-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaReactive Oxygen Species Hydrogen Peroxide Mediates Kaposi's

Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Reactivation from Latency

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) establishes a latent

infection in the host following an acute infection. Reactivation from latency

contributes to the development of KSHV-induced malignancies, which include

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), the most common cancer in untreated AIDS patients,

primary effusion lymphoma and multicentric Castleman's disease. However,

the physiological cues that trigger KSHV reactivation remain unclear. Here, we

show that the reactive oxygen species (ROS) hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) induces KSHV reactivation from latency through

both autocrine and paracrine signaling. Furthermore, KSHV spontaneous lytic

replication, and KSHV reactivation from latency induced by oxidative stress,

hypoxia, and proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines are mediated by

H2O2. Mechanistically, H2O2

induction of KSHV reactivation depends on the activation of mitogen-activated

protein kinase ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 pathways. Significantly,

H2O2 scavengers N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), catalase

and glutathione inhibit KSHV lytic replication in culture. In a mouse model of

KSHV-induced lymphoma, NAC effectively inhibits KSHV lytic replication and

significantly prolongs the lifespan of the mice. These results directly relate

KSHV reactivation to oxidative stress and inflammation, which are physiological

hallmarks of KS patients. The discovery of this novel mechanism of KSHV

reactivation indicates that antioxidants and anti-inflammation drugs could be

promising preventive and therapeutic agents for effectively targeting KSHV

replication and KSHV-related malignancies.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002054

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002054Summary

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) establishes a latent

infection in the host following an acute infection. Reactivation from latency

contributes to the development of KSHV-induced malignancies, which include

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), the most common cancer in untreated AIDS patients,

primary effusion lymphoma and multicentric Castleman's disease. However,

the physiological cues that trigger KSHV reactivation remain unclear. Here, we

show that the reactive oxygen species (ROS) hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) induces KSHV reactivation from latency through

both autocrine and paracrine signaling. Furthermore, KSHV spontaneous lytic

replication, and KSHV reactivation from latency induced by oxidative stress,

hypoxia, and proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines are mediated by

H2O2. Mechanistically, H2O2

induction of KSHV reactivation depends on the activation of mitogen-activated

protein kinase ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 pathways. Significantly,

H2O2 scavengers N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), catalase

and glutathione inhibit KSHV lytic replication in culture. In a mouse model of

KSHV-induced lymphoma, NAC effectively inhibits KSHV lytic replication and

significantly prolongs the lifespan of the mice. These results directly relate

KSHV reactivation to oxidative stress and inflammation, which are physiological

hallmarks of KS patients. The discovery of this novel mechanism of KSHV

reactivation indicates that antioxidants and anti-inflammation drugs could be

promising preventive and therapeutic agents for effectively targeting KSHV

replication and KSHV-related malignancies.Introduction

A hallmark of herpesviral infections is the establishment of latency in the hosts following acute infections [1]. Reactivation of herpesviruses from latency results in production of infectious virions and often development of their associated diseases. KSHV is a gammaherpesvirus associated with KS, a vascular malignancy of endothelial cells commonly seen in AIDS patients [2]. KSHV is also linked to other lymphoproliferative diseases including primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) [2]–[4]. Similar to other herpesviruses, KSHV establishes a lifelong persistent infection in the host [1]. In KS tumors, most tumor cells are latently infected by KSHV, indicating an essential role of viral latency in tumor development [5]. However, KSHV lytic replication also contributes to KS pathogenesis [6]. Both viral lytic products and de novo infection promote cell proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, inflammation and vascular permeability [6]. In fact, higher KSHV lytic antibody titers and peripheral blood viral loads are correlated with high incidence and advanced stage of KS [7]–[13], and KS regressed following anti-herpesviral treatments that inhibit lytic replication [14], [15].

While several cellular pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and protein kinase C delta regulate KSHV lytic replication [16]–[20], the common physiological trigger that reactivates KSHV from latency in patients remains unclear. A number of factors including proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines [21], [22], hypoxia [23], HIV and its product Tat [24]–[26], coinfection with human cytomegalovirus and human herpesvirus 6 [27], [28], and the activation of toll-like receptors [29] can cause KSHV reactivation in cultures. However, none of them is likely the trigger in all the clinical scenarios, which include different forms of KS, PEL and MCD. The mechanisms by which these factors reactivate KSHV from latency also remain unclear.

There are four clinical forms of KS. Patients with all forms of KS are characterized by high levels of inflammation and oxidative stress [30], [31]. Classical KS, mostly seen in elderly men in the Mediterranean and Eastern European regions, is ubiquitously associated with high level of inflammation and oxidative stress because of its close link with aging [32]. In African endemic KS, excessive iron exposure due to high content of iron in the local soils coupled with bare foot walking is a possible cofactor that can induce inflammation and oxidative stress [33], [34]. In transplantation KS, inflammation and oxidative stress are common because of immunosuppression and organ rejection [35]. Patients with AIDS-related KS (AIDS-KS) have high levels of inflammation and oxidative stress as a result of host responses to HIV infection and chronic inflammation [36]. In all clinical forms of KS, inflammation and oxidative stress are also the hallmarks in the tumors [37]. Both PEL and MCD often coexist with KS, and are commonly seen in HIV-infected patients [6]. PEL is often found in elderly men, particularly in HIV-negative cases. Thus, similar to KS patients, these patients often have high levels of inflammation and oxidative stress. Since inflammation and oxidative stress induce ROS, and high level of ROS activates the MAPK pathways [38], we postulated that ROS, as a result of inflammation and oxidative stress, might mediate KSHV reactivation from latency.

The most common ROS molecule in non-immune cells is H2O2, which is mainly produced by mitochondria as a byproduct of oxidative metabolism [38]. Because high level of H2O2 is cytotoxic, cells express multiple antioxidant enzymes such as catalase and glutathione peroxidase to remove H2O2 so that it is below the detrimental threshold in normal condition. During oxidative stress, cells produce and release a large amount of H2O2 as a consequence of lost balance between its production and its scavenging [38]. During infections and inflammatory responses, host phagocytes such as macrophages and neutrophils produce and release excessive amounts of H2O2 [39]–[41]. Thus, KS patients are deemed to have high levels of H2O2. In this study, we investigated the physiological role of H2O2 on KSHV reactivation.

Results

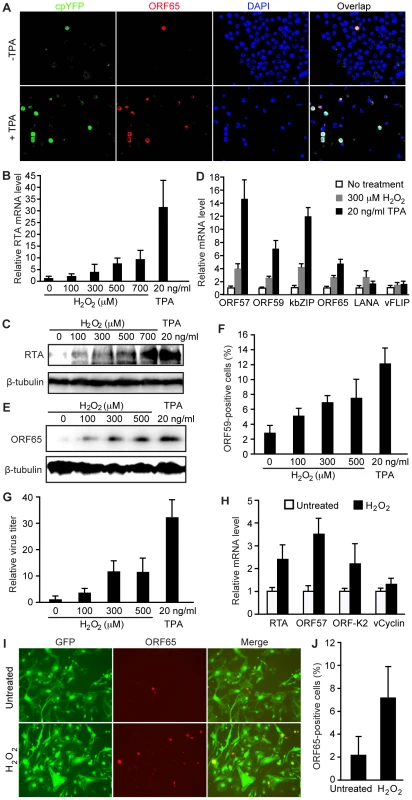

H2O2 induces KSHV reactivation through both paracrine and autocrine mechanisms

To examine the relationship of H2O2 with KSHV lytic replication, we stably expressed an H2O2-specific yellow fluorescent protein (cpYFP) sensor from the HyPer-cyto cassette in KSHV-infected BCBL1 cells [42]. As previously reported [20], the majority of BCBL1 cells were latently infected by KSHV but a small percentage of them underwent spontaneous lytic replication, which was detected by staining for viral late lytic protein ORF65 (Figure 1A). Notably, these ORF65-positive cells were strongly positive for cpYFP (Figure 1A). In contrast, ORF65-negative cells were either weakly positive or negative for cpYFP. Treatment with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), a common chemical inducer for KSHV lytic replication, increased the number of lytic cells, all of which also expressed high level of cpYFP while ORF65-negative cells remained weakly positive for cpYFP (Figure 1A). Extended exposure of the images or adjustment of the contrast showed that almost all the TPA-treated cells were positive for cpYFP albeit with diverse intensities (data not shown). These diverse levels of H2O2 among the individual cells could be due to their different sizes of intracellular antioxidant enzyme pools. Together, these results showed a close correlation between high level of intracellular H2O2 and KSHV lytic replication.

To investigate the role of H2O2 in KSHV lytic replication, we examined whether exogenous H2O2, which uses water channels (aquaporins) to cross the cell membrane [43], is sufficient to induce KSHV reactivation. We observed a dose-dependent induction, at both mRNA and protein levels, of KSHV replication and transcription activator (RTA) encoded by ORF50, a key transactivator of viral lytic replication (Figure 1B–C), by H2O2. Consistent with these results, H2O2 increased the expression of several other KSHV lytic transcripts including ORF57, ORF59, kbZIP (ORF-K8) and ORF65 (Figure 1D). The expression of KSHV major latent gene LANA (ORF73) was also increased by 2.2-fold while that of another latent gene vFLIP (ORF71) remained almost unchanged. Furthermore, H2O2 increased the expression of viral lytic proteins ORF65 and ORF59, and production of infectious virions in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1E–G).

We further extended the observation to primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) latently infected by KSHV [44]. Similar to BCBL1 cells, H2O2 increased the expression of viral lytic transcripts including RTA, ORF57 and ORF-K2 but not latent transcript vCyclin (Figure 1H). H2O2 also increased the expression of ORF65 protein (Figure 1I–J). These results indicate that H2O2 induction of KSHV reactivation is not cell type specific.

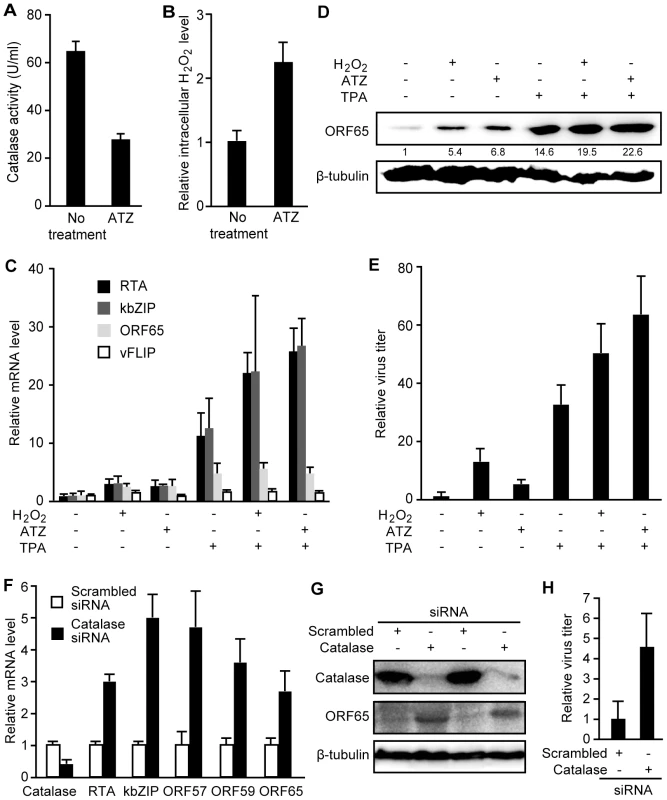

Next, we determined whether an increase in intracellular H2O2 level is sufficient to induce KSHV reactivation. Treatment of BCBL1 cells with 3-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole (ATZ), an inhibitor of H2O2 scavenging enzyme catalase, reduced cellular catalase activity by 57.2% and increased the intracellular H2O2 level by 2.2-fold (Figure 2A–B). ATZ increased the expression of KSHV lytic transcripts of RTA, ORF57, ORF59, kbZIP and ORF65 genes, the expression of lytic protein ORF65, and production of infectious virions (Figure 2C–E). Interestingly, we observed an additive effect when either H2O2 or ATZ was used together with TPA to induce KSHV lytic replication (Figure 2C–E).

To confirm that the effect of ATZ on KSHV reactivation was due to an increase in intracellular H2O2 level, we stably expressed a siRNA specific to catalase in BCBL1 cells harboring a recombinant KSHV BAC36 [45]. Compared to cells stably expressing a scrambled siRNA, those expressing the catalase-specific siRNA had significantly lower expression levels of catalase transcript and protein (Figure 2F–G). Similar to treatment with ATZ, knockdown of catalase increased the expression of KSHV lytic transcripts of RTA, ORF57, ORF59, kbZIP and ORF65, lytic protein ORF65, and production of infectious virions (Figure 2F–H).

Taken together, our results so far have shown that an increase in intracellular or exogenous H2O2 level induces KSHV reactivation, indicating that H2O2 produced during inflammation and oxidative stress in KS patients can be the physiological trigger that reactivates KSHV from latency through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms.

H2O2 scavengers inhibit H2O2-induced KSHV lytic replication

To determine whether H2O2 is required for KSHV lytic replication, we used H2O2 scavengers to reduce the intracellular H2O2 level. As shown in Figure 1A, TPA not only induced KSHV reactivation but also increased the intracellular H2O2 level. At 12 h, TPA increased the intracellular H2O2 level by 3.9-fold (Figure 3A), which could be the result of reduced expression of catalase (Figure 3B). Treatment with H2O2 scavengers including catalase, reduced glutathione and NAC inhibited TPA induction of intracellular H2O2 as shown by the reduced median fluorescent levels in the cpYFP-expressing BCBL1 cells (Figure 3C). None of these treatments affected the viability and growth rate of the cells (data not shown). As expected, H2O2 scavengers inhibited TPA induction of RTA transcript and protein (Figure 3D–E). Consistent with these results, RTA promoter activities were induced 2.2 - and 4.3-fold by H2O2 and TPA, respectively, and these induction effects were inhibited by NAC (Figure 3F). In contrast, a latent LANA promoter was not induced by H2O2 and only marginally induced by TPA for 1.4-fold (Figure 3G). NAC also abolished TPA induction of the LANA promoter activity. Furthermore, TPA induction of ORF65 protein and production of infectious virions were inhibited by H2O2 scavengers in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 3H–I). To examine whether H2O2 scavengers also inhibit KSHV spontaneous lytic replication, we measured the expression of ORF65 protein in BCBL1 cells treated with the scavengers. As shown in Figure 3J, both catalase and NAC inhibited the expression of ORF65 protein after 6 days but not 1 day of treatment, which is consistent with the late expression kinetics of this viral capsid protein. These results indicate that H2O2 is required for KSHV spontaneous lytic replication and TPA-induced KSHV reactivation, and antioxidants such as reduced glutathione and NAC can suppress KSHV lytic replication.

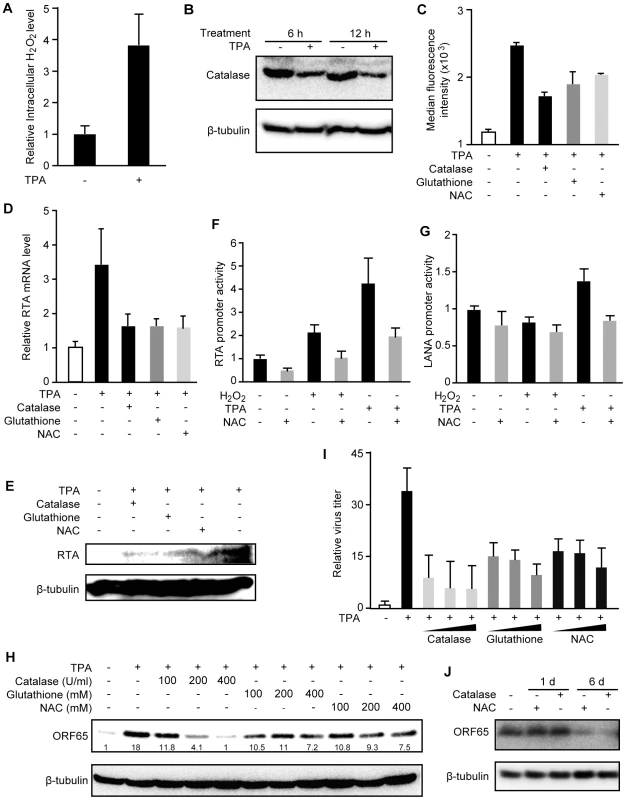

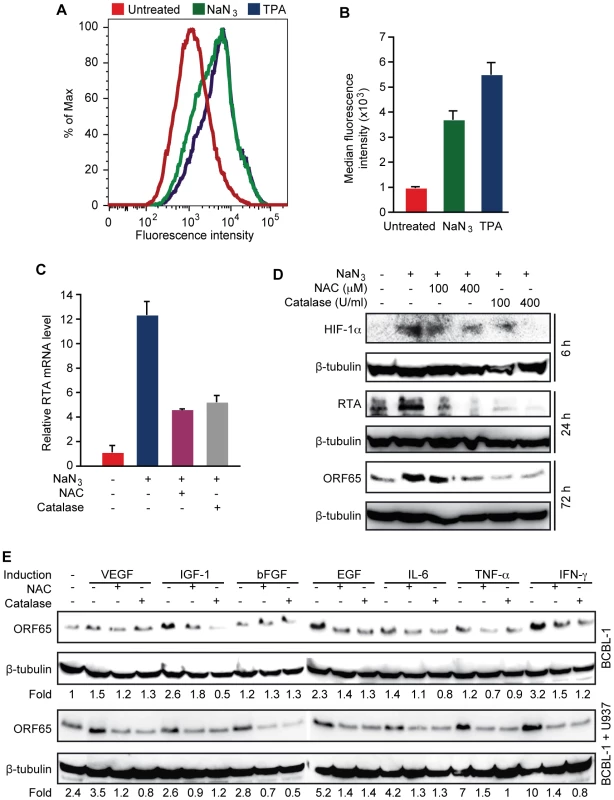

H2O2 scavengers inhibit KSHV lytic replication induced by hypoxia, and proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines

Because high levels of hypoxia, and proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines are features of KS tumors, and previous studies have shown that these conditions can induce KSHV reactivation [21]–[23], we determined whether KSHV reactivation induced by these conditions is mediated by H2O2. Short-time treatment with sodium azide (NaN3), which induces hypoxia [46], increased intracellular H2O2 level as shown by cpYFP fluorescent level in BCBL1 cells (Figure 4A–B). As a result, the expression of RTA transcript was increased 12.2-fold by NaN3, which was inhibited by both NAC and catalase (Figure 4C). Similarly, the expression of RTA and ORF65 proteins were induced by NaN3, which was also inhibited by NAC and catalase (Figure 4D). As expected, HIF-1α was induced by NaN3, which was also inhibited by NAC and catalase, suggesting that H2O2 mediates hypoxia induction of HIF-1α. These results are consistent with previous observations that H2O2 can directly induce HIF-1α [47].

Next, we determined the role of H2O2 in KSHV reactivation induced by proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines. Treatment of BCBL1 cells with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor-B (bFGF), interleukin-6 (IL-6) or tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) alone minimally induced the expression of ORF65 protein by 1.5-, 1.2-, 1.4 - and 1.2-fold, respectively, and these induction effects were reversed by NAC and catalase (Figure 4E). In contrast, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), epithelial growth factor (EGF) and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) were more potent inducers, which increased the expression of ORF65 protein by 2.6-, 2.3 - and 3.2-fold, respectively. Similarly, NAC and catalase inhibited the induction of ORF65 proteins by these cytokines. Since KS tumors contain abundant infiltration of proinflammatory immune cells such as monocytes, we further examined the effects of proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines on KSHV reactivation in the presence of monocytic cells U937 (Figure 4E). Co-culture of BCBL1 cells with U937 cells alone increased the expression of ORF65 protein by 2.4-fold. In the presence of U937 cells, weak inducers VEGF, bFGF, IL-6 and TNF-α more effectively increased the expression of ORF65 protein by 3.5-, 2.8-, 4.2 - and 7-fold, respectively, suggesting a synergistic effect of these cytokines with U937 cells. These synergistic effects were also observed with strong inducers EGF and IFN-γ, which increased the expression of ORF65 protein by 5.2 - and 10-fold in the presence of U937 cells. In contrast, IGF-1 did not further increase the expression of ORF65 protein in the presence of U937 cells. Both NAC and catalase inhibited the induction of ORF65 protein by proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines in the presence of U937 cells (Figure 4E). Together, these results indicate that H2O2 mediates KSHV reactivation induced by proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines with and without co-culture with the monocytic cells.

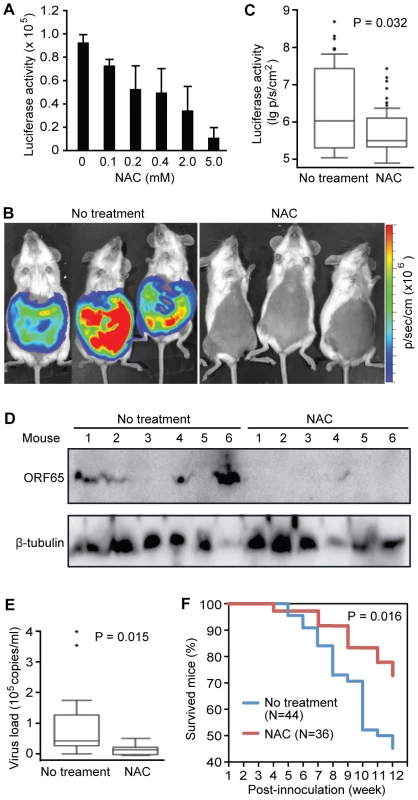

H2O2 scavenger NAC inhibits KSHV lytic replication and tumor progression in vivo

We next sought to inhibit KSHV lytic replication in vivo with H2O2 scavengers. To monitor KSHV lytic activity in vivo, we generated a recombinant KSHV Δ65Luc by replacing ORF65 with a firefly luciferase gene (Figure S1A–C). Because ORF65 is a late viral lytic gene, detection of its expression would imply nearly complete KSHV lytic replication cycle. We reconstituted Δ65Luc in BCBL1 cells and generated a cell line harboring both wild type KSHV and Δ65Luc. As expected, BAC36-Δ65Luc cells expressed low level of ORF65 protein and luciferase, reflecting the spontaneous viral lytic replication in a small number of cells (Figure S1D). Treatment with TPA increased the expression of ORF65 and luciferase proteins. The corresponding luciferase activity was also increased by 6.2-fold (Figure S1E). These results indicate that the luciferase activity closely mimicked the expression of ORF65 protein, and thus can be used to monitor KSHV lytic activity. As expected, addition of NAC inhibited the luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A).

To examine KSHV lytic replication and determine the inhibitory effect of antioxidant NAC in vivo, we intraperitoneally inoculated NOD/SCID mice with BCBL1 cells harboring Δ65Luc. The mice were then fed daily with drinking water containing 5 mM NAC. All mice developed PEL at about five weeks post-inoculation as previously reported [48]. However, mice fed with NAC had an average 15.6-fold lower luciferase activities than those fed with drinking water alone (Figure 5B–C). We also detected lower expression levels of ORF65 protein in lymphoma cells isolated from the NAC-treated mice than those from the control mice by Western-blotting (Figure 5D). Immunohistochemical staining showed that the majority of the lymphoma cells from both groups were positive for LANA; however, cells from NAC-treated mice had significantly lower number of ORF65-positive cells than those from the control group (Figure S2A–B). To determine the production of infectious virions by the lymphoma cells, we used cell-free supernatants from the pleural fluids of the mice to infect HUVEC and examined the presence of infectious virions by staining for ORF65 protein [49]. We observed abundant virus particles in many of the cells infected with supernatants from the control mice while those infected with supernatants from NAC-treated mice had almost no detectable virus particles (Figure S2C). Consistent with these results, mice fed with NAC had an average 2.7-fold lower virus loads in the blood than the control group (Figure 5E). As many as 50% of the mice from both groups also developed solid tumors. ORF65 protein was detected in over 10% of the tumor cells from the control solid tumors but was almost not detectable in the solid tumors from the NAC-treated mice (Figure S2D). By examining the survival curves, we found that NAC-treated mice had an extended lifespan compared to the control group (Figure 5F). At 12-week post-inoculation, 72.2% of the NAC-treated mice survived compared to only 45.4% in the untreated group (P = 0.016). Collectively, results from these in vivo experiments indicated that PEL induced in mice had active KSHV lytic replication, and antioxidant NAC effectively inhibited KSHV lytic replication, and extended the lifespan of the mice.

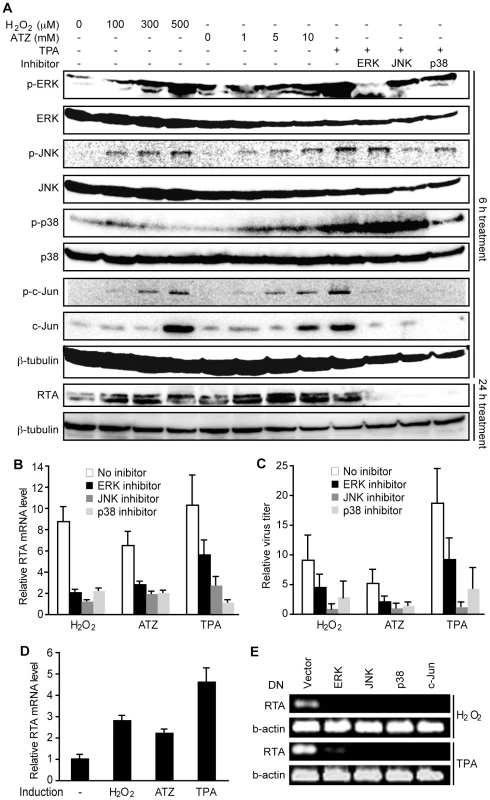

H2O2 induces KSHV reactivation by activating the ERK1/2, JNK and p38 MAPK pathways

H2O2 is known to activate multiple MAPK pathways [50], which are required for KSHV lytic replication [17], [20]. Similar to TPA, both exogenous and ATZ-induced endogenous H2O2 activated ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPK pathways, and increased the total and phosphorylated forms of their downstream target c-Jun in a dose-dependent manner in BCBL1 cells in addition to induction of RTA protein expression (Figure 6A). Treatment with specific inhibitors of all three MAPK pathways effectively inhibited TPA activation of their respective MAPKs and c-Jun, as well as the induction of RTA protein (Figure 6A). Importantly, these inhibitors also strongly inhibited H2O2 and ATZ induction of RTA expression and production of infectious virions (Figure 6B–C).

To further confirm the essential roles of MAPK pathways in H2O2-induced KSHV reactivation, we used dominant negative (DN) constructs to block these pathways. In 293T cells harboring BAC36, treatment with TPA induced KSHV reactivation [51]. Treatment with H2O2 and ATZ induced the expression of RTA transcript (Figure 6D). As expected, DN constructs of all three MAPK pathways and c-Jun effectively inhibited the induction of RTA by TPA and H2O2 (Figure 6E). Together, these results indicate that H2O2 induction of KSHV reactivation is mediated by all three MAPK pathways.

Discussion

We have shown that ROS H2O2 induces KSHV lytic replication through both paracrine and autocrine mechanisms, and in both PEL and endothelial cells. Because oxidative stress and chronic inflammation are characteristic features in patients of all clinical forms of KS, as well as PEL and MCD [6], [30], [31], H2O2 could be an important physiological factor that triggers KSHV reactivation in these patients. Several other factors that induce KSHV lytic replication [21]–[29] also induce oxidative stress and inflammation [36], [52]–[56]. Thus, it is likely that H2O2 mediates KSHV lytic replication induced by these factors. Indeed, our data show that KSHV reactivation induced by oxidative stress, hypoxia, and proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines depends on the induction of H2O2. Importantly, co-culture of BCBL1 cells with monocytic U973 cells enhances KSHV reactivation induced by proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines, particularly IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ, which are highly expressed in KS tumors [6]. Because of the abundance of proinflammatory cells, and proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines in KS tumors, these synergistic effects could further boost KSHV lytic replication. Thus, tumor microenvironments consisting of proinflammatory cells, proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines, and possibly extracellular matrix and other stromal cells are likely to have essential roles in inducing and mediating KSHV lytic replication in KS tumors, which should be further examined in more details.

Mechanistically, we have shown that H2O2 induction of KSHV reactivation is mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK pathways. Previous studies have shown that these pathways are required for KSHV infection and lytic replication [17]–[20]. Consistent with these observations, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and a number of proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines are known to induce MAPK pathways [57]–[65].

Based on our results, we propose a model in which KS tumors are initiated by either the homing of KSHV-infected cells, most likely progenitor endothelial cells or B-cells, from virus reservoirs to the affected sites or de novo infection by the newly produced virions, both of which are promoted by inflammation and oxidative stress [6]. Since KSHV de novo infection and lytic replication further promote inflammation and oxidative stress [6], one can expect the establishment of a positive feedback loop once the cycle is initiated. If these inflammatory conditions are not appropriately contained, they can lead to the rapid progression of KS as in the case of untreated AIDS-KS. Therefore, both active inflammation and host control of viral replication are likely to determine the course of KS.

It is interesting that only a subset of KSHV-infected cells undergo lytic replication in KS tumors or in cell culture induced for KSHV lytic replication (Figure 1A and F). KSHV has evolved a complex mechanism consisting of multiple blocks to regulate its replication [66]. Whether a cell undergoes lytic replication is likely to depend on the extent of release of these blocks. While KSHV lytic replication induces inflammation and promotes the overall tumor growth through a paracrine mechanism, it is also detrimental to the lytic cells [6]. Thus, a fine balance of latent and lytic programs in KS tumors combined with active inflammation and oxidative stress in the tumor microenvironment is likely required for the development of advanced stage of KS.

We have shown that H2O2 scavengers such as NAC can inhibit KSHV lytic replication in vitro and in a KSHV lymphoma animal model. Significantly, NAC extends the lifespan of the lymphoma-bearing mice. These results indicate that antioxidants and anti-inflammation drugs might be effective for inhibiting KSHV lytic replication, and thus could be promising preventive and therapeutic agents for KSHV-induced malignancies. Because many of these agents are affordable, their use is attractive, particularly in the African settings.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and chemical reagents

BCBL1 cells and BCBL1 cells carrying pHyer-cyto or BAC36, a recombinant KSHV [45], were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Human embryonic kidney 293T cells, 293 cells and 293T cells carrying BAC36 were cultured in DMEM plus 10% FBS.

H2O2, ATZ, NaN3, and antioxidants NAC, reduced L-glutathione, and bovine liver catalase were purchased from Sigma Life Science (St. Louis, MO). The ERK inhibitor U0126, p38 inhibitor SB203580, and JNK inhibitor JNK inhibitor II were all purchased from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ). TPA was from Sigma.

Plasmids and lentiviruses

The p38 DN plasmid pcDNA3-p38/AF was provided by Jiahua Han at The Scripps Institute [67]. The JNK DN (HA-JNK1 [APF]) plasmid was from Lin Mantell at New York University School of Medicine [68]. The ERK DN (pCEP4L-HA-ERK1K71R) plasmid was from Melanie Cobb at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center [69]. The c-Jun DN plasmid pCMV-TAM67 was from Bradford W. Ozanne at Beatson Institute [70]. The pHyPer-cyto plasmid was purchased from Biocompare (South San Francisco, CA). Transfection of 293T and BCBL1 cells was carried out using the Lipofectamine LTX Reagent from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The lentiviruses expressing specific siRNA to human catalase and scrambled control were purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). BCBL1-BAC36 cells stably expressing catalase-specific or scrambled siRNAs were obtained following lentiviral infection and puromycin selection according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Measurement of cellular catalase activity and intracellular level of H2O2

A total of 5×106 BCBL1 cells cultured with or without ATZ or TPA for 12 h were harvested by brief centrifugation. The cell pellets were homogenized in 0.5 ml ice cold phosphate saline buffer at pH 7.4 containing 1 mM EDTA. After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatants were collected and used for measuring catalase activity or intracellular H2O2. Cellular catalase activity was determined with the OxiSelect Catalase Activity Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA), and intracellular H2O2 determined with the Fluorescent Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Detection Kit from Cell Technology (Columbia, MD). Alternatively, we tracked the intracellular H2O2 level with a H2O2 sensor by stable transfection of BCBL1 cells with a HyPer-cyto cassette consisting of a circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (cpYFP) under the control of the regulatory domain of the prokaryotic H2O2-sensing protein, OxyR [42].

Induction of viral lytic replication and titration of infectious virions

To induce viral lytic replication, 2×106 BCBL1 cells were treated with H2O2, ATZ or TPA alone, or in combination, in 10 ml RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS for 48 h. The cells were then harvested, washed 1 time by centrifugation to eliminate the chemicals, and cultured in 5 ml fresh RPMI 1640 media with 10% FBS for three additional days. The supernatants were collected following centrifugation to eliminate cells and cell debris at 5,000 g for 15 min, and used for titration as previously described [44]. Relative virus titers were calculated based on the numbers of GFP-positive cells. Detection of virus particles in lymphoma supernatants from mice was carried out by staining for ORF65 with a monoclonal antibody following infection of HUVEC for 4 h as previously described [49].

To examine the effects of antioxidants on KSHV spontaneous lytic replication, BCBL1 cells were cultured in the presence NAC (400 µM) or catalase (400 U/ml) for 1 or 6 day, and cells were collected for Western-blotting analysis of ORF65 protein.

For induction of lytic replication by hypoxia, BCBL1 cells at 1.5×107 cells/ml were treated with 10 mM NaN3 with or without antioxidants NAC (400 µM) and catalase (400 U/ml) for 90 min. Following washing by centrifugation, the cells were cultured for the specified lengths of time with or without NAC and catalase.

For induction of lytic replication by cytokines, BCBL1 cells at 1.5×107 cells/ml were cultured in fresh medium with cytokines with or without antioxidants NAC (400 µM) and catalase (400 U/ml) for 72 h, and collected for Western-blotting. In parallel induction experiments, BCBL1 cells at 1.5×107 cells/ml in fresh medium were induced with cytokines with or without antioxidants by co-culture with U937 cells at 5×104 cells/ml pretreated with cytokines with or without antioxidants for 4 h. The following cytokines and concentrations were used: recombinant human VEGF at 200 ng/ml (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), recombinant human long R IGF-1 at 200 ng/ml (Lonza), recombinant human bFGF at 200 ng/ml (Lonza), recombinant human EGF at 200 ng/ml (Lonza), human IL-6 at 1 µg/ml (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), human TNF-α at 1 µg/ml (R&D Systems) and human IFN-γ at 4000 U/ml (Sigma).

To induce KSHV lytic replication in endothelial cells, latent KSHV-infected HUVEC obtained as previously described [44] were treated with H2O2 (150 µM) for 24 h or 72 h, and cells were collected for RNA analysis or immunostaining for ORF65 protein, respectively.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA was purified using a Total RNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Total RNA (10 µg) was reversely transcribed into first-strand cDNAs by using a Superscript III First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). RT-qPCR was carried out in a DNA Engine Opticon 2 Continuous Fluorescence Detector (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Each sample was measured in triplicate. The expression level of each transcript (mRNA) was first normalized to β-actin mRNA as previously described [71]. The relative expression level of a transcript in the treated cells was compared to the untreated cells, and calculated as fold changes. Specific primers for all KSHV genes were previously described [71]. Primers for human catalase were: 5′aggactaccctctcatcccagttg3′ (forward) and 5′gggtcccaggcgatggcggtgag3′ (reverse).

Immunofluorescence antibody assay (IFA), immunohistochemistry and Western-blotting

KSHV lytic proteins ORF59 or ORF65 in BCBL1 cells were detected by IFA as previously described [51]. Expression of KSHV lytic proteins in lymphomas and solid tumors in mice were detected by immunohistochemistry. Briefly, cells from PEL induced in NOD/SCID mice were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min, fixed with formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections at 5 nm cut from the paraffin blocks were deparaffinized at 60°C, cleared, and rehydrated in xylene and graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was done with citrate buffer at pH 6 for 20 min at 121°C in a pressure chamber. Sections were blocked successively with 3% H2O2 and bovine serum albumin buffer. Sections were then incubated with a monoclonal antibody to ORF65 or a mouse immunoglobulin fraction (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) as a negative control for 1 h at 25°C. After three washes with PBS, the slides were further incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (DAKO) for 15 min. The slides were then incubated with the diaminobenzidine substrate (DAKO), counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted for observation.

Western-blotting was carried out as previously described [51]. The rabbit polyclonal antibodies to ERK1, p-ERK (Tyr 204), JNK1, p-JNK (Thr 183/Tyr 185), p38, p-p38 (Tyr 182), c-Jun, and catalase were from Santa Cruz; a polyclonal antibody to p-c-Jun (Ser73) was from Calbiochem; and a monoclonal antibody to β-tubulin was from Sigma. A rabbit polyclonal antibody to KSHV lytic protein RTA was a generous gift from Dr. Charles Wood at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

Reporter assay

293 cells transfected with either the RTA promoter luciferase reporter plasmid or the latent LANA promoter (LTd) luciferase reporter plasmid using Lipofectamine-2000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) for 24 h were treated with H2O2 (300 µM) or TPA (20 ng/ml) with or without antioxidants NAC (400 µM) or catalase (400 U/ml) for 12 h. Cells were collected and their luciferase activities determined as previously described [51]. Transfection efficiency was calibrated by co-transfection with the pSV-β-galactosidase construct (Promega).

Detection of blood viral loads in mice

Cell-free DNA was isolated from two drops of blood from each mouse collected by tail bleeding using the QiAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen). KSHV DNA was detected by real-time PCR using vCyclin (ORF72) primers and purified BAC36 as copy number control as previously described [71]. KSHV viral loads expressed as genome copies per ml of blood were calculated. PCR assay for human β-actin gene was also carried out for these DNA samples to monitor the absence of any contamination of human cells [71]. None of the samples had any detectable signal for human β-actin gene.

Generation of a recombinant KSHV expressing firefly luciferase under the control of the late lytic ORF65 promoter

A recombinant KSHV genome with the entire ORF65-coding frame deleted and replaced with the firefly luciferase gene was constructed using a “two-step” homologous recombination strategy as previously described (Figure S1A) [51]. Firstly, the firefly luciferase gene was amplified from the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL3-Basic Luciferase Reporter Vector (Promega) using primers 5′ttctcgagatggaagacgccaaaaacataaagaaaggcccg3′ (luciferase forward) and 5′ctcgagttaattaattacacggcgatctttccgcccttc3′ (luciferase reverse). The Kanamycin resistance cassette (KanR) flanked by two LoxP sites was amplified from the transposon EZ-Tn5™ <Kan-2> (Epicenter, Madison, WI) using primers 5′tttttaattaagtgtaggctggagctgcttc3′ (KanR forward) and 5′ttttttaattaacatatgaatatcctccttag3′ (KanR reverse). The two PCR products were ligated using a T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The resulting fragment was then used as a template to generate the KanR-Luc cassette by PCR amplification using primers 5′cttgtgactccacggttgtccaatcgttgcctatttctttttgccagagg tttttaattaagtgtaggctggagctgcttc3′ (forward) and 5′aggtgagagaccccgtgatccaggagcgactggatcatgactacgctcac ttctcgagatggaagacgccaaaaacataaagaaaggcccg3′ (reverse). This PCR product, flanked by a 50 bp sequence from the immediate downstream region of ORF65 at its 5′end and a 50 bp sequence from the start codon (ATG) region of ORF65 at its 3′end, was electroporated into Escherichia coli strain DH10B containing recombinant KSHV BAC36 [45]. Upon homologous recombination, the KanR-Luc cassette was integrated into KSHV genome. The Kanamycin-resistant colonies, containing the mutant KSHV genome, named Δ65Kan-Luc, with ORF65 replaced with KanR-Luc cassette, were selected. To eliminate the KanR cassette, a Cre-expression plasmid pCre carrying a tetracycline resistant marker and a temperature (37°C)-sensitive replication origin was electroporated into the selected bacteria. The expression of Cre protein led to the removal of KanR cassette by LoxP-mediated recombination. The resulting colonies containing the mutant KSHV genome, named Δ65Luc, with ORF65 replaced with firefly luciferase gene, which was Tetracycline resistant but Kanamycin sensitive, were selected. The pCre plasmid was removed by culturing the bacteria at 37°C.

The mutant KSHV genomes were purified using the Large Construct DNA Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), verified for integrity by restriction digestion and PCR amplification of specific genes (Figure S1B–C), and electroporated into BCBL1 cells as previously described [45]. Following Hygromycin selection, a cell line harboring both the wild type KSHV genome and Δ65Luc was established. Expression of luciferase by this cell line was confirmed by Western-blotting using a luciferase-specific antibody (Figure S1D), and by measuring luciferase activity using the firefly luciferase substrate (Promega) and a Veritas Microplate Luminometer (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA) (Figure S1E).

Examination of the effect of antioxidant NAC on KSHV lytic replication in a mouse lymphoma model

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (Animal Welfare Assurance Number: A3345-01). All surgery was performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Male NOD/SCID mice at 6 weeks from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) were intraperitoneally inoculated with BCBL1 cells carrying Δ65Luc at 5×106 per mouse. One week after inoculation, mice (n = 36) were given drinking water supplemented with 5 mM of NAC while the control mice (n = 44) were given drinking water without the antioxidant. Mice were monitored daily for “PEL-like” symptoms. Luciferase activity and GFP intensity were measured five weeks after injection using a Xenogen IVIS 200 Imaging System (Xenogen, Alameda, CA). Mice were monitored daily, and terminated when they became immobile. Lymphoma cells, supernatants and solid tumors were collected and analyzed as indicated.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SpeckSHGanemD

2010

Viral latency and its regulation: lessons from the

gamma-herpesviruses.

Cell Host Microbe

8

100

115

2. ChangYCesarmanEPessinMSLeeFCulpepperJ

1994

Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in

AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma.

Science

266

1865

1869

3. CesarmanEChangYMoorePSSaidJWKnowlesDM

1995

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences

in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas.

N Engl J Med

332

1186

1191

4. SoulierJGrolletLOksenhendlerECacoubPCazals-HatemD

1995

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences

in multicentric Castleman's disease.

Blood

86

1276

1280

5. StaskusKAZhongWGebhardKHerndierBWangH

1997

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression in

endothelial (spindle) tumor cells.

J Virol

71

715

719

6. GreeneWKuhneKYeFChenJZhouF

2007

Molecular biology of KSHV in relation to AIDS-associated

oncogenesis.

Cancer Treat Res

133

69

127

7. WhitbyDHowardMRTenant-FlowersMBrinkNSCopasA

1995

Detection of Kaposi sarcoma associated herpesvirus in peripheral

blood of HIV-infected individuals and progression to Kaposi's

sarcoma.

Lancet

346

799

802

8. MoorePSKingsleyLAHolmbergSDSpiraTGuptaP

1996

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection prior to

onset of Kaposi's sarcoma.

AIDS

10

175

180

9. CattelanAMCalabroMLAversaSMZanchettaMMeneghettiF

1999

Regression of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma following

antiretroviral therapy with protease inhibitors: biological correlates of

clinical outcome.

Eur J Cancer

35

1809

1815

10. CampbellTBFitzpatrickLMaWhinneySZhangX

Schooley RT

1999

Human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi's sarcoma-associated

herpesvirus) infection in men receiving treatment for HIV-1

infection.

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr

22

333

340

11. CannonMJDollardSCBlackJBEdlinBRHannahC

2003

Risk factors for Kaposi's sarcoma in men seropositive for

both human herpesvirus 8 and human immunodeficiency virus.

AIDS

17

215

222

12. EngelsEABiggarRJMarshallVAWaltersMAGamacheCJ

2003

Detection and quantification of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated

herpesvirus to predict AIDS-associated Kaposi's

sarcoma.

AIDS

17

1847

1851

13. BourbouliaDAldamDLagosDAllenEWilliamsI

2004

Short - and long-term effects of highly active antiretroviral

therapy on Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus immune responses and

viraemia.

AIDS

18

485

493

14. JonesJLHansonDLChuSYWardJWJaffeHW

1995

AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma.

Science

267

1078

1079

15. MocroftAYouleMGazzardBMorcinekJHalaiR

1996

Anti-herpesvirus treatment and risk of Kaposi's sarcoma in

HIV infection. Royal Free/Chelsea and Westminster Hospitals Collaborative

Group.

AIDS

10

1101

1105

16. DeutschECohenAKazimirskyGDovratSRubinfeldH

2004

Role of protein kinase C delta in reactivation of Kaposi's

sarcoma-associated herpesvirus.

J Virol

78

10187

10192

17. PanHXieJYeFGaoSJ

2006

Modulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

infection and replication by MEK/ERK, JNK, and p38 multiple

mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways during primary

infection.

J Virol

80

5371

5382

18. CohenABrodieCSaridR

2006

An essential role of ERK signalling in TPA-induced reactivation

of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus.

J Gen Virol

87

795

802

19. FordPWBryanBADysonOFWeidnerDAChintalgattuV

2006

Raf/MEK/ERK signalling triggers reactivation of Kaposi's

sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency.

J Gen Virol

87

1139

1144

20. XieJAjibadeAOYeFKuhneKGaoSJ

2008

Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus from

latency requires MEK/ERK, JNK and p38 multiple mitogen-activated protein

kinase pathways.

Virology

371

139

154

21. ChangJRenneRDittmerDGanemD

2000

Inflammatory cytokines and the reactivation of Kaposi's

sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic replication.

Virology

266

17

25

22. BlackbournDJFujimuraSKutzkeyTLevyJA

2000

Induction of human herpesvirus-8 gene expression by recombinant

interferon gamma.

AIDS

14

98

99

23. DavisDARinderknechtASZoeteweijJPAokiYRead-ConnoleEL

2001

Hypoxia induces lytic replication of Kaposi sarcoma-associated

herpesvirus.

Blood

97

3244

3250

24. HarringtonWJrSieczkowskiLSosaCChan-a-SueSCaiJP

1997

Activation of HHV-8 by HIV-1 tat.

Lancet

349

774

775

25. VarthakaviVSmithRMDengHSunRSpearmanP

2002

Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 activates lytic cycle

replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus through

induction of KSHV Rta.

Virology

297

270

280

26. MeratRAmaraALebbeCde TheHMorelP

2002

HIV-1 infection of primary effusion lymphoma cell line triggers

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)

reactivation.

Int J Cancer

97

791

795

27. VieiraJO'HearnPKimballLChandranBCoreyL

2001

Activation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human

herpesvirus 8) lytic replication by human cytomegalovirus.

J Virol

75

1378

1386

28. LuCZengYHuangZHuangLQianC

2005

Human herpesvirus 6 activates lytic cycle replication of

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus.

Am J Pathol

166

173

183

29. GregorySMWestJADillonPJHilscherCDittmerDP

2009

Toll-like receptor signaling controls reactivation of KSHV from

latency.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

106

11725

11730

30. DouglasJLGustinJKDezubeBPantanowitzJLMosesAV

2007

Kaposi's sarcoma: a model of both malignancy and chronic

inflammation.

Panminerva Med

49

119

138

31. GanemD

2010

KSHV and the pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma: listening to human

biology and medicine.

J Clin Invest

120

939

949

32. KhatamiM

2009

Inflammation, aging, and cancer: tumoricidal versus tumorigenesis

of immunity: a common denominator mapping chronic diseases.

Cell Biochem Biophys

55

55

79

33. SimonartTNoelJCAndreiGParentDVan VoorenJP

1998

Iron as a potential co-factor in the pathogenesis of

Kaposi's sarcoma?

Int J Cancer

78

720

726

34. SalahudeenAABruickRK

2009

Maintaining Mammalian iron and oxygen homeostasis: sensors,

regulation, and cross-talk.

Ann N Y Acad Sci

1177

30

38

35. LaubachVEKronIL

2009

Pulmonary inflammation after lung

transplantation.

Surgery

146

1

4

36. GilLMartinezGGonzalezITarinasAAlvarezA

2003

Contribution to characterization of oxidative stress in HIV/AIDS

patients.

Pharmacol Res

47

217

224

37. MallerySRPeiPLandwehrDJClarkCMBradburnJE

2004

Implications for oxidative and nitrative stress in the

pathogenesis of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma.

Carcinogenesis

25

597

603

38. PanJSHongMZRenJL

2009

Reactive oxygen species: a double-edged sword in

oncogenesis.

World J Gastroenterol

15

1702

1707

39. ChocholaJStrosbergADStanislawskiM

1995

Release of hydrogen peroxide from human T cell lines and normal

lymphocytes co-infected with HIV-1 and mycoplasma.

Free Radic Res

23

197

212

40. ElbimCPilletSPrevostMHPreiraAGirardPM

2001

The role of phagocytes in HIV-related oxidative

stress.

J Clin Virol

20

99

109

41. BaeYSLeeJHChoiSHKimSAlmazanF

2009

Macrophages generate reactive oxygen species in response to

minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein: toll-like receptor 4 - and spleen

tyrosine kinase-dependent activation of NADPH oxidase 2.

Circ Res

104

210

218, 221p following 218

42. BelousovVVFradkovAFLukyanovKAStaroverovDBShakhbazovKS

2006

Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular

hydrogen peroxide.

Nat Methods

3

281

286

43. HenzlerTSteudleE

2000

Transport and metabolic degradation of hydrogen peroxide in Chara

corallina: model calculations and measurements with the pressure probe

suggest transport of H(2)O(2) across water channels.

J Exp Bot

51

2053

2066

44. GaoSJDengJHZhouFC

2003

Productive lytic replication of a recombinant Kaposi's

sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in efficient primary infection of primary

human endothelial cells.

J Virol

77

9738

9749

45. ZhouFCZhangYJDengJHWangXPPanHY

2002

Efficient infection by a recombinant Kaposi's

sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cloned in a bacterial artificial chromosome:

application for genetic analysis.

J Virol

76

6185

6196

46. RoseCRWaxmanSGRansomBR

1998

Effects of glucose deprivation, chemical hypoxia, and simulated

ischemia on Na+ homeostasis in rat spinal cord

astrocytes.

J Neurosci

18

3554

3562

47. ChangSJiangXZhaoCLeeCFerrieroDM

2008

Exogenous low dose hydrogen peroxide increases hypoxia-inducible

factor-1alpha protein expression and induces preconditioning protection

against ischemia in primary cortical neurons.

Neurosci Lett

441

134

138

48. BoshoffCGaoSJHealyLEMatthewsSThomasAJ

1998

Establishing a KSHV+ cell line (BCP-1) from peripheral blood

and characterizing its growth in Nod/SCID mice.

Blood

91

1671

1679

49. GreeneWGaoSJ

2009

Actin dynamics regulate multiple endosomal steps during

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus entry and trafficking in

endothelial cells.

PLoS Pathog

5

e1000512

50. McCubreyJALahairMMFranklinRA

2006

Reactive oxygen species-induced activation of the MAP kinase

signaling pathways.

Antioxid Redox Signal

8

1775

1789

51. YeFCZhouFCXieJPKangTGreeneW

2008

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent gene vFLIP

inhibits viral lytic replication through NF-kappaB-mediated suppression of

the AP-1 pathway: a novel mechanism of virus control of

latency.

J Virol

82

4235

4249

52. YusaTBeckmanJSCrapoJDFreemanBA

1987

Hyperoxia increases H2O2 production by brain in

vivo.

J Appl Physiol

63

353

358

53. BabbarNCaseroRAJr

2006

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases reactive oxygen species by

inducing spermine oxidase in human lung epithelial cells: a potential

mechanism for inflammation-induced carcinogenesis.

Cancer Res

66

11125

11130

54. YangDElnerSGBianZMTillGOPettyHR

2007

Pro-inflammatory cytokines increase reactive oxygen species

through mitochondria and NADPH oxidase in cultured RPE

cells.

Exp Eye Res

85

462

472

55. Soderberg-NauclerC

2006

Does cytomegalovirus play a causative role in the development of

various inflammatory diseases and cancer?

J Intern Med

259

219

246

56. GillRTsungABilliarT

2010

Linking oxidative stress to inflammation: Toll-like

receptors.

Free Radic Biol Med

48

1121

1132

57. WangXMartindaleJLLiuYHolbrookNJ

1998

The cellular response to oxidative stress: influences of

mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways on cell

survival.

Biochem J

333

291

300

58. MullerJMKraussBKaltschmidtCBaeuerlePARupecRA

1997

Hypoxia induces c-fos transcription via a mitogen-activated

protein kinase-dependent pathway.

J Biol Chem

272

23435

23439

59. MatsudaNMoritaNMatsudaKWatanabeM

1998

Proliferation and differentiation of human osteoblastic cells

associated with differential activation of MAP kinases in response to

epidermal growth factor, hypoxia, and mechanical stress in

vitro.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun

249

350

354

60. D'AngeloGStrumanIMartialJWeinerRI

1995

Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by vascular

endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in capillary

endothelial cells is inhibited by the antiangiogenic factor 16-kDa

N-terminal fragment of prolactin.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

92

6374

6378

61. GiorgettiSPelicciPGPelicciGVan ObberghenE

1994

Involvement of Src-homology/collagen (SHC) proteins in signaling

through the insulin receptor and the

insulin-like-growth-factor-I-receptor.

Eur J Biochem

223

195

202

62. WilliamsRSangheraJWuFCarbonaro-HallDCampbellDL

1993

Identification of a human epidermal growth factor

receptor-associated protein kinase as a new member of the mitogen-activated

protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase

family.

J Biol Chem

268

18213

18217

63. SchiemannWPNathansonNM

1994

Involvement of protein kinase C during activation of the

mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by leukemia inhibitory factor.

Evidence for participation of multiple signaling pathways.

J Biol Chem

269

6376

6382

64. VietorISchwengerPLiWSchlessingerJVilcekJ

1993

Tumor necrosis factor-induced activation and increased tyrosine

phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase in human

fibroblasts.

J Biol Chem

268

18994

18999

65. RoseDMWinstonBWChanEDRichesDWHensonPM

1997

Interferon-gamma and transforming growth factor-beta modulate the

activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and tumor necrosis

factor-alpha production induced by Fc gamma-receptor stimulation in murine

macrophages.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun

238

256

260

66. LiQZhouFYeFGaoSJ

2008

Genetic disruption of KSHV major latent nuclear antigen LANA

enhances viral lytic transcriptional program.

Virology

379

234

244

67. HanJRichterBLiZKravchenkoVUlevitchRJ

1995

Molecular cloning of human p38 MAP kinase.

Biochim Biophys Acta

1265

224

227

68. DerijardBHibiMWuIHBarrettTSuB

1994

JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that

binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain.

Cell

76

1025

1037

69. FrostJAGeppertTDCobbMHFeramiscoJR

1994

A requirement for extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)

function in the activation of AP-1 by Ha-Ras, phorbol 12-myristate

13-acetate, and serum.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

91

3844

3848

70. BrownPHChenTKBirrerMJ

1994

Mechanism of action of a dominant-negative mutant of

c-Jun.

Oncogene

9

791

799

71. YooSMZhouFCYeFCPanHYGaoSJ

2005

Early and sustained expression of latent and host modulating

genes in coordinated transcriptional program of KSHV productive primary

infection of human primary endothelial cells.

Virology

343

47

64

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Distribution of the Phenotypic Effects of Random Homologous Recombination between Two Virus SpeciesČlánek SIV Nef Proteins Recruit the AP-2 Complex to Antagonize Tetherin and Facilitate Virion ReleaseČlánek Dual Function of the NK Cell Receptor 2B4 (CD244) in the Regulation of HCV-Specific CD8+ T CellsČlánek A Large and Intact Viral Particle Penetrates the Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane to Reach the CytosolČlánek Interleukin-13 Promotes Susceptibility to Chlamydial Infection of the Respiratory and Genital Tracts

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 5- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Lymphoadenopathy during Lyme Borreliosis Is Caused by Spirochete Migration-Induced Specific B Cell Activation

- Infections Are Virulent and Inhibit the Human Malaria Parasite in

- A Gamma Interferon Independent Mechanism of CD4 T Cell Mediated Control of Infection

- MDA5 and TLR3 Initiate Pro-Inflammatory Signaling Pathways Leading to Rhinovirus-Induced Airways Inflammation and Hyperresponsiveness

- The OXI1 Kinase Pathway Mediates -Induced Growth Promotion in Arabidopsis

- An E2F1-Mediated DNA Damage Response Contributes to the Replication of Human Cytomegalovirus

- Quantitative Subcellular Proteome and Secretome Profiling of Influenza A Virus-Infected Human Primary Macrophages

- Distribution of the Phenotypic Effects of Random Homologous Recombination between Two Virus Species

- Inhibition of Both HIV-1 Reverse Transcription and Gene Expression by a Cyclic Peptide that Binds the Tat-Transactivating Response Element (TAR) RNA

- A Viral Satellite RNA Induces Yellow Symptoms on Tobacco by Targeting a Gene Involved in Chlorophyll Biosynthesis using the RNA Silencing Machinery

- Misregulation of Underlies the Developmental Abnormalities Caused by Three Distinct Viral Silencing Suppressors in Arabidopsis

- Investigating the Host Binding Signature on the PfEMP1 Protein Family

- Human Neutrophil Clearance of Bacterial Pathogens Triggers Anti-Microbial γδ T Cell Responses in Early Infection

- Septation of Infectious Hyphae Is Critical for Appressoria Formation and Virulence in the Smut Fungus

- A Family of Helminth Molecules that Modulate Innate Cell Responses via Molecular Mimicry of Host Antimicrobial Peptides

- Phospholipids Trigger Capsular Enlargement during Interactions with Amoebae and Macrophages

- CTL Escape Mediated by Proteasomal Destruction of an HIV-1 Cryptic Epitope

- Evolution of Th2 Immunity: A Rapid Repair Response to Tissue Destructive Pathogens

- Extensive Genome-Wide Variability of Human Cytomegalovirus in Congenitally Infected Infants

- The Antiviral Efficacy of HIV-Specific CD8 T-Cells to a Conserved Epitope Is Heavily Dependent on the Infecting HIV-1 Isolate

- Epstein-Barr Virus Infection of Polarized Epithelial Cells via the Basolateral Surface by Memory B Cell-Mediated Transfer Infection

- Reactive Oxygen Species Hydrogen Peroxide Mediates Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Reactivation from Latency

- Crystal Structure and Functional Analysis of the SARS-Coronavirus RNA Cap 2′-O-Methyltransferase nsp10/nsp16 Complex

- The Dot/Icm System Delivers a Unique Repertoire of Type IV Effectors into Host Cells and Is Required for Intracellular Replication

- AAV Exploits Subcellular Stress Associated with Inflammation, Endoplasmic Reticulum Expansion, and Misfolded Proteins in Models of Cystic Fibrosis

- Suboptimal Activation of Antigen-Specific CD4 Effector Cells Enables Persistence of In Vivo

- SIV Nef Proteins Recruit the AP-2 Complex to Antagonize Tetherin and Facilitate Virion Release

- Dual Function of the NK Cell Receptor 2B4 (CD244) in the Regulation of HCV-Specific CD8+ T Cells

- Transition of Sporozoites into Liver Stage-Like Forms Is Regulated by the RNA Binding Protein Pumilio

- A Large and Intact Viral Particle Penetrates the Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane to Reach the Cytosol

- Transcriptome Analysis of in Human Whole Blood and Mutagenesis Studies Identify Virulence Factors Involved in Blood Survival

- Interleukin-13 Promotes Susceptibility to Chlamydial Infection of the Respiratory and Genital Tracts

- Structural Insights into Viral Determinants of Nematode Mediated Transmission

- Protective Efficacy of Serially Up-Ranked Subdominant CD8 T Cell Epitopes against Virus Challenges

- Viral CTL Escape Mutants Are Generated in Lymph Nodes and Subsequently Become Fixed in Plasma and Rectal Mucosa during Acute SIV Infection of Macaques

- Taking Some of the Mystery out of Host∶Virus Interactions

- Viral Small Interfering RNAs Target Host Genes to Mediate Disease Symptoms in Plants

- : An Emerging Cause of Sexually Transmitted Disease in Women

- Mitochondrial Ubiquitin Ligase MARCH5 Promotes TLR7 Signaling by Attenuating TANK Action

- The Hexamer Structure of the Rift Valley Fever Virus Nucleoprotein Suggests a Mechanism for its Assembly into Ribonucleoprotein Complexes

- Acquisition of Human-Type Receptor Binding Specificity by New H5N1 Influenza Virus Sublineages during Their Emergence in Birds in Egypt

- Stromal Down-Regulation of Macrophage CD4/CCR5 Expression and NF-κB Activation Mediates HIV-1 Non-Permissiveness in Intestinal Macrophages

- A Component of the Xanthomonadaceae Type IV Secretion System Combines a VirB7 Motif with a N0 Domain Found in Outer Membrane Transport Proteins

- Perturbs Iron Trafficking in the Epithelium to Grow on the Cell Surface

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Crystal Structure and Functional Analysis of the SARS-Coronavirus RNA Cap 2′-O-Methyltransferase nsp10/nsp16 Complex

- Lymphoadenopathy during Lyme Borreliosis Is Caused by Spirochete Migration-Induced Specific B Cell Activation

- The OXI1 Kinase Pathway Mediates -Induced Growth Promotion in Arabidopsis

- : An Emerging Cause of Sexually Transmitted Disease in Women

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání