-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Hippo Pathway Regulates Homeostatic Growth of Stem Cell Niche Precursors in the Ovary

During development, organ growth must be carefully regulated to make sure that organs achieve the correct final size needed for organ function. In organs that are made of many different types of cells, this growth regulation is likely to be particularly complex, because it is important for organs to have appropriate proportions, or relative numbers, of the different kinds of cells that make up the organ, as well as the correct number of total cells. One method that cells use to regulate organ growth is a signaling pathway called the Hippo pathway. However, Hippo signaling has been studied, to date, primarily in organ systems that are made up of one cell type. In this study, we examine how Hippo signaling can work to regulate the proportions of different types of cells, as well as the total number of cells in an organ. To do this, we used the developing ovary of the fruit fly as a study system. We found that (1) Hippo signaling regulates the proliferation of many different cell types of the ovary; and (2) Hippo signaling activity in one cell type influences proliferation of other cell types, thus ensuring appropriate proportions of different ovarian cell types.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004962

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004962Summary

During development, organ growth must be carefully regulated to make sure that organs achieve the correct final size needed for organ function. In organs that are made of many different types of cells, this growth regulation is likely to be particularly complex, because it is important for organs to have appropriate proportions, or relative numbers, of the different kinds of cells that make up the organ, as well as the correct number of total cells. One method that cells use to regulate organ growth is a signaling pathway called the Hippo pathway. However, Hippo signaling has been studied, to date, primarily in organ systems that are made up of one cell type. In this study, we examine how Hippo signaling can work to regulate the proportions of different types of cells, as well as the total number of cells in an organ. To do this, we used the developing ovary of the fruit fly as a study system. We found that (1) Hippo signaling regulates the proliferation of many different cell types of the ovary; and (2) Hippo signaling activity in one cell type influences proliferation of other cell types, thus ensuring appropriate proportions of different ovarian cell types.

Introduction

The Hippo pathway is a tissue-intrinsic regulator of organ size, and is also implicated in stem cell maintenance and cancer [1,2,3]. An outstanding question in the field is whether the Hippo pathway regulates proliferation of cells comprising stem cell niches during development in order to ensure that adult organs have an appropriate number of stem cells and stem cell niches [4]. The adult Drosophila ovary is an extensively studied stem cell niche system. In this organ, specialized somatic cells regulate the proliferation and differentiation of germ line stem cells (GSCs) throughout adult reproductive life [reviewed in 5]. The fact that GSCsare first established in larval stages raises the question of how the correct numbers of GSCs, and their associated somatic niche cells, are achieved during larval development. To date, only the Ecdysone, Insulin and EGFR pathways have been implicated in this process [6,7,8]. Here, we investigate the role of the Hippo pathway in regulating proliferation of somatic cells and GSC niche precursors to establish correct number of GSC niches.

Our current understanding of the Hippo pathway is focused on the core kinase cascade and upstream regulatory members. The Hippo pathway’s upstream regulation is mediated by a growth signal transducer complex comprising Kibra, Expanded and Merlin [9,10,11,12] and the planar cell polarity regulators Fat [13,14,15] and Crumbs [16,17]. Regulation of Hippo signaling further upstream of these factors appears to be cell type-specific [18]. When the core kinase cascade is active, the kinase Hippo (Hpo) phosphorylates the kinase Warts (Wts) [19,20]. Phosphorylated Wts then phosphorylates the transcriptional coactivator Yorkie (Yki), which sequesters Yki within the cytoplasm [21]. In the absence of Hpo kinase activity, unphosphorylated Yki can enter the nucleus and upregulate proliferation-inducing genes [21,22,23,24]. The Hippo pathway affects proliferation cell-autonomously in the eye and wing imaginal discs, glia, and adult ovarian follicle cells in Drosophila [18,19,20,25,26], as well as in liver, intestine, heart, brain, breast and ovarian cells in mammals [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Hippo pathway is often improperly regulated in cancers of these tissues, which display high levels and ectopic activation of the human ortholog of Yki, YAP [27,28,33,34]. Upregulation of YAP is also commonly observed in a variety of mammalian stem cell niches, where YAP can be regulated in a Hippo-independent way to regulate stem cell function [reviewed in 4]. Interestingly, germ line clones lacking Hippo pathway member function do not cause germ cell tumors in the adult Drosophila ovary, which has led to the hypothesis that Hippo signaling functions only in somatic cells but not in the germ line [35,36].

More recently, it has become clear that the Hippo pathway can regulate proliferation non-autonomously: Hippo signaling regulates secretion of JAK/STAT and EGFR ligands in Drosophila intestinal stem cells [37,38,39], and of EGFR ligands in breast cancer cell lines [31], and the resulting changes in ligand levels affect the proliferation of surrounding cells non-autonomously. How autonomous and non-autonomous effects of the Hippo pathway coordinate differentiation and proliferation of multiple cell types has nonetheless been poorly investigated. Moreover, most studies address the Hippo pathway’s role in adult stem cell function, but whether Hippo signaling also plays a role in the early establishment of stem cell niches during development remains unknown.

Here we use the Drosophila larval ovary as a model to address both of these issues. Adult ovaries comprise egg-producing structures called ovarioles, each of which houses a single GSC niche. The GSC niche is located at the anterior tip of each ovariole, and produces new oocytes throughout adult life. The niche cells include both GSC and differentiated somatic cells called cap cells [40]. Each GSC niche lies at the posterior end of a stack of seven or eight somatic cells termed terminal filaments (TFs). Somatic stem cells located close to the GSCs serve as a source of follicle cells that enclose each developing egg chamber during oogenesis [5]. All of these cell types originate during larval development, when the appropriate number of stem cells and their niches must be established. The larval ovary thus serves as a compelling model to address issues of homeostasis and stem cell niche development.

TFs serve as beginning points for ovariole formation and thus establish the number of GSC niches [41]. TFs form during third instar larval (L3) development by the intercalation of terminal filament cells (TFCs) into stacks (TFs) (Fig. 1A; [41]). TFCs proliferate prior to entering a TF, and cease proliferation once incorporated into a TF [42]. The morphogenesis and proliferation of TFCs during the third larval instar (L3) is regulated by Ecdysone and Insulin signaling, and by the BTB/POZ factor bric-à-brac (bab) [6,8,41,43,44,45]. Intermingled cells (ICs) arise from somatic cells that are in close contact with the germ cells (GCs) during L2, and proliferate throughout larval development [46] (Fig. 1A). ICs regulate GC proliferation and differentiation and are thought to give rise to escort cells in the adult niche [6,8,47]. Both Insulin and EGFR signaling promote the proliferation of ICs [6,48]. Finally, larval GCs give rise to GSCs and early differentiating oocytes. GCs proliferate during development and do not differentiate until mid-L3, when the GSCs are specified in niches that form posterior to the TFs [6,8,49], and the remaining GCs begin to differentiate as oocytes. GCs secrete Spitz, an EGFR ligand, and promote proliferation of ICs [49]. In addition, activation of Insulin and Ecdysone signaling in ICs regulates timing of early GC differentiation and cyst formation [6,8], though the identity of the IC-to-GC signal is unknown. ICs can non-autonomously regulate the proliferation of GCs both positively and negatively through Insulin and EGFR signaling respectively [6,7,49].

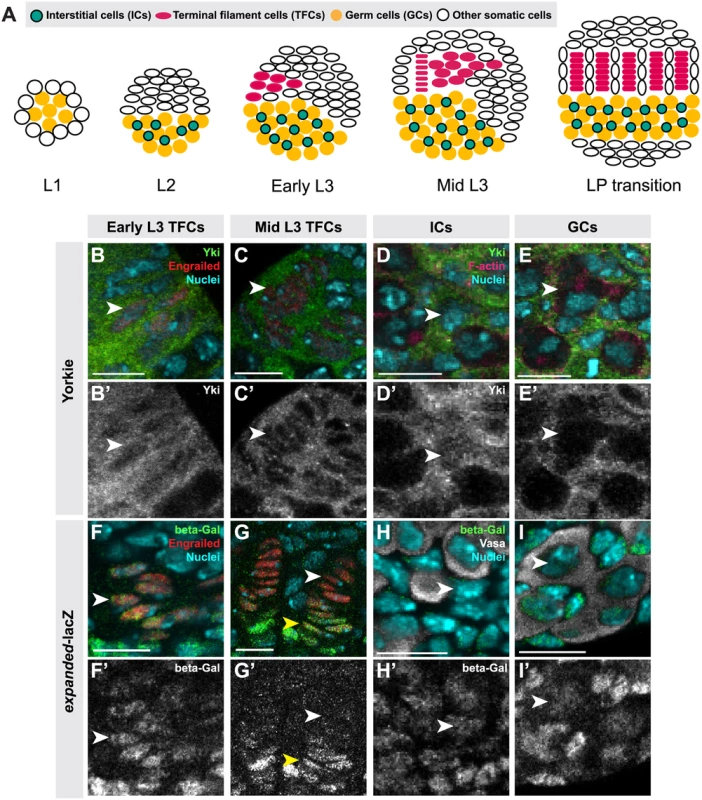

Fig. 1. Hippo pathway activity is cell-type specific in the larval ovary.

(A) Schematic of Drosophila larval ovarian development from first instar (L1) to the larval-pupal (LP) transition stage. The L1 larval ovary consists of germ cells (GCs: yellow) surrounded by a layer of somatic cells. As the ovary grows (L2), some somatic cells intermingle with GCs, becoming intermingled cells (ICs: green). Terminal filament cells (TFCs: pink) emerge during early L3, and begin intercalating to form terminal filaments (TFs), whose formation continues until the LP stage. (B–I, B’–I’) Expression of Yorkie (B–E) and expanded-lacZ (F–I) in larval ovarian cell types. B–I show merged images with Yki (B–E) or ex-lacZ (F–I) in green, nuclear marker Hoechst 33342 in cyan, TFC marker anti-Engrailed (B–C, F–G) or IC marker anti-Traffic Jam (D) in red, and F-actin (E) or GC marker anti-Vasa (H–I) in white. B’-I’ show Yki (B’-E’) or ex-lacZ (F’-I’) signal only. See S2I–J Fig. for quantification. (B) TFCs at early L3 that are intercalating into TFs display nuclear Yorkie localization. (C) Once incorporated into TFs, TFCs display cytoplasmic Yorkie localization. (D) ICs have high levels of nuclear and cytoplasmic Yorkie. (E) Yorkie is detectable only at very low levels in GCs. expanded-lacZ expression is detected in intercalating TFCs (F), ICs (H) and GCs (I) but not in TFCs once they are incorporated into TFs (G). White arrowheads indicate an example of the specific cell types indicated in each column. Yellow arrowheads indicate cap cells posterior to TFs. Scale bar = 10 μm in B–I’. We previously showed that hpo and wts regulate TFC number in a cell-autonomous manner [50]. Here we demonstrate a role for canonical Hippo pathway activity in regulating both TFCs and ICs. We also provide evidence for three novel roles of Hippo pathway members in ovarian development: First, in contrast to a previous report suggesting that yki did not play a role in determining GC number [35], we show that non-canonical, hpo-independent yki activity regulates proliferation of the germ line. Second, we show that Hippo signaling regulates homeostatic growth of germ cells and somatic cells through the JAK/STAT and EGFR pathways. Third, we show that the Hippo pathway interacts with the JAK/STAT pathway to regulate TFC number, and with both the EGFR and JAK/STAT pathways to regulate IC number autonomously and GC number non-autonomously. These data elucidate how Hippo pathway-mediated control of ovarian development establishes an organ-appropriate number of stem cell niches, and thus ultimately influences adult reproductive capacity.

Results

Hippo pathway activity is cell type-specific in the larval ovary

To determine whether Hippo signaling regulates proliferation of the GSC niche precursor cells, we first examined the expression pattern of Hippo pathway members in the larval ovary. Throughout larval development, Hpo was expressed ubiquitously in the ovary (S1A–C Fig.), and Yki was expressed in all somatic cells of the ovary (S1F–H Fig.). However, the subcellular localization of Yki was dynamic during ovariole morphogenesis, and different in distinct somatic cell types. We observed nuclear Yki expression in newly differentiating TFCs (identified by Engrailed expression and elongated cellular morphology) (Fig. 1B–B’, arrowhead; S2I Fig.), while late stage TFs had very little detectable nuclear Yki (Fig. 1C–C’, arrowhead; S2I Fig.). Since Yki localization in the nucleus indicates low or absent Hippo pathway activity [21], these data suggest that Hpo signaling may promote TFC and TFC-progenitor proliferation before TF formation, and then suppress proliferation in TFCs that have entered TFs. This is consistent with previous reports of the somatic proliferative dynamics of the larval ovary [42,48].

We also assessed Yki activity by analyzing expression of the downstream target genes expanded (ex) [21], diap1 (also called thread) [21] and bantam [22]. ex-lacZ (Fig. 1F–G, S2J Fig.) and diap1-lacZ (S2A–B, K Fig.) were expressed in early TFCs, but ceased expression once TFCs were incorporated into a TF. The bantam-GFP sensor is a GFP construct containing bantam miRNA target sites, such that low or absent GFP expression indicates bantam expression and activity. The sensor was not expressed in early differentiating TFCs, but was expressed in TFCs within a TF (S2E–F, L Fig.). These data are consistent with the subcellular localization of Yki in TFCs. Yki activity reporters were also expressed in cap cells of the GSC niche, which are immediately posterior to TFs (Fig. 1G–G’, yellow arrowhead).

In ICs, strong cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of Yki was observed throughout development (Fig. 1D–D’; S2I Fig.). Likewise, all Yki activity reporters examined were expressed in ICs (Fig. 1H–H’, S2C–C’, G–G’, J–L Figs.), consistent with continuous proliferation of these cells throughout larval development.

Hippo signaling regulates terminal filament cell proliferation

The expression patterns described above, and our previous observation that knockdown of hpo or wts increased TFC number [50], suggested that the Hippo pathway regulates TFC proliferation. To further test this hypothesis, we manipulated activity of the core Hippo pathway members hpo, wts and yki in somatic cells using the bric-à-brac (bab) and traffic jam (tj) GAL4 drivers [51,52]. bab:GAL4 is strongly expressed in TFCs during L3 but only weakly in other somatic cell types [50,51]. tj:GAL4 is expressed primarily in somatic cells posterior to the TFs, including ICs, to a lesser extent in newly forming TF stacks during early and mid L3, and in posterior TFCs in late L3 (S3A–D Fig.) [53]. We note that the expression of Tj in intercalating TFCs is not detected with the Traffic-Jam antibody (S3E Fig.). Antibody staining against Hpo and Yki was used to confirm effectiveness of the RNAi-mediated knockdown under both GAL4 drivers (S1D–D’, I–I’ Fig.; see Methods for further details of RNAi validation in these and subsequent experiments).

Lowering Hippo pathway activity in somatic cells by expressing RNAi against hpo or wts under either GAL4 driver significantly increased TFC number (student’s t-test was used for this and all other comparisons: p<0.05; Fig. 2A, S1 Table). We previously showed that TFC number correlates with TF number [50]. Accordingly, driving RNAi against either hpo or wts in somatic tissues significantly increased TF number (p<0.05; Fig. 2B, S1 Table). Conversely, decreasing Yki activity in somatic cells by expressing yki RNAi under either driver significantly reduced both TFC number and TF number (p<0.05; Fig. 2A–B, S1 Table).

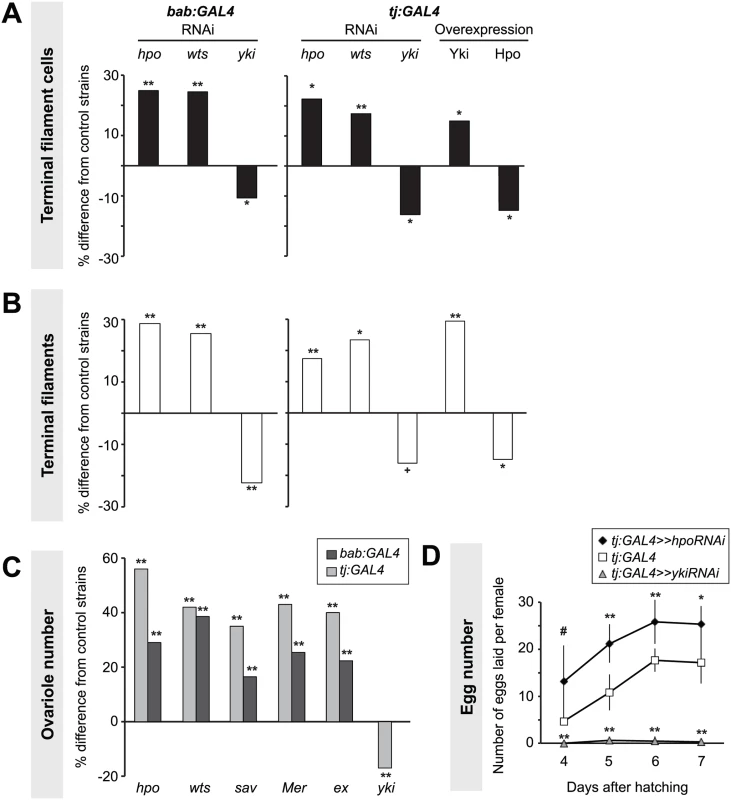

Fig. 2. Hippo pathway influences proliferation of TFCs, thereby influencing ovariole number.

Changes in (A) TFC or (B) TF number in LP ovaries expressing UAS-induced RNAi against hpo, wts or yki, or overexpressing hpo or yki under the bab:GAL4 or tj:GAL4 drivers. Here and in Figs. 3–6, S4 and S5, bar graphs show percent difference from control genotypes of the indicated cell type or structure in each of the experimental genotypes, which are those that carry both UAS and GAL4 constructs. Control genotypes are either parental strains or siblings carrying a balancer chromosome instead of the GAL4 construct (see Methods). When statistical comparisons were performed to parental strains, values from the two parental strains were averaged and percent difference from the average was plotted. Statistical significance was calculated using a student’s two-tailed t-test with unequal variance. ** p<0.01, * p<0.05, + p<0.01 against the UAS parental line and p = 0.08 against the GAL4 parental line. n = 10 for each genotype. Numerical data can be found in S1 Table. (C) Changes in adult ovariole number in individuals expressing hpo, wts, sav, Mer, ex or yki RNAi under bab:GAL4 (dark grey bars) or tj:GAL4 (light grey bars) drivers. ** p< 0.01 against controls. n = 20 for each genotype. (D) Average egg counts from females four to seven days after hatching of tj:GAL4 (control, white squares), tj:GAL4 driving hpoRNAi (black diamonds), tj:GAL4 driving ykiRNAi (grey triangles). Error bars indicate confidence intervals. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. n = 5 vials containing 3 females per vial. Somatic overexpression of hpo or yki under the bab:GAL4 driver resulted in larval lethality, likely due to the known pleiotropic expression of bab in multiple non-ovarian tissues [51]. However, tj:GAL4-driven overexpression of yki or hpo was viable. Using the tj:GAL4 driver, we found that somatic yki overexpression resulted in a significant increase in both TFC number (p<0.05; Fig. 2A, S1 Table) and TF number (p<0.01; Fig. 2B, S1 Table), while somatic hpo overexpression led to a significant reduction in both TFCs and TFs (p<0.05; Fig. 2A–B, S1 Table). A null allele of the Hippo pathway effector expanded (ex1 [54]) and a gain of function allele of yorkie (ykiDB02 [33]) both led to a significant increase in TFC number (S4A Fig., S2 Table), consistent with results obtained from RNAi treatments.

As larval TF number corresponds to the number of GSC niches in the adult (ovariole number) [50], we asked if Hpo signaling might play a role in determining ovariole number. We quantified ovariole number in adults with RNAi-mediated knockdown of Hippo signaling pathway members hpo, wts, salvador (sav), Merlin (Mer), or ex in somatic cells. In all cases adult ovariole number was significantly increased (p<0.01; Fig. 2C). Conversely, yki knockdown under tj:GAL4 significantly decreased ovariole number (p<0.01; Fig. 2C).

Adult females of all reported somatic knockdown and overexpression experiments were viable and did not have defects in adult ovarian structure. Adult females expressing hpo RNAi under the tj:GAL4 driver, which had significantly more ovarioles than controls (Fig. 2B, S1 Table), also laid significantly more eggs than controls (Fig. 2D). Conversely, adult females expressing yki RNAi under tj:GAL4 driver laid significantly fewer eggs than controls, and some appeared to be entirely sterile (Fig. 2D). This shows that by regulating somatic gonad cell number in the larval ovary, the Hippo pathway can influence adult female reproductive capacity.

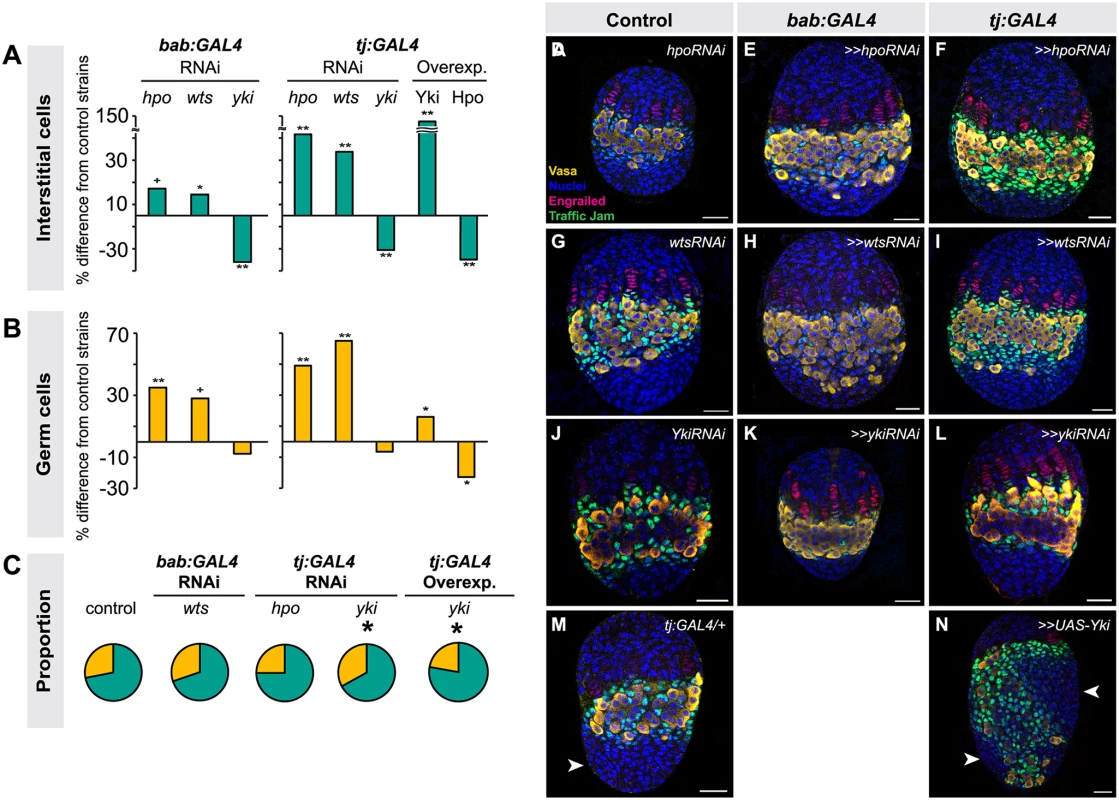

Hippo signaling regulates intermingled cell proliferation

We next asked whether the Hippo pathway also influenced the proliferation of ICs, which do not contribute to TF formation but are in direct contact with germ cells and are thought to give rise to somatic stem cells or escort cells [6,8,47]. Larval-pupal transition (LP) stage ICs were identified by antibody staining against Traffic Jam, which is specific to ICs at this stage of development (Lin et al., 2003). Altering Hippo pathway activity in somatic cells had the same overall effects on IC number as on TFC number: knocking down hpo or wts or overexpressing Yki resulted in a significant increase in IC number (hpo or wts RNAi: p<0.05 for bab:GAL4 and p<0.01 for tj:GAL4; yki overexpression: p<0.01 for both drivers; Fig. 3A, D–I, M–N S3 Table). Conversely, RNAi against yki or overexpression of hpo in the soma significantly reduced IC number (p<0.01; Fig. 3A, J–L, S3 Table). As observed for TFC number, IC numbers in ex1 or ykiDB02 backgrounds were significantly increased (S4 Fig., S2 Table), consistent with the RNAi data. Ovarian morphogenesis, including TF, ovariole and GSC niche formation, was normal in most cases (Fig. 3D–N). However, the 150% increase in IC number caused by yki overexpression correlated with failure of swarm cell migration in some ovaries (Fig. 3M–N, arrowhead; n = 2/10), suggesting that excessive proliferation of ICs above a certain threshold cannot be accommodated by the ovary, leading to disrupted ovariole morphogenesis.

Fig. 3. Altering Hippo pathway activity in somatic cells changes IC and GC number.

Changes in (A) IC or (B) GC number in ovaries expressing hpo, wts or yki RNAi, or overexpressing hpo or yki under the bab:GAL4 or tj:GAL4 drivers. Bar graphs are as explained in Fig. 2 legend. ** p<0.01, * p<0.05, + p = 0.05 against the UAS parental line and p<0.05 against the GAL4 parental line. n = 10 for each genotype. Numerical values can be found in S3 Table. (C) Pie charts of proportions of ICs (green) and GCs (yellow) in ovaries under indicated selected experimental conditions. * p<0.05. Numerical values can be found in S6 Table; pie charts for all experimental conditions shown in S7 Fig. (D–N) LP stage larval ovaries representative of control and experimental samples used to obtain cell type counts. Scale bar = 10 μm. Because the tj:GAL4 and bab:GAL4 drivers are expressed in both ICs and TFCs (albeit at varying levels), we could not use these tools to determine whether ICs and TFCs influence each other’s proliferation non-autonomously. Thus, we tested the utility of ptc:GAL4, which is expressed in ICs (albeit at low levels) but not in TFCs (S5A–C Fig.), and hh:GAL4, which is expressed in a subset of TFCs during and after TF stacking but not in ICs (S5D–F Fig.), for this purpose. However, when we drove RNAi against hpo or wts using either driver, we did not observe any significant changes in IC, TFC or TF number compared to controls (S5G–H Fig.; S5 Table). This is likely due to the facts that (1) hh:GAL4 expression in TFCs arises after TFC proliferation has essentially completed (S5D–F Fig.); and (2) ptc:GAL4 expression is extremely weak in ICs (S5A–C Fig.). We therefore cannot rule out the hypothesis that TFC or IC proliferation has a non-autonomous influence on the other of these two somatic cell types.

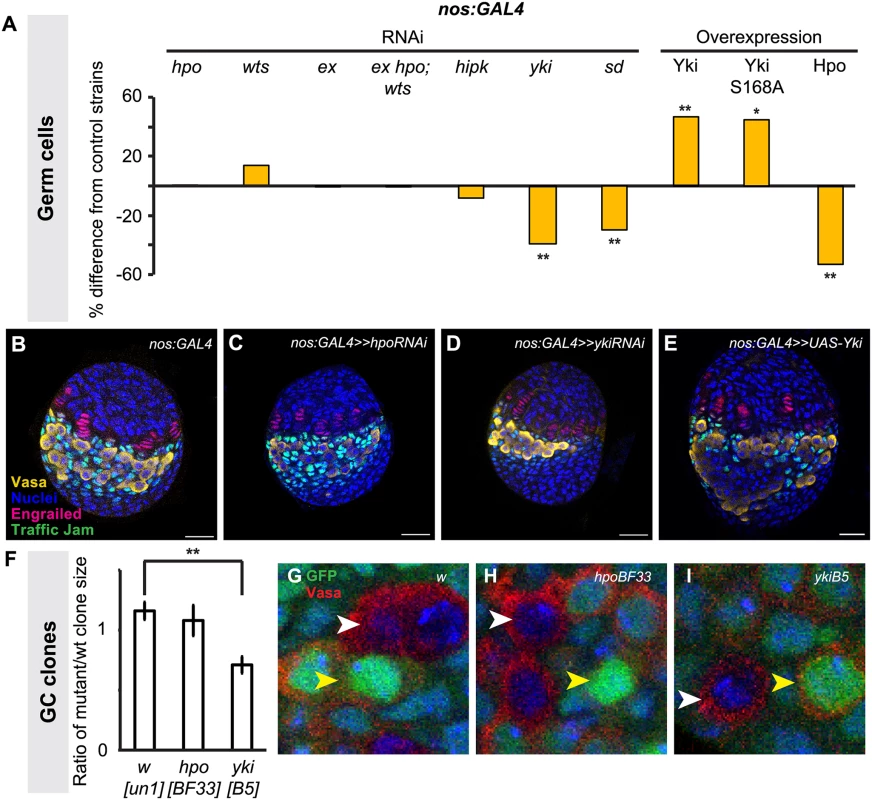

Germ cell proliferation is regulated by yki in a hpo/wts-independent manner

Having observed apparently canonical Hippo pathway activity in the somatic gonad cells, we next asked whether this pathway operated similarly in germ cells, and found a number of significant differences. First, unlike the dynamic expression of Yki in somatic ovarian cells, we detected only extremely low levels of Yki in GCs throughout development (Figs. 1E, E’, S1F–H, S2I). The bantam-GFP sensor also suggested low or absent Yki activity in GCs (S2H–H’, L Fig.). However, we did observe expression of the expanded-lacZ (Figs. 1I–I’, S2J) and diap1-lacZ (S2D–D’, S2K Figs.) reporters in the GCs. We thus performed functional experiments to evaluate the roles of Yki and other Hpo pathway members in GCs.

We disrupted Hippo pathway activity in GCs using the germ line-specific driver nos:GAL4 (S3E–H Fig.). In contrast to the overproliferation of somatic cell types observed in the experiments described above, driving RNAi against hpo or wts in the germ line did not significantly change GC number (Fig. 4A; S3 Table). However, driving yki RNAi in the germ line significantly reduced GC number (p<0.01; Fig. 4A), and a second independent RNAi line [55,56] yielded similar results (p<0.05; S3 Table). Conversely, overexpression of yki in GCs led to a significant increase in GCs (p<0.01, Fig. 4A). Although hpo RNAi had no effect on GC number (Fig. 4A, S3 Table), hpo overexpression significantly decreased GC number (p<0.01; Fig. 4A). Interestingly, we observed a non-autonomous increase in ICs in when yki was overexpressed in GCs, but not in the other experimental conditions (p<0.05, S3 Table).

Fig. 4. Yorkie activity regulates GC number.

Changes in (A) GC number in ovaries expressing hpo, wts, ex, hpo/wts/ex triple, hipk, yki or sd RNAi, or overexpressing hpo, yki or ykiS168A under the nos:GAL4 driver. Bar graphs are as explained in Fig. 2 legend. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 against controls. n = 10 for each genotype. Numerical values can be found in S2 Table. (B–E) LP stage larval ovaries representative of control and experimental samples used to obtain cell type counts. Scale bar = 10 μm. (F) Ratio of size (number of cells per clone) of homozygous mutant versus homozygous wild type twin spot clones for control (wun-1), hpoBF33 and ykiB5 alleles. ** p<0.01 against control. (G–I) LP stage larval ovaries representative of control and experimental samples for clonal analysis showing GCs (Vasa, red), homozygous wild type clones (strong GFP expression; yellow arrowhead), and clones homozygous for tested alleles (no GFP; white arrowhead). n = 10 for each genotype. To validate our findings from the hpo and yki RNAi experiments, we induced hpo [57] and yki [21] null mutant GC clones in L1 larvae and compared the clone sizes (number of cells per clone) of homozygous mutant clones and their homozygous wild type twin spot clones in late L3 ovaries. Consistent with our RNAi analysis, hpoBF33 clones were not significantly different in size from controls (Fig. 4F, H), but ykiB5 clones were significantly smaller than controls (p<0.01; Fig. 4F, I). Taken together, both RNAi and clonal analysis data suggest that yki but not hpo is involved in regulating GC number.

We therefore sought further evidence that yki activity in the germ line was independent of hpo. The FERM domain protein Expanded can bind to Yki independently of Hpo or Wts to sequester Yki to the cytoplasm of Drosophila eye imaginal disc and S2 cells [58], or alternatively can bind to and sequester Yki by forming a complex with Hpo and Wts in Drosophila wing imaginal discs [59]. To determine if one of these mechanisms might be operating in GCs, we knocked down ex alone, or hpo, wts and ex together in GCs. We did not observe significant changes in GC number under either condition (Fig. 4A; S3 Table), suggesting that these phosphorylation-independent mechanisms do not regulate Yki in GCs. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that overexpression of ykiS168A, an allele of Yki that is impervious to Wts-mediated phosphorylation [60], also significantly increased GC number (Fig. 4A). To our knowledge, the only other identified hpo-independent mechanism of yki regulation in Drosophila is via the kinase Hipk, which phosphorylates Yki and induces nuclear translocation in Drosophila wing imaginal discs [61]. However, knocking down hipk in GCs also did not affect GC number (Fig. 4A). Finally, we asked if Yki might still operate together with the transcription factor Scalloped (Sd)/TEAD in germ cells, as has been shown in somatic cells of Drosophila and mammals [24,62,63]. Knocking down sd in GCs significantly reduced GC number (p<0.01, Fig. 4A), suggesting that a Yki/Sd complex could play a role in GC proliferation.

A reduction in GC number could be caused by altered GC proliferation, or by premature differentiation of GCs into oocytes, as has been observed for loss of function mutations in members of the Ecdysone and Insulin signaling pathways [6,8]. To ask if altered yki activity was causing changes in GC number by affecting the timing of oocyte differentiation, we assayed for fusome morphology, an indicator for early cyst cells, in ovaries expressing RNAi against yki or overexpressing yki in GCs (S6 Fig.). We observed no overt signs of early differentiation of PGCs and fusome morphology was similar to controls, suggesting that the reduction of GC number induced by yki knockdown in GCs is likely due to reduced GC proliferation.

Changing Hippo pathway activity in the soma non-autonomously influences GC number

Given our finding that Hippo signaling pathway members regulate autonomous proliferation of both somatic and germ line cells, we asked if this pathway might also coordinate non-autonomous proliferation of both cell types. Such a mechanism might be expected to operate in order to adjust the numbers of one cell type in response to Hippo signaling-mediated changes in the other, which would ensure an appropriate number of operative stem cell niches [8]. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed GC number in conditions where Hippo pathway activity was altered in the somatic cells. Non-autonomous positive regulation of GC number by ICs has been documented, but only in ways that also affect GC differentiation [49]. Whether ICs can positively regulate GC proliferation without affecting their differentiation thus remains unknown [6,8]. We found that increasing somatic cell number by driving hpo or wts RNAi in the soma also significantly increased GC number (p<0.01, p = 0.06 respectively; Fig. 3B–I; S3 Table). Strikingly, GC number increased in precise proportion to the IC number increase, whether this increase was as little as 15% (bab:GAL4>>wtsRNAi; Figs. 3C, S7; S3, S6 Tables) or as much as 70% (tj:GAL4>>hpoRNAi; Figs. 3C, S7; S3, S6 Tables), resulting in a consistent ratio of ICs to GCs (Figs. 3C, S7; S6 Table). However, increasing IC number by 150% via somatic overexpression of yki prompted only a 10% increase in GC number (p<0.05, Fig. 3B). In this condition, the GC:IC ratio was significantly lower than controls (Figs. 3C, S7; S6 Table), and GC:IC proportions were not maintained (Figs. 3C, S7). These results suggest that the Hippo pathway can maintain homeostatic growth of the larval ovary by regulating the number of GCs to accommodate changes of up to 70% in the number of ICs. However, further overproliferation of ICs cannot be matched by proportional GC proliferation.

We then asked if somatic Hippo signaling could also non-autonomously compensate for decreases in IC number via a proportional reduction in GC number. We found that somatic yki RNAi significantly decreased IC number (p<0.05), but did not significantly decrease GC number (p = 0.29, Fig. 3B), thus disrupting the GC:IC ratio (Figs. 3C, S7). However, reducing IC number via hpo overexpression in the soma yielded a marginally significant decrease in GC number (Fig. 3A, B). These results suggest that the Hippo pathway’s role in non-autonomous proliferation of GCs is primarily operative in cases of somatic cell overproliferation, but that to accommodate significant decreases in IC number by reducing GC numbers, Hippo signaling is not always sufficient and additional mechanisms may be required. The latter may include insulin signaling [6].

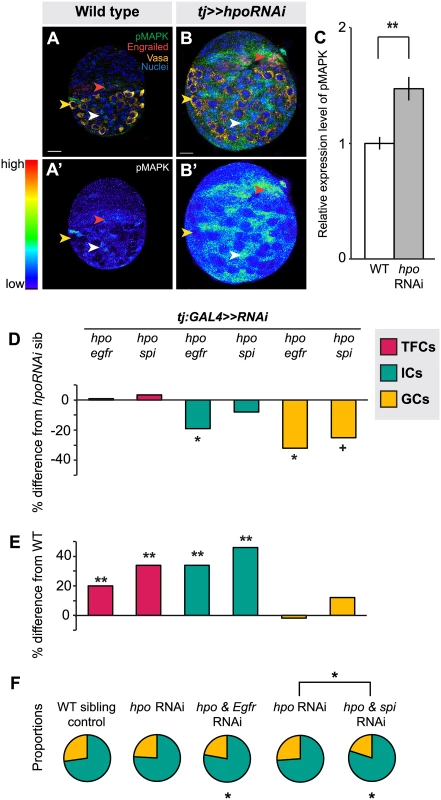

hpo interacts with EGFR signaling in ICs but not TFCs

Finally, we asked which signaling pathways Hippo signaling might interact with in the ovary to regulate proliferation. We also asked whether these pathways were the same or different in distinct somatic cell types (ICs and TFCs). First, we considered the EGFR pathway. The Hippo pathway interacts with the EGFR pathway to regulate non-autonomous control of proliferation in other organs [31,38,64,65,66]. Moreover, the EGFR pathway is known to regulate IC number and to non-autonomously regulate GC number [7,49]. We therefore asked whether the Hippo pathway interacted with EGFR signaling in the larval ovary. In wild type larval ovaries we observed, as previously reported [49], that pMAPK (a readout of EGFR activity) is expressed predominantly in ICs (Fig. 5A, white arrowhead) and in some TFCs (Fig. 5A, red arrowhead), but not in GCs (Fig. 5A, yellow arrowhead). When we knocked down hpo in the soma, we detected significantly increased pMAPK expression in the ovary (p<0.01; Fig. 5B–C), most notably in ICs at mid L3 and late L3 stages (Fig. 5B, white arrowhead), and additionally in some TFCs (Fig. 5B, red arrowhead). These results suggest that in wild type ovaries Hippo pathway activity may limit EGFR activity in somatic cells.

Fig. 5. The Hippo pathway interacts with the EGFR pathway to regulate IC and GC growth.

(A) Expression pattern of EGFR pathway activity marker pMAPK in wild type L3 ovary. Expression is mainly in posterior IC cells. Scale bar = 10 μm and applies also to A’. (B) pMAPK expression in ovary expressing UAS:hpoRNAi in the soma, exposed at same laser setting as (A). Scale bar = 10 μm and applies also to B’. (C) Relative intensity of anti-pMAPK fluorescence in wild type compared to hpo knockdown experimental (n = 8). Overall expression level of pMAPK is higher than controls, most prominently in the ICs. (D–E) Percent difference in TF (red), IC (green), and GC (yellow) number in double RNAi (hpo and egfr, or hpo and spi) compared to hpo single RNAi sibling controls (D), and wild type sibling controls (E). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. Numerical values can be found in S4 Table. (F) Pie charts showing proportions of ICs (green) and GCs (yellow) under indicated selected experimental conditions. * p<0.05, see S6 Table for numerical values; pie charts for all experimental conditions shown in S7 Fig. In order to assess the consequences of hpo/EGFR pathway interactions, we conducted double-RNAi knockdowns of hpo and either the EGFR receptor (egfr) or the EGFR ligand spitz (spi) in the soma using the tj:GAL4 driver. To validate the RNAi constructs, we expressed egfrRNAi or spiRNAi under tj:GAL4, and observed significant reduction in pMAPK levels in L3 ovaries (p<0.05, S8A Fig.). In both hpo and egfr or spi double-RNAi knockdowns, TFC number was not significantly different from hpo single knockdowns (Fig. 5D; S4 Table). In addition, TFC number was not altered when we knocked down egfr or spi alone in the soma (S4 Table). This suggests that the Hippo pathway does not regulate TFC number via EGFR signaling, consistent with the limited pMAPK expression observed in TFCs (Fig. 5A, red arrowhead).

In contrast, and consistent with the strong pMAPK expression in ICs (Fig. 5A, white arrowhead), tj:GAL4-mediated double knockdown of hpo and egfr partially rescued the hpo RNAi-induced overgrowth of ICs (p<0.05; Fig. 5D; S4 Table). However, these ovaries still had 35% more ICs than wild type controls (p<0.01; Fig. 5E). Double knockdown of hpo and spi yielded no significant difference in IC number compared to hpo single knockdowns (Fig. 5D). IC number was unaltered by knockdown of egfr or spi alone (S4 Table). In contrast to the TFCs, the Hippo pathway thus appears to interact with EGFR signaling to regulate IC number.

Finally, we quantified GCs to test whether the EGFR-Hippo signaling interaction in ICs could non-autonomously regulate GCs. Double knockdown of hpo and egfr, which significantly reduced IC number relative to hpo RNAi alone (p<0.05; Fig. 5D; S4 Table), also resulted in significantly fewer GCs (p<0.05; Fig. 5D; S4 Table), completely rescuing the hpo RNAi-induced GC overproliferation (Fig. 5E; S4 Table). Double knockdown of hpo and spi did not alter IC number relative to hpo RNAi alone (p = 0.24; Fig. 5D; S4 Table), but resulted in near-significant reduction of GCs (p = 0.054), also yielding a complete rescue of the hpo RNAi-induced overproliferation (Fig. 5E; S4 Table). Because the degree of hpo RNAi rescue was greater in GCs than in ICs in the hpo/spi double knockdown, the homeostatic balance of these cell types was no longer maintained (S5F Fig.). As previously reported [7,49], we observed a significant increase in GC number when we knocked down egfr alone, but not spi alone, in the soma (S4 Table). Taken together, these results indicate that hpo interacts in the soma with egfr signaling, likely through an additional ligand along with spi, to regulate both IC number autonomously and GC number non-autonomously.

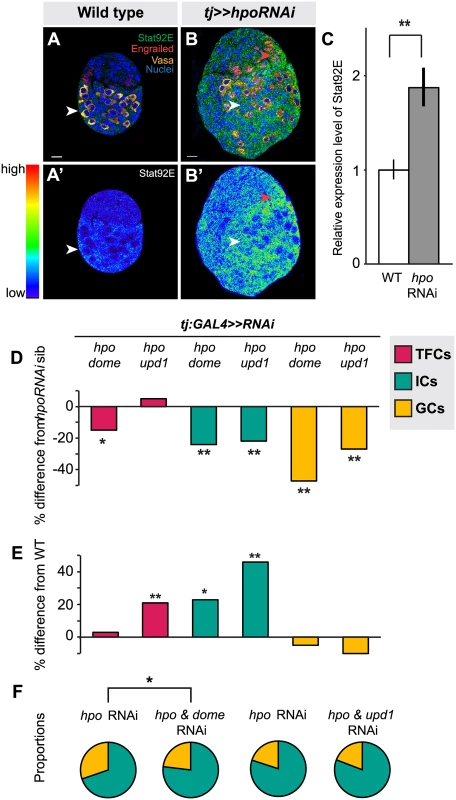

hpo interacts with JAK-STAT signaling in TFCs and ICs

Another characterized interacting partner of the Hippo pathway in various somatic tissues is the JAK/STAT pathway [37,38,39,67,68,69]. We therefore asked whether these two pathways also interact to regulate autonomous and/or homeostatic proliferation in the larval ovary. First, we used detection of Stat92E as a readout of JAK/STAT activity [70,71,72]. We observed strongest Stat92E expression in posterior somatic cells, including ICs, in wild type ovaries (Fig. 6A–A’). Knocking down hpo in the soma led to significantly higher Stat92E levels (p<0.01; Fig. 6B–C), suggesting that, similar to its interaction with EGFR, Hippo pathway activity normally limits JAK/STAT pathway activity in the larval ovary.

Fig. 6. Hippo pathway interacts with JAK/STAT pathway to regulate TFC and IC proliferation, and non-autonomous regulation of GC number.

(A) Expression pattern of JAK/STAT pathway kinase Stat92E in wild type L3 ovary. Scale bar = 10 μm and applies also to A’. (B) Stat92E expression in ovary expressing UAS:hpoRNAi in the soma, exposed at same laser setting as (A). Scale bar = 10 μm and applies also to B’. (C) Relative intensity of anti-Stat92E fluorescence in wild type compared to hpo knockdown experiments (n = 10). (D–E) Percent difference in TF (red), IC (green), GC (yellow) number in double RNAi (hpo and dome, or hpo and upd1) knockdowns compared to hpo single RNAi sibling controls (D), and wild type sibling controls (E). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. Numerical values can be found in S4 Table. (F) Pie charts showing proportions of ICs (green) and GCs (yellow) of hpo RNAi control and hpo and dome/up1 double RNAi. * p<0.05, see S6 Table for numerical values; pie charts for all experimental conditions shown in S7 Fig. Next, we asked if RNAi against either the JAK/STAT receptor dome or the ligand unpaired (upd1) could rescue the effects of hpo RNAi in the soma. While there are three upd orthologues in Drosophila [73,74,75], we focused on upd1, as it is known to regulate GC proliferation in the testis [76] and thought to be a specific yki target in polar cells [77], which are derivatives of the somatic cells of the ovary. Expressing dome or upd1 RNAi under tj:GAL4 significantly reduced Stat92E levels in the larval ovary (p<0.05 for dome, p = 0.06 for upd1; S8B Fig.), confirming functionality of these RNAi lines. In TFCs, double knockdown of dome and hpo, but not of upd1 and hpo, completely suppressed the hpo single knockdown phenotype (p<0.05; Fig. 6D; S4 Table). Knocking down dome alone in the soma significantly decreased TFC number (p<0.05; S4 Table), supporting the hypothesis that JAK/STAT signals positively regulate TFC proliferation. These data suggest that Hippo signaling regulates TFC proliferation via interactions with the JAK/STAT pathway, and that a ligand other than upd1 mediates this interaction.

We next counted IC and GC number to determine whether JAK/STAT-Hippo pathway interactions regulate ICs proliferation autonomously, and/or GC proliferation non-autonomously. Both dome/hpo or upd1/hpo double knockdowns partially rescued the overproliferation caused by knockdown of hpo alone (p<0.01; Fig. 6D; S4 Table), but these ovaries still had significantly more ICs than wild type controls (p<0.05; Fig. 6E). Both double knockdown conditions also completely rescued the non-autonomous increase in GC number caused by hpo RNAi (Fig. 6D; S4 Table). Similar to our experiments on the EGFR pathway, we observed abnormal IC:GC ratios in the hpo and dome RNAi single knockdowns (Figs. 6F, S7; S6 Table). In summary, Hippo signaling interacts with JAK/STAT signaling via upd1 to regulate IC:GC homeostasis.

Discussion

Hippo signaling in somatic cells of the larval ovary

We have shown that canonical cell autonomous Hippo signaling regulates proliferation of two key somatic cell types, TFCs and ICs. Because TFCs form TFs, which are the beginning points of each GSC niche, the number and stacking of TFCs can ultimately influence adult ovariole number and thus reproductive capacity [50,78,79]. We previously showed that the differences in ovariole number between D. melanogaster and closely related Drosophila species results from changes in TFC number [48,50]. This suggests Hippo and JAK/STAT pathway members as novel potential targets of evolutionary change in ovariole number variation. Indeed, loci containing many of these genes have been previously identified in QTL analyses of genomic variation correlated with ovariole number variation [80]. Our study thus provides novel experimental validation of previous quantitative genetics approaches to understanding the genetic regulation of ovariole number.

In TFCs, Hippo signaling regulates proliferation by interacting with dome but not upd1, suggesting that one or both of upd2 or upd3 act as ligands for JAK/STAT signaling in this context. Alternatively, a role for upd1 in TFC number regulation may have been obscured by our use of the tj:GAL4 driver, since this driver is restricted to cells posterior to TFCs in L3. A potential source of JAK/STAT ligands that would not have been captured by our experiments could be the anterior somatic cells that are in close contact with TFCs. While TFCs establish the number of niches, ICs appear to communicate with and regulate the number of GCs that can populate those niches. We hypothesize that TFCs and ICs do not regulate each other’s proliferation non-autonomously. However, we cannot test this hypothesis directly, as to our knowledge, no GAL4 drivers currently exist that are exclusively expressed in only TFCs or only ICs. Nevertheless, a number of lines of evidence support this hypothesis. First, reducing Hippo pathway activity in a subset of TFCs had no effect on IC number (S5H Fig.; S5 Table). Second, a double knockdown of egfr and hpo under the tj:GAL4 driver reduced IC number but had no effect on TFC number (Fig. 5D). Third, loss of germ cell-less (gcl) function leads to reduced GC and IC numbers [49], but has no effect on ovariole number [81]. Given that ovariole number is largely determined by TFC number [50], it is likely that gcl ovaries have reduced ICs but not reduced TFCs. However, we note that both TFCs and ICs respond to hormonal cues provided by Ecdysone and Insulin signaling [6,8]. This suggests that growth of these somatic cell types may be accomplished through their response to systemic hormonal cues, rather than through non-autonomous effects of one somatic cell type on another.

While the Hippo pathway regulates proliferation of both ICs and TFCs, each cell type had a unique pattern of Hippo pathway activity during larval development, suggesting that the upstream regulatory cues of Hippo signaling are different for TFCs and ICs. In Drosophila, glial cells and wing disc cells activate the Hippo pathway using different combinations of upstream regulators [18], indicating that the Hippo pathway can interact with a unique set of upstream regulatory genes depending on the cell type. Addressing these cell type-specific differences in Hippo pathway activation in future studies will elucidate how the Hippo pathway is regulated locally during development of complex organs to establish organ size.

Another notable difference between Hippo pathway operation in ICs and TFCs is its differential interactions with the EGFR and JAK/STAT pathways in distinct ovarian cell types. In Drosophila intestinal stem cell development and stem cell-mediated regeneration [37,38,39,68], as well as in eye imaginal discs [64,67], the Hippo pathway regulates proliferation of these tissues via interactions with both the EGFR and JAK/STAT pathways. In contrast, the Hippo pathway acts in parallel with but independently of both pathways to regulate the maturation of Drosophila ovarian follicle cells [25,36]. We do not know what mechanisms determine whether the Hippo pathway interacts with EGFR signaling, JAK/STAT signaling, or both in a given cell or tissue type. One mechanism that may be relevant, however, is the differential activation of specific ligands. For example, in the Drosophila eye disc, Hippo signaling interacts genetically with EGFR activity induced by vein, but not by any of the other three Drosophila EGFR ligands [31]. Similarly, constitutively active human YAP can upregulate transcription of vein, but not the other three EGFR ligands, in Drosophila wing imaginal discs [31]. That fact that spiRNAi driven in the soma does not rescue the hpoRNAi overproliferation phenotype in the ovary may indicate that other ligands, such as vein, are required for this EGFR-Hippo signaling interaction, or that the relevant EGFR ligands are expressed by GCs rather than the soma. Our results suggest that the larval ovary could serve as a model to examine whether differential ligand use within a single organ could modulate Hippo pathway activity during development.

Hippo signaling in germ cells of the larval ovary

Previous reports [35,36] suggested that the Hippo pathway components were dispensable for the proliferation of adult GSCs. In contrast, we observed that yki controls proliferation of the larval GCs, albeit independently of hpo and wts. These contrasting results are likely due to the fact that Sun et al. [35] sought to detect conspicuous germ cell tumors in response to reduced Hippo pathway activity, whereas we manually counted GCs and in this way detected significant changes in GC number in response to yki knockdown or overexpression. Although hpo, wts, ex or hipk RNAi (Fig. 4A) and hpo null clones (Fig. 4F) suggested that yki activity in GCs was independent of the canonical Hippo kinase cascade, overexpression of hpo in GCs did decrease GC number (Fig. 4A). Taken together, our data suggest that although sufficiently high levels of hpo are capable of restricting Yki activity in GCs, hpo does not regulate yki in GCs in wild type ovaries.

A growing body of evidence shows that hpo-independent mechanisms for regulating Yki are deployed in stem cells of multiple vertebrate and invertebrate tissues. For example, in mammalian epidermal stem cells, YAP is regulated in a Hpo-independent manner by an interaction between alpha-catenin and adaptor protein 14–43 [82]. Similarly, the C-terminal domain of YAP that contains the predicted hpo-dependent phosphorylation sites is dispensable for YAP-dependent tissue growth in postnatal epidermal stem cells in mice [83]. Other known Hpo-independent regulators of Yki include the phosphatase PTPN14 and the WW domain binding protein WBP2, which were identified in mammalian cancer cell lines [84,85]. The flatworm Macrostomum ligano displays a requirement for hpo, sav, wts, mats and yki in regulating stem cell number and proliferation, although it is unknown whether yki operates independently of the core kinase cascade in this system [86]. In contrast, however, in the flatworm Schmidtea mediterranea, while yki plays a role in regulating stem cell numbers, hpo, wts and Mer appear dispensable for stem cell proliferation [87]. We hypothesize that, as in many other stem cell systems, the Drosophila germ line may use Yki regulators that are not commonly used in the soma to regulate proliferation. Further investigation into the Yki interacting partners in GCs will be needed to understand how Yki may be regulated non-canonically in establishing stem cell populations.

A novel role for Hippo signaling in germ line-soma homeostasis

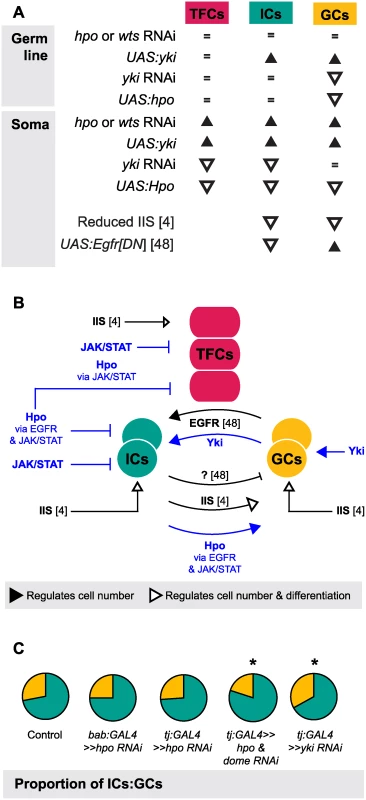

One of the most striking aspects of growth regulation in the larval ovary is the homeostatic growth of ICs and GCs during development. This homeostatic growth is critical to ensure establishment of an appropriate number of GSC niches that each contain the correct proportions of somatic and germ cells. We have summarized the available data on the molecular mechanisms that regulate the number of ICs and GCs (Fig. 7A) and our current understanding of how these mechanisms operate within and between the cell types that comprise the GSC niche (Fig. 7B). Previous work has shown that these mechanisms include the Insulin signaling and EGFR pathways. Insulin signaling function in the soma regulates differentiation and proliferation both autonomously in ICs and non-autonomously in GCs [6] (Fig. 7A, B). The EGFR pathway regulates homeostatic growth of both IC and GC numbers as follows: GCs produce the ligand Spitz that promotes survival of ICs, and ICs non-autonomously represses GC proliferation via an unknown regulator that is downstream of the EGFR pathway [49] (Fig. 7A, B). Our results add four critical new elements to the emerging model of soma-germ line homeostasis in the larval ovary (Fig. 7B, blue elements). First, yki positively and cell-autonomously regulates GC number independently of the canonical Hippo signaling pathway. Second, canonical Hippo signaling negatively and cell-autonomously regulates TFC number via JAK/STAT signaling, and IC number via both EGFR and JAK/STAT signaling. Third, JAK/STAT signaling also negatively regulates IC and TFC number in a cell-autonomous manner. Finally, Hippo signaling contributes to non-autonomous homeostatic growth of ICs and GCs in at least two ways: (1) Yki activity in GCs non-autonomously regulates IC proliferation; and (2) Hippo signaling activity in ICs non-autonomously regulates GC proliferation through the EGFR and JAK/STAT pathways. The latter relationship is, to our knowledge, the first report of a non-autonomous mechanism that ensures that GC number increases in response to increased IC number, without negatively affecting GSC niche differentiation or function.

Fig. 7. The Hippo pathway regulates coordinated growth of the soma and germ line.

(A) Summary of changes in TFC, IC and GC numbers when expression of genes from various growth pathways were altered in our study and two other studies [6,49]. Black triangles indicate significant increase; white triangles indicate significant decrease; = indicate no significant change. (B) Model of how Hippo pathway influences coordinated proliferation of somatic cells and germ cells in the larval ovary. Contributions of the present study are indicated in blue; elements of the model derived from other studies [6,49] are indicated in black. The Hippo pathway interacts with JAK/STAT to regulate proliferation of TFCs, and interacts with EGFR and JAK/STAT pathways to regulate autonomous proliferation of ICs and non-autonomous proliferation of GCs. In addition, yki acts independently of hpo to influence proliferation of GCs in a non-canonical manner. (C) Summary of representative IC (green)/GC (yellow) proportions observed in our experiments, further elaborated in S7 Fig. Proportions of ICs and GCs are similar to controls when we knock down hpo or wts alone in the soma, but disrupting both hpo and EGFR or JAK/STAT pathway members leads to loss of proportional growth. Asterisk denotes p<0.05. See S6 Table for numerical values. Finally, we note that although IC number and GC number had been previously observed to affect each other non-autonomously [6,49], our experiments shed new light on the remarkable degree to which specific proportions of each cell type are maintained, and demonstrate the Hippo pathway’s involvement in this precise homeostasis. This proportionality was not maintained, however, in Hippo/ EGFR or Hippo/JAK/STAT pathway double knockdowns (Figs. 7, S7). This suggests that Hippo pathway-mediated proportional growth of ICs and GCs requires activity of not only the EGFR pathway, as previously reported [49], but also of the JAK/STAT pathway in the soma.

The proportional growth of these cell types maintained by the Hippo-EGFR-JAK/STAT pathway interactions we describe here suggests that the soma releases proliferation-promoting factors to the GCs, and that the GCs can process these signals to maintain optimal proportionality. Similarly, when GC number increased via yki overexpression in GCs, we noticed that IC number increased non-autonomously. Achieving specific numbers and proportions of distinct cell types within a single organ, and linking these processes to final organ size and function, are largely unexplained phenomena in developmental biology and organogenesis. By using the larval ovary as a system to address these problems, we have shown not only that the Hippo pathway is involved in these processes, but also that it can display remarkable complexity and modularity in regulating stem cell precursor proliferation and adjusting organ-specific stem cell niche number during development.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks

Flies were reared at 25°C at 60% humidity with food containing yeast and in uncrowded conditions as previously described [50]. The following RNAi lines from the Bloomington Stock Center (B) [56] or the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC) [55] were used for knockdown: B33614 (UAS:hpoRNAi), B34064 (UAS:wtsRNAi), B34067 (UASykiRNAi), VDRC104523 (UAS:ykiRNAi), VDRC109281 (UAS:exRNAi), VDRC43267 (UAS:egfrRNAi), VDRC19717 (UAS:domeRNAi), B35363 (UAS:hipkRNAi), B35481 (UAS:sdRNAi). For overexpression of hpo or yki we used w*; UAS:hpo/TM3 Sb [19] and w*; UAS:yki/TM6B [21] (courtesy of D. Pan, Johns Hopkins University). GAL4 lines used were: w; P{GawB}bab1Pgal4–2/TM6, Tb1 (bab:GAL4, B6803), P{UAS-Dcr-2.D}1, w1118; P{GAL4-nos.NGT}40 (nos:GAL4, B25751), y w; P{w+mW.hs = GawB}NP1624 (tj:GAL4, Kyoto Stock Center, K104–055), y w hs:FLP122; Sp/CyO; hh:GAL4/TM6B (hh:GAL4, courtesy of L. Johnston, Columbia University), w; P{w+mW.hs = GawB}ptc559.1 (ptc:GAL4, B2017). For GAL4 expression domain analysis, GAL4 lines were crossed to w; P{w+mC = UAS-GFP.S65T}T2 (B1521). For clonal analysis of hpo and yki null alleles, the following lines were used: w1118; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D P{w+mC = Ubi GFP(S65T)nls}2R/CyO (B5626), w1118; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D P{w+t* ry+t* = white-un1}47A (B1928), P{ry+t7.2 = hsFLP}1, w1118; Adv[1]/CyO (B6), hsFLP12 w*; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D ykiB5/CyO [21] (courtesy of D. Pan, Johns Hopkins University), and y* w*; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D hpoBF33/CyO (y+) [57] (Courtesy of J. Jiang, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center). For analysis of cell type numbers in flies homozygous for loss of function Hippo pathway alleles, we used ex1 (B295; [54]) and y*w*eyFLP; FRT42D ykiDBO2 / CyO (Courtesy of K-L Guan, UCSD; [33]).

Validation of RNAi lines was provided by data from a number of independent experiments, as follows: (1) Immunohistochemistry against Hpo or Yki showed that RNAi against these genes reduced protein levels to levels indistinguishable from background in whole mounted larval ovaries (S1D, I Fig.). (2) Germ line clones of null alleles of hpo (hpoBF33 [57]) or yki (ykiB5 [21]) had the same effect on germ cell number as RNAi against these genes driven in the germ line (Fig. 4F). (3) A null allele of expanded [54] had the same effect on TFC number, GC number and IC number as RNAi against Hippo pathway activity (S4 Fig., S2 Table). (4) Two different yki RNAi lines had the same effect on GC number (S3 Table). (5) Expression of pMAPK and Stat92E in the larval was reduced by RNAi against egfr or spi and dome or upd1, respectively (S8 Fig.). In addition, the wtsRNAi and domeRNAi lines we used here have been independently validated by other studies [88,89].

Immunohistochemistry

Larvae were all reared at 25°C at 60% humidity. Larval fat bodies were dissected in 1xPBS with 0.1% Triton-X, and fixed in 4% PFA in 1xPBS for 20 minutes at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. For tissues stained with the rat-Hippo antibody (courtesy of N. Tapon, London Research Institute), fat body tissue was fixed in freshly made PLP fixative [17] for 20 minutes. Tissues were stained as previously described [50]. Primary antibodies were used in the following concentrations: Mouse anti-Engrailed 4D9 (1 : 50, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), guinea pig anti-Traffic Jam (1 : 3000–5000, courtesy of D. Godt, University of Toronto), rabbit anti-Vasa (1 : 500, courtesy of P. Lasko, McGill University), rabbit anti-Yorkie (1 : 400, courtesy of K. Irvine, Rutgers University), rat anti-Hippo (1 : 100, courtesy of N. Tapon, London Research Institute), chicken anti-Beta-galactosidase (1 : 200, Abcam), mouse anti-Alpha spectrin 3A9 (1 : 5, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rabbit anti-dpErk (1 : 300, Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-Stat92E (1 : 200, courtesy of E. Bach, New York University). We used goat anti-guinea pig Alexa 488, anti-mouse Alexa 488, Alexa 555, and Alexa 647, anti-rabbit Alexa 555, Alexa 647, anti-rat Alexa 568, and anti-chicken Alexa 568 at 1 : 500 as secondary antibodies (Life Technologies). All samples were stained with 10 mg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Sigma) at 1 : 500 to visualize nuclei, and some samples were stained with 0.1 mg/ml FITC-conjugated Phalloidin (Sigma) at 1 : 200 to visualize cell outlines. For GAL4 crosses, we crossed virgin females carrying the GAL4 construct with males carrying the UAS construct, and analyzed F1 LP stage larvae. Samples were imaged with Zeiss LSM 700, 710 or 780 confocal microscopes at the Harvard Center for Biological Imaging. Each sample was imaged in z-stacks of 1 μm thickness. For expression level analysis, laser settings were normalized to the secondary only control conducted in parallel to the experimental stain. Expression levels were quantified using Image J (NIH) and were normalized to nuclear stain intensity to control for staining level differences between samples.

Cell type, ovariole number and egg-laying quantification

White immobile pupae were collected from uncrowded tubes (<100 larvae) for cell number analysis. All cell counts were obtained manually using Volocity (Perkin Elmer) after samples were randomized and coded to prevent bias; cells stained with Vasa were counted for germ cell number, and cells stained with Traffic Jam were counted for intermingled cell number. TF number and total TFC number were collected as described in [50]. Experimental crosses were compared to parental GAL4 and RNAi strains using a student’s t-test with unequal variance performed in Microsoft Excel. Changes in number were not considered significant unless p values were significant for both parental strains. For crosses where one or both parents were heterozygous for balanced GAL4 and/or UAS elements, sibling data from F1s carrying balancer chromosomes, rather than parental data, was collected as a control.

Adult ovariole number was counted in mated females that were 3–5 days post hatching from uncrowded vials kept in 25°C at 60% humidity. Adult ovaries were dissected in 1xPBS containing 0.1% Triton-X, and ovariole number was counted under a dissecting microscope by teasing apart ovariole strands using a tungsten needle. F1 ovariole number was compared to the ovariole number of siblings carrying balancer chromosomes for bab:GAL4, and to the tj:GAL4 parental line for the tj:GAL4 crosses.

Adult fecundity was measured by placing three females and one male in a vial for 24 hours, and counting total egg number per vial. Five replicates (vials) were performed for each treatment. The egg count was divided by the number of females to obtain the average egg number per female per 24 hours.

Clonal analysis

P0 flies were mated (for ykiB5 clones: w1118; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D P{w+mC = Ubi GFP(S65T)nls}2R/CyO x hsFLP12 w*; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D ykiB5/CyO; for hpoBF33 clones: P{ry+t7.2 = hsFLP}1, w1118; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D P{w+mC = Ubi GFP(S65T)nls}2R/CyO x y* w*; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D hpoBF33/CyO (y+); for control w clones: P{ry+t7.2 = hsFLP}1, w1118; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D P{w+mC = Ubi GFP(S65T)nls}2R/CyO x w1118; P{ry+t7.2 = neoFRT}42D P{w+t* ry+t* = white-un1}47A) and F1 eggs were collected for 8–12 hours at 25°C. L1 larvae were heat shocked at 37°C for 1 hour 36–48 hours after egg laying. Late L3 to LP stage ovaries were dissected, stained with 10 mg/ml Hoechst 4333 (Sigma) at 1 : 500, FITC-conjugated anti-GFP (1 : 500, Life Technologies), and rabbit anti-Vasa (1 : 500, courtesy of P. Lasko, McGill University), and imaged. GFP-negative mutant GC clone size (number of cells per clone) and GFP++ wild type twin spot clone size were counted manually.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Barry ER, Camargo FD (2013) The Hippo superhighway: signaling crossroads converging on the Hippo/Yap pathway in stem cells and development. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 25 : 247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.12.006 23312716

2. Tumaneng K, Russell RC, Guan K-L (2012) Organ size control by Hippo and TOR pathways. Current Biology 22: R368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.003 22575479

3. Halder G, Johnson RL (2011) Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development 138 : 9–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.045500 21138973

4. Ramos A, Camargo FD (2012) The Hippo signaling pathway and stem cell biology. Trends in Cell Biology 22 : 339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.04.006 22658639

5. Eliazer S, Buszczak M (2011) Finding a niche: studies from the Drosophila ovary. Stem Cell Research and Therapy 2 : 45. doi: 10.1186/scrt86 22117545

6. Gancz D, Gilboa L (2013) Insulin and Target of rapamycin signaling orchestrate the development of ovarian niche-stem cell units in Drosophila. Development 140 : 4145–4154. doi: 10.1242/dev.093773 24026119

7. Matsuoka S, Hiromi Y, Asaoka M (2013) Egfr signaling controls the size of the stem cell precursor pool in the Drosophila ovary. Mechanisms of Development 130 : 241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2013.01.002 23376160

8. Gancz D, Lengil T, Gilboa L (2011) Coordinated regulation of niche and stem cell precursors by hormonal signaling. PLoS Biology 9: e1001202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001202 22131903

9. Hamaratoglu F, Willecke M, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Hyun E, et al. (2006) The tumour-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signalling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nature Cell Biology 8 : 27–36. 16341207

10. Genevet A, Wehr MC, Brain R, Thompson BJ, Tapon N (2010) Kibra Is a Regulator of the Salvador/Warts/Hippo Signaling Network. Developmental Cell 18 : 300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.011 20159599

11. Baumgartner R, Poernbacher I, Buser N, Hafen E, Stocker H (2010) The WW Domain Protein Kibra Acts Upstream of Hippo in Drosophila. Developmental Cell 18 : 309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.013 20159600

12. Yu J, Zheng Y, Dong J, Klusza S, Deng WM, et al. (2010) Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates Hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Developmental cell 18 : 288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.012 20159598

13. Willecke M, Hamaratoglu F, Kango-Singh M, Udan R, Chen CL, et al. (2006) The fat cadherin acts through the Hippo tumor-suppressor pathway to regulate tissue size. Current Biology 16 : 2090–2100. 16996265

14. Silva E, Tsatskis Y, Gardano L, Tapon N, McNeill H (2006) The tumor-suppressor gene fat controls tissue growth upstream of Expanded in the Hippo signaling pathway. Current Biology 16 : 2081–2089. 16996266

15. Bennett FC, Harvey KF (2006) Fat cadherin modulates organ size in Drosophila via the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling pathway. Current Biology 16 : 2101–2110. 17045801

16. Robinson BS, Huang J, Hong Y, Moberg KH (2010) Crumbs regulates Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling in Drosophila via the FERM-domain protein Expanded. Current Biology 20 : 582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.019 20362445

17. Grzeschik NA, Parsons LM, Allott ML, Harvey KF, Richardson HE (2010) Lgl, aPKC, and Crumbs regulate the Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway through two distinct mechanisms. Current Biology 20 : 573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.055 20362447

18. Reddy BV, Irvine KD (2011) Regulation of Drosophila glial cell proliferation by Merlin-Hippo signaling. Development 138 : 5201–5212. doi: 10.1242/dev.069385 22069188

19. Wu S, Huang J, Dong J, Pan D (2003) hippo encodes a Ste-20 family protein kinase that restricts cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in conjunction with salvador and warts. Cell 114 : 445–456. 12941273

20. Udan RS, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Tao C, Halder G (2003) Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nature Cell Biology 5 : 914–920. 14502294

21. Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, Pan D (2005) The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell 122 : 421–434. 16096061

22. Nolo R, Morrison CM, Tao C, Zhang X, Halder G (2006) The bantam microRNA is a target of the Hippo tumor-suppressor pathway. Current Biology 16 : 1895–1904. 16949821

23. Thompson BJ, Cohen SM (2006) The Hippo pathway regulates the bantam microRNA to control cell proliferation and apoptosis in Drosophila. Cell 126 : 767–774. 16923395

24. Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Pan D (2008) The TEAD/TEF family protein Scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the Hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Developmental Cell 14 : 388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.007 18258486

25. Polesello C, Tapon N (2007) Salvador-Warts-Hippo signaling promotes Drosophila posterior follicle cell maturation downstream of Notch. Current Biology 17 : 1864–1870. 17964162

26. Meignin C, Alvarez-Garcia I, Davis I, Palacios IM (2007) The Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway is required for epithelial proliferation and axis specification in Drosophila. Current Biology 17 : 1871–1878. 17964161

27. Hall CA, Wang R, Miao J, Oliva E, Shen X, et al. (2010) Hippo pathway effector Yap is an ovarian cancer oncogene. Cancer Research 70 : 8517–8525. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1242 20947521

28. Zhou D, Zhang Y, Wu H, Barry E, Yin Y, et al. (2011) Mst1 and Mst2 protein kinases restrain intestinal stem cell proliferation and colonic tumorigenesis by inhibition of Yes-associated protein (Yap) overabundance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: E1312–1320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110428108 22042863

29. Striedinger K, VandenBerg SR, Baia GS, McDermott MW, Gutmann DH, et al. (2008) The Neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor gene product, Merlin, regulates human meningioma cell growth by signaling through YAP. Neoplasia 10 : 1204–1212. 18953429

30. Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, et al. (2011) Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science 332 : 458–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1199010 21512031

31. Zhang J, Ji J-Y, Yu M, Overholtzer M, Smolen GA, et al. (2009) YAP-dependent induction of amphiregulin identifies a non-cell-autonomous component of the Hippo pathway. Nature Cell Biology 11 : 1444–1450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1993 19935651

32. Zhao B, Li L, Lei Q, Guan K-L (2010) The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes and Development 24 : 862–874. doi: 10.1101/gad.1909210 20439427

33. Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, Udan RS, Yang Q, et al. (2007) Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes and Development 21 : 2747–2761. 17974916

34. Zhang X, George J, Deb S, Degoutin JL, Takano EA, et al. (2011) The Hippo pathway transcriptional co-activator, YAP, is an ovarian cancer oncogene. Oncogene 30 : 2810–2822. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.8 21317925

35. Sun S, Zhao S, Wang Z (2008) Genes of Hippo signaling network act unconventionally in the control of germline proliferation in Drosophila. Developmental Dynamics 237 : 270–275. 18095349

36. Yu J, Poulton J, Huang YC, Deng WM (2008) The Hippo pathway promotes Notch signaling in regulation of cell differentiation, proliferation, and oocyte polarity. PloS ONEs 3: e1761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001761 18335037

37. Karpowicz P, Perez J, Perrimon N (2010) The Hippo tumor suppressor pathway regulates intestinal stem cell regeneration. Development 137 : 4135–4145. doi: 10.1242/dev.060483 21098564

38. Ren F, Wang B, Yue T, Yun E-Y, Ip YT, et al. (2010) Hippo signaling regulates Drosophila intestine stem cell proliferation through multiple pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 : 21064–21069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012759107 21078993

39. Shaw RL, Kohlmaier A, Polesello C, Veelken C, Edgar BA, et al. (2010) The Hippo pathway regulates intestinal stem cell proliferation during Drosophila adult midgut regeneration. Development 137 : 4147–4158. doi: 10.1242/dev.052506 21068063

40. King RC (1970) Ovarian Development in Drosophila melanogaster. New York: Academic Press. 227 p.

41. Godt D, Laski FA (1995) Mechanisms of cell rearrangement and cell recruitment in Drosophila ovary morphogenesis and the requirement of bric à brac. Development 121 : 173–187. 7867498

42. Sahut-Barnola I, Dastugue B, Couderc J-L (1996) Terminal filament cell organization in the larval ovary of Drosophila melanogaster: ultrastructural observations and pattern of divisions. Roux’s Archives of Developmental Biology 205 : 356–363.

43. Bartoletti M, Rubin T, Chalvet F, Netter S, Dos Santos N, et al. (2012) Genetic basis for developmental homeostasis of germline stem cell niche number: a network of Tramtrack-Group nuclear BTB factors. PloS ONE 7: e49958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049958 23185495

44. Hodin J, Riddiford LM (1998) The ecdysone receptor and ultraspiracle regulate the timing and progression of ovarian morphogenesis during Drosophila metamorphosis. Development, Genes and Evolution 208 : 304–317. 9716721

45. Green DA II, Extavour CG (2014) Insulin Signaling Underlies Both Plasticity and Divergence of a Reproductive Trait in Drosophila. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences 281 : 20132673. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2673 24500165

46. Li MA, Alls JD, Avancini RM, Koo K, Godt D (2003) The large Maf factor Traffic Jam controls gonad morphogenesis in Drosophila. Nature Cell Biology 5 : 994–1000. 14578908

47. Song X, Call GB, Kirilly D, Xie T (2007) Notch signaling controls germline stem cell niche formation in the Drosophila ovary. Development 134 : 1071–1080. 17287246

48. Green DA II, Extavour CG (2012) Convergent Evolution of a Reproductive Trait Through Distinct Developmental Mechanisms in Drosophila. Developmental Biology 372 : 120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.09.014 23022298

49. Gilboa L, Lehmann R (2006) Soma-germline interactions coordinate homeostasis and growth in the Drosophila gonad. Nature 443 : 97–100. 16936717

50. Sarikaya DP, Belay AA, Ahuja A, Green DA II, Dorta A, et al. (2012) The roles of cell size and cell number in determining ovariole number in Drosophila. Developmental Biology 363 : 279–289 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.017 22200592

51. Cabrera GR, Godt D, Fang PY, Couderc JL, Laski FA (2002) Expression pattern of Gal4 enhancer trap insertions into the bric a brac locus generated by P element replacement. Genesis 34 : 62–65. 12324949

52. Hayashi S, Ito K, Sado Y, Taniguchi M, Akimoto A, et al. (2002) GETDB, a database compiling expression patterns and molecular locations of a collection of Gal4 enhancer traps. Genesis 34 : 58–61. 12324948

53. Tanentzapf G, Devenport D, Godt D, Brown NH (2007) Integrin-dependent anchoring of a stem-cell niche. Nature Cell Biology 9 : 1413–1418. 17982446

54. Stern C, Bridges CB (1926) The mutants of the extreme left end of the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 11. 17246473

55. Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, et al. (2007) A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 448 : 151–156. 17625558

56. Ni JQ, Liu LP, Binari R, Hardy R, Shim HS, et al. (2009) A Drosophila resource of transgenic RNAi lines for neurogenetics. Genetics 182 : 1089–1100. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.103630 19487563

57. Jia J, Zhang W, Wang B, Trinko R, Jiang J (2003) The Drosophila Ste20 family kinase dMST functions as a tumor suppressor by restricting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Genes and Development 17 : 2514–2519. 14561774

58. Badouel C, Gardano L, Amin N, Garg A, Rosenfeld R, et al. (2009) The FERM-domain protein Expanded regulates Hippo pathway activity via direct interactions with the transcriptional activator Yorkie. Developmental Cell 16 : 411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.010 19289086

59. Oh H, Reddy BV, Irvine KD (2009) Phosphorylation-independent repression of Yorkie in Fat-Hippo signaling. Developmental Biology 335 : 188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.026 19733165

60. Oh H, Irvine KD (2008) In vivo regulation of Yorkie phosphorylation and localization. Development (Cambridge, England) 135 : 1081–1088. doi: 10.1242/dev.015255 18256197

61. Poon CL, Zhang X, Lin JI, Manning SA, Harvey KF (2012) Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase regulates Hippo pathway-dependent tissue growth. Current Biology 22 : 1587–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.075 22840515

62. Goulev Y, Fauny JD, Gonzalez-Marti B, Flagiello D, Silber J, et al. (2008) SCALLOPED interacts with YORKIE, the nuclear effector of the Hippo tumor-suppressor pathway in Drosophila. Current Biology 18 : 435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.034 18313299

63. Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, et al. (2008) The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Developmental Cell 14 : 377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006 18258485

64. Reddy BV, Irvine KD (2013) Regulation of Hippo signaling by EGFR-MAPK signaling through Ajuba family proteins. Developmental Cell 24 : 459–471. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.020 23484853

65. Huang JM, Nagatomo I, Suzuki E, Mizuno T, Kumagai T, et al. (2013) YAP modifies cancer cell sensitivity to EGFR and survivin inhibitors and is negatively regulated by the non-receptor type protein tyrosine phosphatase 14. Oncogene 32 : 2220–2229. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.231 22689061

66. Herranz H, Hong X, Cohen SM (2012) Mutual repression by Bantam miRNA and Capicua links the EGFR/MAPK and Hippo pathways in growth control. Current Biology 22 : 651–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.050 22445297

67. Reddy BV, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD (2010) Influence of Fat-Hippo and Notch signaling on the proliferation and differentiation of Drosophila optic neuroepithelia. Development 137 : 2397–2408. doi: 10.1242/dev.050013 20570939

68. Staley BK, Irvine KD (2010) Warts and Yorkie mediate intestinal regeneration by influencing stem cell proliferation. Current Biology 20 : 1580–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.041 20727758

69. Ohsawa S, Sato Y, Enomoto M, Nakamura M, Betsumiya A, et al. (2012) Mitochondrial defect drives non-autonomous tumour progression through Hippo signalling in Drosophila. Nature 490 : 547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature11452 23023132

70. Sweitzer SM, Calvo S, Kraus MH, Finbloom DS, Larner AC (1995) Characterization of a Stat-like DNA binding activity in Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 270 : 16510–16513. 7622453

71. Yan R, Small S, Desplan C, Dearolf CR, Darnell JE (1996) Identification of a Stat gene that functions in Drosophila development. Cell 84 : 421–430. 8608596

72. Flaherty MS, Salis P, Evans CJ, Ekas LA, Marouf A, et al. (2010) chinmo is a functional effector of the JAK/STAT pathway that regulates eye development, tumor formation, and stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila. Developmental Cell 18 : 556–568. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.006 20412771

73. Brown S, Hu N, Hombria JC (2003) Novel level of signalling control in the JAK/STAT pathway revealed by in situ visualisation of protein-protein interaction during Drosophila development. Development 130 : 3077–3084. 12783781

74. Agaisse H, Petersen UM, Boutros M, Mathey-Prevot B, Perrimon N (2003) Signaling role of hemocytes in Drosophila JAK/STAT-dependent response to septic injury. Developmental Cell 5 : 441–450. 12967563

75. Harrison DA, McCoon PE, Binari R, Gilman M, Perrimon N (1998) Drosophila unpaired encodes a secreted protein that activates the JAK signaling pathway. Genes and Development 12 : 3252–3263. 9784499

76. Tulina N, Matunis E (2001) Control of stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila spermatogenesis by JAK-STAT signaling. Science 294 : 2546–2549. 11752575

77. Lin TH, Yeh TH, Wang TW, Yu JY (2014) The Hippo Pathway Controls Border Cell Migration Through Distinct Mechanisms in Outer Border Cells and Polar Cells of the Drosophila Ovary. Genetics. doi: 10.1038/ng0115-97b 25552276

78. Hodin J, Riddiford LM (2000) Different mechanisms underlie phenotypic plasticity and interspeficic variation for a reproductive character in Drosophilds (Insecta: Diptera). Evolution 5 : 1638–1653. 11108591

79. David JR (1970) Le nombre d’ovarioles chez Drosophila melanogaster: relation avec la fécondité et valeur adaptive. Archives de Zoologie Expérimentale et Générale 111 : 357–370.

80. Orgogozo V, Broman KW, Stern DL (2006) High-resolution quantitative trait locus mapping reveals sign epistasis controlling ovariole number between two Drosophila species. Genetics 173 : 197–205. 16489225

81. Barnes AI, Boone JM, Jacobson J, Partridge L, Chapman T (2006) No extension of lifespan by ablation of germ line in Drosophila. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences 273 : 939–947. 16627279

82. Schlegelmilch K, Mohseni M, Kirak O, Pruszak J, Rodriguez JR, et al. (2011) Yap1 acts downstream of alpha-catenin to control epidermal proliferation. Cell 144 : 782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.031 21376238

83. Beverdam A, Claxton C, Zhang X, James G, Harvey KF, et al. (2013) Yap controls stem/progenitor cell proliferation in the mouse postnatal epidermis. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 133 : 1497–1505. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.430 23190885

84. Chan SW, Lim CJ, Huang C, Chong YF, Gunaratne HJ, et al. (2011) WW domain-mediated interaction with Wbp2 is important for the oncogenic property of TAZ. Oncogene 30 : 600–610. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.438 20972459

85. Liu X, Yang N, Figel SA, Wilson KE, Morrison CD, et al. (2013) PTPN14 interacts with and negatively regulates the oncogenic function of YAP. Oncogene 32 : 1266–1273. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.147 22525271

86. Demircan T, Berezikov E (2013) The Hippo pathway regulates stem cells during homeostasis and regeneration of the flatworm Macrostomum lignano. Stem Cells and Development 22 : 2174–2185. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0006 23495768

87. Lin AY, Pearson BJ (2014) Planarian yorkie/YAP functions to integrate adult stem cell proliferation, organ homeostasis and maintenance of axial patterning. Development 141 : 1197–1208. doi: 10.1242/dev.101915 24523458

88. Mummery-Widmer JL, Yamazaki M, Stoeger T, Novatchkova M, Bhalerao S, et al. (2009) Genome-wide analysis of Notch signalling in Drosophila by transgenic RNAi. Nature 458 : 987–992. doi: 10.1038/nature07936 19363474

89. Jukam D, Xie B, Rister J, Terrell D, Charlton-Perkins M, et al. (2013) Opposite feedbacks in the Hippo pathway for growth control and neural fate. Science 342 : 1238016. doi: 10.1126/science.1238016 23989952

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína