-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Mutation in Chickens Constitutes a Structural Rearrangement Causing Both Altered Comb Morphology and Defective Sperm Motility

Rose-comb, a classical monogenic trait of chickens, is characterized by a drastically altered comb morphology compared to the single-combed wild-type. Here we show that Rose-comb is caused by a 7.4 Mb inversion on chromosome 7 and that a second Rose-comb allele arose by unequal crossing over between a Rose-comb and wild-type chromosome. The comb phenotype is caused by the relocalization of the MNR2 homeodomain protein gene leading to transient ectopic expression of MNR2 during comb development. We also provide a molecular explanation for the first example of epistatic interaction reported by Bateson and Punnett 104 years ago, namely that walnut-comb is caused by the combined effects of the Rose-comb and Pea-comb alleles. Transient ectopic expression of MNR2 and SOX5 (causing the Pea-comb phenotype) occurs in the same population of mesenchymal cells and with at least partially overlapping expression in individual cells in the comb primordium. Rose-comb has pleiotropic effects, as homozygosity in males has been associated with poor sperm motility. We postulate that this is caused by the disruption of the CCDC108 gene located at one of the inversion breakpoints. CCDC108 is a poorly characterized protein, but it contains a MSP (major sperm protein) domain and is expressed in testis. The study illustrates several characteristic features of the genetic diversity present in domestic animals, including the evolution of alleles by two or more consecutive mutations and the fact that structural changes have contributed to fast phenotypic evolution.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002775

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002775Summary

Rose-comb, a classical monogenic trait of chickens, is characterized by a drastically altered comb morphology compared to the single-combed wild-type. Here we show that Rose-comb is caused by a 7.4 Mb inversion on chromosome 7 and that a second Rose-comb allele arose by unequal crossing over between a Rose-comb and wild-type chromosome. The comb phenotype is caused by the relocalization of the MNR2 homeodomain protein gene leading to transient ectopic expression of MNR2 during comb development. We also provide a molecular explanation for the first example of epistatic interaction reported by Bateson and Punnett 104 years ago, namely that walnut-comb is caused by the combined effects of the Rose-comb and Pea-comb alleles. Transient ectopic expression of MNR2 and SOX5 (causing the Pea-comb phenotype) occurs in the same population of mesenchymal cells and with at least partially overlapping expression in individual cells in the comb primordium. Rose-comb has pleiotropic effects, as homozygosity in males has been associated with poor sperm motility. We postulate that this is caused by the disruption of the CCDC108 gene located at one of the inversion breakpoints. CCDC108 is a poorly characterized protein, but it contains a MSP (major sperm protein) domain and is expressed in testis. The study illustrates several characteristic features of the genetic diversity present in domestic animals, including the evolution of alleles by two or more consecutive mutations and the fact that structural changes have contributed to fast phenotypic evolution.

Introduction

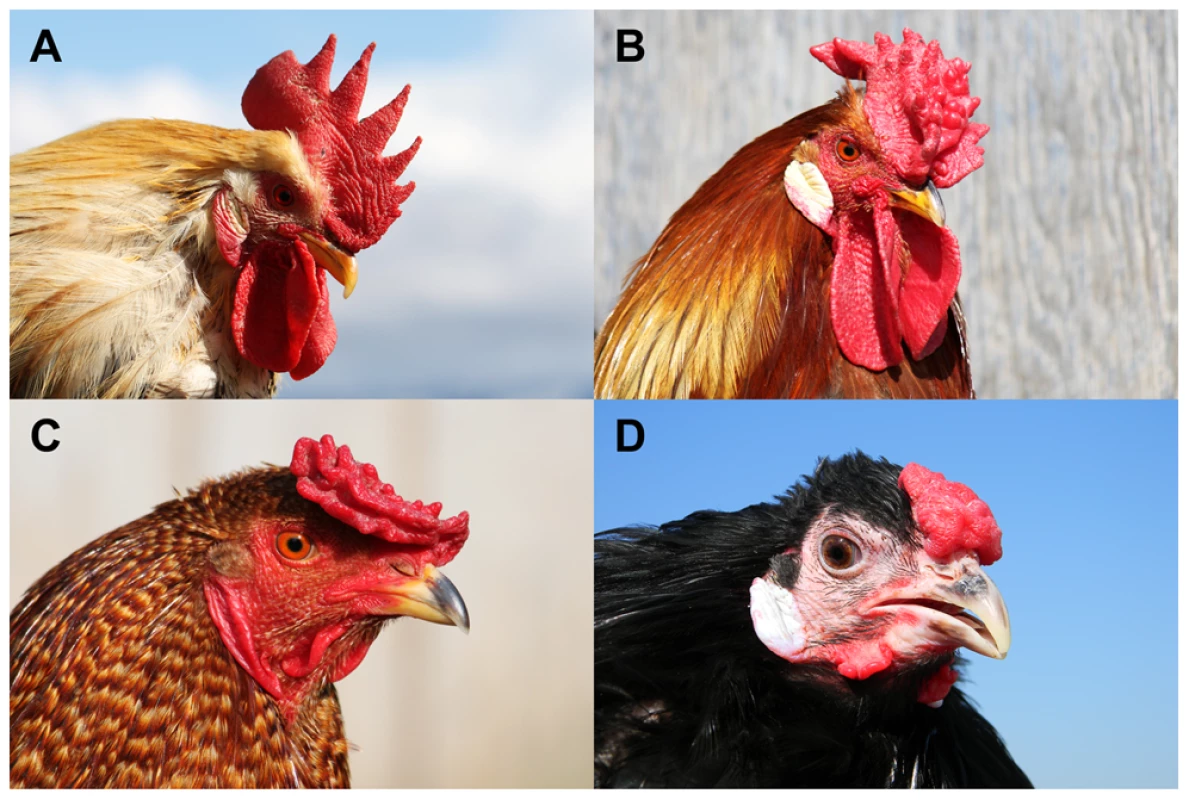

Rose-comb (Figure 1) was one of the autosomal dominant traits William Bateson used in his seminal paper describing Mendelian inheritance in animals for the first time [1]. This mutation probably occurred early in the process of chicken domestication, as it is widespread among chicken populations originating in both Asia and Europe, separated for hundreds of years. A few years after the first description of the mode of inheritance of Rose-comb, Bateson and Punnet [2] reported the first case of epistatic interaction between genes as they demonstrated that individuals carrying both the Rose-comb and Pea-comb alleles exhibit the walnut-comb phenotype (Figure 1). Rose-comb has been described in many breeds and shows extensive phenotypic variability (Figure S1). Most attention has been paid to variation in surface characteristics and texture, angle and number of posterior spikes [3]–[5]. Thus, Rose-comb variability indicates that comb morphogenesis is influenced by several genes and represents an excellent model to study interactions between developmental genes.

Fig. 1. Four comb phenotypes in chickens explained by segregation at the Rose-comb and Pea-comb loci and their interaction.

(A) Single-combed wild-type male (rr pp), (B) Rose-combed male (R- pp), (C) Pea-combed male (rr P-) and (D) walnut-combed male (R- P-). Photos by Freyja Imsland (A–C) and David Gourichon (D). Numerous reports have documented reduced male fertility associated with the Rose-comb allele [6]–[8]. Gradually it was elucidated that defective sperm motility in roosters homozygous for Rose-comb is the cause of the observed poor fertility and duration of fertility [9]–[15]. This reduced motility is thought to result in sperm from a homozygous Rose-comb rooster (RR) being outcompeted by sperm from roosters carrying the wild-type allele (Rr and rr) in promiscuous mating or heterospermic insemination experiments [16], [17]. Heterozygous Rose-comb roosters show normal fertility and transmit their Rose-comb and wild-type alleles to equal number of progeny. Fertility in the hen has been shown to be unaffected by her genotype at the R locus [18]. The unaffected fertility of the heterozygous rooster, combined with the effects of sperm competition, has historically confounded breeders' attempts to establish flocks that breed true for Rose-comb, resulting in an equilibrium of allele frequencies that gives rise to about 15% single-combed chicks in each generation [19].

In the present study, we show that Rose-comb is caused by a large structural rearrangement that leads to transient ectopic expression of an important transcription factor in the chicken, the Mnx-class homeodomain protein MNR2 [20]. This resembles our previous discovery that the Pea-comb mutation constitutes a copy number expansion in intron 1 of SOX5 leading to transient ectopic expression of SOX5 [21]. We also postulate that the sperm motility defect observed in males homozygous for Rose-comb is due to the same structural rearrangement disrupting the CCDC108 gene.

Results

Linkage mapping reveals that Rose-comb is associated with suppressed recombination

Linkage mapping was performed using a pedigree consisting of two F0 males heterozygous for Rose-comb, sixteen F0 single-combed females, and 383 F1 progeny segregating for Rose-comb (Rose-comb 50.7%, single-comb 49.3%). Already in 1940 Rose-comb was mapped to chicken linkage group I [22] and in a recent study Rose-comb was assigned to chicken chromosome 7 (GGA7) [23]. Our linkage data, presented in Table 1, confirmed the assignment to GGA7 and revealed suppression of recombination in Rose-comb heterozygotes as no recombination event was detected over a 7 Mb region, from position 16.1 Mb to 23.4 Mb on GGA7, despite the chicken consensus linkage map indicating a distance of 50 cM across this region [24]. This suppression of recombination associated with Rose-comb was confirmed in a second pedigree, a Chinese Silkie x White Plymouth Rock intercross (Text S1).

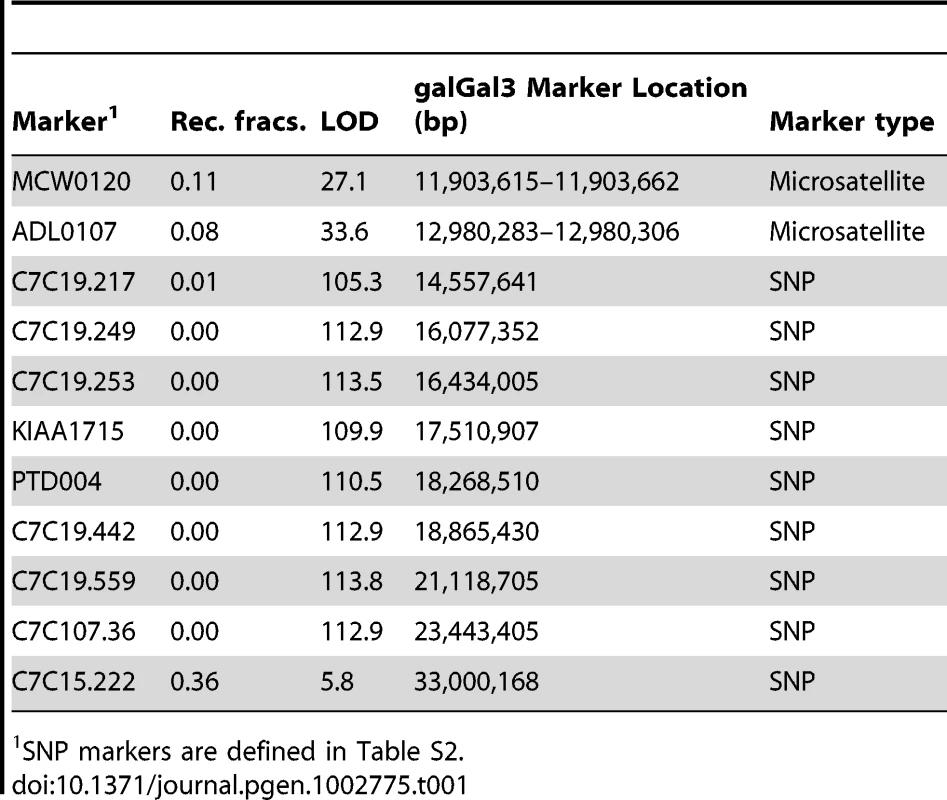

Tab. 1. Two-point linkage analysis of the Rose-comb locus using 11 markers on chicken chromosome 7.

SNP markers are defined in Table S2. Detection and characterization of a large inversion associated with Rose-comb

The observed suppression of recombination suggested that Rose-comb might be associated with an inversion. This hypothesis was strongly supported by a SNP screen using an Illumina 60K SNP array [25] of Rose-comb homozygotes from four Chinese chicken breeds, showing complete homozygosity for all SNPs in the interval 16,424,096 bp to 23,854,241 bp despite this region showing normal levels of heterozygosity in wild-type birds (Figure S2).

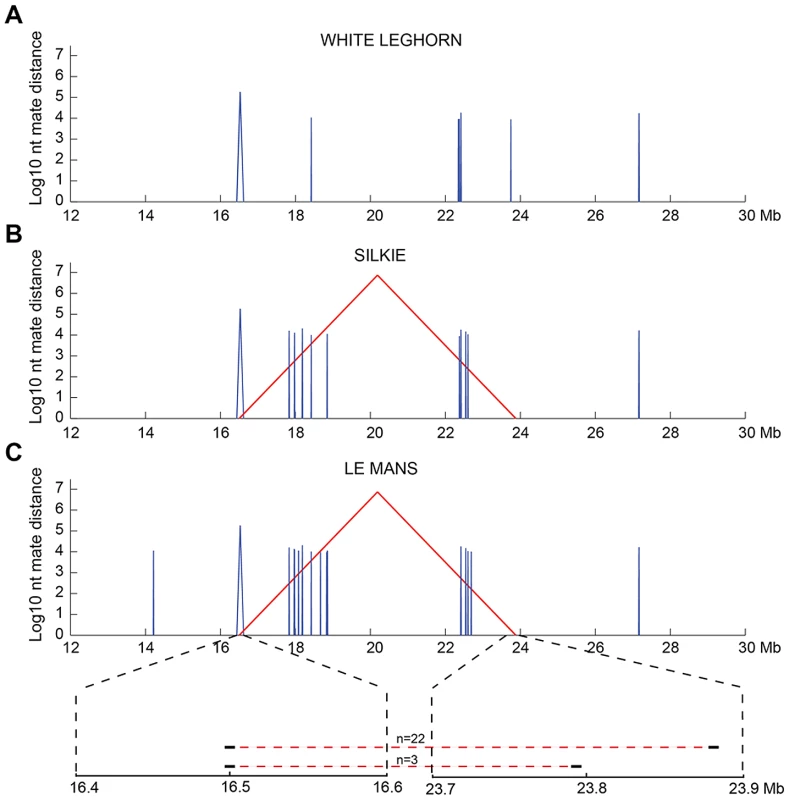

We searched for an inversion associated with Rose-comb using whole-genome resequencing of a 3.9 kb mate-pair library because this approach should precisely predict the location of any inversion breakpoints. The library was prepared from a pool of eight Rose-combed males from the Le Mans breed, all presumed to be homozygous Rose-comb. The library was sequenced to 1× coverage. Bioinformatic analysis of the data revealed aberrant mate pairs consistent with an inversion (Figure 2). Most aberrant reads (n = 22) indicated a 7.38 Mb inversion with breakpoints located approximately at 16.50 Mb and 23.88 Mb. However, three aberrant mate pairs connected the 16.50 Mb region with a region at 23.79 Mb, not consistent with a single inversion in all eight Rose-combed individuals included in the pool (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Candidate structural variants identified from whole-genome resequencing.

Mate-pair information was used to plot structural variants in the region of interest (chr7:12–30 Mb) for sequenced pools of (A) single-combed White Leghorn, (B) Rose-combed Chinese Silkie (C) Rose-combed Le Mans. Structural variants were defined as 1.5 kb windows where at least 25% of the mate pairs had mapping distances exceeding ten standard deviations above the average insert size and those > = 25% that were mapped within 1 kb of each other. Y-axis indicates the size of candidate structural variants in log10 base pairs. X-axis indicates the genomic coordinates of the pairs supporting structural variants. Red colour indicates mates that map to different strands, indicative of inversion. Blue colour indicates mates that map to the same strand, indicative of a deletion or duplication. The structural variants uniquely observed in the two Rose-combed pools included an inversion candidate, stretching between approximately 16.50–23.88 Mb. In the Le Mans pool an additional inversion candidate was also observed between 16.50–23.79 Mb, supported by three read pairs. This is depicted at the magnified region at bottom of (C). Candidate structural changes shared by all genotypes may represent errors in the draft chicken assembly. PCR analysis of genomic DNA from Rose-combed individuals confirmed the inversion breakpoints at nucleotide positions 16,499,781 bp and 23,881,384–23,881,392 bp (Figure 3). A 628 bp gap is predicted around 16.50 Mb in the chicken galGal3 assembly. However, sequencing across the gap in the reference sequence bird (red junglefowl female from the UCD-001 line) revealed that the gap and an additional 87 bp that together constitute the chr7 : 16,499,808–16,500,522 bp region must be an assembly artefact; the correct sequence of this region has been submitted to GenBank with the accession number JN942757.

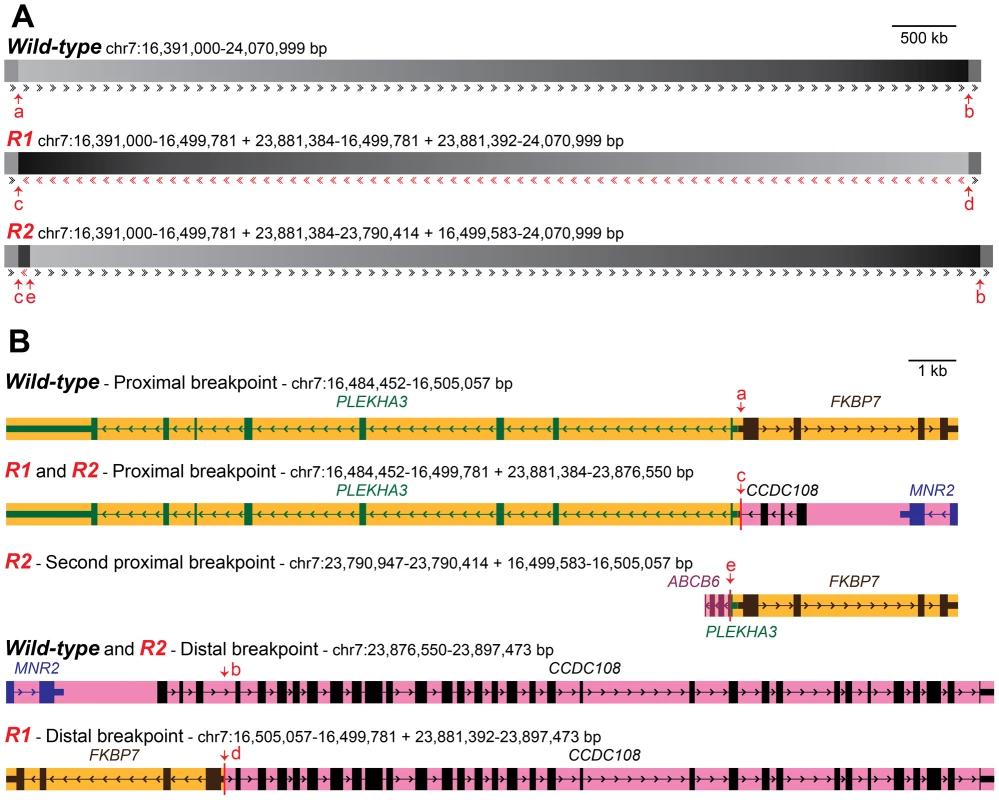

Fig. 3. Organization of wild-type and Rose-comb chromosomes and description of inversion and duplication breakpoints.

(A) Constitution of the two Rose-comb alleles, R1 and R2, in relation to the organization of the wild-type (r) chromosome 7 in chickens. Sequence orientation in relation to the wild-type chromosome is indicated by arrows. Duplicated sequence in R2 (chr7:23,790,414–23,881,384 bp) is in reverse orientation, apart from 198 bps (chr7:16,499,583–16,499,781 bp) flanking the inverted segment. Breakpoint locations are indicated by arrows (a–e). Breakpoints for the R1 inversion are at 16,499,781 and 23,881,384-23,881,392 bp in the wild-type sequence. Additional breakpoints for the R2 duplication are at 16,499,583 and 23,790,414 bp. (B) Organisation of genes in the five different chromosomal configurations associated with Rose-comb. Breakpoint locations are indicated with red arrows. mRNAs with accession numbers XM_422054.2, NM_204929.1, CR353563.1 and AJ719903.1, as well as EST sequences CD218766.1, BG713529.1 and DR426188.1 were used to define the genes illustrated. The copy of ABCB6 that occurs at the second proximal breakpoint unique to the R2 chromosome, is 5′ truncated from the duplication event, and appears 3′ truncated due to a gap in the assembly. An intact full length copy of this gene is expected to occur at its native chromosomal position (around 23.79 Mb) on R1, R2 and r chromosomes. The presence of the inversion had an almost perfect association with the Rose-comb phenotype in a PCR-based screen of a large number of individuals from different breeds. No unambiguously single - or Pea-combed individual (n = 679) carried any of the breakpoints, as expected, and almost all Rose - or walnut-combed chickens (n = 872) carried both the 16.50 Mb breakpoint and the 23.89 Mb breakpoint (Table 2). However, some individuals from five breeds, that had an unambiguous Rose-comb, (n = 45) showed an aberrant pattern, scoring positive for the 16.50 Mb breakpoint but not for the 23.89 Mb breakpoint (Table 2). Therefore we postulated that these birds might carry a second Rose-comb allele, R2, that evolved from the original Rose-comb allele (R1) by a second rearrangement. Such an event would also be consistent with the presence of the aberrant mate-pair reads connecting the 16.50 Mb and 23.79 Mb regions (Figure 2). PCR amplification confirmed the existence of R2, and the results showed that the allele must have originated by a recombination event between the wild-type allele at position 16.50 Mb and the R1 allele at position 23.79 Mb in the inverted region (Multimedia S1). The consequence of this recombination event is that R2 does not carry the entire inversion but instead has two duplicated segments, one 91 kb fragment (23,790,414–23,881,384 bp) that represents a remaining fragment of the inverted region together with a small duplicated fragment of 198 bp (16,499,583–16,499,781 bp) that is present on both sides of the 91 kb duplication (Figure 3). Genotyping the eight resequenced Le Mans males revealed an allele composition of 4 R1, 9 R2, and 3 r, explaining why a large number of mate pairs over the breakpoint located at 16.50 Mb was found, as that is present in both R1 and R2, while few reads spanning the breakpoint at 23.89 Mb were found, as that is only present in R1. The genome assembly is rich in gaps around 23.79 Mb, making it difficult to map reads that span the breakpoint only found in R2, explaining the low number of mapped reads spanning that breakpoint.

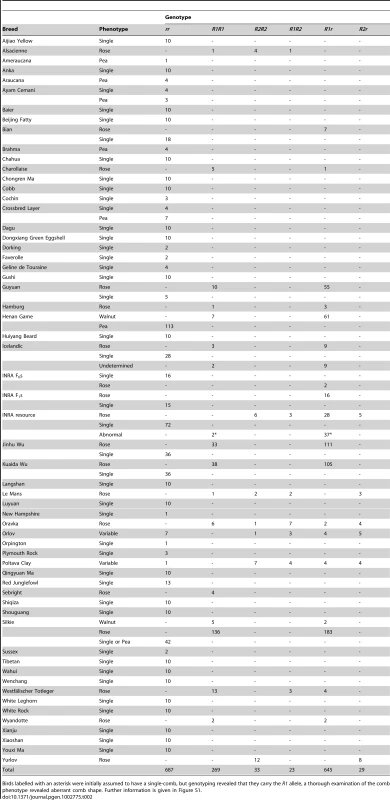

Tab. 2. Genotyping of the Rose-comb locus in various chicken breeds.

Birds labelled with an asterisk were initially assumed to have a single-comb, but genotyping revealed that they carry the R1 allele, a thorough examination of the comb phenotype revealed aberrant comb shape. Further information is given in Figure S1. FISH analysis using four different BAC clones was employed to confirm the existence of two distinct Rose-comb alleles (Figure 4; Figure S3). The BAC clones CH261-95H11 and CH261-5G3 span the inversion breakpoints at 16.50 Mb and 23.88 Mb, respectively. BAC clones TAM32-24B23 and BW27C3 targeted regions within the inversion. A staining of a metaphase spread from an R1r heterozygote confirmed the presence of a large inversion on chromosome 7. The FISH staining of an R2r heterozygote metaphase spread was consistent with an altered organization, as the BACs CH261-95H11, TAM32-24B23 and BW27C3 showed indistinguishable staining for both R2 and r chromosomes, with only two aberrant patterns obtained, one for BAC clone CH261-5G3 that confirmed the translocated duplication of a segment from the 23.88 MB region to the 16.50 MB region, and the other a slight spatial separation of BAC clone CH261-95H11, consistent with the insertion of the translocated duplication (Figure 4).

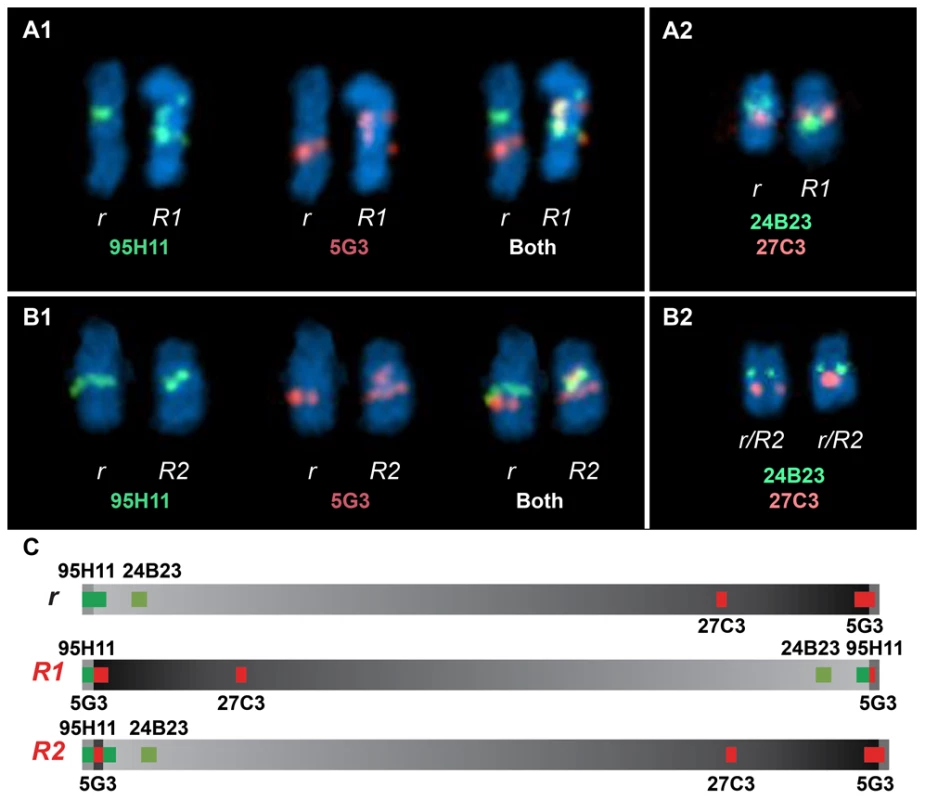

Fig. 4. Two-colour FISH staining of metaphase chromosomes using BACs mapped to GGA7.

(A1) Staining from a heterozygous R1r bird reveals two separate localisations for CH261-95H11 and CH261-5G3 when comparing r Chr7 to R1 Chr7. (A2) The order reversal of BW27C3 and TAM32-24B23 between r Chr7 and R1 Chr7 clearly demonstrates a large inversion. Staining from a heterozygous R2r bird reveals the same localisations obtained for CH261-95H11 (B1), TAM32-24B23 and BW27C3 (B2) both r Chr7 and R2 Chr7, with CH261-5G3 showing an additional localisation on R2 Chr7 (B1), consistent with a translocated duplication of a segment from the 23.88 MB region to the 16.50 MB region. A slight spatial separation for CH261-95H11, consistent with the insertion of the translocated duplication, can be observed on R2 Chr7 (B1). Previous studies of the Rose-comb phenotype have established that it involves both an altered comb morphology, showing dominant inheritance, and reduced male fertility, showing recessive inheritance. The presence of two different Rose-comb alleles facilitates the elucidation of the causal relationship between the observed chromosomal rearrangement and these two different aspects of the Rose-comb phenotype. No obvious phenotypic differences in comb morphology were observed amongst birds carrying R1 and R2, matched for breed and genetic background (Figure S1). Thus the critical genetic lesion causing the Rose-comb morphology must be located at the 16.50 Mb breakpoint including the 91 kb segment transferred from the 23.79–23.88 Mb region, because this is the only alteration present in both R1 and R2.

The proximal breakpoint at 16.50 Mb is located in the 5′UTR of FKBP7 (FK506 binding protein 7) gene, 72 bp upstream of its start codon. Only 9 bp separate the 5′UTRs of FKBP7 and PLEKHA3 (Pleckstrin homology domain containing, family A-phosphoinositide binding specific-member 3), placing the breakpoint 42 bp from the 5′UTR, and 150 bp from the start codon of PLEKHA3 (Figure 3B, Multimedia S1). This rearrangement may alter regulation of PLEKHA3 and FKBP7 in both R1 and R2 alleles.

The second proximal breakpoint, unique to R2, where an inverted duplicated 23.88-23.79 Mb region is joined with a duplicated 198 bp fragment at 16.50 Mb results in the duplication of a part of the ABCB6 (ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member 6) gene. ABCB6 has not been adequately annotated in the chicken genome, but this translocated duplication does not involve the first few exons, judging from annotated Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs). Additionally, the region in which it is located is riddled with gaps in the genome assembly, causing the 3′ region of the EST range of the gene to appear truncated. The breakpoint seems to be close to the 3′ end of what may be exon 5 or 6, duplicating the very end of that exon and the remainder of the gene. This exon fragment copy is in its novel genomic context situated only 8 bp from the duplicated first exon of PLEKHA3. Whilst this could result in a hybrid transcript, the fact that an intact copy of ABCB6 is present on R1, R2 and r chromosomes, as well as the presence of the duplicated segment being unique to R2, make it an unlikely candidate for the Rose-comb phenotype.

The distal breakpoint at 23.88 Mb is located in intron 3 of CCDC108 (coiled-coil domain containing 108). This breakpoint disrupts CCDC108 and transfers the first three exons to the proximal breakpoint present in both R1 and R2. However, due to the intact nature of CCDC108 in R2 it was excluded as causative for the altered comb morphology. The neighbouring gene MNR2 (MNR2 homeodomain protein), located only 3 kb from the inside of the distal inversion breakpoint, is also transferred to the near vicinity of the proximal breakpoint in R1 and R2. The translocation of the transcription factor MNR2 to a novel genomic context was considered the best candidate for causing altered comb morphology in Rose-comb as it belongs to the Mnx-class of homeodomain proteins which act as transcriptional repressors and specifiers of cell identity [26]. Furthermore, hyaluronan (HA), a major component of the extracellular matrix and the comb in chickens, shows strong accumulation around early MNR2-expressing neurons [27].

Expression analysis using comb tissue from wild-type, Rose-combed, Pea-combed, and walnut-combed embryos

Expression analysis of comb tissue from early embryos (single-combed wild-type and R1R1 homozygotes) by RT-PCR revealed that PLEKHA3 and FKBP7 were expressed in both wild-type and homozygous Rose-comb tissue, whereas CCDC108 and MNR2 were expressed in Rose-combed but not in wild-type embryos (Figure S4). The ectopic MNR2 expression was restricted to days E6–E12 of embryonic development. This suggested that the Rose-comb phenotype might be due to ectopic expression of the MNR2 homeodomain protein as a copy of MNR2 is translocated close to the 16.50 Mb breakpoint in both R1 and R2. To further explore this possibility, as well as shed light on the interaction between Rose-comb and Pea-comb causing the walnut-comb phenotype, we performed immunohistochemical staining using an anti-chicken MNR2 antibody and an anti-human SOX5 antibody (previously used in our characterization of Pea-comb [21]) in single-combed wild-type, Rose-combed, Pea-combed and walnut-combed embryos (Figure 5). This analysis revealed transient ectopic expression of MNR2 in Rose-combed embryos, consistent with the results of the RT-PCR analysis. Striking MNR2 expression was observed in a layer of mesenchymal cells located in the area where the comb is developing at day E6.5 but not at E9 (Figure 5C and 5D). This pattern of transient ectopic expression resembles that previously reported for SOX5 in Pea-combed embryos, where expression is weak at day E5, strong at E9 (Figure 5E and 5F) and not present at day E12 [21].

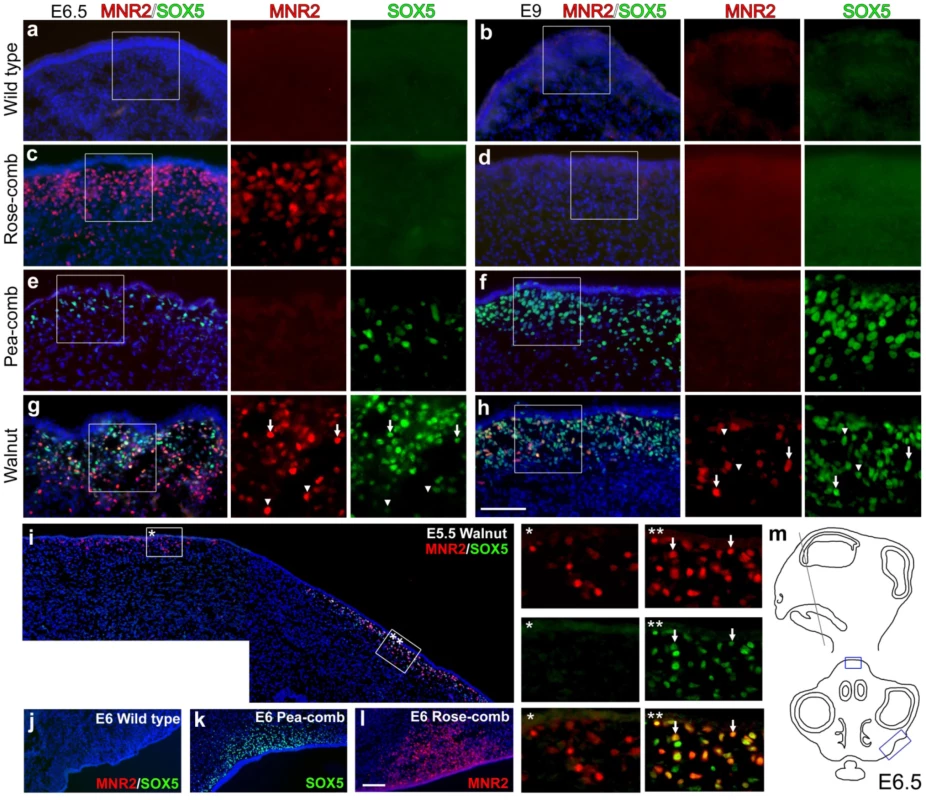

Fig. 5. Immunohistochemical labelling of MNR2 and SOX5 in various comb tissues.

Wild-type single-comb (a, b), Rose-comb (c, d), Pea-comb (e, f) and walnut-comb (g, h) sections from embryonic day (E) 6.5 (a, c, e, g) and 9 (b, d, f, h) were labelled against MNR2 and SOX5. Nuclei are visualized by DAPI. Boxed regions are shown magnified as single colour. Arrows in (g) and (h) indicate double labelled cells whereas arrowheads indicate single labelled cells. (i) E5.5 walnut comb. The two framed regions are shown magnified and arrows indicate double labelled cells. (j–l) The prospective wattle region for wild-type single-comb, Pea-comb and Rose-comb. (m) Schematic view of an E6.5 head where boxes indicate the regions of the comb depicted in (a–h) and wattles depicted in (j–l). Scale bar equals 100 µm in (h) and is valid for (a–h) and 100 µm in (l) valid for (i–l). Walnut-combed embryos showed transient ectopic expression of both MNR2 and SOX5 as expected from their genotype (Figure 5G–5H). The ectopic expression of MNR2 and SOX5 overlapped only partially, with peak expression occurring first for MNR2. The data revealed ectopic expression of MNR2 and SOX5 in the same cell type as well as MNR2-SOX5 coexpression within individual cells (Figure 5I). Furthermore, MNR2 expression was observed at E9 together with SOX5 (Figure 5H) but this was not the case in the absence of SOX5 expression (Figure 5D) suggesting a potential positive interaction between the Pea-comb allele of SOX5 and the Rose-comb allele of MNR2. Interestingly, at day E6 MNR2 and SOX5 also showed ectopic expression in Rose-combed and Pea-combed birds, respectively, in mesenchyme present in the region where the wattles develop (Figure 5J–5L). The ectopic expression of MNR2, with its transcriptional repression activities, is likely to change the identity of the mesenchyme underlying both the comb and wattles. Seminal work on comb primordium development has shown that the comb shape is directly dependent on instructive signals derived from the underlying mesenchyme/dermal structures [28]–[30]. This suggests that the comb and wattle tissue share a common developmental pathway and that the structural variants underlying Rose-comb and Pea-comb activate the expression of MNR2 and SOX5, which both modulate or intercept this pathway. However, wattle phenotype is not altered by the Rose-comb mutation as it is by the Pea-comb mutation (Figure 1).

5′RACE analysis of transcripts initiated from the vicinity of the inversion breakpoints

5′RACE analysis was performed using tissue from early embryonic comb and from adult testis for the three genes located close to the two R1 inversion breakpoints. Results are summarized in Figure S5. The samples were from single-combed wild-type birds and R1R1 homozygotes. A full length PLEKHA3 transcript (denoted PLEKHA3a in Figure S5) was expressed in both tissues and in both genotypes. A PLEKHA3-CCDC108 hybrid transcript (PLEKHA3b) corresponding to exons 1 and 3 from CCDC108 and exons 2–8 from PLEKHA3 was found in Rose-comb testis (Figure S6). The FKBP7 transcripts showed no difference between genotypes but different splice forms were expressed in comb and testis. Full-length CCDC108 transcripts were only found in wild-type testis (Figures S5 and S6), whereas two very similar hybrid transcripts lacking the first three exons of CCDC108 were expressed in both R1R1 testis and comb tissue (Figures S5 and S6).

Analysis of male fertility in Rose-comb homozygotes

Rose-comb is associated with reduced male fertility in homozygotes due to low sperm motility [12], [17], [18]. However, as R1 is the more common Rose-comb allele (Table 2) we wanted to investigate if the fertility effect is also associated with the R2 allele discovered in the present study. A preliminary study to address this question was carried out by mating single-combed and Rose-combed roosters of several genotypes (R1R1, R2R2, R1r and rr) to single-combed and Rose-combed hens. The data were consistent with reduced male fertility in R1R1 males, as expected, but there were no signs of reduced fertility in R2R2 homozygotes (Text S2; Table S1). Thus, the deleterious effect on male fertility appears to be restricted to the R1 allele, suggesting that the lesion causing this phenotypic effect is located at the 23.88 Mb breakpoint (Figure 3). The obvious candidate for this effect is the disruption of the CCDC108 transcript that leads to the expression of a truncated transcript in testis (Figures S5 and S6).

Discussion

The present study illustrates several striking features of the genetic diversity present in domestic animals. Firstly, the R2 allele exemplifies the evolution of alleles by two or more consecutive mutations. Other examples include the Dominant white allele in pigs which involves a 450 kb duplication encompassing the entire KIT gene combined with a splice mutation in one of the duplicated copies [31] and black spotting in pigs which is determined by the combined effects of two mutations in MC1R, a missense mutation associated with black colour and a somatically unstable two base-pair insertion [32]. Secondly, it represents a new example of how structural rearrangements have contributed to rapid phenotypic evolution observed in domestic animals [33], [34]. The majority of the structural changes reported to be associated with phenotypic effects, like the effects of R1 and R2 on comb morphology, constitute cis-acting regulatory mutations. The altered configurations of regulatory elements on the rearranged chromosome lead to altered gene expression patterns. It appears plausible that structural rearrangements similar to those that affect comb development in chickens have also contributed to phenotypic evolution in natural populations, including human populations.

There are several mechanisms by which genomic rearrangements are thought to occur, involving either double strand break repair via primarily non-homologous mechanisms or homology mediated replication and recombination based processes [35], [36]. At the R1 and R2 16.50 Mb breakpoint there is only a single base pair sequence overlap, while at the R1 23.88 Mb breakpoint there is a 7 bp overlap with one mismatch. Although it is not possible to determine the exact mechanism by which the original inversion occurred, it is likely that microhomology at the 23.88 Mb breakpoint was involved in the generation of the R1 allele. The generation of the R2 allele occurred by recombination between a wild-type chromosome and an R1 chromosome (Multimedia S1). On the wild-type chromosome this event occurred 198 bp upstream of the 16.50 Mb breakpoint, on the R1 chromosome the recombination event occurred 91 kb into the inversion from the 16.50 Mb breakpoint. This resulted in the duplication of the 91 kb portion of the R1 chromosome, including the R1 proximal breakpoint and the 199 bp fragment of the wild-type chromosome, effectively inserting the duplicated sequence at 16.50 Mb into a wild-type chromosome. Analysis of the R2 recombination event breakpoint shows 2 bp of sequence homology, again suggesting that sequence microhomology was likely involved. That both events introduced breakpoints around 16.50 Mb, spaced only 198 bp apart, suggests that some characteristic of this region may predispose it to such events.

More than half of the loci identified in human genome-wide association analyses do not overlap coding regions [37], implying that they reflect regulatory polymorphisms. The present study illustrates how challenging it can be to reveal the molecular mechanism underlying even a simple monogenic trait in a model organism such as the chicken. We were able to demonstrate transient ectopic expression of MNR2 during a narrow period of embryonic development because immunohistochemistry provided the spatial resolution allowing the detection of ectopic expression in a subset of cells within the affected tissue (Figure 5).

We postulate that the well-established association between the Rose-comb phenotype and reduced sperm motility is restricted to the R1 allele and that it is caused by the disruption of the CCDC108 transcript. The predicted CCDC108 protein sequence in chickens shows 49% amino acid identity with human CCDC108 (HomoloGene:28093; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). CCDC108 has an unknown function, according to the UNIPROT database (www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q6ZU64), it is a single pass membrane protein composed of 1925 amino acids, containing one MSP (major sperm protein) domain. The MSP domain is present in major sperm proteins and in sperm specific proteins (SSPs) found in various nematodes as well as in the mammalian Motile sperm domain-containing proteins-1, -2 and -3 (MOSPD1-3). All MSP, SSP and MOSPD proteins are small, with a size range of 107–518 amino acids, and thus much smaller than CCDC108. Mouse Ccdc108 is expressed in testis and shows differential expression during progression of spermatogenesis [38]; expression is absent in juvenile mice but is turned on when male mice reach sexual maturity (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; GEO profiles GDS606/164004_at/Ccdc108/Mus musculus). Furthermore, by using reciprocal best-hit protein BLAST searches, putative CCDC108 orthologs can be found in many organisms, including in deep branches on the tree of life. One such orthologous protein has been annotated in Chlamydomonas algae as an axonemal protein named Flagellar Associated Protein 65 (FAP65) [39]. FAP65 expression is strongly induced after deflagellation, when cells regenerate their flagella. This sequence homology suggests that CCDC108 is part of the sperm flagellum and thus that a disruption of CCDC108 function may lead to sperm motility defects as observed in Rose-comb R1R1 homozygotes. This study establishes CCDC108 as a candidate gene for sperm motility disorders in humans.

The present study strongly suggests that Rose-comb and Pea-comb are caused by transient ectopic expression of two potent transcription factors, MNR2 and SOX5, respectively. However, at present we cannot exclude the possibility that altered expression levels of FKBP7 or PLEKHA3, located on either side of the proximal breakpoint, may have some impact on the comb phenotype. However the ectopic MNR2 expression in the developing embryo is by far the most striking molecular consequence of the Rose-comb inversion. The exact downstream mechanisms leading to the altered comb morphology remain undetermined. Comb tissue is composed of layers of epidermis, dermis and central connective tissue comprising primarily collagen and hyaluronan (HA) [40]. The previous report that there is a strong accumulation of HA around early MNR2-expressing neurons [27] may be relevant for the Rose-comb phenotype, but perhaps more importantly, MNR2 acts as a repressor and specifier of cell identity [26]. SOX5 also has an established functional role that makes sense in relation to the altered comb morphology observed in Pea-combed and walnut-combed birds. SOX5 contributes to chondrogenesis, together with SOX6 and SOX9 it activates specific genes during embryonic cartilage formation [41], and has a repressive role in oligodendrogenesis during neural development [42]. A fascinating observation is that both the Rose-comb mutations and the Pea-comb mutation give rise to ectopic expression in the area of the developing comb, leading to altered comb morphology in both mutants, as well as in the wattle area, which only leads to altered morphology in birds carrying Pea-comb (Figure 1). The fact that the transient ectopic expression of MNR2 and SOX5 apparently occurs in the same population of mesenchymal cells, and with at least partially overlapping expression in individual cells in the comb primordium, provides a reasonable explanation of why the combined effect of the two mutations leads to the formation of the walnut-comb. Thus, 104 years after Bateson and Punnett [2] reported the first example of epistatic interaction between genes, we can now provide a molecular explanation for their seminal observation.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal work has been conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines.

Animals

Linkage mapping was carried out using a pedigree consisting of two heterozygous R1r male parentals, each mated with eight homozygous rr females, resulting in 383 progeny segregating for Rose-comb. The Rose-combed roosters were from an INRA (French National Institute for Agricultural Research) resource population, with the R1 allele having been derived from the French breed Charollaise. The wild-type single-combed hens were from another INRA resource population line.

DNA samples from various chicken breeds were genotyped for the R1, R2 and wild-type alleles. These included samples collected as part of the AvianDiv project [43], from resource populations at INRA, and 31 different breeds of Chinese chickens collected by Institute of Poultry Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Blood samples from privately owned Icelandic chickens were obtained at eight different locations in the South-West of Iceland by a veterinarian with permission from owners. Genomic DNA from the reference red junglefowl bird was kindly provided by Dr. J.B. Dodgson.

Linkage analysis

Linkage analysis was performed by genotyping two microsatellites and nine SNPs from chromosome 7 using standard procedures. Custom TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems) were designed by ABI, other primers were designed with the Primer3Plus webtool (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi). See Table S2 for primer and probe sequence information. Linkage analysis was performed with the Crimap software (version 2.4) [44].

Whole-genome resequencing

DNA from eight Rose-combed males from the Le Mans breed, all presumed to be homozygous for Rose-comb, were pooled. Whole genome resequencing data from a pool of Rose-combed Silkie chickens, and another pool of single-combed White Leghorns were obtained at later time points and included in this study to verify the results obtained from the Le Mans pool. A sequencing library was generated for the Le Mans sample using a Mate-pair SOLiD3 protocol and sequenced on SOLiD v.3 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA). The White Leghorn library was generated using a Mate-pair SOLiD3+ protocol and sequenced on SOLiD 3+. The Silkie Library was generated using a Mate-pair SOLiD5500 protocol and sequenced on SOLiD5500XL. The Le Mans, White Leghorn and Silkie reads (2×50 bp mate-pair reads) were mapped to the chicken genome (WUGSC 2.1/galGal3) reference assembly using the software CoronaLite v0.4r2, Bioscope v1.0.1 and LifeScope v2.0, respectively, with average insert sizes estimated as approximately 3.9, 3.1 and 2.6 kb and average read depth approximately 1×, 10× and 20× over the chicken genome. Mapping distances between mate-pairs were used to detect structural variations in relation to the reference assembly. All library kits, alignment software and massively parallel sequencing equipment were used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA).

Fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH)

Heterozygous Rose-combed embryos (R1r and R2r) were produced from parental stock maintained at INRA. The R1 allele originated from Belgian Barbu d'Anvers and the R2 allele from French Alsacienne. BAC clones were chosen considering their position in the chicken genome sequence (Table S3). BW27C3 comes from the Wageningen library [45]. TAM32-24B23 was ordered from TAMU (Texas A&M BAC Libraries, USA). CH261-5G3 and CH261-95H11 were ordered from the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute in Oakland (CHORI), California, USA. BAC clones were grown in LB medium with 12.5 µg/ml chloramphenicol according the instructions of the providers. The DNA was extracted using the Qiagen plasmid midi kit.

FISH was carried out on metaphase spreads obtained from fibroblast cultures derived from 7 days old embryos, arrested with 0.05 µg/ml colcemid (Sigma) and fixed by standard procedures. The FISH protocol is derived from Yerle et al. [46]. Two-colour FISH was performed by labelling 100 ng of each BAC clone with alexa fluorochromes (ChromaTide Alexa Fluor 488-5-dUTP, Molecular probes; ChromaTide Alexa Fluor 568-5-dUTP, Molecular Probes) by random priming using the Bioprim Kit (Invitrogen). The probes were purified using spin column G50 Illustra (Amersham Biosciences). Probes were ethanol precipitated together and hybridised to the metaphase slides for 17 h at 37°C in the Hybridizer (Dako) after denaturation for 8 min at 72°C. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI in antifade solution (Vectashield with DAPI, Vector). The hybridised metaphases were screened with a Zeiss fluorescence microscope. A minimum of twenty spreads was analysed for each experiment. Spot-bearing metaphases were captured and analysed with a cooled CCD camera using Cytovision software (Applied Imaging, Leica-Microsystem). Images were formatted, resized and arranged for publication using Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator.

PCR analysis of rearrangement breakpoints

A set of five PCR primers that together will amplify a series of specific bands over each of the five breakpoints was designed for genotyping the R1, R2 and r alleles. Primer and protocol information are in Table S4. Gel image for the six possible genotypes is presented in Figure S7.

RT–PCR analysis of tissue samples

Comb tissue was collected from homozygous (R1R1) and heterozygous (R1r) Rose-combed birds as well as homozygous (rr) single-combed wild-type birds. Comb tissue was sampled at embryonic (E) days 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15 and 19. Testis tissue was sampled from adult roosters at day 200. Samples from three birds of each type were collected and stored in RNAlater (Ambion). RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized with 1 µg of RNA using oligo(T) primer. Primers spanning introns were used in RT-PCR. The 5′ and 3′ RACE were performed using GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen).

Immunohistochemistry

Homozygous Rose-combed Alsacienne, single-combed INRA resource population, homozygous Pea-combed Cheptel and heterozygous walnut-combed Alsacienne x Cheptel embryos were used. Heads from staged embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for one hour at 4°C. Fixed heads were incubated overnight in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C, embedded in OCT freezing medium (Tissue-Tek, Sakura), frozen and sectioned in a cryostat. Cross sections, 10 µm thick, were collected on glass slides (Super Frost Plus, Menzel-Gläser). The sections were rehydrated in PBS for 5 min and then blocked for one hour in PBS containing 1% fetal calf serum, 0.1% Triton-X and 0.02% Thimerosal. The antibodies MNR2 (Developmental studies hybridoma bank, 81.5C10) and SOX5 (Abcam, a_6226041) were diluted 1∶250 and 1∶1000 respectively in blocking solution and incubated on the slides overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were incubated at room temperature for two hours at a 1∶1000 dilution in blocking solution. Samples were analysed using a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope equipped with Axiovision software. Images were formatted, resized, enhanced and arranged for publication using Axiovision and Adobe Photoshop.

URL

Information on the chicken genome sequence is available at http://www.genome.ucsc.edu.

Accession numbers

The sequence data presented in this paper have been submitted to GenBank with accession numbers JN942757–JN942760, JN880446, JN880447, JQ004983, and JQ004984.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BatesonW 1902 Experiments with poultry. Rep Evol Comm Roy Soc 1 87 124

2. BatesonWPunnettRC 1908 Experimental studies in the physiology of heredity. Poultry. Repts Evol Comm Roy Soc 4 18 35

3. SomesRGJ 1996 Mutations and major variants of plumage and skin in chickens. CrawfordRD Poultry Breeding and Genetics New York Elsevier Science 169 208

4. CavalieAMératP 1965 Un nouveau gène, modificateur de la forme des crêtes en rose, et son incidence possible sur la fertilité. Ann Biol Anim Bioch Biophys 5 451 468

5. PunnettRC 1923 Heredity in Poultry London Mac Millan and Co., Ltd

6. HindhaughWLS 1932 Some observations on fertility in White Wyandottes. Poultry J 17 555 560

7. HuttFB 1940 A relationship between breed characteristics and poor reproduction in white wyandotte fowls. American Naturalist 74 148 156

8. CrawfordRD 1971 Rose comb and fertility in Silver Spangled Hamburgs. Poultry Sci 47 867 869

9. CrawfordRDSmythJRJ 1964 Studies of the relationship between fertility and the gene for Rose Comb in the domestic fowl - 1. The relationship between comb genotype and fertility. Poultry Sci 43 1009 1017

10. CrawfordRDSmythJRJ 1964 Studies of the relationship between fertility and the gene for Rose Comb in the domestic fowl - 2.The relationship between comb genotype and duration of fertility. Poultry Sci 43 1018 1026

11. CrawfordRDSmythJRJ 1964 Semen quality and the gene for Rose Comb in the domestic fowl. Poultry Sci 43 1551 1557

12. PetitjeanMServouseM 1981 Comparative study of some characteristics of the semen of RR (Rose Comb) and rr (Single Comb) cockerels. Reprod Nutr Develop 21 1085 1093

13. KirbyJD 1994 Analysis of subfertility associated with homozygosity of the Rose Comb allele in the male domestic fowl. Poultry Sci 73 871

14. McLeanDJFromanDP 1996 Identification of a sperm cell attribute responsible for subfertility of roosters homozygous for the Rose Comb allele. Biol Reprod 54 168 172

15. McLeanDJJonesLGJFromanDP 1997 Reduced glucose transport in sperm from roosters (Gallus domesticus) with heritable subfertility. Biol Reprod 57 791 795

16. CrawfordRD 1965 Comb dimorphism in Wyandotte domestic fowl. I Sperm competition in relation to Rose and Single Comb alleles. Can J Genet Cytol 7 500 504

17. BucklandRBHawesRO 1968 Comb type and reproduction in the male fowl. Segregation of the Rose and Pea comb genes. Can J Genet Cytol 10 395 400

18. CrawfordRDMerrittE 1963 The relationship between Rose Comb and reproduction in the domestic fowl. Can J Genet Cytol 5 89 95

19. WehrhahnCFCrawfordRD 1965 Comb dimorphism in Wyandotte domestic fowl. II Population genetics of the Rose Comb gene. Can J Genet Cytol 7 651 657

20. TanabeYWilliamCJessellTM 1998 Specification of motor neuron identity by the MNR2 homeodomain protein. Cell 95 67 80

21. WrightDBoijeHMeadowsJRSBed'homBGourichonD 2009 Copy number variation in intron 1 of SOX5 causes the Pea-comb phenotype in chickens. PLoS Genet 5 e1000512 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000512

22. SomesRGJ 1973 Linkage relationships in the fowl. J Hered 64 217 221

23. DorshorstBOkimotoRAshwellC 2010 Genomic regions associated with dermal hyperpigmentation, polydactyly and other morphological traits in the Silkie chicken. J Hered 101 339 350

24. GroenenMAWahlbergPFoglioMChengHHMegensH-J 2009 A high-density SNP based linkage map of the chicken genome reveals sequence features correlated with recombination rate. Genome Res 19 510 519

25. GroenenMAMegensHJZareYWarrenWCHillierLW 2011 The development and characterization of a 60K SNP chip for chicken. BMC Genomics 12 274

26. WilliamCMTanabeYJessellTM 2003 Regulation of motor neuron subtype identity by repressor activity of Mnx class homeodomain proteins. Development 130 1523 1536

27. MészárZFelszeghySVeressGMateszKSzékelyG 2008 Hyaluronan accumulates around differentiating neurons in spinal cord of chicken embryos. Brain Res Bull 75 414 418

28. LawrenceIEJ 1963 An experimental analysis of comb development in the chick. J Exp Zool 152 205 218

29. LawrenceIEJ 1968 Regional influences on development of the single comb primordium. J Exp Zool 167 263 273

30. LawrenceIEJ 1971 Timed reciprocal dermal-epidermal interactions between comb, mid-dorsal, and tarsometatarsal. J Exp Zool 178 195 209

31. MarklundSKijasJRodriguez-MartinezHRönnstrandLFunaK 1998 Molecular basis for the dominant white phenotype in the domestic pig. Genome Res 8 826 833

32. KijasJMHMollerMPlastowGAnderssonL 2001 A frameshift mutation in MC1R and a high frequency of somatic reversions cause black spotting in pigs. Genetics 158 779 785

33. AnderssonL 2011 How selective sweeps in domestic animals provides new insight about biological mechanisms. Journal of Internal Medicine In press

34. DorshorstBMolinA-MJohanssonAStrömstedtLPhamM-H 2011 A complex genomic rearrangement involving the Endothelin 3 locus causes dermal hyperpigmentation in the chicken. PloS Genet 7 e1002412 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002412

35. HastingsPLupskiJRRosenbergSIraG 2009 Mechanisms of change in gene copy number. Nature Reviews Genetics 10 551 564

36. ZhangFCarvalhoCLupskiJR 2009 Complex human chromosomal and genomic rearrangements. Trends in Genetics 25 298 307

37. AltshulerDDalyMJLanderES 2008 Genetic mapping in human disease. Science 322 881 888

38. ShimaJEMcLeanDJMcCarreyJRGriswoldMD 2004 The murine testicular transcriptome: characterizing gene expression in the testis during the progression of spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod 71 319 330

39. PazourGJAgrinNLeszykJWitmanGB 2005 Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. Journal of Cell Biology 170 103 113

40. NakanoTImaiSKogaTSimJS 1997 Light microscopic histochemical and immunohistochemical localisation of sulphated glycoseaminoglycans in the rooster comb and wattle tissues. J Anat 189 643 650

41. LefebvreVLiPde CrombruggheB 1998 A new long form of Sox5 (L-Sox5), Sox6 and Sox9 are coexpressed in chondrogenesis and cooperatively activate the type II collagen gene. EMBO J 17 5718 5733

42. StoltCCSchlierfALommesPHillgärtnerSWernerT 2006 SoxD proteins influence multiple stages of oligodendrocyte development and modulate SoxE protein function. Dev Cell 11 697 709

43. HillelJGroenenMAMTixier-BoichardMKorolABDavidL 2003 Biodiversity of 52 chicken populations assessed by microsatellite typing of DNA pools. Genet Sel Evol 35 533 557

44. GreenPFallsKCrookS 1990 Documentation for CRI-MAP, version 2.4. St Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine

45. CrooijmansRVrebalovJDijkhofRvan der PoelJGroenenM 2000 Two-dimensional screening of the Wageningen chicken BAC library. Mammalian Genome 11 360 363

46. YerleMGalmanOLahbib-MansaisYGellinJ 1992 Localization of the pig luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor gene (LHCGR) by radioactive and nonradioactive in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet 59 48 51

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Uracil-Containing DNA in : Stability, Stage-Specific Accumulation, and Developmental InvolvementČlánek Fuzzy Tandem Repeats Containing p53 Response Elements May Define Species-Specific p53 Target GenesČlánek Preferential Genome Targeting of the CBP Co-Activator by Rel and Smad Proteins in Early EmbryosČlánek Protective Coupling of Mitochondrial Function and Protein Synthesis via the eIF2α Kinase GCN-2Článek Cohesin Proteins Promote Ribosomal RNA Production and Protein Translation in Yeast and Human CellsČlánek TERRA Promotes Telomere Shortening through Exonuclease 1–Mediated Resection of Chromosome EndsČlánek Attenuation of Notch and Hedgehog Signaling Is Required for Fate Specification in the Spinal CordČlánek Genome-Wide Functional Profiling Identifies Genes and Processes Important for Zinc-Limited Growth ofČlánek MicroRNA93 Regulates Proliferation and Differentiation of Normal and Malignant Breast Stem Cells

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 6

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Rumors of Its Disassembly Have Been Greatly Exaggerated: The Secret Life of the Synaptonemal Complex at the Centromeres

- Mimetic Butterflies Introgress to Impress

- Tipping the Balance in the Powerhouse of the Cell to “Protect” Colorectal Cancer

- Selection-Driven Gene Loss in Bacteria

- Decreased Mitochondrial DNA Mutagenesis in Human Colorectal Cancer

- Parallel Evolution of Auditory Genes for Echolocation in Bats and Toothed Whales

- Diverse CRISPRs Evolving in Human Microbiomes

- The Rad4 ATR-Activation Domain Functions in G1/S Phase in a Chromatin-Dependent Manner

- Stretching the Rules: Monocentric Chromosomes with Multiple Centromere Domains

- Uracil-Containing DNA in : Stability, Stage-Specific Accumulation, and Developmental Involvement

- Fuzzy Tandem Repeats Containing p53 Response Elements May Define Species-Specific p53 Target Genes

- Adaptive Introgression across Species Boundaries in Butterflies

- G Protein Activation without a GEF in the Plant Kingdom

- Synaptonemal Complex Components Persist at Centromeres and Are Required for Homologous Centromere Pairing in Mouse Spermatocytes

- An Engineering Approach to Extending Lifespan in

- Incompatibility and Competitive Exclusion of Genomic Segments between Sibling Species

- Effects of Histone H3 Depletion on Nucleosome Occupancy and Position in

- Patterns of Evolutionary Conservation of Essential Genes Correlate with Their Compensability

- Interplay between Synaptonemal Complex, Homologous Recombination, and Centromeres during Mammalian Meiosis

- Preferential Genome Targeting of the CBP Co-Activator by Rel and Smad Proteins in Early Embryos

- A Mouse Model of Acrodermatitis Enteropathica: Loss of Intestine Zinc Transporter ZIP4 (Slc39a4) Disrupts the Stem Cell Niche and Intestine Integrity

- Protective Coupling of Mitochondrial Function and Protein Synthesis via the eIF2α Kinase GCN-2

- Geographic Differences in Genetic Susceptibility to IgA Nephropathy: GWAS Replication Study and Geospatial Risk Analysis

- Cohesin Proteins Promote Ribosomal RNA Production and Protein Translation in Yeast and Human Cells

- TERRA Promotes Telomere Shortening through Exonuclease 1–Mediated Resection of Chromosome Ends

- Stimulation of Host Immune Defenses by a Small Molecule Protects from Bacterial Infection

- A Broad Requirement for TLS Polymerases η and κ, and Interacting Sumoylation and Nuclear Pore Proteins, in Lesion Bypass during Embryogenesis

- Genome-Wide Identification of Ampicillin Resistance Determinants in

- The CCR4-NOT Complex Is Implicated in the Viability of Aneuploid Yeasts

- Gustatory Perception and Fat Body Energy Metabolism Are Jointly Affected by Vitellogenin and Juvenile Hormone in Honey Bees

- Genetic Variants on Chromosome 1q41 Influence Ocular Axial Length and High Myopia

- Is a Key Regulator of Pancreaticobiliary Ductal System Development

- The NSL Complex Regulates Housekeeping Genes in

- Attenuation of Notch and Hedgehog Signaling Is Required for Fate Specification in the Spinal Cord

- Dual-Level Regulation of ACC Synthase Activity by MPK3/MPK6 Cascade and Its Downstream WRKY Transcription Factor during Ethylene Induction in Arabidopsis

- Genome-Wide Functional Profiling Identifies Genes and Processes Important for Zinc-Limited Growth of

- Base-Pair Resolution DNA Methylation Sequencing Reveals Profoundly Divergent Epigenetic Landscapes in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- MicroRNA93 Regulates Proliferation and Differentiation of Normal and Malignant Breast Stem Cells

- Phylogenomic Analysis Reveals Dynamic Evolutionary History of the Drosophila Heterochromatin Protein 1 (HP1) Gene Family

- Found: The Elusive ANTAR Transcription Antiterminator

- The Mutation in Chickens Constitutes a Structural Rearrangement Causing Both Altered Comb Morphology and Defective Sperm Motility

- Control of CpG and Non-CpG DNA Methylation by DNA Methyltransferases

- Polymorphisms in the Mitochondrial Ribosome Recycling Factor Compromise Cell Respiratory Function and Increase Atorvastatin Toxicity

- Gene Expression Profiles in Parkinson Disease Prefrontal Cortex Implicate and Genes under Its Transcriptional Regulation

- Global Regulatory Functions of the Endoribonuclease III in Gene Expression

- Extensive Evolutionary Changes in Regulatory Element Activity during Human Origins Are Associated with Altered Gene Expression and Positive Selection

- The Regulatory Network of Natural Competence and Transformation of

- Brain Expression Genome-Wide Association Study (eGWAS) Identifies Human Disease-Associated Variants

- Quantifying the Adaptive Potential of an Antibiotic Resistance Enzyme

- Divergence of the Yeast Transcription Factor Affects Sulfite Resistance

- The Histone Demethylase Jhdm1a Regulates Hepatic Gluconeogenesis

- RNA Methylation by the MIS Complex Regulates a Cell Fate Decision in Yeast

- Rare Copy Number Variants Observed in Hereditary Breast Cancer Cases Disrupt Genes in Estrogen Signaling and Tumor Suppression Network

- Genome-Wide Location Analysis Reveals Distinct Transcriptional Circuitry by Paralogous Regulators Foxa1 and Foxa2

- A Mutation Links a Canine Progressive Early-Onset Cerebellar Ataxia to the Endoplasmic Reticulum–Associated Protein Degradation (ERAD) Machinery

- The Mechanism for RNA Recognition by ANTAR Regulators of Gene Expression

- Limits to the Rate of Adaptive Substitution in Sexual Populations

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Rumors of Its Disassembly Have Been Greatly Exaggerated: The Secret Life of the Synaptonemal Complex at the Centromeres

- The NSL Complex Regulates Housekeeping Genes in

- Tipping the Balance in the Powerhouse of the Cell to “Protect” Colorectal Cancer

- Interplay between Synaptonemal Complex, Homologous Recombination, and Centromeres during Mammalian Meiosis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání