-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaHox Transcription Factors Access the RNA Polymerase II Machinery through Direct Homeodomain Binding to a Conserved Motif of Mediator Subunit Med19

Mutations of Hox developmental genes in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster may provoke spectacular changes in form: transformations of one body part into another, or loss of organs. This attribute identifies them as important developmental genes. Insect and vertebrate Hox proteins contain highly related homeodomain motifs used to bind to regulatory DNA and influence expression of developmental target genes. This occurs at the level of transcription of target gene DNA to messenger RNA by RNA polymerase II and its associated protein machinery (>50 proteins). How Hox homeodomain proteins induce fine-tuned transcription remains an open question. We provide an initial response, finding that Hox proteins also use their homeodomains to bind one machinery protein, Mediator complex subunit 19 (Med19) through a Med19 sequence that is highly conserved in animal phyla. Med19 mutants isolated in this work (the first animal mutants) show that Med19 assists Hox protein functions. Further, they indicate that homeodomain binding to the Med19 motif is required for normal expression of a Hox target gene. Our work provides new clues for understanding how the specific transcriptional inputs of the highly conserved Hox class of transcription factors are integrated at the level of the whole transcription machinery.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004303

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004303Summary

Mutations of Hox developmental genes in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster may provoke spectacular changes in form: transformations of one body part into another, or loss of organs. This attribute identifies them as important developmental genes. Insect and vertebrate Hox proteins contain highly related homeodomain motifs used to bind to regulatory DNA and influence expression of developmental target genes. This occurs at the level of transcription of target gene DNA to messenger RNA by RNA polymerase II and its associated protein machinery (>50 proteins). How Hox homeodomain proteins induce fine-tuned transcription remains an open question. We provide an initial response, finding that Hox proteins also use their homeodomains to bind one machinery protein, Mediator complex subunit 19 (Med19) through a Med19 sequence that is highly conserved in animal phyla. Med19 mutants isolated in this work (the first animal mutants) show that Med19 assists Hox protein functions. Further, they indicate that homeodomain binding to the Med19 motif is required for normal expression of a Hox target gene. Our work provides new clues for understanding how the specific transcriptional inputs of the highly conserved Hox class of transcription factors are integrated at the level of the whole transcription machinery.

Introduction

The finely regulated gene transcription permitting development of pluricellular organisms involves the action of transcription factors (TFs) that bind DNA targets and convey this information to RNA polymerase II (PolII). Hox TFs, discovered through iconic mutations of the Drosophila melanogaster Bithorax and Antennapedia Complexes, play a central role in the development of a wide spectrum of animal species [1], [2]. Hox proteins orchestrate the differentiation of morphologically distinct segments by regulating PolII-dependent transcription of complex batteries of downstream target genes whose composition and nature are now emerging [3]–[7]. The conserved 60 amino acid (a.a.) homeodomain (HD), a motif used for direct binding to DNA target sequences, is central to this activity. Animal orthologs of the Drosophila proteins make use of their homeodomains to play widespread and crucial roles in differentiation programs yielding the very different forms of sea urchins, worms, flies or humans [8]. They do so by binding simple TAAT-based sequences within regulatory DNA of developmental target genes [9]–[14]. One crucial aspect of understanding how Hox proteins transform their versatile but low-specificity DNA binding into an exquisite functional specificity involves the identification of functional partners. Known examples include the TALE HD proteins encoded by extradenticle (exd)/Pbx and homothorax (hth)/Meis, which assist Hox proteins to form stable ternary DNA-protein complexes with much-enhanced specificity. This involves contacts with the conserved Hox Hexapeptide (HX) motif near the HD N-terminus, or alternatively, with the paralog-specific UBD-A motif detected in Ubx and Abdominal-A (Abd-A) proteins [15], [16]. Other TFs that can serve as positional Hox partners include the segment-polarity gene products Engrailed (En) and Sloppy paired, that collaborate with Ubx and Abd-A to repress abdominal expression of Distal-less [17]. Finally, specific a.a. residues in the HX motif, the HD and the linker separating them play a distinctive role in DNA target specificity, allowing one Hox HD region to select paralog-specific targets [18], [19].

Contrasting with our knowledge of collaborations involving Hox and partner TFs, virtually nothing is known of what transpires at the interface with the RNA Polymerase II (PolII) machinery itself to generate an appropriate transcriptional response. The lone evidence directly linking Hox TFs to the PolII machine comes from the observation that the Drosophila TFIID component BIP2 binds the Antp HX motif [20].

Another key component of the PolII machinery is the Mediator (MED) complex conserved from amoebae to man that serves as an interface between DNA-bound TFs and PolII. MED possesses a conserved, modular architecture characterized by the presence of head, middle, tail and optional CDK8 modules. Some of the 30 subunits composing MED appear to play a general structural role in the complex while others interact with DNA-bound TFs bridging them to PolII. Together, these subunits and the MED modules they form associate with PolII, TFs and chromatin to regulate PolII-dependent transcription [21]–[28].

Our analysis of a Drosophila skuld/Med13 mutation isolated by dose-sensitive genetic interactions with homeotic proboscipedia (pb) and Sex combs reduced (Scr) genes led us to view MED as a Hox co-factor [29]. However, how MED might act with Hox TFs in developmental processes has not been explored. The work presented here pursues the hypothesis that Hox TFs modulate PolII activity through direct binding to one or more MED subunits. Starting from molecular assays, we identify Med19 as a subunit that binds to the homeodomain of representative Hox proteins through an animal-specific motif. Loss-of-function (lof) Med19 mutations isolated in this work reveal that Med19 affects Hox developmental activity and target gene regulation. Taken together, our results provide the first molecular link between Hox TFs and the general transcription machinery, showing how Med19 can act as an embedded functional partner, or “co-factor”, that directly links DNA-bound Hox homeoproteins to the PolII machinery.

Results

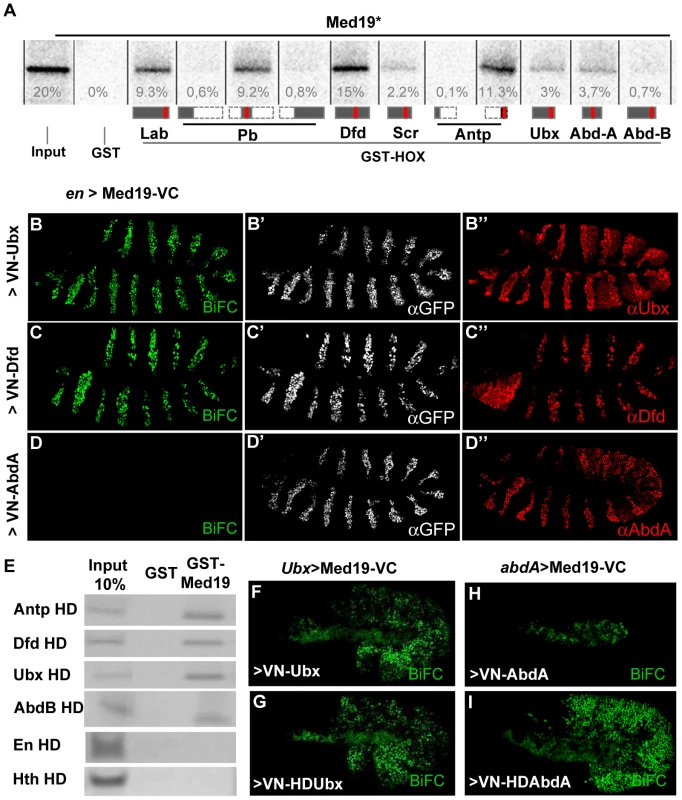

Hox proteins directly bind Med19 via their homeodomain

To search for MED subunits that contact Hox proteins directly, a Hox/MED binding matrix was established with the in vitro GST-pulldown assay. GST fusions of the eight Drosophila Hox proteins (full-length Labial (Lab), Deformed (Dfd), Scr, Ubx, Abd-A and Abdominal-B (Abd-B), or portions of Pb and Antp) were probed with 35S-labelled MED proteins in standard conditions for 11 MED subunits that are not required for cell viability in yeast and/or that are known to interact physically with TFs in mammalian cells (Materials and Methods). The Med19 subunit stood out, binding strongly to multiple GST-Hox proteins in this assay (mean binding, ≥5% of input in multiple tests, except for Abd-B, 0.8%; Figure 1A).

Fig. 1. Hox proteins bind Med19 through their homeodomains in vitro and in vivo.

(A) GST-pulldown binding assays of 35S-Med19 to immobilized GST-Hox fusions containing full length or protein fragments (below each lane: rectangles represent the entire protein; portions present in GST-Hox chimeric proteins are black, except the HD, represented in red). (B–D) BiFC assays were carried out co-expressing Med19-VC with VN-Ubx (B), VN-Dfd (C) or VN-AbdA (D), from UAS constructs under engrailed-Gal4 control (en>). Med19-VC accumulation, detected with antibody against the GFP C-terminal region, is similar in all tests (B′–D′). Gal4-driven Hox protein accumulation is comparable to endogenous, as detected with Ubx, Dfd and AbdA specific antibodies (B″–D″). Relative BiFC fluorescent signals were quantified as in [32]. VN-Ubx signal (B) and VN-Dfd (C) yielded serial rows of nuclear fluorescence; VN-AbdA (D) gave no detectable signal. (E) Direct homeodomain binding to Med19. Pulldowns with immobilized GST or GST-Med19 employed 70 aa-long 35S-labelled peptides centered on the HDs of Antp, Dfd, Ubx, AbdB, En and Hth. (F–I) Direct homeodomain binding to Med19 in BiFC assay. Co-expression of Med19-VC with VN-Ubx (F), or with its HD (VN-HDUbx; G), under Ubx-Gal4 control gives indistinguishable BiFC signals. Expression of Med19-VC under abdA-Gal4 control yielded no fluorescence with VN-AbdA (H) but gave a strong signal with VN-HDAbdA alone (I). To provide an independent and in vivo test for direct Med19/Hox binding, we used the Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) assay. Auto-fluorescence from the Venus variant of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), abolished by truncating Venus protein into N - and C-terminal portions (VN and VC), can be effectively reconstituted when VC and VN fragments are coupled to interacting protein partners that reunite them in cultured cells [30] or living organisms [31], [32]. BiFC tests made use of the Gal4/UAS system [33] to direct co-expression of chimeric VN-Hox and Med-VC proteins. The functional validation of VN-AbdA relative to AbdA has been described [32]. VN-Ubx and VN-Dfd were likewise validated by their gain-of-function (gof) transformations in embryos (Figure S1). Fused Med19-VC was validated by its capacity to rescue lethal Med19 mutants (described below). UAS-directed co-expression of Med19-VC with VN-Ubx, VN-Dfd or VN-AbdA in embryos under engrailed-Gal4 control (en>Med19-VC+VN-Hox) resulted in serial stripes of clear nuclear fluorescent signal for VN-Ubx and VN-Dfd (Figure 1B–C). VN-AbdA was negative in this test (Figure 1D, but see Figure 1H, I below). Nevertheless, the concordant results from GST pulldown and BiFC tests indicate direct Med19 binding to Ubx and Dfd.

The observed direct Med19/Dfd or Ubx binding led us to ask whether these interactions utilize the homeodomain (HD) common to all Hox proteins. Consistent with this possibility, GST fusions containing the HX-HD regions of Pb (middle, a.a. 119–327) and Antp (C-ter, aa 279–378) bound Med19 at levels 15 - to 50-fold superior to Pb N-ter (a.a. 1–158), Pb C-ter (a.a. 267–782) and Antp N-ter (a.a. 1–90) peptides (Figure 1A). On dissecting the HD-containing C-terminal regions of Ubx, GST-Med19 bound similarly to wild-type and HX-mutated Ubx [15], or to the linker-shortened C-terminal region of crustacean Artemia salina Ubx (Figure S2). Tests with the Antp C-ter peptide (a.a. 279–378) containing its HX, linker and HD, led to the same conclusion (not shown). Confirmation came from binding experiments using immobilized GST-Med19 and Antp, Ubx, Dfd and Abd-B HD peptides, where strong binding was observed for all four homeodomains despite marked divergence of their primary sequences (60% identity of Abd-B and Ubx HD) (Figure 1E). Contrary to the four Hox HD, neither Engrailed HD (43% identity with Ubx HD) nor the TALE class Hth HD (21% identity) bound detectably (Figure 1E). Since Med19 binds Dfd, Antp, Ubx and Abd-B HD but not those of En or Hth, we infer that it is specific and can discriminate among homeodomains.

In BiFC assays for Med19/HD association in vivo, comparable signals were observed on co-expressing Med19-VC with full-length VN-Ubx, or its HD alone (VN-HDUbx), in the normal Ubx expression domain (Ubx-Gal4; Figure 1F,G). Co-expressing VN-AbdA with Med19-VC under abdA-Gal4 did not give rise to fluorescence (Figure 1D, H). By contrast, AbdA HD (VN-HDAbdA) yielded a strong fluorescent signal (Figure 1I), confirming that the Hox HD is sufficient for direct Med19 binding. The differing responses obtained for full-length AbdA versus its HD raise the interesting possibility that AbdA sequences outside the HD limit its access to Med19 in vivo. Taken together, these biochemical and in vivo results indicate that the Hox HD is sufficient for direct binding to Med19.

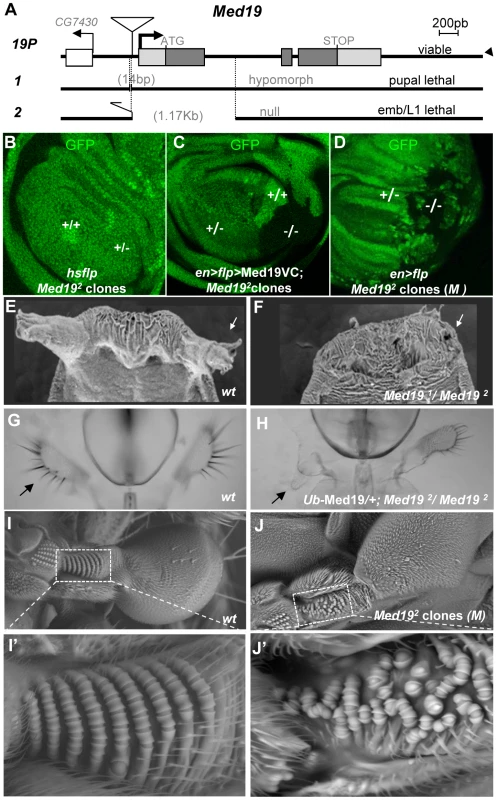

Med19 participates in Hox organizing activity

Apart from yeast, no mutants of Med19 have been described. To address Med19 gene function in vivo, we employed imprecise excision of a viable P element insertion mutant, Med19P to generate two loss-of-function (lof) mutations, Med191 (a pupal-lethal hypomorphic allele harboring a 14 base pair (bp) upstream deletion), and Med192 (deleted for much of its protein coding sequence; see Figure 2A). Homozygotes for the presumptive null mutation Med192 die at the end of embryogenesis but do not show cuticular defects. To remove maternally contributed protein and/or mRNA [34] that might mask early requirements for Med19, we used the Dominant Female Sterile technique to generate mitotic germ-line clones. When clones were induced in females heterozygous for Med192 and for ovoD1, egg-laying was observed. Such embryos devoid of maternally contributed Med19 product undertake development (as visualised by nuclear DAPI staining, Figure S3). Though the first nuclear divisions proceed normally (Figure S3, ≈1 hr), abnormalities are already visible in pre-cellular blastoderm (Figure S3, ≈2 hr), leading to massively disorganised cellular embryos that die soon after (Figure S3). We conclude that a major maternal contribution to embryonic Med19 activity masks its zygotic roles.

Fig. 2. Med19 mutations affect cell viability and Hox-related developmental processes.

(A) Mutant alleles were generated by imprecise excision of a viable P element insertion 37 bp upstream of the putative Med19 transcription initiation site (19P). Med191 is a pupal-lethal hypomorph with 14 bp deleted 5′ to the Med19 transcription start. Med192 is an embryonic lethal amorph deleted for 1174 bp of DNA spanning exon 1 with its ATG initiation codon. (B–D) Clonal analyses of Med192. (B) “Twin spot” analysis. Mitotic recombination induced in hsp70-Flp; Med192 FRT-2A/Ub-GFP FRT-2A larvae (30′ heat shock at 38°C) gave +/+ clones (intense green), but no −/− sister clones (GFP-) were observed. (C) Twin spot analysis in rescue conditions. The engrailed-Gal4 driver was used to simultaneously induce mitotic clones (UAS-Flp) and to direct expression of Med19-VC (UAS transgene). Homozygous Med192/2 (−/−) cells (lacking GFP) are now detected. (D) The Med19− condition is not intrinsically cell-lethal. In this wing imaginal disc (genotype, en-Gal4>UAS-Flp/+; Med192 FRT-2A/Ub-GFP M− FRT-2A), GFP- Med19−/− clones are observed. (E–J) Med19 function is required for multiple Hox-related developmental processes. (E,F) Med19 is required for eversion of anterior pupal spiracles. Normal anterior spiracles (E) are absent from Med191/2 hypomorphs (F). (G,H) One maxillary palp (G, arrow) is absent in a surviving Ub-Med19; Med192/2 hypomorph (H, arrow). (I,J) Med19 is required for haltere-specific sensory organs. (I) Wild-type haltere, with zone of interest (dotted box) showing rows of pedicellar sensillae on the wild-type dorsal haltere (enlargement, I′). (J) Haltere harboring Med19−/− clones (genotype: ap>Flp; Ub-GFP M− FRT-2A/Med192 FRT-2A), with zone of interest in dotted box indicating disorganized sensory organ rows (J′). As an alternative approach to examining Med19 function in embryonic development, we made use of Med19-directed RNAi. Ubiquitous RNAi expression under daughterless-Gal4 control gave rise to cuticular defects in the spiracles and head of L2/L3 larvae (Figure S4) reminiscent of the embryonic consequences of Abd-B lof in the posterior spiracles, or of lab/Dfd/Scr lof in the head. However, the late appearance of these defects, their incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity made it difficult to ascertain a functional link to embryonic Hox activities.

We therefore decided to examine post-embryonic development, making use of partial loss-of-function combinations and of clonal analysis. Med191/Med192 animals die as pupae, but adult viability is restored by ubiquitous transgenic expression of Med19 (Ub-Med19 or arm>Med19-VC; Figure S9). These results show that lethality is due solely to loss of Med19 function. They also functionally validate the UAS-Med19-VC element used in BiFC assays. To better characterize the consequences of Med19 loss-of-function, we employed FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination [35] to generate clones of cells homozygous for Med192 (−/−). In “twin spot” experiments where −/ − and +/+ cells arise from mitotic recombination in a single −/+ cell during mitosis, only +/+ cells were subsequently detected (Figure 2B). This cell lethality is due to loss of Med19, since expressing Med19-VC protein in mutant cells restores viability (Figure 2C); indeed, large Med192/Med192 clones are observed even though Med19-VC accumulation is less than for wild-type protein in adjacent cells (Figure S5,A–A″). Strikingly, Med192/Med192 cells also survived in the presence of a Minute (M) mutation [36] that slows growth of surrounding heterozygous M−/+ cells (Figure 2D). Immune staining with anti-Med19 sera confirmed that Med192 is a protein-null mutation (Figure S5, B–B″). Thus the existence of these clones shows that Med19 is not strictly required for cell viability. The influence of cell environment on cell lethality suggests a role for Med19 in the control of cell competition.

If Hox/Med19 binding is functionally relevant to homeotic activity, Med19 mutants might provoke Hox-like phenocopies or modify Hox-induced homeotic defects. In light of the strong maternal contribution of Med19 present in embryos, we turned our attention to later developmental stages. Hypomorphic Med191/Med192 animals, or Med192/Med192 animals with low-level ubiquitous expression from the Ub-Med19 transgene, survive to the pupal stage and show a fully penetrant loss of anterior spiracles (Figure 2E, F). Rare adult Ub-Med19; Med192/Med192 survivors showed defects including loss of maxillary palps (Figure 2G, H). Tissue-directed induction of Med192/Med192 clones in the dorsal compartment of the haltere imaginal disc (apterous-Gal4>UAS-Flp) is associated with disorganization of the distinctive pedicellar sensillae in halteres [37], where these sensory organs are reduced in number and their well-ordered rows disrupted in adult halteres (Figure 2I–I′ vs. 2J–J′).

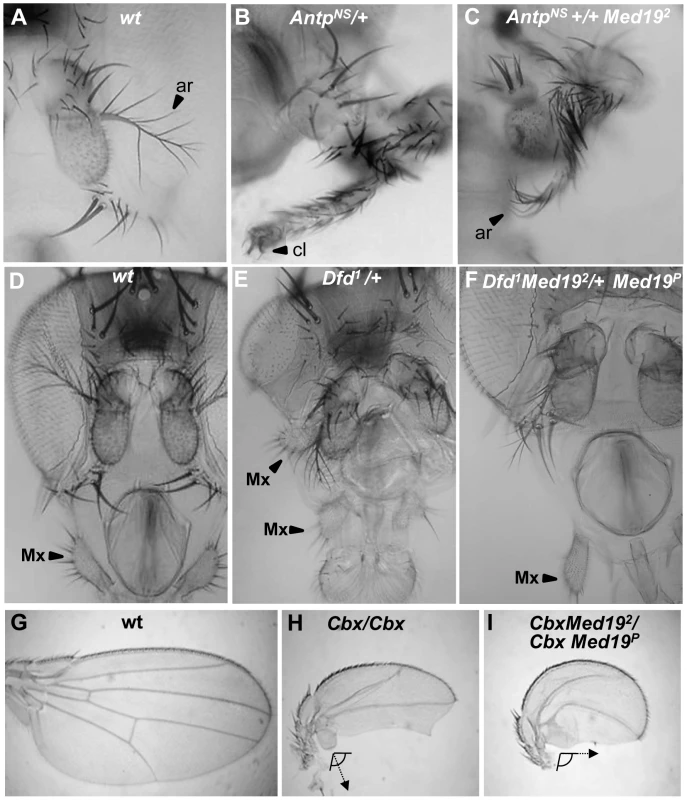

All the preceding defects (Figure 2E–J′) resemble Hox loss-of-function phenotypes: of Antp for the pupal anterior spiracles [38]; of Dfd for the adult maxillary palps [39], [40]; and of Ubx for haltere sensory organs [37]. We therefore asked whether Med19 mutants can act as dose-sensitive modifiers of Hox activity in genetic interaction tests. For Antp, the fully penetrant spiracle loss observed in Med191/Med192 pupae (Figure 2F) is absent from Med19− or Antp− heterozygotes but can be detected in Med19−/Antp− double heterozygotes (Figure S6). This synergistic interaction links Med19 to normal Antp function. Conversely, ectopic expression from the gain-of-function (gof) AntpNs allele directs a fully penetrant transformation of antenna toward leg (Figure 3A, B) that is partially suppressed in Med192 heterozygotes, as shown by the replacement of distal claws by antennal aristae (Figure 3C, Figure S6). Adult maxillary (Mx) palps (Figure 3D, arrowhead) require Dfd function in a territory abutting the antennal primordium of the eye-antennal imaginal disc [40], and the palp loss noted above (Figure 2H) suggested a link to Dfd. In interaction tests, palp loss provoked by Dfd-specific RNAi (patched>dsRNADfd) was enhanced in Med192 heterozygotes (Figure S6). Conversely, ectopic Mx organs observed in heterozygotes for the gof allele Dfd1 (20% of adult heads) were fully suppressed in Dfd1/Med192 double heterozygotes (Figure 3E, F and Figure S6). Similarly, the transformation of the posterior wing (Figure 3G) to a hemi-haltere in UbxCbx1 homozygotes (Figure 3H) was synergistically modified on reducing Med19 activity (Figure 3I). These dose-sensitive modifications of Antp, Dfd and Ubx-dependent phenotypes by Med19 lof mutants support a functional Hox/Med19 link in vivo.

Fig. 3. Synergistic interactions between Med19 and Hox mutations.

Dose-sensitivity for Med19 was tested relative to Hox gain-of-function mutations of Antp (A–C), Dfd (D–F), and Ubx (G–I). (A) Wild-type antenna, with distal arista (ar) indicated by an arrowhead; (B) AntpNs–directed transformation of antenna toward leg with distal claw (cl, arrowhead); (C) the transformation is attenuated in AntpNs/Med192 trans-heterozygotes, as shown by the presence of a partial arista (ar, arrowhead). (D) Wild-type head, with the maxillary palp (Mx) indicated by arrowhead. (E) Dfd1 provokes head defects including reduced eyes and the appearance of ectopic Mx (arrowhead), here positioned behind the antenna. (F) In Dfd1/Med192 heterozygotes (or here, Dfd1Med192/+ Med19P), no ectopic Mx were observed. (G) Wild-type wing. (H) Homozygote for the UbxCbx1 gof allele that expressed Ubx protein in the posterior compartment of the wing. Note the discrete hemi-haltere induced by Ubx, which is oriented at right-angles relative to the longitudinal wing axis. (I) In UbxCbx1 Med192/UbxCbx1 Med19P wings, the posterior wing is no longer organized as a hemi-haltere, and the cellular trichomes are reoriented toward the long wing axis (arrow). Med19 is required for Ubx target gene activation

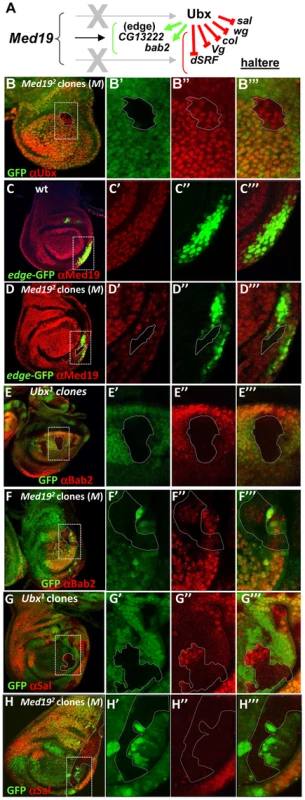

The intensive attention given to Ubx target gene regulation in the haltere imaginal disc [3]–[5], [41], [42] makes it an excellent paradigm for understanding Hox interplay with Med19 in a developmental program. We therefore examined the effect of removing Med19 function on Ubx activity towards selected target genes in the haltere imaginal disc (Figure 4A). Clones of −/− cells induced in haltere discs in the presence of a Minute mutation showed Ubx levels comparable to their +/ − neighbors (Figure 4B–B′″). The presence of normal nuclear Ubx signal in mutant cells after several mitotic divisions shows that the Med19− condition has not generally affected transcription. We next examined the effects of Med19−/− mitotic clones on several Ubx target genes in haltere development [41]. Ubx is known for its role in suppressing wing development, and acts to repress a number of prominent wing developmental genes in the haltere imaginal disc [41]. With the combined use of ectopic Hox expression and analysis of the transcriptome, additional Ubx targets have emerged. The first example of a Ubx-activated target was CG13222, which is regulated through an autonomous cis-regulatory region called “edge” for its expression in a band of cells along the posterior border of the haltere disc [42]. Expression of the edge-GFP reporter construct, that recapitulates Ubx-dependent CG13222 expression [42] is cell-autonomously abolished in Med19−/− haltere clones (Figure 4C,D; identified with anti-Med19 sera). This shows that Med19 is required for activation of the direct Ubx target CG13222 in the haltere disc. A second positively-regulated target identified in recent whole-genome analyses, bric-à-brac2 (bab2), is induced by ectopic Ubx [5] and correlates with direct Ubx binding to regulatory DNA in vivo [3], [4]. Using mitotic recombination, we examined the expression of bab2 in Ubx−/− haltere cells and found that Bab2 accumulation is cell-autonomously abolished (Figure 4E–E′″). On examining bab2 expression with respect to Med19 activity, Bab2 accumulation was cell-autonomously down-regulated in Med19−/− cells (Figure 4F–F′″). This shows that Med19 activity is required in the haltere disc for normal Ubx-mediated activation of bab2. However, contrary to edge, residual low-level bab2 expression is present in some Med19− cells (Figure 4F–F′″). The responses of these two regulatory sequences to Med19 lof indicate that Med19 is required for Ubx target gene activation.

Fig. 4. Med19 acts as a “co-factor” for Ubx-mediated gene activation.

(A) Summary of Ubx target genes analyzed. Ubx can repress (red bars) or activate (green arrows) direct target genes. (B–H) Med19 function in Ubx target gene expression. Images show whole haltere imaginal discs that are wild-type (C), or bear mitotic clones of Med192 in a Minute background (B, D, F, H) or of Ubx1 (E,G). The other columns contain enlargements of boxed images in the first column, showing genotypic markers to identify clones (B′–H′); expression of gene of interest (B″–H″); and merged images (B′″–H′″). (B–B′″) Ubx protein (red) accumulates normally in a Med19−/− clone (GFP-). (C–C′″) edge-GFP reporter gene expression (green) is localized in a row of cells at the posterior border of the disc; ubiquitous expression of wild-type Med19 is revealed by anti-Med19 (red). (D–D′″) edge-GFP expression (green) is absent in a Med19−/− clone (absence of anti-Med19, red; circled) crossing the line of edge-expressing cells. (E–E′″) Bab2 protein (anti-Bab2, red) is absent from Ubx1/1 cells (GFP-). (F–F′″) Bab2 expression (red) is cell-autonomously down-regulated in Med19−/− cells (GFP-). (G–G′″) spalt (sal) expression (anti-Sal, red) appears in centrally positioned cells of Ubx−/− clones (GFP-) in the haltere pouch. (H) Spalt (red) is not de-repressed in Med19 mutant cells (GFP-) positioned as for the Ubx clone (G′). Several targets whose expression is repressed by Ubx were tested for a requirement for Med19 (Figure 4A). For example, the broad central band of spalt (sal) expression in the wing pouch is absent from Ubx-expressing cells of the haltere pouch. sal is de-repressed in Ubx−/− haltere disc cells [41], as shown by the appearance of Sal protein in Ubx mutant cells (Figure 4G–G′″). By contrast, no new expression of Sal is detected in equivalently placed Med19−/− clones (Figure 4H–H′″). De-repression was likewise not observed for other tested Ubx-repressed targets (not shown), lending molecular support to the interpretation that Med19 is not involved in Ubx repressive activities. While further examples will be required to determine whether this illustrates a general property of Med19 action in transcriptional regulation, these results suggest that Med19 collaboration with Ubx is limited to gene activation.

Med19 binds the Hox homeodomain through a conserved motif

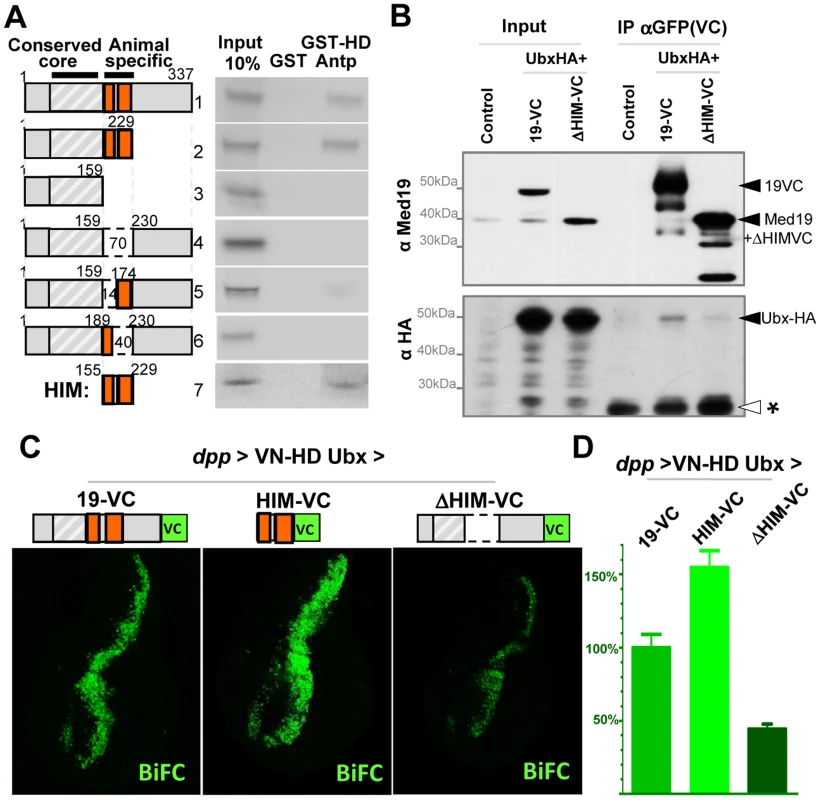

Binding of Hox proteins to Med19 specifically involves their conserved homeodomain. To identify Med19 sequences involved in HD binding, we used GST-pulldown to test full-length or deleted versions of Med19 with GST-HDAntp. Binding was retained on truncating the terminal regions of Med19 (Figure 5A, constructs 1–2), but was abolished on deleting an internal 70 aa region (Figure 5A, constructs 3–4). Smaller deletions confirmed that this region contains sequences required for full binding (Figure 5A, constructs 5–6). This 70 a.a. Med19 peptide is not only required but also proved sufficient to bind the HD (Figure 5A, construct 7), leading us to call it Homeodomain Interacting Motif (HIM).

Fig. 5. Direct HD binding through a conserved 70 a.a. Med19 homeodomain-interacting motif (HIM).

(A) HD binding involves a 70 a.a. region of Med19. 35S-labelled full-length (construct #1) or deleted versions (#2–7) of Med19 were used to probe immobilized GST or GST-HDAntp. Proteins containing a.a. 159–229 bound GST-HD (#1, 2, 7). Deleting the entire interval (#4) or of a 40 a.a. interval from 190–229 (#6) abolished binding. Deleting the N-terminal 14 aa of this region (160–173) resulted in reduced binding (#5). The 70 a.a. HIM peptide (160–229) bound GST-HD (#7). (B) Co-immunoprecipitations. Transfected S2 cells contained pActin-Gal4 driver with pUAS-Ubx-HA and either pUAS-Med19-VC or pUAS-Med19ΔHIM-VC. Negative controls were cells transfected with pAct5C-V5. Inputs represent 2% of extracts used for the IP. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-GFP sera that recognises the VC tag, then analysed by Western blots. In the upper portion, bands were revealed with guinea pig anti-Med19, while in the lower portion, a duplicate blot was stained using rabbit anti-HA sera. Solid arrowheads indicate identified proteins of interest and “*”, a non-specific signal serving as an internal loading control. As the HIM motif and VC tag are of equal size, endogenous Med19 and ΔHIM-VC migrate at the same position. (C,D) BiFC test, co-expressing VN-HDUbx with Med19-VC, Med19ΔHIM-VC or HIM-VC in the wing imaginal disc from UAS constructs under dpp-Gal4 control. (C) The BiFC signal observed for VN-HDUbx with Med19-VC was higher for HIM-VC while it was reduced to background levels with Med19ΔHIM-VC. (D) Quantification of BiFC fluorescent signals. The HIM interval of Med19 was then compared with Med19 orthologs from a spectrum of eukaryotes. Sequence alignments reveal a lysine/arginine-rich sequence that is strongly conserved in Med19 orthologs from six vertebrate or insect species (Figure S7). This striking conservation suggests that the contribution of HIM to Med19 function is subject to strong selective pressure.

Med19 is required for Ubx-mediated activation of specific target genes in vivo, and directly binds Hox HDs in vitro through its conserved HIM motif. This suggested that Ubx function passes through Med19, potentially via its HIM sequence. We therefore sought evidence for Med19/Hox binding in cellulo. Cultured Drosophila cells expressing UAS-Med19-VC or UAS-Med19ΔHIM-VC were used for co-immunoprecipitations with anti-GFP (VC). As shown in the Western blot of Figure S8, the three endogenous Med1 isoforms were associated with both Med19-VC and Med19ΔHIM-VC. This is consistent with the incorporation of full-length and HIM-deleted forms into the MED complex.

We next co-expressed these proteins with Ubx-HA and tested for their association in cellulo. As seen in Figure 5B, Ubx-HA co-precipitates with Med19-VC, indicating the association of Ubx transcription factor with Med19. By contrast, less Ubx-HA was detected on co-precipitating with Med19ΔHIM-VC (relative to a non-specific band that serves as a de facto internal loading control, * in Figure 5B). These results indicate that the HIM domain contributes to Ubx-Med19 interaction.

To further investigate the contribution of the HIM domain to HD binding in vivo, we generated transgenic lines containing the same UAS-Med19-VC, -Med19ΔHIM-VC and -HIM-VC constructs used above, and tested each protein's ability to bind to VN-HDUbx in the BiFC assay. In control experiments, Med19-VC, HIM-VC and Med19ΔHIM-VC accumulated at comparable levels in wing imaginal discs (Figure S8). Med19-VC and HIM-VC are fully nuclear. The Med19ΔHIM-VC protein (lacking the highly basic HIM element) is seen to accumulate in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Figure S8). This indicates that the HIM element contributes to nuclear localisation, together with other Med19 sequences. As noted in embryos (Figure 1G), co-expressing Med19-VC with VN-HDUbx under dpp-Gal4 control in wing imaginal discs resulted in clear fluorescent signal (Figure 5C). When HIM-VC was tested for its ability to interact with the Ubx HD, it gave rise to a fluorescent signal stronger than for intact Med19; by contrast, the Med19ΔHIM-VC fusion yielded only a background-level signal with VN-HDUbx (Figure 5C). Taken together, these results of biochemical and BiFC experiments indicate that Med19 HIM is necessary and sufficient for full HD binding.

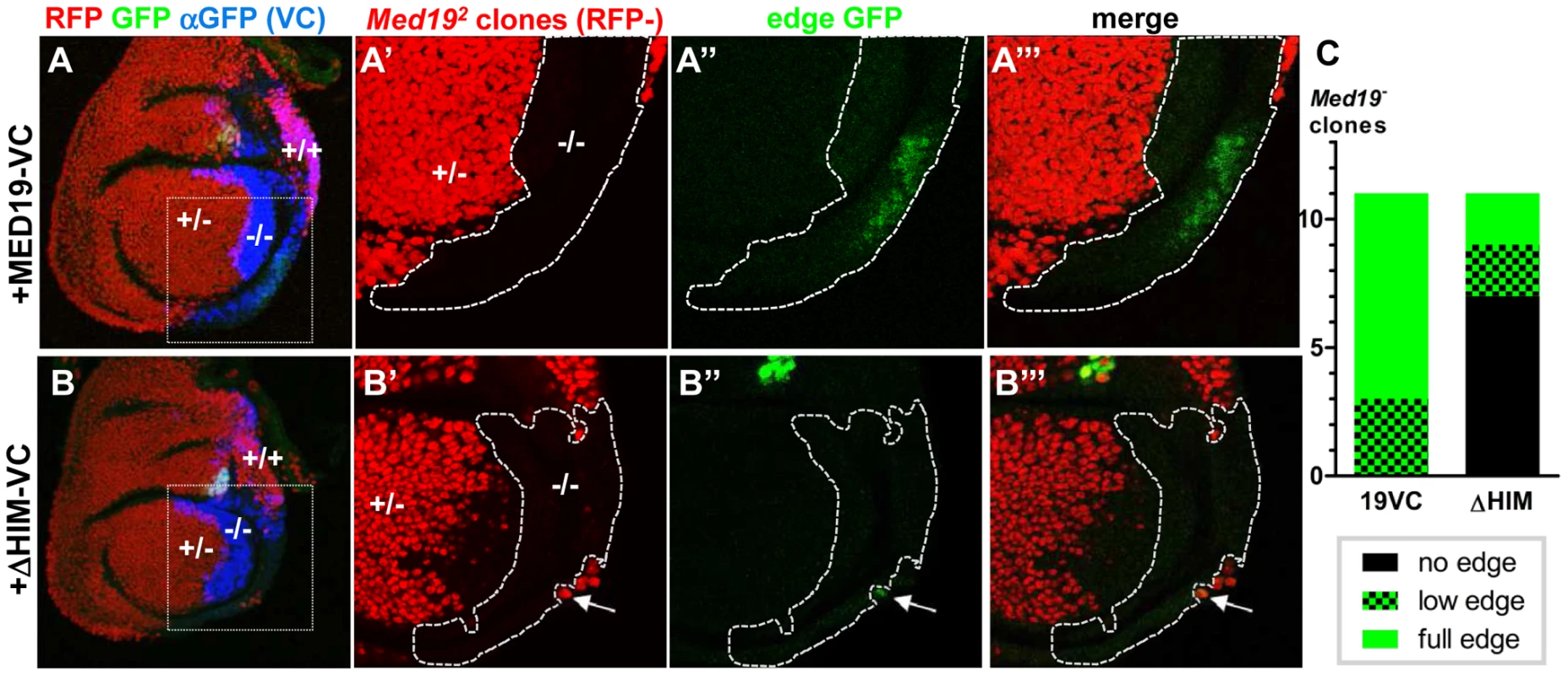

HIM is required for Ubx target gene activation

While Med19 bereft of its conserved HIM element can be incorporated into MED, as shown above, its functional requirements in vivo remained an open question. Accordingly, we tested whether Drosophila HIM is relevant to Med19 developmental functions. In a genetic rescue test, ubiquitous Med19-VC expression restored adult viability to pupal-lethal Med191/Med192 hypomorphs, whereas Med19ΔHIM-VC did not. Med19ΔHIM-VC also showed a reduced aptitude to rescue pupal spiracles, adult maxillary palps and haltere sensillae compared with Med19-VC (Figure S6). These results indicate a requirement for Med19 HIM in several Hox-dependent developmental processes.

We therefore sought to test the influence of the Med19 HIM peptide on Ubx-dependent transcriptional activation of the direct target CG13222/edge. To this end, (i) FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination was used to generate cells devoid of wild-type protein, while (ii) UAS/Gal4-directed expression supplied normal or HIM-deleted Med19-VC, and (iii) the edge-GFP reporter was employed to assess Ubx-mediated activation of CG13222. En-Gal4-directed UAS-Flp expression in the posterior haltere disc compartment served to induce mitotic recombination there, while en-Gal4 simultaneously directed expression of Med19-VC or Med19ΔHIM-VC in the posterior compartment (Figure 6A–B, stained with anti-VC, blue).

Fig. 6. Med19 HIM is required for Ubx target gene activation, but not for cell proliferation/survival.

Med19-VC (A) or Med19ΔHIM-VC (B) proteins were expressed (UAS constructs, en-Gal4) in posterior haltere imaginal discs harboring Med19 mutant clones. Med19-VC or Med19ΔHIM-VC were detected with antisera directed against C-terminal GFP (αVC, blue). (A–A′″, B–B′″) Med19 clones were identified using a ubiquitous RFP marker: −/− (no red), +/− (red), +/+ (intense red). Activation of the Ubx target edge-GFP at the posterior haltere edge was visualized by GFP (green). Regions containing Med19−/− clones of interest are enlarged (A′–A′″, B′–B′″). (A–A′″) Med19-VC restored expression of edge-GFP. (B–B′″) Med19ΔHIM-VC failed to rescue edge-GFP activation here. GFP-expression here is limited to a single wild-type cell that abuts the −/− clone (B′, B″, arrow). (C) Three levels of edge-GFP expression could be discerned: normal, present but reduced, or none. All correctly positioned −/− clones with Med19-VC showed GFP expression (11 of 11) of which 9/11 were normal. Most clones possessing Med19ΔHIM-VC showed no GFP (7 of 11), and only two of 11 clones showed normal expression. These twin-spot experiments provided two important observations. Firstly, large −/ − clones (RFP-) were observed not only in Med19-VC but also in Med19ΔHIM-VC expressing discs (Figure 6A′, B′). The existence of −/ − clones is in marked contrast with their complete absence in Figure 2B. This shows that both Med19-VC and Med19ΔHIM-VC restore cell viability. We conclude that HIM is not necessary for cell viability. Further, it indicates that not only are both forms of Med19-VC incorporated into MED, but they are functional there. Secondly, Med19-VC and Med19ΔHIM-VC differed markedly in their capacities to ensure activation of the Ubx target gene CG13222. Reporter expression was observed within all appropriately positioned clones of −/ − cells expressing Med19-VC (11 of 11 clones; Figure 6A″, C). By contrast, edge-GFP expression was entirely absent from most clones expressing Med19ΔHIM-VC (7 of 11 clones; Figure 6B″, C). The existence of HIM-independent cell proliferation/survival shows that this cellular function of Med19 can be uncoupled from its Hox-related role. These results also provide clear functional evidence that Ubx-dependent activation of its edge-GFP target requires HIM-endowed Med19.

Discussion

Med19, a MED regulatory subunit that binds Hox transcription factors

Hox homeodomain proteins are well-known for their roles in the control of transcription during development. Further, much is known about the composition and action of the PolII transcription machine. However, virtually nothing is known of how the information of DNA-bound Hox factors is conveyed to PolII in gene transcription. The Drosophila Ultrabithorax-like mutant affecting the large subunit of RNA PolII provokes phenotypes reminiscent of Ubx mutants [43], but the molecular basis of this remains unknown. The lone direct evidence linking Hox TFs to the PolII machine is binding of the Antp HX motif to the TFIID component BIP2 [20]. Here, we undertook to identify physical and functional links between Drosophila Hox developmental TFs and the MED transcription complex. Our results unveil a novel aspect of the evolutionary Hox gene success story, extending the large repertory of proteins able to interact with the HD [44] to include the Drosophila MED subunit Med19. HD binding to Med19 via the conserved HIM suggests this subunit is an ancient Hox collaborator. Accordingly, our loss-of-function mutants reveal that Med19 contributes to normal Hox developmental function and does so at least in part via its HIM element. Thus this analysis reveals a previously unsuspected importance for Med19 in Hox-affiliated developmental functions.

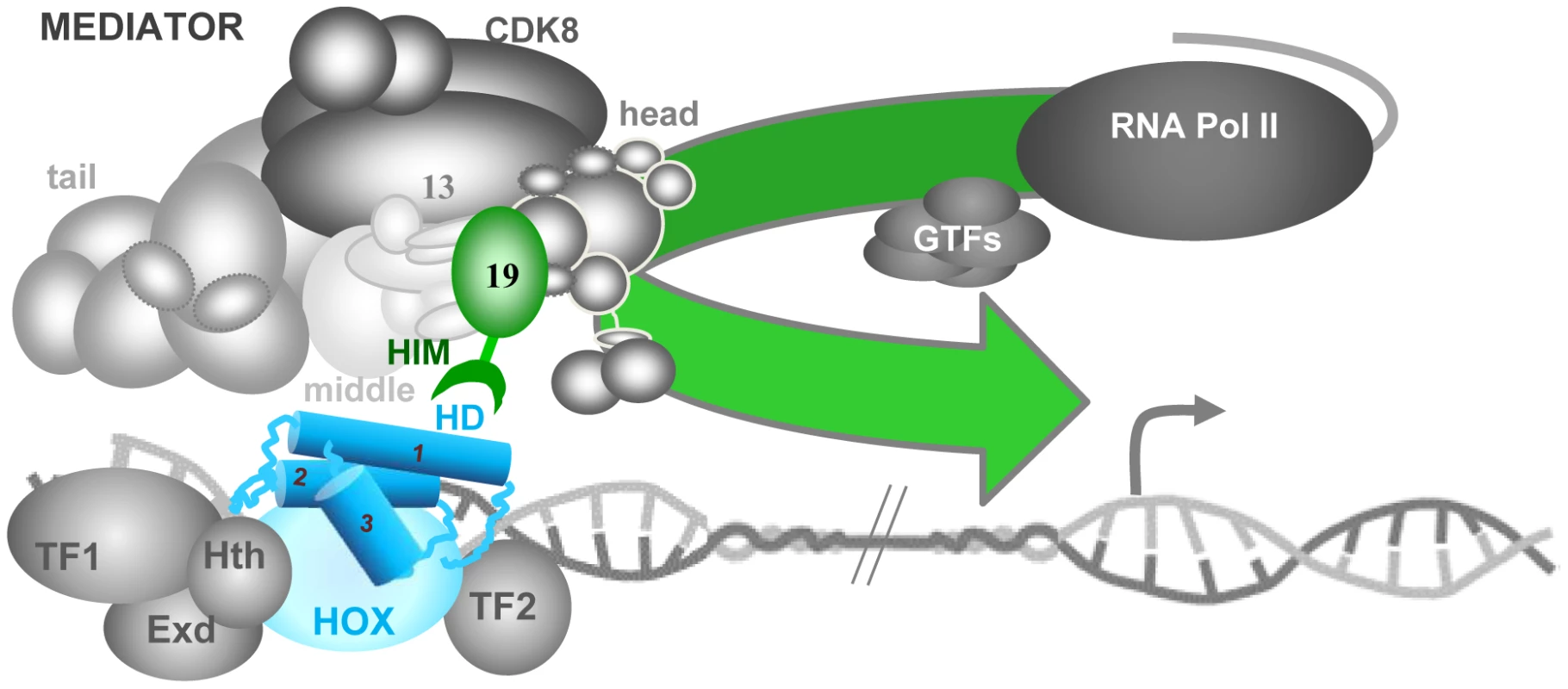

A fundamental property of the modular MED complex is its great flexibility that allows it to wrap around PolII and to change form substantially in response to contact with specific TFs [45]. Recent work in the yeast S. cerevisiae places Med19 at the interfaces of the head, middle and CDK8 kinase modules [46], [47]. Med19 is thus well-positioned to play a pivotal regulatory role in governing MED conformation (Figure 7). Our results raise the intriguing possibility that MED structural regulation and physical contacts with DNA-bound TFs can pass through the same subunit. In agreement with this idea, recent work identified direct binding between mouse Med19 (and Med26) and RE1 Silencing Transcription Factor (REST) [48]. This binding involves a 460 a.a. region of REST encompassing its DNA-binding Zn fingers [48]. The present work goes further, in identifying a direct link between the conserved Hox homeodomain and Med19 HIM (Figure 7) that is, to our knowledge, the first instance for a direct, functionally relevant contact of MED with a DNA-binding motif rather than an activation domain.

Fig. 7. Model for the role of Med19 at the interface of Hox and MED.

The Mediator complex, composed of four modules – tail, middle, head and CDK8 –, binds physically to PolII, principally through its head module. Hox transcription factors (HD in blue, its three α-helices indicated as cylinders) bind to regulatory DNA sequences distant from the transcription start site (grey arrow), together with unknown numbers of other TFs (here, Hox co-factors Exd and Hth plus cell-specific factors TF1 and TF2). We propose that the DNA-bound Hox homeodomain serves to recruit MED directly through Med19 HIM (green hook). This Hox-MED association then permits the general PolII transcription machinery (PolII+GTF) to be recruited to the Hox target promoter. This link to a MED subunit situated at the interface of the head, middle and CDK8 modules could modify overall MED conformation, favoring additional contacts between the TF complex and MED that modulate transcriptional activity. Hox-independent Med19 roles in cell proliferation/survival

Med19 contributes to developmental processes with Antp (spiracle eversion), Dfd (Mx palp), and Ubx (haltere differentiation). Other phenotypes identified with our mutants indicate further, non-Hox related roles for Med19. As shown here, complete loss of Med19 function leads to cell lethality that can be conditionally alleviated when surrounded by weakened, Minute mutation-bearing cells. These observations, that uncouple HIM-dependent functions from the role of Med19 in cell survival/proliferation (Figure 6B), are compatible with reports correlating over-expression of human Med19/Lung Cancer Metastasis-Related Protein 1 (LCMR1) in lung cancer cells with clinical outcome [49]. Further, RNAi-mediated knock-down of Med19 in cultured human tumor cells can reduce proliferation, and tumorigenicity when injected into nude mice [50]–[58]. A recent whole-genome, RNAi-based screen identified Med19 as an important element of Androgen Receptor activity in prostate cancer cells where gene expression levels also correlated with clinical outcome [59]. It will be of clear interest to examine how, and with what partners, Med19 carries out its roles in cell proliferation/survival.

Transcriptional activation versus repression

The role played by mammalian Med19 and Med26 in binding the REST TF, involved in inhibiting neuronal gene expression in non-neuronal cells [48], [60], provides an instance of repressive Med19 regulatory function. We found that Med19 activity is required in the Drosophila haltere disc for transcriptional activation of CG13222/edge and bab2, but is dispensable for Ubx-mediated repression of five negatively-regulated target genes (Figure 4). Ubx can choose to activate or it can repress, at least in part through an identified repression domain at the C-terminus just outside its homeodomain [61]. Conversely Med19, which binds the Ubx homeodomain, appears to have much to do with activation.

Concerning the mechanisms of Ubx-mediated repression, one illuminating example comes from analyses of regulated embryonic Distal-less expression [17]. Ubx can associate combinatorially with Exd and Hth, plus the spatially restricted co-factors Engrailed or Sloppy-paired in repressing Distal-less [17]. Engrailed in turn is able to recruit Groucho co-repressor [62], suggesting that localized repression involves DNA-bound Ubx/Exd/Hth/Engrailed, plus Engrailed-bound Groucho. Groucho has been proposed to function as a co-repressor that actively associates with regulatory proteins and organizes chromatin to block transcription. Wong and Struhl [63] demonstrated that the yeast Groucho homolog Tup1 interacts with DNA-binding factors to mask their activation domains, thereby preventing recruitment of co-activators (including MED) necessary for activated transcription. The number of targets remains too small to be sure Med19 is consecrated to activation. Nonetheless, it will be of interest to determine whether Groucho can play a role in blocking MED/Ubx interactions that could provide an economical means for distinguishing gene activation from repression.

The Hox-MED interface in evolution and development

The conserved Hox proteins and the gene complexes that encode them are well-known and widely used to study development and evolution. As to the evolutionary conservation of the Mediator transcription complex, the presence of MED constituents in far-flung eukaryotic species from unicellular parasites to humans [21] indicates that this complex existed well before the emergence of the modern animal Hox protein complexes. The DNA-binding domains are often the most conserved elements of TF primary sequence, and in the case of the Hox HD, recent forays into “synthetic biology” agree that this was the functional heart of the ancestral proto-Hox proteins [64]–[66]. Indeed, Scr, Antp and Ubx mini-Hox peptides containing HX, linker and HD motifs behave to a good approximation like the full-length forms, directing appropriate gene activation and repression resulting in genetic transformations [64]–[66]. Our results showing direct HD binding to Med19 HIM, and thus access to the PolII machinery, allow the activity of these mini-Hox proteins to be rationalized. We surmise that at the time when the Hox HD emerged to become a major developmental transcription player, its capacity to connect with MED through specific existing sequences was a prerequisite for functional success. One expected consequence of this presumed initial encounter with Med19 – a selective pressure on both partners and subsequent refinement of binding sequences – is in agreement with the well-known conservation of Hox homeodomains, and with the observed conservation of the newly-identified HIM element in Hox-containing eumetazoans. We imagine that subsequent evolution over the several hundred million years separating flies and mammals will have allowed this initial contact to be consolidated through subsequent binding to other MED subunits, ensuring versatile but reliable interactions at the MED-TF interface (Figure 7).

A functional Hox-MED interface

Hox homeodomain proteins are traditionally referred to as selector or “master” genes that determine developmental transcription programs. The low sequence specificity of Hox HD transcription factors is enhanced by their joint action with other TFs, of which prominent examples, the TALE homeodomain proteins Extradenticle/Pbx and Homothorax/Meis are considered to be Hox co-factors. However, a Hox TF in the company of Exd and Hth could still not be expected to shoulder all the regulatory tasks necessary to make a segment with all the coordinated cell-types it is made up of, and collaboration with cell-type specific TFs appears to be requisite. A useful alternative conception visualizes Hox proteins not as “master-selectors” that act with co-factors, but as highly versatile co-factors in their own right that can act with diverse cell-specific identity factors to generate the cell types of a functional segment [67]. We envisage a model where a Hox protein would be central to assembling cell-specific transcription factors into TF complexes that interface with MED (Figure 7).

Such Hox-anchored TF complexes could make use of selective HD binding to Med19 as a beach-head for more extensive access to MED, such that loss of the Hox protein would incapacitate the complex: in the case of Ubx− cells, inactivating bab2 or de-repressing sal. Accordingly, three observations suggest that binding of Hox-centered TF complexes involves additional MED subunits surrounding Med19 (Figure 7) : (i) bab2 target gene expression is entirely lost in Ubx-deficient cells but can persist in some Med19− cells; (ii) edge-GFP in Med19− cells expressing Med19ΔHIM-VC was not altogether refractory to Ubx-activated edge-GFP expression (Figure 6); and (iii) Med19ΔHIM-VC is not entirely impaired for Ubx binding, as seen in co-immunoprecipitations (Figure 5). Thus Hox protein input conveyed through Med19-HIM at the head-middle-Cdk8 module hinge might provide an economical contribution toward organizing TF complexes that influence overall MED conformation [45] and hence transcriptional output. Decoding how the information-rich MED interface including Med19 accomplishes this will be an important part of understanding transcriptional specificity in evolution, development and pathology.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Our work using Drosophila was performed in conditions in conformity with French and international standards.

GST pulldowns

Culture and preparation of GST-fusion proteins, preparation of 35S protein probes, and pulldowns were carried out essentially as described in [68]. Chimeric GST-Hox constructs fused GST to Hox cDNAs. Full-length Hox fusions were used for Labial, Deformed, Sex combs reduced, Ultrabithorax, Abdominal-A and Abdominal-B. Fragments of Pb and Antp were present in the fusion proteins: Pb1 (N-ter, a.a. 1–158), Pb2 (middle with HD, a.a. 119–327) and Pb3 (C-ter, a.a. 267–782). For Antp, two GST fusions were used: Antp1 (N-ter, 1–90) and Antp4 (C-ter with HD, 279–378). Eleven MED putative surface subunits [21] could be expressed at useable levels in coupled in vitro transcription/translation reactions: Med1/Trap220, Med2/Med29/Ix, Med6, Med12/Kto, Med13/Skd, Med15/Arc105, Med19, Med25, Med30, Cdk8 and CycC.

Co-immunoprecipitations

Cultured Drosophila S2 cells were transfected using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche) with pActin-V5 (negative control; pActin-GAL4 driver with either pUAS-Med19-VC or pUAS-Med19ΔHIM-VC (MED co-IP); or adding pUAS-Ubx-HA (Med19-Ubx co-IP). 107 cells were transfected with driver plasmid plus the UAS responder plasmid(s). After 72 hr, cells were harvested by scraping and pooled, collected by centrifuging then washed with 1x PBS. All subsequent steps until Western blotting were carried out at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in IP buffer (50 mM TrisHCl, pH = 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 1 mM EGTA and Roche complete protease inhibitor cocktail), lysed by four-fold passage through a 27G needle, then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,500 rpm. Immunoprecipitation from 1.5 mg of total protein extract (5 µg/µl in IP buffer) was performed with mouse anti-GFP (ROCHE 4 µg/IP), with gentle agitation overnight. 15 µl of G-protein-coupled Sepharose beads (SIGMA, P3296) were added, then gently agitated for 2 hr. The non-bound fraction was discarded. Beads were washed 4 times with fresh IP buffer, taken up in 2X Laemmli buffer containing DTT and SDS, heated to 95°C, and centrifuged. Supernatants were then submitted to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Med1 and Med19 were revealed using polyclonal sera from guinea-pig (diluted 1∶500), while Ubx-HA was detected with rabbit anti-HA (SIGMA) diluted 1∶1000.

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC)

Constructions corresponding to UAS-VN-Ubx, UAS-VN-AbdA and UAS-VN-HDAbdA transgenic lines are described in [32]. UAS-VN-Dfd, UAS-VN-HDUbx: Dfd and Ubx HD sequences were cloned into XhoI-XbaI sites downstream of the Venus VN fragment into the pUAST or pUASTattB plasmids described in [32]. UAS-Med19-VC, UAS-HIM-VC: Full-length Med19 coding sequences, or the internal HIM sequence generated from Med19 cDNA by PCR, were introduced as EcoRI-XhoI fragments to replace Hth coding sequences of pUaHth-VC [32]. For UAS-Med19ΔHIM-VC, internally deleted Med19 was generated from the full-length construct by double PCR, using the overlap extension method. The PCR-derived internal deletion product was cleaved by RsrII and XhoI, then cloned in place of the equivalent fragment of UAS-Med19-VC. All constructs were sequence-verified before fly transformation. Transgenic lines were established by classical P-element mediated germ line transformation or by site-specific integration using the ΦC-31 integrase. Embryos were analysed as described in [32]. For BiFC in imaginal discs, late third-instar larvae of appropriate genotypes were cultured in parallel in the same environmental conditions of temperature and larval density, then were dissected at the same time and fixed in the same solution (20′; 4% para-formaldehyde, 0.5M EGTA, 1X PBS). Wing and haltere imaginal discs were dissected and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Labs). Image acquisition was performed on a Leica SP5 using the same laser excitation, brightness/contrast and z settings. Confocal projections from at least 10 distinct wing discs per genotype were analyzed with ImageJ software.

Fly strains

Stocks and crosses were maintained at 25°C on standard yeast-agar-cornmeal medium. Mutant stocks harboring AntpNs, Dfd1, UbxCbx1 and Df(3L)BSC8 were from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Collection. AntpNs+Rc3 was provided by R. Mann. Edge-GFP and vgQ-lacZ originate from the S. Carroll lab. The Ub-Med19 transgenic line expressing full-length Med19 cDNA under ubi73 control is a homozygous-viable insertion on the X chromosome at attP site ZH 2A. These transgenic elements carry the visible marker mini-white. UAS-RNAi against Dfd is from a non-directed insertion on chromosome 2 (Vienna Drosophila Research Collection stock 50110). UAS-RNAi lines against Med19 are stocks 27559 and 33710 from the Bloomington collection. Gal4-expressing driver lines used were: dpp-Gal4 (imaginal disc-specific, AP boundary, anterior compartment), arm-Gal4 (ubiquitous), ptc-Gal4 (AP boundary, anterior compartment), en-Gal4 (posterior compartment), ap-Gal4 (dorsal compartment of wing and haltere discs), Ubx-Gal4 and abdA-Gal4 (abdominal expression under Ubx or abdA control, respectively).

Generation of Med19 mutants

Loss-of-function Med19 alleles were generated by imprecise excision, mobilizing the viable P{EPgy2}EY16159 insertion marked with mini-w+ (see Flybase). Among 154 white-eyed candidates, two Med191 and Med192 (described in Figure 2) were hemizygous-lethal with Df(3L)BSC8.

Rescue experiments

The following stocks were employed for rescue tests:

Ub-Med19; Med192/TM6B, Hu Tb;

Med191/TM6B, Hu Tb;

Med192/TM6B, Hu Tb;

Arm-Gal4; Med191/TM6B, Hu Tb;

UAS-Med19-VC; Med192/TM6B, Hu Tb;

UAS-Med19ΔHIM-VC; Med192/TM6B, Hu Tb.

Clonal analyses

Mitotic clones were induced by Flp recombinase expressed from a hsp70-Flp transgene on heat induction (30′ at 38°C), or from a UAS-Flp element under Gal4 control as indicated above (en>Flp, ap>Flp). Clones were generated and identified in marked progeny from crosses using the following stocks:

Med192 FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

hsp70-Flp; Ub-GFP FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

Ub-Med19; Ub-GFP FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

UAS-Med19-VC; Ub-GFP FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

en>Flp; Med192 FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

Ub-GFP M FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

ap>Flp; Med192 FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

hsp70-Flp; Ub-GFP M FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

edge-GFP/CyO, Cy; M FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

ap>Flp; FRT-82B Ub-GFP/TM6B, Hu Tb

FRT-82B Ki pb5 pp Ubx1 e/TM6B, Hu Tb

en>Flp; FRT-82B Ub-GFP/TM6B, Hu Tb

edge-GFP, UAS-Med19-VC/CyO, Cy; His2Av-mRFP1 FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

edge-GFP, UAS-Med19ΔHIM-VC/CyO, Cy; His2Av-mRFP1 FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb

Germ-line clones

After crossing y w hsp70-Flp; Med192 FRT-2A/TM6B, Hu Tb females with w; P[ovoD1] FRT-2A/TM3, Sb males, progeny at L3/early pupal stages were subjected to heat shocks (1 hr, 37°C) on two successive days. Resulting y w hsp70-Flp/w; Med192 FRT-2A/P[ovoD1] FRT-2A adult females were crossed with Med192 FRT-2A/TM3, Ser twist>GFP males. Embryos resulting from germline clones were collected on egg lay plates, then analysed by confocal microscopy after mounting in DAPI-containing Vectashield medium. In positive controls where Med19+ replaced Med192, all expected zygotic classes were obtained as viable, fertile adults. In the absence of heat shock, no eggs were laid.

Antibody staining

Performed as described in [40]. Antibodies used were: rat anti-Bab2 (J-L Couderc, used at 1∶3000); mouse anti-GFP (VC) (Roche, 1∶200) or chicken anti-GFP (VC) (Invitrogen); rabbit anti-Spalt (R. Barrio, 1∶100); mouse anti-Col (M. Crozatier/A. Vincent, 1∶200); mouse anti-dSRF (M. Affolter, 1∶1000); rabbit anti β-Gal (Cappel 1∶2500), mouse anti-Wg (1∶200) and anti-Ubx (1∶50) from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa.

Anti-Med19 and -Med1 sera

Guinea pigs were immunized (Eurogentec) with GST-Med19 or GST-Med1 proteins extracted from E. coli and enriched by affinity chromatography. Anti-Med19 sera from terminal bleeds was used for immunocytology without purification at a 1∶500 dilution after prior pre-absorption on wild type larvae.

Phenotypic analyses

Adult phenotypes were analyzed by light microscopy (Zeiss Axiophot) of dissected samples mounted in Hoyer's medium or by scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi TM-1000 Tabletop model) of frozen adults

Sequence alignments

These were generated with the T-Coffee Program, employing the methodology described by [21].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LewisEB (1978) A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature 276 : 565–570.

2. KaufmanTC, LewisR, WakimotoB (1980) Cytogenetic Analysis of Chromosome 3 in DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER: The Homoeotic Gene Complex in Polytene Chromosome Interval 84a-B. Genetics 94 : 115–133.

3. ChooSW, WhiteR, RussellS (2011) Genome-wide analysis of the binding of the Hox protein Ultrabithorax and the Hox cofactor Homothorax in Drosophila. PLoS One 6: e14778.

4. SlatteryM, MaL, NégreN, WhiteKP, MannRS (2011) Genome-wide tissue-specific occupancy of the Hox protein Ultrabithorax and Hox cofactor Homothorax in Drosophila. PLoS One 6: e14686.

5. PavlopoulosA, AkamM (2011) Hox gene Ultrabithorax regulates distinct sets of target genes at successive stages of Drosophila haltere morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 2855–2860.

6. HueberSD, LohmannI (2008) Shaping segments: Hox gene function in the genomic age. Bioessays 30 : 965–979.

7. HueberSD, BezdanD, HenzSR, BlankM, WuH, et al. (2007) Comparative analysis of Hox downstream genes in Drosophila. Development 134 : 381–392.

8. GehringWJ, KloterU, SugaH (2009) Evolution of the Hox gene complex from an evolutionary ground state. Curr Top Dev Biol 88 : 35–61.

9. GehringWJ, HiromiY (1986) Homeotic genes and the homeobox. Annu Rev Genet 20 : 147–173.

10. McGinnisW, KrumlaufR (1992) Homeobox genes and axial patterning. Cell 68 : 283–302.

11. ScottMP, CarrollSB (1987) The segmentation and homeotic gene network in early Drosophila development. Cell 51 : 689–698.

12. ScottMP, WeinerAJ (1984) Structural relationships among genes that control development: sequence homology between the Antennapedia, Ultrabithorax, and fushi tarazu loci of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81 : 4115–4119.

13. GehringWJ, AffolterM, BürglinT (1994) Homeodomain proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 63 : 487–526.

14. McGinnisW, LevineMS, HafenE, KuroiwaA, GehringWJ (1984) A conserved DNA sequence in homoeotic genes of the Drosophila Antennapedia and bithorax complexes. Nature 308 : 428–433.

15. ChauvetS, MerabetS, BilderD, ScottMP, PradelJ, et al. (2000) Distinct hox protein sequences determine specificity in different tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 : 4064–4069.

16. MerabetS, SambraniN, PradelJ, GrabaY (2010) Regulation of Hox activity: insights from protein motifs. Adv Exp Med Biol 689 : 3–16.

17. GebeleinB, McKayDJ, MannRS (2004) Direct integration of Hox and segmentation gene inputs during Drosophila development. Nature 431 : 653–659.

18. JoshiR, SunL, MannR (2010) Dissecting the functional specificities of two Hox proteins. Genes Dev 24 : 1533–1545.

19. JoshiR, PassnerJM, RohsR, JainR, SosinskyA, et al. (2007) Functional specificity of a Hox protein mediated by the recognition of minor groove structure. Cell 131 : 530–543.

20. PrinceF, KatsuyamaT, OshimaY, PlazaS, Resendez-PerezD, et al. (2008) The YPWM motif links Antennapedia to the basal transcriptional machinery. Development 135 : 1669–1679.

21. BourbonHM (2008) Comparative genomics supports a deep evolutionary origin for the large, four-module transcriptional mediator complex. Nucleic Acids Res 36 : 3993–4008.

22. BoubeM, JouliaL, CribbsDL, BourbonHM (2002) Evidence for a mediator of RNA polymerase II transcriptional regulation conserved from yeast to man. Cell 110 : 143–151.

23. BourbonHM, AguileraA, AnsariAZ, AsturiasFJ, BerkAJ, et al. (2004) A unified nomenclature for protein subunits of mediator complexes linking transcriptional regulators to RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell 14 : 553–557.

24. BorggrefeT, YueX (2011) Interactions between subunits of the Mediator complex with gene-specific transcription factors. Semin Cell Dev Biol 22 : 759–768 Epub 2011 Aug 2014.

25. KornbergRD (2005) Mediator and the mechanism of transcriptional activation. Trends Biochem Sci 30 : 235–239.

26. CaiG, ImasakiT, TakagiY, AsturiasFJ (2009) Mediator structural conservation and implications for the regulation mechanism. Structure 17 : 559–567.

27. BaumliS, HoeppnerS, CramerP (2005) A conserved mediator hinge revealed in the structure of the MED7.MED21 (Med7.Srb7) heterodimer. J Biol Chem 280 : 18171–18178 Epub 12005 Feb 18114.

28. MalikS, RoederRG (2010) The metazoan Mediator co-activator complex as an integrative hub for transcriptional regulation. Nat Rev Genet 11 : 761–772 Epub 2010 Oct 2013.

29. BoubeM, FaucherC, JouliaL, CribbsDL, BourbonHM (2000) Drosophila homologs of transcriptional mediator complex subunits are required for adult cell and segment identity specification. Genes Dev 14 : 2906–2917.

30. HuCD, ChinenovY, KerppolaTK (2002) Visualization of interactions among bZIP and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol Cell 9 : 789–798.

31. PlazaS, PrinceF, AdachiY, PunzoC, CribbsDL, et al. (2008) Cross-regulatory protein-protein interactions between Hox and Pax transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 13439–13444.

32. HudryB, VialaS, GrabaY, MerabetS (2011) Visualization of protein interactions in living Drosophila embryos by the bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay. BMC Biol 9 : 5.

33. BrandAH, PerrimonN (1993) Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118 : 401–415.

34. GraveleyBR, BrooksAN, CarlsonJW, DuffMO, LandolinJM, et al. (2011) The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 471 : 473–479.

35. GolicKG (1991) Site-specific recombination between homologous chromosomes in Drosophila. Science 252 : 958–961.

36. MorataG, RipollP (1975) Minutes: mutants of drosophila autonomously affecting cell division rate. Dev Biol 42 : 211–221.

37. ColeES, PalkaJ (1982) The pattern of campaniform sensilla on the wing and haltere of Drosophila melanogaster and several of its homeotic mutants. J Embryol Exp Morphol 71 : 41–61.

38. AbbottMK, KaufmanTC (1986) The relationship between the functional complexity and the molecular organization of the Antennapedia locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 114 : 919–942.

39. MerrillVK, TurnerFR, KaufmanTC (1987) A genetic and developmental analysis of mutations in the Deformed locus in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol 122 : 379–395.

40. LebretonG, FaucherC, CribbsDL, BenassayagC (2008) Timing of Wingless signalling distinguishes maxillary and antennal identities in Drosophila melanogaster. Development 135 : 2301–2309.

41. WeatherbeeSD, HalderG, KimJ, HudsonA, CarrollS (1998) Ultrabithorax regulates genes at several levels of the wing-patterning hierarchy to shape the development of the Drosophila haltere. Genes Dev 12 : 1474–1482.

42. HershBM, NelsonCE, StollSJ, NortonJE, AlbertTJ, et al. (2007) The UBX-regulated network in the haltere imaginal disc of D. melanogaster. Dev Biol 302 : 717–727.

43. MortinMA, ZuernerR, BergerS, HamiltonBJ (1992) Mutations in the second-largest subunit of Drosophila RNA polymerase II interact with Ubx. Genetics 131 : 895–903.

44. MerabetS, HudryB, SaadaouiM, GrabaY (2009) Classification of sequence signatures: a guide to Hox protein function. Bioessays 31 : 500–511.

45. TsaiCJ, NussinovR (2011) Gene-specific transcription activation via long-range allosteric shape-shifting. Biochem J 439 : 15–25.

46. BaidoobonsoSM, GuidiBW, MyersLC (2007) Med19(Rox3) regulates Intermodule interactions in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediator complex. J Biol Chem 282 : 5551–5559 Epub 2006 Dec 5527.

47. TsaiKL, SatoS, Tomomori-SatoC, ConawayRC, ConawayJW, et al. (2013) A conserved Mediator-CDK8 kinase module association regulates Mediator-RNA polymerase II interaction. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20 : 611–619.

48. DingN, Tomomori-SatoC, SatoS, ConawayRC, ConawayJW, et al. (2009) MED19 and MED26 Are Synergistic Functional Targets of the RE1 Silencing Transcription Factor in Epigenetic Silencing of Neuronal Gene Expression. J Biol Chem 284 : 2648–2656 Epub 2008 Dec 2642.

49. ChenL, LiangZ, TianQ, LiC, MaX, et al. (2011) Overexpression of LCMR1 is significantly associated with clinical stage in human NSCLC. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 30 : 18.

50. DingXF, HuangGM, ShiY, LiJA, FangXD (2012) Med19 promotes gastric cancer progression and cellular growth. Gene 504 : 262–267.

51. LiLH, HeJ, HuaD, GuoZJ, GaoQ (2011) Lentivirus-mediated inhibition of Med19 suppresses growth of breast cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 68 : 207–215.

52. WangT, HaoL, FengY, WangG, QinD, et al. (2011) Knockdown of MED19 by lentivirus-mediated shRNA in human osteosarcoma cells inhibits cell proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase. Oncol Res 19 : 193–201.

53. LiXH, FangDN, ZengCM (2011) Knockdown of MED19 by short hairpin RNA-mediated gene silencing inhibits pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 26 : 495–501.

54. CuiX, XuD, LvC, QuF, HeJ, et al. (2011) Suppression of MED19 expression by shRNA induces inhibition of cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in human prostate cancer cells. BMB Rep 44 : 547–552.

55. SunM, JiangR, LiJD, LuoSL, GaoHW, et al. (2011) MED19 promotes proliferation and tumorigenesis of lung cancer. Mol Cell Biochem 355 : 27–33.

56. Ji-FuE, XingJJ, HaoLQ, FuCG (2012) Suppression of lung cancer metastasis-related protein 1 (LCMR1) inhibits the growth of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Biol Rep 39 : 3675–3681.

57. ZouSW, AiKX, WangZG, YuanZ, YanJ, et al. (2011) The role of Med19 in the proliferation and tumorigenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 32 : 354–360.

58. ZhangH, JiangH, WangW, GongJ, ZhangL, et al. (2012) Expression of Med19 in bladder cancer tissues and its role on bladder cancer cell growth. Urol Oncol 30 : 920–927.

59. Imberg-KazdanK, HaS, GreenfieldA, PoultneyCS, BonneauR, et al. (2013) A genome-wide RNA interference screen identifies new regulators of androgen receptor function in prostate cancer cells. Genome Res 23 : 581–591.

60. DingN, ZhouH, EstevePO, ChinHG, KimS, et al. (2008) Mediator links epigenetic silencing of neuronal gene expression with x-linked mental retardation. Mol Cell 31 : 347–359.

61. GalantR, CarrollSB (2002) Evolution of a transcriptional repression domain in an insect Hox protein. Nature 415 : 910–913.

62. HittingerCT, CarrollSB (2008) Evolution of an insect-specific GROUCHO-interaction motif in the ENGRAILED selector protein. Evol Dev 10 : 537–545.

63. WongKH, StruhlK (2011) The Cyc8-Tup1 complex inhibits transcription primarily by masking the activation domain of the recruiting protein. Genes Dev 25 : 2525–2539.

64. PapadopoulosDK, VukojevicV, AdachiY, TereniusL, RiglerR, et al. (2010) Function and specificity of synthetic Hox transcription factors in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 4087–4092.

65. PapadopoulosDK, Reséndez-PérezD, Cárdenas-ChávezDL, Villanueva-SeguraK, Canales-del-CastilloR, et al. (2011) Functional synthetic Antennapedia genes and the dual roles of YPWM motif and linker size in transcriptional activation and repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 11959–11964.

66. LelliKM, NoroB, MannRS (2011) Variable motif utilization in homeotic selector (Hox)-cofactor complex formation controls specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 21122–21127.

67. AkamM (1998) Hox genes: from master genes to micromanagers. Curr Biol 8: R676–678.

68. BenassayagC, PlazaS, CallaertsP, ClementsJ, RomeoY, et al. (2003) Evidence for a direct functional antagonism of the selector genes proboscipedia and eyeless in Drosophila head development. Development 130 : 575–586.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Ribosomal Protein Mutations Induce Autophagy through S6 Kinase Inhibition of the Insulin PathwayČlánek Recent Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Increase the Risk of Developing Common Late-Onset Human DiseasesČlánek G×G×E for Lifespan in : Mitochondrial, Nuclear, and Dietary Interactions that Modify LongevityČlánek PINK1-Parkin Pathway Activity Is Regulated by Degradation of PINK1 in the Mitochondrial MatrixČlánek Rapid Evolution of PARP Genes Suggests a Broad Role for ADP-Ribosylation in Host-Virus ConflictsČlánek The Impact of Population Demography and Selection on the Genetic Architecture of Complex TraitsČlánek Lifespan Extension by Methionine Restriction Requires Autophagy-Dependent Vacuolar AcidificationČlánek The Case for Junk DNA

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 5

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Genetic Interactions Involving Five or More Genes Contribute to a Complex Trait in Yeast

- A Mutation in the Gene in Dogs with Hereditary Footpad Hyperkeratosis (HFH)

- Loss of Function Mutation in the Palmitoyl-Transferase HHAT Leads to Syndromic 46,XY Disorder of Sex Development by Impeding Hedgehog Protein Palmitoylation and Signaling

- Heterogeneity in the Frequency and Characteristics of Homologous Recombination in Pneumococcal Evolution

- Genome-Wide Nucleosome Positioning Is Orchestrated by Genomic Regions Associated with DNase I Hypersensitivity in Rice

- Null Mutation in PGAP1 Impairing Gpi-Anchor Maturation in Patients with Intellectual Disability and Encephalopathy

- Single Nucleotide Variants in Transcription Factors Associate More Tightly with Phenotype than with Gene Expression

- Ribosomal Protein Mutations Induce Autophagy through S6 Kinase Inhibition of the Insulin Pathway

- Recent Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Increase the Risk of Developing Common Late-Onset Human Diseases

- Epistatically Interacting Substitutions Are Enriched during Adaptive Protein Evolution

- Meiotic Drive Impacts Expression and Evolution of X-Linked Genes in Stalk-Eyed Flies

- G×G×E for Lifespan in : Mitochondrial, Nuclear, and Dietary Interactions that Modify Longevity

- Population Genomic Analysis of Ancient and Modern Genomes Yields New Insights into the Genetic Ancestry of the Tyrolean Iceman and the Genetic Structure of Europe

- p53 Requires the Stress Sensor USF1 to Direct Appropriate Cell Fate Decision

- Whole Exome Re-Sequencing Implicates and Cilia Structure and Function in Resistance to Smoking Related Airflow Obstruction

- Allelic Expression of Deleterious Protein-Coding Variants across Human Tissues

- R-loops Associated with Triplet Repeat Expansions Promote Gene Silencing in Friedreich Ataxia and Fragile X Syndrome

- PINK1-Parkin Pathway Activity Is Regulated by Degradation of PINK1 in the Mitochondrial Matrix

- The Impairment of MAGMAS Function in Human Is Responsible for a Severe Skeletal Dysplasia

- Octopamine Neuromodulation Regulates Gr32a-Linked Aggression and Courtship Pathways in Males

- Mlh2 Is an Accessory Factor for DNA Mismatch Repair in

- Activating Transcription Factor 6 Is Necessary and Sufficient for Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Zebrafish

- The Spatiotemporal Program of DNA Replication Is Associated with Specific Combinations of Chromatin Marks in Human Cells

- Rapid Evolution of PARP Genes Suggests a Broad Role for ADP-Ribosylation in Host-Virus Conflicts

- Genome-Wide Inference of Ancestral Recombination Graphs

- Mutations in Four Glycosyl Hydrolases Reveal a Highly Coordinated Pathway for Rhodopsin Biosynthesis and N-Glycan Trimming in

- SHP2 Regulates Chondrocyte Terminal Differentiation, Growth Plate Architecture and Skeletal Cell Fates

- The Impact of Population Demography and Selection on the Genetic Architecture of Complex Traits

- Retinoid-X-Receptors (α/β) in Melanocytes Modulate Innate Immune Responses and Differentially Regulate Cell Survival following UV Irradiation

- Genetic Dissection of the Female Head Transcriptome Reveals Widespread Allelic Heterogeneity

- Genome Sequencing and Comparative Genomics of the Broad Host-Range Pathogen AG8

- Copy Number Variation Is a Fundamental Aspect of the Placental Genome

- GOLPH3 Is Essential for Contractile Ring Formation and Rab11 Localization to the Cleavage Site during Cytokinesis in

- Hox Transcription Factors Access the RNA Polymerase II Machinery through Direct Homeodomain Binding to a Conserved Motif of Mediator Subunit Med19

- Drosha Promotes Splicing of a Pre-microRNA-like Alternative Exon

- Predicting the Minimal Translation Apparatus: Lessons from the Reductive Evolution of

- PAX6 Regulates Melanogenesis in the Retinal Pigmented Epithelium through Feed-Forward Regulatory Interactions with MITF

- Enhanced Interaction between Pseudokinase and Kinase Domains in Gcn2 stimulates eIF2α Phosphorylation in Starved Cells

- A HECT Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase as a Novel Candidate Gene for Altered Quinine and Quinidine Responses in

- dGTP Starvation in Provides New Insights into the Thymineless-Death Phenomenon

- Phosphorylation Modulates Clearance of Alpha-Synuclein Inclusions in a Yeast Model of Parkinson's Disease

- RPM-1 Uses Both Ubiquitin Ligase and Phosphatase-Based Mechanisms to Regulate DLK-1 during Neuronal Development

- More of a Good Thing or Less of a Bad Thing: Gene Copy Number Variation in Polyploid Cells of the Placenta

- More of a Good Thing or Less of a Bad Thing: Gene Copy Number Variation in Polyploid Cells of the Placenta

- Heritable Transmission of Stress Resistance by High Dietary Glucose in

- Revertant Mutation Releases Confined Lethal Mutation, Opening Pandora's Box: A Novel Genetic Pathogenesis

- Lifespan Extension by Methionine Restriction Requires Autophagy-Dependent Vacuolar Acidification

- A Genome-Wide Assessment of the Role of Untagged Copy Number Variants in Type 1 Diabetes

- Selectivity in Genetic Association with Sub-classified Migraine in Women

- A Lack of Parasitic Reduction in the Obligate Parasitic Green Alga

- The Proper Splicing of RNAi Factors Is Critical for Pericentric Heterochromatin Assembly in Fission Yeast

- Discovery and Functional Annotation of SIX6 Variants in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

- Six Homeoproteins and a linc-RNA at the Fast MYH Locus Lock Fast Myofiber Terminal Phenotype

- EDR1 Physically Interacts with MKK4/MKK5 and Negatively Regulates a MAP Kinase Cascade to Modulate Plant Innate Immunity

- Genes That Bias Mendelian Segregation

- The Case for Junk DNA

- An In Vivo EGF Receptor Localization Screen in Identifies the Ezrin Homolog ERM-1 as a Temporal Regulator of Signaling

- Mosaic Epigenetic Dysregulation of Ectodermal Cells in Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Hyperactivated Wnt Signaling Induces Synthetic Lethal Interaction with Rb Inactivation by Elevating TORC1 Activities

- Mutations in the Cholesterol Transporter Gene Are Associated with Excessive Hair Overgrowth

- Scribble Modulates the MAPK/Fra1 Pathway to Disrupt Luminal and Ductal Integrity and Suppress Tumour Formation in the Mammary Gland

- A Novel CH Transcription Factor that Regulates Expression Interdependently with GliZ in

- Phosphorylation of a WRKY Transcription Factor by MAPKs Is Required for Pollen Development and Function in

- Bayesian Test for Colocalisation between Pairs of Genetic Association Studies Using Summary Statistics

- Spermatid Cyst Polarization in Depends upon and the CPEB Family Translational Regulator

- Insights into the Genetic Structure and Diversity of 38 South Asian Indians from Deep Whole-Genome Sequencing

- Intron Retention in the 5′UTR of the Novel ZIF2 Transporter Enhances Translation to Promote Zinc Tolerance in

- A Dominant-Negative Mutation of Mouse Causes Glaucoma and Is Semi-lethal via LBD1-Mediated Dimerisation

- Biased, Non-equivalent Gene-Proximal and -Distal Binding Motifs of Orphan Nuclear Receptor TR4 in Primary Human Erythroid Cells

- Ras-Mediated Deregulation of the Circadian Clock in Cancer

- Retinoic Acid-Related Orphan Receptor γ (RORγ): A Novel Participant in the Diurnal Regulation of Hepatic Gluconeogenesis and Insulin Sensitivity

- Extensive Diversity of Prion Strains Is Defined by Differential Chaperone Interactions and Distinct Amyloidogenic Regions

- Fine Tuning of the UPR by the Ubiquitin Ligases Siah1/2

- Paternal Poly (ADP-ribose) Metabolism Modulates Retention of Inheritable Sperm Histones and Early Embryonic Gene Expression

- Allele-Specific Genome-wide Profiling in Human Primary Erythroblasts Reveal Replication Program Organization

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- PINK1-Parkin Pathway Activity Is Regulated by Degradation of PINK1 in the Mitochondrial Matrix

- Null Mutation in PGAP1 Impairing Gpi-Anchor Maturation in Patients with Intellectual Disability and Encephalopathy

- Phosphorylation of a WRKY Transcription Factor by MAPKs Is Required for Pollen Development and Function in

- p53 Requires the Stress Sensor USF1 to Direct Appropriate Cell Fate Decision

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání