-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaSecreted Bacterial Effectors That Inhibit Host Protein Synthesis Are Critical for Induction of the Innate Immune Response to Virulent

The intracellular bacterial pathogen Legionella pneumophila causes an inflammatory pneumonia called Legionnaires' Disease. For virulence, L. pneumophila requires a Dot/Icm type IV secretion system that translocates bacterial effectors to the host cytosol. L. pneumophila lacking the Dot/Icm system is recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs), leading to a canonical NF-κB-dependent transcriptional response. In addition, L. pneumophila expressing a functional Dot/Icm system potently induces unique transcriptional targets, including proinflammatory genes such as Il23a and Csf2. Here we demonstrate that this Dot/Icm-dependent response, which we term the effector-triggered response (ETR), requires five translocated bacterial effectors that inhibit host protein synthesis. Upon infection of macrophages with virulent L. pneumophila, these five effectors caused a global decrease in host translation, thereby preventing synthesis of IκB, an inhibitor of the NF-κB transcription factor. Thus, macrophages infected with wildtype L. pneumophila exhibited prolonged activation of NF-κB, which was associated with transcription of ETR target genes such as Il23a and Csf2. L. pneumophila mutants lacking the five effectors still activated TLRs and NF-κB, but because the mutants permitted normal IκB synthesis, NF-κB activation was more transient and was not sufficient to fully induce the ETR. L. pneumophila mutants expressing enzymatically inactive effectors were also unable to fully induce the ETR, whereas multiple compounds or bacterial toxins that inhibit host protein synthesis via distinct mechanisms recapitulated the ETR when administered with TLR ligands. Previous studies have demonstrated that the host response to bacterial infection is induced primarily by specific microbial molecules that activate TLRs or cytosolic pattern recognition receptors. Our results add to this model by providing a striking illustration of how the host immune response to a virulent pathogen can also be shaped by pathogen-encoded activities, such as inhibition of host protein synthesis.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001289

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001289Summary

The intracellular bacterial pathogen Legionella pneumophila causes an inflammatory pneumonia called Legionnaires' Disease. For virulence, L. pneumophila requires a Dot/Icm type IV secretion system that translocates bacterial effectors to the host cytosol. L. pneumophila lacking the Dot/Icm system is recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs), leading to a canonical NF-κB-dependent transcriptional response. In addition, L. pneumophila expressing a functional Dot/Icm system potently induces unique transcriptional targets, including proinflammatory genes such as Il23a and Csf2. Here we demonstrate that this Dot/Icm-dependent response, which we term the effector-triggered response (ETR), requires five translocated bacterial effectors that inhibit host protein synthesis. Upon infection of macrophages with virulent L. pneumophila, these five effectors caused a global decrease in host translation, thereby preventing synthesis of IκB, an inhibitor of the NF-κB transcription factor. Thus, macrophages infected with wildtype L. pneumophila exhibited prolonged activation of NF-κB, which was associated with transcription of ETR target genes such as Il23a and Csf2. L. pneumophila mutants lacking the five effectors still activated TLRs and NF-κB, but because the mutants permitted normal IκB synthesis, NF-κB activation was more transient and was not sufficient to fully induce the ETR. L. pneumophila mutants expressing enzymatically inactive effectors were also unable to fully induce the ETR, whereas multiple compounds or bacterial toxins that inhibit host protein synthesis via distinct mechanisms recapitulated the ETR when administered with TLR ligands. Previous studies have demonstrated that the host response to bacterial infection is induced primarily by specific microbial molecules that activate TLRs or cytosolic pattern recognition receptors. Our results add to this model by providing a striking illustration of how the host immune response to a virulent pathogen can also be shaped by pathogen-encoded activities, such as inhibition of host protein synthesis.

Introduction

In metazoans, the innate immune system senses infection through the use of germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharide or flagellin [1]. PAMPs are conserved molecules that are found on non-pathogenic and pathogenic microbes alike, and consequently, even commensal microbes are capable of activating PRRs [2]. Thus, it has been proposed that additional innate immune mechanisms may exist to discriminate between pathogens and non-pathogens [3], [4].

In plants, selective recognition of pathogens is accomplished by detection of the enzymatic activities of “effector” molecules that are delivered specifically by pathogens into host cells. Typically, the effector is an enzyme that disrupts host cell signaling pathways to the benefit of the pathogen. Host sensors monitoring or “guarding” the integrity of the signaling pathway are able to detect the pathogen-induced disruption and initiate a protective response. This mode of innate recognition is termed “effector-triggered immunity” [5] and represents a significant component of the plant innate immune response. It has been suggested that innate recognition of pathogen-encoded activities, which have been termed “patterns of pathogenesis” in metazoans [3], could act in concert with PRRs to distinguish pathogens from non-pathogens, leading to qualitatively distinct responses that are commensurate with the potential threat. However, few if any examples of “patterns of pathogenesis” have been shown to elicit innate responses in metazoans.

The gram negative bacterial pathogen Legionella pneumophila provides an excellent model to address whether metazoans respond to pathogen-encoded activities in addition to PAMPs. L. pneumophila replicates in the environment within amoebae [6], but can also replicate within alveolar macrophages in the mammalian lung [7], where it causes a severe inflammatory pneumonia called Legionnaires' Disease [6]. Because its evolution has occurred primarily or exclusively in amoebae, L. pneumophila appears not to have evolved significant immune-evasive mechanisms. Indeed, most healthy individuals mount a robust protective inflammatory response to L. pneumophila, resulting from engagement of multiple redundant innate immune pathways [8]. We hypothesize, therefore, that as a naïve pathogen, L. pneumophila may reveal novel innate immune responses that better adapted pathogens may evade or disable [9].

In host cells, L. pneumophila multiplies within a specialized replicative vacuole, the formation of which is orchestrated by bacterial effector proteins translocated into the host cytosol via the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system [10]. In addition to its essential roles in bacterial replication and virulence, the Dot/Icm system also translocates bacterial PAMPs, such as flagellin, nucleic acids, or fragments of peptidoglycan, that activate cytosolic immunosurveillance pathways [8], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. There are also recent suggestions in the literature that Dot/Icm+ L. pneumophila may stimulate additional, uncharacterized immunosurveillance pathways [8], [17]. Overall, the molecular basis of the host response to Dot/Icm+ L. pneumophila remains poorly understood.

Here we show that macrophages infected with virulent L. pneumophila make a unique transcriptional response to a bacterial activity that disrupts a vital host process. We show that this robust transcriptional response requires the Dot/Icm system, and cannot be explained solely by known PAMP-sensing pathways. Instead, we provide evidence that the response requires the enzymatic activity of five secreted bacterial effectors that inhibit host protein synthesis. Effector-dependent inhibition of protein synthesis synergized with PRR signaling to elicit the full transcriptional response to L. pneumophila. The response to the bacterial effectors could be recapitulated through the use of pharmacological agents or toxins that inhibit host translation, administered in conjunction with a PRR agonist. Thus, our results provide a striking example of a host response that is shaped not only by PAMPs but also by a complementary “effector-triggered” mechanism that represents a novel mode of immune responsiveness in metazoans.

Results

Induction of an ‘effector-triggered’ transcriptional signature in macrophages infected with virulent L. pneumophila

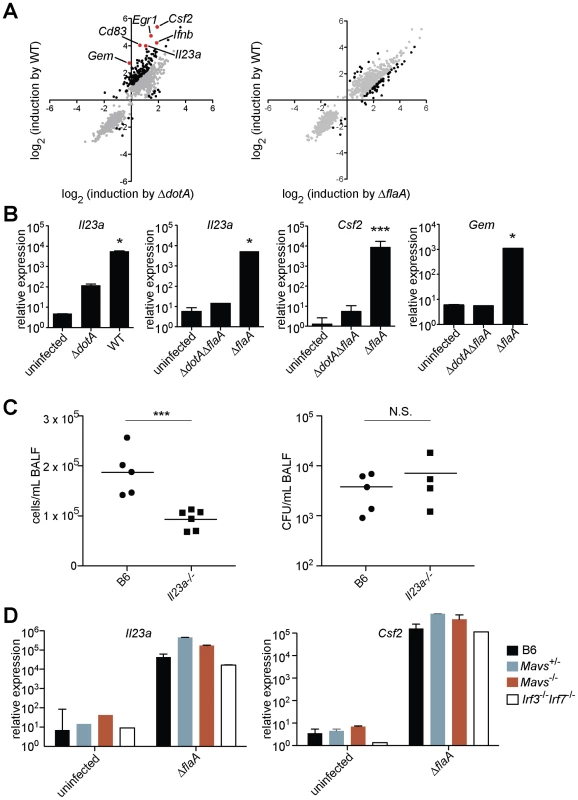

We initially sought to identify host responses that discriminate between pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria. Our strategy was to compare the host response to wildtype virulent L. pneumophila with the host response to an avirulent L. pneumophila mutant, ΔdotA. ΔdotA mutants lack a functional Dot/Icm secretion system, and thus fail to translocate effectors into the host cytosol, but they nevertheless express the normal complement of PAMPs that engage Toll-like receptor pathways. We performed transcriptional profiling experiments on macrophages infected with either wildtype L. pneumophila or the avirulent ΔdotA mutant. In the microarray experiments, Caspase-1−/− macrophages were used to eliminate flagellin-dependent macrophage death, which would otherwise differ between wildtype and ΔdotA infections [12], [14], [16], but our results were later validated with wildtype macrophages (see below). RNA was collected from macrophages at a timepoint when there were similar numbers of bacteria in both wildtype-infected and ΔdotA-infected macrophages. Microarray analysis revealed 166 genes that were differentially induced >2-fold in a manner dependent on type IV secretion (Figure 1A and Table S1). The induction of some of the Dot/Icm-dependent genes, e.g. Ifnb, could be explained by cytosolic sensing pathways that have been previously characterized [11], [13], [18]. However, much of the response to Dot/Icm+ bacteria did not appear to be accounted for by host pathways known to recognize L. pneumophila. For reasons discussed below, we refer specifically to this unexplained Dot/Icm-dependent transcriptional signature as the ‘effector-triggered response,’ or ETR.

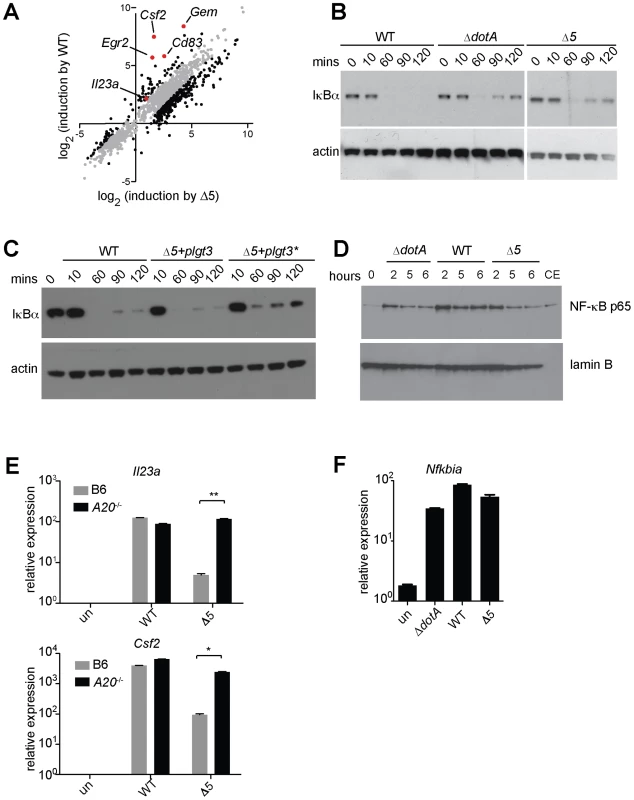

Fig. 1. A unique transcriptional response in macrophages infected with virulent L. pneumophila.

(A) Caspase-1−/− macrophages were infected for 6 h with the specified strains of L. pneumophila. RNA was amplified and hybridized to MEEBO microarrays. Black and red dots, genes exhibiting greater than 2-fold difference in induction between wildtype (WT) and mutant. Red dots indicate labeled genes. Data shown are the average of two experiments. (B) B6 macrophages were infected for 6 h with the specified strains of L. pneumophila. Levels of the indicated transcripts were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. (C) Mice were infected intranasally with 2×106 L. pneumophila and bronchoalveolar lavage was performed 24 h post infection. Host cells recovered from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were counted with a hemocytometer. A portion of each sample was plated on BCYE plates to enumerate cfu. (D) Macrophages were infected for 6 h with L. pneumophila. Levels of the indicated transcripts were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. N.S., not significant. Data shown are representative of two (a, d) or at least three (B, C) experiments (mean ± sd in b, d). *, p<0.05 versus uninfected. ***, p<0.005 versus uninfected. The ETR includes many genes thought to be important for innate immune responses, including the cytokines/chemokines Csf1, Csf2, Ccl20, and Il23a; the surface markers Sele, Cd83, and Cd44; and the stress response genes Gadd45, Egr1, and Egr3. Other ETR targets were genes whose function in macrophages has not been determined (e.g., Gem, which encodes a small GTPase) (Figure 1A and Table S1). We selected several of the most highly induced genes for validation by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR. We confirmed that Il23a, Csf2 and Gem transcripts were induced 100 to >1000-fold more by pathogenic wildtype L. pneumophila as compared to the ΔdotA mutant (Figure 1B). In subsequent experiments we focused on these three genes, as they provided a sensitive readout of the ETR.

To assess whether the ETR might be important during L. pneumophila infection in vivo, we infected B6 and Il23a−/− mice intranasally with L. pneumophila. Il23a−/− mice displayed a significant defect in host cell recruitment to the lungs 24 hours after infection (Figure 1C), consistent with the known role of IL-23 in neutrophil recruitment to sites of infection [19]. The phenotype of Il23a−/− mice was not due to decreased bacterial burden in these mice (Figure 1C). Thus at least one transcriptional target of the ETR plays a role in the host response, though there are clearly numerous redundant pathways that recognize L. pneumophila in vivo [8].

Known innate immune pathways are not sufficient to induce the full ‘effector-triggered response’

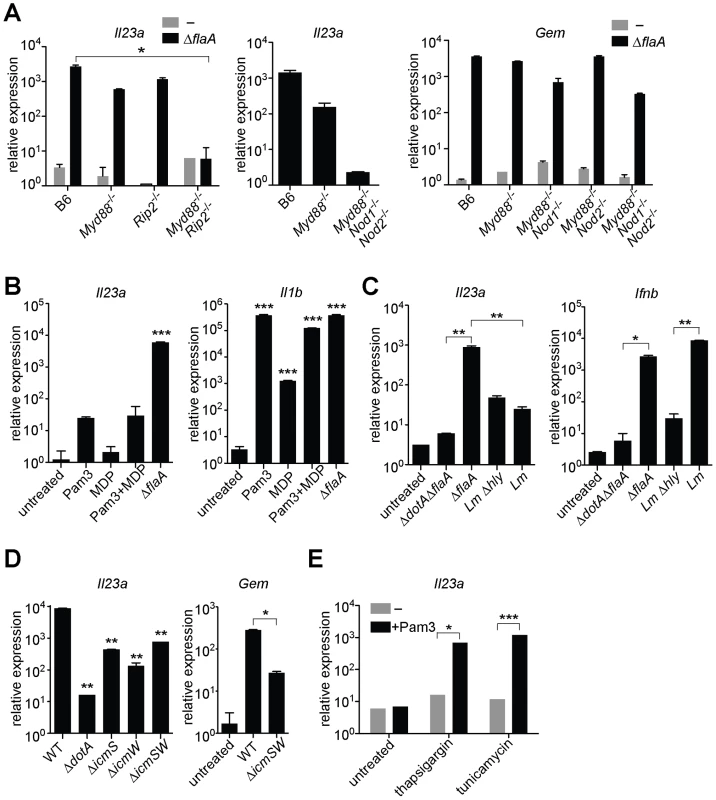

In order to identify the host pathway(s) responsible for induction of the ETR, we first examined innate immune pathways known to recognize L. pneumophila. Induction of the representative genes Il23a, Csf2, and Gem did not require the previously described Naip5/Nlrc4 flagellin-sensing pathway [20], as infection with a flagellin-deficient mutant (ΔflaA) also induced robust expression of these genes (Figure 1A, B and Table S2). Moreover, Il23a, Csf2 and Gem were strongly (>1000-fold) induced in the absence of the Mavs/Irf3/Irf7 signaling axis shown previously to respond to L. pneumophila [11], [13], [18] (Figure 1D, and data not shown). As suggested by previous transcriptional profiling experiments [17], we confirmed that Myd88−/−and Rip2−/−macrophages, which are defective in TLR and Nod1/Nod2 signaling, respectively, strongly upregulated Il23a and Gem following infection with wildtype L. pneumophila (Figure 2A). Induction of Il23a was abrogated in Myd88−/−Rip2−/− and Myd88−/−Nod1−/−Nod2−/− macrophages; however, these macrophages still robustly induced Gem (Figure 2A, and data not shown). These data indicate that TLR/Nod signaling is necessary for induction of some, but not all, genes in the ETR. Furthermore, the intact induction of Gem in Myd88−/−Nod1−/−Nod2−/− macrophages implies the existence of an additional pathway.

Fig. 2. MyD88 and Nod signaling alone do not account for the unique response to virulent L. pneumophila, which can be recapitulated by ER stress inducers that also inhibit translation.

In all panels, the indicated transcripts were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. (A) Macrophages were infected with ΔflaA L. pneumophila for 6 h. (B) Macrophages were infected with L. pneumophila or were treated with Pam3CSK4 (10 ng/mL) and/or transfected with MDP (10 µg/mL) for 6 h. (C) B6 macrophages were infected with L. pneumophila, wildtype L. monocytogenes or the avirulent L. monocytogenes Δhly mutant for 4 h. (D) B6 macrophages were infected with the indicated strains of L. pneumophila for 6 h. **, p<0.01 compared to wildtype (WT). (E) Uninfected B6 macrophages were treated with thapsigargin (500 nM) or tunicamycin (5 µg/mL) for 6 h alone or in conjunction with Pam3CSK4 (1 ng/mL). All results shown are representative of at least three experiments (mean ± sd). Lm, L. monocytogenes. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.005. To address the further question of whether TLR/Nod signaling was sufficient for induction of the ETR, we treated uninfected macrophages with synthetic TLR2 and/or Nod2 ligands (Pam3CSK4 and MDP, respectively). These ligands did induce low levels of Il23a, but could not recapitulate the robust (100–1000 fold) upregulation indicative of the ETR (Figure 2B). The defective induction of ETR target genes was not due to inefficient delivery of the ligands, as Pam3CSK4 and MDP were able to strongly induce Il1b (Figure 2B). To confirm this result in a more physiologically relevant system, we infected macrophages with the Gram-positive intracellular bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes, which is known to activate both TLRs and Nods [21]. Infection with L. monocytogenes resulted only in weak Il23a induction (∼50 fold less than wildtype L. pneumophila at the same initial multiplicity of infection) (Figure 2C). A failure to strongly upregulate Il23a did not appear to be due to poor infectivity of L. monocytogenes, since the cytosolically-induced gene Ifnb [21] was robustly transcribed (Figure 2C). Taken together, these results suggest that TLR/Nod signaling, while necessary for transcription of some ETR targets, is not sufficient to account for the full induction of the ETR by L. pneumophila.

Five L. pneumophila effectors that inhibit host protein translation are required to induce the full effector-triggered response

Though PRRs do play some role in induction of the ETR, we could not identify a known PAMP-sensing pathway that fully accounted for this robust transcriptional response. Therefore we considered the hypothesis that host cells respond to an L. pneumophila-encoded activity in addition to PAMPs. Since L. pneumophila manipulates host cell biology via its Dot/Icm-secreted effectors, we analyzed the transcriptional response of macrophages infected with L. pneumophila ΔicmS/ΔicmW mutants, which express a functional Dot/Icm system [15], but lack chaperones required for secretion of many effectors. Macrophages infected with ΔicmS/ΔicmW L. pneumophila exhibited a ∼50-fold defect in induction of Il23a and Gem (Figure 2D). Thus, secreted effectors (or the physiological stresses they impart) appear to participate in induction of the ETR.

To identify potential host pathways capable of inducing ETR target genes, we treated macrophages with known inducers of host cell stress responses. We found that the pharmacological agents thapsigargin and tunicamycin, which inhibit host translation via induction of endoplasmic-reticulum (ER) stress [22], synergized with a TLR2 ligand to induce high levels of Il23a and Gem (Figure 2E, and data not shown). To test whether L. pneumophila might elicit the ETR via induction of ER stress, we measured Xbp-1 splicing and transcription of classical ER stress markers in macrophages infected with L. pneumophila. However, we found no evidence of ER stress in these macrophages (data not shown). Instead, we considered the possibility that thapsigargin induces the ETR through inhibition of protein synthesis. In fact, the L. pneumophila Dot/Icm system was previously reported to translocate several effector enzymes that inhibit host translation [23], [24], [25]. Therefore we hypothesized that inhibition of host protein synthesis by L. pneumophila [26] might be responsible for induction of the ETR.

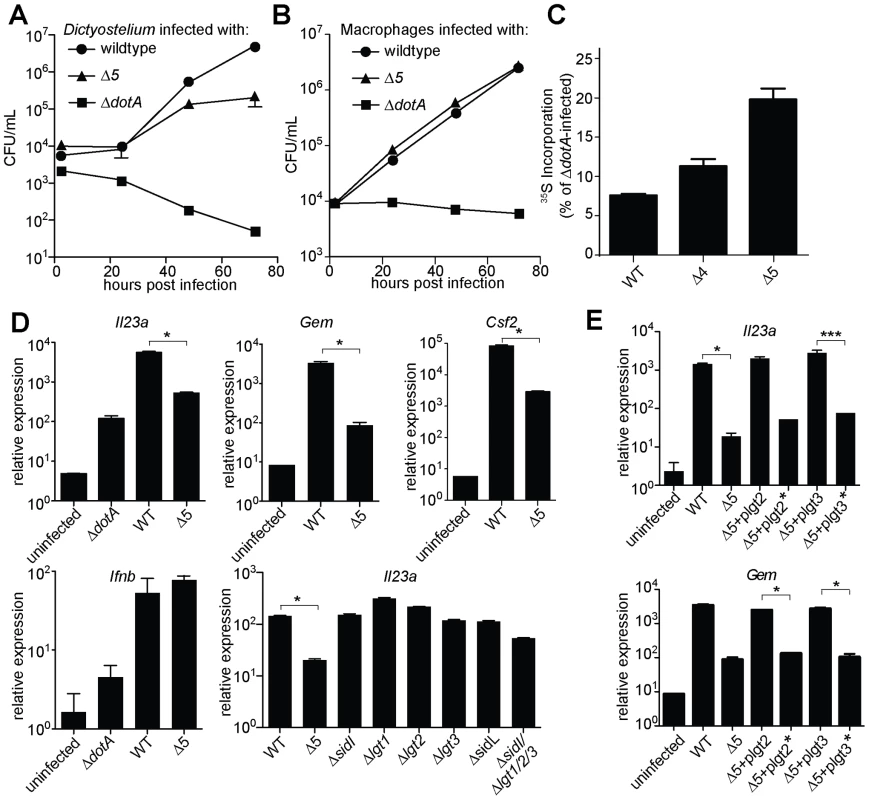

To determine whether inhibition of host translation by L. pneumophila was critical for induction of the ETR, we generated a mutant strain of L. pneumophila, called Δ5, which lacks five genes encoding effectors that inhibit host translation (lgt1, lgt2, lgt3, sidI, sidL; Figure S1; Table S3). Three of these effectors (lgt1, lgt2, lgt3), which share considerable sequence homology, are glucosyltransferases that modify the mammalian elongation factor eEF1A and block host translation both in vitro and in mammalian cells [23], [25]. A fourth effector (sidI) binds both eEF1A and another host elongation factor, eEF1Bγ, and has also been shown to inhibit translation in vitro and in cells infected with L. pneumophila [24]. The fifth effector, sidL, is toxic to mammalian cells and is capable of inhibiting protein translation in vitro via an unknown mechanism (data not shown). Moreover, its expression by L. pneumophila enhances global translation inhibition in infected macrophages (see below).

These 5 effectors appear to be important for survival within the pathogen's natural host, since the Δ5 mutant displayed a ∼10-fold growth defect in Dictyostelium amoebae (Figure 3A). By contrast, the Δ5 mutant showed no growth defect in macrophages (Figure 3B), but was defective, compared to wildtype, in its ability to inhibit host protein synthesis (Figure 3C). Although to a lesser degree than wildtype bacteria, the Δ5 mutant still appears to partially inhibit host protein synthesis, suggesting that L. pneumophila may encode additional inhibitors of host translation. Nevertheless, macrophages infected with Δ5 exhibited striking defects in induction of the ETR, including a ∼50-fold defect in induction of Il23a, Gem, and Csf2 (Figure 3D and Table S4). Importantly, the Dot/Icm-dependent induction of Ifnb, which is induced via a separate pathway [11], [13], [15], remained intact (Figure 3D), implying that the Δ5 mutant was competent for infection and Dot/Icm function. Individual deletion mutants of each of the five effectors showed no defect in Il23a, Csf2, or Gem induction, whereas a mutant lacking four of the five (Δlgt1Δlgt2Δlgt3ΔsidI) had a partial defect (Figure 3D, and data not shown). Complementation of Δ5 with wildtype lgt2 or lgt3 restored induction of Il23a and Gem, but complementation with mutant lgt2 or lgt3 lacking catalytic activity did not (Figure 3E). These results are significant because they show that macrophages make an innate response to a pathogen-encoded activity and that recognition of the effector molecules themselves is not likely to explain the ETR.

Fig. 3. A mutant L. pneumophila lacking 5 bacterial effectors that inhibit host protein synthesis is defective in induction of the host ‘effector-triggered response’.

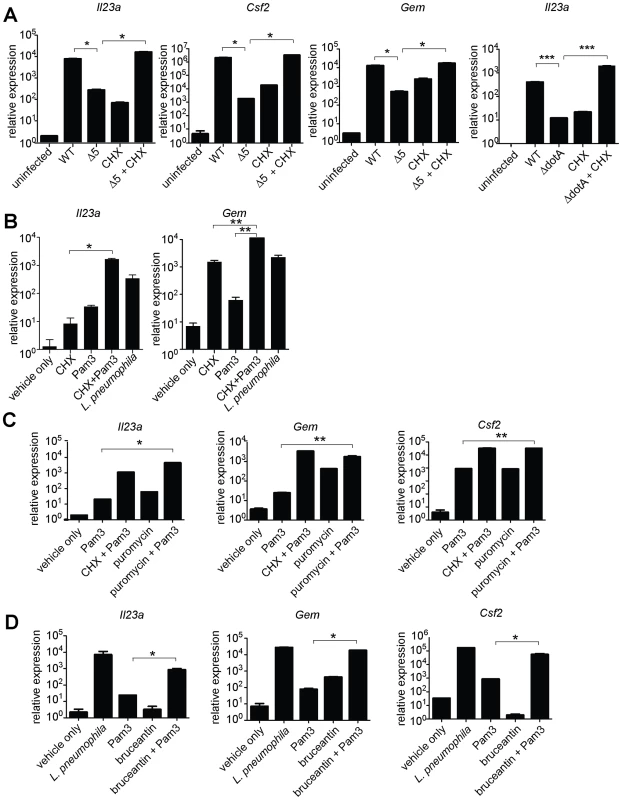

Growth of the indicated strains of L. pneumophila was measured in amoebae (A) or A/J macrophages (B). (C) Global host protein synthesis was measured by 35S-methionine incorporation in macrophages infected for 2.5 h with the indicated strains. (D) Myd88−/− (bottom right graph) or Caspase-1−/− (all others) macrophages were infected for 6 h with the specified strains. The indicated transcripts were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. (E) Caspase-1−/− macrophages were infected for 6 h with the specified strains. Indicated strains carried plasmids that constitutively expressed either a functional (plgt2, plgt3) or a catalytically inactive (plgt2*, plgt3*) bacterial effector. Data shown are representative of two (b, c) or at least three (A, D, E) experiments (mean ± sd). Δ5, Δlgt1Δlgt2Δlgt3ΔsidIΔsidL. Δ4, Δlgt1Δlgt2Δlgt3ΔsidI. *, p<0.05. ***, p<0.005. We then tested more directly whether the ETR was induced by translation inhibition. The defective induction of Il23a, Csf2, and Gem in macrophages infected with ΔdotA or Δ5 was rescued by addition of the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (Figure 4A, and data not shown). These results support the hypothesis that induction of the ETR by L. pneumophila involves inhibition of translation by the five deleted effectors. Importantly, the potent induction of Il23a, Csf2 and Gem by L. pneumophila could be recapitulated in uninfected macrophages by treatment with the translation elongation inhibitors cycloheximide (Figure 4B) or puromycin (Figure 4C), or the initiation inhibitor bruceantin (Figure 4D), in conjunction with the TLR2 ligand Pam3CSK4. These three translation inhibitors possess different targets and modes of action, making it unlikely that the common host response to each of them is due to nonspecific drug effects. Thus, translation inhibition in the context of TLR signaling provokes a specific transcriptional response. Translation inhibitors alone were capable of inducing some, but not all, effector-triggered transcriptional targets (Figure 4B, C, and D), supporting our model that translation inhibition acts in concert with classical PRR signaling to generate the full effector-dependent signature. Microarray analysis indicated that the five effectors accounted for induction of at least 54 (∼30%) of the Dot/Icm-dependent genes (Figure 5A and Table S4).

Fig. 4. Induction of the ‘effector-triggered response’ can be recapitulated by pharmacological inhibitors of translation.

(A) B6 macrophages were infected for 6 h with the indicated strains, alone or with CHX (5 µg/mL). (B, C, D) B6 macrophages were infected or were treated for 4 h with CHX (10 µg/mL; B), puromycin (20 µg/mL; C) or bruceantin (50 nM; D) alone or in conjunction with Pam3CSK4 (10 ng/mL). CHX, cycloheximide. Data shown are representative of two (C, D) or three (A, B) experiments (mean ± sd). *, p<0.05. **, p<0.01. Fig. 5. Expression of the 5 L. pneumophila effectors and induction of ‘effector-triggered’ genes correlates with sustained loss of inhibitors of the NF-κB transcription factor.

(A) Caspase-1−/− macrophages were infected for 6 h with the indicated strains. RNA was amplified and hybridized to MEEBO arrays. Black and red dots, genes exhibiting greater than 2-fold difference in induction between wildtype (WT) and Δ5. Red dots indicate labeled genes. (B, C) Caspase-1−/− macrophages were infected at an MOI of 2 for the times indicated. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-IκBα antibody (top panels) or anti-β-actin antibody (bottom panels). (C) The indicated strains carried a plasmid encoding either a functional (plgt3) or catalytically inactive (plgt3*) effector. (D) B6 macrophages were infected at an MOI of 2 for the times indicated. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-NF-κB antibody (top panel) or anti-lamin-B antibody (bottom panel) as a loading control. Cytoplasmic extract of untreated macrophages (CE) was included for comparison. (E, F) B6 (E, F) or A20−/− (E) macrophages were infected for 6 h, and levels of the indicated transcripts were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Data shown are representative of two experiments (E-F, mean ± sd). Inhibition of translation by L. pneumophila effectors results in sustained loss of IκB

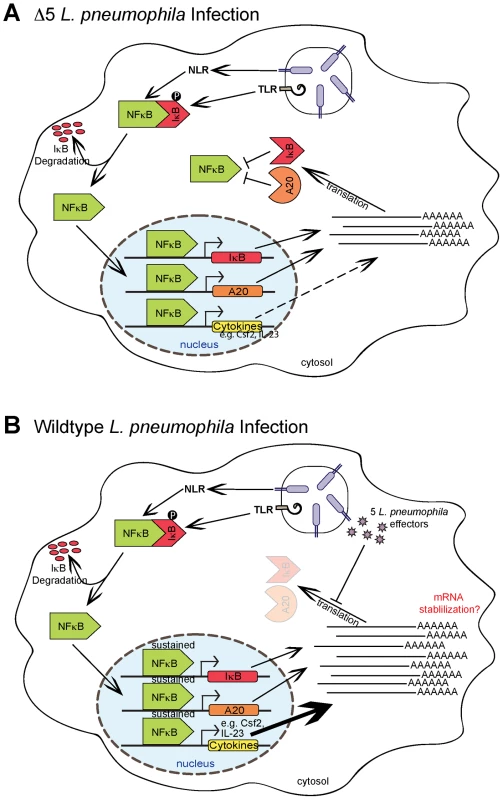

We investigated how inhibition of protein synthesis by L. pneumophila might elicit a host response. Although translation inhibition by cycloheximide has long been reported to induce cytokine production [27], the mechanism by which it acts remains poorly understood. Since the induction of Il23a and Csf2 is NF-κB dependent ([28], and data not shown), we examined a role for this pro-inflammatory transcription factor in induction of these ETR targets. NF-κB is normally suppressed by its labile inhibitor IκB, which is ubiquitinated and degraded in response to TLR and other inflammatory stimuli. IκB is itself a target of NF-κB-dependent transcription, and resynthesis of IκB is critical for the homeostatic termination of NF-κB signaling. In the absence of protein synthesis, we hypothesized that IκB may fail to be resynthesized as it turns over, thereby permitting continued NF-κB activity. To test this hypothesis, we measured IκB levels in infected macrophages over time. We observed a prolonged decrease in levels of IκB protein in macrophages infected with wildtype L. pneumophila, consistent with previous observations [17] (Figure 5B). In contrast, infection with Δ5 triggered only a transient loss of IκB, similar to infection with the secretion-deficient ΔdotA mutant (Figure 5B). The Δ5 mutant could induce sustained IκB degradation when complemented with plasmid-encoded lgt3, but not with a mutant effector lacking glucosyltransferase activity (Figure 5C), demonstrating that the sustained loss of IκB is due to the activity of the bacterial effector. To confirm that the prolonged loss of IκB did indeed result in sustained NF-κB activation, we measured NF-κB translocation to the nucleus in macrophages infected with wildtype, ΔdotA, or Δ5 L. pneumophila. While all three strains initially induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB, at later timepoints we observed decreased levels of nuclear NF-κB in macrophages infected with the ΔdotA or Δ5 strains compared to those infected with wildtype L. pneumophila (Figure 5D). Thus, translation inhibition by the 5 effectors results in sustained loss of IκB and enhanced activation of NF-κB.

NF-κB signaling is also inhibited by other de novo expressed proteins such as A20 [29]. We therefore used A20−/− macrophages, which exhibit prolonged NF-κB activation in response to TLR signaling [29], to further test the hypothesis that sustained NF-κB signaling can induce targets of the ETR. Strikingly, we found that the defective induction of Il23a and Csf2 by Δ5 was rescued in A20−/− macrophages (Figure 5E). Taken together, these observations suggest a model in which disrupted protein synthesis, and the subsequent failure to synthesize inhibitors of NF-κB signaling (e.g. IκB and A20), leads to sustained activation of NF-κB (Figure 6). In turn, we suggest that this prolonged activation of NF-κB results in enhanced transcription of a specific subset of genes.

Fig. 6. Model of NF-κB activation and superinduction by translation inhibitors.

(A) NF-κB activation by TLR signaling, via the adaptor Myd88, or Nod signaling, via Rip2, normally leads to synthesis of inhibitory proteins, including IκB and A20, which act to shut off NF-κB signaling. (B) When translation is inhibited, IκB and A20 fail to be synthesized, allowing sustained activation of NF-κB and subsequent robust transcription of a subset of target genes. Importantly, sustained NF-κB activation did not appear to result in transcriptional superinduction of all NF-κB-dependent target genes. Microarray analysis (Figure 5A and Table S4) suggested that only a subset of NF-κB-induced genes was preferentially induced by translation inhibition. For example, Nfkbia (encoding IκBα), a known NF-κB target gene, was not dramatically superinduced by wildtype compared to Δ5 L. pneumophila (Figure 5F). The molecular mechanism that results in specific superinduction of certain NF-κB-dependent target genes is not yet clear and may be complex (see Discussion). Inhibition of protein synthesis by L. pneumophila may also result in activation of other synergistic signaling pathways [30], such as MAP kinases ([17], data not shown), or in mRNA stabilization. In light of these possibilities, we confirmed that the increase in expression of ETR target genes does involve de novo transcription, by quantifying transcript levels using primers specific for unspliced mRNA (Figure S2A). We also tested whether mRNA stabilization contributed to induction of the ETR by infecting macrophages in the presence of the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D and quantifying ETR target mRNAs at successive timepoints. Our results suggested that RNA stabilization does not play a major role in induction of these particular ETR targets (Figure S2B), though we do not rule it out as a possible mechanism for increasing some mRNA transcripts in the ETR.

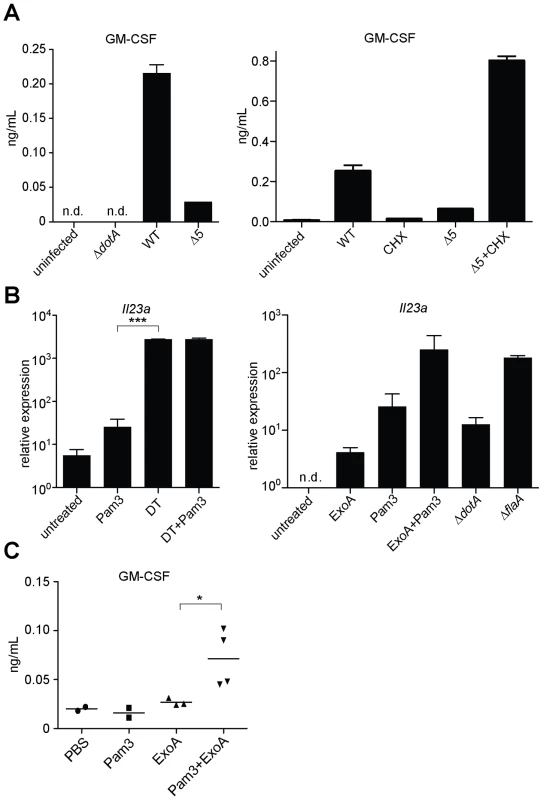

Paradoxical increase in protein production under conditions where protein synthesis is inhibited

Although inhibition of protein synthesis potently induces transcription of certain target genes, a central question is whether this transcriptional response is sufficient to overcome the translational block, and result in increased protein production. Accordingly, we measured the protein levels of GM-CSF (encoded by the Csf2 gene) in the supernatant of infected macrophages. GM-CSF protein was preferentially produced by cells infected with wildtype L. pneumophila as compared to cells infected with Δ5 (Figure 7A). The defect in cytokine production by Δ5-infected macrophages was not due to poor bacterial growth (Figure 3B), increased cytotoxicity (Figure S3A), or defective secretion (Figure S3B), and could be rescued by addition of cycloheximide (Figure 7A). Thus translation inhibition can paradoxically lead to increased production of certain proteins, perhaps because transcriptional superinduction of specific transcripts is sufficient to overcome the partial translational block mediated by L. pneumophila.

Fig. 7. Inhibition of host translation by multiple bacterial toxins provokes an inflammatory cytokine response in vitro and in vivo.

(A) B6 macrophages were infected for 24 h with the indicated strains of L. pneumophila and/or treated with cycloheximide (5 µg/mL). Protein levels in the supernatant were assayed by ELISA. (B) B6 macrophages were treated for 5 h with Diphtheria Toxin (1 ng/mL; left panel) or with Exotoxin A (500 ng/mL; right panel), alone or in conjunction with Pam3CSK4. Il23a transcript levels were assayed by quantitative RT-PCR. n.d., not detected. (C) B6 mice were treated intranasally with Pam3CSK4 (10 µg/mouse) or ExoA (2 µg/mouse) or both in 25 µL PBS. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed 24 h post infection. GM-CSF levels in lavage were measured by ELISA. Data are representative of two (A, C) or three (B) experiments (mean ± sd in A, B). CHX, cycloheximide. DT, Diphtheria Toxin. ExoA, Exotoxin A. *, p<0.05. ***, p<0.005. Host response to translation inhibition by bacterial toxins in vitro and in vivo

We did not observe defects in cytokine induction or altered bacterial replication in B6 mice infected with the Δ5 mutant. This is perhaps not surprising, since many redundant innate immune signaling pathways are known to recognize and restrict the growth of L. pneumophila in vivo [8]. Indeed, we found that dendritic cells infected with L. pneumophila upregulate ETR target genes independently of the Dot/Icm secretion system (Figure S4), and hence translation inhibition appears not to be essential for their response to L. pneumophila.

However, many other pathogens also produce toxins that inhibit host protein synthesis (e.g., Diphtheria Toxin, Shiga Toxin, Pseudomonas Exotoxin A). Thus, to test whether translation inhibition may be a general stimulus that acts with PRRs to elicit a host response to diverse pathogens, we treated uninfected macrophages with Diphtheria Toxin (DT) or Exotoxin A (ExoA) in conjunction with a TLR2 ligand. Importantly, both of these toxins inhibit translation by ADP-ribosylation of eEF2, a mechanism of action distinct from that employed by the five L. pneumophila effectors. When administered with Pam3CSK4, both toxins robustly induced Il23a (Figure 7B). DT alone was sufficient to induce Il23a, most likely due to the presence of TLR ligands in the recombinant protein preparation. Consistent with these findings, Shiga Toxin, which inhibits translation by yet another mechanism, has also been reported to superinduce cytokine responses in a cultured cell line [31]. The existence of a common host response to diverse mechanisms of translation inhibition provides strong evidence that host cells can specifically respond to this disruption of their physiology, in addition to recognizing microbial molecules.

Finally, since in vivo infection with L. pneumophila results in multiple redundant responses that may have obscured our ability to detect an in vivo phenotype for the Δ5 mutant, we turned to a simpler model to ascertain whether the ETR can be induced in vivo. In this model, purified Exotoxin A was administered intranasally to inhibit host protein synthesis in the lungs. Importantly, we found that translation inhibition appears to synergize with TLRs to elicit an immune response in vivo, as mice treated intranasally with ExoA and Pam3CSK4 produced significant amounts of the characteristic effector-triggered cytokine GM-CSF (Figure 7C). Consistent with our observations in vitro (Figure 7B), intranasal instillation of ExoA or Pam3CSK4 individually resulted in a much more modest response, providing further evidence that two signals—PRR activation and translation inhibition—are needed to generate the full effector-dependent signature. ExoA alone was sufficient to induce transcription of Gem and Csf2 mRNA in the lung (Figure S5), again in agreement with in vitro observations that translation inhibition alone can induce transcription of some target genes (Figure 4B, C, and D). Taken together, our results demonstrate that translation inhibition by multiple pathogens can lead to a common innate response in cultured cells and in vivo.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that inhibition of host translation by bacterial effectors or toxins can elicit a potent response from the host. We thus provide strong evidence for a model of innate immune recognition that is complementary to, but distinct from, the classic PAMP-based model. Most notably, we show that the immune system can mount a response to a pathogen-associated activity, in addition to pathogen-derived molecules. In our model, it is important to emphasize that there is no need for a specific host receptor or sensor per se. Instead, our data support the hypothesis that a pathogen-mediated block in the synthesis of short-lived host signaling inhibitors (e.g. IκB, A20) results in the sustained activation of an inflammatory mediator (e.g. NF-κB) (Figure 6). As such, our model more closely resembles the indirect “guard” type mechanisms that plants utilize, in conjunction with PRRs, to sense pathogens [5]. The labile nature of IκB makes it an effective “guard” to monitor the integrity of host translation, since the short half-life of this protein ensures that its abundance will decrease quickly during conditions where translation is inhibited.

There are growing suggestions that host responses to ‘patterns of pathogenesis’ [3], or harmful pathogen-associated activities, may indeed comprise a general innate immunosurveillance strategy in metazoans. For example, ion channel formation by influenza virus appears to activate the Nlrp3 inflammasome [32], and Salmonella effectors that stimulate Rho-family GTPases appear to trigger specific inflammatory responses [33]. However, in these examples, both the precise host cell disruption and the mechanism by which the host responds remain unclear. Our results are significant because we have provided a mechanism by which host cells generate a unique transcriptional response to a specific pathogen-encoded activity, namely, inhibition of host protein synthesis.

An important question is whether the innate response to translation inhibition represents a host strategy for detecting and containing a pathogen, or is rather a manipulation of the host immune system by the bacterium. Given the natural history of L. pneumophila, we consider it unlikely that this pathogen has evolved to manipulate the innate immune system [9]. L. pneumophila is not thought to be transmitted among mammals; instead, our data (Figure 3A) suggest that the five effectors described here probably evolved to aid survival in amoebae, the natural hosts of L. pneumophila. We therefore favor the hypothesis that the innate immune system has evolved to respond to disruptions in protein translation, an essential activity that is targeted by multiple viral and bacterial pathogens.

We observed that inhibition of translation in the context of PRR signaling results in the transcriptional superinduction of a specific subset of >50 genes, including Il23a, Gem, and Csf2, that constitute an ‘effector-triggered’ response. We propose that at least some of these genes are superinduced upon the sustained activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB, although it is important to emphasize that the host response to protein synthesis inhibition is complex and likely involves other pathways as well, such as MAP kinase activation (data not shown). Interestingly, we observed that not all NF-κB-dependent target genes are superinduced by translation inhibition. For example, Nfkbia (encoding the IκB protein) was not superinduced in wildtype L. pneumophila infection (Figure 5F). This selective superinduction of certain target genes may be significant, since it allows the host to respond to a pathogen-dependent stress by altering not only the magnitude but also the composition of the transcriptional response. Moreover, if IκB were superinduced, this would presumably act to reverse or prevent sustained NF-κB signaling, resulting in little net gain.

The mechanism by which prolonged NF-κB signaling may preferentially enhance transcription of the specific subset of effector-triggered genes is not yet clear. However, recent studies have shown that the chromatin context for several of these genes (e.g., Il23a, Csf2) is in a relatively ‘closed’ conformation [34], [35]. This may render the genes refractory to strong transcriptional induction under a normal TLR stimulus, but enable them to become highly induced upon prolonged NF-κB activation. It is interesting to note that genes such as Il23a and Csf2 are classified as ‘primary’ response genes [34], [35] simply because they are inducible in the presence of cycloheximide. What is not often discussed is the possibility, demonstrated here, that inhibition of protein synthesis by cycloheximide is a key stimulus that induces transcription of these genes.

The consequences of the host response to translation inhibition are likely to be difficult to measure in the context of a microbial infection in vivo. Presumably, most pathogens that disrupt host translation derive benefit from this activity, perhaps by increasing availability of amino acid nutrients or by dampening production of the host response. These benefits may be offset by an enhanced host response to translation inhibition itself. It is possible that the robust innate immune response to translation inhibition serves primarily to compensate for the decrease in translation, resulting in little net change in the output of the immune response. Accordingly, the lack of an apparent phenotype during in vivo infection with Δ5 may reflect the sum of multiple positive and negative effects that result from translation inhibition. Additionally, as suggested by our data (Figure S4) the response to L. pneumophila in vivo may involve non-macrophage cell types in which translation inhibition does not play a crucial role.

While PRR-based sensing of microbial molecules is certainly a fundamental mode of innate immune recognition, it is not clear how PRRs alone might be able to distinguish pathogens from non-pathogens, and thereby mount responses commensurate with the potential threat. Our results demonstrate that pathogen-mediated interference with a key host process (i.e., host protein synthesis), in concert with PRR signaling, results in an immune response that is qualitatively distinct from the response to an avirulent microbe. Although induction of some genes in the ETR (e.g., Gem) occurs in response to inhibition of protein synthesis alone, much of the ETR is due to the combined effects of PAMP recognition and effector-dependent inhibition of protein synthesis. A requirement for two signals might be rationalized by the fact that the ETR includes potent inflammatory cytokines such as GM-CSF or IL-23, which can drive pathological inflammation [36] and autoimmunity [37] if expressed inappropriately. Restricting production of potentially dangerous cytokines to instances where a pathogenic microbe is present may be a strategy by which hosts avoid self-damage unless necessary for self-defense. Thus, we propose that the host response to a harmful pathogen-encoded activity may represent a general mechanism by which the immune systems of metazoans distinguish pathogens from non-pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Berkeley (Protocol number R301-0311BCR).

Mice and cell culture

Macrophages were derived from the bone marrow of the following mouse strains: C57BL/6J (Jackson Labs), A20−/− (A. Ma, UCSF), Caspase-1−/− (M. Starnbach, Harvard Medical School), Mavs−/− (Z. Chen, University of Texas SW), Irf3/Irf7−/− (K. Fitzgerald, U. Mass Medical School), Myd88−/− (G. Barton, UC Berkeley), Rip2−/− (M. Kelliher, U. Mass Medical School), Myd88−/−Rip2−/− (C. Roy, Yale University), and Myd88−/−Nod1−/−Nod2−/− (generated from crosses at UC Berkeley). Il23a−/− mice were from N. Ghilardi (Genentech). Macrophages were derived from bone marrow by 8d culture in RPMI supplemented with 10% serum, 100 µM streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 10% supernatant from 3T3-M-CSF cells, with feeding on day 5. Dendritic cells were derived from B6 bone marrow by 6d culture in RPMI supplemented with 10% serum, 100 µM streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, 2 mM glutamine, and recombinant GM-CSF (1 : 1000, PeproTech). Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae were cultured at 21°C in HL-5 medium (0.056 M glucose, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% proteose peptone, 0.5% thiotone, 2.5 mM Na2HPO4, 2.5 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.9).

Bacterial strains

The L. pneumophila wildtype strain LP02 is a streptomycin-resistant thymidine auxotroph derived from L. pneumophila LP01. The ΔdotA, ΔflaA, ΔicmS and ΔicmW mutants have been described [14], [15]. Mutants lacking one or more effectors were generated from LP02 by sequential in-frame deletion using the suicide plasmid pSR47S as described [24]. Sequences of primers used for constructing deletion plasmids are listed in Table S3. Mutants were complemented with the indicated effectors expressed from the L. pneumophila sidF promoter in the plasmid pJB908, which encodes thymidine synthetase as a selectable marker. L. monocytogenes strain 10403S and the isogenic Δhly mutant have been described [21].

Microarrays

Macrophage RNA from 1.5×106 cells (6 well dishes) was isolated using the Ambion RNAqueous Kit (Applied Biosystems) and amplified with the Ambion Amino Allyl MessageAmp II aRNA Amplification Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Microarrays were performed as described [38]. Briefly, spotted microarrays utilizing the MEEBO 70-mer oligonucleotide set (Illumina) were printed at the UCSF Center for Advanced Technology. Microarray probes were generated by coupling amplified RNA to Cy dyes. After hybridization, arrays were washed, scanned on a GenePix 4000B Scanner (Molecular Devices), and gridded using SpotReader software (Niles Scientific). Analysis was performed using the GenePix Pro 6 and Acuity 4 software packages (Molecular Devices). Two independent experiments were performed. Microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession number GSE26491.

Infection and stimulation

Macrophages were plated in 6 well dishes at a density of 1.5×106 cells per well and infected at an MOI of 1 by centrifugation for 10 min at 400× g, or were treated with puromycin, thapsigargin, tunicamycin, cycloheximide (all Sigma), Exotoxin A (List Biological Labs), transfected synthetic muramyl-dipeptide (MDP) (CalBiochem), or a synthetic bacterial lipopeptide (Pam3CSK4) (Invivogen). Dendritic cells were plated at a density of 106 cells per well and infected at an MOI of 2 as described above. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for transfections. Bruceantin was the kind gift of S. Starck and N. Shastri (UC Berkeley), who obtained it from the National Cancer Institute, NIH (Open Repository NSC165563). A fusion of diphtheria toxin to the lethal factor translocation signal (LFn-DT) was the gift of B. Krantz (UC Berkeley) and was delivered to cells via the pore formed by anthrax protective antigen (PA) as described [39].

Quantitative RT-PCR

Macrophage RNA was harvested 4-6 hours post infection, as indicated, and isolated with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA samples were treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) prior to reverse transcription with Superscript III (Invitrogen). cDNA reactions were primed with poly dT for measurement of mature transcripts, and with random hexamers (Invitrogen) for measurement of unspliced transcripts. Quantitative PCR was performed as described [13] using the Step One Plus RT PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and EvaGreen (Biotium). Transcript levels were normalized to Rps17. Primer sequences are listed in Table S5.

mRNA stabilization assay

Macrophages were infected in 6-well dishes at an MOI of 1, as described above. The transcription inhibitor Actinomycin D (10 µg/mL, Sigma) was added 4 hours post infection. RNA was harvested at successive timepoints and levels of indicated transcripts were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR.

In vivo experiments

Age - and sex-matched B6 or Il23a−/− mice were anesthetized with ketamine and infected intranasally with 2×106 LP01 in 20 µL PBS essentially as described [13], or were treated with ExoA or Pam3CSK4 in 25 µL PBS. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed 24 hours post infection by introducing 800 µL PBS into the trachea with a catheter (BD Angiocath 18 g, 1.3×48 mm). Lavage fluid was analyzed by ELISA. Total host cells in the lavage were counted on a hemocytometer. For RT-PCR experiments, all lavage samples receiving identical treatments were pooled, and RNA was isolated from the pooled cells using the RNeasy Kit as described above. FACS analysis of lavage samples labeled with anti-GR-1-PeCy7 and anti-Ly6G-PE (eBioscience) indicated that most cells in lavage were neutrophils. CFU were enumerated by hypotonic lysis of host cells in the lavage followed by plating on CBYE plates.

Western blots

Macrophages were plated in 6 well dishes at a density of 2×106 cells per well and infected at an MOI of 2. For whole cell extract, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with 2 mM NaVO3, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, and 1 X Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche). For nuclear translocation experiments, nuclear and cytosolic fractions were obtained using the NE-PER kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protein levels were normalized using the micro-BCA kit (Pierce) and then separated on 10% NuPAGE bis-tris gels (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and immunoblotted with antibodies to IκBα, NF-κB p65, lamin-B or β-actin (all Santa Cruz).

ELISA

Macrophages were plated in 24 well dishes at a density of 5×105 cells per well and infected at an MOI of 1. After 24 h, supernatants were collected, sterile-filtered, and analyzed by ELISA using paired GM-CSF antibodies (eBioscience). For quantification of intracellular GM-CSF, ELISAs were performed using cytoplasmic extract of macrophages infected for 6 h with the indicated strains. Levels of GM-CSF were normalized to total protein concentration. Recombinant GM-CSF (eBioscience) was used as a standard.

Growth in bone marrow derived macrophages

Intracellular bacterial growth of wildtype and mutant L. pneumophila was evaluated in A/J macrophages as described [24].

Growth in amoebae

D. discoideum was plated into 24-well plates at a density of 5×105 cells per well in MB medium (modified HL-5 medium, without glucose and with 20 mM MES buffer) three hours before infection with the indicated L. pneumophila strains at an MOI of 0.05. The plates were spun at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes and incubated at 25°C. After two hours, wells were washed 3X with PBS to synchronize the infection. At successive time points, infected cells were lysed with 0.2% saponin and bacterial growth was determined by plating on growth medium.

Protein synthesis assay

2×106 macrophages were seeded in 6-well plates and infected with bacterial strains at an MOI of 2. After 2.5 h, the infected cells were incubated with 1 µCi 35S-methionine (Perkin Elmer) in RPMI-met (Invitrogen). After chase-labeling for an hour, the cells were washed 3× with PBS, lysed with 0.1% SDS and precipitated with TCA [24]. The protein precipitates were filtered onto 0.45 mm Millipore membranes and washed twice with PBS. Retained 35S was determined by a liquid scintillation counter.

Cytotoxicity assay

Macrophages were plated in 96 well dishes at a density of 5×104 cells per well and infected at an MOI of 1. At successive timepoints, Neutral Red (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 1% and incubated for 1 h. Cells were then washed with PBS, photographed, and counted [14].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. TakeuchiO

AkiraS

2010 Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 140 805 820

2. Rakoff-NahoumS

PaglinoJ

Eslami-VarzanehF

EdbergS

MedzhitovR

2004 Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 118 229 241

3. VanceRE

IsbergRR

PortnoyDA

2009 Patterns of pathogenesis: discrimination of pathogenic and nonpathogenic microbes by the innate immune system. Cell Host Microbe 6 10 21

4. MedzhitovR

2010 Innate immunity: quo vadis? Nat Immunol 11 551 553

5. ChisholmST

CoakerG

DayB

StaskawiczBJ

2006 Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 124 803 814

6. FieldsBS

BensonRF

BesserRE

2002 Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin Microbiol Rev 15 506 526

7. HorwitzMA

SilversteinSC

1980 Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) multiples intracellularly in human monocytes. J Clin Invest 66 441 450

8. ArcherKA

AderF

KobayashiKS

FlavellRA

RoyCR

2010 Cooperation between multiple microbial pattern recognition systems is important for host protection against the intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun 78 2477 2487

9. VanceRE

2010 Immunology taught by bacteria. J Clin Immunol 30 507 511

10. IsbergRR

O'ConnorTJ

HeidtmanM

2009 The Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole: making a cosy niche inside host cells. Nat Rev Microbiol 7 13 24

11. ChiuYH

MacmillanJB

ChenZJ

2009 RNA Polymerase III Detects Cytosolic DNA and Induces Type I Interferons through the RIG-I Pathway. Cell 138 576 591

12. MolofskyAB

ByrneBG

WhitfieldNN

MadiganCA

FuseET

2006 Cytosolic recognition of flagellin by mouse macrophages restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. J Exp Med 203 1093 1104

13. MonroeKM

McWhirterSM

VanceRE

2009 Identification of host cytosolic sensors and bacterial factors regulating the type I interferon response to Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000665

14. RenT

ZamboniDS

RoyCR

DietrichWF

VanceRE

2006 Flagellin-deficient Legionella mutants evade caspase-1 - and Naip5-mediated macrophage immunity. PLoS Pathog 2 e18

15. StetsonDB

MedzhitovR

2006 Recognition of cytosolic DNA activates an IRF3-dependent innate immune response. Immunity 24 93 103

16. ZamboniDS

KobayashiKS

KohlsdorfT

OguraY

LongEM

2006 The Birc1e cytosolic pattern-recognition receptor contributes to the detection and control of Legionella pneumophila infection. Nat Immunol 7 318 325

17. ShinS

CaseCL

ArcherKA

NogueiraCV

KobayashiKS

2008 Type IV secretion-dependent activation of host MAP kinases induces an increased proinflammatory cytokine response to Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000220

18. StetsonDB

MedzhitovR

2006 Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity 25 373 381

19. KasteleinRA

HunterCA

CuaDJ

2007 Discovery and biology of IL-23 and IL-27: related but functionally distinct regulators of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol 25 221 242

20. LightfieldKL

PerssonJ

BrubakerSW

WitteCE

von MoltkeJ

2008 Critical function for Naip5 in inflammasome activation by a conserved carboxy-terminal domain of flagellin. Nat Immunol 9 1171 1178

21. LeberJH

CrimminsGT

RaghavanS

Meyer-MorseN

CoxJS

2008 Distinct TLR - and NLR-mediated transcriptional responses to an intracellular pathogen. PLoS Pathog 4 e6

22. WongWL

BrostromMA

KuznetsovG

Gmitter-YellenD

BrostromCO

1993 Inhibition of protein synthesis and early protein processing by thapsigargin in cultured cells. Biochem J 289 71 79

23. BelyiY

TabakovaI

StahlM

AktoriesK

2008 Lgt: a family of cytotoxic glucosyltransferases produced by Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol 190 3026 3035

24. ShenX

BangaS

LiuY

XuL

GaoP

2009 Targeting eEF1A by a Legionella pneumophila effector leads to inhibition of protein synthesis and induction of host stress response. Cell Microbiol 11 911 926

25. BelyiY

NiggewegR

OpitzB

VogelsgesangM

HippenstielS

2006 Legionella pneumophila glucosyltransferase inhibits host elongation factor 1A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 16953 16958

26. McCuskerKT

BraatenBA

ChoMW

LowDA

1991 Legionella pneumophila inhibits protein synthesis in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Infect Immun 59 240 246

27. YoungnerJS

StinebringWR

TaubeSE

1965 Influence of inhibitors of protein synthesis on interferon formation in mice. Virology 27 541 550

28. CarmodyRJ

RuanQ

LiouHC

ChenYH

2007 Essential roles of c-Rel in TLR-induced IL-23 p19 gene expression in dendritic cells. J Immunol 178 186 191

29. CoornaertB

CarpentierI

BeyaertR

2009 A20: central gatekeeper in inflammation and immunity. J Biol Chem 284 8217 8221

30. HershkoDD

RobbBW

WrayCJ

LuoGJ

HasselgrenPO

2004 Superinduction of IL-6 by cycloheximide is associated with mRNA stabilization and sustained activation of p38 map kinase and NF-kappaB in cultured caco-2 cells. J Cell Biochem 91 951 961

31. ThorpeCM

SmithWE

HurleyBP

AchesonDW

2001 Shiga toxins induce, superinduce, and stabilize a variety of C-X-C chemokine mRNAs in intestinal epithelial cells, resulting in increased chemokine expression. Infect Immun 69 6140 6147

32. IchinoheT

PangIK

IwasakiA

2010 Influenza virus activates inflammasomes via its intracellular M2 ion channel. Nat Immunol 11 404 410

33. BrunoVM

HannemannS

Lara-TejeroM

FlavellRA

KleinsteinSH

2009 Salmonella Typhimurium type III secretion effectors stimulate innate immune responses in cultured epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000538

34. Ramirez-CarrozziVR

BraasD

BhattDM

ChengCS

HongC

2009 A unifying model for the selective regulation of inducible transcription by CpG islands and nucleosome remodeling. Cell 138 114 128

35. HargreavesDC

HorngT

MedzhitovR

2009 Control of inducible gene expression by signal-dependent transcriptional elongation. Cell 138 129 145

36. DubinPJ

KollsJK

2007 IL-23 mediates inflammatory responses to mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292 L519 528

37. LangrishCL

McKenzieBS

WilsonNJ

de Waal MalefytR

KasteleinRA

2004 IL-12 and IL-23: master regulators of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev 202 96 105

38. McWhirterSM

BarbalatR

MonroeKM

FontanaMF

HyodoM

2009 A host type I interferon response is induced by cytosolic sensing of the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP. J Exp Med 206 1899 1911

39. KrantzBA

MelnykRA

ZhangS

JurisSJ

LacyDB

2005 A phenylalanine clamp catalyzes protein translocation through the anthrax toxin pore. Science 309 777 781

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Compensatory Evolution of Mutations Restores the Fitness Cost Imposed by β-Lactam Resistance inČlánek The C-Terminal Domain of the Arabinosyltransferase EmbC Is a Lectin-Like Carbohydrate Binding ModuleČlánek A Viral microRNA Cluster Strongly Potentiates the Transforming Properties of a Human Herpesvirus

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 2- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Fresh Look at the Origin of , the Most Malignant Malaria Agent

- In Situ Photodegradation of Incorporated Polyanion Does Not Alter Prion Infectivity

- Highly Efficient Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification

- Positive Signature-Tagged Mutagenesis in : Tracking Patho-Adaptive Mutations Promoting Airways Chronic Infection

- Charge-Surrounded Pockets and Electrostatic Interactions with Small Ions Modulate the Activity of Retroviral Fusion Proteins

- Whole-Body Analysis of a Viral Infection: Vascular Endothelium is a Primary Target of Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus in Zebrafish Larvae

- Inhibition of Nox2 Oxidase Activity Ameliorates Influenza A Virus-Induced Lung Inflammation

- STAT2 Mediates Innate Immunity to Dengue Virus in the Absence of STAT1 via the Type I Interferon Receptor

- Uropathogenic P and Type 1 Fimbriae Act in Synergy in a Living Host to Facilitate Renal Colonization Leading to Nephron Obstruction

- Elite Suppressors Harbor Low Levels of Integrated HIV DNA and High Levels of 2-LTR Circular HIV DNA Compared to HIV+ Patients On and Off HAART

- DC-SIGN Mediated Sphingomyelinase-Activation and Ceramide Generation Is Essential for Enhancement of Viral Uptake in Dendritic Cells

- Short-Lived IFN-γ Effector Responses, but Long-Lived IL-10 Memory Responses, to Malaria in an Area of Low Malaria Endemicity

- Induces T-Cell Lymphoma and Systemic Inflammation

- The C-Terminus of RON2 Provides the Crucial Link between AMA1 and the Host-Associated Invasion Complex

- Critical Role of the Virus-Encoded MicroRNA-155 Ortholog in the Induction of Marek's Disease Lymphomas

- Type I Interferon Signaling Regulates Ly6C Monocytes and Neutrophils during Acute Viral Pneumonia in Mice

- Atypical/Nor98 Scrapie Infectivity in Sheep Peripheral Tissues

- Innate Sensing of HIV-Infected Cells

- BosR (BB0647) Controls the RpoN-RpoS Regulatory Pathway and Virulence Expression in by a Novel DNA-Binding Mechanism

- Compensatory Evolution of Mutations Restores the Fitness Cost Imposed by β-Lactam Resistance in

- Expression of Genes Involves Exchange of the Histone Variant H2A.Z at the Promoter

- The RON2-AMA1 Interaction is a Critical Step in Moving Junction-Dependent Invasion by Apicomplexan Parasites

- Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Facilitates G1-S Transition by Stabilizing and Enhancing the Function of Cyclin D1

- Transcription and Translation Products of the Cytolysin Gene on the Mobile Genetic Element SCC Regulate Virulence

- Phosphatidylinositol 3-Monophosphate Is Involved in Apicoplast Biogenesis

- The Rubella Virus Capsid Is an Anti-Apoptotic Protein that Attenuates the Pore-Forming Ability of Bax

- Episomal Viral cDNAs Identify a Reservoir That Fuels Viral Rebound after Treatment Interruption and That Contributes to Treatment Failure

- Genetic Mapping Identifies Novel Highly Protective Antigens for an Apicomplexan Parasite

- Relationship between Functional Profile of HIV-1 Specific CD8 T Cells and Epitope Variability with the Selection of Escape Mutants in Acute HIV-1 Infection

- The Genotype of Early-Transmitting HIV gp120s Promotes αβ –Reactivity, Revealing αβ/CD4 T cells As Key Targets in Mucosal Transmission

- Small Molecule Inhibitors of RnpA Alter Cellular mRNA Turnover, Exhibit Antimicrobial Activity, and Attenuate Pathogenesis

- The bZIP Transcription Factor MoAP1 Mediates the Oxidative Stress Response and Is Critical for Pathogenicity of the Rice Blast Fungus

- Entrapment of Viral Capsids in Nuclear PML Cages Is an Intrinsic Antiviral Host Defense against Varicella-Zoster Virus

- NS2 Protein of Hepatitis C Virus Interacts with Structural and Non-Structural Proteins towards Virus Assembly

- Measles Outbreak in Africa—Is There a Link to the HIV-1 Epidemic?

- New Models of Microsporidiosis: Infections in Zebrafish, , and Honey Bee

- The C-Terminal Domain of the Arabinosyltransferase EmbC Is a Lectin-Like Carbohydrate Binding Module

- A Viral microRNA Cluster Strongly Potentiates the Transforming Properties of a Human Herpesvirus

- Infections in Cells: Transcriptomic Characterization of a Novel Host-Symbiont Interaction

- Secreted Bacterial Effectors That Inhibit Host Protein Synthesis Are Critical for Induction of the Innate Immune Response to Virulent

- Genital Tract Sequestration of SIV following Acute Infection

- Functional Coupling between HIV-1 Integrase and the SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complex for Efficient Integration into Stable Nucleosomes

- DNA Damage and Reactive Nitrogen Species are Barriers to Colonization of the Infant Mouse Intestine

- The ESCRT-0 Component HRS is Required for HIV-1 Vpu-Mediated BST-2/Tetherin Down-Regulation

- Targeted Disruption of : Invasion of Erythrocytes by Using an Alternative Py235 Erythrocyte Binding Protein

- Trivalent Adenovirus Type 5 HIV Recombinant Vaccine Primes for Modest Cytotoxic Capacity That Is Greatest in Humans with Protective HLA Class I Alleles

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genetic Mapping Identifies Novel Highly Protective Antigens for an Apicomplexan Parasite

- Type I Interferon Signaling Regulates Ly6C Monocytes and Neutrophils during Acute Viral Pneumonia in Mice

- Infections in Cells: Transcriptomic Characterization of a Novel Host-Symbiont Interaction

- The ESCRT-0 Component HRS is Required for HIV-1 Vpu-Mediated BST-2/Tetherin Down-Regulation

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání