-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaFine Mapping of Dominant -Linked Incompatibility Alleles in Hybrids

The inviability or sterility of interspecific hybrids is one of the mechanisms of reproductive isolation that keep species apart. In this report, we use the genetic tools of Drosophila melanogaster to assess the cytological locations and relative frequency of dominant X-linked alleles involved in hybrid inviability in three different interspecific crosses. We map the genomic regions of the D. melanogaster X-chromosome that cause inviability in hybrids produced by D. melanogaster females crossed to males of three other Drosophila species: D. simulans, D. mauritiana and D. santomea. For each hybrid inviability allele we identified, we characterized the developmental defects that occur in the inviable hybrids. Our results show that the effect of these X-linked lethal regions is lineage-specific, as is the total number of alleles that cause hybrid inviability. These results can be expanded and will allow for the exact identification of X-linked D. melanogaster alleles in these three different hybrid contexts.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004270

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004270Summary

The inviability or sterility of interspecific hybrids is one of the mechanisms of reproductive isolation that keep species apart. In this report, we use the genetic tools of Drosophila melanogaster to assess the cytological locations and relative frequency of dominant X-linked alleles involved in hybrid inviability in three different interspecific crosses. We map the genomic regions of the D. melanogaster X-chromosome that cause inviability in hybrids produced by D. melanogaster females crossed to males of three other Drosophila species: D. simulans, D. mauritiana and D. santomea. For each hybrid inviability allele we identified, we characterized the developmental defects that occur in the inviable hybrids. Our results show that the effect of these X-linked lethal regions is lineage-specific, as is the total number of alleles that cause hybrid inviability. These results can be expanded and will allow for the exact identification of X-linked D. melanogaster alleles in these three different hybrid contexts.

Introduction

One of the most intensely studied forms of reproductive isolation is intrinsic postzygotic isolation: the inviability or sterility of interspecific hybrids that arises during development. The genetic mechanisms underlying this type of reproductive isolation are thought to be irreversible in evolutionary time [1], [2]. The study of postzygotic isolating mechanisms can reveal the molecular changes that have arisen between species [3], [4]. There is both theoretical and empirical evidence for the role of postzygotic isolation in completing the process of speciation through the action of natural selection [5]–[7], as enhanced prezygotic isolation might evolve as a byproduct of maladaptive hybridization, thus furthering the speciation process [6], [8].

In the Dobzhansky-Muller model (DM model) of the evolution of reproductive isolation, the genetic basis of hybrid breakdown involves (at minimum) two loci with an ancestral genotype of A1A1B1B1. The ancestral species splits into two descendant species that eventually acquire genotypes A1A1B2B2 and A2A2B1B1 through natural selection, meiotic drive or, less likely, genetic drift. This model posits that postzygotic isolation arises in allopatry as a collateral effect of the evolutionary divergence between these two isolated populations. In this case, although species having genotypes A1A1B2B2 and A2A2B1B1 at two loci are fit, the hybrid progeny will have a genotype A1A2B1B2 and therefore might be unfit: either sterile or inviable because the A2 and B2 alleles do not interact properly [1], [3], [9], [10]. The DM model presents a general mechanism for the evolution of postzygotic isolation, and explains a substantial proportion of the cases in which we know the genetic basis of hybrid breakdown [for exceptions see 11], [12], [ reviewed in 13].

Concerted mapping efforts have localized a number of hybrid incompatibility genes (those involved in Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities, or DMI) to small chromosomal regions [reviewed in 4], [13], [14] and have yielded some general patterns about the biology of genes involved in reproductive isolation. The first general pattern of hybrid inviability, Haldane's rule, pre-dates genetic mapping. In a wide variety of organisms, if hybrids of only one of the sexes are inviable or sterile, it will be the heterogametic sex [1], [15], [16]. Second, many (but not all) of the genes that cause hybrid breakdown have evolved under the influence of natural selection or meiotic drive, suggesting that rapid evolution within species leads to the evolution of DMI in hybrids [17]–[19]. Third, the X-chromosome, when compared with the autosomes, plays a disproportionately large role in postzygotic isolation [1], [20]. Fourth, mapping results have shown that the predictions from the DM model hold at the genomic level, and that the number of genes involved in hybrid inviability evolves faster than the accumulation of neutral genetic differences between species [21]–[23]. Finally, hybrid incompatibilities are asymmetric (i.e, A2 is incompatible with B2, but A1 may be compatible with B1). These asymmetries often result from DMIs involving uniparentally inherited genetic factors such as cytoplasmic–nuclear interactions [24]–[29].

Of these five patterns, two—Haldane's rule and the large effect of the X-chromosome on hybrid inviability—can be explained by the hemizygosity of the sex chromosome and the dominance theory ([30]–[33]; see [34] for alternative explanations of Haldane's rule in animals lacking a heterogametic sex). In Drosophila, X-linked genes can have a disproportional effect on hybrid fitness because the heterogametic hybrid males suffer from both the dominant and recessive deleterious X-linked alleles [35]–[37]. In the homogametic females, however, the deleterious effects of recessive alleles are masked by the presence of a second X-chromosome. In Drosophila hybrids, several studies have suggested the presence of recessive alleles in one of the X-chromosomes that can cause hybrid inviability in females when uncovered with a genetic lesion [38]. Surprisingly, in some of these crosses, hybrid males are viable despite all the recessive factors from one X-chromosome being fully exposed [31], [39]. One hypothesis for why males, but not females, can survive in these cases is that epistatic interactions between the two X-chromosomes lead to inviability in females. This idea, first formalized by Orr [30], states that since female hybrids carry two X-chromosomes, they suffer twice as many interactions involving the sex chromosomes but as the alleles involved in hybrid breakdown are on average recessive, the heterogametic sex is still much more prone to suffer hybrid breakdown. The hypothesis that the homogametic sex (females in Drosophila) suffers from negative epistatic interactions between X-chromosomes remains largely untested (but see [40], [41]). One of the prerequisites of such interactions is the existence of dominant partners on one of the X-chromosomes that could potentially cause hybrid inviability in females but not in males. The aim of this study is to determine if this sex-specific epistasis is present in interspecific hybrids and reveal dominant partners in the interactions.

Drosophila melanogaster is particularly useful for the study of the genetic architecture of hybrid inviability because of its armamentarium of genetic tools that can be used to establish the identity and density of alleles involved in DMIs. To date, two studies have used deficiencies in D. melanogaster, cytological aberrations in which a chromosomal segment is deleted, to reveal recessive alleles from the paternal species that cause inviability in D. melanogaster/D. simulans hybrids due to interactions with dominant partners in the D. melanogaster genome. Coyne et al. [38] found three lethal regions in the D. simulans genome with only one of those alleles located on the X-chromosome. Matute et al. [22] identified a total of 11 D. simulans recessive alleles, including two on the D. simulans X-chromosome (Xsim) that interacted with the D. melanogaster genome. In parallel, Matute et al. [22] also aimed to dissect causes of inviability in hybrids between the more diverged species D. santomea and D. melanogaster and determined that at least 71 genomic regions were involved in hybrid inviability. The results from that study indicated at least 13 recessive alleles residing on the D. santomea X-chromosome (Xsan) cause hybrid inviability.

However, these deficiency-mapping efforts focused on identifying a single hybrid inviability allele from what certainly could be complex epistatic interactions (involving three or more loci; [3], [19], [42]–[45]). These studies both localized recessive alleles in the genome of the paternal species (either D. simulans or D. santomea) that are involved in DMIs, but did not explore their possible partners in the maternal genome (D. melanogaster). QTL-mapping and introgression-based approaches share the same drawback: even though they reveal a portrait of the genes involved in hybrid breakdown (e.g., [46], [47]), they do not reveal the full nature of the genetic architecture of hybrid inviability as they do not identify the specific epistatic interactions leading to reduced fitness of hybrids. Three studies have aimed not only to identify single alleles that contribute to hybrid inviability but also to determine the interacting partners of such alleles. Presgraves [48] pursued a genome-wide identification of D. simulans autosomal recessive alleles that cause lethality in male D. melanogaster/D. simulans hybrids (mel/sim). In this case, if the D. simulans X-chromosome was present (as in hybrid females), the autosomal recessive alleles did not cause hybrid inviability, suggesting the existence of epistatic recessive partners on the D. melanogaster X-chromosome (Xmel). This initial screening allowed for the identification of two autosomal nuclear pore proteins (Nup96-98 [49] and Nup160 [50] that in conjunction with unidentified recessive alleles in Xmel cause inviability in mel/sim hybrids.

Sawamura and Yamamoto [40] used a D. melanogaster translocation from the X-chromosome attached to the Y-chromosome [Dp(1;Y) translocation; Precise genotype: Ts(1Lt;Ylt)Zhr/Dp(1;Y)y+;.40] to identify a dominant X-linked allele that causes lethality in hybrid sim/mel sons, and named it zhr (zygotic hybrid rescue). Fine functional analyses, also aided by the use of Dp(1;Y) translocations have revealed that zhr is a repetitive 359 bp DNA satellite, derived in D. melanogaster and absent in D. simulans, that causes hybrid inviability by causing heterochromatin packing problems which in turn leads to mitotic defects early in embryogenesis [51].

Finally, Cattani and Presgraves [41] expanded the results from Coyne et al. [38], and identified a candidate dominant factor on Xmel that could cause hybrid inviability when interacting with one of the D. mauritiana X-linked recessive alleles. Their results point to the existence of one dominant factor that interacts with at least one recessive factor in the heterochromatic region of the D. mauritiana X-chromosome to cause hybrid lethality. These two mapping efforts have uncovered most of the known X-linked dominant DMI partners in Drosophila.

Here, we explore the possibility of negative epistatic interactions between X-chromosomes in several interspecific hybrids by taking advantage of a comprehensive tiling set of duplications of the D. melanogaster X-chromosome attached to the Y-chromosome [52]. In this report, we show the possibility of producing D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrid males. Second, we examine inviable hybrid males from several crosses (D. melanogaster/D. santomea, D. melanogaster/D. simulans and D. melanogaster/D. mauritiana) to study the effect of small regions of the D. melanogaster X-chromosome in an across-species comparative manner; this revealed significant differences in the frequency, developmental timing and lineage specificity of epistatic interactions between X-chromosomes in Drosophila hybrids.

Results

Hybrid mel/san males are viable if they carry a D. santomea X-chromosome

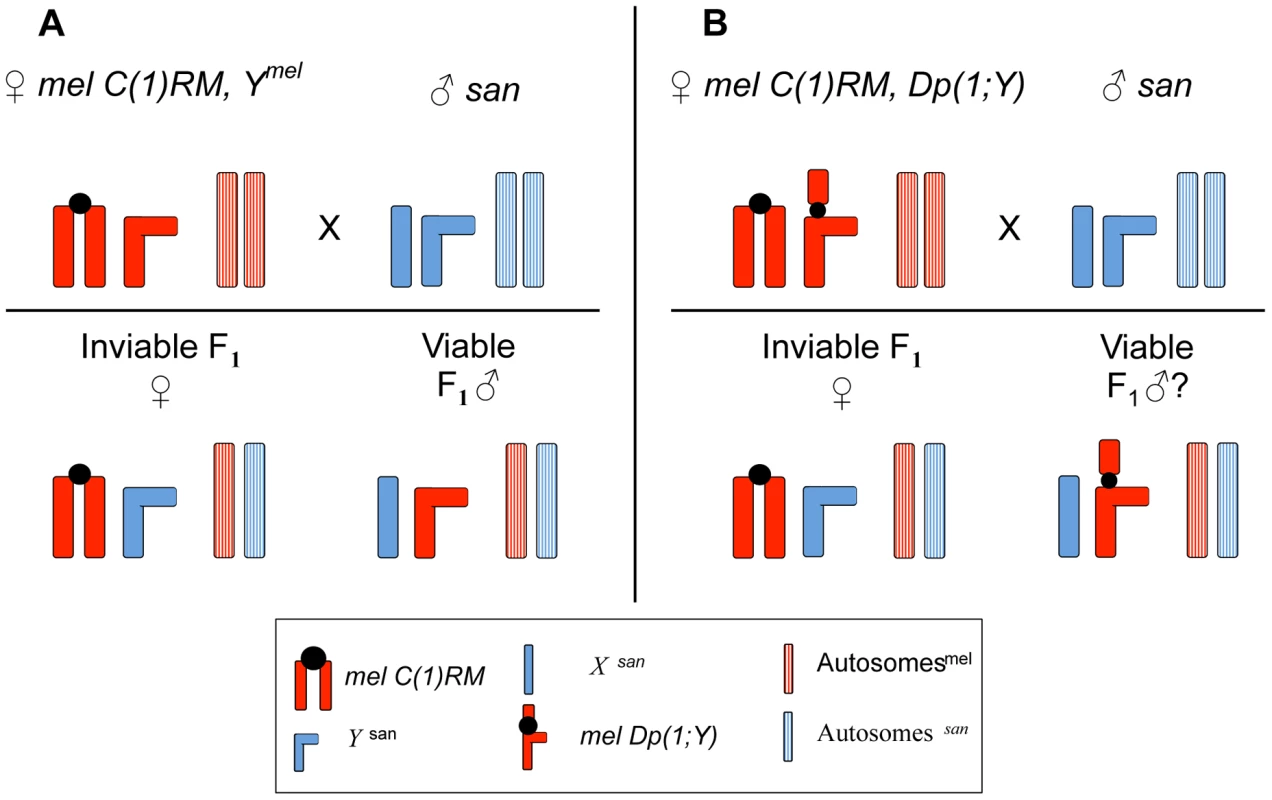

The cross of wild-type D. melanogaster females to wild-type D. santomea males produces only sterile adult female progeny while males with the genotype Xmel/Ysan die as embryos [47]. The reciprocal cross does not produce any progeny as premating isolation seems to be complete in that direction [53]. Recently, we discovered that when mel attached-X females with a Compound Reversed Metacentric chromosome, C(1)RM/0, are crossed to D. santomea males, they produce progeny entirely composed of adult hybrid males with the genotype Xsan/0 while the hybrid females die as embryos (Figure 1). We also observed that the cross of a second type of attached-X females, mel C(1)RM/Ymel, to D. santomea males produces solely Xsan/Ymel hybrid males. Crosses involving an alternative mel attached-X, Compound (1) Double X or C(1)DX, produce identical results. Figure S1 shows two morphological traits of these previously undescribed hybrid males, number of teeth in the sex combs and abdominal pigmentation.

Fig. 1. Crossing scheme to study the effect of X-linked chromosomal duplications in mel/san hybrid males.

A. Crosses between D. melanogaster females carrying an attached-X [C(1)RM] chromosome and D. santomea males produce dead females and viable adult hybrid males. (The Ymel-chromosome has no effect on hybrid male viability, see text.) B. D. melanogaster females carrying an attached-X [C(1)RM] chromosome and a compound Y-chromosome (i.e, an X-chromosome duplication attached to the Ymel-chromosome) are viable and fertile. These females can be crossed to D. santomea males, and even though all the females die as embryos, males survive if the Dp(1;Ymel) does not carry dominant (or semi-dominant) lethal alleles. We were able to tile 72% of the whole euchromatic X-chromosome from D. melanogaster. Results for this screening are shown in Figure 3. Because we can produce hybrid males with and without Ymel, we asked first whether this chromosome had any affect on hybrid male viability, or longevity. We first compared Xsan/Ymel to Xsan/0 hybrid males. (These males were generated by mel attached-X females carrying a Ymel (either C(1)RM/Ymel or C(1)DX/Ymel)×D. santomea males and attached-X mel females carrying only the homocompound chromosome (C(1)RM/0 or C(1)DX/0)×D. santomea males respectively.) Males of these two genotypes showed no differences in viability at any developmental stage (Figure S2). The two types of hybrid males were both sterile and showed similar longevity (Figure S2; Tables S1 and S2). Despite the morphological defects of these hybrid males, particularly in abdominal segments, they survive almost as long as virgin males from both parental species (Figure S2). The fitness of the Xsan/0 and Xsan/Ymel hybrids is effectively zero as both are sterile, however, these results demonstrate that there are no lethal epistatic interactions between Xsan and Ymel, between the D. santomea autosomes and Ymel, or between Xsan and the cytoplasmic elements, including mitochondrial genes or maternally deposited gene products, of D. melanogaster.

We then excluded the possibility that the mel/san males could actually be feminized or sexually chimeric. We assessed the presence of male-specific structures on both sides of the body in Xsan/0 males produced from the cross mel C(1)RM/0×san. The mel/san hybrid males are bilaterally symmetrical, with sex combs, testes and genital arches on both sides. More specifically, the number of teeth in their sex-combs is not significantly different between left and right (Paired Wilcoxon signed rank test with continuity correction on sex comb teeth, left vs. right: V = 4, P = 0.850) and did not have any feminized features (Figure S1). All hybrid males were sterile and had atrophied testes lacking motile sperm. These results indicate that these hybrids are true males are not gynandromorphs or otherwise sexually chimeric.

Following [31], we were also able to perform interspecific crosses between mel C(1)RM/0 females and D. simulans (sim), or D. mauritiana (mau) males. These crosses produce viable hybrid Xsim/0 or Xmau/0 males. We were also able to produce Xsim/Ymel and Xmau/Ymel hybrid males by crossing mel C(1)RM/Ymel to sim or mau males, respectively. Xsim/Ymel and Xsim/0, as well as Xmau/Ymel and Xmau/0 males show similar viability and longevity to the pure parental species regardless of the genetic background of the attached-X D. melanogaster stock (Tables S1 and S2). The existence of these viable hybrid males, similar to the existence of mel/san hybrids, indicates there no lethal epistatic interactions exist between Xsim (or Xmau) and Ymel, between Ymel and the D. simulans (or D. mauritiana) autosomes, or between Xsim (or Xmau) and the cytoplasm of D. melanogaster (Figure S3 and S4).

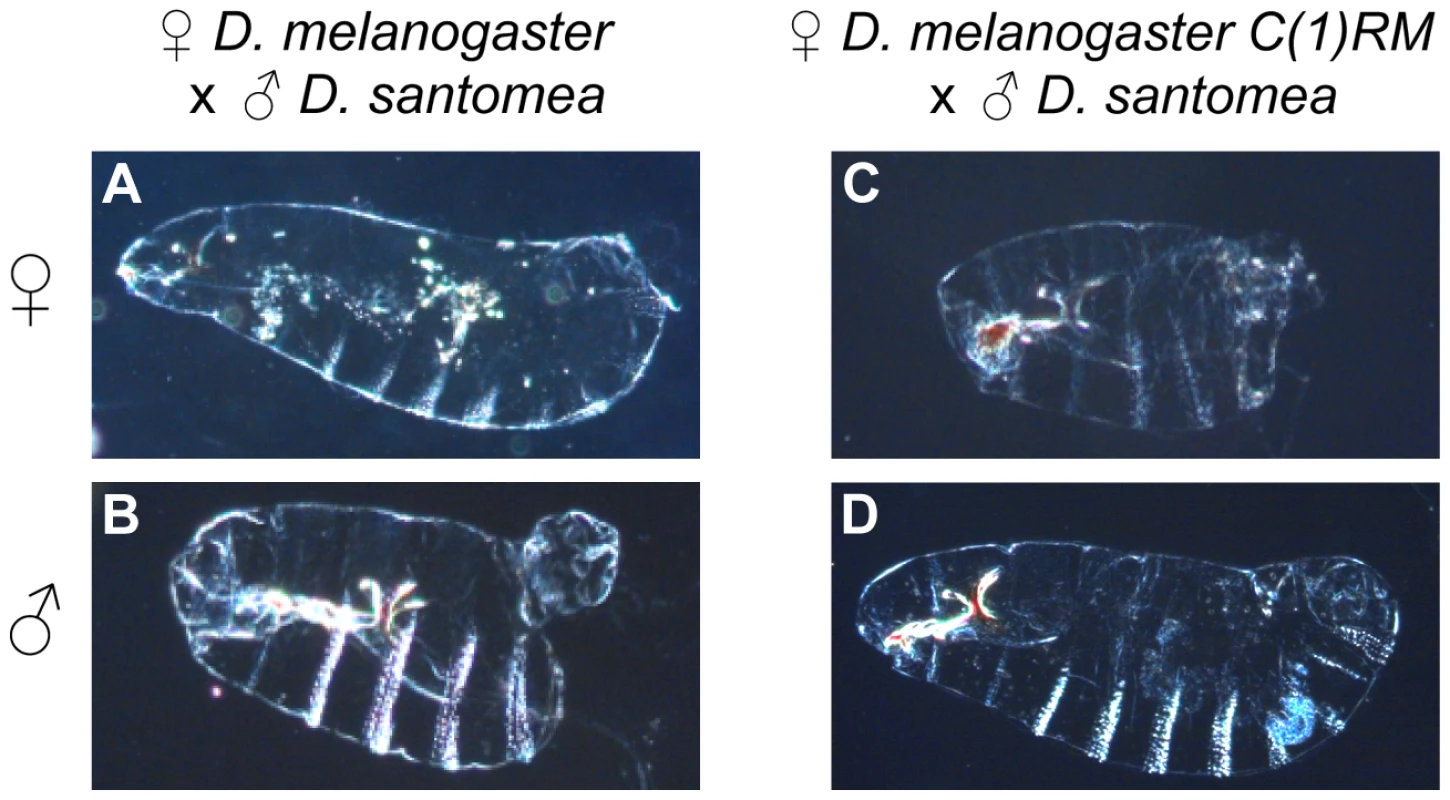

In all three interspecific crosses involving mel C(1)RM/Ymel (and mel C(1)RM/0) females, hybrid females that carry the two Xmel rarely survive to adulthood. In the case of mel C(1)RM/0×san crosses, hybrid females (XmelXmel/Ysan) predominantly die as embryos, the same developmental stage at which wild-type hybrid males (Xmel/Ysan) die. Hybrid female embryos carrying only the C(1)RM chromosome manifest an abdominal ablation in the posterior, very similar to that which we described for wild-type hybrid males who carry an Xmel [53]. This phenotype is present in 71% of the hybrid (XmelXmel/Ysan) females, comparable to the 67% frequency seen in wild-type Xmel/Ysan males, (Figure 2, [53]). In the case of [C(1)RM/0×sim], and [C(1)RM/0×mau] crosses, the hybrid females carrying the compound attached-Xmel chromosome are able to survive through their larval stages but do not transition into pupae, similar to mel/sim (and mel/mau) wild-type hybrid males [54]–[56]. These results indicate that either one or two copies of Xmel chromosome in the absence of another X-chromosome can induce hybrid inviability regardless of the sex of the hybrid in the three interspecific crosses.

Fig. 2. Developmental defects observed in two interspecific crosses between D. melanogaster and D. santomea.

In crosses of wild-type D. melanogaster females and D. santomea males, the majority of females (Xmel/Xsan) emerge as adults. Those that fail to hatch from embryogenesis manifest cuticular defects typified by (A). Hybrid male embryos (Xmel/Ysan) from this cross usually die and show severe abdominal ablations (B). In crosses between D. melanogaster C(1)RM ♀ and D. santomea ♂, the majority of hybrid females embryos (XmelXmel/Ysan) fail to hatch and show abdominal ablations (C), while hybrid males (Xsan/0) usually survive. Those that fail to hatch are typified by (D). To determine which factors residing on Xmel are involved in hybrid inviability we then undertook a duplication mapping screen to identify the regions of Xmel that cause lethality in males carrying a D. santomea, D. simulans or D. mauritiana X-chromosome and a fragment of Xmel attached to the Ymel [Dp(1;Y)]. Our goal was to identify the dominant regions on Xmel that can cause hybrid lethality in the presence of the X-chromosome from another species. All fly stocks are listed in Tables S3 and S4.

The X-chromosome from D. melanogaster contains dominant alleles that cause hybrid inviability in mel/san hybrid males

As the duplication mapping approach [40], [41] has no balancer sibling or other internal controls, this study is limited to the identification of alleles that cause complete (rather than partial) lethality. We used two different criteria to describe dominant lethals. First, we used a qualitative cut-off: an allele was classified as lethal if fewer than 10% of individuals hatched or molted to the next developmental stage. This approach is limited because the cut-off is arbitrary, but our data were resilient to more quantitative analyses (see Methods). Second, the duplication had to cause lethality in both attached-X genetic backgrounds; mel C(1)RM and mel C(1)DX. This approach therefore does not detect putative semi-lethal alleles or those that can cause significant, but incomplete, reductions in viability. To exclude pre-mating isolation from our observations, we only included data from matings in which we observed inseminated females. Twenty females from each of three replicates were dissected for each cross and their reproductive tracts were inspected for the presence of sperm, either motile or dead. Table S5 shows insemination rates for the three interspecific crosses and the two intraspecific crosses, involving mel C(1)RM, Dp(1;Y) females. To further exclude postmating-prezygotic isolation between the two species involved in the cross, herein we only include data from matings that produced embryonic progeny.

When C(1)RM, Dp(1;Ymel) females hybridize with D. santomea males, four genotypes are produced: [Ysan/Dp(1;Ymel)], [C(1)RM/Xsan], [C(1)RM/Ysan], and [Xsan/Ymel, Dp(1;Y)]. Embryos with the genotype [Ysan/Ymel, Dp(1;Y)], also called nullo-X embryos, do not complete cellularization in the early blastoderm stage and fail to differentiate any discernible larval cuticle [57]. Thus, on a gross phenotypic level, they are indistinguishable from unfertilized eggs. Hybrid metafemales embryos, with 3 X-chromosomes C(1)RM/Xsan, also routinely fail to hatch. These females cannot be differentiated from hybrid males as both carry a wild-type yellow allele and have black mouthparts. Adult hybrid metafemales are not to be expected as, even in pure species crosses within D. melanogaster, the frequency of metafemale survival to eclosion is less than 0.2% of total females [58]. In this study male (Xsan/Dp(1;Y)) embryonic lethality was assessed in a qualitative way (i.e, an Xmel region was considered lethal if less than 10% of the total progeny hatched to L1), such that the lack of distinction between hybrid males and metafemales was not a substantial concern. Adult hybrid metafemale or attached Xmel/Ysan females were never recovered in any of the crosses (but see [59]–[62] for studies on viability of hybrid mel/sim metafemales). The remaining two genotypes from these crosses are [C(1)RM/Ysan] females, of which nearly all die as embryos. A majority of these animals manifest abdominal ablations, and are distinguished by their lack of black pigment in their larval mouth parts. The majority of males of the final genotype, [Xsan/Dp(1;Ymel)] males, hatch into L1 and develop into adults, unless the duplication carried on the Ymel chromosome contains a dominant lethal allele which induces hybrid inviability. When C(1)RM, Dp(1;Ymel) females are hybridized with D. simulans or D. mauritiana males, four analogous genotypes are produced with identical survivability.

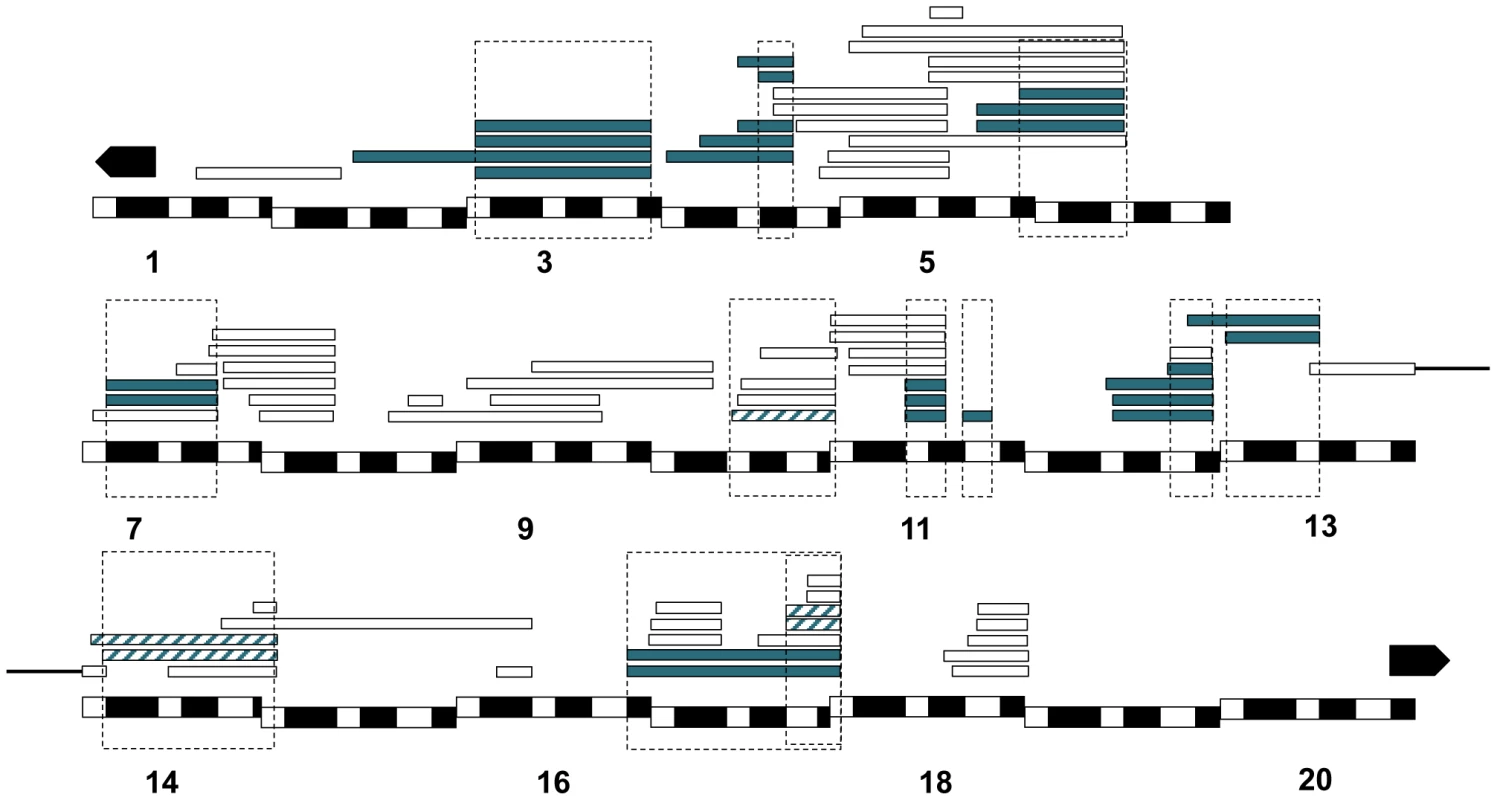

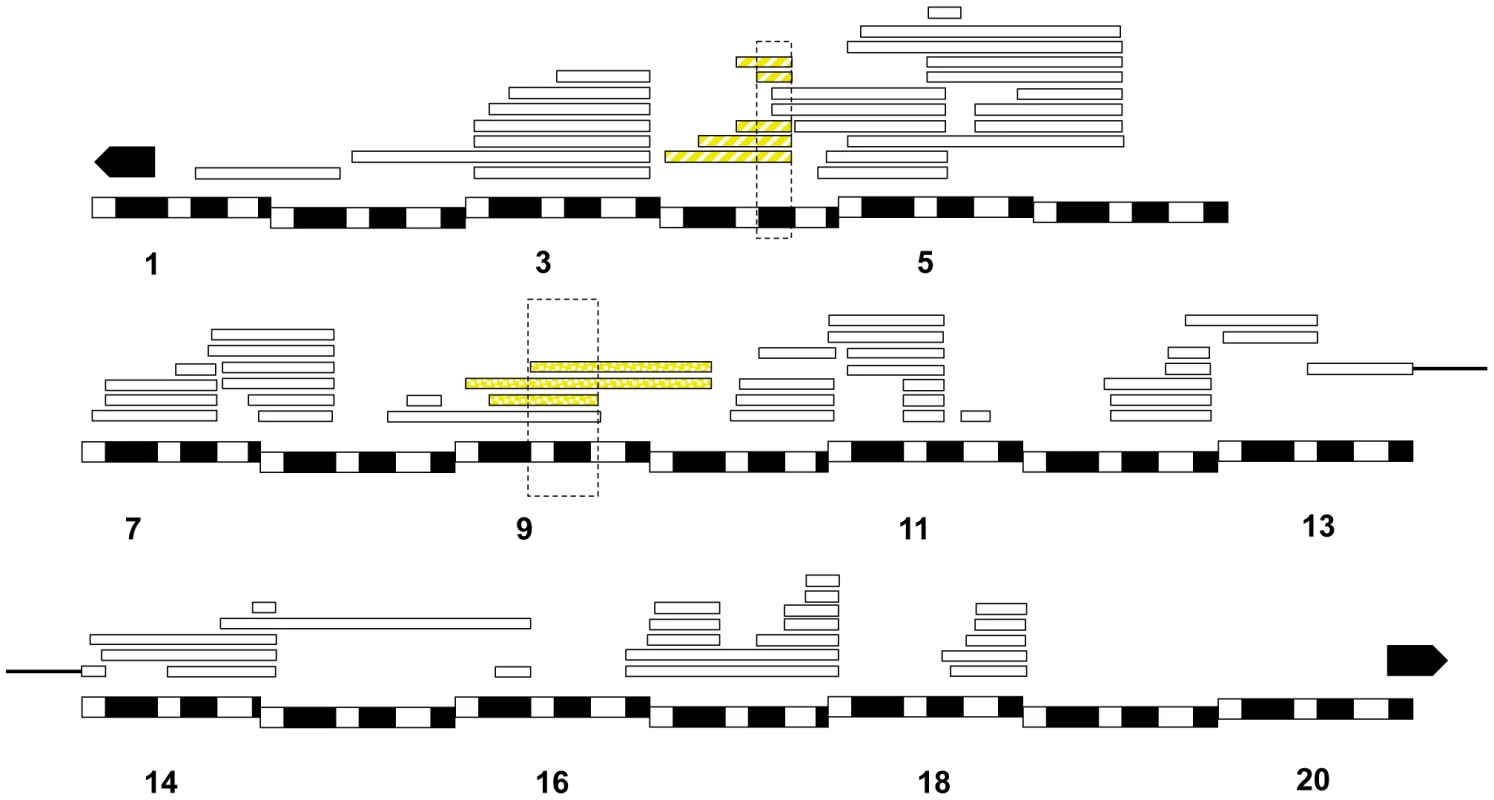

In total, thirty-one duplications carrying twelve distinct chromosomal regions in Xmel caused hybrid lethality at some developmental stage in C(1)RM, Dp(1;Ymel)×san crosses (Figure 3, Table S6). Out of these twelve regions, nine caused complete embryonic lethality, none caused male larval lethality and three caused male pupal lethality.

Fig. 3. Mapping results from mel/san crosses.

We crossed D. melanogaster C(1)RM/Dp(1;Y) females to D. santomea males and assessed what proportion of the males were dead at different stages of development. All the hybridizations that produced progeny are represented by a rectangle. The Xmel regions [Dp(1;Y)] that caused hybrid inviability are shown in two shades of blue depending on where they caused hybrid inviability: solid blue (embryonic lethality), and blue stripes (pupal lethality). Chromosomal segments that did not cause lethality are not colored. Please note the region on 17 contains two lethal regions. We followed the same approach using a different D. melanogaster background and a different attached-X chromosome; C(1)DX. In addition to the twelve lethal regions identified in the C(1)RM background, we detected one additional locus that induces hybrid lethality in the C(1)DX/Dp(1;Ymel)×san crosses (Table S7). The lethality of this additional region, [18F4-19A2; 19A2], in the C(1)DX genetic background is likely due to an increased sensitivity resulting in higher overall lethality rates. We therefore focused only on the twelve duplications that caused lethality in both backgrounds. Figure 3 shows the cytological position of each of the twelve Xmel-linked lethal alleles.

In wild-type crosses involving D. melanogaster×D. santomea, we found that the hybrid males, which carry the full Xmel-chromosome (Xmel/Ysan), die as embryos with profound abdominal ablations [53]. While some hybrid females also manifest abdominal segment pattern defects, they are not as severe, suggesting the presence of the Xsan chromosome ameliorates the patterning defects. Hybrid female embryos carrying only Xmel-chromosomes (genotype attached-X C(1)RM/Ysan) have a much higher penetrance of the abdominal ablation phenotype than the XmelXmel/Xsan metafemale embryos (Figure 2). Parallel analysis with an alternative attached-X chromosome, C(1)DX, shows that 64.6% (SEM = 4.1%) of C(1)DX/Ysan female embryos manifest severe abdominal ablations. These results indicate that Xmel carries at least one allele that induces abdominal ablations in both wild-type hybrid males and in XmelXmel/Ysan hybrid females. This excludes a simple X-chromosome dosage effect as the cause of lethality in the wild-type hybrid male. The incomplete inviability of Xmel/Xsan females in crosses between wild type D. melanogaster females and D. san males indicates that the allele or alleles on Xmel must act semi-dominantly. As 71.5% (SEM 9.3%) of C(1)DX/Xsan metafemales have complete abdominal structures, this implies that in both the wild-type hybrid females and hybrid metafemales, Xsan can serve to partially rescue the ablation phenotype, but not the embryonic lethality of hybrid metafemales.

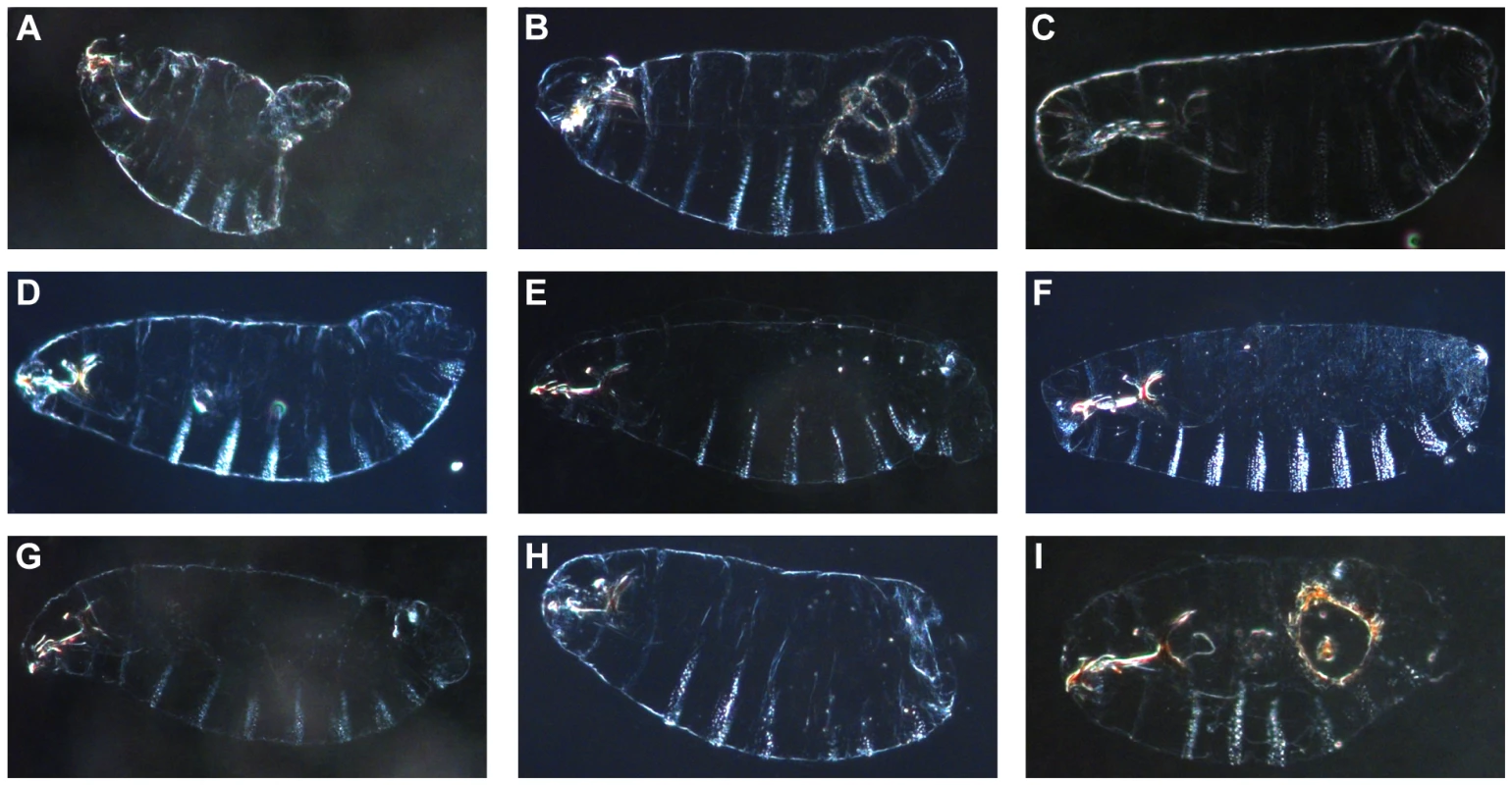

We then searched for the region or regions of Xmel responsible for this abdominal ablation phenotype. We analyzed the cuticular phenotypes of the Dp(1;Ymel)/Xsan male embryos which failed to hatch to discern whether one or more alleles residing on Xmel caused this developmental perturbation. The cuticular phenotypes of these nine genotypes are shown in Figure 4. A typological analysis shows the major morphological differences between these nine genotypes. The allele(s) which induce abdominal ablation and hybrid inviability appears to reside on the tip of the Xmel-chromosome, as that cuticular defect manifests significantly more frequently when this region is present (Figure S4). All the other regions from Xmel that cause embryonic hybrid inviability have a substantially reduced frequency of abdominal ablations (Figure 4, Figure S4) but frequent head involution and segmentation defects.

Fig. 4. Cuticular defects observed in the nine lethal regions from the D. melanogaster X-chromosome.

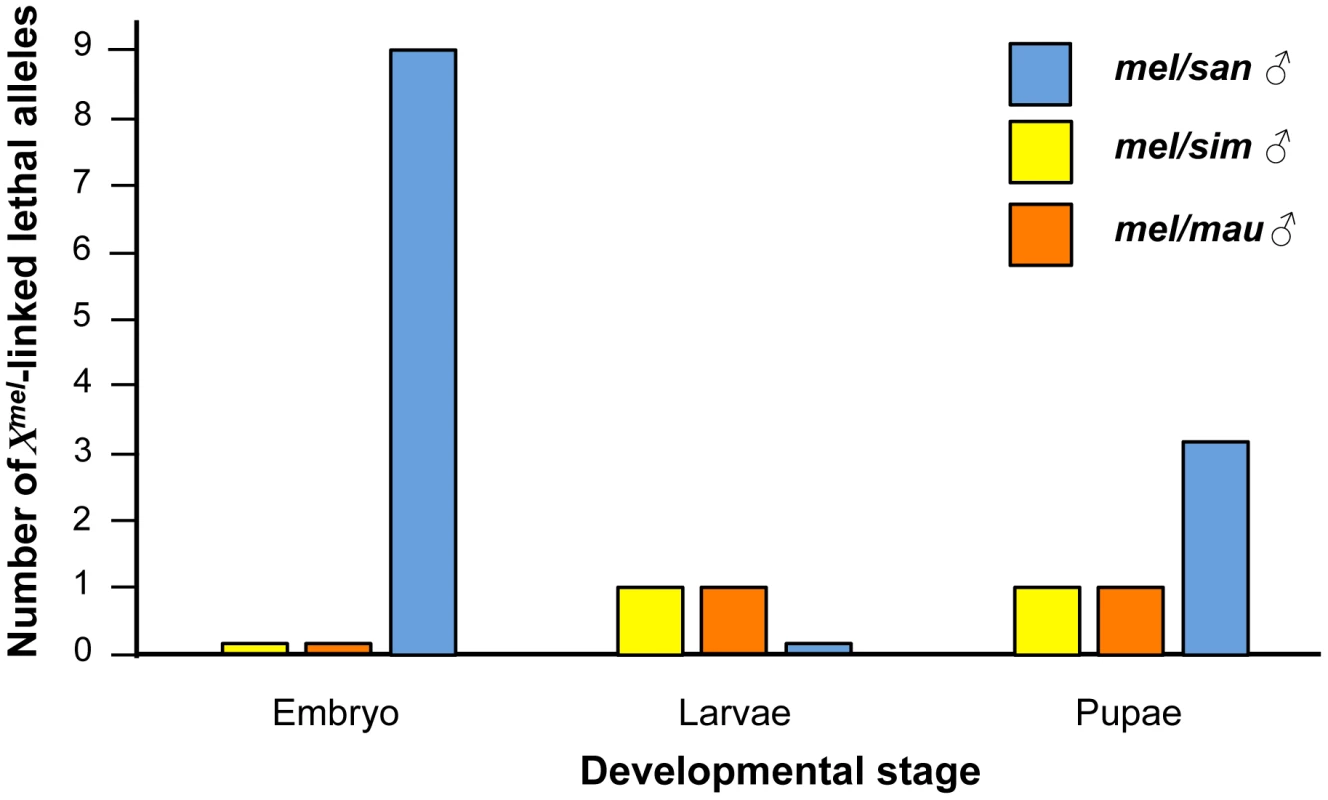

A. Males carrying the 3A–3D region show the abdominal ablation observed in Xmel/Ysan hybrid males and XmelXmel/Ysan hybrid females. B–I. Hybrid males that carry any of the other eight embryonic lethal Xmel-linked regions show different phenotypes and the abdominal ablation is more rare than in Xmel/Ysan males. The genotypes (and the cytological bands of the duplication) of each of the shown males are: A. Dp(1;Y)BSC75 (X:2C1-3E4). B. Dp(1;Y)BSC159 (X:4A5-4D7). C. Dp(1;Y)BSC289 (X:5E1-6C7). D. Dp(1;Y)BSC176 (X:7B2-7D18). E. Dp(1;Y)BSC126 (X:11C2-11D1). F. Dp(1;Y)BSC327 (X:11D5-11E8). G. Dp(1;Y)BSC186 (X:12C1-12F4). H. Dp(1;Y)BSC269 (X:12E9-13C5). I. Dp(1;Y)BSC11 (X:16F6-18A7). We could assess whether alleles caused hybrid inviability in Dp(1;Ymel)/Xsan hybrid males at a particular developmental stage, or whether their effects were uniformly distributed across embryonic, larval, and pupal stages. We found 9 alleles causing embryonic lethality, with none causing larval lethality, and three causing pupal lethality (Figure 5). The distribution of alleles involved in inviability at different stages of development in Dp(1;Ymel)/Xsan hybrid males significantly departs from the expectation that alleles causing hybrid lethality would be uniformly distributed across all stages of development (Figure 5, comparing the observed frequency of lethal alleles at each developmental stage with a uniform distribution of lethals across development (i.e., 4 lethals at each stage; χ2 = 10.5, df = 2, P = 5.25×10−3). These results suggest that in Dp(1;Ymel)/Xsan hybrid males, the very early and very late stages are more prone to failures in proper development.

Fig. 5. Some developmental stages are more prone to show hybrid inviability than others in mel/san hybrids.

Xmel alleles that cause hybrid inviability in mel/san hybrid males are not uniformly distributed across development, and are more likely to act either at embryonic or pupal stages (Blue: mel/san hybrids; Orange: mel/mau hybrids; Yellow: mel/sim hybrids). The uniformity of the effects was assessed neither in mel/sim nor in mel/mau hybrids given the scarcity of Xmel lethals in these crosses. The X-chromosome from D. melanogaster contains dominant alleles that cause hybrid inviability in mel/mau and mel/sim hybrid males

We followed a similar approach to identify Xmel-linked lethal alleles in mel/mau and mel/sim hybrids. We crossed females from the C(1)RM, Dp(1;Y) and C(1)DX, Dp(1;Y) panels to males of D. mauritiana and D. simulans. In the same way we assessed the mel/san hybrids, we measured hatching rates and male viability at different developmental stages for these two interspecific crosses.

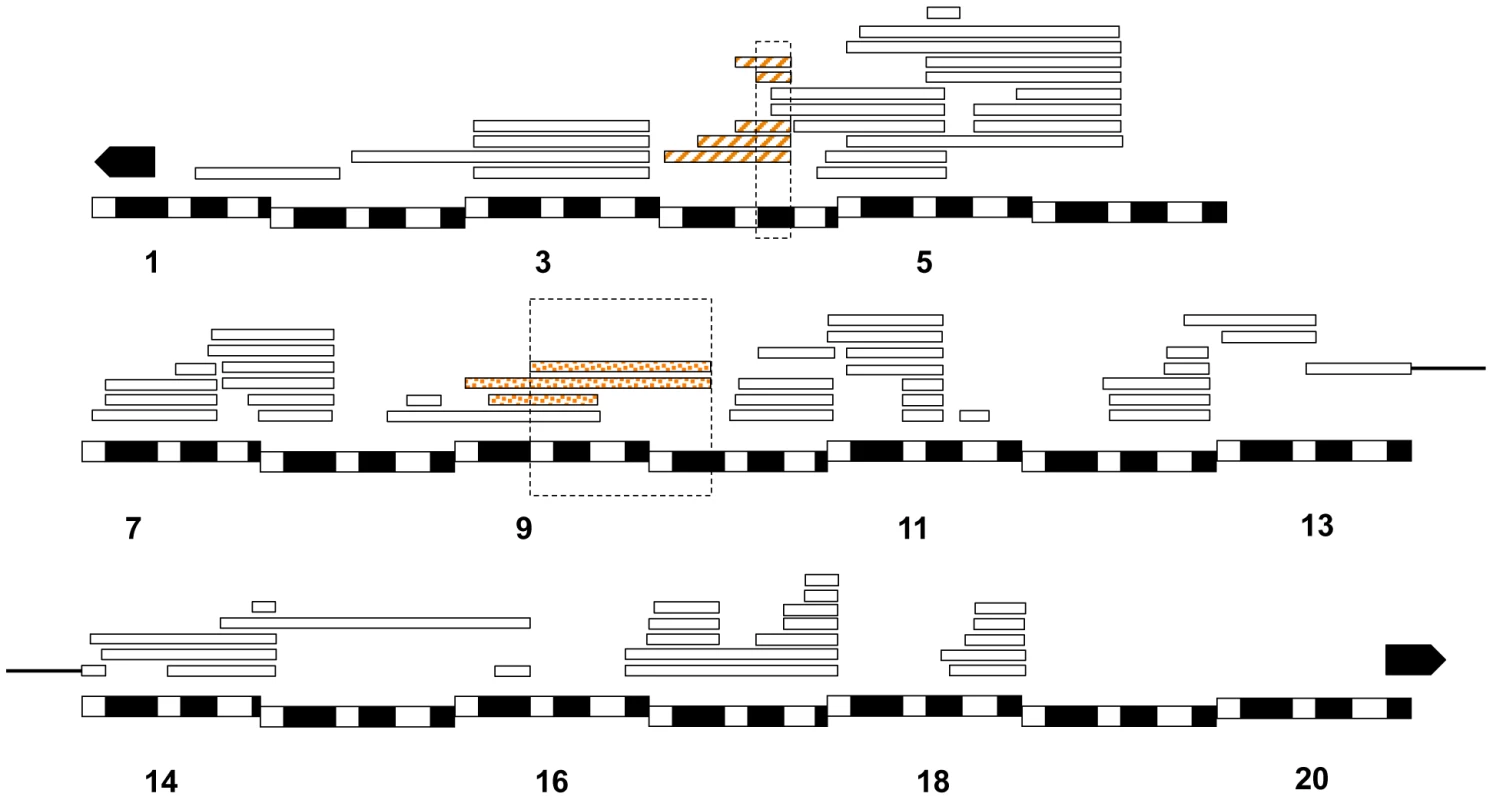

In Dp(1;Ymel)/Xsim males, we found that two unique regions (eight Xmel fragments) that caused larval lethality in both mel attached-X backgrounds (Figure 6). Similarly, in mel/mau males, we found two unique regions (eight Xmel fragments) that caused hybrid inviability (Figure 7). One region, between 4C and 4D, causes adult hybrid inviability in all the three assayed hybrids. The region between 9C and 10B causes lethality in both mel/sim and in mel/mau hybrids. This region contains Hmrmel (hybrid male rescue), which is known to induce hybrid male lethality in mel/sim and mel/mau crosses; as well as CG11160mel, an allele suggested to be lethality-inducing in a previous mapping effort in mel/mau hybrids [38]. With the current mapping resolution, however, it is not possible to discern whether there is a single lethal allele or whether both alleles are lethal. Surprisingly, a larger duplication that contains the region between 8D and 9E (8D9-8E4; 9E2; Stock: 29782) does not cause lethality in either attached-X background. This result suggests that the large duplication might mask recessive alleles on Xsan that are required for the lethal epistatic interaction.

Fig. 6. Relative frequency of hybrid lethal alleles in the D. melanogaster X-chromosome in hybrid males with D. simulans.

Two regions from Xmel cause hybrid lethality in mel/sim hybrid males (one of them encompassing Hmrmel and CG11160mel). The two regions are shared with mel/mau hybrid males and also cause hybrid lethality in postembryonic stages. The chromosomal segment that causes larval lethality is dotted, while the region that causes pupal lethality is striped. Chromosomal segments that did not cause lethality are not colored. Fig. 7. Relative frequency of hybrid lethal alleles in the D. melanogaster X-chromosome in hybrid males with D. mauritiana.

Only two regions from Xmel were lethal in mel/mau crosses (one encompassing CG11160mel and Hmrmel). Both of these lethal regions act during postembryonic development The chromosomal segment that causes larval lethality is dotted, while the region that causes pupal lethality is striped. Chromosomal segments that did not cause lethality are not colored. To exclude dominant lethal effects of the Dp(1;Y) duplications assayed, we examined their effects in intraspecific crosses. We assayed two more crosses: D. melanogaster C(1)RM, Dp(1;Y)×D. melanogaster Malawi-6-3 and D. melanogaster Malawi-9-2. The male and female progeny counts produced in these crosses are shown in Table S8. We did not find any fragment of Xmel that cause embryonic, larval or pupal lethality when carried by Ymel in these intraspecific crosses in either females or males, indicating no dominant epistatic interactions or lethal dosage effects of the Xmel pieces attached to the Ymel chromosome are present in the pure species background.

Rate of evolution of hybrid incompatibilities

We assessed whether the number of dominant alleles causing hybrid inviability followed the predictions of the snowball effect hypothesis of hybrid incompatibilities: the rate of accumulation of hybrid incompatibilities grows faster than linearly with divergence [3], [21]. We used previous genome-wide estimates of the number of silent substitutions per site between D. melanogaster and D. santomea (Ksmel-san = 0.24, [22]) and between D. melanogaster and D. simulans (Ksmel-sim = 0.11, [22]). Since D. mauritiana and D. simulans are equidistant from D. melanogaster [63], we assumed Ksmel-mau = Ksmel-sim = 0.11. Finally since we did not know the number of non-synonymous substitutions between the attached-X stocks and the two tested D. melanogaster lines, we conservatively used the maximum value of π ever reported for D. melanogaster populations (π = 0.03, [64], [65]). We fitted two models, a model in which the number of hybrid incompatibilities grew linearly with molecular synonymous divergence and a model in which the number of incompatibilities grew as a quadratic function of synonymous divergence. This analysis is methodologically similar to previous attempts [22], [23] but focuses on the dominant partners of the negative epistatic interactions and not on recessive (hemizygous) partners. Our analysis shows that the quadratic model explains the data much better than the linear model (Quadratic model: AIC –Akaike Information Criterion-: 6.795; Linear model: AIC: 24.75, Figure S5). This result indicates that the number of lethal alleles on Xmel in crosses between species with different divergence times follows the snowball theory and suggests that, similar to observations of recessive hybrid lethal alleles, the relative frequency of dominant hybrid lethal alleles also increases faster than linearly in hybrid crosses.

Discussion

D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrid males are viable if they carry the X-chromosome from D. santomea

The viability of male D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrid males provides several clues to the broader genetic architecture of hybrid inviability between these two species. In general, the possibility of producing these males indicates that there are no lethal incompatibilities between Xsan and Ymel, or between Xsan and the mel cytoplasmic elements. More specifically, these hybrid males allowed us to address the question of whether Xmel harbors dominant alleles involved in hybrid inviability.

The production of Xsan/0 and Xsan/Ymel hybrid males also sheds some light on previous results generated by pole cell transfers of D. yakuba (the sister species of D. santomea) into D. melanogaster mutants that carried no pole cells [66]. Sanchez and Santamaria [66] reported that it was possible to produce progeny between D. melanogaster females with gametes carrying the genome of D. yakuba (as a result of pole cell transfer) and D. melanogaster males. This hybridization is equivalent to a ♀ D. yakuba×♂ D. melanogaster cross, which has never succeeded with wild-type animals. These crosses produced viable hybrid individuals of both sexes. The yak/mel and mel/san male hybrids are not directly comparable at the cellular level because the two kinds of hybrids have different cytoplasmic elements. Nonetheless, there are certain elements that the two hybrids share. Both of them have a haploid D. melanogaster autosomal genome. Most relevant to the present analysis, the hybrid males from both crosses carry an X-chromosome from either D. santomea or D. yakuba and lack the X-chromosome from D. melanogaster. These results indicate that the architecture of hybrid inviability in hybrids between D. melanogaster and D. santomea might be similar to that in hybrids between D. yakuba and D. melanogaster; both crosses produce viable heterozygote females (in which recessive alleles on one X-chromosome are effectively masked by the other), and males only with the non-mel X-chromosome (although the cross that could produce XmelYyak males has not successfully been attempted). Since D. santomea and D. yakuba are closely related, with a divergence time of 0.4 million years [67], [68], it is reasonable to expect that a substantial proportion of the loci that interact with mel alleles to cause hybrid inviability originated along the lineage leading to both san and yak and are shared between the two species.

D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrid males and some hybrid females suffer from dominant or semi-dominant lethality alleles on Xmel

The difference between the hybrid males from the ♀ D. melanogaster× ♂ D. santomea cross (Xmel/Ysan) and the males from the D. melanogaster ♀ C(1)RM/Ymel× ♂ D. santomea cross (Xsan/Ymel) is the identity of the sex chromosomes the males carry: in the former case they carry Xmel and in the latter they carry Xsan. Hybrid males from both crosses carry a set of autosomes from each of the parental species. These results indicate that Xmel carries deleterious alleles that cause lethality in mel/san hybrid males, but that Xsan does not have the same lethality effect.

The developmental defects that the hybrid males show in the presence of some Xmel fragments indicate that one (or more) genetic factors on Xmel lead to the characteristic abdominal ablation phenotype in mel/san hybrids [53]. This phenotype is present in both hybrid males that have the Xmel and in hybrid females with two attached Xmel and no Xsan, and in a small but consistently observed fraction of the Xmel/Xsan females. Therefore the phenotypic determinant must be dominant or semi-dominant on Xmel. We mapped the determinant(s) to the tip of Xmel (between cytological bands 3A and 3D). In the absence of this determinant element, other Xmel-linked elements can cause hybrid inviability as well as different embryonic patterning defects at later developmental stages (Figure 4, Figure S4).

The sex specific lethality found in mel/san hybrid males is distinct from any known Mendelian sex-specific lethal mutations previously discovered in a pure species; it is dominant/semi-dominant and only partially rescued by the presence of the Xsan chromosome. Our report shows that like hybrid sterility, hybrid inviability can be sex specific because the genetic background of females is different from that of males [30]. Namely, females, or more generally individuals from the homogametic sex, might experience negative epistatic interactions between sex chromosomes, a type of epistasis that the heterogametic sex will usually not experience. On the other hand, the heterogametic sex will suffer more from deleterious recessive alleles on the X-chromosome. An alternative scenario that also leads to sex-specificity in hybrid inviability is the effect of sex-specific lethal alleles. Several mapping efforts in D. melanogaster have uncovered the existence of alleles that cause lethality in only one sex. The majority of male sex lethal (MSL) mutations discovered via mutagenesis screening are both autosomal and recessive [69], [70] and are involved in the regulation of dosage compensation in pure species males [71], [72]. The expression of all dosage compensation genes, is negatively regulated by the X-linked sex determining master gene, Sex-lethal (Sxl [reviewed in 71]). SXL is a binary switch gene that controls all aspects of Drosophila sexual dimorphism. In wild-type animals, SXL is active in females and inactive in males [73]. Notably, different Sxl alleles can induce male or female specific lethality [73]–[75], which makes Sxl one of the prime candidates to cause sex-specific lethality. In our screening, none of the lethal duplications overlap with Sxl (cytological position in the Xmel-chromosome: 6F3–6F5), suggesting that the presence of fragments containing Sxlmel does not to lethal doses of the feminizing allele. In Drosophila hybrids, some interplay between the dosage compensation and sex determination factors might contribute, or at least be correlated, to the inviability of hybrid males [61], [62], [76]. Nonetheless, the literature currently does not pose a consensus model for how these deleterious effects manifest in lethality [61], [76].

D. melanogaster/D. simulans and D. melanogaster/D. mauritiana hybrid males have fewer dominant DMI partners on Xmel

The relative density of dominant factors that cause hybrid inviability on Xmel in mel/sim and mel/mau hybrids is lower than that in mel/san hybrids. This is to be expected given that the phylogenetic distance between these species is lower than between mel and san (Ks between mel and sim = 0.11; Ks between mel and san = 0.24, [22]).

We did not find any dominant Xmel-linked alleles that cause embryonic hybrid lethality in either mau or sim hybrids, but found two regions that cause larval and pupal inviability (Figure 6 and 7). These duplication-mapping results are congruent with the mapping effort conducted by Cattani and Presgraves [41] which found that a single allele on Xmel, CG11160, might cause pupal lethality in mel/mau hybrids, but only when it is allowed to interact with recessive alleles in the heterochromatic region of Xmau. In this study, two overlapping duplications of Xmel region containing both CG11160 and Hmr causes inviability in mel/mau and in mel/sim hybrid males, but the current mapping resolution does not allow us to distinguish between their potential contributions to hybrid inviability.

Epistatic interactions between X-chromosomes might contribute to hybrid breakdown

Sawamura and Yamamoto [40] were the first to report that it is possible to have negative epistatic interactions between X-chromosomes that lead to inviability in hybrid females. Cattani and Presgraves [41] took a systematic approach and tiled a large proportion of the X-chromosome and identified one dominant lethal allele on Xmel. In this report, we demonstrate that these interactions might not be as rare as previously thought [77] and might constitute an understudied phenomenon in the genetics of hybrid breakdown.

Six key findings, from this study and others, shed light on the causal role of sex chromosomes in inviability in interspecific crosses involving D. melanogaster and D. santomea: i) hybrid females that carry one X-chromosome from each species (Xmel/Xsan) are usually, but not always, viable [22], ii) hybrid males carrying Xmel/Ysan are inviable [53], iii) hybrid males carrying Xsan/Ymel are viable (Figure S1), iv) hybrid females carrying XmelXmel/Ysan are inviable (Figure 2), v) hemizygosity for 13 different regions of Xsan causes inviability in hybrid females as revealed by deficiency mapping [22], and vi) the presence of 12 isolated Xmel-linked regions cause inviability in mel/san hybrid males (9 of them induce embryonic lethality and 3 of them induce pupal lethality; Figure 5, Figure S6). These results indicate that the two X-chromosomes are heavily implicated in the inviability of mel/san hybrids.

Our current results present a conundrum in light of the discovery of viable hybrid Xsan/Ymel males. The X-chromosome from D. santomea contains 13 chromosomal regions that cause hybrid inviability when hemizygous in females [22], but apparently allow for viable hemizygous hybrid males in the absence of any Xmel homologous alleles. The same phenomenon (alleles causing inviability in hemizygous females are not lethal in hemizygous males) is observed in mel/sim and mel/mau hybrids as well. Additionally, pieces of Xmel lead to inviability in hybrid males carrying the paternal species X-chromosome, but an intact Xmel in hybrid females carrying the paternal species X-chromosome does not. All of these results can be explained if epistatic interactions between alleles on the X-chromosomes contribute to hybrid breakdown. In the males carrying fragments of Xmel, all the recessive alleles from Xsan that are not masked by the mel Dp(1;Y) will be fully expressed, but unlike Xsan/0 hybrid males, these males will suffer from the epistatic interactions between the fragment of Xmel carried on Dp (1;Y) and the exposed recessive alleles from Xsan. XmelXsan hybrid females, on the other hand, will not experience these epistatic interactions because when the complete Xmel is present, it will mask all the recessive alleles from Xsan.

The viability of mel/san hybrid males was hypothesized to be evidence against the existence of alleles involved in hybrid inviability on the X chromosome of D. santomea discovered by lethal deficiencies in hybrid females [77], [78]; in hybrid males, these alleles would be unmasked and would be free to interact in DMI with dominant alleles on D. melanogaster autosomes. However, in hybrid males, these alleles would not act in DMI with alleles on Xmel. Here we report the existence of dominant hybrid lethal alleles on Xmel that interact with alleles on Xsan. This in turn provides a simple explanation of why Xsan-carrying hybrid males survive to adulthood while partly hemizygous hybrid females do not. If the epistatic partner of Xmel-linked lethal dominant alleles resided in the Xsan-chromosome, then hybrid females would be inviable if the Xsan alleles are dominant and viable if they are recessive; they cause inviability only when not masked by an Xmel counterpart. The position of the regions identified in this report, and the position of the regions identified by deficiency mapping are shown in Figure S6. It is provocative to think these alleles could reside in the chromosomal regions uncovered by Matute et al. [22] but this hypothesis has not been tested.

Our approach to identifying Xmel-linked alleles by using large fragments of Xmel is conservative and underestimates the relative frequency of these elements in two ways. First, each duplication could include more than one allele involved in hybrid inviability. Second, if it is true that Xmel lethal alleles require recessive DMI partners on Xsan, then large Xmel duplications will mask recessive components that are required to cause hybrid inviability (see Caveats). This in turn means that there could be more alleles on Xmel that contribute to hybrid inviability that remain to be identified.

Caveats

The results here presented come with five caveats. First, the lethal alleles identified in the duplication mapping screen could be the result of hybrid-specific lethal dosage effects caused by the presence of Dp (1;Ymel) in mel/san hybrid males. However, simple dosage effects are unlikely to be involved in inviability as no lethal trisomies in pure-species females, or lethal dosage effects in hybrid males were observed in intraspecific crosses. It is possible, however, that hybrid individuals are more susceptible to dosage effects than pure-species individuals. If such dosage effects exist, they must therefore be specific to the hybrid background and mediated by the negative epistasis arising in the hybrids. In that case they would constitute a subcase of DMI mediated by gene dosage rather than physical interactions. The role that dosage compensation can have in mel/san hybrid males that also carry a Xmel-chromosome duplication is beyond the scope of this study (but see [67] for a full genetic test of the role of dosage compensation in mel/sim hybrid inviability).

The second caveat is that this method only presents a minimum estimate of Xmel –linked lethal alleles involved in hybrid inviability. As described above, our mapping used large duplications and each chromosomal segment might include more than one dominant lethal allele, and might mask recessive DMI alleles on Xsan. A third caveat is that in the male viability analyses, we only counted duplications that caused a total reduction of male viability. Since duplication mapping does not have internal controls, we did not count Xmel regions that cause only a partial reduction in viability. We used an arbitrarily stringent 10% viability cut-off to classify alleles as lethal. It is worth nothing that more sophisticated and quantitatively-framed analyses are possible but they will require more statistical power (i.e., more replicates per cross) than that presented here (described in Methods). A fourth caveat is that all the interactions we detected occur in a genetic background in which besides the mel Dp (1;Y) duplication, the regions around yellow (1Lt-1B5), and Xmel heterochromatin elements are also present (20F3 - h29). The presence of these components precludes the study of Xsan recessive alleles in these chromosomal regions.

The final caveat is that since we could not produce hybrid males without Ysan, we could not explore the effect of this chromosome on hybrid viability. This is important because Xmel/Ysan males and hybrid females with attached-X XmelXmel/Ysan both die at the embryonic stage. We have shown that Xmel carries dominant lethals that could cause hybrid inviability in these animals, but we have not tested whether Ysan contributes to hybrid inviability. Hybrid inviability could be caused by negative epistasis between Ysan and Xmel, between Ysan and the D. melanogaster autosomes, or between Ysan and the D. melanogaster cytoplasmic factors. The study of Ysan would require the development of a D. santomea stock with both a attached X-chromosome and a Y-linked X duplication [i.e, C(1)RM/C(1;Y)], as has been done for D. melanogaster [79], [80] and D. simulans [81]. Females from this stock could be crossed with D. melanogaster males. The cross would produce XsanYsan/Ymel embryos whose viability could be compared with that of Xsan/Ymel embryos (assuming that carrying two Y-chromosomes is not deleterious in the hybrids). So far, though, D. santomea females have shown complete premating isolation from D. melanogaster males, indicating that even if the Y-linked X duplications existed, premating isolation might hamper the possibility of studying this hybridization.

Conclusions

The X-chromosome has a large effect on hybrid breakdown, especially in the heterogametic sex. Orr [30], for example, proposed that since the heterogametic sex is subject to the dominant and recessive deleterious effects of the hemizygous sex chromosome, Drosophila males are more prone to hybrid inviability and sterility. This, however, does not mean that sex-linked alleles do not affect hybrid females (the homozygous sex). Nonetheless, the identification of dominant hybrid inviability alleles on the X-chromosome has been challenging (but see [40], [82]–[84]). Our results provide a fine-grained snapshot of the localization and relative frequency of dominant alleles involved in DMI in different hybrid crosses on the D. melanogaster X-chromosome; we infer that they interact with recessive alleles on Xsan in the homogametic females since these dominant alleles do not cause inviability in hybrid males. Furthermore, these epistatic interactions are lineage specific, since crosses between D. melanogaster and different species display different numbers of alleles that cause hybrid inviability in different regions. In accordance with the snowball effect theory for the rate of evolution of hybrid incompatibilities, more Xmel-linked alleles are involved in DMI in mel/san hybrids than in mel/sim or mel/mau hybrids. These results are complementary to the previous results showing the snowball effect holds true in recessive allele partners in Drosophila [22]. This report suggests that snowball theory also holds for the dominant components of DMI.

It is likely that future studies using finer mapping techniques with more and smaller duplications will find more hybrid incompatibility alleles on Xmel than we have. Regardless of the actual abundance of hybrid lethal alleles on Xmel, the results shown here provide evidence of negative epistatic interactions between X-chromosomes of hybrids that can affect the homogametic sex, but not the heterogametic sex. This reveals the existence of an even larger X-effect in hybrid breakdown than was previously ascertained.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks

We recently discovered that crossing mel attached-X females [85]–[87] to D. santomea males produces viable offspring, all of which are sterile males carrying the Xsan chromosome. The attached-X females can also carry a Ymel chromosome, but remain morphologically female since sex is determined by the X:Autosome ratio [88], and produce attached-X gametes and Ymel gametes. When these females are crossed with D. santomea males, the viable F1 hybrid males will carry an Xsan and a Ymel, Figure 1, Panel A.) Attached-X mel females produce viable hybrid males when crossed to three other different species, D. simulans, D. sechellia, and D. mauritiana [31]. For all experiments in this report (unless explicitly stated, we used two different attached-X stocks: C(1)RM (Compound (1) Reversed Metacentric; two X chromosomes in normal sequence attached proximally to the same centromere; [86], [89], [90] and C(1)DX (Compound (1) Double X, Muller [87], [91]). We took advantage of the mel panel of small X-chromosome fragments attached to the Y-chromosome (Dp(1;Y)s) generated by Cook and colleagues [46], to study the genetic basis of hybrid inviability in three of these hybrid males: mel/san, mel/sim, and mel/mau. Briefly, this duplication panel was generated by first creating X inversions using FLP-FRT recombination on attached-XY chromosomes. These inverted XY compound chromosomes are then irradiated to induce large internal X deletions. The resulting chromosome contains a medial X segment flanked by the tip of the X (1Lt;1B5), which carrys the y+ allele and the X centric heterochromatin region (20F3-h28; h28-h29) adjacent to the fused Y [52]. All the used stocks are listed in Table S1.

We first crossed mel C(1)RM females to mel Dp(1;Y) males and the virgin female progeny [mel C(1)RM/Dp(1;Y)] were then crossed to D. santomea males. This cross yielded only F1 hybrid males harboring an Xsan and a [Ymel, Dp(1;Y)] chromosome. Figure 1 (Panel B) shows the crossing scheme. As all the Dp(1;Y) chromosomes also carry y+ this assay only allows the testing of the effect of a mel gene when a y[mel]+ gene is also present. The [C(1)RM, y w f/Dp(1;Y), y+] females were used for both interspecific and intraspecific crosses. For all hybrid crosses involving D. santomea, we used a synthetic line, SYN2005. This outbred line was constructed by combining isofemale stocks and kept in large numbers since its initiation [92], [93]. For crosses involving D. simulans, we used the synthetic line D. simulans Florida City [94]. For crosses involving D. mauritiana, we used the SYN stock, a synthetic stock generated by O. Kitigawa [95], [96]. For the intraspecific crosses, we used two different D. melanogaster inbred lines (37,289: Malawi-6-3 and 30,857: Malawi-9-2; [97], [98]). These two lines make part of the Drosophila Population Genomics Project effort to characterize genetic variation in D. melanogaster (http://www.dpgp.org/). Figure 1 shows the two generations involved in the described crossing scheme.

We followed an identical crossing scheme for heterospecific crosses involving C(1)DX, Dp(1;Y). Hybrid inviability can be the result of specific mutations in the D. melanogaster background of the line used to study inviability. To assess whether this was the case, we repeated all the crosses involving C(1)RM, Dp(1;Y) but instead we used an alternative attached-X chromosome stock: C(1)DX. The rationale behind these experiments is that if the lethality induced in the hybrid males is due to the duplication of the Xmel alleles attached to Ymel, and not an artifact in the background, then the lethality should be reproducible in a different genetic background, namely, the results should be equivalent, or at least similar in experiments using the two types of attached-X chromosome. C(1)RM, Dp(1;Y) and C(1)DX, DP(1;Y) carrying the same duplication have in average only 25% of genetic material.

All D. melanogaster lines (homo - and hetero-compound chromosomes, mutant stocks, and natural lines from DPGP) were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (http://flystocks.bio.indiana.edu/) and are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

Embryonic lethality

D. melanogaster females were housed for three days with males from each of the studied species in 8-drams corn-meal vials to allow for insemination. At the end of this period the flies were transferred without anesthesia to a lightly yeasted apple juice plate collection cup. Females were allowed to oviposit for 24 hours and then they were changed to a new plate. After removal from the collection cup, the plate was incubated for 24 hours at 25°C and scored for hatched vs. dead embryos in a protocol similar to Gavin-Smyth and Matute [53].

Metafemale embryonic phenotypes and cuticle preparation

To distinguish the embryonic lethal phenotypes of the mel C(1)DX/Ysan females from the C(1)DX/Xsan metafemales, we constructed a C(1)DX, y1 w1 f1 stock homozygous for a Sxl::GFP reporter construct on the third chromosome (Stock number: 24105; w*; P{Sxl-Pe-EGFP.G}G78b, [99]). These females were crossed to D. santomea males. Overnight depositions of these crosses were collected and sorted for GFP expression after four hours of incubation. The Sxl::GFP+ (female embryos) were then incubated for a further 24 hours. Embryos that failed to hatch were prepared for cuticle mounting as described in Gavin-Smyth and Matute [53]. Since y1 alleles of the homo-compound Xmel chromosomes (either C(1)RM or C(1)DX) are rescued by the wild-type D. santomea yellow, we could identify female and male embryos. Metafemale cuticles have wild-type pigmentation of the larval mouth hooks, while the XsanYmel remain yellow−.

Larval and pupae lethality

We transferred L1 larvae from the deposition apple juice plates to 8-dram corn-meal fly food vials. All these larvae were males as evidenced by the color of their mouthparts. We then counted how many larvae molted to pupae, and how many pupae eclosed into adults and how many failed to eclose. Pupae were only assigned as dead once they had been formed for at least 14 days and had started to necrotize.

Relative density of dominant lethals

Once the whole Xmel was tiled for the five crosses, we determined the minimal number of lethal alleles in Xmel for each cross. We fitted a general linear model for each developmental stage for each species in which the relative viability was the response, and the genotype (identity of the duplication) and the genetic background (i.e., the type of attached-X stock used in the crosses) were the fixed effects. Nonetheless, the residuals from these all these models deviate from the normality assumptions required for linear models (Figure S7). These deviations from normality persisted after multiple attempts of transformation and precluded the possibility of using linear models. We then resorted to nonparametric tests and used a Kruskal-Wallis test. We tested the efficacy of these tests using the crosses between mel females and sim males. This cross was chosen because it has been previously established that an allele residing in the X-chromosome (precisely in 9D4) causes lethality at the larval stage. We compared the viability of each of these C(1)RM, Dp(1;Y) crosses with that of control crosses (C(1)RM results pooled with C(1)DX results). We detected no regions that significantly reduced the viability in any developmental stage indicating that our experimental design has not enough power to detect lethal alleles using nonparametric tests even though there were Xmel regions that clearly cause hybrid lethality. We thus had to resort to a qualitative approach and classified lethal alleles as those that caused lethality on more than 90% of their carriers. Once lethal duplications were identified, we determined the minimal number of segments that lead to lethality. If two lethal duplications overlapped, then we assumed that the cause for lethality was shared between the two duplications. This approach, also used in deficiency mapping [22], [38], [48], is conservative and tends to underestimate the number of hybrid incompatibilities. For the sake of clarity, we only report crosses which produced progeny for the three interspecific hybridizations. All the attempted intraspecific crosses produced progeny.

Viability and longevity

To measure viability in different interspecific crosses, we set up collection cups and counted all the fertilized embryos (both dead and hatched). We used C(1)DX, y1 w1 f1, +/+, Sxl::GFP/Sxl::GFP and C(1)RM, y1 w1 f1, +/+, Sxl::GFP/Sxl::GFP females and crossed them to males from the five assayed stocks (three intraspecific and two intraspecific crosses). After overnight depositions, we collected the Sxl::GFP− (male embryos), transfer them to a 1 cm×1 cm filter paper square, which in turn was transferred to an eight-dram vial with corn-meal food. Vials were tended daily and for each vial (replicate), we counted how many adults emerged. Male viability was calculated as the proportion of Sxl::GFP− that reached adulthood. The effects of the mel attached-X genetic background viability, and of the presence of Ymel within each set of interspecific crosses were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA that took the form:

Where viabij is the viability per replicate, BGi was the genetic background of the mel attached-X stock of the mother, Yj was whether the males carried a Ymel or not, (BG×Y)ij was the interaction between the two fixed effects, and Eij was the error term. All statistical analyses were done using R [100]. P-values were corrected to control for multiple comparisons following a Sidak's multiple comparison correction [101].We also compared the longevity of three interspecific hybrid males (mel/san, mel/sim and mel/mau) with virgin males from four pure species (D. melanogaster, D. mauritiana, D. santomea, and D. simulans). We measured the longevity of 120 males per genotype, split into ten different vials (12 males per vial). We fitted a linear mixed model for each set of interspecific crosses which took the form:

where Longij was the longevity of each individual, BGi was the genetic background of the D. melanogaster attached-X stock of the mother, Yj was whether the males carried a Ymel or not, (BG×Y)ij was the interaction between the two fixed effects, vial was a random effect, and Eijk was the error term. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons in the same manner as described above (viability linear models). (Nonparametric tests showed similar results to the linear model.)Finally, we assessed the effect of the Ymel chromosome on the number of sex comb teeth in six kinds of interspecific hybrid males: mel/san Xsan/0, mel/san Xsan/Ymel, mel/sim Xsim/0, mel/sim Xsim/Ymel, mel/mau Xmau/0, and mel/mau Xmau/Ymel. For this analysis we only used hybrid males produced in crosses with C(1)RM/Ymel, or C(1)RM/0 females. There were three comparisons per trait, one for each paternal species, for a total of six comparisons. All raw data and analytical software are available from the Dryad Digital Depository (https://datadryad.org/): doi:10.5061/dryad.ft6r5.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Coyne JA, Orr HA (2004) Speciation. Sunderland, Mass, Sinauer Associates.

2. Price TD (2007) Speciation in Birds. Roberts & Co. Publishers. Boulder, CO, USA.

3. OrrHA (2001) The genetics of species differences. Trends Ecol Evol 16 : 343–350.

4. OrrHA, MaslyJP, PhadnisN (2007) Speciation in Drosophila: from phenotypes to molecules. J Hered 98 : 103–110.

5. Dobzhansky T (1937) Genetics and the origin of species. New York: Columbia University Press.

6. ServedioMR, NoorMAF (2003) The role of reinforcement in speciation: theory and data. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 34 : 339–364.

7. Nosil P (2012) Ecological speciation. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

8. HopkinsR (2013) Reinforcement in plants. New Phytol 197 : 1095–1103.

9. MullerHJ (1942) Isolating mechanisms, evolution, and temperature. Biol Symp 6 : 71–125.

10. OrrHA (1995) The population genetics of speciation: the evolution of hybrid incompatibilities. Genetics 139 : 1805–1813.

11. MaslyJP, JonesCD, NoorMAF, OrrHA (2006) Gene transposition as a cause of hybrid sterility. Science 313 : 1448–1450.

12. MoyleLC, MuirCD, HanMV, HahnMW (2010) The contributions of gene movement to the “two rules of speciation”. Evolution 64 : 1541–1557.

13. MaheshwariS, BarbashDA (2011) The genetics of hybrid incompatibilities. Annu Rev Genet 45 : 331–55.

14. NosilP, SchluterD (2011) The genes underlying the process of speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 26 : 160–167.

15. HaldaneJBS (1922) Sex-ratio and unisexual sterility in hybrid animals. J Genetics 12 : 101–109.

16. OrrHA (1997) Haldane's rule. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 28 : 195–218.

17. PresgravesDC, BalagopalanL, AbmayrSM, OrrHA (2003) Adaptive evolution drives divergence of a hybrid inviability gene in Drosophila. Nature 423 : 715–719.

18. TangS, PresgravesDC (2009) Evolution of the Drosophila nuclear pore complex results in multiple hybrid incompatibilities. Science 323 : 779–782.

19. PhadnisN, OrrHA (2009) A single gene causes both male sterility and segregation distortion in Drosophila hybrids. Science 323 : 376–378.

20. MaslyJP, PresgravesDC (2007) High-resolution genome-wide dissection of the two rules of speciation in Drosophila. PLoS Biol 5: e243.

21. OrrHA, TurelliM (2001) The evolution of postzygotic isolation: accumulating Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities. Evolution 55 : 1085–1094.

22. MatuteDR, ButlerIA, TurissiniDA, CoyneJA (2010) A test of the snowball theory for the rate of evolution of hybrid incompatibilities. Science 329 : 1518–1521.

23. MoyleLC, NakazatoT (2010) Hybrid Incompatibility ‘snowballs’ between Solanum species. Science 329 : 1521–1523.

24. BreeuwerH, WerrenJH (1990) Microorganisms associated with chromosome destruction and reproductive isolation between two insect species. Nature 346 : 558–560.

25. BreeuwerJAJ, WerrenJH (1995) Hybrid breakdown between two haplodiploid species: The role of nuclear and cytoplasmic genes. Evolution 49 : 705–717.

26. TurelliM, MoyleLC (2007) Asymmetric postmating isolation: Darwin's corollary to Haldane's rule. Genetics 176 : 1059–1088.

27. BolnickDI, TurelliM, López-FernándezH, WainwrightPC, NearTJ (2008) Accelerated mitochondrial evolution and ‘Darwin's corollary’: Asymmetric viability of reciprocal F1 hybrids in centrarchid fishes. Genetics 178 : 1037–1048.

28. LeeHY, ChouJY, CheongL, ChangNH, et al. (2008) Incompatibility of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes causes hybrid sterility between two yeast species. Cell 135 : 1065–1073.

29. ChouJY, HungYS, LinKH, LeeHY, LeuJY (2010) Multiple molecular mechanisms cause reproductive isolation between three yeast species. PLoS Biol 8: e1000432.

30. OrrHA (1993) A mathematical model of Haldane's rule. Evolution 47 : 1606–1611.

31. OrrHA (1993) Haldane's rule has multiple genetic causes. Nature 361 : 532–533.

32. TurelliM, OrrHA (1995) The dominance theory of Haldane's rule. Genetics 140 : 389–402.

33. OrrHA, TurelliM (1995) Dominance and Haldane's rule. Genetics 143 : 613–616.

34. PresgravesDC, OrrHA (1998) Haldane's rule is obeyed in taxa lacking a hemizygous sex. Science 282 : 952–954.

35. CharlesworthB, CoyneJA, BartonNH (1987) The relative rates of evolution of sex chromosomes and autosomes. Am Nat 130 : 113–146.

36. TurelliM, BegunDJ (1997) Haldane's rule and X chromosome size in Drosophila. Genetics 147 : 1799–1815.

37. TurelliM, OrrHA (2000) Dominance, epistasis and the genetics of postzygotic isolation. Genetics 154 : 1663–1679.

38. CoyneJA, SimeonidisS, RooneyP (1998) Relative paucity of genes causing inviability in hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Genetics 150 : 1091–1103.

39. SawamuraK, TairaT, WatanabeTK (1993) Hybrid lethal systems in the Drosophila melanogaster species complex. I. The maternal hybrid rescue (mhr) gene of Drosophila simulans. Genetics 133 : 299–305.

40. SawamuraK, YamamotoM (1993) Cytogenetical localization of Zygotic hybrid rescue (Zhr), a Drosophila melanogaster gene that rescues interspecific hybrids from embryonic lethality. Mol Gen Genet 239 : 441–449.

41. CattaniMV, PresgravesDC (2012) Incompatibility between X chromosome Factor and pericentric heterochromatic region causes lethality in hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and its sibling species. Genetics 191 : 549–559.

42. CabotEL, DavisAW, JohnsonNA, WuC-I (1994) Genetics of reproductive isolation in the Drosophila simulans clade: Complex epistasis underlying hybrid male sterility. Genetics 137 : 175–189.

43. TurelliM, BartonNH, CoyneJA (2001) Theory and speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 16 : 330–343.

44. OrrHA, TurelliM (2001) The evolution of postzygotic isolation: accumulating Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities. Evolution 55 : 1085–1094.

45. MoyleLC, NakazatoT (2009) Complex Epistasis for Dobzhansky-Muller Hybrid Incompatibility in Solanum. Genetics 181 : 347–351.

46. TrueJR, WeirBS, LaurieCC (1996) A genome-wide survey of hybrid incompatibility factors by the introgression of marked segments of Drosophila mauritiana chromosomes into Drosophila simulans. Genetics 142 : 819–837.

47. PalopoliMF, WuC-I (1994) Genetics of hybrid male sterility between Drosophila sibling species: a complex web of epistasis is revealed in interspecific studies. Genetics 138 : 329–341.

48. PresgravesDC (2003) A fine-scale genetic analysis of hybrid incompatibilities in Drosophila. Genetics 163 : 955–972.

49. PresgravesDC, BalagopalanL, AbmayrSM, OrrHA (2003) Adaptive evolution drives divergence of a hybrid inviability gene between two species of Drosophila. Nature 423 : 715–719.

50. TangS, PresgravesDC (2009) Evolution of the Drosophila nuclear pore complex results in multiple hybrid incompatibilities. Science 323 : 779–782.

51. FerreePM, BarbashDA (2009) Species-specific heterochromatin prevents mitotic chromosome segregation to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. PLoS Biol 7: e1000234.

52. CookRK, DealME, DealJA, GartonRD, BrownCD, et al. (2010) A new resource for characterizing X-linked genes in Drosophila melanogaster: systematic coverage and subdivision of the X chromosome with nested, Y-linked duplications. Genetics 186 : 1095–1109.

53. Gavin-SmythJ, MatuteDR (2013) Embryonic lethality leads to hybrid male inviability in hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and D. santomea. Ecology and Evolution 3 : 1580–1589.

54. SturtevantAH (1929) The genetics of Drosophila simulans. Carnegie Inst Wash Publ 399 : 1–62.

55. OrrHA, MaddenLD, CoyneJA, GoodwinR, HawleyRS (1997) The developmental genetics of hybrid inviability: a mitotic defect in Drosophila hybrids. Genetics 145 : 1031–1040 32.

56. BolkanBJ, BookerR, GoldbergML, BarbashDA (2007) Developmental and cell cycle progression defects in Drosophila hybrid males. Genetics 177 : 2233–2241.

57. WieschausE, SweetonD (1988) Requirements for X-linked zygotic gene activity during cellularization of early Drosophila embryos. Development 104 : 483–93.

58. BirchlerJA, HiebertJC, KrietzmanM (1989) Gene expression in adult metafemales of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 122 : 869–879.

59. FrostJN (1960) The occurrence of partially fertile metafemales in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S 46 : 47–51.

60. TakamuraT, WatanabeTK (1980) Further studies on the Lethal hybrid rescue (Lhr) gene of Drosophila simulans. Jap J Genet 55 : 405–408.

61. Pal BhadraM, BhadraU, BirchlerJA (2006) Misregulation of sex-lethal and disruption of male-specific lethal complex localization in Drosophila species hybrids. Genetics 174 : 1151–1159.

62. ChatterjeeRN, ChatterjeeP, PalA, Pal BhadraM (2007) Drosophila simulans Lethal hybrid rescue mutation (Lhr) rescues inviable hybrids by restoring X chromosomal dosage compensation and causes fluctuating asymmetry of development. J Genet 86 : 203–215.

63. KlimanRM, AndolfattoP, CoyneJA, DepaulisF, KreitmanM, et al. (2000) The population genetics of the origin and divergence of the Drosophila simulans complex species. Genetics 156 : 1913–1931.

64. ShapiroJA, HuangW, ZhangC, HubiszMJ, LuJ, et al. (2007) Adaptive genic evolution in the Drosophila genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 2271–2276.

65. LefflerEM, BullaugheyK, MatuteDR, MeyerWK, SegurelL, et al. (2012) Revisiting an old riddle: what determines genetic diversity levels within species? PLoS Biol 10: e1001388.

66. SanchezL, SantamariaP (1997) Reproductive isolation and morphogenetic evolution in Drosophila analyzed by breakage of ethological barriers. Genetics 147 : 231–242.

67. LachaiseD, HarryM, SolignacM, LemeunierF, BénassiV, et al. (2000) Evolutionary Novelties in Islands: Drosophila santomea, a new melanogaster Sister Species from São Tomé. Proc R Soc Lond B 267 : 1487–1495.

68. LlopartA, LachaiseD, CoyneJA (2005) Multilocus analysis of introgression between two sympatric sister species of Drosophila: Drosophila yakuba and D. santomea. Genetics 171 : 197–210.

69. BeloteJM, LucchesiJC (1980) Male-specific lethal mutations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 96 : 165–186.

70. ClineTW (1984) Autoregulatory functioning of a Drosophila gene product that establishes and maintains the sexually determined state. Genetics 107 : 231–277.

71. ConradT, AkhtarA (2012) Dosage compensation in Drosophila melanogaster: epigenetic fine-tuning of chromosome-wide transcription. Nature Reviews Genetics 13 : 123–134.

72. SunL, FernandezHR, DonohueRC, LiJ, ChengJ, BirchlerJA (2013) Male-specific lethal complex in Drosophila counteracts histone acetylation and does not mediate dosage compensation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: E808–E817.

73. BellLR, HorabinJI, SchedlP, ClineTW (1991) Positive autoregulation of Sex-lethal by alternative splicing maintains the female determined state in Drosophila. Cell 65 : 229–239.

74. BellLR, MaineEM, SchedlP, ClineTW (1988) Sex-lethal, a Drosophila sex determination switch gene, exhibits sex-specific RNA splicing and sequence similarity to RNA binding proteins. Cell 55 : 1037–1046.

75. ClineTW (1978) Two closely linked mutations in Drosophila melanogaster that are lethal to opposite sexes and interact with daughterless. Genetics 90 : 683–697.

76. BarbashDA (2010) Genetic testing of the hypothesis that hybrid male lethality results from a failure in dosage compensation. Genetics 184 : 313–316.

77. BarbashDA (2011) Comment on “A test of the snowball theory for the rate of evolution of hybrid incompatibilities”. Science 333 : 1576.

78. MatuteDR, TurissiniDA, CoyneJA (2011) Response to Comment on “A test of the snowball theory for the rate of evolution of hybrid incompatibilities”. Science 333 : 1576.

79. LindsleyDL, NovitskiE (1950) The synthesis of an attached XY chromosome. Drosophila Information System 24 : 84–85.

80. LindsleyDL, NovitskiE (1959) Compound chromosomes involving the X and Y chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 44 : 187–196.

81. YamamotoMT (1992) Inviability of hybrids between D. melanogaster and D. simulans results from the absence of simulans X not the presence of simulans Y chromosome. Genetica 87 : 151–158.

82. BarbashDA, AshburnerM (2003) A novel system of fertility rescue in Drosophila hybrids reveals a link between hybrid lethality and female sterility. Genetics 163 : 217–226.

83. HutterP, AshburnerM (1987) Genetic rescue of inviable hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and its sibling species. Nature 327 : 331–333.

84. BarbashDA, RooteJ, AshburnerM (2000) The Drosophila melanogaster hybrid male rescue gene causes inviability in male and female species hybrids. Genetics 154 : 1747–1771.

85. MorganLV (1922) Non-criss-cross inheritance in Drosophila melanogaster. Biol Bull Wood's Hole 42 : 267–274.

86. AndersonEG (1925) Crossing over in a case of attached X chromosomes in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 10 : 403–417.

87. Lindsey DL, Zimm GG (1992) The Genome of Drosophila melanogaster. Academic Press, New York.

88. ClineTW (1993) The Drosophila sex determination signal: how do flies count to two? Trends Genet 9 : 385–390.

89. BeadleGW, EmersonS (1935) Further studies of crossing over in attached-X chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 20 : 192.

90. MorganLV (1938) Effects of a compound duplication of the X chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 23 : 423–462.

91. MullerHJ (1943) A stable double X chromosome. Drosophila Information Service 17 : 61–62.

92. MatuteDR, NovakCJ, CoyneJA (2009) Thermal adaptation and extrinsic reproductive isolation in two species of Drosophila. Evolution 63 : 583–594.

93. MatuteDR, CoyneJA (2010) Intrinsic reproductive isolation between two sister species of Drosophila. Evolution 64 : 903–920.

94. CoyneJA, BeecharnE (1987) Heritability of two morphological characters within and among natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 117 : 727–737.

95. SattaY, ToyoharaN, OhtakaC, TatsunoY, WatanabeT, et al. (1988) Dubious maternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila simulans and evolution of Drosophila mauritiana. Genet Res 52 : 1–6.

96. CoyneJA (1992) Genetics of sexual isolation in females of the Drosophila simulans species complex. Genet Res 60 : 25–31.

97. LangleyCH, StevensK, CardenoC, LeeYC, SchriderDR, et al. (2012) Genomic variation in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 192 : 533–598.

98. PoolJE, Corbett-DetigRB, SuginoRP, StevensKA, CardenoCM, et al. (2012) Population genomics of sub-Saharan Drosophila melanogaster: African diversity and non-African admixture. PLoS Genet 8: ee1003080.

99. Thompson JGP, Schedl P, Pulak R (2004) Sex-specific GFP-expression in Drosophila embryos and sorting by Copas flow cytometry technique. Presented at the 45th Annual Drosophila Research Conference, Washington, DC, 24–28 March 2004.

100. R Development Core Team (2005) R: A language and environment for statistical computing, reference index version 2.2.1. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org.