-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe SET-Domain Protein SUVR5 Mediates H3K9me2 Deposition and Silencing at Stimulus Response Genes in a DNA Methylation–Independent Manner

In eukaryotic cells, environmental and developmental signals alter chromatin structure and modulate gene expression. Heterochromatin constitutes the transcriptionally inactive state of the genome and in plants and mammals is generally characterized by DNA methylation and histone modifications such as histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methylation. In Arabidopsis thaliana, DNA methylation and H3K9 methylation are usually colocated and set up a mutually self-reinforcing and stable state. Here, in contrast, we found that SUVR5, a plant Su(var)3–9 homolog with a SET histone methyltransferase domain, mediates H3K9me2 deposition and regulates gene expression in a DNA methylation–independent manner. SUVR5 binds DNA through its zinc fingers and represses the expression of a subset of stimulus response genes. This represents a novel mechanism for plants to regulate their chromatin and transcriptional state, which may allow for the adaptability and modulation necessary to rapidly respond to extracellular cues.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002995

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002995Summary

In eukaryotic cells, environmental and developmental signals alter chromatin structure and modulate gene expression. Heterochromatin constitutes the transcriptionally inactive state of the genome and in plants and mammals is generally characterized by DNA methylation and histone modifications such as histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methylation. In Arabidopsis thaliana, DNA methylation and H3K9 methylation are usually colocated and set up a mutually self-reinforcing and stable state. Here, in contrast, we found that SUVR5, a plant Su(var)3–9 homolog with a SET histone methyltransferase domain, mediates H3K9me2 deposition and regulates gene expression in a DNA methylation–independent manner. SUVR5 binds DNA through its zinc fingers and represses the expression of a subset of stimulus response genes. This represents a novel mechanism for plants to regulate their chromatin and transcriptional state, which may allow for the adaptability and modulation necessary to rapidly respond to extracellular cues.

Introduction

In eukaryotes, chromatin structure regulates the access of the transcriptional machinery to genetic elements, playing an important role in the regulation of gene expression. The transition between transcriptionally active (loosely packed) chromatin and repressed (tightly packed) chromatin states is controlled by covalent modifications of the histone tails, DNA cytosine methylation, and the differential use of histone variants [1]. In mammals and plants, transcriptionally inactive chromatin—or heterochromatin—is typically associated with DNA methylation and histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me). These epigenetic silencing marks are generally thought to be coordinately regulated by cooperation between DNA methyltransferases and histone methyltransferases, contributing to their stability and self perpetuating nature. However, in order to readily adapt to environmental stimuli or developmental cues, some of these marks also need to be reversible, although how this is achieved is currently unclear.

Most histone methyltransferases (HMTases) contain a catalytic SET domain (named after three Drosophila proteins: Suppressor of position effect variegation 3–9, SU(VAR)3–9; Enhancer of zeste, and Trithorax) [2]. The enzymatic activity of the SET domain was first discovered in a mammalian homolog of SU(VAR)3–9, SUV39H1, which was shown to methylate histone H3 at lysine 9 [3]. In plants, there is a relatively large family of SET domain-containing proteins that are closely related to Drosophila SU(VAR)3–9 and its human and S. Pombe homologs (SUV39H and CLR4, respectively) [4]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, of the 14 SET domain-containing proteins most related to SU(VAR)3–9, nine are classified as SU(VAR)3–9 HOMOLOGS (SUVH1–SUVH9), and five as SU(VAR)3–9-RELATED proteins (SUVR1–SUVR5). Arabidopsis SUVH proteins link the epigenetic silencing marks H3K9me2 and DNA methylation through the activity of their SRA domains (for SET and RING finger Associated), which bind different contexts and states of methylated DNA. Contrary to SUVHs, most of the SUVR proteins are of completely unknown function. In addition, because they lack the SRA domain, how they are recruited to chromatin is unknown.

In Arabidopsis, DNA methylation occurs in three different sequence contexts: CG, CHG and CHH (where H is any base other than G). In all cases, de novo DNA methylation is established by DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE 2 (DRM2), a homolog of the mammalian DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE 3 (DNMT3) family [5]. Subsequent to establishment, DNA methylation is maintained through the cell cycle by at least three different pathways depending on the sequence context [6]. The maintenance of CHH methylation is mostly carried out by DRM2 through persistent de novo methylation [6], [7]. The maintenance of CG methylation depends on METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 (MET1), the Arabidopsis homolog of mammalian DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 (DNMT1), in collaboration with the VARIANT IN METHYLATION/ORTHRUS (VIM/ORTH) family [8], [9], [10], the Arabidopsis homologs of the mammalian UHRF1. These proteins contain SRA domains that bind to hemimethylated CG sites [11], [12], [13].

The maintenance of CHG methylation relies on CHROMOMETHYLASE 3 (CMT3), a plant specific DNA methyltransferase that acts together with some of the above mentioned SUVH proteins, KRYPTONITE (KYP)/SUVH4, SUVH5, and SUVH6 [14], [15], [16], [17], which can bind directly to methylated-DNA [11], [18]. The structure of the SUVH5 SRA domain bound to methylated DNA has been solved revealing that two SRA domains bind independently to each strand of the DNA duplex at either a fully or hemimethylated site [19]. These data support a model where regions rich in DNA methylation serve as binding platforms for KYP, SUVH5 and/or SUVH6, leading to H3K9 methylation. Histone methylation would then provide a binding site for CMT3 via its chromodomain, leading to CHG methylation, and thus creating a purely epigenetic self-reinforcing feedback loop for the maintenance of DNA and histone methylation, which explains the stability of epigenetic silent states and their self perpetuating nature [11].

The link between H3K9 methylation and DNA methylation is further supported by the strong genome-wide correlation between heterochromatic H3K9me2 and DNA methylation [20]. In addition, kyp mutants show decreased levels of both H3K9me2 and cytosine methylation [14], [21], [22], which are even further reduced in higher order suvh mutants [16], [17]. Moreover, loss of DNA methylation in met1 mutants correlates with a global loss of H3K9me2 [22].

In this report we show that Arabidopsis SU(VAR)3–9 RELATED 5 (SUVR5), which lacks the SRA domain present in its SUVH counterparts, is able to recognize specific DNA sequences through a DNA binding domain that contains three zinc fingers, and induce silencing through DNA-methylation independent H3K9me2 deposition, possibly acting as part of a histone modifier multimeric complex. We propose that SUVR5 mediates a mechanism for heterochromatin formation that is distinct from the self-perpetuating loop existing between H3K9me2 and DNA methylation, and that this lack of perpetuation allows for the increased plasticity needed in response to environmental or developmental cues during an organism's life.

Results

SUVR5 is important for plant development and contains a zinc finger domain that binds to DNA

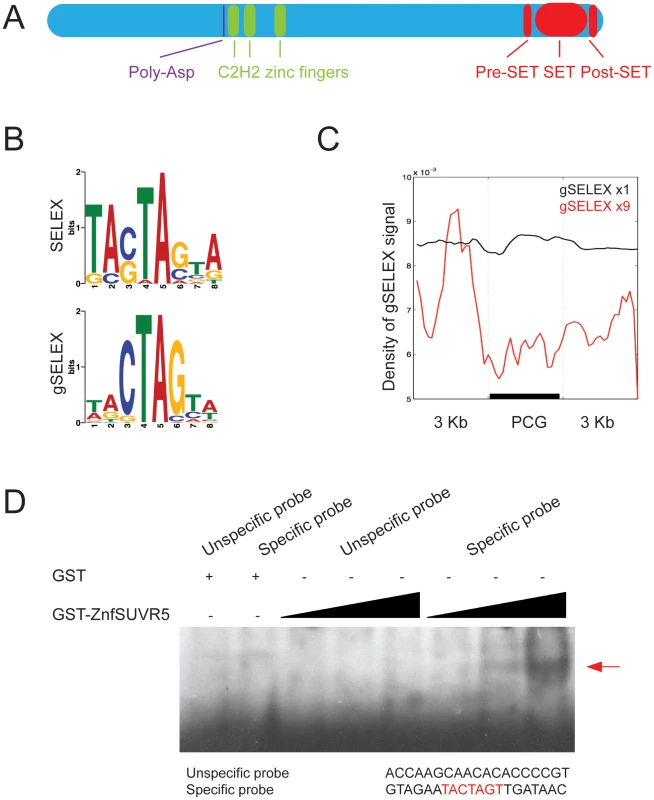

To test the role of Arabidopsis SU(VAR) 3–9 RELATED genes in plant development we screened T-DNA mutants in all five suvr single mutants and higher order combinations for visible morphological defects. We found that the suvr5-1 mutation produces a delay in flowering time that was not further enhanced in the quintuple suvr1 suvr2 suvr3 suvr4 suvr5 mutants (Figure S1). These observations were consistent with results from earlier analysis of a suvr5 mutant [23] and suggested a role for SUVR5 (but not the other SUVR family members) in flowering time. SUVR5 differs from the other SUVR family members in that it contains a set of three C2H2 zinc fingers in tandem in the central part of the protein (Figure 1a). SUVR5 homologs with a similar domain architecture (zinc fingers plus a C-terminal SET domain) are found in all plant species analyzed suggesting that it is widely conserved in the plant kingdom (Figure S2). We hypothesized that the zinc fingers have a DNA-binding function and may direct SUVR5 epigenetic activity to sequence-specific regions of the genome. To test this, we used the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) technique with the recombinant SUVR5 zinc fingers domain to analyze binding to oligonucleotides that included a 15 base-pair (bp) random sequence (Figures S3 and S4). We identified an 8-nucleotide motif favored by SUVR5 binding (Figure 1b, upper panel). Next, we repeated the experiment using 100 bp fragmented Arabidopsis wild-type Col-0 genomic DNA (genomic SELEX, gSELEX) to identify naturally occuring SUVR5 binding sequences (Figure S5). We identified almost the exact same binding motif “TACTAGTA” (Figure 1b, lower panel)—a palindromic octamer that is consistent with the 9-nucleotide that is the maximum expected size of a sequence recognized by three zinc fingers in tandem, since each zinc finger repeat has a predicted alpha-helical core that binds to 3 nucleotides in the major groove of DNA [24]. The binding and its specificity were confirmed by electromobility shift assays (EMSAs) (Figure 1d, Figure S6).

Fig. 1. SUVR5 zinc finger domain binds specific sequences of DNA that map to the promoters of genes.

a, Domain structure of SUVR5 (Poly-Asp: domain of unknown function rich in Asp residues); b, enriched motifs identified in the sequencing data obtained from the SELEX experiments; c, meta-gene analysis of the genomic SELEX (gSELEX) reads showing preferential binding of the SUVR5 zinc finger domain to the 3 Kb region upstream of protein coding genes (PCG). The results obtained after exponential selection of the binding sites for 9 cycles are shown (×9) in contrast with the results obtained after only one cycle of enrichment (×1), included as control; d, mobility shift assay with increasing amounts of GST-zinc finger domain (100, 250 and 500 ng) added to a binding reaction with either an unspecific oligonucleotide probe or a specific probe including the identified binding motif sequence. The high throughput sequencing results from the genomic SELEX experiment allowed us to map the identified SUVR5 binding regions to the Arabidopsis genome. Metaplot analysis showed that these regions mapped preferentially to the area immediately upstream of transcriptional start sites of protein coding genes (Figure 1c).

SUVR5 affects H3K9me2

Given the SUVR5 SET domain homology to Drosophila SU(VAR)3–9 we hypothesized that SUVR5 is an active methyltransferase. Consistent with this, SUVR5 bound to the methyl-group donor SAM (Figure S7) and its SET domain contains all of the crucial residues required for histone methyltransferase activity in the HΦΦNHSC motif. However, we were unable to demonstrate in vitro histone methytransferase activity against various histone substrates. This could indicate that other binding partners are necessary for SUVR5 enzymatic activity, similar to other histone methyltransferase complexes such as those containing Enhancer of Zeste [25], or that SUVR5 biochemical activity is dependent on a particular chromatin context [26].

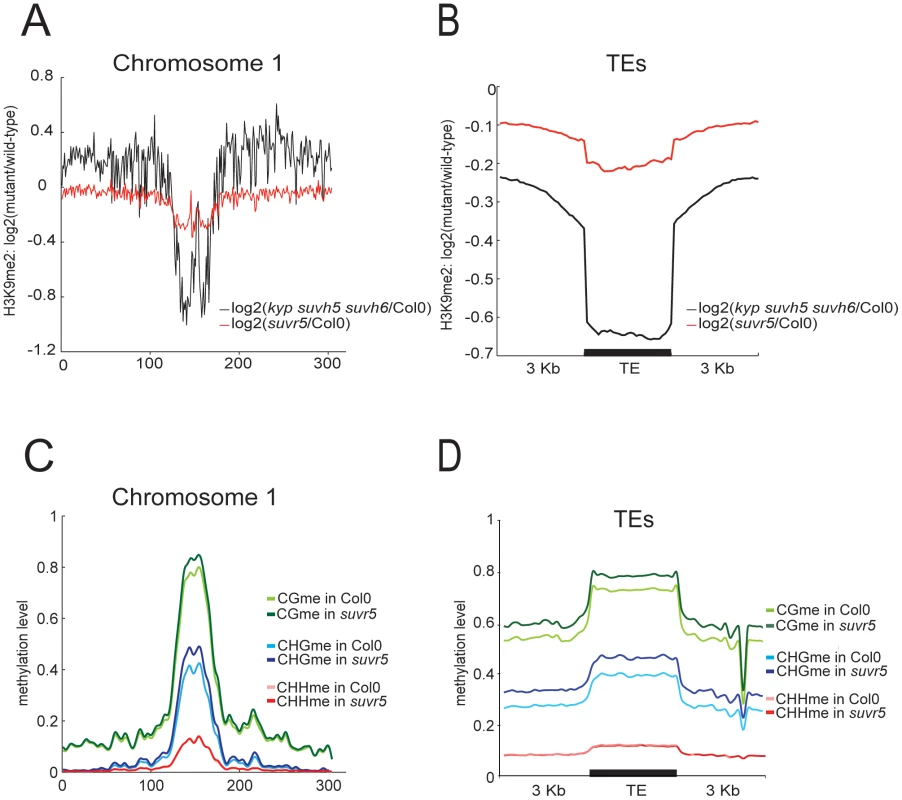

We directly tested for the role of SUVR5 on H3K9me2 levels in vivo by utilizing chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by microarray analysis (ChIP-chip) experiments in mature leaves of wild-type Col-0 and suvr5-1 mutants. The suvr5 mutants showed an overall decrease in H3K9me2 accumulation on pericentromeric heterochromatin (Figure 2a, Figure S8) and transposable elements (TEs) (Figure 2b), although these effects were relatively minor. Heterochromatic H3K9me2 is known to be mostly maintained by KYP, SUVH5 and SUVH6 [14], [16], [17], [21], [22], and ChIP-chip data with the kyp suvh5 suvh6 triple mutants showed a much more dramatic decrease in H3K9me2 levels than with suvr5 (Figure 2a and 2b). These data confirm that KYP, SUVH5, and SUVH6 are the major H3K9m2 enzymes in heterochromatin, but also suggest a minor role for SUVR5.

Fig. 2. SUVR5 is redundant with KYP/SUVH5/SUVH6 in controlling H3K9me2 accumulation in heterochromatin.

a, Chromosome 1 view of the log2 ratio of H3K9me2 signal in suvr5 mutants vs. Col-0 (red), and the log2 ratio of kyp suvh5 suvh6 triple mutants vs. Col-0 (black); b, Chromosome 1 distribution of DNA methylation in suvr5-1 and Col-0; c, meta-analysis of H3K9me2 levels on suvr5 and kyp suvh5 suvh6 mutants vs. Col-0 over TEs; d, meta analysis of CG, CHG and CHH DNA methylation levels in suvr5-1 and Col-0 over TEs. (green = CG, blue = CHG, red = CHH; light colors are Col-0, and dark colors are suvr5-1). H3K9me2 is correlated with DNA methylation in Arabidopsis on a genome wide level [20]. The loss of H3K9me2 in kyp mutants produces a decrease in DNA methylation [14], [21], [22] that is enhanced in the kyp suvh5 or kyp suvh6 double mutants and in the kyp suvh5 suvh6 triple mutant [16], [17]. Importantly, in the case of suvr5 mutants, we did not detect a decrease in DNA methylation at pericentromeric heterochromatin (Figure 2c, Figure S9) or TEs (Figure 2d, Figure S10), suggesting that SUVR5 functions differently than the SUVH proteins.

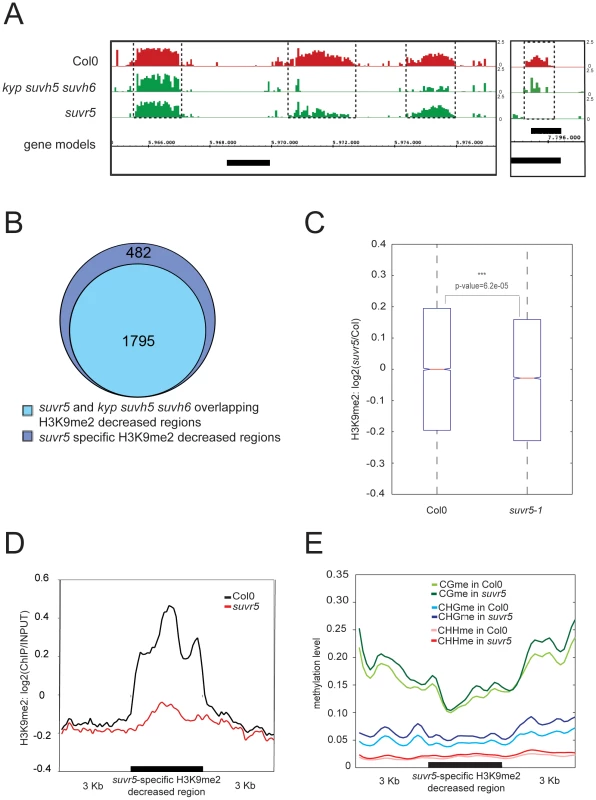

We could also detect regions within the arms of the chromosomes with a decrease in H3K9me2 levels in the suvr5 mutants. Although the majority of these regions overlapped with regions dependent on KYP/SUVH5/SUVH6, over 20% were specific to suvr5 (Figure 3a and 3b). These suvr5-specific regions consisted of discrete patches of H3K9me2 that were solely dependent on SUVR5 (Figure 3d), and were characterized by very low levels of cytosine DNA methylation, and these levels of DNA methylation were not altered by the loss of SUVR5 (Figure 3e). These results suggest that, in those specific locations, SUVR5 is controlling H3K9me2 deposition in a DNA-methylation-independent manner that is not perpetuated by the KYP/CMT3 epigenetic loop. We could also find a small number of transposons in the chromosome arms whose H3K9me2 decrease was specific for suvr5 mutants and independent of kyp/suvh5/suvh6, and these tended to be smaller transposons with lower levels of DNA methylation (Figure S11). We analyzed for the presence of SUVR5 binding motifs within the sequence of these 423 TEs that show decreased levels of H3K9me2 specifically in suvr5 mutants ±2 Kb and 8.5% of them contain the motif TACTAGTA.

Fig. 3. SUVR5-specific H3K9me2 deposition correlates with the zinc finger domain binding and promotes gene silencing.

a, genome browser view of a region in the arms of chromosome 1. H3K9me2 data is represented as log2 ratios from 0 to 2.5. Gene models correspond to TAIR8 protein-coding genes (PCG) and are shown for the plus or minus strand of the genome; b, Venn diagram representation of the number of H3K9me2 decreased regions defined for suvr5 mutants that are specific to them or overlap with the ones in kyp suvh5 suvh6; c, box plot showing the levels of H3K9me2 in the genes that have gSELEX signal in their upstream 3 Kb region; d, meta-analysis of H3K9me2 levels on suvr5-1 and Col-0 over the suvr5-specific H3K9me2 decreased regions; e, meta analysis of CG, CHG and CHH DNA methylation levels in suvr5-1 and Col-0 over the suvr5-specific H3K9me2 decreased regions. To determine if there is a correlation between H3K9me2 levels and SUVR5 binding, we analyzed H3K9me2 levels in the set of genes that were shown to bind the SUVR5 zinc fingers (i.e. with signal 3 Kb upstream of their transcription start site) in the gSELEX experiment. In that specific set of genes, we found a significant decrease of H3K9me2 when comparing suvr5 mutants to wild-type (Figure 3c). This decrease was significant for both of the ChIP-chip replicates analyzed (Figure S12). Analysis of all the genes that show a H3K9me2 decrease in suvr5 mutants compared to wild type showed that around 27% of them have gSELEX signal in their proximal promoter (1 Kb upstream their TSS). Interestingly, when we analyze not only euchromatic regions, but all decreased H3K9me2 regions including those in pericentromeric heterochromatin, only 5.4% of them overlap with the gSELEX signal. This suggests that targeting of SUVR5 to pericentromeric heterochromatin may be mediated by another unknown mechanism, which is likely responsible for the redundancy of SUVR5 with KYP/SUVH5/SUVH6.

Biological relevance of SUVR5 function

To measure the effects of SUVR5 on gene expression, we performed mRNA sequencing (mRNA-Seq) experiments to analyze the transcriptome of suvr5-1 mutants. We observed a large number of genes that were signficantly upregulated, the majority of which were located in the euchromatic chromosome arms (Table S1, Figure S13). Although many of these genes are likely to be indirect targets to SUVR5, 11% of these genes were among those that showed decreased H3K9m2 levels, and 69.5% of these genes contained at least one significant SUVR5 binding motif in their promoter. Examples of genes with a decrease in H3K9me2 levels and upregulated expression in two different alleles of suvr5 mutants can be found in Figure S14 (See Figure S15 for suvr5-2 mutant allele characterization). Consistent with the slight decrease of H3K9me2 levels that occurred in suvr5 at TEs, very few transposons were reactivated in the mutant (Table S2).

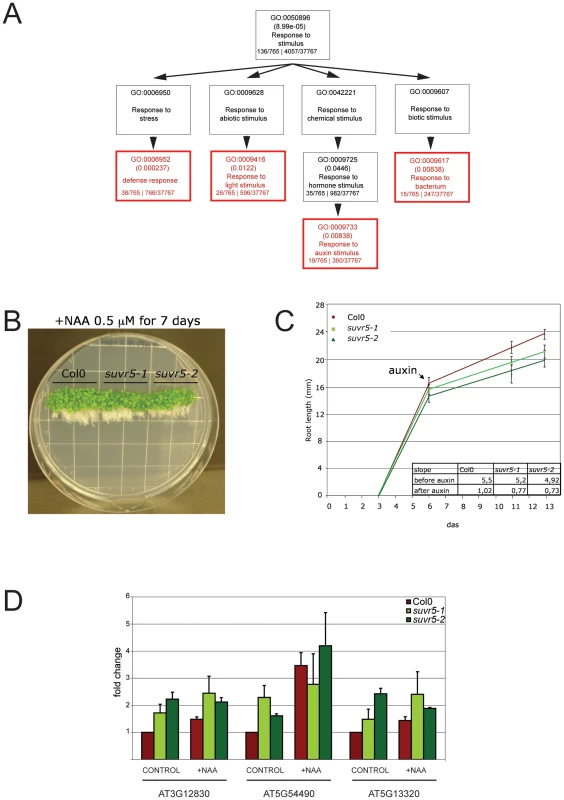

To identify the biological processes that SUVR5 may regulate, we applied gene ontology (GO) term analysis to the genes upregulated in the suvr5 mutant (over 4 fold, p-value<0.01). Of the three broad GO term categories significantly over-represented in this set of genes, the most significantly enriched was “response to stimulus” (Figure S16). This category includes subcategories such as defense response, response to biotic stimuli like bacterium, and response to endogenous stimuli like the plant hormone auxin, which were strongly and significantly enriched (p_value<0.01; Figure 4a).

Fig. 4. SUVR5 significantly affects the expression of genes related to the “response to stimulus” GO term.

a, chart showing the GO term “response to stimulus” category and subcategories under it and the level of significance of their over-representation in the set of suvr5 upregulated genes compared to the whole genome (p-values shown in parentheses). At the bottom of each box, the number of genes that include the particular GO term in the suvr5 upregulated set of genes/total number of suvr5 upregulated genes is shown on the left; the number of genes that include the particular GO term in the whole genome/total number of genes in the whole genome is shown on the right; b, picture of Col-0, suvr5-1 and suvr5-2 13-day-old seedlings treated with 0.5 µM NAA for the last 7 days. Notice the differences in growth; c, time course root length measurements of Col-0, suvr5-1 and suvr5-2 seedlings before and after NAA treatment. The bottom right panel shows the slopes of the curves that represent a measurement of the growth rate. Around 20 seedlings of each line were measured and SE is shown for every point; d, expression levels (relative to ACTIN, relative to Col-0 CONTROL) of 3 selected auxin-responsive genes in seedlings grown for 12 day without auxin (NAA) application (CONTROL) or transfered to NAA media on the fifth day (+NAA 0.5 µM). The experiment was done in triplicate and SE is shown for each sample. Auxin plays a key role in many plant developmental processes [27], [28]. For example auxin plays a central role in elaborating root architecture because of its role in endogenous developmental programs as well as its mediation of environmental stimuli responses [29]. We hypothesized that the overexpression of auxin inducible genes in suvr5 mutants might generate a partially constitutive auxin-response in the abscence of the hormone. Auxin causes inhibition of root growth by reduction of cell division and elongation, and a constitutive response could explain the defects in root growth earlier reported for suvr5 mutants [30], which we also observed here for both of the suvr5 alleles tested (Figure 4b and c). To examine this, we analyzed the expression of three examples of genes annotated as “auxin-responsive” and that have significant SUVR5 binding sites in their promoters (Figure S17). These genes are annotated as a PINOID (PID)-binding protein (At5g54490), an auxin-responsive GH3 family protein (At5G13320), and a SAUR-like auxin-responsive family protein (At3g12830). We found that these genes were indeed upregulated upon auxin treatment (Figure 4d) and that in the suvr5 mutants, these genes also showed increased expression, even in the absence of the hormone (Figure 4d). These data are consistent with a model whereby a stimulus such as auxin treatment overcomes the repression established by SUVR5, activating the genes and thus guaranteeing an appropriate response to environmental and developmental cues.

Interaction of SUVR5 with the LDL1 histone demethylase

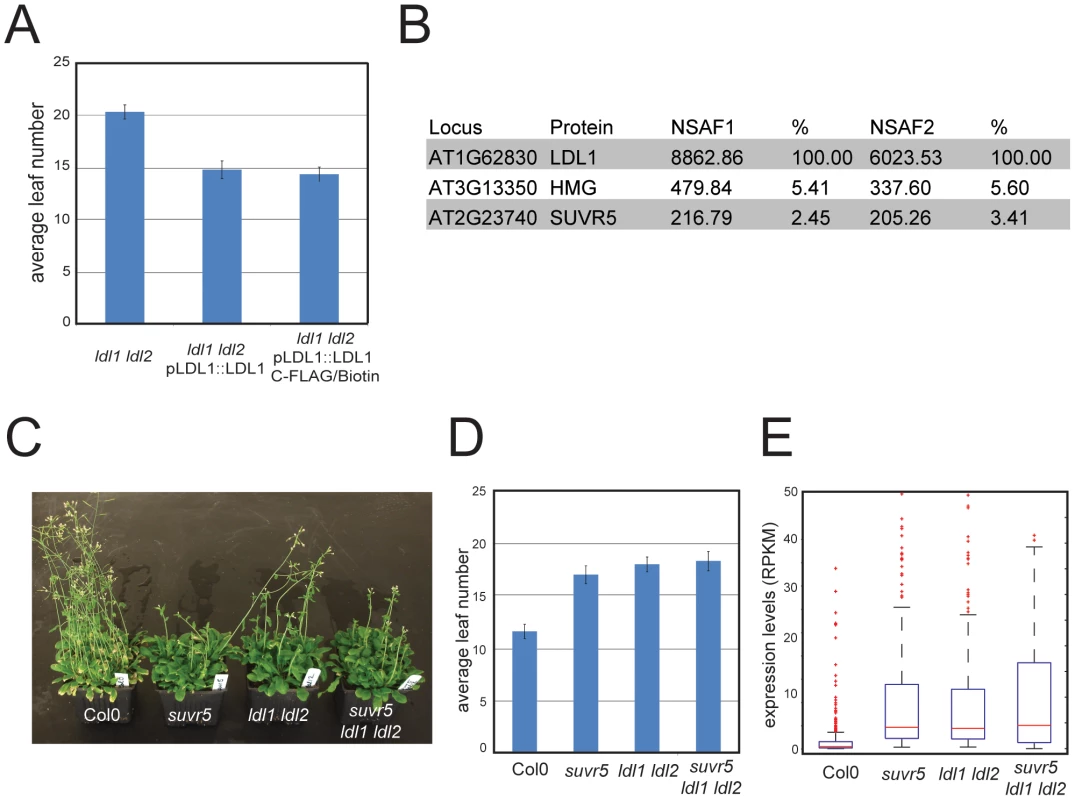

The majority of chromatin modifiers characterized in higher organisms are present in large multi-protein complexes. SUVR5 was shown to interact in vitro with the Arabidopsis homolog of LYSINE-SPECIFIC DEMETHYLASE (LSD), termed LSD-LIKE 1 (LDL1) [23], an H3K4 demethylase partially redundant with its paralog LDL2 [23]. We tested for the existence of this complex in vivo by generating a transgenic line that expressed a FLAG tagged version of LDL1 under its own promoter, which was shown to complement the late flowering phenotype of the ldl1 ldl2 mutant (Figure 5a). Using affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry (IP-Mass Spec [19]) (Figure 5b) we indeed identified an in vivo complex including both SUVR5 and LDL1. We also generated plants carrying a tagged version of SUVR5 expressed under the control of its own promoter, however the very poor expression levels of the tagged protein rendered our purification attempts unsuccessful.

Fig. 5. SUVR5 and LDL1 act together in a repressor complex.

a, analysis of the late flowering phenotype of ldl1 ldl2 mutants and its complementation by the tagged LDL1 transgene measured by scoring number of leaves at bolting; b, table showing the mass spectrometry analyses of LDL1 affinity purifications; c, picture showing the late flowering phenotype of suvr5, ldl1 ldl2 and suvr5 ldl1 ldl2 plants; d, analysis of the late flowering phenotype by scoring number of leaves at bolting; e, box plot showing the expression level (in RPKM) of the 270 genes upregulated in suvr5 and ldl1 ldl2 (over 4 fold and P<0.01 for both, suvr5/Col-0 and ldl1 ldl2/Col-0) in Col-0, suvr5, ldl1 ldl2 and the triple suvr5 ldl1 ldl2 mutants, showing the epistatic relationship between the mutants. The physical interaction between SUVR5 and LDL1 suggests that their H3K9 methyl transferase and H3K4 demethylase activities may work together in collaboration to repress gene expression. To analyze the genetic interaction between SUVR5 and LDL1 we generated the suvr5 ldl1 ldl2 triple mutant and analyzed the effect on flowering time. Flowering time was as late in the triple mutant as in the single suvr5 or double ldl1 ldl2 mutants, indicating an epistatic relationship between SUVR5 and LDL (Figure 5c and 5d). mRNA-Seq in the double and triple mutants revealed 270 genes that were affected by both suvr5 and by ldl1 ldl2 mutations, which is more than 30% of the genes controlled by suvr5 alone. This suggests that SUVR5 and LDLs share a broad regulatory function. Furthermore, the GO category “response to stimulus” was also the most significantly enriched in ldl1 ldl2 mutants when analyzing their upregulated genes, supporting the idea that LDL1 and SUVR5 co-regulate a diverse set of targets involved in environmental responses (for the list of genes, see Table S3, for GO term analysis, see Figure S18).

The 270 genes co-regulated by SUVR5 and LDL1 had very low expression levels in wild-type Col-0, and their degree of upregulation in the triple suvr5 ldl1 ldl2 mutant was the same as in the single suvr5 or double ldl1 ldl2 mutants (Figure 5e). This confirms that the relationship between the genes is indeed epistatic, with likely their H3K9 methylation and H3K4 demethylation activities acting together to repress gene expression for a large number of genes with common biological functions. Consistent with this, the most significantly over-represented GO term for the common 270 genes was again “response to stimulus”, which supports a common role for SUVR5 and LDLs in environmental adaptation (for the list of genes, see Table S3, for GO term analysis, see Figure S19).

Discussion

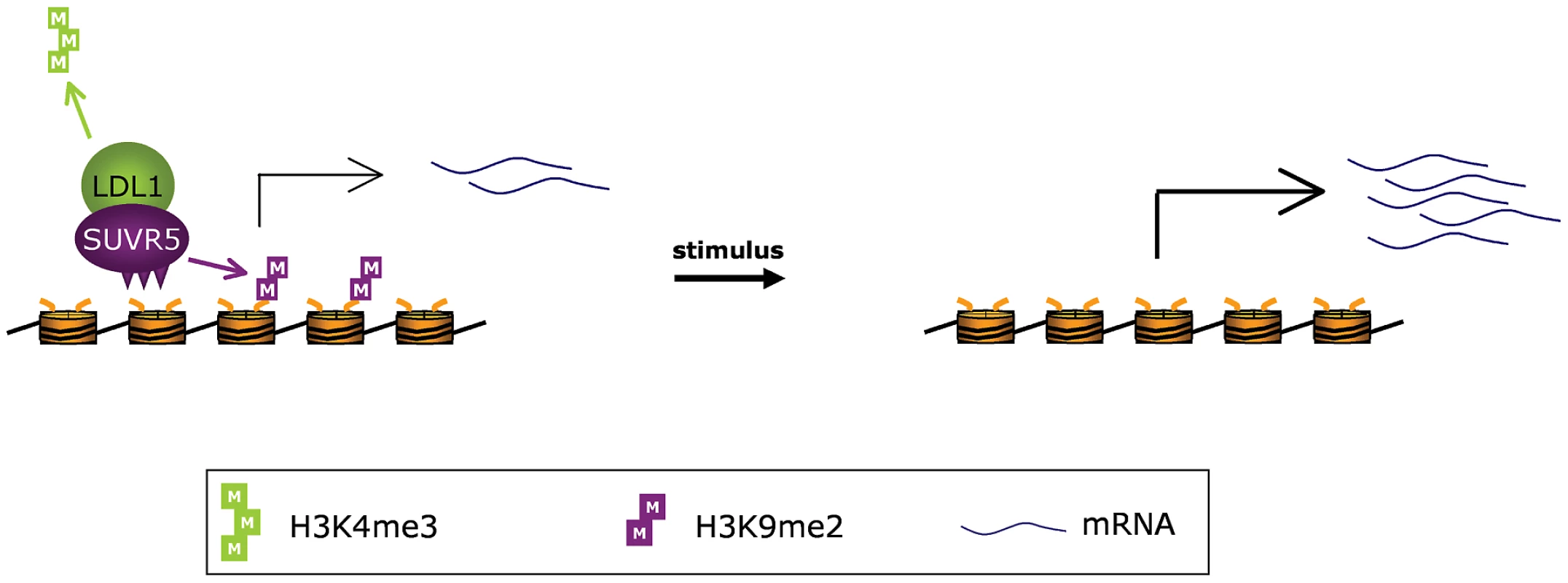

The ability of eukaryotic cells to respond to external stimuli and adapt to their environment depends on the coordinated activation and repression of specific subsets of genes. In order to facilitate this, repressive and permissive chromatin states must be readily altered in response to those stimuli. Our data are consistent with a model in which SUVR5 is part of a multimeric complex including LDL1 (and perhaps also other chromatin modifying enzymes) that recognizes genes with the sequence TACTAGTA (or related sequences) in their promoters and, in the absence of stimuli, represses their expression by altering epigenetic histone marks. This represents a unique form of epigenetic control via H3K9me2 that is independent from DNA methylation, and not perpetuated by the KYP/CMT3 loop, which potentially makes it more adaptable and dynamic for responding to environmental changes (Figure 6). One possibility is that SUVR5 mediated repression acts to modulate responses to various environmental signals as well as to provide an epigenetic memory of transcriptional states.

Fig. 6. Proposed model for SUVR5 function.

SUVR5 is part of a multimeric complex including LDL1 that recognizes gene promoters and represses their expression by altering their epigenetic status. The functioning of SUVR5 has analogies with some repressive chromatin modifiers characterized in animals that are also present in large multiprotein complexes. One example is the mammalian silencing transcription factor REST that is important in neural differentiation. It binds to the conserved RE1 motif through its 8 Krüppel zinc finger motifs and represses many neuronal genes in non-neuronal cells [31]. This transcriptional regulation is achieved by the recruitment by REST of histone deacetylases (like HDAC1/2) [32], [33], [34], [35], demethylases (like LSD1) [36], and methyltransferases (like G9a) [37], in a similar way to the proposed SUVR5 mode of action [30]. Another example is that of PR proteins. PR (PRDI-BF1 and RIZ homology) domain proteins (PRDMs) represent a distinct and unique branch of metazoan proteins that contain a PR domain, which at the amino acid level is 20–30% identical to the SET domain found in many histone lysine methyltransferases (HMTs) [38]. The PR domain is not present in fungi or plant genomes having originated in invertebrates [39], and is almost always accompanied by C2H2-like zinc finger motifs. PRDMs act as specific transcriptional regulators catalyzing histone methylation and/or recruiting interaction partners to modify the epigenetic regulation of target genes [38]. A common feature of PRDM proteins is their ability to act as transcriptional repressors by binding both to G9a and class I histone deacetylase enzymes such as HDAC1–3 [38]. In conclusion, multisubunit complexes containing different histone modifying enzymes targeted by specific DNA binding proteins appears to be a phenomenon conserved in plant and animals and may play a greater role in gene regulation than previously appreciated.

Materials and Methods

Plant strains

The wild-type control in this study was the Columbia 0 ecotype (Col-0). suvr5-1 [23] and suvr5-2 are T-DNA insertion lines obtained from the SALK Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory (SALK_026224 and SALK_085717 respectively). The kyp suvh5 suvh6 line was described in [40]. The ldl1–2 ldl2 line was described in [41].

Recombinant protein purification

The GST fusion protein used for SELEX and EMSA experiments was made by cloning the SUVR5 zinc finger domain (aminoacids 720 to 866) using the Gateway cloning system with pDEST15 as the final destination vector. For the SAM binding assay, the SET domain was cloned (aminoacids 1078 to 1376) also in pDEST15. Protein expression and purification was performed as previously described [11] plus the addition of 100 µM ZnSO4 to the cell culture at the time of protein expression induction (in the case of the Zinc finger domain) and avoiding the use of EDTA during the protein purification.

SELEX

The basic protocol for SELEX experiments described in [42] was followed with some minor modifications. For details, see Text S1. Sequencing data for the genomic SELEX experiment have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (accession number GSE39405).

EMSA

The protocol described in [11] was followed with slight modifications to the binding buffer composition (12% glycerol, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT). For info on the primers used to test the protein binding, see Text S1.

ChIP

H3K9me2 ChIP experiments were performed using 3 week old leaves of wild type Col-0 and suvr5-1 plants, as previously described [43].

The ChIP-chip was performed as described in [20], the results show a comparison of the abundance of DNA pulled down with the anti-H3K9me2 antibody (#1220, monoclonal anti-H3K9m2 antibody, Abcam) versus INPUT.

For info on the primers used to validate the ChIP-chip results by ChIP-qPCR, see Text S1.

ChIP–chip analysis

Each probe in the array was normalized by taking the log2 ratio of H3K9m2 to INPUT intensities, and the scores were scaled so that the average score across the arrays were zero. H3K9me2 hypomethylated regions were defined by tiling the genome into 500 bp bins (250 bp overlap), and computing the log2 ratios of the scores of suvr5 vs Col-0, and Z-score transformed. A Z<−3 cutoff was applied, and regions within 2.5 kb were merged. Data have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (accession number GSE39405).

Bisulfite treatment

DNA from leaves of 3 week old plants was extracted using a standard CTAB protocol. We performed sodium bisulfite treatment using EZ DNA Methylation Gold (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer's instructions, amplified specific fragments using the primers described in Text S1 and cloned the resulting PCR fragments into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) to sequence and analyze around 20 clones per sample. To compare the converted clones to the original unconverted sequence, we used the sequence alignment tool of CLC Workbench software. We counted the converted/unconverted cytosines at each site manually and subsequently calculated the percent of methylation.

BS-Seq was performed as previously described [44]. Sequencing data have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (accession number GSE39405).

mRNA–Seq

Leaves from wild type Col-0, suvr5-1, ldl1–2 ldl2 and suvr5-1 ldl1–2 ldl2 3 week-old plants were used for RNA extraction using Trizol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer instructions. 10 µg of total RNA was treated with DNaseI (Roche), and cleaned up with RNeasy columns (Qiagen). Poly(A) was purified using the Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen) and used to generate the mRNA-seq libraries following the manufacturer instructions (Illumina). The libraries were sequenced using an Illumina Genome Analyzer.

Gene and transposon expression in the RNA-seq data was measured by calculating reads per kilobase per million mapped (RPKM). P-values to detect differential expression were calculated by Fisher's exact test and Benjamini-Hochberg corrected for multiple testing. Genes differentially expressed in wild-type and mutants were defined as those that have log2(suvr5/wild-type)>4 and P<0.01. Sequencing data have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (accession number GSE39405).

IP/mass spectrometry

For affinity purification of LDL1-3xFLAG ∼15 g of inflorescence tissue from transgenic and Col-0 plants was ground in liquid nitrogen, and resuspended in 75 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol v/v 0.02% NP-40 v/v, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mg/mL pepstatin, 1 mM PMSF and 1 protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, 14696200)). Mass spectrometry analyses were performed as described in [19]. The identities of proteins co-purifying with LDL1 in Figure 5b are shown for those proteins appearing in two replicate purifications, and present at levels equivalent to at least 1% of the level of LDL1.

Auxin treatment

Wild type Col-0, suvr5-1 and suvr5-2 plants were either grown for 13 days in vertical MS plates (CONTROL) or grown in vertical MS plates for 5 days before being transferred to MS+0.5 µM NAA (Sigma) plates for 7 additional days.

GO term analysis

The web-based tool agriGO was used for the gene ontology analysis [45].

Accession number

SUVR5 information is available in The Arabidopsis Information Resource under accession number AT2G23740.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. JenuweinT, AllisCD (2001) Translating the histone code. Science 293 : 1074–1080.

2. JenuweinT, LaibleG, DornR, ReuterG (1998) SET domain proteins modulate chromatin domains in eu - and heterochromatin. Cell Mol Life Sci 54 : 80–93.

3. ReaS, EisenhaberF, O'CarrollD, StrahlBD, SunZW, et al. (2000) Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 406 : 593–599.

4. BaumbuschLO, ThorstensenT, KraussV, FischerA, NaumannK, et al. (2001) The Arabidopsis thaliana genome contains at least 29 active genes encoding SET domain proteins that can be assigned to four evolutionarily conserved classes. Nucleic Acids Res 29 : 4319–4333.

5. CaoX, JacobsenSE (2002) Role of the Arabidopsis DRM methyltransferases in de novo DNA methylation and gene silencing. Current Biology 12 : 1138–1144.

6. LawJA, JacobsenSE Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet 11 : 204–220.

7. HendersonIR, JacobsenSE (2007) Epigenetic inheritance in plants. Nature 447 : 418–424.

8. WooHR, PontesO, PikaardCS, RichardsEJ (2007) VIM1, a methylcytosine-binding protein required for centromeric heterochromatinization. Genes Dev 21 : 267–277.

9. WooHR, DittmerTA, RichardsEJ (2008) Three SRA-domain methylcytosine-binding proteins cooperate to maintain global CpG methylation and epigenetic silencing in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 4: e1000156 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000156.

10. KraftE, BostickM, JacobsenSE, CallisJ (2008) ORTH/VIM proteins that regulate DNA methylation are functional ubiquitin E3 ligases. Plant J 56 : 704–715.

11. JohnsonLM, BostickM, ZhangX, KraftE, HendersonI, et al. (2007) The SRA methyl-cytosine-binding domain links DNA and histone methylation. Curr Biol 17 : 379–384.

12. BostickM, KimJK, EstevePO, ClarkA, PradhanS, et al. (2007) UHRF1 plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Science 317 : 1760–1764.

13. SharifJ, MutoM, TakebayashiS, SuetakeI, IwamatsuA, et al. (2007) The SRA protein Np95 mediates epigenetic inheritance by recruiting Dnmt1 to methylated DNA. Nature 450 : 908–912.

14. JacksonJP, LindrothAM, CaoX, JacobsenSE (2002) Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature 416 : 556–560.

15. MalagnacF, BarteeL, BenderJ (2002) An Arabidopsis SET domain protein required for maintenance but not establishment of DNA methylation. Embo J 21 : 6842–6852.

16. EbbsML, BenderJ (2006) Locus-specific control of DNA methylation by the Arabidopsis SUVH5 histone methyltransferase. Plant Cell 18 : 1166–1176.

17. EbbsML, BarteeL, BenderJ (2005) H3 lysine 9 methylation is maintained on a transcribed inverted repeat by combined action of SUVH6 and SUVH4 methyltransferases. Mol Cell Biol 25 : 10507–10515.

18. RajakumaraE, LawJA, SimanshuDK, VoigtP, JohnsonLM, et al. A dual flip-out mechanism for 5mC recognition by the Arabidopsis SUVH5 SRA domain and its impact on DNA methylation and H3K9 dimethylation in vivo. Genes Dev 25 : 137–152.

19. LawJA, AusinI, JohnsonLM, VashishtAA, ZhuJK, et al. A protein complex required for polymerase V transcripts and RNA - directed DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 20 : 951–956.

20. BernatavichuteYV, ZhangX, CokusS, PellegriniM, JacobsenSE (2008) Genome-wide association of histone H3 lysine nine methylation with CHG DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 3: e3156 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003156.

21. JacksonJP, JohnsonL, JasencakovaZ, ZhangX, PerezBurgosL, et al. (2004) Dimethylation of histone H3 lysine 9 is a critical mark for DNA methylation and gene silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Chromosoma 112 : 308–315.

22. TariqM, SazeH, ProbstAV, LichotaJ, HabuY, et al. (2003) Erasure of CpG methylation in Arabidopsis alters patterns of histone H3 methylation in heterochromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 : 8823–8827.

23. KrichevskyA, GutgartsH, KozlovskySV, TzfiraT, SuttonA, et al. (2007) C2H2 zinc finger-SET histone methyltransferase is a plant-specific chromatin modifier. Dev Biol 303 : 259–269.

24. PavletichNP, PaboCO (1993) Crystal structure of a five-finger GLI-DNA complex: new perspectives on zinc fingers. Science 261 : 1701–1707.

25. MullerJ, HartCM, FrancisNJ, VargasML, SenguptaA, et al. (2002) Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111 : 197–208.

26. SchmitgesFW, PrustyAB, FatyM, StutzerA, LingarajuGM, et al. Histone methylation by PRC2 is inhibited by active chromatin marks. Mol Cell 42 : 330–341.

27. WoodwardAW, BartelB (2005) Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann Bot 95 : 707–735.

28. VannesteS, FrimlJ (2009) Auxin: a trigger for change in plant development. Cell 136 : 1005–1016.

29. OvervoordeP, FukakiH, BeeckmanT Auxin control of root development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a001537.

30. KrichevskyA, KozlovskySV, GutgartsH, CitovskyV (2007) Arabidopsis co-repressor complexes containing polyamine oxidase-like proteins and plant-specific histone methyltransferases. Plant Signal Behav 2 : 174–177.

31. SchoenherrCJ, PaquetteAJ, AndersonDJ (1996) Identification of potential target genes for the neuron-restrictive silencer factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 : 9881–9886.

32. GrimesJA, NielsenSJ, BattaglioliE, MiskaEA, SpehJC, et al. (2000) The co-repressor mSin3A is a functional component of the REST-CoREST repressor complex. J Biol Chem 275 : 9461–9467.

33. HuangY, MyersSJ, DingledineR (1999) Transcriptional repression by REST: recruitment of Sin3A and histone deacetylase to neuronal genes. Nat Neurosci 2 : 867–872.

34. NaruseY, AokiT, KojimaT, MoriN (1999) Neural restrictive silencer factor recruits mSin3 and histone deacetylase complex to repress neuron-specific target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 : 13691–13696.

35. RoopraA, SharlingL, WoodIC, BriggsT, BachfischerU, et al. (2000) Transcriptional repression by neuron-restrictive silencer factor is mediated via the Sin3-histone deacetylase complex. Mol Cell Biol 20 : 2147–2157.

36. ShiY, LanF, MatsonC, MulliganP, WhetstineJR, et al. (2004) Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell 119 : 941–953.

37. TachibanaM, SugimotoK, FukushimaT, ShinkaiY (2001) Set domain-containing protein, G9a, is a novel lysine-preferring mammalian histone methyltransferase with hyperactivity and specific selectivity to lysines 9 and 27 of histone H3. J Biol Chem 276 : 25309–25317.

38. FogCK, GalliGG, LundAH PRDM proteins: Important players in differentiation and disease. Bioessays

39. KimKC, HuangS (2003) Histone methyltransferases in tumor suppression. Cancer Biol Ther 2 : 491–499.

40. GrewalSI, MoazedD (2003) Heterochromatin and epigenetic control of gene expression. Science 301 : 798–802.

41. JiangD, YangW, HeY, AmasinoRM (2007) Arabidopsis relatives of the human lysine-specific Demethylase1 repress the expression of FWA and FLOWERING LOCUS C and thus promote the floral transition. Plant Cell 19 : 2975–2987.

42. SasaiN, NakaoM, DefossezPA Sequence-specific recognition of methylated DNA by human zinc-finger proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 38 : 5015–5022.

43. JohnsonL, CaoX, JacobsenS (2002) Interplay between two epigenetic marks. DNA methylation and histone H3 lysine 9 methylation. Curr Biol 12 : 1360–1367.

44. CokusSJ, FengS, ZhangX, ChenZ, MerrimanB, et al. (2008) Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature 452 : 215–219.

45. DuZ, ZhouX, LingY, ZhangZ, SuZ agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res 38: W64–70.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 10

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The Germline Genome Provides a Niche for Intragenic Parasitic DNA: Evolutionary Dynamics of Internal Eliminated Sequences

- Classical Genetics Meets Next-Generation Sequencing: Uncovering a Genome-Wide Recombination Map in

- Calpain-5 Mutations Cause Autoimmune Uveitis, Retinal Neovascularization, and Photoreceptor Degeneration

- Cofilin-1: A Modulator of Anxiety in Mice

- The Date of Interbreeding between Neandertals and Modern Humans

- Embryos of Robertsonian Translocation Carriers Exhibit a Mitotic Interchromosomal Effect That Enhances Genetic Instability during Early Development

- Viral Evasion of a Bacterial Suicide System by RNA–Based Molecular Mimicry Enables Infectious Altruism

- Phosphatase-Dead Myotubularin Ameliorates X-Linked Centronuclear Myopathy Phenotypes in Mice

- Full-Length Synaptonemal Complex Grows Continuously during Meiotic Prophase in Budding Yeast

- MOV10 RNA Helicase Is a Potent Inhibitor of Retrotransposition in Cells

- A Likelihood-Based Framework for Variant Calling and Mutation Detection in Families

- The Contribution of RNA Decay Quantitative Trait Loci to Inter-Individual Variation in Steady-State Gene Expression Levels

- New Partners in Regulation of Gene Expression: The Enhancer of Trithorax and Polycomb Corto Interacts with Methylated Ribosomal Protein L12 Its Chromodomain

- Mining the Unknown: A Systems Approach to Metabolite Identification Combining Genetic and Metabolic Information

- Mutations in (Hhat) Perturb Hedgehog Signaling, Resulting in Severe Acrania-Holoprosencephaly-Agnathia Craniofacial Defects

- The Many Landscapes of Recombination in

- Faster-X Evolution of Gene Expression in

- Loss of Slc4a1b Chloride/Bicarbonate Exchanger Function Protects Mechanosensory Hair Cells from Aminoglycoside Damage in the Zebrafish Mutant

- Regulation of ATG4B Stability by RNF5 Limits Basal Levels of Autophagy and Influences Susceptibility to Bacterial Infection

- and the BTB Adaptor Are Key Regulators of Sleep Homeostasis and a Dopamine Arousal Pathway in Drosophila

- Mutation and Fetal Ethanol Exposure Synergize to Produce Midline Signaling Defects and Holoprosencephaly Spectrum Disorders in Mice

- Specific Missense Alleles of the Arabidopsis Jasmonic Acid Co-Receptor COI1 Regulate Innate Immune Receptor Accumulation and Function

- Deep Genome-Wide Measurement of Meiotic Gene Conversion Using Tetrad Analysis in

- Mismatch Repair Balances Leading and Lagging Strand DNA Replication Fidelity

- Distinguishing between Selective Sweeps from Standing Variation and from a Mutation

- Cytokinesis-Based Constraints on Polarized Cell Growth in Fission Yeast

- Deposition of Histone Variant H2A.Z within Gene Bodies Regulates Responsive Genes

- Functional Antagonism between Sas3 and Gcn5 Acetyltransferases and ISWI Chromatin Remodelers

- The SET-Domain Protein SUVR5 Mediates H3K9me2 Deposition and Silencing at Stimulus Response Genes in a DNA Methylation–Independent Manner

- Morphogenesis and Cell Fate Determination within the Adaxial Cell Equivalence Group of the Zebrafish Myotome

- Muscle-Specific Splicing Factors ASD-2 and SUP-12 Cooperatively Switch Alternative Pre-mRNA Processing Patterns of the ADF/Cofilin Gene in

- Maize Is Required for Maintaining Silencing Associated with Paramutation at the and Loci

- Increasing Signal Specificity of the TOL Network of mt-2 by Rewiring the Connectivity of the Master Regulator XylR

- Use of Pleiotropy to Model Genetic Interactions in a Population

- RAB-Like 2 Has an Essential Role in Male Fertility, Sperm Intra-Flagellar Transport, and Tail Assembly

- Variants Affecting Exon Skipping Contribute to Complex Traits

- Topoisomerase II– and Condensin-Dependent Breakage of -Sensitive Fragile Sites Occurs Independently of Spindle Tension, Anaphase, or Cytokinesis

- Comparison of Family History and SNPs for Predicting Risk of Complex Disease

- Recovery of Arrested Replication Forks by Homologous Recombination Is Error-Prone

- A Mutation in the Gene Causes Alternative Splicing Defects and Deafness in the Bronx Waltzer Mouse

- Comparative Genomics Suggests an Independent Origin of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in

- It Was Heaven: An Interview with Evelyn Witkin

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- A Mutation in the Gene Causes Alternative Splicing Defects and Deafness in the Bronx Waltzer Mouse

- Mutations in (Hhat) Perturb Hedgehog Signaling, Resulting in Severe Acrania-Holoprosencephaly-Agnathia Craniofacial Defects

- Classical Genetics Meets Next-Generation Sequencing: Uncovering a Genome-Wide Recombination Map in

- Regulation of ATG4B Stability by RNF5 Limits Basal Levels of Autophagy and Influences Susceptibility to Bacterial Infection

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání