-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaExtensive Natural Epigenetic Variation at a Originated Gene

Epigenetic variation, such as heritable changes of DNA methylation, can affect gene expression and thus phenotypes, but examples of natural epimutations are few and little is known about their stability and frequency in nature. Here, we report that the gene Qua-Quine Starch (QQS) of Arabidopsis thaliana, which is involved in starch metabolism and that originated de novo recently, is subject to frequent epigenetic variation in nature. Specifically, we show that expression of this gene varies considerably among natural accessions as well as within populations directly sampled from the wild, and we demonstrate that this variation correlates negatively with the DNA methylation level of repeated sequences located within the 5′end of the gene. Furthermore, we provide extensive evidence that DNA methylation and expression variants can be inherited for several generations and are not linked to DNA sequence changes. Taken together, these observations provide a first indication that de novo originated genes might be particularly prone to epigenetic variation in their initial stages of formation.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003437

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003437Summary

Epigenetic variation, such as heritable changes of DNA methylation, can affect gene expression and thus phenotypes, but examples of natural epimutations are few and little is known about their stability and frequency in nature. Here, we report that the gene Qua-Quine Starch (QQS) of Arabidopsis thaliana, which is involved in starch metabolism and that originated de novo recently, is subject to frequent epigenetic variation in nature. Specifically, we show that expression of this gene varies considerably among natural accessions as well as within populations directly sampled from the wild, and we demonstrate that this variation correlates negatively with the DNA methylation level of repeated sequences located within the 5′end of the gene. Furthermore, we provide extensive evidence that DNA methylation and expression variants can be inherited for several generations and are not linked to DNA sequence changes. Taken together, these observations provide a first indication that de novo originated genes might be particularly prone to epigenetic variation in their initial stages of formation.

Introduction

DNA mutations are the main known source of heritable phenotypic variation, but epimutations, such as heritable changes of gene expression associated with gain or loss of DNA methylation, are also a source of phenotypic variability. Indeed, several stable DNA methylation variants affecting a wide range of characters have been described, mainly in plants [1]–[3]. In most instances, epimutations are linked to the presence of structural features near or within genes, such as direct [4]–[6] or inverted repeats [7], [8] or transposable element (TE) insertions [9], which act as units of DNA methylation through the production of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) [3], [10]. Examples of epimutable loci in Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana) include the PAI [7] and ATFOLT1 genes [8], which have suffered siRNA-producing duplication events in some accessions and also the well characterized FWA locus, which contains a set of SINE-derived siRNA-producing tandem repeats at its 5′end [4], [5]. Repeat-associated epimutable loci are almost invariably found in the methylated form [5]–[9] in nature, which reflects, at least in part, that DNA methylation is particularly well-maintained over repeats [11], [12]. Indeed, epigenetic variation at PAI, ATFOLT1 and FWA has only been observed in experimental settings. Similarly, sporadic gain or loss of DNA methylation associated with changes in gene expression has only been documented in A. thaliana mutation accumulation lines [13], [14] and examples of natural epigenetic variation in other plant species are few [15]–[17].

Here we report a case of prevalent natural epigenetic variation in A. thaliana, which concerns a de novo originated gene [18]. We show that expression of this gene, named Qua-Quine Starch (QQS), is inversely correlated with the DNA methylation level of its promoter and that these variations are stably inherited for several generations, independently of DNA sequence changes. Based on these findings, we speculate that epigenetic variation could be particularly beneficial for newly formed genes, as it would enable them to explore more effectively the expression landscape than through rare DNA sequence changes.

Results

QQS Is a Novel Gene Embedded within a TE-Rich Region of the A. thaliana Genome and Is Negatively Regulated by DNA Methylation

The A. thaliana Qua-Quine Starch (QQS, At3g30720) was first described as a gene involved in starch metabolism in leaves [19], [20]. Despite being functional and presumably already under purifying selection (dN/dS = 0.5868; p-value<0.045), QQS is likely a recent gene that emerged de novo. Indeed, QQS has no significant similarity to any other sequence present in GenBank [18], [19], suggesting that it originated from scratch since A.thaliana diverged from its closest sequenced relative A. lyrata around 5–10 million years ago. Furthermore, QQS encodes a short protein (59 amino acids) and it is differentially expressed under various abiotic stresses [18], which are also hallmarks of de novo originated genes [21]–[23].

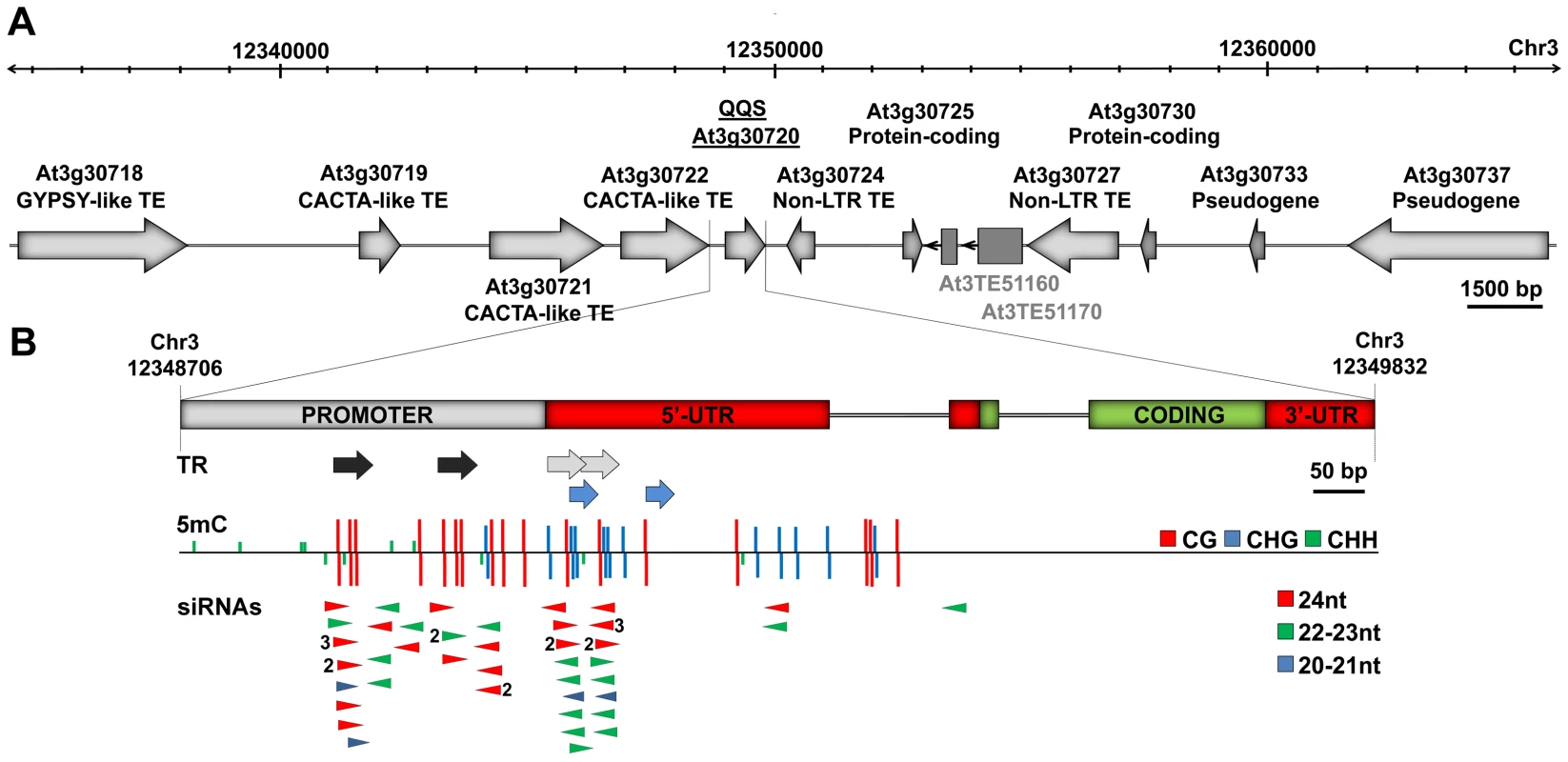

As shown in Figure 1, QQS is surrounded by multiple transposable element sequences (Figure 1A) and contains several tandem repeats in its promoter region and 5′UTR (Figure 1B). In the Columbia (Col-0) accession, these tandem repeats are densely methylated and produce predominantly 24 nt-long siRNAs (Figure 1B, Figure S1A and S1B). Publically available transcriptome data [24], [25] and results of RT-qPCR analyses (Figure S1C) show that steady state levels of QQS mRNAs are higher in several mutants affected in the DNA methylation of repeat sequences, including met1 (DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE 1), ddc (DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 and 2 and CHROMOMETHYLASE 3), ddm1 (DECREASE IN DNA METHYLATION 1) and rdr2 (RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE 2), which abolishes the production of 24 nt-long siRNAs as well as most CHH methylation. These findings indicate that QQS expression is negatively controlled by DNA methylation and point to the siRNA-producing tandem repeats as being potentially involved in this repression.

Fig. 1. QQS is embedded in a repeat-rich region.

(A) Genomic structure of the QQS locus (30 kb window) in the Col-0 accession. Dark grey boxes represent two additional TE sequences predicted by [51], [52]. (B) Magnified view of the QQS gene and upstream sequences, showing tandem repeats (TR), methylation of cytosine residues (5 mC) at the three types of sites (CG, CHG and CHH, H = A, T or C) and locus-specific sense and antisense siRNAs (numbers referring to copy number). DNA methylation and siRNA data are from [25]. Stably Inherited Spontaneous and Induced Epigenetic Variation at QQS

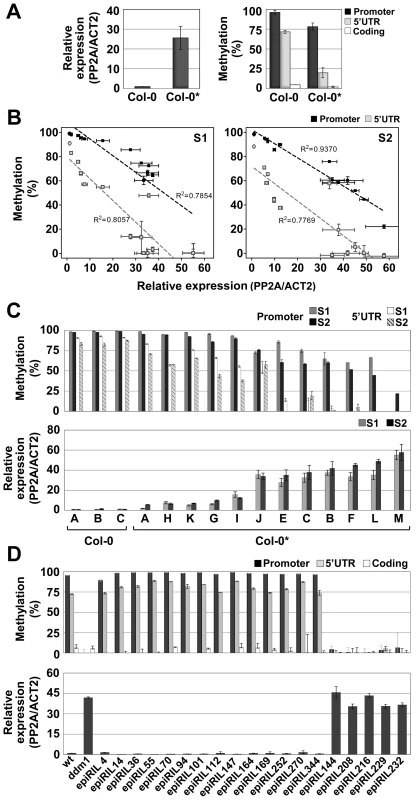

We first observed epiallelic variation at QQS unexpectedly, in a Col-0 laboratory stock (hereafter referred to as Col-0*) with increased expression of the gene and decreased DNA methylation of its promoter and 5′UTR repeat elements (Figure 2A). No sequence change could be detected in the Col-0* stock within a 1.2 kb region covering the QQS gene (Figure 1B), which excluded local cis-regulatory DNA mutations at the QQS locus as being responsible for DNA methylation loss in Col-0*. Additionally, comparative genomic hybridization analysis as well as genome-wide DNA methylation profiling using methylated DNA imunoprecipitation assays revealed no major differences between Col-0 and Col-0* (Figure S2).

Fig. 2. Spontaneous and induced epigenetic variation at QQS.

(A) DNA methylation and expression profiles of QQS in seedlings of the Col-0 and Col-0* stocks. (B) and (C) Negative correlation between QQS DNA methylation and expression levels in pooled seedlings of Col-0 and Col-0* (represented by circles and squares in B, respectively) S1 and S2 generation single seed descent lines. (D) DNA methylation and expression levels of QQS in seedlings of ddm1-derived epiRILs. Error bars represent standard deviation observed in three biological replicates (A–D – expression; A – DNA methylation) or two technical replicates (B–D – DNA methylation). We next investigated the QQS epigenetic status in pooled seedlings (S1) derived from the selfing of 12 individual Col-0* plants (Figure S3). Results revealed a range of QQS epialleles and a strong negative correlation between DNA methylation and expression of the gene (Figure 2B and 2C). To explore further this variation, a single S1 individual was then selfed for each of the 12 lines and seedlings (S2) were analyzed in pool for each line, as above (Figure S3). Remarkably, the differences in QQS expression and DNA methylation observed at the S1 generation were also observed at the S2 generation (Figure 2B and 2C). Taken together, these results suggest therefore the existence of a range of epiallelic variants at QQS, which are stably inherited for at least one generation.

The inheritance of QQS hypomethylated epialleles was also examined in a random sample of 19 ddm1-derived epigenetic Recombinant Inbred Lines (epiRILs) obtained by crossing a Col-0 wild-type (wt) line with an hypomethylated Col-0 ddm1 line [26]. High DNA methylation/low expression and low DNA methylation/high expression of QQS were observed in 14 and 5 epiRILs, respectively (Figure 2D). This is consistent with Mendelian segregation of the highly methylated/lowly expressed Col-0 wt and lowly methylated/highly expressed Col-0 ddm1 parental QQS epialleles (75%/25% expected because of backcrossing rather than selfing of the F1; Chi2 = 0,017, p-value>0.05). Indeed, examination of the epi-haplotype obtained for 17 of these epiRILs [27] confirmed the wt or ddm-origin of the QQS locus in each case (data not shown). These results demonstrate therefore that, like many other ddm1-induced epialleles [28], [29], QQS hypomethylated epialleles can be stably inherited for at least eight generations and are not targets of paramutation.

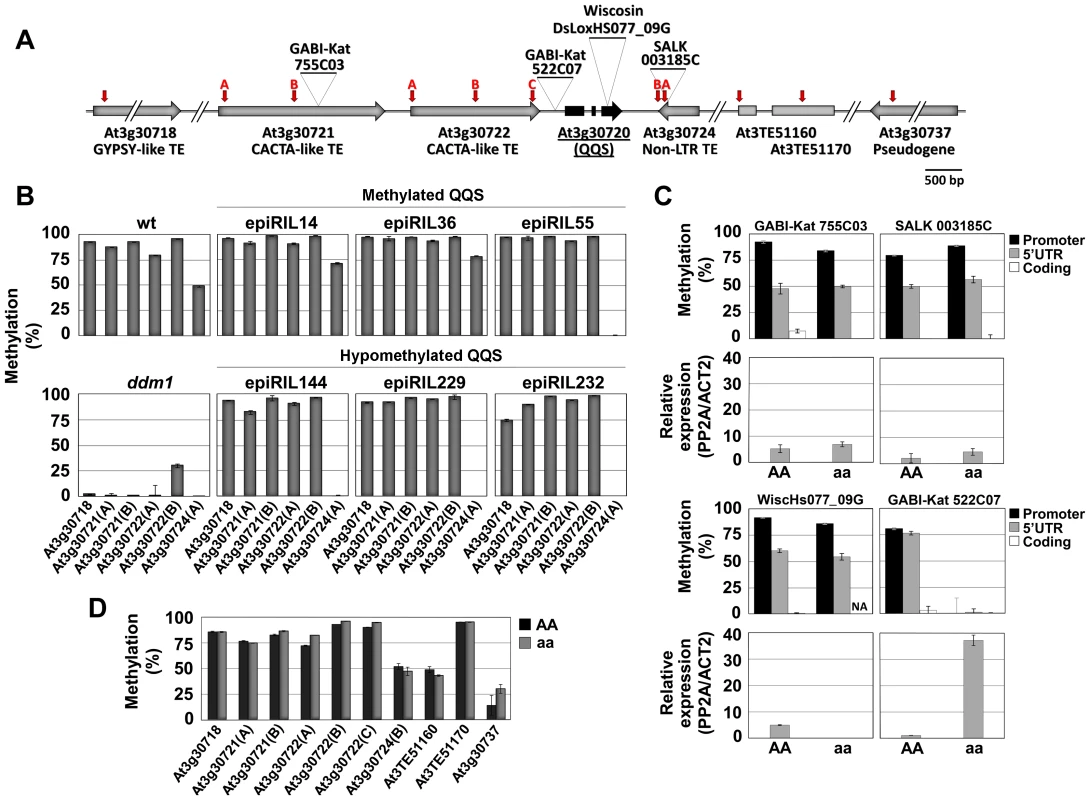

QQS Is under Autonomous Epigenetic Control

We next investigated the degree to which DNA methylation of QQS and of flanking TEs are independent from each other. To this end, we first analyzed DNA methylation patterns of TE sequences flanking QQS in a series of epiRIL with contrasted QQS epialleles. Unlike for ddm1-derived QQS, hypomethylation was not inherited for the three TEs located immediately upstream of the gene, as they did systematically regain wt DNA methylation levels (Figure 3A and 3B), presumably because of their efficient targeting by RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) [28]. In addition, although the TE just downstream of QQS was always hypomethylated when inherited from ddm1, hypomethylation was also observed in one epiRIL that inherited the QQS region from the wt parent. Thus, there is no strict correlation between DNA methylation at QQS and this downstream TE. We next examined the effect of several T-DNA and transposon insertions located ∼3.1 kb or 153 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS), 653 bp downstream of the 3′UTR and within the second coding exon of QQS. Whereas three of these insertions had no effect on DNA methylation and expression levels of QQS, the T-DNA insertion located closest to the TSS was associated with a drastic reduction of DNA methylation of both the promoter and 5′UTR of the gene, as well as with an increase in QQS expression (Figure 3A and 3C). However, this insertion had no impact on DNA methylation of upstream and downstream TEs (Figure 3A and 3D). Taken together, these results suggest that epigenetic variation at QQS is most likely determined by sequences within the promoter and 5′UTR of the gene, not by the TEs that are located immediately upstream or downstream.

Fig. 3. Epigenetic variation at QQS is determined by proximal sequences.

(A) Schematic representation of the T-DNA/Transposon insertion sites (triangles; GABI-Kat 755C03, GABI-Kat 522C07, WiscDsLoxHs077_09G (WiscHs077_09G) and SALK 003185C) and McrBC-qPCR primer pairs used (vertical arrows; A, B and C represent different primer pairs designed for the same element). (B) DNA methylation levels of TEs flanking QQS in epiRILs that had inherited a wt or a ddm1-derived QQS epiallele. (C) DNA methylation and expression levels of QQS in lines carrying the T-DNA/transposon insertions represented in (A). (D) DNA methylation levels of TEs flanking QQS in the GABI-Kat 522C07 T-DNA insertion line. AA and aa represent wt and T-DNA homozygous individuals, respectively, coming from the selfing of one hemizygous (Aa) plant. NA, not analyzed. Error bars represent standard deviation observed in two technical replicates (B and D) or three biological replicates (C). QQS Exhibits Epigenetic Variation among Natural Accessions

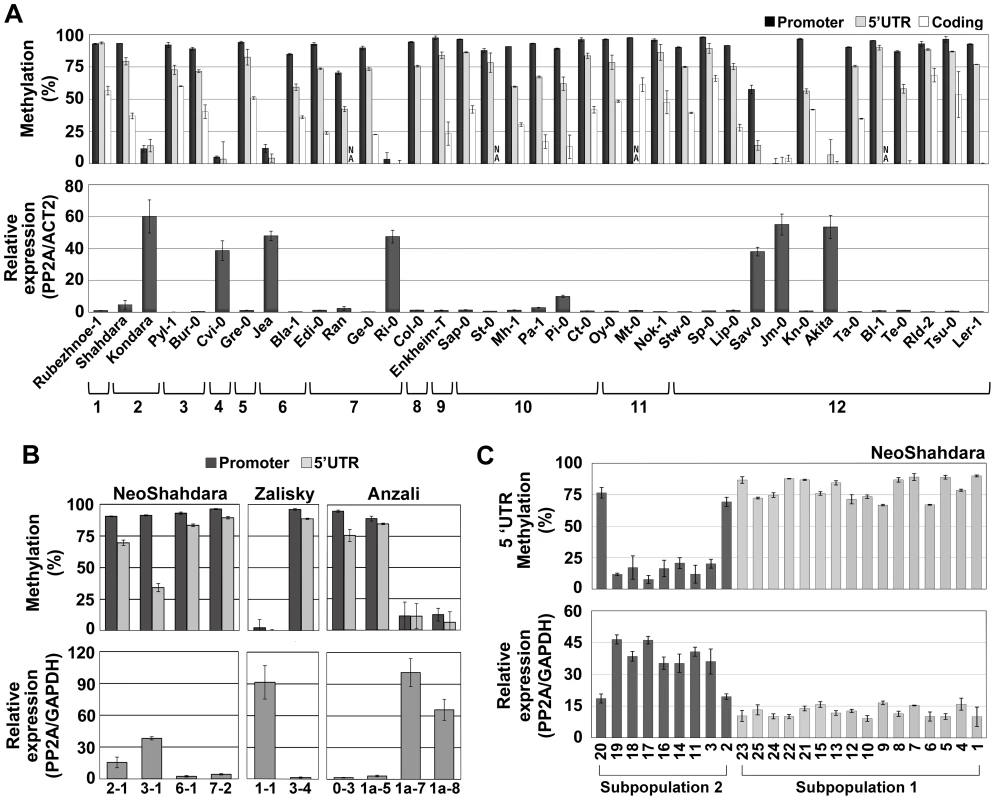

We next investigated the possibility that QQS is subject to epigenetic variation in natural populations. To this end, we first analyzed QQS expression and DNA methylation in 36 accessions representing the worldwide diversity [30]. QQS was methylated and lowly expressed in 29 accessions, but unmethylated and highly expressed in seven accessions distributed over the entire geographic range (Figure 4A). This indicates that epigenetic variation at QQS is widespread in nature. In contrast, upstream and downstream TEs were consistently methylated in all accessions (Figure S4A and S4B), thus confirming that the epigenetic state at QQS is not determined by that of flanking TEs. We then sequenced a 2.8 kb interval encompassing the QQS gene and its flanking regions from the seven accessions carrying the hypomethylated/highly expressed epiallele as well as from three accessions carrying a methylated/lowly expressed epiallele. Although several SNPs and indels were identified (Figure S4C), no correlation between any specific sequence alterations and QQS DNA methylation or expression states could be established (Figure 4A). In addition, while Kondara and Shahdara have identical QQS sequences, they have contrasted DNA methylation/expression patterns at the locus (Figure 4A and Figure S4C), which provides further evidence that natural epiallelic variation at QQS is independent of local cis-DNA sequence polymorphisms and is thus most likely truly epigenetic. Analysis of a Cvi-0 vs. Col-0 Recombinant Inbred Line (RIL) population revealed in addition that QQS expression is controlled by a large-effect local-expression quantitative trait locus (local-eQTL; http://qtlstore.versailles.inra.fr/) [31]. This suggests that like the Col-0 wt and Col-0 ddm1 QQS epialleles (Figure 2D), the Cvi-0 hypomethylated QQS epiallele is stably inherited across multiple generations. This further demonstrates that epigenetic variation at QQS is not appreciably affected by sequence or DNA methylation polymorphisms located elsewhere in the genome and indicates also that QQS is not subjected to paramutation [29].

Fig. 4. Epigenetic variation at QQS is frequent in nature.

(A) DNA methylation and expression profile in natural accessions representing the worldwide diversity. Accessions are organized into clades 1 to 12 according to genetic relatedness [36]. NA, not analyzed. (B) DNA methylation and expression levels of QQS in plants grown from seeds directly collected in the Central Asian wild populations NeoShahdara, Zalisky and Anzali. For each line, one to three sibling plants were tested and gave similar results so that only one is represented per individual parent. (C) QQS epiallelic frequency among 25 NeoShahdara individuals. Plants analyzed here were obtained from seeds produced after two single seed descent generations. Error bars represent standard deviation observed between two (A – DNA methylation) or three (A – expression) biological replicates or two technical replicates (B and C). To validate experimentally the causal relationship between DNA methylation and repression at QQS, seedlings of several accessions were grown in the presence of the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC). In the two accessions Col-0 and Shahdara, which harbor distinct methylated and lowly expressed QQS alleles, treatment resulted in reduced DNA methylation and increased expression of QQS (Figure S4D). In contrast, seedlings of Jea, Kondara and Cvi-0 accessions, all of which harbor a demethylated/highly expressed QQS allele, did not show further reduction of DNA methylation or increased expression when grown in the presence of the demethylating agent (Figure S4D). Moreover, whereas expression of QQS in F1 hybrids derived from crosses between Col-0 (methylated QQS) and Kondara (hypomethylated QQS), was always higher for the epiallele inherited from the hypomethylated parent, further confirming that QQS is not subjected to paramutation [29], treatment with 5-aza-dC reduced dramatically this expression imbalance, most likely as a consequence of demethylation of the Col-0-derived QQS allele (Figure S4E). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that DNA methylation at QQS is causal in repressing expression of the gene.

Wild Populations from Central Asia Exhibit Epigenetic Variation at QQS

Finally, we asked whether epigenetic variation at QQS could be observed in natural settings or if such variation only emerged in the laboratory, where accessions are grown under controlled growth conditions. To this end, we analyzed QQS expression and DNA methylation in plants grown from seeds directly collected from wild populations in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Iran (NeoShahdara, Zalisky and Anzali populations, respectively). Widespread QQS epiallelic variation was observed, both between and within these diverse wild populations (Figure 4B). In addition, QQS epigenetic variation was examined in the offspring (after two single seed descent generations) of 25 NeoShahdara individuals. These individuals were randomly sampled among a single patch of several thousands of plants that presumably represent the direct descendants of the Shahdara accession. Based on 10 microsatellite markers and one InDel marker, two genetically distinct subpopulations could be identified. While QQS was highly methylated/lowly expressed in all 16 individuals of subpopulation #1, clear differences in DNA methylation and expression were detected among the 9 individuals of subpopulation #2 (Figure 4C). Whether epiallelic variation at QQS in subpopulation #2 reflects inherent fluctuations or an intermediary stage in the route to fixation of one of the two epiallelic forms remains to be determined.

Discussion

QQS is a protein-coding gene that likely originated de novo in A. thaliana within a TE-rich region (Figure 1A). We have shown that this gene, which contains short repeat elements matching siRNAs (Figure 1B, Figure S1A and S1B), varies considerably in its DNA methylation and expression in the wild (Figure 4). We also show that these variations are heritable and independent of the DNA methylation status of neighboring TEs or of DNA sequence variation, either in cis or trans (Figure 2 and Figure 3, Figures S2 and S4). Thus, we can conclude that QQS is a hotspot of epigenetic variation in nature. Consistent with this, QQS is among the few genes for which spontaneous DNA methylation variation was observed in Col-0 mutation accumulation lines [13].

Cytosine methylation at QQS concerns CG, CHG and CHH sites, which is the pattern expected for sequences with matching siRNAs (Figure 1B, Figure S1B). All three types of methylation sites likely contribute to silencing of QQS, as judged by the reactivation of QQS in the met1, ddm1, ddc and rdr2 mutant backgrounds (Figure S1C; [24], [25]). Yet, among the different DNA methyltransferases targeting DNA methylation at QQS, MET1 may play a more prominent role, given that DNA methylation at this locus is only fully erased in met1 mutant plants [25]. QQS demethylated epiallelic variants may thus preferentially arise through spontaneous [13] or stress-induced [10] defects in DNA methylation maintenance and be stably inherited for multiple generations as a result of the concomitant loss of matching siRNAs, which would prevent efficient remethylation and silencing of the gene [28], [29]. Indeed, although we could not detect QQS siRNAs by Northern blot analysis, presumably because of their low abundance, deep sequencing data indicate that they accumulate less in met1 mutant plants than in wild type Col-0 [25].

Few genes have been shown so far to be subject to heritable epigenetic variation in A. thaliana [5]–[8], [13], [14], [32] and QQS is unique among these in exhibiting this type of variation in nature (Figure 4). This therefore raises the question as to what distinguishes QQS from other genes, such as FWA, for which epigenetic variation can be readily induced in the laboratory in advanced generations of ddm1 and met1 mutant plants [5], [33], but for which this type of variation is not observed among accessions [11], [34]. One possibility is that unlike QQS epivariants, fwa-hypomethylated epialleles are strongly counter-selected because of their potentially maladapted phenotype, namely late flowering [5]. Consistent with this explanation, epiallelic variation with no phenotypic consequences has been documented at FWA in other Arabidopsis species. In these cases, however, inheritance across multiple generations has not been rigorously tested [35]. Another possibility is that de novo originated genes, such as QQS, are particularly prone to heritable epigenetic variation. This is a reasonable assumption considering that these genes tend to lack proper regulatory sequences initially, unlike new gene duplicates, which by definition come fully equipped [21]. In turn, given that epigenetic variation enables genes to adjust their expression in a heritable manner much more rapidly than through mutation while preserving the possibility for rapid reversion, it could prove particularly beneficial in the case of genes that are created from scratch. Once the most adaptive expression state is reached, it could then become irreversibly stabilized (i.e. genetically assimilated) through DNA sequence changes. Although speculative, this proposed scenario could be highly significant given the recent discovery that de novo gene birth may be more prevalent than gene duplication [23].

Materials and Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

A. thaliana accessions were obtained from the INRA Versailles collection (dbsgap.versailles.inra.fr/vnat/, www.inra.fr/vast/collections.htm) [30], [36], [37]. Insertion lines were obtained from the GABI-Kat at University of Bielefeld, Germany (GABI-Kat 755C03 and 522C07) [38], the ABRC at Ohio State University (SALK 003195C) and University of Wisconsin, Madison, US (WiscDsLoxHs077_09) [39]. Seeds of ddm1-2 [40], rdr2-1 [41] and ddm1-derived epiRIL lines [26] were provided by V.Colot. NeoShahdara individuals were genotyped with 10 microsatellite markers (NGA8, MSAT2.26, MSAT2.4, NGA172, MSAT3.19, ICE3, MSAT3.1, MSAT3.21, MSAT4.18, ICE5; http://www.inra.fr/vast/msat.php) and one InDel marker in MUM2 gene (MUM2_Del-LP TGGTCGTTATTGGGTCTCGT, MUM2 Del-RP TTAAGAACGCCCGAGGAATA). For expression and DNA methylation assays, seedlings were grown in vitro (MS/2 media supplemented with 0,7% sucrose) for eight days in a culture room (22°C, 16 hours light/8 hours dark cycle, 150 µmol s−1 m−2). Treatment with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine was performed as described in [8].

RT–qPCR analysis of QQS expression

Total RNA was isolated as described in [42] and cDNA was synthetized using oligo(dT) primers and IMPROM II reverse transcriptase (Promega). Real time PCR reactions were run on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System using Platinum SYBR green (Invitrogen). QQS expression levels relative to Actin2/PP2A or PP2A/GAPDH internal references were calculated using the formula (2 - (Ct QQS – mean Ct internal references))*100. Primers are listed in Table S1.

Analysis of DNA methylation by McrBC–qPCR

Total DNA was isolated using Qiagen Plant DNeasy kit following the manufacturer's recommendations. Digestion was carried out overnight at 37°C with 200 ng of genomic DNA and 2 to 8 units of McrBC enzyme (New England Biolabs). Quantitative PCR was performed as described above on equal amounts (2 ng) of digested and undigested DNA samples using the primers described in Table S1. Results were expressed as percentage of molecules lost through McrBC digestion (1-(2-(Ct digested sample - Ct undigested sample)))*100. As a control, the percentage of DNA methylation for At5g13440, which is unmethylated in wt, was estimated in all analyses.

Allele-specific expression assays

To assess the relative contribution of each allele to the population of mRNA in F1 individuals from reciprocal crosses between Col and Kondara, a single pyrosequencing reaction using the primers QQS_pyro_F1 (PCR) - TCAAAATGAGGGTCATATC ATGG, QQS_pyro_R1-biotin (PCR) - ATTGGATACAATGGCCCTATAACT and QQS_pyro_S1 (Pyrosequencing) - GATATTGGGCCTTATCAC was set up on a SNP polymorphic between the QQS parental coding sequences (Figure S4C; position +285). Pyrosequencing was performed on F1 cDNA, as well as on 1/1 pools of parents cDNA to establish the allelic contribution to QQS expression. F1 genomic DNA is used as pyrosequencing control to normalize against possible pyrosequencing biases. Anything significantly driving allele-specific expression in hybrids is by definition acting in cis, since F1 nuclei contain a mix of all trans-acting factors [43], [44].

Comparative genome hybridization (CGH)

CGH experiments were performed for Col-0* vs. Col-0 using Arabidopsis whole-genome NimbleGen tiling arrays [45]. The normalmixEM function of the mixtools package on R was used to found the normal distribution for the distribution of the Col-0*/Col-0 ratio with an expected number of gaussians of two. A Hidden Markov model [46] was used to find regions with copy number variation.

Analysis of genome wide DNA methylation (MeDIP–Chip)

DNA was extracted using DNeasy Qiagen kit and MeDIP-chip was performed on 1.8 µg of DNA as previously described in [47]. The methylated tiles were identified using the ChIPmix method [48]. Probes methylated in one line only (Col-0 or Col-0*) were used to create domains. Domains contain at least three consecutive or nearly consecutive (400 nt min, with one gap of 200 nt max) tiles with identical methylation patterns.

Overall codon-based Z-test of purifying selection

Available QQS coding-sequences (464 different accessions) were downloaded from the “Salk Arabidopsis 1001 Genomes” database (http://signal.salk.edu/atg1001/index.php). A. suecica QQS sequence (coming from the A. thaliana genome of this allotetraploid [49]) was also included in the analysis. The aligned sequences were used to calculate the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis (H0) of strict-neutrality (dN = dS; where dN = number of nonsynonymous and dS = number of synonymous substitutions per site) in favor of the alternative hypothesis of purifying selection (HA; dS>dN). The analysis was done using the MEGA5 software under the Nei-Gojobori method [50] with the variance of the difference calculated by the bootstrap method with 100 replicates. Our overall analysis of 465 sequences rejected H0 in favor of HA (dN/dS = 0.5868; p-value<0.045).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. RichardsEJ (2006) Inherited epigenetic variation - revisiting soft inheritance. Nat Rev Genet 7 : 395–401 doi:10.1038/nrg1834.

2. DaxingerL, WhitelawE (2012) Understanding transgenerational epigenetic inheritance via the gametes in mammals. Nat Rev Genet 13 : 153–162 doi:10.1038/nrg3188.

3. WeigelD, ColotV (2012) Epialleles in plant evolution. Genome Biol 13 : 249 doi:10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-249.

4. LippmanZ, GendrelA-V, BlackM, VaughnMW, DedhiaN, et al. (2004) Role of transposable elements in heterochromatin and epigenetic control. Nature 430 : 471–476 doi:10.1038/nature02724.1.

5. KinoshitaY, SazeH, KinoshitaT, MiuraA, SoppeWJJ, et al. (2007) Control of FWA gene silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana by SINE-related direct repeats. Plant J 49 : 38–45 doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02936.x.

6. HendersonIR, JacobsenSE (2008) Tandem repeats upstream of the Arabidopsis endogene SDC recruit non-CG DNA methylation and initiate siRNA spreading. Genes Dev 22 : 1597–1606 doi:10.1101/gad.1667808.

7. BenderJ (2004) DNA methylation of the endogenous PAI genes in Arabidopsis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 69 : 145–153 doi:10.1101/sqb.2004.69.145.

8. DurandS, BouchéN, StrandEP, LoudetO, CamilleriC (2012) Rapid establishment of genetic incompatibility through natural epigenetic variation. Curr Biol 22 : 326–331 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.054.

9. MartinA, TroadecC, BoualemA, RajabM, FernandezR, et al. (2009) A transposon-induced epigenetic change leads to sex determination in melon. Nature 461 : 1135–1138 doi:10.1038/nature08498.

10. PaszkowskiJ, GrossniklausU (2011) Selected aspects of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance and resetting in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 14 : 195–203 doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2011.01.002.

11. VaughnMW, TanurdzićM, LippmanZ, JiangH, CarrasquilloR, et al. (2007) Epigenetic natural variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol 5: e174 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050174.

12. ZhangX, ShiuS, CalA, BorevitzJO (2008) Global analysis of genetic, epigenetic and transcriptional polymorphisms in Arabidopsis thaliana using whole genome tiling arrays. PLoS Genet 4: e1000032 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000032.

13. BeckerC, HagmannJ, MüllerJ, KoenigD, StegleO, et al. (2011) Spontaneous epigenetic variation in the Arabidopsis thaliana methylome. Nature 480 : 245–249 doi:10.1038/nature10555.

14. SchmitzRJ, SchultzMD, LewseyMG, O'MalleyRC, UrichMA, et al. (2011) Transgenerational epigenetic instability is a source of novel methylation variants. Science 334 : 369–373 doi:10.1126/science.1212959.

15. CubasP, VincentC, CoenE (1999) An epigenetic mutation responsible for natural variation in floral symmetry. Nature 401 : 157–161 doi:10.1038/43657.

16. ManningK, TörM, PooleM, HongY, ThompsonAJ, et al. (2006) A naturally occurring epigenetic mutation in a gene encoding an SBP-box transcription factor inhibits tomato fruit ripening. Nat Genet 38 : 948–952 doi:10.1038/ng1841.

17. MiuraK, AgetsumaM, KitanoH, YoshimuraA, MatsuokaM, et al. (2009) A metastable DWARF1 epigenetic mutant affecting plant stature in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106 : 11218–11223 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901942106.

18. DonoghueMTA, KeshavaiahC, SwamidattaSH, SpillaneC (2011) Evolutionary origins of Brassicaceae specific genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Evol Biol 11 : 47 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-47.

19. LiL, FosterC, GanQ, NettletonD, JamesMG, et al. (2009) Identification of the novel protein QQS as a component of the starch metabolic network in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J 58 : 485–498 doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03793.x.

20. SeoPJ, KimMJ, RyuJ-Y, JeongE-Y, ParkC-M (2011) Two splice variants of the IDD14 transcription factor competitively form nonfunctional heterodimers which may regulate starch metabolism. Nat Commun 2 : 303 doi:10.1038/ncomms1303.

21. KaessmannH (2010) Origins, evolution, and phenotypic impact of new genes. Genome Res 20 : 1313–1326 doi:10.1101/gr.101386.109.

22. TautzD, Domazet-LošoT (2011) The evolutionary origin of orphan genes. Nat Rev Genet 12 : 692–702 doi:10.1038/nrg3053.

23. CarvunisA-R, RollandT, WapinskiI, CalderwoodMA, YildirimMA, et al. (2012) Proto-genes and de novo gene birth. Nature 487 : 370–374 doi:10.1038/nature11184.

24. KuriharaY, MatsuiA, KawashimaM, KaminumaE, IshidaJ, et al. (2008) Identification of the candidate genes regulated by RNA-directed DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 376 : 553–557 doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.046.

25. ListerR, O'MalleyRC, Tonti-FilippiniJ, GregoryBD, BerryCC, et al. (2008) Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell 133 : 523–536 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029.

26. JohannesF, PorcherE, TeixeiraFK, Saliba-ColombaniV, SimonM, et al. (2009) Assessing the impact of transgenerational epigenetic variation on complex traits. PLoS Genet 5: e1000530 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000530.

27. Colomé-TatchéM, CortijoS, WardenaarR, MorgadoL, LahouzeB, et al. (2012) Features of the Arabidopsis recombination landscape resulting from the combined loss of sequence variation and DNA methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109 : 16240–1625 doi:10.1073/pnas.1212955109.

28. TeixeiraFK, HerediaF, SarazinA, RoudierF, BoccaraM, et al. (2009) A role for RNAi in the selective correction of DNA methylation defects. Science 323 : 1600–1604 doi: 10.1126/science.1165313.

29. TeixeiraFK, ColotV (2010) Repeat elements and the Arabidopsis DNA methylation landscape. Heredity 105 : 14–23 doi:10.1038/hdy.2010.52.

30. McKhannHI, CamilleriC, BérardA, BataillonT, DavidJL, et al. (2004) Nested core collections maximizing genetic diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 38 : 193–202 doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02034.x.

31. CubillosFA, YansouniJ, KhaliliH, BalzergueS, ElftiehS, et al. (2012) Expression variation in connected recombinant populations of Arabidopsis thaliana highlights distinct transcriptome architectures. BMC Genomics 13 : 117 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-13-117.

32. JacobsenSE, MeyerowitzEM (1997) Hypermethylated SUPERMAN epigenetic alleles in Arabidopsis. Science 277 : 1100–1103 doi:10.1126/science.277.5329.1100.

33. ReindersJ, WulffBBH, MirouzeM, Marí-OrdóñezA, DappM, et al. (2009) Compromised stability of DNA methylation and transposon immobilization in mosaic Arabidopsis epigenomes. Genes Dev 23 : 939–950 doi:10.1101/gad.524609.

34. FujimotoR, KinoshitaY, KawabeA, KinoshitaT, TakashimaK, et al. (2008) Evolution and control of imprinted FWA genes in the genus Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 4: e1000048 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000048.

35. FujimotoR, SasakiT, KudohH, TaylorJM, KakutaniT, et al. (2011) Epigenetic variation in the FWA gene within the genus Arabidopsis. Plant J 66 : 831–843 doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04549.x.

36. SimonM, SimonA, MartinsF, BotranL, TisnéS, et al. (2012) DNA fingerprinting and new tools for fine-scale discrimination of Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. Plant J 69 : 1094–1101 doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04852.x.

37. KronholmI, LoudetO, MeauxJD (2010) Influence of mutation rate on estimators of genetic differentiation - lessons from Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genet 11 : 33 doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-11-33.

38. KleinboeltingN, HuepG, KloetgenA, ViehoeverP, WeisshaarB (2012) GABI-Kat Simple Search: new features of the Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutant database. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D1211–D1215 doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1047.

39. WoodyST, Austin-PhillipsS, AmasinoRM, KrysanPJ (2007) The WiscDsLox T-DNA collection: an Arabidopsis community resource generated by using an improved high-throughput T-DNA sequencing pipeline. J Plant Res 120 : 157–165 doi:10.1007/s10265-006-0048-x.

40. VongsA, KakutaniT, MartienssenRA, RichardsEJ (1993) Arabidopsis thaliana DNA methylation mutants. Science 260 : 1926–1928.

41. XieZ, JohansenLK, GustafsonAM, KasschauKD, LellisAD, et al. (2004) Genetic and functional diversification of small RNA pathways in plants. PLoS Biol 2: E104 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020104.

42. Oñate-SánchezL, Vicente-CarbajosaJ (2008) DNA-free RNA isolation protocols for Arabidopsis thaliana, including seeds and siliques. BMC Res Notes 1 : 93 doi:10.1186/1756-0500-1-93.

43. WittkoppPJ, HaerumBK, ClarkAG (2004) Evolutionary changes in cis and trans gene regulation. Nature 430 : 85–88 doi:10.1038/nature02698.

44. ZhangX, RichardsEJ, BorevitzJO (2007) Genetic and epigenetic dissection of cis regulatory variation. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10 : 142–148 doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2007.02.002.

45. MoghaddamAB, RoudierF, SeifertM, BerardC, MagnietteMLM, et al. (2011) Additive inheritance of histone modifications in Arabidopsis thaliana intra-specific hybrids. Plant J 67 : 691–700 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04628.x.

46. Seifert M, Banaei A, Grosse I, Stricken M (2009) Array-based comparison of Arabidopsis ecotypes using hidden Markov models. In: Encarnação P, Veloso A, editors. BIOSIGNALS 2009. Portugal: INSTICC Press. pp. 3–11.

47. Cortijo S, Wardenaar R, Colome-Tatche M, Johannes F, Colot V (2012) Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis using MeDIP-chip. In: McKeown PC and Spillane C, editors. Treasuring Exceptions: Plant Epigenetics and Epigenomics. New Jersey: Humana Press. In press

48. Martin-Magniette ML, Mary-HuardT, BerardC, RobinC (2008) ChIPmix: mixture model of regressions for two-color ChIPchip analysis. Bioinformatics 24: I181–I186 doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btn280.

49. JakobssonM, HagenbladJ, TavaréS, SällT, HalldénC, Lind-HalldénC, NordborgM (2006) A unique recent origin of the allotetraploid species Arabidopsis suecica: Evidence from nuclear DNA markers. Mol Biol Evol 23 : 1217–1231 doi:10.1093/molbev/msk006.

50. NeiM, GojoboritT (1986) Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol 3 : 418–426.

51. BuisineN, QuenesvilleH, ColotV (2008) Improved detection and annotation of transposable elements in sequenced genomes using multiple reference sequence sets. Genomics 91 : 467–475 doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.01.005.

52. AhmedI, SarazinA, BowlerC, ColotV, QuenesvilleH (2011) Genome-wide evidence for local DNA methylation spreading from small RNA-targeted sequences in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res 39 : 1–13 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr324.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The G4 GenomeČlánek Mondo/ChREBP-Mlx-Regulated Transcriptional Network Is Essential for Dietary Sugar Tolerance inČlánek RpoS Plays a Central Role in the SOS Induction by Sub-Lethal Aminoglycoside Concentrations inČlánek Tissue Homeostasis in the Wing Disc of : Immediate Response to Massive Damage during DevelopmentČlánek Disruption of TTDA Results in Complete Nucleotide Excision Repair Deficiency and Embryonic LethalityČlánek DJ-1 Decreases Neural Sensitivity to Stress by Negatively Regulating Daxx-Like Protein through dFOXO

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 4

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Epigenetic Upregulation of lncRNAs at 13q14.3 in Leukemia Is Linked to the Downregulation of a Gene Cluster That Targets NF-kB

- A Big Catch for Germ Cell Tumour Research

- The Quest for the Identification of Genetic Variants in Unexplained Cardiac Arrest and Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation

- A Nonsynonymous Polymorphism in as a Risk Factor for Human Unexplained Cardiac Arrest with Documented Ventricular Fibrillation

- The Hourglass and the Early Conservation Models—Co-Existing Patterns of Developmental Constraints in Vertebrates

- Smaug/SAMD4A Restores Translational Activity of CUGBP1 and Suppresses CUG-Induced Myopathy

- Balancing Selection on a Regulatory Region Exhibiting Ancient Variation That Predates Human–Neandertal Divergence

- The G4 Genome

- Extensive Natural Epigenetic Variation at a Originated Gene

- Mouse Oocyte Methylomes at Base Resolution Reveal Genome-Wide Accumulation of Non-CpG Methylation and Role of DNA Methyltransferases

- The Environment Affects Epistatic Interactions to Alter the Topology of an Empirical Fitness Landscape

- TIP48/Reptin and H2A.Z Requirement for Initiating Chromatin Remodeling in Estrogen-Activated Transcription

- Aconitase Causes Iron Toxicity in Mutants

- Tbx2 Terminates Shh/Fgf Signaling in the Developing Mouse Limb Bud by Direct Repression of

- Mondo/ChREBP-Mlx-Regulated Transcriptional Network Is Essential for Dietary Sugar Tolerance in

- Sex-Differential Selection and the Evolution of X Inactivation Strategies

- Identification of a Tissue-Selective Heat Shock Response Regulatory Network

- Phosphorylation-Coupled Proteolysis of the Transcription Factor MYC2 Is Important for Jasmonate-Signaled Plant Immunity

- RpoS Plays a Central Role in the SOS Induction by Sub-Lethal Aminoglycoside Concentrations in

- Six Homeoproteins Directly Activate Expression in the Gene Regulatory Networks That Control Early Myogenesis

- Rtt109 Prevents Hyper-Amplification of Ribosomal RNA Genes through Histone Modification in Budding Yeast

- ATP-Dependent Chromatin Remodeling by Cockayne Syndrome Protein B and NAP1-Like Histone Chaperones Is Required for Efficient Transcription-Coupled DNA Repair

- Iron-Responsive miR-485-3p Regulates Cellular Iron Homeostasis by Targeting Ferroportin

- Mutations in Predispose Zebrafish and Humans to Seminomas

- Cytotoxic Chromosomal Targeting by CRISPR/Cas Systems Can Reshape Bacterial Genomes and Expel or Remodel Pathogenicity Islands

- Tissue Homeostasis in the Wing Disc of : Immediate Response to Massive Damage during Development

- All SNPs Are Not Created Equal: Genome-Wide Association Studies Reveal a Consistent Pattern of Enrichment among Functionally Annotated SNPs

- Functional 358Ala Allele Impairs Classical IL-6 Receptor Signaling and Influences Risk of Diverse Inflammatory Diseases

- The Tissue-Specific RNA Binding Protein T-STAR Controls Regional Splicing Patterns of Pre-mRNAs in the Brain

- Neutral Genomic Microevolution of a Recently Emerged Pathogen, Serovar Agona

- Genetic Requirements for Signaling from an Autoactive Plant NB-LRR Intracellular Innate Immune Receptor

- SNF5 Is an Essential Executor of Epigenetic Regulation during Differentiation

- Dialects of the DNA Uptake Sequence in

- Reference-Free Population Genomics from Next-Generation Transcriptome Data and the Vertebrate–Invertebrate Gap

- Senataxin Plays an Essential Role with DNA Damage Response Proteins in Meiotic Recombination and Gene Silencing

- High-Resolution Mapping of Spontaneous Mitotic Recombination Hotspots on the 1.1 Mb Arm of Yeast Chromosome IV

- Rod Monochromacy and the Coevolution of Cetacean Retinal Opsins

- Evolution after Introduction of a Novel Metabolic Pathway Consistently Leads to Restoration of Wild-Type Physiology

- Disruption of TTDA Results in Complete Nucleotide Excision Repair Deficiency and Embryonic Lethality

- Insulators Target Active Genes to Transcription Factories and Polycomb-Repressed Genes to Polycomb Bodies

- Signatures of Diversifying Selection in European Pig Breeds

- The Chromosomal Passenger Protein Birc5b Organizes Microfilaments and Germ Plasm in the Zebrafish Embryo

- The Histone Demethylase Jarid1b Ensures Faithful Mouse Development by Protecting Developmental Genes from Aberrant H3K4me3

- Regulates Synaptic Development and Endocytosis by Suppressing Filamentous Actin Assembly

- Sensory Neuron-Derived Eph Regulates Glomerular Arbors and Modulatory Function of a Central Serotonergic Neuron

- Analysis of Rare, Exonic Variation amongst Subjects with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Population Controls

- Scavenger Receptors Mediate the Role of SUMO and Ftz-f1 in Steroidogenesis

- DNA Double-Strand Breaks Coupled with PARP1 and HNRNPA2B1 Binding Sites Flank Coordinately Expressed Domains in Human Chromosomes

- High-Resolution Mapping of H1 Linker Histone Variants in Embryonic Stem Cells

- Comparative Genomics of and the Bacterial Species Concept

- Genetic and Biochemical Assays Reveal a Key Role for Replication Restart Proteins in Group II Intron Retrohoming

- Genome-Wide Association Studies Identify Two Novel Mutations Responsible for an Atypical Hyperprolificacy Phenotype in Sheep

- The Genetic Correlation between Height and IQ: Shared Genes or Assortative Mating?

- Comprehensive Assignment of Roles for Typhimurium Genes in Intestinal Colonization of Food-Producing Animals

- An Essential Role for Zygotic Expression in the Pre-Cellular Drosophila Embryo

- The Genome Organization of Reflects Its Lifestyle

- Coordinated Cell Type–Specific Epigenetic Remodeling in Prefrontal Cortex Begins before Birth and Continues into Early Adulthood

- Improved Detection of Common Variants Associated with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Using Pleiotropy-Informed Conditional False Discovery Rate

- Site-Specific Phosphorylation of the DNA Damage Response Mediator Rad9 by Cyclin-Dependent Kinases Regulates Activation of Checkpoint Kinase 1

- Npc1 Acting in Neurons and Glia Is Essential for the Formation and Maintenance of CNS Myelin

- Identification of , a Retrotransposon-Derived Imprinted Gene, as a Novel Driver of Hepatocarcinogenesis

- Aag DNA Glycosylase Promotes Alkylation-Induced Tissue Damage Mediated by Parp1

- DJ-1 Decreases Neural Sensitivity to Stress by Negatively Regulating Daxx-Like Protein through dFOXO

- Asynchronous Replication, Mono-Allelic Expression, and Long Range -Effects of

- Differential Association of the Conserved SUMO Ligase Zip3 with Meiotic Double-Strand Break Sites Reveals Regional Variations in the Outcome of Meiotic Recombination

- Focusing In on the Complex Genetics of Myopia

- Continent-Wide Decoupling of Y-Chromosomal Genetic Variation from Language and Geography in Native South Americans

- Breakpoint Analysis of Transcriptional and Genomic Profiles Uncovers Novel Gene Fusions Spanning Multiple Human Cancer Types

- Intrinsic Epigenetic Regulation of the D4Z4 Macrosatellite Repeat in a Transgenic Mouse Model for FSHD

- Bisphenol A Exposure Disrupts Genomic Imprinting in the Mouse

- Genetic and Genomic Architecture of the Evolution of Resistance to Antifungal Drug Combinations

- Transposable Elements Are Major Contributors to the Origin, Diversification, and Regulation of Vertebrate Long Noncoding RNAs

- Functional Dissection of the Condensin Subunit Cap-G Reveals Its Exclusive Association with Condensin I

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The G4 Genome

- Neutral Genomic Microevolution of a Recently Emerged Pathogen, Serovar Agona

- The Histone Demethylase Jarid1b Ensures Faithful Mouse Development by Protecting Developmental Genes from Aberrant H3K4me3

- The Tissue-Specific RNA Binding Protein T-STAR Controls Regional Splicing Patterns of Pre-mRNAs in the Brain

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání