-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaHIV and Mature Dendritic Cells: Trojan Exosomes Riding the Trojan Horse?

Exosomes are secreted cellular vesicles that can induce specific CD4+ T cell responses in vivo when they interact with competent antigen-presenting cells like mature dendritic cells (mDCs). The Trojan exosome hypothesis proposes that retroviruses can take advantage of the cell-encoded intercellular vesicle traffic and exosome exchange pathway, moving between cells in the absence of fusion events in search of adequate target cells. Here, we discuss recent data supporting this hypothesis, which further explains how DCs can capture and internalize retroviruses like HIV-1 in the absence of fusion events, leading to the productive infection of interacting CD4+ T cells and contributing to viral spread through a mechanism known as trans-infection. We suggest that HIV-1 can exploit an exosome antigen-dissemination pathway intrinsic to mDCs, allowing viral internalization and final trans-infection of CD4+ T cells. In contrast to previous reports that focus on the ability of immature DCs to capture HIV in the mucosa, this review emphasizes the outstanding role that mature DCs could have promoting trans-infection in the lymph node, underscoring a new potential viral dissemination pathway.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 6(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000740

Category: Review

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000740Summary

Exosomes are secreted cellular vesicles that can induce specific CD4+ T cell responses in vivo when they interact with competent antigen-presenting cells like mature dendritic cells (mDCs). The Trojan exosome hypothesis proposes that retroviruses can take advantage of the cell-encoded intercellular vesicle traffic and exosome exchange pathway, moving between cells in the absence of fusion events in search of adequate target cells. Here, we discuss recent data supporting this hypothesis, which further explains how DCs can capture and internalize retroviruses like HIV-1 in the absence of fusion events, leading to the productive infection of interacting CD4+ T cells and contributing to viral spread through a mechanism known as trans-infection. We suggest that HIV-1 can exploit an exosome antigen-dissemination pathway intrinsic to mDCs, allowing viral internalization and final trans-infection of CD4+ T cells. In contrast to previous reports that focus on the ability of immature DCs to capture HIV in the mucosa, this review emphasizes the outstanding role that mature DCs could have promoting trans-infection in the lymph node, underscoring a new potential viral dissemination pathway.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) scattered throughout the peripheral tissues act like sentinels and recognize a wide range of microorganisms. At this stage, DCs display an immature phenotype. When pathogen invasion takes place, immature DCs (iDCs) can capture microorganisms via endocytic surveillance receptors, resulting in the classical intracellular lytic pathway that permits processing of antigenic peptides [1]. The signaling through receptors or the detection of proinflammatory cytokines prompts iDC activation and migration from the periphery towards the secondary lymphoid organs. Concurrently, co-stimulatory molecules are expressed in the cell membrane, preparing DCs for competent T cell priming. In the T cell areas of the lymph nodes, fully mature DCs (mDCs) present pathogen-derived epitopes to CD4+ T or CD8+ T lymphocytes. This way, DCs orchestrate immune responses to invading pathogens and have a pivotal role during infections [2].

However, viruses, including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), have evolved different strategies to evade DC antiviral activity. Indeed, it has been known for years that DCs exposed to HIV-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells [3]. Although the frequency of HIV-1-infected DCs is often 10 - to 100-fold lower than that of CD4+ T cells [4], DCs do not need to be productively infected to transmit the virus and spread it in an infectious form [5], which is in contrast to other HIV-1 target cells such as CD4+ T cells or macrophages. Notably, separate pathways mediate the productive infection of DCs and their ability to capture and internalize HIV-1 in the absence of viral fusion [6]. The latter mechanism involves binding and uptake of HIV-1, traffic of internalized virus, and its final release, allowing transfer to CD4+ T cells, a process known as trans-infection [5],[7].

Trans-infection has been related to the ability of C-type lectin receptors like DC-SIGN expressed in certain DCs to tightly bind to the HIV-1 surface envelope glycoprotein gp120 [8] and endocytose viral particles [9]. The initial identification of DC-SIGN as an HIV receptor permitting trans-infection of T cells led to the “Trojan horse” hypothesis, which relates the preliminary establishment of HIV-1 infection to the ability of iDCs to capture the virus via DC-SIGN in the peripheral tissue and then migrate to the lymph nodes, where HIV-1 transferred to CD4+ T cells could easily start the spread of infection [5],[7],[10].

Knowing the antigen-presenting capabilities of DCs, one would expect that after HIV interaction with surveillance receptors like DC-SIGN, endocytosed virus would end up in classical lysosomic pathways (Figure 1), where viral antigens are degraded and presented in MHC-II molecules to CD4+ T cells [11],[12]. Furthermore, part of the internalized virus could also gain access to the cytoplasm and be processed throughout the proteasome, finally being crosspresented in MHC-I molecules to CD8+ T cells [13],[14]. However, in the specific case of HIV interaction with iDCs, it has been proposed that part of the internalized virus escapes these degradation routes and is maintained in endosomal acidic compartments, retaining viral infectivity for the long periods required to promote efficient HIV-1 transfer to CD4+ T cells [5],[9].

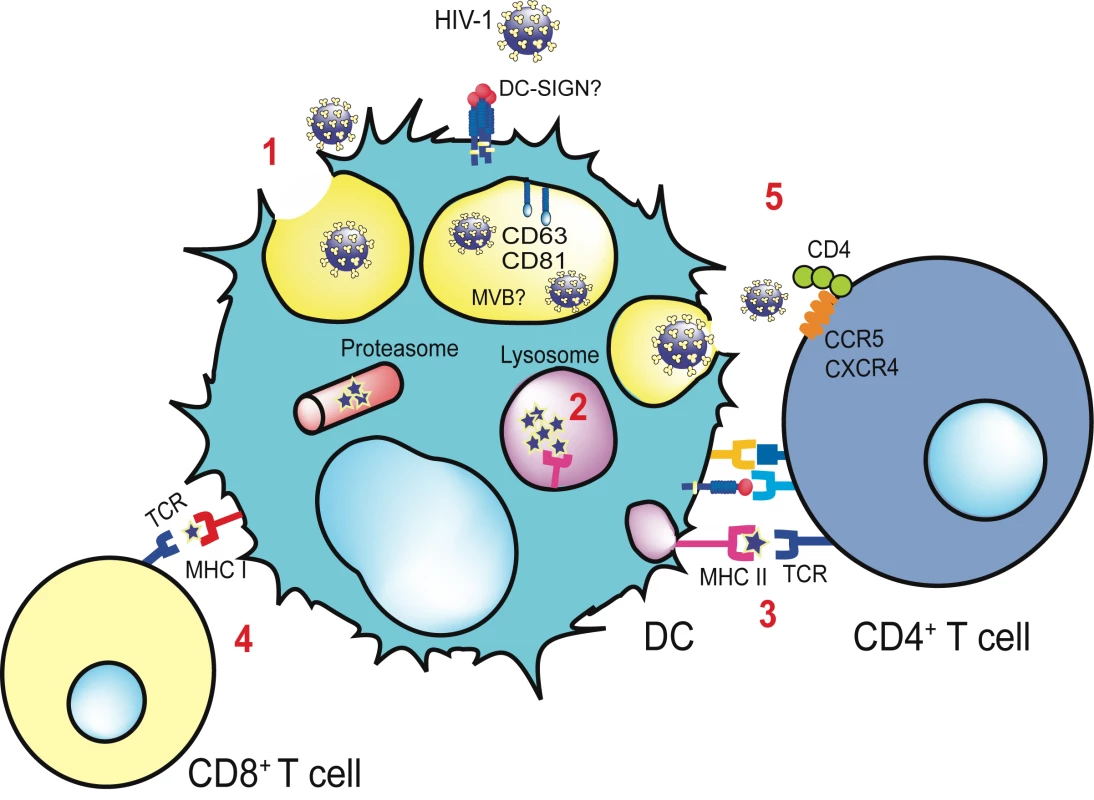

Fig. 1. Antigen presentation and trans-infection of a CD4+ T cell mediated by a DC.

Viral binding to distinct cellular receptors allows viral endocytosis via a non-fusogenic mechanism (1). The virus is retained in the multivesicular body compartment (MVB), where it is enriched in tetraspanins such as CD81 and CD63. Part of the virus is degraded in the lysosomes (2), and viral antigens are presented via MHC-II to the T cell receptor (TCR) of CD4+ T cells (3) through the formation of an immunological synapse. If an endocytosed virus gains access to the cytoplasm of the DC, it can be processed by the proteasome and crosspresented via MHC-I to CD8+ T cells (4). Viral transmission takes place when part of the virus evades classical degradation pathways. MVB recycles back and fuses with the plasma membrane, allowing the liberation of entrapped virus and the productive infection of DC-interacting CD4+ T cells (5), a mechanism known as trans-infection. The contact area between an uninfected DC bearing HIV infectious particles and a CD4+ T cell is termed the infectious synapse. Despite this preliminary model of viral retention, recent studies have demonstrated that iDCs show rapid degradation of captured viral particles, which do not last more than 24 hours before being processed [14]–[17]. These studies suggest a two-phase mechanism of viral transmission mediated by iDCs: one restricted to a short period through the trans-infection process, and a later one due to a long-term transfer of de novo viral particles produced after iDC infection [15],[16],[18].

Trojan Horses and HIV Transmission: Mature DCs Win the Race

Several results ([17], [19]–[21], reviewed in [22]), indicate that iDCs have reduced trans-infection ability. Conversely, mDCs are much less vulnerable to viral fusion events and productive HIV infection than iDCs [23],[24], while displaying a greater ability to capture incoming virions [17],[21],[25], retain them in an infectious form, and transmit them to target T cells through trans-infection [17], [19]–[21]. The location of internalized virions is dramatically different in immature and mature DCs [25]. Strikingly, the poorly macropinocytic mDCs [2],[26],[27] sequester significantly more whole, structurally intact virions into large vesicles within the cells, whereas the endocytically active iDCs not only retain fewer internalized virions, but also locate them closer to the cell periphery [25]. This internalization view has been previously challenged, suggesting that cell-surface-bound HIV is the predominant pathway for viral transmission mediated by DCs [28]. However, a recent report on this topic reconciles these two models by demonstrating that HIV resides in an invaginated domain within DCs that is both contiguous with the plasma membrane and distinct from classical endocytic vesicles [29].

Collectively, these results favor a model in which both direct infection and trans-infection abilities coexist to a different extent in immature and mature DC subsets. Maturation of DCs enhances viral capture activity and trans-infection capacity while diminishing viral fusion events [24] and productive infection [23]. Under these circumstances, iDCs would preferentially transmit de novo synthesized virus upon productive infection [15], and the mDC-enhanced trans-infection ability would play a key role in the lymph nodes, mediating viral transmission to new target CD4+ T cells (Figure 2).

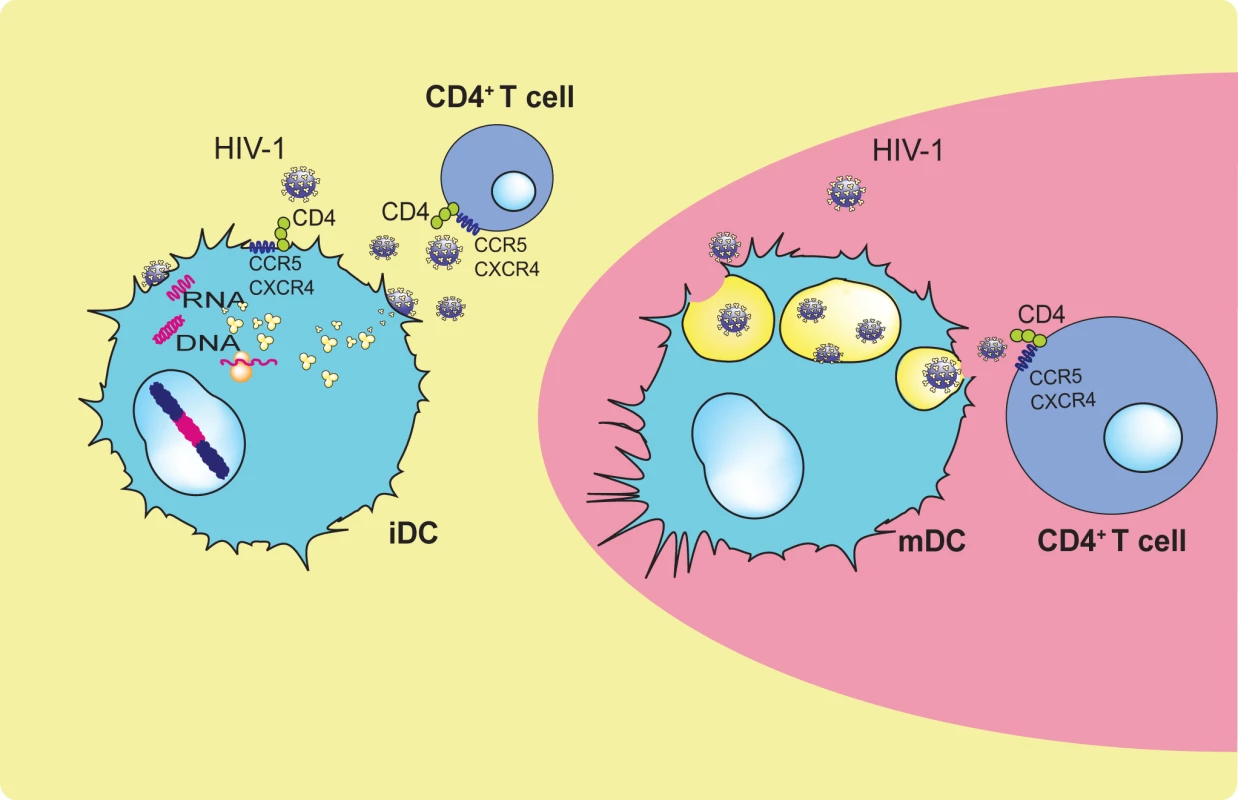

Fig. 2. Proposed major roles of iDCs and mDCs during HIV disease progression.

Productive infection of iDCs allows viral transmission in the peripheral tissues, while mDC viral capture leads to trans-infection in the lymphoid tissues. Given the unique capability of mDCs to promote HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells in vitro, we hypothesize that in vivo, mDC trans-infection could augment viral dissemination in the lymphoid tissue and significantly contribute to HIV disease progression. mDCs have a greater ability to stimulate CD4+ T cell proliferation than iDCs [30],[31]. Accordingly, mDCs presenting viral antigens could activate HIV-specific naïve CD4+ T cells in the course of their first encounters in the lymph node. As a result, HIV-specific naïve CD4+ T cells would undergo several rounds of division during their initial expansion and differentiation into effector CD4+ T cells, becoming highly susceptible to actual HIV infection, as has been previously demonstrated [32]. Notably, the viral dissemination that mDCs can potentially mediate in vivo is enormous: T cells approach mDCs randomly and make exploratory contacts that last only minutes, enabling DCs to contact many T cells per hour [33]. Thus, since viral transmission through trans-infection does not rely on antigen presentation, many CD4+ T cells could be exposed to mDC virus; however, only after antigen presentation would naïve CD4+ T cells be activated and their subsequent proliferation render these cells more susceptible to HIV infection.

Once infected, these activated CD4+ T cells are known to have short half-lives in vivo, lasting fewer than two days [34]. Therefore, under rapid T cell turnover, DCs could be indispensable to permitting continuous infection of new CD4+ T cells [35]. Recently, it has also been suggested that simultaneous priming and infection of T cells by DCs is the main driving force behind the early infection dynamics, when activated CD4+ T cell numbers are low [36].

In vivo, the contribution of mDCs to HIV spread might be also supported by the levels of circulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which are significantly augmented in chronically HIV-infected individuals, due to the increased translocation of bacteria from the intestinal lumen early after primo infection [37]. The bacterial components released could stimulate DCs systemically, contributing to their maturation and therefore enhancing viral spread while creating the pro-inflammatory milieu associated with chronic HIV infection. This hypothesis is further supported by another report showing that in individuals with HIV-1 viremia, DCs from blood have increased expression levels of co-stimulatory molecules (the hallmark of maturation status) that only diminish when highly active antiretroviral therapy suppresses the viral load [38]. Although the plasma LPS concentration found in HIV+ patients is lower than the one used to mature DCs in vitro [17], [19]–[21],[39], it is conceivable that in vivo, higher amounts of LPS could accumulate in the most compartmentalized areas of the mucosa or in the adjacent tissues. Therefore, future experiments should address whether the physiological amounts of LPS found in tissues can trigger the same DC maturation status and viral transmission efficacy described in different reports [17], [19]–[21],[39].

Prior infection with other sexually transmitted pathogens is strongly associated with the sexual transmission of HIV [40]. This implies that the probability of a person acquiring HIV infection is increased when there is a preexisting infection or inflammation of the genital epithelium. Under these circumstances, it is quite likely that mucosal inflammation arising from other sexually transmitted pathogens could directly activate and mature DCs in vivo, promoting HIV settlement and favoring the subsequent spread of the viral infection. Interestingly, a recent report shows that in vitro–activated CD34-derived Langerhans cells mediate the trans-infection of HIV [39], suggesting a potential role for these mature cells during the establishment of HIV infection.

Unfortunately, recent failures in HIV prophylactic vaccine trials provide additional corroboration of the prominent role mDCs could be playing during HIV infection in vivo. The STEP HIV vaccine trial evaluated a replication-defective adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) vector, which is a weakened form of a common cold virus, modified to carry HIV genes into the body to induce HIV-specific immune responses. This clinical trial was recently stopped due to the vaccine's lack of efficacy and the 2-fold increase in the incidence of HIV acquisition among vaccinated recipients with increased Ad5-neutralizing antibody titers compared with placebo recipients [41]. Of note, a recent report demonstrates that the Ad5 vector, with its neutralizing antiserum (present in people with prior immunity), induced a more marked DC maturation than the vector alone, as indicated by increased CD86 expression levels, decreased endocytosis, and production of tumor necrosis factor and type I interferons [42]. Furthermore, when the Ad5 vector and the neutralizing antiserum were added to DCs pulsed with HIV, significantly enhanced viral infection was observed in DC–T cell co-cultures compared to controls lacking the neutralizing antiserum. That is why these authors postulate that mDCs from people with prior immunity to Ad5 virus might have activated CD4+ T cells in vivo, augmenting their susceptibility to HIV infection [42].

Overall, these results highlight the functional relevance that DC maturation could possess under physiological settings, providing the basis for a chronic permissive environment for HIV-1 infection.

Maturation Also Enhances Presentation Skills

Why would mDCs accumulate viral particles instead of degrade them? This paradoxical retention mechanism could in fact aid immunological surveillance, allowing mDCs to have a source of antigen to present to T cells in the absence of surrounding virus, sustaining immune responses for prolonged periods. Intriguingly enough, DCs have an inherent mechanism to control endosomal acidification to preserve antigen cross-presentation over time [43]. We hypothesize that HIV-1 could be exploiting this preexisting cellular pathway of antigen uptake and retention inherent to mDCs, favoring and enhancing viral trans-infection of CD4+ T cells. If this is indeed the case, mDC viral uptake would not rely on the recognition of specific viral proteins, but depend on more ubiquitous signals.

Interestingly, we have recently identified an HIV gp120-independent mechanism of viral binding and endocytosis that is upregulated upon DC maturation [17], further supporting distinct works that have demonstrated that DC-SIGN is not responsible for HIV-1 binding to all DC subsets [21], [44]–[53], and clearly highlighting that additional HIV-1 binding molecules remain to be identified.

Furthermore, several lines of evidence suggest that viral envelope–independent capture of HIV by DCs can allow antigen presentation and induce cytotoxic and humoral immune responses. It has been previously shown that DCs can endocytose viral-like particles (VLPs) and induce immune responses through an endosome-to-cytosol cross-presentation pathway [54]. These VLPs do not have the envelope glycoprotein, meaning that the uptake mechanism could be the same as the one we have shown for virus lacking the envelope glycoprotein [17]. In iDCs, HIV envelope and DC-SIGN-dispensable pathways account for about 50% of the antigen presentation through MHC-II molecules [12]. DCs are also able to capture envelope-pseudotyped HIV Gag VLPs through a DC-SIGN-independent pathway, activating autologous naïve CD4+ T cells that are then able to induce primary and secondary responses in an ex vivo immunization assay [55]. Overall, these findings reinforce the idea that envelope-independent capture pathways allow viral antigen presentation, thus favoring immune responses.

The Role of Exosomes during Antigen Presentation

Although the current view of DC functionality has iDCs encountering an antigen in the periphery and carrying it to lymphoid organs, DCs migrating from the periphery may not always be the ones that present the captured antigen in the lymph nodes. Rather, migrating DCs may transfer their captured antigens to other DCs for presentation. The transfer could occur either by the phagocytosis of antigen-loaded DC fragments by another DC [56] or by the release of antigen-bearing vesicles termed exosomes [57]. During periods of pathogen invasion, these exosomes could act as real couriers, increasing the number of DCs bearing a particular epitope, thus amplifying the initiation of primary adaptive immune responses [58].

Interestingly, as it happens with viral particles, exosomes are also internalized and stored in endocytic compartments by DCs, a prerequisite needed to induce different immune responses. Notably, exosomes do not induce naïve T cell proliferation in vitro unless mDCs are also present, indicating that exosomes do not overcome the need for a competent antigen-presenting cell to stimulate T cells. Exosomes from cultured DCs loaded with tumor-derived epitopes on MHC-I molecules are able to stimulate cytotoxic T lymphocyte–mediated anti-tumor responses in vivo [59]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that tumor cells secrete exosomes carrying tumor antigens, which, after transfer to DCs, also mediate CD8+ T cell–dependent anti-tumor effects [60]. Therefore, distinct studies have shown that exosomes carrying tumor epitopes provide a source of antigen for cross-presentation by DCs.

In addition, exosomes are also able to stimulate antigen-specific naïve CD4+ T cell responses in vivo [58],[61]. This stimulation can take place either by reprocessing the antigens contained in the captured exosomes or by the direct presentation of previously processed functional epitope–MHC complexes exposed in the exosome surface [58],[61]. These alternative pathways were characterized when it was observed that mDC populations could be devoid of MHC-II molecules and still stimulate CD4+ T cells, because MHC-II molecules were already present on the exosomes [61].

In summary, distinct studies have shown that exosomes can be internalized in DCs, allowing final antigen presentation in the absence of lytic degradation. We suggest that HIV and other retroviruses could be exploiting this exosome antigen dissemination pathway intrinsic to mDCs, allowing the final trans-infection of CD4+ T cells (Figure 3). In particular, HIV could be hijacking a pathway that exosomes produced by antigen-presenting cells can follow upon capture by mDCs, mediating the indirect activation of CD4+ T cells by presenting functional epitope–MHC-II complexes through a trans-dissemination mechanism [58],[61]. Our data supports the Trojan exosome hypothesis that proposes that retroviruses take advantage of a cell-encoded intercellular vesicle traffic and exosome exchange pathway, moving between cells in the absence of fusion events [62],[63].

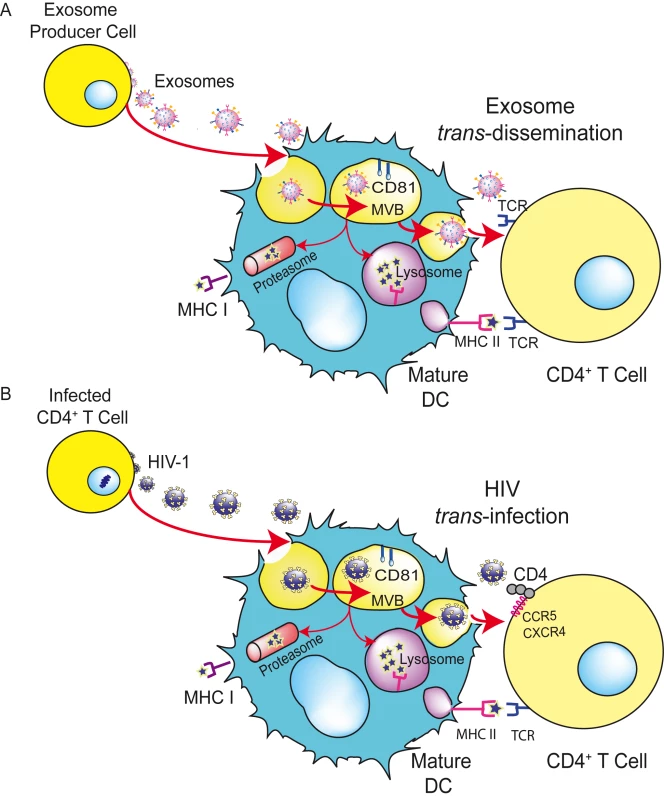

Fig. 3. HIV can exploit a preexisting exosome trans-dissemination pathway intrinsic to mDCs, allowing the final trans-infection of CD4+ T cells.

(A) Exosomes can transfer antigens from infected, tumoral, or antigen-presenting cells to mDCs, increasing the number of DCs bearing a particular antigen and amplifying the initiation of primary adaptive immune responses through the MHC-II pathway, cross-presentation, or the release of intact exosomes, a mechanism described here as trans-dissemination. (B) HIV gains access into mDCs by hijacking this exosome trans-dissemination pathway, thus allowing the final trans-infection of CD4+ T cells. Adapted from [63] © The American Society of Hematology. Are Trojan Exosomes Riding the Trojan Horse?

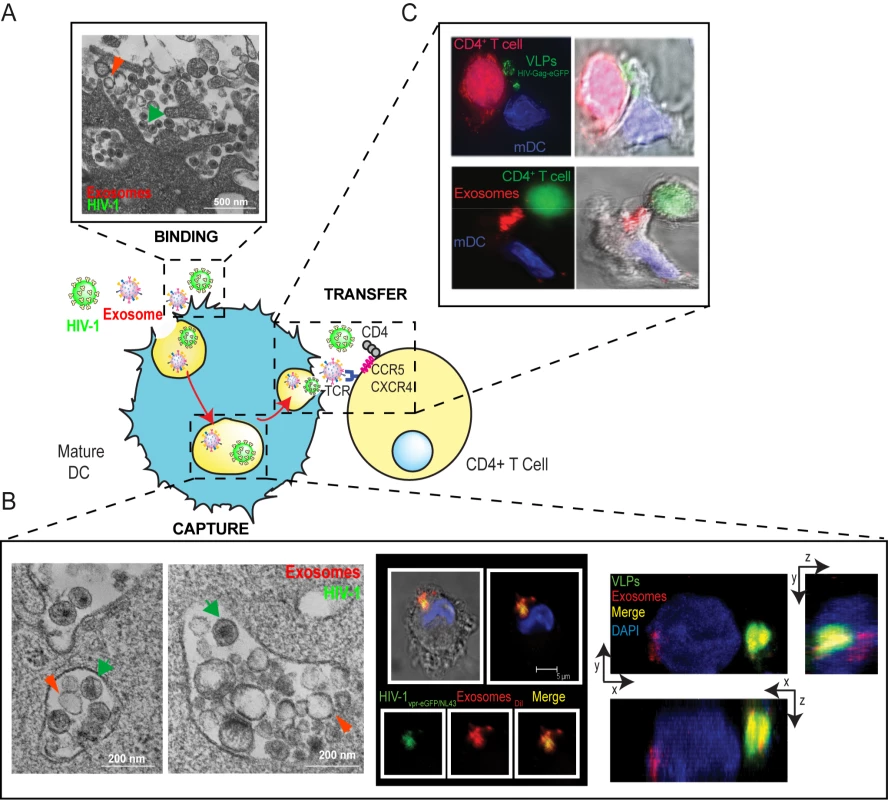

Upon maturation, DCs capture large amounts of HIV-1, HIV-Gag VLPs, and Jurkat-derived exosomes, accumulating these particles in the same intracellular compartment (Figure 4) that stains for tetraspanins such as CD81, is characteristic of multivesicular bodies, and is devoid of LAMP-1 lysosomic markers [63], as previously reported for HIV-1 [64],[65]. These data are in agreement with our previous findings regarding internalization of virus lacking envelope glycoprotein in mDCs and mature myeloid DCs [17].

Fig. 4. Capture and transfer of HIV-1 particles by mDCs converges with the exosome-dissemination pathway.

(A) Binding. Electron microscopy images of mDCs simultaneously pulsed with HIVNL43 and Jurkat-derived exosomes. Particles displaying viral morphology (with an electro-dense core; green arrows) or exosome morphology (with lighter core; red arrows) accumulated in the same area of the membrane. (B) Capture. Left. Electron microscopy as in (A), showing HIVNL43 and Jurkat-derived exosome accumulation within the same vesicles. Middle. Confocal images of a section of an mDC exposed to HIVvpr-eGFP/NL43 and Jurkat-derived exosomes labeled with DiI for 4 h and stained with DAPI. Top images show the mDC, where the red and green fluorescence merged with DAPI either with or without the bright field cellular shape are presented. Bottom images show magnification of vesicles containing these particles where individual green and red fluorescence and the combination of both are depicted. Right. Confocal microscopy analysis of an mDC pulsed simultaneously with HIV Gag-eGFP VLPs and Jurkat-derived exosomes labeled with DiI and then stained with DAPI. Composition of a series of x-y sections of an mDC collected through part of the cell nucleus and projected onto a two-dimensional plane to show the x-z plane (bottom) and the y-z plane (right). (C) Transfer. Infectious-like synapses could also be observed in co-cultures where mDCs were previously pulsed either with HIV Gag-eGFP VLPs (Top) or Jurkat-derived exosomes labeled with DiI (Bottom), extensively washed, and then allowed to interact with Jurkat CD4+ T cells. Images shown, from left to right, depict the red and green fluorescence channels merged with DAPI, the bright field cellular shape, and the combination of both. Therefore, if exosomes use the same trafficking pathway in mDCs as HIV, the receptors dragged from the membrane of infected cells during viral budding that ultimately lead to viral capture should also be present in the membrane of exosomes. Interestingly, both exosomes and HIV can bud from particular cholesterol-enriched microdomains in the T cell plasma membrane [66]–[68], sharing glycosphingolipids and tetraspanin proteins previously used as bona fide lipid raft markers [64],[69],[70]. These similarities in composition and size are a strong argument for the Trojan exosome hypothesis, which suggests that retroviruses are, at their most fundamental level, exosomes [62].

We have further confirmed the existence of a common entry mechanism in mDCs by observing direct competition between different particles (HIV-1, HIV-Gag VLPs, MLV-Gag VLPs, and exosomes) derived from similar cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains, which could not be inhibited by viral-size carboxylated beads or pronase-treated vesicular stomatitis virus particles budding from non-raft membrane locations [71]. Therefore, we consider that budding from lipid raft domains is essential to include specific mDC recognition determinants that allow viral and exosome capture [63].

Interestingly, a previous study revealed an association between endocytosed HIV-1 particles and intraluminal vesicle-containing compartments within iDCs [72]. However, the mechanism we propose differs from this previous paper in two fundamental aspects. First, the earlier work focuses on iDCs, and second, in their case, virus was endocytosed into the compartment where iDCs typically produce exosomes by reverse budding, thus contrasting with the gather mechanism of exosome and HIV uptake that we propose for mDCs. However, our findings concur because HIV-1 particles captured by iDCs were exocytosed in association with exosomes and could mediate trans-infection of CD4+ T cells [72]. Analogously, we found that mDC capture of HIV-1, VLPs, and exosomes allowed efficient transmission of captured particles to target T cells (Figure 4) [63].

The Role of Glycosphingolipids during Capture

Our data also revealed that internalization of HIV-1, VLPs, or exosomes could not be abrogated with an effective protease pretreatment of either of these particles or mDCs [63]. Nevertheless, this observation does not exclude the potential role of proteins during viral or exosome capture, and might just reflect that the molecular determinants involved in capture were not fully processed by the proteases employed. However, treatment of virus-, VLP-, or exosome-producing cells with inhibitors of sphingolipid biosynthesis (such as fumonisin B1 and N-butyl-DNJ) extensively reduced particle entry into mDCs without interfering with their net release from producer cells. Although it has been previously shown that certain ceramide inhibitors diminish the infectivity of released HIV-1 particles after treatment of virus-producer cells [73] and can block HCV replication in vitro [74], at the viral input used in our study differences in infectivity were moderate. Moreover, treatment with a different agent that specifically blocks glycosphingolipid biosynthesis (N-butyl-DNJ) did not affect viral infectivity at all, while inhibiting viral mDC capture. Therefore, our findings establish a critical role for glycosphingolipids during mDC binding and endocytosis of particles derived from cholesterol-enriched domains such as HIV and exosomes [63],[75]. These data could imply a direct interaction of the glycosphingolipids with the plasma membrane of mDCs. Alternatively, the glycosphingolipids could maintain the structural entities required for viral and exosome binding to mDCs, allowing the interaction of pronase-resistant proteins with the mDC membrane surface. Further studies will help to clarify which of the two models our data support actually accounts for particle endocytosis.

Concluding Remarks

The capture of retroviruses and exosomes is upregulated upon DC maturation, leading internalized particles into the same CD81+ intracellular compartment and allowing efficient transmission to CD4+T cells. This novel capture pathway, where retroviruses and exosomes converge, has clear implications for the design of effective HIV therapeutic vaccines. Although mDCs pulsed with inactivated virus could stimulate specific CD8+ T cell immune responses in infected patients, as reviewed in [76], these injected mDCs could also mediate trans-infection of new CD4+ T target cells, amplifying viral dissemination. Therefore, the safety of these strategies should be carefully evaluated, and preferentially explored in patients with undetectable viral load. Regarding prophylactic HIV vaccines, the proposed exosomal origin of retrovirus predicts that HIV poses an unsolvable paradox for adaptive immune responses [62]. Further work should address the specific differences between retroviral particles and exosomes to overcome these difficulties.

Taken as a whole, our results suggest that mDCs, which have a greater ability than iDCs to transmit the virus to target cells and interact continuously with CD4+ T cells at the lymph nodes—the key site of viral replication—could play a prominent role in augmenting viral dissemination. Underscoring the molecular determinants of this highly efficient viral capture process, where retroviruses mimic exosomes to evade the host immune system, could lead to new therapeutic strategies for infectious diseases caused by retroviruses, such as HIV-1, and T lymphotropic agents such as HTLV-1. Furthermore, this knowledge can help in the design of safer candidates for use in a DC-based vaccine.

Zdroje

1. SteinmanRM

1991 The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol 9 271 296

2. SteinmanRM

BanchereauJ

2007 Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature 449 419 426

3. CameronPU

FreudenthalPS

BarkerJM

GezelterS

InabaK

1992 Dendritic cells exposed to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells. Science 257 383 387

4. McIlroyD

AutranB

CheynierR

Wain-HobsonS

ClauvelJP

1995 Infection frequency of dendritic cells and CD4+ T lymphocytes in spleens of human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J Virol 69 4737 4745

5. GeijtenbeekTB

KwonDS

TorensmaR

van VlietSJ

van DuijnhovenGC

2000 DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell 100 587 597

6. BlauveltA

AsadaH

SavilleMW

Klaus-KovtunV

AltmanDJ

1997 Productive infection of dendritic cells by HIV-1 and their ability to capture virus are mediated through separate pathways. J Clin Invest 100 2043 2053

7. van KooykY

GeijtenbeekTB

2003 DC-SIGN: escape mechanism for pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 3 697 709

8. CurtisBM

ScharnowskeS

WatsonAJ

1992 Sequence and expression of a membrane-associated C-type lectin that exhibits CD4-independent binding of human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 8356 8360

9. KwonDS

GregorioG

BittonN

HendricksonWA

LittmanDR

2002 DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of HIV is required for trans-enhancement of T cell infection. Immunity 16 135 144

10. FigdorCG

van KooykY

AdemaGJ

2002 C-type lectin receptors on dendritic cells and Langerhans cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2 77 84

11. EngeringA

GeijtenbeekTB

van VlietSJ

WijersM

van LiemptE

2002 The dendritic cell-specific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN internalizes antigen for presentation to T cells. J Immunol 168 2118 2126

12. MorisA

PajotA

BlanchetF

Guivel-BenhassineF

SalcedoM

2006 Dendritic cells and HIV-specific CD4+ T cells: HIV antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and viral transfer. Blood 108 1643 1651

13. BuseyneF

Le GallS

BoccaccioC

AbastadoJP

LifsonJD

2001 MHC-I-restricted presentation of HIV-1 virion antigens without viral replication. Nat Med 7 344 349

14. MorisA

NobileC

BuseyneF

PorrotF

AbastadoJP

2004 DC-SIGN promotes exogenous MHC-I-restricted HIV-1 antigen presentation. Blood 103 2648 2654

15. TurvilleSG

SantosJJ

FrankI

CameronPU

WilkinsonJ

2004 Immunodeficiency virus uptake, turnover, and 2-phase transfer in human dendritic cells. Blood 103 2170 2179

16. NobileC

PetitC

MorisA

SkrabalK

AbastadoJP

2005 Covert human immunodeficiency virus replication in dendritic cells and in DC-SIGN-expressing cells promotes long-term transmission to lymphocytes. J Virol 79 5386 5399

17. Izquierdo-UserosN

BlancoJ

ErkiziaI

Fernandez-FiguerasMT

BorrasFE

2007 Maturation of blood-derived dendritic cells enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capture and transmission. J Virol 81 7559 7570

18. BurleighL

LozachPY

SchifferC

StaropoliI

PezoV

2006 Infection of dendritic cells (DCs), not DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of human immunodeficiency virus, is required for long-term transfer of virus to T cells. J Virol 80 2949 2957

19. SandersRW

de JongEC

BaldwinCE

SchuitemakerJH

KapsenbergML

2002 Differential transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by distinct subsets of effector dendritic cells. J Virol 76 7812 7821

20. McDonaldD

WuL

BohksSM

KewalRamaniVN

UnutmazD

2003 Recruitment of HIV and its receptors to dendritic cell-T cell junctions. Science 300 1295 1297

21. WangJH

JanasAM

OlsonWJ

WuL

2007 Functionally distinct transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mediated by immature and mature dendritic cells. J Virol 81 8933 8943

22. WuL

KewalramaniVN

2006 Dendritic-cell interactions with HIV: infection and viral dissemination. Nat Rev Immunol 6 859 868

23. Granelli-PipernoA

DelgadoE

FinkelV

PaxtonW

SteinmanRM

1998 Immature dendritic cells selectively replicate macrophagetropic (M-tropic) human immunodeficiency virus type 1, while mature cells efficiently transmit both M - and T-tropic virus to T cells. J Virol 72 2733 2737

24. CavroisM

NeidlemanJ

KreisbergJF

FenardD

CallebautC

2006 Human immunodeficiency virus fusion to dendritic cells declines as cells mature. J Virol 80 1992 1999

25. FrankI

PiatakMJr

StoesselH

RomaniN

BonnyayD

2002 Infectious and whole inactivated simian immunodeficiency viruses interact similarly with primate dendritic cells (DCs): differential intracellular fate of virions in mature and immature DCs. J Virol 76 2936 2951

26. MellmanI

SteinmanRM

2001 Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell 106 255 258

27. VilladangosJA

SchnorrerP

2007 Intrinsic and cooperative antigen-presenting functions of dendritic-cell subsets in vivo. Nat Rev Immunol 7 543 555

28. CavroisM

NeidlemanJ

KreisbergJF

GreeneWC

2007 In vitro derived dendritic cells trans-infect CD4 T cells primarily with surface-bound HIV-1 virions. PLoS Pathog 3 e4 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030004

29. YuHJ

ReuterMA

McDonaldD

2008 HIV traffics through a specialized, surface-accessible intracellular compartment during trans-infection of T cells by mature dendritic cells. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000134 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000134

30. BanchereauJ

SteinmanRM

1998 Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392 245 252

31. MoserM

MurphyKM

2000 Dendritic cell regulation of TH1-TH2 development. Nat Immunol 1 199 205

32. DouekDC

BrenchleyJM

BettsMR

AmbrozakDR

HillBJ

2002 HIV preferentially infects HIV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nature 417 95 98

33. MillerMJ

SafrinaO

ParkerI

CahalanMD

2004 Imaging the single cell dynamics of CD4+ T cell activation by dendritic cells in lymph nodes. J Exp Med 200 847 856

34. PerelsonAS

NeumannAU

MarkowitzM

LeonardJM

HoDD

1996 HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science 271 1582 1586

35. GummuluruS

KewalRamaniVN

EmermanM

2002 Dendritic cell-mediated viral transfer to T cells is required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 persistence in the face of rapid cell turnover. J Virol 76 10692 10701

36. HogueIB

BajariaSH

FallertBA

QinS

ReinhartTA

2008 The dual role of dendritic cells in the immune response to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Gen Virol 89 2228 2239

37. BrenchleyJM

PriceDA

SchackerTW

AsherTE

SilvestriG

2006 Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med 12 1365 1371

38. BarronMA

BlyveisN

PalmerBE

MaWhinneyS

WilsonCC

2003 Influence of plasma viremia on defects in number and immunophenotype of blood dendritic cell subsets in human immunodeficiency virus 1-infected individuals. J Infect Dis 187 26 37

39. FahrbachKM

BarrySM

AyehunieS

LamoreS

KlausnerM

2007 Activated CD34-derived Langerhans cells mediate transinfection with human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol 81 6858 6868

40. ShattockRJ

MooreJP

2003 Inhibiting sexual transmission of HIV-1 infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 1 25 34

41. HIV Vaccine Trials Network 2008 Step study results. Available: http://www.hvtn.org/science/step_buch.html. Accessed 26 February 2010

42. PerreauM

PantaleoG

KremerEJ

2008 Activation of a dendritic cell-T cell axis by Ad5 immune complexes creates an improved environment for replication of HIV in T cells. J Exp Med 205 2717 25

43. SavinaA

JancicC

HuguesS

GuermonprezP

VargasP

2006 NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell 126 205 218

44. TurvilleSG

ArthosJ

DonaldKM

LynchG

NaifH

2001 HIV gp120 receptors on human dendritic cells. Blood 98 2482 2488

45. TurvilleSG

CameronPU

HandleyA

LinG

PohlmannS

2002 Diversity of receptors binding HIV on dendritic cell subsets. Nat Immunol 3 975 983

46. WuL

BashirovaAA

MartinTD

VillamideL

MehlhopE

2002 Rhesus macaque dendritic cells efficiently transmit primate lentiviruses independently of DC-SIGN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 1568 1573

47. GummuluruS

RogelM

StamatatosL

EmermanM

2003 Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to immature dendritic cells can occur independently of DC-SIGN and mannose binding C-type lectin receptors via a cholesterol-dependent pathway. J Virol 77 12865 12874

48. TrumpfhellerC

ParkCG

FinkeJ

SteinmanRM

Granelli-PipernoA

2003 Cell type-dependent retention and transmission of HIV-1 by DC-SIGN. Int Immunol 15 289 298

49. HuQ

FrankI

WilliamsV

SantosJJ

WattsP

2004 Blockade of attachment and fusion receptors inhibits HIV-1 infection of human cervical tissue. J Exp Med 199 1065 1075

50. Granelli-PipernoA

PritskerA

PackM

ShimeliovichI

ArrighiJF

2005 Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin/CD209 is abundant on macrophages in the normal human lymph node and is not required for dendritic cell stimulation of the mixed leukocyte reaction. J Immunol 175 4265 4273

51. BoggianoC

ManelN

LittmanDR

2007 Dendritic cell-mediated trans-enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity is independent of DC-SIGN. J Virol 81 2519 2523

52. Magerus-ChatinetA

YuH

GarciaS

DuclouxE

TerrisB

2007 Galactosyl ceramide expressed on dendritic cells can mediate HIV-1 transfer from monocyte derived dendritic cells to autologous T cells. Virology 362 67 74

53. LambertAA

GilbertC

RichardM

BeaulieuAD

TremblayMJ

2008 The C-type lectin surface receptor DCIR acts as a new attachment factor for HIV-1 in dendritic cells and contributes to trans - and cis-infection pathways. Blood 112 1299 307

54. MoronVG

RuedaP

SedlikC

LeclercC

2003 In vivo, dendritic cells can cross-present virus-like particles using an endosome-to-cytosol pathway. J Immunol 171 2242 2250

55. BuonaguroL

TorneselloML

TagliamonteM

GalloRC

WangLX

2006 Baculovirus-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virus-like particles activate dendritic cells and induce ex vivo T-cell responses. J Virol 80 9134 9143

56. InabaK

TurleyS

YamaideF

IyodaT

MahnkeK

1998 Efficient presentation of phagocytosed cellular fragments on the major histocompatibility complex class II products of dendritic cells. J Exp Med 188 2163 2173

57. TheryC

RegnaultA

GarinJ

WolfersJ

ZitvogelL

1999 Molecular characterization of dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Selective accumulation of the heat shock protein hsc73. J Cell Biol 147 599 610

58. TheryC

ZitvogelL

AmigorenaS

2002 Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol 2 569 579

59. ZitvogelL

RegnaultA

LozierA

WolfersJ

FlamentC

1998 Eradication of established murine tumors using a novel cell-free vaccine: dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Nat Med 4 594 600

60. WolfersJ

LozierA

RaposoG

RegnaultA

TheryC

2001 Tumor-derived exosomes are a source of shared tumor rejection antigens for CTL cross-priming. Nat Med 7 297 303

61. TheryC

DubanL

SeguraE

VeronP

LantzO

2002 Indirect activation of naive CD4+ T cells by dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Nat Immunol 3 1156 1162

62. GouldSJ

BoothAM

HildrethJE

2003 The Trojan exosome hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 10592 10597

63. Izquierdo-UserosN

Naranjo-GomezM

ArcherJ

HatchSC

ErkiziaI

2009 Capture and transfer of HIV-1 particles by mature dendritic cells converges with the exosome-dissemination pathway. Blood 113 2732 2741

64. GarciaE

PionM

Pelchen-MatthewsA

CollinsonL

ArrighiJF

2005 HIV-1 trafficking to the dendritic cell-T-cell infectious synapse uses a pathway of tetraspanin sorting to the immunological synapse. Traffic 6 488 501

65. GarciaE

NikolicDS

PiguetV

2008 HIV-1 replication in dendritic cells occurs through a tetraspanin-containing compartment enriched in AP-3. Traffic 9 200 214

66. BoothAM

FangY

FallonJK

YangJM

HildrethJE

2006 Exosomes and HIV Gag bud from endosome-like domains of the T cell plasma membrane. J Cell Biol 172 923 935

67. FangY

WuN

GanX

YanW

MorrellJC

2007 Higher-order oligomerization targets plasma membrane proteins and HIV gag to exosomes. PLoS Biol 5 e158 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050158

68. NguyenDH

HildrethJE

2000 Evidence for budding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 selectively from glycolipid-enriched membrane lipid rafts. J Virol 74 3264 3272

69. WubboltsR

LeckieRS

VeenhuizenPT

SchwarzmannG

MobiusW

2003 Proteomic and biochemical analyses of human B cell-derived exosomes. Potential implications for their function and multivesicular body formation. J Biol Chem 278 10963 10972

70. KrishnamoorthyL

BessJWJr

PrestonAB

NagashimaK

MahalLK

2009 HIV-1 and microvesicles from T cells share a common glycome, arguing for a common origin. Nat Chem Biol 5 244 250

71. ChazalN

GerlierD

2003 Virus entry, assembly, budding, and membrane rafts. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67 226 237

72. WileyRD

GummuluruS

2006 Immature dendritic cell-derived exosomes can mediate HIV-1 trans infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 738 743

73. BruggerB

GlassB

HaberkantP

LeibrechtI

WielandFT

2006 The HIV lipidome: a raft with an unusual composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 2641 2646

74. SakamotoH

OkamotoK

AokiM

KatoH

KatsumeA

2005 Host sphingolipid biosynthesis as a target for hepatitis C virus therapy. Nat Chem Biol 1 333 337

75. HatchSC

ArcherJ

GummuluruS

2009 Glycosphingolipid composition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) particles is a crucial determinant for dendritic cell-mediated HIV-1 trans-infection. J Virol 83 3496 3506

76. AndrieuJM

LuW

2007 A dendritic cell-based vaccine for treating HIV infection: background and preliminary results. J Intern Med 261 123 131

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 3- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- All Mold Is Not Alike: The Importance of Intraspecific Diversity in Necrotrophic Plant Pathogens

- Tsetse EP Protein Protects the Fly Midgut from Trypanosome Establishment

- Perforin and IL-2 Upregulation Define Qualitative Differences among Highly Functional Virus-Specific Human CD8 T Cells

- N-Acetylglucosamine Induces White to Opaque Switching, a Mating Prerequisite in

- Origin and Evolution of Sulfadoxine Resistant

- Rapid Evolution of Pandemic Noroviruses of the GII.4 Lineage

- Natural Strain Variation and Antibody Neutralization of Dengue Serotype 3 Viruses

- Fine-Tuning Translation Kinetics Selection as the Driving Force of Codon Usage Bias in the Hepatitis A Virus Capsid

- Structural Basis of Cell Wall Cleavage by a Staphylococcal Autolysin

- Direct Visualization by Cryo-EM of the Mycobacterial Capsular Layer: A Labile Structure Containing ESX-1-Secreted Proteins

- Lipopolysaccharide Is Synthesized via a Novel Pathway with an Evolutionary Connection to Protein -Glycosylation

- MicroRNA Antagonism of the Picornaviral Life Cycle: Alternative Mechanisms of Interference

- Limited Trafficking of a Neurotropic Virus Through Inefficient Retrograde Axonal Transport and the Type I Interferon Response

- Direct Restriction of Virus Release and Incorporation of the Interferon-Induced Protein BST-2 into HIV-1 Particles

- RNAIII Binds to Two Distant Regions of mRNA to Arrest Translation and Promote mRNA Degradation

- Direct TLR2 Signaling Is Critical for NK Cell Activation and Function in Response to Vaccinia Viral Infection

- The Essentials of Protein Import in the Degenerate Mitochondrion of

- Dynamic Imaging of Experimental Induced Hepatic Granulomas Detects Kupffer Cell-Restricted Antigen Presentation to Antigen-Specific CD8 T Cells

- An Accessory to the ‘Trinity’: SR-As Are Essential Pathogen Sensors of Extracellular dsRNA, Mediating Entry and Leading to Subsequent Type I IFN Responses

- Innate Killing of by Macrophages of the Splenic Marginal Zone Requires IRF-7

- Exoerythrocytic Parasites Secrete a Cysteine Protease Inhibitor Involved in Sporozoite Invasion and Capable of Blocking Cell Death of Host Hepatocytes

- Inhibition of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Ameliorates Ocular -Induced Keratitis

- Membrane Damage Elicits an Immunomodulatory Program in

- Fatal Transmissible Amyloid Encephalopathy: A New Type of Prion Disease Associated with Lack of Prion Protein Membrane Anchoring

- Nucleophosmin Phosphorylation by v-Cyclin-CDK6 Controls KSHV Latency

- A Combination of Independent Transcriptional Regulators Shapes Bacterial Virulence Gene Expression during Infection

- Inhibition of Host Vacuolar H-ATPase Activity by a Effector

- Human Cytomegalovirus Protein pUL117 Targets the Mini-Chromosome Maintenance Complex and Suppresses Cellular DNA Synthesis

- Dispersion as an Important Step in the Biofilm Developmental Cycle

- Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus ORF57 Protein Binds and Protects a Nuclear Noncoding RNA from Cellular RNA Decay Pathways

- Differential Regulation of Effector- and Central-Memory Responses to Infection by IL-12 Revealed by Tracking of Tgd057-Specific CD8+ T Cells

- The Human Polyoma JC Virus Agnoprotein Acts as a Viroporin

- Expansion, Maintenance, and Memory in NK and T Cells during Viral Infections: Responding to Pressures for Defense and Regulation

- T Cell-Dependence of Lassa Fever Pathogenesis

- HIV and Mature Dendritic Cells: Trojan Exosomes Riding the Trojan Horse?

- Endocytosis of the Anthrax Toxin Is Mediated by Clathrin, Actin and Unconventional Adaptors

- A Capsid-Encoded PPxY-Motif Facilitates Adenovirus Entry

- Homeostatic Interplay between Bacterial Cell-Cell Signaling and Iron in Virulence

- Serological Profiling of a Protein Microarray Reveals Permanent Host-Pathogen Interplay and Stage-Specific Responses during Candidemia

- YfiBNR Mediates Cyclic di-GMP Dependent Small Colony Variant Formation and Persistence in

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus ORF57 Protein Binds and Protects a Nuclear Noncoding RNA from Cellular RNA Decay Pathways

- Endocytosis of the Anthrax Toxin Is Mediated by Clathrin, Actin and Unconventional Adaptors

- Perforin and IL-2 Upregulation Define Qualitative Differences among Highly Functional Virus-Specific Human CD8 T Cells

- Inhibition of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Ameliorates Ocular -Induced Keratitis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání