-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaMyeloid Cell-Restricted Insulin Receptor Deficiency Protects Against Obesity-Induced Inflammation and Systemic Insulin Resistance

A major component of obesity-related insulin resistance is the establishment of a chronic inflammatory state with invasion of white adipose tissue by mononuclear cells. This results in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which in turn leads to insulin resistance in target tissues such as skeletal muscle and liver. To determine the role of insulin action in macrophages and monocytes in obesity-associated insulin resistance, we conditionally inactivated the insulin receptor (IR) gene in myeloid lineage cells in mice (IRΔmyel-mice). While these animals exhibit unaltered glucose metabolism on a normal diet, they are protected from the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance upon high fat feeding. Euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamp studies demonstrate that this results from decreased basal hepatic glucose production and from increased insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in skeletal muscle. Furthermore, IRΔmyel-mice exhibit decreased concentrations of circulating tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and thus reduced c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activity in skeletal muscle upon high fat feeding, reflecting a dramatic reduction of the chronic and systemic low-grade inflammatory state associated with obesity. This is paralleled by a reduced accumulation of macrophages in white adipose tissue due to a pronounced impairment of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 expression and activity in these cells. These data indicate that insulin action in myeloid cells plays an unexpected, critical role in the regulation of macrophage invasion into white adipose tissue and in the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000938

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000938Summary

A major component of obesity-related insulin resistance is the establishment of a chronic inflammatory state with invasion of white adipose tissue by mononuclear cells. This results in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which in turn leads to insulin resistance in target tissues such as skeletal muscle and liver. To determine the role of insulin action in macrophages and monocytes in obesity-associated insulin resistance, we conditionally inactivated the insulin receptor (IR) gene in myeloid lineage cells in mice (IRΔmyel-mice). While these animals exhibit unaltered glucose metabolism on a normal diet, they are protected from the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance upon high fat feeding. Euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamp studies demonstrate that this results from decreased basal hepatic glucose production and from increased insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in skeletal muscle. Furthermore, IRΔmyel-mice exhibit decreased concentrations of circulating tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and thus reduced c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activity in skeletal muscle upon high fat feeding, reflecting a dramatic reduction of the chronic and systemic low-grade inflammatory state associated with obesity. This is paralleled by a reduced accumulation of macrophages in white adipose tissue due to a pronounced impairment of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 expression and activity in these cells. These data indicate that insulin action in myeloid cells plays an unexpected, critical role in the regulation of macrophage invasion into white adipose tissue and in the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance.

Introduction

Obesity in humans and rodents is associated with increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, in white adipose tissue (WAT) [1]–[4]. This results from increased cytokine expression in WAT and more importantly from infiltration of WAT by macrophages [5]–[7]. Elevated concentrations of these cytokines activate the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-, nuclear factor (NF) kB - and Jak/Stat/Socs-signaling pathways in metabolic target tissues of insulin action such as skeletal muscle and liver, thereby inhibiting insulin signal transduction [8]–[10]. Inactivation of the inhibitor of NFkB kinase beta (IKK2), the main activator of TNF-α-stimulated NFkB activation in myeloid cells, protects mice from the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance [11]. These findings suggest that macrophages play a key role in the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. More recently, a critical role in the development of obesity-associated inflammation has also been demonstrated for mast cells and lymphocytes [12], [13].

Early studies indicated that macrophages and monocytes express insulin receptors [14], however, the physiological function of these receptors has been a matter of debate. Macrophages and monocytes have been shown to respond to insulin with increased phagocytosis and glucose metabolism [15] and with increased TNF-α production and inhibition of apoptosis [16], [17]. Additionally, it has been reported that bone marrow-specific deletion of cbl-associated protein (CAP), a downstream molecule of the insulin signaling cascade, protects mice against obesity-induced insulin resistance [18]. To directly address the role of insulin action and resistance in myeloid cells, we generated mice with cell type-specific deletion of the insulin receptor in this lineage (IRΔmyel-mice). We have previously reported that these animals, upon exposure to a high cholesterol diet, exhibit protection from the development of atherosclerosis in the presence of reduced inflammation on an apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-deficient background [19]. However, others reported more complex lesions in the absence of myeloid cell insulin action through activation of the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER) stress pathway on a low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-deficient background [20]. Nonetheless, these studies did not address the role of insulin action and insulin resistance in myeloid lineage cells under conditions of obesity and obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. To analyze the impact of myeloid cell-restricted insulin resistance on the development of systemic insulin resistance associated with obesity, we characterized glucose metabolism in control - and IRΔmyel-mice receiving either a normal chow diet or a high fat diet.

Results

Myeloid cell-restricted insulin resistance does not affect obesity development upon high fat feeding

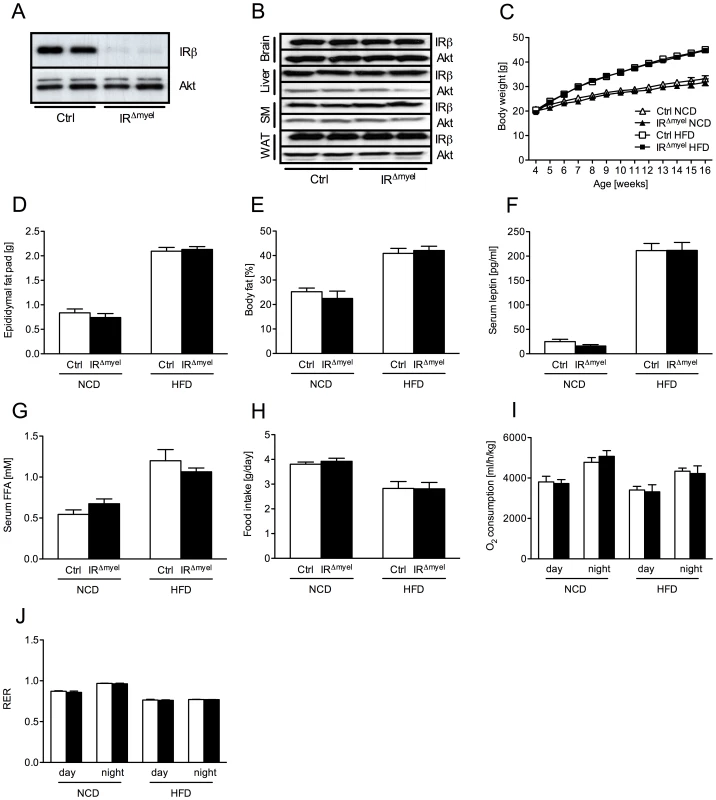

As previously shown, crossing IRflox/flox-mice with mice expressing the Cre-recombinase under control of the lysozymeM promoter resulted in efficient, myeloid cell-restricted ablation of the insulin receptor [19] (Figure 1A and 1B). Under normal chow diet (NCD), control - and IRΔmyel-mice exhibited indistinguishable weight curves, white adipose tissue mass, body fat content, serum leptin concentrations and serum free fatty acids (FFA) (Figure 1C–1G). When exposed to high fat diet (HFD), control-mice significantly gained weight over animals exposed to NCD, and the degree of weight gain was similar between control - and IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 1C). Moreover, white adipose tissue mass, body fat content, circulating leptin concentrations as an indirect measure of fat mass and serum FFA were significantly elevated in mice exposed to HFD, but indistinguishable between control - and IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 1D–1G). Additionally, food intake, oxygen (O2) consumption and respiratory exchange ratio (RER) were modulated by exposure to HFD but did not show any difference between both genotypes (Figure 1H–1J). Taken together, these results indicate that insulin receptors on myeloid cells are not required for energy homeostasis under NCD and HFD feeding and that myeloid cell-restricted insulin resistance does not affect the development of obesity upon high fat feeding.

Fig. 1. IRΔmyel-mice exhibit unaltered response to normal chow and high fat diet.

(A) Western blot analysis of insulin receptor (IR) β and Akt (loading control) expression in thioglycollate-elicited macrophages of control- and IRΔmyel-mice. (B) Western blot analysis of IR-β and Akt (loading control) in brain, liver, skeletal muscle (SM) and white adipose tissue (WAT) of control- and IRΔmyel-mice. (C) Weight curves of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed NCD or HFD. (n = 12 mice per genotype on NCD; n = 32 mice per genotype on HFD.) (D) Epididymal fat pad mass of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 15 mice per genotype and diet.) (E) Body fat content of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 4–10 mice per genotype and diet.) (F) Serum leptin concentrations of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 6–16 mice per genotype and diet.) (G) Serum free fatty acid (FFA) concentrations of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 10–12 mice per genotype and diet.) (H) Daily food intake of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 4–10 mice per genotype and diet.) (I) Oxygen (O2) consumption of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 4–10 mice per genotype and diet.) (J) Respiratory exchange ratio (RER) of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 4–10 mice per genotype and diet.) (Results are means ± SEM; white bars represent controls and black bars represent IRΔmyel-mice). IRΔmyel-mice exhibit improved glucose metabolism upon high fat feeding

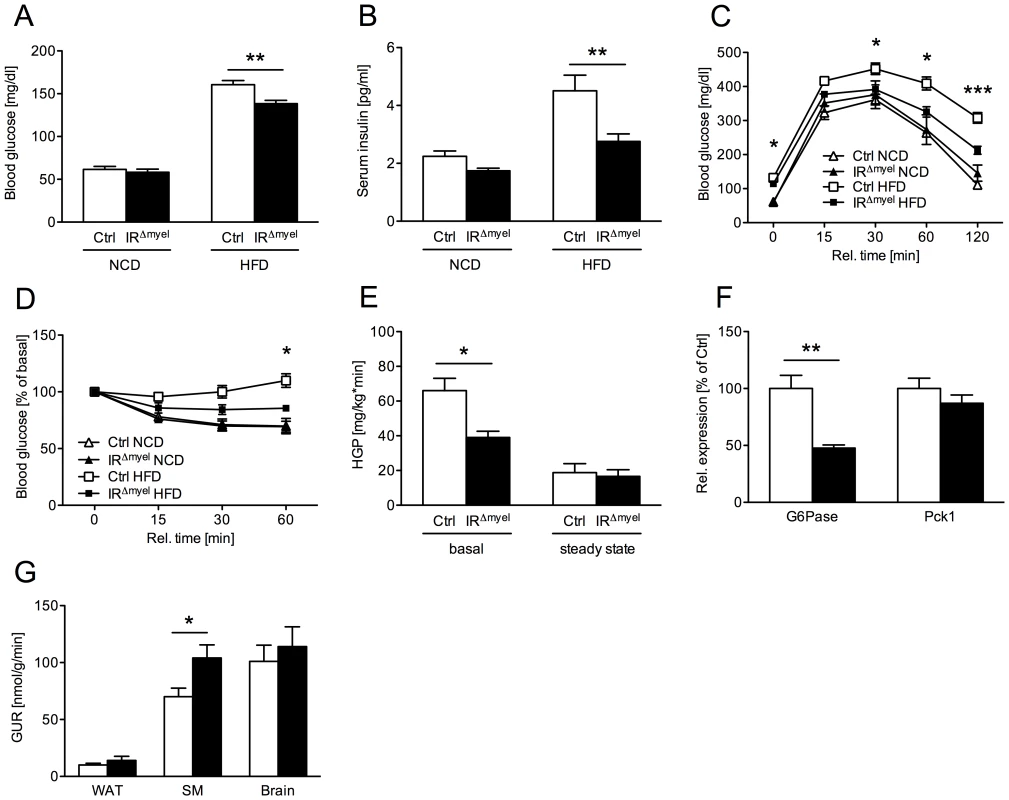

To address the role of myeloid cell insulin action on whole body glucose metabolism, we next determined blood glucose and serum insulin concentrations in control - and IRΔmyel-mice. Both parameters were indistinguishable between genotypes under NCD (Figure 2A and 2B). As expected, on HFD, control-mice developed significantly increased blood glucose and serum insulin concentrations suggestive of insulin resistance (Figure 2A and 2B). Glucose and insulin levels did also rise in obese IRΔmyel-mice, but strikingly, this increase was significantly blunted in these mice lacking insulin receptors in myeloid cells (Figure 2A and 2B).

Fig. 2. IRΔmyel-mice are protected against obesity-induced insulin resistance.

(A) Fasted blood glucose concentrations of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 6–7 mice per genotype on NCD; n = 33–36 mice per genotype on HFD.) (B) Fasted serum insulin concentrations of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 6–7 mice per genotype on NCD; n = 10 mice per genotype on HFD.) (C) Glucose Tolerance Tests were performed with male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed NCD or HFD. (n = 6–13 mice per genotype and diet.) (D) Insulin Tolerance Tests were performed with male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed NCD or HFD. (n = 4–11 mice per genotype and diet.) (E) Hepatic glucose production (HGP) of male, HFD-fed control- and IRΔmyel-mice before (basal) and during (steady state) euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamp analysis. (n = 12 mice per genotype.) (F) Relative expression of G6Pase and Pck1 mRNA in livers of fasted control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed HFD (n = 6 mice per genotype.) (G) Tissue-specific glucose uptake rate (GUR) of male, HFD-fed control- and IRΔmyel-mice under steady state conditions. (WAT = white adipose tissue; SM = skeletal muscle; n = 10 mice per genotype.) (Results are means ± SEM; white bars represent controls and black bars represent IRΔmyel-mice; *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01; ***p≤0.001.) Consistent with this, glucose tolerance was similar in control - and IRΔmyel-mice under NCD and became impaired in control-mice administered a HFD (Figure 2C). In contrast, IRΔmyel-mice receiving the HFD demonstrated only a minimal impairment in glucose tolerance compared to control - or IRΔmyel-mice on NCD (Figure 2C). Similarly, obese IRΔmyel-mice showed significantly higher insulin sensitivity as measured by insulin tolerance test when compared to HFD-fed control-mice, whereas insulin sensitivity was comparable between both groups under NCD (Figure 2D). Taken together, these data reveal that myeloid cell-restricted insulin receptor deficiency leads to striking protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance.

IRΔmyel-mice exhibit reduced hepatic glucose production and improved insulin action in skeletal muscle upon high fat feeding

To further define in which tissues myeloid cell-autonomous insulin resistance affects systemic glucose metabolism on HFD, we performed euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps in control - and IRΔmyel-mice after 12 weeks of exposure to HFD. This analysis revealed a significant decrease in basal hepatic glucose production in IRΔmyel - compared to control-mice, while insulin-suppressed HPG (steady state) was similar in both groups (Figure 2E). Accordingly, obese IRΔmyel-mice exhibited a 50% reduction in the hepatic expression of a key enzyme of gluconeogenesis, glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), while expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pck1) remained unchanged (Figure 2F).

In addition, insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in skeletal muscle was significantly increased in IRΔmyel - compared to control-mice, whereas insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in brain and adipose tissue remained unaltered under clamp conditions (Figure 2G).

In summary, these experiments indicate that the major improvement in glucose metabolism of obese IRΔmyel-mice results from both increased insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle and reduced basal hepatic glucose production.

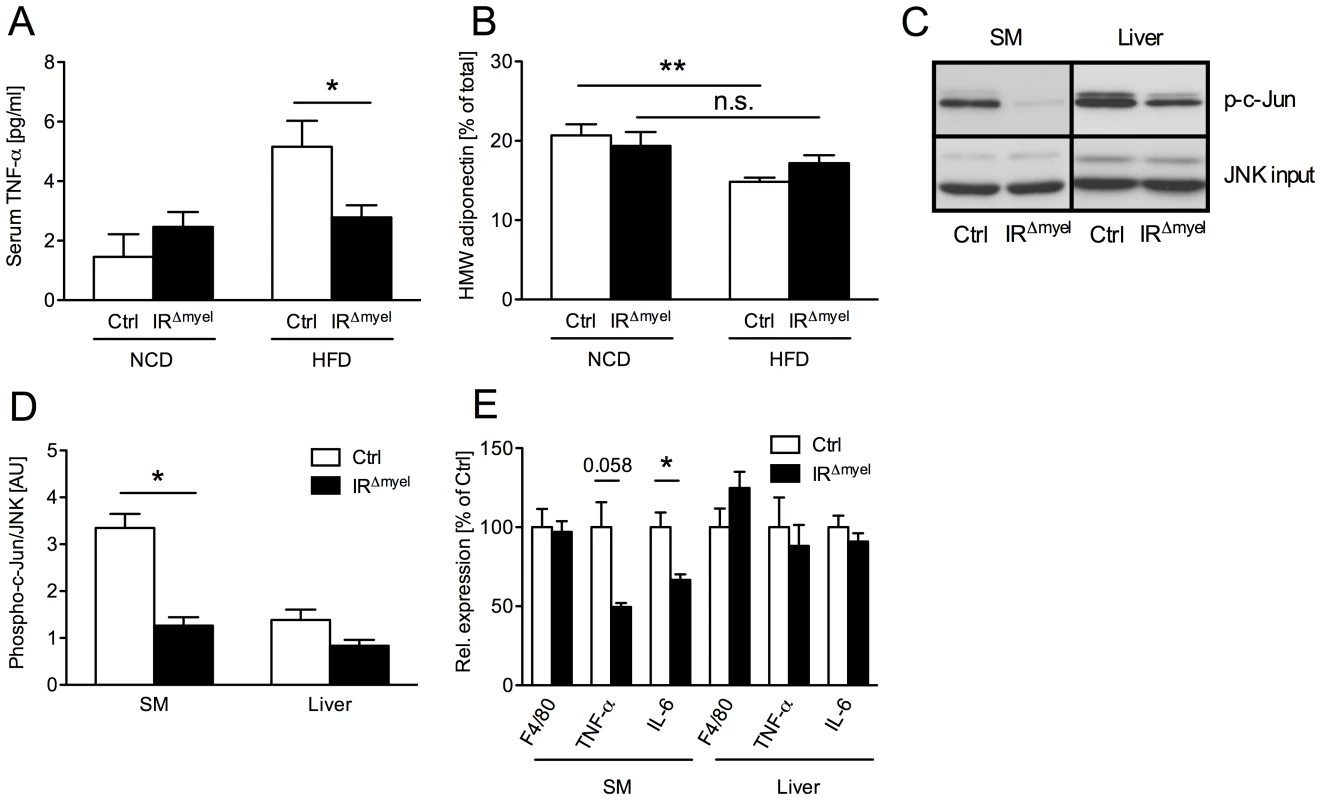

Decreased systemic, obesity-associated inflammatory response in IRΔmyel-mice

As insulin resistance in response to obesity and high fat feeding has been demonstrated to arise from increased concentrations of local and circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines [21] and from a reduction of circulating adiponectin concentrations [22], [23], we determined these parameters in control - and IRΔmyel-mice. Exposure of control-mice to HFD induced a marked increase of serum TNF-α concentrations compared to animals fed NCD. Strikingly, this obesity-induced increase in TNF-α was completely blunted in IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 3A). Moreover, while high fat feeding significantly reduced the portion of high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin of total serum adiponectin in control animals, this diet-induced reduction was not observed in IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. The obesity-associated systemic pro-inflammatory state is reduced in IRΔmyel-mice.

(A) Serum TNF-α concentration in male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 12 mice per genotype on NCD; n = 21 mice per genotype on HFD.) (B) Percentage of serum high molecular weight (HMW) from total adiponectin in male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 10–12 mice per genotype and diet.) (C) In vitro phosphorylation of c-Jun (p-c-Jun) in skeletal muscle (SM) and liver lysates from male, HFD-fed control- and IRΔmyel-mice. Total JNK input was used as loading control. (representative western blot shown). (D) Densitometrical analysis of phospho-c-Jun vs total JNK. (AU = arbitrary units; SM = skeletal muscle; n = 6 mice per genotype.) (E) Relative expression of F4/80, TNF-α and IL-6 mRNA in skeletal muscle (SM) and liver of male, HFD-fed control- and IRΔmyel-mice. (n = 6 mice per genotype.) (Results are means ± SEM; white bars represent controls and black bars represent IRΔmyel-mice; *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01; n.s. = not significant.) Since increased concentrations of TNF-α have been demonstrated to activate inflammatory signaling cascades critical in the development of insulin resistance in classical insulin target tissues, we next directly investigated the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling in liver and skeletal muscle of obese control and IRΔmyel-mice. This analysis revealed, that basal JNK activity, as assessed by phosphorylation of c-Jun, was significantly reduced in skeletal muscle and exhibited a trend towards reduction in liver of obese IRΔmyel-mice compared to controls (Figure 3C and 3D).

Furthermore, expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 was reduced in skeletal muscle, but not liver of obese IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 3E). However, the number of macrophages, which represent a major source for these cytokines, was unaltered in either tissue as demonstrated by similar expression of the macrophage-specific mRNA F4/80 in both groups of mice (Figure 3E).

Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that myeloid cell-restricted insulin resistance protects from obesity-associated systemic changes in the circulating concentrations of cytokines and adipokines as well as the local activation of JNK in skeletal muscle.

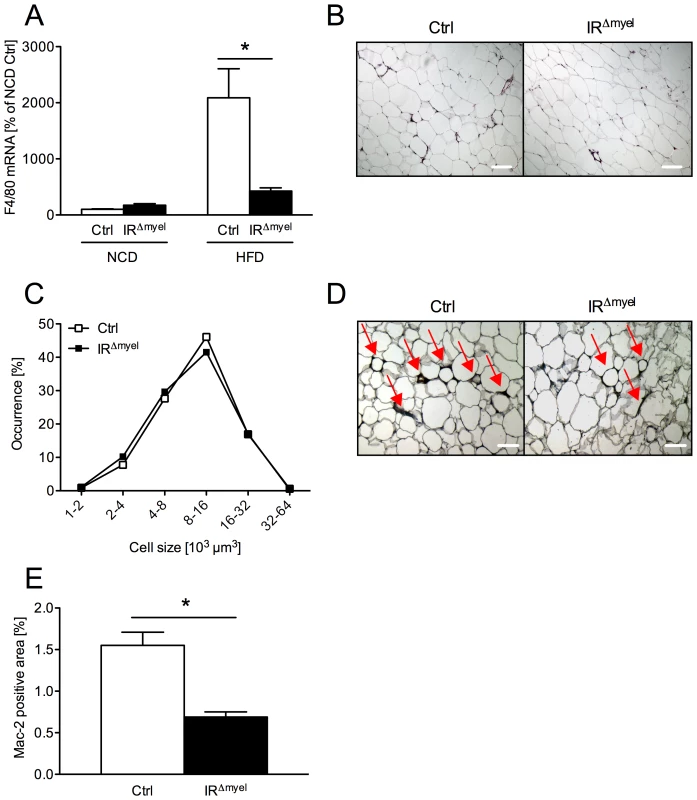

Decreased macrophage recruitment and obesity-associated inflammation in white adipose tissue of IRΔmyel-mice

To address whether the observed reduction in systemic, obesity - associated inflammatory response correlates with alterations of the local, obesity-associated infiltration of adipose tissue by macrophages, we next analyzed the expression of F4/80, a specific marker for this cell-type, in WAT of control - and IRΔmyel-mice by quantitative realtime PCR analysis. Compared to NCD, high fat feeding significantly enhanced expression of F4/80 mRNA in adipose tissue of control animals. Strikingly, the diet-induced increase of this marker was almost completely abolished in WAT of IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 4A). This decrease appeared to represent reduced macrophage recruitment, since bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) of IRΔmyel-mice showed unaltered expression of F4/80 mRNA under basal conditions and after treatment with the saturated fatty acid palmitate compared to control cells (Figure S1A). Importantly, among classical insulin target tissues, only adipose tissue showed drastically increased diet-induced expression of F4/80 mRNA, while expression in obese liver and skeletal muscle was not significantly modulated in wildtype animals compared to NCD (Figure S1B).

Fig. 4. The obesity-associated macrophage infiltration into white adipose tissue is blunted in IRΔmyel-mice.

(A) Relative expression of F4/80 mRNA in WAT of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 8 mice per genotype and diet.) (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of white adipose tissue (WAT) sections from male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed HFD. (C) Adipocyte size distribution in WAT of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed HFD. (n = 9 mice per genotype.) (D) Mac-2 staining of WAT-sections from male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed HFD; Red arrows indicate Mac-2 positive area surrounding the adipocytes. (E) Percentage of Mac-2 positive area per section in male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed HFD. (n = 9 mice per genotype.) (Results are means ± SEM; white bars represent controls and black bars represent IRΔmyel-mice; *p≤0.05; scale bars = 200 µm.) Furthermore, we performed histological analyses of WAT obtained from obese control - and IRΔmyel-mice. No difference was observable in adipocyte morphology or adipocyte size distribution between control - and IRΔmyel-mice on high fat diet (Figure 4B and 4C), consistent with unaltered obesity development in these animals. However, in line with the reduced mRNA expression of macrophage marker genes, immunohistochemical analysis of infiltrating, activated macrophages demonstrated a striking reduction of Mac-2-positive cells in WAT of diet-induced obese IRΔmyel-mice compared to control-mice (Figure 4D and 4E). Thus, the reduced F4/80 mRNA and Mac-2 antigen expression in WAT in the presence of unaltered macrophage-autonomous marker gene expression clearly provides independent experimental evidence for reduced macrophage recruitment to WAT of IRΔmyel-mice upon high fat feeding.

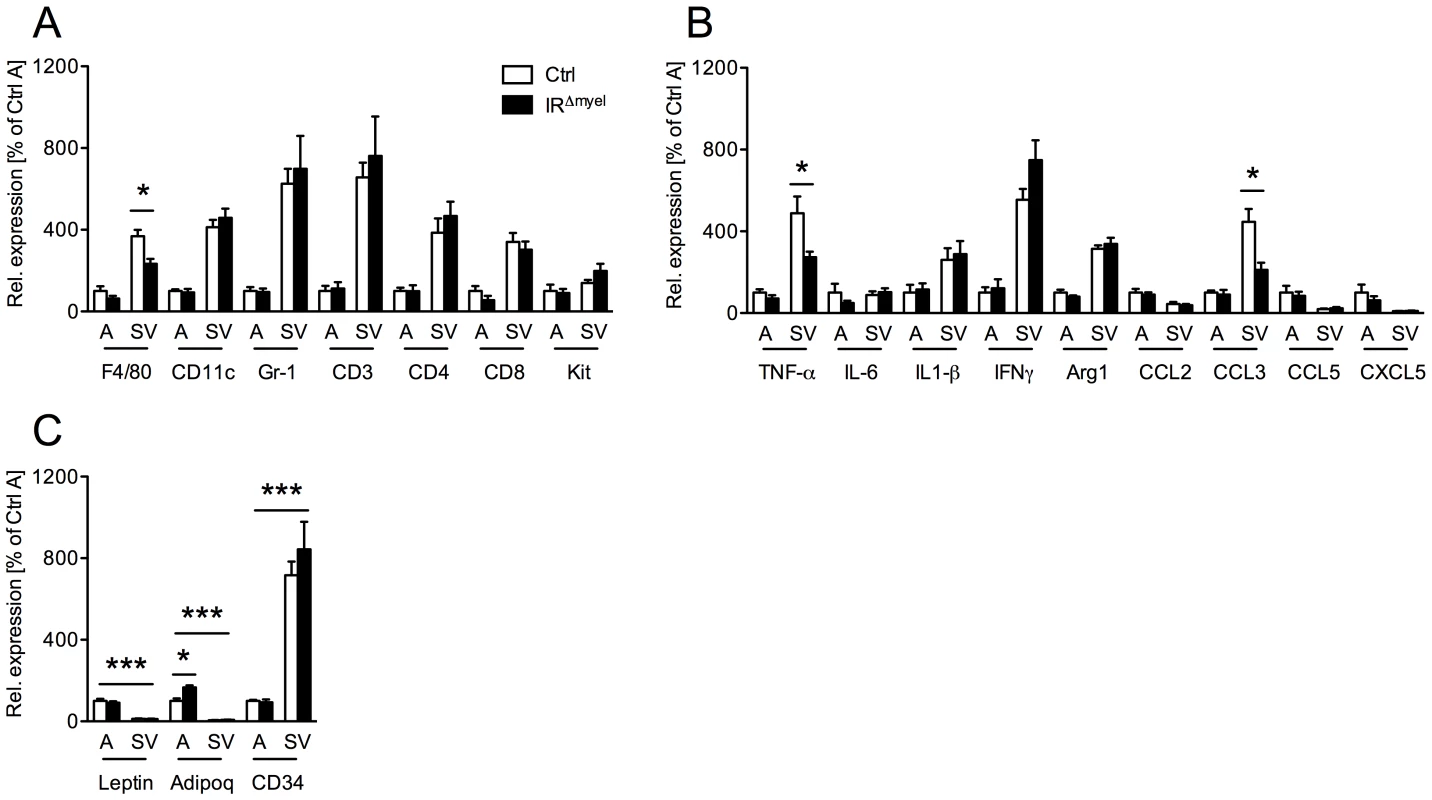

Since not only macrophages, but also a variety of other immune cells are highly abundant in the obese adipose tissue and contribute to the development of obesity-induced insulin resistance [12], [13], [24], we assessed mRNA expression of different immune cell markers in the stromal vascular (SV) fraction of WAT from obese control - and IRΔmyel-mice. In control mice, markers for macrophages (F4/80), dendritic cells (CD11c), granulocytes (Gr-1), T-lymphocytes (CD3, CD4, CD8) and mast cells (Kit) were highly enriched in the SV fraction compared to adipocytes (Figure 5A). However, in line with the data on whole WAT, we observed a specific reduction of the macrophage marker F4/80, but not of markers for granulocytes, mast cells, dendritic cells or T-lymphocytes, in the SV fraction of IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5. Obese IRΔmyel-mice exhibit reduced macrophage marker and pro-inflammatory gene expression in stromal vascular cells of the adipose tissue.

(A) Relative expression of immune cell markers F4/80, CD11c, Gr-1, CD3, CD4, CD8 and Kit mRNA in adipocytes (A) and stromal vascular (SV) fraction of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed HFD. (n = 5 mice per genotype.) (B) Relative expression of cytokines and chemokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IFNγ, Arg1, CCL2/MCP1, CCL3/MIP1α, CCL5/Rantes and CXCL5 mRNA in adipocytes (A) and stromal vascular (SV) fraction of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed HFD. (n = 5 mice per genotype.) (C) Relative mRNA expression of adipocyte-specific genes leptin and adiponectin (adipoq) and stromal vascular cell-specific gene CD34 in adipocytes (A) and stromal vascular (SV) fraction of male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed HFD. (n = 5 mice per genotype.) (Results are means ± SEM; white bars represent controls and black bars represent IRΔmyel-mice; *p≤0.05; ***p≤0.001.) Consistent with the specific reduction of macrophage infiltration, further analysis revealed a decrease in mRNA expression of the cytokine TNF-α and the chemokine CCL3/MIP-1α in SV fraction of IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 5B), indicating reduced inflammation in this compartment. Notably, although TNF-α, interleukin (IL) 1β, interferon (IFN) γ and arginase (Arg) 1 showed higher expression in SV fraction than in adipocytes, IL-6, CCL2/MCP-1, CCL5/Rantes and CXCL5 were equally if not higher expressed by adipocytes compared to SV fraction (Figure 5B).

To verify efficient separation of adipocytes from SV fraction, we analyzed expression of leptin, adiponectin and CD34 in both compartments. As expected, leptin and adiponectin were exclusively expressed in adipocytes, while CD34 expression was highly restricted to the SV fraction (Figure 5C).

Importantly, adiponectin expression was significantly increased in adipocytes from IRΔmyel-mice compared to controls, pointing towards increased insulin sensitivity in these animals (Figure 5C).

Taken together, our data indicate that disruption of the insulin receptor in myeloid cells specifically interferes with the obesity-associated recruitment of macrophages to adipose tissue and ultimately leads to reduced local expression of cytokines and chemokines in WAT.

Insulin receptor–deficient macrophages exhibit increased susceptibility to lipid-induced apoptosis and reduced expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9

The observed reduction of adipose tissue macrophage content in obese IRΔmyel-mice, among other factors, might arise from (i) enhanced susceptibility to apoptosis or (ii) reduced invasive capacity of these cells.

To directly address the hypothesis that IR signaling in macrophages might control these processes, we first analyzed the regulation of apoptosis in response to fatty acids to mimic the metabolic environment present upon high fat feeding. To this end, macrophages were isolated from the bone marrow of control - and IRΔmyel-mice, stimulated with palmitate in the absence or presence of insulin and TUNEL assays were performed. Palmitate stimulation profoundly induced apoptosis in control macrophages and insulin significantly reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells in control cells both in the absence and presence of lipid stimulation (Figure S2A, S2B). However, insulin failed to reduce apoptosis in the IR-deficient macrophages in either the basal or palmitate-stimulated state (Figure S2A, S2B). Furthermore, quantitative realtime PCR analysis suggested that the protective effect of insulin is mediated through stimulation of Bcl-2 mRNA rather than suppression of Bax mRNA expression (Figure S2C, S2D). Nonetheless, this in vitro observation did neither translate into increased numbers of apoptotic macrophages in adipose tissue nor into reduced numbers of circulating monocytes in obese IRΔmyel-mice (data not shown).

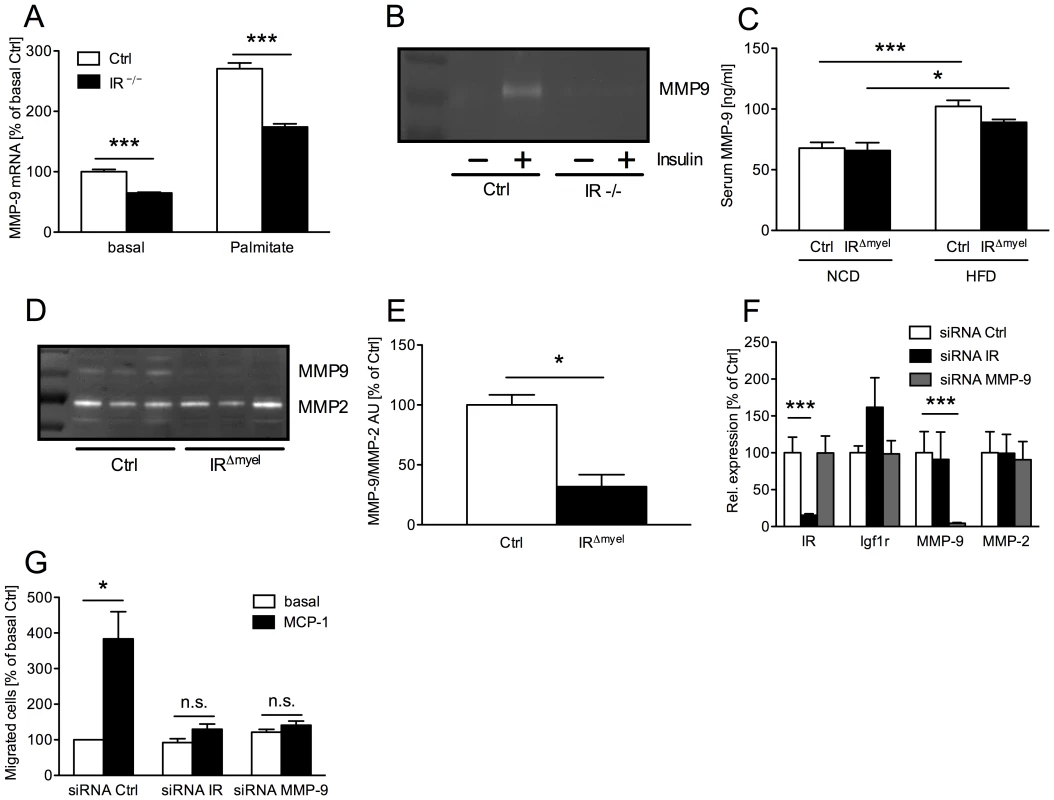

Besides control of macrophage survival, an important prerequisite for macrophage invasion into tissues is their ability to express and secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which then help to degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins to allow trans-ECM migration. Since it has recently been established that MMP-9 (gelatinase B) plays a critical role in inflammatory macrophage migration [25], we assessed MMP-9 expression and activation in macrophages of control - and IRΔmyel-mice. Peritoneally elicited macrophages were either left untreated (basal) or were stimulated with palmitate and expression of MMP-9 mRNA was determined. Intriguingly, IR-deficient cells exhibited a dramatic reduction of MMP-9 mRNA expression both in the basal state as well as upon stimulation with palmitate (Figure 6A). Importantly, IR disruption in macrophages not only affected MMP-9 expression, but also translated into reduced MMP-9 activity. Thus, zymographical analysis of conditioned media revealed higher MMP-9 activity in those obtained from control macrophages compared to those from IR-deficient cells (Figure 6B).

Fig. 6. Myeloid cell-restricted insulin receptor deficiency leads to reduced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 expression in macrophages and white adipose tissue of IRΔmyel-mice.

(A) Relative expression of MMP-9 mRNA in peritoneal macrophages of control- and IRΔmyel-mice. Cells were left untreated (basal) or stimulated with palmitate (500 µM) for 4 h. (n = 3 independent experiments.) (B) Conditioned medium from 24 h untreated (basal) and insulin-stimulated (50 ng/ml) bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) of control- and IRΔmyel-mice (IR −/−) was analyzed for MMP-9 gelatinolytic activtity. (representative zymogram of 3 independent experiments shown.) (C) Serum MMP-9 concentration in male control- and IRΔmyel-mice fed either NCD or HFD. (n = 10–12 mice per genotype and diet.) (D) White adipose tissue lysates from obese control- and IRΔmyel-mice were analyzed for gelatinolytic activity. (E) Densitometrical analysis of MMP-9 vs MMP-2 in zymograms of WAT from obese control- and IRΔmyel-mice. (AU = arbitrary units; n = 3.) (F) Relative expression of insulin receptor (IR), insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (Igf1r), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 and MMP-2 mRNA in silenced BMDM. (white bars = siRNA Ctrl, black bars = siRNA IR, grey bars = siRNA MMP-9; n = 3.) (G) Chemotaxis of silenced BMDM through a gelatin matrix was analyzed using a transwell migration assay. (white bars = basal migration, black bars = migration against 100 ng/ml MCP-1; n = 3 independent experiments.) (Results are means ± SEM; white bars represent controls and black bars represent IR-deficient macrophages/IRΔmyel-mice unless stated otherwise; *p≤0.05; ***p≤0.001; n.s. = not significant.) To verify the in vivo relevance of this cell-autonomous impairment in MMP-9 expression and activation, we first determined serum MMP-9 concentrations in lean and obese control and IRΔmyel-mice. While HFD induced a highly significant increase of circulating MMP-9 in control animals, this increase was less profound in IRΔmyel-mice (Figure 6C). Furthermore, we assessed gelatinolytic activity in WAT lysates of obese control - and IRΔmyel-mice. Strikingly, while MMP-2 activation was unaltered, WAT of IRΔmyel-mice exhibited drastically reduced MMP-9 activation compared to controls, possibly reflecting the reduced accumulation of macrophages in this compartment (Figure 6D and 6E).

To further functionally analyze the effect of IR-deficiency on macrophage migration, we performed transwell migration assays with wildtype BMDM transfected with siRNAs directed against either IR or MMP-9. Compared to a scrambled control siRNA, both oligonucleotides mediated efficient and specific knockdown of their respective target mRNAs without reducing expression of closely related insulin-like growth factor (IGF) 1 receptor and MMP-2 mRNA (Figure 6F). BMDM transfected with the control siRNA showed an approximately 4-fold increase of migrated cells through gelatin-coated membranes in response to MCP-1 compared to the basal level (Figure 6G). However, knockdown of MMP-9 significantly blunted this response and MCP-1 failed to enhance basal migration significantly (Figure 6G). Strikingly, siRNA-mediated ablation of IR reduced macrophage migration capacity to a similar degree as that of MMP-9 (Figure 6G).

Taken together, our experiments reveal that insulin action in macrophages promotes tissue invasion capacity of these cells in vitro and in vivo, thereby critically controlling high fat diet-associated macrophage invasion and activation in WAT upon induction of obesity.

Discussion

Insulin resistance in metabolically relevant insulin target tissues, such as skeletal muscle, liver, adipose tissue and more recently the brain, represents a well-studied key characteristic during the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus [26]–[30]. Insulin resistance can arise via different mechanisms e.g. mutations in genes encoding insulin signaling components or their reduced expression [31], [32]. However, it has been demonstrated that insulin resistance associated with obesity largely stems from posttranslational modifications of insulin signaling proteins, such as inhibitory serine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor or its downstream signaling mediators [33]. Here, activation of pro-inflammatory signaling cascades, particularly JNK and IKK, have been shown to inhibit insulin action, although to different, tissue-specific extent [8], [34]–[36]. The establishment of a chronic pro-inflammatory state during the course of obesity stems from expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in adipose tissue, particularly through the recruitment of cells of the innate immune response system to WAT [5], [7]. The critical importance of innate immune response activation during the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance has been highlighted by the phenotype of mice with targeted disruption of the NFκB pathway in myeloid lineage cells, as well as mice deficient for the chemokine receptor CCR2, which both exhibit reduced WAT inflammation and are therefore protected from obesity-induced insulin resistance [11], [37].

While these findings have provided compelling evidence for the immune response pathway to cause insulin resistance in liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, the primary effect of insulin action and insulin resistance in cells of the innate immune system has been poorly investigated and remains controversial. Thus, while there is considerable evidence for a role of inflammation in producing insulin resistance in individuals with type 2 diabetes [38]–[40], it has also been shown that insulin treatment of obese humans can reverse the pro-inflammatory state in macrophages [41], [42], raising a question of which is cause and which is effect. Also, it is not clear if this anti-inflammatory effect is a direct effect of insulin on cells of the immune system or if the reversal of inflammation occurs secondary to normalization of hyperglycemia and other metabolic abnormalities [43]. To further complicate the matter, insulin has been shown to directly increase TNF-α expression in human monocytes, pointing towards a possible direct pro-inflammatory role for insulin in macrophages [16]. Indeed, the latter is consistent with our previous observation that myeloid cell-restricted insulin resistance protects apolipoproteinE-deficient mice from the development of atherosclerosis due to impaired inflammatory response [19]. Alternatively, differential pro - and anti-inflammatory effects of insulin may represent different stages of a process representing acute versus chronic stimulation [44].

The findings of the present study directly demonstrate an unexpected and pivotal role for insulin signal transduction in the control of innate immune cell behavior in the obese state, such that chronic impairment of insulin action in myeloid lineage cells protects from obesity-associated inflammation. This is further supported by the observation that mice with bone marrow-restricted disruption of cbl-associated protein (CAP), a downstream component of insulin action in control of glucose transport, are protected from obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance [18]. However, these experiments did not specifically address the role of insulin action, as CAP is a scaffold protein implicated both in insulin signaling and also cytoskeleton regulation [45], [46].

The present results not only reveal clearly that IR-dependent signaling is critical for macrophage recruitment to WAT upon obesity development, they also define at least two potential mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon: increased apoptosis of macrophages and reduced tissue invasion by these cells due to decreased expression of MMP-9.

It is well documented that insulin can protect macrophages from apoptosis induced by numerous stimuli, such as serum/glucose deprivation, lipopolysaccharides and UV-irradiation in vitro [17], [20], [47]. More recently, Senokuchi et al. showed that insulin protects macrophages from ER stress-mediated apoptosis by free cholesterol in the development of atherosclerosis [20], [48]. Consistent with the latter notion, we find that saturated fatty acids, such as palmitate, which are increased in the circulation of obese patients [49], can result in macrophage apoptosis and that this effect is inhibited by insulin in vitro. However, we could not observe increased macrophage apoptosis in adipose tissue or altered numbers of circulating monocytes in obese IRΔmyel-mice, questioning the in vivo relevance of this finding.

Aside from regulation of macrophage apoptosis, we find that insulin promotes expression and activation of MMP-9 in these cells, a protease involved in tissue invasion by macrophages [25]. Furthermore, we could directly demonstrate that siRNA-mediated ablation of MMP-9 drastically impairs macrophage transmigration through a gelatin matrix and that this can be phenocopied by loss of the insulin receptor. Consistent with these results, it has been demonstrated that insulin augments MMP-9 in human monocytes in vitro [50] and that degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components by MMP-9 represents a key step during macrophage tissue invasion [51]. Indeed, reduced MMP-9 activity diminishes macrophage trans-ECM migration and protects from local inflammation and inflammation-associated cardiovascular disease [25]. Interestingly, San José et al. have recently demonstrated that insulin activates MMP-9 in murine macrophages in a PI3K/PKC-dependent manner through stimulation of the NADPH oxidase system [52]. Here, the authors propose that insulin-dependent MMP-9 activation might contribute to plaque instability in atherosclerotic lesions. Taking that into account, our results underline the important role of insulin receptor-dependent regulation of MMP-9 in macrophages and further extend it to another hyperinsulinemia-related disease state i.e. the development of obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance.

Notably, the LysMCre transgene mediates recombination of loxP-flanked alleles not only in macrophages but also in other myeloid lineage-derived cell types [53]. Therefore, one key question remains why, in our model, the reduction of adipose tissue infiltration is specific for macrophages while marker expression of other immune cell types e.g. granulocytes, T-lymphocytes and mast cells was unchanged. This might be due to the time-dependent fashion in which different subsets of immune cells invade the adipose tissue over the course of obesity. While adipose tissue granulocytes and T-lymphocytes already appear after 7 days and 6 weeks, respectively [13], [24], macrophage numbers do not significantly increase before 12–16 weeks of high fat feeding [7], [13]. Therefore, we cannot exclude that, despite macrophages, adipose tissue numbers of distinct immune cell subsets may be changed at different stages of obesity in our model. Additionally, immune cells invading the adipose tissue, especially macrophages and T-lymphocytes, can be further divided into distinct subtypes which are characterized by differential expression of specific surface markers [13], [54], [55]. Thus, analysis of adipose tissue immune cell populations by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) could potentially yield a higher resolution of adipose tissue inflammatory cell composition than the quantitative realtime PCR analysis performed in this study. Nevertheless, our experiments indicate that protection from diet-induced insulin resistance appears to be primarily paralleled by reduced WAT-macrophage recruitment.

Another question is why reduced macrophage accumulation in obese IRΔmyel-mice is restricted to adipose tissue, while no significant difference of F4/80 expression could be observed in liver and skeletal muscle of these animals. This might be explained by our finding that in wildtype mice the obesity-induced infiltration of macrophages into adipose tissue is several magnitudes higher (∼20-fold vs NCD) than into liver and skeletal muscle (max. 2-fold). Therefore, the effect of general macrophage-autonomous impairment of migration ability may be particularly predominant in adipose tissue compared to other insulin target tissues.

In conclusion, our study directly demonstrates that, despite its positive effects on glucose metabolism in target tissues such as liver, skeletal muscle and WAT, in vivo insulin can also play a deleterious role during the development of the metabolic syndrome by its actions in cells of the innate immune response system. The molecular mechanism of how the insulin receptor signaling pathway affects macrophage function remains to be further defined, but the present study suggests that this may offer a site for pharmacological intervention that could lead to novel therapeutic strategies for metabolic diseases.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were conducted in compliance with protocols approved by local government authorities and were in accordance with NIH guidelines. Mice were housed in groups of 3–5 at 22–24°C in a 12 : 12 h light/dark cycle with lights on at 6 a.m. Animals were either fed a normal chow diet (Teklad Global Rodent # T.2018.R12; Harlan, Germany) containing 53.5% of carbohydrates, 18.5% of protein, and 5.5% of fat (12% of calories from fat) or from week 4 of age a high fat diet (# C1057; Altromin, Germany) containing 32.7%, 20% and 35.5% of carbohydrates, protein and fat (55.2% of calories from fat), respectively. Water was available ad libitum and food was only withdrawn if required for an experiment. Body weight was measured once a week. Genomic DNA was isolated from tail tips, genotyping was performed by PCR. All experiments on mice were performed at 16 weeks of age.

Generation of mice

LysMCre mice were mated with IRlox/lox mice, and a breeding colony was maintained by mating IRlox/lox with LysMCre-IRlox/lox mice. IRlox mice had been backcrossed for at least 5 generations on a C57BL/6 background, and LysMCre mice – initially established on a C57BL6/129sv background – had been backcrossed for 10 generations on a C57BL6 background before intercrossing them with IRlox mice. Only male animals from the same mixed background strain generation were compared to each other. LysMCre mice were genotyped by PCR as previously described [53]. IRlox/lox mice were genotyped by PCR with primers crossing the loxP site as previously described [26].

Body composition

Body fat content was measured in vivo by nuclear magnetic resonance using a minispec mq7.5 (Bruker Optik, Ettlingen, Germany) as previously described [56].

Indirect calorimetry and food intake

All measurements were performed in a PhenoMaster System (TSE systems, Bad Homburg, Germany), which allows measurement of metabolic performance. Mice were placed at room temperature (22°C–24°C) in 7.1-l chambers of the PhenoMaster open circuit calorimetry. Mice were allowed to adapt to the chambers for at least 24h. Food and water were provided ad libitum in the appropriate devices and measured by the build-in automated instruments. Parameters of indirect calorimetry and food intake were measured for at least the following 48 hr. Presented data are average values obtained in these recordings.

Glucose and insulin tolerance tests

Glucose tolerance tests were performed after a 16–17h fasting period. After determination of fasted blood glucose levels, each animal received an i.p. injection of 20% glucose (10ml/kg) (DeltaSelect, Germany). Blood Glucose levels were detected after 15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes. Insulin tolerance tests were performed with mice fed ad libitum. After determination of basal blood glucose levels, each animal obtained an i.p. injection of insulin, 0.75U/kg (Actrapid; Novo Nordisk A/S, Denmark), and blood glucose was measured 15, 30 and 60 minutes after insulin injection.

Euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamp studies

Catheter implantation

At the age of 16 weeks, male mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of avertin and adequacy of the anesthesia was ensured by the loss of pedal reflexes. A Micro-Renathane catheter (MRE 025; Braintree Scientific Inc., MA, USA) was inserted into the right internal jugular vein, advanced to the level of the superior vena cava, and secured in its position in the proximal part of the vein with 4-0 silk; the distal part of the vein was occluded with 4-0 silk. After irrigation with physiological saline solution, the catheter was filled with heparin solution and sealed at its distal end. The catheter was subcutaneously tunneled, thereby forming a subcutaneous loop, and exteriorized at the back of the neck. Cutaneous incisions were closed with a 3-0 silk suture and the free end of the catheter was attached to the suture in the neck as to permit the retrieval of the catheter on the day of the experiment. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1 ml of saline containing 15µg/g body weight of tramadol and placed on a heating pad in order to facilitate recovery.

Clamp experiment

Only mice that had regained at least 90% of their preoperative body weight after 6 days of recovery were included in the experimental groups. After starvation for 15 hours, awake animals were placed in restrainers for the duration of the clamp experiment. After a D-[3-3H]Glucose (Amersham Biosciences, UK) tracer solution bolus infusion (5µCi), the tracer was infused continuously (0.05µCi/min) for the duration of the experiment. At the end of the 40-minute basal period, a blood sample (50µl) was collected for determination of the basal parameters. To minimize blood loss, red blood cells were collected by centrifugation and reinfused after being resuspended in saline. Insulin (human regular insulin; NovoNordisc Pharmaceuticals, Inc., NJ, USA) solution containing 0.1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was infused at a fixed rate (4µU/g/min) following a bolus infusion (40µU/g). Blood glucose levels were determined every 10 minutes (B-Glucose Analyzer; Hemocue AB, Sweden) and physiological blood glucose levels (between 120 and 150 mg/dl) were maintained by adjusting a 20% glucose infusion (DeltaSelect, Germany). Approximately 60 minutes before steady state was achieved, a bolus of 2-Deoxy-D-[1-14C]Glucose (10µCi, Amersham) was infused. Steady state was ascertained when glucose measurements were constant for at least 30 min at a fixed glucose infusion rate and was achieved within 100 to 130 min. During the clamp experiment, blood samples (5µl) were collected after the infusion of the 2-Deoxy-D-[1-14C]Glucose at the time points 0, 5, 15, 25, 35 min etc. until reaching the steady state. During the steady state, blood samples (50µl) for the measurement of steady state parameters were collected. At the end of the experiment, mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and brain, WAT and skeletal muscle tissues were dissected and stored at −20°C. Assays. Plasma [3-3H]Glucose radioactivity of basal and steady state samples was determined directly after deproteinization with 0.3M Ba(OH)2 and 0.3M ZnSO4 and also after removal of 3H2O by evaporation, using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckmann, Germany). Plasma Deoxy-[1-14C]Glucose radioactivity was directly measured in the liquid scintillation counter. Tissue lysates were processed through Ion exchange chromatography columns (Poly-PrepR Prefilled Chromatography Columns, AGR1-X8 formate resin, 200–400 mesh dry; Bio Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) to separate 2-Deoxy-D-[1-14C]Glucose (2DG) from 2-Deoxy-D-[1-14C]Glucose-6-Phosphate (2DG6P).

Calculations

Glucose turnover rate (mg×kg−1×min−1) was calculated as the rate of tracer infusion (dpm/min) divided by the plasma glucose-specific activity (dpm/mg) corrected for body weight. HGP (mg×kg−1×min−1) was calculated as the difference between the rate of glucose appearance and glucose infusion rate. In vivo glucose uptake for each tissue (nmol×g−1×min−1) was calculated based on the accumulation of 2DG6P in the respective tissue and the disappearance rate of 2DG from plasma as described previously [57].

Isolation of murine macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages

Mice were injected intreaperitoneally with 2 ml thioglycollate medium (4% in PBS). On day 4 post injection, the animals were sacrificed by CO2 anesthesia and cells were collected by peritoneal lavage with sterile PBS. After several washing steps, cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin) and plated at a density of 106 cells/ml.

Bone marrow–derived macrophages

Mice were sacrificed by CO2 anesthesia, rinsed in 70% (v/v) ethanol and bone marrow was isolated from femurs and tibias. After several washing steps, bone marrow cells were resuspended in IMDM (supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10 ng/ml recombinant M-CSF (Peprotech)). Bone marrow cells were plated at a concentration of 1–2×106 cells/ml in IMDM (supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10 ng/ml recombinant M-CSF) on 10 cm bacterial petridishes and differentiated for 7–10 days. Preceding all the experiments, macrophages were washed two times with sterile PBS and, if stimulated with insulin, serum-starved for 16–20 h. Palmitate media was prepared as previously described [58].

siRNA transfections

650 pmole siRNA (Silencer Select siRNA negative control, #4390846; Insr, #S68367; MMP9, #S69944; Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) were transferred to a 4-mm cuvette (Bridge, Providence, RI) and incubated for 3 minutes with 4×106 bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) in 100 µL Optimem (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD) before electroporation in a Gene Pulser X cell + CE module (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Pulse conditions were square wave, 1000 V, 2 pulses, and 0.5-ms pulse length. 72–96 hours after electroporation, RNAi efficiency was tested using quantitative realtime PCR and silenced BMDM were used for functional assays.

Analytical procedures

Blood glucose levels were determined from whole venous blood using an automatic glucose monitor (GlucoMen GlycÓ; A. Menarini Diagnostics, Italy). Leptin, insulin, TNF-α, adiponectin and MMP-9 levels in serum were measured by ELISA using mouse standards according to manufacturer's guidelines (Mouse Leptin ELISA; Crystal Chem, IL, USA / Mouse Insulin ELISA; Crystal Chem, IL, USA / Mouse Adiponectin (HMW & total) ELISA; Alpco, NH, USA / Mouse TNF-α/TNFSF1A and MMP-9 (total) Quantikine ELISA Kit; R&D Systems, Inc., MN, USA). Serum FFAs were determined by colorimetric assay according to manufacturer's guidelines (NEFA kit; Wako chemicals GmbH, Neuss, Germany).

Western blot analysis

Protein isolation from cells and tissues was performed as previously described [26]. Western blot analysis was performed as previously described [26] with antibodies raised against insulin receptor β subunit (IRβ, catalog # sc-711; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) and Akt (catalog # 9272; Cell Signaling) as a loading control. SAPK/JNK Kinase assay (catalog # 9810; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) was performed following the manufacturers instructions. Western blot analysis of total JNK input was performed with an antibody raised against JNK (catalog # 9252; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.). Quantification of changes in optical density was performed with Quantity One (Bio-Rad Laboratories, München, Germany).

Gelatin zymography

Gelatin zymography was performed as previously described [59]. Briefly, cell culture supernatants and tissue extracts were purified from lower molecular weight proteins (<50 kDa) by centrifugation through Microcon YM-50 Centrifugal Filter Units (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). 10–40 µg of protein were separated on SDS polyacrylamide gels (containing 0.1 mg/ml gelatine). Gels were renatured in 2.5% Triton X-100 followed by incubation in MMP activation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 8) at 37°C overnight in a humidified chamber. Gels were stained with 2.5 g/l Coomassie brilliant-blue R-250. Destaining was carried out with 40% (v/v) methanol until the bands appeared clearly.

Isolation of adipocytes and stromal vascular fraction

Animals were sacrificed and epididymal fat pads were removed under sterile conditions. Adipocytes were isolated by collagenase (1 mg/ml) digestion for 45 min at 37°C in DMEM/Ham's F-12 1∶1 (DMEM/F12) containing 1% BSA. Digested tissues were filtered through sterile 150-µm nylon mesh and centrifuged at 250×g for 5 min. The floating fraction consisting of pure isolated adipocytes was then removed and washed three more times before proceeding to experiments. The pellet, representing the stromal vascular fraction containing preadipocytes, macrophages and other cell types, was resuspended in erythrocyte lysis buffer consisting of 154 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM EDTA for 10 min.

Analysis of gene expression

RNA was isolated from cells and tissues using the Qiagen RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The RNA was reversely transcribed with EuroScript Reverse Transcriptase (Eurogentec, Belgium) and amplified using TaqMan Universal PCR-Master Mix, NO AmpErase UNG with TaqMan Assay-on-demand kits (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Relative expression of target mRNAs (Adiponectin Mm00456425_m1, Arg1 Mm00475988_m1, Bcl2 Mm00477631_m1, Bax Mm00432050_m1, Ccl2 Mm00441242_m1, Ccl3 Mm00441258, Ccl5 Mm01302428_m1, Cxcl5 Mm00436451_g1, CD11c Mm00498698_m1, CD3 Mm00442746_m1, CD34 Mm00519283_m1, CD4 Mm00442754_m1, CD8 Mm01182108_m1, F4/80 Mm00802530_m1, G6pase Mm839363_m1, Gr-1 Mm00459644_m1, Il1β Mm00434228_m1, Il6 Mm00446190_m1, Ifng Mm00801778_m1, Igf1r Mm00802841_m1, InsR Mm00439693_m1, Kit Mm00445212_m1, Leptin Mm00434759, Mmp2 Mm00439506_m1, Mmp9 Mm00442991_m1, Pck1 Mm00440636_m1, TNFα Mm00443258_m1) was determined using standard curves based on WAT and samples were adjusted for total mRNA content by hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (Hprt1 Mm00446968_m1) mRNA quantitative PCR. Calculations were performed by a comparative method (2−ΔΔCT). Quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI-PRISM 7900 HT Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Germany). Assays were linear over 4 orders of magnitude.

Apoptosis assay

For assessment of apoptosis in primary macrophages, the DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was used. The protocol for adherent cells was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Slides were mounted with Vectashield DAPI medium (Vector Laboratories Inc, Burlingame, CA, USA) and analyzed under a fluorescence microscope. Quantification of DAPI - and FITC-positive cells was performed using AxioVision 4.2 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany).

Transwell migration assay

Chemotaxis of BMDM was quantified using transwell migration assays. Polycarbonate filters (Costar, Corning, 24-well, 8 µm pore size) were coated with gelatin (0.2%, Sigma) for 1h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. BMDM (2×105 cells in 300 µl IMDM/0,5% FCS) were placed in the upper compartment and subsequently incubated at 37°C/5% CO2 to adhere. After 1h, 100 ng/ml MCP-1 (Peprotech) was added to IMDM/0,5% FCS in the lower compartment. Control assays were performed without chemokine. After incubation for 4 h at 37°C/5% CO2, transmigrated cells were stained with DAPI and nuclei were counted under a fluorescence microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin sections as previously described [60]. Quantification of adipocyte size and Mac-2-positive area was performed with AxioVision 4.2 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistical methods

Data was analyzed for statistical significance using a two-tailed unpaired student's T-Test.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HotamisligilGS

ArnerP

CaroJF

AtkinsonRL

SpiegelmanBM

1995 Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 95 2409 2415

2. HotamisligilGS

ShargillNS

SpiegelmanBM

1993 Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 259 87 91

3. KernPA

RanganathanS

LiC

WoodL

RanganathanG

2001 Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280 E745 751

4. KernPA

SaghizadehM

OngJM

BoschRJ

DeemR

1995 The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue. Regulation by obesity, weight loss, and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. J Clin Invest 95 2111 2119

5. WeisbergSP

McCannD

DesaiM

RosenbaumM

LeibelRL

2003 Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112 1796 1808

6. WellenKE

HotamisligilGS

2003 Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112 1785 1788

7. XuH

BarnesGT

YangQ

TanG

YangD

2003 Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112 1821 1830

8. HirosumiJ

TuncmanG

ChangL

GorgunCZ

UysalKT

2002 A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature 420 333 336

9. UekiK

KondoT

TsengYH

KahnCR

2004 Central role of suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins in hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 10422 10427

10. YuanM

KonstantopoulosN

LeeJ

HansenL

LiZW

2001 Reversal of obesity - and diet-induced insulin resistance with salicylates or targeted disruption of Ikkbeta. Science 293 1673 1677

11. ArkanMC

HevenerAL

GretenFR

MaedaS

LiZW

2005 IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med 11 191 198

12. LiuJ

DivouxA

SunJ

ZhangJ

ClementK

2009 Genetic deficiency and pharmacological stabilization of mast cells reduce diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Nat Med 15 940 945

13. NishimuraS

ManabeI

NagasakiM

EtoK

YamashitaH

2009 CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nat Med 15 914 920

14. BarRS

GordenP

RothJ

KahnCR

De MeytsP

1976 Fluctuations in the affinity and concentration of insulin receptors on circulating monocytes of obese patients: effects of starvation, refeeding, and dieting. J Clin Invest 58 1123 1135

15. Costa RosaLF

SafiDA

CuryY

CuriR

1996 The effect of insulin on macrophage metabolism and function. Cell Biochem Funct 14 33 42

16. IidaKT

ShimanoH

KawakamiY

SoneH

ToyoshimaH

2001 Insulin up-regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in macrophages through an extracellular-regulated kinase-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 276 32531 32537

17. IidaKT

SuzukiH

SoneH

ShimanoH

ToyoshimaH

2002 Insulin inhibits apoptosis of macrophage cell line, THP-1 cells, via phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-dependent pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22 380 386

18. LesniewskiLA

HoschSE

NeelsJG

de LucaC

PashmforoushM

2007 Bone marrow-specific Cap gene deletion protects against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med 13 455 462

19. BaumgartlJ

BaudlerS

SchernerM

BabaevV

MakowskiL

2006 Myeloid lineage cell-restricted insulin resistance protects apolipoproteinE-deficient mice against atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 3 247 256

20. HanS

LiangCP

DeVries-SeimonT

RanallettaM

WelchCL

2006 Macrophage insulin receptor deficiency increases ER stress-induced apoptosis and necrotic core formation in advanced atherosclerotic lesions. Cell Metab 3 257 266

21. RoytblatL

RachinskyM

FisherA

GreembergL

ShapiraY

2000 Raised interleukin-6 levels in obese patients. Obes Res 8 673 675

22. AritaY

KiharaS

OuchiN

TakahashiM

MaedaK

1999 Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257 79 83

23. FarajM

HavelPJ

PhelisS

BlankD

SnidermanAD

2003 Plasma acylation-stimulating protein, adiponectin, leptin, and ghrelin before and after weight loss induced by gastric bypass surgery in morbidly obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88 1594 1602

24. Elgazar-CarmonV

RudichA

HadadN

LevyR

2008 Neutrophils transiently infiltrate intra-abdominal fat early in the course of high-fat feeding. J Lipid Res 49 1894 1903

25. GongY

HartE

ShchurinA

Hoover-PlowJ

2008 Inflammatory macrophage migration requires MMP-9 activation by plasminogen in mice. J Clin Invest 118 3012 3024

26. BruningJC

MichaelMD

WinnayJN

HayashiT

HorschD

1998 A muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout exhibits features of the metabolic syndrome of NIDDM without altering glucose tolerance. Mol Cell 2 559 569

27. MichaelMD

KulkarniRN

PosticC

PrevisSF

ShulmanGI

2000 Loss of insulin signaling in hepatocytes leads to severe insulin resistance and progressive hepatic dysfunction. Mol Cell 6 87 97

28. BluherM

MichaelMD

PeroniOD

UekiK

CarterN

2002 Adipose tissue selective insulin receptor knockout protects against obesity and obesity-related glucose intolerance. Dev Cell 3 25 38

29. BruningJC

GautamD

BurksDJ

GilletteJ

SchubertM

2000 Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science 289 2122 2125

30. KochL

WunderlichFT

SeiblerJ

KonnerAC

HampelB

2008 Central insulin action regulates peripheral glucose and fat metabolism in mice. J Clin Invest 118 2132 2147

31. BruningJC

WinnayJ

Bonner-WeirS

TaylorSI

AcciliD

1997 Development of a novel polygenic model of NIDDM in mice heterozygous for IR and IRS-1 null alleles. Cell 88 561 572

32. KidoY

BurksDJ

WithersD

BruningJC

KahnCR

2000 Tissue-specific insulin resistance in mice with mutations in the insulin receptor, IRS-1, and IRS-2. J Clin Invest 105 199 205

33. HotamisligilGS

PeraldiP

BudavariA

EllisR

WhiteMF

1996 IRS-1-mediated inhibition of insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity in TNF-alpha - and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Science 271 665 668

34. CaiD

YuanM

FrantzDF

MelendezPA

HansenL

2005 Local and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-beta and NF-kappaB. Nat Med 11 183 190

35. RohlM

PasparakisM

BaudlerS

BaumgartlJ

GautamD

2004 Conditional disruption of IkappaB kinase 2 fails to prevent obesity-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 113 474 481

36. WunderlichFT

LueddeT

SingerS

Schmidt-SupprianM

BaumgartlJ

2008 Hepatic NF-kappa B essential modulator deficiency prevents obesity-induced insulin resistance but synergizes with high-fat feeding in tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 1297 1302

37. WeisbergSP

HunterD

HuberR

LemieuxJ

SlaymakerS

2006 CCR2 modulates inflammatory and metabolic effects of high-fat feeding. J Clin Invest 116 115 124

38. HundalRS

PetersenKF

MayersonAB

RandhawaPS

InzucchiS

2002 Mechanism by which high-dose aspirin improves glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 109 1321 1326

39. LarsenCM

FaulenbachM

VaagA

VolundA

EhsesJA

2007 Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 356 1517 1526

40. MavridisG

SouliouE

DizaE

SymeonidisG

PastoreF

2008 Inflammatory cytokines in insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 18 471 476

41. DandonaP

AljadaA

MohantyP

GhanimH

HamoudaW

2001 Insulin inhibits intranuclear nuclear factor kappaB and stimulates IkappaB in mononuclear cells in obese subjects: evidence for an anti-inflammatory effect? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86 3257 3265

42. van den BergheG

WoutersP

WeekersF

VerwaestC

BruyninckxF

2001 Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 345 1359 1367

43. Van den BergheG

WoutersPJ

BouillonR

WeekersF

VerwaestC

2003 Outcome benefit of intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill: Insulin dose versus glycemic control. Crit Care Med 31 359 366

44. IwasakiY

NishiyamaM

TaguchiT

AsaiM

YoshidaM

2008 Insulin exhibits short-term anti-inflammatory but long-term proinflammatory effects in vitro. Mol Cell Endocrinol

45. MatsonSA

PareGC

KapiloffMS

2005 A novel isoform of Cbl-associated protein that binds protein kinase A. Biochim Biophys Acta 1727 145 149

46. TosoniD

CestraG

2009 CAP (Cbl associated protein) regulates receptor-mediated endocytosis. FEBS Lett 583 293 300

47. LefflerM

HrachT

StuerzlM

HorchRE

HerndonDN

2007 Insulin attenuates apoptosis and exerts anti-inflammatory effects in endotoxemic human macrophages. J Surg Res 143 398 406

48. SenokuchiT

LiangCP

SeimonTA

HanS

MatsumotoM

2008 Forkhead transcription factors (FoxOs) promote apoptosis of insulin-resistant macrophages during cholesterol-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. Diabetes 57 2967 2976

49. RossnerS

WalldiusG

BjorvellH

1989 Fatty acid composition in serum lipids and adipose tissue in severe obesity before and after six weeks of weight loss. Int J Obes 13 603 612

50. FischoederA

MeyborgH

StibenzD

FleckE

GrafK

2007 Insulin augments matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in monocytes. Cardiovasc Res 73 841 848

51. Page-McCawA

EwaldAJ

WerbZ

2007 Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 221 233

52. San JoseG

BidegainJ

RobadorPA

DiezJ

FortunoA

2009 Insulin-induced NADPH oxidase activation promotes proliferation and matrix metalloproteinase activation in monocytes/macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 46 1058 1067

53. ClausenBE

BurkhardtC

ReithW

RenkawitzR

ForsterI

1999 Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res 8 265 277

54. NguyenMT

FavelyukisS

NguyenAK

ReichartD

ScottPA

2007 A subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 282 35279 35292

55. LumengCN

BodzinJL

SaltielAR

2007 Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest 117 175 184

56. MesarosA

KoralovSB

RotherE

WunderlichFT

ErnstMB

2008 Activation of Stat3 signaling in AgRP neurons promotes locomotor activity. Cell Metab 7 236 248

57. FerreP

LeturqueA

BurnolAF

PenicaudL

GirardJ

1985 A method to quantify glucose utilization in vivo in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue of the anaesthetized rat. Biochem J 228 103 110

58. ListenbergerLL

OryDS

SchafferJE

2001 Palmitate-induced apoptosis can occur through a ceramide-independent pathway. J Biol Chem 276 14890 14895

59. KappertK

MeyborgH

ClemenzM

GrafK

FleckE

2008 Insulin facilitates monocyte migration: a possible link to tissue inflammation in insulin-resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 365 503 508

60. CintiS

MitchellG

BarbatelliG

MuranoI

CeresiE

2005 Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res 46 2347 2355

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Epistasis of Transcriptomes Reveals Synergism between Transcriptional Activators Hnf1α and Hnf4αČlánek SMA-10/LRIG Is a Conserved Transmembrane Protein that Enhances Bone Morphogenetic Protein SignalingČlánek B1 SOX Coordinate Cell Specification with Patterning and Morphogenesis in the Early Zebrafish EmbryoČlánek Bulk Segregant Analysis by High-Throughput Sequencing Reveals a Novel Xylose Utilization Gene fromČlánek Abundant Quantitative Trait Loci Exist for DNA Methylation and Gene Expression in Human Brain

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 5

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Digital Quantification of Human Eye Color Highlights Genetic Association of Three New Loci

- Common Genetic Variants near the Brittle Cornea Syndrome Locus Influence the Blinding Disease Risk Factor Central Corneal Thickness

- Age- and Temperature-Dependent Somatic Mutation Accumulation in

- All About Mitochondrial Eve: An Interview with Rebecca Cann

- Aging and Chronic Sun Exposure Cause Distinct Epigenetic Changes in Human Skin

- Transposed Genes in Arabidopsis Are Often Associated with Flanking Repeats

- A Survey of Genomic Traces Reveals a Common Sequencing Error, RNA Editing, and DNA Editing

- Gene Transposition Causing Natural Variation for Growth in

- The Polyproline Site in Hinge 2 Influences the Functional Capacity of Truncated Dystrophins

- Epistasis of Transcriptomes Reveals Synergism between Transcriptional Activators Hnf1α and Hnf4α

- Integration of Light Signals by the Retinoblastoma Pathway in the Control of S Phase Entry in the Picophytoplanktonic Cell

- The Proprotein Convertase Encoded by () Is Required in Corpora Cardiaca Endocrine Cells Producing the Glucose Regulatory Hormone AKH

- Sgs1 and Exo1 Redundantly Inhibit Break-Induced Replication and Telomere Addition at Broken Chromosome Ends

- A MATE-Family Efflux Pump Rescues the 8-Oxoguanine-Repair-Deficient Mutator Phenotype and Protects Against HO Killing

- The Relationship among Gene Expression, the Evolution of Gene Dosage, and the Rate of Protein Evolution

- SMA-10/LRIG Is a Conserved Transmembrane Protein that Enhances Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling

- The Nuclear Receptor DHR3 Modulates dS6 Kinase–Dependent Growth in

- Involvement of Global Genome Repair, Transcription Coupled Repair, and Chromatin Remodeling in UV DNA Damage Response Changes during Development

- B1 SOX Coordinate Cell Specification with Patterning and Morphogenesis in the Early Zebrafish Embryo

- Linkage and Association Mapping of Flowering Time in Nature

- Bulk Segregant Analysis by High-Throughput Sequencing Reveals a Novel Xylose Utilization Gene from

- Abundant Quantitative Trait Loci Exist for DNA Methylation and Gene Expression in Human Brain

- Ablation of Whirlin Long Isoform Disrupts the USH2 Protein Complex and Causes Vision and Hearing Loss

- Characterization of Oxidative Guanine Damage and Repair in Mammalian Telomeres

- DNA Adenine Methylation Is Required to Replicate Both Chromosomes Once per Cell Cycle

- Genome-Wide Copy Number Variation in Epilepsy: Novel Susceptibility Loci in Idiopathic Generalized and Focal Epilepsies

- FACT Prevents the Accumulation of Free Histones Evicted from Transcribed Chromatin and a Subsequent Cell Cycle Delay in G1

- GC-Biased Evolution Near Human Accelerated Regions

- Liver and Adipose Expression Associated SNPs Are Enriched for Association to Type 2 Diabetes

- Myeloid Cell-Restricted Insulin Receptor Deficiency Protects Against Obesity-Induced Inflammation and Systemic Insulin Resistance

- The Mating Type Locus () and Sexual Reproduction of : Insights into the Evolution of Sex and Sex-Determining Chromosomal Regions in Fungi

- B-Cyclin/CDKs Regulate Mitotic Spindle Assembly by Phosphorylating Kinesins-5 in Budding Yeast

- Post-Replication Repair Suppresses Duplication-Mediated Genome Instability

- Genome Sequence of the Plant Growth Promoting Endophytic Bacterium sp. 638

- Transcription Factors Mat2 and Znf2 Operate Cellular Circuits Orchestrating Opposite- and Same-Sex Mating in

- The Use of Orthologous Sequences to Predict the Impact of Amino Acid Substitutions on Protein Function

- Mutation in Archain 1, a Subunit of COPI Coatomer Complex, Causes Diluted Coat Color and Purkinje Cell Degeneration

- Shelterin-Like Proteins and Yku Inhibit Nucleolytic Processing of Telomeres

- Affecting Function Causes a Dilated Heart in Adult

- Manipulation of Behavioral Decline in with the Rag GTPase

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Common Genetic Variants near the Brittle Cornea Syndrome Locus Influence the Blinding Disease Risk Factor Central Corneal Thickness

- All About Mitochondrial Eve: An Interview with Rebecca Cann

- The Relationship among Gene Expression, the Evolution of Gene Dosage, and the Rate of Protein Evolution

- SMA-10/LRIG Is a Conserved Transmembrane Protein that Enhances Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání