-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Quality Control Mechanism Coordinates Meiotic Prophase Events to Promote Crossover Assurance

The production of sperm and eggs for sexual reproduction depends on meiosis. During this specialized cell division, homologous chromosomes are linked by at least one crossover recombination event, or chiasma, to promote their proper segregation. How events in meiotic prophase are coordinated to contribute to crossover assurance is not well understood. Here, we show that C. elegans PCH-2 regulates a variety of events during meiotic prophase to promote crossover assurance. In the absence of pch-2, pairing, synapsis and recombination are accelerated, resulting in defects in synapsis and crossover formation. We propose that PCH-2 restrains the events of meiotic prophase to coordinate them, ensure their fidelity and guarantee that each homolog pair has at least one crossover to promote proper meiotic chromosome segregation.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004291

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004291Summary

The production of sperm and eggs for sexual reproduction depends on meiosis. During this specialized cell division, homologous chromosomes are linked by at least one crossover recombination event, or chiasma, to promote their proper segregation. How events in meiotic prophase are coordinated to contribute to crossover assurance is not well understood. Here, we show that C. elegans PCH-2 regulates a variety of events during meiotic prophase to promote crossover assurance. In the absence of pch-2, pairing, synapsis and recombination are accelerated, resulting in defects in synapsis and crossover formation. We propose that PCH-2 restrains the events of meiotic prophase to coordinate them, ensure their fidelity and guarantee that each homolog pair has at least one crossover to promote proper meiotic chromosome segregation.

Introduction

During sexual reproduction, meiotic chromosome segregation generates haploid gametes so that fertilization restores diploidy to the resulting embryo. Meiosis halves the DNA complement by segregating homologous chromosomes in one division and follows that reductional division with an equational division that resembles mitosis, in which sister chromatids are partitioned. Proper segregation of homologous chromosomes during meiosis I requires the formation of a linkage, or chiasma, between homologs. This linkage is introduced by a series of progressively intimate associations between homologs. Homologs identify and pair with their unique partner. The assembly of a proteinaceous structure, the synaptonemal complex (SC), stabilizes this pairing in a process called synapsis. In the context of synapsis, some programmed double strand breaks (DSBs) are selectively repaired to form crossovers, which give rise to chiasmata. However, how these events are coordinated to guarantee that each homolog pair gets at least one chiasma (the obligate crossover) is poorly understood.

In all meiotic organisms studied, DSBs outnumber crossovers (CO) and can be repaired through multiple mechanisms [1], [2]. Therefore, crossover formation is regulated at multiple points during meiotic DNA repair to assure the obligate crossover. Once a DSB forms, it can either be repaired using the homolog or the sister chromatid as a template. Meiotic DNA repair is biased towards interhomolog recombination to promote the formation of chiasmata [3]. Repair intermediates are then routed through crossover (CO) or non-crossover (NCO) pathways. This decision is thought to be made early, soon after DSB formation [4], and is inhibited by the presence of nearby crossovers (or CO-eligible intermediates), a phenomenon known as crossover interference [5]. Next, a subset of CO-eligible intermediates become crossovers, a process called designation [6]. In addition to these levels of control, feedback or surveillance mechanisms appear to respond to the absence of CO-eligible intermediates [7]–[9]. In C. elegans, continued phosphorylation of the nuclear envelope protein SUN-1 is associated with defects in synapsis and recombination, suggesting that this post-translational modification is an indicator of the activation of such a surveillance or feedback mechanism [8], [10].

The role of the conserved meiotic AAA+-ATPase Pch2/TRIP13 has been controversial. In both budding yeast and mice, the PCH2/Trip13 gene has been implicated at various points in this recombination pathway. Budding yeast pch2 mutants exhibit elevated rates of DNA repair from sister chromatids [11], [12], misregulation of CO interference in some genetic intervals and an inability to buffer a reduction in DSBs [13], [14]. This is in addition to other reported defects in meiotic chromosome structure [13], [15] and DSB formation [16], [17]. In mice, the requirement for Trip13 in meiotic chromosome metabolism is conserved [18] and cytological analysis reveals defects in DNA repair and CO formation, distribution and interference in mice deficient in Trip13 function [19], [20]. Work in Drosophila has identified PCH2 as a component of a checkpoint that responds to defects in recombination and meiotic chromosome structure [21], [22]. However, in C. elegans, PCH-2 was identified as a component of a checkpoint that monitors synapsis independent of defects in recombination [23]. PCH-2 is conserved in organisms that undergo synapsis during meiosis [24], raising the possibility that the gene product is involved in this process.

AAA-ATPases typically couple ATP hydrolysis to the disassembly of macromolecular complexes [25]. However, the identity of a PCH-2 substrate has remained elusive. Recently, biochemical analysis has revealed that Pch2 purified from budding yeast is capable of removing the meiotic chromosomal protein Hop1 from DNA in an ATP-dependent reaction [26]. Hop1 is a member of the HORMA domain containing family of proteins [27] and is required for pairing, synapsis and inter-homolog recombination [28]–[32]. In vivo, Pch2 may remodel Hop1 on meiotic chromosomes to promote these events [26].

We show that PCH-2 is required to restrain pairing, synapsis and recombination during meiotic prophase. Synapsis and recombination occur more rapidly in pch-2 mutants than in wildtype worms, producing subtle meiotic defects, and loss of pch-2 suppresses defects in pairing, synapsis and recombination in some mutant backgrounds. PCH-2 is expressed in germline nuclei prior to meiotic entry. Once meiosis initiates and chromosomes are synapsed, PCH-2 localizes to the SC when homolog-dependent repair mechanisms are active in the worm germline and loss of PCH-2 results in premature loss of homolog-dependent repair mechanisms in mid-pachytene. We conclude that PCH-2 inhibits meiotic prophase events by introducing a kinetic barrier to pairing, synapsis and recombination, potentially by destabilizing their intermediates. In support of this model, defects in synapsis and recombination are less frequent when pch-2 mutants are incubated at lower temperature and more frequent in both wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms grown at higher temperature. Since mutation of pch-2 results in more severe meiotic defects when combined with mutations that abrogate germline apoptosis or mildly affect meiotic DNA repair, we hypothesize that PCH-2 restrains meiotic prophase events to coordinate them, promoting quality control and preventing meiotic defects. We discuss how these findings contribute to our understanding of PCH-2 as a checkpoint protein.

Results

PCH-2's role in regulating synapsis and recombination is temperature dependent

To determine what role PCH-2 plays in regulating meiotic prophase events in C. elegans, we analyzed pairing, synapsis and recombination in the hermaphrodite germline. Meiotic nuclei are arrayed in a spatiotemporal gradient in the germline, allowing for the analysis of the progression of meiotic events as a function of position in the germline (see cartoon in Figure 1A). We divided germlines into six zones of equal size and evaluated the steady-state levels of pairing of the left end of the X chromosome (as visualized by the binding of the protein HIM-8) [33] and the 5S rDNA (as visualized by FISH) in each of these zones and observed no difference in the pairing of these two loci in wildtype and pch-2 single mutants (Figure S1).

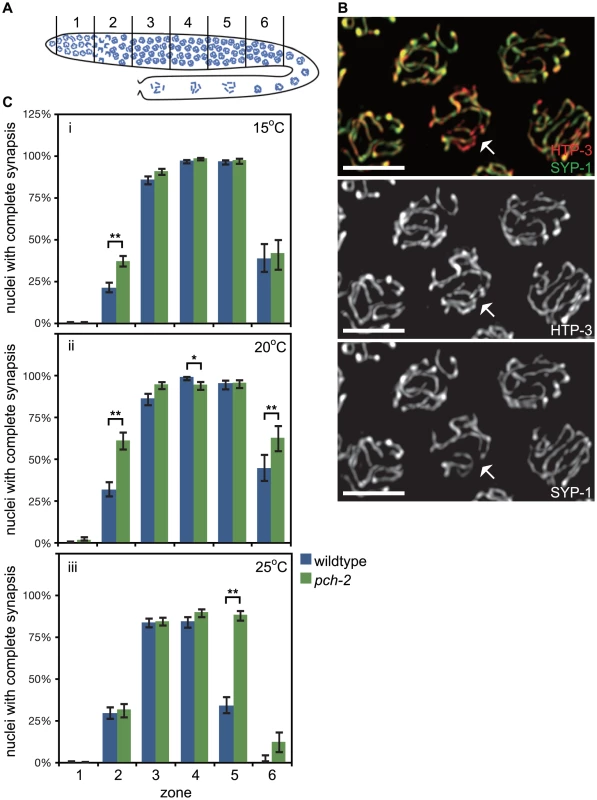

Fig. 1. PCH-2's role in regulating synapsis is temperature sensitive.

A. Cartoon of the C. elegans germline divided into six zones of equal size. In all graphs, meiotic progression is from left to right. B. Meiotic nuclei in wildtype worms stained with antibodies against the axial element component HTP-3 (red) and the central element component SYP-1 (green). Most nuclei exhibit complete colocalization on HTP-3 and SYP-1. One nucleus (indicated by arrow) includes stretches of HTP-3 without SYP-1, indicating the presence of unsynapsed chromosomes. Grayscale images of HTP-3 and SYP-1 are also provided. Unless stated otherwise, scale bars in all images represent 5 microns. C. Histograms representing the percentage of nuclei that exhibit complete synapsis as a function of meiotic progression in wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms at 15°C (i), 20°C (ii) and 25°C (iii). Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval. For all graphs, a * indicates a p value<0.05 and a ** indicates a p value of <0.0001. Significance was assessed by performing Fisher's exact test. We analyzed SC assembly in wildtype and pch-2 mutants. The SC is assembled in two steps: axial element proteins, such as HTP-3 [34], [35], load prior to synapsis, and central element components, such as SYP-1 [36], load concomitant with synapsis. Nuclei that have assembled full SC between all chromosome pairs exhibit complete colocalization of HTP-3 and SYP-1 while nuclei with incomplete synapsis have stretches of HTP-3 without SYP-1 (nucleus indicated by arrows in Figure 1B). We calculated the percentage of nuclei with complete synapsis as a function of meiotic progression. Meiotic nuclei in wildtype hermaphrodites grown at 20°C initiated synapsis in the transition zone, corresponding to zone 2, and 99% of meiotic nuclei had completed SC assembly by zone 4 (Figure 1Cii). pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C also initiated SC assembly in zone 2 but twice as many nuclei completed SC assembly in this early stage of meiotic prophase (Figure 1Cii). Furthermore, nuclei with complete synapsis peaked at 95% in pch-2 mutants (zones 4 and 5), indicating some slight defects in SC assembly in this mutant background (Figure 1Cii). In zone 6, SC disassembly was also disrupted in pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C when compared to wildtype worms (Figure 1Cii). Therefore, pch-2 is required to restrain synapsis early in meiotic prophase and promote SC disassembly in late meiotic prophase when these events occur at 20°C.

In budding yeast, temperature can modify pch2 mutant phenotypes [13]. We investigated what effect temperature might have on SC assembly and disassembly in pch-2 mutants by monitoring synapsis at 15°C and 25°C. At 15°C, pch-2 mutants accelerated synapsis, albeit less dramatically than at 20°C, and exhibited no defects in assembling or disassembling the SC (Figure 1Ci). By contrast, nuclei in pch-2 mutants grown at 25°C completed SC assembly at frequencies similar to wildtype meiotic nuclei (Figure 1Ciii). The similar progression of SC assembly in wildtype and pch-2 mutants was accompanied by an increase in nuclei with unsynapsed chromosomes in zones 3 and 4 of the germline in both genotypes (Figure 1Ciii). By zone 4, when the percentage of nuclei with complete synapsis peaked in both wildtype and pch-2 mutants, 16% and 11% of meiotic nuclei had unsynapsed chromosomes in wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms, respectively. pch-2 mutants also disassembled their SCs less efficiently at higher temperature. These data indicate that we can uncouple the acceleration of SC assembly from the defect in SC disassembly by incubating pch-2 mutants at lower or higher temperature.

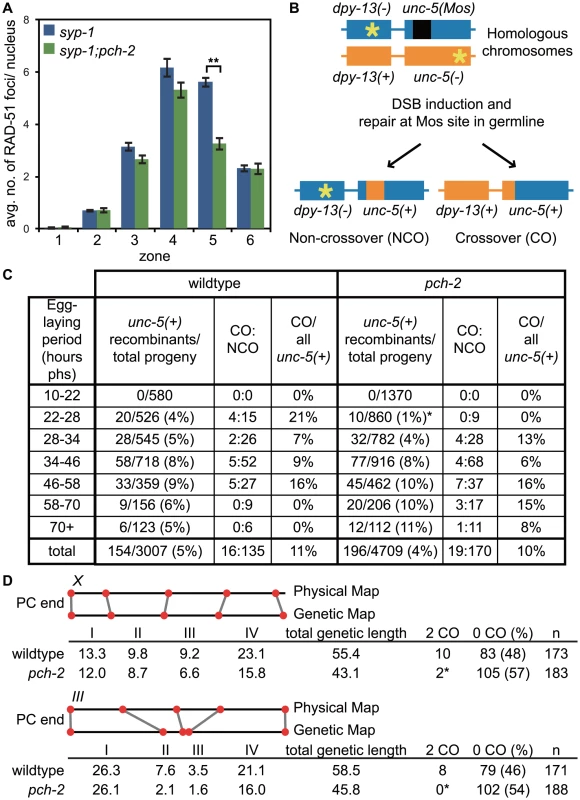

We dissected how recombination was affected by loss of pch-2 at different temperatures. First, we assessed the progress of meiotic DNA repair by localizing the recombination protein, RAD-51, in the germlines of wildtype and pch-2 mutants grown at 15°C, 20°C and 25°C (Figures 2A and B). RAD-51 is required for DNA repair and its presence on chromosomes indicates the introduction of DSBs while its disappearance indicates progression of DSBs through a repair pathway [37]. We determined the average number of RAD-51 foci per nucleus as meiotic nuclei progressed through the germline. At both 15°C and 25°C, average number of RAD-51 foci were similar between wildtype and pch-2 mutants (Figure 2Bi and iii). However, pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C had significantly fewer average number of RAD-51 foci in meiotic nuclei zones 4 and 5 than wildtype worms grown at the same temperature (Figure 2Bii).

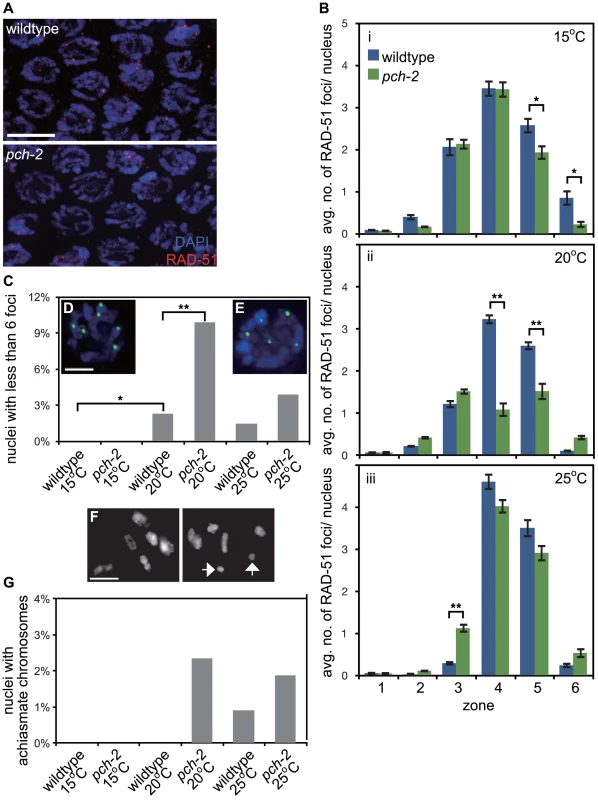

Fig. 2. PCH-2's role in regulating recombination is temperature sensitive.

A. Meiotic nuclei in early pachytene in wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms stained with DNA (blue) and antibodies against RAD-51 (red). B. Histograms representing the average number of RAD-51 foci per nucleus as a function of meiotic progression in wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms at 15°C (i), 20°C (ii) and 25°C (iii). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. C. Histogram representing the percentage of nuclei with less than six GFP::COSA-1 foci per nucleus in wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms grown at 15°C, 20°C and 25°C. The number of nuclei assayed for each genotype are as follows: wildtype at 15°C, 303, at 20°C, 304, and 25°C, 339; pch-2 at 15°C, 318, at 20°C, 293, and 25°C, 360. D. A meiotic nucleus stained with DAPI (blue) with six GFP::COSA-1 foci (green). E. A meiotic nucleus stained with DAPI (blue) with five GFP::COSA-1 foci (green). F. Representative images of late meiotic nuclei without (top) and with (bottom) achiasmate chromosomes (arrows). G. Histogram representing the percentage of meiotic nuclei with achiasmate chromosomes in wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms grown at 15°C, 20°C and 25°C. The number of nuclei assayed for each genotype are as follows: wildtype at 15°C, 91, at 20°C, 156, and 25°C, 109; pch-2 at 15°C, 96, at 20°C, 170, and 25°C, 106. For all graphs, a * indicates a p value<0.05 and a ** indicates a p value of <0.0001. Significance was assessed by performing either a paired t-test (2B) or Fisher's exact test (2C). The reduction in average number of RAD-51 foci on chromosomes in pch-2 mutants at 20°C could either be the product of a reduction in DSBs or more rapid repair of DSBs. To distinguish between these possibilities, we assayed RAD-51 foci in rad-54 and rad-54;pch-2 double mutants (Figure S2). Mutation of rad-54 prevents the removal of RAD-51 from repair intermediates and stalls the progression of meiotic recombination [38]. rad-54 single mutants and rad-54;pch-2 double mutants exhibited a similar profile of RAD-51 loading, both in terms of kinetics and number of foci (Figure S2), indicating that the reduction in average number of RAD-51 foci we quantified in pch-2 single mutants at 20°C was the product of more rapid repair of DSBs and not a decrease in the introduction of DSBs.

We evaluated how these differences in meiotic DNA repair affected crossover formation. We used GFP::COSA-1 as a cytological reporter to monitor putative crossover formation [6] in wildtype and pch-2 mutants grown at different temperatures (Figure 2C). Most nuclei in wildtype worms exhibit six GFP::COSA-1 foci (Figure 2D), corresponding to the six pairs of homologous chromosomes that each undergo one crossover [6]. This was particularly striking at 15°C: no nuclei had fewer than six GFP::COSA-1 foci. At 20°C and 25°C, a low percentage of meiotic nuclei in wildtype worms had fewer than six GFP::COSA-1 foci (2.3% and 1.5% respectively) (Figures 2C and E). pch-2 mutants exhibited a greater range of nuclei with fewer than six GFP::COSA-1 foci. At 15°C, pch-2 mutants had none, similar to wildtype worms (Figure 2C). However, at 20°C, pch-2 mutants had a significantly higher fraction of meiotic nuclei with fewer than six GFP::COSA-1 foci than wildtype worms, indicating that crossover assurance mechanisms were compromised in this mutant background. This difference between wildtype and pch-2 mutants became less severe at 25°C.

To investigate the effects on chiasmata formation, we identified the number of achiasmate chromosomes in wildtype and pch-2 mutants at each temperature (arrows in Figure 2F). Consistent with our analysis of GFP::COSA-1 foci, there were no achiasmate chromosomes in wildtype and pch-2 mutants grown at 15°C (Figure 2G). We also did not observe achiasmate chromosomes in wildtype worms grown at 20°C (Figure 2G). pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C and 25°C had a small percentage of achiasmate chromosomes (2.4% and 1.9% respectively), as did wildtype worms grown at 25°C (1%) (Figure 2G). Thus, our analysis of meiotic DNA repair and crossover formation indicated that performing these tasks at lower temperature suppressed defects observed in pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C and 25°C. Wildtype worms exhibited defects in these events when incubated at 25°C (Figure 2G).

Since both synapsis and meiotic DNA repair were accelerated in pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C, we tested whether meiotic nuclei in pch-2 mutants entered meiosis earlier or progressed through the germline more rapidly than in wildtype worms at 20°C. Phosphorylation of the nuclear envelope protein SUN-1 occurs at meiotic entry [10], [39] and persists until synapsis is complete and meiotic recombination is proceeding normally [10]. We localized SUN-1 phosphorylated on serine 8 (SUN-1 pSer8) in wildtype and pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C and did not detect any difference in its appearance or disappearance between the two genotypes (Figure 3).

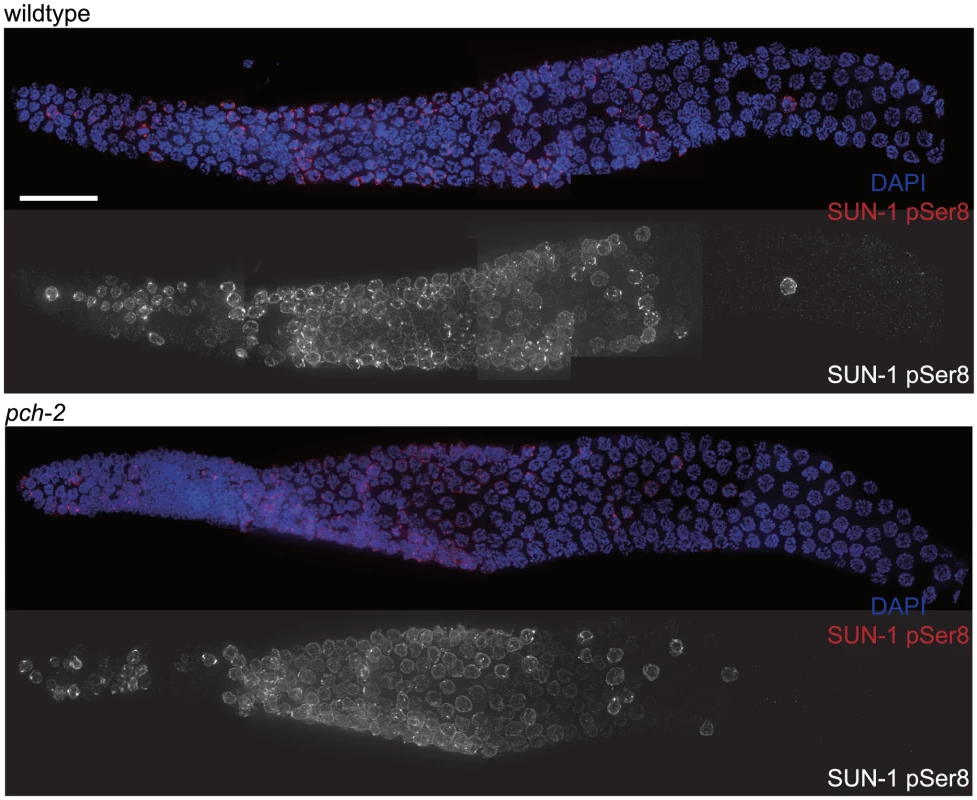

Fig. 3. The appearance and disappearance of phosphorylated SUN-1 is not affected by mutation of pch-2.

Dissected germlines stained with DAPI (blue) and antibodies against SUN-1 pSer8 (red) in wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms. Grayscale images of SUN-1 pSer8 for both genotypes are also provided. Scale bar represents 20 microns. To determine if nuclei were progressing through the germline more rapidly, we EdU labeled [40] meiotic nuclei in both wildtype and pch-2 mutants (Figure S3A) and visualized their progression through the various stages of meiotic prophase. Both wildtype and pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C exhibited a similar progression of EdU labeled nuclei throughout the timecourse (Figures S3B and C). Both of these assays lead us to conclude that the effects on synapsis and recombination that we observed in pch-2 mutants were not merely the result of more rapid meiotic entry or progression of nuclei through the germline but that PCH-2 is specifically required to restrain these events.

In summary, we report accelerated rates of synapsis and meiotic DNA repair, accompanied by subtle defects in synapsis and recombination, in pch-2 mutants grown at 20°C (Figures 1Cii and 2Bii). Synapsis and meiotic DNA repair were less affected in pch-2 mutants cultured at 15°C (Figures 1Ci and 2Bi) and these mutant worms did not have any recombination or synapsis defects (Figures 1Ci, 2C and 2G). Any difference in the rate of SC assembly and meiotic DNA repair between wildtype and pch-2 mutants was lost at 25°C (Figures 1Ciii and 2Biii) and this correlated with an increase in the frequency of synapsis and recombination defects in wildtype worms (Figures 1Ciii, 2C and 2G). Moreover, defects in SC disassembly in pch-2 mutants correlated with defects in meiotic recombination (Figures 1Cii, 1Ciii, 2C and 2G).

Mutation of pch-2 suppresses pairing defects in the absence of synapsis

Our previous experiments indicated that mutating pch-2 had subtle effects on synapsis and recombination. To more completely dissect how PCH-2 might be affecting homolog interactions, we investigated the effect of mutating pch-2 in sensitized mutant backgrounds.

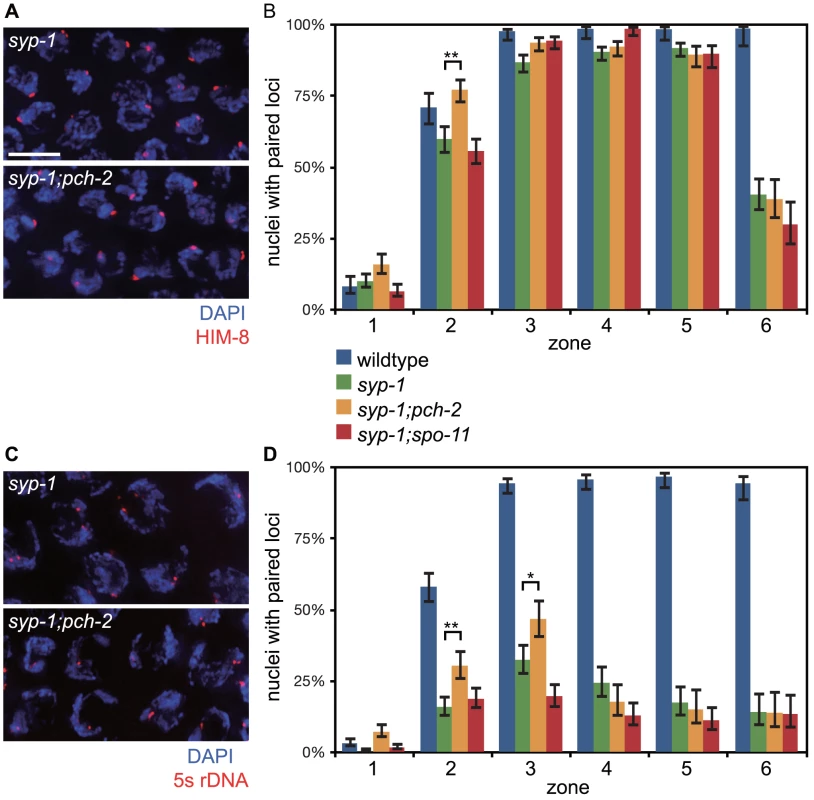

First we analyzed pairing in syp-1 and syp-1;pch-2 double mutants. syp-1 mutants fail to assemble SC between paired homologs, allowing the visualization of pairing intermediates that typically precede and promote synapsis [35], [36]. In C. elegans, cis-acting sites called Pairing Centers (PCs) are required for efficient pairing and synapsis [35]. In the absence of synapsis, homologous chromosomes exhibit stable pairing of PC ends but not non-PC ends of chromosomes [36]. This interaction depends on both homologs having functional PCs [35]. We monitored synapsis-independent, PC-dependent pairing of X chromosomes as a function of meiotic progression by performing immunofluorescence against HIM-8 [41] (Figure 4A). In both syp-1 single mutants and pch-2;syp-1 double mutants, PCs of X chromosomes initiated pairing in zone 2 and maintained this pairing until late meiotic prophase (zone 6) (Figure 4B). Interestingly, the PC end of X chromosomes was more frequently paired in pch-2;syp-1 double mutants in zone 2 than syp-1 single mutants, at levels similar to wildtype in the same region of the germline (Figure 4B). Therefore, loss of pch-2 suppressed the pairing defect of syp-1 mutants early in prophase. To determine if this effect was an indirect consequence of a reduction in apoptosis affecting the overall population of meiotic nuclei inhabiting hermaphrodite germlines, we also monitored X chromosome PC pairing in spo-11;syp1 double mutants, which display a similar level of germline apoptosis as pch-2;syp-1 mutants due to abrogation of the DNA damage checkpoint [23]. This double mutant background did not display more stable association of X chromosome PCs (Figure 4B), indicating that PCH-2 destabilizes synapsis-independent, PC-dependent pairing.

Fig. 4. Mutation of pch-2 suppresses pairing defects in syp-1 mutants.

A. Meiotic nuclei in syp-1 and syp-1;pch-2 mutants stained with DAPI (blue) and antibodies against the X chromosome PC protein HIM-8 (red). B. Histogram representing the percentage of nuclei with paired HIM-8 signals as a function of germline position in wildtype (from Figure S1A), syp-1, syp-1;pch-2, and syp-1;spo-11 mutants. C. Meiotic nuclei in syp-1 and syp-1;pch-2 mutants stained with DAPI (blue) and a FISH probe against the 5 s rDNA locus (red). D. Histogram representing the percentage of nuclei with paired FISH signals as a function of germline position in wildtype (from Figure S1B), syp-1, syp-1;pch-2, and syp-1;spo-11 mutants. Error bars in both graphs indicate 95% confidence intervals. A * indicates a p value<0.05 and a ** indicates a p value of <0.0001. Significance was assessed by performing Fisher's exact test. Loci that are located some distance away from PCs also exhibit synapsis-independent pairing, although to a lesser extent than that observed at PCs [36]. To evaluate the effect of mutating pch-2 on pairing of an autosomal, internally located locus, we performed FISH against the 5 s rDNA locus (Figure 4C). In syp-1 single mutants, there was a gradual increase in pairing of this locus until zone 3 (Figure 4D). Once again, in pch-2;syp-1 double mutants, we observed higher levels of pairing at this locus in both zones 2 and 3 (Figure 4D), indicating that PCH-2 also negatively regulates pairing at a non-PC locus.

Mutation of pch-2 suppresses synapsis defects in meDf2 heterozygotes

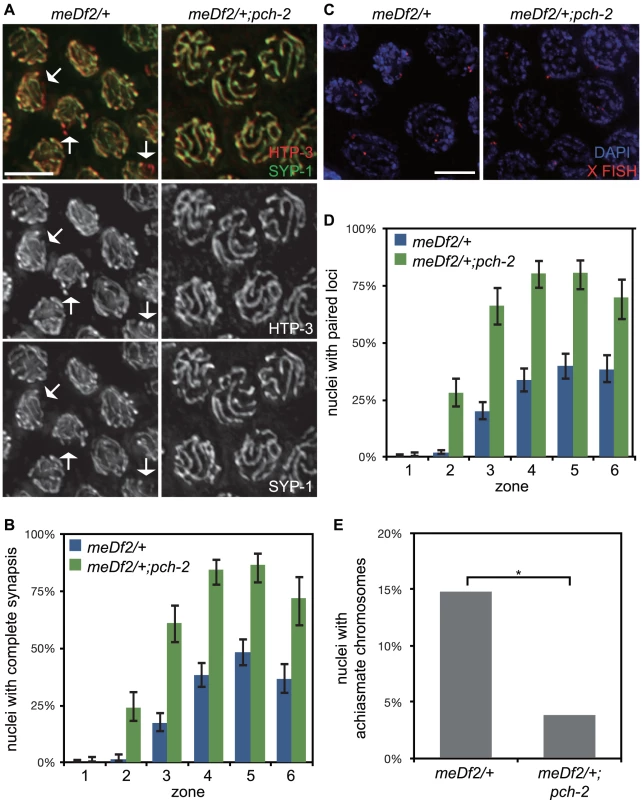

Given that mutation of pch-2 affected homolog interactions at both PC and non-PC loci, we determined what effect loss of pch-2 would have on synapsis that could not initiate at two stably paired PCs. meDf2 is a deficiency that removes the X chromosome PC [35], [42]. Animals heterozygous for meDf2 (meDf2/+) exhibit unsynapsed X chromosomes in 50% of meiotic nuclei [35] (Figure 5B), illustrating that homolog synapsis can occur, albeit inefficiently, when only one chromosome has a functional PC. We tested whether mutation of pch-2 in meDf2 heterozygotes had any effect on the synapsis defect in these hermaphrodites. When we monitored synapsis as a function of meiotic progression in meDf2/+ animals, there was a gradual increase in meiotic nuclei with complete colocalization of HTP-3 and SYP-1, which mirrored the gradual increase in pairing that has been reported for the X chromosome in meDf2 heterozygotes [35]. By zone 5, 48% of meiotic nuclei had completely assembled SC between all homolog pairs while the remainder exhibit stretches of HTP-3 without SYP-1 (arrows in Figure 5A), which are the unsynapsed X chromosomes (Figure 5C). pch-2;meDf2/+ double mutants also exhibited a gradual increase in the percentage of meiotic nuclei with complete synapsis (Figures 5A and B). However, in this double mutant background, most meiotic nuclei (87%) achieved complete synapsis in zone 5 (Figure 5B), indicating that mutation of pch-2 suppressed the synapsis defect of meDf2 heterozygotes. These data explain the reduction in apoptosis we previously reported in meDf2/+;pch-2 double mutants when compared to meDf2/+ single mutants [23]. We verified that synapsis was occurring between homologous X chromosomes by performing FISH against a non-PC locus in pch-2;meDf2/+ double mutants (Figures 5C and D).

Fig. 5. Mutation of pch-2 suppresses synapsis defects in meDf2 heterozygotes.

A. Meiotic nuclei in meDf2/+ and meDf2/+;pch-2 double mutants stained with antibodies against HTP-3 (red) and SYP-1 (green). A fraction of meiotic nuclei in meDf2/+ have unsynapsed X chromosomes (arrows). meDf2/+;pch-2 double mutants exhibit complete colocalization of HTP-3 and SYP-1, indicating complete synapsis. Grayscale images of HTP-3 and SYP-1 are also provided for both genotypes. B. Histogram representing the percentage of meiotic nuclei that exhibit complete synapsis as a function of meiotic progression in meDf2/+ and meDf2/+;pch-2. C. Meiotic nuclei in meDf2/+ and meDf2/+;pch-2 stained with a FISH probe against the X chromosome indicates that X chromosomes are paired in meDf2/+;pch-2 mutants. D. Histogram representing the percentage of nuclei with paired X FISH signals as a function of meiotic progression in meDf2/+ and meDf2/+;pch-2 mutant worms. Error bars in both graphs indicate 95% confidence intervals. E. Histogram representing the number of late meiotic nuclei with achiasmate chromosomes in meDf2/+ (54 nuclei) and meDf2/+;pch-2 (78 nuclei). A * indicates a p value<0.05. Significance was assessed by performing Fisher's exact test. We tested whether the synapsis in pch-2;meDf2/+ double mutants was functional for crossover formation by analyzing the number of nuclei with achiasmate chromosomes in meDf2/+ single mutants and pch-2;meDf2/+ double mutants (Figure 5E). Introduction of the pch-2 mutant allele suppressed the appearance of achiasmate chromosomes in meDf2 heterozygotes (Figure 5E), indicating that synapsis in pch-2;meDf2/+ double mutants can support crossover formation.

We next evaluated the percentage of male-self progeny produced by these double mutants. Since males (with a single X chromosome) typically arise from spontaneous non-disjunction of X chromosomes at a low frequency in wildtype hermaphrodites (with two X chromosomes), mutations that increase the frequency of X chromosome non-disjunction will exhibit an increase in male self-progeny. For example, meDf2/+ hermaphrodites produced 11.6% male progeny (Table 1). Consistent with our analysis of synapsis and recombination in pch-2;meDf2/+ double mutants, these hermaphrodites produced 0.9% male self-progeny (Table 1), indicating that X chromosomes segregated correctly during meiosis. Altogether, these data provide additional evidence that PCH-2 normally acts to restrain synapsis, even in situations in which synapsis cannot initiate from two stably paired PCs [35].

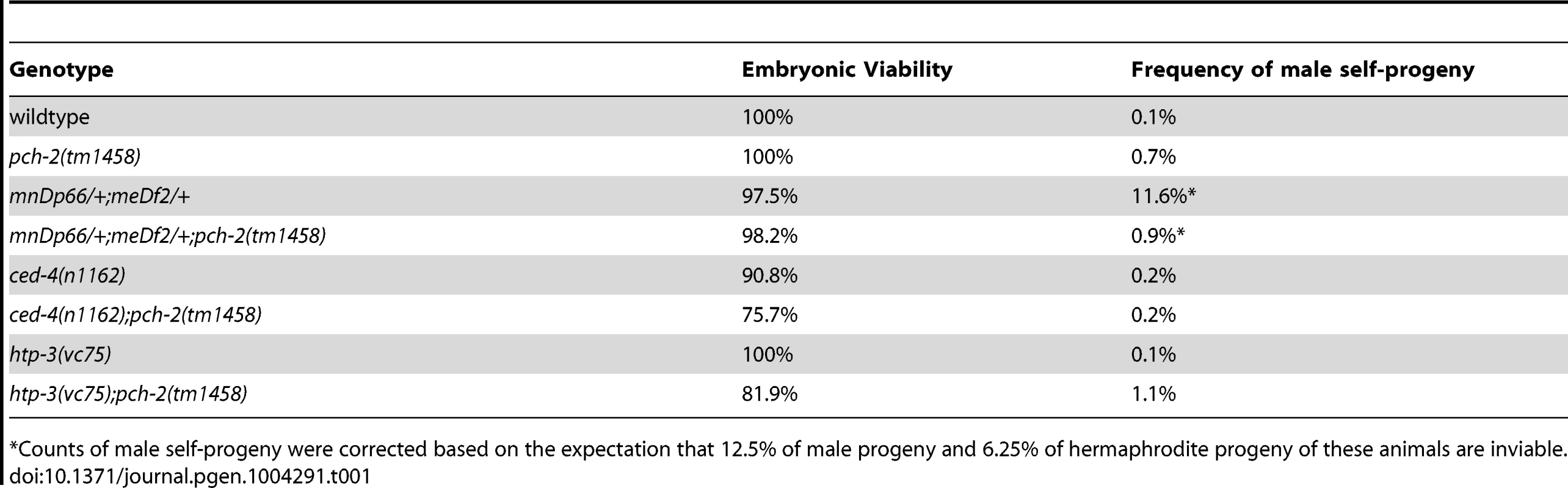

Tab. 1. Embryonic viability and frequency of male self-progeny of various mutants.

*Counts of male self-progeny were corrected based on the expectation that 12.5% of male progeny and 6.25% of hermaphrodite progeny of these animals are inviable. Mutation of pch-2 exacerbates meiotic defects in mutants defective in germline apoptosis and HTP-3 function

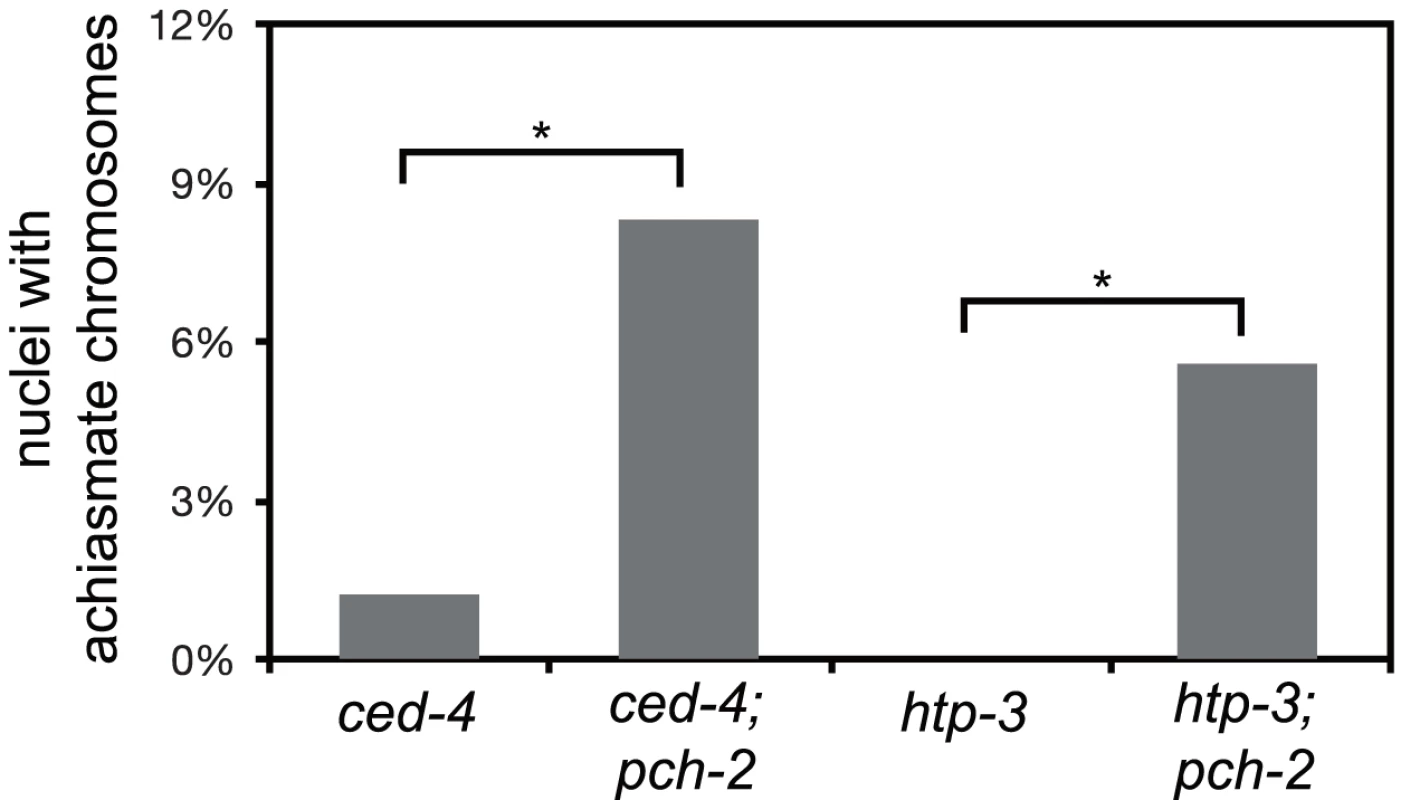

Thus far, the acceleration of pairing, synapsis and DNA repair in pch-2 mutants suggested a role for the gene product in coordinating these events, potentially to promote quality control. If this model is correct, we reasoned that loss of both pch-2 gene function and other known mechanisms that contribute to quality control during meiotic prophase might increase the frequency of meiotic defects. For example, germline apoptosis removes defective nuclei in late meiotic prophase to prevent the production of aneuploid gametes [23]. To test our hypothesis, we introduced a mutation in ced-4, a gene that encodes a core component of the apoptotic machinery that is required for germline apoptosis [43], into pch-2 mutants and monitored the number of nuclei with achiasmate chromosomes. ced-4 single mutants had achiasmate chromosomes in 1% of their late prophase nuclei (Figure 6). This frequency of nuclei with achiasmate chromosomes corresponds with the frequency of wildtype meiotic nuclei with less than six GFP::COSA-1 foci (2%), consistent with germline apoptosis culling defective nuclei even during wildtype meiosis. 8% of nuclei in pch-2;ced-4 double mutants had achiasmate chromosomes (Figure 6), indicating that significantly more meiotic nuclei in pch-2 mutants have meiotic defects than was represented by the frequency of nuclei with achiasmate chromosomes in the single mutant. Moreover, the increase in meiotic nuclei with achiasmate chromosomes pch-2;ced-4 double mutants was accompanied by an increase in the production of inviable progeny, indicating the missegregation of chromosomes during meiosis (Table 1).

Fig. 6. Mutation of pch-2 exacerbates meiotic defects in mutants defective in germline apoptosis and HTP-3 function.

Histogram representing the percentage of late meiotic nuclei in ced-4 (79 nuclei), ced-4;pch-2 (68 nuclei), htp-3 (97 nuclei) and htp-3;pch-2 (107 nuclei) mutants. A * indicates a p value<0.05. Significance was assessed by performing Fisher's exact test. We wanted to further test our hypothesis that PCH-2 was involved in quality control during meiotic prophase by introducing the pch-2 mutation into another mutant background to determine if the double mutants would exhibit a more severe meiotic phenotype. However, since pch-2 mutants suppress some meiotic phenotypes (Figures 4 and 5), we reasoned that we should use a mutation in which the meiotic phenotype was relatively mild, indicating no major defects in meiosis. In this scenario, loss of pch-2 could reveal a more severe meiotic phenotype.

HORMA domain containing proteins promote many events during meiotic prophase, including pairing, synapsis and recombination between homologous chromosomes [34], [44]–[48]. There are four genes in the C. elegans genome that encode meiotic HORMA domain containing proteins (him-3, htp-1, htp-2, and htp-3) and recently a hypomorphic allele of htp-3,vc75, has been identified. Worms with this mutation appear to undergo meiosis normally, producing no achiasmate chromosomes (Figure 6), but exhibit minor defects in DNA repair and SC disassembly [49]. We generated pch-2;htp-3(vc75) double mutants and monitored the viability of its progeny and chiasmata formation in these double mutants. pch-2;htp-3(vc75) double mutants had a synthetic meiotic phenotype: Although each individual mutant produced no inviable progeny, the double mutant generated 20% inviable progeny (Table 1). This reduction in viability can be explained by the significant increase in achiasmate chromosomes (Figure 6), indicating that pch-2;htp-3(vc75) mutants had a more severe defect in recombination than either single mutant. We ruled out that this synthetic meiotic phenotype could be explained by the possibility that pch-2 mutants activate an HTP-3 dependent meiotic DNA damage response by analyzing SC disassembly in double mutants. When mutations that activate an HTP-3 dependent meiotic DNA damage response are combined with the htp-3(vc75) mutant allele, these double mutants disassemble their SCs more rapidly than the htp-3(vc75) single mutant [49]. This did not occur in pch-2;htp-3(vc75) double mutants (data not shown). Thus, introduction of the pch-2 mutation exacerbates the meiotic phenotype of a weak mutant allele of htp-3, consistent with a role for PCH-2 in quality control during meiotic prophase.

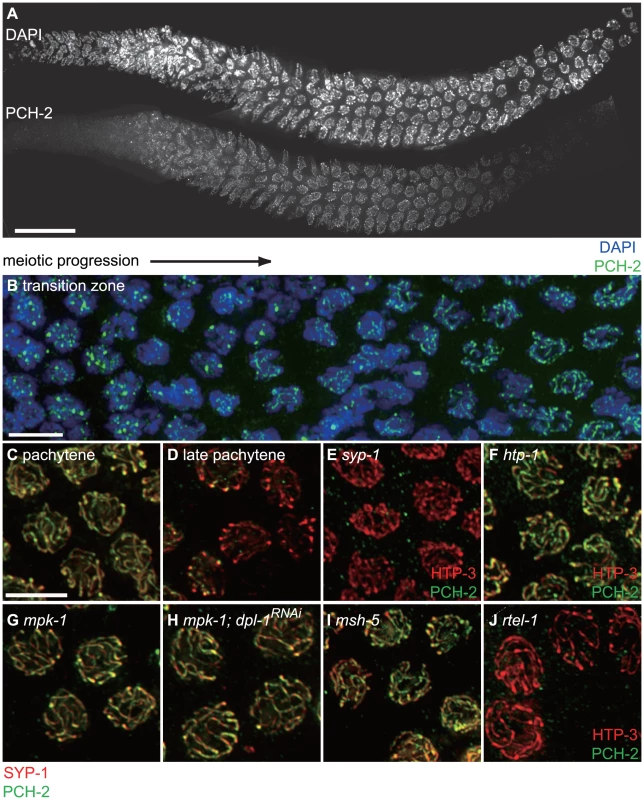

PCH-2 localizes to synapsed chromosomes when inter-homolog DNA repair mechanisms are active

To gain a deeper understanding of how PCH-2 might be regulating pairing, synapsis and recombination, we generated a polyclonal antibody against the PCH-2 protein and localized it in wildtype worms. In wildtype meiotic nuclei, PCH-2 was expressed in germline nuclei before they adopted the polarized morphology that is indicative of meiotic entry, termed the transition zone (Figures 7A and B). In these nuclei, PCH-2 formed foci that did not colocalize with axial elements, such as HTP-3 [34], [35] (data not shown), or with HIM-8 [33] (data not shown). After meiotic entry, PCH-2 localized to meiotic chromosomes in a manner reminiscent of proteins that compose the SC (Figure 7A and B). PCH-2 was loaded into chromosomes in the transition zone (Figures 7A and B) and present in the portion of the worm germline that corresponds to pachytene (Figure 7A). However, unlike SC proteins, PCH-2 was absent from meiotic chromosomes in the most distal region of the germline, corresponding to late pachytene (Figure 6A). To confirm this localization pattern, we co-stained wildtype meiotic nuclei with antibodies against PCH-2 and the SC component SYP-1 [36]. In mid-pachytene, SYP-1 and PCH-2 colocalized (Figure 7C), consistent with PCH-2 localizing to the SC. In late pachytene, SYP-1 was present on meiotic chromosomes but PCH-2 was not (Figure 7D), indicating it was removed from the SC before the SC disassembled.

Fig. 7. PCH-2 localizes to the SC when inter-homolog DNA repair mechanisms are active.

A. A wildtype hermaphrodite germline stained with DAPI and antibodies against PCH-2. PCH-2 is present in germline nuclei prior to the transition zone and removed in late pachytene. Scale bar represents 20 microns. B. Meiotic nuclei in the transition zone stained with DAPI (blue) and antibodies against PCH-2 (green). Meiotic progression for both A and B is from left to right. C. Meiotic nuclei in mid-pachytene stained with antibodies against SYP-1 (red) and PCH-2 (green). PCH-2 colocalizes with SYP-1. D. Meiotic nuclei in late pachytene stained with antibodies against SYP-1 (red) and PCH-2 (green). PCH-2 is absent from meiotic chromosomes. E. Meiotic nuclei in syp-1 mutants stained with antibodies against HTP-3 (red) and PCH-2 (green). F. Meiotic nuclei in htp-1 mutants stained with antibodies against HTP-3 (red) and PCH-2 (green). G. Meiotic nuclei in mpk-1 mutants stained with antibodies against SYP-1 (red) and PCH-2 (green). H. Meiotic nuclei in mpk-1 mutants in which dpl-1 has been knocked down by RNAi stained with antibodies against SYP-1 (red) and PCH-2 (green). I. Meiotic nuclei in late pachytene in msh-5 mutants stained with antibodies against SYP-1 (red) and PCH-2 (green). J. Meiotic nuclei in late pachytene in rtel-1 mutants stained with antibodies against HTP-3 (red) and PCH-2 (green). We tested the genetic requirements for PCH-2 loading on meiotic chromosomes. PCH-2 was not present in germline nuclei when pch-2 was inactivated by RNA interference in wildtype worms (data not shown). Synapsis is required for PCH-2 localization to the SC, since PCH-2 localization was lost in syp-1 mutants [36] (Figure 7E). However, homologous synapsis was not, as illustrated by PCH-2's localization to the SC in htp-1 (Figure 7F) and sun-1 mutants (data not shown), in which chromosomes synapse non-homologously [46], [50], and in ieDf2 mutants (data not shown), in which chromosomes self-synapse [51]. PCH-2 was present on the SC when meiotic recombination is disrupted, such as in msh-5 [52], zhp-3 [53], spo-11 [54] (Figure S5), or rtel-1 mutants [55], [56] (data not shown). We also determined that htp-3(vc75) mutants and wildtype animals grown at 25°C exhibited normal localization of PCH-2 (data not shown).

The region of the germline where PCH-2 was absent from meiotic chromosomes is associated with a shift in double strand break (DSB) repair from use of the homolog as a repair template, presumably to use of the sister chromatid [57], [58]. This shift in DNA repair mechanisms is contemporaneous with the loading of the crossover-promoting factor, COSA-1 [6]. To verify that PCH-2's absence from meiotic chromosomes coincided with these events, we performed immunofluorescence on wildtype hermaphrodites harboring a GFP tagged COSA-1 transgene [6] with antibodies against PCH-2. PCH-2 was indeed absent from nuclei that had robust GFP::COSA-1 foci (Figure S4).

The shift in DNA repair mechanisms is dependent on the activity of the MAP kinase pathway [57], the crossover-promoting factor, msh-5, and the anti-recombinase, rtel-1 [58]. PCH-2's removal from meiotic chromosomes in late pachytene did not occur in mpk-1 (Figure 7G) and msh-5 mutant backgrounds (Figures 7I and S5) but did in rtel-1 mutants (Figure 7J). This relocalization also failed to occur when we alleviate the meiotic progression defect in mpk-1 mutants by RNAi of a downstream effector, dpl-1 [59] (Figure 7H), indicating that an inability to remove PCH-2 from meiotic chromosomes is not merely an indirect consequence of meiotic prophase arrest in mpk-1 mutants. PCH-2 was also present on the SC in late pachytene nuclei in spo-11 and zhp-3 mutants, suggesting that PCH-2's perdurance is a general response to defects in recombination, similar to the persistence of phosphorylated SUN-1 [10] (Figure S5).

PCH-2 is required to promote homolog-dependent meiotic DNA repair

The timing of PCH-2 localization and removal from the SC (Figures 7C and D), along with the effects that mutation of pch-2 had on meiotic recombination (Figure 2), led us to speculate that PCH-2 might specifically be required to promote homolog dependent DNA repair. To test this, we first monitored the dynamics of RAD-51 loading and removal in syp-1 and pch-2;syp-1 mutants (Figure 8A). The complete absence of SC between all homologous chromosomes in syp-1 mutants [36] results in an inability to repair programmed DSBs because of the absence of closely aligned homologous chromosomes that can be used as repair templates [37]. As a result, RAD-51 foci persist until late pachytene (zone 6 in Figure 8A), when a synapsis-independent repair program is activated. When we compared syp-1 and pch-2;syp-1 mutants, we observed that mutation of pch-2 reduced the average number of RAD-51 foci per nucleus in syp-1 mutants in zone 5 (Figure 8A). Since our previous experiments ruled out the possibility that mutation of pch-2 reduced the number of DSBs (Figure S1), these data indicated that some DSBs were being repaired in pch-2;syp-1 double mutants by synapsis-independent mechanisms, presumably by using the sister chromatid as a repair template. Despite this premature activation of synapsis-independent DSB repair mechanisms, pch-2;syp-1 double mutants exhibited an extended transition zone [36] and prolonged zone of meiotic nuclei with phosphorylated SUN-1 [10], indicating that meiotic progression is unaffected by mutation of pch-2 in syp-1 mutants (data not shown). Moreover, our data also raise the possibility that the partial suppression of recombination defects in pch-2;syp-1 double mutants is temporally constrained to mid-pachytene (zone 5) since the average number of RAD-51 foci was not significantly different between syp-1 and pch-2;syp-1 mutants in earlier zones of the germline (Figure 8A).

Fig. 8. pch-2 is required to maintain inter-homolog DNA repair in mid-pachytene.

A. Histogram representing the average number of RAD-51 foci per nucleus as a function of meiotic progression in syp-1 and pch-2;syp-1 mutant worms. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. A ** indicates a p value<0.0001. Significance was assessed by performing a paired t-test. B. Mos1 excision based DSB repair assay. C. Time-course analysis of inter-homolog recombination induced at the Mos1 site. Chart shows the frequency of unc-5(+) recombinants among progeny derived from eggs laid in the indicated time intervals (hours phs) and the frequency of CO and NCO repair types. D. Genetic analysis of meiotic recombination in wildtype and pch-2 mutants. Physical and genetic maps of Chromosome III and the X chromosome are depicted to scale. Genetic distance is shown in centimorgans and was calculated as number of recombinants divided by total number of chromosomes assayed. For both C and D, a * indicates a p value<0.05 and significance was assessed by performing Fischer's exact test. We directly tested the role of PCH-2 in promoting homolog-dependent meiotic DNA repair. We used a meiotic recombination assay recently developed to monitor when meiotic chromosomes can access their homolog for DNA repair [58]. This assay takes advantage of an insertion of the Mos1 transposon into the unc-5 locus on one homologous chromosome, which disrupts the gene. DSBs are generated in young adult hermaphrodites carrying this locus when heat shock induced expression of the Mos transposase excises the Mos1 transposon. Since the other homologous chromosome contains a mutation that inactivates the unc-5 gene elsewhere in the gene, the outcome of DNA repair produces a wildtype unc-5(+) allele, allowing these recombinants to be phenotypically identified among the progeny laid by heat-shocked worms. The mode of DNA repair can be determined by monitoring the progeny of unc-5(+) recombinants, since the presence of a linked marker (dpy-13) can distinguish non-crossover from crossover recombinants (Figure 8B). Given the spatiotemporal organization of meiotic nuclei in the hermaphrodite germline, recombinants laid at different time points reflect the competence of meiotic chromosomes to use their homolog for DNA repair at different stages of meiotic prophase.

When we performed this assay with wildtype and pch-2 mutant hermaphrodites, we did not recover any recombinants in the first time point (10–22 hours post-heat shock) in both genetic backgrounds (Figure 8C), which corresponds to late pachytene in the hermaphrodite germline when homolog-dependent repair is not active [57], [58]. Given the subtle defects in pairing, synapsis and recombination we observed in pch-2 mutants (Figures 1, 2 and 3), we divided the next twelve-hour time point (22–34 hours post heat shock) into two six hour timepoints (22–28 hours post heat shock and 28–34 hours post heat shock). Wildtype animals produced recombinant progeny in the 22–28 hour window after heat shock at a frequency of 4%, reflecting the increased competence of nuclei in mid-pachytene for DNA repair from a homologously synapsed partner. In pch-2 mutants, statistically significant fewer recombinants were generated during this period and of the nine recombinants identified, none were crossovers. In wildtype worms, 21% of recombinants recovered at this timepoint were crossovers.

The difference in the frequency of recombinants between wildtype and pch-2 mutants was lost in later timepoints (Figure 8C). By the next six-hour interval (28–34 hours post heat-shock), wildtype hermaphrodites generated recombinants at a frequency of 5% and pch-2 mutants at a frequency of 4%. Wildtype and pch-2 mutant hermaphrodites generated equivalent frequencies of recombinants until the end of the timecourse. Thus, PCH-2 is required to maintain access to homologous chromosomes for meiotic DNA repair during pachytene.

To determine what effect premature loss of homolog access had on crossover formation in pch-2 mutants, we monitored recombination genetically in wildtype and pch-2 mutant animals using five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that spanned 95% of Chromosome III or the X chromosome [60] (Figure 8D). pch-2 mutants had slightly lower rates of recombination in all intervals across both chromosomes, resulting in a reduction of the genetic length of both Chromosome III (from 55.4 to 43.1 cM) and the X chromosome (from 58.5 to 45.8 cM). However, the decrease in genetic distance between SNPs was less severe at the PC end of both chromosomes. In addition, mutation of pch-2 appeared to more strongly affect the genetic distance between SNPs in the center of Chromosome III. We observed several double crossovers in wildtype animals on both Chromosome III and the X chromosome, 8 and 10 respectively. In contrast to wildtype, pch-2 mutants had significantly fewer double crossovers, only 2 on the X chromosome and none on Chromosome III. Therefore, the acceleration of homolog-dependent DNA repair in pch-2 single mutants at 20°C, as assayed both by the appearance and disappearance of RAD-51 foci (Figure 2Bii) and the ability of chromosomes to access their homolog for DNA repair (Figure 8C), reduced the genetic length of chromosomes, albeit not uniformly among genetic intervals, and the frequency of double crossovers.

Mutation of pch-2 reduces the percentage of nuclei with six GFP::COSA-1 foci in meDf2 homozygotes

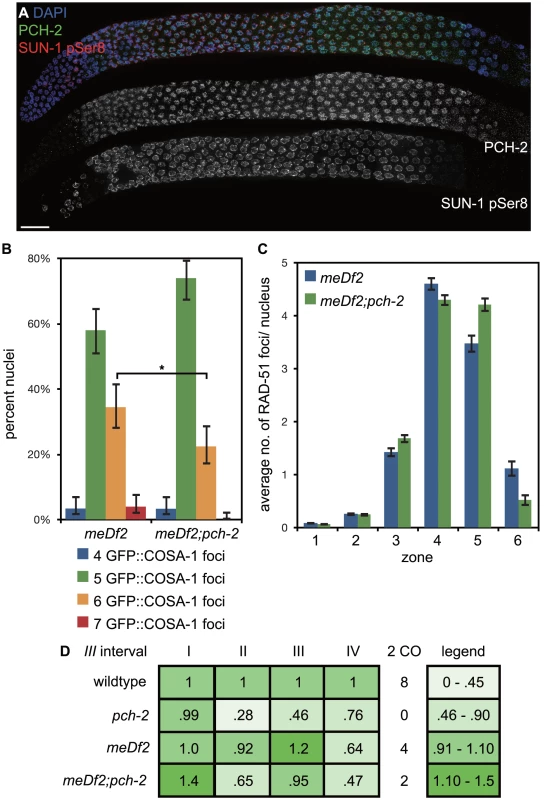

The localization pattern of PCH-2 in msh-5 mutants suggested that the persistence of PCH-2 on meiotic chromosomes into late pachytene might be a cytological read-out for prolonged homolog access and that PCH-2 might be required for this extension. However, we could not directly test this possibility in pch-2;msh-5 double mutants since the assay to monitor homolog access relies on large numbers of viable progeny to assess significance [58]. Instead, we chose to address this possibility in meDf2 homozygotes. In this mutant, asynapsis of X chromosomes produces changes in recombination frequencies in some genetic intervals and a loss of crossover control so that autosomes sometimes experience double crossovers [61]. This redistribution of recombination events in meDf2 homozygotes could, in part, be the consequence of PCH-2 remaining on meiotic chromosomes in late pachytene and promoting inter-homolog recombination in response to defects in synapsis.

First we determined how PCH-2 localization was affected by asynapsis of X chromosomes and whether any change in its localization correlated with characterized responses to asynapsis. We stained meDf2 hermaphrodite germlines with antibodies against PCH-2 and phosphorylated SUN-1 [10]. The staining pattern for both was extended (Figure 9A), in contrast to their staining patterns in wildtype germlines (Figures 3 and 7A). This extension was accompanied by a delay in the appearance of GFP::COSA-1 foci (data not shown).

Fig. 9. Mutation of pch-2 reduces the percentage of nuclei with six GFP::COSA-1 foci in meDf2 homozygotes.

A. A dissected germline stained with DAPI (blue) and antibodies against SUN-1 pSer8 (red) and PCH-2 (green). The extension of PCH-2 staining into late pachytene correlates with the extension of phosphorylated SUN-1 staining. Scale bar represents 20 microns. B. Histogram representing the percentage of meiotic nuclei that contain a given number of GFP::COSA-1 foci in meDf2 and meDf2;pch-2 mutants. 174 meDf2 nuclei and 178 meDf2;pch-2 nuclei were counted. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval. C. Histogram representing the average number of RAD-51 foci per nucleus in meDf2 and meDf2;pch-2 mutants. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. For both graphs, a * indicates a p value<0.05. Significance was assessed by performing either Fisher's exact test (7B) or a paired t-test (7C). D. Genetic analysis of meiotic recombination in wildtype, pch-2, meDf2 and meDf2;pch-2 mutants represented as fractions of wildtype recombination and color-coded according to the legend on the right. Next, we analyzed the number of GFP::COSA-1 foci per nucleus [6] (Figure 9B). In meDf2 mutants, the majority of germline nuclei (58%) exhibited five GFP::COSA-1 foci. However, a substantial fraction of meiotic nuclei (34%) had six GFP::COSA-1 foci. Even taking into account that 10% of these nuclei had undergone successful synapsis of X chromosomes [35], this suggested that about one-quarter of meiotic nuclei had an autosome with an additional putative crossover event. When we analyze GFP::COSA-1 foci in pch-2;meDf2 double mutants, we observed a statistically significant reduction in the number of germline nuclei that have six foci (22%) and a corresponding increase in the number of nuclei with five foci (74%). Mutation of pch-2 had no effect on the percent of nuclei with complete synapsis in homozygous meDf2 mutants (data not shown). These results suggest that cytologically, PCH-2 is required for the increase in putative double crossovers in meDf2 mutants. However, nuclei with six GFP::COSA-1 foci were still present in pch-2;meDf2 double mutants, indicating that additional mechanisms promote homolog-dependent meiotic DNA repair in meDf2 mutants. This possibility was supported by the similar average numbers of RAD-51 foci in both meDf2 and meDf2;pch-2 mutants (Figure 9C).

We also assessed double crossover formation genetically in both meDf2 and pch-2;meDf2 double mutants on Chromosome III. Mutation of pch-2 did not ameliorate the minor shifts in recombination pattern that we observed in meDf2. Indeed, when represented as fractions of wildtype recombination rates, the recombination landscape was more severely affected in pch-2;meDf2 double mutants than meDf2 single mutants. There was no difference in the frequency of double crossovers between meDf2 and meDf2;pch-2 (Figure 9D), likely because of the removal of meiotic nuclei by germline apoptosis (see Discussion).

Discussion

Homolog pairing, synapsis and meiosis specific DNA repair mechanisms are essential for the formation of chiasmata and proper meiotic chromosome segregation. Moreover, pairing synapsis and recombination can be temporally and/or mechanistically linked, depending on the organism in question. Therefore, a major challenge during meiotic prophase is to coordinate these events and monitor their progression to ensure that they are occurring appropriately, in the correct order and ultimately give rise to homologous chromosomes linked by at least one crossover.

The acceleration of pairing (Figure 4), synapsis (Figures 1C and 5) and inter-homolog recombination (Figures 2B, 8A and 8C) in pch-2 mutants results in the loss of crossover assurance (Figures 2C, 2G and Figure 8D), a defect that becomes more severe when germline apoptosis is abrogated or meiotic DNA repair is mildly disrupted (Figure 6). Therefore, we propose that PCH-2 restrains pairing, synapsis and recombination to coordinate them and promote their quality control to assure the obligate crossover. The variability in meiotic defects between pch-2 mutants and wildtype worms grown at different temperatures suggests that PCH-2 restrains these events by introducing a kinetic barrier to the stabilization of pairing, synapsis and/or recombination intermediates. This barrier is largely restored to pch-2 mutants undergoing meiosis at reduced temperature (Figures 1Ci, 2C and 2G), suppressing meiotic defects seen in pch-2 mutants grown at higher temperatures, and overcome in wildtype worms incubated at higher temperature (Figures 1Ciii, 2C and 2G), producing meiotic defects even in the presence of functional PCH-2. A similar observation has been made in budding yeast. pch2 mutants exhibited fewer defects in recombination when cultured at 30°C than at 33°C [13]. Given PCH-2's membership in a family of proteins characterized by their ability to disassemble macromolecular complexes [25], this kinetic barrier is likely the disassembly of pairing, synapsis and/or recombination intermediates.

The localization of PCH-2 is consistent with this model. PCH-2 is expressed when initial pairing interactions likely occur (Figures 7A and B). Once synapsis has initiated, PCH-2's presence on the SC when meiosis specific homolog-dependent DNA repair mechanisms are active [57], [58] (Figures 7A, C and D) suggests that this localization is related to its regulation of meiotic recombination. Indeed, changes in PCH-2 localization when recombination is defective (Figures 7I, S5 and 9A) also support this interpretation. However, its localization to the SC is not strictly necessary for its effect on recombination, since we still observe a reliance on PCH-2 function in syp-1 mutants (Figure 8A), which do not assemble SC [36] and fail to localize PCH-2 (Figure 7E). This might suggest that the localization of PCH-2 in nuclei prior to and in the transition zone (Figures 7A and B) could also have implications for the regulation of recombination.

The proposed role of PCH-2 as a factor that disassembles meiotic intermediates is best illustrated by how loss of pch-2 affects pairing and synapsis. We observe PCH-2's requirement for pairing in syp-1 mutants (Figure 4), in which the inability to synapse reveals pairing intermediates that contribute to efficient synapsis in C. elegans [36]. Homologous PC interactions appear more stable in pch-2;syp-1 double mutants, indicating that pch-2 normally destabilizes these interactions and providing a rationale for the accelerated synapsis we observe in pch-2 single mutants (Figure 1Cii): If efficient synapsis initiates at stably paired homologous PCs [35], enhanced stabilization of PC interactions will promote premature synapsis. However, synapsis can also initiate, albeit less efficiently, in the absence of stably paired PCs, as illustrated by the frequency of synapsis in a mutant in which one homolog has a PC and the other does not (meDf2 heterozygotes) [35]. Since mutation of pch-2 suppresses the synapsis defect of meDf2 heterozygotes (Figure 5) and partially suppresses the pairing defect at a non-PC locus in syp-1 mutants (Figures 4C and 4D), we support a model in which PCH-2 is required to destabilize pairing intermediates that promote synapsis initiation at both PC and non-PC loci. Indeed, the accelerated synapsis in pch-2 single mutants could be a consequence of PCH-2 regulating synapsis at both PC and non-PC sites.

We do not favor a model in which meiotic chromosomes in pch-2 mutants undergo non-homologous synapsis. If accelerated synapsis in pch-2 mutants produced non-homologous synapsis, we predict that pairing at either PC loci, non-PC loci or both would be significantly reduced. Our pairing analysis in wildtype and pch-2 mutant worms (Figure S1) does not indicate this. Either loss of pch-2 does not affect the ability of homologs to identify each other or redundant mechanisms compensate in destabilizing non-homologous interactions.

We hypothesize that loss of pch-2 also inappropriately stabilizes recombination intermediates, producing an acceleration of meiotic-specific DNA repair, as measured both by the disappearance of RAD-51 from meiotic chromosomes (Figure 2Bii) and the reduced ability to access a homolog as a repair template in mid-pachytene (Figure 8A and 8C). However, we have not directly demonstrated this. It is formally possible that PCH-2's effect on synapsis indirectly affects the progress of meiotic recombination. The ability to uncouple recombination defects (Figures 2C and 2G) from the acceleration of synapsis (Figure 1C) when pch-2 mutants are incubated at different temperatures and the activation of synapsis-independent DNA repair pathways in pch-2;syp-1 double mutants (Figures 8A) do not support this interpretation. Moreover, a model in which PCH-2 destabilizes meiotic recombination intermediates could explain the intimate association of PCH2 with early recombination proteins in budding yeast [11] and the phenotypes observed in pch2 and Trip13 mutants. Genetically, the inability to disassemble intermediates that are precursors to crossovers may result in additional crossovers and appear as loss of interference in some genetic intervals, as reported in budding yeast pch2 mutants [13], [14]. Cytologically, this defect would result in an increase in the number of foci containing CO-promoting proteins per chromosome and a loss of cytological interference between these foci, as reported in Trip13 mutant mice [20]. Consistent with our model, stable recombination intermediates that precede crossover formation, such as the single end invasion intermediate, occur with greater frequency and persist for longer in budding yeast pch2 mutants [15]. The reason that pch-2 mutant worms manifest a different recombination defect (fewer crossovers than wildtype) than budding yeast pch2 mutants or Trip13 mutant mice (more crossovers than wildtype) is likely due to the dramatically higher levels of DSB formation reported in budding yeast [62] and mice [1], in contrast to C. elegans [58].

If PCH-2 destabilizes both pairing intermediates that produce synapsis and recombination intermediates that promote crossovers in C. elegans, the question remains whether PCH-2 accomplishes these roles by regulating a single event or factor common to pairing, synapsis and recombination or regulates these events independently of each other. Only the identification of a PCH-2 substrate(s) will directly address this issue. Meiotic HORMA domain containing proteins are very strong candidates, given their role in promoting pairing, synapsis and recombination [34], [44]–[48], their characterized relationship with PCH2/Trip13 in yeast [13], [15] and mice [10] and Pch2's biochemical activity against Hop1/DNA complexes in vitro [26]. If PCH-2 modulates these events independent of each other, cofactors that contribute to substrate specificity of this particular AAA-ATPase [25] may explain PCH-2's ability to modulate multiple meiotic factors and affect multiple meiotic events.

How does the proposed function of PCH-2 explain its role in meiotic checkpoints? Checkpoint signaling is often initiated from a defective intermediate in the process being monitored. We propose that the synapsis checkpoint is activated by the presence of PCs that are not stably paired and is silenced by stably paired, synapsed PCs. We are not suggesting that the checkpoint is merely monitoring unpaired PCs since homologous PCs appear to pair at significant steady-state levels in syp-1 mutants but nonetheless activate the synapsis checkpoint [23]. Instead, we propose that the checkpoint specifically responds to the stability of PC pairing. Thus, PCH-2 promotes checkpoint activation by destabilizing paired homologous PCs and inhibiting synapsis. We hypothesize that pch-2;syp-1 double mutants satisfy the synapsis checkpoint by inappropriately stabilizing paired PCs despite the absence of synapsis, effectively mimicking the stabilization of PC pairing normally accomplished by synapsis. In budding yeast, Pch2 may play a similar role with recombination intermediates that contribute to synapsis initiation, potentially explaining Pch2's initial characterization as a pachytene checkpoint component [63]. Lending support to this hypothesis, budding yeast pch2 mutants display an increase in synapsis initiation complexes [13], cytologically observed foci that include factors required for both meiotic recombination and synapsis [64], [65].

PCH-2 promotes homolog dependent DNA repair to ensure the obligate crossover

PCH-2 is required to maintain interhomolog meiotic recombination (Figure 8). A similar role for Pch2 has been demonstrated in budding yeast [11], [12]. However, our experiments reveal that the requirement for PCH-2 in promoting interhomolog meiotic recombination is temporally constrained to mid-pachytene (Figures 8A and C). We cannot interpret any other differences between wildtype and pch-2 mutants at later timepoints (namely the 58–70 hours phs and 70+ hours phs timepoints) since Mos transposase may persist after induction and continue to introduce DSBs throughout the germline.

Mos-induced DSBs can be repaired by inter-homolog repair in pch-2 mutants prior to this window in mid-pachytene, as indicated by the frequency of recombinants laid soon after the 22–28 hour timepoint (Figure 8C). Thus, PCH-2 appears to be redundant with additional mechanisms that promote inter-homolog meiotic recombination earlier in prophase. In addition, pch-2 mutants do not load GFP::COSA-1 prematurely (data not shown), indicating that switching from meiotic inter-homolog DNA repair to a homolog-independent DNA repair mode can be uncoupled from crossover designation. Alternatively, designation may occur earlier, concomitant with loss of homolog access, and visible COSA-1 recruitment stabilizes the designated crossover.

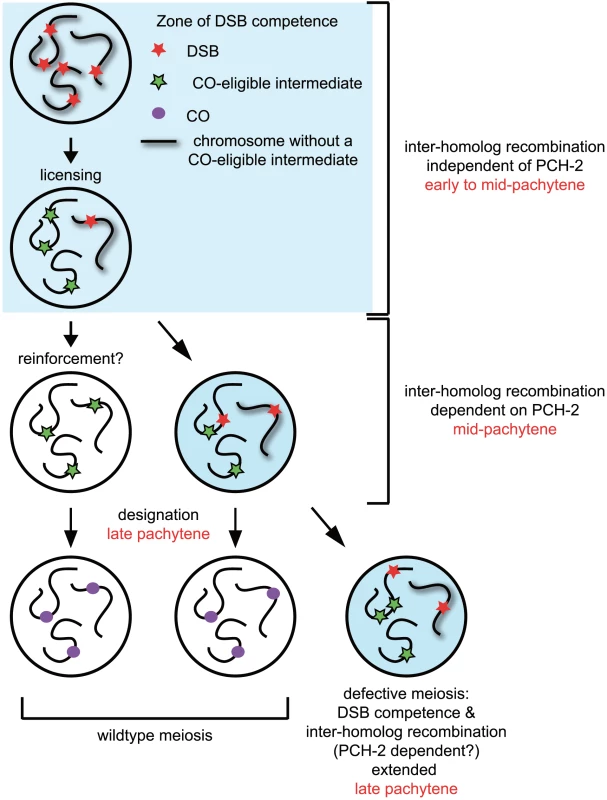

Our model of how PCH-2 regulates meiotic recombination is illustrated in Figure 10. Nuclei begin introducing DSBs coincident with the localization of DSB-1 and DSB-2, proteins required for DSB formation and thought to identify a DSB competent period during prophase [8], [9]. A subset of these DSBs become licensed as CO-eligible recombination intermediates [6]. Nuclei in which all chromosomes have a CO-eligible intermediate progress through mid-pachytene and a subset of these CO-eligible intermediates are designated as crossovers in late pachytene [6]. In a small population of nuclei that contain a chromosome without a CO-eligible intermediate, 5–10% based on our studies of GFP::COSA-1 in pch-2 mutants (Figure 2C), DSB competence is thought to be prolonged to increase the likelihood that a CO-eligible intermediate will be formed. This extension is accompanied by PCH-2-dependent promotion of interhomolog recombination, providing a potential explanation for the presence of double crossovers amongst the progeny of wildtype animals that are lost in the progeny of pch-2 mutants (Figure 8D).

Fig. 10. Model for role of PCH-2 during crossover formation.

See discussion for details. Why is there a mechanism unique to mid-pachytene to maintain homolog access? Our model assumes the requirement for PCH-2 in mid-pachytene is linked to the maintenance of DSB competence when a chromosome does not have a CO-eligible intermediate. Some possibilities that could explain our results are: 1) The redundant homolog-dependent repair mechanism(s) active earlier in prophase is down-regulated in mid-pachytene, even if DSB competence is maintained. We do not favor this possibility (see below). 2) There is something unique about DSBs or the environment in which DSBs are introduced during mid-pachytene that requires additional reinforcement to promote the formation of crossovers. These models are not mutually exclusive.

We favor another interpretation. Since nuclei in mid-pachytene continue to localize PCH-2 to meiotic chromosomes but do not exhibit other molecular markers associated with DSB competence, such as SUN-1Ser8P [7]–[9] (Figure S6), we suggest that the requirement for PCH-2 in mid-pachytene is independent of DSB competence. This possibility takes into account events that are thought to occur during mid-pachytene. CO-eligible intermediates have been licensed but they have not yet been designated. Villeneuve and colleagues have speculated that a reinforcement step precedes designation, whereby a single CO-eligible intermediate per chromosome is reinforced by CO-promoting mechanisms and ultimately stabilized by designation [6]. Since our analysis of pairing, synapsis and meiotic DNA repair indicates that PCH-2 typically restrains meiotic events, another way to interpret the loss of homolog access in pch-2 mutants is that it reveals the prematurity of another event, namely reinforcement of crossovers. Since licensed CO-eligible intermediates that are not reinforced are presumably repaired by NCO mechanisms [6], homolog access would be maintained during this process. In the absence of PCH-2 and the more rapid reinforcement of CO-eligible intermediates, homolog access during mid-pachytene would also be lost. This could explain the redistribution of crossovers in pch-2 mutants (Figure 8D). We think it unlikely that PCH-2 signals the absence of CO-eligible intermediates as its loss does not affect the staining pattern of SUN-1Ser8P [10] and DSB-2 [7]–[9] (data not shown) in genetic backgrounds that have defects in recombination and/or synapsis (i.e. meDf2 and syp-1). Indeed, crossover distribution in pch-2;meDf2 double mutants appears to be the additive effect of loss of pch-2 and the delay in meiotic progression introduced by asynapsis (Figure 9D), suggesting that these events are independent of each other.

Multiple independent feedback mechanisms promote crossover assurance

In contrast to wildtype hermaphrodites, PCH-2 localizes to the SC of meiotic chromosomes in late pachytene when synapsis and/or recombination are defective (Figures 7I, S5 and 9A). This delay in PCH-2 removal correlates with other indicators associated with a delay in meiotic prophase progression, such as phosphorylation of SUN-1 [10] (Figures S5 and 9A) and persistence of DSB-1 and DSB-2 [8], [9] (see nucleus labeled defective meiosis in Figure 10). We suggest that the continued localization of PCH-2 to meiotic chromosomes in mutant backgrounds that perturb synapsis and/or recombination (Figures S5 and 9A) indicates the existence of a feedback mechanism that maintains inter-homolog recombination to promote crossover assurance. Such a model would explain the delay in the appearance of GFP::COSA-1 foci in meDf2 mutants (data not shown) and the reduction in nuclei with six GFP::COSA-1 foci in meDf2;pch-2 double mutants (Figure 9B). It would also explain why the “interchromosomal effect” observed in Drosophila, the global increase in crossovers produced by chromosomal rearrangements, depends on PCH2 [22]. In contrast to our cytological analysis of GFP::COSA-1 foci, we do not see a corresponding decrease in the number of genetically observed double crossovers in meDf2;pch-2 double mutants, likely due to small number of double crossovers observed in both mutant backgrounds (Figure 9D). The discrepancy between cytological and genetic evidence of double crossovers could be the result of germline apoptosis.

Since the number and kinetics of RAD-51 focus formation are indistinguishable between rad-54 and rad-54;pch-2 (Figure S2), we also conclude that this feedback mechanism is distinct from one that has been proposed to prolong DSB competence in response to defects in synapsis and/or recombination [7]–[9]. PCH-2's proposed role in maintaining interhomolog repair mechanisms in response to defects in meiotic recombination potentially clarifies why PCH2 is required for crossover homeostasis [13], [14]. A reduction in DSB formation increases the likelihood that chromosomes do not have a CO-eligible recombination intermediate and would activate described feedback mechanisms, including an attempt to increase DSBs [7]–[9] and prolong interhomolog access for repair. Since DSB formation is compromised, there is a greater reliance on maintaining homolog dependent meiotic DNA repair, a pathway (partially) dependent on PCH2. This potential relationship between defective meiotic recombination and Pch2's ability to maintain inter-homolog repair into late meiotic prophase could also explain why prophase arrest rescues a reduction in DSB activity but only affects wildtype meiosis minimally [66], especially if Pch2 activity is regulated similarly in budding yeast as in C. elegans.

However, mutation of pch-2 does not eradicate nuclei with greater than five GFP::COSA-1 nuclei in the meDf2 background (Figure 9B). Moreover, our analysis of RAD-51 in meD2;pch-2 (Figure 9C) does not indicate the activation of homolog-independent repair mechanisms, in contrast to our studies with syp-1;pch-2 mutants (Figure 8A). Therefore, we also conclude that at least one other pathway in C. elegans, in addition to PCH-2, maintains homolog access in response to defects in synapsis and recombination and that this pathway relies on synapsis for its activity. An attractive candidate for this pathway is the one that we hypothesize acts earlier in meiotic prophase and may be coupled to DSB competence [8], [9].

Materials and Methods

Genetics

The wildtype C. elegans strain background was Bristol N2 [67]. All experiments were performed at 20° under standard conditions unless otherwise stated. Mutations and rearrangements used were as follows:

LG I: mnDp66, rtel-1(tm1866), rad-54&snx-3(ok615), zhp-3(jf61), hT2[bli-4(e937) let-?(q782) qIs48]

LG II: pch-2(tm1458), meIs8 [pie-1p::GFP::cosa-1+unc-119(+)]

LG III: htp-3(vc75), dpy-5(e61), mpk-1(ga111), ced-4(n1162)

LG IV: spo-11(ok79), htp-1(gk174), msh-5(me23), dpy-13(e184) unc-5(ox171::Mos1), unc-5(e791), ieDf2, nT1[unc-?(n754) let-?(m435)] (IV, V), nTI [qIs51]

LG V: sun-1(jf18), syp-1(me17), krIs14 [hsp-16.48::MosTransposase; unc-122::gfp; lin-15(+)]

LG X: meDf2

Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Antibodies, Immunostaining, Fluorescence in situ hybridization, EdU labeling, and microscopy

Polyclonal rabbit antibodies directed against the first 100 amino acids of PCH-2 were generated by Strategic Diagnostic Inc. (SDI, Newark, DE).

Immunostaining was performed as in [23]. Primary antibodies were as follows (dilutions are indicated in parentheses): rabbit anti-SYP-1 (1∶500) [36], guinea pig anti-SYP-1 (1∶500) [36], guinea pig anti-HTP-3 (1∶500) [35], chicken anti-HTP-3 (1∶1000) [35], rabbit anti-RAD-51 (1∶1000) [37], guinea pig anti-SUN-1S8Pi (1∶700) [68] and rabbit anti-PCH-2 (1∶1000). Secondary antibodies were Cy3 anti-chicken, anti-guinea pig and anti-rabbit (Jackson Immunochemicals), Alexa-Fluor 555 anti-rabbit, anti-guinea pig, and anti-chicken (Invitrogen) and Cy5 anti-guinea pig and anti-chicken (Jackson Immunochemicals).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed as described in [33].

Quantification of synapsis, pairing and RAD-51 foci was performed with a minimum of three whole germlines per genotype. For each figure, the number of nuclei assayed for each genotype in each zone is provided in Table S1.

EdU labeling was performed as described in [58]. L4 hermaphrodites were aged for 8–10 hours and moved to plates with E. coli labeled with EdU to promote EdU labeling of C. elegans meiotic nuclei. A minimum of 15 germlines was scored for each genotype at each timepoint.

All images were acquired using a DeltaVision Personal DV system (Applied Precision) equipped with a 100× N.A. 1.40 oil-immersion objective (Olympus), resulting in an effective XY pixel spacing of 0.064 or 0.040 µm, and a 60× oil-immersion objective (Olympus), resulting in an effective XY pixel spacing of 0.11 or 0.067 µm. Three-dimensional image stacks were collected at 0.2-µm Z-spacing and processed by constrained, iterative deconvolution. Image scaling and analysis were performed using functions in the softWoRx software package. Projections were calculated by a maximum intensity algorithm. Composite images were assembled and some false coloring was performed with Adobe Photoshop.

Genetic analysis of meiotic recombination

The wild-type Hawaiian CB4856 strain and the Bristol N2 strain were used to assay recombination between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on Chromosomes III and X. The SNPs used on Chromosome III were: pkP3081, pkP3095, pkP3101, pkP3035, and pkP3080. The SNPs used on the X chromosome were: pkP6139, pkP6120, pkP6157, pkP6161, and pkP6170 [60].

To measure wild-type recombination, N2 males containing bcIs39 were crossed to Hawaiian CB4856 worms. Cross-progeny hermaphrodites were identified by the presence of bcIs39 and contained one N2 and one CB4856 chromosome. These were assayed for recombination by crossing with males containing mIs11 and N2 SNPs. Cross-progeny hermaphrodites from the resulting mate were isolated as L4s, and then cultured individually in 96-well plates in liquid S-media complete supplemented with HB101, carbenicillin, and Nystatin. Four days after initial culturing, starved populations were lysed and used for PCR and restriction digest to detect CB4856 SNP alleles. For recombination in pch-2 mutants, strains homozygous for the CB4856 background of the relevant SNPs were created, then mated with pch-2; bcIs39. Subsequent steps were performed as in the wild-type worms.

Mos1 excision-induced DSB repair assay

The Mos1 excision-induced DSB repair assay was performed as described in [58] with the modification that the second 12 hour window (22–24 hours post-heat shock) was divided into two 6 hour windows (22–28 post-heat shock and 28–34 post-heat shock). Recombinants were identified by their wildtype phenotype and their progeny analyzed to determine whether recombination was the product of a crossover or a non-crossover event. In some cases, whether the recombinants were the products of non-crossover or crossover recombination could not be determined because the recombinant hermaphrodites crawled off the agar and did not produce enough progeny.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BaudatF, de MassyB (2007) Regulating double-stranded DNA break repair towards crossover or non-crossover during mammalian meiosis. Chromosome Res 15 : 565–577.

2. Martinez-PerezE, ColaiacovoMP (2009) Distribution of meiotic recombination events: talking to your neighbors. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19 : 105–112.

3. BhallaN, DernburgAF (2008) Prelude to a division. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 24 : 397–424.

4. BornerGV, KlecknerN, HunterN (2004) Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell 117 : 29–45.

5. BishopDK, ZicklerD (2004) Early decision; meiotic crossover interference prior to stable strand exchange and synapsis. Cell 117 : 9–15.

6. YokooR, ZawadzkiKA, NabeshimaK, DrakeM, ArurS, et al. (2012) COSA-1 reveals robust homeostasis and separable licensing and reinforcement steps governing meiotic crossovers. Cell 149 : 75–87.

7. KauppiL, BarchiM, LangeJ, BaudatF, JasinM, et al. (2013) Numerical constraints and feedback control of double-strand breaks in mouse meiosis. Genes Dev 27 : 873–886.

8. RosuS, ZawadzkiKA, StamperEL, LibudaDE, ReeseAL, et al. (2013) The C. elegans DSB-2 Protein Reveals a Regulatory Network that Controls Competence for Meiotic DSB Formation and Promotes Crossover Assurance. PLoS Genet 9: e1003674.

9. StamperEL, RodenbuschSE, RosuS, AhringerJ, VilleneuveAM, et al. (2013) Identification of DSB-1, a Protein Required for Initiation of Meiotic Recombination in Caenorhabditis elegans, Illuminates a Crossover Assurance Checkpoint. PLoS Genet 9: e1003679.

10. WoglarA, DaryabeigiA, AdamoA, HabacherC, MachacekT, et al. (2013) Matefin/SUN-1 phosphorylation is part of a surveillance mechanism to coordinate chromosome synapsis and recombination with meiotic progression and chromosome movement. PLoS Genet 9: e1003335.

11. HoHC, BurgessSM (2011) Pch2 acts through Xrs2 and Tel1/ATM to modulate interhomolog bias and checkpoint function during meiosis. PLoS Genet 7: e1002351.

12. ZandersS, Sonntag BrownM, ChenC, AlaniE (2011) Pch2 modulates chromatid partner choice during meiotic double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 188 : 511–521.

13. JoshiN, BarotA, JamisonC, BornerGV (2009) Pch2 links chromosome axis remodeling at future crossover sites and crossover distribution during yeast meiosis. PLoS Genet 5: e1000557.

14. ZandersS, AlaniE (2009) The pch2Δ mutation in baker's yeast alters meiotic crossover levels and confers a defect in crossover interference. PLoS Genet 5: e1000571.

15. BornerGV, BarotA, KlecknerN (2008) Yeast Pch2 promotes domainal axis organization, timely recombination progression, and arrest of defective recombinosomes during meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 3327–3332.

16. FarmerS, HongEJ, LeungWK, ArgunhanB, TerentyevY, et al. (2012) Budding yeast Pch2, a widely conserved meiotic protein, is involved in the initiation of meiotic recombination. PLoS One 7: e39724.

17. VaderG, BlitzblauHG, TameMA, FalkJE, CurtinL, et al. (2011) Protection of repetitive DNA borders from self-induced meiotic instability. Nature 477 : 115–119.

18. WojtaszL, DanielK, RoigI, Bolcun-FilasE, XuH, et al. (2009) Mouse HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, two conserved meiotic chromosomal proteins, are depleted from synapsed chromosome axes with the help of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase. PLoS Genet 5: e1000702.

19. LiXC, SchimentiJC (2007) Mouse pachytene checkpoint 2 (trip13) is required for completing meiotic recombination but not synapsis. PLoS Genet 3: e130.

20. RoigI, DowdleJA, TothA, de RooijDG, JasinM, et al. (2010) Mouse TRIP13/PCH2 is required for recombination and normal higher-order chromosome structure during meiosis. PLoS Genet 6: e1001062.

21. JoyceEF, McKimKS (2009) Drosophila PCH2 is required for a pachytene checkpoint that monitors double-strand-break-independent events leading to meiotic crossover formation. Genetics 181 : 39–51.

22. JoyceEF, McKimKS (2010) Chromosome axis defects induce a checkpoint-mediated delay and interchromosomal effect on crossing over during Drosophila meiosis. PLoS Genet 6: e1001059.

23. BhallaN, DernburgAF (2005) A conserved checkpoint monitors meiotic chromosome synapsis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 310 : 1683–1686.

24. WuHY, BurgessSM (2006) Two distinct surveillance mechanisms monitor meiotic chromosome metabolism in budding yeast. Curr Biol 16 : 2473–2479.

25. DouganDA, MogkA, ZethK, TurgayK, BukauB (2002) AAA+ proteins and substrate recognition, it all depends on their partner in crime. FEBS Lett 529 : 6–10.

26. ChenC, JomaaA, OrtegaJ, AlaniEE (2013) Pch2 is a hexameric ring ATPase that remodels the chromosome axis protein Hop1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E44–53.

27. AravindL, KooninEV (1998) The HORMA domain: a common structural denominator in mitotic checkpoints, chromosome synapsis and DNA repair. Trends Biochem Sci 23 : 284–286.

28. HollingsworthNM, ByersB (1989) HOP1: a yeast meiotic pairing gene. Genetics 121 : 445–462.

29. HollingsworthNM, GoetschL, ByersB (1990) The HOP1 gene encodes a meiosis-specific component of yeast chromosomes. Cell 61 : 73–84.

30. NiuH, WanL, BaumgartnerB, SchaeferD, LoidlJ, et al. (2005) Partner choice during meiosis is regulated by Hop1-promoted dimerization of Mek1. Mol Biol Cell 16 : 5804–5818.

31. PanizzaS, MendozaMA, BerlingerM, HuangL, NicolasA, et al. (2011) Spo11-accessory proteins link double-strand break sites to the chromosome axis in early meiotic recombination. Cell 146 : 372–383.

32. CarballoJA, JohnsonAL, SedgwickSG, ChaRS (2008) Phosphorylation of the axial element protein Hop1 by Mec1/Tel1 ensures meiotic interhomolog recombination. Cell 132 : 758–770.

33. PhillipsCM, WongC, BhallaN, CarltonPM, WeiserP, et al. (2005) HIM-8 Binds to the X Chromosome Pairing Center and Mediates Chromosome-Specific Meiotic Synapsis. Cell 123 : 1051–1063.