-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaObesity and Multiple Sclerosis: A Mendelian Randomization Study

Using a Mendelian randomization approach, Brent Richards and colleagues examine the possibility that genetically raised body mass index could affect risk of multiple sclerosis.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 13(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002053

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002053Summary

Using a Mendelian randomization approach, Brent Richards and colleagues examine the possibility that genetically raised body mass index could affect risk of multiple sclerosis.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a debilitating autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that results in chronic disability for the majority of those affected [1]. The disease has an important impact on the health economy of many countries [2], since current treatment regimens are costly and have adverse side-effect profiles and/or limited efficacy [3]. MS etiology is poorly understood and, consequently, additional research is needed to identify potentially causal risk factors that could help guide prevention efforts.

Several observational studies have suggested that an elevated body mass index (BMI) in early adulthood is associated with an increased risk of developing MS [4–6]. In the Nurse’s Health study, a prospective cohort study of 238,371 women, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 at 18 y of age was associated with more than a 2-fold increased risk of MS (relative risk: 2.25, 95% CI 1.50–3.37) [4]. In addition, elevated BMI has been shown to affect the immune system by promoting a proinflammatory state [7–10], and it has been proposed that adipose-derived hormones, such as leptin [11] and adiponectin [12], might mediate this, providing a possible mechanistic link between obesity and risk of MS.

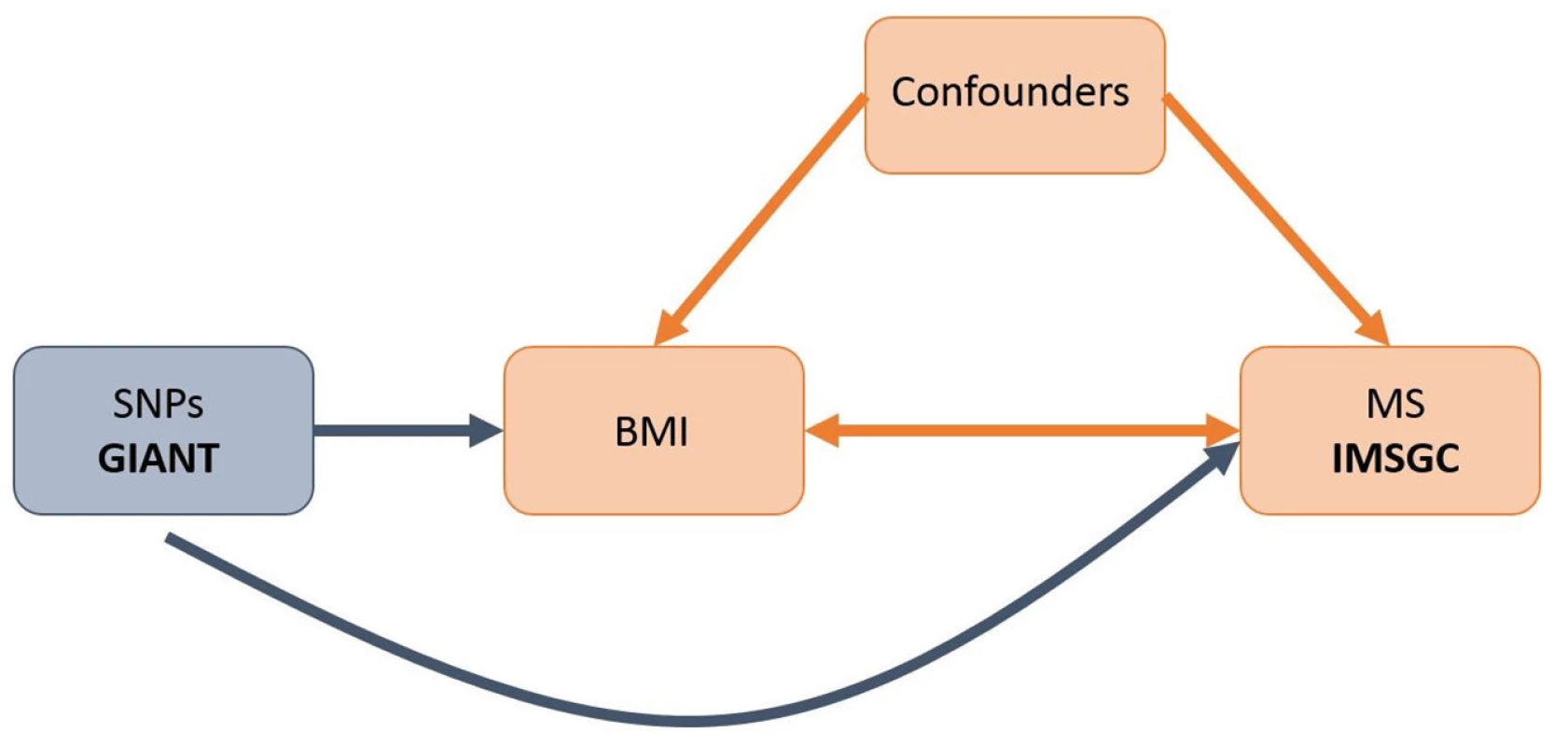

However, it remains uncertain whether this relationship is causal since it is difficult to fully protect observational studies from bias due to reverse causation or confounding. Mendelian randomization (MR) [13] offers a way to investigate potentially causal relationships by using genetic associations to explore the effect of modifiable exposures on outcomes. Since alleles are both independently segregated and randomly assigned at meiosis, bias inherent to observational study designs, such as confounding, is likely to be greatly minimized in MR studies (Fig 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of an MR analysis.

This diagram shows that SNPs associated with BMI were selected from the GIANT consortium. Corresponding effect estimates for these SNPs upon risk of MS were obtained from the IMSGC. Because of the randomization of alleles at meiosis, SNPs are not associated with confounding variables that may bias estimates obtained from observational studies. While increased BMI in childhood has been associated with numerous poor health outcomes [14,15], efforts to control obesity in children has been hindered by a lack of motivation in youth, due in part to the perception that most obesity-related diseases have a late age of onset [16]. However, if obesity were causally associated with MS (median age of onset 29 y) [17], this would provide a more immediate and severe consequence of early-life obesity, increasing motivation for its control.

In order to test whether genetically increased BMI is causally associated with risk of MS, we undertook an MR analysis using summary statistics from the Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT) consortium (up to n = 339,224) [18] and the International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium (IMSGC, up to n = 14,498 cases and 24,091 controls) [19,20], the largest genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to date for BMI and MS, respectively.

Methods

Data Sources and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Selection

Effect estimates for SNPs associated with BMI were obtained from the GIANT consortium, which is a meta-analysis of 125 GWASs in more than 339,224 individuals [18]. For the purpose of this MR, we limited our selection of SNPs to those that achieved genome-wide significance (p < 5 x 10−8) in the European sex-combined analysis (up to n = 322,105). Effect estimates of these BMI-associated SNPs on the risk of MS were assessed using the summary statistics from the IMSGC Immunochip study, which included 14,498 cases and 24,091 controls of European ancestry [19]. When effect estimates were not available in the Immunochip study, since the genotyping platform used was not genome-wide, effect estimates were obtained from the IMSGC/Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (IMSGC/WTCCC2) GWAS, which included 9,772 cases and 17,376 controls [20].

When a BMI-associated SNP was not present in either study, we selected proxy SNPs that were highly correlated with the variant of interest (r2 > 0.8). We identified potential proxies and measured linkage disequilibrium (LD) in samples of European descent from the UK10K consortium (n = 3,781) [21]. If no proxy was found using this method, we verified our search using SNAP [22,23]. As we did with our index SNPs, we selected summary statistics for our proxies first from the Immunochip study and then from the IMSGC/WTCCC2 study if they were not available in the Immunochip study.

Cohorts participating in the IMSGC and GIANT GWAS consortia received ethics approval from local institutional review boards and informed consent from all participants. Summary statistics from these consortia can be downloaded at the following links: IMSGC, https://www.immunobase.org; GIANT, https://www.broadinstitute.org/collaboration/giant/index.php/GIANT_consortium.

SNP Validation

LD assessment

One condition of MR is that the exposure-related SNPs (the instrumental variables) must not be in LD with each other, since this might result in confounding if a SNP is highly correlated with another SNP used as an instrumental variable [24]. To ensure this, we measured LD between all of our selected SNPs in European samples from UK10K (n = 3,781) [21] using PLINK software version 1.90 [25]. SNPs were removed from our analysis if their measured LD had an r2 greater than 0.05. We retained the SNP most strongly associated with BMI, by p-value, when two, or more, SNPs were in LD.

Pleiotropy assessment

An important assumption of MR is that each SNP must only influence risk of the outcome through the exposure under investigation, as the inclusion of SNPs that contribute through a pleiotropic pathway could bias estimates. This can be difficult to test when examining an anthropometric trait such as BMI, which is influenced by many different physiological mechanisms. Consequently, BMI-associated SNPs are likely to lie in genes of different biological effects that may, or may not, influence MS risk independently of BMI. To assess for the presence of pleiotropy, we used MR-Egger regression [26]. In brief, the approach is based on Egger regression, which has been used to examine publication bias in the meta-analysis literature [27]. Using the MR-Egger method, the SNP’s effect upon the exposure variable is plotted against its effect upon the outcome, and an intercept distinct from the origin provides evidence for pleiotropic effects. Funnel plots can also be used for visual inspection of symmetry. Additionally, the slope of the MR-Egger regression can provide pleiotropy-corrected causal estimates; however, this estimate of slope is underpowered unless the SNPs combine to explain a large proportion of the variance in the exposure with varying effect sizes [26]. An important condition of this approach is that a SNP’s association with the exposure variable must be independent of its direct effects upon the outcome (previously described as the InSIDE assumption) [26], which may not always be satisfied in cases in which all pleiotropic effects can be attributed to a single confounder. Nonetheless, the MR-Egger method can provide unbiased estimates even if all the chosen SNPs are invalid [26].

Additionally, the weighted median approach was used to examine pleiotropy [28]. Using this method, MR estimates are ordered and weighted by the inverse of their variance. The median MR estimate should remain unbiased as long as greater than 50% of the total weight comes from SNPs without pleiotropic effects. The weighted median approach offers some important advantages over MR-Egger because it improves precision and is more robust to violations of the InSIDE assumption. Therefore, we employed both methods as sensitivity analyses to assess whether pleiotropy had influenced our results.

Population stratification assessment

Population stratification is another potential source of bias for MR analyses. Because of differences in allele frequencies, a SNP can be associated with ancestry, which itself can be associated with disease risk. To limit this, we selected SNPs and summary statistics from analyses that included only individuals of European descent for both BMI and MS. However, residual population stratification may exist among European subgroups [29]. Therefore, to understand how this may affect our results, we searched the literature to explore whether BMI and MS covary geographically within Europe.

MR Estimates

We have previously applied the principles of MR to investigate the role of vitamin D in the etiology of MS [30]. Here, we employed the same methods to examine BMI as a risk factor for MS [30–32]. In brief, we selected SNPs that were genome-wide significant for BMI in the GIANT consortium and then obtained the effect estimates of these SNPs on BMI. Corresponding genetic effect estimates for these SNPs on the risk of MS were selected from the IMSGC. We then applied a two-sample MR approach by weighting the effect estimate of each SNP on MS by its effect on BMI. These estimates were then pooled using a fixed meta-analytic model [33,34] to produce a summary measure of the effect of genetically elevated BMI upon MS risk. This two-sample approach has equivalent statistical power to one-sample approaches [31] and is favorable in this setting since large GWAS consortia exist for both BMI and MS and are thus better powered than an MR study in a single cohort with a smaller sample size.

Bidirectional MR Analysis

Next, we sought to explore whether MS influences BMI. Therefore, we elected to perform a bidirectional MR analysis to determine the effect of genetically increased risk of MS on BMI. To do so, we selected SNPs that were genome-wide significant (p < 5 x 10−8) for MS in either the Immunochip study, the IMSGC/WTCCC2 study, or other previously reported MS GWASs [19,20,35]. With MS-associated SNPs now as the exposure, we then obtained corresponding effect estimates from GIANT as the outcome. We next applied the same methods as above.

Sensitivity Analyses

To ensure that the inclusion of proxy SNPs did not introduce random error into our results, we conducted sensitivity analyses where groups of SNPs were excluded. First, we removed all proxies and retained only SNPs that had been directly genotyped in the Immunochip or IMSGC/WTCCC2 studies. Next, we excluded only proxies with allele frequencies between 0.4 and 0.6, as it can be difficult to correctly match alleles for SNPs falling within this range since different GWAS studies report slight fluctuations in allele frequencies. Since BMI is calculated using both height and weight measurements, we were concerned that our results might be partially confounded by height. Therefore, we next removed SNPs from our analysis that were found to be in LD (r2 > 0.05) with any loci genome-wide significant for height as reported in GIANT’s 2014 GWAS [36]. Lastly, we performed an analysis in which genetic effect sizes on MS were selected exclusively from the IMSGC/WTCCC2 study.

Results

SNP Selection

Overall, we identified 77 LD-independent SNPs that achieved genome-wide significance for BMI in the GIANT consortium. However, not all of these SNPs were genotyped in the MS datasets. Fourteen of these SNPs were included in the IMSGC Immunochip study, and a further 20 in the IMSGC/WTCCC2 GWAS. Of the remaining SNPs, we next identified 36 proxies with an r2 > 0.8 : 12 from the IMSGC Immunochip study and 24 from the IMSGC/WTCCC2 GWAS. We could not identify proxies for seven of the BMI SNPs. A flow diagram of this SNP selection process is shown in S1 Fig. Therefore, in total we used 70 SNPs for our MR analysis, as shown in Table 1. The mean r2 for proxies was 0.94.

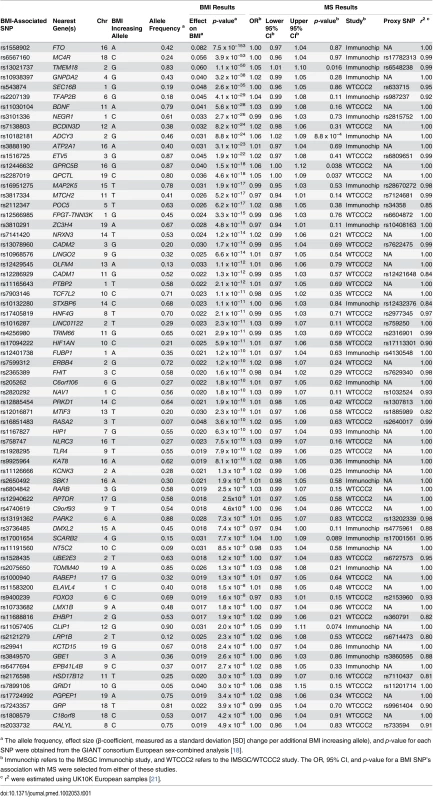

Tab. 1. Characteristics of SNPs used in MR analysis.

a The allele frequency, effect size (β-coefficient, measured as a standard deviation [SD] change per additional BMI increasing allele), and p-value for each SNP were obtained from the GIANT consortium European sex-combined analysis [18]. SNP Validation

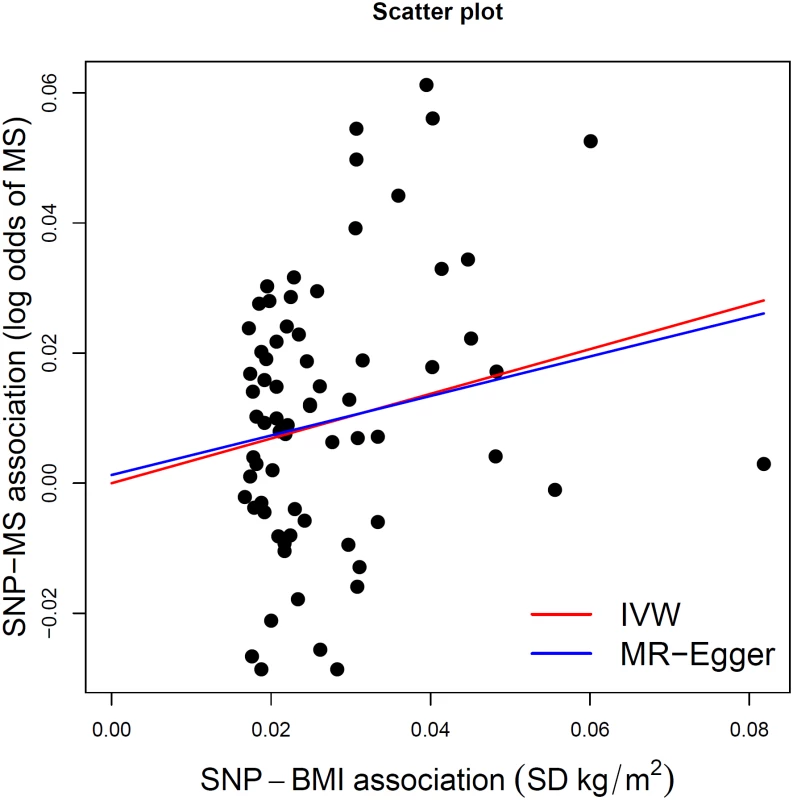

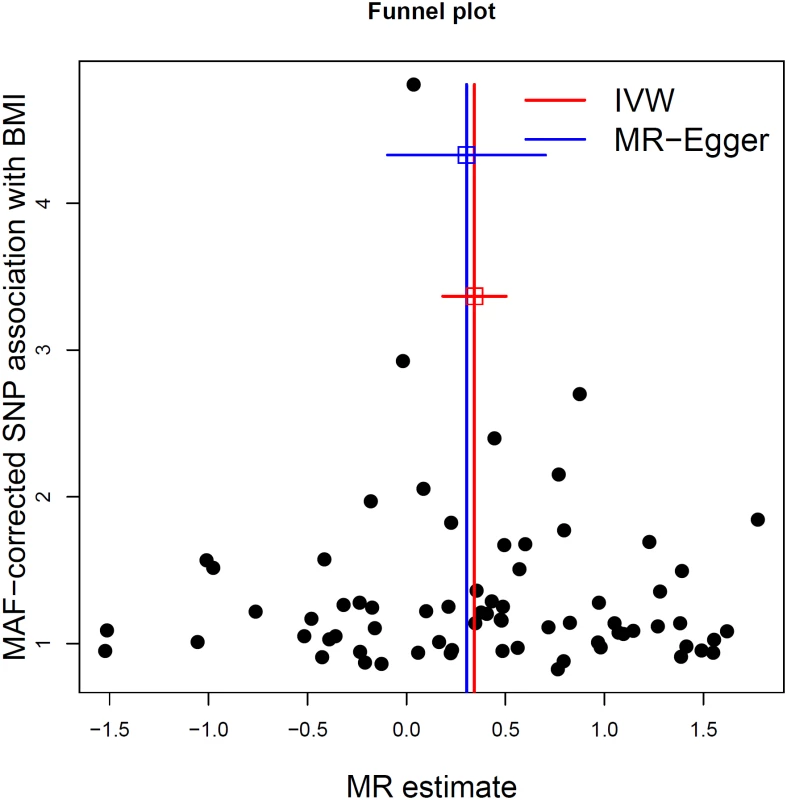

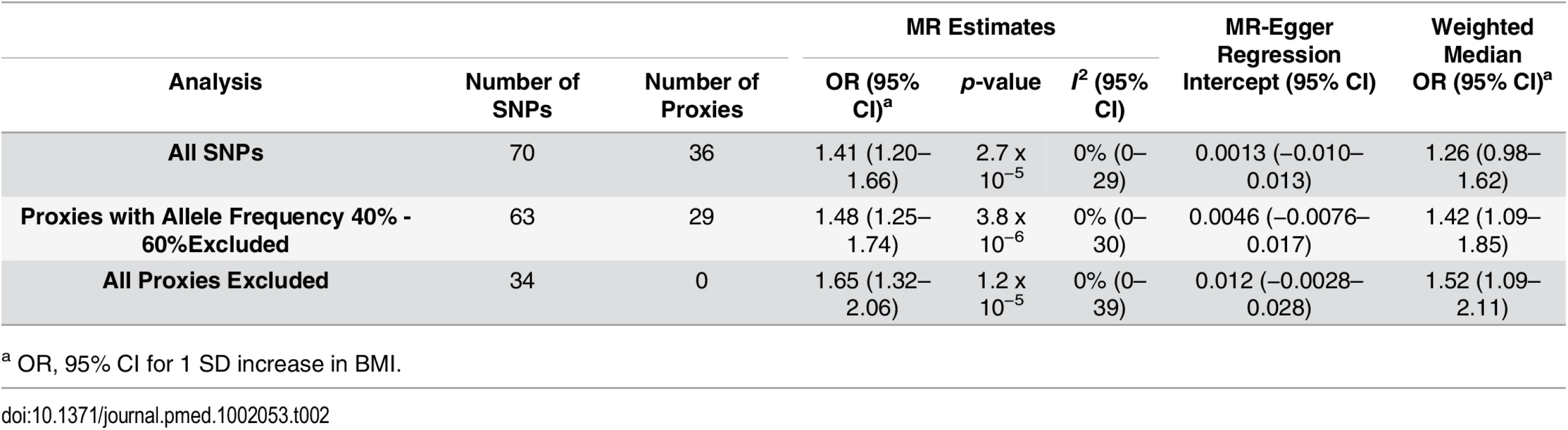

We next tested whether any of the selected SNPs were influenced by LD, pleiotropy, or population stratification. First, none of the SNPs were found to be in LD with each other at an r2 > 0.05. Second, the intercept term estimated from MR-Egger regression was centered at the origin with a confidence interval including the null (0.0013, 95% CI −0.010–0.013, p = 0.83) (Table 2), suggesting that pleiotropy had not unduly influenced the results. This observation was further confirmed by Fig 2, which represents a scatterplot of the effect estimates of SNPs associated with BMI and their corresponding effect on MS risk. The plot also displays the regression lines of our primary MR analysis (in red) and the MR-Egger adjusted for possible pleiotropy (in blue). Additionally, we inspected the funnel plot for any asymmetry, which would be suggestive of pleiotropy, and found the plot to the symmetrical (Fig 3). There is a higher prevalence of obesity among Southern and Eastern European populations [37,38]. Conversely, these populations have a decreased burden of MS relative to their Northern European counterparts [39]. Given the inversely correlated distributions of obesity and MS in Europe, the inclusion of SNPs potentially associated with ancestry within Europe would tend to bias our results towards the null (S2 Fig). Thus, residual effects of within-Europe ancestry would, on average, tend to underestimate true effects.

Fig. 2. MR-Egger regression scatterplot for BMI on MS analysis.

The red line shows the results of standard MR analysis (inverse-variance weighting [IVW]), and the blue line shows the pleiotropy-adjusted MR-Egger regression line. The estimated slope of the MR-Egger regression, expressed as an OR, was 1.35 (95% CI 0.91–2.02). The estimated MR-Egger intercept term was 0.0013 (95% CI −0.010–0.013) Fig. 3. MR-Egger regression funnel plot for BMI on MS analysis.

Each SNP’s MR estimate is plotted against its minor-allele frequency corrected association with BMI. A minor allele frequency (MAF) correction proportional to the SNP-BMI standard error is used since a low-frequency allele is likely to be measured with low precision. Similar to the use of funnel plots in the meta-analysis literature, this plot can be used for visual inspection of symmetry, where any deviation can be suggestive of pleiotropy. We note that our plot appears generally symmetrical. Tab. 2. Results of MR analyses and sensitivity analyses.

a OR, 95% CI for 1 SD increase in BMI. MR Estimates

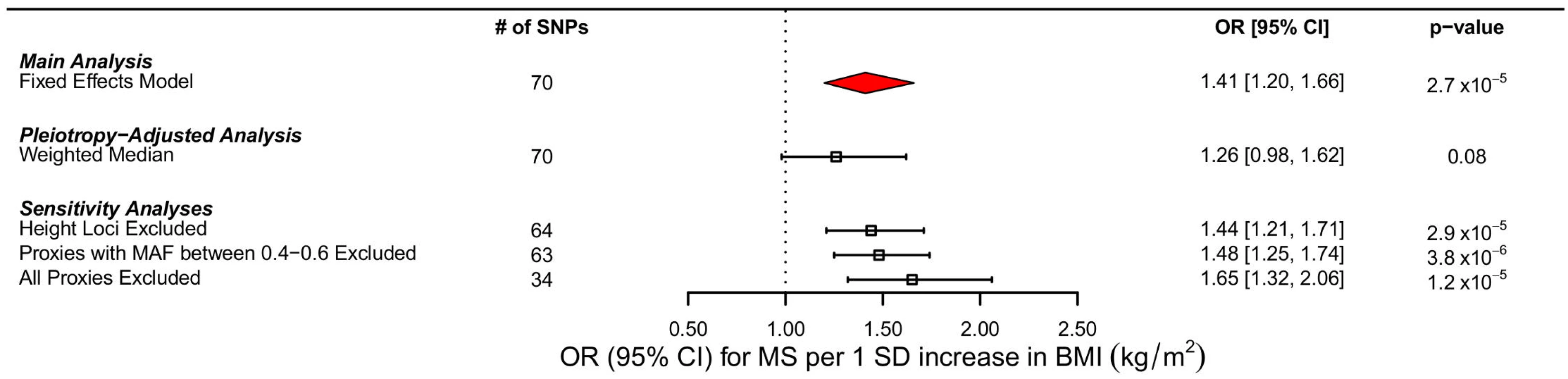

Using MR analyses, a 1 standard deviation (SD) increase in BMI (kg/m2) was associated with a 41% increase in odds of MS (OR: 1.41, 95% CI 1.20–1.66, p = 2.72 x 10−5) (Table 2; Fig 4). The I2 estimate for heterogeneity was 0% (95% CI 0%–29%). The slope of the MR-Egger regression was consistent with these findings (Fig 2). The results obtained using the weighted median approach further replicated this direction and magnitude of effect (OR: 1.26, 95% CI 0.98–1.62, p = 0.08), providing no evidence for pleiotropy.

Fig. 4. Forest plot of MR estimates.

Forest plots of all main and sensitivity analyses. ORs for MS are reported for a 1 SD increase in BMI. Estimates were obtained using a fixed effects model. MAF refers to minor allele frequency. In bidirectional MR analyses, we initially identified 110 SNPs reported by the IMSGC as genome-wide significant for MS; however, not all of these SNPs were ascertained directly in GIANT. Therefore, we used a total of 99 instruments for this analysis. Our results suggest that the genetic determinants of MS do not contribute to BMI (−0.0033 SD change in BMI per log odds increase in MS, 95% CI −0.011–0.0042, p = 0.39). The estimate for heterogeneity was large in this case (I2: 43.5%, 95% CI 28.3%–55.6%). There was also no evidence of pleiotropy from the MR-Egger analyses (the intercept was centered at 0.002 with a 95% CI that included the origin [95% CI −0.0009–0.005, p = 0.17]) and an MR-Egger slope consistent with previous estimates (S3 and S4 Figs). Results from the weighted median analyses also were consistent with the main findings, decreasing the probability that pleiotropy influenced the results.

Sensitivity Analyses

We excluded proxy SNPs to understand if random error, introduced by the use of imperfect proxies, had influenced our results. First, when all proxies were removed, we found a stronger relationship between BMI and MS, with a 1 SD change increasing odds of MS by 65% (OR: 1.65, 95% CI 1.32–2.06, p = 1.18 x10-5 (Table 2; Fig 4). Similarly, when we removed only proxies with allele frequencies between 0.4 and 0.6, we observed an OR of 1.48, similar to that obtained in the primary analysis (OR: 1.48, 95% CI 1.25–1.74, p = 3.82 x 10−6) (Table 2; Fig 4). In addition, we removed six SNPs that were in LD with known height loci (S1 Table), but again, this did not importantly change the results (OR: 1.44, 95% CI 1.21–1.71, p = 2.93 x 10−5) (Fig 4). MR results using only the IMSGC/WTCCC2 study were again concordant with our primary analysis (S1 Text and S2 Table).

Discussion

Using an MR study design, these results provide evidence that genetically elevated BMI is strongly associated with an increased risk of MS, where a 1 SD increase in BMI conferred a 41% increase in the odds of MS. To place this in a clinical context, the mean SD for BMI reported among cohorts in the GIANT consortium was 4.70 kg/m2 [18]. Therefore, our estimates of a 41% increase in odds of MS correspond roughly to a change in BMI category from overweight (≥25 kg/m2) to obese (≥30 kg/m2) as per WHO obesity guidelines [40]. This suggests that childhood and early-adulthood BMI is an important modifiable risk factor for MS. The results of our bidirectional MR analysis indicate that MS does not influence BMI status.

The results of the MR analysis may offer some of the best evidence to assess the causal role of BMI in MS etiology since the results are less likely to be biased by confounding or reverse causation than traditional observational epidemiological study designs. By employing the two-sample MR approach, we were able to increase statistical power by selecting summary statistics from the largest GWAS studies for BMI (n = 322,105) and MS (up to n = 14,498 cases and 24,091 controls). Additionally, since genetic variants are stable over an individual’s life, our results represent lifetime risk of MS due to elevated BMI.

These findings may carry important public health implications because of the high prevalence of obesity in many countries [41]. For instance, results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest that approximately 17% of youth [42] and 35% of adults [43] living in the United States are considered to be obese. Therefore, the identification of elevated BMI as a susceptibility factor for MS places a high proportion of the population at a relatively higher risk for MS. Mean population BMI has increased in many Western countries over the past several decades [41], which coincides with rising MS incidence rates, particularly evident among females [44,45].

Elevated BMI has long been associated with an increased risk of many diseases, including those resulting in adverse cardiometabolic outcomes [46,47]; however, symptoms of these diseases typically do not manifest until the fifth or sixth decade of life [48,49]. In contrast, the median age of onset for MS is 28–31 y [50]; thus, our findings may demonstrate a more immediate consequence of elevated BMI. This provides further rationale to combat increasing youth obesity rates by implementing community and school-based interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition.

Current evidence suggests that there are several potential mechanisms through which increased BMI may affect MS risk; however, it remains unclear which of these pathways are critical. Vitamin D is a strong candidate, given that previous MR analyses demonstrate that genetically elevated BMI decreases 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels [51], and we have recently provided strong evidence supporting a causal role for reduced 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels as a risk factor for MS [30].

Elevated BMI has many physiological effects, and the exact mechanisms underlying the risk for MS conferred by an increased BMI remain unclear. For instance, obesity is known to promote a proinflammatory state [7–10], offering a potential mechanistic link to autoimmunity. In addition, results from a recent MR study show that increased BMI produces important effects on metabolite, lipoprotein, and hormone profiles [10]. In particular, adiponectin and leptin, the adipose-derived hormones, have been previously associated with MS and MS-related disability [52–54]. Under an obesogenic state, serum leptin levels rise whereas adiponectin levels fall, and this has been shown to reduce the production of regulatory T cells [55] and anti-inflammatory cytokines [56]. However, further research, such as prospective cohort studies or MR analyses, is required in order to understand the functional role of obesity in the risk of MS.

Our study also has limitations. First, while we undertook multiple sensitivity analyses to assess for pleiotropy, the possibility of residual pleiotropy is difficult to exclude. However, consistency across these approaches, and the fact that the MR-Egger intercept was centered at the origin, provides evidence that pleiotropy did not greatly influence the results. We can also not directly assess whether population stratification or compensatory mechanisms (otherwise known as canalization) may be influencing our results; however, these would likely bias our estimates towards the null [13]. While we ensured that our SNPs were not in LD with each other, it remains possible that they are in LD with SNPs that influence unknown risk factors for MS. Secondly, we note that both GIANT and the IMSGC used samples from the WTCCC cohort; therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of sample overlap. This may have introduced bias into our results; however, given the sample size employed, this effect would likely be small since the WTCCC comprised ~2.5% of the overall GIANT consortium. Third, because of our use of summary-level statistics, we could not investigate nonlinear effects of BMI. Lastly, we cannot determine whether an established and more actionable intermediate, such as vitamin D, is primarily driving this causal relationship, nor can we conclude whether BMI influences MS progression.

In conclusion, these results provide evidence supporting a causal role for elevated BMI in MS etiology. This provides further rationale for individuals at risk for MS to maintain a healthy BMI. Whether vitamin D, or another established intermediate, is predominantly mediating this relationship warrants further investigation.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372 : 1502–1517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7 18970977

2. Trisolini M, Honeycutt A, Wiener J, Lesesne S. MS International Federation. In: Global Economic Impact of Multiple Sclerosis. 2010 [cited 21 Apr 2016]. http://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Global_economic_impact_of_MS.pdf

3. Hartung DM, Bourdette DN, Ahmed SM, Whitham RH. The cost of multiple sclerosis drugs in the US and the pharmaceutical industry: Too big to fail? Neurology. 2015;84 : 2185–2192. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001608 25911108

4. Munger KL, Chitnis T, Ascherio A. Body size and risk of MS in two cohorts of US women. Neurology. 2009;73 : 1543–1550. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c0d6e0 19901245

5. Munger KL, Bentzen J, Laursen B, Stenager E, Koch-Henriksen N, Sørensen TIA, et al. Childhood body mass index and multiple sclerosis risk: a long-term cohort study. Mult Scler. 2013;19 : 1323–1329. doi: 10.1177/1352458513483889 23549432

6. Hedstrom a. K, Olsson T, Alfredsson L. High body mass index before age 20 is associated with increased risk for multiple sclerosis in both men and women. Mult Scler J. 2012;18 : 1334–1336. doi: 10.1177/1352458512436596

7. Esposito K, Pontillo A, Di Palo C, Giugliano G, Masella M, Marfella R, et al. Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289 : 1799–804. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1799 12684358

8. Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB. Low-Grade Systemic Inflammation in Overweight Children. Pediatrics. 2001;107: e13. 11134477

9. Timpson NJ, Nordestgaard BG, Harbord RM, Zacho J, Frayling TM, Tybjærg-Hansen A, et al. C-reactive protein levels and body mass index: elucidating direction of causation through reciprocal Mendelian randomization. Int J Obes. 2011;35 : 300–308. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.137

10. Würtz P, Wang Q, Kangas AJ, Richmond RC, Skarp J, Tiainen M, et al. Metabolic signatures of adiposity in young adults: Mendelian randomization analysis and effects of weight change. PLoS Med. 2014;11: e1001765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001765 25490400

11. van Dielen FM, van’t Veer C, Schols AM, Soeters PB, Buurman WA, Greve JW. Increased leptin concentrations correlate with increased concentrations of inflammatory markers in morbidly obese individuals. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25 : 1759–1766. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801825 11781755

12. Engeli S, Feldpausch M, Gorzelniak K, Hartwig F, Heintze U, Janke J, et al. Association Between Adiponectin and Mediators of Inflammation in Obese Women. Diabetes. 2003;52 : 942–947. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.942 12663465

13. Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. “Mendelian randomization”: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32 : 1–22. 12689998

14. Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, Venn A, Burns TL, Sabin MA, et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med. 2011;365 : 1876–1885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010112 22087679

15. Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35 : 891–898. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.222

16. Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Management of child and adolescent obesity: summary and recommendations based on reports from pediatricians, pediatric nurse practitioners, and registered dietitians. Pediatrics. 2002;110 : 236–238. 12094001

17. Goodin DS. The epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: insights to disease pathogenesis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;122 : 231–266. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52001-2.00010-8 24507521

18. Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518 : 197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177 25673413

19. Beecham AH, Patsopoulos NA, Xifara DK, Davis MF, Kemppinen A, Cotsapas C, et al. Analysis of immune-related loci identifies 48 new susceptibility variants for multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2013;45 : 1353–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng.2770 24076602

20. Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CCA, Patsopoulos NA, Moutsianas L, et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476 : 214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10251 21833088

21. Walter K, Min JL, Huang J, Crooks L, Memari Y, McCarthy S, et al. The UK10K project identifies rare variants in health and disease. Nature. 2015;526 : 82–90. doi: 10.1038/nature14962 26367797

22. Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, Nizzari MM, O’Donnell CJ, De Bakker PIW. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24 : 2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564 18974171

23. SNAP Proxy Search. In: Broad Institute. 2016 [cited 21 Apr 2016]. https://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/ldsearch.php

24. Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JAC, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: Using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27 : 1133–1163. 17886233

25. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81 : 559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795 17701901

26. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44 : 512–525. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv080 26050253

27. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315 : 629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.469 9310563

28. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent Estimation in Mendelian Randomization with Some Invalid Instruments Using a Weighted Median Estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40 : 304–314. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21965 27061298

29. Huckins LM, Boraska V, Franklin CS, Floyd JAB, Southam L, Sullivan PF, et al. Using ancestry-informative markers to identify fine structure across 15 populations of European origin. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22 : 1190–1200. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.1 24549058

30. Mokry LE, Ross S, Ahmad OS, Forgetta V, Davey Smith G, Leong A, et al. Vitamin D and Risk of Multiple Sclerosis: A Mendelian Randomization Study. PLoS Med. 2015;12: e1001866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001866 26305103

31. Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37 : 658–665. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21758 24114802

32. Dastani Z, Hivert M-FF, Timpson NJ, Perry JRB, Yuan X, Scott RA, et al. Novel loci for adiponectin levels and their influence on type 2 diabetes and metabolic traits: a multi-ethnic meta-analysis of 45,891 individuals. PLoS Genet. 2012;8: e1002607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002607 22479202

33. Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37 : 1148–1157. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn065 18424475

34. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7 : 177–188. 3802833

35. Patsopoulos NA, De Bakker PIW. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies novel multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci. Ann Neurol. 2011;70 : 897–912. doi: 10.1002/ana.22609 22190364

36. Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014;46 : 1173–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng.3097 25282103

37. Berghofer A, Pischon T, Reinhold T, Apovian CM, Sharma AM, Willich SN. Obesity prevalence from a European perspective: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8 : 200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-200 18533989

38. Ahrens W, Pigeot I, Pohlabeln H, De Henauw S, Lissner L, Molnar D, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in European children below the age of 10. Int J Obes. 2014;38: S99–S107.

39. Pugliatti M, Rosati G, Carton H, Riise T, Drulovic J, Vécsei L, et al. The epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13 : 700–722. 16834700

40. WHO. Body mass index—BMI. [cited 3 Dec 2015]. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi

41. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384 : 766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8 24880830

42. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311 : 806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732 24570244

43. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307 : 491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39 22253363

44. Orton S-M, Herrera BM, Yee IM, Valdar W, Ramagopalan S V, Sadovnick AD, et al. Sex ratio of multiple sclerosis in Canada: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5 : 932–936. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70581-6 17052660

45. Koch-Henriksen N, Sørensen PS. The changing demographic pattern of multiple sclerosis epidemiology. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9 : 520–532. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70064-8 20398859

46. Bays HE, Chapman RH, Grandy S. The relationship of body mass index to diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: comparison of data from two national surveys. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61 : 737–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01336.x 17493087

47. Lamon-Fava S, Wilson PWF, Schaefer EJ. Impact of Body Mass Index on Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors in Men and Women: The Framingham Offspring Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16 : 1509–1515. 8977456

48. CDC. Diabetes Public Health Resource. In: Mean and Median Age at Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Adult Incident Cases Aged 18–79 Years, United States, 1997–2011. 2015 [cited 21 Apr 2016]. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/age/fig2.htm

49. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125: e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046 22179539

50. Degenhardt A, Ramagopalan S V, Scalfari A, Ebers GC. Clinical prognostic factors in multiple sclerosis: a natural history review. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5 : 672–682. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.178 19953117

51. Vimaleswaran KS, Berry DJ, Lu C, Tikkanen E, Pilz S, Hiraki LT, et al. Causal relationship between obesity and vitamin D status: bi-directional Mendelian randomization analysis of multiple cohorts. PLoS Med. 2013;10: e1001383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001383 23393431

52. Rotondi M, Batocchi AP, Coperchini F, Caggiula M, Zerbini F, Sideri R, et al. Severe disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis is associated with profound changes in the regulation of leptin secretion. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2013;20 : 341–347. doi: 10.1159/000353567 24008588

53. Emamgholipour S, Eshaghi SM, Hossein-nezhad A, Mirzaei K, Maghbooli Z, Sahraian MA. Adipocytokine profile, cytokine levels and foxp3 expression in multiple sclerosis: a possible link to susceptibility and clinical course of disease. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e76555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076555 24098530

54. Musabak U, Demirkaya S, Genç G, Ilikci RS, Odabasi Z. Serum Adiponectin, TNF-α, IL-12p70, and IL-13 Levels in Multiple Sclerosis and the Effects of Different Therapy Regimens. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2011;18 : 57–66. doi: 10.1159/000317393 20714168

55. Matarese G, Carrieri PB, La Cava A, Perna F, Sanna V, De Rosa V, et al. Leptin increase in multiple sclerosis associates with reduced number of CD4(+)CD25+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102 : 5150–5155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408995102 15788534

56. Wolf AM, Wolf D, Rumpold H, Enrich B, Tilg H. Adiponectin induces the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-1RA in human leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323 : 630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.145 15369797

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2016 Číslo 6- Berberin: přírodní hypolipidemikum se slibnými výsledky

- Příznivý vliv Armolipidu Plus na hladinu cholesterolu a zánětlivé parametry u pacientů s chronickým subklinickým zánětem

- Léčba bolesti u seniorů

- Jak postupovat při výběru betablokátoru − doporučení z kardiologické praxe

- Červená fermentovaná rýže účinně snižuje hladinu LDL cholesterolu jako vhodná alternativa ke statinové terapii

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Direct-to-consumer Marketing to People with Hemophilia

- Geographical Inequalities and Social and Environmental Risk Factors for Under-Five Mortality in Ghana in 2000 and 2010: Bayesian Spatial Analysis of Census Data

- Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors and Risk of Malignant Melanoma: Matched Cohort Study Using Primary Care Data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink

- Age, Spatial, and Temporal Variations in Hospital Admissions with Malaria in Kilifi County, Kenya: A 25-Year Longitudinal Observational Study

- Obesity and Multiple Sclerosis: A Mendelian Randomization Study

- Inter-pregnancy Weight Change and Risks of Severe Birth-Asphyxia-Related Outcomes in Singleton Infants Born at Term: A Nationwide Swedish Cohort Study

- Impact Evaluation of a System-Wide Chronic Disease Management Program on Health Service Utilisation: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study

- Early Childhood Developmental Status in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: National, Regional, and Global Prevalence Estimates Using Predictive Modeling

- Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies

- Exclusive Breastfeeding and Cognition, Executive Function, and Behavioural Disorders in Primary School-Aged Children in Rural South Africa: A Cohort Analysis

- Investigating the Causal Relationship of C-Reactive Protein with 32 Complex Somatic and Psychiatric Outcomes: A Large-Scale Cross-Consortium Mendelian Randomization Study

- Agreements between Industry and Academia on Publication Rights: A Retrospective Study of Protocols and Publications of Randomized Clinical Trials

- Weighing Evidence from Mendelian Randomization—Early-Life Obesity as a Causal Factor in Multiple Sclerosis?

- A Global Champion for Health—WHO’s Next?

- Malaria Epidemiology in Kilifi, Kenya during the 21st Century: What Next?

- Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: the GATHER statement

- Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology—Nutritional Epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An Extension of the STROBE Statement

- Why Most Clinical Research Is Not Useful

- Delinking Investment in Antibiotic Research and Development from Sales Revenues: The Challenges of Transforming a Promising Idea into Reality

- Novel Three-Day, Community-Based, Nonpharmacological Group Intervention for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain (COPERS): A Randomised Clinical Trial

- Prediction of Bladder Outcomes after Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: A Longitudinal Cohort Study

- The Effect of Sitagliptin on Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis in Type 2 Diabetes: The PROLOGUE Randomized Controlled Trial

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Why Most Clinical Research Is Not Useful

- Agreements between Industry and Academia on Publication Rights: A Retrospective Study of Protocols and Publications of Randomized Clinical Trials

- Inter-pregnancy Weight Change and Risks of Severe Birth-Asphyxia-Related Outcomes in Singleton Infants Born at Term: A Nationwide Swedish Cohort Study

- Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology—Nutritional Epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An Extension of the STROBE Statement

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání