-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaSynthesizing and Salvaging NAD: Lessons Learned from

The essential coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) plays important roles in metabolic reactions and cell regulation in all organisms. Bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals use different pathways to synthesize NAD+. Our molecular and genetic data demonstrate that in the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas NAD+ is synthesized from aspartate (de novo synthesis), as in plants, or nicotinamide, as in mammals (salvage synthesis). The de novo pathway requires five different enzymes: L-aspartate oxidase (ASO), quinolinate synthetase (QS), quinolate phosphoribosyltransferase (QPT), nicotinate/nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT), and NAD+ synthetase (NS). Sequence similarity searches, gene isolation and sequencing of mutant loci indicate that mutations in each enzyme result in a nicotinamide-requiring mutant phenotype in the previously isolated nic mutants. We rescued the mutant phenotype by the introduction of BAC DNA (nic2-1 and nic13-1) or plasmids with cloned genes (nic1-1 and nic15-1) into the mutants. NMNAT, which is also in the de novo pathway, and nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) constitute the nicotinamide-dependent salvage pathway. A mutation in NAMPT (npt1-1) has no obvious growth defect and is not nicotinamide-dependent. However, double mutant strains with the npt1-1 mutation and any of the nic mutations are inviable. When the de novo pathway is inactive, the salvage pathway is essential to Chlamydomonas for the synthesis of NAD+. A homolog of the human SIRT6-like gene, SRT2, is upregulated in the NS mutant, which shows a longer vegetative life span than wild-type cells. Our results suggest that Chlamydomonas is an excellent model system to study NAD+ metabolism and cell longevity.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001105

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001105Summary

The essential coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) plays important roles in metabolic reactions and cell regulation in all organisms. Bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals use different pathways to synthesize NAD+. Our molecular and genetic data demonstrate that in the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas NAD+ is synthesized from aspartate (de novo synthesis), as in plants, or nicotinamide, as in mammals (salvage synthesis). The de novo pathway requires five different enzymes: L-aspartate oxidase (ASO), quinolinate synthetase (QS), quinolate phosphoribosyltransferase (QPT), nicotinate/nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT), and NAD+ synthetase (NS). Sequence similarity searches, gene isolation and sequencing of mutant loci indicate that mutations in each enzyme result in a nicotinamide-requiring mutant phenotype in the previously isolated nic mutants. We rescued the mutant phenotype by the introduction of BAC DNA (nic2-1 and nic13-1) or plasmids with cloned genes (nic1-1 and nic15-1) into the mutants. NMNAT, which is also in the de novo pathway, and nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) constitute the nicotinamide-dependent salvage pathway. A mutation in NAMPT (npt1-1) has no obvious growth defect and is not nicotinamide-dependent. However, double mutant strains with the npt1-1 mutation and any of the nic mutations are inviable. When the de novo pathway is inactive, the salvage pathway is essential to Chlamydomonas for the synthesis of NAD+. A homolog of the human SIRT6-like gene, SRT2, is upregulated in the NS mutant, which shows a longer vegetative life span than wild-type cells. Our results suggest that Chlamydomonas is an excellent model system to study NAD+ metabolism and cell longevity.

Introduction

The coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an essential enzyme. Electron transfer between NAD+ and its reduced form NADH are essential to cells as they are involved in glycolysis and the citric acid cycle as well as regeneration of ATP from ADP [1]. NAD+ is consumed in several non-redox processes in cells (see [2] for review). NAD+ is a substrate of ADP-ribosyl transferase, which transfers ADP-ribose from NAD+ to ADP-ribose receptors, which are involved in DNA damage responses, transcriptional regulation, chromosome separation and apoptosis. NAD+ is also the target of ADP-ribosyl cyclases, which produce cyclic ADP-ribose that acts in second messenger signaling pathways. NAD+ is a substrate of sirtuins (SIRT/Sir2, Silent Information Regulator Two), a group of NAD+-dependent deacetylases that remove acetyl groups from lysine residues on histones, microtubules, and other proteins. Thus, NAD+, via sirtuins, modulates many events.

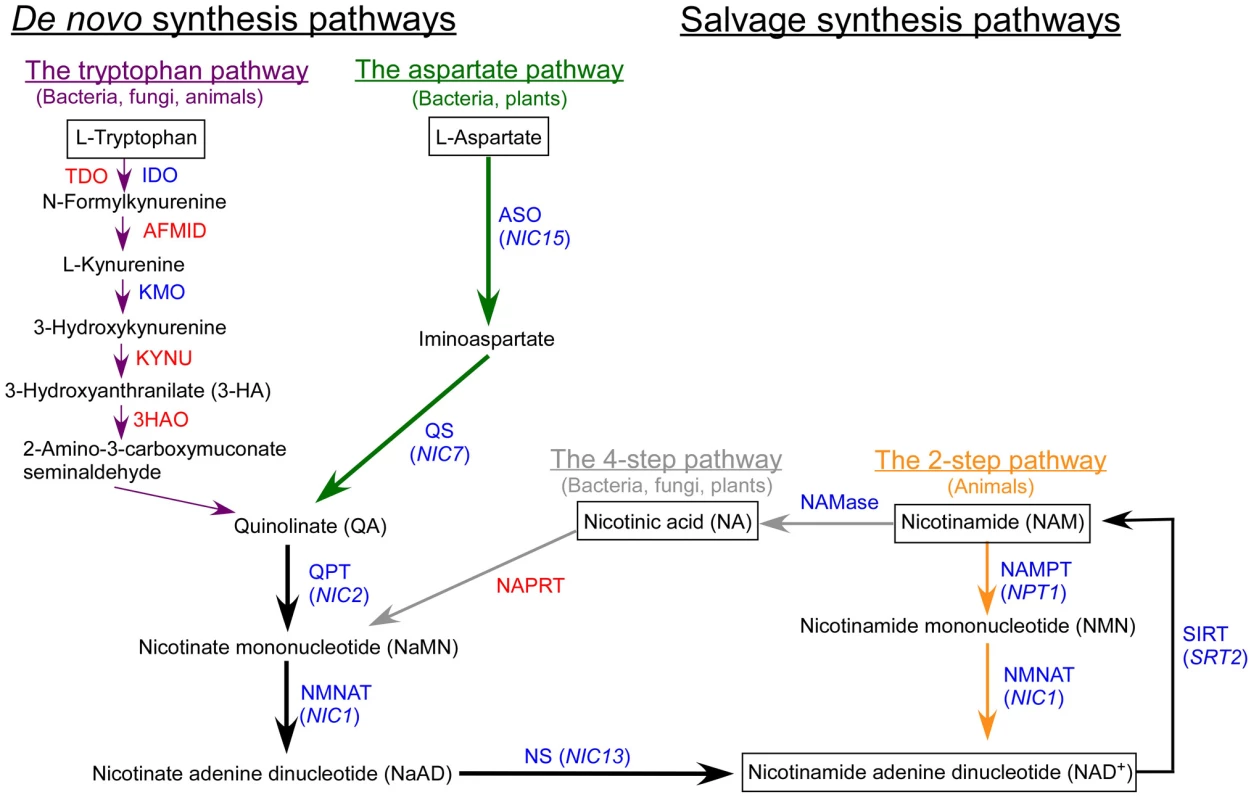

NAD+ synthesis pathways are categorized into either de novo pathways, which start with the amino acid aspartate or tryptophan, or salvage pathways, which start with nicotinamide (NAM) or nicotinic acid (NA) (Figure 1). Plants and some bacteria initiate de novo synthesis from aspartate and use two enzymes, L-aspartate oxidase (ASO) and quinolinate synthetase (QS), to synthesize quinolinate (QA). Fungi, animals and some bacteria synthesize QA from tryptophan via six enzymes, tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO)/indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), arylformamidase (AFMID), kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO), kynureninase (KYNU), and 3-hydroxy-anthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase (3HAO). The three enzymes shared by both de novo pathways, quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase (QPT); nicotinate/nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT); and NAD synthetase (NS), are required for the conversion of QA to NAD+.

Fig. 1. The biosynthetic pathways of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+).

Enzymes that are present in Chlamydomonas are indicated in blue and enzymes that are absent are indicated in red. Green arrows indicate steps specific to the aspartate pathway; dark purple arrows indicate steps specific to the tryptophan pathway; gray arrows indicate steps specific to the 4-step pathway; orange arrows indicate steps specific to the 2-step pathway; black arrows indicate steps that are commonly shared by multiple pathways. Abbreviations: ASO, L-Aspartate oxidase; QS, Quinolinate synthetase; QPT, Quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase; NMNAT, Nicotinate/nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase; NS, NAD+ synthetase; TDO, Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase; IDO: Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; AFMID, Arylformamidase; KMO, Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase; KYNU, Kynureninase; 3HAO, 3-Hydroxy- anthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase; NAMase, nicotinamidase; NAPRT, nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase; NAMPT, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; SIRT, silent information regulator two. Chlamydomonas genes identified in this study are indicated in parentheses. In the salvage pathways, the starting substrate is usually NA or NAM (Figure 1). Fungi, plants, and most bacteria, use NAM in a 4-step process involving nicotinamidase (NAMase), nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT), NMNAT, and NS to synthesize NAD+. In C. elegans, this is the only known pathway to synthesize NAD+ [3]. On the other hand, in mammals and some bacteria, NAD+ is synthesized via a 2-step enzymatic process and the enzymes involved are nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) and NMNAT.

The consumption of NAD+ by sirtuin mediated-protein deacetylation results in the production of nicotinamide. Recent studies have linked SIRT proteins to transcriptional gene silencing [4], DNA break repair [5], cell cycle regulation [6], aging [7], metabolism [8] and apoptosis [9]. In human, seven members of the SIRT protein family, SIRT1-7, are separated into 5 classes, I-IV, and U [10]. Human SIRT6, SIRT7, and some plant SIRT proteins belong to Class IV [10], [11]. The nuclear-localized SIRT6 is a NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase involved in telomeric chromatin modulation [12]. Deficiency of SIRT6 in mice is correlated with defective DNA repair, genomic instability, age-related degeneration [7], as well as increased glucose uptake, which is caused by transcriptional upregulation of several glycolytic genes that are normally repressed by SIRT6 [8]. SIRT7 localizes to the nucleolus and is involved in gene regulation of rDNA [13], [14].

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a unicellular green alga, is evolutionarily related to the seed plants and contains a chloroplast [15], [16]. Additionally, it contains animal specific organelles known as cilia/flagella and centrosomes. As discussed above, NAD+ synthesis pathways are diverse, but enzymes involved at each specific step are conserved in many organisms. Sequence similarity searches indicate that enzymes involved in the aspartate pathway from Arabidopsis, rice, and E. coli are conserved with protein identities ranging from 22% to 70% [17]. With the completion of the Chlamydomonas genome project [15], it became possible to identify Chlamydomonas homologs involved in the NAD+ synthesis pathways via sequence similarity searches.

A group of NAM-requiring mutants (nic) was isolated by Eversole that fail to grow well on medium lacking NAM [18]. The mutations also confer sensitivity to 3-acetylpyridine (3-AP) [19]. Eight NAM-requiring strains were originally isolated and six of these mutant strains are still extant. The NIC7 locus was identified in a walk through the mating-type locus and shown to encode a homolog of QS [20], [21]. We tested whether the remaining NIC loci encode the enzymes of the de novo aspartate NAD+ synthesis pathway. The nic mutant loci define six different loci and map to six different linkage groups (LG) [19]: NIC1 maps to LG XV; NIC2 maps to LG II; NIC7 maps to LG VI; NIC11 maps to LG IV; NIC13 maps to LG X; and NIC15 maps to LG XII/XIII [[20], [ 22]–[25]; see Materials and Methods for linkage group to chromosome translation]. In our study, phenotypic characterization and genetic crosses of nic11 strains obtained from the Chlamydomonas Center indicate that the Nic− phenotype of these nic11 strains (sensitivity to 3-AP or a growth defect on medium lacking NAM) can no longer be scored. Therefore, only five mutant strains are used in our study and we find that they encode the five enzymes in the de novo biosynthesis of NAD+ from aspartate.

Results

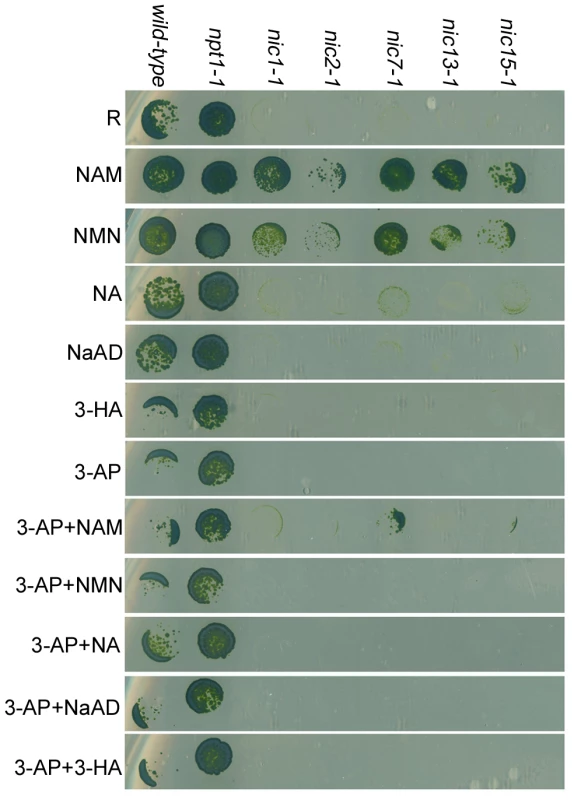

Chlamydomonas Nic− mutant phenotype can be rescued by addition of NAM

Wild-type (CC-124) and five different nic mutant cells (nic1-1, nic2-1, nic7-1, nic13-1, and nic15-1) were tested for their ability to utilize intermediate substrates in different NAD+ biosynthesis pathways (Figure 2). Wild-type cells show no obvious growth defect on any of the media tested. All the nic mutant strains fail to grow on Sager and Granick rich medium without NAM (R) or R medium supplemented with 3-AP, as previously described [19]. These mutants grow well on media supplied with either NAM or NMN, two chemical substances found only in the 2-step salvage biosynthesis pathway of NAD+. Addition of NA, an intermediate substrate found in the 4-step salvage pathway showed very weak rescue of the Nic− mutant phenotype of the mutants. Addition of 3-HA, which is synthesized in the tryptophan de novo pathway could not rescue the growth defect of any nic strains. NaAD, which acts in both de novo pathways, also does not rescue the Nic− mutant phenotype. The failure to rescue may indicate a failure of Chlamydomonas to transport these metabolites into cells.

Fig. 2. Chlamydomonas nicotinamide-requiring nic mutants show 3-AP sensitivity.

Chlamydomonas cells were spotted on solid rich medium (R) or medium supplemented with 10 µM NAM (nicotinamide), 10 µM NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide), 10 µM NA (nicotinic acid), 10 µM NaAD (nicotinate adenine dinucleotide), or 10 µM 3-HA (3-hydroxyanthranilate). For 3-AP (3-acetylpyridine) sensitivity assay, cells were spotted on R medium containing 16.5 mg/l 3-AP with or without the addition of various chemical substances as indicated. 3-AP is considered to be a NA analogue, which causes NA deficiency in mice. Injecting animals with NA, NAM, or tryptophan rescues the NA deficiency [26], [27]. Given that 3-AP causes cell lethality in Chlamydomonas nic mutant cells, we tested whether addition of NAM or NA could rescue the phenotype. Addition of NAM showed weak rescue of the nic7-1 and nic15-1 mutants but not the other mutants (Figure 2). Addition of NA, NMN, NaAD, or 3-HA does not rescue the lethality conferred by 3-AP in any of the mutants.

De novo biosynthesis of NAD+ in Chlamydomonas resembles the pathway used by seed plants

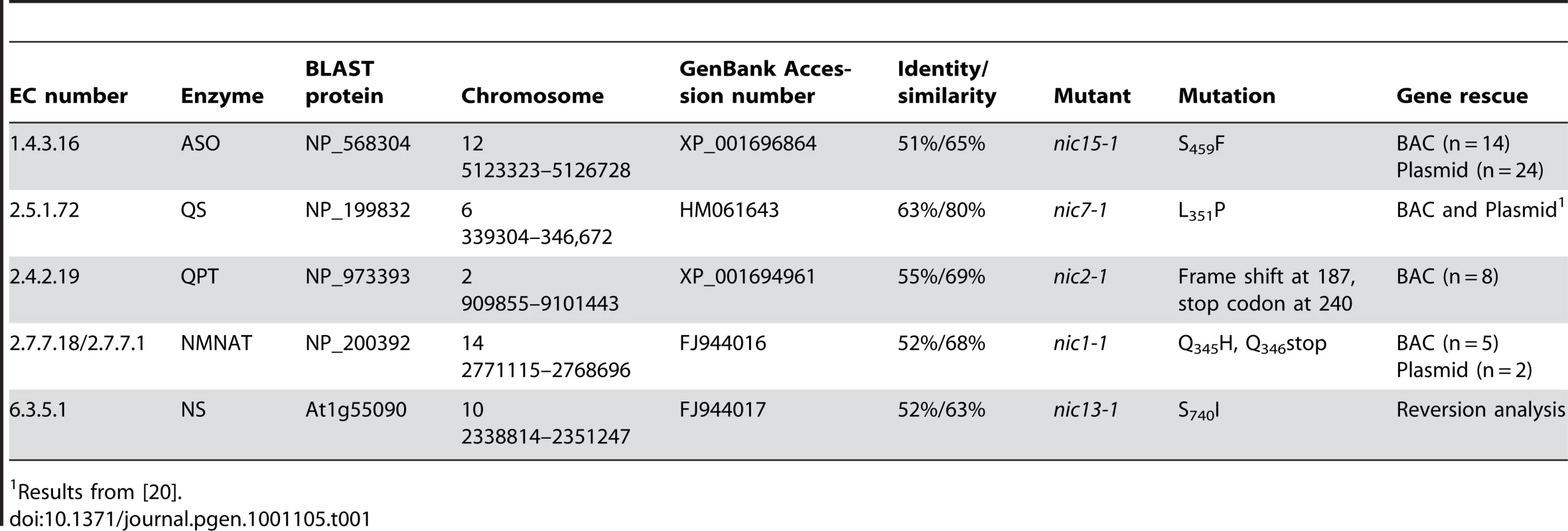

Katoh et al. showed that Arabidopsis synthesizes NAD+ from aspartate and all five enzymes involved in this pathway have been characterized [28], [29]. We identified the Chlamydomonas homologs by sequence similarity and linked the genes to corresponding nic mutants via DNA sequencing and complementation with transgenes. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Tab. 1. List of Chlamydomonas enzymes involved in de novo NAD+ biosynthesis from L-aspartate.

Results from [20]. Chlamydomonas ASO gene, which contains 4 exons and encodes a 669 aa protein (Figure 3A; [15]), is ∼63 kb away from the ODA12 gene [30], which maps to LG XII/XIII [31]. The Chlamydomonas nic15-1 mutant is tightly linked to MAA1 on LGXII/XIII [22]. The nic15-1 strain (See Materials and Methods) contains a single nucleotide change C1376T that predicts a S459F change in the predicted protein (Figure 3A). The S459F change falls in a highly conserved region among bacterial and plant ASO proteins and is likely to affect normal function of this protein (Figure S1). We performed gene complementation with either a BAC (32L22) or a plasmid containing the full-length ASO gene (pNIC15a). Both transformations produced 3-AP-resistant colonies (n = 14 for the BAC and n = 24 for the plasmid), which indicates that Nic− mutant phenotype was rescued by re-introducing the ASO gene.

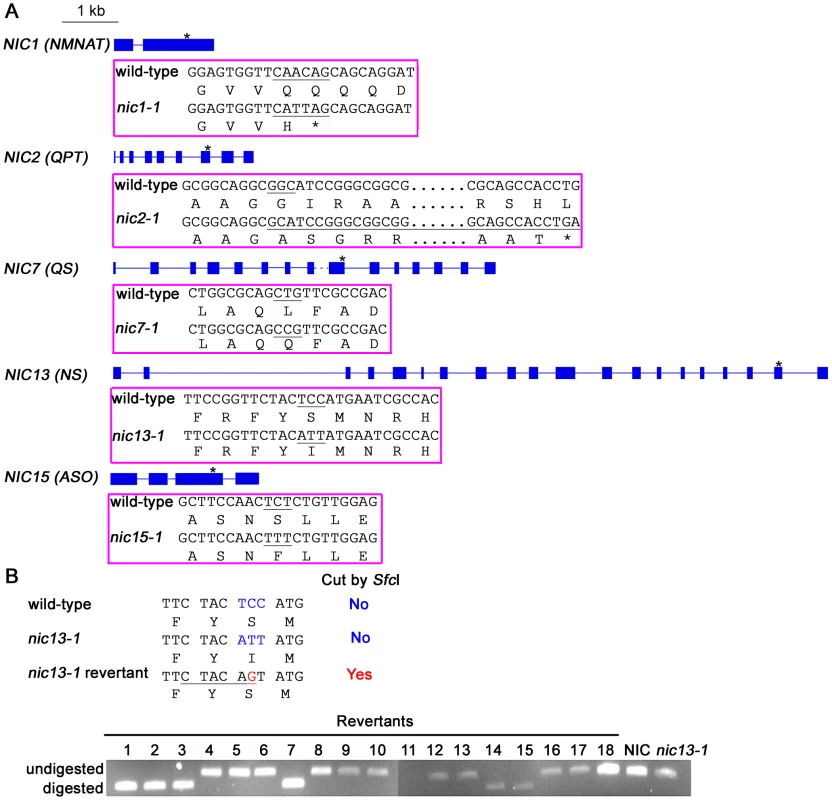

Fig. 3. Chlamydomonas nic mutants carry various point mutations in NIC genes.

(A) Schematic diagrams show the gene structures of NIC1, NIC2, NIC7, NIC13, NIC15 and the positions of mutations are indicated by asterisks. Blue solid box, exon; solid line, intron; dashed line, undefined length of intron. Each magenta box below the gene structure indicates changes in nucleotide/amino acid in the mutants when compared to the wild-type strain. Changes in codon that results in amino acid changes are highlighted in black. (B) PCR and enzymatic digestion to identify nic13-1 I740S reversion from 18 nic13-1 UV revertants. Top, nucleotide and amino acid sequences around the mutation points in various strains. The SfcI restriction enzyme recognition site is underlined in the nic13-1 revertant sequence. Bottom, SfcI digestion products in various strains. The nic7-1 mutant maps to a 7.9 kb region on LG VI. Transformation of this fragment rescues the 3-AP sensitive phenotype of nic7-1 cells, but the nature of this mutant and the gene structure of NIC7 were not determined [20]. Ferris et al. proposed that NIC7 encodes QS, given the NIC7 gene product displays low similarity to bacterial QS [21]. Using RT-PCR and DNA sequencing, we found that the NIC7 gene contains 15 exons and it shares 63% identity to Arabidopsis QS. Sequencing of the NIC7 coding region reveals a L351Q change in the nic7 -1 mutant (Figure 3A). The amino acid L351 within the quinolinate synthetase domain is conserved among almost all plant QS proteins but not in bacterial proteins (Figure S2).

CNA43, a cDNA marker mapped to LG II [31] is ∼212kb from the Chlamydomonas QPT gene as determined by the JGI Chlamydomonas v4.0 genome assembly. The nic2-1 mutant maps to LG II ([24]; M. Miller and S. K. Dutcher, unpublished observations). RT-PCR and sequencing of the QPT coding region in the nic2-1 mutant strain reveal a single nucleotide deletion at nucleotide 559 that leads to a frameshift. The amino acid sequence changes at Gly187 and generates a premature stop codon at amino acid 240 (Figure 3A; Figure S3). The mutant protein contains all the conserved QA-binding sites (Figure S3, blue reversed triangles) but the α8-12 helices and β8-12 sheets required to form α/β barrel are missing [32]. Transformation with a BAC clone (38P5) containing a full-length QPT gene yields 8 independent 3-AP-resistant colonies.

The Chlamydomonas NMNAT gene was predicted to contain 4 exons and encode a 234 aa protein [15]. However, RT-PCR, nested PCR and DNA sequencing shows the coding region of Chlamydomonas NMNAT is composed of only 2 exons that encodes a 524 aa protein, as predicted by the GreenGenie2 algorithm [33]. Sequence alignment reveals that Chlamydomonas NMNAT contains extra glycine/proline/glutamine-rich sequences compared to NMNAT proteins from other organisms (Figure S4). The Chlamydomonas NMNAT gene is ∼262 kb away from the IDA2 gene [34] and maps to LG XV [31], near where the NIC1 gene maps [25]. Sequencing of the NMNAT genomic DNA from a nic1-1 strain indicates two adjacent nucleotide changes A1406C1407→T1406T1407 result in Q345H, Q346stop (Figure 3A; Figure S4). These nucleotide changes are likely to generate a truncated NMNAT in the nic1-1 mutant strain. The 3-AP-sensitive nic1-1 mutant phenotype is leaky and reverts at a low frequency of ∼1 spontaneous 3-AP-resistant colony per 108 cells. Therefore, a co-transformation approach was used for gene complementation. BAC DNA (10M24) or plasmid DNA (pNIC1-56) containing the full-length NMNAT gene was co-transformed with a paromomycin-resistant gene (APHVIII; [35]). A subset of the paromomycin-resistant colonies (5/20 for BAC and 2/2 for plasmid transformation) showed resistance to 3-AP.

The Chlamydomonas NS homolog maps between GP220 and GP441, which are two molecular markers on LG X [31], where nic13-1 maps [25]. RT-PCR and DNA sequencing from wild-type cells indicate this gene contains 20 exons that encode an 832 aa protein. The intron between exons 2 and 3 is unusually long (∼3.5 kb) for a Chlamydomonas gene (Figure 3A). Similar to Chlamydomonas NMNAT, Chlamydomonas NS contains extra sequences not found in other organisms. This insert is rich in alanine residues (Figure S5). The coding region of NS in nic13-1 was sequenced and a triple nucleotide substitution (TCC→ATT) is predicted to produce a S740I change (Figure 3A). The S740 is highly conserved among plants, green algae, and mammals (Figure S5). Further evidence that this point mutation is responsible for the mutant phenotype is provided by reversion analysis. We reasoned that a single base change of ATT (I) to AGT (S) would generate an I740S reversion. This change would also create a SfcI site (TTCTACAGTA), which is not present in either wild-type or nic13-1 cells (Figure 3B). Eighteen 3-AP-resistant colonies were isolated following UV mutagenesis of nic13-1 cells. Six of them contained a SfcI site as monitored by PCR and restriction digestion of the product (Figure 3B). Of these, three revertants were randomly selected for sequencing. The ATT→AGT change was confirmed in all three selected revertants. The other 12 revertants were not analyzed. Transformation of nic13-1 cells with BAC (10H24) produced two 3-AP-resistant colonies and this provides further evidence that the mutation in NS is responsible for the nic13-1 mutant phenotype.

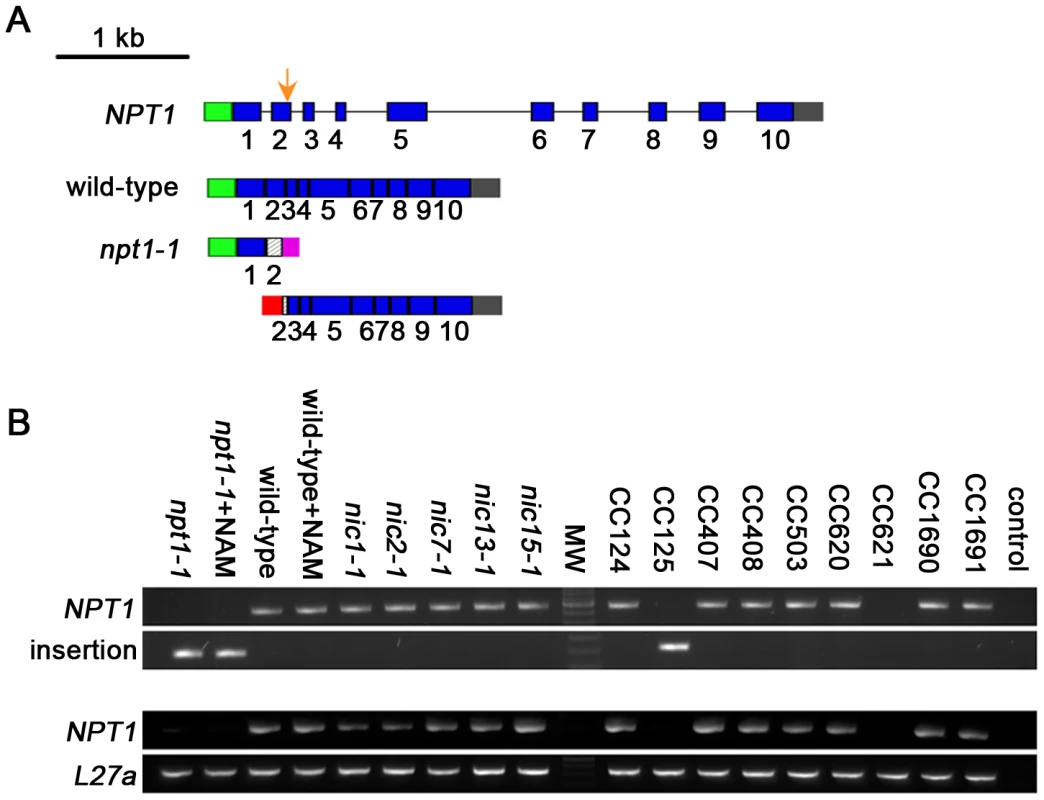

Salvage biosynthesis of NAD+ in Chlamydomonas uses the pathway found in mammals

Since Chlamydomonas nic mutants can utilize both NAM and NMN (Figure 2), two metabolites found in the 2-step salvage pathway, we propose that Chlamydomonas uses this pathway to synthesize NAD+. The 2-step salvage pathway utilizes two enzymes, NAMPT and NMNAT. A NAMPT homolog, which is ∼30% identical to human NAMPT, was identified via sequence similarity search (Figure S6). RT-PCR and DNA sequencing indicated the Chlamydomonas NAMPT gene (NPT1, GenBank HM061641) contains 10 exons and encodes a 543 aa protein (Figure 4A) in CC-124 wild-type cells. However, we failed to amplify the full-length NPT1 transcript (∼2.2 kb) from another wild-type strain (CC-125) (Figure 4C). Further investigation using 3′ RACE and 5′ RACE shows that an insertion in exon 2 of the NPT1 gene is present in the CC-125 strain (Figure 4A, 4B). This region was partially sequenced and the inserted DNA sequence maps to multiple places in the genome and is likely to contain one or more transposable elements. The insertion causes two truncated NPT1 transcripts in the CC-125 strain. The first one is ∼0.6 kb long and contains the endogenous NPT1 promoter and ends within ∼100 bp of the inserted DNA (Figure 4A). It is predicted to contain an open reading frame (ORF), which encodes a 127 aa protein. This predicted protein contains the first 60 aa of the conserved phosphoribosyltransferase domain, which is ∼450 aa long. The second transcript is ∼1.8 kb long and starts with ∼130 bp of the inserted DNA (Figure 4A). This truncated transcript contains part of exon 2 and the rest of the gene and is predicted to contain an ORF encoding a 435 aa protein. The predicted protein lacks the first 65 aa of the conserved phosphoribosyltransferase domain. Thus, we conclude that the CC-125 strain carries a defective NPT1 and we name the allele npt1-1 (nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase). All the nic mutants contain a full-length NPT1 transcript (Figure 4B, 4C).

Fig. 4. Chlamydomonas strain CC-125 contains an insertion in the NAMPT gene.

(A) Schematic diagram shows gene structure of the Chlamydomonas NAMPT gene. An insertion in exon 2 in the npt1-1 mutant strain is indicted by an orange arrow. Blue solid box, exon; black solid line, intron; green solid box, 5′ UTR; gray solid box, 3′ UTR; magenta and red solid boxes, sequences from the putative transposon(s); hatched boxes, incomplete regions of exon 2. (B) PCR amplification of NPT1 genomic DNA around the insertional region. Upper panel, primers spanning the insertional point can amplify the wild-type NPT1 but not NPT1 with an insert. Lower panel, one primer binds to the inserted sequence while the other binds to NPT1. Thus only NPT1 with the specific inserted sequence can be amplified. (C) RT-PCR amplification of the whole coding region of NPT1. L27a, a ribosomal protein gene serves as a control [84]. Control, no DNA template was added in PCR. Given that CC-124 and CC-125 strains are considered to be “wild-type” strains in the Chlamydomonas community, we tested whether any other wild-type strains contain this insertion. The CC-124 and CC-125 strains originated from the 137c zygotic isolate by Smith in 1945 [36]. The meiotic progeny from 137c was distributed to Sager in 1953 and to Ebersold in 1955. Four of the strains we tested, CC-1690 (21gr), CC-1691 (6145c), CC-407 (C8), and CC-408 (C9), originated from the Sager 1953 branch. The other three strains, CC-503 (cw92, used for the genomic sequence by JGI), CC-620 (R3), and CC-621 (NO), as well as CC-124 and CC-125, all came from the Ebersold branch. Genomic DNA PCR was used to identify the transposon insertion event while cDNA PCR indicated the presence/absence of the NPT1 transcript. Most of the strains have an intact NPT1 gene (CC-407, 408, 503, 620, 1690, and 1691). The CC-621 strain (upper panel, Figure 4B) has an insertion in exon 2 of NPT1, but the insertional sequence is not identical to the CC-125 insertion since the PCR primers that recognize the insertion in CC-125 failed in CC-621 (lower panel, Figure 4B). As expected, the CC-621 strain also does not express the full-length NPT1 transcript (Figure 4C). In contrast to the nic mutant strains, the npt1-1 mutant strains, CC-125 (npt1-1) and CC-621 (npt1-2), show no obvious growth defect on rich medium or medium supplied with 3-AP (Figure 2 and data not shown).

Sequence similarity searches indicate that Chlamydomonas does not contain four of the six enzymes required to synthesize NAD+ from the de novo tryptophan pathway and it is missing a homolog of NAPRT from the 4-step salvage pathway. Chlamydomonas has genes for the IDO and KMO enzymes in the tryptophan pathway and has a NAMase homolog in the 4-step salvage pathway. Given the apparent incompleteness of either of these two pathways, we hypothesized that Chlamydomonas is unable to synthesize NAD+ via the tryptophan pathway or the 4-step salvage pathway (Figure 1).

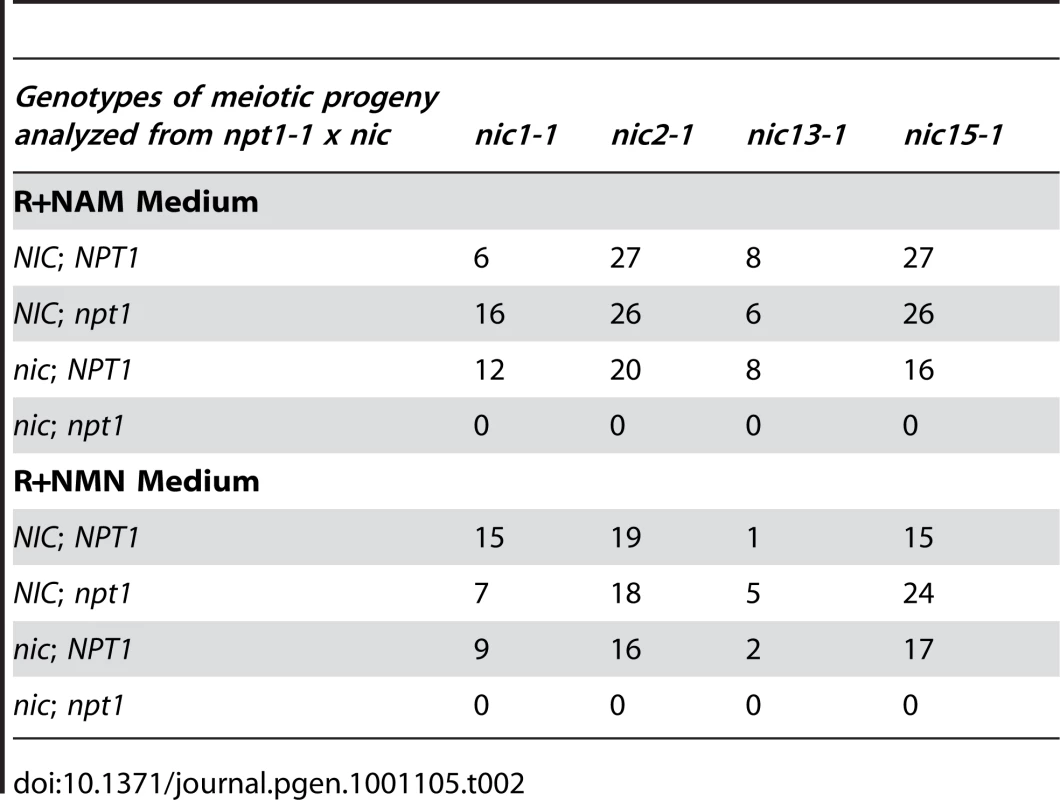

If the hypothesis that Chlamydomonas contains only the de novo aspartate pathway and the 2-step salvage pathway is correct, then double mutant strains containing the npt1-1 mutation as well as one of the nic mutations should be lethal and fail to grow on medium supplied with NAM. Otherwise, if there were additional NAD+ synthesis pathways available, then npt1-1; nic2-1 or npt1-1; nic15-1 double mutants should survive on NAM medium. We performed crosses between the nic mutants and the npt1-1 mutant strain. Genotypes of the meiotic progeny were scored based on their viability (NIC) or inviability (nic) on medium containing 3-AP, and the presence (npt1) or absence (NPT1) of the NPT1 transposon insertion, which was tested by genomic DNA PCR. The results are summarized in Table 2. Out of 198 viable progeny generated from 4 different crosses, no npt1; nic double mutants were recovered on NAM medium. Because addition of NMN rescued the nic mutants and it is downstream of the NAMPT catalyzed step, we expected that npt1; nic double mutants should be viable on medium supplied with NMN. However, we found that no npt1; nic double mutants were isolated out of 148 viable progeny on NMN medium. One potential cause may be the hydrolysis or inefficient uptake of NMN by meiotic progeny compared to vegetative cells. Alternatively, the NIC1 message may not be expressed in meiotic progeny (Figure 2). Thus, based on the results from these genetic crosses between the nic mutants and the npt1-1 mutant, we conclude that Chlamydomonas synthesizes NAD+ via the de novo aspartate pathway and the 2-step salvage pathway and it is very unlikely that there is additional NAD+ biosynthesis pathway.

Tab. 2. Progeny analysis from crosses between <i>npt1-1</i> and <i>nic</i> mutant strains.

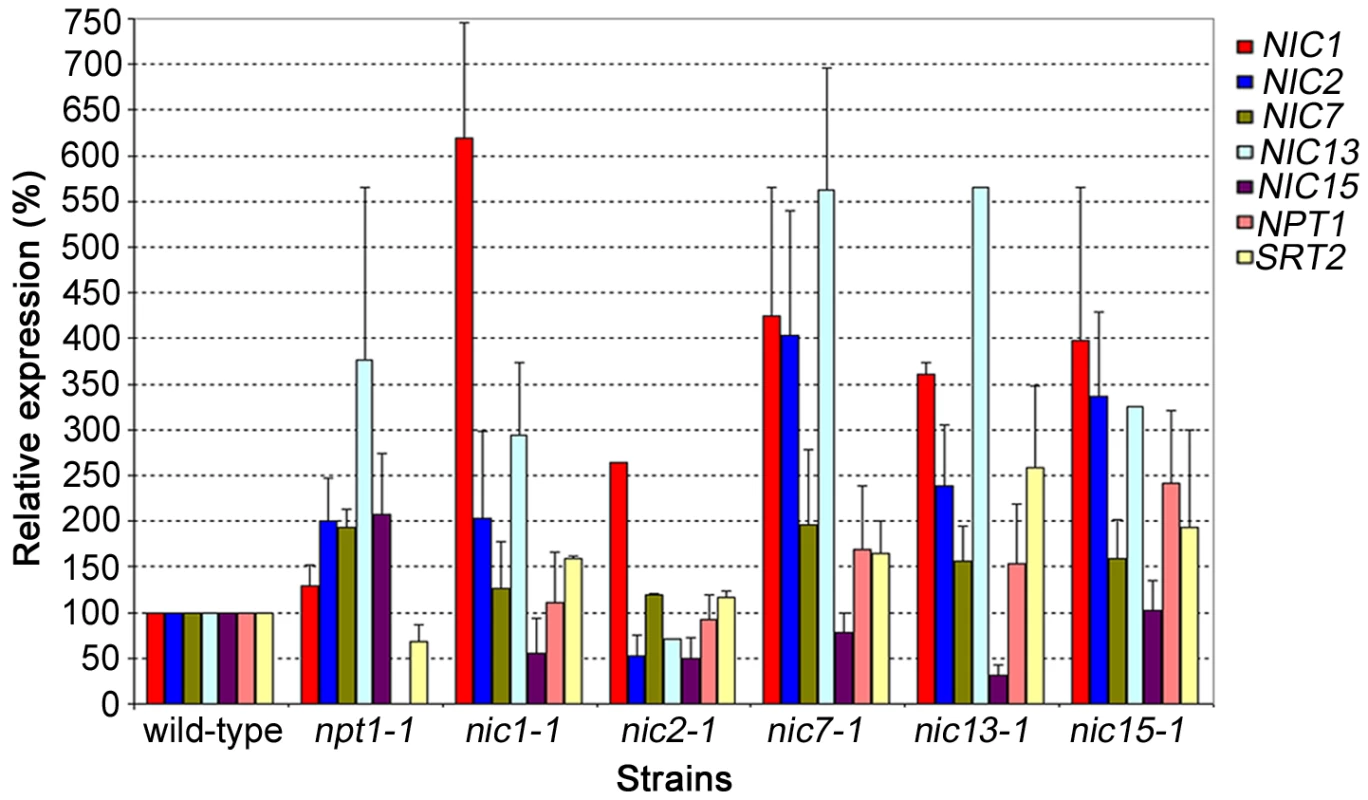

Transcriptional regulation among genes involved in the NAD+ biosynthesis pathways

Previous studies on bacterial and mammalian NAD+ biosynthesis indicate that transcriptional regulation among genes involved in the pathways is common. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica, expression of nadB (encodes ASO) and nadA (encodes QS) is regulated by nadR, which has NMNAT activity [37], [38]. In mammals, the circadian expression of NAMPT is partially regulated by SIRT1, the enzyme that converts NAD+ to NAM, which is the substrate of NAMPT [39]. To investigate whether transcriptional regulation among the NIC genes and NPT1 exists in Chlamydomonas, we measured transcript levels of these genes in nic and npt1-1 mutants by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR, Figure 5). Changes were not considered significant unless a gene is >2-fold upregulated or <2-fold downregulated when compared to its expression level in wild-type cells.

Fig. 5. Gene expression in wild-type, npt1-1, and nic mutant cells.

Relative real-time RT-PCR was used to detect transcripts. Results represent 2 biological replicates and standard errors are indicated by error bars. The first step in the de novo aspartate pathway, which is rate limiting in bacteria, is catalyzed by ASO, encoded by NIC15. As expected, mutations in the downstream enzymes (nic1-1, nic2-1, and nic13-1) result in reduced NIC15 transcript while the npt1-1 mutation causes a 2-fold elevation in NIC15 transcript level. The NIC7 transcript level was not affected in any of the mutants tested. NIC2 and NIC13 transcript levels are upregulated in the npt1-1 mutant and in all the nic mutants except nic2-1. The NIC1 transcript level is upregulated in the nic mutants but not in npt1. Finally, the expression level of NPT1 is only upregulated in the nic15-1 mutant strain.

Overall, gene expression of the NIC, NPT1 and SRT2 genes shows complicate patterns. No single gene is upregulated or downregulated in all mutants and no single mutant shows clear upregulation or downregulation of all genes involved in a pathway. This result suggests that in addition to regulation at the transcription level, NAD+ biosynthesis may be regulated post-transcriptionally.

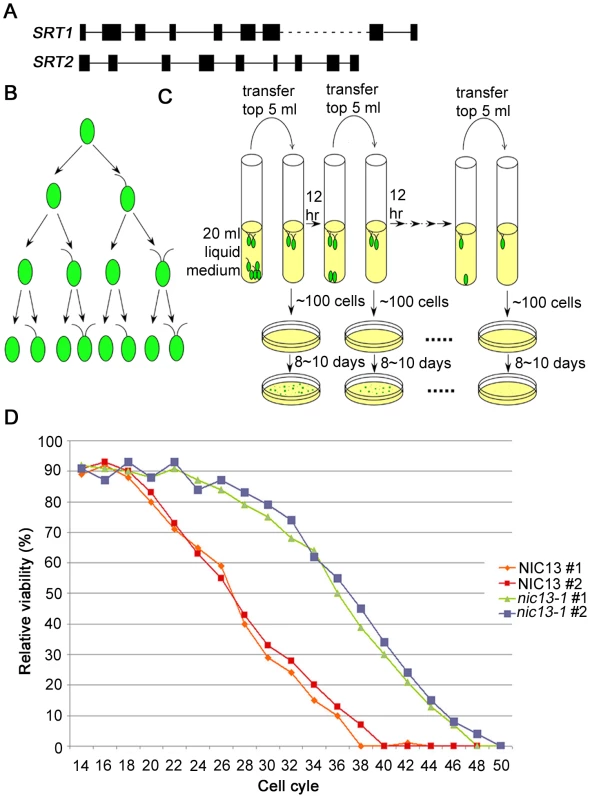

The link between NAD+ biosynthesis in Chlamydomonas and longevity

In studies of yeast, worms, and mammals, upregulation of NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase Sir2/SIRT1 is correlated to longevity [40], [41]. In rice, RNA interference of OsSRT1 leads to DNA fragmentation and programmed cell death [42]. We wanted to test if SIR2 homologs play a similar role in algae. A sequence similarity search using SIR or SIRT proteins finds two proteins in Chlamydomonas. We named the one most to similar to yeast Sir2 protein SRT2. RT-PCR and sequencing show that the Chlamydomonas SRT2 gene contains 9 exons (Figure 6A) and encodes a 320 aa protein (GenBank HM061642). Sequence alignment (Figure S7) shows that this protein contains the NAD-dependent catalytic core domain and is closely related to human SIRT6, SIRT7, and plant SRT proteins, which are class IV SIRT proteins. The second SIR2-like gene, SRT1, is most similar to human SIRT4 [11], which is a mitochondrial protein. This gene encodes a 399 aa protein (GenBank HM161714) and belongs to the class II sirtuin family (Figure 6A and Figure S7).

Fig. 6. Chlamydomonas SRT2 and life span extension in Chlamydomonas nic13-1 mutant strain.

(A) Schematic diagram shows gene structures of Chlamydomonas SRT1 and SRT2. (B) Pedigree of the uni3-1 mutant strain regarding flagellar numbers, redrawn from Dutcher and Trabuco [43]. (C) Schematic diagram shows how the aging experiment was performed with Chlamydomonas cells. (D) Life span in wild-type and nic13-1 cells. Results from 2 biological replicates of each strain are shown. Since Sir2-like proteins are involved in the enzymatic step of converting NAD+ to NAM, we tested the expression of Chlamydomonas SRT1 and SRT2 by qRT-PCR. The transcript level of SRT1 is extremely low and we could not obtain informative qRT-PCR data. Thus, we focused on SRT2 transcript levels in wild-type, nic and npt1-1 mutants (Figure 5), and find that SRT2 remained unchanged in all strains except in nic13-1 cells, which show a ∼2.5 fold increase.

We then tested whether this increase of SRT2 expression in nic13-1 cells affects Chlamydomonas cell longevity. We took advantage of the Chlamydomonas uni3-1 cells, which have a deletion of delta-tubulin. A pedigree analysis of this mutant suggested that the flagellar number is a metric of the mitotic age of cells (Figure 6B). As shown by Dutcher and Trabuco, biflagellate cells are only produced by uni3-1 cells that have undergone at least two cell divisions [43]. Aflagellate cells never produce biflagellate daughters, but a uniflagellate or biflagellate uni3-1 cell produces one aflagellate daughter cell and one biflagellate daughter cell. We suggest that the biflagellate cell is the equivalent of using the mother cell in budding yeast as a marker of generational age. Having two flagella allows a cell to swim effectively to the air-liquid interface of the medium, while an aflagellate or uniflagellate daughter cell sinks to the bottom of the culture tube. The biflagellate daughter cells can then be transferred to a new test tube and of the number of generations that the uni3-1 cells undergoes can be monitored (Figure 6C). As illustrated in Figure 6D, NIC13; uni3-1 biflagellate cells complete 38–40 cell cycles. On the other hand, nic13; uni3-1 cells complete 48–50 cell cycles. This represents a ∼25% increase in reproductive capacity. We assayed a nic2-1; uni3-1 strain since it does not have increased SRT2 levels but has a synthesis defect and found that it completed 37 cell cycles like wild-type cells (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that NAD+ biosynthesis in Chlamydomonas can affect life span and this might be achieved by alternating the expression level of Chlamydomonas SRT2.

Discussion

The essential roles of NAD+ in many metabolic oxidation-reduction reactions are well established. Recent studies link its function to transcriptional regulation [44], epigenetic regulation [45], longevity [2], cell death [46], neurogeneration [47], circadian clocks [48], and signal transduction [49]. Understanding its biosynthetic pathways will facilitate understanding of lifespan extension [50], disease regulation [51], drug design [52], as well as evolution [53].

Recent studies on NAD+ biosynthesis indicate that pathways in different organisms are more diverse than expected. The tryptophan pathway, which was thought to be eukaryotic specific, was identified in several bacteria [54]. The aspartate pathway, which was considered only prokaryotic, is present and essential to Arabidopsis thaliana [28]. An organism may contain all the enzymes required for more than one pathway, but a single pathway is predominantly used. Bacillus subtilis can synthesize NAD+ via aspartate or the 4-step pathway but only genes involved in the conversion from NA to NAD+ are indispensable [55]. Arabidopsis thaliana contains the aspartate pathway and the 4-step pathway. However homozygous ASO and QS mutants, which specifically affect the aspartate pathway, are inviable [28]. In mammals, the enzyme NAMPT, which is the rate-limiting enzyme in the 2-step pathway, is essential even though organisms harbor all the enzymes required to synthesize NAD+ from tryptophan [56]. However in D. melanogaster and C. elegans, there is only one pathway. The de novo NAD+ synthesis pathway is incomplete and they rely on the NAMase-dependent salvage pathway to synthesize NAD+ [53].

Our study indicates that Chlamydomonas can synthesize NAD+ via the aspartate pathway, which is found in land plants and bacteria, or the 2-step salvage pathway, which is found in mammals. This combination in Chlamydomonas makes it a great model for the study of NAD+ biosynthesis. Similar to Arabidopsis, Chlamydomonas contains one copy of each gene that encodes the de novo pathway enzymes and the Chlamydomonas proteins are 51%∼63% identical to Arabidopsis homologs. However, unlike Arabidopsis mutants, which are lethal when homozygous [28], [57], the Chlamydomonas nic mutants show conditional lethality as they are rescued by the addition of NAM or NMN to the medium. Thus, the effects of loss of function mutations, which can not be studied in Arabidopsis, can be easily analyzed in Chlamydomonas. In mammals, NAMPT is essential. It is encoded by three different genes and the proteins localize to different cellular compartments. In addition, mammal NAMPT has an extracellular form; both intracellular (iNAMPT) and extracellular (eNAMPT) forms are involved in NAD+ synthesis and in regulation of insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells [58]. Chlamydomonas contains only one copy of NAMPT (NPT1). The npt1-1 mutant has no growth defect but none of the nic; npt1-1double mutants are viable (Table 2). Since Chlamydomonas cells are haploid and easy to maintain, this mutant provides an alternative for screening for NAMPT-blocking drugs. The potential drugs would have no effect on wild-type cells but would be lethal to nic cells.

In mammals 3-AP acts as an analog of nicotinic acid and inhibits the 4-step salvage pathway. In Chlamydomonas, 3-AP prevents the rescue of nic mutants by NMN and greatly suppresses the rescue by NAM. The easiest explanation for these results would be that Chlamydomonas has the 4-step salvage pathway and it is active. However, the Chlamydomonas genome has only three of the four enzymes; the genome assembly is missing the key enzyme, NAPRT. It remains a possibility that Chlamydomonas has a NAPRT gene, but it is not present in the assembled genome sequence. Two lines of evidence suggest that a functional NAPRT is not likely to be present in Chlamydomonas. First, using 40 million Illumina transcriptome reads (1.2 Gb of sequence) from three independent mRNA preparations, we find evidence for transcription of the first 45 amino acids of NAPRT using a splice aware assembly algorithm, but find no evidence for the transcription of the rest of the gene that contains all of the known active sites needed for function [59], [60] (unpublished data). Given the high identity of this protein from microalgae to mammals, it is likely either that the rest of the Chlamydomonas NAPRT gene was lost or the gene is not transcribed beyond the first 135 bps of the open reading frame. Second, the genome sequence of Volvox carteri (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Volca1/Volca1.home.html), a multicellular green alga that shared a common ancestor with Chlamydomonas around 35 million years ago [61], also lacks NAPRT. Therefore, we suggest that Chlamydomonas cells do not have a functional copy of NAPRT. It remains an open possibility whether an alternative enzyme without sequence similarity exists in Chlamydomonas.

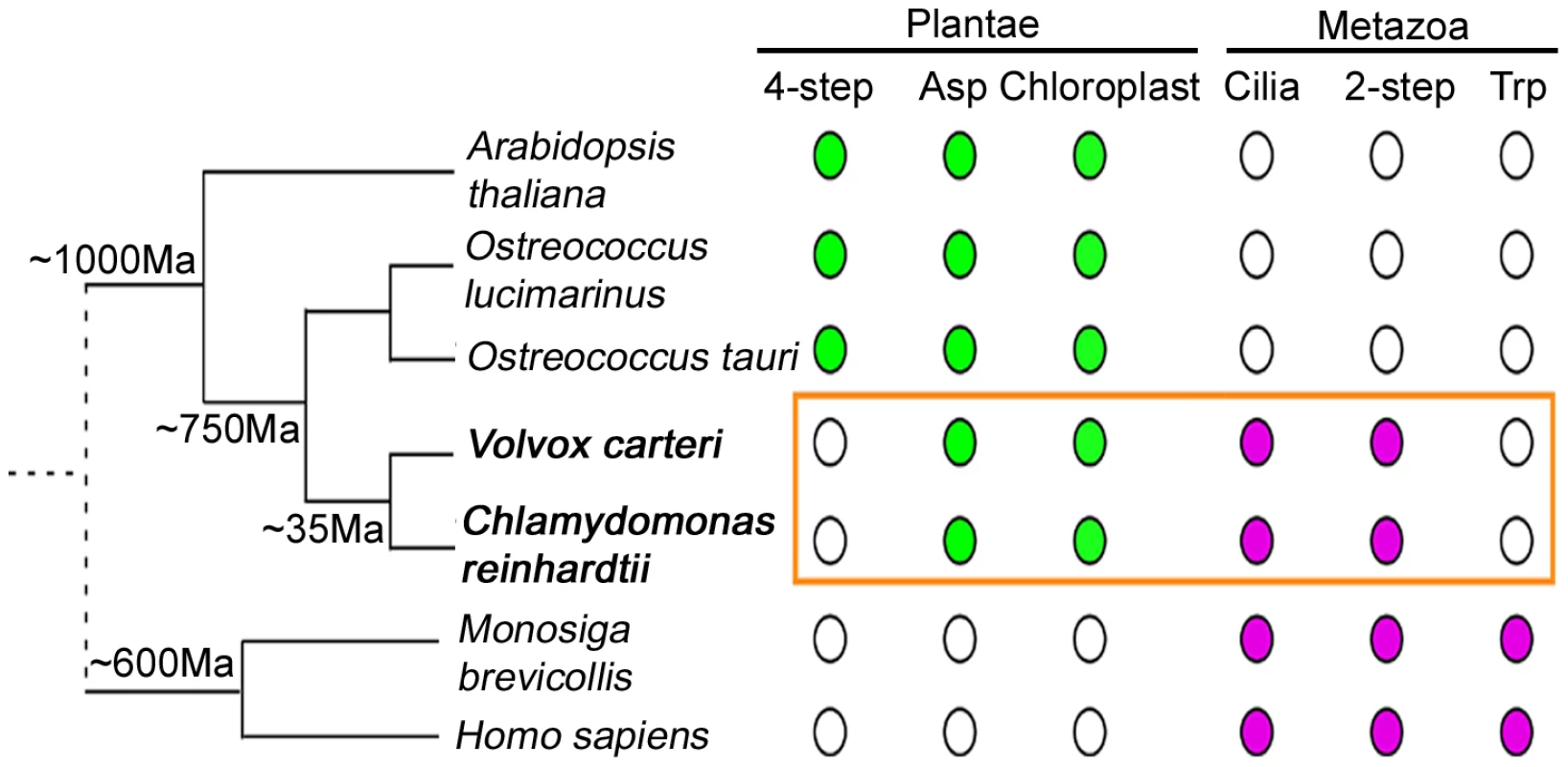

Our study on Chlamydomonas also provides important insights into the evolution of NAD+ biosynthesis (Figure 7). Through sequence similarity searches, we find that Volvox contains enzymes required for the aspartate de novo pathway and the 2-step salvage pathway. Given the common ancestor, it is not surprising that both of them contain NAMPT, the enzyme that is unique to the 2-step pathway. Two unicellular green microalgae, Ostreococcus lucimarinus and Ostreococcus tauri [62], [63], contain enzymes required for the aspartate de novo pathway and the 4-step salvage pathway. Ostreococcus are believed to have diverged from Chlamydomonas around 750 million years ago, ∼250 million years after the separation of chlorophytes (green algae) and streptophytes (seed plants) [64]. The unicellular choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis, which is considered the progenitor to animals and separated from other metazoans more than 600 million years ago [65], has enzymes found in the tryptophan pathway and the 2-step pathway, as in animals. Chlamydomonas, which has remnants of four pathways, may suggest that an ancestral organism had multiple pathways and that most organisms have retained only a subset.

Fig. 7. NAD+ biosynthesis in Chlamydomonas reveals evolutionary aspects.

Evolutionary distances between different organisms are indicated on the left. Branch lengths are not to scale. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Volvox carteri are indicated in bold letters. Filled dots indicate the presence of a trait in organisms and open dots indicate absence. Traits found in photosynthetic organisms are indicated in green and traits associated primarily with the animal lineage are indicated in magenta. The distinct traits of NAD+ biosynthesis in Chlamydomonas and Volvox are highlighted in the orange box. 2-step, 2-step salvage pathway of NAD+ biosynthesis; 4-step, 4-step salvage pathway of NAD+ biosynthesis; Asp, de novo biosynthesis of NAD+ from aspartic acid; Trp, de novo biosynthesis of NAD+ from tryptophan. In Arabidopsis, the first three enzymes, ASO, QS, and QPT, are localized to chloroplasts. It is currently unclear where the other two proteins, NMNAT and QS, are localized. When we used Predotar [66] and TargetP [67] for Chlamydomonas protein localization prediction, ASO, QS, and NS are predicted to localize to mitochondria by both programs. NMNAT is predicted to be in the mitochondria by TargetP while Predotar gives no specific location. The localization of QPT is unspecified by either program. The actual localization of Chlamydomonas proteins will require experimental determination. If all Arabidopsis enzymes are localized to chloroplasts while all Chlamydomonas enzymes are not, it would suggest that having NAD+ biosynthesis in plastids happened after the separation of green algae and seed plants.

As illustrated in Figure 1, NMNAT is an essential enzyme utilized by all NAD+ biosynthetic pathways. We observed that NIC1 has a low basal expression level in wild-type cells compared to the other NIC genes, but is upregulated 2∼6 fold in various nic mutants. This upregulation is consistent with the hypothesis that NMNAT is the key enzyme involved in all NAD+ biosynthetic pathways and any mutation along the pathway affects the expression of NIC1 significantly. The nonsense mutation found in nic1-1 cells presumably generates a truncated protein that must be partially functional as we would expect that a null mutant would disrupt both pathways and be lethal like the double nic; npt1-1 mutant strains. The truncated protein has the catalytic motif residue H30 but only one of two substrate binding motif residues (W98 and not R224) [68], [69].

Through our sequence similarity search, only two of the six homologs in the de novo synthesis pathway starting from tryptophan were identified. Previously, nic1-1 and nic4 mutants were reported to grow on medium supplemented with 3-HA, a metabolite produced in the tryptophan pathway [18]. We find that the growth defect of nic1-1 cannot be rescued by the addition of 3-HA (Figure 1) and this agrees with our finding that NIC1 encodes NMNAT, which acts downstream of 3-HA. In addition, 3-HAO, the enzyme that uses 3-HA as a substrate, is not present in the Chlamydomonas genome sequence. The nic4 mutant is no longer existent in the Chlamydomonas strain collection and was never mapped ([19], www.chlamydb.html). Therefore, we are unable to test its grow ability on medium provided with 3-HA. Similar to our finding, 3-HA and other intermediates found in the tryptophan pathway fail to rescue nicotinamide requiring mutants in Chlamydomonas eugametos [70]. Recent studies indicate that nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinic acid riboside (NaR) are NAD+ precursors in yeast and mammalian cells [71]–[73]. Enzymes involved in the NR and NaR salvage pathways include nicotinamide riboside kinase (NRK1), purine nucleoside phsophorylase (PNP1), uridine hydrolase (URH1), and methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MEU1). Similarity searches using yeast protein sequences identified only one PNP1-like protein in Chlamydomonas, but none of the other proteins. Thus, it is unlikely that Chlamydomonas contains the NR/NaR salvage pathway.

In the study of longevity, several model organisms (S. cerviseae, C. elegans, D. melanogaster, and mouse) have been widely used. Caloric restriction leads to extended life span in these organisms, but the mechanisms behind these findings are not well understood. Studies indicate that caloric restriction-mediated longevity links to upregulation of Sir2 in yeast [41], [74], flies [75], and mammals [76] but is independent of Sir2 expression in worms [77]. However, increasing the dosage of SIR2 in C. elegans leads to longer life span [40]. Our observation that mutant cells with a longer life span have increased SRT2 expression suggests a link between Chlamydomonas SIR2-like genes and longevity. It is intriguing that only the nic13-1 mutant strain has increased levels of SRT2. Since nic13-1 mutants should have increased levels of the intermediate, NaAD, we attempted to ask if exogenous NaAD altered SRT2 levels. Exogenous NaAD failed to rescue upstream mutants, which suggests that it was not effectively imported into cells (Figure 2).

We assayed replicative aging in Chlamydomonas using centriole or basal body age as our marker. In the uni3-1 populations, the biflagellate cells contain a grandmother centriole (at least three cell cycles old) and a daughter centriole. We can recover biflagellate cells by virtue of their ability to swim. The cells that are biflagellate represent the oldest cells in the population. We find that wild-type cells fail to divide after 38–40 generations while the nic13-1 mutant continues for at least 10 more cell divisions. We suggest that this aging may include aging of the centrioles. Recent studies on fruit fly germline stem cells [78] and mouse neural progenitor cells [79] indicate that the mother centriole stays with the self-renewing daughter stem cell while the daughter centriole goes with the differentiating daughter cell. As cells age, misorientation of centrioles accumulates and eventually causes cell cycle delay or arrest in mouse neural progenitor cells. Using Chlamydomonas as a model system to study aging, we can further pursue the link between NAD+ metabolism, Sir2-like genes, and centriole aging. Whether overexpression of SIR2 in Chlamydomonas causes extended life span as shown in other organisms needs additional experimentation.

A recent study on mammalian SIRT1 indicates that it is involved in regulation of circadian rhythm via transcriptional regulation of several key genes [80]. It is currently unclear whether other SIRT proteins have similar effect on circadian rhythm. Given that synchronous Chlamydomonas cell culture can be easily achieved by alternating light/dark cycles, we foresee Chlamydomonas as a model to explore the effect of SRT2 (SIRT6-like) and SRT1 (SIRT4-like) on circadian rhythms [81].

In conclusion, the results presented in this work underscore several key advantages of using Chlamydomonas as a model system for further studies of NAD+ metabolism. The Chlamydomonas genome contains a single copy of each of the proteins that make up the plant-specific de novo NAD+ biosynthesis pathway. However, unlike Arabidopsis, which is homozygous lethal for the first three enzymes, all five Chlamydomonas mutants show conditional lethality. Consequently, Chlamydomonas will facilitate future studies on metabolites involved in NAD+ biosynthesis. Chlamydomonas also contains a single copy of the genes in the mammal-specific 2-step NAD+ salvage pathway. The fact that mammals contain multiple isoforms of NAMPT and that this enzyme is essential to viability impede NAMPT-blocking drug studies in mammal-based model systems. As such, NAMPT targeted drug screens using Chlamydomonas avoid the many confounding factors that are inherent in current screening methods. Our centriole aging results demonstrate how Chlamydomonas may be a valuable model organism for future studies in cellular and organelle aging.

Materials and Methods

Chlamydomonas strains and spotting assay

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strains, CC-14 (nic15-1; mt+), CC-124 (mt−), CC-125 (mt+), CC-407 (C8, mt+), CC-408 (C9, mt−), CC-503 (cw92; mt+), CC-599 (nic1-1; mt+), CC-620 (R3, mt+), CC-621 (NO, mt−), CC-864 (nic13-1; mt+), CC-1079 (ac12; thi9; nic2-1; mt+), CC-1690 (21gr, mt+), CC-1691 (6145c, mt−), and CC-3657 (nic2-1; mt+), were obtained from Chlamydomonas Center (Duke University) and maintained on solid rich growth (R) medium [82] or medium containing 2 µg/ml (16 µM) nicotinamide (NAM). To confirm that the nic mutant strains show the Nic− phenotype, cells were plated on R medium containing 15 µl/l (16.5 mg/l) 3-acetylpyridine (3-AP) [20]. The original nic15-1 strain acquired from the Chlamydomonas Center failed to confer sensitivity to 3-AP, which suggests the possibility of a revertant or an extragenic suppressor. A backcross to the wild-type strain produced progeny sensitive to 3-AP, which reveals the presence of an extragenic suppressor in the original stock culture. The 3-AP sensitivity phenotype of the nic2 strain (CC-3657) was difficult to score, so a second strain CC-1079 (ac12; thi9; nic2-1; mt+) was backcrossed to wild-type cells several times to generate an AC12; THI9; nic2-1 strain that confers sensitivity to 3-AP. For the spotting assay, 104 cells were spotted on R medium or R+3-AP medium supplemented with one of the following compounds: 10 µM NAM, 10 µM nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN, dissolved in water), 10 µM nicotinate adenine dinucleotide (NaAD, dissolved in water), 10 µM nicotinic acid (NA, dissolved in water), or 10 µM 3-hydroxyanthranilate (3-HA, dissolved in DMSO). The plates were placed under constant light at room temperature for 3 days before pictures were taken. All the reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

We have changed the linkage group names to chromosome names as specified in [15]. Linkage groups I-XI correspond to chromosomes 1–11. Linkage group XII/XIII is chromosome 12, and Linkage group XV is chromosome 14.

Identification of Chlamydomonas homologs via sequence similarity search

Protein sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana ASO, QS, QPT, NMNAT, NS (listed in Table 1), human NAMPT (NP_005737), yeast SIR2 (NP_010242), and human SIRT4 (NP_036372) were used in TBLASTN against JGI (Joint Genome Institute) Chlamydomonas reinhardtii genome version 4.0 (JGI v4.0, http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Chlre4/Chlre4.home.html) with expected E-values less than or equal to 1E-5 (1E-3 for SIR2 and SIRT4). The resultant genes were checked for EST coverage. Genes without full-length EST coverage, QS, NMNAT, NS, NAMPT, SRT1, and SRT2, were subjected to exon-intron predictions using GreenGenie 2 (http://bifrost.wustl.edu/cgi-bin/greengenie2/greenGenie2) [33]. The predicted coding regions were used as guidelines in primer design for RT-PCR to amplify the actual coding regions of these genes.

Colorfy for protein sequence alignment

Multiple sequence alignments (MSA) were color-coded using the online MSA column percentage composition coloring tool, Colorfy (http://bifrost.wustl.edu/colorfy). Colorfy takes as input any standard ALN format MSA (e.g. default CLUSTAL output) [83] and outputs the corresponding color-coded MSA.

Amplification of coding regions by RT-PCR

Chlamydomonas total RNA was prepared as previously described [84]. Five µg of total RNA from wild-type cells were used for cDNA synthesis using a 3′ RACE poly (dT)-adaptor primer (Integrated DNA Technologies, Iowa City, IA) in a 50 µl reaction, which contains 1× RT buffer (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM dNTP, 0.2 µM primer, 40 U of RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), and 200 U of SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The reaction was performed according to manufacturer's recommendation (Invitrogen). To remove RNA from the reaction, 2 units of RNase H (Invitrogen) were added at the end of reaction and incubated at 37°C for 20 min.

Amplification of the NMNAT coding region requires nested PCR due to highly repetitive sequences found in the gene. Five µl cDNA (1/10 of the reaction volume) from above was used in a 50 µl PCR reaction using a 3′ RACE primer and a gene-specific primer (nic1-3) that binds 4 nucleotides downstream of the predicted start codon. The reaction, which contained 1× KlentaqLA buffer (pH 9.2), 0.8 mM dNTP, 10% DMSO, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 µl KlentaqLA polymerase [85], was transferred directly from ice to a thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) that was preheated to 93°C. The reaction conditions were: 93°C 5 min, 30 cycles of (93°C 15 sec, 53°C 15 sec, and 68°C 5 min), and 70°C 10 min. The resultant 2.2 kb fragment was used as template for a second round of amplification. A forward primer (nic1-20) that starts 98 nucleotides downstream of the predicted start codon and a reverse primer (nic1-24) that ends at the predicted stop codon were used. The resultant fragment was gel purified and subjected to DNA sequencing.

For amplification of other genes, 1 µl cDNA was used in a 20 µl PCR reaction containing 0.4 U Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes, Woburn, MA), 1× GC buffer (Finnzymes), 0.2 mM dNTP, 3% DMSO, and 0.2 µM each of forward and reverse primers. The general reaction condition was 98°C 30 sec, 30 cycles of (98°C 10 sec, T°C 20 sec, and 72°C 30∼45 sec), and 72°C 10 min. T is the lower Tm of the primers calculated by Finnzymes' Tm calculator. Different sets of primers were used to cover the whole coding region of individual genes. The PCR products were subjected to gel purification and DNA sequencing to identify exon-intron boundaries.

Chlamydomonas genomic DNA preparation

A DNA mini-prep protocol was modified [86] and used. Approximately 1×106 cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml 1× TEN (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0) and pipetted repeatedly until well resuspended. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 13,200 rpm for 10 sec in a microcentrifuge (Hermle Z233 M-2, Labnet, Woodbridge, NJ) and the supernatant was discarded. Cells were resuspended with 150 µl chilled water, followed by the addition of 300 µl SDS-EB buffer (2% SDS, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 400 mM NaCl, 40 mM EDTA pH8.0). DNA was extracted once with 350 µl phenol/chloroform (1∶1), followed by a second extraction using 350 µl chloroform. The volume was determined and twice the volume of 100% ethanol was added to precipitate DNA on ice for 30 min. Precipitated DNA was collected by centrifugation at room temperature for 10 min followed by a wash using 70% ethanol. DNA was dried using Savant SpeedVac (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and resuspended in 50 µl water. The concentration of DNA was determined by spectrophotometry at 260 nm (Eppendorf Biophotometer 6131, Westbury, NY). Approximately 20 ng of genomic DNA was used in PCR and the resultant PCR products were gel-purified and subjected to DNA sequencing. In the nic1-1 cells, the region that carries mutations were amplified by the primer set nic1-10 and nic1-11. In the nic15-1 cells, the region that contains a point mutation was amplified by nic15-3F and nic15-3R.

BAC and plasmid DNA manipulation

Chlamydomonas BAC DNA was prepared using Qiagen Plasmid Midiprep kit. To prepare the pNIC15a plasmid, the BAC (32L22) DNA was digested with XmaI and a 6.1 kb fragment was isolated and cloned into a pBlueScript II SK vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). This fragment contains a 1 kb upstream sequence, the full-length NIC15 gene, and a 2.5 kb downstream sequence, which is predicted to be part of an unknown zinc finger protein (protein id 150664). To prepare the pNIC1-56 plasmid, a 7.1 kb KpnI fragment from the BAC (10M24) DNA was cloned into a pBlueScript II SK vector. The plasmid contains a 0.7 kb upstream sequence, the full-length NIC1 gene, and a 4.7 kb downstream sequence, which is predicted to contain an unknown protein that has a HAD-superfamily hydrolase domain.

Chlamydomonas transformation

This protocol is modified from Iomini et al [87]. Chlamydomonas cells were inoculated in 100 ml liquid R medium for three days under continuous illumination with gentle shaking until cells reached a concentration of ∼5×106 cells/ml. Cells were collected by centrifugation and treated with autolysin for 0.5 hr at room temperature to remove cell walls [19]. Autolysin-treated cells were chilled on ice for 10 min before collected by centrifugation at 4°C. Cells were gently resuspended on ice in R+100 mM mannitol to the final concentration of ∼4×108 cells/ml. Two hundred fifty µl of cells (∼1×108 cells) were used for transformation with 1 µg of BAC DNA or plasmid DNA with (the nic1-1 strain) or without (the nic15-1, nic2-1, and nic13-1 strains) the addition of 1 µg of pSI103, which confers resistance to paromomycin [35], for cotransformation. Cells and DNA were added to an electroporation cuvette (4mm gap, Bio-Rad) and incubated in a 16°C water bath for 5 min before electroporation, which was performed in a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II with the following setting: 0.75 kv, 25 µF, and 50 Ω. Cells were electroporated with one pulse and incubated at room temperature for 10 min before transferring to 50 ml R+100 mM mannitol liquid medium and incubated overnight at room temperature with continuous illumination. Cells were resuspended gently in 1 ml 25% cornstarch in R medium and spread onto 5 R plates with 15 µl/l 3-AP (nic15-1, nic2-1, and nic13-1 cells) or 5 R plates with 10 µg/ml paromomycin (nic1-1 cells). Colonies appear within 5∼7 days at 25°C. The nic1-1 transformants were tested subsequently on medium with 3-AP.

UV-mutagenesis of the nic13-1 cells

nic13-1 cells were inoculated in 200 ml liquid R medium provided with 16 µM NAM for 4 days until cells reached a density of ∼106 cells/ml. These cells were collected and spread evenly on an R+NAM medium plate. The cells were subjected to UV irradiation at 70 mJoules (Stratagene UV stratalinker 1800, Cedar Creek, TX) and recovered in the dark overnight. The plate was divided into 13 sections and cells were scraped off the plate and spread on 13 R+3-AP plates. 3-AP resistant colonies were observed one week later. Genomic DNA from individual cell lines, wild-type, and nic13-1 cells were prepared as above and a short region was amplified by primers nic13-20F and nic13-3R by Phusion DNA polymerase. The PCR products were subjected to overnight digestion with SfcI at 25°C and separated on a 2% agarose gel.

Real-time RT-PCR

Chlamydomonas total RNA was extracted from ∼108 cells using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Cells were homogenized by passing through a 20-gauge needle fitted to a 1 ml RNase-free syringe 20 times. The lysate was centrifuged and RNA extraction was performed according to manufacturer's recommendation. One microgram of total RNA from each strain was treated with 1 U of RNase-free DNAse I (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD) at 37°C for 30 min and the reaction was terminated by adding 1 µl of 25 mM EDTA and incubate at 65°C for 10 min. The DNAse I-treated RNA was added into a 20 µl reverse transcription reaction that contains 200 ng random primers (Invitrogen), 1× RT buffer (Invitrogen), 5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM dNTP, 20 U of RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), and 100 U of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The reaction was performed according to manufacturer's recommendation (Invitrogen).

For real-time PCR, cDNA obtained from above was diluted 1∶10 and 2 µl was used in a 20 µl SYBR Green-PCR reaction [88] which contains 1× homemade PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH8.8, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2; 0.1% Triton X-100); 1× SYBR Green I mix (1× SYBR Green, Molecular Probes; 10 nM Fluorescein, Bio-Rad; 0.1% Tween-20; 0.1 mg/ml BSA; 5% DMSO); 200 µM dNTP; 0.5 µM primers; and 1.6 µl TAQ DNA polymerase [89]. The reactions were carried out using a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ under the following conditions: 95°C 3 min, 40 cycles of (95°C 10 sec and 57°C 45 sec), followed by the melting curve program. The transcript levels of individual genes were standardized by an internal control, CRY1, which encodes the ribosomal protein S14 [90]. Gene expression was set to 100% in wild-type cells and the relative expression levels in various mutants were plotted as % increasing or decreasing related to transcript levels in wild-type cells. Results represent data from 2 biological replicates.

Chlamydomonas aging

nic13-1 cells were crossed to uni3-1 (CC-4179) cells and the nic13-1; uni3-1 double mutants were identified by 3-AP sensitivity and the presence of cells with 0, 1, or 2 flagella. Both NIC13; uni3-1 and nic13-1; uni3-1 cells were inoculated in 20 ml liquid R medium supplied with 16 µM NAM. The top 5 ml of liquid was transferred to a new test tube containing R+NAM every 12 hours. ∼100 cells were plated on R+NAM plates and the fraction of cells that formed colonies was counted under dissecting microscope after 8–10 days.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BakkerBM

OverkampKM

MarisAJA

KotterP

LuttikMAH

2001 Stoichiometry and compartmentation of NADH metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev 25 15 37

2. BelenkyP

BoganKL

BrennerC

2007 NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem Sci 32 12 19

3. VrablikTL

HuangL

LangeSE

Hanna-RoseW

2009 Nicotinamidase modulation of NAD+ biosynthesis and nicotinamide levels separately affect reproductive development and cell survival in C. elegans. Development 136 3637 3746

4. TannyJC

DowdGJ

HuangJ

HilzH

MoazedD

1999 An enzymatic activity in the yeast Sir2 protein that is essential for gene silencing. Cell 99 735 745

5. OberdoerfferP

MichanS

McVayM

MostoslavskyR

VannJ

2008 SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell 135 907 918

6. InoueT

HiratsukaM

OsakiM

OshimuraM

2007 The molecular biology of mammalian SIRT proteins: SIRT2 in cell cycle regulation. Cell Cycle 6 1011 1018

7. MostoslavskyR

ChuaKF

LombardDB

PangWW

FischerMR

2006 Genomic instability and aging-like phenotype in the absence of mammalian SIRT6. Cell 124 315 329

8. ZhongL

D'UrsoA

ToiberD

SebastianC

HenryRE

2010 The histone deacetylase Sirt6 regulates glucose homeostasis via Hif1 [alpha]. Cell 140 280 293

9. LuoJ

NikolaevAY

ImaiS

ChenD

SuF

2001 Negative control of p53 by Sir2a promotes cell survival under stress. Cell 107 137 148

10. FryeRA

2000 Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 273 793 798

11. GreissS

GartnerA

2009 Sirtuin/Sir2 phylogeny, evolutionary considerations and structural conservation. Mol Cells 28 407 415

12. MichishitaE

McCordRA

BerberE

KioiM

Padilla-NashH

2008 SIRT6 is a histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylase that modulates telomeric chromatin. Nature 452 492 496

13. FordE

VoitR

LisztG

MaginC

GrummtI

2006 Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT7 is an activator of RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev 20 1075 1080

14. GrobA

RousselP

WrightJ

McStayB

Hernandez-VerdunD

2009 Involvement of SIRT7 in resumption of rDNA transcription at the exit from mitosis. J Cell Sci 122 489

15. MerchantSS

ProchnikSE

VallonO

HarrisEH

KarpowiczSJ

2007 The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science 318 245 250

16. ArchibaldJM

2009 GENOMICS: Green Evolution, Green Revolution. Science 324 191 192

17. KatohA

HashimotoT

2004 Molecular biology of pyridine nucleotide and nicotine biosynthesis. Front Biosci 9 1577 1586

18. EversoleRA

1956 Biochemical mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardi. Am J Botany 43 404 407

19. HarrisEH

1989 The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook: a comprehensive guide to biology and laboratory use San Diego Academic Press xiv, 780

20. FerrisPJ

1995 Localization of the nic-7, ac-29 and thi-10 genes within the mating-type locus of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics 141 543 549

21. FerrisPJ

ArmbrustEV

GoodenoughUW

2002 Genetic structure of the mating-type locus of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics 160 181 200

22. DutcherSK

PowerJ

GallowayRE

PorterME

1991 Reappraisal of the genetic map of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Hered 82 295 301

23. EbersoldWT

LevineRP

1959 A genetic analysis of linkage group I of Chlamydomonas reinhardi. Z Vererbungsl 90 74 82

24. EbersoldWT

LevineRP

LevineEE

OlmstedMA

1962 Linkage maps in Chlamydomonas reinhardi. Genetics 47 531 543

25. SmythRD

MartinekGW

EbersoldWT

1975 Linkage of six genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and the construction of linkage test strains. J Bacteriol 124 1615 1617

26. WoolleyD

1945 Production of nicotinic acid deficiency with 3-acetylpyridine, the ketone analogue of nicotinic acid. J Biol Chem 157 455

27. WoolleyD

1946 Reversal by tryptophane of the biological effects of 3-acetylpyridine. J Biol Chem 162 179

28. KatohA

UenoharaK

AkitaM

HashimotoT

2006 Early steps in the biosynthesis of NAD in Arabidopsis start with aspartate and occur in the plastid. Plant Physiol 141 851 857

29. SchippersJHM

Nunes-NesiA

ApetreiR

HilleJ

FernieAR

2008 The Arabidopsis onset of leaf death5 mutation of quinolinate synthase affects nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthesis and causes early ageing. Plant Cell 20 2909 2925

30. PazourGJ

KoutoulisA

BenashskiSE

DickertBL

ShengH

1999 LC2, the Chlamydomonas homologue of the t complex-encoded protein Tctex2, is essential for outer dynein arm assembly. Mol Biol Cell 10 3507 3520

31. KathirP

LaVoieM

BrazeltonWJ

HaasNA

LefebvrePA

2003 Molecular map of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii nuclear genome. Eukaryot Cell 2 362 379

32. LiuH

WoznicaK

CattonG

CrawfordA

BottingN

2007 Structural and kinetic characterization of quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase (hQPRTase) from Homo sapiens. J Mol Biol 373 755 763

33. KwanAL

LiL

KulpDC

DutcherSK

StormoGD

2009 Improving gene-finding in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: GreenGenie 2. BMC Genomics 10 e210

34. PerroneCA

MysterSH

BowerR

O'TooleET

PorterME

2000 Insights into the structural organization of the I1 inner arm dynein from a domain analysis of the 1-b dynein heavy chain. Mol Biol Cell 11 2297 2313

35. SizovaI

FuhrmannM

HegemannP

2001 A Streptomyces rimosus aphVIII gene coding for a new type phosphotransferase provides stable antibiotic resistance to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Gene 277 221 229

36. HarrisE

2009 The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook; Second Edition Academic Press

37. RaffaelliN

LorenziT

MarianiPL

EmanuelliM

AmiciA

1999 The Escherichia coli NadR regulator is endowed with nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase activity. J Bacteriol 181 5509 5511

38. GroseJH

BergthorssonU

RothJR

2005 Regulation of NAD synthesis by the trifunctional NadR protein of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol 187 2774 2782

39. NakahataY

SaharS

AstaritaG

KaluzovaM

Sassone-CorsiP

2009 Circadian control of the NAD+ salvage pathway by CLOCK-SIRT1. Science 324 654 657

40. TissenbaumH

GuarenteL

2001 Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 410 227 230

41. LinS

DefossezP

GuarenteL

2000 Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 289 2126

42. HuangL

SunQ

QinF

LiC

ZhaoY

2007 Down-regulation of a SILENT INFORMATION REGULATOR2-related histone deacetylase gene, OsSRT1, induces DNA fragmentation and cell death in rice. Plant Physiol 144 1508

43. DutcherSK

TrabucoEC

1998 The UNI3 gene is required for assembly of basal bodies of Chlamydomonas and encodes delta-tubulin, a new member of the tubulin superfamily. Mol Biol Cell 9 1293 1308

44. ZhangQ

WangS-Y

FleurielC

LeprinceD

RocheleauJV

2007 Metabolic regulation of SIRT1 transcription via a HIC1:CtBP corepressor complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 829 833

45. FragaMF

EstellerM

2007 Epigenetics and aging: the targets and the marks. Trends Genet 23 413 418

46. YangH

YangT

BaurJA

PerezE

MatsuiT

2007 Nutrient-sensitive mitochondrial NAD+ levels dictate cell survival. Cell 130 1095 1107

47. ZhaiRG

ZhangF

HiesingerPR

CaoY

HaueterCM

2008 NAD synthase NMNAT acts as a chaperone to protect against neurodegeneration. Nature 452 887 891

48. RutterJ

ReickM

WuLC

McKnightSL

2001 Regulation of clock and NPAS2 DNA binding by the redox state of NAD cofactors. Science 293 510 514

49. VanderauweraS

De BlockM

Van de SteeneN

van de CotteB

MetzlaffM

2007 Silencing of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in plants alters abiotic stress signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 15150 15155

50. van der VeerE

HoC

O'NeilC

BarbosaN

ScottR

2007 Extension of human cell lifespan by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem 282 10841 10845

51. VaqueroA

SternglanzR

ReinbergD

2007 NAD+-dependent deacetylation of H4 lysine 16 by class III HDACs. Oncogene 26 5505 5520

52. KohanskiMA

DwyerDJ

HayeteB

LawrenceCA

CollinsJJ

2007 A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 130 797 810

53. RongvauxA

AndrisF

Van GoolF

LeoO

2003 Reconstructing eukaryotic NAD metabolism. Bioessays 25 683 690

54. KurnasovO

GoralV

ColabroyK

GerdesS

AnanthaS

2003 NAD biosynthesis identification of the tryptophan to quinolinate pathway in bacteria. Chem Biol 10 1195 1204

55. KobayashiK

EhrlichS

AlbertiniA

AmatiG

AndersenK

2003 Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 4678 4683

56. ImaiS

2009 Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt): a link between NAD biology, metabolism, and diseases. Current Pharmaceutical Design 15 20 28

57. HashidaSN

TakahashiH

Kawai-YamadaM

UchimiyaH

2007 Arabidopsis thaliana nicotinate/nicotinamide mononucleotide adenyltransferase (AtNMNAT) is required for pollen tube growth. Plant J 49 694 703

58. RevolloJR

KörnerA

MillsKF

SatohA

WangT

2007 Nampt/PBEF/Visfatin regulates insulin secretion in [beta] cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab 6 363 375

59. ShinDH

OganesyaN

JancarikJ

YokotaH

KimR

KimSH

2005 Crystal structure of a nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase from Thermoplasma acidophilum. J Biol Chem 280 18326 18335

60. ChappieJS

CànavesJM

HanGW

RifeCL

XuQ

2005 The Structure of a Eukaryotic Nicotinic Acid Phosphoribosyltransferase Reveals Structural Heterogeneity among Type II PRTases. Structure 13 1385 1396

61. KirkDL

1998 Volvox: A Search for the Molecular and Genetic Origins of Multicellularity and Cellular Differentiation Cambridge University Press 399

62. PalenikB

GrimwoodJ

AertsA

RouzeP

SalamovA

2007 The tiny eukaryote Ostreococcus provides genomic insights into the paradox of plankton speciation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 7705 7710

63. DerelleE

FerrazC

RombautsS

RouzeP

WordenAZ

2006 Genome analysis of the smallest free-living eukaryote Ostreococcus tauri unveils many unique features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 11647 11652

64. PeersG

NiyogiKK

2008 Pond scum genomics: the genomes of Chlamydomonas and Ostreococcus. Plant Cell 20 502 507

65. KingN

WestbrookMJ

YoungSL

KuoA

AbedinM

2008 The genome of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and the origin of metazoans. Nature 451 783 788

66. SmallI

PeetersN

LegeaiF

LurinC

2004 Predotar: A tool for rapidly screening proteomes for N-terminal targeting sequences. Proteomics 4 1581 1590

67. EmanuelssonO

NielsenH

BrunakS

von HeijneG

2000 Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J Mol Biol 300 1005 1016

68. GaravagliaS

D'AngeloI

EmanuelliM

CarnevaliF

PierellaF

2002 Structure of human NMN adenylytransferase. A key nuclear enzyme for NAD homeostasis. J. Biol Chem 8 8524 8530

69. ZhaiRG

CaoY

HiesingerPR

ZhouY

MehtaSQ

2006 Drosophila NMNAT maintains neural integrity independent of its NAD synthesis activity. PLoS Biol 4 e416

70. NakamuraK

GowansCS

1965 Genetic control of nicotinic acid metabolism in Chlamydomonas eugametos. Genetics 51 931 935

71. BieganowskiP

BrennerC

2004 Discoveries of nicotinamide riboside as a nutrient and conserved NRK genes establish a Preiss-Handler independent route to NAD+ in fungi and humans. Cell 117 495 502

72. BelenkyP

RacetteFG

BoganKL

McClureJM

SmithJS

2007 Nicotinamide riboside promotes Sir2 silencing and extends lifespan via Nrk and Urh1/Pnp1/Meu1 pathways to NAD+. Cell 129 473 484

73. BelenkyP

ChristensenKC

GazzanigaF

PletnevAA

BrennerC

2009 Nicotinamide riboside and nicotinic acid riboside salvage in fungi and mammals: Quantitative basis for Urh1 and purine nucleoside phosphorylase function in NAD+ metabolism. J Biol Chem 284 158 164

74. KaeberleinM

McVeyM

GuarenteL

1999 The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev 13 2570

75. RoginaB

HelfandSL

2004 Sir2 mediates longevity in the fly through a pathway related to calorie restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 15998 16003

76. CohenH

MillerC

BittermanK

WallN

HekkingB

2004 Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science 305 390

77. SchulzTJ

ZarseK

VoigtA

UrbanN

BirringerM

2007 Glucose restriction extends Caenorhabditis elegans life span by inducing mitochondrial respiration and increasing oxidative stress. Cell Metab 6 280 293

78. ChengJ

TürkelN

HematiN

FullerMT

HuntAJ

2008 Centrosome misorientation reduces stem cell division during ageing. Nature 456 599 604

79. WangX

TsaiJW

ImaiJH

LianWN

ValleeRB

2009 Asymmetric centrosome inheritance maintains neural progenitors in the neocortex. Nature 461 947 955

80. AsherG

GatfieldD

StratmannM

ReinkeH

DibnerC

2008 SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell 134 317 328

81. MatsuoT

OkamotoK

OnaiK

NiwaY

ShimogawaraK

2008 A systematic forward genetic analysis identified components of the Chlamydomonas circadian system. Genes Dev 22 918 930

82. LuxFG

DutcherSK

1991 Genetic interactions at the FLA10 locus: suppressors and synthetic phenotypes that affect the cell cycle and flagellar function in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics 128 549 561

83. LarkinMA

BlackshieldsG

BrownNP

ChennaR

McGettiganPA

2007 Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23 2947 2948

84. LinH

GoodenoughUW

2007 Gametogenesis in the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii minus mating type is controlled by two genes, MID and MTD1. Genetics 176 913 925

85. BarnesWM

1994 PCR amplification of up to 35 kb DNA with high fidelity and high yield from lambda bacteriophage templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91 2216 2220

86. NewmanSM

BoyntonJE

GillhamNW

Randolph-AndersonBL

JohnsonAM

1990 Transformation of chloroplast ribosomal RNA genes in Chlamydomonas: molecular and genetic characterization of integration events. Genetics 126 875 888

87. IominiC

LiL

EsparzaJM

DutcherSK

2009 Retrograde IFT mutants identify complex A proteins with multiple genetic interactions in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics 183 885 896

88. FangSC

De Los ReyesC

UmenJG

2006 Cell size checkpoint control by the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor pathway. PLoS Genet 2 e167

89. EngelkeDR

KrikosA

BruckME

GinsburgD

1990 Purification of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase expressed in Escherichia coli. Analytical Biochemistry 191 396 400

90. NelsonJA

SavereidePB

LefebvrePA

1994 The CRY1 gene in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: structure and use as a dominant selectable marker for nuclear transformation. Mol Cell Biol 14 4011 4019

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Allelic Variation at the 8q23.3 Colorectal Cancer Risk Locus Functions as a Cis-Acting Regulator ofČlánek Allelic Selection of Amplicons in Glioblastoma Revealed by Combining Somatic and Germline AnalysisČlánek Lactic Acidosis Triggers Starvation Response with Paradoxical Induction of TXNIP through MondoAČlánek Rice a Cinnamoyl-CoA Reductase-Like Gene Family Member, Is Required for NH1-Mediated Immunity to pv.Článek Differentiation of Zebrafish Melanophores Depends on Transcription Factors AP2 Alpha and AP2 Epsilon

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 9

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Optimal Strategy for Competence Differentiation in Bacteria

- Mutational Patterns Cannot Explain Genome Composition: Are There Any Neutral Sites in the Genomes of Bacteria?

- Frail Hypotheses in Evolutionary Biology

- Genetic Architecture of Complex Traits and Accuracy of Genomic Prediction: Coat Colour, Milk-Fat Percentage, and Type in Holstein Cattle as Contrasting Model Traits

- Allelic Variation at the 8q23.3 Colorectal Cancer Risk Locus Functions as a Cis-Acting Regulator of

- Allelic Selection of Amplicons in Glioblastoma Revealed by Combining Somatic and Germline Analysis

- Germline Variation Controls the Architecture of Somatic Alterations in Tumors

- Mice Doubly-Deficient in Lysosomal Hexosaminidase A and Neuraminidase 4 Show Epileptic Crises and Rapid Neuronal Loss

- Analysis of Population Structure: A Unifying Framework and Novel Methods Based on Sparse Factor Analysis

- FliO Regulation of FliP in the Formation of the Flagellum

- Cdc20 Is Critical for Meiosis I and Fertility of Female Mice

- dMyc Functions Downstream of Yorkie to Promote the Supercompetitive Behavior of Hippo Pathway Mutant Cells

- DCAF26, an Adaptor Protein of Cul4-Based E3, Is Essential for DNA Methylation in

- Genome-Wide Double-Stranded RNA Sequencing Reveals the Functional Significance of Base-Paired RNAs in

- An Immune Response Network Associated with Blood Lipid Levels

- Genetic Variants and Their Interactions in the Prediction of Increased Pre-Clinical Carotid Atherosclerosis: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study

- The Histone H3K36 Methyltransferase MES-4 Acts Epigenetically to Transmit the Memory of Germline Gene Expression to Progeny

- Long- and Short-Term Selective Forces on Malaria Parasite Genomes

- Lactic Acidosis Triggers Starvation Response with Paradoxical Induction of TXNIP through MondoA

- Identification of Early Requirements for Preplacodal Ectoderm and Sensory Organ Development

- Orphan CpG Islands Identify Numerous Conserved Promoters in the Mammalian Genome

- Analysis of the Basidiomycete Reveals Conservation of the Core Meiotic Expression Program over Half a Billion Years of Evolution

- ETS-4 Is a Transcriptional Regulator of Life Span in

- The SR Protein B52/SRp55 Is Required for DNA Topoisomerase I Recruitment to Chromatin, mRNA Release and Transcription Shutdown

- The Baker's Yeast Diploid Genome Is Remarkably Stable in Vegetative Growth and Meiosis

- Chromatin Landscape Dictates HSF Binding to Target DNA Elements

- The APETALA-2-Like Transcription Factor OsAP2-39 Controls Key Interactions between Abscisic Acid and Gibberellin in Rice

- Accurately Assessing the Risk of Schizophrenia Conferred by Rare Copy-Number Variation Affecting Genes with Brain Function

- Widespread Over-Expression of the X Chromosome in Sterile F Hybrid Mice

- The Characterization of Twenty Sequenced Human Genomes