-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaFunctional Centromeres Determine the Activation Time of Pericentric Origins of DNA Replication in

The centromeric regions of all Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomes are found in early replicating domains, a property conserved among centromeres in fungi and some higher eukaryotes. Surprisingly, little is known about the biological significance or the mechanism of early centromere replication; however, the extensive conservation suggests that it is important for chromosome maintenance. Do centromeres ensure their early replication by promoting early activation of nearby origins, or have they migrated over evolutionary time to reside in early replicating regions? In Candida albicans, a neocentromere contains an early firing origin, supporting the first hypothesis but not addressing whether the new origin is intrinsically early firing or whether the centromere influences replication time. Because the activation time of individual origins is not an intrinsic property of S. cerevisiae origins, but is influenced by surrounding sequences, we sought to test the hypothesis that centromeres influence replication time by moving a centromere to a late replication domain. We used a modified Meselson-Stahl density transfer assay to measure the kinetics of replication for regions of chromosome XIV in which either the functional centromere or a point-mutated version had been moved near origins that reside in a late replication region. We show that a functional centromere acts in cis over a distance as great as 19 kb to advance the initiation time of origins. Our results constitute a direct link between establishment of the kinetochore and the replication initiation machinery, and suggest that the proposed higher-order structure of the pericentric chromatin influences replication initiation.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002677

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002677Summary

The centromeric regions of all Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomes are found in early replicating domains, a property conserved among centromeres in fungi and some higher eukaryotes. Surprisingly, little is known about the biological significance or the mechanism of early centromere replication; however, the extensive conservation suggests that it is important for chromosome maintenance. Do centromeres ensure their early replication by promoting early activation of nearby origins, or have they migrated over evolutionary time to reside in early replicating regions? In Candida albicans, a neocentromere contains an early firing origin, supporting the first hypothesis but not addressing whether the new origin is intrinsically early firing or whether the centromere influences replication time. Because the activation time of individual origins is not an intrinsic property of S. cerevisiae origins, but is influenced by surrounding sequences, we sought to test the hypothesis that centromeres influence replication time by moving a centromere to a late replication domain. We used a modified Meselson-Stahl density transfer assay to measure the kinetics of replication for regions of chromosome XIV in which either the functional centromere or a point-mutated version had been moved near origins that reside in a late replication region. We show that a functional centromere acts in cis over a distance as great as 19 kb to advance the initiation time of origins. Our results constitute a direct link between establishment of the kinetochore and the replication initiation machinery, and suggest that the proposed higher-order structure of the pericentric chromatin influences replication initiation.

Introduction

Centromere function, the ability to assemble a kinetochore and mediate chromosome segregation during meiosis and mitosis, is critical for the survival and propagation of eukaryotic organisms. Defects in centromere/kinetochore complexes lead to genome instability and susceptibility to cancer and cell death [1]–[3]. Therefore, it is important that properly functioning centromeres be established on both sister chromatids following replication of centromeric DNA and prior to the initiation of chromosome segregation. Centromeres in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae replicate early in S-phase [4]–[8] and increasing evidence suggests that early centromere replication is conserved among fungi and is prevalent for at least a subset of centromeres in higher eukaryotes [9]–[13]. Yet surprisingly little is known about the mechanism that accomplishes this early replication. It has been hypothesized that early replication of centromere DNA provides sufficient time for the centromere-specific histone, CenH3, to be incorporated on both sister chromatids and to ensure subsequent microtubule attachment [14]–[16]. Consistent with this idea, Feng et al. showed that a delay in centromere DNA replication in the absence of the replication checkpoint leads to increased aneuploidy [16]. It is thought that this observed increase in aneuploidy is due to the lack of properly bi-oriented sister chromatids.

Currently, it is unclear if centromeres play an active role in their own early replication by influencing activation of nearby origins of replication (origins). An alternative possibility is that centromeres have migrated over evolutionary time to reside in early replicating regions of the genome.

Indirect evidence supporting the idea that centromeres play an active role in their own early replication comes from a study examining epigenetic inheritance of centromeres in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans [11]. The centromeres of C. albicans are considered regional centromeres akin to those of higher eukaryotes because they are not defined by any distinct DNA sequence. Instead, regional centromeres are defined by broad stretches of repetitive DNA sequences ranging from about 3 kilobases (kb) in C. albicans to megabases in humans. Regional centromeres that have been analyzed for replication time have been shown to contain origins within them [9], [10], [17]. Koren et al. showed that the de novo formation of an early activated origin within the neocentromeric region is responsible for the early replication of spontaneously formed neocentromeres in C. albicans [11]. The authors further showed that the origin recognition complex (ORC), which is essential for origin activation, is recruited to the neocentromere. Thus, centromeres of C. albicans appear to recruit at least a subset of the required replication initiation machinery. However, it is unclear from these studies whether centromere function directly influences origin activation time or if these regions merely provide a favorable environment for ORC recruitment, with early origin activation time being determined independently of centromere function.

Distinguishing between these possibilities is difficult because no distinct sequences for either centromeres or origins have been identified in C. albicans. Therefore, the function of the centromere responsible for replication initiation cannot effectively be separated from the kinetochore-binding portion of the centromere. For example, removal of centromere DNA in C. albicans results in removal of the origins contained within that sequence. Therefore, determining if centromeres regulate origin activation time requires a situation in which the activity of the origin responsible for centromere replication can be separated from the centromere. The small sizes and well-defined sequences of centromeres and origins in S. cerevisiae provide us the opportunity to answer this question.

The origins of S. cerevisiae have been extensively studied and are defined by an 11 base pair (bp) consensus sequence that is necessary but not sufficient to initiate DNA synthesis [18]. Unlike C. albicans, the centromeres in S. cerevisiae are small, spanning only 125 bps and do not, with one possible exception (CEN3), contain potential origins [6], [19]–[21]. However, all of the centromeres of S. cerevisiae reside in early replicating portions of the genome, suggesting that centromeres play a role in regulating origin activation time.

Early replication is not restricted to portions of the genome immediately flanking centromeres. In fact, early and late replicating blocks of DNA are interspersed throughout the genome [7], [8]. The patterns in which temporal blocks are arranged indicate that origins can be crudely grouped into four classes with respect to their replication time and chromosomal position: centromere-proximal early, noncentromere-proximal early, telomere-proximal late, and nontelomere-proximal late [6]–[8]. Telomeres delay the activation times of nearby origins while late activation of non-telomeric origins is determined by an unknown mechanism involving unspecified DNA sequences located up to 14 kb away from the origin [22], [23]. Plasmids containing the minimum required sequence for origin activation tend to replicate early, suggesting that early activation is the default state for origins [24]. However, in a plasmid construct, a DNA element immediately downstream of the URA3 gene can advance origin activation time of an adjacent copy of ARS1 through unknown means [25], [26]. In light of these data, we hypothesize that there is no common “default” activation time and that centromeres act as one of the determinants for early origin activation.

By measuring replication time locally as well as genome-wide in a strain with an ectopic centromere, we show that centromeres in S. cerevisiae act in cis to promote early activation on origins positioned as far as 19 kb away. Our results suggest that centromere-dependent early origin activation has a gradient effect such that the closer the origin is to the centromere the more profound is the timing effect on that origin. In addition, we show for the first time that early activation of centromere proximal origins is dependent on centromere function, suggesting that the ability of centromeres to establish proper kinetochore-to-microtubule attachments is important for regulating origin initiation.

Results

Proximity to centromeres influences time of origin activation

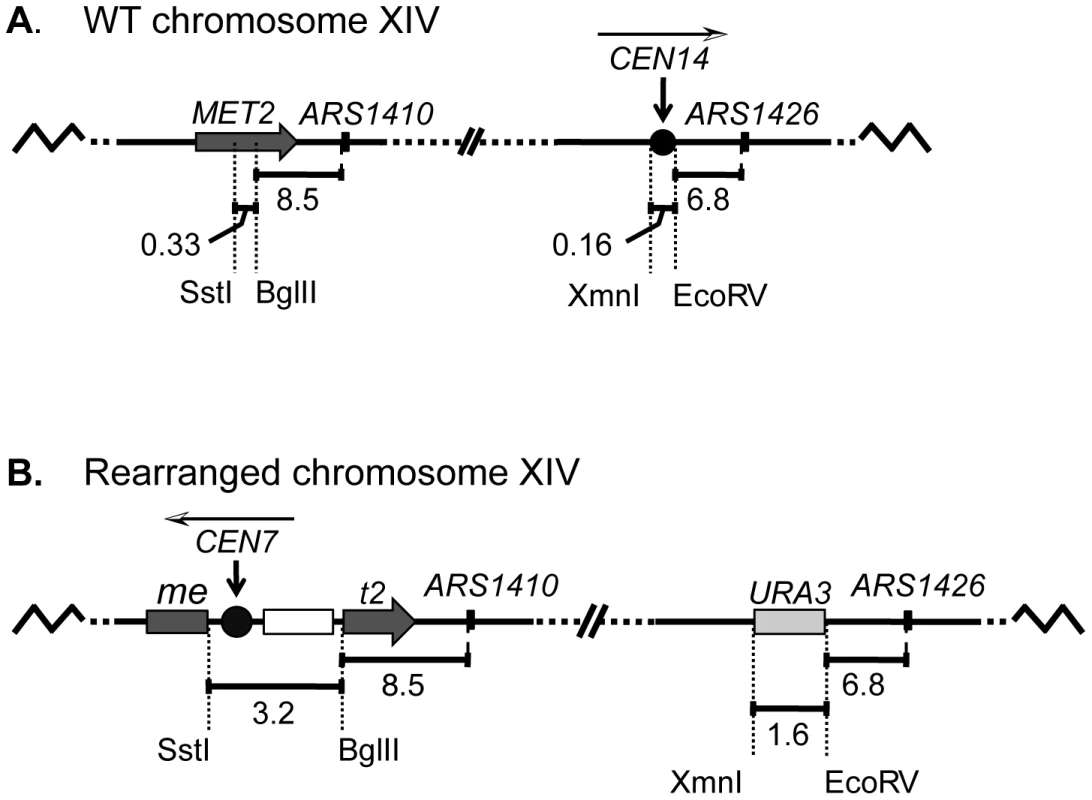

S. cerevisiae centromeres lie close to origins that undergo replication in early S-phase. To test the hypothesis that centromeres contribute to the early activation of these adjacent origins, we obtained a strain in which the centromere on chromosome XIV (Figure 1A) had been relocated to a distal location on the left chromosomal arm [27] (Figure 1B). At this new location the centromere is positioned in a late replicating region near the potential origin ARS1410. We reasoned that if centromeres can influence origin activation time, then the origins that are closest to the moved centromeres would have the greatest chance of being affected.

Fig. 1. A schematic diagram of chromosome XIV in wild-type (WT) and rearranged strains.

(A) In the WT strain, the BglII restriction site in MET2 is located 8.5 kb to the left of ARS1410. Centromere XIV resides in its endogenous position located 6.8 kb to the left of ARS1426. (B) In the rearranged strain the endogenous centromere was replaced with a URA3 selectable marker while a functional centromere was integrated along with LEU2 (open box) into the MET2 locus such that the centromere was positioned ∼11.5 kb from ARS1410. The white and black arrowhead above each centromere indicates the direction of the centromere DNA elements CDEI, CDEII, CDEIII. The replication kinetics of three loci on chromosome XIV (met2 or MET2, ARS1410, and ARS1426) in the rearranged and wild type (WT) strains were examined using a modified version of the Meselson-Stahl density transfer experiment [4]. Haploid cells grown in the presence of dense 13C and 15N isotopes were arrested prior to S-phase. The cells were synchronously released into medium containing isotopically light carbon and nitrogen, and samples were collected at various times during the ensuing S-phase. Newly synthesized DNA was composed of light isotopes resulting in replicated DNA being hybrid or heavy-light (HL) in density whereas unreplicated DNA remained heavy-heavy (HH) in density. DNA was extracted from each cell sample, digested with restriction enzyme EcoRI, and subjected to ultracentrifugation in cesium chloride gradients. The gradients were then drip fractionated, and the kinetics with which the EcoRI restriction fragments containing each of the three loci of interest shifted from heavy to hybrid density were compared via slot blot analysis (Figure 2A; also see Materials and Methods).

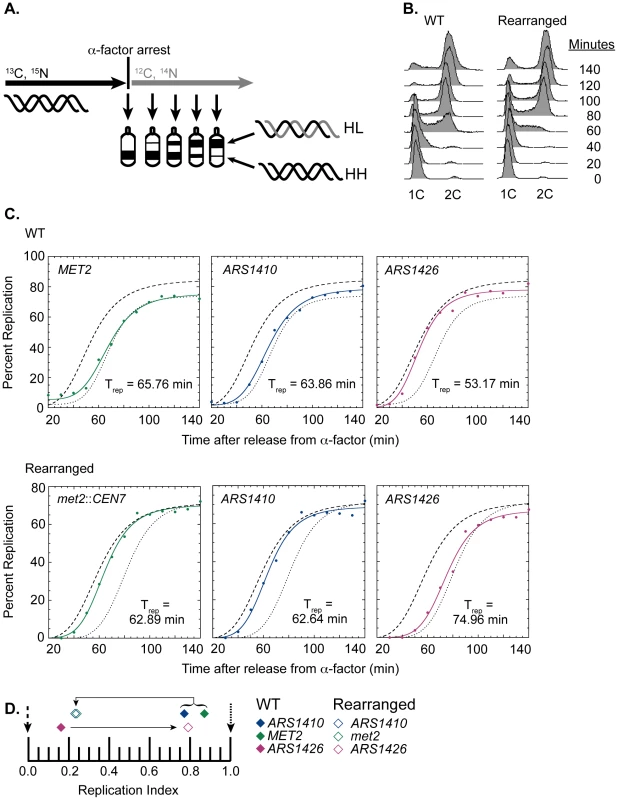

Fig. 2. Replication time of native and relocated centromeres on chromosome XIV.

(A) Cartoon depiction of experimental setup. Cells were grown in medium containing heavy carbon (13C) and nitrogen (15N) isotopes. Upon genome saturation with the heavy isotopes, cells were arrested by the addition of alpha factor and released synchronously in medium containing light carbon (12C) and nitrogen (14N) isotopes. The cells were then collected over the next 140 minutes and their DNA was extracted, digested with EcoRI, and separated via ultra centrifugation in cesium chloride gradients such that unreplicated DNA resides lower in the gradient than newly replicated DNA. DNA samples were then collected and analyzed through drip fractionation. (B) S phase progression of WT (left) and rearranged (right) cells as measured by flow cytometry. Cells from both strains entered S-phase by 40 minutes and achieved 2C DNA content by 140 minutes as indicated by the peak shift from 1C to 2C DNA content. (C) Replication kinetic curves for met2 or MET2, ARS1410, and ARS1426 in WT (top panel) and rearranged (bottom panel) cells. The kinetic curves for ARS306 and R11 are shown as dashed and dotted lines, respectively. Trep is the time of half-maximal replication for each locus (see Materials and Methods). (D) Replication indices for met2 or MET2 (green), ARS1410 (blue), and ARS1426 (magenta) in WT (solid diamonds) and rearranged (empty diamonds) strains. ARS306 (black dashed arrow) and R11 (black dotted arrow) were used as early and late timing standards, respectively. In the WT strain, MET2, ARS1410, and ARS1426 had replication indices of 0.87, 0.77, and 0.16 respectively. In the rearranged strain, met2, ARS1410, and ARS1426 had replication indices of 0.24, 0.23, and 0.79, respectively. Direction of the black arrows indicates the direction of the shift in replication index for each locus between WT and rearranged strains. WT cells entered S-phase by 40 minutes after release from alpha factor arrest, and most of the cells reached 2C DNA content between 120 and 140 minutes (Figure 2B). The percent replication of MET2, ARS1410, and ARS1426 genomic fragments was calculated for each sample and plotted with respect to time (Figure 2C). The time of replication (Trep) for each locus was calculated as the time it reached half maximal replication (see Materials and Methods). ARS306, one of the earliest known origins, and R11, a late replicating fragment on chromosome V, were used as timing standards for comparison. To facilitate comparison between cultures, these Trep values were converted to replication indices [22] by assigning ARS306 a replication index (RI) of 0 and R11 an RI of 1.0. Most other genomic loci have RIs between 0 and 1.0. The Trep values for MET2, ARS1410, and ARS1426 were then converted to RIs corresponding to the fraction of the ARS306-R11 interval elapsed when the Trep for each locus was obtained. As previously observed, MET2 replicated late in the WT strain (RI = 0.87), as did its nearest ARS, ARS1410 (RI = 0.77), while ARS1426 replicated early (RI = 0.16) (Figure 2C and 2D).

Similar to WT cells, the cells with the relocated centromere entered S-phase by 40 minutes following release from alpha factor arrest and reached 2C DNA content between 120 and 140 minutes (Figure 2B). In contrast to the WT strain, both met2 and ARS1410 replicated early with respective RIs of 0.24 and 0.23 (Figure 2C and 2D). Consistent with ARS1410 being the origin from which met2 replicates, ARS1410 maintained a slight timing advantage over met2. Meanwhile, ARS1426 became later replicating (RI = 0.79) in the absence of its nearby centromere (Figure 2C and 2D). Similar results were obtained using an independent segregant (see Figure S1).

There are three explanations for the change in replication time of the met2 locus: (1) the centromere advances the time of activation of ARS1410; (2) the centromere increases the efficiency (percentage of cells in which an origin is active) of ARS1410; and/or (3) insertion of the centromere created a new origin at the site. To distinguish among these possibilities we examined the replication of ARS1410, ARS1426, and met2 or MET2 by two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis [28]. The presence of bubble-arcs indicated that ARS1410 is indeed a functional origin in both the WT and rearranged strains (Figure 3A). Highly efficient origins display a more intense bubble-arc signal relative to the Y-arc [29]. Based on the similarity of bubble - to Y-arc ratios we conclude that the centromere has no obvious effect on the efficiency of ARS1410 (Figure 3A). A similar result was obtained for ARS1426 (Figure 3A) supporting the idea that the observed timing changes are not due to changes in efficiency of existing origins. No bubble-arc was observed for the MET2 locus in the WT strain or the met2 locus in the rearranged strain (Figure 3B), indicating that an origin was not created by insertion of the centromere into the MET2 locus. Together these data suggest that the presence of a nearby centromere or some feature of its pericentric DNA induces early activation of origins.

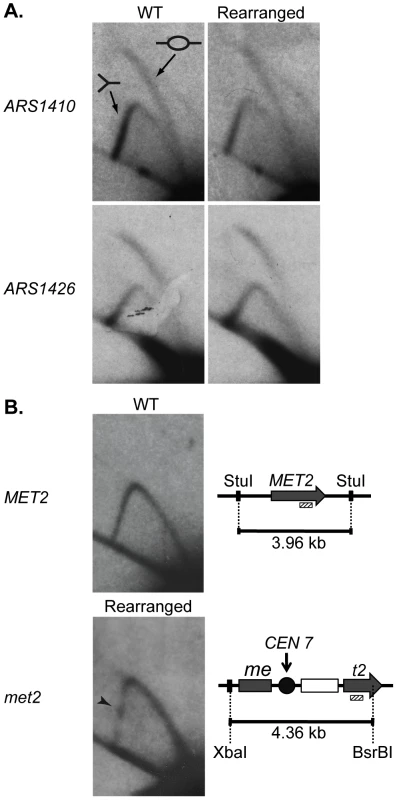

Fig. 3. 2D gel analysis of ARS1410, ARS1426, and MET2 and met2.

DNA fragments containing a functional origin are detected as a bubble arc (depicted by the bubble fragment) while fragments that are passively replicated are detected as a Y-arc (depicted as a Y shaped fragment). (A) ARS1410 and ARS1426 are functional origins in the WT and rearranged strains. (B) 2D gel analysis of the MET2 or met2 locus in the WT and the rearranged strains. WT DNA was digested with the restriction enzyme StuI giving a fragment of 3.96 kb centered on MET2 (grey arrow). Rearranged DNA was double digested with XbaI and BsrBI resulting in a 4.36 kb fragment harboring most of met2, the integrated centromere (black circle), and the LEU2 marker (white rectangle). The absence of a bubble arc when probed for the 3′ end of MET2 and met2 (hashed rectangle) indicates that an origin is not present on either DNA fragment. The centromere in the rearranged construct was detected as a pause site (black arrowhead) visualized as a dot of relatively increased intensity on the descending Y-arc. Centromere function is required for early activation of nearby origins

DNA sequences that determine origin activation time have remained largely elusive. However, previous work has shown that sequences flanking a subset of origins on chromosome XIV delay the activation of those origins [22]. These sequences, coined “delay elements”, can reside up to 14 kb from their affected origins. Therefore, it is possible that by integrating the centromere into the MET2 locus in the rearranged strain, a delay element responsible for making ARS1410 late activating was disrupted or pushed out of its effective range, thereby causing the origin to fire early. Although this scenario would explain the change in the replication times of met2 and ARS1410, the observation that ARS1426 became later replicating when the centromere was removed from its endogenous position argues in favor of the timing changes being a consequence of centromere proximity. Alternatively, it is conceivable that there is an uncharacterized sequence element, distinct from centromeric sequence, residing in pericentric DNA that is promoting early activation of nearby origins. The existence of such an element is formally possible as a cryptic sequence residing at the 3′ end of the URA3 gene was shown to advance the activation time of nearby origins on a plasmid and in an artificial chromosomal setting [25], [26]. We tested these possibilities as described below.

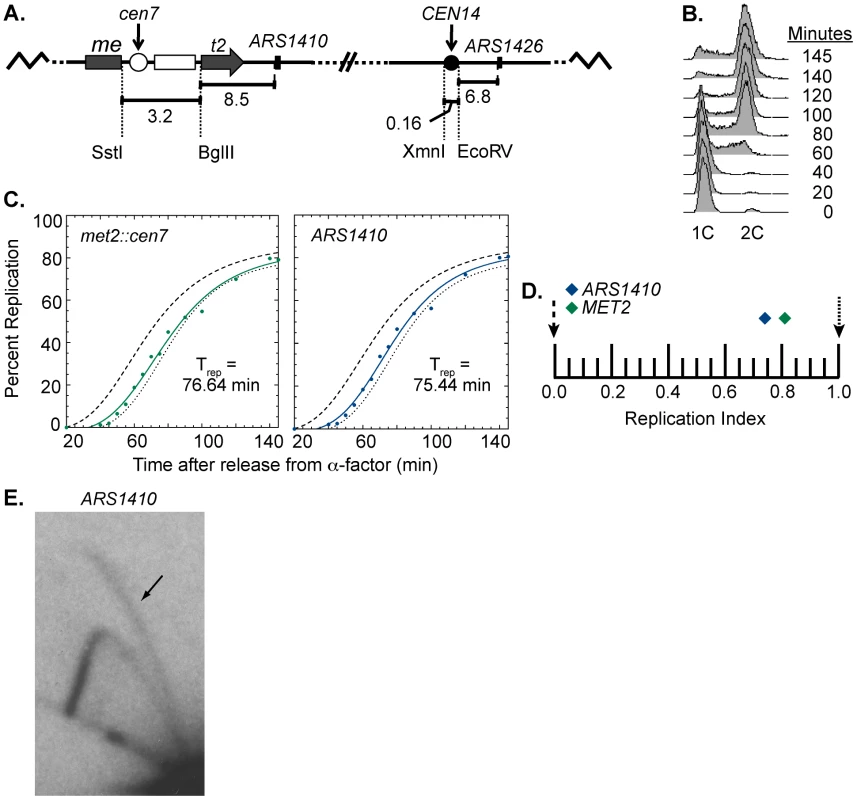

At the sequence level, S. cerevisiae centromeres are composed of three essential elements: CDEI, CDEII, and CDEIII. CDEI and CDEIII are defined by essential consensus sequences whereas CDEII is a 78–86 bp AT-rich sequence that separates CDEI and CDEIII [1], [19], [20]. CDEIII has been found to be the element most important for centromere function as it is the binding site for essential inner kinetochore proteins, notably members of the CBF3 complex [1], [19], [30]. To ask if a functional centromere is required for early activation of nearby origins, we engineered a strain to have a non-functional centromere with a mutated CDEIII motif integrated at the MET2 locus while the functional centromere remained in its endogenous position (Figure 4A). This strain was also subjected to flow cytometry (Figure 4B) and replication timing analysis as described above (Figure 4C). Unlike the dramatic replication timing change observed when we introduced a functional centromere, introducing the mutated centromere caused no replication timing change at met2 and ARS1410 (RI of 0.81 and 0.74, respectively; Figure 4D). Therefore, we conclude that centromere function is needed to effect a timing change on nearby origins. Furthermore, the late replication of this region was not due to inactivation of ARS1410 through insertion of the mutated centromere as indicated by 2D gel analysis (Figure 4E). Together, these data demonstrate that functional centromeres actively advance the activation times of origins over a distance of 11.5 kb.

Fig. 4. Replication time of point mutated centromere on chromosome XIV.

(A) Cartoon depiction of chromosome XIV with a non-functional centromere (white circle) integrated at MET2. Chromosome XIV of WT cells was modified such that MET2 was disrupted with the same sequence used to disrupt MET2 in the rearranged strain (see Figure 1) except that the centromere was made inactive by mutating the essential CDEIII domain. This chromosome is maintained through its wild type centromere at the endogenous location (black circle). (B) Flow cytometry of cells with a non-functional centromere in the MET2 locus. Similar to the WT strain (see Figure 2B), cells from this cell line enter S-phase by 40 minutes and achieved 2C DNA content by 140 minutes. (C) Replication kinetic curves for met2::cen7 and ARS1410. As observed in the WT strain, the replication curves for met2::cen7 (green) and ARS1410 (blue) are positioned more closely to that of R11 (dotted line) than ARS306 (dashed line) (compare to Figure 2C). D) Replication indices for met2:cen7 (green diamond) and ARS1410 (blue diamond). RIs of ARS306 and R11 are indicated by black dashed and dotted arrows, respectively. met2:cen7 and ARS1410 had RIs of 0.81 and 0.74, respectively. (E) 2D gel analysis of ARS1410. Presence of a bubble arc (black arrow) for ARS1410 in the strain in which the non-functional centromere was integrated at MET2 (compare with Figure 1B) indicates that ARS1410 is a functional origin in this strain. Centromeres determine the replication time of their local genomic environment

Upon finding that centromeres advance the activation time of origins to a distance of at least 11.5 kb, we sought to determine how far the centromere's effect extends along the chromosome. Raghuraman et al. presented statistical evidence that the regions of chromosomes within 25 kb of centromeres replicated earlier than the genome average, raising the possibility that centromeres could influence origin activation time over this larger distance [6]. Interestingly, at least one early replicating origin can be found within 12.8 kb of every centromere [16], suggesting that centromeres may be able to influence the activation time of origins over at least this distance. A recent study using an S-phase cyclin mutant [7] showed that early replicating domains that include a centromere can be well over 100 kb, implying that the range over which centromeres can regulate origin activation time might be quite broad.

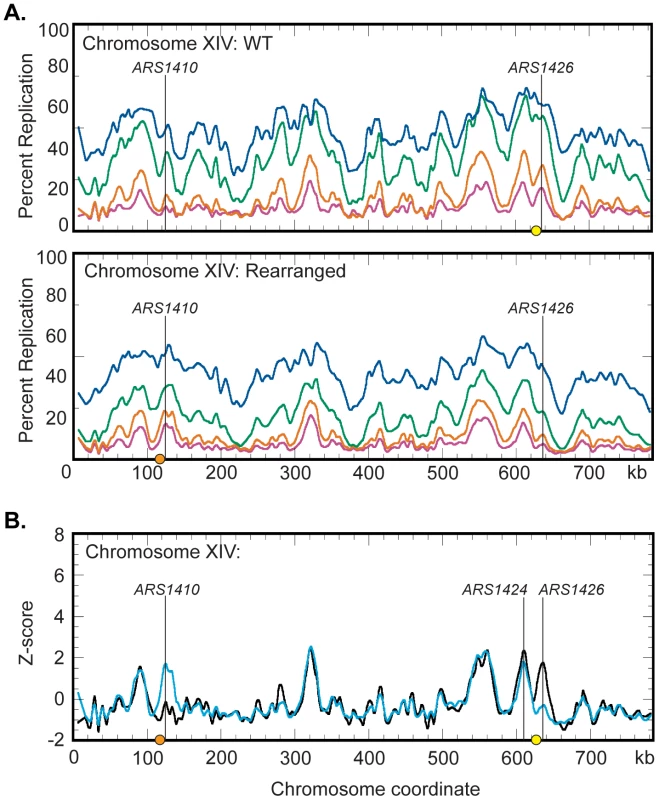

To determine the range over which a centromere can influence replication time we performed a genome wide analysis of replication in the WT and rearranged strains. Cells were grown in dense medium (see Materials and Methods) and timed samples were collected following release into S-phase in light medium. To obtain a genome-wide view, the HH and HL DNAs from each timed sample were labeled with different fluorophores, cohybridized to microarray slides, and replication profiles were generated (Figure 5A, Figures S2 and S3). Peak locations in the profile correspond to the locations of origins while the timed sample in which the peaks first appear gives an indication of the time at which the corresponding origins become active during S-phase [6].

Fig. 5. Replication dynamics for chromosome XIV in WT and rearranged strains.

(A) Replication kinetic profiles of chromosome XIV in WT (top) and rearranged (bottom) strains. Percent replication was monitored across chromosome XIV at 40 (magenta), 45 (orange), 55 (green), and 65 (blue) minutes following release from alpha factor arrest. When the native centromere (yellow circle) is present near ARS1426, a prominent peak is seen in the 40 and 45 minute time samples. In this strain, the peak at ARS1410 is shallow in the 40 and 45 minute samples. When the centromere is repositioned (orange circle) near ARS1410 in the rearranged strain, both the time of appearance and the prominence of the peaks at ARS1410 and ARS1426 are inverted with respect to the WT strain. See Figures S2 and S3 and Datasets S1 and S2 for all chromosomes. (B) Z-score plots of chromosome XIV in WT (black) and rearranged (blue) strains. Replication kinetic profiles from the 40 minute sample were normalized by converting percent replication values to Z-score values (see Materials and Methods). Genomic loci corresponding to ARS1410 and ARS1426 show significant differences in Z-scores. ARS1424 is the next closest active origin to the endogenous centromere residing ∼19 kb to the left. See Figures S4, S5, S6 and Datasets S3 and S4 for all chromosomes and the 45- and 65-minute samples. Replication profiles generated for the WT strain (Figure S2) were consistent with previous studies [8]. Chromosome XIV displayed a strong peak at ARS1426 at the earliest time (40 minutes) in the time course and a less well-defined peak at ARS1410 (Figure 5A). Conversely, replication profiles in the rearranged strain displayed a shallow and late appearing peak at ARS1426 while the peak at ARS1410 appeared strong and early (Figure 5A and Figure S3) confirming the observations made by slot blot analysis of individual restriction fragments. To directly compare replication profiles from the two strains, the percent replication values from the 40, 45, and 65 minute samples were normalized by conversion to Z-scores (see Materials and Methods) and superimposed on the same axes (Figure 5B; Figures S4, S5, and S6).

Comparison of the Z-scores on chromosome XIV (Figure 5B) indicates that centromeres have a drastic influence over the activation times of their closest origins, suggesting that centromeres, mechanistically, operate locally. Z-score profiles for WT and rearranged chromosomes display a prominent early appearing peak centered about 19 kb to the left of the endogenous centromere. ARS1425 is a potential origin located between ARS1424 and the endogenous centromere [31]. However, 2D gel analysis demonstrated that ARS1424 is the origin likely responsible for this peak as ARS1425 is not active in either strain (data not shown). Replication timing analysis of ARS1424 by slot blot hybridization indicates that this origin is influenced by the centromere to a far lesser extent than ARS1426 (WT RI = 0.11, Rearranged RI = 0.27). That this mild effect on ARS1424 is not reflected in the Z-score overlays is likely due to the higher resolution of slot blot analysis compared to microarray analysis.

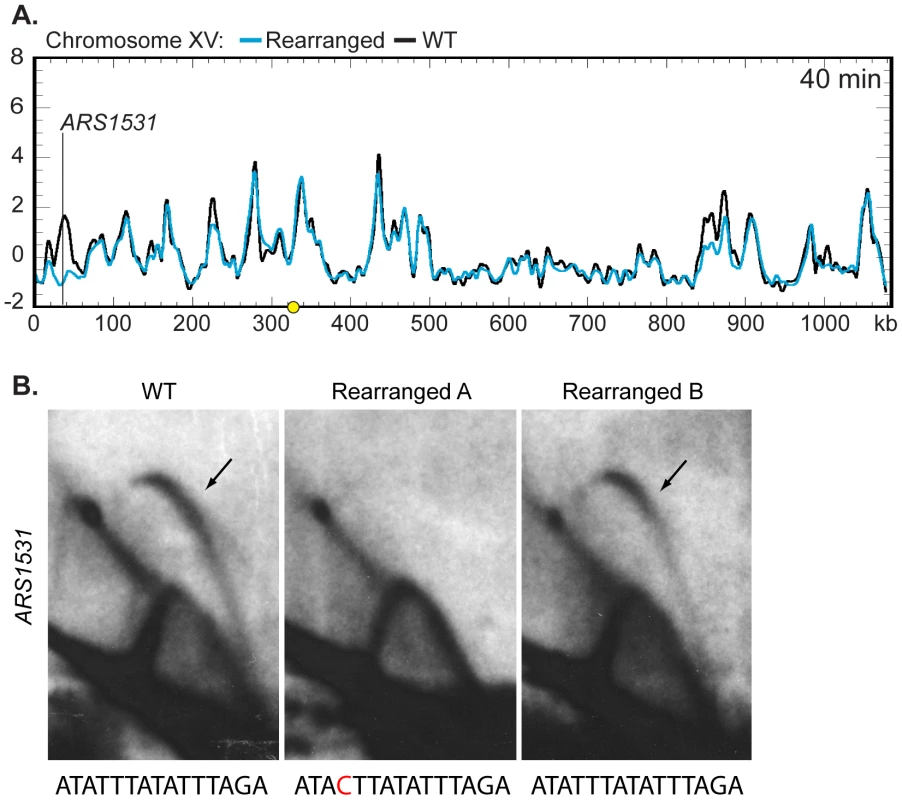

We then asked if the moved centromere influenced the activation times of origins located on other chromosomes. The replication kinetics of ARS1, a well-characterized origin on chromosome IV, were examined by slot blot hybridization and found to be similar between the two strains (WT RI = 0.68, Rearranged RI = 0.66) indicating that the activation time of ARS1 is not influenced by centromere position on chromosome XIV. The remaining profiles were examined by Z-score comparisons looking for possible trans effects of centromere position. The profiles were strikingly similar (Figures S4, S5, and S6). Only one other location, corresponding to ARS1531 on chromosome XV, showed a timing difference as drastic as that seen for ARS1410 and ARS1426 (Figure 6A; Figures S4, S5, S6). A prominent peak of high percent replication corresponding to ARS1531 was present in the WT strain while no peak was observed in the rearranged strain. However, further examination using 2D gel electrophoresis revealed that although ARS1531 is not an active origin in the isolate of the rearranged strain used for microarray analysis it is active in the WT strain as well as in the rearranged independent segregant used in the slot blot analysis of timing (Figure 6B; see Figure S1 for kinetic data for the independent segregant). These data suggest that the apparent timing change at this chromosome location is likely to be a consequence of a polymorphism affecting the ability of ARS1531 to function as an origin rather than from any long-range effect of the centromere. Sequencing of ARS1531 revealed that this origin in strain YTP16 contains a mutation in the essential ARS consensus sequence (ACS) [31] converting it from ATATTTATATTTAGA to ATACTTATATTTAGA (Figure 6B). A change of the T to a C at this position has been shown to entirely abolish origin activity in ARS307 [32]. ARS1531 does not contain this substitution in either YTP12 or YTP15. To confirm that this basepair change is responsible for the observed difference in origin activity, ARS1531 was cloned from YTP12 and YTP16 and tested for its ability to produce transformants in YTP12, YTP16, and YTP19. The “T” version of ARS1531 resulted in the formation of many robust colonies in the three strains tested whereas the “C” version of ARS1531 did not (data not shown).

Fig. 6. Z-score and 2D gel analysis of ARS1531.

(A) Z-score plot of chromosome XV in WT (black) and rearranged (blue) strains. ARS1531 displayed a difference of Z-score values at least as large as that seen for ARS1410 and ARS1426 (see Figure 5B). See Figure S4 for all chromosomes. (B) 2D gel analysis of ARS1531 in the WT (left), the rearranged strain used in microarray analysis (middle), and the rearranged strain used for prior slot blot analysis (right). DNA from all three strains was digested with NcoI and BglII to give a 3.18 kb fragment harboring ARS1531 and then subjected to 2D gel analysis. The presence of a bubble arc in the WT (black arrow) indicates that ARS1531 is a functional origin in this strain. The presence of a bubble arc in one of the two rearranged strains confirms that the absence of origin activity in rearranged A (used in microarray analysis) is not due to relocation of the centromere on chromosome XIV. Below each 2D gel image is the sequence for the WT or mutant (red) ACS. Discussion

In this study we investigated the long-standing question of why centromeres replicate early in S-phase. We considered two possibilities: (1) that some component required for centromere function is also involved in early origin activation, or (2) that evolution has favored the migration of centromeres to early replicating regions. It has been hypothesized that early origin initiation in S. cerevisiae is the default state for origin timing [24], suggesting a more passive mechanism for early centromere replication. However, the observation that early centromere replication is conserved [9]–[11] in conjunction with the identification of a DNA element that is not associated with centromeres but capable of advancing origin activation time [25], [26] indicates that establishment of early origin activation time is more complex than previously thought. Consistent with this idea, a recent study shows that the centromeres of C. albicans can alter the replication times of the loci in which they reside by allowing the formation of a de novo early firing origin [11]. Because the neocentromere in C. albicans creates a new origin, it is unclear whether C. albicans centromeres also directly influence origin activation time. These results raised the question of whether the relocation of a centromere would have a similar effect in organisms with point centromeres. In this study, we took advantage of the well-characterized centromeres and origins in S. cerevisiae to effectively separate the centromere from origin function and address these questions.

We show that centromeres in S. cerevisiae are capable of advancing the replication time of genomic regions in which they reside by inducing early activation of their adjacent origins at distances of 11.5 and 6.8 kb (compare ARS1410 and ARS1426 in WT and rearranged strains, Figure 2C and 2D). We also show that early activation of ARS1410 and ARS1426 depends on centromere function. We find that centromere-mediated early origin activation requires an intact CDEIII region, suggesting that early origin activation is dependent on at least some portion of the DNA-protein complex normally formed at the centromere. Thus, centromeres and at least a subset of the kinetochore proteins they assemble participate as cis-acting regulatory elements of origin firing time. Furthermore, our 2D gel results indicate that centromeres do not affect origin efficiency, suggesting that the mechanisms responsible for centromere-mediated early origin activation are distinct from those that determine efficiency.

S. cerevisiae centromeres are known to reside in large early replicating portions of the genome spanning as much as 100 kb and containing multiple origins [5]–[8]. In light of the finding that centromeres regulate the activation times of their closest origins, we were interested in determining over what distance centromeres exert their effect. Our genome-wide replication timing analysis indicates that the centromere's influence on origin activation time is severely diminished at a distance of ∼19 kb (Figure 5B and 5C) indicating that not all early replicating origins are under the centromere's influence. This result implies that there are at least two distinct mechanisms by which origins can fire early. In contrast to what has been observed in C. albicans, we see no evidence that the centromeres of S. cerevisiae create new origins.

The genome is not randomly organized within the nucleus but particular genomic regions co-localize or cluster into functional foci during processes such as DNA replication [33], [34]. In particular, centromeres in S. cerevisiae cluster throughout the cell cycle [35]. Therefore, it is plausible that centromeres, their neighboring origins, as well as other portions of the genome that interact with them, are clustered in G1 phase when timing decisions are made. This clustering could provide a way for centromeres to mediate replication time through a trans-acting mechanism. To determine if the mechanism responsible for centromere mediated early origin activation is capable of acting in trans, we examined the genome wide replication timing data for other timing changes occurring in the genome as a result of the repositioned centromere on chromosome XIV. We looked for differences in the Z-score profiles between matched S-phase samples, demanding that they persist over the course of S-phase (See Figures S4, S5, S6) to be considered significant.

Upon inspection, only one other location centered on ARS1531 displayed a timing difference of at least the same magnitude as observed for ARS1410 or ARS1426 (compare Figure 6A; Figures S4, S5, S6). 2D gel analysis and sequencing indicate that this timing difference is not a result of relocating the centromere position on chromosome XIV and that it is likely due to a polymorphism affecting the ability of ARS1531 to function in this particular isolate. Other than these three locations, the replication profiles are remarkably similar, suggesting that the mechanisms by which centromeres influence origin activation time are restricted to relatively limited adjacent regions. However, it is possible that centromeres contribute to smaller timing differences observed on other chromosomes such as that observed on chromosome XV at ∼850 kb (Figure 6A; Figures S4, S5, S6). Because the timing change at this location was only present in two of the three Z-scored samples, we did not consider it to be a significant timing difference.

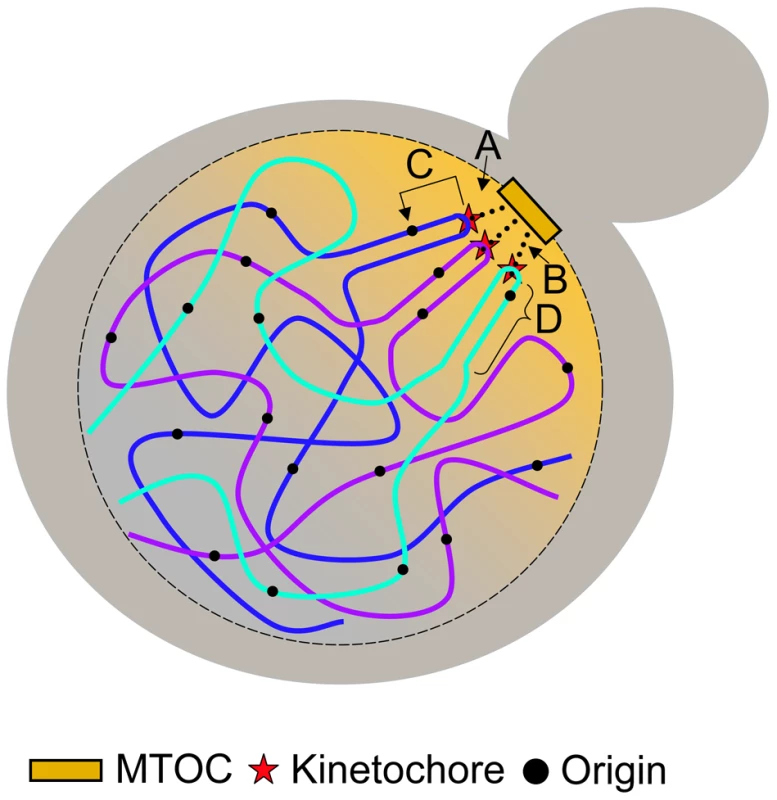

Here we show direct evidence of a molecular link between the establishment of the kinetochore and replication initiation machinery. Although the mechanism of centromere-mediated early origin activation is unknown, we show that such a mechanism is dependent on at least some of the protein components associated with the kinetochore that require an intact CDEIII region. We also show that the mechanism is capable of affecting initiation time of origins that reside up to ∼19 kb away from the centromere. We propose four possible models, which are not mutually exclusive (Figure 7): (1) The nuclear environment near the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) is particularly enriched in replication initiation factors; (2) The tension exerted by the microtubule is translated along the nearby DNA, altering its chromatin structure, thereby influencing the accessibility of the imbedded origins to initiation factors; (3) Proteins within the kinetochore directly (or indirectly) interact with initiation factors, recruiting them to nearby origins; and (4) The C-loop architecture of the pericentric chromatin (see below) ensures the origins within the C-loop will be at the periphery of the chromatin mass and are therefore more exposed to initiation factors. Studies examining the concentration of replication initiation proteins near MTOCs have not been conducted; however, nuclear pore complexes are enriched near MTOCs in S. cerevisiae [36], [37], the significance of which is unknown. While it is tempting to invoke localization to the nuclear periphery in the vicinity of MTOCs as a potential link between replication timing and centromeres, there is as yet no clear causal connection between nuclear localization and replication timing. Late origins tend to dwell at the nuclear periphery while early origins tend to be internal to the nucleus [38]. However, tethering an early origin to the nuclear periphery is not sufficient to alter its replication time [39] and conversely, delocalizing telomeres from the nuclear periphery does not advance their replication time [40]. Although experiments that test for protein-protein, protein-DNA, and DNA-DNA interactions of kinetochore/centromeric components have been reported, we are not aware of any experiments that bear directly on the second model (tension-mediated promotion of early origin activation).

Fig. 7. Models for centromere-mediated early origin activation.

(A) Kinetochore/microtubule interaction orients the centromere and pericentric DNA near the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) where there is an enrichment of replication initiation factors. (B) Tension exerted by the kinetochore/microtubule interaction induces an altered chromatin structure of pericentric DNA that provides accessibility of embedded origins to initiation factors. (C) Kinetochore proteins interact directly (or indirectly) with origin initiation factors recruiting them to nearby origins. (D) The organization of pericentric DNA into the C-loop orients origins within the C-loop to the periphery of the chromatin mass increasing their accessibility to initiation factors. Kinetochores are multiprotein complexes composed of over 60 proteins [19], [41]. Some of these proteins have been shown to interact both genetically and physically with proteins involved in regulating DNA replication [42]–[44]. However, as we are interested in molecular components that specify origin initiation time and these components have yet to be identified, it is not straightforward to determine which interacting protein candidates should be singled out for further study. A systematic way to parse through the various kinetochore components would be to determine if members of the inner-, mid-, or outer-kinetochore complexes are required for early origin initiation through the use of temperature sensitive alleles. Though this method poses it own set of challenges, it may prove to be fruitful in uncovering some of the mechanisms by which centromeres regulate origin activation time.

In vitro studies of protein-DNA interactions have shown that the CBF3 complex (composed of inner kinetochore DNA binding proteins) induces a 55° bend in centromeric DNA [45]. In concordance with this finding, more recent work from the Bloom lab has shown that pericentric DNA adopts a particular tertiary structure coined the C-loop [46]. The C-loop is characterized by an intramolecular loop centered on the centromere resembling a hairpin of duplex DNA. C-loop formation is dependent on a subset of inner kinetochore proteins that physically bind centromere DNA, namely those that bind the CDEIII region [46], [47]. Cohesin, which is enriched in pericentromeric regions [48]–[50], is thought to stabilize the C-loop following centromere replication [46]. Additonally, this study reports that the C-loop is present in G1-phase during alpha factor arrest, suggesting that neither the presence of a sister chromatid nor pericentric cohesin is essential for the maintenance of the structure. Interestingly, the intramolecular interaction of the C-loop is reported to extend more than ∼11.5 kb and less than 25 kb from the centromere, a distance similar to the findings reported in this study over which centromeres can regulate origin activation time. Anderson et al. hypothesized that proteins involved in the C-loop formation provide an essential geometry required for centromere position and accessibility for microtubule binding [47]. In light of these data, it is tempting to hypothesize that this geometry provides a favorable environment for early origin initiation by increasing the accessibility of nearby origins to replication initiation machinery.

Although the DNA binding components of the inner kinetochore are not well conserved, in human cells a DNA binding component of the inner kinetochore, CENP-B, has been shown to induce a ∼59° bend in its target sequence [51], suggesting that regional centromeres also adopt a particular configuration. Therefore, this model can also explain how centromeres can vary greatly at the sequence level yet still affect timing of their associated origins.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains

Strain and vector genotypes can be found in Table S1. Primer sequences can be found in Table S2. All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study were derived from a cross of CH1870 obtained from [27] and S288C. CH1870 is a mating type alpha strain derived from the S288C background. The MET2 locus of this strain (located on chromosome XIV) was disrupted by an insertion of centromere VII sequence and LEU2. The endogenous centromere on chromosome XIV of CH1870 was also replaced with a URA3 selectable marker [27].

The ura3-52 allele in YTP13 (derived from a CH1870 to S288C cross) was restored to URA3 by gene replacement, resulting in YTP15 (WT strain in this study, Table S1). Restoration was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Independent segregants of the rearranged strains (YTP12 and YTP16) were obtained from separate tetrads from a CH1870 to S288C cross as met−, leu+, and ura+ progeny. Three different PCR reactions using primer pairs 71∶72, 72∶88, and 71∶126 were used to confirm that these strains contained the desired inserted sequence at the MET2 locus (data not shown). The desired insertion was further confirmed by Southern blot analysis on genomic DNA that was digested with XbaI (data not shown).

Mutant centromere at the met2 locus

YTP19 was constructed to have the same met2::CEN7.LEU2 cassette as YTP12 and YTP16 save for a 3 bp mutation in CDEIII. The mutation of CDEIII in the centromere sequence integrated at MET2 was made non-functional through site directed mutagenesis [52]. This strain was constructed as follows: Two halves of met2::CEN7.LEU2 were PCR amplified from YTP12 using primer pairs 71∶133, and 72∶134. Primer pair 71∶133 was used to amplify the 5′ end of met2 with primer 71 hybridizing upstream of the BsmI restriction site located in met2 and primer 133 hybridizing downstream of the EcoRV restriction site located in the LEU2 gene. Primer pair 72∶134 was used to amplify the 3′ end of met2 with primer 72 hybridizing downstream of met2 and primer 134 hybridizing upstream of the EcoRV restriction site located in the LEU2 gene. The PCR products were sequentially digested with either BsmI or AatII followed by an EcoRV digest. The two fragments were then inserted into a pUC18 vector that contained KanMX and ARS228 through a tri-molecular ligation reaction, creating plasmid pTP18.

The centromere on plasmid pTP18 was made non-functional, creating pTP19, through site directed mutagenesis using primers 147 and 148 [52]. These primers were used to mutate the Centromere DNA Element III (CDEIII) from TCCGAA to TCTAGA, introducing an XbaI site into the sequence. The most important bases for centromere function are the middle CG in TCCGAA [1], [45]. The mutated centromere sequence on pTP19 was Sanger sequenced to ensure that only CGA had been changed. The lack of centromere activity in pTP19 was confirmed by a plasmid stability assay in which serially diluted cells were spotted to selective medium over 24 generations (data not shown).

The 4025 bp AatII/BsmI fragment of plasmid pTP19 containing met2::cen7.LEU2 was transformed into YTP15 [53], [54]. Transformants were selected on synthetic dropout (SD) medium plates lacking leucine. Cells were then replica-plated to SD medium lacking methionine. Colonies that were prototrophic for leucine and auxotrophic for methionine were further screened similar to the rearranged strains mentioned earlier using PCR primer pairs 71∶72 and 72∶88 and through Southern blot analysis on XbaI digested genomic DNA.

Two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis

Origin activity was analyzed by standard 2D agarose gel electrophoresis techniques performed on total genomic DNA obtained from either asynchronous or synchronous S phase cells [55]–[57]. Asynchronous samples were used for 2D gels conducted on ARS1426, ARS1531, and met2::CEN7. Synchronized samples were used for 2D gels conducted on ARS1410 and MET2. For asynchronous samples, cells were collected in early log phase. For synchronized samples, cells were arrested in G1-phase with alpha factor (final concentration 3 µM) and released synchronously into S-phase by the addition of pronase (0.15 mg/mL). Cells were then collected every 2 minutes and pooled. Genomic DNA was harvested similar to asynchronous samples. In the first dimension, DNA was separated in 0.4% agarose for 18–20 hours at 1 V/cm. The second dimension was run for 3–3.5 hours in 1.1% agarose containing Ethidium Bromide (0.3 µg/mL) at ∼5–6 V/cm at 4°C.

Flow cytometry

Cells were harvested by mixing with 0.1% sodium azide in 0.2 M EDTA and then fixed with 70% ethanol. Flow cytometry was performed as previously described [58] upon staining cells with Sytox Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The data were analyzed with CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Density transfer experiments

Density transfer experiments were performed as described in [4] with slight modifications in cell synchronization and sample preparation for microarray analysis [6]. Cells were grown overnight at 23°C in a 5 mL culture of dense medium containing 13C-glucose at 0.1% (w/v) and 15N-ammonium sulfate at 0.01% (w/v). Cells were then diluted into a larger vessel in dense medium and allowed to reach an optical density of 0.16 (∼2×106 cells/mL). Cells were arrested in G1 by incubating with 3 µM alpha factor until at least 95% of cells were unbudded based on microscopic analysis. Cells were then filtered and transferred to medium containing 12C-glucose (2%), 14N-ammonium sulfate (0.5%), and alpha factor. Cells were then synchronously released from the G1 arrest through the addition of pronase at a concentration of 0.15 mg/mL. Samples were collected every 10 minutes. Cell samples were treated with a mixture of 0.1% odium azide and 0.2 M EDTA then pelleted and frozen at −20°C. Genomic DNA was extracted from pelleted cells, digested with EcoRI, and the DNA fragments were separated based on density by ultracentrifugation in cesium chloride gradients. Gradients were drip fractionated and slot blotted to nylon membrane where they were hybridized with probes of interest. Unreplicated DNA is HH in density while replicated DNA is HL in density.

Replication kinetics and analysis

To construct replication kinetic curves, slot blots were hybridized to sequences of interest, and the percent replication in each timed sample was calculated as described in [4], [6], [8]. A detailed protocol can be found at http://fangman-brewer.genetics.washington.edu/density_transfer.html. The time at which the kinetic curves reach half maximal defines the time of replication (Trep) for each individual locus within the population of cycling cells. However, because not all G1 cells will enter or complete S-phase, Trep for the probed regions in this study were calculated based on the plateau of the replication kinetic curve for a genomic probe consisting of EcoRI digested total genomic DNA from a strain lacking mitochondrial DNA.

To compare timing differences between strains, Trep values were converted to replication indices in the following manner. First the Trep values of two timing standards, ARS306 (a known early replicating region) and R11 (a known late replicating region near ARS501), were obtained and assigned the values of 0 and 1, respectively. Next the Trep values of regions of interest were assigned a replication index corresponding to the fraction of the ARS306-R11 interval elapsed at the time at which the Trep for each locus was obtained. Replication index is calculated as (Trep(X)−Trep(ARS306))/( Trep(ARS306)−Trep(R11)) where X is the fragment of interest.

For microarray analysis, slot blots were hybridized with a genomic DNA probe to indentify fractions containing either HH or HL DNA. Once identified, the HH and HL fractions were separately pooled and differentially labeled with cyanine (Cy3 or Cy5) conjugated dUTP (Perkin Elmer) [8]. Timed samples were hybridized to high density Agilent yeast ChIP-to-chip 4×44 K arrays according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The algorithms for analyzing microarray data are described in [16]. An 18 kb window was used for overall smoothing.

To facilitate direct comparison of replication profiles, percent replication values obtained from microarray analysis were converted to Z-score values. Z-score values were calculated using the following formula: Z = (X−μ)/σ where X = the percent replication value for a given probe, μ = the genomic average percent replication for a given sample, and σ = the standard deviation of the distribution of X. The 55 minute samples were not used because the genomic percent replication values were not well matched between the two strains.

Note added in proof

Two recent findings in yeast add interesting perspectives on the centromere effect on origin activation. First, the lack of forkhead proteins Fkh1 and Fkh2 results in delayed activation of a large number of normally early-firing origins, but centromere-proximal origins remain early-firing (Knott et al. 2012, Cell 148 : 99–111). Second, while many origins show delayed activation in meiotic S phase compared to mitotic S, centromere-proximal origins do not show such a delay (Blitzblau et al., PLoS Genetics, in press). Both findings are consistent with the idea that some aspect of centromere function directly influences the activation of centromere-proximal origins through a mechanism that is independent of other, more global controls.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HegemannJHFleigUN 1993 The centromere of budding yeast. Bioessays 15 451 460

2. McGrewJDiehlBFitzgerald-HayesM 1986 Single base-pair mutations in centromere element III cause aberrant chromosome segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 6 530 538

3. JallepalliPVLengauerC 2001 Chromosome segregation and cancer: cutting through the mystery. Nat Rev Cancer 1 109 117

4. McCarrollRMFangmanWL 1988 Time of replication of yeast centromeres and telomeres. Cell 54 505 513

5. YabukiNTerashimaHKitadaK 2002 Mapping of early firing origins on a replication profile of budding yeast. Genes Cells 7 781 789

6. RaghuramanMKWinzelerEACollingwoodDHuntSWodickaL 2001 Replication dynamics of the yeast genome. Science 294 115 121

7. McCuneHJDanielsonLSAlvinoGMCollingwoodDDelrowJJ 2008 The temporal program of chromosome replication: genomewide replication in clb5Δ Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 180 1833 1847

8. AlvinoGMCollingwoodDMurphyJMDelrowJBrewerBJ 2007 Replication in hydroxyurea: it's a matter of time. Mol Cell Biol 27 6396 6406

9. KimSMDubeyDDHubermanJA 2003 Early-replicating heterochromatin. Genes Dev 17 330 335

10. AhmadKHenikoffS 2001 Centromeres are specialized replication domains in heterochromatin. J Cell Biol 153 101 110

11. KorenATsaiHJTiroshIBurrackLSBarkaiN 2010 Epigenetically-inherited centromere and neocentromere DNA replicates earliest in S-phase. PLoS Genet 6 e1001068 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001068

12. Weidtkamp-PetersSRahnHPCardosoMCHemmerichP 2006 Replication of centromeric heterochromatin in mouse fibroblasts takes place in early, middle, and late S phase. Histochem Cell Biol 125 91 102

13. SchubelerDScalzoDKooperbergCvan SteenselBDelrowJ 2002 Genome-wide DNA replication profile for Drosophila melanogaster: a link between transcription and replication timing. Nat Genet 32 438 442

14. TanakaKMukaeNDewarHvan BreugelMJamesEK 2005 Molecular mechanisms of kinetochore capture by spindle microtubules. Nature 434 987 994

15. FuruyamaSBigginsS 2007 Centromere identity is specified by a single centromeric nucleosome in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 14706 14711

16. FengWBachantJCollingwoodDRaghuramanMKBrewerBJ 2009 Centromere replication timing determines different forms of genomic instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae checkpoint mutants during replication stress. Genetics 183 1249 1260

17. HayashiMKatouYItohTTazumiAYamadaY 2007 Genome-wide localization of pre-RC sites and identification of replication origins in fission yeast. EMBO J 26 1327 1339

18. SclafaniRAHolzenTM 2007 Cell cycle regulation of DNA replication. Annu Rev Genet 41 237 280

19. SantaguidaSMusacchioA 2009 The life and miracles of kinetochores. EMBO J 28 2511 2531

20. Fitzgerald-HayesMClarkeLCarbonJ 1982 Nucleotide sequence comparisons and functional analysis of yeast centromere DNAs. Cell 29 235 244

21. ClarkeL 1990 Centromeres of budding and fission yeasts. Trends Genet 6 150 154

22. FriedmanKLDillerJDFergusonBMNylandSVBrewerBJ 1996 Multiple determinants controlling activation of yeast replication origins late in S phase. Genes Dev 10 1595 1607

23. FergusonBMFangmanWL 1992 A position effect on the time of replication origin activation in yeast. Cell 68 333 339

24. FergusonBMBrewerBJReynoldsAEFangmanWL 1991 A yeast origin of replication is activated late in S phase. Cell 65 507 515

25. KolorK 1997 Advancement of the timing of an origin activation by a cis-acting DNA element. PhD Dissertation, University of Washington

26. BrewerBJFangmanWL 1994 Initiation preference at a yeast origin of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91 3418 3422

27. SpellRMHolmC 1994 Nature and distribution of chromosomal intertwinings in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 14 1465 1476

28. BrewerBJFangmanWL 1987 The localization of replication origins on ARS plasmids in S. cerevisiae. Cell 51 463 471

29. DonaldsonADRaghuramanMKFriedmanKLCrossFRBrewerBJ 1998 CLB5-dependent activation of late replication origins in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell 2 173 182

30. LechnerJOrtizJ 1996 The Saccharomyces cerevisiae kinetochore. FEBS Lett 389 70 74

31. NieduszynskiCAHiragaSAkPBenhamCJDonaldsonAD 2007 OriDB: a DNA replication origin database. Nucleic Acids Res 35 D40 46

32. Van HoutenJVNewlonCS 1990 Mutational analysis of the consensus sequence of a replication origin from yeast chromosome III. Mol Cell Biol 10 3917 3925

33. KitamuraEBlowJJTanakaTU 2006 Live-cell imaging reveals replication of individual replicons in eukaryotic replication factories. Cell 125 1297 1308

34. DuanZAndronescuMSchutzKMcIlwainSKimYJ 2010 A three-dimensional model of the yeast genome. Nature 465 363 367

35. JinQTrelles-StickenEScherthanHLoidlJ 1998 Yeast nuclei display prominent centromere clustering that is reduced in nondividing cells and in meiotic prophase. J Cell Biol 141 21 29

36. WineyMYararDGiddingsTHJrMastronardeDN 1997 Nuclear pore complex number and distribution throughout the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle by three-dimensional reconstruction from electron micrographs of nuclear envelopes. Mol Biol Cell 8 2119 2132

37. HeathCVCopelandCSAmbergDCDel PrioreVSnyderM 1995 Nuclear pore complex clustering and nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA associated with mutation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAT2/NUP120 gene. J Cell Biol 131 1677 1697

38. HeunPLarocheTRaghuramanMKGasserSM 2001 The positioning and dynamics of origins of replication in the budding yeast nucleus. J Cell Biol 152 385 400

39. EbrahimiHRobertsonEDTaddeiAGasserSMDonaldsonAD 2010 Early initiation of a replication origin tethered at the nuclear periphery. J Cell Sci 123 1015 1019

40. HiragaSRobertsonEDDonaldsonAD 2006 The Ctf18 RFC-like complex positions yeast telomeres but does not specify their replication time. EMBO J 25 1505 1514

41. BouckDCJoglekarAPBloomKS 2008 Design features of a mitotic spindle: balancing tension and compression at a single microtubule kinetochore interface in budding yeast. Annu Rev Genet 42 335 359

42. AkiyoshiBSarangapaniKKPowersAFNelsonCRReichowSL 2010 Tension directly stabilizes reconstituted kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Nature 468 576 579

43. FerniusJMarstonAL 2009 Establishment of cohesion at the pericentromere by the Ctf19 kinetochore subcomplex and the replication fork-associated factor, Csm3. PLoS Genet 5 e1000629 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000629

44. RanjitkarPPressMOYiXBakerRMacCossMJ 2010 An E3 ubiquitin ligase prevents ectopic localization of the centromeric histone H3 variant via the centromere targeting domain. Mol Cell 40 455 464

45. PietrasantaLIThrowerDHsiehWRaoSStemmannO 1999 Probing the Saccharomyces cerevisiae centromeric DNA (CEN DNA)-binding factor 3 (CBF3) kinetochore complex by using atomic force microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 3757 3762

46. YehEHaaseJPaliulisLVJoglekarABondL 2008 Pericentric chromatin is organized into an intramolecular loop in mitosis. Curr Biol 18 81 90

47. AndersonMHaaseJYehEBloomK 2009 Function and assembly of DNA looping, clustering, and microtubule attachment complexes within a eukaryotic kinetochore. Mol Biol Cell 20 4131 4139

48. MegeePCMistrotCGuacciVKoshlandD 1999 The centromeric sister chromatid cohesion site directs Mcd1p binding to adjacent sequences. Mol Cell 4 445 450

49. TanakaTCosmaMPWirthKNasmythK 1999 Identification of cohesin association sites at centromeres and along chromosome arms. Cell 98 847 858

50. WeberSAGertonJLPolancicJEDeRisiJLKoshlandD 2004 The kinetochore is an enhancer of pericentric cohesin binding. PLoS Biol 2 e260 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030094

51. TanakaYNurekiOKurumizakaHFukaiSKawaguchiS 2001 Crystal structure of the CENP-B protein-DNA complex: the DNA-binding domains of CENP-B induce kinks in the CENP-B box DNA. EMBO J 20 6612 6618

52. LaibleMBoonrodK 2009 Homemade site directed mutagenesis of whole plasmids. J Vis Exp 27 1135

53. SchiestlRHGietzRD 1989 High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet 16 339 346

54. GietzRDSchiestlRHWillemsARWoodsRA 1995 Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast 11 355 360

55. HubermanJASpotilaLDNawotkaKAel-AssouliSMDavisLR 1987 The in vivo replication origin of the yeast 2 µm plasmid. Cell 51 473 481

56. BrewerBJLockshonDFangmanWL 1992 The arrest of replication forks in the rDNA of yeast occurs independently of transcription. Cell 71 267 276

57. BrewerBJFangmanWL 1991 Mapping replication origins in yeast chromosomes. Bioessays 13 317 322

58. HutterKJEipelHE 1979 Microbial determinations by flow cytometry. J Gen Microbiol 113 369 375

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Dynamic Deposition of Histone Variant H3.3 Accompanies Developmental Remodeling of the TranscriptomeČlánek Integrin α PAT-2/CDC-42 Signaling Is Required for Muscle-Mediated Clearance of Apoptotic Cells inČlánek Prdm5 Regulates Collagen Gene Transcription by Association with RNA Polymerase II in Developing BoneČlánek Acquisition Order of Ras and p53 Gene Alterations Defines Distinct Adrenocortical Tumor Phenotypes

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 5

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Slowing Replication in Preparation for Reduction

- Chromosome Pairing: A Hidden Treasure No More

- Loss of Imprinting Differentially Affects REM/NREM Sleep and Cognition in Mice

- Six Novel Susceptibility Loci for Early-Onset Androgenetic Alopecia and Their Unexpected Association with Common Diseases

- Regulation by the Noncoding RNA

- UDP-Galactose 4′-Epimerase Activities toward UDP-Gal and UDP-GalNAc Play Different Roles in the Development of

- Deletion of PTH Rescues Skeletal Abnormalities and High Osteopontin Levels in Mice

- Karyotypic Determinants of Chromosome Instability in Aneuploid Budding Yeast

- Genome-Wide Copy Number Analysis Uncovers a New HSCR Gene:

- MicroRNA-277 Modulates the Neurodegeneration Caused by Fragile X Premutation rCGG Repeats

- Functional Centromeres Determine the Activation Time of Pericentric Origins of DNA Replication in

- Dynamic Deposition of Histone Variant H3.3 Accompanies Developmental Remodeling of the Transcriptome

- Scientist Citizen: An Interview with Bruce Alberts

- YY1 Regulates Melanocyte Development and Function by Cooperating with MITF

- Congenital Heart Disease–Causing Gata4 Mutation Displays Functional Deficits

- Recombination Drives Vertebrate Genome Contraction

- KATNAL1 Regulation of Sertoli Cell Microtubule Dynamics Is Essential for Spermiogenesis and Male Fertility

- Re-Patterning Sleep Architecture in through Gustatory Perception and Nutritional Quality

- Using Whole-Genome Sequence Data to Predict Quantitative Trait Phenotypes in

- Genome-Wide Analysis of GLD-1–Mediated mRNA Regulation Suggests a Role in mRNA Storage

- Meiotic Chromosome Pairing Is Promoted by Telomere-Led Chromosome Movements Independent of Bouquet Formation

- LINT, a Novel dL(3)mbt-Containing Complex, Represses Malignant Brain Tumour Signature Genes

- The H3K27 Demethylase UTX-1 Is Essential for Normal Development, Independent of Its Enzymatic Activity

- Suppresses Senescence Programs and Thereby Accelerates and Maintains Mutant -Induced Lung Tumorigenesis

- Genome-Wide Association of Pericardial Fat Identifies a Unique Locus for Ectopic Fat

- An Essential Role for Katanin p80 and Microtubule Severing in Male Gamete Production

- Identification of Genes That Promote or Antagonize Somatic Homolog Pairing Using a High-Throughput FISH–Based Screen

- Principles of Carbon Catabolite Repression in the Rice Blast Fungus: Tps1, Nmr1-3, and a MATE–Family Pump Regulate Glucose Metabolism during Infection

- Integrin α PAT-2/CDC-42 Signaling Is Required for Muscle-Mediated Clearance of Apoptotic Cells in

- Histone H3 Localizes to the Centromeric DNA in Budding Yeast

- Collapse of Telomere Homeostasis in Hematopoietic Cells Caused by Heterozygous Mutations in Telomerase Genes

- Hypersensitive to Red and Blue 1 and Its Modification by Protein Phosphatase 7 Are Implicated in the Control of Arabidopsis Stomatal Aperture

- Extent, Causes, and Consequences of Small RNA Expression Variation in Human Adipose Tissue

- TBC-8, a Putative RAB-2 GAP, Regulates Dense Core Vesicle Maturation in

- Regulating Repression: Roles for the Sir4 N-Terminus in Linker DNA Protection and Stabilization of Epigenetic States

- Common Genetic Determinants of Intraocular Pressure and Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

- Prdm5 Regulates Collagen Gene Transcription by Association with RNA Polymerase II in Developing Bone

- Fitness Landscape Transformation through a Single Amino Acid Change in the Rho Terminator

- Repeated, Selection-Driven Genome Reduction of Accessory Genes in Experimental Populations

- Allelic Variation and Differential Expression of the mSIN3A Histone Deacetylase Complex Gene Promote Mammary Tumor Growth and Metastasis

- DNA Demethylation and USF Regulate the Meiosis-Specific Expression of the Mouse

- Knowledge-Driven Analysis Identifies a Gene–Gene Interaction Affecting High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Multi-Ethnic Populations

- A Duplication CNV That Conveys Traits Reciprocal to Metabolic Syndrome and Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice and Men

- EMT Inducers Catalyze Malignant Transformation of Mammary Epithelial Cells and Drive Tumorigenesis towards Claudin-Low Tumors in Transgenic Mice

- Inactivation of a Novel FGF23 Regulator, FAM20C, Leads to Hypophosphatemic Rickets in Mice

- Genome-Wide Association for Abdominal Subcutaneous and Visceral Adipose Reveals a Novel Locus for Visceral Fat in Women

- Stratifying Type 2 Diabetes Cases by BMI Identifies Genetic Risk Variants in and Enrichment for Risk Variants in Lean Compared to Obese Cases

- New Insight into the History of Domesticated Apple: Secondary Contribution of the European Wild Apple to the Genome of Cultivated Varieties

- Activated Cdc42 Kinase Has an Anti-Apoptotic Function

- The Region Is Critical for Birth Defects and Electrocardiographic Dysfunctions Observed in a Down Syndrome Mouse Model

- COP9 Signalosome Integrity Plays Major Roles for Hyphal Growth, Conidial Development, and Circadian Function

- Bmps and Id2a Act Upstream of Twist1 To Restrict Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

- Psip1/Ledgf p52 Binds Methylated Histone H3K36 and Splicing Factors and Contributes to the Regulation of Alternative Splicing

- The Number of X Chromosomes Causes Sex Differences in Adiposity in Mice

- Target Gene Analysis by Microarrays and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Identifies HEY Proteins as Highly Redundant bHLH Repressors

- Acquisition Order of Ras and p53 Gene Alterations Defines Distinct Adrenocortical Tumor Phenotypes

- ELK1 Uses Different DNA Binding Modes to Regulate Functionally Distinct Classes of Target Genes

- Histone H1 Depletion Impairs Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation

- IDN2 and Its Paralogs Form a Complex Required for RNA–Directed DNA Methylation

- Separation of DNA Replication from the Assembly of Break-Competent Meiotic Chromosomes

- Genomic Hypomethylation in the Human Germline Associates with Selective Structural Mutability in the Human Genome

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Inactivation of a Novel FGF23 Regulator, FAM20C, Leads to Hypophosphatemic Rickets in Mice

- Genome-Wide Association of Pericardial Fat Identifies a Unique Locus for Ectopic Fat

- Slowing Replication in Preparation for Reduction

- An Essential Role for Katanin p80 and Microtubule Severing in Male Gamete Production

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání