-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaTelomeric ORFS in : Does Mediator Tail Wag the Yeast?

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004614

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004614Summary

article has not abstract

Introduction

Recent studies of fungal genomes have shown that subtelomeric regions of chromosomes are areas of rapid evolution that facilitate adaptation to novel niches [1]. Several years ago, analysis of the genome of the human pathogenic yeast Candida albicans revealed the presence of a large family of telomeric orfs (TLO genes) [2]. The function of this gene family remained an enigma in C. albicans genetics for many years; however, recent studies have revealed that the TLO genes encode a subunit of the Mediator complex with roles in transcriptional regulation [3,4]. This gene family expansion is unique to C. albicans, the species responsible for the majority of human yeast infections and the species that is most commonly recovered as a human commensal. If selective pressures in the host have driven this expansion, it is likely that this gene family somehow contributes to the success of C. albicans as a commensal and opportunistic pathogen. To support this hypothesis, it was first necessary to determine the exact function of Tlo proteins in C. albicans. Armed with this knowledge, investigators are now beginning to understand how possession of multiple copies of TLO could contribute to the virulence properties of C. albicans.

What Are the Tlo Proteins?

The earliest reference to a TLO gene was made by Kaiser et al. [5] who identified CTA2 (now TLOα3) because it encoded transcriptional activating activity in a yeast one-hybrid screen. Goodwin and Poulter [6] later noted that sequences homologous to this ORF were commonly found at telomeres in C. albicans, indicating that these genes were widely dispersed. Subsequently, annotation of the C. albicans genome revealed 14 TLO family members in strain SC5314 (13 telomeric; one centromeric) [2]. The large expansion of the TLO gene family is, however, unique to C. albicans (there are two copies in C. dubliniensis and only one in the sequenced genomes of other Candida species). In silico analysis of these sequences by Bourbon et al. [7] suggested that the TLO genes encode proteins with a domain similar to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Med2 protein, a component of Mediator.

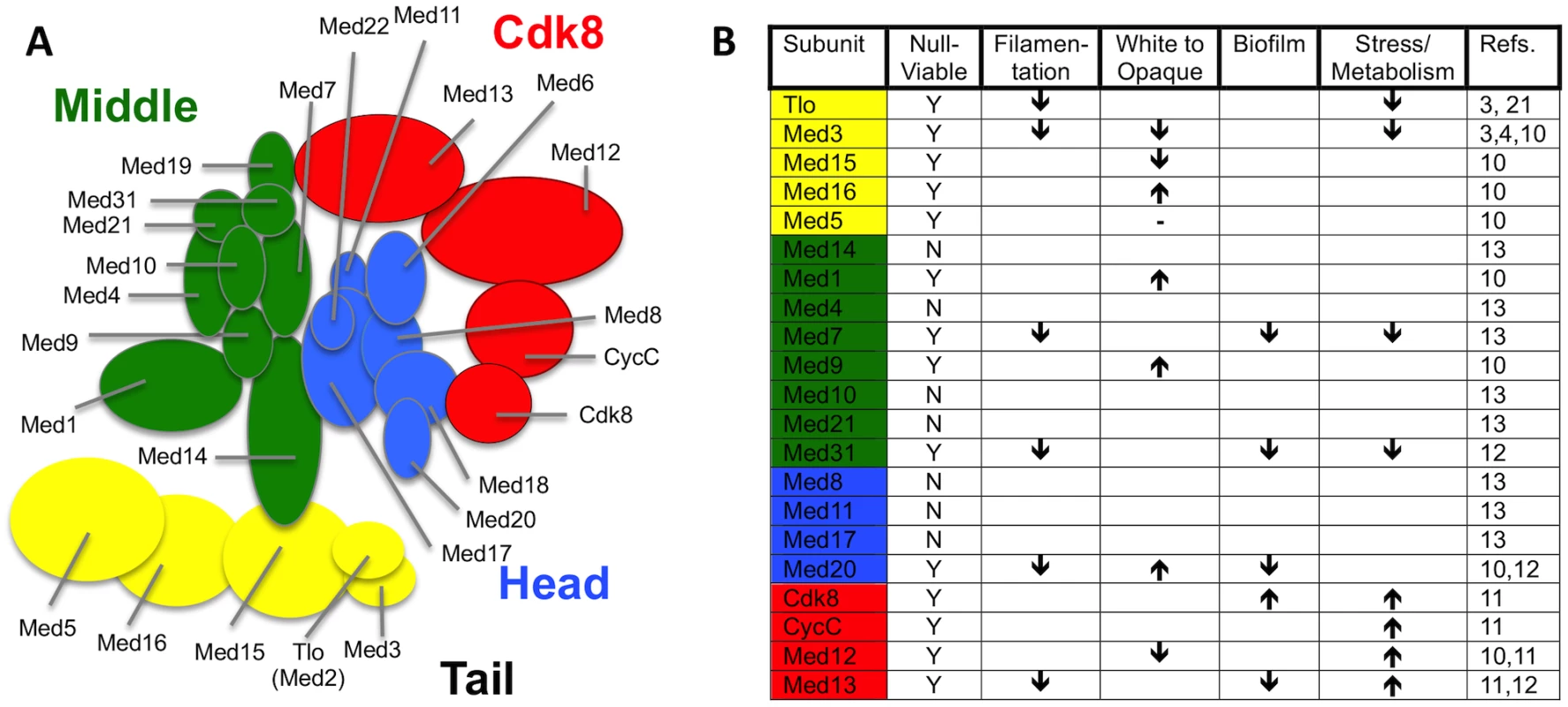

Zhang et al. [4] carried out the first purifications of Mediator complex from C. albicans and were able to identify Tlo proteins as stochiometric components of Mediator. Mediator is a large multisubunit complex that plays a primary role in facilitating physical and functional interactions between DNA-bound transcription factors and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to activate transcription [7–10]. Recent analysis of Mediator functions in C. albicans have shown that this complex plays an important role in regulating many virulence-associated traits such as filamentous growth, white—opaque switching, stress responses, biofilm formation, and phagocyte interactions (Fig. 1) [10–14]. Mediator in fungi has 25 subunits organised into four distinct modules: a head module that interacts with Pol II, a regulatory middle module, and a tail module that includes Med2, Med3, and Med15, and which may play a direct role in transcriptional regulation [8]. A fourth variably associated Cdk8 module both negatively and positively regulates transcription [4,15]. Mediator purified from a med3Δ mutant lacked the Tlo subunit, strongly suggesting that Tlo proteins are Mediator tail subunits anchored to the complex via Med3. However, C. albicans cells also contained an excess of non-Mediator—associated Tlo protein, with this “free Tlo” form estimated to be at least 10-fold more abundant than the Mediator-associated form [4]. Whether the free-Tlo population carries out functions distinct from those of the Mediator bound form, or whether it acts as a reservoir of Tlo protein that can interchange with the Mediator bound subunits remains to be explored. In addition to the expansion of the Tlo orthologs of Med2 in C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, there are several other species and specific circumstances in which the copy number of a Mediator subunit exceeds the norm [7]. Intriguingly, the human fungal pathogen Candida glabrata has two paralogs of the Med15 Tail module subunit, which have both overlapping and non-overlapping functionality [16]. An increase in copy number of the human Mediator subunit Cdk8, which is accompanied by increased expression, is found in 70% of colorectal cancer samples and is significantly correlated with increased colon cancer—specific mortality [17].

Fig. 1. Current knowledge on structure and function of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis Mediator.

(A) Predicted structure of C. albicans (and C. dubliniensis) Mediator based on structural analysis of S. cerevisiae complex [25]. Biochemical analyses of Mediator Tail subunits from C. albicans [3,10] and C. dubliniensis [3] supports the proposed structure of this module in the pathogens. Biochemical studies provide direct evidence that Tloβ2, Tloα3, Tloα9, Tloα12, and Tloα34 are mutually exclusive Med2 orthologs of the C. albicans Mediator complex, while not excluding other expressed Tlo paralogs [4]. Additional biochemical studies show most Mediator in C. dubliniensis incorporates the Tlo1 subunit, but does not rule out the possibility that Tlo2 could associate with the complex under conditions in which its expression is increased [3]. (B) Summary of virulence related phenotypes associated with C. albicans and C. dubliniensis null mutants of genes encoding individual Mediator subunits. “Filamentation” includes defects in the yeast to hyphae transition. The “White to Opaque” arrows refer specifically to the white to opaque cell phenotypic switching frequency, including also the opaque to white cell switch frequency. “Biofilm” defects specifically refer to the ability to form a structure on a hard solid (i.e., plastic) support. “Stress/Metabolism” is a broad catchall that refers to the cell’s ability to remodel its internal metabolic wiring to respond to environmental stresses such as changes in carbon source, as well as oxidative and heat stress. Detailed information on each of these phenotypes can be found briefly within the body of the text, and in more detail in the references cited. How Did the TLO Family Evolve in C. albicans?

Analysis of the synteny of the TLO genes in Candida species suggests that C. albicans TLO2 corresponds to the ancestral locus, as a TLO2 orthologue is present in the same subtelomeric locus in all related Candida species (i.e., C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. dubliniensis). Translocation of an ancestral Med2 gene to this telomeric locus appears to have occurred early in the evolution of the clade, remaining stable until the emergence of the closely related species C. dubliniensis and C. albicans. C. dubliniensis harbors a second TLO gene internally on chromosome 7, whereas C. albicans underwent a massive expansion in TLO copy number, probably facilitated by subtelomeric recombination. Further diversification of the C. albicans TLO gene family was likely driven by retrotransposon activity, as three distinct subfamilies of TLOs (α, β, and γ) can be identified based on the presence of retrotransposon LTR sequences within the 3′-half of the gene [18]. Studies have shown that these TLO gene subfamilies are variably expressed in in vitro—grown cells, with the TLOα and TLOβ genes and their encoded proteins expressed at higher levels than the TLOγ genes [18]. Concomitant with this, biochemical studies have directly shown that Tloβ2, Tloα3, Tloα9, Tloα12, and Tloα34 can be copurified with Mediator in vitro [4].

Mediator: Monolithic or Multifaceted?

Large multisubunit coregulatory complexes, like Mediator, were once thought of as monolithic intermediaries in gene regulation, but the discovery of the Tlos as Mediator subunits are part of an emerging view of these complexes as dynamic entities whose functionality can be regulated. The evidence presented by Zhang et al. [4] suggests that Tlo proteins encode interchangeable Med2-like subunits of the Mediator tail. Most fungi appear to have one copy of Med2, which raises the question, what advantage could the expression of multiple Med2 subunits confer on C. albicans? In S. cerevisiae, Med2, as well as the Mediator tail in general, interacts with transcriptional activators to facilitate the transcription of highly inducible genes [8]. The Mediator tail is thought to be especially important for the regulation of stress responses and nutrient acquisition in S. cerevisiae [9]. These characteristics are also important in pathogenic fungi. However, why this function was amplified to such a great degree in C. albicans and whether this is connected to stress survival and nutrient status is not known.

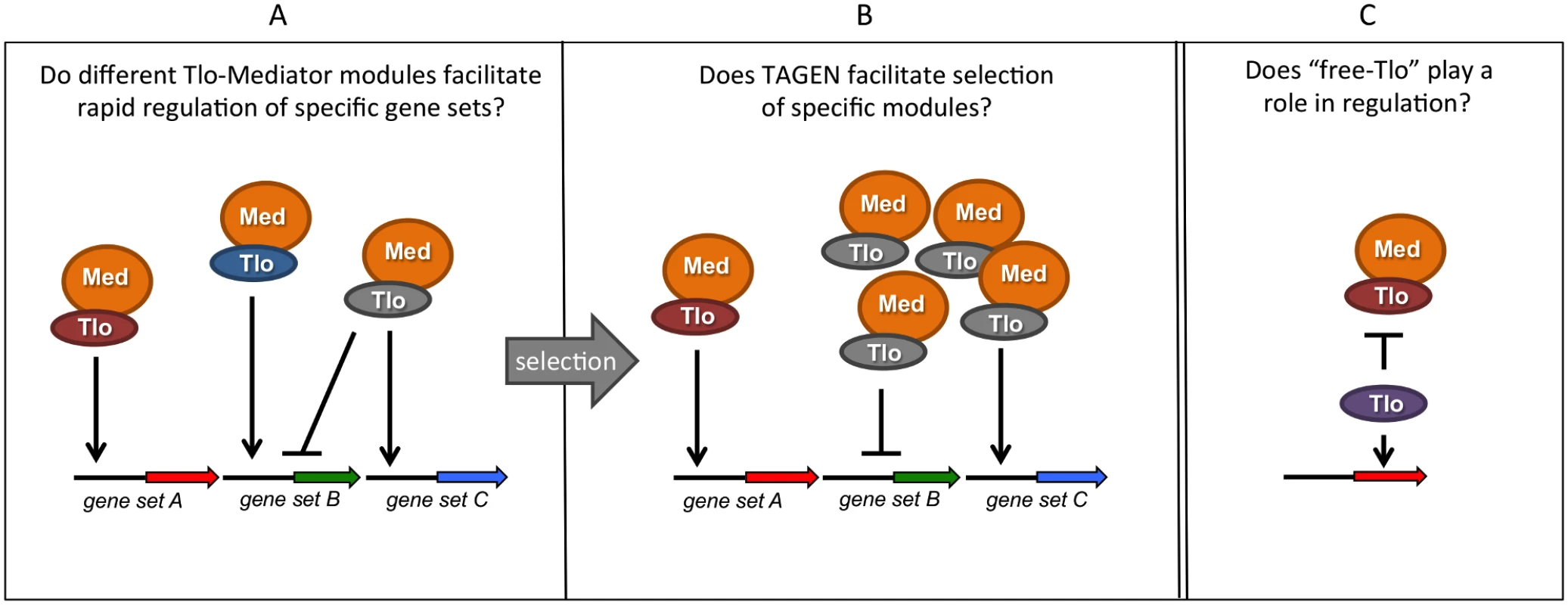

Perhaps the amplification and divergence of the Med2 tail subunit facilitated the emergence of Mediator variants with specific regulatory functions. Transcriptional control of the C. albicans Tlos in response to pathways that impact pathogenesis [19,20] suggests that regulation of the Tlo pool could influence virulence gene expression. Testing such a hypothesis in C. albicans using traditional reverse genetic approaches on the 14 diploid TLO genes is a daunting challenge. Fortunately, the closely related species C. dubliniensis possesses only two TLO gene copies [21]. C. dubliniensis shares many characteristics with C. albicans (including the capacity to produce hyphae), but is responsible for far fewer infections and is generally less pathogenic in animal models of infection [22]. Haran et al. [3] deleted both TLO genes in C. dubliniensis and found virulence-associated phenotypes such as an inability to form true hyphae, increased susceptibility to oxidative stress, and a reduced capacity to assimilate alternative carbon sources. Transcript profiling indicated defective induction of filament-specific genes and regulators, e.g., UME6. Interestingly, many filament-specific genes were induced in tloΔ null mutants, but to a much lower level than in the wild-type parental strain, implying that the Tlo protein is required for full induction of the filament-specific transcriptional response. The tloΔ null mutant also exhibited reduced expression of stress response and galactose utilization genes, indicating a general defect in inducible transcriptional responses. Expression data also suggested that Tlos may have repressor functions, as many starvation responses (gluconeogenesis, glyoxylate cycle, amino acid catabolism) were induced in the mutant [3].

C. dubliniensis yeast cells express Tlo1 at a level comparable to other Mediator subunits. However, expression of Tlo2 is far lower [3]. Deletion of TLO1 appeared to have stronger effects on filamentous growth and growth in galactose, consistent with the near complete restoration by TLO1 of those phenotypes in the tlo∆ null. Restoration of TLO1 or TLO2 expression, at a level comparable to native TLO1, in the tloΔ null mutant was found to restore the expression of overlapping and distinct sets of genes. If each of two C. dubliniensis MED2 orthologs exhibits diversity, does each of the 14 C. albicans TLO/MED2 orthologs also affect expression differently? The answer to this question awaits the results of studies currently underway to analyse the roles of individual CaTLO genes.

Evidence to date suggests that the C. albicans TLO gene family is subject to several layers of transcriptional regulation. The promoters of the telomeric members of the gene family have a strong Gal4 binding site, suggesting they may be coordinately regulated by this transcription factor [23]. TLO genes are also subject to local, chromatin-mediated positional effects that result in highly variable expression patterns from cell to cell and population to population [24]. This “noisy” expression pattern has been termed Telomere-Adjacent Gene Expression Noise (TAGEN) and results in highly variable patterns of TLO expression between individual cells and even between alleles of the same TLO gene. Mechanistically, this variation is dependent on telomere position and silencing regulators such as Sir2 [24]. Ectopically expressed genes at subtelomeric regions were also subject to TAGEN. Interestingly, when the URA3 gene, which can be subjected to both positive and negative selection, was placed adjacent to a TLO gene, and high-level or low-level expression was selected, the level of TAGEN was reduced [24]. This illustrates that some selective pressures can influence the natural level of gene expression noise. Furthermore, because their expression is noisy, the range of assembled Mediator complexes containing a given Tlo/Med2 subunit can vary greatly from cell to cell, generating an epigenetic mechanism for phenotypic diversity within an isogenic population of cells.

Future Directions

Many questions about TLO gene function remained unanswered (Fig. 2). One key piece of information currently absent from our knowledge is whether the C. albicans Tlo proteins exhibit functional diversity. Heterologous expression of the various C. albicans TLO genes in C. dubliniensis may provide clues about their specific regulatory functions. These data may support the hypothesis that differential expression of specific Tlos could provide a selective advantage in specific environments. In support of these heterologous expression experiments, in vitro and in vivo selection experiments with C. albicans may enable us to generate strains of C. albicans with a fitness advantage conferred by expression of specific TLOs. These data may enable us to determine whether the TLO expansion in C. albicans contributes to its greater pathogenicity relative to its TLO-deficient relatives, C. tropicalis and C. dubliniensis.

Fig. 2. Summary of hypotheses on the possible function(s) of multiple TLO genes in C. albicans.

Tlo proteins are subunits of the tail module of the Mediator complex (Med). (A) Different Tlo proteins could facilitate high-affinity interaction of Mediator with specific promoters or transcription factors, facilitating rapid or high level transcriptional responses. (B) As a consequence of telomere-associated gene expression noise (TAGEN) exhibited by TLO genes, adaptive pressure may select populations of cells expressing specific Tlos. (C) Excess, non-Mediator—associated “free Tlo” may also exhibit regulatory functions, either independently of Mediator or perhaps in an antagonisitic fashion.

Zdroje

1. Moran GP, Coleman DC, Sullivan DJ (2011) Comparative genomics and the evolution of pathogenicity in human pathogenic fungi. Eukaryotic Cell 10 : 34–42. doi: 10.1128/EC.00242-10 21076011

2. van Het Hoog M, Rast TJ, Martchenko M, Grindle S, Dignard D, et al. (2007) Assembly of the Candida albicans genome into sixteen supercontigs aligned on the eight chromosomes. Genome Biol 8: R52. 17419877

3. Haran J, Boyle H, Hokamp K, Yeomans T, Liu Z, et al. (2014) Telomeric ORFs (TLOs) in Candida spp. Encode Mediator Subunits That Regulate Distinct Virulence Traits. PLoS Genet 10: e1004658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004658 25356803

4. Zhang A, Petrov KO, Hyun ER, Liu Z, Gerber SA, et al. (2012) The Tlo Proteins Are Stoichiometric Components of Candida albicans Mediator Anchored via the Med3 Subunit. Eukaryotic Cell 11 : 874–884. doi: 10.1128/EC.00095-12 22562472

5. Kaiser B, Munder T, Saluz HP, Künkel W, Eck R (1999) Identification of a gene encoding the pyruvate decarboxylase gene regulator CaPdc2p from Candida albicans. Yeast 15 : 585–591. 10341421

6. Goodwin TJ, Poulter RT (2004) Multiple LTR-retrotransposon families in the asexual yeast Candida albicans. Genome Res 10 : 174–191.

7. Bourbon HM (2008) Comparative genomics supports a deep evolutionary origin for the large, four-module transcriptional mediator complex. Nucleic Acids Res 36 : 3993–4008. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn349 18515835

8. Ansari SA, Ganapathi M, Benschop JJ, Holstege FCP, Wade JT, et al. (2011) Distinct role of Mediator tail module in regulation of SAGA-dependent, TATA-containing genes in yeast. EMBO J 31 : 44–57. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.362 21971086

9. Miller C, Matic I, Maier KC, Schwalb B, Roether S, et al. (2012) Mediator Phosphorylation Prevents Stress Response Transcription During Non-stress Conditions. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287 : 44017–44026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.430140 23135281

10. Zhang A, Liu Z, Myers LC (2013) Differential Regulation of White-Opaque Switching by Individual Subunits of Candida albicans Mediator. Eukaryotic Cell 12 : 1293–1304. doi: 10.1128/EC.00137-13 23873866

11. Lindsay AK, Morales DK, Liu Z, Grahl N, Zhang A, et al. (2014) Analysis of Candida albicans Mutants Defective in the Cdk8 Module of Mediator Reveal Links between Metabolism and Biofilm Formation. PLoS Genet 10: e1004567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004567 25275466

12. Uwamahoro N, Qu Y, Jelicic B, Lo TL, Beaurepaire C, et al. (2012) The Functions of Mediator in Candida albicans Support a Role in Shaping Species-Specific Gene Expression. PLoS Genet 8: e1002613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002613 22496666

13. Tebbji F, Chen Y, Richard Albert J, Gunsalus KTW, Kumamoto CA, et al. (2014) A Functional Portrait of Med7 and the Mediator Complex in Candida albicans. PLoS Genet 10: e1004770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004770 25375174

14. Uwamahoro N, Verma-Gaur J, Shen H-H, Qu Y, Lewis R, et al. (2014) The pathogen Candida albicans hijacks pyroptosis for escape from macrophages. mBio 5: e00003–e00014. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00003-14 24667705

15. Nemet J, Jelicic B, Rubelj I, Sopta M (2014) The two faces of Cdk8, a positive/negative regulator of transcription. Biochimie 97 : 22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.10.004 24139904

16. Paul S, Schmidt JA, Moye-Rowley WS (2011) Regulation of the CgPdr1 transcription factor from the pathogen Candida glabrata. Eukaryotic Cell 10 : 187–197. doi: 10.1128/EC.00277-10 21131438

17. Firestein R, Shima K, Nosho K, Irahara N, Baba Y, et al. (2010) CDK8 expression in 470 colorectal cancers in relation to beta-catenin activation, other molecular alterations and patient survival. Int J Cancer 126 : 2863–2873. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24908 19790197

18. Anderson MZ, Baller JA, Dulmage K, Wigen L, Berman J (2012) The Three Clades of the Telomere-Associated TLO Gene Family of Candida albicans Have Different Splicing, Localization, and Expression Features. Eukaryotic Cell 11 : 1268–1275. doi: 10.1128/EC.00230-12 22923044

19. Doedt T, Krishnamurthy S, Bockmühl DP, Tebarth B, Stempel C, et al. (2004) APSES proteins regulate morphogenesis and metabolism in Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell 15 : 3167–3180. 15218092

20. Zakikhany K, Naglik JR, Schmidt Westhausen A, Holland G, Schaller M, et al. (2007) In vivo transcript profiling of Candida albicans identifies a gene essential for interepithelial dissemination. Cell Microbiol 9 : 2938–2954. 17645752

21. Jackson AP, Gamble JA, Yeomans T, Moran GP, Saunders D, et al. (2009) Comparative genomics of the fungal pathogens Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans. Genome Res 19 : 2231–2244. doi: 10.1101/gr.097501.109 19745113

22. Moran GP, Coleman DC, Sullivan DJ (2012) Candida albicans versus Candida dubliniensis: Why Is C. albicans More Pathogenic? Int J Microbiol 2012 : 205921. doi: 10.1155/2012/205921 21904553

23. Askew C, Sellam A, Epp E, Hogues H, Mullick A, et al. (2009) Transcriptional regulation of carbohydrate metabolism in the human pathogen Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000612. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000612 19816560

24. Anderson MZ, Gerstein AC, Wigen L, Baller JA, Berman J (2014) Silencing Is Noisy: Population and Cell Level Noise in Telomere-Adjacent Genes Is Dependent on Telomere Position and Sir2. PLoS Genet 10: e1004436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004436 25057900

25. Tsai K-L, Tomomori-Sato C, Sato S, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, et al. (2014) Subunit architecture and functional modular rearrangements of the transcriptional mediator complex. Cell 157 : 1430–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.015 24882805

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek 2014 Reviewer Thank YouČlánek Characterization of Metabolically Quiescent Parasites in Murine Lesions Using Heavy Water LabelingČlánek High Heritability Is Compatible with the Broad Distribution of Set Point Viral Load in HIV Carriers

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 2- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- 2014 Reviewer Thank You

- A Case for Two-Component Signaling Systems As Antifungal Drug Targets

- Prions—Not Your Immunologist’s Pathogen

- Telomeric ORFS in : Does Mediator Tail Wag the Yeast?

- Livestock-Associated : The United States Experience

- The Neurotrophic Receptor Ntrk2 Directs Lymphoid Tissue Neovascularization during Infection

- The Intracellular Bacterium Uses Parasitoid Wasps as Phoretic Vectors for Efficient Horizontal Transmission

- CD200 Receptor Restriction of Myeloid Cell Responses Antagonizes Antiviral Immunity and Facilitates Cytomegalovirus Persistence within Mucosal Tissue

- Phage-mediated Dispersal of Biofilm and Distribution of Bacterial Virulence Genes Is Induced by Quorum Sensing

- CXCL9 Contributes to Antimicrobial Protection of the Gut during Infection Independent of Chemokine-Receptor Signaling

- Mitigation of Prion Infectivity and Conversion Capacity by a Simulated Natural Process—Repeated Cycles of Drying and Wetting

- Approaches Reveal a Key Role for DCs in CD4+ T Cell Activation and Parasite Clearance during the Acute Phase of Experimental Blood-Stage Malaria

- Revealing the Sequence and Resulting Cellular Morphology of Receptor-Ligand Interactions during Invasion of Erythrocytes

- Crystal Structures of the Carboxyl cGMP Binding Domain of the cGMP-dependent Protein Kinase Reveal a Novel Capping Triad Crucial for Merozoite Egress

- Non-redundant and Redundant Roles of Cytomegalovirus gH/gL Complexes in Host Organ Entry and Intra-tissue Spread

- Characterization of Metabolically Quiescent Parasites in Murine Lesions Using Heavy Water Labeling

- A Working Model of How Noroviruses Infect the Intestine

- CD44 Plays a Functional Role in -induced Epithelial Cell Proliferation

- Novel Inhibitors of Cholesterol Degradation in Reveal How the Bacterium’s Metabolism Is Constrained by the Intracellular Environment

- G-Quadruplexes in Pathogens: A Common Route to Virulence Control?

- A Rho GDP Dissociation Inhibitor Produced by Apoptotic T-Cells Inhibits Growth of

- Manipulating Adenovirus Hexon Hypervariable Loops Dictates Immune Neutralisation and Coagulation Factor X-dependent Cell Interaction and

- The RhoGAP SPIN6 Associates with SPL11 and OsRac1 and Negatively Regulates Programmed Cell Death and Innate Immunity in Rice

- Lymph-Node Resident CD8α Dendritic Cells Capture Antigens from Migratory Malaria Sporozoites and Induce CD8 T Cell Responses

- Coordinated Function of Cellular DEAD-Box Helicases in Suppression of Viral RNA Recombination and Maintenance of Viral Genome Integrity

- IL-33-Mediated Protection against Experimental Cerebral Malaria Is Linked to Induction of Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells, M2 Macrophages and Regulatory T Cells

- Evasion of Autophagy and Intracellular Killing by Human Myeloid Dendritic Cells Involves DC-SIGN-TLR2 Crosstalk

- CD8 T Cell Response Maturation Defined by Anentropic Specificity and Repertoire Depth Correlates with SIVΔnef-induced Protection

- Diverse Heterologous Primary Infections Radically Alter Immunodominance Hierarchies and Clinical Outcomes Following H7N9 Influenza Challenge in Mice

- Human Adenovirus 52 Uses Sialic Acid-containing Glycoproteins and the Coxsackie and Adenovirus Receptor for Binding to Target Cells

- Super-Resolution Imaging of ESCRT-Proteins at HIV-1 Assembly Sites

- Disruption of an Membrane Protein Causes a Magnesium-dependent Cell Division Defect and Failure to Persist in Mice

- Recognition of Hyphae by Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Is Mediated by Dectin-2 and Results in Formation of Extracellular Traps

- Essential Domains of Invasins Utilized to Infect Mammalian Host Cells

- High Heritability Is Compatible with the Broad Distribution of Set Point Viral Load in HIV Carriers

- Yeast Prions: Proteins Templating Conformation and an Anti-prion System

- A Novel Mechanism of Bacterial Toxin Transfer within Host Blood Cell-Derived Microvesicles

- A Wild Strain Has Enhanced Epithelial Immunity to a Natural Microsporidian Parasite

- Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection by γδ T Cells

- Dimorphism in Fungal Pathogens of Mammals, Plants, and Insects

- Recognition and Activation Domains Contribute to Allele-Specific Responses of an Arabidopsis NLR Receptor to an Oomycete Effector Protein

- Direct Binding of Retromer to Human Papillomavirus Type 16 Minor Capsid Protein L2 Mediates Endosome Exit during Viral Infection

- Characterization of the Mycobacterial Acyl-CoA Carboxylase Holo Complexes Reveals Their Functional Expansion into Amino Acid Catabolism

- Prion Infections and Anti-PrP Antibodies Trigger Converging Neurotoxic Pathways

- Evolution of Genome Size and Complexity in the

- Antibiotic Modulation of Capsular Exopolysaccharide and Virulence in

- IFNγ Signaling Endows DCs with the Capacity to Control Type I Inflammation during Parasitic Infection through Promoting T-bet+ Regulatory T Cells

- Identification of Effective Subdominant Anti-HIV-1 CD8+ T Cells Within Entire Post-infection and Post-vaccination Immune Responses

- Viral and Cellular Proteins Containing FGDF Motifs Bind G3BP to Block Stress Granule Formation

- ATPaseTb2, a Unique Membrane-bound FoF1-ATPase Component, Is Essential in Bloodstream and Dyskinetoplastic Trypanosomes

- Cytoplasmic Actin Is an Extracellular Insect Immune Factor which Is Secreted upon Immune Challenge and Mediates Phagocytosis and Direct Killing of Bacteria, and Is a Antagonist

- A Specific A/T Polymorphism in Western Tyrosine Phosphorylation B-Motifs Regulates CagA Epithelial Cell Interactions

- Within-host Competition Does Not Select for Virulence in Malaria Parasites; Studies with

- A Membrane-bound eIF2 Alpha Kinase Located in Endosomes Is Regulated by Heme and Controls Differentiation and ROS Levels in

- Cytosolic Access of : Critical Impact of Phagosomal Acidification Control and Demonstration of Occurrence

- Role of Pentraxin 3 in Shaping Arthritogenic Alphaviral Disease: From Enhanced Viral Replication to Immunomodulation

- Rational Development of an Attenuated Recombinant Cyprinid Herpesvirus 3 Vaccine Using Prokaryotic Mutagenesis and In Vivo Bioluminescent Imaging

- HITS-CLIP Analysis Uncovers a Link between the Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus ORF57 Protein and Host Pre-mRNA Metabolism

- Molecular and Functional Analyses of a Maize Autoactive NB-LRR Protein Identify Precise Structural Requirements for Activity

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection by γδ T Cells

- ATPaseTb2, a Unique Membrane-bound FoF1-ATPase Component, Is Essential in Bloodstream and Dyskinetoplastic Trypanosomes

- Rational Development of an Attenuated Recombinant Cyprinid Herpesvirus 3 Vaccine Using Prokaryotic Mutagenesis and In Vivo Bioluminescent Imaging

- Telomeric ORFS in : Does Mediator Tail Wag the Yeast?

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání