-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaIdentification of Functional Toxin/Immunity Genes Linked to Contact-Dependent Growth Inhibition (CDI) and Rearrangement Hotspot (Rhs) Systems

Bacterial contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) is mediated by the CdiA/CdiB family of two-partner secretion proteins. Each CdiA protein exhibits a distinct growth inhibition activity, which resides in the polymorphic C-terminal region (CdiA-CT). CDI+ cells also express unique CdiI immunity proteins that specifically block the activity of cognate CdiA-CT, thereby protecting the cell from autoinhibition. Here we show that many CDI systems contain multiple cdiA gene fragments that encode CdiA-CT sequences. These “orphan” cdiA-CT genes are almost always associated with downstream cdiI genes to form cdiA-CT/cdiI modules. Comparative genome analyses suggest that cdiA-CT/cdiI modules are mobile and exchanged between the CDI systems of different bacteria. In many instances, orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules are fused to full-length cdiA genes in other bacterial species. Examination of cdiA-CT/cdiI modules from Escherichia coli EC93, E. coli EC869, and Dickeya dadantii 3937 confirmed that these genes encode functional toxin/immunity pairs. Moreover, the orphan module from EC93 was functional in cell-mediated CDI when fused to the N-terminal portion of the EC93 CdiA protein. Bioinformatic analyses revealed that the genetic organization of CDI systems shares features with rhs (rearrangement hotspot) loci. Rhs proteins also contain polymorphic C-terminal regions (Rhs-CTs), some of which share significant sequence identity with CdiA-CTs. All rhs genes are followed by small ORFs representing possible rhsI immunity genes, and several Rhs systems encode orphan rhs-CT/rhsI modules. Analysis of rhs-CT/rhsI modules from D. dadantii 3937 demonstrated that Rhs-CTs have growth inhibitory activity, which is specifically blocked by cognate RhsI immunity proteins. Together, these results suggest that Rhs plays a role in intercellular competition and that orphan gene modules expand the diversity of toxic activities deployed by both CDI and Rhs systems.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002217

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002217Summary

Bacterial contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) is mediated by the CdiA/CdiB family of two-partner secretion proteins. Each CdiA protein exhibits a distinct growth inhibition activity, which resides in the polymorphic C-terminal region (CdiA-CT). CDI+ cells also express unique CdiI immunity proteins that specifically block the activity of cognate CdiA-CT, thereby protecting the cell from autoinhibition. Here we show that many CDI systems contain multiple cdiA gene fragments that encode CdiA-CT sequences. These “orphan” cdiA-CT genes are almost always associated with downstream cdiI genes to form cdiA-CT/cdiI modules. Comparative genome analyses suggest that cdiA-CT/cdiI modules are mobile and exchanged between the CDI systems of different bacteria. In many instances, orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules are fused to full-length cdiA genes in other bacterial species. Examination of cdiA-CT/cdiI modules from Escherichia coli EC93, E. coli EC869, and Dickeya dadantii 3937 confirmed that these genes encode functional toxin/immunity pairs. Moreover, the orphan module from EC93 was functional in cell-mediated CDI when fused to the N-terminal portion of the EC93 CdiA protein. Bioinformatic analyses revealed that the genetic organization of CDI systems shares features with rhs (rearrangement hotspot) loci. Rhs proteins also contain polymorphic C-terminal regions (Rhs-CTs), some of which share significant sequence identity with CdiA-CTs. All rhs genes are followed by small ORFs representing possible rhsI immunity genes, and several Rhs systems encode orphan rhs-CT/rhsI modules. Analysis of rhs-CT/rhsI modules from D. dadantii 3937 demonstrated that Rhs-CTs have growth inhibitory activity, which is specifically blocked by cognate RhsI immunity proteins. Together, these results suggest that Rhs plays a role in intercellular competition and that orphan gene modules expand the diversity of toxic activities deployed by both CDI and Rhs systems.

Introduction

Many bacteria lead social lives in communities where they cooperate and compete with members of their own species, as well as those of other species [1]. One mechanism of bacterial communication is quorum sensing, in which small signaling molecules are released to coordinate group behavior when a critical cell density has been attained [2]. Other modes of communication based on direct cell-to-cell contact have recently been identified in bacteria. Contact-dependent signaling helps to coordinate cell aggregation and fruiting body formation in Myxococcus xanthus [3], and is also exploited to inhibit the growth of neighboring cells. Contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) was first described in the Escherichia coli isolate EC93 [4], and has subsequently been demonstrated in Dickeya dadantii 3937 [5]. CDI is mediated by the CdiB-CdiA two-partner secretion system. CdiB is a predicted outer membrane β-barrel protein that is required for secretion and presentation of the CdiA exoprotein on the cell surface [6], [7]. Like other two-partner secretion exoproteins, CdiA contains an N-terminal transport domain followed by a hemagglutinin repeat region that is predicted to adopt an extended filamentous β-helical structure [7]–[9]. The CDI growth inhibitory activity resides within the C-terminus of CdiA (CdiA-CT). The cdi locus also encodes a small CdiI immunity protein immediately downstream of cdiA. CdiI protects EC93 cells from CdiA-mediated growth autoinhibition [5].

CDI systems are widespread amongst α-, β-, and γ-proteobacteria [5]. CdiA exoproteins are related throughout most of their length, which varies from 1,400 to 2,000 amino acid residues in Neisseria and Moraxella species to over 5,600 residues for some Dickeya and Pseudomonas strains [5]. However, the CdiA-CT regions are highly variable, with CdiA sequences diverging abruptly after a VENN peptide motif found within the conserved DUF638 domain (Pfam PF04829). Similarly, CdiI sequences are also highly variable, suggesting that these immunity proteins specifically bind to cognate CdiA-CTs and neutralize their toxic activities. In support of this model, we recently showed that CdiA-CTs from Dickeya dadantii 3937 and uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) 536 possess distinct toxic nuclease activities, and that the corresponding CdiI proteins bind to their cognate CdiA-CT and block nuclease activity both in vitro and in vivo [5]. Thus, CdiA-CT/CdiI pairs constitute a polymorphic family of toxin/immunity modules that allow CDI systems to deploy a wide variety of growth inhibition activities.

CdiA proteins share a number of characteristics with the Rhs protein family. The rhs genes were first identified in E. coli by C.W. Hill and colleagues, and were named rearrangement hotspots based on their role in chromosome duplications [10], [11]. Rhs proteins are widely distributed throughout the eubacteria, but their function is poorly understood. Like CdiA, Rhs proteins are large, ranging from ∼1,500 residues in Gram-negative bacteria to over 2,000 residues in some Gram-positive species. Rhs proteins also possess a central repeat region, though the characteristic YD peptide repeats of Rhs proteins are unrelated to the hemagglutinin repeats in CdiA. Moreover, Rhs proteins have variable C-terminal domains that are sharply demarcated by a conserved peptide motif (PxxxxDPxGL in the Enterobacteriaceae) [12]. Remarkably, we find that some CdiA and Rhs proteins share related C-terminal sequences, suggesting the protein families may be functionally analogous. Rhs proteins from a number of species appear to be exported to the cell surface [13]–[15], consistent with a role in cell-to-cell communication.

Here we show that many CDI systems have an unusual genetic organization similar to that described for some Rhs loci [12]. Downstream of the cdiBAI genes, CDI systems often contain fragmentary gene pairs that resemble cdiA-CT/cdiI toxin/immunity modules. The predicted cdiA-CT fragments generally lack translation initiation signals but encode the VENN peptide motif that demarcates the CdiA-CT region in full-length CdiA proteins. These “orphan” CdiA-CT proteins possess growth inhibitory activities, which are specifically neutralized by the corresponding orphan CdiI immunity proteins. Moreover, we show that the orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI region is actively transcribed in E. coli EC93. Although the orphan CdiA-CT does not appear to be synthesized, functional orphan CdiI immunity protein is produced in EC93. We also show that the Rhs systems of D. dadantii 3937 encode toxin/immunity pairs. Rhs-CTs from D. dadantii 3937 inhibit cell growth when expressed in E. coli, and this toxic activity is specifically neutralized by the cognate RhsI protein encoded immediately downstream. These results suggest that Rhs constitutes another class of cell-surface proteins involved in intercellular competition, and that orphan CT/immunity modules may represent a reservoir of toxin/immunity diversity for both CDI and Rhs systems.

Results

Many CDI Systems Contain Orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI Gene Pairs

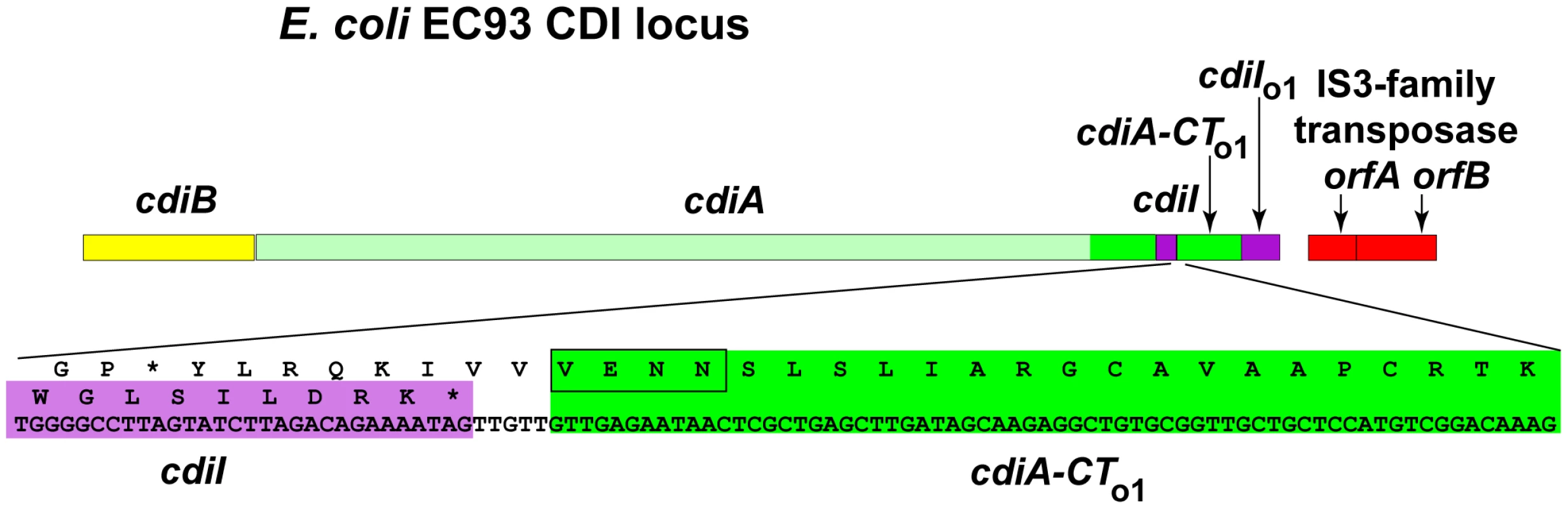

Examination of the cdi locus in E. coli EC93 revealed two short open reading frames (ORFs) immediately downstream of the cdiI immunity gene (Figure 1). The first ORF lacks a translation initiation codon but encodes the VENN motif that typically demarcates variable CdiA-CT regions (Figure 1), suggesting the first ORF encodes a detached CdiA-CT remnant and the second ORF is its associated cdiI gene. A TBLASTN search of bacterial genomes revealed that the encoded proteins are related to the CdiA-CT/CdiI toxin/immunity pair from E. coli UPEC 536 (Figure S1). Thus, the cdiBAI gene cluster in E. coli EC93 is followed immediately by an “orphan” cdiA-CT/cdiI module related to the cdi locus of a different E. coli strain. To differentiate these modules from main cdiBAI clusters, we indicate orphan genes with a subscripted “o” and a number that indicates the position of the module in the cdi locus. Additionally, throughout the text we will indicate bacterial strains as superscripts. According to this nomenclature, the genes in the EC93 orphan module are designated cdiA-CTo1EC93 and cdiIo1EC93.

Fig. 1. E. coli EC93 contains an orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI module.

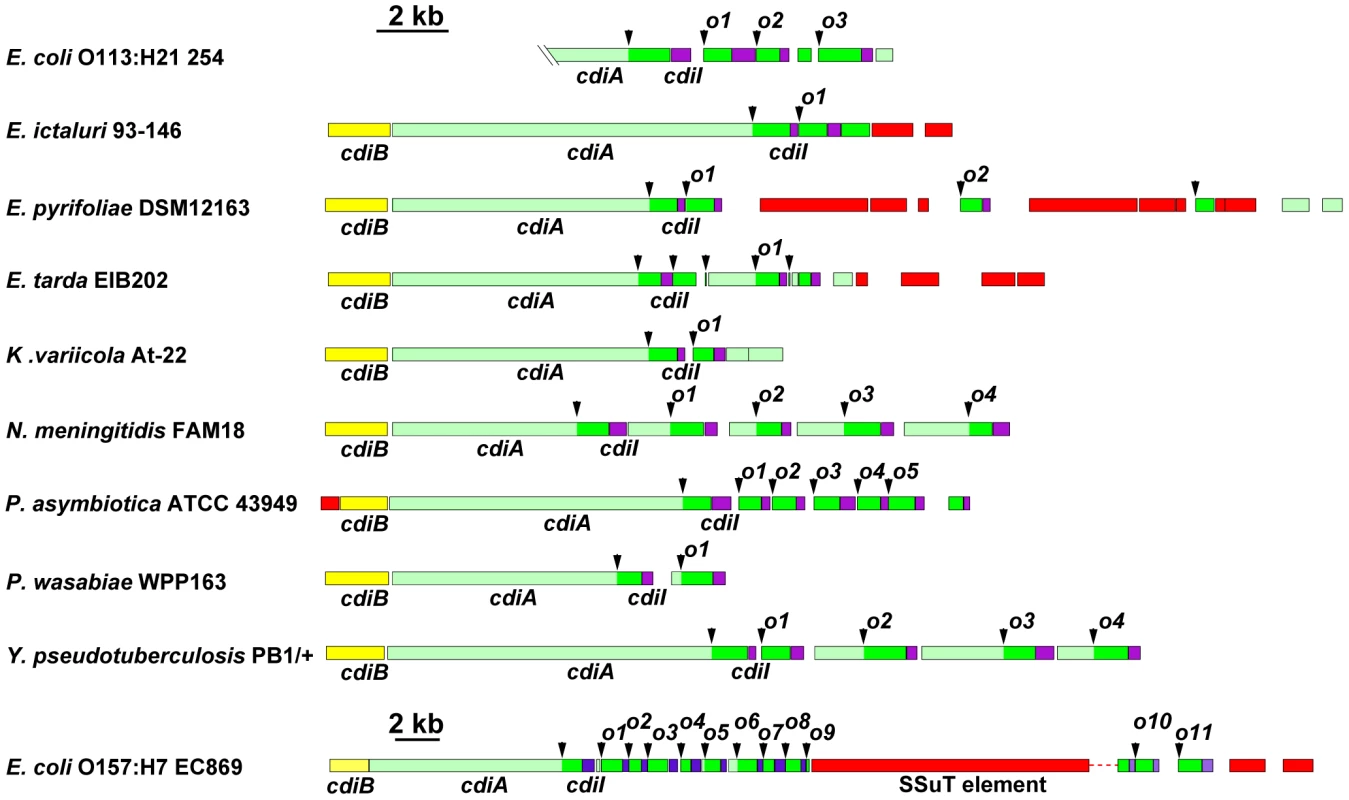

The CDI region of E. coli EC93 is depicted, with cdiB, cdiA and cdiI genes shown in yellow, green and purple, respectively. The cdiA coding region upstream of the encoded VENN motif is shown in light green, and the cdiA-CT sequence is shown in dark green. The orphan cdiA-CT fragment (cdiA-CTo1) and orphan cdiI (cdiIo1) are dark green and purple, respectively. The nucleotide sequence of the cdiI - cdiA-CTo1 junction and the predicted reading frames are shown in detail. Sequences similar to transposable element genes are shown in red. Examination of CDI regions in other bacteria shows that orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI pairs are quite common. Although some CDI systems are comprised solely of the cdiBAI gene cluster, many loci are closely followed by one or more cdiA gene fragments that usually encode the VENN peptide motif (Figure 2). These orphan cdiA-CT genes are typically followed by small ORFs representing potential cdiI immunity genes. For example, the region II CDI system in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis PB1/+ contains four additional cdiA-CT gene fragments encoding the VENN motif, each associated with a putative cdiI gene (Figure 2 and Figure S2A). Three of these gene fragments (cdiA-CTo2PB1(II), cdiA-CTo3PB1(II) and cdiA-CTo4PB1(II)) share significant regions of homology with the upstream cdiAPB1(II) gene. The extent of these homologous regions varies between orphans, but the homology to full-length cdiAPB1(II) is limited to regions upstream of the VENN encoding sequences for cdiA-CTo2PB1(II) and cdiA-CTo3PB1(II) (Figure S2 and Figure S3). In contrast, the orphan cdiA-CTo1PB1(II) gene shares no significant identity with the full-length cdiAPB1(II) gene beyond the sequence encoding the VENN peptide (Figure S2C). Downstream of the VENN encoding region, the orphan cdiA-CToPB1(II) genes are unrelated to one another, but have homology to cdiA genes and cdiA-CT fragments from other bacteria. The predicted orphan CdiA-CTo1PB1(II) (UniProt B2K3A6) is related to CdiA-CTs from E. coli A0 34/86 (Q1RPM1; 87% identity over 107 residues) and Enterobacter cloacae subsp. cloacae ATCC 13047 (D5CBA0; 50% identity over 183 residues), as well as to orphan CdiA-CTs from Dickeya zeae Ech1591 (C6CGV6; 88% identity over 111 residues) and Citrobacter rodentium ICC168 (D2TJP2; 86% identity over 107 residues). Orphan CdiA-CTo2PB1(II) (B2K3A4) is related to the CdiA-CT from Serratia proteamaculans 568 (A8GK56; 63% identity over 131 residues). Orphan CdiA-CTo3PB1(II) (B2K3A2) is related to a CdiA-CT from Erwinia amylovora CFBP1430 (D4HWF3; 63% identity over 127 residues) and to orphan CdiA-CTs from E. coli EC869 (B3BM80; 75% identity over 297 residues) and Neisseria meningitidis MC58 (Q9K0T4; 57% identity over 136 residues). Finally, orphan CdiA-CTo4PB1(II) (B2K3A0) is related to the CdiA-CT encoded by the adjacent cdiAPB1(II) gene (39% identity over 179 residues), and also to CdiA-CTs from Klebsiella pneumoniae 342 (B5Y0C2; 61% identity over 263 residues) and Dickeya dadantii Ech586 (D2BZ75; 59% identity over 263 residues).

Fig. 2. Many bacteria contain orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules.

The cdi loci from selected bacterial species are presented using the color-coding scheme in Figure 1. Arrowheads indicate the positions of VENN encoding regions. Probable orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules are indicated with an “o” and numeral. Note the change in scale for the locus from E. coli EC869. The UniProt accession numbers for the encoded CdiA proteins are: Escherichia coli 254 ser. O113:H21 (A1XT91); Edwardsiella ictaluri 93–146 (C5BAK2); Erwinia pyrifoliae DSM 12163 (D2T668); Edwardsiella tarda EIB202 (D0ZDG0); Klebsiella variicola At-22 (D3RCW8); Neisseria menigitidis FAM18 (A1KSB8); Photorhabdus asymbiotica ATCC 43949 (B6VKN5); Pectobacterium wasabiae WPP163 (D0KFH4); Yersinia pseudotuberculosis PB1/+ (B2K3A8); and Escherichia coli EC869 (B3BM48). The E. coli 254 genomic sequence does not include the 5′-end of the cdiA gene. Although some CDI systems, such as those in Y. pseudotuberculosis PB1/+ and Neisseria meningitidis FAM18, have well-ordered arrays of orphan cdiA-CT gene fragments downstream of cdiBAI, other species have more complex genomic arrangements. Klebsiella variicola At-22 and Erwinia pyrifoliae DSM 12163 both contain cdiA-CT fragments that do not encode VENN and lack associated cdiI genes (Figure 2). In several instances, the orphan cdiA-CT genes are disrupted by IS elements and transposon genes. For example, the orphan cdiA-CTo9EC869 from E. coli EC869 is interrupted by an SSuT antimicrobial resistance element [16]. Orphan cdiA-CT fragments can retain varying amounts of cdiA sequence upstream of the VENN-encoding region, but in some cases these homologous sequences are absent (Figure 2). For example, the orphan cdiA-CTo7EC869 gene from E. coli EC869 is unrelated to the adjacent cdiA-CToEC869 fragments, but is almost identical (99% identity from the VENN region onward) to the orphan cdiA-CTo1254 from E. coli strain 254 (Figure S4). Moreover, the associated cdiI immunity genes are also nearly identical. A comparison of the E. coli EC869 and E. coli strain 254 genomes shows that the homology between these orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules begins at the VENN encoding sequence and extends precisely to the VENN sequence of the next cdiA-CT orphan (Figure S4).

Interchange of cdiA-CT/cdiI Modules

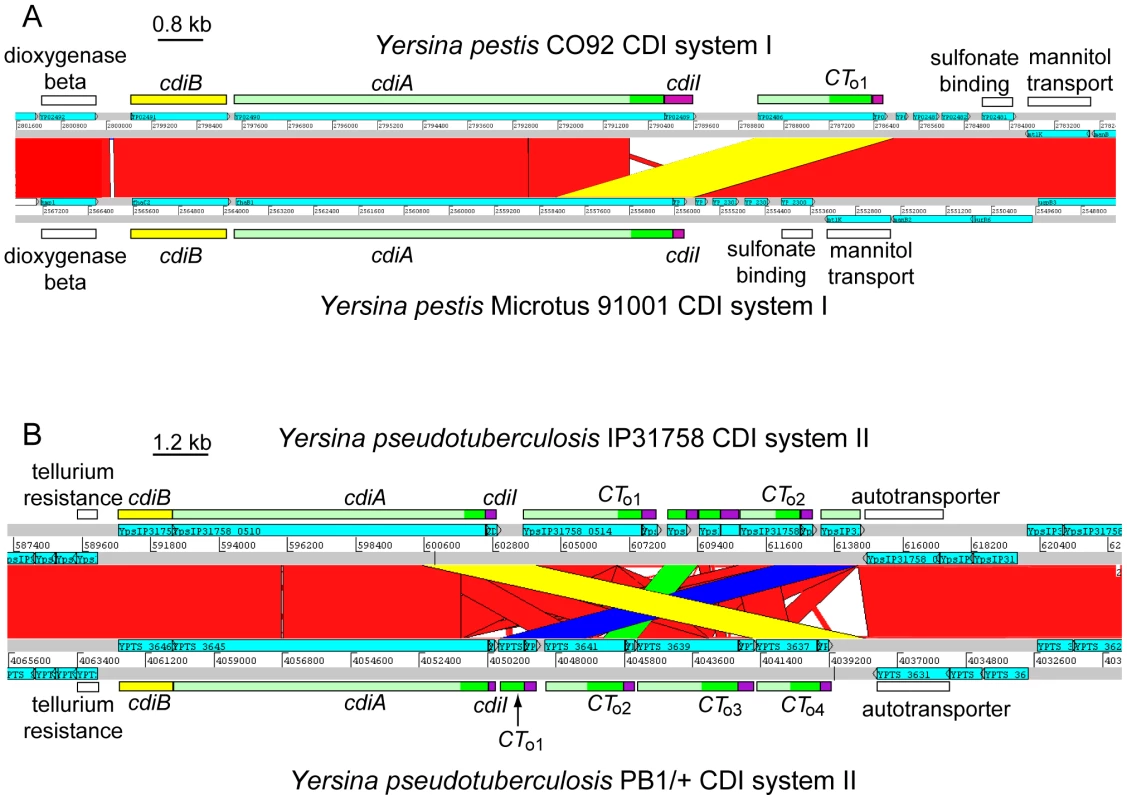

All sequenced Y. pestis strains share two large blocks of conserved DNA that contain cdi loci. For the region I CDI system (positioned between the mannitol transporter and dioxygenase β-subunit genes), the predicted CdiA(I) protein is identical in all fully sequenced Y. pestis strains with the exception of the Microtus 91001 strain. CdiA(I) sequences N-terminal to the VENN motif are essentially identical in Microtus 91001 and other Y. pestis strains, though there is a six amino acid residue deletion within the hemagglutinin repeat region of Microtus 91001. However, following the VENN motif, the CdiA-CT91001(I) of Microtus 91001 diverges from that of other Y. pestis strains (Figure S5). Pairwise comparison of the Y. pestis CO92 and Y. pestis Microtus 91001 genomes revealed a 3,557 base-pair deletion in the Microtus 91001 region I cdi locus that has fused an orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI module to the upstream cdiA91001(I) gene (Figure 3A), producing a CdiA/CdiI toxin/immunity pair that is different from other Y. pestis strains. Thus, the CdiA91001(I) protein from Microtus 91001 contains an orphan CdiA-CT effector domain from the CO92 strain.

Fig. 3. Interchange between cdiA and orphan cdiA-CTs.

A) ACT comparison of the CDI systems (region I) from Y. pestis CO92 (top) and Y. pestis Microtus 91001 (bottom). The cdi loci lie within a highly conserved genomic region (red blocks denote nucleotide conservation), but the sequences encoding CdiA-CT diverge beginning at the VENN region. A 3,557 bp deletion in Y. pestis Microtus 91001 has fused the orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI module to the full-length cdiA gene (highlighted in yellow). B) ACT comparison of region II cdi loci from Y. pseudotuberculosis strains IP31758 (top) and PB1/+ (bottom). The cdi loci lie within a highly conserved genomic region (red denotes nucleotide conservation), but the cdiA-CT sequences exhibit complex rearrangements between the two strains. The orphan cdiA-CTo4PB1(II)/cdiIo4PB1(II) module of strain PB1/+ is essentially identical to the cdiA-CTIP31758(II) and cdiIIP31758(II) sequences from strain IP31758 (99.1% identity over 3,648 nucleotides; highlighted in yellow). Additionally, the orphan cdiA-CTo1PB1(II)/cdiIo1PB1(II) module is nearly identical to the orphan cdiA-CTo2IP31758(II)/cdiIo2IP31758(II) module (98% identity over 2,656 nucleotides, highlighted in blue), and the cdiA-CTo2PB1(II)/cdiIo2PB1(II) module is nearly identical to a cdiA fragment (and associated cdiI gene) found between the two orphan modules in strain IP31758 (98% identity over 1,073 nucleotides; highlighted in green). Another possible example of CdiA-CT interchange is found in the region II CDI system (located between tellurium resistance genes and a predicted autotransporter) shared by Y. pseudotuberculosis PB1/+ and IP31758 strains. The main cdiA-CTIP31758(II) and cdiIIP31758(II) sequences of Y. pseudotuberculosis IP31758 are essentially identical to the cdiA-CTo4PB1(II)/cdiIo4PB1(II) orphan module from strain PB1/+ (99% identity over 3,646 nucleotides) (Figure 3B). Additionally, comparison of these loci revealed other complex rearrangements. The orphan cdiA-CTo1PB1(II)/cdiIo1PB1(II) module of strain PB1/+ is nearly identical to cdiA-CTo2IP31758(II)/cdiIo2IP31758(II) from IP31758 (98% identity over 2,656 nucleotides), and the orphan cdiA-CTo2PB1(II)/cdiIo2PB1(II) from PB1/+ is 98% identical (over 1,073 nucleotides) to a cdiA gene fragment (which lacks the VENN encoding sequence) and its associated cdiI gene in strain IP31758 (Figure 3B). There are at least two possible explanations for these observations. The two Y. pseudotuberculosis strains could have independently acquired the same modules and incorporated them at different sites within the cdi locus. Alternatively, the cdi locus of a common ancestor may have rearranged during strain diversification. Although the mechanisms underlying these complex exchanges are unknown, these observations suggest that orphan cdiA-CT fragments are a potential source of CdiA/CdiI toxin/immunity diversity.

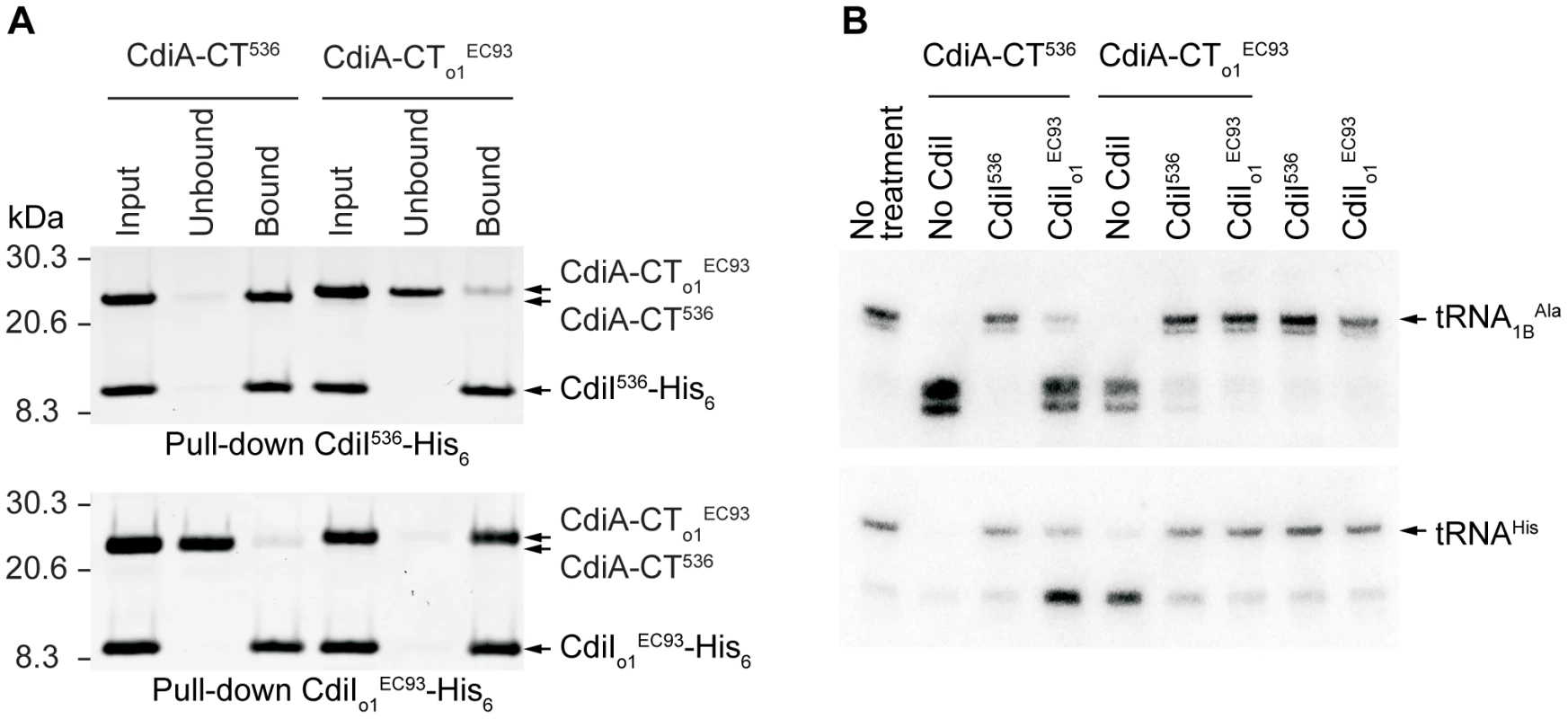

Orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI Modules Are Functional

If orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules are merely unused, nonfunctional remnants of full-length cdiA/cdiI genes, then there should be no selective pressure to maintain CdiA-CT toxin activity and CdiI immunity function. To determine whether orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules encode functional proteins, we characterized the orphan CdiA-CT/CdiI proteins from E. coli EC93. As described above, CdiA-CTo1EC93 and CdiIo1EC93 are very similar to the UPEC 536 CdiA-CTUPEC536/CdiIUPEC536 pair that we have previously characterized [5]. We first tested whether CdiA-CTo1EC93 and CdiIo1EC93 bind to one another as predicted for a toxin/immunity pair. We introduced a translation initiation signal upstream of the cdiA-CTo1EC93 fragment and co-expressed orphan CdiA-CTo1EC93 with CdiIo1EC93 immunity protein carrying a hexa-histidine (His6) epitope tag at its C-terminus. Ni2+-affinity purification of His6-tagged CdiIo1EC93 under non-denaturing conditions resulted in co-purification of CdiA-CTo1EC93 (data not shown), demonstrating that the two proteins bind each other. Given the similarity between CdiA-CTo1EC93 and CdiA-CTUPEC536, we next tested whether the CdiIUPEC536 and CdiIo1EC93 immunity proteins are able to bind near-cognate CdiA-CTs. His6-tagged CdiI proteins were first separated from their cognate CdiA-CT proteins by Ni2+-affinity chromatography under denaturing conditions. The individual proteins were then refolded and tested for binding to their cognate partners. Refolded CdiA-CTo1EC93 and CdiA-CTUPEC536 were able re-bind to their cognate CdiI proteins (Figure 4A). However, the His6-tagged CdiI proteins were unable to bind stably to the near-cognate CdiA-CTs (Figure 4A). These results show that the EC93 orphan CdiA-CT/CdiI proteins physically interact with one another, but appear to have diverged enough from the UPEC 536 system that high-affinity binding between the two systems no longer occurs.

Fig. 4. The tRNase activity of CdiA-CTo1EC93 is blocked by the binding of CdiIo1EC93.

A) Analysis of CdiA-CT/CdiI binding. Purified CdiA-CT and CdiI-His6 proteins were mixed at equimolar ratios then purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography. Input samples represent the protein mixtures prior to chromatography. Unbound fractions contain proteins that failed to bind the affinity resin. Bound proteins were eluted from the affinity resin with imidazole. All fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. B) Northern blot analysis of CdiA-CTUPEC536 and CdiA-CTo1EC93 tRNase activity. S100 fractions containing cellular tRNA was treated with purified CdiA-CT and/or CdiI-His6 proteins and then analyzed by Northern blot hybridization using probes specific for tRNA1BAla and tRNAHis. We previously demonstrated that CdiA-CTUPEC536 is a nuclease that cleaves tRNA [5]; therefore we asked whether CdiA-CTo1EC93 also possesses this biochemical activity. Purified CdiA-CTo1EC93 cleaved a number of different tRNA species in a manner that was indistinguishable from CdiA-CTUPEC536 tRNase activity (Figure 4B and data not shown). This tRNase activity was inhibited by the addition of equimolar His6-tagged CdiIo1EC93 (Figure 4B). Intriguingly, His6-tagged CdiIUPEC536 was also able to neutralize the tRNase activity of CdiA-CTo1EC93, but CdiIo1EC93 had no effect on CdiA-CTUPEC536 activity (Figure 4B). Presumably, CdiIUPEC536 interacts with CdiA-CTo1EC93, but this binding is not of sufficient affinity to allow co-purification by Ni2+-affinity chromatography. Together, these results show that the EC93 orphan CdiA-CT/CdiI proteins retain the biochemical features of a functional toxin/immunity module.

Orphan CdiA-CTs Inhibit Cell Growth

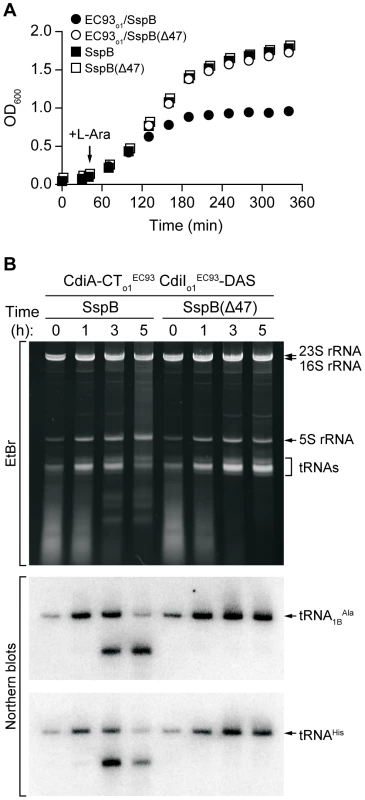

We next asked whether the EC93 orphan CdiA-CT retains growth inhibitory activity. In general, cdiA-CT gene fragments are very toxic and can only be maintained on plasmids if the cognate cdiI immunity gene is also present. However, CdiI immunity proteins efficiently block CdiA-CT activity, making it difficult to assess CdiA-CT toxicity. To circumvent this problem, we used the controllable proteolysis system of McGinness and Sauer [17] to activate CdiA-CTo1EC93 through degradation of the CdiIo1EC93 immunity protein. This strategy uses the SspB adaptor protein to deliver ssrA(DAS) peptide-tagged proteins to the ClpXP protease. We tagged the C-terminus of CdiIo1EC93 with the ssrA(DAS) peptide and co-expressed it with CdiA-CTo1EC93 in E. coli ΔsspB cells. Degradation of tagged CdiIo1EC93 was then initiated by induction of SspB synthesis from a plasmid-borne arabinose-inducible promoter, resulting in growth arrest after approximately 2 hours (Figure 5A). In contrast, growth continued unabated upon induction of SspB(Δ47) (Figure 5A), which lacks the C-terminal motif required for binding to ClpXP. Analysis of total cellular RNA revealed cleavage of tRNAs in the cells expressing wild-type SspB, but not in those expressing SspB(Δ47) (Figure 5B). These results demonstrate that CdiA-CTo1EC93 activity is unmasked upon CdiIo1EC93 degradation. Additionally, the temporal correlation between growth arrest and tRNA cleavage strongly suggests that the tRNase activity of CdiA-CTo1EC93 is responsible for growth inhibition.

Fig. 5. CdiA-CTo1EC93 inhibits the growth of E. coli cells.

A) Growth curves of E. coli ΔsspB cells expressing CdiA-CTo1EC93/CdiIo1EC93-DAS. Degradation of CdiIo1EC93-DAS was initiated by the addition of L-arabinose to induce SspB synthesis. Control cells express SspB(Δ47), which does not deliver CdiIo1EC93-DAS to the ClpXP protease. Growth curves with square symbols represent control strains expressing SspB or SspB(Δ47), but not CdiA-CTo1EC93/CdiIo1EC93-DAS. B) Analysis of in vivo CdiA-CTo1EC93 tRNase activity. Total RNA was isolated from cells expressing CdiA-CTo1EC93/CdiIo1EC93-DAS at varying times after L-arabinose induction. Samples were run on polyacrylamide gels followed by staining with ethidium bromide (EtBr) or Northern blot analysis using probes specific for tRNA1BAla and tRNAHis. To test whether other orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules have growth inhibition activity, we examined orphan gene pairs from Dickeya dadantii 3937 and E. coli EC869. D. dadantii 3937 contains one orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI module in the region I cdi locus. We cloned this module and added a C-terminal His6 epitope tag onto the predicted CdiIo13937 protein. Overproduced CdiA-CTo13937 protein co-purified with CdiIo13937-His6 during Ni2+-affinity chromatography, indicating a binding interaction between these proteins (Figure S6A). Moreover, CdiA-CTo13937 inhibited the growth of E. coli cells upon degradation of ssrA(DAS)-tagged CdiIo13937 (Figure S6B). Examination of the orphan cdiA-CTo11/cdiIo11 module from E. coli EC869 gave similar results, except growth inhibition was delayed compared to the D. dadantii 3937 orphan system (Figure S6). These data demonstrate that other orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules also encode functional toxin/immunity pairs.

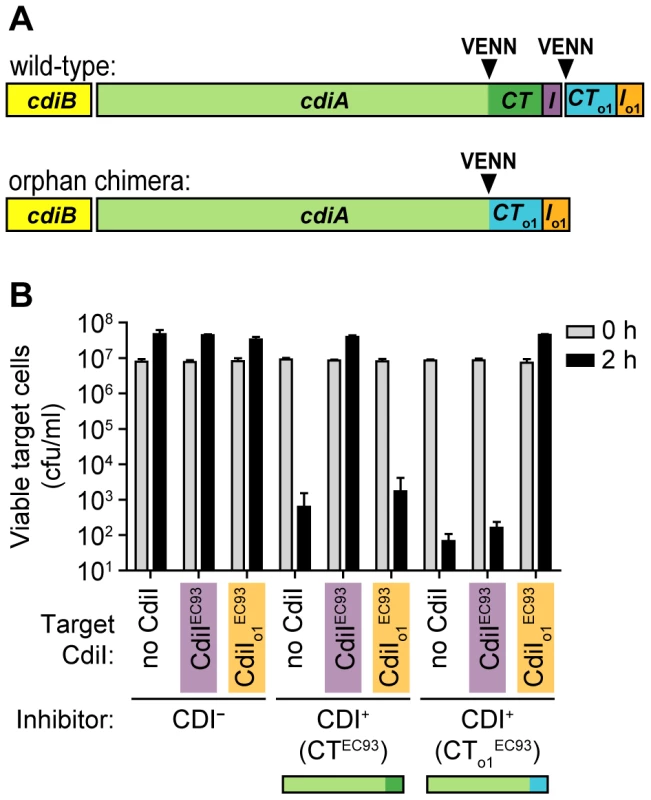

The EC93 orphan cdiA-CTo1EC93 lacks translation initiation signals, suggesting the encoded protein is not synthesized under normal conditions. By analogy with other two-partner secretion proteins, full-length CdiA proteins are secreted through the inner membrane via the general secretory pathway and assembled onto the cell surface through interactions with CdiB [4], [18]. The EC93 orphan cdiA-CTo1EC93 gene also lacks a signal sequence and thus would not be delivered to the cell surface if it were expressed. Therefore to test whether CdiA-CTo1EC93 and CdiIo1EC93 are functional in the context of cell-mediated CDI, we replaced the EC93 cdiA-CTEC93/cdiIEC93 region with the corresponding sequences from the EC93 orphan module. The resulting construct produces a chimeric molecule in which the CdiA-CTo1EC93 is fused to CdiAEC93 at the VENN motif (Figure 6A). E. coli expressing the CdiAEC93-CTo1EC93 chimera inhibited the growth of target cells expressing the CdiIEC93 immunity protein ∼105-fold compared to control CDI− inhibitor cells, but target cells expressing the orphan CdiIo1EC93 were completely protected from growth inhibition (Figure 6B). In contrast, CdiIo1EC93 was unable to protect target cells from growth inhibition mediated by CdiAEC93 (Figure 6B). Thus, the EC93 orphan CdiA-CTo1 is functional in contact-dependent growth inhibition when it is part of a full-length CdiA protein.

Fig. 6. The EC93 orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI module is functional in contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI).

A) The wild-type EC93 and orphan chimera CDI systems are shown schematically. The cdiA-CTEC93/cdiIEC93 region was deleted and orphan module fused onto the cdiAEC93 gene at the VENN encoding sequence. B) Growth competitions. CDI+ inhibitor cells were co-cultured with target cells expressing either CdiIEC93 or orphan CdiIo1EC93 immunity proteins. Viable target cells were quantified by plating on selective media to determine the number of colony forming units (cfu) per milliliter. The Orphan CdiI Immunity Protein Is Expressed in EC93

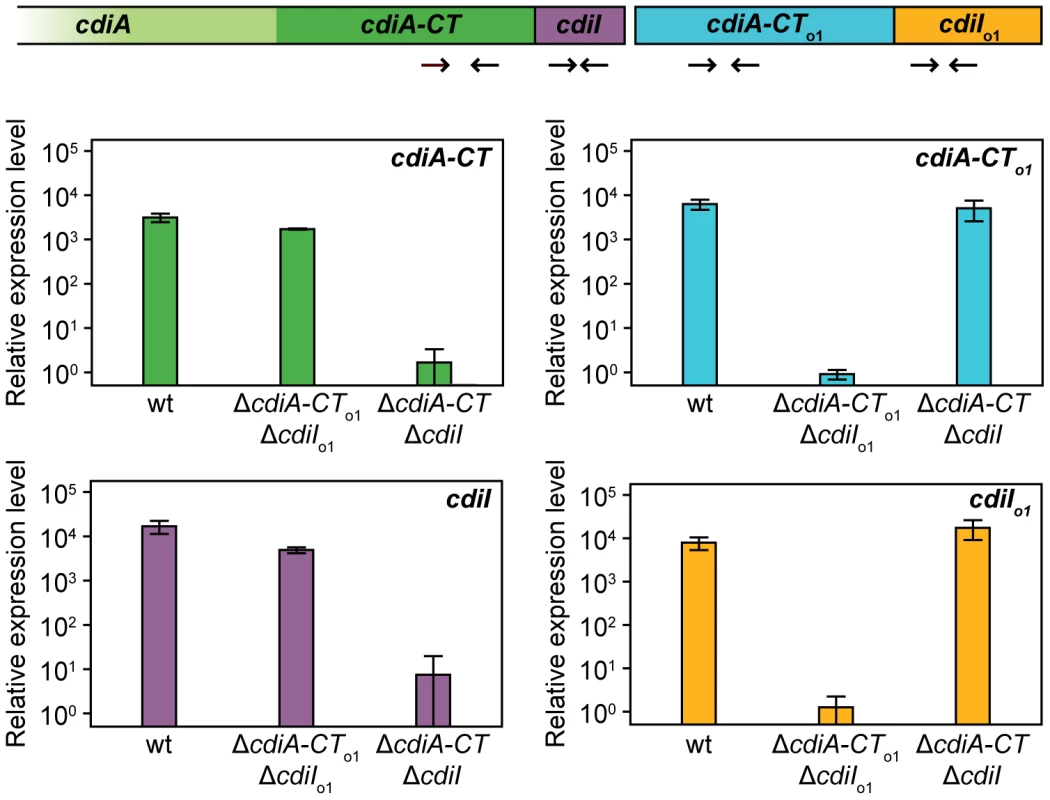

To determine whether orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules are expressed, we isolated total RNA from E. coli EC93 and performed quantitative RT-PCR using primer pairs to amplify from potential cdiA-CTEC93, cdiIEC93, cdiA-CTo1EC93 and cdiIo1EC93 transcripts (Figure 7). This analysis revealed that transcripts encoding orphan cdiA-CTo1EC93 and cdiIo1EC93 are expressed in wild-type EC93 cells, and that orphan message levels are very similar to those encoding the main cdiA-CTEC93 and cdiIEC93 (Figure 7). Additionally, the orphan transcript was expressed at approximately the same level in an EC93 strain deleted for the main cdiA-CTEC93/cdiIEC93 region (Figure 7), indicating that the promoter driving orphan region transcription is upstream of the main cdiA-CTEC93. These results suggest that the orphan region is co-transcribed with the upstream cdiA and cdiI genes. Indeed, a large RT-PCR product was obtained with the forward cdiAEC93 and reverse cdiA-CTo1EC93 primers (data not shown), confirming that all of these ORFs are present on a single transcript. We next sought to detect the CdiA-CTo1EC93 protein by immunoblot using polyclonal antibodies raised against the homologous CdiA-CTUPEC536 from UPEC 536. Although this antiserum detects CdiA-CTo1EC93 produced from a heterologous expression system in E. coli K-12, we were unable to detect CdiA-CTo1EC93 in whole-cell lysates of EC93 (data not shown).

Fig. 7. The EC93 orphan region is transcribed.

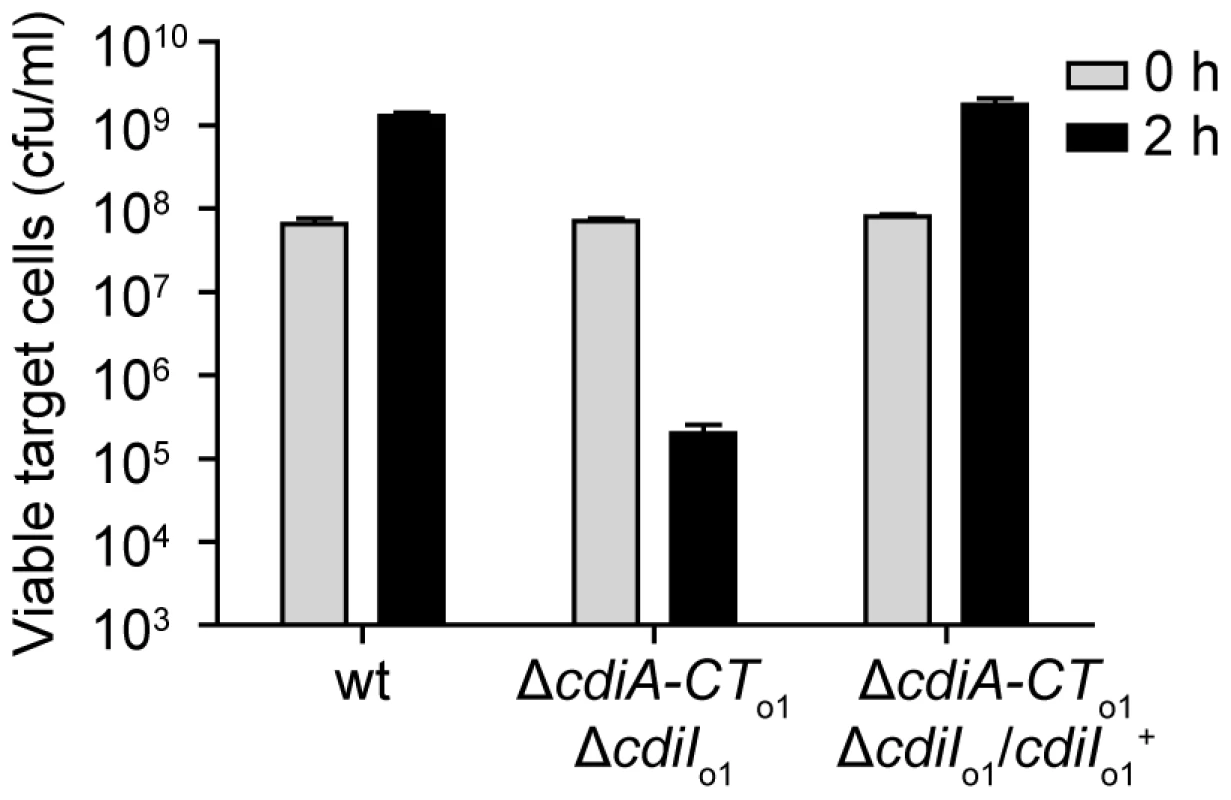

RNA from E. coli EC93, EC93 ΔcdiA-CTEC93ΔcdiIEC93, and EC93 ΔcdiA-CTo1EC93ΔcdiIo1EC93 was subjected to quantitative RT-PCR. The primer binding sites within the cdi locus are depicted schematically as arrows. The relative expression levels represent the mean ± SEM for three independently isolated RNA samples. In contrast to the orphan cdiA-CTo1EC93 fragment, the EC93 cdiIo1EC93 gene has an initiation codon and a properly spaced Shine-Dalgarno sequence, indicating that the CdiIo1EC93 protein is likely to be synthesized in EC93 cells. To determine if orphan CdiIo1EC93 is indeed expressed, we tested whether EC93 cells are resistant to CDI mediated by the chimeric CdiAEC93-CTo1EC93 protein. Because EC93 cells are CDI+, the chimeric inhibitor strain must itself be immune to EC93-mediated CDI. Therefore, we introduced a cosmid encoding the CdiAEC93-CTo1EC93 chimera into EC93 and used the resulting strain as the inhibitor for these experiments. Wild-type EC93 was not inhibited by EC93 expressing the CdiAEC93-CTo1EC93 chimera, but the EC93 ΔcdiA-CTo1EC93/ΔcdiIo1EC93 strain was inhibited approximately 103-fold (Figure 8). This growth inhibition was completely abrogated when orphan CdiIo1EC93 immunity protein was expressed from a plasmid in the EC93 ΔcdiA-CTo1EC93/ΔcdiIo1EC93 cells (Figure 8). Taken together, these results demonstrate that functional CdiIo1EC93 immunity protein is produced from the orphan locus in EC93.

Fig. 8. The EC93 orphan region produces functional CdiIo1 immunity protein.

EC93 expressing chimeric CdiAEC93-CTo1EC93 was used as an inhibitor strain in growth competition experiments. Inhibitor cells were co-cultured with wild-type EC93, EC93 deleted for the orphan region (ΔcdiA-CTo1EC93ΔcdiIo1EC93), and EC93 ΔcdiA-CTo1EC93ΔcdiIo1EC93 cells complemented with a plasmid-borne copy of cdiIo1EC93 (cdiIo1+). Viable target cells were quantified by plating on selective media to determine the number of colony forming units (cfu) per milliliter. rhs Loci Encode Orphan Toxin/Immunity Modules

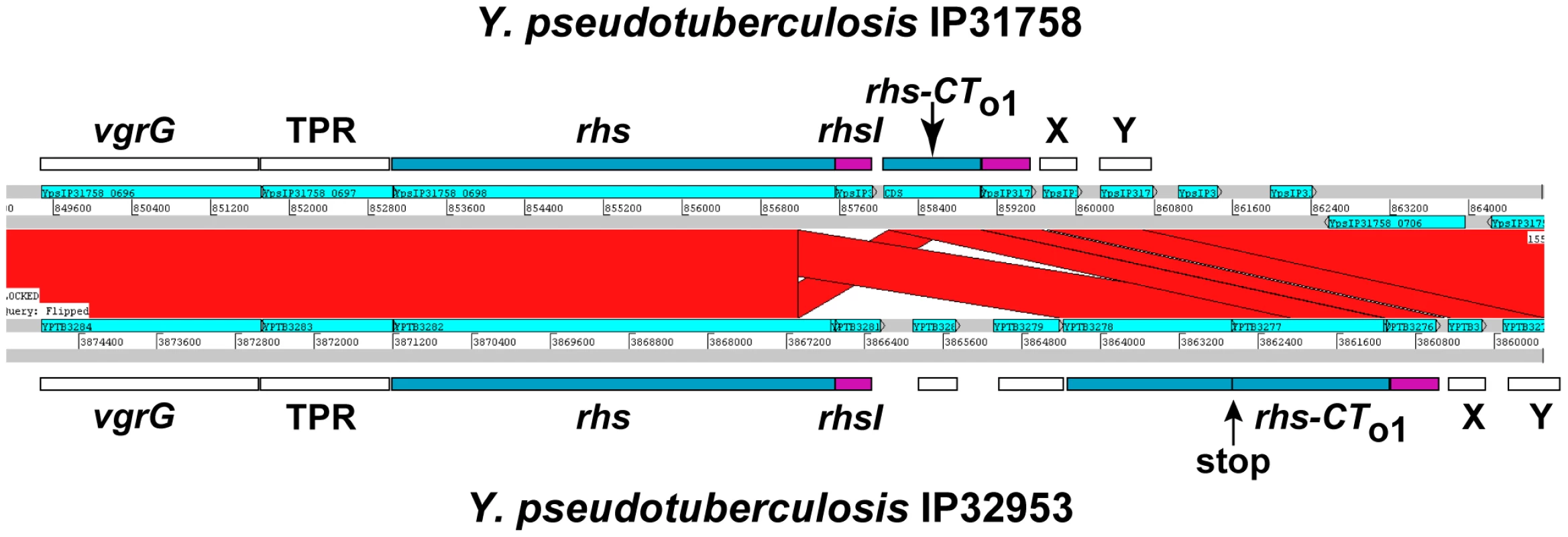

In the course of our bioinformatic analyses, we found that many CdiA-CT sequences share significant identity with the C-terminal regions of Rhs proteins (Table S1). For example, the CdiA-CT91001(I) of Y. pestis Microtus strain 91001 (Q74T84) is similar to the C-terminal region of an Rhs/YD-repeat protein from Waddlia chondrophila WSU 86–1044 (D6YTT8) (Table S1 and Figure S7). The W. chondrophila rhs gene is followed by a small ORF that encodes a protein with similarity to CdiI91001(I) from Y. pestis Microtus 91001 (27% identity over 48 residues), suggesting this locus encodes a toxin/immunity protein pair. Intriguingly, Rhs-CT sequences are variable and demarcated by a well-conserved peptide motif (PxxxxDPxGL) analogous to the VENN motif in CdiA proteins [12], [19]. The parallels between CDI and Rhs systems extend to their genetic organization, with many rhs loci containing numerous “silent cassettes” that resemble CDI orphan modules [12]. Rhs systems also appear to undergo complex rearrangements that diversify Rhs-CT sequences. For example, in one Rhs region shared by Y. pseudotuberculosis strains IP31758 and IP32953, the rhs-CT and putative rhsI sequences are completely unrelated to one another, but the surrounding genomic regions are clearly homologous between the strains (Figure 9). This homology includes rhs coding sequence upstream of the region encoding DPxGL and nearly identical rhs-CT/rhsI orphan modules downstream of the rhs genes (Figure 9 and Figure S8). In addition, orphan rhs-CT/rhsI modules from a given species are often found fused to full-length rhs genes in other bacteria. For example, one of the rhs loci in D. dadantii 3937 contains two orphan rhs-CT/rhsI modules. Both of these predicted orphan Rhs-CT3937 proteins are related to the C-terminal regions of full-length Rhs proteins: Rhs-CTo13937 (E0SGM0) is related to the CT region of a putative Rhs repeat protein (C3K5K6; 49% identity in 147 residues following the DPxGL) from Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25, and Rhs-CTo23937 (E0SGM2) is related to the CT of a predicted YD-repeat protein (C6CNW6; 99% identity in 116 residues) from Dickeya zeae 1591.

Fig. 9. Rhs genes have variable CT encoding sequences, immunity genes, and orphan rhs-CT/rhsI modules.

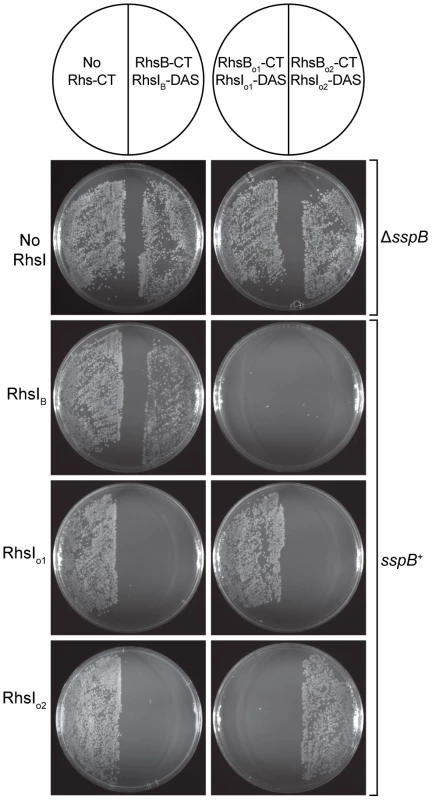

ACT comparison of related Rhs regions from Y. pseudotuberculosis strains IP31758 (top) and IP32953 (bottom). This region is highly conserved between the two strains, but the rhs genes encode unrelated CT sequences and the adjacent rhsI genes are unrelated. Both strains contain a related orphan rhs-CT/rhsI module. The orphan module in strain IP32953 has more upstream rhs coding sequence, but contains an in-frame stop codon in this retained sequence. The vgrG gene is a conserved component of Type VI secretion systems; TPR is a conserved gene encoding a potential tetratricopeptide repeat protein; and X and Y are conserved predicted genes of unknown function. In general, the functions of Rhs proteins are unknown, but data from Hill and colleagues suggest that that the E. coli rhsA locus may encode a toxin/immunity pair [20]. In conjunction with the similarities to CDI systems, these observations suggest that Rhs proteins may be involved in intercellular competition. To test whether other Rhs systems encode toxin/immunity pairs, we examined rhs genes from D. dadantii 3937, which contains three full-length rhs genes that we have termed rhsA (Dda3937_01758), rhsB (Dda3937_02773) and rhsC (Dda3937_04312). Each of these rhs genes is closely followed by a small ORF that encodes a possible immunity protein. Additionally, the rhsC locus contains the two orphan rhs-CT gene fragments described above. We first tested RhsB-CT3937 for growth inhibitory function, because this domain contains an HNH endonuclease motif found in other cytotoxic proteins [21]. We expressed RhsB-CT3937 together with an ssrA(DAS)-tagged version of the putative RhsIB3937 immunity protein in E. coli cells, and found that growth was arrested upon degradation of RhsIB3937-(DAS) (Figure 10 and data not shown). The same results were obtained with the two orphan modules from D. dadantii 3937 (Figure 10 and data not shown), indicating that Rhs-CTo13937 and Rhs-CTo23937 also have growth inhibition activity. These results also demonstrate that the putative rhsI genes do in fact encode proteins with immunity function.

Fig. 10. The Rhs genes of D. dadantii 3937 encode toxin/immunity pairs.

E. coli sspB+ cells expressing RhsI3937 proteins were incubated with supercoiled plasmids encoding the various Rhs-CT3937/RhsI3937-DAS pairs and plated to select stable transformants. All Rhs-CT3937/RhsI3937-DAS constructs were also introduced into E. coli ΔsspB cells to demonstrate that RhsI3937-DAS degradation is required for growth inhibition. Finally, we examined the specificity of RhsI-mediated immunity. Although each Rhs-CT/RhsI-(DAS) expression construct can be maintained stably in E. coli ΔsspB strains, these plasmids cannot be transformed into sspB+ cells due to the Rhs-CT toxicity that results from RhsI-(DAS) degradation (Figure 10 and data not shown). Therefore, we asked whether untagged RhsI protein could rescue cells from Rhs-CT toxicity and allow stable transformation of Rhs-CT/RhsI-(DAS) plasmids into sspB+ cells. Each of the three Rhs-CT/RhsI-(DAS) plasmids were introduced into sspB+ cells expressing individual RhsI proteins, and the transformed cell suspensions plated onto selective media containing L-arabinose to induce Rhs-CT/RhsI-(DAS) synthesis. Transformants carrying the Rhs-CT/RhsI-(DAS) expression plasmid were only obtained if the cells also expressed the cognate RhsI immunity protein (Figure 10). Therefore, each RhsI protein only confers immunity to its cognate Rhs-CT, demonstrating that the Rhs systems of D. dadantii 3937 encode polymorphic toxin/immunity pairs.

Discussion

The results presented here show that many CDI systems have a complex genetic organization in which the cdiBAI genes are followed by an array of orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules. These arrays can be extensive, with eleven orphan gene pairs in the cdi locus of E. coli EC869. The widespread occurrence of orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules in diverse bacterial species argues that these gene pairs confer a selective advantage. Although the majority of orphan cdiA-CT genes lack translation initiation signals, orphan cdiI genes appear to be fully capable of expression. Therefore, bacteria could maintain orphan modules to build a repertoire of immunity genes to protect themselves from neighboring bacteria that express diverse CdiA proteins. Broad range immunity would clearly confer an advantage and our data demonstrate that EC93 does in fact express its orphan CdiI immunity protein. However, if bacteria are collecting immunity genes, then it is unclear why the toxin-encoding cdiA-CT fragments are retained in the process. One model to explain these findings is that orphan modules allow the bacterium to change its toxin/immunity profile by recombination between the highly conserved VENN-encoding sequences. This may have occurred in the cdi locus of Y. pestis Microtus 91001, where a large deletion has loaded an orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI module onto the main cdiA gene. However, such a strategy for generating CdiA-CT diversity could have serious shortcomings. First, although reloading CdiA with a new toxic C-terminal domain would produce a novel weapon, the recombination would also delete cdiI and render the cell susceptible to the original CdiA protein expressed by neighboring bacteria that have not recombined their cdi locus. Second, simple recombination between cdiA and distal orphan cdiA-CT genes would delete all intervening cdiA-CT/cdiI modules. An alternative model is that recombination between cdiA (or rhs) and the orphan regions occurs following tandem duplication of the loci. This mechanism would allow cdiA-CT/cdiI modules to be rearranged without the loss of immunity or genetic diversity, because a copy of the original cdi/rhs system would be present [22], [23].

The results presented here have also revealed a connection between CDI and Rhs systems. The rhs genes were first described in E. coli, and were originally thought to be rearrangement hot spots because of a recombination event between nearly identical sequences within the rhsA and rhsB genes [10], [11]. These proteins are widely distributed throughout the eubacteria and related proteins containing YD peptide repeats are also found in metazoans including all vertebrates. Despite their prevalence, the function of these proteins is almost completely unknown. Our data show that at least some Rhs systems encode toxin/immunity protein pairs, and a recent bioinformatic study has proposed that Rhs proteins contain toxic nuclease domains [24]. These results are consistent with work from Hill and colleagues showing that the C-terminal region of E. coli RhsA blocks the recovery of stationary phase cells [20]. Moreover, this growth inhibition was neutralized by expression of the ORF (yibA) encoded immediately downstream of rhsA [20]. More recently an Rhs-related protein from Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi was found to be associated with bacteriocin activity [25]. Because of the parallels between CDI and Rhs, we suspect that Rhs proteins are also exported to block the growth of neighboring cells and thereby impart a competitive advantage to the inhibitor cell. However, many Rhs proteins from Gram-negative bacteria lack recognizable signal sequences, so the export pathway is unclear in several instances. Many rhs genes are linked to valine-glycine repeat (Vgr)-encoding genes that are associated with Type VI secretion systems [26]. VgrG proteins associated with Type VI secretion systems have structural similarity to bacteriophage cell-puncturing proteins [27], [28], and are therefore ideal for penetrating bacterial envelopes. Indeed, recent work has demonstrated that Type VI systems are used to deliver protein toxins into target bacteria [29]. Whether the close genetic linkage between rhs and vgr genes extends to a functional relationship remains to be determined.

Although the Rhs systems examined here appear to be growth inhibitory, there are indications that Rhs proteins have other signaling modalities. Youdarian and Hartzell found that an Rhs-related YD repeat protein (Q1CXS7) from Myxococcus xanthus plays an important role in social motility [15], which occurs when individual bacteria make contact with one another to coordinate cell movement. The M. xanthus YD repeat protein has a signal sequence and is presumably exported to the surface. The gene encoding Q1CXS7 (MXAN_6679) is closely followed by a small ORF that is suggestive of an rhsI gene. However, it is not clear that immunity would be required in this signaling pathway. Perhaps this small ORF encodes a peptide that is involved in receiving the signal from the C-terminal region of the YD repeat protein. Recent work on the entomopathogen Pantoea stewartii suggests another function for a class of Rhs-related proteins termed Ucp (for you cannot pass) [30]. The P. stewartii genome contains seven ucp homologs that encode large proteins (1,200–1,300 residues) with similar N-terminal regions and variable C-terminal sequences. The Ucp1 protein mediates bacterial aggregation and is a virulence factor required for pathogenicity against the aphid host. It was postulated that Ucp1 and other Ucp proteins function primarily as adhesins and that C-terminal variability is driven by the need to evade host immune responses [30]. Our results suggest an alternative possibility. The C-terminal peptide of Ucp1 could be delivered into insect cells and exert a toxic effect in a manner similar to that proposed for CDI [5]. In this model, the other six Ucp proteins could be targeted against other bacterial competitors or different eukaryotic hosts.

Finally, another intriguing example of Rhs signaling has been proposed for teneurins. The teneurin protein family is comprised of four paralogs that are present in all vertebrates [31]. These proteins are type II integral membrane proteins (single transmembrane span with the C-terminus presented extracellularly) that play a role in axon guidance and neural patterning during development [31], [32]. Like Rhs proteins, the teneurins are large (2,500–2,800 residues) and the C-terminal half is comprised of several YD peptide repeats. Remarkably, all teneurins contain a C-terminal associated peptide (TCAP) that is similar to neuroendocrine signaling peptides [33], [34]. The TCAP region is adjacent to a phylogenetically conserved furin protease cleavage site (RxRR) [31], suggesting that the TCAPs are released and enter target cells to exert neuromodulatory effects. Because some CdiA-CTs and Rhs-CTs have toxic nuclease activity, presumably they must also be cleaved for delivery into the cytoplasm of target cells. The parallel between CDI/Rhs-mediated growth inhibition and the proposed teneurin signaling pathway is striking, suggesting that intercellular communication through the delivery of cleaved C-terminal peptides is ubiquitous and possibly ancient. Perhaps these systems have arisen from a common YD-repeat protein ancestor.

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatic Analysis

Pairwise sequence comparisons were performed using GCG Gap or pairwise BLAST. Related CdiA-CT, Rhs-CT, CdiI, RhsI and orphan sequences were found using TBLASTN against assembled bacterial genomes, because these regions are often not annotated and thus not represented in the non-redundant protein database. Pairwise comparisons of genomic regions were performed using WebACT (www.webact.org) with BLASTN comparisons. The UniProt, GenBank and gene locus accession numbers for each full-length CdiA and Rhs protein discussed in this work are presented in Table S2.

Plasmid Constructs

The orphan cdiA-CTo1EC93/cdiIo1EC93 module from E. coli EC93 was amplified using oligonucleotides, EC93orph-Nco (5′ - TTG CCA TGG AGA ATA ACT CGC TGA GC) and EC93orph-Spe (5′ - ATC ACT AGT GGC ATT AGA TAG CTT ATC TAT TTT TGC) (restriction endonuclease sites are underlined), followed by digesting with NcoI and SpeI, and ligation to plasmid pET21S [5]. The resulting construct overproduces CdiA-CTo1EC93 and C-terminally His6-tagged CdiIo1EC93. The EC93 orphan immunity gene was amplified using primers #1658 (5′ - CAA CAA GCA TGC CCC GAC TTT GAG ACC AGA ATA TC) and #1664 (5′ - ATC AGG AGC ATG GTA TAT GAC AAC ATT TAG ATC). The resulting PCR product was digested with SphI and ligated to EcoRV/SphI digested plasmid pBR322 under control of the tet promoter.

Orphan cdiA-CT/cdiI modules from D. dadantii 3937 and E. coli EC869 were amplified using 3937orph-Nco (5′ - AAG CCA TGG TGG AGA ATA ACT ATC TGA GCA G) and 3937orph-Spe (5′ - TCT ACT AGT AGG CTG GTA ATC TTC ATA TTC C); and EC869orph11-Nco (5′ - ATT CCA TGG GCA CAA ACC AGT CTC TGA CCT TCG) and EC869orph11-Spe (5′ - TCT ACT AGT ACC TTT GCA GCG ACT CAA GGC CAG), respectively. The rhs-CT3937/rhsI3937 modules from D. dadantii 3937 were amplified using the following primer pairs: rhsB-Nco (5′ - CAG CCA TGG AAA GTA ATT ACG GTT ATG TCC) and rhsB-Spe (5′ -AAA CTA GTA ATT TTT CTT GAT TTA TAT TTT ACA AGC); rhs-orph1-Nco (5′ - TCC CAT GGG GTT GGT GGG ATG TCC GC) and rhs-orph1-Spe (5′ - AAA ACT AGT GCC ATC AAG GTA TAC AGA AGG); and rhs-orph2-Nco (5′ - ACC CCA TGG GGC TGG CAG GGG GGC TG) and rhs-orph2-Spe (5′ - TTT ACT AGT AAC AGC TTT GTA ATA ATC GTG). All PCR products were digested with NcoI and SpeI and ligated to pET21S. The D. dadantii rhsI3937 genes were amplified from pET21S constructs using primer pET-Pst (5′ - CGG CTG CAG CAG CCA ACT CAG TGG) in conjunction with primers: rhsIB-Nco (5′ - TAA CCA TGG ATA TTG AAA ATG C), rhsIo1-Nco (5′ - TCA CCA TGG ATT CTA GTG ATA AG), and rhsIo2-Nco (5′ - AAT CCA TGG ATG CTG AAC AAT TTG). The resulting PCR products were digested with NcoI and PstI and ligated to plasmid pCH450 [35].

A cassette encoding the ssrA(DAS) peptide tag (AANDENYSENYADAS) was generated from oligonucleotides, DAS-top (5′ - CTA GTG CTG CGA ACG ATG AAA ATT ACT CCG AAA ATT ATG CGG ATG CGT CTT AAT G) and DAS-bot (5′ - GAT CCA TTA AGA CGC ATC CGC ATA ATT TTC GGA GTA ATT TTC ATC GTT CGC AGC A), and ligated to SpeI/BamHI digested plasmid pKAN [36]. As part of an unrelated study, a fragment of the E. coli hisS gene was cloned into pKAN(DAS) using SacI and SpeI sites. The resulting hisS-(DAS) SacI/BamHI fragment was subcloned into plasmid pTrc99A (Amersham Pharmacia) to generate plasmid pTrc(DAS). All cdiA-CT/cdiI and rhs-CT/rhsI modules were subcloned into pTrc(DAS) using NcoI and SpeI restriction sites. The sspB and sspB(Δ47) genes were amplified using SspB-Nde (5′ - GAG TTA ATC CAT ATG GAT TTG TCA CAG C) in combination with SspBΔ47-Bam (5′ - TGC GGA TCC TTA ATT CAT GAT GCT GGT ATG TTC ATC GTA GGC) and SspB-Bam (5′ - ATA TGA TTG CCA GGA TCC CGC TAT TTT ATT AAG TC), respectively. Both PCR products were digested with NdeI and BamHI and ligated to plasmid pCH410, allowing L-arabinose control of SspB and SspB(Δ47) expression [37].

The orphan cdiA-CTo1EC93/cdiIo1EC93 module from E. coli EC93 was fused to the full-length EC93 cdiAEC93 gene in multiple steps. A fragment of cdiAEC93 (upstream of the VENN encoding sequence) was amplified using primers, #1527 (5′ - GAA CAT CCT GGC ATG AGC G) and #1758 (5′ - CAA GCT CAG CGA GTT ATT CTC AAC CGA GTT CCT ACC TGC CTG). The EC93 orphan module was amplified using primers, #1759 (5′ - CAG GCA GGT AGG AAC TCG GTT GAG AAT AAC TCG CTG AGC TTG) and #1663 (5′ - GGT CTG GTG TCT AAC CTT TGG G). The two products were combined by overlapping-end PCR using primers #1527 and #1663, and the resulting product digested with SphI and AvrII and ligated to plasmid pDAL660Δ1-39 [4].

In Vitro Characterization of Orphan Modules

All CdiA-CT/CdiI-His6 complexes were overproduced and purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography as described [5]. Complexes were eluted from Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid resin with native elution buffer [20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) –10 mM β-mercaptoethanol – 250 mM imidazole], followed by dialysis in storage buffer [20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) – 150 mM NaCl – 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol]. CdiA-CT and CdiI-His6 proteins were separated from one another by Ni2+-affinity chromatography with denaturing buffer [20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) – 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol – 6 M guanidine-HCl]. Denatured proteins were refolded by dialysis into storage buffer. All purified proteins were quantified by absorbance at 260 nm using the following molar extinction coefficients: CdiA-CTUPEC536, 12,950 M−1 cm−1; CdiIUPEC536, 8,480 M−1 cm−1; CdiA-CTo1EC93, 11,460 M−1 cm−1; and CdiIo1EC93, 11,460 M−1 cm−1. The specificity of CdiA-CT/CdiI-His6 binding interactions was determined by Ni2+-affinity co-purification as described [5]. The tRNase activity of isolated and refolded CdiA-CTUPEC536 and CdiA-CTo1EC93 proteins was determined as described [5], [37].

In Vivo Activity of Orphan Modules

E. coli strain CH4180 (×90 ΔsspB) was co-transformed with pTrc(DAS) orphan module constructs and either the SspB or SspB(Δ47) arabinose-inducible expression plasmids. The resulting strains were grown at 37°C with aeration in LB media supplemented with 150 µg/mL ampicillin and 10 µg/mL tetracycline (to maintain plasmids) to mid-log phase and re-diluted into fresh media to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05. After 40 min, SspB or SspB(Δ47) expression was induced by the addition of 0.4% L-arabinose. Cell growth was tracked by measuring the OD600 every 30 min after induction. Cells expressing CdiA-CTo1EC93/CdiIo1EC93-DAS were harvested into an equal volume of ice-cold methanol and RNA extracted as described [38]. Northern blot hybridizations were conducted as described [37], using radiolabeled oligonucleotides tRNAHis probe (5′ - CAC GAC AAC TGG AAT CAC) and tRNA1BAla probe (5′ - TCC TGC GTG AGC AG) as probes.

E. coli sspB+ cells expressing RhsIB3937, RhsIo13937 and RhsIo23937 were transformed with plasmids encoding rhs-CT/rhsI(DAS) modules under control of the PBAD promoter [39]. Competent cells were incubated with 0.5 µg of purified supercoiled plasmid for 20 min on ice, then heat-shocked at 42°C for 45 s. The treated cells were recovered in 1.0 mL of LB media for 2 hr without selection, then 20 µL of the cell suspension was plated onto LB-agar supplemented with ampicillin (150 µg/mL), tetracycline (10 µg/mL) and 0.4% L-arabinose. E. coli ΔsspB cells were also transformed in the same manner with arabinose-inducible rhs-CT/rhsI(DAS) constructs to confirm that growth inhibition was dependent upon RhsI-DAS degradation.

EC93 cdiA-CT/cdiI Deletions

The main cdiA-CTEC93 region and cdiIEC93 gene were deleted from rifampicin-resistant E. coli strain EC93 (DL3852) using allelic exchange as described [4], [40]. Sequence upstream of cdiA-CTEC93 was amplified using oligonucleotides #1683 (5′ - CAA CAA GAG CTC GAA CAT CCT GGC ATG AGC G) and #1684 (5′ - CAG CGA GTT ATT CTC AAC AAC AAC TA CGA GTT CCT ACC TGC CTG) (SacI restriction endonuclease site is underlined). Sequence downstream of cdiIEC93 (including the cdiIEC93 stop codon) was amplified using oligonucleotides #1685 (5′ - CAG GCA GGT AGG AAC TCG tag TTG TTG TTG AGA ATA ACT CGC TG) and #1686 (5′ - CAA CAA TCT AGA CCC GAC TTT GAG ACC AGA ATA TC) (XbaI restriction endonuclease site is underlined). The two PCR products were combined by overlapping-end PCR using primers #1683 and #1686, and the resulting product digested with SacI and XbaI and ligated to suicide vector pRE112 [40].

The orphan cdiA-CToEC93/cdiIoEC93 module was deleted from rifampicin-resistant EC93 in a similar manner. Sequence upstream of cdiA-CTo1EC93 was amplified using oligonucleotides #1714 (5′ - CAA CAA GAG CTC GTG AAG GTG GGC TTA CTC AG) and #1715 (5′ - CGA CTT TGA GAC CAG AAT ATC TAT TTA CTC AAC AAC AAC TAT TTT CTG TCT AAG) (SacI restriction endonuclease site is underlined). Sequence downstream of cdiIo1EC93 (including the cdiIo1EC93 stop codon) was amplified using oligonucleotides #1716 (5′ - CTT AGA CAG AAA ATA GTT GTT GTT GAG TAA ATA GAT ATT CTG GTC TCA AAG TCG) and #1717 (5′ - CAA CAA TCT AGA CCC GTA AGT ATG CTT ATC CCA TG) (XbaI restriction endonuclease site is underlined). The two PCR products were combined by overlapping-end PCR using primers #1714 and #1717, and the resulting product digested with SacI and XbaI and ligated to suicide vector pRE112 [40].

Growth Competition Assays

E. coli strain EPI100 carrying plasmids pWEB-TNC (CDI−), pDAL660Δ1-39 (CdiAEC93), or pDAL879 (CdiAEC93-CTo1EC93 chimera) were grown overnight at 37°C in LB media supplemented 100 µg/mL of ampicillin. Overnight cultures were diluted into fresh medium to OD600 of 0.05, and incubated at 37°C with aeration until the culture reached mid-log phase (OD600≈0.3). The log-phase inhibitor cultures were then mixed with target E. coli cells – CAG18439 pBR322 (no CdiI), pDAL741 (CdiIEC93), or pDAL867 (CdiIo1EC93) – at an inhibitor to target cell ratio of 10∶1. The co-cultures were incubated for 2 hr at 37°C with aeration. Viable target cell counts were determined by serially dilution of the co-cultures into M9 salt solution followed by plating onto LB agar supplemented with 10 µg/mL of tetracycline.

To assay CdiIo1 expression in EC93, growth competitions were conducted with streptomycin-resistant EC93 (DL6104) carrying pDAL879 (CdiAEC93-CTo1EC93 chimera) as the inhibitor strain. Target strains were rifampicin-resistant EC93 carrying plasmid pBR322 (no CdiI), and rifampicin-resistant EC93 ΔcdiA-CTo1 ΔcdiIo1 cells carrying pBR322 (no CdiI) or pDAL867 (CdiIo1EC93). Growth competitions were conducted as described above except that mid-log phase cells were mixed and co-cultured at an inhibitor to target ratio of 1∶1. Viable target cell counts were determined by serial dilution of the co-cultures into M9 salt solution followed by plating onto LB agar supplemented with 150 µg/mL of rifampicin.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from wild-type EC93 and EC93 strains deleted for cdiA-CTEC93/cdiIEC93 and cdiA-CTo1EC93/cdiIo1EC93, followed by treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Roche) to remove contaminating chromosomal DNA. RNA (0.5 µg) was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). A control without reverse transcriptase was also prepared to assess chromosomal DNA contamination. Quantitative PCR was carried out on a Bio-Rad MyiQ single-color real-time PCR detection system using SYBR green supermix. The following primers sets were used for amplification: #1700 (5′ - GGT GAA GGT GGG CTT ACT CA) and #1701 (5′ - TGA TGT GAC AGA GCC AAA GC) for cdiA-CTEC93; #1698 (5′ - TGC TAT GTA CTG TAC TTG GTC) and #1699 (5′ - TAA AGC CTA TGG GAT TCC T) for cdiIEC93; #1647 (5′ - ACT GAC CGC TGA TGA ACT GG) and #1648 (5′ - AGT AGC CGC TTG AAC CTG CAC) for cdiA-CTo1EC93; #1649 (5′ - TGA ACC CAA CAG TCG CTC TTC) and #1650 (5′ - GTC TTC CCC AGC CAG AGG AT) for cdiIo1EC93; #1568 (5′ - TCA CCC CAG TCA TGA ATC AC) and #1569 (5′ - TGC AAC TCG ACT CCA TGA AG) for 16S rRNA. Thermal cycling conditions were: 95°C for 5 min for polymerase activation and collection of experimental well factors and 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 s; 56°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30s followed by a melting curve (55°C to 95°C) to analyze the end product. Data were analyzed using the iQ5 optical system software (Bio-Rad) and exported to Microsoft Excel and Prism 5.0 for further analysis. For each target gene, a standard curve was generated to assess PCR efficiency (E) allowing the expression level (e) to be determined, where (e) = (Etarget)−Ct target/(Eref)−Ct ref [41]. Gene expression was normalized to a 16S rRNA RT-PCR product amplified from the corresponding sample, and the reported values represent the mean ± SEM from three independent RNA extractions.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. NadellCDBasslerBLLevinSA 2008 Observing bacteria through the lens of social evolution. J Biol 7 27

2. NgWLBasslerBL 2009 Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu Rev Genet 43 197 222

3. LobedanzSSogaard-AndersenL 2003 Identification of the C-signal, a contact-dependent morphogen coordinating multiple developmental responses in Myxococcus xanthus. Genes Dev 17 2151 2161

4. AokiSKPammaRHerndayADBickhamJEBraatenBA 2005 Contact-dependent inhibition of growth in Escherichia coli. Science 309 1245 1248

5. AokiSKDinerEJt'Kint de RoodenbekeCBurgessBRPooleSJ 2010 A widespread family of polymorphic contact-dependent toxin delivery systems in bacteria. Nature 468 439 442

6. ChoiPSBernsteinHD 2010 Sequential translocation of an Escherchia coli two-partner secretion pathway exoprotein across the inner and outer membranes. Mol Microbiol 75 440 451

7. MazarJCotterPA 2007 New insight into the molecular mechanisms of two-partner secretion. Trends Microbiol 15 508 515

8. BaudCHodakHWilleryEDrobecqHLochtC 2009 Role of DegP for two-partner secretion in Bordetella. Mol Microbiol 74 315 329

9. ClantinBDelattreASRucktooaPSaintNMeliAC 2007 Structure of the membrane protein FhaC: a member of the Omp85-TpsB transporter superfamily. Science 317 957 961

10. CapageMHillCW 1979 Preferential unequal recombination in the glyS region of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Mol Biol 127 73 87

11. LinRJCapageMHillCW 1984 A repetitive DNA sequence, rhs, responsible for duplications within the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. J Mol Biol 177 1 18

12. JacksonAPThomasGHParkhillJThomsonNR 2009 Evolutionary diversification of an ancient gene family (rhs) through C-terminal displacement. BMC Genomics 10 584

13. FosterSJ 1993 Molecular analysis of three major wall-associated proteins of Bacillus subtilis 168: evidence for processing of the product of a gene encoding a 258 kDa precursor two-domain ligand-binding protein. Mol Microbiol 8 299 310

14. McNultyCThompsonJBarrettBLordLAndersenC 2006 The cell surface expression of group 2 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli: the role of KpsD, RhsA and a multi-protein complex at the pole of the cell. Mol Microbiol 59 907 922

15. YouderianPHartzellPL 2007 Triple mutants uncover three new genes required for social motility in Myxococcus xanthus. Genetics 177 557 566

16. KhachatryanARBesserTECallDR 2008 The streptomycin-sulfadiazine-tetracycline antimicrobial resistance element of calf-adapted Escherichia coli is widely distributed among isolates from Washington state cattle. Appl Environ Microbiol 74 391 395

17. McGinnessKEBakerTASauerRT 2006 Engineering controllable protein degradation. Mol Cell 22 701 707

18. AokiSKMalinverniJCJacobyKThomasBPammaR 2008 Contact-dependent growth inhibition requires the essential outer membrane protein BamA (YaeT) as the receptor and the inner membrane transport protein AcrB. Mol Microbiol 70 323 340

19. ZhaoSHillCW 1995 Reshuffling of Rhs components to create a new element. J Bacteriol 177 1393 1398

20. VlaznyDAHillCW 1995 A stationary-phase-dependent viability block governed by two different polypeptides from the RhsA genetic element of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 177 2209 2213

21. MehtaPKattaKKrishnaswamyS 2004 HNH family subclassification leads to identification of commonality in the His-Me endonuclease superfamily. Protein Sci 13 295 300

22. BergthorssonUAnderssonDIRothJR 2007 Ohno's dilemma: evolution of new genes under continuous selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 17004 17009

23. ReamsABKofoidESavageauMRothJR 2010 Duplication frequency in a population of Salmonella enterica rapidly approaches steady state with or without recombination. Genetics 184 1077 1094

24. ZhangDIyerLMAravindL 2011 A novel immunity system for bacterial nucleic acid degrading toxins and its recruitment in various eukaryotic and DNA viral systems. Nucleic Acids Res 39 4532 4552

25. SistoACiprianiMGMoreaMLonigroSLValerioF 2010 An Rhs-like genetic element is involved in bacteriocin production by Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 98 505 517

26. WangYDZhaoSHillCW 1998 Rhs elements comprise three subfamilies which diverged prior to acquisition by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 180 4102 4110

27. PukatzkiSMaATRevelATSturtevantDMekalanosJJ 2007 Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 15508 15513

28. PukatzkiSMcAuleySBMiyataST 2009 The type VI secretion system: translocation of effectors and effector-domains. Curr Opin Microbiol 12 11 17

29. HoodRDSinghPHsuFGuvenerTCarlMA 2010 A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 7 25 37

30. StavrinidesJNoAOchmanH 2010 A single genetic locus in the phytopathogen Pantoea stewartii enables gut colonization and pathogenicity in an insect host. Environ Microbiol 12 147 155

31. TuckerRPChiquet-EhrismannR 2006 Teneurins: a conserved family of transmembrane proteins involved in intercellular signaling during development. Dev Biol 290 237 245

32. YoungTRLeameyCA 2009 Teneurins: important regulators of neural circuitry. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41 990 993

33. LovejoyDAAl ChawafACadinoucheMZ 2006 Teneurin C-terminal associated peptides: an enigmatic family of neuropeptides with structural similarity to the corticotropin-releasing factor and calcitonin families of peptides. Gen Comp Endocrinol 148 299 305

34. WangLRotzingerSAl ChawafAEliasCFBarsyte-LovejoyD 2005 Teneurin proteins possess a carboxy terminal sequence with neuromodulatory activity. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 133 253 265

35. Garza-SanchezFShojiSFredrickKHayesCS 2009 RNase II is important for A-site mRNA cleavage during ribosome pausing. Mol Microbiol 73 882 897

36. HayesCSBoseBSauerRT 2002 Proline residues at the C terminus of nascent chains induce SsrA tagging during translation termination. J Biol Chem 277 33825 33832

37. HayesCSSauerRT 2003 Cleavage of the A site mRNA codon during ribosome pausing provides a mechanism for translational quality control. Mol Cell 12 903 911

38. Garza-SánchezFJanssenBDHayesCS 2006 Prolyl-tRNAPro in the A-site of SecM-arrested ribosomes inhibits the recruitment of transfer-messenger RNA. J Biol Chem 281 34258 34268

39. GuzmanLMBelinDCarsonMJBeckwithJ 1995 Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol 177 4121 4130

40. EdwardsRAKellerLHSchifferliDM 1998 Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207 149 157

41. PfafflMW 2001 A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29 e45

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The T-Box Factor MLS-1 Requires Groucho Co-Repressor Interaction for Uterine Muscle SpecificationČlánek B Chromosomes Have a Functional Effect on Female Sex Determination in Lake Victoria Cichlid FishesČlánek Distinct Cdk1 Requirements during Single-Strand Annealing, Noncrossover, and Crossover RecombinationČlánek Specification of Corpora Cardiaca Neuroendocrine Cells from Mesoderm Is Regulated by Notch SignalingČlánek Ongoing Phenotypic and Genomic Changes in Experimental Coevolution of RNA Bacteriophage Qβ and

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 8

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Polo, Greatwall, and Protein Phosphatase PP2A Jostle for Pole Position

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Incident Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) in African Americans: A Short Report

- The T-Box Factor MLS-1 Requires Groucho Co-Repressor Interaction for Uterine Muscle Specification

- B Chromosomes Have a Functional Effect on Female Sex Determination in Lake Victoria Cichlid Fishes

- Analysis of DNA Methylation in a Three-Generation Family Reveals Widespread Genetic Influence on Epigenetic Regulation

- PP2A-Twins Is Antagonized by Greatwall and Collaborates with Polo for Cell Cycle Progression and Centrosome Attachment to Nuclei in Drosophila Embryos

- Discovery of Sexual Dimorphisms in Metabolic and Genetic Biomarkers

- Pervasive Sharing of Genetic Effects in Autoimmune Disease

- DNA Methylation and Histone Modifications Regulate Shoot Regeneration in by Modulating Expression and Auxin Signaling

- Mutations in and Reveal That Cartilage Matrix Controls Timing of Endochondral Ossification by Inhibiting Chondrocyte Maturation

- Variance of Gene Expression Identifies Altered Network Constraints in Neurological Disease

- Frequent Beneficial Mutations during Single-Colony Serial Transfer of

- Increased Gene Dosage Affects Genomic Stability Potentially Contributing to 17p13.3 Duplication Syndrome

- Distinct Cdk1 Requirements during Single-Strand Annealing, Noncrossover, and Crossover Recombination

- Hunger Artists: Yeast Adapted to Carbon Limitation Show Trade-Offs under Carbon Sufficiency

- Suppression of Scant Identifies Endos as a Substrate of Greatwall Kinase and a Negative Regulator of Protein Phosphatase 2A in Mitosis

- Temporal Dynamics of Host Molecular Responses Differentiate Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Influenza A Infection

- MK2-Dependent p38b Signalling Protects Hindgut Enterocytes against JNK-Induced Apoptosis under Chronic Stress

- Specification of Corpora Cardiaca Neuroendocrine Cells from Mesoderm Is Regulated by Notch Signaling

- Genome-Wide Gene-Environment Study Identifies Glutamate Receptor Gene as a Parkinson's Disease Modifier Gene via Interaction with Coffee

- Identification of Functional Toxin/Immunity Genes Linked to Contact-Dependent Growth Inhibition (CDI) and Rearrangement Hotspot (Rhs) Systems

- Genomic Analysis of the Necrotrophic Fungal Pathogens and

- Celsr3 Is Required for Normal Development of GABA Circuits in the Inner Retina

- Genetic Architecture of Aluminum Tolerance in Rice () Determined through Genome-Wide Association Analysis and QTL Mapping

- Predisposition to Cancer Caused by Genetic and Functional Defects of Mammalian

- Regulation of p53/CEP-1–Dependent Germ Cell Apoptosis by Ras/MAPK Signaling

- and but Not Interact in Genetic Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- Gamma-Tubulin Is Required for Bipolar Spindle Assembly and for Proper Kinetochore Microtubule Attachments during Prometaphase I in Oocytes

- Ongoing Phenotypic and Genomic Changes in Experimental Coevolution of RNA Bacteriophage Qβ and

- Genetic Architecture of a Reinforced, Postmating, Reproductive Isolation Barrier between Species Indicates Evolution via Natural Selection

- -eQTLs Reveal That Independent Genetic Variants Associated with a Complex Phenotype Converge on Intermediate Genes, with a Major Role for the HLA

- The GATA Factor ELT-1 Works through the Cell Proliferation Regulator BRO-1 and the Fusogen EFF-1 to Maintain the Seam Stem-Like Fate

- and Control Optic Cup Regeneration in a Prototypic Eye

- A Comprehensive Map of Mobile Element Insertion Polymorphisms in Humans

- An EMT–Driven Alternative Splicing Program Occurs in Human Breast Cancer and Modulates Cellular Phenotype

- Evidence for Hitchhiking of Deleterious Mutations within the Human Genome

- A Broad Brush, Global Overview of Bacterial Sexuality

- Global Chromosomal Structural Instability in a Subpopulation of Starving Cells

- A Pre-mRNA–Associating Factor Links Endogenous siRNAs to Chromatin Regulation

- Glutamine Synthetase Is a Genetic Determinant of Cell Type–Specific Glutamine Independence in Breast Epithelia

- The Repertoire of ICE in Prokaryotes Underscores the Unity, Diversity, and Ubiquity of Conjugation

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Autoantibody Positivity in Type 1 Diabetes Cases

- Natural Polymorphism in BUL2 Links Cellular Amino Acid Availability with Chronological Aging and Telomere Maintenance in Yeast

- Chromosome Painting Reveals Asynaptic Full Alignment of Homologs and HIM-8–Dependent Remodeling of Chromosome Territories during Meiosis

- Ku Must Load Directly onto the Chromosome End in Order to Mediate Its Telomeric Functions

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- An EMT–Driven Alternative Splicing Program Occurs in Human Breast Cancer and Modulates Cellular Phenotype

- Chromosome Painting Reveals Asynaptic Full Alignment of Homologs and HIM-8–Dependent Remodeling of Chromosome Territories during Meiosis

- Discovery of Sexual Dimorphisms in Metabolic and Genetic Biomarkers

- Regulation of p53/CEP-1–Dependent Germ Cell Apoptosis by Ras/MAPK Signaling

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání