-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaDNA Methylation Restricts Lineage-specific Functions of Transcription Factor Gata4 during Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation

DNA methylation changes dynamically during development and is essential for embryogenesis in mammals. However, how DNA methylation affects developmental gene expression and cell differentiation remains elusive. During embryogenesis, many key transcription factors are used repeatedly, triggering different outcomes depending on the cell type and developmental stage. Here, we report that DNA methylation modulates transcription-factor output in the context of cell differentiation. Using a drug-inducible Gata4 system and a mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell model of mesoderm differentiation, we examined the cellular response to Gata4 in ES and mesoderm cells. The activation of Gata4 in ES cells is known to drive their differentiation to endoderm. We show that the differentiation of wild-type ES cells into mesoderm blocks their Gata4-induced endoderm differentiation, while mesoderm cells derived from ES cells that are deficient in the DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b can retain their response to Gata4, allowing lineage conversion from mesoderm cells to endoderm. Transcriptome analysis of the cells' response to Gata4 over time revealed groups of endoderm and mesoderm developmental genes whose expression was induced by Gata4 only when DNA methylation was lost, suggesting that DNA methylation restricts the ability of these genes to respond to Gata4, rather than controlling their transcription per se. Gata4-binding-site profiles and DNA methylation analyses suggested that DNA methylation modulates the Gata4 response through diverse mechanisms. Our data indicate that epigenetic regulation by DNA methylation functions as a heritable safeguard to prevent transcription factors from activating inappropriate downstream genes, thereby contributing to the restriction of the differentiation potential of somatic cells.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003574

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003574Summary

DNA methylation changes dynamically during development and is essential for embryogenesis in mammals. However, how DNA methylation affects developmental gene expression and cell differentiation remains elusive. During embryogenesis, many key transcription factors are used repeatedly, triggering different outcomes depending on the cell type and developmental stage. Here, we report that DNA methylation modulates transcription-factor output in the context of cell differentiation. Using a drug-inducible Gata4 system and a mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell model of mesoderm differentiation, we examined the cellular response to Gata4 in ES and mesoderm cells. The activation of Gata4 in ES cells is known to drive their differentiation to endoderm. We show that the differentiation of wild-type ES cells into mesoderm blocks their Gata4-induced endoderm differentiation, while mesoderm cells derived from ES cells that are deficient in the DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b can retain their response to Gata4, allowing lineage conversion from mesoderm cells to endoderm. Transcriptome analysis of the cells' response to Gata4 over time revealed groups of endoderm and mesoderm developmental genes whose expression was induced by Gata4 only when DNA methylation was lost, suggesting that DNA methylation restricts the ability of these genes to respond to Gata4, rather than controlling their transcription per se. Gata4-binding-site profiles and DNA methylation analyses suggested that DNA methylation modulates the Gata4 response through diverse mechanisms. Our data indicate that epigenetic regulation by DNA methylation functions as a heritable safeguard to prevent transcription factors from activating inappropriate downstream genes, thereby contributing to the restriction of the differentiation potential of somatic cells.

Introduction

Development is based on a series of cell-fate decisions and commitments. Transcription factors and epigenetic mechanisms coordinately regulate these processes [1], [2]. Transcription factors play dominant roles in instructing lineage determination and cell reprogramming [3], [4]. Transcription factor and co-factor networks regulate cell-specific gene programs, allowing a given transcription factor to be used repeatedly in different cellular and developmental contexts [5]. In addition, epigenetic mechanisms, which establish and maintain cell-specific chromatin states (or epigenomes) during differentiation and development [6], modulate the functions of transcription factors in cell-type-dependent manners [7], [8]. Alterations of chromatin states can increase the efficiency of transcription factor-induced cell reprogramming [9], [10] and lineage conversion in vivo [11], [12]. However, how epigenetic mechanisms and transcription factor networks coordinately regulate cell differentiation remains elusive.

DNA methylation at cytosine-guanine (CpG) sites is a heritable genome-marking mechanism for epigenetic regulation, modulating gene expression through chromatin regulation [13]. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles have revealed that the methylated CpG in the mammalian genome is specifically distributed in a cell-type-dependent manner [14]–[16], and the methylated CpG sites are dynamically reprogrammed during embryogenesis and gametogenesis [17]–[19]. The DNA methylation profile is established and maintained by three DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b [20], together with DNA demethylation mechanisms [21]. Dnmt1 is required for the maintenance of DNA methylation profiles, whereas Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are required to establish them. The inactivation of Dnmt1 or both Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b in mice leads to early embryonic lethality, showing that DNA methylation has essential roles in mammalian embryogenesis [22]–[24]. DNA methylation is involved in various cell-differentiation processes, and several studies have identified the underlying mechanisms for specific cases [25]–[29]. However, the roles of DNA methylation in differentiation and development remain largely unexplored.

The evolutionarily conserved zinc-finger transcription factor GATA family controls tissue-specific gene expression and cell-fate determination in many cell types [30]. Gata4 is broadly expressed in endoderm - and mesoderm-derived tissues as well as in pre-implantation embryos. Gata4 functions in endoderm formation, cardiac morphogenesis, the establishment of regional identities in the small intestine, and tissue-specific gene expression in the liver and osteoblasts [31]–[36]. Even though Gata4 has a broad expression profile, it still has cell-specific functions, which are determined largely by transcription factor and co-factor networks. Unique interactions with cardiogenic transcription factors and co-factors allow Gata4 to regulate cardiac gene expression specifically in cardiac progenitor cells and their derivatives [37]. In contrast, the overexpression of Gata4 alone causes mouse ES cells to differentiate into extra-embryonic primitive endoderm cells [38], indicating that Gata4 functions as a master regulatory transcription factor for endoderm specification in ES cells. It is likely that Gata4 is unable to activate a cardiac gene program in ES cells, because of the lack of cardiac transcription factors and co-factors. However, it remains unclear how the endoderm-instructive function of Gata4 is suppressed in non-endoderm tissues, such as mesoderm. Epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation may modulate the cell-specific functions of Gata4.

Here, we have established an in vitro experimental system to test the downstream output of Gata4 in two defined cell types, ES and mesoderm progenitor cells, using a drug-inducible Gata4 and an ES-cell differentiation protocol. Using this experimental system, we examined the effect of DNA methylation on Gata4-induced endoderm differentiation and developmental gene regulation during mesoderm-lineage commitment. Our findings suggest that DNA methylation restricts the endoderm-differentiation potential in mesoderm cells and controls the responsiveness of developmental genes to Gata4.

Results

Suppression of the Endoderm-Instructive Function of Gata4 in ES-Cells after Differentiation

To explore the role of DNA methylation in the context-dependent function of transcription factors, we focused on Gata4 as a model. Gata4 instructs the primitive endoderm fate in ES cells [38], while it regulates various endoderm and mesoderm tissue-specific genes in somatic cells [30]. In this study, we took advantage of a drug-inducible Gata4 construct where the Gata4 coding region is fused with the ligand-binding domain of the human glucocorticoid receptor (Gata4GR) [39]. The activation of Gata4GR by adding dexamethasone (Dex), a glucocorticoid receptor ligand, drove the differentiation of wild-type (WT) ES cells into the primitive endoderm lineage, in which all the cells were positive for the primitive endoderm marker Dab2 (Figure S1A–S1D, LIF(+) condition). However, when the ES cells were first differentiated for 3 days by withdrawing leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) from the ES maintenance medium, the cells became resistant to the Gata4-induced endoderm differentiation (Figure S1A–S1D, LIF(−) condition), showing that the endoderm-instructive function of Gata4 is suppressed after somatic cell differentiation.

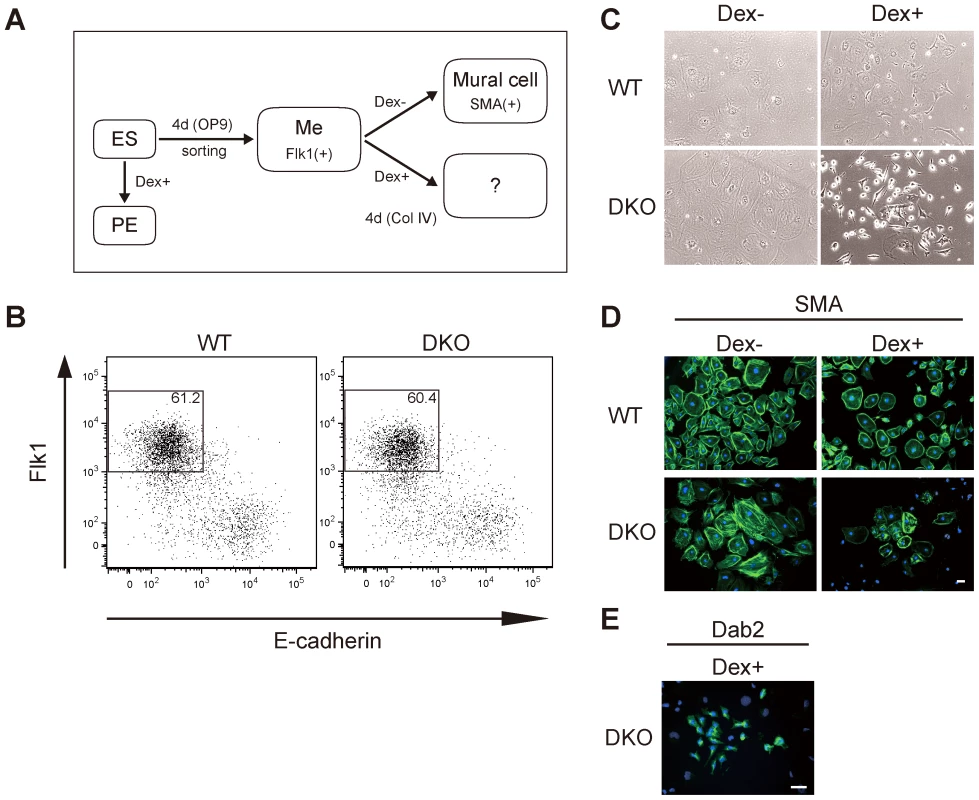

To investigate the Gata4 response in a defined somatic cell population, we employed a mesoderm differentiation protocol, in which ES cells were co-cultured with OP9 stroma cells [40] without LIF for 4 days and then sorted to isolate the Flk1 (also known as VEGFR2 or KDR)-positive (+) population [41] (Figure 1A). Flk1(+) cells derived from ES cells are considered to be equivalent to a mixture of primitive and lateral mesoderm [41], and these cells can differentiate into several mesoderm derived lineages. To eliminate less differentiated cells (including mesendoderm) and ensure their mesoderm commitment, we isolated the Flk1(+)/E-cadherin(−) population by flow cytometry [42] (Figure 1B).

Fig. 1. Gata4-induced primitive endoderm differentiation from Dnmt3a−/−Dnmt3b−/− (DKO) Flk1(+) mesoderm cells derived from OP9 co-culture conditions.

(A) Experimental strategy for isolating mesoderm progenitors from ES cells and the subsequent activation of Gata4. Wild-type (WT) or DKO ES cells stably expressing Gata4GR were differentiated on OP9 stromal cells for 4 days. The Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Me) were sorted and cultured on type IV collagen with or without dexamethasone (Dex) to activate Gata4GR. ES cells were also directly differentiated into primitive endoderm (PE) by adding Dex to ES maintenance medium containing LIF. (B) Flow cytometry profiles of Flk1 and E-cadherin in ES cells differentiated on OP9 stromal cells. The percentages of Flk1(+)/E-cadherin(−) cells are indicated. (C) Phase-contrast photomicrographs of differentiated Flk1(+) mesoderm cells. WT or DKO Flk1(+) cells were cultured with or without Dex for 4 days. (D, E) Immunofluorescence analysis of the mural cell marker SMA (D) or endoderm marker Dab2 (E) (green) in WT or DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells cultured for 4 days with or without Dex. DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). All experiments were performed three times. Scale bar, 50 µm. Flk1(+) mesoderm cells derived from WT ES cells can efficiently differentiate into vascular mural cells, which express alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA), when cultured on type IV collagen [43] (Figure 1A, 1C, 1D, WT Dex−). When we activated Gata4GR by adding Dex, the WT Flk1(+) mesoderm cells also differentiated into mural cells, and the entire cell population was positive for SMA staining at an intensity similar to that of cells without Gata4 induction, although some of the Gata4-induced cells were noticeably smaller in size (Figure 1C, 1D, WT Dex+). We found no round, Dab2-positive cells among the WT Flk1(+) cells that differentiated with Gata4 induction (data not shown). These results indicated that the endoderm-instructive function of Gata4 was suppressed after the differentiation of ES cells into Flk1(+) mesoderm.

Primitive Endoderm Differentiation from DNA-Hypomethylated Flk1(+) Mesoderm Cells in Response to Gata4

We next examined whether DNA methylation was involved in the suppression of the endoderm-instructive function of Gata4 in Flk1(+) mesoderm cells. For this, we used Dnmt3a−/−Dnmt3b−/− double-knockout (DKO) mouse ES cells, which have no de novo methylation activity and low DNA methylation levels at many loci [24], [44]. DKO ES cells expressing Gata4GR differentiated efficiently from ES cells into primitive endoderm in the presence of Dex, similar to WT ES cells (Figure S2). We obtained the DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm population at the same high efficiency as the WT Flk1(+) cells (Figure 1B), and the DKO Flk1(+) cells differentiated into SMA(+) mural cells with a similar efficiency to WT Flk1(+) cells (Figure 1C, 1D, DKO Dex−), indicating that DNA hypomethylation does not by itself inhibit ES-cell differentiation into Flk1(+) mesoderm and SMA (+) mural cells. We then tested the response of the DKO Flk1(+) mesodermal cells to Gata4 activation (Figure 1A). After 4 days of induction with Gata4, most of the differentiated DKO Flk1(+) cells stained weakly for SMA, although the intensity was somewhat variable (Figure 1D, DKO Dex+). Strikingly, a small number of cells in the population (about 1%) had a round, endoderm-like morphology and were positive for the primitive endoderm marker Dab2 (Figure 1C, 1E, DKO Dex+). Morphologies of the SMA-positive cells (flat and large cytoplasm) and the Dab2-positive cells (round and small cytoplasm) were distinct (Figure 1C–1E). These results indicated that some DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells were converted to endodermal identity in response to Gata4.

Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b have transcriptional repression activities that are independent of their enzymatic activities [45], [46]. To examine whether this lineage conversion was DNA methylation-dependent, we prepared Flk1(+) mesoderm cells from Dnmt1−/− (KO) ES cells [23] expressing Gata4GR (Figure S3A), in which DNA methylation in the genome is extensively decreased due to the loss of maintenance methylation activity. Although overall tendencies for low growth and survival were observed, the Dnmt1−/− Flk1(+) cells efficiently differentiated into SMA(+) cells without Gata4 induction, whereas Dab2(+) primitive endoderm-like cells emerged when Gata4 was induced (Figure S3B, S3C). These results indicated that it was the loss of DNA methylation that promoted the Flk1(+) mesoderm cells to convert their lineage to endoderm in response to Gata4. These results also exclude the contribution of clonal effects caused by genetic or epigenetic changes associated with individual cell lines unrelated to DNMT functions.

We observed similar results using DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells obtained using a different mesoderm differentiation condition, in which ES cells were cultured on type IV collagen-coated dishes [41] (Figure S4A). Although the recovery of the Flk1(+) population from DKO ES cells was low (3%) under this condition (Figure S4B), the DKO Flk1(+) cells differentiated into SMA-positive mural cells with an efficiency similar to that of the WT Flk1(+) cells (Figure S4C,D, Dex−), confirming the commitment of the DKO Flk1(+) cells to the mesoderm fate. Using this condition, we observed that Gata4 reproducibly induced highly efficient differentiation of DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells into the endoderm, in which most cells were Dab2-positive with an endoderm-like, round cell morphology, while no such cells were observed in the WT Flk1(+) cell cultures (Figure S4C, S4D, WT DKO Dex+). We used RT-PCR and microarray analysis to obtain gene expression profiles of these cell populations, and found that when DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells were cultured for 4 days with Gata4 activation (DKO Flk1+Dex+), their gene expression profile was similar to that of primitive endoderm cells that were derived directly from ES cells (Figure S4E–S4G).

However, we found that this culture condition was not stable; although it initially gave more efficient Gata4-induced differentiation of DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells into the endoderm (Figure S4C, S4D, DKO Dex+) compared to the OP9 co-culture condition (Figure 1C–1E, DKO Dex+), later, the efficiency of the both conditions became similar. We speculated that stroma-cell-free culture systems, such as the type IV collagen condition, may be more sensitive to factors such as the serum lot used in the culture medium. Because of the consistent differentiation properties and the high recoveries of Flk1(+) mesoderm cells, we used the OP9 co-culture condition for mesoderm differentiation in the remaining analyses.

Transcriptome Analysis of Gata4-Induced, DNA-Hypomethylated Mesoderm Cells

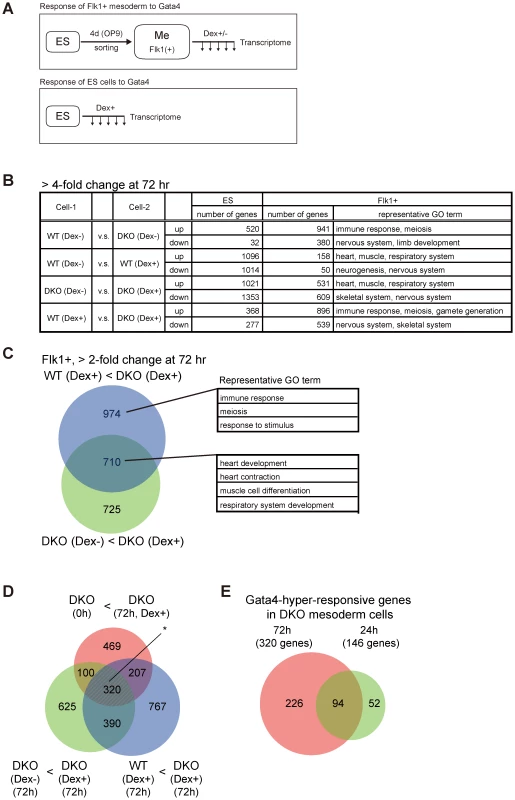

The above results indicated that DNA methylation is involved in the suppression of the endoderm-instructive function of Gata4 in mesoderm cells. Thus, we wondered how the DNA-hypomethylated mesoderm cells reprogrammed their transcription profiles from mesoderm to endoderm in response to Gata4. Previous studies in other cell-differentiation models suggested two possibilities: (1) the loss of DNA methylation together with Gata4 activity de-represses a few gatekeeper genes for endoderm differentiation, and these gatekeepers then activate the endoderm transcriptional program [27], [29]; (2) alternatively, the loss of DNA methylation allows Gata4 to directly activate its endoderm downstream genes [26]. To address these possibilities, we dissected the temporal changes of the transcriptome in response to Gata4 in Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Figure 2A). RNA was isolated at several time points (up to 72 hr) from WT or DKO Flk1(+) cells cultured with or without Gata4 activation, and their genome-wide transcriptional profiles were analyzed using microarrays (Figure 2A, Flk1+ mesoderm). For comparison, we also obtained the temporal transcriptome of ES cells in response to Gata4 at similar time points (Figure 2A, ES).

Fig. 2. Transcriptome analysis of Gata4-induced DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells.

(A) Experimental scheme to examine transcriptome changes in response to Gata4 in mesoderm or ES cells. WT or DKO ES cells stably expressing Gata4GR were differentiated on OP9 stromal cells for 4 days, then the Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Me) were sorted and cultured with or without Dex to activate Gata4GR (top). The same WT and DKO ES cells were also cultured with Dex in ES culture conditions (bottom). The expression microarray data were obtained at several time points (up to 72 hr) after Gata4GR activation in both mesoderm and ES cells. (B) Numbers of genes with a more than 4-fold difference between the indicated cell conditions 72 hr after Gata4GR activation by the addition of Dex in ES or Flk1(+) mesoderm cells. In each comparison, ‘up’ represents genes expressed higher in Cell-2 than Cell-1, and ‘down’ represents genes expressed lower in Cell-2 than Cell-1. Representative gene ontology (GO) terms at Biological Process level 4 (BP4) for differentially expressed genes in Flk1(+) mesoderm cells are shown in the right column. (C) Venn diagram representing the overlap between (i) the genes expressed 2-fold higher in DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm with Dex at 72 hr than WT cells under the same conditions (WT Dex+<DKO Dex+, purple) and (ii) the genes expressed 2-fold higher in DKO Flk1(+) cells with Dex than the same cells without Dex at 72 hr (DKO Dex−<DKO Dex+, light green). Representative GO terms for genes within the indicated areas are shown. Detailed results of the GO analysis are provided in Tables S1 and S2. (D) Extraction of Gata4-hyper-responsive genes in Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient Flk1(+) mesoderm cells from transcriptome data. Venn diagrams of the 2-fold upregulated genes in DKO mesoderm with Gata4 activation at 72 hr compared to (i) WT cells under the same conditions (WT Dex+<DKO Dex+, purple), (ii) the same cells without Gata4 activation (DKO Dex−<DKO Dex+, light green), or (iii) the same cells immediately after Flk1(+) sorting (DKO 0 h<DKO Dex+, orange). The overlapping genes of these three categories (320 genes, marked with an asterisk) are considered to be the genes that are upregulated in response to Gata4 preferentially at low DNA methylation levels. (E) Venn diagram of the Gata4-responsive genes in DNA-hypomethylated mesoderm cells at 72 hr and 24 hr identified in (D) and Figure S5. The 94 overlapping genes were used for the analysis in Figure 3, while the 320 genes at 72 hr were used in Figure S6. We first examined how many genes were differentially expressed as a result of the loss of Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b or Gata4 activation at 72 hr (Figure 2B). In total, 941 genes were expressed at a more than fourfold higher level in DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells cultured without Gata4 activation, compared to WT cells (Figure 2B, WT Dex − vs. DKO Dex−, up), which may represent genes directly repressed by DNA methylation. The gene ontology (GO) terms related to immune response, meiosis, and gametogenesis were significantly enriched in this gene set (Table S1), which is consistent with a previous report showing that promoters of germline - or inflammation-associated genes are methylated de novo during mouse embryogenesis in a Dnmt3-dependent manner [47]. Because DKO Flk1(+) cells without Gata4 activation properly differentiated into mural cells with a cell morphology indistinguishable from that of WT Flk1(+) cells (Figure 1C, 1D), the upregulation of these 941 genes seemed to have little impact on the cellular phenotype of mesodermal differentiation. In contrast, Gata4 activation in both the WT and DKO Flk1(+) cells resulted in differential expression of hundreds of genes, for which the GO terms related to various developmental processes were enriched (Figure 2B, Table S1).

We then extracted the genes that responded to Gata4 preferentially in DKO cells with hypomethylated DNA (Figure 2C–2E, Figure S5). The overlap between (i) the genes expressed more highly in DKO cells than in WT cells with Gata4 induction (WT Dex+<DKO Dex+, >2-fold change) and (ii) the genes expressed more highly in DKO cells with Gata4 induction than in the same cells without Gata4 induction (DKO Dex−<DKO Dex+, >2-fold change) separated the Gata4-responsive genes (710 genes) from the DNA methylation-sensitive genes (974 genes) (Figure 2C, Table S2). Based on the further overlap with (iii) the genes expressed at higher levels in DKO cells after 72 h of mesodermal differentiation with Gata4 induction than in the cells immediately after mesodermal differentiation (DKO 0 hr<DKO Dex+, >2-fold change), we identified 320 genes that responded to Gata4 at the 72 hr time point preferentially on the DKO background in Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Figure 2D). To extract early response genes to Gata4, we identified the same overlaps in gene sets differentially expressed at 24 hr (146 genes, Figure S5). Based on the overlap of these 146 genes with the Gata4 responsive genes at 72 hr, we identified 94 genes that responded to Gata4 within 24 hr and lasted for at least 72 hr, preferentially on the DKO background, in Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Figure 2E, Table S3). These results indicated that a significant number of genes became hyper-responsive to Gata4 in DNA-hypomethylated DKO mesoderm cells.

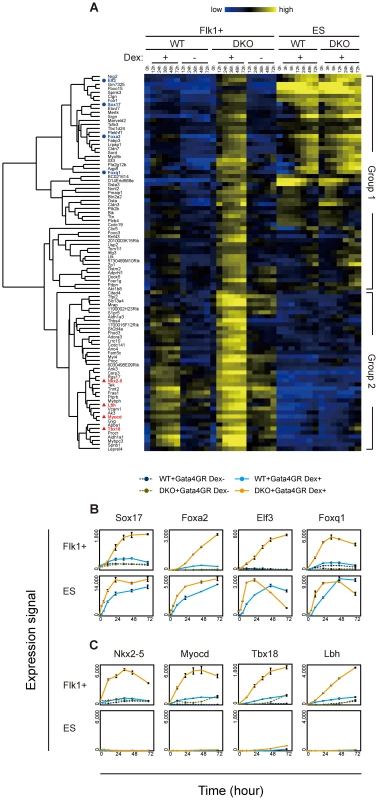

Time-Course Analysis of Transcriptome Changes in Response to Gata4

We then examined the time course of the expression profiles of these Gata4-hyper-responsive genes in Flk1(+) mesoderm and ES cells with or without Gata4 induction (Figure 3A, Figure S6). These Gata4-hyper-responsive genes were divided into two groups by hierarchical clustering (Table S3): group 1 genes responded to Gata4 in ES cells (upper part, Figure 3A, Figure S6), whereas group 2 genes did not (lower part, Figure 3A, Figure S6).

Fig. 3. Time course analysis of transcriptome changes in response to Gata4.

(A) Cluster heat map representing the temporal transcriptional changes for Gata4 response genes in Flk1(+) mesoderm or ES cells. WT or DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells or ES cells expressing Gata4GR were cultured for 72 hr in the presence or absence of Dex, and expression microarray data were obtained at several time points (0, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 hr for Flk1(+) mesoderm cells; 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hr for ES cells). Ninety-four genes whose responses to Gata4 were higher in DKO than WT Flk1(+) mesoderm cells at 24 hr were extracted as described in Figure 2E. The clustering of these 94 genes was based on their temporal expression profiles in Flk1(+) mesoderm and ES cells, and the resulting dendrogram is shown at left. Genes used in (B) and (C) are highlighted as blue circles and red triangles, respectively. Relative gene expression values (log2) are represented as colors, from lowest (blue) to highest (yellow). (B, C) Line graphs of the gene expression values (linear) from the microarray data. The mean values of triplicates (Flk1+, 0 hr and Dex+) or duplicates (others) with their standard deviations are shown. (B) Ectopic expression of endoderm genes in response to Gata4 in DKO mesoderm cells. These genes responded to Gata4 in WT and DKO ES cells, but not in WT mesoderm cells. Note that smaller scales are used for the expression signal for Flk1(+) mesoderm cells compared to those for ES cells. (C) Precocious expression of cardiac genes in response to Gata4 in DKO mesoderm cells. These genes did not respond to Gata4 in WT or DKO ES cells. “WT+Gata4GR Dex+” and “WT+Gata4GR Dex−”, WT cells expressing Gata4GR with and without Dex, respectively; “DKO+Gata4GR Dex+” and “DKO+Gata4GR Dex−”, DKO cells expressing Gata4GR with and without Dex, respectively. Consistent with the endoderm-instructive function of Gata4 in ES cells [38], group 1 contained many genes expressed in endoderm-derived tissues, such as the liver, intestine, and stomach (BioGPS, http://biogps.org/) [48]. Endoderm transcription factor genes (Sox17, Foxa2, Elf3, Foxq1) as well as endoderm lineage-specific genes (Aqp8, Sord, Akr1b8, Pga5) were upregulated in response to Gata4 in the DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells to the same extent as in ES cells (Figure 3B, Figure S7A). In addition, several genes whose expression was not restricted to endoderm-derived tissues (as listed in BioGPS) showed a similar expression profile (Figure S7B). It should be noted that the group 1 genes showed almost no response to Gata4 in WT Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Flk1+ WT Dex−, Figure 3A, Figure S6). These results suggest that the upregulation of group 1 genes represents the ectopic activation of the endoderm genetic program in the DNA-hypomethylated DKO mesoderm in response to Gata4.

Endoderm transcription factor genes Sox7 and endogenous Gata4, which also have mesoderm functions, were expressed in the Flk1(+) mesoderm cells before Gata4 activation, but their expression remained only in the DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells in response to Gata4 (Figure S7D). Interestingly, several primitive endoderm genes (Hnf4a, Fgfr4, Amn, S100g) responded to Gata4 specifically in the DKO mesoderm, but the extent of their response was modest compared to that in the ES cells (Figure S7C). No detectable response of other primitive endoderm genes, such as Gata6 and Snai1, to Gata4 was observed in the DKO mesoderm (Figure S7E).

Group 2 contained many genes involved in heart development and function. Cardiac transcription factor (Nkx2-5, Myocd, Tbx18, Lbh, Tbx5) and heart-specific genes (Ednra, Tnnt2, Fhod3, Acaa2, Ryr2, Kcnj5) were upregulated in response to Gata4 preferentially in the DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm within 24 hr (Figure 3C, Figure S7F). In addition, several genes that are highly expressed in skeletal muscles or osteoblasts (Fbxo32, Thbs4, Gyg, Pdlim3, Leprel4) showed a similar response in the DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Figure S7G). These results are consistent with the cardiac and other mesodermal functions of Gata4 [36], [37]. Because Gata4 regulates cardiac genes through its cooperation with other cardiac transcription factors and co-factors [37], it is likely that the cardiac genes did not respond to Gata4 in ES cells because of the lack of such co-factors.

In contrast, since Flk1(+) mesoderm includes cardiac progenitors [49], Flk1(+) cells may be competent to activate the expression of cardiac genes. Consistent with this idea, unlike the group 1 genes, the group 2 genes, including the cardiac genes, responded weakly to Gata4 in WT Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Flk1+, WT Dex+, Figure 3A, Figure S6). These results suggested that the response of the cardiac genes in group 2 represents the precocious expression of the cardiac gene program in DNA-hypomethylated DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells. In addition, group 2 contained genes highly expressed in endoderm-derived tissues (Tspan8, Aldh1a1, Psen2; Figure S7H), which may represent the ectopic activation of the definitive endoderm program.

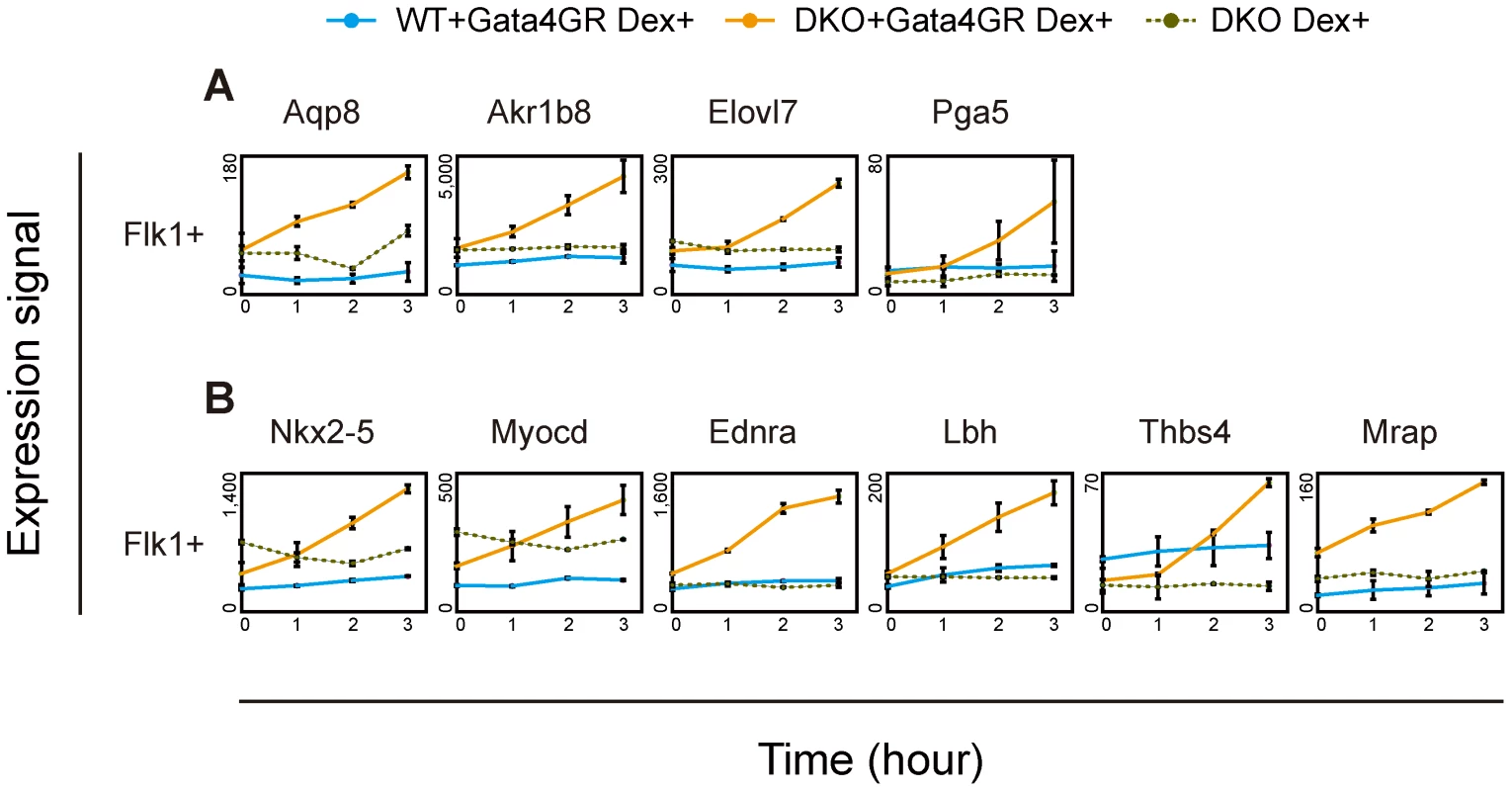

To determine whether the loss of Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b permits Gata4 to directly activate downstream target genes, we examined the immediate response to Gata4 activation by analyzing transcriptome changes occurring within 3 hr. Within the entire transcriptome, the expression of 64 genes were significantly increased, by more than 2-fold, 3 hr after Gata4 activation in DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells. Fifteen of these genes overlapped with the Gata4-hyper-responsive genes identified in Figures 2D and S5 (data not shown). Among them, both group 1 genes (Aqp8, Akr1b8, Elovl7, Pga5, Figure 4A) and group 2 genes (Nkx2-5, Myocd, Ednra, Lbh, Thbs4, Mrap, Figure 4B) immediately responded to Gata4 in the DNA-hypomethylated DKO mesoderm cells, but not in the WT cells. We also confirmed these results by RT-qPCR (Figure S8). These results suggested that DNA methylation contributes to suppress Gata4 from directly activating these genes.

Fig. 4. Immediate response to Gata4 in DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells.

ES cells differentiated on OP9 stromal cells were treated with Dex for 0, 1, 2 or 3 hr. The Flk1(+) mesoderm cells were then sorted by flow cytometry, and their gene expression was analyzed using microarrays. The mean values of duplicates for gene expression values (linear) with their standard deviations are shown. (A) Endodermal Gata4-responsive genes. (B) Cardiac Gata4-responsive genes. “WT+Gata4GR Dex+”, WT cells expressing Gata4GR with Dex; “DKO+Gata4GR Dex+”, DKO cells expressing Gata4GR with Dex; “DKO Dex+”, DKO cells without the Gata4GR transgene with Dex. Gata4-Binding-Site Profiles and DNA Methylation Analysis in Mesoderm Cells

To gain insight into how DNA methylation modulates Gata4 activation, we examined the Gata4-binding sites in WT and DKO Flk1+ mesoderm cells by ChIP and high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq), using anti-Gata4 antibodies. To obtain a large number of cells for the ChIP-seq experiment, WT or DKO ES cells expressing Gata4GR were differentiated in a large-scale culture on OP9 stroma cells, and the Flk1(+) cells were purified by magnetic-activated cell sorting. Gata4 was activated for 3 hr before the cell purification by adding Dex. As controls, WT and DKO ES cells expressing Gata4GR but without Dex treatment were subjected to the analysis. We identified 20,410 peaks for WT Gata4-activatd Flk1(+) cells and 22,733 peaks for DKO Gata4-activated Flk1(+) cells using the DNAnexus software tools.

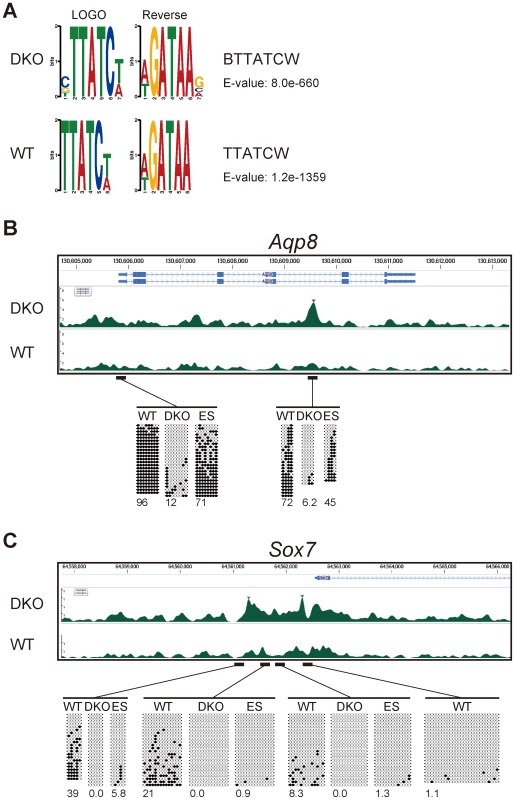

To validate the Gata4-ChIP-seq peaks, we performed two independent motif analyses in the MEME Suite software package (http://meme.nbcr.net/) [50]. Using the JASPAR CORE vertebrate motifs (http://jaspar.genereg.net/) [51] and UniPROBE mouse transcription factor motifs (http://thebrain.bwh.harvard.edu/uniprobe/) [52], ab initio motif discovery analysis by DREME [53] identified the most highly enriched motifs in the Gata4-ChIP-seq peak regions from both WT and DKO Flk1(+) cells with Gata4 activation as Gata factor-binding motifs (Figure 5A). Similarly, central motif enrichment analysis by CentriMo [54], which assumes that the direct DNA-binding sites tend toward the center of the ChIP-seq peak region, identified the three most highly ‘centrally enriched’ motifs as Gata-factor-binding motifs, using the same motif databases (Figure S9). These results indicated that Gata4-binding sites were highly enriched in the Gata4-ChIP-seq peaks.

Fig. 5. Gata4-binding site and DNA-methylation analyses of Gata4-response genes.

(A) Motif discovery of transcription-factor-binding motifs by the DREME algorithm using all the peaks of the ChIP-seq data for WT or DKO Flk1(+) cells in which Gata4GR was activated by Dex addition. Logos for the most enriched motif identified by DREME and its reverse complement sequence, motif IDs, and E-values are shown. (B,C) Gata4 ChIP-seq enrichment at the Gata4-response gene (B) Aqp8 and (C) Sox7 loci in WT or DKO Flk1(+) cells in which Gata4GR was activated by Dex, and the DNA methylation state at the transcription-start sites and Gata4-binding sites. Tracks represent the mapped read enrichment as determined by DNAnexus software. Blue arrowheads mark Gata4 peaks enriched in DKO Flk1(+) cells compared to WT Flk1(+) cells. Above the peak profiles, the nucleotide positions and Refseq genes are indicated. Horizontal bars represent the genomic regions subjected to DNA methylation analysis by bisulfite sequencing. Open circles represent unmethylated CpGs, and filled circles represent methylated CpGs. The percentage of total CpGs that were methylated is shown below each bisulfite sequencing profile. “WT”, WT Flk1(+) cells; “DKO”, DKO Flk1(+) cells; “ES”, WT ES cells. We next examined the Gata4 peaks and DNA methylation states of individual Gata4-response genes. Among 146 genes that transcriptionally responded to Gata4 within 24 hours specifically in DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Figure S5), 70 were associated with the Gata4 peaks in DKO Flk1(+) mesoderm cells, and 52 were associated with DKO-specific Gata4 peaks within a 5-kb distance (data not shown). We then searched for the genes in which either promoter regions [55] or Gata4 peak regions were differentially methylated between WT and DKO mesoderm cells and/or between ES and mesoderm cells, by bisulfite sequencing analysis.

Aqp8 has a low-CpG promoter, and a DKO-specific Gata4 peak was observed in its intronic region in DKO-mesoderm cells (Figure 5B). Gata4 also bound to the same intronic region in WT ES cells in response to Gata4 activation as revealed by ChIP-qPCR (Figure S10). Both regions were highly methylated in WT but not in DKO mesoderm cells. Thus, the DNA methylation of these regions might affect their Gata4-binding ability or the downstream response of Gata4. However, these regions were moderately or highly methylated in WT ES cells, in which Aqp8 responded to Gata4 (Figure S7). Thus, the DNA methylation in these regions may have different functions between ES and differentiated somatic cells, as observed in the retrotransposon IAP [56]. Sox7 has a high-CpG promoter, and DKO-specific Gata4 peaks were observed at this promoter region (Figure 5C). While the 5′-upstream and promoter region of Sox7 was unmethylated at the undifferentiated ES cell stage, this region was de novo methylated, highly at the distal part, during mesoderm differentiation. Similar de novo methylation during mesoderm commitment and inverse correlation with Gata4 peaks were observed at the Cldn7 locus (data not shown). The Gata4-responsive endoderm gene Lgmn was associated with two DKO-specific Gata4 peak regions that were highly methylated in Flk1(+) mesoderm cells (Figure S11A). One of the Gata4 peaks, located in the 3′ region of the neighboring gene Rin3, was methylated de novo during mesoderm differentiation. Since Rin3 itself did not respond transcriptionally to Gata4, the Gata4 peak located at Rin3 may contribute to Lgmn's transcription. Mrap and Thbs4, which have high-CpG promoters, were associated with Gata4 peaks within the gene or the neighboring gene in both WT and DKO mesoderm cells (Figure S11B, S11C). The promoter of Mrap was heavily methylated in a Dnmt3-dependent manner, consistent with a previous study [16], while the promoter of Thbs4 was de novo methylated during mesoderm differentiation. These promoter methylations may modulate downstream response of these genes in response to Gata4 binding. We also confirmed by luciferase reporter assay that at least some short fragments associated with Gata4 peaks had enhancer activities in response to Gata4 activation (Figure S12). Note that we also observed DKO-specific Gata4 peak regions that remained locally unmethylated in WT mesoderm cells (data not shown). These Gata4 peaks may represent cooperative binding with other Gata4 molecules or co-factors, or higher-order chromatin state changes induced by a decrease in DNA methylation. Taken together, the Gata4-peak and DNA-methylation profiles suggested that DNA methylation modulates cellular responses to Gata4 through diverse mechanisms.

Collectively, our results show that a significant number of developmental genes, including transcription factors and terminal differentiation genes, were promptly and simultaneously activated in DKO mesoderm cells by Gata4. This finding supports the model in which DNA methylation globally restricts the responsiveness of downstream genes to Gata4, rather than controlling a few gatekeeper genes.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the role of DNA methylation in the output of the single transcription factor Gata4 in defined cell types using an ES-cell differentiation method. Mesoderm cells derived from Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient ES cells were hyper-responsive to Gata4 and activated inappropriate developmental programs. Gata4 induced ectopic expression of endoderm downstream genes and precocious activation of cardiac and other downstream genes in DNA-hypomethylated mesoderm cells; these genes do not respond or respond only weakly to Gata4 in WT cells, suggesting that inappropriate Gata4 target genes such as endoderm genes are repressed in a DNA methylation-dependent manner. Our results indicate that epigenetic regulation by DNA methylation ensures the proper spatial and temporal developmental gene regulation by Gata4 and stabilizes differentiated cellular traits against the possible influences of natural fluctuation or environmental perturbations.

We showed that a fraction of Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient mesoderm cells, but not WT cells, can convert to endoderm cells in response to Gata4. This effect could be attributable to de-differentiation or the response of a small population of immature cells. However, our data suggest that these possibilities are unlikely. First, we purified the Flk1(+)/E-cadherin(−) cells by flow cytometry, which removes the immature mesendoderm population [42]. Second, Gata4 globally induced endoderm genes in Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient mesoderm cells, and some genes were expressed at the same level as in Gata4-activated ES cells, the whole population of which differentiates to endoderm. Third, many endoderm genes responded to Gata4 within 12 hr in Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient mesoderm, and some even responded within 3 hr. These results suggested that Gata4 globally and promptly activates an endoderm gene program in a large population of Flk1(+) mesoderm cells on the Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient background, but not in WT cells. Thus, it is unlikely that relatively slow processes such as de-differentiation or reversion to pluripotent states [57] are involved in this endoderm differentiation.

Using the mesoderm cells differentiated with OP9 stroma cell co-culture, we found that only a small fraction of the cultured mesoderm cells was differentiated into endoderm based on Dab2 staining (∼1%), even though the expression of endodermal genes were significantly increased (Figure 3, Figure S6, Figure S7). This implies that some cells retaining the mesodermal phenotype express both endoderm and mesoderm genes. During transcription factor induced-somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotent cells, partially reprogrammed cell clones express both stem cell-related genes and lineage-specific genes together [10]. We suggest a model in which an endoderm gene program is activated in a large mesoderm population, priming it for endoderm differentiation, but only a small subset of this population accomplishes the primitive endoderm differentiation.

We showed that the loss of DNA methylation allowed mesoderm cells being converted to endoderm cells in response to Gata4 using both Dnmt1-deficient and Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient mesoderm cells. However, the low efficiency and incomplete reprogramming of the conversion suggest that additional mechanisms such as cell-specific trans-factors or other epigenetic signatures [58], [59] may also restrict the Gata4-induced endoderm differentiation in Flk1(+) mesoderm cells. These other mechanisms may be coordinately regulated or maintained by DNA methylation. We obtained variable ratios of endoderm differentiation from Gata4-activated Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient Flk1(+) mesoderm cells when we used the stroma cell-free condition with type IV collagen-coated dishes for mesoderm cell formation (Figure S4 and data not shown). This variation in differentiation efficiency may be due to effects of such restriction mechanisms other than DNA methylation. It is possible that differentiation conditions without stroma cells are more sensitive to various factors in cell culture, which may affect gene expression or epigenetic signatures of the Flk1(+) mesoderm cells differentiated with this condition.

DNA methylation restricts cell differentiation potential during development. Trophectoderm differentiation is restricted in mouse ES cells, and DNA methylation is involved in this process through the DNA methylation-dependent silencing of trophectoderm transcription factor Elf5 [27]. Pancreatic β cell identity is maintained by DNA methylation-dependent silencing of the lineage-determining transcription factor Arx [29]. In these cases, DNA methylation suppresses a limited number of gatekeeper transcription factors. The loss of DNA methylation de-represses these transcription factors, which subsequently activate their downstream transcriptional programs. In contrast, we showed that, in our cellular models, DNA methylation stabilizes mesoderm identity during cell differentiation by restricting the responsiveness of downstream genes to the transcription factor Gata4.

We found that the induction of Gata4 together with the loss of DNMTs, but not Gata4 alone, activates the endoderm gene program in mesoderm cells and promotes endoderm differentiation. During this process, Gata4 promptly activates many endoderm genes, including both transcription factors and terminal differentiation genes with a similar time frame, suggesting that DNA hypomethylation allows Gata4 to activate endodermal target genes directly in mesoderm cells. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that endoderm transcription factors such as Sox17 and Foxa2, which respond to Gata4 early, may contribute more than other proteins to the endoderm differentiation phenotype.

Our results also showed that the loss of DNA methylation alone does not induce endoderm differentiation, showing that the role of DNA methylation is permissive, not instructive, in this differentiation. This is consistent with a previous study of astrocyte differentiation showing that DNA methylation suppresses the responsiveness of embryonic neuroepithelial cells to the gliogenic LIF signal during mouse embryogenesis [26]. The binding of the transcription factor STAT3 to the promoter region of the astrocyte gene Gfap is suppressed in a DNA methylation-dependent manner. Similarly, DNA methylation restricts the responsiveness of neuroepithelial cells to Notch signaling by suppressing the binding of the transcription factor RBP-J to the Hes5 gene promoter [60]. These reports suggest that regulation of the responsiveness of downstream genes to transcription factors is likely to be a broadly used mechanism of DNA methylation-dependent gene regulation. In hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), a deficiency of Dnmt1 results in impaired self-renewal and skewed myeloid/lymphoid differentiation [61], [62], whereas the inactivation of Dnmt3a leads to an increase in self-renewal associated with the incomplete repression of HSC genes such as Runx1 [63]. Thus, it is likely that DNA methylation modulates cellular differentiation by multiple pathways and mechanisms.

Several transdifferentiation studies have shown that one or a few transcription factors are sufficient to convert somatic cell fate within several days [3], [64]–[67]. It is likely that there are many genes downstream of transcription factors initiating trans-differentiation, but this aspect has yet to be analyzed in depth. Our study focused on the initial processes during cell fate conversion, and uncovered the contribution of DNA methylation in restricting the global response to the single transcription factor Gata4. Several studies have also suggested a link between DNA methylation and transcription factor-induced cell reprogramming to pluripotency (i.e. iPS cells) [4]. DNA methylation and de-methylation are closely correlated with the epigenetic memory of the original donor cells, and this may contribute to the variable differentiation propensity of iPS cells [68]–[71]. In addition, overall efficiency of the reprogramming process can be improved when somatic cells are treated with DNMT inhibitors [10]. Although, the reprogramming to pluripotency is different from Gata4-induced transdifferentiation in that it requires a much longer period of time, DNA methylation-dependent mechanisms similar to those described here may be involved in the reprogramming process.

DNA methylation regulates gene expression by various mechanisms [72]. The promoter regions of germ-cell-specific genes, inflammation-response genes, and some tissue-specific genes are methylated de novo by Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b around the implantation stage of mouse embryogenesis. The expression of these genes is increased by the loss of DNA methylation, indicating that DNA methylation directly represses their transcription [47]. In contrast, in neuronal progenitor cells, the gene body region of neural genes is methylated in a Dnmt3-dependent manner, and the expression of these genes is decreased by the loss of DNA methylation, suggesting that DNA methylation is required to maintain the expression of these genes [73]. Whole-genome DNA methylation analysis showed that the DNA methylation state of distal regulatory enhancers changes dynamically and is linked to changes in the expression of adjacent genes [16], and that the DNA methylation changes of enhancers are driven by transcription-factor binding [16], [74].

In this study, we showed that groups of developmental genes downstream of Gata4 become hyper-responsive to this transcription factor on a Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-deficient background. The loss of DNA methylation together with Gata4 activation induces the expression of these genes, but the loss of DNA methylation alone does not alter their expression, indicating that DNA methylation does not directly regulate the transcription of these genes. This finding implies that the transcriptome for a given methylome depends on the composition of the transcriptional regulators in a cell. This notion is consistent with previous reports that genome-wide DNA methylation profiles are not well correlated with gene expression [15], [63]. Further mechanistic studies will be necessary to connect the DNA methylome to cellular phenotypes.

In conclusion, our results extend our understanding of the role of DNA methylation in cell differentiation and the stabilization of cellular traits. Together with its feature of clonal inheritance [75], DNA methylation is likely to function as a memory of a cell's developmental history. Elucidation of the mechanisms of DNA methylation targeting and its interaction with chromatin may provide insight into the role of epigenetic regulation in development and cellular reprogramming.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Culture

Dnmt3a−/−Dnmt3b−/− DKO ES cells (clone 16aabb), Dnmt1−/− ES cells (clone 36), and WT J1 ES cells were described previously [23], [24]. WT, DKO, and Dnmt1−/− ES cell clones stably expressing dexamethasone (Dex)-inducible Gata4 were generated by introducing by electroporation an expression plasmid for Gata4 fused with the ligand-binding domain of the human glucocorticoid receptor (Gata4GR) driven by the CAG promoter [39], followed by selection with L-histidinol dihydrochloride (HisD) (clones J1G4.211, 16G4.3, and 36G4.3, respectively). ES cells were maintained on gelatinized culture dishes in either ES medium, consisting of Glasgow Minimum Essential Medium (GMEM, Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2000 U/ml LIF, or the same medium except for the replacement of 10% FCS with 10% Knockout Serum Replacement (KSR, Invitrogen) and 0.5% FCS. OP9 stromal cells, kindly provided by Dr. Shin-ichi Nishikawa, were maintained in α-Minimum Essential Medium (α-MEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% FCS.

ES Cell Differentiation

For in vitro differentiation by LIF withdrawal, ES cells were cultured overnight in ES medium containing 10% FCS, then differentiation was induced by replacing the medium with medium lacking LIF, after a wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For primitive endoderm (PE) differentiation, 100 nM Dex was added to ES cells stably expressing Gata4GR, in ES medium containing 10% FCS for 4 days [39]. For the time-course analysis, the cells were recovered by trypsinization at the indicated times after the addition of Dex, and RNA was isolated. For Flk1(+) mesoderm differentiation, ES cells were cultured either on type IV collagen-coated dishes or on OP9 stromal cells [40], [41].

For the type IV collagen-coated dish method, 1×105 WT ES cells or 5×105 DKO ES cells were plated on a type IV collagen-coated 10-cm dish (BioCoat, BD Biosciences) in differentiation medium (α-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol) and cultured for 4 days. The cultured cells were then collected using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, and single-cell suspensions were stained using an allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-Flk1 antibody (AVAS12, eBioscience), a biotinylated anti-PDGFRα antibody (APA5, eBioscience), and phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin (eBioscience). For the OP9 stroma co-culture method, 2×105 WT ES cells or 2.4×105 DKO or Dnmt1−/− ES cells were plated on a 10-cm dish with confluent OP9 stromal cells in the differentiation medium for 4 days.

The cultured cells were collected using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, and single-cell suspensions were stained using an APC-conjugated anti-Flk1 antibody, a biotinylated anti-E-cadherin antibody (Eccd2, TaKaRa Bio or DECMA-1, eBioscience), and phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin. Flk1(+), Flk1(+)/PDGFRα(+), and Flk1(+)/E-cadherin(−) cells were sorted by a FACSAria (BD Biosciences), and the flow cytometry profiles were visualized with FlowJo software (Tree Star). The sorted cells were further cultured on type IV collagen-coated dishes in differentiation medium in the absence or presence of 100 nM Dex for 4 days or the indicated times. For the short-term Gata4-response experiment, ES cells were plated on a 10-cm dish with confluent OP9 stroma cells and cultured for 4 days as described above. One, two, or three hours before cell collection, 100 nM Dex was added to the cell culture. The cells were collected by trypsinization, and the Flk1(+)/E-cadherin(−) cells were sorted as described above. The sorted cells were directly used for RNA isolation.

Immunofluorescence Analysis

Cells grown on gelatin - or type IV collagen-coated dishes were washed in PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After being blocked in 4× saline-sodium citrate (SSC) containing 3% BSA and 0.2% Tween 20 for 30 min at 37°C, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies in detection buffer (4× SSC containing 1% BSA and 0.2% Tween 20) for 1 hr at 37°C, washed twice with 4× SSC, and incubated for 1 hr at 37°C with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 555. For DNA staining, fixed cells were incubated with 0.2 µg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) or 1 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 and then washed in 4× SSC.

The following antibodies were used: anti-Disabled-2/p96 (Dab2) mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 52, BD Biosciences, 610464), anti-Gata4 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-9053), anti-alpha-SMA mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 1A4, Sigma, A5228), anti-Sox17 polyclonal goat antibody (R&D Systems, AF1924), goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A11017), goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen, A11070, A21430), and rabbit anti-goat IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A21222).

RNA Expression Analysis by RT-PCR and RT-qPCR

For RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), and the first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1–5 µg of total RNA with random hexamer primers and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are listed in Table S4.

For RT-qPCR, cytoplasmic RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's cytoplasmic RNA protocol with the DNase digestion option. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 400 ng of total RNA with SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Expression levels of genes of interest in cDNA samples were quantitated by real-time PCR using FastStart SYBR Green Master (Roche Applied Science), based on a standard curve using genomic DNA. The RT-qPCR data were normalized by values of three housekeeping genes, Gapdh, Rps21 and Rps27a as internal control genes. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are listed in Table S4.

Microarray and Data Analysis

For the Affymetrix microarray analysis, total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent and purified using an RNeasy Mini Column (Qiagen). The cRNA probe was prepared using a two-cycle target-labeling assay and hybridized to Affymetrix MOE430v2 oligonucleotide arrays as recommended by the manufacturer (Affymetrix). RNA from two independent experiments were used as duplicates for each experimental condition. The microarray data were analyzed using the Affy package [76] of the Bioconductor suite of programs [77] in combination with the eXintegrator system [78] (http://www.cdb.riken.jp/scb/documentation/). Data from the raw .CEL files were used either to calculate expression values using RMA expression values or as input to the eXintegrator system. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was carried out using the R “prcomp” function [79], and differentially expressed genes were identified using the SAM algorithm [80].

For Agilent microarray analysis, total RNA was isolated with an RNeasy Plus Micro Kit with a gDNA Eliminator column (Qiagen) in most cases. For the short-term Gata4-response experiment (0–3 hr), cytoplasmic RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's cytoplasmic RNA protocol with the DNase digestion option. RNA quality was checked by electrophoresis on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Fifty nanograms of total RNA was labeled by a Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies) and hybridized to a Mouse Gene Expression 8x60k Microarray (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For 72 hr-time-course analysis, each RNA was labeled in triplicate (Flk1(+) cells at 0 hr and at 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 hr in the presence of Dex) or in duplicate (others). For 3 hr-time-course analysis, RNA from two independent experiments for WT or DKO cells expressing Gata4GR transgene (WT+Gata4GR and DKO+Gata4GR) were labeled and used as duplicate for each time point, while each RNA from one experiment was labeled in duplicate for DKO cells without the Gata4GR transgene (DKO). The microarray data were quantile-normalized and analyzed using custom R scripts with the Limma package [81], the Bioconductor package suite [77], and custom Perl scripts. Probe values from the same gene were merged into the mean values to calculate the gene expression values, and the analyses described below were performed only for genes that had a GeneSymbol. To identify differentially expressed genes, we used empirical Bayes methods [82]. Genes that had a p value <0.01 and fold change >2 or 4 were selected. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed in the clustering module for Perl [83] with 1 - (Pearson correlation coefficient) as a distance and average linkage. The clusters were visualized by Java Treeview (http://jtreeview.sourceforge.net/) [84] and custom Perl scripts. Venn diagrams were generated using the BioVenn web application (http://www.cmbi.ru.nl/cdd/biovenn/) [85]. Gene ontology analysis at Biological Process level 4 (BP4) was performed using DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) [86] version 6.7 with default parameters.

The microarray data have been deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession number GSE36814 for the experiment using the type IV collagen-coating condition by Affymetrix microarray analysis and GSE36313 for the experiment using the OP9 co-culture condition by Agilent microarray analysis).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation and High-Throughput Sequencing (ChIP-seq) and Data Analysis

ChIP was performed using the ChIP-IT Express chromatin immunoprecipitation kit (Active Motif, Rixensart, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, WT or DKO ES cells differentiated on 15-cm dishes for 4.5 days using OP9-co-culture were treated with Dex for 3 hours and then collected by trypsinization. The differentiated cells were stained with a biotin-conjugated anti-Flk1 antibody (AVAS12, eBioscience) followed by streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), and then sorted with a magnetic cell separation system (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec). The isolated mesoderm cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, then the formaldehyde was quenched by adding glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. Chromatin was sonicated to an average size of 0.3–0.5 kb using Covaris shearing technology (Covaris, Massachusetts, USA). A mixture of equal amounts of three anti-Gata4 antibodies (sc-1237 and sc-25310, Santa Cruz Biotechnology and L97-56, BD Biosciences), bound to magnetic beads (Active Motif), was added to the sonicated chromatin, and the mixture was incubated for 4 hours at room temperature. After the beads were washed, the chromatin was eluted, and the crosslinking was then reversed. The DNA was purified with a MinElute DNA purification kit (Qiagen). The resultant ChIP DNA was quantified using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and a Quant-it dsDNA assay kit (Invitrogen). Undifferentiated WT or DKO ES cells without Dex treatment were used as controls for ChIP.

Libraries for high-throughput sequencing were prepared with the Illumina ChIP-seq DNA Sample Prep Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. High-throughput sequencing using an Illumina Hiseq and mapping of the resulting reads were performed by Hokkaido System Science Co., Ltd. Japan. Data analysis and visualization of the sequence reads were performed with DNAnexus software tools (https://dnanexus.com/). The ChIP-seq raw data have been deposited into the GEO database (accession code GSE41361). Of the initial 250,590,286 reads for WT Flk1+ cells and 392,760,766 reads for DKO Flk1+ cells obtained in the Gata4-ChIP-seq experiment, 209,514,577 (83.61%) and 368,177,514 (93.74%) were mapped to the mouse reference genome (NCBI v37, mm9), respectively.

The ChIP-seq peaks for Gata4 were determined with DNAnexus software tools using the following settings: KDE (kernel density estimation) bandwidth = 30, ChIP candidate threshold = 5.0, Experiment to background enrichment = 3.0, Minimum ratio of confident to repetitive mapping in region = 3.0. Peak calling with DNAnexus software tools identified 20,410 peaks for WT Flk1+ cells and 22,733 peaks for DKO Flk1+ cells using WT or DKO ES ChIP-seq reads, respectively, as background controls. For DKO-specific Gata4 peak calling, 10,636-enriched peaks were identified from the comparison between WT and DKO Flk1+ cells. The nearest Refseq genes (within 5 kb) were identified from the Gata4 peaks. Transcription-factor binding-site motif analysis for the Gata4 peak sequences was performed using the MEME-ChIP suit (http://meme.nbcr.net/) [50].

ChIP-qPCR Analysis

For ChIP-qPCR, 100 nM Dex was added to WT ES cells stably expressing Gata4GR cultured on 15-cm dishes in ES medium containing 10% FCS. At 3 hours after the addition of Dex, the cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature on the dishes; then the formaldehyde was quenched by adding glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. The fixed cells were recovered by scraping with a rubber policeman in ice-cold PBS and collected by centrifugation (Dex+). WT ES cells without Dex treatment were used as controls (Dex−). Chromatin sonication, ChIP with the mixture of three anti-Gata4 antibodies, and purification of ChIP DNA were performed as described for ChIP-seq, except for using Protein G FG beads (Tamagawa seiki) instead of magnetic beads in the kit. Relative abundance of regions of interest in precipitated DNA to input DNA was quantitaed by real-time PCR using Thunderbird SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO) with the comparative CT method. Gata4 enrichment was calculated as fold change of relative abundance for Dex+ to that for Dex−. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are listed in Table S4.

DNA Methylation Analysis by Bisulfite Sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from ES cells or Flk1(+) mesoderm cells with a QIAamp DNA micro kit (Qiagen) and subjected to bisulfite conversion with an EpiTect Bisulfite kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions with a slight modification [87]. Target sequences of the bisulfite-converted DNA were amplified by PCR, and 24 clones for each sample were sequenced. The primers for bisulfite sequencing were designed using MethPrimer (http://www.urogene.org/methprimer/) [88]. The bisulfite sequencing data were analyzed using QUMA (http://quma.cdb.riken.jp/) [89]. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are listed in Table S4.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

Constructs used for the luciferase reporter assays of Gata4-ChIP target sequences were based on the pFgf3_1.7k-luc vector [39], in which a fragment of DNA encompassing 1.7 kb of sequence immediately 5′ of the Fgf3 coding region containing GATA binding sites [90] was inserted into pGL4.10 (Promega). We generated the pFGF3_0.8k-luc vector by removing the 5′-half (0.9 kb) of FGF3 1.7 kb fragment from the pFgf3_1.7k-luc vector with digestion of 5′-end XhoI site on GL4.10 vector and internal AflII site. Luciferase reporter vectors containing Gata4-ChIP target sequences were constructed by inserting a 0.2–0.3 kb fragments centered around Gata4-ChIP-seq peaks amplified with HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen) using primers containing XhoI site (forward) and AflII site (reverse) sites, between the XhoI and AflII sites of the pFgf3_0.8k vector (See also Figure S12A). The following Gata4-ChIP peak regions were used for the construction and luciferase reporter assay; Aqp8 (intron), Grk5 (promoter), Sord (promoter), Sox7 (promoter), Lgmn (intron), Myocd (intron), and Spon1 (3′UTR). Primer sequences are listed in Table S4.

For transfection of reporter plasmids, 1×104 cells were seeded in each well of a 96-well plate in ES medium containing 10% FCS, and incubated with 330 ng reporter plasmid and 8 ng of the internal control plasmid pRL-CMV (Promega), together with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's protocol. At 3 hr after the transfection, 100 nM Dex was added. Luciferase assays were performed at 30 hr after the addition of Dex using a Dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. NiwaH (2007) Open conformation chromatin and pluripotency. Genes Dev 21 : 2671–2676.

2. JaenischR, YoungR (2008) Stem cells, the molecular circuitry of pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming. Cell 132 : 567–582.

3. DavisRL, WeintraubH, LassarAB (1987) Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell 51 : 987–1000.

4. TakahashiK, YamanakaS (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126 : 663–676.

5. GrafT, EnverT (2009) Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature 462 : 587–594.

6. BernsteinBE, MeissnerA, LanderES (2007) The mammalian epigenome. Cell 128 : 669–681.

7. JohnS, SaboPJ, ThurmanRE, SungMH, BiddieSC, et al. (2011) Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat Genet 43 : 264–268.

8. WhyteWA, BilodeauS, OrlandoDA, HokeHA, FramptonGM, et al. (2012) Enhancer decommissioning by LSD1 during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature 482 : 221–225.

9. HuangfuD, MaehrR, GuoW, EijkelenboomA, SnitowM, et al. (2008) Induction of pluripotent stem cells by defined factors is greatly improved by small-molecule compounds. Nat Biotechnol 26 : 795–797.

10. MikkelsenTS, HannaJ, ZhangX, KuM, WernigM, et al. (2008) Dissecting direct reprogramming through integrative genomic analysis. Nature 454 : 49–55.

11. TakeuchiJK, BruneauBG (2009) Directed transdifferentiation of mouse mesoderm to heart tissue by defined factors. Nature 459 : 708–711.

12. TursunB, PatelT, KratsiosP, HobertO (2011) Direct conversion of C. elegans germ cells into specific neuron types. Science 331 : 304–308.

13. BirdA (2002) DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 16 : 6–21.

14. MeissnerA, MikkelsenTS, GuH, WernigM, HannaJ, et al. (2008) Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature 454 : 766–770.

15. ListerR, PelizzolaM, DowenRH, HawkinsRD, HonG, et al. (2009) Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature 462 : 315–322.

16. StadlerMB, MurrR, BurgerL, IvanekR, LienertF, et al. (2011) DNA-binding factors shape the mouse methylome at distal regulatory regions. Nature 480 : 490–495.

17. ReikW (2007) Stability and flexibility of epigenetic gene regulation in mammalian development. Nature 447 : 425–432.

18. SasakiH, MatsuiY (2008) Epigenetic events in mammalian germ-cell development: reprogramming and beyond. Nat Rev Genet 9 : 129–140.

19. SaitouM, KagiwadaS, KurimotoK (2012) Epigenetic reprogramming in mouse pre-implantation development and primordial germ cells. Development 139 : 15–31.

20. GollMG, BestorTH (2005) Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem 74 : 481–514.

21. WuSC, ZhangY (2010) Active DNA demethylation: many roads lead to Rome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11 : 607–620.

22. LiE, BestorTH, JaenischR (1992) Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 69 : 915–926.

23. LeiH, OhSP, OkanoM, JuttermannR, GossKA, et al. (1996) De novo DNA cytosine methyltransferase activities in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development 122 : 3195–3205.

24. OkanoM, BellDW, HaberDA, LiE (1999) DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 99 : 247–257.

25. TaylorSM, JonesPA (1979) Multiple new phenotypes induced in 10T1/2 and 3T3 cells treated with 5-azacytidine. Cell 17 : 771–779.

26. TakizawaT, NakashimaK, NamihiraM, OchiaiW, UemuraA, et al. (2001) DNA methylation is a critical cell-intrinsic determinant of astrocyte differentiation in the fetal brain. Dev Cell 1 : 749–758.

27. NgRK, DeanW, DawsonC, LuciferoD, MadejaZ, et al. (2008) Epigenetic restriction of embryonic cell lineage fate by methylation of Elf5. Nat Cell Biol 10 : 1280–1290.

28. LeePP, FitzpatrickDR, BeardC, JessupHK, LeharS, et al. (2001) A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity 15 : 763–774.

29. DhawanS, GeorgiaS, TschenSI, FanG, BhushanA (2011) Pancreatic beta cell identity is maintained by DNA methylation-mediated repression of Arx. Dev Cell 20 : 419–429.

30. MolkentinJD (2000) The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem 275 : 38949–38952.

31. NaritaN, BielinskaM, WilsonDB (1997) Wild-type endoderm abrogates the ventral developmental defects associated with GATA-4 deficiency in the mouse. Dev Biol 189 : 270–274.

32. KuoCT, MorriseyEE, AnandappaR, SigristK, LuMM, et al. (1997) GATA4 transcription factor is required for ventral morphogenesis and heart tube formation. Genes Dev 11 : 1048–1060.

33. MolkentinJD, LinQ, DuncanSA, OlsonEN (1997) Requirement of the transcription factor GATA4 for heart tube formation and ventral morphogenesis. Genes Dev 11 : 1061–1072.

34. BosseT, PiaseckyjCM, BurghardE, FialkovichJJ, RajagopalS, et al. (2006) Gata4 is essential for the maintenance of jejunal-ileal identities in the adult mouse small intestine. Mol Cell Biol 26 : 9060–9070.

35. CirilloLA, LinFR, CuestaI, FriedmanD, JarnikM, et al. (2002) Opening of compacted chromatin by early developmental transcription factors HNF3 (FoxA) and GATA-4. Mol Cell 9 : 279–289.

36. Miranda-CarboniGA, GuemesM, BaileyS, AnayaE, CorselliM, et al. (2011) GATA4 regulates estrogen receptor-alpha-mediated osteoblast transcription. Mol Endocrinol 25 : 1126–1136.

37. PeterkinT, GibsonA, LooseM, PatientR (2005) The roles of GATA-4, -5 and -6 in vertebrate heart development. Semin Cell Dev Biol 16 : 83–94.

38. FujikuraJ, YamatoE, YonemuraS, HosodaK, MasuiS, et al. (2002) Differentiation of embryonic stem cells is induced by GATA factors. Genes Dev 16 : 784–789.

39. ShimosatoD, ShikiM, NiwaH (2007) Extra-embryonic endoderm cells derived from ES cells induced by GATA factors acquire the character of XEN cells. BMC Dev Biol 7 : 80.

40. NakanoT, KodamaH, HonjoT (1996) In vitro development of primitive and definitive erythrocytes from different precursors. Science 272 : 722–724.

41. NishikawaSI, NishikawaS, HirashimaM, MatsuyoshiN, KodamaH (1998) Progressive lineage analysis by cell sorting and culture identifies FLK1+VE-cadherin+ cells at a diverging point of endothelial and hemopoietic lineages. Development 125 : 1747–1757.

42. TadaS, EraT, FurusawaC, SakuraiH, NishikawaS, et al. (2005) Characterization of mesendoderm: a diverging point of the definitive endoderm and mesoderm in embryonic stem cell differentiation culture. Development 132 : 4363–4374.

43. YamashitaJ, ItohH, HirashimaM, OgawaM, NishikawaS, et al. (2000) Flk1-positive cells derived from embryonic stem cells serve as vascular progenitors. Nature 408 : 92–96.

44. OdaM, YamagiwaA, YamamotoS, NakayamaT, TsumuraA, et al. (2006) DNA methylation regulates long-range gene silencing of an X-linked homeobox gene cluster in a lineage-specific manner. Genes Dev 20 : 3382–3394.

45. BachmanKE, RountreeMR, BaylinSB (2001) Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are transcriptional repressors that exhibit unique localization properties to heterochromatin. J Biol Chem 276 : 32282–32287.

46. FuksF, BurgersWA, GodinN, KasaiM, KouzaridesT (2001) Dnmt3a binds deacetylases and is recruited by a sequence-specific repressor to silence transcription. Embo J 20 : 2536–2544.

47. BorgelJ, GuibertS, LiY, ChibaH, SchubelerD, et al. (2010) Targets and dynamics of promoter DNA methylation during early mouse development. Nat Genet 42 : 1093–1100.

48. WuC, OrozcoC, BoyerJ, LegliseM, GoodaleJ, et al. (2009) BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol 10: R130.

49. Martin-PuigS, WangZ, ChienKR (2008) Lives of a heart cell: tracing the origins of cardiac progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 2 : 320–331.

50. MachanickP, BaileyTL (2011) MEME-ChIP: motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics 27 : 1696–1697.

51. Portales-CasamarE, ThongjueaS, KwonAT, ArenillasD, ZhaoX, et al. (2010) JASPAR 2010: the greatly expanded open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res 38: D105–110.

52. NewburgerDE, BulykML (2009) UniPROBE: an online database of protein binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D77–82.

53. BaileyTL (2011) DREME: motif discovery in transcription factor ChIP-seq data. Bioinformatics 27 : 1653–1659.

54. BaileyTL, MachanickP (2012) Inferring direct DNA binding from ChIP-seq. Nucleic Acids Res 40: e128.

55. MohnF, WeberM, RebhanM, RoloffTC, RichterJ, et al. (2008) Lineage-Specific Polycomb Targets and De Novo DNA Methylation Define Restriction and Potential of Neuronal Progenitors. Mol Cell 30 : 755–766.

56. MatsuiT, LeungD, MiyashitaH, MaksakovaIA, MiyachiH, et al. (2010) Proviral silencing in embryonic stem cells requires the histone methyltransferase ESET. Nature 464 : 927–931.

57. FeldmanN, GersonA, FangJ, LiE, ZhangY, et al. (2006) G9a-mediated irreversible epigenetic inactivation of Oct-3/4 during early embryogenesis. Nat Cell Biol 8 : 188–194.

58. SvenssonEC, HugginsGS, DardikFB, PolkCE, LeidenJM (2000) A functionally conserved N-terminal domain of the friend of GATA-2 (FOG-2) protein represses GATA4-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem 275 : 20762–20769.

59. HirabayashiY, GotohY (2010) Epigenetic control of neural precursor cell fate during development. Nat Rev Neurosci 11 : 377–388.

60. HitoshiS, IshinoY, KumarA, JasmineS, TanakaKF, et al. (2011) Mammalian Gcm genes induce Hes5 expression by active DNA demethylation and induce neural stem cells. Nat Neurosci 14 : 957–964.

61. BroskeAM, VockentanzL, KharaziS, HuskaMR, ManciniE, et al. (2009) DNA methylation protects hematopoietic stem cell multipotency from myeloerythroid restriction. Nat Genet 41 : 1207–1215.

62. TrowbridgeJJ, SnowJW, KimJ, OrkinSH (2009) DNA methyltransferase 1 is essential for and uniquely regulates hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell 5 : 442–449.

63. ChallenGA, SunD, JeongM, LuoM, JelinekJ, et al. (2012) Dnmt3a is essential for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Nat Genet 44 : 23–31.

64. IedaM, FuJD, Delgado-OlguinP, VedanthamV, HayashiY, et al. (2010) Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell 142 : 375–386.

65. VierbuchenT, OstermeierA, PangZP, KokubuY, SudhofTC, et al. (2010) Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature 463 : 1035–1041.

66. HuangP, HeZ, JiS, SunH, XiangD, et al. (2011) Induction of functional hepatocyte-like cells from mouse fibroblasts by defined factors. Nature 475 : 386–389.

67. SekiyaS, SuzukiA (2011) Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature 475 : 390–393.

68. KimK, DoiA, WenB, NgK, ZhaoR, et al. (2010) Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 467 : 285–290.

69. PoloJM, LiuS, FigueroaME, KulalertW, EminliS, et al. (2010) Cell type of origin influences the molecular and functional properties of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 28 : 848–855.

70. BockC, KiskinisE, VerstappenG, GuH, BoultingG, et al. (2011) Reference Maps of Human ES and iPS Cell Variation Enable High-Throughput Characterization of Pluripotent Cell Lines. Cell 144 : 439–452.

71. OhiY, QinH, HongC, BlouinL, PoloJM, et al. (2011) Incomplete DNA methylation underlies a transcriptional memory of somatic cells in human iPS cells. Nat Cell Biol 13 : 541–549.

72. JonesPA (2012) Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet 13 : 484–492.

73. WuH, CoskunV, TaoJ, XieW, GeW, et al. (2010) Dnmt3a-dependent nonpromoter DNA methylation facilitates transcription of neurogenic genes. Science 329 : 444–448.

74. WienchM, JohnS, BaekS, JohnsonTA, SungMH, et al. (2011) DNA methylation status predicts cell type-specific enhancer activity. EMBO J 30 : 3028–3039.

75. SharifJ, MutoM, TakebayashiS, SuetakeI, IwamatsuA, et al. (2007) The SRA protein Np95 mediates epigenetic inheritance by recruiting Dnmt1 to methylated DNA. Nature 450 : 908–912.

76. GautierL, CopeL, BolstadBM, IrizarryRA (2004) affy–analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics 20 : 307–315.

77. GentlemanRC, CareyVJ, BatesDM, BolstadB, DettlingM, et al. (2004) Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 5: R80.

78. SakuraiH, EraT, JaktLM, OkadaM, NakaiS, et al. (2006) In vitro modeling of paraxial and lateral mesoderm differentiation reveals early reversibility. Stem Cells 24 : 575–586.

79. R Development Core Team (2007) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. URL http://www.R-project.org/.

80. TusherVG, TibshiraniR, ChuG (2001) Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98 : 5116–5121.

81. Smyth GK (2005) limma: Linear Models for Microarray Data. In: Gentleman R, Carey VJ, Huber W, Irizarry RA, Dudoit S, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer. pp. 397–420.

82. SmythGK (2004) Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3: Article3.

83. de HoonMJ, ImotoS, NolanJ, MiyanoS (2004) Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics 20 : 1453–1454.

84. SaldanhaAJ (2004) Java Treeview–extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics 20 : 3246–3248.

85. HulsenT, de VliegJ, AlkemaW (2008) BioVenn - a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics 9 : 488.

86. Huang daW, ShermanBT, LempickiRA (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4 : 44–57.

87. SmithZD, GuH, BockC, GnirkeA, MeissnerA (2009) High-throughput bisulfite sequencing in mammalian genomes. Methods 48 : 226–232.

88. LiLC, DahiyaR (2002) MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics 18 : 1427–1431.

89. KumakiY, OdaM, OkanoM (2008) QUMA: quantification tool for methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 36: W170–175.