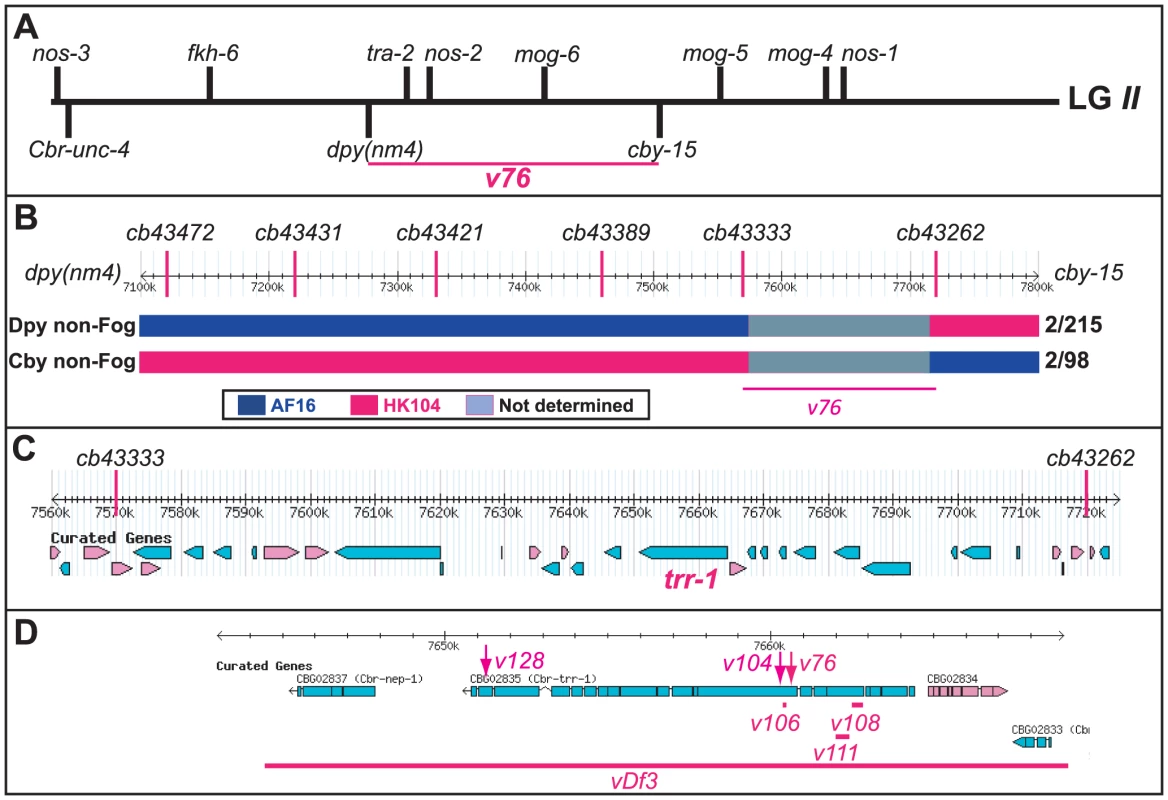

Young adult animals of the following genotypes were photographed using DIC optics. A. Wild-type XX hermaphrodite. B. Wild-type XO male. C. v76 XX female. D. v76 XO Fog male. Expanded images of the boxed regions are shown on the right. Anterior is left and ventral down. The hermaphrodite vulva is indicated with a black arrow, and the male tail with a blue oval. Oocytes are marked with a red “o”, sperm with a blue arrow, and a one-celled embryo in the wild type with and “e”. Fig. 2. Cloning the C. briggsae Fog gene trr-1 by SNP mapping.

(A) Genetic map of LGII, showing the location of trr-1 based on three-factor crosses (Methods). The positions of potential sex-determination genes on the top are from WormBase, and those of the marker genes are from www.briggsae.org. (B) The region extending from 7100 to 7800 kb and the position of each SNP were downloaded from WormBase. The structure of critical recombinant chromosomes is indicated by color, and the frequency of these recombinants is shown at the right. (C) The predicted genes in the region extending from 7560 to 7720 kb were downloaded from WormBase. (D) The predicted structure of trr-1 was downloaded from WormBase, The location of each missense allele is marked by an arrow, and the extent of each deletion by a line. TRR-1 regulates germ cell fates in C. briggsae

We used SNP mapping to clone this gene. Using the linked mutations Cbr-cby-15(sy5148) and Cbr-dpy(nm4), we identified recombinants between the AF16 and HK104 strains, and located each breakpoint using SNPs (Fig. 2B). Next, we studied a 150 kb region of the C. briggsae genome [27] that contained the new gene (Fig. 2C), and used RNA interference to test candidates. Knocking down Cbr-trr-1 activity caused a Fog phenotype. Finally, we sequenced Cbr-trr-1 genomic DNA, and found that both v76 and v104 were missense mutations (Fig. 2D, Table S1). Hence, C. briggsae trr-1 is a fog gene that regulates the decision of germ cells to become sperm or oocytes. It encodes the nematode homolog of the human TRRAP protein, which is a component of several Histone Acetyl Transferase (HAT) complexes [28].

Finally, we used RT-PCR and RACE to clone a complete Cbr-trr-1 transcript, which differs slightly from that predicted at WormBase (Fig. S1). The encoded protein is 4037 amino acids long, and is 67% identical and 82% similar to C. elegans TRR-1.

TRR-1 is essential for spermatogenesis and for embryonic development

Because these alleles of Cbr-trr-1 were missense mutations, it was possible that neither caused a complete loss of function. Thus, we used a non-complementation screen to identify additional alleles (Fig. S2, Table S1). All of the new mutations were also Fog when homozygous, with the exception of the large deletion vDf4, which caused embryonic lethality. The Fog alleles include three small deletions, two of which shift the reading frame, and the deletion vDf3, which removes the entire gene (Fig. 2D). We conclude that eliminating Cbr-trr-1 causes the production of oocytes instead of sperm. Although all Cbr-trr-1 males made oocytes, 34% of v108 males and 44% of vDf3 males produced a few sperm before beginning oogenesis.

TRR-1, like human TRRAP [28], contains a PI-kinase like domain with an inactive catalytic site near its carboxyl terminus. This domain is altered by the new v128 missense mutation, which demonstrates its importance for TRR-1 activity.

Although C. elegans trr-1 regulates vulval development [29], none of the C. briggsae mutants showed vulval defects. Furthermore, Cbr-trr-1(RNAi) Cbr-lin-8(RNAi) animals had normal vulvae, which suggests that C. briggsae trr-1 is not a synthetic multivulva gene.

Finally, we looked for a maternal requirement by crossing homozygous females with heterozygous males. About 33% of the Cbr-trr-1(v76) progeny died as embryos, as well as all of the Cbr-trr-1(v108) progeny and some of the v108 heterozygotes (Table S2A). Since v108 is a deletion, this represents the null phenotype. To test for a strict maternal effect, we crossed homozygous females with wildtype males, and saw that some of their embryos died and some survived (Table S2B). Taken together, these results show that maternal and zygotic TRR-1 work together to promote viability during embryogenesis. In adults, the sperm/oocyte decision is primarily controlled by zygotic TRR-1.

TRR-1 acts through the Tip60 HAT complex to regulate germ cell fates

TRR-1 is the sole nematode TRRAP protein [29]. In eukaryotes, TRRAP proteins are components of both the GNAT and MYST families of HAT complexes [reviewed by 28]. To see if TRR-1 acts through either of these complexes to control germ cell fates, we used RNA interference to knock down other components in C. briggsae (Table 1). Targeting Cbr-pcaf-1, which encodes the catalytic component of the GNAT family, did not affect germ cell fates, and knocking down three other components of this HAT complex also failed to produce Fog animals. However, targeting other components of the Tip60 HAT complex caused phenotypes like that of Cbr-trr-1. Knocking down four genes, including the catalytic component Cbr-mys-1, produced Fog animals at high frequency, and four other genes produced Fog animals at low frequency. For some genes, we saw embryonic lethality and some sterility. Thus, TRR-1 acts through the Tip60 HAT complex to control the sperm/oocyte decision in C. briggsae.

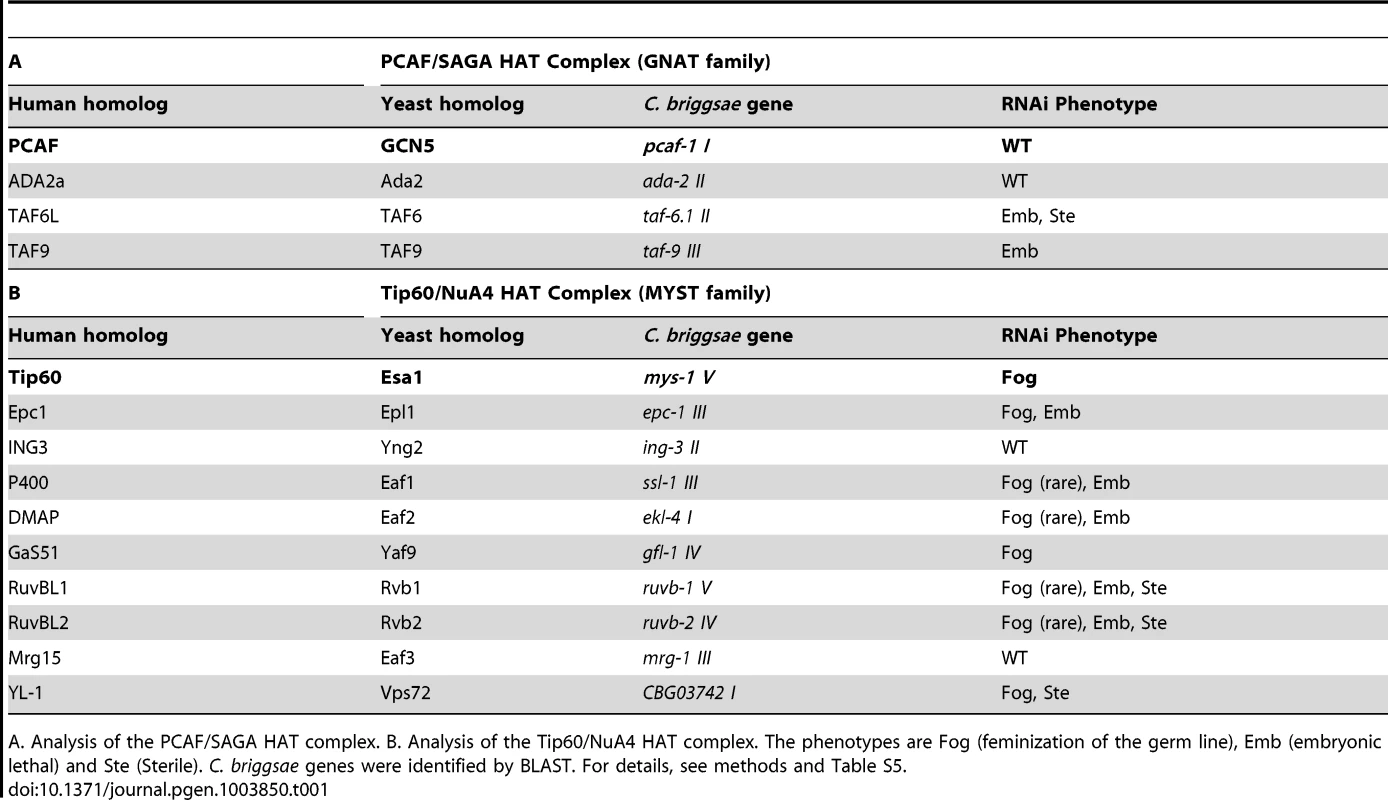

Tab. 1. Components of the Tip60 HAT complex control the sperm/oocyte decision.

A. Analysis of the PCAF/SAGA HAT complex. B. Analysis of the Tip60/NuA4 HAT complex. The phenotypes are Fog (feminization of the germ line), Emb (embryonic lethal) and Ste (Sterile). C. briggsae genes were identified by BLAST. For details, see methods and Table S5. The Tip60 complex acts through TRA-1 to promote spermatogenesis

To determine where the Tip60 complex acts in the sex-determination pathway, we examined double mutants. First, we studied the upstream genes tra-2 and tra-3, which promote female development. Mutations in either gene cause XX animals to produce only sperm, and transform the body towards male fates [30]. Moreover, Cbr-tra-2(nm1) is a nonsense mutation that should act as a null allele, so it is ideal for epistasis. In each case, double mutants with Cbr-trr-1 restored the ability of XX animals to produce oocytes (Table S3), which indicates that Cbr-trr-1 acts downstream of these genes, or in parallel to them.

Next we studied mutations in the Cbr-fem genes, which are required for male somatic development. Although these genes act downstream of tra-2, null mutants produce sperm and oocytes, and develop as normal hermaphrodites [22]. As expected, double mutants with Cbr-trr-1 caused XX animals to produce only oocytes (Table S3). In addition, we saw a synthetic lethal interaction between Cbr-trr-1 and Cbr-fem-2. FEM-2 is a protein phosphatase [31], [32], which also causes synthetic lethality in C. elegans, in combination with Cel-mel-11 mutations [33].

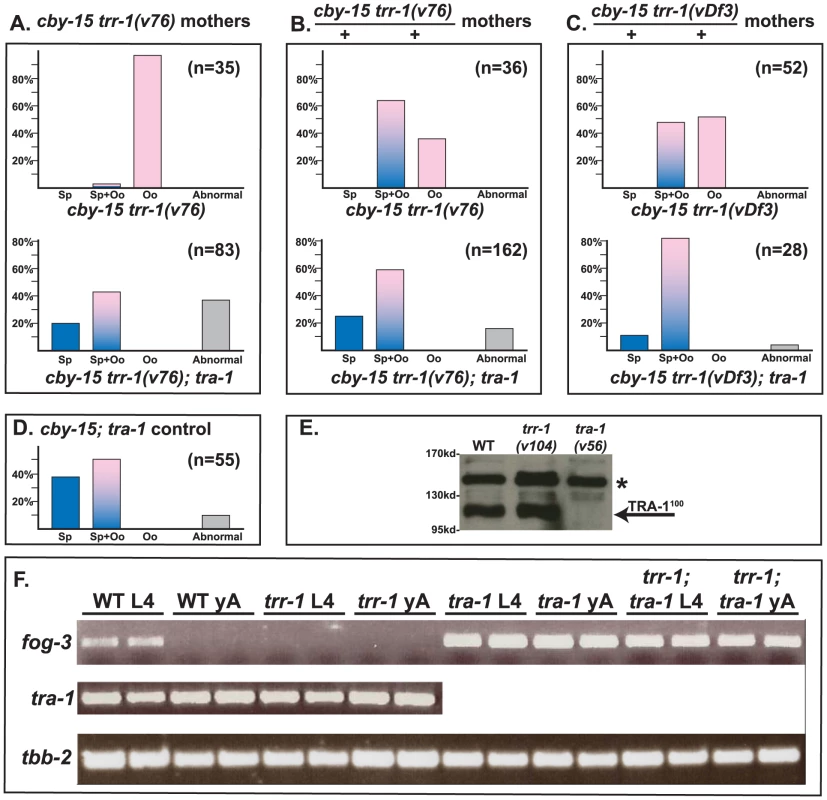

Finally, we studied the interaction of Cbr-trr-1 with Cbr-tra-1, the master regulator of sexual development in nematodes (Fig. 3A–D). We used the Cbr-trr-1 deletion vDf3 and the point mutation v76, which has a strong germline phenotype but causes only low levels of embryonic lethality, so that we could study homozygous children of homozygous mothers. In all cases, we found that the Cbr-tra-1(nm2) mutation restores the production of sperm to Cbr-trr-1 mutants. This tra-1 allele is a nonsense mutation and behaves like a null allele [30]. Thus, the Tip60 complex promotes spermatogenesis, but only if TRA-1 is functional.

Fig. 3. TRR-1 acts through TRA-1 to promote spermatogenesis and fog-3 expression.

A–D. The null allele tra-1(nm2) is epistatic to mutations in trr-1. Animals in A were produced by trr-1(v76) mothers, except for the cby-15; tra-1 control at the bottom. Those in B and C were produced by self-fertilization from heterozygous mothers. Blue colored bars indicate spermatogenesis, pink bars indicate oogenesis, and mixed colors represent animals that make both sperm and oocytes. Abnormal germ lines are gray. E. Western blot showing that the levels of TRA-1100 are not altered in a trr-1 mutant. The absence of TRA-1100 in a tra-1(v56) mutant served as a negative control. (Full-length TRA-1 at the top is obscured by a non-specific band, marked by a star). F. RT-PCR analyses of hand-picked worms. Each age and genotype was run with independent samples, which are presented side-by-side. TRR-1 works through TRA-1 to promote the expression of fog-3

In C. elegans, TRA-1 acts directly on the fog-3 promoter [4], and these binding sites have been conserved in C. briggsae [34]. Moreover, C. briggsae fog-3 is required for germ cells to become sperm, and the level of fog-3 transcripts is correlated with spermatogenesis [34]. Since TRRAP proteins regulate transcription, we studied Cbr-tra-1 and Cbr-fog-3 transcripts, to see if either was affected by inactivation of Cbr-trr-1. We could detect no change in Cbr-tra-1 transcript levels or protein levels in Cbr-trr-1 mutants (Fig. 3E, F), so the Tip60 complex does not control the expression of TRA-1. However, loss of Cbr-trr-1 activity eliminates fog-3 transcripts, but only if TRA-1 is active (Fig. 3F). Thus, we propose that the Tip60 HAT complex cooperates with TRA-1 to increase fog-3 expression and promote spermatogenesis.

TRR-1 also works through TRA-1 to control development of the male tail

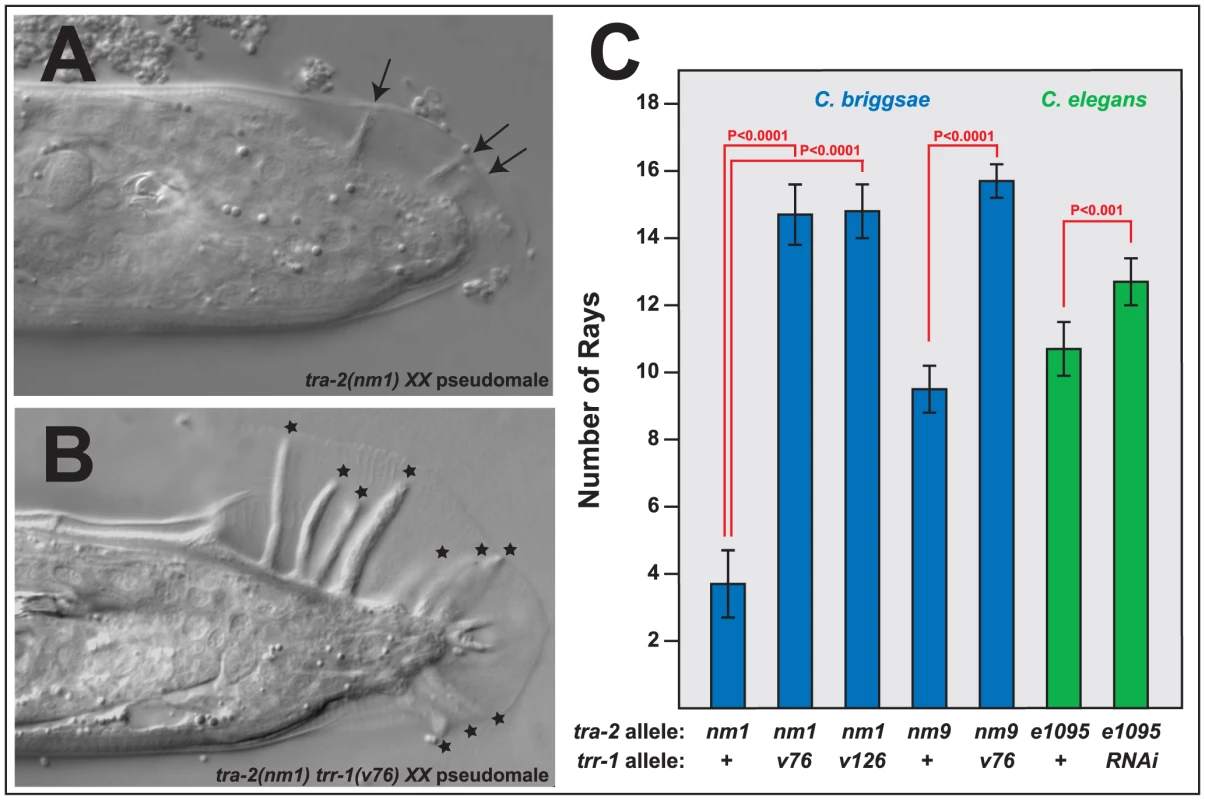

Although the transmembrane receptor TRA-2 acts through TRA-1 to promote female cell fates, two differences between these genes have been conserved among Caenorhabditis species. First, tra-2(null) XX mutants do not make complete male tails, but instead produce stubby tails that lack many of the sensory structures known as rays (Figure 4A); by contrast, tra-1(null) mutants develop perfect male tails [30], [35]. Second, tra-2(null) mutants only produce sperm, whereas tra-1(null) mutants make sperm early in life and then switch to oogenesis [15], [16], [30]. These differences do not reflect the degree of transformation, since tra-2(null) mutants have more strongly masculinized germ lines, but less masculinized tails.

Fig. 4. Mutations in trr-1 and tra-2 act synthetically to produce male tails.

A, B. Photomicrographs of typical XX male tails, prepared using DIC optics. The arrows indicate the small, spindly rays typical of tra-2 mutants, and the stars mark the large rays seen in tra-2 trr-1 double mutants. C. Number of rays detected in single and double mutants. (The wild-type male produces 18 rays). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals, and the indicated probabilities were calculated using the Mann Whitney U test. We were surprised to find that Cbr-tra-2 Cbr-trr-1 double mutants resemble Cbr-tra-1 mutants in both of these traits. The double mutants make oocytes (Table S3), which shows that the Tip60 complex acts downstream of tra-2, or in parallel to it. However, oogenesis usually begins after an initial burst of spermatogenesis, as in Cbr-tra-1 XX animals. Moreover, the double mutants develop much better male tails than those seen in Cbr-tra-2 single mutants, with rays that are almost wildtype in both length (Figure 4B) and number (Figure 4C). Thus, the Tip60 complex is required for precisely the two tra-1 phenotypes that are not dependent on tra-2. As a consequence, Cbr-tra-2 Cbr-trr-1 double mutants appear to have lost all tra-1 activity.

The control of spermatogenesis by TRR-1 has been conserved in nematodes

The trr-1 gene regulates vulval development in C. elegans, and the embryos produced by null mutants die [29]. To see if Cel-trr-1 regulates the sperm/oocyte decision, we used RNA interference to knock it down in males, since the production of oocytes by a male would prove that a change in germ cell fates had occurred. At 20°C, 14% of Cel-trr-1(RNAi) males made oocytes (n = 58). This phenotype was sensitive to temperature, since 23% of males made oocytes at 25°C (n = 62), and an additional 8% failed to produce mature germ cells. Finally, knocking down trr-1 activity in the male/female species C. remanei also caused males to produce oocytes (Fig. S3), so we believe that the male function of the Tip60 complex in germ cell fates has been conserved during Caenorhabditis evolution.

We also tested the ability of C. elegans trr-1 to act synthetically with tra-2, by using RNA interference to knock down Cel-trr-1 activity in Cel-tra-2(e1095) null mutants. As in C. briggsae, lowering trr-1 activity produced better, more masculine tails in tra-2 XX animals (Fig. 4C). In addition, these double mutants also produced sperm and oocytes.

Finally, we tested C. elegans hermaphrodites. Rare Cel-trr-1(RNAi) XX animals developed as females at 25°C (6%, n = 135), although none of them did at 20°C (n = 332). This result suggested that trr-1 influences the sperm/oocyte decision in C. elegans hermaphrodites, but that it plays a smaller role than in C. briggsae. To measure its relative importance in each species, we assayed gene activity in sensitive genetic backgrounds. First, we studied partial loss-of-function mutations in either C. elegans fem-1 or fem-2. At permissive temperatures, these animals usually developed as hermaphrodites; however, if Cel-trr-1 activity was knocked down by RNAi, they became female (Table 2). Thus, trr-1 normally plays a minor role in C. elegans sex-determination because the activity of the fem genes is high.

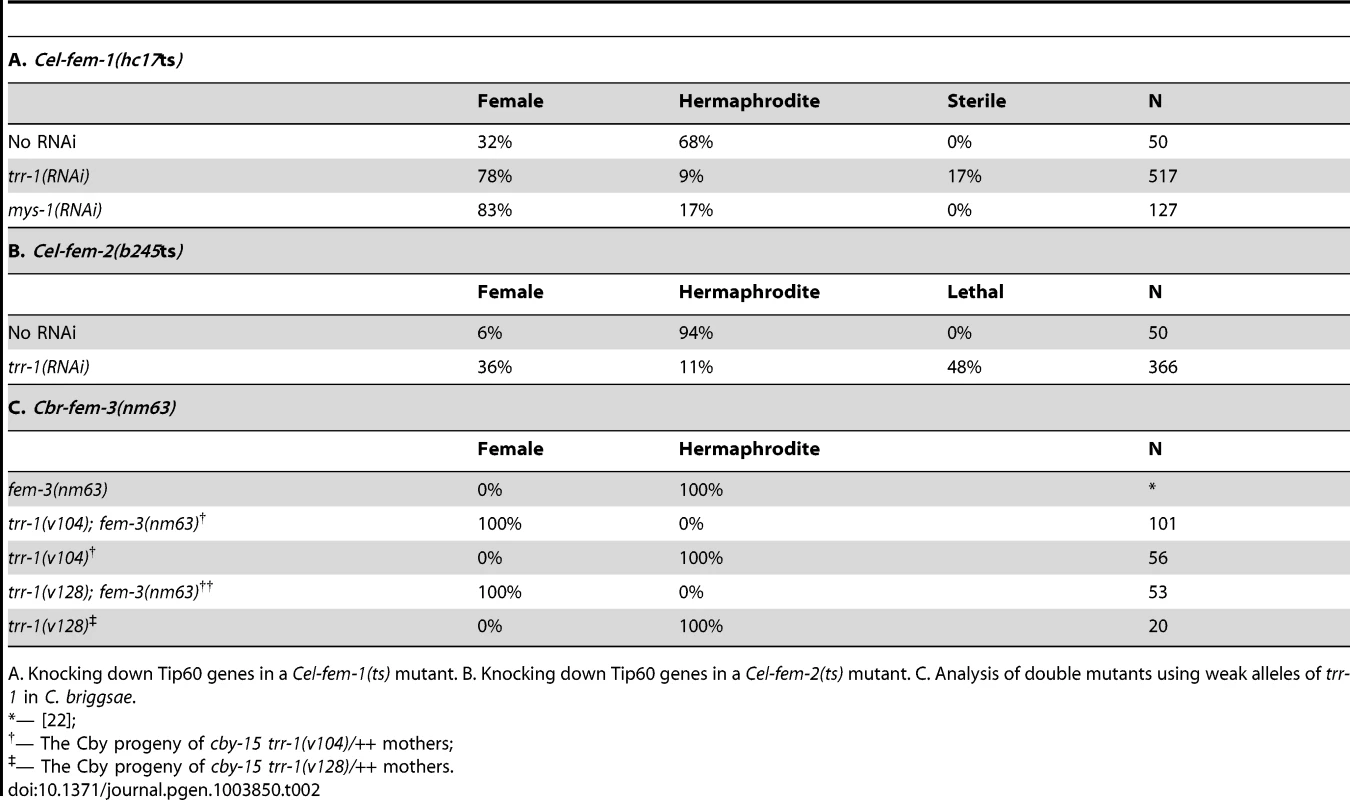

Tab. 2. Tip60 and the FEM complex play complementary roles in germ line regulation.

A. Knocking down Tip60 genes in a Cel-fem-1(ts) mutant. B. Knocking down Tip60 genes in a Cel-fem-2(ts) mutant. C. Analysis of double mutants using weak alleles of trr-1 in C. briggsae. Second, we studied partial loss-of-function mutations in C. briggsae trr-1. These mutants usually develop as hermaphrodites when maternal trr-1 activity is present (Table 2). Furthermore, null alleles of the C. briggsae fem genes are famous for not preventing hermaphrodite development, and Cbr-fem-3(nm63) does not alter the number of sperm produced by hermaphrodites [22]. However, all germ cells in Cbr-trr-1(weak); Cbr-fem-3(nm63) double mutants developed as oocytes rather than sperm (Table 2), and experiments with Cbr-fem-2 gave similar results. Thus, a loss of fem activity has no effect on C. briggsae hermaphrodites because trr-1 activity is normally high. We conclude that the relative importance of each regulator has shifted during the independent evolution of these self-fertile hermaphrodites.

Discussion

Screens in related species can identify conserved regulatory proteins

A major thrust of evolutionary developmental biology has been comparing traits between model organisms like C. elegans or Drosophila melanogaster and closely related species [e.g. 17], [22], [36], [37]. These studies have focused on identifying key differences that provide a window into evolutionary mechanisms.

However, our results emphasize an equally important use of comparative evolutionary studies — conserved aspects of gene regulation are sometimes more easily detected in one species than in another. For example, we found that Fog mutations in the trr-1 gene are common and easy to work with in C. briggsae. By contrast, the role that trr-1 plays in spermatogenesis had not been detected in C. elegans, despite decades of work on sex-determination [reviewed by 3] and the existence of C. elegans trr-1 deletion mutants [29].

What factors might account for this difference? First, mutations in essential genes might be detected more easily in one species than another, because their pleiotropic activities differ. Second, the absence of redundant regulatory pathways might make it easier to identify mutants in one species. Third, the relative importance of the genes might differ in each species. All of these factors may have delayed the identification of the role Tip60 plays in sex determination.

We also note that the combination of forward genetic screens in C. briggsae with cloning by SNP mapping provides a powerful, unbiased approach to studying evolutionary differences. This technique has already been used to clone one other novel C. briggsae gene [17]. In addition, SNP mapping has helped assign new mutations to known genes from several well-characterized pathways [38], [39].

The Tip60 HAT complex works with TRA-1 to regulate cell fates in nematodes

In nematodes, tra-1 plays a critical role in the regulation of sexual development. Null mutations in either C. elegans or C. briggsae cause XX animals to develop as fertile males [30], [35]; a transformation that involves many cell fates. Because TRA-1 also determines the sex of the distantly related nematode Pristionchus pacificus, this role is ancient [40]. Finally, TRA-1 is the sole nematode homolog of the Gli proteins from humans and of Cubitus interruptus from flies [8], and like them, it acts by regulating the transcription of numerous target genes [4]–[6].

The transmembrane receptor TRA-2 acts through TRA-1 to promote female development, but their effects differ in the germ line and male tail [15], [16], [35]. Thus, we were surprised to find that tra-2 trr-1 animals do not look like tra-2 mutants, but instead resemble tra-1 null mutants — they produce excellent male tails and make oocytes after an initial burst of sperm production. Since mutations in trr-1 and tra-2 affect both the germ line and cells of the developing tail, each of these genes must play a general role in the regulation of TRA-1, rather than a tissue-specific function in implementing one particular cell fate.

The Tip60 complex works with TRA-1 to activate target genes

Although Tip60 works through TRA-1, knocking down Tip60 activity causes oogenesis, a phenotype normally associated with increased TRA-1 activity [16]. Since numerous papers have already shown that TRA-1 can repress some male genes [4]–[6], we infer that it is bipotential and can also activate genes needed for spermatogenesis.

To begin, two genetic experiments imply that repression by TRA-1 is mediated by a cleaved form of the protein, known as TRA-1100 [14]. First, the tra-1(e2272stop) mutant encodes a truncated form of the protein slightly shorter than TRA-1100 [41]; when its transcripts are protected from nonsense-mediated decay, they direct female development and oogenesis [42]. Second, a truncated from of TRA-1 created by the duplication eDp24 also directs female development [43]. Since the known targets of TRA-1 are male genes, truncated TRA-1 must work as a repressor. The levels of this repressor are protected by TRA-2, but decreased by three FEM proteins and CUL-2, which form part of a ubiquitin-ligase complex [7].

Previous studies hinted that TRA-1 has a second activity. First, wild-type males produce normal levels of full-length TRA-1, but lack the cleaved form [14]. Since old tra-1 males begin producing oocytes, full-length TRA-1 appears necessary to maintain spermatogenesis [15], [16]. Second, eliminating the TRA-1 binding sites from the promoter of C. elegans fog-3 prevents the transgene from directing spermatogenesis [4]. Taken together, these results imply that full-length TRA-1 might promote the expression of genes that activate spermatogenesis, just as full-length Gli proteins and Cubitus interruptus also work as activators [11], [12]. By identifying a co-factor required for the expression of fog-3, our current studies go farther. TRR-1 activity is needed for the expression of fog-3, but the loss of TRR-1 has no effect when TRA-1 is missing. The simplest explanation is that TRR-1 and the Tip60 HAT complex work with TRA-1 to promote the expression of fog-3, and that without Tip60 this activity is lost (Fig. 5). Because TRA-1 represses fog-3 in other circumstances [4], this bipotential regulation resembles the control of dpp by cleaved and full-length Cubitus interuptus [11]. Furthermore, Ci and Gli3 use CREB-binding protein as a co-activator [44], [45], a protein that also has intrinsic HAT activity.

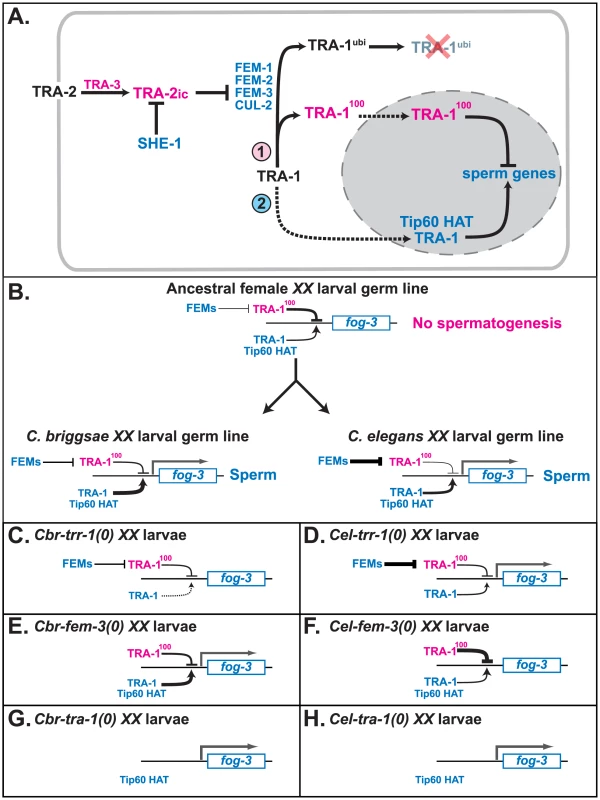

Fig. 5. Model for how TRR-1 regulates sexual development.

A. Proposed regulatory cascade for the specification of sexual fates in germ cells. Proteins promoting oogenesis are magenta, and those promoting spermatogenesis are blue. Arrows denote positive interactions or transformations, and lines with bars indicate negative interactions. Dotted lines mark import into the nucleus. B. Model for the convergent origin of self-fertility. In the ancestral species, the fog-3 gene is inactive in XX larvae because TRA-1 repressing activity outweighs its activating activity. In C. elegans, fog-3 is expressed because increased FEM activity lowers the amount of TRA-1 repressor in the larval germ line. By contrast, in C. briggsae, fog-3 is expressed because of an increase in TRA-1 activating function. C–H. Models for how mutations in C. briggsae and C. elegans affect the expression of fog-3 in larval hermaphrodites. The key factors are that the expression of fog-3 is determined by a competition between TRA-1 activating and repressing activities, that in the complete absence of TRA-1, fog-3 will be transcribed, and that in C. elegans either maternal TRR-1 activity, or an unknown chromatin regulator, allows for spermatogenesis in trr-1 mutants. C. Cbr-trr-1(0). D. Cel-trr-1(0). E. Cbr-fem-3(0). F. Cel-fem-3(0). G. Cbr-tra-1(0). H. Cel-tra-1(0). We suspect that the specificity of the trr-1 phenotype in C. briggsae is due to two factors. First, the requirement for TRR-1 in embryogenesis is fully met by maternal supplies, so the homozygous mutants grow to adulthood. Second, TRA-1 only activates a few genes during development, so the trr-1 sex-determination defect is very specific.

Finally, two types of models could explain how TRR-1 and the Tip60 complex regulate gene expression. On the one hand, they might acetylate histones in target promoters, to open up chromatin conformation and promote transcription [28]. Indeed, several studies indicate that histone acetylation could be a part of the sex-determination process in nematodes. For example, NASP-1, a histone chaperone, and HDA-1, a histone deacetylase, work with TRA-4 to control sexual fates in C. elegans [46]. Moreover, TRA-1 interacts with SynMuv B genes in the development of the C. elegans vulva [47]; and many of these genes regulate chromatin structure [reviewed by 48]. Finally, a polymorphism in C. elegans NATH-10, an acetyltransferase, affects several reproductive traits, including the number of sperm made by hermaphrodites [49]. Although a broad survey of histone modifications in C. elegans did not uncover significant levels of acetylation in histones of the fog-3 promoter during larval development [50], only about 5% of the cells in these animals are becoming spermatocytes, so these experiments might not have been sensitive enough to detect variation in the developing germ line.

On the other hand, HAT complexes sometimes directly acetylate transcription factors, and the TRA-1 homologs Gli1 and Gli2 are acetylated in mammalian cells [51]. Thus, the Tip60 complex might directly acetylate TRA-1, to promote the activation of specific targets. Distinguishing these two models will require new methods for purifying TRA-1 complexes.

The control of TRA-1 by the Tip60 complex has shifted during recent evolution

During evolution, some changes that accumulate in underlying regulatory pathways do not affect the phenotype [52]. In microevolution, this can produce populations with subtle differences in their regulatory architecture. For example, genetic variation that affects sex determination in C. elegans was revealed by different responses to the weak tra-2 allele ar221 [53], and genetic variation that affects vulval development was detected with a variety of weak mutations in the Ras pathway [54]. In macroevolution, this process can lead to species where significant regulatory differences underlie similar phenotypes. For example, the nematode vulva is induced by an EGF signal in C. elegans, but by a Wnt signal in Pristionchus pacificus [55], a distinction that involves many regulatory changes [56]. Because of these effects, mutations in orthologous genes sometimes have slightly different phenotypes in related species. For example, the Axin homolog PRY-1 plays similar roles in the development of the C. elegans and C. briggsae vulva, but the pry-1 mutant phenotypes in these species are not identical [38].

In theory, the internal constraints found in bipotential switches could prevent the accumulation of such changes. Indeed, several aspects of the TRA-1 switch have remained stable during Caenorhabditis evolution. For example, null mutants of tra-1 have similar phenotypes in both C. elegans and C. briggsae [15], [16], [30]. Moreover, the fog-3 gene is a conserved target of TRA-1 that promotes spermatogenesis in each species [4], [34]. Finally, FEM-3 not only regulates TRA-1 activity, but can influence germ cell fates by acting on a separate, downstream target in each species [57], [58]. Under these constraints, what types of regulatory change are possible?

We addressed this issue by studying mutations in genes that control the activating and repressing activities of TRA-1, and found that the relative importance of the Tip60 HAT complex and the TRA-2/FEM degradation pathway has shifted during recent evolution. In C. elegans, null alleles in the fem genes transform XX animals into females [57], but a null allele of trr-1 does not [29]. By contrast, null alleles have the opposite effects in C. briggsae. However, double mutants using weak alleles cause synthetic feminization in both species.

Although variation in sex-determination genes exists in nematode populations [59], there is no evidence it influences sexual development, and we observed no unexpected genetic interactions when mapping trr-1 mutations using different wild isolates. Thus, we believe that these differences between C. elegans and C. briggsae do not involve intra-specific variation, but instead represent unique solutions to the problem of hermaphrodite development.

We propose that the ancestor of these nematodes used Tip60 to regulate TRA-1's activator function, and the FEM genes to control the levels of the TRA-1100 repressor (Fig. 5B). During the independent evolution of self-fertility in C. elegans and C. briggsae, changes within this switch helped promote fog-3 expression and spermatogenesis in the XX animals of each species. We infer that C. elegans primarily relied on increased activity of the FEM proteins to eliminate TRA-1100 repressor in the larval germ line. This change required the novel FOG-2 protein, which increases FEM activity by down-regulating the translation of tra-2 [24], [26]. By contrast, C. briggsae might have relied primarily on increasing the activating activity of TRA-1 and the Tip60 complex.

The evolution of self-fertile hermaphrodites

Finally, the bipotential nature of TRA-1 might have influenced the origin of self-fertility in nematodes. Hermaphrodites evolved from male/female ancestors several times in the genus Caenorhabditis [20], and this transition can be modeled in the laboratory [21]. By contrast, large groups like the insects have not produced hermaphrodites. We suggest that the mutually antagonistic roles of TRA-1 in the sperm/oocyte decision might help explain this difference. In male/female species of worms, full-length and cleaved TRA-1 both have to be present in XX females. If small changes in the regulation of TRA-1 changed the balance between its activating and repressing activities, they might cause XX animals to make sperm, one of the changes needed to produce hermaphrodites. Furthermore, the complex web of regulators that control TRA-1 might have increased the opportunity for mutations that affect this switch, causing XX animals to make both sperm and oocytes. Thus, the structure of this regulatory switch might bias nematodes towards the evolution of self-fertility.

Materials and Methods

Strains

Strains were maintained as described by Brenner [60]. Wild type strains were AF16 and HK104. Mutant alleles were: tra-1(nm2), tra-2(nm1), tra-2(nm9), tra-3(ed24ts) [30], fem-1(nm27), fem-3(nm63) [22], dpy(nm4) [30], and cby-15(sy5148) (P. Sternberg, personal communication).

The tra-1(v56) allele was isolated while screening for she-1 mutations. Homozygous XX mutants have male bodies but make oocytes. The lesion is a 7 bp deletion, removing nucleotides 1244 to 1250 of the tra-1a coding region. Because it causes a frame shift and early stop, it was used in western blots, and no v56 protein was detected.

Mapping

We counted self-progeny from cby-15 trr-1(v76)/+ + mothers, and observed 1044 wild type, 316 Cby Fog, 2 Fog, and 8 Cby hermaphrodites, implying a distance of 0.73 cM. We also counted self - progeny from trr-1(v76) dpy(nm4)/+ +, and observed 2303 WT, 698 Dpy Fog, 11 Fog, and 10 Dpy hermaphrodites, implying a distance of 0.69 cM.

Mutant screens

Two mutants were isolated in screens for F2 females [17]. In the non-complementation screen (Fig. S1), we treated cby-15 tra-2/dpy(nm4) trr-1(v76) animals with 30 µg/ml trimethyl psoralen (TMΨ) followed by UV irradiation [61], or with 0.5% ethylmethane sulfonate [EMS, 60]. The P0 animals were transferred to new plates daily, and their F1 progeny screened for non-Dpy females. Each identified F1 female was crossed with wildtype males, and their F2 hermaphrodite progeny grown on individual plates. Those segregating F3 Cby Fog pseudo-males were identified and crossed with wildtype males. Finally, we screened the progeny of these crosses for recombinant Cby Fog animals that had lost the tra-2 mutation, and backcrossed each at least ten times.

SNP mapping

We mapped v76 with SNPs that differ between the strains AF16 and HK104, as described [17]. Cby non-Fog recombinants were identified among the progeny of trr-1 cby-15 [AF16]/+ + [HK104] mothers, and Dpy non-Fog recombinants from dpy(nm4) trr-1 [AF16]/+ + [HK104] mothers. After establishing homozygous lines, we used the PCR to amplify and score DNA near each SNP from each of the recombinants, using primers in Table S4B [see www.briggsae.org/polymorph.php and 62].

RNA interference

Double strand RNA (dsRNA) was prepared as described [17]. Primers to clone the templates are listed in Table S5. RNA interference was performed by injection of young adults, using solutions of 1 mg/ml dsRNA.

DNA sequencing

PCR products were amplified with primers in Table S4A, purified on QIAquick PCR purification columns (Qiagen), and sequenced. To identify trr-1 lesions, we used genomic DNA templates.

Epistasis analyses

At least 20 animals of each genotype were examined, using Nomarski microscopy.

1. trr-1(vDf3); tra-3(ed24ts)

C. briggsae tra-3(ed24ts) XX mutants are self-fertile hermaphrodites at 15°C and Tra pseudo-males at 25°C [30]. We crossed tra-3(ed24ts)/+ males with trr-1(vDf3) cby-15(sy5148) females, picked individual XX L4 cross progeny to new plates, and shifted them to 25°C. From plates that segregated Tra pseudo-males, we identified F3 Cby progeny; if no recombination had occurred, these should be trr-1(vDf3) mutants, and 25% of them should be tra-3 pseudo-males.

2. tra-2 trr-1

The tra-2 and trr-1 genes map very near each other on LGII. Thus, to make the double mutant, we picked individual dpy(nm4) + trr-1(v76) +/+ tra-2(nm1) + cby-15(sy5148) animals from a balanced strain, and screened their F1 self-progeny for non-Dpy females, which might be + tra-2 trr-1 +/dpy + trr-1 + recombinants. Each F2 female was crossed with AF16 males, and XX L4 cross-progeny were picked to new plates, and screened to identify those that segregated 25% Tra pseudo-males. These Tra pseudo-males should be trr-1 tra-2 homozygotes. We also tested cby-15 trr-1 tra-2(nm1) animals derived from the non-complementation screen.

3. trr-1; tra-1(nm2)

In C. briggsae, tra-1(nm2) XX animals are fertile males, which produce sperm when young and switch to oogenesis as older adults [30]. Thus, we crossed trr-1(vDf3) cby-15 females with tra-1(nm2) XX males, and picked F1 XX larvae to new plates. Then we screened the F2 Cby self-progeny for males; these individuals should be trr-1(vDf3) cby-15; tra-1 mutants. We used the same method to construct trr-1(v76) cby-15; tra-1(nm2) animals. Finally, we also crossed trr-1(v76) cby-15; tra-1(nm2)/+ females with trr-1(v76) cby-15/+ +; tra-1(nm2) males, to produce trr-1(v76) cby-15; tra-1(nm2) mutants that came from homozygous trr-1 mothers.

4. trr-1; fem-2 and trr-1; fem-3

Two methods were used to study the interaction between trr-1 and either fem-2(nm27) or fem-3(nm63), which have no phenotype on their own in XX animals [22]. In these experiments, we separated individual progeny, so that we could confirm that animals were female or hermaphrodite by assaying self-fertility.

First, Cbr-trr-1 dsRNA was injected into either fem-2(nm27) or fem-3(nm63) mothers, and self-progeny were scored using a dissecting microscope. Second, we crossed trr-1 cby-15/+ + males with fem hermaphrodites. Individual F1 males were then crossed with dpy(nm4) hermaphrodites, and we used the PCR to identify dpy(nm4) + +/+ trr-1 cby-15; fem/+ animals among the F2 progeny. From them we obtained dpy(nm4) + +/+ trr-1 cby-15; fem-2 animals, and we scored their Cby children to determine the phenotype of trr-1; fem-2 or of trr-1; fem-3 homozygotes.

RT-PCR

For each genotype, groups of five L4 or young adult worms were collected and processed for RT-PCR as described [17]. Two independent samples were used to confirm reproducibility. PCR reactions were run for 32 cycles, using primers listed in Table S4C, and the conditions were shown to be in the linear range for fog-3 by testing serial dilutions of template.

Western blot

Samples were made from 300 animals that were hand picked and added to 30 µl 2× SDS-PAGE buffer and boiled for 10 minutes. SDS-PAGE was run using the Bio-Rad mini-protein system II. Half of the sample was loaded to each lane, unless indicated otherwise. Gels were transfered to Immun-Blot PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad #162-0177) and blocked with 5% non-fat milk. Anti-TRA-1 antibody was a gift from Dr. David Zarkower, and was diluted to 1∶1000–2000 in 5% non-fat milk. Secondary antibody was HRP Goat anti-rabbit (Bio-Rad #170-5046), and was diluted to 1 : 10000 in 5% milk. Finally, the Immun-Star HRP chemiluminescence kit (Bio-Rad) was used for detection.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Zarkower D (2006) Somatic sex determination. In: Community TCeR, editor. Wormbook.

2. Ellis RE, Schedl T (2006) Sex-determination in the germ line. In: Community TCeR, editor. Wormbook.

3. EllisRE (2008) Chapter 2 Sex Determination in the Caenorhabditis elegans Germ Line. Curr Top Dev Biol 83 : 41–64.

4. ChenPJ, EllisRE (2000) TRA-1A regulates transcription of fog-3, which controls germ cell fate in C. elegans. Development 127 : 3119–3129.

5. ConradtB, HorvitzHR (1999) The TRA-1A sex determination protein of C. elegans regulates sexually dimorphic cell deaths by repressing the egl-1 cell death activator gene. Cell 98 : 317–327.

6. YiW, RossJM, ZarkowerD (2000) mab-3 is a direct tra-1 target gene regulating diverse aspects of C. elegans male sexual development and behavior. Development 127 : 4469–4480.

7. StarostinaNG, LimJM, SchvarzsteinM, WellsL, SpenceAM, et al. (2007) A CUL-2 Ubiquitin Ligase Containing Three FEM Proteins Degrades TRA-1 to Regulate C. elegans Sex Determination. Dev Cell 13 : 127–139.

8. ZarkowerD, HodgkinJ (1992) Molecular analysis of the C. elegans sex-determining gene tra-1: a gene encoding two zinc finger proteins. Cell 70 : 237–249.

9. JiangJ (2006) Regulation of Hh/Gli signaling by dual ubiquitin pathways. Cell Cycle 5 : 2457–2463.

10. AlexandreC, JacintoA, InghamPW (1996) Transcriptional activation of hedgehog target genes in Drosophila is mediated directly by the cubitus interruptus protein, a member of the GLI family of zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev 10 : 2003–2013.

11. MullerB, BaslerK (2000) The repressor and activator forms of Cubitus interruptus control Hedgehog target genes through common generic gli-binding sites. Development 127 : 2999–3007.

12. Ruiz i AltabaA (1999) Gli proteins encode context-dependent positive and negative functions: implications for development and disease. Development 126 : 3205–3216.

13. KoebernickK, PielerT (2002) Gli-type zinc finger proteins as bipotential transducers of Hedgehog signaling. Differentiation 70 : 69–76.

14. SchvarzsteinM, SpenceAM (2006) The C. elegans sex-determining GLI protein TRA-1A is regulated by sex-specific proteolysis. Dev Cell 11 : 733–740.

15. SchedlT, GrahamPL, BartonMK, KimbleJ (1989) Analysis of the role of tra-1 in germline sex determination in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 123 : 755–769.

16. HodgkinJ (1987) A genetic analysis of the sex-determining gene, tra-1, in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev 1 : 731–745.

17. GuoY, LangS, EllisRE (2009) Independent recruitment of F box genes to regulate hermaphrodite development during nematode evolution. Curr Biol 19 : 1853–1860.

18. ChoS, JinSW, CohenA, EllisRE (2004) A phylogeny of Caenorhabditis reveals frequent loss of introns during nematode evolution. Genome Res 14 : 1207–1220.

19. KiontkeK, GavinNP, RaynesY, RoehrigC, PianoF, et al. (2004) Caenorhabditis phylogeny predicts convergence of hermaphroditism and extensive intron loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 9003–9008.

20. KiontkeKC, FelixMA, AilionM, RockmanMV, BraendleC, et al. (2011) A phylogeny and molecular barcodes for Caenorhabditis, with numerous new species from rotting fruits. BMC Evol Biol 11 : 339.

21. BaldiC, ChoS, EllisRE (2009) Mutations in two independent pathways are sufficient to create hermaphroditic nematodes. Science 326 : 1002–1005.

22. HillRC, de CarvalhoCE, SalogiannisJ, SchlagerB, PilgrimD, et al. (2006) Genetic flexibility in the convergent evolution of hermaphroditism in Caenorhabditis nematodes. Dev Cell 10 : 531–538.

23. BartonMK, KimbleJ (1990) fog-1, a regulatory gene required for specification of spermatogenesis in the germ line of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 125 : 29–39.

24. SchedlT, KimbleJ (1988) fog-2, a germ-line-specific sex determination gene required for hermaphrodite spermatogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 119 : 43–61.

25. EllisRE, KimbleJ (1995) The fog-3 gene and regulation of cell fate in the germ line of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 139 : 561–577.

26. NayakS, GoreeJ, SchedlT (2005) fog-2 and the evolution of self-fertile hermaphroditism in Caenorhabditis. PLoS Biol 3: e6.

27. SteinLD, BaoZ, BlasiarD, BlumenthalT, BrentMR, et al. (2003) The genome sequence of Caenorhabditis briggsae: a platform for comparative genomics. PLoS Biol 1: E45.

28. MurrR, VaissiereT, SawanC, ShuklaV, HercegZ (2007) Orchestration of chromatin-based processes: mind the TRRAP. Oncogene 26 : 5358–5372.

29. CeolCJ, HorvitzHR (2004) A new class of C. elegans synMuv genes implicates a Tip60/NuA4-like HAT complex as a negative regulator of Ras signaling. Dev Cell 6 : 563–576.

30. KelleherDF, de CarvalhoCE, DotyAV, LaytonM, ChengAT, et al. (2008) Comparative genetics of sex determination: masculinizing mutations in Caenorhabditis briggsae. Genetics 178 : 1415–1429.

31. PilgrimD, McGregorA, JackleP, JohnsonT, HansenD (1995) The C. elegans sex-determining gene fem-2 encodes a putative protein phosphatase. Mol Biol Cell 6 : 1159–1171.

32. HansenD, PilgrimD (1998) Molecular evolution of a sex determination protein. FEM-2 (pp2c) in Caenorhabditis. Genetics 149 : 1353–1362.

33. PieknyAJ, WissmannA, MainsPE (2000) Embryonic morphogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans integrates the activity of LET-502 Rho-binding kinase, MEL-11 myosin phosphatase, DAF-2 insulin receptor and FEM-2 PP2c phosphatase. Genetics 156 : 1671–1689.

34. ChenPJ, ChoS, JinSW, EllisRE (2001) Specification of germ cell fates by FOG-3 has been conserved during nematode evolution. Genetics 158 : 1513–1525.

35. HodgkinJA, BrennerS (1977) Mutations causing transformation of sexual phenotype in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 86 : 275–287.

36. Prud'hommeB, GompelN, RokasA, KassnerVA, WilliamsTM, et al. (2006) Repeated morphological evolution through cis-regulatory changes in a pleiotropic gene. Nature 440 : 1050–1053.

37. WilliamsTM, SelegueJE, WernerT, GompelN, KoppA, et al. (2008) The regulation and evolution of a genetic switch controlling sexually dimorphic traits in Drosophila. Cell 134 : 610–623.

38. SeetharamanA, CumboP, BojanalaN, GuptaBP (2010) Conserved mechanism of Wnt signaling function in the specification of vulval precursor fates in C. elegans and C. briggsae. Dev Biol 346 : 128–139.

39. BeadellAV, LiuQ, JohnsonDM, HaagES (2011) Independent recruitments of a translational regulator in the evolution of self-fertile nematodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 19672–19677.

40. Pires-daSilvaA, SommerRJ (2004) Conservation of the global sex determination gene tra-1 in distantly related nematodes. Genes Dev 18 : 1198–1208.

41. LumDH, KuwabaraPE, ZarkowerD, SpenceAM (2000) Direct protein-protein interaction between the intracellular domain of TRA-2 and the transcription factor TRA-1A modulates feminizing activity in C. elegans. Genes Dev 14 : 3153–3165.

42. ZarkowerD, De BonoM, AronoffR, HodgkinJ (1994) Regulatory rearrangements and smg-sensitive alleles of the C. elegans sex-determining gene tra-1. Dev Genet 15 : 240–250.

43. HodgkinJ (1993) Molecular cloning and duplication of the nematode sex-determining gene tra-1. Genetics 133 : 543–560.

44. AkimaruH, ChenY, DaiP, HouDX, NonakaM, et al. (1997) Drosophila CBP is a co-activator of cubitus interruptus in hedgehog signalling. Nature 386 : 735–738.

45. ZhouH, KimS, IshiiS, BoyerTG (2006) Mediator modulates Gli3-dependent Sonic hedgehog signaling. Mol Cell Biol 26 : 8667–8682.

46. GroteP, ConradtB (2006) The PLZF-like protein TRA-4 cooperates with the Gli-like transcription factor TRA-1 to promote female development in C. elegans. Dev Cell 11 : 561–573.

47. SzaboE, HargitaiB, RegosA, TihanyiB, BarnaJ, et al. (2009) TRA-1/GLI controls the expression of the Hox gene lin-39 during C. elegans vulval development. Dev Biol 330 : 339–348.

48. CuiM, HanM (2007) Roles of chromatin factors in C. elegans development. WormBook 1–16.

49. DuveauF, FelixMA (2012) Role of pleiotropy in the evolution of a cryptic developmental variation in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol 10: e1001230.

50. LiuT, RechtsteinerA, EgelhoferTA, VielleA, LatorreI, et al. (2011) Broad chromosomal domains of histone modification patterns in C. elegans. Genome Res 21 : 227–236.

51. CanettieriG, Di MarcotullioL, GrecoA, ConiS, AntonucciL, et al. (2010) Histone deacetylase and Cullin3-REN(KCTD11) ubiquitin ligase interplay regulates Hedgehog signalling through Gli acetylation. Nat Cell Biol 12 : 132–142.

52. TrueJR, HaagES (2001) Developmental system drift and flexibility in evolutionary trajectories. Evol Dev 3 : 109–119.

53. ChandlerCH (2010) Cryptic intraspecific variation in sex determination in Caenorhabditis elegans revealed by mutations. Heredity (Edinb) 105 : 473–482.

54. MillozJ, DuveauF, NuezI, FelixMA (2008) Intraspecific evolution of the intercellular signaling network underlying a robust developmental system. Genes Dev 22 : 3064–3075.

55. TianH, SchlagerB, XiaoH, SommerRJ (2008) Wnt signaling induces vulva development in the nematode Pristionchus pacificus. Curr Biol 18 : 142–146.

56. WangX, SommerRJ (2011) Antagonism of LIN-17/Frizzled and LIN-18/Ryk in nematode vulva induction reveals evolutionary alterations in core developmental pathways. PLoS Biol 9: e1001110.

57. HodgkinJ (1986) Sex determination in the nematode C. elegans: analysis of tra-3 suppressors and characterization of fem genes. Genetics 114 : 15–52.

58. HillRC, HaagES (2009) A sensitized genetic background reveals evolution near the terminus of the Caenorhabditis germline sex determination pathway. Evol Dev 11 : 333–342.

59. HaagES, AckermanAD (2005) Intraspecific variation in fem-3 and tra-2, two rapidly coevolving nematode sex-determining genes. Gene 349 : 35–42.

60. BrennerS (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 : 71–94.

61. YandellMD, EdgarLG, WoodWB (1994) Trimethylpsoralen induces small deletion mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91 : 1381–1385.

62. KoboldtDC, StaischJ, ThillainathanB, HainesK, BairdSE, et al. (2010) A toolkit for rapid gene mapping in the nematode Caenorhabditis briggsae. BMC Genomics 11 : 236.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Defending Sperm FunctionČlánek How to Choose the Right MateČlánek Conserved Translatome Remodeling in Nematode Species Executing a Shared Developmental TransitionČlánek Genome-Wide and Cell-Specific Epigenetic Analysis Challenges the Role of Polycomb in SpermatogenesisČlánek The Integrator Complex Subunit 6 (Ints6) Confines the Dorsal Organizer in Vertebrate EmbryogenesisČlánek Multiple bHLH Proteins form Heterodimers to Mediate CRY2-Dependent Regulation of Flowering-Time inČlánek Playing the Field: Sox10 Recruits Different Partners to Drive Central and Peripheral MyelinationČlánek A Minimal Nitrogen Fixation Gene Cluster from sp. WLY78 Enables Expression of Active Nitrogenase inČlánek Evolutionary Tuning of Protein Expression Levels of a Positively Autoregulated Two-Component System

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 10

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Defending Sperm Function

- How to Choose the Right Mate

- A Mutation in the Gene in Labrador Retrievers with Hereditary Nasal Parakeratosis (HNPK) Provides Insights into the Epigenetics of Keratinocyte Differentiation

- Conserved Translatome Remodeling in Nematode Species Executing a Shared Developmental Transition

- A Novel Actin mRNA Splice Variant Regulates ACTG1 Expression

- Tracking Proliferative History in Lymphocyte Development with Cre-Mediated Sister Chromatid Recombination

- Correlated Occurrence and Bypass of Frame-Shifting Insertion-Deletions (InDels) to Give Functional Proteins

- Chimeric Protein Complexes in Hybrid Species Generate Novel Phenotypes

- Loss of miR-10a Activates and Collaborates with Activated Wnt Signaling in Inducing Intestinal Neoplasia in Female Mice

- Both Rare and Copy Number Variants Are Prevalent in Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum but Not in Cerebellar Hypoplasia or Polymicrogyria

- Reverse PCA, a Systematic Approach for Identifying Genes Important for the Physical Interaction between Protein Pairs

- Partial Deletion of Chromosome 8 β-defensin Cluster Confers Sperm Dysfunction and Infertility in Male Mice

- Genome-Wide and Cell-Specific Epigenetic Analysis Challenges the Role of Polycomb in Spermatogenesis

- Coordinate Regulation of Mature Dopaminergic Axon Morphology by Macroautophagy and the PTEN Signaling Pathway

- Cooperation between RUNX1-ETO9a and Novel Transcriptional Partner KLF6 in Upregulation of in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- Mobility of the Native Conjugative Plasmid pLS20 Is Regulated by Intercellular Signaling

- FliZ Is a Global Regulatory Protein Affecting the Expression of Flagellar and Virulence Genes in Individual Bacterial Cells

- Specific Tandem Repeats Are Sufficient for Paramutation-Induced Trans-Generational Silencing

- Condensin II Subunit dCAP-D3 Restricts Retrotransposon Mobilization in Somatic Cells

- Dominant Mutations in Identify the Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease Active Site and an Exonuclease 1-Independent Mismatch Repair Pathway

- The Insulator Homie Promotes Expression and Protects the Adjacent Gene from Repression by Polycomb Spreading

- Human Intellectual Disability Genes Form Conserved Functional Modules in

- Coordination of Cell Proliferation and Cell Fate Determination by CES-1 Snail

- ORFs in Drosophila Are Important to Organismal Fitness and Evolved Rapidly from Previously Non-coding Sequences

- Different Roles of Eukaryotic MutS and MutL Complexes in Repair of Small Insertion and Deletion Loops in Yeast

- The Spore Differentiation Pathway in the Enteric Pathogen

- Acceleration of the Glycolytic Flux by Steroid Receptor Coactivator-2 Is Essential for Endometrial Decidualization

- The Human Nuclear Poly(A)-Binding Protein Promotes RNA Hyperadenylation and Decay

- Genome Wide Analysis Reveals Zic3 Interaction with Distal Regulatory Elements of Stage Specific Developmental Genes in Zebrafish

- Xbp1 Directs Global Repression of Budding Yeast Transcription during the Transition to Quiescence and Is Important for the Longevity and Reversibility of the Quiescent State

- The Integrator Complex Subunit 6 (Ints6) Confines the Dorsal Organizer in Vertebrate Embryogenesis

- Incorporating Motif Analysis into Gene Co-expression Networks Reveals Novel Modular Expression Pattern and New Signaling Pathways

- The Bacterial Response Regulator ArcA Uses a Diverse Binding Site Architecture to Regulate Carbon Oxidation Globally

- Direct Monitoring of the Strand Passage Reaction of DNA Topoisomerase II Triggers Checkpoint Activation

- Multiple bHLH Proteins form Heterodimers to Mediate CRY2-Dependent Regulation of Flowering-Time in

- A Reversible Histone H3 Acetylation Cooperates with Mismatch Repair and Replicative Polymerases in Maintaining Genome Stability

- ALS-Associated Mutations Result in Compromised Alternative Splicing and Autoregulation

- Robust Demographic Inference from Genomic and SNP Data

- Preferential Binding to Elk-1 by SLE-Associated Risk Allele Upregulates Expression

- Rad52 Sumoylation Prevents the Toxicity of Unproductive Rad51 Filaments Independently of the Anti-Recombinase Srs2

- The Serum Resistome of a Globally Disseminated Multidrug Resistant Uropathogenic Clone

- Identification of 526 Conserved Metazoan Genetic Innovations Exposes a New Role for Cofactor E-like in Neuronal Microtubule Homeostasis

- SUMO Localizes to the Central Element of Synaptonemal Complex and Is Required for the Full Synapsis of Meiotic Chromosomes in Budding Yeast

- Integrated Enrichment Analysis of Variants and Pathways in Genome-Wide Association Studies Indicates Central Role for IL-2 Signaling Genes in Type 1 Diabetes, and Cytokine Signaling Genes in Crohn's Disease

- Genome-Wide High-Resolution Mapping of UV-Induced Mitotic Recombination Events in

- Genome-Wide Analysis of Cell Type-Specific Gene Transcription during Spore Formation in

- Playing the Field: Sox10 Recruits Different Partners to Drive Central and Peripheral Myelination

- Two Portable Recombination Enhancers Direct Donor Choice in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin

- Mining the Human Phenome Using Allelic Scores That Index Biological Intermediates

- Yeast Tdh3 (Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase) Is a Sir2-Interacting Factor That Regulates Transcriptional Silencing and rDNA Recombination

- A Minimal Nitrogen Fixation Gene Cluster from sp. WLY78 Enables Expression of Active Nitrogenase in

- A Review of Bacteria-Animal Lateral Gene Transfer May Inform Our Understanding of Diseases like Cancer

- High Throughput Sequencing Reveals Alterations in the Recombination Signatures with Diminishing Spo11 Activity

- Partitioning the Heritability of Tourette Syndrome and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Reveals Differences in Genetic Architecture

- Eleven Candidate Susceptibility Genes for Common Familial Colorectal Cancer

- A GDF5 Point Mutation Strikes Twice - Causing BDA1 and SYNS2

- Systematic Unraveling of the Unsolved Pathway of Nicotine Degradation in

- Natural Genetic Variation of Integrin Alpha L () Modulates Ischemic Brain Injury in Stroke

- Evolutionary Tuning of Protein Expression Levels of a Positively Autoregulated Two-Component System

- Evolutionary Change within a Bipotential Switch Shaped the Sperm/Oocyte Decision in Hermaphroditic Nematodes

- Limiting of the Innate Immune Response by SF3A-Dependent Control of MyD88 Alternative mRNA Splicing

- Multiple Signaling Pathways Coordinate to Induce a Threshold Response in a Chordate Embryo

- Distinct Regulatory Mechanisms Act to Establish and Maintain Pax3 Expression in the Developing Neural Tube

- Genome Wide Analysis of Narcolepsy in China Implicates Novel Immune Loci and Reveals Changes in Association Prior to Versus After the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic

- Mismatch Repair Genes and Modify CAG Instability in Huntington's Disease Mice: Genome-Wide and Candidate Approaches

- The Histone H3 K27 Methyltransferase KMT6 Regulates Development and Expression of Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters

- Hsp70-Hsp40 Chaperone Complex Functions in Controlling Polarized Growth by Repressing Hsf1-Driven Heat Stress-Associated Transcription

- Function and Evolution of DNA Methylation in

- Stimulation of mTORC1 with L-leucine Rescues Defects Associated with Roberts Syndrome

- Transcription Termination and Chimeric RNA Formation Controlled by FPA

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Dominant Mutations in Identify the Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease Active Site and an Exonuclease 1-Independent Mismatch Repair Pathway

- Eleven Candidate Susceptibility Genes for Common Familial Colorectal Cancer

- The Histone H3 K27 Methyltransferase KMT6 Regulates Development and Expression of Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters

- A Mutation in the Gene in Labrador Retrievers with Hereditary Nasal Parakeratosis (HNPK) Provides Insights into the Epigenetics of Keratinocyte Differentiation

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání