-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaGenital Tract Sequestration of SIV following Acute Infection

We characterized the evolution of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) in the male genital tract by examining blood - and semen-associated virus from experimentally and sham vaccinated rhesus monkeys during primary infection. At the time of peak virus replication, SIV sequences were intermixed between the blood and semen supporting a scenario of high-level virus “spillover” into the male genital tract. However, at the time of virus set point, compartmentalization was apparent in 4 of 7 evaluated monkeys, likely as a consequence of restricted virus gene flow between anatomic compartments after the resolution of primary viremia. These findings suggest that SIV replication in the male genital tract evolves to compartmentalization after peak viremia resolves.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001293

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001293Summary

We characterized the evolution of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) in the male genital tract by examining blood - and semen-associated virus from experimentally and sham vaccinated rhesus monkeys during primary infection. At the time of peak virus replication, SIV sequences were intermixed between the blood and semen supporting a scenario of high-level virus “spillover” into the male genital tract. However, at the time of virus set point, compartmentalization was apparent in 4 of 7 evaluated monkeys, likely as a consequence of restricted virus gene flow between anatomic compartments after the resolution of primary viremia. These findings suggest that SIV replication in the male genital tract evolves to compartmentalization after peak viremia resolves.

Introduction

An understanding of HIV-1 biology in the male genital tract will be central to understanding the transmission of this virus. Since HIV-1 is transmitted predominantly by sexual contact [1], [2], [3], semen represents an important source of transmitted virus. While the transmission risk of HIV-1 has been associated with virus RNA levels in the peripheral blood of infected transmitting individuals, virus RNA levels in the blood only serve as a surrogate for the level of virus in ejaculate [1], [3], [4], [5], [6]. Indeed, during primary infection when HIV-1 transmission is high, virus levels in both the blood and the seminal plasma are both elevated [1], [7]. Yet, during chronic infection blood and semen levels of HIV-1 can be discordant [1], [7].

HIV-1 exists as a diverse population of related genetic variants that segregate into subpopulations within anatomic compartments of infected individuals [8], [9]. The intra-host compartmentalization of these variants has been documented in multiple anatomic regions including the peripheral blood, lungs, central nervous system, breast milk, gut and the female genital tract, [1], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16].

Importantly, the male genital tract serves as a reservoir for HIV-1 that has been shown by some investigators to harbor virus that is distinct at the sequence level from virus found in the blood [12], [15], [17], [18], [19]. It has been suggested that this compartmentalization may be a consequence of differences between the male genital tract and peripheral tissues in both immunological and target cell properties [14], [15], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. Histopathologic studies of genital tissues from SIV-infected monkeys have confirmed that infection can occur at these sites [24], [29]. Male genital tract-derived viral variants have been reported to have unique phenotypes with regard to drug resistance [11], [30], [31], [32], [33] and cellular tropism [34], [35]. Some groups have reported that HIV-1 in the male genital tract [1], [36], [37], [38] is similar to that in the blood [39], while other groups have suggested that there is an anatomic sequestration of virus in some individuals during primary infection [10], [34], [35], [40], [41]. Overall, the mechanisms that contribute to compartmentalized virus in the male genital tract are not entirely clear. Virus compartmentalization could be the result of founder effects, differential immune selection, altered tropism or restricted gene flow between resident viral populations [42], [43].

In the present study we sought to define the dynamics of SIV compartmentalization in semen during primary infection in rhesus monkeys. We accomplished this by analyzing SIV envelope (env) sequences in the blood and semen at the peak and set point of SIV replication in rhesus monkeys. We observed a striking progression toward increasing viral compartmentalization over time following infection, raising the possibility that the abrupt reduction in virus replication that occurred in these monkeys after the resolution of peak viremia may contribute to a restriction in viral gene flow in and out of their genital tracts.

Results

Sequence analysis of contemporaneous blood - and semen-derived SIV during primary infection

Twenty-six rhesus monkeys were vaccinated and then monitored for 16 weeks after experimental SIV infection as previously described [44]. Thirteen were vaccinated using Gag-Pol immunogens with a heterologous prime/boost regimen that included both plasmid DNA and replication-defective recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) immunogens. The remaining 13 control monkeys received sham vaccine constructs. Animals were challenged by the i.v. route using a SIVmac251 stock with a previously reported sequence diversity [45].

To determine whether virus in the semen and peripheral blood were compartmentalized following infection, we assessed the phylogenetic relationship between semen - and blood-derived SIV env sequences. Single genome amplification (SGA) was used to generate 789 env amplicons for sequencing and subsequent phylogenetic analysis. Sequence data were generated from 2 time points post-challenge, at week 2 (peak virus replication) and week 16 (virus set point).

Viral RNA levels were comparable for each group, and we detected no significant differences in week-2 and week-16 blood or seminal plasma viral loads between vaccinees and controls. Similarly, no significant differences were detected between animals included in this study and animals excluded as a result of insufficient sequence data (Wilcoxon P>0.01) as described [44].

SIV env sequences were first generated from both the blood and semen of 14 rhesus monkeys (7 vaccinated and 7 control) from specimens obtained 2 weeks following infection. The genetic diversity of the virus from each anatomic compartment of each monkey was calculated as the average pair-wise genetic distance of SIV env within each semen or blood population from the inoculum consensus. Data from the vaccinated and control animals were analyzed independently. Since these represented analyses of sequence from virus obtained very early after infection, little divergence was seen from the founder viruses that initiated infection in each monkey (Table 1). Moreover, we observed little genetic diversity between sequences of blood and semen amplicons at this early time point after challenge, representative examples from 4 monkeys (2 control, 2 vaccinated) are shown (Fig. 1). Among the sequences from the blood, we observed no difference in average pairwise env distance from the inoculum consensus per animal between vaccinees (0.29% versus 0.28% respectively, P = 0.9). The sequence divergence for all week 2 semen isolates were not significantly different in control and vaccinated monkeys, with a mean distance among control animals of 0.27% and 0.15% among vaccinated monkeys (P = 0.4). These differences are consistent with the lower levels of viral replication in the vaccinated group [44].

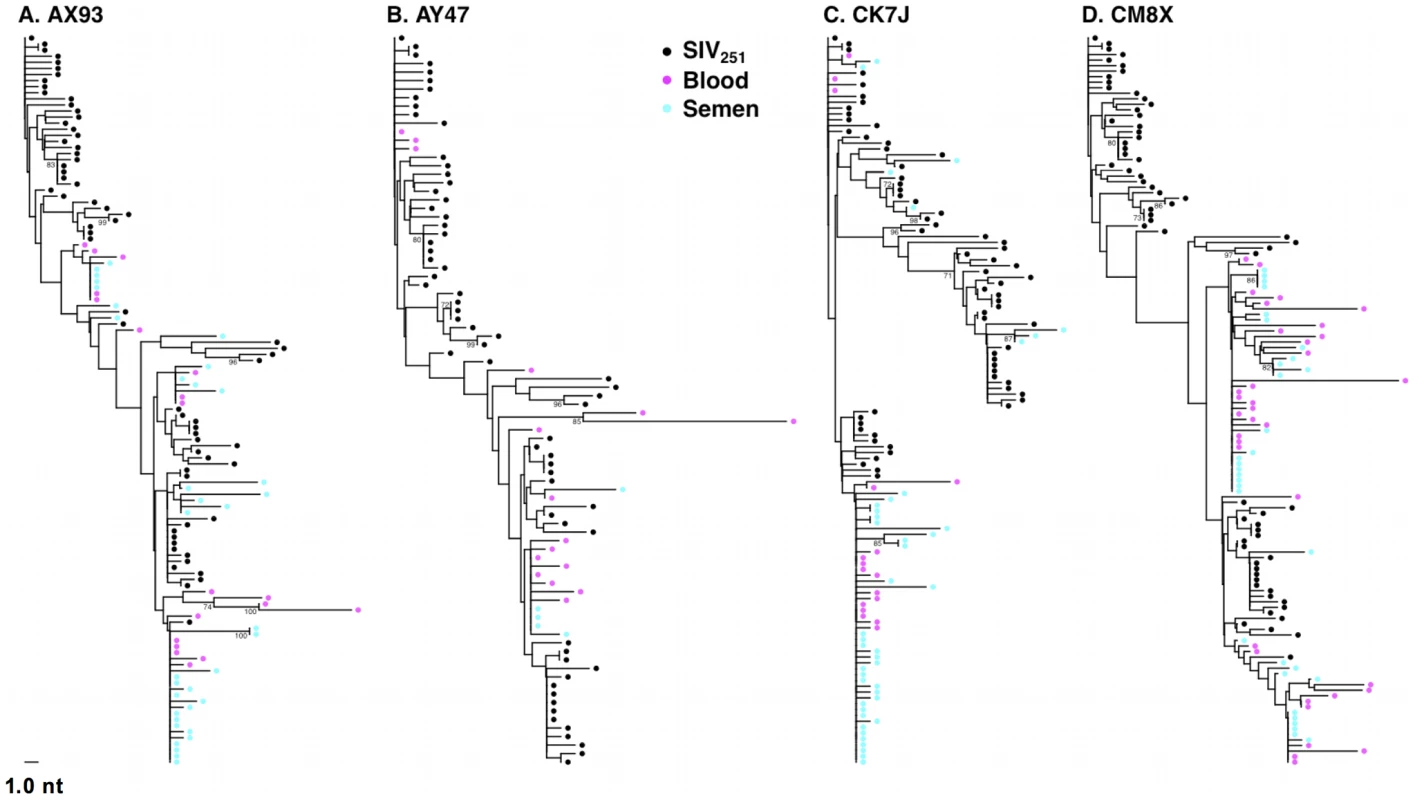

Fig. 1. Intermixing of blood- and semen-derived env sequences during peak SIV replication.

Neighbor-joining trees from vaccinated monkeys (A) AX93, (B) AY47 and control monkeys (C) CK7J and (D) CM8X 2 weeks after challenge with a sequence-defined SIVmac251 challenge stock (stock sequences denoted in black). Tab. 1. Quantity and diversity of sequences obtained per sample.

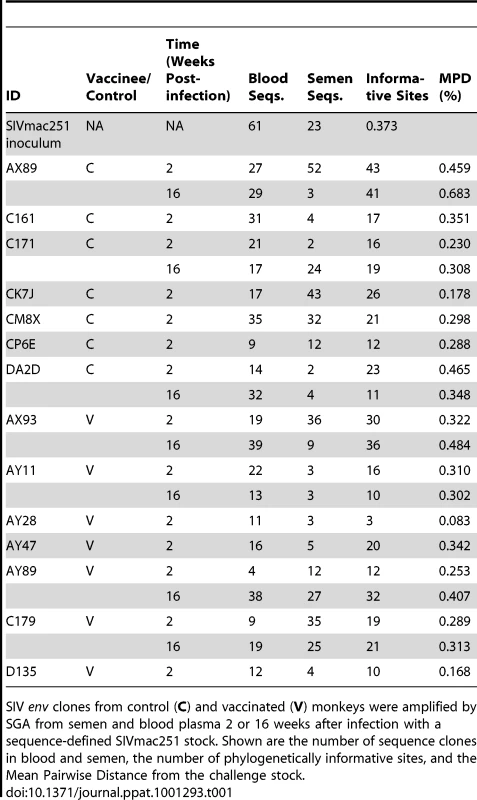

SIV env clones from control (C) and vaccinated (V) monkeys were amplified by SGA from semen and blood plasma 2 or 16 weeks after infection with a sequence-defined SIVmac251 stock. Shown are the number of sequence clones in blood and semen, the number of phylogenetically informative sites, and the Mean Pairwise Distance from the challenge stock. We next analyzed blood and semen sequences from specimens obtained at week 16 following infection. Post set point, we were able to obtain sufficient numbers of concurrent semen - and blood-derived SIV sequences from 7 monkeys to allow a phylogenetic analysis of these viruses. Consistent with the lower level of virus replication in the vaccinated group, we observed reduced diversification of sequences obtained from the vaccinated monkeys, particularly in the seminal plasma. Specifically, blood-derived env sequences from control animals showed a trend towards greater divergence (0.45%) than env sequences derived from the blood plasma of vaccinees (0.35%, P = 0.2). In week 16 sequences obtained from seminal plasma, the mean pair wise distance per animal was 0.31% and 0.22% for controls and vaccinees, respectively (P = 0.2). We next analyzed these sequence data using available algorithms to determine if changes in N-linked Env glycosylation sites had occurred during the sampling period [46]. No significant changes in potential Env glycosylation sites were observed.

We then analyzed the sequences from the inoculum and week 16 samples for evidence of selection on SIV env by fixed-effects likelihood (FEL) [47]. As the results of this test can be influenced by the presence of recombinant sequences, we first used G.A.R.D. [48] to test for recombination and, if significant breakpoints (p<0.01) resulted, performed FEL tests separately for sequence alignments partitioned at the breakpoints.

The presence of negative selection could not be determined as intra-host viral populations had not diversified sufficiently for such events to occur at detectable levels. The positive selection tests that reached significance (p<0.05) are indicated (Table S1). Among the sequences from inoculum and week 16 sequences, we found 12 codons in 6 monkeys (3 vaccinees and 3 from the control group) under positive selection. One of these codons was under positive selection in 2 different animals (codon 427 in AX93 and AY47).

A number of investigators have postulated that specific amino acid signatures may be associated with HIV found in the semen [17], [49], [50]. To investigate this possibility, we applied a tree-corrected contingency table method to identify compartment specific amino acid signatures [51]. This analysis yielded no evidence for specific signatures that might be associated with SIV tropism in the semen up to 16 weeks following infection.

We then conducted additional signature analyses using only compartmentalized animals, but a sample size of 4 compartmentalized animals would lack sufficient statistical power to identify robust predictive signatures of compartmentalization. Therefore, we adapted a related strategy used by Pillai et al. [49]. Pillai reported a combination of HIV ENV residues (HXB2 270, 291, 387, and 464) associated with blood-semen compartmentalization. All of these except the first are located 1-2 residues downstream of putative N-linked glycosylation sites. We evaluated these sites in the SIV env sequences generated in this study by identifying homologous sites in HIV-1 and SIV from an alignment that incorporates HIV-1, HIV-2, HXB2, and SMM239 Seqs. (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/NEWALIGN/align.html).

Reviewing the homologous signature sites in the SIV env sequences, we found 3 of 4 to be located 1–2 residues downstream of glycosylation sites. However, mutations in these sites (and in the neighboring 4 residues) were equally common in sequences derived from blood and semen, regardless of whether we included only sequences from compartmentalized animals. Thus, we were unable to confirm semen signatures in these SIV data.

Unrestricted viral gene flow between the blood and genital tract during early SIV infection

We then sought to determine if SIV compartmentalization was demonstrable during primary infection. To detect compartmentalization in contemporaneous blood - and semen-derived SIV env sequences, we applied both phylogenetic analyses and the Slatkin-Maddison (SM) test from the HYPHY software package (v0.99b) [52], [53]. At the peak of SIV viremia, similar env sequences were observed in the control and vaccinated animals. Importantly, we observed the mixing of env taxa from blood - and seminal plasma-derived virus, and the association of these sequences into closely related phylograms (Fig. 1). Analysis of the week 2 blood and seminal virus sequences indicated that all 14 monkeys are similar on the basis of Neighbor-Joining (NJ) tree topologies. Importantly, we observed clusters of intermixed monotypic blood and semen sequences with minimal genetic divergence from the challenge SIV env sequences, termed “clusters of identity” in all animals, although the amount varied between individual monkeys (Fig. 1).

Representative NJ phylogenetic trees generated from SIV sequences from control monkeys CK7J and CM8X (Figs. 1 A, B), and from vaccinated monkeys AY47 and AX93 (Figs. 1 C, D) are shown. In control monkey CK7J, we observed one cluster of closely related semen and blood-borne sequences in the phylogenetic tree. In control monkey CM8X, two clusters of intermixed blood/semen sequences are apparent in the tree structure. Similar results were observed in the Gag-Pol vaccinated monkeys. For example, in vaccinated monkey AY47 a single phylogenetic cluster of interspersed semen and blood env sequences are apparent in the tree. Monkey AX93, has three clusters of identical, monotypic semen and blood sequences (Fig. 1 C and D).

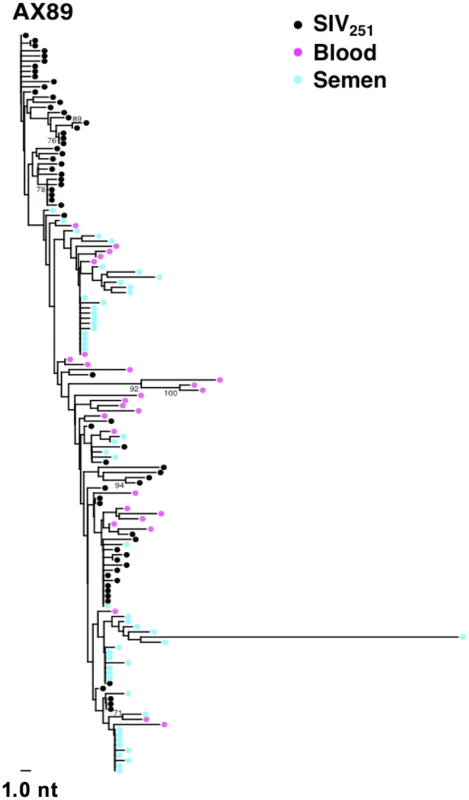

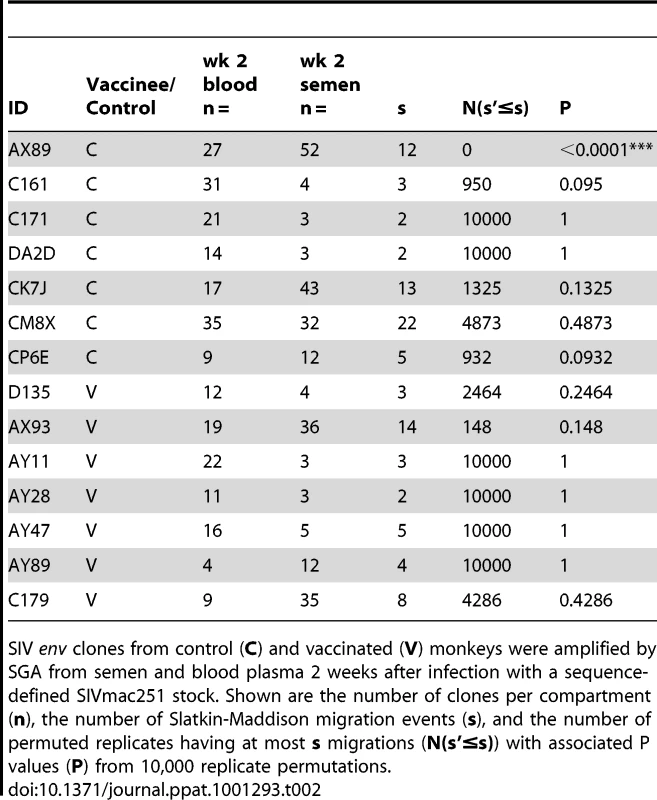

While we did not observe topological evidence for virus compartmentalization between the semen and blood during early infection in any of the 14 monkeys analyzed, compartmentalization effects were also assessed using the SM test. Applying this metric, we observed no evidence of virus sequestration in week 2 blood - or semen-derived sequences in 13 of the 14 monkeys (Table 2). Control monkey AX89 had compartmentalized semen env sequences (s = 14, P<0.0001) (Fig. 2). However, the presence of large numbers of identical monotypic sequences might bias statistical measures of compartmentalization [54], [55]. To ensure that the large numbers of isogenic sequences in the semen of AX89 were not confounding this statistical analysis, we conducted a secondary analysis that collapsed all equivalently rooted monotypic sequences to a single representative env taxon. We then applied the same SM test to the normalized set of env sequences from monkey AX89. This modified analysis also indicated significant compartmentalization between SIV env in the blood and the male genital tract of monkey AX89 (s = 14, P = 0.0007). Therefore, there was weak evidence for virus compartmentalization in only 1 of the 14 monkeys by 2 weeks post-infection.

Fig. 2. Compartmentalization of blood- and semen-derived env sequences during peak SIV replication in monkey AX89.

NJ tree from control animal AX89, 2 weeks after challenge using a sequence-defined SIVmac251 stock (denoted in black). Tab. 2. SIV genetic compartmentalization at peak virus replication.

SIV env clones from control (C) and vaccinated (V) monkeys were amplified by SGA from semen and blood plasma 2 weeks after infection with a sequence-defined SIVmac251 stock. Shown are the number of clones per compartment (n), the number of Slatkin-Maddison migration events (s), and the number of permuted replicates having at most s migrations (N(s'≤s)) with associated P values (P) from 10,000 replicate permutations. Origins of virus in the male genital tract during early infection

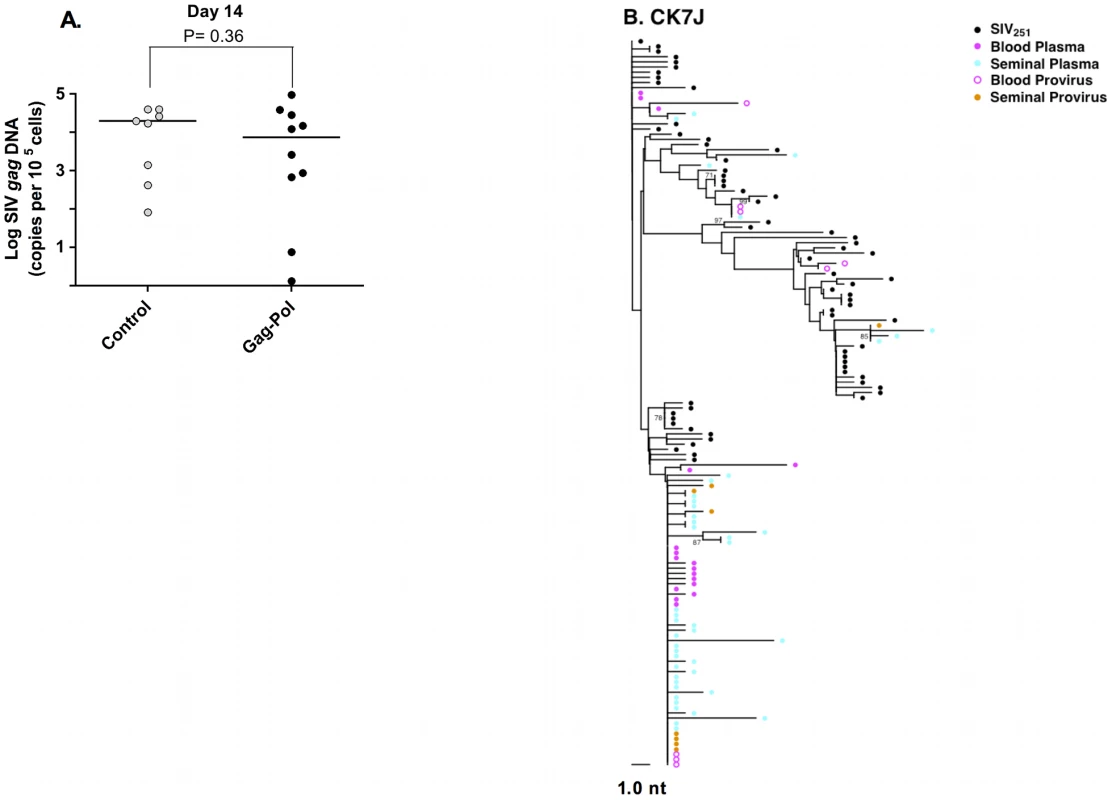

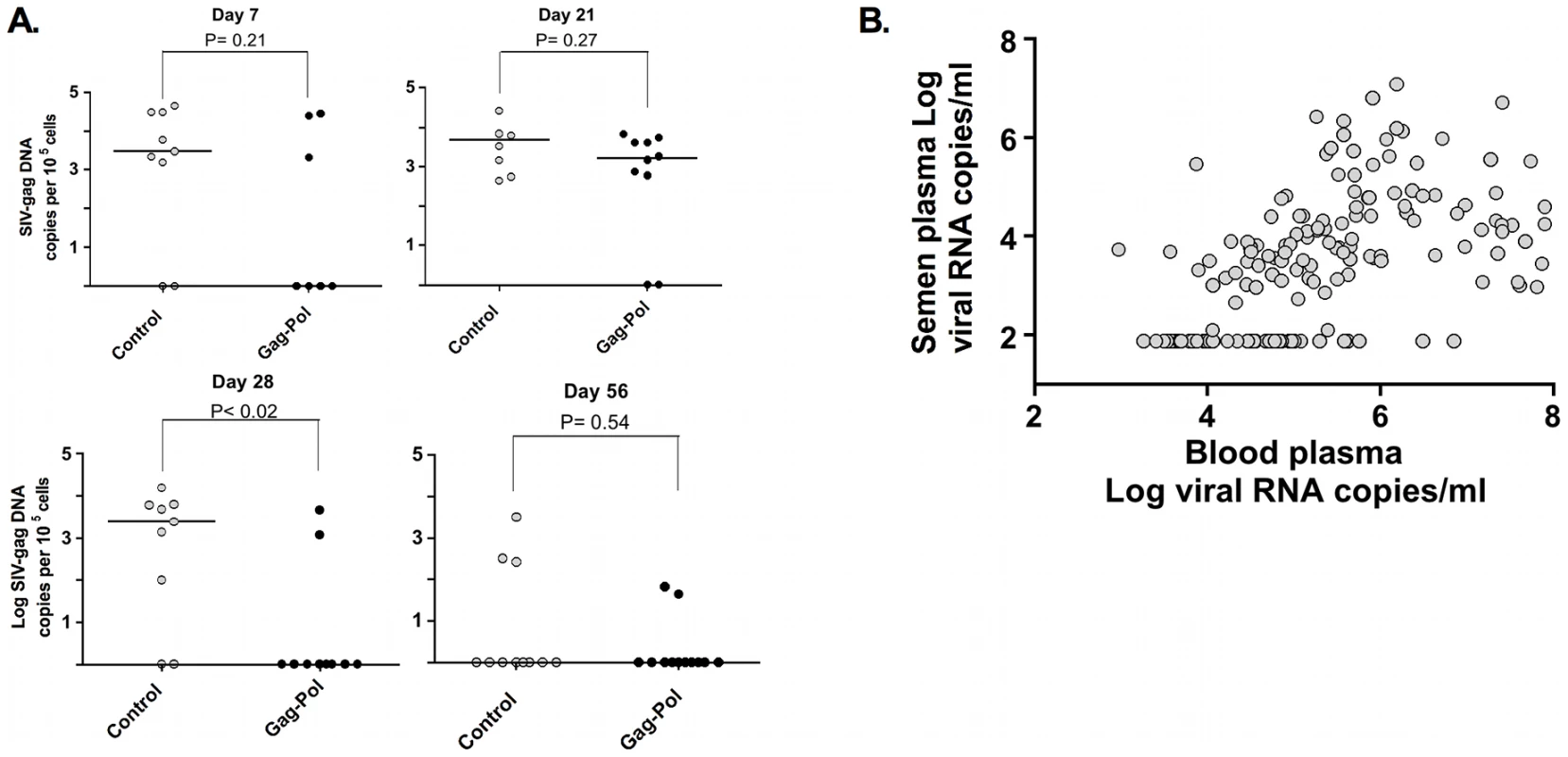

We next explored the source of virus found in the male genital tract at the time of peak viremia. By day 14 following infection, significant levels of cell-free virus RNA and cell-associated provirus are present in the semen of both control and vaccinated animals (Fig. 3A) [44]. Examination of SIV env sequences from seminal plasma and semen-associated cells from monkey CK7J using NJ - tree parameters (Fig. 3B) indicated that several clusters of monotypic cell-free virus were identical in sequence to the semen provirus. Moreover, several clusters of cell-free and cell-associated virus in the genital tract of this monkey were phylogenetically indistinguishable from SIV env sequences derived cell-free and cell-associated virus from the blood. These data argue that in early SIV infection, during the period of peak viremia, there is significant virus gene flow between anatomic compartments. There are also significant levels of cell-associated and cell-free sources of virus present early in infection that may constitute a source of transmissible virus.

Fig. 3. Source of SIV in the semen-associated cell fraction.

(A) Semen virus DNA levels in the control and Gag-Pol vaccinated monkeys 14 days after virus challenge. The comparisons of the data from the Gag-Pol vaccinated and control groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney non-parametric T-test. The absolute number of SIV gag DNA copies was calculated as described previously [44], and is shown as log-transformed copies per 1×105 semen-associated cells. (B) Phylogeny of SIV env in monkey CK7J, 14 days after virus challenge with blood plasma virus, semen plasma and semen cell-associated virus indicated. Male genital tract SIV compartmentalization is observed at virus set point

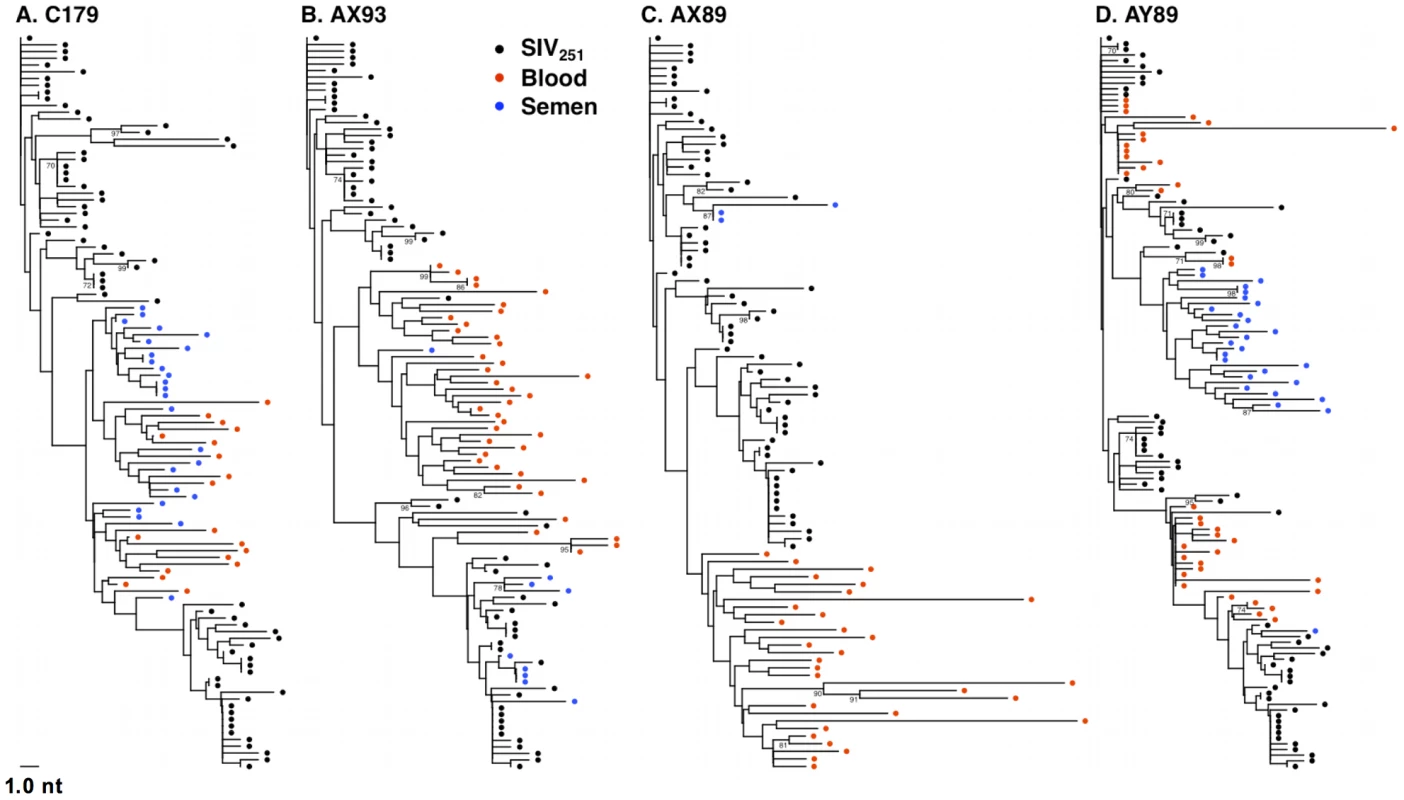

By week 16 following infection, we could readily detect virus compartmentalization by phylogenetic inference in 4 of the 7 monkeys that had sufficient numbers of sequences for analysis (Fig. 4). Compartmentalization is evident in these trees as independent clades consisting of sequences from one a single sample source, i.e. blood or semen. Included as a Supplement, are trees that combine sequencing data from both compartments at both acute and chronic time points (Fig. S1–S10 in Text S1). Typically, we observed that week 16 semen sequences tend to not be associated with those from week 2, rather they are evident as independent clades.

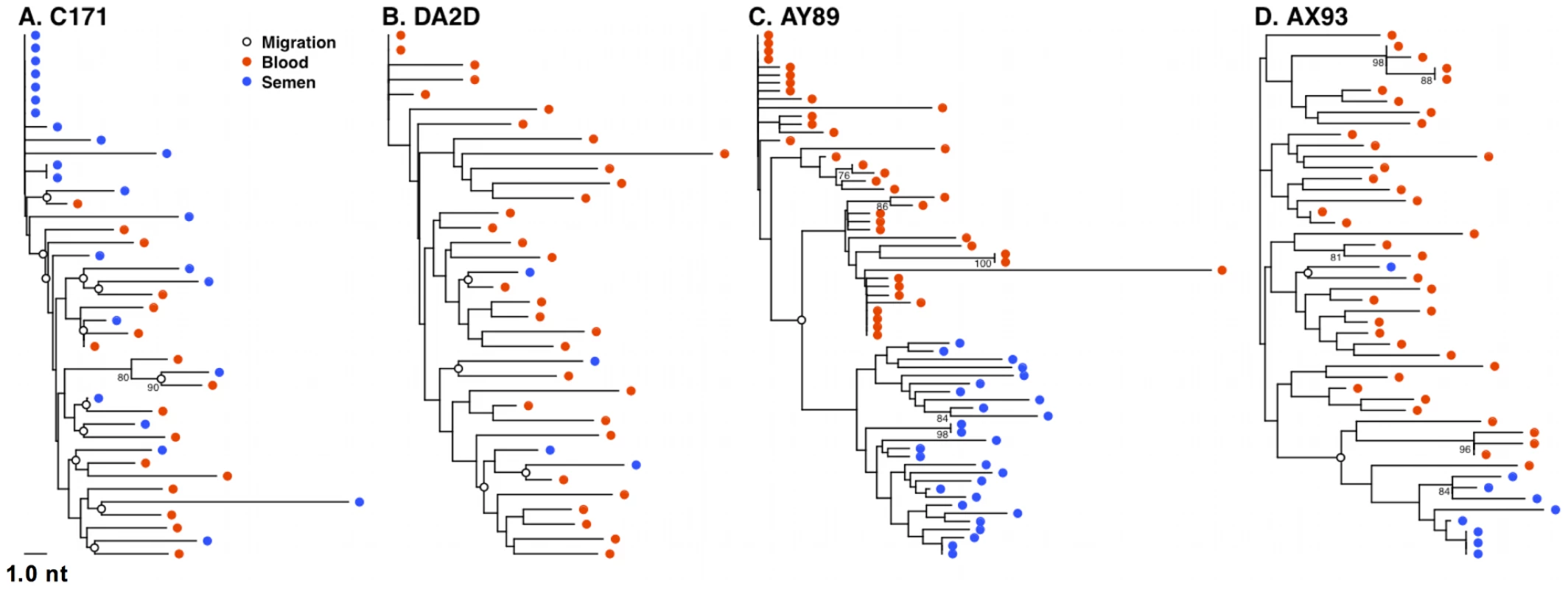

Fig. 4. Anatomic sequestration, and diversification of SIV during set point virus replication.

By 16 weeks after SIV challenge, compartmentalization of virus in semen and blood was apparent in 4 of 7 animals on the basis of tree topology and the SM test. NJ trees of SGA-derived env amplicons for compartmentalized monkeys (A) C179, (B) AX93 (C) AX89, and (D) AY89 are shown. Note that monkey AX89 is a control monkey and C179, AX93 and AY89 are vaccinated animals. We also conducted an analysis, as described above, to ensure that isogenic sequences were not confounding the statistical analyses. This modified analysis did not significantly alter the findings as determined by tree topology. We also applied the SM test to phylogenies obtained from excluding duplicate sequences (Table 3) and found that, after correction for multiple testing, two animals, C179 and AX89, had marginally significant SM values (denoted Pn).

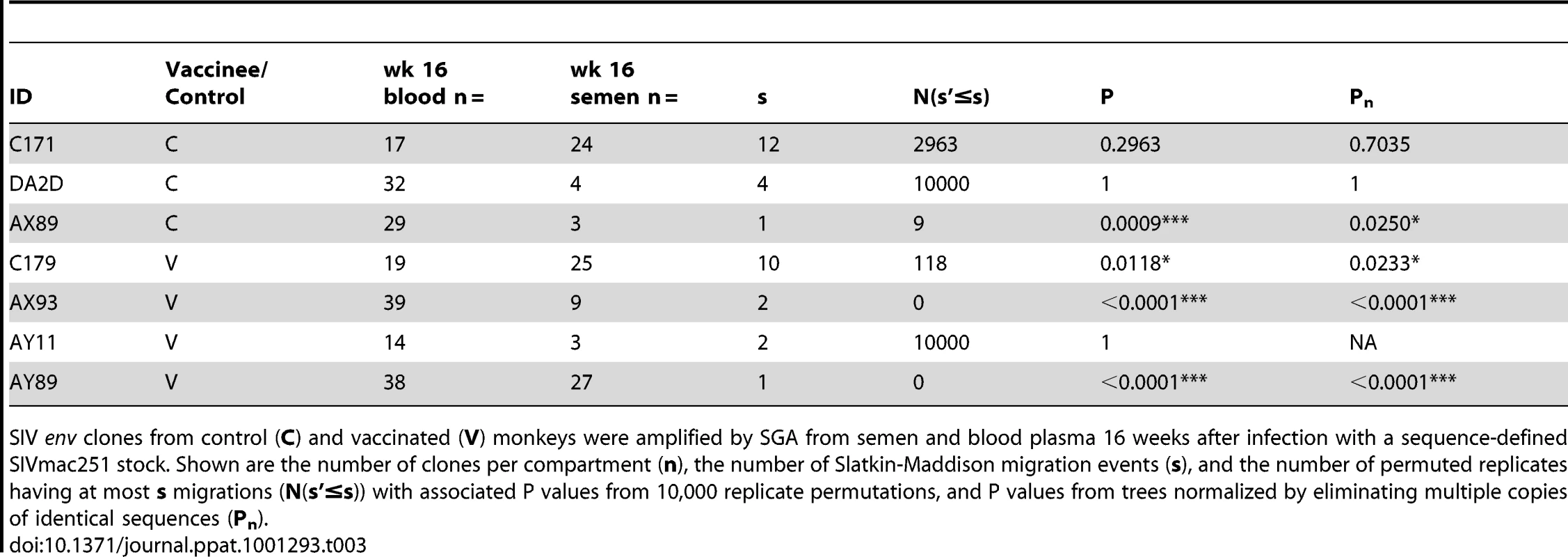

Tab. 3. SIV genetic compartmentalization at virus set point.

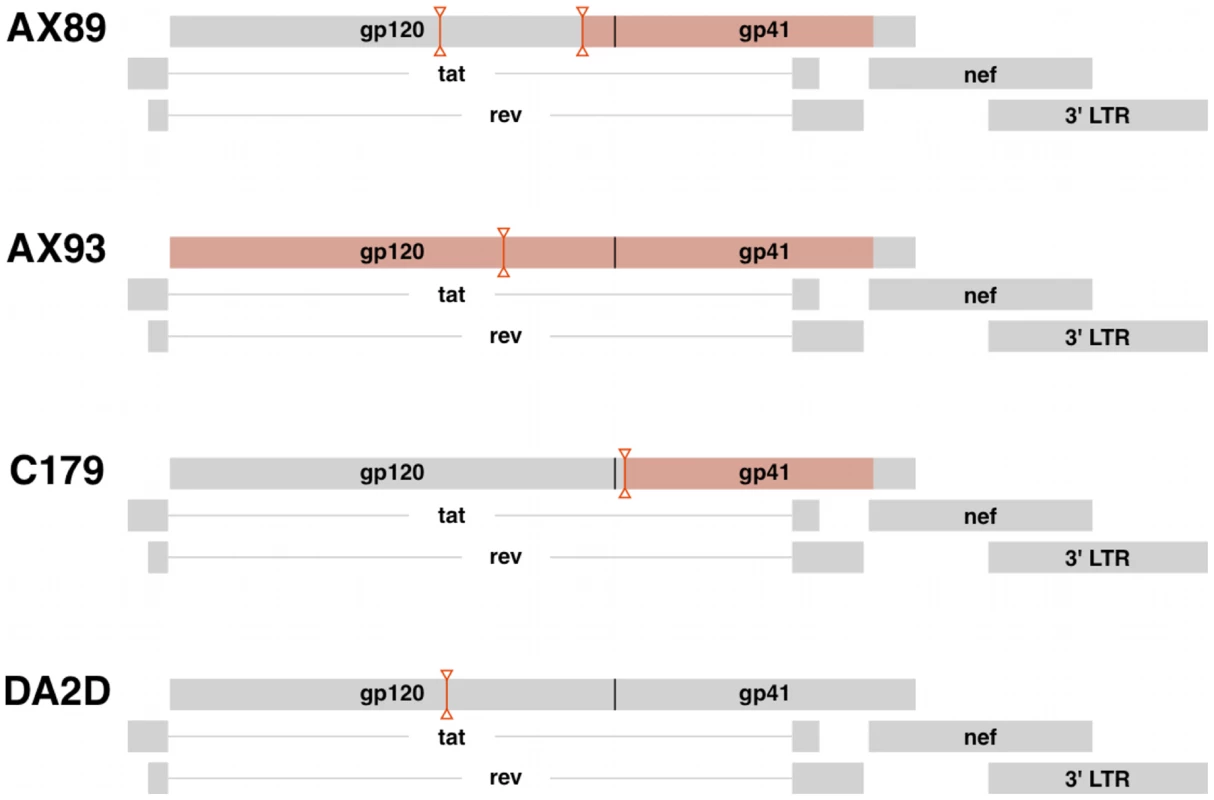

SIV env clones from control (C) and vaccinated (V) monkeys were amplified by SGA from semen and blood plasma 16 weeks after infection with a sequence-defined SIVmac251 stock. Shown are the number of clones per compartment (n), the number of Slatkin-Maddison migration events (s), and the number of permuted replicates having at most s migrations (N(s'≤s)) with associated P values from 10,000 replicate permutations, and P values from trees normalized by eliminating multiple copies of identical sequences (Pn). Our inability to demonstrate definitive compartmentalization of virus using these strategies led us to consider whether other biologic events might be obscuring compartmentalization. Therefore, we evaluated the possibility that recombination may confound the SM analysis. To assess recombination effects we applied the G.A.R.D. algorithm [48], [56] and found significant levels of recombination (P<0.001) within SIV env, (data not shown). Next, we analyzed our data using a “segmented” SM-test based on env recombination breakpoints (not shown) and found specific regions of the SIV envelope from RMs C179 and AX89 were in fact significantly compartmentalized (P<0.0002, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Virus recombination obscures compartmentalization of SIV env sequences.

Diagrams indicating the positions of predicted recombination breakpoints in compartmentalized monkeys AX89, AX93 and C179 and non-compartmentalized monkey, DA2D. Recombination effects were determined by G.A.R.D. analysis as described. Breakpoint partitions are indicated as vertical lines between inverted triangles. SIV env regions with significant compartmentalization as determined by the partitioned SM test on partitioned sequences, P<0.0002 are highlighted in red boxes. Virus migration between compartments

We next determined the relative levels of virus migration between the blood and semen by computing the minimum number of SM migration events for each inferred phylogenetic tree. These migrations occur where an internal node exhibits a change of sample source (blood or semen) among immediate descendents of that node. When these migration points were mapped directly onto phylogenies, we observed a concordance of semen compartmentalization with the number of migration events between these anatomic compartments, in individual monkeys. For example, the frequent migration events between the blood and male genital tract, as shown for monkeys C171, and DA2D (Fig. 6A and B), are consistent with unimpeded gene flow resulting in homogenous co-evolving SIV env populations. Restricted migration, as shown for monkey AY89 and AX93 (Fig. 6C and D) is consistent with the independent evolution of virus replicating in the blood and male genital tract. Therefore, we have documented examples of both unimpeded and restricted gene flow with the latter manifesting itself as virus compartmentalization.

Fig. 6. Restricted gene flow between the blood and semen is temporally associated with compartmentalization.

SM migration events were plotted directly onto NJ trees for the 4 monkeys characterized 16 weeks after SIV challenge. Unrestricted viral gene flow between the blood and semen in monkeys C171 (A) and DA2D (B), and restricted gene flow in compartmentalized monkeys AY89 (C) and AX93 (D). Mechanism of SIV compartmentalization in the male genital tract

We have therefore shown there was no evidence of SIV compartmentalization between the blood and semen in 13 of 14 monkeys analyzed at the peak of virus replication during primary infection. However, SIV compartmentalization was evident in 4 of the 7 analyzed monkeys by the time of virus set point.

To explore the mechanisms responsible for this changing pattern of viral evolution in the male genital tract, we evaluated 2 virologic correlates associated with compartmentalization. First, we observed that cell-associated virus levels in the male genital tract during peak infection are diminished significantly in the animals by week 8 following infection (Fig. 7A). Second, cell-free virus levels in the semen are also significantly diminished between weeks 2 and 16 following infection (Fig. 7B). In fact, these cell-free virus data demonstrate a threshold effect whereby viral RNA is only detectable in the seminal plasma when virus levels in the blood plasma exceed 104 RNA copies/ml. The coincidence of the resolution of primary viremia with the decrease in levels of virus in genital secretions suggest that the dramatic fall in virus replication, with the accompanying restriction of gene flow, during this early period of infection underlies the development of viral compartmentalization.

Fig. 7. Association and threshold-effect between SIV DNA, and RNA levels in blood and semen.

Cell-associated SIV trafficking into the male genital tract during peak and set point SIV infection. The comparisons of the data from the Gag-Pol vaccinated and control groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney non-parametric U-test. The absolute number of SIV gag DNA copies was calculated as described previously, and is shown as log-transformed copies per 1×105 semen-associated cells. (A). Association and threshold effect between levels in blood plasma and seminal plasma from both vaccinated and control monkeys (B). Adapted from Whitney et al. [44]. Discussion

While HIV-1 transmission in humans occurs most frequently through mucosal exposure, the present study was undertaken using rhesus monkeys infected by intravenous inoculation of SIV using artificial means to collect longitudinal semen samples. Although infection by this virus and route therefore does not model mucosal HIV-1 acquisition, the present findings have important ramifications for the understanding of early events leading to infection of the male genital tract, and semen as a source of transmitted virus. Low-risk sexual transmission of HIV-1 usually results in an infection initiated by a very limited number of founder viruses [45], [57], [58]. These viruses very rapidly appear in the blood after the transmission event, presumably as a consequence of the larger number of target cells in the blood than in the genital tract. In the periphery, HIV or SIV rapidly replicates to high levels and any subsequent virus diversification is likely a consequence of differences in virus replication in these compartments, independent of how infection was initiated.

During peak SIV replication we found little evidence for genetic segregation of virus between the semen and blood of infected rhesus monkeys. Instead, we observed an equilibration of SIV between these compartments manifested as closely related clusters of intermixed virus sequences derived from the semen or blood. As we applied SGA technology to generate all sequences [59], [60], the large numbers of identical sequences observed at peak virus replication are not likely to be a methodologic artifact. Moreover, since the SIV population size in the semen during peak virus replication was high, error as a result of re-sampling seems unlikely [61].

Based on the phylogenetic relationship among virus in the semen at peak replication, significant amounts of virus appear to be derived as a result of clonal expansion of infected cells. The homeostatic proliferation of SIV infected cells trafficking from the blood into genital tissues is a plausible means of producing the oligoclonal “bursts” of virus observed in ejaculate. These findings account for the magnitude and delay in peak semen viremia relative to the blood that has been reported in acutely HIV-1 infected patients [7], [36], [44]. Moreover, the influx of large numbers of SIV-infected cells into genital tissues make it unlikely that a specific virus amino acid “signature” could be a determinant of early viral tropism in the male genital tract [17], consistent with our inability to identify SIV Env amino acids that were significantly enriched in the seminal plasma. However, our analysis did not span a sufficient period of time to determine the presence of semen signatures during chronic infection [49], [50].

Mechanistically, the high-level of virus present in the blood during early infection results in a “wave” or spillover of cell-free and cell-associated virus into the male genital tract, equilibrating virus between the two compartments. Host control of SIV replication results in a receding “tide” of virus as virologic set point is achieved. When peak virus replication is reduced to levels below the threshold required for intra-compartment gene flow, free virus or infected cells may be effectively “trapped” within the genital tissues at “low tide.” Continued replication of virus in the male genital tract, in the absence (or reduced rate) of inter-compartment gene flow would then account for the localized diversification of virus variants in the genital tissues.

In fact, we observed less env diversification in the genital tract than in the blood of these monkeys. This finding is consistent with the lower level of SIV replication in the genital tract than in the blood at 16 weeks following infection. Moreover, the difference in virus diversification in these two anatomic compartments was particularly evident in the vaccinated monkeys after challenge (i.e., 3 of the 4 compartmentalized monkeys), consistent with the low-level virus replication in the male genital tract after set point [44]. Vaccine-elicited immune responses and alterations in target cells in the genital tract may have also contributed to the observed effects.

Although the male genital tract is generally considered to be an immune privileged compartment, inflammatory conditions present during acute SIV infection may facilitate the infiltration of both free virus and infected cells. Over time, differences between the blood and the genital tract, as a result of restrictions in gene flow would foster local replication in the genital tract leading to the compartmentalization observed at set point. Inflammation is a likely cause for the trafficking of cells from the peripheral circulation into the genital compartment, and may explain the observations of intermittent viral shedding in the semen of chronically HIV-infected men as a result of bacterial or viral infection of the male genital tract [34], [62], [63], [64], [65]. We did not determine if genital tract infections were present in any of the animals in this study.

These apparent differences in selective pressure between the blood and male genital tract should also be considered in light of the reduced effective SIV population size in the genital tract as virus set point is achieved. Virus populations of reduced size and altered genotype relative to the blood may contribute to the described genetic bottleneck associated with HIV-1 transmission, highlighted by several investigators [58], [66], [67]. This bottleneck is manifested by the acquisition of HIV-1 variants in newly infected individuals that are not highly represented in the peripheral blood of the already infected, transmitting partner. The findings in the present study, despite limitations in experimental infection route and virus dose, suggest an alternative explanation for these observations. Thus, the early compartmentalization of virus in the male genital tract, vis-à-vis restrictions in virus gene flow, may account for the transmission of distinct viral quasispecies that are not represented in the blood of the already-infected individual at the time of transmission.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All Indian-origin rhesus monkeys used in this study and analysis were maintained according to the guidelines of the NIH Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Harvard Medical School and the National Institute of Health. All monkeys were housed in a facility fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC). All procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Harvard University.

Animals, vaccinations and SIV infection

This study monitored 26 adult Mamu-A*01 negative male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mullata) that were 4–6 years of age. All animals were confirmed as Mamu-A*01 negative by both PCR and MHC-amplicon sequencing. All animals were screened and found to be negative for simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and simian retrovirus type D (SRV-1) prior to the initiation of this study. All experiments were conducted in accordance with IACUC standards. Prior to, and routinely after SIV infection, all animals were monitored by physical exam, CBC with differential, and T cell subset analysis. The monkeys were housed under Biosafety level-2+ conditions.

Rhesus monkeys were immunized using a heterologous prime/boost regimen that included both plasmid DNA and replication-defective recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 immunogens. One group of 13 monkeys received these vaccine vectors expressing SIVmac239 gag, and pol, and a second group of 13 monkeys received sham vaccine constructs. The monkeys were challenged by the intravenous route with a pathogenic SIVmac251 quasispecies, 16 weeks after the last immunization. The experimental challenge consisted of injection with a 1 ml bolus of SIVmac251 (2.11×105 viral RNA copies), directly into the saphenous vein.

Sample collection and processing

Viral levels were monitored in the semen and blood for 16 weeks after infection. Specimens were collected weekly for the first 6 weeks; then bi-weekly for the study duration. Semen was collected by eletroejaculation via rectal probe electrostimulation as, described [68]. Briefly, stimulation is provided by rhythmic pulsation from the stimulator, initially to 5 volts, with the voltage increasing over a 2 second period, with the stimulus maintained for 5–15 seconds and being reduced over 2 seconds. This rhythm is repeated with the maximum voltage increasing in 3-volt steps to a maximum of 20 volts. Stimulation can be repeated. Seminal emission is collected into a sterile container. Semen was centrifuged immediately after collection at 4°C and immediately frozen at −80°C. Semen cell pellets were washed 3× in cold PBS followed by the addition of 250 µl of RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX). Samples were immediately frozen and maintained at −80°C until use.

SIV RNA isolation qRT-PCR and assay evaluation

Viral RNA levels were monitored in the seminal plasma and semen-associated cell fraction for 16 weeks after infection. Viral RNA was routinely isolated from 200 µL of cell-free, clarified peripheral blood or seminal plasma using the NucliSENS Isolation Kit (Biomerieux, Lyon, France) following the manufacturer's protocol.

The SIV RNA standard was transcribed from the pSP72 vector containing the first 731 bp of the SIVmac239-Gag gene using the Megascript T7 kit (Ambion Inc.). RNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform purification followed by ethanol precipitation. All purified RNA preparations were quantified by optical density. RNA quality was determined by Agilent bioanalyzer RNA chip (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara CA).

QRT-PCR was conducted in a 2-step process. First, RNA was reverse transcribed in parallel with an SIV-gag RNA standard using the gene-specific primer sGag-R 5′CACTAGGTGTCTCTGCACTATCTGTTTTG-3′under the following conditions: the 50 µL reactions containing 1× buffer (250 mM Tris-HCL pH 8.3, 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2), 0.25 µM primer, 0.5 mM dNTPs (Roche), 5 mM dTT, 500 U Superscript III RT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 100 U RnaseOUT (Invitrogen), and 10 µL of sample. RT conditions were 1 hour at 50°C, 1 hour at 55°C and 15 minutes at 70°C. All samples were then treated with RNAse H (Stratagene) for 20 minutes at 37°C. All real-time PCR reactions used EZ RT PCR Core Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) following the manufacturer's suggested instructions under the following conditions: the 50µL reactions containing 1× buffer (250 mM Bicine, 575 mM potassium acetate, 0.05 mM EDTA, 300 nM Passive Reference 1, 40% (w/v) glycerol, pH 8.2, .3 mM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, .6 mM dUTP, 3 mM Mn (OAc)2, .5 U uracil N-glycosylase, 5 U rTth DNA Polymerase, .4 uM of each primer, and 10µL of sample template. Following 2 minutes at 50°C, the polymerase was activated for 10 minutes at 95°C, and then cycling proceeded at 15 seconds at 95°C and 1 minute at 60°C for fifty cycles. Primer sequences were adapted from those described by Cline et al [69], forward primer s-Gag-F: 5′-GTCTGCGTCATCTGGTGCATTC-3′, reverse primer s-Gag-R: 5′-CACTAGGTGTCTCTGCACTATCTGTTTTG-3′, and the probe s-Gag-P: 5′-CTTCCTCAGTGTGTTTCACTTTCTCTTCTGCG-3′, linked to Fam and BHQ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All reactions were carried out on a 7300 ABI Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) in triplicate according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Preliminary experiments were done to evaluate the quantitation of blood, and seminal plasma viral RNA levels and their correlation with known viral RNA quantities spiked into blood or semen sampled from SIV-uninfected monkeys (data not shown). To determine the linear range of the assay, RNA extraction efficiency and potential inhibition of reverse transcriptase activity, known quantities of serially diluted SIVmac251 viral stock were spiked into samples of peripheral blood, or semen that were recovered from three SIV-naïve monkeys. No significant differences in extraction efficiency were observed between the blood and samples derived from other compartments (data not shown). Furthermore, using the extraction methods described above, we observed no inhibition of RT activity or diminution of input RNA as a consequence of RNAse activity present in any of the virus-spiked specimens (data not shown). These findings indicated, therefore, that it was appropriate to employ this technique to isolate viral RNA from study samples of peripheral blood and semen from infected rhesus monkeys. The analytical sensitivity of our quantitative RT-PCR assay was determined as described [44], [70].

Detection of viral DNA

Cellular DNA was isolated using a QIAamp DNA Mini kit (QIAGEN). The number of SIV gag DNA copies was calculated as described previously [71], [72] and is shown as log-transformed copies per 1×105 semen-associated cells. All target sequences were normalized to Albumen levels in genomic DNA in multiplex reaction performed in duplicate (Vic-labelled Taqman reagents, Applied Biosystems).

Single genome sequencing of SIV envelope

Viral cDNA was diluted in 96-well plates to yield fewer than 30% wells positive for amplification to ensure that positive amplifications were a result of a single cDNA (Palmer et al., 2005). First-round PCR was carried out in a reaction mixture containing: 1× buffer (Platinum Taq HF Kit, Invitrogen), 0.2 mM dNTP mix, 2mM Mg2SO4, 0.2 µM primer OF6207 (5′ – GGGTAGTGGAGGTTCTGGAAG – 3′), 0.2 µM primer OR9608 (5′ – CTCATCTGATACATTTACGGGG – 3′), 0.025 units of Platinum Taq High Fidelity polymerase in a total volume of 20 µL. PCR mixtures were loaded into MicroAmp Optical 96-Well Reaction Plates (Applied Biosciences). PCR conditions were programmed as follows: 5 minutes at 94°C, 35 cycles of 15 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 52°C, 4 minutes and 15 seconds at 68°C, followed by a final extension time of 10 minutes at 68°C [59]. For the second-round PCR, 2 µL of first-round PCR product was mixed with 1× buffer (Platinum Taq HF Kit, Invitrogen), 0.2 mM dNTP mix, 2mM Mg2SO4, 0.3 µM primer IF6428 (5′ – CGTGCTATAACACATGCTATTG – 3′), 0.3 µM primer IR9351 (5′ – CCCTACCAAGTCATCATCTTC – 3′), 0.025 units of Platinum Taq High Fidelity polymerase in a total volume of 20 µL. PCR conditions were: 5 minutes at 94°C, 45 cycles of 15 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 51°C, 3 minutes and 30 seconds at 68°C, followed by a final extension time of 10 minutes at 68°C. Amplicons from cDNA dilutions resulting in less than 30% positive wells were sequenced at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center DNA Resource Core.

Raw cDNA sequence data was assembled using GeneCodes Sequencher 4.8 DNA sequencing software. All assembled sequence contigs were manually corrected for individual ambiguous nucleotide errors and further quality controlled to exclude any amplicons derived from multiple templates according to that described by Learn et al, [73]. Nucleotide alignments were made using the GeneCutter algorithm as described below (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/GENE_CUTTER/cutter.html).

Analysis of SIV envelope diversity

The median and range of diversity was determined for each monkey, for both blood and semen, using a strategy suggested by Gilbert et al., that controls for the correlation of inter-sequence distances from the same animal and compared env divergence between animals receiving vaccine or sham-vaccinated controls. We modified the method described by Gilbert et al., to include a correction for small sample size bias (Giorgi and Bhattacharya, unpublished data), and restricted our analysis to animals those that had more than 3 sequences [74]. A nucleotide alignment of all sequences was generated with using GeneCutter, and then manually refined to maintain intact codons. The aligned sequences were trimmed to 2499 nucleotides, a region spanning the start codon of env through the first 17 nt of nef, to yield consistent phylogenetic signal among sequences, rather than variable signal due to 3′ gaps in some sequences but not others.

We used both Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and maximum likelihood (ML) for phylogenetic inference. The trees in figures 1,3,4,5, and 6 are from NJ via APE, version 2.5–3 [75] and BIONJ [76] with uncorrected pairwise distances and nodes with over 70% support from 1000 bootstrap replicates are labeled. The trees in the Supplementary data section were also obtained using Neighbor-Joining, APE and BIONJ with uncorrected pairwise distances and nodes with over 70% support from 100 bootstrap replicates are labeled. Use of an uncorrected substitution model is justified for representing within-host evolution because multiple mutations at the same site are unlikely to have occurred within 25% of the genome by 16 weeks post-infection. We inferred trees for the SM compartmentalization tests by PhyML [77] using the HKY85 substitution model, a discrete 4-parameter approximation to a gamma distribution of rate variation, and a term for invariant sites. Model parameters were also obtained via ML. We independently recomputed all trees in PAUP*, version 4.0b10 using ML substitution model parameters and NJ trees. Aside from minor differences in branch lengths and a tendency for NJ to yield negative lengths on some short branches, we did not find that results differed whether likelihood or distance-based tree optimality criteria were employed, regardless of the software implementation.

Analysis of compartment-specific amino acid signatures

Signature detection utilized a phylogenetic correction to avoid over-counting amino acid substitutions among lineages of related sequences. To do this, we used methods described previously [78], and constructed a two-by-two contingency table for each amino-acid site in the alignment, populating the table with counts based on the immediate ancestor for each leaf in the tree. Columns in the contingency table correspond to whether or not the amino acid matches the ancestral state and rows correspond to whether the sequence is from blood or semen. Fisher's exact test identified significant deviations from equal proportions of amino-acid substitutions in blood versus semen-derived env sequences, with a false-discovery rate correction applied to the resulting p-values to accommodate multiple tests.

Compartmentalization tests

To test for compartmentalization in contemporaneous blood - and semen-derived SIV env sequences, we used the Slatkin-Maddison test [52] as implemented in the HYPHY software package (v0.99b) as described by Pond et al. [53]. The SM test computes s, the observed number of migration events required to yield the observed distribution of blood and semen sequences on a tree. It then assesses significance by comparing s with a re-sampled null distribution, which is obtained by holding the tree topology constant and randomly permuting the order of blood and semen labels across all leaves on the tree, computing s for each permutation. Statistical support for compartmentalization is attained when a large proportion of permutations yield more migration events than for the empirical s. That is, if fewer than 5% of 10,000 replicate permutations have at most s migration events, then P<0.05.

Viral recombination

Analysis for recombination was performed by the visual inspection of Highlighter plots and confirmed by using the G.A.R.D. analysis, where significance was assessed at (P<0.001) (13, 14).

Methods for detecting positive selection

Protein-coding regions for all Env were tested for specific codons under positive selection using FEL. A Neighbor-Joining tree and nucleotide substitution model were computed for each aligned gene before FEL analysis [47]. Sites with greater nonsynonymous than synonymous substitution rates (dN>dS) and P<0.05 were taken as significant for positive selection. FEL results were not corrected for multiple testing, as according to Pond and Frost.

Statistical inference and hypothesis testing

Statistical analysis was conducted using commercially available software GraphPad Prism version 4.0b (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA 92130 USA). Linear regressions were conducted to determine the significance of correlations. Significance of differences between groups was determined using Kruskall–Wallis ANOVA as appropriate. Probability values of P<0.05 were interpreted as significant.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. PilcherCD

ShugarsDC

FiscusSA

MillerWC

MenezesP

2001 HIV in body fluids during primary HIV infection: implications for pathogenesis, treatment and public health. Aids 15 837 845

2. PilcherH

2004 Snapshot of a pandemic. Nature 430 134 135

3. PilcherCD

EronJJJr

VemazzaPL

BattegayM

HarrT

2001 Sexual transmission during the incubation period of primary HIV infection. Jama 286 1713 1714

4. QuinnTC

WawerMJ

SewankamboN

SerwaddaD

LiC

2000 Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med 342 921 929

5. GrayRH

WawerMJ

BrookmeyerR

SewankamboNK

SerwaddaD

2001 Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet 357 1149 1153

6. WhitneyJB

LuedemannC

HraberP

RaoSS

MascolaJR

2009 T cell vaccination reduces SIV in semen. J Virol 83 20 10840 3

7. PilcherCD

TienHC

EronJJJr

VernazzaPL

LeuSY

2004 Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J Infect Dis 189 1785 1792

8. CoffinJM

1995 HIV population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science 267 483 489

9. NowakM

1990 HIV mutation rate. Nature 347 522

10. KemalKS

FoleyB

BurgerH

AnastosK

MinkoffH

2003 HIV-1 in genital tract and plasma of women: compartmentalization of viral sequences, coreceptor usage, and glycosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 12972 12977

11. EronJJ

VernazzaPL

JohnstonDM

Seillier-MoiseiwitschF

AlcornTM

1998 Resistance of HIV-1 to antiretroviral agents in blood and seminal plasma: implications for transmission. Aids 12 F181 189

12. GuptaP

LerouxC

PattersonBK

KingsleyL

RinaldoC

2000 Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 shedding pattern in semen correlates with the compartmentalization of viral Quasi species between blood and semen. J Infect Dis 182 79 87

13. PolesMA

ElliottJ

VingerhoetsJ

MichielsL

ScholliersA

2001 Despite high concordance, distinct mutational and phenotypic drug resistance profiles in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA are observed in gastrointestinal mucosal biopsy specimens and peripheral blood mononuclear cells compared with plasma. J Infect Dis 183 143 148

14. KiesslingAA

FitzgeraldLM

ZhangD

ChhayH

BrettlerD

1998 Human immunodeficiency virus in semen arises from a genetically distinct virus reservoir. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 14 Suppl 1 S33 41

15. ByrnRA

ZhangD

EyreR

McGowanK

KiesslingAA

1997 HIV-1 in semen: an isolated virus reservoir. Lancet 350 1141

16. PhilpottS

BurgerH

TsoukasC

FoleyB

AnastosK

2005 Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA sequences in the female genital tract and blood: compartmentalization and intrapatient recombination. J Virol 79 353 363

17. DelwartEL

MullinsJI

GuptaP

LearnGHJr

HolodniyM

1998 Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 populations in blood and semen. J Virol 72 617 623

18. DiemK

NickleDC

MotoshigeA

FoxA

RossS

2008 Male genital tract compartmentalization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV). AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 24 561 571

19. ParanjpeS

CraigoJ

PattersonB

DingM

BarrosoP

2002 Subcompartmentalization of HIV-1 quasispecies between seminal cells and seminal plasma indicates their origin in distinct genital tissues. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 18 1271 1280

20. Shehu-XhilagaM

de KretserD

Dejucq-RainsfordN

HedgerM

2005 Standing in the way of eradication: HIV-1 infection and treatment in the male genital tract. Curr HIV Res 3 345 359

21. RouletV

SatieAP

RuffaultA

Le TortorecA

DenisH

2006 Susceptibility of human testis to human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection in situ and in vitro. Am J Pathol 169 2094 2103

22. RouletV

DenisH

StaubC

Le TortorecA

DelaleuB

2006 Human testis in organotypic culture: application for basic or clinical research. Hum Reprod 21 1564 1575

23. Le TortorecA

SatieAP

DenisH

Rioux-LeclercqN

HavardL

2008 Human prostate supports more efficient replication of HIV-1 R5 than X4 strains ex vivo. Retrovirology 5 119

24. Le TortorecA

Le GrandR

DenisH

SatieAP

ManniouiK

2008 Infection of semen-producing organs by SIV during the acute and chronic stages of the disease. PLoS One 3 e1792

25. Le TortorecA

DenisH

SatieAP

PatardJJ

RuffaultA

2008 Antiviral responses of human Leydig cells to mumps virus infection or poly I:C stimulation. Hum Reprod 23 2095 2103

26. Le TortorecA

Dejucq-RainsfordN

2009 HIV infection of the male genital tract - consequences for sexual transmission and reproduction. Int J Androl 33 e98 e108

27. Le TortorecA

Dejucq-RainsfordN

2007 [The male genital tract: A host for HIV]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 35 1245 1250

28. Dejucq-RainsfordN

JegouB

2004 Viruses in semen and male genital tissues–consequences for the reproductive system and therapeutic perspectives. Curr Pharm Des 10 557 575

29. MillerCJ

VogelP

AlexanderNJ

DandekarS

HendrickxAG

1994 Pathology and localization of simian immunodeficiency virus in the reproductive tract of chronically infected male rhesus macaques. Lab Invest 70 255 262

30. ByrnRA

KiesslingAA

1998 Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus in semen: indications of a genetically distinct virus reservoir. J Reprod Immunol 41 161 176

31. GhosnJ

ChaixML

PeytavinG

ReyE

BressonJL

2004 Penetration of enfuvirtide, tenofovir, efavirenz, and protease inhibitors in the genital tract of HIV-1-infected men. Aids 18 1958 1961

32. KroodsmaKL

KozalMJ

HamedKA

WintersMA

MeriganTC

1994 Detection of drug resistance mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) pol gene: differences in semen and blood HIV-1 RNA and proviral DNA. J Infect Dis 170 1292 1295

33. SmithDM

WongJK

ShaoH

HightowerGK

MaiSH

2007 Long-term persistence of transmitted HIV drug resistance in male genital tract secretions: implications for secondary transmission. J Infect Dis 196 356 360

34. PingLH

CohenMS

HoffmanI

VernazzaP

Seillier-MoiseiwitschF

2000 Effects of genital tract inflammation on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 populations in blood and semen. J Virol 74 8946 8952

35. ZhuT

WangN

CarrA

NamDS

Moor-JankowskiR

1996 Genetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in blood and genital secretions: evidence for viral compartmentalization and selection during sexual transmission. J Virol 70 3098 3107

36. PilcherCD

JoakiG

HoffmanIF

MartinsonFE

MapanjeC

2007 Amplified transmission of HIV-1: comparison of HIV-1 concentrations in semen and blood during acute and chronic infection. Aids 21 1723 1730

37. PilcherCD

PriceMA

HoffmanIF

GalvinS

MartinsonFE

2004 Frequent detection of acute primary HIV infection in men in Malawi. Aids 18 517 524

38. TindallB

EvansL

CunninghamP

McQueenP

HurrenL

1992 Identification of HIV-1 in semen following primary HIV-1 infection. Aids 6 949 952

39. RitolaK

PilcherCD

FiscusSA

HoffmanNG

NelsonJA

2004 Multiple V1/V2 env variants are frequently present during primary infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 78 11208 11218

40. ZhangL

RoweL

HeT

ChungC

YuJ

2002 Compartmentalization of surface envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 during acute and chronic infection. J Virol 76 9465 9473

41. NunnariG

OteroM

DornadulaG

VanellaM

ZhangH

2002 Residual HIV-1 disease in seminal cells of HIV-1-infected men on suppressive HAART: latency without on-going cellular infections. Aids 16 39 45

42. KalichmanSC

Di BertoG

EatonL

2008 Human immunodeficiency virus viral load in blood plasma and semen: review and implications of empirical findings. Sex Transm Dis 35 55 60

43. ZarateS

PondSL

ShapshakP

FrostSD

2007 Comparative study of methods for detecting sequence compartmentalization in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 81 6643 6651

44. WhitneyJB

LuedemannC

HraberP

RaoSS

MascolaJR

2009 T-cell vaccination reduces simian immunodeficiency virus levels in semen. J Virol 83 10840 10843

45. KeeleBF

LiH

LearnGH

HraberP

GiorgiEE

2009 Low-dose rectal inoculation of rhesus macaques by SIVsmE660 or SIVmac251 recapitulates human mucosal infection by HIV-1. J Exp Med 206 1117 1134

46. ZhangM

GaschenB

BlayW

FoleyB

HaigwoodN

2004 Tracking global patterns of N-linked glycosylation site variation in highly variable viral glycoproteins: HIV, SIV, and HCV envelopes and influenza hemagglutinin. Glycobiology 14 1229 1246

47. Kosakovsky PondSL

FrostSD

2005 Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol 22 1208 1222

48. Kosakovsky PondSL

PosadaD

GravenorMB

WoelkCH

FrostSD

2006 GARD: a genetic algorithm for recombination detection. Bioinformatics 22 3096 3098

49. PillaiSK

GoodB

PondSK

WongJK

StrainMC

2005 Semen-specific genetic characteristics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env. J Virol 79 1734 1742

50. ButlerDM

DelportW

Kosakovsky PondSL

LakdawalaMK

ChengPM

2010 The origins of sexually transmitted HIV among men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2 18re11

51. BhattacharyaT

DanielsM

HeckermanD

FoleyB

FrahmN

2007 Founder effects in the assessment of HIV polymorphisms and HLA allele associations. Science 315 1583 1586

52. SlatkinM

MaddisonWP

1990 Detecting isolation by distance using phylogenies of genes. Genetics 126 249 260

53. PondSL

FrostSD

MuseSV

2005 HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21 676 679

54. BullME

LearnGH

McElhoneS

HittiJ

LockhartD

2009 Monotypic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genotypes across the uterine cervix and in blood suggest proliferation of cells with provirus. J Virol 83 6020 6028

55. BullM

LearnG

GenowatiI

McKernanJ

HittiJ

2009 Compartmentalization of HIV-1 within the female genital tract is due to monotypic and low-diversity variants not distinct viral populations. PLoS One 4 e7122

56. Kosakovsky PondSL

PosadaD

GravenorMB

WoelkCH

FrostSD

2006 Automated phylogenetic detection of recombination using a genetic algorithm. Mol Biol Evol 23 1891 1901

57. Salazar-GonzalezJF

SalazarMG

KeeleBF

LearnGH

GiorgiEE

2009 Genetic identity, biological phenotype, and evolutionary pathways of transmitted/founder viruses in acute and early HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 206 1273 1289

58. KeeleBF

GiorgiEE

Salazar-GonzalezJF

DeckerJM

PhamKT

2008 Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 7552 7557

59. PalmerS

KearneyM

MaldarelliF

HalvasEK

BixbyCJ

2005 Multiple, linked human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance mutations in treatment-experienced patients are missed by standard genotype analysis. J Clin Microbiol 43 406 413

60. Salazar-GonzalezJF

BailesE

PhamKT

SalazarMG

GuffeyMB

2008 Deciphering human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission and early envelope diversification by single-genome amplification and sequencing. J Virol 82 3952 3970

61. LiuSLRA

ShankarappaR

LearnGH

HsuL

DavidovO

1996 HIV quasispecies and resampling. Science 273 415 416

62. ZhuJ

HladikF

WoodwardA

KlockA

PengT

2009 Persistence of HIV-1 receptor-positive cells after HSV-2 reactivation is a potential mechanism for increased HIV-1 acquisition. Nat Med 15 886 892

63. CelumC

WaldA

LingappaJR

MagaretAS

WangRS

2010 Acyclovir and transmission of HIV-1 from persons infected with HIV-1 and HSV-2. N Engl J Med 362 427 439

64. RiegG

ButlerDM

SmithDM

DaarES

2010 Seminal plasma HIV levels in men with asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections. Int J STD AIDS 21 207 208

65. CohenMS

HoffmanIF

RoyceRA

KazembeP

DyerJR

1997 Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet 349 1868 1873

66. HaalandRE

HawkinsPA

Salazar-GonzalezJ

JohnsonA

TichacekA

2009 Inflammatory genital infections mitigate a severe genetic bottleneck in heterosexual transmission of subtype A and C HIV-1. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000274

67. DerdeynCA

DeckerJM

Bibollet-RucheF

MokiliJL

MuldoonM

2004 Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science 303 2019 2022

68. HarrisonRM

1980 Semen parameters in Macaca mulatta: ejaculates from random and selected monkeys. J Med Primatol 9 265 273

69. ClineAN

BessJW

PiatakMJr

LifsonJD

2005 Highly sensitive SIV plasma viral load assay: practical considerations, realistic performance expectations, and application to reverse engineering of vaccines for AIDS. J Med Primatol 34 303 312

70. WhitneyJB

LuedemannC

BaoS

MiuraA

RaoSS

2009 Monitoring HIV vaccine trial participants for primary infection: studies in the SIV/macaque model. Aids 23 1453 1460

71. DouekDC

BrenchleyJM

BettsMR

AmbrozakDR

HillBJ

2002 HIV preferentially infects HIV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nature 417 95 98

72. MattapallilJJ

DouekDC

HillB

NishimuraY

MartinM

2005 Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature 434 1093 1097

73. LearnGHJr

KorberBT

FoleyB

HahnBH

WolinskySM

1996 Maintaining the integrity of human immunodeficiency virus sequence databases. J Virol 70 5720 5730

74. GilbertPB

RossiniAJ

ShankarappaR

2005 Two-sample tests for comparing intra-individual genetic sequence diversity between populations. Biometrics 61 106 117

75. ParadisE

ClaudeJ

StrimmerK

2004 APE: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20 289 290

76. GascuelO

1997 BIONJ: an improved version of the NJ algorithm based on a simple model of sequence data. Mol Biol Evol 14 685 695

77. GuindonS

GascuelO

2003 A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52 696 704

78. KulkarniSS

LapedesA

TangH

GnanakaranS

DanielsMG

2009 Highly complex neutralization determinants on a monophyletic lineage of newly transmitted subtype C HIV-1 Env clones from India. Virology 385 505 520

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Compensatory Evolution of Mutations Restores the Fitness Cost Imposed by β-Lactam Resistance inČlánek The C-Terminal Domain of the Arabinosyltransferase EmbC Is a Lectin-Like Carbohydrate Binding ModuleČlánek A Viral microRNA Cluster Strongly Potentiates the Transforming Properties of a Human Herpesvirus

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 2- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Fresh Look at the Origin of , the Most Malignant Malaria Agent

- In Situ Photodegradation of Incorporated Polyanion Does Not Alter Prion Infectivity

- Highly Efficient Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification

- Positive Signature-Tagged Mutagenesis in : Tracking Patho-Adaptive Mutations Promoting Airways Chronic Infection

- Charge-Surrounded Pockets and Electrostatic Interactions with Small Ions Modulate the Activity of Retroviral Fusion Proteins

- Whole-Body Analysis of a Viral Infection: Vascular Endothelium is a Primary Target of Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus in Zebrafish Larvae

- Inhibition of Nox2 Oxidase Activity Ameliorates Influenza A Virus-Induced Lung Inflammation

- STAT2 Mediates Innate Immunity to Dengue Virus in the Absence of STAT1 via the Type I Interferon Receptor

- Uropathogenic P and Type 1 Fimbriae Act in Synergy in a Living Host to Facilitate Renal Colonization Leading to Nephron Obstruction

- Elite Suppressors Harbor Low Levels of Integrated HIV DNA and High Levels of 2-LTR Circular HIV DNA Compared to HIV+ Patients On and Off HAART

- DC-SIGN Mediated Sphingomyelinase-Activation and Ceramide Generation Is Essential for Enhancement of Viral Uptake in Dendritic Cells

- Short-Lived IFN-γ Effector Responses, but Long-Lived IL-10 Memory Responses, to Malaria in an Area of Low Malaria Endemicity

- Induces T-Cell Lymphoma and Systemic Inflammation

- The C-Terminus of RON2 Provides the Crucial Link between AMA1 and the Host-Associated Invasion Complex

- Critical Role of the Virus-Encoded MicroRNA-155 Ortholog in the Induction of Marek's Disease Lymphomas

- Type I Interferon Signaling Regulates Ly6C Monocytes and Neutrophils during Acute Viral Pneumonia in Mice

- Atypical/Nor98 Scrapie Infectivity in Sheep Peripheral Tissues

- Innate Sensing of HIV-Infected Cells

- BosR (BB0647) Controls the RpoN-RpoS Regulatory Pathway and Virulence Expression in by a Novel DNA-Binding Mechanism

- Compensatory Evolution of Mutations Restores the Fitness Cost Imposed by β-Lactam Resistance in

- Expression of Genes Involves Exchange of the Histone Variant H2A.Z at the Promoter

- The RON2-AMA1 Interaction is a Critical Step in Moving Junction-Dependent Invasion by Apicomplexan Parasites

- Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Facilitates G1-S Transition by Stabilizing and Enhancing the Function of Cyclin D1

- Transcription and Translation Products of the Cytolysin Gene on the Mobile Genetic Element SCC Regulate Virulence

- Phosphatidylinositol 3-Monophosphate Is Involved in Apicoplast Biogenesis

- The Rubella Virus Capsid Is an Anti-Apoptotic Protein that Attenuates the Pore-Forming Ability of Bax

- Episomal Viral cDNAs Identify a Reservoir That Fuels Viral Rebound after Treatment Interruption and That Contributes to Treatment Failure

- Genetic Mapping Identifies Novel Highly Protective Antigens for an Apicomplexan Parasite

- Relationship between Functional Profile of HIV-1 Specific CD8 T Cells and Epitope Variability with the Selection of Escape Mutants in Acute HIV-1 Infection

- The Genotype of Early-Transmitting HIV gp120s Promotes αβ –Reactivity, Revealing αβ/CD4 T cells As Key Targets in Mucosal Transmission

- Small Molecule Inhibitors of RnpA Alter Cellular mRNA Turnover, Exhibit Antimicrobial Activity, and Attenuate Pathogenesis

- The bZIP Transcription Factor MoAP1 Mediates the Oxidative Stress Response and Is Critical for Pathogenicity of the Rice Blast Fungus

- Entrapment of Viral Capsids in Nuclear PML Cages Is an Intrinsic Antiviral Host Defense against Varicella-Zoster Virus

- NS2 Protein of Hepatitis C Virus Interacts with Structural and Non-Structural Proteins towards Virus Assembly

- Measles Outbreak in Africa—Is There a Link to the HIV-1 Epidemic?

- New Models of Microsporidiosis: Infections in Zebrafish, , and Honey Bee

- The C-Terminal Domain of the Arabinosyltransferase EmbC Is a Lectin-Like Carbohydrate Binding Module

- A Viral microRNA Cluster Strongly Potentiates the Transforming Properties of a Human Herpesvirus

- Infections in Cells: Transcriptomic Characterization of a Novel Host-Symbiont Interaction

- Secreted Bacterial Effectors That Inhibit Host Protein Synthesis Are Critical for Induction of the Innate Immune Response to Virulent

- Genital Tract Sequestration of SIV following Acute Infection

- Functional Coupling between HIV-1 Integrase and the SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complex for Efficient Integration into Stable Nucleosomes

- DNA Damage and Reactive Nitrogen Species are Barriers to Colonization of the Infant Mouse Intestine

- The ESCRT-0 Component HRS is Required for HIV-1 Vpu-Mediated BST-2/Tetherin Down-Regulation

- Targeted Disruption of : Invasion of Erythrocytes by Using an Alternative Py235 Erythrocyte Binding Protein

- Trivalent Adenovirus Type 5 HIV Recombinant Vaccine Primes for Modest Cytotoxic Capacity That Is Greatest in Humans with Protective HLA Class I Alleles

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genetic Mapping Identifies Novel Highly Protective Antigens for an Apicomplexan Parasite

- Type I Interferon Signaling Regulates Ly6C Monocytes and Neutrophils during Acute Viral Pneumonia in Mice

- Infections in Cells: Transcriptomic Characterization of a Novel Host-Symbiont Interaction

- The ESCRT-0 Component HRS is Required for HIV-1 Vpu-Mediated BST-2/Tetherin Down-Regulation

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání