-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaEvolution and Design Governing Signal Precision and Amplification in a Bacterial Chemosensory Pathway

Deciphering the circuit design of signal transduction networks is a fundamental question in cell biology. This task is challenging because many pathways are branched and control multiple cellular processes in response to one or several environmental signals. Studying pathway diversification in bacteria could be a powerful approach because these organisms contain so-called chemosensory systems, modular signaling units that have been adapted multiple times independently to regulate a large number of physiological processes. Here, we studied one such system, the Myxococcus xanthus chemosensory pathway (Frz) that controls the directionality of two distinct motility systems (A - and S-motility). By experimentally uncoupling the regulations, we found that the Frz pathway evolved from a simpler ancestral system that only controlled S-motility originally. Two major pathway remodeling events allowed the recruitment of A-motility to the regulation, (i) the duplication of a connector protein which created the branch point and (ii), the acquisition of a signal amplification mechanism to allow signal partitioning at the branch point. These results reveal the core structure of a complex chemosensory system and generally suggest that gene duplication and signal amplification underlie the diversification of signal transduction pathways.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005460

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005460Summary

Deciphering the circuit design of signal transduction networks is a fundamental question in cell biology. This task is challenging because many pathways are branched and control multiple cellular processes in response to one or several environmental signals. Studying pathway diversification in bacteria could be a powerful approach because these organisms contain so-called chemosensory systems, modular signaling units that have been adapted multiple times independently to regulate a large number of physiological processes. Here, we studied one such system, the Myxococcus xanthus chemosensory pathway (Frz) that controls the directionality of two distinct motility systems (A - and S-motility). By experimentally uncoupling the regulations, we found that the Frz pathway evolved from a simpler ancestral system that only controlled S-motility originally. Two major pathway remodeling events allowed the recruitment of A-motility to the regulation, (i) the duplication of a connector protein which created the branch point and (ii), the acquisition of a signal amplification mechanism to allow signal partitioning at the branch point. These results reveal the core structure of a complex chemosensory system and generally suggest that gene duplication and signal amplification underlie the diversification of signal transduction pathways.

Introduction

In living cells, adaptation to rapid changes in environmental conditions requires coordinated rearrangements of basic cellular processes to adjust the cellular homeostasis to the new conditions. In general, receptor molecules sense environmental changes and translate them into a cellular response by phosphorylation of a downstream regulator. Because the cellular response must be integrated to various cellular processes, the phosphorylation cascade frequently involves a number of intermediates, allowing multiple regulation layers and branch points (nodes) in the regulatory circuit [1,2]. Thus, for a given pathway, identifying nodes and understanding how they participate in the regulation is of fundamental importance to elucidate how signals are integrated toward a cellular response. One possible approach to elucidate the underlying structure of a multi-component signaling pathway is to study its evolution because the diversification of signaling pathways is under strong selection pressure and signaling intermediates may have been selected in some organisms [3]. Consequently, some proteins that appear central to the regulation in a given genetic context may in fact be dispensable in a different context where their function is not required. For example, a protein that insulates a pathway from another will become dispensable if the secondary pathway is removed. Thus, tracking back the evolutionary history of signaling pathways can reveal core regulatory motifs and principles underlying the acquisition of additional regulations [4,5]. Bacteria are exceptional model systems for such studies because they are highly tractable experimentally and thousands of genome have been sequenced.

In bacteria, signal transduction networks are frequently formed by so-called two-component systems. The core motif of a two-component system generally consists of a receptor, generally a membrane localized sensor histidine kinase (HK) and its cognate response regulator (RR). Following activation by environmental signals, the HK uses ATP to autophosphorylate on a conserved histidine residue and the phosphoryl group is transferred to a conserved Asp residue of the RR protein, regulating a number of downstream processes, gene expression, secondary messenger synthesis or protein-protein interaction [6]. HK/RR pairs often form autonomous signal transduction systems [7], but they are also modular and can be incorporated in more complex circuits, multiple phosphorelay systems and chemosensory-type systems [1,8]. In the enteric chemotaxis (Che) system, the HK (CheA) does not act directly as a sensor but resides in the cytosol where it is activated by a transmembrane Methyl-accepting protein (Mcp) via a coupling protein (CheW). Following activation, CheA transfers a phosphoryl group to two RR domains; one of them, the CheY protein constitutes the system output and interacts with a protein of the flagellum (FliM) to switch the direction of its rotation. The second RR domain is carried by the CheB methyl esterase, and its phosphorylation activates the de-methylation of the Mcp to reset the system to a pre-signaling state (adaptation, for a review, see [9]). In many bacteria, the core signaling apparatus of the enteric Che system has been coopted to the regulation of processes other than chemotaxis, such as surface motility, gene regulation and even cellular differentiation [8,10,11]. The genetic structure of these non-canonical chemosensory systems is quite diverse and their circuit architecture is generally poorly understood [8,10,11]. In this study, we investigate the evolution and genetic structure of a chemosensory-type system that controls two distinct motility machineries in Myxococcus xanthus.

Myxococcus xanthus, a gram negative deltaproteobacterium, uses surface motility to form multicellular spore-filled fruiting bodies when nutrient sources become scarce. During this process, the Myxococcus cells can move as single cells or within large coordinated cell groups and reverse their direction of movement in a process where the cell poles rapidly exchange roles [12]. In the cell groups, a Type-IV pilus (Tfp) assembled at the cell pole (the leading pole) acts as grappling hooks and pulls the cell forward by retraction (Fig 1A, [13]). Tfps retract when they are in contact with a cell surface-exposed exopolysaccharide (fibrils), giving rise to a cooperative form of group movements called S (Social)-motility [14]. At the colony edges, the single cells are propelled by the recently characterized Agl-Glt apparatus, otherwise called the A (Adventurous)-motility system [15,16]. The Agl-Glt complex is assembled at the leading cell pole and moves directionally towards the lagging cell pole, promoting movement when it contacts the underlying surface (Fig 1A, [12,16,17]). Thus, both motility systems are activated at the leading cell pole and their activation is switched coordinately to the opposite cell pole when cells reverse (Fig 1A, [18–20]). The frequency of the reversal events is under the genetic control of a chemosensory-like system called Frz [21]. This control is essential for Myxococcus multicellular behaviors because frz mutants that reverse at low frequencies do not form fruiting bodies and form characteristic “frizzy” filament structures [22].

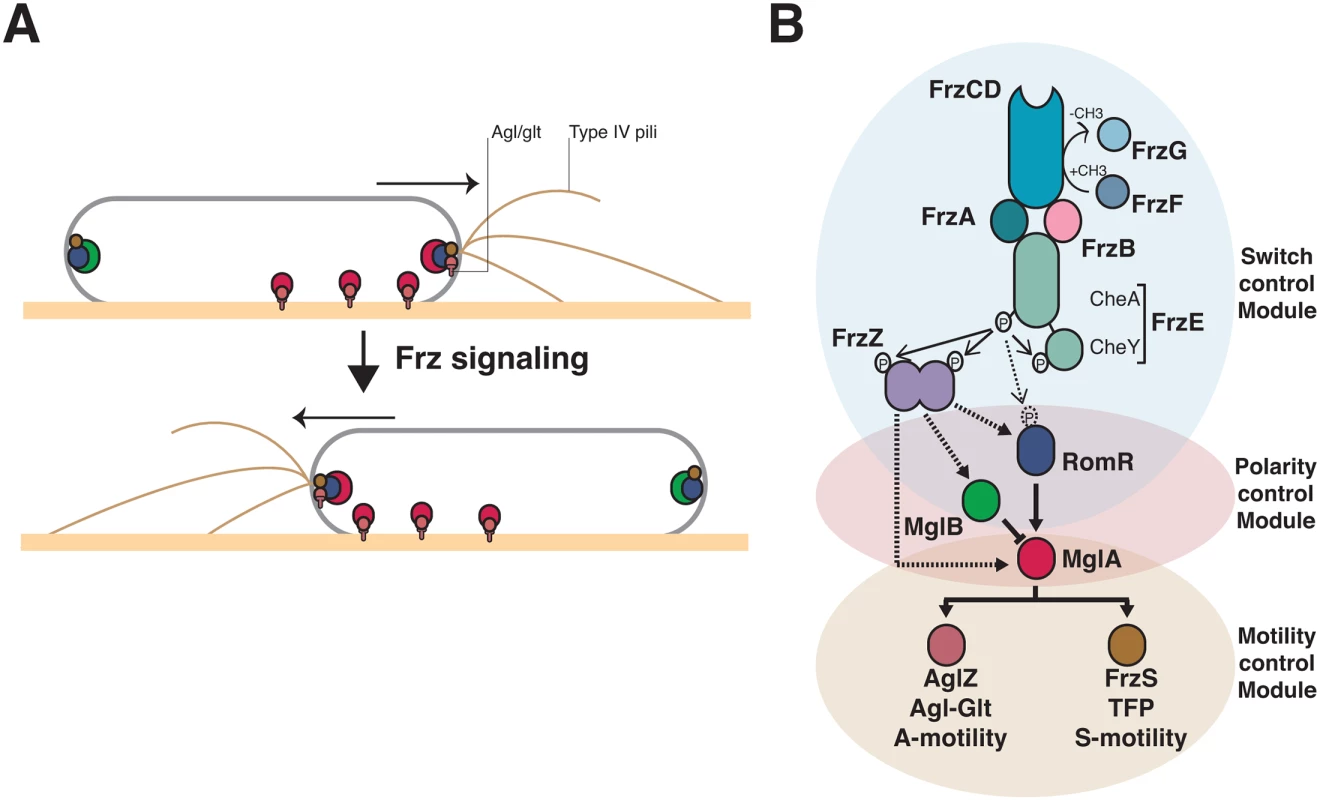

Fig. 1. Genetic control of the Myxococcus A- and S-motility machineries.

(A) Dynamics of the motility machineries and their associated regulators during the reversal cycle. MglA (Red circle) is recruited by RomR (Blue circle) to the leading cell pole where it activates A- motility (Agl/Glt, T-shapes) and S-motility (Type-IV pili) at least partially through AglZ and FrzS, respectively (Crimson and Brown circles). At the lagging cell pole, MglB (green circle) co-localizes with RomR and FrzS where it prevents MglA accumulation by activating GTP hydrolysis by MglA. Frz signaling provokes the concerted polarity switching of MglA and MglB to opposite poles, allowing A- and S-motility activation at the new leading and movement in the opposite direction. (B) Genetic control of the reversal cycle. Schematic of the regulation cascade compiled from previous works. Frz signaling is thought to promote a phosphorylation cascade that activates reversals. In more details, activation of the FrzCD receptor by unknown signals activates the auto-phosphorylation of the FrzE kinase through the FrzA CheW-like protein. The exact function of FrzB, another CheW-like protein, is unknown, contrarily to FrzA it is not absolutely essential for the activation of FrzE. FrzE then transfers a phosphoryl group to up to three response regulator proteins, its cognate receiver domain (FrzERR), the FrzZ protein, a fusion of two RR domains, and the N-terminal RomR receiver domain. The outcome of these phosphorylation events is unknown but the phosphorylated output(s) is thought to interact directly with the polarity proteins and provoke their re-localization to opposite poles. Plain arrows indicate established interactions and dotted arrows indicate suspected interactions. The protein color code applies throughout the manuscript. The molecular link between Frz and the motility systems requires three intermediate polarity proteins, MglA, MglB and RomR (Fig 1A). MglA, a bacterial Ras-like G-protein, activates the motility systems at the leading cell pole (Fig 1A, [23,24]). As all members of this family of molecular switches, MglA is active in association with GTP, a form that interacts with two motility system-specific proteins, AglZ (A-motility) and FrzS (S-motility) [19,20,25]. The polar localization of MglA results from combined regulations: (i), by RomR, which recruits MglA-GTP to the cell poles [26,27]; and (ii), by MglB, a MglA GTPase Activating Protein (GAP), which prevents MglA access to the lagging cell pole (Fig 1A, [23,24,28]). The polarity axis formed by MglA, MglB and RomR is stable unless it is contacted by upstream Frz signals, which provokes its dynamic switching and a reversal (Fig 1A, [29]).

In vivo, unknown signals are sensed by the Mcp homologue (FrzCD) and lead to the autophosphorylation of the kinase of the system (FrzE) from ATP via FrzA, the major CheW-like coupling protein (Fig 1B, [30]. FrzB, another CheW-like homolog may also participate in the activation of the pathway, although contrarily to FrzA, it is not required for all Frz-dependent responses (Fig 1B, [31]). Following activation, FrzE may then activate a handful of RR domains, including the C-terminal RR domain of FrzE (FrzERR), the FrzZ protein and the N-terminal RR domain of RomR itself, to contact the polarity proteins and activate the polarity switch (Fig 1B, [30,32–34]). Thus, the presence of multiple RR domains and a branch point at a circuit node formed by MglA asks how signaling from the FrzE kinase is channeled to the downstream motility systems (Fig 1B).

Overall, the motility regulation circuit is assembled from four interconnected modules with genetically separable functions: the control of the reversal frequency (switch control module), the coordination of the A - and S-motility systems (polarity control module) and the function of A - and S-motility (A - and S-motility modules, Fig 1B). By investigating the evolutionary origin of each module, we identified the core structure of the Frz pathway, genetically uncoupled A - and S-motility regulations and thus identified key regulations that led to the emergence of the evolved pathway. Remarkably, we find that adaptation of the ancestral circuit to A - and S-motility regulation required amplification of the signaling efficiency, suggesting that the evolution of signal reinforcement mechanisms may be linked to signal transduction pathway diversification in cells.

Results

S-motility regulation could be ancestral to the acquisition of A-motility in Myxococcus

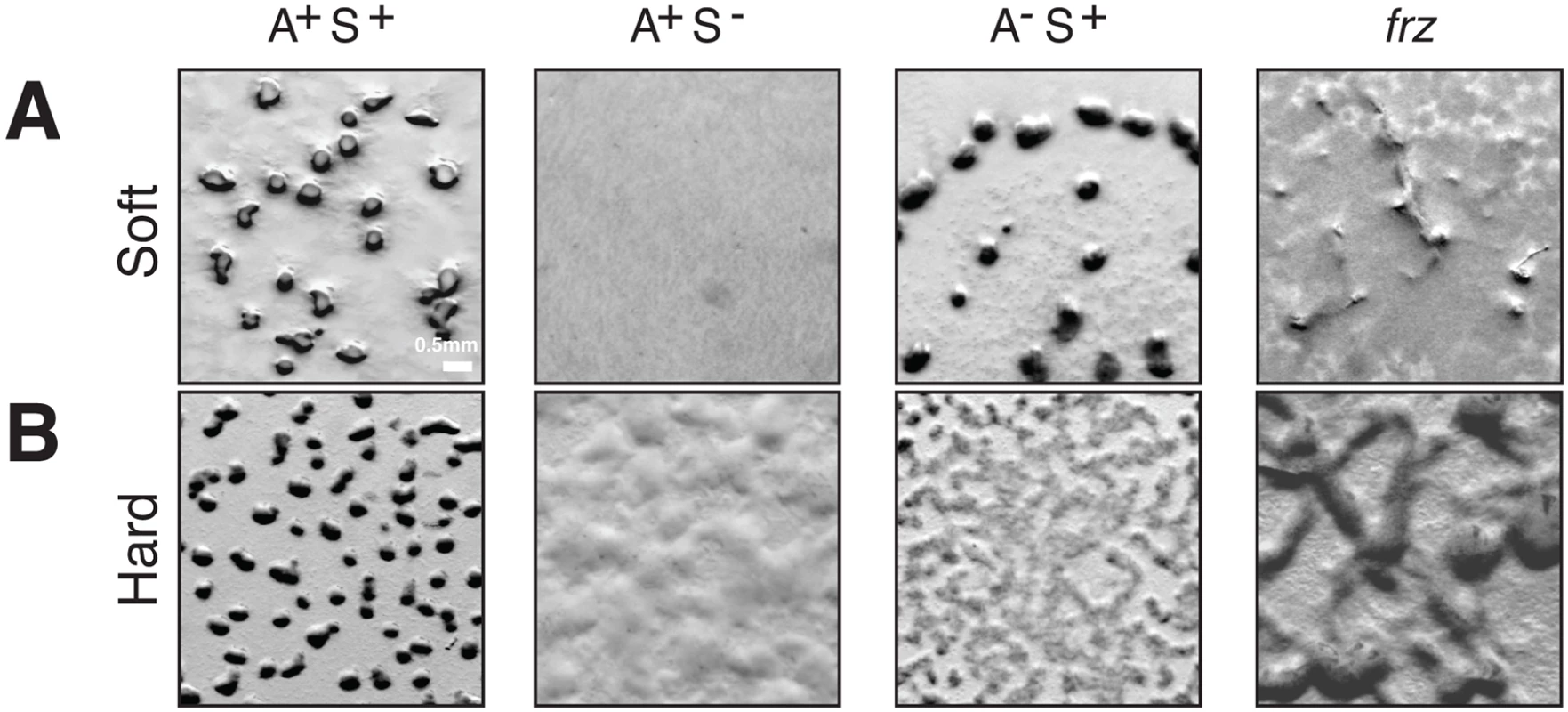

From an evolutionary perspective, the co-regulation of the A - and S-motility complexes by the Frz system implied the connection of two machineries of different origins. While Tfp systems are found in all deltaproteobacterial genomes [26,35], the A-motility Agl-Glt machinery is only present in Cystobacterineae, a Deltaproteobacteria family [15,16,36]. Thus, S-motility may be more ancient than A-motility and the emergence of A-motility in Cystobacterineae could have expanded the phenotypic repertoire and adaptive capabilities of this family of bacteria. Accordingly in Myxococcus, S-motility is required for fruiting body formation on soft and hard surfaces (0.5% vs 1.5% agar) but A-motility is only required on hard surfaces (Fig 2A and 2B). Importantly however, Frz regulation is required on both types of surfaces (Fig 2A and 2B). To further understand how co-regulation of A - and S-motility emerged in Cystobacterineae, we performed in-depth phylogenetic analyses of the components of the switch, polarity and motility control modules.

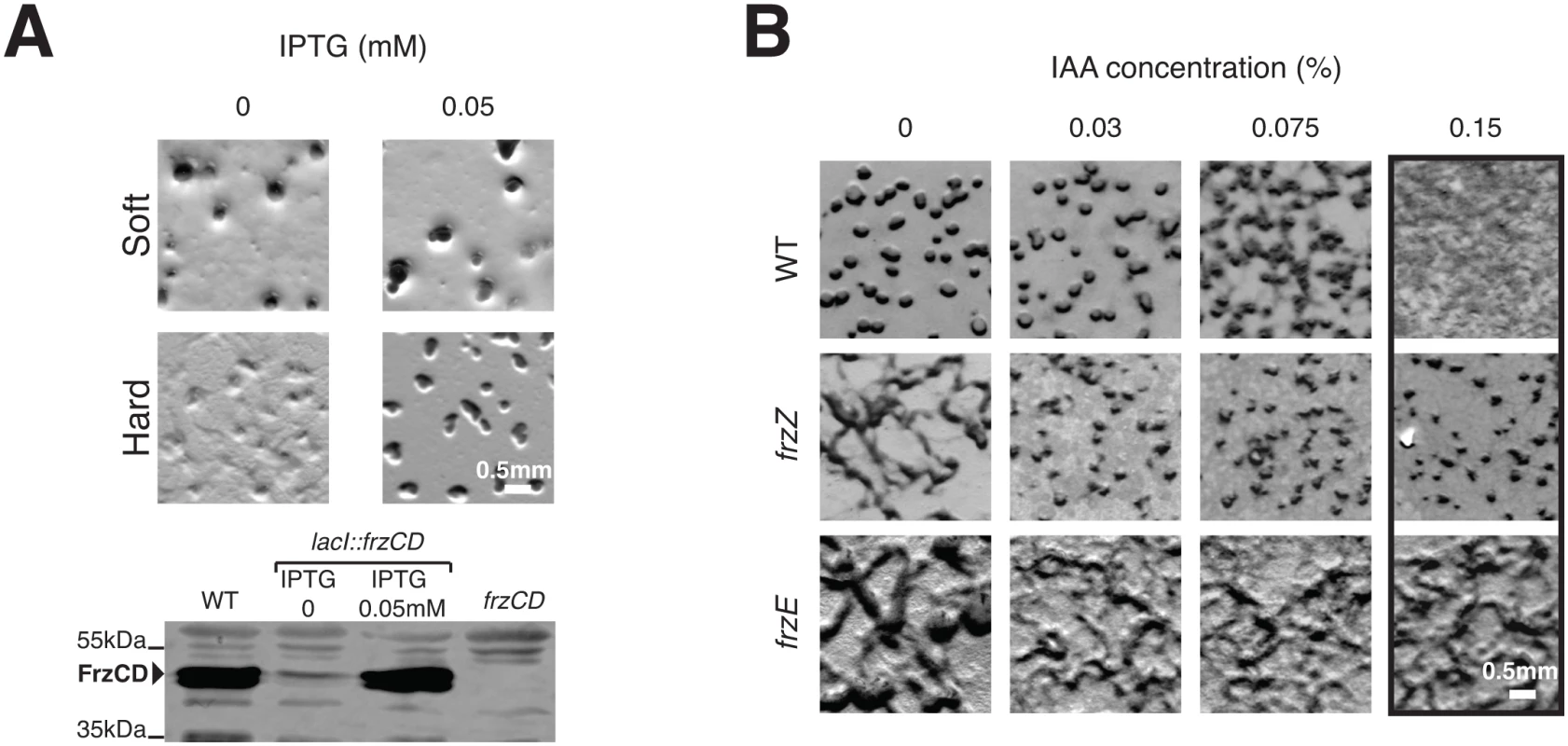

Fig. 2. A- and S-motility diversify the repertoire of Myxococcus multicellular behaviors.

(A) Fruiting body formation on a soft agar surface in WT and mutants. WT, pilA (A+S−), aglZ (A−S+) and frzE (frz) null mutants were tested for their ability to form fruiting bodies on 0.5% CF starvation medium agar plates (Soft). Fruiting bodies are apparent as dense black aggregates. (B) Fruiting body formation on a hard agar surface in WT and mutants. The same strains as in (A) were tested for their ability to form fruiting bodies on 1.5% CF starvation medium agar plates (Hard). Fruiting bodies are apparent as dense black aggregates. Polarity control module

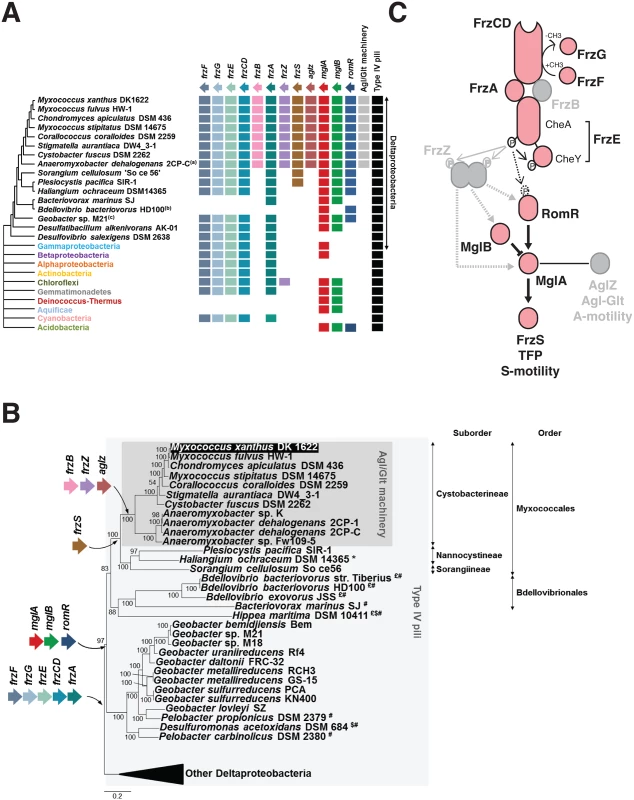

The Myxococcus xanthus MglA protein belongs to a large protein family of MglA-like proteins, and more precisely to the group 1 as defined by Wuichet and Sogaard Andersen ([37], S1A Fig). A total of 146 MglA group 1 homologues were found in 88 bacterial genomes, mainly in the Deltaproteobacteria (80 sequences in 38 genomes) (Figs 3A and S1A). MglB presents a similar taxonomic distribution, 90 sequences were detected in 90 genomes, 36 of which belonging to Cystobacterineae (for a total of 36 genomes, Figs 3A and S1B). When MglA and MglB were found together in a genome, they were encoded by tandem-genes, underscoring the functional link between these two proteins (S2 Fig). Because MglB is an MglA regulator, the absence of mglB in genomes where mglA is present could be linked to the loss of MglA regulation in these bacteria [38]. RomR paralogues showed a more narrow distribution, with the exception of Acidobacteria, they were only identified in 27 deltaproteobacterial genomes, again mainly in Cystobacterineae (Figs 3A and S1C). Interestingly, nearly all these genomes also contain MglA and MglB homologues, further supporting that MglA, MglB and RomR form a functional module. These results are for the most part largely consistent with results by Keilberg et al., except for minor differences in the RomR phylogenies, likely due to different strategies in RomR sequence identifications ([26], see Experimental procedures). All together these results suggest that the Myxococcus polarity module was acquired early during the diversification of the Deltaproteobacteria (Fig 3B). Given that MglA and to a lesser extent MglB and RomR, are required for the regulation and the function of S-motility [23,24,26,27], S-motility could have evolved following their acquisition and the cooptation of a deltaproteobacterial Tfp ancestor.

Fig. 3. The taxonomic distribution of the Myxococcus motility suggests a new structure of the regulation pathway.

(A) Taxonomic distribution of the motility genes. The occurrence of each gene is inferred from the individual phylogenies (S1, S3 and S6 Figs). The phylogenetic relationships between the deltaproteobacterial species shown are inferred from the analysis of 17 genes in total, which are present in a single copy in the deltaproteobacterial genomes (S5 Table). The presence of the Agl-Glt machinery in genomes is inferred from work published in [16]. The presence of Type-IV pili is based on the occurrence of PilM, N, O, P, Q homologues that form a core Tfp-structure, identified from the literature or by BLAST analysis of genomes of interest. (B) Acquisition of the motility genes in the Deltaproteobacteria. $: possible loss of RomR; £: possible loss of MglB; *: possible loss of FrzS; #: possible loss of FrzF, G, E, CD and A. (C) Modular structure of the regulatory pathway. The taxonomic distribution of the motility genes (A,B) regulation pathway may consist of a core signaling apparatus (pink) that regulates S-motility following the direct phosphorylation of RomR by the FrzE kinase. The acquisition of FrzZ, FrzB and AgZ coincides with the emergence of the A-motility system in the Cystobacterineae and could have adapted the regulatory circuit to the control of two outputs. This scenario predicts that FrzZ, thought to be central to the regulation is rather an accessory that adapted the phosphate flow upstream from MglA. Switch control module

The Frz system deviates from the enteric Che system and contains an Mcp (FrzCD), two CheW homologues (FrzA and FrzB), a hybrid kinase (FrzE), a methyl-transferase (FrzF), a methyl-esterase (FrzG) and an unusual tandem response regulator domains containing protein, FrzZ [31]. Based on our analysis, a first group of Frz homologues, composed of the core signaling proteins Mcp (FrzCD), a CheW-like protein (FrzA), a hybrid CheA-type kinase (FrzE) and the methyl transferase/esterase system (FrzFG), presents similar taxonomic distributions. More precisely, these genes are found in a number of deltaproteobacterial genomes, but also in a few representatives of various bacterial phyla and classes (e.g. Gammaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria) (Figs 3A and S3A-S3E). The genes are always clustered together in bacterial genomes and their phylogenies are globally consistent, indicating similar evolutionary histories (including horizontal gene transfer of single blocks, S3, S4 and S5 Figs). In contrast, the second group including FrzB (a CheW-homolog) and remarkably, FrzZ (the RR-RR fusion protein) appears limited to Cystobacterineae (Figs 3A, S3F and S3G), pointing to a more recent evolutionary origin. In Cystobacterineae, two important Frz protein domain modifications suggest major changes in the sensing capability of the system: (i), in the FrzCD protein, the transmembrane segments are replaced by a soluble N-terminal domain of unknown function [31], suggesting that FrzCD senses cytosolic signals in this group of bacteria (S3A Fig and S4 Table); (ii), the RR domain of the FrzG methylesterase is largely degenerate (more specifically in the Cystobacteraceae and Myxococcaceae but not in the Anaeromyxobacteraceae, S3E Fig and S4 Table). The recent loss of a functional RR domain in FrzG suggests important changes in the adaptation mechanism; in fact and contrarily to the proteins of the first group, FrzG is not absolutely required for Frz signaling, suggesting that its core function evolved in Cystobacterineae [31].

Connection to the A - and S-motility modules

How MglA contacts the motility systems is not completely understood but it may occur, at least partially, through an interaction with AglZ and FrzS, two homologous proteins that co-localize with the A - and S-motility systems respectively [25,39]. Remarkably, AglZ and FrzS contain similar protein domains: an N-terminal receiver domain and an extended coiled-coil C-terminal domain (S4 Table). In AglZ, the C-terminal coiled-coil is 1076 residues long while it is 235 residues long in FrzS (S4 Table). In FrzS, the N-terminal domain is essential for the localization of this protein at the leading cell pole [40]. Although this domain folds like a typical receiver domain, it cannot accept a phosphoryl group because an Alanine residue replaces the critical Asp in the catalytic pocket [41]. Because the exact FrzS and AglZ MglA-binding sites have not been mapped, it is not known if these proteins use similar binding motifs to interact with MglA. Our phylogenetic analysis reveals that FrzS and AglZ are paralogues and indicates that they emerged following a gene duplication event that occurred in an ancestor of Cystobacterineae (Figs 3A and S6). FrzS may be the ancestral form and AglZ a derived form because the unique copy present in Cystobacterineae relatives is more similar to FrzS (Figs 3A, 3B, and S6). None of the FrzS and AglZ paralogues contain a functional phosphorylation site, suggesting that the receiver function of the response regulator domain is generally decayed in this protein group (S7 Fig). Worth noticing, the duplication event and the emergence of A-motility occurred in the same branch of the Deltaproteobacteria tree, namely in the ancestor of Cystobacterineae (Fig 3B). Thus, co-option of the new derivative (ie AglZ) by the Agl-Glt machinery could have provided an effective solution to branch the two motility systems to the same regulation pathway downstream from MglA.

In summary, the Myxococcus motility control proteins can be divided in two classes based on their phylogenetic distribution. Remarkably, the acquisition of FrzB, FrzZ and AglZ correlates with the emergence of the Agl-Glt machinery in an ancestor of the Cystobacterineae (Fig 3A and 3B), suggesting that these modifications integrated A-motility regulation to a previously existing S-motility regulation pathway (Fig 3C). This hypothesis predicts that a simpler pathway lacking FrzZ, FrzB and AglZ should be sufficient to regulate S-motility - but not both A - and S-motility-dependent behaviors (Fig 3C), which we decided to test experimentally.

FrzZ, FrzB and AglZ are not required for S-motility dependent reversals

Measuring reversals of the S-motility system is difficult because they occur in large cell groups where single cells cannot be easily tracked. As mentioned in the introduction, S-motility results from the action of an extracellular EPS that provokes Tfp retraction [14]. In fact, the requirement for EPS can be bypassed, in single cell assays where the Myxococcus cells are allowed to move in a carboxymethylcellulose-coated microfluidic chamber (See Experimental procedures). In this system, cells move by Tfp-dependent motility only with an average speed of 1.7 ± 0.8 μm.min-1 (measured for 63 cells) and Frz-dependent cellular reversals are observed and coincide with pole-to-pole oscillations of MglA-YFP and FrzS-YFP, similar to agar (Figs 4A, 4B, and S8A) [19,24]. A-motility is not active on the cellulose surface because the cell velocity and the reversal frequency of an A-motility A− (aglQ) mutant are unchanged compared to WT cells (1.6 ± 0.9 μm.min-1, for 61 cells, S1 Movie and Fig 4B). Therefore, we used A+ strains for the rest of this study.

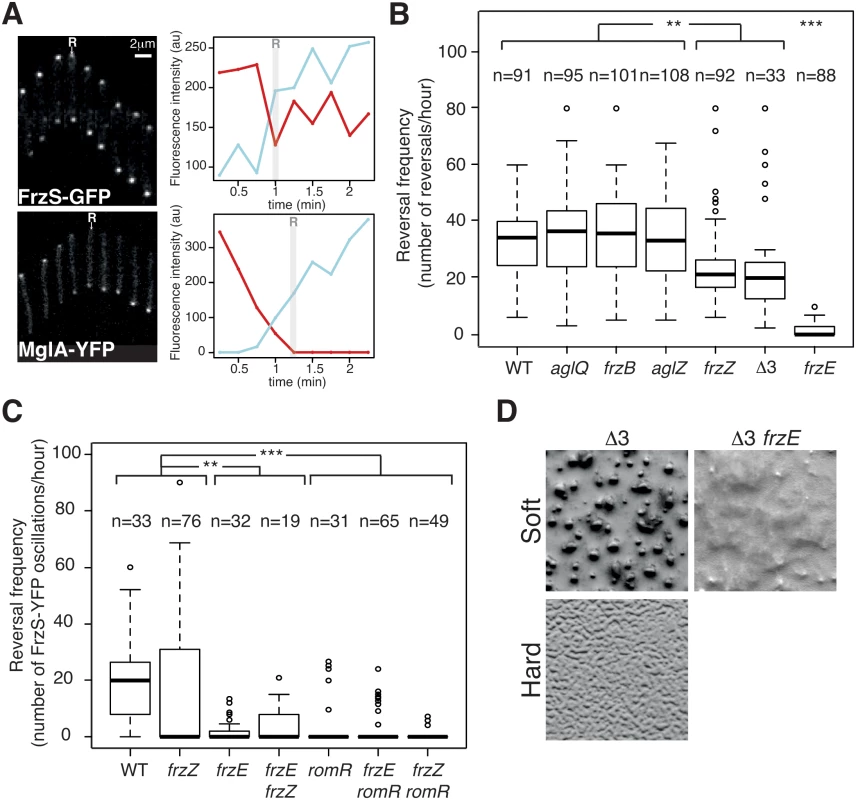

Fig. 4. The core Frz-apparatus can promote S-motility-dependent behaviors.

(A) Single cell Tfp-dependent reversals are observed in carboxymethylcellulose-coated glass microfluidic chambers. FrzS-YFP and MglA-YFP dynamic localization are observed during single cell Tfp-dependent reversals. Fluorescence micrographs (left) and quantification of the corresponding fluorescence intensities (arbitrary units, au) of FrzS-YFP and MglA-YFP at both poles over time are shown (time resolution: 15s). Red line: initial leading pole, blue line: initial lagging pole (Frame 1). R: reversals. (B) Reversal frequency of WT and selected mutants on carboxymethylcellulose. The assays are run in the presence of 0.15% of Isoamyl alcohol (IAA) to allow reversal counts (see Methods). Shown are boxplots of the measured reversal frequency of isolated cells (n, tracked for at least 10 min) for each strain. The lower and upper boundaries of the boxes correspond to the 25% and 75% percentiles, respectively. The median is shown as a thick black line and the whiskers represent the 10% and 90% percentiles. Statistics: Wilcox test (n<40) for Δ3 (frzB frzZ aglZ) and student test (t-test, n>40) for all the other strains. ** p value<0.01, *** p value<0.0001. (C) RomR but not FrzZ is essential for S-motility-dependent reversals. FrzS-YFP pole-to-pole oscillations were counted in the presence of 0.10% of IAA to score reversals (the exact procedure is described in Methods and S9A and S9B Fig). Briefly, for each pole, fluorescence intensity was measured at any given time point as described in Methods and S9A and S9B Fig. The boxplots read as in (B). Statistics: Wilcox test (n<40) for WT, frzE, romR, frzE frzZ or student test (t-test, n>40) for frzZ, frzE romR and frzZ romR. ** p value<0.01, *** p value<0.0001. (D) Multicellular development is restored in a triple mutant frzB frzZ aglZ (Δ3) on soft (0.5%) CF starvation medium agar in a Frz-dependent manner (compare with the Δ3 frzE mutant). On the contrary the frzB frzZ aglZ cannot aggregate on a hard (1.5%) CF agar, where A-motility is also required. We used the cellulose assay and high-throughput automated tracking (S8B Fig and S2 Movie) to test whether the core pathway defined by the phylogenetic analysis is sufficient to regulate Tfp-dependent reversals. Remarkably, Tfp-dependent reversals were still observed in the absence of each of the predicted accessory components, FrzZ, FrzB and AglZ (Fig 4B). The frequency of Tfp-dependent reversals was equivalent to WT levels in the frzB and aglZ mutants, showing that these proteins are dispensable for the control of Tfp-dependent reversals (Fig 4B). In the case of the frzZ mutant, the situation was intermediate, the reversal frequency was affected compared to WT cells but it was still significantly higher than in the frzE mutant (Fig 4B).

Because the reversal frequency of the frzZ mutant was intermediate, we decided to use a more precise reversal-scoring test to determine unambiguously if frzZ mutant cells can still reverse in a Frz-dependent way. Our interpretation could be biased by so-called Tfp-dependent “stick-slip” motions, a Frz-independent Tfp-driven movement that could be mistakenly counted as reversals (S9A and S9B Fig, stick-slip motions are short range and generally appear distinct from bona fide reversals, [42]). Therefore, to score reversals with high accuracy, we monitored FrzS-YFP oscillations as a proxy for Frz-dependent reversals (Figs 4A, S9A and S9B). As expected from the reversal measurements, pole-to-pole switching of FrzS-YFP coincident with directional changes was reduced on average in the frzZ mutant, but they were still observed and sometimes up to WT levels (Fig 4C). Confirming this, pole-to-pole switching of FrzS-YFP was completely abolished in the frzE mutant and a frzE frzZ double mutant behaved like the frzE mutant (Fig 4C). Therefore, although the reduction in the reversal frequency of the frzZ mutant is significant (Fig 4B and 4C), Frz-dependent Tfp-reversals can occur in the absence of FrzZ (but not in the absence of FrzE) suggesting that FrzZ acts positively on Tfp-dependent reversals but is not strictly required for their activation.

To test the properties of the predicted core Frz pathway, we further constructed a frzB, frzZ, aglZ triple mutant (Δ3). The Δ3 mutant still showed Frz-dependent reversals and its reversal frequency was again lower, similar to that of the single frzZ mutant (Fig 4B). However, this lower reversal frequency did not translate into obvious S-motility developmental phenotypes because the Δ3 mutant formed fruiting bodies on soft agar, which is strictly S-motility dependent (Fig 4D). This multicellular development was Frz dependent because a Δ3 frzE quadruple mutant did not form aggregates in similar conditions (Fig 4D). On the contrary and as expected, the Δ3 mutant did not form aggregates on hard agar, a condition where A-motility is required (Fig 4D). We conclude that although the predicted core Frz pathway has a lower activity than the evolved pathway containing FrzZ, this activity could be sufficient to allow strictly S-motility-dependent behaviors, ie the ability to make fruiting bodies on soft 0.5% agar surfaces. Thus, the acquisition of FrzB, FrzZ and AglZ could have further adapted this primary circuit to the regulation of two motility machineries, at least in part by boosting the signaling activity (see below).

RomR is the central output protein of the Frz pathway

The results above show that FrzE signaling is still efficient in the frzZ mutant (albeit at lower efficiency), suggesting that another response regulator delivers FrzE signals to the polarity complex. RomR is a possible candidate because it contains a phosphorylatable Nt-RR domain and because it interacts directly with MglA. Thus, phosphorylation of RomR could link Frz signaling to the polarity switch [34]. The regulatory function of the RomR protein could not be tested in the past because RomR is essential for A-motility (likely because MglA is delocalized in a romR mutant, [26,27,34]), and reversal frequencies are traditionally measured on A-motile cells. In the cellulose system, a romR deletion mutant showed WT Tfp-dependent motility (1.4 ± 0.8 μm.min-1, for 65 cells, S3 Movie) but it was dramatically affected in its ability to reverse in the FrzS-YFP oscillation assay (Fig 4C). A frzZ romR double mutant also had abolished reversals showing that RomR acts downstream from FrzZ in the regulation (Fig 4C). Importantly, while occasional reversals could be observed in frzE mutants, reversals were very rarely observed in romR and frzE romR mutants (Fig 4C). We conclude that RomR acts downstream from FrzE and FrzZ in the reversal pathway and could thus be a central output protein of the Frz pathway.

The coordinate regulation of A - and S-motility requires an increase in steady-state Frz signaling activity, which depends on FrzZ

Both the frzZ and the frzB frzZ aglZ Δ3 mutants have similar and lower reversal frequencies than WT cells (Fig 4B), suggesting that the presence of FrzZ increases the steady-state signaling activity. Because the Δ3 mutant still forms fruiting bodies on 0.5% agar (Fig 4D), lower Frz activity may only translate in a developmental defect when A-motility is required. If so, differential Frz signaling activities may be required to regulate S-motility-dependent behaviors (ie development on soft agar) and A - and S-motility dependent behaviors (ie development on hard agar). This hypothesis can be tested in a strain expressing the frz operon under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter (Fig 5A) where Frz activity should be related to the level of Frz protein expression. In the absence of IPTG, such strain formed fruiting bodies on 0.5% agar but not on 1.5% agar, indicating that promoter leakage is even sufficient to restore S-motility-dependent aggregation (Fig 5A). As expected, the addition of IPTG also restored fruiting body formation on 1.5% agar (Fig 5A). Thus, developmental processes that require the S-motility system require lower Frz activity levels than developmental processes that require A - and S-motility.

Fig. 5. Increased Frz signaling activity is required for the regulation of A- and S-motility, which depends on FrzZ.

(A) Weak Frz protein expression supports S-motility-dependent aggregation but not A- and S-motility-dependent aggregation. The ability of a strain in which the frz promoter has been replaced by an IPTG-inducible promoter to form aggregates is tested on soft (0.5%) or hard (1.5%) CF agar plates in the presence or in the absence of IPTG. A western blot analysis (bottom) of FrzCD expression in this strain reveals that promoter leakage is sufficient to support aggregation on the soft surface. (B) Extracellular complementation of the frzZ mutant developmental aggregation phenotype by IAA. Multicellular development on hard (1.5% agar) starvation CF medium containing increasing IAA concentrations by the WT strain and the frzE and frzZ mutants. Note that the frzE and frzZ mutants are indistinguishable in absence of IAA but that aggregation is only restored for the frzZ mutant in the presence of IAA The FrzZ protein was thought to be central to Frz regulation because a frzZ mutant displays a typical frz phenotype on development hard agar [30]. However, if this phenotype is linked to lower Frz activity, it could be bypassed if Frz signaling is artificially increased in a frzZ mutant. To test this possibility, we took advantage of a chemical, Isoamyl alcohol (IAA) known to activate frz-dependent reversals. Although the exact target of IAA is not known, it appears to act on and de-methylate the FrzCD receptor (directly or indirectly, [43]) and its action is strictly Frz-dependent [31]. When added to hard developmental agar, IAA did not affect development of the WT strain up to concentrations of 0.075%, after which IAA blocked fruiting body formation (Fig 5B). A frzE mutant showed the typical frz phenotype and as expected, this phenotype was neither rescued nor modified by IAA addition (Fig 5B). Consistent with previous observations, the frzZ phenotype was indistinguishable from the frzE phenotype in absence of IAA (Fig 5B). However, and contrarily to the frzE mutant, IAA rescued aggregation of the frzZ mutant up to 0.15% IAA, a high dose that disrupts aggregation in WT cells (Fig 5B). Therefore, artificial activation of Frz signaling rescues the signaling defect of the frzZ mutant, suggesting that FrzZ acts to elevate Frz activity, allowing regulation of the two motility systems.

FrzZ is required for optimal signal transmission

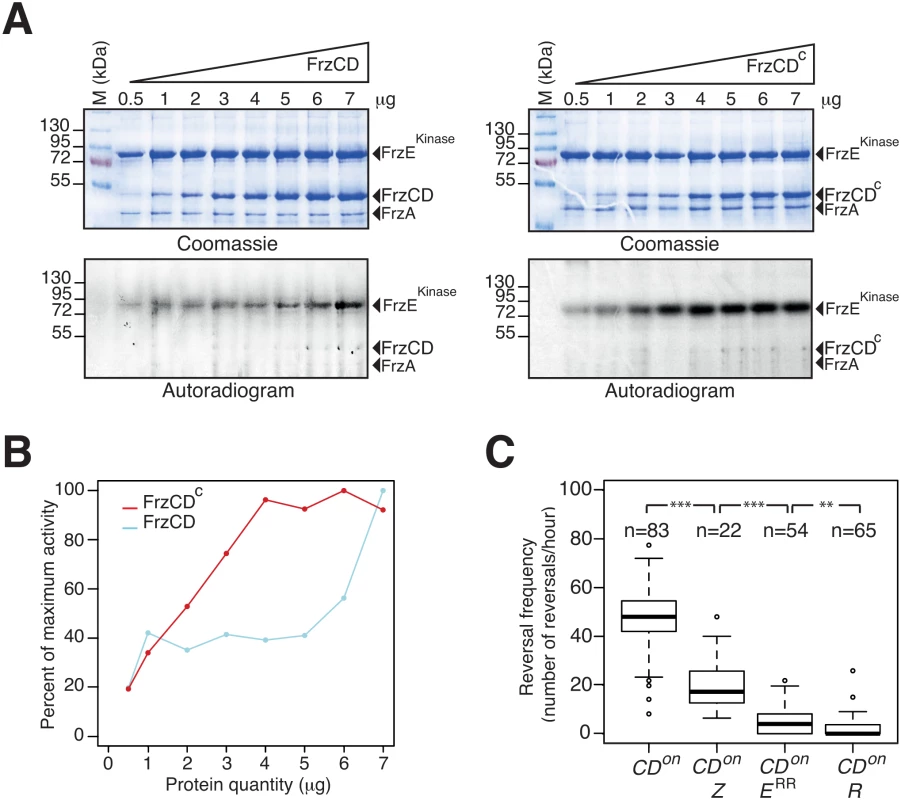

To further investigate the function of FrzZ in Frz-signaling activity, we tested the contribution of FrzZ in a strain where the Frz receptor is hyper active. So-called frzon mutations map to the C-terminal domain of FrzCD and result in the expression of a truncated receptor protein (FrzCDc) [31]. Because the expression of FrzCDc is trans-dominant to the expression of FrzCD, frzon mutations have been suggested to hyper activate Frz signaling [44]. To first test this assumption, we purified FrzCD, FrzCDc, FrzA and the kinase domain of FrzE (FrzEkinase, autophosphorylation of FrzE in vitro can only be detected if FrzERR is removed due to its phosphate sink activity, [32]) and compared the capacity of FrzCD and FrzCDc to activate FrzEkinase autophosphorylation from ATP in vitro. While both FrzCD and FrzCDc were able to activate the autokinase activity of FrzEkinase in a dose-dependent manner, FrzCDc was a more potent activator (Fig 6A and 6B). Thus, frzon mutations induce a hyper signaling state of the FrzE kinase.

Fig. 6. FrzZ is required for optimal transmission of Frz signals.

(A) Auto-phosphorylation of the FrzE kinase domain (FrzEkinase) is stimulated by FrzCDc. The kinetics of FrzEkinase auto-phosphorylation were tested in vitro by incubation of FrzEkinase in the presence of FrzA, FrzCD or FrzCDc and ATPγP33 as a phosphate donor. Note that FrzEkinase auto-phosphorylation is stimulated at lower amounts of FrzCDc than FrzCD. (B) Quantification of FrzEkinase auto-phosphorylation by image densitometry of the autoradiograms shown in (A). (C) Signal transduction by FrzZ, FrzERR and RomR in FrzCDc-expressing strains (frzon mutant). Reversals were counted by automatic tracking in carboxymethylcellulose chambers in the absence of IAA (frzon mutants are blind to IAA). The boxplots read as in Fig 4B. CDon: frzon; CDon Z: frzon frzZ; CDon ERR: frzon frzERR; CDon R: frzon romR. Statistics: Wilcox test (n<40) for CDon Z (frzon frzZ) and student test (t-test, n>40) for the other strains. ** p value<0.01, *** p value<0.0001. We then proceeded to test the contribution of FrzZ to Frz-signaling in a frzon background. In the cellulose chamber assay, frzon mutants reversed at high frequency, as expected (Fig 6C, compare with the WT reversal frequency in Fig 4B). Remarkably, a frzon frzZ mutant still reversed but at a reversal frequency similar to the reversal frequency of the frzZ mutant (Fig 6C, compare with Fig 4B). A frzon romR mutant did not reverse (Fig 6C), confirming that Frz signaling is disrupted in absence of RomR. Thus, FrzZ acts downstream from the FrzCD receptor and exerts a positive effect on the transduction of Frz signals to the polarity switch.

FrzZ and FrzERR exert opposite effects on Frz signaling intensity

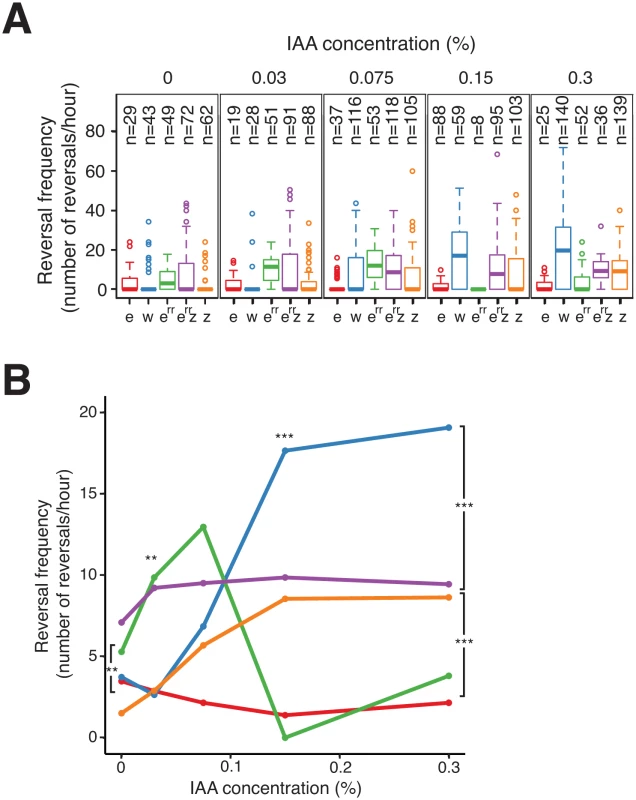

To investigate how FrzZ exerts its positive effect on Frz signaling activity, we took advantage of the cellulose system to develop a high-resolution single cell assay in which FrzS-YFP oscillations are measured directly as a function of stimulation levels; here, the addition of increasing doses of IAA. In this assay, we first established that reversals were induced by IAA in dose - and FrzE-dependent manners. In WT cells, IAA induced a sharp dose-dependent reversal response until a plateau was reached at an IAA concentration of 0.15% (Fig 7A and 7B). As expected, a frzE mutant only reversed occasionally whatever the IAA concentration, showing that the observed IAA effects are strictly Frz-dependent (Fig 7A and 7B). Consistent with previous results, a frzZ mutant still showed an IAA-dependent response but it was more gradual than the WT and showed lower amplitude at the higher IAA doses (Fig 7A and 7B).

Fig. 7. FrzERR inhibits and FrzZ amplifies Frz signaling independently.

(A) S-motility-dependent response to increasing stimulation by WT and frz mutant cells. For each strain, the reversal frequency was measured in carboxymethylcellulose chambers by scoring FrzS-YFP pole-to-pole oscillations in the presence of increasing doses of IAA. The boxplots read as in Fig 4B. e: frzE (red); w: WT (blue); err: frzERR (green); err z: frzERR frzZ (purple); z: frzZ (orange). (B) The average reversal frequencies compiled from (A) are shown as a function of IAA concentration for each tested strain. The same strain color code as in (A) applies. Statistics: Wilcox test. ** p value<0.01, *** p value<0.0001. We also used the IAA single cell assay to test the function of FrzERR, the FrzE receiver domain. The FrzERR domain is not absolutely essential for Frz signaling and has been suggested to inhibit signaling because FrzERR inhibits FrzE autophosphorylation in vitro (Fig 1B, [32]). However, how such inhibition participates in Frz signaling is unclear. In the IAA assay, a frzERR mutant showed a behavior opposite of that of the frzZ mutant: this mutant reversed more than WT cells which was apparent IAA doses ranging between 0–0.075% (Fig 7A and 7B). Thus, FrzERR prevents Frz-signaling at low stimulation levels. Remarkably, at concentrations higher than 0.075% the frzERR mutant stopped reversing and no longer responded to IAA (Fig 7A and 7B). We hypothesize that this collapse is the result of an over-signaling state that disrupts Frz signaling function because (i), a frzERR frzZ double mutant showed a composite phenotype: frzERR-type reversal frequencies at IAA doses ≤ 0.03% and frzZ-type reversal frequencies at the higher IAA concentrations (Fig 7A and 7B); and, (ii), a frzon frzERR double mutant has a strongly reduced reversal frequency (Fig 6C). In the enteric Che pathway, high chemoreceptor stimulation also inhibits signaling suggesting that similar mechanisms are at work in the Frz system [45,46]

All together, the IAA experiments and the frzon mutant reversal frequencies suggest that FrzERR and FrzZ act independently in the pathway, FrzERR blocking activation at low signal levels and FrzZ amplifying signal transmission to allow a rapid switch-like response to stimulation (which is required for the regulation of A - and S-motility).

Discussion

Evolution of the Myxococcus motility apparatus

The Myxococcus motility apparatuses (A - and S-motility) allow this bacterium to perform an array of multicellular behaviors, which likely increases the competitiveness of this bacterium in the environment. Our results are consistent with an evolutionary scenario whereby these behaviors emerged following the stepwise assembly of four distinct functional modules, the Frz chemosensory apparatus, the polarity proteins MglAB, and the A - and S-motility systems, in a regulation pathway. Given that the studied genes likely form a minimal regulatory set and that not all players and interactions have been identified, a complete evolutionary scenario cannot be proposed. Nevertheless, we identify two major steps in the evolution of the pathway:

In bacteria, the cooption of signaling modules formed by Mcp (FrzCD), CheW (FrzA), CheA (FrzE), CheR (FrzF) and CheB (FrzG) homologues underlies the emergence of a large number of chemosensory-type pathways [11]. Therefore, it is likely that the primary deltaproteobacterial S-motility regulation apparatus first evolved by recruitment of MglAB to one such chemosensory system. RomR is a possible candidate to link Frz signaling to polarity regulation because this protein shares a similar evolutionary history (Fig 3A and 3B), it interacts directly with MglA [26,27] and it is essential for reversals (this work). However, we have not demonstrated that FrzE is the RomR kinase and thus formally, other intermediate proteins may relay FrzE signals to RomR. Nevertheless, our genetic analysis suggests that RomR functions as a core protein downstream from FrzE in the regulation pathway. Downstream from MglA, it is also possible that FrzS does not constitute the only link to the S-motility apparatus [12,18,47], but because the interaction between MglA and FrzS is essential for S-motility [25], the acquisition of FrzS was probably a key step for the emergence of the primary pathway.

Diversification of the primary pathway to the regulation of A - and S-motility occurred in the Cystobacterinaea family of bacteria and coincided with profound modifications of the regulation system. Additions of AglZ and FrzZ were probably key to adapt the primary circuit to the emergence of a branch point downstream from the FrzE kinase. First, the duplication of a frzS ancestor gene and connection of AglZ to the A-motility apparatus might have created the branch point itself, connecting A-motility to MglA regulation. Aside from numerous amino acid substitutions, the main difference between AglZ and FrzS resides in the lengths of their coiled-coil domains. Thus, AglZ might have evolved a new interaction with the Agl-Glt machinery (ie via the coiled-coil domain) while retaining its ability to interact with MglA. Consistent with this, AglZ also interacts with MglA and it co-localizes with the Agl-Glt machinery [16,25,39,48]. Second, FrzZ was incorporated into the upstream regulatory circuit, allowing signal partitioning to the two motility systems (see below). Other changes in the pathway not studied here may also participate in this regulation, including domain changes occurring in FrzCD and FrzG and the acquisition of FrzB (S4 Table and Figs 3A, 3B, S3A and S3E). The function of FrzB does not appear redundant to that of FrzA, the major Frz CheW protein, because Bustamante et al. [31] showed that a frzA mutant is indistinguishable from a frzCD or a frzE mutant, while a frzB mutant still responds to IAA stimulation in a bulk agar motility assay [31], which is consistent with our single cell experiments (Fig 4B). This lack of redundancy may not be surprising because FrzB is not phylogenetically related to FrzA (S3B and S3F Fig). It will be interesting to determine the exact function of FrzB and its potential connection to the branching of A-motility in the future.

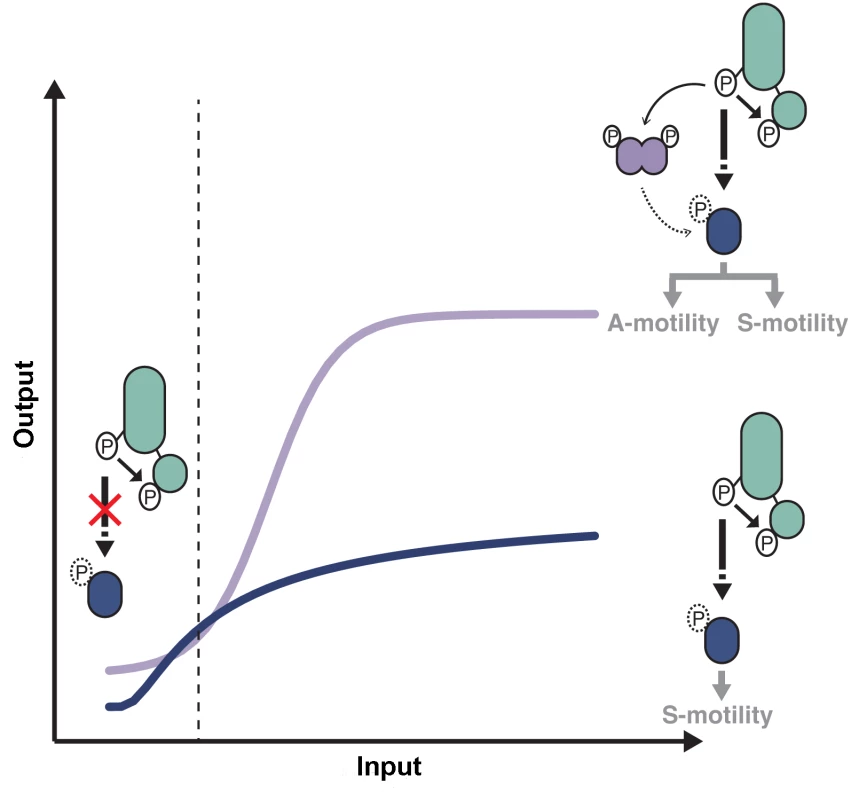

Architecture of the Frz pathway

Using a high-resolution microfluidic single cell assay we were able to elucidate the individual contribution of the RR domain proteins of the pathway. The IAA stimulation Frz-dependent response curve showed a biphasic-type response with an overall sigmoidal shape (Fig 8). Because this response is entirely abolished in a frzERR frzZ mutant but not in the respective individual mutants (Fig 7A and 7B), we conclude that FrzERR and FrzZ independently set distinct regimes of the signaling apparatus (Fig 8).

Fig. 8. Antagonistic regulations by distinct RR domains shape Frz-dependent responses to stimulations.

At low input levels, intramolecular phosphotransfer from the FrzE kinase domain (FrzEkinase) to the FrzE response regulator domain (FrzERR) quenches the signal and prevents unwanted activation of reversals in absence of physiological signals. In the presence of activating signals (dotted line), the kinase activity of FrzEkinase overcomes the phosphatase activity of FrzERR and the signal can be transduced downstream, presumably by the direct phosphorylation of RomR. In absence of FrzZ, signal transmission to the downstream motility machineries is not amplified (blue curve), only allowing S-motility-dependent regulations. In the presence of FrzZ, interactions between FrzE, FrzZ and RomR amplify the signaling activity allowing a steep and high amplitude response required to regulate both A- and S-motility (purple curve). Although the exact amplification mechanism remains to be determined the epistastic interactions between FrzE, FrzZ and RomR suggest that the FrzE kinase might activate reversals both by acting directly or indirectly on RomR and by direct phosphorylation of FrzZ, which would then interact with RomR to further activate it. The blue and purple curves are drawn from data shown in Fig 7B. More precisely, FrzERR inhibits signaling at low stimulation levels, blocking noisy activation of the polarity switch (Fig 8). The inhibition mechanism is likely that of a phosphate sink because hybrid kinases phosphotransfer to their covalently-attached receiver domain at very high efficiency and the half-life of the Aspartate-phosphate bond on FrzERR is very short lived, a property of response regulators with phosphate sink functions [32,49,50]. Signal inhibition by the receiver domain of hybrid kinases is also emerging in other systems [51] and could be a widespread regulation of hybrid kinases.

At higher stimulation levels, the FrzERR inhibitory capacity becomes saturated and allows FrzE to phosphorylate the other receiver proteins of the pathway, FrzZ [30], possibly RomR or any other unidentified receiver domain of the pathway. The combined action of these phosphorylation events results in a steep response (Fig 8). Phosphorylation events downstream from FrzE and independent of FrzZ would transduce the signal to the MglAB proteins, this could occur through RomR or other uncharacterized regulators. In parallel, the phosphorylation of FrzZ amplifies the signal, impacting both the slope and amplitude of the response (Fig 8). Remarkably, processes that require S-motility alone can accommodate a graded response of moderate amplitude, while processes that require A - and S-motility require FrzZ amplification (Fig 8). It will be essential to determine how Frz signals are processed by MglA and each motility system to understand these signaling intensity requirements. At the molecular level, FrzZ must act between the FrzE kinase and RomR because (i), a hyper active FrzE kinase (frzon mutation) still requires FrzZ for maximal signal transmission (Fig 6C), suggesting that FrzZ does not exert its action by feedback stimulation of the autokinase activity of FrzE; and ii), a frzZ romR mutant behaves like a romR mutant (Fig 4C), showing clear epistatic relationships. FrzZ is a dual response regulator protein and it will be important to determine how the phosphorylation of each receiver domain contributes to signal amplification. The FrzZ phosphorylation sites appear partially redundant but only the phosphorylation of D52 and not D220 is important for the polar localization of FrzZ [33]. At the cell pole, the phosphorylated form of FrzZ could interact directly with RomR to facilitate the reversal switch.

Two-component cascades frequently employ accessory response regulator domains to achieve a variety of functions in phosphorelays, signal inhibition or negative feedback loops [52,53]. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a signal amplifier function is identified for a RR protein and because FrzZ-like CheY-CheY fusion proteins are predicted in other complex two component systems (Survey of the Microbial Signal Transduction database,[54]), characterizing the amplification mechanism may generally impact our understanding of bacterial signal transduction.

Conclusions

In summary, this work reveals the modular structure of the Frz signal transduction pathway and suggests that the new pathway branch emerged at least in part by (i), gene duplication followed by new functional specialization (ie the emergence of AglZ and its connection to the A-motility system) and (ii), by the re-wiring of the signal flow, in this case an amplification system to partition signals at the branch point. These modifications are linked to the molecular structure of the Myxococcus regulation circuit where MglA acts as a regulation checkpoint, integrating upstream Frz signals into the coordinate regulation of the A - and S-motility machineries. In principle, amplification systems could operate in any signal transduction pathways that converge to the regulation of a checkpoint protein (also called a master regulator). For example and conceptually similar to the Myxococcus system, eukaryotic Ras-like G-proteins must also partition their activity to several output proteins, ie during chemotaxis [55]. While different circuit designs could have evolved to achieve this function, the Myxococcus system could provide valuable lens to study the evolutionary and mechanistic processes that allowed one such diversification.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth

Strains, plasmids and primers used for this study are listed in S1, S2, and S3 Tables. In general, M. xanthus strains were grown at 32°C in CYE rich media as previously described [31]. Plasmids were introduced in M. xanthus by electroporation. Mutants and transformants were obtained by homologous recombination based on a previously reported method [31]. E. coli cells were grown under standard laboratory conditions in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with antibiotics, if necessary.

Phenotypic assays

Unless otherwise specified, soft and hard agar motility and development assays were performed as previously described [31]. In general, cell were grown up to an OD = 0.5 and concentrated ten times before they were spotted (10μL) on CYE or CF [31] 0.5% (soft) agar or 1.5% (hard) agar plates for motility or for developmental assays. Colonies were photographed after 48 H or 72 H for motility or development, respectively. Developmental assays in the presence of Isoamyl alcohol (IAA, Sigma Aldrich) were performed similarly except that plates also contained IAA at appropriate concentrations.

Single cell motility assays

Single cell Tfp-dependent motility assays were initially developed by Sun et al. [13] in a system where Myxococcus cells are overlaid in methylcellulose. However, in this assay, reversals as observed on agar are not observed. In this media, the cells are loosely attached to the glass surface and they systematically detach and become tethered by one cell pole before a directional change is observed [13]. Many of these events may well result from actual reversal events, but other Tfp-dependent motions have been observed including stick-slip motions, sling-shot motions and walking up-right [42,56,57]. To avoid confusion linked to complex Tfp-dependent movements, we sought to optimize the methylcellulose assay. For this, homemade PDMS glass microfluidic chambers [58] were treated with 0.015% carboxymethylcellulose after extensive washing of the glass slide with water. For each experiment, 1mL of a CYE grown culture of OD = 0.5–1 was injected directly into the chamber and the cells were allowed to settle for 5 min. Motility was assayed after the chamber was washed with TPM 1mM CaCl2 buffer [58]. For IAA injections, IAA solutions made in TPM 1mM CaCl2 buffer at appropriate concentrations were injected directly into the channels and motility was assayed directly under the microscope. In TPM 1mM CaCl2, we found that most WT motile cells left the field of view before reversing, making statistically reliable measurements of reversal frequencies difficult. This low reversal frequency is due to the absence of stimulating signals in these conditions. To increase the reversals counts and unless otherwise stated, Frz signaling was stimulated by adding 0.1–0.15% IAA to the TPM mix. Time-lapse experiments were performed as previously described (Ducret et al., 2013) using a Nikon TE2000-E-PFS inverted epifluorescence microscope.

Automated cell tracking and statistics

Image analysis was performed with a specific library of functions written in Python and adapted from available plugins in FIJI/ImageJ [59]. Cells were detected by thresholding the phase contrast images after stabilization. Cell tracking was obtained by calculating all objects distances between two consecutive frames, thus selecting the nearest objects. The computed trajectories were systematically verified manually and when errors were encountered, the trajectories were removed. The analysis of the trajectories is done automatically by a Python script that calculates the angle formed by the segments between the center of the cell at time t, the center of the cell at time t-1 and the center at time t+1. Directional changes were scored as reversals when cells switched their direction of movement and the angle between segments was less than 90°. For non-reversing strains, the number of reversals for each cells was plotted against time using R software (http://www.R-project.org/). For strains that frequently reversed, the mean time between two reversals for each cells was plotted against time using R software.

To further discriminate bona fide reversal events from stick-slip motions, the fluorescence intensity of FrzS-YFP was measured at cell poles over time. For each cell that was tracked, the fluorescence intensity and reversal profiles were correlated to distinguish bona fide reversals from stick-slip events with the R software. When a directional change was not correlated to a switch in fluorescence intensity, this change was discarded as a stick-slip event. The number of reversals was plotted against time using R software.

Statistics were done using R software: Wilcox test was used when the number of cells was less than 40 in at least one of the two populations compared, and student test (t-test) was used for a number of cells higher than 40.

Cloning, expression and purification of M. xanthus Frz system proteins

The genes encoding FrzEkinase, FrzA, FrzCD and FrzCDc were amplified by PCR using M. xanthus DZ2 chromosomal DNA as template and the forward and reverse primers listed in S3 Table. The amplified product was digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and ligated either into the pETPhos or pGEX plasmids generating pETPhos_frzEkinase, pETPhos_frzCD, pETPhos_frzCDc and pGEX_frzA which were used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3)Star cells in order to overexpress His-tagged or GST-tagged proteins. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Recombinant strains harboring the different constructs were used to inoculate 400 ml of LB medium supplemented with glucose (1mg/mL) and ampicillin (100μg/ml), and the resulting cultures were incubated at 25°C with shaking until the optical density of the culture reached an OD = 0.6. IPTG (0.5 mM final) was added to induce the overexpression, and growth was continued for 3 extra hours at 25°C. Purification of the His-tagged/GST-tagged recombinant proteins was performed as described by the manufacturer (Clontech/GE Healthcare).

In vitro autophosphorylation assay

In vitro phosphorylation assay was performed with E. coli purified recombinant proteins. 4 μg of FrzEkinase were incubated with 1μg of FrzA and increasing concentrations (0.5 to 7μg) of either FrzCD or FrzCDc in 25 μl of buffer P (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1 mM DTT; 5 mM MgCl2; 50mM KCl; 5 mM EDTA; 50μM ATP, 10% glycerol) supplemented with 200 μCi ml-1 (65 nM) of [γ-33P]ATP (PerkinElmer, 3000 Ci mmol-1) for 10 minutes at room temperature in order to obtain the optimal FrzEkinase autophosphorylation activity. Each reaction mixture was stopped by addition of 5 × Laemmli and quickly loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel. After electrophoresis, proteins were revealed using Coomassie Brilliant Blue before gel drying. Radioactive proteins were visualized by autoradiography using direct exposure to film (Carestream).

Inducible expression of FrzCD by IPTG

669 bp upstream from frzCD were amplified with primers CDind1 (gaattcATGTCCCTGGACACCCCCAACGA) and CDind2 (actagtCATGGCCTGGATGAACTCGCCAAT) and cloned into pGEM T-easy (Promega) to obtain plasmid pEM140. pEM140 was digested with SpeI and EcoRI and the excised DNA fragment was cloned into pLacI (a derivative of pAK20 [60]) previously digested with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmid, pEM143, is a derivative of pBBR1MCS carrying the lacI gene under its promoter and followed by the first 669 of frzCD and thus its integration by homologous recombination places the entire frz operon under IPTG control.

Developmental plate assays were conducted in the presence (0.5 mM) or absence of IPTG. For western blotting, strains were grown overnight with or without appropriate concentrations of IPTG. The cultures were concentrated to OD = 4 and western blotting was performed as previously described with 1/10,000 dilutions of anti-FrzCD (Bustamante et al., 2004).

Genomic dataset construction

A local protein database containing the 2,316 complete prokaryotic proteomes available in the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) as of May 23, 2013 was built. This database was queried with the BlastP program (default parameters, [61]) using the full length sequences of the signaling proteins (FrzF (MXAN_4138), FrzG (MXAN_4139), FrzE (MXAN_4140), FrzCD (MXAN_4141), FrzB (MXAN_4142), FrzA (MXAN_4143) and FrzZ (MXAN_4144)), the polarity control proteins (MglA (MXAN_1925), MglB (MXAN_1926) and RomR (MXAN_4461)) and the downstream proteins (FrzS (MXAN_4149) and AglZ (MXAN_2991)) of M. xanthus as a seed. The homology was assessed by visual inspection of each BlastP output (no arbitrary cut-offs on the E-value or score). The retrieved sequences were aligned using MAFFT version 7 (default parameters, [62]). Regions where the homology between amino acid positions was doubtful were removed using the BMGE software (BLOSUM30 option; [63]).

For each protein, preliminary phylogenetic analyses were performed using FastTree v.2 using a gamma distribution with four categories [64]. Most of the studied proteins belong to very large protein families. Based on the resulting trees, the subfamilies containing the sequences from M. xanthus were identified and selected for further phylogenetic investigations. The corresponding sequences were realigned using MAFFT version 7 with the linsi option, which ensures accurate alignments. The resulting alignments were trimmed with BMGE as previously described.

Phylogenetic analyses

Maximum likelihood (ML) trees were computed using PHYML version 3.1 [65] with the Le and Gascuel (LG) model (amino acid frequencies estimated from the dataset) and a gamma distribution (4 discrete categories of sites and an estimated alpha parameter) to take into account evolutionary rate variations across sites. Branch robustness was estimated by the non-parametric bootstrap procedure implemented in PhyML (100 replicates of the original dataset with the same parameters). Bayesian inferences (BI) were performed using Mrbayes 3.2.2 [66] with a mixed model of amino acid substitution including a gamma distribution (4 discrete categories). MrBayes was run with four chains for 1 million generations and trees were sampled every 100 generations. To construct the consensus tree, the first 2000 trees were discarded as “burn in”.

The phylogenetic signal can be substantially increased by combining multiple sequence alignments of proteins involved in the same cellular function/biological process and sharing a common evolutionary history in a single large alignment (also called supermatrix), [16,67–71]. Among the 12 studied genes, we showed that FrzF, FrzG, FrzCD and FrzE are always clustered together in genomes and share a similar evolutionary history. These genes were thus combined to build a supermatrix (S4 Fig). For similar reasons, a second supermatrix was built by combining MglA and MglB (S2 Fig). The ML and BI phylogenetic trees corresponding to these two supermatrices were inferred as previously described [16].

Reference phylogeny of Delta/Epsilonproteobacteria

The 79 complete proteomes of Delta/Epsilonproteobacteria available at the NCBI in May 17, 2013 were retrieved and assembled in a local database (S5 Table). We used SILIX to build the protein families of homologous sequences present in these genomes (default parameters; [72]).The homologous sequences corresponding to protein families present exactly in a single copy per genome (17 proteins) were aligned using MAFFT Version 7 (linsi option), trimmed with BMGE and combined to build a large supermatrix (6958 positions). The ML phylogenetic tree corresponding to this large supermatrix was inferred with PhyML, as described above.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Salazar ME, Laub MT. Temporal and evolutionary dynamics of two-component signaling pathways. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;24 : 7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.12.003 25589045

2. Tian T, Harding A. How MAP kinase modules function as robust, yet adaptable, circuits. Cell Cycle. 2014;13 : 2379–2390. doi: 10.4161/cc.29349 25483189

3. Capra EJ, Perchuk BS, Skerker JM, Laub MT. Adaptive mutations that prevent crosstalk enable the expansion of paralogous signaling protein families. Cell. 2012;150 : 222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.033 22770222

4. Jonas K, Chen YE, Laub MT. Modularity of the bacterial cell cycle enables independent spatial and temporal control of DNA replication. Curr Biol. 2011;21 : 1092–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.040 21683595

5. Murray SM, Panis G, Fumeaux C, Viollier PH, Howard M. Computational and genetic reduction of a cell cycle to its simplest, primordial components. PLoS Biol. 2013;11: e1001749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001749 24415923

6. Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-Component Signal Transduction. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2000;69 : 183–215. 10966457

7. Skerker JM, Perchuk BS, Siryaporn A, Lubin EA, Ashenberg O, Goulian M, et al. Rewiring the specificity of two-component signal transduction systems. Cell. 2008;133 : 1043–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.040 18555780

8. Kirby JR. Chemotaxis-like regulatory systems: unique roles in diverse bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63 : 45–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073221 19379070

9. Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. Making sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5 : 1024–37. 15573139

10. He K, Bauer CE. Chemosensory signaling systems that control bacterial survival. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22 : 389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.04.004 24794732

11. Wuichet K, Zhulin IB. Origins and diversification of a complex signal transduction system in prokaryotes. Sci Signal. 2010;3: ra50. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000724 20587806

12. Zhang Y, Ducret A, Shaevitz J, Mignot T. From individual cell motility to collective behaviors: insights from a prokaryote, Myxococcus xanthus. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36 : 149–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00307.x 22091711

13. Sun H, Zusman DR, Shi WY. Type IV pilus of Myxococcus xanthus is a motility apparatus controlled by the frz chemosensory system. Current Biology. 2000;10 : 1143–1146. 10996798

14. Li Y, Sun H, Ma X, Lu A, Lux R, Zusman D, et al. Extracellular polysaccharides mediate pilus retraction during social motility of Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100 : 5443–8. 12704238

15. Agrebi R, Wartel M, Brochier-Armanet C, Mignot T. An evolutionary link between capsular biogenesis and surface motility in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13 : 318–326. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3431 25895941

16. Luciano J, Agrebi R, Le Gall AV, Wartel M, Fiegna F, Ducret A, et al. Emergence and modular evolution of a novel motility machinery in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2011;7: e1002268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002268 21931562

17. Nan B, McBride MJ, Chen J, Zusman DR, Oster G. Bacteria that glide with helical tracks. Curr Biol. 2014;24: R169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.034 24556443

18. Bulyha I, Schmidt C, Lenz P, Jakovljevic V, Hone A, Maier B, et al. Regulation of the type IV pili molecular machine by dynamic localization of two motor proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74 : 691–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06891.x 19775250

19. Mignot T, Merlie JP, Zusman DR. Regulated pole-to-pole oscillations of a bacterial gliding motility protein. Science. 2005;310 : 855–857. 16272122

20. Mignot T, Shaevitz JW, Hartzell PL, Zusman DR. Evidence that focal adhesion complexes power bacterial gliding motility. Science. 2007;315 : 853–6. 17289998

21. Blackhart BD, Zusman DR. “Frizzy” genes of Myxococcus xanthus are involved in control of frequency of reversal of gliding motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82 : 8767–70. 3936045

22. Zusman DR. “Frizzy” mutants: a new class of aggregation-defective developmental mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1982;150 : 1430–7. 6281244

23. Leonardy S, Miertzschke M, Bulyha I, Sperling E, Wittinghofer A, Sogaard-Andersen L. Regulation of dynamic polarity switching in bacteria by a Ras-like G-protein and its cognate GAP. Embo J. 2010;29 : 2276–89. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.114 20543819

24. Zhang Y, Franco M, Ducret A, Mignot T. A bacterial Ras-like small GTP-binding protein and its cognate GAP establish a dynamic spatial polarity axis to control directed motility. PLoS Biol. 2010;8: e1000430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000430 20652021

25. Mauriello EMF, Mouhamar F, Nan B, Ducret A, Dai D, Zusman DR, et al. Bacterial motility complexes require the actin-like protein, MreB and the Ras homologue, MglA. EMBO J. 2010;29 : 315–326. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.356 19959988

26. Keilberg D, Wuichet K, Drescher F, Søgaard-Andersen L. A response regulator interfaces between the Frz chemosensory system and the MglA/MglB GTPase/GAP module to regulate polarity in Myxococcus xanthus. PLoS Genet. 2012;8: e1002951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002951 23028358

27. Zhang Y, Guzzo M, Ducret A, Li Y-Z, Mignot T. A dynamic response regulator protein modulates G-protein-dependent polarity in the bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. PLoS Genet. 2012;8: e1002872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002872 22916026

28. Miertzschke M, Koerner C, Vetter IR, Keilberg D, Hot E, Leonardy S, et al. Structural analysis of the Ras-like G protein MglA and its cognate GAP MglB and implications for bacterial polarity. EMBO J. 2011;30 : 4185–4197. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.291 21847100

29. Eckhert E, Rangamani P, Davis AE, Oster G, Berleman JE. Dual Biochemical Oscillators May Control Cellular Reversals in Myxococcus xanthus. Biophys J. 2014;107 : 2700–2711. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.09.046 25468349

30. Inclan YF, Vlamakis HC, Zusman DR. FrzZ, a dual CheY-like response regulator, functions as an output for the Frz chemosensory pathway of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65 : 90–102. 17581122

31. Bustamante VH, Martinez-Flores I, Vlamakis HC, Zusman DR. Analysis of the Frz signal transduction system of Myxococcus xanthus shows the importance of the conserved C-terminal region of the cytoplasmic chemoreceptor FrzCD in sensing signals. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53 : 1501–13. 15387825

32. Inclan YF, Laurent S, Zusman DR. The receiver domain of FrzE, a CheA-CheY fusion protein, regulates the CheA histidine kinase activity and downstream signalling to the A - and S-motility systems of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68 : 1328–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06238.x 18430134

33. Kaimer C, Zusman DR. Phosphorylation-dependent localization of the response regulator FrzZ signals cell reversals in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 2013;88 : 740–753. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12219 23551551

34. Leonardy S, Freymark G, Hebener S, Ellehauge E, Sogaard-Andersen L. Coupling of protein localization and cell movements by a dynamically localized response regulator in Myxococcus xanthus. Embo J. 2007;26 : 4433–44. 17932488

35. Karlin S, Brocchieri L, Mrázek J, Kaiser D. Distinguishing features of delta-proteobacterial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103 : 11352–11357. 16844781

36. Wartel M, Ducret A, Thutupalli S, Czerwinski F, Le Gall A-V, Mauriello EMF, et al. A Versatile Class of Cell Surface Directional Motors Gives Rise to Gliding Motility and Sporulation in Myxococcus xanthus. PLoS Biol. 2013;11: e1001728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001728 24339744

37. Wuichet K, Søgaard-Andersen L. Evolution and diversity of the ras superfamily of small GTPases in prokaryotes. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;7 : 57–70. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu264 25480683

38. Milner DS, Till R, Cadby I, Lovering AL, Basford SM, Saxon EB, et al. Ras GTPase-like protein MglA, a controller of bacterial social-motility in Myxobacteria, has evolved to control bacterial predation by Bdellovibrio. PLoS Genet. 2014;10: e1004253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004253 24721965

39. Yang RF, Bartle S, Otto R, Stassinopoulos A, Rogers M, Plamann L, et al. AglZ is a filament-forming coiled-coil protein required for adventurous gliding motility of Myxococcus xanthus. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186 : 6168–6178. 15342587

40. Mignot T, Merlie JP Jr, Zusman DR. Two localization motifs mediate polar residence of FrzS during cell movement and reversals of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65 : 363–372. 17590236

41. Fraser JS, Merlie JP Jr, Echols N, Weisfield SR, Mignot T, Wemmer DE, et al. An atypical receiver domain controls the dynamic polar localization of the Myxococcus xanthus social motility protein FrzS. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65 : 319–332. 17573816

42. Gibiansky ML, Hu W, Dahmen KA, Shi W, Wong GCL. Earthquake-like dynamics in Myxococcus xanthus social motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110 : 2330–2335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215089110 23341622

43. McBride MJ, Kohler T, Zusman DR. Methylation of FrzCD, a methyl-accepting taxis protein of Myxococcus xanthus, is correlated with factors affecting cell behavior. J Bacteriol. 1992;174 : 4246–57. 1624419

44. McBride MJ, Weinberg RA, Zusman DR. “Frizzy” aggregation genes of the gliding bacterium Myxococcus xanthus show sequence similarities to the chemotaxis genes of enteric bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86 : 424–8. 2492105

45. Englert DL, Manson MD, Jayaraman A. Investigation of bacterial chemotaxis in flow-based microfluidic devices. Nat Protoc. 2010;5 : 864–872. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.18 20431532

46. Lamanna AC, Ordal GW, Kiessling LL. Large increases in attractant concentration disrupt the polar localization of bacterial chemoreceptors. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57 : 774–785. 16045621

47. Bulyha I, Lindow S, Lin L, Bolte K, Wuichet K, Kahnt J, et al. Two small GTPases act in concert with the bactofilin cytoskeleton to regulate dynamic bacterial cell polarity. Dev Cell. 2013;25 : 119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.02.017 23583757

48. Sun M, Wartel M, Cascales E, Shaevitz JW, Mignot T. Motor-driven intracellular transport powers bacterial gliding motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 : 7559–7564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101101108 21482768

49. Capra EJ, Perchuk BS, Ashenberg O, Seid CA, Snow HR, Skerker JM, et al. Spatial tethering of kinases to their substrates relaxes evolutionary constraints on specificity. Molecular Microbiology. 2012;86 : 1393–1403. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12064 23078131

50. Sourjik V, Schmitt R. Phosphotransfer between CheA, CheY1, and CheY2 in the chemotaxis signal transduction chain of Rhizobium meliloti. Biochemistry. 1998;37 : 2327–2335. 9485379

51. He K, Marden JN, Quardokus EM, Bauer CE. Phosphate flow between hybrid histidine kinases CheA₃ and CheS₃ controls Rhodospirillum centenum cyst formation. PLoS Genet. 2013;9: e1004002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004002 24367276

52. Goulian M. Two-component signaling circuit structure and properties. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13 : 184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.009 20149717

53. Mitrophanov AY, Groisman EA. Signal integration in bacterial two-component regulatory systems. Genes Dev. 2008;22 : 2601–2611. doi: 10.1101/gad.1700308 18832064

54. Ulrich LE, Zhulin IB. MiST: a microbial signal transduction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35: D386–90. 17135192

55. Charest PG, Firtel RA. Big roles for small GTPases in the control of directed cell movement. Biochem J. 2007;401 : 377–90. 17173542

56. Gibiansky ML, Conrad JC, Jin F, Gordon VD, Motto DA, Mathewson MA, et al. Bacteria use type IV pili to walk upright and detach from surfaces. Science. 2010;330 : 197. doi: 10.1126/science.1194238 20929769

57. Jin F, Conrad JC, Gibiansky ML, Wong GCL. Bacteria use type-IV pili to slingshot on surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 : 12617–12622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105073108 21768344

58. Ducret A, Théodoly O, Mignot T. Single cell microfluidic studies of bacterial motility. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;966 : 97–107. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-245-2_6 23299730

59. Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9 : 676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019 22743772

60. Komeili A, Li Z, Newman DK, Jensen GJ. Magnetosomes are cell membrane invaginations organized by the actin-like protein MamK. Science. 2006;311 : 242–5. 16373532

61. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25 : 3389–3402. 9254694

62. Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30 : 772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010 23329690

63. Criscuolo A, Gribaldo S. BMGE (Block Mapping and Gathering with Entropy): a new software for selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10 : 210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-210 20626897

64. Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE. 2010;5: e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490 20224823

65. Guindon S, Dufayard J-F, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59 : 307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 20525638

66. Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61 : 539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 22357727

67. Brochier C, Bapteste E, Moreira D, Philippe H. Eubacterial phylogeny based on translational apparatus proteins. Trends Genet. 2002;18 : 1–5. 11750686

68. Brown JR, Douady CJ, Italia MJ, Marshall WE, Stanhope MJ. Universal trees based on large combined protein sequence data sets. Nat Genet. 2001;28 : 281–285. 11431701

69. Ciccarelli FD, Doerks T, von Mering C, Creevey CJ, Snel B, Bork P. Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life. Science. 2006;311 : 1283–1287. 16513982

70. Delsuc F, Brinkmann H, Philippe H. Phylogenomics and the reconstruction of the tree of life. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6 : 361–375. 15861208

71. Liu R, Ochman H. Stepwise formation of the bacterial flagellar system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104 : 7116–7121. 17438286

72. Miele V, Penel S, Duret L. Ultra-fast sequence clustering from similarity networks with SiLiX. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12 : 116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-116 21513511

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Loss and Gain of Natural Killer Cell Receptor Function in an African Hunter-Gatherer PopulationČlánek Let-7 Represses Carcinogenesis and a Stem Cell Phenotype in the Intestine via Regulation of Hmga2Článek Binding of Multiple Rap1 Proteins Stimulates Chromosome Breakage Induction during DNA ReplicationČlánek SLIRP Regulates the Rate of Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis and Protects LRPPRC from DegradationČlánek Protein Composition of Infectious Spores Reveals Novel Sexual Development and Germination Factors inČlánek The Formin Diaphanous Regulates Myoblast Fusion through Actin Polymerization and Arp2/3 RegulationČlánek Runx1 Transcription Factor Is Required for Myoblasts Proliferation during Muscle Regeneration

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 8

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Putting the Brakes on Huntington Disease in a Mouse Experimental Model

- Identification of Driving Fusion Genes and Genomic Landscape of Medullary Thyroid Cancer

- Evidence for Retromutagenesis as a Mechanism for Adaptive Mutation in

- TSPO, a Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Protein, Controls Ethanol-Related Behaviors in

- Evidence for Lysosome Depletion and Impaired Autophagic Clearance in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Type SPG11

- Loss and Gain of Natural Killer Cell Receptor Function in an African Hunter-Gatherer Population

- Trans-Reactivation: A New Epigenetic Phenomenon Underlying Transcriptional Reactivation of Silenced Genes

- Early Developmental and Evolutionary Origins of Gene Body DNA Methylation Patterns in Mammalian Placentas

- Strong Selective Sweeps on the X Chromosome in the Human-Chimpanzee Ancestor Explain Its Low Divergence

- Dominance of Deleterious Alleles Controls the Response to a Population Bottleneck

- Transient 1a Induction Defines the Wound Epidermis during Zebrafish Fin Regeneration