-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaPutting the Brakes on Huntington Disease in a Mouse Experimental Model

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005409

Category: Perspective

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005409Summary

article has not abstract

Huntington disease (HD) is a hereditary neurodegenerative disorder that causes a progressively debilitating impact on movement, cognition, speech, and mood. It most commonly develops during adulthood and worsens over a 10–15-year period. The genetic basis of HD is an expansion of the (CAG)n trinucleotide repeat in the first exon of the HTT gene [1,2]. Although the function of the normal HTT protein is not well established, in-frame repeat expansion results in the accumulation of an abnormally long polyglutamine tract, which is believed to contribute to mutant protein toxicity and neural degeneration [3]. Consequently, CAG repeat length is inversely correlated with age of onset and severity of disease. Disease-size CAG repeats are prone to further lengthening, which leads to two distinct aspects of their instability: expansions during intergenerational transmissions and somatic expansions occurring throughout the lifetime of an individual (Fig 1A).

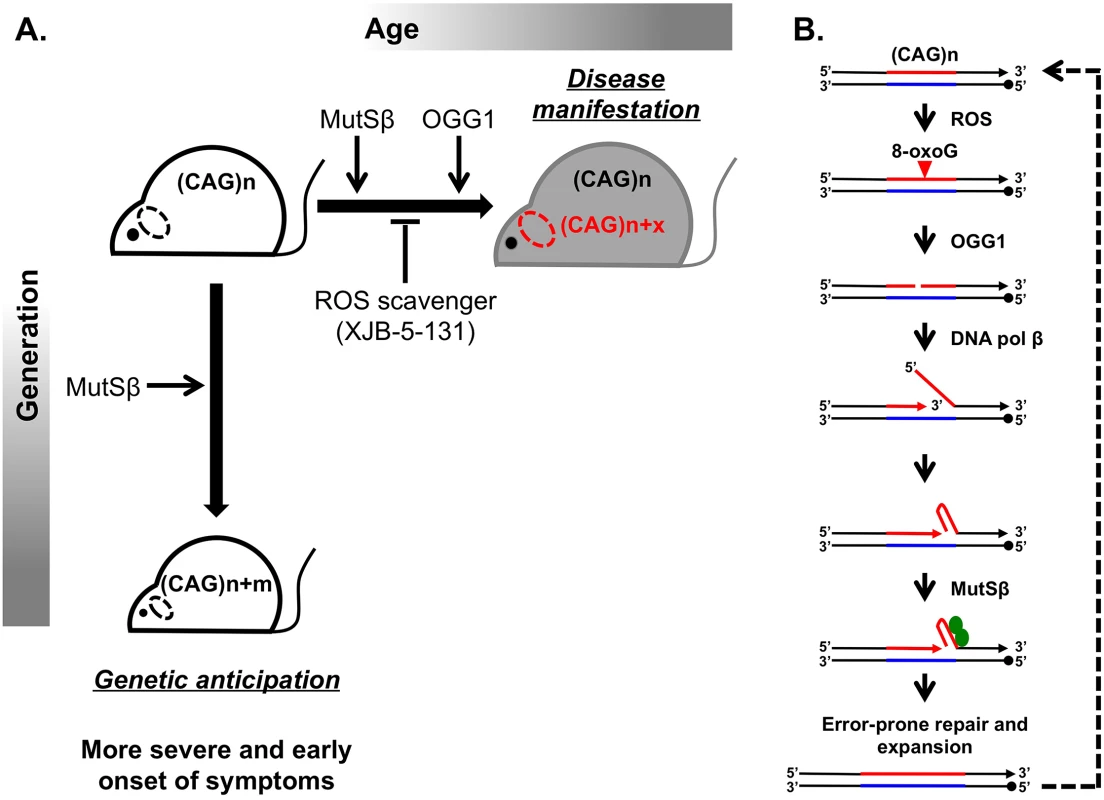

Fig. 1. Inhibiting somatic expansions delays onset of disease in a Huntington mouse model.

(A) Expanded (CAG)n repeats are more susceptible to undergoing further expansions, contributing to two distinct aspects of their instability. Intergenerational transmission (vertical axis) is the general increase in repeat length (m) from parent to offspring, which has been found to be dependent on MutSβ in mice. Somatic expansions (horizontal axis) are an increase in repeat length beyond the inherited length throughout the lifetime of an individual (x) and are dependent on both MutSβ and 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1) in mice. Somatic expansions exhibit tissue-specific differences and, in HD, occur predominantly in the brain (dotted oval). The absence of OGG1 significantly delays the age of disease onset in Hdh mice. This delayed onset of disease symptoms is recapitulated by inhibiting somatic expansion with a ROS scavenger, XJB-5-131. (B) Aberrant repair of DNA oxidative damage at (CAG)n repeats promotes somatic expansions. Initiation of 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) base excision repair by OGG1 leads to a nick in the damaged DNA strand. Subsequent strand-displacement synthesis by DNA polymerase β creates a 5ʹ-flap. A hairpin formed by CAG repeats in this flap could be stabilized by MutSβ and incorporated into the repaired DNA to generate an expansion. This expanded region is further subjected to ROS, possibly generating “toxic oxidation cycles” (dotted line). An outstanding question in the field is whether somatic expansions contribute to disease. The problem is that somatic expansions occur in the context of expressing an already toxic protein, making it difficult to address this question. Two commonly discussed ideas are that (i) disease arises with time because of expression of the toxic protein or RNA or that (ii) the onset of disease depends on gradual accumulation of somatic expansions in patients’ tissues throughout life. To distinguish between these scenarios, it is critical to assess to what extent, if any, somatic expansions accelerate disease progression.

Since 1993 when the cause of HD was first reported, substantial effort has been made to understand the molecular basis of repeat expansions and the mechanisms of disease pathophysiology. While these studies were conducted in various model systems [4,5], mouse models appeared to be particularly well suited for unraveling disease pathophysiology. Despite a few caveats, such as the much longer CAG repeat lengths (i.e., >100 repeats) needed to recapitulate disease symptoms and the relatively small-scale of expansions, mouse models of HD have led to principal contributions in the field. First, they exhibit both intergenerational and somatic repeat expansions. Second, candidate gene analysis uncovered a surprising role of the mismatch repair (MMR) complex MutSβ in promoting rather than protecting against CAG repeat expansions (Fig 1) [6,7].

A breakthrough in distinguishing between the molecular mechanisms of intergenerational and somatic expansions came with the discovery that loss of 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1) specifically decreased CAG expansions in somatic cells, but it had no effect on intergenerational transmissions [8]. The main function of OGG1 is to remove 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), a mutagenic base by-product accumulating in DNA after its exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS). It was hypothesized, therefore, that aberrant repair of DNA oxidative damage specifically elevates repeat instability in long-lived differentiated cells, such as neurons. OGG1 excises 8-oxoG, generating a nick in the damaged DNA strand, which is further processed to permit DNA repair synthesis. DNA polymerase β then conducts strand-displacement synthesis, creating a 5′-flap. Because CAG repeats are prone to hairpin formation, a hairpin formed in the flap could be stabilized by the MutSβ complex and incorporated into the repaired DNA to generate an expansion. This expanded region is further subjected to ROS, possibly generating “toxic oxidation cycles” [8] in which many repeats can be added over time (Fig 1B). In nondividing cells, repetitive hairpins can only be formed during DNA repair synthesis; hence, repeat expansions are triggered by their oxidative damage followed by aberrant base excision repair. In dividing cells, repetitive hairpins are readily formed during DNA replication [9], which makes expansions during intergenerational transmissions independent of OGG1.

The work of Budworth et al. in this issue of PLOS Genetics addresses the role of somatic expansions in disease pathophysiology by further characterizing OGG1 null mice [10]. In effect, this knockout serves as a convenient separation of function tool, since it affects somatic but not intergenerational expansions of CAG repeats in the HD mouse. This is an important advance from previous studies knocking out MMR proteins in mice because it is difficult to distinguish the contribution from both processes on disease progression. They found that decreasing somatic expansion in OGG1-deficient mice delays the onset of disease symptoms, as assessed by endurance tests such as rotorod performance and grip strength analysis, compared to OGG1+ littermates that inherit the same disease-length allele. This conclusion is hard won, since there are several challenges to addressing somatic instability and disease progression. Primarily, there is large variability in both expansion sizes and behavioral outcomes among individual mice. Furthermore, the observed changes in the average repeat lengths are relatively small. The authors deal with these challenges through their experimental design and data analysis. First, they evaluate a large sample size to increase statistical power (1,200 animals). Second, they bin age groups of 5 or 10 weeks and assess behavioral performance before obtaining tissue to test repeat length. This strategy seems superior to tracking a group of animals over time, as it precludes the influence of sampling bias on testing outcomes. Finally, the authors employ statistical tests that look for differences between two repeat length distributions rather than their average values alone.

Because decreasing somatic expansions in OGG1 knockouts delayed disease progression, Budworth et al. attempted to pharmacologically inhibit somatic expansion by treating HD mice with a mitochondrial scavenger of ROS called XJB-5-131. As previously reported, this treatment improved rotarod performance in Hdh (Q150/Q150) mice [11]. Here, the authors demonstrate that these mice also show decreased somatic expansions (Fig 1A). Taken together, these results are strongly indicative that somatic expansions contribute to HD progression, specifically to the “when” rather than “if” of disease onset. As a word of caution, a formal possibility still remains that the absence of OGG1 or decreased ROS could affect HTT toxicity indirectly. These findings are very promising in opening up a new therapeutic target area, since XJB-5-131 or similar pharmacological inhibitors of oxidative damage should have minimal toxic effects and little increase in genomic instability.

HD is just one example of more than 30 diseases caused by unstable microsatellite sequences, many of which also demonstrate somatic instability. It is unclear how the mechanism of repeat instability differs for different repetitive sequences or even for the same repeat located at other genomic loci. Testing OGG1-dependent somatic instability in mouse models of different repeat expansion diseases such as myotonic dystrophy caused by (CTG)n repeats, fragile X syndrome caused by (CGG)n repeats, spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 caused by (AATCT)n repeats, and several spinocerebellar ataxias caused by other (CAG)n repeats will shed light on the extent to which inhibiting oxidative damage may be a common therapeutic course for different repeat expansion diseases. As a first pass, XJB-5-131 treatment will be a useful discriminator to implicate oxidative damage in somatic expansion of different microsatellite sequence. It remains to be seen what is the contribution of various molecular mechanisms on overall somatic instability in HD, but the work from Budworth et al. provides the important foundation that inhibiting somatic expansion is a worthwhile intervention and endeavor toward improving HD patient care.

Zdroje

1. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group (1993) A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. Cell 72 : 971–983. 8458085

2. Andrew SE, Goldberg YP, Kremer B, Telenius H, Theilmann J, et al. (1993) The relationship between trinucleotide (CAG) repeat length and clinical features of Huntington's disease. Nat Genet 4 : 398–403. 8401589

3. Zoghbi HY, Orr HT (2000) Glutamine repeats and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci 23 : 217–247. 10845064

4. Mirkin SM (2007) Expandable DNA repeats and human disease. Nature 447 : 932–940. 17581576

5. Usdin K, House NC, Freudenreich CH (2015) Repeat instability during DNA repair: Insights from model systems. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 50 : 142–167. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2014.999192 25608779

6. Manley K, Shirley TL, Flaherty L, Messer A (1999) Msh2 deficiency prevents in vivo somatic instability of the CAG repeat in Huntington disease transgenic mice. Nat Genet 23 : 471–473. 10581038

7. Kovtun IV, McMurray CT (2001) Trinucleotide expansion in haploid germ cells by gap repair. Nat Genet 27 : 407–411. 11279522

8. Kovtun IV, Liu Y, Bjoras M, Klungland A, Wilson SH, et al. (2007) OGG1 initiates age-dependent CAG trinucleotide expansion in somatic cells. Nature 447 : 447–452. 17450122

9. Kim JC, Mirkin SM (2013) The balancing act of DNA repeat expansions. Curr Opin Genet Dev 23 : 280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.04.009 23725800

10. Budworth H, Harris FR, Williams P, Lee DY, Holt A, Pahnke J, Szczesny B, Acevedo-Torres K, Ayala-Pena S, McMurray CT. (2015) Suppression of somatic expansion delays the onset of pathophysiology in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. PLoS Genet 11(8): e1005267.

11. Xun Z, Rivera-Sanchez S, Ayala-Pena S, Lim J, Budworth H, et al. (2012) Targeting of XJB-5-131 to mitochondria suppresses oxidative DNA damage and motor decline in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. Cell Rep 2 : 1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.001 23122961

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Loss and Gain of Natural Killer Cell Receptor Function in an African Hunter-Gatherer PopulationČlánek Let-7 Represses Carcinogenesis and a Stem Cell Phenotype in the Intestine via Regulation of Hmga2Článek Binding of Multiple Rap1 Proteins Stimulates Chromosome Breakage Induction during DNA ReplicationČlánek SLIRP Regulates the Rate of Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis and Protects LRPPRC from DegradationČlánek Protein Composition of Infectious Spores Reveals Novel Sexual Development and Germination Factors inČlánek The Formin Diaphanous Regulates Myoblast Fusion through Actin Polymerization and Arp2/3 RegulationČlánek Runx1 Transcription Factor Is Required for Myoblasts Proliferation during Muscle Regeneration

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 8

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Putting the Brakes on Huntington Disease in a Mouse Experimental Model

- Identification of Driving Fusion Genes and Genomic Landscape of Medullary Thyroid Cancer

- Evidence for Retromutagenesis as a Mechanism for Adaptive Mutation in

- TSPO, a Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Protein, Controls Ethanol-Related Behaviors in

- Evidence for Lysosome Depletion and Impaired Autophagic Clearance in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Type SPG11

- Loss and Gain of Natural Killer Cell Receptor Function in an African Hunter-Gatherer Population

- Trans-Reactivation: A New Epigenetic Phenomenon Underlying Transcriptional Reactivation of Silenced Genes

- Early Developmental and Evolutionary Origins of Gene Body DNA Methylation Patterns in Mammalian Placentas

- Strong Selective Sweeps on the X Chromosome in the Human-Chimpanzee Ancestor Explain Its Low Divergence

- Dominance of Deleterious Alleles Controls the Response to a Population Bottleneck

- Transient 1a Induction Defines the Wound Epidermis during Zebrafish Fin Regeneration

- Systems Genetics Reveals the Functional Context of PCOS Loci and Identifies Genetic and Molecular Mechanisms of Disease Heterogeneity

- A Genome Scale Screen for Mutants with Delayed Exit from Mitosis: Ire1-Independent Induction of Autophagy Integrates ER Homeostasis into Mitotic Lifespan

- Non-synonymous FGD3 Variant as Positional Candidate for Disproportional Tall Stature Accounting for a Carcass Weight QTL () and Skeletal Dysplasia in Japanese Black Cattle

- The Relationship between Gene Network Structure and Expression Variation among Individuals and Species

- Calmodulin Methyltransferase Is Required for Growth, Muscle Strength, Somatosensory Development and Brain Function

- The Wnt Frizzled Receptor MOM-5 Regulates the UNC-5 Netrin Receptor through Small GTPase-Dependent Signaling to Determine the Polarity of Migrating Cells

- Nbs1 ChIP-Seq Identifies Off-Target DNA Double-Strand Breaks Induced by AID in Activated Splenic B Cells

- CCNYL1, but Not CCNY, Cooperates with CDK16 to Regulate Spermatogenesis in Mouse

- Evidence for a Common Origin of Blacksmiths and Cultivators in the Ethiopian Ari within the Last 4500 Years: Lessons for Clustering-Based Inference

- Of Fighting Flies, Mice, and Men: Are Some of the Molecular and Neuronal Mechanisms of Aggression Universal in the Animal Kingdom?

- Hypoxia and Temperature Regulated Morphogenesis in

- The Homeodomain Iroquois Proteins Control Cell Cycle Progression and Regulate the Size of Developmental Fields

- Evolution and Design Governing Signal Precision and Amplification in a Bacterial Chemosensory Pathway

- Rac1 Regulates Endometrial Secretory Function to Control Placental Development

- Let-7 Represses Carcinogenesis and a Stem Cell Phenotype in the Intestine via Regulation of Hmga2

- Functions as a Positive Regulator of Growth and Metabolism in

- The Nucleosome Acidic Patch Regulates the H2B K123 Monoubiquitylation Cascade and Transcription Elongation in

- Rhoptry Proteins ROP5 and ROP18 Are Major Murine Virulence Factors in Genetically Divergent South American Strains of

- Exon 7 Contributes to the Stable Localization of Xist RNA on the Inactive X-Chromosome

- Regulates Refractive Error and Myopia Development in Mice and Humans

- mTORC1 Prevents Preosteoblast Differentiation through the Notch Signaling Pathway

- Regulation of Gene Expression Patterns in Mosquito Reproduction

- Molecular Basis of Gene-Gene Interaction: Cyclic Cross-Regulation of Gene Expression and Post-GWAS Gene-Gene Interaction Involved in Atrial Fibrillation

- The Spalt Transcription Factors Generate the Transcriptional Landscape of the Wing Pouch Central Region

- Binding of Multiple Rap1 Proteins Stimulates Chromosome Breakage Induction during DNA Replication

- Functional Divergence in the Role of N-Linked Glycosylation in Smoothened Signaling

- YAP1 Exerts Its Transcriptional Control via TEAD-Mediated Activation of Enhancers

- Coordinated Evolution of Influenza A Surface Proteins

- The Evolutionary Potential of Phenotypic Mutations

- Genome-Wide Association and Trans-ethnic Meta-Analysis for Advanced Diabetic Kidney Disease: Family Investigation of Nephropathy and Diabetes (FIND)

- New Routes to Phylogeography: A Bayesian Structured Coalescent Approximation

- SLIRP Regulates the Rate of Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis and Protects LRPPRC from Degradation

- Satellite DNA Modulates Gene Expression in the Beetle after Heat Stress

- SHOEBOX Modulates Root Meristem Size in Rice through Dose-Dependent Effects of Gibberellins on Cell Elongation and Proliferation

- Reduced Crossover Interference and Increased ZMM-Independent Recombination in the Absence of Tel1/ATM

- Suppression of Somatic Expansion Delays the Onset of Pathophysiology in a Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease

- Protein Composition of Infectious Spores Reveals Novel Sexual Development and Germination Factors in

- The Evolutionarily Conserved LIM Homeodomain Protein LIM-4/LHX6 Specifies the Terminal Identity of a Cholinergic and Peptidergic . Sensory/Inter/Motor Neuron-Type

- SmD1 Modulates the miRNA Pathway Independently of Its Pre-mRNA Splicing Function

- piRNAs Are Associated with Diverse Transgenerational Effects on Gene and Transposon Expression in a Hybrid Dysgenic Syndrome of .

- Retinoic Acid Signaling Regulates Differential Expression of the Tandemly-Duplicated Long Wavelength-Sensitive Cone Opsin Genes in Zebrafish

- The Formin Diaphanous Regulates Myoblast Fusion through Actin Polymerization and Arp2/3 Regulation

- Genome-Wide Analysis of PAPS1-Dependent Polyadenylation Identifies Novel Roles for Functionally Specialized Poly(A) Polymerases in

- Runx1 Transcription Factor Is Required for Myoblasts Proliferation during Muscle Regeneration

- Regulation of Mutagenic DNA Polymerase V Activation in Space and Time

- Variability of Gene Expression Identifies Transcriptional Regulators of Early Human Embryonic Development

- The Drosophila Gene Interacts Genetically with and Shows Female-Specific Effects of Divergence

- Functional Activation of the Flagellar Type III Secretion Export Apparatus

- Retrohoming of a Mobile Group II Intron in Human Cells Suggests How Eukaryotes Limit Group II Intron Proliferation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Exon 7 Contributes to the Stable Localization of Xist RNA on the Inactive X-Chromosome

- YAP1 Exerts Its Transcriptional Control via TEAD-Mediated Activation of Enhancers

- SmD1 Modulates the miRNA Pathway Independently of Its Pre-mRNA Splicing Function

- Molecular Basis of Gene-Gene Interaction: Cyclic Cross-Regulation of Gene Expression and Post-GWAS Gene-Gene Interaction Involved in Atrial Fibrillation

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání