-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Genome of a Pathogenic : Cooptive Virulence Underpinned by Key Gene Acquisitions

We report the genome of the facultative intracellular parasite Rhodococcus equi, the only animal pathogen within the biotechnologically important actinobacterial genus Rhodococcus. The 5.0-Mb R. equi 103S genome is significantly smaller than those of environmental rhodococci. This is due to genome expansion in nonpathogenic species, via a linear gain of paralogous genes and an accelerated genetic flux, rather than reductive evolution in R. equi. The 103S genome lacks the extensive catabolic and secondary metabolic complement of environmental rhodococci, and it displays unique adaptations for host colonization and competition in the short-chain fatty acid–rich intestine and manure of herbivores—two main R. equi reservoirs. Except for a few horizontally acquired (HGT) pathogenicity loci, including a cytoadhesive pilus determinant (rpl) and the virulence plasmid vap pathogenicity island (PAI) required for intramacrophage survival, most of the potential virulence-associated genes identified in R. equi are conserved in environmental rhodococci or have homologs in nonpathogenic Actinobacteria. This suggests a mechanism of virulence evolution based on the cooption of existing core actinobacterial traits, triggered by key host niche–adaptive HGT events. We tested this hypothesis by investigating R. equi virulence plasmid-chromosome crosstalk, by global transcription profiling and expression network analysis. Two chromosomal genes conserved in environmental rhodococci, encoding putative chorismate mutase and anthranilate synthase enzymes involved in aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, were strongly coregulated with vap PAI virulence genes and required for optimal proliferation in macrophages. The regulatory integration of chromosomal metabolic genes under the control of the HGT–acquired plasmid PAI is thus an important element in the cooptive virulence of R. equi.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001145

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001145Summary

We report the genome of the facultative intracellular parasite Rhodococcus equi, the only animal pathogen within the biotechnologically important actinobacterial genus Rhodococcus. The 5.0-Mb R. equi 103S genome is significantly smaller than those of environmental rhodococci. This is due to genome expansion in nonpathogenic species, via a linear gain of paralogous genes and an accelerated genetic flux, rather than reductive evolution in R. equi. The 103S genome lacks the extensive catabolic and secondary metabolic complement of environmental rhodococci, and it displays unique adaptations for host colonization and competition in the short-chain fatty acid–rich intestine and manure of herbivores—two main R. equi reservoirs. Except for a few horizontally acquired (HGT) pathogenicity loci, including a cytoadhesive pilus determinant (rpl) and the virulence plasmid vap pathogenicity island (PAI) required for intramacrophage survival, most of the potential virulence-associated genes identified in R. equi are conserved in environmental rhodococci or have homologs in nonpathogenic Actinobacteria. This suggests a mechanism of virulence evolution based on the cooption of existing core actinobacterial traits, triggered by key host niche–adaptive HGT events. We tested this hypothesis by investigating R. equi virulence plasmid-chromosome crosstalk, by global transcription profiling and expression network analysis. Two chromosomal genes conserved in environmental rhodococci, encoding putative chorismate mutase and anthranilate synthase enzymes involved in aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, were strongly coregulated with vap PAI virulence genes and required for optimal proliferation in macrophages. The regulatory integration of chromosomal metabolic genes under the control of the HGT–acquired plasmid PAI is thus an important element in the cooptive virulence of R. equi.

Introduction

Rhodococcus bacteria belong to the mycolic acid-containing group of actinomycetes together with other major genera such as Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium and Nocardia [1]. The genus Rhodococcus comprises more than 40 species widely distributed in the environment, many with biotechnological applications as diverse as the biodegradation of hydrophobic compounds and xenobiotics, the production of acrylates and bioactive steroids, and fossil fuel desulfurization [2]. The rhodococci also include an animal pathogen, Rhodococcus equi, the genome of which we report here.

R. equi, a strictly aerobic coccobacillus, is a multihost pathogen that causes purulent infections in various animal species. In horses, it is the etiological agent of “rattles”, a lung disease with a high mortality in foals [3]. R. equi lives in soil, uses manure as growth substrate, and is transmitted by the inhalation of contaminated soil dust or the breath of infected animals. Pathogen ingestion may result in mesenteric lymphadenitis and typhlocolitis, and multiplication in the fecal content of the intestine contributes to dissemination in the environment. R. equi causes chronic pyogranulomatous adenitis in pigs and cattle and severe opportunistic infections in humans, often in HIV-infected and immunosuppressed patients. Human rhodococcal lung infection resembles pulmonary tuberculosis and has a high case-fatality rate [3], [4].

R. equi parasitizes macrophages and, like Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), replicates within a membrane-bound vacuole. A 80–90 kb virulence plasmid confers the ability to arrest phagosome maturation, survive and proliferate in macrophages in vitro and mouse tissues in vivo, and to cause disease in horses. Virulence-associated protein A (VapA), a major plasmid-encoded surface antigen, is thought to mediate these effects [5]–[7]. The vapA gene is located within a horizontally-acquired pathogenicity island (PAI) together with several other vap genes [8]. Equine, porcine and bovine isolates carry specific virulence plasmid types differing in PAI structure and vap multigene complement, suggesting a role for vap PAI components in R. equi host tropism [8], [9].

Apart from the key role of the plasmid vap PAI, little is known about the pathogenic mechanisms of R. equi. We investigated the biology and virulence of this pathogenic actinomycete by sequencing an analysing the genome of strain 103S, a prototypic clinical isolate. With its dual lifestyle as a soil saprotroph and intracellular parasite, R. equi offers an attractive model for evolutionary genomics studies of niche breadth in Actinobacteria. The comparative genomic analysis of R. equi and closely related environmental rhodococi reported here provides insight into the mechanisms of niche-adaptive genome plasticity and evolution in this bacterial group. The R. equi genome also provides fundamental clues to the shaping of virulence in Actinobacteria.

Results/Discussion

General genome features

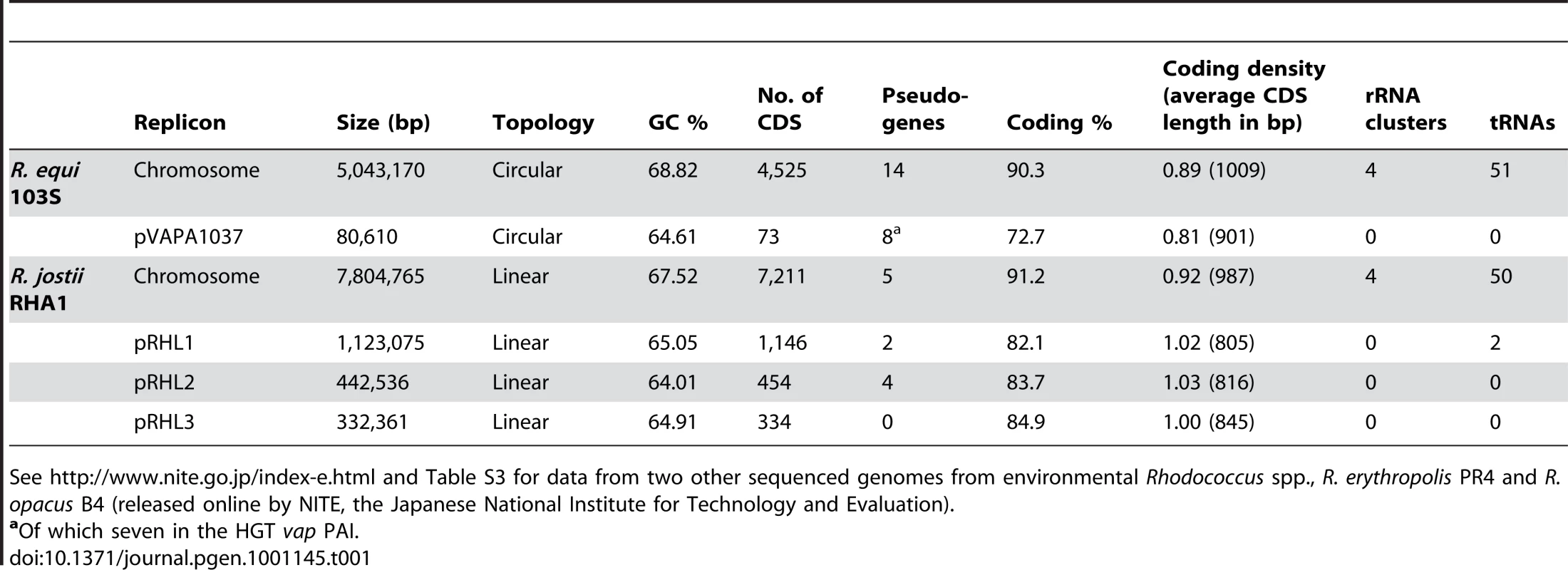

The genome of R. equi 103S consists of a circular chromosome of 5,043,170 bp with 4,525 predicted genes (Figure S1) and a circular virulence plasmid of 80,610 bp containing 73 predicted genes [8]. Overall G+C content is 68.76%. Table 1 summarizes the main features of the R. equi genome.

Tab. 1. General features of the genomes of R. equi 103S and the environmental species, R. jostii RHA1.

See http://www.nite.go.jp/index-e.html and Table S3 for data from two other sequenced genomes from environmental Rhodococcus spp., R. erythropolis PR4 and R. opacus B4 (released online by NITE, the Japanese National Institute for Technology and Evaluation). Comparative analysis

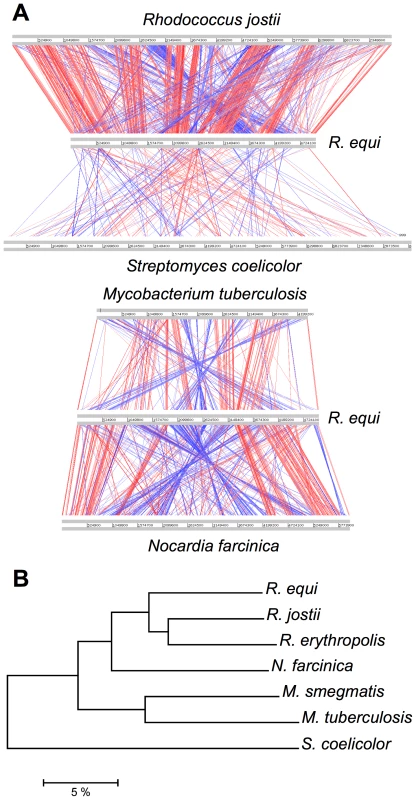

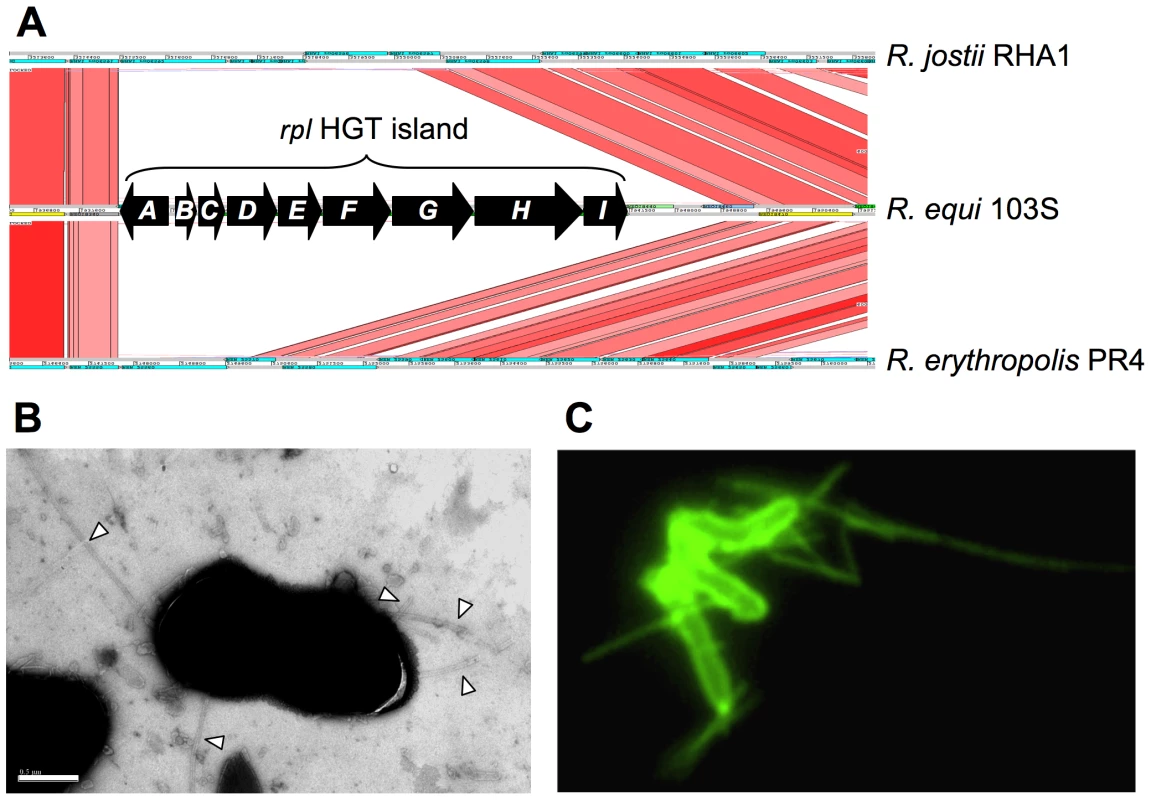

Orthology analyses (Figure S1) and multiple alignments (Figure 1A) with representative published actinobacterial genomes showed the highest degree of homology and synteny conservation with Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 [10]. Next in overall genome similarity was Nocardia farcinica, followed by Mycobacterium spp., whereas Streptomyces coelicolor appeared much more distantly related, consistent with 16S rRNA-derived actinobacterial phylogenies. Some phylogenetic studies have been inconclusive, positioning R. equi either with the nocardiae or rhodococci [1], [11]. Our genome-wide comparative and phylogenomic analyses indicate this species is a bona fide member of the genus Rhodococcus (Figure 1, Figure S2).

Fig. 1. Comparative genomics and phylogenomics of R. equi 103S.

(A) Pairwise chromosome alignments of R. equi 103S, R. jostii RHA1, N. farcinica IFM10152, M. tuberculosis (Mtb) H37Rv and S. coelicolor A3(2) genomes. Performed with Artemis Comparison Tool (ACT), see Table S12. Red and blue lines connect homologous regions (tBLASTx) in direct and reverse orientation, respectively. Mean identity of shared core orthologs between R. equi and: R. jostii RHA1, 75.08%; N. farcinica, 72.1%; Mtb, 64.6% (see also Figures S1, S2, and S5). (B) Phylogenomic analysis of Rhodococcus spp. and four other representative actinobacterial species. Unrooted neighbor-joining tree based on percent amino-acid identity of a sample of 665 shared core orthologs. The scale shows similarity distance in percentage. Interestingly, R. equi has a substantially smaller genome than the soil-restricted versatile biodegrader R. jostii RHA1 (9.7 Mb) [10] and two recently sequenced environmental rhodococci, Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4 (6.89 Mb) and Rhodococcus opacus B4 (8.17 Mb) (see http://www.nite.go.jp/index-e.html). The rhodococcal genomes also differ in structure: R. equi and R. erythropolis have covalently closed chromosomes, whereas those of R. jostii and R. opacus are linear (Table 1, Figure S2). Chromosome topology does not seem to correlate with phylogeny, as R. equi and R. erythropolis belong to different subclades, and the latter is the prototype of the “erythropolis subgroup”, which includes R. opacus [11]. Streptomycetes also have large linear (>8.5 Mb) chromosomes [12], so linearization appears to have occurred independently in different actinobacterial lineages during evolution, apparently in association with increasing genome size.

Overview of functional content

The functional content of the R. equi 103S genome is summarized in Figure S3A. About one quarter of the genome corresponds to coding sequences (CDS) involved in central and intermediate metabolism (n = 1,108) and another quarter corresponds to surface/extracellular proteins (n = 1,073). “Regulators” is the next most populated functional category (n = 464, 10.3%). After adjusting for genome size, the number of membrane-associated proteins is average, but the regulome and secretome are clearly larger than in other Actinobacteria (Figure S4A, S4B, S4C), possibly reflecting specific needs associated with the habitat diversity of R. equi, from soil and feces to the macrophage vacuole. R. equi has 23 two-component regulatory systems, more than twice as many as host-restricted Mtb [13], and more regulators as a function of genome size than S. coelicolor [12] (Figure S4B). About 29% of the genome encodes products of unknown function. This percentage rises to 44.5% for secreted products (Figure S3B), 13% of which are unique to R.equi. Ortholog comparisons with representative closely related mycolata (R. jostii, N. farcinica and Mtb) showed R. equi to have the highest proportion of species-specific surface/extracellular proteins, consistent with its large secretome. By contrast, R. jostii RHA1 has the largest proportion of unique metabolic genes (Figure S5), consistent with its catabolic versatility [10]. Indeed, R. jostii RHA1 is unique among Actinobacteria in its unusual overrepresentation of metabolic genes (Figure S4D).

Expansive evolution of rhodococcal genomes

The 5.0 Mb R. equi chromosome contains relatively few pseudogenes (n = 14, Table 1), most associated with horizontally acquired regions (n = 10, including two degenerate DNA mobility genes), consistent with a slow “core” gene decay rate. This suggests that the differences in chromosome size between rhodococci result mainly from genome expansion in environmental species rather than contraction in R. equi.

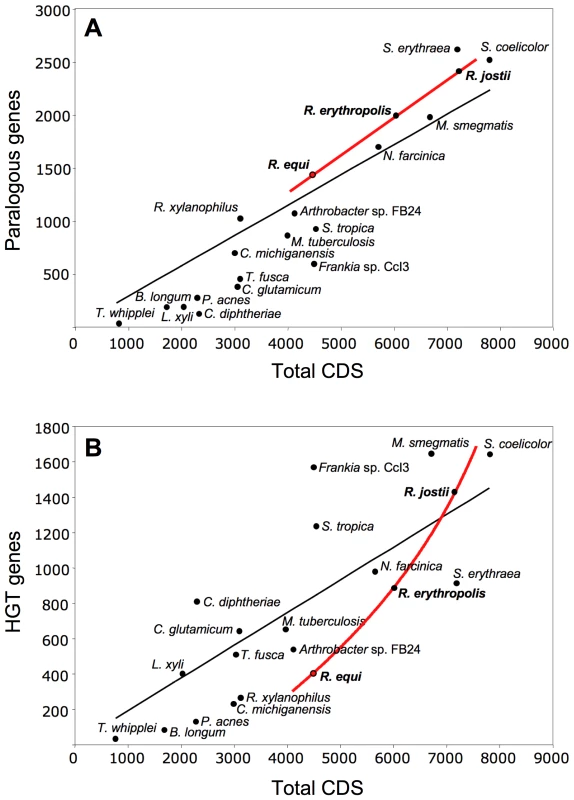

Gene duplication versus HGT

We analyzed the paralogous families and local DNA compositional biases to assess the impact of gene duplication (GD) and horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in rhodococcal genome evolution (Tables S1, S2). As expected, both contributed to the chromosome size increase, but with different patterns: linear for GD (i.e. similar percentage of duplicated genes, 32.1, 33.2 and 33.6%, in R. equi, R. erythropolis and R. jostii, respectively), and exponential for HGT (9.5, 14.8 and 19.5%, respectively) (Figure 2). A possible explanation is that HGT involves the simultaneous acquisition of several genes (mean no. of genes per HGT “island” in rhodococci, 8.2 to 10.6). The probability of HGT in rhodococci also increases with chromosome size, as indicated by the mean frequencies of HGT events (1 every 87.0, 67.0 and 54.2 genes in R. equi, R. erythropolis and R. jostii, respectively) (Table S1). Moreover, recently acquired HGT islands, mostly containing “non-adapted” DNA dispensable in the short term in the new host species, are likely to evolve more freely and to tolerate further HGT insertions. This may be the case for two large chromosomal HGT “archipelagos” of ≈90 and 190 Kb in 103S, which probably were generated by an accumulation of HGT events. The mosaic structure of these HGT regions and the diversity of source species, as indicated by reciprocal BLASTP best-hit analysis, suggest that they are a composite of several independent HGT events rather than the result of a single “en-block” acquisition (Figures S1 and S6). Rhodococcal genome expansion also involves a linear increase in the number of paralogous families (with larger numbers of paralogs per family) and non-duplicated genes (Table S2), and an increasing number of unique hypothetical proteins (e.g. 164 in R. equi, 408 in R. jostii). Thus, genome expansion in rhodococci involves greater functional redundancy, diversity and innovation.

Fig. 2. Role of gene duplication and horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in rhodococcal genome evolution.

Scatter plots of (A) duplicated (paralogous) genes and (B) HGT genes versus the total number of genes in rhodococcal and actinobacterial genomes (curve fits of rhodococcal data in red, general trendline in black). HGT genes were excluded from the paralogy analyses. About 20% of R. equi HGT islands (Figure S1) are located close to tRNA genes, suggesting the involvement of phages or integrative plasmids in their acquisition. However, almost no DNA mobilization genes or remnants thereof were found associated with HGT regions, suggesting that the lateral gene acquisitions in the R. equi chromosome are evolutionarily ancient. Most HGT genes (52.5%) probably originated from other Actinobacteria, 3.5% of the best hits were from other bacteria, and 44% had no homologs in the databases. Only four integrase genes, one of them degenerate, and an IS1650-type transposase pseudogene were identified in the 103S chromosome. R. equi seems therefore to be genetically stable in terms of mobile DNA element-mediated rearrangements. DNA mobility genes —mostly associated with HGT regions and increasing in abundance with genome size — are more numerous in environmental rhodococci (Table S3). Thus, increasing genetic flux and plasticity are associated with increasing chromosome size in rhodococci.

Role of plasmids

Rhodococcal genome expansion can be largely attributed to extrachromosomal elements. R. equi has a single 80 Kb circular plasmid whereas environmental rhodococci have three to five plasmids, including large linear replicons up to 1,123 Kb in size, accounting for a substantial fraction of the genome (e.g. ≈20% in R. jostii RHA1) (Table 1, Table S3). Thus, as observed for chromosomal HGT DNA, the amount of plasmid increases exponentially with genome size. Indeed, one third of the plasmid DNA was HGT-acquired (32.4%, range 19.35–49.7 vs 14.5%, range 9.5–19.5 for the chromosomes), and plasmids may themselves be considered potentially mobilizable DNA. Rhodococcal plasmids also have a much higher density of DNA mobilization genes (Table S3), pseudogenes (Table 1), unique species-specific genes (mean 44.3±16.0% vs 3.6% to 5.6%), and niche-specific determinants (e.g. the intracellular survival vap PAI in R. equi [8] and 11 of the 26 peripheral aromatic clusters in R. jostii [10]) than the corresponding chromosomes. Rhodococcal plasmids are therefore clearly under less stringent selection and are key players in rhodococcal genome plasticity and niche adaptability.

Niche-adaptive features

Basic nutrition and metabolism

No genes with an obvious role in carbohydrate transport were identified in 103S, consistent with the reported inability of R. equi to utilize sugars [14], confirmed here by Phenotype MicroArray (PMA) screens [15] and growth experiments in chemically defined mineral medium (MM) (Figure S7A). By contrast, R. jostii, R. erythropolis and R. opacus can grow on carbohydrates [16]–[18] and their genomes encode sugar transporters, including phosphoenolpyruvate-carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS) permeases. Interestingly, the intracellular pathogens R. equi, Mtb and Tropheryma whipplei are the only mesophilic Actinobacteria lacking PTS sugar permeases (Table S4). However, Mtb grows on carbohydrates transported via non-PTS permeases. As the PTS is widespread in Actinobacteria, including nonpathogenic rhodococci and mycobacteria, the absence of PTS components in R. equi, Mtb and the genome-reduced obligate endocellular parasite T. whipplei probably results from gene loss.

The PMA and MM experiments showed that the only carbon sources used by R. equi 103S were organic acids (acetate, lactate, butyrate, succinate, malate, fumarate; but not pyruvate) and fatty acids (palmitate and the long-chain fatty acid-containing lipids Tween 20, 40 and 80) (Figure S7A). In addition to monocarboxylate and dicarboxylate transporters, the 103S genome encodes an extensive lipid metabolic network, with 36 lipases (16 of which secreted) and many fatty acid β-oxidation enzymes, with 40 acyl-CoA synthetases, 48 putative acyl-CoA dehydrogenases, and 23 enoyl-CoA hydratases/isomerases. Thus, R. equi seems to assimilate carbon principally through lipid metabolism. A mutant in the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase (REQ38290) [19], required for anaplerosis during growth on fatty acids [20], has severely impaired intramacrophage replication and virulence [21], indicating that, as reported for Mtb [22], lipids are a major growth substrate for R. equi during infection in vivo.

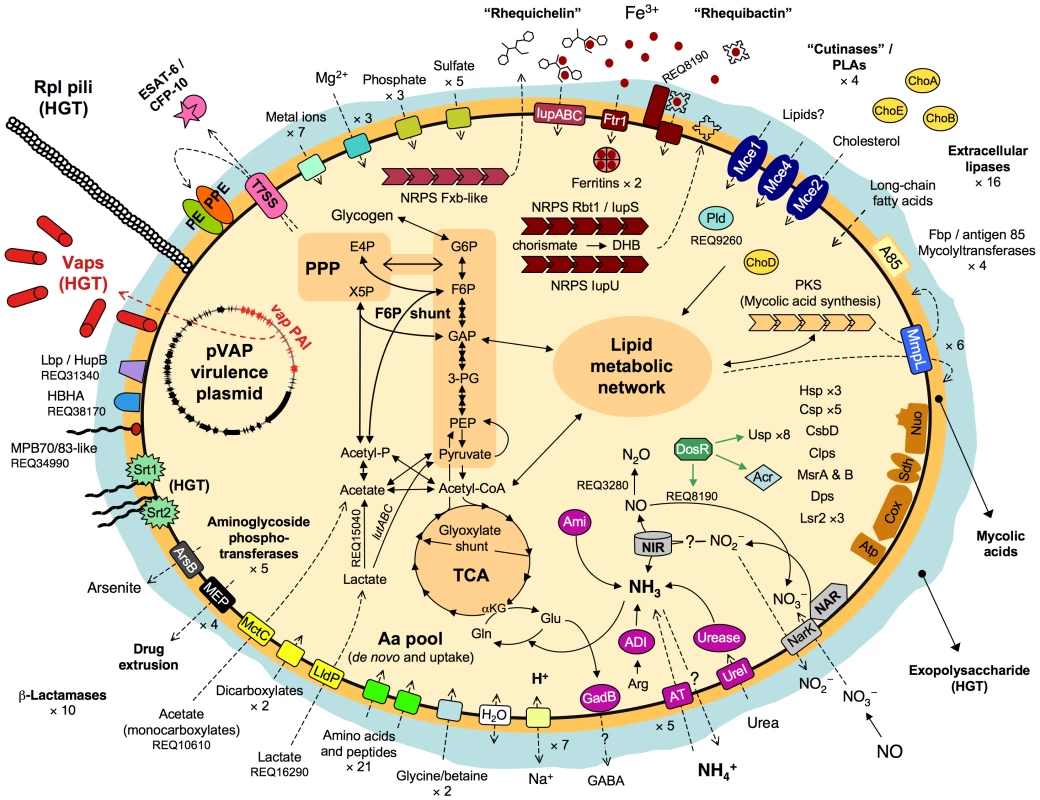

The 103S genome encodes 21 putative amino acid/oligopeptide transporters, and PMA screens and MM growth assays confirmed that R. equi uses several amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine, cysteine, methionine) and dipeptides as sources of nitrogen. However, 103S also has pathways for the de novo synthesis of all essential amino acids, consistent with the ability of R. equi to grow in MM containing only an inorganic nitrogen source (Figure S7A). Thus, R. equi can flexibly adapt to fluctuating conditions of amino-acid availability and grow in amino acid-deficient environments, as typically encountered in the infected host by intracellular pathogens [23]. See Figure 3 for a schematic overview of R. equi 103S nutrition and metabolism.

Fig. 3. Schematic overview of relevant metabolic and virulence-related features of R. equi 103S.

Complete glycolytic, PPP, and TCA cycle pathways, and all components for aerobic respiration, are present. The TCA cycle incorporates the glyoxylate shunt, which diverts two-carbon metabolites for biosynthesis. The methylcitrate pathway enzymes (pprCBD, REQ09040-60) are also present. The lutABC operon may take over the function of the D-lactate dehydrogenase (cytochrome) REQ00650, which is a pseudogene in 103S. REQ15040 (L-lactate 2-monoxygenase) and REQ27530 (pyruvate dehydrogenase [cytochrome]) can directly convert lactate and pyruvate into acetate. Unlike Mtb and other actinomycete pathogens, R. equi 103S has no secreted phospholipase C (Plc), only a cytosolic phospholipase D (Pld, REQ09260); a secreted Plc is however encoded in the genomes of environmental Rhodococcus spp. Rbt1/IupS (REQ08140-60) is a dimodular BhbF-like siderophore synthase [90]. Rbt1 rhequibactins are synthesized from (iso)chorismate via 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate (DHB) as for enterobactin or bacillibactin (REQ08130-100 encode homologs of Ent/DhbCAEB) [90], [91]. Two MFS transporters and a siderophore binding protein (REQ08180-200) encoded downstream from iupS may be involved in rhequibactin export/uptake. There is also a putative Ftr1-family iron permease (REQ12610). R. equi may store intracellular iron via two bacterioferritins (REQ01640-50) and the Dps/ferritin-like protein (REQ14900). IdeR- (REQ20130), DtxR- (REQ19260) and Fur- (REQ04740-furA, REQ29130-furB)-like regulators may contribute to iron/metal ion regulation. Homologs of the Mtb DosR (dormancy) regulon are also present in the R. equi genome (Table S6). Thiamine auxotrophy

R. equi strains cannot grow without thiamine and an analysis of the loci involved in its biosynthesis revealed that thiC is absent from 103S, probably due to an HGT event affecting the thiCD genes (Figure S7B, S7C, S7D). The auxotrophic mutation is probably irrelevant for R. equi in the intestine and manure-rich soil owing to the availability of microbially synthesized thiamine. Host-derived thiamine is also probably available to R. equi during infection.

Specialized metabolism

We investigated the nutritional and metabolic aspects of rhodococcal niche adaptation by comparing the metabolic network of R. equi with that of R. jostii RHA1, the only other rhodococcal species for which a detailed manually annotated genome is available. RHA1 originated from lindane-contaminated soil and was identified by screening for biodegradative capabilities on multiple aromatic compounds, including polychlorinated biphenyls and steroids. Not surprisingly, its genome has an abundance of aromatic degradation pathways and oxygenases involved in aromatic ring cleavage [10]. R. equi is also soil-dwelling but is primarily isolated from clinical specimens and manure-rich environments, involving clearly different selection criteria and habitat conditions. We used reciprocal best-match BLASTP comparisons to identify the species-specific metabolic gene complements, in which the catabolic specialization is likely concentrated. The related pathogenic Actinobacteria, N. farcinica (which shares a dual soil saprophytic/parasitic lifestyle with R. equi) and Mtb (quasiobligate parasite) were also included in the analyses. R. jostii RHA1 contains a disproportionately larger number of unique metabolic genes than R. equi, N. farcinica and Mtb (n = 1,260 or 47.2% of total metabolic CDS vs only 326 to 375 or 22.9 to 29.2%, respectively) (Figure S8). The oversized metabolic network of RHA1 results from an expansion in the number and gene content of paralogous families (Table S5) and nonparalogous genes (643 CDS in RHA1 vs 209 to 288). Only three of the 29 aromatic gene clusters present in R. jostii [10] were identified in the 103S genome. R. equi therefore has a much smaller metabolic network than, and essentially lacks the vast aromatic catabolome of, R. jostii RHA1.

R. equi resembles other environmental Actinobacteria in being able to produce oligopeptide secondary metabolites. The 103S genome encodes 11 large non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), including three involved in siderophore formation (see below). The only polyketide synthase (REQ02050) is involved in the synthesis of mycolic acids. By contrast, RHA1 has 24 NRPS and seven polyketide synthases [10]. Thus, genome expansion in R. jostii has been accompanied by an extensive amplification of secondary metabolism.

Other metabolic traits

R. equi reduces nitrates to nitrites [14] through a NarGHIJ nitrate reductase (REQ04200-30). There is also a NirBD nitrite reductase (REQ32900-30), a NarK nitrate/nitrite transporter (REQ32940) and a putative nitric oxide (NO) reductase (REQ03280) (Figure 3). nirBD is conserved in environmental rhodococci whereas narGHIJ and REQ03280 are not, indicating that R. equi is potentially well equipped for anaerobic respiration via denitrification, a useful trait for survival in microaerobic environments, as typically found in necrotic pyogranulomatous tissue [24], the intestine or manure. A narG mutation has been shown to attenuate R. equi virulence in mice [25], consistent with the bacteria encountering hypoxic conditions during infection, although this may also reflect defective nitrate assimilation in vivo [26].

Intriguingly, R. equi possesses a D-xylulose 5-phosphate (X5P)/D-fructose 6-phoshate (F6P) phosphoketolase (Xfp, REQ21880), the key enzyme of the “Bifidobacterium” F6P shunt, which converts glucose into acetate and pyruvate and is the main hexose fermentation pathway in bifidobacteria [27]. Unexpected fermentative metabolism has been detected in some strictly aerobic bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Arthrobacter [28], but no NAD+ (anaerobic)-dependent lactate dehydrogenase or other obvious pyruvate fermentation enzyme was identified in 103S. As R. equi does not use sugars, a catabolic role for the F6P shunt is possible only if fed via gluconeogenesis/glycogenolysis. Alternatively, the F6P shunt may function in reverse (anabolic) mode in R. equi, in parallel to gluconeogenesis, directing excess acetate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP), generated from lipid metabolism, into the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (Figure 3). R. equi 103S has a lutABC operon (REQ16290-320), recently implicated in lactate utilization via pyruvate in Bacillus [29].

Alkaline optimal pH

R. equi tolerates a wide pH range, but growth is optimal between pH 8.5 and 10 (Figure S9). This alkaline pH is similar to that of untreated manure, potentially providing a selective advantage for colonization of the farm habitat. The 103S genome encodes a urease (REQ45360-410), an arginine deiminase (REQ11880), an AmiE/F aliphatic amidase/formamidase (REQ26530, next to REQ26520 encoding a UreI-like urea/amide transporter in an HGT island) and other amidases which, by releasing ammonia [30], may favor R. equi growth in acidic host habitats such as the macrophage vacuole (pH≤5.5), the airways or the intestine (typical pH values in horse, 5.3–5.7 and 6.4–6.7, respectively [31], [32]).

Stress tolerance

Like other soil bacteria [33], R. equi encodes a large number of σ factors (21 σ70) and stress proteins (e.g. eight universal stress family proteins [Usp], five cold shock proteins, three heat shock proteins and several Clp proteins). It also synthesizes the ppGpp alarmone involved in adaptation to amino acid starvation [34]. R. equi is transmitted by soil dust in hot, dry weather [3] and must therefore resist low water availability and desiccation-associated oxidative damage. There are two ABC glycine betaine/choline transporters (REQ00540-70 and REQ14620-60), an aquaporin (REQ29580), and genes for the synthesis of an exopolysaccharide (see below) and the osmolytes ectoine (ectABC, REQ07850), hydroxyectoine (ectD, REQ07850) and trehalose (REQ27400-30), potentially important for osmoprotection and water stress tolerance. R. equi is well equipped to face oxidative stress, with four catalases, four superoxide dismutases, six alkyl hydroperoxide reductases and two thiol peroxidases. It also synthesizes the unique actinobacterial redox-storage thiol compound, mycothiol [35], the antioxidant thioredoxin (REQ47340-50), and the protein-repairing peptide-methionine sulfoxide reductases MsrA (REQ01570) and MsrB (REQ20650) [36]. Three homologs of the virulence-associated mycobacterial histone-like protein Lsr2 [37] (one plasmid vap PAI-encoded [8], REQ03140 and 05980 chromosomal), and a Dps family protein [38] (REQ14900, cotranscribed with REQ14890 encoding a CsbD-like putative stress protein [39]), may protect against oxidative DNA damage. NO reductase REQ03280 and a putative NO dioxygenase (REQ10890) may confer resistance to nitrosative stress (Figure 3).

“Innate” drug resistance

R. equi 103S showed a degree of resistance to many antibiotics in the PMA screens, including 13 aminoglycosides, nine sulfonamides, six tetracyclines, 10 quinolones, 18 β-lactams and chloramphenicol. Standard susceptibility tests confirmed the resistance of 103S to a number of clinically relevant antibiotics (Table S7). This correlates with the presence in 103S of an array of antibiotic resistance determinants, including five aminoglycoside phosphotransferases, 10 β-lactamases and four multidrug efflux systems. Except for β-lactamase REQ26610, none of the resistance genes are associated with HGT regions or DNA mobility genes, suggesting they are ancient traits selected to confer resistance to naturally occurring antimicrobials rather than recent acquisitions associated with the medical use of antibiotics. Soil organisms tend to carry multiple drug resistance determinants [40], and homologs of most R. equi resistance genes are present in the genomes of environmental rhodococci, at the same chromosomal location in some cases (Figure S10).

Virulence

Potential virulence-associated determinants were identified in silico based on (i) homology with known microbial virulence factors, (ii) literature mining for Mtb virulence mechanisms, (iii) automated genome-wide screening for virulence-associated motifs [41] and (iv) systematic inspection of HGT genes, the secretome, and of genes shared with pathogenic actinomycetes but absent from nonpathogenic species.

Mycobacterial gene families

The 103S genome harbors three complete mce (mammalian cell entry) clusters. Despite their name, the mechanisms by which these clusters contribute to mycobacterial pathogenesis remain unclear [42]. The mce4 operon from R. jostii and its homolog mce2 in R. equi have recently been shown to mediate cholesterol uptake, consistent with emerging evidence that mce clusters constitute a new subfamily of ABC importers [43], [44]. The recently reported lack of effect of an mce2 mutation on R. equi survival in cultured macrophages [43] does not exclude a role in cholesterol utilization in vivo or in IFNγ-activated macrophages, as shown for an Mtb mutant in the homologous mce operon [45]. The surface-exposed PE and PPE proteins account for ≈7% of the coding capacity of the Mtb genome due to massive gene duplication, and are thought to play an important role in mycobacterial pathogenesis [46]. The R. equi genome also harbors PE/PPE genes, although only a single copy of each (Figure S11A). They lie adjacent in an operon (REQ01750-60) with the PE gene first, as frequently observed in Mtb, possibly reflecting the functional interdependence of the PE and PPE proteins [47]. REQ35460-550 is identical in structure to ESX-4, one of the five Mtb ESX clusters, and to the single ESX cluster present in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. ESX loci encode two small proteins, ESAT-6 (REQ35460) and CFP-10 (REQ35440), and their type VII secretion apparatus, which also mediates the export of PE and PPE proteins. ESAT-6 and CFP-10 form heterodimeric complexes and are major T-cell antigens and key virulence factors in Mtb [48]. R. equi possesses six mmpL genes, encoding members of the “mycobacterial membrane protein large” family of transmembrane proteins, which are involved in complex lipid and surface-exposed polyketide secretion, cell wall biogenesis and virulence [49]. There are also four Fbp/antigen 85 homologs (REQ01990, 02000, 08890, 20840), involved in Mtb virulence as fibronectin-binding proteins and through their mycolyltransferase activity, required for cord factor formation and integrity of the bacterial envelope [50].

Cytoadhesive pili

A nine-gene HGT island (REQ18350-430) encodes the biogenesis of Flp-subfamily type IVb pili, recently described in Gram-negative bacteria [51]. We confirmed the presence of pilus appendages in 103S (Figure 4). Gene deletion and complementation analysis demonstrated that the identified R. equi pili (Rpl) mediated attachment to macrophages and epithelial cells (P. González et al., manuscript in preparation). The rpl island is absent from environmental rhodococci and is unrelated to the pilus determinants recently identified in Mtb and C. diphtheriae [52], [53].

Fig. 4. R. equi pilus locus (rpl).

(A) The 9 Kb rpl HGT island (REQ18350-430) is absent from nonpathogenic Rhodococcus spp. rpl genes have been detected in all R. equi clinical isolates (P. Gonzalez et al., manuscript in preparation). Putative rpl gene products: A, prepilin peptidase; B, pilin subunit; C, TadE minor pilin; D, putative lipoprotein; E, CpaB pilus assembly protein; F, CpaE pilus assembly protein; GHI, Tad transport machinery [51]. (B) Electron micrograph of R. equi 103S pili (indicated by arrowheads; generally 2–4 per bacterial cell). Bar = 0.5 µm. (C) R. equi 103S pili visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy (×1,000 magnification). Other putative virulence factors

R. equi is thought to produce capsular material [7], [54], and an HGT region encompassing REQ40580-780 contains genes potentially responsible for extracellular polysaccharide synthesis. Two other HGT islands encode sortases, transpeptidases that attach surface proteins covalently to the peptidoglycan and which are important for virulence in Gram-positive bacteria [55]. Both srt islands encode the putative substrates for the sortases (secreted proteins of unknown function) (Figure S11B).

Several secreted products are putative membrane-damaging or lipid-degrading factors, including a transmembrane protein with a putative hemolysin domain (REQ12980), three cholesterol oxidases (REQ06750, REQ26800, and REQ43910/ChoE [56]), four “cutinases”/serine esterases (REQ00480, REQ02020, REQ08540, REQ46060) with potential phospholipase A activity [57], and 16 lipases. REQ34990 encodes a secreted lipoprotein homologous to MBP70 and MPB83, two major mycobacterial antigens strongly expressed in Mycobacterium bovis BCG [58]. The REQ34990 product has a FAS1/BigH3 domain involved in cell adhesion via integrins [59]. There are also homologs of two mycobacterial cytoadhesins, the heparan sulfate-binding hemagglutinin HbhA (Rv0475) involved in Mtb dissemination (REQ38170), and the multifunctional histone-like/laminin - and glycosaminoglycan-binding protein Lbp/Hlp (REQ31340) [60] (Figure 3).

Iron is essential for microbial growth and the ability to acquire ferric iron from the host is directly related to virulence. Two NRPS, Rbt1/IupS (bimodular, REQ08140-60) and IupU (REQ23810), are involved in the formation of catecholic siderophores [61] or “rhequibactins”. A third NRPS homologous to Mycobacterium smegmatis Fxb (REQ07630) may be involved in the formation of an oligopeptide ferriexochelin-like extracellular siderophore. This “rhequichelin” is probably transported by the iupABC (REQ24080-100)-encoded putative siderophore ABC permease [61], homologous to the M. smegmatis FxuABC ferriexochelin transporter [62] (Figure 3). The redundancy of iron acquisition systems may explain the lack of effect on virulence of individual iupU, rbt1/iupS and iupABC mutations [61].

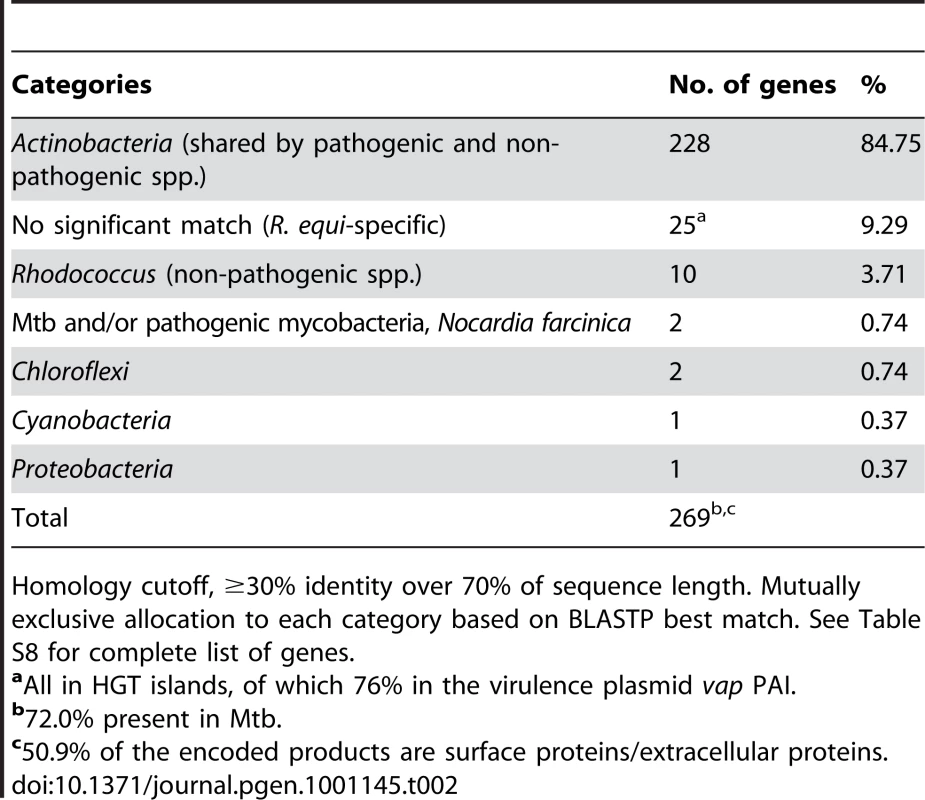

Virulence gene acquistion versus cooption

Only a few species-specific putative virulence loci were found in the 103S genome, all in HGT islands (e.g. the plasmid vap PAI or the chromosomal rpl locus). Most (≈90%) of the potential virulence-related determinants identified in R. equi were present in the environmental Rhodococcus spp. and/or had homologs in nonpathogenic Actinobacteria (Table 2, Table S8). These included orthologs of many experimentally-determined Mtb virulence genes, most of which (≈84%) are conserved among nonpathogenic mycobaceria or have close homologs in environmental actinomycetes (Table S9). The case of the mce, ESX, and PE/PPE loci is illustrative. Initially thought to be Mycobacterium-specific virulence traits, members of these multigene families are present in R. equi and in nonpathogenic rhodococci (Table S8), consistent with growing evidence that they are actually widely distributed among high-G+C gram-positives, whether environmental or pathogenic [42], [63], [64]. Notwithstanding that some of the unknown function genes of the 103S genome may encode novel, previously uncharacterized pathogenic traits, these observations are consistent with a scenario in which R. equi virulence largely involves the “appropriation” or cooption of core actinobacterial functions, originally selected in a non-host environment. Gene cooption (also known as preadaptation or exaptation) is a key evolutionary process by which traits that have evolved for one purpose are employed in a new context and acquire new roles, thus allowing rapid adaptive changes [65]–[67]. Cooptive evolution operates through critical modifications in gene expression and function [65]. These changes are particularly feasible in the larger genomes of soil bacteria, with a characteristic profusion of regulators and functionally redundant paralogs [68], [69]. Without the need for major changes, stress-enduring mechanisms and other housekeeping components, such as the cell envelope mycolic acids or the bacterial metabolic network, may directly contribute to virulence by affording nonspecific resistance or by enabling the organism to feed on host components. We suggest that a few decisive niche (host)-adaptive HGT events in a direct ancestor of R. equi, such as acquisition of the plasmid vap “intramacrophage survival” PAI [8] and the rpl “host colonization” HGT island (Figure 4), triggered the rapid conversion of a “preparasitic” commensal organism into a pathogen via the cooption of preexisting bacterial functions.

Tab. 2. Bacterial groups in which homologs of potential R. equi virulence-associated genes were identified.

Homology cutoff, ≥30% identity over 70% of sequence length. Mutually exclusive allocation to each category based on BLASTP best match. See Table S8 for complete list of genes. Virulence plasmid–chromosome crosstalk

Based on the well-established principle that coexpression with pathogenicity determinants is a strong indicator of involvement in virulence [70], [71], we sought to identify novel R. equi virulence-associated chromosomal factors through their coregulation with the plasmid virulence genes. The expression profiles of 103S and an isogenic plasmid-free derivative (103SP−) were compared, using a custom-designed genomic microarray and in vitro conditions known to activate (37°C pH 6.5) or downregulate (30°C pH 8.0) the virulence genes of the plasmid vap PAI [72], [73]. The plasmid had little effect on the chromosome in vap gene-downregulating conditions, but significantly altered expression was observed for numerous genes in vap gene-activating conditions (n = 88 with ≥2 fold change) (Table S10). Most of the differentially expressed genes (68%) were upregulated in the presence of the plasmid. These data suggest that the virulence plasmid activates the expression of a number of chromosomal genes, but whether this upregulation involves direct, specific (potentially virulence related) interactions or incidental pleiotropic effects is unclear.

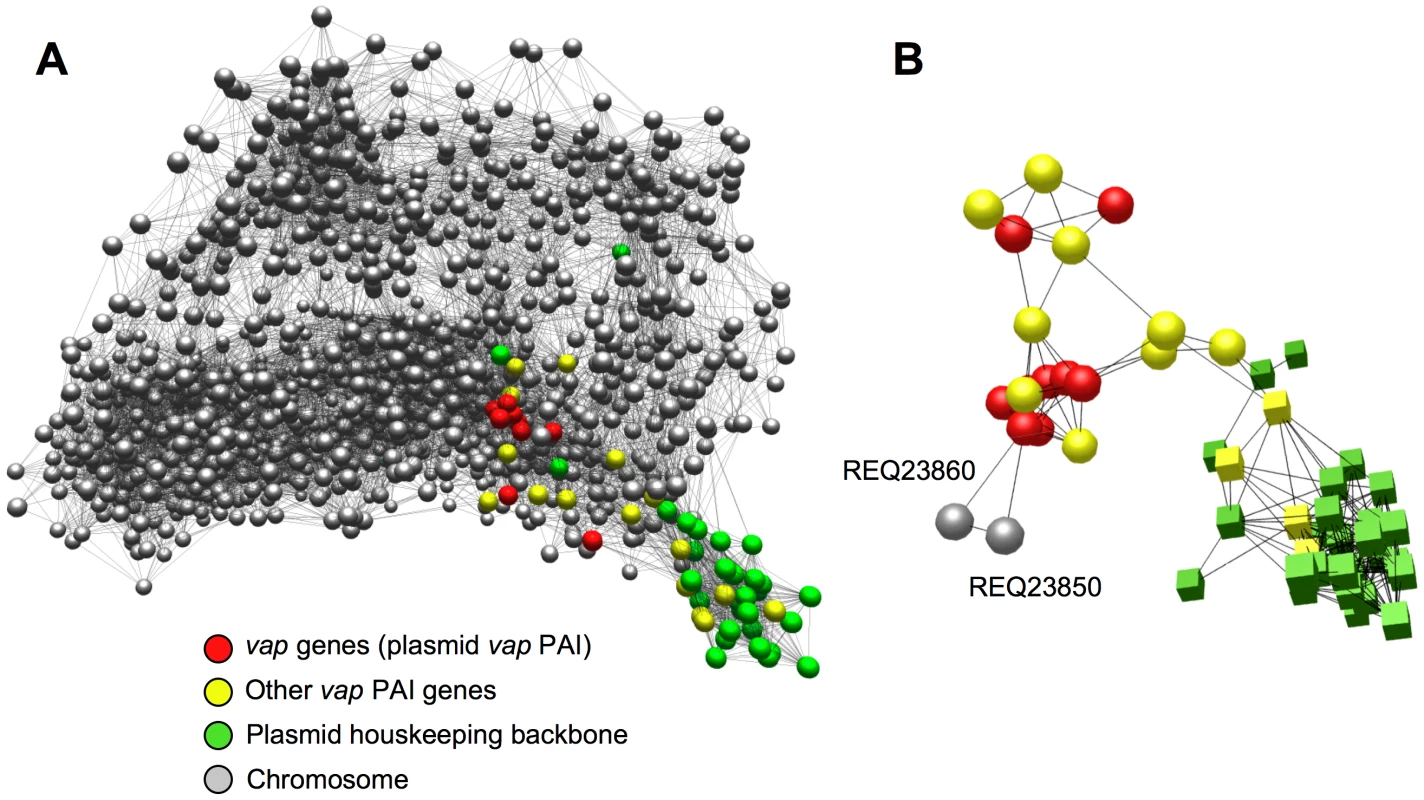

Network analysis

To define the extent and nature of the virulence plasmid-chromosome crosstalk, we subjected the microarray expression data to network analysis. Unlike classical pairwise comparisons, the network approach captures higher-order functional linkages between genes, facilitating the graphic visualization of gene interconnections. It is thus more powerful for biological inference and gene prioritization for experimental validation. Noisy data also tend to be randomly distributed in the network structure [74]. We used BioLayout Express3D, an application that constructs three-dimensional networks from microarray data by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficients between the expression profiles of every gene in the dataset. This is followed by graph clustering using the Markov Clustering (MCL) algorithm to divide the network graph into discrete modules with similar expression profiles [75]. Microarray data of 103S bacteria exposed to various combinations of temperature (20°C, 30°C and 37°C) and pH (5.5, 6.5 and 8) were included in the computations to control for the excessive weight of the variable presence/absence of plasmid and strengthen the correlation analysis.

Figure 5A shows a network representation of the functional connections detected in the R. equi transcriptome with a Pearson correlation threshold r ≥0.85. The graph model grouped the virulence plasmid genes into two distinct coregulated modules or clusters: one comprised 36 of the 73 plasmid genes, alsmost all from the housekeeping backbone (replication and conjugal transfer functions) [8]; the other contained 15 of the 26 vap PAI genes together with a number of chromosomal genes (Table S11). The plasmid housekeeping backbone nodes clustered together outside the main regulation network, reflecting functional independence from the rest of the regulome, as would be expected from the autonomous nature of the extrachromosomal replicon (Figure 5A). This indicates that the graph structure is biologically significant and reflects actual functional relationships, validating the network model. By contrast, the vap PAI nodes were clearly embedded in the network and established multiple connections with chromosomal nodes (Figure 5A, Figure S12A), suggesting that the plasmid virulence genes have undergone a process of regulatory integration with the host R. equi genome. About half of the predicted products of the chromosomal vap PAI-coregulated cluster genes are metabolic enzymes, the others being transcriptional regulators and transporters (Table S11C). Raising the correlation threshold to a highly stringent r≥0.95 disintegrated the network graph into a multitude of discrete, unconnected subgraphs (see Dataset S2). This did not substantially alter the structure of the two plasmid gene-containing clusters, but isolated two chromosomal genes, REQ23860 and REQ23850, as the most significantly and strongly coregulated with the vap PAI genes (Figure 5B), suggesting a direct regulatory interaction [76].

Fig. 5. Network analysis of virulence plasmid–chromosome regulatory crosstalk.

(A) Integration of the virulence plasmid vap PAI in the R. equi regulatory network. 3D graph of the R. equi 103S transcriptome (see text for experimental conditions) constructed with BioLayout Express3D, an application for the visualization and cluster analysis of coregulated gene networks [74], [75]. Settings used: Pearson correlation threshold, 0.85; Markov clustering (MCL) algorithm inflation, 2.2.; smallest cluster allowed, 3; edges/node filter, 10; rest of settings, default. Network graph viewable in Dataset S1. Each gene is represented by a node (sphere) and the edges (lines) represent gene expression interrelationships above the selected correlation threshold; the closer the nodes sit in the network the stronger the correlation in their expression profile. Note that the plasmid vap PAI genes (red spheres) are embedded within, and establish multiple functional connections with, chromosomal nodes (see also Figure S12A) whereas those of the plasmid housekeeping backbone lie outside the main network, reflecting an independent regulatory pattern. (B) Isolated subgraph of the R. equi transcription network obtained with r = 0.95 Pearson correlation threshold, showing the coregulation of the chromosomal genes REQ23860 (putative AroQ chorismate mutase) and REQ23850 (putative TrpEG-like bifunctional anthranilate synthase) (see Figure 7) with the virulence plasmid vap PAI genes. Color codes for nodes as indicated in (A) (spheres, vap PAI-coregulated cluster; cubes, plasmid housekeeping backbone cluster). MCL inflation, 2.2, smallest cluster allowed, 3; rest of settings, default. See Dataset S3. The genes from the plasmid backbone cluster were expressed constitutively in the conditions tested, whereas those from the vap PAI-coregulated cluster responded strongly to temperature, with activation at 37°C. Chromosomal genes in this cluster, particularly REQ23860 and REQ23850, displayed the same pattern, with downregulation in 103SP− at 37°C, suggesting that plasmid factors are required for their induction at high temperature (Figure S12B, Table S11B). The vap PAI encodes two transcription factors, VirR (orf4) and an orphan two-component regulator (orf8) [8], both of which have been shown to influence vap gene expression [77], [78] and could be involved in the observed plasmid-mediated thermoregulation of the vap PAI-coexpressed cluster.

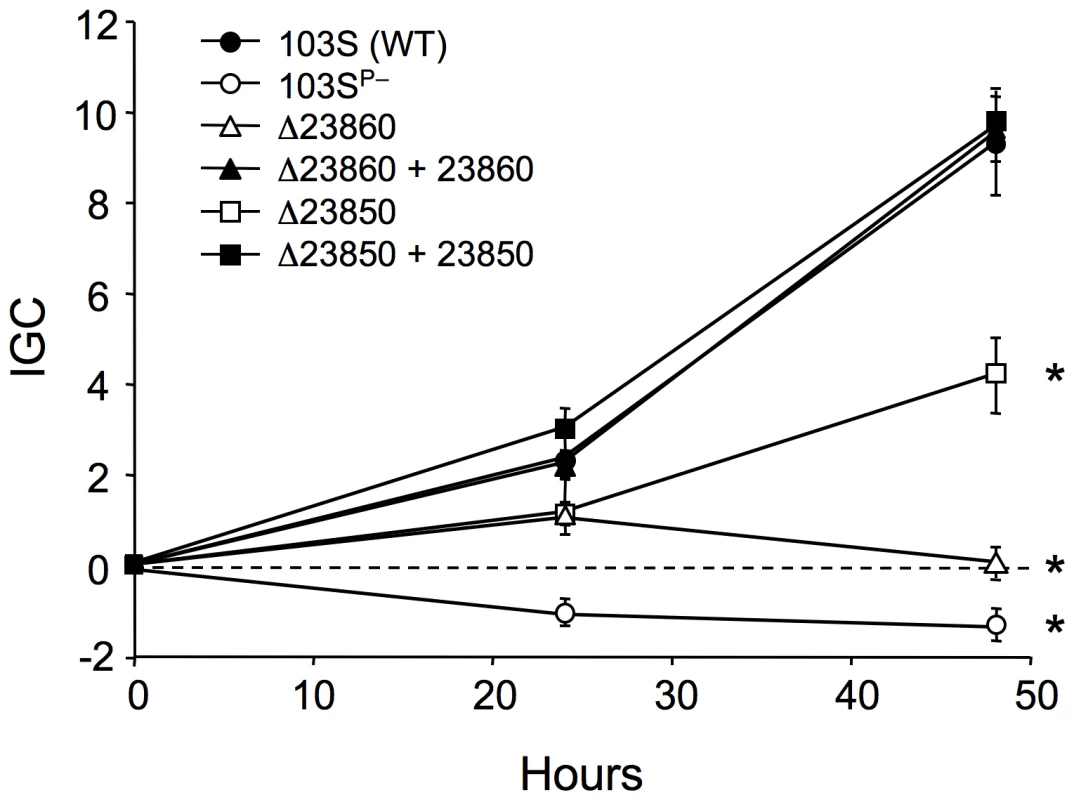

REQ23860 and REQ23850 are required for efficient intracellular proliferation in macrophages

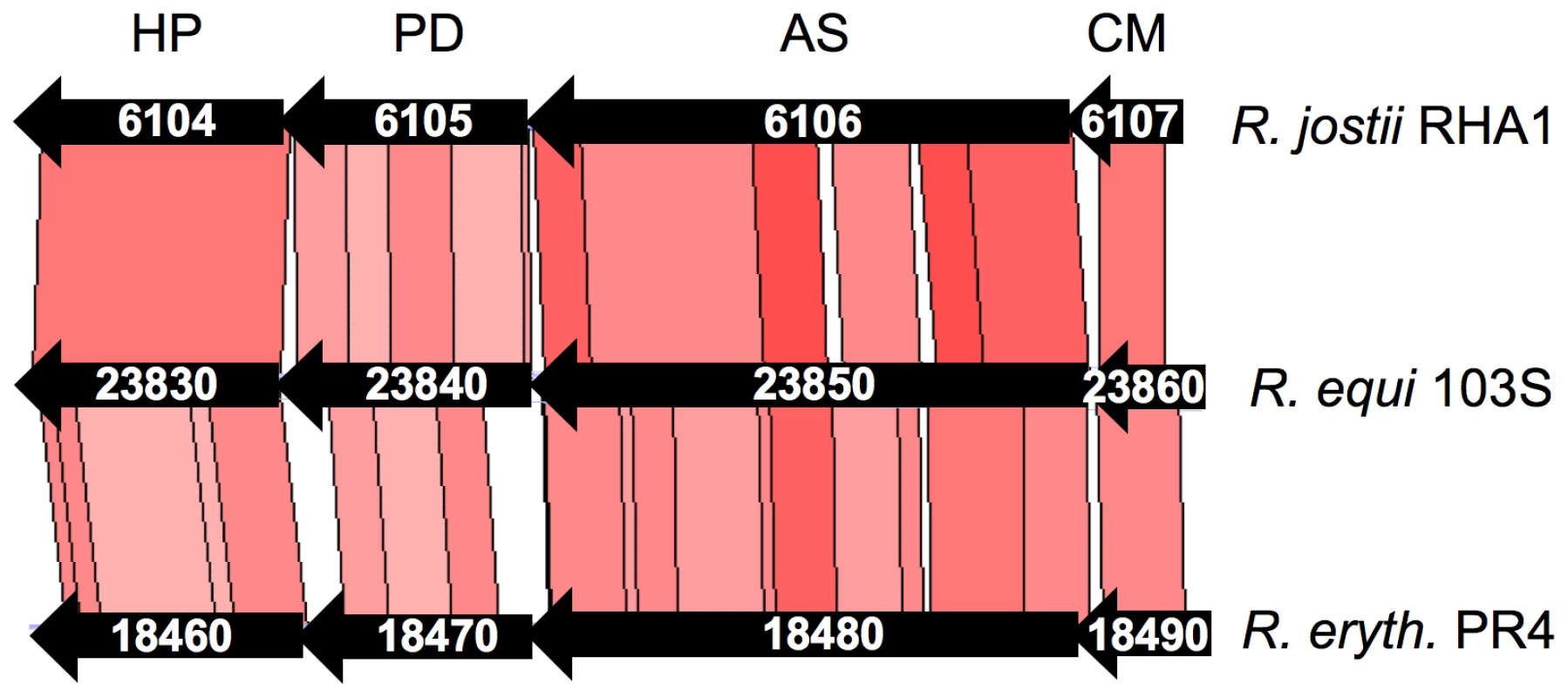

REQ23860 and REQ23850 null mutants were constructed and tested in J774 macrophages to determine whether the observed coregulation with the plasmid vap PAI correlates with a role in virulence. The plasmidless derivative 103SP−, unable to proliferate intracellularly [5], was used as an avirulent control. The two mutants had a significantly attenuated capacity to grow in macrophages, restored to wild-type levels upon complementation with the deleted genes (Figure 6), indicating that REQ23860 and REQ23850 are required for optimal intramacrophage proliferation. The mutated genes encode an AroQ (type II) chorismate mutase (CM) and a bifunctional anthranilate synthase (AS) with fused TrpE and TrpG subunits, respectively, two key metabolic enzymes catalyzing the initial committed steps in aromatic amino-acid biosynthesis. CM generates prephenate, the first intermediate in the pathway leading to phenylalanine and tyrosine, whereas AS catalyzes the first reaction in tryptophan biosynthesis [79]. Downstream at the same locus, REQ23840 encodes a prephenate dehydrogenase (Figure 7), which catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of prephenate to the tyrosine precursor 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate [79]. The intracellular growth defect caused by the mutations may therefore be related to a diminished capacity for de novo synthesis of aromatic amino acids. The R. equi genome encodes four other CM enzymes (including one in the vap PAI [8]) and an additional AS (bipartite, one subunit encoded in a trpECBA operon and the other by a solitary trpG gene elsewhere in the chromosome). Through their coregulation with the plasmid vap PAI, the redundant REQ23850-60-encoded chorismate-utilizing enzymes may be important for R. equi intracellular fitness and full proliferation capacity, by enhancing the de novo supply of aromatic amino acids, which generally appear to be present at limiting concentrations in the in vivo replication niche of intramacrophage vacuole-residing microbial pathogens [23], [80], [81].

Fig. 6. Intracellular growth kinetics of ΔREQ23860 and ΔREQ23850 mutants in J774 macrophages.

Data were normalized to the initial bacterial counts at t = 0 using an intracellular growth coefficient (IGC); see Materials and Methods. Positive IGC indicates proliferation, negative values reflect decrease in the intracellular bacterial population. Bacterial counts per well at t = 0: 103S (wild type), 9.84±0.55×104; 103SP−, 4.67±0.62×104; ΔREQ23860 (putative CM), 11.26±2.78×104; complemented ΔREQ23860, 4.24±0.10×104; ΔREQ23850 (putative AS), 9.67±0.12×104; complemented ΔREQ23850, 8.29±0.22×104. Means of at least three independent duplicate experiments ±SE. Asterisks denote significant differences from wild type with P≤0.001 (two-tailed Student's t test). Except for the intracellular proliferation defect, the two mutants were phenotypically indistinguishable from the wild-type parental strain 103S, including growth kinetics in broth medium. Fig. 7. Structure of the chromosomal locus of the putative chorismate mutase (CM) and anthranilate synthase (AS) genes REQ23860 and REQ23850.

The locus contains two additional genes, REQ23840 and REQ23830, encoding a putative prephenate dehydrogenase (PD) and a hypothetical protein (HP), respectively. The four genes are conserved at the same chromosomal location in the environmental Rhodococcus spp (CDS numbers indicated), including R. opacus B4. Conclusions

Somewhat counterintuitively for an organism with a dual lifestyle as a soil saprotroph and intracellular parasite, the R. equi genome is significantly smaller than those of environmental rhodococci. This may reflect that the main R. equi habitats –herbivore intestine, manure and animal tissues – provide a richer and more stable environment than the chemically diverse and probably nutrient-scarce environments of the nonpathogenic species. In nutrient-poor conditions, the simultaneous use of all available compounds as sources of carbon and energy may offer a competitive advantage, driving the selection of expanded genomes with greater metabolic versatility [10], [68]. Indeed, the much larger genome of the polychlorinated biphenyl-biodegrading R. jostii RHA1 encodes a disproportionately large metabolic network [10], with a wider diversity of paralogous families, unique metabolic genes and catabolic pathways. The relatively small number of pseudogenes and virtual lack of DNA mobilization genes in R. equi suggests that this species has not experienced a sudden evolutionary bottleneck with a concomitant relaxation of selective pressure and increase in mutation fixation [82]. The “coprophilic” and parasitic lifestyle specialization of R. equi seems to result from a “non-traumatic” adaptive process in an organism that, despite having suffered some specific functional losses (e.g. sugar utilization, thiamine synthesis), remains an “average” soil actinomycete with a normal-sized genome under strong selection. The greater genomic complexity of the environmental Rhodococcus spp. may reflect a “multi-substrate” niche specialization necessarily linked to the strict selection criteria —for unusual metabolic versatility — under which these species are generally isolated, [10]. Our analyses show that genome expansion in the environmental rhodococci has involved a linear gain of paralogous genes and an accelerated pattern of gene acquisition through HGT and extrachromosomal replicons, which evolve more rapidly and clearly play a critical role in rhodococcal niche specialization.

The lipophilic, asaccharolytic metabolic profile and capacity for assimilating inorganic nitrogen may be key traits for proliferation in herbivore intestine and feces, which are rich in volatile fatty acids [3], and in the macrophage vacuole and chronic pyogranulome, presumably poor in amino acids and rich in membrane-derived lipids [20], [23]. The potential for anaerobic respiration via denitrification may be critical for survival in the anoxic intestine or, as suggested for Mtb [83], [84], in necrotic granulomatous tissue. The inability to use sugars, unique among related actinomycetes, may confer a competitive advantage in the intestine and feces, dominated by carbohydrate-fermenting microbiota generating large amounts of short-chain fatty acids, which R. equi use as main carbon source. Alkalophily is probably an advantage in fresh manure, a major R. equi reservoir. R. equi is also well equipped to survive desiccation, important for dustborne dissemination in hot, dry weather, when rhodococcal foal pneumonia is transmitted [3], [4].

R. equi infections are notoriously difficult to treat due to the intracellular localization of the pathogen, compounded by a lack of susceptibility to antibiotics (e.g. penicillins, cephalosporins, sulfamides, quinolones, tetracyclines, clindamycin, and chloramphenicol) (Table S7 and refs. therein). With its panoply of drug resistance determinants, the 103S genome illustrates how naturally selected resistance traits, typically abundant in soil organisms, may have an important impact on the clinical management of microbial infections [40].

Finally, our analyses suggest that the appropriation of preexisting core actinobacterial components and functions are key events in the evolution of rhodococcal virulence. Although the underlying notion may be intuitively apparent when considering, for example, the contribution of housekeeping genes to bacterial virulence [85], here we are identifying it specifically as “gene cooption”, a key mechanism enabling rapid adaptive evolution and the emergence of new traits [65]–[67]. Underpinned by a few critical “host niche-accessing” HGT events, such as acquisition of the “intracellular survival” plasmid vap PAI or the “cytoadhesion” chromosomal rpl locus, this evolutionary mechanism is likely to have facilitated the rapid conversion of what was probably an animal-associated commensal into the pathogenic R. equi. Given the pervasive distribution of the “virulence-associated” gene pool among nonpathogenic species (Tables S8, S9), the notion of cooptive virulence is possibly applicable to all pathogenic actinomycetes and, indeed, universally to bacterial pathogens. The incorporation of adaptive changes in the regulation of the “appropriated” genes is a key mechanism in genetic cooption [65]. Our genome-wide microarray experiments and transcription network analyses indicate that the plasmid vap PAI, essential for intracellular survival and pathogenicity, has recruited housekeeping genes from the rhodococcal core genome under its regulatory influence. Among these are two chromosomal genes encoding key metabolic enzymes involved in aromatic amino-acid biosynthesis, coexpressed with the virulence genes of the vap PAI in response to an increase in temperature to 37°C (the body temperature of the warm-blooded host). These two metabolic genes are required by R. equi for full proliferation capacity in macrophages, providing supporting experimental evidence for the cooptive nature of R. equi virulence. A cooptive virulence model is consistent with the sporadic isolation of “nonpathogenic” (pre-parasitic) Actinobacteria, including environmental rhodococci (e.g. R. erythropolis [86]), as causal agents of opportunistic infections. An appreciation of the importance of gene cooption in the acquisition of pathogenicity provides a conceptual framework for better understanding and guiding research into bacterial virulence evolution.

Materials and Methods

Genome sequencing and analysis

We sequenced the original stock of the foal clinical isolate 103, designated clone 103S, to avoid mutations associated with prolonged subculturing in vitro. Strain 103 belongs to one of the two major R. equi genogroups (DNA macrorestriction analysis, unpublished data), is genetically manipulable, and is regularly used for virulence studies [25], [56]. Random genomic libraries in pUC19 were pair-end sequenced using dye terminator chemistry on ABI3700 instruments, with subsequent manual gap closure of shotgun assemblies and sequence finishing, as previously described [8]. The 103S genome sequence was manually curated and annotated with the software and databases listed in Table S12. A conservative annotation approach was used to limit informational noise [8]. For phylogenomic analyses, putative core ortholog genes were identified by reciprocal FASTA using a minimum cutoff of 50% amino acid similarity over 80% or more of the sequence. A similarity distance matrix was built with the average percentage amino acid sequence identity obtained by pairwise BLASTP comparisons (distance = 100 − average percent identity of 665 loci) and used to infer a neighbor-joining tree with the Phylip package [87]. The accession numbers of the genome sequences used in comparative analyses are listed in Table S13.

The sequence from the R. equi 103S genome has been deposited in the EMBL/GenBank database under accession no. FN563149.

Phenotype analysis and microscopy

The nutritional and metabolic profile of R. equi 103S and its susceptibility to various drugs were analysed in Phenotype MicroArray screens (Biolog Inc., http://www.biolog.com) [15]. Substrate utilization was validated in supplemented mineral medium (MM) containing salts, trace elements, and ammonium chloride as the sole nitrogen source [19] (see Figure S7). For electron microscopy, a bacterial cell suspension in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate and observed at 80.0 kV in a Phillips CM120 BioTwin instrument (University of Edinburgh). Fluorescence microscopy was carried out on paraformaldehyde-fixed bacteria with an R. equi whole-cell rabbit polyclonal antiserum and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (both diluted 1∶1000 in 0.1% BSA).

Microarray expression profiling and network analysis

Total RNA was obtained from logarithmically growing R. equi bacteria (OD600 = 0.8) in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, by homogenization in guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform (Tri reagent, Sigma) with FastPrep-24 lysing matrix and a FastPrep apparatus (MP bio), followed by chloroform-isopropanol extraction, DNAase treatment (Turbo DNA-free, Ambion) and purification with RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA quantity and quality were determined with a Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific) and 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA 6000 Nano assay (Agilent). RNA samples (500 ng) were amplified with the MessageAmp II-bacteria kit and 5-(3-amionallyl)-UTP (Ambion), labeled with Cy3 or Cy5 NHS-ester reactive dyes (GE Healthcare), and purified with RNeasy MinElute (Qiagen). Whole-genome 8×15K custom microarrays with up to four different 60-mer oligonucleotides per CDS (13,823 probes for the chromosome, 201 for the virulence plasmid) (Agilent) were hybridized in Surehyb DNA chambers (Agilent) with 300 ng of Cy3/Cy5-labeled aRNA, using Gene Expression Hybridisation and Wash Buffer kits (Agilent). Three experimental replicates per condition were analyzed, one with dye swap. The hybridization signals were captured and linear intensity-normalized, with Agilent's DNA microarray scanner and Feature Extraction software. Data were subsequently LOESS-normalized by intensity and probe location and analyzed with Genespring GX 10 software (Agilent). Network analysis of microarray expression data was carried out with Biolayout Express3D 3.0 software [74], using log base 2 normalized ratios of Cy3/Cy5 signals and methods described in detail elsewhere [75]. Biolayout Express3D is freely available at http://www.biolayout.org/.

Mutant construction and complementation

In-frame deletion mutants of REQ23860 and REQ23850 were constructed by homologous recombination [56], using the suicide vector pSelAct for positive selection of double recombinants on 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC) [43]. Briefly, oligonucleotide primer pairs CMDEL1/CMDEL2 and CMDEL3/CMDEL4 were used for PCR amplification of two DNA fragments of ≈1.5 Kb corresponding to the seven 3′ - and six 5′-terminal codons plus adjacent downstream and upstream regions of REQ23860. The CMDEL2 and CMDEL3 primers are complementary and were used to join the two amplicons by overlap extension. The PCR product carrying the ΔREQ23860 allele was inserted into pSelAct, using SpeI and XbaI restriction sites; the resulting plasmid was introduced into 103S by electroporation and transformants were selected on LB agar supplemented with 80 µg/ml apramycin. The same procedure was followed for ΔREQ23860, with primers ASDEL 1 to 4. Allelic exchange double recombinants were selected as previously described [43], [56]. For complementation, the REQ23860-50 genes plus the entire upstream intergenic region were amplified by PCR with CACOMP1 and 2 primers and stably inserted into the R. equi chromosome, using the integrative vector pSET152 [88]. PCR was carried out with high-fidelity PfuUltra II fusion HS DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The primers used are shown in Table S14.

Macrophage infection assays

Low-passage (<20) J774A.1 macrophages (ATCC) were cultured in 24-well plates at 37°C, under 5% CO2 atmosphere, in DMEM supplemented with 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Lonza) until confluence (≈2×105 cells/well). J774A.1 monolayers were inoculated at 10∶1 MOI with washed R. equi from an exponential culture at 37°C in brain-heart infusion (BHI, OD600≈1.0). Infected cell monolayers were immediately centrifuged for 3 min at 172×g and room temperature, incubated for 45 min at 37°C, washed three times with Dulbecco's PBS to remove nonadherent bacteria, and incubated in DMEM supplemented with 5µg/µl vancomycin to prevent extracellular growth. After 1 h of incubation with vancomycin (t = 0) and at specified time points thereafter, cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS, detached with a rubber policeman and lysed by incutation for 3 min with 0.1% Triton X-100. Intracellular bacterial counts were determined by plating appropriate dilutions of cell lysates onto BHI. The presence of the virulence plasmid was checked by PCR on a random selection of colonies, using traA - and vapA - specific primers [9] to exclude the possibility of intracellular growth defects being due to plasmid loss. As the intracellular bacterial population at a given time point depends on initial numbers, bacterial intracellular kinetics data are expressed as a normalized “Intracellular Growth Coefficient” [89] according to the formula IGC = (IBt = n−IBt = 0)/IBt = 0, where IBt = n and IBt = 0 are the intracellular bacterial numbers at a specific time point, t = n, and t = 0, respectively.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. GurtlerV

MayallBC

SeviourR

2004 Can whole genome analysis refine the taxonomy of the genus Rhodococcus? FEMS Microbiol Rev 28 377 403

2. LarkinMJ

KulakovLA

AllenCC

2005 Biodegradation and Rhodococcus–masters of catabolic versatility. Curr Opin Biotechnol 16 282 290

3. MuscatelloG

LeadonDP

KlaytM

Ocampo-SosaA

LewisDA

2007 Rhodococcus equi infection in foals: the science of ‘rattles’. Equine Vet J 39 470 478

4. Vazquez-BolandJA

LetekM

ValeroA

GonzalezP

ScorttiM

FogartyU

2010 Rhodococcus equi and its pathogenic mechanisms

AlvarezHM

Biology of Rhodococcus, Microbiology Mongraphs 16 Berlin Heidelberg Spinger-Verlag(in press)

5. HondalusMK

MosserDM

1994 Survival and replication of Rhodococcus equi in macrophages. Infect Immun 62 4167 4175

6. WadaR

KamadaM

AnzaiT

NakanishiA

KanemaruT

1997 Pathogenicity and virulence of Rhodococcus equi in foals following intratracheal challenge. Vet Microbiol 56 301 312

7. von BargenK

HaasA

2009 Molecular and infection biology of the horse pathogen Rhodococcus equi. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33 870 891

8. LetekM

Ocampo-SosaAA

SandersM

FogartyU

BuckleyT

2008 Evolution of the Rhodococcus equi vap pathogenicity island seen through comparison of host-associated vapA and vapB virulence plasmids. J Bacteriol 190 5797 5805

9. Ocampo-SosaAA

LewisDA

NavasJ

QuigleyF

CallejoR

2007 Molecular epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi based on traA, vapA, and vapB virulence plasmid markers. J Infect Dis 196 763 769

10. McLeodMP

WarrenRL

HsiaoWW

ArakiN

MyhreM

2006 The complete genome of Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 provides insights into a catabolic powerhouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 15582 15587

11. GoodfellowM

AldersonG

ChunJ

1998 Rhodococcal systematics: problems and developments. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 74 3 20

12. BentleySD

ChaterKF

Cerdeno-TarragaAM

ChallisGL

ThomsonNR

2002 Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417 141 147

13. ColeST

BroschR

ParkhillJ

GarnierT

ChurcherC

1998 Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393 537 544

14. QuinnPJ

CarterME

MarkeyB

CarterGR

1994 Corynebacterium species and Rhodococcus equi. Clinical Veterinary Microbiology London Mosby International 137 143

15. BochnerBR

2009 Global phenotypic characterization of bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33 191 205

16. ZaitsevGM

UotilaJS

TsitkoIV

LobanokAG

Salkinoja-SalonenMS

1995 Utilization of halogenated benzenes, phenols, and benzoates by Rhodococcus opacus GM-14. Appl Environ Microbiol 61 4191 4201

17. SetoM

KimbaraK

ShimuraM

HattaT

FukudaM

1995 A novel transformation of polychlorinated biphenyls by Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl Environ Microbiol 61 3353 3358

18. van der GeizeR

HesselsGI

DijkhuizenL

2002 Molecular and functional characterization of the kstD2 gene of Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 encoding a second 3-ketosteroid Delta(1)-dehydrogenase isoenzyme. Microbiology 148 3285 3292

19. KellyBG

WallDM

BolandCA

MeijerWG

2002 Isocitrate lyase of the facultative intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi. Microbiology 148 793 798

20. Muñoz-EliasEJ

McKinneyJD

2006 Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacteria. Cell Microbiol 8 10 22

21. WallDM

DuffyPS

DupontC

PrescottJF

MeijerWG

2005 Isocitrate lyase activity is required for virulence of the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi. Infect Immun 73 6736 6741

22. McKinneyJD

Honer zu BentrupK

Munoz-EliasEJ

MiczakA

ChenB

2000 Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406 735 738

23. Hingley-WilsonSM

SambandamurthyVK

JacobsWRJr

2003 Survival perspectives from the world's most successful pathogen, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Immunol 4 949 955

24. WayneLG

SohaskeyCD

2001 Nonreplicating persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu Rev Microbiol 55 139 163

25. PeiY

ParreiraV

NicholsonVM

PrescottJF

2007 Mutation and virulence assessment of chromosomal genes of Rhodococcus equi 103. Can J Vet Res 71 1 7

26. MalmS

TiffertY

MicklinghoffJ

SchultzeS

JoostI

2009 The roles of the nitrate reductase NarGHJI, the nitrite reductase NirBD and the response regulator GlnR in nitrate assimilation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 155 1332 1339

27. SchellMA

KarmirantzouM

SnelB

VilanovaD

BergerB

2002 The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 14422 14427

28. EschbachM

SchreiberK

TrunkK

BuerJ

JahnD

2004 Long-term anaerobic survival of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa via pyruvate fermentation. J Bacteriol 186 4596 4604

29. ChaiY

KolterR

LosickR

2009 A widely conserved gene cluster required for lactate utilization in Bacillus subtilis and its involvement in biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 191 2423 2430

30. van VlietAH

StoofJ

PoppelaarsSW

BereswillS

HomuthG

2003 Differential regulation of amidase - and formamidase-mediated ammonia production by the Helicobacter pylori fur repressor. J Biol Chem 278 9052 9057

31. DuzM

WhittakerAG

LoveS

ParkinTD

HughesKJ

2009 Exhaled breath condensate hydrogen peroxide and pH for the assessment of lower airway inflammation in the horse. Res Vet Sci 87 307 312

32. MiyahiM

UedaK

KobayashiY

HataH

KondoS

2008 Fiber digestion in various segments of the hindgut of horses fed grass hay or silage. Anim Sci J 79 339 346

33. MongodinEF

ShapirN

DaughertySC

DeBoyRT

EmersonJB

2006 Secrets of soil survival revealed by the genome sequence of Arthrobacter aurescens TC1. PLoS Genet 2 e214 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020214

34. PotrykusK

CashelM

2008 (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu Rev Microbiol 62 35 51

35. NewtonGL

BuchmeierN

FaheyRC

2008 Biosynthesis and functions of mycothiol, the unique protective thiol of Actinobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72 471 494

36. SasindranSJ

SaikolappanS

DhandayuthapaniS

2007 Methionine sulfoxide reductases and virulence of bacterial pathogens. Future Microbiol 2 619 630

37. ColangeliR

HaqA

ArcusVL

SummersE

MagliozzoRS

2009 The multifunctional histone-like protein Lsr2 protects mycobacteria against reactive oxygen intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 4414 4418

38. HaikarainenT

PapageorgiouAC

2009 Dps-like proteins: structural and functional insights into a versatile protein family. Cell Mol Life Sci

39. PragaiZ

HarwoodCR

2002 Regulatory interactions between the Pho and sigma(B)-dependent general stress regulons of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 148 1593 1602

40. MartinezJL

2009 The role of natural environments in the evolution of resistance traits in pathogenic bacteria. Proc Biol Sci 276 2521 2530

41. UnderwoodAP

MulderA

GharbiaS

GreenJ

2005 Virulence Searcher: a tool for searching raw genome sequences from bacterial genomes for putative virulence factors. Clin Microbiol Infect 11 770 772

42. CasaliN

RileyLW

2007 A phylogenomic analysis of the Actinomycetales mce operons. BMC Genomics 8 60

43. van der GeizeR

de JongW

HesselsGI

GrommenAW

JacobsAA

2008 A novel method to generate unmarked gene deletions in the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi using 5-fluorocytosine conditional lethality. Nucleic Acids Res 36 e151

44. MohnWW

van der GeizeR

StewartGR

OkamotoS

LiuJ

2008 The actinobacterial mce4 locus encodes a steroid transporter. J Biol Chem 283 35368 35374

45. JoshiSM

PandeyAK

CapiteN

FortuneSM

RubinEJ

2006 Characterization of mycobacterial virulence genes through genetic interaction mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 11760 11765

46. Gey van PittiusNC

SampsonSL

LeeH

KimY

van HeldenPD

2006 Evolution and expansion of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis PE and PPE multigene families and their association with the duplication of the ESAT-6 (esx) gene cluster regions. BMC Evol Biol 6 95

47. StrongM

SawayaMR

WangS

PhillipsM

CascioD

2006 Toward the structural genomics of complexes: crystal structure of a PE/PPE protein complex from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 8060 8065

48. SimeoneR

BottaiD

BroschR

2009 ESX/type VII secretion systems and their role in host-pathogen interaction. Curr Opin Microbiol 12 4 10

49. JainM

CoxJS

2005 Interaction between polyketide synthase and transporter suggests coupled synthesis and export of virulence lipid in M. tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog 1 e2 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0010002

50. PuechV

GuilhotC

PerezE

TropisM

ArmitigeLY

2002 Evidence for a partial redundancy of the fibronectin-binding proteins for the transfer of mycoloyl residues onto the cell wall arabinogalactan termini of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 44 1109 1122

51. TomichM

PlanetPJ

FigurskiDH

2007 The tad locus: postcards from the widespread colonization island. Nat Rev Microbiol 5 363 375

52. MandlikA

SwierczynskiA

DasA

Ton-ThatH

2008 Pili in Gram-positive bacteria: assembly, involvement in colonization and biofilm development. Trends Microbiol 16 33 40

53. AlteriCJ

Xicohtencatl-CortesJ

HessS

Caballero-OlinG

GironJA

2007 Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces pili during human infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 5145 5150

54. PrescottJF

1991 Rhodococcus equi: an animal and human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 4 20 34

55. MarraffiniLA

DedentAC

SchneewindO

2006 Sortases and the art of anchoring proteins to the envelopes of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70 192 221

56. NavasJ

Gonzalez-ZornB

LadronN

GarridoP

Vazquez-BolandJA

2001 Identification and mutagenesis by allelic exchange of choE, encoding a cholesterol oxidase from the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi. J Bacteriol 183 4796 4805

57. ParkerSK

CurtinKM

VasilML

2007 Purification and characterization of mycobacterial phospholipase A: an activity associated with mycobacterial cutinase. J Bacteriol 189 4153 4160

58. Said-SalimB

MostowyS

KristofAS

BehrMA

2006 Mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0444c, the gene encoding anti-SigK, explain high level expression of MPB70 and MPB83 in Mycobacterium bovis. Mol Microbiol 62 1251 1263

59. ParkSY

JungMY

KimIS

2009 Stabilin-2 mediates homophilic cell-cell interactions via its FAS1 domains. FEBS Lett 583 1375 1380

60. PetheK

BifaniP

DrobecqH

SergheraertC

DebrieAS

2002 Mycobacterial heparin-binding hemagglutinin and laminin-binding protein share antigenic methyllysines that confer resistance to proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 10759 10764

61. Miranda-CasoLuengoR

PrescottJF

Vazquez-BolandJA

MeijerWG

2008 The intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi produces a catecholate siderophore required for saprophytic growth. J Bacteriol 190 1631 1637

62. RatledgeC

2004 Iron, mycobacteria and tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 84 110 130

63. Gey Van PittiusNC

GamieldienJ

HideW

BrownGD

SiezenRJ

2001 The ESAT-6 gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other high G+C Gram-positive bacteria. Genome Biol 2 RESEARCH0044

64. IshikawaJ

YamashitaA

MikamiY

HoshinoY

KuritaH

2004 The complete genomic sequence of Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 14925 14930

65. TrueJR

CarrollSB

2002 Gene co-option in physiological and morphological evolution. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 18 53 80

66. McLennanDA

2008 The concept of co-option: why evolution often looks miraculous. Evo Devo Outreach 1 247 258

67. GanforninaMD

SanchezD

1999 Generation of evolutionary novelty by functional shift. Bioessays 21 432 439

68. KonstantinidisKT

TiedjeJM

2004 Trends between gene content and genome size in prokaryotic species with larger genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 3160 3165

69. LynchM

KatjuV

2004 The altered evolutionary trajectories of gene duplicates. Trends Genet 20 544 549

70. ParkHD

GuinnKM

HarrellMI

LiaoR

VoskuilMI

2003 Rv3133c/dosR is a transcription factor that mediates the hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 48 833 843

71. Chico-CaleroI

SuarezM

Gonzalez-ZornB

ScorttiM

SlaghuisJ

2002 Hpt, a bacterial homolog of the microsomal glucose - 6-phosphate translocase, mediates rapid intracellular proliferation in Listeria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 431 436

72. ByrneGA

RussellDA

ChenX

MeijerWG

2007 Transcriptional regulation of the virR operon of the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi. J Bacteriol 189 5082 5089

73. ByrneBA

PrescottJF

PalmerGH

TakaiS

NicholsonVM

2001 Virulence plasmid of Rhodococcus equi contains inducible gene family encoding secreted proteins. Infect Immun 69 650 656

74. FreemanTC

GoldovskyL

BroschM

van DongenS

MaziereP

2007 Construction, visualisation, and clustering of transcription networks from microarray expression data. PLoS Comput Biol 3 e206 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030206

75. TheocharidisA

van DongenS

EnrightAJ

FreemanTC

2009 Network visualization and analysis of gene expression data using BioLayout Express3D. Nat Protoc 4 1535 1550

76. BarabasiAL

OltvaiZN

2004 Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat Rev Genet 5 101 113

77. RenJ

PrescottJF

2004 The effect of mutation on Rhodococcus equi virulence plasmid gene expression and mouse virulence. Vet Microbiol 103 219 230

78. RussellDA

ByrneGA

O'ConnellEP

BolandCA

MeijerWG

2004 The LysR-type transcriptional regulator VirR is required for expression of the virulence gene vapA of Rhodococcus equi ATCC 33701. J Bacteriol 186 5576 5584

79. DosselaereF

VanderleydenJ

2001 A metabolic node in action: chorismate-utilizing enzymes in microorganisms. Crit Rev Microbiol 27 75 131

80. FieldsPI

SwansonRV

HaidarisCG

HeffronF

1986 Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83 5189 5193

81. FoulongneV

WalravensK

BourgG

BoschiroliML

GodfroidJ

2001 Aromatic compound-dependent Brucella suis is attenuated in both cultured cells and mouse models. Infect Immun 69 547 550

82. BentleySD

CortonC

BrownSE

BarronA

ClarkL

2008 Genome of the actinomycete plant pathogen Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus suggests recent niche adaptation. J Bacteriol 190 2150 2160

83. SohaskeyCD

2008 Nitrate enhances the survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during inhibition of respiration. J Bacteriol 190 2981 2986

84. VoskuilMI

SchnappingerD

ViscontiKC

HarrellMI

DolganovGM

2003 Inhibition of respiration by nitric oxide induces a Mycobacterium tuberculosis dormancy program. J Exp Med 198 705 713

85. WassenaarTM

GaastraW

2001 Bacterial virulence: can we draw the line? FEMS Microbiol Lett 201 1 7

86. BabaH

NadaT

OhkusuK

EzakiT

HasegawaY

2009 First case of bloodstream infection caused by Rhodococcus erythropolis. J Clin Microbiol 47 2667 2669

87. FelsensteinJ

1989 PHYLIP - Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2). Cladistics 5 164 166

88. HongY

HondalusMK

2008 Site-specific integration of Streptomyces PhiC31 integrase-based vectors in the chromosome of Rhodococcus equi. FEMS Microbiol Lett 287 63 68

89. Gonzalez-ZornB

Dominguez-BernalG

SuarezM

RipioMT

VegaY

1999 The smcL gene of Listeria ivanovii encodes a sphingomyelinase C that mediates bacterial escape from the phagocytic vacuole. Mol Microbiol 33 510 523

90. MayJJ

WendrichTM

MarahielMA

2001 The dhb operon of Bacillus subtilis encodes the biosynthetic template for the catecholic siderophore 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate-glycine-threonine trimeric ester bacillibactin. J Biol Chem 276 7209 7217

91. MiethkeM

MarahielMA