-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaZebrafish Mutation Leads to mRNA Splicing Defect and Pituitary Lineage Expansion

Loss of retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor function is associated with human malignancies. Molecular and genetic mechanisms responsible for tumorigenic Rb downregulation are not fully defined. Through a forward genetic screen and positional cloning, we identified and characterized a zebrafish ubiquitin specific peptidase 39 (usp39) mutation, the yeast and human homolog of which encodes a component of RNA splicing machinery. Zebrafish usp39 mutants exhibit microcephaly and adenohypophyseal cell lineage expansion without apparent changes in major hypothalamic hormonal and regulatory signals. Gene expression profiling of usp39 mutants revealed decreased rb1 and increased e2f4, rbl2 (p130), and cdkn1a (p21) expression. Rb1 mRNA overexpression, or antisense morpholino knockdown of e2f4, partially reversed embryonic pituitary expansion in usp39 mutants. Analysis of pre-mRNA splicing status of critical cell cycle regulators showed misspliced Rb1 pre-mRNA resulting in a premature stop codon. These studies unravel a novel mechanism for rb1 regulation by a neuronal mRNA splicing factor, usp39. Zebrafish usp39 regulates embryonic pituitary homeostasis by targeting rb1 and e2f4 expression, respectively, contributing to increased adenohypophyseal sensitivity to these altered cell cycle regulators. These results provide a mechanism for dysregulated rb1 and e2f4 pathways that may result in pituitary tumorigenesis.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001271

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001271Summary

Loss of retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor function is associated with human malignancies. Molecular and genetic mechanisms responsible for tumorigenic Rb downregulation are not fully defined. Through a forward genetic screen and positional cloning, we identified and characterized a zebrafish ubiquitin specific peptidase 39 (usp39) mutation, the yeast and human homolog of which encodes a component of RNA splicing machinery. Zebrafish usp39 mutants exhibit microcephaly and adenohypophyseal cell lineage expansion without apparent changes in major hypothalamic hormonal and regulatory signals. Gene expression profiling of usp39 mutants revealed decreased rb1 and increased e2f4, rbl2 (p130), and cdkn1a (p21) expression. Rb1 mRNA overexpression, or antisense morpholino knockdown of e2f4, partially reversed embryonic pituitary expansion in usp39 mutants. Analysis of pre-mRNA splicing status of critical cell cycle regulators showed misspliced Rb1 pre-mRNA resulting in a premature stop codon. These studies unravel a novel mechanism for rb1 regulation by a neuronal mRNA splicing factor, usp39. Zebrafish usp39 regulates embryonic pituitary homeostasis by targeting rb1 and e2f4 expression, respectively, contributing to increased adenohypophyseal sensitivity to these altered cell cycle regulators. These results provide a mechanism for dysregulated rb1 and e2f4 pathways that may result in pituitary tumorigenesis.

Introduction

The hypothalamic-pituitary axis regulates stress responses, growth, reproduction and energy homeostasis. Neuropeptides released from the hypothalamus via the hypophyseal portal plexus control synthesis and secretion of anterior pituitary hormones [1]. Different pituitary cell types secrete hormones that regulate post-natal growth (growth hormone, GH), lactation (prolactin, PRL), metabolism (thyroid stimulating hormone, TSH), stress (adrenocorticotrophic hormone, ACTH), pigmentation (melanocyte-stimulating hormone, αMSH), sexual development and reproduction (luteinizing hormone, LHβ, and follicle stimulating hormone, FSHβ) [2]. Corticotropes and melanotropes produce proopiomelanocortin (POMC), which is proteolytically cleaved to give rise to ACTH in corticotropes and αMSH in melanotropes.

Central and peripheral signals including hypothalamic stimulatory hormones, growth factors and estrogen cause pituitary hyperplasia, genetic instability, subsequent monoclonal growth expansion and tumor formation [3]. Pituitary tumors are almost invariably benign, however if untreated, they are associated with increased morbidity and mortality due to tumor mass effect and/or hormonal disruptions leading to serious complications such as acromegaly and Cushing's disease [4], [5]. How developmental or acquired signals elicit plastic change in pituitary cell growth resulting in hyperplasia or benign adenomas is not fully understood [6].

The pituitary gland is highly sensitive to cell cycle regulators including cyclins, cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs), CDK inhibitors (CKIs) and retinoblastoma protein (pRB), all of which are frequently dysregulated in pituitary tumors. pRB, a nuclear pocket protein, binds the E2F transcription factors and regulates the balance between cell quiescence and proliferation [7]. E2Fs control expression of genes crucial for cell cycle re-entry, DNA replication and mitosis. Dephosphorylated pRB binds to E2Fs and inhibits transcription of E2F target genes either by sequestration and inhibition of E2F cell cycle “activators” (E2F1–E2F3), or by formation of pocket protein complexes with “inhibitors” (E2F4–E2F8), which bind to E2F-responsive promoters and repress their transcription [7]. Accordingly, transcriptional repression of pRB activity prevents G1/S progression and promotes cell quiescence.

In mice, Rb heterozygous mutations lead to early onset and increased incidence of endocrine neoplasma including pituitary, thyroid and adrenal tumors [8], [9]. The 100% penetrance of pituitary tumors in Rb+/− mice [8] is partially reversed in Rb+/−; E2f4−/− double mutants, implicating the Rb/E2f4 pathway in pituitary tumorigenesis and also suggesting an E2F4 oncogenic activity [9]. E2F4 is also known as a key regulator associated with p130 in G0/G1 to promote quiescent G0 and terminal differentiation [10], [11]. E2f4 null mice often die shortly after birth with defects of terminal differentiation resulting from an inability to establish cell cycle quiescence [12]. In response to cell cycle re-entry, E2F4 switches from p130 [10], [13] to pRB [10], [14] and p107 [10], [14], [15], which inhibit E2F4 transactivation. Additionally, E2F4 overexpression has been shown to promotes cell proliferation and transformation [14], [15], which prevents growth arrest mediated by p130 [13].

Pituitary development and physiology are conserved in zebrafish [2]. Novel insights into developmental mechanisms have been obtained by in vivo analysis of transgenic zebrafish expressing GFP and RFP driven by regulatory elements of zebrafish pomc [16] and prl [17], respectively. Through a forward genetic screen for novel zebrafish genes regulating adenohypophyseal pomc gene expression, we identified and characterized a mutant that harbors a nonsense mutation in usp39, leading to expansion of all adenohypophyseal cell lineages.

Usp39 encodes a conserved protein termed Sad1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and a 65 kDa (65K) SR-related protein in humans [18], [19]. Both yeast Sad1p and the 65K SR-related protein in humans are involved in assembly of the spliceosome, the RNA splicing machinery [18], [19]. RNA splicing is crucial for eukaryotic gene expression and defective splicing can be detrimental since it leads to an altered genetic message [20]. The spliceosome consists of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), U1, U2, U4, U5 and U6 as well as a large number of non-snRNP proteins [20]. The yeast Sad1p is involved in splicing in vivo and in vitro and in the assembly of U4 snRNP to U6 snRNP [18], while human 65K SR-related protein is essential for recruitment of the tri-snRNP to the pre-spliceosome and is known as a tri-snRNP-specific protein [19], [21]. Additionally, Usp39 is also classified as a deubiquitinating enzyme but lacks protease activity due to absence of key active-site residues of cysteine and histidine [18], [19], [22].

In the present study, we aimed to define novel pathways regulating pituitary development through study of an usp39 mutation. Using microarray gene expression profiling followed by quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) validation we observed a significant reduction of rb1 expression and increased e2f4, rbl2 (p130) and cdkn1a (p21) expression in mutants. Zebrafish usp39 is predominantly expressed in the brain and represents a novel neuronal splicing factor. We show that zebrafish usp39 mutation leads to an rb1 splicing defect responsible for pituitary expansion. In addition, knockdown of e2f4 partially rescued pomc lineage expansion in usp39 mutants. Our finding that usp39 regulates expansion of all embryonic pituitary cell lineages through the rb1/e2f4 pathway may shed light on mechanisms underlying adult pituitary tumor formation.

Results

The hp689 locus encodes usp39

To isolate genes required for adenohypophysis and hypothalamic development a standard forward genetics method was carried out using a three-generation (F3) screen after mutagenesis with ENU, which mostly induces single nucleotide exchanges at random positions of the genome [23]–[25]. The genetic screen was performed using pomc expression as a specific marker. pomc is expressed in subepithelial pituitary cells, dorsal to the oral ectoderm roof and ventral to the ventral diencephalon. A subset of pomc-expressing cells is also located outside the adenohypophysis, corresponding to β-endorphin-synthesizing cells of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus [2]. In zebrafish, spatial distribution of the six different hormone secreting pituitary cell types is subdivided into three regions along the antero-posterior adenohypophyseal axis of the rostral pars distalis, proximal pars distalis and pars intermedia [2]. pomc is expressed in corticotropes of the rostral pars distalis, in melanotropes of the pars intermedia and in the hypothalamus (Figure 1A).

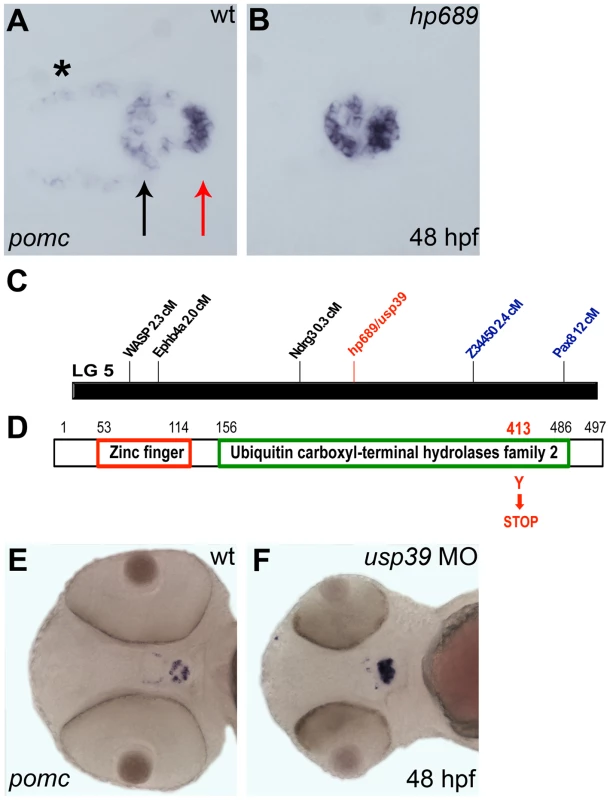

Fig. 1. hp689 is a novel zebrafish gene encoding usp39.

A, B, E, F: Whole-mount in situ hybridization with pomc probe at 48 hpf, ventral view with anterior to left. (A) Wild-type (wt) embryo, pomc is expressed in the rostral pars distalis (black arrow), the pars intermedia (the red arrow), and in the β-endorphin-synthesizing neurons of the hypothalamus (asterisk). The medial domain which lacks pomc expression corresponds to the proximal pars distalis. (B) The hp689 mutant exhibits increased pomc expression in the adenohypophysis, and lower expression in the hypothalamus compared to wt. (C) Genomic map of linkage group 5 (LG5) and position of the hp689 mutation (in red) and mapping markers based on meiotic segregation linkage analysis. hp689 mapped close to markers z34450 and ndrg3 that were located 2.4 cM and 0.3 cM, respectively (see Materials and Methods). (D) Schematic representation of the Usp39 protein, which include a zinc finger and ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolases family 2 domains with the hp689 mutation from a tyrosine to a stop codon indicated in red. (E) Non-injected wt control embryos. (F) wt embryos injected with usp39 MO. Note increased pomc expression and disorganization of the adenohypophysis similar to the increased expression of pomc in usp39 mutant embryos in (B). We isolated an ENU-induced mutant, hp689, which was characterized by reduced hypothalamic but increased pituitary pomc expression at 48-hours post fertilization (hpf) (Figure 1B). In addition, hp689 mutants displayed microcephaly and smaller eyes starting at 33 hpf (data not shown). Using segregation linkage analysis, the hp689 locus was mapped to zebrafish linkage group 5 with a critical interval of 0.03 centimorgan (cM) on marker ndrg3 (Figure 1C, see Materials and Methods). This region contained 7 annotated genes and sequencing of usp39 from mutant embryos revealed a point mutation that converted a TAT codon into a TAA in exon 11, resulting in a premature termination codon rather than a tyrosine amino acid (Figure 1D). PROSITE database search of the Usp39 protein revealed two domains consisting of a zinc finger (ZF_UBP) and a Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolases family 2 (UCH_2_3) region [26]. As a result of the UCH_2_3 domain, Usp39 is classified as a deubiquitinating enzyme. However, it lacks protease activity due to the absence of key active site cysteine and histidine residues [18], [19], [22]. The single allele of hp689 carries a nonsense mutation within the UCH_2_3 region, resulting in a truncated Usp39 protein lacking amino acids after position 412 (Figure 1D).

To confirm that hp689 represents the usp39 mutation, a usp39 antisense morpholino (MO) oligonucleotide targeting the usp39 start codon and consequentially blocking translation was injected into wild-type (wt) embryos [27]. MO injected embryos showed increased pomc expression, similar to the hp689 phenotype (Figure 1F compared to Figure 1B). Furthermore, injection of mRNA encoding wild-type usp39 rescued the mutant phenotype (Table 1), indicating that pituitary pomc upregulation in usp39 mutants results from the nonsense mutation in zebrafish usp39.

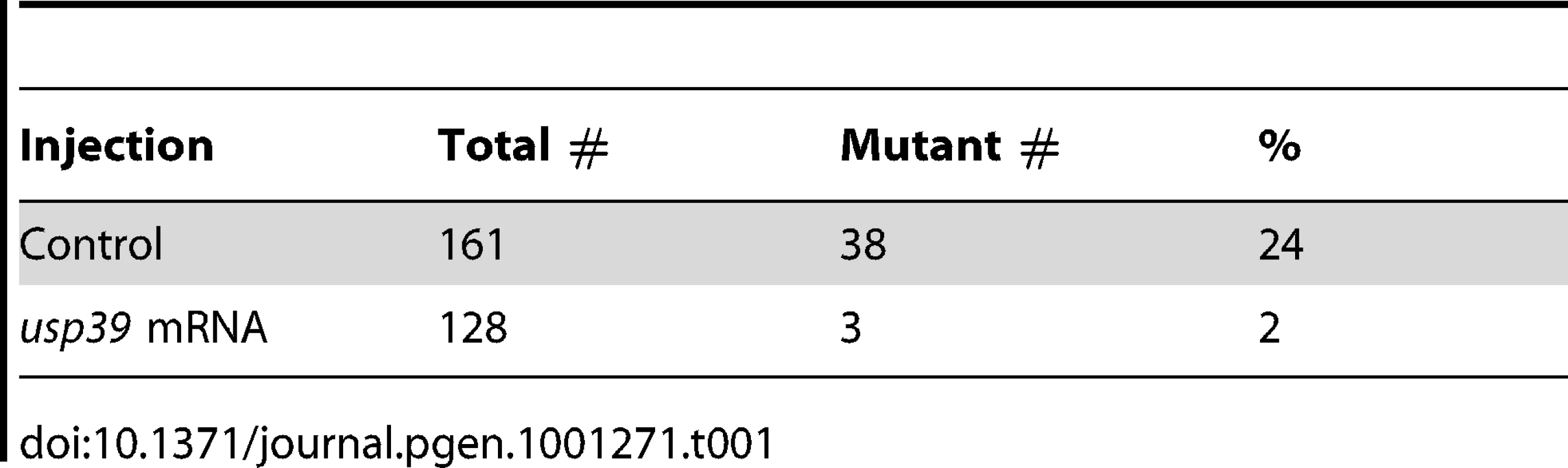

Tab. 1. <i>usp39</i> mRNA overexpression rescues the mutant <i>usp39</i> phenotype.

usp39 is predominantly expressed in the zebrafish embryonic brain

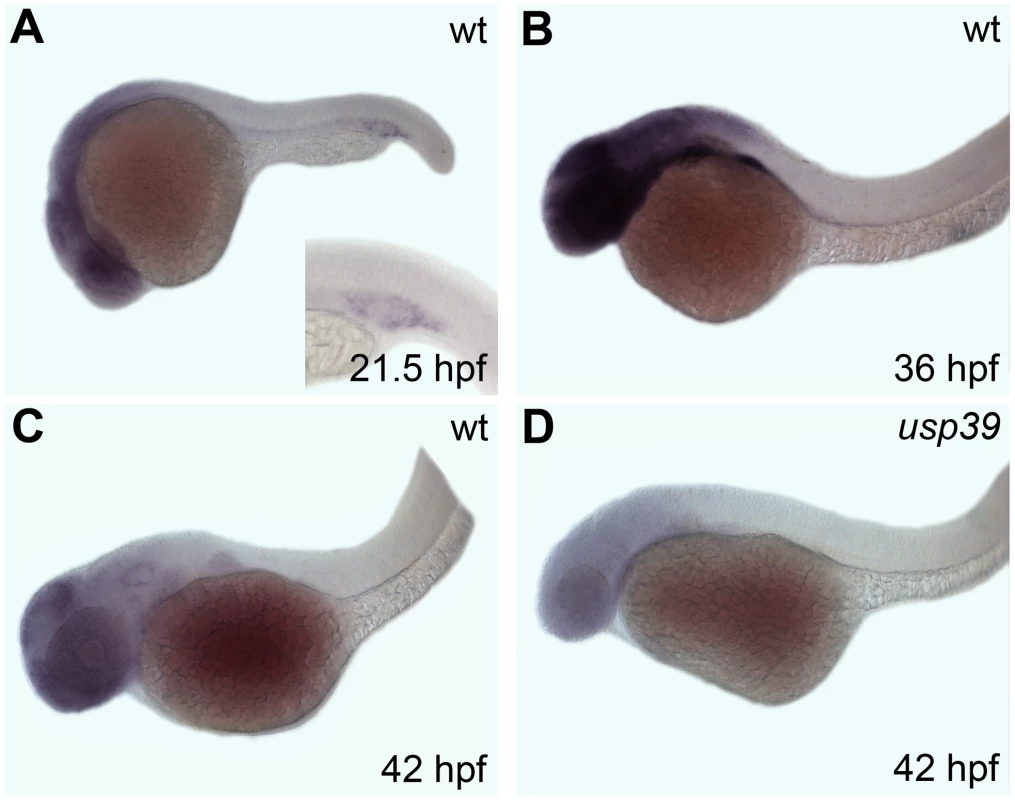

RNA whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed to determine the spatiotemporal expression pattern of usp39 during zebrafish development. Generally weak usp39 expression was detected in early cleavage embryos (data not shown) but tissue specific expression peaked by 36 hpf and decreased by 42 hpf (Figure 2A–2C). Expression was detected predominantly within the brain, including the pituitary region and eyes. At 21.5 hpf, there was also expression in the intermediate cell mass, the site of embryonic zebrafish hematopoiesis (Figure 2A, inset). However, mutants showed persistently lower usp39 expression that was completely lost by 42 hpf (Figure 2D). In addition, loss of usp39 expression by 42 hpf corresponds to the time at which the usp39 mutant embryos fully develop a phenotype of microcephaly, smaller eyes and a pituitary abnormality, indicating the critical time point when usp39 is required for normal development.

Fig. 2. Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis of the zebrafish usp39 expression pattern.

Embryonic ages are shown in the lower right corner, lateral view. A–C: Expression of usp39 in wt is found in the brain and eye region. (A) Inset shows additional usp39 expression in the intermediate cell mass, site of embryonic zebrafish hematopoiesis. (B) usp39 expression is highest at 36 hpf. (C) usp39 expression declines by 42 hpf. (D) The expression pattern of usp39 in usp39 mutants is lower in all stages; expression at 42 hpf is depicted. Pituitary cell lineage expansion in usp39 mutants

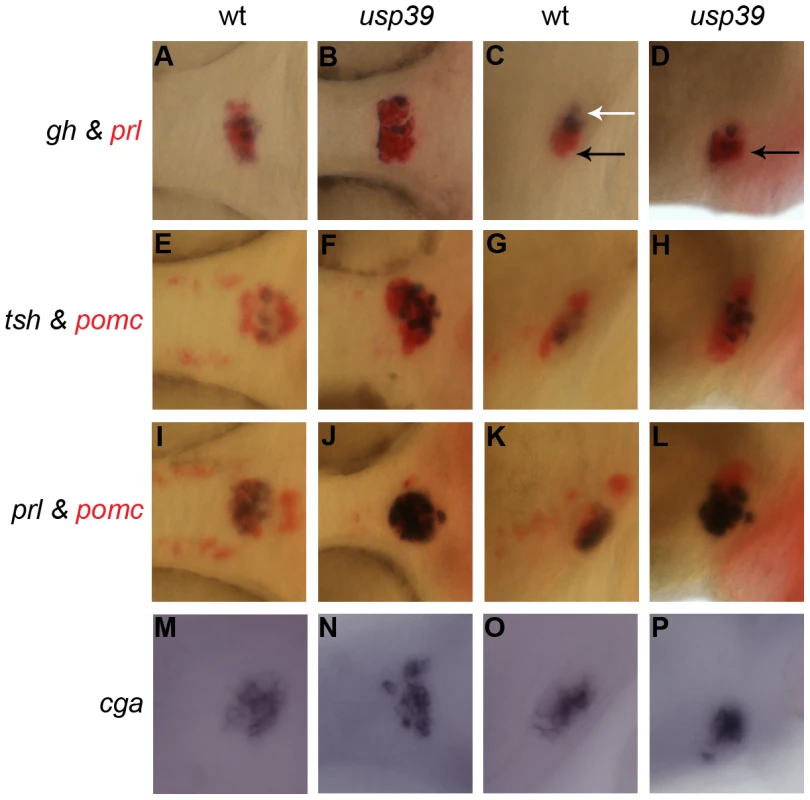

The zebrafish adenohypophysis consists of six different hormone-secreting cell types distributed along the anterior-posterior axis: lactotropes and corticotropes are located anteriorly in the rostral pars distalis, thyrotropes, gonadotropes and somatotropes are found medially in the proximal pars distalis whereas melanotropes are situated posteriorly in the pars intermedia (Figure 3). To determine if additional pituitary lineages are affected by the usp39 mutation, we performed double color RNA in situ hybridization analysis with combinatory pituitary lineage specific marker genes pomc, gh, prl, tsh, and with cga that encodes the glycoprotein α-subunit heterodimerizing with TSHβ, LHβ, or FSHβ subunit [2], [16]. This analysis revealed expansion of all the analyzed cell lineages without apparent cell fate transformation in the usp39 mutant pituitary at 48 hpf (Figure 3A–3P). Cell expansion was most marked in corticotropes and lactotropes, indicating that usp39 is important for regulating embryonic pituitary cell populations (Figure 3B, 3D, 3F, 3H, 3J, and 3L).

Fig. 3. usp39 mutation lead to expansion of all pituitary cell lineages at 48 hpf as indicated by pituitary hormone markers.

A–L: Whole-mount double in situ hybridization with probes indicated on the side. usp39 mutant embryos exhibit higher expression of all pituitary hormone markers compared to wild-type (wt) embryos. Spatial distribution of prl, tsh, pomc and cga are normal in the usp39 mutant. (A, B, E, F, I, J, M, and N) ventral view and (C, D, G, H, K, L, O, and P) lateral view, with anterior to the left. Columns 1 (A, E, I, and M) and 3 (C, G, K and O) show wt siblings; columns 2 (B, F, J, and N) and 4 (D, H, L, and P) show usp39 mutant embryos. A–D: gh (purple) and prl (red) transcripts. (C) The spatial distribution of gh is normally found in the proximal pars distalis (white arrow) and prl is found in the rostral pars distalis (black arrow). (D) Note the spatial distribution of gh in the usp39 mutant; gh is abnormally expressed in the rostral pars distalis (black arrow). E–H: tsh (purple) and pomc (red) transcripts. I–L: prl (purple) and pomc (red) transcripts. M–P: Whole-mount in situ hybridization with cga transcript. Pituitary lineage expansion in usp39 mutants is independent of hypothalamic releasing hormone and dopamine signals

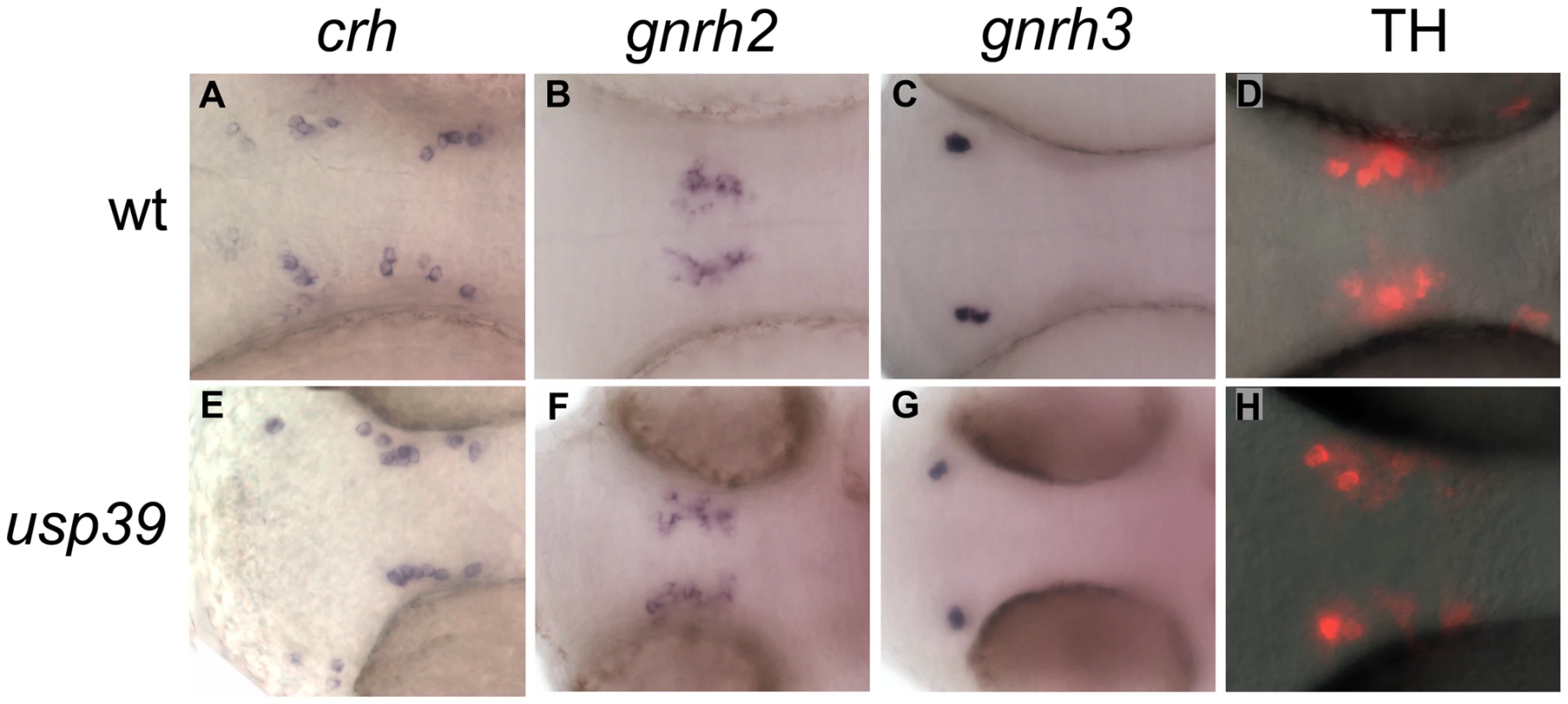

We examined expression of hypothalamic regulators to investigate whether pituitary lineage expansion in usp39 mutants is due to altered hypothalamic neuroendocrine input to the adenohypophysis. One of the primary hypothalamic inhibitory mechanisms controlling pituitary homeostasis is dopamine (DA) released from tuberoinfundibular neurons (TIDA). Pituitary lactotrophs are almost exclusively regulated by tonic inhibition of dopamine, which inhibits lactotroph proliferation, PRL gene expression and secretion by activating D2 dopamine receptor subtype (Drd2) [28]. We therefore processed 48 hpf whole-mount embryos for immunocytochemistry using an antibody against tyrosine-hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme of dopamine synthesis in TIDA neurons, and detected no significant change of hypothalamic dopaminergic neurons in usp39 mutants compared with wt siblings (Figure 4D and 4H). Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) as well as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulates cell growth, hormone synthesis and secretion of pituitary corticotropes and gonadotropes, respectively [29], [30]. However, usp39 mutants exhibit no altered crh or gnrh expression (Figure 4E–4G). Therefore, pituitary lineage expansion of usp39 mutants occurs independently of major hypothalamic neuroendocrine signals.

Fig. 4. The hypothalamic releasing hormone and dopamine signals are unaffected in usp39 mutants.

A–C and E–G: Whole-mount in situ hybridization with hypothalamic probes at 48 hpf, ventral view. (A–C) wild-type (wt) embryos. (E–G) usp39 mutant embryos. Expression of hypothalamic markers crh, gnrh2, and gnrh3 did not change. D and H: Immunocytochemistry with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody at 48 hpf, ventral view. (H) Expression of TH in usp39 mutant embryos did not change. Pituitary transcription factors are upregulated during late stage of development in usp39 mutants

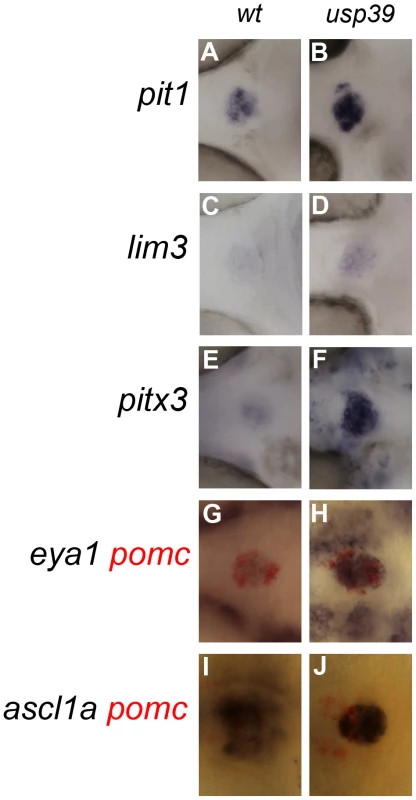

We next studied expression of transcription factors important for adenohypophyseal development. Lim3/Lhx3 is one of the earliest pituitary specifying transcription factors and is required for progenitor proliferation and survival [2]. Pitx3, a Pitx/Rieg homeodomain protein, defines the pituitary placode and is required for Lim3 expression [2]. Pit1 is a Pou domain homeoprotein and a lineage-determining factor for somatotropes, lactotropes and thyrotropes [2]. The Drosophila eye absent homolog, eya1, is required for specification of gonadotropes, corticotropes, and melanotropes [2]. Zebrafish mutation of ascl1a, a homolog of the Drosophila MASH1 [31], resulted in failed endocrine differentiation of all adenohypohyseal cell types [2]. Expression of these zebrafish pituitary regulators coincides within the pituitary placode of the anterior neural ridge (ANR) at 20-somite stage (18 hpf) and persists in the adenohypophyseal anlage throughout 48 hpf (for eya1), or even later (for pit1, lim3, pitx3, and ascl1a). At 36 hpf, usp39 mutants exhibited no increased expression of lim3, however pit1, lim3, pitx3, eya1 and ascl1a showed a significant expression difference at a later state (48 hpf) compared with wt (Figure S1, Figure 5). These results suggest that the usp39 mutation did not affect initial embryonic pituitary progenitor specification but induced their expansion after 36 hpf.

Fig. 5. Loss of usp39 leads to pituitary expansion as indicated by increased expression of pituitary transcription factors.

A–F and G–J: Single and double in situ hybridization with probes indicated on the side, at 48 hpf, ventral view, anterior to the left. (A, C, E, G, and I) wild-type (wt) embryos. (B, D, F, H, and J) usp39 mutant embryos have increased pituitary expression of pit1, lim3, pitx3, eya1, and ascl1a. usp39 mutants exhibit altered expression of cell cycle regulators including rb1 and e2f4

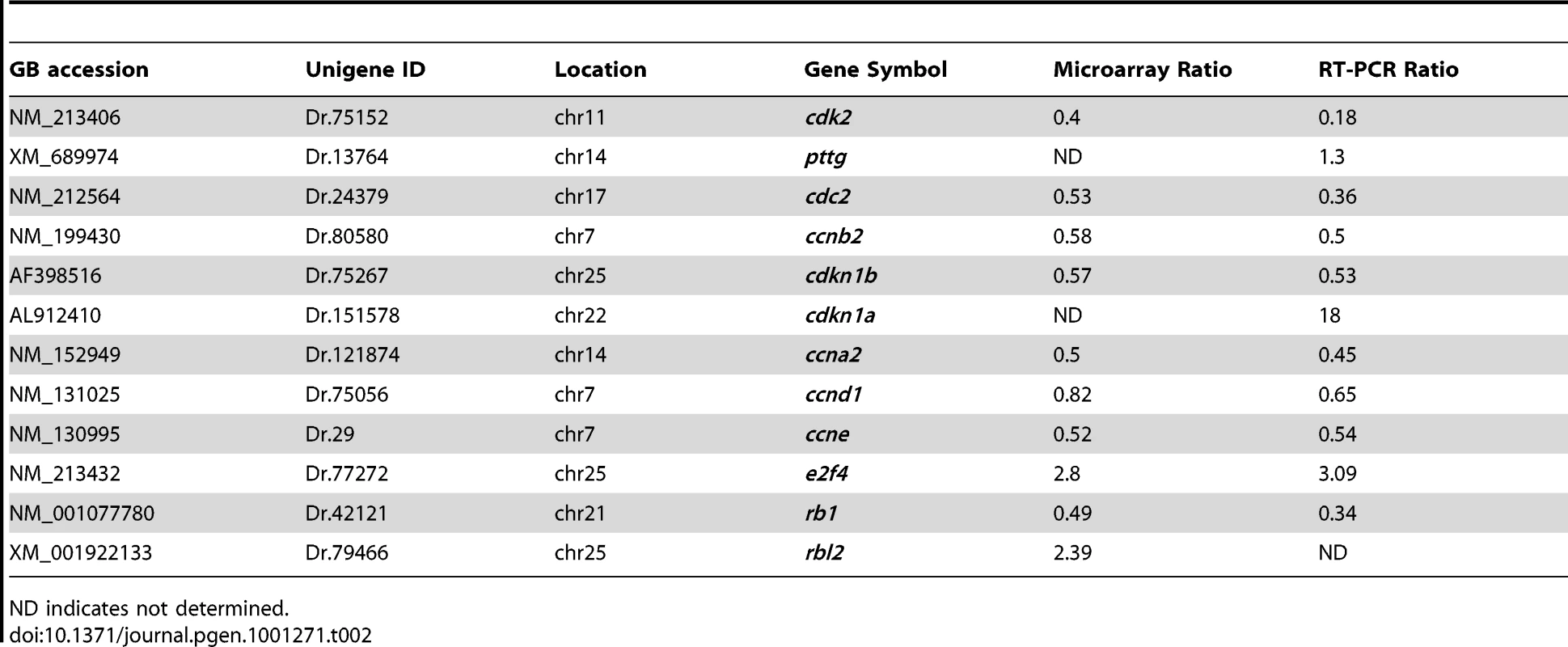

To distinguish whether the altered pituitary signals detected by whole-mount in situ hybridization is due to pituitary hyperplasia or higher expression of pituitary hormone levels we crossed usp39 +/ − fish to POMC-GFP transgenic fish [16]. After identifying mutant usp39 in the POMC-GFP background, we sectioned usp39 and wt whole embryos and performed immunocytochemistry with anti-GFP followed by cell number quantification. Our results demonstrated that there was an increase in the number of POMC-GFP-positive cells in usp39 mutants compare to wt (Figure S2A–S2F). In addition, counting the nuclei stained with DAPI indicated an increase in the total number of pituitary cells in the usp39 mutant compare to wt embryos (Figure S2G). We carried out a BrdU incorporation study and demonstrated that the increase in pituitary cell number seen in usp39 mutants was due to an increase in proliferation (Figure S2H and S2I). It is well established that cell cycle dysregulation is associated with pituitary pathology in animal models and human disease [32]. However, little is known about mechanisms underlying the sensitivity of differentiated pituitary cell lineages to cell cycle regulators. We therefore performed a microarray analysis and focused on cell cycle regulators, 11 of which were confirmed for altered expression in usp39 mutants by quantitative RT-PCR. In summary, expression levels of 3 genes were increased including e2f4, rbl2 (p130) and cdkn1a (p21) and expression of the other 8 cell cycle genes including rb1 were downregulated (Table 2; Figure S3).

Tab. 2. Summary of cell cycle genes affected in usp39 mutant embryos from microarray hybridization and confirmed with quantitative RT-PCR.

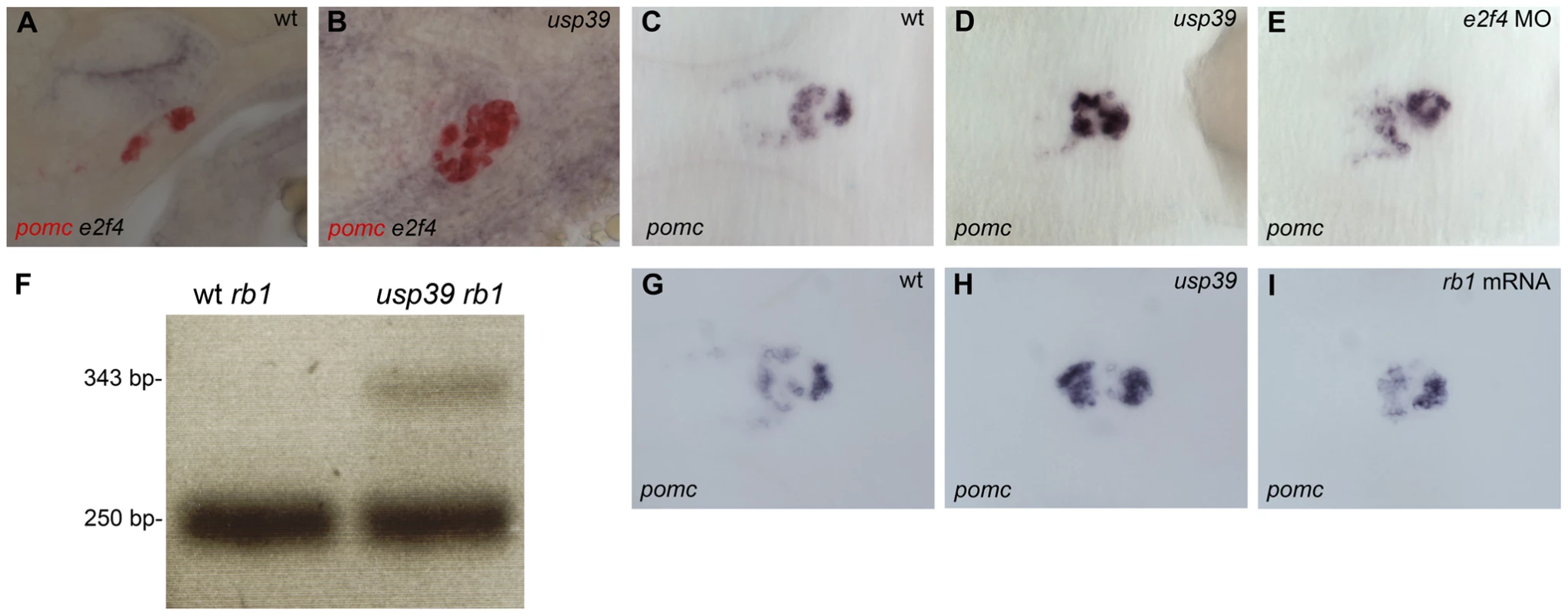

ND indicates not determined. We further examined e2f4 expression by RNA whole-mount in situ hybridization, which confirmed its upregulation in the adenohypophysis of usp39 mutants compared to wt embryos (Figure 6A and 6B). To investigate whether e2f4 upregulation is responsible for adenohypophysis lineage expansion, we injected embryos with antisense MO oligonucleotide to knockdown e2f4 function. The overall usp39 mutant phenotype maintained after e2f4 MO injections, which resulted in partial reversal of pomc expansion in e2f4-MO-injected usp39 embryos at 48 hpf compared to control embryos (Figure 6C–6E, mutant N = 20, ∼60% showed rescue). The phenotypic rescue of usp39 embryos by e2f4-MO is pituitary specific since pomc hypothalamic expression was not altered. In addition, we analyzed prl expression and a partial rescue was also observed in e2f4-MO-injected usp39 embryos (Figure S4). These results indicate that loss of usp39 results in increased e2f4 expression, which at least partially contributes to the observed pomc lineage expansion in zebrafish adenohypophysis.

Fig. 6. Loss of usp39 leads to aberrant Rb1 mRNA splicing and increased pituitary e2f4 expression.

A,B: Whole-mount double in situ hybridization of pomc in red and e2f4 in purple at 48 hpf, lateral view. (A) Wild-type (wt) embryo. (B) Expression of e2f4 is higher and colocalizes with pomc expression in usp39 mutant embryos. C–E and G–I: Whole-mount in situ hybridization of pomc at 48 hpf, ventral view, anterior to left. (C) wt. (D) usp39 mutant. (E) e2f4-MO-injected usp39 mutant embryos showed partial pomc rescue similar to observed in wt embryonic pomc expression (C). F: PCR product with primers designed for region between exon 3 and exon 4 of rb1 in wt and usp39 mutant embryos. wt embryos only contain a 250 base pair (bp) PCR band, indicating that the intron was correctly spliced out. However, in the usp39 mutants there is an additional 343 bp band that contains the intron sequence. G–I: (G) wt. (H) usp39 mutant. (I) rb1 mRNA-injected usp39 mutants exhibit partial rescue of pomc expression similar to wt embryos (G). rb1 splicing defect contributes to the usp39 mutant phenotype

Since usp39 is known to be an essential component of the RNA splicing machinery, the more than 70% decrease of rb1 expression in usp39 mutants may be attributed to defects in RNA splicing. We therefore examined rb1 splicing status by PCR amplification using primers corresponding to each end of 19 out of 27 exons of the rb1 gene. Primers designed for exon 3 and exon 4 resulted in a PCR product of 250 base pairs (bp) in wt and mutant embryos, representing a correctly spliced mRNA fragment. However, mutant embryos exhibited an additional larger PCR product of 343 bp (Figure 6F). Further DNA sequence analysis revealed that the 343 bp PCR product derived from usp39 mutants contain the sequence of an unspliced intron between exon 3 and 4. The splicing defect would lead to a premature stop codon in the intron between exon 3 and exon 4 of rb1 (data not show), which would lead to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. We then performed an rb1 mRNA overexpression experiment in usp39 mutants and observed partial rescue of the adenohypophysis phenotype (Figure 6I, mutant N = 34, ∼50% showed rescue), validating the importance of usp39-mediated rb1 mRNA splicing in controlling pituitary lineage expansion during development. In addition, we performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis on the rb1 mRNA-injected usp39 embryos and observed a 30% reduction of e2f4 expression compared to control uninjected usp39 mutants (Figure S5A), indicating that e2f4 upregulation in usp39 mutant is secondary to Rb1 loss of function. Futhermore, this was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis on the e2f4 MO-injected usp39 embryos and observed that there was no change in rb1 expression compared to control uninjected usp39 mutants (Figure S5B).

Discussion

In this study, we identified and functionally characterized the zebrafish usp39 gene, important for human and yeast pre-mRNA splicing [18], [19]. We demonstrated that loss of usp39 results in defects in rb1 mRNA splicing and downregulation of rb1 expression (Figure 6F, Table 2; Figure S3). Both loss of usp39 as well as rb1 downregulation in usp39 mutants may be explained by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay due to a premature termination codon. RB1 gene mutation leading to pre-mRNA splicing defects have been shown in human cancers [33] and our study suggests a novel mechanism resulting in rb1 splicing defects due to a usp39 mutation.

Control of pituitary progenitor cell proliferation in concert with terminal differentiation during embryonic pituitary development is poorly understood. In mouse pituitary primordia, attenuated proliferation of cells destined to become hormone-expressing cell types occurs days before lineage-specific hormones start to express [34]. In contrast, zebrafish pituitary terminal differentiation is initiated while progenitor cells are still organized in a placodal fashion in the anterior neural ridge [2], [16]. The usp39 mutants demonstrated no early difference of adenohypophyseal primordia compared with wt, until 48 hpf when terminally differentiated cells had already migrated to a mature pituitary destination. Pituitary lineage expansion became apparent at 48 hpf in usp39 mutants, as indicated by expression of pituitary transcription factors and lineage-specific hormone markers (Figure 3 and Figure 5). Similarly, it was found that inactivation of Rb in the small intestines of mice results in increased proliferation of differentiated cells in the villus but not in the stem cells located in the base of the crypts [35]. Therefore, our results suggest that loss of usp39 does not affect pituitary specification, initiation and early differentiation, but does induce lineage expansion at later development stages when the cells are terminally differentiated.

Our results indicate that e2f4 overexpression has at least a partial but direct affect on adenohypophyseal cell lineages in usp39 mutants, as e2f4 antisense MO knockdown partially reverted the pituitary phenotype of usp39 mutants (Figure 6 and Figure S4). The usp39 mutants demonstrated persistently upregulated e2f4 expression, although molecular mechanisms leading to e2f4 overexpression remain to be determined. Overexpression of e2f4 may exert oncogenic activity promoting cell-cycle progression as previously indicated in pituitary, thyroid, lung neuroendocrine hyperplasia [36], intestinal crypt cells, colorectal cancer cells [37] as well as in prostate cancer [38]. We demonstrated an increase of POMC-GFP-positive cells in the usp39 mutant embryos compare to wt (Figure S2). Consequently, e2f4 upregulation in usp39 mutants may contribute to increased proliferation of terminally differentiated pituitary cells leading to lineage expansion as seen in our BrdU studies (Figure S2). On the other hand, E2F4 is a key regulator associated with p130 to promote quiescent G0 and terminal differentiation [13]. The cyclin kinase inhibitor, p21, inhibits decay of the E2F4-p130 complex, promotes senescence and restrains growth, contributing to the benign propensity of pituitary adenomas [39], [40]. Our microarray and quantitative RT-PCR data showed increased cdkn1a (p21), e2f4 and rbl2 (p130), which may indicate an enhanced quiescent G0 phase inducing terminal differentiation and lineage expansion in usp39 mutants.

Although the focus of this study was the role of usp39 in pituitary development, this gene is also expressed in neuronal tissues and when mutated, embryos show microcephaly and smaller eyes, therefore usp39 function may not be restricted to pituitary development. We propose that usp39, through targeting a set of key regulatory genes by modulating RNA splicing, should have a broader role in regulating neuronal cell lineage development. Although how usp39 controls target mRNA splicing remains to be fully elucidated, the usp39 ortholog of the yeast protein Sad1p was found to have two roles: it is involved in the assembly of U4 snRNP to U6 snRNP and is also required for splicing [18]. Furthermore, previous reports have shown that a zebrafish RNA splicing factor, p110, is required for U4 and U6 snRNPs recycling, and a mutation in p110 leads to thymic hypoplasia as well as eye and exocrine pancreas defects [41]. In addition, microarray analysis of p110 mutant shows a compensatory mechanism inducing increased expression of other splicing factors, which may reverse the recycling defects [41]. We observed a similar result in our microarray analysis with upregulation of other U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP proteins, which suggests a compensatory mechanism in usp39 mutants (Table S2 and Figure 6F). The human tri-snRNP specific proteins include 65K, 110K and 27K are encoded by USP39, SART1 and SNRNP27, respectively and play a similar role in splicing [21]. Specifically, both sart1 and snrnp27 were found to be upregulated in our microarray analysis demonstrating a compensatory role due to the absence of usp39 (Table S2). Additionally, we discovered another neuronal gene, otx2, which was also significantly downregulated due to a splicing defect (Figure S6). However, otx2 mRNA overexpression in usp39 mutant embryos did not rescue the pituitary phenotype (data not shown), validating that the Rb1/E2F4 pathway is more specific to pituitary regulation. A systematic analysis of splicing variation of all mRNA transcripts affected by usp39 deficiency will uncover additional pathways that control neuronal and organ development by RNA splicing mechanisms.

In summary, our findings indicate that usp39 plays an important role in pituitary development by regulating rb1 and e2f4. Loss of usp39 leads to pituitary cell lineage expansion through rb1 downregulation due to a splicing defect. In addition, e2f4 overexpression contributes to increased pituitary cell mass, likely as a result of increased terminal differentiation or proliferation. Our studies reveal a novel role of usp39-mediated mRNA splicing of rb1 in pituitary cell growth control, which is critical for maintaining embryonic pituitary homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis and fish husbandry

Mutagenesis with ENU was performed as described [25]. Mutants including hp689 were identified from random sibling crossing from F2 families giving rise to 25% altered pomc expression at 48 hpf.

Genetic mapping

Linkage analysis was established by mating hp689 heterozygote in an AB background to the WIK strain. Random sibling crossing identified F1 carriers, and mutants were identified phenotypically in F2 offspring at 48 hpf. We analyzed linkage between hp689 and simple sequence-length polymorphism markers [42]. Linkage analysis found the z34450 marker located 2.4 cM (4 recombinations in 168 meiosis), G40879 marker located 0.3 cM (1 recombination in 288 meioses), ephb4a located 2.2 cM (5 recombinations in 114 meioses) and marker ndrg3 located 0.3cM (1 recombination in 310 meioses) in linkage group 5 (LG5) linked to the mutation.

Genotyping of usp39 mutants

Total RNA derived from 48 hpf mutant and wild-type embryos was prepared by TRIZOL (Invitrogen) reagent extraction and used to generate cDNA by SuperscriptII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with oligoDT primers (Roche Applied Science). The region near marker ndrg3 contain 7 genes and sequencing the usp39 full-length cDNA with primers CGCGTTCACAGTGCGTTC and TTTCTCATTGTGTGTTTTACTCAGTC from mutant embryos revealed a point mutation that converted a TAT codon into a TAA in Exon 11, resulting in a premature termination codon rather than a tyrosine residue.

Cloning of the zebrafish usp39 cDNA

The usp39 full-length cDNA fragment was generated from wild-type embryos as described above and subcloned into pCRII-TOPO.

Morpholino, mRNA synthesis, and microinjection

Antisense MO'swere injected into embryos as described [27]. The sequence of usp39 MO is 5′-TTCACGCCTCTGATCATATTTTAAG-3′ and for e2f4 MO is 5′-ACTCTCCCATCGCTCCCAGGTCGTT-3′ (Gene Tools, Inc). One - to two-cell stage embryo was injected at 3.9 ng for the usp39 MO and 1.4 ng of e2f4 MO. The usp39 overexpression construct was generated by subcloning full-length usp39 cDNA from vector pCRII-usp39 into the EcoRI site of vector pXT7. The pXT7-usp39 vector was linearized with XbaI and mRNA was transcribed using T7 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). The rb1 overexpression construct was generated by subcloning full-length rb1 cDNA (Accession Number: BC125966, Openbiosystems) to vector pCS2+ in the StuI and XhoI sites. The rb1-pCS2+ vector was then linearized with XbaI and the mRNA transcribed using Sp6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). mRNA injections were performed at the one-cell stage at approximately 200 pg for usp39 and 267 pg for rb1.

RNA in situ hybridization

Single and double whole-mount in situ hybridizations were performed as described [43]. usp39 antisense probe was synthesized from pCRII-usp39 with Sp6 RNA polymerase after linearization with NotI. The following riboprobes were generated from cDNAs as described: pomc [16], gh, prl, tshβ, lim3, pit1 and pitx3 [2], eya1 [44], crh [29], gnrh2 and gnrh3 [30], and ascl1a [31]. Full-length cDNA for cga (Accession Number: BC116611) and e2f4 (Accession Number: BC056832) were purchased from Openbiosystems. e2f4 was subcloned to pCRII-TOPO vector and linearized with SpeI whereas the cga-Express1 was linearized with EcoRI and riboprobes were synthesized with T7 RNA polymerase.

Antibody staining

Whole-mount antibody staining was performed using a rabbit anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) primary antibody at 1∶200 dilution (Chemicon) and detected with an Alexa (A594)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody at 1∶200 dilution (Molecular Probes).

Microarray analysis

Total RNA from 48 hpf usp39 mutants and wild-type embryos was prepared and microarray performed as described [45].

Quantitative RT-PCR

cDNA was generated as described above. RT-PCR was performed using the iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad) and the iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad). Relative cDNA amounts were calculated using the iCycler program (BioRad) and gene expression levels measured by the 2−ΔΔCT method [46], comparing usp39 mutant embryos to WT controls, with β-actin used as the reference gene. This procedure was repeated three times for each gene with three different experimental cDNA pools. At least three replicates were used for each cDNA pool. Gene expression was reported as relative expression change in usp39 mutants over WT embryos ± standard error (for primer sequences see Table S1).

Retinoblastoma splicing primers

cDNA was generated as described above. We designed primers that covered the exon and intron region of Exon 3 to Exon 4 of the rb1 gene. The primers used were: CCGTATTCGAACAGACAGCA and GGTAGAGGGCCAAAGTCACA.

Vibratome sections

After whole-mount in situ hybridization, embryos were washed in PBS, manually deyolked, and mounted on their lateral side in 4% low melting agarose (Fisher Scientific) in PBS. Thin 100 µm slices were cut using a vibratome (Vibratome 1000 Plus) and sections were stored in PBS until imaging.

Image acquisition and processing

The in situ hybridization and the vibratome sections were imaged with an Axiocam digital camera (Zeiss) mounted on an Axioplan 2 compound microscope (Zeiss). OpenLab 4.0.2 software (Improvision) was used to capture all images; Photoshop CS4 software (Adobe Systems) was used for further image processing.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. WellsS

MurphyD

2003 Transgenic studies on the regulation of the anterior pituitary gland function by the hypothalamus. Front Neuroendocrinol 24 11 26

2. PogodaHM

HammerschmidtM

2007 Molecular genetics of pituitary development in zebrafish. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18 543 558

3. MelmedS

2003 Mechanisms for pituitary tumorigenesis: the plastic pituitary. J Clin Invest 112 1603 1618

4. KrudeH

BiebermannH

GrutersA

2003 Mutations in the human proopiomelanocortin gene. Ann N Y Acad Sci 994 233 239

5. DrouinJ

BilodeauS

ValletteS

2007 Of old and new diseases: genetics of pituitary ACTH excess (Cushing) and deficiency. Clin Genet 72 175 182

6. MelmedS

2009 Acromegaly pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Invest 119 3189 3202

7. ChenHZ

TsaiSY

LeoneG

2009 Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat Rev Cancer 9 785 797

8. JacksT

FazeliA

SchmittEM

BronsonRT

GoodellMA

1992 Effects of an Rb mutation in the mouse. Nature 359 295 300

9. LeeEY

CamH

ZieboldU

RaymanJB

LeesJA

2002 E2F4 loss suppresses tumorigenesis in Rb mutant mice. Cancer Cell 2 463 472

10. MobergK

StarzMA

LeesJA

1996 E2F-4 switches from p130 to p107 and pRB in response to cell cycle reentry. Mol Cell Biol 16 1436 1449

11. RaymanJB

TakahashiY

IndjeianVB

DannenbergJH

CatchpoleS

2002 E2F mediates cell cycle-dependent transcriptional repression in vivo by recruitment of an HDAC1/mSin3B corepressor complex. Genes Dev 16 933 947

12. HumbertPO

RogersC

GaniatsasS

LandsbergRL

TrimarchiJM

2000 E2F4 is essential for normal erythrocyte maturation and neonatal viability. Mol Cell 6 281 291

13. VairoG

LivingstonDM

GinsbergD

1995 Functional interaction between E2F-4 and p130: evidence for distinct mechanisms underlying growth suppression by different retinoblastoma protein family members. Genes Dev 9 869 881

14. GinsbergD

VairoG

ChittendenT

XiaoZX

XuG

1994 E2F-4, a new member of the E2F transcription factor family, interacts with p107. Genes Dev 8 2665 2679

15. BeijersbergenRL

KerkhovenRM

ZhuL

CarleeL

VoorhoevePM

1994 E2F-4, a new member of the E2F gene family, has oncogenic activity and associates with p107 in vivo. Genes Dev 8 2680 2690

16. LiuNA

HuangH

YangZ

HerzogW

HammerschmidtM

2003 Pituitary corticotroph ontogeny and regulation in transgenic zebrafish. Mol Endocrinol 17 959 966

17. LiuNA

LiuQ

WawrowskyK

YangZ

LinS

2006 Prolactin receptor signaling mediates the osmotic response of embryonic zebrafish lactotrophs. Mol Endocrinol 20 871 880

18. LygerouZ

ChristophidesG

SeraphinB

1999 A novel genetic screen for snRNP assembly factors in yeast identifies a conserved protein, Sad1p, also required for pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol 19 2008 2020

19. MakarovaOV

MakarovEM

LuhrmannR

2001 The 65 and 110 kDa SR-related proteins of the U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP are essential for the assembly of mature spliceosomes. EMBO J 20 2553 2563

20. ValadkhanS

2007 The spliceosome: caught in a web of shifting interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol 17 310 315

21. LiuS

RauhutR

VornlocherHP

LuhrmannR

2006 The network of protein-protein interactions within the human U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP. RNA 12 1418 1430

22. van LeukenRJ

Luna-VargasMP

SixmaTK

WolthuisRM

MedemaRH

2008 Usp39 is essential for mitotic spindle checkpoint integrity and controls mRNA-levels of aurora B. Cell Cycle 7 2710 2719

23. DrieverW

Solnica-KrezelL

SchierAF

NeuhaussSC

MalickiJ

1996 A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryogenesis in zebrafish. Development 123 37 46

24. HaffterP

GranatoM

BrandM

MullinsMC

HammerschmidtM

1996 The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development 123 1 36

25. KimHJ

SumanasS

Palencia-DesaiS

DongY

ChenJN

2006 Genetic analysis of early endocrine pancreas formation in zebrafish. Mol Endocrinol 20 194 203

26. BairochA

BucherP

HofmannK

1996 The PROSITE database, its status in 1995. Nucleic Acids Res 24 189 196

27. NaseviciusA

EkkerSC

2000 Effective targeted gene ‘knockdown’ in zebrafish. Nat Genet 26 216 220

28. Ben-JonathanN

HnaskoR

2001 Dopamine as a prolactin (PRL) inhibitor. Endocr Rev 22 724 763

29. ChandrasekarG

LauterG

HauptmannG

2007 Distribution of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the developing zebrafish brain. J Comp Neurol 505 337 351

30. StevenC

LehnenN

KightK

IjiriS

KlenkeU

2003 Molecular characterization of the GnRH system in zebrafish (Danio rerio): cloning of chicken GnRH-II, adult brain expression patterns and pituitary content of salmon GnRH and chicken GnRH-II. Gen Comp Endocrinol 133 27 37

31. AllendeML

WeinbergES

1994 The expression pattern of two zebrafish achaete-scute homolog (ash) genes is altered in the embryonic brain of the cyclops mutant. Dev Biol 166 509 530

32. QueredaV

MalumbresM

2009 Cell cycle control of pituitary development and disease. J Mol Endocrinol 42 75 86

33. ZhangK

NowakI

RushlowD

GallieBL

LohmannDR

2008 Patterns of missplicing caused by RB1 gene mutations in patients with retinoblastoma and association with phenotypic expression. Hum Mutat 29 475 484

34. SeuntjensE

DenefC

1999 Progenitor cells in the embryonic anterior pituitary abruptly and concurrently depress mitotic rate before progressing to terminal differentiation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 150 57 63

35. ChongJL

WenzelPL

Saenz-RoblesMT

NairV

FerreyA

2009 E2f1-3 switch from activators in progenitor cells to repressors in differentiating cells. Nature 462 930 934

36. ParisiT

BronsonRT

LeesJA

2009 Inhibition of pituitary tumors in Rb mutant chimeras through E2f4 loss reveals a key suppressive role for the pRB/E2F pathway in urothelium and ganglionic carcinogenesis. Oncogene 28 500 508

37. GarneauH

PaquinMC

CarrierJC

RivardN

2009 E2F4 expression is required for cell cycle progression of normal intestinal crypt cells and colorectal cancer cells. J Cell Physiol 221 350 358

38. WaghrayA

SchoberM

FerozeF

YaoF

VirginJ

2001 Identification of differentially expressed genes by serial analysis of gene expression in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res 61 4283 4286

39. SmithEJ

LeoneG

DeGregoriJ

JakoiL

NevinsJR

1996 The accumulation of an E2F-p130 transcriptional repressor distinguishes a G0 cell state from a G1 cell state. Mol Cell Biol 16 6965 6976

40. ChesnokovaV

ZonisS

KovacsK

Ben-ShlomoA

WawrowskyK

2008 p21(Cip1) restrains pituitary tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 17498 17503

41. TredeNS

MedenbachJ

DamianovA

HungLH

WeberGJ

2007 Network of coregulated spliceosome components revealed by zebrafish mutant in recycling factor p110. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 6608 6613

42. ShimodaN

KnapikEW

ZinitiJ

SimC

YamadaE

1999 Zebrafish genetic map with 2000 microsatellite markers. Genomics 58 219 232

43. HauptmannG

GersterT

2000 Multicolor whole-mount in situ hybridization. Methods Mol Biol 137 139 148

44. SahlyI

AndermannP

PetitC

1999 The zebrafish eya1 gene and its expression pattern during embryogenesis. Dev Genes Evol 209 399 410

45. GomezGA

VeldmanMB

ZhaoY

BurgessS

LinS

2009 Discovery and characterization of novel vascular and hematopoietic genes downstream of etsrp in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 4 e4994 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004994

46. SchmittgenTD

LivakKJ

2008 Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3 1101 1108

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Composite Effects of Polymorphisms near Multiple Regulatory Elements Create a Major-Effect QTLČlánek Horizontal Transfer, Not Duplication, Drives the Expansion of Protein Families in ProkaryotesČlánek Segregating Variation in the Polycomb Group Gene Alters the Effect of Temperature on Multiple TraitsČlánek Global Analysis of the Impact of Environmental Perturbation on -Regulation of Gene ExpressionČlánek H3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone DeacetylasesČlánek A Mutation in the Gene Encoding Mitochondrial Mg Channel MRS2 Results in Demyelination in the Rat

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Scans Identifies IL18RAP, PTPN2, TAGAP, and PUS10 As Shared Risk Loci for Crohn's Disease and Celiac Disease

- Composite Effects of Polymorphisms near Multiple Regulatory Elements Create a Major-Effect QTL

- Horizontal Transfer, Not Duplication, Drives the Expansion of Protein Families in Prokaryotes

- Genome-Wide Association Study SNPs in the Human Genome Diversity Project Populations: Does Selection Affect Unlinked SNPs with Shared Trait Associations?

- Friedreich's Ataxia (GAA)•(TTC) Repeats Strongly Stimulate Mitotic Crossovers in

- Zebrafish Mutation Leads to mRNA Splicing Defect and Pituitary Lineage Expansion

- Histone H4 Lysine 12 Acetylation Regulates Telomeric Heterochromatin Plasticity in

- Bub1-Mediated Adaptation of the Spindle Checkpoint

- Segregating Variation in the Polycomb Group Gene Alters the Effect of Temperature on Multiple Traits

- Signaling Role of Fructose Mediated by FINS1/FBP in

- RNF12 Activates and Is Essential for X Chromosome Inactivation

- Comparative Study between Transcriptionally- and Translationally-Acting Adenine Riboswitches Reveals Key Differences in Riboswitch Regulatory Mechanisms

- Global Analysis of the Impact of Environmental Perturbation on -Regulation of Gene Expression

- Application of a New Method for GWAS in a Related Case/Control Sample with Known Pedigree Structure: Identification of New Loci for Nephrolithiasis

- H3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone Deacetylases

- A Mutation in the Gene Encoding Mitochondrial Mg Channel MRS2 Results in Demyelination in the Rat

- Transcription Initiation Patterns Indicate Divergent Strategies for Gene Regulation at the Chromatin Level

- The Transposon-Like Correia Elements Encode Numerous Strong Promoters and Provide a Potential New Mechanism for Phase Variation in the Meningococcus

- Proteins Encoded in Genomic Regions Associated with Immune-Mediated Disease Physically Interact and Suggest Underlying Biology

- A Novel RNA-Recognition-Motif Protein Is Required for Premeiotic G/S-Phase Transition in Rice ( L.)

- The Mucin-Like Protein OSM-8 Negatively Regulates Osmosensitive Physiology Via the Transmembrane Protein PTR-23

- Genome Sequencing and Comparative Transcriptomics of the Model Entomopathogenic Fungi and

- Rnf12—A Jack of All Trades in X Inactivation?

- Joint Genetic Analysis of Gene Expression Data with Inferred Cellular Phenotypes

- Evolutionary Conserved Regulation of HIF-1β by NF-κB

- Quaking Regulates Expression through Its 3′ UTR in Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- H3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone Deacetylases

- Evolutionary Conserved Regulation of HIF-1β by NF-κB

- Rnf12—A Jack of All Trades in X Inactivation?

- Joint Genetic Analysis of Gene Expression Data with Inferred Cellular Phenotypes

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání