-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaNeuron-Specific Feeding RNAi in and Its Use in a Screen for Essential Genes Required for GABA Neuron Function

Forward genetic screens are important tools for exploring the genetic requirements for neuronal function. However, conventional forward screens often have difficulty identifying genes whose relevant functions are masked by pleiotropy. In particular, if loss of gene function results in sterility, lethality, or other severe pleiotropy, neuronal-specific functions cannot be readily analyzed. Here we describe a method in C. elegans for generating cell-specific knockdown in neurons using feeding RNAi and its application in a screen for the role of essential genes in GABAergic neurons. We combine manipulations that increase the sensitivity of select neurons to RNAi with manipulations that block RNAi in other cells. We produce animal strains in which feeding RNAi results in restricted gene knockdown in either GABA-, acetylcholine-, dopamine-, or glutamate-releasing neurons. In these strains, we observe neuron cell-type specific behavioral changes when we knock down genes required for these neurons to function, including genes encoding the basal neurotransmission machinery. These reagents enable high-throughput, cell-specific knockdown in the nervous system, facilitating rapid dissection of the site of gene action and screening for neuronal functions of essential genes. Using the GABA-specific RNAi strain, we screened 1,320 RNAi clones targeting essential genes on chromosomes I, II, and III for their effect on GABA neuron function. We identified 48 genes whose GABA cell-specific knockdown resulted in reduced GABA motor output. This screen extends our understanding of the genetic requirements for continued neuronal function in a mature organism.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003921

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003921Summary

Forward genetic screens are important tools for exploring the genetic requirements for neuronal function. However, conventional forward screens often have difficulty identifying genes whose relevant functions are masked by pleiotropy. In particular, if loss of gene function results in sterility, lethality, or other severe pleiotropy, neuronal-specific functions cannot be readily analyzed. Here we describe a method in C. elegans for generating cell-specific knockdown in neurons using feeding RNAi and its application in a screen for the role of essential genes in GABAergic neurons. We combine manipulations that increase the sensitivity of select neurons to RNAi with manipulations that block RNAi in other cells. We produce animal strains in which feeding RNAi results in restricted gene knockdown in either GABA-, acetylcholine-, dopamine-, or glutamate-releasing neurons. In these strains, we observe neuron cell-type specific behavioral changes when we knock down genes required for these neurons to function, including genes encoding the basal neurotransmission machinery. These reagents enable high-throughput, cell-specific knockdown in the nervous system, facilitating rapid dissection of the site of gene action and screening for neuronal functions of essential genes. Using the GABA-specific RNAi strain, we screened 1,320 RNAi clones targeting essential genes on chromosomes I, II, and III for their effect on GABA neuron function. We identified 48 genes whose GABA cell-specific knockdown resulted in reduced GABA motor output. This screen extends our understanding of the genetic requirements for continued neuronal function in a mature organism.

Introduction

In C. elegans, there are two basic ways to generate mosaic gene expression: knocking gene function down in specific cells of an otherwise normal animal; or rescuing wild type gene function in a mutant animal. Examples of the first method include triggering local RNAi by targeted expression of hairpin or double-stranded RNA [1], [2]; examples of the second include the use of unstable DNA elements or the targeted expression of wildtype coding sequences [3]. However, all of these methods require the construction of a new transgenic animal for each gene of interest. The requirement for one strain per gene limits the usefulness of these techniques for questions involving many genes, because it is impractical to construct so many transgenic animals.

Gene knockdown in C. elegans can be induced by feeding RNAi [4], and the development of whole-genome feeding RNAi libraries means that RNAi can be used for large-scale genetic analysis, up to and including whole-genome screens [5]–[7]. Moreover, many of the cellular mechanisms that mediate feeding RNAi have been described. In particular, interfering RNA species enter cells using the dsRNA channel SID-1 [8]–[10], while within each cell the Argonaute protein RDE-1 is required to achieve gene knockdown [11]. This molecular understanding has been used to develop a new method for mosaic gene expression that is generated by feeding RNAi, and thus is compatible with the study of many genes. For example, a muscle-specific rde-1 mosaic enables muscle-specific knockdown in response to feeding RNAi [12]. Similarly, manipulating sid-1 expression can alter the response of touch neurons to feeding RNAi [13].

Neurons, however, present particular problems for feeding RNAi. Most C. elegans neurons are resistant to feeding RNAi [14]–[16]. Genetic backgrounds have been developed that enhance the sensitivity of neurons to feeding RNAi, such as the lin-15B; eri-1 mutant [17] and neuronal expression of sid-1 [13]. However, these same genetic backgrounds can also result in increased transgene silencing in the nervous system [17]–[19]. Such transgene silencing could limit expression of the transgenes driving mosaic rescue of RNAi, even while these mutations enhance RNAi sensitivity. Thus, an approach that allows feeding RNAi to generate tissue-specific gene knockdown in neurons that can be generalized to a variety of neuronal subtypes is not currently available. Here, we describe a strategy in C. elegans that allows feeding RNAi to generate cell-specific knockdown in a wide variety of neuronal subtypes. We use this method to examine the genetic requirements of mature GABA motor neurons.

Results

An approach to neuron-specific feeding RNAi

We chose to restrict RNAi sensitivity to selected neurons using rde-1 mosaic animals [12]. At the same time, we also sought to increase RNAi sensitivity in the selected neurons, since many neurons are resistant to RNAi. We used two complementary techniques to increase neuronal sensitivity. First, we used a genetic background (lin-15B; eri-1) that enhances the sensitivity of all neurons to RNAi [17]. Second, we overexpressed the double-stranded RNA transporter sid-1 only in the selected neurons [13]. Thus, our strain carries three background mutations (lin-15B; eri-1; rde-1) and expresses two transgenes in select neurons (rde-1(+) and sid-1(+)) (Fig. 1A). We initially found that our approach was subject to significant transgene silencing effects, likely caused by the combination of the lin-15B; eri-1 background and rde-1 overexpression (see Fig. 2A) [17], [18]. To avoid transgene silencing, we combined the rde-1(+) and sid-1(+) rescue fragments into a single transcriptional unit, separated by an SL2-specific trans-splice site [20]. This artificial operon was placed in a MosSCI-compatible [21] MultiSite Gateway vector for easy manipulation, single-copy integration, and expression under cell-specific promoters.

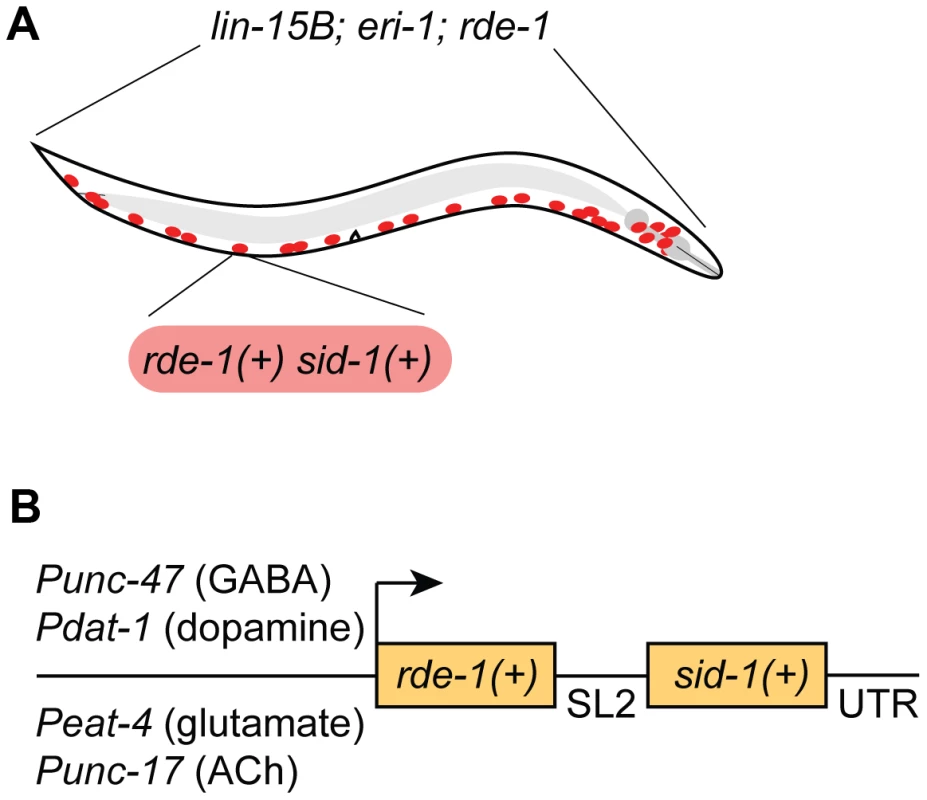

Fig. 1. A feeding RNAi-compatible approach to neuron-specific knockdown.

(A) Animals carry a genetic background of lin-15B(n744); eri-1(mg366); rde-1(ne219), and express wildtype sid-1(+) and rde-1(+) in selected neurons (GABA neurons are depicted). (B) Wildtype sid-1 and rde-1 are expressed from an artificial operon under various neuron sub-type-specific promoters and inserted as a single copy into the genome by MosSCI. Fig. 2. GABA-specific RNAi.

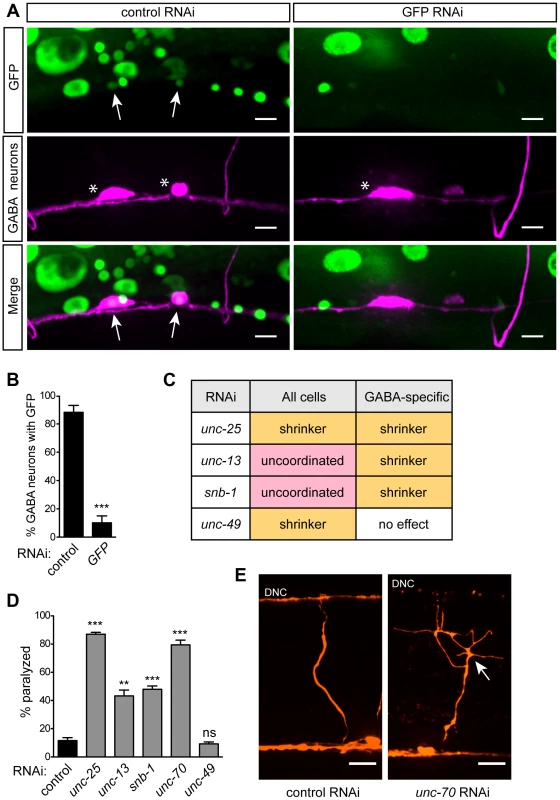

(A) Punc-47 (GABA-specific) RNAi strain expressing ubiquitous, nuclear-localized GFP and GABA mCherry after control or GFP RNAi feeding. Arrows mark GABA neurons with nuclear GFP. Stars mark GABA neuron cell bodies. GFP RNAi eliminates GFP in GABA cells, while GFP remains in other cell types. In control RNAi animals, GFP in GABA neurons is reduced relative to other cells due to increased transgene silencing in these neurons (see text). Scale bars = 5 µm. (B) Quantification of the percent of GABA cell bodies with nuclear-localized GFP under control or GFP RNAi conditions. Error bars are SEM, n = 10 worms, *** p<0.0001 (C) Locomotion behaviors in response to RNAi against genes known to function in GABA neurotransmission, in animals sensitive to RNAi in all cells (lin-15B; eri-1) and in the GABA-specific strain (XE1375). In GABA-specific RNAi strain, a GABA-specific shrinker phenotype is observed when pre- but not post-synaptic GABA signaling genes are targeted. (D) Percent of paralyzed animals after 100 min of acute exposure to 750 µM aldicarb. Error bars are SEM, n = 3 trials of ∼25 animals each, ** p = 0.0023, *** p≤0.0003. (E) GABA commissures after control or unc-70 RNAi. In unc-70 RNAi, the axon has broken and initiated a regenerative growth cone (arrow), and the dorsal nerve cord (DNC) has degenerated. Scale bars = 10 µm. GABAergic neuron-specific RNAi

We first targeted GABA-releasing neurons. We used Gateway recombination to place the rde-1(+); sid-1(+) operon behind the Punc-47 promoter, which drives expression exclusively in the GABA motor neurons (Fig. 1B) [22]. This construct was inserted into the genome as a single copy using the MosSCI technique [21], and this transgene was crossed into the lin-15B; eri-1; rde-1 mutant background to generate a strain of animals in which the interfering response of exogenous dsRNA is limited to GABA neurons.

To determine the effectiveness of our approach, we expressed nuclear-localized GFP in all somatic cells of our GABA-specific RNAi strain and also marked the GABA neurons with mCherry. We fed these animals RNAi against GFP and found that, compared to control RNAi, GFP was efficiently knocked down in GABA neurons but was still present in other cells – including muscles, intestine, skin, and non-GABA neurons (Fig. 2A, B). This suggests that the RNAi response is limited to the tissue in which our artificial operon is expressed and does not spread to other adjacent cells or tissues.

We also tested the viability of our strain when challenged with RNAi against an essential gene. ama-1 encodes the large subunit of C. elegans RNA polymerase II [23], and RNAi against ama-1 results in a larval arrest phenotype with penetrance approaching 100%. By contrast, the GABA-specific strain, and the others described below, were completely resistant to ama-1 RNAi-induced arrest, demonstrating that gene function can be studied in the GABA neurons of an otherwise normal animal even when these genes have essential functions in other tissues.

Next, we sought to determine the effectiveness of our approach against endogenous, single-gene targets. We took advantage of the robust and specific behavioral ‘shrinker’ phenotype generated by lack of either pre - or post-synaptic components of GABA neurotransmission. The GABA-specific shrinker phenotype is readily distinguished from the paralyzed phenotype caused by loss of basal neurotransmission components. We compared the effect of feeding RNAi between a standard neuron-sensitized strain (lin-15B; eri-1) and our GABA-specific strain. We performed RNAi against two GABA-specific genes: unc-25, which encodes glutamic acid decarboxylase [24] and is required in GABA neurons for GABA neurotransmission; and unc-49, which encodes the GABAA receptor [25] and is required in muscles for GABA neurotransmission. We also targeted two components of basal neurotransmission, both of which are required in all neurons for synaptic vesicle release: unc-13, which encodes UNC-13 [26], and snb-1, which encodes synaptobrevin [27]. We found that, as expected, knockdown of GABA genes in the neuron-sensitized strain resulted in a GABA-specific shrinker phenotype, while knockdown of basal neurotransmission genes resulted in an uncoordinated phenotype. By contrast, in our GABA-specific strain, knockdown of the neuronal GABA gene unc-25 resulted in a shrinker phenotype, while knockdown of the muscle GABA gene unc-49 had no effect. Further, in our GABA-specific strain, knockdown of basal neurotransmission genes also resulted in a shrinker phenotype (Fig. 2C). To quantify behavioral changes due to GABA-specific knockdown, we utilized an aldicarb-sensitivity assay to indirectly measure GABA output. Aldicarb is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that causes acute paralysis due to accumulation of acetylcholine at neuromuscular junctions (NMJs). Loss of inhibitory GABA input leads to hypersensitivity to aldicarb, causing more rapid paralysis [28]. As expected, GABA-specific knockdown of unc-25 as well as the basal neurotransmission genes unc-13 and snb-1 led to hypersensitivity to aldicarb, while RNAi against unc-49 had no effect (Fig. 2D).

In addition to synaptic genes, we sought to target a broadly-expressed gene involved in maintenance of the nervous system. unc-70 encodes β-spectrin, a component of the plasma membrane skeleton that is expressed in all cells [29]. Animals lacking unc-70 generate spontaneous breaks in their neurons as a result of mechanical stress [30]. Neuron-sensitized (lin-15B; eri-1) animals fed dsRNA against unc-70 are slow to grow, dumpy, and paralyzed. Knockdown of unc-70 in the GABA-specific strain, however, caused an aldicarb hypersensitivity phenotype (Fig. 2D), with no other obvious phenotypes. When the GABA neurons of these worms were examined, we observed defects consistent with lack of unc-70, including branched processes, broken axons – some of which terminated in regenerative growth cones – as well as substantial degeneration of the dorsal nerve cord, especially where disconnection of distal fragments was apparent (Fig. 2E). Together, these data demonstrate that our approach allows knockdown of endogenous genes within selected neurons, while preventing knockdown of those genes in other cells. Moreover, this method allows for dissection of the site of gene action, easily separating pre - and post-synaptic functions, as well as neuron sub-type-specific effects of gene knockdown.

Other neuron sub-types

To determine whether our system for controlling feeding RNAi was adaptable to other sets of neurons, we used other promoters to drive expression of our artificial rde-1(+); sid-1(+) operon, made single-copy MosSCI integrations of each construct, and placed each resulting MosSCI transgene in the lin-15B; eri-1; rde-1 mutant background. Next, we characterized the resulting strains by challenging them with ama-1 RNAi. Three of these new strains – those using the Pdat-1, Punc-17, and Peat-4 promoters – satisfied the test of ama-1 RNAi resistance in this context, and further experiments with these three strains are discussed below. However, with two other promoters – Prab-3 and Pmig-13 – we found that the resulting strain was not resistant to ama-1 RNAi. Thus, these promoters are not suitable for the analysis of essential genes using our system. By contrast, the Pdat-1, Punc-17, and Peat-4 promoters appear to be tightly controlled, suggesting that the three strains using these promoters can be used for neuron-specific RNAi.

Dopaminergic neuron-specific RNAi

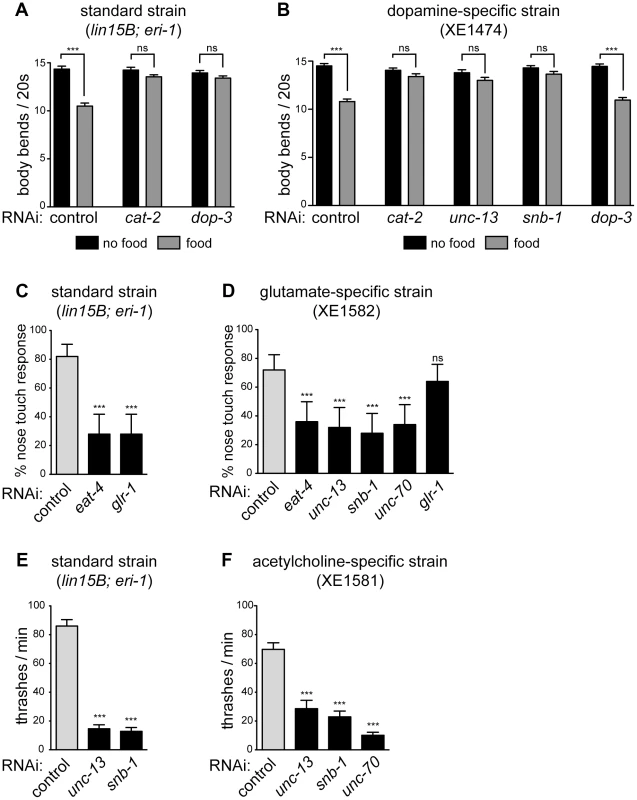

Pdat-1 drives expression in the dopaminergic neurons [31], which comprise eight cells in adult hermaphrodites [32]. One function of dopamine release from these cells is to control a behavioral response to food called “basal slowing,” in which animals slow their rate of locomotion when they encounter a bacterial lawn [33]. We used a basal slowing assay to evaluate the ability of our Pdat-1 strain to restrict RNAi to the dopaminergic neurons. The cat-2 gene encodes tyrosine hydroxylase and is required for dopamine synthesis [34]. Mutant animals that lack cat-2, or animals in which all eight dopamine neurons have been ablated, do not exhibit basal slowing [33]. Basal slowing response is also absent in mutants that lack dop-3, which encodes a D2 dopamine receptor and is not expressed in the dopaminergic neurons [35]. Thus, basal slowing requires factors both intrinsic and extrinsic to the dopamine neurons. We found that both a standard sensitized RNAi strain (lin15B; eri-1) and the Pdat-1 strain exhibited a robust basal slowing response on control RNAi (Fig. 3A, B). Further, the basal slowing response was completely blocked in both strains on RNAi against cat-2, which is required in the dopamine neurons themselves. By contrast, RNAi against dop-3 blocked basal slowing in the control strain but did not affect basal slowing in the Pdat-1 strain. We also tested basal slowing following feeding RNAi directed against unc-13 or snb-1. In these experiments, the standard lin-15B; eri-1 strain could not be tested because knockdown of these genes resulted in an uncoordinated behavioral phenotype (Fig. 2C). By contrast, knockdown of unc-13 and snb-1 in the Pdat-1 strain eliminated the basal slowing response (Fig. 3B). Further, although the basal slowing response was eliminated by knockdown of unc-13 or snb-1, these knockdowns did not affect the rate of locomotion (p = 0.0816 and p = 0.5566 respectively, compared to control off food). These data demonstrate that feeding RNAi in the Pdat-1 strain is effective in dopamine neurons but is blocked in other cells.

Fig. 3. Specific gene knockdown in dopamine, glutamate, and acetylcholine neurons in response to feeding RNAi.

(A) In standard neuron-sensitive strain, RNAi of presynaptic (cat-2) or postsynaptic (dop-3) components of dopamine signaling eliminates basal slowing on a bacterial lawn (gray bars). Error bars are SEM, n = 20 worms, *** p<0.0001. (B) In dopamine-specific strain, RNAi of a presynaptic component of dopamine signaling (cat-2) eliminates basal slowing, while RNAi of a postsynaptic component (dop-3) does not (gray bars). RNAi of presynaptic components of general neurotransmission (unc-13 and snb-1) also eliminates basal slowing. Error bars are SEM, n = 20 worms, *** p<0.0001. (C) In standard neuron-sensitive strain, RNAi of presynaptic (eat-4) or postsynaptic (glr-1) components of glutamate signaling diminish the response to nose touch. Error bars are 95% confidence interval, n = 5 trials/animal, 10 animals, *** p<0.0001. (D) In glutamate-specific strain, RNAi of presynaptic components of glutamate neurotransmission (eat-4, unc-13, snb-1) as well as the structural protein unc-70 inhibit the nose touch response, while RNAi of a postsynaptic component (glr-1) does not. Error bars are 95% confidence interval, n = 5 trials/animal, 10 animals, *** p≤0.0006. (E) In standard neuron-sensitive strain, RNAi of presynaptic components of general neurotransmission (unc-13 and snb-1) slows rate of thrashing. Error bars are SEM, n = 10 worms, *** p<0.0001 (F) In acetylcholine-specific strain, RNAi of presynaptic components of general neurotransmission (unc-13 and snb-1) as well as unc-70 slows rate of thrashing. Error bars are SEM, n = 10 worms, *** p<0.0001. Glutamatergic neuron-specific RNAi

Next, we targeted glutamatergic neurons by driving expression of our artificial operon under the Peat-4 promoter. In C. elegans, one behavior mediated by glutamatergic neurotransmission is reversal in response to nose touch [36]. Glutamatergic control of this behavior requires the gene eat-4, which encodes VGLUT, the glutamate synaptic vesicle transporter [37] that functions intrinsically in glutamatergic neurons. Glutamate control of the nose touch response also requires the gene glr-1, which encodes an AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor [38], [39] and is required in the post-synaptic cells that respond to glutamate. We fed neuron-sensitized (lin15B; eri-1) animals dsRNA against eat-4 and glr-1. Under both conditions, these animals were deficient in their ability to respond to nose touch when compared to controls (Fig. 3C). Thus, feeding RNAi can target both pre - and post-synaptic components of glutamatergic neurotransmission to generate a glutamate-specific behavioral defect. We then tested the glutamatergic neuron-specific RNAi strain. On control RNAi, these animals exhibited a normal nose touch response, similar to the standard sensitized strain (Fig. 3C and D, gray bars; p = 0.3421). Feeding RNAi against eat-4 resulted in a loss of nose touch response compared to empty vector fed controls, similar to the loss in the standard strain (Fig. 3D). Thus, RNAi of an endogenous gene in glutamatergic neurons is effective in the glutamate-specific strain. By contrast, RNAi against glr-1 did not affect the ability of the glutamate-specific strain to respond to nose touch. This result suggests that unlike the standard sensitized strain, the glutamate-specific strain is insensitive to RNAi outside the glutamate neurons. In support of this, we found that feeding RNAi against the basal neurotransmission genes unc-13 and snb-1 resulted in a glutamate-specific behavioral defect in nose touch, rather than a general defect in movement. In addition, glutamate-specific RNAi worms fed dsRNA against unc-70 were also impaired in their response to nose touch when compared to controls (Fig. 3D), suggesting that unc-70 is important for maintaining the integrity of glutamate-releasing neurons.

Cholinergic neuron-specific RNAi

We also targeted cholinergic neurons using the Punc-17 promoter, which drives expression in acetylcholine-releasing neurons, including the excitatory motor neurons that innervate the body wall muscles and are required for proper locomotion [40], [41]. We first measured the thrashing rate in liquid of neuron-sensitized (lin-15B; eri-1) worms and found that they exhibited a significant decrease when fed bacteria producing dsRNA against snb-1 or unc-13 compared to empty vector control (Fig. 2E). We then knocked these genes down in the acetylcholine-specific RNAi strain and observed a similar decrease in the rate of thrashing (Fig. 2F). We also fed the acetylcholine-specific RNAi worms dsRNA against unc-70. These worms were impaired in their thrashing rate but displayed no other phenotypes indicative of systemic RNAi of unc-70, suggesting that RNAi in this strain is restricted to the acetylcholine neurons.

A screen for essential gene function in mature GABA neurons

Neurons are complex cells, and synaptic transmission and maintenance of normal neuronal function requires the concerted action of a large number of genes. Although many such genes have been identified by forward genetic screens, we hypothesized that these screens may have missed important requirements in neurons for essential genes. Essential genes – those required for the growth of an organism to a fertile adult – are difficult to recover in screens for neuronal function because of death, arrest, or sterility of the mutant. Yet such genes might have critical roles in neurons. Accordingly, we sought to expand our ubderstanding of the genetic requirements for proper GABA neuron function by screening our GABA-specific RNAi strain against a large number of essential genes.

We began by curating a list of all essential genes by reported RNAi phenotype of lethal, arrested, or sterile using WormMart (wormbase.org), and we arrayed corresponding Ahringer RNAi [6] clones into a custom essential gene RNAi library. Our primary screen consisted of 1,782 essential RNAi clones from chromosomes I, II, and III. Using the GABA-specific RNAi strain described above, we screened animals fed these clones for hypersensitivity to aldicarb-induced paralysis. Due to the strict experimental control needed for proper neuronal RNAi and phentoyping, such as log-phase culture and age-matched progeny, we were successfully able to screen 1,320 clones (outlined in Table S1) targeting essential genes for their effect on GABA output. From the primary screen, we identified 79 clones (∼6%) that produced aldicarb hypersensitivity of at least two standard deviations above the mean (Figure 4A).

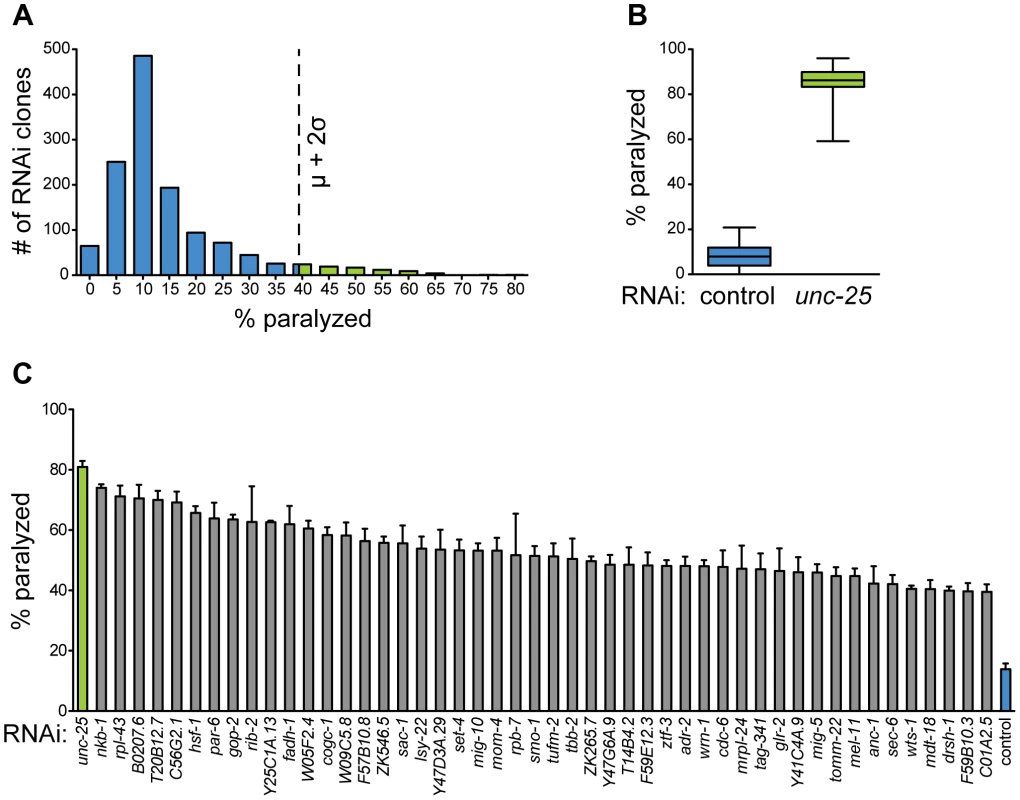

Fig. 4. A screen for essential gene function in mature GABA neurons.

(A) Histogram of primary GABA-specific RNAi screen. 79 RNAi clones (green bars) were selected for retesting with aldicarb hypersensitivity above cutoff (dotted line) of two standard deviations above the mean. μ = 14.40%, σ = 12.15%, cutoff = 38.70%. (B) Aldicarb sensitivity of controls from primary screen. Negative control (L4440, blue box) fed worms are significantly less sensitive to aldicarb than positive control (unc-25, green box) fed worms. N = 42 for each condition. Whiskers are min to max values. p<0.0001. (C) Hits from secondary screen. RNAi against 48 genes causes hypersensitivity to aldicarb above primary RNAi screen cutoff in at least 3 independent trials of ∼25 worms each. p<0.0001 for all clones compared to control RNAi. We also examined the morphology of the GABA nervous system in each experiment for branching, degeneration, or cell death. We found that in contrast to the functional defects, we observed no morphological defects in any of the 1,320 RNAi experiments. Thus, the functional deficits we observe in response to RNAi are the result of altered neurotransmission rather than cell death or degeneration. However, our screen was conducted on young adult animals, so it is possible that longer-term knockdown would result in morphological phenotypes for some genes.

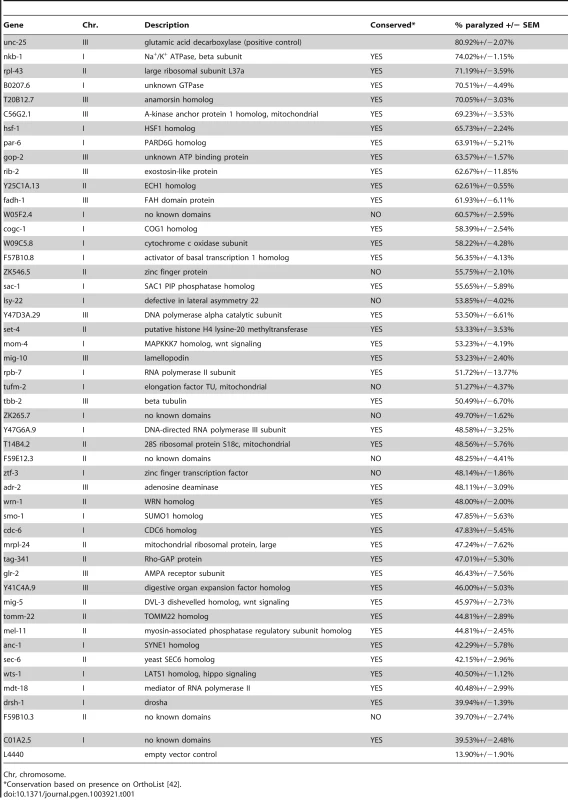

To validate the primary screen hits, we retested each of the clones in at least three independent trials. We selected those that retested above the cutoff from the primary screen, which was well above that needed for statistical significance (p<0.0001 for all selected clones compared to control). These clones were then sequenced to confirm the targeted gene. We discarded any clone that could not be mapped to a single gene target, including clones that mapped to more than one gene, intergenic region, or intron. We identified 48 genes (Figure 4C, Table 1) whose knockdown in GABA neurons led to aldicarb hypersensitivity, and thus decreased GABA motor output. Eighty-three percent (40) of these genes have predicted human orthologs [42], suggesting that we have identified a largely conserved set of genes that are important for post-developmental GABA neuron function.

Tab. 1. Essential gene RNAi clones that affect GABA neuron function.

Chr, chromosome. Discussion

The technique and strains presented here enable cell-specific knockdown in designated neurons simply by performing feeding RNAi. Our results in GABA, dopamine, glutamate, and acetylcholine-releasing neurons suggest that the technique can be used to limit feeding RNAi to any neuron or group of neurons. However, since RDE-1 acts at a rate-limiting step early in the exogenous RNAi pathway, small amounts of misexpression can trigger an amplified interference response – hence, tightly controlled promoters are required to drive expression of the transgene to ensure specificity.

One major use of this technique will be to rapidly determine the site of action of particular genes. For example, our results demonstrate that the dopamine receptor dop-3 does not function in the dopamine neurons, and the glutamate receptor glr-1 does not function in the glutamate neurons.

Another major use will be to easily determine the function in specific neurons of genes that are ubiquitously expressed. For example, our data demonstrate that GABA, acetylcholine, dopamine, and glutamate neurons all rely on unc-13 and snb-1 for neurotransmission. Also, we show that unc-70 is required in GABA, acetylcholine, and glutamate neurons for proper function.

Finally, our technique enables new kinds of forward genetic screens, as we have demonstrated with our GABA-specific RNAi screen of essential genes. Essential genes make up a substantial portion of the genes in the genome, but are virtually inaccessible to traditional genetic screens. These genes, however, are some of the most conserved – while only ∼38% of all C. elegans genes have human orthologs [42], ∼76% of the genes we selected for their essential RNAi phenotype have predicted orthologs. By using a strain that limits RNAi to non-essential neurons (such as our GABA-specific strain), it is now possible to screen for neuronal functions of genes that normally have lethal, sterile, or other pleiotropic phenotypes.

We have identified 48 genes whose cell-specific knockdown lead to deficits in GABA neurotransmission. As expected, we found components of essential cellular processes such as energy metabolism, transcription, and translation. Additionally, components of several important and conserved signaling and gene regulation pathways were identified, such as miRNA (drsh-1), Wnt signaling (mig-5), and Hpo signaling (wts-1). These pathways have been studied extensively for their role in development, but our data suggest that these pathways may be important post-developmentally for maintenance of GABA neuron function. The genes identified in this study provide a more complete understanding of the complex genetic requirements of post-developmental neurons. Additional studies will be required to determine the mechanism through which these genes act to promote GABA neuron function, whether through specific modulation of neuronal functions such as neurotransmitter release, or general cellular health and metabolism.

The four strains presented here enable the rapid knockdown of many single gene targets in a given neuron sub-type. The efficiency of RNAi in each strain varies, possibly due to differences in expression levels of our bi-cistronic transgene when driven by various promoters. In the case of the GABAergic neuron-specific strain, we are able to recapitulate the null phenotype of unc-25(e156) with unc-25 RNAi (Figure S1A, p = 0.0994). The efficiency of the dopaminergic-specific RNAi strain is comparable to that of the standard sensitized RNAi strain – when fed RNAi against cat-2 (Figure 3A, B), basal slowing response is abolished to a similar level in both strains. The efficiency of RNAi in the glutamatergic neuron-specific RNAi strain is also comparable to the standard sensitized strain when nose touch behaviors are compared after feeding with eat-4 RNAi (Figure 3C, D, p = 0.5205). Finally, RNAi in the cholinergic neuron-specific RNAi strain is slightly less efficient than the standard sensitized strain – there is a small, but significant difference in the thrashing rates when these strains are fed RNAi against unc-13 (Figure 3E, F, p = 0.0430) or snb-1 (p = 0.0478). Additionally, RNAi of unc-13 in the cholinergic-specific RNAi strain is unable to fully recapitulate the slowed thrashing rate of unc-13(e51) mutants (Figure S1B, p = 0.0003), due to a combination of decreased penetrance and effect size. All the strains presented, however, show dramatic behavioral defects when fed RNAi against genes that are required for those neurons to function.

An interesting feature of our system is that we do not observe effects for knockdown of gene function during development. For example, although GABA neurotransmission is required at all developmental stages for normal movement, our GABA-specific strain does not exhibit behavioral defects until the L4 and adult stage. Similarly, no developmental defects were observed during our GABA-specific screen of essential genes. A likely reason for this is that in our system, RNAi is not initiated until rde-1 is expressed, and expression from the promoters we use does not begin soon enough to affect behavior at earlier stages. Although this delay means that the developmental functions of genes cannot be studied with our system, it also allows bypassing developmental effects for genes that function both during development and afterward. For example, if a neuronal gene functions in axon guidance and also functions in neurotransmission, our system will allow specific analysis of this later role.

To our knowledge, our approach is the first in any metazoan that enables cell-specific knockdown in any chosen neuron sub-type (with an available promoter), in a way that is high throughput enough to be compatible with questions involving large numbers of genes – including whole-genome screens. As additional specific sensitized strains are developed in addition to the four presented here, it will be possible to combine analysis of neural circuits with genetics, knocking down specific genes in specific parts of circuits and determining the effect on output. In general, we expect this technique will be useful for two major classes of applications: first, to rapidly determine the site of gene function by knocking down a gene of interest in specific neurons; and second, to perform forward genetic screens in a mosaic context, defeating the muddying effects of pleiotropy and biasing the hits toward genes that function intrinsically in the neurons of interest.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction

All entry clones were generated using Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) and Gateway BP Clonase II (Life Technologies). rde-1 and sid-1 were amplified from genomic and cDNA, respectively, from start to stop codons and cloned into pDONR221 (Life Technologies). The bi-cistronic rde-1:SL2:sid-1 entry clone was generated using In-Fusion PCR cloning kit (Clonetech) in two steps: first, the 245 bp SL2-specific trans-splice site from the gpd-2/gpd-3 intergenic region [20] was inserted upstream of the start codon of the sid-1 entry vector, then the rde-1 gene was inserted upstream of the SL2 site. Pdat-1 and Peat-4 promoter entry clones were made by PCR amplification of 717 bp and 2582 bp, respectively, upstream of the corresponding gene start site and cloned into pDONR-P4-P1R. Punc-47 and Punc-17 promoter entry constructs [43] were a gift from Gunther Hollopeter, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT. Expression clones were generated using Gateway LR clonase II Plus (Life Technologies) and inserted into pCFJ150 [21], a Gateway three-fragment compatible destination vector for MosSCI containing a C. briggsae unc-119 rescue fragment and genomic regions flanking the ttTi5605 Mos1 insertion, to generate: pCF1021 (Punc-47::rde-1:SL2:sid-1::let-858UTR), pCF1028 (Punc-17::rde-1:SL2:sid-1::let-858UTR), pCF1035 (Pdat-1::rde-1:SL2:sid-1::let-858UTR), pCF1044 (Peat-4::rde-1:SL2:sid-1::let-858UTR). The unc-70 RNAi construct was made by inserting 1697 bp of unc-70 coding sequence between the SpeI and KpnI sites of L4440 (clone pPD129.36, Fire Kit, Addgene). Primers and templates are outlined in Table S2.

Strains and transgenics

All mutant C. elegans strains were provided by Caenorhabditis Genetics Center and maintained at 20°C as previously described [44]. Transgenic C. elegans lines carrying the transgenes as single copy insertions were created as described [21], [45] using insertion site ttTi5605, then verified by PCR and Sanger sequencing. These insertions were then crossed into lin-15B(n744); eri-1(mg366); rde-1(ne219) mutant animals and genotyped by PCR, Sanger sequencing, and resistance to ama-1 RNAi. XE1583 was created by microinjection of XE1375 with 15 ng µl−1 of pTG96 [46] as described [47]. The following strains were used in this study: N2, KP3948 (lin-15B(n744) X; eri-1(mg366) IV), XE1375 (lin-15B(n744) X; eri-1(mg366) IV; rde-1(ne219) V; wpSi1[Punc-47::rde-1:SL2:sid-1, Cbunc-119(+)] II; wpIs36[Punc-47::mCherry] I), XE1474 (lin-15B(n744) X; eri-1(mg366) IV; rde-1(ne219) V; wpSi6[Pdat-1::rde-1:SL2:sid-1, Cbunc-119(+)] II), XE1581 (lin-15B(n744) X; eri-1(mg366) IV; rde-1(ne219) V; wpSi10[Punc-17::rde-1:SL2:sid-1, Cbunc-119(+)] II), XE1582 (lin-15B(n744) X; eri-1(mg366) IV; rde-1(ne219) V; wpSi11[Peat-4::rde-1:SL2:sid-1, Cbunc-119(+)] II), XE1583 (lin-15B(n744) X; eri-1(mg366) IV; rde-1(ne219) V; wpSi1[Punc-47::rde-1:SL2:sid-1, Cbunc-119(+)] II; wpIs36[Punc-47::mCherry] I; wpEx180[Psur-5::sur-5:gfp:NLS]), CB156 (unc-25(e156) III), MT7929 (unc-13(e51) I).

RNAi

RNAi was induced by feeding as described [15], with modifications. We found the following conditions were optimal for RNAi in these strains. Standard NGM agar [44] was supplemented with 25 µg ml−1 carbenicillin and 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), poured into 6 cm dishes or 12-well plates, and allowed to dry for 7 days at room temperature (RT). E. coli HT115 carrying the appropriate RNAi clones were grown in LB containing 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin and 50 µg ml−1 tetracycline at 37°C overnight. This saturated culture was then seeded 1∶40–1∶200 into LB containing 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin and grown at 37°C until it reached an OD600 of 0.6–0.8, then several drops were seeded onto plates, making sure the culture dried within 1–2 hrs, and induced at RT for 48 hrs. L1 worms were then transferred to the plates (3 per 12-well plate well or 6 per 6 cm plate) and allowed to grow at 20°C for approximately 7 days until young adult (L4+1 day) F1 progeny were visible. The following RNAi clones were used: L4440 empty vector control (clone pPD129.36, Fire Kit, Addgene), GFP (clone pPD128.110, Fire Kit, Addgene), snb-1 (clone T10H9.4, Ahringer Library [6], unc-13 (clone ZK524.2, Ahringer Library), cat-2 (clone B0432.5, Ahringer Library), dop-3 (clone T14E8.3, Ahringer Library), eat-4 (clone ZK512.6, Ahringer Library), glr-1 (clone C06E1.4, Ahringer Library), unc-25 (clone Y37D8A.23, Vidal ORFeome Library [7], unc-49 (clone T21C12.1, Vidal ORFeome Library). See Supplemental Table S1 for the list of clones used in the screen.

Microscopy

Young adult hermaphrodites were mounted in a slurry of 0.1 µm diameter polystyrene beads (Polysciences) on a 5% agarose pad and imaged using a UltraVIEW VoX (Perkin Elmer) spinning disc confocal microscope using a 60× CFI Plan Apo VC, NA 1.4, oil objective. Images were pseudo colored in Fiji [48].

Behavioral assays

Aldicarb hypersensitivity was measured as described [28]. Briefly, NGM agar was poured into 12-well plates and allowed to dry for 14 days at RT. Plates were then weighed, top-spread with 30 mM aldicarb (Ultra Scientific) to a final concentration of 750 µM, and allowed to dry for 6 hrs. Plates were then seeded with 5 µl of OP50 culture and allowed to grow overnight at RT. 25 young adult worms were then transferred to each well, and after 100 min, the number of paralyzed (defined as the cessation of all spontaneous movement) worms was counted. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Basal slowing was measured as described [33]. Locomotion for 20 worms was measured for each RNAi and each treatment.

Thrashing was measured by picking a single young adult worm into a drop of M9 buffer [44] on a glass slide at RT. After equilibrating for 30 sec, the number of body bends (complete movement of the anterior of the worm from one extreme to the other and back) was counted for 30 sec. Rates were measured for 10 worms for each RNAi treatment.

Response to nose touch was measured as described [36]. 10 animals were tested for each condition, 5 trials/animal. The percentage of reversals per total trials was calculated.

Screen

RNAi was performed as described above, with cultures grown in 96-deep-well plates. Two positive (unc-25) and two negative (L4440) controls were included for each 96 clones screened. Only cultures grown to log-phase were seeded onto plates as measured by OD600 using a Perkin Elmer Victor 2 plate reader. Aldicarb hypersensitivity was performed as above. Morphology of GABA neurons was examined using a Leica M165FC epi-fluorescent dissecting microscope under 500× magnification.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed, unpaired Student's t-tests were used to compare GFP RNAi and aldicarb hypersensitivity data in Figures 2 and 4, as well as basal slowing and thrashing in Figure 3. Two-tailed Fisher's exact test was used to compare nose touch behaviors in Figure 3.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. JohnsonNM, BehmCA, TrowellSC (2005) Heritable and inducible gene knockdown in C. elegans using Wormgate and the ORFeome. Gene 359 : 26–34 doi:10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.034

2. EspositoG, Di SchiaviE, BergamascoC, BazzicalupoP (2007) Efficient and cell specific knock-down of gene function in targeted C. elegans neurons. Gene 395 : 170–176 doi:10.1016/j.gene.2007.03.002

3. YochemJ, HermanRK (2003) Investigating C. elegans development through mosaic analysis. Development 130 : 4761–4768 doi:10.1242/dev.00701

4. TimmonsL, FireA (1998) Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature 395 : 854–854 doi:10.1038/27579

5. FraserAG, KamathRS, ZipperlenP, Martinez-CamposM, SohrmannM, et al. (2000) Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature 408 : 325–330 doi:10.1038/35042517

6. KamathRS, AhringerJ (2003) Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30 : 313–321.

7. RualJ-F, CeronJ, KorethJ, HaoT, NicotA-S, et al. (2004) Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res 14 : 2162–2168 doi:10.1101/gr.2505604

8. WinstonWM, MolodowitchC, HunterCP (2002) Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science 295 : 2456–2459 doi:10.1126/science.1068836

9. FeinbergEH, HunterCP (2003) Transport of dsRNA into cells by the transmembrane protein SID-1. Science 301 : 1545–1547 doi:10.1126/science.1087117

10. ShihJD, HunterCP (2011) SID-1 is a dsRNA-selective dsRNA-gated channel. RNA 17 : 1057–1065 doi:10.1261/rna.2596511

11. TabaraH, SarkissianM, KellyWG, FleenorJ, GrishokA, et al. (1999) The rde-1 gene, RNA interference, and transposon silencing in C. elegans. Cell 99 : 123–132.

12. QadotaH, InoueM, HikitaT, KöppenM, HardinJD, et al. (2007) Establishment of a tissue-specific RNAi system in C. elegans. Gene 400 : 166–173 doi:10.1016/j.gene.2007.06.020

13. CalixtoA, ChelurD, TopalidouI, ChenX, ChalfieM (2010) Enhanced neuronal RNAi in C. elegans using SID-1. Nature Methods 7 : 554–559 doi:10.1038/nmeth.1463

14. KamathRS, Martinez-CamposM, ZipperlenP, FraserAG, AhringerJ (2001) Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol 2: RESEARCH0002 doi:10.1186/gb-2000-2-1-research0002

15. TimmonsL, CourtDL, FireA (2001) Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 263 : 103–112 doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00579-5

16. AsikainenS, VartiainenS, LaksoM, NassR, WongG (2005) Selective sensitivity of Caenorhabditis elegans neurons to RNA interference. Neuroreport 16 : 1995–1999.

17. WangD, KennedyS, ConteDJr, KimJK, GabelHW, et al. (2005) Somatic misexpression of germline P granules and enhanced RNA interference in retinoblastoma pathway mutants. Nature 436 : 593–597 doi:10.1038/nature04010

18. KimJK, GabelHW, KamathRS, TewariM, PasquinelliA, et al. (2005) Functional Genomic Analysis of RNA Interference in C. elegans. Science 308 : 1164–1167 doi:10.1126/science.1109267

19. JoseAM, SmithJJ, HunterCP (2009) Export of RNA silencing from C. elegans tissues does not require the RNA channel SID-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106 : 2283–2288 doi:10.1073/pnas.0809760106

20. SpiethJ, BrookeG, KuerstenS, LeaK, BlumenthalT (1993) Operons in C. elegans: polycistronic mRNA precursors are processed by trans-splicing of SL2 to downstream coding regions. Cell 73 : 521–532.

21. Frøkjær-JensenC, Wayne DavisM, HopkinsCE, NewmanBJ, ThummelJM, et al. (2008) Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature Genetics 40 : 1375–1383 doi:10.1038/ng.248

22. McIntireSL, ReimerRJ, SchuskeK, EdwardsRH, JorgensenEM (1997) Identification and characterization of the vesicular GABA transporter. Nature 389 : 870–876 doi:10.1038/39908

23. BirdDM, RiddleDL (1989) Molecular cloning and sequencing of ama-1, the gene encoding the largest subunit of Caenorhabditis elegans RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol 9 : 4119–4130.

24. JinY, JorgensenE, HartwiegE, HorvitzHR (1999) The Caenorhabditis elegans gene unc-25 encodes glutamic acid decarboxylase and is required for synaptic transmission but not synaptic development. J Neurosci 19 : 539–548.

25. BamberBA, BegAA, TwymanRE, JorgensenEM (1999) The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-49 locus encodes multiple subunits of a heteromultimeric GABA receptor. J Neurosci 19 : 5348–5359.

26. MaruyamaIN, BrennerS (1991) A phorbol ester/diacylglycerol-binding protein encoded by the unc-13 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88 : 5729–5733.

27. NonetML, SaifeeO, ZhaoH, RandJB, WeiL (1998) Synaptic transmission deficits in Caenorhabditis elegans synaptobrevin mutants. J Neurosci 18 : 70–80.

28. VashlishanAB, MadisonJM, DybbsM, BaiJ, SieburthD, et al. (2008) An RNAi screen identifies genes that regulate GABA synapses. Neuron 58 : 346–361 doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.019

29. HammarlundM, DavisWS, JorgensenEM (2000) Mutations in beta-spectrin disrupt axon outgrowth and sarcomere structure. J Cell Biol 149 : 931–942.

30. HammarlundM, JorgensenEM, BastianiMJ (2007) Axons break in animals lacking beta-spectrin. J Cell Biol 176 : 269–275 doi:10.1083/jcb.200611117

31. NassR, HallDH, MillerDM3rd, BlakelyRD (2002) Neurotoxin-induced degeneration of dopamine neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99 : 3264–3269 doi:10.1073/pnas.042497999

32. SulstonJ, DewM, BrennerS (1975) Dopaminergic neurons in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Comp Neurol 163 : 215–226 doi:10.1002/cne.901630207

33. SawinER, RanganathanR, HorvitzHR (2000) C. elegans Locomotory Rate Is Modulated by the Environment through a Dopaminergic Pathway and by Experience through a Serotonergic Pathway. Neuron 26 : 619–631 doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81199-X

34. LintsR, EmmonsSW (1999) Patterning of dopaminergic neurotransmitter identity among Caenorhabditis elegans ray sensory neurons by a TGFbeta family signaling pathway and a Hox gene. Development 126 : 5819–5831.

35. ChaseDL, PepperJS, KoelleMR (2004) Mechanism of extrasynaptic dopamine signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Neurosci 7 : 1096–1103 doi:10.1038/nn1316

36. KaplanJM, HorvitzHR (1993) A dual mechanosensory and chemosensory neuron in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90 : 2227–2231.

37. LeeRY, SawinER, ChalfieM, HorvitzHR, AveryL (1999) EAT-4, a homolog of a mammalian sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate cotransporter, is necessary for glutamatergic neurotransmission in caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 19 : 159–167.

38. HartAC, SimsS, KaplanJM (1995) Synaptic code for sensory modalities revealed by C. elegans GLR-1 glutamate receptor. Nature 378 : 82–85 doi:10.1038/378082a0

39. MaricqAV, PeckolE, DriscollM, BargmannCI (1995) Mechanosensory signalling in C. elegans mediated by the GLR-1 glutamate receptor. Nature 378 : 78–81 doi:10.1038/378078a0

40. AlfonsoA, GrundahlK, DuerrJS, HanHP, RandJB (1993) The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-17 gene: a putative vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Science 261 : 617–619.

41. AlfonsoA, GrundahlK, McManusJR, AsburyJM, RandJB (1994) Alternative Splicing Leads to Two Cholinergic Proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Molecular Biology 241 : 627–630 doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1538

42. ShayeDD, GreenwaldI (2011) OrthoList: a compendium of C. elegans genes with human orthologs. PLoS ONE 6: e20085 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020085

43. LiuQ, HollopeterG, JorgensenEM (2009) Graded synaptic transmission at the Caenorhabditis elegans neuromuscular junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106 : 10823–10828 doi:10.1073/pnas.0903570106

44. BrennerS (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 : 71–94.

45. Frøkjær-JensenC, DavisMW, AilionM, JorgensenEM (2012) Improved Mos1-mediated transgenesis in C. elegans. Nature Methods 9 : 117–118 doi:10.1038/nmeth.1865

46. YochemJ, GuT, HanM (1998) A new marker for mosaic analysis in Caenorhabditis elegans indicates a fusion between hyp6 and hyp7, two major components of the hypodermis. Genetics 149 : 1323–1334.

47. MelloCC, KramerJM, StinchcombD, AmbrosV (1991) Efficient gene transfer in C.elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J 10 : 3959–3970.

48. SchindelinJ, Arganda-CarrerasI, FriseE, KaynigV, LongairM, et al. (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods 9 : 676–682 doi:10.1038/nmeth.2019

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Ribosome Synthesis and MAPK Activity Modulate Ionizing Radiation-Induced Germ Cell Apoptosis inČlánek Fission Yeast Shelterin Regulates DNA Polymerases and Rad3 Kinase to Limit Telomere Extension

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 11

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Molecular Recognition by a Polymorphic Cell Surface Receptor Governs Cooperative Behaviors in Bacteria

- The Light Skin Allele of in South Asians and Europeans Shares Identity by Descent

- Ribosome Synthesis and MAPK Activity Modulate Ionizing Radiation-Induced Germ Cell Apoptosis in

- Retrotransposon Silencing During Embryogenesis: Cuts in LINE

- Roles of XRCC2, RAD51B and RAD51D in RAD51-Independent SSA Recombination

- Parallel Evolution of Chordate Regulatory Code for Development

- A Genetic Approach to the Recruitment of PRC2 at the Locus

- Deletion of the Murine Cytochrome P450 Locus by Fused BAC-Mediated Recombination Identifies a Role for in the Pulmonary Vascular Response to Hypoxia

- Elevated Mutagenesis Does Not Explain the Increased Frequency of Antibiotic Resistant Mutants in Starved Aging Colonies

- Deletion of an X-Inactivation Boundary Disrupts Adjacent Gene Silencing

- Interplay between Active Chromatin Marks and RNA-Directed DNA Methylation in

- Recombinogenic Conditions Influence Partner Choice in Spontaneous Mitotic Recombination

- Crosstalk between NSL Histone Acetyltransferase and MLL/SET Complexes: NSL Complex Functions in Promoting Histone H3K4 Di-Methylation Activity by MLL/SET Complexes

- A New Role for the GARP Complex in MicroRNA-Mediated Gene Regulation

- RNAi-Dependent and Independent Control of LINE1 Accumulation and Mobility in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Loss of DNMT1o Disrupts Imprinted X Chromosome Inactivation and Accentuates Placental Defects in Females

- Inhibition of the Smc5/6 Complex during Meiosis Perturbs Joint Molecule Formation and Resolution without Significantly Changing Crossover or Non-crossover Levels

- Disruption of Lipid Metabolism Genes Causes Tissue Overgrowth Associated with Altered Developmental Signaling

- Translation Initiation Factors eIF3 and HCR1 Control Translation Termination and Stop Codon Read-Through in Yeast Cells

- Recruitment of TREX to the Transcription Machinery by Its Direct Binding to the Phospho-CTD of RNA Polymerase II

- MYB97, MYB101 and MYB120 Function as Male Factors That Control Pollen Tube-Synergid Interaction in Fertilization

- Oct4 Is Required ∼E7.5 for Proliferation in the Primitive Streak

- Contrasted Patterns of Crossover and Non-crossover at Meiotic Recombination Hotspots

- Transposable Prophage Mu Is Organized as a Stable Chromosomal Domain of

- Ash1l Methylates Lys36 of Histone H3 Independently of Transcriptional Elongation to Counteract Polycomb Silencing

- Fine-Mapping the Genetic Association of the Major Histocompatibility Complex in Multiple Sclerosis: HLA and Non-HLA Effects

- Genomic Mechanisms Accounting for the Adaptation to Parasitism in Nematode-Trapping Fungi

- Decoding a Signature-Based Model of Transcription Cofactor Recruitment Dictated by Cardinal Cis-Regulatory Elements in Proximal Promoter Regions

- Removal of Misincorporated Ribonucleotides from Prokaryotic Genomes: An Unexpected Role for Nucleotide Excision Repair

- Fission Yeast Shelterin Regulates DNA Polymerases and Rad3 Kinase to Limit Telomere Extension

- Activin Signaling Targeted by Insulin/dFOXO Regulates Aging and Muscle Proteostasis in

- Activin-Like Kinase 2 Functions in Peri-implantation Uterine Signaling in Mice and Humans

- Demographic Divergence History of Pied Flycatcher and Collared Flycatcher Inferred from Whole-Genome Re-sequencing Data

- Recurrent Tissue-Specific mtDNA Mutations Are Common in Humans

- The Histone Variant His2Av is Required for Adult Stem Cell Maintenance in the Testis

- The Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition Targets Actin to Promote Robustness during Morphogenesis

- Reconstructing the Population Genetic History of the Caribbean

- and Are Required for Growth under Iron-Limiting Conditions

- Whole Genome, Whole Population Sequencing Reveals That Loss of Signaling Networks Is the Major Adaptive Strategy in a Constant Environment

- Neuron-Specific Feeding RNAi in and Its Use in a Screen for Essential Genes Required for GABA Neuron Function

- RNA∶DNA Hybrids Initiate Quasi-Palindrome-Associated Mutations in Highly Transcribed Yeast DNA

- Mouse BAZ1A (ACF1) Is Dispensable for Double-Strand Break Repair but Is Essential for Averting Improper Gene Expression during Spermatogenesis

- Genetic and Functional Studies Implicate Synaptic Overgrowth and Ring Gland cAMP/PKA Signaling Defects in the Neurofibromatosis-1 Growth Deficiency

- DUX4 Binding to Retroelements Creates Promoters That Are Active in FSHD Muscle and Testis

- Pathways-Driven Sparse Regression Identifies Pathways and Genes Associated with High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Two Asian Cohorts

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- and Are Required for Growth under Iron-Limiting Conditions

- Genetic and Functional Studies Implicate Synaptic Overgrowth and Ring Gland cAMP/PKA Signaling Defects in the Neurofibromatosis-1 Growth Deficiency

- The Light Skin Allele of in South Asians and Europeans Shares Identity by Descent

- RNA∶DNA Hybrids Initiate Quasi-Palindrome-Associated Mutations in Highly Transcribed Yeast DNA

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání