-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaUpregulation of xCT by KSHV-Encoded microRNAs Facilitates KSHV Dissemination and Persistence in an Environment of Oxidative Stress

Upregulation of xCT, the inducible subunit of a membrane-bound amino acid transporter, replenishes intracellular glutathione stores to maintain cell viability in an environment of oxidative stress. xCT also serves as a fusion-entry receptor for the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), the causative agent of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS). Ongoing KSHV replication and infection of new cell targets is important for KS progression, but whether xCT regulation within the tumor microenvironment plays a role in KS pathogenesis has not been determined. Using gene transfer and whole virus infection experiments, we found that KSHV-encoded microRNAs (KSHV miRNAs) upregulate xCT expression by macrophages and endothelial cells, largely through miR-K12-11 suppression of BACH-1—a negative regulator of transcription recognizing antioxidant response elements within gene promoters. Correlative functional studies reveal that upregulation of xCT by KSHV miRNAs increases cell permissiveness for KSHV infection and protects infected cells from death induced by reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Interestingly, KSHV miRNAs simultaneously upregulate macrophage secretion of RNS, and biochemical inhibition of RNS secretion by macrophages significantly reduces their permissiveness for KSHV infection. The clinical relevance of these findings is supported by our demonstration of increased xCT expression within more advanced human KS tumors containing a larger number of KSHV-infected cells. Collectively, these data support a role for KSHV itself in promoting de novo KSHV infection and the survival of KSHV-infected, RNS-secreting cells in the tumor microenvironment through the induction of xCT.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 6(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000742

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000742Summary

Upregulation of xCT, the inducible subunit of a membrane-bound amino acid transporter, replenishes intracellular glutathione stores to maintain cell viability in an environment of oxidative stress. xCT also serves as a fusion-entry receptor for the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), the causative agent of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS). Ongoing KSHV replication and infection of new cell targets is important for KS progression, but whether xCT regulation within the tumor microenvironment plays a role in KS pathogenesis has not been determined. Using gene transfer and whole virus infection experiments, we found that KSHV-encoded microRNAs (KSHV miRNAs) upregulate xCT expression by macrophages and endothelial cells, largely through miR-K12-11 suppression of BACH-1—a negative regulator of transcription recognizing antioxidant response elements within gene promoters. Correlative functional studies reveal that upregulation of xCT by KSHV miRNAs increases cell permissiveness for KSHV infection and protects infected cells from death induced by reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Interestingly, KSHV miRNAs simultaneously upregulate macrophage secretion of RNS, and biochemical inhibition of RNS secretion by macrophages significantly reduces their permissiveness for KSHV infection. The clinical relevance of these findings is supported by our demonstration of increased xCT expression within more advanced human KS tumors containing a larger number of KSHV-infected cells. Collectively, these data support a role for KSHV itself in promoting de novo KSHV infection and the survival of KSHV-infected, RNS-secreting cells in the tumor microenvironment through the induction of xCT.

Introduction

Patients with immune deficiencies are at risk for life-threatening illnesses caused by herpesviruses, including the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). Bone marrow failure [1], lymphoproliferative syndromes [2],[3], and sarcoma [4] have all been etiologically linked to KSHV infection and occur with greater frequency in the setting of immune suppression related to HIV infection [5],[6] or organ transplantation [7],[8]. The most commonly encountered clinical manifestation of KSHV infection, Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), represents one of the most common tumors arising in the setting of HIV infection, one of the most common transplant-associated tumors, and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [5]–[7]. Moreover, KS is the most common tumor arising in the general population in some geographic areas [9]. Despite the reduced incidence of KS in the modern era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [10], KS is increasingly recognized in HIV-infected patients with suppressed HIV viral loads and elevated CD4+ T cell counts [11],[12]. Clinical responses to cytotoxic agents for systemic KS vary widely in published trials, and these agents incur many side effects which may exacerbate or add to those already incurred by antiretroviral or immunosuppressive agents [10],[13]. Given these shortcomings of existing therapies, novel targeted strategies are needed for the treatment or prevention of KS.

Published data support a role for KSHV-encoded genes in KS pathogenesis, including genes expressed primarily during lytic replication that facilitate angiogenesis and endothelial cell survival [14], and existing clinical data support this concept. An elevated KSHV viral load in the peripheral circulation predicts the onset and progression of both AIDS - and non-AIDS-related KS, and intralesional KSHV viral load correlates directly with tumor progression [15]–[17]. One retrospective clinical study demonstrated that ganciclovir, a nucleoside analog that inhibits viral DNA polymerase activity and reduces KSHV replication [18], reduced the incidence of KS in patients receiving organ transplants [19]. In addition, KS arising in the setting of well-controlled HIV infection may be explained in part by reduced KSHV-specific immunity despite general immune recovery with HAART [20],[21]. Together, these data suggest a role for ongoing KSHV replication and infection of naïve target cells in the progression of KS. Interestingly, neither KS lesional spindle cells nor cultured endothelial cells infected by KSHV in vitro efficiently maintain viral episomes when passed in culture [22],[23], suggesting the potential importance of additional microenvironmental factors within KS tumors for facilitating KSHV infection.

The amino acid membrane transport system xc− consists of a conserved heavy chain, 4F2hc, and an inducible subunit, xCT, that mediates amino acid exchange [24]. xc− exchanges intracellular glutamate for extracellular cystine at the cell membrane, and the latter is rapidly reduced in the intracellular space to cysteine and incorporated into glutathione (GSH) and other protein biosynthesis pathways [25]. This allows for restoration of intracellular GSH stores and protection of xc−-expressing cells from oxidative stress and cell death [25]. xCT expression is upregulated by physiological conditions that impact intracellular GSH levels, such as hypoxia, inflammation, and increased production of reactive species [25]. xCT was also recently identified as a fusion-entry receptor for KSHV and may mediate KSHV entry either in isolation or as part of a complex with other receptors for the virus [26],[27]. KSHV establishes infection within multiple xCT-expressing cell types that have been implicated in KS pathogenesis, including intralesional or circulating monocytes, intralesional macrophages, and endothelial cells [26]–[29]. However, whether KSHV itself also regulates xCT expression to promote viral infection of new cell targets or increase the longevity of KSHV-infected cells in the local environment is unknown.

miRNAs are small (19–23 nucleotides in length), non-coding RNAs that bind target mRNAs, marking them for degradation or post-transcriptional modification, and KSHV encodes 17 mature miRNAs which are expressed within KSHV-infected cells and KS lesions [30]–[33]. xCT expression is regulated through competitive binding of positive and negative transcription factors to an “Antioxidant Response Element” (ARE) in the xCT promoter [34],[35], and existing data suggest that negative transcription regulators of ARE may be targeted by KSHV miRNAs [36]–[40]. Therefore, using cell culture systems employing macrophages and endothelial cells, we sought to determine whether KSHV miRNAs regulate the expression of xCT, and if so, whether this infuences cell permissiveness for KSHV infection and protection of infected cells from oxidative stress.

Results

xCT is a principal determinant of macrophage permissiveness for KSHV infection

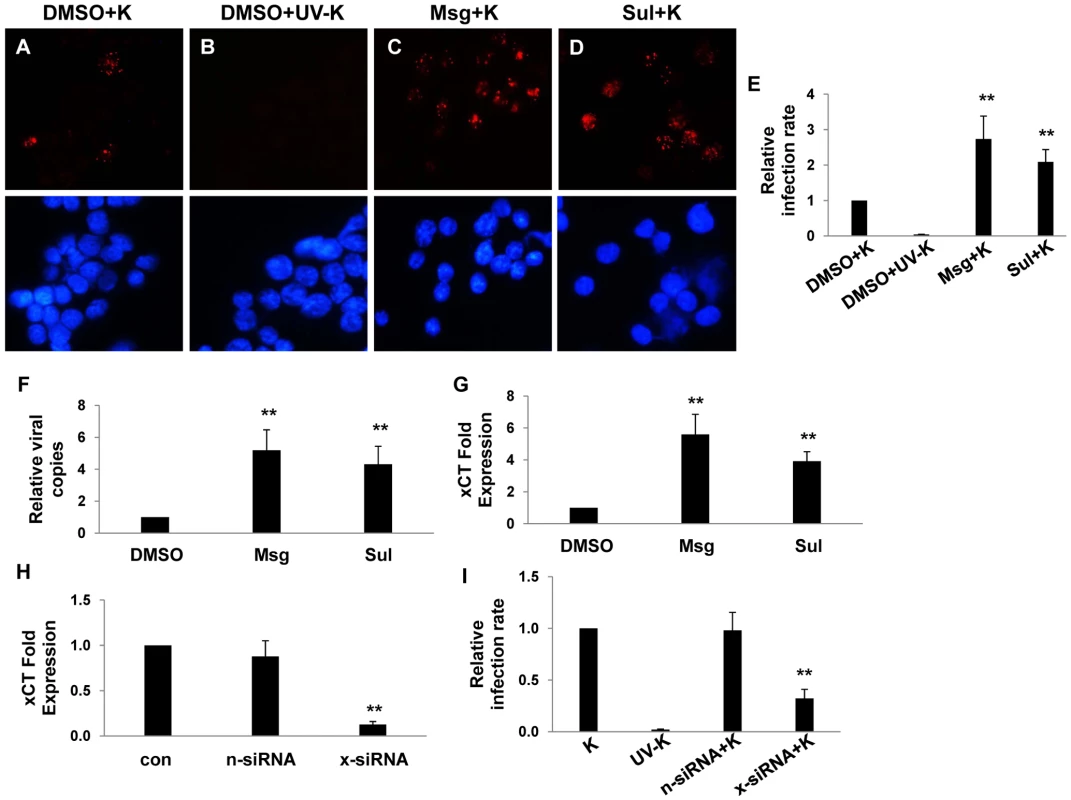

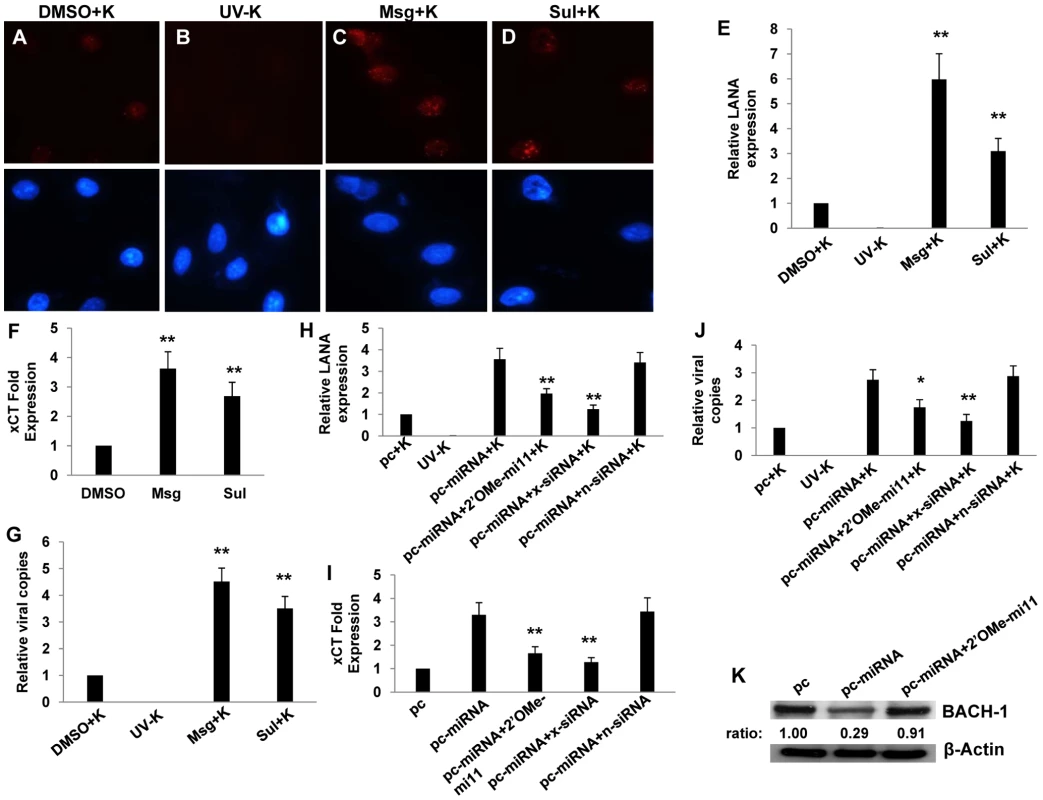

To first determine whether xCT expression correlates with macrophage susceptibility to KSHV infection, we utilized a BALB/c-derived murine macrophage cell line, 264.7 cells (“RAW” cells). We chose RAW cells given the recent demonstration of KSHV infection of murine macrophages in vivo [41], the identity (89%) and similarity (93%) of the murine xCT protein to its human counterpart [25], and the utility of these cells for gene transfer studies. xCT expression is induced indirectly by substrates that compete for cystine uptake by xCT, like monosodium glutamate (Msg) [42] and sulfasalazine (Sul) [43]. We found that Msg or Sul significantly increased the number of RAW cells expressing the KSHV latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) following their incubation with purified KSHV (Fig. 1A–E). This increase in the number of infected cells was reflected in an increase in viral episome copies for cells from Msg - and Sul-treated cultures (Fig. 1F), although IFA suggested that the number of episomes (LANA dots) per cell was unchanged (Fig. 1A–D). Msg and Sul also increased xCT transcript expression by RAW cells (Fig. 1G), and direct targeting of xCT with siRNA significantly reduced the number of LANA-positive cells following RAW cell incubation with KSHV (Fig. 1H and I). These data confirm the role of xCT as a principal determinant of RAW cell susceptibility to KSHV infection.

Fig. 1. xCT mediates KSHV infection of macrophages.

(A–D) 264.7 (“RAW”) cells were first incubated with Monosodium glutamate (Msg), Sulfasalazine (Sul) or vehicle control (DMSO) for 12 h followed by purified KSHV (K). 16 h later, IFA employing anti-LANA monoclonal antibodies and secondary antibodies conjugated to Texas Red were performed to identify expression of LANA signified by the typical punctate intranuclear expression pattern. Nuclei were identified using DAPI (blue). Some cells were incubated with UV-inactivated virus (UV-K) for negative controls. Representative images from one of three independent experiments are shown. (E) Relative infection rate was determined for groups in A–D as outlined in Methods. (F) qPCR was used to determine relative intracellular KSHV DNA content normalized to the vehicle control group (relative viral copies) as explained in Methods. (G) qRT-PCR was used to determine relative xCT transcript expression. (H) qRT-PCR was used to determine xCT transcript expression relative to control cells for cells transfected with either control (n) or xCT-specific siRNA. (I) Relative infection rates were calculated for groups in (H) using LANA IFA. For all assays, error bars represent the S.E.M. for three independent experiments. * * = p<0.01. KSHV miRNAs regulate xCT expression and macrophage permissiveness for KSHV infection

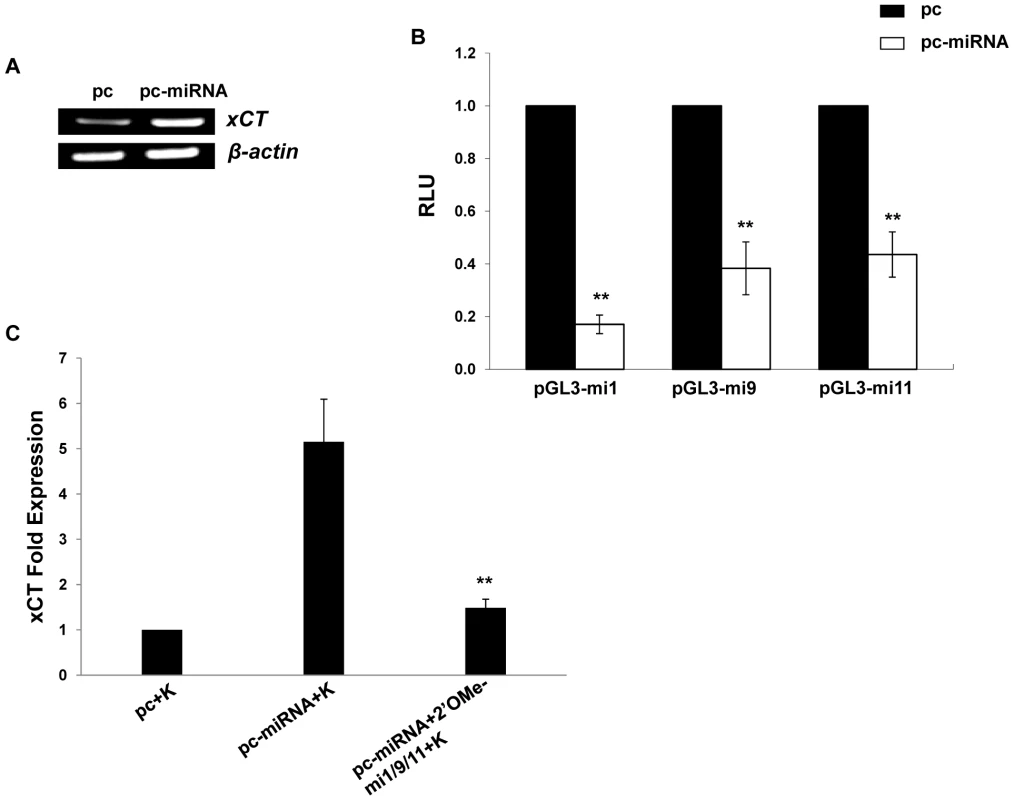

To explore whether KSHV miRNAs regulate xCT expression, we co-transfected RAW cells with a construct encoding 10 of the 17 mature KSHV miRNAs described elsewhere [44]. Using semi-quantitative RT-PCR, we first confirmed upregulation of xCT with the collective expression of KSHV miRNAs encoded in the construct (Fig. 2A). Using a KSHV miRNA target prediction algorithm validated previously [36], we identified KSHV miRNA binding sites within 3'UTR of several murine genes associated with the regulation of xCT. The majority of binding sites were identified for 3 KSHV miRNAs: miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-11 (data not shown). To first determine whether these miRNAs were expressed within KSHV miRNA transfectants, we co-transfected cells with KSHV miRNAs and pGL3 luciferase reporter constructs encoding complimentary sequences for individual miRNAs (upon binding of pGL3 complimentary sequences to mature miRNAs, luciferase expression by pGL3 is repressed as shown elsewhere) [44]. This confirmed expression of miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-11 in these cells (Fig. 2B). Next, using qRT-PCR, we found that miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-11 are responsible for the upregulation of xCT in KSHV miRNA transfectants since targeting these 3 miRNAs with specific 2'OMe RNA antagomirs entirely suppressed this effect (Fig. 2C). Parallel experiments revealed that KSHV miRNAs increase intracellular KSHV viral load and viral transcript expression within macrophages following their incubation with KSHV (Fig. 3A and B). Once again, this effect was entirely suppressed by targeting miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-11 (Fig. 3A and B). In addition, we found that siRNA targeting of xCT significantly suppressed the KSHV miRNA-mediated increase in macrophage susceptibility to KSHV infection (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 2. KSHV miRNAs upregulate xCT expression by macrophages.

(A) RT-PCR was used to determine expression of xCT transcripts in RAW cells transfected with either control (pc) or miRNA-expressing vectors (pc-miRNA). β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) RAW cells were co-transfected with miRNA luciferase reporter constructs (pGL3-miX where X = complimentary sequence for the individual KSHV miRNAs noted) and either control or miRNA-expressing vectors. 48 h later, luciferase expression was determined for miRNA transfectants relative to controls (RLU). (C) Cells were transfected with control or miRNA-expressing vectors with or without 2'OMe RNA antagomirs targeting miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-11 (mi1/9/11). 48 h following subsequent incubation with KSHV (K), qRT-PCR was used to determine relative xCT transcript expression. For all assays, error bars represent the S.E.M. for three independent experiments. * * = p<0.01. Fig. 3. KSHV miRNA upregulation of xCT increases macrophage susceptibility to KSHV infection.

(A) RAW cells were transfected with control or miRNA-expressing vectors then incubated with purified KSHV (K). LANA IFA were performed 16 h later, and relative infection rates were determined as outlined in Methods. (B) qPCR was used to determine relative intracellular KSHV DNA content for groups in A. (C) Cells were co-transfected with control or miRNA-expressing vectors and either control (n) or xCT-specific siRNA then incubated with purified KSHV. 16 h later, LANA IFA were used to determine relative infection rates. For all assays, error bars represent the S.E.M. for three independent experiments. * * = p<0.01. KSHV miR-K12-11 suppresses BACH-1 to induce xCT expression and cell permissiveness for KSHV infection in macrophages and endothelial cells

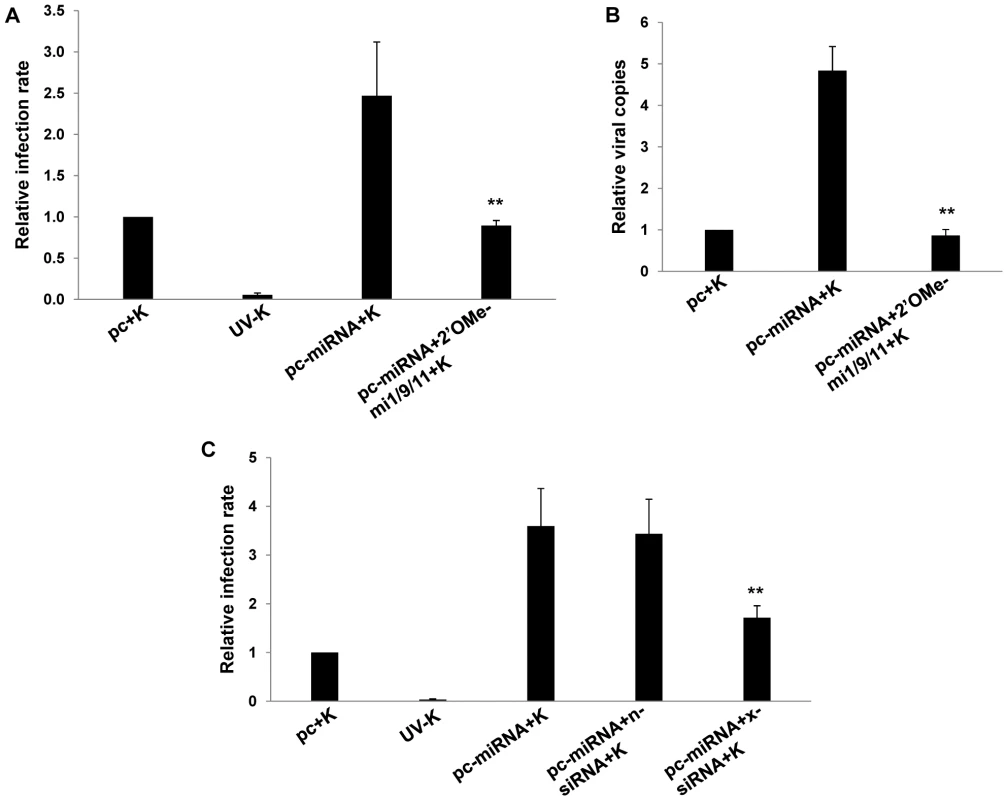

Our bioinformatics analyses revealed putative binding sites for miR-K12-11 within the 3'UTR of the murine BACH-1 gene (Fig. 4A). We subsequently confirmed KSHV miRNA suppression of BACH-1 within RAW cells, an effect largely reversed through direct targeting of KSHV miR-K12-11 (Fig. 4B). In addition, direct siRNA targeting of BACH-1 significantly increased basal levels of xCT expression in these cells (Fig. 4C–E) as well as macrophage permissiveness to KSHV infection (Fig. 4F), although to a lesser degree than the collective expression of miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-11 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4. KSHV miRNAs upregulate xCT expression through repression of BACH-1.

(A) Potential KSHV miRNA binding sites were identified within the 3'UTR of murine BACH-1 using an ad-hoc scanning program as described in Methods. miR-K12-11 nucleotides with matching base pairs depicted in capital letters bind within positions 2318–2339 and 2530–2551. (B) RAW cells were transfected with 1 µg control or miRNA-expressing vectors with or without 300 pmol of 2'OMe RNA antagomirs targeting miR-K12-11. 48 h later, BACH-1 expression was quantified by Western blot. β-Actin was used for loading controls. Numbers represent immunoreactivity relative to control transfectants as quantified using Image-J software. (C–D) RT-PCR (C) and qRT-PCR (D) were used to quantify transcripts for BACH-1 (C) and xCT (C and D), respectively, in controls cells or cells transfected with either control (n) or BACH-1-specific siRNA. (E) Western blots were used to quantify BACH-1 protein expression in siRNA-transfected cells for groups in (C). Immunoreactivity was quantified as in (B). (F) Cells were transfected with control or BACH-1 siRNA as above and subsequently incubated with KSHV. Relative infection rates were determined 12 h later using LANA IFA. Error bars represent the S.E.M. for three independent experiments. * * = p<0.01. Published data have confirmed direct targeting of BACH-1 by miR-K12-11 in human cells [36]. To validate our observations and to determine their broader significance for human cells with known relevance to KS pathogenesis, we repeated our experiments using primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). We found that Msg, Sul or KSHV miRNA transfection significantly increased xCT transcript expression and, based on IFA, KSHV episome copy number per cell following subsequent de novo infection (Fig. 5A–J). In contrast to what was observed for RAW cells, IFA indicated that the total number of infected HUVEC remained unchanged with these interventions (Fig. S1). In addition, either direct suppression of xCT by siRNA or concurrent inhibition of miR-K12-11 reduced xCT expression and intracellular viral load in KSHV miRNA transfectants (Fig. 5H–J). Collective expression of KSHV miRNAs also reduced BACH-1 expression in HUVEC, an effect suppressed with concurrent inhibition of miR-K12-11 (Fig. 5K).

Fig. 5. miR-K12-11 suppresses BACH-1 expression and increases endothelial cell susceptibility to KSHV through upregulation of xCT.

(A–G) HUVEC were incubated with vehicle control (DMSO), Msg, or Sul for 12 h followed by purified KSHV (K) using an MOI∼0.5–1. 16 h later, LANA IFA were performed as previously described. (A–D) Representative images from one of three independent experiments are shown. (H–K) HUVEC were transfected with control or miRNA-expressing vectors along with a 2'OMe RNA antagomir for miR-K12-11 or either control (n) or xCT-specific siRNA. (E,H) Relative LANA expression was determined as described in Methods. (F,I) qRT-PCR was used to determine relative xCT transcript expression. (G,J) qPCR was used to determine relative intracellular KSHV DNA content normalized to controls. (K) Western blots were used to identify BACH-1 protein expression and immunoreactivity quantified as previously described. For all assays, error bars represent the S.E.M. for three independent experiments. * = p<0.05, * * = p<0.01 (For Fig. H–J, comparisons are relative to either pc-miRNA or pc-miRNA+K). KSHV miRNAs upregulate macrophage secretion of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and protect macrophages from RNS-induced cell death

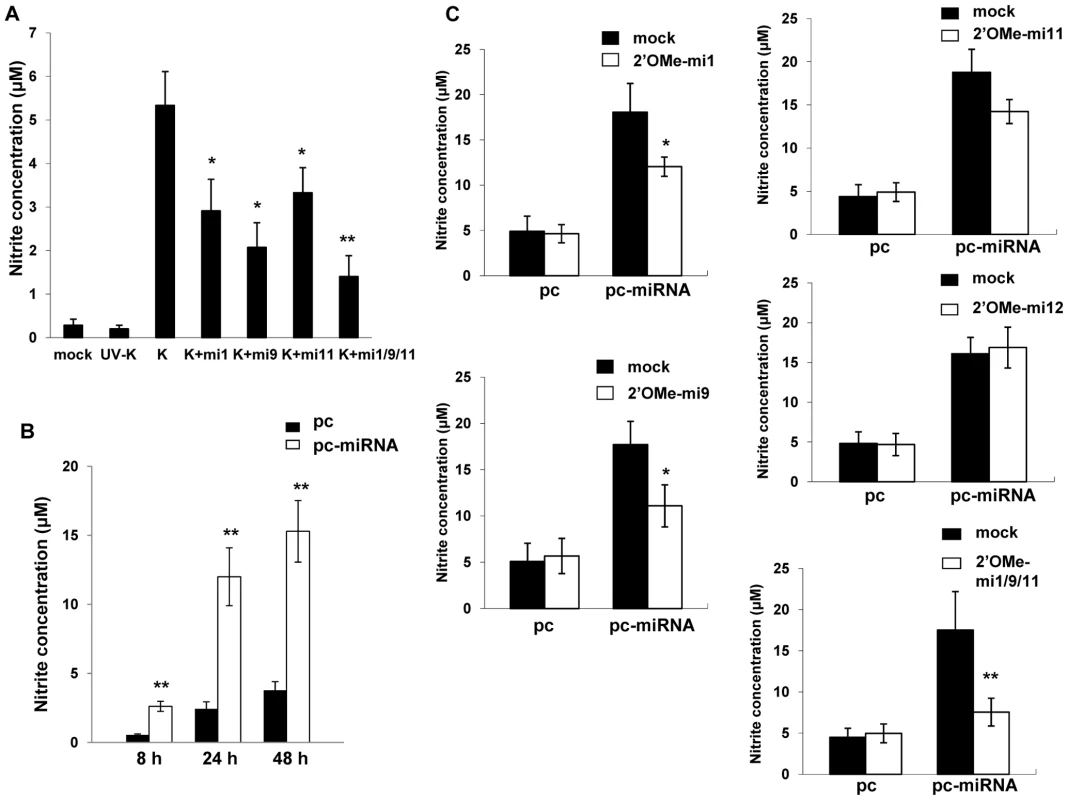

xCT restoration of intracellular glutathione and increased scavenging of free radicals reduces cell death resulting from nitration of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids by RNS [25],[45],[46]. Because we observed increased xCT expression induced by KSHV miRNAs, we hypothesized that KSHV may also increase RNS secretion by macrophages and that xCT upregulation would serve as an auto-protective mechanism in this environment. Using a standard Greiss reaction assay for quantifying nitrite in culture supernatants as a surrogate measure of RNS secretion, we found that KSHV infection of RAW cells induced a ∼20-fold increase in RNS secretion and that the majority of this effect was mediated through the collective expression of miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-11 (Fig. 6A). A similar pattern was observed following overexpression of KSHV miRNAs (Fig. 6B and C). Non-specific TLR activation, as might be initiated by mature miRNAs or their precursors, is capable of inducing RNS production [47],[48]. However, specific inhibitors of MyD88-independent and -dependent toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways failed to reduce induction of RNS secretion by KSHV miRNAs, suggesting that this effect is not mediated through TLR activation (Fig. S2).

Fig. 6. KSHV miRNAs induce reactive nitrogen species (RNS) secretion by macrophages.

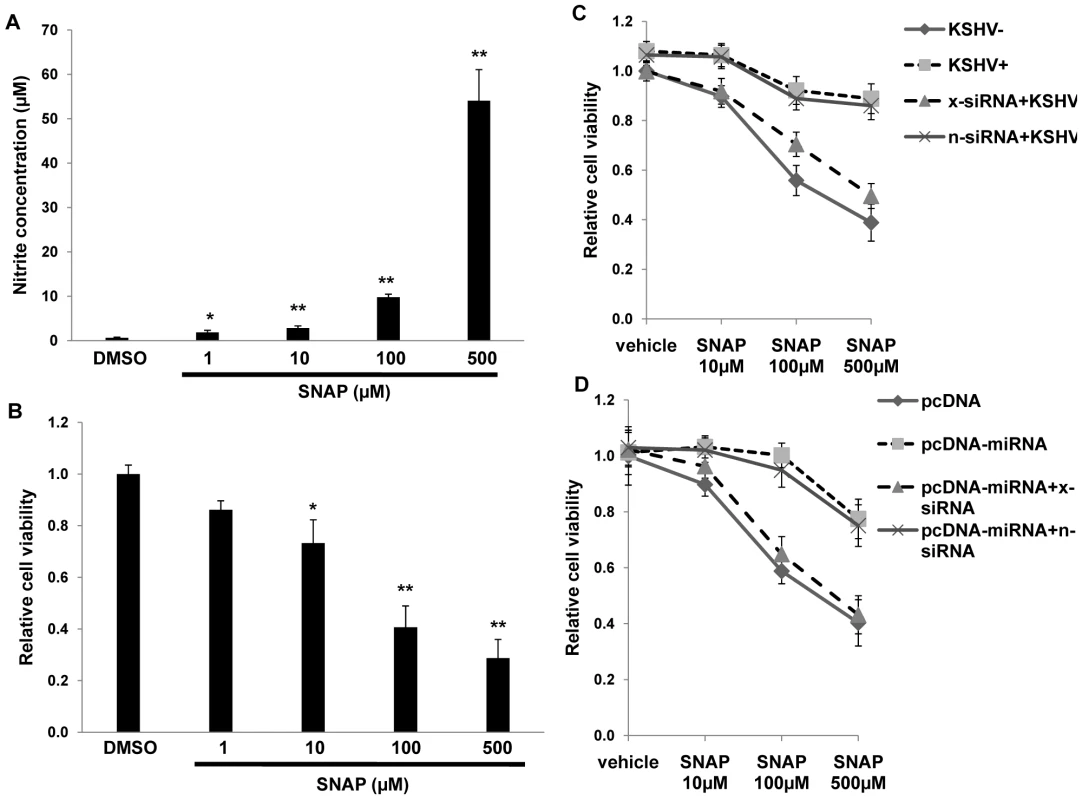

(A) RAW cells were transfected with 2'OMe RNA antagomirs targeting miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-11 or all three together (mi1/9/11). Cells were subsequently incubated with purified KSHV (K) and nitrite quantified within culture supernatants as described in Methods. (B) Cells were transfected with control or miRNA-expressing vectors and nitrite quantified within culture supernatants at the times indicated. (C) Cells were co-transfected with either control or miRNA-expression constructs without (mock) or with specific 2'OMe RNA antagomirs. As an additional control, some cells were transfected with an antagomir targeting miR-K12-12 which is not expressed by the miRNA-expressing construct. For all assays, error bars represent the S.E.M. for three independent experiments. * = p<0.05, * * = p<0.01. To determine whether upregulation of xCT by KSHV miRNAs offers a protective mechanism for macrophages in an environment rich in RNS, we first established that provision of the nitric oxide (NO) donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) [49] increased RNS concentrations within RAW cell culture supernatants and induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A and B). Subsequently, we found that either KSHV infection or overexpression of KSHV miRNAs significantly increased macrophage resistance to SNAP-induced cell death. Moreover, siRNA experiments confirmed that this effect was mediated primarily through the upregulation of xCT (Figs. 7C and D).

Fig. 7. KSHV miRNAs enhance macrophage survival in an environment of oxidative stress through the upregulation of xCT.

(A) RAW cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of SNAP or vehicle control for 12 h prior to nitrite quantification within culture supernatants. (B) Relative cell viability was determined for groups in (A) as described in Methods. (C) Cells were transfected with either control (n) or xCT-specific (x) siRNA and incubated with UV-K (KSHV−) or KSHV (KSHV+) 48 h later. (D) Cells were co-transfected with xCT siRNA and either control or miRNA-expressing vectors for 48 h, then incubated for an additional 12 h with SNAP prior to viability determinations. For all assays, error bars represent the S.E.M. for three independent experiments. * = p<0.05, * * = p<0.01. RNS facilitate KSHV infection of macrophages

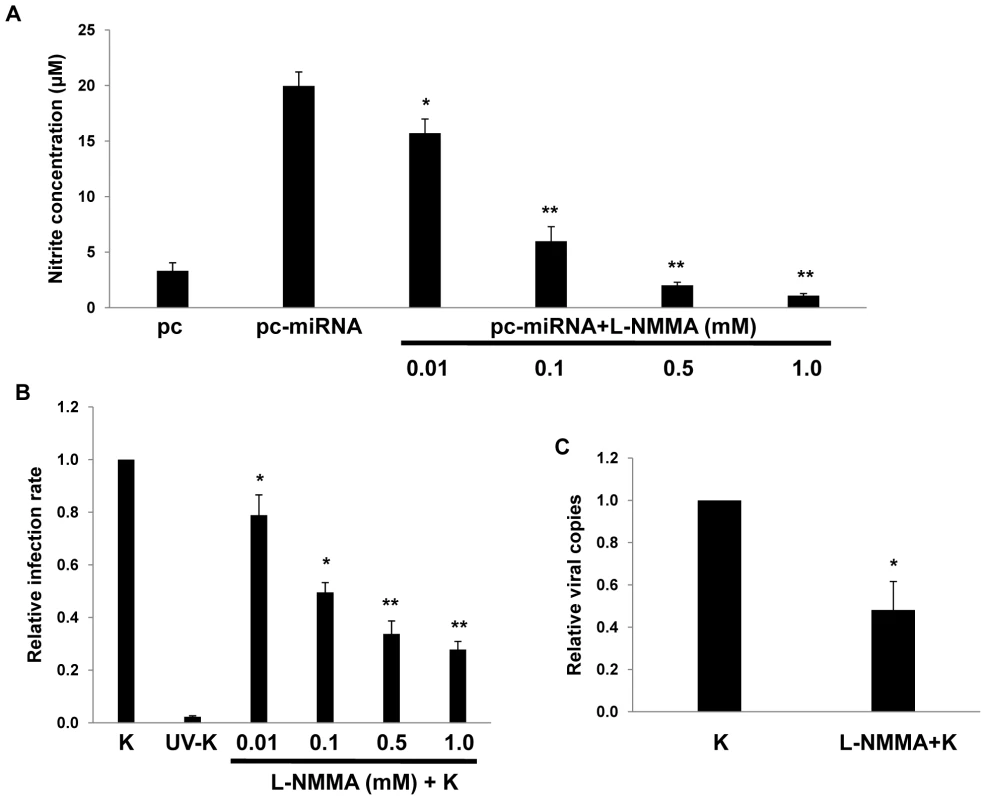

RNS are expressed within KS lesions [50], but whether RNS themselves influence de novo KSHV infection is unknown. To reduce macrophage secretion of RNS, we incubated RAW cells with L-N6-monomethyl-arginine (L-NMMA), an inhibitor of all forms of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) [51] that induces no discernable toxicity for RAW cells over a wide range of concentrations (Fig. S3). Interestingly, L-NMMA significantly reduced secretion of RNS initiated by KSHV miRNAs and reduced de novo KSHV infection of macrophages in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8), suggesting a role for NOS and RNS in facilitating de novo KSHV infection.

Fig. 8. RNS inhibition reduces macrophage susceptibility to KSHV infection.

(A) RAW cells were first transfected with 1 µg of either control or miRNA-expressing vectors then incubated with L-NMMA for 12 h prior to nitrite quantification in culture supernatants. (B) Cells were incubated with L-NMMA for 12 h prior to their incubation with purified KSHV (K) for 2 h. Following an additional 12 h, LANA IFA were performed and relative infection rates determined as described in Methods. (C) qPCR was used to determine relative intracellular KSHV DNA content for KSHV-infected cells pre-treated with either vehicle or 0.5mM L-NMMA. In all assays, error bars represent the S.E.M. for three independent experiments. * = p<0.05, * * = p<0.01. xCT expression is increased within more advanced KS lesions

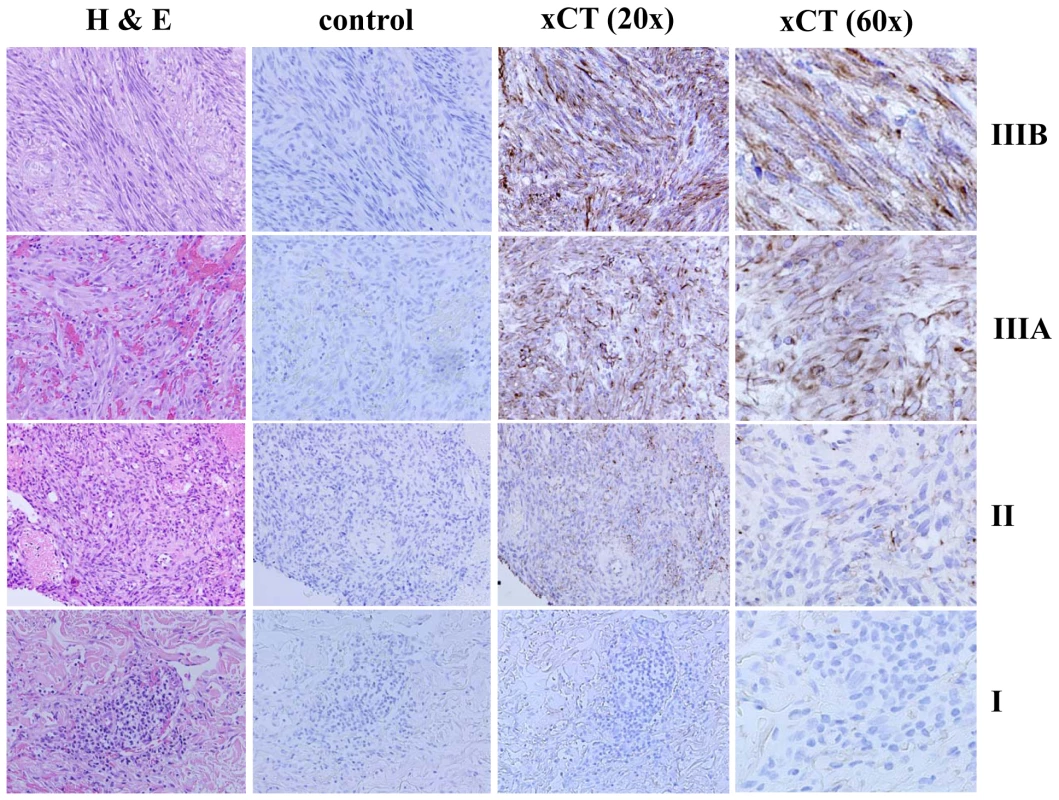

KSHV miRNAs are expressed within KS lesions [30]–[32] but to our knowledge, expression of xCT within KS tissue has never been demonstrated. To address this, we used immunohistochemistry to quantify xCT expression within KS skin lesions representing the full spectrum of histopathologic progression of KS. We found that stage I tumors (patches) and stage II tumors (plaques) exhibited either no or minimally discernable xCT expression, respectively (Fig. 9). In contrast, stage III tumors (nodules) exhibited easily discernable membrane expression of xCT by the majority of cells in these lesions, including nearly all spindle-shaped cells (Fig. 9). Moreover, we confirmed that stage III tumors exhibited significantly more LANA+ cells than stage I lesions (Fig. S4) in agreement with published data [52],[53] as well as our observed correlation between KSHV viral load and xCT expression in our in vitro experiments.

Fig. 9. xCT expression within KS lesions correlates with tumor stage.

KS diagnosis and histopathologic staging were independently confirmed by a dermatopathologist using hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Tumors were then processed for immunohistochemistry as described in Methods using either pre-immune sera (control) or xCT anti-sera. xCT expression is revealed by dark brown membrane-associated staining in contrast to blue nuclear staining. Representative images from all stages (I = patch, II = plaque, III = nodule) are shown, including two different stage III tumors (A and B). All images are shown at original magnification ×20 or 60. Discussion

In this study, we found that KSHV-encoded miR-K12-11 upregulates the expression of xCT in macrophages and endothelial cells, in part through suppression of a negative regulator of gene transcription, BACH-1. We also found that KSHV miRNAs induce macrophage secretion of RNS and protect these cells from RNS-induced cell death through the upregulation of xCT. Moreover, reducing NOS activity and RNS secretion by macrophages reduces their permissiveness for KSHV. Finally, we found that cells within more advanced human KS tumors express more xCT than cells from early-stage lesions. We hypothesize, therefore, that KSHV miRNAs facilitate KS pathogenesis through cooperative mechanisms that regulate xCT and RNS secretion to promote ongoing de novo infection and survival of infected cells in the tumor microenvironment.

Implications of the regulation of BACH-1, xCT expression, and cell susceptibility to KSHV infection by KSHV miRNAs

xCT expression is differentially regulated during oxidative stress through transcription factor binding to the cis-acting ARE in its promoter [34],[35]. Transcription factors that bind to the ARE include a positive regulator known as Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf-2) [35] and negative regulators, including BACH-1 and c-Maf, which competitively reduce Nrf-2 binding to the ARE thereby repressing ARE-mediated gene expression [37],[38]. KSHV miRNAs are expressed within KSHV-infected cells and KS lesions [30]–[32], and existing data suggest that both BACH-1 and c-Maf are targeted by KSHV miRNAs [36],[39],[40]. More specifically, KSHV miR-K12-11, an ortholog of cellular miR-155, targets and reduces expression of BACH-1 [36]. miR-155 downregulates c-Maf expression by T cells [40], and KSHV miRNAs downregulate c-Maf expression in endothelial cells [39]. Therefore, we hypothesized that miR-K12-11, in cooperation with other KSHV miRNAs, regulates xCT expression.

We found that miR-K12-11 downregulated BACH-1 and induced xCT expression in both macrophages and endothelial cells, although additional experiments using site-directed mutagenesis are needed to confirm direct interactions between BACH-1 and the xCT ARE in murine cells. Further validating our findings, we found that BACH-1 targeting by siRNA increased macrophage permissiveness for infection by approximately 70% (Fig. 4F), although overexpression of multiple miRNAs increased permissiveness by approximately 250% (Fig. 3E). Differences in transfection efficiency for siRNA and the KSHV miRNA constructs could be partially responsible for this discrepancy, but we hypothesize that it is due in part to the effect of multiple KSHV miRNAs, including miR-K12-1 and miR-K12-9, and the cooperative targeting of multiple genes. Our initial screen for KSHV miRNA binding sites within murine and human genes known to regulate xCT expression and RNS secretion revealed multiple binding sites for miR-K12-1, miR-K12-9 and miR-K12-11 (data not shown). These analyses also revealed binding sites for miR-K12-4, although not miR-K12-1 or miR-K12-9, within both murine and human BACH-1 3'UTR sequences (not shown), although we have not yet confirmed the functional impact of miR-K12-4 expression on BACH-1 or xCT expression. Additional studies are needed to confirm direct targeting of BACH-1 or other genes by these KSHV miRNAs and to characterize the functional impact of this targeting for expression of xCT and other ARE-containing genes regulated by BACH-1, including those involved in the generation of RNS (see below).

To our knowledge, these data are the first to suggest a role for a herpesvirus in the autocrine upregulation of its own receptor, although whether increased cell permissiveness for KSHV entry following initial infection and miRNA expression is “accidental” or “purposeful” in the context of KSHV-host evolution remains debatable. In addition to promoting cell survival (see below), autocrine upregulation of xCT may provide evolutionary advantages for the virus achieved through an increase in intracellular viral load that were not addressed by our studies. This concept is supported by several reports revealing that a significant proportion of KSHV-infected tumor cells, including those within KS lesions, contain multiple viral clones [54]–[56]. Another study showed that the downregulation of MHC Class I (MHC-I) in KSHV-infected cells is directly proportional to the level of expression of the KSHV modulator of immune recognition 2 (MIR2) and intracellular KSHV episome copy number [57], implying that increasing intracellular viral copies may promote reduced KSHV epitope presentation to CD8+ T cells as a mechanism for immune evasion. Our IFA indicated that for RAW cells, miRNA upregulation of xCT increased the permissiveness of uninfected cells for KSHV, although not viral episome copies within individual cells. In contrast, miRNA upregulation of xCT increased HUVEC viral episome copies per cell following subsequent infection, although not the total number of infected cells. Our studies did not directly address whether the observed increase in episome copies per cell for HUVEC is the result of intracellular episome replication or “superinfection” with exogenous virions. Experiments utilizing limiting dilution PCR [58] or single cell imaging techniques [41],[59] could be used to confirm whether intracellular KSHV viral load and miRNA expression correlate with xCT expression on a single cell level and to address the possibility that KSHV miRNA upregulation of xCT increases cell permissiveness for subsequent virion entry. It is interesting to speculate whether autocrine regulation of surface receptors by KSHV miRNAs differs depending on the cell type, and whether soluble factors released by infected cells differentially influence xCT expression for different cell types.

Implications of the regulation of RNS secretion, xCT expression, and survival of KSHV-infected cells by KSHV miRNAs

Our data indicate a role for KSHV miRNAs in the induction of RNS secretion and the protection of cells from RNS-induced cell death through the upregulation of xCT. Of additional relevance, we found that L-NMMA, an inhibitor of NOS, reduced KSHV miRNA-induced secretion of RNS and de novo KSHV infection. Additional studies are currently underway to elucidate the mechanism for these observations. Through the nitration of either extracellular or intracellular proteins, RNS activate Nrf-2 [34],[35],[60] and, therefore, may upregulate xCT expression through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. It is also conceivable that miR-K12-11 downregulation of BACH-1 increases expression of other ARE-containing genes involved in the induction of RNS or the protection of cells from oxidative stress, including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [34],[35]. Interestingly, HO-1 is expressed within KS lesions, and KSHV infection of endothelial cells induces activation of HO-1 [61]. It is probable that RNS secretion and downstream consequences are mediated through the collective targeting of multiple genes by KSHV miRNAs, and that this may occur within a variety of KSHV-infected cells with the capacity to secrete RNS, including endothelial cells and dendritic cells [25]. Characterization of miRNA regulation of RNS for a broader array of cell types relevant to KS pathogenesis is underway. Furthermore, our studies do not address whether KSHV miRNAs regulate secretion of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by infected cells, and it is conceivable that ROS play a role in the paracrine regulation of xCT or other events pertaining to KSHV infection. Studies are ongoing in our laboratory to define the relative importance of specific reactive species in the regulation of xCT expression and KSHV dissemination in the microenvironment.

Multiple studies implicate RNS in KS pathogenesis [46], [50], [62]–[66]. RNS and NOS are expressed within KS lesions [50],[62], and RNS induce endothelial cell migration, proliferation and angiogenesis [46] as well as T cell apoptosis [63]. Moreover, existing data support a role for KSHV in the regulation of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the KS microenvironment [50],[67], and cytokines associated with KS pathogenesis have been implicated in the activation of RNS secretion by macrophages [64],[65]. Interestingly, a recent publication demonstrated that Rac1 transgenic mice overexpressing NADPH-oxidase-dependent reactive species developed KS-like lesions and that systemic administration of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine reduced KS formation in this model [66]. Preliminary experiments performed in our laboratory have revealed that inhibition of NADPH-oxidase using diphenylene iodonium (DPI) also reduces KSHV miRNA-induced RNS secretion and infection of naïve cells (data not shown). In addition, at least one study has implicated cellular miRNAs in the regulation of Rac1 [68]. Therefore, our findings have important implications for paracrine regulation of cellular events pertaining to KS pathogenesis, and systemic inhibition of RNS may interfere with many of these events including viral dissemination and angiogenesis.

Clinical implications of xCT expression within KS lesions

We have demonstrated that xCT is expressed to a greater extent within more advanced KS lesions containing a greater number of KSHV-infected cells. To our knowledge, these are the first data to demonstrate xCT expression in clinical samples from KSHV-infected patients and are consistent with published data documenting higher KSHV intratumoral viral loads within more advanced KS lesions [52],[53]. Importantly, they also support our hypothesis that KSHV upregulation of xCT facilitates expansion of the KSHV reservoir in the microenvironment and KS progression. Moreover, our observation that spindle-shaped cells within stage III tumors express xCT is consistent with our data revealing upregulation of xCT and KSHV permissiveness for endothelial cells in vitro by KSHV miRNAs. Additional studies are needed to confirm whether KSHV miRNAs, BACH-1 and other putative xCT regulatory factors are differentially expressed during different stages of KS progression. Future translational studies may also shed light on whether quantifying xCT in clinical samples provides additional prognostic information for patients at risk for KS, and whether targeting xCT or its regulatory pathways will offer a useful approach for the treatment or prevention of this disease.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

BCBL-1 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 media (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.02% (wt/vol) sodium bicarbonate. Murine macrophages, RAW 264.7 cells (RAW cells), were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS. HeLa cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were grown in DMEM/F-12 50/50 medium (Cellgro) supplemented with 5% FBS and 0.001 mg/mL Puromycin (Sigma).

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies recognizing BACH-1 (H-130) and β-Actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Sigma (St. Louis, MO), respectively. Msg, Sul and L-NMMA were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). SNAP was purchased from Invitrogen (Eugene, Oregon).

Transfection assays

A 2.8 Kbp construct encoding 10 individual KSHV microRNAs (pcDNA-miRNA, containing miR-K12-1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8/9/11), and luciferase reporter constructs encoding complimentary sequences for individual miRNA (pGL3-miRNA sensors), have been validated previously in transfection assays for expression of KSHV miRNAs [44]. These constructs were used to transiently transfect RAW cells and HUVEC. For inhibition of mature miRNAs, 2'OMe RNA antagomirs were designed and purchased from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL) as previously described [44]. BACH-1, xCT, and non-target (control) siRNAs (ON-TARGET plus SMART pool) were also purchased from Dharmacon. Cells were transfected with 1 µg pcDNA-miRNA, 0.5 µg pGL3-miRNA sensors, 300 pmol 2'OMe RNA antagomirs, siRNAs, and/or 1 µg pcDNA for negative controls in 12-well plates using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and/or DharmaFECT Transfection Reagent (Dharmacon, Chicago, IL) for 48 h prior to their incubation with KSHV. For miRNA inhibitor assays, control cells were transfected with a 2'OMe RNA antagomir targeting miR-K12-12, a KSHV miRNA not encoded by the pcDNA-miRNA construct. For luciferase expression assays, cells were incubated with 100 µL lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), and luciferase activity determined within lysates using a Berthold FB12 luminometer (Titertek, Huntsville, AL). Light units were normalized to total protein levels for each sample using the BCA protein assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Transfection efficiency was assessed through co-transfection of a lacZ reporter construct kindly provided by Dr. Yusuf Hannun (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC), and β-galactosidase activity determined using a commercially available β-galactosidase enzyme assay system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). 3 independent transfections were performed for each experiment, and all samples were analyzed in triplicate for each transfection.

Nitrite quantification

Nitrite concentrations within culture supernatants were determined using the Griess Reagent System (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF and 5 mM Na3VO4. 30 µg of total cell lysate was resolved by SDS–10% PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes prior to incubation with antibodies for proteins of interest as well as β-Actin for loading controls. Immunoreactive bands were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence reaction (Perkin-Elmer), visualized by autoradiography, and quantified using Image-J software.

Bioinformatics analysis

The 3'UTR sequences of BACH-1 and other RNS-associated genes were obtained from Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org). 3'UTRs were analyzed to extract all potential KSHV miRNA binding sites using an ad-hoc scanning program specifically developed to assess 3'UTR KSHV miRNA seed sequence matching, as validated previously [36].

KSHV purification and infection

BCBL-1 cells were incubated with 0.6 mM valproic acid for 4–6 days, and KSHV was purified from culture supernatants by ultracentrifugation at 20,000×g for 3 h, 4°C. The viral pellet was resuspended in 1/100 the original volume in the appropriate culture media, and aliquots were frozen at −80°C. Target cells were incubated with concentrated virus in the presence of 8 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at 37°C. Inactivated KSHV used for negative controls was prepared by incubating viral stocks with ultraviolet (UV) light (1200 J/cm2) for 10′ in a CL-1000 Ultraviolet Crosslinker (UVP). The concentration of infectious viral particles used in each experiment (multiplicity of infection [MOI]) was calculated as previously described [57],[69].

Immunofluorescence assays and determination of relative infection rates

1×104 RAW cells or HUVEC were seeded per well in eight-well chamber slides (Thermo Fisher, Rochester, NY) and incubated with viral stocks (MOI∼10 for RAW cells, MOI∼0.1–1 for HUVEC) in the presence of 8 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at 37°C. 16 h later, cells were fixed and permeabilized following incubation with 1∶1 methanol-acetone for 10′ at −20°C. To reduce non-specific staining, slides were incubated in blocking reagent (10% normal goat serum, 3% bovine serum albumin, and 1% glycine) for 30′. To identify expression of the latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) of KSHV, cells were subsequently incubated with 1∶1000 dilution of an anti-LANA rat monoclonal antibody (ABI) for 1 h, followed by a goat anti-rat secondary antibody (1∶100) conjugated to Texas Red (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 25°C. Nuclei were subsequently counterstained with 0.5 µg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich) in 180 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Slides were examined at 60× magnification using a Nikon TE2000-E fluorescence microscope. Infection rates were determined following examination of at least 200 cells from within 5∼6 random fields in each group. For RAW cell experiments, comparisons between groups are reported as relative infections rates, where relative infection rate = # infected cells per 200 cells in experimental group/infected cells per 200 cells in control group. For RAW cell experiments, comparisons between groups are reported as relative infections rates, where relative infection rate = # infected cells per 200 cells in experimental group/# infected cells per 200 cells in control group. Since HUVEC are more permissive for infection and the majority of cells exhibit at least 1–2 LANA dots (episomes) at MOI∼1, we calculated relative LANA expression for HUVEC experiments as follows: relative LANA expression = # LANA dots per 200 cells in experimental group/# LANA dots per 200 cells in control group.

Biochemical assays

1×104 RAW cells or HUVEC were seeded per well in eight-well chamber slides and incubated with 10 mM Msg, 0.3 mM Sul or 0.01–1.0 mM L-NMMA for 12 h at 37°C, then incubated with cell-free KSHV for 2 h at 37°C. After 12 h, LANA expression within RAW cells was determined by IFA as outlined above.

Toll-like receptor inhibition

RAW cells were transfected with 1 µg of pcDNA-miRNA or empty vector control, and after 24 h, incubated with 10 mM of either drug vehicle or a double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) inhibitor 2-Aminopurine (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) for an additional 3 h. In parallel experiments, transfectants were incubated with 100 µM of MyD88 inhibitory peptide or control peptide (Imgenex, San Diego, CA) for an additional 24 h. Nitrite concentration was quantified within culture supernatants as detailed previously.

Cell viability assays

Cell viability was assessed using a standard MTT assay as previously described [70]. A total of 5×103 RAW cells were incubated in individual wells in a 96-well plate for 24 h. Serial dilutions of L-NMMA were then added and after 24–48 h, cells were incubated in 1 mg/ml of MTT solution (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 3 h then 50% DMSO overnight and optical density at 570 nm determined by spectrophotometer (Thermo Labsystems). For assessing cell viability in an environment of oxidative stress, we transfected or infected RAW cells with pcDNA-miRNA (pcDNA control) or KSHV (or UV-KSHV control) in the presence of siRNA targeting xCT or control non-target siRNA. Thereafter, cells were incubated for 12 h with SNAP and cell viability determined using 0.4% trypan blue (MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio) to identify dead cells under light microscopy. Relative differences for cell viability between groups was determined as follows: relative cell viability = dead cells per 200 cells in experimental group/dead cells per 200 cells in vehicle control group.

PCR

Total DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (QIAGEN). Briefly, cells were trypsinized for 5′ at 37°C and collected with 1 mL of ice-cold DMEM. Cells were pelleted at 2,000 rpm for 5′, washed, and resuspended in 200 µL of 1-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and total DNA was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) as previously demonstrated [41]. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Coding sequences for genes of interest and β-actin (loading control) were amplified from 200 ng input cDNA and using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-rad). Custom primers sequences used for amplification experiments (Operon) were as follows: LANA sense 5′ TCCCTCTACACTAAACCCAATA 3′; LANA antisense 5′ TTGCTAATCTCGTTGTCCC 3′; BACH-1 sense 5′ AGGACCTCACGGGCTCTA 3′; BACH-1 antisense 5′ ACCCAACCAGGGACACTC 3′; xCT sense 5′ GGTGGAACTGCTCGTAAT 3′; xCT antisense 5′ CAAAGATCGGGACTGCTA 3′; β-actin sense 5′ GGGAATGGGTCAGAAGGACT 3′; β-actin antisense 5′ TTTGATGTCACGCACGATTT 3′. Amplification experiments were carried out on an iCycler IQ Real-Time PCR Detection System, and cycle threshold (Ct) values tabulated in triplicate (DNA) or duplicate (cDNA) for each gene of interest for each experiment. “No template” (water) controls were also used to ensure minimal background contamination. Using mean Ct values tabulated for different experiments and Ct values for β-actin as loading controls, fold changes for experimental groups relative to assigned controls were calculated using automated iQ5 2.0 software (Bio-rad). Target amplification for semi-quantitative PCR (RT-PCR) was performed using a DNA thermal cycler (Gene Amp PCR System 9700, Applied Biosystems) under conditions of 94°C for 5′, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s. Amplicons were subsequently identified by ethidium bromide-loaded agarose gel electrophoresis.

Immunohistochemistry

Archived, paraffin-embedded KS skin lesions were collected from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Hollings Cancer Center Tumor Bank and the Maize Center for Dermatopathology (Charleston, S.C.). The diagnosis of KS and the histopathologic stage of each lesion were verified by an independent dermatopathologist. Histopathologic staging was determined using published criteria [71] to characterize lesions as patches, plaques or nodules (with nodules representing the most advanced lesional stage). Tissue sections were deparaffinized and hydrated through xylene and graded alcohol series, rinsed for 5′ in distilled water, incubated for 10′ in 3% hydrogen peroxide, and following PBS wash, incubated for 30′ in a commercial antigen retrieval solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at 100°C. Thereafter, all sections were incubated in 100% rabbit serum for 30′ to reduce non-specific staining then for 1 hour with either control preimmune rabbit sera or xCT antisera diluted 1∶400. In parallel, representative sections were incubated with 1∶1200 dilution of the anti-LANA rat monoclonal antibody (ABI). All sections were subsequently incubated for 30′ with a commercially available biotinylated secondary antibody and reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Bound antibodies were recognized using a 3,3′ - Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate and nuclei identified using either hematoxylin to contrast xCT expression, or Methyl Green to contrast LANA expression. xCT expression was determined for at least 8 independent tumors representing each of three histopathologic stages of KS (patches, plaques, and nodules). LANA expression was determined for patch and nodular lesions in this cohort.

Statistical analysis

Significance for differences between experimental and control groups was determined using the two-tailed Student's t-test (Excel 8.0), and p values <0.05 or <0.01 were considered significant or highly significant, respectively.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LuppiM

BarozziP

SchulzTF

SettiG

StaskusK

2000 Bone marrow failure associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection after transplantation. N Engl J Med 343 1378 1385

2. SoulierJ

GrolletL

OksenhendlerE

CacoubP

Cazals-HatemD

1995 Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood 86 1276 1280

3. CesarmanE

ChangY

MoorePS

SaidJW

KnowlesDM

1995 Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med 332 1186 1191

4. ChangY

CesarmanE

PessinMS

LeeF

CulpepperJ

1994 Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 266 1865 1869

5. EngelsEA

BiggarRJ

HallHI

CrossH

CrutchfieldA

2008 Cancer risk in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Int J Cancer 123 187 194

6. BonnetF

LewdenC

MayT

HeripretL

JouglaE

2004 Malignancy-related causes of death in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer 101 317 324

7. LebbeC

LegendreC

FrancesC

2008 Kaposi sarcoma in transplantation. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 22 252 261

8. ShepherdFA

MaherE

CardellaC

ColeE

GreigP

1997 Treatment of Kaposi's sarcoma after solid organ transplantation. J Clin Oncol 15 2371 2377

9. Cook-MozaffariP

NewtonR

BeralV

BurkittDP

1998 The geographical distribution of Kaposi's sarcoma and of lymphomas in Africa before the AIDS epidemic. Br J Cancer 78 1521 1528

10. VanniT

SprinzE

MachadoMW

Santana RdeC

FonsecaBA

2006 Systemic treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma: current status and perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev 32 445 455

11. MaurerT

PonteM

LeslieK

2007 HIV-associated Kaposi's sarcoma with a high CD4 count and a low viral load. N Engl J Med 357 1352 1353

12. KrownSE

LeeJY

DittmerDP

2008 More on HIV-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med 358 535 536; author reply 536

13. Von RoennJH

2003 Clinical presentations and standard therapy of AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 17 747 762

14. SchulzTF

2006 The pleiotropic effects of Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus. J Pathol 208 187 198

15. CampbellTB

BorokM

GwanzuraL

MaWhinneyS

WhiteIE

2000 Relationship of human herpesvirus 8 peripheral blood virus load and Kaposi's sarcoma clinical stage. AIDS 14 2109 2116

16. QuinlivanEB

ZhangC

StewartPW

KomoltriC

DavisMG

2002 Elevated virus loads of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated human herpesvirus 8 predict Kaposi's sarcoma disease progression, but elevated levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 do not. J Infect Dis 185 1736 1744

17. DupinN

FisherC

KellamP

AriadS

TulliezM

1999 Distribution of human herpesvirus-8 latently infected cells in Kaposi's sarcoma, multicentric Castleman's disease, and primary effusion lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 4546 4551

18. KedesDH

GanemD

1997 Sensitivity of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication to antiviral drugs. Implications for potential therapy. J Clin Invest 99 2082 2086

19. MartinDF

KuppermannBD

WolitzRA

PalestineAG

LiH

1999 Oral ganciclovir for patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis treated with a ganciclovir implant. Roche Ganciclovir Study Group. N Engl J Med 340 1063 1070

20. LambertM

GannageM

KarrasA

AbelM

LegendreC

2006 Differences in the frequency and function of HHV8-specific CD8 T cells between asymptomatic HHV8 infection and Kaposi sarcoma. Blood 108 3871 3880

21. BihlF

MosamA

HenryLN

ChisholmJV3rd

DollardS

2007 Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific immune reconstitution and antiviral effect of combined HAART/chemotherapy in HIV clade C-infected individuals with Kaposi's sarcoma. AIDS 21 1245 1252

22. GrundhoffA

GanemD

2004 Inefficient establishment of KSHV latency suggests an additional role for continued lytic replication in Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis. J Clin Invest 113 124 136

23. LebbeC

de CremouxP

MillotG

PodgorniakMP

VerolaO

1997 Characterization of in vitro culture of HIV-negative Kaposi's sarcoma-derived cells. In vitro responses to alfa interferon. Arch Dermatol Res 289 421 428

24. TsuchiyaS

KobayashiY

GotoY

OkumuraH

NakaeS

1982 Induction of maturation in cultured human monocytic leukemia cells by a phorbol diester. Cancer Res 42 1530 1536

25. LoM

WangYZ

GoutPW

2008 The x(c) - cystine/glutamate antiporter: a potential target for therapy of cancer and other diseases. J Cell Physiol 215 593 602

26. KaleebaJA

BergerEA

2006 Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus fusion-entry receptor: cystine transporter xCT. Science 311 1921 1924

27. VeettilMV

SadagopanS

Sharma-WaliaN

WangFZ

RaghuH

2008 Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus forms a multimolecular complex of integrins (alphaVbeta5, alphaVbeta3, and alpha3beta1) and CD98-xCT during infection of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells, and CD98-xCT is essential for the post entry stage of infection. J Virol 82 12126 12144

28. SirianniMC

VincenziL

FiorelliV

TopinoS

ScalaE

UcciniS

AngeloniA

FaggioniA

CerimeleD

CottoniF

AiutiF

EnsoliB

Gamma-interferon production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes from Kaposi's sarcoma patients: correlation with the presence of human herpesvirus-8 in peripheral blood monocytes and lesional macrophages. Blood 1998; 91(3) 968 76

29. RappoccioloG

JenkinsFJ

HenslerHR

PiazzaP

JaisM

2006 DC-SIGN is a receptor for human herpesvirus 8 on dendritic cells and macrophages. J Immunol 176 1741 1749

30. GanemD

ZiegelbauerJ

2008 MicroRNAs of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus. Semin Cancer Biol 18 437 440

31. CaiX

LuS

ZhangZ

GonzalezCM

DamaniaB

2005 Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 5570 5575

32. SamolsMA

HuJ

SkalskyRL

RenneR

2005 Cloning and identification of a microRNA cluster within the latency-associated region of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 79 9301 9305

33. PfefferS

SewerA

Lagos-QuintanaM

SheridanR

SanderC

2005 Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat Methods 2 269 276

34. SasakiH

SatoH

Kuriyama-MatsumuraK

SatoK

MaebaraK

2002 Electrophile response element-mediated induction of the cystine/glutamate exchange transporter gene expression. J Biol Chem 277 44765 44771

35. IshiiT

ItohK

TakahashiS

SatoH

YanagawaT

2000 Transcription factor Nrf2 coordinately regulates a group of oxidative stress-inducible genes in macrophages. J Biol Chem 275 16023 16029

36. SkalskyRL

SamolsMA

PlaisanceKB

BossIW

RivaA

2007 Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J Virol 81 12836 12845

37. DhakshinamoorthyS

JainAK

BloomDA

JaiswalAK

2005 Bach1 competes with Nrf2 leading to negative regulation of the antioxidant response element (ARE)-mediated NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene expression and induction in response to antioxidants. J Biol Chem 280 16891 16900

38. DhakshinamoorthyS

JaiswalAK

2002 c-Maf negatively regulates ARE-mediated detoxifying enzyme genes expression and anti-oxidant induction. Oncogene 21 5301 5312

39. HongYK

ForemanK

ShinJW

HirakawaS

CurryCL

2004 Lymphatic reprogramming of blood vascular endothelium by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Nat Genet 36 683 685

40. RodriguezA

VigoritoE

ClareS

WarrenMV

CouttetP

2007 Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science 316 608 611

41. ParsonsCH

AdangLA

OverdevestJ

O'ConnorCM

TaylorJR,Jr.

2006 KSHV targets multiple leukocyte lineages during long-term productive infection in NOD/SCID mice. J Clin Invest 116 1963 1973

42. GoutPW

KangYJ

BuckleyDJ

BruchovskyN

BuckleyAR

1997 Increased cystine uptake capability associated with malignant progression of Nb2 lymphoma cells. Leukemia 11 1329 1337

43. GoutPW

SimmsCR

RobertsonMC

2003 In vitro studies on the lymphoma growth-inhibitory activity of sulfasalazine. Anticancer Drugs 14 21 29

44. SamolsMA

SkalskyRL

MaldonadoAM

RivaA

LopezMC

2007 Identification of cellular genes targeted by KSHV-encoded microRNAs. PLoS Pathog 3 e65 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030065

45. GuidarelliA

ScioratiC

ClementiE

CantoniO

2006 Peroxynitrite mobilizes calcium ions from ryanodine-sensitive stores, a process associated with the mitochondrial accumulation of the cation and the enforced formation of species mediating cleavage of genomic DNA. Free Radic Biol Med 41 154 164

46. FreyRS

Ushio-FukaiM

MalikA

2009 NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Signaling in Endothelial Cells: Role in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal 11 791 810

47. LambethJD

2004 NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol 4 181 189

48. AsehnouneK

StrassheimD

MitraS

KimJY

AbrahamE

2004 Involvement of reactive oxygen species in Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of NF-kappa B. J Immunol 172 2522 2529

49. LeeSJ

KimKM

NamkoongS

KimCK

KangYC

2005 Nitric oxide inhibition of homocysteine-induced human endothelial cell apoptosis by down-regulation of p53-dependent Noxa expression through the formation of S-nitrosohomocysteine. J Biol Chem 280 5781 5788

50. MallerySR

PeiP

LandwehrDJ

ClarkCM

BradburnJE

2004 Implications for oxidative and nitrative stress in the pathogenesis of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Carcinogenesis 25 597 603

51. AlexanderJH

ReynoldsHR

StebbinsAL

DzavikV

HarringtonRA

2007 Effect of tilarginine acetate in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock: the TRIUMPH randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297 1657 1666

52. PakF

PyakuralP

KokhaeiP

KaayaE

PourfathollahAA

2005 HHV-8/KSHV during the development of Kaposi's sarcoma: evaluation by polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol 32 21 27

53. PyakurelP

MassambuC

Castanos-VelezE

EricssonS

KaayaE

2004 Human herpesvirus 8/Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus cell association during evolution of Kaposi sarcoma. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 36 678 683

54. GillPS

TsaiYC

RaoAP

SpruckCH3rd

ZhengT

1998 Evidence for multiclonality in multicentric Kaposi's sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 8257 8261

55. StaskusKA

ZhongW

GebhardK

HerndierB

WangH

1997 Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression in endothelial (spindle) tumor cells. J Virol 71 715 719

56. BoulangerE

DuprezR

DelabesseE

GabarreJ

MacintyreE

2005 Mono/oligoclonal pattern of Kaposi Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) episomes in primary effusion lymphoma cells. Int J Cancer 115 511 518

57. AdangLA

TomescuC

LawWK

KedesDH

2007 Intracellular Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus load determines early loss of immune synapse components. J Virol 81 5079 5090

58. BabcockGJ

DeckerLL

FreemanRB

Thorley-LawsonDA

1999 Epstein-barr virus-infected resting memory B cells, not proliferating lymphoblasts, accumulate in the peripheral blood of immunosuppressed patients. J Exp Med 190 567 576

59. AdangLA

ParsonsCH

KedesDH

2006 Asynchronous progression through the lytic cascade and variations in intracellular viral loads revealed by high-throughput single-cell analysis of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection. J Virol 80 10073 10082

60. ZhuJ

LiS

MarshallZM

WhortonAR

2008 A cystine-cysteine shuttle mediated by xCT facilitates cellular responses to S-nitrosoalbumin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294 C1012 1020

61. McAllisterSC

HansenSG

RuhlRA

RaggoCM

DeFilippisVR

2004 Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) induces heme oxygenase-1 expression and activity in KSHV-infected endothelial cells. Blood 103 3465 3473

62. WeningerW

RendlM

PammerJ

MildnerM

TschugguelW

1998 Nitric oxide synthases in Kaposi's sarcoma are expressed predominantly by vessels and tissue macrophages. Lab Invest 78 949 955

63. PyoCW

LeeSH

ChoiSY

2008 Oxidative stress induces PKR-dependent apoptosis via IFN-gamma activation signaling in Jurkat T cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 377 1001 1006

64. YanagisawaN

ShimadaK

MiyazakiT

KumeA

KitamuraY

2008 Enhanced production of nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, and pro-inflammatory cytokines in very long chain saturated fatty acid-accumulated macrophages. Lipids Health Dis 7 48

65. KimSY

KimTB

MoonKA

KimTJ

ShinD

2008 Regulation of pro-inflammatory responses by lipoxygenases via intracellular reactive oxygen species in vitro and in vivo. Exp Mol Med 40 461 476

66. MaQ

CavallinLE

YanB

ZhuS

DuranEM

2009 Antitumorigenesis of antioxidants in a transgenic Rac1 model of Kaposi's sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 8683 8688

67. ThurauM

MarquardtG

Gonin-LaurentN

WeinlanderK

NaschbergerE

2009 Viral inhibitor of apoptosis vFLIP/K13 protects endothelial cells against superoxide-induced cell death. J Virol 83 598 611

68. YuJY

ChungKH

DeoM

ThompsonRC

TurnerDL

2008 MicroRNA miR-124 regulates neurite outgrowth during neuronal differentiation. Exp Cell Res 314 2618 2633

69. TomescuC

LawWK

KedesDH

2003 Surface downregulation of major histocompatibility complex class I, PE-CAM, and ICAM-1 following de novo infection of endothelial cells with Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 77 9669 9684

70. TsutsumiS

ScrogginsB

KogaF

LeeMJ

TrepelJ

2008 A small molecule cell-impermeant Hsp90 antagonist inhibits tumor cell motility and invasion. Oncogene 27 2478 2487

71. GraysonW

PantanowitzL

2008 Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol 3 31

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Polyoma Virus-Induced Osteosarcomas in Inbred Strains of Mice: Host Determinants of MetastasisČlánek Nutrient Availability as a Mechanism for Selection of Antibiotic Tolerant within the CF AirwayČlánek Type I Interferon Induction Is Detrimental during Infection with the Whipple's Disease Bacterium,

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 1- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- CD8+ T Cell Control of HIV—A Known Unknown

- The Deadly Chytrid Fungus: A Story of an Emerging Pathogen

- Characterization of the Oral Fungal Microbiome (Mycobiome) in Healthy Individuals

- Polyoma Virus-Induced Osteosarcomas in Inbred Strains of Mice: Host Determinants of Metastasis

- Within-Host Evolution of in Four Cases of Acute Melioidosis

- The Type III Secretion Effector NleE Inhibits NF-κB Activation

- Protease-Sensitive Synthetic Prions

- Histone Deacetylases Play a Major Role in the Transcriptional Regulation of the Life Cycle

- Parasite-Derived Plasma Microparticles Contribute Significantly to Malaria Infection-Induced Inflammation through Potent Macrophage Stimulation

- β-Neurexin Is a Ligand for the MSCRAMM SdrC

- Structure of the HCMV UL16-MICB Complex Elucidates Select Binding of a Viral Immunoevasin to Diverse NKG2D Ligands

- Nutrient Availability as a Mechanism for Selection of Antibiotic Tolerant within the CF Airway

- Like Will to Like: Abundances of Closely Related Species Can Predict Susceptibility to Intestinal Colonization by Pathogenic and Commensal Bacteria

- Importance of the Collagen Adhesin Ace in Pathogenesis and Protection against Experimental Endocarditis

- N-glycan Core β-galactoside Confers Sensitivity towards Nematotoxic Fungal Galectin CGL2

- Two Plant Viral Suppressors of Silencing Require the Ethylene-Inducible Host Transcription Factor RAV2 to Block RNA Silencing

- A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of Motility Induces the Posttranslational Modification of Myosin Light Chain-1 and Inhibits Myosin Motor Activity

- Temporal Proteome and Lipidome Profiles Reveal Hepatitis C Virus-Associated Reprogramming of Hepatocellular Metabolism and Bioenergetics

- Marburg Virus Evades Interferon Responses by a Mechanism Distinct from Ebola Virus

- B Cell Activation by Outer Membrane Vesicles—A Novel Virulence Mechanism

- Killing a Killer: What Next for Smallpox?

- PPARγ Controls Dectin-1 Expression Required for Host Antifungal Defense against

- TRIM5α Modulates Immunodeficiency Virus Control in Rhesus Monkeys

- Immature Dengue Virus: A Veiled Pathogen?

- Panton-Valentine Leukocidin Is a Very Potent Cytotoxic Factor for Human Neutrophils

- In Vivo CD8+ T-Cell Suppression of SIV Viremia Is Not Mediated by CTL Clearance of Productively Infected Cells

- Placental Syncytiotrophoblast Constitutes a Major Barrier to Vertical Transmission of

- Type I Interferon Induction Is Detrimental during Infection with the Whipple's Disease Bacterium,

- The M/GP Glycoprotein Complex of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Binds the Sialoadhesin Receptor in a Sialic Acid-Dependent Manner

- Social Motility in African Trypanosomes

- Melanoma Differentiation-Associated Gene 5 (MDA5) Is Involved in the Innate Immune Response to Infection In Vivo

- Protection of Mice against Lethal Challenge with 2009 H1N1 Influenza A Virus by 1918-Like and Classical Swine H1N1 Based Vaccines

- Upregulation of xCT by KSHV-Encoded microRNAs Facilitates KSHV Dissemination and Persistence in an Environment of Oxidative Stress

- Persistent ER Stress Induces the Spliced Leader RNA Silencing Pathway (SLS), Leading to Programmed Cell Death in

- Evolutionary Trajectories of Beta-Lactamase CTX-M-1 Cluster Enzymes: Predicting Antibiotic Resistance

- Nucleoporin 153 Arrests the Nuclear Import of Hepatitis B Virus Capsids in the Nuclear Basket

- CD8+ Lymphocytes Control Viral Replication in SIVmac239-Infected Rhesus Macaques without Decreasing the Lifespan of Productively Infected Cells

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Panton-Valentine Leukocidin Is a Very Potent Cytotoxic Factor for Human Neutrophils

- CD8+ T Cell Control of HIV—A Known Unknown

- Polyoma Virus-Induced Osteosarcomas in Inbred Strains of Mice: Host Determinants of Metastasis

- The Deadly Chytrid Fungus: A Story of an Emerging Pathogen

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání