-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaSRFR1 Negatively Regulates Plant NB-LRR Resistance Protein Accumulation to Prevent Autoimmunity

Plant defense responses need to be tightly regulated to prevent auto-immunity, which is detrimental to growth and development. To identify negative regulators of Resistance (R) protein-mediated resistance, we screened for mutants with constitutive defense responses in the npr1-1 background. Map-based cloning revealed that one of the mutant genes encodes a conserved TPR domain-containing protein previously known as SRFR1 (SUPPRESSOR OF rps4-RLD). The constitutive defense responses in the srfr1 mutants in Col-0 background are suppressed by mutations in SNC1, which encodes a TIR-NB-LRR (Toll Interleukin1 Receptor-Nucleotide Binding-Leu-Rich Repeat) R protein. Yeast two-hybrid screens identified SGT1a and SGT1b as interacting proteins of SRFR1. The interactions between SGT1 and SRFR1 were further confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation analysis. In srfr1 mutants, levels of multiple NB-LRR R proteins including SNC1, RPS2 and RPS4 are increased. Increased accumulation of SNC1 is also observed in the sgt1b mutant. Our data suggest that SRFR1 functions together with SGT1 to negatively regulate R protein accumulation, which is required for preventing auto-activation of plant immunity.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 6(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001111

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001111Summary

Plant defense responses need to be tightly regulated to prevent auto-immunity, which is detrimental to growth and development. To identify negative regulators of Resistance (R) protein-mediated resistance, we screened for mutants with constitutive defense responses in the npr1-1 background. Map-based cloning revealed that one of the mutant genes encodes a conserved TPR domain-containing protein previously known as SRFR1 (SUPPRESSOR OF rps4-RLD). The constitutive defense responses in the srfr1 mutants in Col-0 background are suppressed by mutations in SNC1, which encodes a TIR-NB-LRR (Toll Interleukin1 Receptor-Nucleotide Binding-Leu-Rich Repeat) R protein. Yeast two-hybrid screens identified SGT1a and SGT1b as interacting proteins of SRFR1. The interactions between SGT1 and SRFR1 were further confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation analysis. In srfr1 mutants, levels of multiple NB-LRR R proteins including SNC1, RPS2 and RPS4 are increased. Increased accumulation of SNC1 is also observed in the sgt1b mutant. Our data suggest that SRFR1 functions together with SGT1 to negatively regulate R protein accumulation, which is required for preventing auto-activation of plant immunity.

Introduction

To protect themselves from infections by microbial pathogens, plants have evolved a large number of immune receptors to sense pathogen-derived molecules and trigger defense responses [1]. Resistance (R) proteins with nucleotide-binding (NB) and Leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains constitute the main type of intracellular plant immune receptors. In animals, similar nucleotide-binding domain and LRR-containing (NLR) proteins also function as intracellular immune receptors [2]. In plants, activation of NB-LRR R proteins often results in localized programmed cell death known as hypersensitive response (HR), accumulation of defense hormone salicylic acid (SA), and high expression of resistance marker genes termed Pathogenesis-Related (PR) genes [3].

Among the components that are required for R protein triggered immune responses, RAR1, HSP90 and SGT1 are three conserved proteins that function in correct folding and stabilization of NLR R proteins [4]. Loss of RAR1 function leads to compromised resistance mediated by multiple R proteins [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Accumulation of barley MLA proteins, potato Rx, and Arabidopsis RPM1 and RPS5 was reduced when RAR1 function was compromised [7], [10], [11]. Compromising the activity of HSP90 also caused reduced accumulation of several R proteins including RPM1, RPS5 and Rx [11], [12], [13]. The functions of SGT1 appear to be more complex. Silencing of SGT1 in Nicotiana benthamiana resulted in reduced accumulation of Rx, suggesting that similar to RAR1 and HSP90, SGT1 is required for maintaining the protein level of Rx [14]. On the other hand, reduced accumulation of RPS5, but not RPM1 or RPS2, in the rar1 mutant background can be suppressed by the sgt1b loss-of-function mutation. It was suggested that SGT1b antagonize RAR1 in regulating the accumulation of certain R proteins [11].

SGT1 contains three domains including the TPR (tetratricopeptide repeat) domain, the CS (present in CHP and SGT1 proteins) domain and the SGS (SGT1 specific) domain [4]. RAR1 contains two conserved cysteine and histidine rich domains named CHORD-I and CHORD-II [5]. Both SGT1 and RAR1 function as cochaperones of HSP90 [15], [16], [17]. The CS domain of SGT1 and CHORD-I domain of RAR1 bind to HSP90. The CHORDII domain of RAR1 binds to SGT1. In Arabidopsis genome, there are two copies of SGT1 genes, SGT1a and SGT1b. Loss of the function of both genes lead to lethality [14]. Both plant and animal NLR proteins are substrates of the HSP90-RAR1-SGT1 chaperone complex [4]. Binding of SGT1 to these substrates is probably through the SGS domain in SGT1 and LRRs in NLRs [10].

Arabidopsis SNC1 encodes a TIR-NB-LRR type of R protein [18]. In the snc1 mutant, a gain-of-function mutation located in the region between NB and LRR constitutively activates downstream defense responses. snc1 mutant plants exhibit dwarf morphology, accumulate high levels of salicylic acid (SA), and constitutively express pathogenesis-related (PR) genes and resistance to pathogens [19]. Overexpression of SNC1 also results in constitutive activation of defense responses [20]. A recent report showed that the expression of SNC1 is regulated at chromatin level by MOS1, which encodes a large protein with a conserved BAT2 domain [21].

Because autoimmunity is detrimental to plant growth and development, R protein mediated immunity is subjected to tight control. Since overexpression of R genes often leads to constitutive activation of defense responses [20], [22], transcription of R genes need to be controlled properly to keep R protein levels below a threshold to avoid constitutive activation of R protein-mediated immune responses. At protein level, without the presence of the microbial pathogens, R proteins are kept in an auto-inhibited conformation through intramolecular interactions [23]. Here we report that an SGT1-interacting protein negatively regulates R protein accumulation to prevent auto-activation of immune responses.

Results

Identification and characterization of the snc5-1 npr1-1 mutant

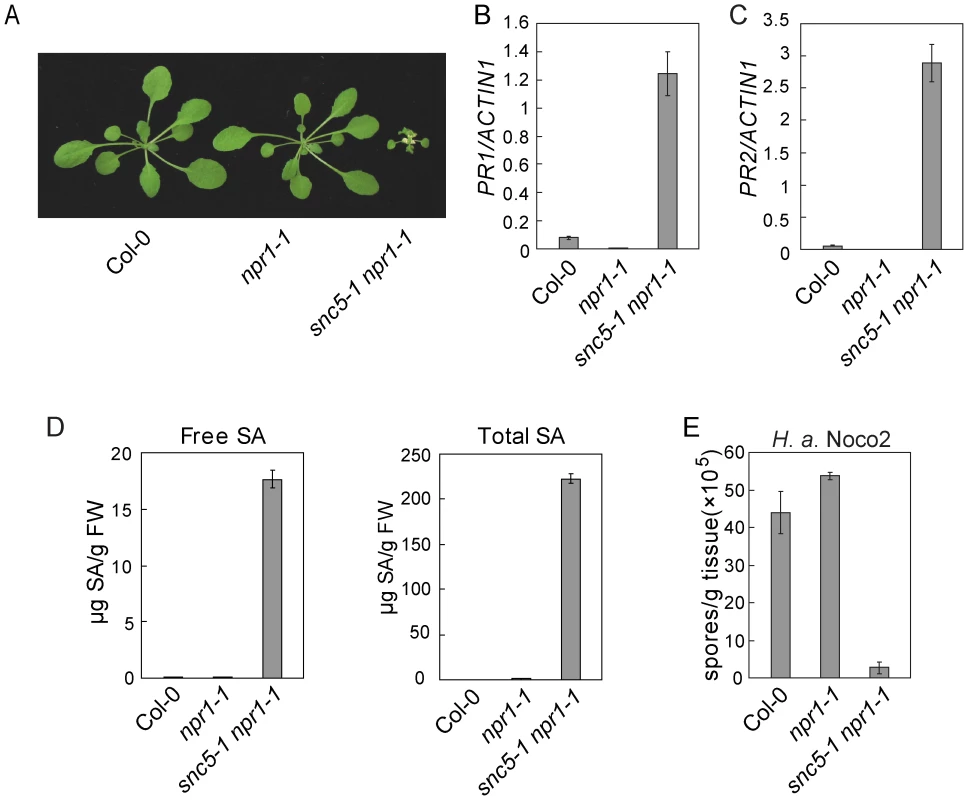

In Arabidopsis, NPR1 (Nonexpresser of PR genes 1) is an essential signaling component downstream of SA [24]. To search for negative regulators of defense responses independent of NPR1, an npr1-1 suppressor screen was previously conducted [25]. A mutant named snc5-1 npr1-1 was found to constitutively express the BGL2 (PR2) Promoter-GUS reporter gene in the npr1-1 mutant background (Figure S1). snc5-1 npr1-1 exhibited a dwarf morphology (Figure 1A) similar to snc1, an auto-activated TIR-NB-LRR R gene mutant identified in an independent npr1-1 suppressor screen [19]. Plants heterozygous for snc5-1 npr1-1 displayed wild type morphology, indicating that the snc5-1 mutation is recessive.

Fig. 1. Defense responses are constitutively activated in snc5-1 npr1-1.

(A) Morphology of wild type (Col-0), npr1-1 and snc5-1 npr1-1 plants grown on soil. The picture was taken when the plants were four weeks old. (B–C) Expression levels of PR1 (B) and PR2 (C) in wild type, npr1-1 and snc5-1 npr1-1 compared to Actin 1. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. (D) Free and total SA levels in wild type (Col-0), npr1-1 and snc5-1 npr1-1. Error bars represent standard deviation from four measurements. (E) Growth of H. a. Noco2 on wild type (Col-0), npr1-1 and snc5-1 npr1-1. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. In snc5-1 npr1-1 mutant plants, both PR1 and PR2 were constitutively expressed (Figure 1B and 1C). To test whether snc5-1 npr1-1 over-accumulates SA, SA levels in snc5-1 npr1-1 and wild type plants were measured with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). As shown in Figure 1D, both free and total SA (free SA plus glucose-conjugated SA) levels in snc5-1 npr1-1 plants were much higher than in wild type controls.

Since the defense marker PR genes were activated in snc5-1 npr1-1, we tested whether snc5-1 npr1-1 has enhanced pathogen resistance. snc5-1 npr1-1 seedlings were challenged with Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis Noco2 (H. a. Noco2), an oomycete downy mildew pathogen virulent on Arabidopsis Col-0 ecotype. As shown in Figure 1E, sporulation of H. a. Noco2 on snc5-1 npr1-1 plants was much less than on wild type plants, indicating that defense responses are constitutively activated in snc5-1 npr1-1.

Map-based cloning of snc5-1

To map the snc5-1 mutation, snc5-1 npr1-1 (in the Col-0 ecotype) was crossed with the wild type Ler ecotype to generate a segregating F2 population. In the F2 progeny, plants homozygous at the snc5-1 locus were identified based on the dwarf morphology of snc5-1. Interestingly, the percentage of plants with dwarf morphology in the F2 population was less than one quarter, suggesting that there may be a natural modifier of snc5-1 in Ler. Crude mapping using 24 dwarf plants suggested that two loci are required for the mutant phenotype: one is closely linked to the lower arm of chromosome 4 (marker F19F18 at 17.7 MB) and the other is linked to the middle of chromosome 4 (marker FCA5, at 9 MB).

For fine mapping of the locus on the lower arm of chromosome 4, we first identified F2 plants homozygous for the Col-0 sequence at marker FCA5 and heterozygous at marker F19F18. About 500 F3 plants from these F2 lines were genotyped with the markers T16L1 and F19F18. The snc5-1 mutation was further mapped to a 92 kb region between markers F6G17 and F19F18 after analyzing the recombinants between T16L1 and F19F18. Sequence analysis of the genes in this region identified a single G to A mutation in At4G37460, which introduces an early stop codon in the middle of the protein (Figure 2A). At4G37460 was predicted to encode a TPR domain-containing protein. Analysis of At4G37460 expression using the microarray database at The Arabidopsis Information Resource found that it is expressed in all tissues.

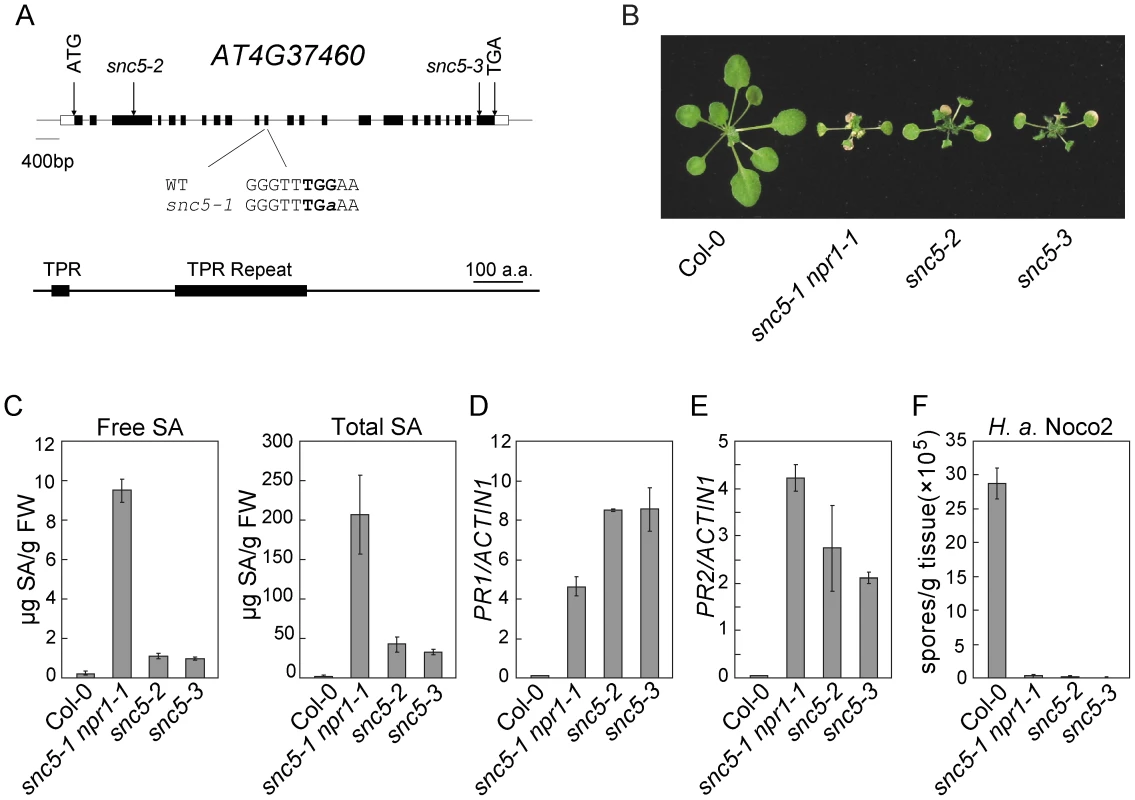

Fig. 2. Map-based cloning of snc5-1.

(A) Gene structure of SNC5 (At4g37460) and positions of the molecular lesions in snc5-1, snc5-2 (SAIL_412_E08) and snc5-3 (SAIL_216_F11). Boxes are exons and lines indicate introns. (B) Morphology of wild type (Col-0), snc5-1 npr1-1, snc5-2 and snc5-3 plants grown on soil. The picture was taken when the plants were four weeks old. (C) Free and total SA levels in wild type (Col-0), snc5-1 npr1-1, snc5-2 and snc5-3. Error bars represent standard deviation from four measurements. (D–E) Expression levels of PR1 (E) and PR2 (F) in wild type (Col-0), snc5-1 npr1-1, snc5-2 and snc5-3 compared to Actin 1. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. (F) Growth of H. a. Noco2 spores on wild type (Col-0), snc5-1 npr1-1, snc5-2 and snc5-3. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. To confirm the mutation in At4G37460 causes the activation of defense responses, we analyzed two additional T-DNA knockout alleles of At4G37460, snc5-2 (SAIL_412_E08) and snc5-3 (SAIL_216_F11), both carrying T-DNA insertions in exons of At4g37460 (Figure 2A). These two mutants showed similar dwarf morphology as snc5-1 npr1-1 (Figure 2B). RT-PCR analysis showed that full length At4G37460 was no longer expressed in the two T-DNA mutants (Figure S2). Both mutants accumulated high levels of SA (Figure 2C). Consistent with previous reports that NPR1 functions in negative feedback regulation of SA accumulation [19], [26], the snc5-1 npr1-1 double mutant accumulated higher levels of SA than the snc5-2 and snc5-3 single mutants. Like snc5-1 npr1-1, snc5-2 and snc5-3 also constitutively expressed PR1 (Figure 2D) and PR2 (Figure 2E) and exhibited enhanced resistance to H. a. Noco2 (Figure 2F), suggesting that the mutations in At4G37460 cause the activation of defense responses. It also indicates that the locus in the middle of chromosome 4 is probably a natural modifier of snc5-1.

Recently it was reported that mutants of At4g37460 named srfr1 (suppressors of rps4-RLD) in the RLD ecotype background exhibited enhanced resistance against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 expressing avrRps4 [27]. Unlike the snc5 mutants in Col background, defense responses are not constitutively activated in the srfr1 mutants identified in RLD ecotype and these mutants remain fully susceptible to the virulent P.s.t. DC3000 strain without avrRps4 [28].

To be consistent with the literature, we renamed snc5-1, snc5-2 and snc5-3 in the Columbia background as srfr1-3, srfr1-4 and srfr1-5, respectively. The protein encoded by At4g37460 is referred to as SRFR1. Sequence analysis revealed that SRFR1 is conserved in plants and vertebrates (Figure S3), but not present in yeast and invertebrates such as C. elegans and D. melanogaster. The biochemical function of the protein is unknown.

snc5-1/srfr1-3 activates SNC1-mediated resistance

To further map the modifying locus affecting srfr1-3 npr1-1 mutant morphology, we identified F2 plants that are homozygous for Col-0 at marker F19F18 (close to SRFR1) and heterozygous at marker FCA5 (close to the modifier). About 500 F3 plants from these lines were genotyped using the markers FCA5 and F1N20. The modifier was further mapped to the region between marker FCA6 and FCA8 after analyzing the recombinants between FCA5 and F1N20. This region contains the RPP4 R-gene cluster (Parker et al. 1997), which SNC1 is a member of.

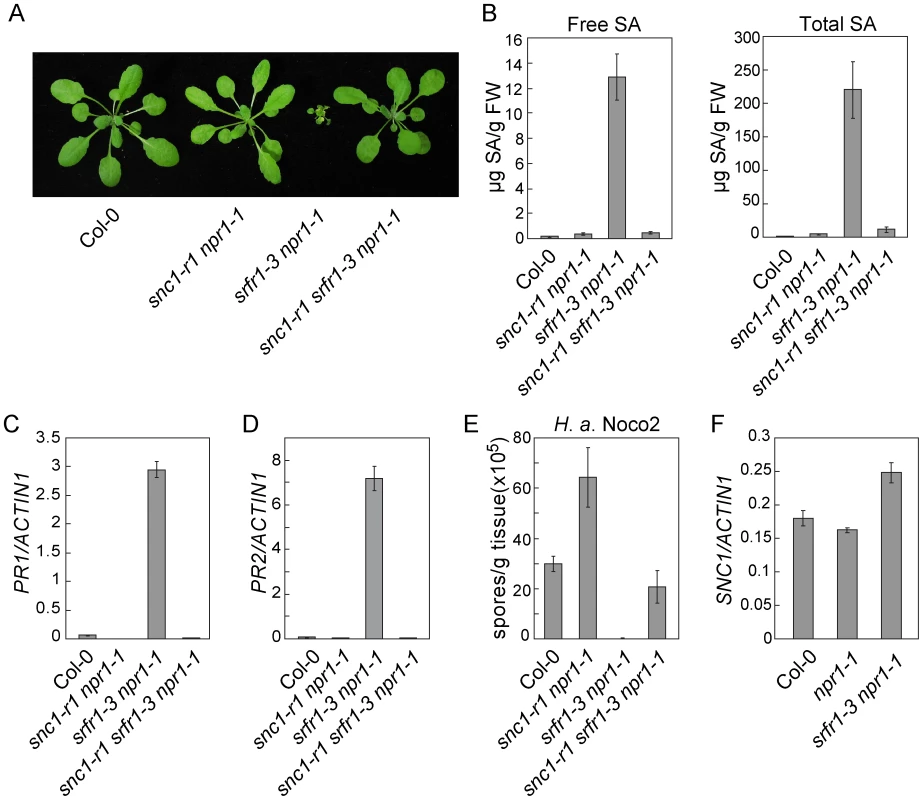

To identify the modifier required for the mutant phenotypes of srfr1-3 npr1-1, we mutagenized srfr1-3 npr1-1 with EMS and looked for suppressors of srfr1-3 npr1-1. Because the SNC1 locus is highly polymorphic in different ecotypes [29], we hypothesized that it may be the natural modifier. When we sequenced the SNC1 locus in four of the suppressor mutants, we found that two of them contained mutations in SNC1 (Figure S4). To confirm that SNC1 is indeed the modifier of srfr1-3 npr1-1, we crossed snc1-r1, a known null mutant allele of SNC1 containing a deletion of 8 bp in the first exon [18], into srfr1-3 npr1-1. We found that the snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 mutant plants displayed wild type morphology (Figure 3A), a stronger suppression compared to mutant alleles with point mutations identified from the srfr1-3 suppressor screen. Further analysis of the triple mutant showed that the elevated SA levels (Figure 3B), constitutive expression of PR genes (Figure 3C–3D) and resistance to H. a. Noco2 (Figure 3E) in srfr1-3 npr1-1 were also blocked by the snc1-r1 mutation, suggesting that srfr1-3 activates SNC1-mediated resistance pathways.

Fig. 3. Loss of SNC1 function suppresses constitutive defense responses in snc5-1/srfr1-3.

(A) Morphology of wild type (Col-0), snc1-r1 npr1-1, srfr1-3 npr1-1 and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 plants grown on soil. The picture was taken when the plants were four weeks old. (B) Free and total SA in wild type (Col-0), snc1-r1 npr1-1, srfr1-3 npr1-1 and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1. Error bars represent standard deviation from four measurements. (C–D) Expression levels of PR1 (C) and PR2 (D) in wild type (Col-0), snc1-r1 npr1-1, srfr1-3 npr1-1 and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 compared to Actin1. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. (E) Growth of H. a. Noco2 on wild type (Col-0), snc1-r1 npr1-1, srfr1-3 npr1-1 and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. (F) Expression levels of SNC1 in wild type (Col-0), npr1-1 and srfr1-3 npr1-1 determined by q-RT-PCR. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. To test whether activation of defense responses in srfr1-3 npr1-1 was caused by overexpression of SNC1 at transcription level, the expression level of SNC1 was determined by real-time RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 3F, SNC1 expression in srfr1-3 npr1-1 is only slightly higher than that in wild type and npr1-1 plants. The small increase in SNC1 transcript level probably is not the cause of the dramatic phenotypes observed in srfr1-3 npr1-1.

Interestingly, the snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 triple mutant is less susceptible to H. a. Noco2 than the snc1-r1 npr1-1 double mutant (Figure 3E), suggesting that srfr1-3 may also affect SNC1-independent resistance responses. To test whether srfr1-3 affects resistance specified by additional R genes, we analyzed resistance mediated by RPP4, RPS2 and RPS4 in snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1. As shown in Figure S5A, the snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 triple mutant displayed enhanced resistance to H. a. Emwa1 comparing to the snc1-r1 npr1-1 double mutant, suggesting that the srfr1-3 mutation enhances RPP4-mediated resistance. In addition, snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 exhibited enhanced resistance to P.s.t. DC3000 carrying avrRpt2 or avrRps4 comparing to npr1-1 (Figure S5B and S5C), indicating that resistance mediated by RPS2 and RPS4 is also enhanced by the srfr1-3 mutation.

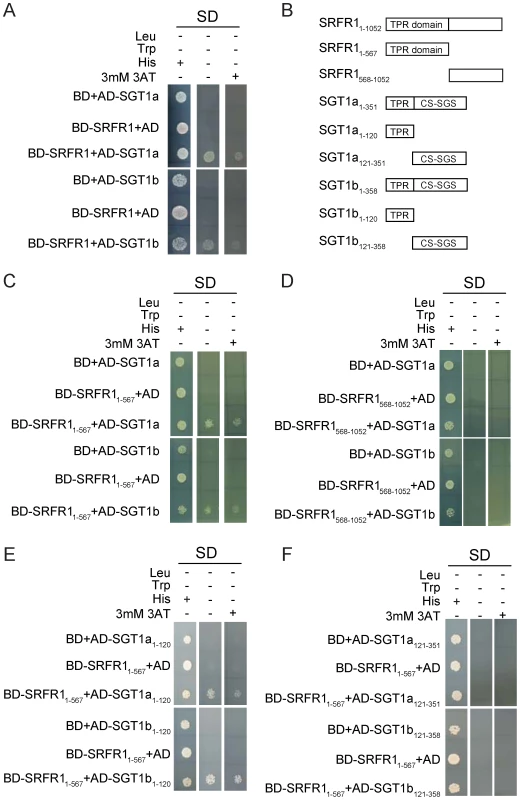

SRFR1/SNC5 interacts with SGT1a and SGT1b

SRFR1 contains a TPR domain at its N-terminal half and a conserved C-terminal domain with unknown function. Since TPR domains are often involved in protein-protein interactions, SRFR1 probably functions through association with other proteins. To identify interacting partners with SRFR1, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using the full-length SRFR1 as bait. Seven positive cDNA clones were identified on synthetic dropout plates lacking Histidine (data not shown). Sequence analysis showed that one clone contained SGT1a (encoding amino acid 1-351) and another contained SGT1b (encoding amino acid 6-358) cDNA. To confirm the interactions between SRFR1 and SGT1a/b, the cDNA clones were recovered from yeast and used for additional assays. As shown in Figure 4A, both SGT1a and SGT1b interact with SRFR1 but not the empty vectors in the yeast two-hybrid assays. β-Gal assays were also performed to confirm the interactions (data not shown).

Fig. 4. SRFR1 interacts with SGT1a and SGT1b in yeast two-hybrid analysis.

(A) Interactions between full-length SRFR1 with SGT1a and SGT1b. (B) A diagram of the truncated proteins of SRFR1, SGT1a and SGT1b expressed in yeast two-hybrid vectors. (C–D) Interactions between the TPR domain (C) and C-terminal part (D) of SRFR1 with SGT1a and SGT1b. (E–F) Interactions between the TPR domain of SRFR1 with the TPR domains (E) or CS-SGS domains of SGT1a and SGT1b. To determine which parts of SRFR1 and SGT1a/1b interact with each other, we created a series of deletion constructs of SRFR1 and SGT1a/1b (Figure 4B). As shown in Figure 4C and 4D, the N-terminal TPR domain but not the C-terminal half of SRFR1 interacted with SGT1a and SGT1b, suggesting that SRFR1 interacts with SGT1 through its TPR domain. When the TPR domain of SRFR1 was expressed together with the truncated SGT1a/1b proteins, it was found to interact with the TPR domains of SGT1a and SGT1b (Figure 4E), but not with the CS plus SGS domains in the yeast two-hybrid assay (Figure 4F). These interactions were further confirmed by β-Gal assays (data not shown). We also tested whether the TPR domain of SRFR1 self-associates in the yeast two-hybrid assays. As shown in Figure S6, the TPR domain of SRFR1 interacts with the TPR domain of SGT1b but not itself.

SRFR1/SNC5 associates with SGT1 in planta

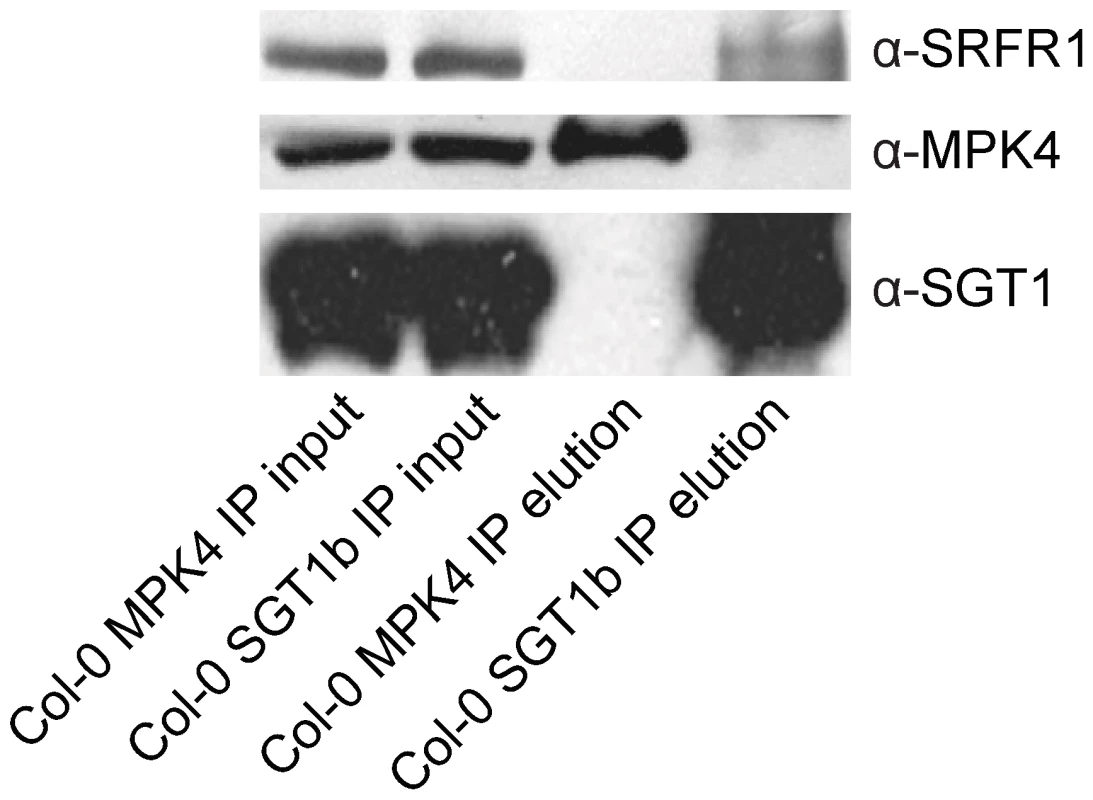

To test whether SRFR1 and SGT1 associate with each other in planta, we conducted co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) analysis. First, we generated a polyclonal antibody against SRFR1, which has a predicted size of 118 kD. The anti-SRFR1 antiserum detected a protein around 120 kD present in wild type but not the srfr1-3 npr1-1 or srfr1-4 mutant plants (Figure S7), indicating that the antibody specifically detects SRFR1. Next we performed IP experiments using an anti-SGT1 antibody that can detect both SGT1a and SGT1b. As a control, we also performed IP using an anti-MPK4 antibody. Both SRFR1 and MPK4 were localized to cytosol and nucleus (Figure S8). Proteins that were immunoprecipitated by the antibodies were subsequently detected by western blot analysis using the SGT1, MPK4 or SRFR1 antibodies. As shown in Figure 5, SRFR1 co-immunoprecipitates with SGT1, but not with MPK4, indicating that SRFR1 and SGT1 associate with each other in planta.

Fig. 5. SGT1 associates with SRFR1 in planta.

Co-IP of SGT1 with SRFR1 in total protein extracts from wild type Col-0 plants. Protein extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-SGT1b or anti-MPK4 agarose beads. Crude lysates (left panels, Input) and immunoprecipitated proteins (right panels) were detected with Anti-SRFR1, anti-SGT1 or anti-MPK4 antibodies. The SNC1 protein level is elevated in snc5/srfr1 mutants

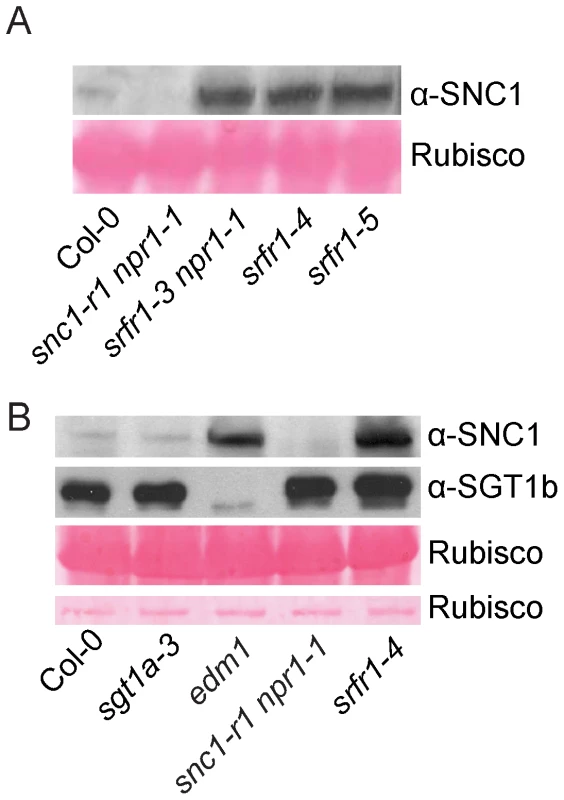

Since SRFR1/SNC5 interacts with SGT1 and SGT1 has been shown to regulate R protein stability through its association with RAR1 and HSP90, we tested whether the accumulation of SNC1 is affected in the srfr1 mutants. We generated a SNC1-specific antibody against a peptide unique in the SNC1 protein. SNC1 has a predicted size of 147 kD. The anti-SNC1 antibody detected a protein around 150 kD in the wild type, but not in the snc1-r1 deletion mutant (Figure 6A), indicating that the antibody is specific against SNC1. In the srfr1-3 npr1-1, srfr1-4 and srfr1-5 mutant plants, SNC1 protein levels are much higher than that in the wild type plants, suggesting that loss of the function of SRFR1 results in over-accumulation of SNC1. To test whether mutations in SGT1b and SGT1a affect the accumulation of SNC1, we also analyzed the SNC1 protein levels in the sgt1b deletion allele edm1-1 [30] and sgt1a-3, a T-DNA knockout allele of sgt1a. Real-time RT-PCR showed that the expression of SGT1a was dramatically decreased in sgt1a-3 (Figure S9). We observed increased accumulation of SNC1 protein in edm1-1, but not in sgt1a-3 (Figure 6B). Taken together, both SRFR1 and SGT1b contribute to the negative regulation of SNC1 stability.

Fig. 6. SNC1 protein levels in srfr1 mutant plants.

(A) Western blot analysis of SNC1 protein levels in total protein extracts of wild type (Col-0), snc1-r1 npr1-1, srfr1-3 npr1-1, srfr1-4 and srfr1-5. (B) Western blot analysis of SNC1 protein levels in total protein extracts of wild type (Col-0), sgt1a-3, edm1-1 (sgt1b), snc1-r1 npr1-1 and srfr1-4. RPS2 and RPS4 protein levels are elevated in snc1-r1 srfr1-3 and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1

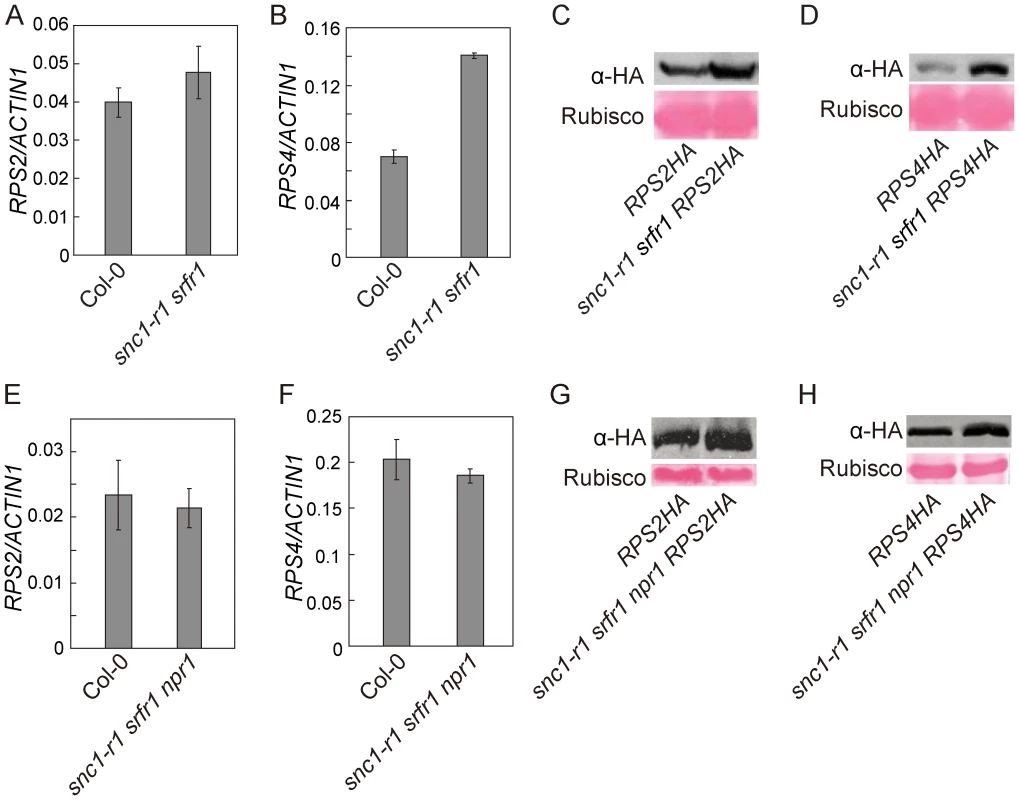

To test whether srfr1 mutations affect the accumulation of RPS2 and RPS4 proteins, we crossed RPS2-HA or RPS4-HA transgenic lines, expressed under their native promoters [31], [32], into snc1-r1 srfr1-3 and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 backgrounds. The snc1-r1 mutation was included in the analysis to avoid the effect of constitutive activation of defense responses on the accumulation of the R proteins. In the snc1-r1 srfr1-3 plants, the transcript level of RPS2 was similar to that in wild type plants whereas the transcript of RPS4 was about twice as much as that in wild type plants (Figure 7A and 7B). As shown in Figure 7C and 7D, both RPS2-HA and RPS4-HA accumulated to higher levels in snc1-r1 srfr1-3 than in wild type plants.

Fig. 7. Analysis of the transcript levels of RPS2 and RPS4 and the accumulation of RPS2-HA and RPS4-HA proteins in snc1-r1 srfr1-3 and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1.

(A–B) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of RPS2 (A) and RPS4 (B) expression in wild type (Col-0) and snc1-r1 srfr1-3. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. (C) Western blot analysis of RPS2-HA protein levels in total protein extracts of RPS2-HA and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 RPS2-HA lines. (D) Western blot analysis of RPS4-HA protein levels in total protein extracts of RPS4-HA and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 RPS4-HA lines. (E–F) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of RPS2 (E) and RPS4 (F) expression in wild type (Col-0) and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1. Error bars represent standard deviation from three measurements. (G) Western blot analysis of RPS2-HA protein levels in total protein extracts of RPS2-HA and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 RPS2-HA lines. (H) Western blot analysis of RPS4-HA protein levels in total protein extracts of RPS4-HA and snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1RPS4-HA lines. In the snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 triple mutant, the transcript levels of RPS2 and RPS4 were similar to those in wild type plants (Figure 7E and 7F). As shown in Figure 7G, RPS2-HA accumulated to a higher level in snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 than in wild type. Accumulation of RPS4-HA was also increased in the triple mutant (Figure 7H), but the increase was not as dramatic as that observed in the snc1-r1 srfr1-3 double mutant, suggesting that the increased RPS4-HA protein level in snc1-r1 srfr1-3 was partly due to increased transcription of RPS4. These data suggest that SRFR1 contributes to the regulation of RPS2 and RPS4 protein levels.

Discussion

In a suppressor screen of npr1-1 to search for negative regulators of immune responses, we identified snc5-1/srfr1-3 that constitutively expresses PR genes and pathogen resistance. Since loss-of-function mutations in SNC1 block activation of defense responses in srfr1-3 npr1-1, the resistance activated by srfr1-3 is mediated by the R protein SNC1. In addition, SNC1 protein over-accumulated in srfr1 mutants, suggesting that SRFR1 regulates the stability of SNC1 and over-accumulation of SNC1 caused the activation of immune responses. A previous study showed that srfr1 mutants in the RLD ecotype background do not activate constitutive defense responses [28]. The lack of constitutive defense responses in the srfr1 mutants is probably due to the absence of a functional SNC1 gene in the RLD background, whereas the enhanced resistance to DC3000 with avrRps4 may be caused by increased accumulation of an unidentified R protein that recognizes AvrRPS4.

From a yeast two-hybrid screen, we found that SRFR1 interacts with SGT1a and SGT1b. In planta interactions between SGT1 and SRFR1 were confirmed by co-IP experiments. Like in srfr1 mutants, elevated SNC1 protein level was also observed in edm1-1, the deletion mutant allele of sgt1b. This is consistent with SRFR1 and SGT1 function together to regulate the stability of SNC1. Interestingly, the over-accumulation of SNC1 in sgt1b mutant plants does not cause constitutive activation of defense responses, suggesting that SNC1 protein over-accumulated in sgt1b mutant may have reduced activity. Since SGT1 may have dual functions in negative regulation of R protein accumulation as well as positive regulation of R protein folding [11], it is likely that the over-accumulated R proteins in sgt1b mutant are not folded correctly without the assistance of SGT1b, thus not able to trigger immune responses.

SGT1 contains three domains, the N-terminal TPR domain, the central CS and C-terminal SGS domain. The CS domain interacts with both RAR1 and HSP90 while the SGS domain may form contacts with the LRRs of R proteins [10], [16]. The function of the TPR domain is unclear. Interestingly, the TPR domain of SGT1 is missing in some non-plant species such as C. elegans [4], suggesting that the TPR domain may have a specialized function. Our study showed that the TPR domain of SGT1 interacts with SRFR1, suggesting that this domain may function in negative regulation of R protein accumulation, which is consistent with the association of SGT1 with components of the SCF (SKP1, Cullin, F-box protein) ubiquitin ligase complex [33], [34] and SGT1 is required for SCF-mediated auxin responses [34]. The TPR domain of SGT1b has previously been shown to be dispensable for the function of SGT1b in regulating R protein mediated resistance as well as auxin signaling when it was overexpressed [14]. It remains to be determined whether a truncated SGT1b without the TPR domain under its own promoter is able to complement the phenotypes of sgt1b as well as the embryo lethality phenotype in the sgt1a sgt1b double mutant.

Analysis of SGT1 functions in Arabidopsis has been complicated by the presence of two closely related SGT1 proteins with overlapping functions [14], [35]. STG1a is expressed at a lower level than SGT1b, but it has intrinsic activity to complement the sgt1b mutant when its expression is increased to a certain level. Thus the mutant phenotypes of sgt1b are probably results of partial loss of SGT1 functions. While SGT1b has been shown to be required for the function of a number of R proteins (reviewed by Shirasu [4]), RPS5 function is not affected in sgt1b. The SGT1a activity may be sufficient for proper folding of RPS5. An unexpected result is that a loss-of-function mutation in SGT1b suppresses the reduced accumulation of RPS5 and loss of RPS5 function in rar1, implicating that SGT1b may also play a role in the negative regulation of R protein accumulation [11]. Our data support the model proposed by Azevedo et al. [14] that SGT1 has dual functions in regulating R protein-mediated immune responses. In addition to its function as a co-chaperone of HSP90 in positively regulating R protein folding, it may also be involved in the negative regulation of R protein stability by association with SRFR1 through its N-terminal TPR domain.

In addition to SNC1, SRFR1 may regulate the accumulation of other R proteins. In the srfr1-3 mutant plants, both RPS2-HA and RPS4-HA fusion proteins accumulate to higher levels than in wild type plants. Because knockout of SNC1 is sufficient to block the constitutive defense responses in the srfr1-3 mutant, the increased accumulation of other R proteins such as RPS2 and PRS4 probably has not reached the threshold levels that would cause activation of these R proteins. Since SRFR1 and SGT1 are both conserved in plants and animals and SGT1 is required for the functions of animal NLR proteins such as NOD1, NOD2 and NLRP3 [36], [37], it will be interesting to test whether the homologs of SRFR1 in animals also function as negative regulators of NLR protein-mediated immune responses.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

All plants were grown under 16 hour light at 23°C and 8 hour dark at 20°C. srfr1-3 npr1-1 was identified from an EMS-mutagenized mutant population in the npr1-1 mutant background as previously described [25]. snc5-2/srfr1-4 (SAIL_412_E08), snc5-3/srfr1-5 (SAIL_216_F11) and sgt1a-3 (SALK_122139C) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). Homozygous plants for snc5-2/srfr1-4 were identified by PCR using primers 5′-tcatcactaattccgcaacg-3′ and 5′-cgacttatgtaacggatcag-3′. Homozygous plants for snc5-3/srfr1-5 were identified by PCR using primers 5′-ctatggttctactgagctcg-3′ and 5′-tgctcatggtttagttagcc-3′. The RPS2-HA and RPS4-HA transgenic lines were described previously [31], [32].

snc1-r1 npr1-1 is a deletion mutant of snc1 described previously [18]. The snc1-r1 srfr1-3 npr1-1 triple mutant was generated by crossing snc1-r1 npr1-1 with srfr1-3 npr1-1 and genotyping the F2 population. srfr1-3 mutation were identified by PCR using primers 5′-caggggaagtaatcttatcggatatcac-3′ and 5′-caattttcctgtcttgaccagggttcg-3′ followed by digestion with TaqI. Plants homozygous for snc1-r1 were identified by PCR using primers 10C-WT-F (5′-cctggtgcctgaatgaattg-3′) and 10C-R (5′-atcatccgatggtgtcatag-3′).

Mutant characterization

Infection of H. a. Noco2 was carried out on two-week-old seedlings by spraying with spore suspensions at a concentration of 50,000 spores per ml of water. The plants were kept at 18°C in 12 h light/12 h dark cycles with 95% humidity. Infections were scored seven days post inoculation by counting the number of spores with a hemocytometer.

RNA was extracted from the 12-day-old seedlings grown on MS plates using the RNAiso reagent (Takara). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using the M-MLV reverse transcriptase from Takara. For gene expression analysis, real-time PCR was carried out using the Perfect Real Time kit (Takara). The sequences of primers used for amplification of PR-1, PR-2 and Actin1 were described previously [38]. SA was extracted as previously described and measured using HPLC [39].

Map-based cloning of snc5-1/srfr1-3

Markers used for mapping were designed based on the Monsanto Arabidopsis polymorphisms and Landsberg sequence collections [40]. The primer sequences for AP20 are 5′-gtcattttctaaaatccaatatgaccg-3′ and 5′-gacgacatattgcacattttcatattg-3′. Primers for F6G17 are 5′-cacttccctggtgcgtccaa-3′ and 5′-ggacagaagatacaggtgag-3′. The primer sequences for F19F18 are 5′-aatcaatgattctatatacacatg-3′ and 5′-gacgaagattgcttggtgag-3′. The primer sequences for FCA5 are 5′-aatgcggtgttacccatggc-3′ and 5′-actcttccgataaacttcctc-3′. The primer sequences for FCA8 are 5′-gtcttcctctgccatttcac-3′ and 5′-gttgcgaaaagcagagattg-3′. All the markers are based on Indel polymorphisms.

Co-immunoprecipitation and antibodies

About 0.9 g of 12-day-old seedlings were ground in liquid nitrogen to fine powder and 0.9 ml of grinding buffer with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 x Protease Inhibitor Coctail (Roche, 11873580001) was added to the powder. The sample was resuspended, transferred to 1.5 ml tubes and spun at 21,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a tube containing 20 µl Protein A agarose beads (GE Healthcare, 17-1279-03) for pre-cleaning. After rotating for 25 minutes, the sample was spun at 21,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. 40 µl of the supernatant was saved as input. Antibody was added to the rest of the supernatant and the sample was kept at 4°C with continuous rotation for 2–3 hours. 20 µl of Protein A agrose beads was subsequently added to the sample and kept at 4°C with continuous rotation for 1 hour. The beads were spun down at 4,000 rpm for 30 sec at 4°C. The beads were washed with 1 ml of grinding buffer for three times before immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with 40 µl 2 x SDS loading buffer.

SGT1b and the TPR domain of SRFR1 (a. a. 1-567) were expressed in E. coli and used to generate the anti-SGT1b and anti-SRFR1 antibodies in rabbit. The Anti-SNC1 antibody was generated against an SNC1-specific peptide (KAKSEDEKQS). The anti-MPK4 antibody was from Sigma (A6979). The anti-HA antibody was from Roche (REF#11867423001). Nuclei-depleted (ΔN) and nuclear (N) protein extracts of wild type plants were prepared as previously described [41].

Yeast two-hybrid screen

To create the SRFR1 bait plasmid, SRFR1 cDNA was amplified by primers 5′-aaaactgcagggcccatgaggcctcaatcgttgtaagtgctaag-3′ and 5′-cgcggatccggccgtcaaggccaatggcgacggcgacggcgaca-3′ and cloned into pGBKT7 (Clontech). The plasmid was sequenced and transformed into the yeast strain Y1348. The Arabidopsis prey library in pGADT7 was kindly provided by Dr. Qi Xie. 40 µg of the library DNA were transformed to yeast strain containing the bait plasmid. The transformed yeast cells were plated on the SD-Leu-Trp-His containing 3 mM 3AT. DNA inserts from the positive clones were amplified by PCR using primers T7 and AD-seq-R (5′-agatggtgcacgatgcacag-3′). The DNA fragments from PCR were digested with HinfI to group the positive clones into different classes. DNAs from representative clones were sequenced. The plasmids from selected positive clones were extracted and transformed into E. coli to amplify the DNA for further analysis. For yeast growth assays, overnight yeast cultures were diluted to different concentration and plated on SD-Leu-Trp and SD-Leu-Trp-His dropout plates.

To make the bait plasmid containing the N-terminal half of SRFR1 (a.a 1-567), the cDNA fragment was amplified using 5′-cgcggatccggccgtcaaggccaatggcgacggcgacggcgaca-3′ and 5′-aaaactgcaggcccatgaggcctcatgcatcaagttccacgtcaa-3′. To make the bait plasmid containing the C-terminal half of SRFR1 (a.a. 568-1052), the cDNA fragment was amplified using 5′-gcgggtacccatatggggccgtcaaggccagtggagaaatttgttcttc-3′ and 5′-aaaactgcagggcccatgaggcctcaatcgttgtaagtgctaag-3′. The DNA fragments were cloned into the pGBKT7.

SGT1 fragments were amplified by PCR and cloned into the prey vector pGADT7. SGT1a-TPR1-120 was amplified using 5′-ccggaattcatggcgaaggagcttgctga-3′ and 5′-gccgaattctcgagtcattctgtgattagaaaattgc-3′. SGT1b1-120 was amplified using 5′-ccggaattcatggccaaggaattagcaga-3′ and 5′-gccgaattctcgagtcattcttctgcaatacgaagat-3′. SGT1a121-351 was amplified using 5′-ccggaattcgaagagaaagatttggttca-3′ and 5′-cgcggatcctcagatctcccatttcttga-3′. SGT1b121-358 was amplified using 5′-ccggaattcgagaaagatttggttcagcc-3′ and 5′-cgcggatcctcaatactcccacttcttga-3′. The bait and prey vectors expressing the SRFR1 and SGT1 fragments were co-transformed into the Y1348 strain for yeast two-hybrid assays.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. JonesJD

DanglJL

2006 The plant immune system. Nature 444 323 329

2. KannegantiTD

LamkanfiM

NunezG

2007 Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity 27 549 559

3. Hammond-KosackKE

JonesJD

1996 Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell 8 1773 1791

4. ShirasuK

2009 The HSP90-SGT1 chaperone complex for NLR immune sensors. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60 139 164

5. ShirasuK

LahayeT

TanMW

ZhouF

AzevedoC

1999 A novel class of eukaryotic zinc-binding proteins is required for disease resistance signaling in barley and development in C. elegans. Cell 99 355 366

6. WarrenRF

MerrittPM

HolubE

InnesRW

1999 Identification of three putative signal transduction genes involved in R gene-specified disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Genetics 152 401 412

7. TorneroP

MerrittP

SadanandomA

ShirasuK

InnesRW

2002 RAR1 and NDR1 contribute quantitatively to disease resistance in Arabidopsis, and their relative contributions are dependent on the R gene assayed. Plant Cell 14 1005 1015

8. MuskettPR

KahnK

AustinMJ

MoisanLJ

SadanandomA

2002 Arabidopsis RAR1 exerts rate-limiting control of R gene-mediated defenses against multiple pathogens. Plant Cell 14 979 992

9. LiuY

SchiffM

MaratheR

Dinesh-KumarSP

2002 Tobacco Rar1, EDS1 and NPR1/NIM1 like genes are required for N-mediated resistance to tobacco mosaic virus. Plant J 30 415 429

10. BieriS

MauchS

ShenQH

PeartJ

DevotoA

2004 RAR1 positively controls steady state levels of barley MLA resistance proteins and enables sufficient MLA6 accumulation for effective resistance. Plant Cell 16 3480 3495

11. HoltBF3rd

BelkhadirY

DanglJL

2005 Antagonistic control of disease resistance protein stability in the plant immune system. Science 309 929 932

12. HubertDA

TorneroP

BelkhadirY

KrishnaP

TakahashiA

2003 Cytosolic HSP90 associates with and modulates the Arabidopsis RPM1 disease resistance protein. Embo J 22 5679 5689

13. LuR

MalcuitI

MoffettP

RuizMT

PeartJ

2003 High throughput virus-induced gene silencing implicates heat shock protein 90 in plant disease resistance. Embo J 22 5690 5699

14. AzevedoC

BetsuyakuS

PeartJ

TakahashiA

NoelL

2006 Role of SGT1 in resistance protein accumulation in plant immunity. Embo J 25 2007 2016

15. LiuY

Burch-SmithT

SchiffM

FengS

Dinesh-KumarSP

2004 Molecular chaperone Hsp90 associates with resistance protein N and its signaling proteins SGT1 and Rar1 to modulate an innate immune response in plants. J Biol Chem 279 2101 2108

16. TakahashiA

CasaisC

IchimuraK

ShirasuK

2003 HSP90 interacts with RAR1 and SGT1 and is essential for RPS2-mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 11777 11782

17. KadotaY

AmiguesB

DucassouL

MadaouiH

OchsenbeinF

2008 Structural and functional analysis of SGT1-HSP90 core complex required for innate immunity in plants. EMBO Rep 9 1209 1215

18. ZhangY

GoritschnigS

DongX

LiX

2003 A gain-of-function mutation in a plant disease resistance gene leads to constitutive activation of downstream signal transduction pathways in suppressor of npr1-1, constitutive 1. Plant Cell 15 2636 2646

19. LiX

ClarkeJD

ZhangY

DongX

2001 Activation of an EDS1-mediated R-gene pathway in the snc1 mutant leads to constitutive, NPR1-independent pathogen resistance. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14 1131 1139

20. StokesTL

KunkelBN

RichardsEJ

2002 Epigenetic variation in Arabidopsis disease resistance. Genes Dev 16 171 182

21. Li Y, Tessaro M, Li X, Zhang Y Regulation of the Expression of Plant Resistance gene SNC1 by a Protein with a Conserved BAT2 Domain. Plant Physiol

22. OldroydGE

StaskawiczBJ

1998 Genetically engineered broad-spectrum disease resistance in tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 10300 10305

23. MoffettP

FarnhamG

PeartJ

BaulcombeDC

2002 Interaction between domains of a plant NBS-LRR protein in disease resistance-related cell death. Embo J 21 4511 4519

24. DongX

2004 NPR1, all things considered. Curr Opin Plant Biol 7 547 552

25. GaoM

LiuJ

BiD

ZhangZ

ChengF

2008 MEKK1, MKK1/MKK2 and MPK4 function together in a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to regulate innate immunity in plants. Cell Res 18 1190 1198

26. DelaneyTP

FriedrichL

RyalsJA

1995 Arabidopsis signal transduction mutant defective in chemically and biologically induced disease resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 6602 6606

27. KwonSI

KimSH

BhattacharjeeS

NohJJ

GassmannW

2009 SRFR1, a suppressor of effector-triggered immunity, encodes a conserved tetratricopeptide repeat protein with similarity to transcriptional repressors. Plant J 57 109 119

28. KwonSI

KoczanJM

GassmannW

2004 Two Arabidopsis srfr (suppressor of rps4-RLD) mutants exhibit avrRps4-specific disease resistance independent of RPS4. Plant J 40 366 375

29. YangS

HuaJ

2004 A haplotype-specific Resistance gene regulated by BONZAI1 mediates temperature-dependent growth control in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16 1060 1071

30. TorM

GordonP

CuzickA

EulgemT

SinapidouE

2002 Arabidopsis SGT1b is required for defense signaling conferred by several downy mildew resistance genes. Plant Cell 14 993 1003

31. WirthmuellerL

ZhangY

JonesJD

ParkerJE

2007 Nuclear accumulation of the Arabidopsis immune receptor RPS4 is necessary for triggering EDS1-dependent defense. Curr Biol 17 2023 2029

32. AxtellMJ

StaskawiczBJ

2003 Initiation of RPS2-specified disease resistance in Arabidopsis is coupled to the AvrRpt2-directed elimination of RIN4. Cell 112 369 377

33. AustinMJ

MuskettP

KahnK

FeysBJ

JonesJD

2002 Regulatory role of SGT1 in early R gene-mediated plant defenses. Science 295 2077 2080

34. AzevedoC

SadanandomA

KitagawaK

FreialdenhovenA

ShirasuK

2002 The RAR1 interactor SGT1, an essential component of R gene-triggered disease resistance. Science 295 2073 2076

35. NoelLD

CagnaG

StuttmannJ

WirthmullerL

BetsuyakuS

2007 Interaction between SGT1 and cytosolic/nuclear HSC70 chaperones regulates Arabidopsis immune responses. Plant Cell 19 4061 4076

36. MayorA

MartinonF

De SmedtT

PetrilliV

TschoppJ

2007 A crucial function of SGT1 and HSP90 in inflammasome activity links mammalian and plant innate immune responses. Nat Immunol 8 497 503

37. da Silva CorreiaJ

MirandaY

LeonardN

UlevitchR

2007 SGT1 is essential for Nod1 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 6764 6769

38. ZhangY

TessaroMJ

LassnerM

LiX

2003 Knockout analysis of Arabidopsis transcription factors TGA2, TGA5, and TGA6 reveals their redundant and essential roles in systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 15 2647 2653

39. LiX

ZhangY

ClarkeJD

LiY

DongX

1999 Identification and cloning of a negative regulator of systemic acquired resistance, SNI1, through a screen for suppressors of npr1-1. Cell 98 329 339

40. JanderG

NorrisSR

RounsleySD

BushDF

LevinIM

2002 Arabidopsis map-based cloning in the post-genome era. Plant Physiol 129 440 450

41. ChengYT

GermainH

WiermerM

BiD

XuF

2009 Nuclear pore complex component MOS7/Nup88 is required for innate immunity and nuclear accumulation of defense regulators in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 2503 2516

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Inhibition of TIR Domain Signaling by TcpC: MyD88-Dependent and Independent Effects on VirulenceČlánek Phylogenetic Approach Reveals That Virus Genotype Largely Determines HIV Set-Point Viral LoadČlánek A Family of Plasmodesmal Proteins with Receptor-Like Properties for Plant Viral Movement Proteins

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 9- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Azole Drugs Are Imported By Facilitated Diffusion in and Other Pathogenic Fungi

- Two Genes on A/J Chromosome 18 Are Associated with Susceptibility to Infection by Combined Microarray and QTL Analyses

- Impact of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection on Chimpanzee Population Dynamics

- Breaking the Stereotype: Virulence Factor–Mediated Protection of Host Cells in Bacterial Pathogenesis

- The Canine Papillomavirus and Gamma HPV E7 Proteins Use an Alternative Domain to Bind and Destabilize the Retinoblastoma Protein

- Rescue of HIV-1 Release by Targeting Widely Divergent NEDD4-Type Ubiquitin Ligases and Isolated Catalytic HECT Domains to Gag

- Steric Shielding of Surface Epitopes and Impaired Immune Recognition Induced by the Ebola Virus Glycoprotein

- Dynamics of the Multiplicity of Cellular Infection in a Plant Virus

- HLA Class I Binding of HBZ Determines Outcome in HTLV-1 Infection

- Pathogenic Bacteria Target NEDD8-Conjugated Cullins to Hijack Host-Cell Signaling Pathways

- The HA and NS Genes of Human H5N1 Influenza A Virus Contribute to High Virulence in Ferrets

- SRFR1 Negatively Regulates Plant NB-LRR Resistance Protein Accumulation to Prevent Autoimmunity

- Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Activity Controls the Onset of the HCMV Lytic Cycle

- The N-Terminal Domain of the Arenavirus L Protein Is an RNA Endonuclease Essential in mRNA Transcription

- Generation of Neutralizing Antibodies and Divergence of SIVmac239 in Cynomolgus Macaques Following Short-Term Early Antiretroviral Therapy

- Inhibition of TIR Domain Signaling by TcpC: MyD88-Dependent and Independent Effects on Virulence

- Intracellular Proton Conductance of the Hepatitis C Virus p7 Protein and Its Contribution to Infectious Virus Production

- The Transcriptome of the Human Pathogen at Single-Nucleotide Resolution

- The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Promotes Uptake of Influenza A Viruses (IAV) into Host Cells

- Surface Co-Expression of Two Different PfEMP1 Antigens on Single -Infected Erythrocytes Facilitates Binding to ICAM1 and PECAM1

- Sequestration and Tissue Accumulation of Human Malaria Parasites: Can We Learn Anything from Rodent Models of Malaria?

- Phylogenomics of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels Predicts Monepantel Effect

- Generation of Covalently Closed Circular DNA of Hepatitis B Viruses via Intracellular Recycling Is Regulated in a Virus Specific Manner

- CpG-Methylation Regulates a Class of Epstein-Barr Virus Promoters

- Molecular and Evolutionary Bases of Within-Patient Genotypic and Phenotypic Diversity in Extraintestinal Infections

- A Bistable Switch and Anatomical Site Control Virulence Gene Expression in the Intestine

- Are Members of the Fungal Genus (a) Commensals; (b) Opportunists; (c) Pathogens; or (d) All of the Above?

- Structures of Receptor Complexes of a North American H7N2 Influenza Hemagglutinin with a Loop Deletion in the Receptor Binding Site

- Phylogenetic Approach Reveals That Virus Genotype Largely Determines HIV Set-Point Viral Load

- The Coevolution of Virulence: Tolerance in Perspective

- Involvement of the Cytokine MIF in the Snail Host Immune Response to the Parasite

- Structure of the Extracellular Portion of CD46 Provides Insights into Its Interactions with Complement Proteins and Pathogens

- A Family of Plasmodesmal Proteins with Receptor-Like Properties for Plant Viral Movement Proteins

- High Content Phenotypic Cell-Based Visual Screen Identifies Acyltrehalose-Containing Glycolipids Involved in Phagosome Remodeling

- A Novel Small Molecule Inhibitor of Hepatitis C Virus Entry

- The Microbiota Mediates Pathogen Clearance from the Gut Lumen after Non-Typhoidal Diarrhea

- RNA Polymerases (L-Protein) Have an N-Terminal, Influenza-Like Endonuclease Domain, Essential for Viral Cap-Dependent Transcription

- Pathogen Specific, IRF3-Dependent Signaling and Innate Resistance to Human Kidney Infection

- Cellular Entry of Ebola Virus Involves Uptake by a Macropinocytosis-Like Mechanism and Subsequent Trafficking through Early and Late Endosomes

- The Length of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Particles Dictates a Need for Actin Assembly during Clathrin-Dependent Endocytosis

- Formation of Mobile Chromatin-Associated Nuclear Foci Containing HIV-1 Vpr and VPRBP Is Critical for the Induction of G2 Cell Cycle Arrest

- Association of Tat with Promoters of PTEN and PP2A Subunits Is Key to Transcriptional Activation of Apoptotic Pathways in HIV-Infected CD4+ T Cells

- Metal Hyperaccumulation Armors Plants against Disease

- Cyclin-Dependent Kinase-Like Function Is Shared by the Beta- and Gamma- Subset of the Conserved Herpesvirus Protein Kinases

- Role of Acetyl-Phosphate in Activation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS Pathway in

- Ebolavirus Is Internalized into Host Cells Macropinocytosis in a Viral Glycoprotein-Dependent Manner

- A Novel Family of IMC Proteins Displays a Hierarchical Organization and Functions in Coordinating Parasite Division

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Structure of the Extracellular Portion of CD46 Provides Insights into Its Interactions with Complement Proteins and Pathogens

- The Length of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Particles Dictates a Need for Actin Assembly during Clathrin-Dependent Endocytosis

- Inhibition of TIR Domain Signaling by TcpC: MyD88-Dependent and Independent Effects on Virulence

- The Coevolution of Virulence: Tolerance in Perspective

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání