-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

Reklama: An Emerging Cause of Sexually Transmitted Disease in Women

Mycoplasma genitalium is an emerging sexually transmitted pathogen implicated in urethritis in men and several inflammatory reproductive tract syndromes in women including cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and infertility. This comprehensive review critically examines epidemiologic studies of M. genitalium infections in women with the goal of assessing the associations with reproductive tract disease and enhancing awareness of this emerging pathogen. Over 27,000 women from 48 published reports have been screened for M. genitalium urogenital infection in high - or low-risk populations worldwide with an overall prevalence of 7.3% and 2.0%, respectively. M. genitalium was present in the general population at rates between those of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Considering more than 20 studies of lower tract inflammation, M. genitalium has been positively associated with urethritis, vaginal discharge, and microscopic signs of cervicitis and/or mucopurulent cervical discharge in seven of 14 studies. A consistent case definition of cervicitis is lacking and will be required for comprehensive understanding of these associations. Importantly, evidence for M. genitalium PID and infertility are quite convincing and indicate that a significant proportion of upper tract inflammation may be attributed to this elusive pathogen. Collectively, M. genitalium is highly prevalent in high - and low-risk populations, and should be considered an etiologic agent of select reproductive tract disease syndromes in women.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001324

Category: Review

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001324Summary

Mycoplasma genitalium is an emerging sexually transmitted pathogen implicated in urethritis in men and several inflammatory reproductive tract syndromes in women including cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and infertility. This comprehensive review critically examines epidemiologic studies of M. genitalium infections in women with the goal of assessing the associations with reproductive tract disease and enhancing awareness of this emerging pathogen. Over 27,000 women from 48 published reports have been screened for M. genitalium urogenital infection in high - or low-risk populations worldwide with an overall prevalence of 7.3% and 2.0%, respectively. M. genitalium was present in the general population at rates between those of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Considering more than 20 studies of lower tract inflammation, M. genitalium has been positively associated with urethritis, vaginal discharge, and microscopic signs of cervicitis and/or mucopurulent cervical discharge in seven of 14 studies. A consistent case definition of cervicitis is lacking and will be required for comprehensive understanding of these associations. Importantly, evidence for M. genitalium PID and infertility are quite convincing and indicate that a significant proportion of upper tract inflammation may be attributed to this elusive pathogen. Collectively, M. genitalium is highly prevalent in high - and low-risk populations, and should be considered an etiologic agent of select reproductive tract disease syndromes in women.

Introduction

An estimated 340 million new curable cases of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are acquired annually throughout the world [1], making these infections an important public health and economic concern. Mycoplasma genitalium is an emerging cause of STIs in the United States [2] and has been implicated in urogenital infections of men and women around the world. More than 25 years after its initial isolation from men with non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU; [3]), M. genitalium is now recognized as an independent etiologic agent of acute and persistent male NGU and is responsible for approximately 20%–35% of non-chlamydial NGU cases [4], [5]. Implicating this organism in male urogenital disease was a significant advancement in our knowledge of STIs, but it has been less clear whether M. genitalium is also a cause of inflammatory reproductive tract disease in women. This comprehensive literature review (PubMed database; MeSH “Mycoplasma genitalium” with no restrictions on publication year) addresses the overall population prevalence and associations of M. genitalium with inflammatory syndromes of the female reproductive tract.

Epidemiology and Prevalence of M. genitalium Infections

After the initial isolation in 1980 [3], few epidemiologic studies of M. genitalium infection were undertaken largely because of difficulties in cultivation of this fastidious organism. Some 10 years later, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was first employed for detection of M. genitalium in patient specimens [6], [7], thereby facilitating larger investigations of prevalence and associations with urogenital disease. Using such molecular methods, sexual transmission of the organism has been suggested by high concordance rates among sexual partners [8]–[15] and documented specifically in infected couples with concordant M. genitalium genotypes [11], [15]. In addition, sexual transmission of M. genitalium infection can be inferred from increased prevalence values in cohorts reporting sexual intercourse and the association with number of sex partners [2], [16]. For the purpose of this review, high-risk individuals were defined as those attending an STI clinic, those enrolled in a study where inclusion criteria included signs of urogenital disease, patients presenting to family planning clinics for termination of pregnancy, or those individuals classified as sex workers. Low-risk enrollees were those not attending an STI clinic, fertility clinic attendees, those chosen randomly from an otherwise healthy population, and all women enrolled in studies of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Considering 27,272 women from 40 independent studies, among women from low-risk populations (n = 8,434; [2], [14], [16]–[24]), the prevalence of M. genitalium infection was 2.0% with most cohorts between <1%–5% (Table S1). In three studies of low-risk individuals where enrollees were randomly selected from community or population-based survey populations ([2], [16], [19]; n = 4,075), the prevalence was also 2%. Among these was the US National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, which showed the genital prevalence of M. genitalium to be approximately 1%, between those of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (0.4%) and C. trachomatis (4.2%), respectively [2]. Thus, M. genitalium prevalence in the general population is on par with other sexually transmitted pathogens of significant public health concern.

Using the above definition of high-risk populations, 18,838 women have been tested for M. genitalium urogenital infection [6]–[8], [10], [13], [25]–[56]with a substantially higher prevalence than low-risk groups (7.3%; Table S1). Among studies of high-risk individuals, the population prevalence values ranged from 0% to 42% and can be explained by several factors, including the clinical setting, specificity of the employed NAAT assay, participant enrollment criteria (e.g., specific symptoms or signs), geographic location of study site, high-risk behavior (e.g., commercial sex workers), co-infection with other STIs, and the reporting of point or cumulative, multi-sampling values. Importantly, we considered only point prevalence values in the overall prevalence calculations because cumulative, multi-sampling values were not directly comparable. In conclusion, considering sexual transmission and the high prevalence worldwide, the public health significance of M. genitalium infections in women is potentially very large.

Clinical Correlates with Lower Urogenital Tract Inflammation in Women

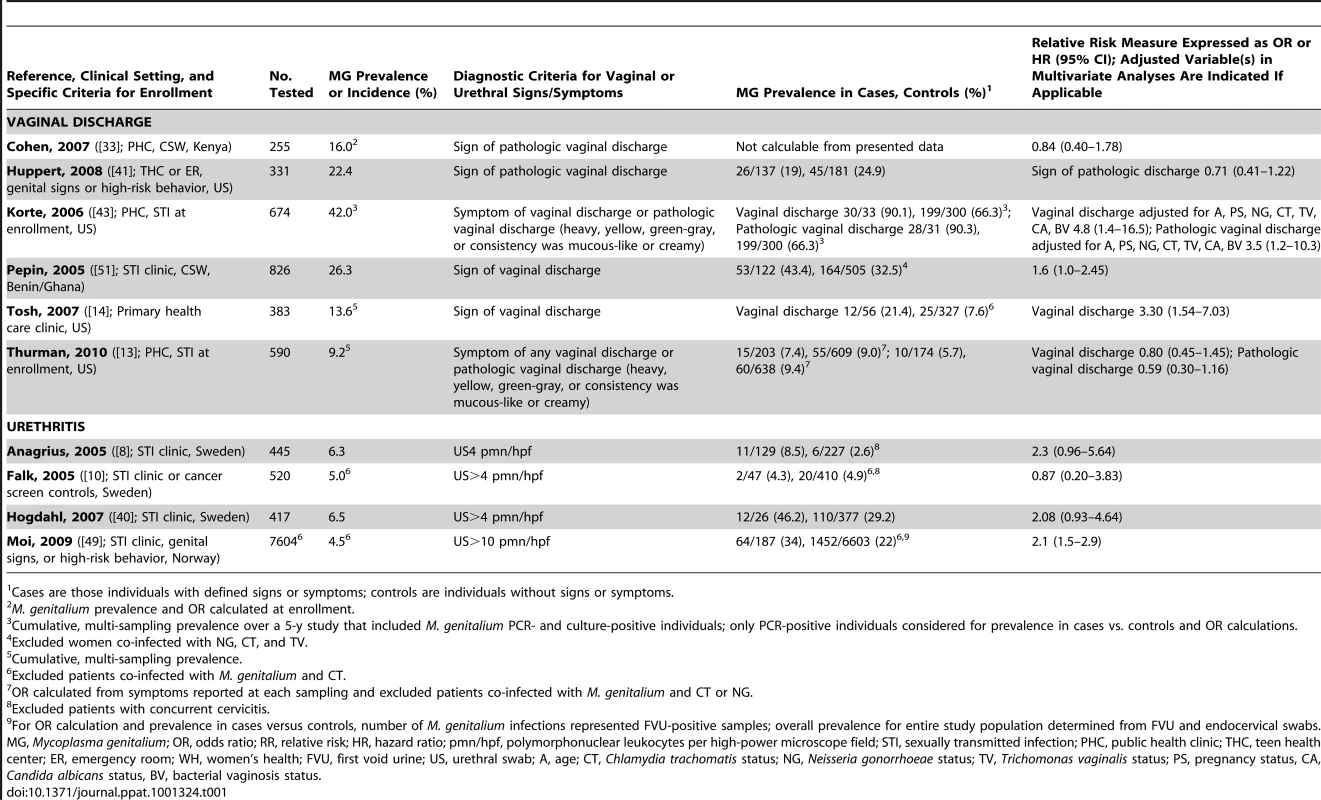

Vaginal Discharge

In more than 20 independent clinical studies, M. genitalium has been evaluated as a cause of inflammatory lower genital tract syndromes including urethritis, cervicitis, and vaginal discharge. From 2002 to 2010, six studies addressed the relationship between M. genitalium infection and vaginal discharge (n = 3,059; Table 1) with significant associations observed in three [14], [43], [51]. Vaginal discharge was measured either as a symptom or sign among the cited studies and the criteria varied from any sign of discharge to defined pathologic symptoms such as discharge characterized as heavy, yellow, or green-gray with mucous-like or creamy consistency (see Table 1 for specific diagnostic criteria for each study). No clear trend was evident as to whether signs or symptoms were better predictors of M. genitalium infection, as only two studies used vaginal symptoms in their diagnostic criteria.

Tab. 1. Characteristics of published studies evaluating the associations of M. genitalium with vaginal discharge or urethritis.

Cases are those individuals with defined signs or symptoms; controls are individuals without signs or symptoms. Etiologies of vaginal discharge are extremely diverse, can be either microbial or non-microbial, may be normal or abnormal, and can be attributed to inflammation in other parts of the reproductive tract (reviewed in [57]). Only one study adjusted for the presence of bacterial vaginosis (BV; [43]) and, despite a high rate of BV in the cohort, demonstrated significant associations of M. genitalium with vaginal discharge. However, evaluation of a similar population 4 years later did not reproduce the finding [13]. Further, the case definition of pathologic discharge was variable between studies and, most importantly, patient-reported symptoms are a highly subjective measure. Therefore, the disparity among studies is not surprising. Future studies with defined and/or quantitative signs that control for co-infection with other STIs and concurrent inflammatory syndromes (e.g., bacterial vaginosis) will be necessary to determine whether M. genitalium is independently associated with vaginal discharge.

Urethritis

Considering only microscopic signs of urethral inflammation (>4–5 or >10 polymorphonuclear leukocytes per high-powered microscope field [PMNL/hpf]), positive associations with M. genitalium infection were found in three of four studies [8], [40], [49]. One study, the largest of Scandinavian women ([49]; n = 7,604; Table 1), found a significant association between M. genitalium and microscopic urethritis. Three other Scandinavian studies of urethritis failed to show a significant association with M. genitalium infection even when patients co-infected with C. trachomatis [10] were removed or after adjusting for concurrent cervicitis [8], [9]. However, Anagrius and colleagues showed a significant association with microscopic signs of urethritis and/or cervicitis in Swedish women [8]. This study exemplifies that exclusion of women with concurrent cervicitis or other inflammatory syndromes is important because inflammation from other sites may contaminate the urethra leading to a false diagnosis of urethritis. Two of the studies that failed to show a significant association between M. genitalium and urethritis, but did control for concurrent cervicitis [8], [40], showed a strong trend towards association with lower bounds of their respective 95% CIs close to the null. Importantly, M. genitalium is a recognized cause of sexually acquired acute and persistent urethritis [4], [5] in men. However, considering the disparate results of the cited studies, we cannot conclusively implicate M. genitalium as a cause of female urethritis. Additional investigations of M. genitalium urethritis are warranted, especially in populations outside of Scandinavia.

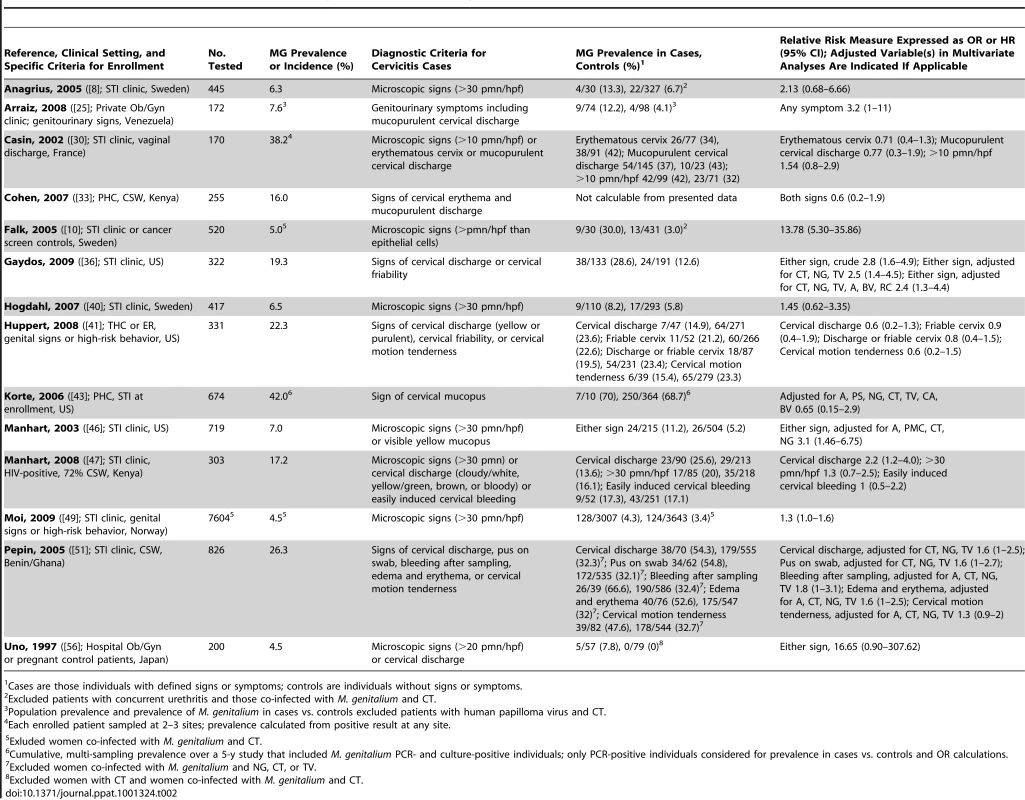

Cervicitis

Cervicitis, often termed mucopurulent cervicitis [58], is characterized by the presence of clinical signs such as mucopurulent discharge, friability at the external os (easily induced bleeding), elevated counts of PMNL detected by Gram staining of endocervical swab material, or a combination of these signs [58]. However, there is no generally accepted case definition of cervicitis. Among epidemiologic studies of cervicitis in high - and low-risk populations (Table 2; n = 13,000 women), M. genitalium has been positively associated with cervical inflammation in all studies where microscopic signs were considered independent of non-microscopic signs [8], [10], [30], [40], [47], [49]. Of these, only two studies showed significant correlations [10], [49]. Considering non-microscopic criteria (see study by Pepin et al. [51] for diversity of non-microscopic signs), cervical discharge was the most consistently measured among the retained studies. Four of eight studies showed positive associations between cervical discharge and M. genitalium infection, all of which were significant relative to women without this sign (Table 2; [25], [36], [47], [51]).

Tab. 2. Characteristics of published studies evaluating the associations of M. genitalium with cervicitis.

Cases are those individuals with defined signs or symptoms; controls are individuals without signs or symptoms. Two studies have addressed whether microscopic or non-microscopic signs are better predictors of M. genitalium cervicitis within the same patient population. Casin et al. found no significant associations using either cervical discharge or microscopic signs (>10 pmn/hpf) [30], but all women in this study had vaginal discharge. However, Manhart and colleagues found no significant association between M. genitalium infection and cervicitis defined by >30 PMNL/hpf, but statistical significance was observed with abnormal cervical discharge ([47]; Table 2). Further, considering all studies of M. genitalium cervicitis, those where a high threshold of microscopic cervicitis (>20 or >30 PMNL/hpf, or more PMNL than epithelial cells) was employed, only three of seven studies showed a significant correlation between microscopic signs and M. genitalium infection ([10], [46], [49]; Table 2). This suggests that a high microscopic threshold of inflammation is not a more specific sign of M. genitalium cervicitis and might also fail to detect less severe inflammation. Collectively, it is clear that discrepancies among these studies can be attributed to the variable case definition of cervicitis and studies with uniform criteria will be required to address which sign(s) best predict M. genitalium cervicitis.

C. trachomatis is a common cause of cervicitis and a potentially confounding variable for implicating M. genitalium as an independent etiologic agent. Where possible, we excluded subjects with C. trachomatis co-infection for all OR calculations (see Table 2). Six of nine studies where C. trachomatis co-infection was either excluded or adjusted for in multivariate analyses found significant associations between M. genitalium and cervicitis [10], [25], [36], [46], [49], [51], whereas only a single study [47] showed significant associations without this adjustment. Studies controlling for N. gonorrhoeae infection are lacking. Despite these differences, several clinical investigations of urogenital disease in women indeed indicate that M. genitalium should be considered an independent risk factor for cervicitis, particularly when urogenital specimens are negative for other known pathogens. Importantly, this magnitude of increased risk is similar to those of other known causes of cervicitis, including C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae [46].

Upper Reproductive Tract Infection by M. genitalium

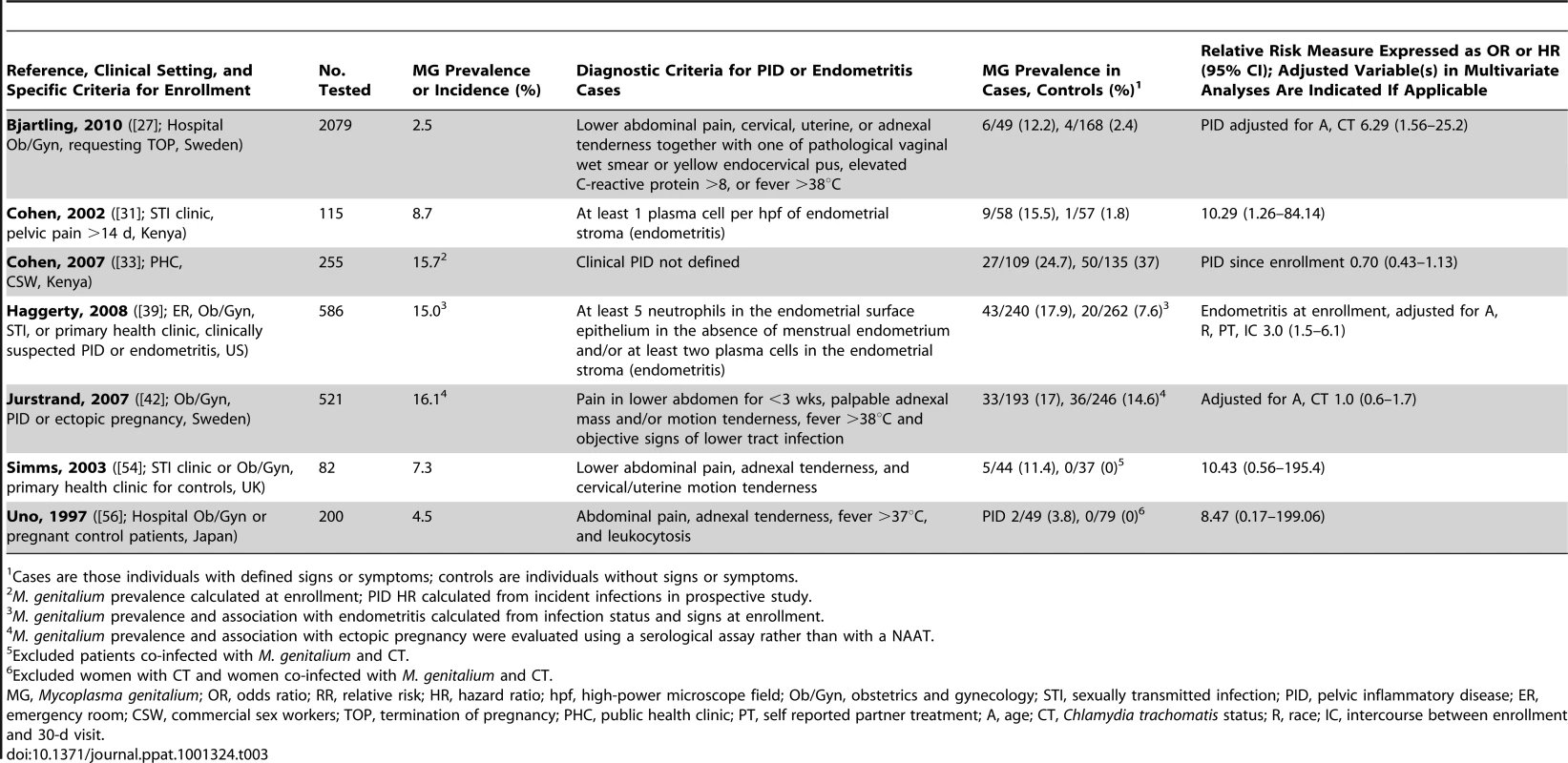

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Following sexual transmission, cervical passage of M. genitalium could result in ascending infection of the endometrium or further to the fallopian tubes leading to tubal inflammation and infertility. M. genitalium was first suspected as a cause of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in 1984 [59]. Since, five PCR-based studies have found a positive association of M. genitalium with clinical PID from geographically diverse populations around the world ([27], [31], [39], [54], [56]; Table 3). In the first of these, of 58 Kenyan women with histologically confirmed endometritis, M. genitalium was found significantly more often in women with endometritis compared to women without this condition (16% versus 2%; [31]). Similarly, in a sub-study from the US PID Evaluation of Clinical Health cohort, women with M. genitalium were three times more likely to have endometritis at enrollment compared to women without M. genitalium [39].

Tab. 3. Characteristics of published studies evaluating the associations of M. genitalium with pelvic inflammatory disease.

Cases are those individuals with defined signs or symptoms; controls are individuals without signs or symptoms. In two cross-sectional studies where the endometrium was sampled directly to measure the associations of current infection and upper tract disease [31], [33], [39], M. genitalium was associated significantly with endometritis [31], [39]. In contrast, one prospective study of commercial sex workers in Kenya failed to find an association of M. genitalium infection with PID [33] over 36 months. Considering the persistent nature of M. genitalium, as with other STIs, it is possible that the follow-up period and high percentage of loss to follow-up was not adequate to detect incident PID. Importantly, clinical diagnosis of PID includes several variable signs (see Table 3) that often do not correlate with laparoscopic findings [54]; this undoubtedly contributes to variability among PID studies and could impact the associations with M. genitalium infection. Further, no clear trend was observed when comparing studies that removed co-infections with C. trachomatis or controlled for co-infections in multivariate analyses. Overall, M. genitalium has been associated with microscopic endometritis and PID, and confirmatory studies are clearly necessary to establish an independent role and investigate the mechanisms for upper reproductive tract inflammation.

Pregnancy-Related Complications and Infertility

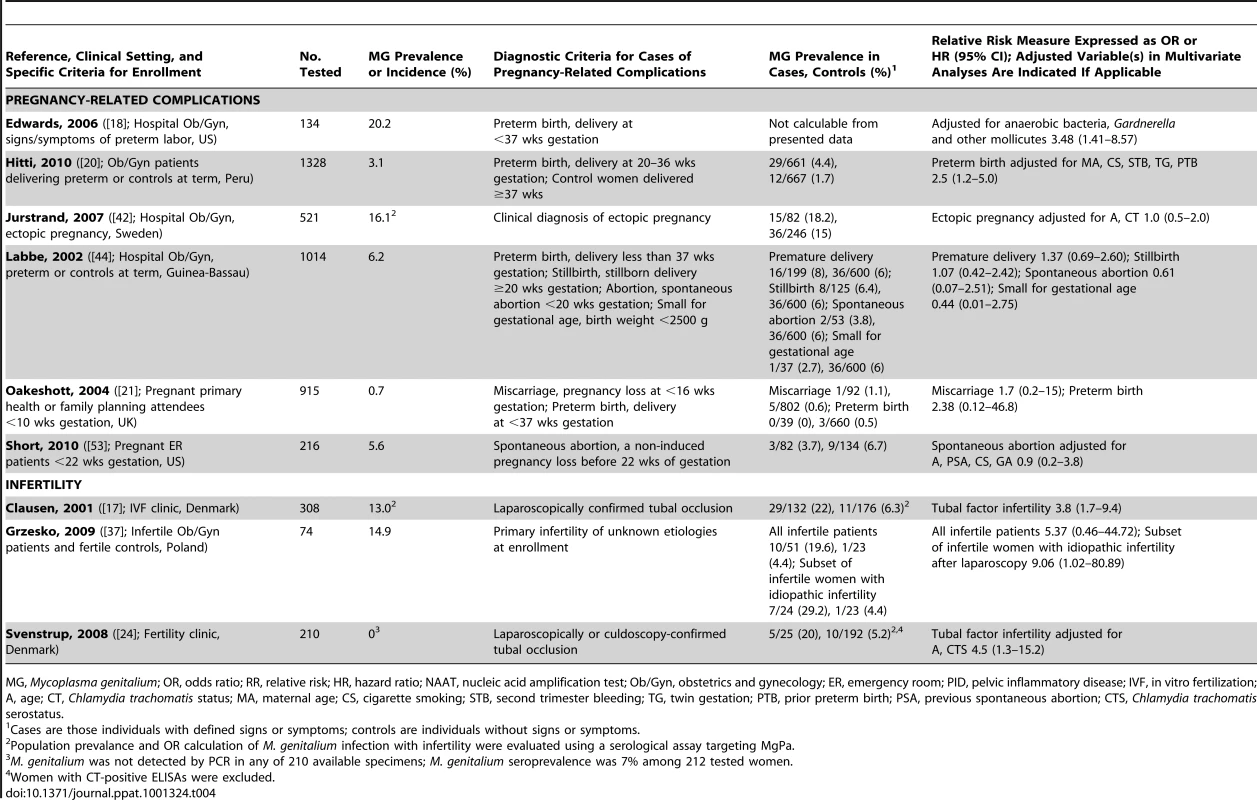

PID can be a pre-cursor to several significant upper tract complications, including ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain and tubal factor infertility [60]. No association between M. genitalium and ectopic pregnancy was observed in a single study using serological testing for M. genitalium exposure ([42]; Table 4). Considering other adverse pregnancy outcomes including preterm birth, spontaneous abortion or miscarriage, stillbirth, and small for gestational age, of five independent studies ([20], [21], [42], [44], [53]; Table 4), two studies have indeed shown an independent association of M. genitalium with preterm birth [18], [20], but no other syndromes have been linked to this infection.

Tab. 4. Characteristics of published studies evaluating the associations of M. genitalium with pregnancy-related complications or infertility.

MG, Mycoplasma genitalium; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; HR, hazard ratio; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; Ob/Gyn, obstetrics and gynecology; ER, emergency room; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; IVF, in vitro fertilization; A, age; CT, Chlamydia trachomatis status; MA, maternal age; CS, cigarette smoking; STB, second trimester bleeding; TG, twin gestation; PTB, prior preterm birth; PSA, previous spontaneous abortion; CTS, Chlamydia trachomatis serostatus. In contrast, investigations into M. genitalium as a cause of infertility have consistently shown a strong correlation. Two Danish studies have found a significant association between women with M. genitalium–specific serum antibodies and laparoscopically confirmed tubal infertility ([17], [24]; Table 4). Exclusion of women with prior C. trachomatis infection still resulted in significant association between M. genitalium and infertility ([24]; Table 4). In one study, PCR detection of M. genitalium was attempted from endocervical swabs with no success, suggesting that previous M. genitalium infection might cause permanent damage to the oviduct, or that endocervical swabs are ineffective for detecting upper genital tract infection. However, in a recent study of Polish women by Grzesko and colleagues, M. genitalium was detected by PCR more often in cervical swabs from infertile patients compared to healthy, fertile women [37], suggesting that endocervical swabs can predict upper tract infection. It is important to note that NAAT studies make associations between current infection and infertility, while serological studies determine associations with prior M. genitalium exposure. Because tubal scarring can result in long-term infertility, serological studies probably best address whether M. genitalium is a cause of tubal-factor infertility and can be useful in determining recent or long-term infections (e.g., IgM versus IgG antibodies).

Experimental animal models have also provided evidence that M. genitalium can colonize upper reproductive tract tissues, leading to salpingitis or endometritis [61]–[63]. Thus, it is evident that M. genitalium could be an independent cause of tubal factor infertility. Importantly, however, the few studies to date have been relatively small in size and longitudinal studies would be of tremendous benefit for understanding this complex condition whereby prior infection can lead to long-term sequelae.

Recommended Treatment of M. genitalium and Important Considerations

Evaluation of M. genitalium treatment efficacy has been a subject of obvious importance but conclusive recommendations are lacking largely because, to date, only a single randomized controlled clinical trial has been reported [64]. In this trial, a single 1-g dose of azithromycin was more effective than 7-day, multi-dose doxycycline for eradication of M. genitalium infection in men. In patients diagnosed with PID, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend therapy with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline or cefoxitin and probenecid plus doxycycline [65]. These treatments are primarily targeted towards C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae, to which less than half of PID cases can be attributed [66]. Importantly, several reports suggest these treatment regimens would be ineffective for eradicating M. genitalium, as male and female genital infections persist in a significant proportion of patients treated with tetracyclines [67]–[71] or levofloxacin [68], [72].

Using azithromycin (1 g; single dose), clinical cure rates are only between 79% and 87% for M. genitalium–positive male and female patients, leaving a significant subset of patients with persistent urogenital tract infections [29], [64], [67], [73]. Extended 5-day regimens of azithromycin therapy increase cure rates to 96% after doxycycline treatment failure [67], and additional randomized trials are now required to determine the optimum dosage and regimen. If patients fail extended azithromycin therapy, moxifloxacin is the only available antibiotic with a successful rate of cure [73] and should be used only with patients failing other therapies. Successful treatment of M. genitalium infection in female patients is of particular importance because prolonged inflammation at upper genital tract sites might lead to significant reproductive tract morbidity and infertility [74]. In women, treatment must be effective for both lower and upper genital tract infection.

Conclusions and Implications for Future Research

Following the firm establishment that M. genitalium causes NGU in men and is a cause of STI, many studies have now found significant associations with lower and upper reproductive tract disease in women. Taken together, M. genitalium should be considered an etiologic agent of cervical inflammation and upper tract disease syndromes, including PID and infertility. Importantly, additional studies with defined diagnostic criteria will be required to fully understand the relationship between M. genitalium and cervicitis. A systematic review and meta-analysis would be of significant benefit for defining the associations of M. genitalium infection with reproductive tract disease in women.

Although not addressed in this review, M. genitalium likely maintains persistent infection through intracellular survival in mucosal epithelial cells [75], [76] resulting in inflammation [75], [77]. The observed correlations between M. genitalium reproductive tract infection and HIV-1 (reviewed in [78]) may be explained by long-term inflammation elicited by M. genitalium infection; these associations are likely of particular importance considering the enormous public health burden of HIV infections worldwide. Therefore, continued research will be important to understand the dynamics of persistent HIV-1 and M. genitalium co-infections of vaginal and cervical tissues, particularly when dissecting clinical correlates with disease.

We still have much to learn about reproductive tract infections from both a clinical and basic science standpoint. Overall, M. genitalium appears to be a highly prevalent sexually transmitted bacterial pathogen that, if not diagnosed and the patient treated appropriately, can cause persistent urogenital inflammation in men and women and increase the risk of HIV transmission and infection. Continued investigation of M. genitalium's role in sexually transmitted disease will be pivotal for understanding the complex and dynamic inflammatory syndromes of the female reproductive tract.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. World Health Organization

2007

Sexually transmitted infections fact sheet.

Available: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs110/en/. Accessed 22 April 2011

2. ManhartLE

HolmesKK

HughesJP

HoustonLS

TottenPA

2007

Mycoplasma genitalium among young adults in the United States: an emerging sexually transmitted infection.

Am J Public Health

97

1118

1125

3. TullyJG

Taylor-RobinsonD

ColeRM

RoseDL

1981

A newly discovered mycoplasma in the human urogenital tract.

Lancet

1

1288

1291

4. JensenJS

2004

Mycoplasma genitalium: the aetiological agent of urethritis and other sexually transmitted diseases.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol

18

1

11

5. MartinDH

2008

Nongonococcal urethritis: new views through the prism of modern molecular microbiology.

Curr Infect Dis Rep

10

128

132

6. JensenJS

UldumSA

Sondergard-AndersenJ

VuustJ

LindK

1991

Polymerase chain reaction for detection of Mycoplasma genitalium in clinical samples.

J Clin Microbiol

29

46

50

7. PalmerHM

GilroyCB

ClaydonEJ

Taylor-RobinsonD

1991

Detection of Mycoplasma genitalium in the genitourinary tract of women by the polymerase chain reaction.

Int J STD AIDS

2

261

263

8. AnagriusC

LoreB

JensenJS

2005

Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence, clinical significance, and transmission.

Sex Transm Infect

81

458

462

9. FalkL

FredlundH

JensenJS

2004

Symptomatic urethritis is more prevalent in men infected with Mycoplasma genitalium than with Chlamydia trachomatis.

Sex Transm Infect

80

289

293

10. FalkL

FredlundH

JensenJS

2005

Signs and symptoms of urethritis and cervicitis among women with or without Mycoplasma genitalium or Chlamydia trachomatis infection.

Sex Transm Infect

81

73

78

11. HjorthSV

BjorneliusE

LidbrinkP

FalkL

DohnB

2006

Sequence-based typing of Mycoplasma genitalium reveals sexual transmission.

J Clin Microbiol

44

2078

2083

12. KeaneFE

ThomasBJ

GilroyCB

RentonA

Taylor-RobinsonD

2000

The association of Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium with non-gonococcal urethritis: observations on heterosexual men and their female partners.

Int J STD AIDS

11

435

439

13. ThurmanAR

MusatovovaO

PerdueS

ShainRN

BasemanJG

2010

Mycoplasma genitalium symptoms, concordance and treatment in high-risk sexual dyads.

Int J STD AIDS

21

177

183

14. ToshAK

Van Der PolB

FortenberryJD

WilliamsJA

KatzBP

2007

Mycoplasma genitalium among adolescent women and their partners.

J Adolesc Health

40

412

417

15. MaL

TaylorS

JensenJS

MyersL

LillisR

2008

Short tandem repeat sequences in the Mycoplasma genitalium genome and their use in a multilocus genotyping system.

BMC Microbiol

8

130

16. AndersenB

SokolowskiI

OstergaardL

Kjolseth MollerJ

OlesenF

2007

Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence and behavioural risk factors in the general population.

Sex Transm Infect

83

237

241

17. ClausenHF

FedderJ

DrasbekM

NielsenPK

ToftB

2001

Serological investigation of Mycoplasma genitalium in infertile women.

Hum Reprod

16

1866

1874

18. EdwardsRK

FergusonRJ

ReyesL

BrownM

TheriaqueDW

2006

Assessing the relationship between preterm delivery and various microorganisms recovered from the lower genital tract.

J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med

19

357

363

19. GhebremichaelM

PaintsilE

LarsenU

2009

Alcohol abuse, sexual risk behaviors, and sexually transmitted infections in women in Moshi urban district, northern Tanzania.

Sex Transm Dis

36

102

107

20. HittiJ

GarciaP

TottenP

PaulK

AsteteS

2010

Correlates of cervical Mycoplasma genitalium and risk of preterm birth among Peruvian women.

Sex Transm Dis

37

81

85

21. OakeshottP

HayP

Taylor-RobinsonD

HayS

DohnB

2004

Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in early pregnancy and relationship between its presence and pregnancy outcome.

BJOG

111

1464

1467

22. OlsenB

LanPT

Stalsby LundborgC

KhangTH

UnemoM

2009

Population-based assessment of Mycoplasma genitalium in Vietnam–low prevalence among married women of reproductive age in a rural area.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol

23

533

537

23. RahmanS

GarlandS

CurrieM

TabriziSN

RahmanM

2008

Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in health clinic attendees complaining of vaginal discharge in Bangladesh.

Int J STD AIDS

19

772

774

24. SvenstrupHF

FedderJ

KristoffersenSE

TrolleB

BirkelundS

2008

Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis, and tubal factor infertility–a prospective study.

Fertil Steril

90

513

520

25. ArraizRN

Colina ChS

MarcucciJR

RondonGN

ReyesSF

2008

Mycoplasma genitalium detection and correlation with clinical manifestations in population of the Zulia State, Venezuela.

Rev Chilena Infectol

25

256

261

26. BaczynskaA

HvidM

LamyP

BirkelundS

ChristiansenG

2008

Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis and Chlamydia trachomatis among Danish patients requesting abortion.

Syst Biol Reprod Med

54

127

134

27. BjartlingC

OsserS

PerssonK

2010

The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy.

BJOG

117

361

364

28. BlanchardA

HamrickW

DuffyL

BaldusK

CassellGH

1993

Use of the polymerase chain reaction for detection of Mycoplasma fermentans and Mycoplasma genitalium in the urogenital tract and amniotic fluid.

Clin Infect Dis

17

Suppl 1

S272

279

29. BradshawCS

ChenMY

FairleyCK

2008

Persistence of Mycoplasma genitalium following azithromycin therapy.

PLoS ONE

3

e3618

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003618

30. CasinI

Vexiau-RobertD

De La SalmoniereP

EcheA

GrandryB

2002

High prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in the lower genitourinary tract of women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic in Paris, France.

Sex Transm Dis

29

353

359

31. CohenCR

ManhartLE

BukusiEA

AsteteS

BrunhamRC

2002

Association between Mycoplasma genitalium and acute endometritis.

Lancet

359

765

766

32. CohenCR

MugoNR

AsteteSG

OdondoR

ManhartLE

2005

Detection of Mycoplasma genitalium in women with laparoscopically diagnosed acute salpingitis.

Sex Transm Infect

81

463

466

33. CohenCR

NosekM

MeierA

AsteteSG

Iverson-CabralS

2007

Mycoplasma genitalium infection and persistence in a cohort of female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya.

Sex Transm Dis

34

274

279

34. de BarbeyracB

Bernet-PoggiC

FebrerF

RenaudinH

DuponM

1993

Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Mycoplasma genitalium in clinical samples by polymerase chain reaction.

Clin Infect Dis

17

Suppl 1

S83

S89

35. EdbergA

JurstrandM

JohanssonE

WikanderE

HoogA

2008

A comparative study of three different PCR assays for detection of Mycoplasma genitalium in urogenital specimens from men and women.

J Med Microbiol

57

304

309

36. GaydosC

MaldeisNE

HardickA

HardickJ

QuinnTC

2009

Mycoplasma genitalium as a contributor to the multiple etiologies of cervicitis in women attending sexually transmitted disease clinics.

Sex Transm Dis

36

598

606

37. GrzeskoJ

EliasM

MaczynskaB

KasprzykowskaU

TlaczalaM

2009

Occurrence of Mycoplasma genitalium in fertile and infertile women.

Fertil Steril

91

2376

2380

38. HaggertyCL

TottenPA

AsteteSG

NessRB

2006

Mycoplasma genitalium among women with nongonococcal, nonchlamydial pelvic inflammatory disease.

Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol

2006

30184

39. HaggertyCL

TottenPA

AsteteSG

LeeS

HoferkaSL

2008

Failure of cefoxitin and doxycycline to eradicate endometrial Mycoplasma genitalium and the consequence for clinical cure of pelvic inflammatory disease.

Sex Transm Infect

84

338

342

40. HogdahlM

KihlstromE

2007

Leucocyte esterase testing of first-voided urine and urethral and cervical smears to identify Mycoplasma genitalium-infected men and women.

Int J STD AIDS

18

835

838

41. HuppertJS

MortensenJE

ReedJL

KahnJA

RichKD

2008

Mycoplasma genitalium detected by transcription-mediated amplification is associated with Chlamydia trachomatis in adolescent women.

Sex Transm Dis

35

250

254

42. JurstrandM

JensenJS

MagnusonA

KamwendoF

FredlundH

2007

A serological study of the role of Mycoplasma genitalium in pelvic inflammatory disease and ectopic pregnancy.

Sex Transm Infect

83

319

323

43. KorteJE

BasemanJB

CagleMP

HerreraC

PiperJM

2006

Cervicitis and genitourinary symptoms in women culture positive for Mycoplasma genitalium.

Am J Reprod Immunol

55

265

275

44. LabbeAC

FrostE

DeslandesS

MendoncaAP

AlvesAC

2002

Mycoplasma genitalium is not associated with adverse outcomes of pregnancy in Guinea-Bissau.

Sex Transm Infect

78

289

291

45. LawtonBA

RoseSB

BromheadC

GaitanosLA

MacDonaldEJ

2008

High prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in women presenting for termination of pregnancy.

Contraception

77

294

298

46. ManhartLE

CritchlowCW

HolmesKK

DutroSM

EschenbachDA

2003

Mucopurulent cervicitis and Mycoplasma genitalium.

J Infect Dis

187

650

657

47. ManhartLE

MostadSB

BaetenJM

AsteteSG

MandaliyaK

2008

High Mycoplasma genitalium organism burden is associated with shedding of HIV-1 DNA from the cervix.

J Infect Dis

197

733

736

48. MelleniusH

BomanJ

LundqvistEN

JensenJS

2005

Mycoplasma genitalium should be suspected in unspecific urethritis and cervicitis. A study from Vasterbotten confirms the high prevalence of the bacteria.

Lakartidningen

102

3538

3540–3531

49. MoiH

ReintonN

MoghaddamA

2009

Mycoplasma genitalium in women with lower genital tract inflammation.

Sex Transm Infect

85

10

14

50. MusatovovaO

BasemanJB

2009

Analysis identifying common and distinct sequences among Texas clinical strains of Mycoplasma genitalium.

J Clin Microbiol

47

1469

1475

51. PepinJ

LabbeAC

KhondeN

DeslandesS

AlaryM

2005

Mycoplasma genitalium: an organism commonly associated with cervicitis among west African sex workers.

Sex Transm Infect

81

67

72

52. RossJD

BrownL

SaundersP

AlexanderS

2009

Mycoplasma genitalium in asymptomatic patients: implications for screening.

Sex Transm Infect

85

436

437

53. ShortVL

JensenJS

NelsonDB

MurrayPJ

NessRB

2010

Mycoplasma genitalium among young, urban pregnant women.

Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol

2010

984760

54. SimmsI

EastickK

MallinsonH

ThomasK

GokhaleR

2003

Associations between Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis and pelvic inflammatory disease.

J Clin Pathol

56

616

618

55. TsunoeH

TanakaM

NakayamaH

SanoM

NakamuraG

2000

High prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Mycoplasma genitalium in female commercial sex workers in Japan.

Int J STD AIDS

11

790

794

56. UnoM

DeguchiT

KomedaH

HayasakiM

IidaM

1997

Mycoplasma genitalium in the cervices of Japanese women.

Sex Transm Dis

24

284

286

57. SpenceD

MelvilleC

2007

Vaginal discharge.

BMJ

335

1147

1151

58. MarrazzoJM

MartinDH

2007

Management of women with cervicitis.

Clin Infect Dis

44

Suppl 3

S102

S110

59. MollerBR

Taylor-RobinsonD

FurrPM

1984

Serological evidence implicating Mycoplasma genitalium in pelvic inflammatory disease.

Lancet

1

1102

1103

60. WestromL

1975

Effect of acute pelvic inflammatory disease on fertility.

Am J Obstet Gynecol

121

707

713

61. McGowinCL

SpagnuoloRA

PylesRB

2010

Mycoplasma genitalium rapidly disseminates to the upper reproductive tracts and knees of female mice following vaginal inoculation.

Infect Immun

78

726

736

62. MollerBR

Taylor-RobinsonD

FurrPM

FreundtEA

1985

Acute upper genital-tract disease in female monkeys provoked experimentally by Mycoplasma genitalium.

Br J Exp Pathol

66

417

426

63. Taylor-RobinsonD

FurrPM

TullyJG

BarileMF

MollerBR

1987

Animal models of Mycoplasma genitalium urogenital infection.

Isr J Med Sci

23

561

564

64. MenaLA

MroczkowskiTF

NsuamiM

MartinDH

2009

A randomized comparison of azithromycin and doxycycline for the treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium-positive urethritis in men.

Clin Infect Dis

48

1649

1654

65. WorkowskiKA

BermanS

2010

Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010.

MMWR Recomm Rep

59

1

110

66. NessRB

SoperDE

HolleyRL

PeipertJ

RandallH

2002

Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: results from the Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Randomized Trial.

Am J Obstet Gynecol

186

929

937

67. BjorneliusE

AnagriusC

BojsG

CarlbergH

JohannissonG

2008

Antibiotic treatment of symptomatic Mycoplasma genitalium infection in Scandinavia: a controlled clinical trial.

Sex Transm Infect

84

72

76

68. DeguchiT

YoshidaT

YokoiS

ItoM

TamakiM

2002

Longitudinal quantitative detection by real-time PCR of Mycoplasma genitalium in first-pass urine of men with recurrent nongonococcal urethritis.

J Clin Microbiol

40

3854

3856

69. FalkL

FredlundH

JensenJS

2003

Tetracycline treatment does not eradicate Mycoplasma genitalium.

Sex Transm Infect

79

318

319

70. HornerPJ

GilroyCB

ThomasBJ

NaidooRO

Taylor-RobinsonD

1993

Association of Mycoplasma genitalium with acute non-gonococcal urethritis.

Lancet

342

582

585

71. WikstromA

JensenJS

2006

Mycoplasma genitalium: a common cause of persistent urethritis among men treated with doxycycline.

Sex Transm Infect

82

276

279

72. MaedaSI

TamakiM

KojimaK

YoshidaT

IshikoH

2001

Association of Mycoplasma genitalium persistence in the urethra with recurrence of nongonococcal urethritis.

Sex Transm Dis

28

472

476

73. JernbergE

MoghaddamA

MoiH

2008

Azithromycin and moxifloxacin for microbiological cure of Mycoplasma genitalium infection: an open study.

Int J STD AIDS

19

676

679

74. QuayleAJ

2002

The innate and early immune response to pathogen challenge in the female genital tract and the pivotal role of epithelial cells.

J Reprod Immunol

57

61

79

75. McGowinCL

PopovVL

PylesRB

2009

Intracellular Mycoplasma genitalium infection of human vaginal and cervical epithelial cells elicits distinct patterns of inflammatory cytokine secretion and provides a possible survival niche against macrophage-mediated killing.

BMC Microbiol

9

139

76. UenoPM

TimenetskyJ

CentonzeVE

WewerJJ

CagleM

2008

Interaction of Mycoplasma genitalium with host cells: evidence for nuclear localization.

Microbiology

154

3033

3041

77. McGowinCL

MaL

MartinDH

PylesRB

2009

Mycoplasma genitalium-encoded MG309 activates NF-kappaB via Toll-like receptors 2 and 6 to elicit proinflammatory cytokine secretion from human genital epithelial cells.

Infect Immun

77

1175

1181

78. Napierala MavedzengeS

WeissHA

2009

Association of Mycoplasma genitalium and HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

AIDS

23

611

620

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Distribution of the Phenotypic Effects of Random Homologous Recombination between Two Virus SpeciesČlánek SIV Nef Proteins Recruit the AP-2 Complex to Antagonize Tetherin and Facilitate Virion ReleaseČlánek Dual Function of the NK Cell Receptor 2B4 (CD244) in the Regulation of HCV-Specific CD8+ T CellsČlánek A Large and Intact Viral Particle Penetrates the Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane to Reach the CytosolČlánek Interleukin-13 Promotes Susceptibility to Chlamydial Infection of the Respiratory and Genital Tracts

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 5- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Lymphoadenopathy during Lyme Borreliosis Is Caused by Spirochete Migration-Induced Specific B Cell Activation

- Infections Are Virulent and Inhibit the Human Malaria Parasite in

- A Gamma Interferon Independent Mechanism of CD4 T Cell Mediated Control of Infection

- MDA5 and TLR3 Initiate Pro-Inflammatory Signaling Pathways Leading to Rhinovirus-Induced Airways Inflammation and Hyperresponsiveness

- The OXI1 Kinase Pathway Mediates -Induced Growth Promotion in Arabidopsis

- An E2F1-Mediated DNA Damage Response Contributes to the Replication of Human Cytomegalovirus

- Quantitative Subcellular Proteome and Secretome Profiling of Influenza A Virus-Infected Human Primary Macrophages

- Distribution of the Phenotypic Effects of Random Homologous Recombination between Two Virus Species

- Inhibition of Both HIV-1 Reverse Transcription and Gene Expression by a Cyclic Peptide that Binds the Tat-Transactivating Response Element (TAR) RNA

- A Viral Satellite RNA Induces Yellow Symptoms on Tobacco by Targeting a Gene Involved in Chlorophyll Biosynthesis using the RNA Silencing Machinery

- Misregulation of Underlies the Developmental Abnormalities Caused by Three Distinct Viral Silencing Suppressors in Arabidopsis

- Investigating the Host Binding Signature on the PfEMP1 Protein Family

- Human Neutrophil Clearance of Bacterial Pathogens Triggers Anti-Microbial γδ T Cell Responses in Early Infection

- Septation of Infectious Hyphae Is Critical for Appressoria Formation and Virulence in the Smut Fungus

- A Family of Helminth Molecules that Modulate Innate Cell Responses via Molecular Mimicry of Host Antimicrobial Peptides

- Phospholipids Trigger Capsular Enlargement during Interactions with Amoebae and Macrophages

- CTL Escape Mediated by Proteasomal Destruction of an HIV-1 Cryptic Epitope

- Evolution of Th2 Immunity: A Rapid Repair Response to Tissue Destructive Pathogens

- Extensive Genome-Wide Variability of Human Cytomegalovirus in Congenitally Infected Infants

- The Antiviral Efficacy of HIV-Specific CD8 T-Cells to a Conserved Epitope Is Heavily Dependent on the Infecting HIV-1 Isolate

- Epstein-Barr Virus Infection of Polarized Epithelial Cells via the Basolateral Surface by Memory B Cell-Mediated Transfer Infection

- Reactive Oxygen Species Hydrogen Peroxide Mediates Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Reactivation from Latency

- Crystal Structure and Functional Analysis of the SARS-Coronavirus RNA Cap 2′-O-Methyltransferase nsp10/nsp16 Complex

- The Dot/Icm System Delivers a Unique Repertoire of Type IV Effectors into Host Cells and Is Required for Intracellular Replication

- AAV Exploits Subcellular Stress Associated with Inflammation, Endoplasmic Reticulum Expansion, and Misfolded Proteins in Models of Cystic Fibrosis

- Suboptimal Activation of Antigen-Specific CD4 Effector Cells Enables Persistence of In Vivo

- SIV Nef Proteins Recruit the AP-2 Complex to Antagonize Tetherin and Facilitate Virion Release

- Dual Function of the NK Cell Receptor 2B4 (CD244) in the Regulation of HCV-Specific CD8+ T Cells

- Transition of Sporozoites into Liver Stage-Like Forms Is Regulated by the RNA Binding Protein Pumilio

- A Large and Intact Viral Particle Penetrates the Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane to Reach the Cytosol

- Transcriptome Analysis of in Human Whole Blood and Mutagenesis Studies Identify Virulence Factors Involved in Blood Survival

- Interleukin-13 Promotes Susceptibility to Chlamydial Infection of the Respiratory and Genital Tracts

- Structural Insights into Viral Determinants of Nematode Mediated Transmission

- Protective Efficacy of Serially Up-Ranked Subdominant CD8 T Cell Epitopes against Virus Challenges

- Viral CTL Escape Mutants Are Generated in Lymph Nodes and Subsequently Become Fixed in Plasma and Rectal Mucosa during Acute SIV Infection of Macaques

- Taking Some of the Mystery out of Host∶Virus Interactions

- Viral Small Interfering RNAs Target Host Genes to Mediate Disease Symptoms in Plants

- : An Emerging Cause of Sexually Transmitted Disease in Women

- Mitochondrial Ubiquitin Ligase MARCH5 Promotes TLR7 Signaling by Attenuating TANK Action

- The Hexamer Structure of the Rift Valley Fever Virus Nucleoprotein Suggests a Mechanism for its Assembly into Ribonucleoprotein Complexes

- Acquisition of Human-Type Receptor Binding Specificity by New H5N1 Influenza Virus Sublineages during Their Emergence in Birds in Egypt

- Stromal Down-Regulation of Macrophage CD4/CCR5 Expression and NF-κB Activation Mediates HIV-1 Non-Permissiveness in Intestinal Macrophages

- A Component of the Xanthomonadaceae Type IV Secretion System Combines a VirB7 Motif with a N0 Domain Found in Outer Membrane Transport Proteins

- Perturbs Iron Trafficking in the Epithelium to Grow on the Cell Surface

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Crystal Structure and Functional Analysis of the SARS-Coronavirus RNA Cap 2′-O-Methyltransferase nsp10/nsp16 Complex

- Lymphoadenopathy during Lyme Borreliosis Is Caused by Spirochete Migration-Induced Specific B Cell Activation

- The OXI1 Kinase Pathway Mediates -Induced Growth Promotion in Arabidopsis

- : An Emerging Cause of Sexually Transmitted Disease in Women

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání