-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaPrinciples of Carbon Catabolite Repression in the Rice Blast Fungus: Tps1, Nmr1-3, and a MATE–Family Pump Regulate Glucose Metabolism during Infection

Understanding the genetic pathways that regulate how pathogenic fungi respond to their environment is paramount to developing effective mitigation strategies against disease. Carbon catabolite repression (CCR) is a global regulatory mechanism found in a wide range of microbial organisms that ensures the preferential utilization of glucose over less favourable carbon sources, but little is known about the components of CCR in filamentous fungi. Here we report three new mediators of CCR in the devastating rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae: the sugar sensor Tps1, the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins, and the multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE)–family pump, Mdt1. Using simple plate tests coupled with transcriptional analysis, we show that Tps1, in response to glucose-6-phosphate sensing, triggers CCR via the inactivation of Nmr1-3. In addition, by dissecting the CCR pathway using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated mutagenesis, we also show that Mdt1 is an additional and previously unknown regulator of glucose metabolism. Mdt1 regulates glucose assimilation downstream of Tps1 and is necessary for nutrient utilization, sporulation, and pathogenicity. This is the first functional characterization of a MATE–family protein in filamentous fungi and the first description of a MATE protein in genetic regulation or plant pathogenicity. Perturbing CCR in Δtps1 and MDT1 disruption strains thus results in physiological defects that impact pathogenesis, possibly through the early expression of cell wall–degrading enzymes. Taken together, the importance of discovering three new regulators of carbon metabolism lies in understanding how M. oryzae and other pathogenic fungi respond to nutrient availability and control development during infection.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002673

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002673Summary

Understanding the genetic pathways that regulate how pathogenic fungi respond to their environment is paramount to developing effective mitigation strategies against disease. Carbon catabolite repression (CCR) is a global regulatory mechanism found in a wide range of microbial organisms that ensures the preferential utilization of glucose over less favourable carbon sources, but little is known about the components of CCR in filamentous fungi. Here we report three new mediators of CCR in the devastating rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae: the sugar sensor Tps1, the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins, and the multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE)–family pump, Mdt1. Using simple plate tests coupled with transcriptional analysis, we show that Tps1, in response to glucose-6-phosphate sensing, triggers CCR via the inactivation of Nmr1-3. In addition, by dissecting the CCR pathway using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated mutagenesis, we also show that Mdt1 is an additional and previously unknown regulator of glucose metabolism. Mdt1 regulates glucose assimilation downstream of Tps1 and is necessary for nutrient utilization, sporulation, and pathogenicity. This is the first functional characterization of a MATE–family protein in filamentous fungi and the first description of a MATE protein in genetic regulation or plant pathogenicity. Perturbing CCR in Δtps1 and MDT1 disruption strains thus results in physiological defects that impact pathogenesis, possibly through the early expression of cell wall–degrading enzymes. Taken together, the importance of discovering three new regulators of carbon metabolism lies in understanding how M. oryzae and other pathogenic fungi respond to nutrient availability and control development during infection.

Introduction

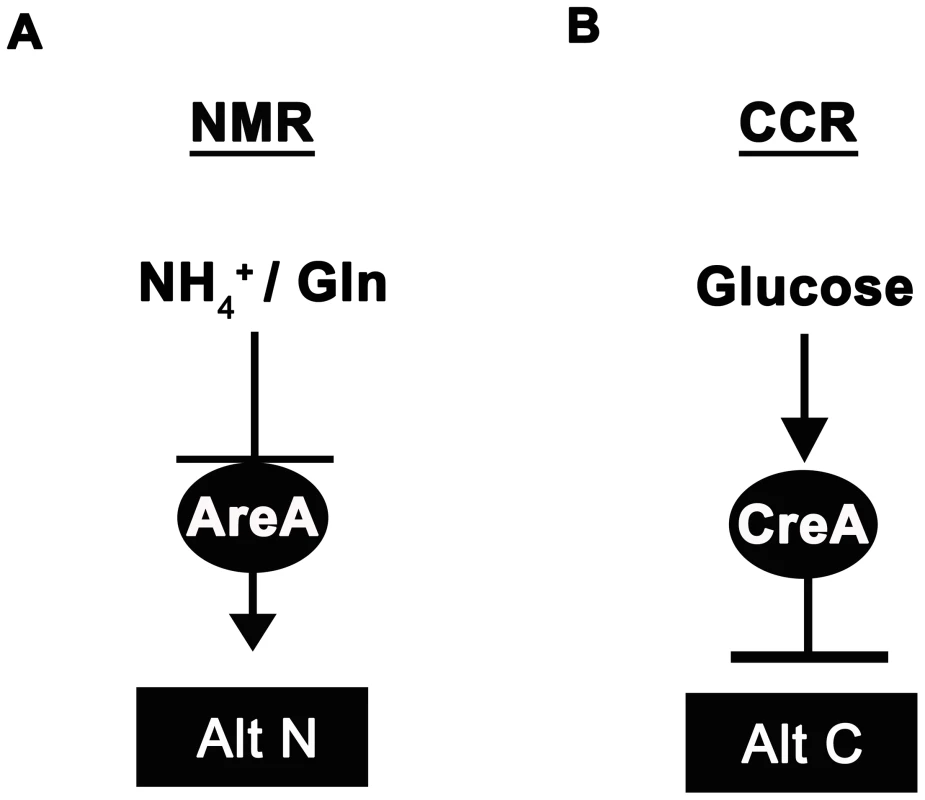

Fungi cause recalcitrant diseases of humans, animals and plants. In order to survive in environments with limited and variable resources, they have developed elegant and efficient genetic regulatory systems to enable them to respond rapidly to fluctuating nutritional conditions, but little is known about the components of these metabolic control pathways in multicellular fungal pathogens. Carbon and nitrogen metabolic regulation has, however, been extensively studied in model filamentous fungi such as the bread mold Neurospora crassa [1] and the soil saprophyte Aspergillus nidulans [2]–[8]. A. nidulans uses pathway specific gene induction to metabolize a wide range of carbon and nitrogen compounds, but this voracity is tempered by two global regulatory systems that ensure the preferential utilization of a few favoured carbon and nitrogen sources. The positive-acting GATA family transcription factor AreA functions in global nitrogen metabolite repression (NMR) to allow utilization of the most preferred nitrogen sources ammonium (NH4+) and L-glutamine (Figure 1A; reviewed in [7] and [8]). In the presence of NH4+or L-glutamine, the inhibitor protein NmrA [9] interacts with AreA to prevent nitrogen catabolic gene expression, but in the presence of less-preferred nitrogen sources such as nitrate (NO3−), NmrA dissociates from AreA, allowing it to activate the expression of more than 100 genes involved in alternative nitrogen source usage [7]. Carbon catabolite repression (CCR) on the other hand, operates via the negatively-acting zinc finger repressor CreA [4], [6], [10], [11] to ensure glucose is utilized preferentially by preventing the expression of genes required for the metabolism of less preferred carbon sources (Figure 1B).

Fig. 1. Ammonium and glucose are preferred nitrogen and carbon sources in filamentous fungi.

(A) Nitrogen metabolite repression (NMR) ensures the preferential utilization of ammonium (NH4+) or L-glutamine as nitrogen sources by modulating the activity of a GATA family transcriptional activator (AreA in Aspergillus nidulans) necessary for the expression of genes involved in assimilating and utilizing alternative nitrogen sources (Alt N). (B) In the presence of glucose, carbon catabolite repression (CCR) acts via a negatively-acting transcriptional repressor (CreA in Aspergillus nidulans) to prevent the expression of genes required for utilizing alternative carbon sources (Alt C). Interestingly, both CCR and NMR regulatory systems converge on genes required for metabolizing a few key compounds that can be used as both carbon and nitrogen sources. For example, A. nidulans utilizes proline as both a carbon and nitrogen source [2], [3], [12], [13]. Dual CCR/NMR control of proline utilization ensures proline can be used as a nitrogen source in the presence of a repressing carbon source, and can be used as a carbon source in the presence of a repressing nitrogen source. Moreover, strains carrying areA loss-of-function mutations (areA−) are unable to utilize proline as a source of nitrogen if a repressing carbon source (e.g. glucose) is present, but grow on proline in the presence of non-repressing carbon sources [2], [3]. Thus AreA is only required for the expression of proline structural genes in the presence of an active CreA protein. Loss of growth of areA− strains on glucose+proline media has been used as a selection to generate revertants of areA−, restored for growth on this media, that result from mutations in CreA and the inactivation of CCR [3].

Like other fungal pathogens, the filamentous fungus Magnaporthe oryzae, cause of the devastating rice blast disease [14], [15], also faces challenges of nutrient limitation and variability but in a significantly different environment to that of A. nidulans. Rice blast disease is a grave threat to global food security [16] and results in 10–30% crop loss annually [17], although in some regions destruction of rice can reach 100%. The life cycle of M. oryzae begins when a three-celled conidium lands on the surface of the leaf and germinates [15]. In a nutrient-free and hydrophobic environment (ie. the leaf surface), the germtube swells and forms the dome-shaped infectious cell called the appressorium. Enormous turgor in the appressorium, formed from the accumulation of glycerol, acts on a thin penetration peg emerging from the base of the cell, forcing it through the surface of the leaf. However, this “brute-force” entry mechanism belies the fact that once within the host cell, the fungus spreads undetected from cell to cell in a biotrophic growth phase, extracting nutrients from the host in a manner that does not immediately kill the plant cell [18], [19]. Only after 72 hrs does M. oryzae enter its necrotic phase, forming characteristic lesions on the surface of the leaf from which aerial hyphae release spores to continue the infection process. During the infection cycle, global regulatory systems in M. oryzae must cope temporally with acquiring nutrients by stealth during biotrophy and by absorption during necrotrophy; and must respond spatially to the fluctuations in nutrient quality and quantity encountered throughout the host leaf. Moreover, plate tests show M. oryzae can grow on a wide range of carbon and nitrogen sources likely controlled by NMR and CCR ([20], [21]; Quispe and Wilson, unpublished data).

Although an AreA homologue, Nut1, has been characterized in M. oryzae and is not required for virulence [22], [23], no global regulators of carbon metabolism have been characterized in this fungus. In addition, little is known about CCR in other fungal pathogens, although overexpressing the CREA homologue in the plant pathogen Alternaria citri results in severe symptoms of black rot in citrus fruit [24]; CCR has been shown to be involved in isocitrate lyase and cell wall degrading enzyme production in the tomato pathogen Fusarium oxysporum [25]; and the absence of either hexokinase or glucokinase protein in the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus results in loss of CCR and the induction of isocitrate lyase activity in the presence of glucose [26]. Recently, trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (Tps1) has emerged as a glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) sensor that, inter alia, integrates carbon and nitrogen metabolism to regulate infection by M. oryzae [21], [23]. Tps1 controls infection-related gene expression via a novel NADPH-dependent genetic switch. In response to G6P, Tps1 activates glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, leading to the elevated production of the reduced dinucleotide NADPH from NADP and G6P. As NADPH levels increase at the expense of NADP, three M. oryzae homologues of the NmrA inhibitor protein - Nmr1, Nmr2 and Nmr3 - become inactivated, resulting in the activation of at least three GATA factors (including Nut1) and the expression of genes required for pathogenicity (Figure S1).

We undertook this study to determine whether G6P sensing by Tps1 in filamentous fungi regulates carbon metabolism via CCR, to identify what proteins constitute CCR, and to understand how CCR impacts pathogenicity - processes currently unknown in M. oryzae and little understood in other fungi [10], [11]. Here we show for the first time in filamentous fungi that the G6P sensor for triggering CCR is Tps1. We show in M. oryzae how Tps1 regulation of CCR involves Nmr1-3, and how the modulation of CCR by the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins occurs independently of Nut1 - thus revealing a hitherto unrecognized role for Nmr-like proteins in carbon regulation. Δnut1 strains, like areA− strains, are unable to grow on proline in the presence of glucose. To identify additional components of CCR and to characterize their role in pathogenicity, we used Agrobacterium tumefaciens- mediated mutagenesis to target CCR by selecting for Δnut1 strains restored in their ability to grow on media containing glucose and proline. In this manner we identified a MATE-family efflux pump [27], Mdt1, as an additional regulator of CCR. Characterization of mutants disrupted in the MDT1 gene showed they were misregulated for carbon metabolism even in the presence of glucose. They were also severely attenuated in sporulation and, although they could form appressoria and were not sensitive to reactive oxygen species (ROS), they were unable to cause disease. Therefore, we demonstrate Mdt1 is essential for nutrient adaptability and pathogenicity in M. oryzae. In toto, this work describes three new classes of global carbon metabolic regulators in filamentous fungi; it is the first study to characterize a MATE-family efflux pump in filamentous and plant pathogenic fungi; and is the first study to assign a regulatory function to a MATE protein in any organism.

Results/Discussion

Genes for metabolizing compounds that are both carbon and nitrogen sources are subject to CCR and NMR in M. oryzae

This study began with an interest in understanding how the metabolism of compounds having the potential to be both carbon and nitrogen sources are regulated in M. oryzae. Our initial investigations found that Δnut1 strains generated by Wilson et al. in a previous study [23] could not utilize three such compounds - aminoisobutyric acid, proline and glucosamine – in the presence of glucose compared to the wild type Guy11 strain. The inability of Δnut1 strains to grow on proline as a nitrogen source contradicts an earlier study by Froeliger and Carpenter, where deletion of NUT1 was shown to allow growth on proline [22]. We therefore independently generated new Δnut1 strains (Figure 2A) and verified that they also cannot grow on proline, in addition to aminoisobutyric acid and glucosamine, in the presence of glucose. This suggests the metabolism of proline, glucosamine and aminoisobutyric acid requires an active Nut1 protein for utilization as nitrogen sources when glucose is present (Figure 2A).

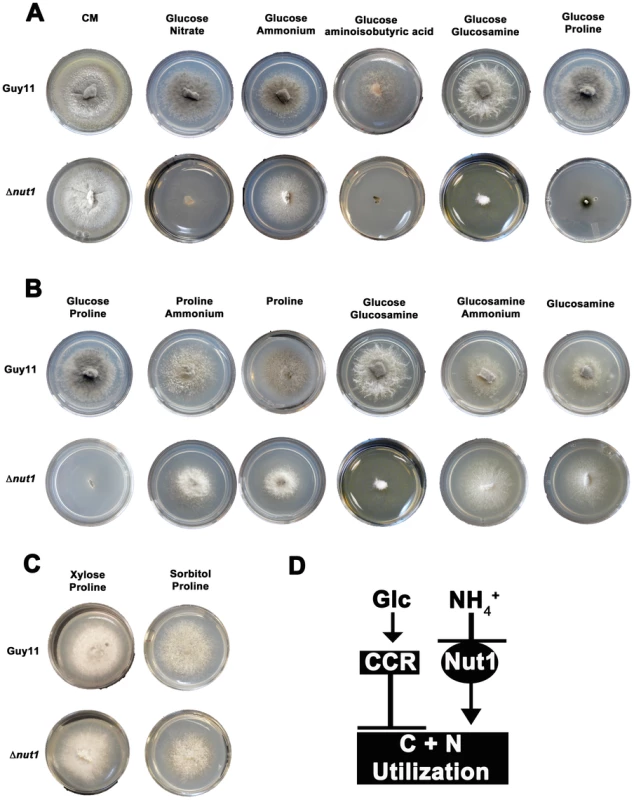

Fig. 2. Compounds that are both carbon and nitrogen sources are subject to CCR and NMR.

(A) Plate tests of nitrogen utilization by Guy11 and Δnut1 strains in the presence of glucose. Strains were grown for 10 days on complete media (CM) or minimal media containing 10 mM glucose supplemented with 10 mM of the appropriate compound. Because Δnut1 strains are defective for nitrogen metabolite repression, they can grow on ammonium (NH4+) as nitrogen source but cannot grow on alternative nitrogen sources that require a functional Nut1 protein, such as nitrate (NO3−). In addition, Δnut1 strains cannot grow on aminoisobutyric acid, glucosamine and proline as sole nitrogen sources in the presence of glucose, demonstrating these compounds require an active Nut1 protein for utilization as nitrogen sources. (B) Both Guy11 and Δnut1 strains can metabolize glucosamine and proline as sole carbon sources in the presence or absence of a repressing nitrogen source, suggesting the utilization of these compounds as carbon sources is subject to CCR. (C) Replacement of glucose with the derepressing (i.e. CCR inactivating) carbon sources xylose or sorbitol fully restores the ability of Δnut1 strains to use proline as a nitrogen source, confirming these genes are under dual CCR and NMR. (D) Taken together, the expression of genes required for metabolizing compounds that are both nitrogen and carbon sources (represented by the box labeled C+N utilization) are subject to both CCR and NMR. Glc is glucose. CCR represents a signal transduction pathway of unknown components leading to glucose repression. Nut1 is the Nut1 protein. Other than an inability to use proline as a nitrogen source, in all other aspects, our Δnut1 strains have the same phenotype as that reported by Froeliger and Carpenter [22]. This includes an inability to grow on defined minimal media containing nitrate (NO3−) or nitrite as sole nitrogen sources (Figure S2A); good growth on ammonium (NH4+), glutamate and alanine as sole nitrogen sources (Figure S2A); and small lesion sizes on host leaf [23]. We cannot explain this discrepancy, but in light of the analyses that follow, we conclude deleting NUT1 abolishes proline utilization in the presence of glucose.

We next determined that the wild type strain, Guy11, could not utilize aminoisobutyric acid as a carbon source (Figure S2B). This compound is therefore not both a carbon and nitrogen source for M. oryzae, and was excluded from further analysis. Focusing on glucosamine and proline, we found that although unable to use these compounds as sole nitrogen sources in the presence of glucose, Δnut1 strains, like Guy11, utilized these compounds as carbon sources in the absence of glucose - both in the presence and absence of a repressing nitrogen source (NH4+) (Figure 2B). This suggests these compounds do not require an active Nut1 when metabolized as a carbon source and are therefore under CCR control. In addition, Δnut1 strains were restored for growth on proline as a nitrogen source in the presence of the derepressing carbon sources xylose and sorbitol (Figure 2C), confirming the metabolism of these compounds is subject to both CCR and nitrogen metabolite repression. We conclude that an active Nut1 protein is required for using these dual compounds as nitrogen sources in the presence of glucose (ie. when CCR is active), but is not required in the absence of glucose or in the presence of derepressing carbon sources (ie. when CCR is inactive) (Figure 2D).

G6P sensing by Tps1 is required to activate CCR

The above results suggested that CCR plays an active regulatory role in M. oryzae carbon metabolism. We continued our characterization of carbon metabolism in the rice blast fungus by determining what role, if any, Tps1 might play in carbon regulation. Tps1 is a G6P sensor that integrates carbon and nitrogen metabolism and is essential for pathogenicity. In response to G6P, Tps1 modulates NADPH levels to inactivate the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins and activate transcription factors including Nut1 [23]. Thus, Δtps1 mutants cannot grow on nitrate as nitrogen source because the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins constitutively inactivate Nut1 in this strain [21], [23], [28]. Δtps1 strains are also affected in glycogen metabolism [21], suggesting Tps1 might regulate carbon metabolism. To determine how extensive Tps1-dependent carbon regulation might be, we generated a Δtps1 Δnut1 double mutant and showed that, unlike the Δnut1 single mutant, it can utilize proline and glucosamine as nitrogen sources in the presence of glucose (Figure 3A). This suggests CCR, at least for proline and glucosamine metabolism, is Tps1-dependent.

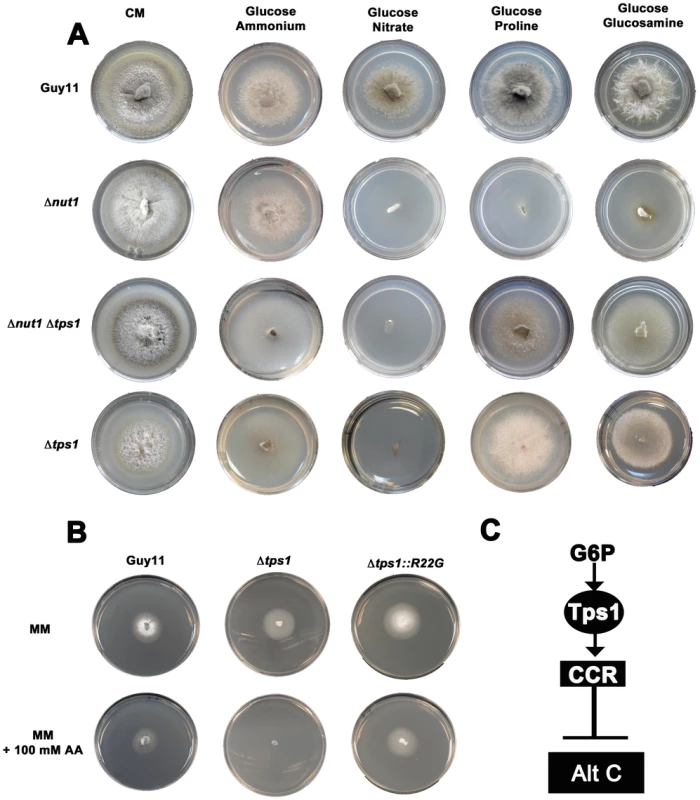

Fig. 3. Tps1 regulates CCR in response to G6P sensing.

(A) CCR is Tps1 dependent. Strains were grown for 10 days on CM or minimal media supplemented with 10 mM of the appropriate carbon and nitrogen source. Like Δnut1, Δtps1 and Δtps1 Δnut1 strains are unable to utilize nitrate as nitrogen source. However, deleting the TPS1 gene in Δnut1 strains restores growth on proline and glucosamine as nitrogen sources, demonstrating that CCR is inactivated in Δtps1- carrying strains. (B) G6P sensing by Tps1 activates CCR. To mitigate against AA evaporation, best results were obtained when Guy11, Δtps1 and Δtps1::R22G strains were grown for 5 days on 85 mm petri dishes containing either glucose-rich minimal media with 55 mM glucose and 10 mM NH4+ as sole carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively, or the same medium supplemented with 100 mM of the toxic analogue allyl alcohol (AA). Δtps1 strains were sensitive to 100 mM allyl alcohol, indicating they are carbon derepressed (i.e. CCR is inactivated) in the presence of glucose. Like Guy11, Δtps1::R22G strains were not sensitive to 100 mM allyl alcohol, suggesting CCR operates correctly in the Δtps1::R22G G6P sensing strains. (C) G6P sensing by Tps1 is the trigger for CCR resulting in the inhibition of alternative carbon source (Alt C) utilization by M. oryzae. In addition to compounds that are both carbon and nitrogen sources, might Tps1-dependent CCR also regulate the metabolism of compounds that are carbon sources only? In the presence of glucose, CCR is known to inhibit the expression of genes encoding alcohol dehydrogenases that convert alcohols into acetyl-coA. Allyl alcohol is used as an assay for carbon derepression because it is converted by alcohol dehydrogenase to the very toxic compound acrylaldehyde. Wild type M. oryzae strains are resistant to allyl alcohol when grown on repressing carbon sources (i.e. glucose) but inactivation of CCR by derepressing carbon sources renders M. oryzae sensitive to allyl alcohol [20]. Mutations that inactivate CCR should also result in carbon derepression and sensitivity to allyl alcohol in the presence of glucose. In our study, Δtps1 mutant strains were grown on a glucose-rich minimal media containing 55 mM glucose (ie. 1% glucose) with 10 mM NH4+ as sole carbon and nitrogen source, respectively, with or without 100 mM allyl alcohol (AA). Figure 3B and Figure S3A show that, compared to Guy11, ally alcohol was extremely toxic to Δtps1 strains at this concentration, suggesting Δtps1 strains were strongly derepressed for alcohol metabolism in the presence of glucose. This indicates Tps1 controls CCR to regulate, in addition to proline and glucosamine, broad aspects of carbon metabolism in response to glucose.

We next asked whether regulation of CCR by Tps1 occurs via G6P sensing. G6P and UDP-glucose are native substrates for Tps1. Previous work showed Tps1 proteins carrying the amino acid substitutions R22G or Y99V in the G6P binding pocket were abolished for trehalose-6-phosphate production but could still sense G6P and were pathogenic, thus demonstrating a sugar signaling role for Tps1 independent of its biosynthetic function [21]. We found that compared to Δtps1 strains, strains carrying the constructs Δtps1::R22G (Figure 3B and Figure S3A) and Δtps1::Y99V (Figure S3A) - encoding the R22G and Y99V substitutions in Tps1, respectively - were insensitive to 100 mM AA in the presence of glucose and, unlike the Δtps1 parental strains, were not inactivated for CCR. Thus, G6P sensing by Tps1 is required for CCR.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, phosphorylation of glucose and fructose by the hexokinase protein Hxk2p results in CCR [29]. In addition, Hxk2p regulates CCR independently of hexose phosphorylation because mutant Hxk2p proteins with reduced catalytic activity still demonstrate some glucose repression, suggesting Hxk2p might induce CCR via a non-metabolic process likely requiring nuclear localization [30]. Magnaporthe oryzae carries genes encoding two putative hexokinases (HXK1 and HXK2) and one glucokinase (GLK1). Δhxk1 [21] and Δglk1 [31] gene deletion strains are fully pathogenic, but the role of these genes in CCR has not been examined. To determine if Magnaporthe hexose kinase proteins have a non-metabolic role in CCR upstream of Tps1 in the G6P signaling pathway, we deleted GLK1, HXK1 and the previously uncharacterized HXK2 gene from the Guy11 genome by homologues gene replacement [23] and tested the resulting deletion strains for loss of CCR. Figure S3B shows that neither hexose kinase deletion strain demonstrated susceptibility to 100 mM allyl alcohol in the presence of 55 mM glucose, suggesting CCR is still operating in these deletion strains. Thus, unlike yeast but similar to A. nidulans [11], loss of the hexokinase or glucokinase proteins in Magnaporthe does not affect CCR. However, multiple hexose kinase deletion mutants would be expected to be inactive for CCR in the presence of glucose by virtue of their inability to form G6P, the trigger for CCR. The generation and analysis of multiple hexose kinase gene deletion strains is a future goal of our research.

Taken together, these results suggest G6P sensing by Tps1 is the key step in the regulation of CCR in Magnaporthe (Figure 3C), and is the first report of how G6P triggers CCR in filamentous fungi.

Transcriptional studies, plate growth tests, and proteomic analysis reveal Tps1 regulates glucose metabolism and suppresses alternative carbon source utilization

To understand how Tps1-dependent CCR might regulate carbon metabolism, we used quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) to analyze the expression of genes required for glucose metabolism and alternative carbon source utilization in Guy11, compared to Δtps1 strains, following growth on minimal media containing glucose and NH4+. Nitrogen-repressing media was chosen to eliminate a role for Nut1 in the expression of these genes (see below), but similar fold changes were also seen when the strains were grown on NO3− minimal media (Figure S4). Strains were grown in complete media (CM) for 48 hr before switching to minimal media containing 55 mM glucose with 10 mM NH4+ or 10 mM NO3− as sole nitrogen sources for 16 hr (following [23]). CM is used as the initial growth condition in Magnaporthe switch experiments because when fresh CM is added at 24 hr, it allows strong mycelial growth of Magnaporthe strains without resulting in the rapid melanization of mycelia observed for growth in minimal media. Similarly, mycelia was switched to minimal media for 16 hr to allow maximum gene induction while avoiding the melanization of mycelia that occurs after this time.

By sequence homology to known glucose transporters in yeast, we studied the expression of genes encoding two putative high affinity glucose transporters (GHT2 and RGT2), and one putative low affinity glucose transporter (HXT1) (Figure 4A; Table S1). We also studied the expression of hexose kinase genes likely involved in the first step of glucose metabolism: HXK1, HXK2 and GLK1 (Figure 4B, Table S1). Figure 4A and Figure 4B show that genes for importing and metabolizing glucose are reduced in expression in Δtps1 strains compared to Guy11 during growth on minimal media containing glucose.

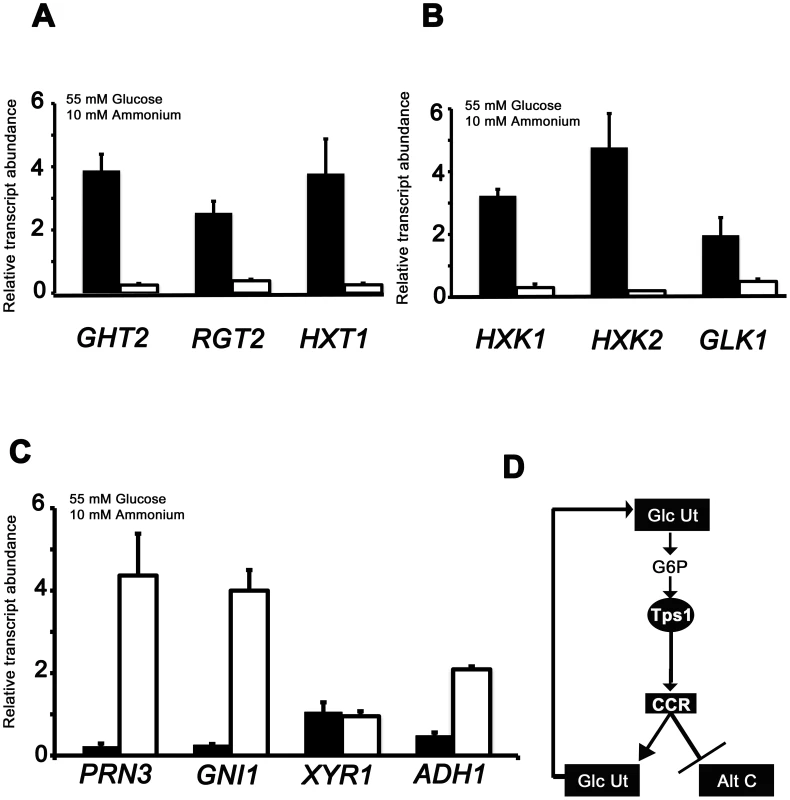

Fig. 4. qPCR analysis of Tps1-dependent gene expression.

The expression of carbon metabolizing genes were analyzed in strains of Guy11 (black bars) and Δtps1 (open bars) that were grown in CM media for 48 hr before switching to 55 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+ minimal media for 16 hr. Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2). Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (A) The expression of three genes encoding putative glucose transporters, GHT2, RGT2 and HXT1, is Tps1-dependent. (B) qPCR analysis of hexose kinase gene expression in Guy11 and Δtps1 strains shows that HXK1, HXK2 and GLK1 expression is Tps1-dependent. (C) Tps1 is required for repressing proline (PRN3) glucosamine (GNI1) and alcohol (ADH1) metabolic gene expression during growth on glucose-containing media. (D) Based on plate tests and transcriptional data, we propose available glucose is taken up into the cell and phosphorylated to G6P by hexose transporters and hexose kinases, collectively termed glucose utilization processes (Glc Ut). In response to G6P sensing, Tps1 activates CCR, leading to the repression of genes required for alternative carbon source utilization (Alt C) and the expression of genes required for glucose utilization (Glc Ut), which would in turn increase the availability of G6P in the cell. The differences in gene expression of glucose transport and metabolism genes in Guy11 or Δtps1 strains were similar regardless of nitrogen source (Figure 4 and Figure S4). One notable exception was GHT2 that appeared to be elevated in Δtps1 strains during growth on NO3− media (Figure S4A) compared to Guy11. Because Δtps1 strains are unable to utilize nitrate, we considered that GHT2 might be expressed in response to nitrogen starvation. To test this, we studied the expression of GHT2 in the mycelia of Guy11 strains grown in NH4+ minimal medium with 55 mM glucose, or in 55 mM glucose minimal media lacking a nitrogen source. Figure S4C shows GHT2 is elevated in Guy11 under nitrogen starvation conditions. Thus, a real lack of a metabolizable nitrogen source (in the case of Guy11 on nitrogen starvation media) or a perceived lack of nitrogen source (in the case of Δtps1 strains on nitrate media) induces GHT2 expresssion, suggesting multiple nutritional signals converge on GHT2. Identifying what these signals might be warrants further analysis in the future.

We also examined the expression of four genes in Guy11 and Δtps1 strains necessary for alternative carbon source utilization following growth on 55 mM glucose and 10 mM NH4+minimal media: PRN3 encoding a putative L-Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase likely required for proline utilization; GNI1 encoding a putative glucosamine-6-phosphate isomerase/deaminase required for glucosamine metabolism; XYR1 encoding a putative xylose reductase involved in xylose metabolism; and ADH1 encoding a putative alcohol dehydrogenase (Figure 4C and 4D; Table S1). In contrast to glucose importing and metabolizing genes, the expression of genes for utilizing some alternative carbon sources (proline, glucosamine and alcohol but not xylose) are significantly elevated in Δtps1 during growth on glucose (Student's t-test p≤0.05).

The expression of PRN3, GNI1 and XYR1 following growth on nitrate media is shown in Figure S4D. The expression of ADH1 following growth on nitrate media is shown in Figure S4E and is strongly up-regulated in Δtps1 strains.

The expression of a proline-metabolizing gene in Δtps1 in the absence of inducer might arise from internal proline carried over from the nutrient rich CM starter culture. To determine if this is the case, we repeated the mycelial switch experiment of Guy11 and Δtps1 but following 48 hr growth in CM, each strain was transferred to a starvation minimal media lacking both a source of glucose and nitrogen for 12 hr before switching into minimal media with 55 mM glucose and 10 mM NO3− for 16 hr. The rationale is that internal sources of proline should be metabolized during growth under starvation conditions and would not be available to induce proline gene expression during growth in minimal media with a carbon and nitrogen source. Nonetheless, even when including a starvation shake condition, expression of PRN3 was still significantly elevated in Δtps1 strains compared to Guy11 (Student's t-test p≤0.01; Figure S4F), suggesting derepression of at least one proline utilizing gene can occur in Δtps1 strains in the absence of an inducer.

Together with Figure 3B, we conclude that Tps1-mediated CCR, via G6P sensing, is required for the glucose-mediated induction of glucose utilization genes and the repression of genes required for metabolizing alternative carbon sources (Figure 4D).

Next, we considered how loss of CCR in Δtps1 strains affects fungal physiology. Figure 3C and the transcriptional results shown in Figure 4 and Figure S4 indicated Δtps1 strains should be impaired in glucose metabolism due to the inactivation of CCR in the presence of glucose and the resulting abherrant affect on glucose metabolizing gene expression. Altered glucose metabolism in Δtps1 strains compared to Guy11 is supported by two lines of evidence in Figure 3A. First, Figure 3A shows that Δtps1 and Δtps1 Δnut1 strains were reduced for growth on minimal media with 10 mM glucose and 10 mM NH4+ compared to the parental strains (Figure 3A). This is in contrast to previous reports that demonstrated strong growth of Δtps1 on ammonium minimal media [21], [23]. However, previous studies used 1% (ie 55 mM) glucose as carbon source, with nitrate or ammonium as nitrogen source, and Figure 5A shows that Δtps1 strains grew better on ammonium minimal media when high (55 mM) glucose concentrations were used compared to lower (10 mM) levels of glucose. Thus, Δtps1 strains grow poorly on low concentrations of glucose compared to Guy11. It should be noted that Δtps1 strains were not improved for growth on nitrate-media under any glucose conditons tested (up to 10% glucose, not shown), consistent with the hypothesis that Tps1 is required for integrating G6P availability, G6PDH activity and NADPH production during growth on nitrate [21].

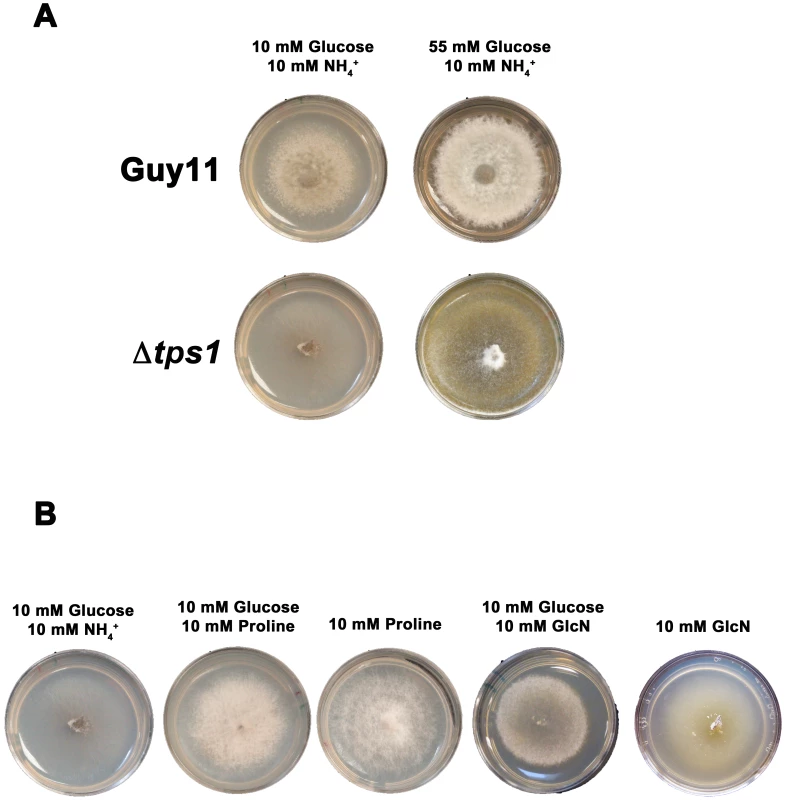

Fig. 5. Glucose metabolism is impaired in Δtps1 strains.

(A) Guy11 and Δtps1 strains were grown for 10 days on minimal media containing 10 mM NH4+ and either 10 mM or 55 mM (1%) glucose. Δtps1 strains grew better on 55 mM glucose. (B) Δtps1 strains were grown for 10 days on minimal media containing the indicated carbon and nitrogen sources. Better growth was obtained when an alternative carbon source to glucose – such as proline or glucosamine (GlcN) - was used. A second piece of evidence for glucose metabolic defects of Δtps1 strains comes from the analysis of growth on proline and glucosamine containing minimal media. Figure 3A shows that growth of Δtps1 strains on 10 mM glucose+10 mM proline and 10 mM glucose+10 mM glucosamine minimal media was much weaker than in Guy11, but stronger than growth of Δtps1 strains on 10 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+. This suggested proline and glucosamine might be used as alternative but poorer sources of carbon for Δtps1 strains even in the presence of glucose. To test this, we looked at the growth of Δtps1 on proline and glucosamine as sole carbon and nitrogen sources. Figure 5B shows that compared to growth on 10 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+ media, Δtps1 strains grew stronger on media containing proline or glucosamine as a sole nitrogen source, a sole carbon source, or as both a carbon and nitrogen source. Taken together, deletion of Tps1 results in poor growth on glucose media compared to Guy11, which is partially remediated by alternative, less-preferred carbon sources such as proline and glucosamine.

We next sought to determine whether Δtps1 strains were impaired in glucose metabolism due to defects in sugar uptake and phosphorylation or because they were unable to assimilate phosphorylated glucose. The sugar transport and hexose kinase expression data presented in Figure 4A and 4B suggested that reduced uptake and phosphorylation of glucose by Δtps1 strains might result in low internal G6P levels and the observed loss of CCR. Indeed, a class of carbon derepressed mutants of A. nidulans were found to result from defective glucose uptake [3]. However, several lines of evidence suggest Δtps1 strains are not reduced for glucose uptake and phosphorylation during growth on glucose-rich (55 mM) minimal media. Firstly, Wilson et al. [21] demonstrated that although G6PDH activity was reduced in Δtps1 strains during growth on nitrate compared to Guy11, hexokinase activity in Δtps1 strains was not affected, suggesting different mechanisms for hexokinase transcriptional and post-translational control that warrant further investigation in the future. Secondly, G6P levels are significantly elevated, not depleted, in the mycelia of Δtps1 strains under both NO3− and NH4+ nitrogen regimes [21] suggesting G6P assimilation –via the pentose phoshate pathway - but not G6P production was impaired. Thirdly, although Δtps1 strains grow with reduced hyphal mass on minimal media with 10 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+ compared to Guy11 (Figure 5A), radial growth was not affected, again suggesting glucose assimilation but not uptake is impaired. Indeed, growth of glucose uptake mutants would be significantly inhibited on low glucose media, but the radial growth of Δtps1 strains on low glucose concentrations (0.2% to 0.05% glucose final concentration) was comparable to that of Guy11 on the same media (Figure 6A). This suggested that Δtps1 strains do not grow significantly different to Guy11 on carbon-limiting (ie glucose-derepressing) media, as would be expected if CCR was constitutively inactivated in Δtps1 strains. Finally, the carbon derepressed mutants of A. nidulans that were found to result from defective glucose uptake [3] were also resistant to both the toxic glucose analogue 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG), which requires uptake and phosphorylation by hexokinase activity for toxicity, and the toxic sugar sorbose [32] during growth under carbon derepressing conditions. When grown on carbon derepressing minimal media comprising 55 mM xylose and 10 mM NH4+ as sole carbon and nitrogen sources, we observed, however, that disruption of Δtps1 did not confer resistance to these toxic analogues (Figure 6B). Taken together, these four lines of evidence indicated uptake and phosphorylation of glucose was not greatly impaired in Δtps1 strains during growth under the conditions tested. This conclusion is consistent with work in A. nidulans that showed CCR inactivation and constitutive carbon derepression in a creAd mutant strain did not impair glucose uptake [3].

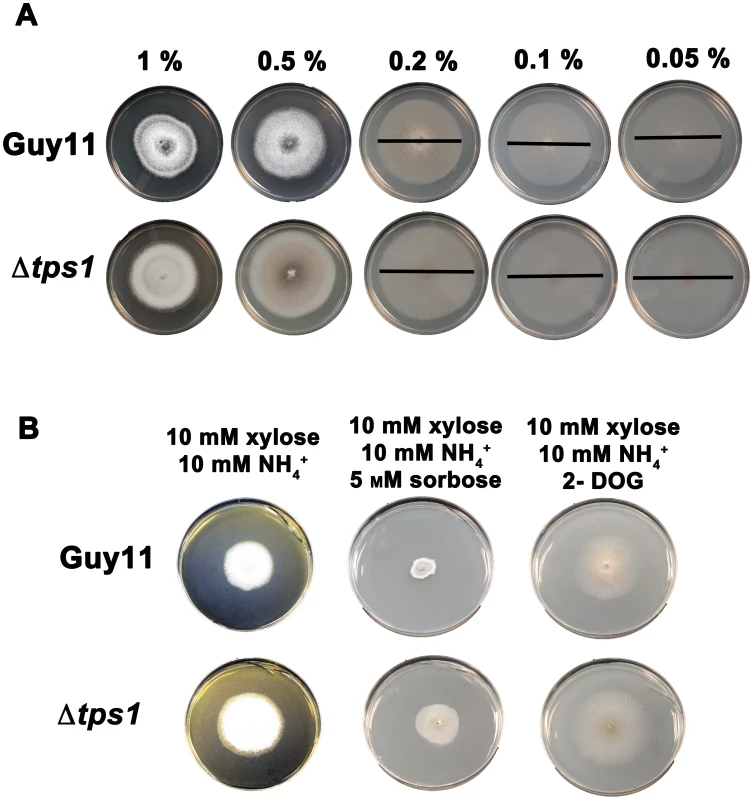

Fig. 6. Glucose uptake and phosphorylation is not impaired in Δtps1 strains.

(A) To determine if Δtps1 strains were defective in glucose uptake, Guy11 and Δtps1 were grown for 10 days on 85 mm petri-dishes containing minimal media with 10 mM NH4+ and glucose at final concentrations in the range of 1%–0.05% (indicated above the plates). Δtps1 radial growth was not reduced compared to Guy11 at low glucose concentrations. The diameters of sparsely growing colonies on low glucose media are indicated with a black bar for ease of viewing. (B) To determine if Δtps1 strains were defective in glucose uptake, Guy11 and Δtps1 were grown for 10 days on 85 mm petri-dishes containing carbon derepressing minimal media consisting of 10 mM xylose+10 mM NH4+ as sole carbon and nitrogen sources and the same media supplemented with 5 mM sorbose or 50 µg/mL 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG). Δtps1 were not more resistant to sorbose or 2-DOG compared to Guy11, suggesting glucose uptake and phosphorylation is not significantly impaired in Δtps1 strains. We next asked whether impaired growth of Δtps1 strains on glucose media was due to defects in G6P assimilation into the Δtps1 metabolome, such as suggested by the observed G6P accumulation in Δtps1 strains. Glucose assimilating defects could result from the misregulation of CCR in these strains, where genes for metabolizing alternative carbon sources are expressed in the presence of glucose. To determine what affect CCR misregulation might have on glucose metabolism in the cell, we undertook a comparative proteomics study of Δtps1 and Guy11 mycelial samples (Table S2) to identify at least some of the metabolic processes altered in Δtps1. It should be noted that in this proteomics study, absence of a protein from a sample indicates its level of abundance did not reach the threshold of detection by the current LC/MS/MS set-up used and does not necessarily imply it was not present at all. In support our transcriptional data, proteomic analysis of Δtps1 and Guy11 mycelial samples grown in glucose-minimal media showed a putative hexose transporter, MGG_08617 (highlighted in Table S2), was more abundant in Guy11 samples compared to Δtps1 samples and is consistent with the role for Tps1 in regulating glucose uptake and metabolism. In addition, malate dehydrogenase (MGG_09872) was detected in Δtps1 samples but not the Guy11 proteome (highlighted in Table S2). MGG_09872 was predicted by PSORTII to be localized to the cytoplasm (60.9% probability it is localized to the cytoplasm and 8% it is localized to the mitochondrion), indicating it could be involved in the conversion of malate into oxaloacetate during gluconeogenesis. On the other hand, the enzyme enolase (MGG_10607, involved in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis) and 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase (MGG_00901) were not detected in Δtps1 samples, but were identified in Guy11 samples, following growth on glucose-containing minimal media (highlighted in Table S2). On the basis of the protein abundance data, some enzymes of gluconeogenesis and glycolysis could be misregulated in Δtps1 strains in the presence of glucose compared to Guy11.

Using the proteomics data as a clue, we sought to determine if Δtps1 strains were impaired for glucose assimilation due to the misregulation of genes associated with gluconeogenesis or glycolysis. We studied the expression of PFK1, encoding phosphofructokinase and considered the most important control element in the glycolytic pathway due to the irreversible phosphorylation of fructose-6-phosphate to give fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; and FBP1 encoding fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase I that performs the reverse reaction to PFK1 in gluconeogenesis by dephosphorylating fructose-1,6-bisphosphate to give fructose-6-phosphate. Figure 7A shows that PFK1 gene expression was elevated in Guy11 strains compared to Δtps1 strains on glucose - minimal media. Conversely, FBP1 was expressed most highly in Δtps1 strains on glucose-minimal media. These results are consistant with a previous study which showed phosphofructokinase activity was decreased, and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate activity was increased, in an Aspergillus strain carrying an extreme creAdmutation, compared to wild type, during growth on glucose [33]. We also looked at the expression of a second important gluconeogenic gene, ICL1, encoding isocitrate lyase. Isocitrate lyase is necessary for the cleavage of isocitrate to succinate and glyoxylate in the glyoxylate cycle and is required for synthesizing glucose via gluconeogenesis from acetyl-CoA. Isocitrate lyase has also been shown to be subject to CCR control in the tomato pathogen Fusarium oxysporum [25]. Figure 7A shows ICL1 gene expression was significantly elevated in Δtps1 strains during growth on glucose compared to Guy11. Therefore, consistent with other CCR mutants, Δtps1 strains are upregulated for the expression of genes for alternative carbon source assimilation and down-regulated, relative to Guy11, for the expression of a central gene of glycolysis, indicating poor growth of Δtps1 strains on glucose could result from impaired glucose assimilation. It should be noted that PFK1 is still expressed in Δtps1 strains, thus allowing some growth on glucose.

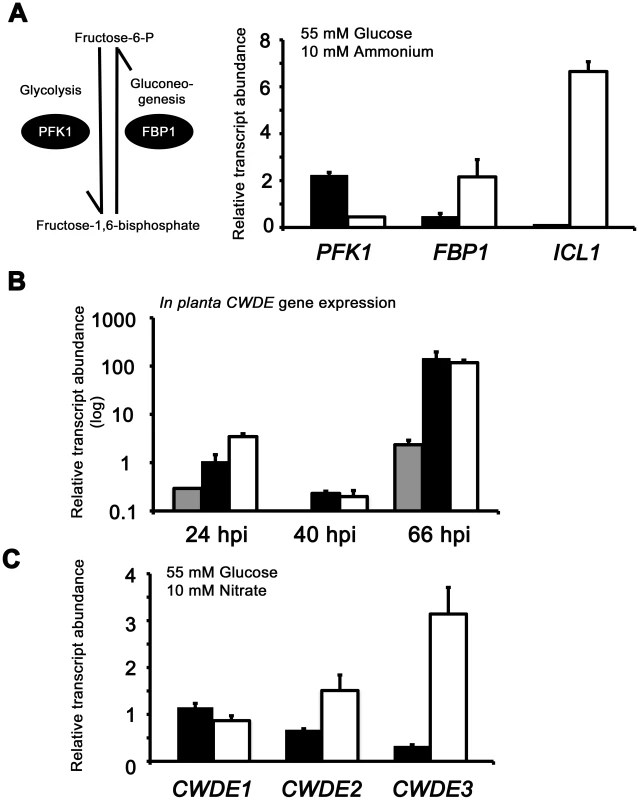

Fig. 7. Inactivating CCR in Δtps1 strains results in the misregulated expression of genes for assimilating glucose and metabolizing alternative carbon sources.

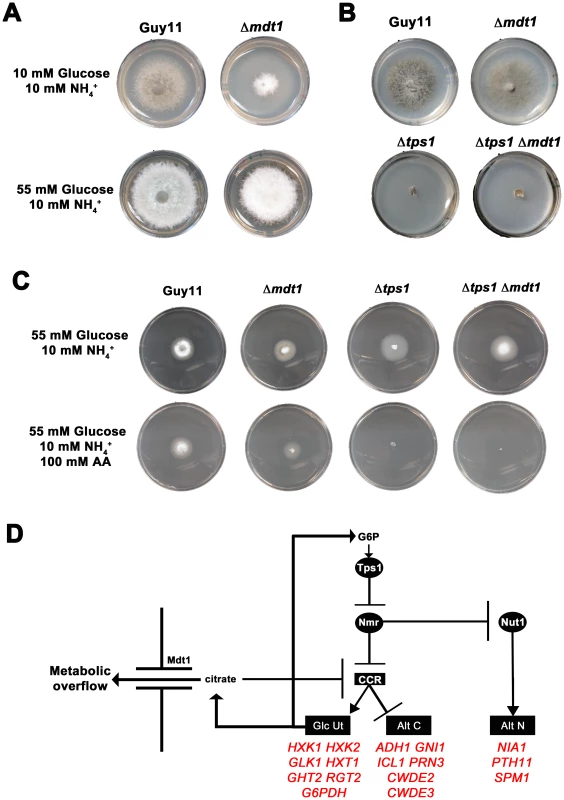

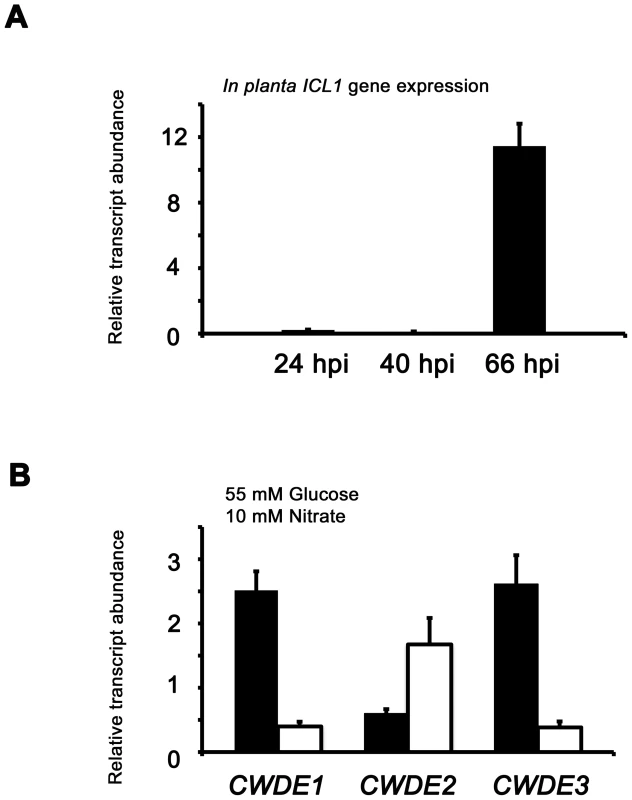

(A) Phosphofructokinase (PFK1) and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP1) are glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes, respectively, which catalyze the interconversion of fructose-6-phosphate and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (left panel). Right panel, PFK1 gene expression is elevated in Guy11 strains (black bars) compared to Δtps1 strains (open bars) when grown on minimal media with glucose as sole carbon source. FBP1 and ICL1 - encoding isocitrate lyase involved in gluconeogenesis - are elevated in expression in Δtps1 strains compared to Guy11 strains when grown on glucose minimal media. Strains were grown in CM media for 48 hr before switching to 55 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+ minimal media for 16 hr (following [23]). Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2). Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (B) Cell wall degrading enzymes (CWDEs) have been shown to be under the control of CCR in M. oryzae. To confirm the expression of genes encoding ß-glucosidase 1 (gray bar), feruloyl esterase B (closed bar) and exoglucanase (open bar) during infection by Guy11, their expression was monitored at 24, 40 and 66 hpi and shown to be highly expressed when necrotic lesions were developing. Due to cross-reactivity between fungal and rice ß-tubulin orthologues, gene expression results were normalized against expression of the M. oryzae actin gene (ACT1). Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (C) To determine if ß-glucosidase 1, feruloyl esterase B and exoglucanase encoding genes (labeled CWDE1, CWDE2 and CWDE3, respectively) are subject to Tps1-dependent CCR, their expression was monitored in Guy11 and Δtps1 strains following growth in CM for 48 hr and a shift into minimal media with 55 mM glucose and 10 mM NO3− for 16 hr. Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2). Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. The proteomic data in Table S2 also revealed additional genes likely controlled by Tps1 via CCR. Genes encoding cell wall degrading enzymes (CWDEs) have previously been shown to be glucose-repressed and elevated in expression under glucose-derepressing conditions in M. oryzae, although the genes involved in regulating CWDE gene expression in response to carbon source was not previously known [34]. We identified proteins corresponding to putative CWDEs that were more abundantly present in Δtps1 samples than Guy11 samples following growth on glucose-containing minimal media (highlighted in Table S2). These included glucan 1,3-beta-glucosidase (MGG_00263, 26-fold more abundant in Δtps1 samples than Guy11 samples); a putative cutinase G-box binding protein; chitinase 18-11; feruloyl esterase B; ß-glucosidase 1 and exoglucanase 1 (MGG_00501, MGG_06594, MGG_05529, MGG_09272, and MGG_10712 respectively, detected in Δtps1 samples but not detected in Guy11 samples); and D-galacturonic acid reductase (MGG_07463, elevated in abundance in Δtps1 samples compared to Guy11). These observations suggested the expression of CWDE-encoding genes were perturbed in Δtps1 strains and is consistent with a role for Tps1 in repressing the expression of genes required for metabolizing alternative carbon sources, such as cell wall polysaccharides, in the presence of glucose. To confirm this, we first analyzed the in planta expression of the genes encoding ß-glucosidase 1, feruloyl esterase B and exoglucanase (termed CWDE1, CWDE2 and CWDE3, respectively) by isolating RNA from infected leaves at 24 hpi (the time of appressorium penetration), 40 hpi (before necrotic lesions had developed) and 66 hpi (when lesions had formed). Figure 7B shows how each gene is highly expressed during the latter stages of infection. Next, we looked at the expression of these genes in Δtps1 and Guy11 strains following growth in glucose-media. Figure 7C shows that at least feruloyl esterase B and exoglucanase - encoding genes are derepressed in Δtps1 strains compared to Guy11, suggesting they are subjected to Tps1-dependent CCR in the presence of glucose and are misregulated in Δtps1 strains.

Taken together, the plate growth, transcriptional and proteomic data describe an essential role for Tps1 in controlling CCR and allowing the fungus to respond correctly to glucose availability.

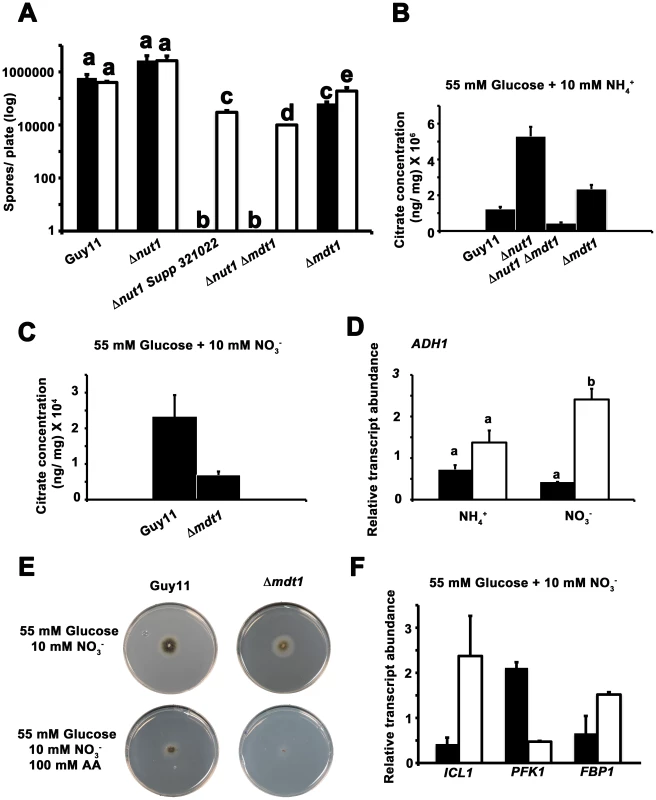

Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins regulate carbon metabolism downstream of Tps1 and independently of Nut1

A previous study showed that in response to G6P sensing, Tps1 alleviates Nmr1-3 protein inhibition via modulation of NADPH levels resulting, inter alia, in nitrogen derepression [23]. Yeast two-hybrid studies demonstrated Nmr1-3 physically interacted with Asd4, an essential regulator of appresorium formation; Nmr2 interacted with the white collar-2 homologue Pas1; and Nmr1 and Nmr3 interacted with Nut1. Interestingly, deletion of all three NMR orthologues was required for full derepression of Nut1 activity under repressing conditions, implying that although not detected in Nut1 binding studies, Nmr2 did have a role in regulating Nut1 activity. In addition, deletion of any one NMR gene in the Δtps1 background partially restored fungal virulence to Δtps1 strains, albeit with reduced lesion sizes compared to Guy11 (shown for Δtps1 Δnmr1 leaf infection in Figure S5). Thus Δtps1 strains have constitutively active Nmr inhibitor proteins, and deleting NMR genes in the Δtps1 background results in activation of Tps1-dependent gene expression and partial suppression of the Δtps1 phenotype [23]. Although Nmr proteins have only previously been described in the literature as mediators of nitrogen metabolism (reviewed in [8]), we sought to establish if Tps1-dependent CCR occurred via Nmr1-3 inhibition in order to shed more light on the role(s) and interaction(s) of Nmr1-3 during infection. We first compared the susceptibility of Δtps1, Δtps1 Δnmr1, Δtps1 Δnmr2 and Δtps1 Δnmr3 strains to 100 mM AA in glucose minimal media under nitrogen repressing conditions. Δnut1 strains were included to determine if the global nitrogen regulator had any influence on AA metabolism. Figure 8A shows that Δtps1 strains were susceptible to 100 mM AA in minimal media containing 55 mM glucose and 10 mM NH4+, whereas the Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains, like Guy11 and Δnut1 strains, were resistant to 100 mM AA and thus restored for CCR. Because Δnut1 and Δtps1 strains do not grow on plates of nitrate-media, we also looked at the expression of ADH1 in these strains after growth on CM followed by a switch to nitrate minimal media. Figure 8B shows ADH1 gene expression was reduced almost 25-fold in Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains compared to the Δtps1 parental strain and confirms CCR is restored to Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains relative to Δtps1. Figure 8A and 8B together show that this modulation of CCR by the Nmr inhibitor proteins occurs irrespective of nitrogen source or an active Nut1 protein.

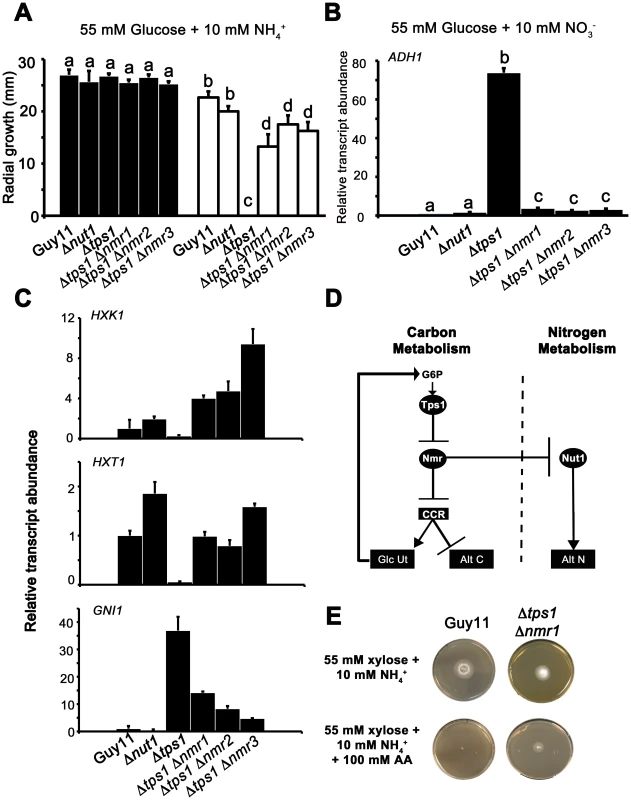

Fig. 8. The Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins regulate CCR independently of Nut1.

(A) Guy11, Δnut1, Δtps1, Δtps1 Δnmr1, Δtps1 Δnmr2, and Δtps1 Δnmr3 strains were grown on minimal media with 55 mM glucose and 10 mM NH4+ as sole carbon and nitrogen sources (closed bars), or the same media supplemented with 100 mM of the toxic analogue allyl alcohol (open bars). Strains were grown for 5 days, and radial diameters were measured. Results are the average of three independent replicates. Error bars are standard deviation. Bars with the same letters are not significantly different (Student's t-test p≤0.01). (B) The expression of ADH1 was analyzed in Guy11, Δnut1, Δtps1, Δtps1 Δnmr1, Δtps1 Δnmr2, and Δtps1 Δnmr3 strains that were grown in CM media for 48 hr before switching to 55 mM glucose+10 mM NO3− minimal media for 16 hr (following [23]). Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2) and given relative to the expression of ADH1 in Guy11. Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (C) The expression of HXK1 (top panel), HXT1 (middle panel) and GNI1 (bottom panel), was analyzed in strains that were grown in CM media for 48 hr before switching to 55 mM glucose+10 mM NO3− minimal media for 16 hr. This media was chosen to determine if genes subjected to CCR are expressed independently of Nut1. Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2) and given relative to the expression of each gene in Guy11. Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (D) Model for control of CCR and nitrogen metabolite repression in response to G6P. CCR is a signal transduction pathway of unknown components that responds to glucose by inhibiting alternative carbon source utilization (Alt C) and promoting glucose uptake and utilization (Glc Ut) via feed-forward transcriptional regulation. In the absence of glucose, the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins inactivate CCR, resulting in carbon derepression, while G6P sensing by Tps1 results in Nmr1-3 inactivation and active CCR. The Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins also negatively regulate Nut1 to control alternative nitrogen source utilization (Alt N), but Nut1 plays no role in CCR, demonstrating for the first time independent roles for the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins in regulating carbon and nitrogen metabolism in response to glucose. (E) Guy11 strains are susceptible to allyl alcohol (AA) toxicity when grown on a derepressing carbon source such as xylose. Consistent with a role for Nmr inhibitor proteins in suppressing CCR, the Δtps1 Δnmr1 double mutant strain is shown to be partially resistant to 100 AA under carbon derepressing growth conditions (minimal media with 55 mM xylose as sole carbon source), suggesting CCR is at least partially active and suppressing alternative carbon utilization pathways (Alt C), in the absence of glucose, in strains lacking at least Nmr1 activity. To further explore a role for the Nmr inhibitor proteins in carbon metabolism and CCR, we next looked at the expression of the Tps1-dependent hexose kinase genes, HXK1 (Figure 8C), HXK2 (Figure S6A) and GLK1 (Figure S6B) in Δtps1, the Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains, and Δnut1 compared to Guy11 following growth on minimal media with nitrate. Nitrate was chosen to determine if expression of these genes requires an active Nut1. Hexose kinase gene expression was shown to be elevated in Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains compared to the Δtps1 single mutant strains (Figure 8C and Figure S6A and S6B). Similarly, expression of the putative hexose transporter gene HXT1 (Figure 8C) was elevated in Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains compared to Δtps1 and in all cases expression was not affected in Δnut1 strains compared to Guy11. In addition, the expression of G6PDH was shown previously to be reduced in Δtps1 strains compared to Guy11 but was restored to wild type levels of expression in the Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains [23], and Figure S6C shows G6PDH gene expression is also independent of Δnut1. Finally, the expression of GNI1, subjected to Tps1-dependent CCR, was partially repressed in Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains compared to Δtps1. Thus, glucose-utilizing genes are expressed, and alternative carbon source utilization is repressed, in Δtps1 Δnmr1-3 double mutant strains compared to Δtps1 strains, in the presence of glucose, while Nut1 is shown to have no role in CCR. Consequently, this is the first description of a role for an NmrA-family protein in regulating both carbon and nitrogen metabolism in a filamentous fungus.

Together, this data suggests the model in Figure 8D, whereby carbon metabolism is regulated by the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins independently of Nut1 and in response to G6P sensing by Tps1. Under glucose-repressing conditions, modulation of NADPH levels by Tps1 would inactivate the Nmr inhibitor proteins and result in CCR. Under carbon derepressing conditions, the Nmr inhibitor proteins would be active and suppress CCR. Consistent with this model, we found that Δtps1 Δnmr1 (but not Δtps1 Δnmr2 or Δtps1 Δnmr3) were able to grow on 100 mM AA in the presence of the derepressing carbon source xylose (Figure 8E), suggesting CCR was at least partially active under derepressing conditions in this strain.

Nmr1-3 controls Nut1 in response to glucose

With regards to nitrogen metabolism, the model in Figure 8D also predicts that Nmr1-3 should control Nut1 in response to glucose availability and is consistent with our observations that loss of G6P sensing in Δtps1 strains locks Nut1 in its inactive form regardless of nitrogen source [21], [23]. Additional evidence for the model proposed in Figure 8D comes from studying the activity of Nut1-dependent processes under different nutritional conditions. Nut1 is required to express NIA1, encoding nitrate reductase (NR), under nitrogen derepressing conditions. Nitrate reductase activity was detected in M. oryzae mycelial samples grown under NR inducing conditions (glucose and NO3− minimal media, Figure 9A) but was absent following growth under nitrogen repressing conditions, ie glucose and NH4+ [23]. NR activity was also not detected in NR induction media lacking a source of carbon (−C+NO3−, Figure 9A), consistent with previous observations in A. nidulans which showed NR activity rapidly disappeared from mycelial samples switched from NR induction media into media lacking a carbon source [35]. In M. oryzae, NR activity was also not detected in mycelia grown under nitrogen and carbon starvation conditions (-C –N, Figure 9A). Interestingly NR activity was detected in our M. oryzae mycelia grown in glucose minimal media lacking a nitrogen source (-N, Figure 9A). This is different to the observations by Hynes of A. nidulans NR activity [35], where absence of an inducer resulted in rapid loss of NR activity, but consistent with a previous M. oryzae report that showed NIA1 expression was elevated under nitrogen starvation conditions in M. oryzae compared to growth on nitrate media in the presence of glucose [36]. Figure S7A confirms that NIA1 is expressed in the absence of inducer, but not the absence of a carbon source, in wild type Guy11 strains. In addition, NIA1 is expressed in condia and appressoria in the absence of an inducer [23], and we show in Figure S7B that in appressoria, NIA1 expression is dependent on Tps1.

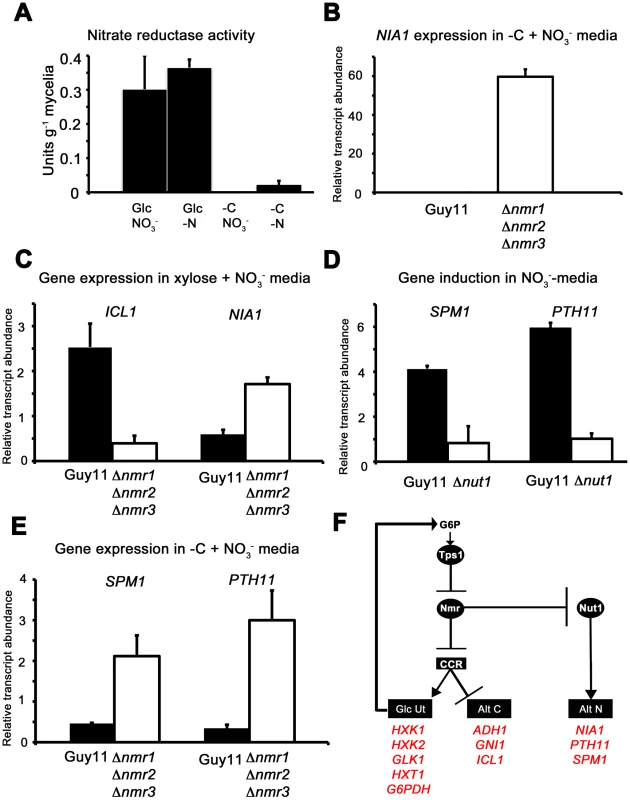

Fig. 9. The Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins regulate nitrogen and carbon metabolism in response to G6P.

(A) As predicted by our model in Figure 8D, Nitrate reductase activity is dependent on glucose availability. Nitrate reductase activity was determined as described in [21], where strains were grown in CM media for 48 hr before switching to minimal media containing either 55 mM glucose (Glc) or no carbon source (-C), with 10 mM nitrate (NO3−) or no nitrogen source (-N). Enzyme activity is given as units of nitrate reductase activity per gram of lyophilized mycelia. Results are the average of at least three independent replicates and bars are standard deviation. (B) NIA1 expression was analyzed in Guy11 and Δnmr1 Δnmr2 Δnmr3 triple mutant strains following growth in CM for 48 hr followed by growth in nitrate minimal media lacking a carbon source for 16 hr. Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2). Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (C) ICL1 and NIA1 gene expression was analyzed in Guy11 and Δnmr1 Δnmr2 Δnmr3 triple mutant strains following growth in CM for 48 hr followed by growth in carbon and nitrogen derepressing minimal media (55 mM xylose+10 mM NO3−). Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2). Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (D) To explore how the expression of characterized virulence factors, known to be expressed in nitrogen starvation conditions are controlled, we first confirmed that SPM1 and PTH11 are elevated in expression on 55 mM glucose+10 mM NO3− minimal media compared to growth on 55 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+, and that this induction is abolished in Δnut1 strains. Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2) and are relative to their expression in NH4+-containing minimal media. Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (E) Having confirmed that SPM1 and PTH11 gene expression is nitrate inducible in a Nut1-dependent manner, we next analyzed whether they were regulated by the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins. We looked at the expression of these genes on −C+10 mM NO3− minimal media in Guy11 and the Δnmr1 Δnmr2 Δnmr3 triple mutant strains, and found they were significantly elevated in expression in the latter strain compared to Guy11. Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the ß-tubulin gene (TUB2). Results are the average of at least three independent replicates, and error bars are the standard deviation. (F) Summary of gene regulation discussed in Figure 8 and 9. In A. nidulans, although NR activity requires an inducer, several other activities - such as acetamidase, histidase and formamidase - are present at high levels in nitrogen starvation media in the absence of an inducer. Todd et al [37] examined the expression of amdS to demonstrate for A. nidulans that under nitrogen starvation conditions, in the presence of glucose, AreA located to the nucleus. AreA nuclear accumulation was rapidly reversed by the addition of an exogenous nitrogen source, and was not seen in nitrogen starvation media lacking a carbon source. Our results might be consistent with this model of AreA/Nut1 activity in M. oryzae under at least some starvation conditions where NIA1 gene expression does not appear to require an inducer.

The model in Figure 8D suggests carbon metabolism and nitrogen metabolism are regulated by the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins in response to glucose, and Figure 9A and Figure S7A confirm NR activity and NIA1 gene expression is abolished in carbon starvation media in the presence of nitrate. However, the model in Figure 8D predicts that inactivating the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins should result in NIA1 gene expression in carbon starvation media. Consistent with this hypothesis, Figure 9B shows that NIA1 gene expression is significantly elevated in the Δnmr1 Δnmr2 Δnmr3 triple mutant [23] following growth on −C+NO3− media compared to Guy11.

The model also predicts that in Guy11, under carbon and nitrogen derepressing conditions (for example 55 mM xylose+10 mM NO3−), Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins would be active, resulting in both Nut1 inhibition and CCR repression. The outcome of this growth condition is expected to be both decreased NIA1 expression and increased expression of genes for alternative carbon source utilization. Conversely, growth of the Δnmr1 Δnmr2 Δnmr3 triple mutant under the same conditions should result in increased NIA1 gene expression, and active CCR and decreased expression of alternative carbon utilization genes, relative to Guy11 (Figure 8D). Figure 9C shows this to be the case, with ICL1 gene expression reduced, and NIA1 gene expression elevated, in Δnmr1 Δnmr2 Δnmr3 triple mutant strains compared to Guy11 following growth on 55 mM xylose and 10 mM NO3−.

Taken together, these results support a role for Tps1 in integrating carbon and nitrogen metabolism such that in glucose-rich conditions, Tps1 senses G6P and inactivates Nmr1-3 regardless of nitrogen source, resulting in active Nut1 and CCR. Conversely, in the absence of G6P, Nmr1-3 would simultaneously repress CCR and nitrogen metabolism regardless of nitrogen source.

The role of Nmr1-3 inhibition in the expression of known virulence factors under nitrogen starvation conditions

In M. oryzae and other plant pathogens, it has been noted that virulence-associated gene expression is induced on glucose minimal media lacking a nitrogen source [36], [38], and Figure 8D suggests one mechanism by which these genes could be controlled during infection. To explore this further we looked at the expression of two genes essential for virulence and encoding the vacuolar serine protease Spm1 [36] and the plasma membrane protein Pth11 [39]. PTH11 gene expression had previously been shown to be under Tps1 control [21] and both PTH11 and SPM1 were shown to be elevated in expression under nitrogen starvation conditions compared to nitrate inducing conditions [21]. However, whether the expression of PTH11 and SPM1 was ammonium-repressible, and whether that repression occured via Nmr1-3 control of Nut1, was not known. Figure 9D shows therefore that in Guy11, both SPM1 and PTH11 gene expression is induced in NO3− media compared to NH4+ media (with 55 mM glucose in both cases), and that this induction is dependent on Nut1. Figure 9E shows that SPM1 and PTH11 are also regulated by the Nmr1-3 inhibitor proteins in response to glucose whereby expression of both genes is elevated in the Δnmr1 Δnmr2 Δnmr3 strain during growth on carbon starvation media in the presence of nitrate, compared to Guy11. Figure 9F summarizes the transcriptional data in Figure 8 and Figure 9 to show how carbon and nitrogen metabolism is integrated in response to G6P availability, and how this could provide a framework for understanding how known virulence genes, expressed under nitrogen starvation conditions, are regulated during infection.

An extragenic forward suppressor screen identified MDT1, encoding a MATE–family efflux pump, as an additional regulator of the CCR signal transduction pathway in M. oryzae

At the start of this study, nothing was known about the downstream target(s) of Tps1 and Nmr1-3 involved in CCR, or what additional factors constitute the CCR signaling pathway in M. oryzae. Because CREA deletion mutants can often not be obtained [25], we used our Δnut1 deletion strain in a forward genetics screen to identify components of CCR by selecting for extragenic suppressors of Δnut1 that were restored in their ability to utilize proline or glucosamine in the presence of glucose. Our rationale for defining CCR in M. oryzae lies in understanding how carbon metabolism is regulated in M. oryzae and how such nutrient adaptability contributes to pathogenicity during plant infection. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated mutagenesis using the binary vector pKHt [40] randomly introduced T-DNA into the genome of a Δnut1 parental strain, and the resulting suppressor strains were selected for growth on minimal media containing 10 mM glucose with 10 mM proline or 10 mM glucosamine as nitrogen source. We obtained a total of six transformats on 10 mM glucose+10 mM proline (Δnut1 Supp 3121021–Δnut1 Supp 3121026) and one transformant on 10 mM glucose+10 mM glucosamine (Δnut1 Supp 312104). Three transformants selected on 10 mM glucoe+10 mM proline were lost due to Agrobacterium contamination before we were able to identify the disrupted gene. For the remaing four strains (Δnut1 Supp 312102, Δnut1 Supp 3121023, Δnut1 Supp 3121025 and Δnut1 Supp 312104), inverse PCR and the known T-DNA sequence [40] were used to identify genes that had been disrupted by T-DNA insertion in our suppressor strains. Interestingly, all four Δnut1 suppressor strains resulted from T-DNA insertions into the same 3′ coding region of MDT1 encoding a MATE-family efflux pump [27] (Table S3, Figure S8A). Specifically, all resulted from T-DNA insertions immediately 3′ to nucleotide 1503, except Δnut1 Supp 3121023 which resulted from insertion of T-DNA immediately 3′ to nucleotide 1502. The position of these insertions could indicate that all the suppressors generated were not independent transformants. However, Δnut1 Supp 312104 was selected on 10 mM glucose+10 mM glucosamine using different Guy11 mycelial samples to the suppressors selected on glucose+proline. In addition, previous reports of using Agrobacterium -mediated mutagenesis in Arabidopsis [41] and Magnaporthe [42] demonstrated nonrandom integration of T-DNA, and “hotspots” of integration were determined. Therefore, our suppressors could result either from multiple insertions of Agrobacterium T-DNA into a “hotspot” region within MDT1, or result from clones of one transformant isolated during selection. The suppressor strains generated in Table S3, regardless of the selection media used, were able to grow on both glucosamine and proline as nitrogen source compared to the Δnut1 parental strain, and we arbitrarily chose Δnut1 Supp 3121022 for further characterization. To confirm MDT1 as the suppressing locus in Δnut1 suppressor strains, a Δnut1 Δmdt1 double deletion strain was generated by homologous gene replacement of MDT1 in the Δnut1 background (Figure S6B). MDT1 was also deleted in Guy11 to generate a single Δmdt1 deletion strain that was subsequently complemented with the full length MDT1 coding region.

Figure 10A shows how both the Δnut1 Supp 3121022 suppressor strain and the Δnut1 Δmdt1 double deletion strain, like the Δnut1 parental strain, could not use nitrate as a sole nitrogen source. Unlike Δnut1 deletion strains, however, Δnut1 Supp 3121022 and Δnut1 Δmdt1 strains could grow on proline and glucosamine as nitrogen source, and were sensitive to 100 mM AA in 55 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+ minimal media (Figure 10B), indicating they were derepressed for carbon metabolism in the presence of glucose.

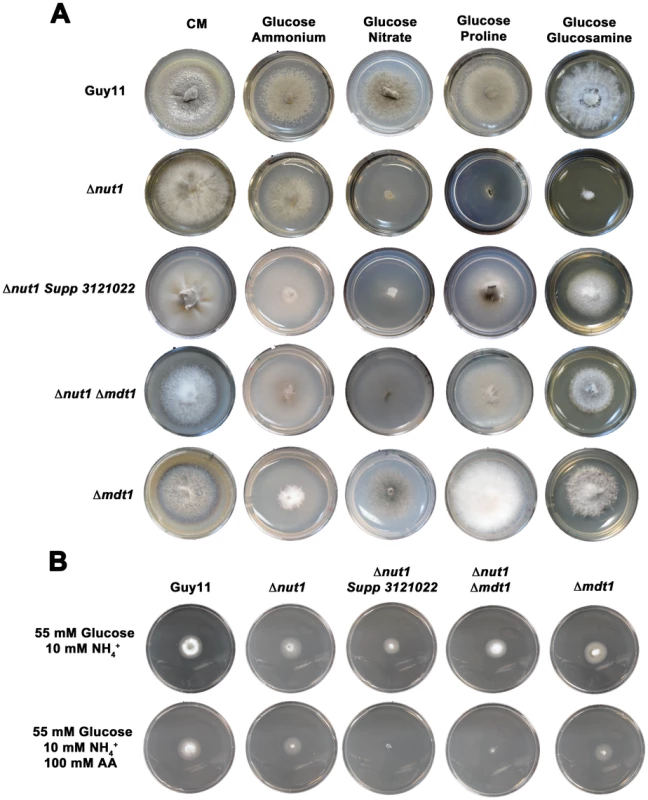

Fig. 10. Disruption of Mdt1 function affects carbon metabolism.

(A) Strains were grown for 10 days on CM or minimal media supplemented with 10 mM of the appropriate carbon and nitrogen source. Like the Δnut1 parental strain, both Δnut1 Supp 321022 extragenic suppressor strains and Δnut1 Δmdt1 double deletion strains were unable to grow on NO3− - containing media. Unlike the Δnut1 parental strain, both MDT1 disruption strains were restored for growth on proline and glucosamine as nitrogen source, indicating T-DNA insertion or homologous gene replacement of MDT1 resulted in carbon derepression in the presence of glucose. (B) Disruption of MDT1 in the Δnut1 background resulted in strains that were carbon catabolite derepressed and significantly reduced in growth on 55 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+ minimal media with 100 mM AA compared to growth on NH4+ minimal media alone. Single Δmdt1 deletion strains were less sensitive to 100 mM AA on this media. The Δmdt1 single mutant strains could grow on nitrate, glucosamine and proline as nitrogen sources, and were slightly more sensitive to glucose minimal media with 100 mM AA than Guy11. Δmdt1 strains were also reduced in growth on minimal media with 10 mM glucose+10 mM NH4+ (discussed below).

MDT1 encodes a predicted membrane-spanning protein and is expressed during appressoria development

MDT1 is a member of the Multidrug and Toxin Extrusion (MATE) gene family found in bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes [43], [44], [45]. They have a wide range of cellular substrates and function as fundamental transporters of metabolic and xenobiotic organic cations in kidneys [46]; transporters of organic anions such as citrate in plants [47]; and contribute to antimicrobial drug resistance and protection against ROS damage in bacteria [48]. In M. oryzae, the MDT1 locus, MGG_03123, is one of three loci encoding putative MATE-family efflux pumps, the other two being MGG_04182 and MGG_10534 [49]. MGG_03123 consists of 2510 nucleotides, has three predicted introns, and encodes a 748 amino acid protein. PSortII analysis predicted the gene product has a 73.9% chance of being localized to the plasma membrane, and a 26.1% chance of being localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. TMpred and PSIPRED analysis predicted the protein carries 12 membrane-spanning helices located in the C-terminal region of the protein. An EST corresponding to MGG_03123,10_GI3391884.f, was detected in appressorial stage specific cDNAs deposited at the M. oryzae community database (www.mgosdb.org/).

MDT1 is required for sporulation and plant infection but not appressorium formation

Disruption of MDT1 by T-DNA insertion or homologous recombination, in wild type or Δnut1 backgrounds, resulted in significant reductions in spore production on minimal media with 55 mM glucose and 10 mM NH4+ compared to the Guy11 and Δnut1 parental strains (Figure 11A). Sufficient spores were harvested from CM plates to show that after 24 hrs, spores of Δmdt1, Δnut1 Δmdt1 and Δnut1 Supp 321022 strains formed appressorium normally on hydrophobic surfaces compared to Guy11 (Figure 11B). However, despite forming appressoria, Δmdt1, Δnut1 Δmdt1 and Δnut1 Supp 321022 strains were unable to establish disease when inoculated onto rice leaves (Figure 11C). To ensure loss of pathogenicity was solely due to the loss of a functional MDT1 gene, we show Δmdt1 strains complemented with the full length MDT1 gene are restored for pathogenicity (Figure 11C). Thus MDT1 is not required for appressorium development but is essential for both full sporulation and rice blast disease and is a new determinant of virulence in M. oryzae.

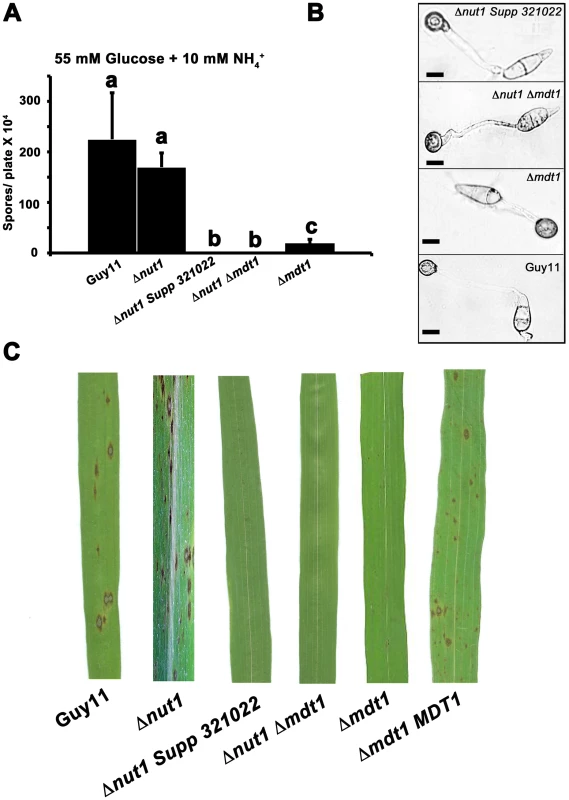

Fig. 11. Disrupting Mdt1 function affects sporulation and pathogenesis.

(A) MDT1 disruption mutants were impaired in spore production on minimal media. Spores were harvested from plates following 12 days of growth. Values are the mean of at least three independent replicates. Error bars are standard deviation. Bars with the same letter are not significantly different (Student's t-test p≤0.01). (B) The Δnut1 Supp 321022 suppressor strain, the Δnut1 Δmdt1 double deletion strain and the Δmdt1 single mutant form appressoria on artificial hydrophobic surfaces. Spores of Guy11, the Δnut1 Supp 321022 suppressor strain, the Δnut1 Δmdt1 double deletion strain and Δmdt1 strains were applied to plastic cover slips. Scale bars are 10 µM. (C) The MATE-family efflux pump Mdt1 is essential for pathogenesis in Δnut1 strains. Because of the reduced sporulation rates of MDT1 disruption strains, spores were inoculated onto rice leaves at a low rate of 2×104 spores/mL. Compared to Guy11 and Δnut1 parental strains, Δmdt1, Δnut1 Δmdt1 and Δnut1 Supp 321022 strains were unable to cause the necrotic lesions associated with successful rice infection. Introducing the full length MDT1 coding region into Δmdt1 strains restored pathogenicity in Δmdt1 MDT1 complementation strains. MDT1 is involved in citrate efflux and carbon regulation

We sought to identify the likely function of Mdt1 in order to understand how a MATE-family efflux pump might regulate carbon metabolism and mediate the fungal-host plant interaction. Only one other MATE-family transporter had previously been described in fungi, Erc1 from S. cerevisiae, which functions to confer fungal resistance to the toxic methionine analog ethionine [50]. We observed that although Guy11 is sensitive to the addition of 50 mM ethionine to glucose minimal media, MDT1 disruption strains did not demonstrate increased susceptibility compared to Guy11, suggesting Mdt1 is not involved in ethionine efflux in M. oryzae (Figure S9A).

Considering Δnut1 Supp3121022 and Δnut1 Δmdt1 strains were carbon derepressed in the presence of glucose (Figure 10B), we sought to determine if Mdt1 might be involved in glucose uptake and phosphorylation in the cell. As noted previously, a class of carbon derepressed mutants of A. nidulans were found to result from defective glucose uptake [3] and were consequently resistant to both the toxic glucose analogue 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG), and the toxic sugar sorbose [32] during growth under carbon derepressing conditions. When grown on carbon derepressing minimal media comprising 10 mM xylose and 10 mM NH4+ as sole carbon and nitrogen sources, we observed, however, that disruption of MDT1 in all backgrounds tested (wild type and Δnut1) did not confer resistance to 50 µg/mL 2-DOG or 5 mM sorbose in M. oryzae (Figure S9B). This suggests Mdt1 is not involved in glucose uptake in M. oryzae.

In bacteria, the MATE-family efflux protein NorM protects GO-deficient strains against the deleterious effects of exogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) [48]. As M. oryzae transitions from the surface of the leaf to the underlying tissue, it encounters basal plant defense strategies in the form of a plant-derived oxidative burst, which the fungus needs to neutralize in order to establish infection [51]. We wondered if Mdt1 might play a similar role to NorM in protecting M. oryzae against ROS, and if loss of this protection in MDT1 disruption strains might result in the observed loss of pathogenicity. However, Figure S9C shows how Δnut1 Δmdt1 double mutant and Δmdt1 single mutant strains were not significantly more sensitive to oxidative stress than wild type, as evidenced by their ability to grow like wild type and Δnut1 parental strains on CM supplemented with 10 mM H2O2. In contrast, Des1 is an M. oryzae gene product necessary for neutralizing plant ROS during infection [51]. Δdes1 mutant strains are unable to detoxify plant ROS and are severely attenuated in growth on CM containing only 3 mM H2O2 compared to wild type. Therefore Figure S9C suggests that, compared to Des1, the role of Mdt1 in protecting the fungus against ROS during infection is very minor.

Considering the wide range of MATE substrates demonstrated in other organisms, additional roles for Mdt1 could also include conferring toxin resistance during growth in planta through the extrusion of plant-derived defense compounds from the fungal cell, such as has been reported previously in M. oryzae for the transmembrane ATP binding cassette (ABC) proteins, Abc1 [52] and Abc3 [53]. However, it should be noted that unlike Δabc1 and Δabc3 mutant strains, MDT1 disruption strains evince physiological defects and inactivation of CCR under glucose-rich conditions in the absence of the plant host. This suggests Mdt1 has a major physiological role in carbon metabolism and any additional role(s) it might have in mediating resistance to plant toxins during infection is likely to be a minor function of this efflux pump.

In Arabidopsis thaliana and rice (Oryza sativa), root-associated MATE-family transporters, AtFRD3 and OsFRDL1 respectively, are indirectly involved in cellular metal uptake and homeostasis [54]–[57]. MATE proteins likely do not transport metal ions directly but are proposed to secrete citrate that chelates extracellular metal ions and conditions their translocation into the cell by other systems [47], [56], [58]. MATE proteins involved in citrate efflux have also been described for sorghum [59], barley [60], maize [61] and wheat [47]. In addition, fungi have been shown to secrete citrate, where it is considered overflow metabolism similar to that seen during growth on excess glucose [62]. We first sought to determine if Mdt1 was involved in metal uptake in M. oryzae. Figure 12A demonstrates that compared to growth on minimal media containing 55 mM glucose and 10 mM NH4+, growth on the same media supplemented with ten-fold the normal concentration of zinc, but not copper or iron (not shown), significantly increased sporulation rates in Δnut1 Supp 312022, Δnut1 Δmdt1 double deletion and Δmdt1 single deletion strains, but not Guy11 or Δnut1 parental strains, following 12 days of growth. This suggests the MDT1 disruption strains were impaired in zinc uptake.

Fig. 12. Elucidating the function of the Mdt1 efflux protein.