-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaTargeting Cattle-Borne Zoonoses and Cattle Pathogens Using a Novel Trypanosomatid-Based Delivery System

Trypanosomatid parasites are notorious for the human diseases they cause throughout Africa and South America. However, non-pathogenic trypanosomatids are also found worldwide, infecting a wide range of hosts. One example is Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) theileri, a ubiquitous protozoan commensal of bovids, which is distributed globally. Exploiting knowledge of pathogenic trypanosomatids, we have developed Trypanosoma theileri as a novel vehicle to deliver vaccine antigens and other proteins to cattle. Conditions for the growth and transfection of T. theileri have been optimised and expressed heterologous proteins targeted for secretion or specific localisation at the cell interior or surface using trafficking signals from Trypanosoma brucei. In cattle, the engineered vehicle could establish in the context of a pre-existing natural T. theileri population, was maintained long-term and generated specific immune responses to an expressed Babesia antigen at protective levels. Building on several decades of basic research into trypanosomatid pathogens, Trypanosoma theileri offers significant potential to target multiple infections, including major cattle-borne zoonoses such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Brucella abortus and Mycobacterium spp. It also has the potential to deliver therapeutics to cattle, including the lytic factor that protects humans from cattle trypanosomiasis. This could alleviate poverty by protecting indigenous African cattle from African trypanosomiasis.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002340

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002340Summary

Trypanosomatid parasites are notorious for the human diseases they cause throughout Africa and South America. However, non-pathogenic trypanosomatids are also found worldwide, infecting a wide range of hosts. One example is Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) theileri, a ubiquitous protozoan commensal of bovids, which is distributed globally. Exploiting knowledge of pathogenic trypanosomatids, we have developed Trypanosoma theileri as a novel vehicle to deliver vaccine antigens and other proteins to cattle. Conditions for the growth and transfection of T. theileri have been optimised and expressed heterologous proteins targeted for secretion or specific localisation at the cell interior or surface using trafficking signals from Trypanosoma brucei. In cattle, the engineered vehicle could establish in the context of a pre-existing natural T. theileri population, was maintained long-term and generated specific immune responses to an expressed Babesia antigen at protective levels. Building on several decades of basic research into trypanosomatid pathogens, Trypanosoma theileri offers significant potential to target multiple infections, including major cattle-borne zoonoses such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Brucella abortus and Mycobacterium spp. It also has the potential to deliver therapeutics to cattle, including the lytic factor that protects humans from cattle trypanosomiasis. This could alleviate poverty by protecting indigenous African cattle from African trypanosomiasis.

Introduction

Human health is intimately linked to animal health through the impact of infectious agents on livestock productivity and their potential for zoonosis [1]. Indeed, animal borne disease represents the major source of both emergent and resurgent pathogens in humans, this affecting communities in both the developed and developing world. One major source of such zoonotic infections is cattle, which threaten human health in the developed world through their capacity to transmit bacterial infections including Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Brucella spp. and mycobacteria. In the developing world, livestock are also a reservoir for Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) caused by Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. This parasite, and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, is closely related to Trypanosoma brucei brucei, which cannot infect humans. The basis of this host restriction is that human serum contains a trypanolytic component of high-density lipoprotein, ApoLI, that kills T. brucei brucei [2], but to which the human infective parasites have evolved resistance [3], [4].

Although trypanosomes are important causes of human and animal disease, many species are non-pathogenic. One of these is Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) theileri, a cosmopolitan parasite of bovids that infects most cattle worldwide [5]–[11]. Although one report describes reduced milk yield in three infected cows [12], the ubiquity of infection with this organism in cattle herds suggests that it has no significant impact on health or productivity in healthy animals, while cases of disease in immuno-compromised animals are sufficiently rare as to merit individual case reports [13]–[15]. The parasite is transmitted in the contaminated faeces of tabanid flies and gains entry into the host through breaks in the skin or via contamination of the oral mucosa [16]. Thereafter, it lives extracellularly, being sustained at a low level (∼100 organisms/ml) for the life of the host. Being non-pathogenic, systemic, related to the genetically well-characterised T. brucei, and sustained long-term, we conceived that T. theileri would make a suitable protein delivery system in cattle, able to generate immunity to expressed antigens. As a naturally non-pathogenic kinetoplastid, T. theileri offers considerable advantages over alternative vaccine delivery systems that comprise engineered, attenuated pathogens such as Salmonella [17], [18], Mycobacterium [19], [20], E. coli [21], Vibreo cholera, Listeria or Shigella [22]. Furthermore, being maintained over long periods at low level, T. theileri offers the potential to generate sustained immune responses of greater efficacy than conventional vaccination approaches and to deliver therapeutic proteins of benefit to bovine health or to limit the zoonotic potential of cattle borne diseases.

Results

To develop T. theileri as a protein delivery system, the conditions for its axenic in vitro growth and genetic manipulation were established. To achieve this, a T. theileri isolate, originally identified as a contaminant of a primary bovine reticulocyte culture, was cultured under various conditions, optimal and sustained growth being achieved using a semi-defined medium containing 50% conditioned media from a bovine cell culture. In this medium, cell densities of 1×105 – 2×106 cells/ml were achieved during routine passage (Figure S1 in Text S1). Under these conditions, the position of the kinetoplast (a specialised mitochondrial genome in trypanosomatid parasites; [23]) varied in relation to the cell nucleus but this was not clearly dependent upon the cell culture density (Figure 1A, Figure S1 in Text S1). To generate stable transfectants, bi-cistronic and tri-cistronic expression constructs were developed that comprised a drug selectable marker gene and a reporter gene, this being integrated into the small subunit 18S ribosomal RNA gene locus (Figure 1B). Here, RNA polymerase I-mediated read-through transcription can drive efficient gene expression, transcripts being processed and capped via trans splicing of a T. theileri-specific spliced leader (SL) RNA sequence, matching the situation in other kinetoplastids [24], [25]. This SL sequence was identified by 5′RACE of T. theileri transcripts and matched the determined SL sequence of one previously isolated T. theileri sample, T. theileri D30 (Figure S2 in Text S1; [26]), this matching the trypanosomatid consensus. In order to drive effective gene expression, RNA processing signals derived from T. theileri were used. Since almost no molecular information for these organisms was available, we isolated T. theileri intergenic sequences using degenerate primers able to amplify between the coding regions of well conserved genes (i.e. paraflagellar rod, tubulin, actin genes) predicted from the analysis of other kinetoplastid genomes to be tandemly arranged (Figure S3 in Text S1; [27]). The resulting expression constructs were transfected into T. theileri via nucleofector technology and selected using blasticidin or phleomycin drug selection. Unlike other kinetoplastid organisms, G418 and hygromycin B were not effective for selection in T. theileri, wild type cells exhibiting high levels of resistance to these drugs. This may have developed in natural T. theileri populations through long-term use of aminoglycoside antibiotics for the treatment of infections such as those responsible for bovine mastitis.

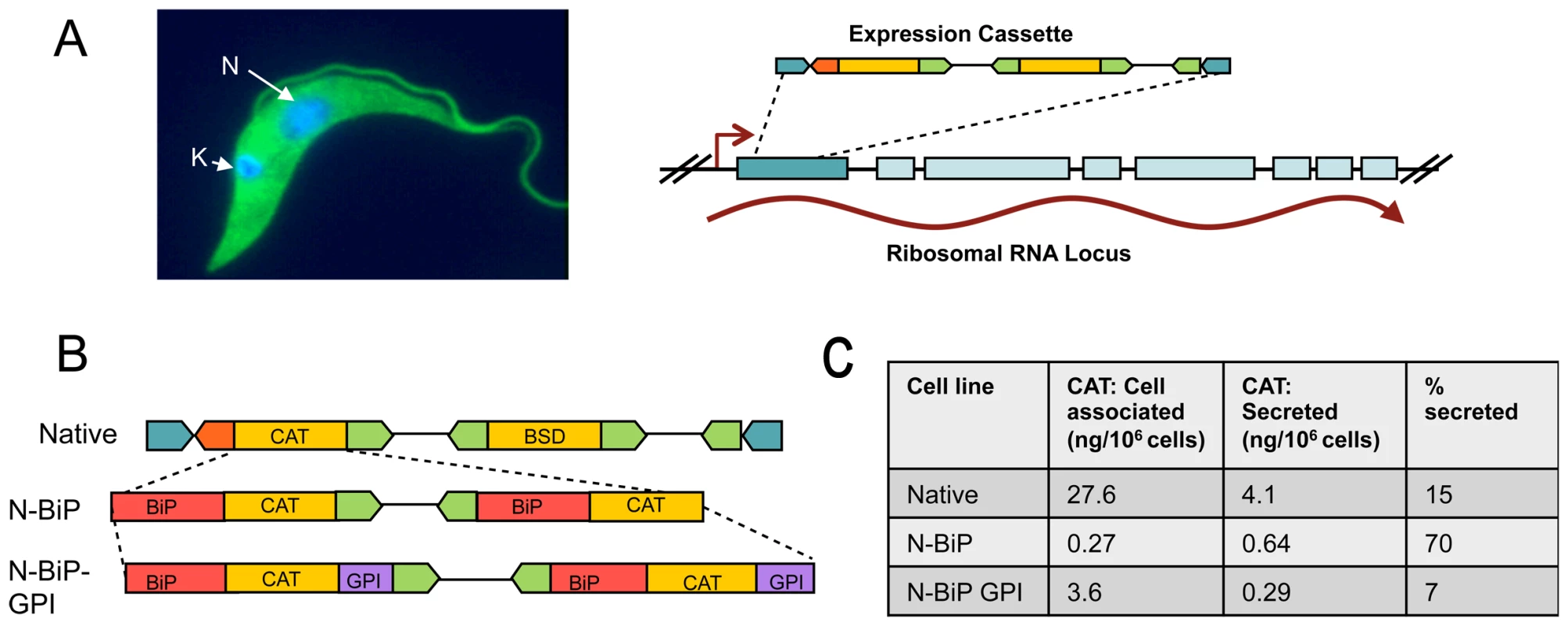

Fig. 1. Heterologous proteins can be expressed and specifically localized in T. theileri.

(A) An immunofluorescence image of Trypanosoma theileri stained with antibody to T. brucei alpha tubulin; the kinetoplast and nuclear DNA is stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Schematic representation of the integration of an expression cassette into the SSU rRNA locus of the T. theileri genome by homologous recombination. Read-through transcription drives expression from the integrated cassette. (C) Expression vectors used to assay CAT protein expression in T. theileri, this being as an unmodified protein (“Native”) or modified for secretion (“N-BiP”) or surface expression (“N-BiP-GPI”). For the N-BiP and N-BiP-GPI fusions, two gene copies were inserted in tandem to improve overall expression, these being separated by the T. theileri beta-alpha tubulin intergenic region. The respective distribution of CAT protein to the cell pellet or extracellular milieu is indicated on the right hand side, this being quantitated by CAT ELISA assay. In order to develop the system for the optimal delivery of proteins to the bovine host, the potential to target expressed heterologous proteins to distinct cellular locations in T. theileri was investigated. For secretion, fusion proteins were created comprising the N-terminus of the T. brucei BiP/GRP78 protein (PMID:8227199) (N-BiP), which in T. brucei targets proteins for release into the extracellular milieu [28]. For cell surface expression, signals providing a C-terminal GPI-addition sequence were also added (N-BiP-GPI), whereas for internal expression, native proteins were expressed. Quantitative expression analysis of a chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) reporter protein confirmed protein expression and accurate targeting, with the percentage of protein released to the cell medium being 70% for the N-BiP fusion, 7% for the N-BiP-GPI fusion and 15% for the native protein, the latter probably including protein released from dead cells in the culture (Figure 1C). Although the overall expression efficiency was reduced considerably (10 to 50-fold) by the inclusion of heterologous targeting signals (N-BiP, N-BiP-GPI), this could be compensated somewhat by the expression of two copies of the reporter gene in tandem, generating a tri-cistronic construct (Figure 1C).

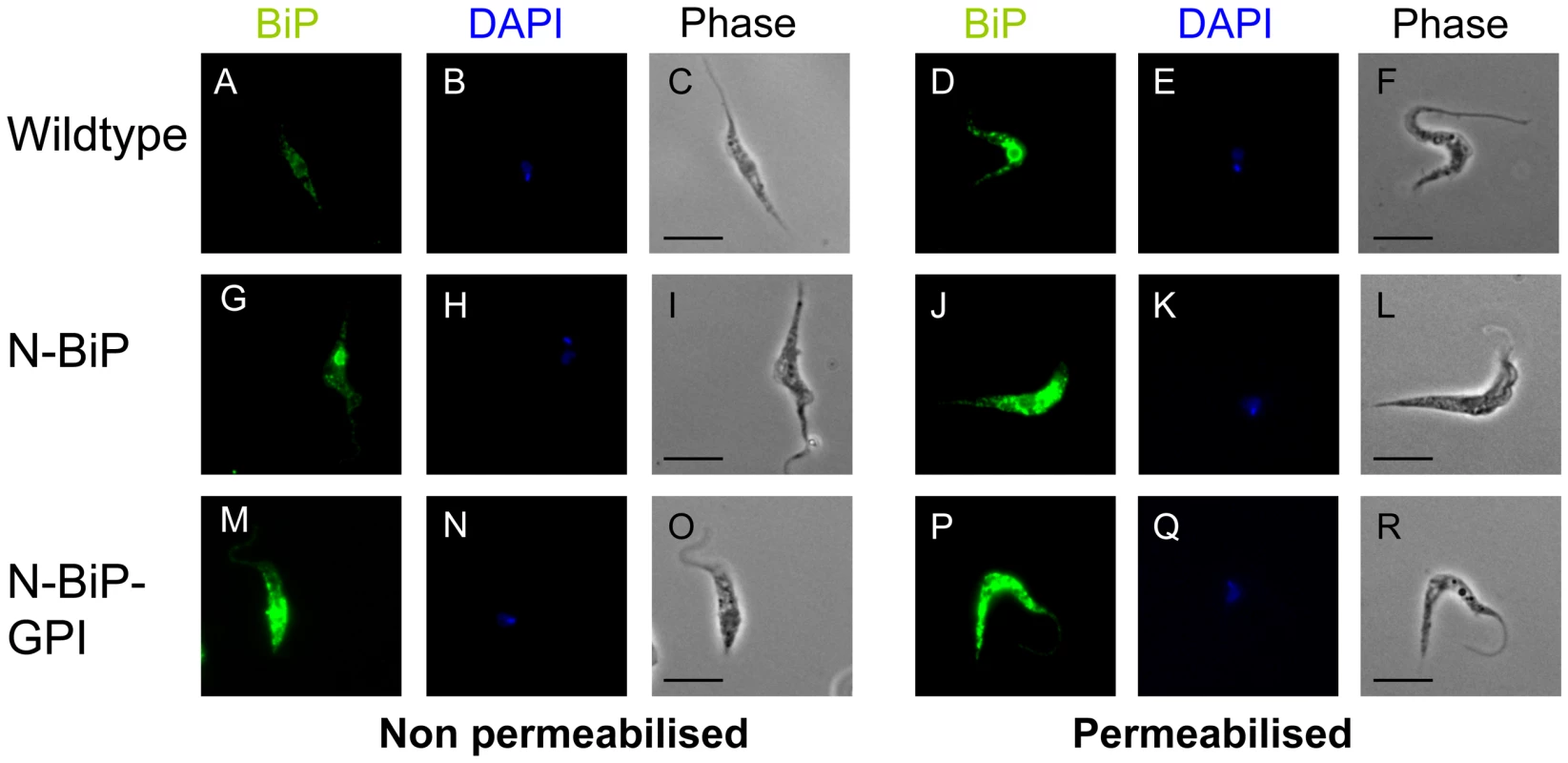

To evaluate T. theileri as a vaccine delivery system, cells were engineered to express the Bd37 antigen from the cattle pathogen, Babesia divergens [29]. In general, protection against Babesia is thought to require components of the innate and adaptive immune systems (Reviewed in [30]). Effector arms of the adaptive immune system include antigen-specific antibodies, which have been hypothesized to target both infected erythrocytes and extracellular merozoites. There is also evidence that antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) plays a role in parasite control during acute infection [31], [32]. A recombinant version of the Bd37 protein has been shown to stimulate antibody-directed protective immunity to B. divergens when administered in the context of an adjuvant [33], [34]. In our study, Bd37 protein was targeted for internal expression, surface localization or extracellular release by the expression of unmodified Bd37, N-BiP-Bd37-GPI or N-BiP-Bd37 fusion proteins. Since anti-Bd37 antibody was not effective in immunfluorescence assays, localisation was assessed for surface and secreted expression by incubating non-permeabilised or 0.1% TRITON X100 permeabilised cells with an antibody against T. brucei BiP, this recognising the N-terminal BiP component of the expressed fusion protein. In wild type cells, a signal was detected in permeabilised cells (Figure 2 D–F), reflecting the recognition of T. theileri BiP protein by antibody raised against T. brucei BiP. However, as expected, non-permeabilised cells showed little reactivity (Figure 2 A–C). In contrast, in transgenic T. theileri expressing Bd37, a strong punctate signal was detected in non-permeabilised cells for the N-BiP-Bd37-GPI fusion (Figure 2 M–O), whereas N-BiP-Bd37 cells exhibited a somewhat weaker signal concentrated close to the kinetoplast (Figure 2 G–I). This supported a surface-associated expression for the N-BiP-Bd37-GPI protein and flagellar pocket associated signal (the route for protein secretion in trypanosomatids) for N-BiP-Bd37, although staining of flagellar pocket-proximal vesicles cannot be excluded. Transcripts generated from the expressed reporter constructs were of the expected size, with the polyadenylation sites used for mRNAs derived from each of the constructs being approximately coincident with each other and with the site of beta tubulin polyadenylation (Figure 3 and Figure S4 in Text S1).

Fig. 2. Cellular location of expressed N-BiP and N-BIP-GPI fusion proteins.

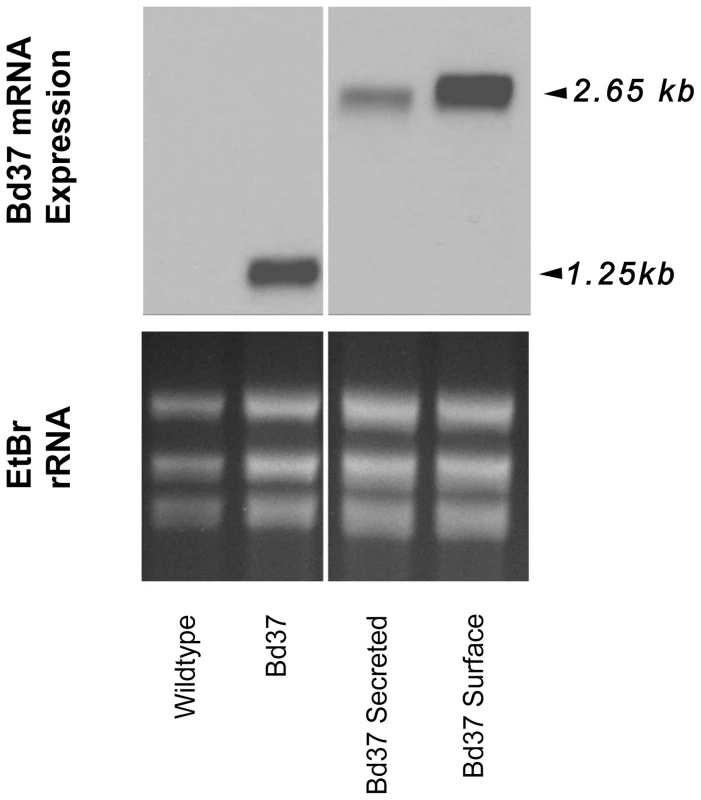

Distribution of expressed Bd37 assayed via its fusion to T. brucei BiP and detected using a BiP-specific antibody. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and then either 0.1% Triton-X100 permeabilised, or not, to distinguish intracellular from surface exposed protein following immunofluorescence. In wild-type cells, only weak staining was observed (A–C) in the absence of permeabilisation whereas permeabilisation (D–F) allows visualisation of endogenous, intracellular T. theileri BiP protein, which cross-reacts with the T. brucei BiP antibody. In contrast, the N-BiP-Bd37 fusion protein generates intense staining at the flagellar-pocket in intact cells (G–I), plus an intense intracellular staining in permeabilised cells comprised of endogenous BiP and N-BiP-Bd37 protein in the ER (J–L). Expression of the N-BiP-Bd37-GPI fusion protein generates a strong signal on intact cells indicating the presence of cell-surface protein (M–O); permeabilised cells also show strong straining representing the combined endogenous BiP and the expressed fusion protein (P–R). Camera exposures with respect to the BiP fluorescence and image handling were precisely consistent between cells under each condition to allow comparison of the relative intensity of signal. DAPI images reveal the kinetoplast and nuclear position, these often overlying one another. Scale Bar = 10 µm. Fig. 3. Transcript expression of exogenous genes in transgenic T. theileri.

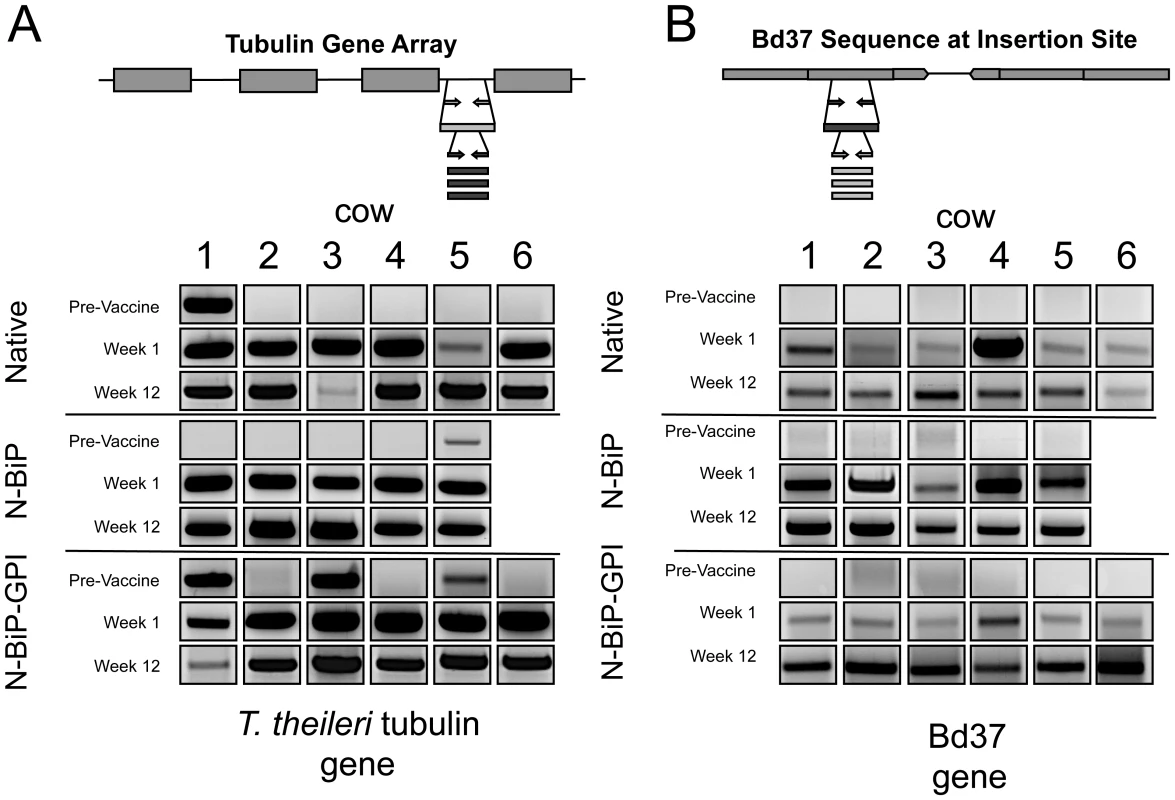

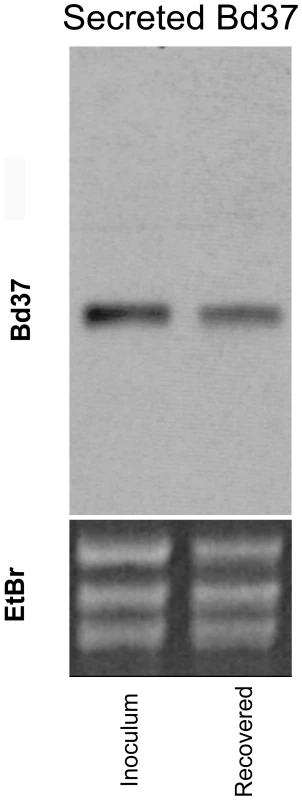

Northern blots of untransfected T. theileri and T. theileri engineered to express native Bd37, N-BiP Bd37 (‘Bd37 secreted’) or N-BiP Bd37 GPI (‘Bd37 surface’), transcripts being detected using a riboprobe detecting Bd37. Respective loading is indicated by the Ethidium bromide stained rRNA (lower panel). Having established protein localisation at different cellular locations, each T. theileri cell line was inoculated intravenously into groups of cattle (internal expression, n = 6 animals; secreted expression, n = 5 animals; surface expression, n = 6 animals), these being maintained in a fly-free, high containment facility. Of these, 5 of the 17 animals had been found to contain a pre-existing natural T. theileri population by screening blood using a specific, nested PCR assay for the T. theileri tubulin gene array (Figure 4A). Regardless of this, the transgenic T. theileri established in all animals within one week, these being detectable by nested PCR specific for the Bd37 gene present within the integrated expression construct (Figure 4B). In each of the experimental groups, the transgenic T. theileri was sustained in all animals throughout the 12 weeks after inoculation. This was without any adverse effects on animal health being detected. Moreover, the transgenic T. theileri could be recovered after several weeks of growth in cattle and was found to maintain Bd37 gene expression (Figure 5).

Fig. 4. Inoculation with the vaccine vehicle results in successful establishment of the population in cattle.

(A) Schematic representation of the amplicon used to detect T. theileri genomic DNA. The amplicon, specific for the T. theileri tubulin gene array, will detect both endogenous T. theileri infection and the presence of the transgenic vaccine vehicle. PCR products were derived from individual calves either before inoculation with transgenic T. theileri, or 1 week and 12 weeks post inoculation. Prior to inoculation 5/17 animals harboured a naturally occurring T. theileri population. (B) A second amplicon specific for the expressed Bd37 gene detects only genomic DNA from the transgenic T. theileri. The cattle all became positive for the transgenic vaccine vehicle within 1 week, regardless of their original infection status, this being sustained throughout the 12 weeks of the experiment for all animals. Fig. 5. Sustained transgene expression in T. theileri after growth in cattle.

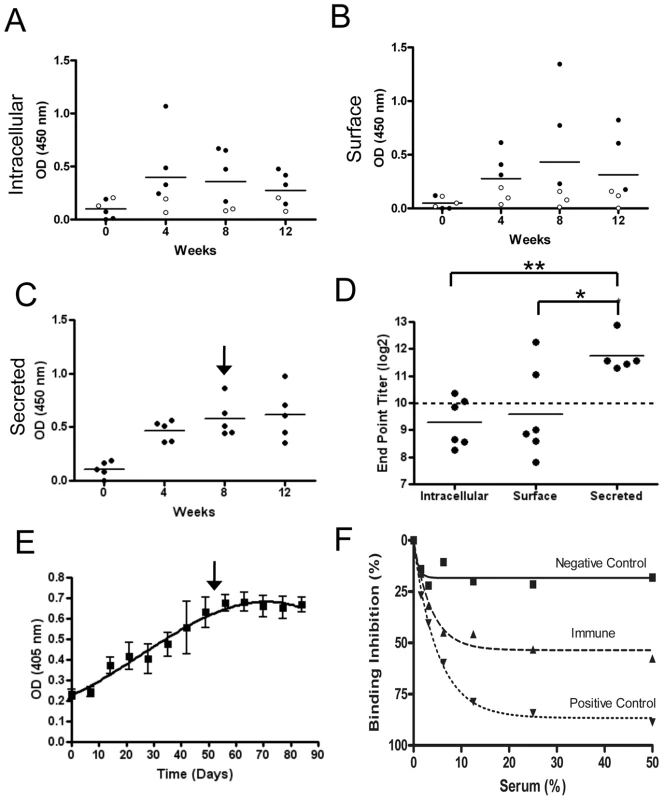

Northern Blot to determine N-BiP Bd37 transcript expression in cultured T. theileri cells used to inoculate cattle, or harvested after 3 weeks growth in inoculated cattle. Expression of the Bd37 transcript was maintained. Respective loading is indicated by the Ethidium bromide staining rRNA (lower panel). To assess whether the inoculated animals were able to generate a specific immune response to the delivered antigen, serum samples were tested weekly for Bd37-specific IgG responses by ELISA. Under all treatment conditions, sero-conversion was observed, i.e. at least a 3-fold increase in ELISA OD compared to pre-immunisation control sera from the same animal (Figure 6A–C). Interestingly, the route of antigen expression affected both the sero-conversion frequency and the resulting antibody titre, with sero-conversion occurring in 4/6 animals receiving the cytosolically expressed antigen, 3/6 animals receiving the surface expressed antigen, and 5/5 animals receiving the secreted antigen. Moreover, the secreted antigen produced a significantly higher end-point serum titre than either the surface expressed antigen (Kruskal-Wallis one way ANOVA, p<0.05) or the cytosolically expressed antigen (p<0.001) (Figure 6D), with antibody levels continuing to increase for 60 days post inoculation before plateauing and remaining high for at least a further 24 days (Figure 6E). Inoculation of a further 1×106 cells expressing the secreted antigen on week 8 had no detectable stimulatory effect on the levels of antibody generated (vertical arrow, Figure 6C, E).

Fig. 6. Inoculation with the vaccine vehicle stimulates an effective antibody response to the expressed antigen.

(A-C) Quantification of anti-Bd37 antibody responses by ELISA assay demonstrate that calves exposed to Bd37 that is expressed at an internal (A) or surface location (B) on T. theileri, or is secreted (C), show sero-conversion (filled circles) within 12 weeks of inoculation. Animals that did not sero-convert are shown as open circles. (D) End-point titres measured for all experimental animals show that those cattle receiving secreted Bd37 achieved significantly higher antibody levels than the other treatment groups (* p<0.05, ** p<0.001). (E) Time-course of antibody response to secreted Bd37 vaccine vehicle in all cattle. (F) Sera from vaccinated animals are able to compete with an anti-Bd37 monoclonal antibody for ELISA binding; assay details are provided in the ‘Materials and Methods’. Vertical arrows in Panels C and E indicate inoculation of a further 1×106 transgenic T. theileri. To compare the antibody responses generated by transgenic T. theileri with conventional immunisation approaches, the antibody titres were assessed with respect to those established in a prime-boost vaccination study using the same antigen. This demonstrated that the levels of anti-Bd37 antibody stimulated by the transgenic T. theileri delivery system were equivalent to those generated by the same antigen delivered in conventional adjuvant, producing titres that are protective against Babesia in challenge trials (dashed line, Figure 6D). Furthermore, the immune response generated to the T. theileri-secreted Bd37 could effectively compete with a monoclonal antibody able to confer passive immunity to Babesia infection in a gerbil model (Figure 6F), demonstrating the recognition of common, potentially protective epitopes. Combined, these assays confirm that T. theileri represents an effective antigen delivery system able to generate sustained immune responses equivalent to, or exceeding, those generated by standard vaccination and at levels known to be protective against a target pathogen.

Discussion

Our work describes a naturally non-pathogenic eukaryotic organism, T. theileri, engineered to deliver antigens and therapeutic proteins to cattle. Importantly, T. theileri is a flexible and adaptable system for the targeted expression of individual, or cocktails of multiple, heterologous proteins simultaneously. This allows for the targeting of different pathogens, or multiple defined antigens of a specific pathogen, providing an effective approach to limiting the transmission of disease from livestock to man, as well as maintaining bovine health and maximising bovine productivity. This system has many advantages over traditional vaccine delivery technologies, including the possibility of oral delivery, a natural route of T. theileri infection, and the potential for sustained immune stimulation through prolonged infection without adverse consequence on productivity or health. It also provides an explicit example of an unanticipated applied benefit derived from the extensive research investment in the basic biology of kinetoplastid pathogens.

A number of kinetoplastid parasites have been successfully transfected to drive ectopic expression of endogenous genes or heterologous expression of reporter genes[35] . In general, these have been used for the analysis of gene function in the transfected organisms or for protein expression in vitro. In particular, the kinetoplastid protozoa T. brucei, Crithidia fasciculata, Leishmania amazonensis and Leishmania tarentolae have each been engineered as eukaryotic vehicles for the expression of proteins which are appropriately post-translationally modified, that retain biological activity, or which are suitable for meaningful inhibition studies for drugs targeted against kinetoplastids [36]–[40]. In each case, the basic organisation of the expression vectors employed was similar. However, there is no predictable cross functionality of RNA processing signals . For example, in one study, transfection of a range of kinetoplastid protozoa with a common expression construct developed in Leishmania major resulted in reporter gene expression in other Leishmania spp., but not in T. brucei or T. cruzi [41].

The specificity of RNA processing signals among kinetoplastids necessitated that we isolated intergenic sequences from T. theileri. To our knowledge, no protein coding gene sequence have been characterised in these organisms to date. Despite this, we were able to make use of the tandem arrangement of several conserved housekeeping genes in trypanosomatids to isolate intergenic sequences between alpha and beta tubulin genes, beta and alpha tubulin genes, actin genes and the PFR genes. Conservation in these genes allowed successful amplification between genes using degenerate oligonucleotides. In each case, the predicted protein sequences were highly similar to those in other kinetoplastids over the sequenced region, this being reinforced by the reactivity of monoclonal antibodies specific for alpha tubulin, PFRA and BiP in T. brucei with T. theileri (Figure 1A, Figure 2 and data not shown). Extensive protein coding similarity is also evident from a whole genome analysis of T. theileri that we have recently completed (our unpublished observations). Despite this similarity in coding regions, there was no recognisable similarity in the intergenic regions of each gene between species. This emphasised the requirement to use endogenous intergenic sequences in the developed expression constructs. Indeed, transient transfection of T. theileri with a reporter construct generated for use in T. brucei did not result in detectable heterologous gene expression (unpublished observations). Cloning and sequencing of 5′RACE products derived from the actin gene transcript identified the SL sequence common to all trypanosomatid mRNAs. Interestingly, the sequence of the leader RNA did not match the SL sequence of a previous T. theileri isolate (K127), which was reported to exhibit a 1 nucleotide distinction from the sequence identified on the majority of trypanosomatid parasites . Instead, the leader sequence identified in the isolate of T. theileri used in our study matched exactly the trypanosomatid consensus and shared with T. theileri D30 . This suggests variation in this sequence amongst different T. theileri isolates.

Previous approaches have used kinetoplastid parasites as vehicles for protein expression in vitro, or for potential medicinal use via expression of biomolecules from attenuated pathogens in vivo. In these, and other cases of pathogen-based vaccine vectors (for example, using attenuated Salmonella , Mycobacterium , E. coli , V. cholera, Listeria or Shigella), the vehicles have a potential to revert to pathogenicity raising issues of long-term efficacy and safety. Moreover, recombination with non-attenuated pathogens can generate vaccine escape mutants, as observed after pneumococcal vaccination in the USA [42]. By exploiting an already non-pathogenic organism (T. theileri) for protein expression in its natural host, the possibility of reversion to, or unanticipated, pathogenicity is greatly reduced. Supporting this, the T. theileri isolate used in our studies has been maintained in tissue culture for over 6 years and yet, when inoculated into cattle, generated no ill effects and was sustained at low abundance throughout a 12-week trial. The transgenic parasites could also establish and be sustained in the context of a pre-existing natural infection. This is an important consideration since T. theileri is almost ubiquitous in cattle herds worldwide with, for example, 44%–80% incidence levels reported in New York State and up to 93% in Louisiana [43]. A survey of local adult cattle in Edinburgh revealed that all animals tested (16/16) were positive for T. theileri infection by the nested PCR assay for tubulin intergenic sequence (data not shown).

T. theileri has clear potential as a flexible vaccine vehicle, able to target a wide range of pathogens, including viruses (e.g. Foot and Mouth Disease Virus, Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus), bacteria (e.g. E. coli, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Brucella spp. and mycobateria), ectoparasites (e.g. ticks, mites, lice) as well as pathogenic eukaryotic parasites (Babesia spp., Neospora caninum, Coccidia spp., Trichomonas spp. and helminths). However, T. theileri also has potential to deliver therapeutic proteins such as antimicrobials systemically in cattle, able to limit the impact of bacterial infections, for example. Furthermore, we propose that it may be possible to avoid the need to engineer transgenic cattle to express ApoLI or mutant variants [44], [45], allowing indigenous and disease-resistant African livestock to combat pathogenic trypanosome infection via T. theileri directed ApoL1 expression. Such an approach would require that the ApoL1 is expressed in a form that is non-immunogenic and active in cattle. Nonetheless, this could provide a simple and cost effective route to limiting the effects of trypanosome infection on the productivity or zoonotic potential of indigenous African cattle. This has the potential to increase their productivity and eliminate an important reservoir for human disease, alleviating poverty and disease in afflicted regions.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Animal trials in this manuscript were reviewed and approved through the ethical review committee at Moredun Research Institute (Experiment approval no. E28/10). Experiments were carried out under a UK Home Office Licence (PPL 60/4044) in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986.

Cell culture

Bovine conditioned media was produced by growing Madin-Darby Bovine Kidney (MDBK) cells in Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium with Earle's Balanced Salt Solution and sodium bicarbonate (Sigma, M2279) supplemented with 1% MEM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen, 11140), 1% L-Glutamine solution (from 200 mM solution, Sigma, G7513), and 10% FCS until confluence (2–3 days). The MDBK-conditioned media was then harvested and filtered prior to use. T. theileri were cultured in 50% HMI-9 medium [46] supplemented with 20% FCS and 10% Serum+ and 50% MDBK-conditioned media as described above.

Creation of recombinant cell lines

The plasmid backbone used for construction of all expression vectors was derived from the pGemT Easy plasmid (Promega). All elements of the vector were prepared through PCR of the noted sequence, followed by cloning into the vector backbone, and construction was accomplished through the insertion of appropriate restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of each segment. The segments used for the construction of the expression cassettes and the corresponding primers used in this study include: the 5′ fragment of the T. theileri SSU rRNA gene (SSU5-ApaI-For and SSU5-AvrII-Rev), the 3′ fragment of the T. theileri SSU rRNA gene (SSU3-PacI-For and 3SSU-Rev-XmaI), the trans-splicing addition site from the actin IR sequence (splice-AvrII-For and splice-FseI-Rev), the Bd37 coding sequence (Bd37-Core-F-FseI or Bd37-Core-F-AvrII and Bd37-Core-F-AvrII and Bd37-Core-R-HindIII), the CAT coding sequence (CAT For FseI or CAT For XhoI and CAT Rev XbaI or CAT Rev AscI), the blasticidin resistance cassette (BSDKpn-F and BSDBgl-R), the beta-alpha tubulin IR sequence (ba-tub-AscI-For or ba-tub-BglII and ba-tub-KpnI-Rev or ba-tub-PacI), the T. brucei BiP N-terminal fragment sequence (BiP-For-FseI or BiP-For-FseI-SpeI and BiP-Rev-XhoI), and the GPI addition signal (GPI-For-HindIII and GPI-Rev-AscI). In fusion protein cassettes, care was taken to preserve the reading frame and appropriate start and stop codons were provided. The plasmids containing the expression cassettes were then digested with appropriate restriction enzymes to liberate the plasmid backbone from the linear expression cassette, which was isolated via gel electrophoresis and gel purification. The linear cassette was then purified by ethanol precipitation and resuspended in 5 ml of TE buffer (1 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 0.1 mM EDTA).

From a culture of logarithmically growing T. theileri parasites, 10 ml of culture at ∼5×105 cells/ml were used for each transfection. Cells were centrifuged at 1000 × g, for 10 minutes at room temperature and resuspended in 1 ml of sterile PBS to wash the cells. Cells were then re-centrifuged and resuspended in 100 µl Ingenio transfection buffer (Mirus Bio). The cells were added to the prepared linear DNA and transferred to a cuvette for the Nucleofector II electroporation device (Lonza). Transfection was done with Nucleofector program X-001 (recommended for mouse CD8+ T cells) and cells transferred to a culture flask containing 10 ml of pre-warmed media and incubated for 24 hrs at 37°C, in 5 % CO2. Cells were then transferred to media containing the selective drug concentration (10 µg/ml of blasticidin) and plated using a variety of dilutions into a 24-well cell culture plate. After selection clones were recovered under normal cell culture conditions.

Immunofluorescence assay

The localisation of the BiP-Bd37 fusion protein was determined using 2% paraformaldehyde fixed cells permeabilised, or not, with TBS: 0.1% Triton X-100 for 2 minutes. Cells were quenched for 30 minutes with TBS:0.1% glycine and then blocked for 1 hr with TBS: 1%BSA. Cells were then reacted with anti-BiP antibody (a gift of Jay Bangs, University of Wisconsin) diluted 1∶200 in TBS:1%BSA, washed three times with TBS and then incubated with anti-rabbit FITC conjugated antibody (Sigma) diluted 1∶100 inTBS:1%BSA. Prior to mounting in MOWIOL, cells were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for 5 minutes to visualize cellular DNA.

Experimental animals, sampling and DNA extraction

Calves (6-weeks old) were injected intravenously with 1×105 T. theileri parasites. Blood samples were taken weekly into EDTA-containing tubes (Becton-Dickinson) and DNA extracted. DNA extraction from whole blood samples was performed as follows: 1 ml of blood was mixed thoroughly with 0.5 ml of RBC lysis buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.75% Triton X-100) in a microfuge tube. The samples were then centrifuged at 14, 000 rpm for 1 minute to pellet all cells and the supernatant removed. The pellets were repeatedly resuspended and recovered from 0.5 ml aliquots of RBC lysis buffer until no red blood cells were present. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 100 µl of lysis buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml gelatin, 0.45% NP40, 0.45% Tween-20, 60 µg/ml proteinase K) and kept at 55°C for 60 minutes. The samples were then incubated at 95°C for 10 minutes prior to storage at −20°C until use.

Nested PCR

Nested PCR reactions were designed to amplify either the T. theileri β-α tubulin intergenic sequence (to identify any T. theileri population) or the Bd37 coding sequence (specific for the vaccine vehicle). The primers used were as follows:

Tub Diagnostic F1 : 5′-AGTAGCAACGACAGCAGCAGT-3′

Tub Diagnostic R1 : 5′-GTAAAGTGTTTGAAGAAGAGCTCG-3′

Tub Diagnostic F2 : 5′-CGATTCTCTTCGCCTGTTTGT-3′

Tub Diagnostic R2 : 5′-ACTAACCGCGACCAAAGAAGT-3′

Bd37 Diagnostic F1 : 5′-GCTCACAGGAGCCAGCAGCGG-3′

Bd37 Diagnostic R1 : 5′-CCAGAGCTTTGAGATTAGCTGGTA-3′

Bd37 Diagnostic F2 : 5′-ACGCAGCAAGGTGGTGCGAA-3′

Bd37 Diagnostic R2 : 5′-AGCAAGGCCTCACCGCCCTTGGC-3′

Each 25 µl reaction contained the following components: 5 µl of template, 1X PCR buffer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1.25 mM MgCl2, 0.4 µM of each primer and 0.25 U GoTaq Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega). The first stage PCR reactions were heated to 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 45 seconds and elongation at 72°C for 45 seconds. Following the final cycle, the reactions were elongated for a further 4 minutes. The second stage nested PCR reaction was conducted using the same conditions with 5 µl of the first reaction as template. The resulting products were electrophoresed on a 1% Tris-acetic acid-EDTA agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized.

Serum preparation and ELISA assay

Serum samples were prepared from 10 ml of fresh blood and stored at −20°C until use. Recombinant (E. coli) expressed His-tagged Bd37 antigen was diluted to 5 µg per ml in coating buffer (0.01 M sodium carbonate pH 9.6), and 100 µl were added to each well of microtiter plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. The coating buffer was removed and 200 µl blocking buffer (10% horse serum in 10 mM PBS) were added, and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. The plates were washed 3 times with 200 µl washing buffer (10 mM PBS, pH 9.6 with 1% Tween-20). Bovine serum samples were diluted in blocking buffer as appropriate, and 100 µl were incubated in the coated and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. For standard ELISA plates were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-bovine IgG antibody diluted 1∶1000 in blocking buffer and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. For competitive ELISA assays, 100 µl of mouse monoclonal anti-Bd37 antibody (1 mg/ml diluted 1∶1000 in blocking buffer) were added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. Plates were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody diluted 1∶1000 in blocking buffer and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. Plates were washed, treated with TMB supersensitive substrate (Sigma), stopped with 2M sulphuric acid and the OD was measured at 450 nm in an ELISA plate reader.

Statistics

To analyse serum antibody titres, a Kruskal-Wallis one way ANOVA was used.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. CokerRRushtonJMounier-JackSKarimuriboELutumbaP 2011 Towards a conceptual framework to support one-health research for policy on emerging zoonoses. Lancet Infect Dis 11 326 331

2. VanhammeLPaturiaux-HanocqFPoelvoordePNolanDPLinsL 2003 Apolipoprotein L-I is the trypanosome lytic factor of human serum. Nature 422 83 87

3. XongHVVanhammeLChamekhMChimfwembeCEVan Den AbbeeleJ 1998 A VSG expression site-associated gene confers resistance to human serum in Trypanosoma rhodesiense. Cell 95 839 846

4. KieftRCapewellPTurnerCMVeitchNJMacLeodA 2010 Mechanism of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (group 1) resistance to human trypanosome lytic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107 16137 16141

5. KennedyMJ 1988 Alberta. Trypanosoma theileri in cattle of central Alberta. Can Vet J 29 937 938

6. MatthewsDMKingstonNMakiLNelmsG 1979 Trypanosoma theileri Laveran, 1902, in Wyoming cattle. Am J Vet Res 40 623 629

7. WooPSoltysMAGillickAC 1970 Trypanosomes in cattle in southern Ontario. Can J Comp Med 34 142 147

8. VillaAGutierrezCGraciaEMorenoBChaconG 2008 Presence of Trypanosoma theileri in Spanish Cattle. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1149 352 354

9. NiakA 1978 The incidence of Trypanosoma theileri among cattle in Iran. Trop Anim Health Prod 10 26 27

10. FarrarRGKleiTR 1990 Prevalence of Trypanosoma theileri in Louisiana cattle. J Parasitol 76 734 736

11. VerlooDBrandtJVan MeirvenneNBuscherP 2000 Comparative in vitro isolation of Trypanosoma theileri from cattle in Belgium. Vet Parasitol 89 129 132

12. RisticMTragerW 1958 Cultivation at 37°C of a Trypanosome (Trypanosoma theileri) from Cows with Depressed Milk Production. J Protozool 2 146 148

13. DohertyMLWindleHVoorheisHPLarkinHCaseyM 1993 Clinical disease associated with Trypanosoma theileri infection in a calf in Ireland. Vet Rec 132 653 656

14. Lanevschi-PietersmaAOgunremiODesrocherA 2004 Parasitemia in a neonatal bison calf. Vet Clin Pathol 33 173 176

15. SeifiHA 1995 Clinical trypanosomosis due to Trypanosoma theileri in a cow in Iran. Trop Anim Health Pro 27 93 94

16. BoseRFriedhoffKTOlbrichSBuscherGDomeyerI 1987 Transmission of Trypanosoma theileri to cattle by Tabanidae. Parasitol Res 73 421 424

17. RobertssonJALindbergAAHoisethSStockerBA 1983 Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves: protection and survival of virulent challenge bacteria after immunization with live or inactivated vaccines. Infect Immun 41 742 750

18. HoisethSKStockerBA 1981 Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291 238 239

19. BarlettaRGSnapperBCirilloJDConnellNDKimDD 1990 Recombinant BCG as a candidate oral vaccine vector. Res Microbiol 141 931 939

20. ChenTMMazaitisAJMaasWK 1985 Construction of a conjugative plasmid with potential use in vaccines against heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun 47 5 10

21. RadfordKJJacksonAMWangJHVassauxGLemoineNR 2003 Recombinant E. coli efficiently delivers antigen and maturation signals to human dendritic cells: presentation of MART1 to CD8+ T cells. Int J Cancer 105 811 819

22. SizemoreDRBranstromAASadoffJC 1995 Attenuated Shigella as a DNA delivery vehicle for DNA-mediated immunization. Science 270 299 302

23. GullK 1999 The cytoskeleton of trypanosomatid parasites. Annu Rev Microbiol 53 629 655

24. BorstP 1986 Discontinuous transcription and antigenic variation in trypanosomes. Annu Rev Biochem 55 701 732

25. TschudiCUlluE 1994 Trypanosomatid protozoa provide paradigms of eukaryotic biology. Infect Agents Dis 3 181 186

26. GibsonWBingleLBlendemanWBrownJWoodJ 2000 Structure and sequence variation of the trypanosome spliced leader transcript. Mol Biochem Parasitol 107 269 277

27. El-SayedNMMylerPJBlandinGBerrimanMCrabtreeJ 2005 Comparative genomics of trypanosomatid parasitic protozoa. Science 309 404 409

28. BangsJDBrouchEMRansomDMRoggyJL 1996 A soluble secretory reporter system in Trypanosoma brucei. Studies on endoplasmic reticulum targeting. J Biol Chem 271 18387 18393

29. DelbecqSPrecigoutEValletACarcyBSchettersTP 2002 Babesia divergens: cloning and biochemical characterization of Bd37. Parasitol 125 305 312

30. BrownWCNorimineJGoffWLSuarezCEMcElwainTF 2006 Prospects for recombinant vaccines against Babesia bovis and related parasites. Parasite Immunol 28 315 327

31. GoffWLWagnerGGCraigTM 1984 Increased activity of bovine ADCC effector cells during acute Babesia bovis infection. Vet Parasitol 16 5 15

32. GoffWLWagnerGGCraigTMLongRF 1984 The role of specific immunoglobulins in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity assays during Babesia bovis infection. Vet Parasitol 14 117 128

33. PrecigoutEDelbecqSValletACarcyBCamillieriS 2004 Association between sequence polymorphism in an epitope of Babesia divergens Bd37 exoantigen and protection induced by passive transfer. Int J Parasitol 34 585 593

34. Hadj-KaddourKCarcyBValletARandazzoSDelbecqS 2007 Recombinant protein Bd37 protected gerbils against heterologous challenges with isolates of Babesia divergens polymorphic for the bd37 gene. Parasitol 134 187 196

35. ClaytonCE 1999 Genetic manipulation of kinetoplastida. Parasitol Today 15 372 378

36. BiebingerSWirtzLELorenzPClaytonC 1997 Vectors for inducible expression of toxic gene products in bloodstream and procyclic Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol 85 99 112

37. KellyJMWardHMMilesMAKendallG 1992 A shuttle vector which facilitates the expression of transfected genes in Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania. Nucl Acids Res 20 3963 3969

38. TetaudELecuixISheldrakeTBaltzTFairlambAH 2002 A new expression vector for Crithidia fasciculata and Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol 120 195 204

39. CoburnCMOttemanKMMcNeelyTTurcoSJBeverleySM 1991 Stable DNA transfection of a wide range of trypanosomatids. Mol Biochem Parasitol 46 169 179

40. FurgerAJungiTWSalomoneJYWeynantsVRoditiI 2001 Stable expression of biologically active recombinant bovine interleukin-4 in Trypanosoma brucei. FEBS letters 508 90 94

41. ClaytonCEHaSRuscheLHartmannCBeverleySM 2000 Tests of heterologous promoters and intergenic regions in Leishmania major. Mol Biochem Parasitol 105 163 167

42. BrueggemannABPaiRCrookDWBeallB 2007 Vaccine escape recombinants emerge after pneumococcal vaccination in the United States. PLoS Pathog 3 e168

43. SchlaferDH 1979 Trypanosoma theileri: a literature review and report of incidence in New York cattle. Cornell Vet 69 411 425

44. ThomsonRMolina-PortelaPMottHCarringtonMRaperJ 2009 Hydrodynamic gene delivery of baboon trypanosome lytic factor eliminates both animal and human-infective African trypanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 19509 19514

45. LecordierLVanhollebekeBPoelvoordePTebabiPPaturiaux-HanocqF 2009 C-terminal mutants of apolipoprotein L-I efficiently kill both Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000685

46. HirumiHHirumiK 1989 Continuous cultivation of Trypanosoma brucei blood stream forms in a medium containing a low concentration of serum protein without feeder cell layers. J Parasitol 75 985 989

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Quorum Sensing in Fungi: Q&AČlánek Blood Feeding and Insulin-like Peptide 3 Stimulate Proliferation of Hemocytes in the MosquitoČlánek The DEAD-box RNA Helicase DDX6 is Required for Efficient Encapsidation of a Retroviral GenomeČlánek A Phenome-Based Functional Analysis of Transcription Factors in the Cereal Head Blight Fungus,Článek A Wide Extent of Inter-Strain Diversity in Virulent and Vaccine Strains of AlphaherpesvirusesČlánek The Anti-Sigma Factor TcdC Modulates Hypervirulence in an Epidemic BI/NAP1/027 Clinical Isolate ofČlánek Critical Roles for LIGHT and Its Receptors in Generating T Cell-Mediated Immunity during InfectionČlánek Frequent and Recent Human Acquisition of Simian Foamy Viruses Through Apes' Bites in Central Africa

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 10- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Quorum Sensing in Fungi: Q&A

- Discovery of an Ebolavirus-Like Filovirus in Europe

- Toll-like Receptor 7 Controls the Anti-Retroviral Germinal Center Response

- Tubule-Guided Cell-to-Cell Movement of a Plant Virus Requires Class XI Myosin Motors

- Herpesvirus Telomerase RNA (vTR) with a Mutated Template Sequence Abrogates Herpesvirus-Induced Lymphomagenesis

- Mitochondrial Peroxiredoxin Plays a Crucial Peroxidase-Unrelated Role during Infection: Insight into Its Novel Chaperone Activity

- Sustained CD8+ T Cell Memory Inflation after Infection with a Single-Cycle Cytomegalovirus

- Novel Mouse Xenograft Models Reveal a Critical Role of CD4 T Cells in the Proliferation of EBV-Infected T and NK Cells

- Toll-8/Tollo Negatively Regulates Antimicrobial Response in the Respiratory Epithelium

- Exhausted Cytotoxic Control of Epstein-Barr Virus in Human Lupus

- Structural and Functional Analysis of Laninamivir and its Octanoate Prodrug Reveals Group Specific Mechanisms for Influenza NA Inhibition

- Infection Drives IL-17-Mediated Neutrophilic Allergic Airways Disease

- Blood Feeding and Insulin-like Peptide 3 Stimulate Proliferation of Hemocytes in the Mosquito

- HIV-1 Replication in the Central Nervous System Occurs in Two Distinct Cell Types

- Deep Molecular Characterization of HIV-1 Dynamics under Suppressive HAART

- Fitness Landscape of Antibiotic Tolerance in Biofilms

- The DEAD-box RNA Helicase DDX6 is Required for Efficient Encapsidation of a Retroviral Genome

- Preventing Sepsis through the Inhibition of Its Agglutination in Blood

- A Phenome-Based Functional Analysis of Transcription Factors in the Cereal Head Blight Fungus,

- IFITM3 Inhibits Influenza A Virus Infection by Preventing Cytosolic Entry

- Targeting Cattle-Borne Zoonoses and Cattle Pathogens Using a Novel Trypanosomatid-Based Delivery System

- A Wide Extent of Inter-Strain Diversity in Virulent and Vaccine Strains of Alphaherpesviruses

- Coordinated Destruction of Cellular Messages in Translation Complexes by the Gammaherpesvirus Host Shutoff Factor and the Mammalian Exonuclease Xrn1

- Signal Transduction through CsrRS Confers an Invasive Phenotype in Group A

- Biochemical and Structural Insights into the Mechanisms of SARS Coronavirus RNA Ribose 2′-O-Methylation by nsp16/nsp10 Protein Complex

- Histone Deacetylase 8 Is Required for Centrosome Cohesion and Influenza A Virus Entry

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Regulates Cell Stress Response and Apoptosis

- Co-opts the FGF2 Signaling Pathway to Enhance Infection

- IRAK-2 Regulates IL-1-Mediated Pathogenic Th17 Cell Development in Helminthic Infection

- Trafficking of Hepatitis C Virus Core Protein during Virus Particle Assembly

- The Anti-interferon Activity of Conserved Viral dUTPase ORF54 is Essential for an Effective MHV-68 Infection

- A Viral Nuclear Noncoding RNA Binds Re-localized Poly(A) Binding Protein and Is Required for Late KSHV Gene Expression

- Suppression of Methylation-Mediated Transcriptional Gene Silencing by βC1-SAHH Protein Interaction during Geminivirus-Betasatellite Infection

- ISG15 Is Critical in the Control of Chikungunya Virus Infection Independent of UbE1L Mediated Conjugation

- Non-Hematopoietic Cells in Lymph Nodes Drive Memory CD8 T Cell Inflation during Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection

- RNA Polymerase II Stalling Promotes Nucleosome Occlusion and pTEFb Recruitment to Drive Immortalization by Epstein-Barr Virus

- Noninfectious Retrovirus Particles Drive the / Dependent Neutralizing Antibody Response

- Endophytic Life Strategies Decoded by Genome and Transcriptome Analyses of the Mutualistic Root Symbiont

- An Integrated Approach to Elucidate the Intra-Viral and Viral-Cellular Protein Interaction Networks of a Gamma-Herpesvirus

- as an Animal Model for the Study of Biofilm Infections

- Homeostatic Proliferation Fails to Efficiently Reactivate HIV-1 Latently Infected Central Memory CD4+ T Cells

- The Anti-Sigma Factor TcdC Modulates Hypervirulence in an Epidemic BI/NAP1/027 Clinical Isolate of

- Enhances Protective and Detrimental HLA Class I-Mediated Immunity in Chronic Viral Infection

- The Mouse IAPE Endogenous Retrovirus Can Infect Cells through Any of the Five GPI-Anchored EphrinA Proteins

- The Urgent Need for Robust Coral Disease Diagnostics

- HacA-Independent Functions of the ER Stress Sensor IreA Synergize with the Canonical UPR to Influence Virulence Traits in

- A Novel Core Genome-Encoded Superantigen Contributes to Lethality of Community-Associated MRSA Necrotizing Pneumonia

- Critical Roles for LIGHT and Its Receptors in Generating T Cell-Mediated Immunity during Infection

- The SARS-Coronavirus-Host Interactome: Identification of Cyclophilins as Target for Pan-Coronavirus Inhibitors

- Frequent and Recent Human Acquisition of Simian Foamy Viruses Through Apes' Bites in Central Africa

- Mechanisms of Trafficking to the Brain

- Defining Emerging Roles for NF-κB in Antivirus Responses: Revisiting the Enhanceosome Paradigm

- The Role of Sialyl Glycan Recognition in Host Tissue Tropism of the Avian Parasite

- Evolutionarily Divergent, Unstable Filamentous Actin Is Essential for Gliding Motility in Apicomplexan Parasites

- The Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Transactivator Infected Cell Protein-4 Drives VEGF-A Dependent Neovascularization

- Distinct Single Amino Acid Replacements in the Control of Virulence Regulator Protein Differentially Impact Streptococcal Pathogenesis

- Soluble Rhesus Lymphocryptovirus gp350 Protects against Infection and Reduces Viral Loads in Animals that Become Infected with Virus after Challenge

- A Genetic Screen Reveals Arabidopsis Stomatal and/or Apoplastic Defenses against pv. DC3000

- Hepatitis C Virus Reveals a Novel Early Control in Acute Immune Response

- Fumarate Reductase Activity Maintains an Energized Membrane in Anaerobic

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Regulates Cell Stress Response and Apoptosis

- The SARS-Coronavirus-Host Interactome: Identification of Cyclophilins as Target for Pan-Coronavirus Inhibitors

- Biochemical and Structural Insights into the Mechanisms of SARS Coronavirus RNA Ribose 2′-O-Methylation by nsp16/nsp10 Protein Complex

- Evolutionarily Divergent, Unstable Filamentous Actin Is Essential for Gliding Motility in Apicomplexan Parasites

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání