-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaCommon Transcriptional Mechanisms for Visual Photoreceptor Cell Differentiation among Pancrustaceans

Visual systems are populated by one of two fundamental types of photoreceptors, ciliary and rhabdomeric. Each photoreceptor type is defined by the opsin molecule expressed and the final morphological form adapted to house the phototransduction machinery. Here we address whether a common transcriptional mechanisms exists for the differentiation of rhabdomeric photoreceptors. We demonstrate that orthologs of two Drosophila (fruit fly) transcription factors, Pph13 and Orthodenticle, are expressed in photoreceptors of Pancrustaceans, Tribolium (red flour beetle) and Daphnia (water flea), and are capable of executing conserved functions of rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation. In particular, Tribolium and Daphnia orthologs are capable of substituting and rescuing the photoreceptor differentiation defects observed in their corresponding Drosophila mutants. Furthermore, loss of function analysis in Tribolium of both Pph13 and orthodenticle genes demonstrate they regulate opsin transcription and morphogenesis of the photoreceptor apical membrane. Our data illuminate a framework for rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation and provide the foundation for defining the ancestral regulatory modules for rhabdomeric differentiation and potential modifications that underlie the functional diversity observed in rhabdomeric photoreceptors.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004484

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004484Summary

Visual systems are populated by one of two fundamental types of photoreceptors, ciliary and rhabdomeric. Each photoreceptor type is defined by the opsin molecule expressed and the final morphological form adapted to house the phototransduction machinery. Here we address whether a common transcriptional mechanisms exists for the differentiation of rhabdomeric photoreceptors. We demonstrate that orthologs of two Drosophila (fruit fly) transcription factors, Pph13 and Orthodenticle, are expressed in photoreceptors of Pancrustaceans, Tribolium (red flour beetle) and Daphnia (water flea), and are capable of executing conserved functions of rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation. In particular, Tribolium and Daphnia orthologs are capable of substituting and rescuing the photoreceptor differentiation defects observed in their corresponding Drosophila mutants. Furthermore, loss of function analysis in Tribolium of both Pph13 and orthodenticle genes demonstrate they regulate opsin transcription and morphogenesis of the photoreceptor apical membrane. Our data illuminate a framework for rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation and provide the foundation for defining the ancestral regulatory modules for rhabdomeric differentiation and potential modifications that underlie the functional diversity observed in rhabdomeric photoreceptors.

Introduction

Rhabdomeric (r) photoreceptors are one of two fundamental types of photoreceptors that have been described [1]. Typically, r - photoreceptors populate the visual systems of protostomes including insects, crustaceans, and annelids (reviewed in [2]). This wide phylogenetic distribution and the presence of both types of photoreceptors in many species imply that r - photoreceptors, like their deuterostome counterparts, ciliary photoreceptors, were present before the split of bilaterian animals [3]–[6]. Despite this wide utilization of r - photoreceptors, knowledge about r - photoreceptor differentiation has been virtually exclusively defined from studies in the Drosophila (fruit fly) visual system (reviewed in [7], [8]). Generally, two features characterize r - photoreceptor differentiation. The first is the expression of an r - opsin for light detection, which upon the absorption of a photon leads to the activation of a Phospholipase C cascade and the depolarization of the photoreceptor. This phototransduction cascade permits the amplification of responses to single photons of light [9]. The second program concerns the generation of the rhabdomere, an expansion of the photoreceptor apical membrane to house the phototransduction machinery. This adaptation is necessary for increasing the accuracy of measuring light intensity required for vision [10]. Therefore, understanding the development and evolution of rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation requires clarification of how these processes are transcriptionally regulated and whether this regulation is conserved within all rhabdomeric photoreceptor types.

In Drosophila, two homeodomain proteins have been identified that are critical for regulating r - photoreceptor differentiation. The first, Orthodenticle (Otd), is the Drosophila ortholog of a conserved family of Otd/Otx homeodomain transcription factors, which are essential for head and brain development across species [11], [12]. In the r - photoreceptors of Drosophila eyes, otd is required for both aspects of differentiation [13]. Otd promotes the proper morphogenesis of rhabdomeres and directs multiple aspects of the differential expression of r - opsin paralogs, which characterizes the complex visual organization of the Drosophila retinas (for a review see [14]). In particular, Otd is required for the expression of rh3, an ultra-violet (UV) sensitive r - opsin, and rh5, a blue (B) sensitive r - opsin in the two inner photoreceptors of Drosophila ommatidia [15], [16]. In addition, Otd is critical for repressing rh6, the Drosophila ancestral long-wave (LW) opsin [17] in the six outer photoreceptors of the Drosophila ommatidium [16].

The second critical transcription factor is PvuII-PstI homology 13 (Pph13), a paired-class homeobox protein that is similar to the vertebrate Aristaless-related homeodomain (Arx) proteins [18], [19]. Like Otd, the loss of Pph13 results in defects in rhabdomere morphogenesis in the Drosophila eye [19]. Interestingly, the concurrent removal of Pph13 and Otd results in complete elimination of the rhabdomeres in Drosophila, suggesting that the two proteins cooperate and have overlapping functions with respect to photoreceptor morphology [20]. Pph13 is also essential for the expression of r - opsins rh6 and rh2 [20]. In contrast to otd mutants, phototransduction is abolished in Pph13 mutants due to the loss and reduced transcription of several key components of the phototransduction machinery [19], [20]. Lastly, Pph13 regulates photoreceptor differentiation by binding to a subset of Rhodopsin core sequence I (RCSI) elements [20], [21], which are conserved elements present in Drosophila Rhodopsin promoters [22]–[24]. Consistent with this, Drosophila Pph13 is necessary and sufficient for driving photoreceptor specific reporter gene expression from the artificial 3XP3 promoter [20], which has been assembled from a Pax6 homeodomain binding site [25]. Given the central role of both Pph13 and Otd in r - photoreceptor differentiation in Drosophila, the question we address here is whether Pph13 and Otd functions represent a common regulatory pathway of arthropod r-visual photoreceptor differentiation.

To examine whether Pph13 and Otd could represent a common set of transcription factors required for r - visual photoreceptor differentiation, we chose to investigate their orthologs from two key nodal species, Tribolium castaneum (red flour beetle), a second insect, and Daphnia (water flea), a crustacean. Together, insects and crustaceans define the superclade Pancrustacea within the Arthropoda [26], [27] and any similarities between Daphnia, Tribolium, and Drosophila r - photoreceptor differentiation would indicate a pathway common to the ancestor that generated both lineages, at least 500 million years ago [28], [29]. First, we demonstrate that Otd and Pph13 orthologs are present and expressed in the visual systems of both species. Consistent with conservation of Pph13 mediated r - opsin regulation, the Pph13 RCSI binding site is conserved in the promoters of the r-opsin genes of both Tribolium and Daphnia and found only within LW r - opsins. Further, the Tribolium and Daphnia Pph13 homologs have retained similar DNA binding capabilities to their respective endogenous RCSI sites and we confirmed their functional equivalency to direct photoreceptor differentiation in Drosophila photoreceptors by transgenic rescue. The Otd paralogs of Tribolium and Daphnia are comparable in their ability to direct rhabdomere morphogenesis but exhibit differential abilities with respect to r - opsin regulation in Drosophila. Lastly, functional analyses in Tribolium reveal that both Pph13 and Otd homologs are essential for both aspects of photoreceptor differentiation, rhabdomere creation and r-opsin expression. In particular, Pph13 is a critical factor for LW r-opsin expression and Otd2 is necessary for the transcription of UV sensitive r-opsin. In summary, our data identify common components for rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation among Pancrustaceans, providing a foundation for defining the ancestral transcriptional mechanisms for rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation throughout Bilateria.

Results

Evolutionary conservation of the Pph13 and orthodenticle transcription factor genes in insects and crustaceans

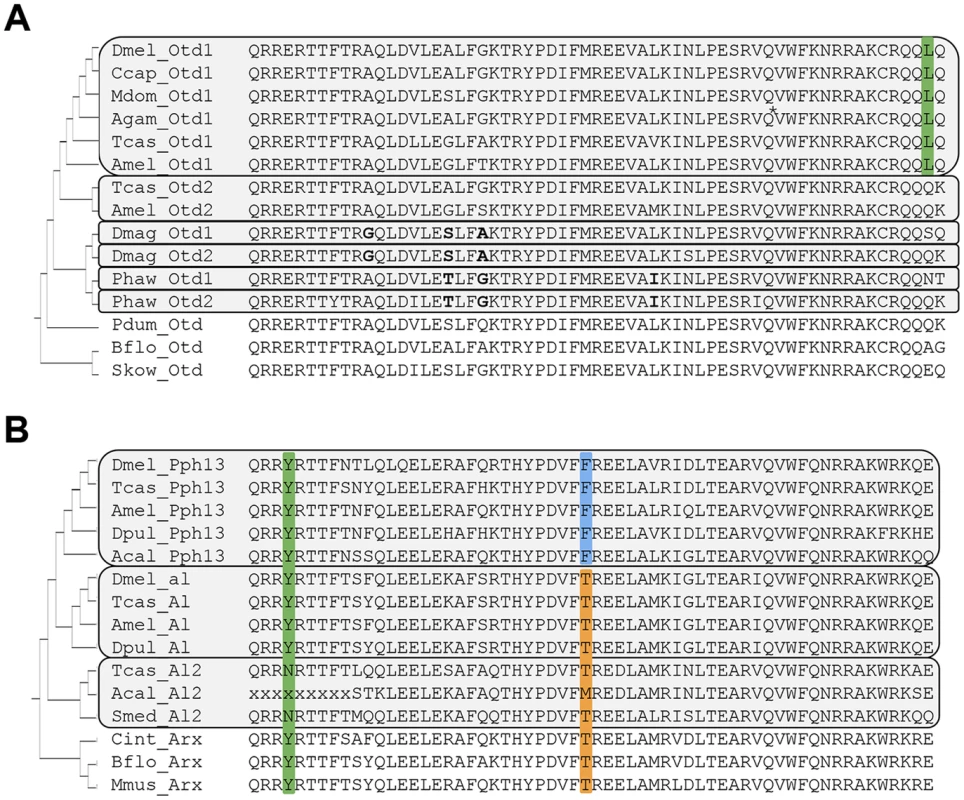

As a first step towards examining whether the role of Pph13 and Otd in Drosophila r - visual photoreceptor differentiation was conserved, we investigated the conservation of orthologs in the genome sequences of the distantly related arthropod species, Tribolium castaneum and Daphnia pulex [30], [31]. Tribolium had been previously shown to possess two paralogs of Otd: Otd1 and Otd2 [32]. The same state was described in the Crustacean Parhyale hawaiensis [33]. However, the relationships of the crustacean and coleopteran Otd homologs to the singleton homolog of Drosophila were previously considered unresolved due to the low level of sequence conservation outside the homeodomain; within Diptera there has been a reduction to only one otd paralog (Figure 1A, S1 and [33]). As in Parhyale, our search in Daphnia pulex as well as Daphnia magna identified two Otd homologs. Protein sequence alignment of an expanded set of Otd homologs (Figure 1A) revealed a highly conserved leucine (L) residue at the C-terminal end of the Otd1 homeodomain, which was unique for Paired-class homeodomain proteins in general [34], distinguished the insect representatives of the Otd1 subfamily, including all dipteran homologs. This finding established Drosophila Otd as a member of the insect Otd1 subfamily, implying the loss of insect Otd2 in the evolutionary lineage to Diptera. This conclusion was tentatively supported in a molecular phylogenetic analysis of the relationships between Otd homologs (Figure S1). The latter approach and amino acid residues in the homeodomain that were unique to each of the Parhyale and Daphnia Otd sequences further suggested that the latter duplicates represented the results of independent gene duplications in crustacean and insect lineages. Thus, the use of the previously introduced acronyms Otd1 and Otd2 for Parhyale and Daphnia paralogs do not imply specific orthology to insect Otd1 and Otd2.

Fig. 1. Protein sequence conservation in Otd and Pph13 homologs.

A. Otd homologs. Grey boxes outline paralog Otd subfamilies generated by independent gene duplications. The annotation of the Anopheles gambiae (Agam) Otd1 contains a putative insertion (VSVGE), which has been removed at the position indicated by asterisk. Green background: Leucine residue diagnostic for insect Otd1. Bold font highlights shared residues in each the Daphnia and Parhyale Otd duplicates, which support their independent origins in the two lineages. B. Pph13 homologs. Grey boxes outline invertebrate Arx paralog subfamilies generated by independent gene duplications. Green background: Tyrosine (Y) residue diagnostic for Arx gene family members. Blue background: Phenylalanine (F) residue diagnostic for Pph13 subfamily members. Orange background: Threonine (T) residue diagnostic for the Al subfamily and singleton Arx homologs. Species abbreviations: Acal = Aplysia californica, Agam = Anopheles gambiae, Amel = Apis mellifera, Bflo = Branchiostoma floridae, Ccap = Ceratitis capitata, Cint = Ciona intestinalis, Dmag = Daphnia magna, Dmel = Drosophila melanogaster, Dpul = Daphnia pulex, Mdom = Musca domestica, Mmus = Mus musculus, Pdum = Platynereis dumerilii, Phaw = Parhyale hawaiensis, Skow = Saccoglossus kowalevskii, Smed = Schmidtea mediterranea, Tcas = Tribolium castaneum. In contrast to the well-characterized deep conservation of the Otd/Otx gene family, homologs of Pph13 have thus far been identified only in a limited number of insects. Previous efforts identified Pph13 homologs in the Tribolium [17] and honey bee genomes [35] but not in the Daphnia pulex genome [36]. Closer inspection of candidate Daphnia pulex orthologs revealed one annotated locus encoding a 5′ truncated Pph13-related homeodomain, suggesting that the annotation for this locus (JGI_V11_8835 –wfleabase.org) was incorrect. Further examination of upstream genomic regions revealed that the DNA encoding the 5′ portion of the homeodomain was present. This conclusion was confirmed by RT-PCR (data not shown) and in the genome draft of a second related species: Daphnia magna. The complete Daphnia pulex Pph13 cDNA sequence thus included sequence from previously annotated loci JGI_V11_8835 and JGI_V11_313449. Sequence conservation between Daphnia, Tribolium, and Drosophila homologs was confined to the homeodomain (Figure 1B). However, examination of a larger sample of Pph13 homeodomain sequences in combination with that of members of the Aristaless (Al/Arx) gene family revealed amino acid residues that defined each subfamily and added further support of their hypothesized common descent (Figure 1B and Figure S2) [35]. A tyrosine (Y) residue at the fourth homeodomain position, otherwise not observed in the Drosophila Paired-class homeodomain proteins [34], characterized all members of the Arx gene family (Figure 1B). Furthermore, a phenylalanine (F) residue at homeodomain position 30 specifically marked the Pph13 orthologs, in contrast to the threonine (T) residue in the large majority of Al and Arx orthologs. While this variation was in line with the overall variability at homeodomain position 30, we noted the singularity of the Pph13 characteristic phenylalanine (F) among all Drosophila homeodomain proteins [34]. Based on these clues, we also identified putative orthologs of Pph13 and Al in the mollusk Aplysia californica. Taken together, these alignment data indicated that a gene duplication at least predating the origin of the Pancrustacea gave rise to Pph13. Finally, we noted the presence of a third Al-related Arx gene family member in the Tribolium genome (Tcas A12) that may be of similar ancient origin based on conservation in non-arthropod invertebrates (Figure 1B).

Pph13 and Orthodenticle are expressed in the developing photoreceptors of Daphnia and Tribolium

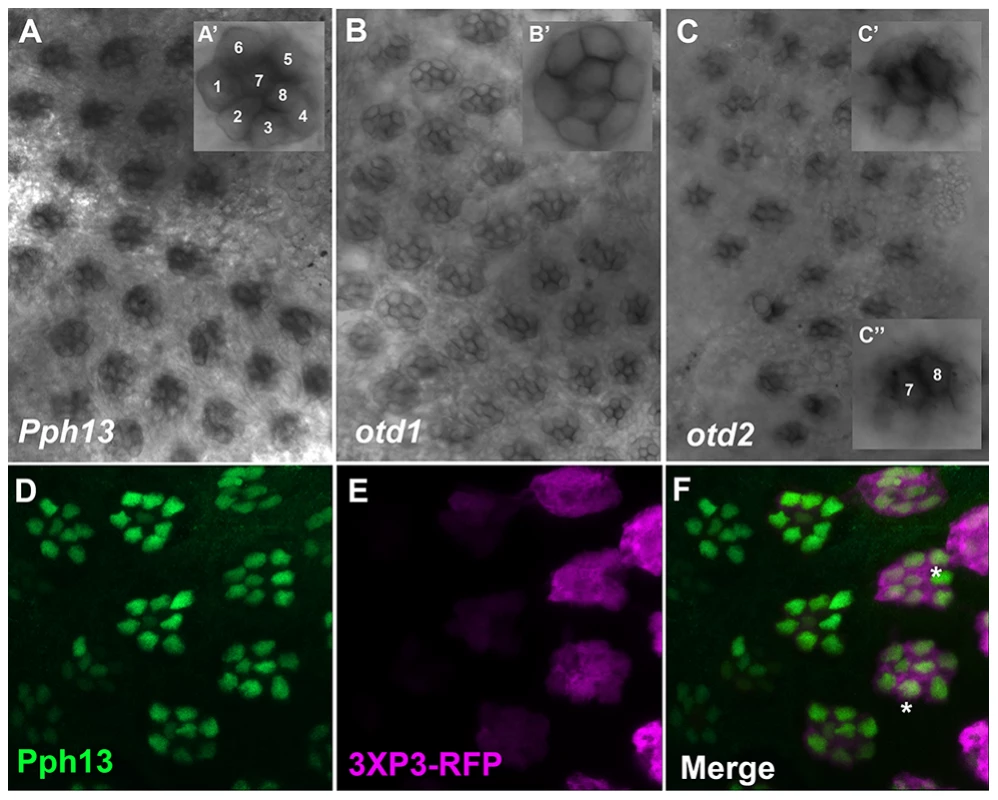

The presumed functional conservation of the Pph13 and Otd homologs predicted their expression in photoreceptors of Tribolium and Daphnia. We therefore assayed the spatial expression patterns of Pph13, otd1 and otd2 during adult eye development in both Tribolium and Daphnia. Like Drosophila, the Tribolium adult compound eye consists of individual ommatidia each of which contains six outer and two inner photoreceptors [37]. Approximately 30–40 hours after pupation we detected a signal from antisense probes to each transcript in all eight photoreceptors of a single ommatidium (Figure 2), whereas the corresponding sense probes did not generate any specific pattern (Figure S3). Pph13 and otd1 appeared to have similar expression patterns, with equal levels of transcript in each photoreceptor (Figure 2A and B). An antibody raised against Tribolium Pph13 confirmed its expression in the nucleus of each photoreceptor (Figure 2D–F). Together the Pph13 RNA in situ pattern and immunofluorescence staining suggested Pph13 is expressed in every photoreceptor of the eye as observed in Drosophila. We also detected otd2 in all eight photoreceptors but its expression in the two central photoreceptors, R7 and R8, was considerably stronger than in the outer photoreceptors (Figure 2C).

Fig. 2. Spatial expression patterns of Pph13, otd1 and otd2 in the developing adult Tribolium visual system.

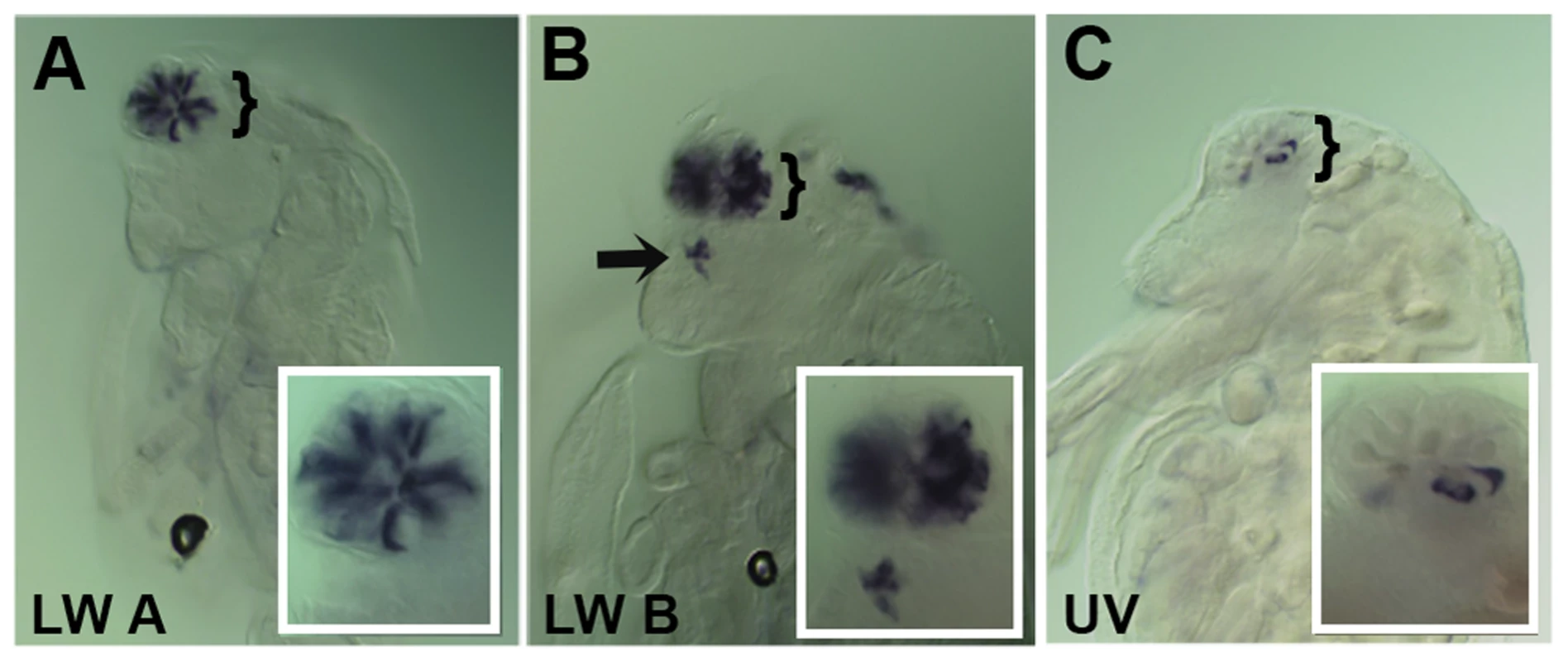

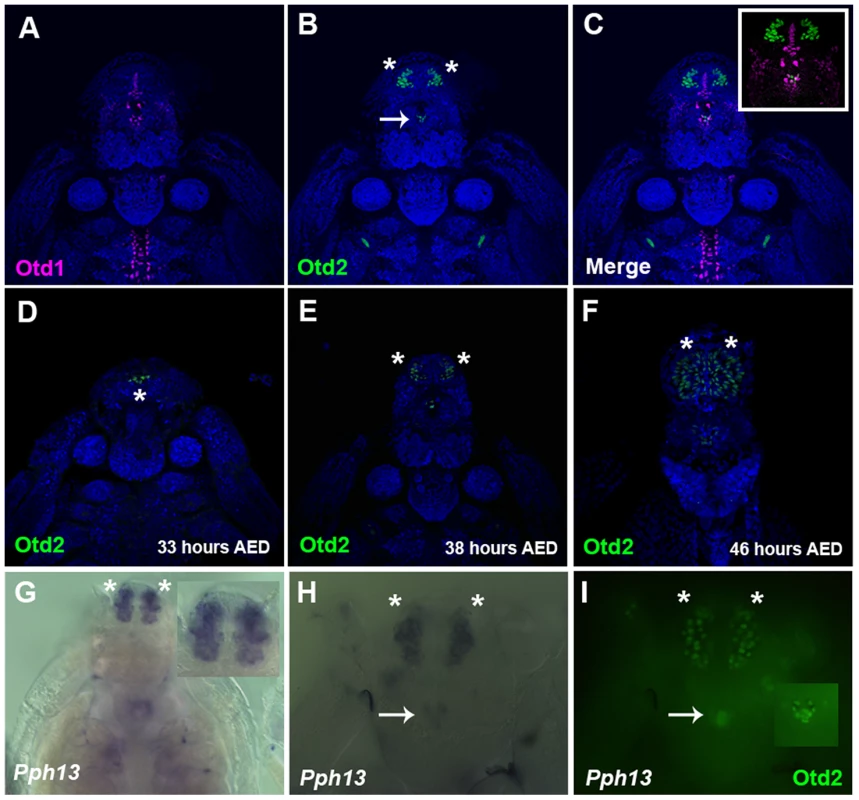

A–C. Dissected retinas 30–40 hrs APF. A. Pph13 is detected in the developing photoreceptor field and can be observed in all eight photoreceptors of a single ommatidium (A′). B. otd1 expression is limited to all eight photoreceptors of each developing ommatidium (B′). C. otd2 expression like Pph13 and otd1 is detected in developing photoreceptor field. Expression is greater in the two central photoreceptors R7 and R8 (C″) as compared to the outer six photoreceptors (C′). D–F. Dissected retina 24 hrs APF from Tribolium castaneum adult visual system stained for Pph13 protein (green) and 3XP3-RFP (magenta). An antibody recognizing Pph13 (green) demonstrates that Pph13 is located in each photoreceptor nucleus. 3XP3-RFP is a cytoplasmic marker for the developing photoreceptors and labels the cell bodies and axon projections of the eight photoreceptors in each ommatidium [25]. Note the expression of Pph13 appears prior to 3XP3-RFP expression (asterisks). In all panels anterior is to the left. Numbers label the eight photoreceptors of a single ommatidium. In Daphnia, the adult eye consists of a single bilaterally symmetrical compound eye, containing a total of twenty-two ommatidia with eight photoreceptors in each ommatidium [38]. Each Daphnia eye is generated by the fusion of two lateral groups of ommatidia along the midline late in embryogenesis. Due to the lack of molecular markers, the exact biogenesis of the photoreceptors has not been described. However, previous transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies of the development of the axonal photoreceptor connections with lamina neurons predict a model in which the photoreceptors begin to differentiate at the midline and move laterally as they mature [39]–[41]. To confirm and differentiate the developing photoreceptors we first examined the expression of a limited set of r-opsins in Daphnia magna. In Daphnia pulex, there are 27 annotated r-opsin paralogs [30]. Like Drosophila, Daphnia pulex contain representatives of UV, LW and B - light sensitive r-opsins. This diversity includes 23 LW opsins that split between the LOPA and LOPB clades [30] (Figure S4). The r-opsin family has not been defined for Daphnia magna but for our examination we assayed the expression of a pool of three putative representatives from LOPA (Figure 3A) and LOPB (Figure 3B) and the putative UV opsin (Figure 3C). Besides observing a differential display of expression between all three groups, the RNA in situ hybridization patterns confirmed and delineated the embryonic tissue that gives rise to the photoreceptors of the eye and ocellus (Figure 3 and Figure S5A–F). Our expression analysis of Otd1, Otd2, and Pph13 in Daphnia magna also yielded results that were consistent with this model of eye formation (Figure 4 and Figure S5G–J). The expression of Otd1 was limited to the midline region of the embryo and not necessarily associated with visual photoreceptors (Figure 4A,C). In contrast to Otd1, Otd2 was expressed in an increasing number of cells in two lateral symmetrical regions of the head during embryogenesis (Figure 4B–F). By 48 hours after egg deposition (AED), each lateral cluster contained approximately 75–78 Otd2 positive cells (Movie S1). Considering that the adult eye consists of two lateral clusters of eleven ommatidia, this suggested that there were seven Otd2 positive photoreceptors per ommatidium. Furthermore, the additional Otd2 staining present in the central portion of the embryo corresponded to the region where the ocellus develops (Figure 4A–F and Figure 3B). Similar and consistent expression patterns were detected for Daphnia magna homolog of Pph13, which was expressed in two symmetrical lateral clusters of cells, in the cells of the presumptive ocellus (Figure 4G–I) potentially colocalizing with Otd2 protein expression (Figure 4H,I).

Fig. 3. Spatial expression patterns of Daphnia magna r- opsins during Daphnia eye development.

A–C. Daphnia embryos 50 hours after egg deposition. A. RNA in situ hybridization of a pool containing three antisense probes against potential Daphnia magna long wave (LW) clade A r- opsins. B. RNA in situ hybridization of a pool containing three antisense probes against potential Daphnia magna long wave (LW) clade B r- opsins. C. RNA in situ hybridization of an antisense probe against the single potential Daphnia magna ultra violet (UV) r- opsin. In all three cases, the probes label photoreceptors in the visual system, and the LW clade B probes also mark and label the photoreceptors of the ocellus (arrow). Insets represent a higher magnified view. Fig. 4. Spatial expression patterns of Daphnia magna Otd1, Otd2 and Pph13 during Daphnia eye development.

A–C. Daphnia embryos 40 hours after egg deposition (AED) stained for Otd1 (magenta) and Otd2 (green) protein. The nuclei were countered stained with DAPI (blue). Otd1 expression is limited to the midline and Otd2 can be detected in the ocellus (arrow) and in the visual system (asterisks). Inset in C is a higher magnification of the head region. D–F. Temporal expression profile of Otd2 expression (green). Otd2 is expressed in an increasing number of positive cells in two lateral symmetrical regions of the head during embryogenesis. G. Pph13 RNA in situ pattern. Inset is a higher magnification of the expression of Pph13 in the presumptive visual system. H. Pph13 RNA in situ pattern of the same embryo as in I. I. Double label of Pph13 and Otd2 protein. Note the localization of both Pph13 and Otd2 in the developing eye and ocellus (inset). Asterisks mark the two lateral halves of the developing visual system and arrows mark the ocellus. RCSI-like sites are present in the promoters of r-opsin genes of Tribolium and Daphnia

To further explore the possibility of conserved regulatory roles of Pph13 and Otd in visual photoreceptor differentiation, we probed for the conservation of the RCSI site in candidate target genes of Pph13 in Tribolium and Daphnia. Previous work has shown that Pph13 binds a subset of RCSI sites and that this binding site is essential for transcriptional activation [19], [20]. The same studies defined a Pph13 RCSI site as a palindromic sequence of TAAT spaced by three nucleotides with one half site matching the consensus sequence of 5′-CTAATTG-3′ [20]. In Drosophila, these Pph13-specific RCSI sites are present in the 5′ cis-regulatory DNA of r - opsin genes and in several other key phototransduction proteins, including the heterotrimeric G-protein β subunit (Gβ76C) [19], [20]. Tribolium contains two r - opsins, one of which belongs to the LW opsin subfamily and one of which belongs into the UV sensitive subfamily [42]. Scanning their upstream regions for the RCSI motif, we found a potential RCSI site in both of them. Furthermore, in the upstream region of the Tribolium homolog of Drosophila visual Gβ (Gβ76C), LOC662674 (beetlebase.org), we also detected a RCSI site (Table S1 and Figure S6). Examining the immediate upstream regions of Daphnia LW, UV, and B opsins revealed putative RCSI motifs only in the LOPB clade of LW opsins (Figure S4 and Table S1). In addition, the closest homolog to both Drosophila and Tribolium visual Gβ subunit in Daphnia (JGI_V11_210534 -wfleabase.org) contained a potential RCSI site (Figure S6 and Table S1).

Conserved binding specificity of Pph13 homologs to Tribolium and Daphnia RCSI sites

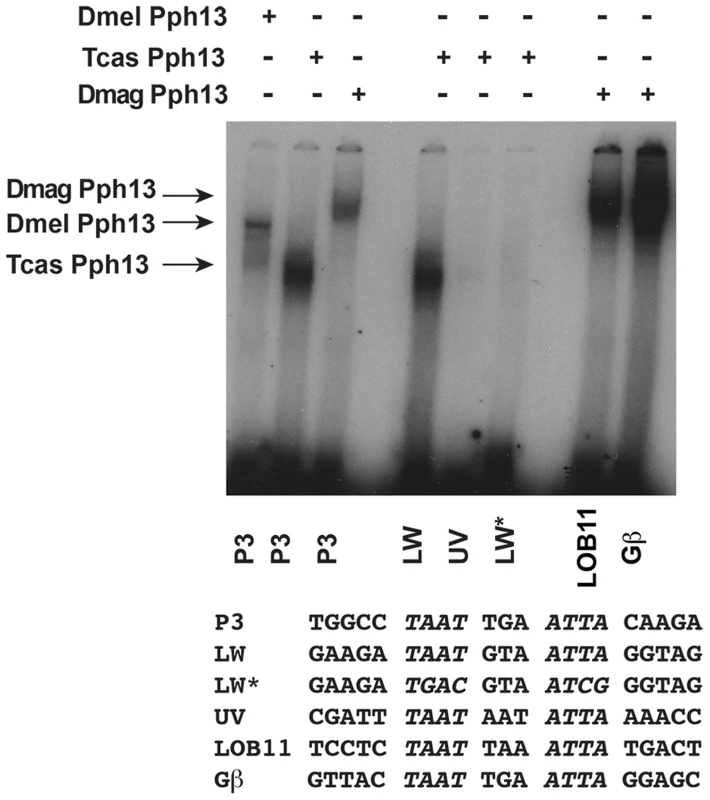

The presence of potential RCSI sites in photoreceptor-expressed genes of all three species suggested that these sites could serve as Pph13 binding sites. To test this possibility, we investigated whether the Pph13 homologs could bind the putative endogenous RCSI sequences with electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). These experiments revealed that Tribolium and Daphnia Pph13 have similar binding abilities to a consensus RCSI site (P3) [24], [43] as well as specific Drosophila RCSI sites (Figure 5 and data not shown). Furthermore, each has the capability to bind to their endogenous RCSI sites (Figure 5 and Figure S7). Interestingly, in Tribolium like Drosophila [20], we observed a differential affinity of Pph13 to the identified RCSI sites of UV and LW r-opsins. Tribolium Pph13 bound efficiently to the LW opsin RCSI site but binding was barely detectable on the UV opsin RCSI element, suggesting that the simple presence of a correctly spaced palindromic sequence of TAAT was not sufficient to bind Pph13.

Fig. 5. DNA binding properties of Pph13 are conserved among Pancrusteceans.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of Drosophila (Dmel) and Tribolium (Tcas) and Daphnia magna (Dmag) Pph13 protein on a Pax6 homeodomain binding site (P3) and on endogenous Tribolium and Daphnia RCSI sites. Each homolog has the ability to bind the P3 consensus binding site as well as endogenous sites within its genome. Tribolium Pph13 demonstrates a differential binding to the RCSI sites identified in the cis-regulatory regions of the LW and UV r- opsins and binding is disrupted upon the mutation of the LW RCSI site (LW*). Arrows indicate the specific mobility shift for each protein examined. Equivalent in vivo function of Pph13 homologs

The in vivo expression patterns and in vitro binding assays provided strong evidence that Pph13 and Otd regulate r - visual photoreceptor cell differentiation in Drosophila, Tribolium and Daphnia. To test for functional equivalency among the orthologs and, more importantly, the ability to direct photoreceptor differentiation, we examined whether Daphnia and Tribolium orthologs were capable of rescuing the photoreceptor defects observed in Drosophila Pph13 and otd mutants.

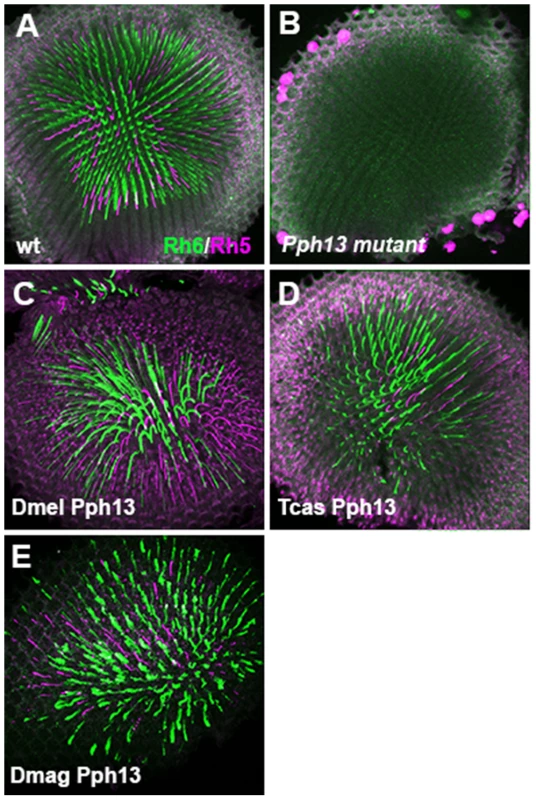

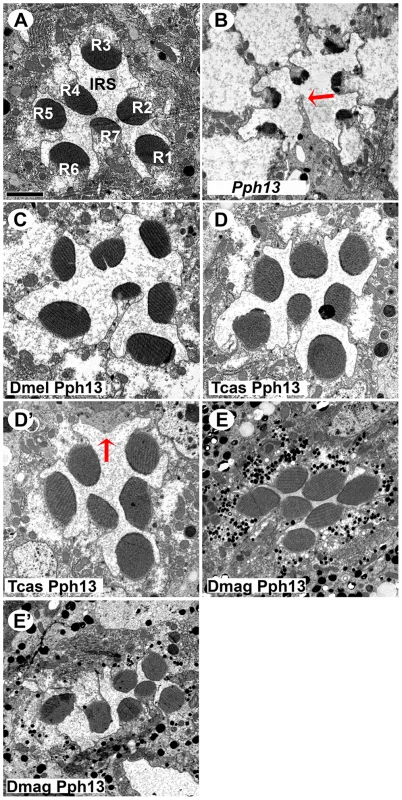

Drosophila Pph13 mutants have two distinct characteristics. First, Pph13 is necessary for expression of opsin rh6 (Figure 6A,B) in 70% of the R8 photoreceptor cells [44]. Second, Pph13 mutants have severe defects in rhabdomere morphology (Figure 7A,B). The morphological defects are acute enough to hamper the detection and accumulation of other r-opsins [20], [21] (Figure 6B). For rescue experiments, each homolog was placed under the control of GAL4 transcription [45] and inserted into the identical locus in the Drosophila genome. To drive expression, we generated a GAL4 driver under the control of the endogenous Drosophila Pph13 cis-regulatory region – Pph13-Gal4. In testing the Pph13 homologs of Daphnia and Tribolium, we evaluated both the restoration of Rh6 opsin expression and rhabdomere morphogenesis as compared to rescue with Drosophila Pph13. We found that all Pph13 homologs were capable of restoring Rh6 expression. In addition, we also detected a mosaic expression pattern of Rh6 in the R8 photoreceptors (Figure 6C–E). Of note, this result also demonstrated the specific rescue of rhabdomere morphology in the R8 photoreceptors that express Rh5 opsin in a Pph13 independent manner. To assay rhabdomere morphology directly, TEM analysis of each rescue condition was performed. We observed wild-type rescue of rhabdomere morphology with all three Pph13 homologs (Figure 7). However, the rescue was not fully penetrant with Tribolium and Daphnia Pph13. In particular, we observed photoreceptors missing rhabdomeres with Tribolium Pph13 (Figure 7D′) and with Daphnia Pph13, the rhabdomeres did not maintain their position and morphology along the proximodistal axis of the photoreceptor (compare Figure 7E and E′).

Fig. 6. In vivo rescue of opsin expression in Pph13 null mutant Drosophila.

A–E. Rh6 (green) and Rh5 (magenta) opsin protein expression in adult Drosophila retinas. A. Wild-type retina. Opsin protein accumulates in the rhabdomeres and thus appears as a tube like structure. Rh6 and Rh5 are expressed a non-overlapping subsets of central R8 photoreceptors. B. Pph13 mutant. Neither Rh6 nor Rh5 opsin can be detected, reflecting the facts that Rh6 is a direct transcriptional target of Pph13 and that the deformed development of rhabdomeres in Pph13 mutants prevents the accumulation of detectable levels of Rh5 opsin. C–E. Rescue of the Drosophila Pph13 mutant with: C. Drosophila (Dmel) Pph13. D. Tribolium (Tcas) Pph13. E. Daphnia magna (Dmag) Pph13. In all rescue experiments we observe the restoration of Rh6 and Rh5 protein expression in the rhabdomeres. Furthermore, the non-overlapping expression of Rh6 and Rh5 in R8 photoreceptors is likewise rescued. Each panel represents a projection of a confocal stack of laser scanning confocal microscope images. Fig. 7. In vivo rescue of rhabdomere morphology in Pph13 null mutant Drosophila.

A–E. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of adult Drosophila eyes. A. Wild-type ommatidium. Seven of the eight photoreceptors and associated rhabdomeres (R1–R7) can be observed per section and each rhabdomere is separated by an inter-rhabdomeral space (IRS). B. Pph13 mutant. The absence of Pph13 activity results in the reduction, malformation or loss of rhabdomeres (arrow). C–E. Rescue of the Drosophila Pph13 mutant with: C. Drosophila (Dmel) Pph13. Rhabdomere morphology is restored. D. Tribolium (Tcas) Pph13. Rhabdomere morphology is restored but occasionally a missing rhabdomere is observed (D′). The arrow denotes a missing rhabdomere of a photoreceptor but the photoreceptor is present. E. Daphnia magna (Dmag) Pph13. Whereas apical sections (E) demonstrate complete restoration of rhabdomere morphology, basal sections (E′) demonstrate that many rhabdomeres do not extend completely or maintain their shape throughout the length of the photoreceptor. Scale bar 2 um. Orthodenticle orthologs demonstrate differential abilities with respect to photoreceptor differentiation

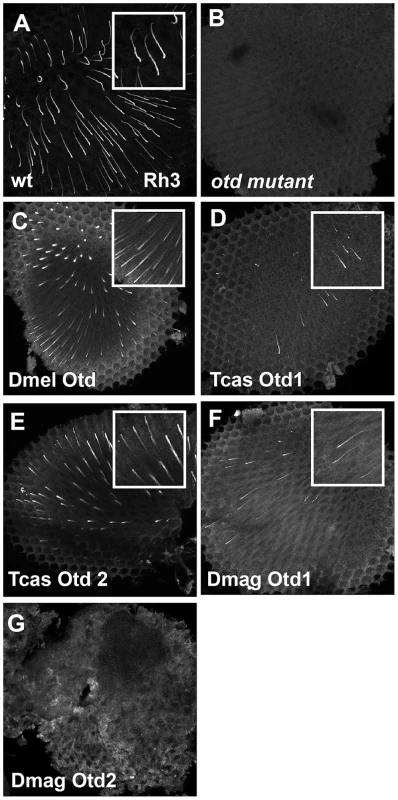

For examination of functional equivalency among Otd orthologs, we used a previously established rescue paradigm [46], [47]. Otd is required for rh3 opsin expression in the distally located inner photoreceptor, the activation of rh5 in the proximal inner photoreceptor, repression of rh6 opsin in the outer photoreceptors, and correct rhabdomere morphology in every photoreceptor [13], [15], [16]. In our rescue experiments, we assayed for all these functions.

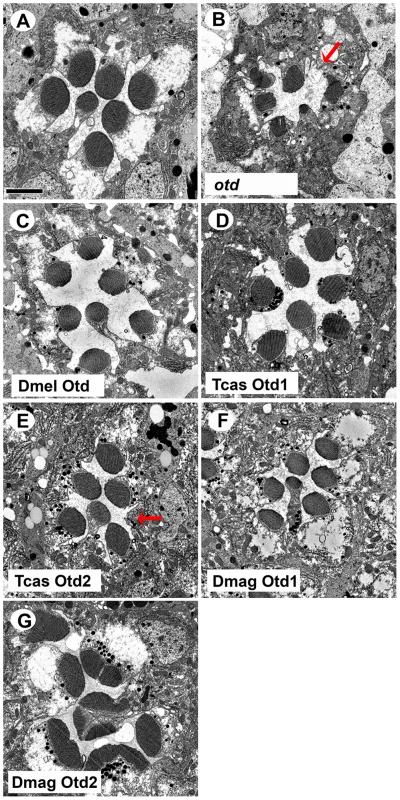

With respect to rhabdomere morphology (Figure 8), TEM analysis demonstrated that both Tribolium Otd paralogs (Figure 8D,E) and Daphnia Otd1 (Figure 8F) could direct rhabdomere morphogenesis in Drosophila. In these three rescue experiments, we observed the return of symmetrical wild-type pattern of rhabdomere shape and size. However, the rescue was not fully penetrant with Tribolium Otd2 and Daphnia Otd1. For example, some ommatidia have photoreceptors that lack a detectable rhabdomere. The expression of Daphnia Otd2 resulted in an adult eye that contained a mosaic of intact and dead tissue, regardless of the presence of endogenous Otd (Figure S8); this phenotype was not observed with any of the other Otd orthologs. TEM analysis confirmed the lack of photoreceptors in the discolored regions (data not shown). In the normal pigmented regions we observed the presence of rhabdomeres that were not characteristic of the otd mutant or normal rhabdomeres in Drosophila suggesting these defects resulted from the misexpression of the non-endogenous Otd (Figure 8G), which prevented further analysis.

Fig. 8. In vivo rescue of rhabdomere phenotype of Drosophila orthodenticle mutant background.

A–G. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of adult Drosophila eyes. A. Wild-type ommatidium. B. otd mutant. The absence of Otd activity results in smaller malformed or even absent rhabdomeres (arrow). C–G. Rescue of otd mutant with: C. Drosophila (Dmel) otd. D. Tribolium (Tcas) otd1. E. Tribolium (Tcas) otd2. The arrow denotes a missing rhabdomere of a photoreceptor. F. Daphnia magna (Dmag) otd1. G. Daphnia magna otd2. In all cases, except Dmag otd2, rhabdomere morphology is restored. The rhabdomere phenotype observed with Dmag otd2 differs from both wild type and the otd mutant phenotype. Scale bar 2 um. As for rescue of r - opsin regulation (Figure 9 and Figures S9 and S10), our results exposed differential effects among the Otd orthologs. For example, Tribolium Otd1 could activate rh3 expression (Figure 9D) but failed to repress rh6 expression (Figure S9D). Tribolium Otd2 in contrast was capable of both (Figure 9E and S9E). On the other hand, Daphnia Otd1 could activate rh3 expression and repress rh6 expression (Figure 9F and S9F), even though Daphnia Otd1 does not appear to be expressed in photoreceptors. Despite the associated cell death and irregular rhabdomere morphology with expression of Daphnia magna Otd2, we observed that the expression of Rh6 appeared to be limited to a single photoreceptor of each ommatidium suggesting Daphnia magna Otd2 can execute the rh6 repression function (Figure S9G). However, we did not detect any expression of Rh3, suggesting that Daphnia magna Otd2 failed to execute the rh3 activation function (Figure 9G). In Drosophila, the expression of opsin rh5 in a subset of R8 photoreceptors is dependent on direct activation by Otd. Moreover, Otd also regulates the feedback loop responsible for generating the correct ratio of Rh5 and Rh6 expressing R8 photoreceptors [16], [48]. In agreement with previous results utilizing this rescue paradigm Drosophila Otd is relatively insufficient in activating rh5 expression [47] and only detected Rh5 expression upon the rescue with Tribolium Otd2 (Figure S10).

Fig. 9. In vivo rescue of Rh3 opsin expression in Drosophila orthodenticle mutant background.

A–E. Rh3 opsin protein expression in adult Drosophila retinas. A. Wild-type retina. Rh3 opsin protein accumulates in the rhabdomeres of approximately 30% of the R7 photoreceptor cells. B. otd mutant. Consistent with the requirement of Otd for the transcriptional activation of rh3, no protein is detected. C–G. Rescue of otd mutant with: C. Drosophila (Dmel) otd. D. Tribolium (Tcas) otd1. E. Tribolium (Tcas) otd2. F. Daphnia magna (Dmag) otd1. G. Daphnia magna otd2. All Otd orthologs are capable of restoring Rh3 expression in an otd mutant except Dmag otd2. Insets represent a magnified view of a region from each panel. Each panel represents a projection of a confocal stack. In vivo requirements of Pph13 and Orthodenticle in Tribolium rhabdomere formation

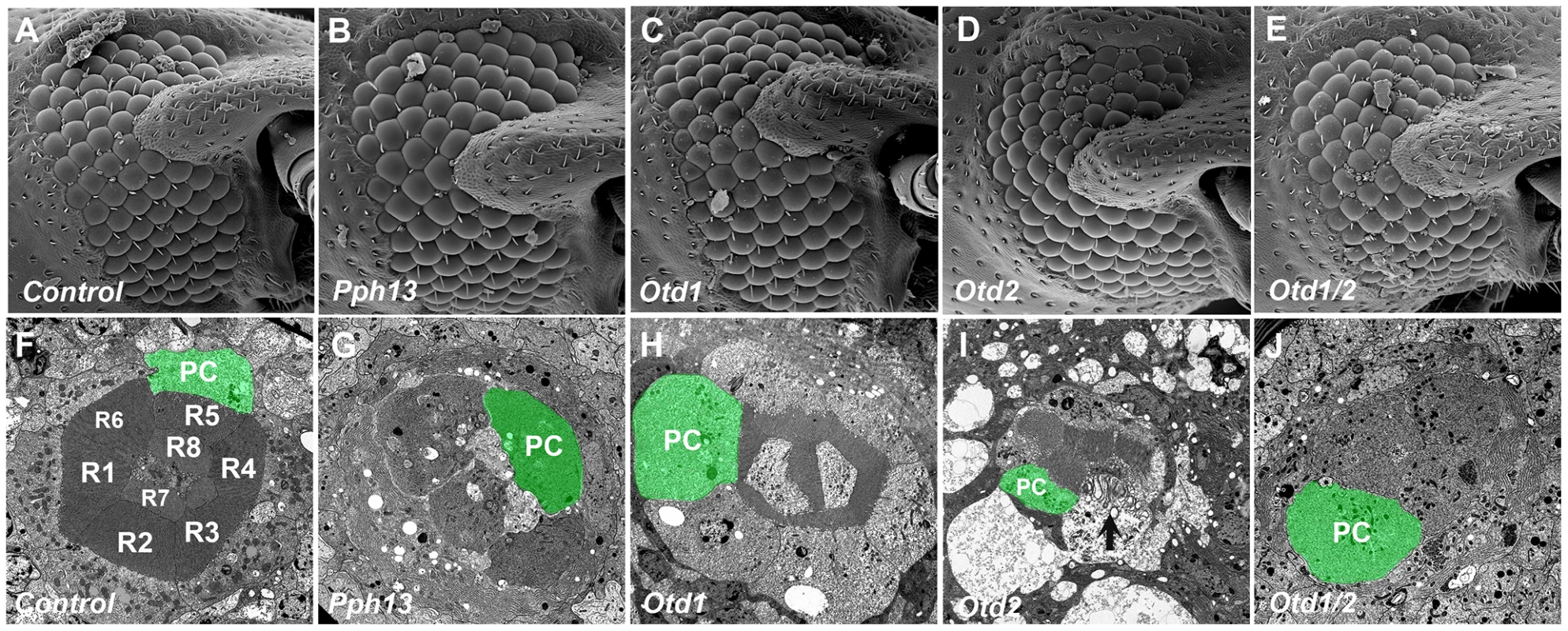

Taken together, our expression and rescue assays supported a common role of Pph13 and Otd in r - visual photoreceptor differentiation among Pancrustaceans. For further functional verification, we took advantage of the effective RNAi protocol in Tribolium [49]. Thus to examine the in vivo role of the Tribolium Pph13, otd1, and otd2 genes, we generated double stranded RNA (DsRNA) against each corresponding mRNA for injection into Tribolium larvae. None of the DsRNAs affected developmental timing, viability, or external morphological structures as compared to mock injections; scanning electron microscopy of the adult eye did not reveal any major effects on the external organization of the compound eyes (Figure 10A–E). To investigate the possible role of Pph13 and Otd in rhabdomere morphogenesis, RNAi knockdown adults were prepared for TEM analysis within twelve hours after eclosion to minimize any potential later disruptions of photoreceptor morphology as a result of long-term degeneration. In these specimens, we found that the knockdown of Tribolium Pph13 resulted in the complete absence of rhabdomeres (Figure 10G). The knockdown of either Tribolium otd1 or otd2 caused a completely distinct set of defects. In otd1 knockdowns, the rhabdomeres were present but reduced compared to wild-type controls (Figure 10H). The ordered array of microvillar projections was normal in each of the rhabdomeres but the microvilli were smaller but no evidence of photoreceptor degeneration could be detected. In otd2 knockdown animals, the rhabdomeres were in a state of disarray suggesting degeneration (Figure 10I and Figure S11). We detected whole rhabdomeres that however appeared to be unraveling; as suggested by the presence of large membrane protrusions into the photoreceptor cell body and enlarged distances between microvillar projections. In addition some photoreceptors completely lacked rhabdomeres. Lastly, the combinatorial removal of both otd paralogs resulted in the absence of all rhabdomere structures (Figure 10J).

Fig. 10. Knockdown of Tribolium Pph13, otd1 and otd2 affects rhabdomere biogenesis.

Scanning and transmission electron microscopy analyses of Tribolium adult eyes. A,F. Mock injection. B,G. Pph13 RNAi. C,H. otd1 RNAi. D,I. otd2 RNAi. E,J. otd1 and otd2 RNAi. The green shading marks the cell body of one of the eight photoreceptors (PC) found in each ommatidium. Each photoreceptor produces a rhabdomere (R1–R8) that remains juxtaposed to the others. The knockdown of Pph13 and orthodenticle paralogs did not affect the overall structure of the adult eye (A–E). However, the knockdown of Pph13 (G) and the combinatorial removal of both otd paralogs result in a complete absence of rhabdomeres (J). Photoreceptors are detected but the microvillar rhabdomere structures are absent. The knockdown of otd1 generates smaller rhabdomeres (H) and the removal of otd2 (I) alone results in rhabdomeres in an active state of degeneration (arrow). Differential requirements of Pph13 and Orthodenticle for r - opsin expression in Tribolium

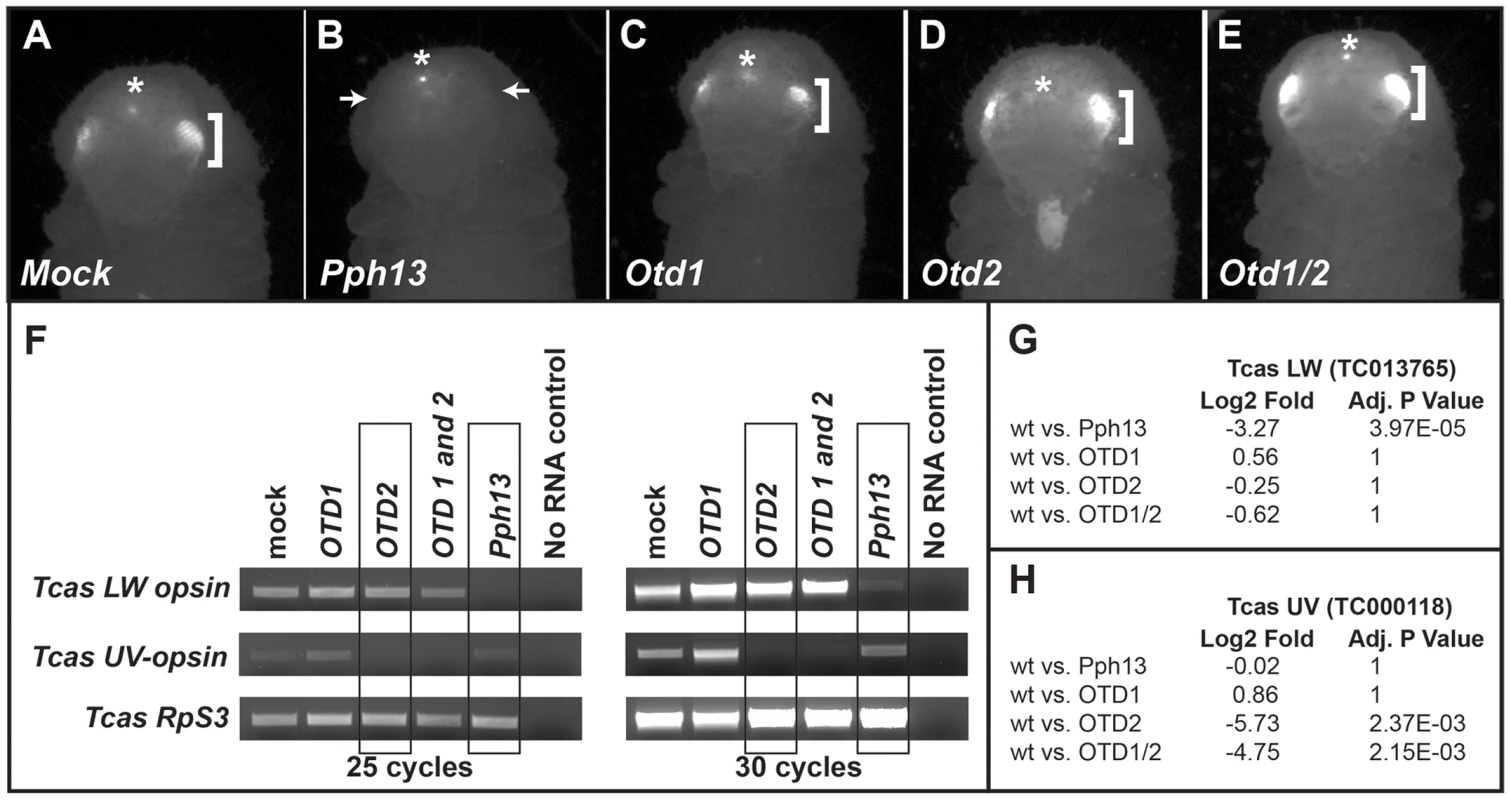

As a first approximation of whether Pph13 and Otd homologs may be required for the second step defining r - visual photoreceptor differentiation, i.e. the transcription of the phototransduction machinery, we asked if 3XP3-RFP, an in vivo transcriptional reporter for Pph13 activity in Drosophila [20], was disturbed upon reduction of Pph13, otd1 or otd2 (Figure 11). DsRNAs against each transcript were injected into Tribolium m26 larvae, which express RFP from a 3XP3-RFP reporter transgene. In these experiments, only the Pph13 knockdown resulted in the elimination of the photoreceptor specific expression of RFP (Figure 11B and Table S2). Single as well as combinatorial injection of the Tribolium otd1 and otd2 dsRNAs did not affect the expression of 3XP3 reporter (Figure 11C–E).

Fig. 11. Tribolium Pph13 and Otd2 are required for r-opsin expression.

A–E. 3XP3-RFP expression in RNAi knockdown animals. Photoreceptor specific RFP fluorescence can be detected through the pupal case in the developing adult eyes (brackets). Only the knockdown of Pph13 results in the loss of the transcriptional reporter 3XP3-RFP fluorescence (arrows). The asterisks mark the non-visual enhancer trap expression of RFP that is present in each RNAi knockdown animal. F. RT-PCR analysis of r-opsin transcription in Tribolium (Tcas) Pph13, otd1, otd2, and otd1/2 RNAi knockdown animals. The transcriptional levels of LW r-opsin are only reduced/absent with the reduction of Pph13 and transcription levels of UV r- opsin are only affected by the reduction of otd2. The transcription of Tribolium ribosomal protein subunit three (RpS3) was used as a control for comparisons. G–H. RNA-seq quantification of r- opsin expression levels, LW (G) and UV (H) in the knockdown animals. The RNA-seq data confirms the requirement of Pph13 and Otd2 for transcription of r- opsin LW (TC013765) and UV (TC000118), respectively. Wild type (wt) are represented by the control mock injections. P-Values have been adjusted for multiple testing. To further explore whether Tribolium Pph13 and Otd were required for r - opsin expression in Tribolium, we assayed the transcription of the Tribolium LW and UV opsins by RT-PCR (Figure 11F) and by RNA-seq (Figure 11G,H and Table S5 and S6) in the RNAi knockdown conditions. Based on our DNA binding assays and the requirement of Pph13 for 3XP3 expression, we predicted that the knockdown of Pph13 should affect only LW r - opsin transcription. Indeed, the knockdown of Tribolium Pph13 was associated with the reduction of LW transcription but not UV opsin transcription (Figure 11F,G). There was a 3.27 Log2 fold decrease in LW opsin expression in Pph13 knockdown animals as compared to mock injections. The knockdown of Otd2, however, resulted in the virtual absence of UV opsin transcription (Figure 11F,H), as indicated by 5.73 Log2 fold decrease compared to control animals. Finally, DsRNA directed against both Tribolium otd paralogs had no discernible effect on LW opsin transcription (Figure 11F,G). Although Tribolium otd1 is expressed in all photoreceptors, we did not detect any significant effect on UV expression alone or enhancement in combination with knockdown of otd2 (Figure 11F,H).

Discussion

The photoreceptor-specific function of Pph13 extends to the ancestor of Pancrustaceans

Our results demonstrate a key role of both Pph13 and Otd for visual r - photoreceptor differentiation among Pancrustaceans. While the conservation of Otx transcription factors in metazoan eye development has been documented by numerous studies [47], [50]–[53], our data provide the first evidence of a deeper evolutionary conservation of Pph13. In combination with the initial failure to detect orthologs in other species beyond Drosophila, the specificity of Pph13 expression and function to a single developmental context, terminal photoreceptor differentiation and maintenance [19], [20], raised the possibility that Pph13 represented a more recently evolved regulator in insect retinal development; our findings here refute this scenario. Moreover, our comparative sequence analyses consolidate that Pph13 arose by duplication of an ancestral singleton member of the Arx gene family of homeodomain transcription factors, as previously hypothesized [18], [19]. Further identification of orthologs will be required to date the exact time point of this gene duplication. In our preliminary analyses we have also identified putative Pph13 and Al orthologs in the mollusk Aplysia califonica. However, searches in genome and transcriptome data from other invertebrates as well as non-Pancrustacean arthropods recovered only orthologs of Al/Arx at this point.

Here, in this study, we have deployed a combination of assays to assess the functional conservation of Pph13 over hundreds of millions of years of Pancrustacean evolution. Our expression analyses revealed that Pph13 is specifically expressed in the visual systems of Daphnia and Tribolium. Furthermore, this study and previous work now identifies the binding of Pph13 to the RCSI site as the driver of default activation of LW-opsins in both Drosophila and Tribolium. Our findings demonstrate the conserved ability of Pph13 homologs to discriminate between RCSI sites, preferably binding the RCSI sites in LW r-opsins [20]. Moreover, the functional analysis in both Drosophila as well as Tribolium reveals that Pph13 is required for transcription of only the LW r - opsins. We therefore believe that activation through Pph13 at the RCSI site was a module in the cis-regulatory control of the ancestral singleton LW-opsin. Consistent with the conservation of this evolutionarily conserved target sequence, all three homologs are capable of rescuing both aspects of r - photoreceptor differentiation in Drosophila Pph13 mutants: rhabdomere biogenesis, and opsin regulation. The observed decrease in Pph13 rescue efficiency with evolutionary distance may be the result of a failure to interact with the required cofactors in Drosophila or to activate transcription through the Drosophila RCSI sites. Given the conserved binding activity of all Pph13 homologs, it is most likely that the lack of sequence conservation outside the homeodomain compromises interactions with cofactors in the across-species rescue experiments.

Diversified subfunctionalization of Otd paralogs in rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation

Our data also demonstrate conserved critical roles of Otd in both aspects of rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation. However, the presence of two paralogs in Tribolium and Daphnia, and their differential expression patterns and functional abilities complicate defining the ancestral role of Otd in visual r - photoreceptor differentiation. In all three species at least one Otd ortholog is expressed in developing photoreceptors. Further, the downregulation of Otd orthologs leads to a disruption of rhabdomere formation in both Drosophila and Tribolium. Moreover, with the exception of Daphnia magna Otd2, each Otd homolog that we tested has maintained the ability to direct rhabdomere morphogenesis in Drosophila. The expression of Daphnia magna Otd2 in Drosophila resulted in cell death and as such precluded assessment of its ability to rescue the Drosophila otd mutant. Taken together, these data suggest that the requirement of Otd in rhabdomere morphogenesis is ancestral. In agreement with this, previous studies demonstrated that all three vertebrate OTX paralogs were capable of rescuing rhabdomere morphogenesis when expressed in Drosophila otd mutant photoreceptors [47].

Consistent with the evidence of independent duplication events in the insect and crustacean lineages, we find that there is no simple correlation between the expression profiles of otd paralogs and their ability to direct r - opsin expression in our data set. Most conspicuously, Daphnia magna Otd1, which is not detected in photoreceptor cells within Daphnia magna, has the ability to execute both the repression of rh6 and activation of rh3 r - opsins in the Drosophila Otd rescue paradigm. Daphnia magna Otd2, on the other hand, which is endogenously expressed in photoreceptor cells, was only able to rescue the appropriate repression of Drosophila rh6, which however works in conjunction with defective proventriculus (Dve) [48]. It is also noteworthy that while we could not establish that Daphnia Otd1 is orthologous to Drosophila Otd or Tribolium Otd1, it has the ability to rescue both rh6 repression and rh3 activation whereas Tribolium Otd1 the ortholog of Drosophila Otd rescued only the activation of rh3. Moreover, even though Tribolium Otd1 is expressed in all photoreceptors and has the ability to activate r - opsin transcription in Drosophila, this ortholog is apparently dispensable for r - opsin expression within Tribolium. Interestingly, the three vertebrate Otx homologs also exhibited differential rescuing activities of rh3, rh5 and rh6 regulation [47]. The sum of these data indicates that the paralogs, which originated through independent duplications of the otd locus in insect and crustacean lineages contributed to different subfunctionalization trajectories. While the functional diversification that resulted from this appears bewildering, it implies continued evolutionary interchangeability, which may have been key to consolidating all Otd-related functions onto a single homolog during the loss of otd2 in the lineage to dipteran species.

Evidence of evolutionarily diversified target gene distribution between Pph13 and Otd with respect to rhabdomere biogenesis

The activation of structural gene batteries forms the endpoint in the gene regulatory network control of cell differentiation [54]. The synergistic activation of the structural genes by both Otd and Pph13 in the Drosophila eye is a good example of this paradigm. Interestingly, our functional analysis in Tribolium reveals differences in how Pph13 and Otd are employed in directing rhabdomere morphogenesis compared to Drosophila. First, within Tribolium, the reduction of either Otd1 or Otd2 generates non-overlapping defects in rhabdomere morphogenesis while the simultaneous knockdown of both genes leads to complete failure of rhabdomere formation. This outcome could result from incomplete subfunctionalization, leaving a limited degree of genetic redundancy in place. Alternatively, the two paralogs may have limited capacities to compensate for the downregulation of the sister paralog via expression level increase. Second, in Drosophila, both Pph13 and Otd are providing independent and overlapping functions to generate the rhabdomere [20]. As a result, the removal of both Otd and Pph13 is required to generate photoreceptors that lack rhabdomeres. In Tribolium, the knockdown of either Pph13 alone or the knockdown of both otd paralogs is sufficient to eliminate rhabdomeres. Thus, there appears to be significantly less redundant control of rhabdomere formation in Tribolium in contrast to Drosophila. Assuming the general conservation of rhabdomere structure target genes, this finding implies evolutionary turnover of Otd and Pph13 dedicated target genes in the context of rhabdomere formation. Given the well defined binding properties of Pph13 and Otd and the conservation of the Pph13 binding sites between Drosophila and Tribolium, it should be feasible to elucidate the diverged distribution of Otd versus Pph13 targets in Tribolium versus Drosophila. Such studies will expand our understanding of the evolution of gene regulatory networks by specifically testing the proposal that downstream network components enjoy greater degrees of evolutionary freedom than intermediate upstream components [55].

Ancestral and regulatory switches driving opsin expression and morphogenesis in both rhabdomeric and ciliary photoreceptors

Ever since Darwin pondered about the evolution of the eye [56], the process has and continues to be a challenge to investigators [57]. To date, with respect to photoreceptors, it is now accepted that the two fundamental types, ciliary and rhabdomeric, were present before the split of bilaterian animals and share a common ancestor [3]–[6]. However, compounding the study of the evolution of photoreceptors is the fact that the photoreceptors are utilized in various visual and non-visual light detection systems and obtain diverged morphological states in both protostomes and deuterostomes. Therefore, a critical component to provide clarity for defining homologous photoreceptors [3] is to identify the conserved regulatory proteins and switches required for the differentiation of the various classes of animal photoreceptors. Our studies have now identified two common regulators of one type of photoreceptor: rhabdomeric visual photoreceptors. Nonetheless, a key for a complete understanding will be to not only document their presence in but also confirm their functional roles in the visual systems of emerging model systems; to date our attempts with RNAi against Daphnia Pph13 and otd2 have not been successful. Fortunately, with the advent of TALEN and CRISPR technology [58], [59] functional studies may no longer be the limiting step. Thus future work will seek to define the ancestral mode of rhabdomeric photoreceptor differentiation among protostomes and in addition determine how the regulatory cascade is modified to generate diversity. For example, it will be interesting to explore how the origin of Pph13 relates to the diversification of ciliary and rhabdomeric photoreceptors during early metazoan evolution and whether Pph13 or Otd is required for the differentiation of non-visual rhabdomeric photoreceptors, as exemplified by intrinsic photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGC) [60], [61]; ipRGCs express an r - opsin but do not develop the characteristic membrane folds of a rhabdomere. With respect to Pph13, we have not observed a vertebrate ortholog. While, Arx transcription factors are known to carry out patterning functions in the developing forebrain that could affect the visual system [62], [63] no Arx functions have been reported that relate to the terminal differentiation of photoreceptors. Furthermore, the identification of Otd orthologs as critical components in both rhabdomeric and ciliary photoreceptor cell differentiation [50]–[53] raises the question whether Otd represents the ancestral mechanism for regulating photoreceptor differentiation in both fundamental types of photoreceptors. Overall, these answers will come from comprehending how the differences in phototransduction and morphology between the two fundamental types of photoreceptors are transcriptionally regulated, whether the regulation is conserved within each photoreceptor type, and how transcriptional regulation is modified dependent upon whether the photoreceptor is incorporated into a visual or non-visual system.

Materials and Methods

cDNAs, transgenic constructs, and Drosophila strains

cDNAs representing Tribolium Pph13 and otd2 were constructed from RT-PCR reactions from total RNA isolated from beetle heads. The otd1 cDNA was a gift from Dr. G. Bucher. cDNAs representing Daphnia magna Pph13 and otd2 were constructed from RT-PCR reactions from total RNA isolated from whole adults. The Daphnia magna cDNA of otd1 was isolated by screening an embryonic cDNA library [64]. For transgenics, all cDNAs were cloned into pUASTattB vector and integrated into genome position 65B2 (Rainbow Transgenic Flies, Inc.). Pph13-GAL4 was generated by inserting the immediate upstream 1.6 kb of genomic DNA extending from the first coding Methionine of the Pph13 locus into pCHS-GAL4. Drosophila strains utilized: cn bw, cn bw Pph13hzy [19], otduvi [65], [66], y w; Sp/Cyo; UAS-Flag-otd/TM2 [46], [47], and otduvi; otd-GAL4, Pwiz6/Cyo; TM2/TM6B [46], [47]. For otd rescue experiments females of otduvi; otd-GAL4, Pwiz6/Cyo; TM2/TM6B were crossed to w; +; UAS – otd X transgenic lines and only non CyO;TM6B male progeny were examined. For Pph13 rescue experiments w; cn bw Pph13/CyO; Pph13-GAL4/TM6B homozygous flies were crossed to w; cn bw Pph13/CyO; UAS - Pph13 X/TM6B and only non CyO; TM6B progeny were examined.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs)

All cDNAs were cloned into pCDNA 3.1(Invitrogen) and EMSAs were performed as described in [19], [67]. Proteins were generated in reticulocyte lysates (Promega). The sequences of probes utilized are listed in Table S1.

Tribolium RNAi injections

To generate RNAi knockdown animals, 1 ug/ul of total probe, DsRNA was injected into pu11, m26, or vw late stage larvae; pu11 and m26 contain a 3XP3-GFP and a 3XP3-RFP reporter, respectively [68], [69]. Two independent DsRNAs for each gene were tested and eyes from at least five different subjects were examined to confirm phenotypes. The regions listed for each gene are listed in Table S3. For all the results reported here a mixture of the two DsRNAs for each gene were utilized. The mixtures of DsRNAs contained equal amounts of each individual DsRNA and were used and a final concentration of 1 ug/ul was injected. Dark-reared, newly eclosed (<12 hours old) beetles were collected, scored and utilized for various procedures.

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol and DNAase treated. First strand synthesis was accomplished with the Superscript III (Invitrogen) kit. Each reaction contained 2 ug of total RNA and oligo-dT as primers. PCR amplification was performed with 1 ul (1/20th) of RT reaction and samples were collected at 25 or 30 cycles. All reactions were repeated three times with two independent sets of total RNA. Equal amounts of PCR reactions were analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The list of PCR primers used can be found in Table S4.

RNA-Seq

For each condition, duplicate sets of total RNA from entire animals (<12 hours old) were isolated. Stranded RNA sequencing libraries were constructed using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Libraries were quantified using the KAPA SYBR FAST Roche LightCycler 480 2X qPCR Master Mix (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), pooled in equal molar amounts, and sequenced on a HiSeq2000 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA) using a 100 bp paired-end run. HISeq read sequences were cleaned using Trimmomatic version 0.30 [70] to remove adapter sequences and perform quality trimming. Trimmomatic was run with the following parameters, “3 : 30 : 10 LEADING:3 TRAILING:3SLIDINGWINDOW:4 : 20 MINLEN:75”. The resulting reads were mapped against the Tribolium release 3.0 gene models (http://www.Beetlebase.org/) using TopHat2 version 2.0.9 [71] with the parameters “–b2-very-sensitive–read-edit-dist 2 –max-multihits 100 –library-type fr-firststrand”. Read counting was done for each gene using htseq-count from the HTSeq package version 0.5.4p3 [72] with the “–stranded = reverse” parameter. For Tribolium, read counts were normalized across samples using the DESeq package (version 1.12) in R/Bioconductor [73]. DESeq [72] was further used to detect statistically significant differences in expression between two conditions using the binomial test with a .05 adjusted p-value cutoff. The complete data set will be presented and discussed elsewhere but total read data and reads specific to Tribolium LW and UV opsin are listed in Tables S5 and Tables S6.

Transmission electron microscopy analysis

Drosophila and Tribolium heads were prepared as previously described [20], [74]. All samples were from newly emerged adults and for each genotype at least three retinas from three different heads were examined. Samples were observed under transmission electron microscope (TEM), operated at 60 KV and digital images were captured and imported into Adobe Photoshop.

Antibody production

The Tribolium Pph13 polyclonal antibody, 171, was created by injecting rats with a GST-fusion protein representing amino acids 104–220 of the protein. The Daphnia magna Otd2 polyclonal antibody was prepared in guinea pigs against a bacterially expressed C-terminal portion of the protein (amino acids 235–395). The Daphnia magna Otd1 polyclonal antibody was prepared in rats against a bacterially expressed portion of the protein (amino acids 220–351).

Whole mount RNA in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence

Whole mount RNA in situ hybridization in Tribolium and Daphnia was performed as previously described [42], [75]. The regions of the sense and ant-sense probes are listed in Table S3. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-Rh6 (1∶2500; Dr. C. Desplan), rat anti - Tribolium Pph13 (1∶20), rat anti - Daphnia Otd1 (1∶500; Dr. Y. Shiga), guinea pig anti - Daphnia Otd2 (1∶500; Dr. Y. Shiga) mouse anti-Rh3 (1∶50; Dr. Steve Britt), mouse anti-Rh5 (1∶50; Dr. Steve Britt) and rabbit anti-Rh6 (1∶1000; Dr. Claude Desplan). For Otd2, in Daphnia, signals were amplified with the Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) system (PerkinElmer). FITC and Rhodamine conjugated secondary antibodies were utilized (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Immunofluoresence studies were performed as previously described [47], [76]. All Drosophila samples were from newly emerged adults and for each genotype at least three retinas from three different heads were examined.

Sequences

Many of the sequences utilized in this study can be found in Table S7.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. EakinRM (1965) Evolution of photoreceptors. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 30 : 363–370.

2. ArendtD, WittbrodtJ (2001) Reconstructing the eyes of Urbilateria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 356 : 1545–1563.

3. ArendtD (2008) The evolution of cell types in animals: emerging principles from molecular studies. Nat Rev Genet 9 : 868–882.

4. LambTD, ArendtD, CollinSP (2009) The evolution of phototransduction and eyes. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences 364 : 2791–2793.

5. NilssonDE, ArendtD (2008) Eye evolution: the blurry beginning. Current Biology: CB 18: R1096–1098.

6. PlachetzkiDC, SerbJM, OakleyTH (2005) New insights into the evolutionary history of photoreceptor cells. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 20 : 465–467.

7. MollereauB, DomingosPM (2005) Photoreceptor differentiation in Drosophila: from immature neurons to functional photoreceptors. Dev Dyn 232 : 585–592.

8. TsachakiM, SprecherSG (2012) Genetic and developmental mechanisms underlying the formation of the Drosophila compound eye. Dev Dyn 241 : 40–56.

9. FainGL, HardieR, LaughlinSB (2010) Phototransduction and the evolution of photoreceptors. Current Biology: CB 20: R114–124.

10. NilssonDE (2013) Eye evolution and its functional basis. Visual neuroscience 30 : 5–20.

11. AcamporaD, AvantaggiatoV, TuortoF, BaroneP, ReichertH, et al. (1998) Murine Otx1 and Drosophila otd genes share conserved genetic functions required in invertebrate and vertebrate brain development. Development 125 : 1691–1702.

12. SharmanAC, BrandM (1998) Evolution and homology of the nervous system: cross-phylum rescues of otd/Otx genes. Trends in Genetics 14 : 211–214.

13. VandendriesER, JohnsonD, ReinkeR (1996) orthodenticle is required for photoreceptor cell development in the Drosophila eye. Dev Biol 173 : 243–255.

14. JohnstonRJJr (2013) Lessons about terminal differentiation from the specification of color-detecting photoreceptors in the Drosophila retina. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1293 : 33–44.

15. RanadeSS, Yang-ZhouD, KongSW, McDonaldEC, CookTA, et al. (2008) Analysis of the Otd-dependent transcriptome supports the evolutionary conservation of CRX/OTX/OTD functions in flies and vertebrates. Dev Biol 315 : 521–534.

16. TahayatoA, SonnevilleR, PichaudF, WernetMF, PapatsenkoD, et al. (2003) Otd/Crx, a dual regulator for the specification of ommatidia subtypes in the Drosophila retina. Dev Cell 5 : 391–402.

17. BaoR, FriedrichM (2009) Molecular evolution of the Drosophila retinome: exceptional gene gain in the higher Diptera. Molecular Biology and Evolution 26 : 1273–1287.

18. GorielyA, MollereauB, CoffinierC, DesplanC (1999) Munster, a novel paired-class homeobox gene specifically expressed in the Drosophila larval eye. Mech Dev 88 : 107–110.

19. ZelhofAC, KoundakjianE, ScullyAL, HardyRW, PoundsL (2003) Mutation of the photoreceptor specific homeodomain gene Pph13 results in defects in phototransduction and rhabdomere morphogenesis. Development 130 : 4383–4392.

20. MishraM, OkeA, LebelC, McDonaldEC, PlummerZ, et al. (2010) Pph13 and orthodenticle define a dual regulatory pathway for photoreceptor cell morphogenesis and function. Development 137 : 2895–2904.

21. JukamD, XieB, RisterJ, TerrellD, Charlton-PerkinsM, et al. (2013) Opposite Feedbacks in the Hippo Pathway for Growth Control and Neural Fate. Science 342 : 1238016.

22. FortiniME, RubinGM (1990) Analysis of cis-acting requirements of the Rh3 and Rh4 genes reveals a bipartite organization to rhodopsin promoters in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev 4 : 444–463.

23. MismerD, MichaelWM, LavertyTR, RubinGM (1988) Analysis of the promoter of the Rh2 opsin gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 120 : 173–180.

24. PapatsenkoD, NazinaA, DesplanC (2001) A conserved regulatory element present in all Drosophila rhodopsin genes mediates Pax6 functions and participates in the fine-tuning of cell-specific expression. Mech Dev 101 : 143–153.

25. BerghammerAJ, KlinglerM, WimmerEA (1999) A universal marker for transgenic insects. Nature 402 : 370–371.

26. CaravasJ, FriedrichM (2010) Of mites and millipedes: recent progress in resolving the base of the arthropod tree. Bioessays 32 : 488–495.

27. ShultzJW, RegierJC (2000) Phylogenetic analysis of arthropods using two nuclear protein-encoding genes supports a crustacean+hexapod clade. Proc Biol Sci 267 : 1011–1019.

28. RehmP, BornerJ, MeusemannK, von ReumontBM, SimonS, et al. (2011) Dating the arthropod tree based on large-scale transcriptome data. Mol Phylogenet Evol 61 : 880–887.

29. RiegerD, StanewskyR, Helfrich-ForsterC (2003) Cryptochrome, compound eyes, Hofbauer-Buchner eyelets, and ocelli play different roles in the entrainment and masking pathway of the locomotor activity rhythm in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Rhythms 18 : 377–391.

30. ColbourneJK, PfrenderME, GilbertD, ThomasWK, TuckerA, et al. (2011) The ecoresponsive genome of Daphnia pulex. Science 331 : 555–561.

31. Tribolium Genome SequencingC, RichardsS, GibbsRA, WeinstockGM, BrownSJ, et al. (2008) The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature 452 : 949–955.

32. LiY, BrownSJ, HausdorfB, TautzD, DenellRE, et al. (1996) Two orthodenticle-related genes in the short-germ beetle Tribolium castaneum. Development Genes and Evolution 206 : 35–45.

33. BrowneWE, SchmidBG, WimmerEA, MartindaleMQ (2006) Expression of otd orthologs in the amphipod crustacean, Parhyale hawaiensis. Development Genes and Evolution 216 : 581–595.

34. NoyesMB, ChristensenRG, WakabayashiA, StormoGD, BrodskyMH, et al. (2008) Analysis of homeodomain specificities allows the family-wide prediction of preferred recognition sites. Cell 133 : 1277–1289.

35. ZhongYF, HollandPW (2011) HomeoDB2: functional expansion of a comparative homeobox gene database for evolutionary developmental biology. Evol Dev 13 : 567–568.

36. RiveraAS, PankeyMS, PlachetzkiDC, VillacortaC, SymeAE, et al. (2010) Gene duplication and the origins of morphological complexity in pancrustacean eyes, a genomic approach. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10 : 123.

37. FriedrichM, RamboldI, MelzerRR (1996) The early stages of ommatidial development in the flour beetle Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae). Development Genes and Evolution 206 : 136–146.

38. GuldnerFH, WolffJR (1970) [Ultrastructure of the compound eye of Daphnia pulex]. Zeitschrift fur Zellforschung und mikroskopische Anatomie 104 : 259–274.

39. FlasterMS, MacagnoER (1984) Cellular interactions and pattern formation in the visual system of the branchiopod crustacean, Daphnia magna. III. The relationship between cell birthdates and cell fates in the optic lamina. The Journal of Neuroscience 4 : 1486–1498.

40. LoprestiV, MacagnoER, LevinthalC (1973) Structure and development of neuronal connections in isogenic organisms: cellular interactions in the development of the optic lamina of Daphnia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70 : 433–437.

41. MacagnoER, LoprestiV, LevinthalC (1973) Structure and development of neuronal connections in isogenic organisms: variations and similarities in the optic system of Daphnia magna. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70 : 57–61.

42. JackowskaM, BaoR, LiuZ, McDonaldEC, CookTA, et al. (2007) Genomic and gene regulatory signatures of cryptozoic adaptation: Loss of blue sensitive photoreceptors through expansion of long wavelength-opsin expression in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Front Zool 4 : 24.

43. WilsonDS, ShengG, JunS, DesplanC (1996) Conservation and diversification in homeodomain-DNA interactions: a comparative genetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 : 6886–6891.

44. CookT, PichaudF, SonnevilleR, PapatsenkoD, DesplanC (2003) Distinction between color photoreceptor cell fates is controlled by Prospero in Drosophila. Dev Cell 4 : 853–864.

45. BrandAH, PerrimonN (1993) Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118 : 401–415.

46. McDonaldEC, XieB, WorkmanM, Charlton-PerkinsM, TerrellDA, et al. (2010) Separable transcriptional regulatory domains within Otd control photoreceptor terminal differentiation events. Dev Biol 347 : 122–132.

47. TerrellD, XieB, WorkmanM, MahatoS, ZelhofA, et al. (2012) OTX2 and CRX rescue overlapping and photoreceptor-specific functions in the Drosophila eye. Dev Dyn 241 : 215–228.

48. JohnstonRJJr, OtakeY, SoodP, VogtN, BehniaR, et al. (2011) Interlocked feedforward loops control cell-type-specific Rhodopsin expression in the Drosophila eye. Cell 145 : 956–968.

49. PosnienN, SchinkoJ, GrossmannD, ShippyTD, KonopovaB, et al. (2009) RNAi in the red flour beetle (Tribolium). Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2009

50. ChenS, WangQL, NieZ, SunH, LennonG, et al. (1997) Crx, a novel Otx-like paired-homeodomain protein, binds to and transactivates photoreceptor cell-specific genes. Neuron 19 : 1017–1030.

51. FurukawaT, MorrowEM, CepkoCL (1997) Crx, a novel otx-like homeobox gene, shows photoreceptor-specific expression and regulates photoreceptor differentiation. Cell 91 : 531–541.

52. KoikeC, NishidaA, UenoS, SaitoH, SanukiR, et al. (2007) Functional roles of Otx2 transcription factor in postnatal mouse retinal development. Molecular and Cellular Biology 27 : 8318–8329.

53. NishidaA, FurukawaA, KoikeC, TanoY, AizawaS, et al. (2003) Otx2 homeobox gene controls retinal photoreceptor cell fate and pineal gland development. Nature Neuroscience 6 : 1255–1263.

54. BrittenRJ, DavidsonEH (1969) Gene regulation for higher cells: a theory. Science 165 : 349–357.

55. HinmanVF, DavidsonEH (2007) Evolutionary plasticity of developmental gene regulatory network architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 : 19404–19409.

56. Darwin CR (1859) On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: John Murray. 502 p.

57. Salvini-PlawenL, MayerE (1977) On the evolution of photoreceptors and eyes. Evol Biol 10 : 207–263.

58. GajT, GersbachCA, BarbasCF3rd (2013) ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol 31 : 397–405.

59. WeiC, LiuJ, YuZ, ZhangB, GaoG, et al. (2013) TALEN or Cas9 - rapid, efficient and specific choices for genome modifications. J Genet Genomics 40 : 281–289.

60. GooleyJJ, LuJ, ChouTC, ScammellTE, SaperCB (2001) Melanopsin in cells of origin of the retinohypothalamic tract. Nat Neurosci 4 : 1165.

61. ProvencioI, RodriguezIR, JiangG, HayesWP, MoreiraEF, et al. (2000) A novel human opsin in the inner retina. J Neurosci 20 : 600–605.

62. FriocourtG, PoirierK, RakicS, ParnavelasJG, ChellyJ (2006) The role of ARX in cortical development. Eur J Neurosci 23 : 869–876.

63. MarshE, FulpC, GomezE, NasrallahI, MinarcikJ, et al. (2009) Targeted loss of Arx results in a developmental epilepsy mouse model and recapitulates the human phenotype in heterozygous females. Brain 132 : 1563–1576.

64. ShigaY, YasumotoR, YamagataH, HayashiS (2002) Evolving role of Antennapedia protein in arthropod limb patterning. Development 129 : 3555–3561.

65. ReinkeR, KrantzDE, YenD, ZipurskySL (1988) Chaoptin, a cell surface glycoprotein required for Drosophila photoreceptor cell morphogenesis, contains a repeat motif found in yeast and human. Cell 52 : 291–301.

66. Van VactorDJr, KrantzDE, ReinkeR, ZipurskySL (1988) Analysis of mutants in chaoptin, a photoreceptor cell-specific glycoprotein in Drosophila, reveals its role in cellular morphogenesis. Cell 52 : 281–290.

67. ZelhofAC, YaoTP, ChenJD, EvansRM, McKeownM (1995) Seven-up inhibits ultraspiracle-based signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 15 : 6736–6745.

68. LorenzenMD, KimzeyT, ShippyTD, BrownSJ, DenellRE, et al. (2007) piggyBac-based insertional mutagenesis in Tribolium castaneum using donor/helper hybrids. Insect Molecular Biology 16 : 265–275.

69. TomoyasuY, DenellRE (2004) Larval RNAi in Tribolium (Coleoptera) for analyzing adult development. Dev Genes Evol 214 : 575–578.

70. LohseM, BolgerAM, NagelA, FernieAR, LunnJE, et al. (2012) RobiNA: a user-friendly, integrated software solution for RNA-Seq-based transcriptomics. Nucleic Acids Research 40: W622–627.

71. KimD, PerteaG, TrapnellC, PimentelH, KelleyR, et al. (2013) TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biology 14: R36.

72. AndersS, HuberW (2010) Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology 11: R106.

73. GentlemanRC, CareyVJ, BatesDM, BolstadB, DettlingM, et al. (2004) Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biology 5: R80.

74. ZelhofAC, HardyRW, BeckerA, ZukerCS (2006) Transforming the architecture of compound eyes. Nature 443 : 696–699.

75. SagawaK, YamagataH, ShigaY (2005) Exploring embryonic germ line development in the water flea, Daphnia magna, by zinc-finger-containing VASA as a marker. Gene Expression Patterns 5 : 669–678.

76. NieJ, MahatoS, MustillW, TippingC, BhattacharyaSS, et al. (2012) Cross species analysis of Prominin reveals a conserved cellular role in invertebrate and vertebrate photoreceptor cells. Dev Biol 371 : 312–320.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Comparative Phylogenomics Uncovers the Impact of Symbiotic Associations on Host Genome EvolutionČlánek Distribution and Medical Impact of Loss-of-Function Variants in the Finnish Founder PopulationČlánek Integrative Genomics Reveals Novel Molecular Pathways and Gene Networks for Coronary Artery DiseaseČlánek An ARID Domain-Containing Protein within Nuclear Bodies Is Required for Sperm Cell Formation inČlánek Knock-In Reporter Mice Demonstrate that DNA Repair by Non-homologous End Joining Declines with Age

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 7

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Cuba: Exploring the History of Admixture and the Genetic Basis of Pigmentation Using Autosomal and Uniparental Markers

- Clonal Architecture of Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukemia Defined by Single-Cell Sequencing

- Mechanisms of Functional Variants That Impair Regulated Bicarbonate Permeation and Increase Risk for Pancreatitis but Not for Cystic Fibrosis

- Nucleosomes Shape DNA Polymorphism and Divergence

- Functional Diversification of Hsp40: Distinct J-Protein Functional Requirements for Two Prions Allow for Chaperone-Dependent Prion Selection

- Comparative Phylogenomics Uncovers the Impact of Symbiotic Associations on Host Genome Evolution

- Activation of the Immune System by Combinations of Common Alleles

- Age-Associated Sperm DNA Methylation Alterations: Possible Implications in Offspring Disease Susceptibility

- Muscle-Specific SIRT1 Gain-of-Function Increases Slow-Twitch Fibers and Ameliorates Pathophysiology in a Mouse Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

- MDRL lncRNA Regulates the Processing of miR-484 Primary Transcript by Targeting miR-361

- Hypersensitivity of Primordial Germ Cells to Compromised Replication-Associated DNA Repair Involves ATM-p53-p21 Signaling

- Intrapopulation Genome Size Variation in Reflects Life History Variation and Plasticity

- SlmA Antagonism of FtsZ Assembly Employs a Two-pronged Mechanism like MinCD

- Distribution and Medical Impact of Loss-of-Function Variants in the Finnish Founder Population

- Determinative Developmental Cell Lineages Are Robust to Cell Deaths

- DELLA Protein Degradation Is Controlled by a Type-One Protein Phosphatase, TOPP4

- Wnt Signaling Interacts with Bmp and Edn1 to Regulate Dorsal-Ventral Patterning and Growth of the Craniofacial Skeleton

- Common Transcriptional Mechanisms for Visual Photoreceptor Cell Differentiation among Pancrustaceans

- UVB Induces a Genome-Wide Acting Negative Regulatory Mechanism That Operates at the Level of Transcription Initiation in Human Cells

- The Nesprin Family Member ANC-1 Regulates Synapse Formation and Axon Termination by Functioning in a Pathway with RPM-1 and β-Catenin

- Combinatorial Interactions Are Required for the Efficient Recruitment of Pho Repressive Complex (PhoRC) to Polycomb Response Elements

- Recombination in the Human Pseudoautosomal Region PAR1

- Microsatellite Interruptions Stabilize Primate Genomes and Exist as Population-Specific Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms within Individual Human Genomes

- An Intronic microRNA Links Rb/E2F and EGFR Signaling

- An Essential Nonredundant Role for Mycobacterial DnaK in Native Protein Folding

- Integrative Genomics Reveals Novel Molecular Pathways and Gene Networks for Coronary Artery Disease

- The Genomic Landscape of the Ewing Sarcoma Family of Tumors Reveals Recurrent Mutation

- Evolution and Genetic Architecture of Chromatin Accessibility and Function in Yeast

- An ARID Domain-Containing Protein within Nuclear Bodies Is Required for Sperm Cell Formation in

- Stage-Dependent and Locus-Specific Role of Histone Demethylase Jumonji D3 (JMJD3) in the Embryonic Stages of Lung Development

- Genome Wide Association Identifies Common Variants at the Locus Influencing Plasma Cortisol and Corticosteroid Binding Globulin

- Regulation of Feto-Maternal Barrier by Matriptase- and PAR-2-Mediated Signaling Is Required for Placental Morphogenesis and Mouse Embryonic Survival

- Apomictic and Sexual Germline Development Differ with Respect to Cell Cycle, Transcriptional, Hormonal and Epigenetic Regulation

- Functional EF-Hands in Neuronal Calcium Sensor GCAP2 Determine Its Phosphorylation State and Subcellular Distribution , and Are Essential for Photoreceptor Cell Integrity

- Comparison of Methods to Account for Relatedness in Genome-Wide Association Studies with Family-Based Data

- Knock-In Reporter Mice Demonstrate that DNA Repair by Non-homologous End Joining Declines with Age

- Cis and Trans Effects of Human Genomic Variants on Gene Expression

- 8.2% of the Human Genome Is Constrained: Variation in Rates of Turnover across Functional Element Classes in the Human Lineage

- Novel Approach Identifies SNPs in and with Evidence for Parent-of-Origin Effect on Body Mass Index

- Hypoxia Adaptations in the Grey Wolf () from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

- A Loss of Function Screen of Identified Genome-Wide Association Study Loci Reveals New Genes Controlling Hematopoiesis

- Unraveling Genetic Modifiers in the Mouse Model of Absence Epilepsy

- DNA Topoisomerase 1α Promotes Transcriptional Silencing of Transposable Elements through DNA Methylation and Histone Lysine 9 Dimethylation in

- The Coding and Noncoding Architecture of the Genome

- A Novel Locus Is Associated with Large Artery Atherosclerotic Stroke Using a Genome-Wide Age-at-Onset Informed Approach

- Brg1 Loss Attenuates Aberrant Wnt-Signalling and Prevents Wnt-Dependent Tumourigenesis in the Murine Small Intestine

- The PTK7-Related Transmembrane Proteins Off-track and Off-track 2 Are Co-receptors for Wnt2 Required for Male Fertility

- The Co-factor of LIM Domains (CLIM/LDB/NLI) Maintains Basal Mammary Epithelial Stem Cells and Promotes Breast Tumorigenesis

- Essential Genetic Interactors of Required for Spatial Sequestration and Asymmetrical Inheritance of Protein Aggregates

- Meiosis-Specific Cohesin Component, Is Essential for Maintaining Centromere Chromatid Cohesion, and Required for DNA Repair and Synapsis between Homologous Chromosomes

- Silencing Is Noisy: Population and Cell Level Noise in Telomere-Adjacent Genes Is Dependent on Telomere Position and Sir2

- The Two Cis-Acting Sites, and , Contribute to the Longitudinal Organisation of Chromosome I