-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaLet-7 Represses Carcinogenesis and a Stem Cell Phenotype in the Intestine via Regulation of Hmga2

Cancer develops following multiple genetic mutations (i.e. in tumor suppressors and oncogenes), and mutations that cooperate or synergize are often advantageous to cancer cell growth. To study how multiple genes might cooperate, it is usually informative to generate candidate mutations in cells or in mice. Large gene families, such as the Let-7 family, are difficult to silence or mutate because of the large amount of redundancy that exists between similar copies of the same gene; the mutation of one will often be masked or compensated by the continued function of others. In the mouse intestine we have achieved comprehensive depletion of all Let-7 miRNAs in this large multi-genic family through use of an inhibitory protein, called LIN28B, that specifically represses Let-7, and genetic inactivation of another gene cluster called MirLet7c-2/Mirlet7b. Mice with this comprehensive depletion of Let-7 develop intestinal cancers that resemble human colon cancers. Our further analysis identified another gene, HMGA2, downstream of this pathway that is critical to this outcome.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005408

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005408Summary

Cancer develops following multiple genetic mutations (i.e. in tumor suppressors and oncogenes), and mutations that cooperate or synergize are often advantageous to cancer cell growth. To study how multiple genes might cooperate, it is usually informative to generate candidate mutations in cells or in mice. Large gene families, such as the Let-7 family, are difficult to silence or mutate because of the large amount of redundancy that exists between similar copies of the same gene; the mutation of one will often be masked or compensated by the continued function of others. In the mouse intestine we have achieved comprehensive depletion of all Let-7 miRNAs in this large multi-genic family through use of an inhibitory protein, called LIN28B, that specifically represses Let-7, and genetic inactivation of another gene cluster called MirLet7c-2/Mirlet7b. Mice with this comprehensive depletion of Let-7 develop intestinal cancers that resemble human colon cancers. Our further analysis identified another gene, HMGA2, downstream of this pathway that is critical to this outcome.

Introduction

Micro-RNAs (miRNAs) are critical for tumor suppression, which is most notably revealed following genetic manipulation of Dicer1, an enzyme needed for miRNA processing, in which haplo-insufficiency of Dicer1 and global reduction of miRNA levels significantly accelerates tumorigenesis [1,2]. Let-7 miRNAs comprise one of the largest and most highly expressed families of miRNAs, possessing potent anti-carcinogenic properties in a variety of tissues [3]. This activity is likely mediated via Let-7 repression of a multitude of onco-fetal mRNAs and other pro-proliferative and/or pro-metastatic targets, such as HMGA2, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, and NR6A1 [4–6]. Let-7 biogenesis is tightly regulated, revealed by the discovery of several proteins that regulate processing by DGCR8/DROSHA in the nucleus, and by DICER1 cleavage in the cytoplasm. Most notable are LIN28A and LIN28B, which are RNA-binding proteins that directly bind to and block the processing of Let-7 mRNAs [7,8]. LIN28A works in concert with TRIM25 and TUT4 to mediate terminal uridylation and subsequent degradation of immature precursor-Let-7 (pre-Let-7) miRNA molecules [9–11]. LIN28B appears to act by sequestering primary-Let-7 (pri-Let-7) miRNAs within the nucleolus to prohibit processing by DGCR8 and DROSHA [9]. The critical nature of maintaining sufficient levels of mature Let-7 miRNAs is reflected in the large number of studies that have found LIN28A or LIN28B up-regulated in human cancers, with expression often associated with an aggressive disease phenotype and/or predictive of poor outcomes [12–15]. LIN28B appears somewhat more frequently up-regulated than LIN28A in cancer, and may reflect the greater expression potential of LIN28B in adult tissues: LIN28B exhibits a later temporal pattern of expression in adult tissues such as the intestine, plays a greater role in post-natal growth, and can be re-activated by inflammation and NF-kappa-B [16–19].

In efforts of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) research consortia to define miRNA-mRNA associations across multiple different cancers (i.e. the pan-cancer initiative), the LIN28B:Let-7b interaction was identified as one of the most significant relationships discovered across nine different human malignancies [20]. The tight functional interplay between LIN28 proteins and Let-7 is delineated clearly, on biochemical and biological levels. However, Let-7 action appears dependent on the particular mRNA targets affected, although Let-7 represses de-differentiation in multiple contexts. For example, Let-7 regulates insulin-PI3K-mTOR signaling in muscle by inhibiting expression of INSR, IGF1R, and IRS2 [21], yet can also inhibit mTORC1 without affecting insulin-PI3K signaling [22], whereas we have observed no effects on insulin-PI3K-mTOR signaling following depletion of Let-7 miRNAs in the small intestine [18]. Micro-RNAs have many targets, including both coding and non-coding mRNAs, and to address the functional impact of these miRNAs, one must dissect the cascade of integrated signals that ensue following alterations of a miRNA. Many studies have focused on RAS and MYC as cancer-relevant Let-7 targets, although recent high-throughput sequencing (mRNA-seq, miRNA-seq, and CLIP-seq) and meta-analyses indicate that these mRNA targets are not frequently regulated by Let-7, especially in the context of cancer [5,6,20,23]. Onco-fetal Let-7 targets such as HMGA2 and IGF2BP1-3 appear to be more frequently up-regulated in multiple contexts, across multiple tissues, and in association with somatic stem cell potential [4,5,20,24–29].

We have demonstrated that LIN28B is a potent driver of colorectal cancer (CRC) progression, cellular invasion, and in mouse models, a regulator of intestinal growth and tumorigenesis [15,18,30]. The exploration of Let-7-dependence through genetic manipulation in mouse models is currently untenable due to the large number of miRNA clusters, with 12 Let-7 genes located at 8 separate clusters on 7 different chromosomes. To circumvent this obstacle and elucidate the mechanistic roles of Let-7 miRNAs in intestinal tumorigenesis in a genetic mouse model we have combined a Vil-Lin28bLow (Lin28bLo) transgene with intestinal deletion of the MirLet7c-2/Mirlet7b bi-cistronic cluster (Let-7IEC-KO) to achieve robust repression of all Let-7 miRNAs expressed in the intestinal epithelium. Concurrent deletion of the MirLet7c-2/Mirlet7b bi-cistronic cluster is necessary as Lin28b is unable to effectively target and inhibit processing of these specific Let-7 miRNAs [18].

These Lin28bLo/Let-7IEC-KO mice develop intestinal polyps with 100% penetrance and develop adenocarcinomas in the majority of animals, coincident with reduced survival. Examination of Let-7 targets in these tumors and in tumoroid cultures suggest that HMGA2 is likely playing a major role in driving carcinogenesis following Let-7 depletion, a novel in vivo finding. Furthermore, we find that tumorigenesis and a stem cell signature are driven by Let-7 depletion in mouse and human intestinal tumors, in which HMGA2 appears to play a functional role in reinforcing.

Results

Comprehensive Depletion of Let-7 miRNAs Leads to the Development of Intestinal Adenocarcinomas in Mice

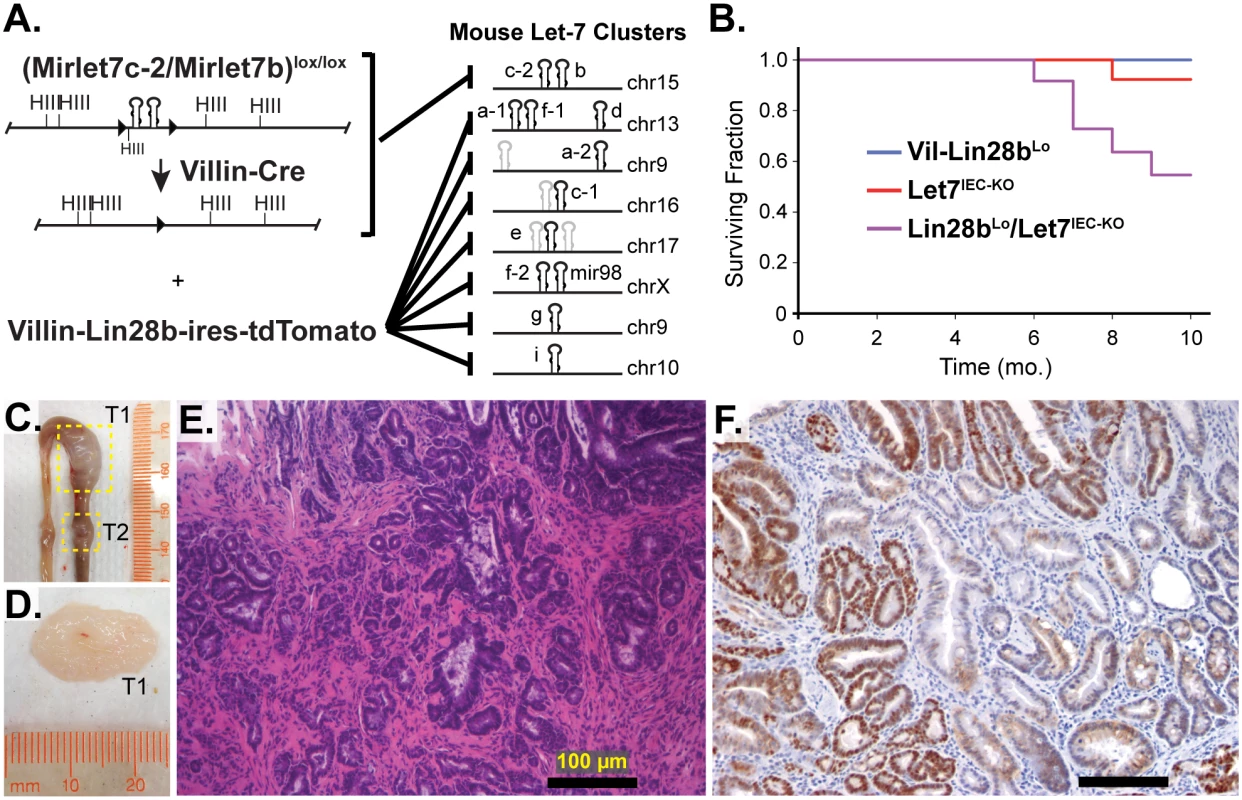

Vil-Lin28bLow mice and Let7IEC-KO mice were generated and described previously [18]. To generate compound mutant animals we used a low-expressing transgenic line (Lin28bLo), in which we could not detect measureable changes in either protein or mRNA levels of Let-7-independent Lin28b targets [18]. These compound Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice, exhibit depletion of all Let-7 miRNAs specifically in intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) achieved through deletion of the MirLet7c-2/MirLet7b locus and repression of all other Let-7 miRNAs through inhibition by Lin28b [18] (and Fig 1A). Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice thrived initially, with normal behavior and weight gain, but displayed significantly increased mortality and morbidity starting around 6 months of age, whereas neither Vil-Lin28bLo nor Let7IEC-KO age-matched mice exhibited any overt phenotype (Fig 1B). Surviving Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO were sacrificed between 10 and 14 months of age and exhibited a significant incidence of adenomas and adenocarcinomas, restricted to the small intestine, with an average of 2.86 lesions per mouse and 100% penetrance (S1 Table and Fig 1C, 1D and 1E). Six of seven Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice developed invasive adenocarcinoma (S1 Table and Fig 1C, 1D and 1E). Tumors from mice also displayed nuclear localization of β-catenin (Fig 1F), indicative of constitutive activation of the Wnt signaling pathway. The severity of the Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO phenotype was substantially more dramatic than in Vil-Lin28bLo or Vil-Lin28bMed mice (18). Vil-Lin28bMed mice express higher levels of Lin28b, have partially depleted Let-7 miRNAs and develop adenocarcinomas of the small intestine as do Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice but do not exhibit a phenotype as severe as Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice (18).

Fig. 1. Comprehensive depletion of all Let-7 miRNAs leads to the development of intestinal adenocarcinomas.

A) Schematic of the intestine-specific deletion of the Mirlet7c-2/Mirlet7b floxed locus via Villin-Cre and expression of Lin28b with a Villin-Lin28b-ires-tdTomato transgene, which repress all 8 of the Let-7 clusters. Let-7 miRNA genes are shown as black hairpins while non-let-7 miRNA genes are depicted as gray hairpins. B) Kaplan-Meier plot showing survival over 10 months. C) Representative small intestine from a Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mouse containing two tumors, T1 and T2 (box outline with yellow dotted lines). D) Large tumor from (C) dissected with luminal side facing outward. E) H&E stained paraffin section of adenocarcinoma from a Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mouse. F) Representative section of adenocarcinoma from a Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mouse immunostained for β-catenin, showing a nuclear pattern of localization. Scale bars in (E) and (F) = 100 μm. Identification of Relevant Let-7 Target mRNAs in the Intestinal Epithelium and Tumors

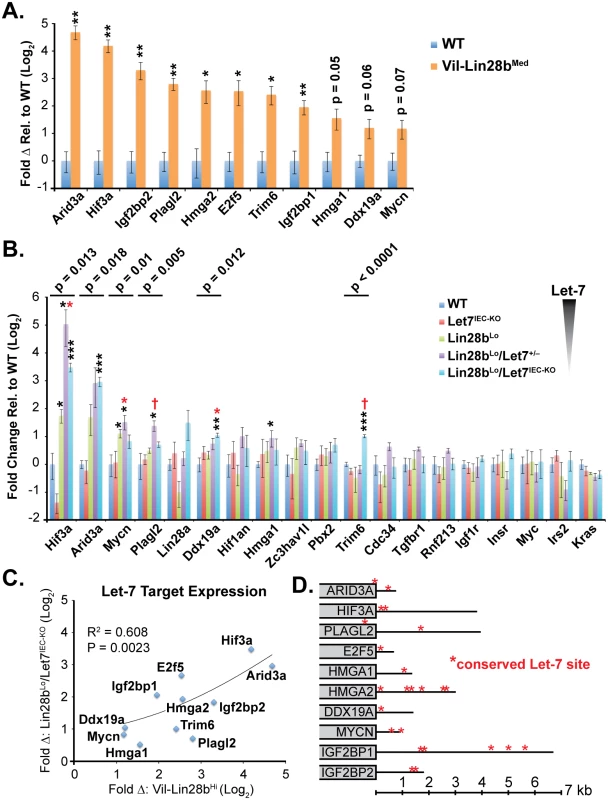

Let-7 targets were examined in small intestine crypts from Vil-Lin28b and Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice. RNA microarray expression analysis was previously performed on Vil-Lin28bMed total small intestine epithelia and we verified elevation of Hmga1, Hmga2, Igf2bp1, Igf2bp2, E2f5, Acvr1c, Nr6a1, Hif3a, Arid3a, Plagl2, Trim6, Ddx19a, and Mycn (Fig 2A and [18]). We also observed significant elevation of mRNAs for these Let-7 targets in crypts from small intestine epithelia from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO (Fig 2B). Expression of all Let-7 targets also correlated significantly between Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO and Vil-Lin28bMed intestine crypts, with Hmga2, Igf2bp2, Hif3a, Arid3a, and E2f5 being the most highly induced targets in both models (Fig 2C). All targets contained conserved Let-7 sites in the 3’UTR or coding sequence, except for Trim6, for which only the mouse mRNA possesses Let-7 sites (Fig 2D). In addition to our findings for HMGA2, IGF2BP1, and IGF2BP2, there is experimental evidence that HMGA1, E2F5, and ARID3A are also direct targets of Let-7 [6,31,32].

Fig. 2. Quantification of Let-7 target mRNA levels in intestinal epithelium crypts.

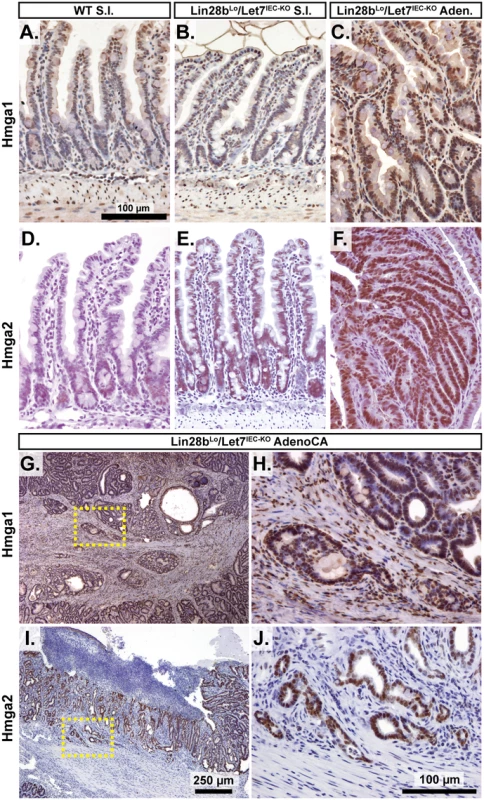

A) Expression of Let-7 target mRNA levels in small intestine crypts isolated from wild-type (WT) and Vil-Lin28bMed mice. B) Expression of Let-7 target mRNA levels in small intestine (jejunum) crypts isolated from wild-type (WT), Vil-Lin28bLo, Let7IEC-KO, Lin28bLo/Let7+/-, and Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice. C) Comparison of Let-7 target mRNA changes in small intestine crypts from Vil-Lin28bMed mice vs. Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice reveals similar expression changes in each model of Let-7 depletion, with significant correlation (Pearson correlation shown). Expression analysis was performed by Q-RT-PCR, normalized to Hprt and Actb, with n = 3 mice for each genotype at 12 weeks of age with error bars representing +/–the S.E.M. D) Identification of conserved Let-7 target genes in ten of eleven Let-7 target genes based upon TargetScan.org prediction. Student’s two-tailed T-tests were performed to determine significance with * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, and *** p-value < 0.001, relative to WT small intestine. One-way ANOVA standard weighted-means analysis was also performed in B, with p-values < 0.05 indicated above each gene. Tukey's HSD (honest significant difference) post-test was also performed in B, with samples p < 0.05 (red asterisk) and p < 0.01 (†) indicated, relative to mean of WT small intestine. To gain insight into the association of several Let-7 targets with tumorigenesis in vivo, we examined Hmga1, Hmga2, Arid3a, and Hif3a protein expression by immunostaining adenomas and adenocarcinomas, as well as adjacent normal tissue, from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice. These targets exhibited little or modest up-regulation in normal small intestine epithelia of Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice, but dramatic increases in tumors (Fig 3A–3J and S3A–S3H Fig). Pathological assessment of the staining pattern revealed that Hmga1 and Hmga2 staining was most intense in areas of invasive adenocarcinoma (Fig 3G, 3H and 3I).

Fig. 3. Hmga1 and Hmga2 proteins are increased in invasive areas of adenocarcinomas.

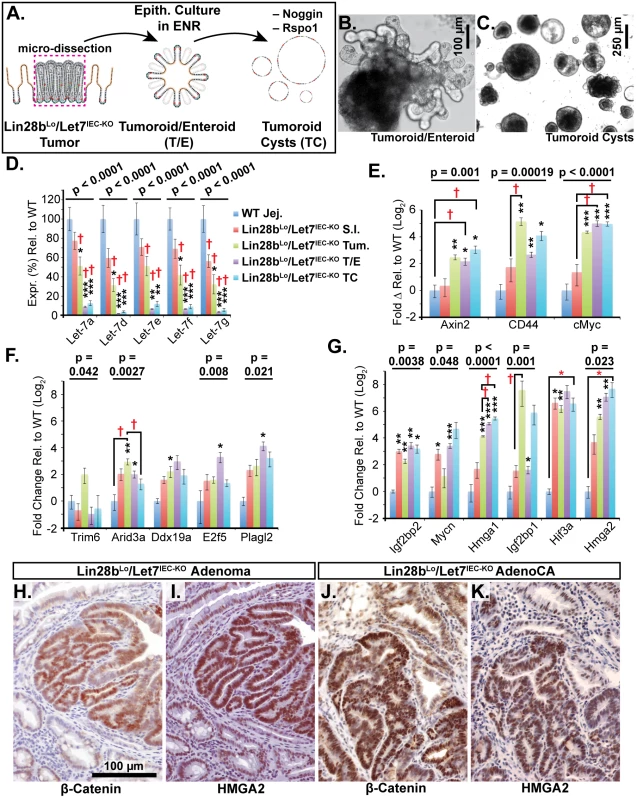

Immunohistochemical staining for Hmga2 (A-C, G, H) and Hmga2 (D-F, I, J), in sections from WT small intestine (S.I.) (A, D), Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO S.I. (B, E), Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO adenoma (C, F), and Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO adenocarcinoma (AdenoCA) (G-J). An enlargement of a region containing invasive HMGA1-positive tumor cells from G (dotted yellow box) is pictured in H, while a region containing invasive HMGA2-positive tumor cells from I is likewise displayed in J. Pictures in A-F, H, and J are at same magnification (200x), with scale bar = 100 μm, while pictures in G and I are both at 40x, with scale bar = 250 μm. We next examined Let-7 targets that might mediate programs of tumorigenesis in Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice in the context of tumors and cellular transformation. To model intestinal epithelial carcinogenesis we developed a 3-D culture model to examine only the epithelium and to select transformed tumor cells (Fig 4A). Enteroids derived from CRC tumors appear to faithfully recapitulate the major expression signatures of un-manipulated whole tumors [33]. To pursue this, we micro-dissected and dissociated adenocarcinomas from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice and cultured “tumoroids” from these lesions in medium supplemented with EGF, Noggin, and Rspo1, as described previously for enteroid culture [34]. These tumoroid/enteroids (T/E) resembled normal small intestine enteroids (Fig 4B) and are likely a mixture of different cell types, but upon withdrawal of Noggin and Rspo1, a small population of growth-factor independent cells expanded into tumoroid cysts (TC) (Fig 4C), which likely possess cell-autonomous activation of Wnt signaling and Noggin-independent resistance to BMP signaling. Quantification by Taqman RT-PCR confirmed that Let-7 miRNAs are severely repressed in tumoroid/enteroids and transformed tumoroid cysts (Fig 4D). Tumors and tumoroids, but not normal tissue from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice, also exhibited up-regulation of Wnt target genes Axin2, CD44, and cMyc (Fig 4E), suggesting spontaneous and constitutive activation of Wnt signaling. Analysis of Let-7 target mRNAs revealed two basic patterns of expression, with one group displaying expression highest in intact tumors or tumoroids/enteroids (Fig 4F). The other group displayed increasing or plateauing expression, with higher levels in tumoroid/enteroids or tumoroid cysts (Fig 4G). In this latter group we find known and suspected oncogenes, such as Hmga1, Hmga2, Igf2bp1, Igf2bp2, and Mycn. As Hmga2 appeared to exhibit pronounced up-regulation (>200-fold) in the tumoroid/enteroid and tumoroid cyst populations, and increased staining in invasive areas of adenocarcinomas (Fig 3H), we evaluated Hmga2 co-localization with nuclear β-catenin in mouse tumors, to assay potential coincident activation of canonical Wnt signaling with nuclear Hmga2. Immunostaining in both adenomas and adenocarcinomas from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice revealed frequent and intense co-staining of Hmga2 with nuclear β-catenin (Fig 4H–4K). This pattern of co-staining was not observed for Hmga1, Arid3a, or Hif3a.

Fig. 4. Identification of Let-7 targets up-regulated specifically in transformed cells from intestinal adenocarcinomas.

A) Schematic of experimental procedure where tumors were micro-dissected from the small intestine (S.I.) of Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice and cultured as epithelial tumoroid/enteroids (T/E), grown in ENR medium, and tumoroid cysts (TC), grown in medium lacking Noggin and Rspo1. B) Typical tumoroid grown in ENR medium. C) Tumoroid cysts grown in basal medium containing EGF. D) Let-7 miRNAs are repressed consistently in tumoroid/enteroids (TE) and tumoroid cysts (TC). E) Wnt (Tcf4/β-catenin) target genes Axin2, CD44 and cMyc mRNAs were up-regulated in tumors, T/E, and TC. F) Transcripts with highest expression in tumor or tumoroid, but tend to be down-regulated in tumoroid cysts. G) Transcripts that maintain high expression and/or are increased in tumoroid cysts. Note logarithmic scale where Hmga2 mRNA is induced approximately 200-fold in TC compared to wild-type S.I. Immunostaining in Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO adenomas (H, I) and adenocarcinomas (J, K) revealed that nuclear β-catenin (H, J) and Hmga2 (I, K) are often co-expressed at high levels. Expression analysis was performed by Q-RT-PCR, normalized to Hprt and Actb, with n = 3–4 for each tissue/organoid with error bars representing +/–the S.E.M. Student’s two-tailed T-tests were performed to determine significance with * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, and *** p-value < 0.001, relative to wild-type small intestine. One-way ANOVA standard weighted-means analysis was also performed in D-G, with p-values < 0.05 indicated above each gene. Tukey's HSD (honest significant difference) post-test was also performed in D-G, with samples p < 0.05 (red asterisk) and p < 0.01 (†) indicated, relative to mean of WT small intestine (jej.). Let-7 Down-Regulation and HMGA2 Up-Regulation Are Associated with a Stem Cell Signature in Intestinal Cancers in Humans and Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO Mice

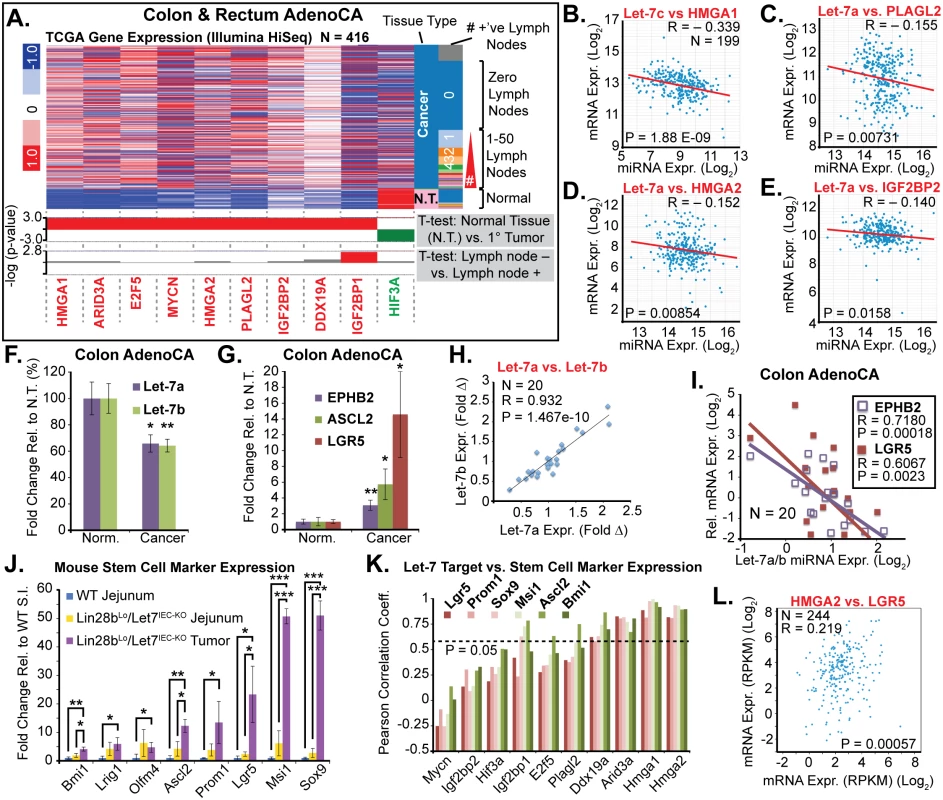

To extrapolate relevance to human CRC from these mouse models, we examined expression data from human samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [35] by querying for expression of Let-7 target mRNAs, with a focus on targets that exhibited significant up-regulation in either Vil-Lin28bMed or Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mouse models (namely, ARID3A, PLAGL2, HMGA1, HMGA2, MYCN, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, and E2F5). We examined a cohort of 416 CRC patients from a TCGA dataset and found that all transcripts except HIF3A mRNA were significantly elevated in cancer tissue compared to expression levels in normal tissues (Fig 5A). IGF2BP1 expression in primary tumors was also associated with an increased likelihood of having nodal metastases (Fig 5A). Levels of HMGA1, HMGA2, PLAGL2, IGF2BP2, E2F5, and ARID3A transcripts were also inversely proportional to levels of Let-7 miRNA by examination of a cohort of 199 CRC patients from the TCGA Pan-Cancer analysis project [20] (Fig 5B–5E and S1D–S1I Fig). Since Let-7a and Let-7b appear to be the most highly expressed Let-7 miRNAs in normal colonic epithelium, and are significantly depleted in CRC specimens [20,30] (S1A, S1B and S1C Fig), we examined these miRNAs in a subset of colon cancer specimens. We also compared their expression with the crypt-base-columnar (CBC) stem cell markers EPHB2, ASCL2, and LGR5, which are markers of stem cells in human intestine/colon and CRC, and are associated with aggressive CRC [36]. We found that Let-7a and Let-7b were significantly down-regulated in CRC specimens, while stem cell markers were significantly up-regulated (Fig 5F and 5G). Let-7a and Let-7b levels were also correlated tightly, suggesting co-regulation (Fig 5H), and were also inversely proportional to the expression of the stem cell markers EPHB2 and LGR5 (Fig 5I). This suggests provocatively that Let-7a and Let-7b depletion may contribute to a stem cell phenotype in the intestine, and perhaps CRC.

Fig. 5. Let-7 and HMGA2 are associated with a stem cell signature in intestinal adenocarcinomas.

A) Heat map of TCGA mRNA-seq colon and rectal adenocarcinoma dataset from UCSC Cancer Genome Browser (genome-cancer.ucsc.edu) comparing expression of Let-7 target mRNAs in normal tissue (N.T.) vs. cancer. Significant up-regulation (red) or down-regulation (green) is indicated below heatmap in plots of the-log(p-value) of Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected T-tests on the y-axis. T-test results are shown for expression in tumors vs. N.T. and in tumors associated with at least one lymph node metastases vs. tumors with no associated lymph node metastases. Inverse relationships for Let-7 and target mRNAs could be discerned by plotting miRNA-seq data against mRNA-seq data for Let-7c vs. HMGA2 (B), Let-7a vs. PLAGL2 (C), Let-7a vs. HMGA2 (D), and Let-7a vs. IGF2BP2 (E). F) Taqman QPCR for mature Let-7a and Let-7b miRNAs in a cohort of colon adenocarcinomas (N = 20) indicates that Let-7a and Let-7b are down-regulated. G) Intestinal epithelial stem cell markers EPHB2, ASCL2, and LGR5 are significantly up-regulated in colon cancer vs. normal adjacent tissues. H) Mature Let-7a and Let-7b levels are tightly correlated in these tissue specimens. I) Let-7a and Let-7b levels are inversely proportional to mRNA levels of stem cell markers EPHB2 and LGR5, suggesting that Let-7 may repress a stem cell signature. J) Expression of stem cell markers is dramatically up-regulated in Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO tumors, relative to WT jejunum, with a trend for up-regulation in Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO jejunum, relative to WT. K) Comparison of stem cell marker expression and Let-7 target mRNA expression levels in WT jejunum, Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO jejunum, and Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO tumors by linear regression yielded Pearson correlation coefficients, with Arid3a, Hmga1, and Hmga2 correlating very highly with expression of stem cell markers. L) HMGA2 and LGR5 expression from the TCGA mRNA-seq colon and rectal adenocarcinoma dataset exhibit significant positive correlation. Expression analysis (F-K) was performed by QPCR, normalized to Hprt and Actb, with n = 3–4 for each mouse genotype with error bars representing +/–the S.E.M. Human QPCR was normalized to PPIA and B2M, with error bars representing +/–the S.E.M. Student’s two-tailed T-tests were performed to determine significance with * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, and *** p-value < 0.001. To further examine this relationship we evaluated small intestine stem cell markers in wild-type intestine, Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO intestine, and in tumors from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice. In normal adjacent tissue we observed a trend toward increased expression of multiple stem cell markers in Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO small intestine (Fig 5J). In contrast, tumors from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice exhibited a pronounced up-regulation of all stem cell markers assayed, including Bmi1, Lrig1, Olfm4, Ascl2, Prom1, Lgr5, Msi1, and Sox9 (Fig 5J), perhaps suggesting an expansion of CBC and +4 stem cell-like compartments. While Let-7a and Let-7b depletion and increased expression of stem cell markers may appear to be a general feature of colon cancer, our discovery of a relationship between expression of Let-7 and stem cell markers suggests a functional connection. To examine a possible relationship between Let-7 target mRNAs and stem cell markers, we evaluated co-expression in mouse samples (from Fig 5I) and found that Hmga1 and Hmga2 had very high correlation with all of the markers we examined (Fig 5K). Likewise, in human CRC samples the expression of HMGA2 directly correlates with LGR5 levels (Fig 5L).

HMGA1 or HMGA2 Expression Is Associated with Aggressive CRC in Patients

In order to explore any disease relevance connecting HMGA1 and HMGA2 expression and tumor phenotype, we stained CRC tumor tissue arrays for these proteins and evaluated expression in relationship to various parameters including tumor stage, histopathologic characteristics, and disease outcomes. High-level HMGA1 expression predicted poor survival for patients with stage II tumors (S2A Fig). HMGA1 staining was also more intense in stage II tumors (S2C and S2D Fig) and in tumors with perineural invasion (S2E and S2F Fig). Interestingly, expression data from TCGA mRNA-seq studies [37] indicated that high-level expression of HMGA2 correlates inversely with survival (S2B Fig). In tissue arrays HMGA2 expression was greater in non-mucinous tumors (S2G and S2H Fig) and in stage III tumors (S2I and S2J Fig). In aggregate, these data suggest that HMGA1 and HMGA2 are expressed in non-overlapping tumor types, but are both associated with more aggressive phenotypes, and perhaps reduced patient survival.

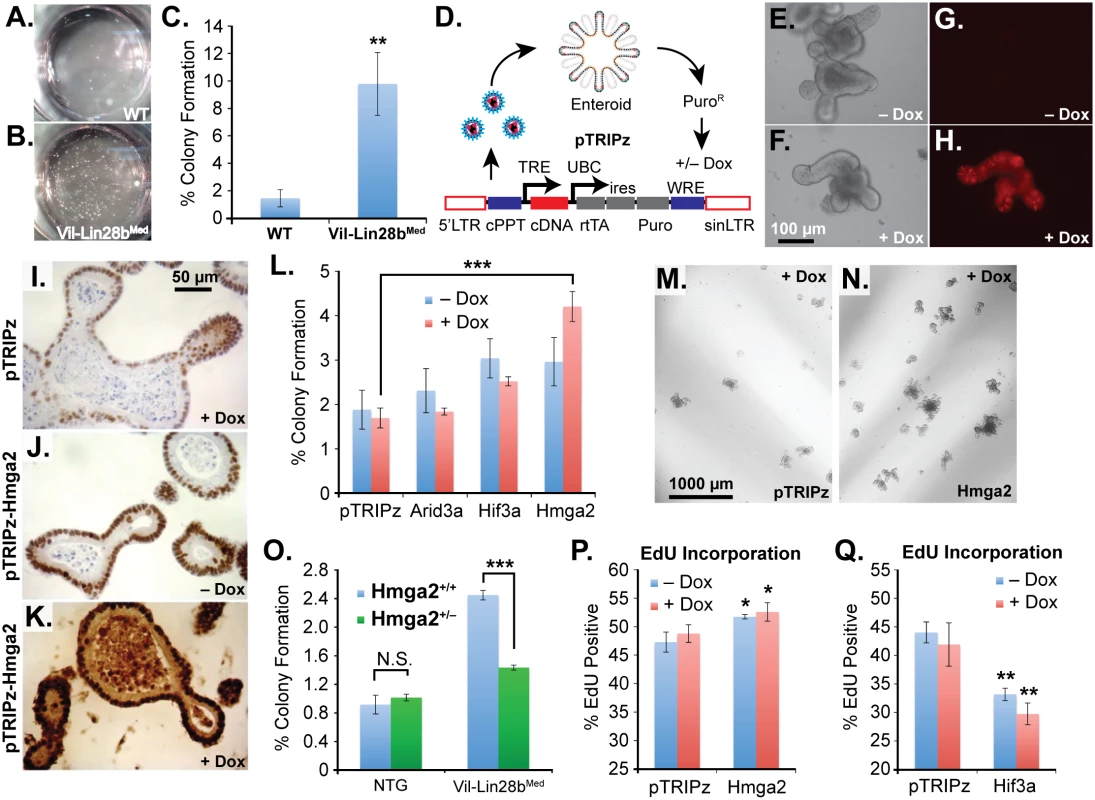

HMGA2 Drives a Stem Cell Phenotype and Is Required for Lin28b-Mediated Tumorigenesis

We next pursued 3-D culture and manipulation of intestinal organoids (enteroids) to explore the relationship between Let-7 targets and a stem cell phenotype. This method has facilitated the examination of stem cell phenotypes in the intestinal epithelium in multiple studies [34,38–44]. For these experiments we derived enteroids from Vil-Lin28bMed mice [18]. We have previously shown that crypt hyperplasia and Hmga2 expression is dependent on Let-7 depletion in crypts from Vil-Lin28bMed mice [18]. Enteroids derived from Vil-Lin28bMed mice exhibited enhanced colony forming potential of single cells (Fig 6A, 6B and 6C). This is unlikely to be a feature secondary to enhanced stem cell potential conferred by increased association with Paneth cells, as described previously [34], since this cell type is severely depleted following Let-7 repression [18]. To assay exogenous expression of Let-7 targets in enteroids, we used a lentivirus vector for transduction of wild-type mouse small intestine enteroids (Fig 6D–6G). This vector system yields low (Fig 6J) or high-level (Fig 6K) expression, in a doxycycline-dependent manner. We generated stable enteroid lines for inducible expression of mouse Hmga2, Igf2bp2, E2F5, Arid3a, or Hif3a and assayed colony forming potential and EdU incorporation. We focused on Hmga2, rather than Hmga1, as it is consistently up-regulated in non-malignant intestinal tissue from Vil-Lin28bMed and Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO and thus appears highly dependent on Let-7 [18]. For colony formation, only Hmga2 over-expression (O/E) exhibited a significant effect, with enhanced formation of new enteroids from singly plated cells (Fig 6L, 6M and 6N), whereas Igf2bp2, E2F5, Arid3a, and Hif3a had no apparent effect (Fig 6L and S4A Fig). Expression of Hmga2, Arid3a, Hif3a, or Igf2bp2 via lentiviral vectors did not induce any change in stem cell markers (S4B–S4K Fig). To determine if Hmga2 was necessary for the enhanced colony formation in Vil-Lin28b enteroids, we crossed Vil-Lin28bMed mice onto background in which one allele of Hmga2 is inactivated specifically in the intestine (Vil-Cre+/Hmga2CK/+) [45], and generated enteroids. We used Vil-Lin28bMed mice because their phenotype appears Let-7-dependent [18] and for simpler breeding. Effects on colony formation by Lin28b were greatly blunted by inactivation of a single Hmga2 allele (Fig 6O). Hmga2 could also trigger increased EdU incorporation in intestinal enteroids, whereas Hif3a repressed it, suggesting opposing effects of Hmga2 and Hif3a on cellular proliferation (Fig 6P and 6Q). Lentiviral-mediated expression and manipulation of the Hmga2 conditional allele were restricted to coding sequence only [45]. Perhaps consistent with its association with a stem cell phenotype, HMGA2 is also frequently co-expressed with the stem cell markers MSI1 and LGR5 in human CRC, and notably, more frequently than any of the other Let-7 targets evaluated here in this study (Fig 5L and S2 Table). Lastly, to evaluate the role of Hmga2 in intestinal tumorigenesis in the context of Let-7 depletion we examined tumor burden in Vil-Lin28bMed and Vil-Lin28bMed/Hmga2+/IEC-KO mice. As mentioned earlier, Vil-Lin28bMed mice have a lower penetrance of intestinal tumorigenesis compared to Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice, with about 50% of animals developing tumors by 9 months of age (S3 Table). Inactivation of one allele of Hmga2 in the intestinal epithelium significantly reduced disease penetrance and tumor burden in Vil-Lin28bMed/Hmga2+/IEC-KO mice (S3 Table).

Fig. 6. Hmga2 mediates Lin28b effects on stem cell colony formation and enteroid proliferation.

Colony formation assay of small intestine enteroids from wild-type (WT) mice (A) and Vil-Lin28bMed mice (B). Two wells of a 24-well plate are pictured. C) Quantification of colony forming assay of WT mice and Vil-Lin28bMed mice. D) Schematic of lentiviral vector-mediated transduction of enteroids with a “tet-on” doxycycline (dox)-inducible vector. Inducible expression of a turbo RFP reporter in the unmodified pTRIPz vector is readily observed in enteroids (H) vs. untreated cells (G). Phase contrast images of untreated and doxycycline treated enteroids are pictured in (E) and (F), respectively. Immunostaining for Hmga2 in sectioned enteroids from pTRIPz-transduced (I), pTRIPz-Hmga2-transduced (J), and pTRIPz-Hmga2-transduced plus doxycycline (K). L) Comparison of colony forming potential of cells from dissociated enteroids transduced with pTRIPz (empty), Arid3a, Hif3a, or Hmga2 vectors. Phase contrast images of colony formation assays from enteroids transduced with pTRIPz (empty) (M) or Hmga2 (N) vectors. O) Colony forming assays of non-transgenic mice (NTG) or Vil-Lin28bMed mice with and without inactivation of one conditional Hmga2 allele using Vil-Cre. EdU incorporation of enteroids, as assayed by flow cytometry, transduced with pTRIPz-Hmga2 (P) or pTRIPz-Hif3a (Q) vectors. Cultures were treated with 100 ng/ml doxycycline in all experiments except in (F) and (H), which were treated with 500 ng/ml doxycycline. All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Student’s two-tailed T-tests were performed to determine significance with * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, and *** p-value < 0.001, relative to pTRIPz vector controls, unless noted otherwise. Discussion

We have achieved comprehensive depletion of all Let-7 miRNAs in the intestinal epithelium and demonstrated the critical nature of their cumulative tumor-suppressive properties. These effects appear to be due to Let-7, although LIN28B can bind mRNAs and modulate protein levels of targets in the intestinal epithelium [18]. However, this appears unlikely in Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice since LIN28B did not have any effect on RNA or protein levels of targets in the context of low-level expression in Vil-Lin28bLo mice [18]. While tumors from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice appear to be more advanced than those from Vil-Lin28bMed mice [18], surprisingly there is not a significant difference in tumor multiplicity. Nascent tumorigenesis beginning with aberrant crypt foci and/or microadenomas may occur spontaneously in our mouse model of Let-7 depletion, likely due to sporadic deregulation of Wnt signaling or potential spontaneous loss of other tumor suppressive mechanisms. Therefore, Let-7 may not have the “gatekeeper” function that is characteristic of tumor suppressors such as APC. Despite this, there is a link between LIN28B expression in human colon cancer samples and aggressive disease in early stages, which may reflect a role for LIN28B in early neoplastic growth [15]. Supporting this hypothesis is the documentation that LIN28 proteins and Let-7 miRNAs do indeed affect proliferation, migration, and invasion in cell culture models and xenografts of various malignancies [16,17,46–49]. However, the differences between Let-7 target mRNAs in each of these models can be quite disparate; e.g. KRAS has a larger effect on tumorigenesis than does HMGA2 in a non-small cell lung cancer model [49], whereas HMGA2 appears to have a much larger role in other cancer models [28,50–53], likely as a modifier of chromatin structure and gene expression [54–57].

As documented in developmental programs in C. elegans and in human cancers, Let-7 miRNAs repress a stem cell phenotype and tumor-initiating phenotype [3], an association we observe here as well. The connection between HMGA2 and a stem cell phenotype in the intestinal epithelium is also intriguing. HMGA2 promotes somatic stem cell specification, with such roles in neural stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells [25–27]. In some contexts, HMGA2 can enhance Wnt signaling, a known driver of the crypt-base-columnar (CBC) intestinal epithelial stem cell phenotype [34,58,59]. This was observed in a mouse model of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, where overexpression of Hmga2 in cancer-associated fibroblasts enhances expression of the Wnt ligands Wnt2, Wnt4, and Wnt9b, concomitant with enhanced Wnt signaling and nuclear β-catenin in adjacent neoplastic epithelium [60]. Wnt signaling is required for the enhanced prostatic intraepithelial tumorigenesis induced by Hmga2 in this model [60]. However, we do not observe any effects on Wnt target genes or β-catenin localization in non-malignant Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO intestine tissue, suggesting that Wnt deregulation may be an independent event. A recent study that largely replicated our earlier work found that tumors triggered by transgenic LIN28B expression in the mouse small intestine frequently have mutations in Ctnnb1 (β-catenin), but not Apc [61]. Although the level of induced LIN28B expression in this study is likely much higher than in Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice, and therefore different, we suspect that derangements of the Wnt pathway, e.g. in Ctnnb1, are also occurring in tumors in Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice, as evidenced by frequent nuclear β-catenin.

Alternatively, the co-localization of nuclear β-catenin with intense Hmga2 staining in mouse tumors (Fig 6K–6N) could reflect Wnt signaling enhancement of Hmga2 expression, a phenomenon observed in triple-negative breast cancer, a subtype that also tends to express high LIN28B levels [9,62]. Curiously, in our genetic manipulations of enteroids, exogenous Hmga2 does not affect expression of stem cell markers (such as those assayed in Fig 6I) in transduced intestinal enteroids (S4 Fig). Alternatively, increased Hmga2 expression may enhance survival of stem cells or facilitate the recruitment of a facultative population (such as the quiescent “+4” secretory progenitor stem cell) and entry into the cell cycle. Or, Hmga2 may synergize with deregulated Wnt signaling in the promotion of a stem cell phenotype, which could account for the dramatic up-regulation of stem cell markers we see in tumors from Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice. Others have also reported that HMGA2 expression is predictive of aggressive disease and poor outcomes in CRC [63], as similarly found in other cancers [50].

While HMGA2 is playing a key role, it is likely that the effects of Let-7 on an intestinal stem cell phenotype and epithelial tumorigenesis are dependent on the collective and/or cooperative role of multiple Let-7 targets. Not uncommonly, additive roles of target genes are uncovered in the genetic dissection of a single pathway, such as that seen for PDGF-receptor signaling and the collective biological contribution of multiple target genes dependent on Pdgfra and Pdgfrb [64]. However, it is challenging to dissect the combinatorial relationships among a dozen candidate targets, especially in mouse models. An oncogenic function of HMGA1 and IGF2BP1 has been reported in other cancers, including colon cancer, with evidence that both factors enhance tumorigenesis [65,66]. Dissecting the interaction and possible cooperation of Let-7 target mRNAs is critical for designing strategies to ameliorate the loss of Let-7 in human cancers via combinatorial targeted therapies against multiple oncogenes.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Mouse studies were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Animal Care and Use Committee, protocol #802791.

Mouse Models

Vil-Lin28bLo, Vil-Lin28bMed, and Let7IEC-KO mice were described previously [18], and were maintained via backcrosses to C57BL/6J. Vil-Lin28bMed mice express Lin28b protein approximately 2-fold higher than Vil-Lin28bLo mice. To obtain Lin28bLo/Let7IEC-KO mice, VilCre+/Let7lox/lox mice were mated with Vil-Lin28bLo/Let7lox/lox mice to get Vil-Lin28bLo/VilCre+/Let7lox/lox, and all other possible genotypes. Let7lox/lox mice were considered wild-type and possess all Let-7 miRNAs at levels insignificantly different from wild-type mice [18]. Conditional null Hmga2Ck mice were described previously [45]. Mice were sacrificed at 12 weeks or between 10 and 14 months of age for dissection, isolation of tissues for histology and immunohistochemistry, and isolation of intestinal epithelia. Pathological criteria for mouse intestinal tumors were used as previously defined [67]. Intestinal adenomas are exophytic growths without evidence of invasion characterized by enlarged variably hyperchromatic nuclei with altered glandular architecture, including enlarged crypts and budding, irregular glands. For purposes of defining an adenocarcinoma, tumor invasion through the lamina propria into the muscularis mucosa and eventually beyond must clearly be seen.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For mRNA expression analysis of mouse tissue, whole jejunum, total intestinal epithelium, or crypt epithelium was isolated for homogenization in Trizol (Life Technologies). Total epithelium or crypts were isolated as described previously [18]. Total RNA (2–5 μg) was used for cDNA synthesis with oligo dT primers and Superscript III RT (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer instructions. QPCR was performed using Taqman technology or Sybr green using the TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (2X), no AmpErase UNG (Life Technologies) or the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies). Expression levels of queried mRNAs were normalized to β-actin (Actb) and Hprt or Gapdh mRNA levels. Let-7 miRNAs were quantified using Taqman Q-RT-PCR kits (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturers instructions and normalized to U6 and SNO135 small RNA levels. Primers and Taqman probes are listed in S3 Table.

Human colon cancer tumor specimens, along with adjacent matched non-malignant tissue, were obtained from the Siteman Cancer Center Tissue Procurement Core as fresh frozen sections. Twenty samples (11 pairs) were obtained and total RNA was isolated following homogenization with Trizol (Life Technologies). For qualitative evaluation of RNA integrity 2 μg of total RNA was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel. For evaluation of mRNAs, 1 μg of total RNA was used for reverse transcriptase using the iScript reverse transcriptase kit (BioRad), while miRNAs were quantified using Taqman Q-RT-PCR kits (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturers instructions. Levels of mRNAs were assayed using standard primer pairs and SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Biorad) and normalized to cyclophilin-A (PPIA) and β-2 microglobulin (B2M). Let-7a and Let-7b miRNAs were normalized to U6 and RNU6B RNAs.

Enteroid/Tumoroid Culture

Crypts were isolated as described previously [18] and cultured in EGF, Noggin, and Rspo1 (ENR) medium [34]. Before plating, crypts were counted and re-suspended in a mixture of 80% Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and 20% ENR at a concentration of 20 crypts per μl. For initial plating and the first three days of culture, crypts were grown in the presence of 10 μM Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitor (Y27632). Medium was then changed every 3 days with fresh ENR medium. For lentiviral transduction the pTRIPz vector was modified for expression of mouse Hmga2 (NM_010441.2), E2f5 (NM_007892.2), Igf2bp2 (NM_183029.2), Arid3a (NM_001288625.1) or Hif3a (NM_016868.3) by cloning the open reading frames from these cDNAs between the AgeI and MluI sites within pTRIPz. Enteroids were transduced with lentiviral particles as described previously and selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin [68].

Colony Formation Assays

Enteroids were mechanically dissociated by pipetting up and down in 4 ml basal medium and centrifuged at 100 x g for 2 min. Enteroids were then re-suspended in 0.5 ml TrypLE Express (Life Technologies) containing 250 U/ml DNase I (1 : 200) and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor. Enteroids were incubated 5 minutes at 37°C with periodic vortexing every 60 sec. To this we added one volume basal medium with 5% FBS (with DNase and ROCKi) and spun 5 min at 200 x g. Cells were re-suspended in 0.5 ml pre-warmed basal medium with 50 U/ml DNase I and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor and incubated 5 minutes at room temperature with periodic vortexing. Single cells were then plated in triplicate at a concentration of 2500 cells per cm2 in 80% Matrigel, 20% ENR, and over-layed with ENR medium plus 10 μM ROCK inhibitor. Colonies of growing, budding enteroids were counted 5–7 days after plating.

For assaying 5-ethynyl-2´-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation, enteroids were given fresh new medium containing 10 μM EdU and incubated for 2 hours. Enteroids were then isolated as performed above to obtain a single cell suspension, then fixed for Click-iT labeling and flow cytometry using the Click-iT Plus EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Life Technologies). Fixation and labeling was carried out according to the manufacturer instructions.

Tumoroid Cultures

Mouse intestinal tumors were isolated for culture by micro-dissecting tumor tissue away from normal adjacent mucosa using a dissecting microscope. Two pieces of tumor were processed for RNA isolation and histology and immunohistochemistry while a third piece was dissociated for culture. For tumoroid culture, tumors were placed into HBSS containing 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor (Y27632) and incubated at 37°C with periodic vortexing for approximately 5 to 10 minutes until the epithelium began to detach. Isolated epithelium was then washed three times with sterile basal medium and plated in culture as done above for enteroids in ENR medium. After 1–2 weeks of continuous culture and 1–2 passages, tumoroids were placed into medium lacking Noggin and Rspo1. While most enteroids died, small rare surviving colonies could be observed after 3–5 days of culture. These tumoroid cysts were maintained in medium lacking Noggin and Rspo1.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Paraffin-embedded enteroids, intestinal tissue, and tissue microarrays were incubated at 56°C prior to de-waxing and rehydration. Antigens were retrieved by boiling sections in 10 mM citric acid, pH 6.0, for 2 hrs. Samples were blocked in 1% BSA, 0.3% Triton-X-100, and 10% normal goat serum for 1 hr. Endogenous peroxidases were quenched in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 minutes. In conjunction with biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, diluted 1 : 200) stains were developed with the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, cat# PK-6100) and the DAB Peroxidase (HRP) Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories, cat# SK-4100). Tissues were dehydrated and cover-slipped with Cytoseal (Thermo Scientific, cat# 8310–4). Primary antibodies used for IHC were anti-ARID3A (1 : 100, ProteinTech, Chicago IL, cat# 14068-1-AP), anti-β-catenin [D10A8] XP Rabbit mAb (1 : 100, Cell Signaling, Danvers MA, cat# 8480), rabbit anti-HIF3A antibody (1 : 200, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO, cat# SAB2900410), anti-HMGA1 antibody [EPR7839] (1 : 250, Abcam, Cambridge MA, cat# ab129153), and anti-HMGA2 [D1A7] rabbit mAb (1 : 400, Cell Signaling, Danvers MA, cat# 8179).

Human Cancer Dataset Analyses

We examined gene expression in CRC specimens from a cohort of 416 CRC patients from a TCGA dataset using the cancer genome browser at UCSC (https://genome-cancer.ucsc.edu/proj/site/hgHeatmap/) (Cline MS 2013; Lopez-Bigas N 2013; Goldman M 2012; Sanborn JZ 2011; Vaske CJ 2010; Zhu J 2009). For examination of Let-7 miRNA expression and expression relative to candidate target genes we examined a cohort of 199 CRC patients from the TCGA Pan-Cancer analysis project visualized using the starbase miRNA CLIP-seq portal (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/) (Li JH et al., Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; Yang JH et al., Nucleic Acids Res. 2011).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Kumar MS, Pester RE, Chen CY, Lane K, Chin C, et al. (2009) Dicer1 functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Genes & development 23 : 2700–2704.

2. Lambertz I, Nittner D, Mestdagh P, Denecker G, Vandesompele J, et al. (2010) Monoallelic but not biallelic loss of Dicer1 promotes tumorigenesis in vivo. Cell death and differentiation 17 : 633–641. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.202 20019750

3. Bussing I, Slack FJ, Grosshans H (2008) let-7 microRNAs in development, stem cells and cancer. Trends Mol Med 14 : 400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.07.001 18674967

4. Lee YS, Dutta A (2007) The tumor suppressor microRNA let-7 represses the HMGA2 oncogene. Genes Dev 21 : 1025–1030. 17437991

5. Boyerinas B, Park SM, Shomron N, Hedegaard MM, Vinther J, et al. (2008) Identification of let-7-regulated oncofetal genes. Cancer Res 68 : 2587–2591. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0264 18413726

6. Gurtan AM, Ravi A, Rahl PB, Bosson AD, JnBaptiste CK, et al. (2013) Let-7 represses Nr6a1 and a mid-gestation developmental program in adult fibroblasts. Genes Dev 27 : 941–954. doi: 10.1101/gad.215376.113 23630078

7. Piskounova E, Viswanathan SR, Janas M, LaPierre RJ, Daley GQ, et al. (2008) Determinants of microRNA processing inhibition by the developmentally regulated RNA-binding protein Lin28. J Biol Chem 283 : 21310–21314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800108200 18550544

8. Viswanathan SR, Daley GQ, Gregory RI (2008) Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science 320 : 97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1154040 18292307

9. Piskounova E, Polytarchou C, Thornton JE, LaPierre RJ, Pothoulakis C, et al. (2011) Lin28A and Lin28B inhibit let-7 microRNA biogenesis by distinct mechanisms. Cell 147 : 1066–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.039 22118463

10. Heo I, Joo C, Kim YK, Ha M, Yoon MJ, et al. (2009) TUT4 in concert with Lin28 suppresses microRNA biogenesis through pre-microRNA uridylation. Cell 138 : 696–708. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.002 19703396

11. Choudhury NR, Nowak JS, Zuo J, Rappsilber J, Spoel SH, et al. (2014) Trim25 Is an RNA-Specific Activator of Lin28a/TuT4-Mediated Uridylation. Cell Rep 9 : 1265–1272. 25457611

12. Hamano R, Miyata H, Yamasaki M, Sugimura K, Tanaka K, et al. (2012) High expression of Lin28 is associated with tumour aggressiveness and poor prognosis of patients in oesophagus cancer. British journal of cancer 106 : 1415–1423. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.90 22433967

13. Hu Q, Peng J, Liu W, He X, Cui L, et al. (2014) Lin28B is a novel prognostic marker in gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7 : 5083–5092. 25197381

14. Cheng SW, Tsai HW, Lin YJ, Cheng PN, Chang YC, et al. (2013) Lin28B is an oncofetal circulating cancer stem cell-like marker associated with recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One 8: e80053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080053 24244607

15. King CE, Cuatrecasas M, Castells A, Sepulveda AR, Lee JS, et al. (2011) LIN28B promotes colon cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer research 71 : 4260–4268. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4637 21512136

16. Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K (2009) An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell 139 : 693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.014 19878981

17. Viswanathan SR, Powers JT, Einhorn W, Hoshida Y, Ng TL, et al. (2009) Lin28 promotes transformation and is associated with advanced human malignancies. Nat Genet 41 : 843–848. doi: 10.1038/ng.392 19483683

18. Madison BB, Liu Q, Zhong X, Hahn CM, Lin N, et al. (2013) LIN28B promotes growth and tumorigenesis of the intestinal epithelium via Let-7. Genes Dev 27 : 2233–2245. doi: 10.1101/gad.224659.113 24142874

19. Shinoda G, Shyh-Chang N, Soysa TY, Zhu H, Seligson MT, et al. (2013) Fetal deficiency of lin28 programs life-long aberrations in growth and glucose metabolism. Stem Cells 31 : 1563–1573. doi: 10.1002/stem.1423 23666760

20. Jacobsen A, Silber J, Harinath G, Huse JT, Schultz N, et al. (2013) Analysis of microRNA-target interactions across diverse cancer types. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20 : 1325–1332. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2678 24096364

21. Zhu H, Shyh-Chang N, Segre AV, Shinoda G, Shah SP, et al. (2011) The Lin28/let-7 axis regulates glucose metabolism. Cell 147 : 81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.033 21962509

22. Dubinsky AN, Dastidar SG, Hsu CL, Zahra R, Djakovic SN, et al. (2014) Let-7 coordinately suppresses components of the amino acid sensing pathway to repress mTORC1 and induce autophagy. Cell Metab 20 : 626–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.001 25295787

23. Li JH, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu LH, Yang JH (2014) starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D92–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248 24297251

24. Jonson L, Christiansen J, Hansen TV, Vikesa J, Yamamoto Y, et al. (2014) IMP3 RNP safe houses prevent miRNA-directed HMGA2 mRNA decay in cancer and development. Cell Rep 7 : 539–551. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.015 24703842

25. Copley MR, Babovic S, Benz C, Knapp DJ, Beer PA, et al. (2013) The Lin28b-let-7-Hmga2 axis determines the higher self-renewal potential of fetal haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 15 : 916–925. doi: 10.1038/ncb2783 23811688

26. Nishino J, Kim I, Chada K, Morrison SJ (2008) Hmga2 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal in young but not old mice by reducing p16Ink4a and p19Arf Expression. Cell 135 : 227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.017 18957199

27. Nishino J, Kim S, Zhu Y, Zhu H, Morrison SJ (2013) A network of heterochronic genes including Imp1 regulates temporal changes in stem cell properties. Elife 2: e00924. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00924 24192035

28. Park SM, Shell S, Radjabi AR, Schickel R, Feig C, et al. (2007) Let-7 prevents early cancer progression by suppressing expression of the embryonic gene HMGA2. Cell Cycle 6 : 2585–2590. 17957144

29. Parameswaran S, Xia X, Hegde G, Ahmad I (2014) Hmga2 regulates self-renewal of retinal progenitors. Development 141 : 4087–4097. doi: 10.1242/dev.107326 25336737

30. King CE, Wang L, Winograd R, Madison BB, Mongroo PS, et al. (2011) LIN28B fosters colon cancer migration, invasion and transformation through let-7-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Oncogene 30 : 4185–4193. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.131 21625210

31. Schubert M, Spahn M, Kneitz S, Scholz CJ, Joniau S, et al. (2013) Distinct microRNA expression profile in prostate cancer patients with early clinical failure and the impact of let-7 as prognostic marker in high-risk prostate cancer. PLoS One 8: e65064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065064 23798998

32. Kropp J, Degerny C, Morozova N, Pontis J, Harel-Bellan A, et al. (2015) miR-98 delays skeletal muscle differentiation by down-regulating E2F5. Biochem J 466 : 85–93. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141175 25422988

33. Matano M, Date S, Shimokawa M, Takano A, Fujii M, et al. (2015) Modeling colorectal cancer using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated engineering of human intestinal organoids. Nat Med 21 : 256–262. doi: 10.1038/nm.3802 25706875

34. Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, et al. (2009) Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459 : 262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935 19329995

35. Cline MS, Craft B, Swatloski T, Goldman M, Ma S, et al. (2013) Exploring TCGA Pan-Cancer data at the UCSC Cancer Genomics Browser. Sci Rep 3 : 2652. doi: 10.1038/srep02652 24084870

36. Merlos-Suarez A, Barriga FM, Jung P, Iglesias M, Cespedes MV, et al. (2011) The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell 8 : 511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.020 21419747

37. Cancer Genome Atlas N (2012) Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487 : 330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252 22810696

38. Gracz AD, Ramalingam S, Magness ST Sox9 expression marks a subset of CD24-expressing small intestine epithelial stem cells that form organoids in vitro. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298: G590–600. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00470.2009 20185687

39. Takeda N, Jain R, LeBoeuf MR, Wang Q, Lu MM, et al. (2011) Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science 334 : 1420–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.1213214 22075725

40. Buczacki SJ, Zecchini HI, Nicholson AM, Russell R, Vermeulen L, et al. (2013) Intestinal label-retaining cells are secretory precursors expressing Lgr5. Nature 495 : 65–69. doi: 10.1038/nature11965 23446353

41. Wang F, Scoville D, He XC, Mahe MM, Box A, et al. (2013) Isolation and characterization of intestinal stem cells based on surface marker combinations and colony-formation assay. Gastroenterology 145 : 383–395 e381–321. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.050 23644405

42. Yin X, Farin HF, van Es JH, Clevers H, Langer R, et al. (2014) Niche-independent high-purity cultures of Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells and their progeny. Nat Methods 11 : 106–112. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2737 24292484

43. Heijmans J, van Lidth de Jeude JF, Koo BK, Rosekrans SL, Wielenga MC, et al. (2013) ER stress causes rapid loss of intestinal epithelial stemness through activation of the unfolded protein response. Cell Rep 3 : 1128–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.031 23545496

44. Davis H, Irshad S, Bansal M, Rafferty H, Boitsova T, et al. (2015) Aberrant epithelial GREM1 expression initiates colonic tumorigenesis from cells outside the stem cell niche. Nat Med 21 : 62–70. doi: 10.1038/nm.3750 25419707

45. Chiou SH, Kim-Kiselak C, Risca VI, Heimann MK, Chuang CH, et al. (2014) A conditional system to specifically link disruption of protein-coding function with reporter expression in mice. Cell Rep 7 : 2078–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.031 24931605

46. Johnson CD, Esquela-Kerscher A, Stefani G, Byrom M, Kelnar K, et al. (2007) The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res 67 : 7713–7722. 17699775

47. Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, Zhang X, Pan Q, et al. (2007) let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell 131 : 1109–1123. 18083101

48. Sampson VB, Rong NH, Han J, Yang Q, Aris V, et al. (2007) MicroRNA let-7a down-regulates MYC and reverts MYC-induced growth in Burkitt lymphoma cells. Cancer Res 67 : 9762–9770. 17942906

49. Kumar MS, Erkeland SJ, Pester RE, Chen CY, Ebert MS, et al. (2008) Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712321105 18308936

50. Shell S, Park SM, Radjabi AR, Schickel R, Kistner EO, et al. (2007) Let-7 expression defines two differentiation stages of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 11400–11405. 17600087

51. Peng Y, Laser J, Shi G, Mittal K, Melamed J, et al. (2008) Antiproliferative effects by Let-7 repression of high-mobility group A2 in uterine leiomyoma. Mol Cancer Res 6 : 663–673. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0370 18403645

52. Yang MY, Chen MT, Huang PI, Wang CY, Chang YC, et al. (2014) Nuclear Localization Signal-enhanced Polyurethane-Short Branch Polyethylenimine-mediated Delivery of Let-7a Inhibited Cancer Stem-like Properties by Targeting the 3'UTR of HMGA2 in Anaplastic Astrocytoma. Cell Transplant.

53. Motoyama K, Inoue H, Nakamura Y, Uetake H, Sugihara K, et al. (2008) Clinical significance of high mobility group A2 in human gastric cancer and its relationship to let-7 microRNA family. Clin Cancer Res 14 : 2334–2340. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4667 18413822

54. Zha L, Wang Z, Tang W, Zhang N, Liao G, et al. (2012) Genome-wide analysis of HMGA2 transcription factor binding sites by ChIP on chip in gastric carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biochem 364 : 243–251. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1224-z 22246783

55. Li Z, Gilbert JA, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Qiu Q, et al. (2012) An HMGA2-IGF2BP2 axis regulates myoblast proliferation and myogenesis. Dev Cell 23 : 1176–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.10.019 23177649

56. Cleynen I, Brants JR, Peeters K, Deckers R, Debiec-Rychter M, et al. (2007) HMGA2 regulates transcription of the Imp2 gene via an intronic regulatory element in cooperation with nuclear factor-kappaB. Mol Cancer Res 5 : 363–372. 17426251

57. Brants JR, Ayoubi TA, Chada K, Marchal K, Van de Ven WJ, et al. (2004) Differential regulation of the insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding protein genes by architectural transcription factor HMGA2. FEBS Lett 569 : 277–283. 15225648

58. Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, et al. (2007) Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449 : 1003–1007. 17934449

59. Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, Vries RG, et al. (2011) Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature 469 : 415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637 21113151

60. Zong Y, Huang J, Sankarasharma D, Morikawa T, Fukayama M, et al. (2012) Stromal epigenetic dysregulation is sufficient to initiate mouse prostate cancer via paracrine Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E3395–3404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217982109 23184966

61. Tu HC, Schwitalla S, Qian Z, LaPier GS, Yermalovich A, et al. (2015) LIN28 cooperates with WNT signaling to drive invasive intestinal and colorectal adenocarcinoma in mice and humans. Genes Dev 29 : 1074–1086. doi: 10.1101/gad.256693.114 25956904

62. Wend P, Runke S, Wend K, Anchondo B, Yesayan M, et al. (2013) WNT10B/beta-catenin signalling induces HMGA2 and proliferation in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. EMBO Mol Med 5 : 264–279. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201320 23307470

63. Wang X, Liu X, Li AY, Chen L, Lai L, et al. (2011) Overexpression of HMGA2 promotes metastasis and impacts survival of colorectal cancers. Clin Cancer Res 17 : 2570–2580. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2542 21252160

64. Schmahl J, Raymond CS, Soriano P (2007) PDGF signaling specificity is mediated through multiple immediate early genes. Nat Genet 39 : 52–60. 17143286

65. Belton A, Gabrovsky A, Bae YK, Reeves R, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, et al. (2012) HMGA1 induces intestinal polyposis in transgenic mice and drives tumor progression and stem cell properties in colon cancer cells. PLoS One 7: e30034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030034 22276142

66. Hamilton KE, Noubissi FK, Katti PS, Hahn CM, Davey SR, et al. (2013) IMP1 promotes tumor growth, dissemination and a tumor-initiating cell phenotype in colorectal cancer cell xenografts. Carcinogenesis 34 : 2647–2654. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt217 23764754

67. Boivin GP, Washington K, Yang K, Ward JM, Pretlow TP, et al. (2003) Pathology of mouse models of intestinal cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Gastroenterology 124 : 762–777. 12612914

68. Koo BK, Stange DE, Sato T, Karthaus W, Farin HF, et al. (2012) Controlled gene expression in primary Lgr5 organoid cultures. Nat Methods 9 : 81–83.

69. Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, et al. (2012) The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2 : 401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 22588877

70. Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, et al. (2013) Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 6: pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088 23550210

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Loss and Gain of Natural Killer Cell Receptor Function in an African Hunter-Gatherer PopulationČlánek Binding of Multiple Rap1 Proteins Stimulates Chromosome Breakage Induction during DNA ReplicationČlánek SLIRP Regulates the Rate of Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis and Protects LRPPRC from DegradationČlánek Protein Composition of Infectious Spores Reveals Novel Sexual Development and Germination Factors inČlánek The Formin Diaphanous Regulates Myoblast Fusion through Actin Polymerization and Arp2/3 RegulationČlánek Runx1 Transcription Factor Is Required for Myoblasts Proliferation during Muscle Regeneration

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 8

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Putting the Brakes on Huntington Disease in a Mouse Experimental Model

- Identification of Driving Fusion Genes and Genomic Landscape of Medullary Thyroid Cancer

- Evidence for Retromutagenesis as a Mechanism for Adaptive Mutation in

- TSPO, a Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Protein, Controls Ethanol-Related Behaviors in

- Evidence for Lysosome Depletion and Impaired Autophagic Clearance in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Type SPG11

- Loss and Gain of Natural Killer Cell Receptor Function in an African Hunter-Gatherer Population

- Trans-Reactivation: A New Epigenetic Phenomenon Underlying Transcriptional Reactivation of Silenced Genes

- Early Developmental and Evolutionary Origins of Gene Body DNA Methylation Patterns in Mammalian Placentas

- Strong Selective Sweeps on the X Chromosome in the Human-Chimpanzee Ancestor Explain Its Low Divergence

- Dominance of Deleterious Alleles Controls the Response to a Population Bottleneck

- Transient 1a Induction Defines the Wound Epidermis during Zebrafish Fin Regeneration

- Systems Genetics Reveals the Functional Context of PCOS Loci and Identifies Genetic and Molecular Mechanisms of Disease Heterogeneity

- A Genome Scale Screen for Mutants with Delayed Exit from Mitosis: Ire1-Independent Induction of Autophagy Integrates ER Homeostasis into Mitotic Lifespan

- Non-synonymous FGD3 Variant as Positional Candidate for Disproportional Tall Stature Accounting for a Carcass Weight QTL () and Skeletal Dysplasia in Japanese Black Cattle

- The Relationship between Gene Network Structure and Expression Variation among Individuals and Species

- Calmodulin Methyltransferase Is Required for Growth, Muscle Strength, Somatosensory Development and Brain Function

- The Wnt Frizzled Receptor MOM-5 Regulates the UNC-5 Netrin Receptor through Small GTPase-Dependent Signaling to Determine the Polarity of Migrating Cells

- Nbs1 ChIP-Seq Identifies Off-Target DNA Double-Strand Breaks Induced by AID in Activated Splenic B Cells

- CCNYL1, but Not CCNY, Cooperates with CDK16 to Regulate Spermatogenesis in Mouse

- Evidence for a Common Origin of Blacksmiths and Cultivators in the Ethiopian Ari within the Last 4500 Years: Lessons for Clustering-Based Inference

- Of Fighting Flies, Mice, and Men: Are Some of the Molecular and Neuronal Mechanisms of Aggression Universal in the Animal Kingdom?

- Hypoxia and Temperature Regulated Morphogenesis in

- The Homeodomain Iroquois Proteins Control Cell Cycle Progression and Regulate the Size of Developmental Fields

- Evolution and Design Governing Signal Precision and Amplification in a Bacterial Chemosensory Pathway

- Rac1 Regulates Endometrial Secretory Function to Control Placental Development

- Let-7 Represses Carcinogenesis and a Stem Cell Phenotype in the Intestine via Regulation of Hmga2

- Functions as a Positive Regulator of Growth and Metabolism in

- The Nucleosome Acidic Patch Regulates the H2B K123 Monoubiquitylation Cascade and Transcription Elongation in

- Rhoptry Proteins ROP5 and ROP18 Are Major Murine Virulence Factors in Genetically Divergent South American Strains of

- Exon 7 Contributes to the Stable Localization of Xist RNA on the Inactive X-Chromosome

- Regulates Refractive Error and Myopia Development in Mice and Humans

- mTORC1 Prevents Preosteoblast Differentiation through the Notch Signaling Pathway

- Regulation of Gene Expression Patterns in Mosquito Reproduction

- Molecular Basis of Gene-Gene Interaction: Cyclic Cross-Regulation of Gene Expression and Post-GWAS Gene-Gene Interaction Involved in Atrial Fibrillation

- The Spalt Transcription Factors Generate the Transcriptional Landscape of the Wing Pouch Central Region

- Binding of Multiple Rap1 Proteins Stimulates Chromosome Breakage Induction during DNA Replication

- Functional Divergence in the Role of N-Linked Glycosylation in Smoothened Signaling

- YAP1 Exerts Its Transcriptional Control via TEAD-Mediated Activation of Enhancers

- Coordinated Evolution of Influenza A Surface Proteins

- The Evolutionary Potential of Phenotypic Mutations

- Genome-Wide Association and Trans-ethnic Meta-Analysis for Advanced Diabetic Kidney Disease: Family Investigation of Nephropathy and Diabetes (FIND)

- New Routes to Phylogeography: A Bayesian Structured Coalescent Approximation

- SLIRP Regulates the Rate of Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis and Protects LRPPRC from Degradation

- Satellite DNA Modulates Gene Expression in the Beetle after Heat Stress

- SHOEBOX Modulates Root Meristem Size in Rice through Dose-Dependent Effects of Gibberellins on Cell Elongation and Proliferation

- Reduced Crossover Interference and Increased ZMM-Independent Recombination in the Absence of Tel1/ATM

- Suppression of Somatic Expansion Delays the Onset of Pathophysiology in a Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease

- Protein Composition of Infectious Spores Reveals Novel Sexual Development and Germination Factors in

- The Evolutionarily Conserved LIM Homeodomain Protein LIM-4/LHX6 Specifies the Terminal Identity of a Cholinergic and Peptidergic . Sensory/Inter/Motor Neuron-Type

- SmD1 Modulates the miRNA Pathway Independently of Its Pre-mRNA Splicing Function

- piRNAs Are Associated with Diverse Transgenerational Effects on Gene and Transposon Expression in a Hybrid Dysgenic Syndrome of .

- Retinoic Acid Signaling Regulates Differential Expression of the Tandemly-Duplicated Long Wavelength-Sensitive Cone Opsin Genes in Zebrafish

- The Formin Diaphanous Regulates Myoblast Fusion through Actin Polymerization and Arp2/3 Regulation

- Genome-Wide Analysis of PAPS1-Dependent Polyadenylation Identifies Novel Roles for Functionally Specialized Poly(A) Polymerases in

- Runx1 Transcription Factor Is Required for Myoblasts Proliferation during Muscle Regeneration

- Regulation of Mutagenic DNA Polymerase V Activation in Space and Time

- Variability of Gene Expression Identifies Transcriptional Regulators of Early Human Embryonic Development

- The Drosophila Gene Interacts Genetically with and Shows Female-Specific Effects of Divergence

- Functional Activation of the Flagellar Type III Secretion Export Apparatus

- Retrohoming of a Mobile Group II Intron in Human Cells Suggests How Eukaryotes Limit Group II Intron Proliferation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Exon 7 Contributes to the Stable Localization of Xist RNA on the Inactive X-Chromosome

- YAP1 Exerts Its Transcriptional Control via TEAD-Mediated Activation of Enhancers

- SmD1 Modulates the miRNA Pathway Independently of Its Pre-mRNA Splicing Function

- Molecular Basis of Gene-Gene Interaction: Cyclic Cross-Regulation of Gene Expression and Post-GWAS Gene-Gene Interaction Involved in Atrial Fibrillation

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání